The effectiveness of creative enterprise policies: What programmes work?

This briefing documents and analyses the various interventions that are available to support creative enterprises and to understand what drives their economic, social, and cultural impact. The briefing sets out four types of programmes to support capability of creative practitioners, alongside four types of complimentary policies to support the capacity of the sector.

Executive Summary

Support for creative enterprises, typically small and medium sized enterprises operating in the creative industries, is often located at the intersection of economic and cultural policies. However, public support for the creative industries has leaned towards promoting economic value and has been criticised for failing to promote the range of enterprises that exist across the industry. As such, which policy interventions and programmes can help to co-create social, cultural, and economic value is not fully understood.

The aim of this report is to document and analyse the various interventions that are available to support creative enterprises and to understand what drives their economic, social, and cultural impact. To achieve this aim, a realist synthesis was conducted by integrating insights from 105 evaluation documents for 84 programmes that support creative enterprises.

The findings of this report highlight that:

Training and advice programmes report short-term increases in the ability of practitioners to develop new products and services, develop self-belief, and leadership skills. These benefits, however, take time to materialise into wider economic impacts. Return on investment for these programmes is generally negative in the short-term but rises over time. Key to realising these benefits are approaches tailored to creative practitioners, including having a practical hands-on learning environment, industry-specific advisors, peer collaboration, and access to additional support.

Many finance initiatives report short-term increases in capacity and ability of both practitioners and cultural intermediaries to deliver services. However, these benefits dissipate over the long-term. The provision of additional support (including access to training, networks, infrastructure, and events) is important to reduce the dissipation of short-term benefits and generate longer-term impact.

The analysis of physical infrastructure and place-based development programmes highlights that the curation of programmes of events, festivals, exhibitions, and attractions can provide a boost to local economies through visitor spend. The construction and operation of physical cultural spaces can create job opportunities in the sector and other short-term benefits. The development of regional networks can help to increase the capacity of local organisations to deliver these initiatives. Seemingly, having a mix of these different types of initiatives can assist with place-based economic, cultural, and social development.

Based on this analysis, this briefing sets out four types of complimentary programmes to support the individual capability of creative practitioners and four types of complimentary policies to support the institutional capacity of the sector. These types of programmes and policies are not prescriptive and should be considered as a sense checking exercise for decision-makers.

Furthermore, the briefing contains a broad outline for evaluating various creative enterprise policies which distinguishes between the context (building individual competence or institutional capacity), input mechanisms (i.e., what goes into a successful programme?), short-term programme outputs, and longer-term cultural, social, and economic outcomes. This distinction could be used by evaluators to meet the goals of short-term evaluations and the lag between the development of long-term programme impacts which funders need evidence for.

Introduction

Policy background

The creative and cultural industries have a significant place within Scotland's policy landscape. They contribute £5.5 billion to the economy each year1. Before the COVID-19 pandemic they were the second fastest growing sector in Scotland, with GVA increasing 11% from 2016 to 20191 . While it is important to recognise the economic impact of the creative and cultural industries, the social and cultural impact is also crucial. The sector makes invaluable contribution to health and wellbeing, education, entertainment, and promotes Scottish culture3.

As such, the Scottish Government makes a significant commitment to supporting the industry. The Government committed £64 million to support Creative Scotland's activities in the 2023-34 Budget4. Investment is also made through infrastructure and place-based projects, such as V&A Dundee and Edinburgh Festival, as well as training and network programmes aimed to support practitioners and an extensive network of third-sector partners. Supporting creative self-employed and business owners is a key feature in the Scottish Government's Culture Strategy 2020. They outline a need for Scottish Enterprise, Creative Scotland, and third-sector partners to work collaboratively to achieve maximum benefits5.

The Scottish Government's definition of the creative and cultural industries includes many different sectors – visual and performing arts, cultural education, crafts, textiles, fashion, photography, music, writing and publishing, advertising, libraries, archives, antiques, architecture, design, film and video, TV and radio, software and electronic publishing, and computer games6. Creative enterprises are small and medium sized enterprises operating in these sectors.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on these culture sectors has been well recognised alongside tourism, hospitality, and personal services. Creative Scotland and other public agencies are currently looking to meet the challenges of sector recovery from the effects of the pandemic, as well as the parallel cost-of-living crisis7. Key to meeting these challenges are effective support policies and programmes that not only incentivise business development but also encourage cultural and social impact.

Aims and objectives of this fellowship

The aims of this SPICe Academic Fellowship are to document and analyse the various interventions that are available to support creative enterprises and to understand what drives their economic, social, and cultural impact. The purpose is to create a bank of knowledge regarding the different types of interventions available, the scale and size of their impact, the contexts in which they operate, and how they are designed and delivered. The specific objectives of this project are:

To scope the UK landscape for creative enterprise policy and programme evaluations that are available.

To integrate this information and evaluate the impact of various programmes and initiatives regarding economic, social, and cultural value.

To detail the impact drivers that contribute to the relative success (or not) of these programmes, including details on design and delivery.

From this analysis, develop a creative enterprise toolkit as a resource for policy decision-makers, creative enterprise intermediaries, and wider stakeholders.

Research approach

To explore these aims and objectives a realist synthesis approach was used which allows a range of evidence on various policy programmes and initiatives to be collected, integrated, and evaluated. The objective is to increase the applicability of evaluation findings and develop new knowledge into what works by integrating information from multiple different programmes in comparable contexts. Its relevance and contribution to policy intervention and programmes is highlighted in the UK government's Magenta book1. The realist review methodology was conducted via a three-stage process presented in Table 1.

| Stage | Details |

|---|---|

| Stage 1: Data curation |

|

| Stage 2: Data coding and analysis |

|

| Stage 3: Data presentation |

|

Report structure

This report is structured as follows:

Section 2 provides a background to creative enterprise policy in Scotland

Section 3 presents an initial programme theory for synthesising policy and programme evaluations.

Section 4 details the results for training, advice, and networking programmes.

Section 5 details the results for grants, loans, and finance programmes.

Section 6 details the results for physical infrastructure and place-based development programmes.

Section 7 provides an outline for eight exemplary programmes and suggestions on how to evaluate creative enterprise policies going forward.

Section 8 concludes the briefing and provides recommendations.

About the author

Dr Knox is the Senior Lecturer in Entrepreneurship and Innovation and the University of Stirling.

Dr Knox has been working with the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) as part of its Academic Fellowship programme. This aims to build links between academic expertise and the work of the Scottish Parliament.

The views expressed in this briefing are the views of the author, not those of SPICe or the Scottish Parliament.

Glossary of terms

Creative practitioner: an individual or organisation which offers a creative or cultural product or service.

Cultural intermediary: an organisation which aims to support the creative industries, such as Creative Scotland.

Realist synthesis: this is a methodology for carrying out a literature review of how policy interventions function in a complex landscape. This involves identifying the underlying causes and exploring the conditions which contribute to how effective they are.

Background to creative enterprise policy in Scotland

A brief history of cultural and creative industry policy

Since devolution creative industries policy has gone through three major periods of development. This development has been influenced by both UK and global contexts as well as the Scottish specific policy landscape. An overview is presented in Table 2 with each stage summarised below.

| Key periods | Scotland | UK | Global |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 - 2007 |

|

|

|

| 2008 - 2014 |

|

|

|

| 2015 - current |

|

|

|

1999 to 2007

Since the late 1990s, Scottish and UK policy makers, academics, and consultants have identified the creative industries as driving force in the national economy. This stemmed from 1997 ‘creative industries mapping document’ which merged the creative industries with the information economy, thus repositioning culture as a key high growth sector1.

The first devolved administration in Scotland maintained a close alignment with the UK creative industry policy2. Through a series of extensive consultation, they reported that the existing cultural agency infrastructure was uncoordinated and ineffective, particularly Scottish Arts Council3.

Concurrently, the ‘creative economy’ become popular and was adopted by the European Commission as having central importance in the EU's Lisbon Strategy in 2000. Likewise, the economic potential of the creative class became mainstream in global policy discourse, including in Australia and the United States4. Collectively, this moved creative industry policy away from direct grant financing of the arts and towards investing in ‘human capital’ by developing the business and technical skills of practitioners, developing fiscal measures and initiatives to promote specific industries, and investing in culture-led urban regeneration.

2008 to 2014

The Scottish Government continued to position the creative economy as central to economic growth. They established Creative Scotland, which replaced Art Council Scotland1. The UK Government largely followed existing creative industry policy and placed emphasis on education, skills programmes, and creative clusters. Creative cluster policies were also pursued by the EU and US. The globalisation of the creative economy is evident in 2008 with UN’s Creative economy reports which position the creative economy as a new sustainable development paradigm.

2015 to present

The 2018 UK government's Creative Industries Sector Deal, a central part of the Industrial Strategy, reaffirms the creative industries as drivers of regional growth and expressed a desire to create more industrial clusters to narrow the gap between London and other areas. This follows the 2017 Bazelgette review which highlights the significant contributions that the creative industries make to the UK economy, forecasting that £130bn in GVA and one million new jobs can be created by 20251. Cluster development is a relatively inexpensive intervention approach which focuses on developing skills, R&D, and networks that can apply across sectors.

The EU's Europe 2020 does not explicitly mention creative or cultural enterprises, instead emphasising smart inclusive growth and regional resilience with a focus on knowledge and innovation. In Scotland, creative industries feature as a key growth sector, with many Growth Deal Regions developing individual creative and cultural agendas. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Scottish Government directed millions in funding to support the cultural and creative industries2.

Challenges within cultural and creative industry policy

Positioning the creative industries firmly within the economic sphere has posed several interrelated challenges for effectively delivering policy and support to creative practitioners. These main challenges, recognised globally, include:

The economic impact of cultural and creative industry policies has been reported as being limited and unevenly spread1.

The prioritisation of the economic value generated by the creative and cultural industries has resulted in a suppressed understanding of how cultural and social value, alongside economic value, are co-created2.

The promotion of the creative economy has masked precarious working conditions and a lack of job security which generates social issues3.

Policies have been criticised for a lack of strategic planning, best-practice models, and empirical evidence4.

Many creative practitioners, include small business owners, prioritise creative practice over business growth and can be ‘put-off’ by formal and non-sector specific business support5.

Balancing the tension between the ‘cultural’ and the ‘commercial’ aspect of creative work pose dilemmas for government agencies regarding whether to drive culture through subsidy-dependent approaches or focus on commercialisation and growth through ‘R&D investment’6.

Cultural intermediaries, who deliver supportive policies to creative enterprises, face difficult positions caught between top-down remits for supporting governments economic agenda and a situated understanding of creative practitioners needs7.

Current creative enterprise policy landscape in Scotland

Creative enterprise policy focuses on supporting and developing both new and existing enterprises, both directly and indirectly, within the cultural and creative industries. It sits at the intersection of cultural and creative industries and economic policies. As such, there are several important current policies that influence the development of creative enterprises.

Scottish Government's Cultural Strategy 2020

The Scottish Government's Cultural Strategy 2020 outlines three main pillars:

To strengthen culture through developing skills, valuing creative practitioners, encouraging cultural events, and fostering international collaboration.

To transform through culture by placing culture as cross-cutting other policy agenda including health, education, and the economy to drive opportunities.

To empower through culture by celebrating talent, broadening views, increasing opportunities for participation, and recognising community and local place.

Scottish Government's creative industries policy

In the National Strategy for Economic Transformation (2022), the creative industries are positioned as one of fourteen key industries. Key policies within these strategies include:

Funding the screen industry to promote film and TV production in Scotland.

Funding Creative Scotland as the national body for the arts, screen, and creative industries.

Working with Skills Development Scotland to develop creative industry skills.

Charing the Creative Industries Advisory Group.

Creative Scotland's Annual Plan 2022/23

Creative Scotland, including Screen Scotland, is a non-departmental public body whose remit is set out in Part 4 of the Public Services Reform (Scotland) Act 2010. It supports the arts, screen and creative industries through funding and support by working in partnership with Government, Local Authorities, and the wider ecosystem of public, private, and third sector organisations. They also distribute funds from the National Lottery. Funding and support programmes include:

‘Regular Funding’ to various organisations that support the industry.

‘Open Fund’ for individuals to support creative activity for up to 24 months.

Operate ‘Our Creative Voice’, a platform for demonstrating the benefits that art and creativity create.

‘Gaelic Language Plan’ to encourage, develop, and support creative work in Gaelic across art forms.

Develop skills, screen education, international outreach, and the development of Scotland-based film-makers as apart of Screen Scotland.

Work with UK's Public Service Broadcasters to foster and deliver talent.

International Outreach through engagement between Scotland and International film and television industries.

Business and market development support through consultations, training, and industry connection to support Scotland's production companies.

‘Film Festival’ and ‘Screening Programming Fund’ to deliver events and festivals.

