Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill

The aim of the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill is to improve the application process for legal gender recognition. It does this through provisions to amend the Gender Recognition Act 2004.

Summary

The aim of the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill is to improve the application process for legal gender recognition, which the Scottish Government says can have an adverse impact on applicants. The Bill’s provisions will amend the current gender recognition process under the Gender Recognition Act 2004 (GRA), and introduce a statutory declaration-based system.

The GRA provides a way for trans people, aged 18 or older, to apply for legal recognition in their acquired gender. The Gender Recognition Panel makes decisions on issuing gender recognition certificates (GRC). The Gender Recognition Panel must be satisfied that the applicant:

has provided medical evidence of gender dysphoria

has been living in their acquired gender for two years.

The applicant must make a statutory declaration that they intend to continue to live in their acquired gender for the rest of their life.

There is no requirement under the GRA for an applicant to undergo surgery or hormone therapy.

Once someone has been successful in changing their gender they will be issued with a GRC and, following this, a new birth certificate.

The Bill’s provisions will:

remove the requirement for an applicant to have, or have had gender dysphoria, and therefore removes the requirement for medical evidence to be provided

reduce the minimum age for application from 18 to 16

remove the Gender Recognition Panel from the process; instead applications will be made to the Registrar General for Scotland

reduce the period for which an applicant must have lived in their acquired gender before making an application from two years to three months

introduce a mandatory three month reflection period and a requirement for the applicant to confirm at the end of that period that they wish to proceed with the application before the application can be determined

introduce a new duty on the Registrar General for Scotland to report the number of applications for GRCs made, and the number granted, on an annual basis.

It will also be a criminal offence to make a false statutory declaration or false application. A person who commits such an offence is liable to imprisonment for up to two years and/or a fine.

There has been extensive consultation on reforming the Gender Recognition Act 2004, both for Scotland, and for England and Wales.

Views on whether to reform the Gender Recognition Act 2004 are highly polarised. This led the Scottish Government to delay reform after its first consultation in 2017, despite a majority of the 15,697 respondents supporting the proposals.

Those in support of the proposals made the following points:

gender identity is a personal matter, and gender recognition is sought following thoughtful consideration by people who know their own mind

the existing system can be complex, intrusive and distressing and act as a barrier to people who wish to change their gender.

Those not in favour frequently stated that:

it could pose a threat to safety in women-only spaces (such as toilets, changing rooms, refuges and hospital wards), being open to abuse by men who wish to gain access

it could undermine measures aimed at promoting female representation by allowing trans women to take up places on all-women short lists, on public boards, or awards.

The Scottish Government consulted on a draft bill in 2019. Reform was delayed again, this time as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Analysis of the 17,058 consultation responses found:

Most respondents were either broadly in support of, or broadly opposed to, a statutory declaration-based system.

A small majority of organisations broadly supported the proposals, while around 4 in 10 organisations did not. Around 1 in 10 either did not take a view or their view was not clear.

Of those in support of a statutory declaration-based system:

they saw a case for change as being clear and pressing

they supported making the current GRC process simpler

they disagreed with some elements, such as the requirement to live in the acquired gender, or that there should be a reflection period

they tended to be in agreement on reducing the minimum age to 16.

Of those opposed to a statutory declaration-based system:

they thought a convincing case for change had not been made

they viewed the current system as broadly fit for purpose, and had concerns about removing the need for a medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria

they were concerned about the potential impact on society in general, and particularly on the safety and wellbeing of women and girls

they generally disagreed with reducing the minimum age to 16.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) broadly supported the Scottish Government's proposals in response to both consultations. However, it has since changed its position and has called for more detailed consideration before any changes are made. This is based on concerns from "some lawyers, academics, data users and others” about the potential consequences of changing the criteria for legal gender recognition from a small defined group to a “wider group who identify as the opposite gender at a given point”.

In response to this, both the Scottish Government and the Scottish Human Rights Commission have sought further detail from the EHRC on the reasons for its change in position.

To date 6,010 gender recognition certificates have been granted across the UK. Scottish figures are not available, but it is estimated that there are 25-30 gender recognition certificates granted to people born or adopted in Scotland each year. The Scottish Government estimates that if the Bill passes, there could be 250-300 applicants a year.

Introduction

The Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill was introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 2 March 2022 by the Cabinet Secretary for Social Justice, Housing and Local Government, Shona Robison MSP.

The aim of the Bill is to improve the application process for legal gender recognition, which the Scottish Government says can have an adverse impact on applicants. This is due to the requirement for a medical diagnosis and supporting evidence and the intrusive and lengthy process.1

In a Ministerial Statement to the Parliament on 3 March 2022,2 the Cabinet Secretary said:

The current system has been in place for the past 18 years. There is evidence from extensive consultation—two of the largest consultations ever undertaken by the Scottish Government and one from the United Kingdom Government—that applicants find the current system intrusive and invasive, overly complex and demeaning. Many trans people do not apply because of those barriers. That is why we propose to reform the process to make it simpler, more streamlined, more compassionate and less medicalised.

Central to the approach is the removal of the medical element of the process. Applicants would be able to make a statutory declaration, which they also do now, rather than provide evidence to the Gender Recognition Panel (GRP) that they have been diagnosed with gender dysphoria.

Two other key changes proposed to the application process are that:

the minimum age should be lowered from 18 to 16

applicants must have lived in their acquired gender, but that the minimum period for that should be reduced from two years to three months, with an additional three-month reflection period.

The Cabinet Secretary said that the process will:

...remain serious and substantial. Making a false application will be an offence with penalties of up to two years’ imprisonment or an unlimited fine.

Given the polarisation of views on the proposals, a key feature of the Ministerial Statement, and the questions that followed, was the request for respectful debate. The Presiding Officer, Alison Johnstone MSP, also commented at the start:

There is a great deal of interest in the work of the Parliament on the issue and it is, as always, important that we set the correct tone in our debate. The Parliament is charged with careful scrutiny of any proposed legislation and debates many issues about which people feel very passionately. In our debate, we must be able to hear each other and we must treat each other with respect, even when we disagree whole-heartedly. We can accept that there are opposing views while not sharing them. I am sure that all members will consider very carefully, as always, not just their choice of words but the spirit and tone in which they are delivered.

It is likely that the Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee will be the lead committee on the Bill.

The following impact assessments were also published on 3 March 2022:

Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill: business and regulatory impact assessment

Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill: child rights and wellbeing impact assessment

Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill: child rights and wellbeing screening

Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill: equality impact assessment

as well as:

This briefing will cover:

the Gender Recognition Act 2004 (GRA) and its history

the current GRA application process

reasons for reform

various consultations and inquiries on GRA reform

exceptions in the Equality Act 2010

the Bill

Terminology

A range of different terms are used in this briefing. It is important to note that trans terminology has changed and evolved over time and continues to do so. These terms have been adapted from a range of sources.123

Acquired gender – the 2004 Act describes this as the gender in which an applicant is living and seeking recognition.

the Bill - Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill.

GRA - Gender Recognition Act 2004.

GRC - a gender recognition certificate. A full GRC provides legal recognition of a person's acquired gender.

the GRP - the Gender Recognition Panel. This is a UK Tribunal which currently deals, across the UK, with applications for legal gender recognition.

Gender dysphoria – used to describe when a person experiences discomfort or distress because there is a mismatch between the sex they were assigned at birth and their gender identity.

Gender identity– a person's internal sense of self and how they see themselves in terms of being a man or a woman, or being somewhere in between or beyond these categories (see non-binary below).

