The Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill

The Scottish Government introduced the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill in September 2023. The bill gives Scottish Ministers the powers to develop a new package of rural policy and support. This briefing includes an explanation of what the bill does, as well as background information on rural policy development to date.

Summary

The Scottish Government introduced the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill (‘the bill’) in September 2023. The bill as introduced is a ‘framework bill’. It confers powers, places some duties on Scottish Ministers, and enables changes to be made, but does not include the detail of a future agriculture policy for Scotland. This policy is under development, with most recent indications set out in the Agriculture Reform Route Map. The bill is therefore part of an ongoing process of agriculture policy reform to make Scotland “a global leader in sustainable and regenerative agriculture” and deliver “high quality food production, climate mitigation and adaptation, and nature restoration.”1

Among other things, the bill:

Sets four key objectives of agriculture policy. These are (a) the adoption and use of sustainable and regenerative agricultural practices, (b) the production of high-quality food, (c) the facilitation of on-farm nature restoration, climate mitigation and adaptation, and (d) enabling rural communities to thrive.

Requires the Scottish Ministers to produce a ‘rural support plan’ about the Scottish Government’s priorities for providing support in a five-year period. The bill requires certain matters to be considered when producing a rural support plan. These include the overarching objectives above, proposals and policies in the climate change plan related to agriculture, forestry and rural land use, any other environmental statutory duty, and developments at EU level.

Confers powers for Scottish Ministers to provide support for a number of purposes, including (among other things) general support for agriculture, support for particular products or sectors, food and drink production or processing, environment, forestry, knowledge exchange, and animal health and welfare. Scottish Ministers may also make regulations about support, regarding e.g. eligibility criteria, amounts of support, conditions for support, and enforcement and monitoring.

Requires Scottish Ministers to produce a Code of Sustainable and Regenerative Agriculture and confers a power to make regulations in relation to the Code or in relation to other guidance about support.

Confers a power to, by regulations, limit, or ‘cap’, support provided to a single person within a payment period or provide that the amount of support progressively reduces once a certain threshold is exceeded.

Confers a power to make regulations regarding refusal or recovery of support where this is in the public interest.

Provides that Scottish Ministers may provide financial support to producers in Scotland under exceptional market conditions and outlines the process around this.

Amends existing powers in the Agriculture (Retained EU Law and Data) (Scotland) Act 2020 to amend retained CAP legislation, and removes the time-limit for using these powers.

Confers a power on Scottish Minister to make regulations regarding continuing professional development of farmers, crofters, land managers, advisors or other relevant people.

Amends the Scottish Government's powers in relation to identifying animals.

This briefing is in two parts. The background section sets out agriculture policy development to date. This is broader than the Bill, but provides up-to-date context on policy developments for land use and management. The second section considers the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill section by section.

Background

EU exit and agriculture policy

This section explains the structure of agriculture policy under the EU's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) when the UK was a member of the EU. During the transition to a new agriculture policy, Scotland has retained the main elements of the CAP as it was when the UK was a member. The EU CAP has since gone through a review, and the new CAP for 2023-27 looks a bit different - this is set out in the next section.

The CAP provided a shared frameworks of rules and regulations around agricultural standards and agricultural support. Scottish agriculture and rural sectors received funding for agriculture, forestry, and environmental interventions from the EU. Since EU exit, funding for support comes to the Scottish Government from the UK Treasury.

The CAP is governed by an extensive set of regulations, for example around how agricultural support must be financed and run.

Within the UK context, agriculture policy is devolved, and whilst a member of the EU, the Scottish Government therefore designed and implemented a Scottish agriculture policy under the shared EU framework. As a result of the CAP, UK nations had in common with each other, and shared with the EU, the following:

A common subsidy regime. EU regulations determine the amounts that can be paid by member states, the basis for calculating payments, the schemes that must be offered to farmers and the schemes that can be offered on a voluntary basis.

A common arrangement with the World Trade Organisation (WTO) through the Agreement on Agriculture. Domestic support for agriculture (e.g. subsidies) is subject to WTO agreements which aim to ensure balanced trading arrangements between states. Domestic support is divided into three categories: Amber Box (trade distorting payments, e.g. Support linked to production for certain sectors), Blue Box (trade distorting payments that also require farmers to limit production) and Green Box (non-trade-distorting payments, e.g. Payments for environmental measures, also called 'agri-environment' payments).1 The EU has agreed maximum levels of support that can be paid out to farmers by EU member states in the Amber Box.

A common regulatory framework. Much of the regulation governing Scottish agriculture originates from the EU, and now takes the form of retained EU law (law that continues to be in force will be called 'assimilated' EU law after 1 January 2024). This includes environmental, animal welfare and food safety standards, regulation on plant protection products (pesticides, herbicides and insecticides), and other regulations on public, animal and plant health.2

A common sanction mechanism in cross-compliance. In order to receive EU payments (and the payments that have replaced them since EU exit), farmers and crofters must abide by cross-compliance rules. The rules are a combination of statutory management requirements (e.g. the regulations outlined above) and standards for good agricultural and environmental conditions (e.g. good soil management). Cross-compliance adds an additional mechanism to ensure compliance with common standards; failure to meet these can result in not only legal liability, but loss of support payments.2

Funding under the CAP is split into two 'pillars'. Pillar 1 provides income support for agriculture and Pillar 2 provides financial support for rural development, including community projects, environmental management, forestry, and extra support for 'less favoured areas' (LFA), where farming is more challenging due to geography and weather conditions.

Approximately 70% of CAP funding goes to Pillar 1, and 30% to Pillar 2.

The main schemes in Pillar 1 are:

The Basic Payment Scheme: This provides direct income support. It is a non-competitive fund, but farmers and crofters must be eligible to claim it. The budget for 2023-24 is £282m.4

Greening payments: Greening payments consist of one-third of the total budget for direct payments. They are also non-competitive payments, but are paid in return for certain minimum requirements on permanent grassland, and, for those farmers who meet the threshold for this requirement, maintaining 5% of their arable land as an 'ecological focus area'. It is mandatory to participate in Greening to claim funding under the Basic Payment Scheme. The Scottish Government notes that "Many businesses already comply with Greening requirements as part of their normal agricultural practices"5. The budget for 2023-24 is £142m.4

Voluntary coupled support schemes: the Scottish Suckler Beef Support Scheme and Scottish Upland Sheep Support Scheme pay farmers per head of livestock under certain conditions. The budget for both schemes is around £47m.78

The main schemes in Pillar 2 are:

The Forestry Grants Scheme: Forestry grants fund woodland creation and management, tree health, processing and infrastructure. The budget for this scheme in 2023-24 is approximately £77.2m.4

The Less Favoured Areas Support Scheme (LFASS): LFASS provides funding for farmers in areas of Scotland that are more difficult to farm due to e.g. geographic conditions. The budget for this scheme is £65.5m.4

The Agri-Environment Climate Scheme (AECS): AECS provides funding for farmers and crofters in exchange for specific environmental interventions. This funding is competitive; land managers must apply to undertake specific actions. The budget for this scheme is around £35.8m.4

These are the largest schemes under Pillar 2 in terms of funding. Other smaller, though still significant, funding schemes include the LEADER legacy scheme (now called Community-Led Local Development) which funds rural development projects, the Food Processing, Marketing and Co-Operation Grant (not available in 2023-24), support for crofters, and advice and knowledge exchange.

More detail on the Scottish programme and individual schemes is available from the Rural Payments and Inspections Division's website.

The new CAP: 2023-27

Since the UK left the EU, the EU has adopted a new Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) for 2023-2027.

The shape of the EU's new agriculture policy remains relevant for Scotland due to political commitments to alignment. The 2021-22 Programme for Government stated that:

As the EU develops a new Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), and Scotland develops a new agriculture policy, we will ensure our future policy stays broadly in line with the objectives of the new CAP as far as possible, to allow us to rejoin the EU at a future point with minimal disruption.

