Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill

The Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill aims to introduce measures to help develop a circular economy, including setting circular economy targets, and makes provision about the reduction, recycling and management of waste. This briefing summarises the background to the Bill, the current regulatory and policy framework, changes proposed by the Bill and international developments in circular economy policy.

Summary and key Bill documents

The Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill was introduced on 13 June 2023 and is published on the Scottish Parliament website. The Scottish Government states that:

The Bill will establish the legislative framework to support Scotland's transition to a zero waste and circular economy, significantly increase reuse and recycling rates, and modernise and improve waste and recycling services.

Key provisions of the Bill are:

A requirement for a Circular Economy Strategy with associated consultation, review and reporting requirements.

Powers to introduce circular economy targets with associated monitoring and reporting.

Powers to introduce restrictions on the disposal of unsold consumer goods for the purpose of reducing waste.

Powers to introduce charges for single-use items (expected to be initially used to introduce a charge for disposal beverage cups).

A new criminal offence for a householder to breach their duty of care in relation to household waste, and new fixed penalty regime for that offence.

Introduction of new enforcement measures around household waste disposal and recycling (fixed penalty and civil penalty charges).

A new statutory code of practice on household waste recycling.

Powers to set targets for local authorities relating to household waste recycling.

Introduction of a new civil penalty charge for littering from a vehicle.

Powers to introduce mandatory public reporting requirements for businesses in respect of waste and surpluses.

Powers to enable enforcement authorities to seize and search vehicles to tackle waste crime.

Supporting documents published by the Scottish Government alongside the Bill include:

Consultation on proposals for the Bill

The Scottish Government consulted on proposals for a Circular Economy Bill from 30 May 2022 to 22 August 2022 and has published submitted responses.

An analysis of consultation responses was published by the Scottish Government on 30 November 2022.

The Scottish Government had previously published a consultation on proposals for a Circular Economy Bill in 2019, with a view to introducing a Bill in 2020. This was delayed by the pandemic.

Context: consultation on a 2025 circular economy routemap

In tandem with the consultation on proposals for the Bill, the Scottish Government also consulted on Delivering Scotland's circular economy A Route Map to 2025 and beyond, aimed to be complementary consultations. The routemap provides the wider context for the Bill, noting that the Scottish Government already has significant powers under a range of legislation for circular economy interventions, many interventions are non-legislative in nature, and a number of important interventions are taking place at a UK-wide level (more information below).

The draft 2025 routemap was published on 30 May 2022 alongside other supporting documents, including a Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment (BRIA) and a Review of High Performing Recycling Systems (an independent report commissioned by the Scottish Government).

Context for the Bill

What is a circular economy?

Often the model of consumption and production is linear - resources are extracted or harvested, materials are produced consuming energy, products and services are used, and then waste products are discarded. This is sometimes described as a "take, make and dispose" model. Despite efforts to disrupt this model of consumption e.g. through efforts towards more reuse and recycling, globally it is still the dominant model, with associated environmental, economic and social implications (explored further below).

A circular economy refers to an economic model which has moved away from "take, make and dispose" to one where resources are kept in circulation for longer, and we are not unsustainably drawing down our natural resources, sometimes called our 'natural capital'. Essentially, in a circular economy, waste is either completely designed out, or is minimal and the impacts of waste disposal do not threaten our 'planetary boundaries' - the environmental limits within which humanity can safely operate. Global studies suggest we are currently overshooting six of the nine boundaries crucial to the health of our planet - including in relation to climate change, chemical pollution and biodiversity loss - putting people and nature at risk.1

Exact definitions or models of how a circular economy is expressed can differ, but generally the emphasis is on circularity of resource use, minimising or designing out waste, and doing so in a way that addresses the twin climate and nature crises.

For example, the Ellen Macarthur Foundation defines a circular economy as follows:

The circular economy is a system where materials never become waste and nature is regenerated. In a circular economy, products and materials are kept in circulation through processes like maintenance, reuse, refurbishment, remanufacture, recycling, and composting. The circular economy tackles climate change and other global challenges, like biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution, by decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources.

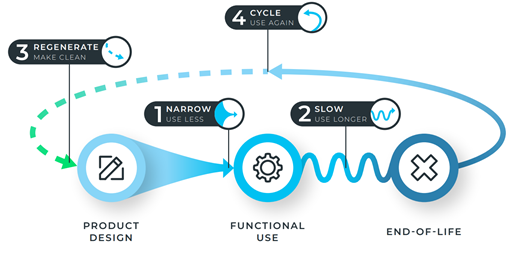

The 2023 global Circularity Gap Report sets out a 'four flows' model for a circular economy where we (1) ''narrow' by using less material in product design, (2) 'slow' the flow of resources by using resources for longer, (3) 'regenerate' products and materials for use again, and (4) 'cycle' materials for use again (see Figure 1 below).

Definitions of a circular economy can also emphasise socio-economic opportunities. For example the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) states:

The circular economy is a new and inclusive economic paradigm that aims to minimize pollution and waste, extend product lifecycles, and enable broad sharing of physical and natural assets. It strives for a competitive economy that creates green and decent jobs and keeps resource use within planetary boundaries.

The Policy Memorandum for the Bill states that "A circular economy gives us an alternative economic model that can benefit everyone within the limits of our planet" and that a circular economy:

cuts waste, carbon emissions and pressures on the natural environment

opens up new market opportunities, improves productivity, increases self-sufficiency and resilience by reducing reliance on international supply chains and global shocks

strengthens communities by providing local employment opportunities and lower cost options to access the goods Scotland needs.

Why do we need a circular economy?

As described above, the current, dominant global 'linear' model of consumption and disposal of resources is threatening our planetary boundaries. Unsustainable consumption and production is a global issue with diverse environmental and socio-economic impacts. The United Nations states:

Unsustainable patterns of consumption and production are root causes of the triple planetary crises of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution. These crises, and related environmental degradation, threaten human well-being and achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are UN countries' shared framework for promoting, pursuing and measuring sustainable development. Sustainable Development Goal 12 is to 'Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns'. As background, the UN states that the material footprint per capita in high-income countries is 10 times the level of low-income countries. The UN states:

Responsible consumption and production must be integral to recovery from the pandemic and to acceleration plans of the Sustainable Development Goals. It is crucial to implement policies that support a shift towards sustainable practices and decouple economic growth from resource use.

As well as clearly having direct relevance for the goal of promoting responsible consumption and production, a circular economy has also been described as a tool that could support progress towards multiple UN SDGs (see Figure 2 below showing all of the UN SDGs).

Unsustainable consumption in Scotland

If everyone on Earth consumed resources as we do in Scotland, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) state that we would need three planets to support this level of consumption. This is because our consumption of products often relies on unsustainable use of resources. Unsustainable use of resources can relate to:

the climate impacts of extraction of resources, production, use and disposal of products

other environmental impacts across the lifecycle of products we consume- from extraction through to production, use and disposal - including on biodiversity, air quality, and the water environment - which in turn can have implications for our health and wellbeing

the socio-economic impacts of how we consume products. Although the socio-economics of consumption can be positive e.g. where we use products to support our wellbeing, or by supporting livelihoods, unsustainable socio-economic impacts can take place where the extraction, production or disposal of products harms people and communities.

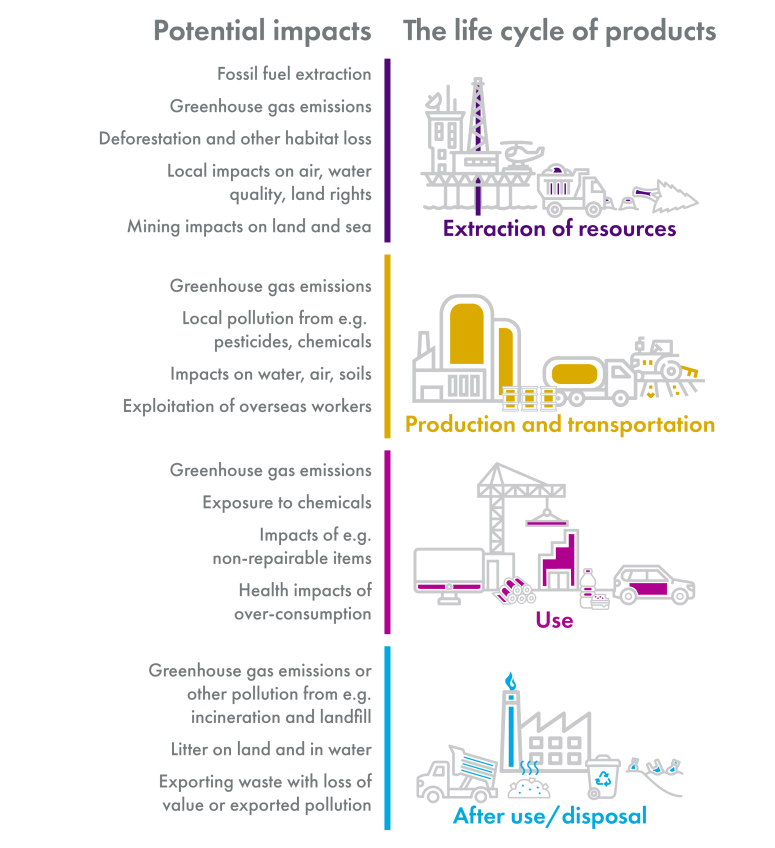

The above impacts can take place in Scotland, but often take place in other countries - where resources are extracted, or where production takes place, or where waste or used and recycled materials are exported. Some of the different aspects of the lifecycle of products, and key potential negative impacts of over-consumption are summarised in Figure 3 below.

The Circularity Gap in Scotland - Scotland is 1.3% circular

Zero Waste Scotland and Circle Economy published the Circularity Gap Report Scotland in November 20221 stating:

Scotland is only 1.3% circular—leaving a Circularity Gap of more than 98%. This means that Scotland almost exclusively uses virgin resources to satisfy its residents' needs and wants, such as for Housing, Nutrition and Mobility. In 2018, the country consumed 117.8 million tonnes of virgin materials—around 21.7 tonnes per capita. This is nearly double the global average, which rests at 11.9 tonnes.

And:

Despite representing just 0.073% of the world's population, it consumes a total of 119.4 million tonnes of materials per year—0.1% of the globe's virgin material use. In other words, the Scottish economy is largely driven by overconsumption.

The complex implications of unsustainable consumption, and corresponding opportunities of a more circular economy are discussed further in below sections.

Tackling Scotland's carbon footprint (consumption emissions)

According to Zero Waste Scotland, around 80% of our carbon footprint in Scotland comes from consumption - "from all the goods, materials and services which we produce, use and in the case of products, often throw out after just one use"i. Research by Zero Waste Scotland also suggests that only one-fifth of people in Scotland are fully aware of the negative environmental impacts of our consumption of new products.1

There are two main ways of calculating a country's carbon emissions:

Production-based emissions: often referred to as territorial emissions, are calculated by adding up all the emissions that are produced within a country (e.g. emissions produced from industry, manufacturing, energy production, transport etc.).

Consumption-based emissions: often referred to as a "carbon footprint" are calculated by adding up all the emissions associated with the goods and services consumed within that country (e.g. emissions from the products and service we buy and consume).

Much of the focus of climate policy is on production-based emissions. This is because production-based emissions form the basis of national accounting for the purposes of the legally binding international treaty agreed under the 2015 Paris Agreement and associated domestic legal targets implementing this treaty. Territorial emissions are therefore the basis for our legal emissions reductions and net zero target set out in the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009, as amended by the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019.

A significant challenge with this climate governance framework, centred around production emissions reduction targets, is where nations might reduce production emissions without reducing consumption emissions by decarbonising industry and increasing imports of the goods and services we consume. This is sometimes called 'offshoring'. For example, a country could close down its steel manufacturing industry and import the steel from another country to meet its consumption needs.