Gender reassignment - this is the protected characteristic in the Equality Act 2010. A person has this protected characteristic if they are proposing to undergo, are undergoing or have undergone a process (or part of the process) for the purposes of reassigning the person's sex by changing physiological or other attributes of sex. A transsexual person has this characteristic.

Non-binary – an umbrella term for people who do not identify as men or women.

the Registrar General - the Registrar General for Scotland.

Transgender or trans – umbrella terms used to describe a diverse range of people who find that their gender does not fully correspond with the sex they were assigned at birth. Non-binary people can also be included under the trans umbrella, although some may not consider themselves as trans.

Transsexual - this is seen by many as an outdated term for transgender/trans, but is used in the Equality Act 2010 under the definition of gender reassignment.

Gender Recognition Act 2004

History

UK Government

Twenty-two years ago, in 2000, the Home Office published the Report of the Interdepartmental Working Group on Transsexual People.1 The Working Group, which included the devolved administrations, had the following terms of reference:

... to consider, with particular reference to birth certificates, the need for appropriate legal measures to address the problems experienced by transsexual people, having due regard to scientific and societal developments, and measures undertaken in other countries to deal with this issue.

Submissions to the Group suggested that the principal areas where the trans community was seeking change were birth certificates, the right to marry, and full recognition of their new gender for all legal purposes. The Group therefore proposed three options:

to leave the current situation unchanged

to issue birth certificates showing the new name and, possibly, gender

to grant full legal recognition of the new gender subject to certain criteria and procedures.

European Court of Human Rights

In 2002, the European Court of Human Rights found the UK to be in contravention of Article 8 (the right to respect for private and family life) and Article 12 (the right to marry) of the European Convention of Human Rights with regard to the rights of transsexual people.

This was in relation to two cases: Christine Goodwin v the United Kingdom2 and I v the United Kingdom.3

Christine Goodwin had undergone male to female gender reassignment surgery, but she remained "for legal purposes, a male, with consequent effects on her life where sex was of legal relevance." The Court said, under Article 8, it was illogical to refuse to recognise the legal implications and that "difficulties posed by any major change in the system were not insuperable if confined to post-operative transsexuals". The Court found no concrete evidence of detriment on the rest of society as a result of allowing transsexuals to legally change their sex. Christine lived as a woman and would only want to marry a man, but had no possibility of doing so. The Court said that there was no justification for barring transsexual people from the right to marry, under any circumstances.

In the case of I v the United Kingdom, 'I' was a post-operative male to female transsexual. In 1985, at the age of 30, she enrolled for a nursing qualification, but was not admitted because she refused to present her birth certificate. At 33, she retired with a disability pension on the basis of ill-health. Five years later she wrote to various institutions requesting changes to legislation to allow for recognition of her changed gender. In 2001, she applied for a student loan and for a job, but both required an original birth certificate to support the application. The Court's conclusions were very similar to the Goodwin case.

Gender Recognition Bill

The Interdepartmental Working Group on Transsexual People was reconvened in 2002 to consider the implications of the Goodwin judgment. This led to the UK Government's announcement on 13 December 2002 that legislation would be introduced and to the publication of a draft Bill on 11 July 2003.4

The draft Bill was considered by the Joint Committee on Human Rights,5 and, while there were differences of opinion between the Committee and the Government, it was on the whole satisfied that the Bill would bring the UK into compliance with its obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights.4

The Bill was introduced in the House of Lords and had its second reading on 18 December 2003.7 It then had its second reading in the House of Commons on 23 February 2004.4

The UK Government referred to its commitment to "reforming the constitution so that it better meets the needs of all people", that transsexual people are a small and vulnerable minority and the Bill seeks to address one of the key problems they face. David Lammy MP, the then Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Constitutional Affairs said:

The Bill provides transsexual people with the opportunity to gain the rights and responsibilities appropriate to the gender in which they are now living. At present, transsexual people live in a state of limbo. Their birth gender determines their legal status.4

Legislative Consent Motion - consideration in the Scottish Parliament

The UK Government drafted the Gender Recognition Bill for England and Wales. Before introduction it was expanded to include Northern Ireland. Then, through a legislative consent motion (LCM), it was expanded to include Scotland.

On 9 December 2003, the Equal Opportunities Committee held an evidence session on the Gender Recognition Bill.10 The evidence was heard before the Scottish Executive submitted its LCM. The LCM (S2M-0813)11 was lodged by Cathy Jamieson, then Minister for Justice, on 22 January 2004:

That the Parliament endorses the principle of giving transsexual people legal recognition of their acquired gender and agrees that the provisions in the Gender Recognition Bill that relate to devolved matters should be considered by the UK Parliament thereby ensuring a consistent UK approach and early compliance with the rulings of the European Court of Human Rights with respect to the Convention rights of transsexual people under Article 8 (right to respect for private life) and Article 12 (right to marry).

The LCM was considered by the Justice 1 Committee on 28 January 200412 and then debated in the Chamber on 5 February 2004.13 Many Members were concerned that the LCM process was rushed and did not allow sufficient time to consider and scrutinise the Bill, particularly in relation to Scots law. One concern at the time was whether the application for gender recognition should be possible from the age of 16 rather than 18.

There were also some Members who felt that the Scottish Executive should have introduced its own primary legislation on gender recognition.

However, the Scottish Executive view was that the UK had to meet its legal obligations and the purpose of the LCM was to enable Scotland to do the same.

The LCM was agreed to: For 76; Against 35; Abstentions 7.

The Gender Recognition Bill was passed in the House of Commons on 25 May 2004.14 It achieved Royal Assent on 1 July 2004, and came into force on 4 April 2005.

The application process

The Gender Recognition Act 2004 (GRA) provides a way for trans people, aged 18 or older, to apply for legal recognition in their acquired gender. The Gender Recognition Panel (GRP) makes decisions on issuing gender recognition certificates (GRCs). The GRA, Schedule 1, requires that GRP members must have a relevant legal qualification or be registered medical practitioners or registered psychologists. The GRP must be satisfied that the applicant:

has provided medical evidence of gender dysphoria

has been living in their acquired gender for two years.

The applicant must make a statutory declaration that they intend to continue to live in their acquired gender for the rest of their life.

There is no requirement under the GRA for an applicant to undergo surgery or hormone therapy.

Once someone has been successful in changing their gender they will be issued with a GRC and following this, a new birth certificate.1 When a GRC is granted, this changes the person's legal sex, as set out in section 9 of the GRA:

Where a full gender recognition certificate is issued to a person, the person's gender becomes for all purposes the acquired gender (so that, if the acquired gender is the male gender, the person's sex becomes that of a man and, if it is the female gender, the person's sex becomes that of a woman).

Routes for application

There are three routes for application. The 'standard track' is the process that most applicants would go through.

Figures available from 2009/10 to 2021/22 show that the vast majority of GRCs are granted by Track 1, the standard track.1

| Financial year | Track 1Standard | Track 2Alternative | Track 3Overseas |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009/10 | 232 | 6 | |

| 2010/11 | 250 | 9 | |

| 2011/12 | 256 | 8 | |

| 2012/13 | 228 | 7 | |

| 2013/14 | 306 | 12 | |

| 2014/15 | 232 | 1 | 11 |

| 2015/16 | 302 | 20 | 7 |

| 2016/17 | 301 | 3 | 12 |

| 2017/18 | 323 | 5 | 23 |

| 2018/19 | 307 | 1 | 15 |

| 2019/20 | 338 | 3 | 23 |

| 2020/21 | 339 | 1 | 27 |

| Total | 3,474 | 34 | 160 |

Reason for reform

The Policy Memorandum sets out the Scottish Government's reasons for reform of the GRA.1

At the outset, the Scottish Government states that it:

... aims to create a more equal Scotland where people and communities are valued, included and empowered and which protects and promotes equality, inclusion and human rights.

In line with this, the Bill aims to:

improve the process for those applying for legal gender recognition as the current system can have an adverse impact on applicants, due to the requirement for a medical diagnosis and supporting evidence and the intrusive and lengthy process

simplify the current application process for those applying in Scotland to address the negative impact on those going through the process for legal gender recognition

allow 16 and 17 year olds to apply for legal gender recognition, who are negatively impacted by not being allowed to apply for legal gender recognition, despite being able to vote, get married and consent to surgical and medical procedures.

These points have been evidenced in responses to the two Scottish Government consultations.2

For example, in response to the first consultation, it was argued:

there are difficulties encountered when applying for a GRC, even where a person may have lived in the acquired gender for many years, such as the intrusive nature of the process, difficulties providing evidence, or costs

that the existing gender recognition process either contributes to ill health or leads to the stigmatising of trans people: a simpler process may help alleviate this impact

that the requirement to provide medical evidence medicalises something which is not an illness, that gender dysphoria is not a mental illness and should not require psychiatric assessment or diagnosis

trans men and women who have not yet obtained gender recognition may have transitioned socially with most of their identification documents, including Government issued ones, such as a passport and driving licence reflecting this, but will have an inconsistent birth certificate and legal status.

The Bill amends the GRA to introduce a new process for applying for legal gender recognition in Scotland and new criteria which require to be satisfied by applicants to obtain a GRC. The Policy Memorandum states: "it does not change the effects of a GRC and the rights and responsibilities which a person has on obtaining legal gender recognition."

The Scottish Government also cites the following in relation to reform:

World Health Organisation's reclassification of gender identity

During the Ministerial Statement on 3 March 2022, the Cabinet Secretary for Social Justice, Housing and Local Government, Shona Robison MSP, said:

The World Health Organisation’s revised international classification of diseases, which was approved in 2019, redefined gender identity-related health and removed it from a list of “mental and behavioural disorders”. It took that step to reflect evidence that trans-related identities are not conditions of mental ill health, and that classifying them as such can cause distress.1

The WHO's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11) is a document that provides standardized data and vocabulary to help diagnose and monitor health problems around the world.

The 11th edition was revised in 2019:2

[It] redefined gender identity-related health, replacing diagnostic categories like ICD-10’s “transsexualism” and “gender identity disorder of children” with “gender incongruence of adolescence and adulthood” and “gender incongruence of childhood”, respectively. Gender incongruence has thus broadly been moved out of the “Mental and behavioural disorders” chapter and into the new “Conditions related to sexual health” chapter. This reflects evidence that trans-related and gender diverse identities are not conditions of mental ill health, and classifying them as such can cause enormous stigma.

The WHO said that trans people share many of the same health needs as the general population, but may also have specialist health care needs, such as gender-affirming hormone therapy and surgery. According to WHO, evidence suggests that trans people often experience a disproportionately high burden of disease, including in mental, sexual and reproductive health. Some trans people seek medical or surgical transition, others do not.

The WHO also said that trans people are at an increased risk of mental ill health related to transphobia, discrimination and violence. Transphobia and discrimination can act as barriers to accessing health services. Legal gender recognition is described as "important for protection, dignity and health."

International human rights developments

The Policy Memorandum referred to two human rights developments relating to legal gender recognition:

Yogyakarta Principles

The 2006 non-binding Yogyakarta Principles1 were agreed by a wide-ranging group of human rights law experts, representatives of non-governmental organisations and others. Principle 3 asks countries to:

take all necessary … measures to ensure that procedures exist whereby all State-issued identity papers which indicate a person’s gender/sex including birth certificates … reflect the person’s profound self-defined gender identity.

Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE)

Resolution 2048 of PACE2, made in 2015, expressed concerns that requiring someone seeking legal recognition of their acquired gender to have been medically treated or diagnosed is a breach of their right to respect for their private life under Article 8 of the ECHR. The resolution calls on all Member States to:

develop quick, transparent and accessible procedures, based on self-determination, for changing the name and registered sex of transgender people on birth certificates, identity cards, passports, educational certificates and other similar documents; make these procedures available for all people who seek to use them, irrespective of age, medical status, financial situation or police record

PACE also said that states should:

abolish a mental health diagnosis as a necessary legal requirement for legal gender recognition

consider including a third gender option in identity documents for those who seek it

ensure the best interests of the child are a primary consideration in all decisions concerning children.

International practice on legal gender recognition

The Cabinet Secretary said in her Ministerial Statement:

Moving to a system that is based on personal declaration rather than medical diagnosis will bring Scotland into line with well-established systems in Norway, Denmark and Ireland, and recent reforms in Switzerland and New Zealand. We are aware of at least 10 countries that have introduced similar processes.1

The Scottish Government's analysis of international practice is available in Annex E of its 2019 consultation on the draft bill.2

Resources on international practice include:

Trans and intersex equality rights in Europe – a comparative analysis (2018) by the European Commission, drafted by legal experts in gender equality and non-discrimination.

Legal gender recognition in the EU (2020), by the European Commission.

Transgender Europe includes a range of resources, including interactive maps on legal gender recognition.

ILGA Trans legal mapping report (2020), which details the impact of laws and policies on trans persons across the globe.

Consultation on reforming the Gender Recognition Act 2004

There has been extensive consultation on whether and how to reform the GRA since 2016, both for Scotland and for England and Wales.

This section provides an overview, in time order, of inquiries and consultations on gender recognition reform:

Women and Equalities Committee inquiry 2016

The House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee called for a change to the GRA in 2016, following an inquiry on Transgender Equality.1 The Committee said:

Legislation on gender recognition and equality for trans people was pioneering, but is now outdated. The medicalised approach in the Gender Recognition Act 2004 pathologises trans identities and runs contrary to the dignity and personal autonomy of applicants. It should be updated in line with the principles of self-declaration.

The Committee heard:

The process for applying for a GRC was described as “bureaucratic”, “expensive” and “humiliating”.

The UK Government justified the £140 fee for GRC applications on grounds that charging for a range of official services is normal (this fee has now been reduced to £5).

While the GRA does not require an applicant to have received medical treatment, such treatment will be accepted as part of the supporting evidence for a GRC application. It can be proved by means of a letter from the applicant’s GP giving details of treatment. Where no evidence of treatment is provided, the GRP may ask for evidence regarding why treatment has not been commenced.

The requirement to provide documentation regarding a diagnosis of gender dysphoria caused distress because it pathologises trans identities.

The requirement to live in the acquired gender for two years was seen as arbitrary and unreasonable, and that this caused problems with identity documents (given that this must be done before legal gender recognition has been granted).

Concerns about spousal consent, in relation to marriage law in England and Wales at that time.

Concerns that various bodies and authorities make inappropriate requests for the production of a GRC.

In a series of countries, gender recognition now takes place on the basis of gender self-declaration by the applicant, without the onerous requirements that exist under the GRA.

On reducing the minimum age for people to apply for a GRC, the Committee said:

For some young people the decision regarding gender recognition is straightforward; for some it is not. It is important that clear safeguards are in place to ensure that long-term decisions about gender recognition are made at an appropriate time. Subject to this caveat, a persuasive case has been made to us in favour of reducing the minimum age at which application can be made for gender recognition. We recommend that provision should be made to allow 16- and 17-year-olds, with appropriate support, to apply for gender recognition, on the basis of self-declaration.

The Committee remained cautious about recommending gender recognition in respect of children aged under 16 and said the Government should further consider the possible risks and benefits.

Scottish Government consultation 2017

The Scottish Government first consulted on a review of the Gender Recognition Act 2004 between 9 November 2017 to 1 March 2018.1 It received 15,967 responses; 15,532 from individuals and 165 from organisations.

