Fisheries Management and Support Common Framework

This briefing discusses the Fisheries Management and Support Common Framework (FMS) . The FMS Framework sets out how governments across the UK will work together on the sustainable management of fisheries and the wider seafood sector. The briefing also provides background information on the common frameworks programme.

Summary

This briefing provides detailed information on the Fisheries Management and Support (FMS) Common Framework. The FMS Framework sets out how governments across the UK will work together on the sustainable management of fisheries and the wider seafood sector.

The Scottish Parliament's Rural Affairs, Islands and Natural Environment Committee is leading on scrutiny of this framework. Background information on, for example, what common frameworks are and how they have been developed is also provided in this briefing. The policy context of the framework is also briefly covered.

The SPICe common frameworks hub collates all publicly available information on frameworks considered by committees of the Scottish Parliament.

In session five, the Finance and Constitution Committee reported on common frameworks and recommended that frameworks should include the following:

their scope and the reasons for the framework approach (legislative or non-legislativei) and the extent of policy divergence provided for;

decision making processes and the potential use of third parties;

mechanisms for monitoring, reviewing and amending frameworks including an opportunity for Parliamentary scrutiny and agreement;

the roles and responsibilities of each administration; and

the detail of future governance structures, including arrangements for resolving disputes and information sharing

The Scottish Government’s response highlighted that there may be a "range of forms" which frameworks could take.

More detail on the background to frameworks is available in a SPICe briefing and also in a series of blogs available on SPICe spotlight.

What are common frameworks?

A common framework is an agreed approach to a particular policy, including the implementation and governance of it. The aim of common frameworks is to manage divergence in order to achieve some degree of consistency in policy and practice across UK nations in areas formerly governed by EU law.

In its October 2017 communique on common frameworks, the Joint Ministerial Committee (EU Negotiations) (JMC (EN)) stated that:

A framework will set out a common UK, or GB, approach and how it will be operated and governed. This may consist of common goals, minimum or maximum standards, harmonisation, limits on action, or mutual recognition, depending on the policy area and the objectives being pursued. Frameworks may be implemented by legislation, by executive action, by memorandums of understanding, or by other means depending on the context in which the framework is intended to operate.

Joint Ministerial Council (EU Negotiations), 16 October 2017, Common Frameworks: Definition and Principles

The Scottish Government indicated in 2019 that common frameworks would set out:

the area of EU law under consideration, the current arrangements and any elements from the policy that will not be considered. It will also record any relevant legal or technical definitions.

a breakdown of the policy area into its component parts, explain where the common rules will and will not be required, and the rationale for that approach. It will also set out any areas of disagreement.

how the framework will operate in practice: how decisions will be made; the planned roles and responsibilities for each administration, or third party; how implementation will be monitored, and if appropriate enforced; arrangements for reviewing and amending the framework; and dispute resolution arrangements.

However, the Food and Feed Safety and Hygiene Law framework outline considered by the session five Health and Sport Committee noted that:

the framework itself is high level and commits all signatories to early, robust engagement on policy changes within scope.

Framework Outline Agreement and Concordat, 30 November 2020

The framework outline went on to note that the framework:

is intended to facilitate multilateral policy development and set out proposed high level commitments for the four UK Administrations. It should be viewed as a tool that helps policy development, rather than a rigid template to be followed.

As such, it is likely that there will be significant variation between frameworks in terms of whether they set policy or set out how decisions on policy within the scope of the framework will be taken.

There are, however, similarities between frameworks in terms of their overall structure, with the agreements setting out the roles and responsibilities for parties to the framework, how the framework can be reviewed and amended, and how disputes are to be resolved.

Why are common frameworks needed?

During its membership of the European Union, the UK was required to comply with EU law. This means that, in many policy areas, a consistent approach was often adopted across all four nations of the UK, even where those policy areas were devolved.

On 31 December 2020, the transition period ended, and the United Kingdom left the EU single market and customs union. At this point, the requirement to comply with EU law also came to an end. As a result, the UK and devolved governments agreed that common frameworks would be needed to avoid significant policy divergence between the nations of the UK, where that would be undesirable.

The Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland was signed as part of the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement and ratified in UK law by the EU Withdrawal (Agreement) Act (2020). The Protocol requires that Northern Ireland aligns with a limited set of EU laws relating to the Single Market for goods and the Customs Union. The Northern Ireland Protocol Bill was introduced to the UK Parliament on 13 June 2022. If passed, the Bill may affect the requirement for Northern Ireland to align with EU regulations of goods. In addition, policy positions (or framework governance arrangements) set out in this Common Framework briefing may also be affected.

The Joint Ministerial Committee (JMC) was a set of committees that comprised ministers from the UK and devolved governments. The JMC (EU Negotiations) sub-committee was created specifically as a forum to involve the devolved administrations in discussion about the UK’s approach to EU Exit. Ministers responsible for Brexit preparations in the UK and devolved governments attend these meetings.

In October 2017, the JMC (EN) agreed an underlying set of principles to guide work in creating common frameworks. These principles are set out below.

Common frameworks will be established where they are necessary in order to:

enable the functioning of the UK internal market, while acknowledging policy divergence;

ensure compliance with international obligations;

ensure the UK can negotiate, enter into and implement new trade agreements and international treaties;

enable the management of common resources;

administer and provide access to justice in cases with a cross-border element; and

safeguard the security of the UK.

Frameworks will respect the devolution settlements and the democratic accountability of the devolved legislatures, and will therefore:

be based on established conventions and practices, including that the competence of the devolved institutions will not normally be adjusted without their consent;

maintain, as a minimum, equivalent flexibility for tailoring policies to the specific needs of each territory, as is afforded by current EU rules; and

lead to a significant increase in decision-making powers for the devolved administrations.

What is the process for developing frameworks ?

Frameworks are inter-governmental agreements between the UK Government and the devolved administrations.

They are approved by Ministers on behalf of each government prior to being sent to all UK legislatures for scrutiny.The UK Government Cabinet Office is coordinating the work on developing common frameworks.

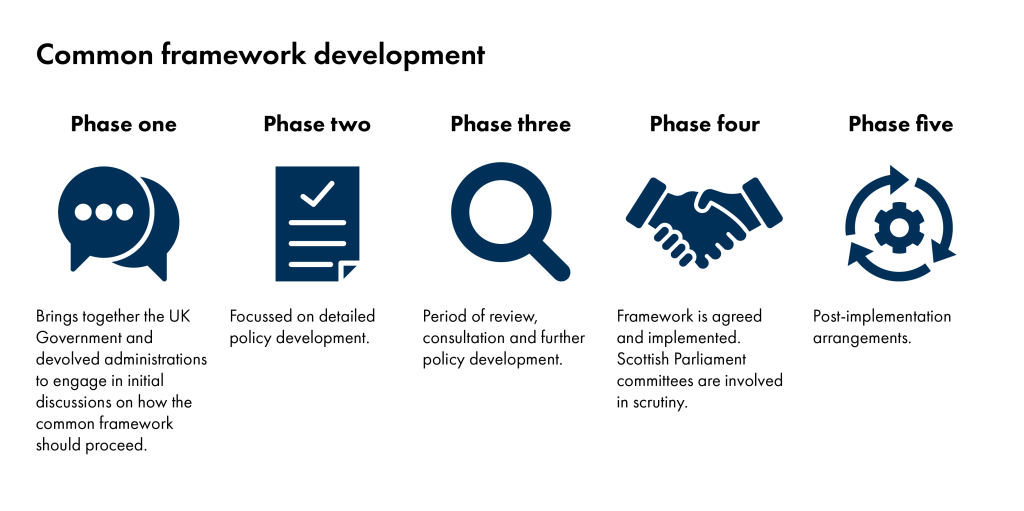

Common frameworks go through four phases of development before implementation at phase five. The stages are set out below. The parliament receives frameworks for scrutiny at phase four.

How will the Scottish Parliament consider frameworks?

Frameworks which have reached phase four are available to be considered by the Scottish Parliament. Subject committees can consider frameworks which sit within their policy areas.

Each legislature in the UK can consider common frameworks. Issues raised by legislatures during this scrutiny are fed back to their respective government. Governments then consider any changes which should be made to frameworks in light of scrutiny by legislatures before implementing the framework. Changes in light of scrutiny are not, however, a requirement.

The Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee has an oversight role in relation to frameworks and will lead on cross-cutting issues around transparency, governance and ongoing scrutiny.

The Scottish Government has previously acknowledged the ongoing role of the Scottish Parliament in relation to frameworks:

Consideration will also need to be given to what role the Parliament might have in the ongoing monitoring and scrutiny of frameworks post-implementation.

Scottish Government response to the session five Finance and Constitution Committee report on common frameworks, June 2019

The Scrutiny Challenge

The way in which common frameworks have been developed and will operate raises some significant scrutiny challenges for the Scottish Parliament.

Common frameworks are intergovernmental agreements and the scope for parliamentary influence in their development is significantly limited with scrutiny taking place at phase four.

The ongoing operation of frameworks will take place at an official level between government departments. It is therefore unclear how much information the Parliament may be able to access to scrutinise the effect of frameworks on policy-making.

The Scottish Government and the UK Government have differing objectives in relation to frameworks. The UK Government is seeking “high levels of regulatory coherence”.1 The Scottish Government believes that they are about “allowing legitimate policy choices”.1

The interconnected nature of common frameworks and the UK Internal Market Act 2020 (see section on the UK Internal Market Act).

The impact of common frameworks on the Scottish Government’s stated policy position of keeping pace with EU law.

The fact that most frameworks have been operating on an interim basis since 1 January 2021 in spite of being unavailable for scrutiny by legislatures3.

The legacy expert panel report to the session five Finance and Constitution Committee noted these scrutiny challenges. The Committee had previously recommended that the Scottish Government should have to report on the operation of each common framework, noting interactions with cross-cutting issues such as keeping pace with EU law, on an annual basis.

Scrutiny at other legislatures

The framework was considered by the Northern Ireland Assembly Committee for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs, which published a position paper. The House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee also considered the framework. In a letter to George Eustice MP, Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, the House of Lords Committee:

asked why a common framework was considered necessary for the policy area, given that there are already a several legislative and non-legislative arrangements in place that establish a fisheries management regime in the UK;

suggested that the Framework Outline Agreement, which is one of the framework documents supplied, should be reviewed regularly as are its other components;

requested an explanation of the impact of the Subsidy Control Bill (since enacted) on the operability of the framework. This point will be discussed further in the framework analysis section.

Scrutiny at the House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee and the Northern Ireland Assembly Committee for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs is discussed in detail in the Framework Analysis section of this briefing.

The UK Internal Market Act 2020

The UK Internal Market Act 2020 was introduced in the UK Parliament by the UK Government in preparation for the UK’s exit from the EU. The Act establishes two market access principles to protect the flow of goods and services in the UK’s internal market.

The principle of mutual recognition, which means that goods and services which can be sold lawfully in one nation of the UK can be sold in any other nation of the UK.

The principle of non-discrimination, which means authorities across the UK cannot discriminate against goods and service providers from another part of the UK.

The Act means that the market access principles apply even where divergence may have been agreed in a framework.

The introduction of the UK Internal Market Act had a significant impact on the common frameworks programme because of the tension between the market access principles contained in the Act and the political agreement reached that “common frameworks would be developed in respect of a range of factors, including "ensuring the functioning of the UK internal market, while acknowledging policy divergence"."i

UK Government Ministers have the power to disapply the market access principles set out in the Act where the UK Government has agreed with one or more of the devolved governments that divergence is acceptable through the common frameworks process.

Although UK Ministers can disapply the market access principles in such circumstances, they are not legally obliged to do so.

On 2 December 2021, Angus Robertson MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Constitution, External Affairs and Culture wrote to the Convener of the Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee to give an update on the common frameworks programme.

The letter indicated that at a recent Ministerial quadrilateral, agreement had been reached between the UK Government and the Scottish Government and other devolved administrationsii on an approach to "securing exemptions to the Act for policy divergence agreed through common frameworks".

The meeting agreed an approach to securing exemptions to the Act for policy divergence agreed through common frameworks, and endorsed the text of a statement that UK Ministers will shortly make to the House of Commons. This will give effect to firm commitments made to the UK Parliament during the passage of the Bill that “…divergence may occur where there is agreement under a common framework, and that such divergence could be excluded from the market access principles. Regulations to give effect to such an agreement can be made under Clauses 10 and 17. In those cases, the Secretary of State would be able to bring to the House a statutory instrument to exclude from the market access principles a specific agreed area of divergence.

This would follow consensus being reached between the UK Government and all the relevant parties that this is appropriate in respect of any specific defined topic within a common framework.

Letter from the Cabinet Secretary for Constitution, External Affairs and Culture, 2 December 2021

Process for considering UK Internal Market Act exclusions in common framework areas

The UK Government and devolved administrations have agreed a process for considering exclusions to the market access principles of the UK Internal Market Act 2020. The process was published on 10 December 2021.

The process requires that if a party to the framework wishes to seek an exclusion to the market access principles, it must set out the scope and rationale for this. The proposed exclusion is then considered by the appropriate framework forum, taking into account evidence including about the likely direct and indirect economic impact of the proposed exemption. If the exemption is agreed, it is for UK Ministers to introduce a draft instrument to the UK Parliament to give effect to the exclusion. The UK Parliament will then consider the draft instrument.

The process is set out in full below.1

Proposal and consideration of exclusions

1. Sections 10 and 18 and Schedules 1 and 2 of the UK Internal Market Act contain provisions excluding the application of the United Kingdom market access principles in certain cases.

2. Whenever any party is proposing an amendment to those Schedules in areas covered by a Common Framework:

a. the exclusion seeking party should set out the scope and rationale for the proposed exclusion; and

b. consideration of the proposal, associated evidence and potential impact should be taken forward consistent with the established processes as set out in the relevant Common Framework, including an assessment of direct and indirect economic impacts.

3. It is recognised that all parties will have their own processes for considering policy proposals. Administrations should consult and seek agreement internally on their position before seeking to formally agree the position within the relevant Common Frameworks forum.

Agreement of an exclusion request

4. Where policy divergence has been agreed through a Common Framework this should be confirmed in the relevant Common Framework forum. This includes any agreement to create or amend an exclusion to the UKIM Act 2020’s market access principles.

5. Evidence of the final position of each party regarding any exclusion and whether an agreement has been reached should be recorded in all cases. This could take the form of an exchange of letters between appropriate UK Government and Devolved Administration ministers and include confirmation of the mandated consent period for Devolved Administration ministers regarding changes to exclusions within the Act.

6. Parties remain able to engage the dispute resolution mechanism within the appropriate Common Framework if desired.

Finalising an exclusion

7. Under section 10 or section 18 of the UK Internal Market Act 2020 amendments to the schedules containing exclusions from the application of the market access principles require the approval of both Houses of the UK Parliament through the affirmative resolution procedure. Where agreement to such an exclusion is reached within a Common Framework, the Secretary of State for the UK Government department named in the Framework is responsible for ensuring that a draft statutory instrument is put before the UK Parliament.

Fisheries Management and Support Framework

The Fisheries Management and Support Framework ("the framework") has reached phase four and has, as such, been received by the Scottish Parliament for scrutiny. Scrutiny is being undertaken by the Rural Affairs, Islands and Natural Environment Committee.

