Environmental Fiscal Measures for Scotland:

This research was commissioned by SPICe on behalf of the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee in Session 5. The report aims to support consideration, in the Scottish Parliament and more broadly by policy-makers, of environmental fiscal measures in Scotland. It explains a range of different types of environmental fiscal measures that may be relevant to improving environmental outcomes in Scotland, and seeks to identify case studies and review literature in the context of key Scottish targets and commitments, to propose what a strategic approach to environmental fiscal reform could look like.

About the author

Callum Blackburn is an independent consultant with over 20 years experience of developing and delivering strategies and policies in sustainable development, waste management, climate change, energy and circular economy.

The arguments expressed in this commissioned research report are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of any other party including SPICe. All reasonable measures have been taken to ensure the quality, reliability, and accuracy of the information in this report. This report is intended to provide information and general guidance only. Any decisions made based on the information and guidance in this report are the reader's responsibility.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks and acknowledges the information sources provided by the following individuals: Andrew Faulk, Phil Williams, Ewan MacGregor, Morag Watson, Jeremy Sainsbury, Robin McAlpine, Martin Charter, Jodie Bricot, Izzie Erikson, Duncan Simpson, Andy Dick, Robin Baird, Peter Cairns, Eric McCrory, David McIntosh, Ian Fleming, Scott Richards, Daniel Stunell, Jean Paul Ventere, Morag Gordon, and Dominic Phinn.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this report is to support consideration, in the Scottish Parliament and more broadly by policy-makers, of environmental fiscal measures in Scotland, and indicate where they may be used to address the climate and ecological emergencies we face. It explains a range of different types of environmental fiscal measures that may be relevant to improving environmental outcomes in Scotland, and seeks to identify case studies and review literature in the context of key Scottish targets and commitments, to propose what a strategic approach to environmental fiscal reform could look like. This includes a list of principles that MSPs and other policy-makers may wish to consider to guide the identification and prioritisation of any new measures.

In the previous Parliamentary session, as part of the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform (ECCLR) Committee's financial scrutiny, the Committee was interested in the role of environmental fiscal measures including taxes, levies and other charges. The Committee undertook some initial work to discuss the success of existing devolved measures (i.e. the carrier bag charge and landfill tax) and the potential and priorities for further devolved fiscal measures in various areas of environmental policy.

In its work programme the Committee agreed to “explore opportunities and risks of making use of new tax powers to change behaviour” and to commission research to support this work. This report supports the previous commitment to explore the opportunities and risks of new tax/charging mechanisms and also incentives to change behaviours. It may be relevant to the forthcoming work of the Scottish Parliament; in the Tax Policy and the Budget Consultation, August 2021 the Scottish Government has stated its commitment to investigate more green taxes:

The challenges facing Scotland over the course of this Parliament are significant, and generating sustainable devolved tax revenues, along with spending and capital expenditure, act as vital fiscal levers to tackle the challenges we face. For instance, we will consider how the tax powers that we have could help change behaviour supporting the transition to a net zero economy. Whilst the majority of green tax powers are reserved, we will pursue changes at every level to deliver on Scotland's climate and environmental ambitions, beginning with COP26.

This report is structured into a number of sections covering the following information:

an Executive Summary;

an explanation of the main types of environmental fiscal measures;

a brief summary of the use of environmental fiscal measures in Scotland to date;

a discussion of the main themes emerging from a literature review;

an illustration of six sectors and associated case studies focused on some of the specific challenges facing Scotland and the environmental fiscal measures that may be helpful in addressing them;

and finally, the information gained from these sections is used to outline a potential strategic approach to making future changes to environmental fiscal measures in Scotland.

2. Executive summary

2.1 Key messages

For the environmental fiscal measures covered in this report the strategic aim for them has been assumed to be addressing the interlinked environmental crises of climate change and biodiversity loss, defined here in simplified terms as Net Zero and Ecological Restoration. This could mean that such measures are focused on either net zero, or ecological restoration, or both.

In this report a very broad definition of environmental fiscal measures has been used – in general terms these are measures where there is a flow of money involved, focused on addressing an environmental issue. This includes not only the traditional fiscal instruments, such as taxes, levies & duties but also grants, subsides & loans. It also includes measures that are both simultaneously a flow of money and a regulation, such as producer responsibility schemes.

In effect both “carrots” and “sticks” have been included to ensure that all fiscal possibilities are considered. These possibilities have then been funnelled down to a narrower range of measures that appear to offer the most opportunity for the Scottish Government. As a devolved government this range is much more restricted than is available to the UK Government.

With the strategic aim in mind the key findings from this research are:

Currently there are a plethora of taxes and charges used by the UK and Scottish governments. These are trying to do various things including reducing climate change emissions and other environmental damage. This complexity perhaps reflects the wider UK tax system, which is reputed to have the longest tax code in the world. Within this complexity, various existing measures have attempted to internalise the costs to society of these emissions and other environmental impacts while effectively charges differing prices for them.

There appear to be no “silver bullets” available, however moving towards an overarching simplified carbon tax, that could be applied universally across the economy, could be the most efficient, fair and effective tax measure in relation to supporting progress to net zero.

The UK Emissions Trading Scheme could be seen as a proxy for a carbon tax but the long term effectiveness of trading schemes is questionable. The Scottish Government appears to have no powers to introduce a carbon tax, without the agreement of the UK Government, and so other solutions, albeit more fragmented ones, are more likely possibilities.

Similar to the taxation landscape there are a huge range of grants and subsides provided by the UK and Scottish Government, particularly across agriculture and land management. Here the Scottish Government may have more significance and control, subject to the UK Subsidy Control Bill, and so could repurpose these to ensure delivery of the strategic aim.

This could be even more significant as part of a “Whole Government” approach where all government expenditure, including the £12 billion annual public procurement spend, is brought into alignment with the strategic aim. This would undoubtedly require considerable capacity building and new skills in the finance and related areas of government.

The Scottish Government has ambitious interim emissions reduction targets for 2030 and ambitious targets for ecological restoration are expected in the Natural Environment Bill and next Biodiversity strategy. Experience shows that the introduction of new measures can often be a long process. Therefore, given the short time frame, repurposing existing fiscal measures to deliver the strategic aim may be the best course of action. This is likely to be easier than introducing new measures from a standing start; because key stakeholders are probably already involved, and budgets and government or agency staff/technical resources are likely already present managing the existing measures.

Where introducing new measures is deemed necessary, a key consideration is not only the lead time to implementation but also the complexity – a measure that requires consultation with a few large stakeholders is going to be quicker to implement than one that involves engagement with hundreds of smaller ones. The natural resistance of industry to the introduction of changes in one part of the UK market makes the case for the Scottish Government overtly seeking to maximise benefits from measures introduced at a UK level.

Fiscal measures must work holistically with other policies and on their own they may not drive enough change. In some areas where a major cultural change and inconvenience will be caused these measures will need to work alongside other policy measures such as skills development, support and advice, and product bans; for example this would apply to the rolling out of renewable heating systems to replace gas boilers.

Taxation of resource use and emissions should increase but with the benefit of reduced taxation elsewhere. This is a challenge for governments because the tax base becomes less stable. The Scottish Government has already demonstrated it can manage instability from its experience with, for example, the Scottish Landfill Tax, however managing instability on multiple fronts would be a greater challenge.

Over time the measurement of climate related emissions may move from a territorial basis to a carbon footprint basis; thereby including the embedded carbon in materials and products as well as direct emissions. This will lead to a bigger emphasis on circular economy fiscal measures, such as Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), and this is where the Scottish Parliament arguably has a more extensive devolved remit than it does in energy. Resources for delivery in this area, along with the implications of the UK Internal Market Act may be key considerations. Lobbying for UK schemes to be favourably designed for the Scottish economy and environment, at an early stage, may therefore be important.

EPR schemes are often fiscal measures co-designed between industry sectors and government. Applying deposits on appropriate items, such as household batteries and small electrical items, would be an easy way to engage citizens and ensure much higher collection rates for some end of life products.

In the absence of powers to vary taxation, such as VAT rates, changes to local taxation and charges could have a significant supporting role in helping the Scottish Government's meet its net zero and ecological restoration targets and commitments.

2.2 Case studies

Included in the report are six case studies that are relevant to the big challenges Scotland faces in achieving net zero and ecological restoration. Some of these relate to measures that may be forthcoming in a Scottish context and others which demonstrate the possibilities that are available. The key summary from each is as follows.

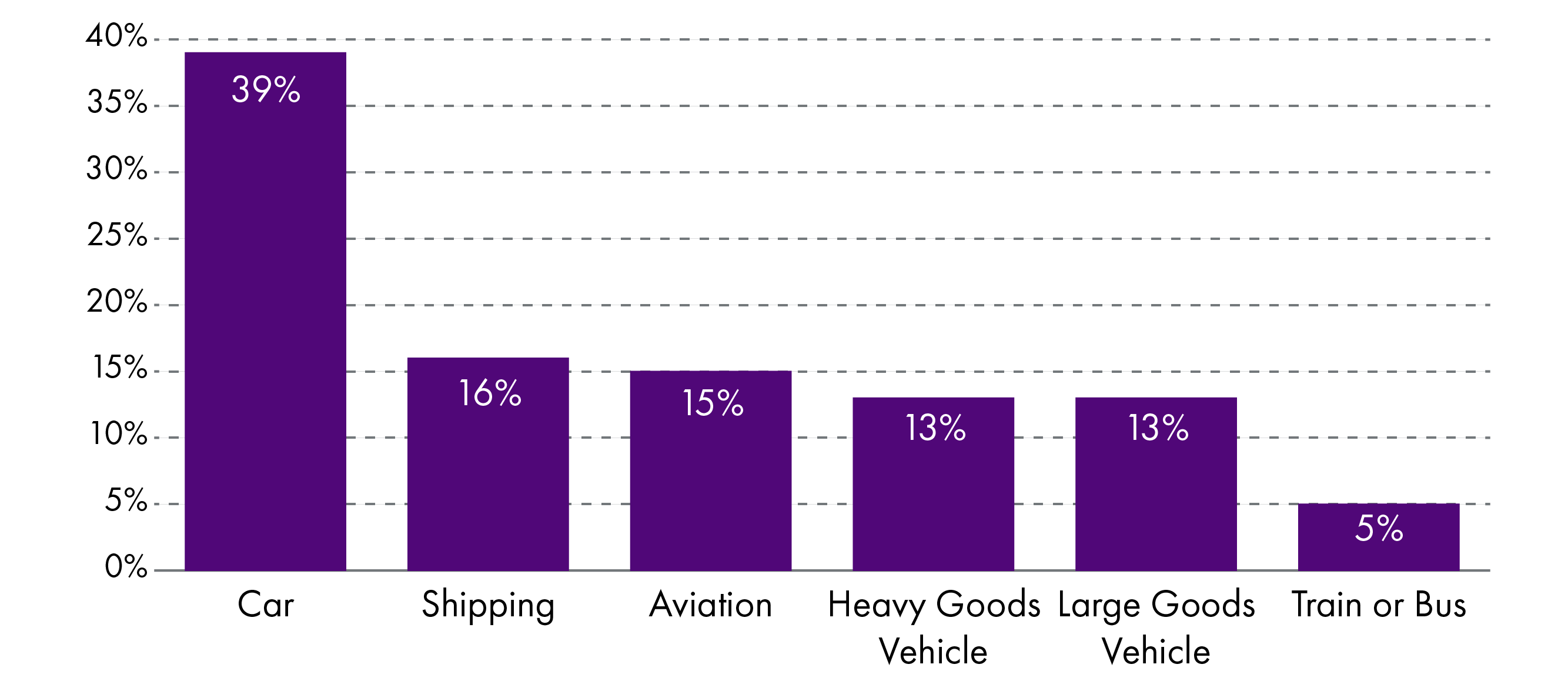

The electrification of transport

This is a complex picture with a mix of vehicle bans, financial & market pressures, and infrastructure provision at play along with the use of various UK and Scottish fiscal measures.