The EU typically reviews and agrees to a new CAP every seven years, to coincide with the EU's multi-annual financial framework (essentially, its long-term budget). The current financial framework runs from 2021-2027. There was some delay to implementing a new CAP due to lengthy negotiations; it was formally adopted in December 2021, and came into force on 1 January 2023.

The European Commission states that this CAP is "fairer, greener, and more performance-based". Key aspects of the new CAP include:

Greater responsibility given to member states to design 'strategic plans' within the CAP framework, and a greater focus on evaluation and performance.

Requirements for redistribution of payments to small- and medium-sized farms to improve income. At least 10% of direct payments must be redistributed for this purpose (there was previously no mandatory redistribution, though member states could do so voluntarily). In addition, 3% of the direct payments budget must be distributed to young farmers in the form of income or investment support, or start-up aid. 'Social conditionality' has also been brought in to ensure good working and employment conditions on farms.

Increased focus on environmental outcomes. The European Commission notes that "agriculture and rural areas are central to the European Green Deal" and that the new CAP is a "key tool" in the EU's achievement of the Farm to Fork and biodiversity strategies.1

Improving the competitiveness of agriculture and strengthening the position of farmers by, for example, extending support for producer organisations to all sectors (other than wine and beekeeping), and establishing a new financial reserve to cope with crises.

In December 2021, the European Parliament adopted new regulations governing the CAP from 2023-2027, repealing the old 2013 regulations from the previous CAP period. The new regulations are:

The 'Strategic Plan regulation' (Regulation (EU) 2021/2115), which sets out rules on support for strategic plans to be drawn up by member states under the Common Agricultural Policy.

The 'Horizontal regulation' (Regulation (EU) 2021/2116) on financing, management and monitoring the CAP.

The 'Common Markets Organisation regulation' (Regulation (EU) 2021/2117) amending regulations for a common market in agricultural products.

The new CAP aims to deliver ten specific objectives. These are set out in Article 6 of the new CAP 'Strategic Plan regulation':

(a) To support viable farm income and resilience of the agricultural sector across the Union in order to enhance long-term food security and agricultural diversity.

(b) To enhance market orientation and increase farm competitiveness.

(c) To improve the farmers’ position in the value chain.

(d) To contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation.

(e) To foster sustainable development and efficient management of natural resources.

(f) To contribute to halting and reversing biodiversity loss, enhance ecosystem services and preserve habitats and landscapes.

(g) To attract and sustain young farmers and new farmers and facilitate sustainable business development in rural areas.

(h) To promote employment, growth, gender equality.

(i) To improve the response of Union agriculture to societal demands on food and health, as well as to improve animal welfare and to combat antimicrobial resistance.

CAP 2023-27 continues to be delivered in two 'pillars'. The funding split is similar to previous CAP rounds: 75% of the CAP budget is allocated to Pillar 1; 25% is allocated to Pillar 2. Up to 25% of Pillar 1 funds can go to Pillar 2 funds, and vice versa.

In Pillar 1:

Direct payments for farmers continue to be paid on a per-hectare basis.

Receiving direct payments is contingent on meeting conditions ('Conditionality'). The European Commission states that the payments are now "linked to a stronger set of mandatory requirements"1. On every farm at least 3% of arable land is dedicated to biodiversity and non-productive elements, and there is a new obligation to protect wetlands and peatlands.3'Greening' payments, which previously made up one-third of the budget are no longer in place.

'Eco-schemes' are a new part of Pillar 1. These are voluntary schemes paid per hectare for environment and animal welfare practices which go beyond the regulatory baseline. It is possible to, for example, receive support through eco-schemes to extend areas dedicated to biodiversity to 7%.1 At least 25% of the budget for direct payments must be allocated to eco-schemes.

Sector-specific programmes for certain sectors, including fruit and vegetables, hops, table olives and olive oil, bee-keeping, and wine.

Market measures - emergency market interventions, school food programmes.

Pillar 2 continues to consist of voluntary rural development interventions. Article 69 of the Strategic Plan regulation sets out that rural development support can be provided for the purpose of:

Environmental, climate-related and other management commitments.

Natural or other area-specific constraints.

Area-specific disadvantages resulting from certain mandatory requirements.

Investments, including investments in irrigation.

Setting-up of young farmers and new farmers and rural business start-up,

Risk management tools.

Cooperation.

Knowledge exchange and dissemination of information.

The Strategic Plan regulation specifies, among other things, that:

At least 5% of funding in Pillar 2 must go to the LEADER schemes which fund local rural community development projects (Article 92).

35% of funding in Pillar 2 must be spent on the Article 6 objectives (above) on climate change (d), sustainable development and management of natural resources (e), biodiversity (f), and animal welfare (i) (Article 93).

A summary of the approved CAP strategic plans from member states is available from the European Commission.

A large driver for CAP reform has been the climate and nature crises. Though the new system aims to make a positive difference, Professor Alan Matthews (Professor Emeritus in European Agricultural Policy at Trinity College Dublin) has suggested that, though there are some grounds for optimism, the new CAP "will be much less effective in achieving the Green Deal targets than it could have been"5. Criticism has also been directed at some member states by the Institute for European Environmental Policy, a sustainability think-tank, for "not tak[ing] the opportunity of using the increased flexibility to significantly increase support for environmental and climate action"6.

Overall, the new CAP regulations specify that "Actions under the CAP are expected to contribute 40% of the overall financial envelope of the CAP to the achievement of climate-related objectives", up from around 25% in the last CAP. However, whether this succeeds in reducing emissions remains to be seen; EU auditors had previously found that the funding attributed to climate change mitigation in the 2014-2020 CAP period had little impact on emissions. A special report from the European Court of Auditors stated:

During the 2014-2020 period, the Commission attributed over a quarter of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)’s budget to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

We examined whether the CAP supported climate mitigation practices able to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. We found that the €100 billion of CAP funds attributed to climate action had little impact on such emissions, which have not changed significantly since 2010. The CAP mostly finances measures with a low potential to mitigate climate change. The CAP does not seek to limit or reduce livestock (50 % of agriculture emissions) and supports farmers who cultivate drained peatlands (20 % of emissions).7

A similar report from the European Court of Auditors investigating contributions to halting biodiversity decline found that it is difficult to measure progress, but where known, "the Commission and member states have favoured low-impact options".8 CAP funding in 2014-2020 made up 77% of the EU's spending on biodiversity.

Further information

European Commission factsheet - 'A Greener and Fairer CAP'

Developing a new Scottish agriculture policy: 2016-2021

Post-Brexit, UK nations are no longer required to follow CAP rules nor do they receive CAP support payments from the EU. Payments to UK farmers are now provided by the UK Treasury. Agriculture is a devolved policy area, therefore Scotland can decide on a new policy for Scottish farmers and crofters.

The Scottish Government’s post-EU approach initially centred around a period of ‘stability and simplicity’ – a transition where existing rules and funding programmes are largely maintained in the short term but simplified where feasible. A consultation held in 2018 set out proposals for this period of little change to 20241, with a new policy to be developed for roll-out in 2025. Existing schemes are set out in brief in a previous section, or can be explored in more detail on the Scottish Government Rural Payments and Inspections Division's website.

During this transition period, the same rules that applied under CAP have largely continue to apply in Scotland, as they have been ‘retained’ - in essence, copied over - as part of a new category of law called ‘retained EU law’. i

These EU-derived laws remain the law in Scotland unless the Scottish Parliament decides to pass a new law to change them. Recent legislation – the Agriculture (Retained EU Law and Data) (Scotland) Act 2020 ('the 2020 Act')– provided Scottish Ministers with powers to, by regulation, simplify and improve the operation of the retained CAP rules in Scotland. Key powers in the Act are currently available to ministers until 2026, at which time it is expected that new arrangements will be in place - though provisions in the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill propose to change this. The purpose of Part 1 of the 2020 Act in relation to retained EU law was to “maintain the operation of current CAP schemes, while also enabling the Scottish Ministers to make simplifications and improvements.”

The Scottish Government have used these powers to, for example, make changes to the 'greening' rules, to shorten the required length of land-management contracts under agri-environment and organic schemes, and to amend the penalties for overclaiming certain subsidies.

Under Section 22 of the 2020 Act, Scottish Ministers must lay a report before the Scottish Parliament on progress towards establishing a new Scottish agricultural policy. The report must include policies and proposals regarding:

the sustainability of agriculture and resilience to climate change,

the simplicity of future agricultural schemes,

the profitability of Scottish agriculture and the agri-food supply chain,

the support given to innovation and good practice,

the inclusion of new entrants, and

the improvement of productivity in Scottish agriculture

It must also include an outline of any legislation that is required and a timeline of when this will be introduced, as well as details of any consultation. This report must be laid before Parliament by 31 December 2024.

Calls for longer-term change in land use policy in Scotland have been many and varied. A key driver for reform is the climate emergency and biodiversity loss, but there have been calls for reform in a number of areas. Stakeholders have identified a need for a future land use policy to, e.g. better consider land uses holistically, as opposed to siloing agriculture, forestry and other sectors2; better support innovation and productivity improvements3; drive down agricultural emissions and ensure support for biodiversity4; and better support small units and those in geographically constrained areas5.

As a result, many stakeholder proposals have been published since the Brexit referendum (including from the Scottish Wildlife Trust, the National Farmers Union for Scotland, Scottish Environment LINK, and Scottish Land & Estates), in addition to research, pilots (e.g. trialling an ‘outcome-based approach’ to delivering environmental benefits from land management), and joint stakeholder inquiries such as the Farming for 1.5° Inquiry. The Scottish Government also convened several groups which have made recommendations, including:

Four Agriculture Champions;

Sectoral groups - the 'farmer-led climate change groups' - focused on policy solutions to climate change within their sector (a group was convened in the suckler beef, dairy, hill, upland and crofting, pig industry, and arable sectors).

Some clarity has emerged on the shape of a new rural policy, though much detail is yet to be announced. This is discussed in the following sections.

Consultation

The Scottish Government has published two consultations in the lead-up to introducing the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill. In August 2021 it published the consultation 'Agricultural transition - first steps towards our national policy'. This consultation asked for views on the recommendations and key issues arising from the farmer-led climate change groups set up in Session 5.

An analysis of responses was published in August 2022. The consultation found, among other things, that (note that this is a brief summary, for a full summary, please see the analysis):

85% of respondents agreed that agricultural businesses who receive financial support should be required to undertake baseline data collection, and 85% agreed that the data should be collected nationally. There were repeated calls for straightforward data collection which reflects farm diversity, and calls for training and guidance and data collection.

64% disagreed with only funding capital items with a clear link to reducing emissions. Respondents felt that there should be capital funding for a wider range of environmental improvements (e.g. biodiversity, land, soil, crop management), not just greenhouse gases. Respondents felt that capital funding can also be provided to improve productivity, efficiency and profits.

89% agreed that farms and crofts should be incentivised to undertake actions which enhance biodiversity. Views were mixed on the role of forestry, grazing and livestock numbers in carbon sequestration, but there was support for the protection of peatland. Many also noted the importance of integrating trees into land use, and integrated land use planning, being wary of blanket tree-plantations.

Both opportunities and challenges were identified in a just transition to net zero. Opportunities include enhancing profitability for high-quality produce, and challenges include the financial cost, ingrained or established attitudes and practices and lack of knowledge and skills.

56% disagreed that future support should be dependent on improvements in productivity, a preference was expressed for support based on positive environmental impact over time. It was noted that there is uncertainty about the definition of productivity, e.g. if it means profitability, higher production figures, or if it could encompass environmental impact.

66% agreed additional measures were needed to ensure research supports the agricultural sector to meet climate targets, and for accessible communication of research recommendations to farmers.

There were calls for more individualised knowledge and skills support, peer-to-peer knowledge exchange, local discussion groups, and access to skills development opportunities. Respondents were divided on whether CPD should be a condition of support.

There were calls for shorter supply chains, and an emphasis on transparency and traceability in the supply chain.

A second consultation was held on specific legislative proposals. 'Delivering our Vision for Scottish Agriculture - Proposals for a new Agriculture Bill' was published in August 2022 and sought views on proposals for the structure of a new agricultural policy, and the powers to be available to Scottish Ministers to deliver it.

. The Scottish Government also undertook 9 in-person and 5 online engagement events.

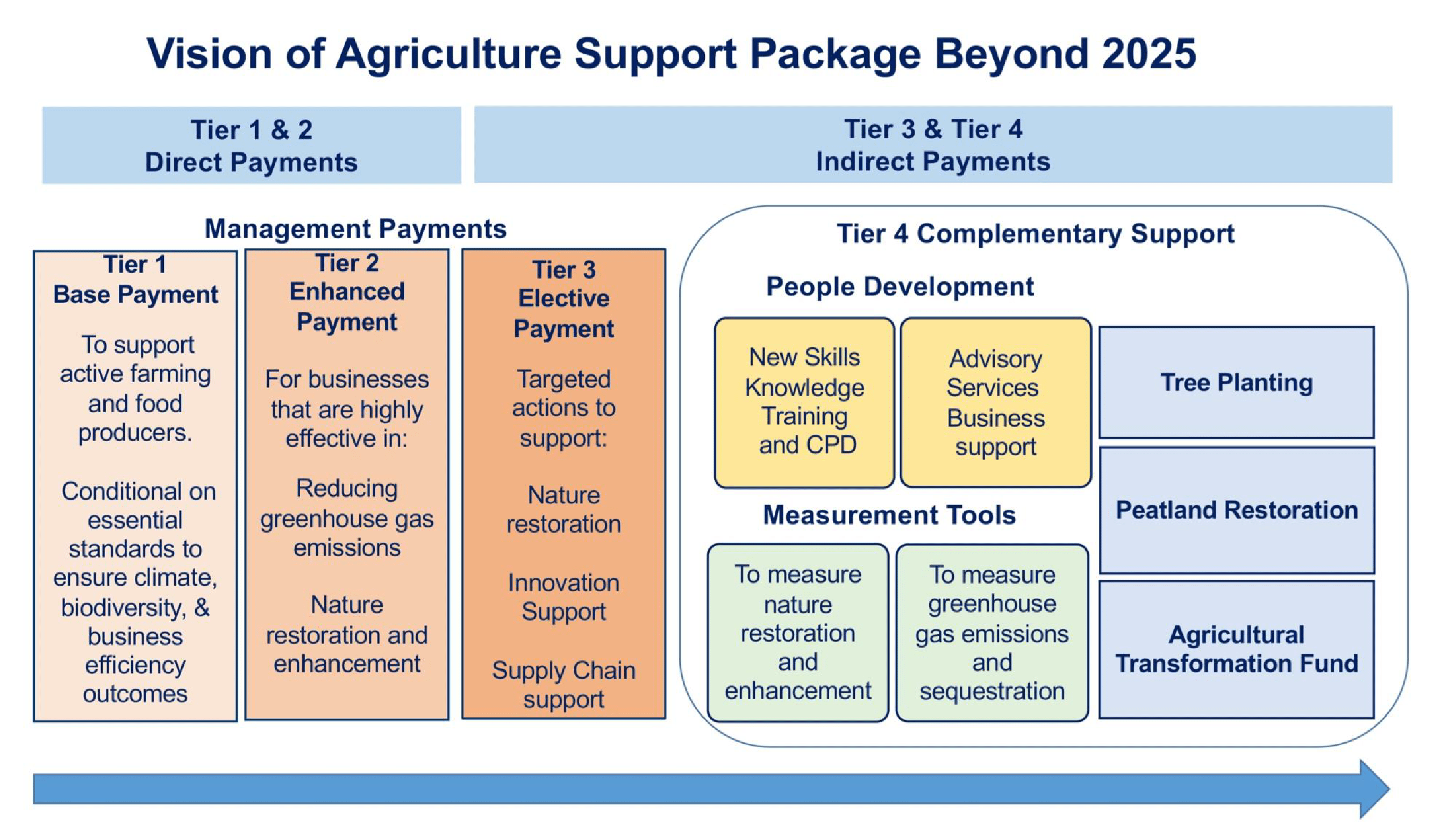

The consultation sought views on a proposed 4-tier support model for 2025 and beyond. A visual of the proposed model is set out below. It includes:

