Scottish Budget 2024-25

This briefing considers the Scottish Government's spending and tax plans for 2024-25. More detailed presentation of the budget figures can be found in our budget spreadsheets. Infographics produced by Andrew Aiton, Kayleigh Finnigan, and Fraser Murray.

Executive Summary: Income tax increases and budget cuts to fund government priorities

"Values" drive Budget choices

It is often said that budgets are about choices, a representation of the priorities of the government of the day. This budget was no different, and the Deputy First Minister (DFM) was keen to make this point, with her speech using the word "values" no less than eleven times. The "values" of the Scottish Government was the key theme of the DFM's budget speech.

So what has the Scottish Government chosen to prioritise?

Yet again, the Health Budget has been prioritised, and has been awarded higher increases than other spending areas. Indeed, the DFM told the Chamber that prioritising health spending has meant the government is less able to offer support to the business sector – for example, not being able to replicate the UK government's policy of 75% rates relief to the retail, hospitality and leisure sector in England.

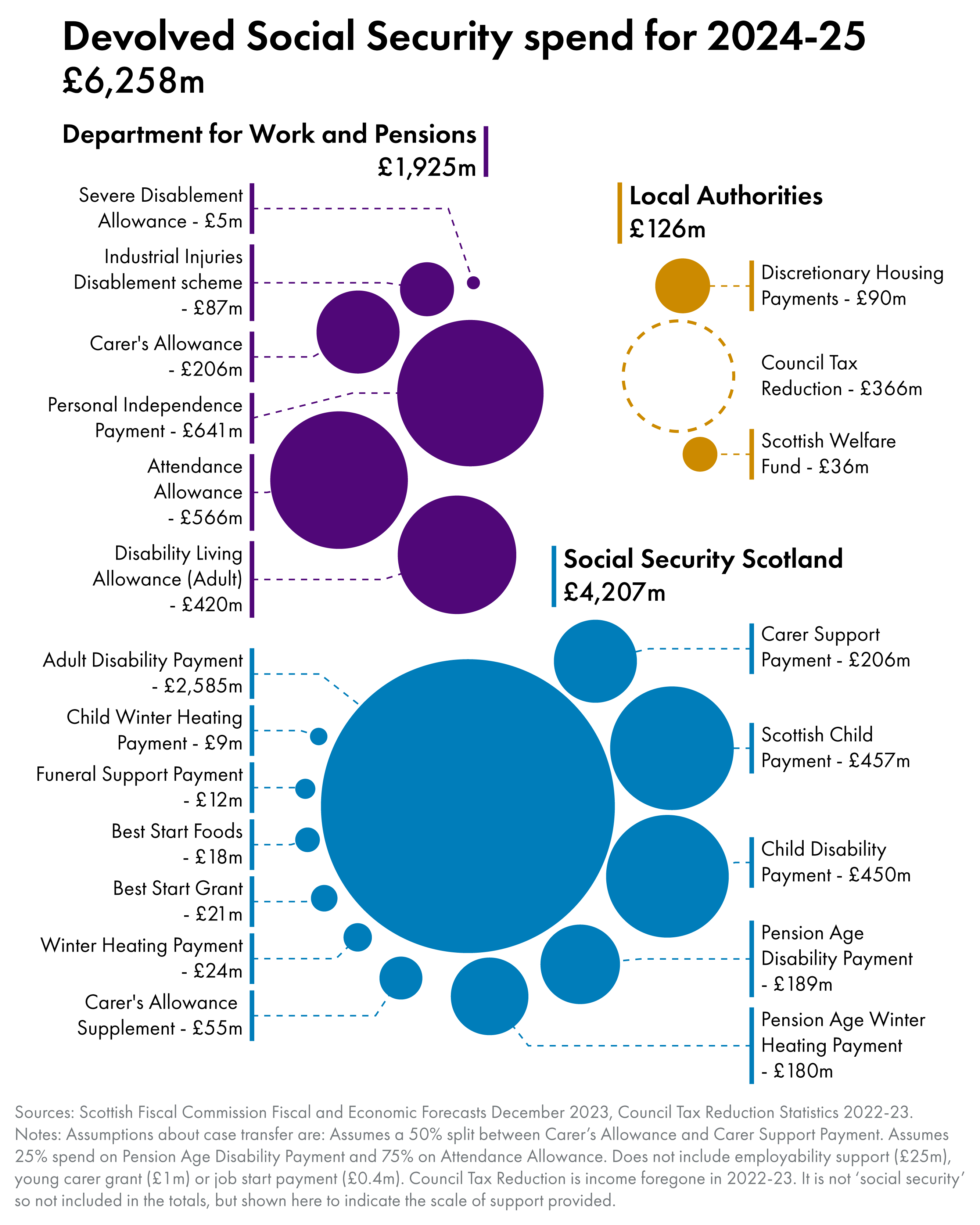

Social Security has also been prioritised. Devolved benefits, as in the rest of the UK, will increase by 6.7% next year, but the Scottish Budget also funds benefits like the Scottish Child Payment that will only be available in Scotland. Application process changes for the Adult Disability Payment are expected to result in a higher number of claimants and again, the cost implications of this must be found in the Scottish Budget. The key impact of the social security choices of the Scottish Government is that spending in this policy area in 2024-25 will exceed the block grant adjustment added to the Scottish budget by more than £1 billion. The Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) forecasts suggest that this gap will rise to £1.5 billion by the end of the forecast period in 2028-29. Spending £1 billion over and above the block grant addition to the Scottish budget, means that there is £1 billion less for the other parts of the Scottish budget. Another budgetary choice.

Local government's wish list for this year's Budget probably included a hope for increased funding, an expectation of less ring-fencing from central government and an ask for some multi-year certainty. In some of these areas, the Budget has delivered, in others it has not.

Total revenue funding for local government– used for day-to-day spending such as salaries and the purchasing of goods and services – will go up by 5% in real terms. Capital spending falls by 24% in real terms, although this partly reflects a change in the treatment of capital money previously transferred to the revenue budget to support pay deals. The proportion of local government funding formally ring-fenced for national policies is also smaller than last year. This should allow councils more flexibility over how they spend their allocations, and allow them to use more of their budgets to fund local solutions for local problems.

This is the first budget since the much trumpeted Verity House Agreement, signed by the Scottish Government and COSLA in June. A commitment to reducing ring-fencing was part of this, but so too was an agreement to provide multi-year spending plans "wherever possible". Councils will be disappointed that this year's budget, once again, is for a single year only. Such a situation makes medium-term financial planning difficult for councils and is arguably counter to the Verity House Agreement's stated aim of supporting the delivery of sustainable public services.

Additional funding of £144 million is provided to local authorities next year, provided they all agree to freeze council tax. With the freeze applying to all properties, including the largest and most expensive, it is arguable whether this particular policy is consistent with the value outlined by the DFM of asking "those with the broadest shoulders…to contribute a little more".

Despite a positive settlement for the revenue budget for local authorities, capital budgets are seeing a significant reduction. This could present challenges in maintaining and improving the school estate and in delivering against net zero targets.

The wider reductions to the capital budget are also seen in the Affordable Housing Supply Programme (AHSP) budget. This is being reduced by 27% in real terms in 2024-25. It is unclear how this will affect the Scottish Government's commitment to complete 110,000 affordable homes by 2032 and to invest £3.5 billion in the AHSP this parliamentary term.

Those with the "broadest shoulders" are certainly contributing more when it comes to income tax.

The introduction of the new "advanced" rate tax band means that those earning more than £75,000 will be paying more than they would have under the 2023-24 Scottish income tax policy. Someone earning £100,000 next year will pay £740 more than they did last year, and £3,346 more than someone earning the same salary in the rest of the UK. The income tax bill on earnings of £150,000 will be £2,120 more than last year and £5,978 more than in the rest of the UK.

When compared with income tax policy in the rest of the UK (rUK), Scottish taxpayers earning less than £28,850 will pay up to £23 less income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK. This accounts for just over half (51%) of all Scottish taxpayers. Above this earnings level, Scottish taxpayers pay more tax than they would in the rest of the UK and the gap widens rapidly for those earning above £50,000. Those earning more than £50,000 will be paying at least £1,500 more income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK.

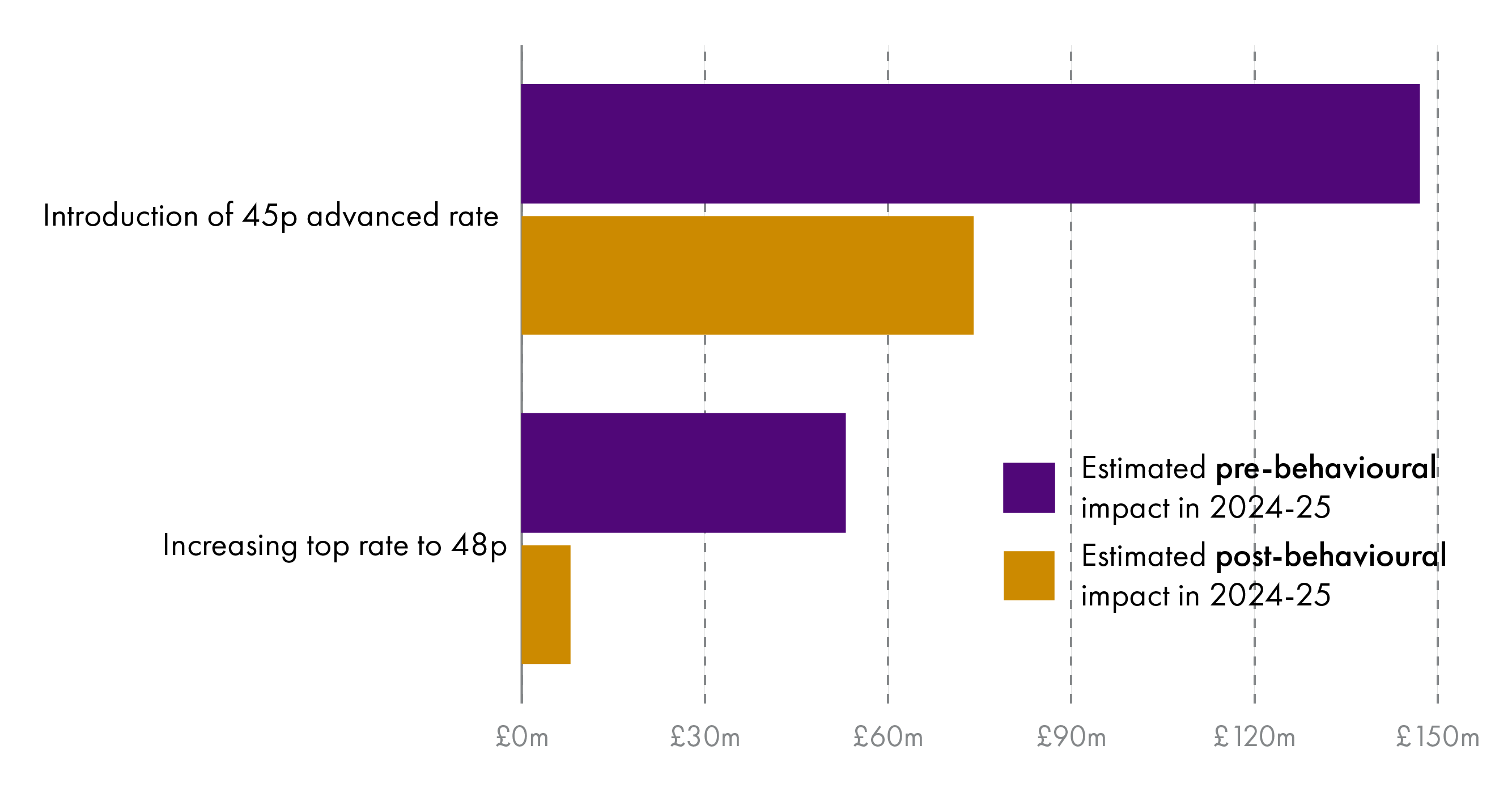

The so-called behavioural impacts of these policies will be something to keep an eye on in the coming years. Behavioural effects might involve steps such as increasing pension contributions (to reduce taxable income), reducing hours worked or moving outside Scotland. The SFC forecast that the creation of the new "advanced" rate of 45p for earning between £75,000 and £125,140 will raise £74 million after taking account of behavioural effects (around 50% of the "static costing" – i.e. before taking account of behaviour). The increase in the top rate of tax is expected to generate just £8 million after accounting for behaviour (only 15% of the static costing).

These costings are the estimated in-year revenue that the new proposals for 2024-25 are expected to raise. Over the years, the various different policy decisions of the Scottish Government in respect of income tax mean that Scottish taxpayers are now paying a total of around £1.5 billion more than they would under rUK income tax policy. The longer term economic impact of a growing tax differential between Scotland and the rest of the UK is not yet clear and is something that the Scottish Fiscal Commission and Scottish Government will continue to explore in the years to come. Many of the assumptions used to analyse Scotland's tax divergence are currently based on international evidence (e.g. different US states having differing tax regimes), but the Scottish Government now has the opportunity to understand the trade-offs of its tax strategy in a far more local context as more evidence emerges.

Tax revenues forecast to perform well and provide significant new resource to the Scottish Government

The creation of a new tax band (increasing Scotland's total to six bands compared with three in the rest of the UK), fiscal drag and better than expected income tax revenues have boosted the Scottish budget.

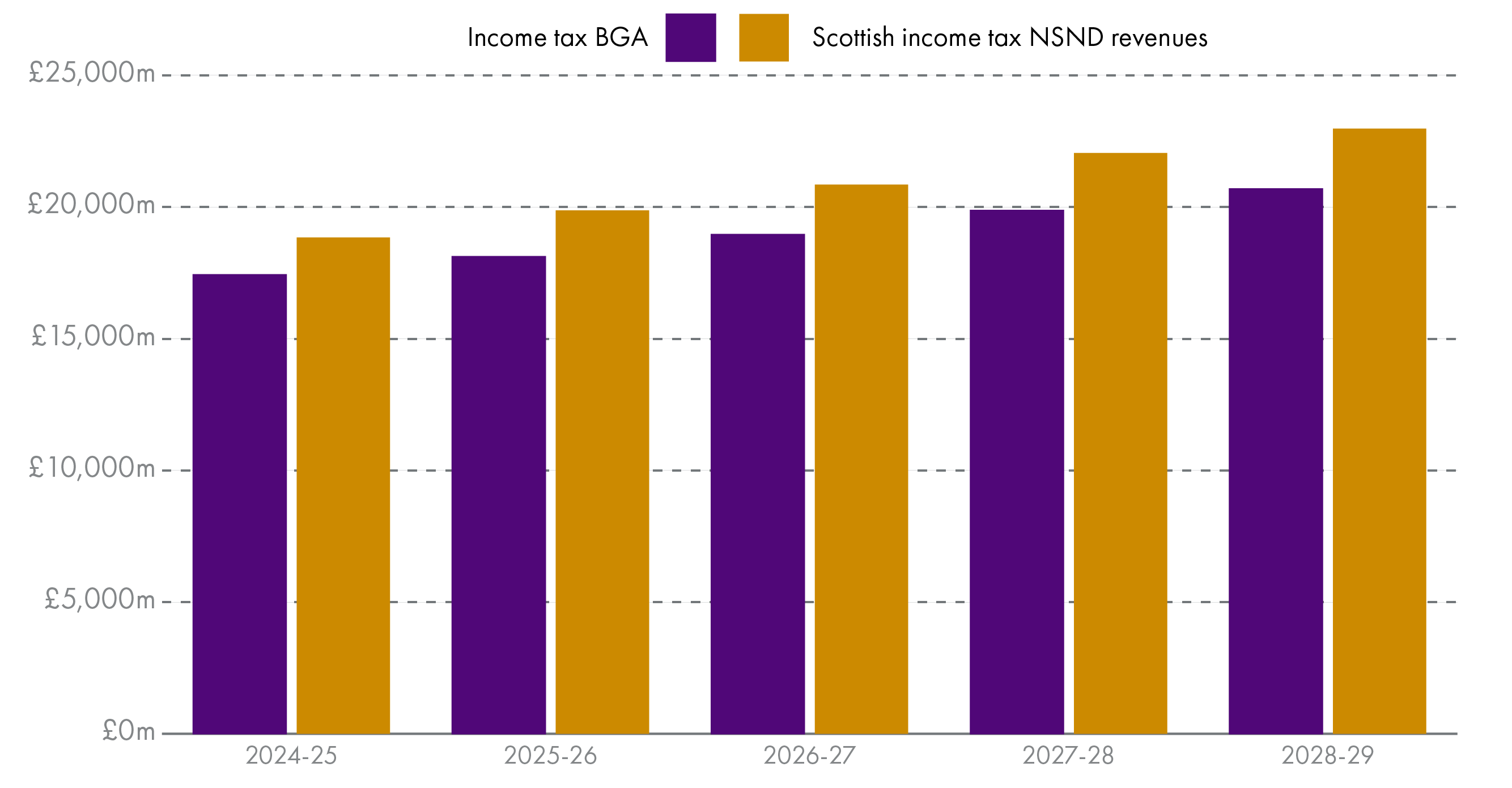

In 2024-25, the income tax net position is expected to be £1.4 billion. That is, non-savings non-dividend (NSND) income tax revenues in Scotland are expected to exceed the block grant adjustment (BGA) for income tax by £1.4 billion. The income tax BGA is the amount that is removed from the Scottish budget to account for the fact that most income tax decisions have been devolved to the Scottish Parliament. It reflects what Scotland would have raised in income tax if it had retained the same tax policy as the rest of the UK and if Scotland's per capita tax revenues had grown at the same rate as the rest of the UK. This is a much improved position relative to previous forecasts and is double the income tax net position for 2024-25 that had been estimated at December 2022. This largely reflects much stronger earnings growth in Scotland, both relative to previous forecasts and relative to the rest of the UK. This increases the number of taxpayers and the amount of income tax paid and also pulls taxpayers into higher tax bands ("fiscal drag"). It is these factors that are driving the improved income tax net position, rather than the income tax changes announced this year. As outlined above, these have a relatively minor impact on revenues of £82 million.

