Justice Sub-Committee on Policing

Report on Police Scotland’s proposal to introduce the use of digital device triage systems (cyber kiosks)

Introduction

The Justice Sub-Committee on Policing undertook an inquiry into Police Scotland’s intention to introduce the use of digital device triage systems (known colloquially as cyber kiosks), to search mobile devices throughout Scotland from September 2018. The inquiry’s remit also included scrutiny of two previous trials of the use of cyber kiosks by frontline police officers in Edinburgh and Stirling.

The Sub-Committee began its inquiry on 10 May 2018 and held 5 evidence sessions where this issue was scrutinised, concluding on 31 January 2019. It received a number of written submissions from key stakeholders, which have been invaluable in informing its scrutiny of Police Scotland’s introduction of this new technology.

Digital device triage systems / cyber kiosks

Over the last 25 years, modern electronic wireless digital devices have become commonplace in Scottish society. As a result, the investigation of cybercrime, and the digital forensic examination of IT devices, have become a central part of criminal investigations work carried out by the police in Scotland.

Police forces across the UK have been using a variety of specialised software tools to examine and recover various forms of data held on modern digital devices, like PCs and mobile phones, as part of their investigation of crime. As a result, developing an up-to-date digital and ICT strategy is a core element of 21st century policing.

Cyber kiosks are software systems, which look like small laptops, and are designed to image or extract electronic data held on a variety of digital devices, such as mobile phones, tablet/surface devices etc. This allows that data to be analysed by a third party, such as the police. Cyber kiosks form part of the wider digital forensic systems used by some UK police forces as part of modern policing.

Over the last two decades a large majority of the day-to-day interactions the police may have with the public involves dealing with a digital device, such as a mobile phone or tablet. There are various reasons why the police may need to access data stored on such a device when investigating a crime, or why the police would need to retain such a device.

Digital devices like mobile phones normally have security features, such as passwords and data encryption, to prevent anyone other than the owner of the device from accessing the data stored on it. Cyber kiosks enable the police service to bypass passwords, overcome locks and encryption security to access the data held on a mobile device. This data can be wide-ranging, such as biometric data, and data stored externally from the device, such as information held on cloud-based server accounts.

Cyber kiosks enable the police service to access a large volume of personal and private data about a person, and also data about third-parties who may be connected with the owner of a device.

Police Scotland purchased 41 Cellebrite cyber kiosks in April 2018 with the intention to deploy their use throughout Scotland in autumn 2018. The Cellebrite cyber kiosk is a desktop personal computer which can take an image of all of the data on a mobile device, and can also extract and store data. It enables search parameters to be inserted to search the data on the device. The cyber kiosks are not able to change or delete any data held on a mobile device.

During the Sub-Committee’s inquiry, stakeholders raised a number of concerns with the proposed introduction of cyber kiosks, including the legal basis for their use, and whether human rights and data protection assessments were in place.

In response to these concerns, Police Scotland postponed the deployment of cyber kiosks to frontline officers from September, to October, to November, and then again until December 2018. The Chief Constable of Police Scotland confirmed to the Sub-Committee in January 2019 that cyber kiosks would not be deployed until the issues of legality and policing by consent had been addressed.

While the Sub-Committee’s scrutiny of plans for cyber kiosks is on-going, we are mindful that it has been almost a year since we began to consider this issue. Therefore, we believe there is value in drawing together the evidence we have gathered to date, by way of a report to the Parliament. At the time of publishing the Sub-Committee’s report, cyber kiosks had not been introduced by Police Scotland.

This report details the Sub-Committee’s scrutiny of this proposal, the issues raised during that scrutiny, and our view at this point in time on the proposed introduction of this new technology. The Sub-Committee intends to keep this issue under review.

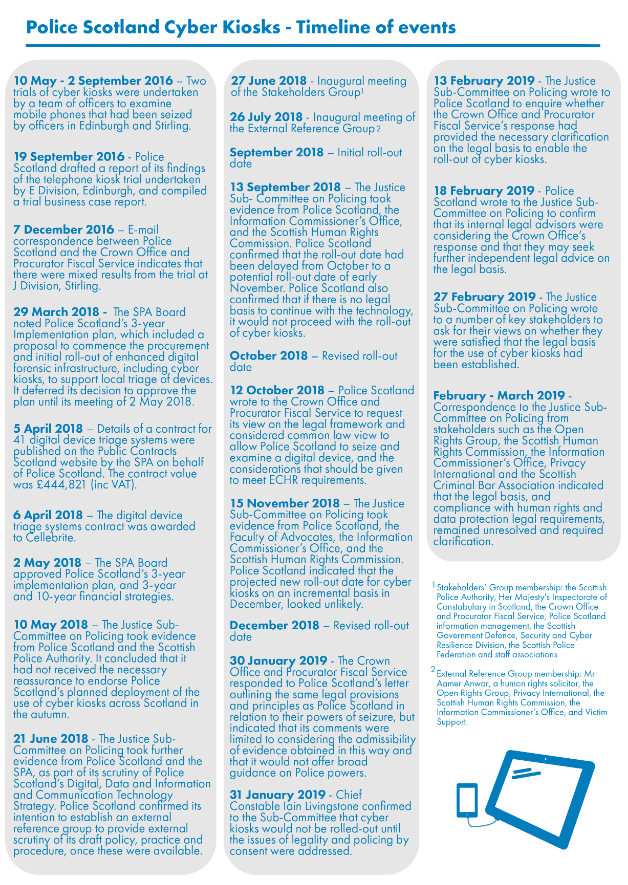

Timeline of events

Justice Sub-Committee on Policing consideration

The Justice Sub-Committee on Policing held five evidence sessions from May 2018 to January 2019,i where the issue of Police Scotland’s proposal to introduce the use of cyber kiosks for frontline officers was considered. Details of the evidence sessions can be found at Annex A. The Sub-Committee also received a number of written submissions, which are detailed in Annex B. The Sub-Committee would like to thank all those who provided oral and written evidence to inform our scrutiny of this issue.

Throughout the evidence sessions the Sub-Committee heard of concerns about Police Scotland’s use of this new technology in two separate trials, the governance and oversight of the decision to undertake the trials and purchase cyber kiosks for use by frontline police officers across Scotland, the legal basis to seize and search mobile devices, human rights, privacy, data protection and security concerns, and informed consent. These issues are considered within this report.

Trials conducted in Edinburgh and Stirling

The Sub-Committee became aware of media reports that Police Scotland had previously undertaken trials of the cyber kiosks at police stations in Edinburgh and Stirling.

At the Sub-Committee meeting of 10 May 2018 Detective Superintendent Nicola Burnett confirmed that Police Scotland had carried out an evaluation of both trials, and that no problems were highlighted, saying that: “A couple of brief reports were completed at the end of the trials and, prior to moving to the procurement of the kiosks”. Detective Superintendent Burnett agreed to provide a copy of both reports to the Sub-Committee.1

The Sub-Committee wrote to the Scottish Police Authority on 15 May 2018 to request further information on the use of cyber kiosks for the two trials in Edinburgh (E Division) and Stirling (J Division) in 2016. This included a request for details of the impact assessments undertaken prior to the trials commencing, and the assessment and analysis of the trials once they had concluded, to inform the decision to purchase 41 cyber kiosks for use across Scotland.

The Sub-Committee also wrote to Police Scotland on 15 May 2018 to ask for information on how the trials were agreed, conducted and analysed, and to formalise its request for copies of the reports of the trials in Edinburgh and Stirling.

Governance and scrutiny

In its response of 6 June 2018 Police Scotland indicated that the purpose of the trials was to enable frontline officers to determine whether mobile phones required to be submitted to Cyber Digital Forensics for full examination. It was also an opportunity to consider the advantages and viability of introducing a triage system, as well as any training requirements. The trial was to test the usability of the technology by front end officers, and to better understand the potential to improve efficiency and service delivery.

Police Scotland confirmed that over the trial period a total of 195 mobile phones and 262 SIM cards were examined using the terminals in Edinburgh, and 180 mobile devices were examined by frontline officers in Stirling.

A team of officers from both areas were trained in the use of the technology and had the ability to conduct a triage examination of seized mobile devices.

Police Scotland also provided the Sub-Committee with a redacted copy of the trial business case. It indicated that the examinations being carried out would only be allowed on summary cases and would be collated for statistical analysis. The information provided indicated that the outcome of the trial was successful, as it had positively reflected upon the submissions made to Cybercrime East during the trial period. The redacted business case did not specify who had provided the equipment that was used in the trials.

The trial business case stated that Police Scotland had consulted other UK police forces for their opinions on the use of cyber kiosks. The redacted report provided to the Sub-Committee did not include details of any issues encountered.

At the Sub-Committee meeting of 10 May 2018, Detective Superintendent Nicola Burnett confirmed that she was aware of the Police and Crime Commissioner for North Yorkshire’s report on its investigation into North Yorkshire Police's processes for examining mobile phones, which was published on 11 November 2015. Detective Superintendent Burnett also confirmed that she was aware that the report concluded that there was a failure to receive authorisation for the use of phone extraction tools in half the cases sampled, and that poor training resulted in practices that undermined the prosecution of serious crimes such as murder and sexual offences. The report also found that there were inadequate data security practices, including the failure to encrypt, and the loss of files that might have contained intimate details of people who were never charged with a crime.

Police Scotland provided a copy of the redacted report of the trial in Edinburgh, which indicated that the trial had lasted for over four months from 10 May to 2 September 2016. The report from the trial in Stirling was not provided by Police Scotland. The Sub-Committee requested the Stirling trial report again on 6 March 2019. Police Scotland responded on 26 March indicating that despite earlier comments to the contrary, no report of the Stirling trial exists.

The Sub-Committee repeated its request for a copy of the Stirling trial report on 29 March 2019. Police Scotland stated in its response that it may have caused some confusion in its evidence to the Sub-Committee about the number of reports generated by the trials, clarifying that the two reports referred to were the Edinburgh trial report and the trial business case. Police Scotland confirmed that: “there is no report available for the Stirling trials”, adding that: “In respect of the Stirling ‘kiosk’ trials, the response from local officers was largely positive”.

The report indicated that the trial in E Division allowed 25 trained users to conduct examinations and download the content of a mobile phone and/or SIM card. It stated that:

The terminal provides the facility to export data on both PDF and Excel documents and also allows data to be exported to a USB saving on the cost of repeatedly downloading to disk. It also allows the users to carry out their own research, searching previously downloaded phones for names, number etc of interest to ongoing enquiries.

Police Scotland indicated that upon the trial’s conclusion it updated the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service ('COPFS') and sought support for the wider roll-out of the triage devices to support all types of criminal enquiries. Adding that, no specific issues were raised by local Prosecutors in relation to the 2016 pilots.

Police Scotland provided the Sub-Committee with redacted e-mail correspondence with the COPFS. The e-mail correspondence indicates that Police Scotland wished to proceed with purchasing cyber kiosks for further roll-out to frontline officers. Police Scotland refer to the outcome of both of the trials in this correspondence, saying that there were “excellent results in E Division and mixed results in J Division”. Police Scotland requested that the COPFS support further roll-out of cyber kiosks solely on the basis of the Edinburgh trial, asking: “Do you have a view on the use of such technologies at the frontline given the clear benefits that we established in E Division”.

In response to a question about the briefing that the COPFS received following the trials, Detective Chief Superintendent McLean told the Sub-Committee that: “… there could probably have been better record keeping for some of the trials”, adding that “… if we were to run the trials again I would ensure that there was better governance with regard to the provision of detail”.1

Police Scotland stated that the Scottish Police Authority ('SPA') had not received any specific briefing on cyber kiosks prior to commencing the trials, saying that: “The SPA receive regular updates on policing matters, including cybercrime and although no specific briefing to SPA occurred prior to trial commencement the proposal to procure cyber kiosks was presented and supported at Police Scotland Change Board”.

Kenneth Hogg, former interim Chief Officer of the SPA, confirmed that was the case, telling the Sub-Committee that: “The position is that the SPA did not receive a specific briefing about the trials in advance of the deployment of the devices”.2

In response to a question on whether the SPA was sighted on either of the reports and its response to them, Kenneth Hogg told the Sub-Committee that: “I do not know whether the reports were shared with the SPA”.3

Impact assessments

Police Scotland confirmed to the Sub-Committee that no assessments were carried out prior to the trials, saying that: “No assessments i.e. human rights, equalities, community impact assessments and data protection and security assessments were completed prior to trial commencement”. Police Scotland added that it accepted that the introduction of the cyber kiosks had wider implications for data privacy and security, and would require its current protocols to be reviewed and that there would need to be wider engagement to inform the required impact assessments.

In a letter provided to the Sub-Committee in June 2018, Kenneth Hogg stated: “The decision to proceed with a limited trial of the digital device triage systems was taken by Police Scotland and I have no information on whether any aspects of the initial trial were reported to the SPA."

In response to a question on whether the SPA should have wanted a community impact assessment to be carried out prior to the trials, Kenneth Hogg said that he did not believe a community impact assessment was required.1

Mr Hogg told the Sub-Committee that he held this view as the introduction of cyber kiosks was not a change to operational policing, as: “It allowed police officers to do in local police stations what they were already doing in regional hubs”.2

Detective Chief Superintendent ('DCS') Gerry McLean, Head of Organised Crime and Counter Terrorism at Police Scotland told the Sub-Committee that, as introducing the cyber kiosks was a change of use, Police Scotland were of the view at the time of the trials that impact assessments were not required. DCS McLean accepted that best practice would be to make an assessment in advance of doing something rather than at the conclusion, telling the Sub-Committee that Police Scotland is now developing policy and procedure around their use.3

Diego Quiroz of the Scottish Human Rights Commission ('SHRC'), told the Sub-Committee that human rights and equality impact assessments are essential prerequisites, as they ensure that police policy, programmes and projects are compliant with human rights. In relation to the trials Mr Quiroz said that the assessments should have been undertaken in advance, adding that the Commission questioned the legality of the trials, saying that:

The Commission has significant concerns about the trial of 600 phones and the legality of how the process has been run so far. We must also acknowledge that we do not have the full information about the trial.4

In response to a question on whether anyone who was involved in the trial without their knowledge has complained, DCS McLean told the Sub-Committee that no-one had complained, to his knowledge, adding that: “I am sure that many people will be watching this meeting with interest”.5

Evaluation

In its letter of 6 June 2018 Police Scotland confirmed that only data on the number of devices examined had been collated. Adding that: “Further data in terms of nature of seizure, specific lawful policing purpose under which the device was seized and subsequently examined and the evidential efficacy of those examinations in supporting a prosecution were not collated. The reason for this being that this was not the purpose of the trial”.

The Sub-Committee is concerned to learn that Police Scotland undertook trials of using cyber kiosks to search the mobile phones of suspects, witnesses and victims of crimes in Edinburgh (E Division) and Stirling (J Division) without undertaking the required governance, scrutiny and impact assessments. Those members of the public whose phones were seized and searched were not made aware that their phones were to be searched using cyber kiosks as part of a trial, or the implications, and were not provided with the option of giving their consent.

Cyber kiosks are able to access personal and private data including data protected by passwords, and to copy large quantities of data. The Sub-Committee is concerned that this technology was used on a trial basis without any human rights, equality or community impact assessments, data protection or security assessments, and in the absence of any public information campaign. The decision to purchase 41 cyber kiosks seems to have been taken without any analysis of the outcomes of the two trials by the Scottish Police Authority.

The Sub-Committee fully supports Police Scotland’s ambition to transform to effectively tackle digital crime. However, prior to the introduction of any new technology to be used for policing purposes, an assessment of both the benefits and the risks should have been carried out. It appears that, in relation to the introduction of cyber kiosks, only the benefits were presented by Police Scotland to the SPA, with the known risks identified in the Police and Crime Commissioner for North Yorkshire’s report, and any issues raised in feedback from those within J Division, not provided. The Scottish Police Authority, for its part, seems to have accepted the information provided with very little critical assessment.

This lack of effective scrutiny puts the reputation of the police service, and the rights of the public, at risk. It has also led to the investment of over half a million pounds in technology that, at present, Police Scotland is unable to use.

The Sub-Committee recommends that the Scottish Government assess the scrutiny and approval process undertaken by Police Scotland and the Scottish Police Authority prior to the trials being approved and report its findings to the Sub-Committee. This should include lessons to be learned to avoid any proposed future technology being trialled by frontline officers, without the necessary safeguards being put in place, and the vital human rights and data protection impact assessments being carried out before any such technology is deployed.

Oversight and governance

On Thursday 5 April 2018, details of a contract for 41 cyber kiosks were published on the Public Contracts Scotland website by the Scottish Police Authority on behalf of Police Scotland. The contract was for a value of £370,000, or £444,821 including VAT. The contract was awarded to Cellebrite on Friday 6 April 2018.

The Sub-Committee considered the governance and scrutiny of Police Scotland’s proposal to introduce the use of cyber kiosks by frontline officers throughout Scotland.

On 31 March 2015, the SPA Board approved Police Scotland’s 2015-16 capital plan, which included the implementation of its ICT Infrastructure Blueprint, costed at £8.1 million. It proposed a programme of investment in ICT infrastructure to rationalise and modernise the technology deployed to support operational policing in Scotland.1

Police Scotland state in its written evidence that the business case for cybercrime infrastructure was approved by the SPA Board in March 2015, and that this included the provision of a range of cybercrime infrastructure, including cyber kiosks. Police Scotland add that a revised 2017-18 Capital Plan was then approved by the SPA Board in September 2017, which included funding of £3.6m for cyber infrastructure.

Police Scotland state that:

As a business case had already been approved by the SPA Board, the business case financial model was updated for changes in technology specification and pricing, whilst keeping in line with the strategic direction of the original business case. The infrastructure was purchased and delivered in full in 2017/18.2

On 19 March 2019, the Sub-Committee requested a copy of the paper that Police Scotland provided to the SPA to enable it to consider the policy intentions and detail of the proposal to introduce the use of cyber kiosks to frontline policing in Scotland. Police Scotland responded on 26 March and provided the strategic business case and financial approval process for the cyber kiosks. The business case containing the finer details of the policy intention to introduce the use of cyber kiosks was again requested on 29 March 2019.

In its response of 3 April, Police Scotland refer to its authority to tender and contract awards for goods and services of up to £500,000 without a requirement for additional authorisation by the Chief Officer of the SPA and indicate that it was their understanding that this authority meant that there was not a requirement to submit a business case for the SPA to consider. DCS Gerry McLean stated that: “I can confirm that no specific business case was submitted to the SPA in relation to Digital Device Triage Systems (Cyber Kiosks) procurement as it was not our understanding there was a requirement to do so”.

To assist the Sub-Committee in understanding the associated business cases and policy proposal for cyber kiosks DCS McLean directed the Sub-Committee to the presentation given by Police Scotland to the SPA Board on cyber kiosks on 29 March 2018. The presentation was on Police Scotland’s ‘Serving a Changing Scotland 3-Year Implementation Plan: 2017-2020’.

Police Scotland’s ‘Serving a Changing Scotland 3-Year Implementation Plan: 2017-2020’ included a commitment in year one to: “Commence procurement and initial roll out of enhanced digital forensic infrastructure, including cyber kiosks to support local triage of devices”.3

The implementation plan was considered by the SPA Board on 19 December 2017, and indicated that: “procurement for the kiosks and associated infrastructure has been completed with installation planned to take place over Q1 & Q2 18/19”.4

The SPA Board noted that work would be undertaken over the next few months to develop the 3-year plan further and agreed to reconsider the implementation plan again at its meeting of 29 March 2018.

At the SPA Board meeting of 29 March 2018, the Board noted Police Scotland’s 3-year Implementation Plan, ‘Serving a Changing Scotland’. The plan described how Police Scotland intended to deliver its 10-year strategy, Policing 2026, within the first three years, from 2017 to 2020. The SPA Board agreed to defer its decision on whether to approve Police Scotland’s 3-year implementation plan until it could be considered alongside the related 3-year financial plan at its next meeting, which was scheduled for 2 May 2018.

In a written submission to the Sub-Committee on 30 April 2018, the SPA confirmed that the proposal for cyber kiosks featured in the 3-year implementation plan, “as an early element in delivery of an enhanced digital forensic infrastructure”, and that the plan was considered for approval at the SPA Board meeting of 2 May 2018.

Police Scotland also confirmed in its written submission that cyber kiosks were included in the 3-year implementation plan, stating that:

Cyber Kiosks were identified as a key deliverable in supporting the aspiration to digitally enable frontline officers and provide greater access and improved delivery of cyber digital forensic capabilities. As a consequence, the procurement of cyber kiosks was included in the 3-year implementation plan as a way of maximising efficiency, improve service delivery and thus provide capacity to modernise.5

The 3-year implementation plan, and the 3-year and 10-year financial strategies, were approved by the SPA Board at its meeting of 2 May 2018. However, the contract for cyber kiosks had already been awarded on 6 April 2018.

In a letter from Police Scotland on 26 March 2019, Assistant Chief Constable Steve Johnson describes the Cyber Kiosks Procurement Timeline as follows:

“19 January 2018 - Invitation to Tender Issued

6 February 2018 - Suppliers Submission Received

16 February 2018 - Contract Award Recommendation

26 February 2018 - Contract Formally Awarded

26 February 2018 - Kiosks Purchased”.

The timeline suggested by ACC Johnson is contrary to the dates when the contract was published and awarded, which were 5 and 6 April 2018 respectively. The timeline provided also indicates that Police Scotland concluded its financial considerations, and the SPA awarded the contract, prior to the SPA Board granting approval for the 3-year implementation plan.

In March 2018, Privacy International published its report on ‘Digital Stop and search: how the UK police can secretly download everything from your mobile phone’. Privacy International wrote to the former Cabinet Secretary for Justice, Michael Matheson, on 4 May 2018 to highlight its concerns about a lack of clear legislation, policy framework, regulation or independent oversight in place for Police Scotland’s use of cyber kiosks. The Sub-Committee did not receive any evidence that the SPA considered the Privacy International report as part of its scrutiny of Police Scotland’s proposed policy to introduce the use of cyber kiosks for use by frontline officers throughout Scotland.

The Scottish Police Authority has considered the proposal to improve Police Scotland’s cybercrime infrastructure over a number of years. The SPA has an important role to effectively scrutinise proposed changes to policing policies and practice, and to reassure itself and the public about the implications of those changes. From the evidence we have received, it appears that the SPA did not carry out this function effectively or ask the most basic questions about the legality and implications of introducing this new technology, and did not seem to share the concerns that have been expressed by a range of key stakeholders.

Police Scotland’s 3-year implementation plan is key to the delivery of Policing 2026. The draft 3-year implementation plan provided the SPA Board with the opportunity to critically assess the detail of Police Scotland’s proposal to purchase and distribute 41 digital device triage systems (cyber kiosks), with the intention to roll-out their use to police officers across Scotland.

The timeline of the approval process for the cyber kiosks seems to suggest that the contract for the digital device triage systems was awarded by the SPA prior to the SPA Board’s approval of Police Scotland’s 3-year implementation plan, and their associated 3-year and 10-year financial plans.

The Sub-Committee asks the Scottish Police Authority to provide details, and the timeline, of its governance and approval process for the purchase of 41 digital device triage systems.

Training

The Sub-Committee considered the nature and timing of the training to be provided to police officers to operate cyber kiosks.

Diego Quiroz, from the SHRC, told the Sub-Committee that he was unaware of the type of training that was to be provided. However, he stated that the training must include human rights as a key element, and be accompanied by clear guidance and oversight arrangements.1

David Freeland, from the Information Commissioner's Office ('ICO'), agreed, telling the Sub-Committee that the training needs to be on-going and linked to internal and external oversight and audit.2

On 14 November 2018 Police Scotland informed the Sub-Committee that the draft data protection impact assessment and the draft equality and human rights impact assessment were sufficiently progressed to support training officers to operate the cyber kiosks. Police Scotland indicated that the training would be provided to 410 nominated officers, that the duration of the training course was two days, and that the estimated completion date of the training would be by November 2018.

In response to a question about introducing training prior to the necessary safeguards being put in place, DCS McLean explained, that Police Scotland had decided to begin training to balance the logistical challenge of training more than 400 people and also to enable an evaluation of the training before introducing cyber kiosks. DCS McLean confirmed that the evaluation would be completed within the next two to three weeks.3

The Sub-Committee questions the rationale for commencing training of police officers in the use cyber kiosks prior to the question of the legal basis of their use being determined and the necessary equalities and human rights and data protection impact assessments being finalised. The timing of any training for officers seems to have prejudged the outcome of any such assessments, which had not been completed by that point in time.

The Sub-Committee asks Police Scotland to provide details of the results of its evaluation of the training provided to officers to operate cyber kiosks.

The Sub-Committee asks Police Scotland to confirm whether training provided to police officers for the use of cyber kiosks is to be on-going, and updated to include human rights, data protection and security requirements.

Capital and revenue costs

The Sub-Committee considered the rationale for Police Scotland’s proposal to purchase 41 cyber kiosks, and the scrutiny implications of that decision.

The value of the contract for 41 cyber kiosks, published on the Public Contracts Scotland website by the Scottish Police Authority on behalf of Police Scotland, was £444,821, including VAT. Kenneth Hogg, former interim Chief Officer of the SPA told the Sub-Committee that as the amount of the contract was below the authorisation threshold of £500,000 Police Scotland did not require the SPA’s authority to purchase the cyber kiosks. Mr Hogg stated that: “A capital investment of more than half a million pounds would need to be submitted to me as the accountable officer for approval”.1

Police Scotland indicated in written evidence that the contract value of £444,821 included the purchase of the Cellebrite cyber kiosks, the central management software used on those devices, and the training package. Police Scotland added that there was also an initial revenue cost of £101,000, commencing from 2019-20.

In response to a request for further information on the capital and revenue costs of the cyber kiosks, the SPA wrote to the Sub-Committee on 20 July 2018. The SPA explained that its Scheme of Delegation provides that tenders and contract awards for goods and services of up to £500,000 can be authorised by Police Scotland without a requirement for additional authorisation by the Chief Officer of the SPA. The SPA indicated that only the capital costs were taken into account for the contract, as this is its practice, stating that: “The SPA’s practice in relation to the application of the Scheme of Delegation to the purchase of capital assets is to apply the delegated expenditure limit to the capital asset alone”.

The SPA confirmed that the SPA Board did not examine the revenue and capital costs because they fell below the delegated financial limits at which Board approval is required. It also confirmed that it awarded one “all-encompassing contract” which included provision for the kiosks, operating licences and the training package. The SPA explained that: “Most capital expenditure requires associated ongoing revenue expenditure over the life of the capital asset purchased, although often the combined capital and revenue whole-life cost of the asset will not be known at the time of initial purchase”.2

Police Scotland confirmed in written evidence that it anticipated the renewal cost of licences for a number of Cellebrite products over a four-year period to be £833,249 (excluding VAT). Police Scotland confirmed that the renewal of licences related to the proposed cyber kiosks accounts for 38% of the contracted cost, which would be £316,634 (excluding VAT) or £379,960 (including VAT).

DCS McLean explained to the Sub-Committee that Police Scotland initially intended to purchase 39 kiosks, but increased this number to 41, for operational and financial reasons, saying that:

The business requirement was to provide three kiosks to each of the 13 local policing areas, which is how we came to the figure of 39. Given our expectation that we would get hardware failures from time to time, we wanted to keep one or two devices in the cybercrime unit, to add resilience. At the time, we were working on a figure of about 40 devices. Did we want more, and would more devices deliver more benefits? Probably, and we will have to review the position. However, we were trying to work within the financial framework and the capital funds that were available at the time.3

David Page, Deputy Chief Officer with Police Scotland (with responsibility for Corporate Services, Strategy and Change) told the Sub-Committee that sums of £500,000 to £1 million go to the accountable officer for approval, and sums of more than £1 million go to the SPA Board. Mr Page explained that Police Scotland try to ensure that they approach IT purchases with a modular and right-sized approached, rather than large contracts similar to the i6 programmei, saying that: “We would like to have more smaller-sized programmes, where benefits are linked to the expenditure”.4

David Page explained that a decision on the business case for major capital expenditure would have been made by a committee within Police Scotland, or the force executive board, stating that “There would be an audit record for each of the individual governance boards of the decision that was made and who was present at the meeting”. Mr Page added that: “The expenditure might be relatively small, but the effect on the public or organisation might be such that it warrants a discussion at the force executive board”.5

As the contract award notice included known capital and revenue costs, which combined were above the £500,000 threshold of Police Scotland’s authority, the Sub-Committee would have expected the SPA to consider this expenditure prior to publishing the contract.

Digital transformation of the police service is a key component to implementing Police Scotland’s 10-year strategy, Policing 2026. The approach for implementation of the 10-year digital, data and ICT strategy is to be incremental, with smaller IT contracts awarded. It is clear that the on-going annual revenue costs for the IT equipment could run into millions of pounds, with no scrutiny of these costs by the SPA Board.

The Sub-Committee recommends that the SPA review its practice to apply the delegated expenditure limit for Police Scotland to the capital asset alone, and the SPA Board’s practice not to undertake scrutiny of capital or revenue costs, where capital costs fall below the £500,000 threshold. In any case, where such technologies have far-reaching human rights and data protection impacts, the SPA must scrutinise the policy impact of such devices irrespective of the financial size of any contract.

Engagement and consultation

Following the Sub-Committee’s evidence session on 10 May 2018, Police Scotland established two groups of consultees to consider its proposed implementation of the introduction of the use of cyber kiosks by front-line officers to search mobile devices.

It established a stakeholders’ group to inform the development, the direction and the implementation of policy. Its membership comprises the Scottish Police Authority, Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary in Scotland (HMICS), the COPFS, Police Scotland information management, the Scottish Government Defence, Security & Cyber Resilience Division, the Scottish Police Federation and staff associations.

Police Scotland also established an external reference group to inform the development, directions and implementation of the policy supporting the introduction of cyber kiosks. Its membership comprises Mr Aamer Anwar, a human rights solicitor, the Open Rights Group, Privacy International, the Scottish Human Rights Commission, the Information Commissioner’s Office, and Victim Support. The director and assistant director from the Scottish Institute for Policing Research also attend meetings of the external reference group, as does the SPA representative on the stakeholders’ group.

The inaugural meeting of the stakeholders group was held on 27 June 2018 and the inaugural meeting of the external reference group held on 26 July 2018.

Both groups have met a number of times, and continue to meet, to consider a number of issues in relation to the introduction of the use of cyber kiosks by frontline police officers.

The Sub-Committee welcomes Police Scotland’s establishment of the stakeholders’ group and the external reference group to consult on its proposal to use cyber kiosks.

The Sub-Committee views consultation with relevant stakeholders prior to the implementation of new policing policies or technology as best practice. It is essential for public confidence that Police Scotland demonstrates that it has given due consideration to the views of the stakeholders’ group and the external reference group on its proposed introduction of the use of cyber kiosks.

Legal basis for the use of cyber kiosks

The legal basis for cyber kiosks has proved a contentious issue with various stakeholders questioning the powers that Police Scotland seek to rely on. The main arguments advanced by Police Scotland, and other stakeholders, on this issue are set out below.

Legal powers identified by Police Scotland

Police Scotland outline four broad legal bases for the use of cyber kiosks: common law powers, statutory powers, a warrant granted by a court and consent to search from the owner of the device.1 Consent would be most relevant in relation to victims or witnesses submitting their devices to be examined.

DCS Gerry McLean acknowledged that Police Scotland had been advised of the importance of making distinctions to all concerned between victims and witnesses. DCS McLean told the Sub-Committee that “More particularly, advice was given to us that it is important to make distinctions to all concerned between victims and witnesses, and to be clear about the circumstances in which there is no compulsion on the part of individuals to hand over their devices— that must be done on a voluntary basis”.2

The other justifications for seizure and examination allow for a device to be examined without the consent of the owner. Concerns about these devices centred on a lack of clear legal basis for their use, particularly reliance on common law powers which were considered by a number of stakeholders to be insufficiently clear.

Police Scotland draw on case law to justify their position – specifically they rely on two cases: J.L. and E.I. v HMA and HMA v Rollo.3 Both of these cases concern the seizure and examination of devices. Police Scotland rely on the J.L. case as authority that powers to seize evidence are also powers to search or examine that evidence once seized (a position criticised by the Scottish Human Rights Commission)4. They state that the position set out in that case was that: “where a lawful power of search exists that power of search enables a police officer to search for an item, seize it and examine it”.5

Privacy International argues that these cases are “not sufficiently analogous / do not give full consideration to the matter in question both in terms of the technology and that our devices are becoming ever more personal and pervasive in our lives with more and more data”.6 The Scottish Criminal Bar Association (“SCBA”) also question the reliance on these cases.7 In relation to J.L and E.I the SCBA argue that the decision was specific to the particular legislative provision that gave the search power and that: “It cannot therefore be assumed, as Police Scotland appear to assume, that the decision in JL& EI will necessarily apply in relation to different legislative provisions”. In relation to Rollo, SCBA similarly argue that this decision was:“dealing particularly and discretely with the issue as to whether an electronic notepad or diary fell within the meaning of a ‘document’ for the purposes of a search specifically carried out in terms of in terms of s. 23(3)(b) of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. It is not readily apparent that the decision in Rollo can be read so as to provide the blanket approval of the use of such devices”.

The SCBA take the view that Police Scotland are seeking to draw principles from these cases that may be broader than the court intended. They also point out that in Rollo the seizure took place with a warrant and state: “It is not clear what assistance the decision provides in relation to searches that are not carried out under the auspices of any warrant”.7

Use of similar devices

Police Scotland argue that the cybercrime hubs currently in operation have a sufficient legal basis and therefore that the cyber kiosks must also be justifiable.1

The COPFS also note that similar technology is already in use and evidence obtained from it has been used in court. They state:

It is perhaps of note that Police Scotland Digital Forensic Hubs currently examine thousands of digital devices every year, providing evidence to COPFS which is in turn presented in Court, subject to legal scrutiny, and is often crucial in securing convictions.2

The COPFS do not consider that the use of cyber kiosks would change the process currently in use for obtaining relevant evidence from cybercrime hubs.

Other stakeholders did not agree with this position.iThe ICO indicated the existing technology is under review due to potential data protection issues arising from its use.3

David Freeland of the ICO explained that this work includes considering whether the legislative frameworks being relied upon to seize and examine digital evidence is lawful, saying that:

We want to find out whether those statutory powers are fit for purpose and whether they allow an intrusion into the digital space, given that they might have been formulated decades ago when the issue was not considered. We want to understand better what the legal position is. Is such action lawful in the first place? If it is not lawful in the first place, a legislative solution needs to be found to bring the statutory powers up to date.4

The cyber kiosks are viewed by some stakeholders as an improvement on the existing cybercrime hubs from a data protection perspective as no data is stored through use of the kiosks.iiThe comparison with existing technology in order to establish a legal basis is therefore a further issue of complexity.

Views of stakeholders

The COPFS gave some support to the views of Police Scotland in their submission by outlining the same legal provisions and principles as Police Scotland in relation to their powers of seizure.1 They confirm that there are legal principles which allow the Police to do this and that evidence resulting from such legal seizures would be admissible in court. However, COPFS comments are limited to considering the admissibility of evidence obtained in this way. COPFS do not offer “broad guidance on Police powers”, further stating: “In terms of the Data Protection and Human Rights implications of processing information whilst seizing and investigating digital devices that is a matter on which Police Scotland as a public authority must satisfy themselves”.

The SCBA indicate that Police Scotland’s view that “We do not believe the position described by Crown (sic) necessarily contradicts our understanding of the legal basis”, infers that the COPFS has not provided an unqualified endorsement of Police Scotland’s own assessment of the current legality of the use of this new technology.2

The chief concern of the SHRC is with article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (the right to private and family life, home and correspondence). This is also a key concern for Privacy International and the Open Rights Group (“ORG”) who considered both human rights and data protection principles in their submissions. Data protection was also the focus of the evidence from the ICO.

Clare Connelly of the Faculty of Advocates raised additional issues in relation to how far technology has moved on, telling the Sub-Committee that: “we are dealing with current technology, and the legal regulation of that involves the application of laws that could not have envisaged when they were developed that we would have that level of technology”.3 Ms Connelly argues that “the traditional legal approach is not fit for purpose, and that is a matter that needs to be looked at again”.

Compliance with human rights legislation

The Sub-Committee considered what work had been done by Police Scotland and the SPA to assess the impact of the use of this new technology by frontline police officers on human rights, and whether the use of cyber kiosk was compliant with European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) requirements.

The external reference group has been considering a draft equalities and human rights impact assessment since June 2018. It was not finalised, at the time of drafting the Sub-Committee’s report.

Diego Quiroz outlined the SHRC’s concerns about the draft assessment, telling the Sub-Committee that it did not give consideration to ECHR articles 6 (right to a fair trial), 7 (no punishment without law), 9 (freedom of thought, conscience and religion) and 10 (freedom of expression). Mr Quiroz said that: “There are significant concerns with the impact assessment, but we are willing to work with the police to try to help solve some of those questions”.1

DCS McLean confirmed that members of the external reference group had raised ECHR issues with regards to article 6, (the right to a fair trial), and article 8, (the right to privacy). DCS McLean explained the issues concerned, telling the Sub-Committee that “Generally, the group would like to see a bit more detail and a fleshing out of some of the considerations in the document. There is perhaps a bit too much police jargon, and it needs to detail some of the wider implications for the general public”. DCS McLean indicated that Police Scotland hoped to sign off the assessment in the following few weeks.2

Article 8 of the ECHR protects the right to private life and family life, home and correspondence.

Police Scotland acknowledged that article 8 was engaged in the use of cyber kiosks but noted that article 8 is not an absolute right.3 This right can be interfered with if it is in accordance with law and necessary in a democratic society. The prevention of disorder or crime is recognised as a basis on which interference might be “necessary”. Police Scotland argued that the criteria justifying interference with article 8 were met and, therefore, the cyber kiosks were not incompatible with it.

However, a number of stakeholders disagreed with Police Scotland’s view. The main criticism from stakeholders was that the current legal framework does not meet the necessary standard of being “clear, foreseeable and accessible”.i This is required so that individuals understand their rights and the scope of any interference with them. It was not felt by stakeholders that the legal basis set out above was sufficiently clear to be foreseeable to affected persons being based on “two named cases and a patchwork of statutory provisions”.4 These groups also raised concerns in relation to the need for adequate and effective guarantees against abuse. Of particular concern in this regard was the ability to act without a warrant, on which we comment further below.

Clare Connelly, from the Faculty of Advocates, highlighted the difficulty in setting strict search parameters when searching digital devices and the ability to access external sources of information, such as data stored remotely. Ms Connelly stated that these issues are relevant both for the seizure and searching of digital devices, saying that: “The 2016 act certainly empowers police officers to stop and search, but that does not necessarily give the article 8 protections that are clearly of concern to the panel and to you (see ref)ii”.5

Diego Quiroz highlighted the SHRC’s concern that cyber kiosks can access everything on a mobile phone, including texts, photos, web browsing history, biometric data, journalistic material and legally privileged information. Mr Quiroz told the Sub-Committee that:

We know that cyberkiosks can access private data—everything from texts to photos and web browsing—and even more sensitive data, such as biometric data. My phone has my fingerprints and my voice, for example. In a criminal law context, there can even be information about journalistic material or legally privileged information.6

DCS McLean explained that the cyber kiosks can image the whole device and as this could include sensitive, legally privileged or journalistic material Police Scotland “will always run the risk of some collateral intrusion (see ref)iii”, which it would try to mitigate. DCS McLean told the Sub-Committee that “If we take a device and we examine it, we image the whole device and we extract, download and examine all the data on that device”. DCS McLean added that whilst the cyber kiosks have the ability to export data, Police Scotland had decided, at this time not to export any data on to external storage. DCS McLean added that this may change, depending on the outcome of Police Scotland’s on-going review, stating that “As part of the on-going review, we will see whether there is an evidence base but, in the absence of that, we are not going to put that process in place at this time”.7

However, no one indicated that cyber kiosks were entirely incapable of being compliant with article 8. They argued only that the law as it exists at present is insufficiently clear. They called for a clearer legal basis for use of this technology. Stakeholders suggested various ways that this could be achieved. These suggestions are set out below.

In its written evidence, the SHRC refer to the discretion to be applied prior to authorising the browsing or extraction of data and the type of offences which may give rise to the use of cyber kiosks, stating that: “The law must indicate the scope of any such discretion and the manner of its exercise with sufficient clarity to give the individual adequate protection against arbitrary interference (Roman Zakharov vs Russia, 2015). If there is any risk of arbitrariness in its implementation, the law will not be compatible with the lawfulness requirement (Bykov vs Russia, 2009)”.8

Article 6 (right to a fair trial) and article 10 (freedom of expression and information) of the ECHR were also considered to be engaged by the use of cyber kiosks and Police Scotland received some criticism from SHRC for giving insufficient consideration to these issues. Mr Quiroz told the Sub-Committee that in relation to the draft impact assessment “There is no consideration of article 6 and there is no consideration of article 10, which concerns freedom of information and speech”.9 These articles were addressed by Police Scotland in their updated Equality and Human Rights Impact Assessment. The assessment acknowledged the rights were engaged by the use of cyber kiosks but, as in relation to article 8, that this interference was justified.3

Compliance with data protection legislation

The Sub-Committee considered what work had been done by Police Scotland and the SPA to ensure that the use of this new technology by frontline police officers was compliant with data protection legislation.

The external reference group has been considering a draft data protection impact assessment since July 2018.

On 15 November 2018, David Freeland informed the Sub-Committee that the ICO had given substantive comment back to Police Scotland on a number of issues with the draft data protection impact assessment. Mr Freeland told the Sub-Committee that “We have now seen a copy of the data protection impact assessment and have provided substantive comment back to Police Scotland on a number of the issues”. The draft data protection impact assessment was not finalised, at the time of drafting the Sub-Committee’s report.1

The ICO submitted that data protection law requires information to be obtained for a specific, explicit and legitimate purpose and raised a particular concern with the cyber kiosks ability to image a large amount of data, much of which could be irrelevant.2 The ICO and ORG considered that the lack of clarity over the legal basis causes issues in relation to compliance with data protection law.

David Freeland from the ICO, explained why the use of cyber kiosks could lead to Police Scotland not complying with data protection law, telling the Sub-Committee that:

If the police went through all of someone’s text messages, that would potentially be an intrusion into other people’s private conversations that were not relevant to the case; it would not simply be a case of focusing on the conversations between the particular persons who were already of interest. If that kind of interrogation leads to other people of interest, that evidence would be of further relevance to the case, but extracting everything wholesale in that way puts the police at a risk of non-compliance.3

The ORG raised a more specific concern in relation to the data protection principle of data minimisation.4 This principle means that the data controller (Police Scotland in this instance) should collect only the data they actually need. There is a concern that more data will be collected than that which is actually needed as this will be difficult to filter out in advance of the search due to the nature of the technology involved. In particular, ORG draw attention to the categories of data subject that the police identify: suspects; witnesses; victim; unknown. The category of “unknown” raises concerns that this data may not be sufficiently relevant to be justifiable under data protection principles. The ICO echoed this concern stating:

One of the other principles of data protection law is that the information that is obtained must be adequate, relevant and limited to the specific purpose. In this context, that means that we should have evidence-led policing, rather than everything being obtained just in case there might be something there.5

A further issue in relation to data protection is the sensitive nature of the data which requires extra justification for processing. Police Scotland acknowledge this but argue that they meet the necessary criteria.6 ORG call this into question as one of these requirements is for an “appropriate policy document” to be in place.4 ORG question whether the current documents are appropriate given the lack of clarity that remains about the legal basis for processing the data.

Approaches to addressing issues around legal basis

In general terms, stakeholders called for a clear legal basis to be established to address the issues discussed above. Some specified what might be required to ensure a clear legal basis exists and these suggestions are discussed below.

Some stakeholders seemed to indicate that where warrants were used this might provide a sufficient legal basis. The SHRC submission stated that: “there should be a judicial warrant requirement for any search of mobile phone (and digital media) unless it is explicitly and clearly defined by other law. This will provide the required legal precision and necessary oversight under human rights law”.1 The SHRC argue that this technology has the potential to be as intrusive as the search of a home which would generally require a warrant, so the same should apply for these searches. Privacy International also emphasised the significance of warrants stating that the use of this technology without “the safeguards of an independent warrant” is amongst their “most critical concerns”.2

Some stakeholders called for legislation to address this issue. SHRC indicate in their written submission that new legislation which provides a “code of conduct for forensics” is something the Scottish Parliament should consider.1 Clare Connelly, from the Faculty of Advocates, as discussed above, stated the need for a new legal approach in this area as technology has advanced past what the law envisioned.4 She argued that legislation is probably necessary as it is not “possible or reasonable to expect the existing common-law case law to be developed in court process for an issue as important as this, which has been flagged up in advance.” When the Sub-Committee questioned whether this is an issue which the Scottish Law Commission should consider, this suggestion received support as this “would allow the possibility that the legislation could have some longevity.” In the SCBA’s written submission they endorse these statements from Clare Connelly and similarly state that legislative change may be required.5

However, in a Sub-Committee evidence session, Diego Quiroz from the SHRC indicated that a code of practice that was subject to Parliamentary scrutiny may suffice – though Mr Quiroz did not offer any opposition to more formal legislation if that was the route Parliament chose.4 He stated “Another path to go down might be to develop a code of practice for the specific issue, which could be laid before Parliament for scrutiny. There are different paths that you could take, but it is important that the Parliament keeps oversight of the process”.7

Mr Quiroz added that the legal framework being relied upon is complex, stating that: “The point here is to provide Police Scotland and the police in other authorities with an adequate framework so that they can do their important work”.8

Police Scotland acknowledged the legal complexity in a letter to the Sub-Committee, saying that: “we recognise this is a complex area of the law which may be worthy of review by Parliament”.9

Chief Constable Iain Livingstone confirmed to the Sub-Committee that until the issues raised had been addressed, cyber kiosks would not be deployed for use by police officers across Scotland, stating that: “Until I am satisfied that we can be clear that policing by consent underpins the use of cyber kiosks, we will not be using them. That is why I was clear that the rollout will be halted until the issues are addressed”.10

Police Scotland informed the Sub-Committee that the COPFS response was being considered by its internal legal advisors, and that this consideration may include a proposal to seek further independent legal advice.11

The Sub-Committee wrote to the Chief Constable on 28 March 2019 to request an update on Police Scotland’s consideration. A reply was not received prior to publishing this report.12

The Sub-Committee is still not reassured that the legal framework being relied upon by Police Scotland for the use of cyber kiosks is suitably robust or provides the necessary safeguards for members of the public. Any process must be mindful to protect the integrity and robustness of the investigation and prosecution service.

The Sub-Committee recognises the importance of public confidence in policing and policing by consent. There is, therefore, an urgent need for clarity and public reassurance before this new technology can be introduced.

The Sub-Committee believes that a legal framework is required which ‘keeps pace’ with technology. The Sub-Committee recommends that the Cabinet Secretary for Justice considers whether the current legal framework enables Police Scotland to seize and search digital devices, and considers the suggestions provided to the Sub-Committee to resolve the legality issue.

The Sub-Committee asks the Scottish Police Authority to explain how the use of this new technology was approved, and substantial investment made, prior to the legal basis being established.

The Sub-Committee asks the Scottish Police Authority to consider introducing a code of conduct for the use of cyber kiosks, and recommends that any such code should include a risk assessment of collateral intrusion and details of how to mitigate that risk.

The Sub-Committee asks the Scottish Police Authority to confirm its planned scrutiny of Police Scotland’s review of its use of digital device triage systems, including the proposal to consider extending their use to export and store data, and Police Scotland’s data security and retention policies and practices to support its proposed use of cyber kiosks.

The Sub-Committee do not believe that the cyber kiosks should be deployed by Police Scotland until equalities and human rights and data protection impact assessments are agreed by key stakeholders.

The Sub-Committee do not believe that the cyber kiosks should be deployed by Police Scotland until clarity on the legal framework is established.

Police Scotland’s digital forensic hubs

The Sub-Committee did not consider Police Scotland’s digital forensic hubs as part of its inquiry into the proposal to deploy cyber kiosks for use by frontline officers. However, a number of key stakeholders indicated that many of the issues raised in evidence about the use of cyber kiosks to search mobile devices, might also apply to the cyber hubs. As the hubs have the facility to download data from mobile devices issues of data security and retention were also raised.

Police Scotland have 5 digital forensic hubs located throughout Scotland. Mobile devices are currently sent to the hubs for investigation. Part of the rationale for introducing cyber kiosks is to enable frontline officers to use their discretion to ascertain whether a mobile device requires to be sent to the hub, or whether it could be returned to the owner. Police Scotland indicate that this process would significantly reduce the number of mobile devices being sent to the hubs and reduce the time taken to return mobile devices to their owners.

DCS McLean told the Sub-Committee that as many as 15,000 devices are submitted to the cybercrime hubs each year, and that anecdotal evidence from other UK police forces suggests that more than 90 per cent of mobile devices would not be submitted in the future if cyber kiosks were used. They would instead be returned to their owner or excluded from the relevant investigation.1

Clare Connelly of the Faculty of Advocates, told the Sub-Committee that the cyber kiosks issue had raised a much broader issue with the cyber hubs and advised that: “It is something that needs to be carefully considered, but time is of the essence”.2

DCS McLean agreed that the discussion was wider than cyber kiosks, concluding that: “possibly there is a need for a review and recommendations. We should not frame the discussion solely around cyber kiosks”.3

In its letter of 19 February 2019, the ORG indicate that the lack of clarity of legal powers also affects the existing “Cyber Hub” examination centres. It asked the Sub-Committee to expand its inquiry to include the full seizure and search of digital devices in Scotland and the existing Cyber Hubs.4

In response to this request the Sub-Committee asked Police Scotland to provide the following specific information on the cyber hubs:

Copies of the formal proposal by Police Scotland to create the initial 3 cyber hubs, and then to extend the number to 5, the date/s that these proposals were considered and approved by the Scottish Police Authority Committees / Board.

The location of the initial 3 hubs, and then the additional 2 cyber hubs.

Details of the equipment to be included in the hubs, the rationale for their use, and the date/s when these proposals were considered and approved by the Scottish Police Authority Committees / Board. Also, details of any contracts published following these decisions.

Details of the process and engagement undertaken by Police Scotland to ensure that the hubs were using processes and equipment that were legal and satisfied human rights, privacy, data protection and security requirements, including copies of any equalities impact assessments, and data protection impact assessments made at the time of approval etc.

Details of any equipment used in the hubs that can capture, access or download data from mobile devices.

Details of how the processes undertaken in the cyber hubs differs from practice prior to the establishment of Police Scotland to capture, access or download data from mobile devices.

Details of Police Scotland’s consideration of informed consent from those whose phones etc. are to be sent to the hub, in particular, witnesses.

In its response, Police Scotland provided some of the background information requested, but was unwilling to provide details of the equipment used in the hubs, citing that providing this information may provide criminals with an unnecessary advantage in evading law enforcement, what they were used for, how the practices differed from the procedures of the legacy forces, or the impact assessments and informed consent considerations.

The Sub-Committee is therefore unable to make any informed assessment of the work carried out in Police Scotland’s digital forensic hubs.

Similar legal concerns regarding Police Scotland’s digital forensic hubs were raised in evidence. This issue was not part of the remit of the Sub-Committee’s inquiry, but would merit consideration by the Cabinet Secretary for Justice.

Annex

Extracts from the minutes of the Justice Sub-Committee on Policing and associated written and supplementary evidence

5th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Thursday 19 April 2018

Work programme (in private): The Sub-Committee considered its work programme and agreed to request information from Police Scotland and the Scottish Police Authority on Police Scotland's ICT strategy.

6th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Thursday 10 May 2018

Police Scotland's proposed use of digital device triage systems: The Sub-Committee took evidence from—

Detective Superintendent Nicola Burnett, Police Scotland;

Kenneth Hogg, Interim Chief Officer, Scottish Police Authority.

Work programme (in private): The Sub-Committee considered its work programme and agreed to undertake further work before the summer recess on [ . . . ] and (b) Police Scotland's digital data and ICT strategy.

Written evidence

Police Scotland

Scottish Police Authority

8th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Thursday 21 June 2018

Police Scotland's digital, data and ICT strategy: The Sub-Committee took evidence from—

David Page, Deputy Chief Officer, Martin Low, Acting Director of ICT, Detective Chief Superintendent Gerry Mclean, Head of Organised Crime and Counter Terrorism, and James Gray, Chief Financial Officer, Police Scotland;

Kenneth Hogg, Interim Chief Officer, Scottish Police Authority.

Supplementary written evidence

Police Scotland

Scottish Police Authority

9th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Thursday 13 September 2018

Police Scotland's proposed use of digital device triage systems: The Sub-Committee took evidence on the proposed use of digital device triage systems (cyber-kiosks) from—

David Freeland, Senior Policy Officer, Information Commissioner's Office;

Detective Chief Superintendent Gerry McLean, Head of Organised Crime and Counter Terrorism, and Peter Benson, Cybercrime Forensic Team Leader, Police Scotland;

Diego Quiroz, Policy Officer, Scottish Human Rights Commission.

Supplementary written evidence

Police Scotland

12th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Thursday 15 November 2018

Police Scotland's proposed use of digital device triage systems: The Sub-Committee took evidence on the proposed use of digital device triage systems (cyber-kiosks) from—

Clare Connelly, Advocate, Faculty of Advocates;

David Freeland, Senior Policy Officer, Information Commissioner's Office;

Detective Chief Superintendent Gerry McLean, Head of Organised Crime and Counter Terrorism, Police Scotland;

Diego Quiroz, Policy Officer, Scottish Human Rights Commission.

The Sub-Committee agreed to write to the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and the Chief Constable to seek their views on the issues raised during the evidence taking session.

Written evidence

Information Commissioner's Office

Scottish Human Rights Commission

Supplementary written evidence

Information Commissioner's Office

Police Scotland

Police Scotland

Police Scotland

13th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Thursday 6 December 2018

Work programme (in private): The Sub-Committee considered its work programme and agreed [ . . .] (b) to ask Police Scotland for further clarification of issues relating to its proposed use of digital device triage systems (cyber-kiosks); (c) to continue to monitor Police Scotland's digital, data and ICT strategy; [ . . . ]

2nd Meeting, 2019 (Session 5) Thursday 31 January 2019

Police Scotland's priorities and draft budget for 2019-20: The Sub-Committee took evidence from—

Chief Constable Iain Livingstone, Police Scotland.

Written evidence

Police Scotland

3rd Meeting, 2019 (Session 5) Thursday 4 April 2019

Police Scotland's proposed use of digital device triage systems: The Sub-Committee considered a draft report. Various changes were agreed to and the Sub-Committee agreed its report to the Parliament.