Tier 1: base payments to support farmers and food producers,

Tier 2: enhanced payments for businesses effective in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and restoring and enhancing nature,

Tier 3: elective payments to support targeted action for nature restoration, innovation support, and supply chain support, and

Tier 4: Complementary support in the form of skills, knowledge, training and professional development, advisory services and business support, and measurement tools for climate change and nature restoration. It also includes funding for tree planting, peatland restoration and the Agricultural Transformation Fund, which to date has funded capital grants for equipment aimed at making farms more sustainable.

The consultation further sought views on powers for Scottish Ministers to provide payments and other support to farmers, crofters, and land managers for a variety of purposes, including:

Mitigating and adapting to climate change.

Restoring and protecting nature.

Supporting high quality food production.

Supporting wider rural development.

Protecting animal health and welfare.

Protecting plant health and plant genetic resources.

Supporting knowledge and skills exchange.

In addition, the consultation asked for views on:

Powers for Scottish Ministers regarding administration and control of the payment system.

Setting conditions for receiving support, for example, in relation to climate change mitigation or adaptation, nature restoration, maintenance and enhancement, public and animal health, and soil health.

Ensuring all Fair Work conditions, including the real Living Wage, are applied to all Scottish agricultural workers.

Modernising agricultural tenancies, including:

Giving Scottish Ministers a power to determine what counts as acceptable diversification for tenant farms. The aim would be to include diversification activities which benefit the climate and biodiversity.

Giving Scottish Ministers the power to add to the list of improvements for which farmers receive compensation from landlords at the end of a tenancy (a process called 'waygo'), to include climate change and biodiversity measures, and introducing a set timescale for concluding this compensation process.

Amending the rules of good husbandry and good estate management for tenant farmers and landlords to enable them to undertake a wider range of activities.

Modernising rent reviews and introducing a new rent calculation.

Considering whether the provisions relating to compensation for disturbance where a tenancy is ended are fair.

An analysis of consultation responses was published in June 2023. Among other things, this found that (as above, note that this is a brief summary, for a full summary, please see the analysis):

The majority of respondents agreed with proposals in relation to the proposed four-tier support structure, though many called for more detail to be published. There were mixed views or concerns on specific aspects.

The majority of respondents support proposals around future payments to support climate change mitigation and adaptation, but there were calls for more clarity on how payments would be made and on what basis, a view that food production should also be in focus and a sense that not enough information had been provided.

There was broad agreement on proposals in relation to nature restoration, with some raising that there needs to be recognition of work already done in this space which should be supported further.

There was general agreement on proposals for high quality food production, with a sense that these are necessary in a changing landscape.

There was broad support for measures to support wider rural development. However, there were mixed views on including non-agricultural sectors in support.

There was broad support for the proposals in relation to animal health and welfare, though some raised that proposals may duplicate efforts that are already being done through existing high welfare standards and assurance schemes.

There was widespread agreement in relation to plant health and plant genetic resources.

There was widespread agreement with support for skills, knowledge transfer and innovation. It was argued that current support is insufficient and there are gaps in delivery and improvements to certain areas were identified.

There were mixed views on the proposals to give Scottish Ministers a power to determine acceptable diversification for tenant farms, and on the proposals relating to the compensation process for tenant farmers at the end of a tenancy (waygo).

The majority agreed that Scottish Ministers should be able to amend the rules of good husbandry and good estate management to enable tenants and landlords to meet future global challenges.

Most respondents agreed that adaptability and negotiation in rent calculations are needed and there was general support for rent reviews, though there was little consensus about what best practice would look like.

There were mixed views regarding the proposals around compensation for disturbance.

The majority agreed that Fair Work conditions should be applied to all Scottish Agricultural workers, though some noted that accommodation and other provisions for farm workers would need to be taken into account. Others argued that a requirement to pay the real Living Wage would have a impact on businesses where this is not financially viable.

Where are we now?

Most recently, the Scottish Government published its Agricultural Reform Route Map, which sets out a structure for future support and a timeline for the transition. This is discussed further below. The following sections set out recent developments leading up to this point.

At the beginning of Session 6 in September 2021, the Scottish Government created the 'Agriculture Reform Implementation Oversight Board' (ARIOB). The board is comprised of farmers, crofters, representatives across the supply chain, and environmental interests and is supported by an academic advisory panel. The group was established to "support implementation of policy reform, incorporating the relevant recommendations from the farmer-led groups to:

"cut emissions across agriculture

"support the production of sustainable, high quality food

"address the twin crises of climate and nature/loss of biodiversity

"design a new system and approach".1

The Scottish Government has made three high-level commitments to reforming agriculture policy. These are:

To target at least half of all funding for farmers and crofters towards actions with outcomes which support climate mitigation, adaptation, and biodiversity gain.2

To maintain direct support for farmers and crofters.3 This means that there is an intention to continue some form of non-competitive payment for land managers based on the land that they farm.

To introduce conditions for receiving agricultural support2. In June 2023, the Cabinet Secretary announced that, from 2025, farmers and crofters will need to adopt the following practices to qualify for payments:

foundations of a ‘Whole Farm Plan’ which will include soil testing, animal health and welfare declaration, carbon audits, biodiversity audits and supported business planning,

protections for peatlands and wetlands to help farmers restore these vital habitats to sequester more carbon, and

meet new conditions to the Scottish Suckler Beef Support Scheme to help cut emissions intensity and make beef production more efficient.

The next sections discuss developments in more detail.

Agriculture Transformation Fund and National Test Programme

In February 2020, the Scottish Government announced a new £40m Agriculture Transformation Fund to "support the agricultural industry to undertake a range of potential actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and support sustainable farming and land use". This money was subsequently spent on a new 'Sustainable Agriculture Capital Grants Scheme', which aimed to support farming businesses with grants to buy equipment to reduce emissions, such as slurry covers and spreaders. However, due to disruptions in the supply chains after the Covid-19 pandemic, there were difficulties in spending the full amount of committed funding. In the 2022-23 and 2023-24 budget years, a much smaller budget of around £5m has been spent on supporting farmers to manage slurry and digestate (a source of greenhouse gases) in order to meet new regulations.

In October 2021, prior to COP26 in Glasgow, the Scottish Government announced a new 'National Test Programme', with £51m of funding to be spent over three years. The aim of the programme is to:

support and encourage farmers and crofters to learn about how their work impacts on climate and nature, including offering financial support to carry out carbon audits and nutrient management plans.

In March 2022, the Scottish Government published its 'vision' for Scottish agriculture which set out the government's ambition for Scotland becoming "a global leader in sustainable and regenerative agriculture", and also included details for the new National Test Programme.