In relation to the purchase of Electric Vehicles (EVs), the proportion of new car sales suggests that current market mechanisms, combined with the signal providing certainty on longer term bans on internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, are already working for “able to pay” drivers, and there may be no reason at present to change this.

There remains the issue of ensuring access to EVs for lower income drivers. As with all new technologies, it is likely that lower cost EVs will progressively appear on the market as costs fall. The current Energy Savings Trust (EST) EV loan scheme could be reviewed, with any necessary changes made, to help meet this need under changing circumstances.

In terms of expanding the EV charging network, the combination of policy drivers suggests that cost reflective financial charges should be introduced on the publicly funded network. This would have two benefits: firstly, it would encourage overnight charging at home among EV owners who have that option, and secondly, it would encourage private sector investment to extend the network.

The exceptions to this approach are,

Firstly, areas of Scotland where residents are less likely to have the option of off-street charging. There is likely to be a continuing need to provide publicly available chargers.

Secondly, as with Norway, the aim in rural Scotland should be to have a minimum number of fast chargers per set length of A road, to address range anxiety issues among potential drivers.

Overall, although financial incentives for drivers have and will continue to encourage take up of EVs, supporting policy measures in Scotland are more likely to involve consideration of extending the charging network in specific areas, managing wider issues to minimise grid upgrade costs and associated price increases for electricity consumers, and maximising the public fleet of EVs.

Renewable heat

There are a limited range of options for the Scottish Government given that the majority of energy and tax policy instruments are reserved to the UK Government.

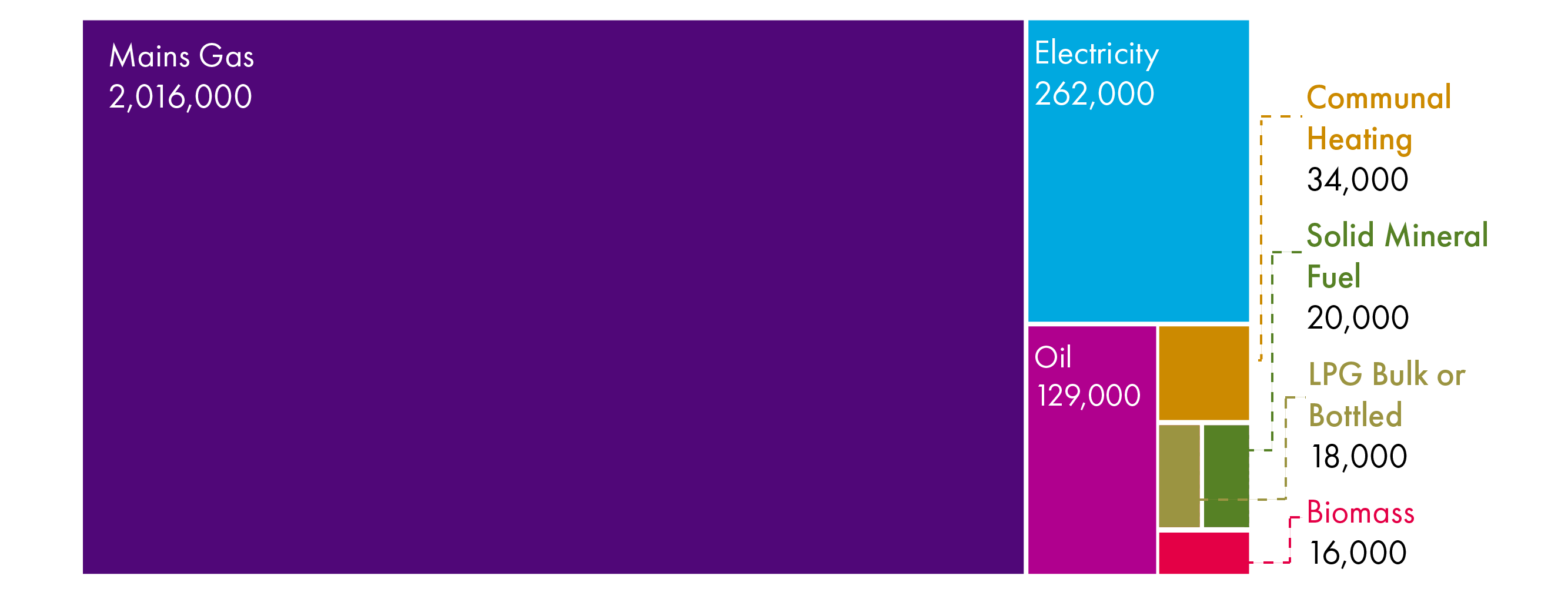

While all fossil fuel heating systems will need to be decarbonised, there is some uncertainty about the best approach to achieve this for buildings connected to the mains gas network. Low carbon heating approaches should therefore initially concentrate on the replacement off-gas grid fossil fuel systems, with heat pumps seen as the favoured option.

The UK Government has, since 2014, provided financial assistance for the installation of renewable heating systems through the Renewable Heat Incentive, and Air Source Heat Pumps have indeed been the most popular heating system supported. However, installation rates are extremely low, averaging only around 2,200 domestic systems in Scotland each year since then.

There are non-financial barriers to the take up of heat pumps, including disruption at installation and the need for energy efficiency measures to ensure retrofitted systems are effective. A greater barrier is that of running costs; UK levies on electricity are comparatively higher at around 25% than levies and taxes on fossil fuels (before taking into account the recent dramatic increase in prices) used for heating. This means that there are unlikely to be significant gains in terms of heating costs for households retrofitting heat pumps, regardless of the scale of subsidy for the capital costs.

Comparable countries which have been more successful in encouraging this transition have comparatively lower charges on electricity, and higher charges on fossil fuels, in addition to subsidies for renewable heating systems. The Scottish Government has already recognised the need to reduce the cost differential between electricity and fossil fuels and should continue to raise this with the UK government.

The Scottish Government could also look to use a Heat Pump Sector Deal in tandem with Home Energy Scotland householder advice and support as additional measures to accelerate the transition and reduce overall cost.

Product stewardship for textiles

The adoption of Circular Economy measures has the potential to have a major impact on global climate change emissions. Around 45% of climate change emissions are estimated to be related to consumption of products and materials. The fashion industry is estimated to be responsible for 4% of global emissions. Product Stewardship measures can help to reduce lifecycle impacts.

In line with the EU's increased focus on textile waste, an EPR for Textiles is under consideration by the UK government. Collaborating using UK wide government resources to develop the scheme, while ensuring the design, targets and benefits are appropriate for Scotland may be an efficient approach given the time and internal resources required to develop a separate scheme.

Scotland and the UK are unlikely to be able to significantly influence the global supply chain for clothes and textiles. The long standing French Textile EPR scheme with its product levy provides an effective European example of the beneficial impact of EPR. Focused on funding and investing in domestic collection and sorting infrastructure, plus research and development, it demonstrates a useful model to prepare for the investment and support needed to achieve higher recycling rates for textiles.

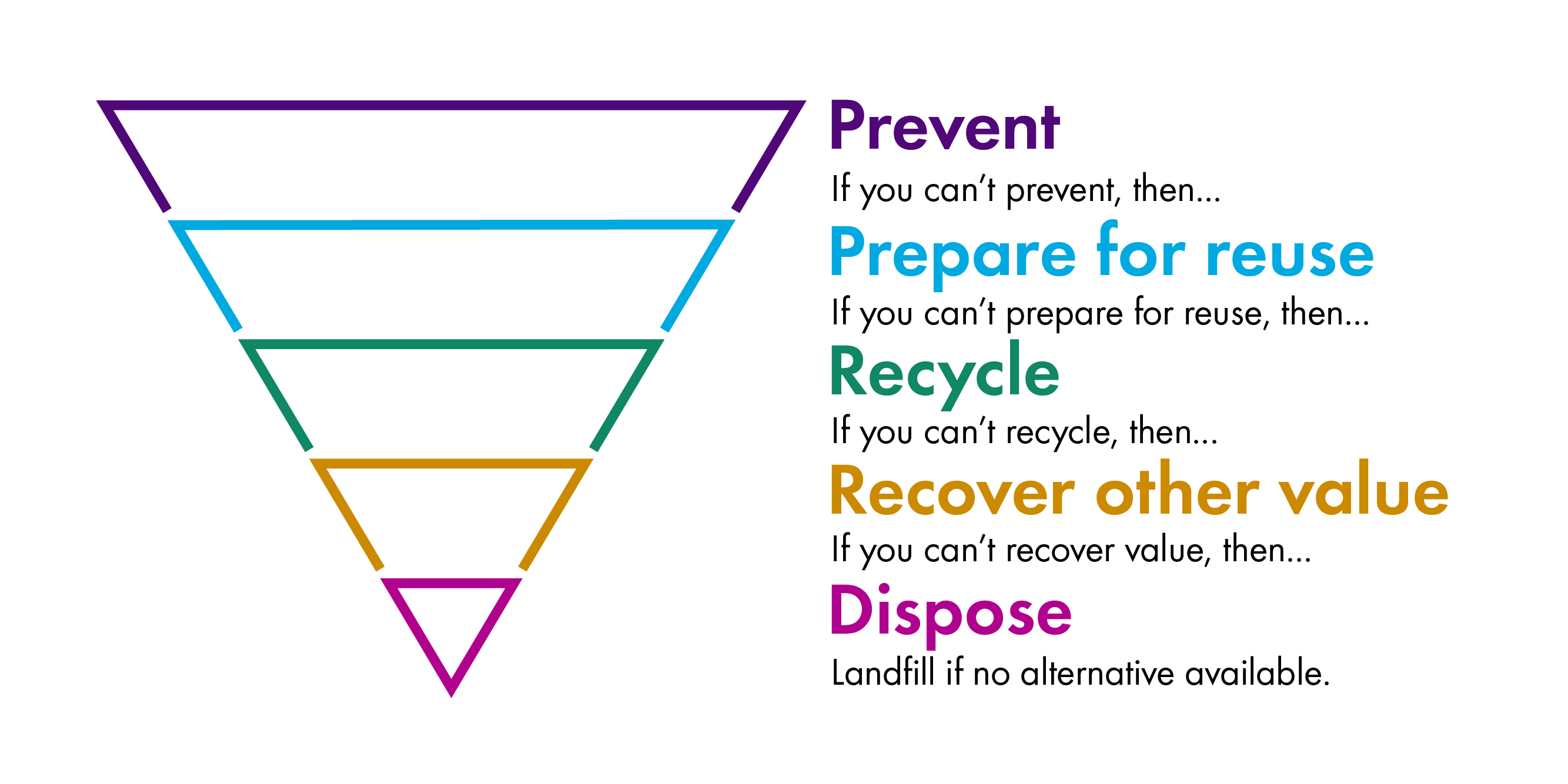

Waste management

The success of the Scottish Landfill Tax has led to an increasing move to Energy from Waste (EfW) treatment for residual (non recyclable) waste.

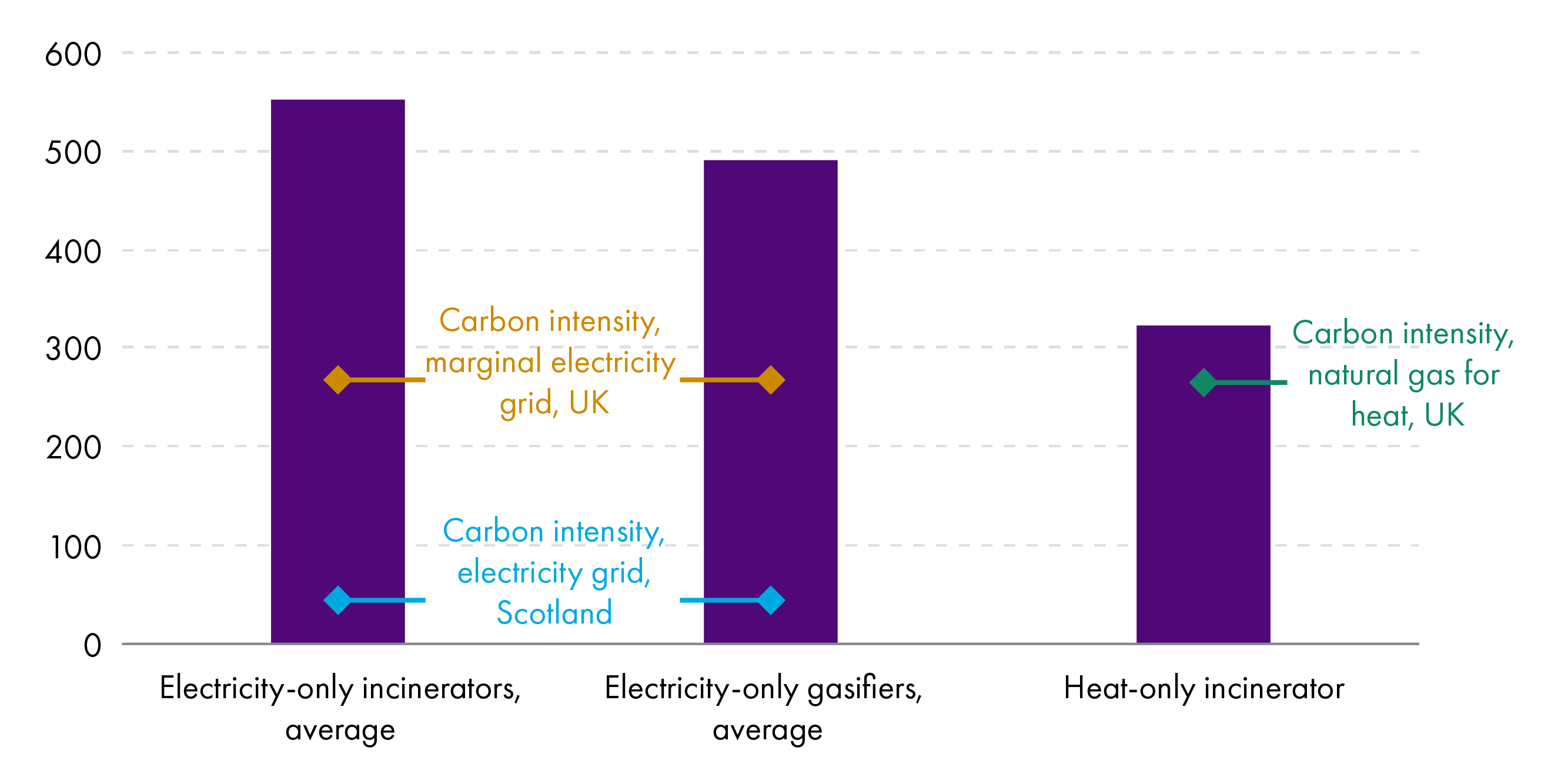

Climate Change emissions from EfW plants may be higher than fossil fuel gas plants and as food waste and card/paper are increasingly separated from residual waste these could become higher than the impact from landfilling waste.

An EfW or “Incineration” tax is used in many countries and could be used in Scotland to help push more waste materials into recycling and composting with associated benefits.

The Scottish Government has several options to address this, with an EfW tax similar to Scottish Landfill Tax being the most realistic and effective option, subject to any questions around devolved competence.

Alternatives to this measure include exploring a minimum price mechanism, inclusion in the UK ETS, or a voluntary EfW reduction agreement with the Waste Management Sector.

The current Scottish local authority waste & recycling systems are based on householder goodwill.

Local authority funding pressures are forcing Councils to charge for green (compostable) waste collections; distorting the fiscal incentives for recycling.

Direct Variable Charging (DVC) or Pay As You Throw (PAYT) mechanisms work well in other European countries and can have a significant impact on reducing residual waste and increasing recycling and food waste collections.

Providing local authorities with the powers to introduce direct variable charges based on weight, volume or frequency of collection from householders could provide an effective fiscal incentive, support local investment in infrastructure and services while reducing climate change emissions.

Land management

The replacement of the former Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) agricultural subsidy regime offers a huge opportunity to integrate biodiversity and climate change aims using incentivised support mechanisms.

However this is a very challenging and complex area with many stakeholders and competing interests. It will take time for the Scottish Government to develop and finalise a new subsidy regime and get it operating effectively to help meet 2030 targets.

Payments for Environmental Services (PES) schemes used in Sweden and other countries for incentivising the protection of wildlife, and Costa Rica for regenerating forestry, are successful examples of the type of incentives that could be incorporated into the new regime.

In addition to lower emission farming practices, new taxation options may also need to be considered on the demand side for meat and dairy consumption; if current incentives for a more plant-based diet, such as the perceived health benefits or personal environmental drivers, are not sufficient enough to change behaviour.

While the powers to implement new taxation options of land use emissions reside at a UK level, the John Muir Trust's proposal for a Natural Carbon Land Tax is one example which could potentially be implemented at a local authority level.

Creating the right investment framework through the Woodland Carbon Code and Peatland Code for offset money may add significantly to public funding; increasing the likelihood of ambitious climate change targets being met and enable public subsidy to be directed towards the more challenging aspects of emissions reduction, biodiversity and environmental services.

An environmental tourism tax

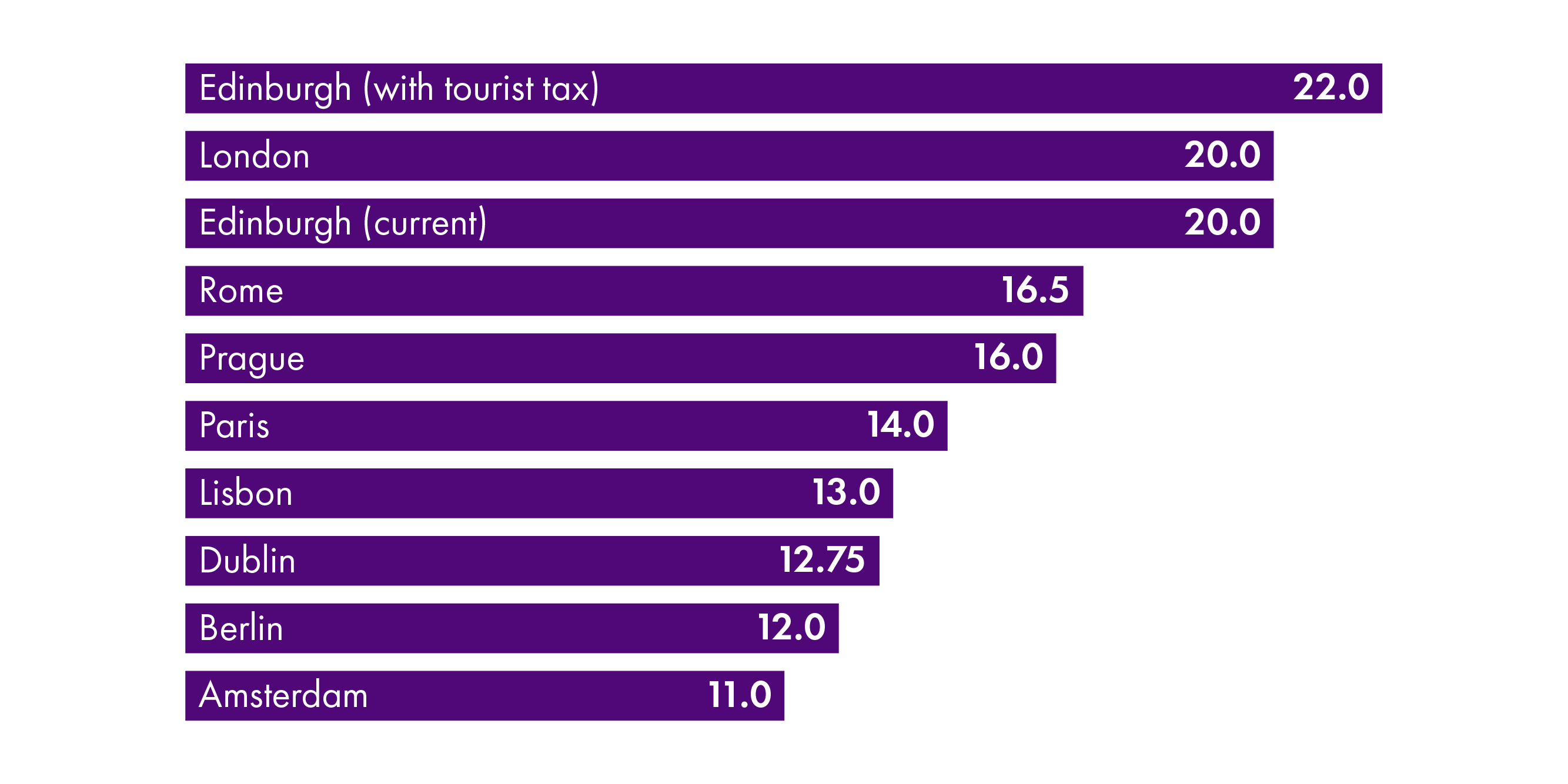

The Scottish Government and some Scottish Councils have already undertaken engagement, consultation and development work in exploring tourism taxation. Edinburgh City is the local authority which is leading in the UK; already approving a Transient Visitor Levy (TVL) subject to future Scottish Parliament legislation, development of which was paused in 2020 due to the pandemic.

The benefit of a TVL targeted at visitors is an increase in tax revenue for communities without increasing the overall tax burden on them, and it appears to be a fiscal measure that can be introduced quickly despite the new administrative arrangements required.

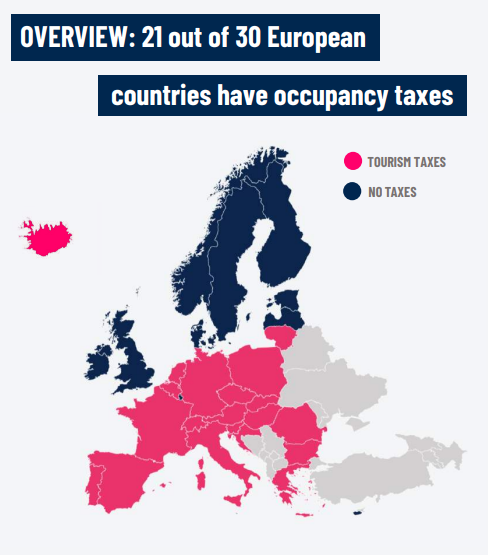

However it has to be recognised that in countries where a tourist tax is applied there are often reduced rates of VAT whereas the UK has one of the highest taxed visitor accommodation sectors in Europe. This high tax burden may affect visitor numbers.

A tourism tax is a form of specialist tax, naturally lending itself to hypothecation and ring fencing. While not fundamentally an environmental fiscal measure, having the environment as the key purpose or core of the tax may make it more acceptable to visitors and residents.

Administration of the tax revenue by a designated body with the involvement of key stakeholders can help to provide confidence that any tax revenue is spent appropriately, and provide expertise for the ongoing monitoring and evaluation of the impact of the tax.