Section 37 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 requires Scottish Ministers to report on annual emissions from Scottish consumption of goods and services. The most recent report providing statistics on Scotland's carbon footprint was published in March 2023 and provides estimates of Scotland's greenhouse gas emissions on a consumption basis for the period 1998 to 2019.

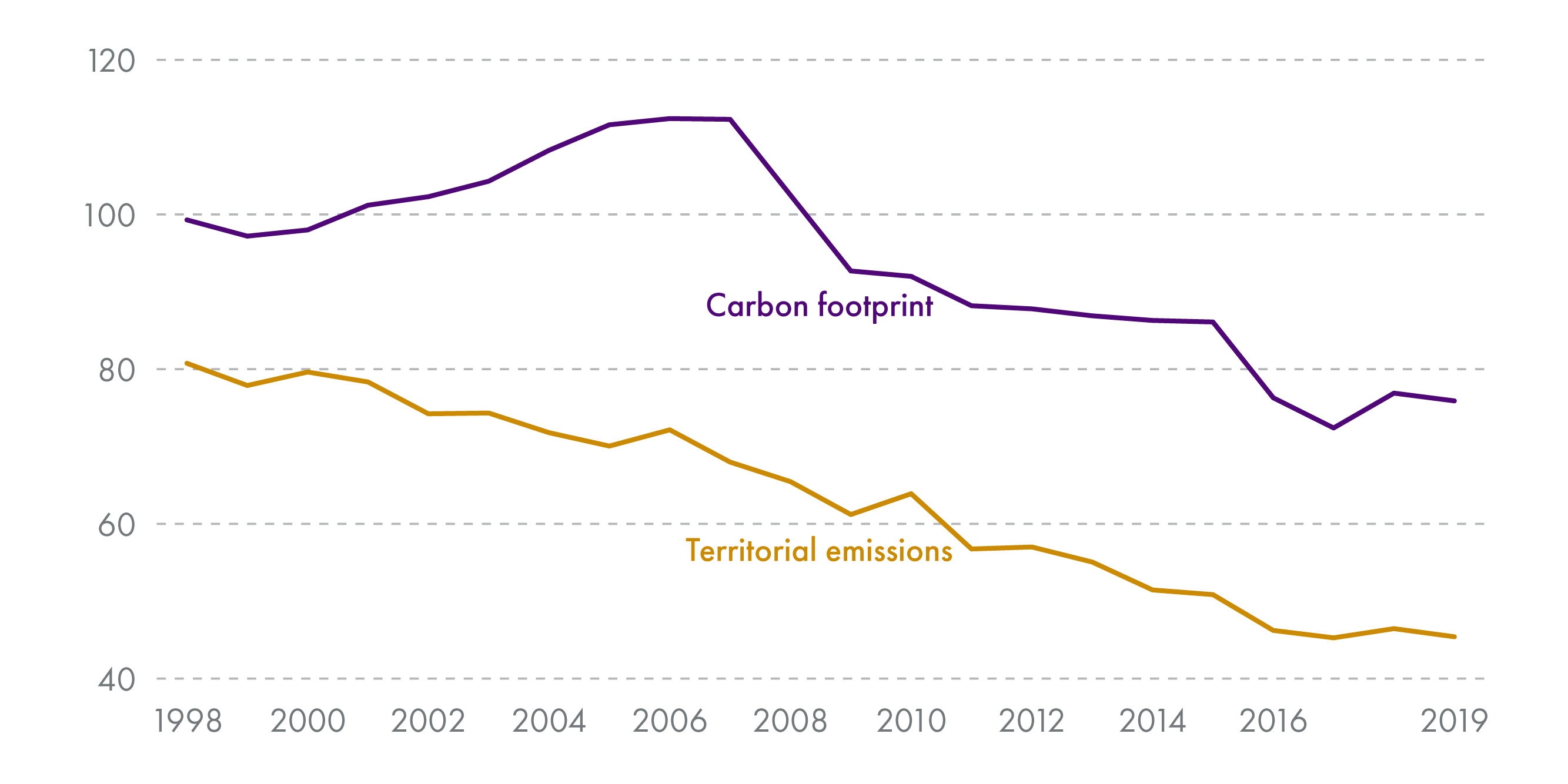

The report shows that Scotland's consumption emissions are notably larger than those based on production accounting. Whilst the carbon footprint (consumption emissions) fell by 23.6 per cent between 1998 and 2019, equivalent greenhouse gas emissions on a territorial basis (production emissions) fell by 43.8 per cent over the same time period. These trends are shown in Figure 4 below.2

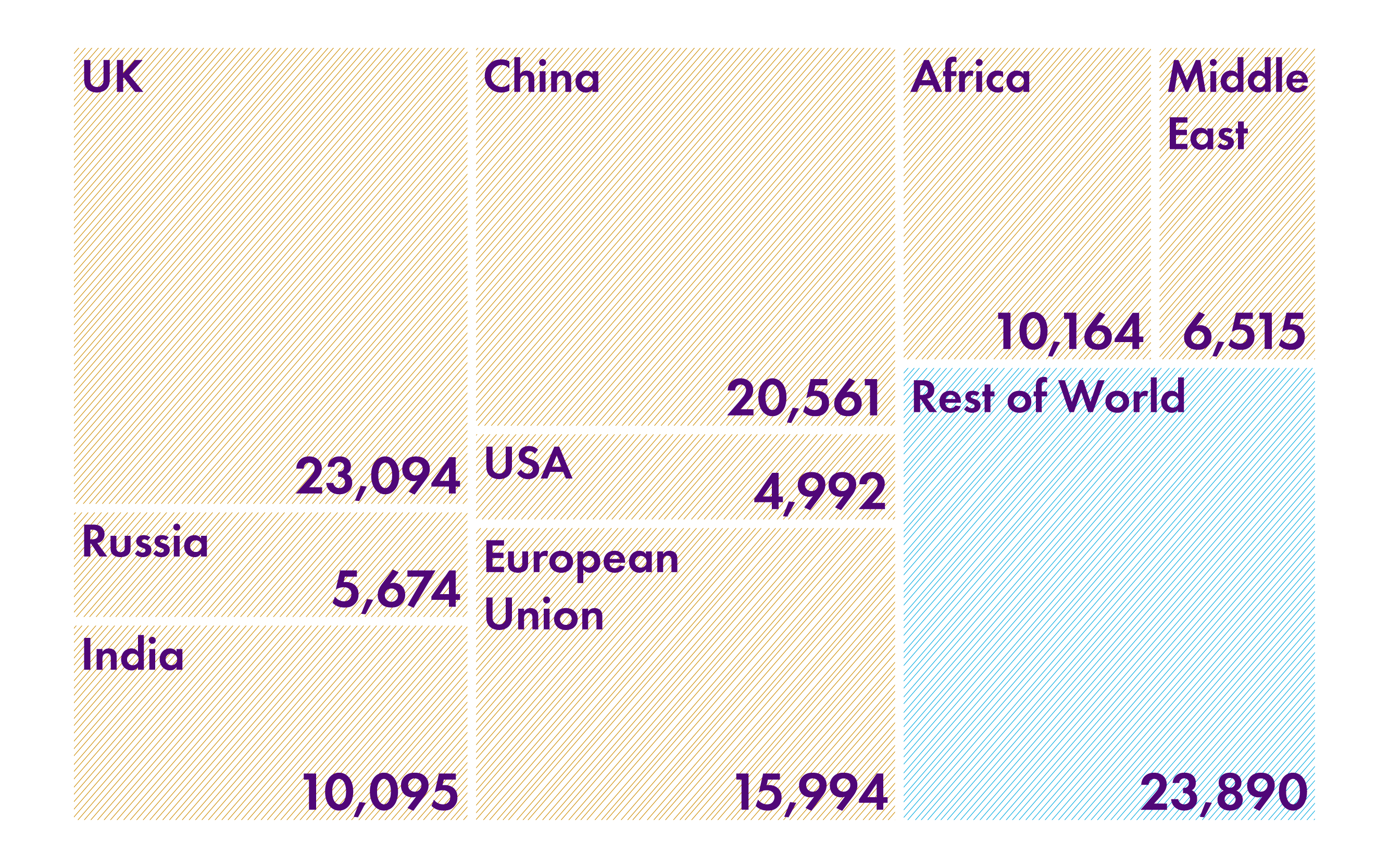

The report also provides a calculation of the the embedded material requirements (goods and services that are produced outwith Scotland) by country of origin in 2019 associated with final consumption in Scotland. In other words, how much of the materials consumed in Scotland come from elsewhere. Figure 5 below provides a breakdown of these statistics.

Environmental Impacts

Environmental impacts of unsustainable consumption could include impacts on the water environment, soil and air quality, pollution of chemicals or plastics, biodiversity and habitat loss e.g. through deforestation and land use change. Those impacts can in turn impact on human health and wellbeing. Selected areas are discussed further below.

Nature conservation and restoration and biodiversity

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) identifies that per capita consumption levels are emerging as a potentially more important driver of biodiversity and ecosystem change than population growth. Furthermore, pollution, climate change, land-use change and natural resource use and exploitation are all identified as key drivers of global biodiversity loss. These drivers are also intrinsically linked to human consumption under a linear economic model.1

The Scottish Government states in its draft 2025 circular economy routemap that "90% of global biodiversity loss and water stress is caused by resource extraction and processing"2. The draft Biodiversity strategy also states:

The global use of natural resources has more than tripled since 1970 and continues to grow. This, in turn, has led to a huge increase in waste of raw and manufactured food and other goods, and an entire industry based on recycling the materials and embodied energy they represent. Both increased consumption and, in response, production is an outcome of people's increasing distance from, and understanding of how the products they consume are produced and their impact on biodiversity and the natural environment more generally.3

A 2023 research report published by NatureScot, Understanding the Indirect Drivers of Biodiversity Loss in Scotland, underlines the multiple ways in which consumption is a key driver of biodiversity loss. For example it states:

"Around 30% of threatened species have been linked to the impacts of global trade and the UK is the 5th ranked country in exporting its biodiversity footprint to other countries: reducing imports with poor sustainability records, improving certification schemes and moving towards a zero-waste society and a circular economy will reduce Scotland's global biodiversity footprint, whilst reporting the environmental impact of imported materials will enable consumers to make choices based on sustainability".

A 2021 report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation identifies how overarching principles of a circular economy can tackle root causes of biodiversity loss:

Eliminating waste and pollution to reduce threats to biodiversity: E.g. eliminating unnecessary plastics and re-designing products to have value post-use so they can circulate in the economy rather than polluting the environment.

Circulating products and materials - to leave room for biodiversity: Reducing demand for natural resources e.g. business models that keep cotton clothing in use for longer could reduce the amount of land needed to grow cotton.

Regenerating nature - to enable biodiversity to thrive. Circular economic activity could rebuild biodiversity. For example, regenerative agricultural approaches such as agroecology and agroforestry.4

Reduced pollution - including plastic pollution

Potentially harmful releases to the environment associated with production and consumption include air pollutant and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, effluent discharges to water bodies, soils and waste, and burdens that are less well recognised, such as noise and light pollution. Releases can occur across every stage of economic activity — from raw material extraction to goods production, consumption and use, and waste material management. 5

One area where it is hoped that a circular economy could have a significant impact is on reducing plastic pollution in the marine environment. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), at least 14 million tons of plastic end up in the ocean every year, and plastic makes up 80% of all marine debris found from surface waters to deep-sea sediments.The Marine Conservation Society state that Beachwatch Volunteers recorded an average of 346 items of litter per 100m of beach surveyed in Scotland during the 2021 Great British Beach Clean.

Plastic pollution harms marine species through ingestion and entanglement6. Plastic pollution also affects many aspects of human well-being: affecting the aesthetics of beaches, blocking drainage and wastewater engineering systems, and providing a breeding ground for disease vectors7. There is also increasing public concern and research about the impacts of microplastics on human health (both via inhalation and ingestion through our diets), although our understanding of impacts is still limited8.

