Finance and Public Administration Committee

Budget Scrutiny 2022-23

Introduction

The Scottish Budget 2022-231 was published on 9 December 2021 and presents the Scottish Government's proposed spending and tax plans for the next financial year. This report sets out the Finance and Public Administration Committee's conclusions in relation to the Scottish Budget 2022-23, informed by our pre-budget report on 'Scotland's public finances 2022-23 and the impact of Covid-19'2 of 5 November 2021, as well as the Scottish Government's response to that report.3 Our report also considers the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body's (SPCB) budget submission for 2022-23, as required by the Session 6 Written Agreement between the Committee and the SPCB.4

The need to balance the short-term demands from the response to, and recovery from, Covid-19, with continuing longer-term pressures on Scotland such as demography, poverty, inequality, and structural imbalances, was a key theme of our pre-budget report, which also included recommendations aimed at achieving future fiscal sustainability. Accompanying the Scottish Budget 2022-23 is the Scottish Fiscal Commission's (SFC's) latest set of forecasts for the economy, tax revenues and social security spending, 'Scotland's Economic and Fiscal Forecasts December 2021'.5

The SFC's Forecasts determine the overall size of the Budget and therefore how much the Scottish Government is able to spend. While these forecasts show increasing optimism that the Scottish economy will return to pre-pandemic levels by mid-2022, there is some evidence emerging that the recovery and economic performance in Scotland is not as strong as in the UK as a whole, which is likely to put more pressure on Scotland's public finances. The SFC has advised that the Scottish Budget 2022-23 is 2.6% lower than in 2021-22. After accounting for inflation the reduction is 5.2%.

This suggests that more work is needed to understand what is behind these trends in Scotland and how they can best be addressed. This report explores these issues in more detail.

Alongside the Scottish Budget 2022-23, the Scottish Government also published the fourth Medium-Term Financial Strategy6 (MTFS) and its 'Investing in Scotland's Future: Resource Spending Review Framework'7 (RSR Framework). While both the MTFS and RSR Framework have informed our budget scrutiny, the Committee is undertaking a separate short, focussed inquiry aimed at influencing the resource spending review and a targeted content review of the MTFS to ensure future strategies best support parliamentary scrutiny. We will be reporting on these documents separately by March 2022.

The Committee was supported in our scrutiny of the Scottish Budget 2022-23 by our adviser, Mairi Spowage, and the Financial Scrutiny Unit in the Scottish Parliament's Information Centre (SPICe). We also thank our witnesses from the SFC, Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), Institute for Fiscal Studies and SPCB, as well as David Eiser from the Fraser of Allander Institute, Professor Graeme Roy of the University of Glasgow, and the Cabinet Secretary for Finance and the Economy, for their valuable evidence.

Economic and Fiscal Outlook

UK Economy

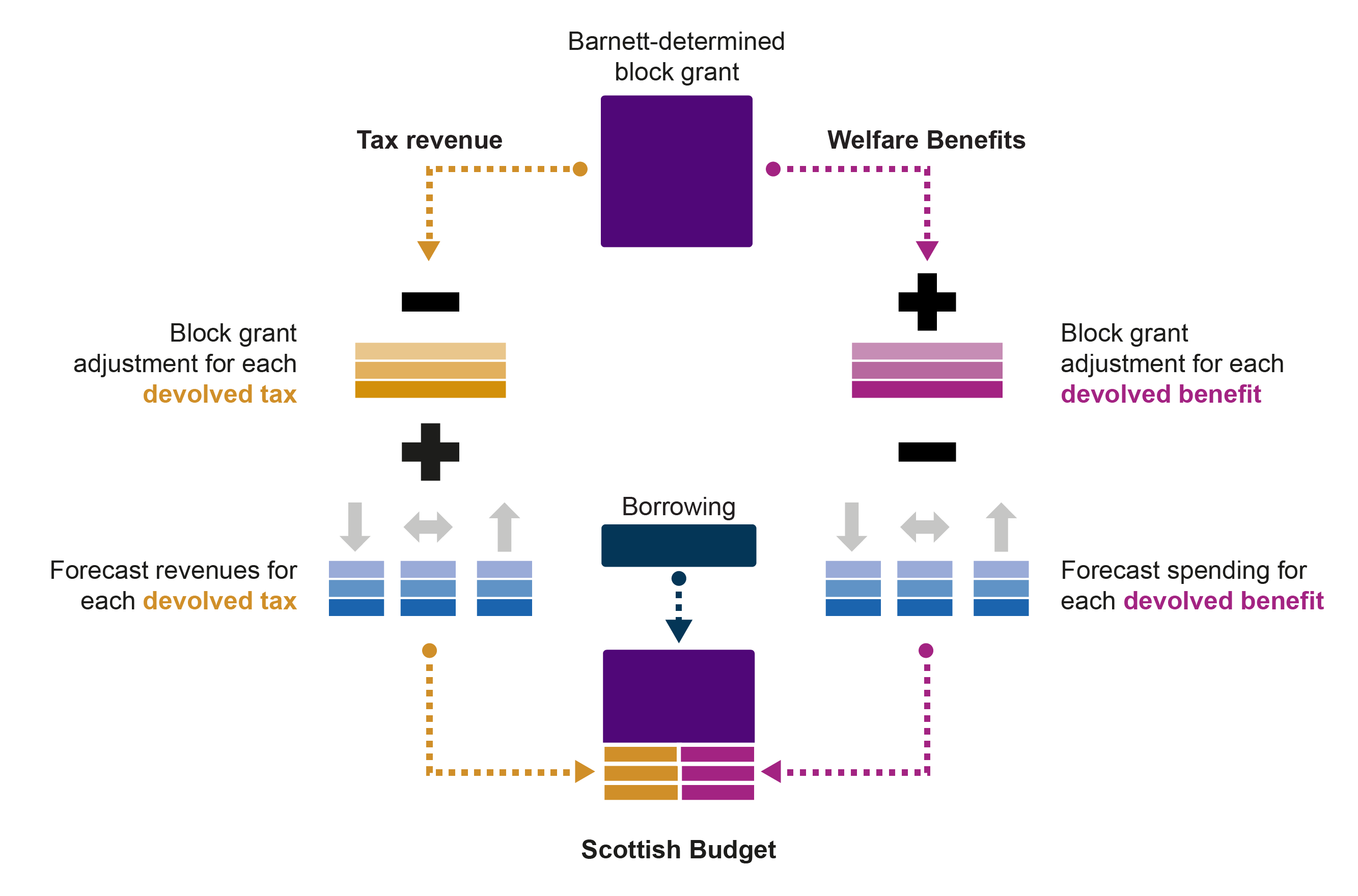

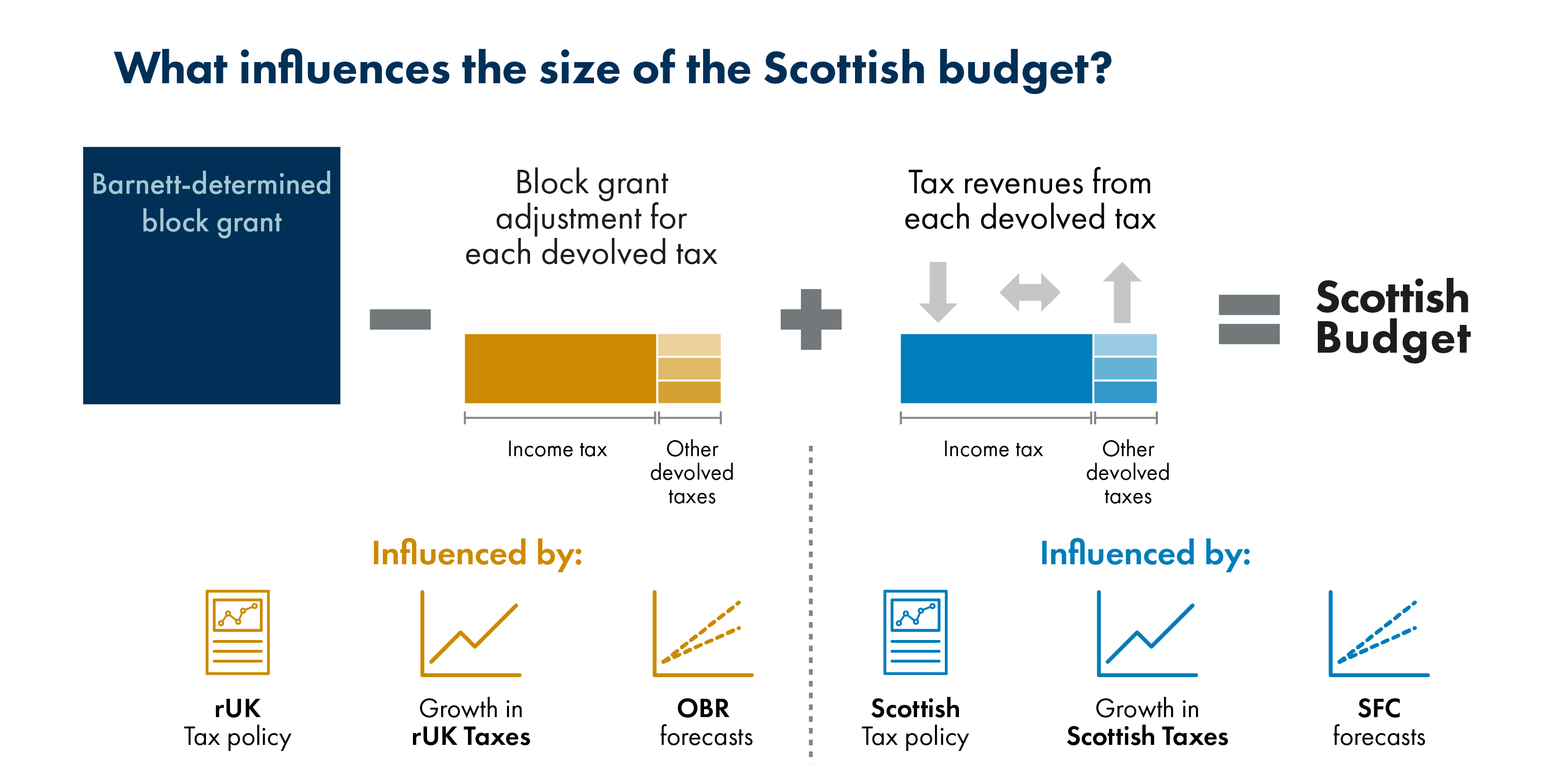

The latest set of official forecasts for the UK were published by the OBR alongside the UK Budget on 27 October.1 These were the first forecasts produced by the OBR since the previous Budget in early March 2021. OBR Forecasts determine the size of the Block Grant Adjustments for both devolved taxes and welfare benefits, whereas SFC Forecasts inform the tax revenues and welfare spending presented in the Budget. The diagram below shows how this influences the Scottish spending envelope.

Following stronger than expected growth in the first half of 2021, supported by the vaccine roll out during that period, the OBR revised upward its expectations for growth over the next five years. In particular, it revised upward growth for 2021, bringing forward some of the growth it was expecting in early 2022. Overall, the OBR considered that, over 2021 and 2022 combined, the economy would grow more quickly than was forecast in March. The economy then moves back to more ‘normal’ levels of growth from 2023 onwards.

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forecast Oct 2021 | 6.5 | 6.0 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| Forecast March 2021 | 4.0 | 7.3 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

However, we note that these forecasts come with caveats. Firstly, concern about the outlook for inflation, and secondly, these OBR forecasts were produced well before the emergence of the Omicron variant.

The OBR itself flagged that "inflationary risks have intensified" since it closed its forecast, and this has been borne out in reality, with the latest Office for National Statistics data from December2 showing CPI inflation at 5.4%. The impact this has on economic activity and tax receipts will depend on how this feeds through to wages and how much price rises constrain consumer spending in the short term.

Our adviser highlighted that the emergence of the Omicron variant will also have significantly changed the short-term outlook for growth, given the economic restrictions that have been brought in over the last month or so. How much these may constrain growth over 2022 as a whole is currently very uncertain. It may be for example that growth lost over the last month or so can be regained over the rest of the year. However, as our adviser noted, looking across independent forecasters, there has been a definite weakening of the outlook for 2022 during the month of December.

In the UK Budget published in October, the Chancellor of the Exchequer made use of some of the fiscal headroom given to him by the more optimistic forecasts and forthcoming tax rises. Our adviser has observed that, if the OBR’s next set of forecasts are more pessimistic, this may present challenges for the Chancellor in meeting his fiscal rules.

Scottish Economic and Fiscal Outlook

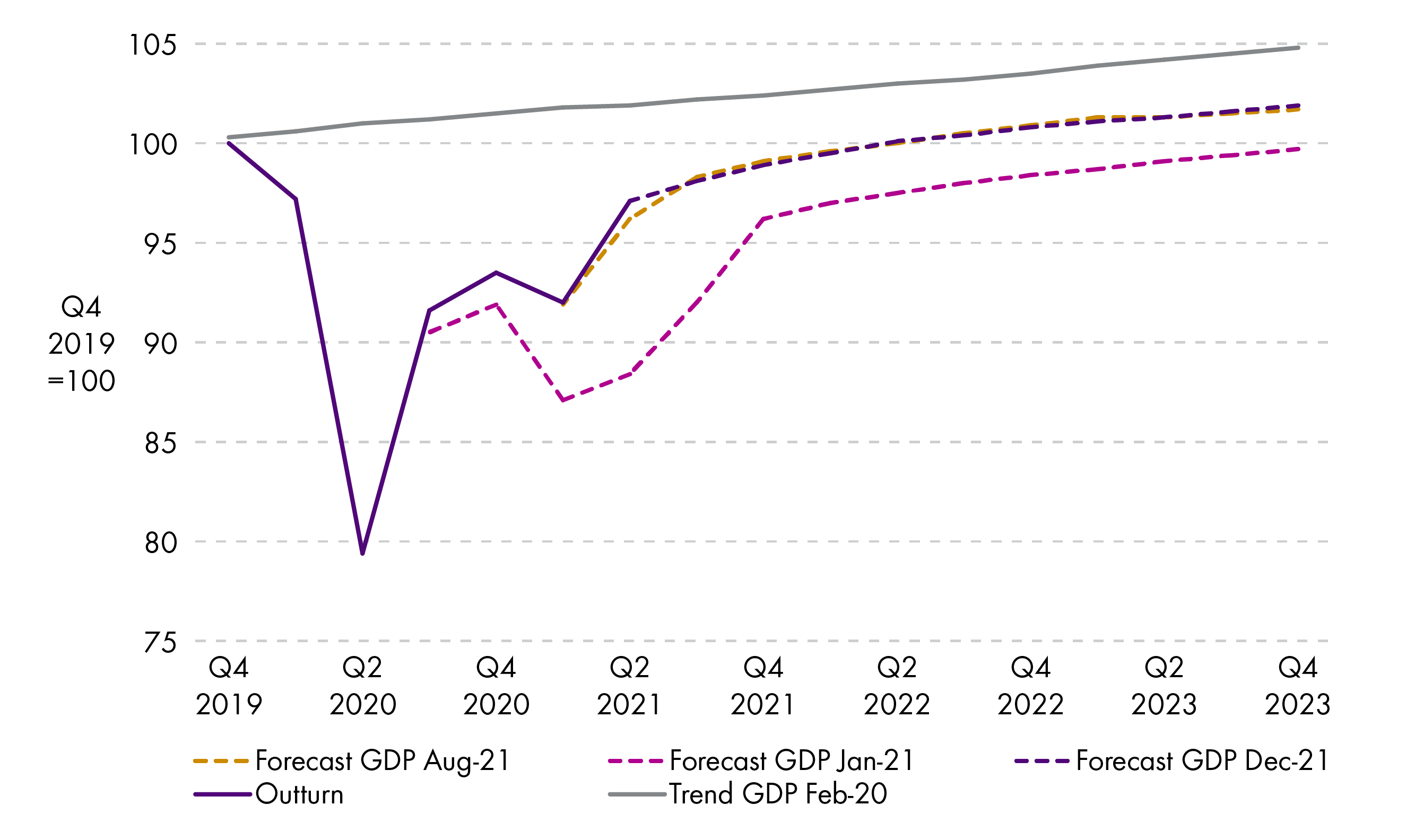

The SFC set out its latest forecasts for the Scottish economy over the next five years alongside the Scottish Budget on 9 December1 as illustrated in Figure 2 below. These were broadly unchanged from its August forecast, assuming growth of 6.7% in 2021 and 3.8% in 2022. It is essentially still forecasting that the economy will return to pre-pandemic levels by the second quarter of 2022. Again, like the OBR, these forecasts were produced in advance of the emergence of the Omicron variant.

The SFC’s Forecasts point to a slower recovery in wage growth and income tax receipts as we emerge from the Covid-19 pandemic in Scotland and the UK. This trend of slower growth in income tax receipts is forecast to continue into the medium-term, which has important implications for the tax revenues forecast by the SFC and consequently for the Scottish Budget in future years. While we highlight these issues in this section, we go on to explore them in more detail later in the report.

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 2021 | 1.8 | 7.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.7 | |

| August 2021 | 6.7 | 4.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| December 2021 | 6.7 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| OBR October 2021 | 6.5 | 6.0 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

The SFC’s outlook for earnings has also changed significantly since its previous forecast was produced in August. Although much of the SFC’s narrative focuses on the changes since the January forecast, the SFC also sets out the reason for the significant changes since August.

| 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFC January 2021 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.3 | |

| SFC August 2021 | 2.7 | 5.1 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.5 |

| SFC December 2021 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 |

| OBR October 2021 | 1.4 | 5.2 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 3.6 |

The SFC states that—

In August 2021, we increased our forecast significantly from January 2021, in line with higher inflation. Our new forecast is lower than in August because, with inflation being driven primarily by global energy prices rather than domestic factors, we now assume a lower degree of pass-through to nominal earnings. This means less upward pressure on nominal earnings, and more downward pressure on real earnings, than we had assumed in August.1

This judgement by the SFC has significant implications for the income tax forecast compared to the position from August 2021.

| 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 2021 | 11,838 | 11,850 | 12,263 | 12,907 | 13,481 | 14,080 | 14,718 |

| Change Jan to August | +88 | +899 | +1,162 | +1,364 | +1,580 | +1,838 | |

| August 2021 | 11,833 | 11,938 | 13,162 | 14,069 | 14,845 | 15,660 | 16,556 |

| Change Aug to December | -160 | -399 | -532 | -604 | -766 | ||

| December 2021 forecasts | 11,833 | 11,938 | 13,002 | 13,671 | 14,313 | 15,056 | 15,790 |

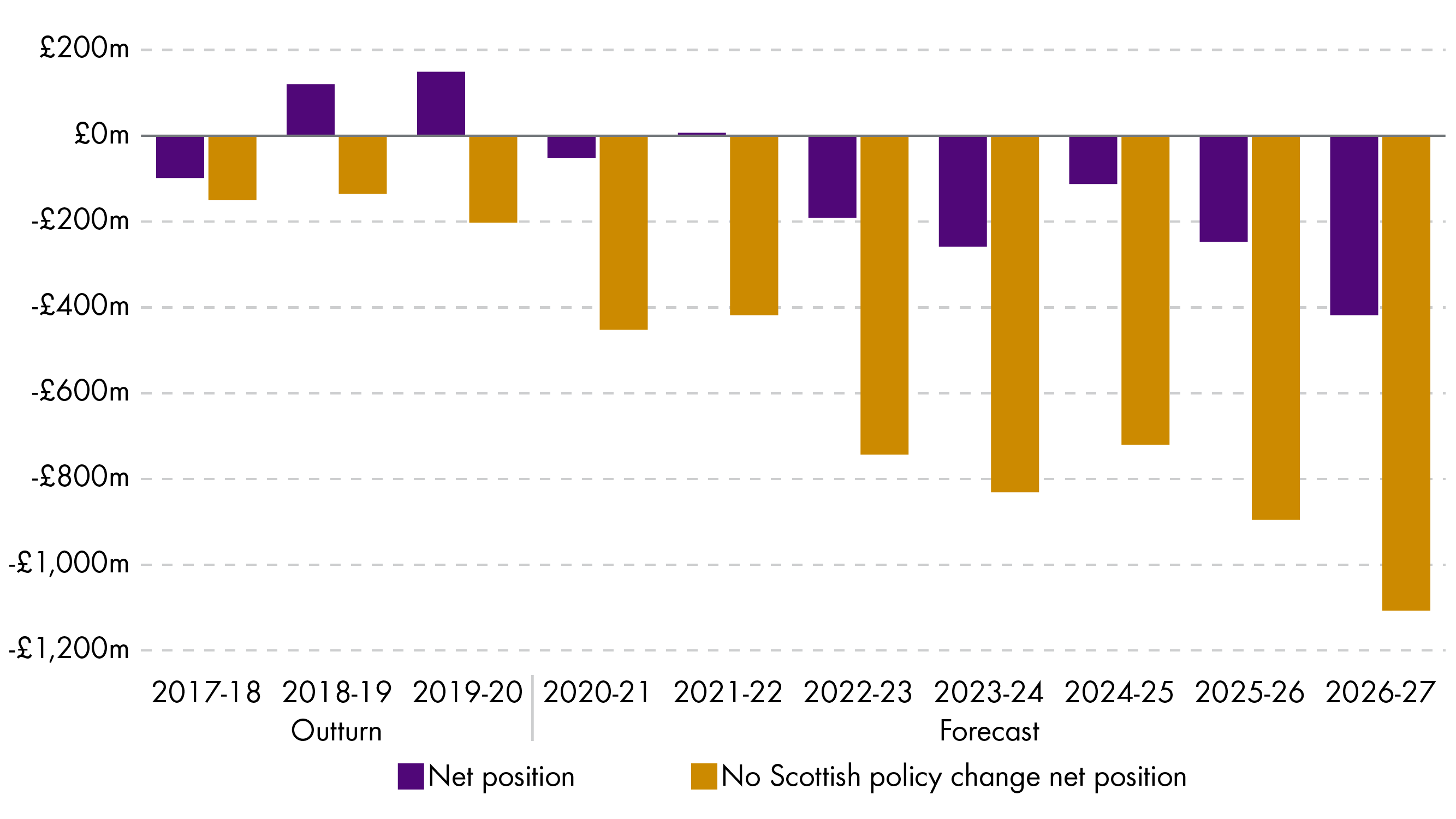

The Forecast leads to a “net tax position” for the 2022-23 budget of -£190 million after the BGA and the addition of forecast tax revenue. This is despite income tax bands and rates set by the Scottish Government raising more revenue than the rates and bands set by the UK Government.

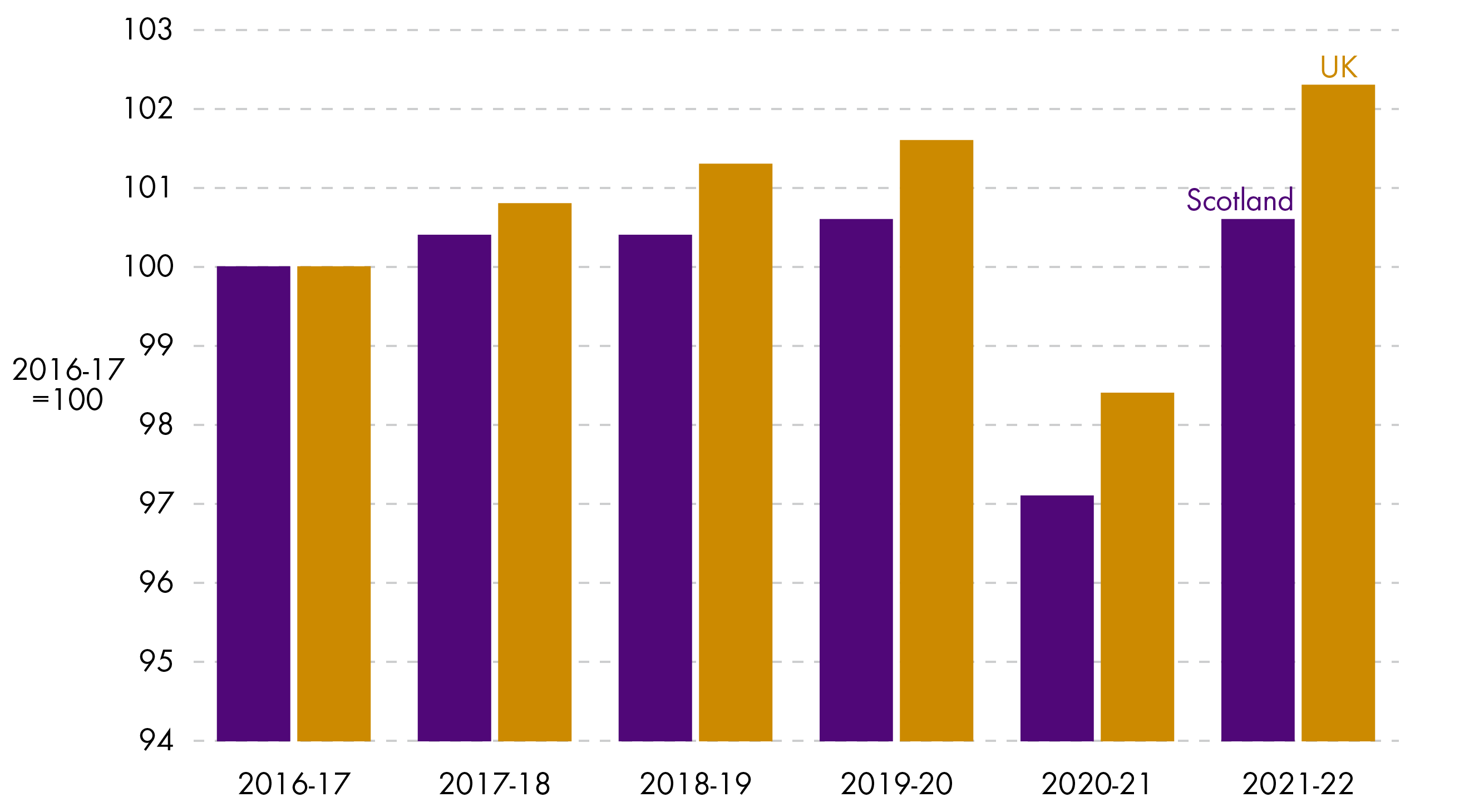

As illustrated in the chart below, the SFC explains that, "in the absence of Scottish policy changes to raise additional income tax revenue, the net position would have been negative in every year since 2017-18, and 2022-23 is a continuation of this trend". So, income tax policy changes in Scotland have largely offset the poorer growth in receipts in Scotland.

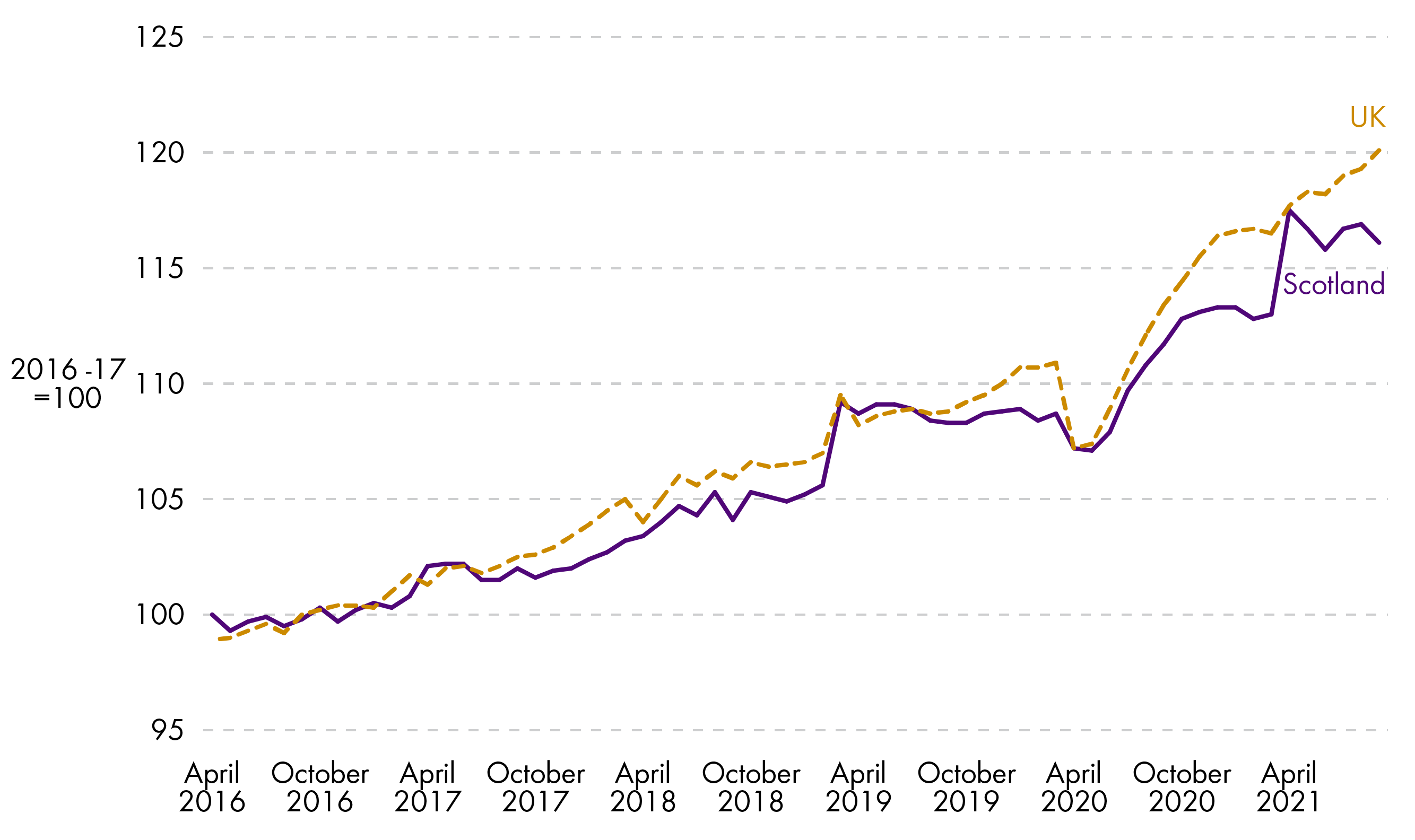

The explanation provided by the SFC and our adviser is that two main issues are driving the negative net tax position: the growth in average earnings, and the growth in participation in the labour market, both of which have been weaker in Scotland than in the UK as a whole. Scottish average earnings have grown by 16% since 2016-17, compared to 20% in the UK.

The SFC discusses the possible reasons for slower pay growth in Scotland in Box 3.2 of its report, which focuses on the likely impact on earnings over the period of the pandemic. It states that "when it comes to PAYE mean pay growth relative to pre-pandemic levels, the Scottish regions are … spread across the distribution but all are below the UK average", adding "London emerges as an outlier, with mean pay growth outpacing that of all other regions. It goes on to explain that this reflects "both compositional effects, to the extent that lower-paid jobs lost during the pandemic have been slower to come back in cities, and strong PAYE mean pay growth in the financial services sector which is central to the London economy".1

Loss of highly-paid oil and gas jobs in North East Scotland is identified by the SFC as a particular source of these issues. Given the historic importance of this sector to overall income tax receipts and the projected decline of North Sea oil and gas, there is concern about the impact this will have on the net tax position in the future.

As well as average earnings, the SFC reports that there is also a poorer outlook for participation in the labour market, which also affects the outlook for income tax. Even when slower population growth is taken into account, labour market participation has been growing more slowly in Scotland than it has in the UK as illustrated in Figure 5 below.

As the SFC explains in Box 3.1 of its report, poorer labour market participation is being driven by demographic factors and changing participation rates in different parts of the age distribution. A larger share of the population in older age groups, and the relative participation in younger age groups, are highlighted as particular issues.

Scottish Budget 2022-23

Summary

Published on 9 December 2021, the Scottish Budget 2022-231 sets out the Scottish Government’s cross-government spending priorities as:

Tackling inequalities;

Ending Scotland's contribution to climate change; and

Supporting Scotland's recovery.

The Scottish Budget 2022-23 notes that the 2022-23 capital budget grant from HM Treasury is reduced by 9.7% in real terms compared with 2021-22. The Scottish Government can borrow up to £450 million in each year for capital investment, up to a cumulative total of £3 billion. It plans to borrow the maximum of £450 million to support infrastructure expenditure in 2022-23. Lower levels of capital borrowing are expected in future years, reaching a total of £2.73 billion of the Scottish Government's £3 billion capital borrowing limit by the start of 2026-27.1

According to SPICe, the Scottish Budget 2022-23 allocation for capital (infrastructure) is expected to increase by 1.2%, after including borrowing and adjusting for inflation, while the resource budget, which is day-to-day spend, is projected to fall by 2.8% in real terms this year.3

Specific spending commitments for 2022-23 include doubling the Scottish Child Payment to £20 from April 2022 and starting delivery of the new Adult Disability Payment. Funding has also been made available for decarbonisation of homes, buildings, transport and industry, and the minimum wage rises to £10.50 an hour for social care staff and those covered by the public sector pay policy.

In terms of tax policy, the Budget 2022-23 proposes that income tax rates remain unchanged, but starter and basic rate bands will increase by CPI inflation whilst the remaining thresholds will remain frozen. Land and Buildings Transaction Tax rates and bands are maintained at current levels, including those for the Additional Dwelling Supplement4. Standard and lower rates of landfill tax are increased to maintain consistency with rates in the rest of the UK. The council tax freeze on rates agreed for 2021-22 will end in 2022-23 so councils will have full flexibility to set their own council tax rates for the first time since 2007. There will be a 50% rates relief from business rates (Non-Domestic Rates or NDR) for the first three months of 2022-23 for properties in the retail, hospitality and leisure sectors, capped at £27,500 per ratepayer, and NDR basic rate poundage will be 49.8p, a below inflation rise.

The Fiscal Framework

The Scottish Government has sought to expand its 2022-23 spending power by using some of the flexibilities in its Fiscal Framework with the UK Government.1 Under the Fiscal Framework, the Scottish Government is able to borrow up to £600 million each year, within a statutory overall limit for resource borrowing of £1.75 billion. Resource borrowing can only be undertaken for: in-year cash management, with an annual limit of £500 million, or for forecast errors in relation to devolved and assigned taxes and social security expenditure, with an annual limit of £300 million. For 2022-23, the Scottish Government plans to borrow £15 million under resource borrowing to smooth the impact of forecast error (although actual borrowing drawdown will be determined based on in-year financial position).2

It is also able to build up, and draw down, funds from the Scotland Reserve, which is capped in aggregate at £700 million, and limited to £250 million annual drawdowns for resource and £100 million for capital. The Scottish Government intends to draw down £179 million from the Scotland Reserve in 2022-23.

As mentioned earlier in this report, the Scottish Government also plans to borrow the maximum of £450 million in capital to support infrastructure expenditure in 2022-23. The SFC is required to assess the reasonableness of the Scottish Government's borrowing plans and has assessed its 2022-23 capital borrowing plans as "reasonable", noting that although the Scottish Government usually plans to borrow the maximum of £450 million in the budget, actual borrowing is typically lower than planned for.

The Scottish Government further intends to use various funding streams from the UK Government to supplement the amount available for capital expenditure in 2022-23, including financial transactions funding and recycling receipts received from previous loans, capital allocations in relation to Network Rail funding arrangements, City Deal funding, and receipts from the fossil fuel levy.3

When asked about the implications of the cut in capital resources, the Cabinet Secretary confirmed that the capital being allocated through the UK Government's Comprehensive Spending Review is lower than the Scottish Government's “conservative and cautious estimates”. Therefore, some of the capital commitments made in the Scottish Government's Capital Spending Review 2021 may “need to be managed over a longer period”. She added, however, that "there is a clear and ambitious willingness in the Budget to use as much capital as possible, particularly next year, when economic recovery will still be vitally important."4

John Ireland from the SFC told the Committee that, between the first year of the budget and the final year of its forecasts (2026-27), there is a 15% fall in the capital budget that is available to the Scottish Government, which is largely based on forecasts of falls in UK Government capital spending. He added that the Scottish Government's upper limit on capital borrowing “will certainly start to bite before the end of the forecast period."5

David Eiser highlighted that the capital budget over the next few years is relatively high in historical terms, but it is "fairly flat" over the course of this parliamentary session. As such, he suggested that the Scottish Government could use its capital borrowing powers to increase that budget "a bit at the margins", adding "you could probably make a case for the Scottish Government to have greater capital borrowing powers". The Fiscal Framework allows for no inflationary adjustment in the capital borrowing annual and total limit, meaning it has effectively been frozen since 2017-18. David Eiser therefore suggests "at the very least, there is a good case for the annual borrowing limit and the overall cap to increase in line with some measure of inflation or of the overall budget" and that this would be a matter for negotiation between the Scottish and UK governments during a review of the Fiscal Framework, which is now expected to take place in 2022.5

A similar point is made in a paper published on 21 December on 'Options for reforming the devolved fiscal frameworks post-pandemic'7 produced by Professor David Bell, David Phillips and David Eiser. They argue that there should be modest increased flexibilities in borrowing and reserve drawdowns in 'normal' times and the reintroduction of funding guarantees and extended borrowing powers for devolved governments during times of extreme and rapidly moving adverse shocks like the Covid-19 pandemic. They explain that "this would ensure that policy-making is not held up by having to wait until funding becomes available via the Barnett formula, after policies have been announced for England."7

The Committee’s recommendation, in its pre-budget report, that the merits of additional capital borrowing schemes, such as prudential borrowing, be considered as part of the upcoming Fiscal Framework review, was endorsed by the Scottish Government in its response.

We note that the scope of the independent report to precede the Fiscal Framework review will focus on Block Grant Adjustments only, but that the review itself will be broader and that stakeholder views will be sought as part of both processes.

At the time of writing, the independent report, which was due to be produced by the end of 2021, has not yet been commissioned. The Committee believes that continued slippage in starting this work, and resulting delays to delivering its outcomes, is detrimental to the effective management of the Scottish Budget. We therefore urge the UK Government, in conjunction with the Scottish Government, to make swift progress in the commissioning of the independent report, and thereafter in conducting the Fiscal Framework review. We continue to seek updates on progress with this work and intend to feed in our views to both the independent report, following our current scrutiny of the operation of Block Grant Adjustments, and to the review itself.

Given that the review process may take some time to complete, the Committee considers that it would be prudent to put in place plans now to manage the potential risks of the Scottish Government almost reaching its capital borrowing limit in a few short years.

Extra Sources of Income

The Scottish Government has assumed that it will receive extra income of £620 million for the resource budget in 2022-23 from a range of sources. These are: additional UK Government funding at Supplementary Estimates, additional UK Government funding at a Spring fiscal event, agreement between the UK and Scottish governments on funding transfers for a spillovers dispute relating to income tax, and income from the Crown Estate offshore wind leasing.1

In its latest forecasts, the SFC expresses "reservations about the likelihood and amount of income available from some of these sources" but concludes that, given "the possibility of resource underspends materialising in the current financial year, we consider that, on balance across all the sources together, the Scottish Government assumptions are reasonable".2 David Eiser further noted that, on the basis of previous budgets, it was almost inevitable that extra resources of a similar sum would flow from additional UK Government spending and that it was perhaps more prudent to factor this into the Budget when it can be used more strategically and be subject to greater scrutiny than if it was included in the Spring Budget Revision. However, he also recognised that, if the full sum did not materialise, additional pressure would be placed on the Scottish Budget.3

The Cabinet Secretary explained to the Committee that "we have considered all those sources individually and collectively, to arrive at a prudent risk-assessed figure of £620 million of additional expected resource funding". Asked specifically about the personal allowance spillover dispute, which dates back to 2017-18, Ms Forbes indicated that the two governments had agreed both that a transfer to the Scottish Government is due, and the methodology to be used. She added, "my assumption that funding will be allocated is rock solid [but] there is some disagreement about the quantum of funding that should be transferred". She clarified that figures being considered ranged between £400 million and £1.7 billion.4

The Scottish Government’s assumption that it will receive £620 million in additional sources of income for the resource budget which have not yet been confirmed, gives the Committee some cause for concern. While we accept that this approach has benefits in providing greater opportunities for transparency, scrutiny and effective financial management, should this sum not materialise, it will place significant additional pressure on the Scottish Budget at a time when the impact of Covid-19 and other continuing pressures persist. We therefore request that the Scottish Government updates the Committee as and when these sources of income are confirmed and, in the meantime, we seek clarification of how the Scottish Government proposes to address any shortfall should these funds not materialise.

We welcome the agreement between the two governments that funds should be transferred to the Scottish Government regarding the personal allowance policy spillover. We note the significant divergence in the positions of the two governments on the actual sums involved and we therefore urge the UK and Scottish governments to bring a swift resolution to the matter so that the final agreed funding can then be transferred to the Scottish Budget.

Presentation of Figures

Since publication of the Scottish Budget 2022-23, there has been some debate about whether the headline figures are increasing or falling, relative to 2021-22, due to a differing presentation of the figures by the Scottish and UK governments. The Scottish Government, in its Budget document, uses the total 2021-22 baseline figure to compare with the 2022-23 data, whereas the UK Government, in its Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021,1 removes the Covid-19 Barnett consequentials from the 2021-22 baseline figure. The Scottish Government argues its approach is appropriate, as the pandemic will continue to require financial interventions, while the UK Government suggests its way of presenting the figures is a fair like-for-like comparison, as it had signalled its intention to wind-down direct pandemic-related fiscal interventions back in October 2021.

As an illustrative example, table 5 below shows the effect of this difference in approach on how the level of change in the Scottish Budget 2022-23 compared to 2021-22 is presented.

| Real terms, £ billion | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| HM Treasury presentation (Autumn Budget 2021) | 36.7 | 39.5 | 7.7% |

| Scottish Government presentation (Scottish Budget 2022-23) | 45.4 | 44.4 | -2.3% |

Note: UK Budget numbers exclude Social Security spending and various fiscal flexibilities from the Fiscal Framework. Scottish Government numbers are from Annexe of document and show what the SG is proposing to spend in 2022-23.

The Committee accepts that there may always be a degree of 'political spin' about how the level of UK Government funding affects the Scottish Budget. However, we believe that greater transparency regarding the headline figures would better assist effective scrutiny and constructive political debate around Scotland's public finances. It would be helpful if in future years the Scottish Fiscal Commission's forecasts were to form the basis of budgetary calculations.

COVID-19 Funding

2021-22

The SFC Forecasts were finalised before the emergence of the new Omicron variant of Covid-19, however, at the time it was published, the SFC considered it was "reasonable to assume the effects of Omicron fit within our central assumptions" that from April 2022 Covid-19 would become endemic and begin to be managed through guidance and voluntary measures. The Scottish Budget 2022-23 too was published at a time when information on the effects of Omicron were limited. Indeed, the Cabinet Secretary for Finance and the Economy told the Committee on 21 December that these "events over the past two weeks have almost overtaken the budget that was published."1 The increased transmissibility of the virus and increasing case numbers led to the reintroduction of some restrictions affecting individuals and businesses in Scotland, along with announcements of additional financial support.

The first of these funds was announced2 by the First Minister on 14 December with £200 million being found from existing budgets in 2021-22 to provide £100 million for self-isolation grant funding and £100 million for hospitality and culture businesses impacted by cancellations in the run-up to Christmas. Asked how these measures had been funded, the Cabinet Secretary explained to the Committee on 21 December that “we have looked right across the board and identified funding on a portfolio-by-portfolio basis for that £200 million”.1 Ms Forbes wrote to the Committee on 22 December with some further details, indicating "we have taken challenging decisions to support the additional spend, by repurposing health consequentials to directly support public health compliance via business restrictions and self-isolation, re-profiling commitments across a wide range of different spending lines, including some on employability and by reducing our expected income in 2022-23 so that it can be deployed in 2021-22."4

The UK Government on 14 December also announced funding for the Scottish Budget of £220 million "to progress the vaccine rollout and wider Covid-19 response."5 Further announcements followed on 20 December of an additional £220 million,6 and on 21 December of another £80 million7 to provide Covid measures. However, the Cabinet Secretary, in her 22 December letter to the Committee, advised that HM Treasury had since confirmed the £80 million figure announced on 21 December was already included "within the £440 million envelope they notified to us earlier this week".4

The Scottish Government disputes how much of this £440 million is 'new' money and how much may need to be repaid to the UK Government after the Supplementary Estimates in early 2022. In her letter to the Committee of 22 December, the Cabinet Secretary explained that she had written to the Chief Secretary to the Treasury expressing her disappointment at "the intention to undertake a reconciliation with the UK Supplementary Estimate consequentials in the new year, with any funding in excess of the consequentials to be repaid" and seeking an urgent Finance Ministers' Quadrilateral "to help broker a reasonable way through this."4 Similar points were made by the First Minister, in her statement to Parliament on 21 December, when she also clarified that "the Treasury announcement gives us additional spending power now of £175 million" and confirming that these funds would be allocated in full to business support.10

The First Minister has since announced to Parliament, on 5 January 2022, a further £55 million to support sectors impacted by the response to the new variant, including taxi and private hire drivers, beauticians, hairdressers, sport and tourism.11 No information has been provided on how this additional £55 million is being funded.

All additional funding announced is for 2021-22 and will be formally allocated in the Spring Budget Statement due to be published in early February.

The Committee asks for more detail on exactly how the financial package for those businesses hit by Omicron is being funded.

We consider, in the interests of transparency and efficient management of Scotland’s public finances, that both governments should, as part of the Fiscal Framework review, consider and agree a process by which Barnett consequentials are clearly communicated to bring greater certainty over what is ‘new’ money and what is being reprofiled.

Our view remains that the Fiscal Framework review presents an opportunity to consider more broadly how communication and transparency between the UK and Scottish governments can be improved, to enable more effective financial management. We note from its response to our pre-budget report that the Scottish Government shares our view that the review is a chance to consider "what improvements can be made to support better intergovernmental engagement, coordination and dispute avoidance and resolution."

2022-23

Unlike the 2021-22 Scottish Budget, which included a table setting out allocations of Covid-19 funding by portfolio, this year’s Scottish Budget document does not include any specific Covid allocations, despite the likely impacts of, and recovery from, the pandemic remaining with us for some time to come.

The Committee heard at its meeting on 14 December that the distinction between pandemic spending and non-pandemic spending had become increasingly blurred in the Budget.1 This followed evidence from the Auditor General for Scotland (AGS) during pre-budget scrutiny in which he raised concerns that tracking Covid-19 related funding would become more challenging over time. Noting this observation in our pre-budget report, we asked the Scottish Government to "commit to providing transparent and timely information on all Covid-19 allocations to allow proper scrutiny of where, and how effectively, the money has been spent, so that any lessons can be learned for the future."2 The Scottish Government responded that it "understands the importance of this information and will continue to provide transparent information on all Covid-19 funding allocations through timely provision of information to the Committee and through the formal budget revision process."3

The AGS, commenting on Audit Scotland's recent report on the Scottish Government's Consolidated Accounts 2020-21 published on 16 December 2021, repeated his calls for more transparency around Covid spending. He stated that the Scottish Government "now needs to be more proactive in showing where and how this money was spent and show a clearer line from budgets to funding announcements to actual spending", adding that "this will support scrutiny and transparency of a matter of such significant public interest and importance."4

With the Covid-19 pandemic continuing to require financial interventions, it is imperative that the Scottish Government continues to provide full, transparent and timely information on all Covid-19 allocations. The Committee also asks how the Scottish Government is assessing the effectiveness of its Covid-19 interventions. This type of information not only allows proper scrutiny of where, and how effectively, the money is being spent, it also enables us to identify any effects of diverting funds from other areas, and to learn lessons for any future health emergency.

Underspends

Audit Scotland's report on the Scottish Government's consolidated accounts for 2020-21 highlighted a £580 million underspend that year. In his remarks on the report, the AGS called on the Scottish Government to be "more proactive in providing more comprehensive and detailed information and clearly link budgets, funding announcements and spending, given the significant public interest."1

In response to questioning about this underspend, the Cabinet Secretary reiterated that "it is illegal for me to overspend … therefore, as we get closer to the end of the financial year, coming in under budget is a bit like landing a 747 on a postage stamp."2

In response to questions about the exact figures involved, Ms Forbes told the Committee that the underspend is "against an overall budget of about £50.7 billion", so it is about 1% of the total”. She explained that the £207 million underspend on capital projects was primarily due to the impact of the lockdown in the last quarter of the financial year. There had also been an appeal from community groups, local government and others to try to manage that slippage into this year and so "all of that funding has been allocated on an ongoing basis to capital needs, including for infrastructure", a budget line with an underspend of £321 million. Finally, in resource, late health consequentials for the vaccine programme and Covid response were managed into the 2021-22 financial year rather than having to all be spent by the end of March 2021. She clarified that managing significant additional sums late in the financial year can "lead to poor decision-making" if it cannot be carried forward beyond 31 March. She also pointed to the 2021 Autumn Budget Revision3 published in September, which formally allocates £560 million of that original £580 million underspend.2

Asked whether she expected a similar underspend to be carried forward from this year into the 2022-23 budget, Ms Forbes said that, while some uncertainty remains over Covid funding, she did not expect there to be much, if any, resource underspend otherwise she would have "baked it into the assumptions for next year's budget."2

The Committee accepts that the Scottish Government faces challenges in managing its budget where there is a limit on the funds that can be carried forward into the next financial year, particularly during a crisis such as the pandemic when funding allocations and spending decisions can be more fluid and reactive. We believe, however, that there is scope for the Scottish Government to be more open and transparent about its approach, which we consider may help to foster greater public understanding of this issue.

We further seek clarification as to whether the underspend balance for 2021-22 of £20 million will be formally allocated in the Spring Budget Revision.

Income Tax

Proposals for Income Tax Bands and Thresholds

The Scottish Government’s proposals for income tax from 2022, set out in the Scottish Budget 2022-23, require to be approved by the Scottish Parliament through a Scottish Rate Resolution before Stage 3 of the Budget Bill can take place. Once set, income tax rates cannot then be changed in-year. The Committee notes that, this year, very modest changes are proposed. There are no proposed changes to income tax rates however, the basic rate threshold is increased by 0.4%, and the intermediate rate threshold by 1.5%. All other thresholds remain unchanged.1

The SFC estimates that the Scottish Government's decision to freeze the higher rate threshold at £43,662 results in additional revenues to the Scottish Government of £106 million compared to what would have been raised if this threshold had been increased in line with inflation. As a result, more individuals will pay tax at the higher rate of 41%, as their earnings rise to take them above this threshold.2

The SPICe briefing notes that the Scottish Government's proposals mean that all Scottish taxpayers would pay less income tax in 2022-23 than in the previous year, however the savings are very small—65p a year for those on incomes below £25,000, rising to £4.57 per year for those earning above this amount.3

The proposed rates and bands are shown in table 6 below.

| Bands | Band Name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £12,570* - £14,732 | Starter | 19 |

| Over £14,732 - £25,668 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £25,668 - £43,662 | Intermediate | 21 |

| Over £43,662 - £150,000** | Higher | 41 |

| Above £150,000 | Top | 46 |

*Assumes individuals are in receipt of the standard UK personal allowance (£12,570 in 2022-23) ** Those earning more than £100,000 will see their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000

The tax-free Personal Allowance, which is set by the UK Government, remains unchanged from 2021-22 at £12,750. The UK Government has also frozen the higher rate threshold at £50,270 and announced as part of its Spring 2021 UK Budget that it will leave these levels unchanged until 2025-26.

Decisions on national insurance contributions (NICs) are also made by the UK Government and are linked to UK tax thresholds. The NIC rate drops from 12% to 2% at the UK higher rate threshold of £50,270, with the effect that Scottish taxpayers who earn between the proposed higher rate threshold of £43,662 and the UK higher rate threshold of £50,270 will pay 41% income tax and 12% on NICs on their earnings within that range, a combined tax rate of 53%, rising to 54.25% from April. This compares with 43% for those earning above £50,270, which will rise to 44.25% from April.

The Cabinet Secretary was asked to explain how this married up with the Scottish Government's stated priority to “make the tax system fairer and more progressive, and to protect low and middle-income taxpayers”. Ms Forbes said that this is "to my mind, another sign of the inadequacy of the devolution settlement". She indicated that she had recently written to the Chief Secretary to the Treasury to request that the national insurance upper earnings limit for Scottish taxpayers be aligned with the Scottish higher rate threshold, however that request had not been granted. Her view is that the Scottish Government should "have a voice" regarding such decisions that affect taxpayers in Scotland.4

More broadly, the Cabinet Secretary outlined that the Scottish Government had chosen to make income tax fairer and more progressive, with 54% of taxpayers paying less income tax next year than they would if they lived elsewhere in the UK, and that "those who can afford it are being asked to contribute a little more". She added that "in return, those living in Scotland continue to have access to a wider and better funded range of public services…, whether that is prescription charges or tuition fees."4

The Committee believes that there should be engagement between the two governments on the potential effects of tax policies set in the UK, such as national insurance contributions, that interact with devolved tax policy, to ensure that Scottish taxpayers are not negatively impacted. The Fiscal Framework review provides an opportunity to put in place formal arrangements for inter-governmental working to ensure the potential interactions between tax policy decisions by the UK and Scottish Government are fully considered.

Income Tax Revenue

The Fiscal Framework sets out the method for adjusting the Scottish budget to account for certain taxes now being set and raised in Scotland, including income tax.

The Forecast for the Block Grant Adjustment (BGA) is based on OBR forecasts of income tax revenues from the rest of the UK (rUK), published at the same time as the UK Budget announcement. The SFC Forecasts for income tax receipts determine the actual revenue that the Scottish Government will be able to draw down from HM Treasury during the year ahead. The SPICe briefing on the Scottish Budget 2022-23 notes that, “where the SFC’s tax forecasts are higher than the offsetting BGA for taxes, the Scottish Budget is better off than it would be without fiscal devolution [and] therefore, the converse is also true – if the SFC tax forecasts are lower than the offsetting tax BGA, the Scottish Budget is worse off than it would have been without fiscal devolution.”1 The diagram below shows these various factors that influence the Scottish budget, looking at tax revenues only.

As we note earlier in this report, for the first time since devolution, the SFC highlights that Scottish income tax revenues have fallen behind the BGA, with a shortfall of £190 million forecast in 2022-23, rising to a shortfall of £417 million by 2026-27.

The Committee’s adviser explained that the deterioration in the SFC’s income tax forecasts since its August publication was unexpected and that this was despite income tax policies in Scotland to raise additional revenue above what would have been the case if Scottish income tax policy was completely aligned to the UK. The SFC Forecasts confirm that, “in the absence of Scottish policy changes to raise additional income tax revenue, the net position would have been negative in every year since 2017-18, and 2022-23 is a continuation of this trend”.2

The Cabinet Secretary confirmed in her evidence that the choices made by the Scottish Government on tax policy “have created additional spending power for the Scottish budget—there is often a misunderstanding about that”. She went on to suggest that “the challenge falls in the relationship of the BGA and the Fiscal Framework” and that “a lot of that is to do with unequal growth between the highest and lower earners”. She added that “this is accounted for in the Welsh Fiscal Framework but not the one in Scotland, and I think that needs to be part of the review of our Fiscal Framework”.3

The Committee notes that income tax policy divergence in Scotland has, since devolution, largely offset the poorer growth in receipts in Scotland. However, the deterioration in the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s income tax forecasts would appear to bring additional pressure on Scotland’s public finances. Our report goes on to explore the reasons behind these trends and how we might start to address them.

We further consider that the Fiscal Framework review presents an opportunity to shape the framework to better take account of the Scottish tax base. While the evidence we have heard suggests that there are no easy answers, we look forward to providing our views on Block Grant Adjustments to the authors commissioned with writing the independent report in due course.

Lower Growth in Income Tax Revenues

Asked what was behind the shortfall between the forecasts for income tax revenues and the BGA, Professor Alasdair Smith of the SFC told the Committee that this “could be explained by relatively low growth in Scottish earnings, which derives from productivity, and by the lower level of labour force participation in Scotland than in the rest of the UK, which exists partly because of the greater proportion of older people in the population and partly because the proportion of young people in the labour force in Scotland has declined”. He went on to highlight “the other big factor in Scottish participation rates is the ageing population” and that “the demographic effect of Scotland having a relatively high proportion of its population over the age of 65 will be with us for a long time.1 Each of these issues are explored below.

Between 2016-17 and 2026-27, the SFC expects the Scottish participation rate to decline by around 0.2% points per year relative to the rUK and, “as an illustrative calculation, all else equal, this could reduce the income tax net position by around £50 million per year”. The forecasts highlight that activity rates amongst young people are of particular concern and, while these figures have been declining since the mid-2000s, Covid-19 has had a disproportionate impact on younger people, who are traditionally employed in those industries most affected.2

The forecasts highlight that PAYE mean pay growth relative to pre-pandemic levels show the Scottish regions are “more spread across the distribution, but all are below the UK average”, with London an outlier. The SFC further reports that North East Scotland is a particularly poor outlier and, “given the contribution of high-paid oil and gas jobs to the Scottish income tax take in the past, there is particular concern about the impact this will have on the net tax position in the future”.2

In evidence to the Committee, Professor Graeme Roy suggested that “we know the technical reasons [for lower income tax revenues] are weaker earnings growth and weaker participation [however] we need to better understand what is driving these long-term trends”.4

Asked how the Scottish Government would look to address the evidence of Scotland lagging behind most other areas of the UK in relation to earnings growth, Ms Forbes was also of the view that more needed to be done to understand “the way in which certain sectors have been hit by Covid, the way in which higher earners in particular have been affected by the downturn in oil and gas, and how we solve the participation and economic activity question”. She pointed to early work in progress for example, on the ‘No One Left Behind Strategy’ in relation to employability, ensuring everyone is paid the real living wage, creating jobs in high wage sectors, such as the green economy, technology and life sciences, and undertaking analysis on a regional basis and creating jobs throughout the country.5

The Committee explored in evidence the recent CBI/KPMG Productivity Index6 compiled using data from 2020-21 and its Business Advisory Group discussions. It found that “Scotland lags behind other parts of the UK or international competitors in 9 of the 13 productivity indicators for which comparable data was available (down from 11 out of 15 in 2020), including on business investment, exporting and innovation”. While the Index does note some improvements, including entrepreneurial activity, and business research and development spend, the CBI concludes that “improving Scotland’s productivity performance is a long-term challenge and remains the only sustainable way of increasing wages and ultimately improving living standards”, adding “Scotland needs to keep improving productivity to build a stronger economy”.6

Professor Roy reiterated some of these points to the Committee, observing that “our core business is naturally less productive, less entrepreneurial and less innovative than many of our key competitors”. He suggested that, rather than always looking to Scotland’s high-performing businesses and new technology, improving productivity was actually more about using existing technologies better and “boosting” the overall core skills base and the digital base of our economy.1

Ms Forbes went on to explain that “one of the primary ways” of addressing the productivity challenge was through the Scottish Government’s upcoming 10-year National Strategy for Economic Transformation, which would include core data on productivity and look at “the need for public investment in core infrastructure, at private investment, or how we incentivise business to invest in businesses, and, lastly, at skills, or how we ensure that the workforce are in the right jobs, for the right businesses, during the right times”. She added that “those are the three areas that I would quickly recommend we step up our activity on”. The Scottish Government’s Global Capital Investment Plan 2021, which aims to attract additional investment, and its Inward Investment Plan published in 2020, were both also highlighted by Ms Forbes as being key to improving business investment performance,5 a particular weakness highlighted in CBI’s Scotland Productivity Index.

As noted by the SFC, demographic challenges continue to persist. It states that “Scotland’s natural rate of population change, defined as births minus deaths, is below zero and the labour force has grown since the early 2000s only because of positive net migration”.2 The impact of Brexit and the pandemic in reducing international migration has prompted the SFC to lower its migration assumption and has placed downward pressure on the potential size of the labour force. The Committee argued in our pre-budget report that reversing these demographic trends would require a focused and sustained approach to policy-making over a number of years. We note from the Scottish Government’s response to our pre-budget report that it is looking to address this challenge through a variety of measures, including the Scottish Government’s Ministerial Population Taskforce and continuing to explore a Demographic Commission.

We, also in our pre-budget report, highlighted that public finances would be under significant pressure in the next few years and that the Scottish Government faces difficult decisions on how it prioritises spend and raises revenue. The latest SFC Forecasts showing significant shortfalls in both income tax revenues and social security spending against BGAs in 2022-23 and beyond, suggests that these pressures may be even more acute than we warned in November.

The Scottish Government’s first multi-year RSRi since 2011 provides an important opportunity to take more immediate and sustained action, over the remainder of the parliamentary term. We also note the preparatory work being undertaken to start producing the SFC’s first fiscal sustainability report, which will look ahead to the next 30 to 50 years and “identify particular pressures on spending or revenue” and consider “whether major alterations will be required to adjust for changing circumstances”.11

The Committee agrees with the Scottish Government that it “must rise to the challenges of the future by putting our public finances on a sustainable trajectory”ii, and we suggest that productivity, wage growth, and labour market participation should be a particular focus for the Scottish Government.

We consider that evidence showing that Scotland is lagging behind almost all other areas of the rest of the UK in key indicators of economic performance is deeply worrying. We are particularly concerned to note the latest SFC Forecasts showing Scotland’s income tax receipts falling behind the Block Grant Adjustment, which we consider could, if they come to pass, put Scotland’s future fiscal sustainability at risk.

We note the Cabinet Secretary’s evidence that she would be looking to various initiatives including the ‘No One Left Behind Strategy’, the National Strategy for Economic Transformation, and the Population Taskforce, to help address the trends affecting income tax receipts. We heard in evidence that they include Scotland’s underlying low earnings growth, labour force participation rates and productivity, as well as demographic challenges. We recognise that reversing these trends will not happen overnight and that the initiatives highlighted by the Cabinet Secretary are at an early stage. We also understand that the Scottish Government is providing support to the SFC in preparing to produce its first fiscal sustainability report. We believe this could make an invaluable contribution to this debate and seek an update on this work.

In our pre-budget report we reported on the evidence we heard regarding a complicated landscape of Scottish Government strategies and plans which have been recently produced, or are soon to be, all with a bearing on the economy and fiscal sustainability. We called on the Scottish Government to outline how it could streamline and link up its various strategies and plans, a recommendation which was not addressed by the Scottish Government in its pre-budget response. We reiterate this recommendation and also request a response to our pre-budget finding that “the Scottish Government considers how the National Performance Framework could be more closely linked to budget planning and therefore seek further information on this matter”.

We welcome the inclusion of ‘changing demographics’ as one of the three primary drivers of public spending within the Resource Spending Review Framework. This appears to provide scope, as noted in our pre-budget report, for a renewed, more focused and sustained approach to policies aimed at reversing these demographic trends.

Social Security

Budgets for social security payments are based on SFC Forecasts, however, being demand-led, the Scottish Government needs to meet this spending as it arises throughout the year, even if it differs from the forecast used to set the Budget.

As with tax devolution, the BGAs are based on OBR forecasts, but for social security are additions rather than deductions, as forecasts are of spending rather than revenues. The allocations for each devolved benefit in the Scottish Budget will be based on SFC Forecasts and so, if the SFC forecasts higher spending on benefit payments in Scotland than the OBR is forecasting for England and Wales, then the Scottish Government needs to find the funding from elsewhere in its Budget.

In 2022-23, the SFC forecasts that social security spending by the Scottish Government will exceed the value of the BGA received from the UK Government by £478 million. This gap is expected to grow by 2024-25 to £764 million, which the Scottish Government would need to source from elsewhere in its budget. This difference is largely explained by the introduction by the Scottish Government of new social security payments (such as the Scottish child payment), which are unique to Scotland and as such would not be expected to be covered by the BGA.1

The SFC expects social security spending to increase in future forecasts “as it has not yet incorporated any changes in spending arising from the Scottish Government’s replacement payments for carer’s allowance, attendance allowance, industrial injuries scheme, and winter fuel payments, which it aims to launch by the end of 2025.1 The SFC told the Committee in evidence that the figures also do not take account of the undertaking by Social Security Scotland to try to increase uptake of benefit payments.3 The Cabinet Secretary explained that this “slightly different approach in Scotland” to promote uptake is “because we think that people have a right to those”.4

Professor Smith noted that, “since the Scottish budget has to be balanced every year, and since there is a commitment to spend more through social security payments to benefit society as a whole, those additional outflows of money will have to be balanced against other spending priorities”. A similar point was made by David Eiser, who suggested “the fact that the Scottish Government is setting a distinctive agenda based on its new social security levers … is clearly a great illustration of the benefits of devolution, but such policy choices come with cost implications [and] that is undoubtedly going to add to the medium-term challenges”.3

Asked whether there would be cost savings from the new social security benefits having the effect of moving families out of poverty and therefore out of benefits, Professor Smith explained that these sums would be relatively small compared to the cost of doubling the child payment. There was also unlikely to be any reduction in the cost of adult disability payments as this is typically drawn down for long-standing disabilities.4

The Cabinet Secretary accepted that the uncertainty around social security being a demand-led budget would require “some very difficult decisions”, adding “there is not really any other answer but that we will need to manage that within our resource spending review”. She clarified that “we will need to take intelligent decisions about the nature of social security in order to meet that demand [and] we need to manage other budget lines on a trajectory of getting to a position where we are dealing not with huge cuts but with a plan that gets us there”.4

While the Committee understands that the Scottish Government’s approach to social security is specific to the challenges and inequalities faced in Scotland, we are concerned at the resulting downward pressure on other budget lines that the Cabinet Secretary accepts would be necessary to meet the increasing costs of social security. Difficult decisions on priorities lie ahead and we therefore agree with Cabinet Secretary that the Scottish Government will need to “take intelligent decisions about the nature of social security in order to meet demand”. We seek further details as to exactly how the Scottish Government plans to use the resource spending review to manage the shortfall across other budget lines.

Forecast Error

We noted in our pre-budget report the inherent risks in forecasting, summarised in our predecessor committee’s joint report1 on the Fiscal Framework as: the extent of the underlying uncertainty about the economy, availability of relevant and robust data, robustness of, and differences in, methodologies and judgements, and forecast horizonsi. We also noted that these risks are of course more acute during periods of economic uncertainty such as the pandemic.

The Committee heard similar points during budget scrutiny, including on the potential implications for the Scottish Budget of divergence between the OBR and SFC in their forecasts and their use of different methodology. Specific questions were raised as to whether the OBR in its October forecasts had been more optimistic, while the SFC’s December forecasts were more cautious.

Professor Breedon of the SFC disputed this suggestion, stating that, “given how volatile the economic circumstances have been in the past few years, there is a remarkable consensus among forecasters”, adding, however, that “all those forecasts were produced before Omicron took hold, which means that all of us might have to make significant revisions if the situation worsens”. He further indicated that “fundamentally, differences in forecasting approaches will always cause some differences in forecasts [and] as you know, all of that comes out in the wash with reconciliations”.2

The Cabinet Secretary made the point, however, that it “creates a real challenge for us with regard to Block Grant Adjustments and the overall funding that is available to us”, if one forecaster bases its forecasts on a far more optimistic scenario than the other. She said she had recently met with both the OBR and SFC about the need to align methodologies as much as possible and that the Scottish Government had tried to avoid disparity in timings by publishing the Scottish Budget closely after the UK Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021.3

Ms Forbes further reiterated a point made by the Scottish Government “throughout the Fiscal Framework discussions” that “we need borrowing for forecast error to recognise the levels of volatility, whereby, in one year, the error could be £309 million and, in another year, it could be £14 million”. She added that these “borrowing powers are intended to smooth that path or trajectory, and to avoid our having to use real spending power for forecast error, because that is what it is—when it comes to the reconciliation process we are talking about forecast error”.3

We reiterate the conclusions from our pre-budget report that the limits on the Scottish Government’s resource borrowing powers to cover forecast error and resource management, and the Scotland Reserve, are not currently sufficient and that these should, as a minimum, be linked to inflation.

We further repeat the recommendation that “the two governments should consider the extent of the risk arising from potential divergence in forecast error between the SFC and the OBR, learning any lessons from the experience of an economic shock being triggered due to a quirk in timings”. We note the Scottish Government’s response that “the Fiscal Framework review must consider and make changes to these powers to support sound financial planning and management for future years”. As before, we seek regular updates on the progress of discussions between the two governments in relation to the independent report, which is due to precede the Fiscal Framework review, and on the review itself.

Local Government Funding

The Local Government Settlement for 2022-23

On 22 December the Cabinet Secretary wrote1 to the Committee confirming that the Local Government Finance Circular 9/2021, which sets out the provisional details of the Local Government Settlement for 2022-23 and Redeterminations of General Revenue Grant for 2021-22 had been published on the evening of 20 December.

The Circular in recent years has been published alongside the Scottish Budget but the letter explains that, “due to the pre-announced publication of Education statistics that are key to the distribution formula on 14 December, that was not feasible this year”. The letter also draws the Committee’s attention to the individual council allocations in the Circular currently being £483 million lower in aggregate than councils will actually receive in 2022-23. The Cabinet Secretary explained that this is due to the “challenging UK Budget settlement” which “required it to take a number of late decisions” that are still subject to consideration by the joint Scottish Government and COSLA Settlement and Distribution Group. Therefore, this amount remains undistributed at that time. The Committee notes that this is standard practice although the sums involved this time are higher than usual.

In addition, the Circular confirms that an additional £64 million of resource will be allocated in-year, which increases total funding allocated in-year to £1,367 million. The overall Local Government Settlement has increased as a consequence to £12,538.3 million, an increase of £917.9 million on 2021-22, equivalent of a 5.1% real terms’ increase, up from 4.5% on 9 December.

The Committee was disappointed to receive the Cabinet Secretary’s letter informing us of an increase in the proposed Local Government Settlement 2022-23, one day after the Cabinet Secretary appeared before the Committee to give evidence on the Scottish Budget on 21 December. This meant there was no opportunity to scrutinise these issues in evidence with the Cabinet Secretary. We therefore seek clarification as to from where, and when, this additional £64 million was found. We are also interested in when both the Scottish Government and COSLA became aware of it, and the reasons why the Cabinet Secretary was not able to share this information with the Committee at or before our meeting on 21 December.

At this meeting, clarification was sought from the Cabinet Secretary regarding COSLA’s claim that there is a cut of approximately £100 million to revenue funding for councils and that capital is flat cash compared to last year. In response, she confirmed that comparing this year’s core budget with last year’s, “you will see protection in cash terms”, adding “I do not recognise the £100 million figure that local government is using”, though she said she was “trying to get underneath it” following representations from COSLA on the matter.2

Ms Forbes was pressed on whether a large amount of the £100 million might relate to employer national insurance contribution increases. She clarified that all public bodies are being expected to absorb national insurance contributions.1

The Committee understands that the Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee is conducting detailed scrutiny of the proposed Local Government Settlement 2022-23. We note that COSLA has recently written to both the Cabinet Secretary and the First Minister seeking further discussions on the matter. At the time of writing, agreement has still to be reached.

The Committee seeks assurances that the Scottish Government will engage with COSLA at the earliest opportunity with a view to resolving any remaining concerns regarding the Local Government Settlement for 2022-23.

Prevention and Reform

In our pre-budget report, the Committee said we could see “real economic and societal benefits in prioritising spend for preventative measures, whether that be to protect the environment or the health of the nation in future years. We highlighted the RSR as providing an opportunity to introduce bold preventative measures to protect funds for the longer-term. Our view remains.

The Scottish Budget for 2022-23 confirms that the Scottish Government “remains committed to preventative spend”, and prevention is also mentioned within the context of both its RSR Framework and MTFS. In presenting the Budget to the Parliament in the Chamber on 9 December 2021, the Cabinet Secretary further advised that she could point to examples where the Scottish Government has tried to shift the balance of spend in favour of preventative spend.1

We seek clarification from the Scottish Government as to how it has prioritised preventative measures, along with examples of how this approach has resulted in a shift in policy direction and expenditure, across this Budget.

The RSR Framework states that, “with limited resources, increased investment in the Scottish Government’s priorities will require efficiencies and reductions in spending elsewhere: we need to review long-standing decisions and encourage reform to ensure that our available funding is delivered effectively for the people of Scotland”.2

During evidence, Professor Roy noted that the RSR “is an opportunity to undertake a significant review of how public services are delivered and what we can do in order to do what the Government is talking about, through greater collaboration, reform, prevention and so on”. He went on to say that this would “involve difficult choices, but that is ultimately what the Government has to do to make the public finances sustainable”, adding however that changes made in the spending review this Spring relating to prevention and public service reform would “not really change the dial over the next few years.2

The Cabinet Secretary agreed that it can be challenging to drive reform on a year-to-year basis, “as we end up budgeting for the immediate challenges in front of us, rather than for the challenges in three years’ time, but that the RSR “will allow us to spend over multiple years, which can drive reform”.4

The Committee believes that the outlook for Scotland’s economic performance and the downward pressure on the Scottish Budget, requires greater emphasis on prevention and reform. We seek further details from the Scottish Government as to how it intends to deliver this.

Net Zero

Ending Scotland’s contribution to climate change is one of the spending priorities in the Scottish Budget 2022-23. The Committee heard previously from the Fraser of Allander Institute about research it has been commissioned to undertake, on behalf of the Scottish Government, aimed at improving the climate change information included in the budget. Interim changes were made and the Scottish Budget 2022-23 contains a carbon assessment of the capital Budget.1 This assessment highlights a substantial increase in investment for low carbon projects in the coming year, for example on active travel and energy efficiency, while the share of high carbon investment has fallen, with the main areas of spending being improving and maintaining road and bridge networks and funding to help Highlands and Islands Airport Ltd to improve links between airports in the region.

The Committee on Climate Change progress report called the Scottish Government’s political commitment and policy ambitions to reach net zero by 2045 laudable, but said it remains unclear exactly how those pledges and the finances against them will translate into the scale and pace of action urgently required.2

The MTFS notes that, while the Scottish Government still expects to be able to meet the targets for increased infrastructure investment set in the National Infrastructure Mission, it warns that lower-than-anticipated capital budgets could impact on its ability to meet its net zero targets. The Net Zero, Energy and Transport portfolio is one of four portfolios in the Scottish Budget that falls in both cash and real terms.3

In her evidence to the Committee, the Cabinet Secretary reiterated that there had been hard choices to make in setting this Budget, but highlighted the following areas the Scottish Government had chosen to prioritise—

“In the net zero, energy and transport portfolio, we have absolutely prioritised investment in the transition to net zero; you can see in the Budget the significant investment that is being made in climate change initiatives and the huge investment in energy. We are ramping up delivery of the heat in buildings programme, doubling Home Energy Scotland’s Budget to deal with energy efficiency and investing in hydrogen and carbon capture and storage via the emerging energy technologies fund. Significant investments are being made.”4

The Committee supports the work being undertaken to improve the climate change information included in the Scottish Budget and welcomes the recent update provided by the Fraser of Allander Institute on its related research. We would be keen to continue to receive regular updates.

In our pre-budget report, we recommended that the Scottish Budget 2022-23 and Medium-Term Financial Strategy each set out how the Scottish Government plans to manage the economy to meet its net zero commitments by 2045. The Scottish Government has not provided a response to this recommendation explaining how this has been done. While meeting climate change targets and securing a stronger, greener, fairer economy are prominent goals in each, there appears to be little detail to show that the plans we asked for being in place. We therefore repeat this recommendation to which we request a swift response.

Replacement of EU Structural Funds in Scotland, post-Brexit

In our pre-budget report, we set out the three key UK Government funds that form part of the replacement of EU Structural Funds, post- Brexit but which also form part of the UK Government policy to level up the United Kingdom. In summary those three funds are:

A UK Community Renewal Fund (UKCRF) providing £220 million of funding in 2021/22 to help places across the UK prepare for the introduction of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF).

A UKSPF designed to “increase funding for projects that are supporting people and places across the UK, focused on our domestic priorities, growing local economies, and breathing new life into our communities”. worth over £2.6 billion over the next 3 years. The UK Government has confirmed that the UKSPF will be used to fund Multiply, a new UK wide numeracy programme.

A Levelling Up Fund (LUF) for which the UK Government has committed an initial £4 billion for England over the next four years (up to 2024-25) and set aside at least £800 million for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

In addition to the funding streams listed above, the UK Government has also launched a new £150 million Community Ownership Fund “to help ensure that communities across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland can support and continue benefiting from the local facilities, community assets and amenities most important to them.”

Bids for the UKCRF and LUF opened earlier in 2021 with 9% of the CRF funding now awarded by the UK Government as of early November 2021 to Scottish bids (this equates to £18,428,681).1 This funding must be spent by June 2022. In relation to the LUF, the prospectus for the Fund confirms that, for the first round of funding, at least 9% of total UK allocations will be set aside for Scotland. In the first round of funding eight projects led by Scottish Local Authorities were announced as successful. They had a combined value of just under £172 million (around 10% of the total award).2

As noted in our pre-budget 2022-23 report, we wrote to Scottish local authorities to ask for their views and experiences of the UKCRF and LUF. We also sought any information on communications from the UK Government? regarding the UKSPF. We received 16 responses from local authorities as well as submissions from the Scottish Local Authority Economic Development Group and COSLA.3

There were a number of key themes raised in those responses and on which we have sought a response from the Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (the Secretary of State). This is in advance of his attending the Committee to give evidence following our invitation of 15 October 2021. Those key themes relate to:

The robustness and accuracy of the methodology used to identify which parts of Scotland (and the UK) should receive greater priority when bidding for funding,

The adequacy of the timescales and resources required to bid for funding including the extent to which there is equality of opportunity across Local Authorities of different sizes to bid for funding,

The governance arrangements for each of the funding streams including how the progress towards levelling up will be reported and the role of the Scottish Parliament, its committees and MSPs in scrutinising the effectiveness of the funding spent in devolved policy areas.4

In our pre-budget report 2022-23 we recognised the importance of greater communication and sharing of information between the UK and Scottish governments in relation to the provision of this funding “to enable effective public spending in areas where there may be a shared interest”. Responding to our report recommendations the Cabinet Secretary stated that the approach of the UK Government in choosing to use its UK Internal Market powers without engaging with the Scottish Government or Scottish Parliament “introduces considerable additional uncertainty to future devolved funding settlements, and risks duplication and waste in the delivery of policies and services.”

The Cabinet Secretary also highlighted the ongoing lack of clarity regarding the nature of the UKSPF stating that “we have had no input into its development and have seen no evidence that it will meet the needs of Scotland’s places and people.”5

Speaking in the UK Parliament, the Secretary of State explained that “the Department is determined to make sure that it has a relationship with the devolved Administrations that is constructive and pragmatic, that we learn from them, and that at the same time we have a relationship with local government in every part of the United Kingdom.”6

On 21 December, City and Region Growth Deals for Falkirk and Moray were announced with funding from both the UK Government and Scottish Government contributing to each deal. Speaking in relation to the £32.5 million contributed by the UK Government to the Moray deal, the Secretary of State for Scotland explained that “the UK Government's £32.5 million support for the deal is part of £1.7 billion we are investing right across Scotland to level up communities and build back better from the pandemic."7

As this report recognises, ensuring that public funds are used effectively is essential given the scale of the challenges that Scotland faces. We recognise therefore that, taken together, these new EU replacement and levelling up funds represent a significant level of funding which has already been committed to being spent in Scotland and which is not allocated as part of the usual Scottish budget process.

However, if funding is to be spent effectively then transparency and clarity over the purpose and outcome that each funding stream is intended to achieve is vital. We therefore welcome the Secretary of State’s commitment in early November 2021 to give evidence to the Committee in person. Whilst it is disappointing that we have yet to agree a date for the session, we will continue to pursue this, as well as seeking a response to the points in our letter of 8 December.

Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body: Budget proposal 2022-23

Background

The Committee is required to consider the budget proposal from the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body (SPCB). The SPCB has a prior call on the Consolidated Fund, meaning that its budget is allocated before the Scottish Government makes any other allocations. The SPCB budget provides for the operating costs of the Parliament along with the costs of the Ombudsman and Commissioners (termed 'Officeholders') which fall within the definition of SPCB supported bodies.

The SPCB Budget was submitted to the Committee on 10 December 2021.1 We heard evidence from the SPCB, led by Jackson Carlaw MSP, on this Budget at our meeting on 21 December 2021, when we raised the issues as explored below.2

Enhanced Parliamentary Scrutiny Function

During last year’s budget scrutiny, the Session 5 Committee’s consideration of the SPCB bid chiefly focussed on the impact of Brexit on the devolution settlement and how the Parliament’s role would need to evolve to effectively scrutinise this impact. This scrutiny was complemented by the work of the Legacy Expert Panel (LEP), which was commissioned by the Session 5 Committee with a remit to consider these issues.1

The Committee recommended in its budget report for 2021-222 that “discussions about increased resources need to flow from an initial consideration of the level of additional scrutiny.” The former Presiding Officer in response3 stated “I am sure that this issue will be a priority issue for the incoming SPCB in the context of setting a budget for 2022-23 once a new committee structure has been agreed”.