Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults (Scotland) Bill - Republished

The Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults (Scotland) Bill seeks to legalise assisted dying for adults with a terminal illness. This briefing outlines the current law in Scotland in relation to assisted dying as well as the policy background to the Bill. It also explores public opinion and assisted dying internationally. It then goes on to detail the Bill’s provisions as well as some of the issues raised in the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee’s call for views.

Summary

The current law on assisted dying

The current law on assisted dying has been argued to be unclear. There is no specific offence of dying by suicide in Scotland and therefore - unlike in England and Wales - no specific offence of assisting someone to commit suicide.

However, where someone's actions lead directly to the death of another person, they can be charged with offences as serious as murder or culpable homicide.

A recent human rights challenge to the lack of specific guidance on the approach prosecutors would take in assisted dying cases in Scotland was unsuccessful. However, one of the judges expressed the clear view that neither supplying drugs to someone intent on dying by suicide nor travelling with someone who intended to die by suicide abroad were criminal matters in Scotland.

However, the position of doctors assisting their patients to die may be more tricky. A key factor is the relationship of trust and mutual respect between a doctor and their patient. In England and Wales, the fact that the suspect was a healthcare professional and the victim was in their care is one of the factors which may support prosecution in cases of assisting someone to commit suicide.

Assisted dying and human rights

The courts in the UK - as well as the European Court of Human Rights - have recognised that the right to decide how and when to die is protected by Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. However, states have wide discretion to set the law in this area, including ensuring protection for vulnerable people.

The law in England and Wales has not yet been found by the courts to breach human rights. However, the Director of Public Prosecutions has been required to provide more clarity as to when people could be prosecuted for assisting someone to commit suicide.

History of Assisted Dying Legislation in Scotland

This is the fourth attempt to legislate for assisted dying and the third Bill to be introduced in Scotland.

Each Bill has shared certain features such as a minimum age of 16 and the involvement of doctors in the assessment process. However, areas of evolution include; a narrowing of the eligibility criteria to terminal illness, shortening the period of reflection to 14 days, inclusion of a conscientious objection clause, creation of an offence for coercion and specifying the means of death.

Assisted Dying in the Rest of the UK and Crown Dependencies

Other parts of the UK are currently considering proposals to introduce assisted dying, including two recently introduced Bills at Westminster. Jersey and the Isle of Man are also actively considering proposals.

Assisted Dying Internationally

We identified 30 jurisdictions which already have some lawful form of assisted dying and an additional 10 which are currently considering proposals. Key differences in the models pursued include eligibility and whether it is limited to people with terminal illnesses or suffering more broadly, and the type of assistance physicians can give.

End of Life Decisions in Scotland

There are around 63,000 deaths annually in Scotland and the most common causes are heart disease, lung cancer and cerebrovascular disease.

Around 89% of those who died had a palliative care need but previous audits have found not everyone who needs palliative care will receive it. Marie Curie estimates 1 in 4 people who need palliative care do not receive it.

Other end-of-life practices which can take place in Scotland include; continuous deep sedation, higher doses of painkillers to alleviate pain but which may also hasten death (known as the 'doctrine of double effect'), as well as the refusal and withdrawal of treatment. It is unclear how common such practices are.

Dignitas has reported that, in 23 years, they are aware of 16 people from Scotland having an assisted death at its assisted dying facilities in Switzerland. Analysis by the Office for National Statistics found that a diagnosis or first treatment for certain conditions was associated with an elevated rate of death due to suicide.

Public Opinion

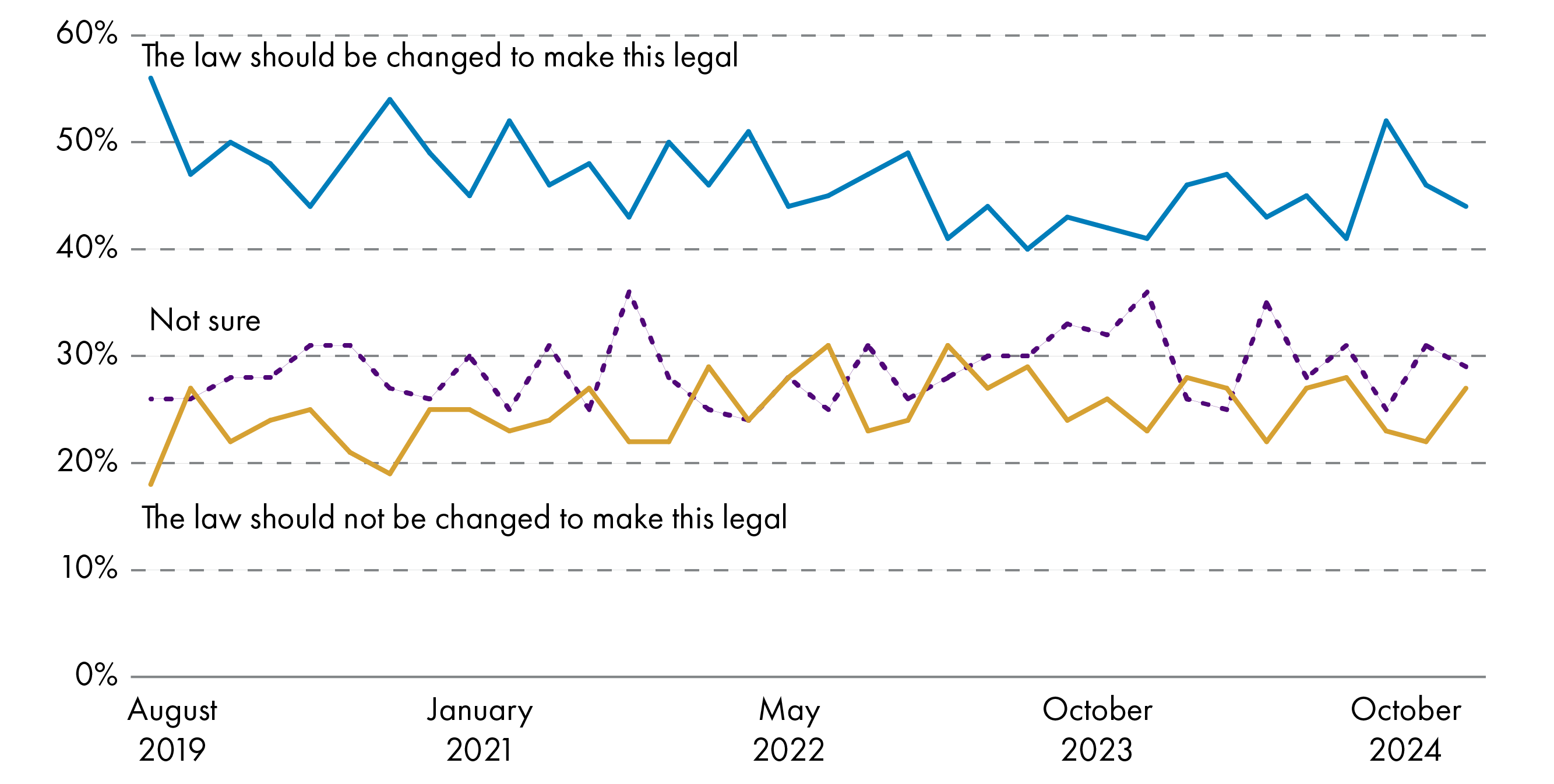

Polls generally show that the majority of Scottish and British people are supportive of changing the law to assist in the suicide of someone who is terminally ill. However, this support tends to drop when the question asks about a change in the law to allow assisting someone who is suffering from an incurable condition but not a terminal illness.

The public also tends to be more supportive of proposals which involve doctors. However, opinion within medics is divided. Surveys have found that doctors are more supportive of prescribing drugs for assisted dying, than administering them. But opinion is still divided and the largest proportion would not be willing to participate in either. Support also differs between specialities, with doctors in palliative medicine, clinical oncology and geriatric medicine least likely to support a change in the law. Doctors in anaesthetics, emergency medicine and intensive care medicine were more supportive of a change in the law.

Consultation on the Current Bill

Liam McArthur MSP undertook a consultation on the draft Bill and received 14,038 responses. It found 76% of respondents were fully supportive of the proposed Bill and a further 2% were partially supportive. 21% of respondents were fully opposed and 0.4% were partially opposed. Please note that respondents were self-selecting and so the results cannot be considered as representative of Scottish opinion.

The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee undertook two calls for views on the Bill as introduced. These were a short survey for people who wished to express general views about the Bill as a whole, and a detailed call for views for those who wished to comment on specific aspects of the Bill. Again, please note that respondents were self-selecting and so the results cannot be considered as representative of Scottish opinion.

The Committee received 13,820 responses to the short survey and 7,236 responses to the detailed call for views. A qualitative analysis of the detailed call for views was undertaken and the main themes to emerge are included in the key issues sections of the briefing.

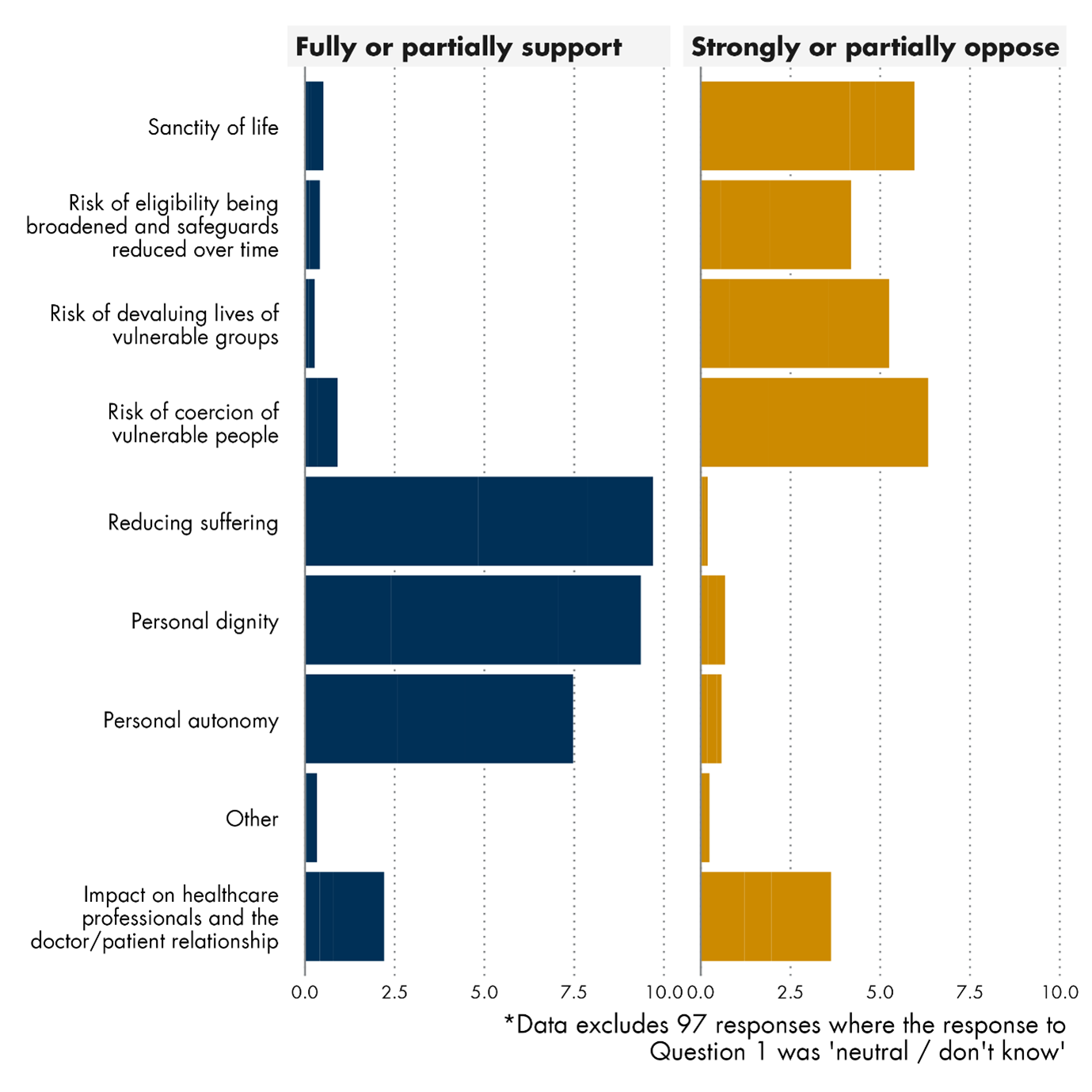

Both calls for views were analysed for the main factors influencing people's opinions on the Bill. This found that those in support of the Bill were more likely to choose reducing suffering, personal dignity and personal autonomy . While those opposed to the Bill chose the sanctity of life, the risk of coercion of vulnerable people and the risk of devaluing the lives of vulnerable groups.

The Bill's Provisions

Eligibility

The Bill defines someone as terminally ill if they ‘have an advanced and progressive disease, illness or condition from which they are unable to recover and that can reasonably be expected to cause their premature death’. An adult is defined as someone aged 16 or over. To be eligible a person would also need to have capacity and have been resident in Scotland for at least 12 months and be registered with a GP practice.

Key issues raised in relation to this part of the Bill included the breadth and clarity of the definition of terminal illness, the lack of a prognostic timescale, the age of eligibility and how capacity will be assessed.

Procedure and Safeguards

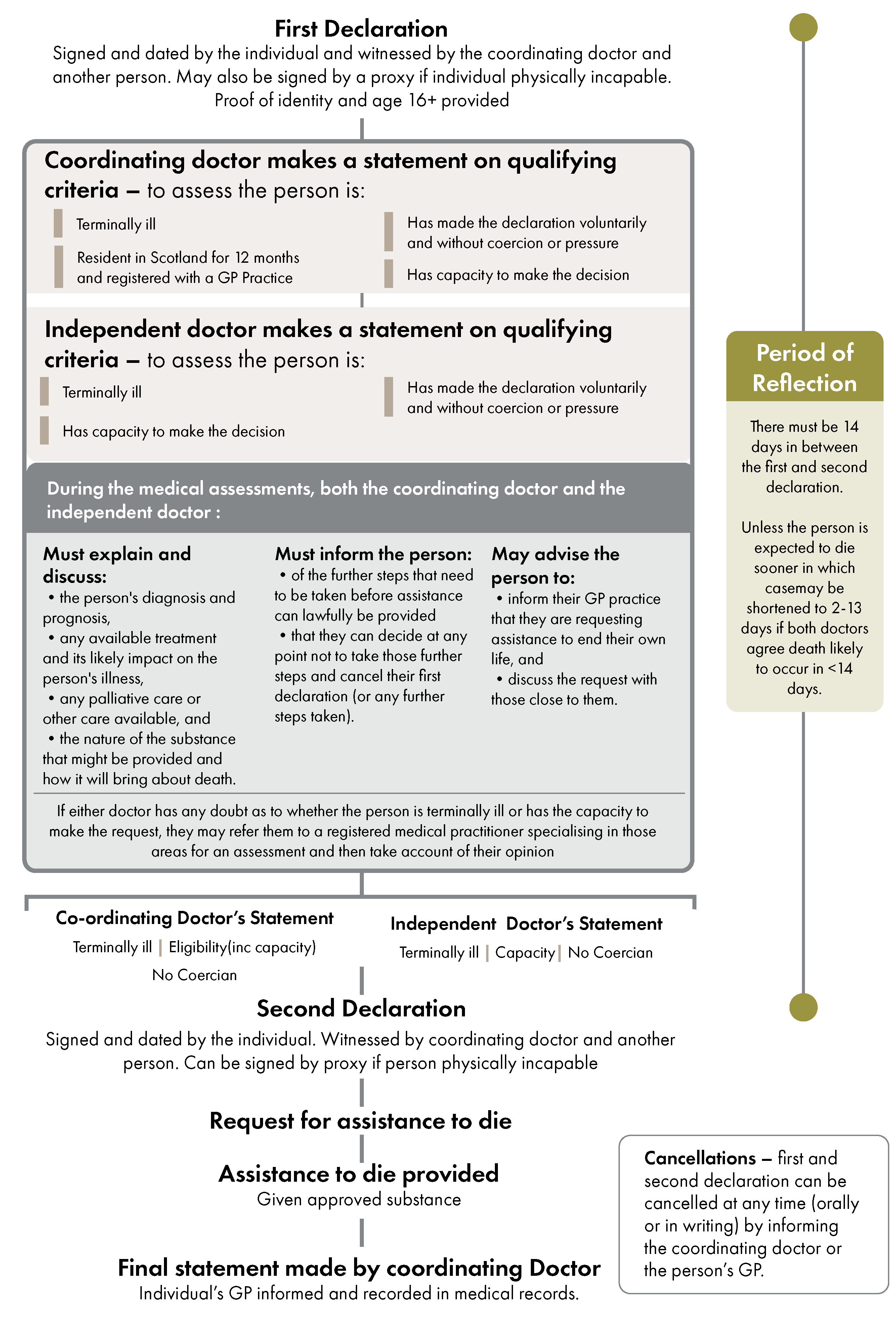

The Bill describes a three-stage process which would be in place for those wishing to have an assisted death. It also sets out various safeguards, including assessment by two doctors involving an assessment of eligibility, capacity and coercion, as well as a period of reflection. There is also the option of a referral to specialists.

Key issues raised in relation to this part of the Bill included; the length of the period of reflection, how coercion will be assessed and which professionals will provide assistance.

Provision of Assistance to End Life

The Bill authorises a medical practitioner or authorised health professional to provide an eligible adult with a substance with which they can end their own life. What this substance is would be set out in regulations. The accompanying documents to the Bill emphasise that the substance would need to be self-administered.

Key issues raised in relation to this part of the Bill included; the evidence around substances used in assisted dying, the potential for complications, what type of assistance can be given and whether different means of administration would be allowed.

Civil and Criminal Liability

The Bill would exempt healthcare professionals from criminal and civil liability when they aid an assisted death, so long as the assistance complies with the Bill's provisions. It would continue to be a criminal offence to end someone's life directly. There is also no change in the law for any action to assist dying outside of the process provided for in the Bill. The Bill would also make it an offence to coerce or pressure a terminally ill adult into an assisted death.

There were few comments on this part of the Bill but Police Scotland highlighted the factors they would consider important when conducting an investigation into a possible offence under the Bill.

Reporting and Monitoring

The Bill contains several reporting and monitoring requirements. These include a requirement for Public Health Scotland to collect data on assisted dying and for the Scottish Government to lay a report annually before the Scottish Parliament.

The Bill would also require the Scottish Government to review the operation of the legislation within five years and lay a report before the Scottish Parliament.

Key issues in relation to this part of the Bill included several suggestions around the type of data that should be collected, and suggestions around when the review period should take place.

Conscientious Objection

The Bill requires the direct involvement of medical practitioners and authorised health professionals in the assisted dying process. However, it also includes a provision allowing individuals to opt out as a matter of conscience.

Key issues raised in relation to this part of the Bill included who and what activities the conscientious objection would apply to, and concerns about how it might work in practice.

Financial Memorandum

The costings for the Bill are based on estimates that there will be 25 assisted deaths in the first year, rising to up to 400 deaths by year 20. This is also based on an assumption that 33% of people who enter the process will not proceed.

The Financial Memorandum calculates that the main costs of the Bill would fall on the health service and will come from clinician's time, staff training and the substances used to end life. The estimated health service costs range from £208,795 - £221,254 in the first year to £141,755 - £342,973 by year 20. There are other less substantial costs expected for the Scottish Administration.

The Financial Memorandum also details that there may be some savings from the reduced cost of care and the reduced cost of accessing services such as Dignitas.

Overall, the Financial Memorandum concludes that the Bill is likely to be 'effectively cost neutral'.

Key issues raised in relation to the Financial Memorandum include a potential underestimate of training costs and the extent to which costs can be borne within existing budgets.

Legislative competence and the Bill

Full implementation of the proposals in the Bill may require action which is currently outwith the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament. Key areas of concern are:

the specification of the drugs used to end life, which may be covered by the reserved matters of misuse of drugs, and medicines, medical supplies and poisons

the conscientious objection clause, training requirements and treatment of second opinions, which may be covered by the reserved matter of regulation of the health professions.

The Member in charge of the Bill has called on the Scottish Government to work with the UK Government to address these issues if the Scottish Parliament supports the general principles of the Bill at Stage 1.

Introduction

Liam McArthur MSP introduced the Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adutls (Scotland) Bill1 ('the Bill) in the Scottish Parliament on 27 March 2024. The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee was designated as lead committee for Stage 1 consideration of the Bill on 16 April 2024.

The Bill and its accompanying documents are available on the Scottish Parliament website.

The policy memorandum to the Bill sets out the following policy objective:

The aim of the Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults (Scotland) Bill is to allow mentally competent terminally ill eligible adults in Scotland to voluntarily choose to be provided with assistance by health professionals to end their lives.