This consultation set out the Scottish Government's initial view on reform of the GRA, in favour of a system of self-declaration:

The Scottish Government considers that, subject to views expressed during this consultation, Scotland should adopt a self-declaration system for legal gender recognition. This would mean that applicants under a Scottish system would not have to demonstrate a diagnosis of gender dysphoria or that they had lived for a period in their acquired gender. This would align Scotland with the best international practice demonstrated in countries who have already successfully adopted self-declaration systems.

It sought views on a range of areas, including:

the requirement to produce medical evidence or evidence that the applicant has lived in their acquired gender for a defined period

whether applicants should provide a statutory declaration confirming they know what they are doing and intend to live in their acquired gender until death

whether there should be a limit on the number of times a person can get legal gender recognition

whether eligibility should be open only to people whose birth or adoption was registered in Scotland, or who are resident in Scotland, or everyone

reducing the minimum age to 16

options for those under 16.

There were also questions regarding non-binary people, spousal consent and privacy issues.

Consultation analysis

The independent analysis found that:2

A majority of respondents, around 60%, agreed with:

the proposal to introduce a self-declaratory system for legal gender recognition, and that no medical evidence should be required

the minimum age should be reduced to 16

the recognition of non-binary people.

Those in support of the proposal for a system of self-declaration of gender recognition made the following points:

gender identity is a personal matter, and gender recognition is sought following thoughtful consideration by people who know their own mind

the existing system can be complex, intrusive and distressing and act as a barrier to people who wish to change their gender.

Those not in favour frequently stated that:

it could pose a threat to safety in women-only spaces (such as toilets, changing rooms, refuges and hospital wards), being open to abuse by men who wish to gain access

it could undermine measures aimed at promoting female representation by allowing trans women to take up places on all-women short lists, on public boards, or awards.

Delayed reform

On 20 June 2019, the then Cabinet Secretary for Social Security and Older People, Shirley-Anne Somerville MSP, made a statement in the Scottish Parliament.3 She said that, despite support for reform, additional issues had been raised since the consultation, and sought to build consensus on the way forward.

Commitments were made to:

Develop guidance to support the collective realisation of both women’s and trans rights. This was due for publication summer 2020 but has been delayed by COVID-19 and reprioritisation.

Replace the LGBT Youth Scotland schools’ guidance for supporting transgender young people with guidance from the Scottish Government by the end of 2019. The

Supporting transgender young people in schools: guidance for Scottish schools was published in August 2021.

Establish a working group to address wider concerns about the disaggregation and use of data by sex and gender. The working group published Sex, gender identity, trans status - data collection and publication: guidance in September 2021.

The Cabinet Secretary set out plans for a draft bill and announced it would not extend legal gender recognition to non-binary people at this stage. Instead, a working group would be established to identify other ways to improve equality for non-binary people. The work of the group was put on hold due to COVID-19, but was able to restart in February 2021.

UK Government consultation 2018

The UK Government ran a consultation on Reform of the Gender Recognition Act between 3 July 2018 and 22 October 2018.1 It received over 100,000 responses.

The consultation sought views on whether:

there should be a requirement in the future for a diagnosis of gender dysphoria

there should be a requirement for a report detailing treatment received

an applicant should have to provide evidence that they have lived in their acquired gender for a period of time before applying, and the length of time that should be

there should be a period of reflection between making the application and being awarded a GRC.

It also sought views on the experience of trans people, and any impacts on the Equality Act 2010. It did not seek views on reducing the age limit.

Consultation analysis

The independent analysis2 found that:

nearly two-thirds of respondents (64.1%) said that there should not be a requirement for a diagnosis of gender dysphoria in the future, with just over a third (35.9%) saying that this requirement should be retained

around 4 in 5 (80.3%) respondents were in favour of removing the requirement for a medical report which details all treatment received

a majority of respondents (78.6%) were in favour of removing the requirement for individuals to provide evidence of having lived in their acquired gender for a period of time

the majority of respondents (83.5%) were in favour of retaining the statutory declaration requirement of the gender recognition system.

UK Government response

After some delay, the UK Government announced its response to the consultation in September 2020. It concluded that:

the GRA did not need to change in England and Wales, stating that it provides "proper checks and balances in the system and also support for people who want to change their legal sex"

but, that there was a need to improve the process and experience that trans people have when applying for a GRC. To address this it would:

place the application process online

reduce the £140 fee to a nominal amount. The fee was reduced to £5 on 4 May 20213 under the Civil Proceedings and Gender Recognition Application Fees (Amendment) Order 2021 and applies across the UK.

Scottish Government consultation 2019

The Scottish Government published its consultation on the draft Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill on 17 December 2019, which ran until 17 March 2020.1 The proposals included:

Removing the requirement for people to apply to the UK Gender Recognition Panel. Instead, people seeking legal gender recognition would apply to the Registrar General for Scotland.

Removing the requirement to provide medical evidence.

Applicants must have lived in their acquired gender for a minimum of three months, and then confirm after a reflection period of three months that they wish to proceed.

Applicants would have to confirm that they intend to live permanently in their acquired gender.

Applicants would still be required to submit statutory declarations, made in front of a Notary Public or a Justice of the Peace.

It will be a criminal offence to make a false statutory declaration or false application.

Reducing the minimum age of application from 18 to 16.

The consultation sought views on these proposals, as well as asking for any other comments, and comments on the draft impact assessments.

Reform delayed

On 1 April 2020, it was announced that the draft Bill, along with a number of other bills, would be delayed due to the impact of COVID-19.2 The analysis had been impacted by COVID-19 and the intention was to publish it as ‘soon as practicable’ in the next parliamentary session.3

Consultation analysis

The Scottish Government commissioned independent analysis of the consultation, and the report was published in September 2021.4 There were 17,058 responses available for analysis. Of these, 16,843 were from individuals, and 215 from organisations. The organisational responses are available alongside the consultation and analysis. Annex 1 lists the organisational responses in categories.

Those resident in Scotland accounted for 55% of respondents, with 32% resident in the rest of the UK, and the remaining 14% resident in the rest of the world.

In summary, the consultation analysis found:

Most respondents were either broadly in support of, or broadly opposed to, a statutory declaration-based system.

A small majority of organisations broadly supported the proposals, while around 4 in 10 organisations did not. Around 1 in 10 either did not take a view or their view was not clear.

One area of shared concern was about the nature and tone of the debate, and consensus that the debate has become highly polarised and seen by some as toxic, especially on social media.

Of those in support of a statutory declaration-based system:

they saw a case for change as being clear and pressing

they supported making the current GRC process simpler

they disagreed with some elements, such as the requirement to live in the acquired gender, or that there should be a reflection period

they tended to be in agreement on reducing the minimum age to 16.

This was the perspective of many individual respondents, and all, or the considerable majority of Children and Young People's Groups, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) and Trans Groups, Union or Political Parties, Local Authorities, Health and Social Care Partnerships (H&SCPs) or NHS respondents and Third Sector Support Organisations.

Of those opposed to a statutory declaration-based system:

they thought a convincing case for change had not been made

they viewed the current system as broadly fit for purpose, and had concerns about removing the need for a medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria

they were concerned about the potential impact on society in general, and particularly on the safety and wellbeing of women and girls

they generally disagreed with reducing the minimum age to 16.

This was the perspective of many individual respondents, and the considerable majority of the Women's Groups and Religious or Belief Bodies that responded.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) was established under the Equality Act 2006 and is responsible to the UK Government. It is a regulatory body responsible for enforcing the Equality Act 2010. It is accredited as an ‘A Status’ National Human Rights Institution and monitors the UK's compliance with the seven UN human rights treaties it has signed and ratified.

