Health and Sport Committee

Supply and demand for medicines

Executive Summary

In undertaking this inquiry into the supply and demand for medicines, we were anticipating exploring issues relating to the efficiency of the system and the levels of waste generated. However, in considering the themes raised with us a fundamental problem has become apparent - the system of supply and demand for medicines in Scotland does not have a focus on patients.

Instead, the system is burdened by market forces, public sector administrative bureaucracyi and reported under resourcingii, inconsistent leadership and a lack of comprehensive, strategic thinking and imaginationiii, allied to an almost complete absence of useable dataiii.

The lack of data collection and analysis on outcomes achieved via the prescriptions of medicines is of huge concern. The impact on individual patients of taking medicines is not being examined and worse, it is not routinely sought. Patients in primary care are not receiving follow up care to ensure the medicines prescribed were effective or even to ensure they were used.

We found the lack of care taken to understand people's experience of taking medicines impacted the system at every stage. We are clear that gathering, analysing and sharing this information in a comprehensive, systematic way across Scotland would be the single most beneficial action to result from this inquiry. This needs to be prioritised as a matter of urgency, which will require strong leadership.

Those we consider should have responsibility for solving problems or developing innovative solutions were often the very people who recounted the issues for us, but without accompanying ideas or impetus for changeiii. The vague statements we heard of the utility or need to do something without accompanying detail on how it would be achieved are ineffective in driving forward innovation and change, particularly in reference to data and evidence collectioniii.

Little detail was offered as to how change might actually be brought about, let alone at a pace proportionate to the prize to be gained. Nobody seemed willing or able to take on responsibility for driving forward the change many identified as essential. These issues are not new and we heard little by way of solutions and strategies from senior leaders within the health service about what would actually be done to address them at the pace and scale required. We propose energetic, imaginative, accountable, focused leadership is required in order to achieve the changes required. We strongly recommend the Scottish Government examine the lack of accountability for improvement allied to the reasons why leaders at all levels are not proposing innovative, coherent and comprehensive solutions which many told us would deliver efficiencies and savings.

Given their responsibility for developing a plan to implement the National health and wellbeing outcomes framework, we were surprised to hear little of the role of Integrated Joint Boards (IJBs) in more cost and clinically effective use of medicines. For bodies with such a fundamental role to be notable by their absence in this inquiry again suggests a lack of strategic oversight in this area.

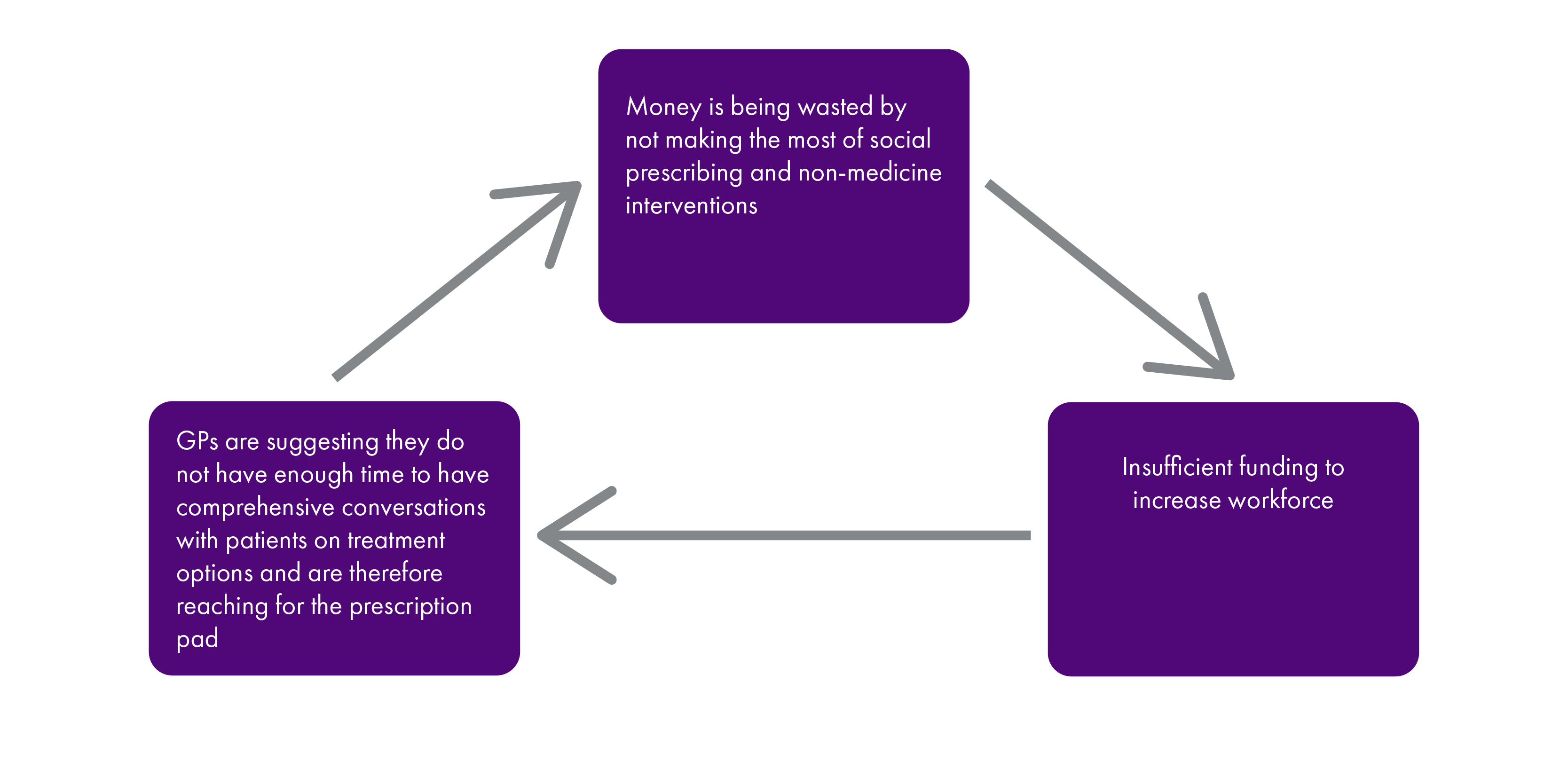

The relationship between prescriber and patient was stark throughout the inquiry. The power of the prescriber to determine the clinical and cost effectiveness of a patient's treatment was described as almost absolute, and it is clear prescribers are instinctively reaching for the prescription pad, and are not taking the time to discuss medicines with patients to a degree that ensures the clinical and cost effectiveness of the prescription. Nor are comprehensive reviews of polypharmacy or long-term prescriptions taking place and there is nothing in place to monitor, evaluate or mandate this, resulting in at best waste and at worst harm to the patient. It also appears to us there is not a strict adherence to the principles of realistic medicine, patients are not equal partners in discussions on their treatment. One of the areas this is most exposed is social prescribing and prescriptions for non-medicine alternatives.

We believe the Scottish Government's contract with GPs is failing to mandate these behaviours and actions and must be revised. In the long term, without systematic changes the Scottish Government should consider whether the system of GPs being external contractors works well for patients. An approach which pays GPs from the public purse with no monitoring or evaluationvii of their actions is not acceptable.

The role of community pharmacists in dispensing medicines was clear and well defined, however we heard a wealth of evidence on the other benefits community pharmacists could bring in ensuring the cost and clinical effectiveness of medicines in Scotland. However, the lack of structure surrounding their relationships with both patients and the rest of the health services means they are failing to exploit their skills, knowledge and position for the benefit of patients. Discussions on whether and how medicines were taken, and the effects of these, are at best being recorded on Post It Notesiii and at worst disappearing without recordix. Patients expect and deserve a better system than this.

We are extremely disappointed that once again all roads lead to the dismal failure of the NHS in Scotland to implement comprehensive IT systems which maximise the use of patient data to provide a better serviceiii. Commentsiii on patients' surprise at how badly information is handled, particularly at junctions of care, were casually made, once again exposing attitudes not focused on patient care. Worse still, where a lack of patient focus was acknowledgediii, this was not followed by a solution or plan to take action, but simply left hanging for us to add to the list of issues with medicine management.

We again urge the Scottish Government to consider the IT and data requirements of the NHS across the country in a strategic way and design systems with long term utility as a matter of urgency. We recognise this is a large undertaking but similarly, we cannot keep concluding in reports as we have for the last 4 years that savings, efficiencies and above all better patient care are possible with modern IT, capable of data gathering, analysing and sharing, without demanding urgent action in this area.

Introduction

The Health and Sport Committee agreed to hold an inquiry into the supply and demand for medicines. This was in part based on the frequency of occasions the issue was raised with us by representatives of health boards and special health boards as part of our scrutiny of such bodies.

We agreed the inquiry would focus on four distinct areas—

Purchasing (including procurement and medicine price regulation, a reserved area undertaken at a UK level);

Prescribing (covering all licensed to write prescriptions);

Dispensing (covering hospital, pharmacy and GPs); and

Consumption (looking at effectiveness and wastage).

The overarching aim for our inquiry was to examine the management of the medicines budget, including the cost and clinical effectiveness of prescribing.

We also agreed that the purpose of the inquiry was not to consider the cost effectiveness of new medicines or whether particular medicines should be routinely available for prescribing by the NHS in Scotland. This issue arose in the written and oral evidence we received and we have limited our comments on these processes to their overall impact on the clinical and cost effectiveness of medicines throughout the system.

Engagement

We sought views from a wide range of bodies and individuals, and our call for submissions ran from September to November 2019. We requested comments on 4 areas—

Does the system ensure patients receive the most clinically and cost effective treatments and, if not, how can this be improved?

Does the NHS in Scotland achieve the most value from the money spent on medicines and, if not, how can this be improved?

In what ways can the system be made more efficient?

How can the medicines budget be controlled while maintaining clinical and cost effectiveness?

We received 58 written submissions. Further information was sought during our inquiry along with supplementary evidence from several witnesses who gave evidence. All correspondence and supplementary evidence can be found at Annexe B.

We are extremely grateful to all those who contributed to its inquiry, without the input we received, both written and oral, we would not have been able to undertake our work.

Structure of the report

Our inquiry was broad and wide ranging, covering the supply and demand for medicines in Scotland from the research and development of a drug, to the consumption by a patient. The report reflects the distinct areas we have examined and received evidence on—

Licensing and acceptance for use in the NHS - this includes how consideration of new medicines by the European Medicines Agency, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency and the Scottish Medicines Consortium contributes or detracts from ensuring Scotland maximises spend on medicines

A glossary of terms and acronyms has also been provided at the end of the report.

Background

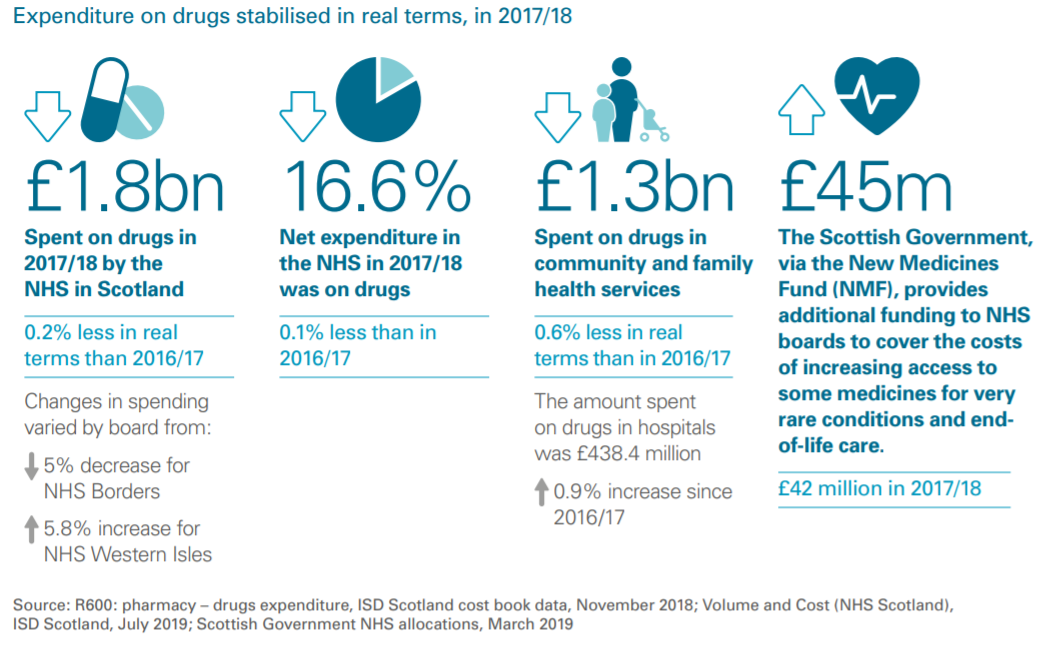

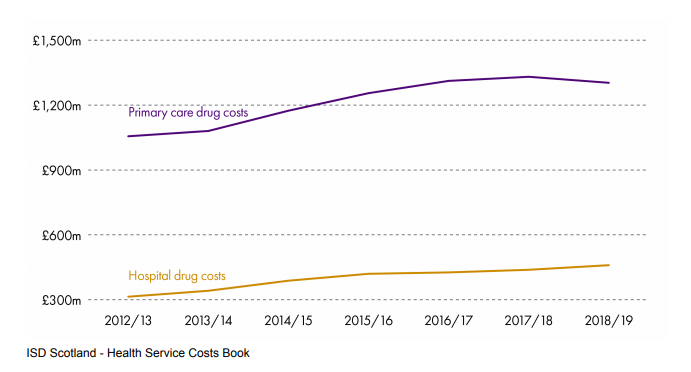

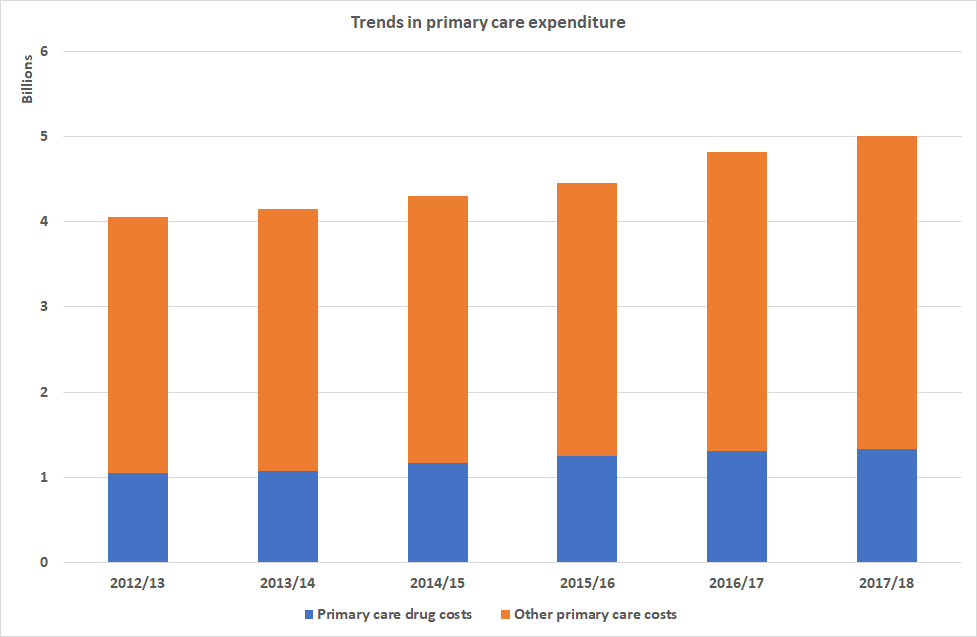

Our inquiry took place against the back drop of the most recent Audit Scotland report on spending in the NHS in Scotland, which notes "drugs costs have stabilised"i. The report states—

"The NHS in Scotland spent almost £1.8 billion on drugs in 2017/18, a reduction of 0.2 per cent in real terms since 2016/17. Good progress continues to be made in the proportion of generic medicines prescribed. This increased from 83.9 per cent in 2017/18 to 84.3 per cent in 2018/19."i

The net expenditure on medicines by the NHS in Scotland in 2017/18 was 16.6%, down 0.1% on the year before. The majority of spending on drugs takes place in community and family health services and this was again reduced from the previous year.

Stakeholders agreed medicines spend in Scotland is going in the right direction, with many telling us of the tightly controlled and meticulously scrutinised budget for spending on drugs, especially when compared to spending in other parts of the health service.

In relation to branded medicines, there are built in limits to spending increases as a result of the Voluntary Pricing and Access Scheme (VPAS) which it was noted provides a degree of predictability of spending. We were toldiii the UK compares favourably to other countries when it comes to prices paid for generic medicinesiii.

Research and development

We heard there was potential for the NHS in Scotland to achieve better value from medicines based on activity at the research, development and manufacturing phases of a medicine's existence.

These included—

Use of data from real-world experience of using medicines as opposed to reliance on evidence gathered during clinical trials; and

Preparedness for personalised medicines, including within manufacturing.

Each are explored in turn.

Real-world experience and clinical trials

Submissions we received suggested the evidence gathered in clinical trials, and on which Scottish Medicine Consortium (SMC) and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) appraisals are based, did not always match the data collected based on real-world use of a medicine. Several reasons were cited for this—

The "eligibility criteria"i for clinical trials did not always match the groups to which a medicine was eventually prescribed;

Patients who eventually take medicines may have co-morbidities and this could affect the resultsii; and

Smaller populations were available to participate in the trials for some drugs, resulting in a lack of economic information required for SMC assessmentiii.

Celgene UKiii cited Cancer Research UK research showing clinical trials could prove a drug's safety and efficacy but did not always demonstrate the benefits to be derived for patients. They further noted "a greater emphasis on using real-world data of patients' treatment outcomes will be necessary to ensure, not only that outcomes for patients are personalised and optimal, but that the NHS can be confident it receives value for its medicines spend."iii

We recognise the value of knowing the wider benefits to be gained from medicines and the implications for clinical and cost effectiveness. As various stakeholders told us, medicines which are not having the desired effect are not good value for money.

Lindsay McClure, Associate Director, Medicines Pricing and Supply, NHS National Services Scotland, said—

"Having that real-world evidence over time could greatly help us to evaluate what [medicine] is the most cost effective, once there is experience of using the medicine. However, to do that, we need much more efficient IT systems to collect outcomes data. As we have already heard, there are some great initiatives, such as the cancer medicines optimisation programme, but it is still early days and there is more work to be done."ii

The data on real-world application of medicines is important to both manufacturers and the NHS alike in terms of the value of medicines. As stated above, medicines which are not having the desired effect are not good value for money. This is a theme explored further in the VALUE AND OUTCOME BASED PRICING part of our report.

Personalised medicine

Personalised medicine involves tailoring drugs and treatment to the specific requirements of an individual's version of an illness and their biology.

The benefits include—

Increased efficacy of a drug (and therefore better value);

Reduced adverse reactions (and therefore better clinical effectiveness); and

Reduced waste.

Several themes were pursued in evidence on personalised medicine—

Waste;

Manufacturing technology; and

Preparedness for personalised medicine in the healthcare system.

Waste

Several representations, including the Chief Pharmaceutical Officeri and the University of Strathclydeii, noted the potential for personalised medicine to reduce or even eradicate waste of medicines by ensuring maximum tailoring to the specific need of the patient.

Manufacturing technology

Alison Culpan of the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) suggested data enabling the identification of patients who could benefit from innovations in gene therapy was lacking, and this was squandering the opportunity to get the "right outcomes and value for money from what is spent on medicines."i

The University of Strathclyde stated manufacturers were reliant on outdated technology and called for new production and supply chain technologies to "revolutionalise healthcare delivery"ii. However, they said such a project was unlikely to be achieved by one company or group acting independently and called for cross sector and Government intervention.

Preparedness for personalised medicine in the healthcare system

Although it was clear to us the technology is in its infancy, a range of witnesses spoke of the need for current systems to adapt to the medicines of the future.

We received several representations urging the SMC to consider future proofing assessment processes. The Blood Cancer Alliancei welcomed approvals of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T cell therapyi) but said challenges lay ahead in terms of greater demand and therefore budget impact. They called for further work with industry to "scope the likely challenges and financial impacts of these innovative treatments."i

It was noted personalised medicines would represent higher costs in some circumstances but this should be assessed and balanced against the likely benefits. There were calls for reform of the SMC assessment to accommodate personalised medicine and for a review similar to the work NICE are carrying out in this area.

Dr Alan MacDonald, Chair of the SMC, informediv us about the SMC's horizon scanning activities (discussed further in the SCOTTISH MEDICINE CONSORTIUM HORIZON SCANNING section of this report) and preparations for the next generations of medicines. The ABPI noted the substantial evidence which would be required by the SMC for advanced therapies, indicating "the NHS needs to balance the risk of treatment failure with a manufacturer's need to recoup the enormous cost associated with development."i

Technology in manufacturing was another area where stakeholders felt systems would require to be updated to accommodate innovations.

We note and welcome the ambitions in the area of personalised medicine described by the Chief Pharmaceutical Officer. We seek from the Scottish Government specific detail as to—

Which areas it currently considers require adaptation to embrace personalised medicine;

How this will link with other data and technology projects such as the National Digital Platform; and

Budgetary planning for the accommodation of personalised medicines within the health and social care service in Scotland.

We encourage the Scottish Government to consider the technology used by manufacturers and wholesalers in the creation and delivery of personalised medicines and consider what further incentives and support could be provided to develop these.

We recommend the Scottish Government make provision for the use of personalise medicine in the future, including data collection (a theme considered in detail in the DATA and IT section of this report).

Research and Development - conclusions

On the use of real-world data rather than clinical trials, we share the enthusiasm of stakeholders for better utilisation of such information. We also share their views on the data infrastructure required to achieve a system for proactively and comprehensively gathering this information.

The advent of personalised medicines is an exciting prospect in terms of cost and clinical effectiveness according to many who spoke to us. Above all, the potential for personalised medicine to achieve positive impacts on budgets and waste, and improved clinical outcomes for patients, is clear. This is a theme we return to throughout the report.

We believe the Scottish Government should be doing all it can to support the use of personalised medicine, and encourage and support innovation in Scotland, while remaining mindful of the need to have in place appropriate systems and means of tracking and measuring outcomes.

However, we are clear such a development requires to be properly planned in terms of assessment processes, data and technology and budget required. In addition, we would expect cost implications along with measurement of effectiveness to be included in processes at the outset.

Licensing and acceptance for use in the NHS

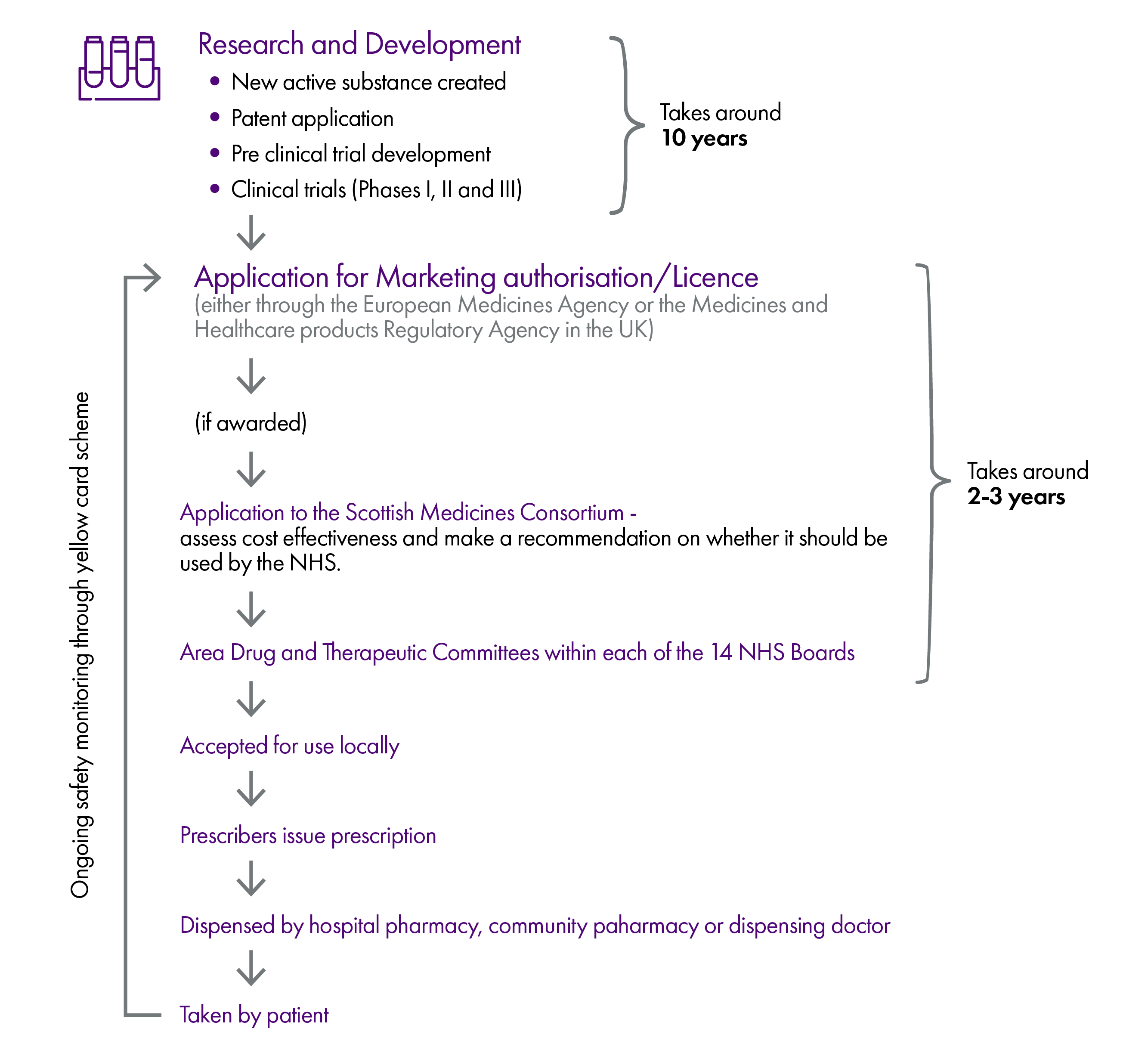

The following sections cover how medicines are licensed and accepted for use within the NHS in Scotland. Products must first obtain a licence or marketing authorisation, before being assessed by the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) for use within the NHS in Scotland.

The impact of these processes on clinical and cost effectiveness was the subject of various representations to us as part of our inquiry.

Licensing

The Scottish Parliament Information Centre has described the licensing of drugs in the UK and the role of the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)—

"Before any medicine can be used in the UK, it usually has to receive a marketing authorisation from either the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), or the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The MHRA is the UK's licensing and regulatory authority and its functions are reserved to Westminster. It therefore operates on behalf of the 4 UK countries. A marketing authorisation is often referred to as a 'licence' and can only be issued following the completion of clinical trials that show—

- the medicine treats the condition it was developed for;

- the medicine meets safety and quality standards; and

- the medicine does not cause unacceptable side effects.

At the moment there are a number of routes for a medicine to obtain a marketing authorisation in the UK but at a very basic level this boils down to either applying via the EMA, or applying to the MHRA"i

We were particularly interested in two specific aspects of licensing and their impact on the use of medicines in Scotland—

Licensing for more than one indication; and

Evidence provided by pharmaceutical companies to support licensing.

Licensing for more than one indication

We were interested in medicines which could have alternative uses to their original design and how this could achieve both savings and better results for patients (a current example which has arisen since our evidence sessions being the use of Remdesivir, an anti-viral drug, to shorten the recovery time from COVID-19). Given the complexities described to us, we were also keen to understand how applications could be encouraged for licences for existing medicines which could have an impact on conditions beyond that which they were originally designed for.

Representatives of the pharmaceutical industry suggested there was work going on from their perspective as to how this could be progressed.

Warwick Smith, Director General, British Generic Manufacturers Association (BGMA), discussed the scope for looking "at older medicines that can be repurposed for new uses"ii. He described discussions as "well advanced"ii on this. Alison Culpan of the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) saidii it was hard to quantify how much a licence application for an additional indication may cost. She providedv detail on recommendations of an Association of Medical Research Charities reportvi on ways to incentivise repurposingvii, including research and development tax credits, creation of a fund, prescribing resources and support for clinicians. It also covered ways to enable the MHRA to communicate more easily with those seeking to research repurposing and for including repurposed medicines in the Accelerated Access Pathway.

She also highlighted work undertaken on this issue by the European Commission Expert Group on Safe and Timely Access to Medicines for Patients (STAMP). She said the ABPI had been working on a draft framework with the Commission—

"This framework operates by improving communication between academia (who are often the first to identify medicines for repurposing), the regulator and industry partners. The process would enable an academic to contact the regulator for advice around the eligibility of a molecule, this advice would then enable the “academic champion” to take this project to an industry partner who can subsequently evaluate the risks and opportunities involved. A lack of awareness and communication between academia, the regulator and industry is often the first and largest barrier which prevents older drugs from being repurposed. This framework provides a template to de-risk and improve the process."v

We were told of circumstances in which medicines were being used for indications for which they were not licensed and Lindsay McClure, Associate Director, Medicines Pricing and Supply, NHS National Services Scotland, spokeii of legal challenges in this regard.

We were interested in whether there was a role for an organisation to encourage pharmaceutical companies to apply for licences for different indications for existing drugs. Both the MHRAii and the SMCxi told us they could have no role in encouraging applications. Dr Alan MacDonald, Chair of the SMC, added—

"In certain circumstances HIS [Healthcare Improvement Scotland] can advise on the off-label/unlicensed use of cancer medicines. HIS hosts an Off-label Cancer Medicines Programme recently commissioned by Scottish Government’s Cancer Division in response to its Beating Cancer: Ambition and Action strategy. This programme aims to provide advice to NHS Board Area Drug and Therapeutics Committees on the managed entry of off-label uses of cancer medicines. Through this advice the programme will facilitate equity of access to off-label uses of cancer medicines and reduce unwarranted variation for patients across NHSScotland. This programme is expected to deliver the first piece of advice to NHSScotland in summer 2020."xi

Rose Marie Parr, Chief Pharmaceutical Officer, said the Scottish Government encouraged pharmaceutical companies to assess their licence. She added—

"We see some older medicines being repurposed and used for very different things. There needs to be some consideration of that huge burden on some parts of pharmaceutical industry to get their medicines to licence—that is very costly and takes time. Some of those processes could be shortened a bit, which would help."ii

Alison Strath, Principal Pharmaceutical Officer, Scottish Government, added "...we would need to work to understand what levers there might be to support repurposing"ii and although the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Jeane Freeman, foresaw challenges, she did not consider these to be "insurmountable".ii

We request the Scottish Government provide details of what plans it has to respond to the suggestions provided by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) on how applications for additional licences for medicines can be encouraged and incentivised.

We recommend the Scottish Government works with the UK Government and the MHRA to streamline and shorten the processes it described to us as causing barriers to pharmaceutical companies applying for additional licences and health care technology assessments for new indications for existing drugs.

We encourage the Scottish Government to provide details of how it will encourage pharmaceutical companies to apply for new licences for new indications for previously licensed medicines, including how timescales can be shortened to assist with this and the other levers proposed by the Scottish Government.

We also request the Scottish Government give consideration to commissioning and funding clinical trials on medicines for use in conditions of significant public health impact or where there is a significant lack of cost effective treatments.

Adaptive licensing

Alison Culpan, Scotland Director of the ABPI, highlightedi the issue of adaptive licensing, which she described as "emerging"—

"Adaptive licensing predominantly applies to new treatments where ‘drug candidates’ that meet a serious unmet medical need can be initially approved for use in a restricted patient group. This is then gradually expanded to broader patient populations as additional safety and efficacy data is generated. Whilst this doesn’t apply to older molecules or those in limited indications, it does demonstrate that flexibility is required to ensure patients continue to benefit from fast access to new medicines."i

We request details of whether adaptive licensing can be applied to new indications for existing drugs and the role the Scottish Government can play in encouraging this.

Evidence in support of licence applications

Jonathan Mogford, Director of Policy, MHRA explainedi the process by which evidence to support licence applications was peer reviewed. He said the licensing process was "part of the important interaction with companies that ensures that the claims that are made for products are backed by clear scientific evidence"i and notedi the agency's enthusiasm for the debate about using "real-world" evidence (please refer to the REAL-WORLD EXPERIENCE AND CLINICAL TRIALS section of this report) and suggested improved data on outcomes would fuel this further (this issue is considered fully in the OUTCOMES section of this report).

In correspondence with us, he further outlined the basis of decisions on evidence—

"All decisions on approval of medicines, wherever these are taken, are based on satisfactory demonstration by the applicant of the safety, quality and efficacy of new medicines. In the UK, the decisions are informed by independent advice from the Commission on Human Medicines. The MHRA does not plan to change the evidence standards for approval of new medicines and will use existing flexibilities, such as conditional approval and incentives for rare diseases to ensure that unmet clinical needs can be met by licensing of new products."iv

Dr Alan Macdonald, Chair of the SMC, outlined how the organisation treated medicines with less supporting evidence than they might otherwise expect and said "...if a medicine that is licensed by the EMA comes to us, we have to assume that it has been shown that the benefits outweigh the risks. However, our job is different; it is to say whether the benefits justify the cost."i

Licensing - conclusions

The opportunities presented by licensing medicines for more than one indication are currently being missed in our view, due to barriers described to us by stakeholders. We have recommended the Scottish Government consider how it can better encourage trials and expedite licensing for additional indications of existing drugs to maximise their use within the NHS.

On the standard of evidence required for new medicines, we are satisfied the processes are working although refer to our previous conclusion better use could be made of 'real-world' experience of using medicines, rather than relying solely on clinical trial data.

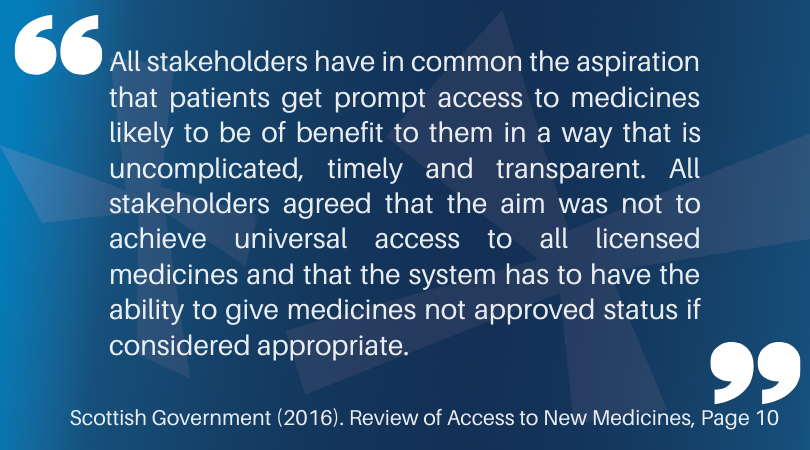

Access to new medicines

While the subject of access to new medicines does not form the focus of our inquiryi, many of the submissions received reflected on how new medicines are assessed in Scotland. Issues raised by work by the previous Health and Sport Committee in its session 4 inquiryi on Access to New Medicines are relevant to this area.

In the period since that inquiry was undertaken, an independent review was held "to assess the impact of the new approach introduced in 2014 by [Scottish Medicines Consortium] SMC" and it reportediii to the Scottish Government in December 2016. The Scottish Government provided us with updates on progress towards delivery of the recommendations in the review in November 2017iv, February 2018v, May 2018vi, June 2018vii and 13 January 2020viii.

This section will consider evidence received on the following themes

Scottish Medicine Consortium (SMC) Assessments;

Patient Access Schemes;

Evidence Based Approvals; and

Interaction with the Pharmaceutical industry.

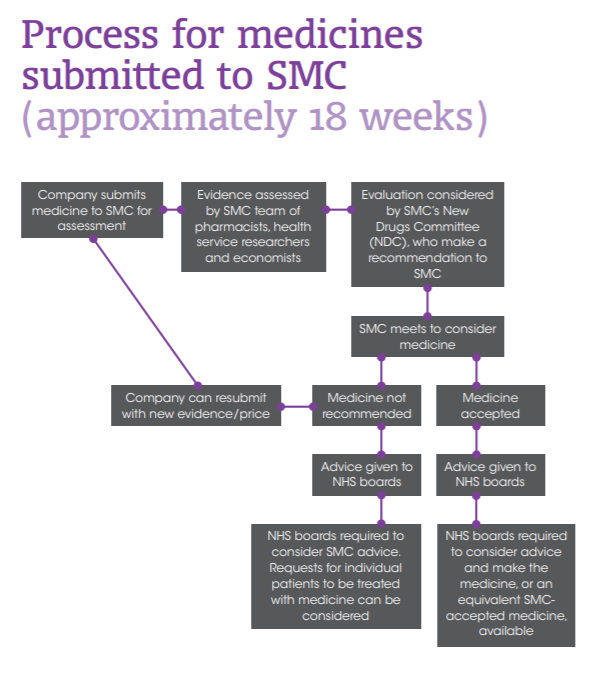

Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) assessments

The SMC is a branch of Healthcare Improvement Scotland (HIS) which carries out assessments on all new medicines for use in Scotland. It consists of a committee of "clinicians, pharmacists, NHS board representatives, the pharmaceutical industry and the public". It also has a horizon scanning function, which according to HIS "aims to support health boards with financial and service planning for new medicines in the pipeline that may be accepted into routine clinical use."ii As previously indicated, its primary role is to say whether the benefits of a new medicine justify the costs.

The following diagram describes the process by which drugs are assessed—

Many, such as Celgeneii and the British Medical Association (BMA)ii praised the efficacy of the assessment processes of the SMC and suggested these kept the budget under control while also allowing for access to new medicines. The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) saidii the healthcare technology assessment conducted by the SMC was a "leader" in balancing cost and medical value, and said it made Scotland an attractive place for manufacturers to test new products.

The Royal College of Physicians of Edinburghii and others highlighted the potential waste from not using the most clinical and cost effective medicines available, stating the prescription of drugs of limited efficacy could "adversely apply pressure on the use of existing drugs of very good cost effectiveness, and on other treatments which provide better cost effectiveness". The difficulties in assessing cost effectiveness of medicines are discussed in the VALUE section of this report.

While many heralded the SMC assessment process and said their approval status inferred clinical and cost effectiveness, a number of questions were also raised.

We considered the following themes presented to us in evidence on the assessment processes of the SMC—

Speed of the assessment process compared with the rest of the UK;

Changes since the Review of Access to New Medicinesvii (the Montgomery Review), including—

Review of assessment methods;

Peer Approved Clinical System (PACS) Tier 2;

Patient and Clinician Engagement (PACE);

Clinical and cost effectiveness of new medicines;

Access to end of life, orphan and ultra-orphan medicines; and

Interim acceptance.

The assessment of value; and

Horizon scanning.

Speed of assessment compared with the rest of the UK

Merck, Sharp and Dohmei, Pfizer UKi, the Blood Cancer Alliancei and Rocheiv suggested SMC assessments were slower than UK counterparts, thus denying availability of medicines to patients and the cost benefits to the NHS for longer.

Others such as Prostate Cancer UKi expressed their concerns about delays and Jansseni were among those who called for investment of "money and resource" to allow the SMC to deal with delays in assessment.

While noting the issues raised with us were predominantly from bodies with an interest in seeing medicines becoming available quickly, we would welcome the view of the Scottish Government as to the reasons for potential differences in assessment speeds throughout the UK and what, if any, action is required by the Government or the SMC to rectify this.

Assessment of licensed medicines for cost effectiveness

We note the process of approval by the SMC starts with companies submitting medicines for assessment. The MS Society Scotlandi suggested there should be a more effective system for accessing medicines which were licensed but had not yet been assessed by the SMC in order to ensure patients can access the most effective treatments. We concur with this view.

We recommend the Scottish Government work with the SMC to develop a more effective system for accessing medicines which have not been submitted for assessment to the SMC based on the premise every newly licensed medicine should be assessed for cost effectiveness regardless of whether the manufacturer applies.

Changes since the Montgomery Review - review of assessment methods

In the Review of Access to New Medicines, Dr Brian Montgomery, Chair of the Review, wrote "...the overwhelming sense encountered was that there was a high level of satisfaction with SMC and that its processes remain robust."i

Dr Alan MacDonald, Chair of the SMC, said—

"The process has changed to allow greater access to medicines for cancer and rare conditions, which was a specific policy intent."ii

Nonetheless, there were several areas highlighted to us where stakeholders felt improvements could go further—

The BMA impliediii there is still an imbalance in the system based on the difficulties in prescribing off-formulary or unlicensed medicines contrasted with the high approvals for drugs approved at speed for small groups of patients;

The ABPIiii , Jansseniii and the Blood Cancer Alliancevi suggested assessments for combination therapies should be considered, noting the difficulty in demonstrating value and the financial barriers to companies to bringing these forward for assessment, meaning patients were missing out on clinically effective treatments. The ABPI also said the SMC should maintain an awareness of other assessment bodies' approach to consideration of combination therapies;

Roche Products Ltd said "Whilst robust, Roche believes that current methods of value assessment are becoming restrictive and patients in Scotland are not getting access to some clinically and cost-effective medicines when compared to the rest of the UK. Evolution of process must be seen as a priority to ensure delivery of best value and equitable access to cost-effective treatments across the UK."iii They suggested further reforms to Patient Access Schemes and Genomic Profiling.

Merck Sharp and Dohme noteiii a lack of commitment to review assessment processes for specialised medicines for which the quality adjusted life year (QALY) and Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) measures are not appropriate, resulting they say in patients missing out on medicines for specialised conditions. They believed such assessments were not suitable for every medicine.

Cancer Research UK suggested assessment of clinical and cost effectiveness was becoming more challenging and new "commercial and commissioning approaches are required in response to this trend, to ensure effective management of the medicines budget".iii

When questioned, Dr Alan MacDonald, Chair of the SMC, defendedii the "rigour" of the SMC appraisals process, acknowledging there may still be debate around access levels. He describedii the SMC function of comprehensive consideration of new medicines as compared with existing options as unique. Dr Brian Montgomery outlinedii his views on how changes implemented since his review of access to new medicines in Scotland had ensured the SMC had more flexibility which meant less circumvention of the process for patients to gain access to new medicines, therefore improving the robustness of the SMC appraisal system.

The BMAiii, the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburghiii and the Royal College of GPsiii were critical of the approval of medicines following political pressure and the importance of evidence based assessments and prescribing was emphasised by many throughout the inquiry.

Changes since the Montgomery Review - Peer Approved Clinical System (PACS) Tier 2

While the SMC assesses and takes decisions on medicines for routine use in the NHS as a whole, there are routes for patients and clinicians to access rarer medicines. Prior to the Review of Access to New Medicinesi, the Peer Approved Clinical System (PACS) and the Individual Patient Treatment Request (ITPR) systems were available.

The review recommended the Scottish Government should—

"Review and evaluate the experience of PACS to date with a view to deciding on any required modifications and thereafter agree the final model and timescales for implementation in NHSScotland."i

In response to this, a review of PACS Tier 1 was undertaken and a second tier was developed to replace the ITPR process. In June 2018, the Peer Approved Clinical System (PACS) Tier 2 was introduced to provide a new route for patients to access rarer medicines.

The advent of PACS Tier 2 was welcomed by respondents to our call for evidence such as Celgeneiii, who said it strengthened the system, Cancer Research UKiii and Pfizer UKiii.

NHS Fife Area Drug and Therapeutic Committee (ADTC)iii, NHS Lothian ADTCiii and NHS Bordersiii said PACS removed a health board's ability to consider cost or affordability where the SMC had already deemed a medicine not to be cost effective and more patients would access them as a result (as PACS facilitates access and does not allow boards to consider the cost). We sought the view of the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport on this issue in correspondenceix and also her view of when the second stage of the review of PACS would be completed.

However, others identified areas for further consideration including consistency of application and review of PACS Tier 2.

Changes since the Montgomery Review - Patient and Clinician Engagement (PACE)

Celgenei were supportive of the Patient and Clinician Engagement (PACE) process and the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Jeane Freeman, informed us of both the fulfilment of the recommendations on PACE but also of the next steps to "explore how PACE actually shapes decision-making"ii.

We welcome this work and look forward to receiving details of developments.

Changes since the Montgomery Review - Clinical and cost effectiveness of new medicines

While recognising the welcome outcome of increased access to new medicines as a result of changes implemented since the Review of Access to New Medicines, we were disappointed to hear some thought this was at the expense of clinical and cost effectiveness.

The Royal College of GPs expressedi the view changes in policy had seen medicines approved which may not have been previously and said "the clinical effectiveness of new medicines as a result may not be to the same level as they were historically". NHS Grampian ADTCi said medicines were approved with less evidence of clinical or cost effectiveness than would previously have been the case while Gail Caldwell, Director of Pharmacy, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde said "Through the changes to the policy position in Scotland, boards are now making available medicines that we would consider to be no longer cost effective. That has an impact in that it diverts resources away from other interventions that we might consider to be cost effective."iii

The views of NHS Grampian ADTC and Gail Caldwell provide an example of a frustration experienced throughout this inquiry on the role of NHS leaders, although we sympathise with the predicament.

If an ADTC does not have control over items for inclusion on a formulary, what is their purpose? Senior pharmacists we heard from throughout the inquiry helpfully identified a number of issues within health boards for us, but provided no solutions to these. If a Director of Pharmacy is not in a position or empowered to ensure resources are being applied to the most effective interventions, this is a larger problem than ineffective medicine prescription.

We recommend the Scottish Government consider the role of health boards within PACS decision making processes to make clear what the role of ADTCs, directors of pharmacy and other senior leaders is.

Changes since the Montgomery Review - access to end-of-life, orphan and ultra-orphan medicines

Rarer medicines defined as end-of-life, orphan and ultra-orphan can be defined as follows—

| End-of-Life Medicine | "A medicine used to treat a condition at a stage that usually leads to death within 3 years with currently available treatments."i |

| Orphan Medicine | "A medicine with European Medicines Agency (EMA) designated orphan status (i.e. conditions affecting fewer than 2,500 people in a population of 5 million) or a medicine to treat an equivalent size of populations irrespective of whether it has designated orphan status."i |

| Ultra-Orphan Medicine | "To be considered as an ultra-orphan medicine all criteria listed should be met—

|

Recommendations 6 and 7 in the Review of Access to New Medicines were—

"Review the definitions for end-of-life, orphan and ultra-orphan medicines to ensure that the definitions used remain suitable to deal with the assessment of anticipated new treatments such as targeted medicines, increasing use of combination therapies and the impact of genomics.

Develop, agree and implement a new definition of “true ultra-orphan medicine” to take account of low-volume, high-cost medicines for very rare conditions."i

Recommendation 11 called on the Scottish Government to "Develop and implement a new assessment and approval pathway for true ultra-orphan medicines that restricts the role of SMC to health technology assessment and places the responsibility for the final decision on availability elsewhere."i

In January 2020, the Cabinet Secretary informedvi us all three recommendations had been implemented. While the definitions for end-of-life and orphan medicines were deemed suitable, a new definition for ultra-orphan medicines was devised. As of January 2020, the new definition had tested "more than twenty medicines".vi We were interested in whether new definitions had posed any issues thus far and the Cabinet Secretary said positive feedback had been received by pharmaceutical companies. This tallied with responses to our call for views, with organisations such as Celgene praising the strength and adaptiveness of Scotland's healthcare technology assessment processes, which it said "are ensuring Scotland receives good value for the money it spends"viii.

However, others were reserved about the success of the new processes, with companies such as Chiesi Ltd saying it was "early days"ix for the new pathway. The European Medicines Group called for "similar energy to be put behind access to medicines for common conditions as well as orphan and end-of-life conditions".viii

We recognise it is still early days for the new definitions and pathways, and request the Scottish Government publish reports on evaluations.

Changes since the Montgomery Review - interim acceptance

The SMC said it was working on extending interim acceptance to more new medicines. The notion of conditional approval was welcomed by stakeholders including the European Medicines Groupi and we were told of several areas where the new interim acceptance would be beneficial.

Dr Alan MacDonald, Chair of the SMC, said the debate on outcome based pricing (see the VALUE AND OUTCOME BASED PRICING section for further analysis) would be one the SMC would have to consider as its interim acceptance option became more "mature"ii, noting there was a grey area for medicines which worked, but not quite as well as originally claimed.

The ABPIi described challenges ahead for the SMC, including evidence from trials based on decreasing participant samples, and suggested expansion of the number of medicines accepted under the "interim acceptance" status could help. Bristol-Myers Squibbi said this route should be available for a "wider group of medicines not just those with conditional marketing authorisation."

The Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport told us the SMC was "....now exploring extending the use of the conditional acceptance option, specifically in the context of clinical uncertainty whether further data is likely to [be] forthcoming at a relatively early stage as a consequence of ongoing clinical trials."v

Value

The concept of value was highlighted to us in several written submissions. Stakeholders suggested this was a subjective assessment and could have multiple meanings - what is good value for an individual may not be good value for the population. It was also argued the value of a medicine could change depending on its age or its successors. The question of the efficacy of a cheaper medicine and whether this was worth the spend in comparison to better clinical results from more expensive medicines was also raised.

Matt Barclay of Community Pharmacy Scotland said "The cost of medicines should also be seen in terms of value, rather than in terms only of cost. When they are used appropriately, most medical interventions using medicines are perfectly good value for money. The situation has to be looked at in that light."i Similar points were made by a number of pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Prostate Cancer UKii were among those who asserted the use of medicines which may carry a high price tag, but which achieve huge savings in other forms of treatment, should be considered good value. The European Medicine Groupii and Healthcare Improvement Scotland (HIS)ii suggested medicines spend should not be considered in isolation from the health and social care budget as it risked discounting savings to be achieved across a pathway. Pfizer UKii also suggested wider societal costs, including to the economy, should be accounted for when considering the value of medicines, while the MS Society Scotlandii called for consideration of the impact on the welfare budget. HIS noted the "cost effectiveness analysis to drive value for money is not used uniformly across all areas of medicines spend."ii and the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Jeane Freemani, suggested evidence gathering in this area was hard and there was not a Scotland wide approach.

Many believed the SMC processes achieve good value for money and praised the system.

Scottish Medicine Consortium horizon scanning

The Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) described its horizon scanning functions as—

"SMC provides Health Boards with early intelligence on new medicines in development to support their financial and service planning. SMC is involved in the use and development of UK PharmaScan, a UK-wide horizon scanning database that provides information on new medicines, indications and formulations in the pharmaceutical pipeline. Forward Look, the SMC’s annual horizon scanning report, is published in October each year, it provides concise information on new medicines/indications that are expected to impact Boards over the following financial year. The report is accompanied by a financial planning tool describing estimated uptake and potential budget impact. SMC provides biannual updates to allow Boards to adjust their financial plans within year. We know that Forward Look reports are highly valued by Boards."i

In terms of recent activity to prepare for the next generation of medicines, the SMC told us it had issued briefings recently on "advanced therapy medicinal products and medicines with histology-independent indications" and anticipated more personalised medicines for patients with specific biomarkers, regenerative cell therapies and "complex combination regimes for cancer medicines"i.

We were interested in whether the horizon scanning function of the SMC was working effectively.

Dr Scott Jamieson of the Royal College of GPsiii posed the question of whether the SMC was assessing medicines against the qualities of value to patients and suggested it was not. David Coulson, Assistant Director of Pharmacy, NHS Tayside iii said the SMC's work was vital to ensure there were no surprises and emphasised the importance of a good evidence based to ensure value from medicines. Dr Jamiesoniii also stressed the need to collect good outcomes data to achieve this (see the OUTCOMES section of this report for further detail).

Many stakeholders believed the SMC processes for horizon scanning would have to be updated to accommodate personalised medicines (discussed fully in the PREPAREDNESS FOR PERSONALISED MEDICINE IN THE HEALTHCARE SYSTEM section of this report). Rochevi called for a consultation, akin to a review undertaken by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), on SMC processes and preparedness for assessing personalised medicine and updated horizon scanning. Pfizer UKvi suggested there was room for ongoing review in this area also to ensure patients could gain early access to new innovations.

The Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Jeane Freeman, said—

"The new medicines fund is vital, but we need to parallel the work that the SMC is doing in considering its processes in anticipation of precision medicine and coming innovations. We need to consider how we fund and whether we should alter our approach in the light of innovative and important developments for patients."iii

We request detail of how and the planned timescale in which the Scottish Medicines Consortium processes will be reviewed and updated to accommodate innovations in medicines.

We recommend the Scottish Government review how it intends to fund this work, as well as the innovative medicines of the future to ensure Scottish patients are world leaders in receiving the best possible pharmaceutical treatment.

SMC assessment processes - conclusions

The healthcare technology assessments of the SMC were lauded as world leaders and the processes, as well as recent updates to these, were welcomed in the main for their contribution to the clinical and cost effectiveness of medicines used by the NHS in Scotland. There was general consensus improvements had been achieved through the Review of Access to New Medicines, but that the programme of reform and review must continue to ensure processes remain able to accommodate innovation.

There were calls for updates to assessment methods and measures to speed up assessments and we suggest the Scottish Government and the Scottish Medicines Consortium consider these suggestions. We also look forward to seeing how measures such as interim acceptance and the new definitions of end-of-life, orphan and ultra-orphan medicines progress.

Finally, we are in full agreement with evidence suggesting the value of medicines should be considered as well as the cost, and the full range of benefits and savings medicines could provide, both in health and across the economy, should be accounted for in decisions (see the VALUE section of this report for further detail).

Patient Access Schemes

According to Jansseni, 54% of the medicines for which the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) published review advice between 1 January 2018 and 31 October 2019 had a Patient Access Scheme (PAS) discount and Celgenei noted a steady increase in their use also. Patient Access Schemes are used to discount the cost of new drugs in the early years of their use.

Roche Products Ltd proposed revisions could be made to the criteria for PAS to "drive further value"i and Pfizer UK called for revisions to the system.

The Blood Cancer Alliance noted two types of PAS are available: a simple scheme and a complex schemeiv. The group called for a more "flexible and transparent commercial framework"i, referring to the use of complex discount schemes and the difficulties these could bring. The group called for the guidance to be "revised to deliver a more mature, flexible and transparent framework for commercial discussion, focused on overcoming identifiable barriers to access and incentivising early engagement and flexibility on the part of industry."i

The Blood Cancer Alliancei described the dichotomy between the commercial confidentiality of the schemes and the need for transparency in decision making for the public, noting the former helped ensure good value for the NHS. They further added—

"In Scotland a further complexity exists in that some treatments do not have a formally approved PAS, although they are reimbursed by NHS Scotland at a discounted price. Where this is the case, the SMC will not take into account the discount price for the purpose of assessing the cost effectiveness and instead apply the full list price. This means that cost effectiveness decisions are not being based on the true cost of the combination to NHS Scotland. This is leading to inefficient decisions."i

Bristol-Myers Squibb said—

"Any scheme not presented as a simple discount is regarded as complex and PASAG assessment is made with their established view that these schemes introduce cumulative administrative burden for the NHS and that their perceived financial benefits may not be fully realised in practice. They therefore tend to be rejected. The Committee should investigate the proportion of SMC submissions that include a PAS, what proportion are regarded as simple or complex and what proportion of complex PAS are accepted."i

We recommend the Scottish Government should review, along with the Scottish Medicines Consortium and the Patient Access Scheme Assessment Group, how the actual cost to be charged to the NHS on approval of medicines can be "assessed in the absence of a formal [Patient Access Scheme] PAS"i.

We would welcome the view of the Scottish Government on how confidentiality in the negotiation of Patient Access Schemes can ensure best value for the NHS.

We recommend the Scottish Government provide detail of "...the proportion of Scottish Medicine Consortium submissions that include a PAS, what proportion are regarded as simple or complex and what proportion of complex PAS are accepted."i

Interaction with the pharmaceutical industry

In the Review of Access to New Medicines, Dr Brian Montgomery stated—

"To date the interaction between the various players, and certainly that between NHSScotland and the pharmaceutical industry has tended to begin only once a medicine has been granted a license and a submission to SMC is being considered. All spoken to consider this to be too late, missing as it does the opportunity to collaborate on issues such as horizon scanning, the optimal use of specific medicines, wider assessments of impact and value and more pragmatic pricing strategies."i

We also heard there was still a case for review of interaction with the pharmaceutical industry, with groups such as the European Medicines Groupii, Merck, Sharp and Dohmeii and Janssensii calling for further engagement with companies. The Blood Cancer Alliance suggested a "more flexible, better resourced and transparent commercial framework for negotiation with the industry is essential if the most clinically effective medicines are to be made cost effective in the future."ii

The British Dental Associationii called for stronger negotiations with drug companies in order to save money. The role of the SMC is not to negotiate on price, merely to assess whether the benefits of the medicine offered are worth the stated cost. This left us wondering where the room for negotiations on price are within the tendering and national procurement systems.

We recommend the Scottish Government and the Scottish Medicines Consortium consider the views on interactions with the pharmaceutical industry during assessment of new medicines we received and what benefits could accrue for the NHS in Scotland from improvement in this area.

Access to new medicines - conclusions

Although consideration of access to new medicines did not form part of the inquiry, we have considered views presented on the role of the SMC in as far as this impacts on the clinical and cost effectiveness of medicines used in the NHS. While we believe advances have been made in light of the recommendations of the Montgomery Review, we urge the Scottish Government to consider the views proposed to us on further potential improvements. We also suggest there is scope to consider the operation of Patient Access Schemes further to ensure these are best serving the NHS and to look at interactions with the pharmaceutical industry during assessment of medicines.

Scrutiny of non-medicine interventions

Throughout the inquiry, we heard a general theme there is inequality of scrutiny between medicines compared to other healthcare interventions.

Other interventions such as medical devices, appliances, technology, and procedures do not receive the same robust level of scrutiny as medicines before being used on patients. It is also not clear to us how the potential benefits of medicines are assessed against the benefits of non-medicine interventions.

On licensing, the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Jeane Freeman, told us "We continue to press the [Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency] MHRA to make its process for medical devices comparable with the process that we all expect for clinical trials, licensing and so on of medicines."i She suggested the Medicines and Medical Devices Bill at Westminster may be a vehicle for discussions on improving the MHRA's processes. We requestedii details of the discussions which have taken place on this issue with the MHRA and look forward to considering a legislative consent memorandum on the Bill.

Dr Ewan Bell, National Clinical Lead, Area Drug and Therapeutics Committee Collaborative, Healthcare Improvement Scotland, said—

"..there are other interventions that are non-medical but are not social prescribing, such as bariatric surgery, which is much more effective for the treatment of type 2 diabetes than any medicine. There has not been sufficient evaluation of different interventions outwith medicines in NHS Scotland......The health boards have a variety of inputs—from the Scottish Medicines Consortium, the Scottish health technologies group, clinical guidelines, patient support groups and targets—and there is no national, once-for-Scotland comparison or health technology-type evaluation of those different inputs. There is no comparison of all those different interventions, and no ranking—I do not want to use the word “prioritisation”—of what NHS Scotland believes that it is important to deliver on."i

This issue is further discussed at length in the NON-PHARMACEUTICAL INTERVENTIONS and SOCIAL PRESCRIBING sections of this report.

David Coulson, Assistant Director of Pharmacy, NHS Taysidei suggested the single national formulary (considered fully at the FORMULARY section of this report) may be a way to consider national governance for the prescription of non-medicine interventions.

In June 2018, the then Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Shona Robison, told us—

"A policy team for medical devices within the Scottish Government is in the process of being set up which will consider, with stakeholders, the need for further policies and strategies on medical devices' use in Scotland."v

We ask the Scottish Government to provide detail as to how the assessment process for new medicines compares the benefits of medicines with non-medicine interventions (such as surgery, digital technology and lifestyle changes).

We ask the Scottish Government to provide an update on the work of the established policy team within the Scottish Government considering use of medical devices in Scotland, including remit, timescales for work, engagement activities with stakeholders to date, the outcomes of this work and plans, including timescales, for further scrutiny and governance in the area of medical devices.

Purchase and Procurement

The process of purchase and procurement was one of the four central pillars of our inquiry.

Several submissions, predominantly from the pharmaceutical industry, focused on how budgets were already well managed and predictable due to pricing schemes and the close scrutiny of the drugs budget. The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) observed the "...percentage cost of what we spend on medicines in 2020 is only 1 per cent more than what was spent on medicines in 1948."i They also note "...and yet we have made great advances in this area over the past 40 years."i

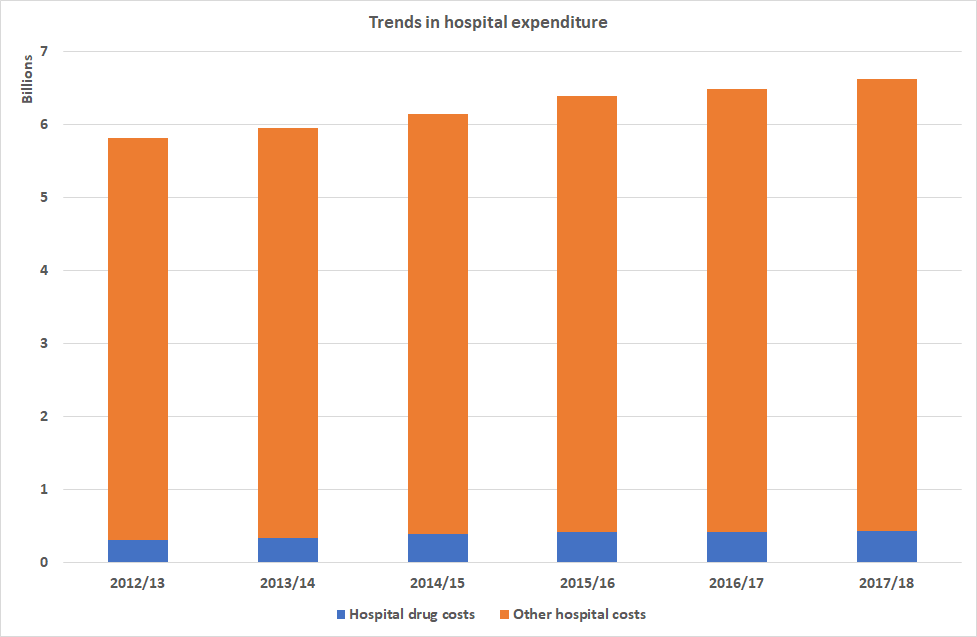

To put this in a different perspective, Spending on medicines constitutes 13.1% of the overall health budgetiii totalling £1.76bn.

The wealth of evidence on spending on medicines we received will be considered in the following sections of this report—

Achieving best value in procurement;

International pricing markets;

Wholesale Supply Chains;

Pricing - branded medicines;

Pricing - generic medicines;

Purchasing in secondary care; and

Purchasing in primary care.

A. Achieving best value in procurement

In the previous chapter of this report, we considered aspects of the Review of Access to New Medicines which said—

"During evidence gathering from stakeholders much was made of the need to take a more sophisticated approach to benefits that includes patient reported outcomes, wider societal benefits such as the ability to continue working or a reduction in care or support requirements. The term “overall budget impact” was used on several occasions and requires the application of sophisticated health economic modelling which takes account not just of medicine costs but of whole system value and impact and introduces the concept of multiple “currencies” not just financial cost. The integration of health and social care presents Scotland with a particular opportunity in this regard."i

That report's author, Dr Brian Montgomery, explainedii to us how the options in terms of new diseases and how to treat them were exceeding the increasing budget being made available in healthcare. He notedii savings may be achieved from disinvestment in a particular drug but these may not be monetary, but the "currency" of "capacity".

David Coulson, Assistant Director of Pharmacy, NHS Tayside, and Rose Marie Parr, Chief Pharmaceutical Officerii, also warned against considering medicines in terms of their cost alone, with the former telling us—

"We need to consider the whole-system cost of medicines, which involves the issues you mention, such as the phlebotomist’s time, lab time and the use of reagents, and not just the procurement cost. We need to take that considered approach to medicines to ensure that we are making the right choices. We must make decisions that are based on sound clinical evidence."ii

B. International pricing markets

We were interested in how the UK's decision to leave the European Union would impact on pricing in the UK and Scotland of medicines.

Warwick Smith, Director General, British Generic Manufacturers Association (BGMA) was supportive of the regulatory landscape in the UK, which he said allowed the market to thrive, emphasising the importance of market forces in maintaining attractive prices when compared with more interventionist regimes in the rest of Europe.i

While Elizabeth Woodeson, Director of Medicines and Pharmacy, Department of Health and Social Care, saidi the UK Government had been clear the price of medicines would not be an issue for discussion in future trade negotiations, there was concerni about potential regulatory or licensing provisions which could be part of trade negotiations with the United States of America. The Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Jeane Freeman, said it was too early to tell whether the outcomes of trade negotiations conducted by the UK Government would impact on price preferring to focus on "standards of governance, patient safety, and regulations that we want to see replicated"i.

C. Wholesale Supply Chains

We heard how the supply chain of medicines impacts on their cost effectiveness.

NHS Ayrshire and Arrani and NHS Scotland Directors of Pharmacyi each stressed the challenges posed by complexities and the time taken for procurement of medicines in both primary and secondary care. Community pharmacists also outlined the least efficient areas of interaction with the supply chain from their perspective although they were at pains to note how they did not allow challenges to impact on the service provided to patients (this is further explored in the COMMUNITY PHARMACY PROCUREMENT section of this report).

Warwick Smith, Director General, British Generic Manufacturers Association (BGMA), toldiii us delays in the supply chain could arise from issues such as availability of raw materials and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), price competition, regulatory change, increased cost of goods, tender processes or penalties for non-supply.

The main points raised with us in terms of the supply chain were related to shortages.

Shortages

Warwick Smith (BGMA) providedi us with examples of why shortages of medicines occur, such as manufacturing changes abroad and reduced capacity due to adherence to regulatory requirements for packaging. He also notedi how this could impact on individual ingredients and how safety concerns could contribute to shortages.

Martin Sawer, Executive Director, Healthcare Distribution Association, defended the current approach suggestingi the decision to leave the European Union had caused the NHS to become better at analysing shortages and horizon scanning, stating there was a "much better understanding of how much stock is around"i. He further described steps taken by wholesalers to improve efficiency within the system, such as updated communication systems to provide better intelligence to pharmacists as to when they may expect stock to be available. He also advocatedi working with the private sector who he said were incentivised to prevent or plug gaps, rather than establish centralised supply management.

Both Warwick Smithi and Martin Saweri noted ongoing European wide strategic discussions on resilience in the supply chain and the geographical centralisation of production of certain medicines and chemicals. We were also interested in the impact of leaving the European Union in terms of the current 'just in time' approach to drug supply and how potential border checks would affect this.

Similarly, Martin Sawer expressed concern about any potential barriers which could impact on price. Alison Culpan, Scotland Director, Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI), said the organisation wanted a "frictionless border so that our medicines can come straight in"i. Angela Timoney, Director of Pharmacy, NHS Lothiani, spoke of the impact of the 'just in time' approach and said where the normal rate of shortages was around 80, there were currently around 120-130 shortages. She praised the efforts of national procurement to mitigate shortages.

Despite assurances to the contrary from industry the number of shortages is steadily increasing and we recommend the Scottish Government discuss this with industry representatives as a matter of urgency.

D. Pricing - Branded Medicines

Voluntary Pricing and Access Scheme (VPAS)

Spending on branded medicines is partly controlled by the Voluntary Pricing and Access Scheme (VPAS) which "caps the rate of growth in spend on branded medicines at 2 per cent. Spend above that is reimbursed; payments are made by industry to the NHS in England—and in Scotland, through the arrangements that we have to repay the devolved Administrations."i It is "expected to save the NHS in Scotland around £90 million in 2019"i. Both the UK Governmenti and industryi were enthusiastic about collaboration and negotiation between them in establishing the scheme.

The advantages of the scheme with regard to spending and cost effectiveness for the Scottish NHS are—

Predictability of budgets - several stakeholders were keen to emphasise how the scheme ensured predictability by capping rises in spending at 2%.

Applies to a significant proportion of medicines - the ABPI noted "In 2018, 58% of medicines accepted for use by the [Scottish Medicines Consortium] SMC were discounted and of the top 300 branded products used in the NHS, 90% had a patient access scheme discount attached."v

Accelerates and streamlines access to medicines - Merck, Sharp and Dohme suggestedv this was particularly helpful in the context of the UK leaving the European Union and it suggested the pricing scheme was a "crucial element of securing global confidence in the UK as a market post-Brexit".

A good model - Roche Products Ltd saidv the principle of a pricing agreement should be replicated across other areas of NHS spending to ensure "stability and surety for the overall finances of the NHS in Scotland".

Allows for commercial flexibility - Kwoya Kirin International highlighted how this allowed for flexibility regarding pricing for different indications (the specific use for a medicine where there may be more than one - see the MULTI INDICATION PRICING section of this report for further details).

However, there were also notes of caution in accepting the virtues of VPAS. The Blood Cancer Alliance advocatedv managing budgets was not the same as delivering value, and this was determined by the SMC.

Efficacy of the Voluntary Pricing and Access Scheme (VPAS)

Elizabeth Woodeson, Director of Medicines and Pharmacy, Department of Health and Social Care, UK Government, told us the UK Government believed "VPAS is an effective mechanism for capping the rate of growth in branded medicine spend, which is, by far, the bulk of expenditure on medicines"i.

Transparency in pricing around the UK

The VPAS includes a clause stating—

"The details of national commercial arrangements agreed with the purchasing authority in one UK country will be made available on a confidential basis to purchasing authorities in any part of the UK. Scheme Members will work with purchasing authorities to achieve comparable arrangements that provide an acceptable value proposition in each part of the UK."i

Written submissions we received were supportive of the ability to share such information and Rose Marie Parr, Chief Pharmaceutical Officer, Scottish Government, notedii transparency of pricing had been a Scottish Government priority in the 2018 negotiations.

However, others noted there was still discrepancy in pricing around the UK, despite this clause. In its written submission, Cancer Research UKiii noted these existed despite the VPAS commitment which should drive value for money in future commercial negotiations with medicines manufacturers.

NHS National Services Scotland (NHS NSS) agreed, observing instances where the price offered in Scotland has been higher than the price offered in England, adding—

"This is directly linked to differences in health technology assessment (HTA) processes."iv

Elizabeth Woodeson said the aim of the scheme was to achieve transparency in pricing across the UK but that this "does not necessarily mean that each country is required to agree the same price."v

Alison Culpan, Scotland Director, ABPI, expanded on this by stating the organisation "encourages its members to give each of the four nations the same arrangement"v and described how other elements may impact on the price paid for a medicine in each country (such as the collection of data). Merck, Sharp and Dohmevii elaborated, comparing the lack of provision for innovative pricing provided through the Commercial Framework and the data collection requirements of the Cancer Drugs Fund in England. They said "The Scottish system requests equitable pricing but equitable pricing does not mean equitable access for Scottish patients. Scotland cannot expect equity on one parameter without providing it in another".vii Alison Strath, Principal Pharmaceutical Officer, Scottish Government, added "We need to consider the different parameters that are sometimes attached to deals."v

Lindsay McClure, Associate Director, Medicines Pricing and Supply, NHS NSSv, said provision to share pricing information among purchasing authorities was in the process of being implemented and her organisation was "delighted" to see "provision for comparable arrangements to be offered to other home countries" in the VPAS agreement. She added work was ongoing to implement the VPAS provision on ensuring comparable arrangements around the UK.

We were surprised to hear UK wide pricing information was not collected, seeing this as a potential source of savings by learning from the approach of comparable countries and sought to discover if the Scottish Government was monitoring whether counterparts received better prices for the same products and if so, on what basis this was achieved. Alison Strath, Principal Pharmaceutical Officer, told us the Scottish Government was "setting up arrangements that will allow information sharing between the organisations that are involved in pricing and negotiations on price, so that we have sight of the prices and can enter negotiations about them."v We were also surprised to hear from NHS National Services Scotlandxii board purchasing and stock holding data would assist in the secondary care procurement process, but this is not currently gathered.

The issue of how pricing around the UK was monitored and shared was at best unclear to us, meaning it is hard to see how Scotland can be comparing the price paid and the arrangements on which these are based to achieve best value.

We recommend the Scottish Government routinely collect information on pricing around the UK along with the arrangements on which those prices were agreed, with a view to maximising the opportunity to obtain the best price for medicines.

We recommend the Scottish Government ensure the NHS is gathering data on purchasing and stock holding by individual boards to improve procurement processes.

Rebate to Scotland and the New Medicines Fund

The ABPI noted that while spending on medicines in 2017/18 was stated at £1.8bni, the actual cost would be lower thanks to rebates and confidential discounts offered by the industry through VPAS.

The Scottish Government has chosen to allocate most of the funding received from the rebate to the New Medicines Fund which Rose Marie Parr, Chief Pharmaceutical Officer, described as "a really positive policy"ii. She continued—

"People can see the increase in medicines and the increase in medicines use, but they can also see that rebate being used transparently for the new medicines fund. Boards have gained over the past five years and they are due to gain up to £90 million or so in the current year."ii

She later noted "To date, around £200 million has been made available to Boards in Scotland through the New Medicines Fund which is a significant contribution to achieving value based pricing itself."iv However, representations from pharmaceutical companies and others highlighted the VPAS scheme and rebates returned £258m to the NHS in Scotland in the last five years. Bristol-Myers Squibbv also suggested the fund was not transparent and called for more data on how this was used by boards.

We were also interested in the extent to which the New Medicine Fund met boards' need with regards to spend on new medicines. David Coulson, Assistant Director of Pharmacyii, said affordability of new medicines was challenging and boards relied on the advice of the SMC as to whether a medicine was worth the resource. The Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Jeane Freeman, said—

"My suspicion is that, in truth, the fund will never be big enough, because pharmaceutical companies will continue to introduce new medicines that people will want to access."ii

We are interested in what happens to applications for end of life, orphan and ultra-orphan medicines when the fund is exhausted. The Cabinet Secretary also suggested there was a need to consider how personalised medicines would be funded in the future.ii

"The new medicines fund is vital, but we need to parallel the work that the SMC is doing in considering its processes in anticipation of precision medicine and coming innovations. We need to consider how we fund and whether we should alter our approach in the light of innovative and important developments for patients."ii

We ask the Scottish Government to clarify the significant discrepancy in the level of rebate received and the amount allocated to the New Medicines Fund.

We request a detailed breakdown by Board of the spend on new medicines each year and the amount they have received from the New Medicines Fund.

Voluntary Pricing and Access Scheme - conclusions