Scottish Budget 2025-26

This briefing considers the Scottish Government's spending and tax plans for 2025-26. More detailed presentation of the budget figures can be found in our budget spreadsheets. Infographics and supporting analysis provided by Andrew Aiton, Kayleigh Finnigan, Fraser Murray and Maike Waldmann.

Executive Summary

Minority government means this is likely not the end of this year’s budget story

Scottish Budget 2025-261 comes in a changed political environment resulting from the collapse of the SNP-Green power sharing arrangement earlier this year. It means that for the first time during this parliamentary session, the Scottish Government is operating as a minority administration.

As such, the publication of these spending and tax proposals is likely an opening hand played by the Scottish Government as it attempts to win the support of at least one opposition party in order to get the Budget passed. The SFC notes in its forecast that the Scottish Government has yet to allocate £1.3 billion in resource funding for this financial year (2024-25). Some of that will have been allocated internally, some may be underspent and put in the Scotland Reserve to smooth pressures in the future. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has said this would be a sensible move. But, it is likely that the Scottish Government has held back some resource for deals with other parties to get this 2025-26 Budget passed.

This is not the end of this year’s budget story!

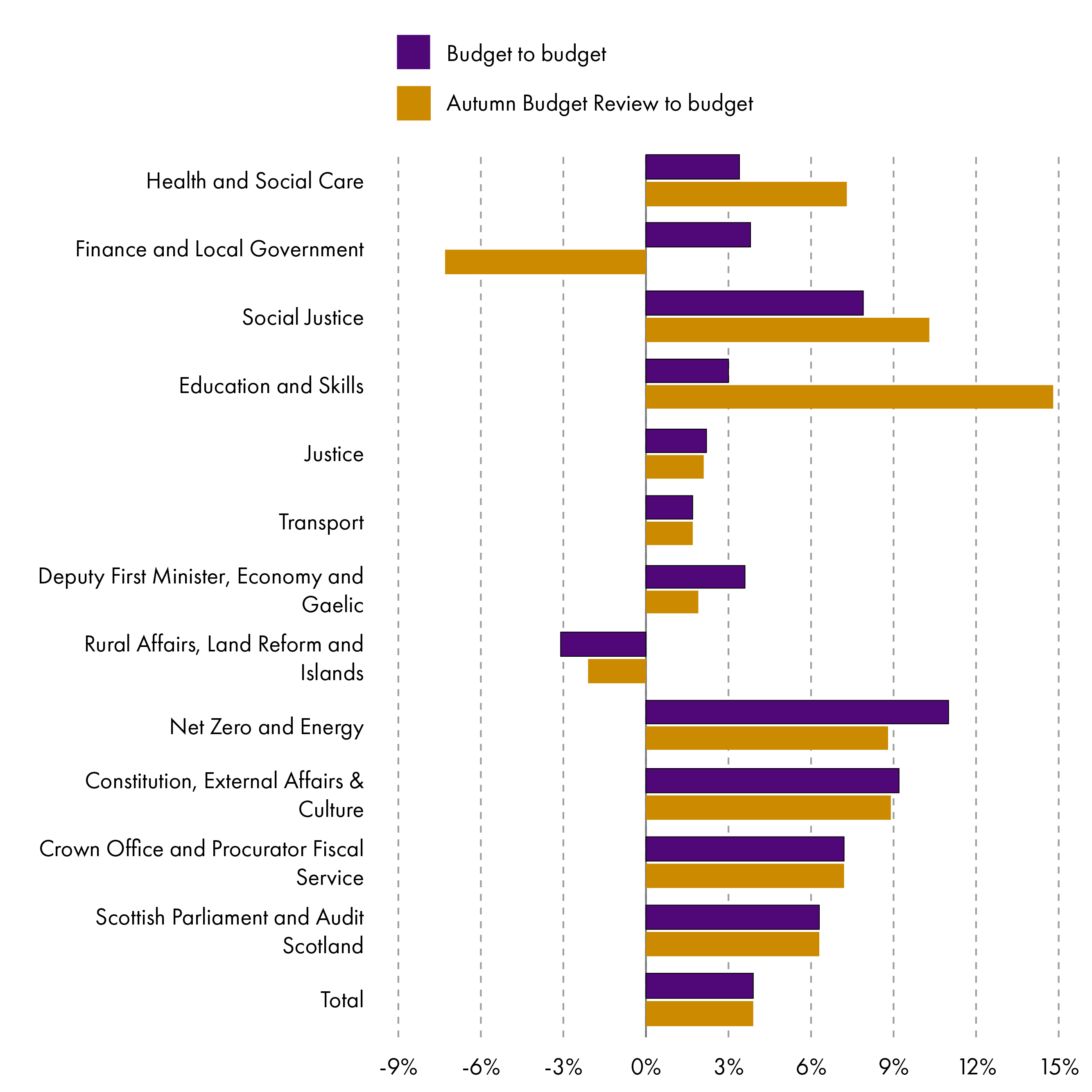

Scope to iron out confusing presentation

The first thing that struck us on looking at the budget numbers was the confusion caused by using the Autumn Budget Revision (ABR) numbers as the 2024-25 baseline (as had been requested by the Finance and Public Administration Committee), but not making adjustments to strip out routine in-year transfers. Although this might sound like a technical point, the use of baselines has a significant and material impact on the Budget narrative as shown in the visual below. This shows that the picture for certain portfolios (in particular the resource budgets for Education and Skills, Health and Local Government) changes dramatically depending on the baseline used. These issues should be addressed by the Scottish Government in time for their next budget.

Another complication this year is that there was a large addition of in-year Barnett consequentials (totaling £1.5 billion) for 2024-25 from the recent UK Budget, nearly all of which have yet to be allocated (and won’t be until the Spring Budget Revision in late January/early February 2025).

Depending on where these are allocated, this has the potential effect of making the percentage increases to certain budget lines for 2025-26 look larger than they will be. All in all, any focus on specific percentage changes to budget lines feels rather meaningless this year, and potentially misleading.

Nowhere are these presentational difficulties more apparent than in the Local Government budget, and the Financial Scrutiny Unit’s (FSU) best forensic investigation skills have been required to get to the bottom of what’s happening to that budget.

Next year’s local government allocation will be over £15 billion for the first time ever, representing a 4.7% real terms increase when compared to the 2024-25 Budget. This may seem like a significant increase but COSLA has already set out its stall arguing that local government needs a total allocation of £15.4 billion next year.

Local government is by far the largest public sector employer in Scotland, and up to 70% of local authority budgets are spent on workforce costs. Meeting the pay demands of its 262,000 workers is one of the biggest financial challenges faced each year by councils. That will be compounded in 2025-26 by the employer National Insurance Contribution (NICs) increases announced by the UK government, and not yet accounted for in this Budget.

Perhaps optimistically, the Cabinet Secretary is of the view that “with record funding [for local government], there is no reason for big increases in council tax next year”. But that’s now a decision for councils themselves to make. A recent survey conducted by the Local Government Information Unit found that around a fifth of local authorities are considering increasing council tax by at least 10% next year. With the Scottish Government having secured freezes and caps for much of the last 17 years, increases of this magnitude could come as quite a shock to many households, especially as levels of satisfaction with council services are not particularly high.

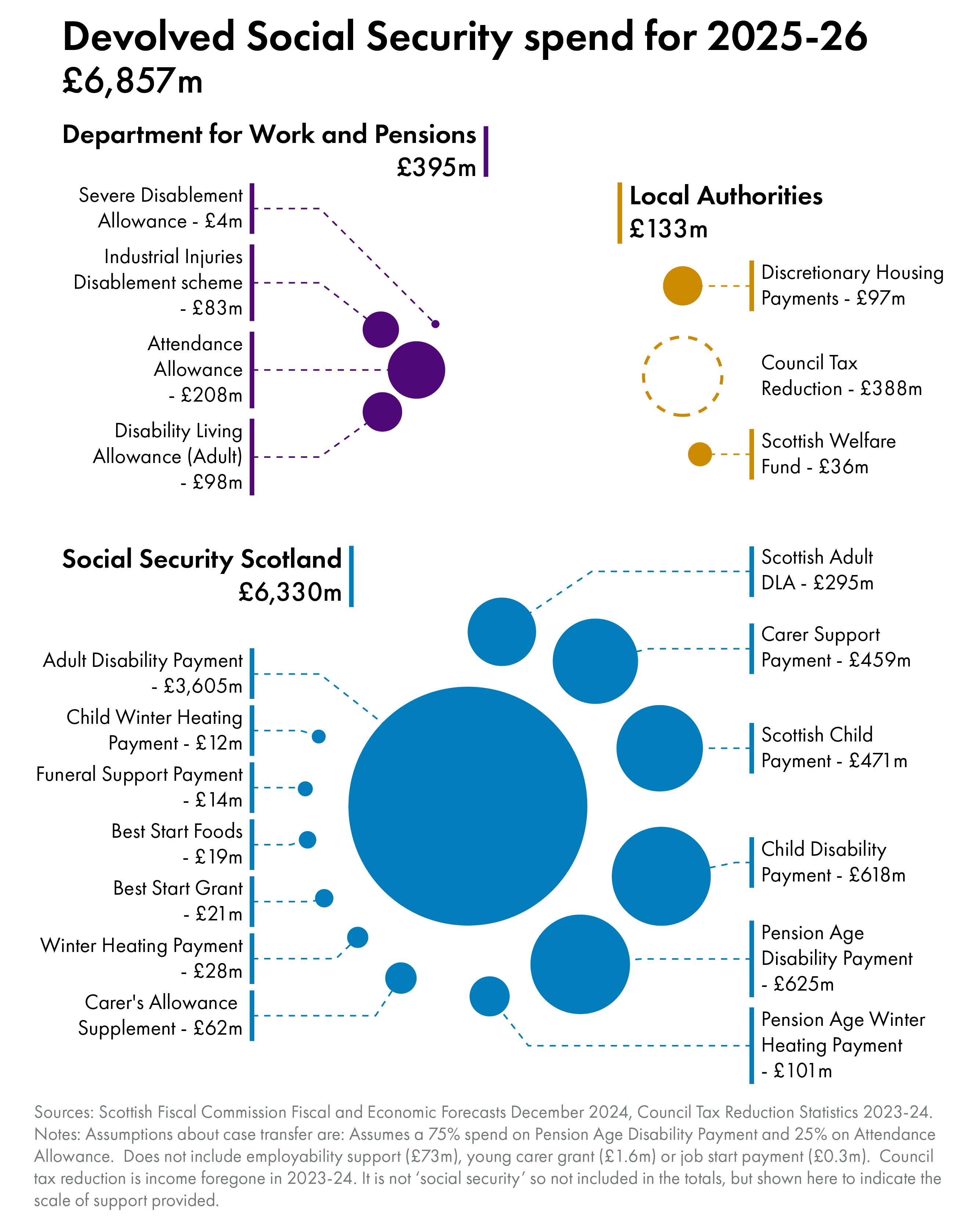

Social Security choices are storing up challenges for the Scottish budget, something that will likely be compounded in future with demographic and fiscal sustainability challenges highlighted by the work from the SFC in this area. We can already see the impact social security spend is having on other parts of the Budget – social security is forecast to account for 13.5% of resource spending in 2025-26, compared with 9.7% in 2022-23.

Some elements of social security spending are devolved. This has given the Scottish Government more powers to shape Scotland’s social security system, but also more budgetary risk. This is because any expenditure above the social security block grant adjustment (BGA) must be funded from within the Scottish Budget. The BGA broadly reflects the hypothetical amount that would have been spent on equivalent social security payments had they not been devolved.

This budgetary risk is materialising. Scottish Government decisions on social security have cumulatively added significant cost pressures to its budget. Broadly speaking, this is because the Scottish Government:

Has introduced benefits that are not available in the rest of the UK (rUK), such as the Scottish Child Payment, which is forecast to cost £471 million in 2025-26.

Is spending more on benefits that attract a BGA than is added to the budget via the corresponding BGA. In other words, where devolved benefits have an rUK equivalent, the Scottish Government is spending more than would have been spent if these benefits had not been devolved. It must meet this additional cost from within the Scottish Budget. The most notable example is the Adult Disability Payment, where a policy of maximising take-up has resulted in a higher number of recipients, which is forecast to add £314 million to the social security bill above BGA funding.

The Scottish Government has also chosen to get involved in areas that aren’t directly devolved responsibilities. By indicating a desire to “mitigate” the UK government’s two child cap on Universal Credit payments from 2026-27, the Scottish Government is planning to spend its budget on a reserved benefit (as it did with the “bedroom tax”) which will leave less funding available for other parts of the devolved budget. [Note that as this will not be introduced until 2026-27, there is no funding in the 2025-26 Budget other than for preparatory work.]

The Health and social care portfolio is again a budgetary priority as it has been throughout the devolution years, increasing by £2 billion in cash terms. Most of this will benefit the NHS Board budgets, but there is also a planned increase of £184 million to the health capital budget. Much of the increase for health and social care will reflect the commitment to pass on health-related Barnett consequentials received as a result of the UK October Budget. Increased planned UK government spending on health and social care resulted in an additional £1.7 billion for Scotland in 2025-26.

However, as noted above, health and social care is one of the budget areas impacted by the change in presentation of the budget figures for this year. The 2024-25 baseline is likely to increase following the 2024-25 Spring Budget Revision, which will allocate remaining Barnett consequentials for the year. Meanwhile, the 2025-26 health and social care budget line is likely to decrease when regular transfers (including to local government for social care) take place. These transfers are already reflected in the 2024-25 baseline. So, the baseline is likely to increase and the 2025-26 budget line decrease, which will have the effect of making any increase considerably smaller than the budget figures would imply. In this context, reference to specific increases feels a little meaningless.

Is public service reform sufficient?

There has been much UK-wide discussion in recent times, and especially since the UK Budget, about whether big increases in public spending should be taking place without guarantees over reform of service. Specifically, many have expressed concerns that this additional resource will simply be swallowed up in an unreformed public sector with little impact on outcomes.

This discussion around public service reform is alive and well in Scotland. The need for public service reform has been highlighted by many stakeholders for many years, but progress is still hard to see. Audit Scotland has noted that “there is no evidence of large-scale change on the ground” and the Parliament’s Finance and Public Administration Committee has expressed some frustration around the lack of any clear action. The Budget document states that:

We must also be efficient and effective in how we deliver public services. We have set out a 10-year programme of [public sector reform] PSR to Parliament, with a strong focus on the data, levers and workforce that will drive efficiency. To enable this work, we will deliver an Invest to Save fund in 2025-26, backed by up to £30 million of funding recognising the need to catalyse efficiency, effectiveness and productivity projects as part of the PSR programme.

It is hard to see how £30 million will really shift the dial when the Budget also notes that health and social care reform is a key element of the approach and showing “signs of strain” with “significant challenges” to navigate.

Capital

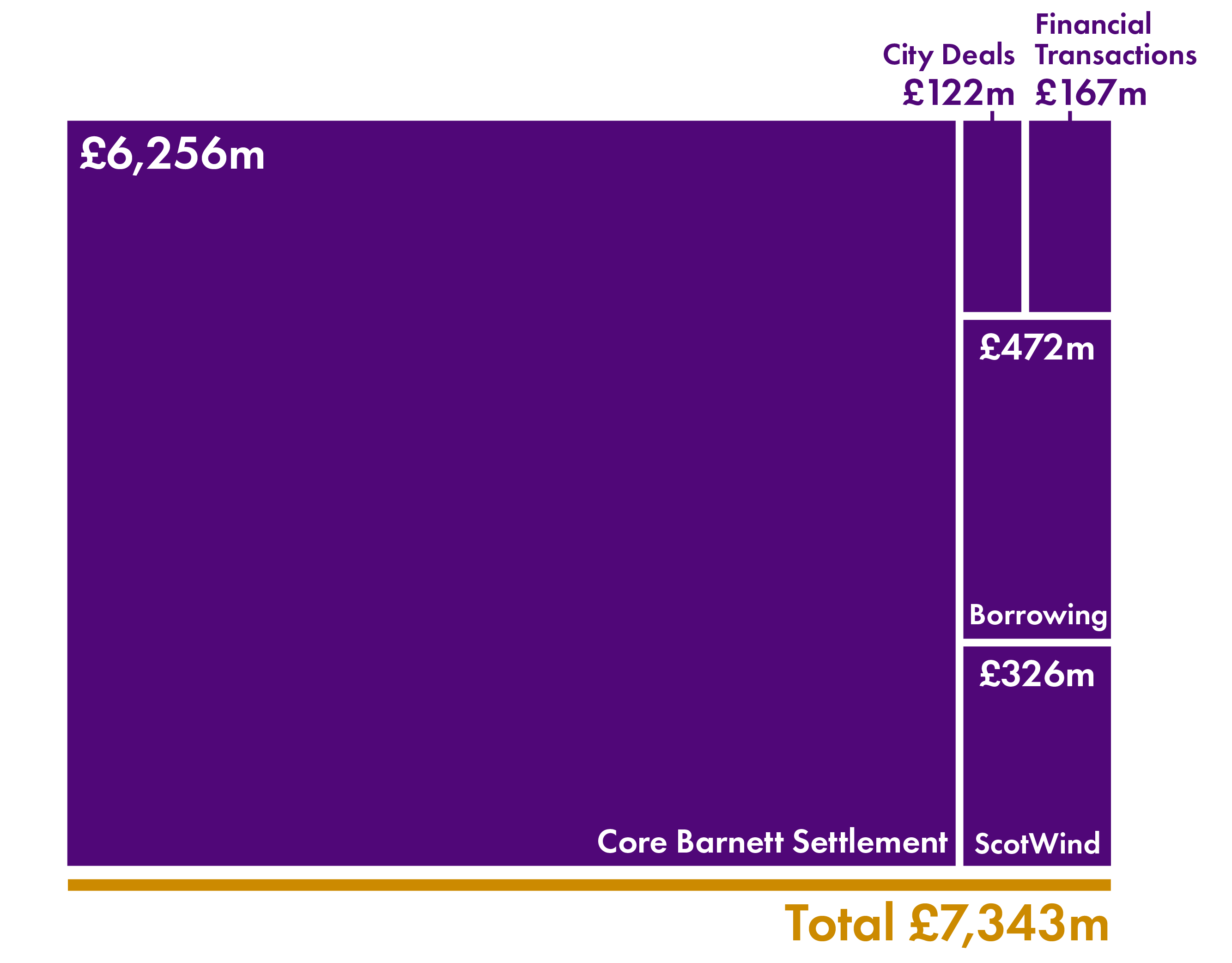

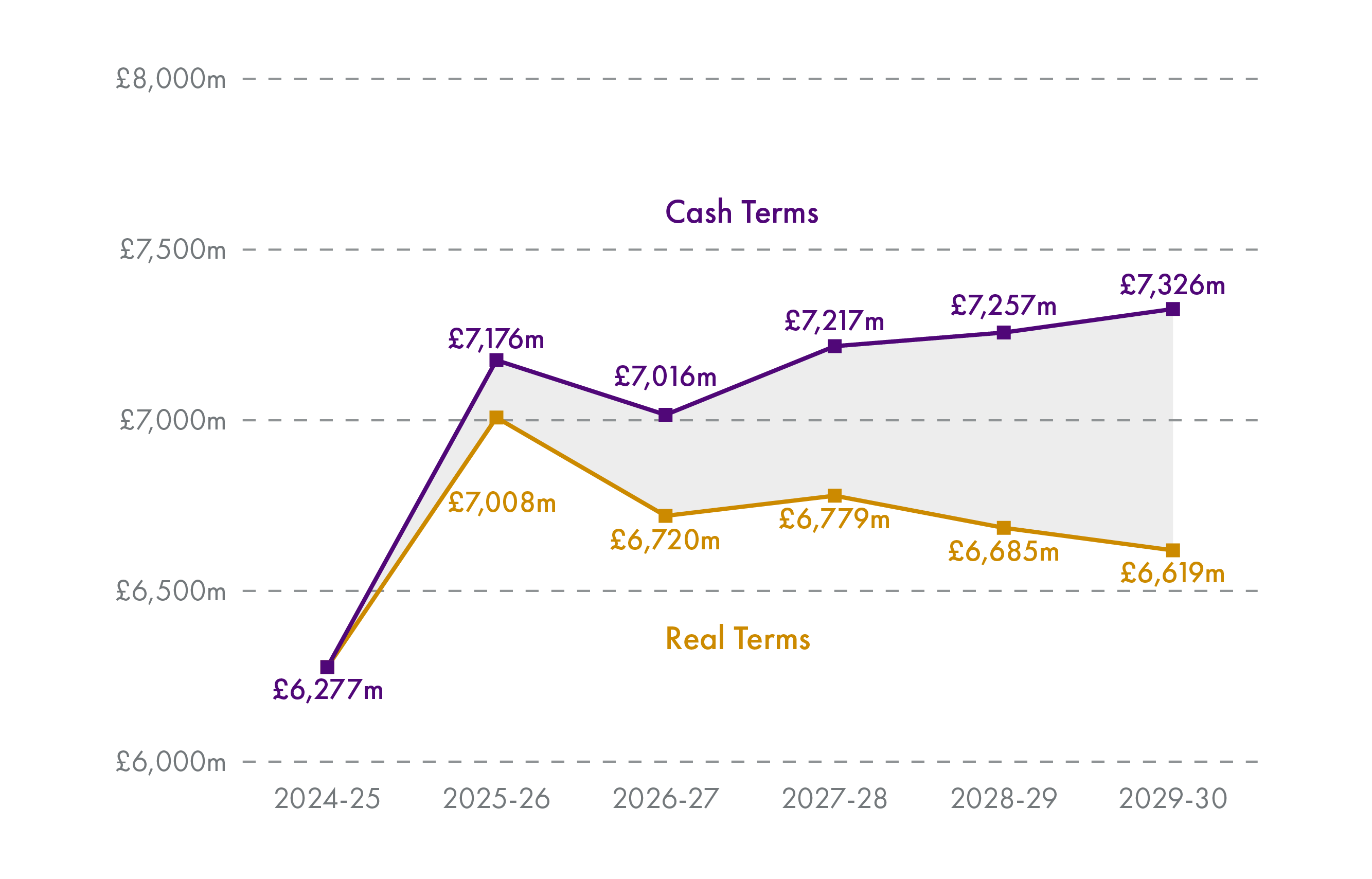

The capital budget has increased from £6.4 billion in 2024-25 to £7.3 billion in 2025-26, which is a 12% increase in real terms. Much of this change is driven by policy decisions in the UK Budget in October, with the settlement from the UK government increasing from £5.7 billion to £6.4 billion. In addition, the Scottish Government has utilised £330 million from ScotWind revenues, and the maximum amount of borrowing under the fiscal framework (£472 million, as the limit has increased in line with the GDP deflator since last year). This would increase the stock of capital borrowing to 87% of the cumulative limit of £3.1 billion, an increase of 8 percentage points from 2024-25, and suggests that the Scottish Government will need to reduce the amount of borrowing in future years.

The SFC has forecast that total capital resources available to the Scottish Government will dip slightly in 2026-27 and largely remain flat throughout the forecast period – however, this picture could well change after the UK government completes its spending review in 2025.

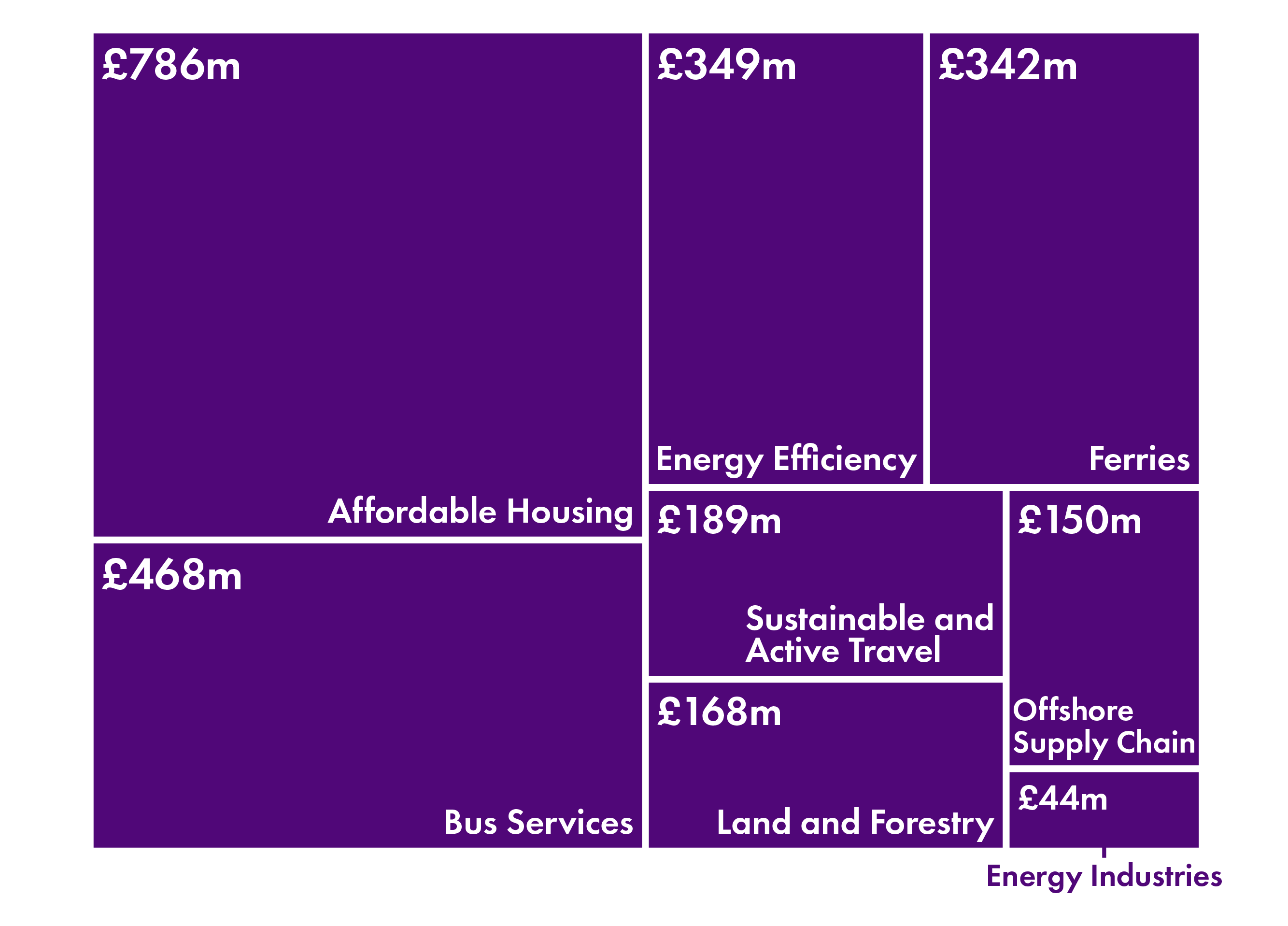

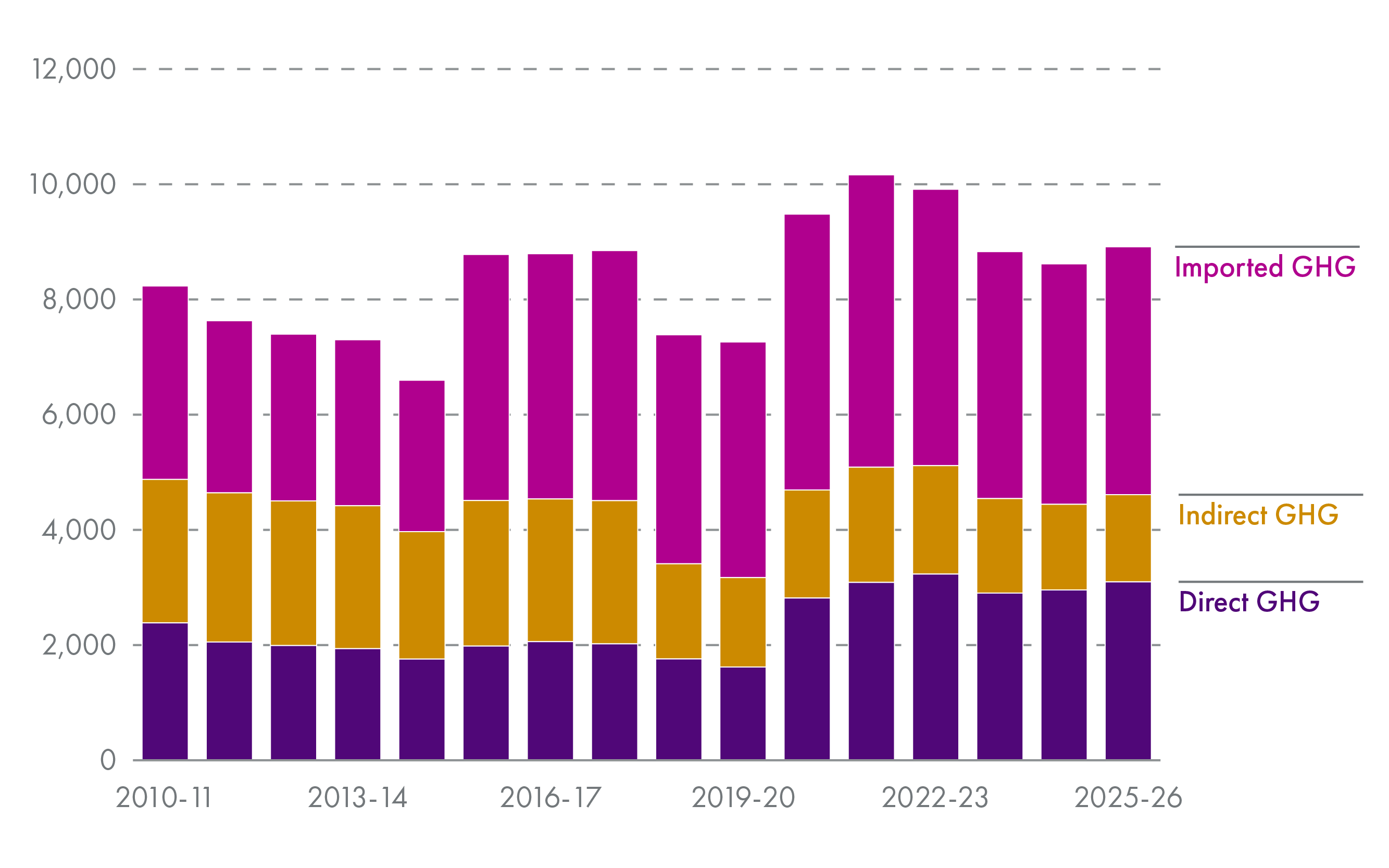

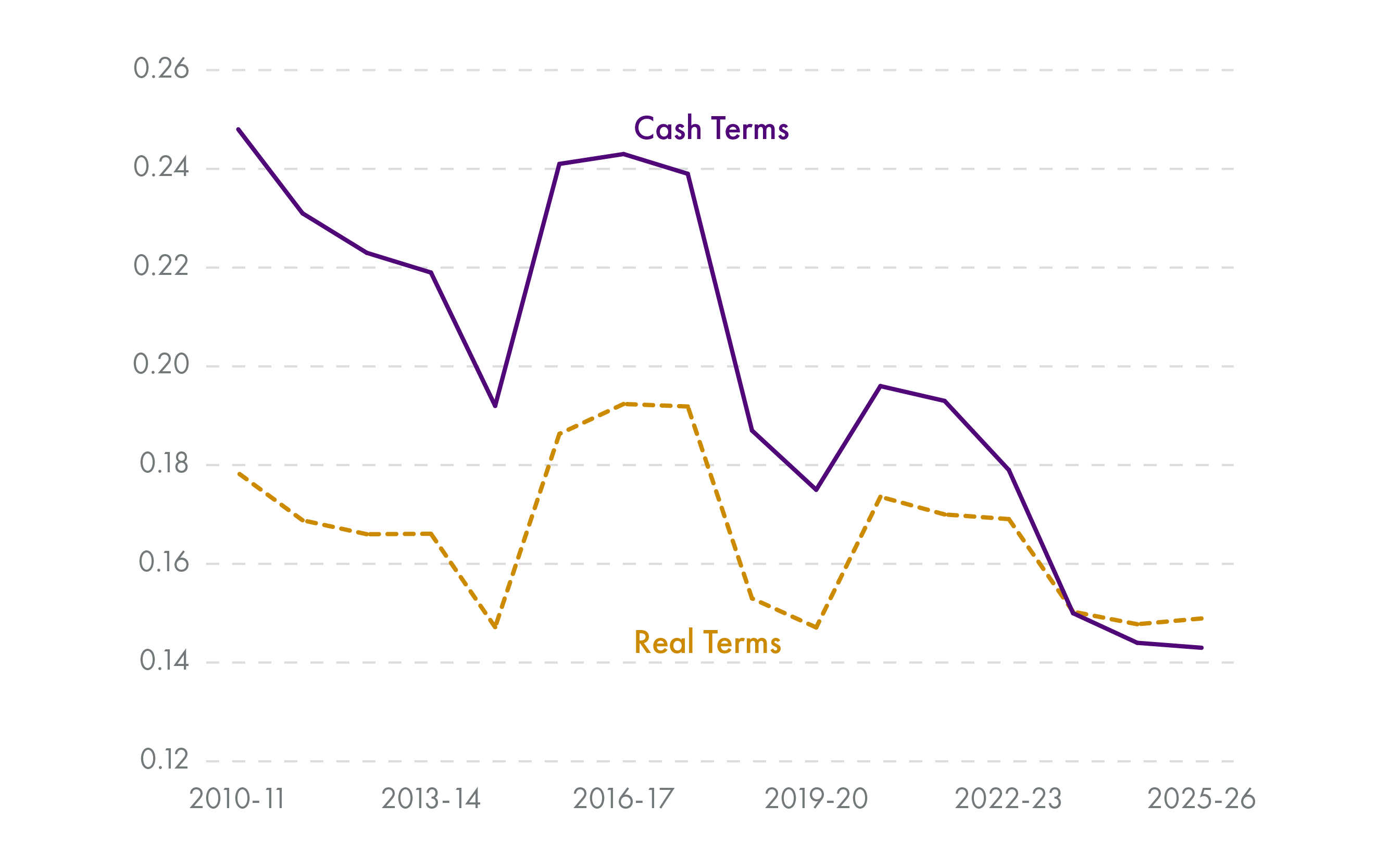

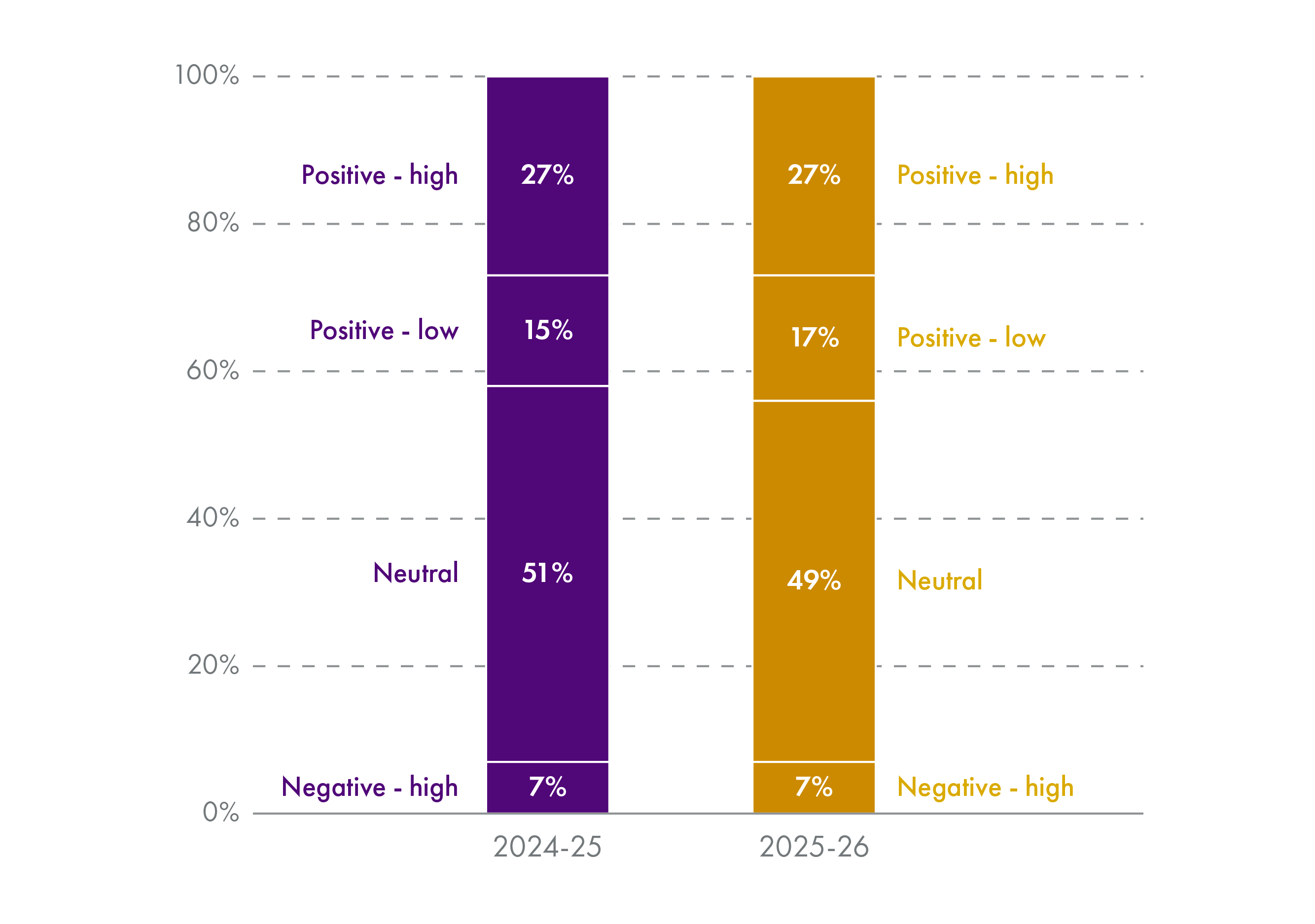

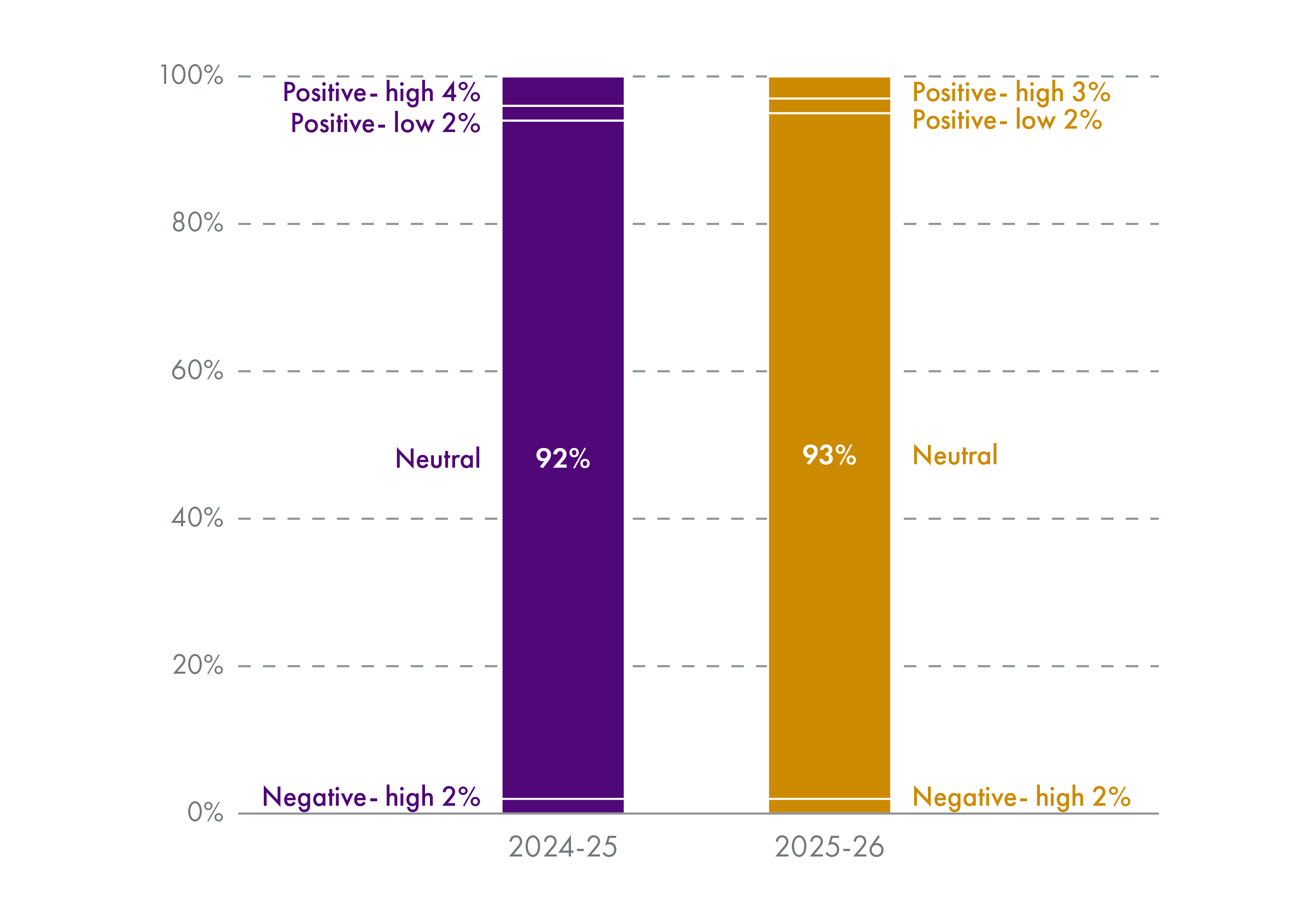

In 2024-25, 42% of capital spending (£2.7 billion) was categorised as positive for Scotland’s climate targets. In 2025-26, the proportion of spend categorised as positive has increased slightly to 44%, and as it is a larger capital budget, this amounts to just under £3 billion of spending.

The Cabinet Secretary also announced a budget of £768 million for investment in affordable housing, an increase (in real terms) of 26% from the current year. Pressure had been mounting on the Scottish Government to increase resources for the budget given the declaration of the national housing emergency in June and the cut in the 2024-25 budget. However, the budget is still lower (by 3% in real terms) compared to 2023-24.

SFC forecasts point to fiscal risks

In addition to risks around increasing social security spending, the SFC highlight other fiscal risks in their report.

The SFC also points to risks from the public sector pay policy assumptions contained in the Budget. Although the Scottish Government has published a pay policy (assuming a 3% uplift in 2025-26) alongside its budget for the first time in four years, it did not provide the SFC with information on workforce. This leads to the SFC highlighting further fiscal risks around public sector pay coming from pay pressures or the size and composition of the workforce being different than budgeted for. The need to adjust budgets in-year to allow for higher-than-planned public sector paybills has resulted in emergency budget statements in recent years.

The SFC point out that there is no provision in the budget for the public sector employer NICs increase announced in the recent UK Budget, and for which there is now a legal obligation. While the Scottish and UK governments are still at odds over the amount the Scottish budget will be compensated by, it is nevertheless a risk to the fiscal position for which no provision has been made in this Budget.

Income tax

The Budget proposes to increase the thresholds for the basic and intermediate thresholds by 3.5% in 2025-26, and freeze the higher, advanced and top thresholds.

Compared to the rest of the UK, the Scottish Government’s income tax proposals mean that all taxpayers earning below £30,300 will pay less income tax in Scotland than they would if they lived elsewhere in the UK. However, the differences are small for this group of taxpayers – only £28 per year for most in this group. For those earning above this amount, the gap between what they pay in Scotland and what they would pay elsewhere in the UK widens rapidly as earnings increase. Those earning £50,000 will pay around £1,500 more in Scotland than they would elsewhere in the UK, while someone earning £150,000 will pay almost £6,000 more over the year.

The SFC forecast strong growth in income tax revenues, driven by higher than previously expected nominal earnings growth. However, the equivalent OBR forecast for the UK as a whole has increased even further. This means that the 2025-26 income tax net position, which was forecast to be £1,749 million this time last year, is now forecast to be £838 million. This is the difference between Scottish income tax revenues and the income tax Block Grant Adjustment (BGA). The income tax BGA is an estimate of what would have been raised had income tax policy and per capita earnings growth mirrored that of the UK since income tax was partially devolved.

This means that overall, the Scottish Budget is better off by £838 million because of the partial devolution of income tax. However, the SFC also point out that Scottish income taxpayers pay £1,676 million more in income tax than in the rest of the UK. So, in return for paying £1,676 million more in income tax, the Scottish Budget is only benefitting by £838 million. They describe this as an “economic performance gap”.

The SFC now projects a negative reconciliation of £701 million will be applied to (i.e. deducted from) the 2027-28 Scottish Budget. The Scottish Government does have limited borrowing powers to smooth out the effects of reconciliations – but £701 million exceeds the annual borrowing limit for forecast error.

The Scottish Government also published its tax strategy alongside the Budget. Beyond some commitments not to make any significant changes to income tax before the end of the Parliament, the Tax Strategy provides little in the way of detail in relation to tax plans, with much reference to “exploring”, “considering” and “engaging” on a range of taxes, including council tax and non-domestic rates. There is a commitment to reporting on progress in early 2026.

Non-Domestic Rates

The continuation of the 100% rates relief for hospitality properties on Islands and in designated remote areas and 40% relief for mainland hospitality and grassroots music venues were the key non-domestic rates announcements. The cost of these measures is estimated at a relatively modest £27 million as these sectors represent a small proportion of properties in Scotland, and many will already be eligible for relief through the Small Business Bonus Scheme. Criticism has been levied at the Scottish Government for not replicating the UK government’s relief for retail premises, however doing so would come at a significant cost – estimated at £220 million by the Fraser of Allander Institute, and £350 million by the Scottish Government. Both estimates are considerably higher than the £145 million that the Scottish Government received in Barnett consequentials from the UK government policy.

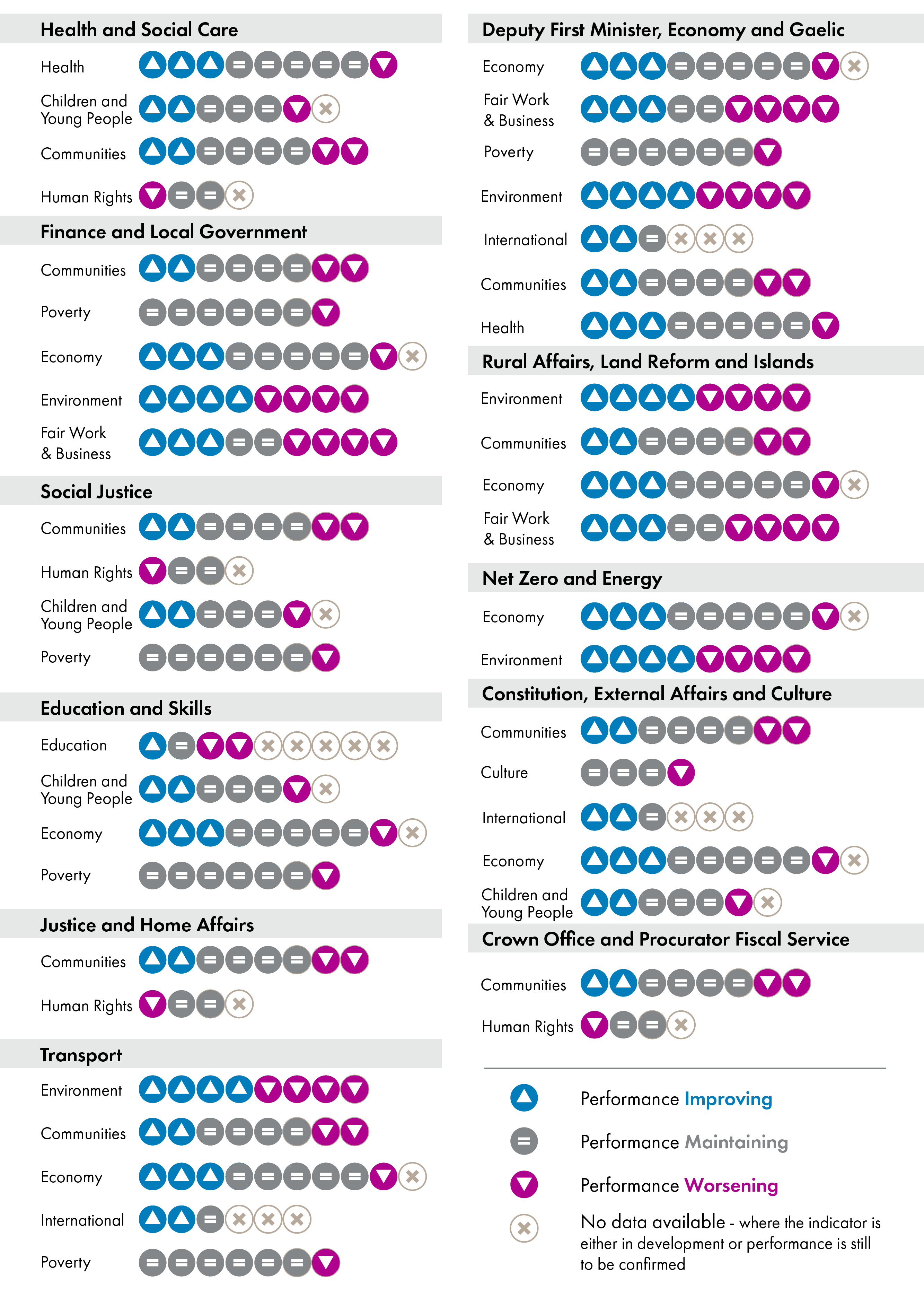

Equalities and Human Rights

The evidence of the Scottish Government’s stated commitment towards a human rights budgeting approach is limited, with considerable barriers to transparency and a lack of public consultation. Whilst the Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement has undergone a sleek makeover and is now less repetitive and a better illustration of a mainstreamed approach, it appears that existing approaches are being heralded as ‘new’. The long-awaited findings of the OECD-supported Gender Budgeting Pilot have been published alongside the Budget, but this highlights the challenges of a siloed approach to budget-setting and concludes that there is a lack of strategic over-arching gender goals. The additional detail in the Distributional Analysis is useful in understanding policy impacts by income quintile, however there is still little detail on the impact of spending decisions on non-poverty related inequality.

Context for Scottish Budget 2025-26

Scottish Budget 2025-261 was published on 4 December 2024 and presents the Scottish Government’s proposed spending and tax plans for next year. The publication signals the start of a period of parliamentary scrutiny culminating in MSPs voting on these proposals in early 2025. Unlike previous Budgets in this parliamentary session, the Scottish Government now operates as a minority, so will require support from at least one other party to get its Budget passed.

The Budget incorporates devolved tax forecasts undertaken by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC).2 As well as producing point estimates for each of the devolved taxes for the next five years, the SFC is also mandated to produce forecasts for Scottish economic growth and spending forecasts for devolved social security powers. The SFC forecasts are considered in greater detail later in this briefing.

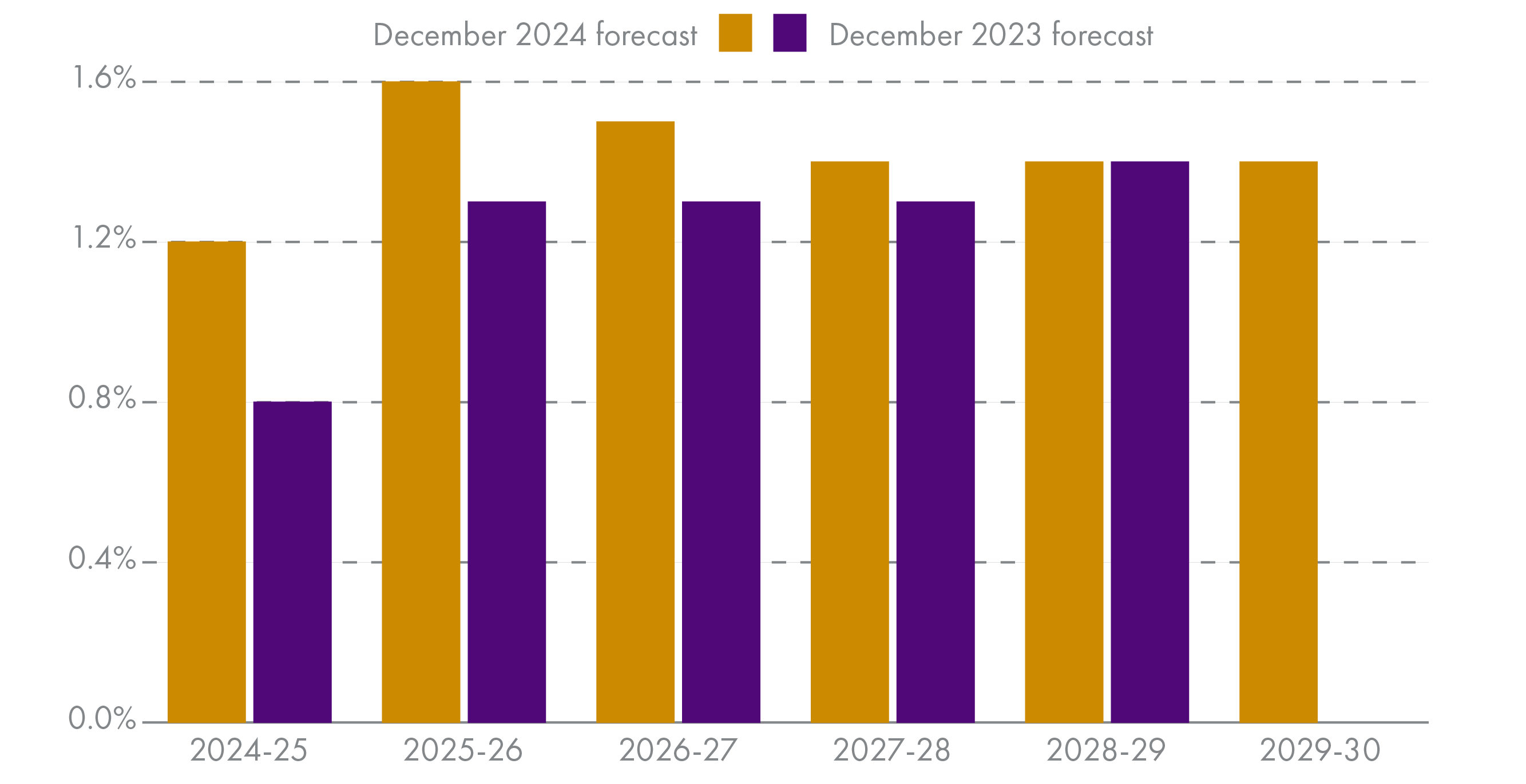

The SFC forecasts that economic growth will be boosted (relative to its previous forecast) in the short term by increases in government spending which will see GDP growth of 1.2% this year (+0.4 percentage points on the previous forecast), followed by 1.6% next year (+0.3 percentage points on previous forecast). Growth of 1.5% is forecast in 2026-27.

| GDP growth | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | 2029-30 |

| Economy % growth | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

The inflationary effects we have seen in recent years have begun to wane in the forecasts. The SFC is forecasting earnings growth to be higher in Scotland in 2025-26 (3.7%) than the OBR is forecasting for the UK (3.0%), due to Scotland’s relatively tighter labour market. However, after a period of high inflation, nominal earnings growth is falling back to more normal levels, and is expected to settle around its long term average of 3% from 2026-27.

The baseline numbers and comparability

This year, the presentation of the budget differs from previous years. This has some important implications – it may seem technical, but it is important in relation to interpretation of budget changes.

Previously, the baseline year for comparison has been presented as agreed at the last budget. So, comparisons were between the figures agreed at the last budget and the figures proposed in the current budget (referred to as a “Budget to Budget comparison”). The problem with this approach is that, if budgets change during the year (as they often do), you are comparing with a baseline figure that is not reflecting the actual budget, which can lead to misleading conclusions. For example, if a budget increases significantly during the year, then comparing a proposed budget with the original budget figure from the previous year would give a higher change than if you compared with the adjusted budget figure.

This year, the 2024-25 baseline figure is presented “after Autumn Budget Revision (ABR)” adjustments. This means it reflects some in-year changes to budget lines that we know have taken place. But there are still more that we know are yet to come.

Changes to budgets in-year can reflect a number of factors, but the most important reasons are:

In-year transfers between portfolio areas (which take place each year at Autumn and Spring Budget revisions). The 2024-25 Autumn Budget revision1 has taken place and changes are reflected in the baseline, but the 2024-25 Spring Budget revision is yet to come, so will not be reflected in the baseline Budget figures. There are some significant transfers between portfolios that take place routinely in-year e.g. from health to local government, so the choice of baseline makes a big difference for these two portfolio areas in particular.

Allocation of Barnett consequentials in year. After UK fiscal events, the Scottish Government often receives Barnett consequentials. For example, after the UK Budget in October, the Scottish Government received an additional £1.5 billion for 2024-25 and £3.4 billion for 2025-26. While the £3.4 billion will have been factored into the budget allocations for 2025-26, £1.3 billion of the Barnetts for 2024-25 have not yet been allocated and will not be allocated until the Spring Budget Revision (likely to be in January 2025).

The impact of this change in presentation is significant and is discussed further in the Portfolio allocations section. Some of the biggest portfolio areas in terms of spend - Health and Social Care, Local Government and Education and Skills - are particularly affected by this change and so budget movements should be interpreted with caution. Figure 1 highlights the impact of the different baseline approach.

Taking, for example, the Health and Social Care portfolio, the ABR-Budget presentation shows a 7.3% increase, while the Budget-Budget presentation shows a 3.4% increase. Ultimately, the percentage change could be smaller than this once 2024-25 Barnetts are allocated.

The Scottish Parliament’s Finance and Public Administration Committee (FPAC) had been pushing for changes to the budget presentation so that that baseline gave a more representative picture of the actual budget position. While there is some merit in the new approach, it also presents some major challenges in terms of analysis and budget scrutiny. In relation to the two specific issues highlighted above:

In-year transfers between portfolios – there are significant transfers between portfolio areas that take place each year and have a significant impact on certain budget lines. To prevent the distortionary effect of these, the Scottish Government could consider baselining these so that the monies are allocated to the intended area from the outset. For example, funding for social care is intended to be transferred to local government and this is known at the time of budget setting, this should be allocated to the local government budget line from the outset, rather than via an in-year adjustment.