The policy memorandum also goes on to explain:

The Bill establishes a lawful process for an eligible person to access assisted dying, which is safe, controlled and transparent, and which the Member believes will enable people to avoid the existential pain, suffering and symptoms associated with terminal illness, which will in turn afford the person autonomy, dignity and control over their end of life

Assisted Dying Terminology

Assisted dying suffers from a confusion of terminology, with different terms often being used interchangeably. There are no universally agreed definitions of any of the terms in question, however, some of the most frequently used terms are ‘assisted suicide’ and ‘euthanasia’. These are commonly understood to mean:

Euthanasia - (also sometimes referred to as ‘mercy killing’) the deliberate taking of another person’s life to relieve their suffering.

Assisted suicide - the situation where a competent person ends their own life but with the assistance of another person to perform the act, for example by providing the means to do so.

The distinguishing characteristic between the two is who carries out the act which brings about death. In assisted suicide, it is the person seeking death who carries out the final act, whereas euthanasia requires another person to perform the act that will lead to death. However, the term ‘euthanasia’ has become very emotive and its application is contentious. Assisted dying can also be viewed on the basis of the key distinguishing factors of whether the individual consented or not, and whether the death was brought about through active or passive means. The different categories are explained in more detail below:

1. Consent

Voluntary - meaning carried out at the request of the person in question.

Non-voluntary - which refers to the situation where the person is unable to express a decision on the matter, for example because of severe brain damage or dementia or because they are in a permanent vegetative state.

Involuntary - which refers to the situation where the person in question is competent to consent to his or her own death but does not do so, either because he or she was not asked or because his or her choice to live was ignored.

2. Means of death

Active - where there is a positive action to end life, such as injecting a lethal substance into a person.

Passive - where there is an omission of an act, for example the withdrawal or withholding of treatment.

Figure 1 illustrates different forms of assisted dying based on the above factors. The term ‘assisted dying’ is being used in this briefing to generally describe ways of hastening death. As a result, figure 1 includes suicide, but it is recognised that some may not consider this to be an ‘assisted’ death in the sense that no other individual is involved at any point.

.png v2)

The Current Law on Assisted Dying

It is not against the law to die by suicide in Scotland. It therefore follows that, unlike in England, there is no specific offence relating to assisting in the suicide of another person. However, beyond that, the law is unclear.

There has been concern that, depending on the circumstances, someone assisting a suicide may faces charges as serious as culpable homicide or murder.

This section of the briefing looks at

The Current Law on Murder and Culpable Homicide

Someone whose actions lead to the death of another could be charged with murder or culpable homicide

The distinction is important as murder carries a mandatory life sentence, whereas the court has complete sentencing discretion where someone is found guilty of culpable homicide. There are examples of outcomes ranging from a life sentence to admonishment (where the accused is warned not to offend again).

The Stair Memorial Encyclopaedia (a leading text on Scots law) defines murder as follows (Criminal Law, paragraph 222):

Murder is constituted by any wilful act causing the destruction of life, whether (wickedly) intended to kill, or displaying such wicked recklessness as to imply a disposition depraved enough to be regardless of consequences.

Broadly speaking, the element that differentiates murder from culpable homicide is the state of mind of the accused.

The technical term for this in Scots law is "mens rea".

For murder, the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS) must be able to prove the accused had a wicked intention to kill or was so reckless in relation to their actions as to not care about the likely consequence of death.

Where death is the result of someone’s actions but they had no deliberate intention to kill, the appropriate charge will usually be culpable homicide. For example, where death results from an assault (which was not sufficiently reckless to meet the requirements for murder), the charge will usually be culpable homicide. This is because an accused who only intends to hurt a victim lacks the mens rea for murder.

The defence of diminished responsibility can reduce a murder charge to culpable homicide

A charge of murder is reduced to culpable homicide where an accused successfully raises the defences of provocation (not discussed further) or diminished responsibility. Diminished responsibility is where someone's ability to control their conduct is “substantially impaired by reason of abnormality of mind” (from the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 Section 51B)..

There are other defences to murder and culpable homicide, including self-defence.

The actions of the accused must lead directly to the death of the victim for a homicide charge to be appropriate

It is key for a charge of murder or culpable homicide to be successful that the accused’s actions directly caused the death of another person. This is referred to as causation.

The courts in England have found that, where a mentally competent adult makes an autonomous decision to ingest illegal drugs, the chain of causation between the supply of those drugs by an accused and any death which may result, will usually be broken. Thus, the supplier of the illegal drugs will not usually meet the requirements to be charged with murder or manslaughter.

However, the courts in Scotland have not been so clear. In a decision relating to two cases involving the supply of illegal drugs, the High Court of Justiciary found that acts of the victim could leave the chain of causation unbroken. It stated (MacAngus v HMA [2009] HCJAC 8, paragraph 42):

These Scottish authorities tend to suggest that the actions (including in some cases deliberate actions) of victims, among them victims of full age and without mental disability, do not necessarily break the chain of causation between the actings of the accused and the victim's death. What appears to be required is a judgment (essentially one of fact) as to whether, in the whole circumstances, including the inter-personal relations of the victim and the accused and the latter's conduct, that conduct can be said to be an immediate and direct cause of the death.

Nevertheless, the later civil court case of Ross v Lord Advocate (discussed in the section on How the current law may apply to assisted dying) seems to suggest that, in an assisted suicide situation, an independent decision to consume drugs made by a competent adult will break the chain of causation.

The Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service has significant discretion in how it chooses to prosecute criminal cases

This is referred to as prosecutorial discretion. It is entirely up to the Crown to decide whether to bring charges against an individual and which charges to bring. The Crown also decides whether to accept a plea in defence (eg. of diminished responsibility) or to abandon proceedings (eg. because it is no longer in the interests of justice to continue the prosecution).

It is therefore open to the Crown to charge an accused with culpable homicide rather than murder – or indeed, not to charge them at all. The textbook Gordon’s Criminal Law in Scotland (Volume 4, paragraph 31.01) refers to “unofficial factors” which may result in a charge of culpable homicide rather than murder. These include infanticide, necessity and euthanasia.

The guiding factor in prosecutorial decisions made by the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service is the public interest. The Prosecution Code1 provides an overview of the issues Procurators Fiscal may take into account when reaching a decision about whether a prosecution is in the public interest.

How the Current Law May Apply to Assisted Dying

Depending on the specific circumstances of the case, it may be possible to charge someone who assists a suicide with a criminal offence. Options could include charges as significant as murder or culpable homicide.

The Scottish Law Commission is currently reviewing the law on homicide. This review does not include consideration of assisted suicide. However, in a discussion paper on the mental element in homicide cases1, the Commission commented (paragraph 1.24):

We fully acknowledge that this area of the law continues to produce difficult and delicate decisions where similar facts may result in either a prosecution for murder or no prosecution at all.

A murder charge in a recent euthanasia case

The case of Gordon v HMA ([2018] HCJAC 21) involved a situation where a husband smothered his wife with a pillow. She was in significant pain due to respiratory problems and had herself taken an overdose of painkillers. The husband’s motivation for his actions was to end his wife’s suffering.

Crown investigations did not disclose sufficient evidence of diminished responsibility. Mr Gordon was therefore charged with murder. However, during the course of the trial, further evidence of the accused’s mental state came to light and the Crown accepted a plea of diminished responsibility. The trial court imposed a sentence of three years and four months in prison. However, this was substituted, on appeal, for an admonition.

A human rights challenge provides further clarity to the law on assisted dying

Ross v Lord Advocate (2016 CSIH 12) was a civil rather than criminal case. Mr Ross was suffering from a number of physical conditions which made him reliant on others for his care. He considered that, at some point in the future, he may wish to end his life but would need someone to help him to do so. He was concerned that they could face criminal charges as a result.

He brought a civil court case arguing that it was a breach of his right to a private and family life (Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights) that the Lord Advocate had not published a policy outlining how decisions on whether to prosecute would be made in assisted suicide cases. This followed several English court cases on similar grounds.

Ultimately, the court rejected the claim that the Lord Advocate was required to publish a policy on this issue. However, it made several statements which could be argued to clarify the law in this area.

It should be noted that these statements on the criminal law are made by one judge in the course of civil court action. They would not be considered binding on a criminal court considering the issue in practice. However, they may still be seen as offering useful clarity to the law.

On the issue of providing drugs to someone who intended to die by suicide, Lord Carloway said (paragraph 30):

Nevertheless, the voluntary ingestion of a drug will normally break the causal chain. When an adult with full capacity freely and voluntarily consumes a drug with the intention of ending his life, it is this act which is the immediate and direct cause of death. It breaks the causal link between any act of supply and the death.

And, on the matter of assisting someone to travel abroad to end their life, Lord Carloway stated (paragraph 31):

In the same way, other acts which do not amount to an immediate and direct cause are not criminal. Such acts, including taking persons to places where they may commit, or seek assistance to commit, suicide, fall firmly on the other side of the line of criminality. They do not, in a legal sense, cause the death, even if that death was predicted as the likely outcome of the visit. Driving a person of sound mind to a location where he can jump off a cliff, or leap in front of a train, does not constitute a crime. The act does not in any real sense amount to an immediate and direct cause of the death

The Law in England and Wales

Assisting a suicide is a specific offence in England and Wales. This catches actions which are unlikely to be criminal in Scotland. There is also a specific role for the Director of Public Prosecutions, which has led to a number of human rights challenges in that jurisdiction.

Section 2 of the Suicide Act 1961 retains a specific offence of encouraging or assisting a suicide

While section 1 of the 1961 Act abolished the offence of committing suicide, assisting in the suicide of another person is still a specific offence under section 2. It has a maximum penalty of 14 years in prison.

The crime of assisting a suicide is a wide one. The current offence covers any actions which are intended to – and are capable of – encouraging or assisting another person to commit or attempt to commit suicide.

This could include, for example, travelling abroad with someone to access assisted dying in another country. It would cover supplying the drugs used by an individual to end their lives.

Section 2 of the 1961 Act also requires that any prosecutions have the consent of the Director of Public Prosecutions

The Director of Public Prosecutions is the head of the Crown Prosecution Service. This body is responsible for most prosecutions in England and Wales, although it is also possible for other bodies, and private individuals, to bring prosecutions.

Note that the situation in Scotland is different as prosecutions here always require the agreement of the Lord Advocate (the broad equivalent to the Director of Public Prosecutions).

Requiring the consent of the Director of Public Prosecutions ensures that prosecutions will only be brought where it is government policy to do so. A number of human rights cases in England and Wales have also focussed on this role. Human rights in this context are discussed in more detail in the section dealing with Assisted dying and human rights considerations.

In the case of R (Purdy) v DPP ([2009] UKHL 45), the House of Lords found that the law in England and Wales in this area was not sufficiently clear to meet human rights requirements. It ordered the Director of Public Prosecutions to produce guidance outlining what factors would be considered in reaching a decision about whether to prosecute someone for assisting another person’s suicide.

