Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill

The Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill ("the Bill") makes changes to the regulation of legal services in Scotland. This briefing summarises the current regulatory framework, the background to the Bill and the changes proposed by the Bill.

Summary

Over the years, the regulation of the legal profession has been a relatively controversial subject in Scotland. Although there are a range of viewpoints, two main strands of thought are:

Those who take the view that the current regulatory system, where professional bodies also have a regulatory role, overly favours solicitors and advocates and that this approach does not benefit consumers. They argue that there should be an independent regulator and that there should be more room for innovation and new forms of business.

Those who take the view that the current system provides high quality legal services and that risks lie more in the market for unreserved legal services which are not subject to the same regulatory obligations as solicitors and advocates. They stress the importance of the independence of the legal profession and the judiciary from government.

In addition, there have also been arguments that the current complaints process does not work effectively, and that much of the legislation regulating the profession is outdated and in need of consolidation and renewal (for details see the background section of the briefing).

In April 2017, the former Minister for Community Safety and Legal Affairs, Annabelle Ewing MSP, invited Esther Roberton to Chair an Independent Review of Legal Services Regulation in Scotland.

The Chair’s Report, ‘Fit for the Future – Report of the Independent Review of Legal Services Regulation in Scotland’(“the Roberton report”) made 40 recommendations intended to reform and modernise the current regulatory framework.

The main recommendation was that an independent body should be set up to regulate legal professionals (similar to the situation in England and Wales), with the professional bodies only retaining their role as representatives of the profession. The new system would be financed by a levy on practitioners.

The Scottish Government consulted on these proposals, but ultimately decided not to follow the Roberton report's main recommendation to set up a single independent regulator. The Scottish Government's response to the consultation analysis on 22 December 20221 concluded that it wished to, "build on the existing framework" and that,

"the existing regulators should retain their regulatory functions, with a greater statutory requirement to incorporate independence, transparency and proportionate and risk-based accountability."

The Bill reflects this position and amends and builds on the existing framework (albeit with some more fundamental changes) rather than following the more radical approach proposed in the Roberton report of setting up an independent regulator.

The main changes proposed by the Bill are as follows:

The setting up a framework whereby regulators can be assigned as either a category 1 regulator (consumer facing) or category 2 regulator (less consumer facing and more specialist areas of law). The Law Society of Scotland (regulator of solicitors) is assigned as a category 1 regulator. The Faculty of Advocates (regulator of advocates) and the Association of Commercial Attorneys (regulator of commercial attorneys) are assigned to category 2.

New rules which allow professional bodies to apply to become a category 1 or category 2 regulator. The policy aim is to allow for the expansion of regulated professionals which could provide legal services and, potentially, to provide opportunities to widen the scope of those who qualify to practise law in Scotland (para. 184 of the Policy Memorandum )

Rules aimed at increasing transparency. For example, Category 1 and 2 regulators will have to report annually on performance. The work of regulatory committees of category 1 regulators would also become subject to freedom of information requests under the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002.

The introduction of powers for the Scottish Ministers to review the regulatory performance of category 1 or 2 regulators. The Law Society has argued that these powers, "risk seriously undermining the independence of the legal profession from the state."2 The Scottish Government's view is that they balance the public interest in regulation and the independence of the legal profession (para. 142 of the Policy Memorandum).

The updating of the legislation on the regulatory objectives and professional principles for those providing legal services.

The regulation of legal businesses ("entity regulation") in additional to individual solicitors. Both the Roberton report and the Law Society recommended this approach arguing that it would improve quality standards, create a level playing field for different forms of business and provide better protection for consumers.

Updating the current rules on alternative business structures (ABS) with the aim of increasing the number of business and other bodies which can operate as ABSs.

Making it an offence to use the title of ‘lawyer’ with intent to deceive in connection with providing legal services to the public for a fee, gain or reward. The term ‘solicitor’ is a already a protected title. Both the Law Society and the Roberton report argued that similar rules should apply to the term 'lawyer' which is currently not protected.

Updating and modernising the way in which complaints about legal services are handled with the aim of benefiting both consumers and legal practitioners.

Allowing charities to directly employ legal professionals to undertake reserved legal services (e.g. representation in court proceedings).

Allowing legal services providers to apply to their regulator for a direction that certain rules do not apply or may be modified in a specific case. The aim is to allow for new services and legal technology to be trialled, thus leading to more innovation.

The Lord President (Head of the Scottish Judiciary) will retain his/her regulatory role in the new system including oversight of admission to the profession, approving professional practice rules, and conduct and discipline matters.

Glossary

| 1980 Act | Solicitors (Scotland) Act 1980 |

| 1990 Act | Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Scotland) Act 1990 |

| 2007 Act | Legal Profession and Legal Aid (Scotland) Act 2007 |

| 2010 Act | Legal Services (Scotland) Act 2010 |

| ABS | "Alternative business structure" - a business where non-legal professionals co-own a legal practice together with legal professionals |

| ACA | Association of Commercial Attorneys - the professional body which regulates commercial attorneys |

| Accredited regulator | Sections 25-37 of the Bill provide rules which allow bodies to apply to become a new regulator. These are referred to in the Bill as "accredited regulators" |

| Advocates | Self-employed legal professionals with training in advocacy who specialise in representing clients in the highest courts in Scotland. All advocates must be members of the Faculty of Advocates |

| Authorised legal business | The term used in the Bill for legal businesses which would be regulated as entities under the Bill (sections 38-50 of the Bill) |

| The Bill | The Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill |

| Category 1 and category 2 regulators | The Bill takes sets up a framework whereby regulators can be assigned as either a category 1 or category 2 regulator.Category 1 regulators are those with a significant membership or whose members provide largely consumer-facing services.Category 2 regulators are those whose membership is less consumer-facing or more specialist in nature, and whose membership is smaller in numberSection 8 of the Bill directly assigns the Law Society to category 1 with the Faculty and the ACA being assigned to category 2. |

| Commercial attorneys | Qualified engineers, architects or surveyors with legal experience who have certain rights to appear in court and to conduct litigation in respect of construction law |

| The Commission | The Bill renames the SLCC as "the Scottish Legal Services Commission" and grants it a range of new functions. "The Commission" is the term which the Bill documentation uses to refer to this body |

| Conduct complaint | A complaint to the SLCC relating to professional misconduct or unsatisfactory professional conduct |

| Conveyancing practitioners | Legal professionals permitted to provide conveyancing services as defined in section 23 of the 1990 Act |

| Executry practitioners | Legal professionals permitted to provide executry services as defined in section 23 of the 1990 Act |

| Entity regulation | The regulation of legal businesses as an entity (e.g. law firms) as opposed to the regulation of individual legal professionals (e.g. solicitors) |

| The Faculty | The Faculty of Advocates - a self-governing, non statutory body which both represents and regulates advocates |

| Handling complaint | The SLCC has powers to investigate how a professional body has dealt with a conduct complaint. This is termed a "handling complaint" |

| Hybrid complaint | A complaint to the SLCC which contains elements of both poor conduct and inadequate services in respect of the same factual issue |

| The Law Society | The Law Society of Scotland - the body which represents the interests of the solicitors' profession in Scotland, as well acting as the regulator for solicitors (and also conveyancing and executry practitioners) under rules laid down in statute |

| Licensed legal service provider | The 2010 Act put in place provisions (as yet unused) which allow for ABSs. The 2010 Act refers to these entities as "licensed legal service providers" ("licensed providers") |

| Lord President | Head of the Scottish Judiciary who also has a key role in regulating the legal profession |

| Notaries public | Practising solicitors who are responsible for the administration of oaths, and witnessing and authenticating the execution of certain types of document |

| Roberton report | The 2018 report, ‘Fit for the Future – Report of the Independent Review of Legal Services Regulation in Scotland’ which made recommendations intended to reform and modernise the current regulatory framework |

| Regulatory complaint | A complaint relating to a failure by a licensed provider (i.e. ABS) to have regard to the regulatory objectives or professional principles set out in the 2010 Act |

| Regulated legal professionals | Legal professionals who are authorised to provide reserved legal services (or certain elements of reserved legal services), i.e. those regulated by the Law Society, the Faculty or the ACA |

| Reserved legal services | Legal services restricted by law (Section 32 of the Solicitors (Scotland) Act 1980) to legal professionals regulated by relevant professional bodies (primarily solicitors and advocates, but also certain others) |

| Services complaint | A complaint to the SLCC relating to inadequate professional services |

| SLCC | Scottish Legal Complaints Commission - the non-departmental body set up by the 2007 Act to deal with complaints about "regulated legal professionals". The Bill renames the SLCC as "the Scottish Legal Services Commission" and grants it a range of new functions |

| Solicitors | Legal professionals who have qualified as a solicitor and who have a practising certificate issued by the Law Society of Scotland (the normal route to qualification involves an LLB degree in Scots law, the postgraduate Diploma in Legal Practice and a two year traineeship with a solicitor/firm of solicitors). Solicitors traditionally act as general legal advisers whilst also carrying out work in the lower courts |

| Solicitor advocates | Solicitors who are permitted to appear in the highest courts in Scotland where they have sufficient experience and have passed additional exams/training courses |

| Unregulated legal professionals | Legal professionals who are not authorised to provide reserved legal services |

| Unreserved legal services | Legal services which can be carried out by regulated legal professionals and also by unregulated legal professionals, including those who may or may not have legal qualifications or training |