A TVL may offer significant revenue for investment by Scotland's local authorities subject to the overall tax burden on visitors being considered.

A scheme that is designed with a clear purpose, transparency, and community and stakeholder involvement in any revenue reinvestment, appears to be a necessary prerequisite for success.

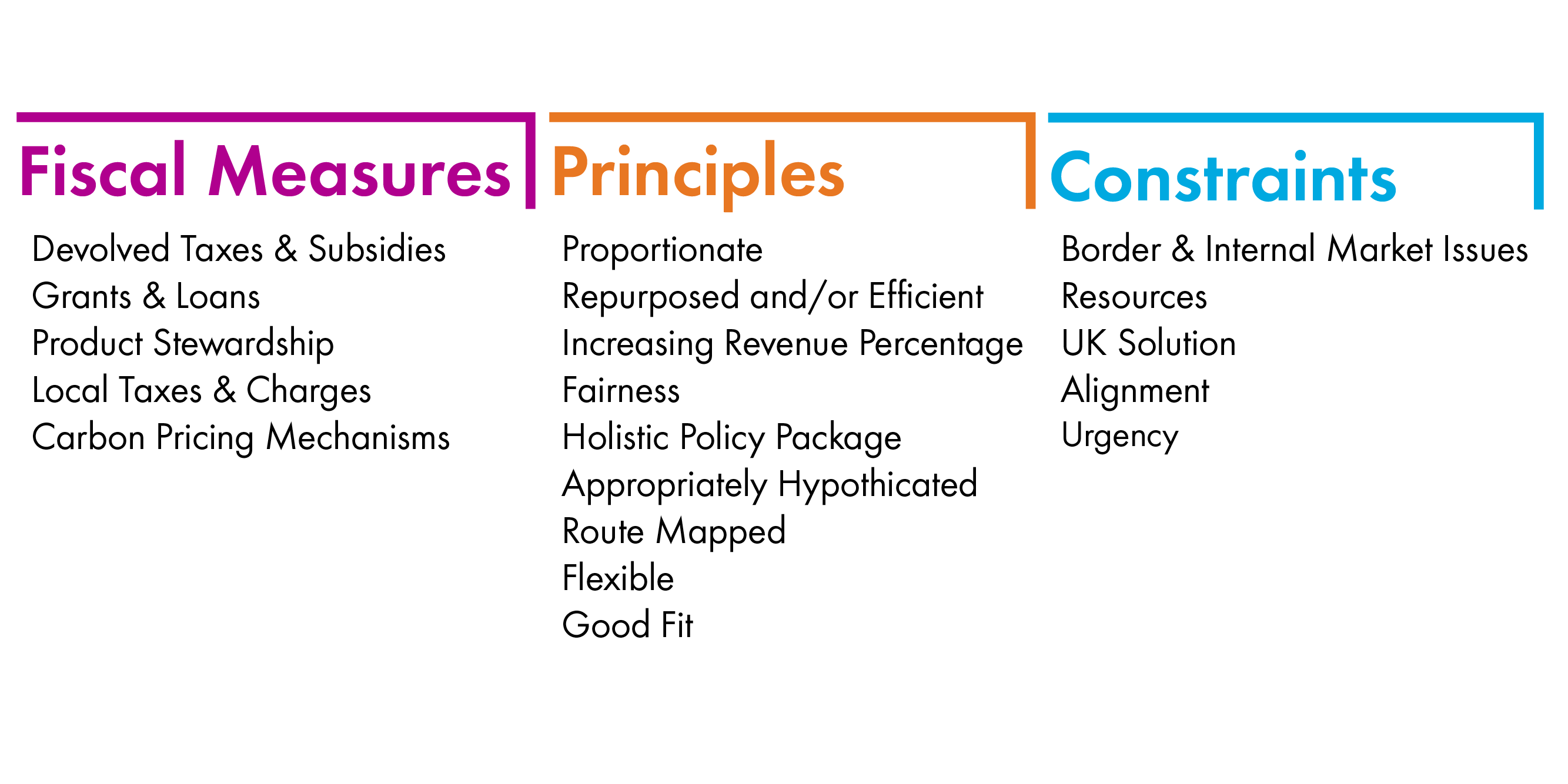

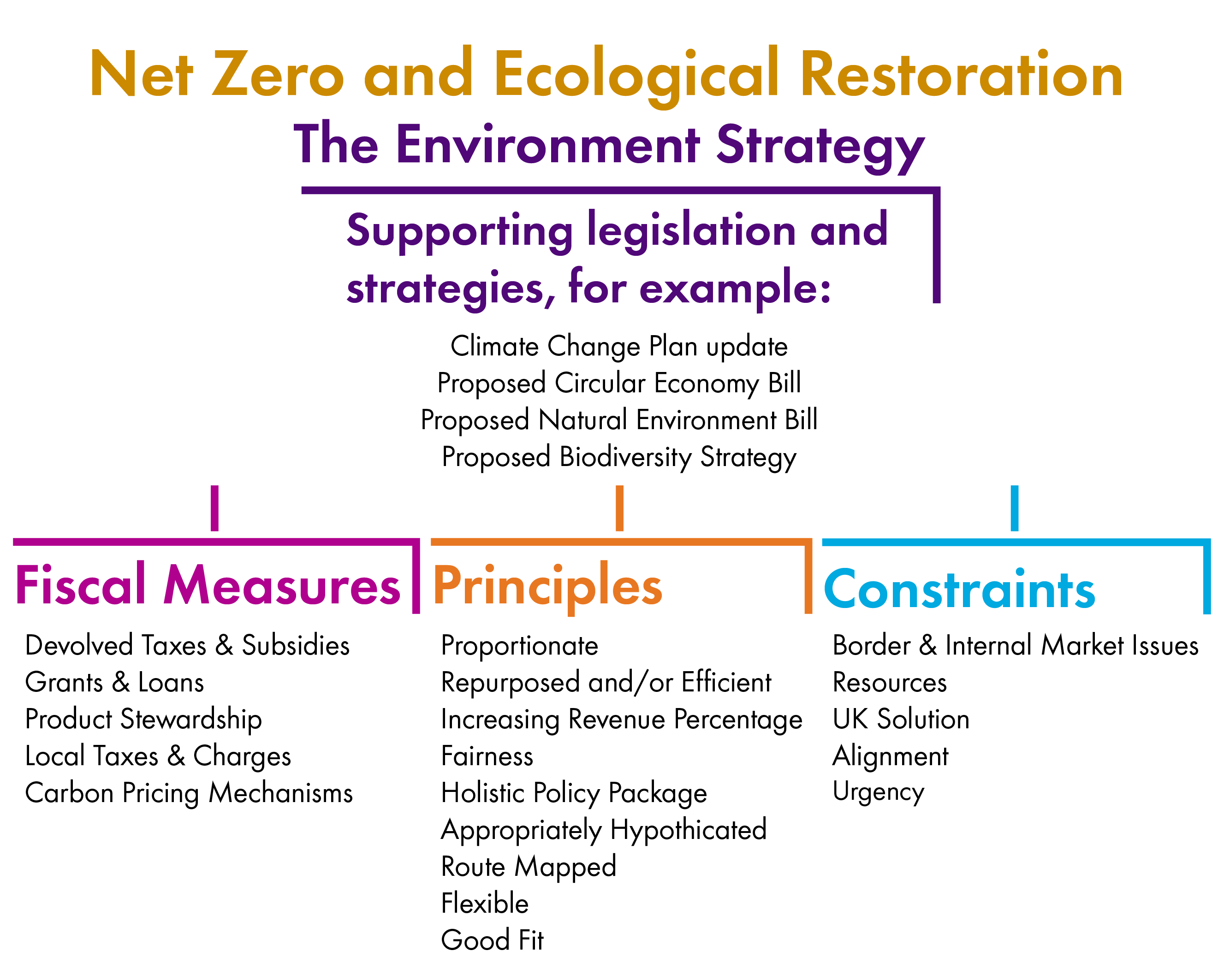

2.3 A potential framework

There are a range of considerations that could be used when applying environmental fiscal measures. There does not appear to be any established international best practice in this area at present. In this report a suggested list of viable fiscal measures for the Scottish Parliament, principles to apply in designing them, and constraints to be assessed, have been combined to provide a potential strategic approach for the consideration of any new measures.

2.3.1 Principles

Below is a suggested list of principles that are drawn from the different elements of this report, including the key literature, and the various case studies and sectors explored.

Proportionate: New taxes or charges planned should be levied in proportion to the tax or charge payers’ ability to pay.

Repurposed and/or Efficient: New taxes or charges should maximise the economic efficiency of collection, and the cost of delivery of grants or subsidies should be equally efficient. Wherever possible it is likely to be more efficient to alter an existing fiscal measure (grant, subsidy, charge or tax) to make it fit the strategic aim rather than create a new one.

Increasing Revenue Percentage: Overall there should be a move towards greater taxes/charges on resource use and activities that are damaging and a corresponding decline on taxes on employment and labour.

Fairness: Any measure that reduces our resource use should also take into account citizens and business’ varied circumstances and avoid discrimination against disabilities, gender, ethnicity and other characteristics.

Holistic Package: Environmental fiscal measures are likely to be most effective when they are part of a package of measures that seek to work together towards a shared outcome or goal and wherever possible fiscal measures should not conflict with each other.

Appropriate Hypothecation: Hypothecation in some environmental fiscal measures schemes is essential because you must reinvest the charges/levies to fund services and green infrastructure in order to achieve the purpose of the measure. In other taxes and duties, hypothecation may be key to making it both an environmental fiscal measure and acceptable to the public.

Route Mapped: There is need for widespread engagement on any new or repurposed measures. Changes should be justified and, where possible, follow a predictable route map.

Flexible: Revenue from environmental fiscal measures may not be stable because the need is primarily to drive change and that context does not align well with stable revenue from taxes and charges. The exceptions to this are schemes that are essentially fully hypothecated to support wholly additional programmes.

Good Fit: Environmental fiscal measure outcomes should be in line with Scotland's National Performance Framework and the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

2.3.2 Constraints

There are a number of constraints that should be evaluated and assessed before taking forward a new fiscal measure or a significant change to an existing one.

Border/Internal Market Issues: there are practical implications of having taxes & charges radically different from the rest of the UK including border effects with England due to the land border we share.

Resources: there are limited staff and technical resources within government and its agencies to implement and manage new fiscal measures, whether they are grants, subsidies or taxes.

Alignment: Any fiscal measures must be aligned to a range of legal structures and agreements in place, or proposed, including the Internal Market Act 2020, the Subsidy Control Bill, Common Frameworks and the Scottish Government’s Fiscal Framework.

UK Solution: In some cases an ambitious approach to a Scottish fiscal measure may be desired but if the UK government is implementing a similar measure, even if this is considered to be less effective, it may be more advantageous to work with the UK measure.

Urgency: for any measure considered the time for planning, development and implementation must be considered carefully with the challenge of the 2030 interim climate change targets in mind.

Incorporating the information above, the most practical fiscal measures, suggested principles, and known constraints have been visualised in the diagram below.

3. Background

3.1 What are fiscal measures in Scotland

In the broadest sense, every action a government takes which has a financial component can be viewed as a fiscal measure, regardless of whether the measure was designed primarily to raise revenue, to influence the spending behaviour of individuals or businesses, or a mix of both. In effect a fiscal measure involves a flow of money.