Barnett allocations – the scale of Barnett consequentials resulting from the UK October budget was large, and the timing meant that these could not be allocated at the ABR. But adding an additional £1.3 billion to the 2024-25 baseline makes a significant difference to the percentage changes in both the overall budget position and those of individual budget lines. There is nothing that the Scottish Government can do about the timing of Barnett consequentials, but it is worth noting that the SFC commented that the absence of any reflection of the impact of future adjustments to the 2024-25 baseline “is a material limitation to information available to the Scottish Parliament for its scrutiny of the Budget and in the spending analysis we can do.”

The challenges in providing meaningful comparisons this year highlights the importance of the choice of baseline. There is no perfect solution and any chosen baseline will have pros and cons. The Scottish Government could improve transparency by allocating known transfers to the recipient budget area from the outset. But challenges around the timing of Barnett consequentials will persist. Ultimately, it is just important to be aware of what is and isn’t included in any baseline and how this might impact on the changes calculated from a particular baseline position.

Budget allocations

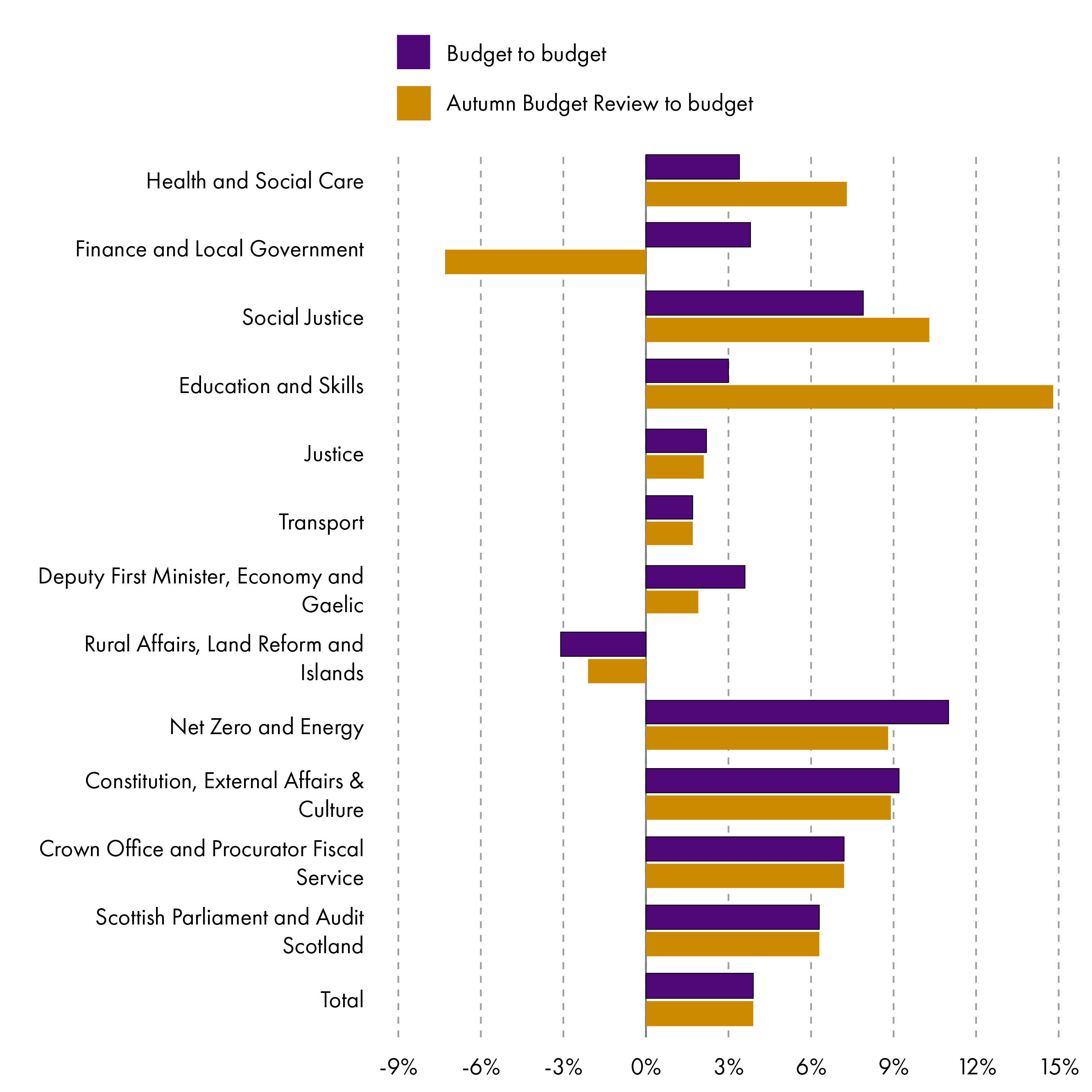

Total Managed Expenditure (TME) comprises Resource, non-cash Resource, Capital and Annually Managed Expenditure (AME). TME in 2025-26 is £63,482.9 million. Figure 2 shows how this is allocated.

Resource (which covers day-to-day expenditure) and capital (covering spending on buildings and physical assets) are the elements of the budget over which the Scottish Government has discretion. As we can see from the chart below, the budget document shows (based on the ABR baseline for 2024-25) that resource is due to increase by 4% in real terms in 2025-26 and capital is set to increase by 12% in real terms. However, as is noted elsewhere in this briefing, the 2024-25 numbers do not include £1,344 million in resource Barnett consequentials that are available to use in 2024-25 but have not yet been allocated to portfolios. When these are added to the 2024-25 baseline, the 2025-26 resource budget grows by 0.8% in real terms.

AME is expenditure which is difficult to predict precisely, but where there is a commitment to spend or pay a charge, for example, pensions for public sector employees. Pensions in AME are fully funded by HM Treasury, so do not impact on the Scottish Government's spending power. AME falls significantly next year due to the significantly lower forecast costs of managing the Teachers and NHS Pension schemes. This is a UK funded AME line and does not arise from any Scottish Government decision or impact on the discretionary spending power of the Scottish budget.

Non-Domestic Rates income is also classed as an AME item in the budget and forms part of local government spending.

The non-cash reduction is largely explained by the “negative RAB charge” forecast on the Cost of Providing Student Loans. The RAB charge reflects current economists’ estimations on future loan write-offs and interest subsidies. There’s an approximate £750 million swing from the £344 million budget currently forecast in 2024-25 to the £396 million credit balance forecast in 2025-26.

Portfolio allocations

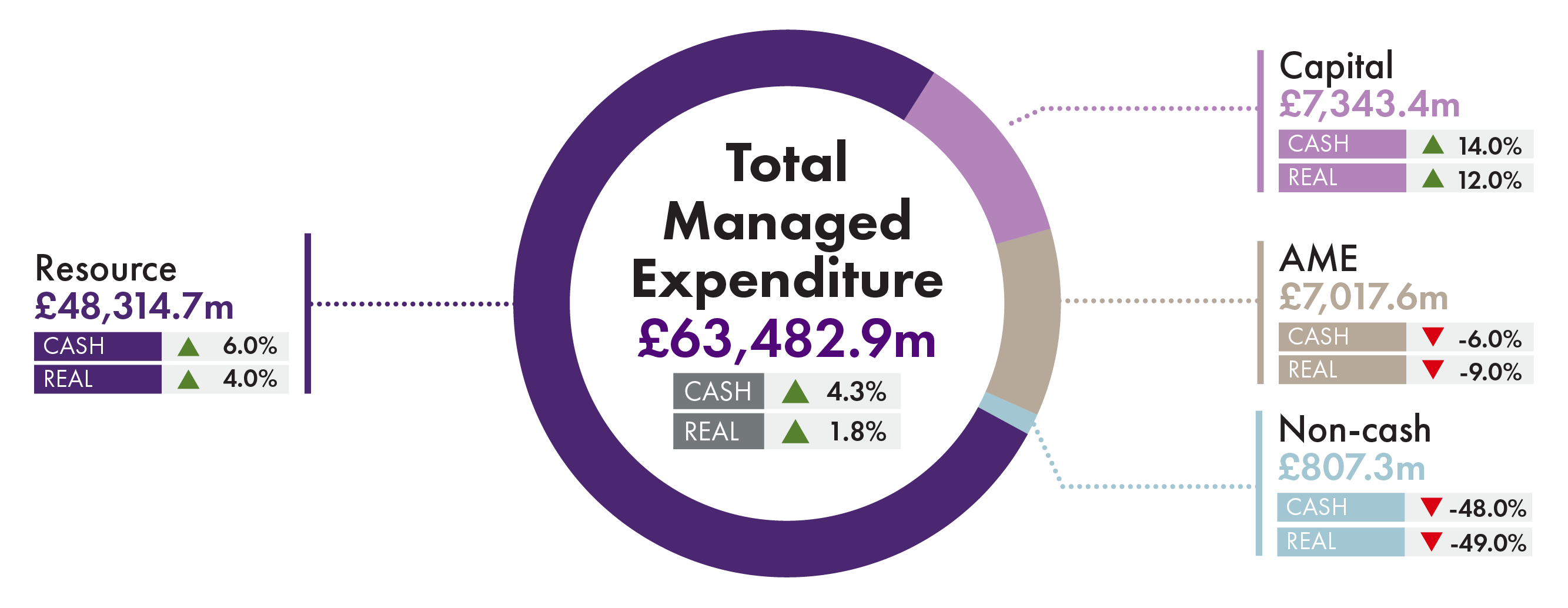

As mentioned in the Context section, the use of the ABR baseline means the portfolio comparisons are not like-for-like and we have decided to not include our usual resource plus capital portfolio allocation infographic.

However, analysis is possible on the resource side due to the inclusion of table A.07 in the Scottish Government Budget. Figure 3 below shows resource allocations to portfolios for 2025-26 and how they differ from the ABR when the internal transfers from, for example health to local government, are excluded from the 2024-25 baseline.

This figure shows that, on this basis, all resource portfolios will increase in both cash and real terms next year with the exception of the Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands portfolio.

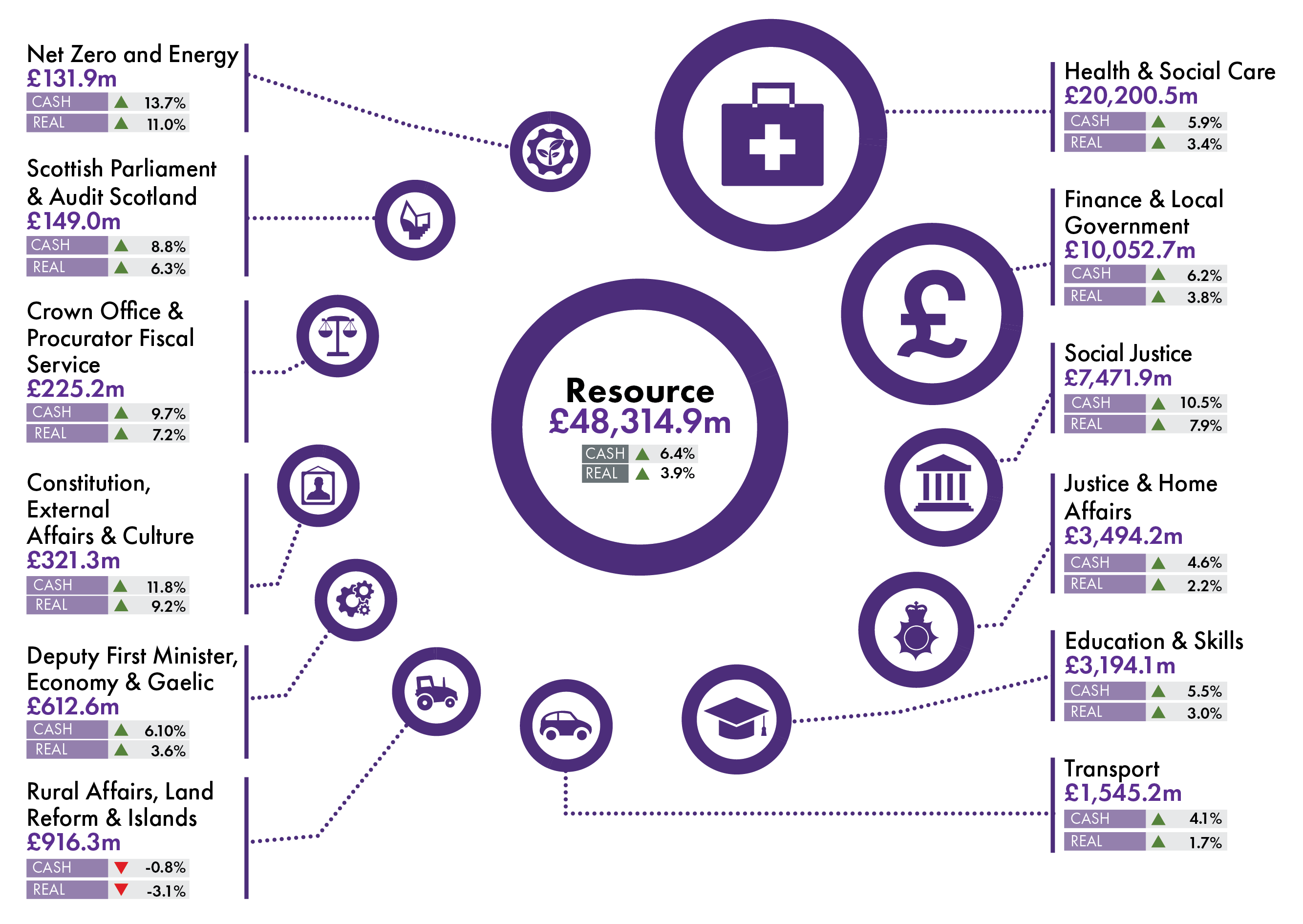

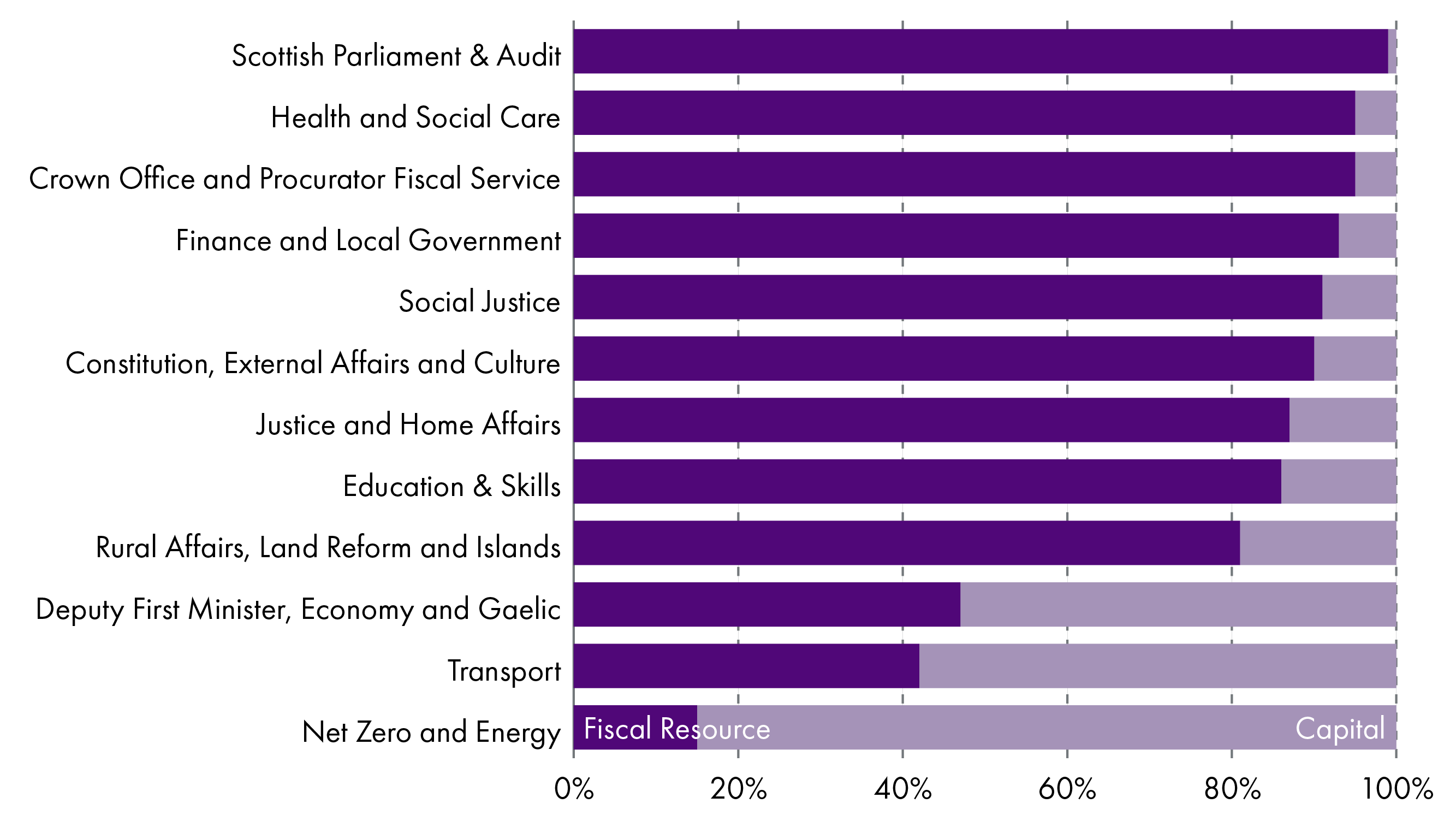

Resource and Capital allocations

Figure 4 below shows the split between resource and capital by portfolio. This shows that most portfolios are heavily weighted towards funding day-to-day spending commitments (the resource budget).

The Net Zero and Energy and Transport portfolios have highest proportion of their budget comprising capital spending. This will include projects to progress towards net zero, rail and roads investment and capital investment by Scottish Water. The Deputy First Minister, Economy and Gaelic portfolio also includes significant capital spending on areas like digital connectivity, cities and investment by the Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB).

Local government

When it comes to the local government allocation, there is an apparent mismatch between reported increases and what some of the tables in the Budget document appear to show. The local government settlement has indeed increased, but you have to look long and hard to find the figures showing this in the Budget document! The overall local government allocation – resource plus capital - is over £15 billion for the first time ever. And this represents a 4.7% real terms increase when compared to the 2024-25 Budget.

The confusion in the Budget document comes from the use of Autumn Budget Revision (ABR) figures rather than Budget figures for 2024-25. We won’t have ABR figures for 2025-26 until next October, by which point over £1 billion is likely to have been transferred to local government from other portfolio budget lines. So, Tables 4.01 and 4.13 in the Budget document do not compare like-with-like. By comparing Budget document 2024-25 and Budget document 2025-26, this section explores some of the key changes for local government in the Scottish Government’s budget on a like-for-like basis.

Allocations to individual local authorities have not been published yet. These will appear in a Local Government Finance Circular on Thursday the 12th. This is later than usual because the Scottish Government/COSLA Settlement and Distribution Group is waiting for the teacher-pupil census results which are expected on the 10th. Once the Finance Circular is published SPICe will publish analysis showing how resource and capital allocations are changing for each of Scotland’s 32 local authorities.

