Female Genital Mutilation (Protection and Guidance) (Scotland) Bill

The aim of the Female Genital Mutilation (Protection and Guidance) (Scotland) Bill is to strengthen the existing legal protection for those at risk of female genital mutilation (FGM). This briefing includes an explanation of FGM, the legal and policy context, the main provisions of the Bill, and the Scottish Government's consultation.

Executive Summary

The aim of the Female Genital Mutilation (Protection and Guidance) (Scotland) Bill is to strengthen the legal protection for women and girls at risk of female genital mutilation (FGM). It will do this in two ways:

Makes provision for FGM Protection Orders, a form of civil order that can impose conditions or requirements on a person, with the aim or protecting a person from FGM, safeguarding them from harm if FGM has already happened, or reducing the likelihood that FGM offences will happen. It will be a criminal offence to breach an FGM Protection Order.

Makes provision for statutory guidance on matters relating to FGM, as well as statutory guidance on FGM Protection Orders.

FGM describes all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs, for non-medical reasons.

There are no health benefits. The procedure is likely to cause both short term and long term physical and psychological harm.

The practice of FGM violates a number of rights and freedoms protected under international law.

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) has been a criminal offence in the UK since the Prohibition of Female Circumcision Act 1985.

The Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005 repealed and re-enacted the existing offences in the 1985 Act. It also made it an offence to have FGM carried out abroad, and increased the maximum penalty from five to 14 years imprisonment. The aim was to ensure equal legal protection in Scotland as with the rest of the UK which had made similar changes under the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003.

Scotland already has Multi-Agency Guidance on FGM, although it is advisory and not statutory. It provides specific guidance on dealing with cases of FGM for the NHS, Police Scotland, education and social work services.

The Multi-Agency Guidance on FGM reinforces Scotland's child protection guidance.

Under the child protection system in Scotland there are emergency powers that can be used in relation to FGM:

The child protection order, where a child could be moved to keep them safe from significant harm.

The compulsory supervision order, where a child becomes looked after and responsibility for their care, protection and control is assumed by the local authority.

The Bill's provisions follow similar provisions in the Serious Crime Act 2015 regarding FGM which apply to England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Scottish Government has not proposed to introduce some of the FGM provisions in the Serious Crime Act 2015, namely:

anonymity for victims of FGM

offence of failure to protect from FGM, by a person with parental responsibility

duty on regulated professionals to notify police of FGM.

The Scottish Government's consultation on strengthening protection for FGM set out its position to introduce FGM Protection Orders and statutory guidance, but also sought views on the additional provisions contained in the Serious Crime Act 2015.

Based on the 71 responses to the consultation, there was strong support for FGM Protection Orders and statutory guidance. There was also strong support for the introduction of anonymity for victims of FGM, and mixed views for the introduction of a failure to protect from FGM and a duty to notify the police.

Estimating the costs of the Bill's provision is difficult because there is no accurate data on the prevalence of FGM in Scotland. The Scottish Government has estimated that there could be between 4 and 9 applications for an FGM Protection Order each year, resulting in costs between:

a range of £72,000 and £300,000 a year for up to 9 FGM Protection Orders, including two breaches and cases brought to trial

a range of £220,000 and £270,000 for implementation costs, including training costs and the development of statutory guidance.

Introduction

The Female Genital Mutilation (Protection and Guidance) (Scotland) Bill (the 'Bill') is a Scottish Government Bill, introduced by the Cabinet Secretary for Social Security and Older People, Shirley-Anne Somerville MSP, on 29 May 2019.

The aim of the Bill is to strengthen the existing legal protection for those at risk of female genital mutilation (FGM).1 The Bill does this in two ways, by making provision for:

FGM Protection Orders. These are a form of civil order which can impose conditions or requirements on a person, with the aim of:

protecting a person from FGM

safeguarding them from harm if FGM has already happened

reducing the likelihood that FGM offences will happen.

Guidance. A power for Scottish Ministers to provide statutory guidance on matters relating to FGM, as well as on FGM Protection Orders. Those exercising public functions will be obliged to have regard to the statutory guidance.

While the Bill is short, it may be helpful to understand the different legislative approach taken in the rest of the UK as well as existing mechanisms in Scotland to protect children from harm. Therefore, this briefing provides:

background information on FGM, its impact and prevalence

the legal and policy framework on FGM in Scotland

the child protection system in Scotland and the use of civil protection orders

a discussion of the Bill's provisions and estimated costs

the Scottish Government's consultation on strengthening from FGM.

Along with the other documents, the Scottish Government has also published an Equality Impact Assessment and a Child Rights and Wellbeing Impact Assessment.

What is FGM?

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is a term used to describe all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs, for non-medical reasons.1

FGM has no health benefits for girls and women, and procedures can cause immediate and long term physical and psychological harm.

FGM is a form of violence against women and girls, and it is recognised internationally as a violation of their human rights. See section on International and European law.

FGM is also referred to as 'cutting' or 'female circumcision', as well as a wide range of traditional terms in different languages.2

Where does it originate and where is it practised?

It is estimated that FGM has been practised for over 5,000 years across different continents, countries, communities and belief systems.1 UNICEF reports that the practice occurs in 30 countries across three continents, with half of those cut living in Egypt, Ethiopia and Indonesia.2

Because of the worldwide movement of people, FGM is found in communities all over the world, including Europe.31

Who is at risk?

FGM is mostly carried out on young girls, from soon after birth to young adult, and occasionally adult women.12

Because of the different ages FGM is carried out, it can be difficult to identify when a girl faces an imminent risk of FGM. There are various risk factors:1

the family is from a community in which FGM is practised

the girl's mother, or siblings/cousins have experienced FGM

older family members can be very influential, and may place pressure on younger family members to have FGM

the family is not well integrated within the UK.

Imminent risk factors include:

parents say that they, or a relative, intends to take the girl out of the country for a prolonged period

the girl says she is going on a long holiday to her country of origin, or a country where FGM is common

the girl may tell a professional she is going to have a 'special procedure' or is to attend a special occasion to 'become a woman'.

There are also indicators of when FGM has been performed:

the girl has difficult walking, sitting or standing and seems uncomfortable

the girl leaves the classroom for extended periods and spends longer in the bathroom

the girl is absent from school, which may be for prolonged or repeated periods

the girl shows significant behaviour change, and may be withdrawn and depressed.

How common is FGM?

There is little reliable data on the prevalence of FGM, and there are challenges to collecting and monitoring data. The European Institute for Gender Equality has been working on developing an approach to data collection on FGM across the European Union.1

However, UNICEF estimates that 200 million girls and women alive today have undergone FGM in 30 countries.2 It is estimated that, globally, more than 3 million girls are at risk of FGM each year.3

Across Europe it has been estimated that 180,000 girls and women are at risk of FGM each year, including 137,000 women and girls in the UK.4 Therefore, it is estimated that the majority of all those at risk in the EU, are in the UK.

In 2014, the Scottish Refugee Council published a report that analysed census, birth register, and other data in order to estimate the location and number of communities that might be affected by FGM in Scotland.5 It found that:

"Around 24,000 men, women and children living in Scotland were born in a country where FGM is practised to some extent.

There are communities potentially affected by FGM in every local authority area, with the largest communities in Glasgow, Aberdeen, Edinburgh and Dundee respectively.

Between 2001 and 2012, 2,750 girls were born in Scotland to women born in countries where FGM is practised to some extent".6

Why is it practised?

FGM is usually carried out by 'traditional circumcisers', who may play a central role in communities, such as attending childbirths.1 They will often be older women, for 'whom it can be a lucrative source of income and prestige'. 2 However, there have been some asylum claims made from women who are to become cutters and are trying to escape.3 The procedure is often carried out without anaesthesia or attention to hygiene2, though in some settings health care providers perform FGM due to the belief that the procedure is safe when medicalised.1

It is practised for a range of reasons, and these vary between regions, as well as over time. WHO lists the most commonly cited reasons:1

FGM may be a social convention, with social pressure to conform to what others do. The need to be accepted socially, and the fear of rejection by the community is a strong motivation. In some communities, FGM is almost universally performed and unquestioned.

FGM is often considered a necessary part of raising a girl, and a way to prepare her for adulthood and marriage.

FGM is often motivated by beliefs about what is considered acceptable sexual behaviour. It aims to ensure premarital virginity and marital fidelity.

FGM is more likely to be carried out where it is believed that being cut increases marriage prospects.

FGM is associated with cultural ideals of femininity and modesty, which include the notion that girls are clean and beautiful after removal of body parts that are considered unclean, unfeminine or male.

While some practitioners may believe that FGM has religious support, no religion condones it.

Local structures of power and authority, such as community leaders, religious leaders, circumcisers, and even some medical personnel can contribute to upholding the practice.

In most societies where FGM is practised, it is considered a cultural tradition, which is often used as an argument for its continuation.

In some societies, recent adoption of the practice is linked to copying the traditions of neighbouring groups.

Types of FGM

The World Health Organisation (WHO) describes four types of FGM:1

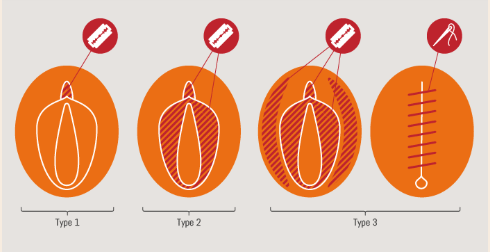

Type 1: Often referred to as clitoridectomy, this is the partial or total removal of the clitoris (a small, sensitive and erectile part of the female genitals), and in very rare cases, only the prepuce (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris).

Type 2: Often referred to as excision, this is the partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora (the inner folds of the vulva), with or without excision of the labia majora (the outer folds of skin of the vulva ).

Type 3: Often referred to as infibulation, this is the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the labia minora, or labia majora, sometimes through stitching, with or without removal of the clitoris (clitoridectomy).

Type 4: This includes all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, e.g. pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area.

De-infibulation refers to the practice of cutting open the sealed vaginal opening in a woman who has been infibulated, which is often necessary for improving health and well-being as well as to allow intercourse or to facilitate childbirth.

Health impact of FGM

The possible health consequences of FGM are extensive as identified by WHO1 and in the Scottish Government's guidance.2

Immediate physical health consequences can include:

severe pain

emotional and psychological shock, exacerbated by being subjected to the trauma by loving parents, carers, extended family and friends

excessive bleeding (haemorrhage)

fever

infections, such as tetanus, HIV, Hepatitis B and C

urinary retention

wound healing problems

injury to surrounding genital tissue

death.

Long-term physical consequences can include:

urinary problems (painful urination, urinary tract infections)

vaginal problems (discharge, itching, vaginal infections)

menstrual problems (painful menstruations, difficulty in passing menstrual blood)

keloid scar formation (raised, irregularly shaped, progressively enlarging scars)

sexual problems (pain during intercourse, decreased satisfaction)

complications during pregnancy and childbirth - a woman who has been subjected to Type 3 FGM, infibulation, will need to be de-infibulated, otherwise labour will be obstructed and be life threatening for mother and child3

Long-term mental health consequences can include:

post-traumatic stress disorder

depression, anxiety, low self-esteem

suppressed feelings of anger, bitterness or betrayal.

Legal and policy framework on FGM in Scotland

Scotland has developed specific legislation and policy on FGM. It also has a broad range of legislative and policy tools to help support and protect women and girls who have been subjected to FGM.

This section will first focus on the specific legislation and policy directed at dealing with FGM. It will then consider the consider the wider legal and policy framework that can also be applied to support women and girls at risk of FGM.

The Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005

FGM has been a criminal offence in the UK for 34 years, since the Prohibition of Female Circumcision Act 1985.

The Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005 repealed and re-enacted the existing offences in the 1985 Act. It also made it an offence to have FGM carried out abroad, and increased the maximum penalty from five to 14 years imprisonment. The aim was to ensure equal legal protection in Scotland as with the rest of the UK which had made similar changes under the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003. The 2005 Act also changed the terminology from circumcision to FGM, removing any form of acceptability the term 'circumcision' might imply.

To date, there have been no criminal prosecutions brought in Scotland (there has been one in England), either under the 1985 Act or the 2005 Act. Reasons for the lack of prosecutions are varied, but are likely to include that:

it is difficult to challenge family members

there may be a lack of evidence

perpetrators may be aware of the risk and take a different course of action

professionals may be reluctant to speak out on what they mistakenly believe is a cultural or religious practice.123

Policy and guidance on FGM in Scotland

Equally Safe: Scotland's strategy to eradicate violence against women and girls

Equally Safe is the Scottish Government's and COSLA's overarching strategy to prevent and eradicate violence against women and girls1. It was first published in 2014, and updated in 2016.

The Scottish Government's definition of violence against women and girls views gender inequality as a root cause of such violence. The definition, based on a UN declaration on violence against women, sets out that ‘Gender based violence is a function of gender inequality, and an abuse of male power and privilege’. The violence can be physical, emotional, sexual or psychological. The Scottish Government's list of such violence includes FGM.

The Equally Safe strategy committed to implementing Scotland's National Action Plan to tackle Female Genital Mutilation.1 The Equally Safe: Delivery Plan for 2017-2021 was published in November 20173, with a one year progress report published in November 20184. The one-year update set out the Scottish Government's intention to introduce a further Bill on FGM in order to "strengthen the protection of women and girls from this extreme form of gender based violence". It also referred to progress in terms of raising awareness of FGM in affected communities, as well as the publication of multi-agency guidance on FGM.

National Action Plan to tackle FGM

Scotland's National Action Plan to prevent and eradicate Female Genital Mutilation was published in February 2016. 1 An Implementation Group was set up to oversee the actions and objectives of the plan.2 The National Action Plan, one year report, provided detail on the progress made, which included:2

funding of £226,000 for 2016-17 and £270,000 for 2017-18 to progress the actions

development of Multi-Agency Guidance (see below)

distribution of training and awareness training material on FGM

community based organisations funded to challenge the practice in communities.

Multi-Agency Guidance on FGM

The Scottish Government published the Multi-Agency Guidance on FGM in November 2017.i1 It reinforces child protection guidance (see below) and applies it specifically to cases where a girl is at risk of FGM or has been subjected to FGM.

The guidance advises that statutory agencies such as the NHS, Police Scotland, education and social work services should:

have a designated FGM lead or point of contact

review data recording and monitoring systems to include FGM where possible

strengthen information sharing on FGM to protect women and girls

train staff on FGM.

The guidance also provides advice on:

how to talk about FGM with survivors

how to identify the imminent risk of FGM

how to identify when FGM has already been performed.

There is further detailed specific guidance for health care workers, the police, teachers, social work staff, and staff working in third sector organisations.

Guidance for healthcare services on FGM

In addition to the Multi-Agency guidance, the Scottish Government's Chief Medical Officer and Chief Nursing Officer issued a guidance letter for health boards in February 2016.1 The letter provides guidance on how to:

support women and girls when FGM is disclosed or identified, and

to prevent FGM and protect those at risk of FGM.

The guidance sets out some key components for health services to consider, such as:

Contact details of a named FGM Clinical Lead in each Health Board, with a named deputy to cover absences, who should be known to the community and other professionals.

Professional practice involves asking sensitive questions. "A professional's personal fears of being thought 'racist' or 'discriminatory' should not compromise the duty to provide effective support and protection."

Appropriate intervention will depend on the type of FGM which presents with symptoms, and whether a woman is pregnant. FGM is often identified during antenatal care, but sometimes not until delivery.

An interpreter of a specified sex may be preferred.

Some women may strongly resist any surgical procedure that she believes 'reverses' FGM. This is because of social pressure to go along with the wishes of her husband or family or wider community. "Such circumstances will pose a challenge to protect the woman's rights".

Child protection

Getting it right for every child

Getting it right for every child (GIRFEC) is the Scottish Government's national approach to supporting children's and parent's rights. It is based on values and principles that are central to all government policies that support children, young people and their families. The aim is to provide children and families with the right support at the right time. This approach is used by all agencies and professionals who work with children and their families.

The Children and Young People Act 2014 is rooted in the GIRFEC approach and put a number of key duties and provisions in statute, including a framework for the assessment of a child's well-being. Assessing risk to a child's well-being is a key part of the child protection system.

Child protection system

The child protection system is currently central to tackling FGM in Scotland. The Policy Memorandum to the Bill (at para 14) says the FGM Protection Order is designed to complement this existing system.1

Child protection is ‘multi-agency’, involving social work, the police, schools, the NHS and the third sector. Local authorities’ social work departments and the police play particularly important roles.

A key piece of legislation is the Children’s Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011 (‘the 2011 Act’), supplemented by secondary legislation and guidance. Part 4 of the National Guidance for Child Protection in Scotland sets out the required response for a professional if they come across FGM.2 It notes FGM should trigger child protection concerns and a multi-agency response is required. The Scottish Government's multi-agency guidance on FGM (see above) builds on this, setting out three levels of response, depending on the level of risk.

Between 1 April 2013 and September 2016, there were 52 referrals or child welfare concerns made to the police from partner agencies about FGM. The concerns related to girls being at risk of FGM. The concerns were investigated and no criminality was found - no cutting had taken place in any of the cases referred.1

In terms of key statutory powers, the child protection system has emergency powers, to be used in exceptional circumstances, and the power to grant a compulsory supervision order (CSO). The latter sets out any long-term supervision measures required for a child.

A vital part of the child protection system is the children's hearing system, which decides whether to grant a CSO. This specialist system is unique in being separate from the functioning of the main court system. It has no direct equivalent in England and Wales.

The sheriff courts in Scotland do still play some role in the child protection system. For example, they deal with CSOs in limited circumstances (see below). They are also involved in relation to emergency powers.

Definition of a 'child'

In Scotland, the definition of a 'child' varies according to legal circumstances, making the law in this area complex.

Some legislation says a child is under 18 (e.g. Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009) and Part 1 of the National Guidance for Child Protection in Scotland applies to children under 18.1 However, in some child protection contexts, a child is under 16. Significantly, this includes, for most purposes, children's hearings and child protection orders (one form of emergency power).

Where a young person between the age of 16 and 18 requires protection, agencies need to consider which legislation or policy, if any, can be applied. This will depend on the young person's individual circumstances as well as on the particular legislation or policy framework. Sometimes it will be legislation applicable to adults which will apply.

The structure of the children's hearing system

The main components of the children's hearings system are children's hearings, which make decisions; Reporters to the children's hearing, who support the process in various ways; and local authorities, which implement children's hearing decisions.

The decision-makers at children' hearings (panel members) are (unsalaried) representatives of the local community, who are not legally qualified. They are supported by a public body, Children's Hearings Scotland.

Hearings are less formal than the ordinary civil court system. Solicitors can represent people whose interests are affected but the environment is intended to be “non-adversarial.” The focus is on the child's needs and finding solutions, rather than two sides arguing with each other. The key principles of the system are, as follows:

the welfare of the child is the paramount consideration

an order will only be made if it is necessary (i.e. the state should not interfere with the child's life more than is strictly necessary), and

the views of the child will be considered, with due regard for age and maturity.1

A public official, a safeguarder, whose role is to protect the child's interests, can be appointed at any time during the hearings process.

An important role is played in the children's hearing system by the Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration (SCRA), a public body, who employ Reporters to the children's hearing system (including a Principal Reporter). One duty of a Reporter is to carry out an initial investigation into a case and decide whether it should be referred to a children's hearing for a decision. Reporters typically have backgrounds in law or social work.

Emergency powers

There are two main emergency powers in the child protection system: child protection orders (CPOs) and police powers to remove a child to a place of safety.

A child protection order (CPO) is a civil order granted by the sheriff court. Any person can apply for such an order, but it is usually the local authority which does so.

In applying for the order, the local authority must have reasonable grounds to believe a child is likely to be significantly harmed, or has suffered significant harm, and needs to be immediately moved to keep them safe. As well as authorising the child's removal, the CPO can authorise other steps. These include an assessment of the child's health or how he or she has been treated.

A CPO can last for up to eight days. Once the order is granted the case is referred to a children's hearing (to decide on the need for longer-term measures). Although it is a civil order, “intentional obstruction” of a CPO is a criminal offence (punishable by fine up to £1,000).

Another important power is the police's power to remove a child to a place of safety (e.g. with family members living elsewhere or to emergency foster care). This lasts for up to twenty-four hours and can be used where the grounds for a CPO are met but there is no time to apply for a CPO. Use of this power also triggers a referral of the case to the Reporter in the children's hearing system. (The Reporter can then apply for a CPO).

Compulsory supervision order

As mentioned earlier, compulsory supervision orders (CSOs) are for long-term supervision of a child. Furthermore, it is a children's hearing, rather than the sheriff courts, which decide whether to grant a CSO and on what terms. The sheriff court will only become involved if: (i) the grounds of referral to the hearing are disputed or not understood; or (ii) there is an appeal against a decision of a hearing.

The legal effect of a CSO is that a child becomes looked after and responsibility for their care, protection and control is assumed by the local authority, usually carried out in practice by social work departments. A looked after child may or may not be required to live away from the family home.

Referrals to the Reporter on the possible need for a CSO come from a variety of sources. On FGM specifically, the 2017 multi-agency guidance says:

If a child has been a victim of FGM, or is at risk of becoming a victim of FGM, (for example, she lives in the same household as a victim of FGM or a person who has previously committed an offence involving FGM) then she can be referred to the Reporter…The police, the local authority, health services, schools or by any other person or agency who has concerns about the child can refer her.

Furthermore:

The court has specific power to refer affected children if someone has been convicted by that court of an offence which involves FGM.1

More generally, local authorities are subject to a statutory responsibility to investigate the child’s circumstances if they think:

it is likely a child requires protection, guidance, treatment or control; and

it might be necessary for a CSO to be made.

Furthermore, if the bullets above turn out to apply, the local authority must make a referral to the Reporter. The police are subject to a similar statutory duty.

A CSO lasts for as long as is required but there are various statutory provisions designed to ensure there are opportunities for regular reviews.

It is also possible for a children's hearing (or, some circumstances a sheriff court) to make an interim CSO, pending final consideration of the case. An interim CSO functions as a further type of emergency power. It lasts 22 days but can be extended.

Other civil protection orders

Outside the child protection system, there are a variety of other civil protection orders which might be relevant in the context of FGM. For example, one parent might be exposed to violent or threatening behaviour from the other parent (or other relative) for attempting to protect a child from FGM. Also, in some cases, a young person may remain at risk of FGM into adulthood.1

The table below summarises the main types of civil court order.

| Type of order | Description |

|---|---|

| Non-harassment order (NHO) | Introduced by the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 (the 1997 Act). Harassment is something which causes alarm or distress. It can be one-off conduct (where the harassment amounts to domestic abuse) or a course of conduct (in other cases). An NHO can be applied for by a victim (very rare in practice). Although a civil court order, it can also be applied for by a procurator fiscal at the end of a criminal case (more common). Since April 2019, it has been the case that, in domestic abuse cases, the criminal court can also act on its own initiative (and it is encouraged in the new statutory provisions to do so).For domestic abuse cases, the NHO can also contain directions relating to a child involved in the case.Breach of an NHO is criminal offence punishable by fine and/or imprisonment up to five years. The fact that a breach is a criminal offence means the police have general powers of arrest. |

| Interdicts | An interdict aims to stop or prevent behaviour by another person, including violent or other abusive behaviour. Types of interdict include a common law interdict, originally created by judges, rather than by legislation; a matrimonial interdict, only available between spouses; an interdict under the 1997 Act, which can be granted instead of an NHO; and a domestic abuse interdict, discussed in more detail below.A warrant to arrest is an authorisation from the court to arrest someone. In 2001, it became possible for powers of arrest (without a warrant) to be attached to any interdict relating to abuse. This is only possible where the person applying for the interdict also applied for the powers of arrest. On breach of such an interdict, the perpetrator can be detained in police custody. The court can later imprison the person for up to two days.Separately, fresh court proceedings might also be raised for the perpetrator to be found in contempt of court, punishable by fine and/or imprisonment for up to three months.On application to the court, an interdict can also be labelled a domestic abuse interdict. If certain conditions are satisfied, breach of a domestic abuse interdict is, of itself, a criminal offence (and can be investigated as such by the police). That offence is punishable by fine and/or imprisonment (up to five years). |

| Exclusion orders | Spouses or cohabitants (in some circumstances) can apply for an exclusion order in relation to a perpetrator of abuse. This suspends a person's right to occupy their home and overrides their legal occupancy rights, e.g. as tenant or owner. Under a different statute, a local authority can also apply for an exclusion order in similar circumstances to where a child protection order could be applied for.Applications for both types of exclusion order are rare in practice, probably because there are some grounds to argue the order should not be granted. Some research suggests there is a lack of faith in the effectiveness of the first type of exclusion order on breach.2 |

| Forced Marriage Protection Order (FMPO) | AN FMPO can protect both adults and children at risk of being forced into marriage and can offer protection for those who already have been forced into marriage. Any person, permission of the court, can apply for an FMPO. However, the victim, a local authority, the Lord Advocate and any other person specified by secondary legislation may apply without permission.Breach of a FMPO is a criminal offence and is punishable by imprisonment for up to two years and/or a fine. |

| Adult Support and Protection (Scotland) Act 2007 (‘the 2007 Act’) | Part 1 of 2007 Act has various powers to protect a specified group of vulnerable adults (aged 16 or over). Part 1 of the Act allows a council to apply to the sheriff court for a protection order for such adults. This can take one of three forms:

|

Current law in the rest of the UK

In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 repealed and re-enacted the provisions of the 1985 Act. As with the Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005, it made it an offence to have FGM carried out abroad, and increased the maximum penalty to 14 years imprisonment.

The Serious Crime Act 2015 is a UK wide Act that introduced six provisions in relation to FGM, only one of which was extended to Scotland - Section 70 (see table below). Section 73 made provision for FGM Protection Orders, and section 75 made provision for the Secretary of State to issue guidance about FGM.

During the passage of the 2015 Act, the Scottish Government and UK Government agreed a legislative consent motion, in relation to section 70, which amended the 2005 Act. This closed a loophole in the law to extend the reach of extra-territorial offences to habitual, as well as permanent, UK residents.1

While in the UK there has only been one prosecution for FGM 2, there have been 321 applications and 348 FGM Protection Orders made since July 2015 up to the end of December 2018. Most cases have resulted in multiple orders, which is why there is a higher number of Orders than applications.3 It is difficult to know how well FGM Protection Orders are working in England and Wales, but some challenges in applying for the Orders have been noted.4

Guidance

The UK Government's statutory guidance and a range of factsheets are all available on online. These include:

| Provision | Description |

|---|---|

| Section 70: Offence of FGM and extra-territorial acts (FGM carried out abroad) | This amended sections 3 and 4 of the 2005 Act to ensure that it applies to 'UK nationals and residents', rather than 'UK nationals and permanent UK residents'. A similar amendment was made to the 2003 Act.The definition of a 'permanent UK resident' was changed to 'UK resident', which is someone who is habitually resident in the UK. The term 'habitually resident' covers a person's ordinary residence, as opposed to a short, temporary stay in a country. Whether a person is habitually resident will be determined on the facts of a case. It may not be necessary for all, or any, of the period of residence in the UK to be lawful.5In effect, this means it is now possible to prosecute a non-UK national for the offence of FGM where that person is habitually resident in the UK, rather than permanently resident in the UK.5 |

| Section 71: Anonymity for victims of FGM | This prohibits the publication of any matter that would be likely to lead members of the public to identify the victim of an offence under the 2003 Act. The prohibition lasts for the lifetime of the alleged victim. Publication is given a broad meaning and would include traditional print media, broadcasting and social media.5 |

| Section 72: Offence of failing to protect a girl from risk of FGM | This is a new offence of failing to protect a girl under the age of 16 from the risk of FGM. A person is liable for the offence if they are responsible for a girl when an offence under the 2003 Act is committed against the girl.There are two classes of persons responsible for a girl:

|

| Section 73: FGM protection orders | This introduced FGM protection orders in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. An order can be made by a court either to protect a girl at risk of FGM, or to protect a girl against whom FGM has been committed. The orders may contain prohibitions, restrictions or requirements and other terms the court considers appropriate to protect the girl in question. An order can be made for a specified period or to continue indefinitely.Breach of an FGM protection order is a criminal offence subject to a maximum penalty of five years' imprisonment on conviction on indictment or a maximum of six months' imprisonment on summary conviction. Alternatively, a breach of an FGM protection order may be dealt with by the civil route as a contempt of court, punishable by up to two years' imprisonment.5 |

| Section 74: Duty to notify the police of FGM | This applies in England and Wales. It requires those who work in 'regulated professions' - healthcare professionals, teachers, social workers - to notify the police when, in the course of their work, they discover that FGM appears to have been carried out on a girl who is under 18.The term 'discover' includes where the victim has specifically disclosed to the regulated professional that she has been subject to FGM, or where the regulated professional has observed physical signs of FGM.5 |

| Section 75: Guidance about FGM | This provides a power for the Secretary of State to issue guidance on any provision of the 2003 Act or matters relating to FGM. |

International and European law

International law

The practice of FGM violates a number of rights and freedoms protected under international law. For example, freedom from violence, freedom from discrimination on the basis of sex, freedom from torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, the right to physical and mental integrity, and the right to life.1

These rights are protected in the:

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) - Ratified by UK in 1976

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) - Ratified by UK in 1976

Convention Against Torture (CAT) - Ratified by UK in 1988

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) - Ratified by UK in 1986

Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) - Ratified by UK in 1991.

The 1951 Refugee Convention defines who is a refugee, their rights, and the legal obligations of the country they seek refuge in. The core principle of the convention is non-refoulement, which means that a refugee should not be returned to a country where they face serious threats to their life or freedom. UK Home Office guidance on 'Gender issues in the asylum claim' advises asylum caseworkers on how to consider FGM in a woman's claim for asylum, although fear of FGM does not automatically guarantee asylum.2 If a woman or girl sought asylum from fear of FGM, they would need to show their fear was well-founded, that they could not seek protection from the authorities, and that they could not relocate to another area in their country. 3

European Union law

At EU level there are a range of legislative and policy documents that reference FGM. The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights provides the basis for EU policy making on FGM. The European Parliament has passed resolutions condemning FGM several times since 2001.4 There are also a number of EU Council Directives that are applicable in FGM cases concerning asylum provisions.i The Directives have been transposed into UK legislation. Even after a no-deal Brexit, EU law will be copied over into UK law after exit day.

Council of Europe

The Council of Europe requires its Member States to sign up to the European Convention on Human Rights, which includes, for example, the right to life and freedom from torture.

The UK has signed the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (also known as the Istanbul Convention), which includes FGM.1 The UK Government has made a commitment to ratify this Convention.6

Approaches to eradicating FGM in the EU

The European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) has conducted a range of analysis on approaches to dealing with FGM in European Union countries.

Member States' legal frameworks

FGM is a criminal offence in all EU Member States. It is either incorporated into general criminal law or, as in 18 Member States, explicitly mentioned in a specific provision or law.1

Four Member States have legislation devoted to tackling FGM: Ireland, Italy, Sweden and the UK. Other Member States, such as France, use criminal law provisions to criminalise FGM, referring to bodily injury and serious harm or mutilation.

'Extraterritoriality' is the principle of criminalising FGM when it is committed abroad. The latest EIGE report says that the principle is applied in 25 Member States, but not Bulgaria, the Czech Republic or Luxembourg.1

Prosecutions

Across the European Union there have been few court cases and prosecutions on FGM. An outlier is France, which had 30 court cases, up to the end of 2012.1 A report by the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee in 2014 states that France has had more than 40 prosecutions since 1979, resulting in the punishment of more than 100 parents and cutters.4

According to the Home Affairs Committee report, in France there are regular medical check-ups on children, which includes examination of their genitals, up to the age of six. The system is not mandatory, but receipt of social security is dependent on participation. Girls that are identified to be at risk of FGM are required to have medical examinations every year, and whenever they return from abroad. There is also a requirement on medical practitioners to set aside patient confidentiality and report cases of physical abuse against children. French law also criminalises acts of omission—failure to assist a person in danger can result in a heavy fine or imprisonment. This approach has helped to provide evidence to mount a prosecution where FGM has taken place.

However, there is also evidence that the approach in France has had the effect of increasing the age at which girls may be forced to undergo FGM. In response to introducing regular medical check-ups in England and Wales, the UK Government said it had no plans to introduce such a measure that it considered intrusive.4

Member States' policy frameworks

The national strategies undertaken by Member States varies.1 Although not itself a Member State, Scotland is mentioned alongside Finland and Portugal as having a specific national action plan to tackle FGM. England and Wales is referred to alongside France and Belgium as incorporating detailed measures to combat FGM in broader national action plans to combat violence against women. There are 14 other Member States that integrate FGM into national strategies that promote gender equality.

The national action plans focus on:

health

education and awareness raising

working with migrant communities to tackle FGM

asylum and migration.

Recommendations to help eradicate FGM

Following its latest study, the EIGE concludes that strong laws and anti-FGM campaigns are powerful deterrent factors against FGM.1 The EIGE argue that law enforcement, as well as working with FGM-practicing communities, are both essential to ending the practice of FGM.

In addition, the EIGE recommends, across the EU, improvements in data collection on FGM prevalence, the development of specialised services to support victims of FGM, multi-agency cooperation on the protection of girls and women at risk of FGM, and a network of experts and key actors on gender-based violence.

The Bill

This section will cover the main provisions of the Bill regarding FGM Protection Orders and Statutory Guidance. It also refers to the Scottish Government's consultation on strengthening protection on FGM, which is considered in further detail in the Consultation section.

FGM Protection Orders

Section 1 of the Bill is the main provision relating to FGM Protection Orders. It inserts additional statutory provisions in the Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005 (‘the 2005 Act’). Statutory references in this section of the briefing are to the proposed new sections of the 2005 Act, unless otherwise stated.

The purpose of an FGM Protection Order

Section 5A(3) says a court can make an FGM Protection Order for the purposes of:

preventing or reducing the likelihood that a person, more than one person or a class of people are subjected to FGM, for example, any person falling within a particular religious congregation or perhaps particular school1

protecting a person who has already been subjected to FGM, and

otherwise preventing or reducing the likelihood of an FGM offence being committed.

Section 5F says the court can make an interim FGM Protection Order in situations which there is an immediate risk of significant harm or that the person to be protected may be taken out of the United Kingdom for FGM purposes.

What would an FGM Protection Order do?

Section 5B gives the court broad powers, saying that a court can impose prohibitions, restrictions or requirements in an FGM Protection Order that it considers appropriate. Section 5B gives a non-exhaustive list of possibilities (s.5B(3)).

The court can require a person to do something or not do something. For example, it can require a person to give up their passport and travel documents (s.5B(3)(i)) or to disclose someone's whereabouts (s.5B(3)(f)). It can restrict them from taking a protected person to a specified place (including outwith Scotland) (s.5B(3)(g)). It can require a person to refrain from violent, threatening or intimidating conduct (s.5B(3)(d)).

The possibility of both positive and negative requirements follows the approach taken with Forced Marriage Protection Orders.However, the proposed FGM Protection Order differs from a number of other civil protection orders, which can only impose restrictions on behaviour.

The (non-exhaustive) list of things the court can do makes no reference to the power to remove a perpetrator from their home. In other words, there is no explicit suggestion that an FGM Protection Order could function as an alternative to an exclusion order, discussed in the table above. However, on this, the Scottish Government Bill Team has commented “it would be open to the courts to consider whether or not to exclude a perpetrator from the family home.”1

Which court can grant the FGM Protection Order?

The Bill proposes that a civil court (the sheriff court) would be able to grant an FGM Protection Order, both on application to it and on its own initiative (for example, at the end of other civil court proceedings) .Although the FGM Protection Order would be a civil order, the Bill also proposes that a criminal court can also grant an FGM Protection Order at the end of criminal proceedings relating to FGM. Again, this can be on the court's own initiative or on application to it by a prosecutor (s.5A(3) and 5G(2)).

To date, there have been no criminal prosecutions for FGM offences in Scotland.1 Unless the level of criminal prosecutions changes significantly in Scotland, use of a criminal court's statutory power to impose an FGM Protection Order will be rare in practice.

A key point is that a children's hearing cannot grant an FGM Protection Order. However, section 8 of the Bill would enable a court in proceedings relating to an FGM Protection Order to refer a case to the Principal Reporter under the children's hearing system. If the matter reaches a children's hearing, the hearing could then use its ordinary powers (i.e. a CSO or interim CSO). The Principal Reporter could, however, refer a case relating to FGM to the local authority (who could, in turn, apply for an FGM Protection Order).23

Who can apply for an FGM Protection Order?

In terms of who can apply for an FGM Protection Order, there are a wide of range of possibilities. Section 5C says a victim or person at risk can apply, in keeping with the approach for many other civil protection orders.

In addition, section 5C says other public bodies/officials can apply, notably a local authority; the Chief Constable of Police Scotland and the Lord Advocate. Any other person (e.g. a parent or other family member) can also apply with the permission of the court. A "person" can include a voluntary organisation, as is the case in England and Wales.1In terms of who will apply in practice, the experience in England and Wales is helpful. In 2017, 3% of applications were by the person who is to be protected by the FGM Protection Order, 39% were made by a local authority and 58% were made by the police or other third parties.2 Victim applications are likely to be rare due to the age of the typical victim (or person at risk). Furthermore, there are difficulties typically associated with individuals applying for civil protection orders. For example, potential legal costs (unless these are entirely met out of the civil legal aid budget) and stress for the individual concerned.

The policy advantage of courts or public bodies being able to act on their own initiative is that it removes pressure from an individual to make the application.

A possible disadvantage is that the individual may experience, or fear, a loss of control over the process. Under section 5C(5), a court would be required to consider a victim or person at risk's wishes and feelings. However, this is only to the extent the court thinks appropriate, taking account of the person's age and understanding.

What are the consequences of breach of an FGM Protection Order?

What is proposed?

The Bill makes breach of an FGM Protection Order a criminal offence in specified circumstances. This includes when a person knowingly does something which they (or another person) is prohibited from doing under an FGM Protection Order. Also, where a person knowingly hinders a person from carrying out an obligation they are required to do under an FGM Protection Order (s.5N).

Unless there is a successful criminal prosecution, an alternative remedy is for a court to rule that a breach of a civil court order is a contempt of court (a failure to follow an instruction of the court). Contempt of court is punishable by fine (to a maximum of £2,500) and/or imprisonment up to three months.

Contempt of court usually requires the person or body who raised the original court proceedings to raise fresh court proceedings. Depending on who raised the original action, this might be, for example, by the victim, other family member or by another body, such as a local authority or voluntary organisation.

The merits of retaining contempt of court as an alternative in some circumstances was discussed in the consultation for England and Wales (on FGM Protection Orders).1One issue respondents raised was whether there might be a drawback to having two methods of dealing with breaches of FGM Protection Orders. In particular, the victim might feel increased pressure from other family members not to report the matter to the police (which might result in a criminal prosecution) but instead to begin court proceedings for contempt of court.1 (There was no comparable discussion in the Scottish consultation or associated analysis of responses.)

How this compares to other civil orders

What is proposed in the Bill can be compared to the approach taken in respect of other civil orders. For some civil orders, the only option is to start fresh court proceedings for contempt of court. This can cause delay. Furthermore, when it is a private individual that must do this, additional legal costs and stress can be significant.

Most civil protection orders now bolster the enforcement powers by relying on some degree to the criminal justice system. As noted in the table earlier, for most civil protection orders, there are now police powers to arrest (without a warrant) and associated police/court powers to detain the person in breach for a short period.

Furthermore, as is the case in the Bill, in some cases, a breach of a civil protection order is, of itself, a criminal offence. This means enforcement is a matter for the police and the criminal courts. These offences are punishable by fine and/imprisonment (for longer periods than is possible for contempt of court).

Policy considerations

Criminalisation of breaches is said to send a strong message that breaches are to be taken seriously.1 It also means the victim and families members do not have to raise court proceedings for contempt, with the associated drawbacks of that. On the other hand, one suggested advantage of a civil order is that it does not involve criminalisation “particularly important for those concerned about criminalising family members.”2 Making a breach a criminal offence could dilute that benefit somewhat. It also means, that, again, victims and their families might lose some control (or feel they have lost control) over any enforcement action taken.3

How the penalties in the Bill compare to other legislation

One of the issues the Scottish Government consulted on in the context of the Bill was whether the proposed penalties for the criminal offence of breach of an FGM Protection Order were set at the right level.1

In this context, it is helpful to be aware that there are two criminal court procedures. One is for the most serious criminal cases. It may lead to a conviction on indictment. The other may lead to a summary conviction. These terms appear in the Bill in relation to penalties.

For a conviction on indictment the proposed penalty is a fine (with no maximum limit) and/or imprisonment for up to five years (s.5N(7)(b)). This is the same as the approach taken for NHOs and domestic abuse interdicts. For the Forced Marriages Protection Order there is the same approach to fines, but imprisonment is for up to two years.

For a summary conviction the penalty proposed in the Bill is imprisonment for up to twelve months and a fine not exceeding £10,000 (s.5N(7)(a)). This is the same as for domestic abuse interdicts and Forced Marriage Protection Orders. For NHOs the fine is the same, but imprisonment can be for up to six months.

Views on the appropriate penalties were mixed on consultation. Many respondents suggested penalties similar to those for breaches of Forced Marriage Protection Orders. Other respondents to the Scottish Government's consultation suggested that criminal penalties for breach of an FGM Protection Order should be comparable to those for breaches of the current FGM criminal offences in the 2005 Act. In other words, those offences in the 2005 Act which criminalise FGM and assisting with FGM. Alternatively, respondents suggested penalties should be comparable to those for grievous bodily harm (GBH).2

Penalties for the existing criminal offences under the 2005 Act are i) (unlimited) fine/and or imprisonment for up to fourteen years (for conviction on indictment); and ii) a fine up to £10,000 and/or imprisonment for up to six months (for summary conviction).

GBH is an English criminal law term used to describe the severest forms of assault. It has no direct counterpart in Scots law (although common law serious assault would be an approximate Scots law equivalent). There are two offences relating to GBH, one carrying a maximum prison sentence of five years and the more serious one carrying the maximum sentence of life imprisonment.

Key issues raised in the consultation

On consultation, there was widespread support among the respondents (85%) for the introduction of FGM Protection Orders, which were viewed as having numerous benefits. There were limited objections to introducing FGM Protection Orders, largely founded on the fact that Child Protection Orders were already in existence.

One issue raised was the need for legal advice to individuals be available free of charge. In the Scottish legal aid system, automatic legal aid is available to applicants in some specified circumstances, without any financial eligibility tests being applied. This was proposed in the member's bill which became the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2011 (for domestic abuse interdicts). It was removed at a later stage of the Bill's parliamentary passage.

Automatic legal aid is not provided for under the Bill in relation to FGM Protection Orders. Scottish Government officials commented, "We are continuing to develop our [legal aid] policy".12

The consultation paper said that legal aid would be available for applicants for FGM Protection Orders “subject to the usual criteria”.3 The criteria for eligibility for legal aid in civil cases are based on financial circumstances and other factors. Children's finances are assessed according to their parents’ financial circumstances.4

Even if someone qualifies for some legal aid support, they may still have to contribute to a proportion of the legal costs of the case, depending on their financial circumstances.

On consultation, there were requests for consistency in the process of applying for, making and enforcing FGM Protection Orders, with the view that guidance would help with this.

Another point was that the training of the professionals who would be applying for orders would be necessary, as well as awareness-raising in local communities. How to accurately assess risk was also raised by respondents.

The issue of how long FGM Protection Orders would last and the context in which they would cease was also raised (probably because there was limited information on this in the consultation). Sections 5I–5L contain detailed provisions on the duration, extension, variation and discharge of the proposed FGM Protection Orders. Under these provisions, FGM Protection Orders can be for a fixed period or can run until they are discharged. The court would be able to extend, vary or discharge an order on its own initiative. A range of people would also be able to apply to extend, vary or discharge an order. These include the people who could apply for an order in the first place and “a person affected by an order”.

Guidance

Sections 2 and 3 of the Bill provide for Scottish Ministers to introduce guidance relating to FGM, and relating to FGM Protection Orders, respectively. These provisions will amend the Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005 (‘the 2005 Act’).

Section 2 gives Scottish Ministers a power to issue statutory guidance on FGM about the effect of the 2005 Act as it has been amended by the Bill, or any other matters relating to FGM. Scottish Ministers may revise the guidance from time to time.

Section 3 provides that Scottish Ministers must issue statutory guidance on FGM Protection Orders, and to specify who the guidance applies to. Scottish Ministers may revise the guidance from time to time, and must published the first guidance on FGM Protection Orders when they come into force.

Both these provisions apply to people who 'exercise public functions', that is, people who work for public bodies, or are contracted to deliver public services. Such people must have 'regard' to the guidance when undertaking their work, which means they must take the guidance into consideration.

Scottish Ministers may not give either guidance to the courts, tribunals or prosecution service, as this would interfere with their independence.

What guidance already exists?

As discussed above, the Scottish Government published multi-agency guidance on FGM in November 2017. The guidance sets the policy context for FGM, sets out good practice for all the agencies that might be involved in supporting women and girls, as well as specific responses for individual agencies such as: maternity staff, school nurses, GPs, police, teachers, social work staff, and third sector organisations.

Why is the guidance being made statutory?

The aim of the Bill is to strengthen the legal protection for women and girls at risk of FGM. The current multi-agency guidance is non-statutory and advisory only. In contrast, the Policy Memorandum states that:

Statutory guidance will ensure that there is clarity about the responsibilities of those covered by the Bill under FGM Protection Orders. The fact that those exercising public functions will be obliged to have regard to such guidance will better ensure that public bodies work effectively and collaboratively.1

The Scottish Government has said that the purpose and content of statutory guidance would be similar to the multi-agency guidance, but that statutory guidance would "better ensure that public bodies work effectively together to ensure that women and girls are protected."2

Views from the consultation

There was strong support for statutory guidance on FGM, with 79% of respondents to the consultation supporting this proposal.1 Key benefits were perceived as:2

Ensuring widespread knowledge of the subject, reducing regional variations

Ensuring a shared national approach among professional bodies

Improving inter-agency collaboration and reducing regional variations in responses.

Several respondents emphasised the merits of the current guidance, and that future guidance should be based on this.

There were limited objections to the introduction of statutory guidance, but the point was raised that some important guidance is advisory and that this has not limited its application or utility.

Consultation

The Scottish Government ran a consultation on strengthening protection from FGM between 4 October 2018 and 4 January 2019.1 There were 71 responses to the consultation, received from individuals, public bodies and organisations involved in FGM.2 An analysis of the consultation responses was published on 24 May 2019.3 It is not possible to tell from the consultation analysis which type of respondents supported a particular measure, or opposed it. The 71 responses have not, to date, been published, but some organisations have published their responses online, see: Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health; Law Society of Scotland; Scottish Social Services Council; Nursing and Midwifery Council; and, General Medical Council.

The consultation sought views on all the provisions that were in the Serious Crime Act 2015, because the Scottish Government had previously indicated it would consider whether the provisions were appropriate for Scotland.

Consultation responses regarding the two main provisions of the Bill are referred to in the section above.

Anonymity for victims of FGM

Section 71 of the Serious Crime Act 2015 provides for the lifelong anonymity of the alleged victim in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. It prohibits publication of any matter that could identify the victim of an offence under the Female Genital Mutilation 2003 Act.

The Scottish Government's view is that the courts in Scotland already have the necessary powers to ensure the protection of a victim or complainer's identity in any relevant case.

Criminal courts have the power to put in place measures to protect the identities of those involved in a case. Under sections 271N-271Z of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995, either party in a case can apply to the court for a witness anonymity order. An order will be granted where certain conditions are all met:

it is necessary to protect the safety of the witness or another person, or to prevent real harm to the public interest

where it is consistent, in all circumstances, with a fair trial

the evidence of the witness is so important that it is in the interests of justice for them to testify

the witness would not testify without the order.

The judge is also obliged to direct the jury to ensure that the existence of the order does not prejudice the accused.1

Under section 47 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995, there are reporting restrictions on cases involving children (under the age of 18). No newspaper can report any court proceedings that reveal the name, address, school or any particulars that lead to the identification of the child, either as the accused or a witness.

The Scottish Government also refers to the self-regulation of the media. There is a long-standing convention in Scotland that alleged victims of sexual offences are not named in the media.

This position has been in place for many years and it is very closely adhered to by the media when reporting sexual offence cases. It is not underpinned by legislation and so operates on the basis of a decision made by the media to self-regulate in terms of how they report sexual offence cases.1

Views from the consultation

There was strong support for the introduction of anonymity for the victims of FGM, with 75% of those responding agreeing that the Bill should have provision for anonymity of victims.3

The arguments in favour of anonymity included that it would:4

protect the dignity of those reporting the offence

encourage women and girls to come forward

ensure that individuals were protected from potential harm or repercussions from coming forward

be in line with England and Wales.

The arguments against introducing anonymity included:

the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 already provides sufficient protection

additional laws could make the procedure more complicated.

Scottish Government response

Based on the responses on anonymity for victims, the Scottish Government has said it would keep this under review and "would welcome views of the scrutinising committee and stakeholders."3

Offence of failure to protect from FGM

Section 72 of the Serious Crime Act 2015 created a new offence in England, Wales and Northern Ireland of failing to protect a girl under the age of 16 from the risk of FGM. A person is liable for the offence if they are responsible for a girl when an offence under the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 is committed against the girl. The maximum penalty is seven years' imprisonment, a fine, or both. To be 'responsible' a person either has to have parental responsibility (eg mothers, fathers, guardians) and have frequent contact with the girl; or an adult who has assumed responsibility 'in the manner of a parent'.

It would be a defence for the accused to show they did not think there was a significant risk of FGM, and could not reasonably have been expected to aware of any such risk. Another defence would be that the accused took reasonable steps to protect the girl from being the victim of FGM.

The Scottish Government did not propose this offence, noting the following challenges:

Prosecution of such an offence would be predicated on proving an absence of action where the person could have reasonably acted, which is difficult to prove (as opposed to a specific course of conduct). Noting the social context in which risk of FGM may exist, we are also concerned about a number of adverse consequences in relation to potentially criminalising individuals who do not have the agency to protect girls (as opposed to being held accountable for a proactive course of conduct) and potentially reinforcing the hidden nature of the practice.

Views from the consultation

There were mixed views on this, with 48% of those who responded supporting a provision on failure to protect, and 33% not supporting such a provision. 1

Arguments in favour of an offence of failure to protect included:2

those caring for someone subjected to FGM were responsible for them, and therefore prosecution of this offence would be justified

the offence would convey how seriously FGM is taken and may encourage a cultural shift

it would harmonise laws with England and Wales.

Several of those who supported such an offence, qualified their support by saying there might be mitigating factors, and that therefore:

consideration should be given as to whether the person in question has any agency in relation to decision-making

individual circumstances would need to be taken into account.

Arguments against the introduction of an offence of failure to protect included:2

the offence could risk alienating communities where there has been a commitment to work collaboratively

it risks criminalising those with limited power or say in the outcomes for their children

it may risk diverting people from reporting the offence if there is a fear that they may be prosecuted.

Scottish Government response

The Scottish Government does not propose to introduce an offence of failure to protect:

While we appreciate the need to hold enablers of FGM to account we agree with respondents to the consultation who felt that this could potentially impact negatively on individuals, especially women, who do not have the power or agency to protect persons who may be at risk of FGM.1

Duty to notify police of FGM

Section 74 of the Serious Crime Act 2015 requires regulated health and social care professionals and teachers, in England and Wales, to notify the police when, in the course of their work, they discover an act of FGM has been carried out on a girl who is under 18.

The Scottish Government sought views on introducing such a duty in Scotland. However, it referred to the existing child and adult protection structures, procedures and policies, which are described in the Multi-Agency Guidance on FGM.1 A number of challenges were also noted:

We are mindful of the importance of not inadvertently placing barriers in the way of those who would seek to access support services but be dissuaded from doing so in the knowledge those services have a duty to report to the Police. We are not sure that introducing such a duty would support a policy objective whereby someone who has experienced FGM has access to support, and we think that services would be better to focus on this rather than notifying the Police. We note that child protection procedures are already in place for those under 16 and would expect that these would be activated in the event of FGM being identified by a professional.

Views from the consultation

There were mixed views on this from the consultation, with 48% of respondents not in favour of a duty to notify police, and 35% in favour of such a duty.2

Arguments in favour of a duty to notify the police included:

it may improve protection for victims

it sends a strong message about FGM and may potentially improve reporting in schools

it might improve data on the prevalence of FGM, and raise greater awareness of its prevalence

it would align with the duty in England and Wales.

Arguments against a duty to notify the police included:

there is already guidance in offering protection without the need for an additional duty to notify the police

it may dissuade reporting due to the fear that this will lead to a criminal investigation

a possibility that this could create distrust with professionals, and may, for example, discourage the reporting of FGM related health problems

it was not clear why there should be a line between FGM and other forms of child abuse, for which there is no mandatory reporting.

Scottish Government response

The Scottish Government does not propose to introduce a duty to notify the police of FGM.

...it is important not to put obstacles in the way of people, including vulnerable individuals, who would seek to access support services and could be dissuaded from doing so in the knowledge those services would be under a duty to report FGM to the police.

Costs

Estimating the costs of the introduction of FGM Protection Orders is challenging because there are no accurate data of the prevalence of FGM in Scotland.

The Scottish Government has used the applications for FGM Protection Orders in England as a way to estimate the potential applications in Scotland.1

| Year | Applications | Total FGM Protection Orders made |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 (2 quarters) | 47 | 32 |

| 2016 | 74 | 64 |

| 2017 | 103 | 109 |

| 2018 | 97 | 143 |

NB: cases can result in multiple orders, hence the sometimes higher number of orders than application.2

The Scottish Government has estimated that there could be between 4 and 9 applications for an FGM Protection Order a year:1

Using the years 2017 and 2018, there is an average of 100 FGM Protection Order applications a year. On the basis that Scotland's population is 9% of the population of England and Wales, that could mean there would be up to 9 applications for FGM Protection Orders in Scotland per year.

Another way to estimate the number of applications is to consider the size of communities originating from countries where FGM is carried out. Using the figures from the Scottish Refugee Council research4, there could be 12,000 women and girls in these communities in Scotland. This would be 4% of the 283,000 girls and women aged 15-49 estimated to be resident in England and Wales from FGM-practicing countries5. Therefore, there could be 4 applications a year for FGM Protection Orders, based on 4% of the average number of applications made in England and Wales in 2017 and 2018.

The Scottish Government has estimated that for the financial year 2021-22, the cost of applications for FGM Protection Orders and breaches will be in the range of £72,369 and £301,335, based on:

the application of up to nine FGM Protection Orders a year

up to two FGM Protection Orders being breached a year and cases brought to trial.

The Scottish Government has estimated that the following implementation costs for the financial year 2020-21, will be in the range of £221,511 and £271,511.

training costs for local authorities and the police

the costs of developing statutory guidance.

It does not mention health boards, which may also need to provide additional training if the Bill is passed.