In practice, discussions around environmental fiscal measures usually concentrate on a much smaller subset of measures (taxes & charges), designed specifically to influence consumer or business behaviour by varying the price of goods and services. The aim is to make sure that spending decisions better reflect environmental costs and benefits, and therefore affect environmental outcomes: in effect, this is a logical extension of the ‘polluter pays’ principle which is a guiding principle of Scottish law and policy underpinned by the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021.

There are two broad ways of achieving this outcome:

Governments can increase the cost of a good or service through an additional tax/ levy/ duty or a mandated minimum price;

Governments can decrease the cost of a good or service, or encourage less damaging activities, through grants or subsidies.

There are various types of increased costs, including taxes such as Income Tax, Corporation Tax, and specific environmental taxes such as Landfill Tax. These taxes are mainly used to pay for general public spending.

A duty is a type of tax that's charged specifically on the value of goods and services, such as VAT, Customs Duties, or a Sales Tax. And a levy is an obligatory payment to the Government or another organisation.

An example of a levy is the UK Climate Change Levy (CCL) which is chargeable on the supply of lighting, heating and power for large users. Revenue raised through the CCL is received back by businesses through a 0.3% reduction in national insurance contributions. However in practical terms a tax, levy or a duty operate in the same way and often the difference can be more semantics than real.

However there is a difference with regards to minimum prices, where the money from the minimum price flows back to the seller and not government. This happens in the case of the minimum price for a single use carrier bag in Scotland where the retailer retains the charge or fee.

Fees or charges are service focused and the term “fee” is described as follows:

As for fees, these differ from taxes and duties in that they are paid to cover all or part of the cost of a service rendered. They are payable only by actual users of the service and so are not compulsory, in the sense that it is possible to avoid the charge simply by not using the service. Fees may be charged for activities relating to conservation of the environment, such as water treatment or waste collection.

European Parliamentary Research Service. (2020, January). Understanding environmental taxation. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/646124/EPRS_BRI(2020)646124_EN.pdf [accessed 2022 January 21]

The decreased cost options include providing grants, subsidies or low cost finance. These are often used to encourage and support new innovations and new business models that are proven, but don’t yet make financial sense in our current economic framework. There is a timing element to these. Grants are often used for a set period of time to establish new practices whereas subsidies are more an ongoing support to compensate for where our economic model does not adequately price wider societal benefits.

Environmental fiscal measures usually do not work in isolation but are part of a package of policy measures including regulations, stakeholder engagement, advice/support, associated voluntary measures, bans and awareness campaigns. Therefore using an environmental fiscal measure, and the type of measure used, must be based on an assessment of the policy area and the best fit policy options.

3.2 Environmental fiscal measures in Scotland

There are a wide range of fiscal measures available to any country and its government. However in practical terms, with Scotland's devolved status, only some of these are available to the Scottish Parliament; or are available only with permission from the UK Government.

Section 80 B of the Scotland Act 1998 (as amended) provides a mechanism for the UK Parliament to devolve the necessary powers for a new national tax in Scotland, with the agreement of the Scottish Parliament – which could enable the Scottish Government to create new environmental taxes, with the agreement of the UK Government.

This mechanism was utilised for the first time in 2018 to enable the introduction of a tax on wild fisheries, via the Scotland Act 1998 (Specification of Devolved Tax) (Wild Fisheries) Order 2018 – although these tax powers have not been used at the time of writing.

Fiscal powers have changed since the Scottish Parliament was created and this is likely to continue. The Scotland Act 2016, for example, brought expanded fiscal responsibilities including Air Departure Tax, the Aggregates Levy and powers in relation to social security payments. There can be fairly frequent changes to these powers, for example the Scottish Government will now deliver winter fuel payments to those of pension age from November 2022.

There are many different types of fiscal measure in use in Scotland either by the Scottish or UK Government. Table 1 sets out a range of the incentive or expenditure measures and Table 2 sets out a range of disincentive or tax/charge measures. These lists are not meant to be exhaustive but instead set out some of the key measures in use and whether they may be available to the Scottish Parliament. These measures can also be categorised in many different ways and the Tables are just one form of classification. In layman's terms the incentives and disincentives are referred to as “carrots and sticks”.

Within the scope of this work general government expenditure, capital expenditure and public procurement related expenditure has been excluded. However these areas offer enormous opportunities to achieve Scotland's Net Zero and Ecological Restoration aim. Public procurement is one of the most significant mechanisms for changing standards and expectations that influence the wider economy. While not part of this report, the annual spend of £12.6 Billion1 has the capacity to be repurposed to ensure that Scotland's public sector is driving the change towards better environmental outcomes, whether it is procurement of buildings, medical devices, vehicles, services, or food.

It is arguable that everything a government does is intended to change behaviour in one way or another, and that there will be unintended consequences from this; from an environmental perspective, the lack of tax on aviation fuel compared to fuel for ground based public transport is perhaps an obvious example of a distortion. Avoiding these distortions is something that is discussed further in the case studies in this report.

It is worth noting at this point that changing the focus of existing measures, as with existing public procurement spend, is arguably both easier and more effective than introducing something entirely new; as long as those existing measures have the potential to influence the level of change required. The funding already exists, key stakeholders, businesses and citizens are familiar with the measures already in place and you may not need to consider the interaction between other measures as this work may have already been done. In resourcing terms, less government/government agency work and parliamentary scrutiny time is required too, meaning that changes can be introduced considerably faster.

| Mechanism | Current or past examples applied in Scotland | Available to Scottish Parliament? | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grants |

| Yes | May have a limited impact if there is a lack of sufficient funding resources to provide scale. May also have a minimal behaviour change impact, as limited to the grant recipients only. |

| Low cost loans | Domestic insulation and renewable energy installations. | Yes | May have a limited impact due to lack of sufficient funding resources to provide scale. May also have a minimal behaviour change impact, as limited to the loan recipients only. |

| Subsidies |

|

|

|

| Guaranteed prices |

| No | Both measures have resulted in significant increases in renewable electricity generation. However, in both these cases the funding comes from energy suppliers which results in rising electricity prices. |

| Tax & Capital Allowances | Allowances for business buying new zero-emission goods vehicles. | No | These reward beneficial investment in assets/ infrastructure or research (targeted at high earners and companies). |

| Local tax relief (Business Rates/Council Tax) | There are Business Rate reliefs’ in place for District Heating, Renewable Energy, Charities and Reverse Vending machines. | Yes | Since Business Rates and Council Tax are devolved the Scottish Government can use these to incentivise businesses and householders. |

| Other fiscal incentives |

| Some are | A range of technical measures that may be helpful when other options are constrained. |

| Mechanism | Examples applied in Scotland and other countries | Available to Scottish Parliament? | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxes/Duties | Differential VAT rates, specific taxes such as Landfill Tax. | Some are | VAT not available as an option but Landfill Tax and others are. Depending on the specific measure, cross-border effects may limit use in Scotland. |

| Levies |

| Yes but subject to UK Government approval if the levy revenue is accrued by the Scottish Government. | Acts like a Carbon Tax where used in relation to fuels and large industrial energy users. May simply be a tax called a levy e.g. Aggregates Levy. |

| Minimum Prices | Single use carrier bags. | Yes | When used have demonstrably had a significant behaviour change impact. |

| Extended Producer Responsibility |

| Yes | The Scottish Government often agrees to work on a UK basis for these. Evidence from other countries shows these offer significant behaviour change impact and emissions reduction if designed ambitiously. |

| Local Taxes and Charges |

| Yes | Operated by Local Authorities and offer a range of opportunities. Dependent on supporting Scottish Government legislation or regulation. |

| Trading Schemes |

| Unclear | Complex and their effectiveness may be questionable but in the case of emissions trading they are being used as a form of proxy for a Carbon Tax. |

3.2.1 Commentary on Specific Measures

Most of the measures contained in Table 1 and 2 are probably familiar to most people from their daily lives with the exception of a few. These are explained in more detail here along with specific issues to note.

Levies

Where a levy does not result in revenues being accrued by the Scottish Government, Scotland does have the power to introduce them; it’s worth noting in this context that sometimes the term “levy” can be used where the instrument is actually a minimum price or charge. However, where a levy or tax results in such Scottish Government revenues then the UK Government must approve the proposal. The UK government has said in its Strengthening Scotland's Future, Command Paper, 20101 that it would consider the extent to which any proposal might:

create or incentivise economic distortions and arbitrage within the UK.

create opportunities for tax avoidance across the UK.

impact on compliance burdens across the UK.

Guaranteed prices

These measures can take many forms but the overall objective is to provide a guaranteed price of some sort at level which is sufficient to encourage investment, for example in new renewable energy technologies. The Feed In Tariff (FIT) mechanism was used to accelerate the take up of domestic solar PV panel installations by guaranteeing a price for all electricity generated, paid to the householder by their energy company. Without this mechanism there would be no financial incentive to install solar PV on an existing house. Since the replacement of FITs by the Smart Export Guarantee, installation rates of domestic solar systems have declined significantly.2

Other fiscal incentives

This category is a “catch all” for other incentives that a government may have at its disposal that can influence the flow of money, particularly in terms of investment. Strictly speaking some of these may not be true fiscal measures but they are worth considering, especially in a context of constrained access to other measures such differential VAT rates. They include ring fencing public budgets, so that an organisation can only spend a proportion of their own or government funding on a particular thing e.g. waste management services or energy efficiency measures. Another option is fixing a higher carbon price in a project's Cost and Benefit Analysis to encourage low emission options in the design of new infrastructure or services.

VAT

Value Added Tax (VAT) is an indirect tax levied on the purchase of many goods and services. It is reflected in the price paid when items are bought. VAT can either be charged at 20 per cent (standard rate), 5 per cent (reduced rate) or zero per cent (zero rated). Some items or activities can also be exempt from VAT.

Differential VAT rates offer an opportunity to support activities that are more aligned to environmental sustainability, such as reduced or zero VAT rates for energy efficiency related products, e.g. insulation. However, differential rates, if not considered carefully, can also distort incentives. For example this applies in construction activities; where building maintenance and refurbishment activities are charged at 20%, while building new houses is charged at 0%. Notwithstanding the benefits of new zero emission buildings, the maintenance or refurbishment of existing buildings is more carbon efficient than constructing new buildings and clearly has other societal benefits. This is being recognised by the construction sector:

It is no longer fair to say that a new building will be more energy efficient without embodied carbon being considered as part of the decision-making process.

British Property Federation. (2021, October 25). To build or refurbish – the embodied carbon dilemma?. Retrieved from https://bpf.org.uk/media/blogs/to-build-or-refurbish-the-embodied-carbon-dilemma/ [accessed 9 February 2022]

Extended Producer Responsibility

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) has various definitions but a simple one is - when responsibility for the environmental effects that products can cause in their life cycle is shared among producers and users involved with the product. EPR is often used interchangeably with terms such as Producer Responsibility and Product Stewardship. The OECD provides a useful definition of Extended Producer Responsibility (with emphasis added):

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) as an environmental policy approach in which a producer’s responsibility for a product is extended to the post-consumer stage of a product’s life cycle. An EPR policy is characterised by:

1. the shifting of responsibility (physically and/or economically; fully or partially) upstream toward the producer and away from municipalities; and

2. the provision of incentives to producers to take into account environmental considerations when designing their products.

OECD. (n.d.) Extended Producer Responsibility. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/env/waste/extended-producer-responsibility.htm [accessed 21 January 2022]

EPR schemes at an international level take many forms, but one of the most common are deposit & return schemes for drinks containers, which influences consumer behaviour by placing a value at point of purchase on what is otherwise waste. In the UK we have many EU (legacy) producer responsibility schemes for products such as packaging, electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE), batteries, and End of Life Vehicles (ELVs). The UK Government and Scottish, Welsh and Northern Ireland Governments are in the process of reviewing these on varying timescales.