The framework has also been received by other UK legislatures. This briefing is intended to facilitate scrutiny of the framework by the Scottish Parliament.

Policy Area

The framework covers the following policy areas:

Catching, processing and supply industries

Access to fishing opportunities

Licensing

Stock recovery

Enforcement

Data collection

Aquaculture

Recreational sea angling

Scope

The policy area in scope of the framework was previously governed by EU law through the Common Fisheries Policy, which comprised EU regulations. With the requirement to comply with EU law now at an end, most of these regulations have been converted into domestic law as retained EU law.i However, the Fisheries Act 2020 that forms part of this framework amends some of these regulations as set out in the section on framework legislation.

A non-statutory 'Fisheries Concordat' was agreed between the four fisheries authorities (UK Secretaries of State, Scottish Ministers, Welsh Ministers, and the Northern Ireland Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA)) in 2012. The framework documents state that the contents of that Fisheries Concordat have been included in the framework. The framework will operate alongside the UK Marine Strategy, Marine Policy Statement, and Marine Plans, which pre-date the UK's exit from the EU.

Fishing is mostly a devolved matter, which means that each fisheries policy authority has control over the management of its fleets , the distribution of its fishing opportunities, enforcement and regulations in its own waters. However, international negotiations and the allocation of the UK's fishing opportunities between the parties, are reserved. The powers for the UK Government to determine the allocations for fishing opportunities and the powers for all parties to determine the distribution of those allocations for their respective territories is set out in the Fisheries Act 2020 which forms part of the framework.

Although international negotiations are reserved, the framework documents commit the UK Government to "work closely with the Scottish Government, Welsh Government, and DAERA to develop shared policy positions as far as is possible, applying the principles set out in the [framework]". It also commits the parties to act in accordance with the conclusions of the recently published Intergovernmental Relations Review in developing international fisheries policy.

Several international agreements to which the UK is a party are relevant to fisheries:

Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic

Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, the Work in Fishing Convention 2007

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals

The Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) between the UK and the EU is particularly important with respect to the framework. As part of the TCA, the UK and EU agreed to cooperate on the management of shared fish stocks. The TCA also establishes a Specialised Committee on Fisheries, which will consider fisheries management issues of mutual interest. As part of the framework, the UK Government commits to consulting with the devolved governments if a UK-EU meeting concerns a devolved issue as well as facilitating the attendance of a representative of the relevant devolved government.

As a result of the Northern Ireland Protocol, Northern Ireland remains aligned with the EU on fisheries rules.ii The Northern Ireland Protocol includes a section on Fisheries and Aquaculture, which lists specific EU law which will continue to apply in Northern Ireland. The framework documents affirm that the provisions in Article 18 of the Protocol, on democratic consent, will be respected and state that the governance structures and decision-making, dispute resolution and review processes set out in the framework are intended to help manage cases in which rules in Northern Ireland change in alignment with the EU, or where GB-only proposals are made.

However, in a written submission published on 19 January 2022 to House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee, Professor Katy Hayward, Dr Viviane Gravey, and Dr Lisa-Claire Whitten noted that the frameworks that had been published at the time of writing showed a lack of discussion with Irish officials in the development of common frameworks, something required to ensure North-South cooperation in the future. Specifically with regards to the fisheries framework (not published until 17 February 2022), Professor Hayward and Drs Gravey and Whitten noted that the framework area would overlap directly with an area of existing North-South cooperation.

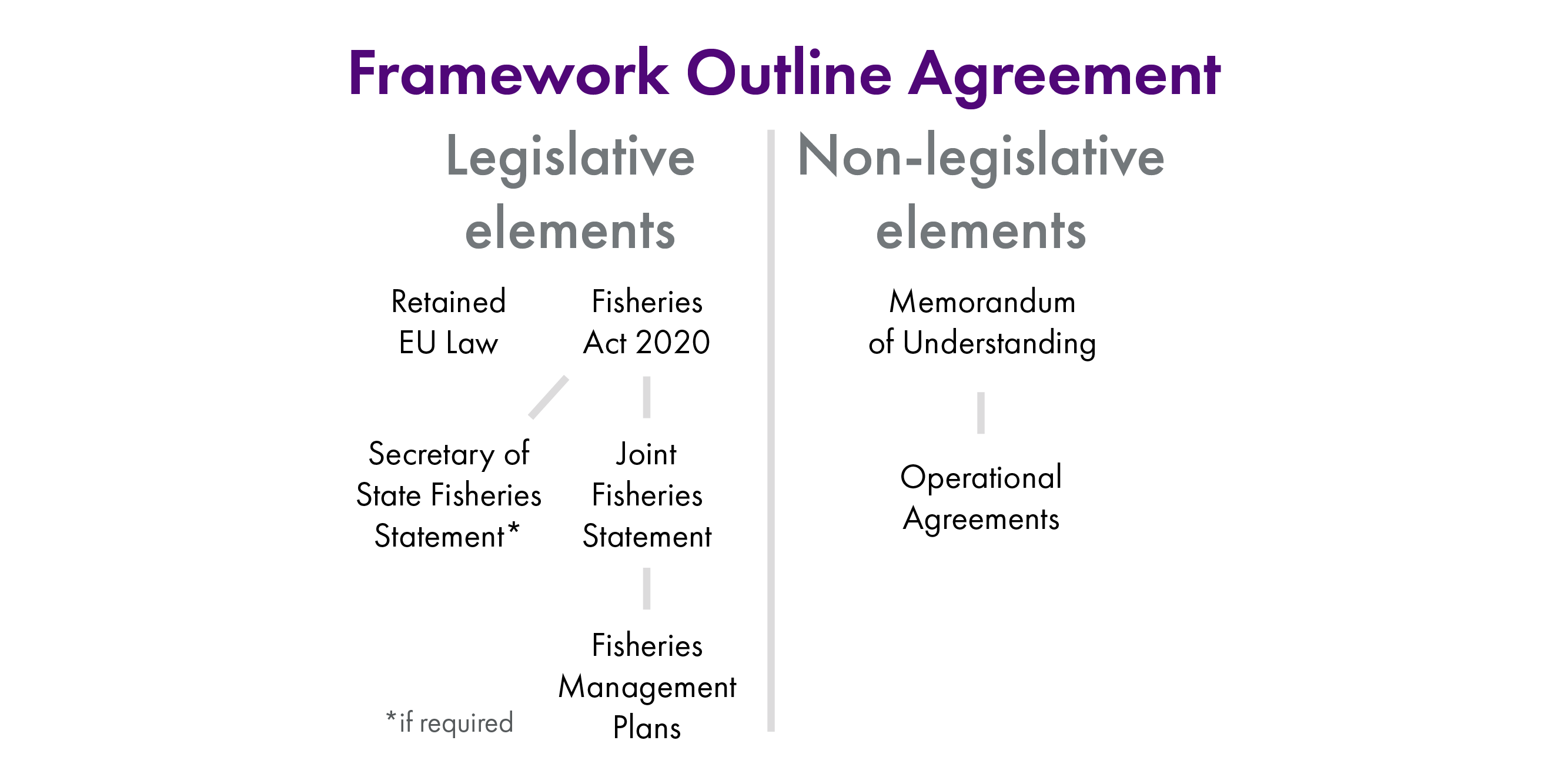

The framework comprises both legislative and non-legislative components. These elements are described in the sections on legislation and non-legislative arrangements components of the framework.

Definitions

The framework documents define a number of key terms, including:

'Aquaculture' refers to the breeding, rearing, growing or cultivation of (a) any fish or other aquatic animal, (b) seaweed or any other aquatic plant, or (c) any other aquatic organism. This definition is used in the Fisheries Act 2020.

'Fish' refers to marine and estuarine finfish and shellfish, including migratory species such as European eel and salmon.

'Fisheries' refers to the capture of wild marine organisms (fish and shellfish).

'Marine Protected Areas' (MPA) refers to areas of the sea protected by law for nature conservation purposes.

'Quota' refers to (a) a catch quota or an effort quota, or (b) any other limit relating to the quantity of sea fish that may be caught or the time that fishing boats may spend at sea.

'Shellfish' refers to molluscs and crustaceans of any kind found in the sea and inland water. This definition is used in the Fisheries Act 2020.

'Total Allowable Catch' refers to a catch limit set for a particular fishery or stock, generally for a year or a fishing season.

Summary of proposed approach

The FMS Framework is a complex framework, comprising several legislative and non-legislative components.

The next two sections of this briefing describe the legislative and non-legislative components of the framework in more detail.

Detailed overview of proposed framework: legislation

This section provides information on the legislation contained within the framework.

Primary legislation

The Fisheries Act 2020, ("the Act"), includes legislative provisions that are considered part of the framework. Specifically, the Act requires that parties to the framework develop a Joint Fisheries Statement (JFS), to be published by 23 November 2022. This statement will set out their policies, including goals with regards to sustainability of fishing activities, data- collection and sharing, minimising by-catch, aquaculture, and climate change measures. Fisheries policy authorities (i.e. the parties to the framework) may set out either joint or divergent policies.

The Act also requires fisheries policy authorities to develop joint Fisheries Management Plans (FMPs), which set out how fisheries policy authorities intend to restore stocks of sea fish or maintain them at sustainable levels. These FMPs must undergo public consultation. The Act requires that both the JFS and the FMPs are regularly reviewed, as described in the section on review mechanisms. In addition, the Act also requires access for UK vessels throughout UK waters and a common licensing regime for foreign vessels across the UK.

Other pieces of primary legislation associated with the framework appear to be the Sea Fish Conservation Act 1967, the Fisheries Act 1981, and the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 (as amended by the Fisheries Act 2020.) It is unclear from the framework documents whether these Acts are subject to the framework (see analysis section)

Secondary legislation:

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 converted EU law into domestic law, called 'retained EU law', and gave Ministers power to amend this legislation to make it operational as domestic law. With regards to EU fisheries legislation, secondary legislation was made to amend around 100 pieces of EU Common Fisheries policy legislation. Other secondary legislation amended the Marine Strategy Framework Directive and Directives on the protection of habitats and species.

This secondary legislation can be replaced with other domestic legislation by parties to the framework. The Fisheries Act 2020 also provides powers for the Secretary of State to make UK-wide regulations in areas of devolved competence, with the consent of the other fisheries policy authorities. In such cases the Scottish Parliament would get a notification that Scottish Ministers intended to consent to UK regulations being made. They could therefore scrutinise the Scottish Government Ministers' decision, but not directly the regulations themselves. i

Detailed overview of proposed framework: non-legislative arrangements

The framework comprises a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), which is an agreement between parties to the framework.

The MoU lists plans for a number of operational agreements (OAs), which are delivery documents that will describe how the parties will work together in operational terms. For example on license issuing, fisheries science, subsidies, the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland, enforcement, and international negotiations. Some of these documents have deadlines for production.i For the rest, the MoU states that they will be published "in due course on gov.uk" (the UK Government website).

The MoU articulates a number of principles which the parties commit to acting in accordance with. The principles include an affirmation of the recognition that fisheries management is a largely devolved policy area but also includes some areas that are reserved. The parties also acknowledge that they all have:

"a responsibility on all authorities to manage fishery stocks, migratory fish species, the marine environment and aquaculture, in a sustainable way in line with our international obligations and the fisheries objectives."

Parties to the MoU also affirm their commitments to the principles of mutual respect, information sharing and dispute resolution. This rest of this section of the briefing sets out the governance structures and ways of working that are intended to put these principles into practice.

Stakeholder engagement

The framework documents list more extensive stakeholder engagement than many of the other frameworks published to date. The key legislative component of the framework, the Fisheries Act 2020, involved a formal consultation on the 2018 UK Government White Paper 'Sustainable fisheries for future generations' as well as engagement on the Joint Fisheries Statement (JFS). As part of the requirements of the Fisheries Act 2020, a formal public consultation on the Joint Fisheries Statement is currently taking place and will close in April 2022. The JFS is also receiving scrutiny from legislatures to which parties to the framework will be required to provide a response.

The framework documents mention that there has been prior engagement with parliamentary committees on the development of the framework as a whole. It also mentions a workshop on the JFS in 2019 and that the JFS has undergone stakeholder development via a 'Community of Interest' (CoI) which "was set up with membership across the catching and retail sector, as well as NGOs". However, it is not clear whether this stakeholder engagement involved discussion of other non-legislative elements of the framework..

The Fisheries Framework in practice

Decision-making

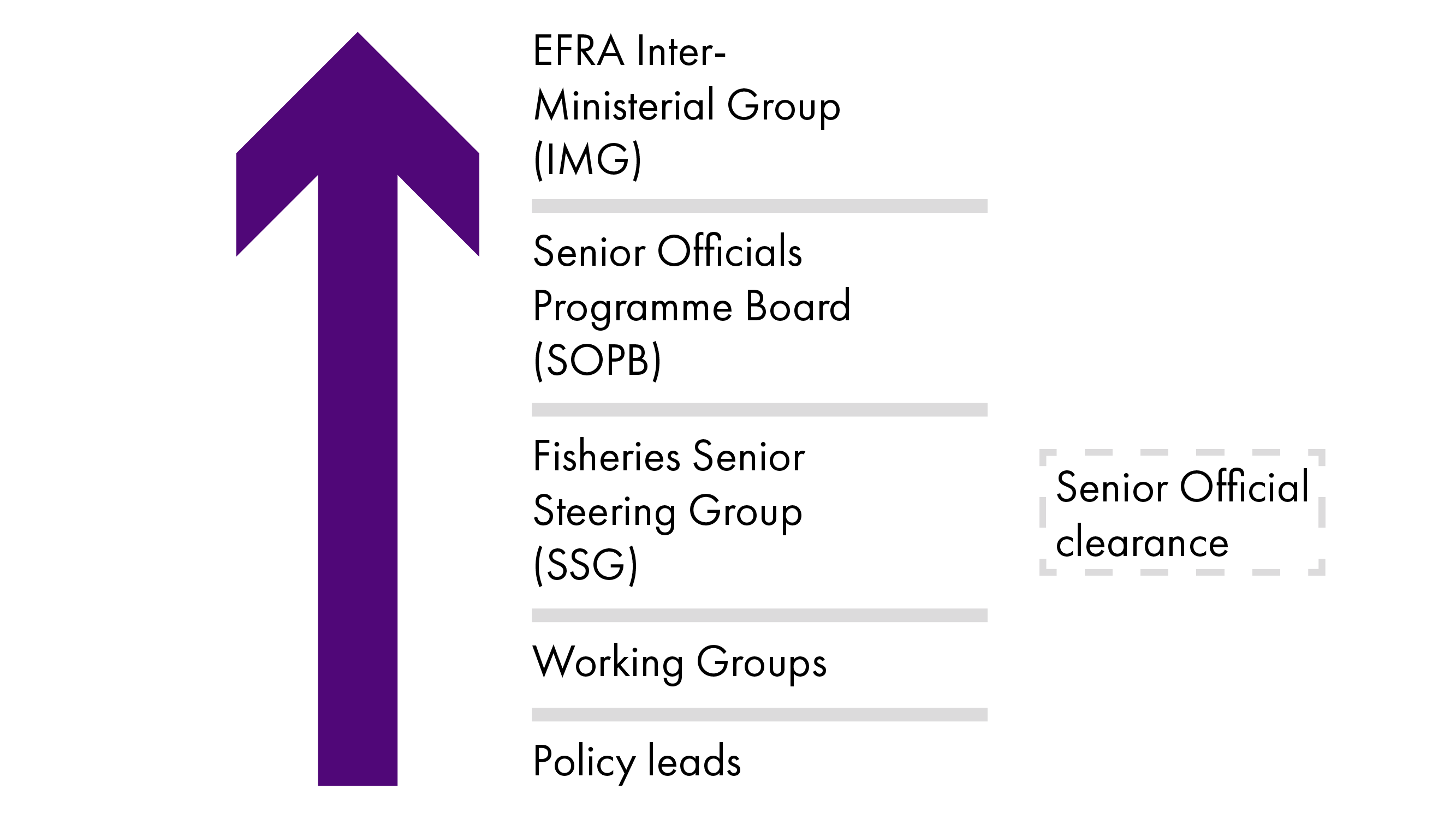

The framework documents acknowledge that as fisheries management is a largely devolved matter, each fisheries policy authority has the power to take its own decisions on devolved policy areas. However, the framework documents set out decision-making mechanisms intended to facilitate discussion between parties where divergence by one party would impact others. The decision-making structure is illustrated below.

Day-to-day fisheries matters will be considered by policy leads on a one-to-one basis or through working groups . For decisions requiring senior official-level discussion, the Fisheries Senior Steering Group (SSG) will meet regularly. This group will consist of key senior officials. It is noted that a Fisheries and Marine Senior Steering Group (FMSSG) is already in operation and that the SSG will build on this. It is not clear whether the SSG replaces the FMSSG or whether they are different groups. If different, it is unclear how the FMSSG links to the framework. Decisions can be escalated from the SSG to the Senior Officials Programme Board (SOPB), consisting of directors of government departments, and, if required, the Interministerial Group for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, which consist of Ministers from all four governments.

A diagram contained in the framework documents (paragraph 6.1) also shows "Internal senior official clearance" at the level of the SSG. It is unclear when such clearance may be required or the purpose of it. Whether it is intended, for example, to allow senior officials within one government to come together to discuss issues within the framework which cut across other policy or framework areas is not made clear.

The framework outline agreement suggests that it would not be helpful to "describe in detail group structures and roles", due to the "dynamic nature of fisheries management [which] requires flexible structures", but that the parties will maintain up-to-date Terms of Reference for the SSG , one of the core decision-making forums. It is notable that such documents have been supplied for decision making forums for other frameworks.

Roles and Responsibilities: parties to the framework

This section sets out the roles and responsibilities of each party to the framework.

The parties to the framework are:

UK Government

Scottish Government

Welsh Government

Northern Ireland Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA)

As part of the framework agreement, the parties commit to share information with one another and work together as per the decision-making, monitoring, reviewing and dispute resolution mechanisms described in the MoU.

Roles and responsibilities: existing or new bodies

This section sets out the roles and responsibilities of any bodies associated with the framework which already exist, or which are to be created.

The Marine Managment Organisation (MMO) will act as the Single Issuing Authority to issues licenses providing access to the UK fisheries authorities' waters to other coastal states and vice versa. This does not involve licensing of boats themselves or the issuing of licenses to UK vessels to fish in their own waters, which will continue to be done by individual fisheries authorities.

The MMO will also host the Fisheries Export Service - a digital system developed by the fisheries policy authorities to facilitate the validation of catch certificates. These catch certificates will be required for UK vessels landing fish into Northern Ireland and for fish products moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland, as a result of provisions in the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland.i

Senior Official Programme Board

The Senior Official Programme Board (SOPB) is made up of senior officials from each government and appears to be a feature of framework governance structures for most Environment, Food and Rural affairs (EFRA-related) common frameworks. The SOPB and IMG-EFRA sit above framework-specific governance structures for the following frameworks:

Agricultural support

Animal health and welfare

Air Quality

Plant varieties and seeds

Integrated pollution prevention and control: developing and setting of Best Available Techniques (BAT)

Fertilisers

Plant health

Organics

Chemicals and pesticides

Fisheries management and support

Ozone Depleting Substances (ODS) and Fluorinated Greenhouse Gases (F-gases)

Some framework documents contain virtually no information about the SOPB and its membership whereas others contain full terms of reference. Legislatures have asked questions about how the membership of the SOPB differs from other framework forums, its role in dispute resolution, and its additional tasks.

The primary role of the SOPB appears to be to sift disputes before they are escalated for Ministerial attention. In response to a letter by the House of Lords Common Framework Scrutiny Committee, George Eustice, MP Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, further stated that:

[the SOPB] can also play a role in helping to avoid the need for a dispute to be referred to ministers, for example if a resolution and consensus can be achieved at the SOPB.

Monitoring and enforcement

The framework documents note that operational agreements associated with the MoU will provide further information on monitoring and engagement, but that the general governance structures described in the section on decision-making, will be utilised.

Review and amendment

As the framework is complex and includes both legislative and non-legislative components, there are several ways in which it will be reviewed.

With regards to its legislative components, the Act requires that the Joint Fisheries Statement (JFS) must be reviewed by the Fisheries Senior Steering Group (SSG) at least every six years, or earlier if fisheries policy authorities "consider it appropriate to do so". Any amendments to the JFS must be published.

The Act also requires that a progress report on the JFS must be produced three years after the JFS is published or reviewed. The JFS is due to be published by 23 November 2022, meaning that the first progress report will be due November 2025. This report must also contain information on the extent to which policies contained in the Fisheries Management Plan has been implemented and the extent to which they have affected sea fish stock levels. In contrast to many other frameworks, there is a requirement to lay the reports before legislatures.

With regards to the framework's non-legislative components, the MoU will be reviewed by the SSG within three years at the latest, but a review can be initiated by any party to the agreement at any time. The framework documents state that it "is not considered necessary to review the FOA [Framework Outline Agreement] as the framework documents themselves are actively managed and have robust and dynamic review processes". It is true that those components other than the FOA have specific reviewing requirements, however, in correspondence, the House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee disagreed with this, writing that

"we consider that as the FOA is also a component of the Common Frameworks Programme, its operation should be also be kept under review and amended if necessary, as part of any ongoing evaluation of the Programme".

Dispute resolution official level

This section considers the dispute resolution process set out within the framework.

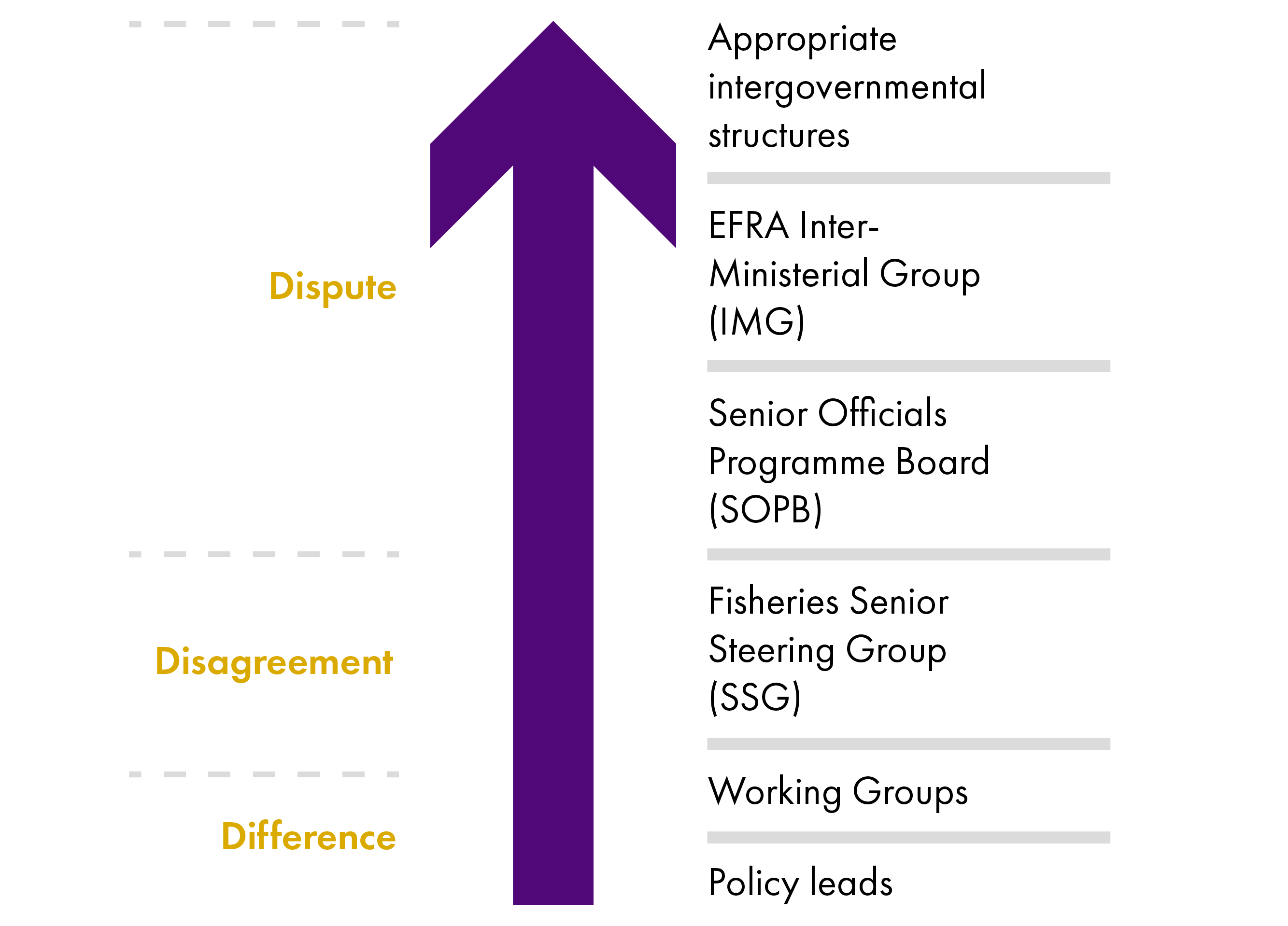

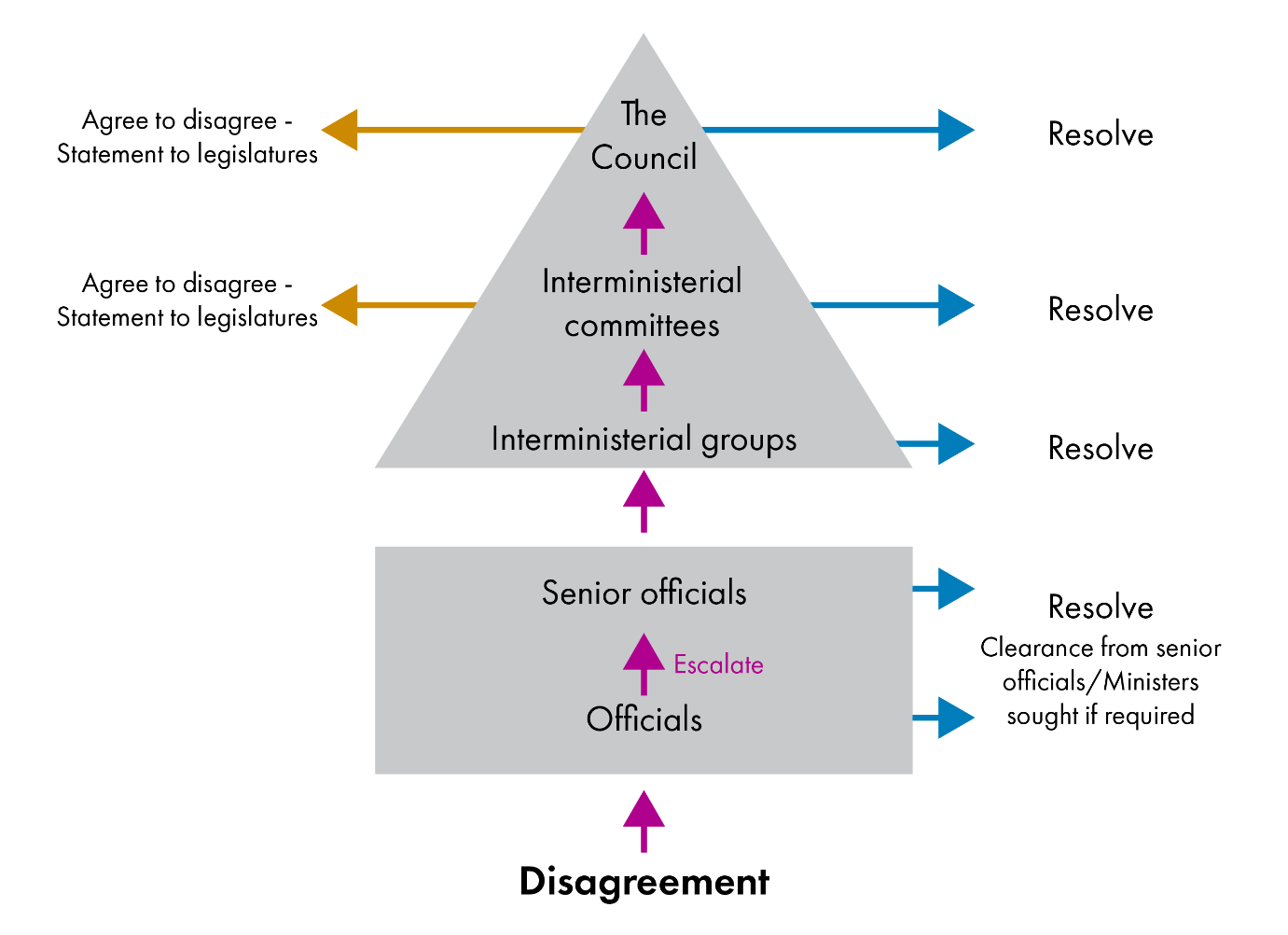

The parties to the framework commit to resolving any issues at the lowest possible level. The framework documents specify that steps to resolve issues should "proceed in a timely manner", but do not specify deadlines. The diagram below illustrates the dispute resolution process for the framework.

Any disagreements that cannot be resolved between policy leads or working groups can be brought to the SSG. If the SSG is unable to resolve the disagreement, it is considered a 'dispute' and dealt with by the SOPB. If the SOPB cannot resolve the dispute, it can be escalated further through the Ministerial dispute resolution process described in the next section.

Dispute resolution Ministerial level

It is anticipated that recourse to resolution at Ministerial level will be as a last resort and only sought where dispute resolution at official level has failed. Disputes which reach Ministerial level will be resolved through intergovernmental dispute resolution mechanisms. Relevant intergovernmental disputes may concern the "interpretation of, or actions taken in relation to, matters governed by […] common framework agreements".

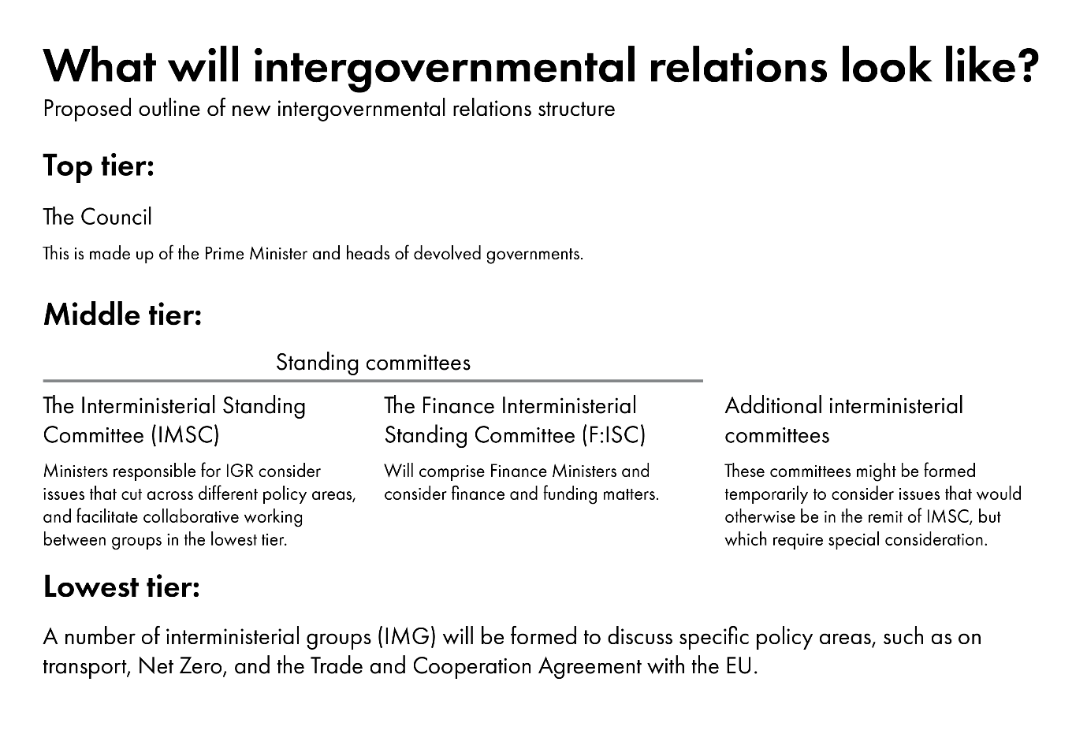

Intergovernmental dispute resolution mechanisms were considered as part of the joint review on intergovernmental relations (IGR). The conclusions of the joint review were published on 13 January 2022 and set out a new approach to intergovernmental relations, which the UK Government and devolved governments have agreed to work to. The joint review created a new three-tiered system for intergovernmental discussions, doing away with the old Joint Ministerial Committee structure.

The lowest and middle tiers have specific responsibilities for common frameworks. At the lowest tier, interministerial groups (IMGs) are responsible for particular policy areas, including common frameworks falling within them. At the middle-tier, the Interministerial Standing Committee (IMSC) is intended to provide oversight of the common frameworks programme.

The new IGR dispute resolution process follows on from the process at the official level. If a dispute cannot be resolved at the official level as set out in individual frameworks, it is escalated to the Ministerial level. The diagram below illustrates the general dispute resolution process for frameworks, including discussions between officials (square) and Ministers (triangle).i

At the lowest level interministerial groups comprising portfolio Ministers attempt to resolve the disagreement. The framework states that any issues which cannot be resolved by the SOPB, can be escalated to the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Interministerial Group. If its attempts are unsuccessful, the issue can be escalated to an interministerial committee. If the interministerial committee is unsuccessful in resolving the issue, they can either agree to disagree, in which case they need to make a statement to their legislatures or escalate the dispute further. If a dispute is escalated to the highest level, third-party advice or mediation should normally be sought and made available to the Council. If the Council fails to find agreement, they are again required to make a statement to their legislatures.

The new process includes more extensive reporting requirements about disputes. The IGR secretariat is required to report on the outcome of disputes at the final escalation stage, including on any third-party advice received. Each government is also required to lay this report before its legislature.

The Office for the Internal Market (OIM) can provide expert, independent advice to the UK Government and devolved governments. Its advice and reports may, however, be used by governments as evidence during a dispute on a common framework.

Rachel Merelie of the OIM explained the position whilst giving evidence to the House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee in November 2021:

The OIM is not involved in dispute resolution. We are here to provide advice to government, using our economic and technical expertise…It is of course possible…that our reports are considered in some shape or form as evidence in support of that process, and we remain open to being used in that way.

Implementation

The framework documents do not note any particular implementation deadlines or requirements.

The Joint Fisheries Statement that forms part of this framework is currently undergoing public consultation and needs to be published by 23 November 2022.

Framework Analysis

Current policy position

Fisheries is largely a devolved matter. A separate SPICe briefing provides a detailed overview of how fisheries are governed in Scotland and the UK after post-EU exit.

Key issues

House of Lords Scrutiny

Necessity of the Fisheries Framework

The House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee questioned whether the Fisheries Framework was necessary. In a letter to the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Baroness Andrews, Chair of the Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee wrote:

Considering this common framework is part of a complex network of arrangements that establish a wider UK fisheries management regime, including the Fisheries Act 2020, the Joint Fisheries Statement (JFS), and the FFMoU [Fisheries Framework Memorandum of Understanding], it could be considered that these qualify as sufficient intergovernmental arrangements to manage any risk of divergence.

Subsidy Control Act

The Subsidy Control Bill (now Act) was passing through the UK Parliament when the framework was being considered. The Subsidy Control Act established a new domestic subsidy control scheme. The Welsh and Scottish legislatures have withheld legislative consent to the Bill.

Baroness Andrews, Chair of the House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee, wrote a letter on the Subsidy Control Bill and its interaction with frameworks to Lord Callanan, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State. In this letter, she stated that the Committee had become:

"increasingly concerned as to how the Bill will impact on [...]frameworks which we currently assess are likely to interact with the Bill. These include the Fisheries Management and Support Framework [...]."

We acknowledge, of course, that subsidy control is a reserved area. However, equally clear is the fact that powers and requirements within the Bill could have implications for devolved policy areas across the UK, in that these powers severely threaten the operability of relevant common frameworks agreed in devolved areas. For example, within the Bill, we note that there are powers under which the Secretary of State can refer subsidies or subsidy schemes made by the devolved governments to the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). This could potentially have the effect of overriding the devolved governments when it comes to proposing subsidies (clauses 52 and 60).

The Scottish Government refused to give legislative consent for these provisions1 stating:

If enacted, these powers would undermine the long-established powers of the Scottish Parliament and Scottish Ministers to act in relation to matters within devolved competence such as economic development, the environment, agriculture and fisheries.

The Committee received a response form Lord Callanan, in which he contested that the Subsidy Control Bill would have the effects feared by the Committee. With regards to particular provisions highlighted by the Committee:

It is my view that these provisions are all appropriate for a reserved policy matter, including where the Secretary of State has been given specific powers to ensure the effective functioning of the regime.

The framework documents do not mention the Subsidy Control Bill. The only reference to subsidies occurs in Annex 1 of the MoU, which lists plans for the Operational Agreements (OAs) that form part of the non-legislative arrangements of the framework. One of these OAs will be the 'Subsidies Grants and Future Funding Operational Agreement' and will, according to the framework documents, "set out how the fisheries policy authorities will work together on the division and allocation of subsidies and grants in the UK, as well as data sharing, success evaluation and delivery mechanisms such as the use of common IT platforms."

In its letter to George Eustice MP, Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, about the Fisheries Framework the House of Lords Common Framework Scrutiny Committee writes:

"Considering the devolved administrations have withheld legislative consent to the Subsidy Control Bill because they believe it has concerning implications for devolved areas, can you clarify how you envision reconciling this commitment within the OA with the Bill? What are the implications of the Bill for the Subsidies Grants and Future Funding OA? Can you also provide detail on any discussions concerning the Subsidy Control Bill taking place within the framework?"

The Scottish Government has recently established a new domestic funding scheme by secondary legislation under the Fisheries Act 2020. The scheme allows Scottish ministers to provide financial assistance through grants or loans for the following purposes:

the conservation, enhancement or restoration of the marine and aquatic environment;

the promotion or development of commercial fish or aquaculture activities;

the reorganisation of businesses involved in commercial fish or aquaculture activities;

contributing to the expenses of persons involved in commercial fish or aquaculture activities;

maintaining or improving the health and safety of individuals who are involved in commercial fish or aquaculture activities;

the training of individuals who are, were or intend to become involved in commercial fish or aquaculture activities, or are family members of such individuals;

the economic development or social improvement of areas in which commercial fish or aquaculture activities are carried out;

improving the arrangements for the use of catch quotas or effort quotas;

the promotion or development of recreational fishing.

The Scottish Government intends to publish guidance setting out the specific range of activities that can be funded, and the eligibility criteria. However, it is not clear how the Subsidy Control Act will interact with this scheme, and whether it might restrict the range of activities the Scottish Government may provide financial support for under the scheme.

Recommendations

The House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee published its final recommendations on the framework in a letter to the Secretary of State on 23 March 2022. Recommendations include:

that the functioning of the Fisheries Management and Support common framework should be regularly reviewed as a whole, and the FOA be subject to regular updates where relevant to reflect changes made to the other documents within the common framework.

that the text in the FOA and FFMoU is updated to state that the UK Government “will” facilitate the attendance of the devolved administrations at EU-UK meetings, where an agenda item concerns implementation in an area of devolved competence. This would ensure adherence to the JMC principles underpinning the Common Frameworks Programme and that the devolution settlements are respected.

that the FOA and FFMoU are updated to include text setting out the UK Internal Market Act exclusions process.

that the FOA and FFMoU should be updated to include a commitment to update the House of Lords, House of Commons and the three devolved legislatures on the ongoing functioning of the common framework as a whole after the conclusion of scheduled reviews.

that the Government carefully consider how the Subsidy Control Bill might contradict the aims of common frameworks and impede their successful operation. Decisions made through cooperation between the devolved powers via a common framework should take priority in areas where the Subsidy Control Bill is relevant.

that the FOA and FFMoU is updated to include that reviews should analyse how the common framework as a whole is interacting with the Subsidy Control Bill. This information should be presented at the regular updates to legislatures we have recommended.

that when the OAs published, they are also laid before the legislatures for formal scrutiny as part of the Common Frameworks Programme.

Northern Ireland Assembly Scrutiny

The Northern Ireland Assembly Committee for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs has published a position paper on the draft Joint Fisheries Statement & Fisheries Management and Support Common Framework. The paper lists the following observations on the framework:

There is a lack of detail regarding the nature of issues which will be raised at SSG and the criteria for including matters on the group's working agenda

The Framework document references that Operational Agreements (OAs) – "delivery documents" - will be developed to support the Framework and a list of proposed OAs is outlined in the appendices. However, there is no timeframe provided for when the OAs will be made publicly available and it is stated that these will be accessible on gov.uk "in due course".

Further, the proposed scope of the OAs encompasses a number of fundamentally important issues regarding how administrations will interact including:

Landing obligations and access to waters

Consultation on, and apportionment of, fishing opportunities

Coordination on science and research

Division and allocation of subsidies and grants

In the absence of any detail on these matters it is not possible to consider holistically the proposals for how administrations will engage under the auspices of the Framework.

The document states that the Framework will provide a mechanism to discuss and manage proposed policy changes "Where one or more of UK Government, the Scottish Government or the Welsh Government proposes to change rules in a way that has policy or regulatory implications for the rest of the UK, or where rules in Northern Ireland change in alignment with the EU" – this suggests that NI may be prohibited from proposing policy changes under the auspices of the Framework which are unconnected to its obligations under retained EU law

The Common Framework as drafted outlines that should Ministers fail to reach agreement on a dispute that the matter can be referred to Intergovernmental Relations (IGR) Ministers for review. Clarity should be provided as to how such an issue would be managed at IGR level and if the Dispute Resolution process as outlined in the Review of Intergovernmental Relations (January 2022) would apply

There is no reference to the need for continued parliamentary engagement in terms of the review, effectiveness and operation of the Common Framework

It is unclear to which forum issues should be highlighted in the event that NI is precluded from aligning with policy changes made in Great Britain as a result of compliance with Protocol-related EU legislation, and whom would represent NI's interests at such a forum

There is significant duplication in the Common Framework document

While the Framework outlines that local authorities will maintain good relations and treat each other with mutual respect, there is no information provided about how this will be facilitated, monitored or enforced

Mechanisms for engaging with sea fish industry representatives to ensure their views are considered in policy deliberations are unclear. It may be helpful to include within the Common Framework an obligation on the SSG to consult with industry representatives on particular policies and when the Framework is subject to a planned review

It is unclear in what circumstances a dispute will be escalated from EFRA IMG-level to Intergovernmental Structures and whether this will require consensus by all Ministers, or can be triggered by a Minister acting independently

While the Framework proposes that jurisdictions will work together as "equal partners", the influence of each authority will likely be dictated by the relative scope of their sea-fish industry and resource capabilities

There is relatively little detail about how the decision-making fora formed under the Framework will interact which presents challenges in terms of scrutiny

The Framework document states that "The policy area covered by this Common Framework intersects with the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement and therefore topics relevant to the framework may be considered from time to time by relevant TCA Specialised Committees or the Partnership Council." However, there is no detail provided on how this be delivered operationally.

Legislative elements of the framework

It is not clear from the framework document whether additional primary legislation is included in the framework, or if they interact with it. Paragraph 4.8 of the Outline Agreement refers to other primary legislation:

Aside from the Act, other existing domestic primary legislation will be used to manage the marine environment. This includes the Sea Fish Conservation Act 1967, the Fisheries Act 1981, and the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 (as amended by the Fisheries Act 2020).

Figure 1 on page 11 of the framework's outline agreement does not show these Acts as legislative components of the framework. However, retained EU law is included in the figure.

Paragraph 3.2 of the Memorandum of Understanding provides a more broad statement:

[The Fisheries Framework] operates within a wider statutory framework which includes, but is not limited to, the UK Marine Strategy, the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009, the Marine Policy Statement, and Marine Plans.

Operational Agreements

As discussed above, much of the detail on how the fisheries policy authorities will work together will be covered by Operational Agreements (OAs) which are under development and yet to be published. On 15 March 2022, the Scottish Government launched consultations on its future catching policy (including measures to reduce discards and bycatch of fish) and the implementation of Remote Electronic Monitoring (the use of cameras, GPS and sensors on board vessels to monitor fishing activity).

These consultations cover aspects of fisheries managements that are listed as the subject of proposed OAs. Therefore, they may provide an early test for how the fisheries policy authorities develop OAs, how they will ensure consistency in approach across the UK and whether any disputes arise during the development of OAs.

The Future Catching Policy consultation document states:

As part of this process we will liaise with other UK administrations as well as other Coastal States and the European Commission in order to determine how our decisions will affect their vessels when fishing in Scottish waters.

Similarly the Remote Electronic Monitoring consultation document states:

In developing this policy, the Scottish Government intends to work closely with other UK administrations to ensure that REM policies and requirements are aligned across the 4 nations.

However, there is no mention of how the policy proposals interact with the Fisheries Framework or OAs under development.