The picture is forecast to remain positive in subsequent years, On the basis of latest forecasts, the income tax net position (the difference between expected revenues and the BGA) is expected to reach £2.3 billion by 2028-29, although the SFC note that the net position is highly sensitive to changes in the SFC and UK Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts that underpin the calculation.

In contrast to previous years, the net income tax position is now broadly in line with the additional amount that Scottish taxpayers are paying relative to what they would be paying under rUK income tax policy. The Scottish Government estimate that Scottish taxpayers are paying an additional £1.5 billion relative to what they would be paying under rUK income tax policy. This provides additional resources for the Scottish budget, enabling the Scottish Government to fund different policy choices.

A lack of clarity in key policy areas

Despite stating in this year's medium-term financial strategy (MTFS) and in a recent letter to the Finance and Public Administration Committee that the Scottish Government would publish multi-year budgets, the DFM delivered a single-year Budget in a move that is likely to have disappointed local government and other public and third sector bodies. These bodies had been hoping for a direction of travel for their funding position in the coming years.

The Scottish Government had also stated it would publish revised capital spending plans following an evaluation of existing plans in light of rising costs (from inflation) and reduced capital funding from the UK government. No revised plans were published.

There was also a lack of detail on public service reform and workforce planning.

Despite stating in advance of the Budget, that "the size of the workforce will have to reduce", there was no information provided in the Budget as to what that might mean in practice. The only additional information came in the form of a letter sent to the Finance and Public Administration Committee on budget day, which set out some government work and planning in this area, but this was about processes rather than the actual implications. The Finance and Public Administration Committee will continue to scrutinise progress in this area.

The Finance and Public Administration Committee had also requested in its Pre-Budget reportthat the Scottish Government provide a full response to the Fiscal Commission's recent work on long-term fiscal sustainability and hold a debate on this in the Chamber. The response to the Committee report noted support for the debate, but was silent (as was the Budget document itself) on producing a full response to the SFC fiscal sustainability work.

For the second year in a row, there was no public sector pay policy published with the Budget. The Scottish Government stated that it will "set out pay metrics for 2024-25 following the [UK] Spring Budget", though this is scheduled for 6 March 2024 and likely to take place after the Scottish Budget Bill for 2024-25 has been voted on. Given that public sector pay makes up over half of the Scottish resource budget, this presents another risk to the Scottish budget. In the previous and current financial years, significant revisions to budget plans were required in order to accommodate in-year pay deals.

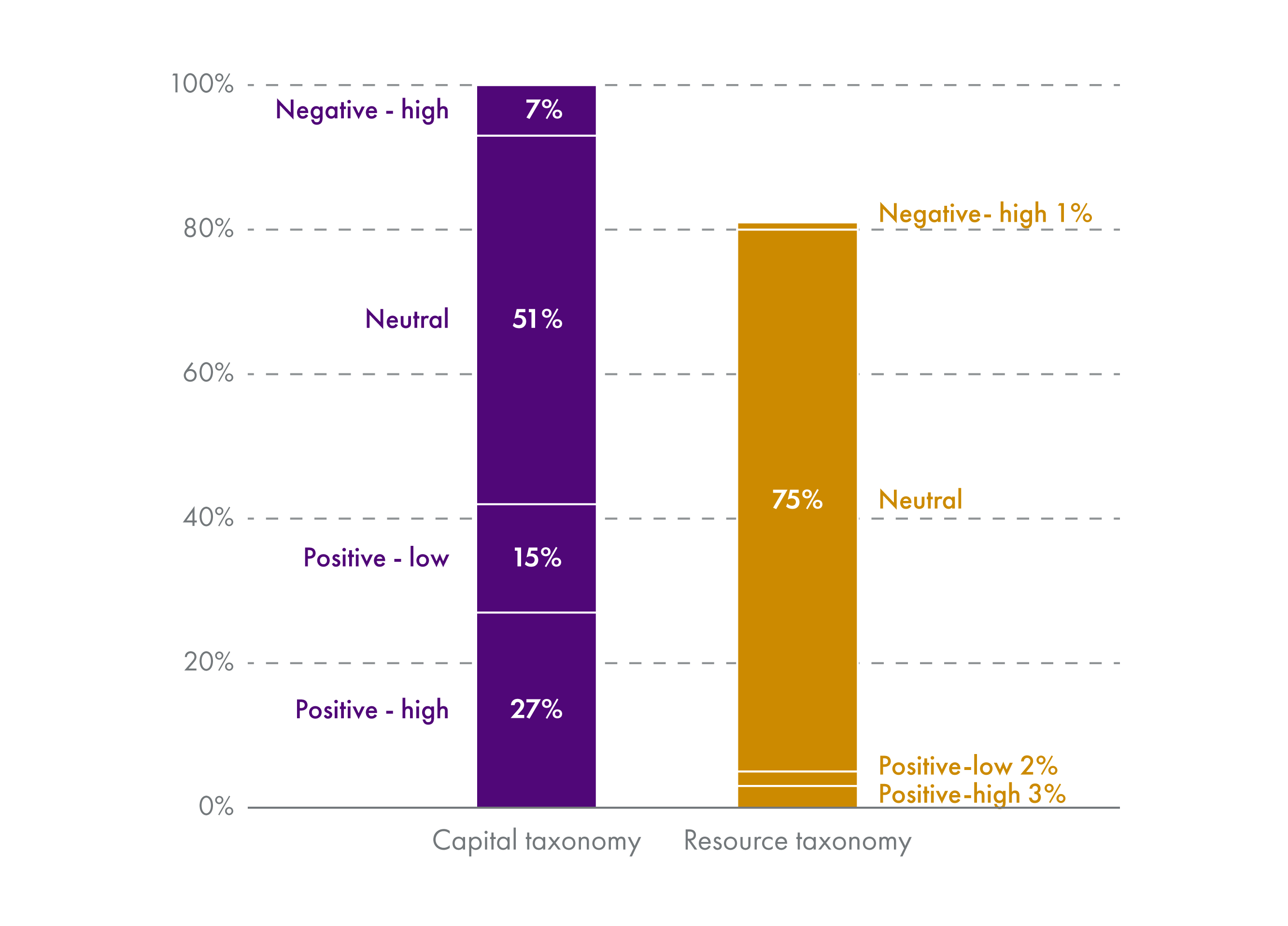

We noted in our initial Budget blog that the Scottish Government's Climate Change Assessment of the Budget would include an expanded taxonomy of capital and resource spend, with the aim of improving information on the climate impact of public spending decisions in Scotland. We concluded, however, that the new taxonomy does little to increase the ability of Parliament to understand or scrutinise the impact of the Budget on Scotland's climate.

The previous taxonomy categorised capital spending as either low, neutral or high carbon. There is some additional detail in the new taxonomy – low and high carbon spend has been renamed positive and negative to indicate how it aligns to the Scottish Government's intended outcomes, and split to identify low and high impact spend within these categories. However, the document does not allow for an understanding of how this spending will contribute to meeting Scotland's climate targets. We do not know what outcomes will be achieved by this spending – do the current allocations of negative spending set Scotland on a path to meet the emission reduction targets, to what degree is 'positive' spending offset by 'negative', and how will spending decisions in 2024-25 contribute to emissions in future years?

There is plenty for Parliament to get its teeth into in the coming weeks as it considers whether these Budget and tax proposals should be enacted.

Areas for ongoing Parliamentary scrutiny

The Budget Process Review Group recommended in 2017 that individual ministers respond to committee pre-budget reports and letters within five sitting days of the Budget being published and provide a summary in the Budget document of how the submissions from committees have influenced the formulation of the proposals. As we noted in our initial blog after the Budget, this was not included in the main Budget document, but in an online-only annex. Committees should now have government responses and will now consider these responses before Stage 1 in early February.

In a continuation of the approach of the last three years, within the main Budget document each portfolio includes a table on "intended contribution to the national outcomes", split into "primary" and "secondary" outcomes. This is a useful overview, as far as it goes. However, given the high-level nature of both the outcomes and the portfolios, it is questionable how useful this will be for scrutiny. In pre-budget scrutiny, Committees again expressed frustration at the lack of connection between spending and the national outcomes.

With revised national outcomes due to be published in 2024, committee scrutiny in this area will be important in ensuring the National Performance Framework is more effectively used and linked to spending decisions in future.

The Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement comes in at a total of 265 pages, including annexes. It presents some illustrative case studies of how tackling inequalities has informed policy making, and details at great length the impact on inequalities of different portfolios' spending. However, it is hard to understand how the trade-offs inherent in budget setting have been shaped by equalities issues, and therefore how much of a priority tackling inequality is. The sheer volume of information can make scrutinising it more challenging.

Context for Scottish Budget 2024-25

Scottish Budget: 2024 to 20251 was published on 19 December 2023 and presents the Scottish Government's proposed spending and tax plans for next year. The publication signals the start of an intensive period of parliamentary scrutiny, before MSPs vote on these proposals in the early part of 2024.

The Budget incorporates devolved tax forecasts undertaken by the Scottish Fiscal Commission. As well as producing point estimates for each of the devolved taxes for the next five years, the SFC is also mandated to produce forecasts for Scottish economic growth and spending forecasts for devolved social security powers. The SFC's forecasts can be found in Scotland's Economic and Fiscal Forecasts2 published alongside the Scottish Budget.

The spectre of inflation that escalated following the illegal Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 continued to dominate budget deliberations. This has impacted on the Scottish Budget with significant in-year changes being required in both 2022-23 and the current financial year (2023-24). These changes have been required to fund inflationary pressures on people's "cost of living" and previously unbudgeted pay deals to maintain public services, resulting in knock-on implications across all other "non-pay" parts of the budget, and indeed, future budgets.

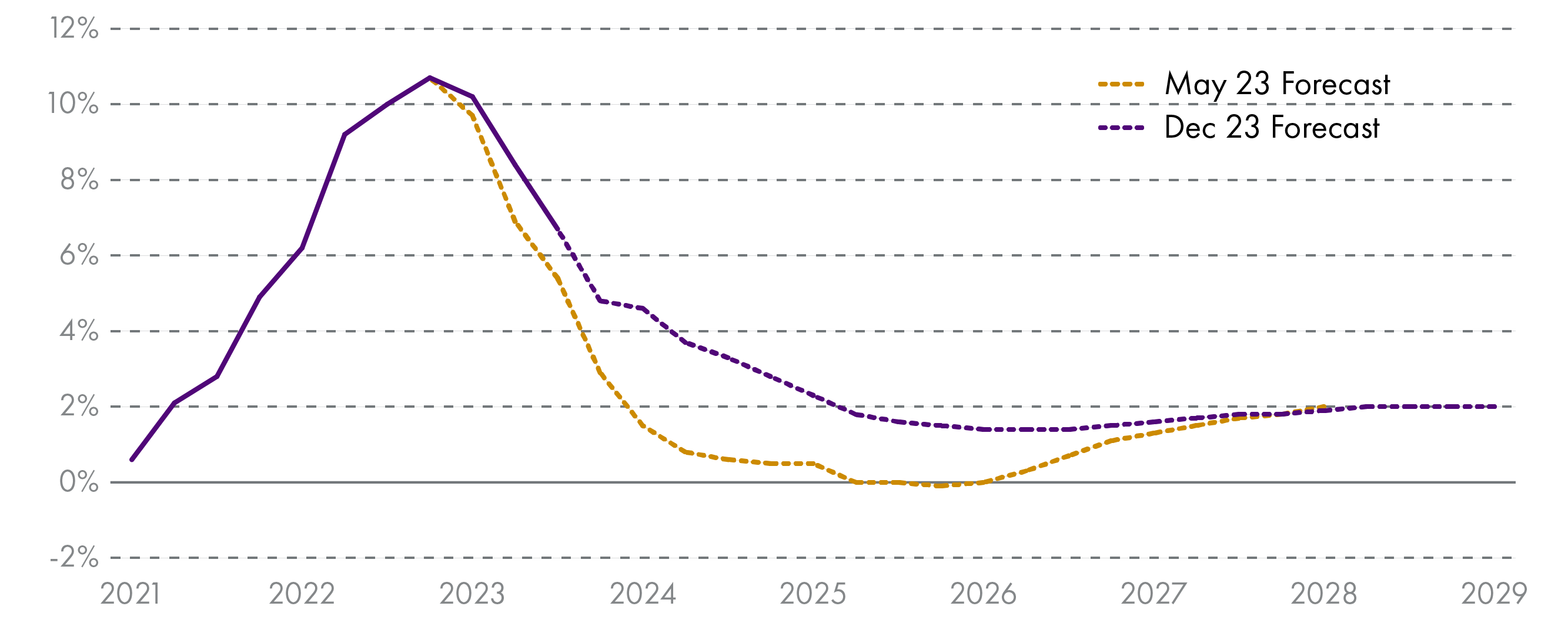

The SFC forecasts that inflation will be higher and more persistent than anticipated last year, although there will still be a considerable easing from the levels seen in the last two years. Higher inflation has fed-in to higher earnings growth, and the SFC has revised up its forecast of real disposable income per person – however the SFC notes that the fall between 2021-2024 is still the largest reduction in Scottish living standards since Scottish records began in 1998.

The SFC forecasts that economic growth will remain fragile in the medium term, albeit the Scottish economy has proven more resilient in 2023 than previously forecast. In December 2022, the SFC was forecasting Scottish GDP would fall by 1% this year, but now expects GDP growth of 0.2% in 2023-24.

The SFC's forecasts of Scottish economic output over the forecast period are presented in the table below.

| 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economy % growth | 0.2 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

What numbers should be used?

As seems to happen every year, there is an abundance of figures being quoted in relation to the overall change in the size of the budget.

In an effort to improve the transparency of the budget numbers presented in the documentation, the Finance and Public Administration Committee wrote to the Deputy First Minister on 21 September 2023, requesting that the Scottish Government consider presenting:

alongside the Scottish Budget 2024-25 (1) what has actually been spent in each area in 2022-23, (2) what the Scottish Government expects to spend in each area in 2023-24, and (3) what the planned spending is for each area in 2024-25. This same comparative approach can then be followed in subsequent years.

Finance and Public Administration Committee, Correspondence to the Deputy First Minister, 21 September 2023

However, the Budget published on 19 December 2023 did not contain the information requested by the Committee. Instead, the Scottish Government continued to present its budget document on a "budget to budget" basis meaning that all budget lines were presented in comparison to the previous year's budget as passed by Parliament.

While this approach continues the established convention for budgetary presentation over a number of years, it fails to take into account in-year budgetary movements. As mentioned above, in both 2022-23 and 2023-24 these in-year changes have been significant as revised pay deals and cost-of-living interventions have been required to combat soaring inflation. The result of these changes is that the usual "budget-to-budget" comparisons could be, in some circumstances, misleading, or at least not give the full picture of the effect of the changes in budget from one year to the next.

Helpfully, the SFC forecast document provides a fiscal overview setting out the changes in-year against the plans for next year. This shows that the Scottish Government's budget next year is set to increase by £1.3 billion from the latest position for 2023-24, after taking account of in-year changes. This is a rise of 2.6% in cash terms, or a 0.9% rise after taking inflation into account (so called "real terms").

For the purposes of this briefing, however, we will set out the budgets as presented by the Scottish Government in the Budget documentation. This will allow the best read across between the numbers referred to in the Budget and SPICe analysis.

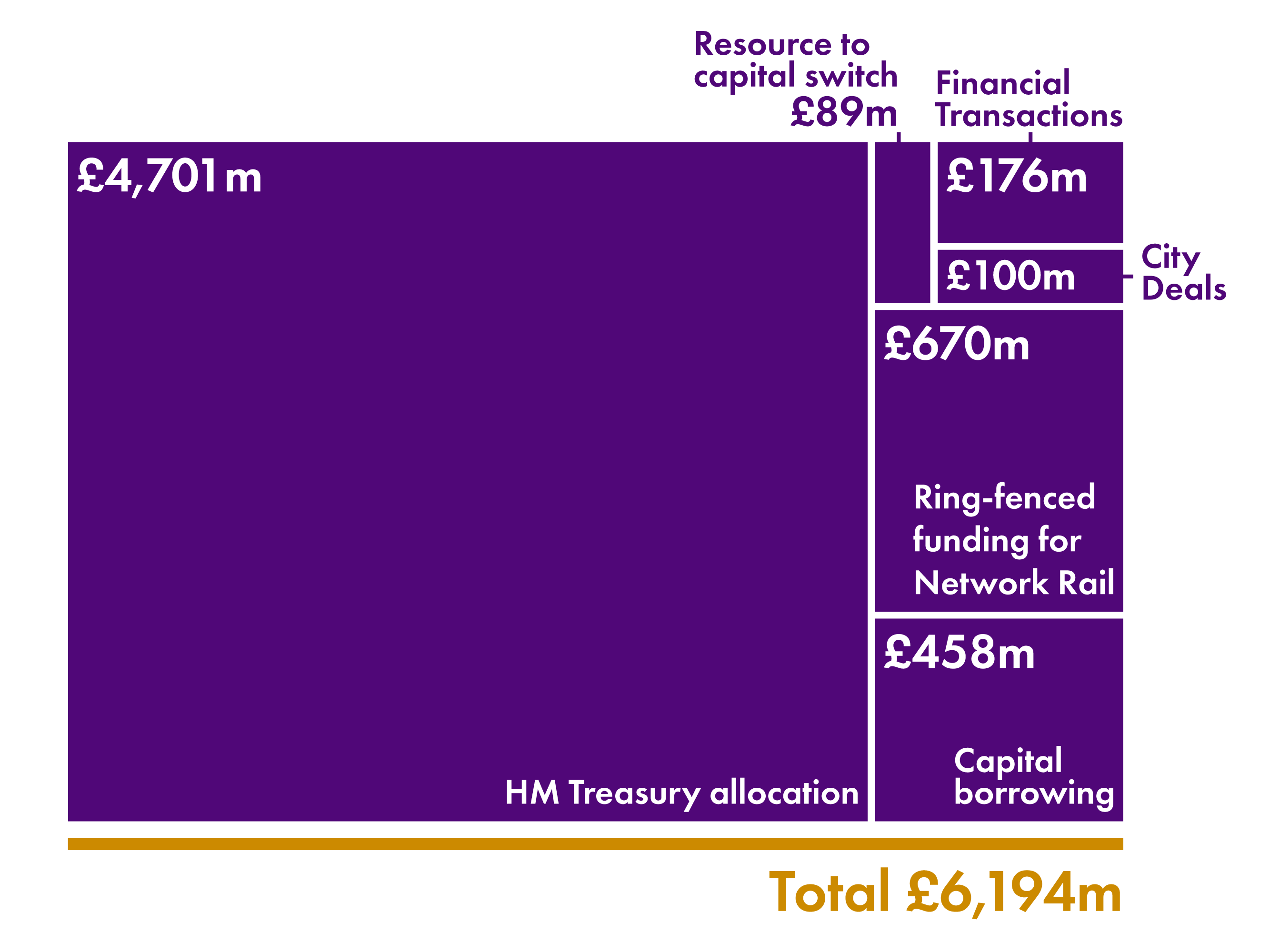

Budget allocations

Total allocations

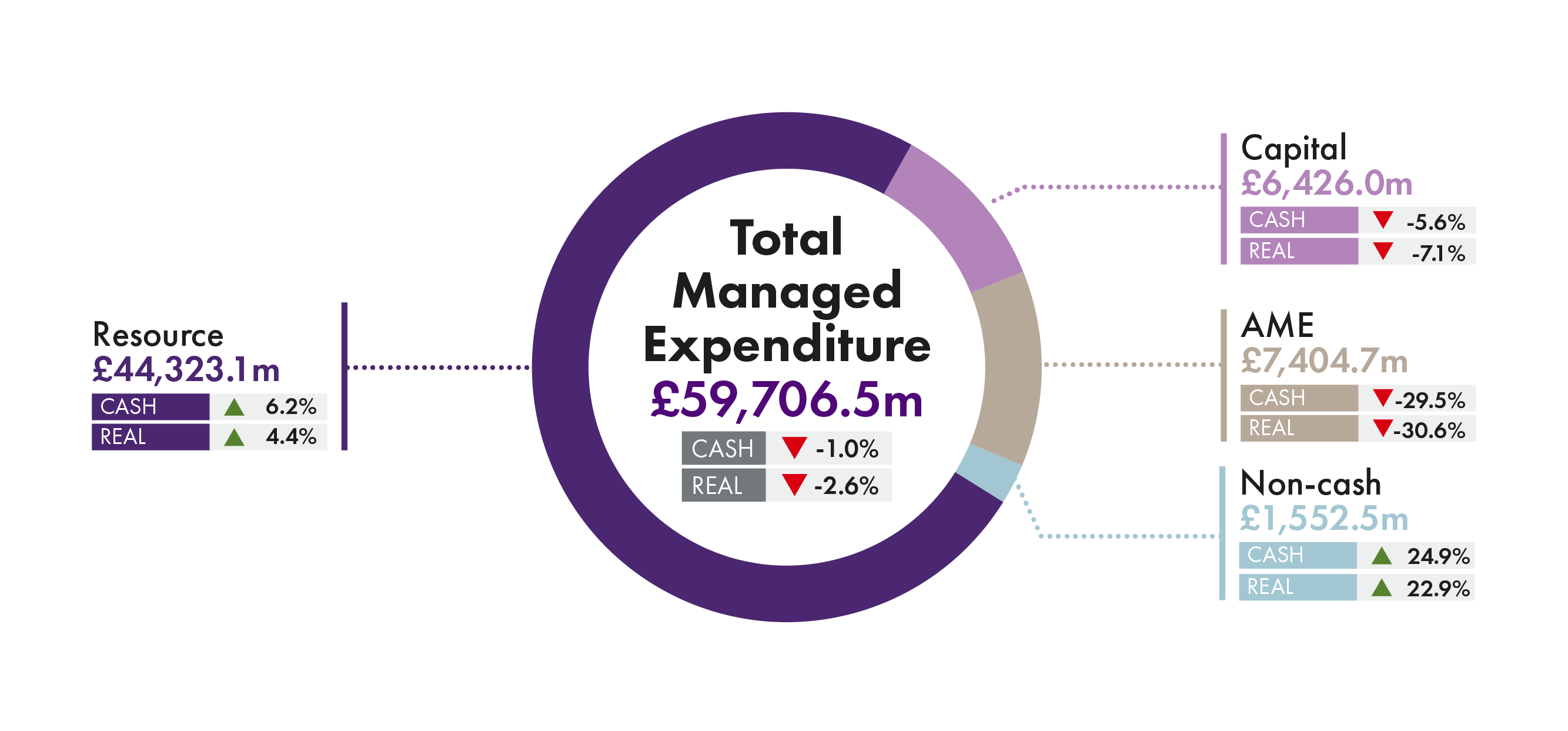

Total Managed Expenditure (TME) comprises Resource, non-cash Resource, Capital and Annually Managed Expenditure (AME). TME in 2024-25 is £59,706.5 million. Figure 1 shows how this is allocated.

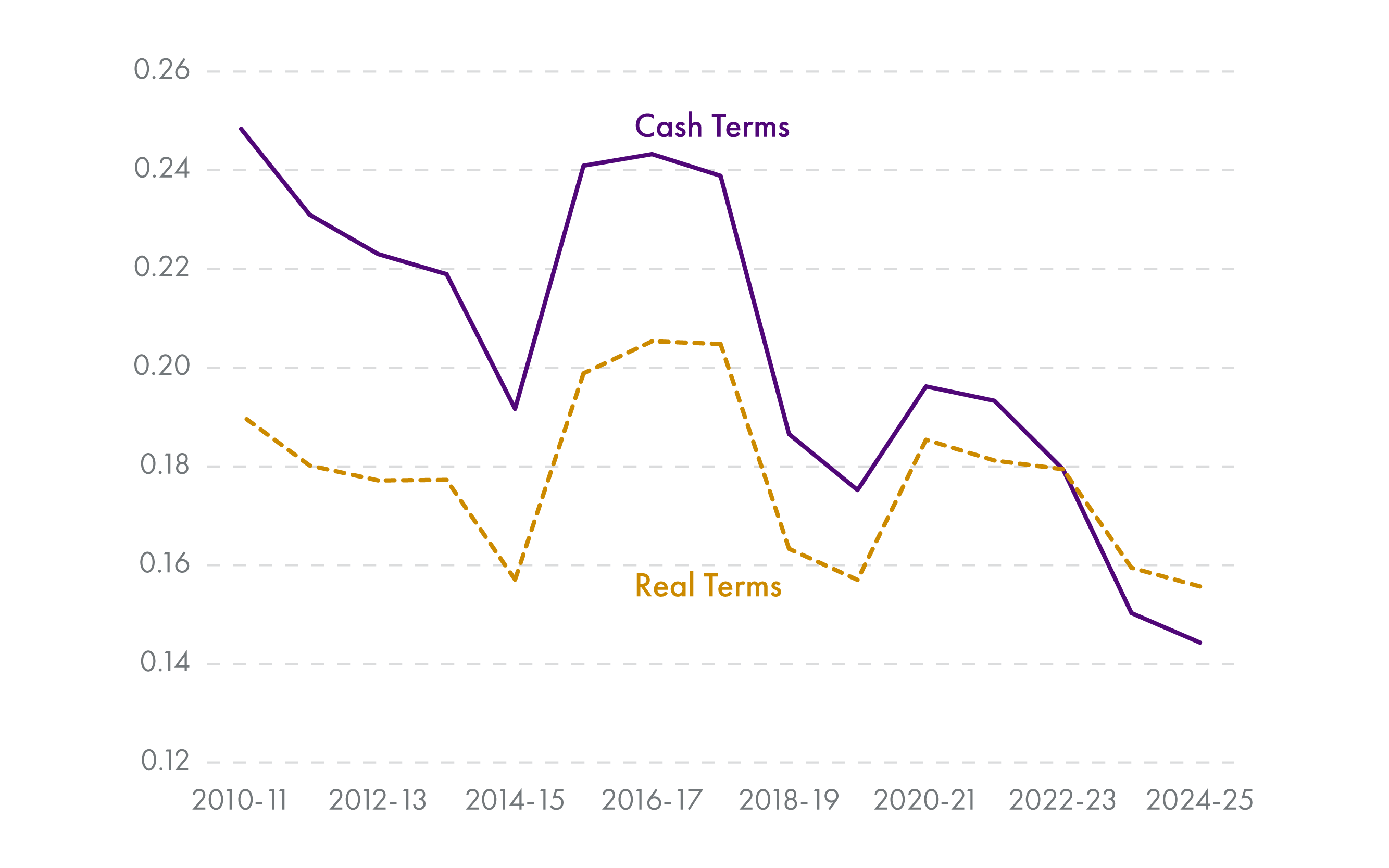

Resource (which covers day-to-day expenditure) and Capital (covering spending on buildings and physical assets) are the elements of the budget over which the Scottish Government has discretion. As we can see from the chart, Resource is due to increase by 4.4% in real terms in 2024-25 and Capital is set to fall by 7.1% in real terms.

AME is expenditure which is difficult to predict precisely, but where there is a commitment to spend or pay a charge, for example, pensions for public sector employees. Pensions in AME are fully funded by HM Treasury, so do not impact on the Scottish Government's spending power. AME falls significantly next year due to a technical change to the discount rate for calculating the scale of future pension liabilities for teachers and NHS pensions. This is a UK funded AME line and does not arise from any Scottish Government decision or impact on the discretionary spending power of the Scottish budget.

Non-Domestic Rates income is also classed as an AME item in the budget and forms part of local government spending.

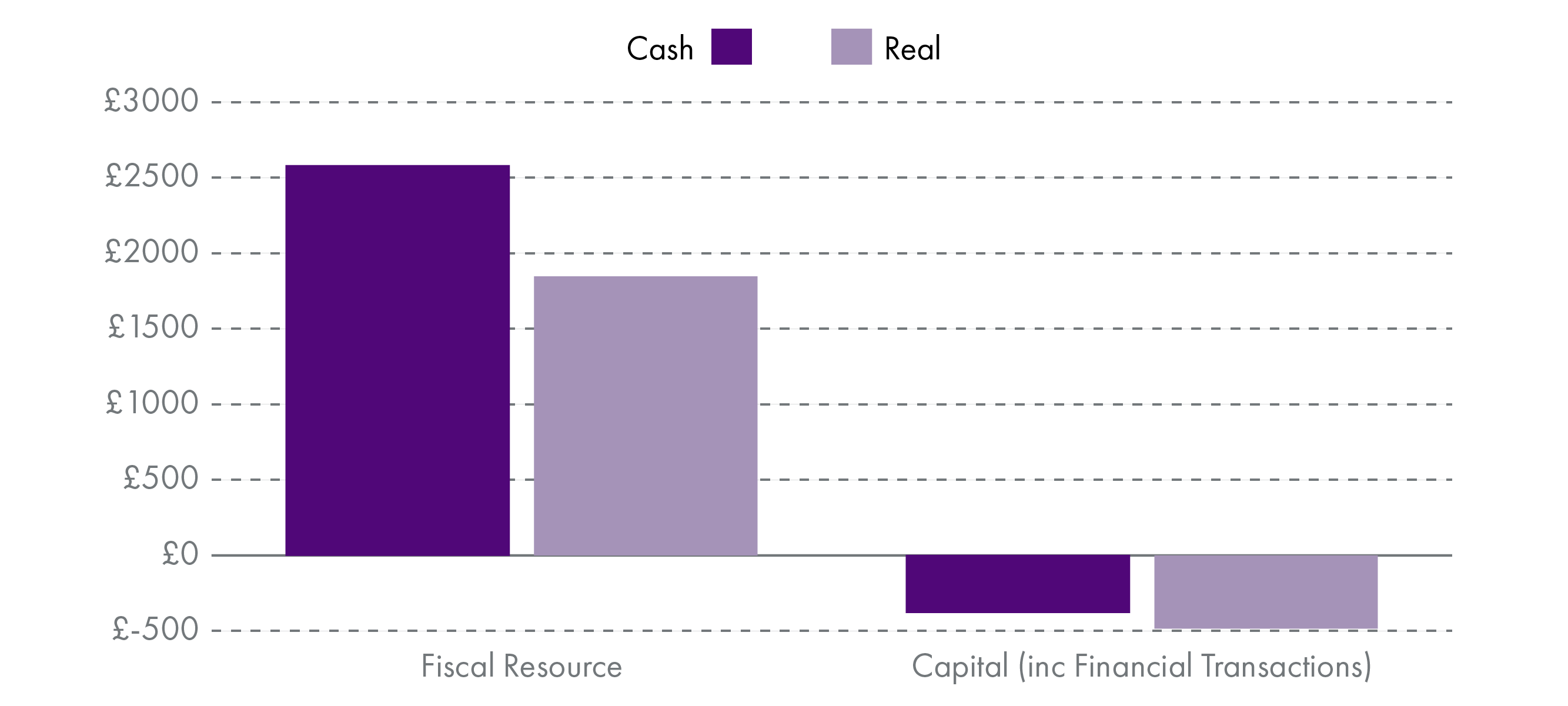

Figure 2 below shows the absolute change in Resource and Capital presented in the document between 2023-24 and 2024-25. Resource will increase by £1,847 million in real terms next year, and Capital (including financial transactions monies) will fall by £484 million.

Portfolio allocations

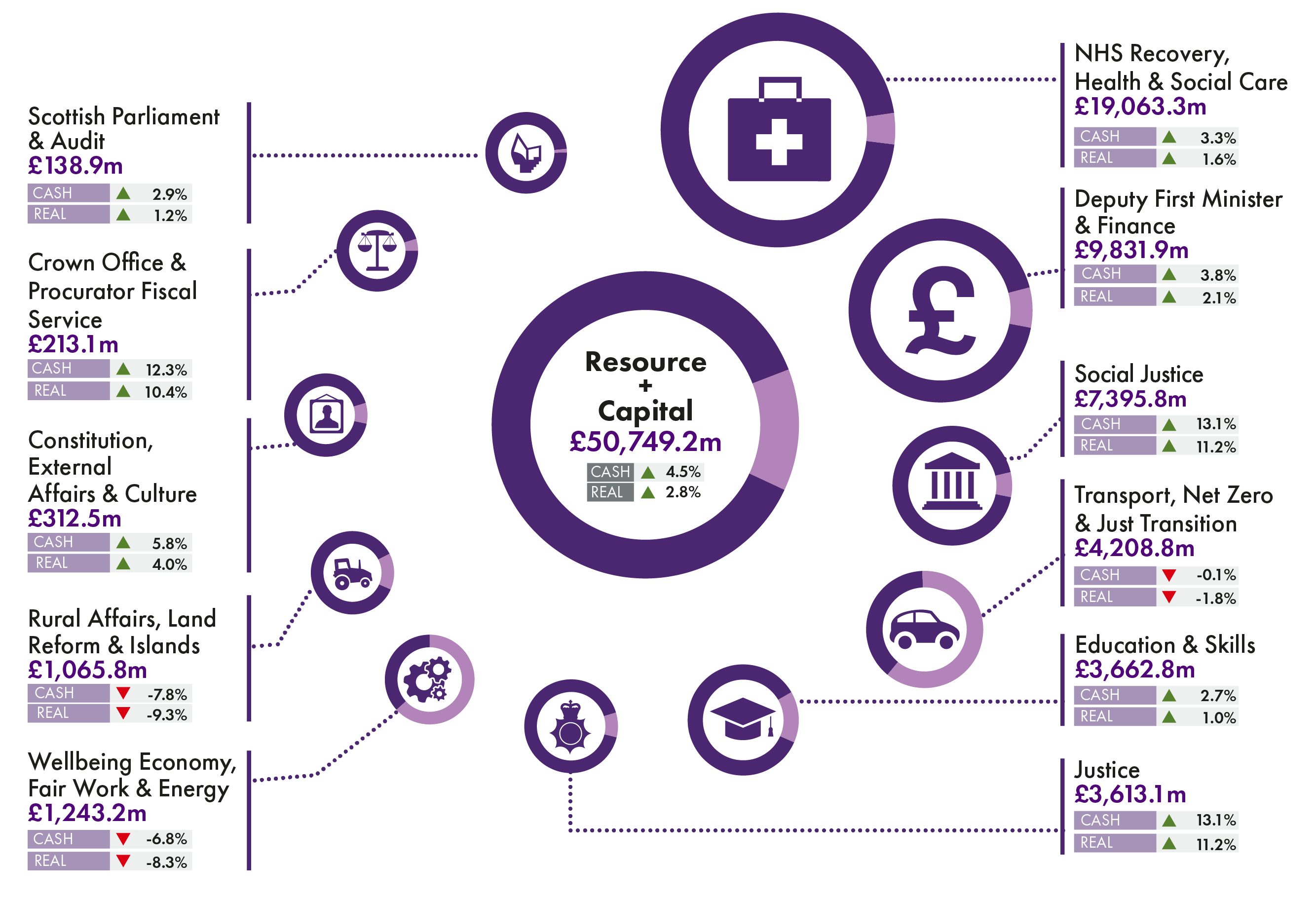

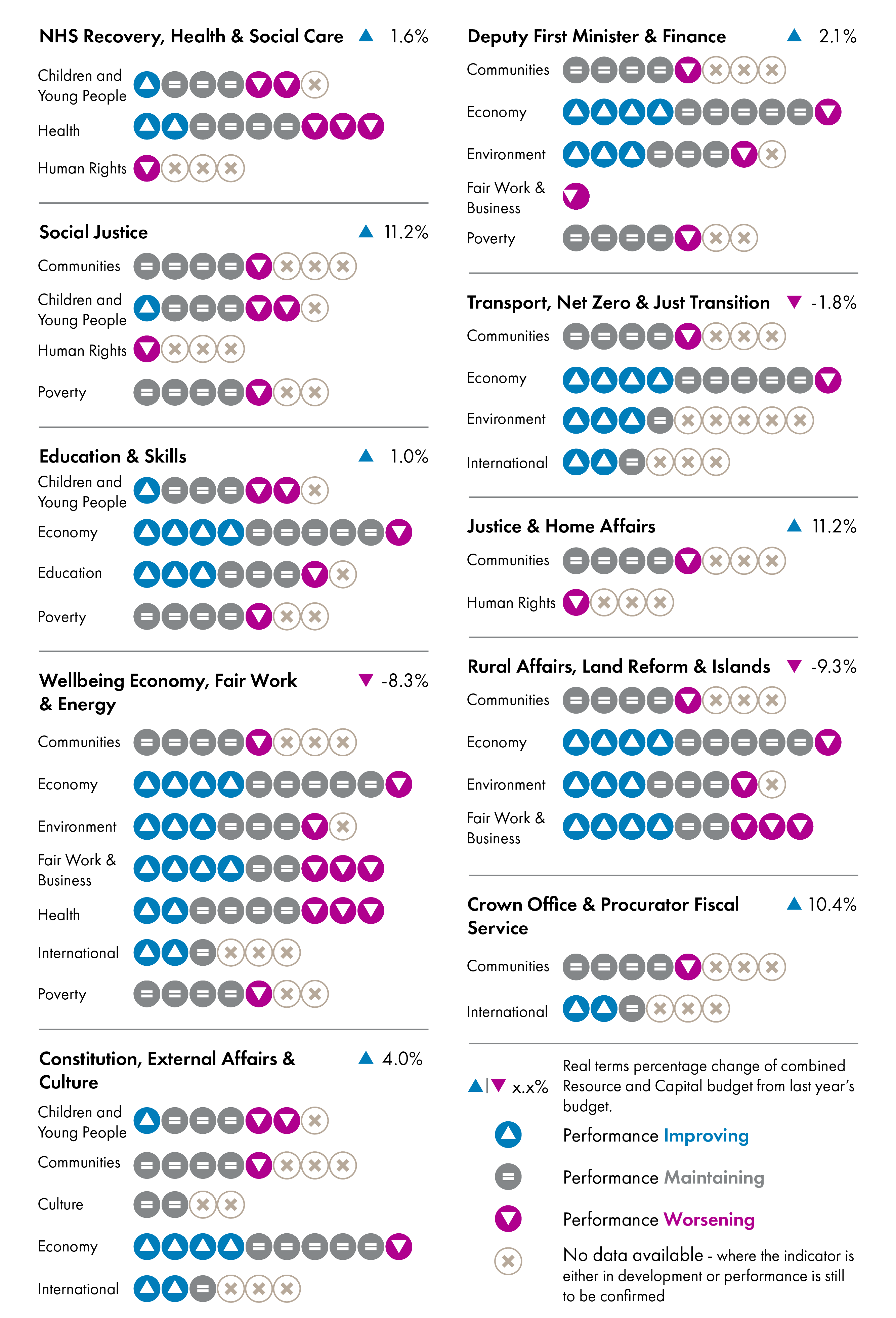

Figure 3 shows Resource and Capital allocation to portfolios for 2024-25, and how they have changed from the Budget passed by Parliament for the previous year.

Figure 3 shows the Budget to Budget 2023-24 to 2024-25 portfolio changes in cash and real terms. Key points to note are as follows:

NHS Recovery, Health and Social Care remains the largest portfolio, comprising 38% of the discretionary spending power (Resource and Capital) of the Scottish Budget in 2024-25.

Deputy First Minister and Finance is the next largest portfolio comprising 19% of Resource and Capital spend combined. Local government sits within this portfolio, although non-domestic rates income (NDRI) and pensions are not included within the above figure as they are classed as AME items of income/spending.

Eight of the portfolios increase in both cash and real terms. The largest real terms percentage increases are in Social Justice (which includes social security spending) and Justice – both these portfolios increase by 11.2% in real terms.

Rural Affairs, Land reform and Islands; Wellbeing, Economy, Fair Work and Energy; and Transport, Net Zero and Just Transition fall in cash and real terms. The largest percentage fall is in the Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands portfolio which falls by 9.3% in real terms.

Resource and Capital allocations

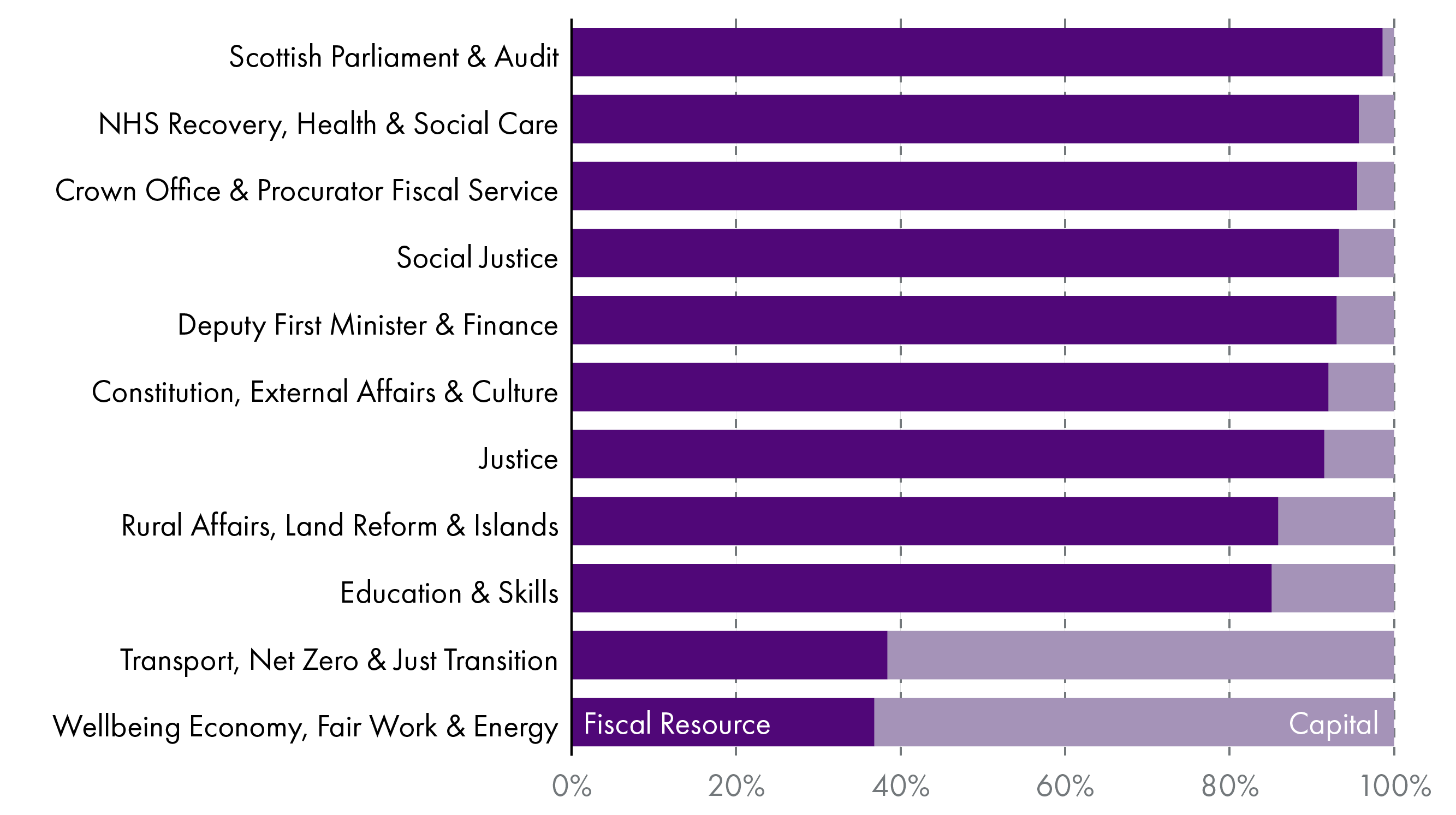

Figure 4 below shows the split between Resource and Capital by portfolio. This shows that most portfolios are heavily weighted towards funding day-to-day spending commitments (the Resource budget).

The Transport, Net Zero and Just Transition and Wellbeing, Economy, Fair Work and Energy portfolios have the highest proportion of their budget comprising Capital spending – both over 60%. For the Transport, Net Zero and Just Transition portfolio, this will include projects to progress towards net zero, rail and roads investment and capital investment by Scottish Water. For the Wellbeing, Economy, Fair Work and Energy portfolio, this includes spending on digital connectivity, City Regions, offshore wind projects and investment by the Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB).

Social Security

With the devolution of certain Social Security powers by Scotland Act 2016 came over £3 billion of spending power via a positive block grant adjustment (BGA) to the Scottish Budget. However, it also brought with it increased budgetary risks, as any spending over and above the BGA must be found from other resources within the Scottish Budget.

The SFC is forecasting that social security spending will significantly exceed the size of the BGA added to the Scottish budget from the UK Government's equivalent spend in 2024-25, and is forecasting that this will increase in subsequent years of the forecast period. This reflects policy decisions around disability benefits and the increase in both the payment amount and eligibility for the Scottish Child Payment.

With spending forecast to be over £6 billion in 2024-25 (see figure 5 below), the SFC expects Social Security spend to be £1.1 billion above the BGA next year and rise to £1.5 billion more than the BGA by the end of the forecast period in 2028-29. This is discussed in more detail in the section of the briefing on the SFC forecasts.

In line with the approach taken by the UK government, the Scottish Government will increase all Social Security benefits over which it has control by the September 2023 rate of inflation of 6.7%.

Largest budget changes

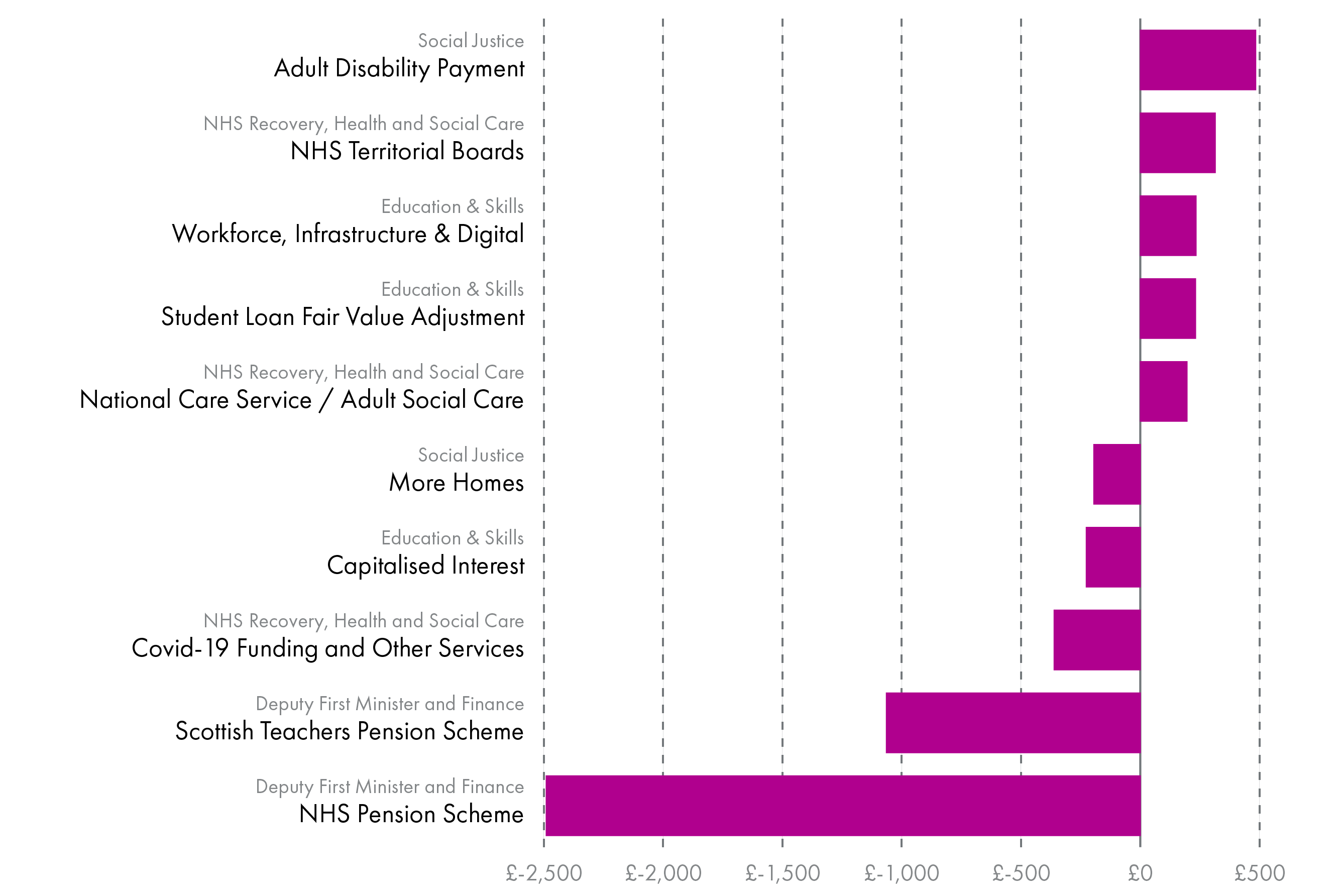

Figure 6 presents the largest (real terms) changes proposed for Level 3 budget lines. (Level 1 is portfolio level budgets, moving to Level 4 for the most detailed budget lines.)

The largest real terms increase next year comes in the Adult Disability payment which increases by just under £500 million in real terms, reflecting differences in the Scottish Government's approach to the payment of this benefit and increased demand. The increase in the NHS territorial boards funding reflects the continued budgetary priority given to Health spending.

The largest reductions come in the Annually Managed Expenditure Teachers and NHS pensions budget lines. As mentioned elsewhere in the briefing, these reflect a technical change to the discount rate for calculating the scale of future pension liabilities and have no impact on the spending power of the Scottish budget. COVID-19 funding and Other Services is the next largest spending reduction, although this budget line includes many items that are not COVID-19 related, making it difficult to understand what is contributing to the reduction.

Topical issues

Public service reform, workforce and pay

There was much discussion in advance of the Budget about the need for public service reform, and the likelihood of reductions to the size of the public sector workforce.

In an interview prior to the Budget, the Deputy First Minister stated that "the size of the workforce will have to reduce."

This followed the unbudgeted increases in the paybill which have resulted from the high inflation experienced since 2022. In its Economic and Fiscal Forecast report, the Scottish Fiscal Commission states:

Increases in public sector pay have been larger than the Scottish Government has previously planned due to inflationary pressures. When the Scottish Government presented its Medium-Term Financial Strategy (MTFS) in May 2023 was based on a central scenario of pay awards growing by 3.5 per cent in 2023-24 and 2 per cent in 2024-25. The Scottish Government now estimates the average public sector pay award in 2023-24 was 6.5 per cent, 3 percentage points higher than estimated in May 2023. The Scottish Government set out in November 2023 how pay deals were around £800 million higher in 2023-24 than had been budgeted for. Pay increases are cumulative and therefore past increases result in higher pay in the future.

Scottish Fiscal Commission. (2023, December 19). Scotland’s Economic and Fiscal Forecasts – December 2023. Retrieved from https://www.fiscalcommission.scot/publications/scotlands-economic-and-fiscal-forecasts-december-2023/ [accessed 22 December 2023]

These increases in the paybill have created a budgetary imperative to deal with the size of the paybill, and by implication, the numbers working in the public sector.

The Finance and Public Administration Committee has been critical of the Scottish Government's lack of strategy and leadership in the area of public sector reform. In its pre-budget report it stated:

…that the focus of the Scottish Government's public service reform programme has, since 2022, changed multiple times, as have the timescales for publishing further detail on what the programme will entail. Given the financial challenges facing the Scottish Budget, this represents a missed opportunity to be further along the path to delivering more effective and sustainable public services.

Finance and Public Administration Committee, Pre-Budget Scrutiny 2024-25: The Sustainability of Scotland's Finances, 6 November 2023

It came as a bit of a surprise, therefore, that the Budget contained no details on plans around public service reform, the size of the public sector workforce, or any details on assumptions and policy for public sector pay in 2024-25. The Scottish Government did say that it will “set out pay metrics for 2024-25 following the [UK] Spring Budget.”, which has since been confirmed for 6 March 2024. This timing might be considered unusual in that it will likely be after the Scottish Parliament has voted through the Budget Bill for 2024-25.

Speaking to the Finance and Public Administration Committee on 20 December, the Chair of the Scottish Fiscal Commission noted that the Scottish Government had not provided the SFC with final policy for public sector pay in 2024-25. As such, in its forecasts1, the SFC assumes a 3% increase in pay awards next year and an increase in the overall paybill of 4.5% (after including staff movements up the pay-grade increment scales).

Having no pay policy presents another risk to the Scottish Government's budget for next year. Where pay increases are larger than the growth in the resource budget, there is a requirement to either reduce the number of public sector employees or reduce spending in other parts of the budget. Audit Scotland made this point in a recent report on Scotland's public sector workforce and highlighted the need for better strategic workforce planning.

The detailed Level 4 Budget lines, which the Scottish Government publishes online separately to the Budget document does refer in the Constitution, External Affairs and Culture (CEAC) portfolio to a "5% efficiency saving that has been taken across all public bodies as part of Public Sector Reform". However, there is no mention of a 5% efficiency savings requirement in the Deputy First Minister's Statement, the main budget document or indeed in the other portfolio level 4 budget lines aside from CEAC. The NHS Recovery, Health and Social Care Level 4 budget includes a rather unhelpfully titled "Other Board Services and Miscellaneous Income" line, which makes reference to efficiency savings in the description, but the scale of efficiencies required is unclear. The DFM has made clear that the health service will be protected from any public sector redundancies, so any savings here would not be in respect of staffing.

The DFM did write separately to the Finance and Public Administration Committee on Budget day providing a "Progress Update" on public service reform. At 48 pages long, this document will be considered in more detail by the Committee in the coming months.

The update notes four new "key" workstreams:

Convening: Agreeing a common vision across the public sectors for achieving sustainable public services and establishing the infrastructure that enables us to collectively make progress.

Saving: Identifying where the Scottish Government and public bodies can deliver clear and quantifiable, cashable savings, setting out clear targets for cost reduction/cost avoidance through achieving efficiencies and which support the longer-term approach to reformed services.

Enabling: Creating the conditions for systemic reform, removing barriers to change and establishing ways that the public can see, understand, and influence the changes. This includes the key efficiency levers outlined in the RSR.

Aligning: Driving policy coherence and consistency across significant policy led reforms that will shape the future service landscape.

Over the next three months, the Scottish Government says it will:

Agree a shared approach, working with colleagues in local government and with the wider public and third sector to align, enable and deliver.

Require all Scottish Government portfolios to lay out their savings and reform plans by the end of the financial year, in line with the principles in this document and set out clear savings targets to public bodies.

In relation to savings, the document states that Portfolios and Public Bodies will be asked to follow a "cascade of options" in delivering savings:

Taking all opportunities to increase the efficiency with which they deliver their functions.

Taking all opportunities to offer services in different ways.

Considering reclassification/alignment/merger of bodies or function.

Reducing service only where these options are exhausted.

The document also makes reference to the need for reductions in workforce in some areas:

We must also consider the balance of pay and workforce, with some sectors needing to grow to respond to pressures and others reducing in line with reform opportunities and re-prioritisation of our work.

Deputy First Minister, Correspondence to the Finance and Public Administration Committee, 19 December 2023

However, there remains a lack of detail on the specifics of what this programme of reform will mean in practice, or how it will help to address the immediate pressures on the budget.

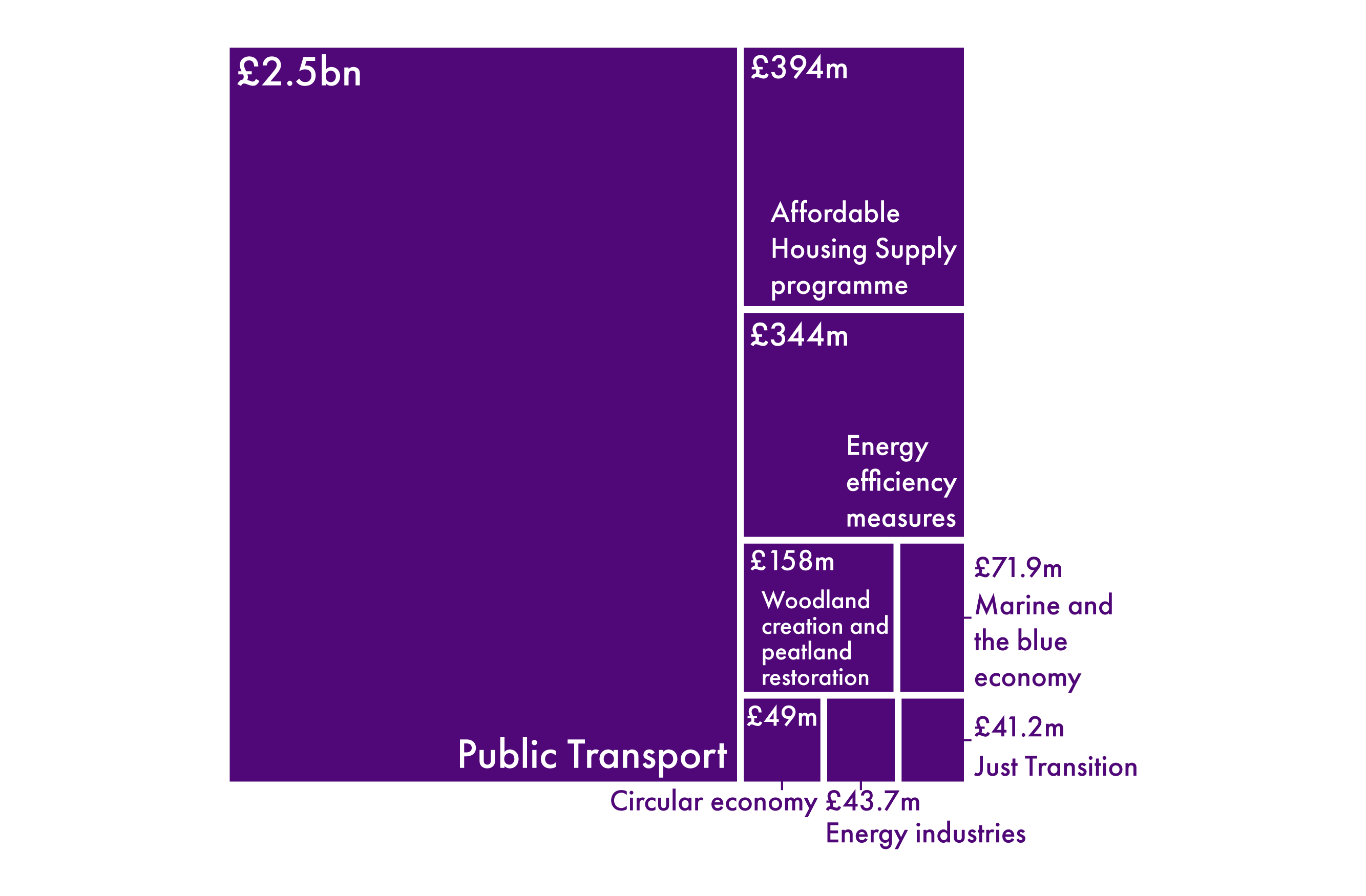

Just transition

The transition to net zero will involve long term structural changes to the economy and key industries. Managing these changes in a way that spreads the benefits and risks equitably is a key challenge for policy makers. In general terms, this is referred to by the Scottish Government as delivering a "just transition".

From a budget angle, delivering the transition to net zero generally requires capital funding. This can finance the infrastructure needed to develop renewable energy industries, decarbonise transport networks, retrofit homes, and develop new technologies (in hydrogen, for example). Delivering this in a "fair" way is key to the concept of a just transition. The Scottish Government's plans for a just transition may therefore have been constrained by the decreasing capital budget, which is forecast to fall by 20% in real terms by 2028-29.

At this stage, a detailed plan for managing a just transition is still emerging. The Scottish Government has published a draft Energy Strategy and Just Transition Plan. It is also developing Just Transition Plans for the Grangemouth area and three sectors: agriculture and land use, construction and the built environment, and transport. Whilst there are few line items in the Budget that explicitly relate to the just transition, different areas of the Budget will shape how the Scottish Government's plans will be delivered.

One of many affected industries is the energy sector, as the renewable energy and oil and gas industries play very different roles in the transition to net zero. Developing a renewable energy industry is a key element of the transition to net zero, particularly somewhere like Scotland, which lends itself to offshore wind power. The Budget includes £32.9 million of capital funding to support the offshore wind supply chain, which forms part of a recently announced commitment by the Scottish Government to spend £500 million on offshore wind supply chain development. Details on what outcomes this funding is expected to achieve are not given.

Conversely, £30 million of capital funding has been withdrawn from the Energy Industries budget line (a 43.8% decrease), within the Wellbeing Economy, Fair Work and Energy portfolio. This expenditure supports industrial decarbonisation and includes funding for the Scottish Industrial Energy Transformation Fund, the Hydrogen Innovation Scheme and the Energy Transition Fund.

One area particularly affected by this transition is the North East, which has a large energy sector workforce. The Scottish Government have committed to a 10-year £500 million Just Transition Fund for the North East and Moray to support delivery of a just transition for the region. Funding announced in 2024-25 is £12 million, down from £50 million in 2023-24. In total, budgets between 2022-23 and 2024-25 have allocated £82 million to the fund over the first three years of the fund's life-span.

The Scottish Government's explanation for the forthcoming reduction is a decrease in capital funding and financial transactions allocated to the Scottish Government. Existing multi-year projects will continue to be funded, but the 75% reduction does raise questions over the whether the fund will be open to new applications in 2024-25 and what the future direction of the fund will be.

Also worth noting is that financial transactions allocated to the Scottish National Investment Bank will fall from £238 million in 2023-24 to £174 million in 2024-25. (See section on Financial transactions). Financial transactions have been repeatedly used to capitalise SNIB. One of SNIB's three missions is "Achieving a Just Transition to net zero by 2045".

There was also an interesting section in the Scottish Fiscal Commission's forecasts:

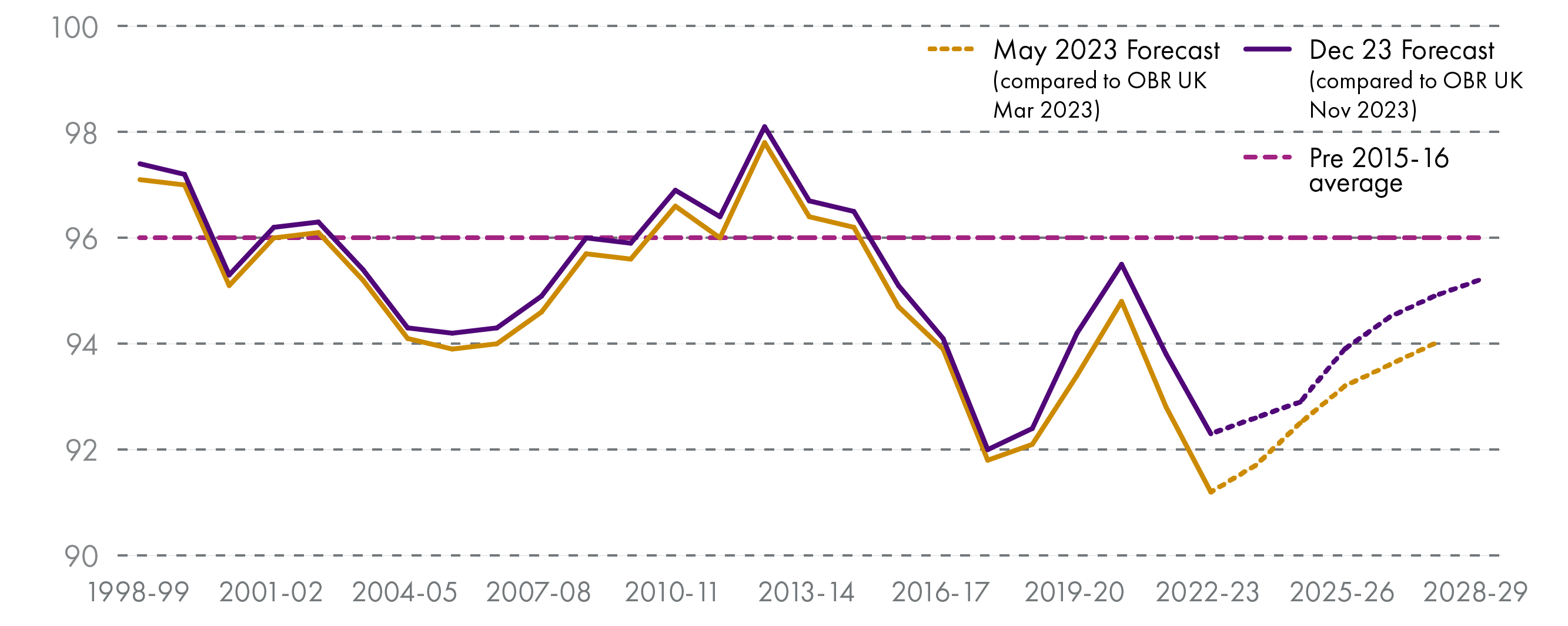

The decline of North Sea oil and gas activity is one factor explaining slower employment and earnings growth in Scotland relative to the UK since 2016-17… New energy sectors will not fully replace oil and gas as a source of high-paid jobs and income tax revenues over the longer term.

Scottish Fiscal Commission. (2023, December 19). Scotland’s Economic and Fiscal Forecasts – December 2023. Retrieved from https://www.fiscalcommission.scot/publications/scotlands-economic-and-fiscal-forecasts-december-2023/ [accessed 22 December 2023]

If this judgement materialises, it has implications for the size and spending power of future Scottish budgets, but also raises questions over the future of Scotland's economy and industrial base, which is a key aspect of the just transition. In the Economy and Fair Work Committee's inquiries into a Just Transition, many witnesses have noted the importance of avoiding “the mistakes of the past” in planning for a just transition. In the SFC's judgement, this may be more complicated than simply replacing oil and gas jobs with renewables jobs.

Social security

The Scottish Fiscal Commission has projected that spending on devolved social security will reach £8.0 billion by 2028-29, a significant increase from £4.2 billion in 2022-23. Crucially, there are elements of this that do not trigger funding from block grant adjustments and must be funded from within the Scottish Budget. This occurs when the Scottish Government spends more on a devolved benefit than would be the case if reserved policy applied in Scotland, or if it delivers a benefit that is unavailable in rUK.

The gap between funding from BGAs and the projected spending on social security is forecast to rise from an already-significant £894 million in 2023-24 to £1,502 million in 2028-29. Around two thirds of this gap is due to the Scottish Child Payment and Adult Disability Payment alone. All of this must be funded either by raising additional devolved tax revenues or by reallocating expenditure that could otherwise be spent on other parts of the Budget.

Other budgetary issues

Health and social care

As has been the case for many years now, the health and social care budget has been awarded higher increases than other areas of spending. The total budget for health and social care is going up 3.3% in cash terms, or 1.6% in real terms. The Scottish Government explicitly state that their decision to prioritise health spending has resulted in them being less able to offer support to the business sector.

The increase in the health and social care budget represents over £600 million in additional funding and goes beyond the Scottish Government's commitment to pass on any additional funds that it receives as a result of increased UK government spending on health. Pay demands are likely to present ongoing challenges for the health budget and there is also a commitment to increase pay for adult social care workers to £12 per hour, which comes at a cost of over £200 million.

The progress of the Scottish Government's flagship National Care Service (NCS) Bill has been delayed and costs have been revised. The budget document does not make clear how much has been set aside for the NCS, with NCS funding included under the broader heading of 'National Care Service / Adult Social Care'. Some of the £1 billion included under this heading will ultimately be transferred to local government for the delivery of social care.

Housing

The Scottish Government has committed to investing £3.5 billion in the Affordable Housing Supply Programme this parliamentary term. The investment in the AHSP funds the Scottish Government's commitment to complete 110,000 affordable homes by 2032.

It is not easy to track progress against this commitment from the Budget document. The AHSP budget for 2024-25 is £556 million, although this figure is not provided explicitly in any of the budget tables in the budget documents except as a footnote to table A3.03 and in the accompanying text.

The 2024-25 AHSP budget represents a decrease of £196 million (-26%) in cash terms from the previous year and a 27% reduction in real terms. According to the notes accompanying the detailed Level 4 data, these reductions "reflect wider budgetary pressures across Scottish Government".

Enterprise

Enterprise agencies have been particularly impacted, most significantly Scottish Enterprise which effectively loses all Financial Transactions (FT) funding, falling from a net £28 million in 2023-24 to zero. All agencies face falling resource budgets in cash terms, while the Scottish National Investment Bank's FT budget drops from £238 million to £174 million (net of repayments). This is the lowest budget settlement since 2019-20 when SNIB was launched. Another area within the Wellbeing Economy, Fair Work and Energy portfolio to face a material fall in allocations is capital funding for the energy transition, which falls by around £30 million. However, capital funding for digital is boosted by £60 million, mostly related to the delivery of the R100 broadband programme.

Local government

The local government element of the budget is always one of the most fraught, and complicated, parts of the annual budget process. It is the second largest spending area in the Scottish Budget, after health, and helps fund vital services such as school education, social care, roads, parks, leisure and culture facilities, community and economic development, planning, environment, and so much more. But local government is not a delivery agent of the Scottish Government, albeit that's where most of its budget comes from. Rather, councils have their own democratic mandates and local priorities which they are accountable to their electorates for delivering.

There are two factors which make this year's discussions different to previous years. Firstly, this Budget is published only five months after the Verity House Agreement (VHA), signed between the Scottish Government and COSLA. We therefore have some high-level principles in place – agreed by both parties - which we can measure spending decisions against. These include an assumption against ring-fencing, a commitment to sustainable public services and an agreement to the underlying principle of "no surprises" when it comes to budget discussions. This brings us to the second factor in play this year: the Scottish Government's surprise announcement of a planned council tax freeze at the SNP annual conference in October and the subsequent debate about what "fully funding" a freeze actually means.

This section summarises some of the changes to the local government settlement in 2024-25 compared to the 2023-24 Scottish Budget document. More detailed analysis of local government budget matters – including a summary of changes over time and discussion of allocations by local authority – will be available in a separate SPICe briefing due for publication in mid-January.

Revenue settlement

The following tables present figures from the Scottish Budget documents for both 2023-24 and 2024-25. This is to ensure we compare like-for-like between the two years. There may well be changes to the 2024-25 local government allocation between now and March when the Local Government Finance Order is finalised. Likewise, there are likely to have been in-year changes made to the 2023-24 settlement which the following tables do not capture.

Tables 2 and 3 show a cash increase of 6.8%, or 5% real-terms, in the total local government revenue settlement when compared to the 2023-24 Budget. This is one of the largest year-on-year increases to the local government settlement seen over the past decade.

| Local Government (Revenue) | 2023-24 Budget document | 2024-25 Budget document | Cash change (£m) | Cash change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Revenue Grant | 7,133.9 | 8,403.9 | +1,270.0 | +17.8% |

| Non-Domestic Rates | 3,047.0 | 3,068.0 | +21.0 | +0.7% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) Resource Grants | 752.1 | 238.8 | -513.3 | -68.2% |

| Revenue within other portfolios | 1,471.8 | 1,534.4 | +62.6 | +4.3% |

| Total revenue settlement | 12,404.8 | 13,245.1 | 840.3 | +6.8% |

| Local Government (Revenue) | 2023-24 Budget document | 2024-25 Budget document | Real change (£m) | Real change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Revenue Grant | 7,133.9 | 8,265.3 | +1,131.4 | +15.9% |

| Non-Domestic Rates | 3,047.0 | 3,017.4 | -29.6 | -1.0% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) Resource Grants | 752.1 | 234.86 | -517.2 | -68.8% |

| Revenue within other portfolios | 1,471.8 | 1,509.1 | +37.3 | +2.5% |

| Total revenue settlement | 12,404.8 | 13,026.6 | 621.8 | +5.0% |

The above tables show a significant increase in the General Revenue Grant (GRG) and a big reduction in the Specific Revenue Grant element of the revenue settlement compared to the 2023-24 Budget document. These changes are partly explained by the shifting of £521.9m of previously ring-fenced funding for Early Learning and Childcare Expansion into the GRG. The reduction in ring-fencing is discussed below but will be seen as a positive development for local authorities, giving them greater discretion over how they spend their budget. Furthermore, an additional £120.6 million has been switched from the capital to revenue budget in 2024-25, to help fund local government pay deals, and this has also contributed to the increase in GRG compared to 2023-24.

Tables 2 and 3 also show an increase in the amount of revenue being transferred to local government from other portfolios, mainly relating to education and social care policies. There is always debate over the extent to which this money is ring-fenced or directed (to be discussed further in the Local Government Budget SPICe briefing in January).

Ring-fencing and in-year transfers

The Budget document tells us that reducing ring-fencing is part of the post-Verity House Agreement relationship between the Scottish Government and local government:

[the Budget] displays our commitment to that partnership by reducing levels of ringfenced and directed expenditure by baselining almost £1 billion of funding across Health, Education, Justice, Net Zero and Social Justice, giving authority and autonomy to local partners to achieve the outcomes we share in a way that best meets the needs of local communities.

Scottish Government. (2023, December 19). Scottish Budget: 2024 to 2025. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-budget-2024-25/ [accessed 22 December 2023]

The £1 billion figure quoted above comprises previously ring-fenced Early Learning and Childcare Expansion grant (£521.9 million) plus a number of funds previously transferred from other portfolios in-year (combined £429 million). These, according to the Budget document, have been "baselined" into the General Revenue Grant in 2024-25. This goes some way to explaining the big increase seen in the General Revenue Grant in Tables 2 and 3.

Although the combined ring-fenced grants plus in-year transfers for 2024-25 remains very high (at £1.7 billion), as a proportion of the total revenue settlement it is smaller than in the previous two years. Figure 7 shows that the 2024-25 Budget goes some way to reversing the trend of rising ring-fencing/transfers seen in recent years:

.png)

Capital allocation

The local government budget from the Scottish Government also includes capital funding, which councils spend on new or existing physical assets, e.g. new buildings, repairs, roads, etc., as well as the purchase of vehicles and machinery. Like revenue allocations, capital grants from the Scottish Government take the form of general and specific (ring-fenced) grants. Unlike the revenue budgets discussed above, the 2024-25 capital settlement sees reductions in cash and real terms:

| Local Government (Capital) | 2023-24 Budget document | 2024-25 Budget document | Cash change (£m) | Cash change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Capital Grant | 607.60 | 476.90 | -130.7 | -21.5% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) capital grants | 139.00 | 121.10 | -17.9 | -12.9% |

| Total "core" Capital | 746.6 | 598.0 | -148.6 | -19.9% |

| Capital Funding within other Portfolios | 80.00 | 40.00 | -40.0 | -50.0% |

| Total capital in Finance Circular | 826.6 | 638.0 | -188.6 | -22.8% |

| Local Government (Capital) | 2023-24 Budget document | 2024-25 Budget document | Real change (£m) | Real change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Capital Grant | 607.60 | 469.03 | -138.6 | -22.8% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) capital grants | 139.00 | 119.10 | -19.9 | -14.3% |

| Total "core" Capital | 746.6 | 588.14 | -158.5 | -21.2% |

| Capital Funding within other Portfolios | 80.00 | 39.34 | -40.7 | -50.8% |

| Total capital in Finance Circular | 826.6 | 627.48 | -199.1 | -24.1% |

The Verity House Agreement includes three shared priorities: tackling poverty, a just transition to net zero and delivering sustainable person-centred public services. The capital budget is clearly central to local government's efforts to move their buildings and vehicles towards a net zero future. In a recent lobbying document, COSLA stated:

The scale of this challenge is enormous. One Council estimates that reaching net zero for their own properties alone would cost in excess of £1.2 billion – more than twenty-five times the size of that council's 2023/24 General Capital Grant allocation.

COSLA, News release, 4 December 2023

Much of the reduction in the capital allocation is accounted for by the £120.6 million switch from capital to revenue budgets (to help fund pay deals). This £120.6 million was in the capital budget line in 2022-23 and 2023-24 (even though it was subsequently transferred to support revenue budget). The treatment is different this year, and it has been included in the GRG line this year. However, even accounting for this, capital budgets are reducing. As such, working towards a net zero future may have become even more challenging for Scotland's councils.

The council tax freeze announcement

Four months after the signing of the VHA, the First Minister announced at the SNP party conference the Government's intention to freeze council tax next year, without having first consulted COSLA. Council leaders expressed their "extreme disappointment" with the announcement, stating that "the First Minister chose to undermine the spirit and the letter of the Verity House Agreement, so soon after it being signed". Despite this, the Scottish Government argued that it remains "wholly committed" to the VHA, with the Minister for Community Wealth and Public Finance telling the Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee in November:

We are very much committed to partnership working right across all aspects of the new deal with local government and specifically with regard to the council tax freeze. We are committed to ensuring that we can implement it in a way that meets the requirements set by the First Minister that it be fully funded and that it deliver a freeze that will be of benefit to people across Scotland.

Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee 14 November 2023 [Draft], Tom Arthur, contrib. 157, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=15547&c=2533631

Council tax is Scotland's only truly local tax, in the sense that Band D rates are set by councils each year, local authorities collect the money, and they use it to fund local services. It is therefore up to councils themselves whether there is a freeze or not.

In addition to the principle of central government announcing a freeze on a local tax before having first consulted local government, there is the practical question of how much a "fully funded" freeze would cost the Scottish Government should local authorities decide to implement a freeze. In her statement to the Parliament, the Deputy First Minister stated:

Let me be clear that the Government will fully fund the council tax freeze. This year, in 2023-24, councils set their average council tax increases below the level of inflation. The OBR projection for inflation in the coming year based on the consumer prices index is 3 per cent. Of course, I could fund an inflation-proof 3 per cent council tax freeze, but I want to help support services, so I will go further than that. I will fund an above-inflation 5 per cent council tax freeze, delivering more than £140 million of additional investment for local services.

Deputy First Minister, Budget statement, 19 December 2023

In its response to the Scottish Budget, COSLA argued that a fully-funded freeze would require the Scottish Government to provide funding of £300 million, £156 million more than the £144 million being offered in the Budget for this purpose. In a news release published two days after the Budget publication, COSLA's President Councillor Shona Morrison said:

COSLA's initial analysis of the Budget is that the Council Tax freeze is not fully funded. Leaders from across Scotland agreed today that decisions on Council Tax can only be made by each full Council, and it is for each individual Council to determine their own level of Council Tax. With any sort of shortfall in core funding, the £144m revenue offered for the freeze is immediately worth less.

COSLA, News release, 21 December 2023

Given COSLA's position on the freeze, and their overall argument that the local government settlement for 2024-25 is far short of what councils need to avoid service cuts and job losses, there is likely to be much more negotiation taking place between these two spheres of government between now and March.

Tax

Income tax

Income tax proposals

The Scottish Government set out its proposals for income tax from April 20241 as part of the Scottish Budget 2024-25. These proposals need to be approved by a Scottish Rate Resolution, which must precede Stage 3 of the Budget Bill process. Income tax then cannot be changed during the financial year.

The proposals set out by the Scottish Government involve:

Increasing the basic rate and intermediate rate thresholds by 1.0% and 3.4% respectively

Freezing the higher and top rate thresholds

Introducing a new "advanced" rate band for earnings between £75,001 and £125,140, with a tax rate of 45p

Increasing the top rate of tax from 47p to 48p.

The proposed increases to the basic and intermediate rate thresholds are below inflation, but have the effect of ensuring that the amount of income at which starter rate tax and basic rate tax is paid increases in line with inflation. For example, in 2023-24, the first £2,162 of taxable income was taxed at 19%. Under the proposals for 2024-25, the first £2,306 will be taxed at 19%, which is in line with the September 2023 consumer price index (CPI) increase of 6.7%.

The proposed rates and bands are shown below.

| Bands | Band name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £12,570* - £14,876 | Starter | 19 |

| Over £14,877 - £26,561 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £26,562 - £43,662 | Intermediate | 21 |

| Over £43,663 - £75,000 | Higher | 42 |

| Over £75,001 - £125,140** | Advanced | 45 |

| Above £125,140** | Top | 48 |

* Assumes individuals are in receipt of the standard UK personal allowance (£12,570 in 2024-25)

** Those earning more than £100,000 will see their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000

The UK government sets the personal allowance and this is unchanged from 2022-23, at £12,570. The UK government has also frozen its own higher rate threshold at £50,270 and plans to keep both the personal allowance and higher rate threshold at the current levels until 2027-28, as announced at the Autumn Statement 2022.

| Bands | Band name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £12,570* - £50,270 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £50,270 - £125,140** | Higher | 40 |

| Above £125,140** | Additional | 45 |

* Assumes individuals are in receipt of the standard UK personal allowance (£12,570)

** Those earning more than £100,000 will see their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000

Income tax revenues

The Scottish Fiscal Commission forecasts that, with the proposals set out in the budget, non-savings non-dividend income tax revenues will total £18,844 million in 2024-25. Forecasts for subsequent years are shown in Table 4. These forecasts are based on the assumption that the Scottish Government will continue to freeze the higher and top rate thresholds, and also the newly-introduced advanced rate threshold, but that the width of lower tax bands will be uprated in line with the previous September's CPI inflation.

| 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSND income tax | 18,844 | 19,873 | 20,856 | 22,056 | 22,981 |

The SFC income tax estimates for 2024-25 are more than £2 billion higher than had been forecast in the December 2022 forecasts. This reflects both a stronger outlook for nominal earnings growth and Scottish Government policy decisions.

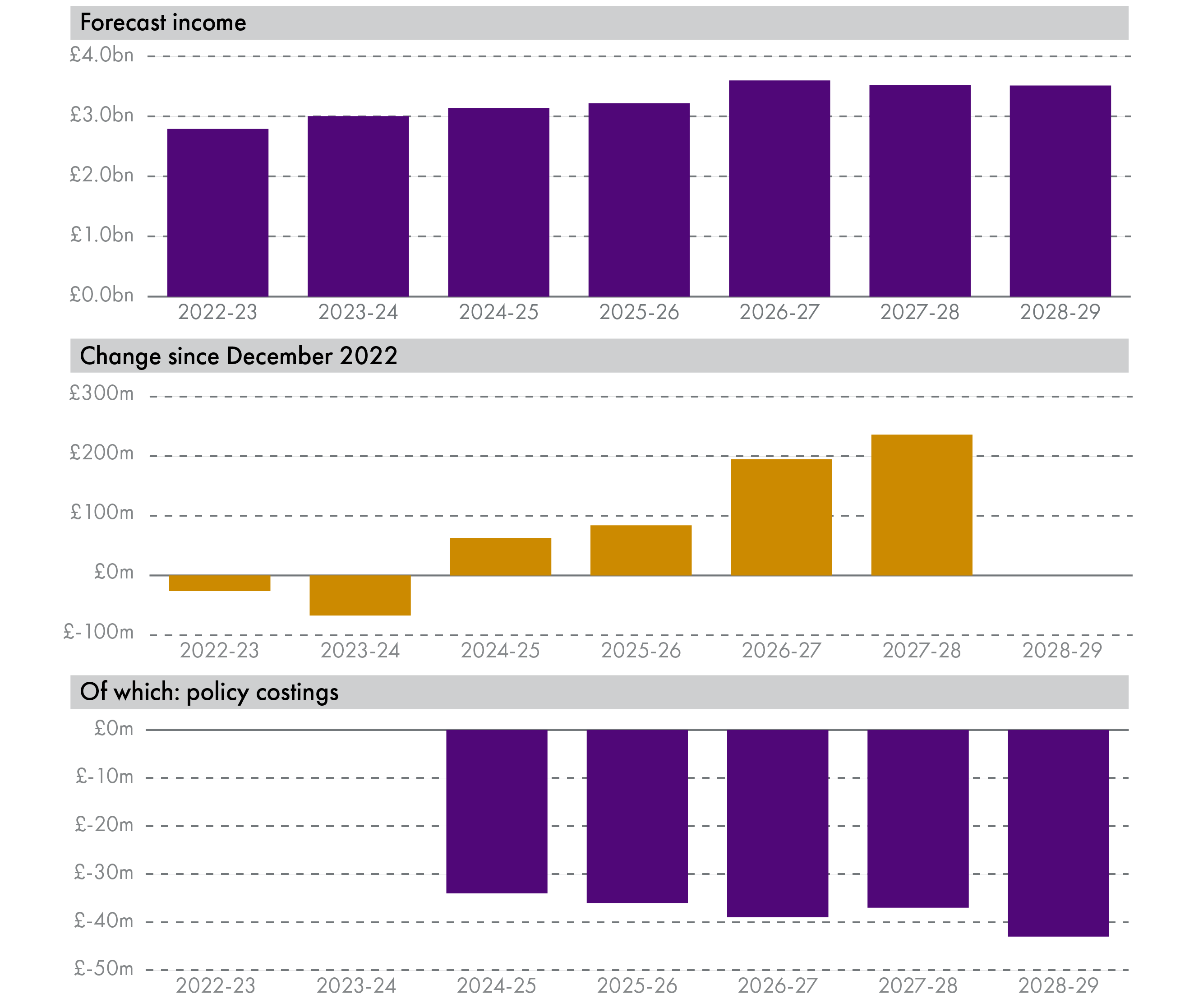

The SFC estimates that the income tax decisions taken by the Scottish Government in this year's budget will, after taking account of behavioural changes, raise an additional £82 million relative to what would have been raised if the starter and basic rate band widths had been increased in line with inflation. Figure 8 shows how this total is broken down, showing both the estimated impact before behavioural responses and the post-behavioural estimate.

This shows that most of the increase in revenues results from the introduction of the new "advanced" rate of 45p for earnings between £75,000 and £125,140. This is expected to raise £74 million after taking account of behavioural responses of taxpayers to the change in tax policy. The increase in the top rate from 47p to 48p is expected to raise only £8 million after behavioural effects. This is because taxpayers are expected to take measures in response to the tax increase to limit their exposure to the higher tax. This might involve steps such as increasing pension contributions (to reduce taxable income), reducing hours worked or moving outside Scotland. The SFC note that estimates of behavioural responses are, by their nature, "highly uncertain". A SPICe blog provides further discussion of the modelling of behavioural responses.

Income tax net position

In 2024-25, the income tax net position is expected to be £1.4 billion. That is, NSND income tax revenues in Scotland are expected to exceed the block grant adjustment for income tax by £1.4 billion. The income tax BGA is the amount that is removed from the Scottish budget to account for the fact that most income tax decisions have been devolved to the Scottish Parliament. It reflects what Scotland would have raised in income tax if it had retained the same tax policy as the rest of the UK and if Scotland's per capita tax revenues had grown at the same rate as the rest of the UK. This is a much improved position relative to previous forecasts and is double the income tax net position for 2024-25 that had been estimated at December 2022. This largely reflects much stronger earnings growth in Scotland, both relative to previous forecasts and relative to the rest of the UK.

On the basis of latest forecasts, the income tax net position (the difference between expected revenues and the BGA) is expected to reach £2.3 billion by 2028-29, although the SFC note that the net position is highly sensitive to changes in the SFC and OBR forecasts that underpin the calculation.

In contrast to previous years, the net income tax position is now broadly in line with the additional amount that Scottish taxpayers are paying relative to what they would be paying under rUK income tax policy. The Scottish Government estimate that Scottish taxpayers are paying an additional £1.5 billion relative to what they would be paying under rUK income tax policy. This provides additional resources for the Scottish budget enabling the Scottish Government to fund different policy choices.

Impact on individuals

Income tax at various levels of earnings under the Scottish Government proposals is shown in Table 9.

When compared with rUK income tax policy, Scottish taxpayers earning less than £28,850 will pay up to £23 less income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK. This accounts for just over half (51%) of all Scottish taxpayers. Above this earnings level, Scottish taxpayers pay more tax than they would in the rest of the UK and the gap widens rapidly for those earning above £50,000. Those earning more than £50,000 will be paying at least £1,500 more income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK.

The introduction of the new "advanced" rate tax band means that those earning more than £75,000 will be paying more than they would have under last year's income tax policy. However, the majority of taxpayers will pay slightly less tax next year than they are paying this year – around £10 less over the whole year for most taxpayers.

| Annual earnings | Scottish Government proposals 2024-25 income tax payable - £ per year | Difference compared with 2023-24 - £ per year | Difference compared with rUK - £ per year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15,000 | 463 | -1 | -23 |

| 20,000 | 1,463 | -1 | -23 |

| 25,000 | 2,463 | -1 | -23 |

| 30,000 | 3,497 | -10 | 11 |

| 35,000 | 4,547 | -10 | 61 |

| 40,000 | 5,597 | -10 | 111 |

| 45,000 | 6,928 | -10 | 442 |

| 50,000 | 9,028 | -10 | 1,542 |

| 55,000 | 11,128 | -10 | 1,696 |

| 60,000 | 13,228 | -10 | 1,796 |

| 65,000 | 15,328 | -10 | 1,896 |

| 70,000 | 17,428 | -10 | 1,996 |

| 75,000 | 19,528 | -10 | 2,096 |

| 80,000 | 21,778 | 140 | 2,346 |

| 85,000 | 24,028 | 290 | 2,596 |

| 90,000 | 26,278 | 440 | 2,846 |

| 95,000 | 28,528 | 590 | 3,096 |

| 100,000 | 30,778 | 740 | 3,346 |

| 150,000 | 59,681 | 2,120 | 5,978 |

Impact on household incomes

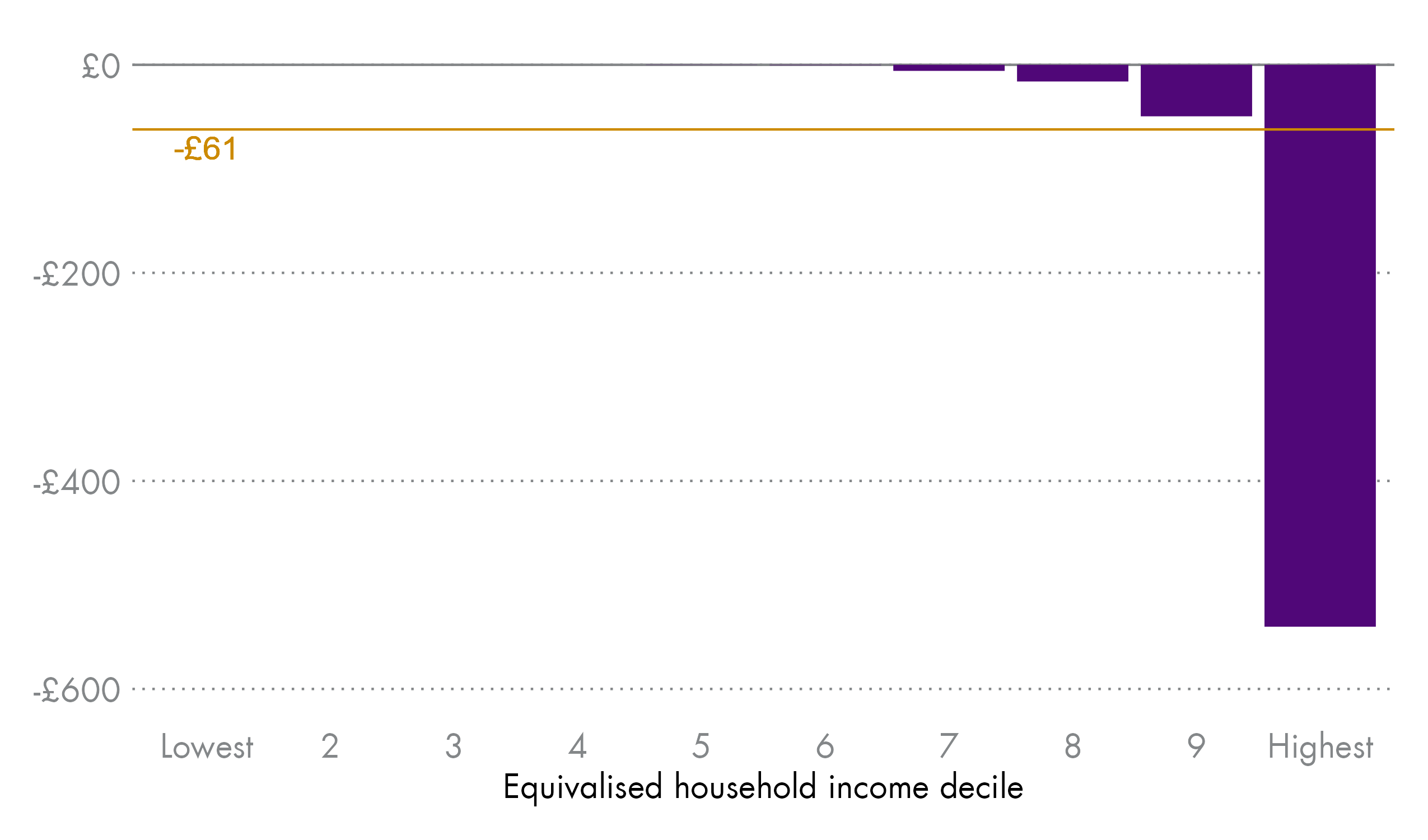

The proposed income tax changes do not affect all households equally. The households with the highest incomes see the largest tax increases. However, these increases reduce overall household incomes only slightly. This is because household income is made up of the earnings of all individuals in the household plus income from other sources, such as social security payments. High earners might share a household with people who have lower or no earnings and are less affected by the proposed income tax changes.

On average, household incomes are reduced by £61 per year, but this is driven by larger reductions for the 10% of households with the largest incomes (average reduction is £540), whereas most households (the bottom 60%) see hardly any change.

Note that this analysis is similar to analysis produced by the Scottish Government; however, we use different baselines for comparison. In line with the SFC, we compare the proposed income tax policy to a hypothetical policy without the new advanced rate and the 1p increase to the top rate. By contrast, the Scottish Government's baseline includes an uprated higher rate threshold, thereby treating the freeze of the higher rate threshold in the 2024-25 income tax policy an explicit policy decision. However, the SFC now considers a frozen higher rate threshold the default position and note that this approach was previously agreed with the Scottish Government. As a result of this difference in our baseline assumptions, our analysis shows smaller effects.

Interaction with rUK tax policy

Decisions on national insurance contributions (NICs) are made by the UK government, but will interact with the Scottish Government's decisions on NSND income tax to determine overall tax rates. In the 2023 Autumn Statement1, the UK government announced plans to reduce the main form of NICs (Class 1 employee NICs) by two percentage points. This means that the NICs rate on earnings between the personal allowance and £50,270 will be 10% from 6 January 2024. Above this level of earnings, the NICs rate drops to 2%. However, since this NICs threshold is linked to the rUK higher rate threshold of £50,270, it means that Scottish taxpayers who earn between the proposed Scottish higher rate threshold (£43,662) and the rUK higher rate threshold (£50,270) will pay 42% income tax and 10% NICs on their earnings between these two amounts – a combined tax rate of 52%.

There are also very steep marginal tax rates for those earning between £100,000 and £125,140 due to the tapering of the personal allowance (which is withdrawn at a rate of £1 for every £2 earned above £100,000). In Scotland, with the new advanced rate, taxpayers face a marginal rate of 69.5% (including NICs) on earnings in the range £100,000-£125,140. However, the decision to taper the personal allowance is reserved to the UK government so the Scottish Government has no control over this.

Devolved tax policy and forecasts

This section sets out the Scottish Government's proposals on devolved taxes other than Non-Savings Non-Dividend income tax. The taxes covered in this section are:

Non-domestic rates

Non-domestic rates (NDR) are local taxes paid on land and heritages used for non-domestic purposes in the private, public and third sectors. The tax is administered and collected by local authorities, but tax rates and reliefs are set by the Scottish Government.

The amount of tax due depends on the rateable value of the property, set by independent assessors, multiplied by the poundage rates set by the Scottish Government. The Scottish Government proposes to maintain the poundage rates from 2023-24 at 49.8 pence for the basic property rate, but to increase the intermediate and higher property rates in line with inflation. Figure 11 below sets out the three different rates proposed for 2024-25.

In the recent UK Autumn Statement, the Chancellor announced a one-year extension of their retail, hospitality and leisure (RHL) relief introduced in the 2022 Autumn statement. This RHL relief provides a 75% discount to businesses occupying eligible retail, hospitality and leisure properties in England, with a cap of £110,000 per business. It does not apply in Scotland as non-domestic rates are devolved. The OBR estimated the UK announcement generated £230 million in Barnet consequentials for the Scottish Budget. In their Budget Report, the Fraser of Allander Institute suggested that replicating this relief in Scotland would cost up to £360 million, explaining that this would be more expensive in Scotland as:

The higher cost of the relief is largely due to there being less concentration in the RHL industries in Scotland, which means relatively fewer businesses affected by the cap. We think less than 1% of RHL businesses would get no relief at all if the same cap applied.

Fraser of Allander Institute, Scotland's Budget Report 2023, 15 December 2023

The Scottish Government did not introduce a relief for the wider hospitality sector but did announce that hospitality businesses on Scottish islands would benefit from 100% rates relief for 2024-25, capped at £110,000 per business. The SFC estimates that this will cost £4 million. The Scottish Government has also announced plans to phase out the enterprise areas relief, which the SFC forecasts will generate £1 million more NDR revenue from 2025-26 onwards.

A widening of the eligibility criteria for the District Heating relief, and a two-year extension to the telecommunications mast relief are not expected to have a material impact on revenues and so have not been costed by the SFC.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission notes there are five new policies announced in the 2024-25 Budget which will materially impact NDR revenues:

Freezing the basic property rate

Increasing the intermediate property rate

Increasing the higher property rate

The introduction of 100% relief for hospitality businesses in Scottish Islands

The phasing out of enterprise areas relief over the next two years

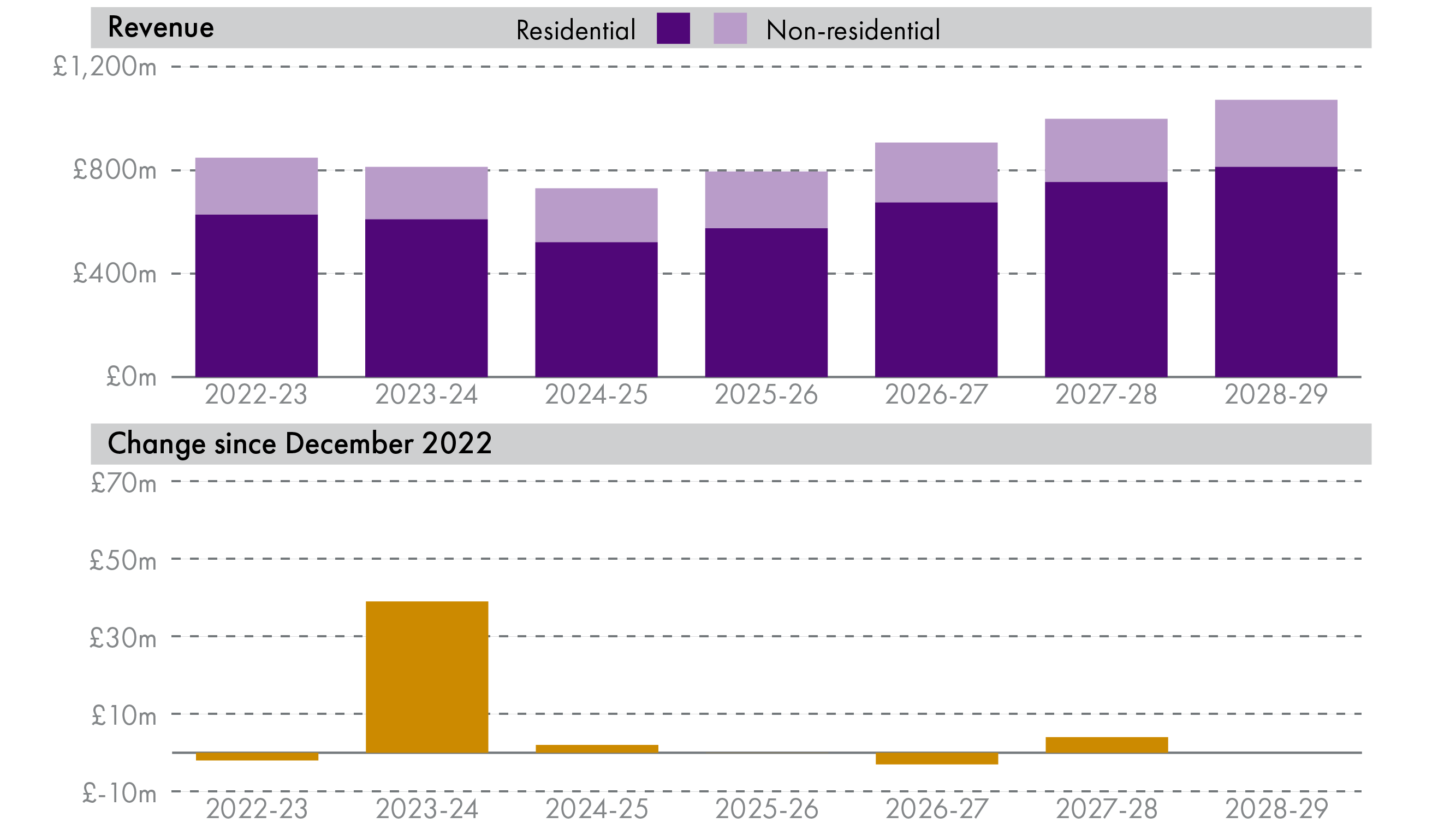

Of these changes, the most significant impact on revenues come from the decisions on poundage. The SFC forecasts that the cost of freezing the basic property rate is around £200 million per year, however the increase to the intermediate and higher property rates will increase revenues by around £170 million each year giving a smaller net effect. Figure 12 below shows the forecast for NDR revenue and the total change since the December 2022 forecast:

Land and buildings transaction tax (LBTT)

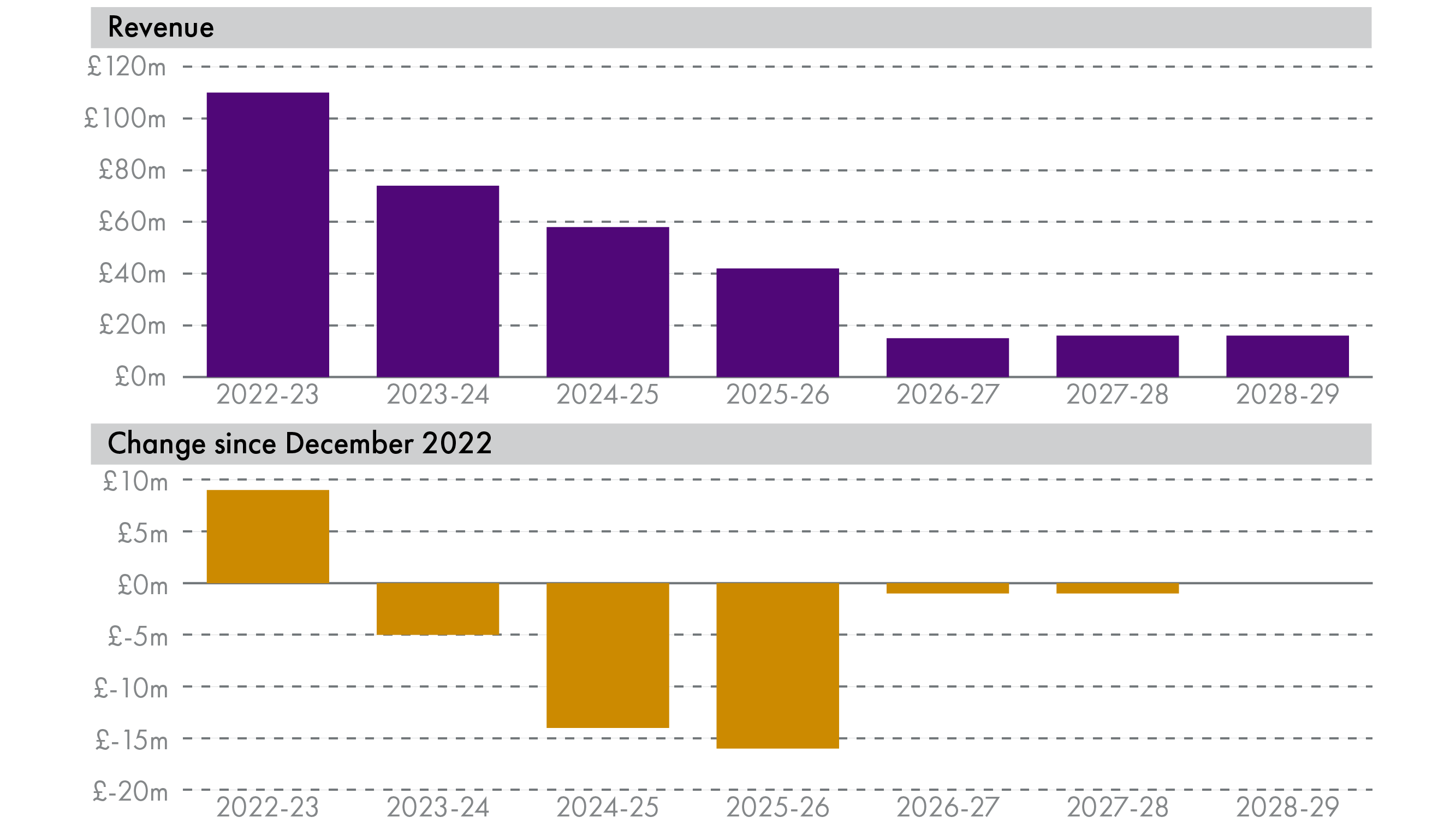

Land and buildings transaction tax is the tax applied to purchases of residential and non-residential land and buildings, as well as commercial leases. The Scottish Government has maintained the residential and non-residential rates and bands at their current level, along with the relief available to first time buyers.

In the Budget, the Scottish Government does commit to introduce legislation to make various amendments to LBTT, including to extend the timelines related to the additional dwelling supplement, addressing concerns around scenarios with joint buyers, and extending the scope of residential LBTT relief for local authorities. The Scottish Government published a summary of responses to a consultation on these changes on 8 February 2023.

The SFC forecasts that LBTT will raise a total of £730 million in 2024-25, a small increase from the forecast in December 2022. The majority of LBTT revenues are expected to come from residential transactions over the forecast period, with total receipts falling in 2024-25 before recovering in the outer years of the forecast period. The main driver of this is the expected fall in house prices up to 2025-26, before a gradual recovery. The projected fall in house prices, of around 4 per cent from the 2022-23 peak, is smaller than the SFC expected in the December 2022 or the May 2023 forecast. This is also a smaller fall than the OBR expects, with the SFC explaining that:

In line with a judgement made in our prior two forecasts, we assume the Scottish housing market will remain more resilient than the wider UK market as a result of the average stock of outstanding debt per household relative to income being lower in Scotland compared to the rest of the UK, and average house prices being lower in Scotland compared to the rest of the UK. As a result, we assume homeowners and prospective homebuyers will be less vulnerable to higher mortgage payments in Scotland in the face of higher interest rates.

Scottish Fiscal Commission. (2023, December 19). Scotland’s Economic and Fiscal Forecasts – December 2023. Retrieved from https://www.fiscalcommission.scot/publications/scotlands-economic-and-fiscal-forecasts-december-2023/ [accessed 22 December 2023], Para 4.101

Figure 13 below sets out the forecasts for revenues from LBTT.

Scottish landfill tax (SLfT)

The Scottish Government has increased the standard and lower rates of SLfT to £103.70 per tonne and £3.30 per tonne for 2023-24 respectively. As in previous years, these changes maintain parity with the UK rates. The SFC forecasts relatively minor changes to revenues since December 2022, noting that outturn data in 2023-24 has been significantly lower than expected, offset by modelling changes which increase the amount of waste which is liable to SLfT. The policy goal of SLfT remains behavioural change – the expectation is that over time these revenues will reduce. The SFC now expects a faster reduction in 2024-25 and 2025-26.

Other devolved taxes

There are no new policy announcements in relation to the Airport Departure Tax (ADT), with the Scottish Government restating its position that it remains committed to introduce ADT "in a way that protects Highlands and Islands connectivity and complies with the UK Government's subsidy control regime".

The Scottish Government introduced the Aggregates Tax and Devolved Taxes Administration (Scotland) Bill in November 2023, which makes provision for a Scottish Aggregates Tax. Subject to Parliamentary approval, the Scottish Government intends to introduce a Scottish Aggregates Tax from 1 April 2026. The Bill provides for a replacement tax that retains the fundamental structure of the UK Aggregate Levy, while allowing scope to consider a tailored approach in Scotland.

On VAT Assignment, which was also devolved in the Scotland Act 2016, the Scottish Government notes the 2023 Fiscal Framework Agreement1 with the UK Government and states:

The 2023 Fiscal Framework Agreement with UK Government outlines that once completed and agreed by officials the assignment methodology and operating arrangements will be presented for joint UK and Scottish Government ministerial sign-off.

Scottish Government. (2023, December 19). Scottish Budget: 2024 to 2025. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-budget-2024-25/ [accessed 22 December 2023]

The Budget also outlines plans for five new taxes, many of which were announced in the 2023-24 Programme for Government:

The Scottish Government is seeking powers from the UK Government to introduce a Building Safety Levy, which would raise revenues to fund the Scottish Government's cladding remediation programme. This would replicate the UK Government's own levy which covers England.

The Scottish Government pledges to continue to work with COSLA and local authorities to scope the request that discretionary powers be provided to introduce a Cruise Ship Levy. While the Scottish Government is 'exploring' whether this can be included in the Visitor Levy Bill, it notes that significant engagement with businesses and other stakeholders will be required, and that the Visitor Levy Bill will not be delayed.

The John Muir Trust has proposed a Carbon Emissions Land Tax, and the Scottish Government pledges to work with stakeholders during 2024-25 to explore this and other fiscal options.

The Scottish Government plans to explore reintroducing a Public Health Supplement for large retailers ahead of the next budget. The previous iteration of this tax was levied on large supermarkets which sell alcohol and tobacco, and expired in 2015.

Finally, the Scottish Government pledges to continue to explore an Infrastructure Levy, to be implemented by spring 2026.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission forecasts

Economic growth and living standards

The Scottish Fiscal Commission's December forecasts for Scotland's economy1 are largely unchanged from their May 2023 forecasts. GDP is forecast to grow by 0.2% in 2023-24 and 0.8% in 2024-25, compared with May 2023’s forecast of 0.3% and 1.0% respectively. Recent data revisions mean that Scottish GDP returned to its Q4 2019 level in Q4 2021, but growth has largely been flat since.

Crucially, the outlook for growth remains low over the longer term. This would constrain future budgets and household living standards. The SFC notes that the main drivers of subdued long term GDP growth are falling productivity growth, slowing population growth, and a declining participation rate due to an ageing population.

.png)

Beyond the headline figures, there are some changes in the composition of forecasted GDP growth. A small growth in household consumption in 2023-24 contrasts with a previously forecasted fall, primarily driven by higher-than-expected pay growth and a reduction in household savings. The higher cost of borrowing and changes to the UK's tax treatment of capital allowances see forecasted business investment fall in 2023-24 and 2024-25, but return to growth thereafter.

Living standards are measured by real disposable income per person. Whilst earnings are now rising in real terms, this is largely offset by an increasing personal tax burden at a UK and Scottish level, and higher mortgage interest payments. Living standards are forecast to fall by 2.7% between 2021-22 and 2023-24 and not recover until 2026-27. The SFC notes that the outlook will vary across household types, with lower income households facing particular pressures, as they spend a greater share of income on energy, food and housing costs. Higher income households and those who own their home outright are more likely to hold savings, and so will benefit from rising interest rates.

Inflation

Inflation has been a key driver of increasing cost pressures on the Budget but has also resulted in additional income tax revenues. This is due to a combination of nominal earnings growth and fiscal drag – the freezing of income tax thresholds at the higher rate and above, and the UK government's decision to freeze the personal allowance.