In a further court case in 2014 (R (on the application of AM) v Director of Public Prosecutions [2014] UKSC 38) considered the position of someone who was not a friend or relative – such as a professional carer – who provided assistance to someone to end their lives. During the course of legal action, the Director of Public Prosecutions confirmed that, in circumstances where a relative would not be prosecuted under the policy, someone who did not benefit from their actions would be unlikely to be prosecuted.

The current guidance – Suicide: policy for prosecutors in respect of cases of encouraging or assisting suicide (2014)1 – has been updated in light of the latter case. It lists a range of factors which would support or indicate against prosecution.

The factors which may support a prosecution include:

that the victim was under 18

that the victim lacked the mental capacity to reach an informed decision

that the suspect pressured the victim to commit suicide

that the suspect was a healthcare professional and the victim was in their care

that the suspect had given support to more than one, unrelated victim.

The factors which may indicate against a prosecution include:

that the victim had reached a voluntary, clear and settled decision to die by suicide

that the suspect was motivated only by compassion

that the actions of the suspect were only of minor encouragement or assistance

that the suspect reported the suicide to the police and assisted their investigation.

How the Current Law May Apply to Healthcare Professionals

There are factors in the relationship between healthcare professionals and their patients which make their role in assisted dying legally tricky.

Healthcare professionals such as doctors and nurses are recognised as having an important relationship with their patients, which is often characterised as one of trust and mutual respect. Doctors in particular are also recognised as often being in a position of power over patients, in that they have access to knowledge and information which the patient does not.

The special relationship between a healthcare professional and a patient may be a factor which would make prosecution more likely

The Ross case (discussed in the section on How the current law may apply to assisted dying) would appear to suggest that providing drugs to someone who has reached their own decision to die by suicide is unlikely to be criminal. It also suggests that accompanying someone abroad to commit suicide would not breach the criminal law in Scotland. It isn’t clear if this means that healthcare professionals who act in these ways would also be unlikely to face prosecution.

However, the guidance on prosecution for assisted suicide provided by the Director of Public Prosecutions in England and Wales notes that having a professional relationship with a victim in a healthcare context is one of the factors which may support a decison to prosecute. This may be in recognition of the expectations of the relationship between healthcare professionals and patients. There is no equivalent statement on the role of a healthcare professional in Scotland.

An article from the Medical and Dental Defence Union of Scotland (MDDUS)1 from 2023 notes that it is unaware of any prosecutions of doctors in the context of assisted dying. It highlights two cases involving doctors in England who took an active role in supporting suicides which led to investigation but not prosecution. However, it emphasises that any doctor taking direct steps to end the life of a patient would likely face prosecution for murder.

Healthcare professionals can make treatment decisions which end life

Nevertheless, it is within the law – and common in practice – for doctors to make treatment decisions which end life. Doctors are able to decide to withdraw treatment which is futile, such as artificial nutrition or hydration, or support for breathing. In contexts where the wishes of the patient are unclear, they will usually seek court guidance on the appropriate approach.

Doctors can also authorise treatment which may limit life, such as pain relief.

The contexts in which these medical decisions are made is discussed in more detail in the section dealing with End of life decisions in Scotland.

Healthcare professionals also need to consider the standards expected of their professional regulatory bodies

For example, the General Medical Council (GMC) is the professional regulatory body for doctors. It sets professional standards for doctors. Where doctors fail to adhere to those professional standards they can, if conduct is serious enough, lose their right to practise.

The GMC provides guidance covering "When a patient seeks advice or information about assistance to die"2 (2015). Broadly, this notes that doctors can discuss treatment options with a patient and address concerns they may have about their condition. However, requests from a patient for information about assisting them to end their lives should be met with an explanation that this is against the law.

The GMC also provides "Guidance for the Investigation Committee and case examiner when considering allegations about a doctor’s involvement in encouraging or assisting suicide"3. This looks at its role in protecting the public and public confidence in the medical profession. It discusses some factors to be considered in whether to investigate a doctor’s fitness to practice.

Assisted Dying and Human Rights Considerations

There have been several cases in England – and one in Scotland – which have challenged the law on assisted dying on human rights grounds. The courts have found that Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) includes a right to decide how to die. However, states have wide discretion in deciding how that right is exercised.

This part of the briefing looks at:

Rights under the European Convention on Human Rights and assisted dying

The ECHR includes a right to life (Article 2) and a right to respect for private and family life (Article 8). Public bodies (such as the Scottish and UK Governments, NHS bodies and the police) are legally required to respect the rights contained in the ECHR.

The Human Rights Act 1998 incorporated the ECHR into the law of the UK. This means that people can bring cases alleging that public bodies have breached their human rights in the UK courts.

Article 2 – right to life

Article 2 requires states to protect life, with exceptions for self-defence and in performance of duty. The European Court of Human Rights (in a UK case – Pretty v UK (2002)) held that the right to life did not encompass a right to decide when and how to die.

Article 8 – right to a private and family life

Article 8 creates a right to make decisions about your private life free from government interference. There are exceptions for things like protecting public safety, health and morals.

The European Court of Human Rights has found that Article 8 does cover the right to decide when and how to die. However, it has held that states have significant discretion in how this right is controlled – referred to as a wide “margin of appreciation”. This concept recognises that individual states are better placed than an international court to reach decisions about how rights should be balanced in the context of their society.

Restricting human rights

Most of the rights contained in the ECHR are not absolute rights. Instead, they can be restricted on various grounds, usually reflecting factors such as national security, public safety, health and morals, and protecting the rights of others. However, restrictions must be proportionate.

The European Court of Human Rights has set out a three-stage process for judging whether restrictions on Convention rights are proportionate. To meet the requirements of the ECHR, restrictions must:

be prescribed in law - the law should be accessible. It should also be clear enough that it is possible for a citizen to foresee - with the help of appropriate advice if necessary - how it would apply to them

pursue a legitimate aim - the legitimate aim must be one of the justifications detailed in the ECHR - such as the protection of health or the rights of others

be necessary in a democratic society - the European Court of Human Rights has developed several tests relating to this. However, broadly, restrictions must be proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued.

How the UK courts and the European Court of Human Rights have approached Article 8 and assisted suicide

There have been a number of cases in which the positions of UK and Scottish Governments – and their prosecution agencies – have been challenged on human rights grounds. The main cases are summarised below.

R (Purdy) v Director of Public Prosecutions ([2009] UKHL 45)

Ms Purdy had Multiple Sclerosis and wanted to know that her husband would not be prosecuted if he helped her travel abroad to end her life. The UK House of Lords found that her Article 8 rights were being restricted by the criminalisation of assisting a suicide. The current law was not clear enough to meet the requirement that such a restriction must be prescribed by law.

The House of Lords required the Director of Public Prosecutions to publish a policy outlining what additional factors (beyond those already set out in the Code for Crown Prosecutors1) would be taken into consideration in deciding whether a prosecution was in the public interest.

R (Nicklinson and another) v Ministry of Justice ([2014] UKSC 38)

Mr Nicklinson was paralysed after a severe stroke. He wanted to end his life but needed assistance to do so. He argued that it should either be legal for a doctor to assist him or the law in England was incompatible with his rights under Article 8 of the ECHR. He was joined in the court action by Mr Lamb, who had been paralysed in a car crash.

The judges in the UK Supreme Court were split on how to approach this issue. However, the overall result was a refusal to declare the law in England incompatible with Article 8 of the ECHR at that time.

A majority of judges considered that the UK courts did have the power to issue a declaration of incompatibility. Of those, three thought that the UK Parliament should be given the opportunity to clarify the law first, while two would have made such a declaration straight away. The four remaining judges thought that the issue was for the UK Parliament rather than the courts to decide.

The case was taken to the European Court of Human Rights. That court agreed that, in the constitutional arrangements in the UK, it was open to the Supreme Court to defer to the UK Parliament on this issue.

R (AM) v Director of Public Prosecutions ([2014] UKSC 38)

The case of Mr Martin was considered by the UK Supreme Court at the same time as the Nicklinson and Lamb case. Mr Martin was reliant on a professional carer and would need their assistance to end his life. He asked the court to require the Director of Public Prosecutions to clarify that professional carers would not be prosecuted for assisting a suicide in these circumstances.

The court declined to order the Director of Public Prosecutions to alter the policy. However, during the course of the case, representatives of the Director of Public Prosecutions had agreed that a professional carer would be unlikely to be prosecuted if they were acting in a way which would not result in prosecution for a family member.

History of Assisted Dying Legislation in Scotland

The Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults (Scotland) Bill is the fourth attempt to legislate for assisted dying in Scotland and the third Bill to be introducedi. The table below details the key characteristics of each of the Bills to show how the provisions have evolved.

| End of Life Assistance (Scotland) Bill1 (introduced 2010) | Assisted Suicide (Scotland) Bill2 (introduced 2013) | Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults (Scotland) Bill | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility - age | 16 years + | 16 years + | 16 years + |

| Eligibility - qualifying conditions | Must fall into one of the following categories:a) the person has been diagnosed as terminally ill (death is foreseen in the next 6 months) and finds life intolerable;orb) the person is permanently physically incapacitated to such an extent as not to be able to live independently and finds life intolerable. | Must fall into one of the following categories:a) have an illness or terminal condition that is life shorteningorb) has a condition that is, for the person, progressive and either terminal or lifeshortening.In either case, the person must see no prospect of improvement in the quality of their life and have concluded that the quality is unacceptable. | Available only to someone with an advanced and progressive disease, illness or condition from which they are unable to recover and that can reasonably be expected to cause their premature death. |

| Eligibility - residency | Must be registered with a medical practice in Scotland for a continuous period of at least 18 months. | Must be registered with a Scottish medical practice. | Need to have been resident in Scotland for at least 12 months and be registered with a GP practice. |

| Involvement of health professionals | Doctors responsible for the assessment process and also required a psychiatric assessment. | Doctors responsible for the assessment process. | Doctors responsible for the assessment process and prescribing. Other health professionals such as nurses may be involved in the provision of assistance and pharmacists for dispensing the required substance. |

| Conscientious objection clause | No | No | Yes |

| Process | Required two formal requests and a written agreement on the provision of assistance. Needed the approval of one medical practitioner. | Required a preliminary declaration to be made before a formal request could be made. Needed the approval of two medical practitioners at the formal request stage. | Requires two declarations and the approval of two registered medical practitioners. Referral to a specialist may also occur. |

| Psychiatric assessment | Required a psychiatrist to meet with the person at both the first and second request and report back to the medical practitioner that the person had capacity, was acting voluntarily and was not under undue influence. | No requirement for Psychiatrist involvement. Capacity to be confirmed by the two medical practitioners at each request. | Capacity to be confirmed by the assessing registered medical practitioners, with option to refer to a specialist if considered necessary. |

| Time between approval and provision of assistance | Once approval had been given, the person would have had 28 days to make use of the assistance given. | Once approval has been granted, the person would have 14 days to make use of the assistance given. | Once approval has been granted, there is no time limit on when the person can be provided with assistance.A shorter period could be granted in cases where death is expected in less than 14 days but it should be no less than 48 hours |

| Provision of assistance | Did not specify what constituted assistance. This was to be decided between the person requesting an assisted death and the doctor. | The Bill specified that nobody can perform any action which in itself would bring about another person’s death. The Bill specifically stated that the cause of the individual’s death must be as a result of the person’s own deliberate act. | Describes assistance as; providing the substance to end the person's life, staying with the adult until they have decided they wish to use the substance or, removing the substance if they decide they do not wish to use it. |

| Means for ending life | Did not specify the means other than to say it “must be humane and minimise the distress to the person receiving end of life assistance". | Did not specify the means on the face of the Bill, but the policy memorandum envisaged that a person's GP would prescribe a drug such as barbiturates. | An approved substance to be set out in regulations. |

| Criminal offence(s) created by the Bill | No | No | Yes - would create a new offence for coercing or pressuring someone into an assisted death. |

There are several areas of commonality between the Bills, for example, the role of doctors in the assessment process and limiting eligibility to those aged 16+.