Legal services and legal service providers in Scotland

Legal services

Legal services cover a wide range of issues. Sometimes there is simply a need for legal advice, i.e. how the law applies to an individual case. However, in other cases, legal representation in a court or tribunal may be necessary. In addition, the law can also be crucial to getting things done, for example when making a will, renting or buying a property, or getting married or cohabiting.

This range of work is reflected in one of the key pieces of legislation, the Legal Services (Scotland) Act 2010 ("2010 Act"). It specifies in section 3 that legal services include:

the provision of legal advice or assistance in connection with: (i) any contract, deed, writ, will or other legal document, (ii) the application of the law, or (iii) any form of resolution of legal disputes; or

the provision of legal representation in connection with: (i) the application of the law, or (ii) any form of resolution of legal disputes.

Legal service providers

There are a large range of legal service providers in Scotland. The two most commonly known types are arguably:

advocates - they have special training in advocacy and specialise in representing clients in the highest courts (Court of Session for civil cases, High Court of Justiciary for criminal cases and UK Supreme Court for certain appeals), although they can represent people in any Scottish court.

There are many more solicitors than advocates. The Law Society’s annual report for 2022 indicated that there were 12,872 solicitors at the end of year.1 Based on the Faculty of Advocate’s website, there appear to be roughly 450 practising advocates.2

However, there are also various other professionals who carry out legal work including paralegals, Citizens Advice advisors, financial advisers, claims managers, specialist will writers etc. 3 A report from Europe Economics from 2018, entitled 'The Regulated and Unregulated Legal Services Market in Scotland: a Review of the Evidence', suggests that there are around 13,000 such individuals in Scotland, including at least 10,000 paralegals, 3,000 Citizens Advice advisors and around 60 specialist will-writers.3

As outlined in more detail below, the various professionals providing legal services in Scotland are subject to very different regulatory regimes.

Large differences also exist in the type of work provided by different lawyers. For example, some legal service providers (e.g. certain large firms of solicitors) primarily focus on work for corporate clients (e.g. corporate law, mergers and acquisitions etc.), whereas others have more of a focus on individuals and consumers (e.g. family law, conveyancing, personal injury etc.).3

As outlined elsewhere in this briefing, although some work is restricted by legislation to certain types of lawyers who are subject to regulation (i.e. solicitors and advocates), a large element of legal work is not restricted in this way.

There are also important differences in how legal service providers are structured which can be relevant for regulation. For example, services may be provided by individuals, partnerships, corporate bodies or, in some cases, charities. In addition, legal services are often provided "in-house", i.e. in companies or in local government.

Regulatory objectives - consumer and public interests

In one sense, legal services are like other services. One of the main issues for any regulation is what the needs of consumers are, i.e. does the system work well as regards the choice and type of legal service providers, price, quality etc.? Much of the debate is economic, focussing on market forces, competition, etc., 1 but also on the potential need for sector-specific protections for consumers over and above those in general consumer law.2

However, there is a general view that there is also a broader public interest in the regulation of legal services.3 For example, in its 2020 report on Legal Services in Scotland, the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) states that:

2.1 Legal services are of public importance. They are an important foundation of a well-functioning society and an essential input to the economy as a whole. Consumers often use legal services providers at critical moments in their lives. The advice they receive in these situations can have major personal and financial consequences, which may not be possible to reverse or remedy. These factors distinguish legal services from many other services that are purchased by consumers and increase the importance of a well-functioning legal services sector.

2.2 Effective regulation is critical to this outcome given that certain key characteristics of the legal services sector – notably an inherent asymmetry of information between providers and consumers which can often hinder consumers from making fully informed purchasing decisions, and the potential for a service to negatively impact unrelated third parties – would otherwise give rise to a material risk of market failure.

Competition and Markets Authority. (2020, March 24). Legal Services in Scotland - Research Report. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5e78cc9b86650c296f6eda63/Research_report_-_Legal_services_in_Scotland_publication.pdf [accessed 30 May 2023]

Other areas of public interest in relation to regulation include:

Access to justice – i.e. people's ability to access legal advice and support (cost of services and availability of legal aid are important elements of this).5

The independence of the legal profession - a key principle in liberal democracies is that the legal profession and judiciary should be independent from government and other bodies.6

The rule of law – i.e. the constitutional principle that all persons, including the state, should be accountable to the law.7

Ethical duties held by lawyers - for example, duties to the court, duties to keep clients' information confidential, and duties not to act where there is a conflict of interest.

Consumer interests and public interests do not necessarily align.8 For example, regulatory rules on entry to the market or conduct on the market can potentially restrict competition. Similarly, rules allowing new entrants to the market can potentially impact negatively on areas of public interest. Consequently, a key issue for any regulatory system is establishing what the right balance should be between consumer and public interests.

Self-regulation, co-regulation and independent regulation

There is a long-standing debate about who should have the main responsibility for regulating the legal profession. For example, who sets the rules on admission to the legal profession, or the conduct of lawyers, or complaints about lawyers?

Regulation was traditionally the responsibility of the courts and judiciary in combination with professional bodies such as law societies or bar associations (“self-regulation”).

These professional bodies often had a dual role of acting as:

regulator; and

promoting and representing the legal profession.

In many countries regulation is still carried out by bar associations which also represent the profession.12

However, in recent times there have been moves towards “co-regulation” or “joint-regulation” where government also mandates certain standards.

In addition, in certain jurisdictions, there are regulators which are independent of bodies representing the legal profession. For example, in 2007 the independent Solicitors Regulation Authority was set up to regulate solicitors in England and Wales, with the Bar Standards Board regulating barristers. The Legal Services Board is responsible for approving these bodies and six other regulators in England and Wales.

Similarly, in Ireland, the independent Legal Services Regulatory Authority was set up in 2016 to regulate both solicitors and barristers.

One of the main aims behind independent regulators is to address the risk of conflicts of interests arising due to professional bodies both representing the legal profession and also regulating it. The 'Review of the Regulatory Framework for Legal Services in England and Wales of 2004' ("Clementi Review"), which led to the setting up of independent regulators in England and Wales, summarised this as follows:

There is a conflict of interest between the two roles which should be tackled. In a regulatory body the public interest should have primacy. Issues such as changes in practice rules should be examined, not against the wishes of the membership, but against the test of the public interest. In a representative body the interests of the membership should have primacy

Clementi, D. (2004, December). Review of the Regulatory Framework for Legal Services in England and Wales - Final Report. Retrieved from http://www.avocatsparis.org/Presence_Internationale/droit_homme/PDF/Rapport_Clementi.pdf [accessed 30 May 2023]

The Clementi Review also argued that independent regulation would benefit competition and innovation in the market for legal services.

Alternative business structures

Another issue in any regulatory regime is the extent to which non-legal professionals (e.g. accountants or surveyors) should be permitted to co-own legal practices together with lawyers, and also the way in which these bodies should be regulated.

Such businesses are often referred to as "alternative business structures" ("ABSs") or "multi-disciplinary partnerships" ("MDPs") and have been proposed as a potential way of improving legal services in Scotland since at least the 1980s.12

One argument in favour of ABSs is that they can provide consumers with greater choice and expertise at a lower price as they can offer a "one stop shop" of legal and non-legal services .1 For example, the Clementi Review stated in 2004 that:

85 ... one can readily see, for example in the areas of consumer debt, inheritance planning or personal taxation, that a combination of both legal and accounting skills could be a valuable asset for the client.

Clementi, D. (2004, December). Review of the Regulatory Framework for Legal Services in England and Wales - Final Report. Retrieved from http://www.avocatsparis.org/Presence_Internationale/droit_homme/PDF/Rapport_Clementi.pdf [accessed 30 May 2023]

Another argument in favour of ABSs is that they can lead to increased investment in law firms as they make it more attractive for non-legal professionals to invest in the sector.1

There are, however, counter-arguments. For example, the risk that ABSs might pose to areas of legal ethics, e.g. "legal professional privilege"("LPP"). In essence, LPP protects certain communications between lawyers and clients (e.g. legal advice) from being disclosed to third parties, even in relation to legal proceedings. The aim behind it is to ensure that lawyers and clients can candidly discuss legal issues. Other professionals are not bound by this principle.

Another fundamental issue is which professional bodies should regulate ABSs, and which rules should apply, given that, in many cases, ABSs merge professionals belonging to different regulatory regimes (e.g. solicitors and accountants).

Traditionally ABSs were prohibited in most legal systems as qualified lawyers were not permitted to share fees or enter into partnerships with unqualified persons. Collaboration between legal professionals and other professionals was therefore limited to law firms working with non-lawyers through employment/consultancy arrangements1 or through looser associations (e.g. accountancy firms setting up their own law firms as happened in the 1990s).78

However, in many jurisdictions ABSs are now permitted. In England and Wales, for example, the Legal Services Act 2007 allowed lawyers and non-lawyers to offer legal services through the same corporate entity.9

In Scotland, the 2010 Act put in place provisions to allow for ABSs. However, the system has still not yet been set up due to long delays in the process of appointing the Law Society as the regulator (for details see elsewhere in this briefing). The Law Society was authorised as an approved regulator of licensed providers in December 2021.

Regulation of legal services in Scotland

The approach taken to regulation in Scotland is one of co-regulation, i.e. based on legislation, judicial input and the rules of professional bodies (primarily the Law Society of Scotland and the Faculty of Advocates). The main elements of the regulatory and legislative framework are as follows.

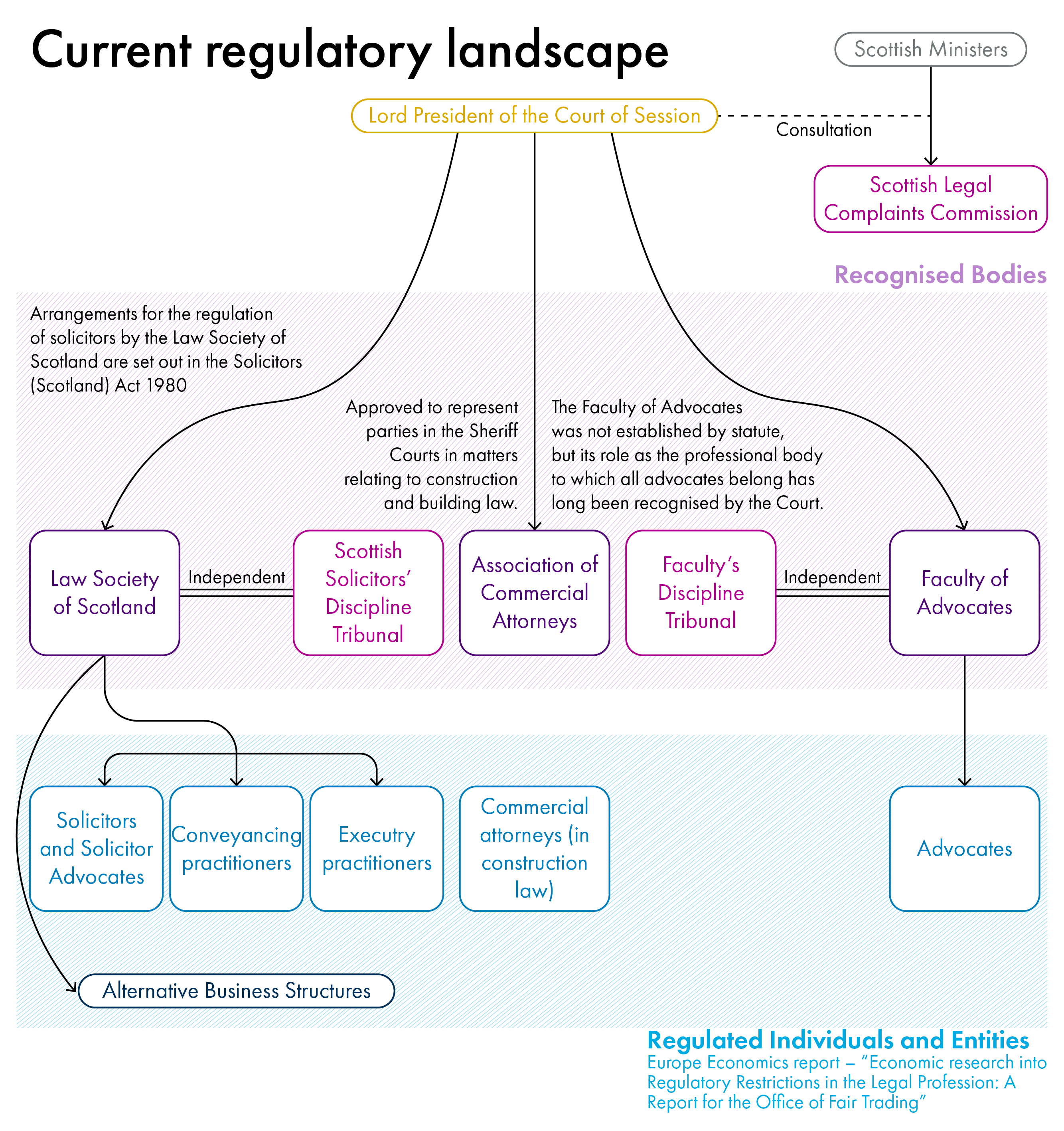

A diagram summarising the existing framework can be found at Annexe 1.

Reserved and unreserved legal services

It is sometimes assumed that all legal work is restricted to qualified legal professionals such as solicitors. However, that is not the case. Instead, a distinction can be made between what are sometimes referred to as:

reserved legal services - restricted to legal professionals regulated by relevant professional bodies (primarily solicitors and advocates, but also some others); and

unreserved legal services which can be carried out by legal professionals regulated by relevant professional bodies and also other professionals, including those who may or may not have legal qualifications/training.

These terms are explained further below.

Reserved legal services

Section 32 of the Solicitors (Scotland) Act 1980 ("1980 Act") makes it an offence for "unqualified persons" to prepare the following documents:

any writ relating to heritable or moveable estate (e.g. elements of conveyancing work)

any writ relating to any action or proceedings in any court (this covers much actual court work, although not all preparatory work)

any papers on which to found or oppose an application for a grant of confirmation in favour of executors (“confirmation” is the court document which gives executors authority to administer a deceased person’s estate).

Section 65 of the 1980 Act defines “unqualified person” as those not qualified to act as a solicitor. As a result reserved services are in principle restricted to solicitors.

There are, however certain exceptions to the offence in section 32(1) of the 1980 Act, which means that certain other legal professionals can also provide reserved legal services, or certain elements of reserved legal services.

This includes advocates. They can carry out all reserved services (although in practice they will specialise in court proceedings).

In addition, the following legal professionals have rights to provide certain reserved services:

Executry practitioners - these are permitted to provide executry services as defined in section 23 of the Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Scotland) Act 1990 ("1990 Act")

Conveyancing practitioners - these are permitted to provide conveyancing services as defined in section 23 of the 1990 Act

Commercial attorneys - these are qualified engineers, architects or surveyors who have certain rights to appear in court and to conduct litigation in respect of construction law.

Section 57 of the 1980 Act also states that notaries public ("notaries") must hold a current practising certificate from the Law Society of Scotland. The role of a notary public is therefore restricted to practising solicitors. Notaries are responsible for the administration of oaths, and witnessing and authenticating the execution of certain types of document. Detailed information on their role can be found on the Law Society of Scotland's website. 1

Unreserved legal services

Unreserved legal services are not defined in legislation and, in effect, cover all other legal services which are not reserved. The result is that these services can be provided by the legal professionals noted above and also other professionals, including those who may or may not have legal qualifications/training.

Some unreserved legal services are, however, regulated by a statute other than the 1980 Act. For example, it is a criminal offence to provide immigration advice unless regulated by the Office of the Immigration Services Commissioner.1 In addition, voluntary regulation through professional bodies is also possible, e.g. the Scottish Society of Will Writers.2

In this briefing, those who are authorised to provide reserved legal services (or certain elements of reserved legal services) are referred to as "regulated legal professionals". These are:

solicitors

advocates

conveyancing practitioners

executry practitioners

notaries public

commercial attorneys.

Other legal professionals who are not authorised to provide reserved legal services are referred to as "unregulated legal professionals."

Regulatory bodies

Three regulatory bodies regulate legal professionals in Scotland: the Law Society of Scotland, the Faculty of Advocates and the Association of Commercial Attorneys.

Law Society of Scotland

The Law Society of Scotland ("Law Society") is the largest regulator of legal service professionals in Scotland. It regulates:

solicitors -they traditionally act as general legal advisers whilst also carrying out court work in the lower courts. They are not permitted to appear in the Court of Session, High Court of Justiciary or UK Supreme Court

solicitor advocates - unlike other solicitors, they are permitted to appear in the highest courts (Court of Session, High Court of Justiciary and UK Supreme Court) where they have sufficient experience and have passed additional exams/training courses1

notaries public - practising solicitors who are responsible for the administration of oaths, and witnessing and authenticating the execution of certain types of document

conveyancing and executry practitioners - they were regulated by the Scottish Conveyancing and Executry Services Board. However, the role was transferred to the Law Society by the Public Appointments and Public Bodies etc. (Scotland) Act 2003. There are less than ten such practitioners.2

The legislative framework is primarily set out in the 1980 Act. Under that Act the Law Society has a dual role of:

Promoting the interests of the solicitors' profession in Scotland; and

acting as the regulator for solicitors (and also conveyancing and executry practitioners).

The 1980 Act also lays down that one of the Law Society's objects is "the interests of the public in relation to that profession".

Section 1 of the the 2010 Act provides the following more detailed regulatory objectives:

supporting the constitutional principle of the rule of law and the interests of justice

protecting and promoting the interests of consumers and the public interest generally

promoting access to justice

promoting competition in the provision of legal services

promoting an independent, strong, varied and effective legal profession

encouraging equal opportunities

promoting and maintaining adherence to the professional principles in section 2 of the 2010 Act.

The Law Society's regulatory function is delegated by its Council (the decision-making body) to its Regulatory Committee. The Regulatory Committee was created by the 2010 Act with the aim of ensuring that the Law Society's regulatory functions are exercised independently. At least 50% of the Regulatory Committee must be made up of lay persons with the chair also being a lay person.

The Regulatory Committee, through various sub-committees, regulates areas such as:

rules on entry to the profession - i.e. admission to the roll of solicitors (the standard route to qualify as a solicitor involves an LLB degree in Scots law, the postgraduate Diploma in Legal Practice and a two year traineeship with a solicitor/firm of solicitors)

rules and guidance governing professional practice by solicitors (including standards of conduct and client care)

The Law Society also administers the Client Protection Fund to which solicitors contribute annually. Clients who have suffered monetary loss as a result of the dishonesty of a solicitor or their staff may make a claim on the fund. Solicitors in private practice also have to purchase professional indemnity insurance through a Master Policy which the Law Society maintains on behalf of its members.

Solicitors are regulated by the Law Society for all legal services – i.e. whether or not the service provided is a reserved one under section 32 of the 1980 Act.

Regulation of individuals rather than legal businesses

The current legal framework is largely focussed on the regulation of the activities of individual solicitors rather than legal businesses (i.e entities).

There are, however, certain exceptions, for example in relation to financial inspections and the requirement for firms to have professional indemnity. 3The Law Society can also make rules on professional practice, conduct and discipline in relation to Incorporated Practices under section 34(1A) of the 1980 Act.4

Further details of the Law Society's regulatory role can be found on the Law Society's Regulation and Compliance webpage.5

Faculty of Advocates

The Faculty of Advocates ("Faculty") is a self-governing, non-statutory body which has been delegated responsibility for the regulation of advocates by the Court of Session under the Legal Services (Scotland) Act 2010. As a body it dates back to the foundation of the Court of Session in 1532.1Advocates are self-employed lawyers who have special training in advocacy. Together with solicitor-advocates they have exclusive rights of audience in the highest courts (Court of Session, High Court of Justiciary and UK Supreme Court).

The Faculty is led by elected office bearers (including the Dean of Faculty) and an elected Faculty Council .2

The Faculty's Guide to the Professional Conduct of Advocates ("Guide to Professional Conduct") summarises the status of advocates as follows:

1.1.2 The Faculty of Advocates is a self-governing body consisting of those admitted to the office of Advocate in the Court of Session. The formal act of admission to that office is an act of the Court and an Advocate can ultimately be deprived of his office only by the Court. But, by long tradition, the Court has left it to the Faculty of Advocates (a) to lay down the qualifications for admission, (b) to determine whether an applicant for admission satisfies those qualifications, (c) to lay down the rules of professional conduct, and (d) to exercise disciplinary authority.

Faculty of Advocates. (2022, January). GUIDE TO THE PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT OF ADVOCATES. Retrieved from https://www.advocates.org.uk/media/4086/guide-to-conduct-7th-edition-october-2019-rev-jan-2022.pdf [accessed 9 June 2023]

It outlines the role of the Dean as follows:

1.1.3 The Dean of Faculty is the elected leader of the Faculty of Advocates and, again by long tradition, the Faculty entrusts him with wide powers to make rulings on matters of professional conduct and, subject to the Disciplinary Rules of Faculty, to exercise disciplinary authority. The Dean's Council is a consultative body whose function is to advise the Dean on these and other matters.

1.1.4 In practice therefore, the legal and professional rights and obligations of an Advocate depend:- (i) upon the fact that he holds the office of Advocate in the supreme Courts of Scotland; and (ii) upon the fact that he is a Member of the Faculty of Advocates and is subject to the disciplinary authority of the Faculty and its Dean.

Faculty of Advocates. (2022, January). GUIDE TO THE PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT OF ADVOCATES. Retrieved from https://www.advocates.org.uk/media/4086/guide-to-conduct-7th-edition-october-2019-rev-jan-2022.pdf [accessed 9 June 2023]

Areas of regulation include:

Rules on becoming an advocate - the standard route involves qualifying as a solicitor followed by training with an experienced advocate (known as "pupillage" or "devilling") and passing additional Faculty examinations.

Rules on professional standards which are subject to approval by the Lord President. This includes the Guide to Professional Conduct which sets out the principles and rules of professional conduct applicable to advocates in Scotland.

Complaints handing and disciplinary procedures in relation to advocates’ conduct.Disciplinary rules and procedures are governed by the Faculty's Disciplinary Rules. The Dean of Faculty may also, subject to the Lord President’s approval, issue Dean’s Rulings on particular matters of professional practice.5

Traditionally advocates have fulfilled a different role to solicitors in Scotland. The current regulatory rules contain restrictions reflecting this.

For example, advocates have to comply with the "cab rank" rule which lays down that, when available, advocates cannot refuse to take on a case which would be accompanied by payment of a reasonable fee (para. 8.4.1 of the Guide to Professional Conduct). The rationale is that clients should not be deprived of an advocate because the client or the client’s cause could be seen as objectionable or unpopular.6

Advocates are also members of an “independent referral bar” so are not normally permitted to provide services directly to the public, but are instead instructed by solicitors.

In addition, unlike solicitors and solicitor advocates, advocates are required to be self-employed sole practitioners (para. 16.1 of the Guide to Professional Conduct). Therefore, they cannot form partnerships with solicitors, for example.

This approach contrasts with the situation in England and Wales, where barristers can take direct instructions to carry out certain work under the "Public Access Rules" if they complete specific training7 and can enter into partnerships or operate through other legal entities8

The Association of Commercial Attorneys

The Association of Commercial Attorneys ("ACA") is a professional body which regulates commercial attorneys (qualified engineers, architects and surveyors with legal experience who are permitted to carry out construction litigation).

The body has its origin in the Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Scotland) Act 1990 ("1990 Act"), which also included provisions aimed at liberalising the market for executry and conveyancing services.

The 1990 Act included the introduction of a right for the members of professional bodies to appear in court and to conduct litigation where the Lord President and Scottish Ministers approved their regulator's regulatory scheme (section 25 of the 1990 Act). The broad aim was to provide more options for representation in court than using advocates or solicitors.