Resource allocation

Comparing Budget document 2024-25 and Budget document 2025-26, as SPICe has done in the past, we see both cash and real terms increases in the overall revenue/resource allocation (see Tables 2 and 3).

| Local Government | 2024-25 Budget document | 2025-26 Budget document | Cash change (£m) | Cash change % |

| General Revenue Grant | 8,403.90 | 9,458.40 | 1,054.5 | +12.5% |

| Non-Domestic Rates | 3,068.00 | 3,114.00 | 46.0 | +1.5% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) Resource Grants | 238.8 | 247.4 | 8.6 | +3.6% |

| Revenue within other portfolios | 1,534.4 | 1,438.3 | -96.1 | -6.3% |

| Total revenue in Finance Circular | 13,245.10 | 14,258.10 | 1,013.0 | +7.6% |

| Local Government | 2024-25 Budget document | 2025-26 Budget document | Real change (£m) | Real change % |

| General Revenue Grant | 8,403.90 | 9,237.98 | 834.1 | +9.9% |

| Non-Domestic Rates | 3,068.00 | 3,041.43 | -26.6 | -0.9% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) Resource Grants | 238.8 | 241.63 | 2.8 | +1.2% |

| Revenue within other portfolios | 1,534.4 | 1,404.78 | -129.6 | -8.4% |

| Total revenue in Finance Circular | 13,245.10 | 13,925.83 | 680.7 | +5.1% |

The 2024-25 figures in the table above do not include the £144 million provided to local authorities for the 2024-25 council tax freeze. When this is factored in, we see a cash terms increase of £869 million over the year, or a 4% increase in real terms.

COSLA state that much of this increase relates to funding commitments announced in 2024-25 (or earlier) with costs being carried forward into 2025-26. Table 4 shows how these commitments are being met in the 2025-26 allocation.

| Revenue Change | Cost in 2025-26 (£m) |

| Discretionary Housing Payment increase | 6.5 |

| Early Learning and Care Pay | 25.7 |

| Free Nursing Care | 10.0 |

| Real Living Wage | 125.0 |

| Additional Support for Learning | 28.0 |

| School workforce | 41.0 |

| Teachers Pay | 43.0 |

| Teachers Pension | 86.2 |

| Local Government Pay | 77.5 |

| 24-25 GRG Baselined | 62.7 |

| Mental Health Baselined | 15.0 |

| Minor in-year transfers Reductions | -0.8 |

| Child Social Care staff | 33.0 |

| Council tax freeze | 3.3 |

| Inter Islands (Ferries) Specific Grant | 8.6 |

| Free school meals increase | 15.0 |

| General Revenue Grant Uplift | 289.3 |

| Total Revenue increase | 869.0 |

After accounting for these costs, the remainder of the increase represents the General Revenue Grant uplift of £289.3 million. This, according to the Scottish Government, is “to deliver real terms protection” to councils, with COSLA noting that “the Budget reality is that there is £289.3m of additional uncommitted local government core revenue funding”.

Reducing ring-fencing is a stated aim of the Verity House Agreement, and Table 2 (above) shows that specific resource grants account for only 1.7% of the total revenue allocation in 2025-26. Compared to three or four years ago, when the proportion ring-fenced was around 7%, this demonstrates considerable progress towards this joint commitment.

Capital allocation

There is a significant increase in capital allocations when comparing budget to budget, with a real terms increase of £121 million, or 19%, between 2024-25 and 2025-26. This comes after a big reduction in the capital allocation the previous year.

| Local Government (Capital) | 2024-25 Budget document | 2025-26 Budget document | Cash change (£m) | Cash change % |

| General Capital Grant | 476.90 | 556.00 | 79.1 | +16.6% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) capital grants | 121.10 | 196.10 | 75.0 | +61.9% |

| Total "core" Capital | 598.0 | 752.1 | 154.1 | +25.8% |

| Capital Funding within other Portfolios | 40.00 | 25.00 | -15.0 | -37.5% |

| Total capital in Finance Circular | 638.0 | 777.1 | 139.1 | +21.8% |

| Local Government (Capital) | 2024-25 Budget document | 2025-26 Budget document | Real change (£m) | Real change % |

| General Capital Grant | 476.90 | 543.04 | 66.1 | +13.9% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) capital grants | 121.10 | 191.53 | 70.4 | +58.2% |

| Total "core" Capital | 598.0 | 734.57 | 136.6 | +22.8% |

| Capital Funding within other Portfolios | 40.00 | 24.42 | -15.6 | -39.0% |

| Total capital in Finance Circular | 638.0 | 758.99 | 121.0 | +19.0% |

As with the revenue budget increase, COSLA has provided additional information showing that much of the £139 million increase in capital has already been committed, with the “uncommitted” part of this increase amounting to £48.1 million.

| Capital Change | Cost in 2025-26 (£m) |

| Local government pay* | 31.0 |

| Climate | 40.0 |

| SPT Specific Grant | 12.4 |

| VDLF Specific Grant | 2.6 |

| Free school meals capital (24-25) | -40.0 |

| Inter Islands (Ferries) | 20.0 |

| 25-26 Playparks | 25.0 |

| GCG Uplift | 48.1 |

| Total Capital increase | 139.1 |

*Although a resource budget item, this is included because the Scottish Government allowed local authorities to switch some capital to resource to help support the 2024-25 pay deal. In a letter to council leaders at the time, the Scottish Government recognized that this “would need to be replaced as additional capital funding in 2025-26”.

In its pre-budget letter to the Scottish Government, the Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee noted “the continuing pressures on capital budget allocations” and the need for local authorities to invest in infrastructure “to facilitate the effective delivery of services in the most efficient way possible”. In her response, the Cabinet Secretary highlighted the real terms increase in capital in the Budget whilst also stressing “the importance of considering more innovative measures to fund capital projects”. We do not have details of these measures, but it is worth remembering that local government debt already sits at around £22 billion (see Local Government Finance: facts and figures 2024).

Local government workforce costs

Local government is by far the largest public sector employer in Scotland, and up to 70% of local authority budgets are spent on workforce costs. Meeting the pay demands of its 262,000 workers is one of the biggest financial challenges faced each year by councils. Over the summer, the local government trade unions negotiated above inflation pay deals for their members, at an additional cost of over £300 million for Scotland’s local authorities (see COSLA briefing). This was supported by the Scottish Government, including additional revenue funding of £34.5 million. It is very possible that a similar scenario could arise next year.

There is nothing in the Budget document about how increases to employer National Insurance contributions (NICs) could impact local government, but we know from COSLA that this could cost councils around £265 million (with the Fraser of Allander Institute estimating this to be nearer £244 million). With an apparent disagreement between the UK government and Scottish Government over the cost to Scotland’s public sector of NIC increases, this has the potential to be another flashpoint in the relationship between Scotland’s three tiers of government.

Council tax

Much media attention since the Budget statement has focused on council tax and the fact that no freeze or cap was announced by the Cabinet Secretary. This shouldn’t come as a surprise considering the reaction that met the shock announcement made by former First Minister, Humza Yousaf, at last year’s SNP conference. Since then, council leaders, and many others, have consistently argued for councils being able to make decisions locally about council tax.

Perhaps optimistically, the Cabinet Secretary is of the view that “with record funding, there is no reason for big increases in council tax next year”. But that’s now a decision for councils themselves to make. A recent survey conducted by the Local Government Information Unit found that around a fifth of local authorities are considering increasing council tax by at least 10% next year. Increases of this magnitude could come as quite a shock to many households, especially at a time when levels of satisfaction with council services appear to be declining (see recent Scottish Household Survey results and last year’s Local Government Benchmarking Framework annual report).

Tax

Income tax

The Scottish Government set out its proposals for income tax from April 2025 as part of the Scottish Budget 2025-26. These proposals need to be approved by a Scottish Rate Resolution, which must precede Stage 3 of the Budget Bill process. Income tax then cannot be changed during the financial year.

The proposals set out by the Scottish Government involve:

Increasing the basic rate and intermediate rate thresholds by 3.5%

Freezing the higher, advanced and top rate thresholds

Maintaining existing tax rates for each band.

Overall, these are modest changes. The Tax Strategy that accompanied the Budget (see Tax Strategy section) signals that there will be very little further change to income tax policy within this session of Parliament. The Scottish Government has ruled out introducing new bands or rate increases, and will continue to uprate the starter and basic rate bands by at least inflation.

The net result of these proposals is the Scottish income tax schedule shown in Table 8.

| Band | Taxable income | Rate |

| Starter rate | £12,571* - £15,397 | 19% |

| Basic rate | £15,398 - £27,491 | 20% |

| Intermediate rate | £27,492 - £43,662 | 21% |

| Higher rate | £43,663 - £75,000 | 42% |

| Advanced rate** | £75,001 - £125,140 | 45% |

| Top rate** | Over £125,140 | 48% |

* Assumes individuals are in receipt of the standard UK personal allowance (£12,570 in 2025-26). The personal allowance is reserved and set by the UK government.

** Those earning more than £100,000 will see their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000. This policy is reserved to the UK government.

Note that Scottish income tax only applies to non-savings non-dividend (NSND) income.

Impact on individuals

The proposed 2025-26 income tax schedule sees a marginally lower tax liability for all income levels compared with 2024-25. This difference is no more than £15 per year.

When compared with income tax policy in the rest of the UK (rUK), Scottish taxpayers earning less than £30,300 will pay up to £28 less income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK. The SFC project that the median taxpayer will have NSND income of £29,750, meaning that just over half (51%) of all Scottish income taxpayers will pay less than they would in rUK.

Taxable income above £30,300 attracts a higher tax liability than in rUK and the gap widens rapidly for those earning above the higher rate threshold of £43,663. For example, those earning more than £50,000 will be paying at least £1,500 more income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK.

| Annual taxable income | Scottish Government proposals income tax payable 2025-26 | Difference compared with 2024-25 | Difference compared with rUK |

| £15,000 | £462 | -£1 | -£24 |

| £20,000 | £1,458 | -£5 | -£28 |

| £25,000 | £2,458 | -£5 | -£28 |

| £30,000 | £3,483 | -£15 | -£3 |

| £35,000 | £4,533 | -£15 | £47 |

| £40,000 | £5,583 | -£15 | £97 |

| £45,000 | £6,914 | -£15 | £428 |

| £50,000 | £9,014 | -£15 | £1,528 |

| £55,000 | £11,114 | -£15 | £1,682 |

| £60,000 | £13,214 | -£15 | £1,782 |

| £65,000 | £15,314 | -£15 | £1,882 |

| £70,000 | £17,414 | -£15 | £1,982 |

| £75,000 | £19,514 | -£15 | £2,082 |

| £80,000 | £21,764 | -£15 | £2,332 |

| £85,000 | £24,014 | -£15 | £2,582 |

| £90,000 | £26,264 | -£15 | £2,832 |

| £95,000 | £28,514 | -£15 | £3,082 |

| £100,000 | £30,764 | -£15 | £3,332 |

| £150,000 | £59,666 | -£15 | £5,963 |

Note that Scottish income tax only applies to non-savings non-dividend (NSND) income.

Income tax revenues

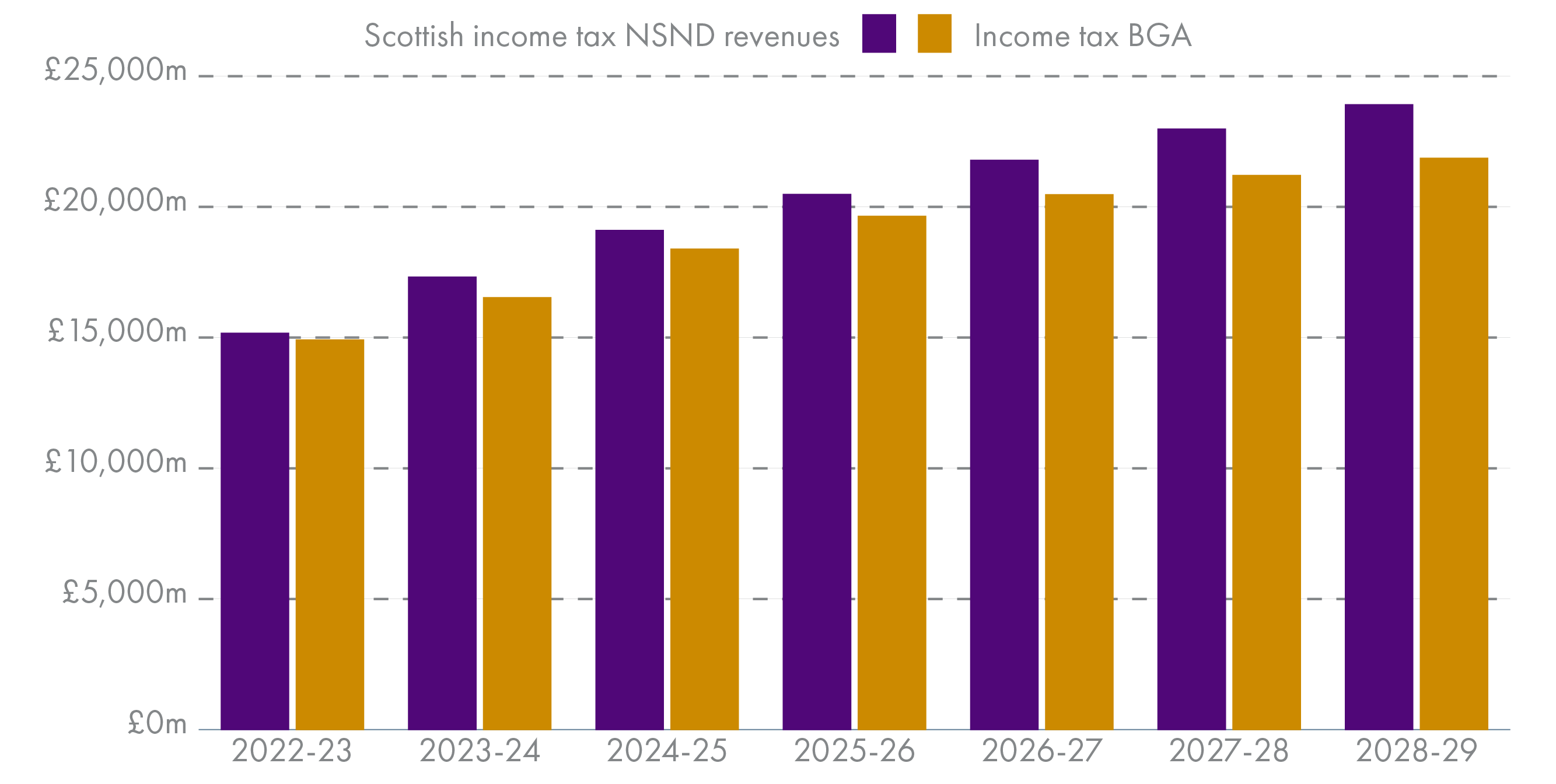

The SFC forecast strong growth in income tax revenues in 2025-26. Forecasted income tax revenues for 2025-26 are £1,378 million (7.2%) higher than in 2024-25 and £604 million (3.0%) higher than the SFC’s December 2023 forecast. This is driven by higher than previously expected nominal earnings growth.

| NSND income tax revenue forecast | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | 2029-30 |

| Income tax | 17,315 | 19,099 | 20,477 | 21,782 | 22,980 | 23,913 | 24,930 |

The impact of individual policy choices in this Budget adds relatively little revenue (£52 million in 2025-26). Compared with a counterfactual where all income tax bands (not thresholds) are increased in line with CPI inflation, the cumulative impact of the Scottish Government’s proposed changes to income tax thresholds is set out in Table 11. These are forecasted by the SFC.

| Impact of Scottish Government tax policy decisions on income tax revenues | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | 2029-30 |

| Basic rate threshold increase of 3.5% | - 13 | - 14 | - 14 | -15 | -15 |

| Intermediate rate threshold increase of 3.5% | -11 | -12 | -12 | -13 | -13 |

| Higher rate threshold freeze | 71 | 197 | 209 | 219 | 229 |

| Advanced rate threshold freeze | 4 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 |

| Top rate threshold freeze | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 52 | 185 | 197 | 206 | 215 |

Income tax net position

The logic behind the partial devolution of income tax is that the Scottish Budget should benefit from any revenue raised above what would have been raised had income tax devolution not occurred.

This means that the amount of revenue added or deducted from the Scottish Budget via the partial devolution of income tax depends on two factors: the growth in the size of the tax base (i.e. total earnings) relative to rUK and the policy choices of the Scottish Government relative to the UK government.

If earnings grow faster in Scotland than in rUK, devolved tax revenues will be higher than if income tax had not been partially devolved. Likewise, if the Scottish Government increases income tax rates compared with rUK policy, then any additional revenue raised flows to the Scottish Budget.

The amount added or deducted from the Scottish Budget through the partial devolution of income tax is known as the ‘income tax net position’. This is the difference between Scottish NSND income tax revenues and the income tax Block Grant Adjustment (BGA). The income tax BGA reflects what Scotland would have raised in income tax had it retained the same tax policy as rUK and if Scotland's per capita tax revenues had grown at the same rate as the rest of the UK.

In 2025-26, the SFC forecast that the income tax net position will be £838 million. This means that the Scottish Budget benefits by £838 million through the partial devolution of income tax.

However, in December 2023, the SFC forecast that the income tax net position for 2025-26 would be £1,749 million – far higher than it is now forecasting. This is because, although the SFC forecast strong growth in income tax revenues for Scotland, the equivalent OBR forecast for the UK as a whole has increased even further, which increases the amount deducted from the block grant in respect of income tax (the BGA).

Since income tax was first partially devolved, the Scottish Government has adopted a different income tax policy to the UK government. This has primarily had the effect of increasing tax rates on earnings above £43,663 relative to rUK. However, over the same time period, earnings have grown more slowly in Scotland than in rUK (although the SFC project that there has been some catchup more recently).

The net result is that in 2025-26 Scottish income taxpayers are forecast to pay £1,676 million more in income tax than in rUK but the Scottish Budget only benefits by £838 million. The SFC describe this as an “economic performance gap”.

It is also worth cautioning that the income tax net position is highly sensitive to small changes in OBR and SFC forecasts, as shown by the large fall in the net position forecasts in this year’s forecast relative to last year.

Income tax reconciliation

All of this also matters for future budgets. The income tax net position is based on forecasted tax revenues in Scotland and rUK. A reconciliation is then applied to future budgets once actual tax revenues are known. When the 2024-25 Budget was set, the income tax net position was forecast to be £1,412 million for that year. Since then, the OBR's projections of 2024-25 income tax revenues for the UK have increased by more than the SFC's equivalent for Scotland, which suggests the eventual income tax net position for 2024-25 will be smaller than was forecasted when the Budget was set. If borne out, the SFC now projects a negative reconciliation of £701 million will be applied to (ie. deducted from) the 2027-28 Scottish Budget. The Scottish Government does have limited borrowing powers to smooth out the effects of reconciliations - but £701 million exceeds the SFC's forecasted borrowing limits.

Non-domestic rates

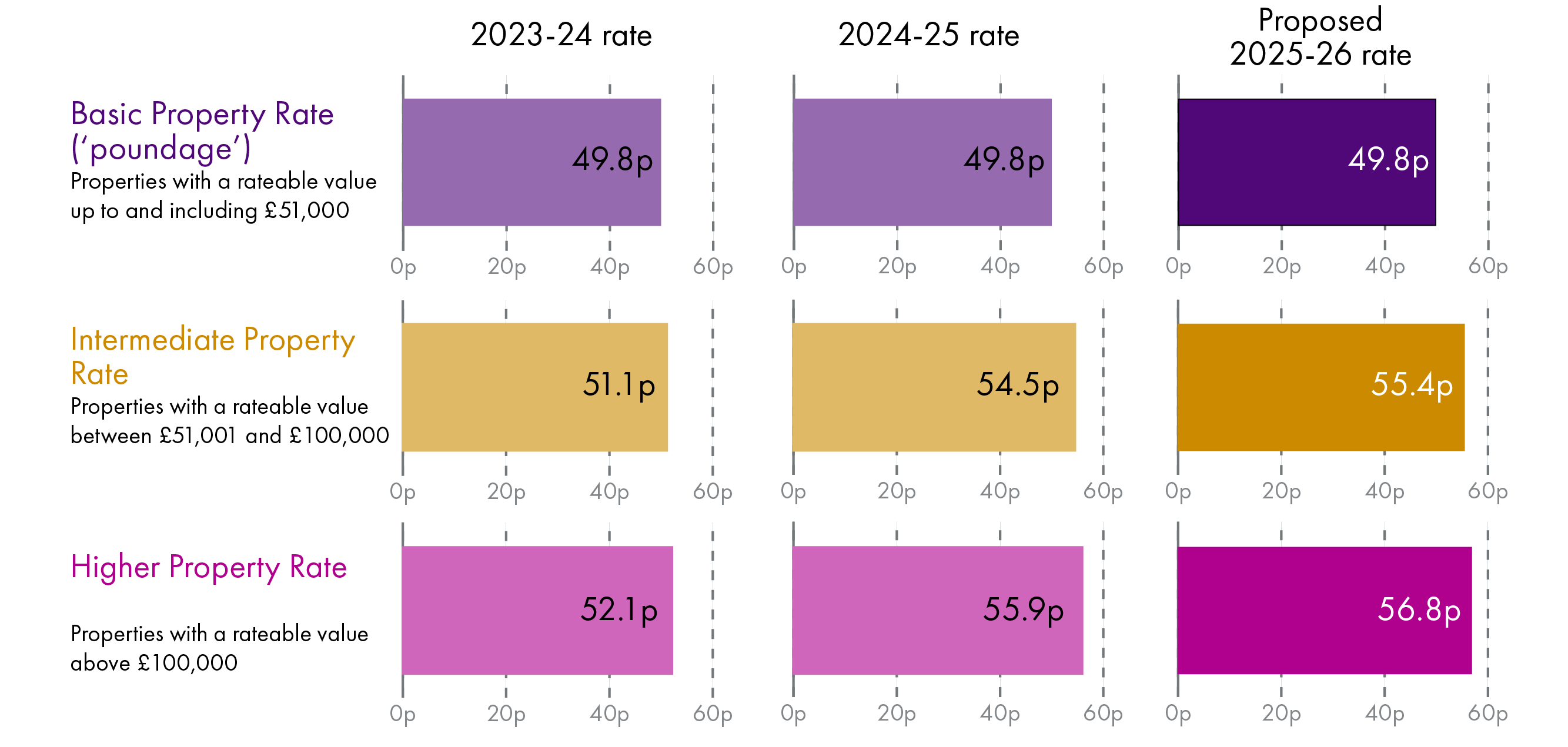

Non-domestic rates (NDR) are local taxes paid on land and heritages used for non-domestic purposes in the private, public and third sectors. The tax is administered and collected by local authorities, but tax rates and reliefs are set by the Scottish Government.

The amount of tax due depends on the rateable value of the property, set by independent assessors, multiplied by the poundage rates set by the Scottish Government. In the 2024-25 Budget, the Scottish Government maintained the poundage rates from 2023-24 at 49.8 pence for the basic property rate and increased the intermediate and higher property rates in line with inflation. This approach has again been taken for 2025-26.

New NDR relief

In 2022, the UK government introduced a 75% Retail, Hospitality and Leisure (RHL) relief for businesses occupying eligible retail, hospitality, and leisure properties in England, with a cap of £110,000 per business. This was continued through into 2024-25.

In 2024-25, the Scottish Government did not meet calls to replicate this approach, emphasising that the “Small Business Bonus Scheme is ‘the most generous in the UK’”. It did, however, introduce 100% rates relief to hospitality businesses on Scottish Islands and in certain remote areas. Given the small number of properties affected, this cost of this relief to the Scottish Government has been a relatively small £3.98 million in 2024-25 according to the 2024 rates relief statistics.

For 2025-26, the new UK government announced an alternative approach to that of its predecessor. The Chancellor announced within the Autumn Budget 2024 a 40% relief for RHL properties (with the £110,000 cap remaining) and a freeze on the small business multiplier, totalling £1.9 billion of support. This was billed as a transitional approach, with the intention being to permanently lower the business rates multipliers for RHL properties from 2026 onwards.

The Scottish Budget 2025-26 sees the 100% relief for hospitalities on islands maintained. In addition, the Cabinet Secretary announced that a new 40% relief will be available for “the 92% of hospitality premises liable for the Basic Property Rate, capped at £110,000 per business”.

The Fraser of Allander Institute has highlighted that, primarily through the Small Business Bonus Scheme, 48% of RHL properties in Scotland already receive 100% rates relief. The Non-domestic rates relief statistics 2024 show that 37% of public houses and restaurants, and 61% of hotels, already receive some form of relief, with 21% and 43% respectively receiving 100% relief, so it should be noted that a significant proportion of properties eligible for the new relief will already be in receipt of support.

The wholly new announcement is that this relief will also cover Grassroots Music Venues with a capacity of up to 1,500, echoing the UK government approach announced in the Autumn Budget. Details on the number of properties benefitting are unclear, but a look at SFC costings methodology and the valuation roll suggests this may be a headline grabbing statement that only affects a small number of businesses.

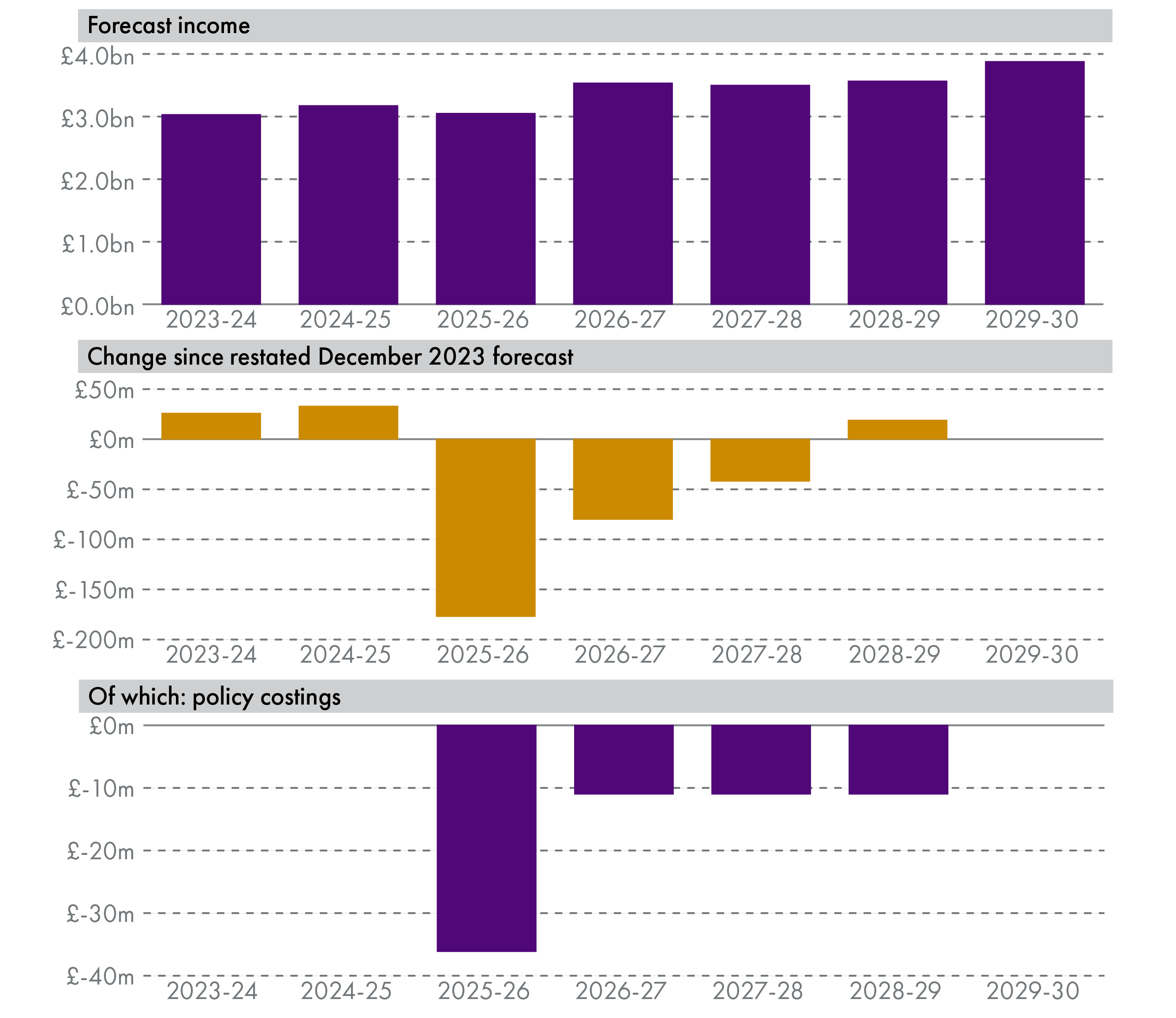

Taken all together, the Scottish Fiscal Commission estimate that the new 40% relief will cost the Scottish Government £22 million in 2025-26, in addition to the £5 million cost of extending the Islands relief for a further year.

The news that relief will not be extended to retail businesses has not been well received by stakeholders, with a spokesperson the Federation of Small Businesses calling it “a bitter pill to swallow” and arguing that “the pressures they are facing are exactly the same as those in England and Wales, where relief has continued to be available since July 2022 – the last time such relief was offered in Scotland.”. Given that shops make up roughly a fifth of properties on the Valuation Roll, compared to hotels, restaurants and pubs comprising 3.6% of properties, it’s a large demographic that are not being offered any relief. However, replicating the UK government approach would come at a significant cost, an estimated £220 million according to the Fraser of Allander Institute.

During the Budget debate, when asked why relief had not been extended to retail, the Cabinet Secretary set out a considerably higher estimate:

When it comes to retail premises, I have set out an affordable proposition for hospitality businesses that will mean that about 11,000 hospitality businesses benefit. I say to Craig Hoy that going further would not be sustainable. His proposition would cost more than £350 million, and we would not get that money from the UK Government. We got only £145 million this year in consequentials, and there will be no consequentials next year, because the UK Government is moving to a different business tax rate system that cannot be replicated here.

The Scottish Government had been considering the reintroduction of the Public Health Supplement for large retailers, a tax on large retailers selling alcohol and tobacco formerly in place between April 2012 and March 2015. In the Budget document, the Scottish Government explains that:

...following exploratory discussions with stakeholders and taking into consideration cumulative burdens, including UK Government increases in employer national insurance contributions, we have no plans to introduce this at this time.

Non-domestic rates forecasts

In February 2024, the SFC specified a revised policy baseline for non-domestic rates, in which it assumed that the Basic Property Rate (BPR), Intermediate Property Rate (IPR) and Higher Property Rate (HPR) will increase in line with inflation each year. This led to publication of a restated forecast for December 2023 forecast, first published in the August 2024 fiscal update. This restated figure is the baseline shown here, rather than the figures used in last year’s briefing.

Other devolved taxes

Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (LBTT)

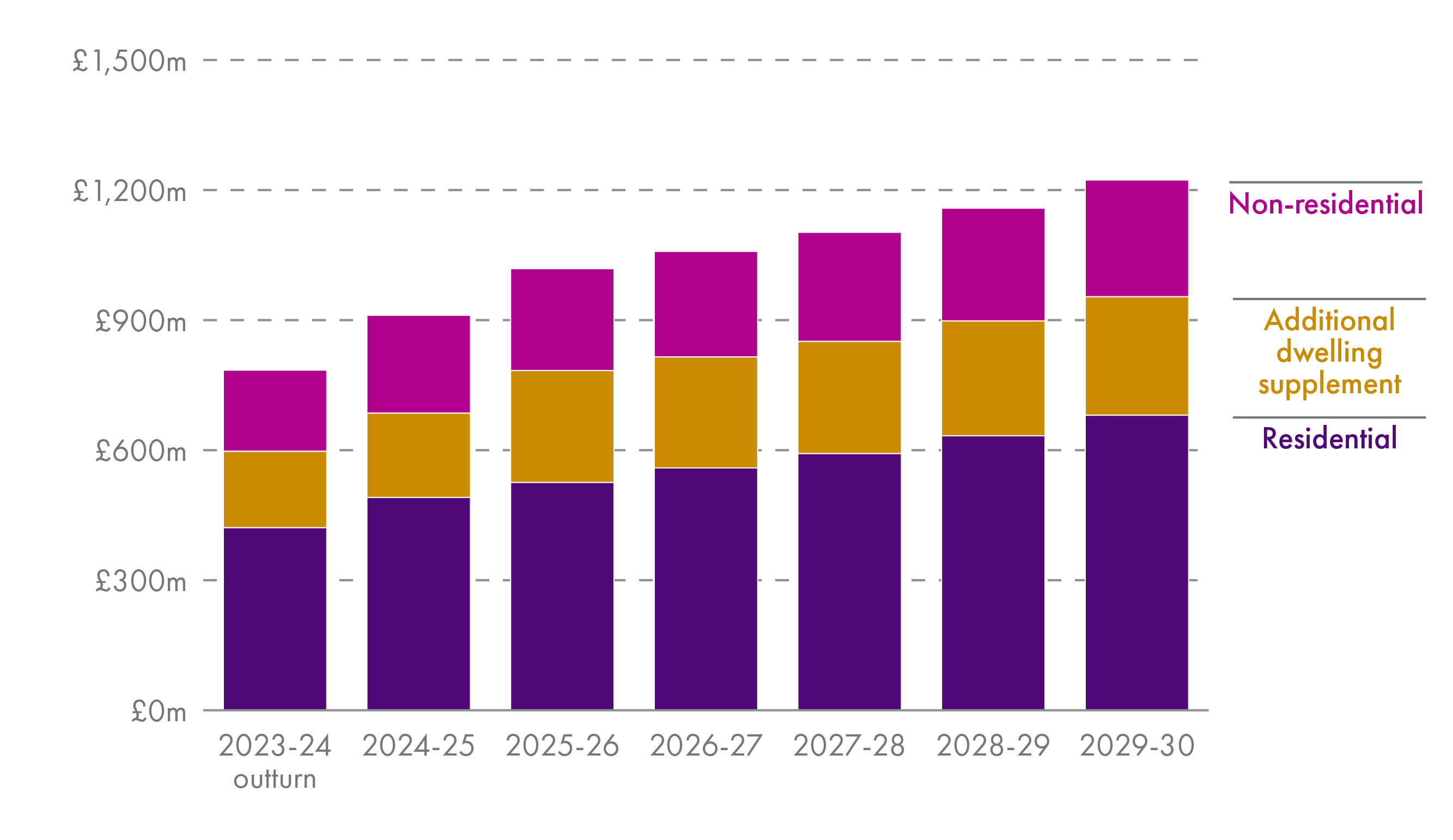

Land and Building Transaction Tax is the tax applied to purchases of residential and non-residential land and buildings, as well as commercial leases. The Scottish Government has maintained the residential and non-residential rates and bands at their current level, along with the relief available to first time buyers, stating that this approach “preserves our progressive system, delivering certainty and stability for taxpayers”. The Additional Dwelling Supplement (ADS) was increased from 6% to 8%, taking effect from the day after the budget, for any transactions for which legal missives had not been signed. The SFC forecast that this increase will raise £32 million in additional revenue in 2025-26, after taking account of spillover effects on residential LBTT. The Scottish Government stated that the increased ADS rate supports its commitment to protect opportunities for first-time buyers in Scotland.

The Scottish Government has committed to undertaking a review of LBTT over the remainder of this Parliament, commencing in Spring 2025 to ensure the policy intentions of LBTT continue to be met.

The SFC forecast that LBTT will raise a total of £1,019 million in 2025-26, a significant increase from the forecasts in December 2023, before taking account of the impact of policy measures. This reflects a change in the outlook for the property market, which the SFC consider to be recovering, with growth in prices and numbers of transactions. The majority of LBTT revenues are expected to come from residential transactions over the forecast period, with total receipts increasing throughout the forecast period to 2029-30. The main driver of this is the expected fall in house prices up to 2025-26, before a gradual recovery.

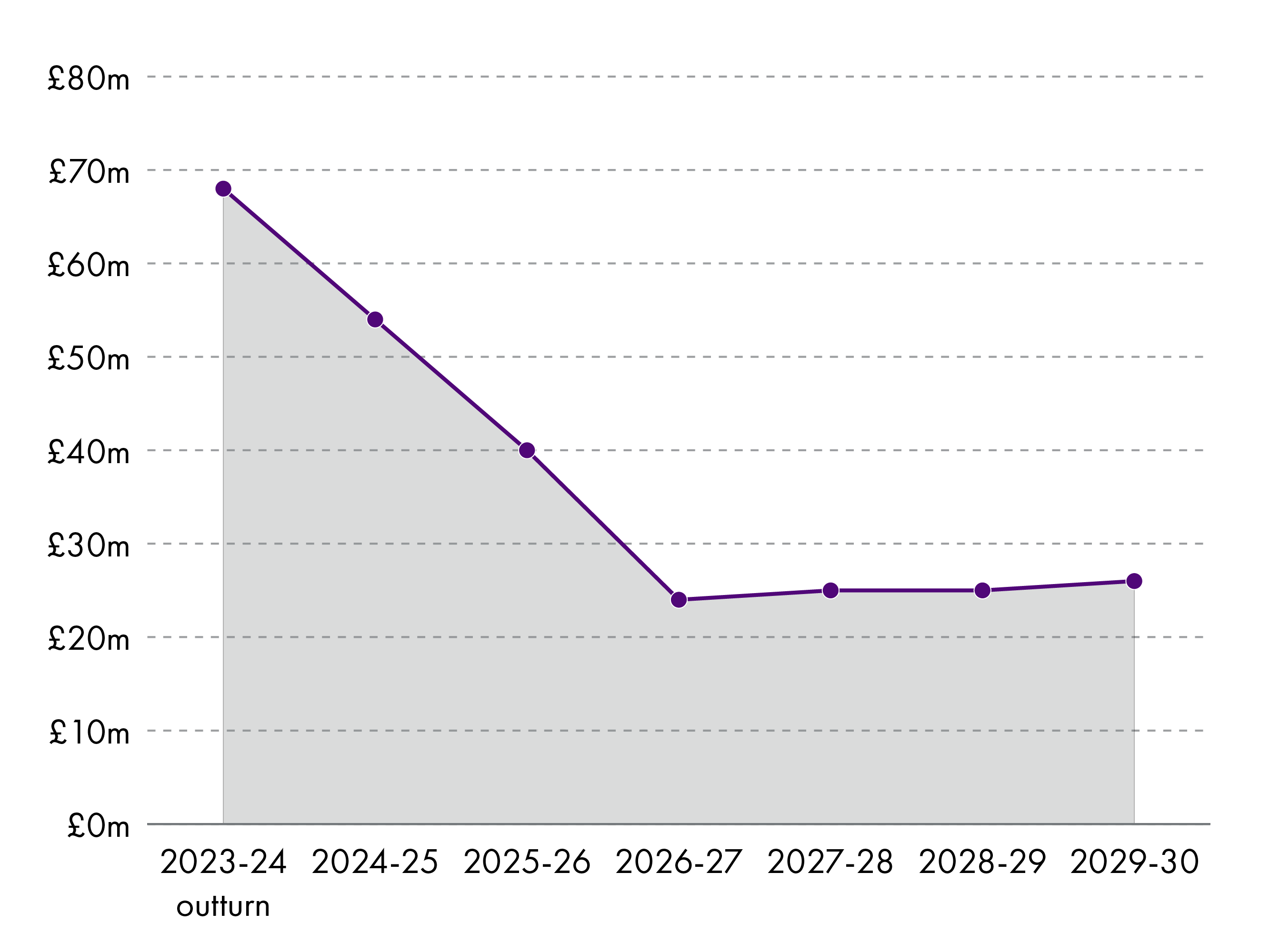

Scottish Landfill Tax (SLfT)

SLfT applies to the disposal of waste to landfill, charged by weight on the basis of two rates: a standard rate; and a lower rate for less polluting materials. The tax is intended to provide a financial incentive to support a more circular economy, reduce overall waste and the amount going to landfill and increase recycling.

The Scottish Government has increased the standard and lower rates of SLfT to £126.15 per tonne and £4.05 per tonne for 2025-26 respectively. As in previous years, these changes maintain parity with the UK rates. The SFC forecast that SLfT will raise £40 million in 2025-26. Following the introduction of a legislative ban on the landfilling of all biodegradable municipal waste on 31 December 2025, SLfT revenues are expected to reduce to an average of £25 million per year over the remainder of the forecast period. The policy goal of SLfT remains behavioural change – the expectation is that over time these revenues will reduce, albeit at a slower rate than the SFC had previously assumed.

The Scottish Government is commissioning independent research on the ongoing effectiveness of the lower rate of Scottish Landfill Tax in supporting the Scottish Government’s circular economy and waste objectives.

Other devolved taxes and proposed taxes

There are no new policy announcements in relation to the Airport Departure Tax (ADT), with the Scottish Government restating its position that it remains committed to introduce ADT “in a way that protects Highlands and Islands connectivity and complies with the UK Government’s subsidy control regime”. The Budget document states that the Scottish Government will review the rates and bands of ADT – including those which apply to private jet flights – prior to its implementation to ensure the tax is aligned with net zero ambitions. The UK-wide Air Passenger Duty will continue to apply in Scotland until ADT is implemented.

The Aggregates Tax and Devolved Taxes Administration (Scotland) Act 2024 received Royal Assent in November 2024, making provision for a Scottish Aggregates Tax. The intention is to introduce the tax on 1 April 2026, subject to the approval of the necessary Scottish and UK secondary legislation.

On VAT Assignment, which was also devolved in the Scotland Act 2016, the Scottish Government notes the 2023 Fiscal Framework Agreement with the UK Government and states:

The 2023 Fiscal Framework Agreement with UK Government outlines that, further work is required by UK Government and Scottish Government to mitigate the risks of VAT Assignment implementation. Once agreed by both governments, assignment methodology and operating arrangements will require joint UK and Scottish Government Ministerial sign-off.

The Budget also outlines plans for three new taxes:

The Scottish Government intends to introduce legislation in 2025-26 to establish a Building Safety Levy, which would raise revenues to fund the Scottish Government’s cladding remediation programme. This would replicate the UK Government’s own planned levy which will cover England.

The Scottish Government is exploring a potential Cruise Ship Levy, including the practicality, deliverability, and impacts of such a levy, with a public consultation set to be launched in January 2025.

The Scottish Government is committed to considering options for a Carbon Land Tax. The Budget document states that the Scottish Government will work with the Scottish Land Commission to consult with a range of stakeholders and to develop the evidence necessary to identify and assess options for future taxation in this area.

One tax that had previously been suggested is no longer proposed (the Public Health Supplement – see section on Non-Domestic Rates).

There is no mention in the Budget document of the Infrastructure Levy, which had previously been proposed for implementation by spring 2026. A consultation concluded in September 2024, but there is no firm commitment to its introduction in the Budget document. The infrastructure levy powers in the Planning (Scotland) Act 2019 are subject to a “sunset clause”, meaning that they will lapse if regulations establishing the levy are not made by July 2026.

Tax Strategy

The Scottish Government published a Tax Strategy alongside the Budget, intended to set out the steps that will underpin the Scottish Government’s approach to developing tax policy. In terms of firm commitments, these are limited and – given where we are in the political cycle, effectively only cover the next budget. In respect of income tax, the Scottish Government is committing:

to not introducing any new bands or rates

to ensuring that more than half of Scottish taxpayers will pay less income tax than they would in the rest of the UK – currently this is achieved, but these individuals pay only £28 less per year at most than they would in the rest of the UK, so it is not a major difference

to uprating the starter and basic rate bands by at least inflation

to freezing the higher, advanced and top rate thresholds.

There are plans to introduce a Scottish Aggregates Tax by 1 April 2026, and to resolve the subsidy control issues that are standing in the way of implementing a Scottish Air Departure Tax. A Building Safety Levy is also planned.

Beyond the specific commitments, there is lots of talk of “exploring”, “considering” and “engaging” on a range of taxes, including council tax and non-domestic rates. There is a commitment to reporting on progress in early 2026.

The main Budget document refers to plans for a Cruise Ship Levy and Carbon Land Tax, but these are not referred to in the Tax Strategy document.

Social security

Some elements of social security spending are devolved. This has given the Scottish Government more powers to shape Scotland’s social security system, but also more budgetary risk. Any expenditure by the Scottish Government above the social security block grant adjustment (BGA) must be funded from within the Scottish Budget. The BGA broadly reflects the hypothetical amount that would have been spent on equivalent social security payments had they not been devolved.

This budgetary risk is materialising. Scottish Government decisions on social security have cumulatively added significant cost pressures to its budget. Broadly speaking, this is because the Scottish Government:

Has introduced benefits that are not available in the rest of the UK (rUK), such as the Scottish Child Payment and Carers Allowance Supplement.

Is spending more on benefits that attract a BGA than is added to the budget via the corresponding BGA. In other words, where devolved benefits have an rUK equivalent, the Scottish Government is spending more than would have been spent if these benefits had not been devolved. It must meet this additional cost from within the Scottish Budget.

In 2025-26, the Scottish Government has decided to increase benefit payments in line with September 2024’s CPI inflation rate.

Detail of social security spending

In recent Scottish Budgets, the amount spent on social security has risen sharply - and is forecast to continue rising. Social security is forecast to account for 13.5% of resource spending in 2025-26, compared with 9.7% in 2022-23.

| Devolved benefit | 2023-24 outturn | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | 2029-30 |

| Adult Disability Payment | 2,632 | 3,177 | 3,605 | 3,983 | 4,340 | 4,675 | 5,030 |

| Pension Age Disability Payment | 659 | 768 | 834 | 889 | 933 | 962 | 992 |

| Child Disability Payment | 425 | 524 | 618 | 675 | 708 | 732 | 755 |

| Scottish Adult Disability Living Allowance | 445 | 424 | 394 | 365 | 339 | 312 | 287 |

| Scottish Child Payment | 429 | 459 | 471 | 488 | 501 | 507 | 515 |

| Carer Support Payment | 358 | 402 | 459 | 505 | 525 | 546 | 574 |

| Carer's Allowance Supplement | 48 | 54 | 62 | 67 | 70 | 73 | 76 |

| Pension Age Winter Heating Payment | - | 32 | 101 | 103 | 102 | 104 | 108 |

| Child Winter Heating Payment | 8 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 15 |

| Winter Heating Payment | 23 | 29 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 |

| Other benefits | 303 | 345 | 348 | 354 | 361 | 366 | 371 |

| Total spending | 5,330 | 6,224 | 6,930 | 7,471 | 7,922 | 8,321 | 8,754 |

Note that the total does not match Figure 10 because Figure 10 excludes £73 million of spending on employability support.

Furthermore, social security spending is rising faster than the amount added to the Budget from the BGA. In 2025-26, spending commitments on social security are forecast to be £1,334 million higher than the BGA and are set to rise further. This must be funded from within the Scottish Budget. The trade off, of course, is that this money cannot be spent on other areas of the Budget.

Indeed, once social security is accounted for, the resource funding available to fund day-to-day expenditure in public services is forecast by the SFC to fall by 0.3% in real terms between 2024-25 and 2025-26.

| Social security spending and funding | 2023-24 outturn | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | 2029-30 |

| Block Grant Adjustment | 4,432 | 5,182 | 5,596 | 6,018 | 6,447 | 6,846 | 7,291 |

| Spending on social security payments with a BGA | -4,629 | -5,445 | -6,125 | -6,637 | -7,063 | -7,446 | -7,858 |

| Payments unique to Scotland | -569 | -618 | -644 | -674 | -697 | -713 | -732 |

| Other social security spending | -132 | -162 | -161 | -160 | -161 | -162 | - 163 |

| Total effect on the Scottish Budget | -899 | -1,042 | -1,334 | -1,453 | -1,475 | -1,476 | -1,463 |

Note: Other social security spending includes payments for which funding comes through the general Block Grant. The SFC were therefore unable to estimate funding for individual benefits.

It is worth noting that despite much of the commentary around the Budget being focused on Scottish Government plans to mitigate the two child cap and introduce a more generous version of the Winter Fuel Payment, by far the biggest financial commitments made by the Scottish Government on social security are in relation to the Adult Disability Payment (ADP) and Scottish Child Payment (SCP). Spending on ADP in 2025-26 is forecast to exceed its related BGA by £314 million (see next section). Spending on SCP is forecast to be £471 million, for which no BGA is received, as this payment is unique to Scotland.

For context, the SFC forecast that the expanded Pension Age Winter Heating Payment will require a commitment by the Scottish Government of £69 million in 2025-26, above the related BGA. The mitigation of the two child cap on Universal Credit payments will not be introduced until 2026 at the earliest, so there is no impact on the 2025-26 Budget, other than costs related to developing systems to allow for future payments.

Adult Disability Payment

As it constitutes over half the social security budget, it is worth setting out what is driving increases in the amount spent on ADP.

ADP was introduced in 2022 as the devolved replacement for Personal Independence Payments (PIP). This is a non-means tested payment provided to adults with a disability or long term health condition that affects their daily life. It is not linked to employment status.

When establishing the devolved benefit, the Scottish Government designed its administration differently to PIP. The Scottish Government has adopted a policy of seeking to maximise take-up of the benefit. Most notably, the application process has been streamlined and a ‘light touch’ periodic review process for renewal of claims has been introduced.

This has affected the number of people in receipt of ADP. The rate of successful new applications is higher than before ADP was devolved. Furthermore, the rate at which recipients come off ADP is lower. The net result is higher spending on ADP, which is forecast to exceed the BGA funding it attracts by £314 million in 2025-26.

Even without this different approach to administering ADP, another important factor to note is that there is a UK-wide trend of increasing demand for disability benefits. This is driving up spending on ADP, but also increases the associated BGA funding.

Pension Age Winter Heating Payment

This year, the UK government’s Winter Fuel Payment (WFP) was devolved to the Scottish Government. The devolved replacement benefit is the Pension Age Winter Heating Payment (PAWHP).

In July 2024, the UK government announced that the WFP in England and Wales would be restricted to households where at least one person over the state pension age receives certain qualifying benefits.

The Scottish Government has since announced that from 2025-26, PAWHP will follow a different payment policy. Where one person in a household is above the state pension age but below 80 and is in receipt of qualifying benefits (primarily Pension Credit), the household will receive a payment of £203.40. If the lead claimant receives qualifying benefits and is over 80, the household will receive £305.10. Where one person is above the state pension age but does not receive qualifying benefits, the household will receive £100.

The SFC forecasts that spending on PAWHP will be £32 million in 2024-25, which rises to £101 million in 2025-26 with the expanded eligibility criteria. This is £69 million above the forecasted 2025-26 BGA for the UK government’s Winter Fuel Payment. This means that, due to the expanded eligibility in Scotland, the Scottish Government must fund the additional cost (£69 million) itself.

The SFC estimates that the caseload for PAWHP will increase from 137,000 in 2024-25 to 812,000 in 2025-26. In 2025-26, 83% of households are forecast to receive the minimum payment of £100. Note that these payments will not be made until Winter 2025, so this winter, pensioner households will only receive payments if they are in receipt of the qualifying benefits (Pension Credit in most cases).

Mitigating the two child cap

One of the top headlines from the Budget was the Scottish Government’s announcement that it intends to mitigate the impact of the UK government’s two child benefit cap. This cap prevents parents from claiming Universal Credit and Child Tax Credit for third and subsequent children born after 6 April 2017. The Scottish Government claims that this will lift 15,000 children out of poverty.

The two child cap is a reserved policy in relation to reserved benefits. The Scottish Government intends to “develop the systems necessary to effectively scrap the impact of the two child cap”. It is not yet clear how this intention will be implemented and the Cabinet Secretary made it clear that the ability to mitigate will depend on access to relevant data from the UK Department for Work and Pensions.

The proposal is for mitigation of the two child cap to be operational in Scotland by 2026-27. This means that there is no impact on the 2025-26 Scottish Budget figures. Indeed, the SFC were not informed of the policy until after its final policy deadline, meaning that it has not included a costing of the policy in its fiscal forecasts.

However, the SFC has conducted an illustrative analysis that estimates the cost of mitigating the two child cap could be around £150 million in 2026-27, rising to £200 million in 2029-30. Since the Budget announcement, the SFC has confirmed that it will publish a report on the impact of mitigating the two child cap on the Scottish Budget on 7 January 2025. Parliament will be interested in scrutinising this report, given that mitigating the two child cap will incur further annual costs to the Scottish Budget that will not attract BGA funding.

Scottish Fiscal Commission forecasts

The SFC’s forecasts tell us about the current state of, and future outlook for, Scotland’s economy. It also informs some key elements of the Budget itself, such as forecasted tax revenues and social security spend. This section sets out what the SFC are forecasting on GDP, inflation, employment, earnings and living standards. More detail can be found in the SFC’s December 2024 Economic and Fiscal Forecasts.

GDP and living standards

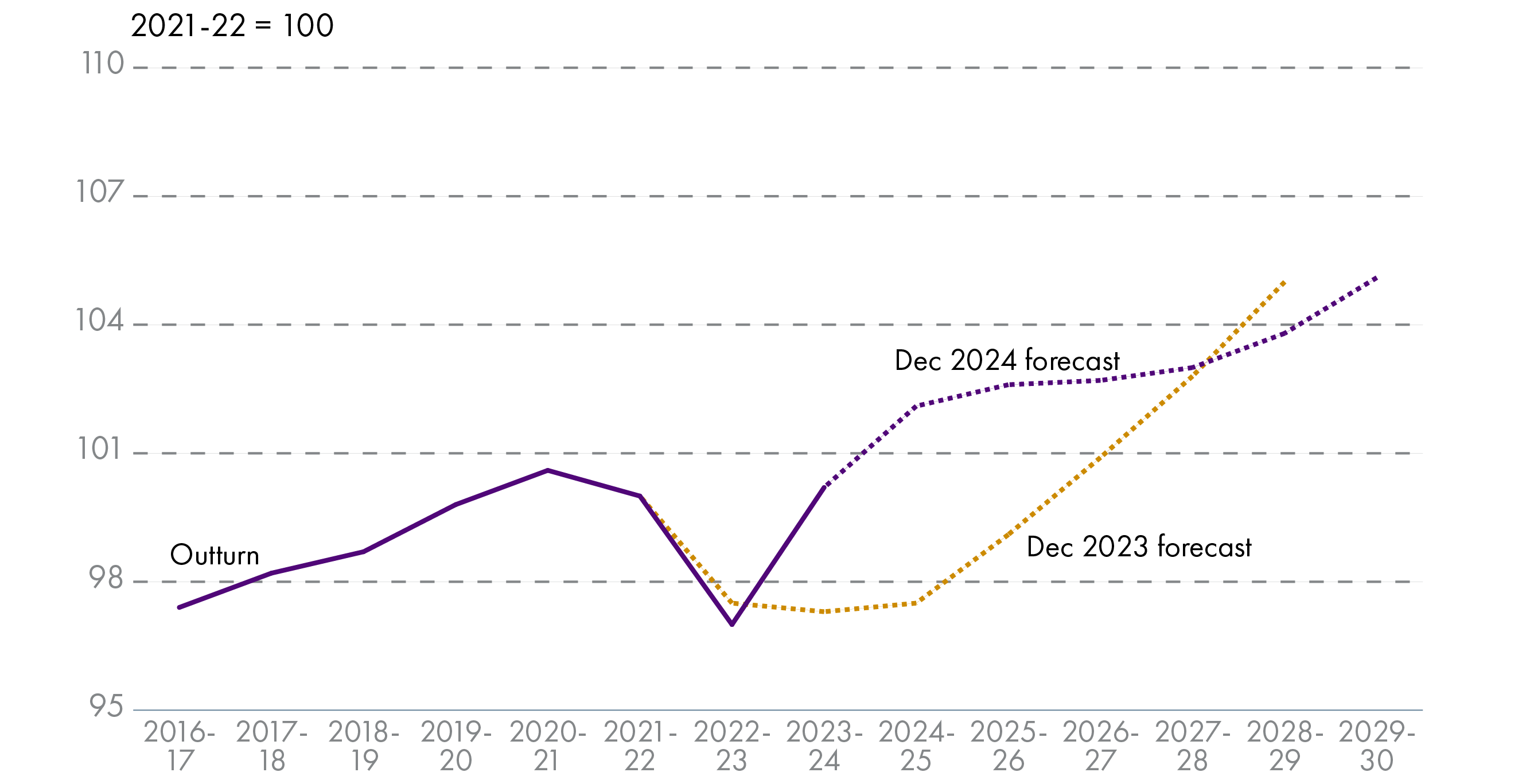

The SFC’s latest forecasts for the Scottish economy show an improved outlook compared to December 2023’s forecasts. GDP is higher in the short term, with growth projected to be 1.2% in 2024-25, 1.6% in 2025-26, and 1.5% in 2026-27, up from 0.8%, 1.3%, and 1.3% respectively in last year’s forecasts.

This is in large part due to additional spending announced in the UK October 2024 Budget1, which is expected to stimulate a demand-side boost to GDP (the trade off is higher prices and interest rates across the UK). However, the effect on GDP is temporary. Annual GDP growth is forecast to return to trend levels of 1.4% by 2027-28.

It is worth noting that this trend growth is 0.2 percentage points higher than in December 2023’s forecasts. This is primarily because the SFC is now assuming net international migration of 30,000 in 2023-24, which falls to 16,000 by 2027-28, versus an assumption of 13,000 net migration per year in last year’s forecasts. More working age adults in an economy can produce more goods and services, hence the forecasted boost to GDP.

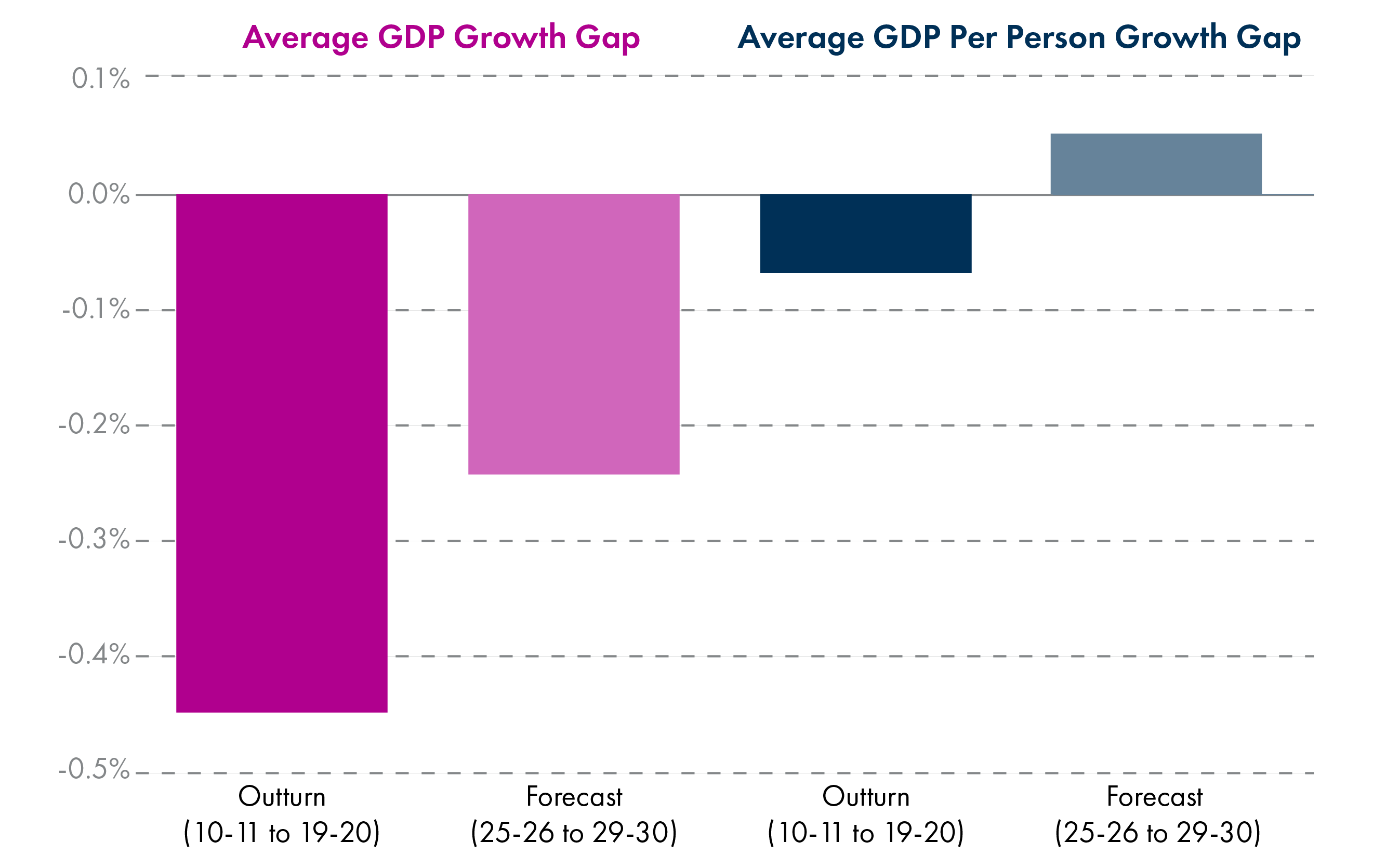

Changes in population also account for a significant amount of the difference in GDP growth between Scotland and the wider UK. Between 2010-11 and 2019-20, GDP growth in Scotland was an average of 0.4 percentage points below the UK.

However, this is largely due to higher population growth south of the border. The growth gap in GDP per capita over the same time period was 0.06 percentage points and is forecast to be reversed in the second half of this decade. This means that Scotland is forecast to have slightly higher GDP per capita growth than the UK between 2025-26 and 2029-30. Ultimately, GDP per capita is more closely related to living standards than GDP.

On living standards, there is some good news after some sharp falls following 2022-23’s energy price shock. Living standards, which the SFC measure as real disposable income per person, are now forecast to have returned to their 2021-22 levels in 2023-24 – three years earlier than had been forecast at last year’s Scottish Budget. The key driver of this improved picture for living standards is a combination of higher than expected earnings growth and lower than expected inflation.

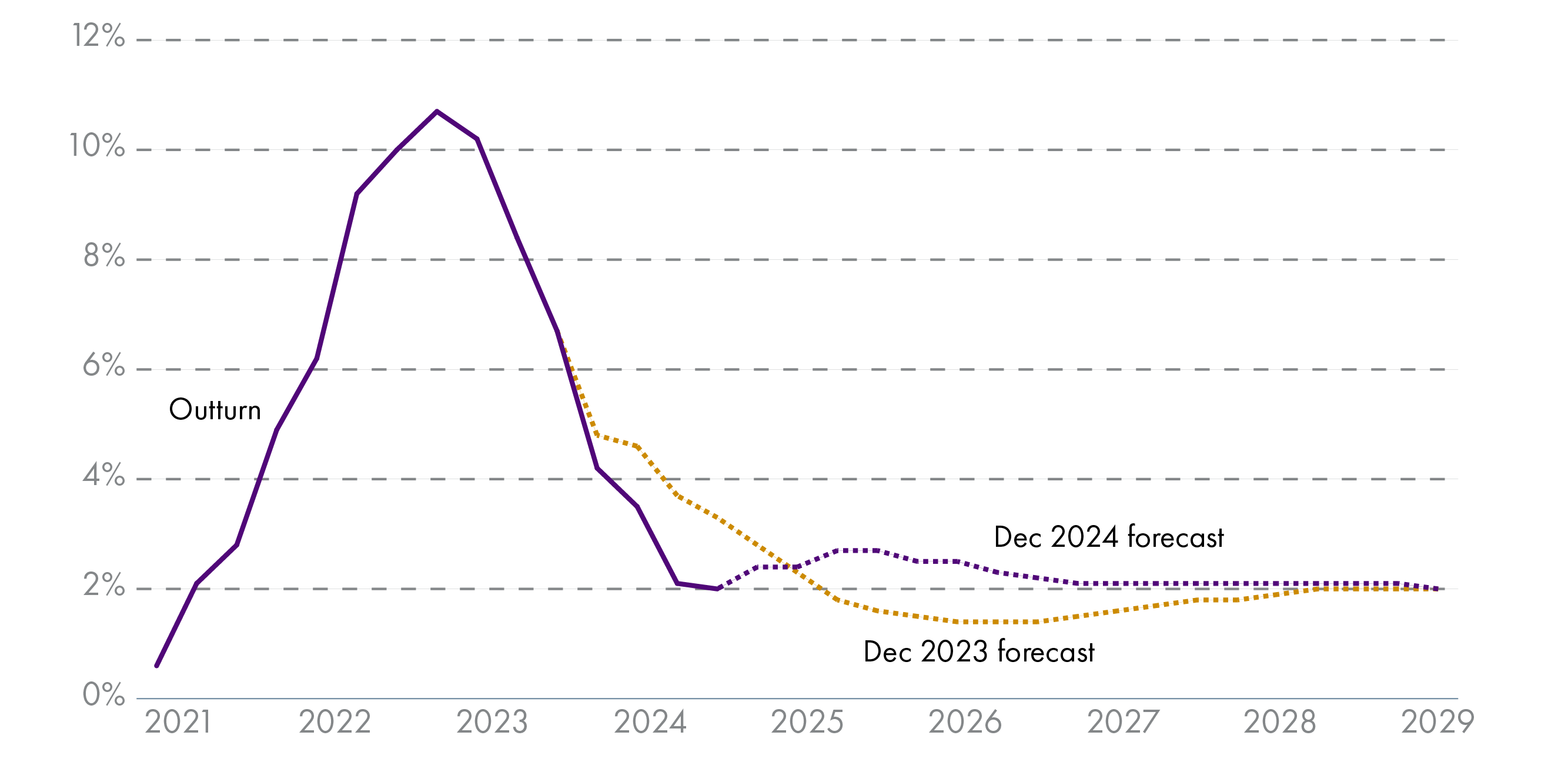

Inflation

High inflation has been a key factor in recent years’ budgets. Rising prices have put pressure on budgets for households and government departments alike, but have also been accompanied by high nominal earnings growth and a higher tax take, due to fiscal drag.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation is now at more ‘normal’ levels and is forecast to stay at, or close to, the Bank of England’s 2% target throughout the SFC’s forecast period. This should make financial planning easier, particularly in areas such as public sector pay.

Although CPI inflation fell faster than previously forecast, it is expected to increase slightly in 2025-26 to 2.6%. This is driven by more persistent domestic inflation (which excludes, for example, the effects of imported energy prices) and the effects of some of the employer National Insurance Contributions rise being passed on to consumer prices.

Labour market and earnings

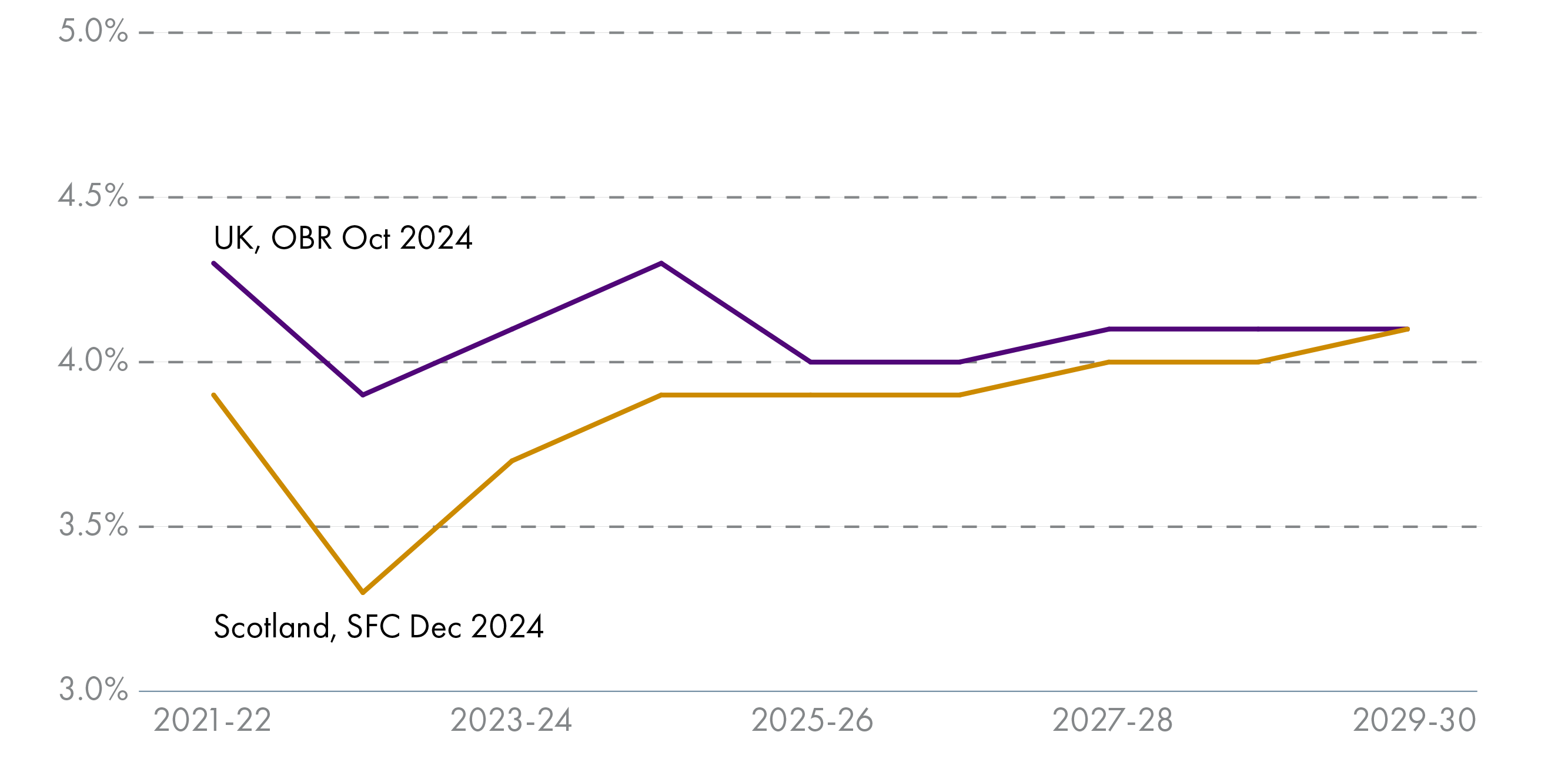

The SFC’s latest labour market projections are similar to December 2023’s.

Unemployment is forecast to rise from a near historic low of 3.7% in 2023-24 to 4.1% by 2029-30, which is assumed to be its long run trend level. The latest data from the Business Insights and Conditions Survey (BICS) suggests more job vacancies and therefore a tighter labour market in Scotland compared with the UK. The result is slightly lower unemployment (3.9% vs 4.0%) and faster nominal earnings growth (3.7% vs 3.0%) forecasted in Scotland in 2025-26 compared with the UK.

This stronger relative earnings growth benefits the Scottish Budget, as it boosts the tax base for income tax – a key revenue generator for the Scottish Government. However, the SFC point out a downside risk to future budgets if earnings growth turns out to be more similar north and south of the border than currently forecast. This matters because the size of future budgets is sensitive to small changes in SFC and OBR forecasts. More information on this can be found in the income tax net position section.

The SFC also highlight concerns over the reliability of the ONS Labour Force Survey, which is used to compile official labour market statistics. This is discussed in the SFC’s 2024 Statement of Data Needs. In short, response rates to the survey have fallen since the Covid-19 pandemic and reported unemployment is higher than other data sources (such as PAYE data from HMRC) suggest. The SFC therefore use a broader range of data sources to inform their forecasts.

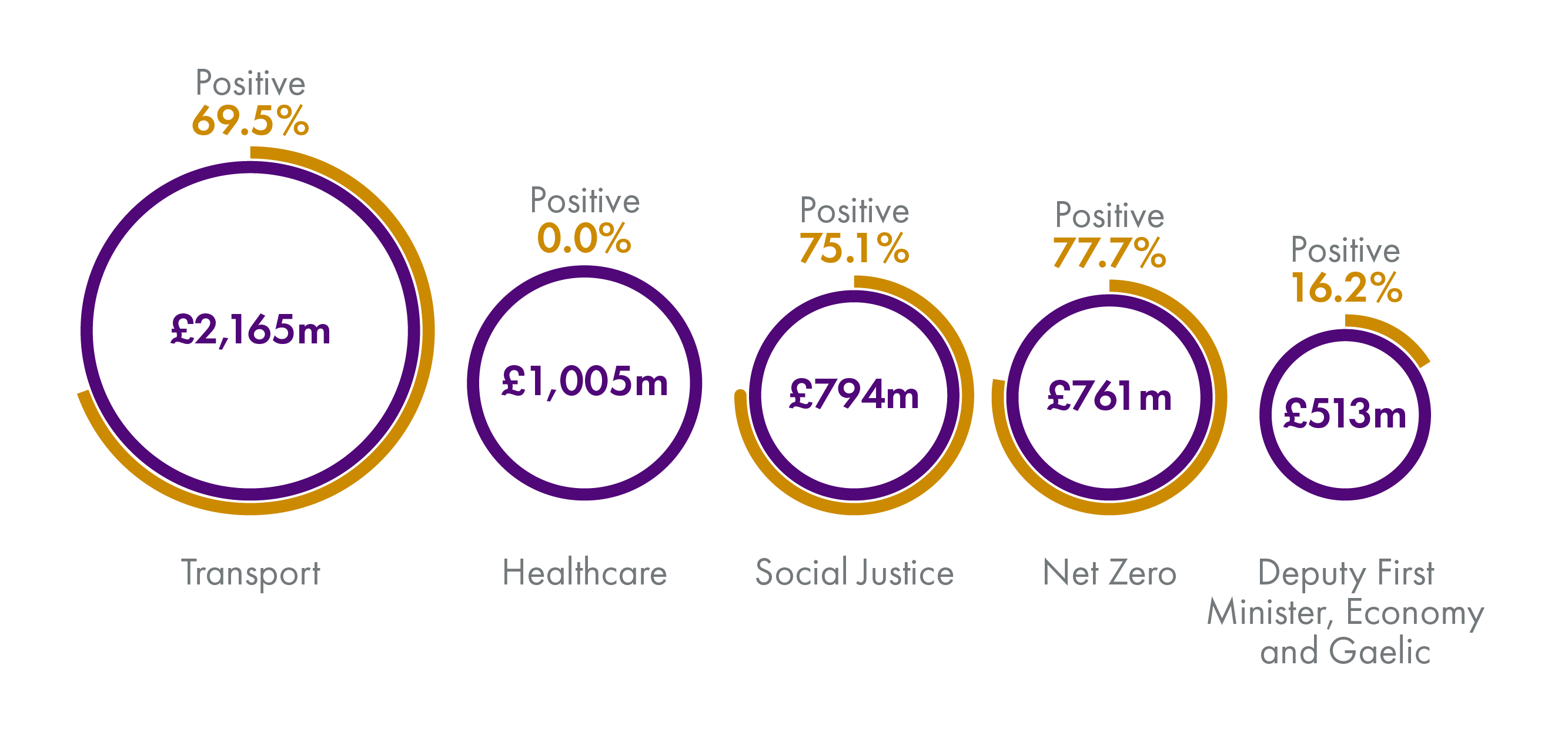

Capital and infrastructure

The 2025-26 Budget has a total of £7,343 million in capital and financial transactions resources available, which is an increase of £942 million compared to the 2024-25 Budget (14.7% higher in cash terms, or 12% in real terms).

The majority of the capital budget comes from HM Treasury. The core Barnett settlement increased by £1,323 million to £6,256 million (85% of total capital budget). Part of this increase is due to ring fenced funding for Network Rail, which was separately identified in previous years, now being part of the core settlement. The remainder of the increase is the result of policy decisions taken in the October UK Budget. There is also £122 million in capital funding anticipated to come from the UK government in support of City Deals.

The UK Government have provided Financial Transactions (FT) funding of £167 million, an increase from the £124 million that was available in 2024-25.

The Scottish Government has once again stated it intends to make full use of its capital borrowing powers, which adds a further £472 million to available funding. This is an increase of £14 million compared to 2024-25, as the revised Fiscal Framework agreed with the UK government increases the annual and cumulative borrowing limits in line with inflation (this uses the GDP deflator, which is 2.4% for 2025-26).

In addition to the capital borrowing, the Scottish Government plan to utilise £326 million of ScotWind proceeds. This was money passed to the Scottish Government by Crown Estate Scotland, relating to the recent ScotWind auctions. The Crown Estate auctioned ‘options’ to prospective developers, who in exchange for the fee have ten years to develop their proposals for offshore wind farms. In total, the Scottish Government has received £756 million in revenues. During the Emergency Budget Review in September 2024 the Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Local Government had indicated that ScotWind revenues would be deployed to support revenue spending in year, but the improved financial position in the Scottish Budget means that this is no longer required. In her statement to Parliament, the Cabinet Secretary stated that:

Members will be pleased to hear that ScotWind has not been used up in this financial year.

Instead, I am able to deploy over £300 million of ScotWind revenues in 2025-26 for exactly the kind of long-term investment it should be spent on.

This £300 million will deliver substantial investment in jobs, and in measures to meet the climate challenge; Presiding Officer, all of it an investment in the long-term success of our nation.

Figure 16 below sets out the sources of the Scottish capital budget for 2025-26.

Table 14 below sets out the capital and financial transaction budgets by portfolio.

| Portfolio | £ million |

| Transport | 2,118 |

| Health and Social Care | 1,005 |

| Finance and Local Government | 796 |

| Net Zero and Energy | 758 |

| Social Justice | 702 |

| Deputy First Minister, Economy and Gaelic | 696 |

| Justice | 511 |

| Education and Skills | 500 |

| Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands | 209 |

| Constitution, External Affairs & Culture | 35 |