Trading schemes

The UK Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) is a cap-and-trade system which caps the total level of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions. The UK ETS came in to force on 1 January 2021 to replace the UK’s participation in the EU ETS. The Scottish Government explains:

Participants in the scheme are required to obtain and surrender allowances to cover their annual greenhouse gas emissions. Participants can purchase allowances at auction or trade them amongst themselves, which allows the market to find the most cost-effective way to reduce emissions. Industrial sectors considered at risk of carbon leakage (whereby carbon costs would make them uncompetitive prompting industry to relocate outside the country in which the ETS applies) receive a proportion of allowances for free.

Scottish Government. (n.d.) Climate change. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/policies/climate-change/emissions-trading-scheme/ [accessed 21 January 2022]

It covers around 100 participants in Scotland who account for 28% of Scotland's GHG emissions. It applies to energy intensive industries, the power generation sector and aviation, where the total rated thermal input exceeds 20MW, but excludes installations for the incineration of hazardous or municipal waste.6

There is the potential for the UK ETS to be linked to the EU ETS and there will be periodic reviews of the UK ETS Cap to ensure the cap is in line with Scotland's net zero ambitions.

There is a lot of interest in Trading Schemes as solutions to cut carbon dioxide equivalent emissions, particularly from economists who are attracted to the potential for such schemes to operate efficiently from a cost perspective. However in practice trading schemes are complex and difficult to manage. They can work well in a closed and strongly regulated environment, such as within an individual company context. However in a wider complex environment there are difficulties in obtaining sound data, avoiding loop holes for participants, effective price setting and also ensuring follow through by authorities (See section 4.3 for more information on this topic).

3.3 The current status of devolved environmental fiscal measures in Scotland

In this section a brief overview of the main devolved environmental fiscal measures is provided. These are measures that are specifically targeted to address issues of an environmental nature.

3.3.1 Single-use carrier bags

The single-use carrier bag charge was introduced in October 2014 at a rate of 5p and was subsequently increased to 10p1. The Scottish Government states that before the charge was introduced, around 800 million single use carrier bags were issued annually in Scotland.

By 2015 this number had fallen by 80% and the Marine Conservation Society noted in 2016 that the number of plastic carrier bags being found on Scotland's beaches dropped by 40% two years in a row with a further drop of 42% recorded between 2018 and 20192.

Although the charge is paid directly to the issuer of the bag, with no revenue collection by authorities, the charge has raised £2.5m for charitable purposes (however the amount of this spent in Scotland is unknown). Overall the charge has been very successful at reducing terrestrial and marine litter and has also been successful in altering citizens’ daily behaviour around resource use i.e. away from single use and towards reusable carrier bags.

Inevitably as the wider public have become more familiar with the charge the rate has had to be raised from 5p to 10p to maintain the same impact. This is a feature of behaviour change measures; the initial novelty of the change and the motivation to avoid the charge wanes over time. As a result flexibility to alter charges easily, without extensive use of resources by the Scottish Government or the Parliament, perhaps should be considered in whatever instrument or published route map is used for such measures.

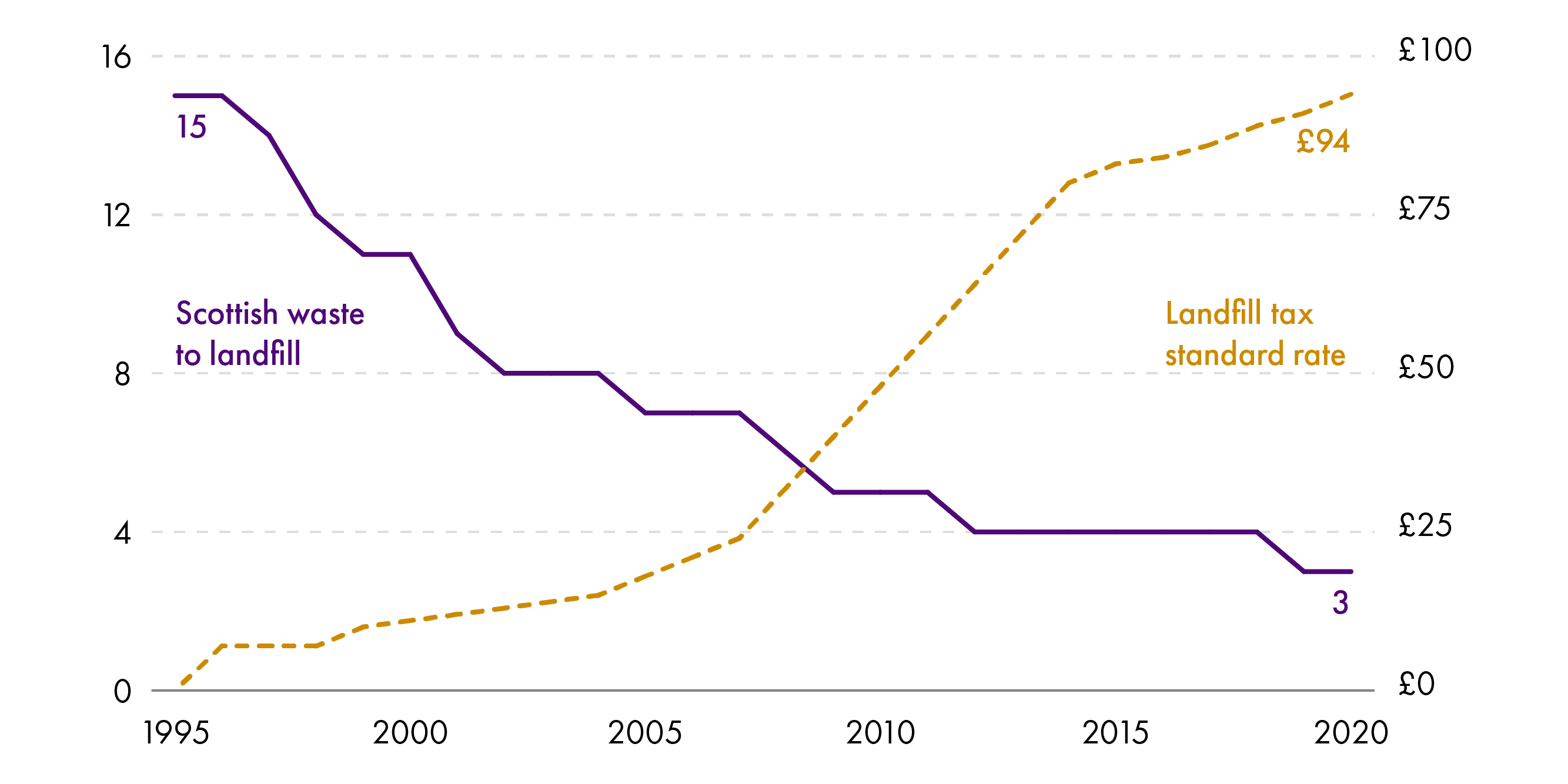

3.3.2 Scottish landfill tax

The UK Landfill Tax was devolved through the Scotland Act 2012 and the Scottish Landfill Tax (SLfT) has been in place since 1 April 2015. The Scottish Parliament sets tax rates paid on the disposal of waste at landfill and determines which waste qualifies for the tax. SLfT is a fully devolved tax collected by Revenue Scotland The current rates set by the Scottish Landfill Tax (Standard Rate and Lower Rate) Order 2021 are:

Standard rate: £96.70 per tonne

Lower rate: £3.10 per tonne

The Landfill Tax has been a major part of the success in driving change in Scotland's waste performance. A significant factor in this has been the escalator built into the tax rate. This effectively laid out a route map of future costs for all the stakeholders involved. Landfilling waste was therefore going to become increasingly expensive and investing in alternative solutions, such as recycling and reuse activities, would often be in waste producers own financial interest regardless of the wider environmental and societal benefits. The chart below from the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) demonstrates the impact of the tax.1

There is also a partial hypothecation of the SLfT. The Scottish Landfill Communities Fund (SLCF) is a tax credit scheme, which encourages landfill site operators to provide contributions to Approved Bodies, who can then pass the funds onto community and environmental projects. There are six categories of environmental project that can be funded in this way. The SLCF replaced the UK scheme in Scotland in April 2015 and landfill operators cannot directly fund projects or control how the SLCF funding is spent (see Figure below).

However one of the unintended consequences of Landfill Tax and the increasing price of landfill disposal for waste is that Energy from Waste (EfW) disposal solutions have become more attractive. This is discussed further in section 5.4.

3.3.3 Renewable energy and energy efficiency grants/loans

There are a wide variety of low cost loans and grants made available by the Scottish Government through the Energy Savings Trust (EST) and Zero Waste Scotland (ZWS). These include:

EST Home Energy Scotland loan – up to £17,500 interest-free to install home renewables such as heat pumps.

ZWS Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) Loan - interest-free loan funding of up to £100,000 for a variety of energy efficiency improvements, such as insulation, heating or double glazing. The loan can also support the installation of a variety of renewable technologies.

EST Low Emission Support Fund for Business - offering micro businesses and sole traders, with an operating site within 20km of the forthcoming city low emission zones, a £2,500 grant towards the safe disposal of non-compliant vehicles.

EST Used Electric Vehicle Loan (for householders and businesses) - interest-free loan for householders and businesses with up to £20,000 to cover the cost of purchasing a used electric car or used electric or plug-in hybrid electric van.

3.3.4 Air Passenger Duty

Air Passenger Duty (APD) was devolved by the Scotland Act 2016 and so it warrants a mention here although these devolved powers have not been used yet. The Scottish Government planned to replace it with Air Departure Tax (ADT)1 and made provision for such a tax however the original proposals could not continue the exemption for the Highlands and Islands (related to EU laws on state aid) and were not aligned with the 2045 Net Zero target. The latest Scottish Government position is:

We will engage with the UK Government on its current consultation on APD reform to find a solution that remains consistent with our climate ambitions. The UK Government will maintain the application and administration of APD in Scotland in the interim.2

APD is a per person charge, rather than per unit of fuel. Hence the impact on a passenger is the same whether they travel by a commercial airline or a private jet. It also doesn't take account of the efficiency of the individual aircraft. An escalating tax on aviation fuel may be a more equitable option and would encourage a change in aircraft operators’ behaviours but faces the challenge of operators simply refuelling aircraft elsewhere to avoid the tax.

The UK Government published the responses to its consultation on APD reform in October 20213. Environmental stakeholders called for a change from APD to a frequent flyer levy, which would directly target those generating the most emissions, however the UK Government has responded to the aviation industries’ concerns over the administrative burden created by a frequent flyer levy and has chosen to implement a revised structure to the APD international distance bands from April 2023. The bands with be set at 0-2,000 miles (short haul); 2,000-5,500 miles (long haul); and 5,500 miles (ultra long haul).

3.3.5 Agricultural subsidies/grants

Agricultural subsidies arise from the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) support regime. These still operate in Scotland after leaving the EU, albeit with the funding now coming from the UK Treasury. The Scottish Government is continuing the CAP based system until a new approach has been developed, in line with the 2018 policy1 of maintaining the stability and simplicity of the regime until 2024; with a new regime planned for implementation in 2025. This is a significant area of policy development for Scotland and the Scottish Government has made commitments to ensure the new regime aligns with environmental outcomes (see section 5.5 for more detail on this).

The existing regime is structured under two main pillars:

Pillar 1 of the CAP is Rural Payment support to farmers' incomes. This support is provided in the form of direct payments with the majority of the payments based on a per-hectare of land basis. This makes up around 70% of the funding2.