These rules didn't come into force automatically, but were dependent on the introduction of secondary legislation. There was an extremely long delay in the introduction of this secondary legislation. It was only brought into force in March 2007 some seventeen years after the introduction of the primary legislation.1

Thus far, the ACA is the only professional body which has used this route to gain rights to conduct litigation for its members. It applied to be the regulator of commercial attorneys in 2007 following the coming into force of the secondary legislation. Its proposed regulatory scheme was approved in 2009 with a revised regulatory scheme being approved in 2019.2

The regulatory scheme allows qualified engineers, architects and surveyors with relevant construction experience and legal experience (as a minimum, an accredited Bachelor of Laws) to apply to become members of the ACA and to be granted a practising certificate.

Commercial attorneys with a practising certificate have certain rights of audience (i.e. the right to appear in court) and rights to conduct construction litigation in Scotland. The right of audience does not apply to the Court of Session.3

In addition to regulating entry requirements, the ACA's regulatory scheme also lays down rules covering areas such as continual professional development, professional conduct, professional indemnity insurance and complaints procedures.

The Minister for Victims and Community Safety, Siobhian Brown MSP, with agreement from the Lord President, recently approved a revised scheme that defines the powers and operation of the ACA as regards a request from the ACA to change their name to the Association of Construction Attorneys. The Scottish Government's website is in the process of being updated to reflect this name change.i

According to the Policy Memorandum, there are currently only around five commercial attorneys operating in Scotland.4 This contrasts with almost 13,000 solicitors.5

Lord President of the Court of Session

The Lord President of the Court of Session is the head of the Scottish Judiciary but also has a key role in regulating the legal profession. This includes oversight of the rules on admission to the legal profession and the approval of regulatory bodies’ practice rules.

Details of this role are outlined on the webpage of the Scottish Judiciary “Regulating the Legal Professions”1. The website of the Scottish Judiciary also contains a table with more details of the statutory functions the Lord President exercises in regulating the legal profession.2

Alternative business structures - licensed providers

The 2010 Act allows solicitors to enter business relationships with non-solicitors to provide legal services under a licence issued by a regulator approved by the Scottish Ministers ("approved regulator").1 The 2010 Act refers to these entities as "licensed legal service providers" ("licensed providers").

The 2010 Act includes a range of eligibility criteria for licensed providers. The main ones are that:

The licensed provider has to be at least 51% owned by solicitors or members of another "regulated profession" (section 49). The professions which currently qualify as "regulated professions" are set out in a Schedule to the Licensed Legal Services (Specification of Regulated Professions) (Scotland) Regulations 2012

The services have to be offered for "a fee, gain or reward" (section 47). Therefore law centres or charities cannot currently apply to become licensed providers.

Under the 2010 Act, a body can become an approved regulator by submitting a "regulatory scheme" to the Scottish Ministers detailing, amongst other things, the regulator's licensing rules, practice rules and compensation fund (section 12). There is then a two-stage process involving the Scottish Ministers first assessing and approving the application with agreement of the Lord President and then granting authorisation for the approved regulator to exercise its regulatory functions (sections 7-10; for details see para. 163 of the Policy Memorandum).2

The Law Society is the only body which is currently an approved regulator of licensed providers. It applied to the Scottish Ministers to be an approved regulator in December 2015 with approval being granted on 17 January 2017. The Law Society of Scotland then submitted an application for authorisation as an approved regulator on 22 July 2021. This was granted on 22 December 2021.14 Although the Law Society is an approved regulator, its regulatory scheme has, however, not yet come into operation and there are currently no licensed providers operating in Scotland. One of the main aims of the 2010 Act has therefore not been put into effect.

Complaints

Complaints against regulated legal professionals

Specific procedures exist for dealing with complaints about regulated legal professionals, i.e. those regulated by the Law Society, the Faculty or the ACA. These procedures apply in addition to other legal remedies, e.g. under consumer law or the law of professional negligence, and are outlined in more detail below.

The key body is the Scottish Legal Complaints Commission ("SLCC") which was set up by the Legal Profession and Legal Aid (Scotland) Act 2007 ("2007 Act").

The SLCC is a non-departmental public body, with a Board appointed by the Scottish Ministers (in consultation with the Lord President).1 Its procedures are governed by rules in the 2007 Act and in the SLCC's Rules.

The SLCC operates independently of government and is funded by regulated legal professionals in Scotland who pay an annual levy to the SLCC via their professional organisation, known as "the general levy", as well as a complaints levy when a complaint is upheld.2 The levies are set annually by the SLCC following a consultation on its budget.

In recent years, the level of these fees, in particular the general levy, has been a source of contention between the Law Society and the SLCC with the Law Society frequently questioning whether it provides value for money.3

First tier complaints

The first stage in the process requires complainants to raise a complaint directly with the legal professional or legal firm in order to give them an opportunity to resolve it. Although there are limited exceptions (Rule 9(3) of the SLCC's Rules), if this stage isn't followed, the SLCC is not required to consider the complaint (section 4(1) of the 2007 Act).

SLCC is the single gateway for services complaints and conduct complaints

The SLCC acts as the single gateway for all complaints against regulated legal professionals in Scotland. Under Section 33 of the 2007 Act, if a relevant professional organisation receives a complaint it has to send it without delay to the SLCC.

After assessing the eligibility of a complaint (for example whether it is time-barred or vexatious),1 the SLCC categorises a complaint as either relating to:

Inadequate professional services (a "services complaint"); or

Professional misconduct or unsatisfactory professional conduct (a "conduct complaint").

Services complaints are then investigated by the SLCC itself, whereas complaints about conduct are passed back to the relevant professional body to investigate under its disciplinary rules and/or rules of conduct.

The Policy Memorandum provides the following examples of common services and conduct complaints:

21 ... An example of a common services complaint may include poor communication which resulted in an avoidable delay, while a conduct complaint may relate to a legal professional breaching their professional rules by operating without instructions or failing to meet a court-mandated deadline.

Scottish Parliament. (2023, April 20). Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill - Policy Memorandum. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/s6-bills/regulation-of-legal-services-scotland-bill/introduced/policy-memorandum-accessible.pdf [accessed 8 June 2023]

Sanctions for services complaints

The SLCC can try to seek agreement between the parties with the aim of settling a services complaint, but also has a range of sanctions at its disposal if a complaint is upheld (see the SLCC webpage "Action we might take"). This includes rectifying any errors as well as compensation for loss to a maximum of £20,000. The SLCC's website notes that, "it is very rare for the compensation to be £20,000."1

Hybrid complaints

By definition, complaints about lawyers can often relate to both poor service and misconduct/ unsatisfactory professional conduct.

The 2007 Act allows cases to be split into conduct and service elements when they relate to a different factual issue. However, as noted in the Policy Memorandum:

28 ... Where a complaint appears to contain elements of both poor conduct and inadequate services in respect of the same issue (referred to as a ‘hybrid issue complaint’) there is no provision in the 2007 Act to enable it to be progressed jointly in a way which would allow both elements to be investigated.

Scottish Parliament. (2023, April 20). Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill - Policy Memorandum. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/s6-bills/regulation-of-legal-services-scotland-bill/introduced/policy-memorandum-accessible.pdf [accessed 8 June 2023]

As a result of this problem, the SLCC developed its own procedure to deal with hybrid complaints which meant that both the professional body and the SLCC independently investigated the complaint on service and conduct grounds respectively.

The SLCC's procedure was challenged in the Court of Session in 2016 with the court finding that the 2007 Act did not give the SLCC the power to categorise complaints as "hybrid complaints" in this way.i The SLCC cannot, therefore, currently consider service elements of a conduct complaint remitted to the relevant professional body in respect of the same factual issue.

Handling complaints

Although it is for the relevant professional body to investigate conduct complaints, the SLCC also has powers to investigate how the professional body has dealt with the conduct complaint. This is referred to as a "handling complaint."1 The Policy Memorandum notes that:

36 ... Where a handling complaint is upheld, the SLCC may make certain recommendations which the regulator may comply with. If it fails to comply with the recommendations, the SLCC may direct it to comply. The SLCC may seek an order from the court where the regulator fails to comply with such a direction.

Scottish Parliament. (2023, April 20). Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill - Policy Memorandum. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/s6-bills/regulation-of-legal-services-scotland-bill/introduced/policy-memorandum-accessible.pdf [accessed 8 June 2023]

Complaints against ABSs - regulatory complaints

The 2010 Act amended the 2007 Act so that services complaints could be made against licensed providers (i.e. bodies set up as alternative business structures) and conduct complaints against practitioners within those providers.

The 2010 Act also introduced what are known as "regulatory complaints". These allow complaints to be made where there has been a failure by the licensed provider to have regard to the regulatory objectives or professional principles set out in the 2010 Act. The procedure is broadly the same as in conduct complaints. The SLCC has powers to investigate how an approved regulator of licensed providers has handled a regulatory complaint.

Appeals

Complainants, legal practitioners, firms and professional organisations can appeal SLCC decisions to the Court of Session (with leave of the court) under certain defined grounds (section 21 of the 2007 Act). Section 21 of the 2007 Act refers to the right to appeal "any decision of the Commission under the preceding sections of this Part". The appeal right therefore covers a wide range of SLCC decisions and not only its final decision on a complaint.

Complaints against unregulated legal professionals

The SLCC does not currently have the power to consider complaints against unregulated legal professionals. However, depending on the type of legal professional involved, other complaints processes may exist, e.g. to professional bodies, in addition to options under consumer law or the law of negligence.

The Europe Economics report 'The Regulated and Unregulated Legal Services Market in Scotland: a Review of the Evidence' states at page 55 that:

Regarding unauthorised professionals, there are established complaints procedures in place for the other regulated legal services, i.e. immigration and insolvency. There is also typically an established complaints procedure in place for ancillary service providers who are regulated in other sectors (e.g. for financial services firms, consumers can complain to the Financial Ombudsman Service ... In addition, some voluntary self-regulatory associations offer complaints processes, e.g. the Scottish Society of Will Writers, has an established complaints procedure for consumers who access will writing services from one of their members.

Europe Economics. (2018, October). The Regulated and Unregulated Legal Services Market in Scotland: A Review of the Evidence. Retrieved from https://webarchive.nrscotland.gov.uk/20191009234128/https:/www2.gov.scot/About/Review/Regulation-Legal-Services [accessed 2 June 2023]

Background to the Bill

Over the years, the regulation of the legal profession has been a relatively controversial subject. On the one hand, there have been arguments that the regulatory regime overly favours solicitors and advocates and that consumers would benefit from more liberalisation. On the other hand, there are those who take the view that the current system provides high quality legal services and that risks to consumers lie more in the market for unreserved legal services which are not subject to the same regulatory obligations as solicitors and advocates.

Prior to the current developments, the last major analysis of this issue was around fifteen years ago when the Scottish Government set up a Research Working Group (“RWG”) to research the Scottish legal services market.1 This was followed by a "super-complaint" by Which? to the Office of Fair Trading which argued that various regulatory restrictions in Scotland should be lifted including the restrictions on direct access to advocates and the restrictions surrounding ABSs.2

These developments ultimately led to the 2010 Act. It changed the rules on ABSs but did not introduce some of the other liberalising measures which were argued for.

Further details on these developments can be found in the Policy Memorandum to the Legal Services (Scotland) Bill3 and the SPICe briefing on that Bill.4

Law Society and SLCC papers recommending change

In December 2015, the Law Society of Scotland submitted a paper 'The Solicitors (Scotland) Act 1980 Case for Change’ to the Scottish Government which set out proposals for reforming the regulatory powers of the Law Society.1 This was followed up by 'The Case for Change: Revisited' in January 2018.2 Both papers argued that the Law Society should retain its dual role of both regulating and representing Scottish solicitors, but that the regulatory framework needed updating in other ways

In 2016, the SLCC also published a paper setting out its priorities for reform.3 The SLCC raised concerns that the legislation underpinning the legal complaints system was too restrictive and unable to act in a proportionate and risk-based way, adding undue cost and time for consumers and legal professionals.

Roberton review

In response to the proposals from the Law Society and SLCC, in April 2017 the former Minister for Community Safety and Legal Affairs, Annabelle Ewing MSP, invited Esther Roberton to Chair an Independent Review of Legal Services Regulation in Scotland.

The Chair’s Report, ‘Fit for the Future – Report of the Independent Review of Legal Services Regulation in Scotland’(“the Roberton report”), which was published in October 2018, made 40 recommendations intended to reform and modernise the current regulatory framework.1

The main recommendation was that an independent body should be set up to regulate legal professionals, with the professional bodies only retaining their role as representatives of the profession. The new system would be financed by a levy on practitioners.

Other recommendations included:

allowing the new regulator to regulate legal entities (e.g. partnerships) rather than just individual solicitors as is the case at present

restricting the use of the term ‘lawyer’ to qualified lawyers in the same way as ‘solicitor’ is restricted at present.

a new complaints process.

In relation to complaints, the Roberton report identified a “unanimous view that the system for handling complaints is not fit for purpose”. It stated that:

the current legal complaints system is too complicated, both from the consumer and solicitor’s perspective. There are too many duplicated layers of investigation, and the process takes too long. There is a need for clarity and reform.

Roberton, E. (2018, October). Fit for the Future - Report of the Independent Review of Legal Services Regulation in Scotland . Retrieved from https://webarchive.nrscotland.gov.uk/20191009234128mp_/https:/www2.gov.scot/Resource/0054/00542583.pdf [accessed 13 June 2023]

The Roberton report also recommended that regulation should reflect the "Better Regulation Principles" noting that:

The proposed new regulatory model – should be principles based and embed the Better Regulation Principles set out in the Regulatory Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 and deliver a risk-based regulatory regime. It needs to deliver independent regulation within a context of clear accountability for the delivery of the key principle of public interest, whilst also having a degree of accountability to the professions it serves.

Roberton, E. (2018, October). Fit for the Future - Report of the Independent Review of Legal Services Regulation in Scotland . Retrieved from https://webarchive.nrscotland.gov.uk/20191009234128mp_/https:/www2.gov.scot/Resource/0054/00542583.pdf [accessed 13 June 2023]

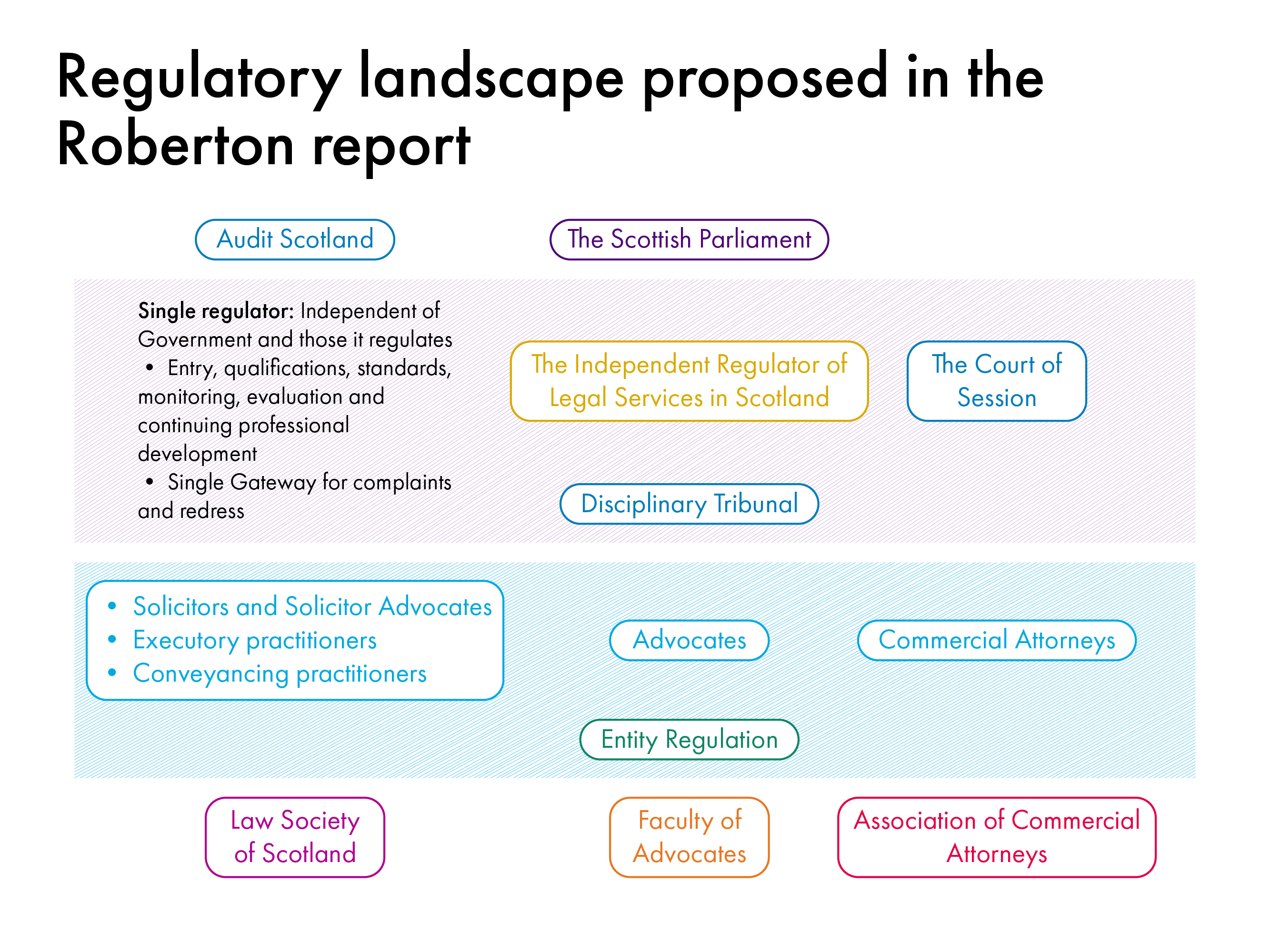

A diagram summarising the framework proposed by the Roberton report can be found at Annexe 2.

Competition and Markets Authority Report

The UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) responded to the Roberton Review in June 2019 and also launched its own research into aspects of the Scottish legal services market.1 The research was aimed at supporting the Scottish Government’s response to the Roberton Review and followed on from the CMA's market study into the supply of legal services in England and Wales.2

The CMA published its report, 'Legal Services in Scotland' on 24 March 2020.3 The report stressed that the regulatory framework can affect competition in two main ways:

by influencing how providers engage with consumers, or

by raising barriers to competition among providers or would-be providers.

Broadly speaking, the report indicated that there is a lack of competition and that the sector in Scotland "may not be delivering good outcomes for consumers". It noted that:

2. ... Consumer complaints are on the rise, with general disaffection about the process governing how they are handled. High street solicitor firms are facing challenging conditions. In addition, there are indications that consumers are not seeking legal services when they have a legal need (see Chapter 3). There are also concerns that regulation in Scotland has not adequately responded to new market pressures, affecting the sector’s competitiveness with an influx of firms from England and Wales and an erosion of the use of Scots law (see Chapter 4).

Competition and Markets Authority. (2020, March 24). Legal Services in Scotland Research report. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5e78cc9b86650c296f6eda63/Research_report_-_Legal_services_in_Scotland_publication.pdf [accessed 5 July 2023]

According to the report,

there are significant barriers for consumers in choosing legal services providers, shopping around for better services, and gauging the value of the service they are receiving

there are unmet needs for legal services and low engagement by consumers

there is limited transparency in price information provided by solicitors in Scotland

there are a low number of firms covering rural Scotland which appears to suggest lower levels of competition for many rural towns or areas than in urban areas

regulation in Scotland has not kept pace with more liberalised jurisdictions

there are features of the existing regulatory framework in Scotland that act as unnecessary restrictions on competition (e.g. the lack of ABSs and the restriction on advocates from forming partnerships or accepting instructions directly from consumers)

there is a lack of transparency in the regulatory activities of the current institutions as well as instances where conflicts between representative and regulatory roles are apparent

with the exception of solicitor advocates, there has been limited evidence of new entry by alternatives to solicitors and advocates, (for example, the report notes that in total there were only eight conveyancing and executry practitioners in 2019).

The report made a number of recommendations for change, These included:

the Law Society reviewing the impact of its price transparency guidance and working with consumer bodies to consider how providers can best strengthen transparency on levels of quality

implementation of the existing provisions for ABSs in the 2010 Act and further liberalisation by removing the requirement for solicitors or other regulated professionals to hold majority ownership in an ABS

the removal of restrictions on advocates forming partnerships or accepting instructions directly from consumers.

The report also supported the key recommendation of the Roberton report that there should be an independent regulator for legal services in Scotland.

Scottish Government response to the Roberton report

The Scottish Government published its response to the Roberton report in June 2019.1 This indicated that, while many recommendations were widely supported, views on the need for an independent regulator were much more polarised. The Scottish Government therefore proposed "a public consultation to seek to build consensus on the way forward".

The public consultation which closed on 24 December 2021 set out three models for change:

Option 1 was based on the primary recommendation in the Roberton report - an independent regulator

Option 2 was a “Market Regulator Model” resembling the system in England and Wales where the Legal Services Board provides regulatory oversight of "approved regulators"

Option 3 was described as an "enhanced accountability and transparency model" where each of the current regulators would have an independent regulatory committee accountable to the Scottish Parliament or the Lord President.2

The analysis of the consultation was published on 8 July 2022.3

The Scottish Government published its response to the consultation analysis on 22 December 2022.4 In its response the Scottish Government concluded that it wished to, "build on the existing framework" and that "the existing regulators should retain their regulatory functions, with a greater statutory requirement to incorporate independence, transparency and proportionate and risk-based accountability."

The Scottish Government, therefore, decided not to follow the Roberton report's main recommendation to set up a single independent regulator.

What does the Bill do?

A brief overview follows of the main provisions in the Bill. A diagram summarising some of the main changes proposed can be found at Annexe 3.

Regulatory objectives, professional principles, legal services and legal service providers

The Roberton report recommended that the regulatory objectives and professional principles for those providing legal services should be set out in primary legislation, as should the definition of legal services. The Bill follows this general approach.

Section 2 of the Bill states that the objectives of regulating legal services ("regulatory objectives") include principles linked to the public interest such as the rule of law, access to justice and an independent legal profession as well as consumer-focused objectives such as “quality, innovation and competition”. To a degree these are the same as the current regulatory objectives in section 1 of the 2010 Act. However, the Bill also includes new regulatory objectives such as the promotion of "effective communication between regulators, legal services providers and bodies that represent the interests of consumers".

Section 3 of the Bill requires regulatory authorities to exercise their "regulatory functions" in a manner compatible with the regulatory objectives in section 2 and taking into account a range of consumer principles and aspects of the 'Better Regulation Principles' derived from the Regulatory Reform (Scotland) Act 2014. The requirement to follow consumer principles and the 'Better Regulation Principles' is an additional change to the current regulatory objectives in section 1 of the 2010 Act.

"Regulatory functions" is defined widely in section 7 to cover areas such as: admissions, training, complaints-handling, rule-making, and complying with the requirements imposed on the regulator by the Bill.

Section 4 of the Bill sets out the professional principles (e.g. integrity, independence etc.) that persons providing legal services should adhere to.

The Bill allows the Scottish Ministers to modify the regulatory objectives and the professional principles by regulation following consultation with various parties, including the Lord President (section 5).

Section 6 of the Bill defines "legal services" in line with the existing definition in the 2010 Act. "Legal services provider" is defined so as to cover persons or bodies providing legal service whether or not regulated.

Category 1 and category 2 regulators

The approach the Bill takes is to set up a framework whereby regulators can be assigned as either a category 1 or category 2 regulator.

Section 8 of the Bill directly assigns the Law Society to category 1 with the Faculty and the ACA being assigned to category 2.

The Policy Memorandum explains the difference between category 1 and category 2 regulators as follows:

108. Category 1 regulators would be those regulators with a significant membership or whose members provide largely consumer-facing services. ...

117. Category 2 regulators would be those regulators whose membership is less consumer-facing or more specialist in nature in terms of the legal work undertaken, and whose membership is comparably less in number.

Scottish Parliament. (2023, April 20). Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill - Policy Memorandum. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/s6-bills/regulation-of-legal-services-scotland-bill/introduced/policy-memorandum-accessible.pdf [accessed 8 June 2023]

The Bill lays down the requirements which regulators have to comply with. For category 1 regulators which also have the role of represening the profession, this includes setting up an independent regulatory committee made up of legal and lay members (sections 9-12). In addition, in line with the Law Society's current Client Protection Fund, category 1 regulators must set up a fund for making grants to compensate persons who suffer loss by reason of dishonesty (section 14). They must also issue annual reports on the exercise of their regulatory functions which the Scottish Ministers must lay before the Scottish Parliament (section 13).

The Bill does not require category 2 regulators (i.e. currently the Faculty and the ACA) to delegate their regulatory functions to a regulatory committee. The Policy Memorandum makes the argument that this would be “disproportionate to the size and lack of direct consumer contact for such regulators”. Category 2 regulators do, however, have to comply with specific requirements in section 15 of the Bill (e.g. to exercise regulatory functions independently of other functions). Category 2 regulators also have to produce an annual report on the exercise of their regulatory functions (section 16).

Category 1 and category 2 regulators have to establish and maintain a register of the legal services providers that they regulate which are authorised to provide legal services (section 17).

Section 18 sets out that each category 1 and category 2 regulator must have rules concerning professional indemnity insurance.

These provisions restate much of the structure of the current regulatory system whilst also adding certain new provisions. One additional major change is that the work of regulatory committees of category 1 regulators would become subject to freedom of information requests under the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 when these committees are exercising administrative regulatory authority (section 28).

Applications to become a new regulator - accredited regulators

Sections 25-37 of the Bill provide rules which allow bodies to apply to become a new regulator. These are referred to in the Bill as "accredited regulators".

The process involves applicant bodies submitting a draft regulatory scheme to the Scottish Ministers and the Lord President so that their members can acquire rights to provide certain legal services (these are referred to in the Bill as "acquired rights").

If the Lord President and the Scottish Ministers are satisfied with the draft regulatory scheme, the Lord President is to approve the application (section 29(2)).

The body is then assigned as a category 1 or 2 regulator by regulations laid before the Scottish Parliament (section 29(4)) and legal services providers authorised by the accredited regulator may exercise an acquired right or rights (section 30(2)). To be authorised, a legal services provider will (among other things) require to be a fit and proper person (section 26(4)).

The Policy Memorandum notes that, "much of this is a restatement of material from the 1990 Act", but that the rights to provide legal services are broader.

As outlined in the section of this briefing on the Association on Commercial Attorneys (ACA), the 1990 Act introduced a right for the members of professional bodies to appear in court and to conduct litigation where the Lord President and Scottish Ministers approved their regulator's regulatory scheme.

The Bill replaces these provisions and adds a right to apply to be a regulator for "other types of legal services" (section 25(2)(c) of the Bill) in addition to the existing rights in the 1990 Act to apply to appear in court and to conduct litigation (see paragraph 77 of the Explanatory Notes).1

The Bill also allows the Lord President and Scottish Ministers to request an accredited regulator to review their regulatory scheme (section 33) with the potential for the regulator's authorisation being revoked if necessary revisions are not made (section 34).

The Explanatory Notes include information on the practical effects and scope of the right to apply to become a new regulator noting that the impact is likely to relate to specialist areas of law. It states that:

92. In practical terms, this means that a person who wishes to provide legal services that are regulated by an accredited regulator can apply to the regulator for authorisation to provide those services. This is distinct from persons who wish to be solicitors or advocates and is more likely to relate to specialist areas, for example commercial or employment law.

Scottish Parliament. (2023, April 20). Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill - Explanatory Notes. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/s6-bills/regulation-of-legal-services-scotland-bill/introduced/explanatory-notes.pdf [accessed 22 June 2023]

The Policy Memorandum also links the provisions to opportunities to widen the scope of those who qualify to practice law in Scotland beyond those who have the postgraduate Diploma in Legal Practice and have completed a two year traineeship with a solicitor. It states:

184 .... In respect of the question on fitness to practice, the consultation analysis reported a view by some that the diploma is a barrier to entry and should be removed or alternative routes should be provided (as entry into the profession via diploma was considered to be too high and too costly). This provision could provide a mechanism for a body which adopts an apprentice-style approach to legal qualification to apply for rights of audience and rights to litigate. For example, in England and Wales the Chartered Institute of Legal Executives provides a route for its members to practice law through an apprenticeship.

Scottish Parliament. (2023, April 20). Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill - Policy Memorandum. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/s6-bills/regulation-of-legal-services-scotland-bill/introduced/policy-memorandum-accessible.pdf [accessed 8 June 2023]

The Scottish Parliament's then Justice Committee considered the issue of professional legal education in 2018 following a round-table evidence session with stakeholders. Its report 'Training the next generation of lawyers: professional legal education in Scotland' stated that:

While positive steps have been taken to widen access to legal education and training, the Committee's round-table evidence session suggested that progress to date has been insufficient and there is a need for further action.

Scottish Parliament. (2018, September 23). Training the next generation of lawyers: professional legal education in Scotland. Retrieved from https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/Committees/Report/J/2018/9/23/Training-the-next-generation-of-lawyers--professional-legal-education-in-Scotland#Introduction [accessed 5 July 2023]

Regulation of legal businesses - entity regulation

Both the Roberton review and the Law Society recommended the introduction of rules to regulate legal businesses ("entity regulation") in additional to individual solicitors. They argued, amongst other things, that this would improve quality standards, create a level playing field for different forms of business and provide better protection for consumers.

The Bill follows this approach and provides new rules for the regulation of legal businesses (sections 38-50) which will operate in conjunction with the existing rules which regulate individuals. Such businesses will be known as "authorised legal businesses".

The Policy Memorandum stresses that entity regulation has been a feature in England and Wales since the Legal Services Act 2007 came into force and that not introducing it in Scotland would be a failure to keep pace with Scotland's counterparts (para. 192).

Under the new rules (section 39), legal businesses have to be authorised by the relevant category 1 regulator if they meet the criteria below (operating without authorisation is an offence):

they are a legal business, owned wholly by solicitors or other individuals regulated by a category 1 regulator

they provide legal services, as defined by the Bill, to the public

they operate for profit (fee, gain or reward).

The Explanatory Notes to the Bill indicate that this definition would cover the following:

108. ... sole traders, partnerships and corporate bodies, including those which are regulated as incorporated practices under the 1980 Act.

Scottish Parliament. (2023, April 20). Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill - Explanatory Notes. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/s6-bills/regulation-of-legal-services-scotland-bill/introduced/explanatory-notes.pdf [accessed 22 June 2023]

However, employers of in-house lawyers will not be covered as they do not normally provide legal services to the public for a fee (instead they advise their employing business). The Policy Memorandum states though that "their solicitor employees will continue to be regulated on an individual basis through the current system of regulation".2

Not for profit organisations will also not be regulated directly. The Policy Memorandum states that there were mixed views on this in the Scottish Government consultation:

195. ... There were, however, mixed views on not-for-profit organisations, with some agreeing that they should not be subject to entity regulation to ensure that free legal advice could still be provided, whereas others felt that any organisation providing legal services to consumers should be subject to entity regulation, including non-profit organisations.

Scottish Parliament. (2023, April 20). Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill - Policy Memorandum. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/s6-bills/regulation-of-legal-services-scotland-bill/introduced/policy-memorandum-accessible.pdf [accessed 8 June 2023]

ABSs (licensed providers) also do not fall under the new rules as they are separately regulated as entities under the 2010 Act.

The process which the Bill puts in place is that category 1 regulators will be required to prepare and operate rules authorising and regulating legal businesses ("ALB rules"). Under section 41, the ALB rules have to include:

Authorisation rules - i.e. the procedure and fees for becoming an authorised legal business, terms of authorisation, and the renewal, review and suspension of authorisation (section 42). Authorisation decisions can be appealed to the sheriff court (section 43).

Practice rules - i.e. the operation and administration of authorised legal businesses, standards, accounting and auditing, professional indemnity, complaints handling etc. (section 44). The practice rules also have to require authorised legal businesses to have regard to the regulatory objectives and to adhere to the professional principles in the Bill. They may include financial penalties where the rules are breached.

Provision for reconciling different sets of regulatory rules (section 46).

The Scottish Ministers can specify in regulations other matters which the rules have to include.

In preparing (or amending) its ALB rules, a category 1 regulator must consult its members and a range of other parties including the Lord President (section 41(5)). Material amendments to ALB rules need the prior approval of the Scottish Ministers who in turn need the Lord President's agreement (section 41(4)). There is also scope for ALB rules to cover non-legal services (section 41(6)). On this point the Explanatory Notes state that:

114. The Scottish Ministers may by regulations give authority for the rules of a regulator to also deal with the provision of particular non-legal services (for example where they offer ancillary services like estate agency, accountancy or tax advice)

Scottish Parliament. (2023, April 20). Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Bill - Explanatory Notes. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/s6-bills/regulation-of-legal-services-scotland-bill/introduced/explanatory-notes.pdf [accessed 22 June 2023]