An initial programme theory for evaluating creative enterprise policy

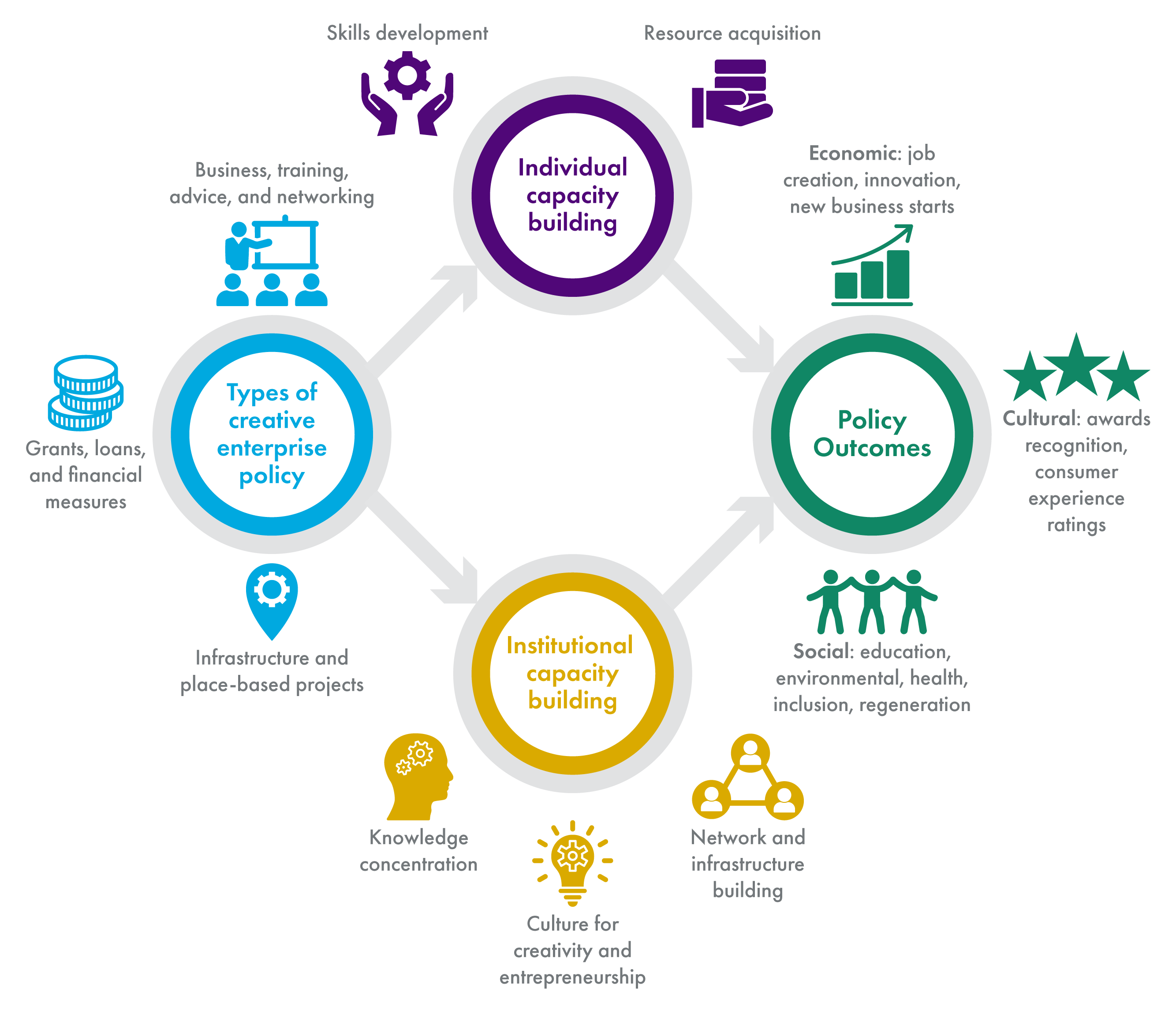

To analyse the various policies and programmes that support creative enterprises, an initial programme theory was used as a guide. This programme theory is presented in Figure 1.

Over the last 25 years, policies that support the creative industries have been firmly positioned as driving economic growth through the generation and exploitation of new knowledge and innovation. To achieve this aim, policies have taking on two approaches:

Increasing the individual capacity of creative entrepreneurs and practitioners by developing their skills and increasing access to resources.

Improving the institutional environment for creative entrepreneurs to pull individuals into business ownership through developing concentrations of knowledge, support culture, networks, and infrastructure.

Creative enterprise policies aim to achieve this through three different types of interventions12. To increase individual capacity there are two main types:

The provision of business development, training, advice, and network building programmes.

The provision of direct grants and loans to overcome the financial constraints of business ownership and operation.

To improve the institutional environment for creative industries the main type of intervention is:

Infrastructure projects and place-based initiatives which aim to regenerate urban landscapes and form ‘creative clusters’ or ‘creative hubs.’ This includes funding the development of specialist infrastructure to support creative enterprises, including art studios, incubators, and managed workspaces.

There are three focal dimensions for assessing policy performance in the creative industry:

Cultural impact is closely associated with merit and the artistic value placed on creative industries3. This is typically measured with regards to awards and recognitions, but also captures co-created value through focusing on consumers’ experience of creative outcomes4.

Social impact recognises efforts to generate positive change within communities and can include achieving environmental sustainability goals, social inclusion, and promoting health benefits3.

The economic impact reflects commercial outputs, which concerns the financial assets, liquidity, or monetary income of a business owner3. It also includes wider regional impact as the creative industries are recognised with providing economic growth through job creation, new business starts, and innovation7.

Training, advice and networking

The provision of business development, training, advice, and network building programmes looks to develop the individual capacity of creative practitioners by increasing business awareness, skills, and knowledge. The evaluation evidence highlights that this type of programme is often accompanied by access to finance. Considering this, both types of programmes (those that provide finance and those that don't) were reviewed. In total, 19 different programmes were analysed from 23 evaluations.

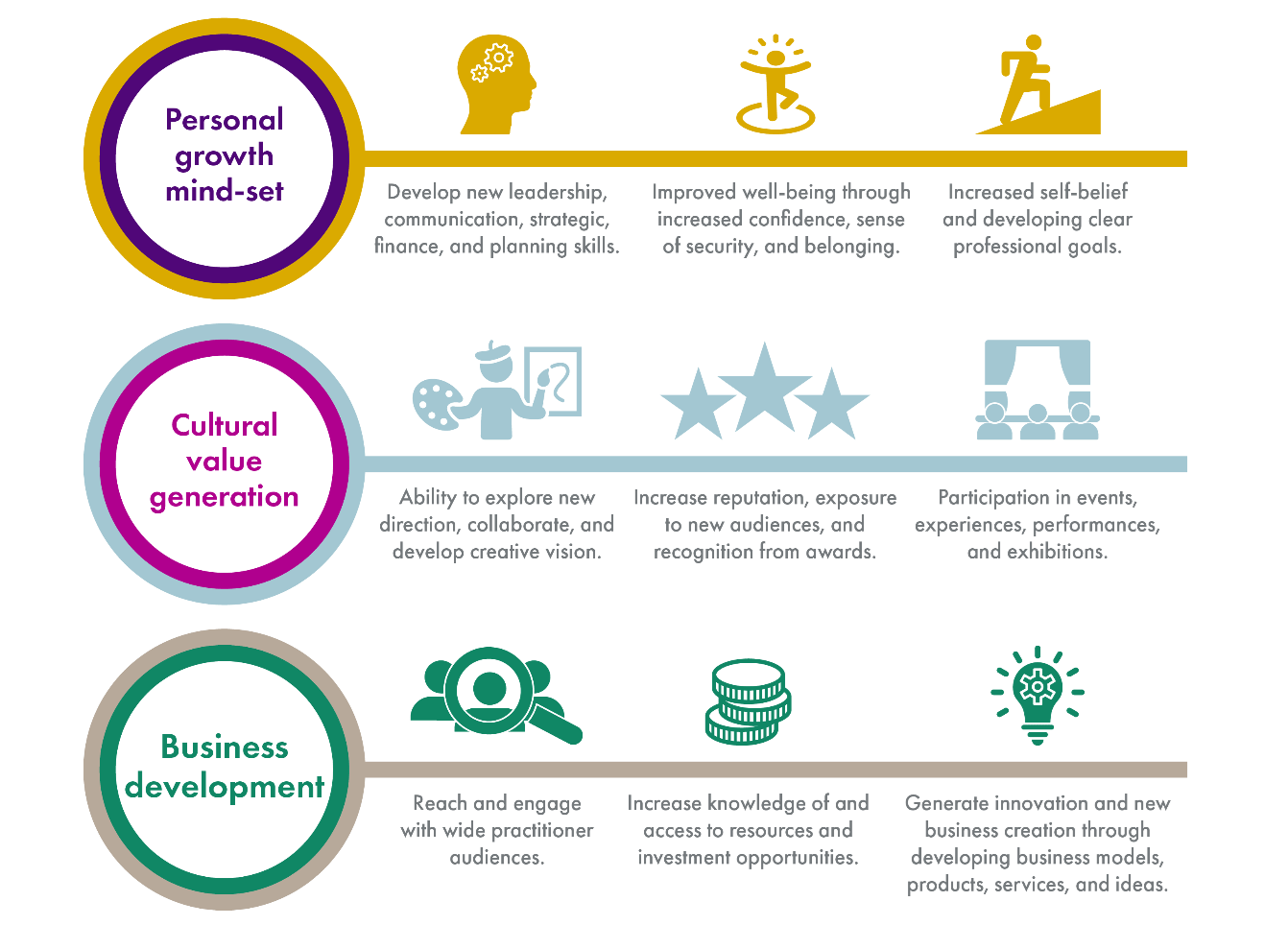

Training, advice, and networking programmes aimed at creative practitioners provide several short-term and longer-term benefits:

They help to foster a personal growth mindset. This involved developing new leadership, communication, strategy, finance, and planning skills. It also involved improving well-being through increasing confidence, sense of security, and belonging. Self-belief was also increased through helping practitioners to develop clear professional goals.

They helped practitioners explore new creative directions, form new collaborations, and develop creative vision. They helped to increase reputation, expose practitioners to new audiences, and gain recognition from awards and commissions. They also increased participation in events, experiences, performances, and exhibitions.

They increase practitioner knowledge of and access to resources and investment opportunities. They help to generate innovation and new business creation through helping to develop new business models, products, services, and ideas.

Increase to business turnover of between 15% and up to 60% which was credited to training and advisory support that was received was reported in several evaluations. There was, however, generally little impact on job creation, which was attributed to the nature of the creative industries which is dominated by self-employment and gig-based work.

In terms of productivity, several programmes report positive contributions to local economies over the medium term. The cost of delivering a programme against expected returns increases from less than £0.90 in the short-term to around £1.40 over about five-year periods. This indicates that although returns on programme investment are negative in the short-term, they generate positive economic impacts over longer periods of time.

There are many impact drivers that can be attributed as key to the delivery of effective training, advice, and networking programmes:

Ensuring a practical, hands-on, design-led learning environment. Creative practitioners generally responded better in programmes that used a design-led means of delivery. This approach incorporates design practices, tools, collaboration, design games, prototyping, and modelling to facilitate creative exploration and practical learning.

Flexibility for practitioners to decide and be involved in their own support journeys. Having a choice of development topics was generally well-received.

Having industry-specific advisors who adopted relational approaches to delivery had a bigger impact on engagement and skills development. This approach focuses on the long-term personal development of the client, and not solely on short-term functional advice to a specific problem being faced.

A slower-paced support programme was beneficial to give practitioners time for creative exploration and socialisation.

Language and terminology were important for engagement. Many creative practitioners are put-out by the commercial and business development language used in mainstream support services.

The collaborative delivery of programmes between specialist organisations enabled additional resources and expertise to be invested. This also increased the potential programme reach and enhanced reputation.

The presence of a strong regional network that facilitates communication between different support organisations and incentivised joined-up approaches to working also helps practitioners to connect with other support programmes.

Peer networks of practitioners with similar challenges encouraged collaborative learning and extended the longevity of support.

The availability of small grants to participants, to be used for developing and refining new ideas and opportunities helped to incentivise participants to experiment, explore, and apply the skills and knowledge gained through training and advice.

Many programmes also provided participants with opportunities to showcase their ideas and practices. This included pitching to investors and participation in exhibitions and shows. This was highlighted as supporting creative practitioners’ routes to market.

A couple of programmes provided participants with co-working space which was found to incentivise peer networking and creative exploration.

A couple of programmes provided opportunity to learn new skills through placements which enabled practical hands-on learning.

Training, advice, and networking summary

Many programmes report short-term increase in the ability of both practitioners to develop new products and services, develop self-belief, and leadership skills. These benefits, however, take a longer-period of time to materialise. Return on investment for these programmes is generally negative in the short-term and rises over time. Key to realising these benefits are approaches tailored to creative practitioners, including having practical hands-on learning environment, industry-specific advisors, peer collaboration, and access to additional support.

Grants, loans and finance

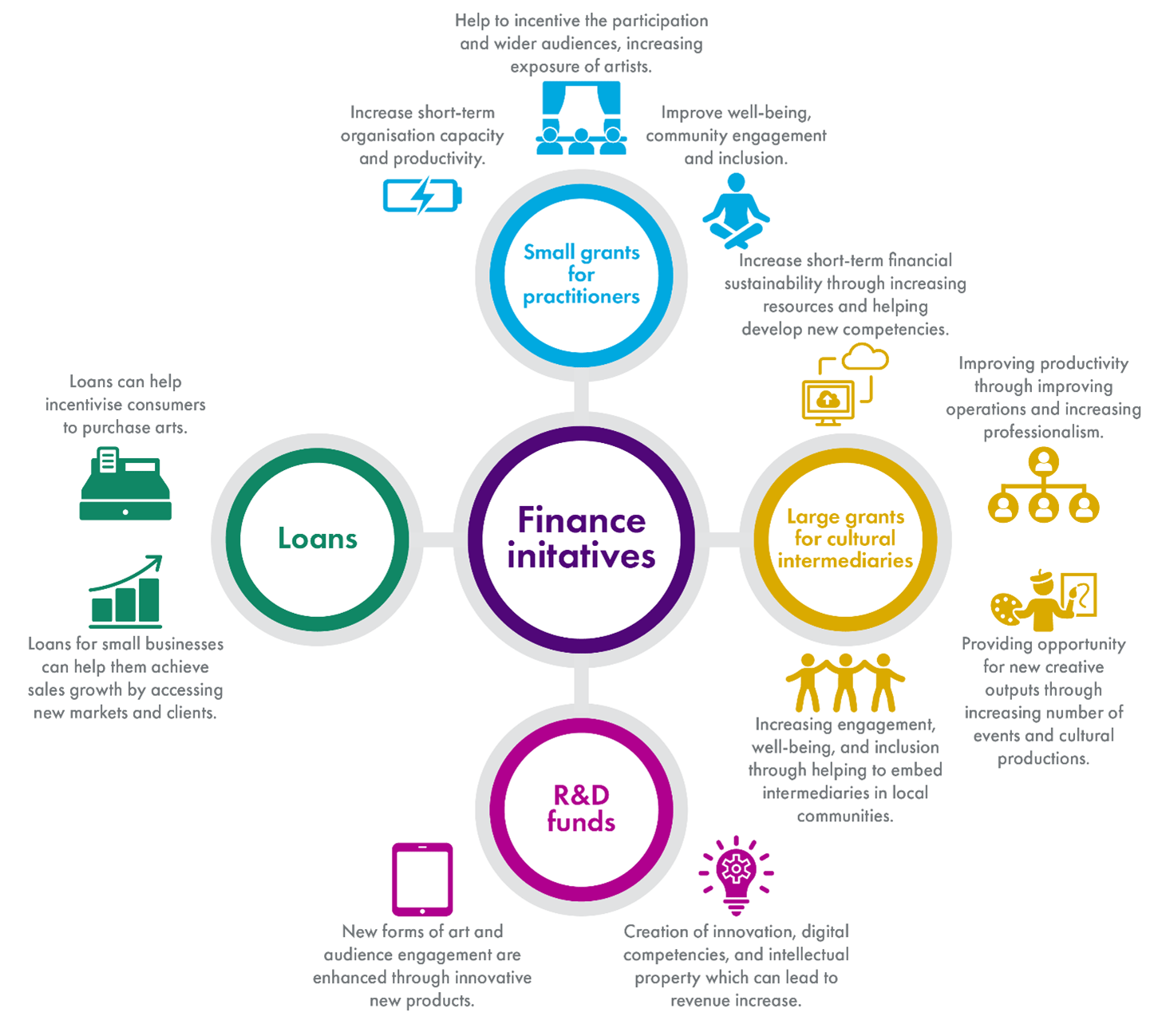

The provision of direct grants and loans can help to overcome the financial constraints of business ownership and operation. The evaluation evidence highlights four types of programmes that aim to do this.

Small grants aimed at improving individual capacity of creative practitioners.

Larger grants for creative intermediaries.

R&D funds that connect practitioners, intermediaries, and universities together.

Loans with different targets and aims.

In total, 33 different programmes were analysed from 42 evaluations. A list of the programmes included in the analysis is presented in the Annex.

Small grants for practitioners

Smaller grants, aimed at creative practitioners, are less than £25,000 and are typically around £5,000. Generally, demand for these grants is extremely high, with initiatives receiving high numbers of applications. This makes the success rate when applying for a grant very low. For those that receive grants several benefits are created:

Building organisational capacity and increasing productivity. New activities adopted by practitioners when receiving a grant include new collaborations, entering new markets, creating intellectual property, developing new skills and management experience, refining value propositions to make products and services more attractive to customers, increasing income and bookings, and supporting new job creation or ‘working days’ of other practitioners.

Incentivising the participation of wider audiences into art and cultural activity through increased capacity to deliver; increasing the exposure of creative practitioners to wider audiences; and giving them the ability to experiment creatively, which generates unique artistic value.

Improvements in well-being through the creation of joy, feelings of belonging, and increased confidence; engagement with communities through developing events, improving community life, and strengthening local relationships; and social inclusion for those that are sometimes marginalised from communities through the ability to participate in cultural activity.

There are two main impact drivers which generate these benefits. The first factor is the availability of additional development support, such as training and networking. This helps to further build the capacity of practitioners to deliver longer-term impact.

The second is the ease of application processes and flexibility in the conditions of grants. Complicated and timely application procedures restrict up-take and make it harder for diverse audiences to apply. A lack of flexibility in grant conditions constrains the ability of practitioners to experiment. Short-term funding cycles (typically less than one year) are also damaging to outcomes. They restrict the ability for recipients to build capacity, plan, and experiment which help them to maximise impact going beyond the programme duration. Furthermore, short cycle programmes increase the pressure for distributors to ‘get money out the door’ which can restrict up-take, outreach, and quality of application.

Larger grants for creative intermediaries

Larger grants, targeted at arts intermediaries (organisations that provide support to artists and cultural practitioners) are typically greater than £50,000 and can be up to £1,000,000 in rare cases. They often require intermediaries to raise match-funding from other sources. They also generate several benefits:

Increasing short-term financial sustainability through growing organisational capacity and helping to develop competencies which improves the ability to use resources. This includes developing new fundraising knowledge, IT and technology skills, taking on new staff, developing collaborations and networks, investing in training, and gaining management skills.

Improving productivity through increasing the efficiency of organisation operations. This includes business model innovation, new membership schemes, marketing campaigns, increasing professionalism, strategic planning, monitoring, increasing income, and reducing costs.

Providing opportunity for new art and creative outputs through increasing the number of events, festivals, exhibitions, and cultural productions available to practitioners.

Increasing engagement, wellbeing, and inclusion by embedding arts intermediaries further into local communities, engaging wider hard-to-reach audiences, and generating a sense of belonging.

Key to realisation of these impacts is whether intermediaries can develop skills and competencies to maximise increased resources. Only a couple of programmes report that they can turn the capacity increase of a grant into longer-term abilities that enable organisations to become more efficient in the longer-term. To do this, intermediaries need to develop strategic leadership skills, engage in peer-learning, and develop cross-sector and cross-geographic networks.

Research and development funds

The aim of R&D funds is to link creative practitioners, intermediaries, technology partners, and universities together to develop innovations. Typically, R&D funds in the creative industries focus on exploring digital technology to engage audiences and develop business models. These funds are often small – around £10,000 – to develop and test new products, services, or designs. Often, organisations have to match-fund and there is also sometimes opportunity to apply for larger funding after the initial pilot phase. There are a couple of main benefits for these initiatives:

Increase in productivity through the creation of new innovative digital products, refining business models, and creating intellectual property. This is accompanied by the development of innovation skills, competencies, and collaborations which can lead to short-term increase in revenue.

New forms of art and audience engagement are generated through innovative new products.

Key to the delivery of successful R&D initiatives is the ability for organisers to broker relationships between organisations. However, very little long-term impact on this is reported. There is a need for on-going innovation support and capacity building, including the ability to plan and build long-term partnerships. A key barrier organisations face is a lack of resources in the long-term to continue investing in R&D.

Loans

Only three programmes reported on the impact of loan schemes, and each had different aims. While there was not enough programme evidence to make firm conclusions, the positive impact justifies a larger investigation into alternative funding programmes rather than grants.

One programme aimed to give citizens loans to facilitate the purchase of artists work in Wales. The take-up was high with lots of artists benefiting from the scheme. The flexible repayment option was attributed as important for this.

One programme was aimed at SMEs who had previously been rejected from mainstream financial credit. These programmes reported increased business growth through turnover, accessing new clients and markets. Furthermore, no loans had been written-off from the scheme. Again, the flexible options for the loans and the availability of wrap-around business support were attributed as important for this.

Grants, loans and finance summary

While many finance initiatives report short-term increase in capacity and ability of both practitioners and cultural intermediaries to deliver services, these benefits seemingly dissipate over the long-term. The challenge is to investigate under what conditions short-term capacity and competency can be converted to longer-term capabilities. The provision of additional support and opportunity for development appears important.

Physical infrastructure and placed-based development

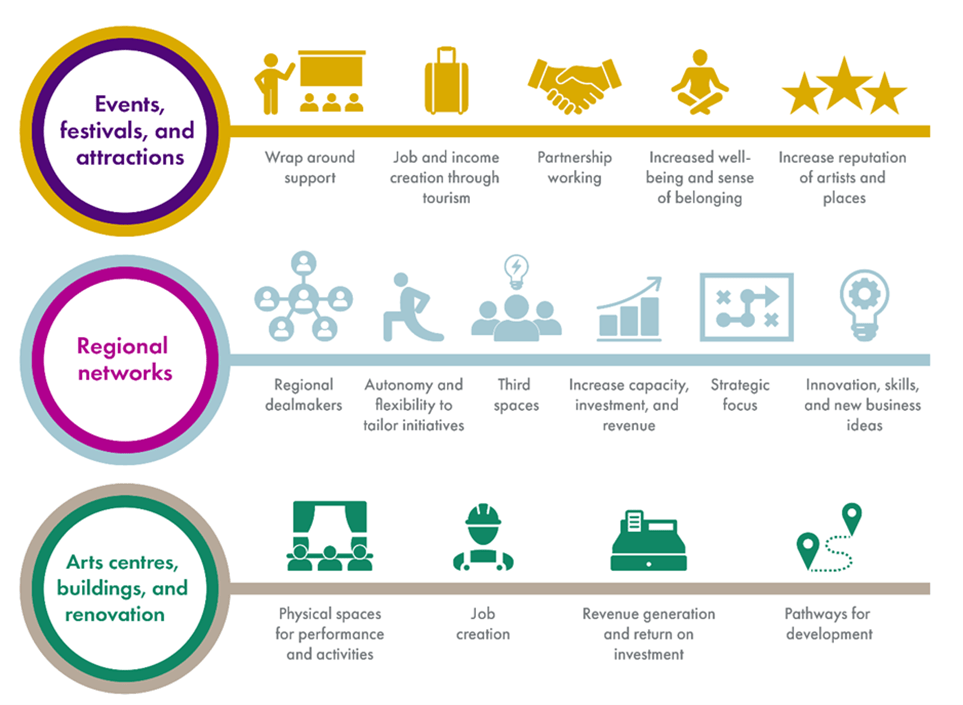

Infrastructure projects and place-based initiatives aim to regenerate urban landscapes through the development and organisation of creative and cultural infrastructure. The evaluation evidence highlights three different types of programmes that aim to do this.

The organisation of cultural events, festivals, and attractions.

The development of regional networks to help connect people and organisations together.

The construction, renovation, and management of dedicated building such as arts centres, studios, and managed spaces.

In total, 32 different programmes were analysed from 41 evaluations. A list of the programmes included in the analysis is presented in the Annex.

Events, festivals and attractions

Events, festivals, and attractions are temporary programmes of cultural activities. They may be repeated, such as the Edinburgh Festivals, or occur only once, such as the Glasgow 2014 Cultural Programme which was centred around hosting the Commonwealth Games. These events provide several impacts:

Economic benefits, including job and income creation, mainly through attracting tourism. This provides opportunities for artists and small businesses in the hospitality sector. Indeed, many evaluations of events and festivals report very strong returns on investment due to the ability of cultural events to attract visitors to local places.

When audience engagement is high at these events, both artists and places can increase their reputation which can develop longer-term cultural impact.

Events, festivals, and attractions also promote several social benefits to places, including helping to build local networks and increasing the capacity to deliver events. They can increase feelings of belonging, sense of community, and the well-being of artists and audiences. They also have an educational role to play and can promote inclusion and attention to social issues.

Key to unlocking these benefits is audience satisfaction and engagement, which is created by quality programming and showcasing diverse talent. Helping to drive this are two main factors:

Wrap-around support, such as training and finance, for artists and practitioners to help develop performances, exhibitions, or shows.

Strong partnership working to help deliver support, promote events to wider audiences, attract more resources, and develop the capacity for local places to deliver.

Regional networks

Regional network initiatives look to establish connections between people and organisations within regions and places. The general rationale behind these initiatives is that by having strong social networks in a place new opportunities, increased capacity, and wider inclusion in cultural activity can be achieved. The reviewed evidence highlights several benefits:

Regional network initiatives can help to develop the capacity, investment, and revenue of participating organisations. This helps to develop strong regional infrastructure, open new markets, and increase the resources directed to the arts.

There is also reported increase in skills and innovation through partnership investment in R&D and experimentation, and the generation of new business or project ideas.

However, direct economic impact, such as job creation or sales income are less commonly reported. This is because they are hard to measure directly. The focus, however, is to improve regional governance to better deliver cultural activity and expand the sector capacity which creates in-direct benefits.

To establish effective regional networks there are several important impact drivers:

Regional dealmakers who act to ‘glue’ networks together as they have strong connections with other organisations and individuals and can incentivise collaborative work.

Third spaces, such as co-working hubs, which act as important neutral places where different stakeholders from across the sector can meet to experiment and collaborate freely.

Autonomy and flexibility in network activities and funding criteria which can allow for initiatives to be locally tailored to individual places which can maximise value.

Having a strategic focus, which includes having a clear collective agenda, strategic links to other sectors, a consumer-centred focus, and the ability to assemble resource from wider areas.

Art centres, buildings and renovation

This initiative typically involved capital build programmes in which arts centres, or other cultural buildings were developed, creating permanent places for cultural activity. These programmes created several short-term and longer-term benefits:

In the short-term the construction and operation of physical sites creates jobs and provides training opportunities.

Over longer-periods this attracts visitors, which generates income and a return on capital investment.

The development of these initiatives results in places for consumption of culture which can increase access, social inclusion, reduce isolation, and increase sense of belonging.

Key to driving these benefits is:

Having physical spaces for performance, exhibitions, and participation in cultural activity.

Developing pathways for development, including training, and allowing practitioners places to work and increase their exposure to audiences.

Infrastructure and placed-based summary

The results from this analysis highlight that the curation of programmes of events, festivals, exhibitions, and attractions can provide a boost to local economies through visitor spend. The development of regional networks can help to increase the capacity of local organisations to deliver these initiatives. The construction and operation of physical cultural spaces can create job opportunities in the sector. Seemingly, having a mix of these different types of initiatives can assist with place-based economic, cultural, and social development.

Towards a creative enterprise policy toolkit

Based on the review it is possible to synthesise exemplary programmes and the complementary features which drive cultural, economic, and social impact. These ‘best practice’ guides offer options for funders to develop the creative enterprise support landscape in Scotland.

Individual capacity building programmes

To develop the individual capacity of creative practitioners and business owners through increasing access to resources and skills there are four programme archetypes (Figure 5). Effective training & advice programmes focus on providing practical and flexible hands-on learning tailored for creative practitioners and delivered by industry-specific advisors and educators. Programmes that aim to develop business planning skills through design-thinking approaches, such as the Collective Futures programme, are particularly effective at equipping creative practitioners with business planning skills. They place social and cultural impact at the heart of design thinking processes which resonates well with practitioners1.

Furthermore, the inclusion of elements which can incentivise peer networking can enhance the benefits of training and advice. Such interventions incentivise collaboration and learning which can enhance creative processes. These programmes run well when they incentive cross-industry exchanges, with dedicated spaces, such as co-working spaces, where multiple practitioners can come together. Programmes, such as the Network for Creative Enterprise report strong results for bringing cohorts together within spaces.

For these types of programmes, the economic outcomes do not fully materialise in the short term. Several evaluations, such as the London Creative Network or StartEast, highlight returns on investment (ROI) as being negative within short-term. However, the skills that these generate have longer-term effects, with ROI rising significantly within 3–5-year scales. Access to finance, therefore, is important to increase the shorter-term capacity of practitioners. Access to finance through small grants and loans, seemingly has a contrasting effect on outcomes, with immediate returns on investment which diminish over time. Working alongside training & advice and peer networking, finance programmes that can incentivise creative product and service development have the biggest impact. Being flexible in the conditions of the grant and having easy to access application services are important.

The final programme archetype which is key is the availability of exhibitions for practitioners to showcase their work, products, and services. The effects of increasing both the longer-term skills acquisition, and shorter-term resource capacity of practitioners is dampened if there is limited access to markets. Ensuring access for practitioners to participate in festivals, markets, and events can be facilitated by multiple cultural intermediaries working in collaboration.

Institutional capacity building programmes

To develop the institutional capacity to support creative enterprises there are also four intervention archetypes (Figure 6). Programmes that build and renovate infrastructure are important to provide the space for performance and events. Repurposing existing infrastructure to facilitate variety of different mediums can be important for the cultural industries and can bring diverse stakeholders together.

Having a rich programme of events & festivals is also vital for creative enterprises. Ensuring these programmes encourage diverse performances and focus on developing quality content through linking up with cross-sector partners and focusing on also building individual capacity are key. To deliver rich programmes of events & festivals having vibrant regional networks is crucial. These networks bring stakeholders together to drive place-based growth and act as an anchor within a region. For regional networks the focus in on developing capacity and strategic focus which facilitates organising cultural events and delivering individual capacity programmes.

To help facilitate regional networks, R&D funds and large grants, aimed at creative intermediaries and support organisations can help to develop leadership capabilities. It is important for these funds to both allow for organisations to experiment with new products and services that can increase their sustainability and develop new partnerships and collaborations to increase value. Programmes such as the REACT Network, can incentive partnership working, create new value-added services, and reach a greater number of cultural consumers.

Evaluating creative enterprise policy

Evaluating different creative enterprise programmes poses several challenges. Some of the challenges evident in evaluations include:

Programme funding and reporting typically works to a one-year period, with programme impacts often taking longer than that to materialise. Funders generally need to evidence impact that is hard to capture in one-year funding cycles.

There is a tendency to focus predominately on economic outcomes to justify costing. This places cultural and social outcome as secondary. However, over longer periods cultural and social value can drive economic value.

Some hard measures (such as GVA) can be hard to capture accurately, as such many programmes report softer measures (such as outreach or skills development). Understanding which softer programme outputs can generate longer-term ‘harder’ outcomes is less known.

Many programmes work in combination with multiple different types (e.g., small grants, training, networking). Understanding the individual impact of programmes is a challenge.

The costs of conducting rigorous evaluation can be prohibitive. Especially for ‘best practice’ methodologies such as longitudinal randomised control trials1. Furthermore, it can be hard for public funders to justify the random inclusion and exclusion of eligible applicants.

These challenges could make potentially very impactful programmes underappreciated. Table 3 presents a high-level guide for potentially alleviating some of these challenges. For this guide, several assumptions are made:

Social, cultural, and economic value are equally important. Social and cultural value can drive economic benefits in the longer-term.

Programmes do not work in isolation and are co-dependent on other types of support that are available directly or indirectly. As such, evaluation could focus on individual capacity building and institutional capacity building considering multiple programmes concurrently.

Evaluations can capture various input mechanisms that drive outputs. Inputs help to either drive or restrict programme outputs by explaining what works and for whom in a particular context.

Outputs can be captured in the short-term, typically less than a year after programme duration. Various outputs from programmes include value generating activities, actions, and obtainments.

Short-term outputs generate longer-term outcomes which are typically the goals of policy programmes. It is possible to capture various longer-term social and cultural value through subjective well-being valuation or other similar methodologies that can put economic value on cultural and social outputs.

| Programme type | Inputs (what helps drive impact?) | Outputs (<1 year) | Outcomes (3-5 years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual capacity building(Training & advice, peer networking, small grants & loans, exhibitions & events) |

|

|

|

| Institutional capacity building(Infrastructure, events & festival programmes, regional networks, R&D funds & large grants) |

|

|

|

Conclusions and recommendations

Summary

Despite the economic benefits of creative industries being well acknowledged, the findings of this study further highlight that the impact is also widespread across cultural and social domains. The findings of this study suggest that policy decision-makers could consider the following key points when considering policies to support creative enterprises.

Short-term programme impact is often hidden and/or difficult to calculate. This does not mean it doesn’t exist. One way to mitigate this challenge is to look at the programme inputs and outputs during evaluation which ultimately leads to longer term impact of programmes.

While there is no recipe for success that can be replicated across all contexts, there are some key input mechanisms that seemingly work well.

Tailoring business support programmes to creative practitioners can increase impact.

Encouraging both within sector and across sector networking and collaborations can increase value.

Ensuring joined-up access to markets, events, performances, exhibitions, and festivals can further support the development of creative practitioners.

Support programmes seemingly work well in conjunction with one another. For example, while training & advice programmes increase the competency of practitioners which generate impact over long periods, the availability of small funds can increase short-term impact. Likewise, having access to market opportunities creates an outlet for these competencies and capacities.

Infrastructure projects and event & festival programmes create many short-term economic benefits, but without developing rich regional networks, with leadership capabilities, this landscape may not be exploited to its full potential.

Recommendations for future work

Despite a shortage in evaluation evidence for the various creative industries and enterprise support programmes that are available in Scotland, there are a number of programmes and agencies which comprise the support landscape. Creative Scotland have several grant programmes for practitioners and intermediaries, while Business Gateway provide blanket training and advice support to all business in Scotland. Support organisations, such as the Creative Entrepreneurs Club, provide practitioners throughout each local authority in Scotland access to a peer network. Based on the findings from this study, however, two main recommendations can be made:

There is a need for bespoke business training and advice services to be delivered in conjunction with current peer network and funding opportunities. Having strong links with chances to showcase cultural activities is important as well. Joining-up the current support system can help the impact of individual programmes.

Working with existing Regional Growth teams there is need for the establishment of networks that can develop cultural event programmes. Efforts can be made to bring cultural intermediaries and actors together to co-create value by developing and showcasing regional talent.

Considering some of these key insights, there is scope for three directions for future work to help develop creative enterprise policy.

The toolkit developed in this work can be used to sense-check the environment for supporting creative enterprises in Scotland. Working with existing sector groups, cultural intermediaries, and policy decision-makers to determine the effectiveness of the support landscape for practitioners. This exercise should consider the following:

A user-centred approach which focuses on cultural consumption should be placed at the heart of the exercise.

An understanding should be developed as to current policy efforts to establish both institutional and individual capacity.

Such an exercise could help to integrate and build-upon the joined-up thinking of the sector.

Creative enterprise stakeholders could establish a shared approach to evaluating programmes considering inputs, outputs, and outcomes. Having agreed upon guidelines for evaluating programmes could bring clarity and help alignment of goals. This approach should consider dual objectives:

Policy makers require summative evidence of impact to quantify their public investments.

Evaluations should also be considered as formative to direct learning and development for programme deliverers.

Further work can consider the cause and effect between various programme outputs (short-term) and outcomes (long-term). This can help to cement a more concrete list of outputs that can indicate programme impact and be used in evaluation.

Annex

| Programme | Geographic context | Description |

| Art Works | UK wide | Professional development of artists through training mentoring, residencies, and peer networks. |

| Creative Advantage | Dorset, Hampshire, and Surrey, England | Training, networking, placement, and internships for university graduates. |

| Creative Fuse North East | North East England | Support business growth through training workshops, advisory sessions, work placements, small grant fundings, and networking events such as hackathons. |

| Creative Local Growth Fund | England | Business advice, mentoring, network, grants, workshops, hackathons, and exhibitions delivered through regional networks of intermediaries. |

| Cultivator | Cornwall, England | To grow creative industries through grants, export programme, peer support networks, graduate start up programme, collaborative projects, internships and apprenticeships, mentoring, and skills development (through group workshops and an individual skills development fund). |

| Cultural Enterprise Offices | Scotland | Help creative practitioners through one-to-one specialist advisory sessions, group training workshops and networking events. They also ran three dedicated training and advice support programmes - Starter for 6, The Fashion Foundry, and Flourish. |

| Developing Cultural Sector Resilience | East London and Birmingham, England | To help organisations through one year mentoring programme and training labs looking at a range of issues, including strategy, planning, innovation, and governance. |

| London Creative Network | London, England | Support business development through one-to-one advice, coaching, and seminars, networking events, and showcases over a period of 6 months. |

| Music Business Support Programme | Northern Ireland | To promote industry development through seminars and events, mentoring, market development networking. |

| Network for Creative Enterprise | West, England | Help industry sustainability through free workspace, skills development workshops, bespoke business support, small bursaries, one-to-one mentoring, showcasing opportunities and resources. |

| New Creative Markets | London, England | To improve sustainability through workshops, talks and panel discussions from industry experts, and one-to-one mentoring on a wide variety of topics such as strategy, financial planning, social media, online presence, and production methods. |

| Prosper Business Support Project | England | To improve resilience through one-to-one business advice, group workshops, masterclasses, webinars, and free online business support resources. |

| South West Creative Technology Network | South West, England | To support business growth through prototype commissions, microgrant opportunities, knowledge exchange, business development and ongoing mentorship. |

| StartEast | Norfolk and Suffolk, England | Specialised business support programme using networking events, advisory session, group workshops and webinars, support to attend festivals and trade fairs, and financial grants. |

| Starter for 6 | Scotland | To support innovation through business training and coaching, peer mentoring, aftercare support, and opportunity to pitch for £10,000. |

| The Creative Skills Initiative | England | Training, apprenticeship, and paid internship programme to move youth into employment market. |

| The Design for Business Programme | Northern Ireland | Champion design as a key tool for business competitiveness through awareness raising events, advice, mentoring, and consultancy support. |

| The Design Service Programme | Northern Ireland | Develop design innovation as a tool for business competitiveness through awareness events, one-to-one advice, mentoring, and business clinics. |

| The Digital Arts and Culture Accelerator | England | To increase investor readiness through accelerator programme with dedicated workshops, coaching, mentoring, and pitching sessions. |

| Programme | Geographic context | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Artists' International Development Fund | England | Grants of up to £5,000 to develop links with artists, organisations, and/or creative producers in another country. |

| Arts Impact Fund | England | Unsecured loans of £150,000 to £600,000, at affordable interest rates, repayable over 3 - 5 years to bridge gaps in cashflows, develop new income streams, acquire, or repurpose buildings. |

| Building Peace through the Arts: Re-imaging Communities Programme | Northern Ireland | Funding for community arts projects. |

| Cashback for Creativity | Scotland | Open Arts Fund - awards of up to £10,000 for a project of a duration of up to 12 months; strategic Fund for projects between 9 - 18 months looking to create learning and development activities; training and Employment Fund to support the development of training programmes. |

| Catalyst | England | Endowments for 18 organisations with a strong track record of funding. Awards for consortium of arts organisation with less of a track record to work together to build fund-raising potential. |

| Catalyst: Evolve | England | Grant to help build capacity and invest in activities to help raise funds and generate private income. Match-funding to incentivise on a pound-to-pound basis |

| Collectorplan | Wales | Interest-free Arts Council of Wales loan scheme to help UK residents buy original work of art by living artists. Loans of between £50 and £5,000. |

| CReATeS | Scotland | Funding for collaboration with technology partners. |

| Creative Credits | England | R&D fund - innovation vouchers for business-to-business credits worth £4,000, with match-funding needed of £1,000 for SMEs to engage with creative business. |

| Creative England Investment Programme | England | Individual investments to 350 companies for a total value of nearly £20 million to support business sustainability, growth, job creation, international trade and exports, innovation, and cluster development. |

| Creative Europe | UK | Creative Europe: Culture provides financial support to projects with a European dimension - mainly through co-operation projects or through development of hubs or networks between 200,000 and 2,000,000 EurosCreative Europe: Media provides support the EU film and audio-visual industries in the development, distribution, and promotion of their work. |

| Creative Industry Finance pilot programme | England | Loans of between £5,000 and £25,000 and free business development support (business advice). |

| Creative Industries Innovation Fund | Northern Ireland | 100% grants for projects up to £10,000. 75% for £75,000 for companies looking to develop capacity and become NI clients. All other cases 75% for grants of up to £50,000 |

| Digital Innovation Fund for the Arts | Wales | Small grant £5,000 to experiment and investigate high-risk projects with technology companies with business support in the form of workshops and advice. |

| Digital R&D Fund for the arts | England and Wales | Funds to develop digital innovation with technology and research partners. |

| Grants for the arts | England | Grants of varying sizes (very small <£1,000 to large >£150,000). |

| Intercultural Arts Programme | Northern Ireland | Grants to support collaborations between organisations, communities, and artists.Individual artist awards and Artists in the community awardsA programme of training networking and development. |

| Media Sandbox | England | Grants to support collaborations between organisations, communities, and artists.Individual artist awards and Artists in the community awardsA programme of training networking and development. |

| Momentum | England | Targeted financial support through grants of £5k to £15k available to artists and bands looking to take their career to the next level. |

| Museum Development | England | Funding for small and medium-sized museums to develop sustainability, resilience, and innovation. |

| Our Space | Wales | Funding of between £5,000 and £50,000 for R&D and community outreach programmes. |

| Re-imaging Communities Programme | Northern Ireland | Funding for community arts projects. |

| Senses of the city | England | Small grants up to £5,000. |

| Stabilisation and Recovery Programmes | England | Grants from 70k to £12.1m with average of £1.5m. |

| Strategic Touring Programme | UK | Grants of varying sizes (small £20,00 to very large £1,000,000). |

| Theatre Sandbox | England | Research and development funds of £10,000 and structured support commissioning, mentoring, performances, knowledge exchange and PR. Technology support grant £800 for equipment and £2,500 from technology consultants. |

| The Breakthrough Fund | UK | Grants of between £83,000 and £360,000. |

| The Creative Communities Programme | Scotland | Project funding of up to £40,000 to deliver a project in a local community. 10 organisations given £2,000 seed funding to increase capacity to deliver their communities. |

| The Regional Arts Lottery Programme | England | Provide capital grants (up to £100,000); project grants (up to £30,000); and organisational development grants (up to £30,000). |

| Visual Artist and Craft Maker Awards | Scotland | The programme offers grants of between £500 and £1,500 to support visual artists and craft makers in creative and professional development. |

| West Midlands Cultural and Creative Social Enterprise Pilot Programme | England | Business development grant to support business model pivoting. £20,000 to the two-core creative and cultural enterprises. £1,500 towards bespoke mentoring and training; £5,000 towards supporting five micro cultural and creative social enterprises within the area; and £3,500 towards purchasing external bespoke mentoring and training for each organisation (£700 each). |

| Women Make Music | England | Grants of average size of £3,600 to women. |

| Year of the Artist | England | Financing arts residencies at £150 per day. |

| Programme | Geographic context | Description |

| Artist Links England-Brazil | England | Provide artists with opportunities to develop their artistic practice by immersion in another culture and by cross-cultural collaboration; most usually in the form of exchanges, placements, residencies, and research periods. |

| Canvas | England | An online showcase destination for arts video content, through a multi-channel network of organisations. |

| Capital Build Programme | Northern Ireland | Distributed over £70m of capital funding to establish a wide range of dedicated cultural venues in towns and cities. |

| Community Libraries Programme | England | Grants of between £250,000 and £2 million to renovate, extend or build new libraries so that they can offer a broader range of activities to their communities, with a focus on reaching new audiences. |

| Creative Edinburgh | Edinburgh, Scotland | Networking and collaboration amongst creative companies in Edinburgh to raise standards and ambition. |

| Creative Partnerships | England | Regional networks between, schools, creative practitioners, and organisations to deliver teaching through creative practitioners. |

| Creative People and Places | England | Programme of events to create opportunities in arts participation. |

| Creative Producers International | England | Network of creative producers from across the world provided with time, space, and financial support. |

| Cultural Compacts Initiative | England | Support local cultural sectors enhance contribution to development, with a special emphasis on cross-sector engagement beyond the cultural sector and the local authority. |

| Decibel Programme | England | A celebratory programme to develop diversity in the arts in England, helping to build a sustainable base for the support and encouragement of diverse arts. |

| Dundee Contemporary Arts | Tayside, Scotland | Arts centre in Dundee with museum-standard galleries, cinemas, and extensive production facilities for artists, including a print studio. |

| Edinburgh Festivals | Edinburgh, Scotland | Annual Festival programme. |

| Glasgow 2014 Cultural Programme | Scotland | Cultural programme of national and international content for the Commonwealth Games. |

| Grampian Film Office | Grampian, Scotland | Film Office to increase the volume and value of TV and Film productions that were coming into the Grampian region. |

| Hull UK City of Culture | Hull, England | Programme of events, exhibitions, installations, and cultural activities delivered across Hull and the East Riding of Yorkshire. |

| Interactive Tayside | Tayside, Scotland | Support, promote and develop the digital media sector within Tayside by encouraging collaboration between businesses and between businesses and academia to develop new commercial opportunities. |

| Knowledge Exchange Hubs for the Creative Economy | England | Academic collaboration with the creative economy. |

| Liverpool Biennial | Liverpool, England | 15-week festival was underpinned by a weekly programme of events and included partner exhibitions. |

| Luminate | Scotland | National festival, which celebrates people’s creative lives as they age. |

| Mackintosh and Merchant City Projects Review | Glasgow, Scotland | Create new tourist attractions and develop cultural spaces to continue to grow the Merchant City and Mackintosh tourism sector. |

| Media Innovation Support Programme | Scotland | Enable independent production companies based in Glasgow to invest in research and development (R&D). |

| MTV Awards | Edinburgh, Scotland | 2003 MTV Europe Music Awards in Leith. |

| National Leadership and Peer Learning Programme | England | Partnership shared learning and leadership development programme working across sectors to drive a more joined-up cultural education offer, share resources, and improve the visibility of cultural education. |

| Random Acts Network Centres | England | Five Random Acts Network Centres (RANC), to identify, develop and support diverse young artists to make films to be considered for inclusion in Channel 4 broadcasting. |

| REACT Network | Bristol and the South West, England | Knowledge Exchange Hubs for the Creative Economy to support collaboration between partner universities and companies active in the creative economy. |

| Scotland's London 2012 Cultural Programme | Scotland | Programme of projects and events across Scotland in response to the 2012 Cultural Olympiad. |

| Scottish Opera and Theatre Royal | Glasgow, Scotland | The Theatre Royal, Scottish Opera, and travelling tours. |

| Textiles Technology Facilitator Service | Scotland | Encourage and co-ordinate technical collaboration both within the sector and with other sectors to maximise global opportunities. |

| The Cultural Destinations Programme | England | Encourage the cultural and tourism sectors to work together in innovative ways to raise the profile of culture in local visitor economies. |

| The Space | England | Temporary, not-for-profit digital service through which audiences could access digital works covering a wide range of arts. |

| Transported | South Lincolnshire, England | Programme of events to engage local communities in the arts. |

| Turning Point Network | England | Setup 13 regional groups and a national network. |