‘Track 1’ of the programme - called 'Preparing for Sustainable Farming ' - launched in April 2022 and has offered financial support to farmers and crofters to complete carbon audits and carry out soil sampling and analysis. The Cabinet Secretary told the Rural Affairs and Islands Committee on 31 May 2023 that in the first year of the National Test Programme there were over 1000 claims made to carry out carbon audits and soils tests, with "just over" 500 carbon audits done, and the remainder made up of soil tests. This is in addition to 500 carbon audits through the Farm Advisory Service. The Cabinet Secretary noted that £1m in funding had been allocated to this.

The Scottish Government has indicated that this funding will continue until March 2025, "and from then, soil testing, animal health and welfare declarations and carbon audits will be part of the productivity baseline for a whole farm plan"1.

The Scottish Government set out that the purpose of ‘Track 2’ is to:

design, test, improve and standardise the tools, support and process necessary to reward farmers, crofters and land managers for the climate and biodiversity outcomes they deliver.

Track 2 began in the summer of 2022 with the launch of a ‘Sustainable Farming Survey’, which offered farmers a cash incentive to complete questions “to understand current awareness and experience of sustainable and regenerative agriculture”. The Cabinet Secretary for Rural Affairs and Islands, Mairi Gougeon MSP, told the Rural Affairs and Islands Committee on 31 May 2023 that the survey received around 1000 responses, and "showed that the majority of people had undertaken an action such as a carbon audit or nutrient management planning. It was also important in helping us to identify people’s motivations for undertaking actions, as well as in identifying barriers or what was preventing people from undertaking specific actions. Getting those views from the survey was really helpful." The Cabinet Secretary noted that barriers included knowledge and support, and access to funding. Officials highlighted in the same session that the Scottish Government is undertaking more focussed work with a smaller group of farmers and crofters drawn from the survey respondents.

Agricultural Reform Route Map

In February 2023, the Scottish Government published the 'Agricultural Reform Route Map'.

The route map sets out indications of the shape of a future agriculture policy in Scotland, timelines for the transition, and illustrates the four-tiered model first introduced in the consultation on an agriculture bill. The route map also includes an indicative "Agricultural Reform List of Measures", which sets out the types of actions the government may expect from farmers and crofters who wish to receive certain agricultural support payments in the future.

The route map sets out that the existing framework of support will continue in 2023 and 2024, with changes beginning in 2025.

From 2025, some changes will be introduced, such as:

Protections for wetlands and peatlands as a new condition on basic payments.

The foundations of a 'whole farm plan' will be in place - the Scottish Government explains that this is "a tool to help farmers and crofters integrate food, climate and biodiversity outcomes on their holdings and inform where they can seek support from the future support framework". By 2025, the foundations will be in place; this is described as "'productivity baselines': soil testing, animal health and welfare declaration, carbon audits, biodiversity audits, and the support for effective business planning."

New conditions on the Scottish Suckler Beef Support Scheme will be in place, linked to calving intervals (the amount of time between the birth of two calves from the same cow) to encourage livestock keepers to reduce the emissions intensity of their cattle production systems.

From 2026, the Basic Payment Scheme and Greening will become 'base support' and 'enhanced support'. Base support will be available to all farmers and is conditional on essential standards to ensure climate, biodiversity & business efficiency outcomes. Enhanced support will be for businesses who are highly effective in farming and crofting for a better climate, and for nature restoration.

However, there are still details to be developed. The route map notes, for example, that rural development schemes (such as the Less Favoured Area Support Scheme, and the Agri-Environment and Climate Scheme) will "continue until 2026 with some potential changes in 2025/26. For example - new conditions or new delivery".

The Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill, as discussed in the second half of this briefing, is intended to be the legislative vehicle to deliver the changes needed to set up a new agricultural support scheme.

Related changes in Scotland's land policy

Outcomes in several policy areas depend on a new rural policy.

Declining biodiversity, escalating climate change effects, and a closing window to mitigate global warming whilst ensuring a just transition to net zero emissions are prompting reform across all policy areas and sectors, with significant implications for land ownership and use.

This has driven the Scottish Government’s existing programme of land reform as well as being one of the drivers for the ongoing agriculture policy reform. As a result, several policies related to Scotland’s land are in flux at the same time. Over the remainder of this Parliamentary session, the following developments are expected in addition to the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill:

A new land reform bill.

A natural environment bill.

A revised Climate Change Plan (must be in place by March 2025).

A new biodiversity strategy and delivery plan is currently under consultation.

These and other developments are discussed in turn in more detail below.

Climate change: Climate change and the environment have become key drivers for changes to Scottish land use policies. As part of the Scottish Government’s most recent update to its climate change plan, it committed to, among other things, scaling up activities such as the 'Agriculture Transformation Programme' and advisory services, to introducing environmental conditions on receiving agricultural payments, and creating a new rural support policy to deliver “a more productive, sustainable agriculture sector that significantly contributes towards delivering Scotland’s climate change, and wider environmental outcomes”. A new climate change plan must be in place by March 2025, and the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill proposes that Scottish Ministers should be required to have regard to measures set out in the climate change plan when making plans for rural support.

The UK Climate Change Committee (CCC) has stressed that more action is needed on both climate change mitigation and adaptation in relation to agriculture, forestry and land use. In its most recent assessment of Scotland's climate change adaptation efforts published in November 2023, the CCC stated that

The proposed Land Reform Bill, Agriculture Bill and Natural Environment Bill could be transformational in how Scotland prepares its land and seas for future climate change. If designed and implemented effectively, these bills have the potential to support a wide range of adaptation action including improving upstream flood management and reducing urban heat risks, as well as supporting the resilience of natural ecosystems.1

Biodiversity: Land uses remain key pressures on biodiversity. At an EU-wide level, the CAP impacts on biodiversity have been found to be difficult to measure and member states have favoured low-impact options. However, farmers and crofters, and agricultural policies and support are also key to approaches to halt and reverse biodiversity decline. The Scottish Government is currently consulting on a new Biodiversity Strategy and 5 year Delivery Plan, which aims to implement global biodiversity agreements. A number of specific objectives and actions proposed for the Delivery Plan require land or are linked to other land use activities. Examples of these objectives and actions which are related to Scotland’s land use include:

Introduce an agricultural support framework which delivers for nature restoration and biodiversity alongside climate and food production outcomes.

A commitment to protecting 30% of land and seas for nature by 2030 and ensuring that every local authority area has a nature network to improve ecological connectivity across Scotland.

Identify and facilitate partnership projects for six large scale landscape restoration areas with significant woodland components by 2025 and establish management structures with restoration work progressing by 2030.

Develop best practice guidance on measures for upland restoration to regenerate peatlands, increase native woodland cover, manage grazing, protect certain target species and priority habitats, and increase habitat heterogeneity.

Ensure that forests and woodlands deliver increased biodiversity and habitat connectivity alongside timber and carbon outcomes.

This policy development is happening in conjunction with forthcoming primary legislation on biodiversity in the form of a proposed Natural Environment Bill. The current consultation on the Biodiversity Strategy and Delivery Plan also includes a consultation on elements of the proposed Natural Environment Bill. The proposed bill is expected to put in place key legislative changes to restore and protect nature including targets for nature restoration. The consultation invites views on setting and selecting statutory nature restoration targets and proposes a list of potential topics for targets. It is expected that these targets will drive changes in land use and management.

Land reform: Following legislative proposals from the Scottish Land Commission, in July 2022 the Scottish Government published Land Reform in a Net Zero Nation, a consultation on measures to “address the impact of scale and concentration of land ownership” and ensure that communities and the public are part of a just transition.

The proposals made in the consultation may have implications for land use and management in Scotland. Proposals included, among other things:

A legal duty on ‘large-scale landholdings’ (as defined in a future bill – the consultation proposed a set of criteria) to comply with the (currently voluntary) Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement and associated codes of practice, which would be made statutory.

Compulsory land management plans for large-scale landholdings, which would need to demonstrate how the owner is complying with the Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement, how land will be used and managed to meet requirements of codes of practice, and how the owner will engage with communities.

Regulating the market in large-scale land transfers through a new public interest test, and a requirement to notify an intention to sell.

Creating a new ‘flexible’ land-use tenancy, “which would help agricultural holdings, small landholding tenants and others to deliver multiple eligible land use activities within one tenancy”, e.g. woodland management, nature restoration and agriculture.

2019 work by the Scottish Land Commission on scale and concentration of ownership recommended that relevant fiscal incentives for agriculture, forestry and renewable energy should be reviewed to ensure consistency with the “policy objectives of community empowerment, rural development, and land reform”.

Food and Drink:The Scottish Government is currently working with Scotland Food & Drink to "accelerate the current core work of the Scotland Food & Drink Partnership" to refresh Ambition 2030, Scotland's food and drink industry strategy.

Meanwhile, industry has been significantly affected in recent years by Brexit, and the Covid-19 pandemic, prompting the publication of an industry recovery plan, which includes discussions of resilience within food production sectors.

Moreover, a new Scottish agriculture policy is linked to Scotland's overarching food policy - referred to as 'Good Food Nation'. The Scottish Parliament passed the Good Food Nation (Scotland) Act 2022, which requires Scottish Ministers and certain public authorities to produce good food nation plans. A national good food nation plan is expected to be developed in the future. The Act also provided for a new Scottish Food Commission, which will be charged with scrutinising and making recommendations for achieving the outcomes in the good food nation plans, conducting research, and providing advice to Scottish Ministers and relevant authorities in relation to their duties under the Act.

Crofting and rural communities: Discussions around reform of crofting legislation have been ongoing for some time.

In October 2013 the Crofting Law Sump group was established. The purpose of ‘the Sump’ was to gather together details of the significant problem areas within existing crofting legislation. Its final report was published in November 2014, and made a number of propositions for reform.

In 2017, the Scottish Government held a consultation on crofting policy and legislative options and priorities for a new crofting bill. In April 2018, then Cabinet Secretary Fergus Ewing announced that the Scottish Government would take a 'two-phased approach' to crofting reform. The first phase was to "focus on delivering changes which carry widespread support...and result in practical everyday improvements to the lives of crofters and/or streamline procedures that crofters are required to follow".2 A bill was planned to do this in Session 5, though this was paused in October 2019 due to the pressures of preparing for Brexit. The second phase was planned for the longer-term, aiming to review crofting legislation more fundamentally. This was planned for a future Parliamentary session. Legislation is intended to complement a programme of non-legislative reform, set out in a National Development Plan for Crofting.

In the 2023-24 Programme for Government, the Scottish Government committed to, in the coming year, "develop and consult on proposals to reform crofting law, create new opportunities for new entrants, encourage the active management and use of crofts and common grazings, and support rural population retention through action on non-residency."3

More generally, support for, e.g. new entrants to farming and crofting, to crofting communities, and to support women in agriculture through a new rural policy can have a wider impact on resilience and diversity in the agricultural sector. The 2023-24 Programme for Government also committed to "develop a gender strategy for agriculture and fund practical training opportunities for women, new entrants, and young farmers"3.

Strategic land use: Many demands are placed on land, resulting in both a national Land Use Strategy (which is currently in its third iteration) and proposals for Regional Land Use Partnerships aiming to maximise the benefits from land. Mechanisms under a new rural policy will influence how this is achieved.

The Bill

The bill states that its purpose is:

...to make provision enabling the support of agriculture, rural communities and the rural economy through the creation of a framework for that support; to make provision for continuing professional development for those involved in agriculture and related industries, to make provision in relation to the welfare and identification of animals, to repeal spent and superseded agricultural enactments; and for connected purposes.

A 'framework bill'

The policy note states that the bill is intended to be a 'framework bill'.

It confers a number of powers, places some limited duties on Scottish Ministers, and enables changes to be made to existing agricultural rules and regulations. It does not set out broad parameters for, or include the detail of, a future agriculture policy for Scotland. This is expected in secondary legislation, using the powers provided to Scottish Ministers in the Bill.

Agriculture policy is already under development, with most recent indications set out in the Agriculture Reform Route Map, discussed in a previous section.

The bill is therefore part of an ongoing process of agriculture policy reform to make Scotland “a global leader in sustainable and regenerative agriculture” and deliver “high quality food production, climate mitigation and adaptation, and nature restoration", as set out in the Scottish Government's vision for Scottish agriculture.

Making regulations, and the negative and affirmative procedures

The bill gives the Scottish Ministers a large number of powers to do different things, or to make regulations about different things. This means that much of the legal detail of a new agriculture policy is expected in secondary legislation, using the powers provided to Scottish Ministers in the Bill.

The following sections frequently refer to making regulations according to the affirmative or the negative procedure. This refers to the different processes that Scottish Ministers must follow when making new secondary legislation. The negative procedure does not require explicit consent by the Scottish Parliament, the Parliament has 40 days to scrutinise the instrument and it will become law after 40 days if the Parliament does nothing more. This is the most common procedure. The affirmative procedure requires the Scottish Parliament's explicit scrutiny and consent, before it can become law.

More information on what is meant by this can be found in the Scottish Parliament's guidance.

Part 1: Objectives and Planning

Section 1 sets out the objectives of agricultural policy. These are:

the adoption and use of sustainable and regenerative agricultural practices,

the production of high-quality food,

the facilitation of on-farm nature restoration, climate mitigation and adaptation, and

enabling rural communities to thrive.

Section 2 places a duty on Scottish Ministers to prepare a plan, called the 'rural support plan', which sets out how Scottish Ministers aim to use the powers given to them to provide rural support for different purposes set out in the Bill. It must also set out how Scottish Ministers plan to carry out their functions under the bill whilst having regard to the plan.

The plan must specify:

a 'plan period' of five years,

Scottish Ministers' strategic priorities for providing rural support during that period, and

A description of the support schemes that are or will be in operation during the plan period. It is up to Scottish Ministers to decide how this is presented and how much detail is appropriate.

There is no fixed time-frame in which a first plan must be produced. The bill requires a plan to be laid before the Scottish Parliament "as soon as practicable" after that section of the bill comes into force. For each subsequent plan, it must be laid in Parliament at least 6 months before the end of the plan period of the preceding plan.

Scottish Ministers may amend the plan if strategic priorities change or the plan becomes inaccurate or incomplete, in which case they must lay the amended plan before the Parliament once again. If Scottish Ministers amend the plan, this does not start a new 5-year plan period.

Section 3 specifies that Scottish Ministers must have regard to the following things when preparing a rural support plan:

The objectives for rural support in Section 1,

Proposals and policies related to agriculture, forestry and rural land use in the statutory Climate Change Plan. The most recent Climate Change Plan was published in December 2020 and sets out a number of land-use policies to contribute to reducing emissions. A new Climate Change Plan must be in place by March 2025.

Any other statutory duty of the Scottish Ministers relating to agriculture or the environment, and

Developments in law and policy of the EU.

Scottish Ministers may amend this list of matters by regulations under the affirmative procedure.

Part 2: Support for agriculture, rural development and related matters

Power to provide support

Section 4 gives Scottish Ministers the power to provide support for a number of purposes, including (among other things) general support for agriculture, support for particular products or sectors, food and drink production or processing, environment, forestry, knowledge exchange, and animal health and welfare. The full list of purposes is set out in Schedule 1 of the bill.

This section also gives Scottish Ministers the power to modify Schedule 1 to add, amend, or remove a purpose for which support may be provided. They may do this by regulations under the negative procedure.

Section 5 specifies that support can be provided to third party organisations who, in turn, support people or businesses. The Explanatory Notes to the bill explains that this is for situations such as the LEADER legacy programme (now known as Community Led Local Development), which provides funding for rural community development. As part of this programme, funding is currently awarded to Local Action Groups (LAGs), who in turn award grants to initiatives in their local area. The rationale for this is that "LAGs are best-placed to understand the needs and opportunities of their communities and are thus best placed to manage and deliver the funding."

General provision about support

Section 6 sets out that support may be provided in such a way that Scottish Ministers consider appropriate. Examples of appropriate support include, in particular, financial support, such as a grant, loan or guarantee. The Explanatory Notes also explain that support can be provided in other ways, such as in the form of advice, equipment or other assistance.

This section also provides that support can be provided as part of a formal scheme set up by regulations, but that does not need to be the case. The Explanatory Notes state:

There may be situations where the Scottish Ministers choose to provide support without a formal scheme being in place. This might arise, for example, in the event of unforeseen circumstances causing exceptional hardship in a particular rural or island community or where a key part of the agri-supply chain needs urgent assistance.

Section 6 also provides that Scottish Ministers may make receiving support subject to meeting certain conditions, including through regulations about support made under the power in Section 13 (more information on this below). The Explanatory Notes state that:

Conditions may relate to a very wide range of matters, including requirements on farmers to keep land in good agricultural or environmental condition or to take certain steps in order to mitigate climate change. Where conditions are not complied with, the Scottish Ministers can require the repayment of the support, including with interest.

Section 7 provides that Scottish Ministers may make regulations under the negative procedure in relation to guidance about support.

Scottish Ministers may, in particular, require that guidance be laid before the Scottish Parliament, published, or both. They may require certain people to have regard to guidance that has been produced, or specify that compliance with guidance is relevant for determining whether a person has complied with a statutory duty or with a condition of support. They may also make regulations specifying the admissibility or evidential value of the guidance in legal proceedings.

This enables Scottish Ministers to give legal effect to guidance, for example, by specifying the consequences for not complying with guidance, or requiring that guidance is followed as a condition of support.

This is particularly relevant to the duty set out in Section 26 to produce a Code of Practice on Sustainable and Regenerative Agriculture ('the Code'). The power in Section 7 may be used to give legal effect to the code in some way.

Section 8 enables Scottish Ministers to delegate functions relating to providing support to any other person. These functions include, for example, preparing guidance, and exercising discretion. This section allows Scottish Ministers to delegate certain responsibilities to, for example, NatureScot.

Section 9 gives Scottish Ministers the power to limit, or 'cap' support by regulations under the negative procedure. Scottish Ministers may limit the overall amount of support or assistance (or both) that a person may receive within a payment period. Scottish Ministers may also stipulate that once a person has received a specified amount of support within one payment period, their support will progressively reduce.

Scottish Ministers must consult appropriate people before making regulations under this section.

Section 10 gives Scottish Ministers the power make regulations under the negative procedure which may specify, among other things:

The types of person which Scottish Ministers do not believe it is in the public interest to provide support to,

The circumstances in which Scottish Ministers may refuse or recover support,

Matters that the Scottish Ministers must consider when deciding whether or not to refuse or recover support.

Before making these regulations, Scottish Ministers must consult appropriate people.

This section also gives Scottish Ministers the power to refuse to provide support to a person if they do not believe it is in the publish interest. They may also recover support that has already been provided if they do not believe it was in the public interest to provide it. They must do so in accordance with regulations they have made.

Intervention in agricultural markets

Section 11 gives Scottish Ministers the power to provide financial support to agricultural producers in Scotland who have been, are being, or are likely to be, adversely affected by exceptional market conditions. Scottish Ministers may provide grants, loans, guarantees or any other forms of assistance and may be subject to any conditions that the Scottish Ministers consider appropriate.

In order to provide support for exceptional circumstances, Scottish Ministers may make and publish a declaration under Section 12, called an 'exceptional market conditions declaration', if they consider that there are exceptional market conditions. There are exceptional market conditions if:

there is a severe disturbance in agricultural markets or a serious threat of a severe disturbance in agricultural markets, and

the disturbance or threatened disturbance has, or is likely to have, a significant adverse effect on agricultural producers in Scotland.

An exceptional market conditions declaration must state that the Scottish Ministers believe there are exceptional market conditions, and describe the conditions by specifying:

the disturbance or threatened disturbance in agricultural markets (including horticultural markets),

any agricultural product which is or is likely to be affected by the disturbance or threatened disturbance,

the grounds for considering that the disturbance or threatened disturbance has, or is likely to have, a significant adverse effect on agricultural producers.

The declaration must also provide justification for using its powers in Section 11 to provide financial support in that situation. It must specify an end date until which Scottish Ministers may use its powers to provide financial support; the end date may be no later than 3 months after the declaration is published. Scottish Ministers may revoke a declaration, and they may extend the exceptional market conditions declaration by publishing an additional declaration specifying that the declaration is extended and support may continue to be provided.

Administrative matters, eligibility and enforcement

The provisions under this sub-heading provide powers to shape new support schemes, including determining payment amounts, conditions that may be imposed when providing support, and who is eligible.

A note on the structure of these provisions: Section 13 gives Scottish Ministers the basic powers to do a number of things, in particular, in relation to the things specified in Section 13(2). Sections 14 to 17 then provide additional clarity on how the powers in Section 13 may be used in relation to some of the specified aspects in Section 13(2). These sections do not require Scottish Ministers to use their powers in those ways, or set out an exhaustive list of how the powers may be used.

Section 13 provides that Scottish Ministers may make regulations about providing support for the purposes set out in Schedule 1.

This section does not require Scottish Ministers to address any particular matters in regulations made under this power, but sets out things which Scottish Ministers may consider when making regulations. Regulations may, in particular, include provisions about:

13(2)(a) - Eligibility criteria for receiving support,

13(2)b) - Payment entitlements (more on this below),

13(2)(c) - The amount of support (e.g. how the amount of support is to be determined, setting a minimum amount of support, or reducing the amount of payments of support in particular circumstances - other than those described in Section 9 in relation to capping or tapering support.),

13(2)(d) - How support is to be paid or provided,

13(2)(e) - Conditions that may or must be imposed when providing support,

13(2)(f) - Checking, enforcing and monitoring support,

13(2)(g) - Administrative and procedural matters that the Scottish Ministers consider appropriate, and

13(2)(h) - Publication of information about support.

The Scottish Ministers must consult appropriate people before they make regulations under this section. Regulations can be made either under the affirmative or the negative procedure, depending on whether Scottish Ministers believe the regulations are significant.

The section specifies that 'significant' regulations include ones which establish a scheme that has a significant number of recipients or a significant impact on recipients, affects a significant amount of land or significantly impacts a type of land, has a significant monetary value, or creates an offence. The regulations are also significant if they make significant changes to an existing significant support scheme.

Section 14 provides further detail on regulations that may be made about eligibility criteria. The Section specifies that any regulations made under Section 13(2)(a) (in relation to specifying eligibility criteria for support) may address:

The activity being carried out,

The way a person carries out a particular activity (including whether the person carries out the activity personally or through some other arrangement),

A person's characteristics or personal, financial or business circumstances (for example, a new entrant to farming),

The type or location of land on which a person carries out an activity,

The amount of land on which a person carries out an activity,

The way in which titles or occupancies of land are registered or recorded (e.g. if the land is registered in the Land Register of Scotland).

The Explanatory Notes highlight that this list is not exhaustive, and there may be other criteria that are appropriate which the Scottish Ministers may decide to set.