The Scottish Rural Development Programme (SRDP) delivers Pillar 2 through a range of different funding schemes; for example funding woodland creation, organic farming, and paths, amongst others. The main priorities are: enhancing the rural economy, supporting agricultural and forestry businesses, protecting and improving the natural environment, addressing the impact of climate change and supporting rural communities. This makes up the remaining 30% of the funding.

3.3.6 Forestry grants

The Scottish Government's Forestry Grant Scheme (FGS) 1 supports the creation of new woodlands – contributing towards the Scottish Government target of 12,000ha of new woodlands per year, rising to 18,000 hectares from 2024/5 - and the sustainable management of existing woodlands. For the Scottish Rural Development Programme 2014–2020, £252 million is estimated to have been made available through this scheme.

The support comes under eight categories, two for the creation of woodland and six for management of existing woodland. These cover agro-forestry and woodland improvement as well as the planting of various types on new woodland. Scotland was praised for the level of new planting by the Forestry Journal in 20212, when compared to other nations in the UK. However according to Scotland's Forestry Strategy 2019–20293only 3,000-5,000 hectares of this annual total will be new native woodland and so the focus appears to be primarily upon commercial woodland for economic value rather than biodiversity or ecosystem value.

3.3.7 Fishing subsidies/grants

The environmental impact of fishing, aquaculture and related industries is primarily managed through regulation, however since management of our seas is essential for protecting and enhancing our biodiversity it seems appropriate to include fiscal measures here too. This section highlights the main schemes.

The European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF) finished in 2020. This was a European grants scheme which supported fisheries, aquaculture, the seafood supply chain (including processing and fishing communities), wider maritime sectors and statutory data collection with specific aims including sustainable fishing/aquaculture. The Scottish Government identified in 2019:

Together with associated indirect assistance, EMFF could be worth up to £150m to Scotland between 2014 and 2020.1

The Scottish Government's Seafood Producers Resilience Fund ran from 5 February to 7 March 2021. The fund provided support to eligible shellfish catchers and eligible shellfish and trout aquaculture undertakings. This support was provided as a result of COVID-19, and the difficult trading conditions that have resulted from the end of the transition period following the UK's withdrawal from the EU.

Grant funding is available under the one-year Marine Fund Scotland (MFS) programme, but work must be completed by 31 March 2022. There are three priorities, one of which is “delivering a low carbon blue economy which contributes to our climate change targets and helps sustain and enhance the natural capital in Scotland's seas”2

The Scottish Government's commitment to a 'Blue Economy Action Plan'3 sets out criteria for future support. This includes overarching/public good criteria:

Supporting collaboration, partnerships, knowledge and technical expertise which enable better decision-making, regulation, science and innovation

Enhancing the marine environment, including its quality, reputation and its marine products

Reductions in emissions or removal of waste

3.3.8 Others

There are non-environmental fiscal measures where reliefs, discounts or modulations for environmental benefit have been incorporated. Some of these are mentioned in the later sections of the report. The repurposing of existing fiscal measures could be one of the easiest routes for early and acceptable implementation of incentives/disincentives.

3.3.9 The post EU legal framework

At this point it is worth highlighting the impact of the UK Internal Market Act 2020 and the UK Subsidy Control Bill. The Act seeks to prevent internal trade barriers among the four countries of the United Kingdom. It could significantly restrict the Scottish Governments ability to introduce new fiscal measures different from the rest of the UK, including Minimum Prices for products. The two key principles are:

Mutual Recognition: A good, which complies with regulation permitting its sale in the part of the UK it is produced in or imported into, can be sold in other parts of the UK, without complying with equivalent regulation there.

Non-Discrimination: Regulatory requirements that discriminate against a good from another part of the UK, whether directly or indirectly, will not be enforceable

The Act does not prevent the Scottish Parliament from passing legislation, or the enforcement of any requirements on goods produced in Scotland or imported directly into Scotland from outside the UK. However, it could significantly impact on the extent to which new fiscal measures in Scotland could make a difference and achieve their intended outcomes; where the Act means requirements do not apply to goods or services produced in, or imported into, other parts of the UK before being marketed in Scotland.

There are also a number of Common Frameworks (intergovernmental agreements to set out shared UK or GB-wide approaches) being developed following the exit from the EU and these include areas such as Agricultural Support, Emissions Trading and Resources and Waste. A number of environmental Common Frameworks have been provisionally agreed and are expected to be made available for Parliamentary scrutiny in 20221. These frameworks in combination with the Internal Market Act may affect the latitude that the Scottish Government has in pursing different Land use, Circular Economy and Waste policy from the rest of the UK. Common Frameworks may also be used to agree exclusions from the UK Internal Market Act principles, which might enable policy divergence in areas that would otherwise be prevented or hindered by the Act. The UK Government has recently published a process for this2.

This situation is, at the time of writing this of the report, being tested by the introduction of the Single Use Plastics Regulations where Scotland is aligning with aspects of the EU Single Use Plastics (SUP) Directive. The Minister for Green Skills, Circular Economy and Biodiversity, Lorna Slater MSP, recently told the Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee:

Although we still fundamentally oppose the act, officials have been engaging on the preferred option of securing an exclusion in this policy area through a common frameworks process. Agreement has now been reached on the process by which agreements can be reached on the common framework areas that can be excluded, and UK ministers will shortly make a parliamentary statement to that effect. This is an early test of UK ministers’ commitment to acting in a way that respects the framework process. It will not make the 2020 act any more compatible with devolution, but it will allow a degree of protection for policy areas that are covered by common frameworks.

If no exemption is allowed to the impact of the 2020 act, it will still be possible for any products that are produced in or imported by another part of the UK to be sold in Scotland, and hundreds of millions of pieces of plastic will still end up on our beaches. Without an exemption, the act will undermine our ban on these environmentally damaging plastic products. We will continue to work with the other UK Administrations to agree an approach to managing the implications of the act for the ban.

The UK Subsidy Control Bill may also have an impact on subsidies applied to businesses within Scotland. The main focus of the bill is ensuring subsidies from public bodies are in compliance with a series of subsidy control principles set out in the Bill. Principle F in Schedule 1 of the bill requires “subsidies should be designed to achieve their specific policy objective while minimising any negative effects on competition or investment within the United Kingdom”. This will require the Scottish Government to consider the effect of any subsidy on competition and investment across the United Kingdom. In addition there are both environment and energy principles as extra principles in Schedule 2 of the Bill which may be relevant in terms of constraining policy options for the Scottish Government.

While this new legal framework is still to be tested and is subject to how Common Frameworks are used, taken all together it could make it challenging to introduce new environmental fiscal measures that differ from the rest of the UK.

3.3.10 Environmental fiscal reform in a devolved context

Action to address climate change is primarily focused on eliminating the use of fossil fuel based energy and the control of other GHGs such as methane (the types of fiscal mechanisms available to the Scottish Government under existing devolved powers are discussed previously in section 3.2). With energy policy being primarily controlled from Westminster this poses extra challenges for the Scottish Parliament – but Scotland can and has in a number of cases put in place measures which build on incentives introduced at UK level. Most obviously, the Scottish approach to enabling renewable electricity developments through the planning system has encouraged much greater than population-share development of renewable energy. Similarly, but at a smaller scale, funding for Energy Saving Trust ( EST) advisors has helped individual households access UK-wide renewable heating support.

The Scottish Government's Heat in Buildings Strategy states:

Whilst regulating for emissions, heat and energy efficiency are largely devolved matters, the regulation of energy markets, fossil fuels, consumer protection and competition are reserved to the UK Government. As such, there is a risk that in exercising devolved powers we cut across into areas that are reserved to the UK Government. Given that the UK Government faces the same challenge to decarbonise heat in buildings that we face, we will engage with them ahead of introducing new legislation – as has also been recommended by respondents to the consultation – to secure agreement on changes that are necessary to the energy markets in reserved areas to ensure a just transition to zero emissions heating, or to secure further devolution of the powers needed to make such changes in Scotland.

Scottish Government. (2021). Heat in Buildings Strategy - achieving net zero emissions in Scotland's buildings. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/heat-buildings-strategy-achieving-net-zero-emissions-scotlands-buildings/documents/

The great majority of policy discussions on climate change emissions focus on energy use within the boundaries of individual countries but this focus may ignore some significant aspects. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation has calculated that climate change is caused by 55% direct emissions from energy use and 45% from embedded carbon in the materials and products we use2. Other organisations have come up with similar estimates. This measurement is based on the overall carbon footprint emissions of a country, which includes the emissions we are responsible for from imported products and materials we purchase. Territorial emission measurements are more limited and tend to focus on direct emissions from energy use and land use.

To decarbonise an economy there is a need to consider the overall carbon footprint of the society as you could simply “offshore” your emissions to the manufacturing industry in another country. In essence net zero cannot be achieved without addressing the embedded carbon in materials and products and adopting a Circular Economy (CE) may be essential to this.

Key benefits of a transition to a CE are commonly accepted as reduced extraction of virgin natural resources, reducing the impact on biodiversity, reducing environmental impacts on air, water and reducing climate impact. The other benefits in these challenging times are: reduced exposure to geopolitical supply risk(s); new economic opportunities, which may include improved quality of jobs; and also greater community cohesion as supply chains become more local – e.g. through leasing, reuse and repair. The CE has been recognised in G20 reports and the EU’s Circular Economy Action Plan:

CE measures are now a core component of both the European Union’s (EU’s) 2050 long-term strategy to achieve a climate-neutral Europe and China’s current Five Year Plan.

Greco, E., Botti, F. and Bilotta, N. (2020). Global Governance at a Turning Point. The Role of the G20. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/49295495/Global_Governance_at_a_Turning_Point_The_Role_of_the_G20

Global material use has tripled in the past few decades, and in the absence of specific measures to counter such a trend it is expected to further double by 2060.

European Commission. (2019). Communication on a new Circular Economy Action Plan. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/%20EN/TXT/?uri=pi_com:Ares(2019)7907872

Notwithstanding the new post EU-exit legal framework mentioned above (in Section 3.3.9), Scotland has a range of devolved competences in waste and resources and the wider environment covering agriculture, forestry and land management. Scotland also measures both its territorial and footprint GHG emissions; with the decline in footprint emissions being notably less than the territorial emissions5. It is therefore important that, with these competences, the parliament considers the opportunity and significant role the circular economy has, and the way Scotland’s carbon emissions are measured within any future environmental fiscal framework.

3.4 Planned environmental fiscal measures

There are a range of fiscal measures already in the pipeline for implementation within Scotland and the UK, or that are in a stage of consultation or early planning. These include UK-wide plans where the policy area is devolved and consent of Scottish Ministers or the Scottish Parliament will be required, for example EPR schemes, and where the UK Government is seeking to introduce measures that will impact on devolved areas, for example the proposed Plastic Packaging Tax. In this section what is considered to be the most relevant of these are summarised from a Scottish perspective; please note that there may be others in development that were not made aware to the author at the time of preparing this report.

The two Tables below summarise the measures that may be forthcoming and therefore may require some scrutiny by the Scottish Parliament. It may also be necessary to consider proposed measures alongside relevant Common Frameworks.

| Fiscal Measure | Description | Estimated Timescale |

| Tax : Scottish Aggregates Levy | The current UK aggregates levy is £2 per tonne for aggregate material quarried or imported. A Scottish Levy replacing the UK one is planned. | Expected in 2021-26 parliament following the Final Report on options in August 2020. |

| Tax: UK Plastic Packaging TaxThis is a UK government measure without the involvement of Scottish or Welsh Governments. | This is a new tax that will apply to plastic packaging manufactured in, or imported into the UK, that does not contain at least 30% recycled plastic. | Expected April 2022. |

| Producer Responsibility: Scottish Deposit Return Scheme | 20p Deposit on drinks containers (Glass bottles, Cans, Plastic bottles). | Expected August 2023 (Regulations already passed in the Scottish Parliament). |

| Producer Responsibility: UK wide packaging reform | Revised system for responsibility for packaging on products. Will result in payments from the packaging industry to Councils to cover the costs of packaging collection through their household recycling services. | Expected 2023. |

| Fiscal Measure | Description | Status (in consultation or in development) |

| Scottish Subsidy: Scottish Agricultural Subsidy regime | The Scottish Government is committed to replacing the existing CAP regime with half of funding conditional on environmental impacts. | Initial consultation document issued by SG. New Act expected in 2023 and implementation in 2025. |

| UK wide Producer Responsibility: WEEE/Batteries | UK wide schemes being reviewed with the four nations. | Consultation process planned for 2020 but delayed due to the pandemic. |

| UK Tax: VAT (partially assigned) | The Scotland Act 2016 states that receipts from the first 10p of standard rate of VAT and the first 2.5p of reduced rate of VAT in Scotland will be assigned to the Scottish Government’s budget. | Timescale will be known following the Fiscal Framework Review. However assignment of a share of VAT does not enable the use of differential rates or to make any other changes to VAT policy. |

| Scottish Tax: Workplace Parking Licensing (WPL) | Employers would pay an annual levy to their local authority for parking spaces they provide to their employees. Powers to introduce WPL are included in the Transport (Scotland) Act 2019. | Publication of regulations & guidance by Transport Scotland expected in 2022. The discretionary revenue raised will fund local transport strategies. |

| UK wide Producer Responsibility: Fishing Gear | A scheme to ensure the recovery of end of life fishing gear (aligns with EU Single Use Plastics Directive). | An initial inventory report and policy options for the UK nations to be published by DEFRA in 2022. |

| UK wide Producer Responsibility: Textiles | Potential UK wide scheme options being developed. | Consultation with stakeholders by the end of 2022 on options for an Extended Producer Responsibility scheme. |

| Scottish Producer Responsibility: Minimum Single Use Cup Price | Recommendation by EPECOM to the Scottish Government. | May be included in the forthcoming Circular Economy Bill along with a range of other potential measures. |

| Scottish Tax: Transient Visitor Levy (TVL) | Would enable local authorities to apply a “tourist tax” to visitor accommodation at their discretion. | Awaiting outcome from the recent Scottish Government consultation. |

In the UK Autumn 2021 budget the chancellor announced some changes to UK wide environmental fiscal measures. Flights between airports in the UK nations will be subject to a new lower rate of Air Passenger Duty from April 2023. From April 2023, a new ultra long haul band in Air Passenger Duty for flights of over 5,500 miles will be introduced. Many commentators appeared surprised at the lack of further “Green” measures in the budget given the approaching COP26 in Glasgow (e.g. the BBC1).

3.5 Programme for Government and the Climate Change Plan 2020 commitments

There are a range of targets and commitments contained within the Scottish Government’s Programme for Government (PfG) and the Climate Change Plan 2020 update (CCPu). Some of these come with commitments to review or examine fiscal measures. Where not already highlighted in Tables 3.4.1 and 3.4.2 the key ones for this report are raised within case studies in Section 5.

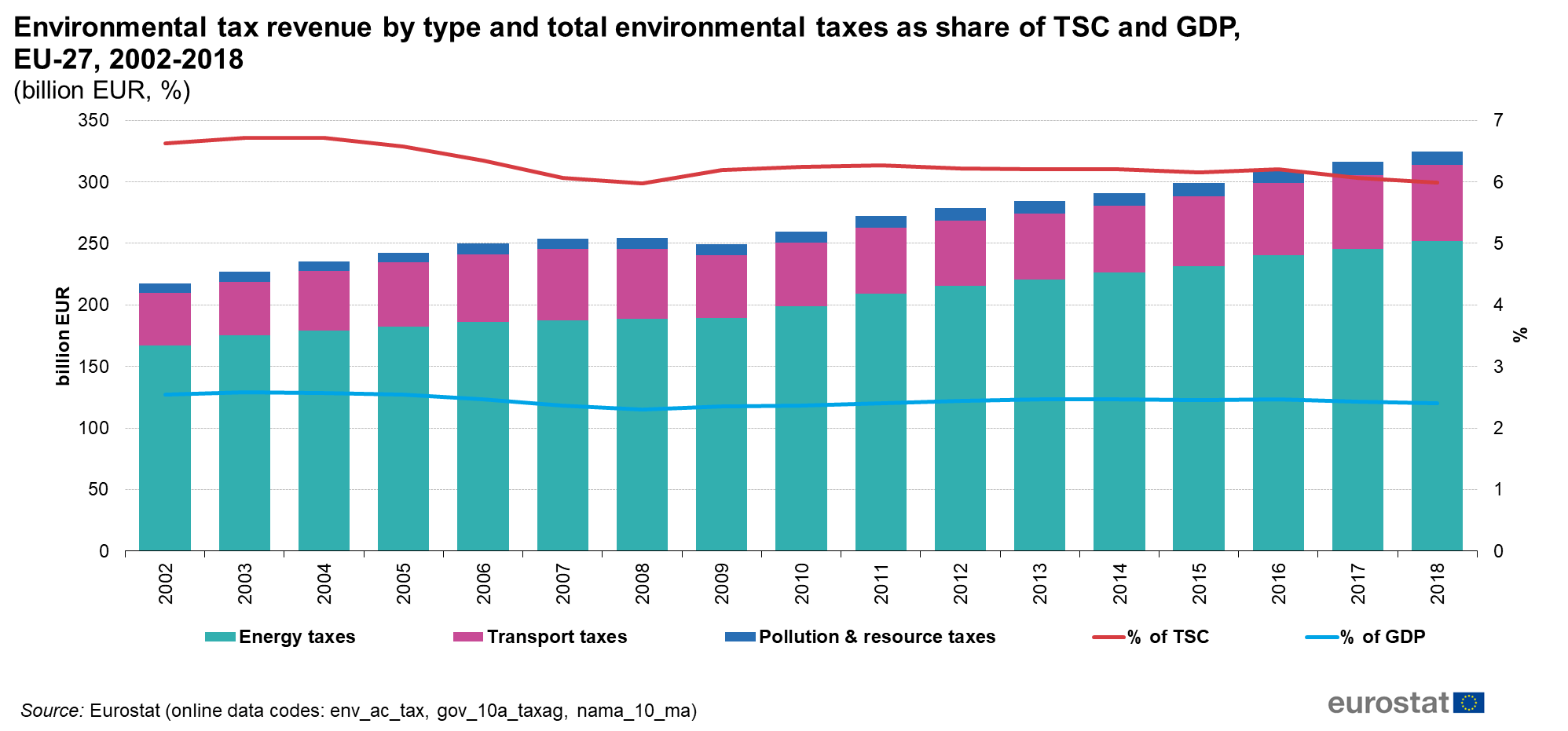

3.6 European Union measures

The EU is proposing a range of new measures that may influence the UK and Scotland. The most significant is the Cross Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). On 14 July 2021, the European Commission adopted a proposal which will put a carbon price on imports of a targeted selection of products so that ambitious climate action in Europe does not lead to ‘carbon leakage’. The Commission states that:

This will ensure that European emission reductions contribute to a global emissions decline, instead of pushing carbon-intensive production outside Europe. It also aims to encourage industry outside the EU and our international partners to take steps in the same direction.

European Commission. (2021). Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/green-taxation-0/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en

As the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) summarises, with reference to it as a potential UK fiscal measure, one option “... to preventing taxes in a country leading to emissions-generating activities simply moving abroad is to place a tax on imports according to their embedded and untaxed GHG emissions (or ‘carbon’ content). Under such a tax, there would be no tax-induced incentive for a UK producer that is selling to UK consumers to move production abroad and import into the UK, and they would not face unfair competition from a producer in a location with lower taxes on GHG emissions.”2

If adopted by both the European Parliament and the Council – the CBAM would, from 2023, require importers of such goods to report the direct and indirect (embedded) emissions and any carbon-related tax paid abroad for all imports. This would represent a significant increase in reporting requirements. Additional tax would start to be due from 2026 when importers of cement, iron and steel, aluminium, fertilisers and electricity would need to buy ‘CBAM certificates’ to cover the carbon emissions created in the production of the imports from countries that are not part of the EU ETS. See figure 3.6 below.

The implications of the CBAM are that Scottish exporters may face additional costs and administration to export these goods and services into the EU with uncertain economic impacts. There are a number of options to address this. One option is the linking of the UK ETS, which Scotland is part of, to the EU ETS, an option available under the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA). While this would provide greater alignment with the EU and would likely make the UK exempt from the CBAM this would also limit the UK’s ability to design its own carbon pricing structures in the future.

If linking to the EU ETS is not pursued importers in the EU may be able to take account of any carbon price paid in the UK when determining how many CBAM certificates they need to purchase3. The IFS has also noted that the UK Government has indicated that it is considering a possible tax on imported emissions2 - in effect a UK CBAM.

In response to concerns raised by the Just Transition Commission about offshoring emissions and jobs the Scottish Government has responded (via the PfG 2021/22) that through the jointly‑administered UK ETS, the Scottish Government will ensure that the Free Allocation system continues to appropriately protect Scottish industries from the risk of carbon leakage. The Scottish Government has also commissioned research to better understand the impacts and potential benefits of carbon border adjustment mechanisms and committed to publish a position in 2022; those companies that have already taken action to reduce GHG emissions from their products or services may be the ones that could potentially benefit.

In addition to the CBAM the EU is expanding the role of its ETS to include more industries and adopting further measures as part of its action on the Circular Economy.

The EU Circular Economy Action plan 2021 requires that member states achieve high levels of separate collection of textile waste by 2025 and boost the sorting, re-use and recycling of textiles. The European Union’s Waste Framework Directive mandates that EU member states must set up separate collection for used textiles and garments by January 1st 2025, and that this waste can no longer be sent to landfill or incinerated. EPR will most likely be the financial instrument that ensures this happens.

However this is not a comprehensive list of EU measures and the situation is dynamic – EU measures in this space are likely to continue to develop. The Scottish Government may need to consider how it approaches delivery in some of these areas in relation to its policy commitment to keep pace with EU environmental standards.

4. Exploring opportunities for environmental fiscal reform

4.1 Filtering the many options

With such a wide range of fiscal measures available there is a need to focus upon those ones that have the best chance of being able to be implemented successfully and achieving the desired outcomes. A range of filters have been used to funnel this wide range of options into a smaller list of measures and case studies that could be used to inform a framework for environmental fiscal measures reform.

The aim has been to identify viable options and case studies that cover the breadth of areas covered by the Scottish Parliament, which includes for example, transport, land and sea-use, climate change, energy efficiency, biodiversity, sustainability of food supply, waste management, planning, sustainable tourism, and natural resource protection and management. This has, however, been tempered by the filtering below. The filters are as follows:

Relevance: to major scrutiny work in the parliament such as the Programme for Government 2021/22, the Climate Change Plan 2020 update and the forthcoming Circular Economy and Natural Environment Bills;

EU related: Measures being adopted by the European Union that Scotland may wish to follow (e.g. EU Single Use Plastics Directive or action on the collection of textiles);

Green recovery: Relevance to “Green Recovery” opportunities and the Scottish economy;

Magnitude: The likely magnitude of the beneficial impact of the measure or where a measure addresses a major technical challenge Scotland has;

Evidence of market failure: where costs of an environmentally beneficial option are greater than the alternative, fiscal measures can change prices at the point of decision making by business and individual consumers to support the alternative option;