However, key areas of evolution include:

the narrowing of eligibility to terminal illness,

shortening the period of reflection to 14 days,

removing the requirement for assistance to be given within a specific timescale,

the inclusion of a conscientious objection clause for health professionals,

specifying the means of death,

the creation of an offence to coerce or pressure someone into an assisted death.

Assisted Dying in the Rest of the UK and Crown Dependencies

Assisted dying is currently being debated in other parts of the UK.

England and Wales

Lord Falconer of Thoroton introduced the Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults Bill to the House of Lords on 26 July 2024.

The key provisions of Lord Falconer's bill include:

it would apply to terminally ill adults with less than six months to live,

the minimum age would be age 18,

it would require the approval of two independent doctors to confirm the diagnosis and ensure the person was making an informed, voluntary decision,

It would require an application to the family division of the High Court,

It allows the provision of assistance to help the person ingest the medicine.

In addition, Kim Leadbetter MP introduced the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill on 16 October 2024.

The full text of the bill has not yet been published, but its long title states it will “allow adults who are terminally ill, subject to safeguards and protections, to request and be provided with assistance to end their own life”

Isle of Man

Dr Alex Allinson introduced a private member’s Bill on assisted dying to the Parliament of the Isle of Man in 2023. The Bill was passed by the House of Keys and has now progressed to the Legislative Council.

The main provisions of the Bill include:

it would apply to terminally ill adults with less than 12 months to live,

the minimum age would be 18,

it would only be available to those who have lived on the Isle of Man for 5 years,

the medicine would have to be self-administered.

Jersey

Jersey has approved the principle of legalising assisted dying and on 21 May 2024, the States Assembly approved proposals on processes and safeguards. The Assembly subsequently requested the Minister for Health and Social Services to bring forward primary legislation to permit assisted dying in Jersey for those with a terminal illness.

Assisted Dying Internationally

The following countries and jurisdictions are known to have legalised a form of assisted dying:

Nine American States - Oregon, California, Hawaii, Washington, Colorado, Vermont, New Jersey, New Mexico, Maine;

The US district of Washington DC;

All six Australian States (Victoria, Tasmania, Queensland, New South Wales, South Australia, Western Australia) and the Australian Capital Territory;

New Zealand;

Canada;

Colombia;

Belgium;

The Netherlands;

Luxembourg;

Switzerlandi;

Spain;

Portugal.

There are also several other jurisdictions where assisted dying is partially available due to court rulings. These include:

Montana, USA;

Italy;

Germany;

Columbia.

Several other jurisdictions are currently considering changes to the law on assisted dying:

France;

New York;

Massachusets;

Minnesota;

Maryland;

Virginia;

Austria;

Ireland;

Isle of Man;

Jersey.

.png)

The Scottish Parliamen'ts Health, Social Care and Sport Committee is planning to take evidence during stage 1 from Oregon, Canada and Australia. More detail on these jurisdictions is outlined in the following sections.

Australia

Background to Assisted Dying

Australia has six states and two territories. Assisted dying is currently legal in all six Australian States and the Australian Capital Territory.

The Northern Territory is the only part of Australia which does not have an assisted dying law in place, although, in 1995, it was the first jurisdiction in the world to pass such a law before it was overruled by the Federal Government the following year.

The federal ban preventing the Northern Territory from legislating in this area was removed in 2022 and an independent panel report has recently recommended the Territory aligns its law with the rest of Australia.

Victoria subsequently became the next part of Australia to introduce legislation, and the Australian Capital Territory is the most recent to pass a law on assisted dying.

The model of assisted dying is similar across Australia in that the person must:

be terminally ill, suffering unbearably and approaching the end of their life,

be aged 18+,

meet residency requirements such as being resident in that area for at least 12 months and have evidence of Australian Citizenship/permanent residency status,

be assessed by at least two health professionals,

make at least three separate requests for assisted dying, including one written request,

have capacity throughout the process,

be referred to a specialist if their capacity is in doubt,

be acting voluntarily and free from coercion.

Each area with assisted dying legislation allows for both self-administration and physician administration of the drug if the person is physically incapable. Assisted dying is prohibited on the grounds of mental illness or disability alone.

Other key features include:

mandatory training for healthcare practitioners involved in assisted dying,

offences for wrongdoing,

conscientious objection for health professionals and protection for health professionals acting in good faith,

independent oversight bodies,

statutory reviews of the law.

Data and Monitoring

The following table shows data describing the key characteristics of assisted dying in Australia and the people who have used it.1

| Victoria | Western Australia | Tasmania | South Australia | Queensland | New South Wales | Australian Capital Territory | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Came into effect | 2019 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2023 | 2023 | 2024 |

| Legislation | Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2017 | Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2019 | End-of-Life Choices (Voluntary Assisted Dying) Act 2021 | Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2021 | Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2021 | Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2022 | Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2024 |

| % of all deaths in the population | 0.65% | 1.4% | 0.5%i | 1.0% | 1.6%ii | 0.8%iii | Not available yet |

| Median Age | 74 | 74 | 72 | 73 | 73 | 70-79 | Not available yet |

| Gender % (Male) | 54 | 58.4iv | 59 | 54 | 56 | 56.9 | Not available yet |

| Cancer as primary diagnosis | 76 | 70.7%iv | 66 | 75vi | 77 | 71.1 | Not available yet |

| Also receiving palliative care | 81 | 85.7iv | ~71 | 82viii | 77.5ix | Not published yet | Not available yet |

| Self Administration % | 85 | 19.7 | Not published | 86 | 33.5 | 29.7 | Not available yet |

| Physician Administration % | 15 | 80.3 | Not published | 14 | 66.5 | 70.3 | Not available yet |

| Number of Assisted Dying Practitioners | 347 | 97 | 67 | 74 | 378 | 250 | Not available yet |

The table shows that most people seeking assisted dying in Australia are; in their 70s, have been diagnosed with cancer and are in receipt of palliative care.

There is more variation between the states when it comes to whether someone self-administers the drug, or if the physician administers it. For example, the majority of assisted deaths in Western Australia, Queensland and New South Wales are physician administered, whereas self-administration is the most common method in Victoria and South Australia,

The proportion of deaths accounted for by assisted dying ranges between 0.5% and 1.6%.

Canada

Background to Assisted Dying

In February 2015, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in Carter v. Canada that parts of the Criminal Code would need to change to satisfy the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

This meant that the parts of the code that prohibited medical assistance in dying would no longer be valid and the Supreme Court gave the Federal Government until 6 June 2016, to create a new law.

The Canadian Parliament subsequently passed federal legislation that allowed eligible adults to request medical assistance in dying (MAID).

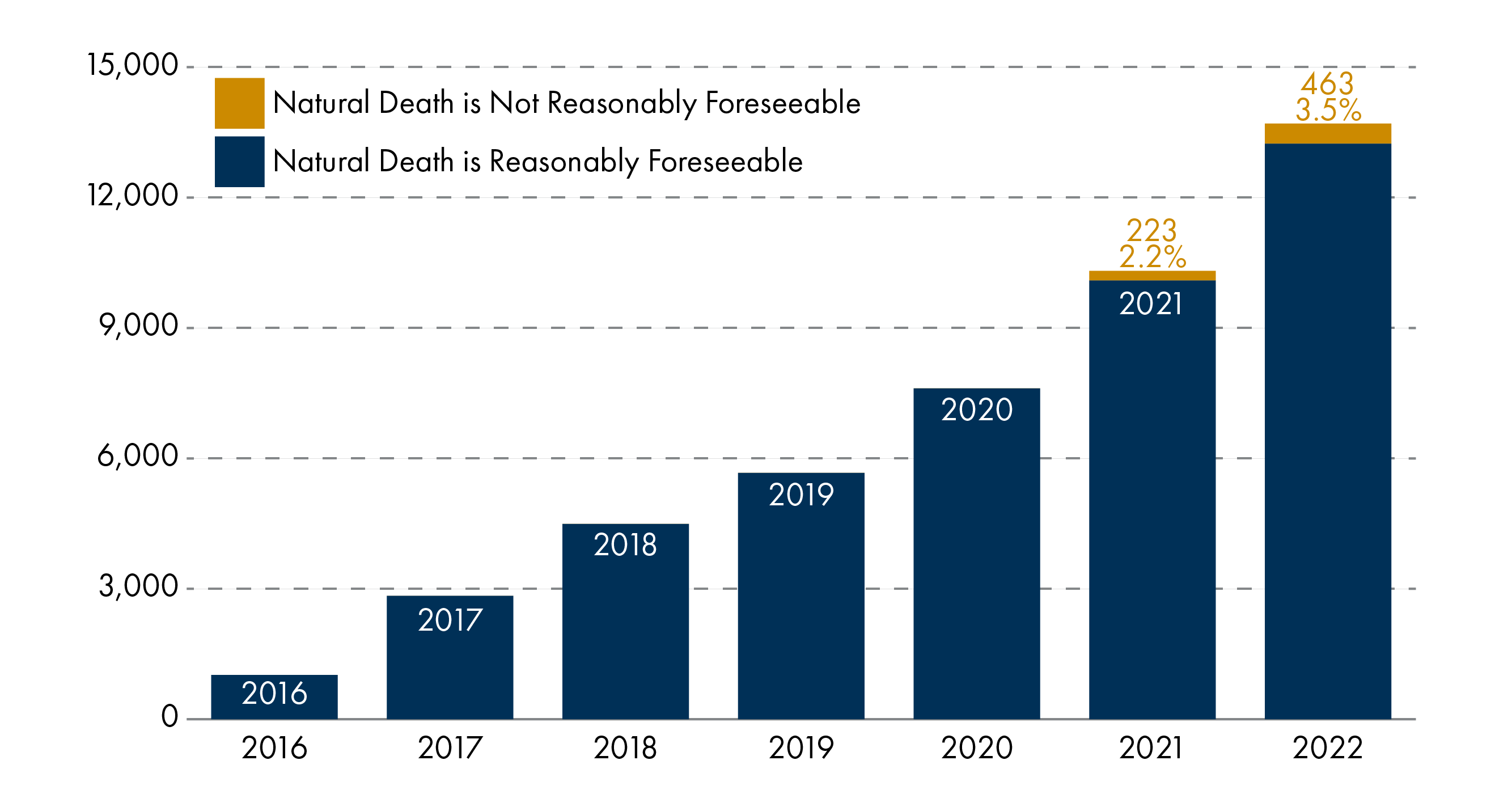

Since then, the law on MAID has continued to evolve in response to court rulings and public consultation. Notably, the Superior Court of Quebec found the criterion of the 'reasonable foreseeability of natural death' to be unconstitutional.

This led to a Bill in 2021 to amend the criminal code further to remove the requirement that a natural death must be foreseeable.

To be eligible for MAID now, a person must:

have a grievous and irremediable medical condition, and meet all of the following criteria;

have a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability,

be in an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability, and

experiencing enduring physical or psychological suffering that is caused by their illness, disease or disability or by the advanced state of decline in capability, that is intolerable to them and that cannot be relieved under conditions that they consider acceptable.

be eligible for publicly funded health services,

be at least 18 years old,

have capacity,

make one request in writing and signed by two independent witnesses,

be assessed as eligible by two independent doctors/nurse practitioners,

make the decision free from pressure or coercion,

give informed consent,

wait 90 days between starting the assessment and receiving MAID if the death is not reasonably foreseeable,

there is no minimum waiting period for those whose death is reasonably foreseeable.

Any residency requirements are set by each of the provinces and territories but, generally, visitors to Canada are not eligible for MAID.

Self-administration is available in all jurisdictions except Quebec, and clinician administration is permissible in all jurisdictions.

Canada is also relativelyunusual in that, with the exception of British Columbia, there is no prohibition on healthcare professionals initiating a discussion about MAID. However, they must not discuss MAID with the aim of inducing, persuading, or convincing the patient to request MAID.1

Following another Supreme Court ruling , there were plans to further extend the eligibility criteria to those with a mental illness as the sole underlying medical condition. However, the Federal Government legislated to delay the implementation of this change until March 2024, and then until 2027.

In February 2024, a press release from Health Canada explained:

[ … ] in its consultations with the provinces, territories, medical professionals, people with lived experience and other stakeholders, the Government of Canada has heard–and agrees–that the health system is not yet ready for this expansion.

Data and Monitoring

Annual monitoring reports are produced by Health Canada and these show the growth of assisted deaths since introduction. The latest report indicates an average annual growth rate of 31.1% between 2019 and 2022.

Fourth Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada 2022

The fourth report also details that in 2022:

slightly more males (51.4%) than females (48.6%) received MAID,

the average age of MAID recipients was 77,

77.6% of recipients had received palliative care,

all but 7 assisted deaths across Canada were clinician-administered,

MAID deaths accounted for 4.1% of all deaths in Canada, an increase from 2% in 2019, 2.5% in 2020 and 3.3% in 2021,

63% of people receiving MAID hadi cancer, 18.8% had cardiovascular conditions, 14.9% had 'other conditions', 13.2% had respiratory conditions, 12.6% had neurological conditions, 10.1% had multiple co-morbidities and 8.2% had organ failure,

of those with neurological conditions, the most common were Parkinson's disease (20.7%), amyotrophic lateral sclerosisii (18.5%), multiple sclerosis (11.3%), dementia (9.0%), spinal stenosis (8.1%) and supranuclear palsy (4.3%),

of those with 'other conditions', these included 'frailty' (25%), diabetes (11.9%), chronic pain (8%) and autoimmune conditions (5%),

of those whose death was not reasonably foreseeable, the most common underlying condition was a neurological disorder (50%).

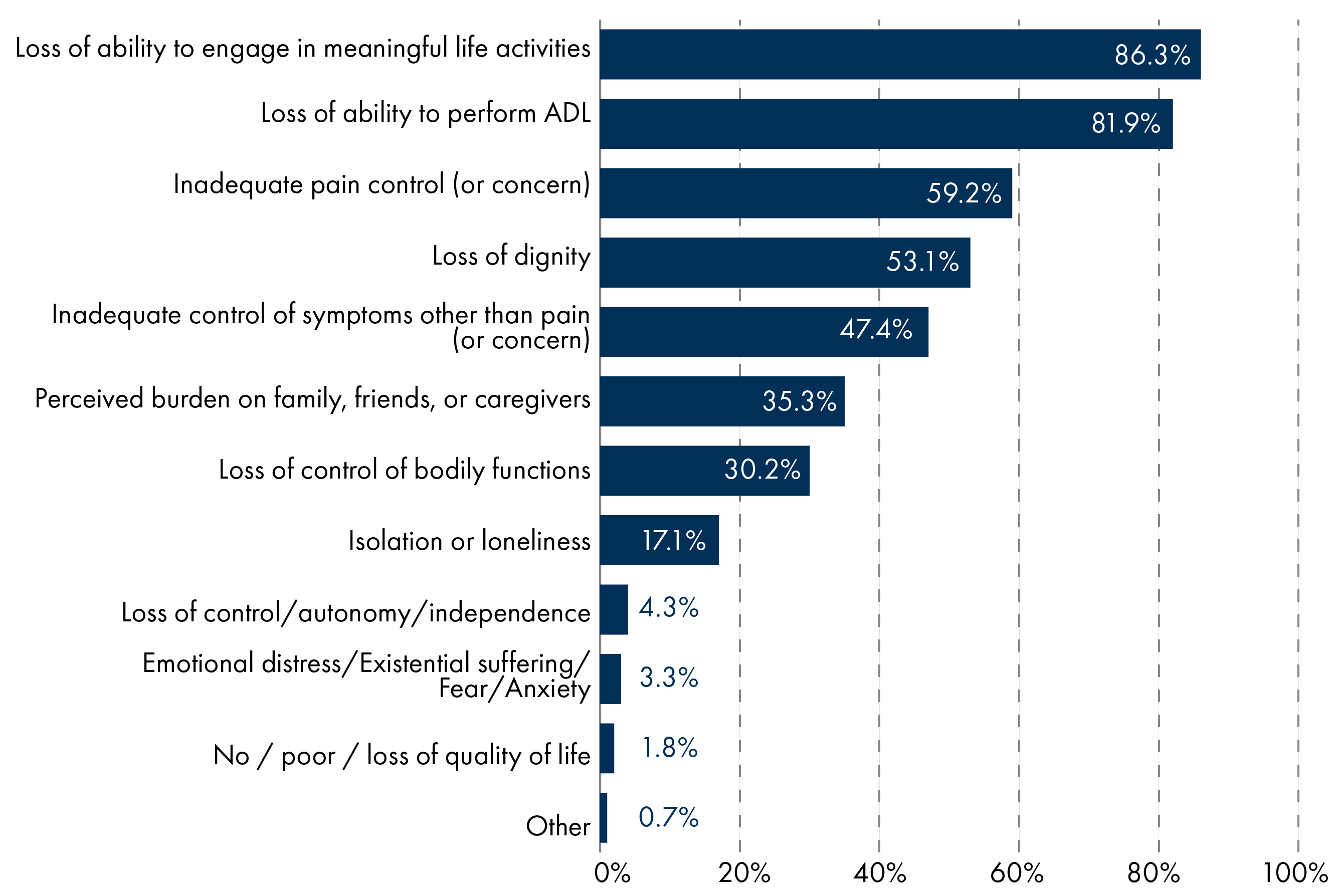

In order to be eligible for MAID, an individual must experience intolerable physical or psychological suffering that is caused by their condition and that cannot be relieved. The nature of a person's suffering is also recorded and categorised.

The two most common types of suffering were 'loss of ability to engage in meaningful life activities' (86.3%) and 'loss of ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL)' (81.9%).

Oregon

Background to Assisted Dying

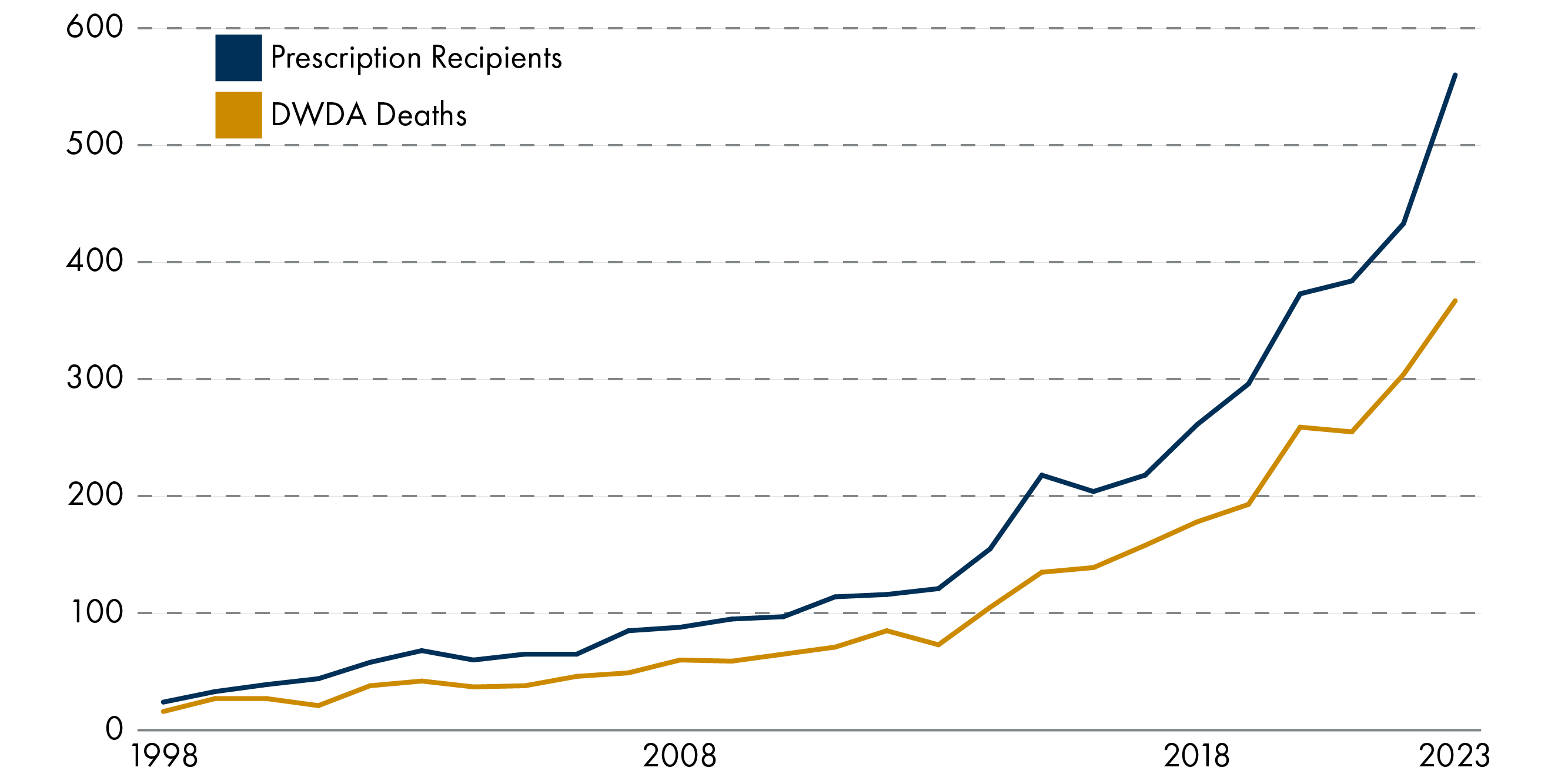

Oregon was the first US state to introduce legislation on assisted dying, passing the Death with Dignity Act 1994 (DWDA). The Act came into force in 1997 and Oregon now has the longest-standing assisted dying statute globally.

To be eligible for assisted dying in Oregon, a person must:

be diagnosed with a terminal illness that will lead to death within six months,

be at least 18 years old,

be capable of making and communicating health care decisions to healthcare practitioners,

make two verbal requests separated by 15 days, as well as a written request singed in the presence of two witnesses.

The drugs to bring about death must be self-administered.

The eligibility criteria in Oregon have remained largely unchanged with the exception of the removal of the residency requirements in 2022. These were repealed after a challenge to the law and Oregon can now provide assisted dying to people from outwith the state and the country.

In addition, since 2019, there can now be exceptions to the 15 day waiting period if the person has less than 15 days to live.

Data and Monitoring

The Act requires the Oregon Health Authority to collect information on the functioning of the Act and produce an annual report.

The most recent report shows there has been a steady increase in the number of assisted deaths taking place in Oregon since the legislation came into effect. It also shows that the number of prescriptions obtained is greater than the number of deaths, and this gap is increasing. The law in Oregon allows people to obtain a prescription and use it when they want.

Since 1997, 4,274 people have obtained prescriptions under the Act and, of these, 2,847 (67%) have died from ingesting the medication.

The report also details that assisted deaths account for 0.8% of annual deaths in Oregon. The characteristics of those receiving an assisted death included:

a median age of 75,

56% male and 44% female,

the most common underlying illnesses were cancer (60%), neurological disease (11%) and heart disease (10%),

87% were receiving palliative care, and

the most common concerns influencing the request for assisted dying were; loss of autonomy (92%), decreasing ability to participate in activities that make life enjoyable (88%), and loss of dignity (64%).

End of Life Decisions in Scotland

There are around 63,000 deaths per year in Scotland and the most common causes of death in 2022 were:

Ischaemic heart disease (11.3%)

Lung cancer (6.2%)

Cerebrovascular disease (6.1%)

Dementia (5.8%)

Chronic lower respiratory disease (5%)

Alzheimer's disease (4.2%)

COVID-19 (3.7%)

Other heart diseases (3.4%)

Accidents (2.5%)

Blood cancer (1.9%)

Palliative and End-of-life Care

The Scottish Government describes palliative care as follows:

Palliative care prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification of people who need this care, individualised assessment and management of pain and other symptoms, along with mental health, social, family, or spiritual problems.1

An estimated 56,416 people died with a palliative care need in Scotland in 2021. This accounted for 89% of all deaths.2

The Scottish Government's palliative care strategy estimates that, by 2040, the number of people dying with palliative care needs will rise to an estimated 63,353. This is 90% of forecasted deaths and a 12% increase from 2021.

There are currently no routine measures of unmet need for palliative care in Scotland but previous audits have found specialist palliative care was not available to everyone who needed it3and Marie Curie found that 1 in 4 people with a palliative care need do not receive it.4

A mapping exercise by the Scottish Government showed that palliative care service provision is variable across the country.5

Analysis by the Scottish Government also shows high levels of unscheduled, emergency care for people in the last months of their life.6

For 2022/23, during the last six months of life:

7,359 patients (12%) had 3 or more emergency admissions recorded

59,112 emergency department attendances (1.0 per death) were recorded

69,867 emergency admissions (1.1 per death) compared to 4,743 elective admissions (0.1 per death) were recorded.

Emergency admissions represented 94% of total admissions.

Patients with metastatic cancer had the highest rate of emergency admissions (1.74 per death) followed by those with liver conditions (1.53 per death), heart failure (1.40), lung disease (1.40), and other cancers (1.40). People dying with dementia had the lowest rate of emergency admissions per death (0.80).

Doctrine of double effect

Claims are sometimes made that clinicians in the UK already participate in assisted dying through certain end-of-life practices.

Commonly they are referring to the administration of high doses of painkillers or continuous deep sedation (CDS). CDS is a practice sometimes used in palliative and end-of-life care (PEOLC) which involves the continuous use of sedation to relieve severe, intractable symptoms.

While the intention of these practices is not to hasten death, it is recognised that they may have such an effect. This is referred to as the 'doctrine of double-effect'i.

There are some older surveys of the prevalence of CDS, which found 19% of UK physicians attending a dying patient reported the use of CDS (Seale et al, 2010). A later survey put this figure at 17% of deaths(Anquinet et al, 2012).

Refusal and Withdrawal of Treatment

The common law in the UK supports the right of mentally competent patients to refuse treatment, even if the treatment is needed to prevent harm or sustain life.

There can be various reasons behind a person's decision to refuse treatment,including the desire not to prolong suffering. Such decisions may also hasten death.

These decisions can take several forms but include; 'Do Not Resuscitate' (DNR) orders, Advance Directives, the refusal of treatments aimed at prolonging life, and the refusal of artificial hydration and nutrition.

Doctors can also lawfully withhold or withdraw treatment from a patient who lacks capacity if they deem it is not in their best interests. There is also no obligation to give treatment which is considered futile or burdensome7.

There are no clear estimates of how common such decisions and practices are in Scotland.

Assisted death overseas

It is not known how many people from the UK or Scotland access assisted dying in other countries. Countries where assisted dying can be accessed by people from the UK include:

Switzerland

Belgium, and

The Netherlands.

Statistics on country of residence are not available in Belgium and the Netherlands but, in 2023, Dignitas (Switzerland) reported it had 1900 members from Great Britain and it facilitated 40 deaths in British people.

The statistics also show a total of 571 people from Britain have accessed an assisted death at Dignitas between 1998 and 2023. This is 14.6% of all deaths that have occurred within Dignitas during that time.

In response to the Member’s consultation on the draft Bill, Dignitas reported 16 people from Scotland had travelled to Switzerland to end their life in the past 23 years.

Suicide

One of the claims often made during the debate on assisted dying is that, without a lawful alternative, people may choose to die by suicide.

The official statistics on deaths by suicide do not detail the reasons why someone took their own life. However, research by the Office for National Statistics found that a diagnosis or first treatment for certain conditions was associated with an elevated rate of death due to suicide8.

The report looked at death from suicide in England and Wales between 2017 and 2020, and found:

One year after diagnosis for low survival cancers, the suicide rate for patients (22.2 deaths per 100,000 people) was 2.4 times higher than the suicide rate for the matched controls (9.1 deaths per 100,000 people).

One year after diagnosis for [Continuous Obstructive Pulmonary Disease], the suicide rate for patients (23.6 deaths per 100,000 people) was 2.4 times higher than the suicide rate for the matched controls (9.7 deaths per 100,000 people).

One year after diagnosis for chronic ischaemic heart conditions, the suicide rate for patients (16.4 deaths per 100,000 people) was nearly two times higher than the suicide rate for the matched controls (8.5 deaths per 100,000 people).

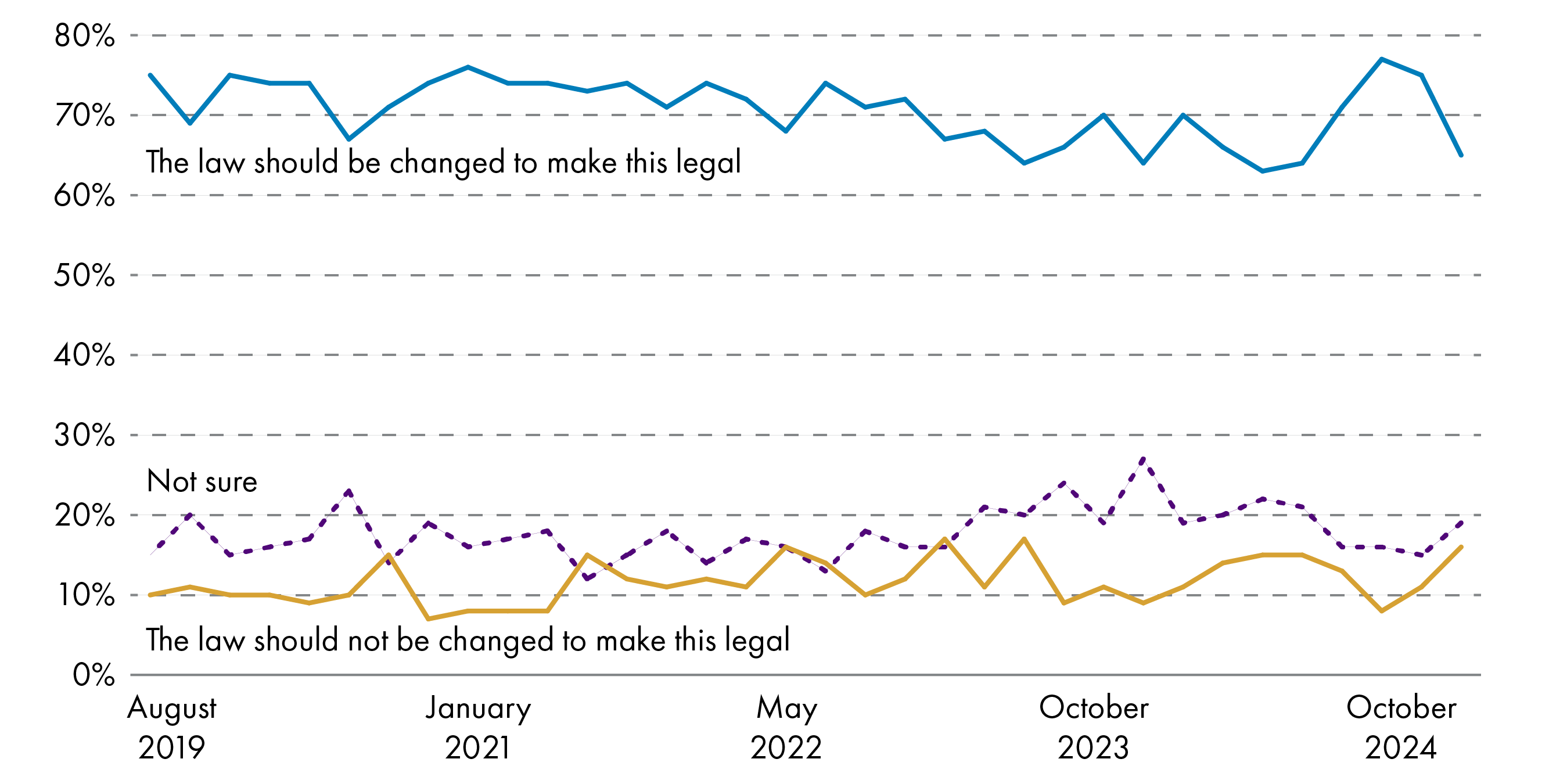

Public Opinion

General Public

The conclusions of opinion polls and surveys on public attitudes to assisted dying often differ depending on the detail of the questions asked, for example:

the nature of the person's illness,

the type of assistance provided, and

who is involved in the process.

Polls generally show that the majority of Scottish and British people are supportive of changing the law to allow someone to assist in the suicide of someone who is terminally ill, for example:

However, this support tends to drop when the question asks about a change in the law to allow assisting someone who is suffering from an incurable condition but not a terminal illness:

In evidence to the House of Commons inquiry into assisted dying, NatCen summarised its findings over the years from the British Social Attitudes Survey in relation to voluntary euthanasiai:

| % saying the law definitely/probably should allow | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 2005 | 2016 | |

| … voluntary euthanasia by a doctor for a person with an incurable and painful disease from which they will die | 80% | 82% | 78% |

| … voluntary euthanasia by a relative for a person with an incurable and painful disease from which they will die | 31% | 45% | 39% |

| … voluntary euthanasia by a doctor for a person with an incurable and painful disease from which they will not die* | 41% | 46% | 51% |

| … voluntary euthanasia by a doctor for a person who is completely dependent on relatives for all their needs | 51% | 44% | 50% |

*In 1995, this question referred specifically to arthritis, so any change over time should be viewed with caution

The results show levels of support for different scenarios have remained largely stable and;

there has been consistently high support for voluntary euthanasia in terminally ill people with the assistance of a doctor, and

support was consistently lower for voluntary euthanasia in people with non-terminal illnesses and for allowing relatives to assist.

NatCen also details that it found little difference in opinion between social groups, with the exception of religious affiliation. This is borne out in the submissions to the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee's call for views, where 28 of the 36 responses from religious or faith organisations were strongly or partially opposed to the Bill.

NatCen also noted there were some differences between age groups, with older age groups (75+) more likely to express caution in their attitudes to assisted dying and middle-aged people (45-64) most likely to be supportive.

Citizens' Jury

On 13 September 2024, the Nuffield Council on Bioethics published an interim report on the voting of a Citizens' Jury on assisted dying in England.1

The jury consisted of 28 members of the public who were chosen as a representative sample of the English population. During an 8-week process of deliberation, they heard from a wide range of experts and considered a range of evidence to obtain a balance of perspectives.

At the end, 20 jury members either strongly agreed or tended to agree that the law should change to permit assisted dying in England. Seven jury members said they either strongly disagreed or tended to disagree with a law change. One person was undecided.

The jury also came up with recommendations for what a change in the law should look like. These recommendations were:

people accessing assistance to die should have a terminal condition,

people must have the capacity to make their own decision,

both physician assisted suicide (where healthcare professionals would prescribe lethal drugs to eligible patients to take themselves) and voluntary euthanasia (where a healthcare professional would administer lethal drugs to patients with the intention of ending their life) should be permitted.

Medical Profession

While public opinion polls tend to show greater support for methods of assisted dying that involve doctors, opinion within the medical profession is far from consensual.

Almost all medical organisations in the UK have adopted a neutral stance on assisted dying and often this is driven by a recognition that there is a range of opinions within their membership.

In 2020, the British Medical Association (BMA) conducted a survey of its members on physician assisted dying2. This found:

In relation to prescribing drugs for self-administration:

50% of members personally supported it, 33% opposed it and 11% were undecided,

45% of members would not be willing to participate, 36% would be willing to participate and 19% were undecided.

In relation to administering drugs with the intention of ending a person's life:

46% of members personally opposed it, 37% supported it and 17% were undecided,

54% of members would not be willing to participate, 26% would be willing to participate and 20% were undecided.

There were also noticeable differences in opinion between specialities, with doctors in palliative medicine, clinical oncology and geriatric medicine least likely to support a change in the law.

The specialities most supportive of a change in the law were anaesthetics, emergency medicine and intensive care medicine.

Consultation on the Current Bill

The following sections provide further detail of the consultations carried out on the draft proposal for a Bill, and the Bill as introduced.

Member's Consultation

Liam McArthur MSP, undertook a consultation on a draft proposal for a Bill on assisted dying for terminally ill adults between 23 September 2021 and 22 December 2021.

A total of 14,038 responses were received. Of these, 81 were from organisations and 13,957 were from individuals, including academics, professionals and members of the public.

A summary of consultation responses is available on the Scottish Parliament website.

The policy memorandum accompanying the Bill outlines key findings from the consultation:

Views on the proposal to introduce assisted dying for terminally ill competent adults in Scotland were broadly polarised, with strong views expressed both in support and opposition. Only 3% of respondents expressed a view other than full support or full opposition. Among those that did were some representative organisations which did not give a view as opinions amongst the relevant memberships were mixed. Views on the details of the proposal, and how assisted dying should be implemented in Scotland, were more nuanced, with a wide range of issues, questions, and concerns raised by respondents on both sides of the debate.

The consultation report writes that a clear majority of responses were fully supportive of the proposed Bill (76%) and a further 2% were partially supportive. 21% of respondents were fully opposed and 0.4% were partially opposed.

Please note that respondents were self-selecting and so the balance of opinion cannot be taken as representative of the general population.

Of those in support of the draft Bill proposal, the most common reasons given were:

The avoidance of a 'bad death', pain and suffering

It is more humane

People should have the autonomy to end their lives in a safe and regulated way

The proposed bill is an improvement on previous attempts to legislate, for example, it has improved safeguards and a conscientious objection clause for health professionals.

Of those opposed to the draft Bill proposal, the most common reasons given were:

A fundamental belief in the sanctity of life and that it should not be purposefully ended in any circumstances

No safeguards will ever be enough to prevent coercion or people feeling pressured to end their lives

Passing legislation would become a 'slippery slope' in that it would likely be amended in future to weaken safeguards and expand eligibility

It would increase the vulnerability and stigmatisation of certain groups in society, for example, the young, the old and those with a disability.

Other submissions expressed a desire for specific changes to the draft Bill, most commonly these were around the definition of terminal illness and the requirement that the substance must be self-administered.

Scottish Government's Position on the Bill

On 30 September 2024, the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care wrote to the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee outlining the Scottish Government's position on the Bill1.

In this letter, the Cabinet Secretary raised specific points in relation to the Bill including that:

the costs outlined in the Financial Memorandum may be an underestimate, and

the Bill in its current format is outwith the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament. (See the section on Legislative Competence for more discussion)

However, the letter also detailed that Scottish Ministers will have a free vote on the issue:

24. We recognise that there are strong feelings in this debate, and that a range of deeply felt views will be expressed as this Bill is being considered. Our hope is that this debate can be conducted with sensitivity and respect.

25. Whilst the Scottish Government will be maintaining a neutral position on the Bill at this Stage, we will be listening carefully to the evidence given to the Committee.

The letter goes on to say that, if the Bill passes stage 1, the steps required to bring the Bill within legislative competence will need to be revisited.

Health, Social Care and Sport Committee's Consultation

The Scottish Parliament's Health, Social Care and Sport Committee issued two calls for views which were open between Friday 7 June and Friday 16 August 2024:

A short survey for people who wished to express general views about the Bill as a whole.

A detailed call for evidence for people, groups, bodies or organisations who wished to comment on specific aspects of the Bill.

The Committee received 13,820 responses to the short survey and 7,236 responses to the detailed call for views. A summary of the results is available on the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee's website. Again, please note that respondents were self-selecting and so the results cannot be considered as representative of Scottish opinion.

In both calls, respondents were asked to highlight the top three factors which influenced their opinion on the Bill. A breakdown is shown in the figure below.

Additional comments from respondents were then analysed to determine key arguments in favour and opposition to the Bill. These are summarised below but are explored in greater detail in a separate analysis.

General Arguments on Assisted Dying

Dignity and Suffering

A substantial proportion of those supporting the Bill argued that many people at the end of their lives experience pain, suffering, a loss of dignity and a level of dependence that is unacceptable to them. These submissions were generally of the opinion that it is inhumane to force a person to suffer when their wish is to die. Many drew upon personal experiences of witnessing a loved one die.

Conversely, those in opposition to the Bill also spoke of dignity, insisting that this does not diminish because a person is ill or requires assistance from others. These responses were of the opinion that a person’s sense of dignity is shaped by societal attitudes and norms and therefore, they felt assisted dying would change these norms and reinforce any perceived loss of dignity.

Assisted dying was also viewed by some as society sending the message that certain individuals’ lives are less valuable than others and a burden on society. Such an idea was considered to be particularly threatening to people with disabilities and to older people.

Opponents to the Bill also contended that society should aim to ease people's suffering. Many submissions on both sides of the debate highlighted the importance of palliative care (see Sanctity of Life and Palliative Care).

Autonomy

The ‘right to autonomy’ was cited both by those supporting and opposing the Bill. Supporters argue that individuals have the right to determine the value and quality of their own lives and to make end of life decisions based on that judgement.