According to a 2020 study, without meaningful action, by 2040 municipal solid plastic waste is set to double, plastic leakage to the ocean is set to nearly triple and plastic stock in the ocean is set to quadruple. It found that that current government and industry commitments to tackle plastic pollution add up to a 7 per cent reduction in plastic pollution to the ocean by 2040 relative to business as usual. However, a more ambitious approach, utilising technology and circular economy approaches, could reduce plastic pollution by 78% by 2040.7

Chemicals

Stakeholders highlight that sustainable use and robust regulation of chemicals is inter-linked with achieving a circular economy. For example, environmental NGO Fidra states in response to the Bill:

Critical to the success of this Bill will be the need to reduce the use of harmful chemicals in products and materials and improve their transparency and traceability to ensure products remain in use for as long as possible and are able to be safely repurposed or recycled. If this doesn’t happen, we will continue to see items such as sofas having to be incinerated due to their persistent organic pollutant contamination which can cause harm to human health and the environment. In Scotland, that is over 125,000 sofas per year.

Chemicals regulation for environmental purposes is a devolved area but intersects with a number of reserved areas, and in practice most regulation takes place at UK-level. A UK Chemicals Strategy is expected to be published in 2023.

ChemTrust and Wildlife & Countryside Link have published a briefing, A UK Chemicals Strategy That’s Fit for Purpose, which underlines the linkages between chemicals regulation and circular economy goals, stating that "Knowing the use to which a chemical will also be put is increasingly challenging as the UK moves towards a circular economy promoting re-purpose, and recycling of goods and materials. Chemicals often end up as contaminants in recycled goods". Policies proposed to be required in order to enable a safe circular economy include more emphasis on transparency of chemicals in products, as well as phasing out hazardous chemicals from non-essential uses.

Socio-economic drivers

The Scottish Government's draft 2025 circular economy routemap states:

a circular economy is not only about protecting our natural environment nor is it just about waste management and cutting our emissions. It holds huge opportunities for our economy, by improving productivity and opening up new markets, and for our communities by providing local employment and access to the goods we need. And a more circular economy is also more self-sufficient – it reduces our reliance on imported goods and materials, and provides increased economic resilience.

Wellbeing economy

The Scottish Government's Economic Recovery Implementation Plan published in 2020 as a response to the pandemic explicitly recognised the linkages between the development of a wellbeing economy, investing in natural capital and transitioning to a circular economy - and states that these are necessary for economic resilience.1 The Scottish Government's National Strategy for Economic Transformation published in March 2022 committed to achieving its vision of a wellbeing economy which is defined as "a society that is thriving across economic, social and environmental dimensions, and that delivers prosperity for all Scotland's people and places. We aim to achieve this while respecting environmental limits, embodied by our climate and nature targets."2 In November 2022, the Scottish Government published its Wellbeing Economy Toolkit which further links transitioning to a circular economy as a necessary component to achieve a wellbeing economy3.

Supply chain resilience

Our current linear economy relies heavily on the supply of virgin raw materials. Events in recent years such as changes to customs processes associated with EU exit, the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have demonstrated the vulnerability of supply chains when the global supply of raw materials is interrupted, with resulting impacts on increasing costs. It is suggested that a circular economy can potentially offer more localised, diversified, and distributed production—through repair, refurbishment, re-manufacturing, and local production4.

A 2020 report by Circle Economy assessed the opportunities and risks to resilience associated with a circular economy. It found that several circular economy policies can increase resilience e.g. by:

in cycling resources, increasing the diversity of raw material supply

in sharing resources, increasing localised management and participation.

It also explored risks to resilience of circular economy policies, for example if designing out redundancies and over-supply in supply chains might increase supply chain vulnerability.5

Job creation and security

The 2020 resilience assessment by Circle Economy found that labour markets in a circular economy require ample skills transferability, and could increase the labour market's recovery in times of crises of shocks. It suggests that in supporting lifelong learning, individuals and companies can quickly develop solutions, experiment and be less at risk of job-loss. 5

The Scottish Government's circular economy routemap also recognises opportunities for job creation in a circular economy:

Delivering a circular economy provides local employment opportunities and lower cost options to access the goods we need. 10,000 tonnes of waste can create up to 296 jobs in repair and reuse, compared to 1 job in incineration, 6 jobs in landfill or 36 jobs in recycling. This represents a profound opportunity to support communities and stimulate job creation.

Consumer benefits

A circular economy approach may provide benefits to consumers such as:

More durable and innovative products through emphasis on re-use and repairability and discouraging practices such as planned obsolescence (a business strategy in which the obsolescence of a product is planned and built into it).7

Reduced costs through emphasis on practices like buying used items and leasing or renting instead of owning.8

Health and wellbeing benefits

Potential health benefits of circular economy approaches have been suggested. For example, a 2022 report by Public Health Wales identified potential "positive impacts of reduce, reuse, and recycle, as part of a wider circular economy approach" as including:

improved air quality

an "indirect" pathway to addressing the climate emergency with associated health benefits of avoiding catastrophic climate change

improvements to diet through more sustainable production of food

improved mental health and wellbeing.

There is also an increasing body of evidence that excessive materialism and consumerism has links to poorer mental health91011.

Value recovery

Circular economy interventions can seek to ensure or encourage that more of the maximum value is extracted from products - for example by consumers themselves or in how product disposal is handled and value recovered e.g. as opposed to valuable materials being landfilled, incinerated or exported without recovering value.

The Scottish Government's 2016 Making Things Last Strategy for example stated that between 2016 and 2020, in Scotland we were expected to import "about £50 million worth of gold into Scotland hidden away in our TVs, mobile phones and computers", but expected to recover "just a tiny fraction of that".

Existing circular economy policy, laws and targets

Key circular economy and waste policy

The Scottish Government's intention to support the development of a circular economy is already set out in a number of key government strategies, including:

Scotland's Environment Strategy: Vision and Outcomes (published 2020) - an overarching framework for climate and environmental policy strategies. It recognises the need for Scotland to transition to a circular economy, and includes commitments to reduce the global impact of our consumption, end 'throwaway' culture, and gather evidence on the nature of Scotland’s international environmental impact.

Making Things Last - Scotland's First Circular Economy Strategy. The Scottish Government published its first Circular Economy Strategy in 2016 stating that the transition to a circular economy was "an economic, environmental and moral necessity".

The Scottish Government published 'Delivering Scotland’s circular economy A Route Map to 2025 and beyond' for consultation in May 2022. This routemap provides wider context for the Bill given a number of circular economy interventions are being planned or pursued using existing powers or non-legislative means. Proposed priorities in the route map are to:

Promote responsible consumption and production including reducing consumption of single-use items, promoting product design and stewardship and mainstreaming reuse

Reduce food waste from households and businesses

Improve recycling from households and businesses

Embed circular construction practices

Minimise the impact of disposal of waste that cannot be reused or recycled

Strengthen data and evidence, sustainable procurement, skills and training

The Scottish Government's Economic Strategy, Delivering Economic Prosperity(published March 2022) identifies the circular economy as one of Scotland's 'current and future key industries', with opportunities for creating new markets, innovation and jobs.

The 2020 Climate Change Plan update (published December 2020) included a number of circular economy commitments, including:

To embed circular economy principles in to the wider green recovery

Recognising the importance of tackling consumption emissions

Milestones for 2032 and 2045, where by 2045 "we will have moved completely from a ‘take, make and dispose’ linear economy to a fully circular economy".

The fourth National Planning Framework (NPF4) (published 13 February 2023) seeks to support the circular economy through policies aimed at transitioning to a more circular construction sector, as well as policies on waste management infrastructure.

Key circular economy policy interventions to date

Some significant policy interventions made by the Scottish Government aimed at supporting the transition to a circular economy include:

A ban on biodegradable municipal waste going to landfill by 2025. The following section of the briefing shows progress towards this. The landfilling of biodegradable municipal waste was banned from 2021 under the Waste (Scotland) Regulations 2012. The Scottish Government subsequently delayed enforcement until 2025.

In 2022 a single-use plastics ban came into force for a number of items including plastic cutlery, plates and stirrers.

Current and previous funding includes:

The Scottish Government launched a £70 million five-year Recycling Improvement Fund in 2021 to provide capital funding grants for local authorities to improve recycling infrastructure and services

Now closed, an £18 million Circular Economy Investment Fund, was disbursed by Zero Waste Scotland (originating from European Regional Development Funds), to Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs) for circular economy business innovation.

Zero Waste Scotland provides various forms of support through its Circular Economy Business Support Service.

Regulations were approved by the Scottish Parliament in 2020, following a consultation in 2018, with a view to introducing a Deposit Return Scheme (DRS) for single-use drinks containers. The introduction of the scheme, originally planned for 2021, has been delayed by a number of factors, including most recently the question of interoperability of UK schemes under the market access principles of the UK Internal Market Act, which led the Scottish Government to delay implementation of the scheme until earliest October 2025.

The Scottish Government commissioned a review of Energy from Waste infrastructure due to concerns about the compatability of levels of incineration of waste with net zero and other environmental goals. As part of its response to this review, updated planning policies in relation to energy from Waste (EfW) infrastructure were set out in the fourth National Planning Framework (NPF4).

UK-wide interventions (in devolved areas)

Some key circular economy interventions have taken place, or are being developed, at UK-level. In some areas such as eco-design standards for products, there can be a complex mix of devolved and reserved competence. In the draft 2025 circular economy route map, the Scottish Government states:

The Bill will increase the levers we have available to us and the Route Map sets out actions to accelerate progress within devolved competence, but some of the policy measures required to drive the transition to a fully circular economy are dependent upon UK Government action. We are working with the UK Government and other Devolved Administrations on some key measures, like reform of the packaging producer responsibility system, but it is vital the UK Government steps up to accelerate action in other areas.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes are currently being developed across the UK for packaging, waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE), batteries, and accumulators. EPR schemes set out to make producers responsible for the environmental costs of the items that they place onto the market, for example in order to incentivise product design change. Plans in this area are summarised in the consultation on the proposed circular economy routemap to 2025 and beyond.

Other devolved areas relevant to the circular economy, but which tend to be organised on a UK-wide basis (and again can engage a mixture of reserved and devolved areas), include UK-wide approaches to chemicals regulation and the UK Emissions Trading Scheme (for example the draft 2025 circular economy routemap sets out proposals to consult with other UK governments on expanding the UK Emissions Trading Scheme to include Energy from Waste).

The UK and devolved Governments have also set out a provisional Common Framework setting out how they plan to work together on resources and waste.

Reserved areas relevant to the circular economy

A number of potential levers for supporting the transition to a more circular economy are reserved, such as reserved fiscal and economic policy e.g. VAT, product labelling, aspects of energy policy and global trade policy. Examples of key interventions in reserved areas include a plastics packaging tax which came into force in 2022. There has also been disagreement between the Scottish and UK Governments about the extent of devolved competence in areas such as mandatory due diligence requirements for business and finance to tackle the environmental impacts of global supply chains (highlighted for example when the UK Government imposed requirements on UK businesses to assess their supply chains for 'forest-risk commodities' via the Environment Act 2021, which the Scottish Government considered to be a devolved area). There is potentially still a discussion around what the scope of devolved levers are to tackle global supply chain impacts on the environment.

Scottish waste targets and trends

To date, targets in circular economy policy have centred around waste and recycling. Key Scottish Government targets are to:

reduce Scotland's waste by 15% by 2025 (against 2011 levels)

recycle 70% of all waste by 2025

recycle 60% of all household waste by 2020 (this target has been missed)

reduce food waste by 33% by 2025 (against 2013 levels)

reduce the percentage of all waste sent to landfill to 5% of all waste by 2025

end the landfilling of biodegradable municipal waste - with a ban coming into force from 31 December 2025.

The Scottish Government has stated in its draft 2025 circular economy route map that 2025 waste and recycling targets are unlikely to be met without large-scale, and rapid system change.