Section 15 provides further details in relation to regulations which may be made about payment entitlements. Currently, to claim funding from e.g. the Basic Payment Scheme (BPS), you must own 'payment entitlements' and have corresponding hectares of eligible land. Land managers can either use payment entitlements that they hold to claim funding from the BPS on their eligible land, or they can sell, lease, or otherwise transfer them (e.g. as a gift or inheritance) to another farmer or crofter who can then activate them on appropriate land to claim BPS funding if they meet the criteria to do so.

The Section specifies that regulations made under Section 13(2)(b) (in relation to payment entitlements) may address:

The number of payment entitlements available,

The allocation of payment entitlements,

The value of payment entitlements,

The transfer of payment entitlements,

Payment entitlements that are held by the Scottish Government for allocation to specified categories of person, such as new entrants to farming,

Scottish Ministers' ability to surrender, reclaim or cancel payment entitlements,

Creating and maintaining a register of people allocated payment entitlements,

Charging fees for making changes to a register of payment entitlements when entitlements are transferred (e.g. bought , sold, gifted) between people.

This is not an exhaustive list.

The Explanatory Notes state that "it is envisaged that the Scottish Ministers will use the power to create a new system of payment entitlements which is similar to that which already exists in relation to the Basic Payment Scheme (BPS)."

Section 16 sets out additional detail about the regulations that can be made about checking, enforcing and monitoring support. The Section specifies that regulations made under Section 13(2)(f) may address:

Checking whether eligibility criteria for support have been met,

The consequences of support being provided where eligibility criteria are not met,

Enforcing compliance with conditions for support,

Monitoring the outcomes of providing support (i.e. whether support has achieved its intended purpose),

Creating offences and providing for investigation of offences in relation to applications for support.

This Section further specifies that regulations may make provision for e.g. requiring information to be provided, powers of entry, inspection, search and seizure, record keeping, recovering and making good on support (with or without interest), and other processes connected with enforcement (see Section 16(2) for full list).

The Section specifies that regulations may not authorise entry to a private dwelling without a warrant. Where regulations made under the powers in this section create an offence, the maximum penalty for the offence is to be an unlimited fine for more serious offences ('on conviction on indictment'), or a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum (currently £10,000) for less serious offences ('on summary conviction').

Section 17 sets out more information about regulations that can be made regarding publishing information about support. The Section specifies that regulations made under Section 13(2)(h) may impose a requirement on any person (including Scottish Ministers) in relation to publishing information. Regulations may also require that the information to be published about support must include information about the recipients, amount, and purpose of support.

Section 18 gives Scottish Ministers the power to make regulations under the negative procedure about processing information in relation to:

support made under the bill or other relevant assistance,

Carrying out functions in relation to continuing professional development activities under the bill (see Section 27).

Regulations may address requirements to produce information, and sharing data with public authorities or others in line with the Data Protection Act 2018.

Part 3: Powers to modify existing legislation relating to support

This part amends the Agriculture (Retained EU Law and Data) (Scotland) Act 2020 ('the 2020 Act'). According to the Explanatory Note, the reason for amending the 2020 Act "is to provide the Scottish Ministers with the ability to adjust and use the existing [Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)] rules beyond 7 May 2026. This enables the continuation and adjustment of existing payment rules and schemes."

Section 19 amends Sections 1 and 2 of the 2020 Act.

Adding to the list of relevant CAP legislation

The amendment to Section 1 of the 2020 Act adds the EU Common Markets Organisation Regulation ('the CMO Regulation') to the list of relevant retained EU CAP legislation which Scottish Ministers may amend using the powers in the 2020 Act.

The main purposes of the CMO regulation are to provide a safety net to agricultural markets through the use of market-support tools, exceptional measures and aid schemes for certain sectors, to encourage producer cooperation through producer organisations and to lay down marketing standards for certain products.

Updating the 2020 Act following the REUL Act

The amendments to Section 2 enable the Scottish Ministers' powers to 'restate' (as well as modify) relevant CAP legislation.

The Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Act 2023 ('the REUL Act') gave UK Ministers and Scottish Ministers the power to 'restate' (i.e., replicate) most retained EU law (or 'assimilated law' as it will become known from 1 January 2024) by regulation for a time-limited period (depending on the type of law, up to 23 June 2026). The power to restate in the REUL Act cannot be used to make substantive changes to policy. Nevertheless, a restatement can use different wording or concepts to the REUL or assimilated law it is restating. More information on the REUL Act more generally can be found in a SPICe blog.

The amendment to the 2020 Act similarly allows Scottish Ministers to restate the relevant CAP legislation. The powers in sections 2, 3 and 4 of the 2020 Act were time limited and could not be exercised by the Scottish Ministers after 7 May 2026. Section 22 of the bill (see below) removes the automatic sunsetting of the Scottish Ministers’ powers to make regulations under those sections of the 2020 Act, with the effect being that the modification powers will continue to be available after 7 May 2026. This means that, unlike the power to restate in the REUL Act itself, the powers in the 2020 Act, once amended, will not be time-limited.

Furthermore, this section broadens the purposes for which relevant CAP legislation can be modified or restated. The existing provisions limit Scottish Ministers to making changes that they consider will "simplify or improve the operation of the provisions of the legislation". In addition to simplifying and improving, the bill amends the 2020 Act so that CAP legislation can be modified or restated to take account of changes in technology or developments in scientific understanding. This reflects wording in the REUL Act which provides that restatements of EU-derived legislation can be made to take account of these types of changes.

The bill further clarifies how the Scottish Ministers may use their powers to restate relevant CAP legislation, by mirroring the provisions in the REUL Act. Scottish Ministers may make changes to the legislation that they consider appropriate for the purposes of resolving ambiguity, removing doubt or anomaly, and facilitating improvements in the clarity or accessibility of the law. As noted above, a restatement may also take account of changes in technology or scientific understanding.

Section 20 amends Section 3 of the 2020 Act, which provides that the Scottish Ministers may provide for the operation of CAP legislation beyond 2020. Section 20 provides that Scottish Ministers may also make regulations which modify the relevant CAP legislation in a way that stops it applying for a period of time, or ceases to have effect in Scotland.

This section also repeals Sections 3(2) and 3(3) of the 2020 Act which specified that Scottish Ministers could use their power to determine a 'national ceiling'. The national ceiling under EU CAP is the maximum amount of payments that can be provided by a member state. This section of the bill also provides that regulations made under Section 3 of the 2020 Act can be made under either the affirmative or negative procedure, as Scottish Ministers consider appropriate. The 2020 Act currently provides that amendments may only be made by affirmative procedure.

Section 21 also modifies the 2020 Act regarding the power to modify financial provision in CAP legislation. Section 4(1) of the 2020 Act gives Scottish Ministers the power to make regulations which modify CAP legislation relating to setting maximum ceilings for the amount which may be spent for any purpose, or transferring amounts of funding between different purposes. Section 21 of the bill removes references in Section 4(2) of the 2020 Act to specific articles of CAP regulations which may be modified using the power in Section 4(1). This section of the bill also provides that regulations made under Section 4 of the 2020 Act can be made under either the affirmative or negative procedure. As above, the 2020 Act currently provides that amendments may only be made by affirmative procedure.

The titles of both Sections 3 and 4 of the 2020 Act are amended to reflect their new functions.

Section 22 repeals Section 5 of the 2020 Act. Section 5 of the 2020 Act provides that the powers to modify the CAP legislation in Sections 2, 3, and 4 of that Act may only be used until 7 May 2026.

Section 5, known as the 'sunset clause' was inserted into the 2020 Act at stage 2. The purpose of this section was to limit what were considered to be quite wide-ranging powers in the 2020 Act. A sunset clause was a recommendation of the then Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee's Stage 1 report, and was also recommended by the Parliament's Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee (DPLRC) in its report on the bill (DPLRC recommended a sunset date of between 2024 and 2030).

The Policy Memorandum to the bill currently being considered sets out the Scottish Government's rationale for removing the sunset clause. It states: