Seafood processing in Scotland: an industry profile

This briefing provides an overview of Scotland's seafood processing sector. It outlines the size and scale of the industry, employment trends and its importance to specific areas of the country, including the North East. The briefing also details the contribution seafood processing makes to the wider Scottish economy and highlights some of the potential challenges facing the sector as the UK prepares to withdraw from the European Union.

Executive Summary

The UK seafood processing industry is one of the largest in the European Union (EU), with a turnover of around €5.3 billion (£3.8 billion) in 2015. Only the French industry, with a turnover of €5.5 billion (£4.0 billion), generated more income.

While seafood processing and other fishing related industries make up a very small proportion of the Scottish economy as a whole, they are a significant part of the marine economy and make an important contribution to many coastal communities.

There were 139 seafood processing sites in Scotland in 2018, providing 8,900 Full Time Equivalent (FTE) jobs - this adds up to approximately 39% of the sites in the UK and 46.3% of the jobs.

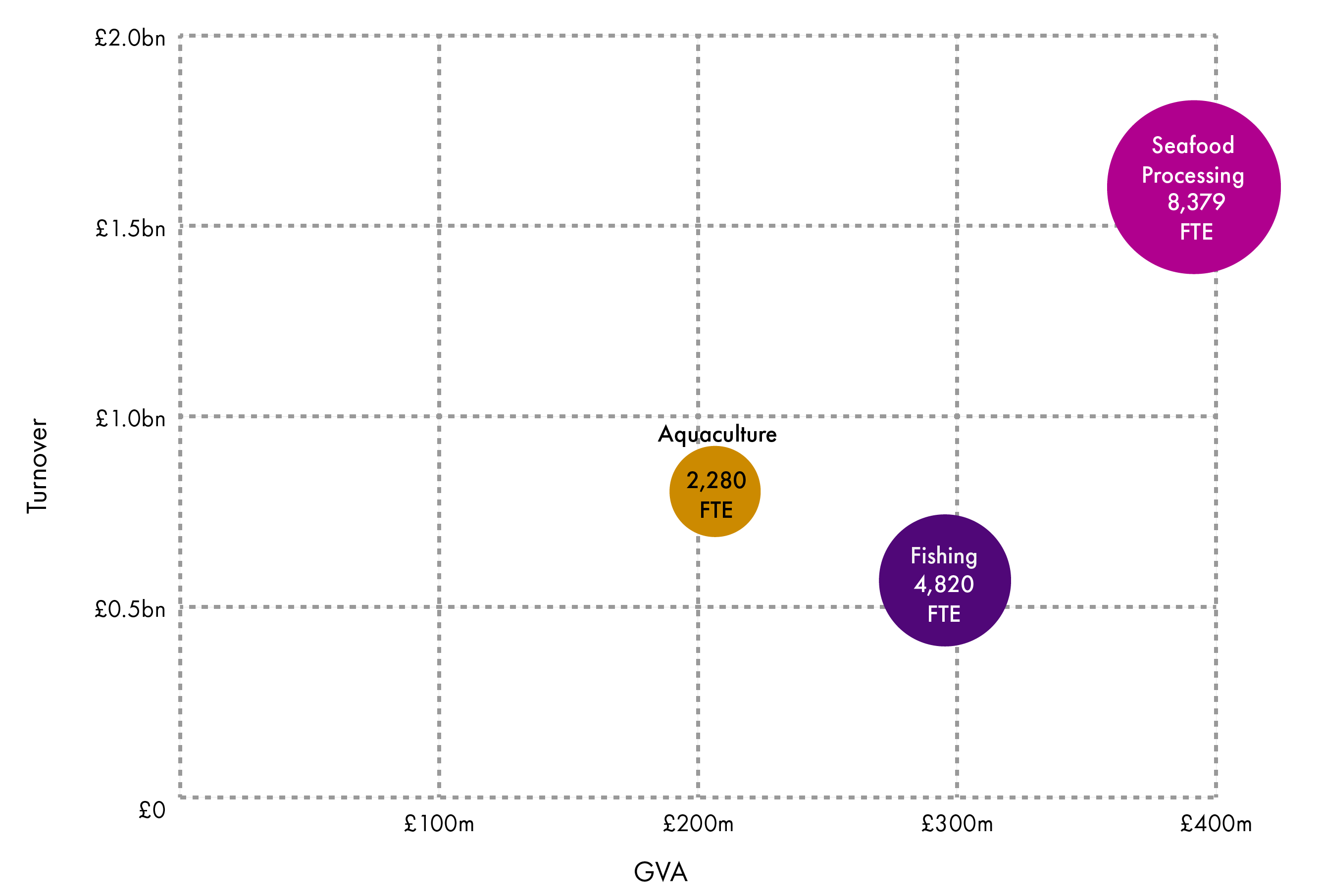

The seafood processing sector is larger than both the aquaculture and fishing industries, with a turnover of £1.6 billion by 2016 - just over double that of aquaculture and nearly three times that of fishing.

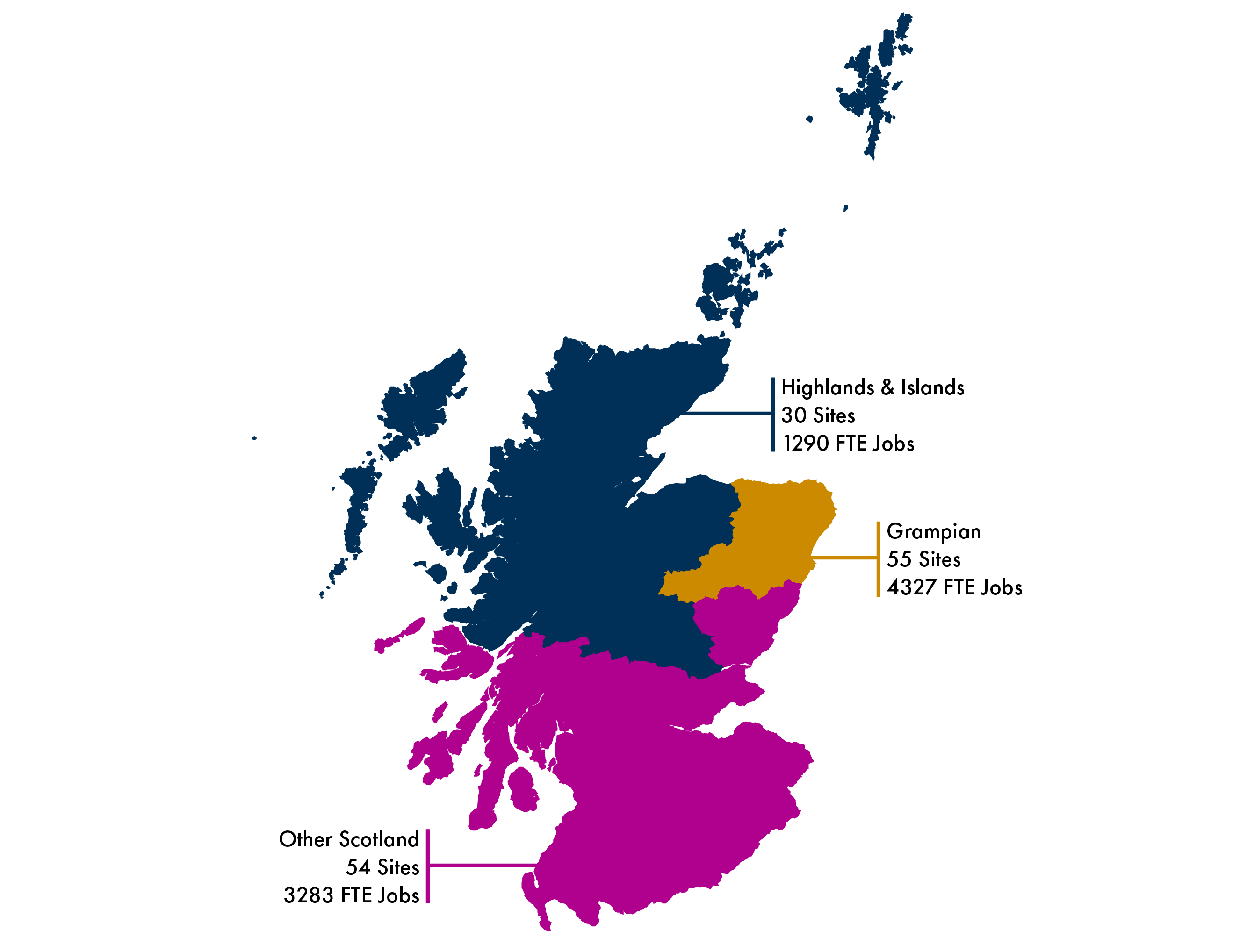

In Scotland, the sector is based in the North East, the Highlands and Islands and on the West Coast, and makes a significant contribution to the local economies in these areas.

The Grampian region has the largest share of Scotland's processing sector, with 4,327 FTE jobs (48.6% of the Scottish total) based at 55 sites in 2018. In 2015 alone, it is estimated that processing businesses in the region generated more than £725 million in turnover.

The seafood processing sector in the UK relies heavily on workers from other European Economic Area (EEA) countries. This trend is even more pronounced in Scotland - based on survey data, Seafish has estimated that, in 2018, 59% of those employed in the sector in Scotland were from non-UK EEA countries, compared with 51% in the UK as a whole.

Overall, the UK is a net importer of fish - it exports most of what it catches and imports the majority of the fish that are processed or consumed within the UK.

The UK's decision to withdraw from the European Union presents the sector with fresh challenges, particularly around workforce and future immigration arrangements, sources of funding and international trade opportunities.

Introduction

The Office for National Statistics defines seafood processing as an industry involved in the "preparation and preservation of fish, crustaceans and molluscs" and the manufacturing of related products1.

Typically, seafood processing plants are located near major fish ports, which means that fish can be prepared quickly before onward transportation to consumers and other customers. Plants can generally be divided into three broad categories:

primary processors: deal with cutting, peeling, gutting and washing fish and shellfish

secondary processors: deal with brining, smoking, freezing, canning and the manufacture of fish products such as fishcakes, breaded fillets and packaged meals

mixed processors: carry out a mixture of these activities

The UK seafood processing industry is one of the largest in the European Union (EU), with a turnover of around €5.3 billion (£3.8 billion) in 2015. Only the French industry, with a turnover of €5.5 billion (£4.0 billion), generated more income2.

Seafood processing is an important part of Scotland's marine economy, and is larger than both the fishing and aquaculture industries in terms of the number of full time jobs provided, turnover and Gross Value Added (GVA). For example, in 2016 alone, the sector in Scotland provided 8,380 Full Time Equivalent (FTE) jobs3, generated an estimated £1.6 billion in turnover and contributed £391 million in Gross Value Added (GVA)4. In comparison, the fishing industry provided 4,820 FTE jobs, had an estimated turnover of £571 million and contributed £296 million in GVA. Aquaculture provided 2,280 FTE jobs, had an estimated turnover of £797 million and contributed £216 million in GVA.

Seafood processing in Scotland is largely based in the North East, the Highlands and Islands and on the West Coast, and makes a significant contribution to the local economies in these areas. In the North East, the industry works mainly with sea caught fish and shellfish. In the Highlands and on the West Coast, it is most often focused on processing Atlantic salmon and other farmed fish and shellfish.

The UK's decision to withdraw from the EU has presented the industry with fresh challenges, not least the uncertainty around future international trade opportunities, immigration arrangements and sources of funding.

Profile of the Scottish seafood processing industry

Number and average size of sites

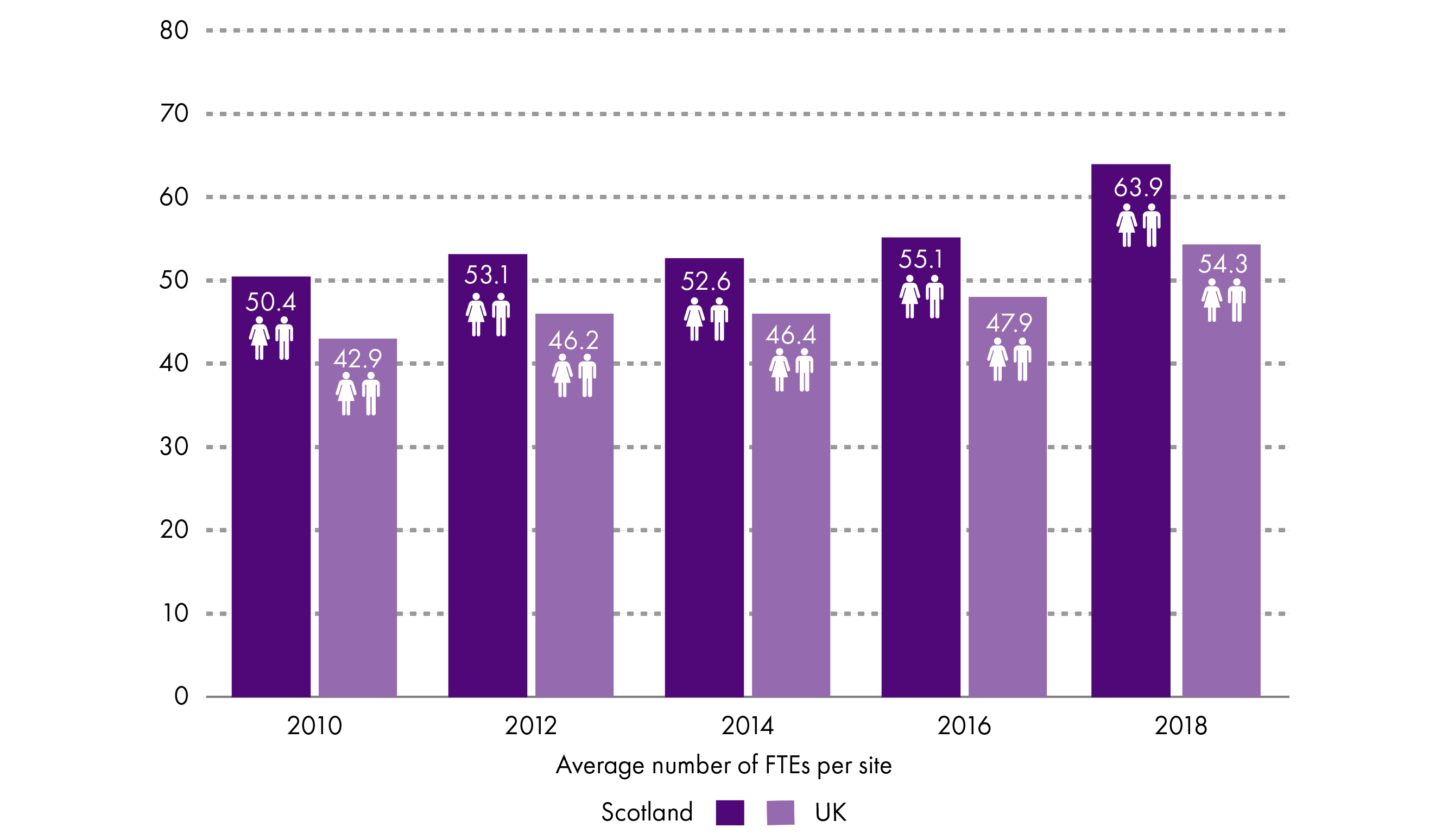

In 2018 Scotland had 139 seafood processing sites (i.e. individual factories or facilities for processing fish), approximately 39% of the UK total. The number of sites decreased by almost 25% between 2010 and 2018 while the average number of Full Time Equivalent (FTE) jobs per site increased by just under 27%, indicating a trend towards consolidation.

| Year | Number of sites | Average FTEs per site | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scotland | UK | Scotland | UK | |

| 2010 | 185 | 446 | 50.4 | 42.9 |

| 2012 | 167 | 405 | 53.1 | 46.2 |

| 2014 | 167 | 401 | 52.6 | 46.4 |

| 2016 | 152 | 376 | 55.1 | 47.9 |

| 2018 | 139 | 353 | 63.9 | 54.3 |

The pattern was similar across the UK as a whole - the total number of sites decreased by 21% over the same period while average FTE jobs per site increased by 27%.

The data indicates that, in Scotland, the trend is towards larger processing sites, with significantly more staff per site (nearly 18% more in 2018), than in the rest of the UK -this is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Employment

The sector provided 8,900 FTE jobs across Scotland in 2018, or 46.3% of the UK total1. This was largely the result of significantly increased employment at sites processing salmon and other freshwater species.

| Year | FTE jobs in Scotland | FTE jobs in UK | Scottish % of UK total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 9,322 | 19,133 | 48.7% |

| 2012 | 8,864 | 18,718 | 47.4% |

| 2014 | 8,785 | 18,608 | 47.2% |

| 2016 | 8,379 | 17,999 | 46.6% |

| 2018 | 8,900 | 19,179 | 46.3% |

Table 3 breaks this data down to show the number of FTE jobs in majority fish processing premises that only process sea fish, premises that only process salmon and/or other freshwater species and premises that process both.

| FTE jobs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea fish | Salmon and other freshwater species | Mixed | All sites | |

| Scotland | 3,244 | 1,675 | 3,981 | 8,900 |

| UK | 7,303 | 2,118 | 9,770 | 19,191 |

| Scottish jobs as % of UK total | 44% | 79% | 41% | 46% |

Breakdown of workforce nationality

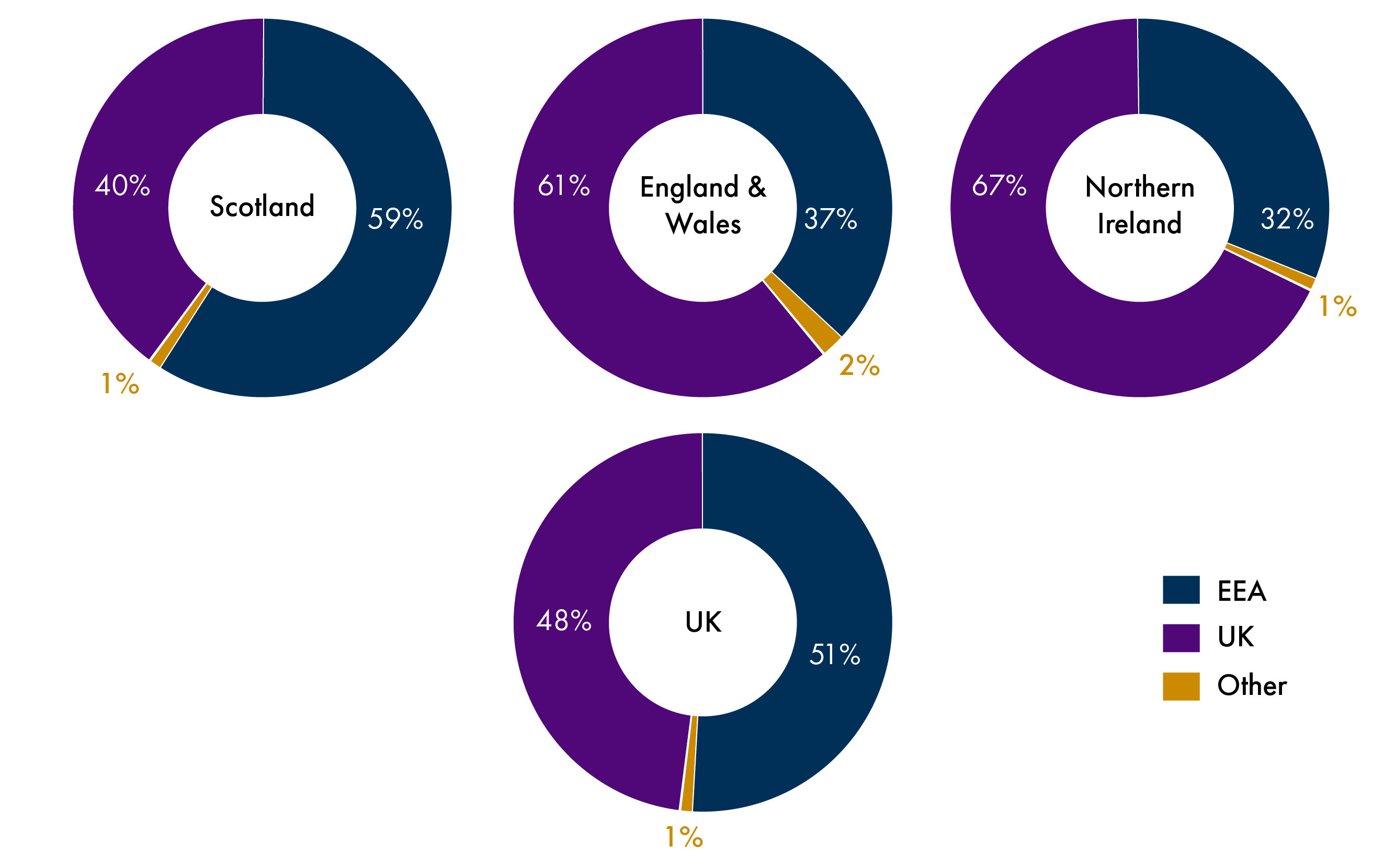

Research by Seafish, the non-departmental public body charged with supporting the UK seafood industry, has shown that the processing sector in the UK relies heavily on workers from other European Economic Area (EEA) countries. The results of a recent survey of processing businesses suggest that EEA workers represented 51% of those employed in the sector across the UK in 2018, a figure that rises to 59% for Scotland as a whole and 69% for the Grampian region in particular1 (see figure 2, below).

These figures broadly align with research published by Marine Scotland in January 2018, which found that 58% of workers in the sector in Scotland were from EEA countries3 other than the UK.

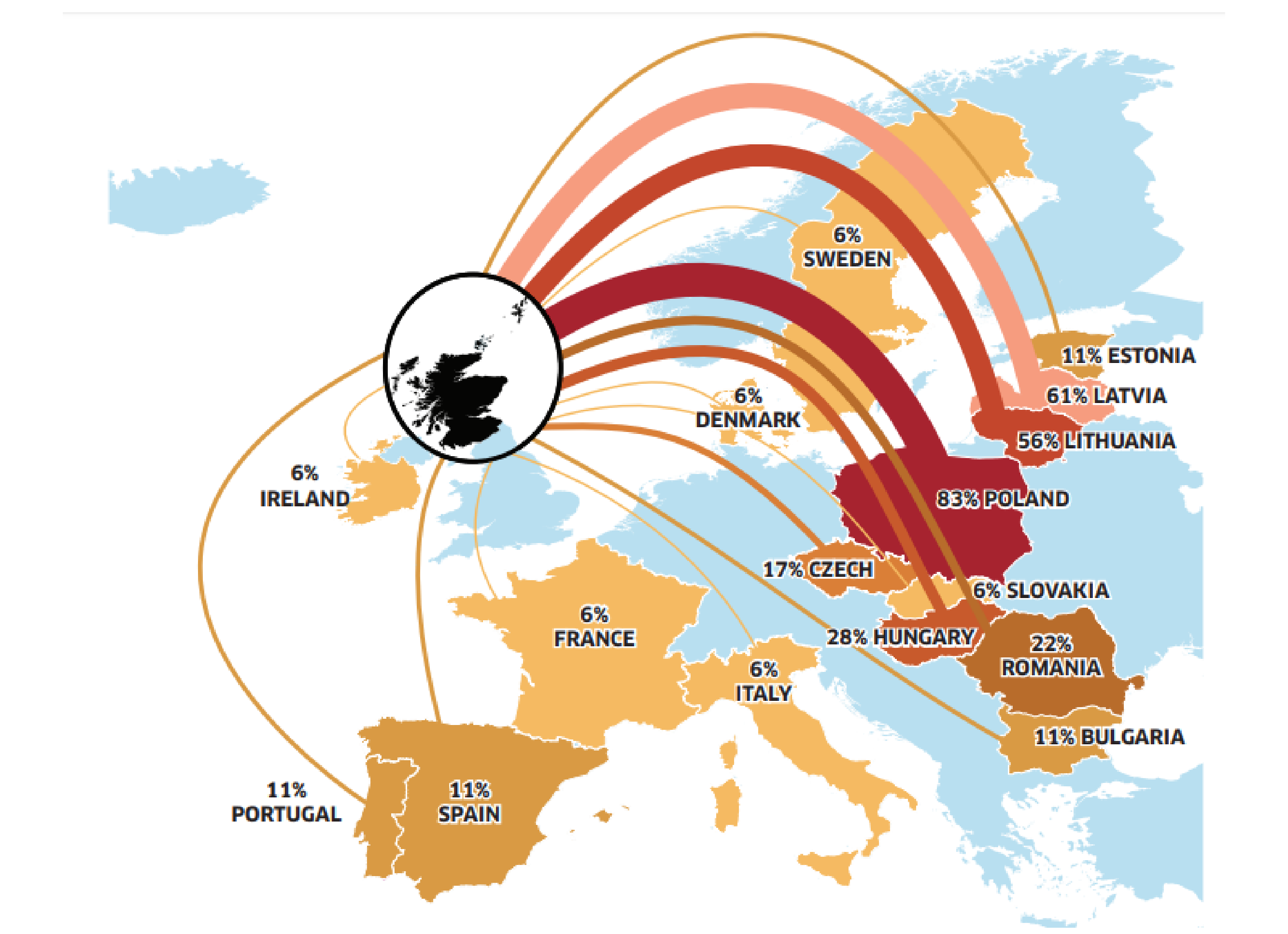

Detailed statistics on the specific nationalities of those employed in the sector are hard to come by. However, of those businesses surveyed by Marine Scotland that employed EEA staff, 83% employed Polish nationals, 61% employed Latvian nationals and 56% employed Lithuanian nationals. While these were the most common countries from which businesses recruited, employees also came from wide a range of other EEA countries, as illustrated at Figure 3.

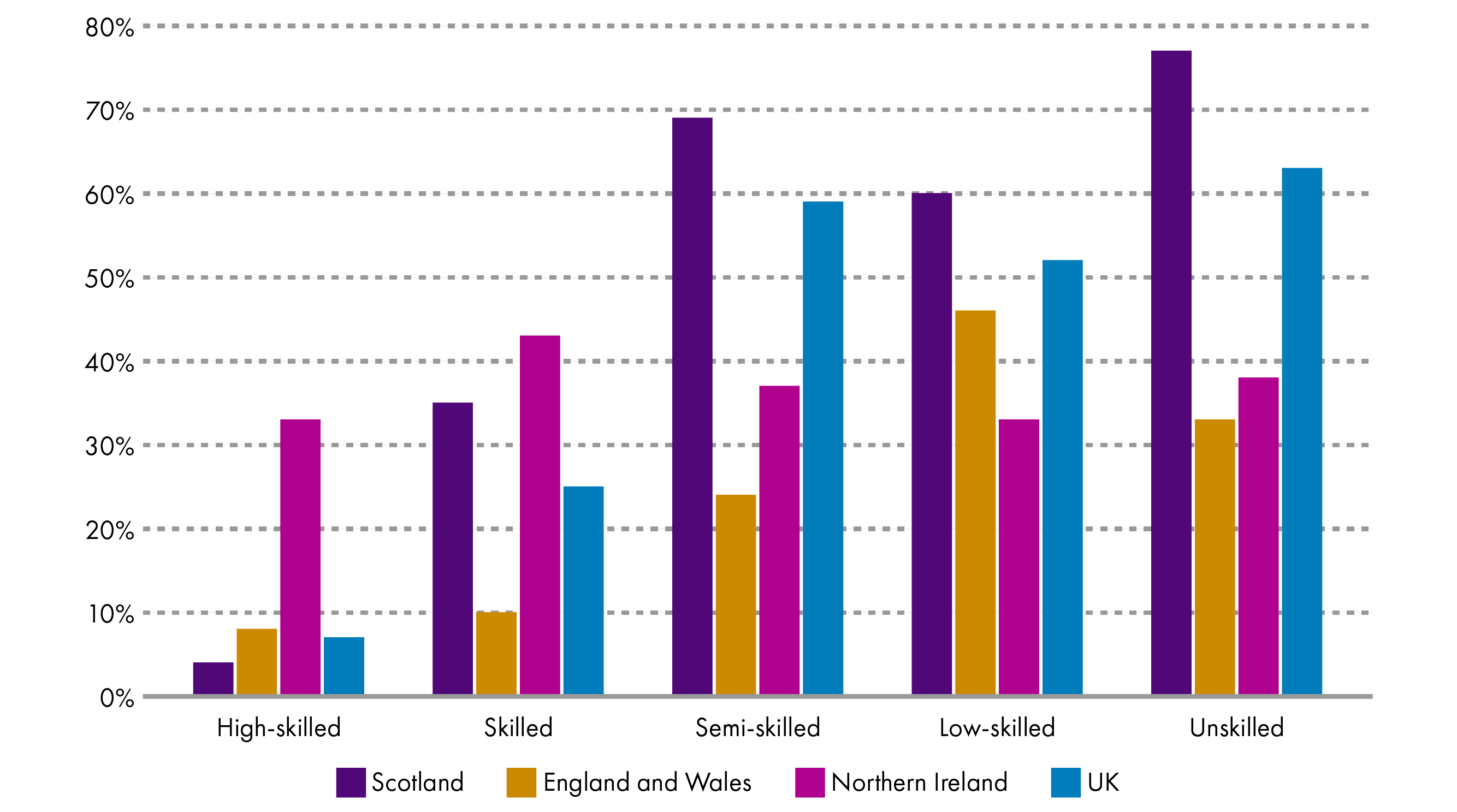

In 2018, Seafish conducted its second annual survey of workforce composition in the UK processing sector. Processors were asked to provide data on the skill level of their workers - more specifically, the skill level of each job rather than the individual employees themselves. Results of the survey indicated that, across all sites sampled, an estimated 93% of high skilled roles were held by British workers. This skill band included jobs such as senior managers, engineers and new product development technicians. Only an estimated 7% of these roles were held by workers from other EEA countries1.

The proportion of workers from other EEA countries generally increased as job skill level decreased. An estimated 59% of semi-skilled roles were filled by EEA nationals, 52% of low-skilled roles and 63% of unskilled roles. These skill bands cover a range of roles, including general operatives, machine minders, filleters and shellfish shuckers/pickers.

While this trend in relation to lower skilled roles was present across the UK, figure 4 demonstrates just how much variation there was between the home nations.

The survey data suggests that seafood processing in Scotland is more reliant on immigrant labour than in any other part of the UK. Across Scottish sites sampled, an estimated 69% of semi-skilled roles, 60% of low skilled roles and 77% of unskilled roles were held by EEA workers.

Contribution to Scottish and UK economies

The UK seafood processing industry is one of the largest in the European Union (EU), with a turnover of over €5.3 billion in 2015 . Only the French industry, with a turnover of €5.5 billion, generated more income1.

| Country | Total jobs | Turnover (€m) | Net profit (€m) | GVA (€m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | 17,520 | 5,516 | 271 | 1,200 |

| UK | 20,110 | 5,306 | 507 | 1,283 |

| Spain | 19,030 | 4,944 | N/A | 877 |

| Poland | 17,740 | 2,503 | 124 | 365 |

| Denmark | 3,610 | 2,489 | 126 | 357 |

As table 4 shows, the UK industry employs more people, generates more net profit and contributes more in Gross Value Added (GVA) than any of its closest competitors elsewhere in the EU. And Scotland plays a significant part in that success - when taken on its own, the Scottish seafood processing sector would come fifth in the EU in terms of employment and eighth in both turnover and GVA contributed3.

Seafood processing is a significant part of Scotland's marine economy, and is larger than both the fishing and aquaculture industries. Figure 5 demonstrates how substantial the sector is, with a turnover of £1.6 billion by 2016 - more than double that of aquaculture and nearly three times that of the fishing industry.

In addition, seafood processing in Scotland provided approximately 8,379 Full Time Equivalent (FTE) jobs4 in 2016 and contributed £391 million in GVA3. In comparison, the fishing industry provided 4,820 FTE jobs and contributed £296 million in GVA, while aquaculture provided 2,280 FTE jobs and contributed £216 million in GVAi.

Table 5 demonstrates that, although the sector forms only a very small part of the wider Scottish economy, the £400 million it generates in GVA makes up over 10% of the total contributed by the entire marine economy.

| Industry | GVA (£m) | GVA as % of total marine economy | GVA as % of total Scottish economy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fishing | 296 | 7.7 | 0.22 |

| Aquaculture | 216 | 5.6 | 0.16 |

| Seafood processing | 391 | 10.2 | 0.29 |

Regional importance

Seafood processing in Scotland is largely based in the North East, the Highlands and Islands and on the West Coast, and makes a significant contribution to the local economies in these areas. In the North East, the industry works mainly with sea caught fish and shellfish. In the Highlands and on the West Coast, it is most often focused on processing Atlantic salmon and other farmed fish and shellfish.

Figure 6 shows Scotland divided into the three regions used by Seafish for reporting purposes - Grampian, the Highlands and Islands and Other Scotland. As the data makes clear, the Grampian region has the largest share of Scotland's seafood sector, with 4,327 FTE jobs (48.6% of the Scottish total) based at 55 sites 2018 - an average of 78.7 FTE jobs per site. The concentration of processing sites in places like Aberdeen, Peterhead and Fraserburgh ensured that, in 2015 alone, the industry generated more than £725 million in turnover and £116 million in GVA for the region (see table 6 below). In fact, Grampian is the second biggest seafood processing area in the UK, just behind Humberside in the north of England.

| Turnover (£m) | GVA (£m) | |

|---|---|---|

| Grampian | 725 | 116 |

| Highlands and Islands | 275 | 72 |

| Other Scotland | 692 | 114 |

| Scotland total | 1,692 | 302 |

| UK total | 5,306 | 1,283 |

The sector in the Highlands and Islands provided 1290 FTE jobs in 2018, spread across 30 sites - an average of 43 FTE jobs per site. The industry generated £275 million in the region in 2015 and added £72 million in GVA to the local economy.

The 'Other Scotland' region includes much of the West Coast and the Lowlands. In 2018, seafood processing provided 3283 FTE jobs in the region, spread across 54 sites - an average of 60.8 FTE jobs per site. The industry generated £692 million in turnover across this part of the country in 2015, and added £114 million in GVA to the economy - a strong performance, placing the region in third place in the UK behind Humberside and Grampian.

International trade

Trade in fish and seafood is a global industry. The UK exports most of what it catches to other countries and imports the majority of the fish that are processed or consumed within the UK1. One of the most significant reasons for this is that many of the most common species landed by the UK fleet (e.g. mackerel, herring) do not meet the tastes of UK consumers, while those that are more popular in the UK (e.g. cod, haddock, tuna) can often only be sourced in sufficient quantities from abroad. Overall, the UK is a net importer of fish, with imports exceeding exports by a considerable margin.

705,000 tonnes of fish (excluding fish products) were imported into the UK in 2017. This was a 3% reduction from 2016. Imports totalled 809,000 tonnes when fish products, such as fish meal and fish oils, were included. Tuna was the highest imported fish by weight at 114,000 tonnes, closely followed by cod at 110,000 tonnes2.

In the same year, exports of fish rose by 5 per cent to 460,000 tonnes, or 504,000 tonnes when fish products were included. Exports were highest for salmon at 116,000 tonnes, followed by mackerel at 78,000 tonnes and herring at 42,000 tonnes.

In 2017, the countries from which the UK imported the greatest volumes of fish and fish products were2:

China (67,000 tonnes)

Iceland (56,000 tonnes)

Germany (50,000 tonnes)

Denmark (43,000 tonnes)

Faroe Islands (36 thousand tonnes)

The largest markets for UK exports of fish and fish products were:

France (89,000 tonnes)

Netherlands (68,000 tonnes)

Spain (45,000 tonnes)

Ireland (37,000 tonnes)

United States (36,000 tonnes)

European funding

The Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) is the mechanism and set of rules for managing European fishing fleets and conserving fish stocks. The European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF) co-finances the implementation of the CFP alongside projects focused on transitioning to sustainable fishing and aquaculture, creating new jobs, diversifying coastal economies and making it easier for applicants to access finance.

The EMFF is one of five European Structural & Investment (ESI) funding programmes and is worth €6.4 billion across the European Union between 2014 and 20201. Each Member State is allocated a share of the total, based on the size of its fishing industry. Industry size is measured by:

the level of employment in the fisheries and marine and fresh water aquaculture sectors, including employment in related processing

the level of production in the fisheries and marine and fresh water aquaculture sectors, including related processing

the share of the small-scale coastal fishing fleet as part of the overall EU fishing fleet

The UK will receive €243 million over the 2014-20 funding period, the eighth largest allocation of the 27 eligible Member States (Luxembourg is not a recipient). The UK Government's Marine Management Organisation (MMO) determines how the funds will be spent and defines UK-wide objectives, activities and targets, however significant responsibilities are delegated to the Scottish Government. Marine Scotland delivers the Scottish element of the programme on the Scottish Government's behalf, including the selection of projects and the payment and scrutiny of claims.

Using broadly similar criteria to those outlined above, the UK Government allocated €108 million (£86 million) to Scotland, roughly 44% of the total2. By May 2018, Marine Scotland had awarded almost £42 million in funding to 492 projects across the country.

Hundreds of projects across Scotland have received EMFF support during the EU's current budget period. By May 2018, £8.3 million had been awarded to 44 projects specifically related to marketing and fish processing, including:

£1.1 million towards the development of a salmon processing factory at Gretna

£0.8 million for the construction of a new shellfish grading and processing facility in South Lanarkshire

£0.75 million towards the installation of plant and equipment at a seafood processing site in Fraserburgh

£0.6 million to purchase and install new plant and equipment at a seafood processing site in Aberdeen

Source: Marine Scotland

Future challenges: the implications of Brexit

Immigration and workforce

On 18 September 2018 the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) published its final report on European Economic Area (EEA) migration into the UK. The report presented the MAC's findings on migration trends and included recommendations for the design of future immigration policy1.

In its report, the MAC outlined a series of recommendations to the UK Government. Among the most significant were that the UK should:

Move to a migration system in which EU citizens do not get preferential access to the UK, on the assumption that UK immigration policy is not included in a future trade agreement with the EU.

Remove the cap on the current Tier 2 immigration system, which relates to higher-skilled workers with a salary of over £30,000 per year.

Expand the Tier 2 system to include medium-skilled workers, while retaining the £30,000 minimum salary threshold (which the MAC acknowledges would be "difficult, but not impossible, to meet for medium-skilled jobs").

In addition, the MAC did not recommend any explicit work-related migration route for lower skilled workers, with the possible exception of a seasonal agricultural workers scheme. The report acknowledged that this was "likely to be strongly opposed by the affected sectors.”

On 20 December 2018, the UK Government introduced its Immigration and Social Security Co-ordination (EU Withdrawal) Bill ('the Immigration Bill') to the House of Commons. If passed, the Bill would end the EU's rules on free movement of people into the UK and make EEA and Swiss nationals, and their families, subject to UK immigration controls2. The Bill also makes provisions to protect the rights of Irish citizens in line with existing Common Travel Area arrangements, ensuring that they would not require permission to enter or remain in the UK, regardless of the changes to free movement. In addition, the Bill will give UK Ministers (and, where appropriate, devolved authorities) the power to amend retained EU legislation on social security.

The Bill does not set out the future immigration system for EU/EEA nationals who move to the UK after Brexit. However, on 19 December 2018, the Home Office published detailed proposals in its White Paper, The UK's future skills-based immigration system3. For the most part, these new arrangements will be set out in the UK's Immigration Rules , creating a single, unified immigration system that will apply to everyone who wants to come to the UK after Brexit. This system will be based on a modified version of the current rules for non-EU nationals, with a focus on skills rather than country of origin, and a particular priority placed on attracting higher skilled migrants.

The White Paper acknowledges that some employers have become reliant on lower skilled workers from EU countries so, as a transitional measure only, it proposes a time-limited route for temporary short-term workers. This would allow people to come to the UK to work for a maximum of 12 months, after which they would have to leave for a minimum of 12 months before being allowed to re-enter. Those making use of this route would have no right to extend their stay, bring dependants to the UK or settle permanently. These arrangements would be subject to a full review in 2025 and may be discontinued. The UK Government does not intend to establish sectoral labour schemes, with a possible exception for seasonal agricultural work (a small-scale, two-year pilot scheme has been running since March 2019).

The status of EU citizens in the UK after Brexit

Under the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement currently before the UK Parliament, free movement would continue until the end of the transition period on 31 December 2020. After that, the legal status of EU citizens residing in the UK would be regularised by the UK Government's proposed EU Settlement Scheme1. The Scheme opened on 30 March 2019 and provides new immigration categories of 'settled status' and 'pre-settled status' for EU, EEA and Swiss nationals and their family members lawfully residing in the UK.

Settled status is available to EU citizens who have accrued five years of continuous residence in the UK prior to 31 December 2020. Those who moved to the UK prior to 31 December 2020 (or the date of the UK's departure from the EU in the case of a no deal scenario), but who have not yet lived in the UK for five years, may be eligible for pre-settled status2.

Potential implications for the seafood processing sector

With its heavy reliance on workers from other EEA countries, the seafood processing sector has a keen interest in in the UK Government's proposed changes to existing immigration arrangements. Proposals in relation to low-skilled worker migration will be of particular interest to processing businesses due to the high proportion of lower skilled workers from outside the UK employed in the industry. Indeed, there is already evidence that businesses are starting to feel an impact, even before the UK's formal withdrawal from the EU.

We are worried about the apparent lack of concern about the food industry as a whole. We've been told there will be concessions for low-skilled migrant workers for the agricultural sector but no information for the seafood industry.

Seafood processor in Humberside, quoted in Seafish. (2019). UK seafood processing sector labour analysis 2019. Retrieved from to be added [accessed 6 June 2019]

With this reliance on non-UK EEA workers even more pronounced in Scotland than elsewhere in the UK, Scottish processors will need to be particularly alert to changes to the immigration system.

We have been able to get just enough workers to meet our needs, but with 85% of our workers from Eastern Europe and the labour situation worsening we are concerned.

Seafood processor in Grampian, quoted in Seafish. (2018, October). UK seafood processing labour analysis 2018 - quarter 4. Retrieved from https://www.seafish.org/media/october_2018_quarter_4_processing_labour_report.pdf [accessed 31 May 2019]

In its October 2018 quarterly processing sector labour report, Seafish highlighted that 41% of businesses it had surveyed were finding it harder to fill vacancies than in the previous quarter2. This rose to 56% among processors in the Grampian region. 17% of respondents said that workers from EEA countries were less willing to come to the UK while 20% said that existing EEA workers were leaving in increasing numbers. One of the most common reasons given for this was the uncertainty surrounding both Brexit and the future status of EEA workers in the UK. Other suggested reasons included the decreasing value of Sterling, improving economies elsewhere in Europe making other countries more attractive destinations, and some EEA citizens feeling less welcome in the UK than previously.

The Scottish Government has also expressed concern at the impact the end of free movement could have on the seafood processing sector, highlighting the dependence of many Scottish processors on workers from other EEA countries4. While responding to a question in the Scottish Parliament on 14 November 2018, the Cabinet Secretary for the Rural Economy, Fergus Ewing MSP, stressed that:

The loss of freedom of movement, which provides opportunities for people from the European Union to live and work in Scotland, is key. Given that more than 70 per cent of the seafood processing workforce in north-east Scotland are non-United Kingdom nationals from the European Economic Area, the processing sector has every right to be concerned.

Fergus Ewing MSP, Scottish Parliament Official Report. (2018, November 14). Response to S5O-02543 (taken in the Chamber). Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11775 [accessed 3 June 2019]

EU and government funding

Should the UK leave the EU with an agreement similar to that currently before the UK Parliament, the funding available under EMFF would continue until the end of 2020. Should the UK leave the EU without an agreement, new projects would be unable to access that funding. HM Treasury has provided a guarantee to the devolved administrations to underwrite the UK's allocation for structural and investment fund projects, including under the EMFF, to the end of the current EU budget period in 20201. The Scottish Government has confirmed that it will pass that guarantee on in full.

Once the UK leaves the EU, however, access to structural funding will end. In its White Paper, Sustainable fisheries for future generations, the UK Government has said that it would consider whether to replace the EMFF with a domestic alternative2.

As to what that alternative might look like, the Conservative Party manifesto for the 2017 UK General Election did commit to a UK-wide replacement for EU structural funds - the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF)3. In July 2018, the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government, James Brokenshire MP, made a Written Statement to the House of Commons, setting out more details about the Fund1. Key points included:

The purpose of the Fund will be to tackle inequalities between communities by raising productivity, especially in those parts of the country whose economies are furthest behind.

The Fund will have simplified administrative processes to ensure that investment is targeted effectively to align with the challenges faced by places across the country.

The Fund will operate right across the UK. The UK Government will "respect the devolution settlements in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland" and will engage the devolved administrations to ensure that it operates effectively.

Originally, the UK Government had planned to consult on its proposals before the end of 2018. That consultation has now been delayed and it is not clear when it will take place, although recent indications are that further details will be announced following the Spending Review in autumn 2019. The precise role of the Scottish Government in the design of the Fund, or the level of funding that will be allocated to Scotland, is not clear at this time.

Trade and market access

The UK's decision to leave the EU is likely to have a major impact on its future international trade policy. As a member of the EU, the UK is part of both the Single Market and Customs Union - a territory without any internal borders or other regulatory obstacles to the free movement of goods and services. Under these arrangements, trade policy is largely determined by the EU - the European Council gives authorisation to the European Commission to negotiate trade agreements on behalf of all EU Member States1. The European Commission also represents the EU as a whole at the World Trade Organization (WTO), acts on the EU's behalf in the event of trade disputes and protects the EU market by implementing trade defence measures allowed for under WTO rules2.

These arrangements will cease once the UK withdraws from the EU, and the UK will become wholly responsible for conducting its own international trade policy. On 9 October 2017, the Department for International Trade published 'Preparing for our future UK trade policy', a White Paper setting out the UK Government's proposed approach to trade policy post-Brexit. In his foreword, the Secretary of State for International Trade, Liam Fox MP, set out the UK Government's intentions:

As we develop our own independent trade policy and look to forge new and ambitious trade relationships with our partners around the world, we will build a truly Global Britain upon a strong economy with open and fair trade at its heart.

Liam Fox MP, Department for International Trade. (2017, October 9). Preparing for our future UK trade policy. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/654714/Preparing_for_our_future_UK_trade_policy_Report_Web_Accessible.pdf [accessed 20 June 2019]

On 7 November 2017, the UK Government introduced the Trade Bill to the House of Commons. The Bill is currently progressing through Parliament and contains provisions on the following:

the implementation of international trade agreements

establishing the Trade Remedies Authority and conferring functions on it

the collection and disclosure of information relating to trade.

The Bill aims to help transition the EU's existing trade agreements into UK agreements and will cover agreements signed by the EU before the UK's formal exit day - "new" trade agreements are not covered. In addition, the Bill only contains provisions relating to non-tariff barriers (e.g. labelling and packaging). Tariff barriers (e.g. customs duties on imports and exports) are the subject of separate legislation - the Taxation (Cross-Border Trade) Act 20181.

Future economic relationship with the European Union

The UK Government has repeatedly made clear that, in its view, the UK must leave the Single Market and Customs Union when it withdraws from the EU. Ministers have, however, stressed that they want the future economic relationship to be a very close one. Indeed, in the Political Declaration agreed between the UK Government and the EU, both sides have stated their intention to move towards "a trading relationship that is as close as possible, combining deep regulatory and customs cooperation"1.

Key aspects of the future UK-EU economic partnership proposed in the Political Declaration include:

A free trade area for goods that provides for no tariffs or quotas, and ensures a trading relationship that is as close as possible, combining deep regulatory and customs cooperation.

Ambitious arrangements for services and investment that go well beyond WTO commitments and build on recent EU Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), including new arrangements on financial services, alongside timely equivalence decisions under existing frameworks.

A new fisheries agreement covering, amongst other things, access to waters and quota shares, which the UK will negotiate as an independent coastal state.

Commitments to open and fair competition — proportionate to the overall economic relationship — covering state aid, competition, social and employment standards, environmental standards, climate change, and relevant tax matters

Source: 1

Potential implications for the seafood processing sector

The UK's withdrawal from the EU will present the seafood processing sector with both opportunities and significant challenges. On the one hand, the UK will be free to pursue bespoke trade deals with countries around the world, potentially opening up new markets and new sources of raw material for Scottish seafood processors. On the other, even if the UK and the EU agree a close future trading relationship, exports to what is currently the largest external market for UK seafood products will likely face more barriers than they do at present.

According to the UK Seafood Industry Alliance (SIA), the majority of fish consumed in the UK comes from outside EU waters, under a variety of different tariff and market access arrangements, while the majority of what is caught by the UK fleet is currently exported - mainly tariff free to other EU Member States1. In its evidence to House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee during scrutiny of the UK Government's Fisheries Bill, the SIA stressed that these are very different supply chains, with only limited scope for import substitution following Brexit, regardless of any increase in quota share for the domestic fishing fleet. Put simply, in the UK "we import most of what we eat and export most of what we catch"2. The SIA's evidence goes on to state that:

The shape of future trade arrangements - between the UK and the EU and between the UK and third countries - will therefore be critical to existing business models for all parts of the industry, whether in the processing, trading or catching sectors. New tariffs would affect price and supply of fish to the market and our ability to compete with other protein products in meeting consumer needs. And, as in other food sectors, new non-tariff barriers or customs procedures could result in additional cost and delay.

UK Seafood Industry Alliance. (2018, December 5). Written evidence to the House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee's scrutiny of the UK Fisheries Bill. Retrieved from http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/environment-food-and-rural-affairs-committee/scrutiny-of-the-fisheries-bill/written/92837.html [accessed 20 June 2019]