Resource Spending Review and pre-Budget scrutiny

This briefing considers a range of issues arising from the Scottish Government's recent Resource Spending Review. It is designed to assist parliamentary committees in their pre-budget scrutiny work in the Autumn.

Executive Summary

This briefing provides a summary analysis of some of the key issues arising from the recent Scottish Government Resource Spending Review (RSR). It is designed to support Parliamentary committees in undertaking pre-budget scrutiny in the Autumn. Committees will also have the guidance from the Finance and Public Administration Committee. The aim is for this briefing to be complementary to that guidance.

Scotland, like much of the world, is facing a challenging economic context, as encapsulated in the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s economic and fiscal forecasts, published alongside the RSR. This document reveals a number of challenges for Scotland, from slowing growth, to inflation, to a weakening “net income tax” position. For example, in the current financial year, the relative income tax net position of Scotland compared with rUK means that the Scottish budget will be £428 million worse off than it would be without income tax devolution, despite Scottish taxpayers paying in aggregate £500 million more in income tax than they would under the income tax policy of the rest of the UK.

The Cabinet Secretary was at pains to emphasise that the Resource Spending Review (RSR) was “not a budget” and that spending would be revisited on a budget-to-budget basis. Nevertheless, the document did give an indication of the Government’s budget priorities based on the current public finance trajectory. Of course, this also gives an indication of what is less of a priority.

Health and Social care (+2.6% in real terms to £19 billion by 2026-27) and Social Security spending (+48% in real terms by 2026-27) are clear spending priorities of the Government.

Therefore, other “unprotected” parts of the spending envelope (like local government, the police, prisons, rural affairs, higher education, enterprise, tourism and trade) see their indicative spending envelopes fall in real terms. The reasons behind this, and the potential implications, are areas that respective subject committees may wish to consider.

This briefing contains a section on the local government settlement, and as always, that will undoubtedly be a key political debate in coming budget cycles. One interesting new angle to this debate comes in the creation of the National Care Service (NCS) which will result in “significant changes to functions currently delivered in full or in part by local authorities”.

The Spending Review does not estimate how much funding currently going to local authorities could be impacted by the creation of the NCS. However, Scottish local authorities spent £3,528 million on social work and social care in 2020-21, 32% of total local government net revenue expenditure.

The Scottish Government also published a review of its Capital Spending Review which had previously been published in February 2021. This was designed to update infrastructure plans in light of several matters:

a lower than expected UK Government capital allocation

the establishment of a new Scottish Government following the May 2021 election

the impacts of high inflation, supply chain pressures, and business disruption resulting from a combination of the impact of the UK’s exit from the European Union, the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

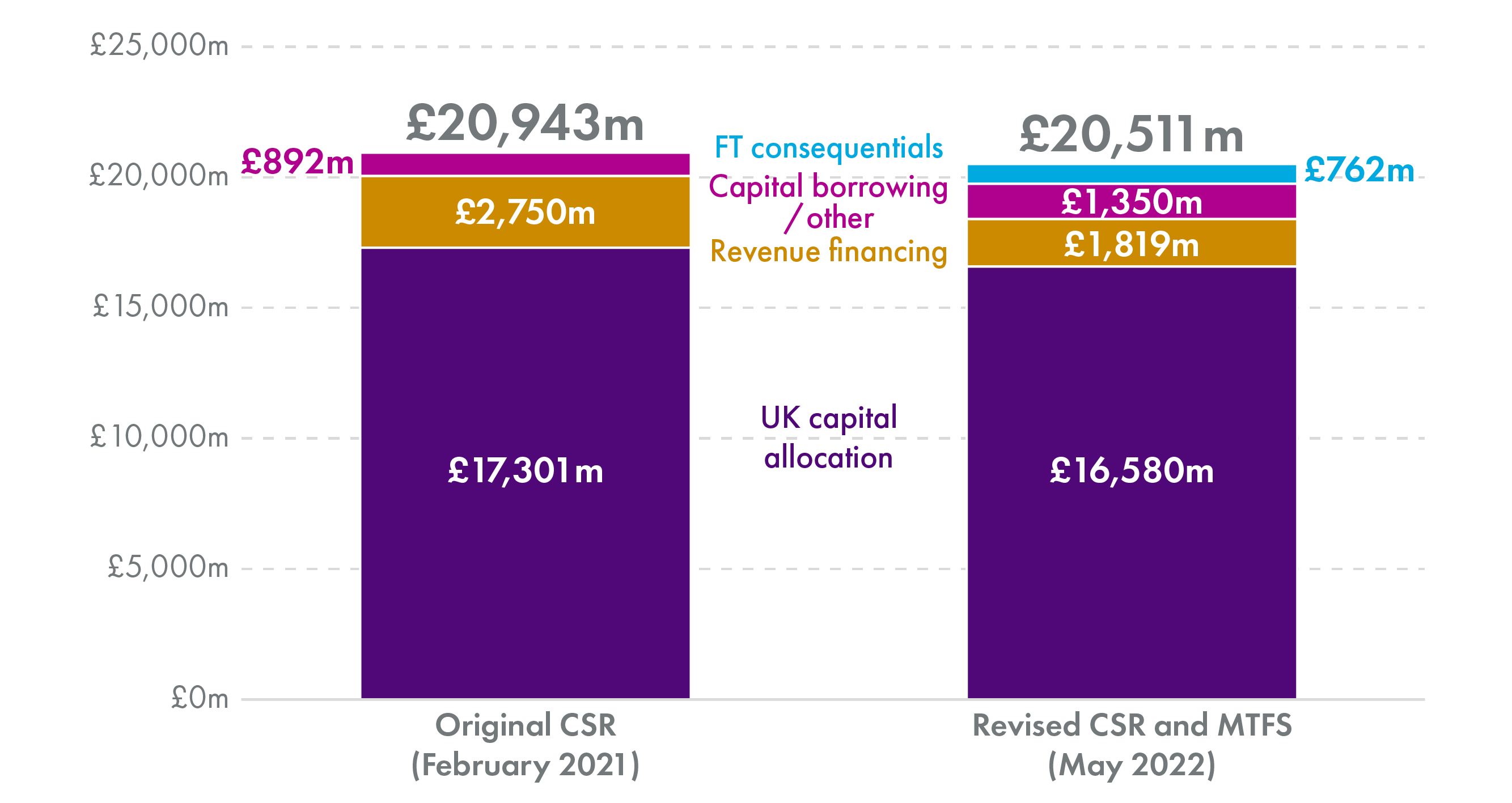

Overall, for the three-year period 2023-24 to 2025-26, planned capital investment is now £0.4 billion lower, at £20.5 billion, compared with £20.9 billion in the earlier plans set out in February 2021.

The Resource Spending Review outlined the Scottish Government’s intention to instigate reforms to Scottish public services. The devolved public sector in Scotland employs more than half a million individuals and currently accounts for one in five of those in employment in Scotland. There are 129 public bodies in Scotland, but the Resource Spending Review noted that “shrinking fiscal resources together with our commitment to environmental and fiscal sustainability mean that reform is inevitable”.

The RSR goes on to state that: “We expect all public bodies to demonstrate that they remain fit for purpose against the present and future needs of Scotland’s people, places and communities”.

The RSR also sets out an ambition to freeze the public sector pay bill, which currently stands at £22 billion per annum. Keeping the public sector pay bill at its current level while still allowing for pay increases will only be achieved alongside reductions in staffing levels.

Finally, on public service reform, the RSR states the Scottish Government’s intention to seek efficiency savings across the public sector. In line with previous requirements for efficiency savings, the Review states that recurring annual efficiencies of at least three per cent will be required from public bodies. To achieve this, the document sets out plans to seek efficiencies through:

further use of shared services

management of the public sector estate (which includes around 30,000 properties)

effective procurement (with current levels of procurement spending at £13.3 billion, or around a quarter of the Scottish budget)

management of public sector grants

Public sector reform, pay and efficiencies will be a key area of scrutiny for the Parliament in coming Budget cycles.

The briefing raises a number of areas for subject committees to explore, covering:

The economy – for example, how the RSR will support the delivery of the National Strategy for Economic transformation. In particular how might the ambitions of the Strategy be delivered in the context of significant indicative real terms cuts to enterprise agencies?

Capital investment – what the scaling back of capital investment and different mix of funding mechanisms might mean for different portfolio’s capital investment plans?

Net zero, energy and transport – for example, how net zero targets might be delivered in light of these indicative spending plans?

National Outcomes - for example, how subject committees might use the National Performance Framework to:

use the NPF to help provide a focus to budget scrutiny

identify key questions relating to the different stages of the policy/spending process

link these key budget questions to the NPF's outcomes and indicators

use the NPF to improve the depth and scope of budget scrutiny.

Equalities – for example, the Equality and Fairer Scotland Statement sets out what the Scottish Government consider to be 9 key “opportunities and challenges” in delivering greater equality and fairness. Committee scrutiny may involve considering stakeholder views on whether these are correctly focused, tangible and measurable.

Budget outlook

The Resource Spending Review - context

The Resource Spending Review1(RSR) was the first multi-year spending review in Scotland since 2011. It followed a Scottish Government consultation on spending priorities launched in December last year. At the time of the consultation launch, the Cabinet Secretary said the Resource Spending Review (RSR) would “outline resource spending plans to the end of this Parliament in 2026-27" and would:

give our public bodies and delivery partners greater financial certainty to help them rebuild from the pandemic and refocus their resources on our long-term priorities.

Alongside the RSR, the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) presented its latest economic and fiscal forecasts2. SFC forecasts give estimates of the revenues that will materialise from tax receipts over the next five years, and the levels of spending that will be required to fulfil social security policy commitments. They also set out important judgements on the likely trajectory for economic growth and inflation.

The Medium-term financial strategy (MTFS)3 was also published as well as an Equality and Fairer Scotland statement4.

Taken together, these documents will help to inform parliamentary committees’ pre-budget scrutiny. In addition to this briefing, committees will also have the guidance from the Finance and Public Administration Committee. The aim is for this briefing to be complementary to that guidance.

After years of single-year budgets the RSR was a very helpful document in providing priorities and the budget choices over a multi-year timescale given current projections.

It is important to note, however, as the Cabinet Secretary was keen to emphasise, that the RSR is not a Budget, and the numbers contained within it will inevitably change. This is useful for subject committees to keep in mind during their pre-Budget scrutiny. When looking at their spending portfolios, it may be that they want to make suggestions for the Scottish Government around priorities they would recommend in the event that additional resources become available.

For example, the following exchange related to university funding from the Finance and Public Administration Committee shows the nature of discussions that might emerge if the funding envelope increases:

Kate Forbes: Like many other spending lines, universities are hugely important, and we will protect them as far as possible. If you want funding in any part of the public sector to increase, you need to either take it from elsewhere or increase the pot.

Liz Smith: If extra money that you are not currently expecting became available to you, would universities benefit from it?

Kate Forbes: I would hope so, yes.

Liz Smith: We might hold you to that.

Less detail provided due to current uncertainties

The budget numbers were presented to “level 2” budget level detail. This is less detail than the normal budget document which presents budgets to “level 3” with “level 4” numbers published alongside. It is also less detailed than the previous Spending review which also provided budget information to level 3.

For example, in the portfolio of Health and Social Care, the Level 2 Budget lines presented in the document were for Health (£17,527 million in 2023-24) and Food Standards Scotland (£23 million in 2023-24). Level 3 Budget lines which would normally be included in Budget documents (for example budget lines for NHS Territorial Boards, NHS National Boards, Health Capital Investment, Workforce and Nursing, General Medical Services among others) were not provided.

Given what the Cabinet Secretary said when launching the RSR consultation in December, about providing greater certainty to public bodies, this may disappoint public bodies who have not received details of their broad spending envelope. For example, it is not possible to look at the document and see the funding outlook for key public bodies which are presented in level 3 budget lines like Health boards, Skills Development Scotland and Scottish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA) among others.

The Cabinet Secretary acknowledged that the information was less detailed than she would have liked, but cited uncertainties around economic volatility and inflation as being barriers to providing a greater level of granularity in the plans:

It is extremely difficult to be any more granular than level 2. Even providing level 2 detail was challenging.

The reason for that is partly driven by inflation. As I have already said, much of our spending review is based on the UK Government spending review, as members would expect. Inflation was at 3.1 per cent; it is now at 9 per cent, and it is going to rise. We have to make a judgment about the risk. Being too granular carries its own risk in terms of planning things that might not come to pass.

It is not easy and, at the end of the day, this is not a budget. We will set out our tax rates and our public sector pay policy, for example, in advance of each budget...

We have pushed as hard as possible to be as granular as possible in an extremely volatile situation.

Subject Committees may wish to consider whether they have been provided with sufficient detail to undertake effective pre-Budget scrutiny. If looking at a specific part of public spending, subject committees may wish to request additional levels of budget granularity in that area.

Spending plans

The funding envelopes for the RSR are presented by portfolio in table 1 of the document. They show the Resource spending (on the day-to-day costs of running public services) expected to rise from £41,802 million in 2022-23 to £47,500 million in the final year of this spending review, in 2026-27. After adjusting for inflation (so in “real terms”), this represents an increase of just under 5% (see box below for further information on the different types of inflation).

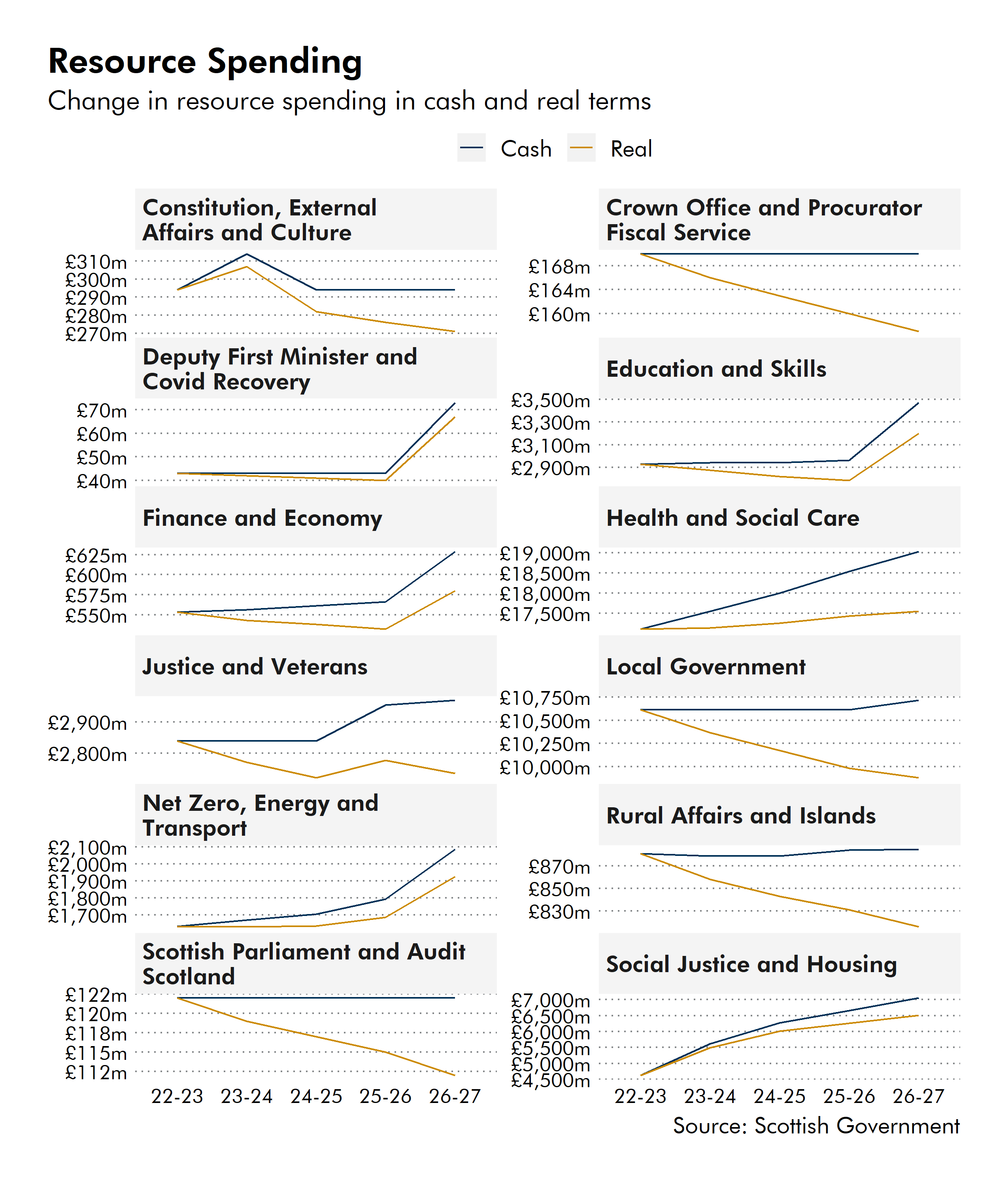

This allocation of this spending by portfolio over the course of the RSR period is presented in figure 1 below.

All individual Budget lines presented within the document are available in cash and real terms from the Financial Scrutiny Unit on request.

Different measures of inflation

There are many different measures of inflation. The most common is the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The Office of National Statistics (ONS) use this measure to track the changes in price of a standard basket of goods bought by households in the UK. CPI is designed to capture changes in consumer prices.

CPI, however, is not generally suitable to analyse the real spending power of governments. This is because governments do not purchase the same goods and services as consumers. The GDP (Gross Domestic Product) deflator is a more general indicator of price changes in the economy, and is usually used to adjust for the effect of inflation on public spending over time. The GDP deflator is used to show inflation for all goods and services produced in the UK, including government services investment goods and exports. It excludes the price of imports.

Is the GDP deflator the best measure to use?

In normal circumstances, the GDP deflator is the best measurement of inflation for government spending.

However, the current high inflation is being driven by high energy prices which is an import cost, not covered by the GDP deflator. This means that rather than running in line with CPI inflation of approaching 10%, the GDP deflator for this year and next is considerably lower.

All of this means that the “real” cost of delivering public services, as measured by the GDP deflator, is likely to be artificially low this year with energy price inflation running so high. As such, whilst energy price inflation remains high, the settlements provided to all parts of the Budget will be tougher than these real terms figures imply, especially for the unprotected parts of the Budget.

Budget priorities

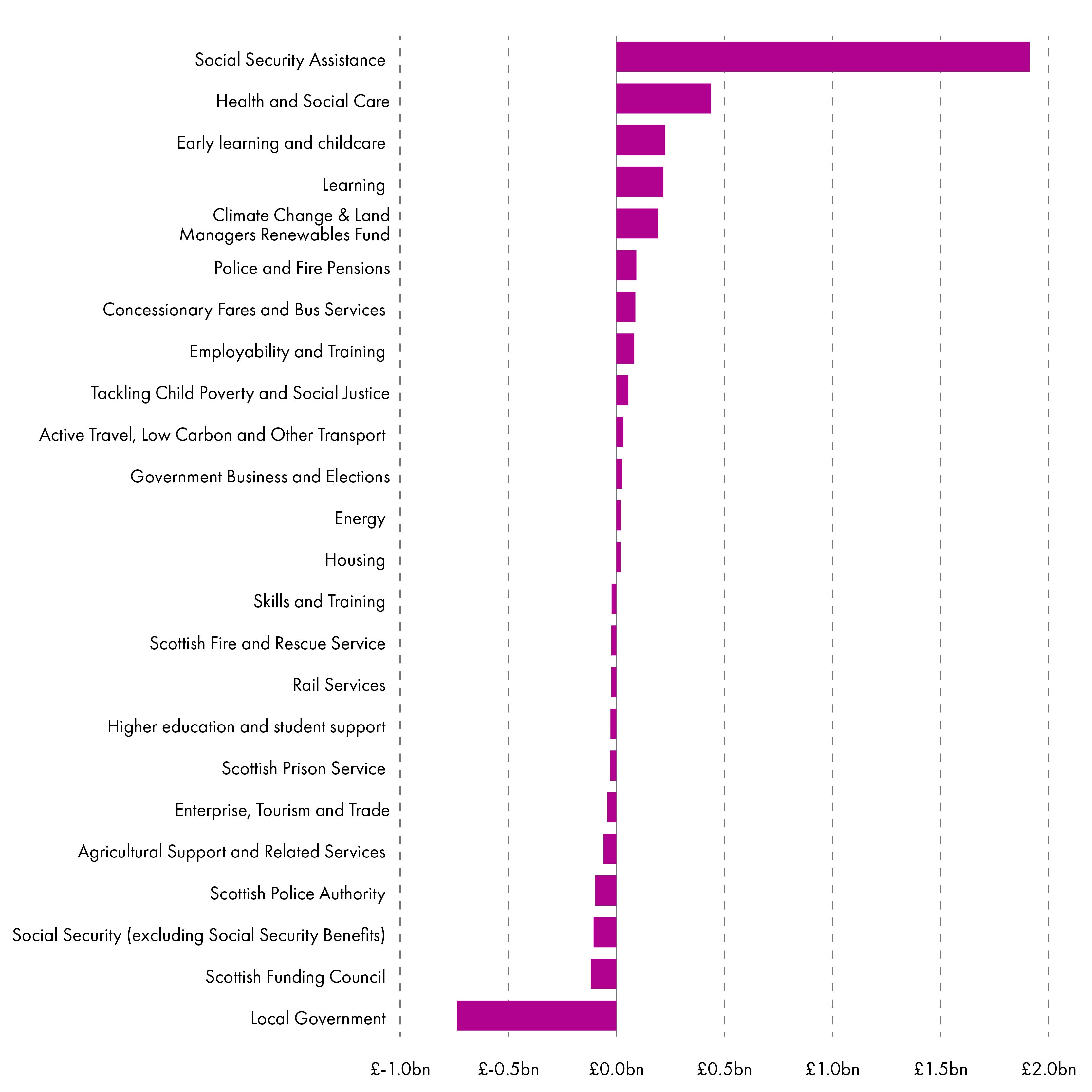

The stand-out priorities in budgetary terms are clearly health and social care and social security. Spending on the health and social care portfolio is projected to increase to over £19 billion in 2026-27, an increase of 2.6% in real terms over the course of the RSR period. This equates to an average annual increase of 0.6% in real terms. By comparison, the 2022-23 health and social care budget was 1.9% higher in real terms than the previous year.

Some commentators, for example, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) and the Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI), have said that even this real terms protection will equate to a tight settlement for health, given the post pandemic backlogs and pressures facing that sector. For example, energy price inflationary pressures and drug price pressures are quite significant in the health service. Pay also makes up a significant element of the health budget and there may be pressures in this area in the light of cost of living pressures. The IFS and Health Foundation have previously said that spending on healthcare would need to increase by an average of 3.3% per year in real terms over the next 15 years in order to maintain NHS provision at current levels, and that social care funding would need to increase by 3.9% per year to meet the needs of a population living longer and an increasing number of younger adults living with disabilities. The current settlement looks modest in that context.

The Scottish Government has committed to updating the 2018 Medium Term Financial Framework for Health and Social Care, which should provide further detail on how the Scottish Government plans to use the increased resources allocated to this priority area. In particular, there is very limited detail on the plans to increase funding for social care and how the proposed National Care Service will be funded. The document states only that social care investment will increase by 25% to £840 million. This will place further strains on the combined health and social care budget.

Social security assistance is forecast to increase by just under 50% over the period, reaching £6.5 billion in 2026-27, reflecting the Scottish Government’s use of devolved social security powers. Indeed, the SFC points to an increasing gap between the amount the Scottish budget will receive in its block grant adjustment for social security and the amount the budget plans to allocate to social security benefits.

In the current year (2022-23) social security payments are forecast to be £462 million higher than the amount added to the Scottish Budget (the block grant adjustment, or BGA) for payments devolved from the UK Government. In 2026-27, spending above the funding received by the UK will increase to just under £1.3 billion. This extra spending has to be found from within the Scottish Government’s tax and spending envelope.

In recent budget documents, the Government has included an annex which sets out its own operating costs. See for example Annex F in the 2022-23 Budget. Total operating costs cover all the core Scottish Government staff and associated operating costs, such as accommodation, IT, legal services and HR. In 2022-23, these were budgeted at £670 million, a significant increase from £543 million in 2020-21 and £599 million in 2021-22. The RSR does not set out any assumptions directly related to the Government's own operating costs over the period of the spending review.

Unprotected budgets face a squeeze

There is very little explicitly said about those budget lines that are not stated as priorities. This therefore must be inferred by looking at those budget lines that are not rising.

The Scottish Government plans to increase spending on health and social security…..Before adjusting for inflation, the remaining funding is lower for the first three years of the RSR than in 2022-23. Only in 2026-27 is funding for other areas expected to increase above the current level.

Once adjusted for inflation, funding for other areas falls more substantially for the first three years of the RSR and is 8 per cent below 2022-23 levels by 2025-26. In 2026-27 funding is expected to be 5 per cent below 2022-23 levels in real terms. This reduction in real funding for other areas has consequences for how the Scottish Government has allocated funding to different portfolios.

By prioritising health and social security as it has, other parts of the Budget will be squeezed. For example, Local Government’s “core” resource budget is projected to be cut by 7% in real terms over the period. The £10,616 million local government figure used in the Spending Review is the combination of the General Resource Grant, guaranteed non-domestic rate income and specific revenue grant figures (as set out in the SG’s 2022-23 Budget) plus the additional £120 million announced at Stage 1.

There are similar real terms reductions being faced by other significant areas of the Budget, for example justice, the police, prisons, rural affairs and higher education,

In addition, the enterprise, tourism and trade budget line will fall by 16% in real terms – this is something that parliamentary committees may wish to consider, given the impact of the pandemic on tourism and the economy.

Largest level 2 increases and decreases over the RSR period

A list of the largest real terms level 2 indicative Budget line increases and decreases over the RSR period is presented in the following figure. This takes the budget in 2022-23 and compares with the indicative figures for 2026-27 in real terms. Although this doesn’t take into account any movements in intervening years (it is a 2022-23 v 2026-27 comparison) it provides an indication of priorities.

Subject committees may wish to scrutinise the reasons for, and implications of, increasing or decreasing indicative budget lines within their portfolio.

Scottish Fiscal Commission forecasts

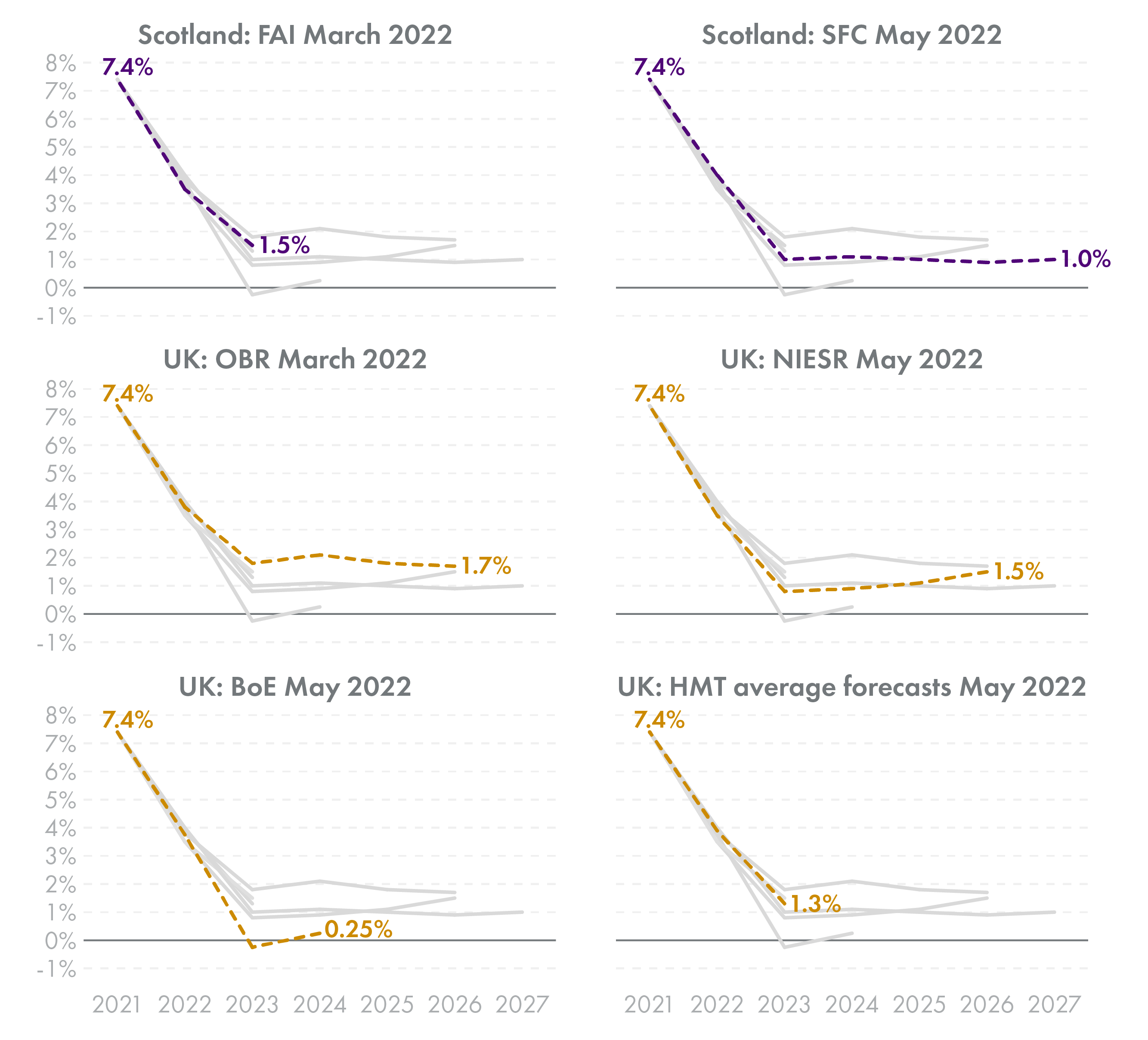

As has become the norm in recent years, this latest fiscal event comes at a time of great economic uncertainty. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, steeply rising energy prices and supply chain disruptions in China, have all added to the difficult economic outlook.

Together these effects have contributed to rising inflation and slowing growth. The SFC states that after Scottish GDP growth of 2.1 per cent this year “we expect growth to slow to 1.1 per cent in 2023-24, slightly lower than we forecast in December 2021.”

Despite this slightly slower outlook, the SFC outlook for overall economic growth is perhaps not a downbeat as might have been expected. For example, unlike the Bank of England for the UK, the SFC is not forecasting a recession for Scotland. Having said that, the SFC’s forecasts for economic growth are broadly in line with other forecasters, as shown in the following chart (where the Bank of England now sits as somewhat of an outlier).

The main driver of the economic gloom at the current time is inflation, being driven by big increases in energy prices. The SFC forecast annual Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation to peak at 8.7% this year, before starting to fall. However, this is perhaps likely to be an under-estimate given the increases we have seen in energy prices since the SFC closed its forecast. For example, monthly UK CPI inflation in April hit 9% and is expected by the Bank of England to rise to around 10% this year.

During pre-budget scrutiny, committees may wish to consider the implications arising from high inflation for their respective portfolio budgets.

Overall net tax position

The net tax position is the amount by which the forecast revenues being raised from tax is higher or lower than the amount being removed from the Budget by the block grant adjustment, or BGA. The BGA is the amount that is deducted from the block grant by the UK Government now that certain taxes are devolved to the Scottish Parliament. It represents the income that the UK Budget has foregone by devolving tax powers to the Scottish Parliament.

A positive net tax position means that the Scottish budget is better off than it would have been without tax devolution, and a negative net tax position means the budget is worse off than it would have been without tax devolution.

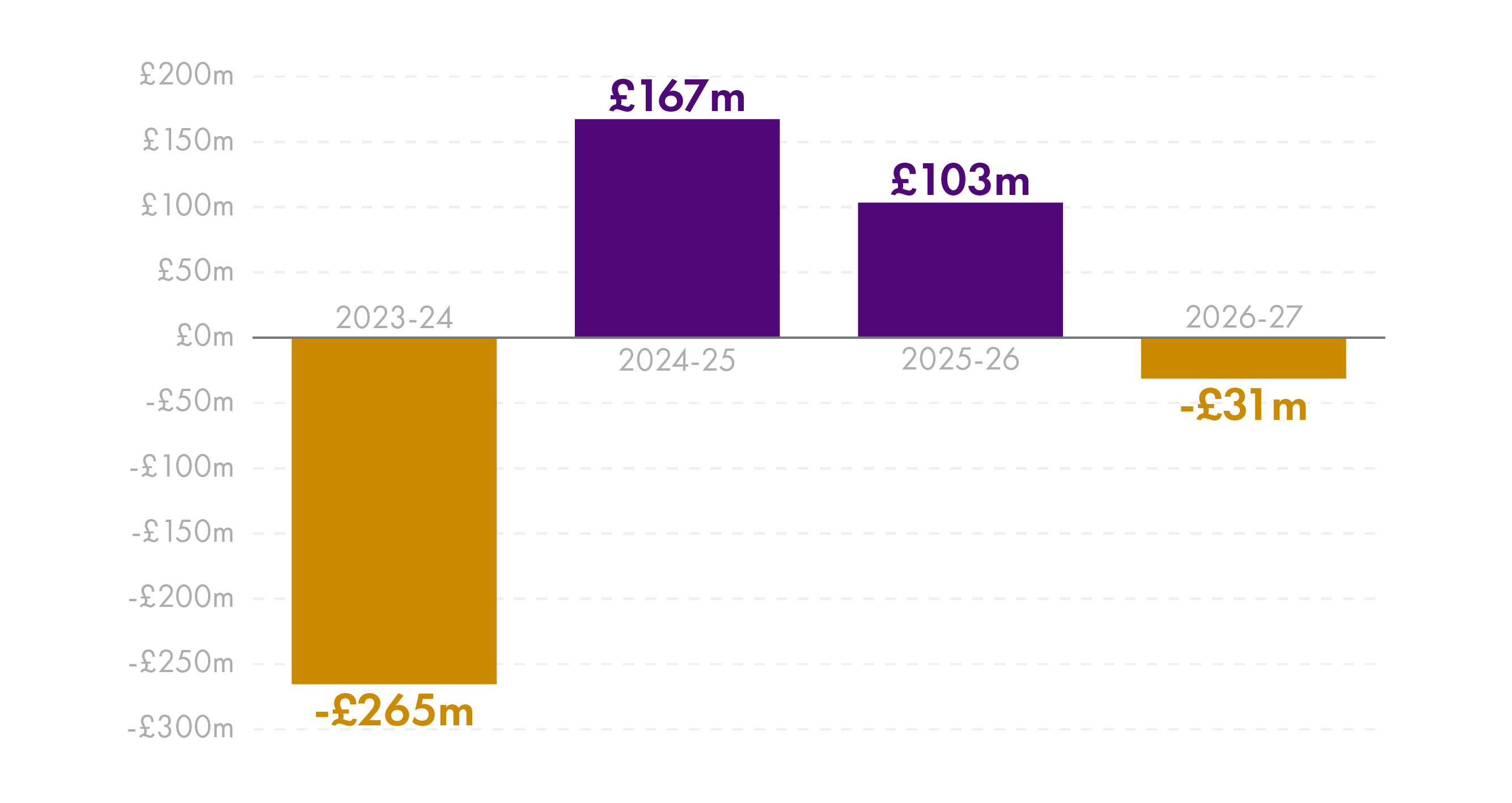

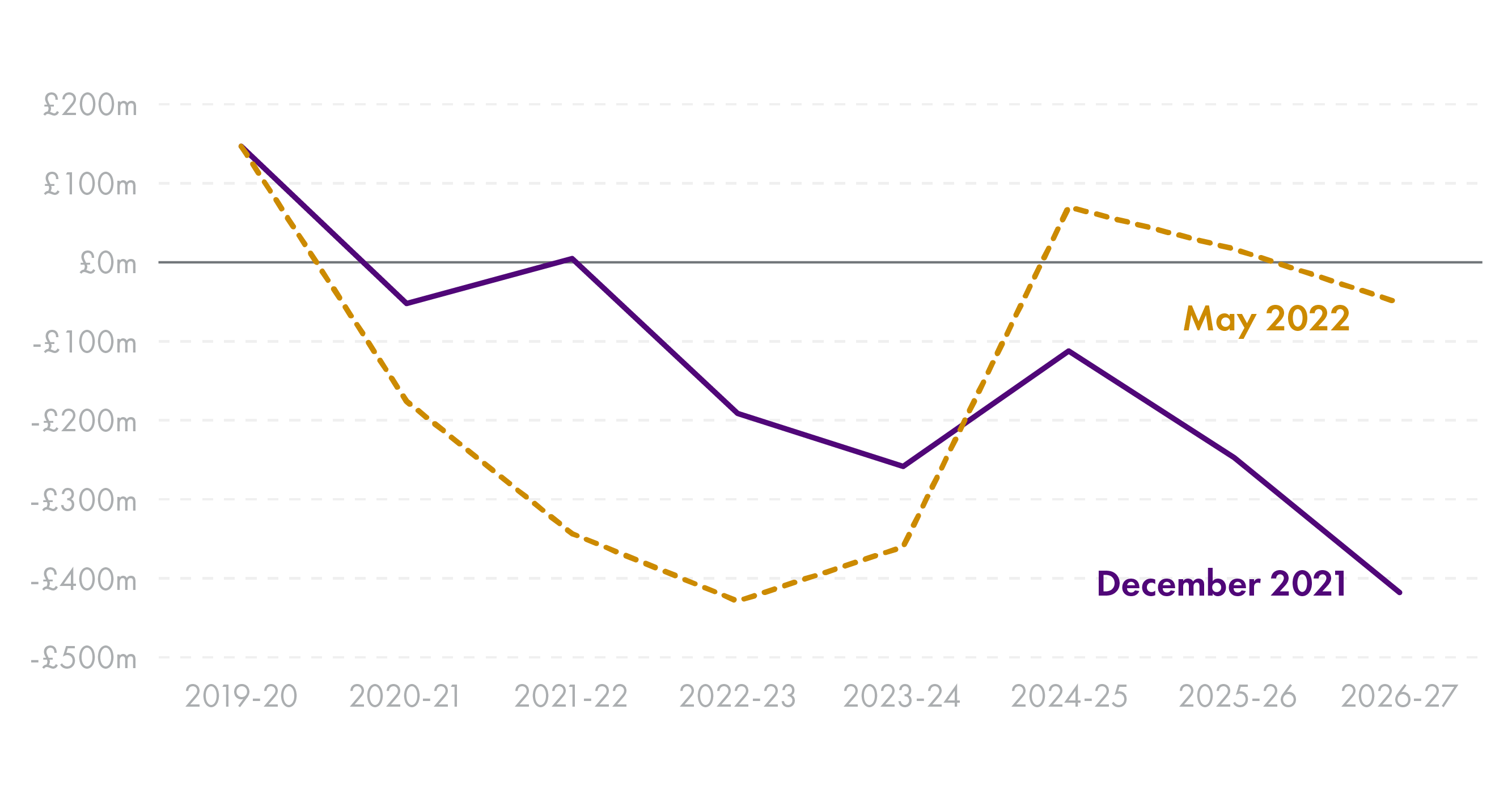

The following figure shows the latest implied overall net tax position for all devolved taxes based on the most recent OBR and SFC forecasts. As can be seen, latest forecasts point to the net tax position being -£265 million next before turning positive in 2024-25 and 2025-26. Although the net position for LBTT and SLfT is mostly positive throughout the forecast period, the larger negative income tax net position brings the overall position down – the net income tax position is discussed in the next section.

Income tax net position worsening

The other main story from the SFC forecasts is the latest implied “net tax position” for income tax.

The following figure shows that the net tax position has worsened since the last SFC forecasts in December 2021, driven by strong UK data in 2020-21 and 2021-22 and accompanying BGA revisions. The effect of that is to move the net position in a negative direction from 2020-21 to 2023-24.

In the current year (2022-23), the income tax net position is expected to be -£428 million based on the latest set of SFC and OBR forecasts. This means that the Scottish budget will be £428 million worse off that it would have been without income tax devolution, despite Scots paying in aggregate around £500 million more in income tax than they would under the income tax policy of the rest of the UK.

The income tax net position moves in a positive direction from 2023-24 onwards due to two new factors coming through in this set of forecasts.

The first is the assumption now made by the SFC in their forecasts that the Scottish Government will keep the higher rate threshold in Scotland frozen, which has the effect of bringing more taxpayers into the higher rate band and increases revenues – previous forecasts had assumed the higher rate band threshold would rise in line with inflation. It is important to note, however, that the freezing of the higher rate income tax threshold is not a confirmed policy. The Cabinet Secretary made clear that tax policies will be made on a budget-by-budget basis. The UK government also intends to freeze the higher rate threshold until 2025-26.

The second factor relates to a UK Government policy to cut the basic rate of income tax to 19p which reduces the size of the income tax BGA, shifting the net position in a positive direction. It will be interesting to see whether the Scottish Government opts to replicate this basic rate income tax policy in Scotland, or decides to “bank” the additional monies for public spending.

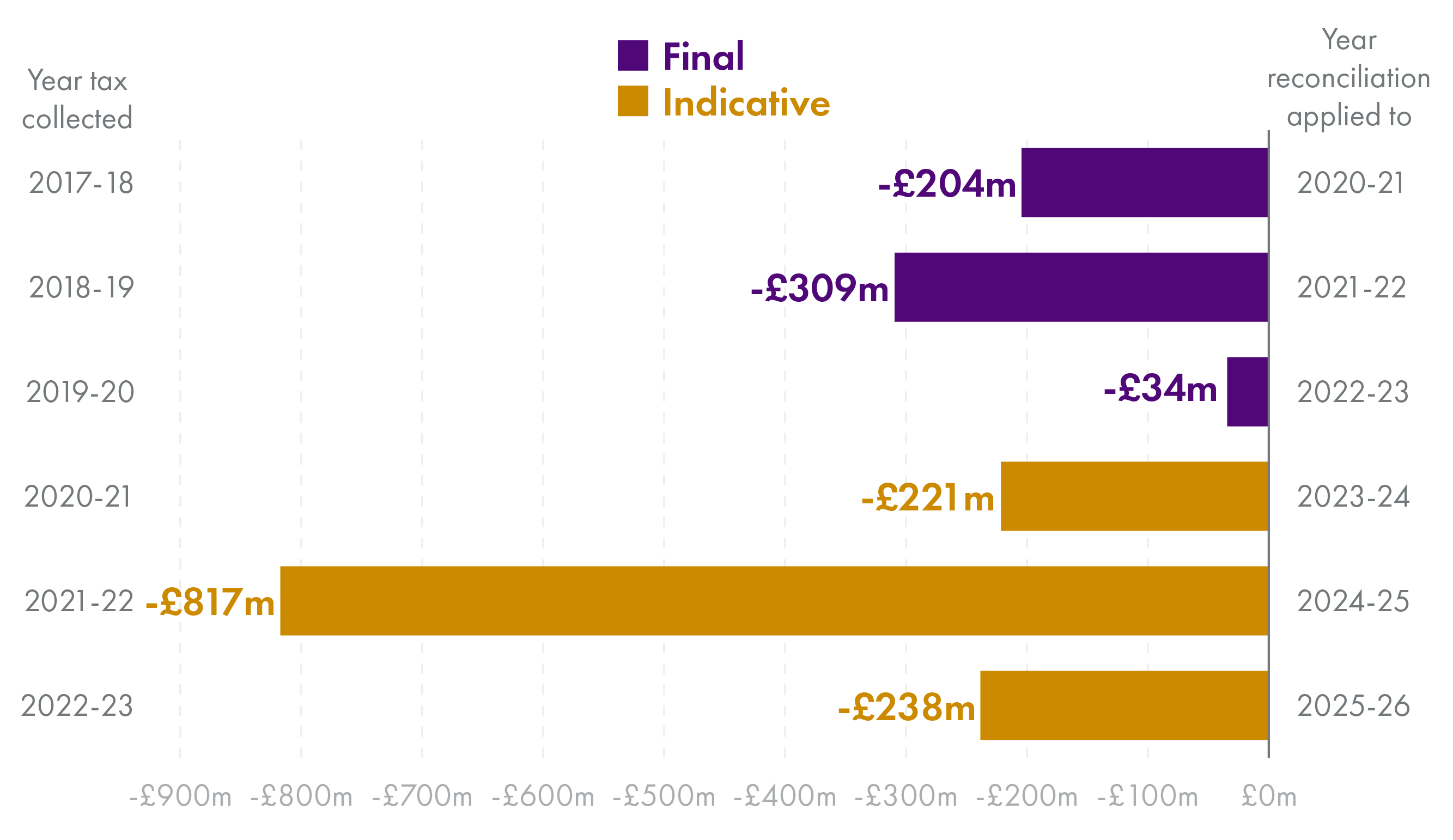

Large income tax reconciliations ahead

When the budget is set, funding from income tax for the financial year is based on forecasts and is fixed for the year ahead. It is only when income tax is collected and counted – the so called “outturn” information – that we know how accurate the forecasts made at the time the budget actually were.

When outturn data becomes available for income tax receipts, there is then a need for a “reconciliation” to be applied to the BGA (based on OBR forecasts) and the Scottish tax forecasts (based on SFC estimates) to account for this forecast error.

As can be seen in the following figure, income tax reconciliations have been negative since current income tax powers were devolved in 2017-18, and are expected to continue to be negative in future years.

The fiscal framework provides for Scottish Government borrowing powers of up to £300 million to smooth these forecast errors. This £300 million limit is clearly dwarfed by the £817 million income tax reconciliation forecasts are currently pointing at for 2021-22 outturn, to be applied to the 2024-25 Budget. If this negative reconciliation comes to light, there will be a significant pressure added to the Scottish Budget two years from now.

During pre-budget deliberations, committees may wish to question the Scottish Government over how it intends to deal with these potentially large negative reconciliations in upcoming budgets.

The Finance and Public Administration Committee will be interested in seeing how the Fiscal Framework review negotiations deal with the issue of borrowing limits for forecast error. For example, the £300 million borrowing limit agreed in 2016 has not been increased in line with any measure of inflation, and is likely to be significantly short of the reconciliation required in the 2024-25 Scottish budget.

Classification of Functions of Government (COFOG)

In possibly a more technical and niche section of its report the SFC report states:

Normally, our commentary on Scottish Government spending covers only social security as we are responsible for producing the forecasts the Scottish Government uses. However, in 2023 we will be publishing a Fiscal Sustainability Report which will project spending in all devolved areas. Currently the Scottish Government’s Budget documents focus on spending by portfolio area. However, portfolios change over time to reflect different ministerial responsibilities. This makes tracking spending over time difficult.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) developed the Classification of Functions of Government (COFOG). It is used to reflect spending in a consistent way by identifying spending under set definitions. We would like the Scottish Government to publish its Budget later this year with information on how spending is split by COFOG as well as by portfolio.

This would provide a baseline level of spending for us to use in our Fiscal Sustainability Report, and provide a benchmark for comparisons of the Scottish Budget in future years.

This recommendation is certainly a welcome one from a parliamentary budget scrutiny point of view. If delivered it would allow parliamentary committees improved transparency in terms of budget information by area of government.

For example, it would allow for the consistent presentation of budgetary information by function of government (for example, Health, Education, Housing, Economy, Environment), which is not always possible from looking at portfolio information. This would provide a much clearer hook for subject committee budget scrutiny than is sometimes currently available, and would be consistent with recent efforts by the Scottish Government to improve budget transparency. It would also assist with comparisons over time when portfolio definitions are revised.

It will be interesting for subject committees and the wider Parliament to see whether the Scottish Government takes on this recommendation when it delivers its 2023-24 Budget later this year.

Economy

One of the four key Scottish Government priorities is to deliver a “stronger, fairer, and greener economy, which will prioritise investment in inclusive growth”. As covered elsewhere in this briefing, this must be achieved during a period of heightened economic uncertainty and in the context of significant inflation which erodes real spending power.

Labour and capital markets

Achieving these aims will require higher levels of investment by Scottish businesses, which must be sustained over the spending review period and beyond. The RSR notes that this investment can only be unlocked if businesses can draw on an increasingly skilled and dynamic labour market. Existing skills and labour shortages in the labour market must be addressed to boost productivity growth. The RSR notes that this is required not only to achieve the Scottish Government’s economic aims, but to sustain a sufficient tax base to protect public services.

The Scottish Government published the National Strategy for Economic Transformation in March 2022 which aims to boost productivity and to deliver a wellbeing economy. The strategy sets out five programmes of action:

Entrepreneurial People and Culture

New Market Opportunities

Productive Businesses and Regions

Skilled Workforce

A Fairer and More Equal Society.

The Scottish Government has pledged to publish delivery plans for each of the five programmes of action within six months of the publication of the strategy. Committee members may want to ask how the RSR supports the delivery of these plans once more detail is available.

Fair work

The RSR states that ensuring ”fair work” will be ‘central’ to improving labour market outcomes and supporting investment in skills and employability. The Government states that this is supported by a significant, real terms increase in funding for employability services from 2023-24 onwards, rising by £83 million over the period of the spending review. It also includes pledges to implement the next phase of the green jobs workforce academy.

Within the economy portfolio, the enterprise agencies face real terms cuts in resource funding under the RSR. Between 2022-23 and 2026-27, funding for the enterprise agencies (Scottish Enterprise, Highlands and Islands Enterprise, South of Scotland Enterprise, as well as Visit Scotland) declines by £42 million (19%) in real terms. Committee members may wish to explore how this increased collaboration is being embedded, and how achievable this is in a period of real terms cuts to agencies' resource budgets.

Committee Members might want to explore how this additional resource will be deployed, and what has informed the profile of spend with all the rises occurring in the later years of the spending review period.

Increased collaboration across national bodies

The National Strategy for Economic Transformation pledged to establish a ‘culture of delivery’ across the public, private and third sector, and the RSR builds on this theme noting that:

To deliver on our future plans in a greener and fairer way will require action and investment from all parts of government, but government cannot and should not do everything on its own. As part of the spending review, we have completed a significant amount of internal and external engagement. Going forward, active collaboration and partnership with national and regional partners across the private, public and third sectors will be crucial for realising Scotland’s ambitions to become a Wellbeing Economy.

Previous Scottish Government strategies have sought to better align the skills and enterprise agencies, but this enhanced collaboration has proven difficult to achieve. Members may wish to explore what the Scottish Government is doing differently to achieve greater collaboration, particularly in the context of the enterprise agencies who face a challenging resource settlement.

Capital investment

Context

Alongside the Resource Spending Review, the Scottish Government published “The Outcome of the Targeted Review of the Scottish Government’s Capital Spending Review”1. The Scottish Government had previously published a Capital Spending Review in February 2021 alongside its latest Infrastructure Investment Plan.

The Scottish Government identified three developments since February 2021 that, it says, made it appropriate to review its capital plans:

A lower than expected capital settlement from the UK Government’s Autumn 2021 Spending Review. In the absence of confirmed capital budgets for 2022-23 to 2024-25, the February 2021 Capital Spending Review had been based on estimated future budgets. However, the actual capital plans for Scotland set out in the UK government’s Autumn 2021 Spending Review were £752 million lower over the three-year period than had been modelled.

The establishment of a new Scottish Government following the May 2021 elections. The new government includes a Cooperation Agreement between the Scottish Government and the Scottish Green Party with an increased focus on measures to tackle climate change, and this has influenced priorities for capital investment.

The impacts of high inflation, supply chain pressures and business disruption resulting from a combination of the impact of the UK’s exit from the European Union, the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

In the introduction to the capital spending review, the Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Economy notes that:

Without a significant change in the position of the UK Government to release additional capital or to agree an increase in the Scottish Government’s borrowing capacity, alongside other UK Government actions such as the reduction or removal of VAT on energy and construction costs, it will not be possible to meet all of our commitments within the funding available.

The review of the capital spending plans was also undertaken in the light of the key themes of the Resource Spending Review, namely reducing child poverty, addressing the climate crisis, building a strong and resilient economy and helping public services recover from the pandemic.

Revised capital spending plans

Overall, for the three-year period 2023-24 to 2025-26, planned capital investment is now £0.4 billion lower, at £20.5 billion, compared with £20.9 billion in the earlier plans set out in February 2021. The chart below shows how the various elements of capital investment have changed within this total.

The UK government’s capital budget allocation has fallen by £721 million over this period, although this is offset by an increase of £762 million in Financial Transactions (FTs) money compared with what had previously been expected. So, the net effect of UK government decisions is positive, although there is less flexibility in how FT money can be used (see Financial Transactions section). There is less reliance on revenue financed investment in these new plans, compared with earlier plans (see Revenue Financing section).

The capital spending review update sets out areas in which there will be increased investment over the spending review period, but there is no direct comparison with previous plans, making it difficult to determine how plans have changed. The update also notes:

The challenging external market conditions of inflation and supply chain impacts described above are already causing delays and placing pressure on budgets associated with certain projects. Reflecting this, as well as the challenging fiscal position, within this targeted review of the 2021 Capital Spending Review, there are a number of areas where the funding profile has had to be slowed down - such as road improvement programmes. It is now unlikely that the Capital Spending Review’s ambition to double the level of spending on maintenance of infrastructure will be reached. These are not choices that the Government has taken lightly and it will ensure that the maintenance of our assets will still be prioritised where possible.

And goes on to state:

The Scottish Government remains committed to the projects and programmes set out in the Capital Spending Review and Infrastructure Investment Plan where business cases continue to demonstrate value for money. For a small number of major projects and programmes which span this and future spending review periods, due to the uncertainty about long term pricing and market conditions, funding is not able to be confirmed in full at this time. The Scottish Government remains committed to investing in Scotland’s future and will regularly assess future funding and financing opportunities to deliver the right strategic assets in the right places.

It is unclear from the published documents which specific projects have been affected, or are likely to be affected in the future. The Scottish Government's latest six monthly Major Capital Projects Update was published on 16 June 2022 and will be considered by the Parliament’s Public Audit Committee. However, this does not provide details of how the revised plans will affect individual projects. As portfolio definitions have changed since the original capital spending review was published, it is not possible to make direct comparisons between the original plans and the revised plans at portfolio level, or below portfolio level. However, where budget lines have remained the same, some limited comparisons can be drawn between the previous plans and the latest review:

There is higher planned investment in measures to tackle climate change, such as environmental services, climate change policy measures, fuel poverty/energy efficiency and public transport investment. Taken together, planned investment in these areas is set to increase by £440 million over the five year period 2021-22 to 2025-26.

By contrast, investment in motorways and trunk roads is set to decrease by just over £280 million over the same period, but as yet it is not clear which specific projects will be affected. Major planned road projects include the dualling of the A9, the A720 Sheriffhall Junction and the A83 access to Argyll and Bute.

Committees may want to explore how any major capital projects in their specific areas might have been affected by the reduction in planned capital expenditure over the next four years and also how the change in the mix of planned financing might affect individual projects. This is explored further below.

Financial Transactions

FTs for the three-year period are now £762 million, whereas the Scottish Government had previously not planned on any FT money for that period. There is, however, less flexibility in how FT funding can be used. The Scottish Government can only use FTs to support equity or loan schemes beyond the public sector. This means that FTs cannot directly support public infrastructure projects, such as transport projects. However, they can be used where investment is led by private or third sector bodies.

The capital spending review update states:

Whilst Financial Transactions are not interchangeable with capital grant and there are limitations on their use, they can be used to continue the capitalisation of the Scottish National Investment Bank and provide further funding for the enterprise agencies and key Government activities such as the North East and Moray Just Transition Fund and the Heat in Buildings strategy, where there is an interaction with the private sector or a role for loans or equity support. Financial Transactions are a useful tool for being able to support businesses and investment in the private sector however the uncertainty and volatility of their funding presents a challenge for managing these programmes and providing certainty and a pipeline. Current market conditions may also impact on the appetite to take on additional debt through Financial Transactions loans.

The availability of new FT money that had not previously been anticipated opens up opportunities for investment in areas that can make use of this type of funding. Committees may want to explore how the availability of FT funding affects planned investment in their specific areas. FTs have previously been used in areas such as:

Capitalisation of the Scottish National Investment Bank

Equity investment and loans to businesses via the enterprise agencies

Loans to households e.g. for energy efficiency schemes

Housing equity schemes.

FT monies must ultimately be repaid to HM Treasury.

Revenue financing

The revised capital investment plans involve a reduction in planned use of revenue financing. Although the Capital Spending Review Update does not make reference to specific amounts, details are set out in the separate Medium Term Financial Strategy (MTFS). In its February 2021 plans, the Scottish Government set out the intention to fund £2.8 billion of capital investment through revenue financing over the period 2023-24 to 2025-26. The Medium Term Financial Strategy shows that the current plans involve a lower reliance on revenue financing of £1.8 billion over this period.

Revenue financing involves the private sector funding capital projects upfront and the public sector paying for the investment once the project is complete through annual repayments. Earlier revenue finance schemes include the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) and the Scottish Government’s Non-Profit Distributing (NPD) model. The Scottish Government had previously set out plans to introduce a revised revenue finance model known as the Mutual Investment Model (MIM).

There is no mention of the MIM in the revised capital spending plans. The Medium Term Financial Strategy (MTFS) published alongside the Resource Spending Review says:

Although there has been a decrease in the forecast deployment of revenue finance over the CSR period, the updated Capital Borrowing policy and the increased deployment of Financial Transactions, at a lower servicing cost than Revenue Finance, ensure the Scottish Government is still on target to successfully deliver against the National Infrastructure Mission.

The Scottish Futures Trust (SFT) had indicated in its initial options appraisal of the MIM that borrowing would always be preferable to revenue financing for funding investment due to the lower costs involved. The use of the MIM for funding the remaining stages of the A9 dualling project had previously been identified as a possibility by the Scottish Government, so it is unclear how this project might be affected by the apparent scaling back of plans for revenue-financed investment.

Committees may want to explore how the scaling back of plans for revenue-financed investment affects projects in their areas.

Capital borrowing

Within the terms of the Fiscal Framework, the Scottish Government is allowed to borrow a maximum of £450 million per year for capital investment, up to a cumulative total of £3 billion. The Scottish Government had previously set out plans to borrow between £250 million and £450 million per year.

The MTFS sets out a revised capital borrowing policy:

We are…amending the policy to assume £450 million of annual funding will be available through borrowing, the Scotland Reserve and Barnett consequentials of which £250 million will initially be assumed to be capital borrowing.

In the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s May 2022 Economic and Fiscal Forecasts, the SFC notes that:

The new borrowing approach will allow the Scottish Government to continue to borrow at a more consistent level for a longer period. Our analysis suggest that borrowing £250 million annually and repaying over 15 years would reach the limit of the cap by 2040-41, nearly 15 years later than the previous plans.

The SFC considered this to represent a more sustainable approach than the previous borrowing plans, but noted the risk that, if other sources, such as the Reserve or Barnett consequentials do not provide as much as anticipated, borrowing would have to increase in order to meet the plans. This would make the policy less sustainable.

Committees may wish to explore how capital investment plans in their areas might be affected by the change in the borrowing policy.

The 5% cap on repayment commitments

The Scottish Government has, for some years now, committed to spending no more than 5% of its total Departmental Expenditure Limit (DEL) budget on repayments arising from revenue financing and borrowing. This is a self-imposed fiscal rule. In 2019-20, this rule was tightened so that repayments cannot exceed 5% of the resource budget (excluding social security) from 2019-20.

The MTFS published alongside the Resource Spending Review re-states this rule:

The Scottish Government is committed to sustainable deployment of revenue financed investment and capital borrowing to ensure there is no undue financial burden on future policy choices. That is why the Scottish Government has a self-imposed revenue finance investment limit of 5% of the Scottish Government resource budget excluding social security. The latest modelling suggests that over the remaining capital spending review period these costs peak in 2025-26 with planned and committed projects and borrowing costs estimated to be 2.61% of the resource budget excluding social security.

Public sector

The need for reform

The Resource Spending Review outlined the Scottish Government’s intention to instigate reforms to Scottish public services:

the Scottish Government will use this spending review as a springboard to begin a new and purposeful phase of engagement with delivery partners and public sector bodies, trade unions, public sector employees and service users to help Scotland navigate the challenge of a post-COVID-19 pandemic reset.

The devolved public sector in Scotland employs more than half a million individuals and currently accounts for one in five of those in employment in Scotland. There are 129 public bodies in Scotland, but the Resource Spending Review noted that “shrinking fiscal resources together with our commitment to environmental and fiscal sustainability mean that reform is inevitable”. The Review goes on to state that: “We expect all public bodies to demonstrate that they remain fit for purpose against the present and future needs of Scotland’s people, places and communities.”

The Scottish Government intends to set out proposals for the future public body landscape alongside the 2023-24 Scottish Budget, which would be expected to be published in late 2022. Committees may want to explore how the Scottish Government would expect public bodies to demonstrate that they are “fit for purpose” and how such a review might affect public bodies within their areas.

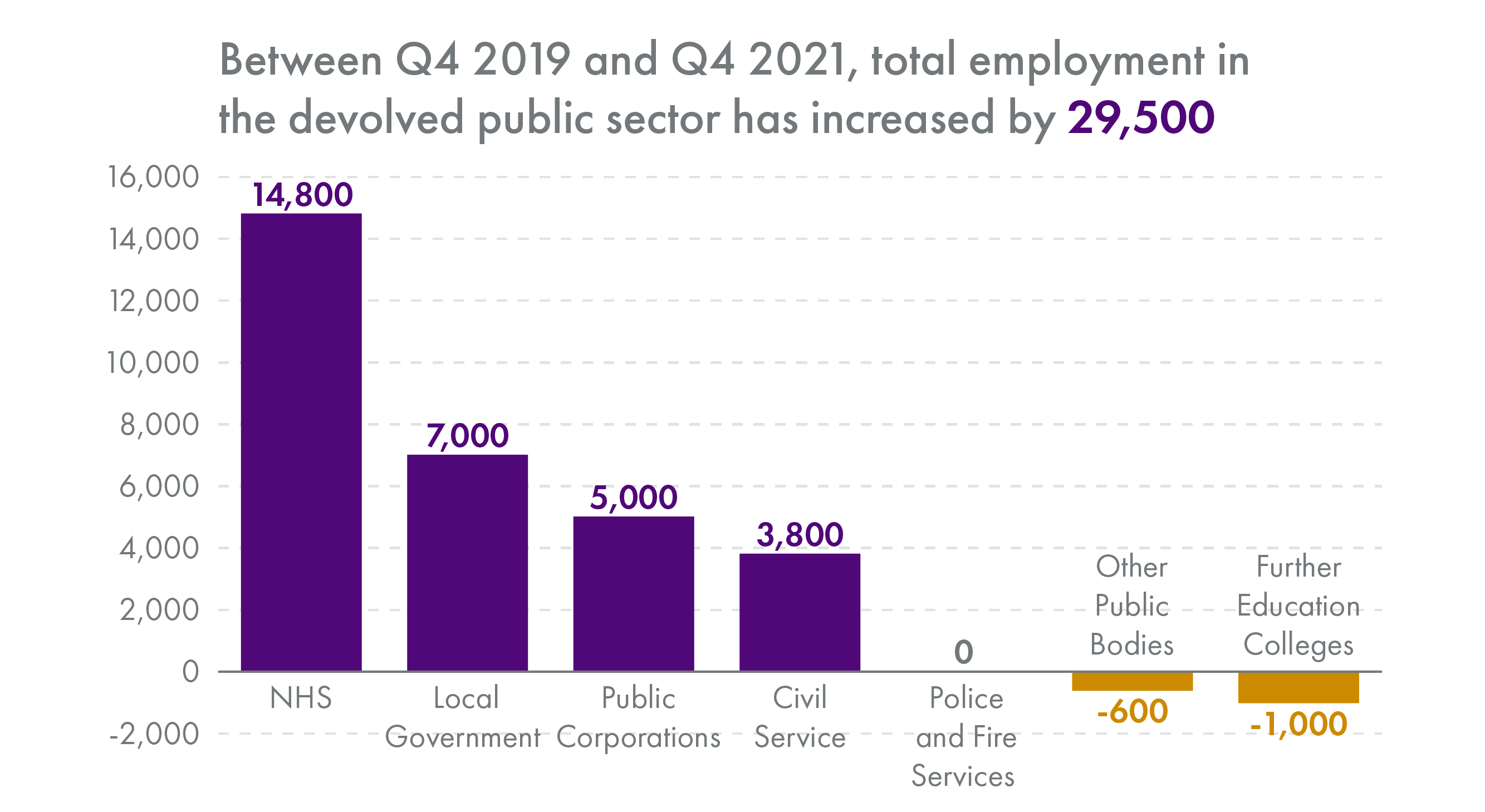

The scale of the devolved public sector

Employment in the devolved public sector has grown over the last three years. While the Resource Spending Review notes that some of this will reflect new functions taken on by the Scottish Government in respect of tax and social security, the document also notes that “continued growth of the public sector away from frontline services is not sustainable”. The Review document refers to the public sector “returning to a pre-pandemic size”. As can be seen in the chart below, over the two years since the end of 2019 (just before the onset of the pandemic), employment in the devolved public sector has grown by almost 30,000.

However, around half of this growth has been in the NHS and the Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Economy has stated that she would not expect to see any reductions in the NHS workforce. Giving evidence to the Finance and Public Administration Committee on 7 June, she said:

It is unlikely that we will see [a headcount reduction of 14,000] in the NHS. I have intentionally set out a flexible approach because we know that some parts of the public sector have grown and probably will need to grow further. For example, the national care service will need to be able to employ people and expand in some areas flexibly.

Rather than setting plans for specific reductions in staff numbers, she stated that the Scottish Government will instead aim to freeze the public sector pay bill. She added:

That does not equate to a freeze in pay levels; we want to work with employers and trade unions during the next few months in advance of the budget to understand how we can manage workforce numbers in a flexible way that will allow some parts of the public sector, such as the health service, to continue to grow where it needs to grow, and other areas to decrease their staff figures when they do not need those post-Brexit, post-pandemic levels of staffing.

The Resource Spending Review also signalled the intent to instigate pilots in parts of the public sector of the four day working week proposal that had been set out in the Programme for Government.

Public sector pay

The Resource Spending Review sets out the Scottish Government’s intention to freeze the public sector paybill at current levels. This is currently stands at over £22 billion per year.

The Scottish Government sets out its Public Sector Pay Policy alongside its budget each year. The pay policy does not apply directly to all public sector staff. It only affects the pay of Scottish Government staff, and the staff of agencies, non-departmental public bodies (NDPBs) and public corporations, which together account for around 10% of the devolved Scottish public sector workforce (around 42,000 full-time equivalent staff). Large parts of the public sector, such as local government and the NHS, are not directly covered by the Scottish Government’s pay policy and pay is determined separately for these groups, although often in line with the Scottish Government's pay policy and - in some cases - with some Ministerial control.

Keeping the public sector paybill at its current level while still allowing for pay increases will only be achieved alongside reductions in staffing levels.

The Review document also notes:

Public sector pay in Scotland is around 7 per cent higher than in the rest of the UK due to the increases we have provided over the last few years.

The Scottish Government has, for example, provided for more generous pay settlements for NHS staff when compared with England and recently agreed a 5% pay increase for NHS staff for 2022-23. The Resource Spending Review states that the Scottish Government remains committed to its Fair Work principles, including payment of the Real Living Wage and supporting the lowest paid.

Committees may wish to explore how public sector employment has changed in its particular areas and where pay pressures might present particular challenges in respect of managing the overall paybill.

Public sector efficiencies

The Resource Spending Review also states the Scottish Government’s intention to seek efficiency savings across the public sector. In line with previous requirements for efficiency savings, the Resource Spending Review states that recurring annual efficiencies of at least 3 per cent will be required from public bodies. To achieve this, the document sets out plans to seek efficiencies through:

further use of shared services

management of the public sector estate (which includes around 30,000 properties)

effective procurement (with current levels of procurement spending at £13.3 billion, or around a quarter of the Scottish budget)

management of public sector grants.

Local government

As noted by COSLA and others, the single-year nature of recent annual budgets has been problematic for local authorities as it makes longer-term planning very difficult. Councils - and their partners in the third sector - seek the certainty multi-year allocations can provide. In October 2021, the Parliament’s Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee was in agreement and called on the Scottish Government to provide multi-year funding plans.

Core funding “protected” in cash terms

The Spending Review provides multi-year “resource spending envelopes” up to 2026-27. The document talks about protecting local government budgets in “cash terms” by guaranteeing resource budgets at existing levels to 2025-26 (with a £100 million increase in 2026-27). However, accounting for the possible impact of inflation, council resource allocations could see a 7% reduction in “real terms” over the 5-year period.

| 2022-23 (£m) | 2023-24 (£m) | 2024-25 (£m) | 2025-26 (£m) | 2026-27 (£m) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Government (cash) | 10,616 | 10,616 | 10,616 | 10,616 | 10,716 |

| Local Government (“real terms”) | 10,616 | 10,366 | 10,177 | 9,982 | 9,879 |

The above table shows that the local government settlement could see a real terms reduction of £737 million over the Spending Review period (-7%).

Compared to the 2013-14 Draft Budget - the earliest comparable budget figures - “core” resource budget for local government could see a 13% real terms reduction by 2026-27. The following table puts Draft Budget figures for 2013-14 and Spending Review 2026-27 into 2020-21 prices using Treasury deflators:

| 2013-14 (£m) | 2026-27 (£m) | Difference (£m) | Difference (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core LG resource budget (“cash”) | 9,392 | 10,716 | +1,324 | +14% |

| Core LG resource budget (“real”) | 10,978 | 9,592 | -1,386 | -13% |

The £10,616 million local government figure used in the Spending Review is the combination of the General Resource Grant, guaranteed non-domestic rate income and specific revenue grant figures (as set out in the SG’s 2022-23 Budget) plus an additional £120 million announced at Stage 1 of this year’s Budget process. The total figure is what the Scottish Government and COSLA both refer to as “core” resource budget.

COSLA voiced their disappointment at the real terms cut to the resource allocation, arguing that the Spending Review:

shows no prospect of an increase to Local Government’s core funding for the next 3 years, which is especially concerning in the current context of soaring inflation and energy costs. This “flat-cash” scenario gives extremely limited scope for recognising the essential work of our staff, whose expectations around pay continue to be, quite rightly, influenced by Scottish Government’s decisions in relation to other parts of public sector. Put simply, the plans as they stand will mean fewer jobs and cuts to services. COSLA is seeking an urgent meeting with the First Minister and Cabinet Secretary for Finance to discuss this further.

The Scottish Government responded by reiterating its view that pay negotiations are a matter for council workers (represented by their unions) and local authority employers (represented by COSLA). Unions including the GMB and Unison are currently balloting their local government members for strike action over pay.

Resource funding to local government transferred from other portfolios

As noted in the SPICe briefing published earlier this year, a growing proportion of local government’s total resource funding is comprised of in-year transfers from other portfolios. These are not included in the “core” resource calculations discussed above. On this, the recent Spending Review document states

To support councils to plan for the future, the spending review confirms that existing transfers for Health and Social Care, Early Learning and Childcare and additional teachers worth £1 billion will also be maintained. Final decisions about the annual local government settlement including: additional funding to reflect the devolution of Empty Property Relief to councils on 1 April 2023; confirmation of any in-year transfers from other portfolios 28 which were worth £345 million in 2022-23; and individual council allocations will be taken as normal through the annual Scottish Budget process.

In response to questions on her Spending Review statement, the Cabinet Secretary for Finance and the Economy confirmed that the spending review “will go hand-in-hand” with a new fiscal framework for local government. Such a framework, to be agreed between the Scottish Government and local government, has been in development for quite some time (see update from 2019). However, the Spending Review document mentions “a new deal for Local Government in Scotland in advance of the next financial year”, so progress appears to have been made.

Local government allocations and the National Care Service

The Spending Review also confirms that over the review period there will be “significant changes to functions currently delivered in full or in part by local authorities”. This will be most evident in the area of social care with the planned creation of a new National Care Service (NCS). The Spending Review does not estimate how much funding currently going to local authorities could be impacted by the creation of the NCS; instead details are features in the NCS Bill accompanying documents. However, it is worth noting that Scottish local authorities spent £3,528 million on social work and social care in 2020-21, 32% of total local government net revenue expenditure (see Scottish Local Government Finance Statistics, 2020-21).

A New Deal for Local Government

The Spending Review confirms the Scottish Government’s commitment to work closely with COSLA and SOLACE over the coming months “to agree a new deal for Local Government in Scotland in advance of the next financial year”. This will be in the context of “re-setting” and “strengthening” the partnerships between the Scottish Government and local government. Amongst other things, the Spending Review highlights the Government’s intentions to:

Develop a deeper dialogue on how Scottish and Local Government will work together to achieve better outcomes for people and communities.

Seek to balance greater flexibility over financial arrangements for local government with increased accountability for the delivery of national priorities.

Explore greater scope for discretionary revenue-raising, such as the Visitor Levy and the newly created Workplace Parking Levy.

A review of local governance has been taking place for a number of years now, with proceedings seemingly delayed by elections and the pandemic. The wording of the Spending Review document would suggest that meaningful progress has been made over recent months, and more information on the new, re-set relationship between local government and the Scottish Government could be available soon

Net Zero, Energy and Transport

The Net Zero, Energy and Transport area of the Scottish budget is responsible for achieving the progress towards a net zero economy in line with the Scottish Government’s Climate Change Plan, and the portfolio includes climate change policy, heat and energy, transport, environment, forestry and land reform. Spend in the portfolio is expected to grow by 18% in real terms over the spending review period, but this growth is not uniform. Total spending is flat in real terms to 2024-25, but then increases rapidly in the later years.

The spending review highlights the importance of capital funding to achieving the transition, noting that:

The investment required to address the climate crisis is weighted towards capital funding (including financial transactions). The targeted review of capital spending carried out alongside this Resource Spending Review supports critical low carbon capital spending, with an increase of over half a billion pounds directed towards net zero programmes to address the climate crisis over the next three years.

Resource spending on delivering the Heat in Buildings strategy, which sets out the actions the Scottish Government is taking to decarbonise the heating of buildings, will rise to £75 million in cash terms over the spending review period, and £4 million in resource spending for delivery of the ten year £500 million Just Transition Fund to support the North East of Scotland and Moray in the transition away from carbon intensive industry to a net zero economy, for which the Scottish Government have recently issued a call for year one projects. £95 million will be available to support the Scottish Government’s target of 18,000 acres of woodland creation by 2024-25.

The Scottish Government also notes that public investment alone will not be enough to achieve these targets:

To harness this investment effectively and maximise the impact of collective action to address the climate crisis, activity to move from a “funding to financing” policy model will be scaled up to ensure that future climate change policy leverages private sector investment and action, better amplifying the impact of public investment.

The spending increase in the later years of the spending review period is largely driven by a near tenfold increase in annual spend on the ‘climate change and land managers renewables fund’, rising from £29 million in 2022-23 to £220 million in 2026-27. The Scottish Government note that the significant increase to the this fund is to:

support delivery of future climate change policies to meet statutory climate change targets and commitments.

Following the Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee’s session with the Cabinet Secretary on the Scottish Budget on 1 February 2022, the Cabinet Secretary provided more information on the proposed spending profile of the Heat in Buildings strategy to 2026. This response provided a breakdown of how the £1.8 billion will be allocated; £465 million is earmarked for those least able to pay and a further £400 million is for large scale heat networks for example, but this did not provide any indication as to the expecting timing of the expenditure.

In response to a written question, the Minister for Zero Carbon Buildings, Active Travel and Tenants’ Rights noted that:

Reaching our emissions targets requires a significant acceleration in installation of zero emissions heat technologies in homes and installation of connections to heat networks, recognising the time needed for supply chains to grow. As set out in the 2021-22 Programme for Government, domestic installations must scale up such that the total number of installations between 2021 and 2026 is at least 124,000. The Heat in Buildings Strategy sets out that installation rates will need to peak at over 200,000 per year in the latter part of this decade.

Committees may wish to explore this in further detail to understand what is driving the increase in spending in the outer years of the spending review period, and what assumptions underpin this (for example, how much the available skills and capacity in business are reflected in the anticipated spending profile).

The spending review also anticipates a shift in the priorities among transport budgets. The budget for air services declines by 16% in real terms, the budget for Motorway and trunk roads declines by 5% and the budget for rail services declines by 6% over the spending review period – in total the spending review projects a £47 million decline in spend across these three budget lines. Conversely, spending on Active travel, low carbon and other transport rises by £32 million (47%) in real terms, while spending on ferry services is up by £6 million (3%) in real terms. The biggest shift in transport resource spending is in the ‘concessionary fares and bus services line’, which increases by £88 million in real terms over the spending review period (24%). The spending review notes that this shift in resource spending, along with the accompanying £150 million capital investment in active travel, is to support the Scottish Government commitment to cut car kilometres by 20 per cent by 2030.

Committees may wish to explore how this increased resource spending on active travel will deliver the anticipated reduction in car use, and explore how the reduction in rail resource spending will be achieved.

National Outcomes

Much of the language in the RSR appears to be focused around “outcomes” – chapter 2 is headed “Delivering Strategic Outcomes for Scotland” and chapter 3 “Improving outcomes.” However, there are only a few mentions of the National Performance Framework and the National Outcomes. Some of the language of the high-level national outcomes is used, for example “we will invest public funding to build a Scotland where communities are fairer, inclusive and empowered, and people grow up loved and respected, well-educated, and healthy.

But, there does not appear to be any analysis of the impact of the spending plans in the RSR on the delivery of the different national outcomes and the outcomes in totality, or of how the data in the NPF has informed these spending plans.

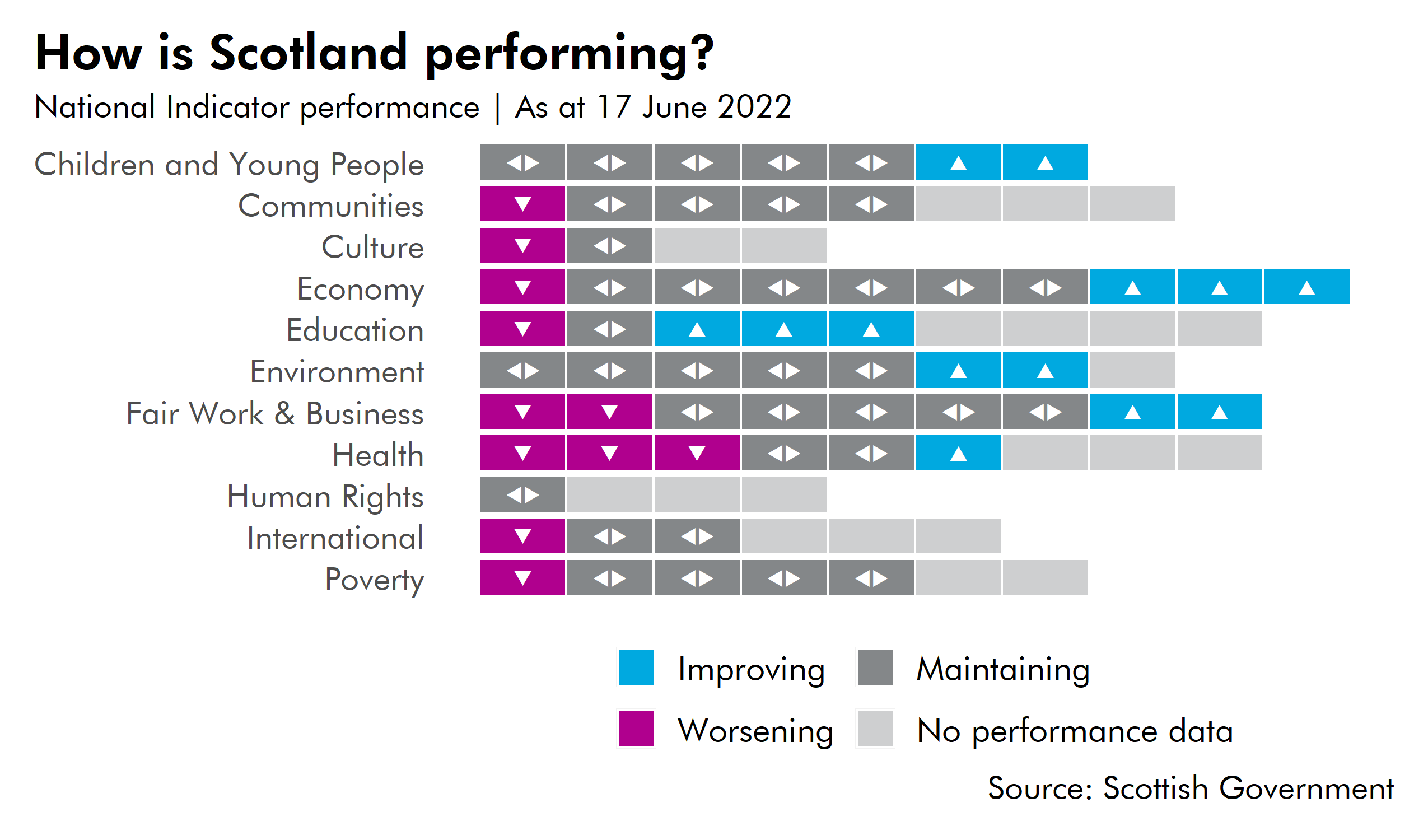

There are currently a range of issues with collection of data in the NPF indicator set, some due to issues with survey collection during COVID-19. However, some indicators are still to be developed since the last refresh of the framework in 2018. These are explored in a monthly blog post on SPICe Spotlight, which also provides a performance snapshot. The most recent performance snapshot, as of 17 June 2022 shows:

In most cases (36) performance is maintaining, whilst improvement is seen for 13 Indicators, and for 11 Indicators the position is worsening.

Current gaps in data are notable in Education (no performance data for 4 out of 9 Indicators), Human rights (no performance data for 3 out of 4 indicators), Communities (no data for 3 out of 8 indicators) and for International (only 3 out of 6 Indicators are currently measuring performance).

Use of outcome data was seen by the Budget Process Review Group as an area that could be the source of rich scrutiny by parliamentary committees. To assist with this, SPICe published a detailed briefing which set out practical suggestions for how committees could use the NPF to improve their budget scrutiny. It demonstrates how committees can:

use the NPF to help provide a focus to budget scrutiny

identify key questions relating to the different stages of the policy/spending process

link these key budget questions to the NPF's outcomes and indicators

use the NPF to improve the depth and scope of budget scrutiny.

In advance of the publication of the Resource Spending Review, and alongside the Scottish Government Budget 2022-23 and fourth Medium Term Financial Strategy, the Scottish Government published a consultative document, 'Investing in Scotland's Future: resource spending review framework'. The Scottish Parliament’s Finance and Public Administration Committee carried out its own brief inquiry, which highlights that:

A theme running through the Committee's pre- and budget scrutiny was the extent to which the national outcomes in the National Performance Framework influence policy-making and spending decisions. Indeed, in both reports, we have recommended that "the Scottish Government considers how the National Performance Framework could be more closely linked to budget planning". We are disappointed that this recommendation remains outstanding.

This echoes calls made in the Scottish Leaders’ Forum’s March 2022 report, Leadership, Collective Responsibility and Delivering the National Outcomes.

The Finance Committee is currently undertaking an inquiry on the 'National Performance Framework: Ambitions into Action'; which builds on these issues.

Equalities

Since 2009, the Scottish Government has included an Equality Budget Statement alongside annual budget documents. The aim of this statement is to highlight the equalities implications of spending decisions. This was renamed the Equality and Fairer Scotland Statement (EFSS) in 2018. As part of the development of the statement, the Scottish Government is supported by an Equality Budget Advisory Group (EBAG). The Equality, Budget, Advisory Group (EBAG) report on equalities and human rights budgeting, published in July 2021, recommended that the:

Scottish Government should produce a pre-budget statement, in-year reports and a mid-year review in line with international standards (with specific recommendations on the information and associated equalities analysis that should be in these reports).

To date, the Scottish Government’s Medium Term Financial Strategies (first published in May 2018, most recently in December 2021) have not included an Equality and Fairer Scotland Statement. Nor did the Capital Spending Review published in February 2021. The Equality and Fairer Scotland Statement featured alongside the Resource Spending Review is the first time such a statement has been presented alongside a longer-term strategic finance document published by the Scottish Government.

In the Resource Spending Review: Equality and Fairer Scotland Statement, the Scottish Government has accompanied its multi-year spending plans with an exploration into how upcoming challenges and opportunities will interact with its equality, fairness, and human rights agenda.

The Scottish Government explains in the document that:

This EFSS, and the ongoing gathering and use of relevant evidence, will provide a framework to support the development of specific Equality Impact Assessments and Fairer Scotland Duty Assessments. It also supports the consideration of human rights as we take forward impact assessments.

Key challenges and opportunities

The document sets out what the Government sees as the nine key challenges/opportunities, as detailed below:

Support an economic recovery which continues to progress action to tackle structural inequality in the labour market, including through good green jobs and fair work.

Ensure that the devolved taxation system is delivered in a way which is based on ability to pay and that the devolved social security funding increases the resources available to those who need it.

Ensure that inequalities in physical and mental health are tackled through the effective delivery of health and social care services as well as broader public health interventions.

Build digital services that are responsive to individuals and address inequality of access to digital participation.

Deliver greater progress towards meeting statutory child poverty targets.

Deliver greater progress towards closing the attainment gap.

Improve the availability and affordability of public transport services, to ensure those more reliant on public transport can better access it.

Ensure that policies, action and spend necessary to mitigate and adapt to the global impacts of climate change deliver a just transition for people in Scotland.

Better realise the right to an adequate home that is affordable, accessible, of good quality, and meets individual need whilst ensuring that progress on tackling current inequality of housing outcome is addressed.

These challenges/opportunities are set against relevant national outcomes and human rights, and equality outcomes where relevant. This is the same approach used in the Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement 2022-23.

Human Rights Budgeting and Equalities Budgeting

In its ‘Budget 2022-23: Pre-Budget Scrutiny’ letter, the Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice (EHRSJ) Committee highlighted that:

19. Scotland’s new human rights framework will have wide reaching implications for the delivery of Scotland’s public services. Unless budgets are set to ensure the resources are in place to deliver human rights, there will remain a gap between our aspirations and the actual delivery of human rights on the ground

20. However, it is also essential if there is to be a focus on human rights budgeting that there is not an unintended consequence of losing a focus on structural inequalities. Now may be the time for further progress on, for example, gender budgeting to be made (see below for further details).

21. Overall, the Committee agrees this is the start of a longer-term conversation and that further work should be undertaken on human rights budgeting. In addition, the Committee recognises the significant impact that spend on infrastructure such as social care, could have on gender and disability equality.

On Equalities Budgeting, the Committee concluded:

29. The Committee considers that the [Scottish Government’s] response to the detailed report from EBAG requires some urgent consideration, and requests an update on the Scottish Government’s thinking as part of the budget.

As part of its Budget scrutiny work this year, the EHRSJ committee will be receiving research from an academic research fellow on how human rights budgeting might apply to people with learning disabilities. Again, it will be interesting to see the extent to which the Committee, and indeed the EBAG, feel that the inclusion of an Equality and Fairer Scotland Statement alongside the Resource Spending Review can lead towards more tangible outcomes within equalities and human rights budgeting.