Despite previously indicating support for proposed reform of the GRA to the Scottish Government's first5 and second6 consultation, as well as the UK Government's consultation7, the EHRC has changed its view.

In a letter to Shona Robison MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Social Justice, Housing and Local Government, on 26 January 2022, Baroness Falkner, Chair of the EHRC called for more detailed consideration before any change is made to the provisions of the GRA.8

The letter refers to concerns from "some lawyers, academics, data users and others" about the potential implications of changing the current criteria for obtaining a GRC. It states:

These concerns centre on the potential consequences for individuals and society of extending the ability to change legal sex from a small defined group, who have demonstrated their commitment and ability to live in their acquired gender, to a wider group who identify as the opposite gender at a given point. The potential consequences include those relating to the collection and use of data, participation and drug testing in competitive sport, measures to address barriers facing women, and practices within the criminal justice system, inter alia.

And further that:

We otherwise consider that the established legal concept of sex, together with the existing protections from gender reassignment discrimination for trans people and the ability for them to obtain legal recognition of their gender, collectively provide the correct balanced legal framework that protects everyone.

In correspondence to Baroness Falkner on 31 January 20229, the Cabinet Secretary sought:

... a more detailed explanation of the basis for EHRC’s significant policy shift on this issue. You have not set out any explanation of what consultation activity, evidence or legal basis has led to this change.

In response to the Cabinet Secretary on 4 February 2022,10 Baroness Falkner said:

As you would expect, the Commission bases all its decisions on the law and on evidence, including in this case from relevant UK and Scottish Government consultations, the 2018 National LGBT Survey, responses to the consultation process for our 2022-25 Strategic Plan, and evidence from a range of civil society bodies, legal experts and international organisations.

And further that:

As an independent regulator, we have an obligation to set out our authoritative views on equality issues, even if they are at odds with the views held by some stakeholders. As you know, the polarised nature of the debate on issues of sex and gender has grown considerably since we first responded to the Scottish Government proposals in 2018. The divergence of views is in part related to different understandings of the effect of the law, and in part to the impact of potential changes to the law, including on service providers and data users. It is also related to disputed terminology, which has evolved significantly since the GRA was passed in 2004. This has resulted in increasing numbers of court cases to resolve contested claims, with jurisprudence still evolving around use of the terms sex and gender, for example.

The Cabinet Secretary responded to Baroness Falkner on 21 February 2022, 11 seeking again:

... a more detailed explanation of the evidence base, consultation activity and legal considerations that informed EHRC’s significant policy change on gender recognition reform.

She also sought:

... an explanation of what differences of understanding of the effect of the law, and what potential changes, this is referring to so we can ensure we have considered them.

Scottish Human Rights Commission

The Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC) was established under the Scottish Commission for Human Rights Act 2006, and is accountable to the people of Scotland, through the Scottish Parliament. The Commission is accredited as an ‘A Status’ National Human Rights Institution within the United Nations system.

Human rights in relation to devolved areas (such as the police) is the responsibility of the SHRC. The EHRC also has responsibility for human rights in Scotland in relation to reserved policy areas (such as immigration). In practice, the two areas are often interwoven.

On 24 February 2022, the SHRC issued a statement, clarifying the mandates of the SHRC and the EHRC.12 This referenced a letter sent to Baroness Falkner on 11 February 2022 from the SHRC.13 The SHRC confirmed its unchanged position of support for reform of legal gender recognition in Scotland, which is based on its human rights analysis of the Scottish Government's draft bill proposals.14

The statement recognises that the EHRC is Scotland's equality regulator, and that it retains a human rights mandate in Scotland in relation to reserved matters. However, the EHRC is required to seek the consent of the SHRC where it proposes to take action on devolved human rights matters.

The SHRC said that under section 7 of the Equality Act 2006:

... the EHRC is not empowered to take human rights action in Scotland where it falls within the mandate of the Scottish Human Rights Commission. Where it proposes to take such action, it is required to seek our consent.

And further that:

The Scottish Human Rights Commission wishes to make clear that the EHRC has not sought our consent in relation to its recent commentary and interventions on the human rights implications of reforming gender recognition processes. Therefore, any analysis, commentary or engagement about the human rights implications of this (or any other) devolved legislation and policy is for the Scottish Human Rights Commission to make.

In the SHRC's letter, it seeks a meeting with the EHRC to review the terms of their working relationship and to discuss the boundaries and interrelationships between their respective mandates.

The SHRC is concerned about the process employed by the EHRC in relation to its intervention on GRA reform, and that their respective policy positions no longer align.

We have specific concerns about your Commission’s change of position on the value of introducing legislation to reform gender recognition processes in Scotland, given this now diverges from both our own analysis of the human rights issues engaged, and our previous understanding of your own position. We would therefore welcome the opportunity to better understand the detailed rationale behind this change, and to discuss the boundaries and interrelationship between our respective mandates on this subject.

Women and Equalities Committee's inquiry 2021

The House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee published its report on Reform of the Gender Recognition Act on 21 December 2021.1

The Inquiry was set up in October 2020, following the UK Government's announcement that there would be no reforms to the GRA in England and Wales, other than a reduction in the fee (applies across the UK) and making the application process available online.

The Committee heard oral evidence from stakeholders with a range of views, including trans rights groups and women’s rights groups.

The Committee's report called on the UK Government to urgently reform the GRA in England and Wales in the following areas:

Remove the requirement of a 'gender dysphoria' diagnosis from the process of obtaining a GRC, to de-medicalise transition. Instead, the focus must be shifted to a system of self-declaration.

Remove the requirement for trans people to have lived in their acquired gender for two years, which entrenches outmoded gender stereotypes.

There was also a call for a review of the conduct of the 'opaque' Gender Recognition Panel, and consideration whether it would be appropriate to replace it with the Registrar General for England and Wales.

Statistics on the trans population

Gender Recognition Certificates (GRCs)

The UK Government's Ministry of Justice publishes quarterly statistics on GRCs. 1

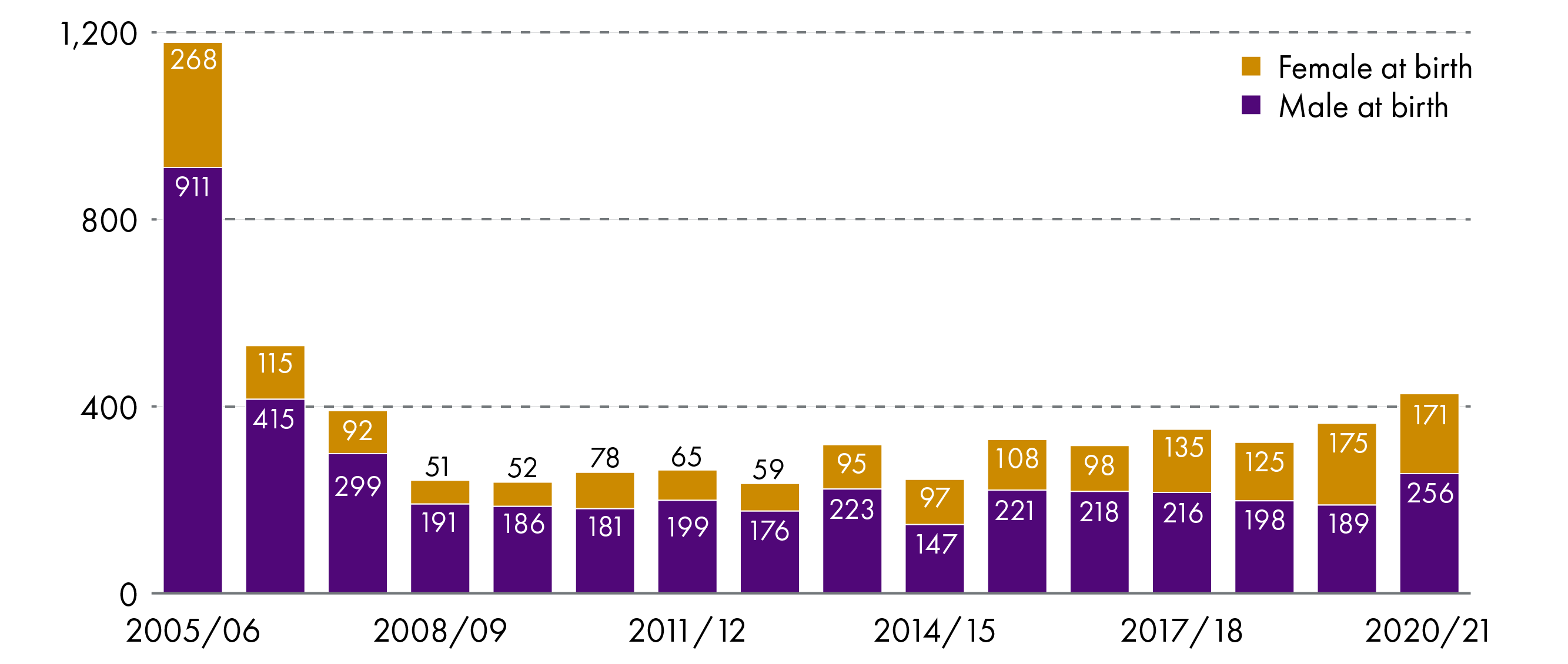

To date, there have been 6,010 GRCs granted, of which 4,226 were male at birth (70%), and 1,784 were female at birth (30%). However, the graph below indicates that this balance might be changing over time, as in the last year 427 full GRCs were granted, of which 256 were male at birth (60%), and 171 were female at birth (40%).

The GRC statistics are only available for the UK as a whole. The Scottish Government estimates that around 25-30 people born or adopted in Scotland obtain legal gender recognition each year, based on information held by National Records of Scotland.3 Over 16 years that would be around 480 people who have been granted legal gender recognition in Scotland. There are no statistics available for applicants resident in Scotland (but not born or adopted there) who apply under the current arrangements.3

The Scottish Government has estimated an overall increase in the number of applicants for legal gender recognition of between 250-300 applications a year. This is based on comparison with other countries of a similar sized or smaller population that have introduced legal gender recognition based on self-declaration.3

Estimates of the trans population

There are no exact figures on the number of trans people in the UK population, only estimates.

Making estimates can be difficult because of the inconsistent use of questions to identify trans and non-binary respondents. There may also be variations in the age limits of survey populations, such as whether the age limit is 16 or 18 years. Also, not all trans people will identify as 'trans' and would describe themselves as a man or a woman, and others may not wish to disclose their status.6

UK Government estimate

The UK Government said, in its 2018 consultation on GRA reform, that it estimated that there are approximately 200,000-500,000 trans people in the UK, based on a prevalence range of 0.35% and 1% of the population.7 This is based on work carried out by GIRES (Gender Identity Research and Education Society) on prevalence in the UK, and other international prevalence estimates.6

UK Government LGBT survey

The Government Equalities Office conducted an LGBT survey in 2017, and published the results in 2018. 9 It received 108,100 valid responses from individuals who self-identified as having a minority sexual orientation or gender identity, or as intersex, and were aged 16 or above and living in the UK.

Trans respondents accounted for 13% of the individuals identifying as having a minority sexual orientation or gender identity, or as intersex, and were aged 16 or above and living in the UK. This equates to 14,053 people. Of trans respondents, 52% (7,308) identified as non-binary, 26% (3,654) identified as a woman or trans woman, and 22% (3,092) identified as a man or trans man.

Census data

For the first time in census history, both the Census 2021 for England and Wales, and the Census 2022 for Scotland (delayed a year due to COVID-19), include a voluntary question which seeks to gather information on the trans population. Both questions are for those aged 16 and over. Both questions are slightly different; for England and Wales it focuses on gender identity, and for Scotland the focus is on trans status.

The Scottish Census 2022 asks:

Do you consider yourself to be trans, or have a trans history?10

It describes 'trans' as a term used to describe people whose gender is not the same as the sex they were registered at birth. People can respond 'No' or 'Yes'. If the answer is 'Yes', people are asked to describe their trans status, "for example, non-binary, trans man, trans woman." This question is voluntary.

The Census 2021 for England and Wales asked:

Is the gender you identify with the same as your sex registered at birth?11

The options are 'Yes' or 'No, write in gender identity'.

As the questions are voluntary, the results will only provide a full picture of the population who are trans.

Most census questions are mandatory. If a person refuses to answer a census question, or gives a false answer, they are liable to a fine not exceeding £1,000 under section 8 of the Census Act 1920. The only exceptions are the voluntary questions on religion, sexual orientation and gender identity.

Equality Act 2010

The Equality Act 2010 protects individuals from discrimination and harassment because of specified ‘protected characteristics’. This applies to the protected characteristics of ‘sex’ and ‘gender reassignment’. The majority of the Act came into force in October 2010 and covers Great Britain. The Act is mainly reserved, save a few exceptions.1

There are concerns that reforms to gender recognition might impact on the single-sex exceptions in the Equality Act 2010, and potentially place women in danger from men who might abuse a new self-identification system.

There are no plans from the UK Government to amend the Equality Act 2010,2 and the Scottish Government has considered the exceptions and concluded that reforming the GRA would not adversely affect women's rights.3

The Equality Act refers to ‘sex’ in binary terms – man and woman (s.11). It defines ‘woman’ as ‘female of any age’, and ‘man’ as ‘male of any age’ (s. 212(1)).

As explained above, the GRA provides a process for people to legally change their sex. This means a person who was born biologically male or female, can legally become a woman or a man.

Therefore, in law, a woman is either biologically female, or is someone who has legally changed their sex to be a woman, and vice versa for men.

The Equality Act 2010 (section 7) definition of gender reassignment is:

(1) A person has the protected characteristic of gender reassignment if the person is proposing to undergo, is undergoing or has undergone a process (or part of a process) for the purpose of reassigning the person's sex by changing physiological or other attributes of sex.

(2) A reference to a transsexual person is a reference to a person who has the protected characteristic of gender reassignment.

(3) In relation to the protected characteristic of gender reassignment—

(a) a reference to a person who has a particular protected characteristic is a reference to a transsexual person;

(b) a reference to persons who share a protected characteristic is a reference to transsexual persons.

The definition of gender reassignment under the Equality Act 2010 is broad. A person would not have to have a GRC or seek a legal change to their gender to be protected from unlawful discrimination.

Individuals are treated under the sex discrimination provisions of the Equality Act 2010 in line with their legal sex. A trans person with a GRC is treated as having the sex recorded on their new birth certificate. A trans person who does not have a gender recognition certificate is treated as having the sex recorded on their birth certificate. All trans people, who are proposing to undergo, are undergoing or have undergone (part of) a process of gender reassignment, with or without a GRC, are protected from discrimination under gender reassignment.4

Equality Act 2010: single-sex exceptions

Separate and single-sex exceptions

Under the Equality Act 2010, it is unlawful to discriminate because of the protected characteristic of sex. However, under Schedule 3, para 26 and 27, there are a range of exceptions which allow for separate and single-sex services. These exceptions will not change if the Bill passes.

Under Schedule 3, para 28, service providers can provide a different service or exclude a trans person from the service who falls under the gender reassignment definition. This exception will not change if the Bill passes.

However, the EHRC's Equality Act 2010 Code of Practice: Services, public functions and associations, para 13.57, explains that:

If a service provider provides single- or separate sex services for women and men, or provides services differently to women and men, they should treat transsexual people according to the gender role in which they present.1

Service providers can exclude trans people from separate or single-sex services, but this will only be lawful where the exclusion is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

The Scottish Government's 2019 consultation provided the following example:

This provision would, for example, allow the operator of a domestic abuse refuge designed for women only to exclude a trans woman from the service if the operator judges that this is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. This is likely to involve carrying out a risk assessment.2

Calls for further guidance on separate and single-sex exceptions

There have been calls for further guidance on the practical application of the separate and single-sex exceptions, particularly given the absence of case law in this area.

In 2019, the House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee published a report on ‘Enforcing the Equality Act: the law and the role of the Equality and Human Rights Commission’.3

Recommendation 15 set out the following:

We do not believe that non-statutory guidance will be sufficient to bring the clarity needed in what is clearly a contentious area. We recommend that, in the absence of case law the EHRC develop, and the Secretary of State lay before Parliament, a dedicated Code of Practice, with case studies drawn from organisations providing services to survivors of domestic and sexual abuse. This Code must set out clearly, with worked examples and guidance, (a) how the Act allows separate services for men and women, or provision of services to only men or only women in certain circumstances, and b) how and under what circumstances it allows those providing such services to choose how and if to provide them to a person who has the protected characteristic of gender reassignment.

The UK Government responded:

As set out in response to recommendation 14, the Government is planning to develop and publish non-statutory guidance on how the Equality Act 2010’s single and separate sex service exemptions apply. There are limitations to what could be achieved through statutory guidance as there is no case law in this space that moves beyond interpretation of the original legislation, so it would not be possible to set out ‘rules’ for the application of exemptions: statutory guidance must reflect existing law, it is not a means of establishing new law.4

The Scottish Government said that it agrees that, while the Equality Act 2010 exceptions will continue after GRA reform, non-statutory guidance by the UK Government could be helpful.2

In the House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee recent report on Reform of the Gender Recognition Act,6 it said that concerns raised about the interplay between the GRA and Equality Act fall into three broad categories:

a lack of confidence or understanding amongst service providers about how to apply exceptions

the need for better guidance to assist service providers with exceptions

how a system of self-declaration might affect the provision of single-sex services.

The Committee noted that the EHRC had responded to the former Committee’s recommendation, stating that it was “producing a guide for service providers to aid their decision making”. However, neither the UK Government or the EHRC has published guidance yet.

At an annual evidence session with the EHRC, Baroness Falkner (Chair of the EHRC) told the committee that the EHRC’s “target is to publish this in January 2022”.

The Committee reiterated the former Committee's recommendation for better guidance on separate and single-sex exceptions:

... and urge the Government Equalities Office and Equality and Human Rights Commission to publish this guidance, using worked examples and case studies from organisations providing these services. We also strongly recommend that the Government Equalities Office and Equality and Human Rights Commission urgently develop and publish guidance, in collaboration with trans rights groups, on best practice to provide trans and non-binary inclusive and specific services, including specifically relating to domestic violence and sexual abuse. This guidance should use worked examples and case studies from organisations providing these services.

In a letter to the Scottish Government, on 26 January 2022, which called for a pause in GRA reform, Baroness Falkner said “We will write to you shortly to update you on our forthcoming guidance for single-sex service providers”.7

The EHRC issued a news release on 11 February 2022 regarding online misinformation about single-sex spaces guidance, stating that "It is false to suggest that we are looking to bar trans people from accessing spaces, such as public toilets, without a Gender Recognition Certificate". It also states that guidance will be available in "due course".8

Equality Act 2010: other exceptions

The Equality Act 2010 includes further exceptions, which are examined in the Scottish Government's 2019 consultation.1

Sport - section 195 allows for restrictions on trans people participating in sport to be imposed if necessary to uphold fair competition or the safety of competitors. This provision will not change if the Bill passes.

Occupational requirements - Schedule 9 sets out exceptions in relation to work.

Paragraph 1 of Schedule 9 provides a general exception to what would otherwise by unlawful direct discrimination, including a requirement that the person not be a trans person, where there is an occupational requirement due to the nature or context of the work, and this is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.1 These provisions will not change if the Bill passes.

Reference is made to the Equality Act 2010 Explanatory Notes, which provide an example:

a counsellor working with victims of rape might have to be a woman and not a transsexual person, even if she has a Gender Recognition Certificate, in order to avoid causing them further distress

There has been some concern raised about whether section 22 of the GRA, on prohibition of disclosure of information, could make it harder to use the general occupational requirement exception.

Section 22 makes it an offence for a person who has acquired protected information in an official capacity to disclose the information to any other person. “Protected information” means information which relates to a person who has made an application for a GRC and which concerns that application or, if the application is granted “otherwise concerns the person’s gender before it becomes the acquired gender.”

The Scottish Government's 2019 consultation said:

There are a variety of exceptions in section 22, at subsection (4) and in an Order made by the Scottish Ministers under section 22(6).3 One point which might arise when using the general occupational requirements exception is that some people in an organisation (eg people in its HR department) may know about a person’s trans history but those actually taking the decisions on staff deployment (eg line managers) may not. In these circumstances, and when there is a legitimate case to use the general occupational requirements exception, the Scottish Government considers that it would be appropriate for information about a person’s trans history to be shared in a strictly limited, proportionate and legitimate way.

The Scottish Government said in its 2019 consultation that it would consider whether:

further exceptions to section 22 should be made, by way of a further Order under section 22(6)

Scottish Government guidance on section 22 should be issued.

During the Ministerial Statement on 3 March 2022, the Cabinet Secretary for Social Justice, Housing and Local Government, Shona Robison MSP, responded to a question on this and said there would be no change to the general occupational requirement exception, and provided the following example:

If someone was working in the field of providing intimate care, it is, as is the case at the moment, absolutely legitimate for a patient or someone receiving social care to say who they do and do not want to provide that service. That is underpinned by the general occupation exception under the 2010 act. This bill does not change that at all. It remains as was.4

The Scottish Government's 2019 consultation on the draft bill covered the range of exceptions in the Equality Act and concluded that reforming the GRA would not adversely affect women's rights.

The Bill

This section summarises the key sections of the Bill, and includes comments from the Scottish Government's consultation on the draft Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill.

Key changes proposed

The Bill provides for the following changes to the current process for applying for a GRC:1

removing the requirement for an applicant to have, or to have had gender dysphoria, and therefore removes the requirement for medical evidence to be provided

reducing the minimum age for application from 18 to 16

removing the Gender Recognition Panel from the process, instead applications will be made to the Registrar General for Scotland

reducing the period for which an applicant must have lived in their acquired gender before making an application, from two years to three months

introduction of a mandatory three month reflection period and a requirement for the applicant to confirm at the end of that period that they wish to proceed with the application before the application can be determined

introduction of a new duty on the Registrar General for Scotland to report the number of applications for GRCs made, and the number granted, on an annual basis.

The Bill's provisions also restate some aspects of the current process, such as granting a full GRC after an interim GRC is issued.

The Bill creates two offences:

of knowingly making a false statutory declaration in an application for a GRC

of knowingly including false information in an application for a GRC.

A person who commits such an offence is liable to imprisonment for up to two years and/or a fine.

Applicants must also have a Scottish birth or adoption certificate, or be ordinarily resident in Scotland.

The Bill also provides for automatic recognition of gender recognition obtained outwith the UK, "unless it would be manifestly contrary to public policy to do so."

Application for a GRC

Sections 2-7 of the Bill make provision for the application process.

Eligibility for a GRC

Section 2 of the Bill inserts a new section in the GRA 2004, and provides that a person may apply to the Registrar General for Scotland for a GRC "on the basis of living in the other gender" if:

they are aged at least 16

they have either a Scottish birth or adoption certificate, or are ordinarily resident in Scotland.

Issues raised in the consultation

Lowering the age of eligibility

The consultation asked whether the minimum age at which a person can apply for legal gender recognition be reduced from 18 to 16. Overall, 56% of those responding to this question supported lowering the age to 16.1

| Respondent | Yes | No | Don't know | Not answered | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organisations | 107 | 84 | 9 | 15 | 215 |

| % | 54 | 42 | 5 | ||

| Individuals | 9,294 | 6,944 | 390 | 215 | 16,843 |

| % | 56 | 42 | 2 | ||

| Total who responded to the question | 9,401 | 7,028 | 399 | 230 | 17,058 |

| % | 56 | 42 | 2 |

Those who supported a statutory declaration-based system generally support lowering the age to 16. There was also a view from this group of respondents that those under the age of 16 could seek a legal gender change, with parental approval, and cited evidence from other countries. Some suggested that under 16s should have the right to legally change their gender without parental consent.

Arguments included that:

a child is legally an adult at 16 and the proposed change would bring gender recognition into line with other rights exercised at 16

many 16 year olds are mature, capable and responsible enough to make a decision on their legal gender identity

it could have a positive impact on mental health

legal gender recognition is about documentation and would not impact on other aspects of transition, such as social presentation or accessing gender clinics

some argued that provision should be made for those under 16, suggesting that as children over 12 are deemed to have legal capacity to make decisions in certain circumstances, this principle should apply.

Those who opposed a statutory declaration-based system expressed concern that the draft bill makes no provision for parental consent for those aged 16 and 17 who wish to seek legal gender recognition. They asserted that other countries make additional requirements for young people seeking legal gender recognition, such as parental consent.

Arguments included that:

A 16 year old is still a child and that the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child defines children as those under 18.

Sixteen is too young to legally change gender, citing a lack of emotional maturity or life experience.

Other rights exercised at 16 are reversible in a way that legal gender recognition does not appear to be. References were made to getting a tattoo, buying alcohol or cigarettes, which are only allowed at 18.

The pressures on young people at that age, such as school work and exams, would make it wrong to introduce the possibility of legal gender change at such an important time. It was also suggested that hormonal and physical changes can lead to some teenagers feeling uncomfortable with their bodies.

It could set young people on a medical pathway that is difficult to stop or reverse.

Appendix A of Child Rights and Wellbeing Impact Assessment provides international examples of the legal gender recognition process for those under 18. Some countries/territories have no minimum age, some set the minimum age at 16. In many of the examples, some form of parental/guardian consent must be obtained for those under 18.

The Scottish Government will consider the need for further guidance for 16 and 17 year olds "to ensure they understand and have carefully considered their decision".2 In the Ministerial Statement, the Cabinet Secretary explained further:

We have concluded that the minimum age should be reduced to 16, with support and guidance being provided to young people through schools, third sector bodies and National Records of Scotland. Under the oversight of the registrar general, National Records of Scotland will routinely give additional, careful consideration to applications from 16 and 17-year-olds. It will provide support on the process and, when necessary, will undertake sensitive investigation, which could include face-to-face conversations with applicants. Every 16 or 17-year-old who applies will be offered and encouraged to take up the option of a conversation with NRS to talk through the process.3

Ordinarily resident

Some respondents to the consultation:

queried what is meant by ordinarily resident in Scotland

raised concerns about who might be prevented from applying, e.g. asylum seekers and refugees, and those who have come to Scotland to study.

There were also occasional concerns that without appropriate restrictions being in place, Scotland could become a 'gender tourism destination', particularly for residents of England, Wales or Northern Ireland.

The Policy Memorandum states:

Whether a person is ordinarily resident in Scotland will depend on their individual circumstances. Broadly speaking, a person is ordinarily resident in a place if they live there on a settled basis, lawfully and voluntarily.2

Notice to be given on receipt of application

Section 3 of the Bill inserts a new section in the GRA 2004, and provides for the Registrar General for Scotland to give notice to the applicant of the following:

That the application has been received.

The reflection period has begun, and the date that period ends. The reflection period is 3 months, beginning with the day the Registrar General gives notice.

Whether, if the application were granted, it would be a full or interim GRC.

Any statutory declaration or evidence the applicant would have to give about whether the applicant is in a marriage or civil partnership in order for the Registrar General to issue a full GRC rather than an interim GRC.

Information as to the effect of a GRC.

The Registrar General must not determine the application unless, after the end of the reflection period, the applicant confirms they wish to proceed.

The application is treated as withdrawn, if, after two years from when the reflection period ends, the applicant has neither given the Registrar General written notice of their wish to proceed, nor otherwise withdrawn the application.

Issues raised in the consultation

The consultation sought views on the requirement for applicants to go through a period of reflection for at least three months before obtaining a GRC.1

Of those who supported a statutory declaration-based system:

they did not agree there was a need for a three month reflection period before obtaining a GRC, because many trans people will have been aware of their gender, and 'reflecting' on their situation for all of their lives

there is no equivalent period in place for changing other forms of identity documentation

the need for a statutory declaration in front of a Notary Public was considered a sufficient requirement to underline the gravity of the decision

the three month reflection period implies that trans people cannot be trusted to make their own informed decisions.

Of those who opposed a statutory declaration-based system:

The three month reflection period is considered a tacit acknowledgement that some people will change their minds. This was often connected to a view that the reflection period should be longer than the three months proposed, or that it would be unnecessary if applicants were required to spend a longer period living in their acquired gender.

It is not clear how someone would be able to prove they had reflected.

The three month reflection period is too short, and does not reflect the magnitude of a legal gender change, particularly for young people.

Grounds on which an application is granted

Section 4 of the Bill inserts a new section in the GRA 2004 and provides that the Registrar General must grant an application for a GRC, if:

The application includes a statutory declaration that they:

are aged at least 16

were born or adopted in Scotland or are ordinarily resident in Scotland

have lived in the acquired gender 'throughout the period' of three months, ending with the day the application is made

intend to continue to live in the acquired gender permanently.

The applicant must also provide a statutory declaration regarding whether they are in a marriage or civil partnership.

A statutory declaration is an existing feature of the process for obtaining legal gender recognition. It is a formal statement that "something is true to the best of the knowledge of the person making the declaration." The statutory declaration will be made in the presence of a notary public (most solicitors in Scotland are notaries public) or a justice of the peace.1

If these conditions are not met, the Registrar General must reject the application.

Issues raised in the consultation

The consultation sought views on the requirement for applicants to live in their acquired gender for three months before applying for a GRC.2

Of those who supported a statutory declaration-based system:

The shortening of the current two-year timescale for receiving a GRC was often described as representing a significant improvement, although many thought the proposals could and should go further and that no period of living in the acquired gender should be required.

There was concern that the description of a gender as being ‘acquired’ is in itself both wrong and offensive as it implies a degree of choice or preference that is simply not the case.

It was not clear whether this would require the applicant to make any change at all to their outward appearance or lifestyle and whether people would effectively be expected to perform a role in public, based on how they dressed or acted. It was seen as demeaning and potentially harmful, and that many trans people may not be able to live in their acquired gender because of fear of discrimination or concern for their safety.

There was concern how applicants might be required to provide evidence of living in their acquired gender for three months.

Of those who opposed a statutory declaration-based system: