Mainstreaming nature - international approaches to biodiversity conservation

This briefing supports consideration of biodiversity mainstreaming in Scotland, by setting out a diverse range of examples of international approaches to biodiversity conservation.

Background - biodiversity in Scotland

Biological diversity – or biodiversity – is the variety of life on earth. It encompasses the diversity of species and habitats, and genetic diversity within species. Scotland's biodiversity encompasses a large number of species - approximately 90,000 - and a rich variety of habitats and landscapes, from lowland grassland, to Caledonian pine forest, coastal machair, and underwater kelp forests. Biodiversity can be found in our urban roadsides and gardens, as well as the vast blanket bogs of the Flow Country.

Scotland's Economic Strategy (2015) states that 'Protecting and enhancing this stock of natural capital, which includes our air, land, water, soil and biodiversity and geological resources is fundamental to a healthy and resilient economy'. Biodiversity is also embedded in Scotland's National Outcomes within the National Performance Framework. Under the National Outcome for Environment - "we value, enjoy, protect and enhance our environment", the vision is for a Scotland that is "at the forefront of carbon reduction efforts, renewable energy, sustainable technologies and biodiversity practice".

Scotland's biodiversity targets stem from the international Convention on Biological Diversity which set five strategic goals and 20 global targets, the Aichi Targets, to be met by 2020 (see Annex 1). The Aichi targets were adopted in October 2010 in Nagoya after 2010 global biodiversity targets were missed, and aimed to provide a framework for a step change in efforts to halt the continued loss of biodiversity.

The Scottish Government's approach to meeting the Aichi targets is set out in the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy (2004) and the 2020 Challenge for Scotland’s Biodiversity (2013), and further developed in Scotland’s Biodiversity a Route Map to 20201 (2015).

Key pressures on biodiversity in Scotland include climate change, invasive species, habitat fragmentation, pollution, land use intensification, marine exploitation, and lack of recognition of the value of nature in decision-making1. Scotland’s Biodiversity Route Map sets out 'Six Big Steps for Nature' required to address these issues, summarised as:

Ecosystem restoration – to reverse historical losses of habitats and ecosystems;

Investment in natural capital – understanding the benefits which nature provides;

Quality greenspace for health and education benefits;

Conserving wildlife in Scotland – to secure the future of priority habitats and species;

Sustainable management of land and freshwater; and

Sustainable management of marine and coastal ecosystems.

The Scottish Government works with Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) on biodiversity policy development, implementation and monitoring, and SNH produce reports on Scotland's progress towards the 2020 targets. The 2017 report set out that of the 20 targets, 7 were on track, 12 were showing progress but insufficient to meet the target and 1 target (financial resources) was getting worse3.

The 2016 State of Nature Scotland report (a collaboration between conservation and research organisations) provides further detail on biodiversity trends and drivers of change in Scotland - including land-use change and intensification of land management, climate change and other human pressures - but emphasises that "well-planned, targeted and adequately resourced conservation action can turn around the fortunes of our wildlife"4.

In September 2019, the Scottish Government published its 2019-2020 Programme for Government, committing to a further step change in efforts:

We recognise the importance of biodiversity and the complexities and challenges that tackling its loss presents. Biodiversity loss and the climate emergency are intimately bound together: nature plays a key role in defining and regulating our climate and climate is key in shaping the state of nature. We continue to deliver on our Biodiversity Strategy and work towards achieving the ‘Aichi’ 2020 international targets – 79 different pieces of work are underway to help us to meet these and we will publish a further report on our progress by April next year...

The 2019 IPBES review - a global call to address 'Nature's Dangerous Decline'

In May 2019, the publication of a landmark report on biodiversity by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) - the most comprehensive review of the global state of biodiversity to date - came with a stark warning about biodiversity decline:

"Nature is declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history — and the rate of species extinctions is accelerating, with grave impacts on people around the world now likely...

Despite progress to conserve nature and implement policies, the Report also finds that global goals for conserving and sustainably using nature and achieving sustainability cannot be met by current trajectories, and goals for 2030 and beyond may only be achieved through transformative changes across economic, social, political and technological factors. With good progress on components of only four of the 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets, it is likely that most will be missed by the 2020 deadline."1

Notable findings of the Report2 include:

Around 25% of species in assessed animal and plant groups are threatened with extinction;

The average abundance of native species in most major land-based habitats has fallen by at least 20%, mostly since 1900;

75% of the land-based environment and about 66% of the marine environment has been significantly altered by human actions.

Based on an analysis of the available evidence, the five direct drivers of change in nature with the largest relative global impacts so far were considered to be, in descending order: (1) changes in land and sea use; (2) direct exploitation of organisms; (3) climate change; (4) pollution and (5) invasive alien species. Key indirect drivers include increased per capita consumption – with resource extraction and production often occurring in one part of the world to satisfy consumers in other regions.

The report predicts that global negative trends in nature will continue to 2050 and beyond, except where policy scenarios include transformative change (recognising there are significant differences between regions).

SNH welcomed the report and recognised the need for transformative change:

The IPBES report shows that the pressures on nature are increasing. We know that the loss of species and ecosystems is a global and generational threat to human well-being. The Report also highlights that it is not too late, and that decisive action now to protect and restore nature can help to reverse the loss of biodiversity. It is also clear that enhancing and protecting our nature is part of the solution to the climate emergency. 3

The Scottish Government said in its 2019-2020 Programme for Government:

We are carefully considering the recent IPBES global biodiversity assessment and, by the end of this year, we will write to Parliament with our initial assessment of our current activity, what more needs to be done and what we need to do differently. This will inform a step change in our programme of work to address biodiversity loss, which will take account of the new post-2020 international biodiversity framework and targets to be agreed at a Convention on Biological Diversity Conference of the Parties in China in late 2020.

Mainstreaming biodiversity - the IPBES call to action

Mainstreaming, in the context of biodiversity, means integrating actions or policies on biodiversity into broader development processes such as sustainable development, poverty reduction, and climate change adaptation/mitigation, as well as trade and international cooperation. The concept also applies to sector-specific plans such as agriculture, fisheries, forestry, mining, energy, tourism and transport. The mainstreaming of biodiversity was the overall conference theme at the 2016 United Nations Biodiversity Conference of the Parties (COP) in Cancún, Mexico, and was extended into the following 2018 Biodiversity COP in Egypt.

The 2016 Biodiversity COP adopted the ‘Cancún Declaration on Mainstreaming the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity for Well-Being’ to guide deliberations, which committed delegates to:

[W]ork at all levels of government and across all sectors to mainstream biodiversity, establishing effective institutional, legislative and regulatory frameworks through, among others: ensuring that sectoral and cross-sectoral policies, plans and programmes, as well as legal and administrative measures and budgets integrate actions for the conservation, sustainable use, management and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems; incorporating biodiversity values into national accounting and reporting systems; updating and implementing National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) to strengthen the mainstreaming of biological diversity; and strengthening institutional support and capacities for biodiversity mainstreaming1.

The concept stems from a recognition that challenges of reversing biodiversity decline often involve interconnected ecological and social systems, declining resource availability, and climate change. The OECD state in a 2019 report that mainstreaming biodiversity - by integrating it into national and sector-level plans, policies and processes - is essential to improving biodiversity outcomes.2

Scope of this briefing

This briefing supports consideration of biodiversity mainstreaming in Scotland, by setting out a diverse range of examples of international approaches to biodiversity conservation and restoration. Examples selected span different sectors and types of initiative - including private and public, local to national in scale, using a range of tools including legal frameworks, policies and development of networks and partnerships.The briefing does not seek to present a comprehensive critical analysis of these approaches or discuss their applicability to the domestic context in detail, but seeks to inform debate by setting out a variety of approaches.

The approaches considered are loosely categorised as examples of legal frameworks, financing approaches, biodiversity networks, planning approaches and incentive schemes. In practice however, there is often significant overlap and inter-connection between these, and other themes such as governance approaches are cross-cutting. A legal framework may be designed to deliver a biodiversity network, a funding approach may be linked to the planning system, or a 'green deal' approach may encompass financing, policy and regulatory tools. This reflects that biodiversity conservation, and particularly models that seek to mainstream biodiversity, may be less likely to be deliverable through a single type of mechanism - and may function as a package of measures across legislation, policy and funding structures.

The focus of the briefing is on central Government-led initiatives, policies and approaches, although some examples are driven at more local scale e.g by local government or by non-governmental actors. However it should be recognised that a multitude of bottom-up, grassroots and voluntary-sector led initiatives exist that make a significant contribution to international efforts to halt biodiversity loss globally.

Legal frameworks

An 'ecosystem resilience' duty and the wellbeing approach - Wales

The Environment (Wales) Act 2016 puts in place a modern statutory process to manage natural resources in Wales in a joined, sustainable way, and aims to go "beyond protection"1. Biodiversity recovery is a key goal of the Act, including the introduction of an enhanced biodiversity and resilience of ecosystems duty for public bodies (section 6).

Public authorities must "seek to maintain and enhance biodiversity in the exercise of functions in relation to Wales, and in so doing promote the resilience of ecosystems, so far as consistent with the proper exercise of those functions". Natural Resources Wales, the statutory nature body, consider that sustainable management of natural resources requires a focus on resilience - meaning the capacity of ecosystems to deal with disturbances, whilst retaining their ability to deliver services2.

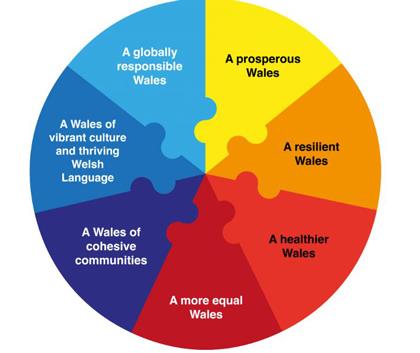

The Environment (Wales) Act 2016 was introduced as part of a package of legislation that also included the Planning (Wales) Act 2015 and the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 - the first legislation in the world to create a responsibility to work towards the wellbeing of current and future generations. The Act sets out seven wellbeing goals (see diagram below) that public bodies must work towards, including the ‘Resilient Wales’ Goal, for a Wales that ‘maintains and enhances a biodiverse natural environment with healthy, functioning ecosystems that support social, economic and ecological resilience’3. The Act also makes the sustainable development principle the basis for all actions by Welsh public bodies.

A 2017 assessment of the Welsh Government’s response to the Well-being Act including implications for biodiversity4 identified the Single Revenue Grant to Local Authorities in Wales as an example of alignment of funding with the wellbeing and environmental framework. The funding (£60 million in 2017-18), distributed by Government, enables local authorities to submit a combined annual spend proposal for natural resources management, including for biodiversity, flooding, waste and local environment quality. Applicants must set out how plans will contribute to the wellbeing goals. The report describes this as an example of Government creating conditions for local authorities to respond to the Act. The RSPB described the wellbeing approach, with a recognition in law of biodiversity's role, as a major achievement for the Welsh Assembly5.

Environmental courts - Chile, Kenya and Sweden

The number of countries with dedicated environmental courts or tribunals has significantly increased in recent decades, with approximately 1,200 environmental courts established by 2016, and 1,500 tribunals by 20181. The Chief Judge of the Land and Environment Court of New South Wales in Australia said that successful environmental courts and tribunals are "better able to address the pressing, pervasive and pernicious environmental problems that confront society (such as climate change and loss of biodiversity)"2.

The Scottish Government is reviewing environmental governance in Scotland due to governance gaps expected to emerge due to EU Exit, and may introduce new arrangements in a Continuity Bill3. Scottish Environment LINK argue that environmental governance and access to justice in Scotland would be strengthened through the introduction of a specialised environmental court4. The Scottish Government consulted on environmental courts in 2017 and concluded that, partly because of Brexit uncertainty, it was not appropriate to set up a specialised environmental court or tribunal at that time, but committed to keeping the issue under review5.

Chile established an environmental court system relatively recently, passing Law 20600 Creating Environmental Courts in 2012. The law created three environmental courts, one for each of the northern, central and southern regions. The Environmental Court of Santiago became the first Chilean judiciary to broadcast all of its public hearings live. Both individuals and institutions have legal standing to bring a claim of violation of environmental laws and regulations. The three courts are competent to hear cases involving compensation for environmental damage and claims filed against Government or Government agencies in respect of environmental decisions. A 2016 OECD review of environmental performance in Chile6 highlighted that the courts have strengthened access to justice, as showed by the high number of environmental actions brought - but also noted that the cost of legal counsel deters many people and organisations from bringing cases.

Sweden introduced five regional environment courts and a Land and Environment Court of Appeal in 1999, together with the adoption of a new Environmental Code. The courts decide on issues requiring scientific assessments and environmental expertise. Individuals seen as concerned parties (defined in the Environmental Code) have legal standing, and NGOs have standing in specific areas such as in relation to environmental permits and administrative decisions on environmental liability. A high profile 2018 case brought by the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation (SSNC) included the rejection by the Land and Environment Court of a nuclear waste companies license application for a final repository for spent nuclear fuel.

A 2019 review of Swedish environmental policy highlighted strong public participation in environmental decision-making, but identified a need for the public to be better informed about their access to justice rights, including in relation to nature7.

Kenya was the first country to authorise an environmental court or tribunal in its Constitution. The National Environment Tribunal has a limited jurisdiction, but deals with cases with potentially large environmental impact. Its principal function is to decide appeals from decisions of the national environmental agency on licenses for major developments (such as roads, housing and marine activities). It has powers to confirm, overturn or vary the national environment agency’s decisions. It also has the power to make its own rules of procedure and attempts to keep proceedings informal, particularly for self-represented parties, an aspect described as global best practice in a UNEP review8. Its fees are lower than the other national courts with the aim of being more accessible to the public. The Tribunal consists of 5 members: a chair (with qualifications to be a judge of the High Court), two lawyers, and two experts in environmental management.

Game bird licensing - Sweden, Spain and France

A Grouse Moor Management Group was established by the Scottish Government in 2017 to examine the environmental impact of grouse moor management practices in Scotland, and advise on the option of licensing grouse shooting businesses. The outcomes of this review (also known as the 'Werritty review') are expected in 2019.

Game birds are widely managed in a number of countries to maintain hunting yields, a practice which can have a significant impact on biodiversity1. In some cases this management is intensive, in order to maintain the high numbers of birds required for “driven shooting”, where a team of "beaters" walk towards the guns and flush the birds over them (as opposed to "walked-up" shooting), a practice which is common in Scotland and other parts of central and southern Europe.

A number of countries have developed regulatory frameworks, including licensing systems, which aim to ensure the sustainability of hunting - this section sets out brief information on how hunting is regulated in selected European countries, with particular reference to where systems are linked to funding wildlife management. The pros and cons of a variety of European approaches were discussed in a 2017 review by SNH2.

Hunting is popular in Sweden and around forty species of birds are hunted including grouse, waders, ducks and geese, mainly on state-owned land. The Hunting Registry of the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) administers a hunting licensing system. Every hunter must have a licence, and the fee is payable to a Wildlife Protection Fund, also administered by the EPA. Hunting licence fees in Norway and Germany are similarly ring-fenced and paid into designated ‘wildlife funds’. To get a hunting licence hunters must hold insurance and pass the Swedish hunting exam - the licence can be revoked if the licensee breaches regulations.

Red partridge - hunted in Spain

In Spain, partridge and other game birds are managed on privately owned estates. Funds from the licensing system are invested into conservation work. Having experienced issues with wildlife crime, in particular bird of prey persecution, Spanish authorities have taken steps to improve enforcement of nature laws . An EU LIFE project (LIFE+ VENENO) to increase effective enforcement introduced specifically trained police officers to work with NGOs and to raise public awareness of wildlife poisoning. The public were engaged via a freephone reporting line. The project also sought to influence the public by estimating a monetary value of individual birds killed illegally, which incorporated levels of public investment in protecting that species. In 2007 penalties for bird crime were increased to a maximum fine of 2 million EUR, imprisonment of up to two years and disqualification from a profession2.

France has the largest number of hunters in Europe with approximately 2% of the population registered to hunt. The French Environmental Code, which sets out a principle of sustainable management of habitats in the public interest, embraces authorised hunting as part of "balanced management of ecosystems". Most land where hunting takes place is privately owned. A hunting licence is required, and applicants must undertake workshops on wildlife and nature conservation law. Revenue from licensing fees is invested into wildlife crime prevention, an environmental police force (the largest in Europe), conservation work and communication programmes2. In 2011, hunting licensing fees represented approximately 70% of the budget for the French national wildlife agency.

Historical tensions between hunting groups and conservationists in France, including over implementation of hunting seasons in line with the Birds Directive, are thought to be gradually dissipating. A significant proportion (48%) of hunters are now estimated to be involved in conservation volunteering2.

Rivers as legal persons - New Zealand, India and the US

An emerging international approach to addressing pressures on natural resources is the use of legal personality to protect nature in law. This involves recognising nature, either as a whole, or a specific part, as a legal person, and has been described as a significant development in environmental law1.

The concept of granting legal rights to non-human entities is not new, but has only recently begun to be implemented for nature. In 2008, for example, Ecuador granted legal rights to nature in its constitution. More recently, the approach has been applied to specific features such as rivers. In 2017, three rivers, the Whanganui River in New Zealand, and the Ganges and Yamuna rivers in India, were given personhood, and in 2011 the concept was used to protect the rivers of the state of Victoria in Australia.

In New Zealand, the approach is rooted in processes developed to recognise indigenous community rights and associated land reform. The Whanganui River runs for 290 km from the centre of New Zealand’s North Island to the Tasman Sea. The Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017 recognises the river and catchment as a legal entity with all the rights, powers and duties of a legal person. An institutional framework is being developed to support these rights, with the involvement of stakeholders, government, conservation groups and hydropower companies. Two people, a representative of the New Zealand Crown and a representative of the tribal community, will be appointed to act on the river’s behalf. The Government also committed to create a $30 million fund for restoration2.

The trend has not been uncontroversial. The Indian Supreme Court later overturned the decision recognising the Ganges and Yamuna rivers as legal persons, after a petition by the Uttarakhand Government claiming that the legal status of the rivers was unsustainable and created uncertainty about who the custodians are. The Lake Erie Bill of Rights, adopted in February 2019 in the US, granted Lake Erie the rights to a clean ecosystem. However, the Ohio Legislature voted in July 2019 to ban local laws that give residents power to sue polluters on behalf of the lake3.

Assessment of different approaches to environmental personhood is at an early stage, with academics beginning to analyse comparative approaches and whether rights created will prove to be enforceable4.

Biodiversity financing models

Green Deals - the Netherlands and Belgium

The Green Deal approach in the Netherlands is a joint initiative including the Dutch Ministries of Economic Affairs, Infrastructure and the Environment. The objective is to encourage innovation and investment in the form of activities that contribute to both economic growth and improve the environment. Central themes of Green Deals include energy, food, water, biodiversity, mobility, climate and construction1.

Via Green Deals, the government supports businesses, civil society or other governmental bodies in various ways - for example by adjusting legislation, or acting as a mediator to access new markets, for example abroad. On average, Green Deals run for two to three years. In the period between 2011 and 2014, 176 Green Deals were agreed in the Netherlands, involving a 1,090 participants2.

In January 2019, 25 organisations and educational institutes signed a Green Deal for Nature-Inclusive Agriculture in Green Education. By signing the deal, parties agreed to embed nature-inclusive agriculture into education, as an integral part of the curriculum3. Other examples include a deal which aims to decrease discards of fishing-sector waste in the sea, and one aiming to improve the sustainability of the concrete supply chain, including addressing biodiversity issues associated with gravel extraction4.

In Belgium, the Government of Flanders has also sought to incentivise biodiversity action via Green Deals. In 2018, 110 businesses, organisations and local authorities signed the Green Deal ‘business & biodiversity’, which includes a commitment to convert 1250 hectares of industrial estate into wildlife habitats5. The Flemish Government has also explored the use of Green Deals to work with the health sector on increasing people's interaction with nature, and wider integration of nature and health6.

Valuing Natural Capital - National and regional investment banks

Natural Capital is the stock of natural assets, including water, forests, soils, air, oceans and biodiversity: the elements of the natural world that provide goods and services to people. A number of 'mission-oriented' investment banks (i.e. activities are driven by social or environmental objectives) have sought to develop approaches to financing environmental protection, including biodiversity, through the concept of valuing natural capital.

In Germany, the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) is a state-owned development bank with a mission to ‘work towards economic, social and ecological sustainability in order to foster sustainable development.’ The KfW aligns its decisions with the Federal Government’s sustainability strategy and dedicates roughly one third of new commitment volume to climate change and the environment1. Funded programmes include large-scale rewetting of peatlands in Russia, to help reverse the climate and ecological impacts of the 2010 peat fires near Moscow2. Its Blue Action Fund for international marine protection supports NGOs in partner countries to establish new marine conservation areas and promote sustainable fishing and ecotourism3.

In Italy, the public financial institution Cassa Depositi e Prestiti introduced a Green, Social and Sustainability Bond in 2018, in accordance with the global Green Bond Principles and Sustainability Bond Guidelines published by the International Capital Market Association. Projects funded to date include innovative green infrastructure projects to tackle multiple social and environmental challenges. For example, it played a role in a 266 million euro project to fund the (under development) world’s largest therapeutic garden on top of a hospital in Milan. The aim of the project is to encourage health benefits and transform old buildings into 'environmentally friendly real estate'4, and plans to incorporate green areas for therapeutic functions.

In France, the Caisse des Dépôts Groupe is a public investment bank which ‘carries out missions of public interest in support of the public policies implemented by the State and local government bodies…’. One of its two core priorities is the 'ecologic and energy transition', including encouraging and protecting natural heritage5. A subsidiary – CDC Biodiversité – is dedicated to natural heritage. In May 2019, the European Investment Bank (EIB) signed a 5 million euro loan with CDC Biodiversité to support the rehabilitation and management of conservation sites around France6. The loan will enable the sale of biodiversity offsets to companies which are required to offset their impacts on habitats and species as a condition of planning permission. It is is the first loan issued by the EIB Natural Capital Financing Facility - which was set up to fund projects which promote the conservation, restoration and enhancement of natural capital inside the EU.

Forest Resilience Bonds - USA

Conservation investing— investments aiming to generate a financial return and a measurable environmental benefit —is growing rapidly. Between 2014 and 2016 the total private capital committed to conservation investments increased by an estimated 62%. However, significant challenges with developing biodiversity investments at scale include the lack of available deals that can provide returns, measure outcomes and accurately estimate risk1.

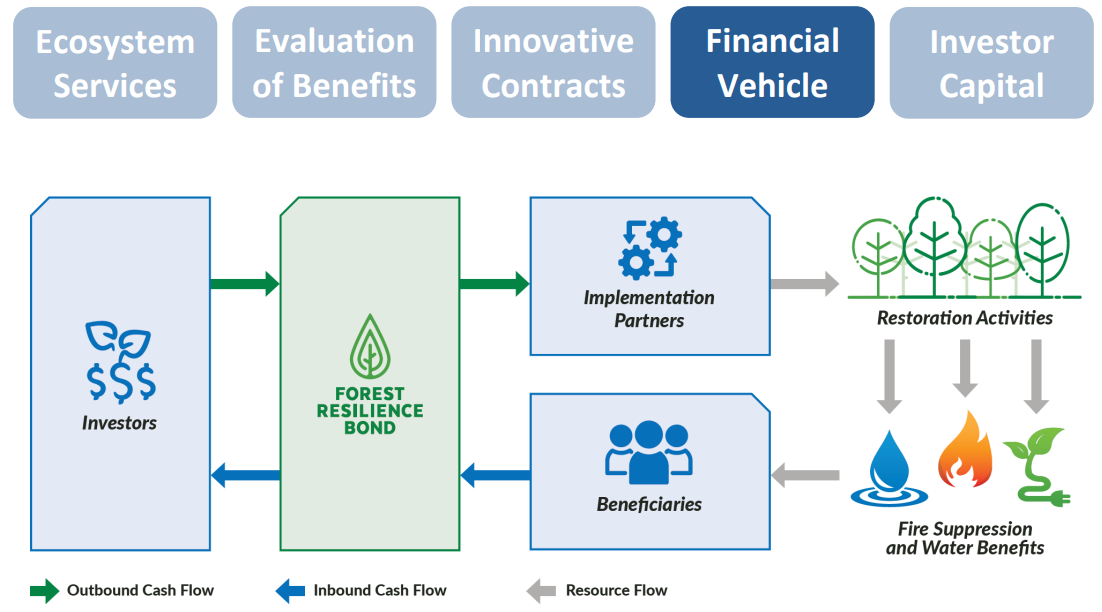

Supported by a Conservation Innovation Grant from the US Government and other funders, the American Forest Foundation, Blue Forest Conservation, and the World Resources Institute partnered to develop a financial instrument called the Forest Resilience Bond (FRB)2. Its development was driven by the idea that private capital should play a greater role in sustainability goals.

The bond deploys private capital to fund forest restoration in the Western US, in areas under pressure from wildfires. The investment supports restoration with a particular view to lowering the risk of wildfires, protecting water resources, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Beneficiaries, including private landowners, public agencies and utilities, repay investors such as foundations and state pension funds over time. Restoration can have significant biodiversity benefits through habitat enhancements and controlling invasive species. Benefits are expected to be monetised through contracts designed to share cost savings among beneficiaries and provide returns for investors (see diagram below).

The World Resources Institute state that by bringing together multiple payers to share the cost of restoration and tying payments to economic benefits, the FRB creates a compelling case for investors. They also highlight that similar public-private models (known as social impact bonds) have been applied in the US in education and criminal justice resulting in better outcomes3.

The FRB has been in development since 2014. A pilot project aims to protect 6000 hectares of forest in the North Yuba River watershed using ecologically-based tree thinning, meadow restoration and invasive species management, designed to reduce fire risk and improve water resources. The Yuba Water Agency, a utility provider, has committed $1.5 million to reimburse investors4. If pilots are successful, the coordinators hope the mechanism could be scaled up to apply to National Forests throughout the US.

Building biodiversity networks

National ecological networks - the Netherlands

The sustainable conservation of biodiversity requires some level of spatial connectivity to allow species to move between habitat patches. 'Ecological networks' aim to create a coherent network of natural areas (locally, nationally or internationally) to prevent biodiversity loss and have been established in a number of countries.

Scotland's Biodiversity Routemap to 2020 committed to "develop a national ecological network to enable characterisation of the nature of Scotland, and to help with the identification of priority areas for action on habitat restoration, creation and protection." SNH is undertaking some initial work to develop a vision of a National Ecological Network for Scotland. There is a Central Scotland Green Network (CSGN), which is a national development in the National Planning Framework and aims to make ‘a significant contribution to Scotland's sustainable economic development’1. The 2019 Programme for Government commits to a targeted map for the CSGN that "identifies the best opportunities for greenspace projects that will deliver the biggest climate change and biodiversity benefits to communities across the central belt"2.

The idea of the ecological network was first suggested in the Netherlands in the 1980s, and in the 1990s the Natuurnetwerk Nederland (NNN) was set out as a part of the national plan for nature conservation. Whilst the Netherlands were a frontrunner in developing its NNN, budget cuts are considered to have limited its capacity to deliver ecosystem services. In the 2013 Nature Pact (Natuurpact) the national and provincial governments agreed to raise ecological quality through the NNN and make extra efforts in habitat restoration3. It is considered by the Dutch Government to be its most important contribution to international efforts to stop biodiversity decline3.

The NNN is designed to link habitats more effectively, including surrounding farmland5. The network encompasses all Natura 2000 areas (protected areas designated under EU law), agricultural land under nature-friendly management, and over six million hectares of lakes, rivers, the North Sea coastal zone and Wadden Sea. Responsibility for the NNN lies with provincial authorities, and is supported by Government guidance which promotes ‘nature combinations’ - combining nature with agriculture, private estates, recreation, water extraction, cities, business areas, and waterways. The aim is for the NNN to span 728,500 hectares by 20256. In 2017 more than 108,000 hectares of land had been acquired (including change of designated land use) for realising the NNN7.

Part of the work to support the network is eliminating barriers caused by infrastructure, preventing species from moving between natural areas. At the end of 2017, 114 ecological barriers caused by transport infrastructure had been removed and there were almost 2,100 wildlife crossings on motorways and roads8.

Nature within the NNN that is not part of Natura 2000 is protected from activities that have a significant impact on the main features of the area, unless there is a ‘large societal interest’ and there are no realistic alternatives. The multifunctional character of nature areas within the NNN is acknowledged, as well as different policy goals such as water safety, recreation and maintenance of cultural and historical values of landscapes.

The Dutch Government expects that the NNN will eventually be linked up with nature areas in other countries to form a Pan-European Ecological Network. Other EU countries that have committed to implementing national ecological networks include Bulgaria, Croatia, Germany and Hungary6.

The first nature island (300 ha) on the Marker Wadden is being realised as part of the NNN, with 50 million euro funding from the Dutch Society for Nature Conservation, the National Lottery, the government and the province Flevoland. The project aims to restore natural processes in the Markermeer, an area cut off from the North Sea and rivers by dams and reclaimed land. It will create islands and marshes, providing habitat for fish and birds.

Citizen science networks - Germany and Australia

Citizen science has various definitions, but can be understood as scientific work undertaken by the general public, often in collaboration with, or under the direction of, professional scientists or institutions. Citizen science can be used to track distribution and abundance of species, which in turn can inform biodiversity policies, targets and conservation outcomes, such as on pollinators or invasive species. However, barriers to realising the potential of citizen science can include lack of resources or infrastructure to collate and publish data, disparate recording avenues, uncertainty over quality of data and questions around ownership of and access to data. Citizen science is also often linked with outreach activities to engage people with science and nature1.

In Scotland, over 120 organisations came together in 2017 through the Scottish Biodiversity Information Forum (SBIF) 'Review of the Biological Recording Infrastructure in Scotland'2 to consider how to improve access to knowledge of Scotland’s biodiversity. The review concluded that shortcomings in Scotland's biodiversity recording infrastructure are stifling volunteer energy and hampering our contribution to global biodiversity targets.

Some countries and regions are seeing a trend of institutionalisation of citizen science, and associated development of biological data recording infrastructure as networks have grown. National data networks in countries including Germany, New Zealand, China and Austria, are transitioning from informal networks to legal entities.

In Germany, a two-year citizen science capacity-building programme was implemented in 2014–2016 by the German Government's Ministry of Research and Education to assess the potential of citizen science. The resulting Greenpaper Citizen Science Strategy 2020 for Germany received significant attention from policy makers, and in 2017 the Government introduced a funding scheme to support citizen science projects, resulting in submission of over 300 proposals. The German Citizen Science Association (Bürger schaffen Wissen) provides a central platform for citizen science in Germany. A 2018 evaluation of the potential of environmental citizen science looked in detail at approaches in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. It found that citizen science can be successfully employed to achieve multiple goals of generating knowledge, enabling learning, and promoting transformation at the societal level - but also recommended areas for improvement to build the capacity of the citizen science community, and linkages with policy makers and the scientific community. These included recommendation for more guidance and training, more systematic evaluation of whether programs are meeting their goals, the development of more citizen science formats that involve the public, and funding schemes that are better aligned with the needs of practitioners3.

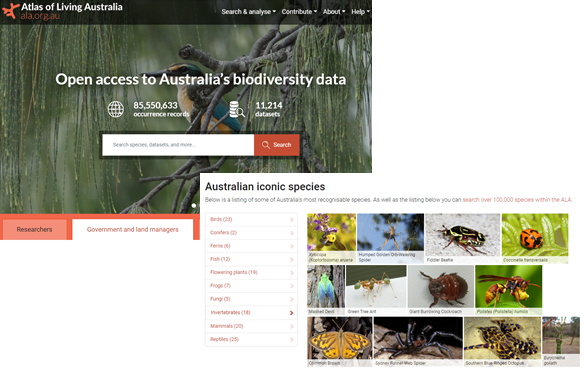

In Australia, the Atlas of Living Australia was developed to provide a reliable biodiversity data infrastructure to enhance scientific standards, visibility and application of citizen science data. The Australian Citizen Science Association was established to provide a forum for knowledge exchange and development of best practice. The Atlas, developed with support from the Australian government, includes a suite of tools, freely available under open source licences. It was established by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and multiple partner organisations including museums, research organisations and government to provide a single point of access for Australia’s biodiversity data and species information.

The web-based infrastructure includes a suite of connected databases and mobile apps. It is used for a range of purposes, including research, biodiversity documentation, environmental monitoring and reporting, conservation planning, biosecurity activities, education and citizen science. Prior to its development, fragmentation and inaccessibility of data across universities, research organisations, government agencies, as well as with individual citizen scientists and researchers was considered to be a major barrier to Australia’s biodiversity research and management efforts1.

The NBN Atlas Scotland, launched in 2017, is based on the Atlas of Living Australia - redesigned to create a bespoke system for UK users. The NBN Atlas Scotland website states that “there will eventually be separate Atlases for each of the four countries of the UK of which the NBN Atlas Scotland is the first and is continuing to be developed...”. The SBIF review recommended the establishment of a Scottish arm of the National Biodiversity Network (NBN) to provide in-country governance to develop this system, and the creation of a Community Fund to scale up citizen science participation across Scotland2.

Marine Protected Areas management and funding - California and Malaysia

The number and size of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) - a key tool in conserving and enhancing marine biodiversity and building the resilience of marine ecosystems - is increasing internationally, but ensuring they are well governed and sustainably financed is frequently cited as a challenge1.

The designation and management of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) is a relatively recent practice in Scotland. The first 30 nature conservation MPAs (17 inshore, 13 offshore) were designated in 2014 under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 and a further one in 2017. Four more MPAs (which aim to protect minke whales, Risso’s dolphins and basking sharks) are currently being developed, and the Scottish Government also plans to consult on a new deep sea marine reserve to the West of Scotland. Some management measures are in place in MPAs, but some are yet to be agreed and implemented (e.g. fisheries protection measures for a number of inshore sites, and management measures for offshore MPAs). The Marine Conservation Society recently called for a step-change in approach to efforts to restore and protect marine ecosystems in Scotland - which included a call for the MPA network to be completed and "properly protected"2.

California MPAs are widely recognised as good examples of combining stakeholder participation and scientific knowledge3, as well as being underpinned by a legal framework and strong political buy-in, which enable coordinated efforts over relatively large scales. The Marine Life Protection Act mandated that California create marine protected areas that were to be managed as a network, and managed adaptively (i.e. 'learning by doing', responding to changes in ecosystems and changing management practices accordingly). MPAs were intended to be ecologically connected, therefore design guidelines included minimum size and maximum spacing of MPAs (based roughly on fish movement rates)4.

Strong emphasis was placed on collecting local knowledge to inform MPA design, and this information was made available through an online decision support tool, MarineMap, which enabled stakeholders, scientists, and decision makers to contribute to the design of MPA proposals. One review of engagement in global MPA development highlights the Californian example as good practice, describing that "a regionally staged approach to network planning allowed for stepwise optimization of the stakeholder process design to fit both regional differences and lessons learned over time"5. The state government and non-government actors are working together to support a co‐management approach, as public resources necessary to enforce the MPAs are limited6.

In Malaysia, in reaction to declining fish abundance, the government introduced an ecosystem-based fisheries management initiative, and established a first MPA in Peninsular Malaysia. There are now 42 MPAs with a total area of 2318 km2, governed by a mixture of federal, state, and local government agencies. In 1987, an MPA trust fund was established as a financing mechanism. Whilst research on the role of MPAs in Malaysia in supporting the health of fisheries is still developing, there is wider evidence that MPAs can play a supportive role in enhancing the nursing, feeding and recruitment areas for fish7.

Pulau Payar Marine Park, situated around four islands, with a total area 188 km2 , lies within the Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem. Before the establishment of this MPA, the area was a major fishing ground and resources were significantly depleted. Within 10 years there was a marked recovery of fish stocks - assessments of snapper and grouper showed higher abundances at Palau Payar Marine Park than at any other island surveyed in Malaysia. This recovery inside the MPA contributed to a spill-over into the surrounding areas, resulting in increased support from the fishing community (low when the MPA was introduced)8.

Government funding tends to be the primary funding source for MPAs, particularly in developed countries. Other sources of funding either in place, or being trialled internationally, include user fees, fines (e.g. a share of fines for fishing infractions or fishing licence fees), trust funds, fiscal measures (e.g. a share of tourism-related taxes) and marine biodiversity offsetting linked to development1. In Malaysia, MPAs receive funding from the federal budget, where they face strong competition from other areas. Marine tourism has put increasing environmental pressure on MPAs, as an increasing number of tour operators have visited them to provide activities such as scuba diving. To help address these dual challenges and link funding to levels of use, in 2003 the Malaysian Department of Fishery introduced a RM5.00 (approximately US$1.70) per individual entry fee to any MPA, earmarking revenues to the site10. The revenue to-date has covered an estimated 40% of the costs of managing the MPAs.

Integrating nature into planning and development

Green infrastructure - Sweden, Denmark and Canada

Urban green infrastructure (such as parks, green corridors such as canals and walkways, green roofs and allotments) can enhance biodiversity by increasing habitats and their connectivity and quality, while also generating other potential benefits such as improved health and wellbeing1.

Green infrastructure has been a focal point in recent years in urban development in Sweden. The city of Umeå in northern Sweden has developed a tool called the ‘Green Target’ that is used in the planning process to ensure that all citizens have access to greenspace within 250m of their homes. In 2015, 89% of the city residents were estimated as living within 300m of green areas larger than 5,000 m22.

An example of innovative green infrastructure funding was developed by the City of Gothenburg in Sweden. The City issued its first green bonds for SEK 500 million (approximately £42 million) in 2013, ear-marked for investment in green infrastructure and other environmental projects, with a particular emphasis on climate mitigation and resilience - the first initiative of this kind at that level of government3. In 2016 the City received the UN Momentum for Change award for the programme2.

Canada's Long-Term Infrastructure Plan5 recognises the role of green infrastructure and sets it out as as one of five key investment streams, which aims to ensure "access to safe water, clean air, and greener communities". At a municipal level, the City of Edmonton aims to incorporate biodiversity into urban design via a ‘biologically sensitive approach’ to city planning. They have adopted a Green Network Strategy called ‘Breathe’, a 30-year programme which aims to ensure that as the city grows, each neighbourhood will be supported by a network of open space. Planning policies seek to maintain the connectivity of greenspace at local and city-wide levels. Delivery is supported by a database with an inventory of the city’s open spaces, with information about habitat function and connectivity6.

As part of its approach to green infrastructure, in 2018 the City of Toronto approved a Pollinator Strategy to incentivise the creation of habitat corridors for pollinators. In 2019, the City launched its PollinateTO grants of $5,000 to assist residents in planting pollinator-friendly gardens7. Thirty-seven projects (amounting to around 9,500 square metres) were selected for funding from 151 applications, and include community gardens, school gardens, and multiple residential gardens along important pollinator pathways8.

A Green Map of Denmark (Grønt Danmarkskort) was introduced in the Danish Spatial Planning Act in 2015, with the aim to ensure that Danish nature is sufficiently interconnected. The resource maps the distribution of threatened and vulnerable species, and gives an overview of high value natural areas in order to support land-use planning and guide the location of new green infrastructure. According to the Danish Spatial Planning Act, municipalities are to designate areas to the Green Map based on common criteria, and include these in plans from 2017 onwards.

Copenhagen was awarded the 2014 European Green Capital for their approach to green infrastructure. Its strategy 'Nature in Copenhagen' details 30 measures intended to create more greenspace - including an action plan for making trees a greater priority in the city without hampering development, and ultimately achieving a 20% coverage in the city. Green roofs are part of the City of Copenhagen’s Climate Adaptation Plan, and are required for all new buildings in planned areas where buildings are suitable9.

A European Commission report on green infrastructure highlights Denmark as an example of a country engaged in more holistic environmental planning. It highlights however that potential biodiversity (and other environmental and social) benefits of green infrastructure will only be fully delivered if green infrastructure elements are 'functional' i.e. big enough, in the right place and ecologically connected, and notes the importance of planning at the local level to build coherent ecological networks10.

Rigs to reefs: Oil and gas decommissioning in the Gulf of Mexico - USA

The decommissioning of offshore oil and gas platforms raises complex issues in terms of determining the most environmental, efficient and equitable approach. In the North Sea the OSPAR convention requires the removal of all assets; however in other areas assets are sometimes left in situ or placed as artificial reefs, an approach described as 'rigs-to-reefs'. It has been suggested by some NGOs that leaving offshore oil and gas structures in place should be explored in Scotland, as a potential mechanism for supporting biodiversity - through both creating artificial reefs and channelling associated savings into marine conservation1. Global policy in this area is subject to debate, with concerns that decisions need to be based on robust evidence about environmental impacts.

The United States of America hosts the largest rigs to reef programmes in the world. Since 1985, over 500 platforms previously installed on the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf had been 'reefed' in the Gulf of Mexico2. The Rigs to Reefs Habitat Protection Act outlines steps to be taken, permits states with a rig-to-reef programme to enter agreements to assume liability for structures, and establishes a Reef Maintenance Fund into which a proportion of the savings from partial removal are to be paid.

In California, a bill was enacted in 2010, which enables the state to authorise platform operators to leave facilities partially in place to form “rigs-to-reefs”. The bill enables provision for a public hearing in advance, to review environmental information. The state must take ownership of any platform in federal waters before it may be partially removed - with the state then responsible for management plans and their implementation. The operator retains liability associated with seepage or oil spill. A portion of the cost savings resulting from partial removal compared to full removal must be paid to the state3.

Understanding of whether rigs-to-reefs programmes actually enhance marine biodiversity is developing. A 2016 review of evidence of impacts of rigs-to-reefs found that artificial reefs have been shown to provide reef-like habitat and support secondary fish production, but that more research is needed to fully understand the impacts and benefits of such programmes3.

Biodiversity net gain and a Nature Recovery Network - England

The UK Government's 25 Year Environment Plan, published in 2018, committed to embed an 'environmental net gain' approach in the planning system in England alongside existing regulations that protect the most threatened or valuable habitats and species. Beginning with embedding biodiversity net gain (a narrower concept than environmental net gain) in the planning system, the Plan proposes to expand the approach in future to include wider natural capital benefits such as flood protection and improved air quality.

A Defra consultation at the beginning of 2019 set out how biodiversity net gain might work in practice1. The proposed rules would require developers to assess the type of habitat and its condition before submitting plans. Developers would then be required to demonstrate how they are improving biodiversity – such as through the creation of green corridors, planting trees, or local nature spaces. Improvements on site would be prioritised, but in circumstances where they are not possible, the Government proposes to charge developers a levy to pay for improvement elsewhere via a central fund. A new 'biodiversity unit' metric would be developed to apply values to habitats, to enable biodiversity net gain to be demonstrated, alongside a 'spatial hierarchy' directing where biodiversity units should be delivered. For example, car parks and industrial sites would come lower on the scale, while natural grasslands and woodlands would be given a higher ranking.

Current legislation in England requires public bodies to have regard to conserving biodiversity, and the 'mitigation hierarchy' applies to development: avoiding loss of habitats and environmental features wherever possible; then minimising impacts or, if not possible, adequately mitigating; or, as a last resort, compensating for losses. This principle makes it clear that planning should "identify and pursue opportunities for securing measurable net gains for biodiversity". However, it was recognised by the UK Government that the current system tends mainly to avoid the most severe impacts on biodiversity, but is not preventing gradual loss of lower value habitats1.

Beneath the national level there appears to be some momentum building around biodiversity net gain, with some local authorities and developers in England adopting net gain approaches. All development in Lichfield District is required to deliver a net gain for biodiversity3, and Dorset County Council applies a biodiversity net gain requirement to developments over 0.1ha4. The Berkeley Group have committed to creating a net biodiversity gain within all their development sites. They are working with London Wildlife Trust to build a 4,800 home development in East London incorporating 20 hectares of parkland. Warwickshire County Council aim to ensure all developments lead to no net loss of biodiversity, with every development preparing a Biodiversity Impact Assessment5.

The UK Government also committed to developing a Nature Recovery Network in its 25 year plan, which could then be linked to the planning system through delivery of net gain. The plan states that the network will provide 500,000 hectares of additional wildlife habitat, more effectively link existing protected sites and landscapes, as well as urban green and blue infrastructure (e.g. pools, ponds and artificial water courses).

Incentivising sustainable management

Developing ecosystem-based fisheries management - Norway

The overall objective of the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management (EAFM), adopted by many governments (including the Scottish Government1) since the 1990s, is to sustain healthy marine ecosystems. There are different definitions of ecosystem-based approaches, but all include the need to maintain ecosystem resources for sustainable use.

Ecosystem-based management requires a framework that integrates scientific evidence, administrative and regulatory complexity, effective communication and stakeholder engagement. This section describes the practical approach taken to ecosystem-based management of fisheries in Norway.

A number of institutional changes have taken place in fisheries management in Norway in recent decades. Efforts to rebuild cod stocks in the 1980s included a recognition that fishing subsidies were negatively impacting the fishery, and the phasing out of a number of mechanisms reduced subsidies to Norwegian fisheries by more than 80% from 1991 to 19962. It is worth noting in this regard that the 2019 global IPBES report on biodiversity emphasised that subsidies with harmful effects on nature are still prevalent globally, and that incorporating the value of ecosystems into economic incentives have been shown to permit better ecological, economic and social outcomes3.

In 2009, a new Marine Resources Act entered into force in Norway. The previous act relating to fisheries focused mainly on commercial exploitation, whereas the 2009 act applies more broadly to the marine environment, with a purpose to ensure sustainable and profitable management. Under article 7, it is mandatory for fisheries management to apply “an ecosystem approach, taking into account habitats and biodiversity”. This has been described as a paradigm shift in the management of Norwegian fisheries4.

Most of the economically important fish stocks in Norway are transboundary, so Norway shares management responsibilities with other states. The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea provides annual advice on Total Allowable Catch (TAC), based on fish stock monitoring and assessments. The relevant coastal states – bilaterally or multilaterally – conduct annual negotiations where TACs and other issues such as access to waters and sharing of quotas are agreed.

As a simple tool to provide an overview of issues related to stocks and fisheries relevant for Norwegian fisheries management and thus assist in defining priorities and actions, the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries has developed two Excel spreadsheets – the Stock Table and the Fisheries Table, updated annually, forming a basis for discussions with stakeholders. So far, 74 species/stocks and 57 fisheries have been included. The Stock Table includes information on the status of stocks, exploitation level, management objectives and priorities. The Fisheries Table includes information on species, discard problems, mortality and wider habitat issues.

Prioritised issues are then included in the work plan of the Directorate of Fisheries and/or the Institute of Marine Research and remain until appropriate measures have been developed and implemented. Measures can include revision of management plans to improve technical regulations, new technology, catch limitations, or area closures.

Scoping work on the ecosystem-based approach in Norway has also concluded that testing harvesting strategies and rules in multi-species and ecosystem models (rather than estimating impacts on species in isolation) is particularly important when initiating or escalating harvesting of species with (potentially) key functions in a marine ecosystem. The scoping work found that the overall system vulnerabilities and risks associated with cumulative impacts of fisheries removal should be assessed, recognizing that managing interacting fish stocks individually may result in ecosystem overfishing5.

Public money for public goods - Croatia, Switzerland and Costa Rica

The model of 'public money for public goods' is where land managers are incentivised by Government for activities that generate generally non-monetised benefits for wider society such as biodiversity, climate mitigation and flood protection (also see the SPICe briefing, 'Agriculture and Land Use - Public Money for Public Goods?'). Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) refers to where land managers are compensated for activities that support the provision of ecosystem services - funding can come from public or private sources (or a mixture of the two). A model of 'public money for public goods' essentially refers to a publicly-funded PES scheme. There are a large number of PES schemes globally, local to national (and international) in scale, with different levels of private and public sector involvement.

The Lonjsko Polje area of Croatia represents a unique landscape and ecological systems of flooded river plain. Land abandonment is an issue as traditional management such as low intensity grazing is becoming less popular, as the intensification of modern practices was anticipated to result in loss of important ecosystems. The Lonjsko Polje project adopted a PES model to help reduce land abandonment and maintain biodiversity. Opportunity costs (i.e. the difference in income between traditional and alternative management practices) were calculated using more intensive farming as a benchmark, and payments made available for maintaining traditional practices over and above existing agricultural subsidies - with further funding available for the introduction of organic methods.

One of the most internationally well-known PES schemes is in Costa Rica. Created in 1996, the programme is a mix of regulations and rewards. The PSA (Pago por Servicios Ambientales) programme is a national payment programme for carbon storage, hydrological services, and protection of biodiversity and landscapes. An institution, Fonafifo, was established as an intermediary (a key role in PES schemes) to broker deals, and a share of fuel tax revenues provided funding to kick-start the process. The scheme is thought to have been central to reversing the trend of deforestation, leading to increased national forest cover. Although the fuel tax provided a starting point, further sources of finance were needed, resulting in 25% of water tax revenue being reserved for PES in key watersheds (e.g. river basins). Agreements with companies such as hydroelectric companies also provide small amounts of resources, although the majority of the programme is Government funded. The programme makes payments to land managers under 5-year contracts for different combinations of forest protection, reforestation, sustainable forest management and agroforestry. Following results of a `conservation gap’ analysis, funding is focused on priority areas and improving connectivity through biological corridors.1

In Switzerland, to access public support the farmer must first provide ‘Proof of Ecological Performance’ (PEP). A number of policies have been developed to incentivise a reduction in pesticide use for example. Pesticides can harm a wide range of non-targeted life including birds, fish, and insects. Studies have shown that areas close to organic farms are characterised by greater biodiversity than those near conventional farms2. Financial support for Integrated Pest Management (strategies that focus on long-term prevention of pests or their damage with the least possible disruption to ecosystems) is available to Swiss farmers and encourages preventative measures, and enables farmers to take a flexible and phased approach, earning points as they show continuous improvement. Switzerland has also banned the use of herbicides on roofs, balconies, storage areas, roads, squares, and grass strips along streets and railways (excluding motorways and railway tracks)3.

Eco-labelling and procurement - Mexico, Germany and Norway

A large number of voluntary certification standards and associated labels exist to certify the sustainability credentials of products, from agriculture to fisheries to forestry - and those standards can include the protection of biodiversity among their objectives or requirements. Eco-labels can support a change in the perspective of producers to support biodiversity and the adoption of best practices1.

One such voluntary initiative with a particular biodiversity focus is the development of a bat-friendly tequila label in Mexico. Mexico’s exports of tequila have more than doubled since 1995, reaching 197.9 million litres in 2016. Tequila is exclusively produced from the blue agave plant, and the lesser long-nosed bat is the plant’s primary pollinator. However, industrial practices used for the production of tequila led to the loss of genetic diversity of agaves and loss of an important food source for the lesser long-nosed bat, listed as a threatened species in Mexico in 1994. Management practices were contributing to this decline, as tequila makers often cut off the flowers before they could be pollinated, to boost the agave’s sugar content.

An NGO and consumer advocacy group called the Tequila Interchange Project approached producers to develop a ‘bat-friendly tequila’ label in 2010. Producers had to be verified as allowing 5% of agave plants to flower, and producing seeds to support increased genetic diversity. By late 2016, the project released over 300,000 bottles of tequila from 5 brands23. When the lesser long-nosed bat was listed as endangered, there were thought to be fewer than 1,000 bats left. In 2018, the population had grown to an estimated 200,000 across the southwestern United States and Mexico4. The development of bat-friendly tequila is thought to have contributed to this increase, alongside other conservation measures to.

Public procurement policies can be used to advance international biodiversity conservation, recognising that indirect drivers of biodiversity loss include consumption trends which drive unsustainable resource extraction or management in other parts of the world. Procurement standards can link to eco-labelling schemes (such as Fair Trade, Rainforest Alliance, Forest Stewardship Council certification) with the aim of reducing those impacts. Palm oil and its consumption - for food or fuel - is a major current issue in relation to consumption drivers of global deforestation and resulting loss of biodiversity. In June 2017, the Norwegian Parliament voted to ban all public purchases of palm oil for use as biofuels. The ban is part of a wider pledge to make Norway’s public procurement policy 'deforestation free'5.

The German Government launched a project in 2018 to develop public procurement guidelines for municipalities, Federal States and the Federal government, targeting at purchasing products with certified palm oil. The project will also work directly with 3000 Indonesian smallholders, in areas where tropical deforestation is driven by palm oil demand, to support certification according to the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) Smallholder Standard6. The RSPO standard prohibits the use of converted forest and peat areas and promotes cultivation methods with reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

Annex 1: The Aichi 2020 biodiversity targets

Strategic Goal A: Address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss by mainstreaming biodiversity across government and society.

Target 1 By 2020, at the latest, people are aware of the values of biodiversity and the steps they can take to conserve and use it sustainably.

Target 2 By 2020, at the latest, biodiversity values have been integrated into national and local development and poverty reduction strategies and planning processes and are being incorporated into national accounting, as appropriate, and reporting systems.

Target 3 By 2020, at the latest, incentives, including subsidies, harmful to biodiversity are eliminated, phased out or reformed in order to minimize or avoid negative impacts, and positive incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity are developed and applied, consistent and in harmony with the Convention and other relevant international obligations, taking into account national socio economic conditions.

Target 4 By 2020, at the latest, Governments, business and stakeholders at all levels have taken steps to achieve or have implemented plans for sustainable production and consumption and have kept the impacts of use of natural resources well within safe ecological limits.

Strategic Goal B: Reduce the direct pressures on biodiversity and promote sustainable use.

Target 5 By 2020, the rate of loss of all natural habitats, including forests, is at least halved and where feasible brought close to zero, and degradation and fragmentation is significantly reduced.

Target 6 By 2020 all fish and invertebrate stocks and aquatic plants are managed and harvested sustainably, legally and applying ecosystem based approaches, so that overfishing is avoided, recovery plans and measures are in place for all depleted species, fisheries have no significant adverse impacts on threatened species and vulnerable ecosystems and the impacts of fisheries on stocks, species and ecosystems are within safe ecological limits.

Target 7 By 2020 areas under agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are managed sustainably, ensuring conservation of biodiversity.

Target 8 By 2020, pollution, including from excess nutrients, has been brought to levels that are not detrimental to ecosystem function and biodiversity.

Target 9 By 2020, invasive alien species and pathways are identified and prioritized, priority species are controlled or eradicated, and measures are in place to manage pathways to prevent their introduction and establishment.

Target 10 By 2015, the multiple anthropogenic pressures on coral reefs, and other vulnerable ecosystems impacted by climate change or ocean acidification are minimized, so as to maintain their integrity and functioning.

Strategic Goal C: To improve the status of biodiversity by safeguarding ecosystems, species and genetic diversity.

Target 11 By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.

Target 12 By 2020 the extinction of known threatened species has been prevented and their conservation status, particularly of those most in decline, has been improved and sustained.

Target 13 By 2020, the genetic diversity of cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and of wild relatives, including other socio-economically as well as culturally valuable species, is maintained, and strategies have been developed and implemented for minimizing genetic erosion and safeguarding their genetic diversity.

Strategic Goal D: Enhance the benefits to all from biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Target 14 By 2020, ecosystems that provide essential services, including services related to water, and contribute to health, livelihoods and well-being, are restored and safeguarded, taking into account the needs of women, indigenous and local communities, and the poor and vulnerable.

Target 15 By 2020, ecosystem resilience and the contribution of biodiversity to carbon stocks has been enhanced, through conservation and restoration, including restoration of at least 15 per cent of degraded ecosystems, thereby contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation and to combating desertification.

Target 16 By 2015, the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization is in force and operational, consistent with national legislation.

Strategic Goal E: Enhance implementation through participatory planning, knowledge management and capacity building.

Target 17 By 2015 each Party has developed, adopted as a policy instrument, and has commenced implementing an effective, participatory and updated national biodiversity strategy and action plan.

Target 18 By 2020, the traditional knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, and their customary use of biological resources, are respected, subject to national legislation and relevant international obligations, and fully integrated and reflected in the implementation of the Convention with the full and effective participation of indigenous and local communities, at all relevant levels.

Target 19 By 2020, knowledge, the science base and technologies relating to biodiversity, its values, functioning, status and trends, and the consequences of its loss, are improved, widely shared and transferred, and applied.

Target 20 By 2020, at the latest, the mobilization of financial resources for effectively implementing the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 from all sources, and in accordance with the consolidated and agreed process in the Strategy for Resource Mobilization, should increase substantially from the current levels. This target will be subject to changes contingent to resource needs assessments to be developed and reported by Parties