Justice Committee

Pre-budget scrutiny of the Scottish Government's draft budget 2020/21: justice and policing

Introduction

The purpose of pre-budget scrutiny is for committees to reflect on a range of financial matters that they have considered throughout the parliamentary year and to then provide views and recommendations to the Scottish Ministers so that they can take them into account in advance of the publication of the draft budget. The next draft budget for 2020/21 is due for publication before the end of the calendar year.

The justice portfolio has responsibility for the civil, criminal and administrative justice systems, which include Scotland's prisons, courts, tribunals, the legal aid system and criminal justice social work services. It also supports the police and fire and rescue services.

This year, in particular, the Justice Committee agreed to focus on scrutinising budgets for prisons and prison-related health, education, employment and through-care programmes. The Committee also wanted to hear wider views on third and voluntary sector funding in the criminal justice sector.

The Justice Committee focussed on the following matters:

Priorities for operating and capital spend for 2020/21 and beyond within the Scottish prison system.

Effectiveness of spend, progress to date and spending levels proposed for the current prison modernisation programme.

Budgets provided to the public, third and voluntary sectors for health, education, employment, through-care, family contact, rehabilitation/re-offending, in-cell technology and other services provided to prisoners.

Longer-term challenges and financial requirements to tackle issues such as staffing levels in prisons, over-crowding, drug use, safety and security of staff and prisoners, the use of the open estate and an ageing prison population.

Views on how to achieve a rebalancing over the longer-term in expenditure on prisons and that of community-based alternatives to incarceration and preventative spend, including the challenges of provision in remote or rural areas.

Any wider views on the current spending priorities for 2020/21 in the justice portfolio, including third and voluntary sector funding in the criminal justice sector.

The Committee received a number of written submissions of evidence during its scrutiny and members are grateful to all of those who took the time to contribute their views.

The Committee is also grateful to the chief executive of the Scottish Prison Service, Colin McConnell, Governor Mick Stoney and all of the staff at HMP Barlinnie for facilitating a valuable visit to this prison by members of the Committee on 5 November 2019. The members were impressed by the professionalism and dedication of the staff and the particular challenges faced in this ageing prison.

In addition to the work of the Justice Committee, its Sub-Committee on Policing focussed its pre-budget scrutiny on the police budget and, in particular, the capital budget. The Sub-Committee published its report on 22 November 2019.

Prison budgets and statistics: some facts and figures

Prison population

In 1999-00, the total average daily prison population in Scotland was just under 6,000. In 2018-19, it was 30% higher (at almost 7,800).i The total figure rose from 5,975 in 1999-00 to a peak of 8,179 in 2011-12. It did fall back somewhat during the following years but rose again in 2018-19. Currently available weekly figures for 2019-20 show an average prison population again exceeding 8,000 – ranging between 8,099 (19 April 2019) and 8,283 (30 August 2019).

Splitting this into sentenced and remand prisoners, annual figures show that the average number of:

sentenced prisoners rose from 4,997 in 1999-00 to a peak of 6,588 in 2012-13

remand prisoners rose from 976 in 1999-00 to a peak of 1,679 in 2008-09

Despite some reduction in annual figures since those peaks, both categories experienced significant increases during the 20-year period up to 2018-19. In percentage terms, there was a particularly large increase in remand prisoners – up 56% (from 976 in 1999-00 to 1,525 in 2018-19).

Weekly figures for 2019-20 currently show the average number of:

sentenced prisoners ranging between 6,416 (9 August) and 6,536 (5 July)

remand prisoners ranging between 1,619 (19 April) and 1,808 (9 August)

The Scottish Prison Service has an operating capacity of 7,676 prisoners and a design capacity of 7,886 prisoners. According to Audit Scotland, the Scottish Prison Service has a maximum operating emergency capacity of 8,492 prisoners. On 4 October 2019, the Scottish Prison Service reported 8,270 prisoners were being held in custody; a figure in excess of both the operating and design capacities and only 222 prisoners short of the operating emergency capacity.

In the women's estate, there were 207 women prisoners in 2000-01, rising to 370 in 2017-18, of which 89 were on remand. Weekly figures for 4 October 2019 show 414 women in custody (with 82 untried).

Factors driving the prison population

The Scottish Government's Programme for Scotland 2019-20 stated that, “We are progressing action to tackle Scotland's internationally high rate of imprisonment – the highest in Western Europe.” Some of the possible reasons for any rise or fall in the prison population include changes in the:

level and nature of criminal activity

likelihood of offences being reported to the police

approach of the police and prosecution to law enforcement

approach of the courts to questions of bail/remand and sentencing, e.g. longer sentences, more convictions overall or for certain offences

approach of the courts to alternative disposals such as community-based options, supervised bail etc.

proportion of custodial sentences served in custody

According to the HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland in her recent 2018-19 Annual Report, the sharp rise in prison population can be attributed to a variety of reasons including longer sentences for the most serious of crimes, a rise in the number of people being convicted of sexual offences, and more serious and organised crime being successfully prosecuted. In her view, other contributing factors include the reduction of prisoners being released on Home Detention Curfews (HDCs), very few prisoners subject to an Order for Lifelong Restriction achieving parole, and a legislative change that halted automatic early release for people serving long-term sentences.

The figures for HDCs in the week of 4 October 2019 were 34 men and 5 women had been released on this form of disposal. At the same point in time in 2018, the figures were 212 and 25 respectively.

Rehabilitation and reintegration of prisoners

In her 2018-19 Annual Report, the HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland stated that—

Scotland's incarceration rate is one of the highest in Europe. A high proportion of remand prisoners, despite being involuntarily incarcerated, do not routinely access the available opportunities that could inhibit future criminogenic behaviour. The culture change required to address this lost opportunity has been highlighted in many of our inspection reports.

The additional number of prisoners and an increasingly complex population places a heavy burden on an already overstretched prison service in Scotland. I am very concerned that the number of prisoners is starting to exceed design capacity, resulting in not only additional pressures on staff, the prison regime and activities, but also on the essential programme and through-care activities designed to reduce recidivism.

The loss of the Through-care service was one of the triggers that resulted in the Justice Committee focussing this year's pre-budget scrutiny on prison budgets. In July 2019, this service was suspended by the Scottish Prison Service (SPS) and the prison officers on secondment to the scheme were sent back to their former roles within prisons due to operational need. The suspension took full effect from September 2019.

The Through-care scheme paired prisoners up with a Through-care Support Officer (TSO) who helped them make arrangements for housing, medical provision and benefits upon their release, thereby reducing the difficulties than former prisoners faced upon release and reducing the risk of re-offending. In total, 41 officers and 3 managers were removed from the scheme and returned to other duties within SPS.

As a consequence of the above, the ‘New Routes’ and ‘Shine’ partnerships currently operating in the Scottish Prison Service through third sector bodies were expended temporarily to make support available for more prisoners released from short-term sentences of up to four years and supporting male and female prisoners respectively. It is not immediately clear to the Committee, however, whether all prisoners previously supported by the Through-care scheme are now being covered by these programmes and if the services being provided are the same.

Violence, self-harm and suicide

In the context of the rise in the prison population, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland commented, in the introduction to her 2018-19 Annual Report, that—

I am pleasantly reassured to see that levels of violence, self-harm and prison suicide, although rising, have not risen as drastically as they did under similar conditions in the English prison service. I have been impressed by the SPS’ efforts to manage the additional population safely, and it is reassuring to note that in all of our prison inspections, and return visit inspections in this reporting year, staff and prisoners regularly reported feeling safe.

According to Audit Scotland, there has been a slight improvement in the levels of seriousi prisoner on staff violence in 2018/19 compared to 2017/18, but not compared to 2016/17. Minor assaults on staff and both serious and minor prisoner on prisoner assaults are up. Table 1 below sets out the statistics on violence produced by this body.

| Indicator | 2016/17 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serious prisoner on staff assaults | 5 | 14 | 10 |

| Minor and no injury prisoner on staff assaults | 193 | 283 | 410 |

| Serious prisoner on prisoner assaults | 74 | 94 | 135 |

| Minor and no injury prisoner on prisoner assaults | 2,136 | 2,120 | 2,994 |

The Scottish Prison Service provides information on prisoner deaths. In some cases, this sets out the cause of death (e.g. suicide or natural causes). However, the cause of death for many (including those who died in previous years) is recorded as awaiting determination so it is not yet possible to attribute the cause of death.

In 2019, the SPS has recorded 18 deaths in custody to date. In 2018, there were 32 deaths in custody over the calendar year, a slight rise from the 29 deaths in 2017. In 2016, the causes of death amongst the 28 prisoners who died in custody were 8 of natural causes-sudden, 3 of natural causes-expected, 9 by suicide and 7 still awaiting determination.

Meaningful/purposeful activities within prisons

One of the consequences of increased prisoner numbers is the challenge placed on prisoner officers in assisting prisoners to take part in meaningful or purposeful activities, such as education, training and employment. Table 2 below sets out the statistics on purposeful activity produced by Audit Scotland in its 2018-19 Audit of the SPS.

| Indicator | 2016/17 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purposeful activity hours | 6,758,800 | 6,500,472 | 6,258,125 |

| Average purposeful activity hours per week per convicted prisoner | 22 | 21 | 20 |

| Vocational and employment-related qualifications | 20,311 | 18,793 | 26,883 |

| Vocational and employment-related qualifications (SCQF level 5 or above) | 2,465 | 1,976 | 1,781 |

What the above table does not show is that purposeful activity in Scottish prisons is targeted primarily at longer-term convicted prisoners and not at those on shorter sentences or on remand.

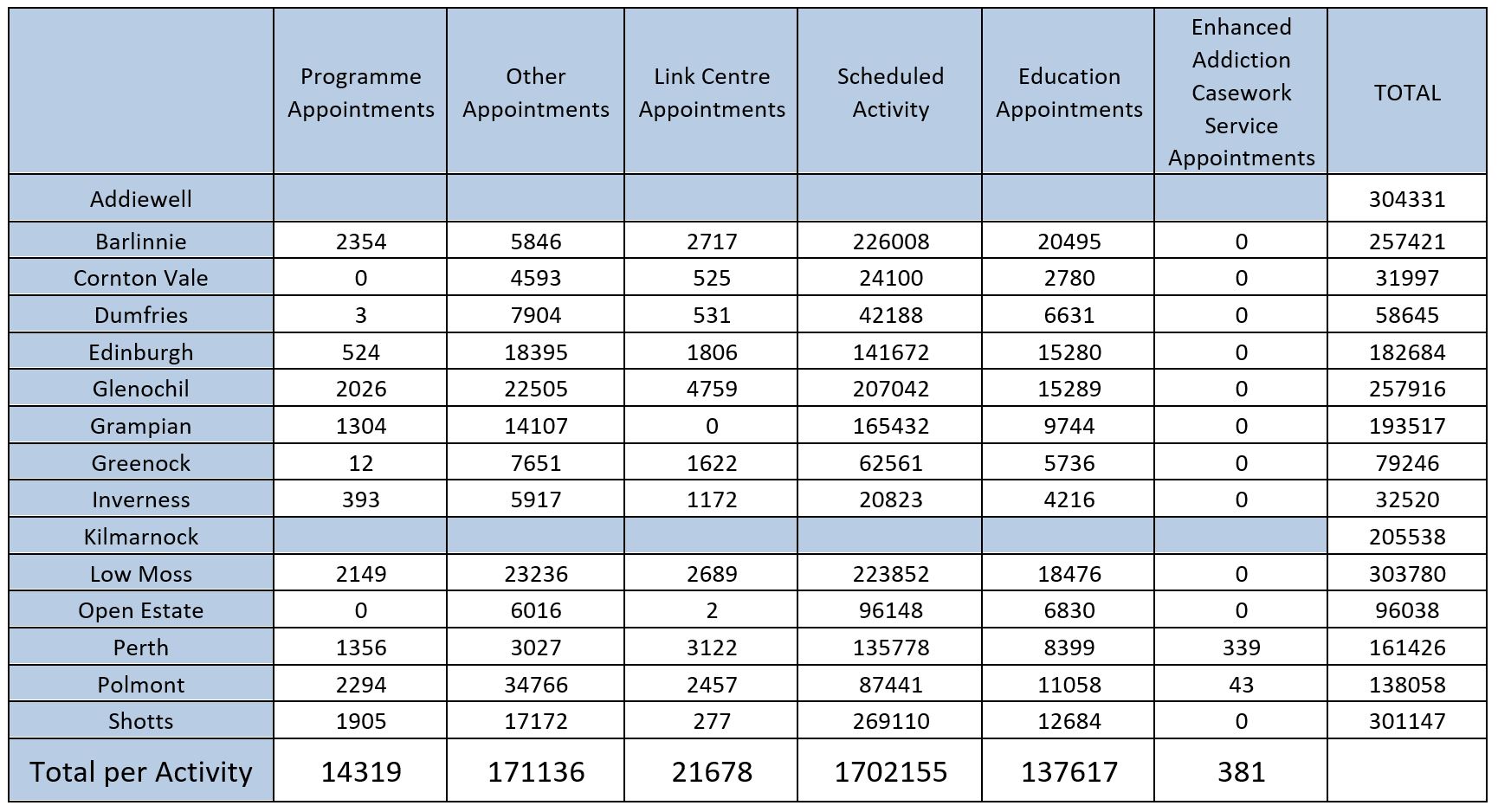

Further figures were provided by the Scottish Prison Service by prison and by type of purposeful activity; see Figure 1 below.

Prison staff

In 2018-19, staffing costs represented just over 50% of SPS's total operating expenditure. In 2019, SPS employed 2,865 staff. The figures for staff numbers were 2,868 in 2018 and 2,867 in 2017.

Sickness absences statistics are currently high and rising according to Audit Scotland. The average number of days lost to sickness was 10 in 2015/16, rising to around 16 in 2018/19. The figure in July 2019 is now 17 days. In comparison, the figure for England and Wales was an average of 9.3 working days in 2018/19. The total number of sick days lost to stress in Scotland was just over 6,000 in 2015/16 and is now in excess of 14,100.

SPS is managing to maintain its current service primarily because existing staff are working increased hours (which are not eligible as overtime). SPS has made significant voluntary ex gratia payments of £4.25 million (up from £2.15 million over the last three years) according to Audit Scotland.

Staffing vacancy levels are reasonable. However, according to the SPS, over 80% of its vacancies are in the Grampian region and are the result of the relative labour market conditions in this part of Scotland.

Scottish Government funding

Prisons

Scottish Government funding for prisons is provided in the Scottish Prison Service budget. The Scottish Budget 2019-20 (December 2018) sets out the following information on what it covers—

The Scottish Prison Service (SPS) budget covers expenditure associated with operating the prison system (both publicly-and privately-managed prisons) and the provision of a Court Custody and Prisoner Escorting Service (CCPES) on behalf of Scottish Courts, Police Scotland and the wider justice system. The SPS provides a wide range of services to care for and support those who are in custody and their families, as well as operating a Victim Notification Scheme for registered victims of crime.

Table 3 reproduces cash terms figures from the Scottish Budget 2019-20. Table 4 provides real terms figures (i.e. adjusted for the effects of inflation).

| (£ million) | 2017/18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal resource | 311.2 | 312.2 | 312.2 |

| Non-cash | 34.0 | 33.0 | 34.0 |

| Capital | 15.8 | 16.2 | 47.5 |

| Total | 361.0 | 361.4 | 393.7 |

| (£ million) | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal resource | 323.1 | 318.4 | 312.2 |

| Non-cash | 35.3 | 33.7 | 34.0 |

| Capital | 16.4 | 16.5 | 47.5 |

| Total | 374.8 | 368.6 | 393.7 |

According to Audit Scotland, the SPS's revenue budget represents a flat cash settlement for the third year since 2017/18. In real-terms, SPS's revenue budget has reduced by 12.5% between 2014/15 and 2018/19 from £394.7 million to £345.2 million. Its revenue budget for 2019/20 is a further 1.7% reduction.

At the end of March 2019, the chief executive of the SPS wrote to the Scottish Government seeking additional budget due to an inability to make all the necessary savings and because of the costs of buying additional prisoner places in the private HMP Addiewell. Cover of up to £24 million has been provided by the Scottish Government in this financial year (2019/20) according to the SPS.

According to information received by the Committee from the SPS, the service has purchased 96 places in HMP Kilmarnock and 96 places in HMP Addiewell in 2019. These places in privately-run prisons come with additional costs to the SPS. Tables 5 and 6 below set these costs out.

| £ | Cost per place per day | Min per day | Max per day | Min per annum | Max per annum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tranche 1-24 | 45.31 | 45.31 | 1,087.44 | 16,538 | 396,916 |

| Tranche 25-96 | 54.16 | 1,141.6 | 4,986.96 | 416,684 | 1,820,240 |

HMP Addiewell Prices are set for the period to 11th December 2019

| £ | Variable cost per place | Tranche cost | Min per day | Max per day | Min per annum | Max per annum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tranche 1-48 | 14.29 | 14.29 | 685.96 | 5,216 | 250,377 | |

| Tranche 49-96 | 14.29 | 1,510.07 | 2,210.32 | 2,882 | 806,768 | 1,051,929 |

| Tranche 97-144 | 14.29 | 3,398.19 | 4,784.41 | 5,456.08 | 1,746,309 | 1,991,469 |

| Tranche 145-192* | 14.29 | 5,295.45 | 7.367.63 | 8,039.30 | 2,689,185 | 2,934,345 |

Prices for HMP Kilmarnock cover the period 25 March 2019 - 24 March 2020

* On first use, each tranche of Additional Prisoner Places at HMP Kilmarnock has attracted a charge. The final tranche has not yet been utilised, and would attract a one-off cost of £173,290.46 to bring these places into use.

Community Justice and Criminal Justice Social Work

Scottish Government funding for community justice and criminal justice social work (CJSW) is provided for under the:

community justice services budget line (part of the Justice portfolio budget)

ring-fenced central government grant to local authorities for CJSW

The Scottish Budget 2019-20 provided the following information on what these budget lines cover:

What the Community Justice Services budget does

This budget includes funding to support offenders who are serving community-based sentences, electronic monitoring of offenders (e.g. through Restriction of Liberty Orders) and offender mentoring services. It supports the work of Community Justice Scotland, Scotland's national body for promoting the highest standards of community justice services across Scotland.

What the Central Government Grants to Local Authorities budget does

This ring-fenced funding supports local authorities in providing Criminal Justice Social Work services across Scotland. These services include supervising those offenders aged 16 and over who have been subject to a community disposal from the courts; providing reports to courts to assist with sentencing decisions; and providing statutory supervision (Through-care) for certain offenders on release from prison. There are also special services for certain key groups of offenders.

Table 7 sets out the budget in cash terms figures from the Scottish Budget 2019-20. Table 8 provides real terms figures.

| (£ millions) | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community Justice Services | 33.6 | 35.4 | 37.1 |

| CJSW | 86.5 | 86.5 | 86.5 |

| Total | 120.1 | 121.9 | 123.6 |

| (£ millions) | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community Justice Services | 34.9 | 36.1 | 37.1 |

| CJSW | 89.8 | 88.2 | 86.5 |

| Total | 124.7 | 124.3 | 123.6 |

Other areas of funding which may be of relevance include elements of the miscellaneous budget line (part of the Justice portfolio budget). The Scottish Budget 2019-20 included £18 million for victim/witness support, noting that it provided core funding for third sector organisations whose work supports the victims of crime and support for the justice contribution to tackling violence against women and girls.

Key issues - prisons

Prison numbers

As the Committee's report sets out above, the current number of people held in the prison estate (8,270 as at 4 October 2019) is above the SPS's operating capacity (7,676) and its design capacity (7,886). The figure is only 222 short of the Service's maximum operating emergency capacity. Similarly, in the women's estate, the current population of 414 prisoners (on 4 October 2019) is 160 over the proposed new capacity for the smaller, trauma-informed centres currently being constructed.

In his evidence to the Committee, Deputy Chief Inspector of Prisons, Stephen Sandham, said that he was "extremely concerned about the really dramatic rise in the prison population" and that this "has quite a dramatic impact on the safety of prisoners, but also on the safety of prison officers". He also said that this has an impact on other activities within the prison, such as the dispensing of medicine to prisoners.1

Other bodies providing evidence to the Committee also expressed their concerns. Families Outside said that it wanted "to see a clear and immediate commitment and action to reduce the prison population". One suggestion made by this body was to consider a cap on the maximum number of people that can be held in prison or to legislate to prevent over-crowding. It said that these models (used for example in Sweden) should be "considered as a matter of urgency".2

Howard League Scotland noted that, in December 2018, nine out of Scotland's 15 prisons were at or above capacity, and that "it is clear that prison overcrowding can adversely affect recidivism in the wider community." It warned that "Scotland's falling rates of re-offending could thus be negatively affected by these conditions."3

Speaking about the current overcrowding, Colin McConnell, chief executive of the Scottish Prison Service, confirmed that "overcrowding has serious implications for not just the lives and working conditions of those in prison, but how the prison service sets about operating day by day". He added that there is "still headroom in the system, but the organisation is being stretched to its limits." In terms of impact, he said—

For staff, it involves more work, stress, encounters and problems to deal with. For those who live with us, it means restriction on regime access, more confrontation, less space to move around in, and, frankly, a bit more downtime than we would otherwise like there to be.4

Speaking later in the same meeting, Jim McMenemy of the SPS set out some of the measures that the Service had had to take to accommodate extra prisoners. For example, he said that to alleviate pressures in some of the larger and older local jails, SPS had "stripped out single beds in single cells in Low Moss and replaced them with 100 bunk beds".5 Elsewhere, SPS confirmed that the number of cells that are holding more than one person is 1,568, with only half of those cells designed for two people. In HMP Barlinnie, 92 per cent of prisoners are sharing cells that were designed for one person. 5

Home Detention Curfews

As set out earlier, there are a range of factors behind the current high prison population. One of those factors is the changed regime for the authorisation of Home Detention Curfews. The change to the HDC regime was brought about by the SPS and the Scottish Government following the tragic murder of Craig McClelland by James Wright in Paisley, whilst the latter was unlawfully at large during his release on an HDC regime.

Previously, the numbers released at any given time on HDCs were of the order of 250+ as figures provided to the Committee above have shown. Currently, the figure for HDCs is 39. This substantial fall in the numbers of prisoners on a community-based HDC disposal is one of the factors behind the higher number of people being held in prisons.

Colin McConnell explained that the "constriction in the number of HDCs came about because something terrible happened" and confirmed that the current regime was being revisited. He wanted to "implement the new HDC procedures with a mind to ensuring that every decision is right and that the public is appropriately protected". He noted that—

The way things have gone recently is that, because of individual events that have happened, there has been an absolute focus on the service and its decision makers, and incredible criticism has been levelled against the service for those events. You will have heard the term “error terror”. I think that we are in a period in which decision makers in the service are concerned about the degree to which they will be held accountable if they take a significant decision and something then happens elsewhere. You might say that it is absolutely right that, in public service, there is such accountability and, to a degree, that is the case, but individual decision makers, who must take into account lots of different information from different sources, different contributors and different professions, are always in the position of making the best judgment possible rather than an infallible one.

My counsel to the committee and the Parliament is to avoid the counsel of perfection. I worry about the fact that I often hear it said at the moment that, somehow, there are magic, perfect solutions out there if only we could achieve them. I must say to the committee that there are not.

Justice Committee 08 October 2019 [Draft], Colin McConnell, contrib. 47, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12315&c=2208661

The Cabinet Secretary for Justice also commented on the HDC figures and said that he hoped that the "revised guidance—together with political signals from the Parliament to the effect that there is too much risk aversion in the system—will help to rebalance the HDC regime slightly". He confirmed that whilst he did not necessarily envisage that the number of prisoners won these would go up to 300, he thought that "most people would agree that since it has gone from 300 to 37 the pendulum has perhaps swung too far the other way."2

Bodies such as the Criminal Justice Voluntary Sector Forum were supported of these moves but noted that, "while there are certainly steps that can be taken to relieve the pressure on prisons, such as increasing the use of Home Detention Curfew and parole, any long term solution to the current problems will require a reduction in the prison population and a focus on prevention and community based approaches to stop people entering the justice system in the first place."3

Use of remand and bail supervision

The current use of remand instead of alternative, community-based disposals, is another factor behind the high prison population.

In its evidence to the Committee, Apex Scotland said that the loss of third sector bail supervision programmes has increased the numbers on remand1 Community Justice Scotland noted that, almost half of all local authority areas did not undertake any bail supervision during 2017/18.2 Families Outside said that "reduction in the use of remand is another important issue that needs to be addressed in order to reduce the use of imprisonment."3

One of the consequences of the high numbers being held in remand and the overall high numbers held in prisons is, as SPS confirmed, that some remand prisoners are being held in the same cells/areas as convicted prisoners.4 This is despite the requirement to keep them separate in prisons, to manage them separately and to provide them with appropriate regimes.

In his evidence to the Committee, the Cabinet Secretary confirmed that "remand is one of the areas of priority that I will look at" and that "bail supervision will be an area of focus for us."5 He said overall that "If we take a suite of measures over the longer term, I am quite confident that we will be in the position of closing down prisons, not building additional prisons."6 Some of the reasons behind the continued use of remand were, according to the Cabinet Secretary, because of the increasing numbers of people charged with sexual offences (whereby public protection issues favoured remand) and a growth in the number or people charged with serious and organised crime (where again bail was unlikely to be favoured).6 The Cabinet Secretary confirmed that the Scottish Government had commissioned research on the law on bail and remand, to provide some of the detail on the underlying factors.

In the latest figures available (2013/14), the Scottish Government provided a breakdown of the types of offences that prisoners on remand have been charged with:

27% were for non-sexual crimes of violence (of which 3% were homicide and 15% were for serious assaults or attempted murders)

4% were for sexual crimes

19% were for crimes of dishonesty

4% were for fire-raising/vandalism

27% were for other crimes (including 5% drug crimes and 6% were handling offensive weapons)

18% were for miscellaneous crimes8

These figures are, however, somewhat out of date but are the latest available.

Presumption against short sentences

One of the measures which - particularly in the case of women offenders - is hoped to have some impact on prison numbers or at least one the churn rate is the introduction of a presumption against short sentences.

Professor Nancy Loucks of Families Outside told the Committee that, "the presumption against short sentences is extremely important, particularly in relation to women who have been sentenced to less than 12 months, because it will prevent the churn of people going through prison."1

That said, Howard League Scotland said that whilst the presumption may marginally reduce the overall prison population, other legislative changes, such as the Prisoners (Control of Release)(Scotland) Act 2015i and changes to the criteria for Home Detention Curfew (HDC) have had the opposite effect.2

HMIPS agreed in its written evidence that "it is logical to assume that extending the presumption against sentences of up to 12 months may lead to a significant reduction in the women's population over time, as 90% of women receive sentences under 12 months."3

From a budgetary perspective, however, Includem warned that the extension of presumption against short sentences to 12 months is expected to result in an increased in the number of community disposals. It said that "it is not enough to provide funding to increase the numbers of social workers to supervise these orders" and that "significant funding to the third sector is required if the Scottish Government aim of Smart Justice is to be achieved."4

Colin McConnell's view was that "it will take some time yet for the expectations and behaviours of society that influence the judiciary, court procedures and what happens in prisons to work through and to get us to the ambitious position that Scotland wants to achieve."5

The Cabinet Secretary said that he was "not waiting to hit the 8,400-plus figure that is often cited as the maximum [number of prisoners], but [was] taking action now" and that "that is why we introduced the presumption against short sentences."6 He thought that those changes would those probably reduce prisoner numbers by between 200 and 300 a year.

Prison estate

The state of the prison estate was another feature of the evidence heard by the Committee. Of particular note were the current challenges of upkeep and a replacement for prisons such as HMPs Barlinnie, Inverness and Greenock, and the timescale for the replacement of the current women's prison at Cornton Vale with a number of smaller units.

Delays in replacements for HMP Barlinnie and that Women’s National Facility (Cornton Vale) have caused, according to Audit Scotland, an underspend of £4.7 million in SPS's capital budget in 2018/19. It has reported underspends against its capital budget in the past three years demonstrating that this has been an issue for some years now.

HMP Barlinnie

As Audit Scotland notes in its recent audit—

Delays in redeveloping parts of the prison estate present significant risks. HMP Barlinnie in Glasgow is currently housing 17.6 per cent of all prisoners and operating around 50 per cent above capacity. It presents the biggest risk of failure in the prison system as it has the capacity to buffer fluctuations in the national prison population. The prison's Victorian design does not support the delivery of a modern prison service. Its age also means that it is expensive to maintain and there is a high risk of failure in some parts of the building, for example the drainage and sewerage systems. If it were to fail, there is no clear contingency plan for accommodating the 1,460 prisoners it currently holds.

There are a significant number of problems with HMP Barlinnie in addition to overcrowding according to HMIPS. Stephen Sandham told the Committee that it "should not be in doubt at all that it is a Victorian prison that is not fit for purpose in a modern prison service" and that "the sooner that we can get a replacement for it, the better."1 He noted that the prison had "drainage issues that make it high risk for the SPS." Phil Failie of the Prison Officers Association (POA) Scotland agreed on the need for replacement, noting also that he "genuinely [did] not know where inside the Scottish prison system we would deal with the prisoner movement that would be required" if there was a serious maintenance problem at the prison.1

Mr Sandham also noted that, "in Barlinnie, for example, for a population of 1,300 or 1,400 prisoners, there are only five cells that are suitable for disabled prisoners" describing this as "unacceptable in a modern prison service."3

During our visit to the prison, we saw first hand some of the challenges with this prison, noting that HMP Barlinnie has only one cell suitable for hosting a prisoner requiring a wheelchair.

HMIPS further noted that—

HMP Barlinnie is the main mechanism for coping with surges in the prison population, using single cells to accommodate two prisoners, but in some cases this breaches the minimum space standard of 4m2 per prisoner (excluding toilet area) and is well below the minimum desirable standard of 5m2 per prisoner set by the Council of Europe European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT).4

Colin McConnell noted that, as far back as 1997, the then 51 per cent overcapacity at the prison was described as a “national disgrace”. In October 2019, the prison was around 50% over capacity. He confirmed that over the past 10 years, £30 million has been invested to keep the prison functioning to a reasonable standard.5 Mr McConnell confirmed that, after a period of nearly eight years, SPS were at the final stages of purchasing the land for a new site and that "we should have a new Barlinnie by the end of 2024, or perhaps 2025".6

In his evidence, the Cabinet Secretary said that he took the issues around HMP Barlinnie "with the utmost seriousness" and that "the issue with the infrastructure causes [him] grave concern".7 He confirmed that he had asked Scottish Government officials to work with the SPS to consider whether they can take interim measures to ensure that the estate is in a better condition.

Women’s National Facility (Cornton Vale)

Weekly figures for 4 October 2019 show 414 women are currently in custody. Previously, the bulk of these would have been held at HMP YOI Cornton Vale in Stirling. Currently, women prisoners are being held elsewhere in Polmont, Edinburgh, Greenock and Grampian prisons.

Initially, the Scottish Government planned to replace Cornton Vale by constructing HMP Inverclyde, a large women's prison near the existing HMP Greenock. In 2015, the then Justice Secretary revised plans and announced he wanted to replace Cornton Vale with a much smaller facility, and add to this capacity by building up to five, smaller, regionally based units. The Scottish Government said it also intended to promote the use of community-based alternatives to short-term prison sentences, including the restriction of liberty through the increased use of electronic monitoring.

In 2018, the Scottish Government said that it would move initially to two community custodial units (CCUs). The first of the CCUs will be located in Maryhill (24 places) in Glasgow and the second at a site in Dundee, and are due for completion by the end of 2021/22.

One of the challenges the SPS will face is that the expected capacity of the smaller, trauma-informed units is to be around 250 whereas the current women's prison population is over 400. As HMIPS notes, the current design capacity of 250 requires continued location of women in male establishments.

In evidence to the Committee on how the gap can be tackled and by when, Colin McConnell said—

Everything we do between now and the end of 2021-22 must be geared towards taking a broader, more trauma-informed and individualised view of what will work best for women who have to come into the justice system. For the vast majority, that will not mean prison. If we do not grasp that need and do something about it as a nation and a Parliament, I absolutely entertain the possibility that we will have more women in our care than the new facilities and strategies are primarily intended to care for. We will have to put in place workarounds for that. That is the reality of the situation.

Justice Committee 08 October 2019 [Draft], Colin McConnell, contrib. 38, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12315&c=2208652

The Cabinet Secretary also commented on this matter, saying—

With the new national facility, and when the five community custody units are eventually in place, there will be a smaller footprint than there is at the moment for the number of women in our prisons. We have other options, and we will look to reduce those numbers through the presumption against short sentences; the work on bail and remand; and early intervention, prevention and so on. We have enough sites—Greenock, Edinburgh and Polmont—that hold women. I hope that, once we have the national facility and all five CCUs up and running, we will not require that extra capacity, but it is there if it is needed.

Justice Committee 08 October 2019 [Draft], Humza Yousaf, contrib. 134, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12315&c=2208748

He confirmed, however, that this "extra capacity" is not part of the trauma-informed estate that is currently being put in place although some elements of the approach in these units could be used.

Other prisons

HMP Barlinnie and HMP YOI Cornton Vale were not the only prisons that the Committee took evidence on. HMIPS noted in its written submission that even with changes to the former, "that will still leaves Scotland operating with old Victorian prisons at HMP Inverness, HMP Greenock, HMP Dumfries, and parts of HMP Perth." HMIPS said "there needs to be sufficient capital funding to support work on the design and planning of replacement facilities, while recognising that planning consent and securing a suitable site may still inhibit an early start to construction of these other replacement prisons."1

In its audit, Audit Scotland noted that—

The previous three-year Infrastructure Investment Plan included a replacement for HMP Greenock but this has been replaced in the forward plan with the headquarters ‘work smart’ initiative that aims to enhance digital infrastructure, records management and human resources. It is anticipated that this will be delivered in 2020/21.

Stephen Sandham of HMIPS noted that—

As historical cases come to court, an increasing number of sex offenders will come into jail at a relatively older age and will stay in prison for a long time as older prisoners. Therefore, it is a particular priority for the SPS to consider how it looks after older prisoners.2

The issue of a lack of suitable facilities to house an increasing older and more infirm group of prisoners has been raised with the Committee previously.

Purposeful activity

Table 2 above, from Audit Scotland, shows that purposeful activity within Scottish prisons has by and large declined in the year where statistics are available. The figures show a 7% fall in purposeful activity from 2016/17 to 2018/19. The average number of hours of such activity has fallen too from 22 to 20 hours per week per convicted prisoner. Although the number of vocational and employment-related qualifications is up overall, the number at SCQF level 5 or above, has fallen.

As we note above also, these figures mask the actual picture in prison across all types of prisoners as purposeful activity, such as education, training, employment within prisons, is primarily targeted at longer-term prisoners, not those on remand or short-term sentences.

According to Howard League Scotland (HLS), the situation in specific prisons is deteriorating due to a lack of resources. It said that, in a recent Freedom of Information request, a very low completion of programmes to address offending behaviour was revealed in Scottish prisons with only 41 people at HMP Barlinnie, which holds approximately 1,300 prisoners, appearing to take part in any accredited rehabilitative activity for the whole of 2017-18. In HLS's view, "this further emphasises the pressure that SPS are under, and their inability to provide the services which can best support prisoners during their sentences".1

Overall, HMIPS said that—

For a sustained period the prison population has been over 8,300 - more than 500 above the planned operational capacity of the prison system, which is the level at which the SPS can provide an effective and purposeful regime for prisoners. The current level of resource funding for the SPS is insufficient to manage the challenge of maintaining order and providing adequate levels of purposeful activity and time out of cell for prisoners, or make adequate progress with running national programmes focussed on rehabilitation and reducing the risk of reoffending.2

In relation to employment specifically, Apex Scotland's view is that the key problem seems to be that there is little obvious linkage between the Employability and Skills Division and the Justice Division in the Scottish Government when it comes to funding and strategic thinking. In its opinion, while employability and employment are key factors in the justice strategy given the acknowledged impact employment has on desistance, the funding for services tends to come through Employment sources. As a result, it says, there is no clear strategic pathway which ensures that the mainstream (one size fits all) approach of the Employability Division is fit for purpose in achieving the needs of the justice strategy. 3

One example, according to Apex Scotland, is the Fairstart programme which copied the model pioneered in the UK under the Work Programme. According to Apex Scotland, the Scottish Government has said that this scheme is not what is needed. Apex Scotland says that prisoners now fall through the net as they are not economic for the large providers of Fairstart to take on. It says that this is particularly the case with people who have additional barriers to work such as sex offenders reporting restrictions or mental health and addiction issues.3

The POA Scotland agree with HMIPS that one of the reasons for a decline in purposeful activity is staffing, or lack thereof. Phil Fairlie of the POA Scotland told the Committee that—

... part of the reason for the numbers being down is that staff who are qualified to deliver purposeful activities to the prisoner population have, simply because of staff shortages, been taken off those posts to supplement and assist staff in residential areas. We have staff who are supposed to be contracted from 8 to 5 or 9 to 5 during the week to provide purposeful activities who have come off such contracts to do to shift work to assist in residential areas, just because of the numbers.

Justice Committee 17 September 2019 [Draft], Phil Fairlie, contrib. 38, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12264&c=2200144

Jim McMenemy of the SPS agreed. He said "SPS has a finite ability to deliver purposeful activity, which means that although we might have more people in prison, we cannot get more people into work and education-related activity". He noted that programmes relating to tackling sexual offences and violence reduction had been affected and that, in the long-term, it was these areas where the SPS had to focus on.6

Mr McMenemy also made reference to SPS's new contract with Fife College, which is focused on individual learning plans, particularly the needs of people who require to learn the basics, focusing on Scottish vocational qualification levels 1, 2, 3 and 4. According to him, the SPS annual report showed that there was a significant increase lin those qualifications ast year, which was linked to the new partnership with Fife College.

In his evidence, the Cabinet Secretary recognised that the high prison population was a factor in the amount of purposeful activity in which inmates can take part.7

Role for the third sector

One line of questioning explored by some members of the Committee was whether, in the absence of prison staff being able to ensure prisoners could receive purposeful activity, the SPS could make greater use of the third sector as providers.

Phil Fairlie explained however that the fundamental problem was the ability of his officers to get the prisoner population to education services across the various sites, rather than an absence of these services in the first place. He explained that—

The fact that staff who are tasked with providing the purposeful activity inside prisons are not doing that is not down to them, but down to the prison system’s not having enough prison officers on the front line in the residential areas. 1

Through-care and rehabilitation

One of the most high-profile examples of the current challenges brought on by a high prison population and problems with staffing (e.g. absence levels) is the removal of the Through-care scheme in the summer of 2019.

In 2015, the Scottish Prison Service appointed just over 40 Through-care Support Officers (TSOs) across the prison estate (with the exception of Open Estate and Shotts) to support people on their journey into desistance. TSOs helped prisoners prepare for and successfully make the transition from custody into the community.

An independent evaluation of Through-care in 2017 showed that overall, progress was being made on tackling a range of individual issues affecting service users at a strategic and operational level (e.g. benefits and finance; housing; substance misuse; physical and mental health; education and employability). Additionally, there were improvements to self-efficacy and desistance.

Jim McEnemy explained that the reasons behind the closure of the Through-care scheme in the summer of 2019 were operational and were due to the need to bring the 45 TSOs back on to the wings in prisons to provide "front-line residential functions".1 Colin McConnell described the service as "paused" and "postponed".2

It is clear from the wider evidence taken by the Committee that the Through-care service enjoyed substantial support from other bodies in the criminal justice sector and that the decision to postpone/pause the service will have wider consequences.

For example, Howard League Scotland said—

The reassignment of Throughcare Support Officers (TSOs) is perhaps the most vivid illustration of the damaging effects of the financial pressures on SPS: the important work that TSOs do in helping people make the difficult transition from prison to “normal” life has been rendered impossible by the lack of resources and the immediate need to maintain order in badly understaffed prisons.3

Similarly, the Robertson Trust said that whilst it recognised the challenges that budget constraints and over-crowding in Scottish prisons present, it was "concerned that the suspension of such a valuable support service will make the transition from prison to community life harder for people with convictions". In the long term, it said, "it might also lead to increased rates of reoffending."4

Local authority body COSLA explained that the decision will have a direct impact on its membership. It said that previously TSOs had been responsible for helping offenders make arrangements for housing, medical provisions and benefits. In its view, the consequence of the closure is that "there will be no service in place to provide the necessary support in some parts of the country and it will fall to local authorities to fill the gap." Its most immediate concern was "around homelessness, and the repeat offending that can occur as a result". 5

The Scottish Government and the SPS has responded to this situation with the former providing additional resources to two programmes operated by the third sector; the Shine and New Routes Public Sector Partnerships (PSPs). These previously provided rehabilitation support to women and younger offenders respectively. These restrictions have been removed so that the programmes can provide some form of cover along the lines previously provided by TSOs. The Cabinet Secretary explained that that was the reasoning behind the now annual investment of £3.4. million in these schemes.6

In subsequent comments, the Cabinet Secretary said that restarting the Through-care service was a matter for the SPS but he did not see this starting until the beginning of 2020 or after that. He said he would "keep the situation under regular review."7

Family contact officers

The Through-care service was not the only programme in Scottish prisons to be covered in the evidence we received. Families Outside, for example, raised issues regarding the role of Family Contact Officers.

Families Outside explained that funding from the SPS for family support is entirely for the limited pool of Family Contact Officers. Professor Loucks of Families Outside was concerned that the decision taken on Through-care could be replicated elsewhere. She said—

Our concern at Families Outside is that we will see other vulnerable roles go a similar way—the family contact officers are a prime candidate for that— and we really cannot afford to see that, not least because things like family contact, which seem not to be related to justice, are, in fact, critical to people's resettlement when they come out of prison.1

In her view, in theory, family contact is prioritised in prisons. In practice, she said, the priority is dealing with overcrowding and so there has been a reduction in the level of attention on family contact, even though it was, in her view, critical to successful resettlement. She explained that family contact ensures that people have a place to live, financial and social support, links to employment etc. In her view, this "is a problem if the Prison Service has to restrict access to visits, for example if the staff are overpressed and cannot support visits in the same way."2

The value of family contact was also highlighted by HMIPS. It said that "there is strong evidence on the value of supporting family contact in promoting good behaviour and reducing tensions in prison, encouraging reintegration back into family life on liberation, and laying the groundwork for successful rehabilitation."3

Staffing issues

As noted above, some of the evidence the Committee heard around the suspension of the Through-care scheme and the fall in purposeful activity in Scottish prisons relates to staffing issues. In the evidence received, a number of other staffing matters were raised, including:

overall staffing levels

recruitment and retentions issues

terms and conditions (including comparators with private prisons)

sickness and absence levels

levels of violence facing staff

an ageing workforce and the physical challenges of some aspects of the job of a prison officer

retirement age and pensions

According to the SPS, overall staffing levels have been fairly static over the last four years at around 2,867 prison officers. This, however, according the Jim McMenemy of the SPS, is a staffing level designed to manage a prison population of 7,700.1 With the population now nearly 8,300, there are clearly some staffing challenges facing the SPS.

The Committee has touched previously on some of these challenges, such as the ability of officers to assist prisoners with purposeful activity such as education and training. Additionally, as both prisoner numbers rise and the number of staff remain static, we have heard about rising tensions in Scottish prisons resulting in increased levels overall of prisoner on staff assaults and prisoner on prisoner assaults.

One of the more physical challenges outlined to the Committee is the increasing difficulties faced by a relatively ageing prison workforce required at the moment to work until 67 years of age before an officer can gain access to his/her pension, as a result of a change by the UK Government. The physical challenge of dealing with prisoners, especially in the case of a violent event and/or in the case of a prisoner becoming unruly through the use of drugs or psychoactive substance, should not be underestimated.

Tackling the smuggling of drugs and psychoactive substances into prisons and thereby preventing some of the physical challenges faced by prisons officers has been problematic. As Phil Fairlie of POA Scotland explained, psychoactive substances are an issue in every single establishment and although the SPS uses the Rapiscan system to search for drugs "it requires capital investment to buy that equipment and so prevent the substances from coming in". Mr Fairlie said that there are only three Rapiscans for the whole estate and that they rotate around the service. It was therefore "pot luck whether one is available at any given time". He said, "when they are available, they are very effective" but that there should be one in every prison. 2 Each scanner costs approximately £30,000.

In relation to sickness absence, according to Colin McConnell, one of the most significant reasons behind the current levels of staff absence are musculoskeletal issues, secondly only to stress and mental health. The Cabinet Secretary said he recognised this problem, explaining that—

For a prison officer, having to work until the age of 67—soon to be 68—is an issue. Members have probably seen reports about new psychoactive substances that can give the people who take them additional strength. If you consider what happens when a prison officer in their 60s tries to deal with an incident that involves a person who has double, triple or quadruple the strength that they normally have, you can imagine the musculoskeletal damage that can be caused. A number of sickness absences are related to musculoskeletal issues. Indeed, I have the figure here: approximately 15,000 days per annum are lost because of musculoskeletal issues. That is a huge number.3

The Cabinet Secretary stated that efforts were being made to tackle this problem. He pointed to a pilot physiotherapy scheme in HMPs Edinburgh and Polmont launched in October 2018. He said that the SPS will review the service at the end of the financial year and consider whether it should be rolled out across all establishments.

Phil Fairlie also highlighted staff sickness and absences in his evidence. He said that they were "a significant factor in describing the impact of overcrowding on the health and welfare of staff inside prisons". He said that the current 60 per cent increase in sick absence levels indicates "clearly what is going on with the staff’s ability to cope in that environment."4 He also explained that one of the consequences of increased staff absence is that other staff were working longer and doing overtime and were then themselves reporting sick.

Staff sicknesses and absences were also an issue for HMIPS. Stephen Sandham told the Committee that the current levels of additional sick leave were equivalent to the SPS "being 50 people down". He also noted that the service is about "60 staff down in respect of what it would need to cover the additional prisoner numbers and it has about 100 staff who cannot be deployed for various reasons—they are on maternity leave or phased returns to work."5 HMIPS also said that "the 60% increase in sickness over the last three years includes a 32% increase in staff sickness due to stress, no doubt related to the pressures caused by the overcrowding".6

Colin McConnell indicated that the absence rate was also one of people being off on long-term sick. He said—

The absence rate is therefore about people who go off work ill and stay off, which is why the number of days lost is compounded. It is not the case that an increasing number of people are taking sickness absence; it is clearly that when people go off, they stay off for a long time. That suggests that there are deep-rooted, long-term issues with the people who have to go off sick. Our challenge as an organisation is to try to find some way to relate to those people, to keep them supported and to target them to possible solutions in order that they always believe that there is a way back to the organisation.7

In addition to staffing levels and problems caused by staff sickness and absences, some of those who gave evidence to the Committee indicated that the SPS also had a issue with recruitment and retention.

Phil Fairlie was concerned that some of the current challenges in the SPS and the amount of media coverage about prisons was putting people off from joining the service. He said—

I think that the problem is partly to do with media coverage in the past year and, maybe even more so, in the past six months, that has highlighted issues inside our prisons. What people on the outside who are looking for a career change see and read about what happens inside prisons does not make it look like a particularly attractive career move, no matter what the salary is.

[...]

The pay deal that we have just done has made the employment more attractive salarywise, but the real test will come when people start to look at the service as a career move, and look away from the headlines that are currently running, which are all about overcrowding, an increase in violence and huge sickness absence levels, which suggest a particularly unattractive environment for people to come and work in.

Justice Committee 17 September 2019 [Draft], Phil Fairlie, contrib. 54, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12264&c=2200160

Overall, according to Colin McConnell, "SPS has an enviable brand in the marketplace and [has] no difficulty at all in recruiting." However, he accepted that there were problems in the North-East of Scotland. He said that 80% of the SPS’s vacancies are in Grampian, and that was "all to do with the economy and the marketplace". Analysis produced for SPS suggested that it was somewhere "between £8,000 and £10,000 per annum off the market rate for equivalent work."9

Prison budgets

In this section of the Report, the Committee looks specifically at the financial and budgetary situation in the SPS and for prison-related programmes.

During 2018/19, SPS spent over a third of a billion pounds (£358.2 million). It currently looks after over 8,200 people across 15 prisons. Private sector organisations operate two of these prisons (HMP Addiewell and HMP Kilmarnock).

The Audit Scotland audit of 2018-19 concluded—

SPS is facing threats to its financial sustainability and its operational safety and effectiveness. SPS has received no increase in revenue budget since 2017/18 and its 2019/20 budget is under pressure from rising prisoner numbers and increased costs.1

Similarly, HM Inspectorate of Prisons for Scotland said that there were two key priorities for SPS at the moment:

An urgent need to increase resource/revenue funding for SPS to cope with the very significant rise in Scotland's prison population.

The planned investments to replace our antiquated prisons should proceed without delay and interim measures sought to relieve the overcrowding pressures.2

Others, such as Howard League Scotland also provided commentary, with this body saying that the result of the financial pressures facing the SPS are such that—

We find ourselves in a situation where current budget constraints mean that we cannot expand in-cell technology; we cannot extend the use of video links for family visits; we cannot adequately control the influx of new psychoactive substances (NPS) by increasing the number of whole body scanners available across the estate; we cannot provide suitably accessible cells for more than 5 disabled prisoners in Barlinnie; and we cannot ask any more of staff already covering the increasing levels of sickness of their colleagues. 3

Melanie Allan, Head of Financial Policy and Services at the SPS told the Committee that—

It is important to point out that, over the last three years, the Prison Service has received a flat cash settlement. Out of that settlement, we have to absorb the cost pressures in relation to pay, major contract inflation and additional pension costs. A flat cash settlement does not take account of that, so having written to the Cabinet Secretary we have secured some cover, of up to £24 million for this financial year. That is a one-off for the current financial year and we will need to plan for the future.

Justice Committee 08 October 2019 [Draft], Melanie Allan (Scottish Prison Service), contrib. 56, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12315&c=2208670

This evidence sets out the fact that the SPS has, over the last three years, been managing with a real-terms reduction in its budget and, as at March 2019, had to ask the Scottish Government for additional funds to meet its operating needs, and that a sum of up to £24 million was provided by the Government. It should be noted that £6 million of this additional sum was provided in order to meet the consequences of UK Government changes to public sector pension employer contributions.5

In his evidence to the Committee, the Cabinet Secretary said that he had secured an additional £31 million in SPS's capital budget for the modernisation of its estate and that he would keep the operating costs "under review and will factor in the operational pressures that the SPS faces when [he has] discussions with the Finance Secretary about the future spending review."5

As the Committee has heard above, however, estate modernisation is not the only draw on SPS's capital budget. There are also challenges in investing in new technology.

In-cell technology and other IT-related investment

In previous work undertaken by some of the Committee, and during our recent visit to HMP Kilmarnock, members have seen at first hand the use of in-cell technology and other IT equipment. Such technology, now being piloted at HMP YOI Polmont, allows prisoners to be more in touch with their families and reduces social isolation. Other IT equipment such as the kiosks in use in Kilmarnock allow prisoners to take more control of their affairs (e.g. booking courses, ordering meals etc.) and thereby reducing the demands on SPS staff and freeing them for other duties.

Bodies such as Families Outside say that they "enthusiastically welcome the introduction and roll-out of in-cell technology". It its experience, people who maintain positive family ties are "up to six times less likely to reoffend on release, as these are the ones who will have a place to stay, social support, financial support, links to employment, etc. – factors essential to successful resettlement."1

Similarly, HMIPS told the Committee that there was—

... already clear evidence of its value when introduced in prisons in England and Wales, where it has been shown to reduce violence and incidents of self-harm. We understand the cost of putting this technology into our older prisons, but its introduction into the more modern facilities of Low Moss and Grampian should be relatively inexpensive. Similarly, information kiosks allow prisoners to book appointments and visits, make menu choices, and get information on other activities contributing to the responsible prisoner agenda and the normalisation of the regime. These kiosks are well established in our private sector prisons and in other legal jurisdictions, and have been proven to cover the cost of installation, in stationery reduction and staff time in dealing with these issues. We support capital investment for these developments.2

There have, however, already been challenges in implementing a wider IT strategy than enabled the use of video-conferences and online links for family contact where this could not take place face-to-face. One of the problems is that the various institutions in the prison estate are not, unlike in Northern Ireland, connected to each other. 3

There are also issues with finding sufficient staff to facilitate such virtual visits although the Committee were told that similar schemes in other parts of the world use unpaid volunteers to make this happen.

The impact of using private prisons on SPS's budget

As the Committee heard, one of the ways in which the SPS has managed the currently high prison population is by purchasing, at an additional cost, extra places at the two privately-run prisons at HMP Kilmarnock and HMP Addiewell. The Scottish Government agreed to provide an in-year budget increase to the SPS to cover these costs.

As Stephen Sandham pointed out to the Committee, these places come with "a significant financial cost". Audit Scotland noted that—

SPS does not currently have a medium-term financial strategy. It is preparing a strategy covering 2019–22 to align with its revised corporate plan, but there is no financial planning in place beyond this three-year period. It is critical that SPS has a strategy to respond to the challenges it faces and achieve financial sustainability over a longer period. The need for this is highlighted by the financial pressures of operating two PFI/PPPi prisons. Inflation-linked increases built into the contracts for these two prisons will require additional recurring savings of around £12 million a year by 2022/23. 1

Melanie Allan confirmed that both contracts have obligations for increases of the Retail Price Index plus 1.5 per cent, so the cost of both contracts increases over the term of the contract. She also said that this was "part of the cost pressures that we have identified for four years going forward and that is not sustainable on a flat-cash settlement."2

Audit Scotland also indicated that SPS predicts it will need to buy additional provision from HMP Addiewell at a cost of £1.82 million per annum and that this not currently budgeted for.1 It is not clear to the Committee whether the additional in-year sum provided by the Scottish Government included this sum.

Long-term and preventative spend

As many bodies stated in their evidence to the Committee, the longer-term trend in the criminal justice system has to be a move away from incarceration towards effective community-based disposals whilst maintaining public protection. Similarly, many submissions also stressed the need to spend on programmes which prevent offending behaviour in the first place. Such a system requires, unless additional money is provided, a shift in resources over the longer-term from spending on prisons to spending on community justice and preventative actions.

Alastair Muir of the Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) stated that "prevention is key" and that efforts need to go "right back to education". He highlighted the VRU's Mentors in Violence Prevention projects in 30 of the 32 local authorities, which look right across violence, including gender-based violence. Mentors in Violence Prevention is a peer-to-peer education programme that helps young people to challenge others if they see inappropriate behaviour and ensure they are equipped and are sufficiently confident to challenge that behaviour.The projects look at a range of issues, from bullying to controlling behaviour and sexting. This is one of a number of programmes being run by the VRU.1

Similarly, Sean Duffy of the Wise Group spoke of the prison mentoring scheme offered by his organisation and the Public Sector Partnership (PSP) model that the Wise Group has now in place through the New Routes programmei to secondary S4, S5 and S6 pupils. The Wise Group had been working with Police Scotland to develop programmes in the area of education to prevent offending behaviour from occurring.2 According to Mr Duffy, only 9.7 per cent of the people who are worked with through the New Routes PSP return to prison within the first year.

Despite some of the positives, Tom Halpin of Sacro said that "there is a huge gap between the rhetoric about preventative spend and the resourcing of it" and that "discretionary spend on innovation and prevention has virtually disappeared."3 His view was that we know what works, but are we going to do things differently and reflect on where we are today?" He concluded that "we have to be big not just in our ambition and our rhetoric but in what we do about system change."

In her evidence to the Committee, Professor Loucks commented on some of the models used in other countries to move away from prisons, citing Sweden which passed legislation to restrict prisons from being overcrowded. Swedish prisons operate a waiting list to go in, or offer weekend prisons. She said that "there is merit in looking at how we use prisons" and also commented on the work of the McLeish Commission which considered capping the number of people in prison. In conclusion, she said—

We need to look at what our priorities are for justice in Scotland and whether we want to spend our resources on prison and have a never-ending supply of people going into prison, or whether we want to examine ways of preventing people from going into, and keeping them out of, prison.4

Similarly, the Criminal Justice Voluntary Sector Forum said that its "members believe that it is necessary to revisit the concluding recommendations of the Scottish Prisons Commission that Scotland should pursue a prison population of 5000 people through focusing the use of imprisonment on those who have committed serious crimes and constitute a danger to the public." They noted that "while this is a bold commitment, [they] believed that it is necessary to drive transformational change in justice." 5

In the Cabinet Secretary's view—

There will come a point at which part of the solution will require some rebalancing of funding from prisons to community justice. We are not at that stage yet; we cannot reduce the prisons budget, for all the reasons that we have just spoken about. However, that does not mean that we cannot consider whether funding is being used in the best possible way, whether the frameworks are appropriate and whether we can increase investment—and, if so, how we should target it. 6

Key issues - other sectors

Third sector funding in the justice portfolio

In addition to looking in-depth at the SPS's budget and for prison-related projects, the Committee also sought wider views on the current spending priorities for 2020/21 in the justice portfolio, including third and voluntary sector funding in the criminal justice sector.

As such, the Committee received a number of submissions on such matters, many of which repeat some of the concerns that the Committee heard it its pre-budget scrutiny last year.

One of the challenges of looking at funding for voluntary sector delivery of services in prison is, as pointed out by the Criminal Justice Voluntary Sector Forum, there is no single, dedicated budget for this. The CJVSF said that, in terms of spending on prisons, it would welcome "a review to establish current levels of funding for voluntary sector provision of services in prison and how funding can best be joined up to ensure maximum availability and effectiveness of resources."1

The CJVSF also said, more widely, that its members continued to "report uncertain or short term funding arrangements". In its view, "short term funding and late decisions on renewals of funding or decommissioning of services leads to considerable difficulties for providers of justice services". Its members also expressed "considerable concerns about the over-reliance of both local and national funders on “pilot projects” that are then not mainstreamed into general justice budgets."1

For Apex Scotland, "funding of third sector activity is extremely wasteful and inefficient, being subject to annualised funding rounds, competitive tendering, non-strategic commissioning and competitive mission creep." Apex Scotland also said that—

Many third sector organisations provide services under grant funding arrangements. However these are usually short term funded on the basis of ‘proving the value of an innovative service model’. The reality is that such pilot schemes rarely if ever achieve mainstream funding because however good the results are, to implement them would mean disinvesting in something else. As a direct result of this the justice machinery including Sheriffs and criminal justice social work cite a lack of confidence in third sector provision which may be available for a couple of years and then vanish as the funding runs its course. This creates many other problems not least the inability of the sector to recruit and retain quality staff given the short term nature of contracts, the inability to plan ahead, improve or invest in staff development and of course the impact on service users who may engage with a service only for it to be removed without any replacement once the money is no longer available. The net result of this lack of confidence in community disposal options is that sentencing to prison becomes more likely with its concurrent expenses. Compounding this is the ‘requirement’ for local authorities to put services which they fund out to tender after a year. This is a massive disincentive to innovation because good models attract bids from larger organisations who are able to promise very low cost and powerful infrastructure. In reality these race to the bottom tactics often backfire with serious financial consequences but in the interim the originating organisation has lost staff, income and motivation.3

Community Justice Scotland said that issues in this sector were well known and included reduced overall funding levels; short term funding cycles; insecure funding sources (one-off grants rather than mainstreamed funding, etc.). For smaller providers, in their view, there are issues of constrained capacity and constrained capability, resulting in an imbalance in provision - larger providers continue to grow or dominate, despite not always being able to tailor services to local needs due to scale. 4

Similarly, Includem said that "short term funding cycles are prohibitive not only in terms of organisations’ ability to deliver services but also in achieving meaningful, lasting outcomes for young people, families and communities."5

The Cabinet Secretary also commented on third sector, stating—

In 2019-20, we have invested more than £11.6 million in third sector services, which is aimed at reducing reoffending and bolstering capacity in relation to community sentences and support services. That investment includes annual funding of £3.4 million to the New Routes and Shine partnerships, to support Through-care services for men and women leaving short-term sentences. 6

Local authority funding of criminal justice

One of the particular challenges reported by a number of third sector bodies to the Committee is the funding of criminal justice projects where the money has been channelled through local authorities. At present, criminal justice activity, such as social work in local authorities, has funding provided to local authorities in a ring-fenced grant provided under sections 27A and 27B of the Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968 as amended (referred to hereafter as the section 27 grant). As such, the majority of funding that is then provided to third sector organisations comes from this section 27 funding stream.

In its evidence to the Committee, Apex Scotland said that there was "little accountability for how this is spent or where." In its view, "the vast majority of [its] funding is brokered through an organisation which is a competitor" because local authorities can themselves decide whether to compete for projects in the criminal justice sector and do them 'in-house'. Apex Scotland said that local authorities—

... have a vested interest in providing the services internally and retaining as much of the funding as possible to ensure their own stability. For instance local authorities are providers of justice services and are increasingly reluctant to commission external services. The almost complete lack of a platform for co-design of service makes this increasingly the case during times of austerity. Even government broker organisations such as Skills Development Scotland are themselves providers of the same services they are funded to commission externally. This does not make for a smooth or outcomes centred model of service provision.1

Apex Scotland also said that "the absence of a commissioning framework means that most services come under some form of competitive procurement process which means constant re-tendering, competitive behaviour, race to the bottom bidding and the waste of millions of pounds as each organisation commits staff time and effort into bids which may well not even amount to the amount spent on obtaining the contract."1

Similarly, the Criminal Justice Voluntary Sector Forum said that "budgetary pressures and the funding structures for community justice have meant that Local Authorities are prioritising the in house provision of services, where previously the third sector would have been commissioned to deliver services". In its view, recent allocations of additional funding for supported bail services and money to prepare for the expansion of the electronic monitoring and the introduction of a presumption against short sentences have been administered through the same processes. 3

The Forum said that it was "therefore unlikely that this money will be used to fund voluntary sector services; this, together with ongoing concerns about the general withdrawal of funding from third sector providers, means that there is a considerable risk that the voluntary sector will not be adequately resourced to provide services that are integral to the success of these initiatives. "3

In response, the Cabinet Secretary said that Community Justice Scotland was doing some work on what a commissioning framework might look like and that, "once it has done further work on that, we can ask it to provide the Committee with appropriate details."5

Funding of other justice sector bodies

Criminal Justice Social Work

Work undertaken by criminal justice social work (CJSW) departments in local authorities is an important component of the criminal justice sector and in particular the rehabilitation and management of individuals subject to community-based supervision.