The Scottish Parliament's casework service: understanding the hidden work of MSPs

This research looks at how MSPs deal with cases brought to them by constituents. It concludes that this often hidden work constitutes a substantial, publicly-funded advice service. It was conducted as part of SPICe's Academic Fellowship programme.

About the author

Dr Chris Gill is a Senior Lecturer in Public Law in the School of Law at the University of Glasgow. Before joining the university, he worked in regulatory and ombudsmen services. His research has focussed on the design and operation of the administrative justice system.

Dr Gill has been working with the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) as part of its Academic Fellowship programme. This aims to build links between academic expertise and the work of the Scottish Parliament.

The views expressed in this briefing are the views of the author, not those of SPICe or the Scottish Parliament.

What this briefing does

This briefing summarises the findings of a research project investigating how MSPs and their caseworkers deal with cases brought to them by constituents.

The research involved interviewing MSPs and their caseworkers to collect both quantitative and qualitative information about their casework, as summarised in the Methodology section.

A sample of 10% of MSP offices (13 out of 129) took part in the research. This included a mix of:

different geographical locations;

urban and rural constituencies and regions;

list and constituency MSPs;

political parties.

A summary of the sample can be found in the annex.

This briefing presents the findings of the research in six sections:

Section 1: The nature of MSP casework. This section explores the number of cases dealt with, how they are raised, what constituents are hoping to achieve, and what the cases are about.

Section 2: The MSP’s role in casework. This section considers how MSPs perceive the casework role, the differences between how different MSPs work, the types of actions taken in responses to cases, the limitations MSPs perceive they have in helping their constituents, and the issue of referrals between elected representatives.

Section 3: The outcomes of casework. This section looks at how quickly cases were closed, what the typical outcomes of cases were for constituents, examples of successful and unsuccessful casework, and the value of the casework service both for constituents and for broader public policy and public service delivery.

Section 4: The caseworker’s role. This section sets out the skills needed to conduct the caseworker role, their training needs, the IT systems they use, and the overall resource devoted to casework.

Section 5: Perceptions of the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) and the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman (SPSO). This section explores how SPICe and SPSO were perceived by MSPs and their staff.

Section 6: Potential improvements to the casework service. This section considers a range of measures that could enhance the casework service, including more resources, more support for induction and training, more dedicated casework advice, and greater ownership by the Scottish Parliament of casework.

The report ends with a summary of the findings and a set of recommendations about how the MSP casework service could be developed in future.

Summary of findings

This research investigated how MSPs deal with cases brought to them by constituents. It involved interviewing MSPs and their caseworkers. Ten per cent of MSPs (13 out 129) took part in the research.

The nature of casework

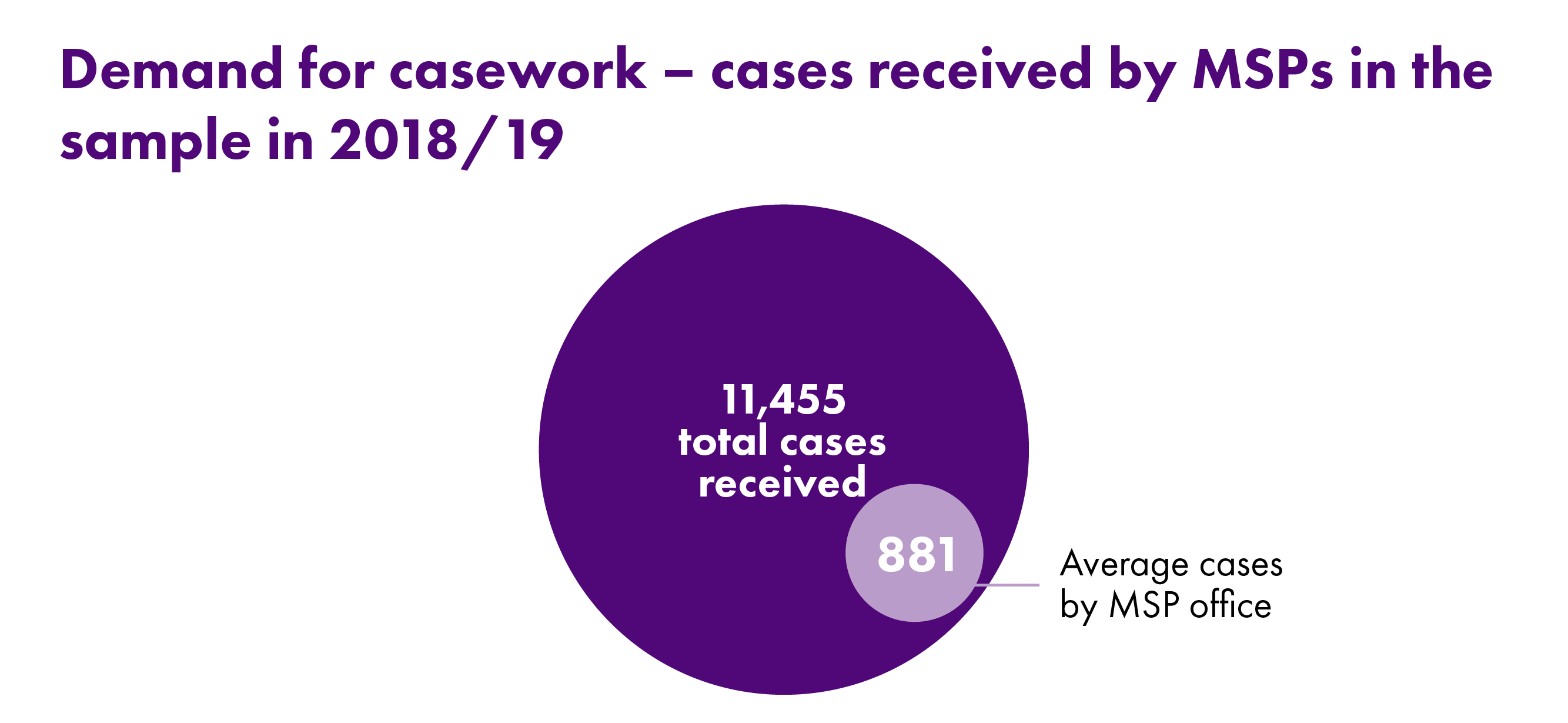

The research found that casework has developed into a sizeable publicly-funded advice service, with MSPs receiving an average of 880 cases a year. Cases ranged from minor (“poo and potholes”) to very serious, with the top three subjects of complaint being health, housing, and transport.

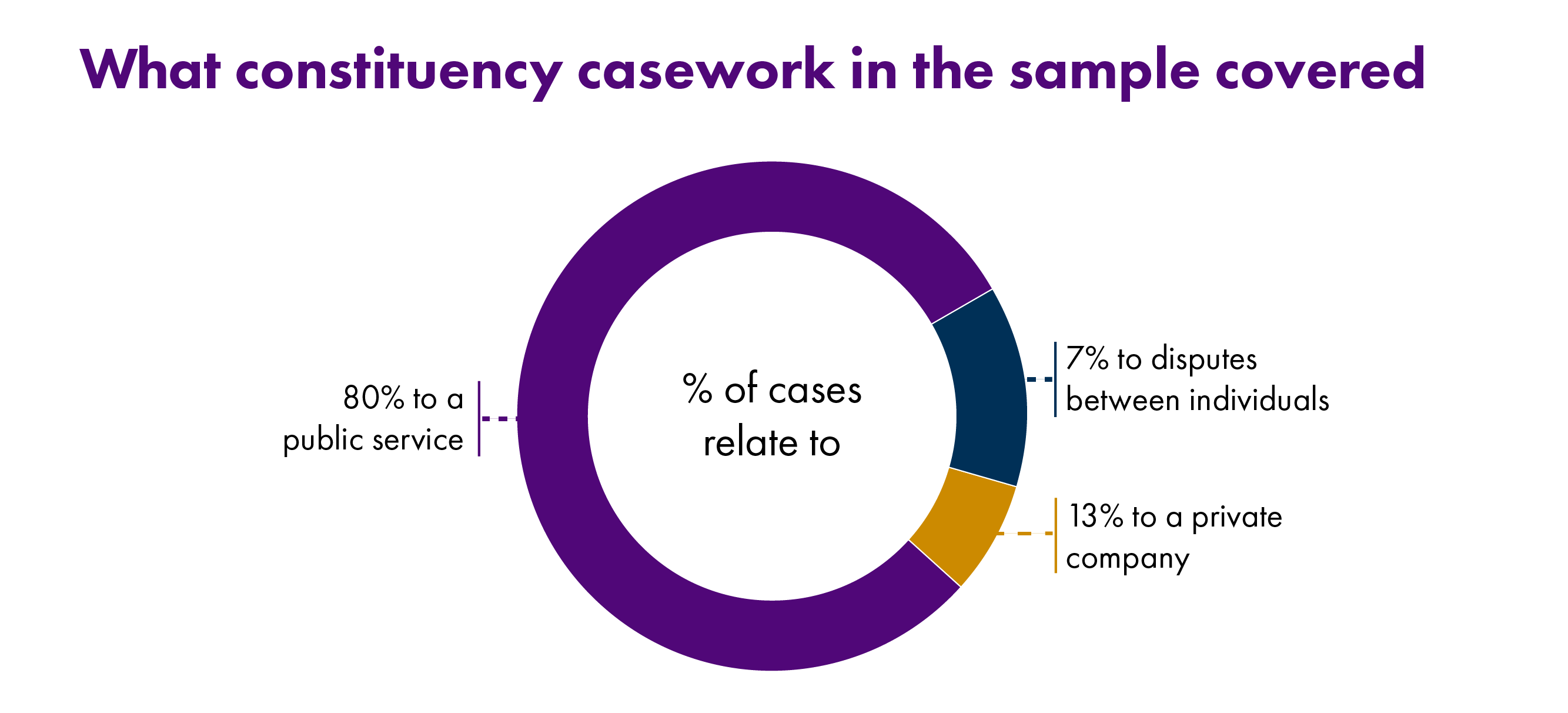

Eighty per cent of cases were about a public body, 13% about a private company, and 7% about civil disputes.

Constituents used the casework service for various reasons, including:

as a last resort;

because MSPs were more visible and accessible than other services;

because MSPs were perceived as independent and informal; and

because of a belief that MSPs could use their influence to resolve cases.

How MSPs perceive the casework role

MSPs thought that casework was crucial to the work of the Scottish Parliament. What MSPs did with cases depended on the circumstances of the case. Some MSPs took a cautious approach, largely relaying the views of constituents to other organisations, while other MSPs were more likely to advocate for their constituents.

There were a number of perceived limitations on MSPs’ ability to conduct casework, including resource pressures, lack of expertise, a lack of formal power, legislative limitations, and the unrealistic expectations of constituents.

Cases were sometimes referred between list and constituency MSPs and more often between MSPs and MPs. However, rules around referral were unclear and not always adhered to.

Casework outcomes

The outcome for constituents was usually that their situations improved as a result of contact with an MSP. Numerous examples of successful case resolutions were reported.

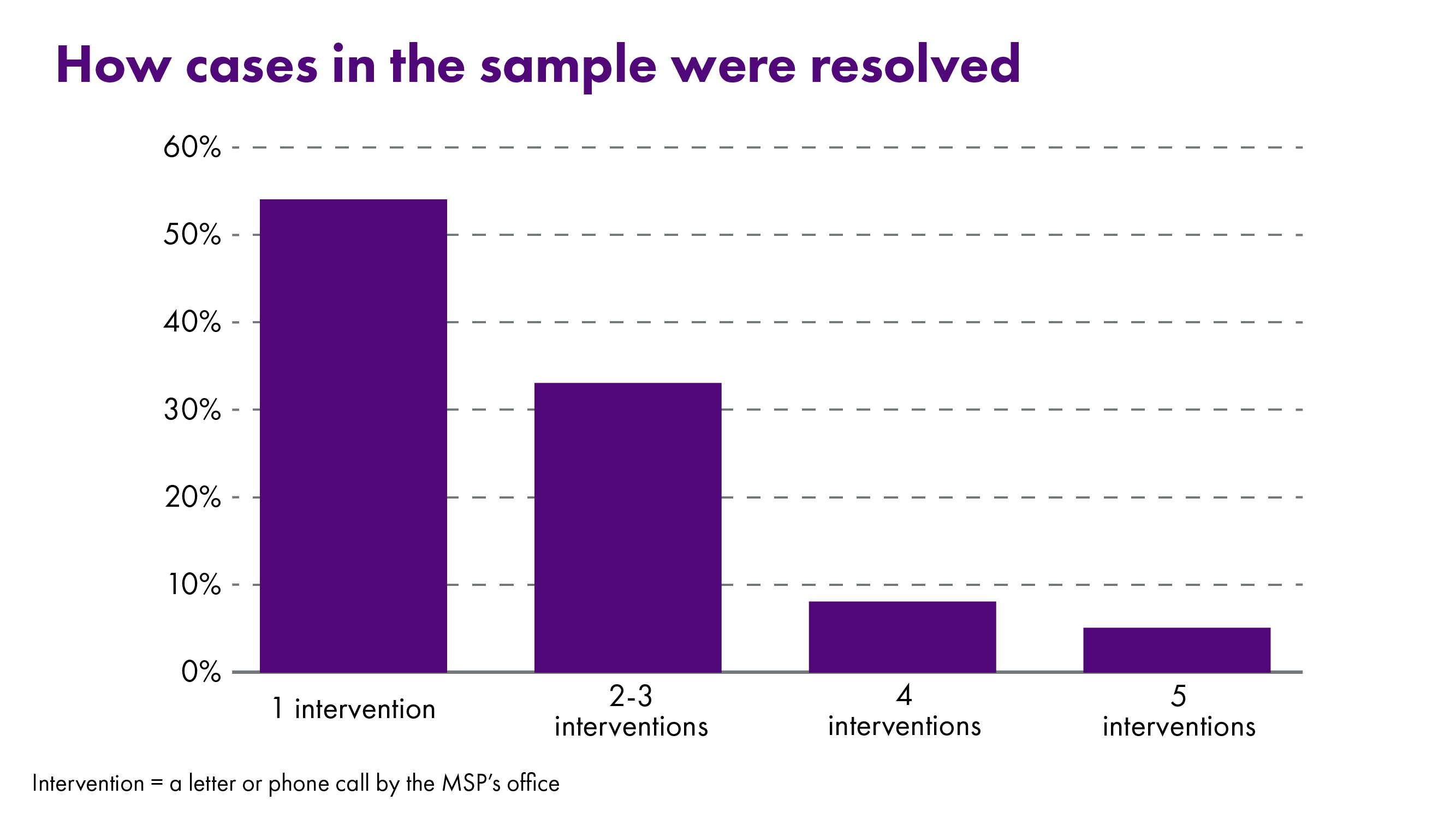

The average time to close a case was 6 weeks. Most cases (56%) were closed after a single intervention by the MSP, with 33% closed after 2-3 interventions, and 13% requiring 4 or more interventions.

Even where a positive outcome was not possible, MSPs provided value by making people feel heard. In addition, casework had broader benefits, such as:

allowing MSPs to represent local issues more effectively,

highlighting failures in policy implementation,

helping shape policy positions,

pressuring public bodies to deal with systemic issues, and

enhancing legislative scrutiny.

At the same time, there was a perception that not all MSPs had the same level of engagement with casework, and that the service could be variable.

The caseworker role

Being a caseworker is a challenging, multi-faceted, and skilful role. The skills required include empathy, understanding, patience, tenacity, interpersonal skills, good organisation, good research skills, and political awareness.

Some caseworkers felt isolated in their work and that there was insufficient support and training available for them. An average of 1.4 (full time equivalent) members of staff were employed to deal with casework in each MSP office.

Perceptions of the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) and the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman (SPSO)

Both SPICe and the SPSO provide services that MSPs can use to support constituency casework. The research asked about experiences of using these services.

There was a unanimous view that SPICe provided outstanding support to MSPs. However, some respondents were keen for SPICe to provide more directive advice, while others suggested there was a need for greater clarity on the extent to which SPICe was a resource that could be used to support casework.

Views on the SPSO were mixed. MSPs preferred to deal with cases directly and suggested that a referral to the SPSO would be rare. Some felt that the SPSO could be helpful, but others believed its restricted jurisdiction and long timescales did not meet the needs and expectations of constituents.

Areas for development

There were several areas in which MSPs in the sample believed their service could be enhanced. The strongest theme was a view that the Scottish Parliament could take more ownership of the casework function and provide more support and training for the caseworker role. The perception was that casework was an a-political role and that the quality of the casework service ultimately reflected on all politicians and the institution of the Scottish Parliament itself.

Conclusion

The casework service delivered by MSPs amounts to a substantial, publicly-funded advice service for citizens. If the volume of cases reported here is replicated across all Members, MSPs could be expected to deal with 106,613 cases annually and to employ over 180 caseworkers. This briefing demonstrates the value of this hidden work, but also suggests that we need to know more about potential variations in how it is delivered. There are also opportunities for casework to be used systematically to inform public policy.

Recommendations

The Scottish Parliament should consider:

Recommendation 1: reviewing and enhancing the induction, training, and ongoing support provided to MSPs and caseworkers in relation to casework.

Recommendation 2: creating a network or forum for caseworkers, where issues of common interest and best practice could be discussed.

Recommendation 3: investigating the feasibility of making casework data publicly available as a source of intelligence for policymakers, public service providers, and the Scottish Parliament.

Recommendation 4: clarifying SPICe’s role in relation to supporting MSPs with casework and outlining the types of cases and issues on which it is and is not available to advise.

Recommendation 5: re-issuing guidance on transfer of cases between constituency and regional MSPs and between MSPs and MPs.

Methodology

An email was sent to all MSPs by SPICe asking them to participate in the research. This was followed up by an email invitation from the researcher. In addition, the researcher’s personal contacts provided introductions to several MSPs who took part. As a result, the sample was based on convenience sampling and participants self-selected into the research.

13 MSP offices took part in the research. See the annex for a breakdown of their characteristics.

The fieldwork had two aspects. A semi-structured interview was conducted with each MSP, which lasted between 30 minutes and 1 hour. This was followed by an interview with the MSP’s caseworker (in some cases several caseworkers and/ or the office manager) which lasted around 1 hour. This interview began with a structured section, consisting of 14 questions which asked caseworkers for quantitative information. The rest of the interview involved qualitative questions relating to the caseworker’s role.

Quantitative information displayed in this briefing is based on self-reports and estimates provided by respondents. In some cases, such as in relation to the overall number of cases received, the estimates provided were based on information derived from computer databases. In other cases, respondents were asked to provide estimates based on their general perceptions of their casework. The data therefore has the limitations normally associated with self-reported data.

It should be noted that a random sample would be required to draw statistically valid conclusions about the wider population of MSPs. However, given that the sample is spread across geography, party gender, and MSP type, as set out in the annex, the sample is nevertheless useful in pointing to some broad trends amongst MSPs generally.

Figures are reported to the nearest whole number.

All interviews were professionally transcribed and subjected to qualitative thematic analysis using Nvivo computer software. Research participants were provided with an opportunity to comment on a draft of this briefing.

Section 1: The nature of MSP casework

This section looks at the following issue

What is casework?

In this study, casework is defined as communications from constituents which required a problem-solving response on the part of the MSP to a particular issue.

Thus, casework was distinguished from individuals raising general matters of policy and from mass-campaigning correspondence (such as e-petitions).

… anything where people write to me where they expect me to do something for them or at least give them a considered response, I would class as casework.

MSP 5

How many cases do MSPs receive annually?

In total, the 13 MSP offices included in this research reported receiving 11,455 cases in the preceding year, an average of 881 cases each a year.

There was a significant distinction between list and constituency MSPs in terms of case receipts. List MSPs received between 100 and 346 cases a year (on average 184 cases), while constituency MSPs reported receiving between 800 and 3,000 cases a year (on average 1,317 cases).

Some MSPs believed that there had been an increase in casework over time, such that what had begun as an informal way of helping people who happened to ask for help, had “developed now into a rather more sophisticated machine” (MSP 1).

You know, email didn’t exist effectively in 1999… and I think email has led to an exponential increase in the number of enquires you get... So, the whole pattern of demand for the casework has changed enormously in 20 years.

MSP 12

What are the cases about?

MSPs said that constituents raised a very wide variety of issues.

The variety of stuff that comes forward is mindboggling. You just never know what’s going to hit your desk. I couldn’t even list them.

MSP 1

The merits and relative seriousness of these cases varied considerably. Some related to relatively minor issues (“poo and potholes”) while, at the other end of the scale, major unremedied injustices were being raised. Most constituents raised genuine issues and, even where they objectively lacked merit, there was usually a reason why someone felt aggrieved.

…someone will come in with a horrendous problem, and then somebody else will come in complaining about dog dirt.

MSP 9

In terms of the subject matter of casework, there was some variation between offices, although, overall, the most common issues were:

Health (1)

Housing (2)

Transport (3)

Utilities (4)

Social care (=5)

Education (=5)

Agriculture, land, forestry (=5)

Environment (=5)

Across the sample, 80% of cases related to a public service, 13% to a private company, and 7% to disputes between individuals (such as civil legal disputes).

How do individuals raise their cases?

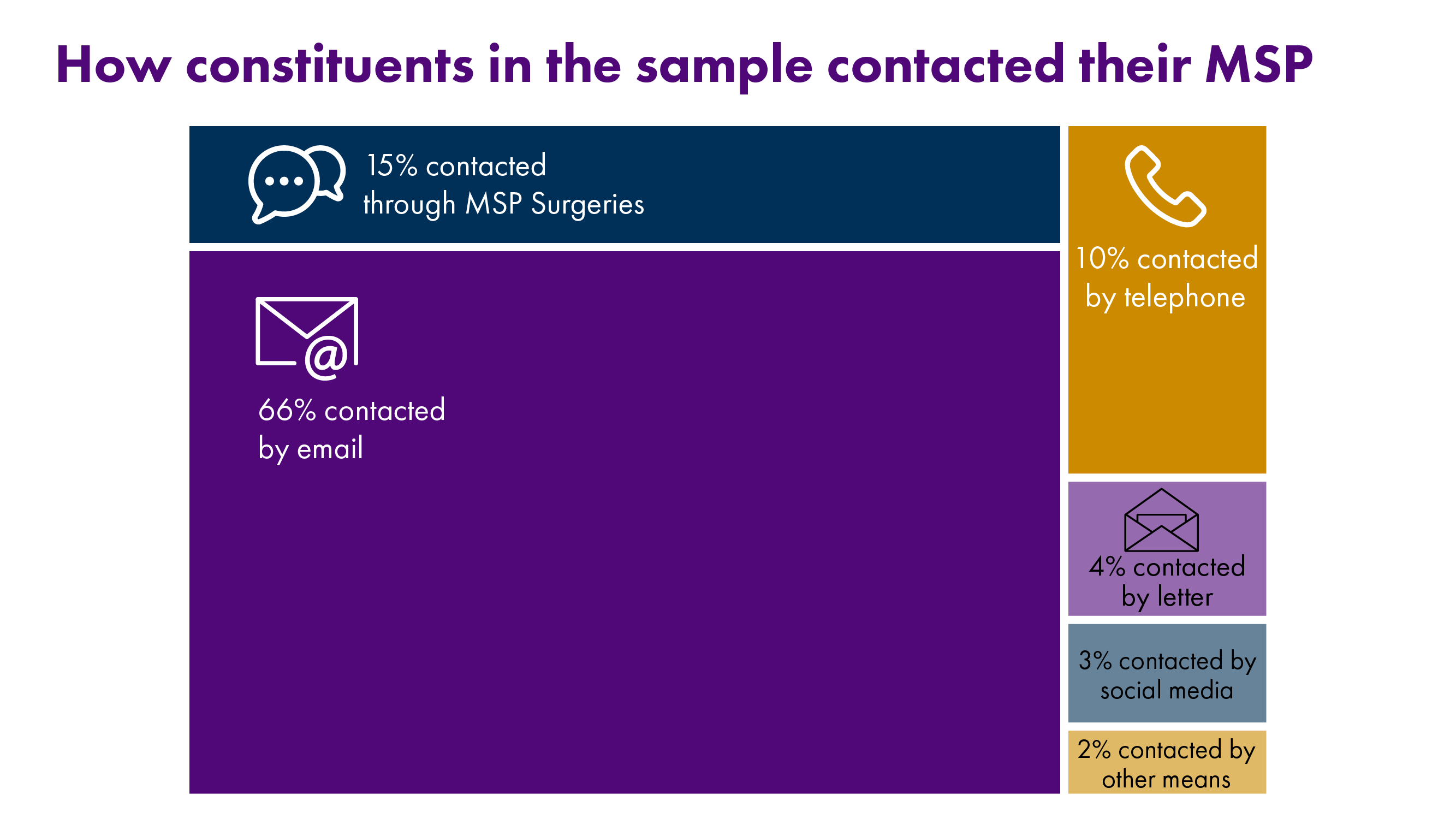

There were wide variations within the sample in how individuals raised issues with MSPs. Overall, 66% of cases were submitted by email, 15% in the course of MSP surgeries, 10% by telephone, 4% by letter, 3% through social media, and 2% by “other means”.

There was some debate in relation to the value of surgeries. Some MSPs felt that these were now largely symbolic and not a particularly useful way of dealing with casework.

I tend not to do as many surgeries as some of these folk – they’ll sit in an empty hall for an hour and think that’s a surgery… one person will show up – and it’s somebody that you know already that just wants to say hello.

MSP 6

Others argued that surgeries remained important in ensuring that MSPs were accessible to all and in providing a direct route to speak to an MSP. For them, being able to speak directly to an elected representative was one of the main ways in which MSPs could make constituents feel heard and valued.

I think that open surgeries are still very important to do… making yourself available is, I believe, a strong part of the democratic process.

MSP 1

There was significant variation in terms of the number of surgeries held, with the lowest number being 4 a year and the highest number being 173 a year. List MSPs held fewer surgeries than constituency MSPs: the former held an average of 9 surgeries a year, while the latter held an average of 68 surgeries.

Why do constituents approach MSPs?

Respondents said there was a wide range of reasons why constituents chose to approach an MSP rather than seek help from another source or public service:

wishing to raise a political point;

the belief that an MSP could pull strings/ use their influence;

the need to be heard;

an altruistic desire to ensure that their problem was not experienced by others;

the perception that the MSP was independent from the body complained about;

the MSP was seen as being less formal, more approachable and as a local person;

local word-of-mouth that the MSP was effective;

because they had tried everything else and the MSP was a last resort;

MSPs were more visible and accessible than other sources of help or information;

because they could not deal with the complexity of engaging with public services;

because the MSP’s politics were shared by the constituent; and

because the MSP had shown an interest in the issue the constituent wished to raise.

People want to be listened to, want their voice to be heard. And I think there is something in going to see an elected representative, that even if nothing happens, even if you don't get any result, you feel that you’ve sort of fed back into the sort of political machine, the government, you know, the people who are responsible.

MSP 7

They think it's less official in some ways. They don't like going to organisations, but dealing with an MSP or a councillor or whoever, they feel as if that's their local person, so that person is there to help them specifically.

MSP 10

Section 2: The MSP's role in casework

How did MSPs view their casework role?

MSPs were unanimous on the importance of their casework role. For some, it was their most important role, while for others it was important but needed to be held in balance with other roles (such as committee work and parliamentary activity).

Now there’s a whole wider question as to whether you want, as it were, 129 people who can do that [devote themselves to casework] in Scotland or 129 people who’ve also got a grip of what the national education policy looks like, you know, what needs to happen with economic growth, whether we are really tackling climate change.

MSP 4

Despite its importance, MSPs considered that casework was “hidden work” (MSP 13) which was not recognised fully by members of the public, political parties or the Scottish Parliament. This was despite the fact that several MSPs believed there had been a very significant increase in casework over the years since the creation of the Scottish Parliament.

The importance of casework for MSPs was partly that it was a practical way of helping people, and this was why they had entered politics in the first place. It was also a way of achieving more direct results than the much slower process of helping people through legislative change.

It’s one bit of it that I feel I’m doing something really positive and I get satisfaction from… sorting out injustice and ensuring that people understand how to get through what is often a bureaucratic nightmare for people.

MSP 8

Some MSPs actively enjoyed casework, whilst a small minority saw it more as “a grind”. Regardless of the level of personal satisfaction that derived from casework, all MSPs thought that casework helped them to fulfil their roles as MSPs by:

informing them in relation to local issues that mattered to their constituents;

helping them understand policy implementation and what was not working well; and

allowing them to provide feedback to public bodies and policymakers and seek changes in policy or service delivery.

.... your casework often informs what you do in the Parliament as well, because it kind of flags up where the issues are happening with people. So, one, I think it's your role to help people, and as a representative, but also, the information that then feeds back to you.

MSP 9

You do get a good impression, area by area… what the priorities are, where there are grits in the cog. And on a bigger issue, you can put it all together. I meet, for example, every quarter with the chief executive of [local authority]and I can bring these up.

MSP 1

For most MSPs, there was a need to balance personal casework involvement with other activities, as casework could end up taking over. Effective delegation was seen as crucial, as well as ensuring personal involvement at key stages of a case.

What were the differences in how MSPs approached casework?

MSPs stressed that the action they take on a case depended on the circumstances. Nonetheless, it was clear that some saw the MSP’s role as being one that was very powerful and proactive, while others stressed that the role was in fact highly constrained and limited.

Some also raised questions around their role, noting that there was a lack of clarity over what their powers were and what they could expect from public bodies.

One of the great difficulties with casework is getting constituents to understand that as an MSP you have pretty much no direct authority over any of the agencies... it is about appealing to the goodwill of those organisations.

MSP 3

I don’t care if I annoy the chief executive of the health board or the chief executive of the council or some social worker who thinks they’re god. My job is to fight the case and I’ll fight it tooth and nail until I can take it no further.

MSP 12

Some MSPs saw their role as conveying the views of their constituents to decision makers, and some saw the role as ensuring that correct processes had been followed. Others said the MSP’s role also involved challenging laws and processes where they had an iniquitous impact on an individual. Generally, these roles were not perceived as mutually exclusive, although there was a sense that MSPs brought different approaches to their work.

Some emphasised the former aspects, while others talked more about “fighting” for constituents and encouraging public bodies to consider the “moral” aspects of cases, as well as their technical and legal aspects.

So, you know, some of the cases I deal with around persuading the system that, actually, taking that stance might be legally correct but morally there’s an issue there. And actually, are you really wanting to behave in a way that is not... I wouldn’t go as far as morally reprehensible, but it certainly begs the question.

MSP 8

Differences in fundamental outlook on casework were also reflected in terms of how MSPs perceived constituents’ complaints. Some adopted a “customer is always right” approach while others took a more cautious view, where they made no assumptions about the merits of the case.

I'm always very careful in letters that I put out from my office, that we phrase what is being told to me as, ‘my constituent tells me’,… not that it's a matter of fact.

MSP 13

I work on the basis that the constituent is always right. And even when I doubt that myself, I will still raise what they ask me to do.

MSP 7

In addition to any action that might be taken, MSPs felt that a key role for them was simply to listen and make sure that the constituent had felt heard. This provided a route to relay experiences to people seen as having political power and a say in government.

Nobody’s heard them. You know, they’ve stood in the middle of a housing office at the council, or whatever, and by their interpretation they’ve been poorly treated, homeless, treated as dirt basically. Whether that’s true or not, they certainly feel it within themselves. Coming here, just being able to unburden is a huge thing.

MSP 1

Generally, helping constituents to articulate their problems and helping them cut through bureaucracy and complexity were seen by MSPs as core elements of their role.

What do MSPs do with casework?

What MSPs did with cases depended on the nature of the case. Some required no more than writing to the body concerned, some required signposting to other agencies, while others required more proactive advocacy on the part of the MSP’s office.

So, you play a multiple role. You are… a source of information, advice, advocacy and signposting but you’re also a sort of friend… they just want some support, some moral support.

MSP 12

Most cases (54%) were resolved after a single intervention (e.g. writing a letter or making a phone call) by the MSP’s office. In 33% of cases, 2-3 interventions were required, while 4 interventions were required in 8% of cases, and more than 5 interventions occurred in 5% of cases.

There was therefore a distinction between routine cases that required little effort to bring to a conclusion and a smaller number of more complex cases that required more protracted intervention.

Signposting was an important function, with MSPs describing working in partnership with other services. This approach recognised that others had more knowledge and resources to help the constituent, depending on the issues.

That said, most MSPs said they would always try to help the constituent directly where that was possible. Where referrals were made, the most common were to third sector organisations, the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman (SPSO), or another government body.

Often, it’s a case of putting people in front of those who are better skilled than we are. We’re not experts at everything....

MSP 1

How do MSPs handle political differences with constituents?

Referrals were also made to other MSPs where, for example, the issue was political and there was disagreement between an MSP and constituent. There was some disagreement within the sample about an MSP’s responsibility to advocate for a constituent where the issues were political and went against the MSP’s publicly adopted policy positions.

I take the judgement that rather than annoying someone, and just coming back and getting into an argument with them… actually saying to them, do you know what, there's someone else who is elected to represent you, who covers this region, who shares your views in this campaign, and on this issue.

MSP 7

[When a constituent raises] something you're not sympathetic to, like someone says, I'm paying too much tax, I'm not happy about that. You kind of still have to give them some voice, you might say, my constituent tells me, or my constituent would like you to know… you try and give them voice, regardless.

MSP 9

What do MSPs do to resolve cases?

In most cases, routine casework was delegated to caseworkers. Nevertheless, many MSPs stressed the importance of personal contact with a constituent and would make sure that they were personally involved at key stages.

And I think that’s quite important, to have that face to face… it's also a much more personal experience for your constituent as well, they meet their representative, their representative commits to act on their behalf, their representative then sends them a letter to evidence they’ve acted on their behalf, and then, another letter to show the result of that action.

MSP 13

MSP 3 referred to actions being in a “pyramid” with writing to public bodies being most frequent, then seeking a meeting with a public body, and finally seeking meetings or raising matters with Ministers being less frequent.

Writing to Ministers was seen as a useful way of applying additional pressure in cases that had not been resolved by other means. This was seen as a more appropriate and “behind the scenes” way of raising issues rather than using parliamentary processes or the media.

If you write to people, sometimes the things that come back can be quite helpful… even just a little bit of pressure from the Government around housing issues, or around educational issues, it's a sort of funny coincidence that you write a letter and then suddenly things that were a problem sort of get fixed.

MSP 4

How do MSPs use the parliamentary process to deal with constituents' issues?

There were a range of views in the sample about the appropriateness and effectiveness of using parliamentary and media mechanisms in relation to casework, and some examples of these being used.

But, generally, MSPs felt that using soft power was more effective because parliamentary processes and the media tended to politicise issues rather than help achieve resolution.

You can use politics, you use your contacts with ministers, you use the political system to also raise casework. And I think the test is to do it appropriately and responsibly… But I think on casework what most of us seek to do, certainly what I seek to do is to raise these things conscientiously, quietly and effectively.

MSP 4

What limitations were there on the effectiveness of the MSP's casework role?

As noted before, MSPs expressed a range of different views about their casework role. This also had an effect on how they saw the limitations of their roles.: Factors mentioned by MSPs as limiting their effectiveness in resolving their constituents’ problems included:

legislation, policies and processes that were “against” a constituent;

their lack of formal power, meaning they needed to rely on the goodwill of public bodies to reach a solution;

a lack of public resources to deliver the services required by the constituent to meet their needs;

a lack of flexibility and responsiveness on the part of public bodies;

difficult behaviour (such as being aggressive or unduly persistent) and the unrealistic expectations of constituents;

a lack of expertise on the part of the MSP, which meant challenging certain issues could be difficult; and

a history of conflict or relationship breakdown between a constituent and a public body.

We do get a response, but sometimes what’s in that response is not particularly helpful… there’s just a no and there’s no way roundabout... there’s no negotiation… not looking at the individual circumstances is a barrier. I appreciate you’re dealing with a whole country full of people, but sometimes… come on.

Caseworker 5

If you take, for example, housing… the long and the short is... they probably are in that position because there is no house in the possession of the council or the housing association to meet their needs and nothing I do is going to change that. I can’t go out and build them a house.

MSP 3

What are the issues in relation to referrals between elected representatives?

The default position in relation to list and constituency MSPs was that the MSP who had been approached would take the case on the basis of respecting the constituent’s choice.

However, there was some concern over how this worked in practice. Some constituency MSPs noted that this could lead to an “ambulance chasing” approach by list MSPs seeking constituency election. Some respondents suggested that there was a need for the rules on referrals to be re-stated and enforced more effectively.

When George Reid… was the deputy presiding officer, he produced a paper which was adopted by everybody in the Parliament outlining the principles of when an MSP takes up a case, when a list member takes up a case, to try to cut duplication and take the heat out of the situation… the Reid Principles… they haven’t changed them, they haven’t overturned them so it’s a failing of the parliamentary authorities that they’re not enforcing them.

MSP 12

Generally, there was consensus that list MSPs dealt with fewer cases. Some constituency MSPs commented that constituency MSPs were under-resourced given how many more cases they had to deal with. Some list MSPs said that, while they dealt with fewer cases, they often had more complicated cases that required more in-depth work.

In relation to reserved matters, MSPs often referred cases on to MPs in situations where UK government departments would only respond to an MP. However, this was not a strict practice.

Most MSPs discussed taking cases on even where they related to reserved matters, unless it was clear that there was nothing they could do personally.

Section 3: Outcomes of casework

How long did casework take to complete?

Respondents were asked to estimate how long, on average, cases took before they were resolved or otherwise closed. The shortest average case closure time was 2.5 weeks and the longest as 12 weeks. The average case closure time across the sample was 6 weeks.

What examples of successful casework were there?

Respondents noted that it was not always possible to resolve a constituent’s case. But, in most cases, the constituent felt that their situation had been improved as a result of the MSP’s intervention.

In order of frequency, the most common outcomes reported by respondents were that information and advice were provided to a constituent, followed by resolving cases to their satisfaction and, finally, signposting.

Well, 95 per cent of cases… we improve their situation which is sometimes as much as you can hope for… And a very small percentage, there is no solution for them.

MSP 1

Respondents gave examples of cases that had been particularly successful for the constituent:

€500 compensation for a flight cancellation;

renovations to a constituent’s house;

helping secure a care assessment for an elderly man;

ensuring a road repair was prioritised;

getting a constituent a consultant appointment;

improving provision for a child with Additional Support Needs (ASN);

helping a family living with overcrowding get a bigger house;

refund for elderly couples getting high energy bills;

faster appointment times with the NHS;

re-instatement of benefit and £3,000 back payments;

persuading a local authority not to take enforcement action over a planning matter;

ensuring a fence was built to make a garden safe for children to play in;

securing an investigation into multiple problems at a local hospital;

helping to ensure eviction action was taken against an anti-social neighbour;

policy change on business rates for nurseries;

ensuring the delivery of a care package; and

helping a student get back into university and access childcare and funding.

What kinds of cases were not resolved successfully?

MSPs said that some issues were intractable and not capable of satisfactory resolution. This was partly because MSPs were often approached as a last resort. A lack of resources, legislative and policy limitations, MSPs lacking the power to push for change, and the lack of realism on the part of some constituents were also barriers to resolution.

It's infuriating when you can't get a result for people, although that’s, I think, one of the most demoralising things about being a politician, the realisation that you actually can't help some people.

MSP 13

Examples of cases where no successful outcome was possible included:

where the underlying issue related to mental health issues;

where constituents were asking for impossible outcomes;

where services were simply not available (e.g. care packages for hospital discharge);

cases involving challenges to clinical judgement;

anti-social behaviour cases;

housing cases where limited housing is available;

where the relationship between constituent and public body had broken down;

cases where the constituent was wrong but refused to give up; and

cases where a legitimate need had been identified but no service or funding existed to meet it.

What was the value to constituents of bringing their case to an MSP?

Although MSPs did not know what constituents thought of the service, they believed that it delivered value for individuals in various ways. Particularly where constituents were vulnerable, enlisting the help of their MSP to put their case across in ways that were understood by public bodies could be useful. MSPs were often able to identify and articulate issues more clearly.

Some people write to you, emails usually, and partially because they're very emotionally involved, but partially because educationally they're maybe not as well on as they might have been, and you can actually get something which is about 12 paragraphs written as one, sometimes with no punctuation, et cetera, et cetera, and if they send that away to a lot of these organisations they get nothing back.

MSP 10

MSPs helped constituents to navigate and cut through complexity, which was seen as an increasing feature of public service delivery.

And it's one of probably the main selling points of when you go round and you tell people that if they come to you and you take an issue to a body, that that body has to reply to you… You get to cut through. So you're seen as someone who can get answers.

MSP 2

MSPs gave constituents individual attention and had a willingness to see things from their perspective.

All of them [cases] can be looked into in a way which is there to actually put the advantage on their [the constituent’s] side, as opposed to the side of bureaucracy… So, that they actually feel as if someone is working for them… So, if they’ve got an issue somebody has actually listened, and it's not just that they're sitting behind a desk and they’ve got 3,000 sheets of paper in front of them.

(MSP 10)

MSPs could also sometimes work around formal rules and positions to improve things for constituents, even where legal or procedural barriers stood in the way.

People come because you’re relatively high profile and, you know, wee Jeanie at CAB isn’t… in certain cases, we escalate things to the minister or Cabinet Secretary responsible. And as an MSP, you have access.

MSP 1

I mean, three little letters after your name are powerful when dealing with most things. You know, you can stick your nose in places where you really shouldn’t be, just because people would tell you to, it's nothing to do with you. So you are trading on your position a lot, to solve things.

MSP 9

MSPs provided a safety net and helped make sure that people did not fall through gaps left by stretched public services and advice services. Having list and constituency MSPs provided a double safety net and a degree of choice for individuals.

You find, particularly these days with public services under so much pressure, that without an MSP to go to, a lot of people would be left pretty high and dry… the role of the MSP fills a gap that needs to be filled particularly for the more vulnerable members of the community.

MSP 12

MSPs were seen to bring a degree of independence to constituents’ disputes with public bodies. This could take the heat out of disputes and provide a more solution-focused approach.

So sometimes it allows an objective person to just say, stop everybody, hang on a minute, let’s stop this back and forward of fighting and let’s look for a resolution.

MSP 6

What was the wider value of casework to public policy or public service provision?

Respondents provided examples of how cases they had dealt with had ended up having a wider influence than simply helping an individual constituent.

one MSP noted that casework had provided the initial intelligence which led to the development of a member’s bill;

casework informed legislative scrutiny;

casework informed the development of policy positions and priorities;

casework would be used in meetings with public service leaders to highlight areas that needed attention; and

casework was useful in ensuring that the public’s concerns penetrate the “bubble” of politics.

Casework is very helpful in informing you about issues that you need to highlight in the Parliament and to other organisations... So, from that point of view, it’s an invaluable source of information.

MSP 12

I'm as good as the last person I speak to. Because I can't know everything about, you know… when you get into the bubble of the Parliament, your personal experience is not always resonating with what’s happening on the streets.

MSP 9

Several MSPs suggested that, although casework currently influenced policy and parliamentary work in an instinctive way, more could be made of casework data if they were analysed systematically.

There was also a view among some respondents that casework data could be valuable for public service providers and the Scottish Parliament. This was because the data formed part of the general intelligence on what was working well and not so well in terms of public policy and its implementation. At the same time, there was concern expressed by some about how this might work in practice.

If I were the government and the local authorities, I actually would be trying to gather some of the information coming out of casework. It’s a very good proxy for how well government agencies are or are not delivering services… And I think if government and local authorities listen more to what MSPs were saying as a result of their casework, they would actually be able to more effectively address some of those systemic issues.

MSP 12

I think that would be helpful, to inform the work of the Parliament, actually, to say, hang on a second, this isn't just a local issue, we know it's happening in X, and we know it's happening here as well, so. But then, the flip side of that is, your constituents come to you and it's like going to see the doctor, there's a confidentiality there.

MSP 13

What is the relationship between casework and electoral success?

There were mixed views on whether a relationship existed between casework and electoral success. It was recognised that, often, national level issues could be more important than a reputation for being a good local MSP.

MSPs also stressed that they did not do casework for electoral reasons, but from a desire to help constituents and to fulfil their responsibilities as parliamentarians. That said, most MSPs said that having a good reputation among constituents could be helpful electorally, particularly in more marginal constituencies.

It helps a lot if you can actually help, if you can do things for people, they’ll speak well of you... Electorally, yes, it can, and if you're never seen, and nobody knows about you… there is no reason why they should vote for you anyway, sort of thing. So, electorally it can be an advantage, it should, if you do it properly.

MSP 10

In terms of the benefit to political parties, whatever, I’m not sure that there is very much to be honest. I think, you know, it’s a mistake to believe that a constituent will vote for you because you helped them... when they come to vote will vote according to what they, you know, what they believe in.

MSP 3

Section 4: The caseworker's role

What skills did caseworkers need to fulfil their roles?

There was general agreement among respondents that the caseworker role required a range of skills for which it could be difficult to recruit. MSP 1 noted that effective caseworking was “a major skill”.

I think it's very difficult to get good staff in this line of work. Because you're dealing with the public, it can be hard going, it can be long hours, it is political but it's not political because it's not party politics… So, there are big challenges, I think, in getting the right people… who are grounded, and actually want to help people, are the best kind of people to employ.

MSP 13

The skills respondents required of caseworkers included:

listening and making people feel heard

dealing with distressed individuals

being patient

tenacity

being empathetic, compassionate, and understanding

having good research skills

good communication and interpersonal skills – with public and MSP

attention to detail

a confidential approach and knowledge of data protection

organisational skills

writing skills

resilience

political awareness

passion for the work

detachment and impartiality

honesty and integrity

problem solving skills.

People who can kind of think imaginatively about stuff, and, you know, do all that kind of thing. You know, you don't want somebody who just goes through the motions, you want a fixer.

MSP 9

You need to be tenacious. It’s too easy just to write a letter to the council, get their reply and say, right, this is the reply, that’s it. We don’t do that… we need a bit of tenacity, we need a willingness to sometimes stick your neck out.

MSP 1

Empathy, understanding, patience. Really to be compassionate. You know? Have an understanding that people are in dire straits by the time they come to us. And often angry.

Caseworker 13

What training and support would caseworkers benefit from?

Some caseworkers, particularly those based outwith the Scottish Parliament building at Holyrood, felt isolated and said they did not get much support with their casework.

They noted that there would be value in having a support network with other caseworkers. This could provide moral support, camaraderie and provide a forum where practical casework issues could be discussed.

I feel quite remote from the whole... I don’t feel part of a team… to be able to, you know, share good practice. Share how do we get off the telephone from another caller. Those sorts of things would be valuable and a sense of camaraderie, you know, you’re not the only person doing this. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel would be useful.

Caseworker 5

There is probably more stuff down at Westminster I’d say… there is not really that much of a community of caseworkers, whereas there seems to be more of a community down there.

Caseworker 8

There were mixed views within the sample on whether training could adequately prepare people for the reality of casework. Some had the view that “on the job” learning was inevitable and perhaps more effective. That said, most respondents suggested that training that was specifically focused on casework would be helpful

I’m trying not to use the word statutory training but some pencilled in training as soon as people are employed would benefit them in the long run… It would save a lot of floundering around if they knew some of the signposts and some of the procedures when the MSP takes office… You’ve got to go on a firefighting course, et cetera, so why not show them how to do their job a wee bit?

Caseworker 10

I would say there’s no training. It’s got slightly better. I mean, recently I did a kind of suicide awareness course… And even the suicide awareness wasn’t quite what I thought it would be… It’s not about somebody going away and committing suicide, it’s about somebody trying to get that message across.

Caseworker 11

Even where training was available, this was described as “parliament-centric” and not accessible to all.

I’m not able to access the training that I would like to access, be that in management skills, time management skills, organisational skills, whatever… Those are all parliament-centric and there’s very little available online for me to access.

Caseworker 5

Respondents highlighted a range of areas in which training and support could enhance caseworkers’ effectiveness:

data protection

record-keeping

writing formal correspondence

signposting

managing expectations

having difficult conversations

casework training

What casework IT system do caseworkers use?

With one exception, all the offices in the sample used a commercial casework provider rather than the system supported by the Scottish Parliament. The office that used the Scottish Parliament system found it effective.

Generally, the casework systems used were seen to be effective in supporting casework delivery, but there was acknowledgement that they tended not to be used systematically to analyse statistics.

How much resource was devoted to casework within MSPs' offices?

An average of 1.4 full time equivalent staff time was devoted to casework across the sample.

Section 5: How did MSPs perceive SPICe and the SPSO

Both the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) and the Scottish Publich Services Ombudsman (SPSO) provide services that MSPs can use to support constituency casework. The research asked about experiences of using these services.

This section looks at:

How was the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) perceived?

The Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) provides a research and enquiry service to all MSPs and their staff, including those who work in regional and constituency offices. These services cover both devolved and reserved matters, but SPICe cannot provide legal advice to Members or their staff.

The service provided by SPICe encompasses support to MSPs and their staff to deal with constituency enquiries. For example, they can ask SPICe for background information about a particular constituent’s problem or what options might be available to resolve a situation.

SPICe was unanimously seen as a very effective service. Both MSPs and caseworkers emphasised the speed and high quality of the information provided in response to queries.

Well, I love the SPICe service, I think it's fantastic. I will often get quicker answers from SPICe than I will from the Scottish Government… They're very approachable, and they're really helpful with all my enquiries.

MSP 13

I think they're excellent. I think, I'd be surprised to find anyone who’s got a bad word to say about them, to be honest. Very professional, meticulous, they always adhere to any deadline that I've put to them.

Caseworker 12

There were two areas in which some respondents suggested change might be required. In some cases, caseworkers wanted more direction from SPICe, going beyond providing background research. Others suggested that more clarity was required in relation to SPICe and the role it had in supporting casework. It was not currently always clear what SPICe could and could not do in terms of providing casework support.

Sometimes I wish they would just tell you what they think you should do… sometimes I think, please just tell what you think because I’m stuck here.

Caseworker 1

I don’t think there’s any role for SPICe to be involved in individual cases. I don’t think that would be appropriate. But certainly, policy issues highlighted as a result of casework I take up with SPICe and it’s a first-class service.

MSP 12

While always being mentioned in the context that SPICe provides an excellent service, respondents noted other, smaller issues that they had when dealing with SPICe. These included:

variability between individual researchers;

the service was less accessible by telephone;

occasionally providing information that lacked depth and detail;

providing responses that were a bit narrow; and

a lack of regular briefings on casework.

How was the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman (SPSO) perceived?

The Scottish Public Services Ombudsman (SPSO) provides the final stage for complaints about public service organisations in Scotland. It also carries out independent reviews of decisions that councils make on community care and crisis grant applications. The SPSO is also in the process of developing its role as Independent National Whistleblowing Officer (INWO) for the NHS in Scotland.

Referring an issue to the SPSO is an option for MSPs and constituents where it has not been possible to resolve the matter with a public body directly.

The Ombudsman was used as a point of referral by MSPs, but was perhaps used less than might be expected. This was particularly so given that, in a number of cases, issues appeared to be intractable and incapable of resolution through the intervention of the MSP.

There were some quite critical views of the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction among respondents. There was a perception that the timescales and the narrowness of the matters the office could look at were reasons why the Ombudsman is used less often than it otherwise might.

I think the issue with it is, it's quite a sort of legalistic process, and you know, their interest is on people’s statutory duties, and sort of whether they’ve followed the rules. I find, most times when things have gone wrong, it's actually about human error… And I think the Ombudsman doesn’t really capture those things... And I think people find that frustrating.

MSP 7

I think people expect a lot more from it, I think they expect them to kind of force authorities to do things, and the like. But no, I find them reasonably effective. And I think if you go to them with the right cases, then they're fine.

MSP 9

We very rarely use the ombudsman… on occasion we have suggested that an ombudsman might be the best way to go, but that's fairly rare actually

MSP 10

A few respondents in the sample had quite negative views of the ombudsman.

I have used the Ombudsman in the past. I have to say, I’m thoroughly disenchanted with the Ombudsman Service… The problem with the Ombudsman is what the Ombudsman can look at is so narrowly drawn, it’s all about failures and process, and to say if you’re not happy go to the Ombudsman, you know, is a total shrug off, you know, don’t bother us, and it’s a complete cop-out.

MSP 5

I don’t know a political colleague across the parties who bothers with the ombudsman… I think if the Scottish system works to a large extent it’s because you can get something sorted out in the ways which we’ve described [political influence, contacts, using influence behind the scenes]. But if I was waiting for the ombudsman to sort things out I would never… I’d just abolish that whole office and start again, you know… I just don’t think it works… that’s very firmly my view based on experience.

MSP 4

Section 6: Potential improvements to the casework system

There was an emphasis among constituency MSPs on the relative lack of resources available for casework.

There was a view that this was now a significant operation, yet was run on a shoestring. MSPs were sanguine about the possibility of more resources being available but nonetheless pointed out that this was a limitation. Several said that MPs tended to be better resourced.

I think that there are an increasing number of people using the service. We are not as well-resourced as our Westminster colleagues who get multiples of what we get.

MSP 1

I don’t think it’s like at crisis point or anything, but, you know... it is tight. I mean, the number of staff that we can have, given the resources we’ve got, does make doing the job quite, sort of, tight.

MSP 3

A number of MSPs suggested that support for new MSPs could be enhanced. Some of that could be done by political parties prior to election to help prospective candidates prepare for roles in casework. But, mostly, given the apolitical nature of casework, this was seen as a job for the Scottish Parliament.

I think it's something for Parliament to be doing. I do believe that, because I don't think that casework should be party political… I think the work of MSPs in their constituency reflects the Parliament as a whole…. And I think where people have a poor quality experience with casework, and don't feel properly represented, then that’s, you know, a sort of plague on all politicians, and all political parties, and on the system.

MSP 7

Yes, parties actually should, because Parliament can’t do it until you're elected, by which time you're at the coalface, so parties should give much more thought to the fact that someone will be representing them as a, you know, a member of their party and they should give them training basically. So, I think parties are very important, but once you are here, I think Parliament could do more actually.

MSP 10

New MSPs can be faced with instant demands from constituents and could easily become overwhelmed by casework. Interviewees thought support in relation to caseworker recruitment and training, casework systems, and an overview of the casework role, its responsibilities and its limitations would be helpful for new MSPs. Some of this support was available informally through colleagues but was not very consistent.

I know a lot of my colleagues kind of floundered the first couple of weeks, because nobody told them how to do it… So, yeah, it's definitely something the Parliament could help with in supporting MSPs. And I don't think that just relates to when you first become an MSP, I think there should be some element of continuing professional development there. Because there are still some cases to this day where I think, I don't know what to do with this, you know.

MSP 13

I think that there's more the Parliament could do, you know, initially, to help people understand that [the MSP role]. And bluntly, explaining to people that it's quite acceptable, at least to give it a try, you know…, it's almost sort of, not like an idiot’s guide to being an MSP, but it's that sort of thing.

MSP 7

While the Scottish Parliament provided helpful inductions to parliamentary processes, MSPs perceived a gap in relation to induction and ongoing support for casework.

But my feeling, still, is that there are inductions and help with parliamentary process, you know, how you lodge your question, how you do your expenses, how long you speak in a debate, how the parliamentary week works. I don't think there is anything that teaches people how you deal with someone coming round the door and saying, I need your help.

MSP 9

In addition to induction, training, and provision of greater ongoing support, some MSPs noted that more specific resources to provide advice on difficult casework would be beneficial. Some MSPs considered, however, that if additional resources were to be provided for casework these should go to caseworkers in “the trenches” (MSP 1).

I also think they could have a pool of, I don't know, they could have a pool of sort of casework trainers, and send them out, sort of across the region. And also, as a stopgap right at the beginning, to have some people on hand who could offer advice, not about every single case, but particular cases.

MSP 7

So I've got a really difficult constituent at the moment, and my office are trying to find out what the rules are around about how you stop representing somebody. This woman is mentally unwell, and I can't represent her, she's quite dangerous… So, yeah, definitely Parliament could help more with that.

MSP 13

Generally, as noted above, MSPs in the sample tended to agree that casework was an apolitical activity, funded by the Scottish Parliament. As a result, the view was that the Scottish Parliament should take more ownership regarding support for casework. An inadequate casework service could create a reputational risk to the Scottish Parliament and a missed opportunity to ensure the legitimacy of Parliament as a public institution.

Greater ownership could involve:

providing more financial resources for casework;

providing more information resources and casework advice;

providing more training for caseworkers and MSPs;

making more use of data resulting from casework.

An important example mentioned by most MSPs related to problems that could occur when the Parliament goes into dissolution prior to a general election. Here casework may simply disappear as there is no process to transfer it to a newly elected MSP. This was not acceptable from the perspective of individual constituents who needed help. This indicates that some kind of mechanism for dealing with handovers could improve the service for the constituent.

If Parliament feels that it should be running a caseworker system in the same way that Citizens Advice does or whatever organisation does, then I don't see any objection to that, you wouldn't. And I suppose my worry is when individuals are doing it, you know, if I get beaten next time round and when a new MSP comes in, there's no handover. And so I think if a parliament is about constituency, constituency MSPs looking after constituents in the constituency, then the current set-up is not really in line with that where every five years… you know, I could be looking after a case, and if I lose and the new person comes in, they might not have any interest in that case, no history in that case, and that person would have to explain it all again to that person, there's certainly no continuity through election.

MSP 2

If you lose an election all the staff lose their jobs and everything… There’s no capability just to say, right, these are our active files, carry on. So, I think from that point of view the constituent doesn’t get a good deal.

MSP 1

Conclusions

The Scottish Parliament, its MSPs, and their staff, deliver an important public service by helping individuals to resolve their problems.

This work is largely hidden and is under-appreciated, particularly given the evidence presented in this briefing that it delivers tangible benefits to individuals in need of help and advice. It also delivers broader benefits in informing the development of public policy and public service delivery.

While the casework service is in many ways valuable, it is unclear whether this value is delivered consistently across the board. A limitation of the present research is that the 13 MSP offices that took part volunteered to do so. It might therefore be expected that those with more interest in casework participated. There was certainly a view within the sample that the approach to casework varied considerably between MSP offices and that the commitment to casework they showed might not be replicated across the board.

In effect, the Scottish Parliament’s casework service now consists of a relatively sizeable publicly-funded advice service for citizens. If the volume of cases in the sample was replicated across the board, MSPs could be expected to receive 106,613 annually and to devote over 180 caseworkers to the task of giving advice to citizens in needi. This is a substantial endeavour and yet at present:

We know little about the way the service is delivered across the board and the extent to which it is successful in meeting citizens’ needs.

The standards which citizens can expect are unclear, as is the extent to which the service represents good value for money relative to the resources expended on it.

Some of the broader value of the service is limited by a lack of aggregate data on casework being made publicly available in a way that might inform policy and public service delivery.

Thus, there are two principal conclusions that arise from this research:

MSPs and their staff perform a valuable public service, which supplements and, in some cases, plugs gaps in the provision of advice and support services. The public benefit that is derived from this work deserves to be recognised more broadly, at the same time as being supported more effectively by the Scottish Parliament;

While this research provides strong indications that the casework service provided by MSPs is valuable, there is currently limited (if any) publicly available data. It is unclear to what extent variations in quality and consistency of casework exist, with the effect that some individuals may receive a better service than others, which in turn has potential implications for the way in which all politicians and the Scottish Parliament itself, are viewed by the public.

Recommendations

The Scottish Parliament should consider:

Recommendation 1: reviewing and enhancing the induction, training, and ongoing support provided to MSPs and caseworkers in relation to casework.

Recommendation 2: creating a network or forum for caseworkers, where issues of common interest and best practice could be discussed.

Recommendation 3: investigating the feasibility of making casework data publicly available as a source of intelligence for policymakers, public service providers, and the Scottish Parliament.

Recommendation 4: clarifying SPICe’s role in relation to supporting MSPs with casework and outlining the types of cases and issues on which it is and is not available to advise.

Recommendation 5: re-issuing guidance on transfer of cases between constituency and regional MSPs and between MSPs and MPs.

Annex - Characteristics of the MSPs in the sample

| MSP type | |

|---|---|

| Constituency | 8 |

| List | 5 |

| Gender | |

|---|---|

| Male | 7 |

| Female | 6 |

| Political party | |

|---|---|

| SNP | 5 |

| Conservative | 4 |

| Labour | 3 |

| Liberal Democrat | 1 |

| Green | 0 |

| Independent/no affiliation | 0 |

| Electoral region | |

|---|---|

| South Scotland | 5 |

| Mid Scotland and Fife | 2 |

| Highlands and Islands | 2 |

| North East Scotland | 1 |

| Central Scotland | 1 |

| Lothian | 1 |

| Glasgow | 1 |

| West Scotland | 0 |