The following sections summarise progress against each of these targets alongside selected other waste data. SEPA is responsible for reporting national waste statistics and publishes various annual waste and recycling data. Waste data reporting was disrupted by a cyberattack on SEPA in 2020, resulting in some data gaps for 2019 and 2020. Given that key waste data is lacking for this period, and during 2021 the Scottish economy was significantly disrupted by the pandemic, SEPA suggest care should be taken in comparing recent waste data with longer term trends.

To reduce Scotland's total waste by 15% by 2025 (against 2011 levels).

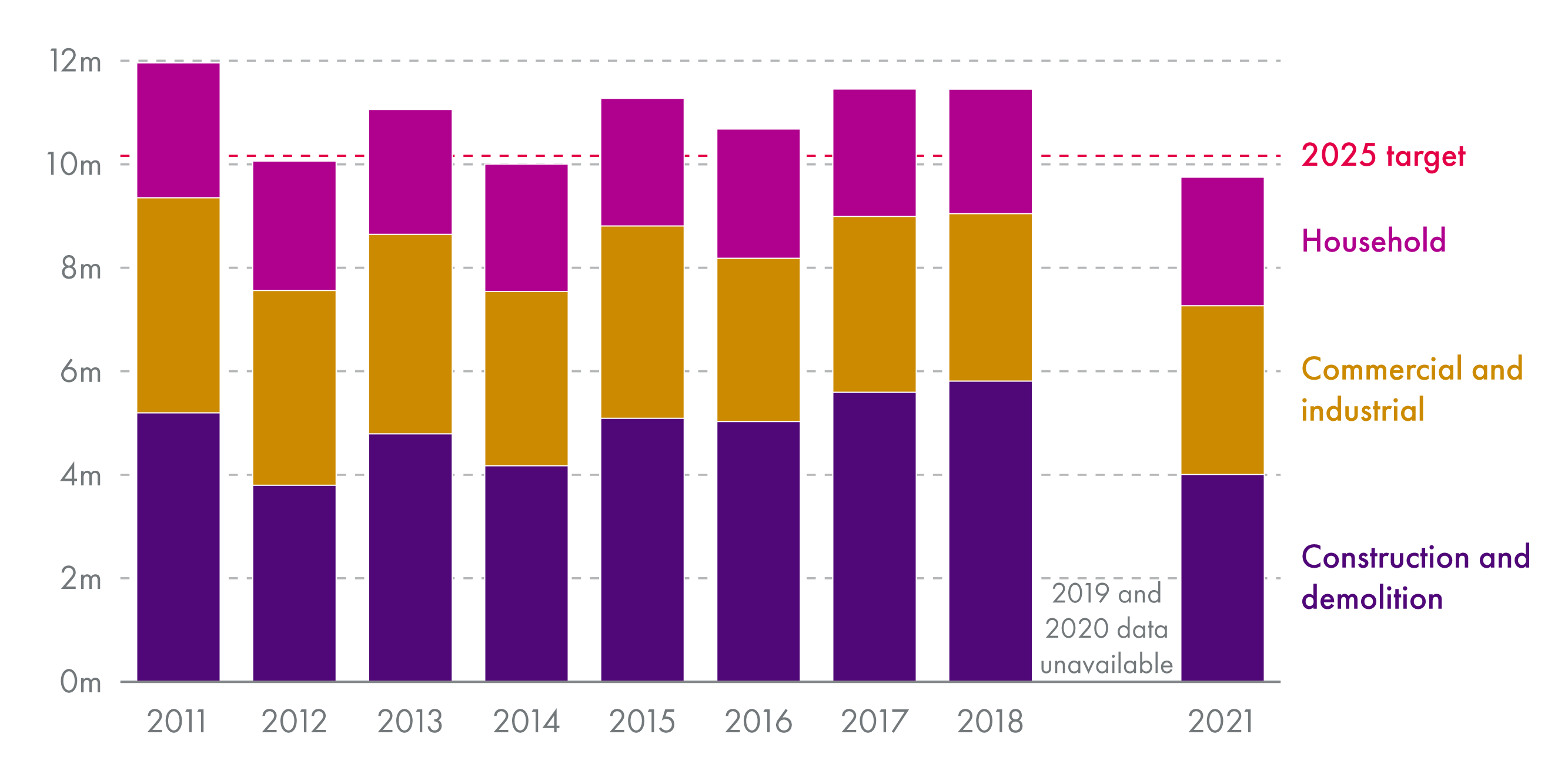

The estimated total quantity of Waste From All Sources (WFAS) generated in Scotland in 2021 was 9.75 million tonnes, a reduction of 14.8% (1.70 million tonnes) from 2018 and a reduction of 18% compared to the baseline year of 2011. Figure 6 below shows the composition of Scottish WFAS by category and progress against the 2025 target to reduce waste by 15% by 2025 from 2011 levels.

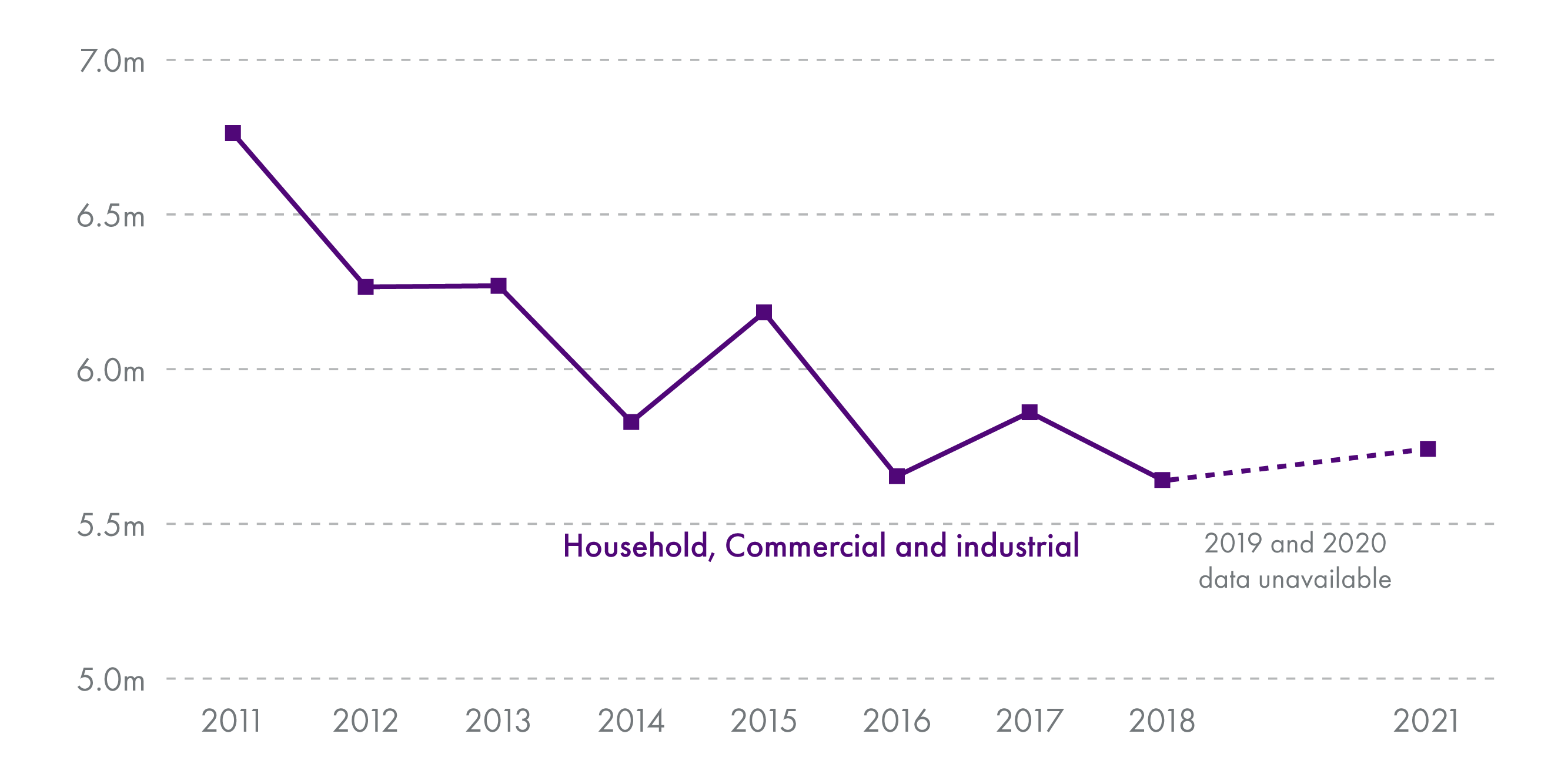

Whilst the 2025 target was met in 2021, and two of the other eight years in the above graph, SEPA emphasise that waste generated year-on-year is strongly influenced by fluctuations in Construction and Demolition waste, which is sensitive to large projects which can cause significant year-on-year variations. This can lead to challenges in interpreting the general waste trend. When Construction & Demolition waste is excluded, the waste generation trend has been generally downward for the 2011 – 2021 period, a reduction of around 15% (see Figure 7 below).

2. To recycle 70% of all waste by 2025.

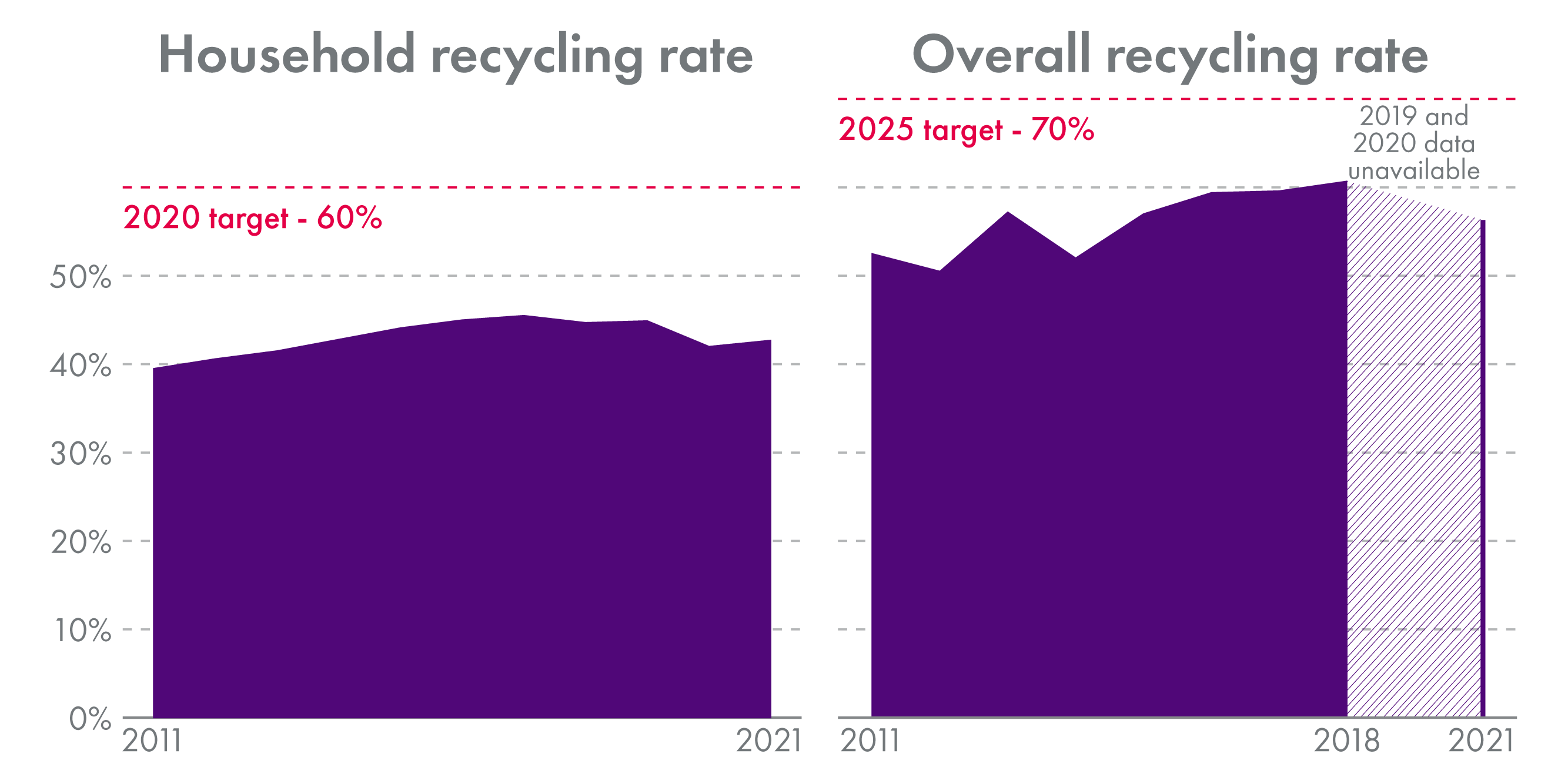

The WFAS recycling rate in 2021 was 56.3%, a decrease from the 60.7% of waste recycled in 2018. SEPA state that the reduced recyling rate "reflects a marked reduction in waste in construction and demolition wastes, such as soils and mineral wastes, which typically have a relatively high recycling rate".

Whilst long-term progress has been made with recycling towards the target of 70% by 2025 (from 52% in 2011 to 61% in 2018), progress has also somewhat flatlined over the past few years of available data, and according to 2021 figures has fallen to pre-2015 levels (see Figure 8 below). In 2021, a drop in the recycling rate to 56% was observed. This was the first available data point following the onset of the pandemic, which SEPA states is likely to have impacted on recycling levels.

3. To recycle 60% of all household waste by 2020 - target missed.

The 2020 target to recycle 60% of household waste has been missed with rates stalling for several years following previous increases from 40% in 2011 to 46% in 2017. In 2021, the household recycling rate was 42.7%, a slight increase from the 42% figure in 2020 (see Figure 8 below), with both years likely to have been impacted by the pandemic. The highest level was in 2017 when the household recycling rate was 45.5%.

SEPA state that the small "increase in waste recycled between 2020 and 2021 is likely due to a bounce back from the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown and other restrictions in 2020, in which the amount of waste recycled and the waste recycling rate was the lowest recorded since 2013".

4. To reduce food waste by 33% from the 2013 baseline by 2025.

Zero Waste Scotland's report ‘How much food waste is there in Scotland?’ published in 2016 is considered to provide the best insight to date on the scale of food and drink waste. In 2013 (with a view to establishing the baseline for a target), an estimated 987,890 tonnes of food and drink in Scotland was wasted, broken down as follows:

Household (solid and liquid waste) – 598,946 tonnes (60.6%)

Food and drink manufacturing – 248,230 tonnes (25.1%)

Other sectors – 140,714 tonnes (14.2%)

Food losses incurred in primary production are currently excluded from these baseline figures. Zero Waste Scotland state that:

The report shows that just under half of food waste comes from households, with the majority arising from industry and commercial enterprise. It highlights the need to work with business to reduce food waste from farm to fork.

Zero Waste Scotland also estimate that household food waste accounts for 2,240,000 tonnes CO2e which represents 2.9% of Scotland's carbon footprint.1

There are currently very little data on progress towards reducing food waste in Scotland. On 22 June 2023, Gillian Martin MSP, Minister for Energy and the Environment stated that the Scottish Government "aim to publish an estimate on food waste levels in Scotland in the coming months". The draft 2025 circular economy routemap states:

In 2018, food waste in Scotland was estimated to be 4% below the 2013 baseline, broadly in line with the UK reduction reported by WRAP. There is some evidence that the COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020 led to a 43% reduction in household food waste across the UK, but this appears to have rebounded as lockdowns have relaxed. While there is a high degree of uncertainty around food waste data, we are clear that we are not seeing the speed and scale on change we would need to meet the 33% target.

Food waste is not just an environmental issue. In 2021, 9% of adults surveyed were worried about running out of food due to a lack of money or other resources. Levels of food insecurity did not change significantly between 2017 and 2021. 2

5. To reduce the percentage of all waste sent to landfill to 5% of all waste by 2025.

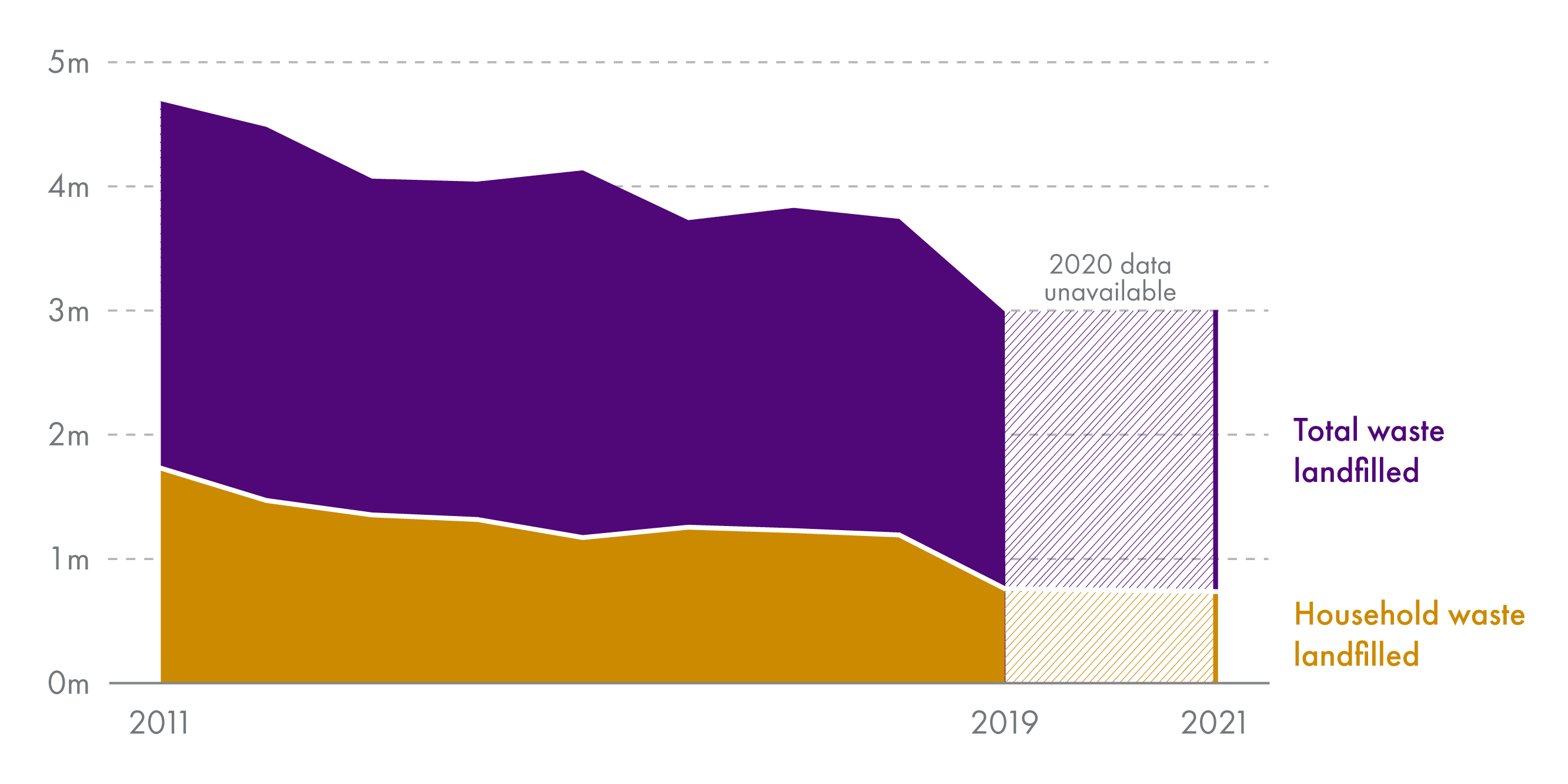

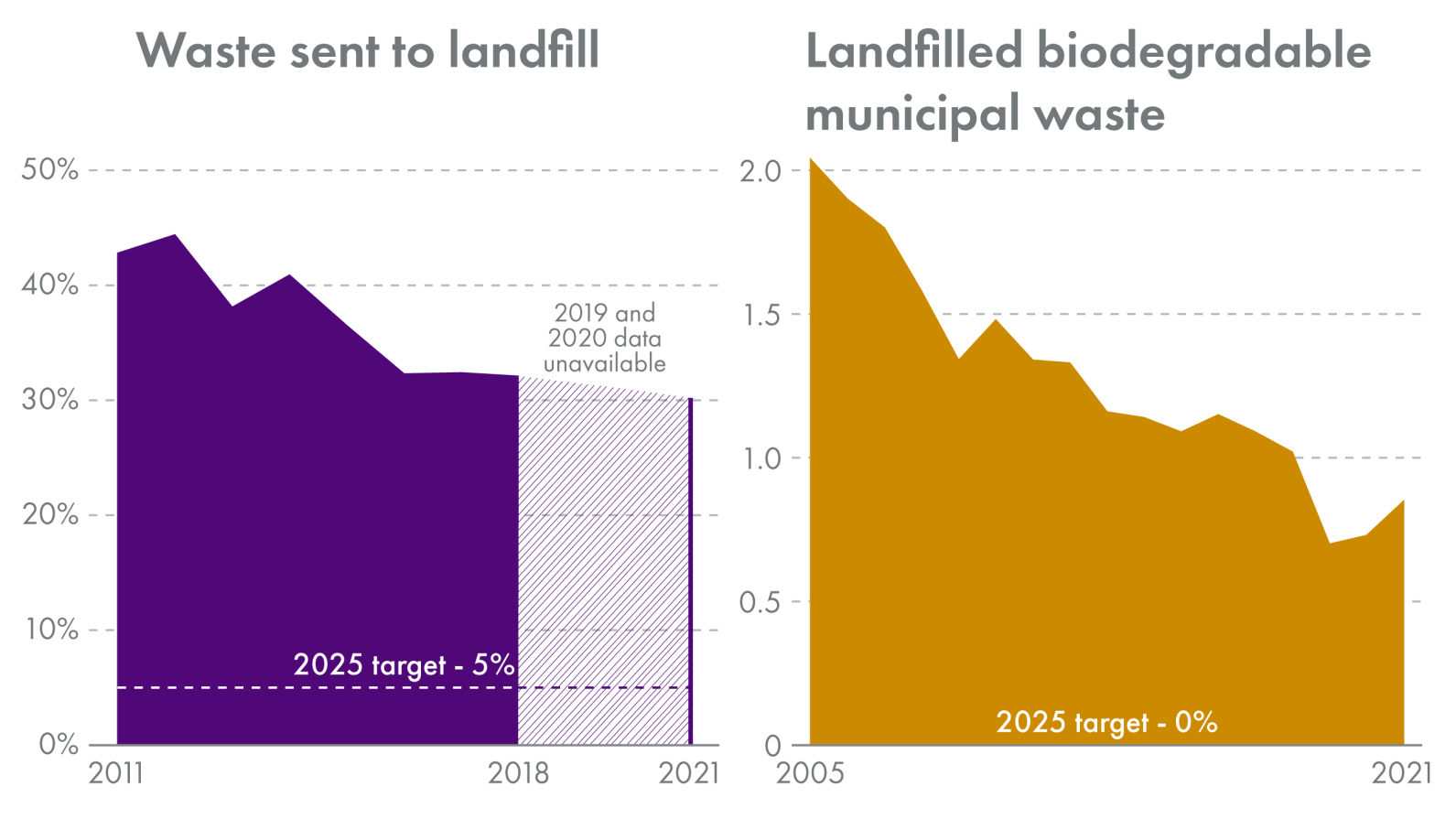

In 2021, Scotland sent 3.00 million tonnes (Mt) of waste to landfill, a slight increase of 11,000 tonnes (0.4%) from the 2.99 million tonnes landfilled in 2019. The longer-term trend is of decreasing disposal to landfill (see Figure 9 below), from 4.7 million tonnes in 2011 to 3.0 million tonnes in 2019. In percentage terms, in 2021 30.2% of all waste was sent to landfill. This proportion has been slowly dropping towards the 5% target (see Figure 10 below), but clearly, as recognised in the 2025 routemap, the 2025 target is unlikely to be met without rapid changes.

6. To end the landfilling of biodegradable municipal waste - with a ban coming into force on 31 December 2025.

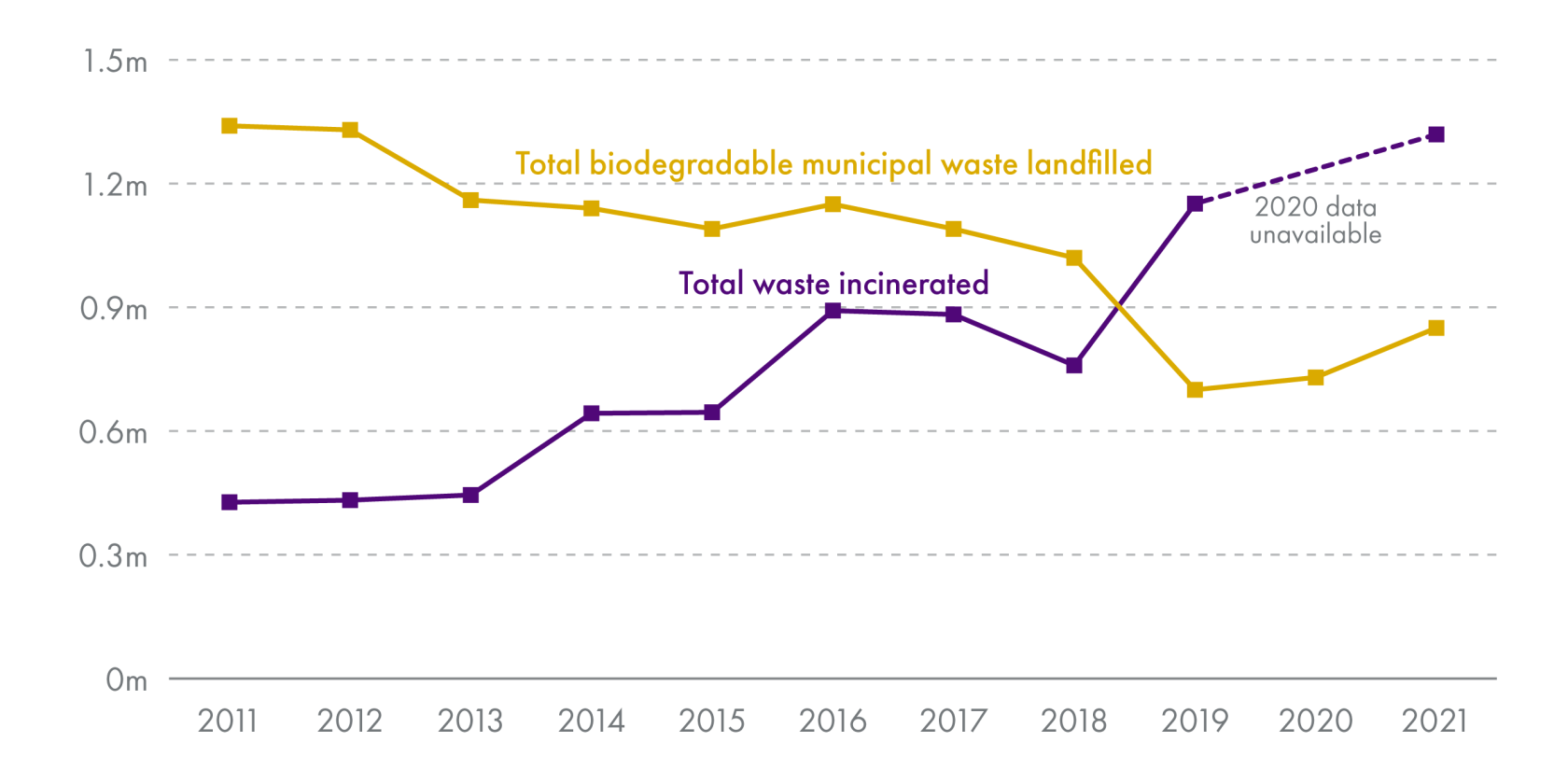

In 2021, 0.85 million tonnes of biodegradable municipal waste (BMW) was sent to landfill. Between 2005 and 2020, the amount of BMW sent to landfill has more than halved, with a significant drop between 2018 and 2019, however there has been a slight increase since 2019 (see Figure 10 below). The overall trend is considered to reflect increased recycling, the impacts of Scottish landfill tax and other preparations for the 2025 ban on BMW being sent to landfill - including diversion to incineration.

Incineration trends and 2022 review

Over the same period in which total BMW landfilled has decreased, there has been an increase in incineration in Energy from Waste facilities in Scotland. In 2021, 1.32 million tonnes of Scottish waste was incinerated, an increase of 168,000 tonnes (14.6%) from 2019, following the longer-term trend of increasing incineration of waste (see Figure 11 below).

In May 2022, the Scottish Government published an independent Review of the Role of Incineration in the Waste Hierarchy in Scotland.3 The aim of the review was to ensure that the management of residual waste in Scotland aligns with Scotland's carbon reduction ambitions. The review provided a view on how incineration should be managed in the context of a circular economy transition:

Incineration should be thought of as a transitional technology that helps Scotland bridge the gap from mass landfill to a low waste, low carbon, more circular economy. We are currently in the growth phase, but as set out by several stakeholders, if Scotland is to meet its resource and waste management and climate change mitigation targets, there will be a corresponding future phase down. Planning by central and local government for how to manage this is essential to avoid unnecessary expense or environmental damage.

Key related legislation

Waste legislation including the waste hierarchy

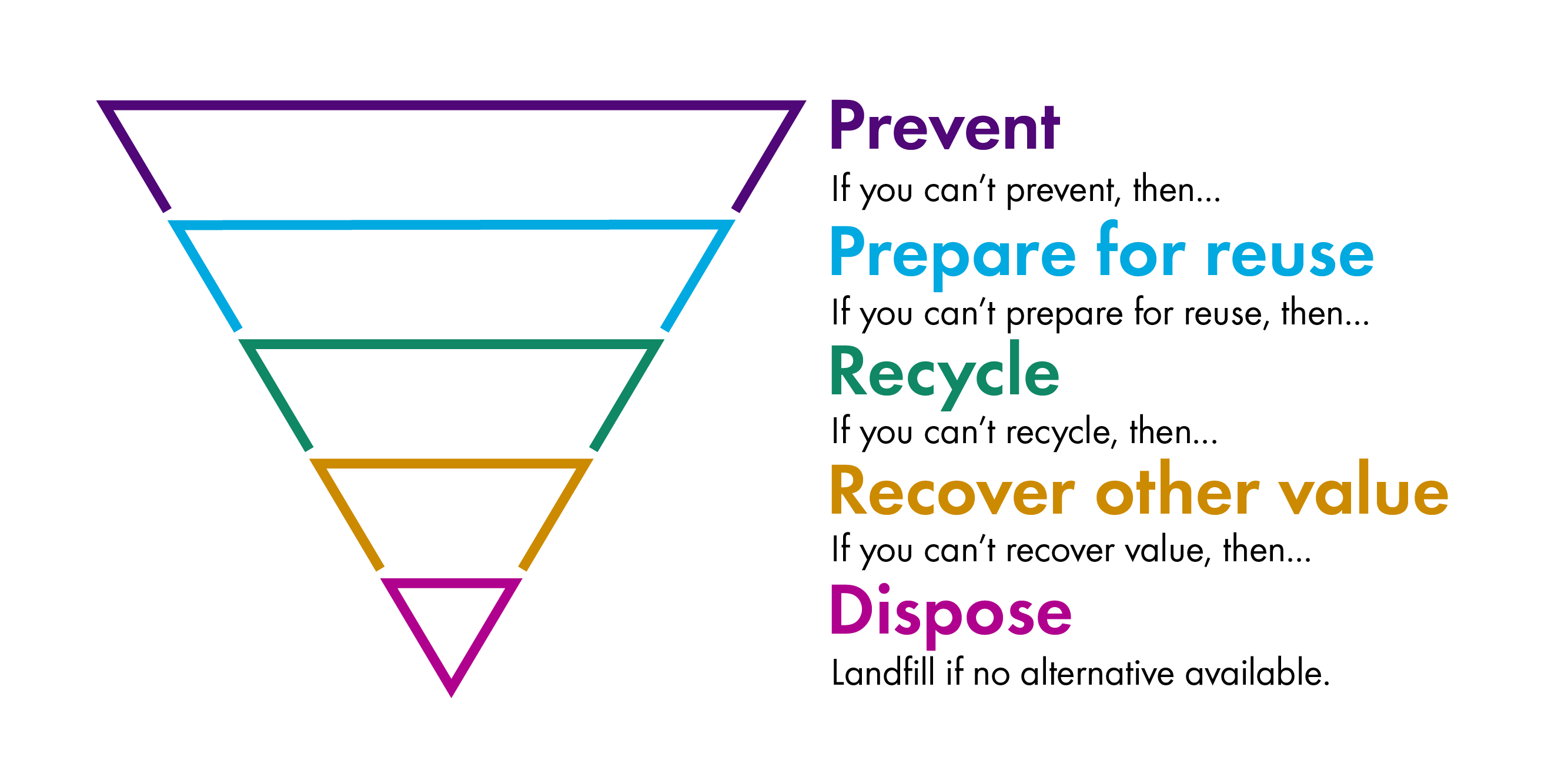

Whilst the concept of the circular economy is only more recently becoming embedded in policy and legislation, the concept is closely related to the 'waste hierarchy' (see Figure 12 below) which has been embedded in Scottish law since 2008 in relation to production and disposal of waste - introduced to transpose requirements of the EU Waste Framework Directive.

Under the waste hierarchy, waste prevention through efficient use and reuse of resources, recycling and recovery of value should be prioritised in that order, with landfill or other disposal a last resort (see Figure 12). Section 34 of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 (as amended) makes it the duty of everyone (with the exception of occupiers of domestic properties as respects the household waste produced at those properties) who produces, keeps or manages controlled waste, or as a broker or dealer has control of such waste, to take reasonable measures to apply the waste hierarchy. Producers of waste also have a duty under the Act to take reasonable steps to increase the quantity and quality of recyclable materials.

Climate legislation

The Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 gave Scottish Ministers powers in a number of areas relevant to the transition to a circular economy including to:

establish Deposit Return Schemes (DRS)

require specified persons to produce waste prevention or management strategies

require specified persons to report on waste produced

set targets for the reduction of packaging

require charging for the supply of single-use carrier bags.

The Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019 amended the 2009 Act to include a requirement for a climate change plan - which must include policies and proposals in specified sectors including in waste management (although circular economy policies could cut across all sectors specified, not just waste management).

In preparing climate change plans, the 2019 Act requires that Scottish Ministers must have regard to both just transition principles, and the climate justice principle. The climate justice principle is defined as including the importance of taking action to reduce global emissions of greenhouse gases. In other words, the importance of tackling Scotland's consumption emissions is recognised in existing climate legislation.

Environmental Protection Act 1990

The Environmental Protection Act 1990 gives Scottish Minsters powers to prohibit or restrict the importation, use, supply or storage of "injurious substances or articles", where that is considered appropriate for the purpose of preventing "pollution of the environment or harm to human health or to the health of animals or plants". These powers were used by the Scottish Government for example to ban certain single-use plastics in 2021 via the Environmental Protection (Single-use Plastic Products) (Scotland) Regulations 2021.

UK Environment Act 2021

Whilst the UK Environment Act 2021 largely does not apply to Scotland, Scottish Minsters have powers under the Act (these powers are concurrent with the UK Secretary of State who could introduce UK-wide regulations with devolved administrations' consent) to introduce regulations for:

establishing producer responsibility schemes

setting resource efficiency requirements for products placed on the market

requiring that resource efficiency information is available on products.

Public body duties

Some existing legal duties on Scottish Ministers and other public bodies are potentially relevant to the development of a circular economy, notably:

The sustainable procurement duty set out in the Procurement Reform (Scotland) Act 2014.

Public body duties under Part 4 of the Climate Change Act 2009. Scottish Government guidance on these duties states that "Waste management is a key area as all organisations produce waste and all bodies can, through their own waste treatment decisions, influence the way waste is managed in society and businesses".

UK Internal Market Act 2020

The UK Internal Market Act (2020) or 'UKIMA' established two Market Access Principles of mutual recognition and non-discrimination to preserve the ability to trade unhindered in every part of the UK. This was a post EU exit measure, to seek to provide a replacement framework for the UK internal market, which was previously underpinned by membership of the EU Single Market. There is background to the Act and its potential implications for circular economy policy in a 2020 SPICe blog. The mutual recognition principle for goods provides that goods which have been produced or imported into one part of the UK, and which can be sold or supplied there without contravening any relevant requirement, can be sold in any other part of the UK, free from any relevant requirements which would otherwise apply.

The Act means that where the Scottish Government wishes to introduce new, divergent standards in pursuit of a circular economy which are different from the rest of the UK (or being introduced earlier than the rest of the UK, such as the single-use plastics ban), and engage these two principles, this may require agreement with the UK Government on an exclusion from the UK Internal Market Act principles. The process for this is set out in a SPICe blog. The full implications of UKIMA on the future development of circular economy policy, how the UK and devolved governments will work together to advance a circular economy under the UKIMA framework, and what level of policy divergence across the UK will be possible, largely remains to be seen. There have been early examples of significant disagreement (e.g. the Deposit Return Scheme) as well as apparent agreement (e.g. the single-use plastics ban).

International developments (including EU Circular Economy Programme and 'keeping pace' considerations)

EU Circular Economy Programme

Following the UK's departure from the EU there is no longer a requirement to continue to comply with EU law. However, Scottish Ministers have indicated that, where appropriate, they would like to see Scots Law continue to align with EU law. The Scottish Government's Environment strategy: Vision and Outcomes states "We will seek to maintain or exceed EU environmental standards".

EU waste and circular economy policy has been a key driver of Scottish and UK-wide legislation and policy. The Waste Framework Directive, for example, which has now been subject to many amendments, established the waste hierarchy, minimum waste targets, and frameworks in areas such as producer responsibility. The Ecodesign Directive established a framework for reducing the energy intensity of a number of products. The WEEE Directive introduced rules with the aim of reducing the environmental impacts caused by end-of life electronic and electrical items.

The European Commission adopted a new circular economy action plan (CEAP) in March 2020. It is one of the main building blocks of the European Green Deal, Europe's new agenda for sustainable growth. The CEAP policy framework is focussed around three key principles:

Designing sustainable products: a sustainable product legislative initiative to widen the Ecodesign Directive beyond energy-related products, with aims to improve product durability, reusability, upgradability and repairability, addressing the presence of hazardous chemicals in products, and increasing energy and resource efficiency.

Empowering consumers and public buyers: proposals include a revision of EU consumer law to ensure that consumers receive trustworthy and relevant information on products including on their lifespan and on the availability of repair. The Commission will also consider further strengthening consumer protection against green washing and premature obsolescence, and the Commission has committed to work towards establishing a ‘right to repair’.

Circularity in production: Proposals include assessing options for further promoting circularity in industrial processes.

Since March 2022, the European Commission has adopted a package of measures proposed in the circular economy action plan. This includes:

A Sustainable Products Initiative: including the proposal for the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation.

Proposal for a revised Construction products Regulation: including requirements for greener and safer construction products.

Proposal for empowering consumers in the green transition: aims to ensure consumers get adequate information on products’ durability and repairability before purchasing.

Revision of EU rules on Packaging and Packaging Waste including measures such as:

targets for packaging waste reduction in Member States and mandatory reuse or refill targets in sectors such as retail and catering

EU-wide standards for over-packaging

design criteria for all packaging to increase recycling rates

mandatory compostability for some packaging

mandatory deposit return system for plastic bottles and aluminium cans

Labels on all packaging to facilitate correct waste sorting by consumers.

Communication on a policy framework for biobased, biodegradable and compostable plastics with the aim of improving the understanding around these materials.

Proposal on common rules promoting repair of goods which introduces a ‘right to repair'.

Proposal for a Directive on green claims to stop companies from making misleading claims about environmental merits of their products and services.

Measures to reduce the impact of microplastic pollution on the environment.

Other international developments - Irish Circular Economy Bill

The Circular Economy and Miscellaneous Provisions Act 2022 was passed in Ireland in 2022 and:

defines the Circular Economy for the first time in Irish domestic law

incentivises the use of reusable and recyclable alternatives to a range of single-use disposable packaging and other items (including through powers to set levies)

re-designates Ireland's existing Environment Fund as a Circular Economy Fund, which will be ring-fenced to provide support for environmental and circular economy projects

introduces a mandatory segregation and incentivised charging regime for commercial waste, similar to what exists for the household market. This aims to increase waste separation and support increased recycling rates

provides for the use of a range of technologies, such as CCTV for waste enforcement purposes, to support efforts to tackle illegal dumping and littering

places Ireland's Circular Economy Strategy and National Food Loss Prevention Roadmap on a statutory footing, establishing a legal requirement for governments to develop and periodically update these policies

consolidates the Irish Government’s policy of keeping fossil fuels in the ground – by introducing prohibitions on exploration for and extraction of coal, lignite and oil shale.

On introducing new levies on single-use items, the Irish Government states that:

As it passed through the Dáil, the Act received broad cross-party support to introduce levies on all single-use packaging over time and where more sustainable alternatives are available and it comprises more social protections, including measures to protect low-income households and people with disabilities.

The Irish Government also states that under the Act, over time, a range of single-use disposable products will be phased out. The process will begin with a ban on the use of disposable coffee cups for sit-in customers in cafés and restaurants, followed by introduction of a charge on disposable cups that can be avoided completely. The Act also allows for levies on all single-use packaging to be introduced.

Debates leading up to the passing of the Irish Act include discussions of the function and impact of national legislation on the circular economy in the context of international markets, supply-chains and market forces, and the potential for environmental issues to continue to be exported e.g. where waste can be exported to avoid increasing restrictions - highlighting the need for global as well as national action.

Other international developments - regional circular economy laws

In March 2023, the Regional Government of Andalusia in Spain passed Law 3/2023 of 30 March on the Andalusian Circular Economy (Ley 3/2023, de 30 de marzo, de Economía Circular de Andalucía) - the first circular economy law to pass in the country. Amongst other things, the new legislation provides for:

the creation of the Andalusian Office of Circular Economy and preparation of a Andalusian Strategy for the Circular Economy

the incorporation of environmental and circular clauses for public procurement

increased analysis of the life cycle of products, public works and services - including establishing an Andalusian Public Registry of Life Cycle Analysis.

Securing circular economy benefits - academic critique of the circular economy model

A circular economy is not an end in itself - it is generally expressed as transition that is necessary to tackle the negative environmental and socio-economic impacts of unsustainable consumption.

Some research on the circular economy model highlights a risk that circular economy interventions which seem intuitively beneficial, unless carefully designed, may not have the intended benefits, or could even have unintended negative consequences. This can be described as the possibility for 'rebound effects'1.

For example, secondary production of goods using recycled material could increase overall demand or supply of goods rather than displace primary production e.g. increasing our consumption of used clothes may not displace our consumption of virgin textiles if that displacement is not incentivised. This potential risk of 'rebound effects' has led some academics to argue that a circular economy will only have environmental benefits where it fundamentally reduces production and consumption1.

Even more broadly, there is discussion around to what extent, circular economy interventions will be able to successfully tackle the twin climate and nature crises within economic systems that prioritise growth. A 2023 NatureScot research report on drivers of biodiversity loss highlights challenges of tackling cultural factors where we have strong ties to increasing consumption, and consumption which depletes nature has been strongly linked to measurements of economic growth.

The Scottish Government's economic strategy aims to deliver economic growth but also commits to creating a wellbeing economy acknowledging that "the narrow pursuit of growth at all costs, without resolving the structural inequalities in our communities or respecting environmental limits, is reductive."3

There is an argument that circular economy interventions, where they result in circularity of resource use, act to 'decouple' economic growth from consumption of finite resources, and is regenerative by design, creating the foundations for sustainable economic growth4.5

However, recent academic debate has also questioned the circular economy concept on the grounds that it will not be able to decisively reduce environmental impacts where it supports economic growth. Some researchers have argued that both energy and material consumption are so tightly linked to economic activity that the circular economy in its current form is not likely to be able to decouple this link. 6 A recent research article argues that past experience has shown that efforts to increase resource efficiency have not led to the desired reduction in resource consumption, because efficiency gains can drive further increases in consumption (known as Jeavons' Paradox).7 Some academics consider the only long-term viable solution is a post-growth or steady state approach to our economies.7

A full discussion of rebound effects, and whether a circular economy is compatible with goals of economic growth is outwith the scope of this briefing. It is likely however, that these issues will be subject to further academic debate and research as more countries adopt, define and seek to measure the impact of circular economy strategies.

Circular Economy Strategy

What the Bill does - sections 1 - 5

Sections 1 to 5 of the Bill set out requirements for Scottish Ministers to prepare a circular economy strategy and related requirements.

Section 1 requires Scottish Ministers to prepare a circular economy strategy which must set out:

Scottish Ministers’ objectives relating to developing a circular economy

Scottish Ministers’ plans for meeting those objectives (including priorities for action)

arrangements for monitoring progress towards meeting the objectives.

The strategy also may set out any other matters relating to developing a circular economy that the Scottish Ministers consider should be included.

Whilst the Bill itself does not technically include a definition of 'a circular economy', section 1 (3) sets out that in preparing the circular economy strategy, the Scottish Ministers must have regard to the desirability of the economy being one in which:

processes for the production and distribution of things are designed so as to reduce the consumption of materials

the delivery of services is designed so as to reduce the consumption of materials

things are kept in use for as long as possible to reduce the consumption of materials and impacts on the environment

the maximum value is extracted from things by the persons using them

things are recovered or, where appropriate, regenerated at the end of their useful life.

The above criteria are repeated again later in the Bill as underpinning considerations for setting circular economy targets - in practice therefore the Scottish Government is framing a circular economy as meaning these aspects. The Bill does not refer to the waste hierarchy.

In considering priorities for action within the circular economy strategy, the Bill requires Scottish Ministers to have particular regard to sectors and systems most likely to contribute to developing a circular economy.

Consistency with other strategies including the Climate Change Plan

The circular economy strategy must be prepared with a view to achieving consistency, so far as practicable, with:

the climate change plan prepared under section 35 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009

the environmental policy strategy prepared under section 47 of the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021, and

any other strategy or plan which the Scottish Ministers consider to be relevant.

Other requirements

Other key requirements in relation to the circular economy strategy are:

introduction of a duty on Scottish Ministers to have regard to the circular economy strategy in making policies (including proposals for legislation)

A requirement to consult on a draft strategy and lay a copy of the strategy before the Scottish Parliament (within 2 years of relevant provisions of the Bill coming into force)

Scottish Ministers must review and revise the strategy at least every 5 years

Scottish Ministers must report on progress made against objectives and plans included in the strategy, "as soon as practicable after the end of each reporting period" - where “reporting period” means 30 months i.e. 2.5 years since the strategy was last published. Reports must be laid in the Scottish Parliament.

Background

The draft 2025 circular economy routemap (published May 2022) sets out context for the statutory circular economy strategy, stating that it:

...would sit within the framework of Scotland’s Environment Strategy, supporting the delivery of its vision and outcomes, meet requirements outlined in the Waste Framework Directive and also link to the forthcoming Biodiversity Strategy. As part of the strategy it is also proposed that Resource Reduction Plans are developed for key sectors...

And:

A Circular Economy Strategy would also include, or signpost to, a new monitoring and indicator framework that will allow for tracking of Scotland’s consumption and wider measures of circularity. In turn this could be used to establish relevant targets to drive targeted action.

The draft routemap also sets out a range of proposed or ongoing areas of work designed to underpin the development of the strategy and inform circular economy policy more broadly, such as:

A strategy to improve waste data

A programme of research in 2022 and 2023 on waste prevention, behaviour change, fiscal incentives and material-specific priorities.

Interaction of Circular Economy strategy with other strategies

The Circular Economy Strategy sits within a framework of a large number of environmental and economic strategies (set out in above background sections), where there are potential inter-linkages, relationships and a need for coherence.

The Scottish Government has stated that Scotland’s Environment Strategy will seek to provide "an overarching framework" to bring multiple environmental strategies and plans together and identify strategic priorities and opportunities - including the circular economy strategy.

The Scottish Government published an Environment Strategy for Scotland: Vision and Outcomes on 25 February 2020 and is required by the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021 to prepare and publish an environmental policy strategy. The Vision and Outcomes are set out in a Box below.

Scotland's Environment Strategy: Vision and Outcomes

By 2045: by restoring nature and ending Scotland’s contribution to climate change, our country is transformed for the better – helping to secure the wellbeing of our people and planet for generations to come.

The six Outcomes:

Scotland’s nature is protected and restored with flourishing biodiversity and clean and healthy air, water, seas and soils.

We play our full role in tackling the global climate emergency and limiting temperature rise to 1.5°C.

We use and re-use resources wisely and have ended the throw-away culture.

Our thriving, sustainable economy conserves and grows our natural assets.

Our healthy environment supports a fairer, healthier, more inclusive society.

We are responsible global citizens with a sustainable international footprint.

Interaction with Climate Change Plans (and previous Parliamentary scrutiny)

As mentioned in a previous section, the 2020 Climate Change Plan (CCP) update (published December 2020) included a number of circular economy commitments, and a new CCP is expected in the coming months. The CCPu committed to embedding circular economy principles across sectors, prioritising areas considered to have the most opportunities: construction; agriculture/food and drink; energy and renewables; procurement; skills and education; and plastics.

In its scrutiny of the draft CCPu, the Scottish Parliament's Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform (ECCLR) Committee recommended in 2021 that the plan should include tangible commitments to deliver circular economy strategies for each of the priority sectors identified in the plan. In response, the Scottish Government noted that "Work is underway on the development of roadmaps for each of the priorities listed, which will be taken forward alongside the development of the 2025 Routemap."

Tensions between climate and circular economy policy?

In considering the compatibility or coherence across Climate Change Plans and any future Circular Economy Strategy produced under the framework of the Bill - questions may arise around possible tensions between drivers to reduce terrestrial emissions vs consumption emissions. The clear driver for policies in the CCP is to reduce terrestrial emissions to progress Scotland towards net zero. The drivers for actions in a Circular Economy Strategy may be more aligned with reduction of consumption emissions, or reducing the extent to which we, in Scotland, export other environmental impacts of our consumption.

There are possible strategic actions (e.g. increasing reprocessing of waste in Scotland, increasing local food production) that could support the transition to a more circular economy, which could reduce Scotland's carbon footprint, but have a negligible impact on terrestrial emissions (or even, conceivably, increase terrestrial emissions). There are also likely to be clear opportunities for win-wins e.g. reducing food waste, reducing overall consumption - where outcomes are likely to be both a reduction of terrestrial and consumption-based emissions.

Stakeholder views

The analysis published by the Scottish Government of consultation responses on proposals for the Bill sets out that:

Many respondents endorsed the proposal to introduce a duty to develop a Circular Economy Strategy.

On strategic focus, some respondents highlighted specific issues to cover including planning, the built environment, investment, the just transition, procurement, waste, materials, skills, education the marine litter, data collection and end-of-life waste.

A small number suggested that plans for the circular economy should be incorporated to a wider economic strategy.

Some respondents highlighted the need for cross-sectoral working to develop and implement any new Circular Economy strategy.

Circular Economy Targets

What the Bill does - section 6

Section 6 of the Bill gives the Scottish Ministers a power to impose targets by regulations relating to developing a circular economy.

Subsection (2) sets out particular aspects of the circular economy to which Ministers must have regard in considering imposing targets in regulations under subsection (1). This includes:

processes for the production and distribution of things are designed so as to reduce the consumption of materials

the delivery of services is designed so as to reduce the consumption of materials

things are kept in use for as long as possible to reduce the consumption of materials and impacts on the environment

the maximum value is extracted from things by the persons using them

things are recovered or, where appropriate, regenerated at the end of their useful life.

Subsection (3) provides further illustrative provision about what targets set in regulations may relate to including:

reducing the consumption of materials

increasing reuse

increasing recycling

reducing waste.

It also allows the regulations to make provision for review of the targets.

Subsection (5) requires the Scottish Ministers to consult appropriate persons, and the general public, before laying a draft of regulations under subsection (1) before the Scottish Parliament.

Subsection (6) allows for regulations under subsection (1) to make the ancillary provision listed there, including e.g. different provision in relation to different areas of Scotland, and transitional and saving provision to manage the transition should the targets change.

The Scottish Government recognises that robust data on waste is required to set evidence-based circular economy targets. The Policy Memorandum highlights consultation responses that indicated that targets should be "science-based and relevant to identified outcomes".

The Scottish Government further explains its reservations for including targets for carbon and material footprint on the face of the Bill, as suggested by responses to the consultation, is due to a lack of consensus on methodologies and datasets to inform targets:

[...] the Scottish Government believes targets should be set on the basis of a developed monitoring and indicator framework that considers a range of circular economy measures. This should be underpinned by rigorous stakeholder engagement to ensure there are no unintended consequences of target setting. This is a developing field, particularly in relation to consumption reduction, with no firm consensus on methodologies and datasets; for example, the recently published Circularity Gap Report and the Material Flow Accounts arrive at different, albeit similar, figures for Scotland’s Material Footprint. The recently published report by the Scottish Science Advisory Council noted that “Complex, interconnected, and circular material flows require a robust universal system of digital data recording with free and open sharing”. The UK Government has taken a similar approach to setting resource efficiency targets through secondary regulations under powers in its Environment Act 2021. 1

Background

As described earlier in the briefing, the Circularity Gap report highlights that the Scottish Economy is driven by overconsumption. The consultation paper and policy memorandum note the following context for introducing proposals for circular economy targets:

The Scottish Government's commitment to reduce consumption and waste by embracing society-wide resource management and reuse practices in response to Scotland's Climate Assembly and Children's Parliament recommendations in December 2021.

The European Parliament calling on the European Commission to consider EU targets for 2030 to significantly reduce the EU material and consumption footprints and to introduce a suite of indicators to measure resource consumption.

Zero Waste Scotland's publication in May 2021, of Scotland's first Material Flow Accounts and other potential existing high-level indicators that could be used to measure consumption to set targets.12

Draft 2025 circular economy routemap

The Scottish Government's draft 2025 circular economy routemap gives some further detail on work planned to support the development of future targets using these powers. It states that"any targets will need to be underpinned by a robust monitoring and indicator framework that gives holistic tracking of Scotland’s consumption levels and wider measures of circularity which would need to be developed first". It also notes this is "consistent with calls from the European Parliament for a suite of indicators to measure resource consumption"

The draft routemap also states the Scottish Government will investigate a reuse target:

We propose to investigate the feasibility and impact of setting reuse targets in Scotland by 2025 in order to encourage measures that extend product lifespan, mainstream opportunities for reuse, and support progress towards metrics that monitor consumption. Few countries have national, legislated reuse targets, but a range of initiatives to implement re-use and preparation for re-use targets are underway throughout Europe . In Scotland, we know that a wide range of reuse activities already take place, from formal redistribution networks to informal sale or exchange. However, we currently have no way to monitor the type, volume or impact of this activity.

Arguments for more emphasis on consumption emissions

Some reports have recommended that the climate governance framework in Scotland should give more emphasis to consumption emissions. SPICe commissioned research published in 2022, Environmental Fiscal Measures for Scotland: learning from case studies and research to create a potential strategic approach, states:

Over time the measurement of climate related emissions may move from a territorial basis to a carbon footprint basis; thereby including the embedded carbon in materials and products as well as direct emissions. This will lead to a bigger emphasis on circular economy fiscal measures...

The Report of the Advisory Group on Economic Recovery (established by the Scottish Government to advise on Covid-recovery) argued there was a case for more emphasis to be put on reducing Scotland's carbon footprint rather than focusing on terrestrial emissions:

Taking carbon out of our economy and out of our lifestyles will require sustained investment and the creation of new jobs, industries and supply chains. And we must do this in a way which ensures that global emissions are reduced, not simply relocated. This is a potential unintended consequence of Scotland’s net-zero target which is based on territorial emissions, and there is a case for having a more explicit focus on consumption-based emissions (e.g. carbon footprint). This could be in the form of new or additional targets, or a greater role for those consumption-based measures in government decision-making and could provide an opportunity to embed the principles of a circular economy within government.

Stakeholder views

Respondents to the Scottish Government's consultation expressed support (86% approved) for the proposal to provide enabling powers to set statutory circular economy targets. The consultation analysis found that there was a common acknowledgement that voluntary waste-based and resource consumption targets had largely been ineffective and focused too narrowly on recycling.3 Respondents also stated that targets should take into account the impact of the Scottish economy abroad, for example the impact of imported goods. There were suggestions that statutory targets should be set as soon as possible and no later than 2025. Suggestions for targets included material and carbon footprint targets, a reuse target and a more ambitious food waste target of 50% by 2030.

In a position paper published in April 2022, Scottish Environment Link called for the inclusion of a headline material footprint target to be included in the Bill.

The Bill must require annual publication of Scotland's material footprint and set long term, interim and year on year reduction targets, based on scientific advice. Scotland's material footprint covers the raw materials used for all goods consumed in Scotland. It includes metals, fossil fuels, non-metallic minerals and biomass, for example timber. Scotland must aim for sustainable levels of material use, estimated at about 8 tonnes per capita per year. We suggest an interim target for metals, minerals and fossil fuels of 50% reduction by 2030 (following the Netherlands) with a target for biomass to be developed to ensure that increased demands for biomass do not result in habitat destruction and biodiversity loss.4

Improving waste and consumption data

SEPA is responsible for reporting national waste statistics to the Scottish Government. In October 2017, SEPA published a strategy for improving waste data in Scotland. The aim of the strategy is "to identify and deliver the waste data needs of Scotland, meeting current and future requirements." The strategy sets out the following objectives:

collect and report waste data that is reliable and relevant and share it on a timely basis in an integrated, coherent and open format

explore new approaches to collect and report data, embracing digital solutions and innovative ways of working

further develop the use of non-weight based measures, e.g. carbon assessment, to increase our understanding of the economic, environmental and social impacts of waste

identify what waste materials we need to track and the methods required to measure and monitor the movement of waste flows.

The strategy pre-dates the 2020 cyber attack on SEPA, so it is not clear to what extent this has impacted on progress in improving waste data.

Circular economy targets in other countries

In 2022, Zero Waste Scotland published research on the status of consumption-based targets in other countries1. Key results of this research were: