UK-EU Future Relationship Negotiations: Fisheries

This briefing examines the UK-EU future relationship negotiations on fisheries. It sets out the context of the negotiations in terms of international commitments for shared management of fish stocks and the negotiating positions of the UK and EU. The briefing also explores the elements of fisheries agreements using examples of EU agreements with other coastal states and highlights the economic, cultural and social importance of fisheries to Scotland and the UK. Cover Photo by Richard Bell on Unsplash

Executive Summary

The EU and UK have set a deadline of 1 July 2020 to conclude and ratify a new fisheries agreement. These negotiations began on 2 March 2020 but have been delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides an overarching legal framework for the negotiations on a future UK-EU fisheries agreement. This includes obligations to fish sustainably using the best available science and to cooperate on the management of fish stocks that migrate across international boundaries.

The UK and EU negotiating positions set out opposing aims. The UK seeks an agreement based on the EU's relationship with other coastal states with annual negotiations on access to waters and fishing opportunities. It also seeks to to abandon the principle of sharing fishing opportunities on the basis of historical catches. The EU seeks to maintain existing access to the UK's waters and quota shares.

Fishing's contribution to the UK's economy is very small in monetary value compared to other sectors of the economy, leading to industry concern of concessions being made on access and quota shares in the future relationship negotiations. However, the social and cultural value of fishing is central to the identity of many coastal communities.

The UK is subject to several commitments to fish sustainably and protect marine ecosystems. Meeting these commitments will require cooperation between the UK and the EU to jointly manage shared stocks. Disagreement may lead to overfishing.

A UK-EU fisheries agreement is likely to be a 'framework agreement', which sets out the basic parameters under which cooperation will take place, leaving the details to future negotiation.

A fisheries agreement may comprise the following key elements:

a set of shared principles and objectives;

a process for agreeing quota shares and other fisheries measures in relation to the conservation and management of shared stocks;

a procedure for agreeing access for EU vessels in the UK's waters and vice versa and any transitional provisions;

provision for scientific cooperation to ensure a science-based approach to fisheries management and possibly the protection of the marine environment;

cooperation on the monitoring, control and enforcement of fishing vessels and mutual recognition of associated regulations. This could also include the sharing of vessel tracking data;

institutional arrangements to oversee the implementation of the agreement, common conservation and management measures, address disagreements and provide a forum for discussion;

a dispute settlement procedure and mechanism for independent scrutiny of each party.

Both parties have advantages with regards to negotiating a new fisheries agreement. The UK has the advantage of controlling access to some of the most productive fishing grounds in Europe, whilst the EU has the advantage of the reliance of the UK on selling its catch tariff-free to EU markets.

Reaching an agreement will require compromise and each party will have to carefully balance the needs of their fishing and processing sectors with wider economic aims.

The EU has a number of existing fisheries agreements with third countries such as Norway, Iceland, Greenland and the Faroes. This briefing discusses these agreements as potential models for a UK-EU fisheries agreement.

The European Council is responsible for approving and ratifying an agreement. The European Parliament must also consent to most agreements concluded by the EU. In the UK, ratification of international treaties is a prerogative of the UK government.

The Constitutional and Reform and Governance Act 2010 codifies a constitutional convention whereby treaties must be laid before the UK Parliament for at least 21 days before ratification takes place. International relations are a reserved matter; the Scottish Parliament has no direct involvement in treaty ratification.

The UK Secretary of State has expressed the UK Government's intention to actively engage the devolved Administrations in the negotiations.

If no agreement is reached, the UK as an independent coastal state may set unilateral conservation and management measures. However, they must meet the underlying obligation to ensure that the maintenance of the living resources is not endangered by overexploitation. The UK would also have to give due regard to the rights of other coastal states, meaning that it cannot ignore the fact that other states may also be exploiting the same stock.

Author contributions

This briefing was led by Professor James Harrison, Professor of Environmental Law at the University of Edinburgh with contributions from SPICe researchers. The work was conducted with Professor Harrison through the SPICe Framework Agreement for Research Services in Relation to Brexit.

James Harrison teaches on a number of international law courses, including specialist courses in the international law of the sea, international environmental law, and international law for the protection of the marine environment. His research interests span these areas, considering how the legal rules evolve and interact, as well as examining how international law and policy influences the domestic legal framework.

Key Terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) | An area of sea that extends up to 200 nautical miles from territorial sea baselines of a state, or up to an agreed maritime boundary with neighbouring coastal states. |

| Flag state | A flag state is the location of where a commercial ship is registered. Flag states have the legal authority and responsibility to enforce regulations upon vessels that are registered under its flag. |

| High seas | Any area of ocean, seas and waters outside of national jurisdiction. |

| Total Allowable Catch (TAC) | TAC, also known as 'fishing opportunities' are catch limits (expressed in tonnes or numbers) that are set for many commercial fish stocks. |

| Relative stability | TACs are shared between EU countries in the form of national quotas. For each stock a different allocation percentage per EU country is applied for the sharing out of the quotas. This fixed percentage is known as the relative stability key and is based on historical fishing patterns in a reference period from 1973 - 1978. |

| Zonal attachment | The principle that fishing opportunities should be allocated based upon the temporal-spatial distribution of fish stocks, rather than on the basis of historical catches by vessels from a particular country. |

| Coastal State | Coastal States are universally understood to be States with a sea-coastline. A coastal State's jurisdiction relates to its own maritime zones, and encompasses the resources and activities therein. |

| Gross Value Added (GVA) | GVA is a measure of the total value added by all industries in the economy, but does not include the value of taxes or subsidies on products (such as VAT and excise duties), which are paid by the consumer. |

| Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) | MSY is the largest average catch or yield that can continuously be taken from a stock under existing environmental conditions. |

| Bycatch | Unwanted fish and other marine creatures trapped by commercial fishing nets during fishing for a different species. |

| Blim | 'Blim' is a spawning stock biomass reference point in fisheries science identified as the stock size below which recruitment (the addition of young fish to the population) has a high likelihood of being “impaired.” If stock biomass falls below Blim, ICES advises action to restore biomass, such as further reduction or suspension of targeted fishing. |

1. Background: the Common Fisheries Policy and Brexit

Fishing was a major issue during the campaign leading up to the June 2016 referendum on whether the United Kingdom (UK) should leave the European Union (EU). There was a feeling amongst many people involved in the UK fishing industry that their interests had been neglected during the establishment of the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) during the late 1970s and early 1980s, and subsequent reforms to the CFP had not altered their dislike of EU regulation, which they believe to be overly bureaucratic and disadvantageous to the UK.

Now that Brexit is a reality, the task has begun of deciding what the future of UK fisheries should look like once it formally “takes back control”1 of its waters at the end of the transition period. The EU negotiates fishing opportunities and access to waters with independent coastal states as a single entity, and whatever future fisheries policy looks like in the UK, it will involve some continued engagement with the EU, given that a large proportion of UK fish stocks are shared with the EU. Negotiations for a new relationship agreement between the EU and the UK commenced on 2 March 2020 and fisheries is a key component of those talks.

According to the non-binding Political Declaration agreed between the EU and the UK at the same time as the Withdrawal Agreement, “The Parties will use their best endeavours to conclude and ratify their new fisheries agreement by 1 July 2020 in order for it to be in place in time to be used for determining fishing opportunities for the first year after the transition period.” (Article 74) Yet, fisheries are expected to be one of the most challenging aspects of the UK-EU negotiations, as confirmed by Michel Barnier, the Chief EU Negotiator, in his announcement at the end of the first round of negotiations on 6 March.2The challenges of reaching a fisheries agreement by 1 July have also been highlighted by the House of Lords European Union Committee, in particular given that this deadline includes approval of the new agreement through relevant constitutional processes (see section 9 below), meaning that any agreement must be forthcoming by early June.3Further rounds of negotiations were planned throughout March, April and May (see Table B), although this timetable has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Rounds 2020 | Start Date | AM/PM | Finish date | AM/PM | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | Monday 2 March | PM | Thursday 5 March | AM | Brussels |

| Round 2 | Wednesday 18 March | PM | Friday 20 March | PM | London |

| Round 3 | Monday 6 April | AM | Wednesday 8 April | PM | Brussels |

| Round 4 | Monday 27 April | PM | Thursday 30 April | PM | London |

| Round 5 | Wednesday 13 May | AM | Saturday 16 May | AM | Brussels |

On 15 April, David Frost, the UK's Chief negotiator announced that negotiating rounds lasting a full week following the structure in Table B would take place via videoconference on the following dates:

week commencing 20 April

week commencing 11 May

week commencing 1 June

This briefing looks at the issues that are likely to be addressed during those negotiations, the procedures that apply to the negotiation of a new agreement and the broader legal context for the conservation and management of shared fish stocks.

2. Relevant rules of international law relating to the conservation and management of shared fish stocks

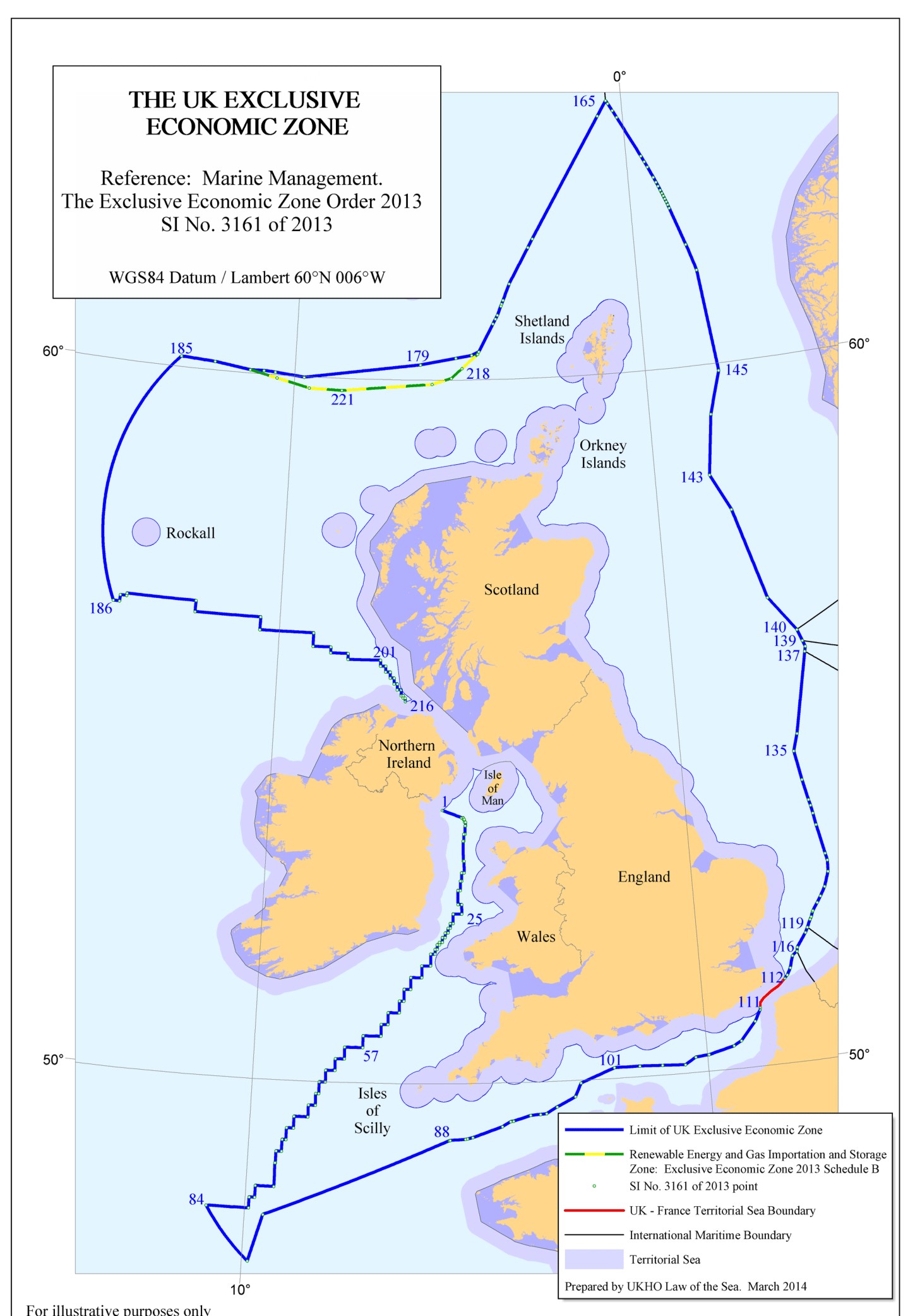

As a matter of international law, every coastal state has rights relating to fishing taking place within their exclusive economic zone (EEZ), which is an area that extends up to 200 nautical miles from territorial sea baselines or up to an agreed maritime boundary with neighbouring coastal states. The area beyond the EEZ is known as the high seas and it is subject to freedom of fishing, meaning that all states have a right for vessels flying their flag to fish on the high seas, subject to their obligations to ensure the conservation and management of fish stocks.

The United Kingdom has one of the largest EEZs in the North-East Atlantic and it shares maritime boundaries with Ireland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. In practice, the EU exercises exclusive competence over the regulation of fishing on behalf of its Member States and therefore it acts as a coastal State when negotiating with other states and other fishing entities such as the Faroe Islands and Greenland (see Section 8 below). 1

The rights and obligations of the coastal state in relation to fishing in its EEZ are set out in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)2. For stocks that are solely within the EEZ, a coastal state has exclusive sovereign rights over the conservation and management of marine living resources, meaning that it may decide upon the total allowable catch (TAC) of a stock, as well as other conservation and management measures that apply to that stock. In doing so, the coastal state must take into account “the best scientific evidence available to it” (UNCLOS, Article 61(2)) and it is under a duty to ensure that fishing does not lead to overexploitation of the stocks.

The coastal state is also under an obligation to promote the optimum utilisation of fish stocks, meaning that if its own fishing fleet cannot catch the entire TAC, the coastal state must grant access to other states to allow them to catch any surplus. Whilst these provisions are expressed as obligations for the coastal state, UNCLOS expressly recognises that coastal states have a significant amount of discretion in determining the surplus and in deciding how to allocate any surplus to other states.

Access may be granted under arrangements agreed in an international treaty or access may be granted on an ad hoc basis. Should any foreign fishing vessels be granted access, they must comply with the conservation and management measures set by the coastal state.2

At the same time, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea has emphasised that other states, particularly the flag state , continue to have obligations to control their vessels whilst fishing in the EEZ of another state. This means that the flag state may be required to cooperate with the coastal state in the investigation of any of its vessels suspected of breaching coastal state laws. 4 The flag state may also, if appropriate, take direct action against the vessel concerned, such as suspension of its licence to fish.

In practice, many fish stocks move across international boundaries (so-called shared stocks – see Table C) and so there may be more than one state with fishing rights. It is estimated that the EU and the UK share more than 100 fish stocks, some of which also straddle onto the high seas.5 UNCLOS imposes an obligation on states to cooperate in the conservation and management of such shared stocks2 and so relevant states should attempt to reach an agreement on how those stocks should be managed.

| Type of shared stock | Description |

|---|---|

| Transboundary stock | A stock which occurs within the exclusive economic zones of two or more coastal states |

| Straddling stock | A stock which occurs both within the exclusive economic zone and in an area on the high seas beyond and adjacent to that zone |

| Highly migratory stock | A stock of a species listed in Annex I of UNCLOS, including tunas, marlins, sail-fishes, swordfishes, sauries, dolphins, oceanic sharks, and cetaceans; typically these stocks move both through the exclusive economic zone of a number of states and through the high seas |

| High seas stock | A stock that is located exclusively beyond national jurisdiction, i.e. beyond the exclusive economic zone of coastal states |

The provisions on cooperation in the management of shared stocks recognise that negotiations may take place either directly or through a relevant regional fisheries management organisation.

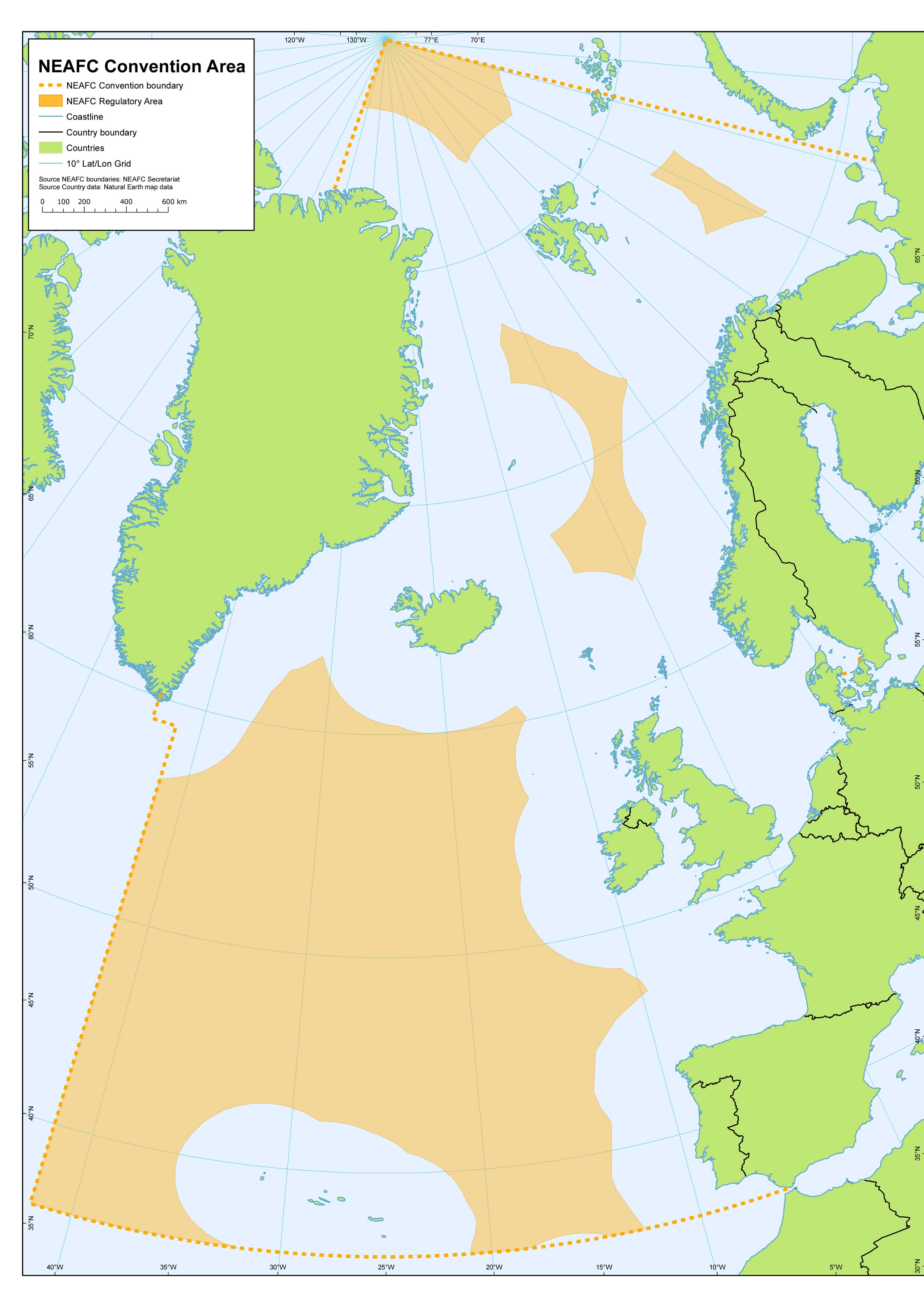

A regional fisheries management organisation (RFMO) is an international organisation established by an international treaty and conferred with powers to adopt conservation and management measures for stocks falling within its mandate. An important RFMO which could play a role in determining conservation and management measures for shared stocks in the context of UK-EU future relations is the North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC), which was established by the Convention on Future Multilateral Cooperation in the North-East Atlantic in order to promote “the long-term conservation and optimum utilisation of the fishery resources in the Convention Area, providing sustainable economic, environmental and social benefits.” (Article 2). The UK plans to join NEAFC, as well as several other RFMOs, at the earliest opportunity.7

NEAFC is given powers to adopt conservation and management measures concerning fisheries, including, but not limited to, the regulation of fishing gear, closed seasons, closed areas, the establishment of TACs and the regulation of fishing effort. (Article 7). Whilst the Convention Area covers both waters within and beyond national jurisdiction in the North-East Atlantic, NEAFC may only apply conservation and management measures to waters within national jurisdiction with the express consent of the coastal states concerned.8

Therefore, in practice, NEAFC tends to focus on high seas stocks (particularly deep sea species) and straddling fish stocks (e.g. mackerel, herring, blue whiting, and Rockall haddock) and its recommendations are generally addressed at fishing that takes place on the high seas, leaving coastal states to determine appropriate measures for fishing that takes place within national jurisdiction.

It follows that cooperation between the UK and the EU on shared stocks is likely to be pursued in a bilateral context, apart from those stocks which may be shared with a third state, such as Norway. See further discussion below in the section on ‘What happens if there is no agreement?’

3. The Withdrawal Agreement and the Political Declaration

3.1 The Withdrawal Agreement and fisheries relations during the transition period

The Withdrawal Agreement between the UK and the EU, published on 17 October 2019, sets out arrangements for fisheries during the transition period. As part of the terms of agreement, the UK continues to be bound by the Common Fisheries Policy until the end of the transition period, i.e. until 31 December 2020. In particular, the agreement maintains the relative stability keys for the allocation of fishing opportunities, meaning that the fixed proportion of quotas assigned to EU Member States will remain in place during the transition period.

During the transition period, the UK will also remain bound by any international agreements entered into by the EU and the UK is not able to participate in the work of any bodies set up by such international agreements unless it does so in its own right or it is included in the delegation of the EU.

In this context, the fisheries provisions of the Withdrawal Agreement expressly provide that the EU may exceptionally invite the UK to attend international consultations and negotiations on fisheries matters “with a view to allowing the UK to prepare for its future membership in relevant fora” (Article 130(2)).

Also, the agreement does allow the UK to negotiate, sign and ratify new international agreements provided that they do not enter into force or apply during the transition period (Article 129(4)). This will allow the UK to prepare for leaving the CFP by negotiating agreements with relevant actors, including the EU and other North-East Atlantic coastal states.

3.2 The Political Declaration and the future fisheries relationship

The joint Political Declaration published alongside the Withdrawal Agreement provides greater insight into how future relationship negotiations will be conducted.

Section XII of the Political Declaration, on fishing opportunities makes two high-level points:

the UK will become an independent coastal state

a new fisheries agreement on access to waters and quota shares will be established.

The Political Declaration sets a deadline to conclude and ratify a new fisheries agreement by 1 July 2020.

The most controversial text in the joint Political Declaration is paragraph 75 which appears to link access to waters to wider negotiations on the future UK-EU economic relationship. It states:

Within the context of the overall economic partnership the Parties should establish a new fisheries agreement on, inter alia, access to waters and quota shares.

The European Council published a declaration on the Withdrawal Agreement and Political Declaration which provided further details on its position. It made two key points with regards to fishing:

that "the European Council will demonstrate particular vigilance ... to protect fishing enterprises and coastal communities."

that "a fisheries agreement ... should build on, inter alia, existing reciprocal access and quota shares."

The catching sector of the UK fishing industry responded with a caution that the UK Government should not maintain existing arrangements on access to waters in exchange for wider economic ambitions in negotiations on its future trading relationship with the EU. For example, the Scottish Fishermen’s Federation said:

The industry’s priority has always been taking back control of decision-making over who catches what, where and when in our waters, so that we can end once and for all the grossly unfair situation where 60% of our stocks are taken, gratis, by boats from other EU nations.

That would mean the UK becoming a fully independent Coastal State with its own seat at all the relevant international fisheries negotiations from December 2020 on and regaining its proud status as one of the world’s major fishing nations. Negotiations over trade terms for seafood products would follow on from this.

Any linkage between access and trade contravenes all international norms and practice and is simply unacceptable in principle. Therefore we have asked the Prime Minister for assurances that the establishment of a new fisheries agreement as laid out in the Brexit arrangements does not imply that EU vessels will be guaranteed continued access to our waters in return for favourable trade terms.1

Since the publication of the Withdrawal Agreement and Political Declaration, the EU position has provided further statements providing a more explicit link between access to waters and the future UK-EU economic relationship. This is discussed further in sections 4 and 8 of this briefing.

4. The EU and UK negotiating mandates

4.1 The EU Negotiating Mandate

On 25 February 2020, the EU published its negotiating guidelines. The guidelines made it clear that its objective in negotiations for a future trade deal is for a continuation of the status quo in terms of access to waters by UK and EU vessels. They state that the provision on fisheries should:

...aim to avoid economic dislocation for Union fishermen that have been engaged in fishing activities in the United Kingdom waters.

To reach this objective, the provisions on fisheries should uphold existing reciprocal access conditions, quota shares and the traditional activity of the Union fleet...1

According to the EU, failing to secure an agreement on fisheries would have wider implications for the negotiations as a whole. Bearing in mind the aim of reaching agreement on fisheries by 1 July 2020, the mandate is explicit that the outcome of the negotiations on fisheries access and quota shares will determine the wider terms of the economic partnership:

The terms on access to waters and quota shares shall guide the conditions set out in regard of other aspects of the economic part of the envisaged partnership, in particular of access conditions under the free trade area as provided for in Point B of Section 2 of this Part [on establishing a Free Trade area].

The EU is seeking a permanent arrangement based on the, "existing reciprocal access conditions, quota shares and the traditional activity of the Union fleet" as part of the overall future relationship.

The EU's negotiating mandate proposes a framework for the management of shared fish stocks and common technical and conservation measures for EU boats in UK waters and UK boats in EU waters.

The mandate also proposes that the management of fish stocks should be underpinned by the long-term conservation and sustainable exploitation of marine biological resources.

On the day that Round 2 negotiations were due to begin (18 March 2020), the European Commission published a draft legal agreement. This document translates the European Commission's negotiating mandate into legal text. An accompanying press release explained that the document:

...translates into a legal text the negotiating directives approved by Member States in the General Affairs Council on 25 February 2020, in line with the Political Declaration agreed between the EU and the UK in October 2019.2

The EU's draft legal text proposes to generally maintain the current arrangements on access to waters and quota shares under the EU's Common Fisheries Policy (CFP).

The text would establish a reciprocal right of access for UK and EU fishing vessels to fish in each others' waters.

Article FISH.10: Reciprocal access to waters

Each Party shall authorise the fishing vessels of the other Party to engage in fishing activities in its waters in accordance with the provisions set out in ANNEX FISH-3.

The authorisation shall cover access to pursue fishing of stocks subject to joint management and all other stocks.

Specific conditions set by each Party when authorising access to its waters shall be directly related to the fishing opportunities established pursuant to Article FISH.11 [Fishing opportunities].

ANNEX FISH-3 lists the fish species to which fishing vessels will have access:

Outside of 12 nautical miles this includes all fish species.

Within 12 nautical miles the annex defines certain geographies and species.

The EU's draft text proposes annual negotiations on "fishing opportunities", i.e. the total amount of fish that can be collectively caught by the UK and EU fleet.

Article FISH.11: Fishing opportunities 1. By 31 January of each year, the Parties shall set the agenda for consultations with the aim to agree on fishing opportunities in Union and United Kingdom waters for the following year.

The provisions for these quota negotiations are set out in more detail, including:

The Parties shall establish... the fishing opportunities for the following year... in accordance with the allocation set out in ANNEX FISH-2.

ANNEX FISH-2 does not yet explicitly set out an allocation sharing the total allowable catch out between the UK and EU. But a note in the annex states "It is planned to uphold here existing quota shares". It is assumed this refers to the fixed "relative stability key" which is the existing way that total allowable catch is shared out between Member States. In other words, the EU's text proposes that the UK's existing share of quota under the CFP is maintained.

4.2 The UK Negotiating priorities

The EU's negotiating mandate is at odds with the UK's approach to the future relationship negotiations. The UK's approach paper emphasises the fact that the UK will become an "independent coastal state" after the transition period and says:

The UK will no longer accept the ‘relative stability’ mechanism for sharing fishing quotas, which is outdated, based on historical fishing activity from the 1970s. This means that future fishing opportunities should be based on the principle of zonal attachment, which better reflects where the fish live, and is the basis for the EU’s fisheries agreement with Norway.

The UK Government is silent on trying to reach a fisheries agreement by 1 July 2020. The UK Government's negotiating priorities sets out its aim for a separate agreement on fisheries covering access to fish in UK and EU waters, fishing opportunities and future cooperation on fisheries management. Specifically, the UK Government would like to agree to annual negotiations on reciprocal access to UK and EU waters and on total allowable catches.

It states:

The UK is ready to consider an agreement on fisheries that reflects the fact that the UK will be an independent coastal state at the end of 2020. It should provide a framework for our future relationship on matters relating to fisheries with the EU. This would be in line with precedent for EU fisheries agreements with other independent coastal states. Trade in fisheries products should be covered by the CFTA [Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement]. Overall, the framework agreement on fisheries should provide a clear basis for an on-going relationship with the EU, akin to the EU’s relationship with other coastal states, one that respects the UK’s status as an independent coastal state and the associated rights and obligations that come with this.

Specifically the UK negotiating priorities sets out the following aims:

Annual negotiations on access to the parties’ exclusive economic zones and fishing opportunities (total allowable catch and shares); with fishing opportunities based on the principle of zonal attachment, negotiated annually based on the best available science for shared stocks provided by the International Council for Exploration of the Seas (ICES);

EU vessels granted access to fish in UK waters are required to comply with UK rules and would be subject to licensing requirements including reporting obligations;

the UK is open to the creation of a forum for cooperation on wider fisheries matters outside of annual negotiations including cooperation on matters such as data-sharing, science and control and enforcement;

provisions for sharing vessel monitoring data and information to deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing;

Arrangements for dispute settlement along the lines common to other fisheries agreements, including provision for the suspension of the agreement on fisheries if necessary.

the UK will be negotiating separate fisheries framework agreements with other independent coastal states, notably Norway;

the UK Government recognises the interests of the devolved administrations in this area and is committed to working with them in the consideration of any agreement.

Speaking in Greenwich on 3 February 2020, the Prime Minister said:

We are ready to consider an agreement on fisheries, but it must reflect the fact that the UK will be an independent coastal state at the end of this year 2020, controlling our own waters. And under such an agreement, there would be annual negotiations with the EU, using the latest scientific data, ensuring that British fishing grounds are first and foremost for British boats.

When giving evidence to the House of Lords EU Energy and Environment Sub-Committee on 4 March 2020, the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs further confirmed the UK Government’s intention to reduce foreign access to UK waters, particularly within the territorial sea, which he indicated should be “reserved predominantly for our own vessels.”1

Further consideration of the role of fisheries in the negotiations can be found in a House of Commons Library insight published on 12 February 2020 on "Brexit next steps: Fisheries."

5. What is at stake for the UK?

5.1 The economic value of fishing in the UK & Scotland

The Scottish fishing fleet accounts for a significant proportion of the UK's fishing activity. In 2018, Scottish vessels landed 446 thousand tonnes of sea fish and shellfish with a gross value of £574 million. Landings by Scottish vessels accounted for 58 per cent of the value and 64 per cent of the tonnage of all landings by UK vessels.1

However, the risk for UK fisheries in the future relationship negotiations is the economic value of fishing in the context of the wider economy. As discussed in section 4, the EU has explicitly linked the outcome of the fisheries negotiations to wider negotiations on the future UK-EU economic partnership. Specifically the EU mandate refers to Point B of Section 2 aimed at "establishing a free trade area ensuring no tariffs, fees, charges".

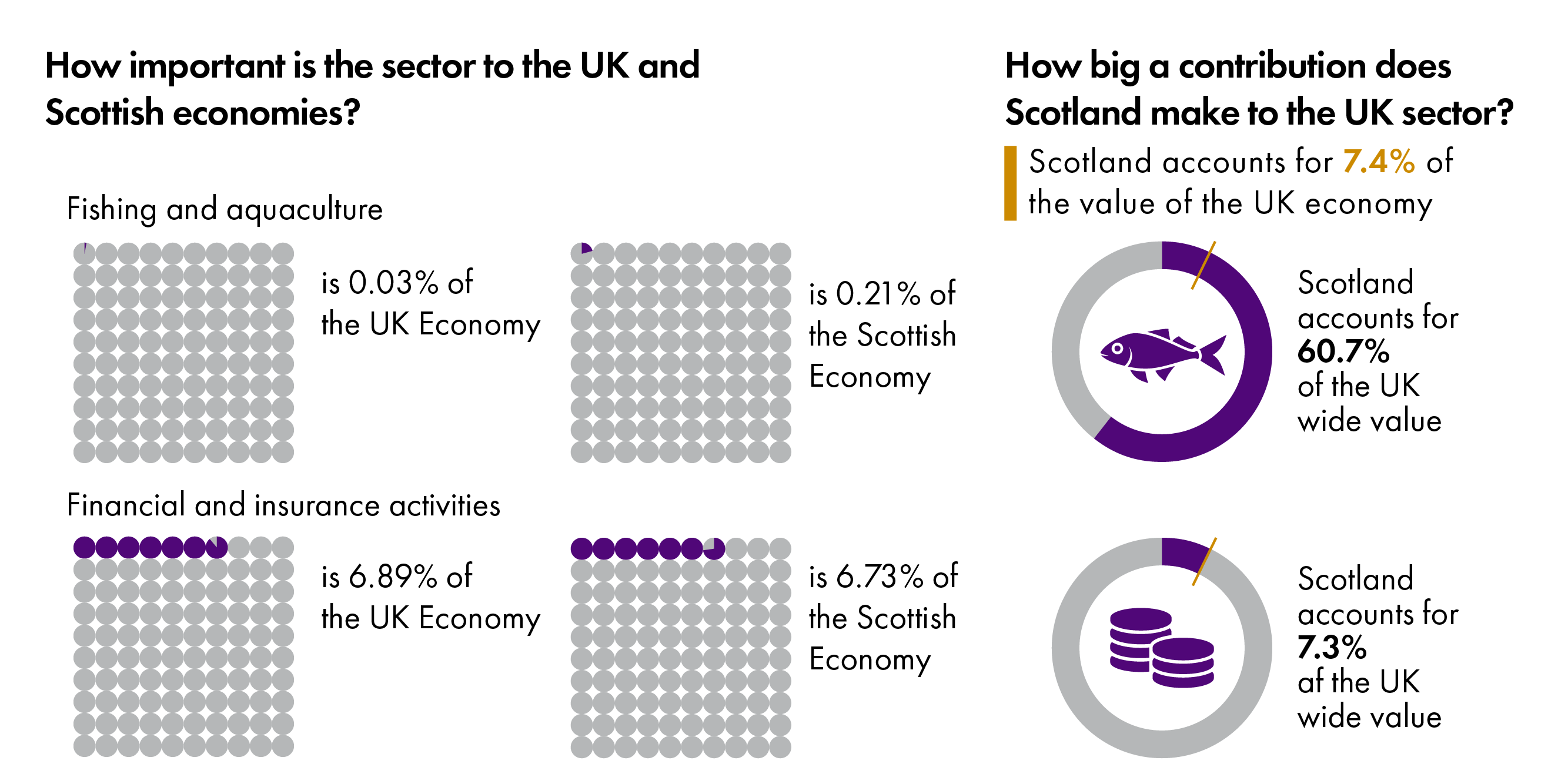

The figure below shows that, when put in the context of the wider economy, the contribution of fisheries to the UK economy is quite small. In 2018, fishing and aquaculture contributed 0.03% of the UK's gross value added (GVA). For comparison, the contribution of financial and insurance activities was over 200 times greater at 6.89%. The inclusion of fisheries in the overall negotiating package puts pressure on the UK to make concessions on access and fishing opportunities for favourable conditions on wider economic access to EU markets. This is discussed further in section 7.

The contribution of fisheries and aquaculture to the Scottish economy is much greater than it is to the UK economy as a whole. In 2018, fishing and aquaculture contributed 0.21% of Scotland's GVA, seven times greater than the contribution of fishing and aquaculture to the UK 's GVA as a whole, but still relatively small in terms of the Scottish economy. The contribution of financial and insurance activities to Scotland's GVA is similar to that of the UK's (6.73% and 6.89% respectively), meaning that Scotland has more to lose if the UK does not reach a favourable deal with the EU with respect to fisheries.

5.2 The social and cultural value of fishing in the UK & Scotland

The previous section demonstrated the relatively small contribution of fisheries to the UK and Scottish economy. However, fisheries has been at the forefront of the politics of Brexit, demonstrating that its importance transcends monetary value. This is because fishing is an age-old industry and is central to the cultural identity of many coastal communities, particularly those in remote regions and the islands of Scotland.

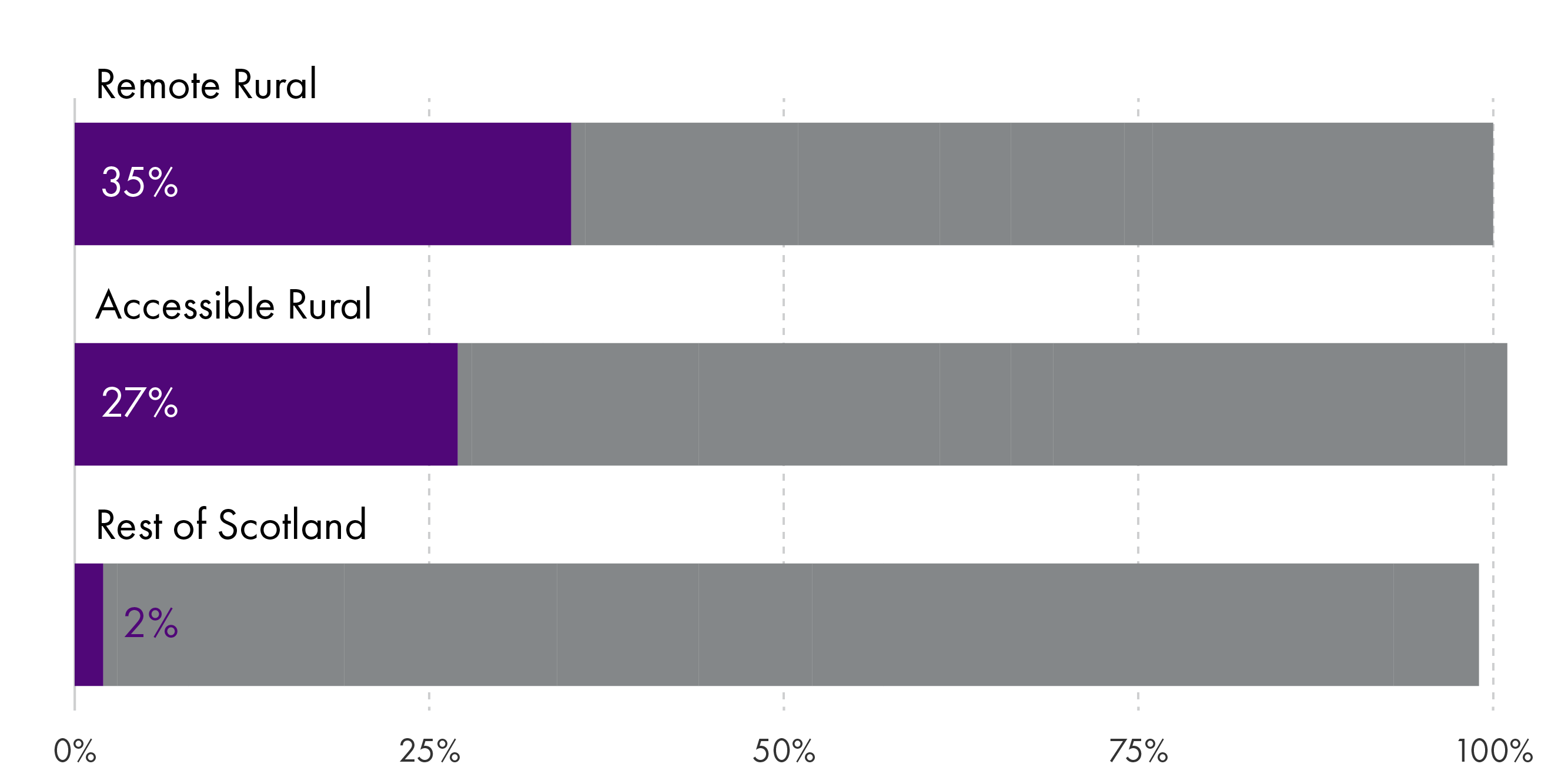

The chart below demonstrates how remote rural regions are disproportionately dependent upon agriculture, forestry and fishing compared to the rest of Scotland. A 2018 report by the Scottish Government showed that in 2017, 35% of small and medium enterprises in remote rural areas were in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector compared to just 2% in the rest of Scotland.

Box 1 below summarises key aspects of the cultural and social value of fishing from a 2014 study by the University of Greenwich which addressed the challenge of incorporating the socio-economic and cultural importance of inshore fisheries to coastal communities along the English Channel and Southern North Sea more explicitly into fisheries and maritime policy, coastal regeneration strategies and sustainable community development. 1

Box 1. The social and cultural value of fishing (Urquhart and others, 2014)

Cultural identity – Fishing shapes the identity of those who live in coastal places and increases over time. It is both perceptual and linked to the attachments that people form with place, but is also influenced by place character in terms of the physical environment and man-made objects (e.g. buildings, fishing gear and boats, artworks, signs etc.) and the fishing activity associated with it.

Place character and aesthetic values – Fishing places have a particular aesthetic that is shaped by the physical environment and landscape along with the material culture associated with fishing.

Individual and group attachment to place – Fishing facilitates and strengthens attachment to place through genealogical ties, long-standing association with the place and the co-existence of a place of work and residence, along with the fishing underpinning the social fabric.

Place meaning – The meanings attached to places may differ for those associated with fishing and those not, with fishers relating to the place as a working environment and, often, based on genealogical place attachment. For those not associated with fishing those meanings may focus on the aesthetics of the place, based on both the physical landscape and a (sometimes romanticised) perception of the fishing industry.

Cultural heritage and memory – As an activity that has often taken place for generations, fishing is deep-rooted in many coastal towns and villages. It is represented through the built cultural heritage in the form of the remains of old buildings or equipment, some of which are reused for other purposes. Fishing heritage is also about the non-tangible memories of those who have lived there and these are passed on through oral histories, preserved traditions and representations in museums.

Inspiration – The activity of fishing and the particular nature of coastal environments provides inspiration and wellbeing benefits for those living there, enhancing quality of life. This is also reflected in the work of artists who try to capture the particular quality of these environments.

Connection to the natural world – For fishers this may occur through daily engagement with the marine environment, sometimes in very harsh conditions. For others, living by the coast may provide a certain perspective and sometimes religious and spiritual meanings for those communities.

Tourism – The presence of fishing, or the idea of ‘fishing culture’, provides an attraction for tourism. Visitors like to watch the boats in the harbour, the fishermen unloading the daily catch and they enjoy eating locally-caught fish in a harbourside restaurant. With traditional coastal industries such as fishing and shipbuilding on the decline in many areas, tourism is becoming an increasingly important alternative economic activity.

Knowledge – Fishers may have a particular knowledge about the marine environment in which they work, along with the skills and traditions associated with that activity. Educating and passing on that knowledge is an important part of maintaining cultural identity.

5.3 The environmental importance of fisheries negotiations

In addition to economic, social and cultural considerations, the outcome of fisheries negotiations may affect Scotland and the UK's ability to sustainably manage fisheries, and meet domestic and global environmental targets which rely on sustainable fisheries management.

What are Scotland's commitments when it comes to fisheries?

Scotland has a number of domestic policies and international obligations that relate to sustainable fisheries management. Many of these stem from UK international commitments which require the UK to cooperate with the EU and other independent coastal states on the shared management of fish stocks. These are outlined in Box 2 below.

Box 2: Scotland's environmental commitments related to fisheries

The UK is party to the UN Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks (in force as from 11 December 2001) (UN Fish Stocks Agreement). The agreement:

"sets out principles for the conservation and management of those fish stocks and establishes that such management must be based on the precautionary approach and the best available scientific information. The Agreement elaborates on the fundamental principle, established in the Convention, that States should cooperate to ensure conservation and promote the objective of the optimum utilisation of fisheries resources both within and beyond the exclusive economic zone."1

The FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries

The Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries was adopted in 1995 by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations as an overarching framework of principles to promote responsible fishing and fisheries activities. The Code covers all aspects of fisheries policy, including harvesting, processing and trade of fish. At the core of the Code is the requirement for the users of aquatic resources to conserve aquatic ecosystems and the Code calls for the adoption of conservation and management measures which inter alia:

promote the long-term sustainable use of fisheries resources;

avoid excessive fishing capacity;

protect endangered species and conserve biodiversity of aquatic ecosystems;

allow depleted stocks to recover;

promote the development and use of selective, environmentally safe and cost-effective fishing gear and techniques.

The Convention on Biological Diversity and Aichi Target 6

The Convention on Biological Diversity obliges parties to work towards the conservation of biological diversity, including the sustainable use of natural resources, such as fish stocks. The parties have developed a series of targets, known as the Aichi Targets, to measure their success in implementing the Convention. Target 6 reads:

"By 2020 all fish and invertebrate stocks and aquatic plants are managed and harvested sustainably, legally and applying ecosystem based approaches, so that overfishing is avoided, recovery plans and measures are in place for all depleted species, fisheries have no significant adverse impacts on threatened species and vulnerable ecosystems and the impacts of fisheries on stocks, species and ecosystems are within safe ecological limits."

In relation to this target, the most recent assessment of Scotland's progress against the Aichi Targets (from 2017) states:

"The latest fishery stock assessments show that many are being harvested at sustainable levels, with biomass increasing in the North Sea. In the North Western Waters, the situation is less positive, with a number of stocks being harvested at unsustainable levels and having very low biomasses. In 2016, of 19 ‘key’ Scottish stocks 13 (70%) were fished at or very close to being fished at the Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY); 5 in the North Sea, 6 in the west of Scotland and 2 Northern Shelf stocks. Biomass is also steadily improving with 14 of these stocks (74%) currently above biomass action points for fisheries management (MSY Btrigger). For comparison in 2015, 11 stocks were fished at or very near MSY (almost 60%)."

The UK is a party to the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR Convention), which places a general obligation on states to take the necessary measures to “protect the maritime area against the adverse effects of human activities so as to safeguard human health and to conserve marine ecosystems.” (Article 2).

Whilst the Convention does not directly regulate fisheries, the biological diversity and ecosystems strategy adopted by the OSPAR Commission promotes the “integration of fisheries management with ecosystem-based management of the North-East Atlantic [and] the sustainable management of fisheries consistent with OSPAR Ecological Quality Objectives.”

Sustainable Development Goal 14: Life Below Water

Scotland has been committed to the Sustainable Development Goals since July 20152. The goals underpin Scotland's National Performance Framework, and guide the development of a number of policies, including the February 2020 Environment Strategy.

Goal 14 relates to "life below water" and includes:

- Maintaining fish stocks at a biologically sustainable level;

- Combating illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing; and

- Promoting small-scale fishers' access to productive resources, services and markets.3

National Marine Plan

Scotland’s National Marine Plan was adopted in 2015 as an overarching framework for managing maritime activities and spaces around Scotland. The plan calls for fisheries to be harvested sustainably with a view to creating a fishing fleet that is seen as “an exemplar in global sustainable fishing practices.” To deliver this objective, the fisheries policies require the environmental impact of fishing to be taken account by decision-makers, including avoiding damage to fragile habitats and protecting vulnerable stocks.

Future of Fisheries Management in Scotland: National Discussion Paper

The March 2019 Future of Fisheries Management in Scotland: National Discussion Paper is Scotland's most recent policy document on fisheries. This was accompanied by a national consultation, ahead of the expected development of Scotland's Future Fisheries Management Strategy.

Two of the principles for future fisheries management relate to the environment. The discussion paper states:

- "[We will] Manage our fisheries in a way that protects biological diversity and which ensures that marine ecosystems continue to provide economic, social and wider benefits for people, communities and industry"; and

- "[We will] Set fishing limits in line with the best available scientific advice, using the precautionary principle, and aligned with the delivery of Maximum Sustainable Yield within an ecosystem context, in line with International obligations"

Acting in line with these principles will be dependent on the outcome of fisheries agreements.

It is unlikely that the UK or Scotland will be able to achieve the objective of sustainable fisheries, or related biodiversity targets, without some form of cooperation with the EU, given that most fish stocks are transboundary in nature and therefore both sides must take coordinated action.

In the past, failure to agree on quota on a collaborative basis has led to countries unilaterally setting their own quota, and resulting unsustainable fishing practices. This has raised concerns about the ability of fish stocks to support the total amount of fish caught, exemplified recently in the disputes over mackerel quota in the North Atlantic between the UK/EU and Norway on the one hand, and Iceland and the Faroe Islands on the other (See Box 6, Section 10).

Why is the outcome of the negotiations important for achieving sustainable fisheries management?

As outlined in Section 4, the UK and EU negotiating objectives are not currently fully aligned when it comes to fisheries. EU negotiating objectives emphasise avoiding change for Union fishers and traditional fishing patterns, while the UK aims for a new basis for a fisheries agreement between the UK and the EU.

There are therefore clear differences in approach, which may make reaching an agreement challenging. For example, the UK has stressed the need for a "fairer system"4 for determining quota. Griffin Carpenter, Senior Researcher at the New Economics Foundation, highlighted the potential challenges posed by countries having differing approaches in 2018:

But what if the EU’s concept of a ‘fair share’ and the UK’s concept of a ‘fair share’ exceed the available budget?

It is possible that neither party is overfishing from their own perspective - but adding 70 percent and 70 percent equals systematic overfishing.5

Even with an agreement, there is still the potential to set quotas above scientific advice67. Researchers found in 2016 that

the European Council set TACs above scientific advice by an average of 20% per year, with around 7 out of every 10 TACs exceeding advice. Of all Member States, Denmark and the United Kingdom received the highest TACs in volume above scientific advice. 6

As such, whether or not an agreement is reached between the UK and the EU on future fishing opportunities, and the shape of any such agreement, may have an impact on the sustainability of fisheries in Scottish waters and in wider UK waters. Overfishing on both sides may affect both parties' abilities to meet their international and domestic obligations, where these rely on sustainable fisheries management.

6. Elements of a Future UK-EU Fisheries Agreement

The final text of a future UK-EU Fisheries Agreement is going to be the product of negotiation and compromise. It is impossible to predict the precise form and contents of such an agreement, if indeed an agreement is forthcoming. However, like most other fisheries agreements, any UK-EU fisheries agreement is likely to be a framework agreement, which does not contain detailed rules for the regulation of fishing and the exchange of fishing opportunities. Instead, it would likely set out the basic parameters under which cooperation will take place, leaving the details to future negotiation.

This section considers some of the elements which may be included in a future agreement, informed by the past practice of the EU and the broader international legal framework relating to fisheries cooperation.

6.1 Shared Values and Principles

It is common for an international treaty to begin with a preamble which sets out the motivations of the parties in concluding an agreement, as well as the objectives of the agreement. Whilst a preamble is not legally binding, it can inform the interpretation and application of a treaty.

Whereas the preambles of the older fisheries agreements entered into by the EU with Norway and the Faroe Islands simply refer for the need for fisheries relations to be conducted “in accordance with principles of international law”, it must be remembered that these agreements were concluded before the emergence of many key principles of international fisheries law that are widely accepted today. Indeed, more modern fisheries agreements, such as the EU-Greenland Fisheries Partnership Agreement, make a more explicit reference to “the principles established by the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries” in the preamble and they also incorporate specific principles into the body of the agreement, for example the precautionary approach.

Given that both the UK and the EU have stated that they are committed to ensuring that any fishing partnership should seek to ensure the sustainable management of stocks (see above), a new fisheries agreement could provide an opportunity to agree on the principles which should inform decision-making.

The draft text of a partnership agreement proposed by the European Commission on 18 March 2020 includes an article on common objectives, which covers the following:

(a) upholding clear and stable rules and existing reciprocal conditions on access to waters and resources;

(b) ensuring that fishing activities are environmentally sustainable in the long term and contribute to achieving economic, social and employment benefits;

(c) applying and maintaining the maximum sustainable yield exploitation rate in order to restore and maintain populations of harvested species at levels which can produce the maximum sustainable yield;

(d) ensuring the rapid recovery of stocks below Blim to levels which can produce the maximum sustainable yield;

(e) cooperating on the development of measures for the conservation, management and regulation of fisheries in a non-discriminatory manner, while preserving the regulatory autonomy of the Parties;

(f) eliminating discards by avoiding and reducing unwanted catches, and by ensuring that all catches are landed;

(g) promoting the protection of marine biological resources and their environments and coastal areas;

(h) applying the ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management and ensuring that negative impacts of fishing activities on the marine ecosystem are minimised;

(i) following a precautionary approach to fisheries management;

(j) ensuring cooperation on data collection and scientific advice to support stock assessments;

(k) ensuring cooperation on monitoring, control and surveillance activities, including the fight against illegal unreported and unregulated fisheries;

(l) establishing management measures in accordance with the best available scientific advice;

(m) upholding the existing fishing activities;

(n) contributing to a fair standard of living for those who depend on fishing activities, bearing in mind coastal fisheries and socio-economic aspects;

(o) ensuring a level playing field.

Whilst some of these objectives are likely to be highly contested, particularly when they touch upon access and quota allocation, there are other objectives on which the two sides may be able to readily agree, such as maintaining stocks above levels which can produce maximum sustainable yield, following a precautionary approach, establishing management measures in accordance with the best available scientific advice, and applying an ecosystem approach.

6.2 Process for agreeing on quota and other conservation and management measures in relation to transboundary stocks

Cooperation in the conservation and management of transboundary stocks is a core objective of any future fisheries agreement. Given the number of shared stocks between the UK and the EU, the process for fixing a TAC and related technical measures for transboundary stocks should be a key part of any fisheries relationship.

A new fisheries agreement may simply emphasise the need for the two sides to cooperate in the adoption of conservation and management measures for stocks of common interest, including a TAC. An agreement could also make clear that any such measures should be based upon the best available scientific evidence, in accordance with UNCLOS. The need for a science-based approach is emphasised in the EU negotiating mandate (paragraph 87). ICES (see Box 5, Section 10) could play an important role in this respect, by providing a source of independent scientific advice, although any decision on TACs is ultimately a political decision of the states concerned.

One issue that is likely to divide the two sides is how any agreed TAC should be distributed. Whilst the EU has indicated its desire to “uphold stable quota shares” (EU Negotiating mandate, para. 89), the UK has made clear, both in its White Paper on Sustainable Fisheries and in its February 2020 document outlining the UK’s Approach to Negotiations that:

The UK will no longer accept the ‘relative stability’ mechanism for sharing fishing quotas [and] future fishing opportunities should be based on the principle of zonal attachment, which better reflects where the fish live, and is the basis for the EU’s fisheries agreement with Norway.1

Achieving a compromise between these two positions is going to be one of the most challenging aspects of the negotiations.

6.3 Access arrangements

Access arrangements are likely to be at the centre of any new fisheries agreement between the UK and the EU.

In particular, the EU is concerned to maintain “continued reciprocal access, for all relevant species, by Union and United Kingdom vessels” and “the traditional activity of the Union fleet” with the aim of avoiding “economic dislocation for Union fishermen that have been engaged in fishing activities in the United Kingdom waters.”1The EU has also pointed out the complexities of having to negotiate access arrangements for over 100 stocks on an annual basis and the implications that it would have for the ability of the fishing industry to plan in advance.

In contrast, the UK has maintained that “British fishing grounds are first and foremost for British boats” and any new agreement should be limited to setting out “the scope and process for annual negotiations on access to the parties’ [EEZ].”2 The UK also recalls that this is the model adopted with most other neighbouring coastal states with which the EU has fisheries agreements in place.

Were this latter model adopted, the agreement would simply lay down the procedure to be followed. An agreement could also lay down the factors to be taken into account in agreeing on access arrangements, including for example the objective of “a mutually satisfactory balance” as set out in the EU-Norway Agreement. In practice, access negotiations are tied up with TAC negotiations, which further complicates any potential outcome to this issue.

Drawing upon previous practice exemplified in the EU-Norway Fisheries Agreement (see section 8.1), it would also be possible for a new fisheries agreement to include transitional provisions, whereby access levels would be gradually reduced over a certain period of time with a view to minimising the immediate economic impact on fleets. It is also important that an Agreement identifies the situations in which any access arrangements may be adjusted due to unforeseen circumstances. Access is linked to licensing arrangements. Therefore, an agreement is likely to contain provisions setting out the process for obtaining a licence.

6.4 Scientific cooperation

A common provision in existing fisheries agreements entered into by the EU is a duty to cooperate on the gathering and sharing of scientific information concerning fisheries. The UK also supports a science-based approach to fisheries management and the UK Fisheries Bill currently making its way through Parliament includes a scientific evidence objective. As noted above, ICES already provides a forum for such cooperation to take place and the UK is committed to continuing its engagement through this forum. ICES as an institution predates the European Union and is independent from the EU (see Box 5 below).

It would be possible for the provisions on scientific cooperation to extend beyond fisheries matters to include cooperation on the protection and preservation of the marine environment, as is the case with the EU-Iceland Agreement. Such cooperation may be particularly important where there are marine protected areas located close to maritime boundaries so that cooperation may be needed to ensure that the conservation objectives are met.

6.5 Monitoring, control and enforcement of fishing vessels

A standard set of provisions in existing EU fisheries agreements underline that the fishing vessels of one party fishing in the waters of the other party should comply with the latter’s laws and regulations and the latter is able to take measures to enforce its laws and regulations. Each party should also provide notification of any changes to its laws and regulations in order to provide sufficient notice to the fishing vessels of the other party.

The draft text of the partnership agreement proposed by the European Commission on 18 March 2020 goes a step further and it requires any new technical measures to be “proportionate, non-discriminatory and effective”, establishing a consultation procedure where the other party has concerns that any proposed measures are liable to adversely affect its fishing vessels.

Reflecting that flag states continue to have obligations to ensure that their vessels fish lawfully within the waters of another state, a clause is also often included in the EU’s fisheries agreements requiring the flag state to take all necessary measures to ensure compliance by their vessels with the relevant rules. In this respect, a new agreement could go further and elaborate a procedure through which the coastal state party could request information from the flag state party concerning a particular vessel and the latter would be under an obligation to provide that information within a reasonable period of time.

One aspect of monitoring and control that requires particular attention is the provision of vessel monitoring system (VMS) data. VMS is a system of gathering data on the location, course and speed of a fishing vessel throughout its voyage whereby the information is automatically relayed directly to the flag state authorities by way of satellite. VMS is a requirement for certain fishing vessels as a matter of EU law1 and Commission Regulation 404/2011 provides for the automatic and simultaneous provision of information to the fisheries management centre of a coastal state when the vessel is operating in its waters.

Whilst such transfer of data only applies to other EU Member States, Article 9(4) provides that “if a Community fishing vessel operates in the waters of a third country … and, if the agreement with that third country … so provide[s], those data shall also be made available to that country.”

The EU has entered into agreements with other countries, such as Norway, to share VMS data. Therefore, it would be possible for a fisheries agreement between the UK and the EU to continue the transfer of VMS data, which would be to the benefit of both sides in facilitating the policing of their waters.

There appears to be some convergence between the two sides on this issue: the UK Government has suggested that data sharing arrangements should be part of a new fisheries partnership2 and the EU draft text of 18 March 2020 also proposes that “the Parties shall exchange electronically all relevant data to facilitate control and enforcement actions, in particular catch, fleet and vessel position data.”3

Building upon broader practice between the EU and other coastal states in the region, further issues that could be addressed in the context of monitoring, control and enforcement of fisheries are:

The electronic exchange of catch and activity data from fishing vessels, in accordance with agreed procedures and formats;

The exchange of information concerning enforcement, including information on inspections and investigations;

The exchange of inspectors and observers to monitor enforcement by the other party.

6.6 Institutional arrangements

Many existing EU fisheries agreements do not set up any specific form of institutional framework, but rather rely upon informal annual consultations. However, given the number of shared stocks between the UK and the EU, it may be that some more formalised institutional structure is appropriate.

A common format would be a Joint Committee composed of representatives of the two sides. The mandate of such a Joint Committee would be:

to oversee the implementation of the agreement;

agree upon common conservation and management measures, where it is deemed necessary;

address any disagreements concerning the interpretation and application of the agreement;

and to provide a forum for addressing other fisheries related matters.

The Joint Committee may establish subcommittees or working groups to address particular issues.

6.7 Dispute settlement

It is not common for EU fisheries agreements with independent coastal states to contain elaborate dispute settlement clauses. Most agreements simply stipulate that disputes should be settled by consultation, e.g. the EU-Norway Fisheries Agreement. The UK government has suggested in its document outlining its approach to the negotiations that any fisheries agreement “should include arrangements for dispute settlement along the lines common to other fisheries agreements, including provision for the suspension of the agreement on fisheries if necessary.”1

States have traditionally been reluctant to subject themselves to the scrutiny of international courts and tribunals in the context of fisheries disputes. For example, UNCLOS provides an explicit exception from its compulsory dispute settlement procedures for any disputes concerning the exercise of sovereign rights with respect to fisheries in the EEZ. However, it does allow such disputes to be submitted to non-binding conciliation instead (Article 297(3)), meaning that a commission of experts is asked to recommend an appropriate solution to the dispute, but the final settlement is left to the parties themselves.

Of course, states can agree to take such disputes to an international court or tribunal if they wish. Indeed, it is widely recognised that “without adequate implementation and enforcement, the best [fisheries] agreements can be useless.”2 Therefore, consideration should be given to what mechanism can be put in place to provide independent scrutiny of each party, when they are not able to settle their differences between them.

7. Relationship between a Future UK-EU Fisheries Agreement and a Future UK-EU Free Trade Agreement

Both parties have advantages with regards to negotiating a new fisheries agreement. The UK has the advantage of controlling access to some of the most productive fishing grounds in Europe, on which other European fishing industries are heavily reliant, whilst the EU has the advantage of the reliance of the UK on selling its catch tariff-free to EU markets.

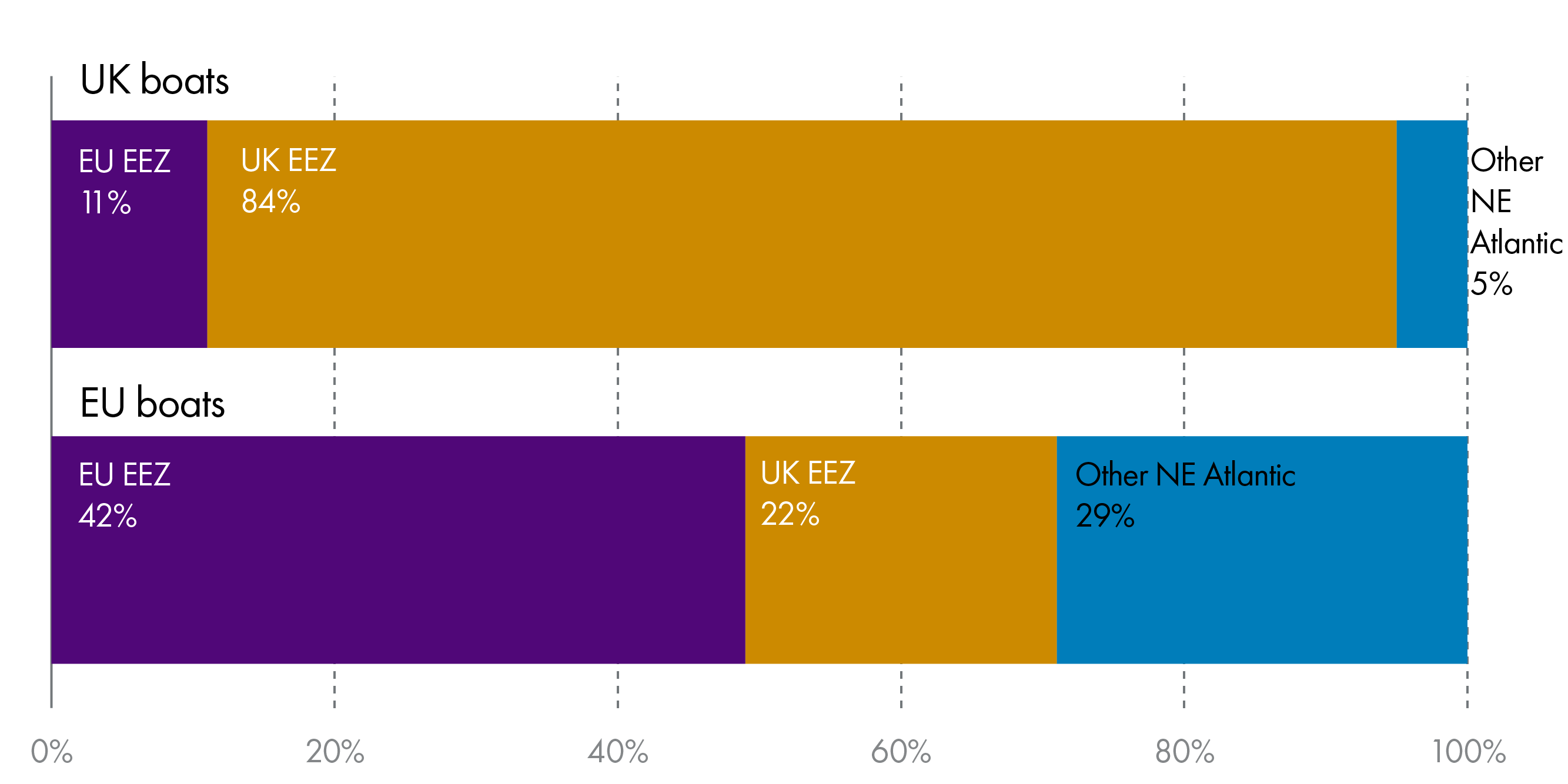

A 2016 study by the NAFC Marine Centre in Shetland found that non-UK EU boats caught 22% of their landed catch in the UK EEZ. In contrast, UK boats only caught 11% of their landed catch in EU waters outside of the UK EEZ.

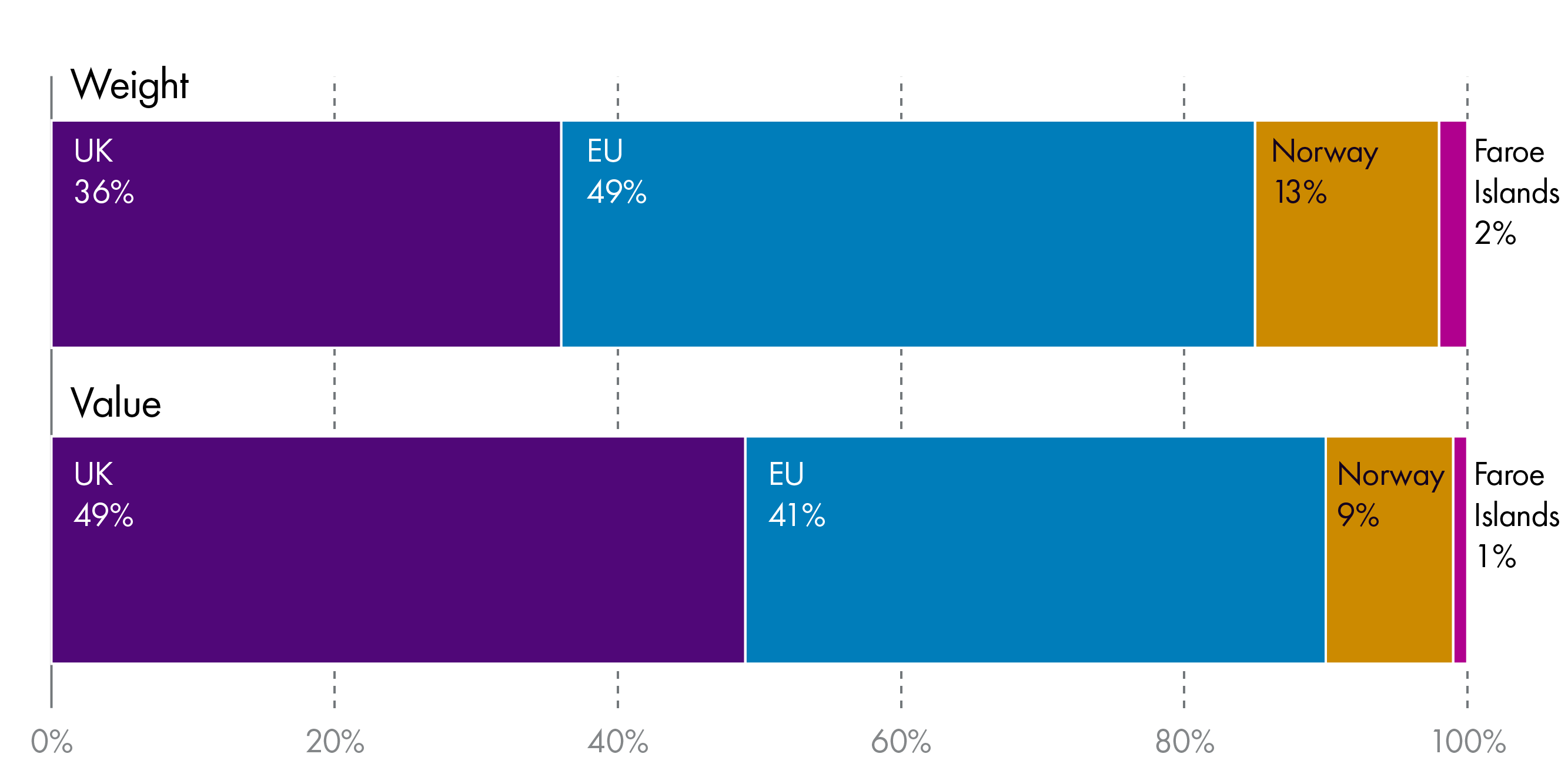

A further study by the NAFC Marine Centre found that UK vessels accounted for less than half of the landings of fish and shellfish from the UK EEZ by weight and value in 2018. Non-UK EU vessels accounted for 49% of landings by weight and 41% by value.

The UK Government wants to redress this imbalance of fishing opportunities available to UK fishing fleets under the relative stability principle. Its Fisheries White Paper published in July 2018 states:

We will be seeking to move away from relative stability towards a fairer and more scientific method for future TAC [Total Allowable Catch] shares as a condition of future access. Initially, we will seek to secure increased fishing opportunities through the process of ‘annual exchanges’ as part of annual fisheries negotiations.3

Fishing industry representatives will be keeping a close eye on how the UK Government proceeds with negotiations. As discussed in section 5.1 of this briefing, a key concern expressed by some in the fishing industry is that the UK Government will concede access in the context of wider negotiations on the future UK-EU economic partnership.

A day after becoming Prime Minister on 24 July 2019, Boris Johnson responded to a question on fisheries in the House of Commons with the following statement:

We will become an independent coastal state again, and we will, under no circumstances, make the mistake of the Government in the 1970s, who traded our fisheries away at the last moment in the talks. That was a reprehensible thing to do. We will take back our fisheries, and we will boost that extraordinary industry.

The Scottish Fishermen's Federation has been one of the most strident voices in campaigning for a rebalance in catching opportunities for Scotland's offshore fleets after Brexit. However, Scotland's fishing industry is diverse.

Inshore fisheries primarily target non-quota shellfish species such as crab, lobster and nephrops (langoustine). The majority of this catch is exported as live or fresh product to European markets tariff-free. Increased tariffs and non-tariff barriers such as customs delays and new certification requirements could reduce the inshore fleet's already narrow profit margins.4

Seafood processing is also a significant part of Scotland's marine economy, and is larger than both the fishing and aquaculture industries. As with inshore fisheries, the Scottish seafood processing industry is heavily reliant on tariff-free access to European markets both for imports and exports, and for labour.5

Brexit will potentially open up new markets and new sources of raw material for Scottish seafood processors. However, even if the UK and the EU agree a close future trading relationship, exports to what is currently the largest external market for UK seafood products will likely face more barriers than they do at present.5

The chart below demonstrates the importance of trade to the EU for seafood. From 2014-19, on average, just under a third of the UK's seafood is imported from the EU and just over two-thirds of the UK's seafood exports goes to EU markets.

Negotiating a future fisheries and trade agreement with the EU that meets the needs of all sectors of Scotland's fishing industry will be no mean feat. Negotiations inevitably require compromise, and the UK Government will have to consider carefully how to balance promises it has made on fishing since the 2016 referendum with other needs.

8. Existing EU fisheries agreements with third countries

The EU already participates in a complex web of fisheries agreements and arrangements with other coastal states in the North Atlantic. This section discusses the history of these arrangements, including how they were made and how they function, with a view to understanding some of the precedents for fisheries cooperation between the EU and other countries in the North Atlantic.

8.1 EU – Norway Fisheries Relations

8.1.1 Background to the EU-Norway Fisheries Agreement

To date, Norway has been the most significant fisheries partner of the EU. The Agreement on Fisheries between the European Economic Community and the Kingdom of Norway was negotiated in the late 1970s, in response to the extension of exclusive fisheries limits to 200 nautical miles, although it was not formally adopted until 1980.1 The agreement was initially valid for ten years but it continues to apply for additional periods of six years at a time, unless one of the parties gives notice that it intends to terminate the agreement at least nine months before the expiry of that period.

The key purpose of the agreement is to promote cooperation between the two states relating to fisheries. It applies to both the management of shared stocks, as well as the exchange of fishing opportunities between the two parties.

8.1.2 Cooperation in the management of shared stocks

The two parties have agreed to cooperate to ensure proper management and conservation of stocks which occur within the jurisdiction of both parties. This includes the facilitation of necessary scientific research “with a view to achieving, as far as practicable, harmonisation of measures for the regulation of fisheries of such stocks.” (Article 7) In practice, the EU and Norway seek the advice of ICES (Box 5 below) on what conservation measures may be necessary.

The agreement itself does not specify what conservation and management measures must be taken; these are the subject of annual fisheries consultations. One of the most important objectives of these consultations is the setting of an agreed TAC for transboundary stocks. For example, the EU and Norway have in the past agreed TACs for cod, haddock, whiting, plaice, saithe, and herring in the North Sea.

Where a common TAC is agreed, the EU and Norway will normally divide this between them based upon the principle of 'zonal attachment'. In addition, the two parties consult on other technical measures - such as seasonal closures, real time closures, gear restrictions - and they are currently working on long-term management strategies for shared stocks in order to guide future decision-making.

8.1.3 Cooperation in the exchange of fishing opportunities

Alongside the management of shared stocks, the agreement also addresses the question of access to fish stocks within the jurisdiction of the other party. The agreement itself does not determine levels of access, but establishes an agreed procedure for determining access on an annual basis. Essentially, the agreement confirms the right of each party to determine on a yearly basis how many vessels of the other party shall be allowed to fish within its waters and how much of the TAC is granted to those vessels.

Prior to making such a determination, the two parties should carry out consultations and the agreement specifies that the resulting decision should seek to achieve a “mutually satisfactory balance in their reciprocal fisheries relations.” This balance relates to the value of catch, rather than to the volume of catch; as explained by Churchill and Owen:

this is important because traditionally Norwegian vessels have caught predominantly relatively low value species, such as herring and mackerel, in [EU] waters, whereas [EU] catches in Norwegian waters have been mainly of higher value species such as cod and haddock.1

The Annex to the agreement sets out a number of considerations that must be taken into account in determining a mutually satisfactory balance (see Box 3).

Box 3: EU-Norway Agreement on Fisheries, Annex

1. In determining the allotments for fishing under Article 2 (1) (b) of the Agreement, the Parties shall have as their objective the establishment of a mutually satisfactory balance in their reciprocal fisheries relations.

Subject to conservation requirements, a mutually satisfactory balance should be based on Norwegian fishing in the area of fisheries jurisdiction of the Community in recent years. The Parties recognise that this objective will require corresponding changes in Community fishing activity in Norwegian waters.

2. Each Party will take into account the character and volume of the other Party's fishing in its area of fisheries jurisdiction, bearing in mind habitual catches, fishing patterns and other relevant factors.

3. The Parties will, in pursuance of the objective set forth in paragraph 1, effect a gradual reduction with a view to achieving that objective by 31 December 1982.

The Annex made clear that fishing by EU vessels in Norwegian waters would have to be reduced in order to achieve a mutually satisfactory balance, but it also expressly provided for a transition period of six years (1977- 1982) over which this reduction must be achieved.2 This approach mirrors previous practice when exclusive fisheries limits were extended under the 1964 London Fisheries Convention and a transition period was provided “in order to allow fishermen of other Contracting Parties, who have habitually fished in the [six nautical mile belt] to adapt themselves to their exclusion from that belt.”3

The EU-Norway agreement foresees several circumstances in which adjustments to the reciprocal access arrangements can be made. Firstly, Article 2 explains that any decision on access by foreign vessels is “subject to adjustment when necessary to meet unforeseen circumstances.” This would appear to confer a unilateral right on each party to alter the access conditions, provided that the stated conditions are met, i.e. that the adjustment is “necessary” and it is in response to “unforeseen circumstances.” Secondly, Article 3 provides that:

In the event of a significant distortion of the fishing patterns of one Party in areas crucial to the achievement of a mutually satisfactory balance in the reciprocal fisheries relations between the Parties, the Parties shall promptly enter into consultations with a view to securing the continuance of reciprocal fisheries relations. If, within three months from the request for consultations, a solution satisfactory to the Party which has requested consultations, is not found, that Party may, notwithstanding the provisions of Article 13, suspend or terminate the Agreement on giving 30 days notice.

A major adjustment to the balance between EU and Norwegian fishing opportunities took place in 1993, when the EU and Norway entered into a supplementary agreement under which Norway increased the EU’s access to fish in the Norwegian EEZ north of 62 degrees in recognition of the additional trade benefits arising to Norway under the Agreement on the European Economic Area concluded in the previous year.4

According to Churchill and Ørebech, “at an early stage in the EEA Agreement negotiations, the EC made it clear that the quid pro quo for any trade concessions it was prepared to make in respect of imports of fishery products from EFTA states would be increased access for EC fishing vessels to the fishery resources found in the waters of EFTA states.”5

Once access has been agreed, the agreement provides for licences to be granted by the relevant coastal state. It also confirms that any foreign fishing vessel will have to comply with laws and regulations adopted by the coastal state.

8.1.4 Other provisions

There is no formal dispute settlement procedure under the Agreement, which only mentions the possibility of consultations. (Article 8)

8.2 EU- Faroes Fisheries Relations

The Agreement on Fisheries between the European Economic Community of the one part and the Government of Denmark and the Home Government of the Faroe Islands of the other part was adopted in the same period as the agreement with Norway, and its content is similar. The key difference relates to the factors to be taken into account in determining access (see Box 4).

Box 4: EU-Faroes Fisheries Agreement, Article 2(b)

The two Parties shall have as their aim the realisation of a satisfactory balance between their fishing possibilities in their respective fishery zones. In determining these fishing possibilities, each Party shall take into account:

(i) the habitual catches of both Parties,

(ii) the need to minimise difficulties for both Parties in the case where fishing possibilities would be reduced,

(iii) all other relevant factors.

The measures to regulate fisheries taken by each Party for the purpose of conservation by maintaining fish stocks at, or restoring them to, levels which can produce the maximum sustainable yield shall not be of such a nature as to jeopardise the full exercise of the fishing rights allocated under the Agreement.”

8.3 EU – Iceland Fisheries Relations

The EU also has an agreement with Iceland on fisheries, which was concluded in 1992.1 The text of this agreement differs to some extent from the earlier agreements with Norway and the Faroe Islands. In particular, the scope of the EU-Iceland Agreement would appear to be broader, dealing both with fisheries and the marine environment, although the substance of the agreement still places a greater emphasis on fisheries cooperation.

The agreement begins by calling in Article 1(1) for cooperation:

to ensure the conservation and rational management of the fish stocks occurring within the areas of fisheries jurisdiction of both Parties and in adjacent areas

and it expressly lays down an obligation to:

seek either directly or through appropriate regional bodies to reach agreement with third Parties on measures for the conservation and rational utilisation of these stocks, including the total allowable catch and the allocation thereof.

Alongside fisheries consultations, the agreement provides in Article 3:

the Parties shall consult, bilaterally or in the appropriate regional or international fora, on matters pertaining to the marine environment.

In relation to the critical issue of access, the text of the EU-Iceland Agreement is far simpler than the other agreements discussed above, providing in Article 4(1) that: