Economy and Fair Work Committee

Closing the Disability Employment Gap in Scotland

Membership Changes

The following changes to Committee membership occurred during the course of this inquiry—

On 19 June 2024, Willie Coffey replaced Evelyn Tweed, Lorna Slater replaced Maggie Chapman, and Michelle Thomson replaced Colin Beattie.

Summary of recommendations

The Committee welcomes the reduction in the disability employment gap over the past decade but notes the findings of the SPICe academic fellowship that this has largely been due to a rise in people who are already in employment formally reporting a disability for various reasons.

The Committee notes the points made by witnesses on the lack of disaggregated data around employment outcomes for disabled and neurodiverse people, and shares the concerns raised by witnesses on the lack of data on the barriers faced, on learning disabilities, learning difficulties, neurodivergence, and individuals’ journeys.

The Committee calls on the Scottish and UK governments to consider how they will make their data gathering more strategic and take account of the lived experience of disabled and neurodiverse people; and how they can encourage better coordination between the different organisations and agencies responsible for collecting data to ensure that this can better inform both policy interventions and the provision of support.

The Committee agrees that disabled people in Scotland should have equal access to the labour market and that their work should be valued fairly. Any strategy to halve the disability employment gap therefore must be delivered in line with a strategy to close the disability pay gap.

The Committee shares the view of witnesses that failure to support disabled young people at an early age, and to foster aspirations in them, is perhaps the biggest barrier to closing the disability employment gap. If any real progress is to be made then it is vital that we change the way we view disabled people, their abilities, and life aspirations. As the Scottish Government develops its policies and action plans to close the disability employment gap, it should consider how to effect cultural change more widely.

Over the course of the inquiry, the Committee heard of changes that could be made across various sectors (e.g. national and local government, businesses and employers, employability services, and education) to improve the experience of disabled people in preparing for; transitioning to; and retaining employment. It is vital that these sectors, and others, work collaboratively and share best practice to allow it to become embedded. Such collaboration across both the public and private sectors could go some way towards reducing the disability employment gap.

When reviewing its targets, the Scottish Government must consider how it will drive a cross-portfolio cultural shift across the whole of Government and its agencies.

The Committee notes the arguments made by some witnesses that the disability employment gap target should be more ambitious. However, given the scale of the challenge and the societal change required to meet the 50% target, the Committee understands the Scottish Government's rationale for setting it at that level.

The Committee agrees that urgent and tangible intervention is necessary if the Scottish Government is to achieve its aim of halving the disability employment gap by 2038. Many of the stakeholders we heard from believe the target will not be met on the basis of current policy, and the Committee believes that the Scottish Government needs to listen to the voices of lived experience to ensure future actions are effective in meeting the Scottish Government's targets. The current strategy does not contain sufficient detail on how the targets will be achieved.

Given the scale of the barriers faced by disabled and neurodiverse people, and the scale of the Scottish Government's ambition to deliver one of the biggest transformations in Scotland's labour market in modern history, the Committee agrees that the Scottish Government must now deliver a concrete action plan at a scale and pace that the target demands.

This action plan must include a detailed implementation plan outlining exactly how it intends to achieve this goal, how any policy interventions will be funded, what improvements disabled people can expect to see, and a projected timescale for delivery of these improvements. A regular assessment of the impact of these policy interventions should also be published to monitor progress.

The Committee also calls on the Scottish Government to provide an update on the actions taken following the review of supported employment and to indicate when an implementation plan will be published for the National Transitions to Adulthood Strategy.

The Committee notes the Scottish Government has consulted on a Learning Disabilities, Autism and Neurodivergence Bill with the aim of “protecting, respecting and championing the rights of people with learning disabilities and neurodivergent people.”1

The Committee welcomes this work and notes that many of the findings of this inquiry could inform its development. The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to provide an update on the development of this legislation, when it intends to introduce it, and the expected impact it will have on employment.

The Committee notes the Scottish Government's commitment to establish a fair work resource for employers and asks for an update on this work. This should include—

a timescale for its launch;

how the lived experience of disabled and neurodiverse people has informed its development;

how it will address the perceptions amongst many SMEs around the recruitment and employment of disabled and neurodiverse people;

how many employers it expects to make use of this resource;

how it will maximise its reach;

what impact it is expected to have; and

how its effectiveness will be monitored taking account of the lived experience of disabled and neurodiverse people.

The Committee shares the views of witnesses that this resource must be easily accessible, concise, and must seek to minimise any resource burden on employers. It calls on the Scottish Government to take this into account when producing its forthcoming Fair Work resource for employers.

The Committee agrees that efforts to make progress in this area are not solely the responsibility of the Scottish Government. Employers themselves have a significant role to play. The Committee encourages all employers in Scotland to make use of the support currently available to them, as well as the forthcoming Fair Work resource, to make recruitment processes and roles as accessible as reasonably possible for disabled and neurodiverse people.

The Committee welcomes the support available via the Access to Work scheme and the intent behind it. It agrees with witnesses however that the scheme, in its current form, is too slow and restrictive, especially with regards to the lengthy application process and funding cap.

The Committee calls on the UK Government to set out when it intends to review the scheme to make it more streamlined and responsive. In particular, the Committee recommends to the UK Government that it considers removing the funding cap, which was suggested by witnesses as a major limitation of the scheme. The Committee further recommends that the establishment of a specific scheme for self-employed and freelance workers, who are currently not best served by it, be considered.

This section of the report, and the lived experience of those that contributed to it, is drawn to the attention of the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions and the Secretary of State for Scotland.

The Committee welcomes the No One Left Behind approach and the allocation of funding directly to local authorities, allowing them to tailor services to their specific needs.

The Committee however notes that reported statistics only currently illustrate headline outcomes, and that these numbers show little sign of improving for disabled people. There is, as yet, no quantifiable evidence that employability services for disabled people are helping to ‘shift the dial’ on disability employment overall.

Unlike other strategies, such as the Tackling Child Poverty Delivery Plan 2022-26, there appears to be no specific detail in the No One Left Behind strategy on the number of disabled and neurodiverse people it aims to help. Given the scale of the ambition, the Scottish Government is asked to set out how many disabled people it expects to support into work under No One Left Behind, over what timescale, and what the expected impact on the disability employment gap will be.

The Committee notes the examples of good practice across different local authorities, and that many are working well together, but also notes the criticisms of the lack of consistency and transparency in decision making across the country.

Given this lack of consistency, the Committee agrees it is vital that there is a mechanism for good practice to be shared across the 32 local authorities. This would allow each council to build on successes and develop the best bespoke models for their specific needs, such as a consistent provision of job coaches.

The Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government to outline how good practice will be shared across all local authorities so that they can learn from each other and accelerate progress towards reducing the disability employment gap.

The Committee welcomes the establishment of the Shared Measurement Framework, but shares the concerns raised around data gaps on those not currently in the employability system.

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to outline how it will seek to develop a means to collect data on unmet need to better inform the allocation of resources.

The Committee agrees that halving the disability employment gap by 2038 would significantly benefit the wider economy by supporting a larger, more diverse, and more resilient labour force.

It notes however the conflict between the scale of this ambition, and the 24.2% cut in real terms to employability budgets, which is much higher than cuts in other areas.

The Committee recognises the difficult fiscal circumstances which influence the Scottish Government's decision-making in relation to the Scottish Budget. However, given the Scottish Government's commitment to halve the disability employment gap by 2038, and the scale of the challenge in meeting this aim, the Committee has difficulty in understanding the rationale for such a significant reduction in funding for employability services.

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to set out how it will provide an appropriate level of funding for employability services moving forward so that the necessary support can be put in place to help achieve its aim of halving the disability employment gap by 2038.

The Committee recognises the constraints of current funding payment cycles. It notes however the benefits, as highlighted by local authorities, that increased certainty of funding (at least for each financial year, if not multi-year funding) could bring to provide these services in-house or to fund third sector providers.

The Committee welcomes the Minister's commitment to work with colleagues to ensure prompt allocation and payment of funding. Given the evidence heard around the amount of time needed to properly support disabled people into work, and the benefits of wrap-around support, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government to set out how it intends to provide long term certainty to providers of employability services to address the concerns raised.

The Committee did not hear directly from Jobcentre Plus during the inquiry but notes the concerns raised in evidence.

The Committee calls on the UK and Scottish governments to set out how they will better align the Jobcentre Plus network in Scotland with the devolved employability services, to allow them to work better together and provide better signposting to specialist organisations. The voices of lived experience must be at the heart of the formation of policy and service delivery.

The Committee also calls on the UK Government to outline what training is in place for Jobcentre Plus staff around the needs of disabled and neurodiverse people, and whether there are any plans to refresh this.

The Committee agrees with witnesses that the provision of transition coordinators in schools would greatly aid smoother transitions to further education or employment.

Much of the evidence heard during the inquiry comes under the remits of both this Committee and the Education, Children and Young People Committee. This report is therefore drawn to the attention of the Education, Children and Young People Committee to help inform any future work it may decide to undertake in this area.

Every young person in Scotland should be able to access support in their transition from education to employment. The Committee notes the Scottish Government's forthcoming National Transitions to Adulthood Strategy and seeks an update from the Scottish Government on when the final strategy will be published.

The Committee agrees that this strategy must include training for teaching staff and careers advisors on the specific needs of disabled and neurodiverse young people.

The Committee notes the evidence heard around the difference that transition co-ordinators can make to bring together different services and calls on the Scottish Government to consider the provision of transition co-ordinators as part of the National Transitions to Adulthood Strategy.

The Committee agrees with calls for a clear implementation plan and seeks confirmation from the Scottish Government that this will be included in the final strategy.

Concerns were raised that some disabled people are being asked to use their social care Self Directed Support budgets to undertake placements that amount to unpaid work. The Committee welcomes the Minister's commitment to investigate this issue, encourages the Minister to look at this holistically with his colleagues, and looks forward to his response to the specific concerns raised with the Committee, recognising that this is a cross-portfolio issue.

Introduction

The “disability employment gap” is the term used to refer to the difference in employment rates between disabled and non-disabled people.

Statistics show that disabled people in Scotland have a much lower employment rate than non-disabled people. The Scottish Government has an ambition to halve this gap by 2038.

In some of its previous inquiries, the Committee heard of labour and skills shortages across the country, making it more difficult for businesses to expand and grow. Whilst most disabled people are willing and able to work and could contribute to reducing these shortages, they are often prevented from doing so by both structural and societal barriers.

As part of this inquiry, the Committee wanted to understand what more could be done to reduce the disability employment gap and ensure that everyone who wants to work has the opportunity to access suitable employment and fulfil their true potential.

Terms of reference

The Committee undertook some initial work in this area in 2023. This included visits to disability employment support organisations, an evidence session with stakeholder organisations, and a session with the then Minister for Just Transition, Employment and Fair Work.

The Committee found that progress had been made towards closing the disability employment gap, though progress was inconsistent across different groups, and it was not clear what was behind it. The Committee also noted a lack of reliable baseline data and identified several barriers to disabled and neurodiverse people accessing the workforce.

In response, the Scottish Government highlighted its new No One Left Behind Strategy which it stated aims to simplify the employability system, benefiting all those seeking to enter the workforce, including disabled and neurodiverse people. The Scottish Government stated that this strategy should also improve data gathering under a new Shared Measurement Framework and would also help to address the regional variation of services and concerns around funding.

A letter outlining the Committee's initial findings, together with the then Cabinet Secretary's response can be accessed online.

Following this, the Committee agreed on 21 February 2024 to undertake an inquiry to build on these findings, considering—

the help available for disabled people to access the labour market;i

the support available for employers for more inclusive recruitment practices and workplaces;

specific barriers faced by people with learning disabilities and neurodivergent people; and

the support available to young disabled people as they transition to adulthood.

Evidence received

The Committee's call for views on the inquiry ran from 20 December 2022 to 16 February 2023 and 41 responses were received. The Committee thanks all those who contributed.

The Committee heard oral evidence over a five-week period in May and June 2024 from witnesses representing disabled peoples’ support organisations, local authorities, providers of employability services, business organisations, representatives from academia, and the Scottish Government. Full details of evidence sessions can be found at Annexe A.

The Committee was keen to hear directly from disabled people with lived experience of seeking employment, and those working to support them. To this end, Members visited several organisations around the country that help disabled people to develop their skills and find sustained employment. These included the National Autistic Society Scotland in Glasgow, Enable and Dovetail Enterprises in Dundee, and the Giraffe Kitchen and PUSH Reuse Centre in Perth.

During these visits, members met with individuals using these services, and the staff providing them. The Committee also hosted an informal engagement session in the Parliament with a group of young people and staff from the Usual Place in Dumfries.

A selection of comments from some of the individuals the Committee met during these engagement activities is set out below—

The Committee was struck by the honesty and passion of the disabled and neurodiverse people at these events, and of their desire to make a positive contribution in the workplace and fulfil their potential. These insights were invaluable and significantly informed members’ lines of inquiry during the formal evidence sessions. The Committee thanks all those who took the time to share their experiences.

Overview of the current situation in Scotland

Statistics show that employment rates for disabled people, both in Scotland and at a UK level, have improved over the past decade. In Scotland, the disability employment gap has reduced from 38.3% in 2014 to 30.3% in 2023. This is outlined in the table below.

Table 1: Disability employment gap, Scotland and UK

| Scotland | UK | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Disabled employment rate | Not disabled employment rate | Disability employment gap | Disabled employment rate | Not disabled employment rate | Disability employment gap |

| 2014 | 41.5% | 79.7% | 38.3% | 46.0% | 78.2% | 32.2% |

| 2015 | 41.9% | 80.5% | 38.6% | 47.3% | 79.5% | 32.2% |

| 2016 | 42.8% | 80.4% | 37.5% | 48.7% | 79.8% | 31.1% |

| 2017 | 45.3% | 81.3% | 36.0% | 50.7% | 80.4% | 29.7% |

| 2018 | 45.6% | 81.3% | 35.7% | 50.9% | 80.9% | 29.9% |

| 2019 | 49.0% | 81.8% | 32.8% | 53.1% | 81.5% | 28.4% |

| 2020 | 47.2% | 80.3% | 33.2% | 52.8% | 81.0% | 28.2% |

| 2021 | 49.6% | 81.2% | 31.5% | 53.3% | 81.0% | 27.6% |

| 2022 | 50.7% | 82.8% | 32.2% | 54.7% | 81.9% | 27.2% |

| 2023 | 52.7% | 83.1% | 30.3% | 54.9% | 82.3% | 27.4% |

Source: ONS' Annual Population Survey, accessed at Nomis by SPICe

The above table shows that, although higher in Scotland than the wider UK, the disability employment gap has reduced more quickly in Scotland over the past decade.

It is recognised that within these figures there is substantial regional variation. Between 2021 and 2023, the disability employment gap in Dumfries and Galloway, for example, was more than double that of Midlothian (43.0% vs 18.4%). Furthermore, progress towards closing the disability employment gap has been uneven. Between 2014-2016 and 2021-2023, the disability employment gap decreased by more than ten percentage points in Midlothian, Inverclyde, Glasgow City, South Lanarkshire, Scottish Borders and Falkirk, whereas it actually increased in Na h-Eileanan Siar, East Dunbartonshire, East Renfrewshire, Dumfries and Galloway and Renfrewshire.

Disability employment rates are lower for women than men, and progress towards increasing the disability employment rate has been faster for men than women. In the year to March 2024, for example, the employment rate for disabled women in Scotland was 51.6%, compared to 53.8% for men. Five years previous, the disability employment rate for women was 46.5%, compared to 45.0% for men.

What's behind the recent progress?

The Committee's initial work on the disability employment gap in 2023 found that it was not entirely clear what had driven this reduction. Subsequently, in January 2024, a SPICe academic fellowship studied disability employment rates in Scotland, and found that—

Scotland's disability employment rate has largely increased due to an increase in disability prevalence (70% of the total change), meaning that most of the progress in increasing disability employment has been due to a rise amongst those already in work reporting a disability.

On average, Scotland's disabled working age population grew by about 4.6% each year between 2014 and 2022, while Scotland's total working age population grew by less than 0.1%.

Over half of the change in disability prevalence is due to an increase in reporting of mental health-related disabilities and learning difficulties. In 2014, over a third of disabled people in Scotland reported musculoskeletal conditions as their main health condition, and around a quarter reported a mental health condition or learning difficulty. These proportions have now switched.

Musculoskeletal conditions (those affecting arms, legs, feet, neck, and back) have had significant increases in employment rates, without significant increases in disability prevalence. By comparison, rates of reported mental illness grew substantially in both employment rates and in total prevalence.

Disabled people are disproportionately less likely to work in manufacturing; professional, scientific, and technical activities; or construction, and are more likely to work in education, retail, and health and social work.1

These findings suggest that policy interventions aimed at supporting out-of-work disabled people into the labour force have had limited impact to date. The findings also indicate considerably more complexity when considering the most effective policy interventions.

Quality of data

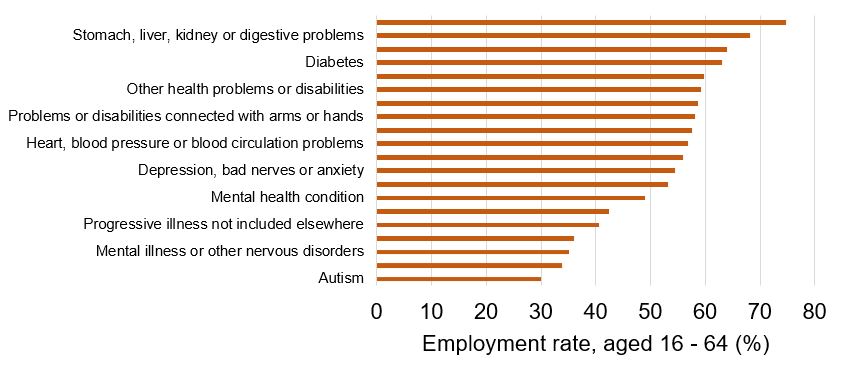

It is important to note however, that disability employment figures cover a wide range of individuals, with different impairments and conditions, as well as outcomes. Disabled people are not a homogenous group and data shows that outcomes for people with different impairments are not the same and will vary widely.

As per the definitions used in the ONS’ Annual Population Survey, employment rates in the UK are highest for those who report difficulty in hearing as their primary health condition. They are lowest for those who report autism and severe or specific learning difficulties as their primary health condition, although it is noted that the employment rate for these groups has increased in recent years, according to ONS statistics.

However, data is not always disaggregated to allow for a clear understanding of the barriers to employment that different groups within the disabled population face.

Joanna Panese from Scottish Autism, stated that data around disability and neurodivergence is often conflated and that—

there is a range of things underneath those terms, and it becomes difficult to segment that data and really understand it fully. Then we get lumped-together statistics, that, because they are hard to digest and understand, people think might not be reliable, so they decide not to pay attention to disability.1

Some witnesses suggested there is a need for more strategic data gathering. Angela Matthews (Business Disability Forum), for example, argued that the data collected should be “fit for purpose” and not just be on the number of disabled people, or the type of disability they have. She suggested that data on the employment barriers faced by individuals should also be tracked. It was also suggested that more longitudinal data should be gathered, more specific to individuals, looking at what enables people to get into work, to stay in work, and if they leave employment, the reasons behind that. This type of data could then inform policy decisions to deliver the most effective support for workers across the disabled population.1

The Committee also heard concerns throughout the inquiry about the breadth of the data on disability and the disability employment gap. As noted earlier, disabled people are not a homogenous group, yet the available data is often not disaggregated, making it harder to understand the scale of the employment gap and where best to allocate resources to help to reduce it.

This was of particular concern around people with learning disabilities, as they often have unique support needs. Currently, there is no way of knowing how many of this cohort are in work, and where there is unmet need for employment support.3

The Committee was also told of the vital importance of information on people’s lived experience to give more meaning to any data gathered. Heather Fisken (Inclusion Scotland) told the Committee, when discussing data gaps, that—

One of the biggest gaps arises from the reliance on statistics. They are very important if you are painting by numbers, but they do not give you any colour or tone, and we believe that lived experience information is crucial in making those numbers more meaningful. I am not saying that they are not meaningful or useful, but they are just part of the picture.3

Given the compelling stories told to members during the various engagement events during the inquiry, this is a view shared by the Committee.

The Committee heard that data gathering was disconnected, that those agencies who produce statistics do not coordinate effectively, and that there is no consistency between UK nations, making agreeing baseline data to guide policy difficult.1

Alan Thornburrow (Salvesen Mindroom Centre) summed up the consequence of these data gaps by noting that “what gets measured gets managed”.1 Indicating that without clear data on the scale of the problem, and the array of barriers faced by disabled people, the ambition to halve the gap is unlikely to be realised.

This lack of data makes it difficult to understand what policy interventions could make the biggest difference. Additionally, the lack of clarity around how data has informed current policies, suggests that data collection is not properly aligned to any wider Scottish Government strategy.

The Committee welcomes the reduction in the disability employment gap over the past decade but notes the findings of the SPICe academic fellowship that this has largely been due to a rise in people who are already in employment formally reporting a disability for various reasons.

The Committee notes the points made by witnesses on the lack of disaggregated data around employment outcomes for disabled and neurodiverse people, and shares the concerns raised by witnesses on the lack of data on the barriers faced, on learning disabilities, learning difficulties, neurodivergence, and individuals’ journeys.

The Committee calls on the Scottish and UK governments to consider how they will make their data gathering more strategic and take account of the lived experience of disabled and neurodiverse people; and how they can encourage better coordination between the different organisations and agencies responsible for collecting data to ensure that this can better inform both policy interventions and the provision of support.

Disability pay gap

Although not within the remit of the Committee's inquiry, concerns were also raised by some witnesses about the disability pay gap.

Skills Development Scotland told the Committee that Scotland had the largest disability pay gap in the UK, stating that—

In 2021, median pay for disabled workers was £11.54 per hour compared to £14.16 per hour for non-disabled workers.

Disabled women across the UK earn 36% less than non-disabled men.

Five years after graduation, disabled graduates earn £2,900 less than graduates with no known disability.1

Ashley Ryan (Enable) told the Committee that disabled people “work the last 53 days of the year for free”.2

It was suggested by witnesses that one explanation for this was that disabled people are more likely to be employed in “low-paid, precarious and part-time work” (Heather Fisken, Inclusion Scotland)3 when compared to non-disabled people. This may be linked to the wider issues around culture, aspiration, and the support available to disabled people, which will be discussed later in this report.

The Committee agrees that disabled people in Scotland should have equal access to the labour market and that their work should be valued fairly. Any strategy to halve the disability employment gap therefore must be delivered in line with a strategy to close the disability pay gap.

Cultural change

One of the key overall themes to emerge during the inquiry was the need for cultural change in the way that society views disability and disabled people. Witnesses drew comparisons with other protected characteristics such as sex and race, stating that these are routinely monitored and discussed, but that disability does not seem to have the same status in the workplace or in the national consciousness. Disability, the Committee heard, “tends to come last”.1

Witnesses also stated that because of this, the aspirations of young disabled people can often be tempered or dismissed. David Cameron (Scottish Union of Supported Employment) stated, for example, “people do not ask them [disabled young people] “what do you want to do when you grow up? What job will you have?””1

Charlie McMillan (Scottish Commission for People with Learning Disabilities) agreed, noting that, for people with learning disabilities, the cultural change required is even greater—

We are dealing with hard-wired prejudice and discrimination at societal level, at school level, at educational level, at college level and at employment level. The lack of expectation that is placed on people with learning disabilities is profound, and that means that they start from way behind in trying to live the lives that they choose.3

Indeed, Heather Fisken (Inclusion Scotland) spoke of presenting information to a group of young disabled people on independent living, and then being advised that “this isn't for them”.4

The Committee heard that these low aspirations and expectations can become “self-fulfilling” (Chirsty McFadyen, Fraser of Allander Institute). If disabled young people are told they will probably never work, then they do not expect to work as adults.4

Whilst delivering such cultural change presents a significant challenge, delivering tangible improvements in how disabled people are supported in accessing and retaining work would greatly contribute towards meeting it.

The Committee shares the view of witnesses that failure to support disabled young people at an early age, and to foster aspirations in them, is perhaps the biggest barrier to closing the disability employment gap. If any real progress is to be made then it is vital that we change the way we view disabled people, their abilities, and life aspirations. As the Scottish Government develops its policies and action plans to close the disability employment gap, it should consider how to effect cultural change more widely.

Over the course of the inquiry, the Committee heard of changes that could be made across various sectors (e.g. national and local government, businesses and employers, employability services, and education) to improve the experience of disabled people in preparing for; transitioning to; and retaining employment. It is vital that these sectors, and others, work collaboratively and share best practice to allow it to become embedded. Such collaboration across both the public and private sectors could go some way towards reducing the disability employment gap.

When reviewing its targets, the Scottish Government must consider how it will drive a cross-portfolio cultural shift across the whole of Government and its agencies.

The Scottish Government's employment gap target

In 2016, the Scottish Government published A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People. This plan ran from 2016 to 2021 and included an ambition to—

reduce barriers to employment for disabled people and seek to reduce by at least half, the employment gap between disabled people and the rest of the working age population.1

In 2018, the Scottish Government published A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People: Employment Action Plan. This built on the previous plan and included a target to increase the employment rate of disabled people to 50% by 2023 (which was met in 2022) and to 60% by 2030.2 It also contained an overall ambition to halve the disability employment gap by 2038 (from a 2016 baseline of 37.4%). This ambition was also re-stated in the latest Fair Work Action Plan.2

The Employment Action plan states that reducing the disability employment gap—

is good for the wider economy and for individual health and wellbeing;

provides a source of income;

fosters social interaction;

contributes to a sense of happiness and self-esteem;

supports independent living;

reduces isolation and poverty; and

will allow individuals to fulfil their potential.2

The Scottish Government's ambition to halve the disability employment gap was welcomed by witnesses, but some questioned whether this was ambitious enough. Heather Fisken (Inclusion Scotland) argued that the ambition should be to eliminate the employment gap as far as possible, not just by half, stating that—

We cannot imagine another protected characteristic having an employment programme that aims only to halve the employment gap between the people with that characteristic and the general working-age population.5

Other witnesses argued that this target has essentially “written off a whole generation of people who will not work” (Charlie McMillan, Scottish Commission for People with Learning Disabilities).6

The Committee notes the arguments made by some witnesses that the disability employment gap target should be more ambitious. However, given the scale of the challenge and the societal change required to meet the 50% target, the Committee understands the Scottish Government's rationale for setting it at that level.

The need for a clear and tangible action plan

Halving the disability employment gap by 2038 would represent one of the biggest transformations in Scotland's labour force in recent decades. The Committee heard it is likely the progress achieved via increased reported disability prevalence in the labour force will soon plateau.

The barriers to employment for many disabled people are entrenched and addressing these will require a concerted effort from multiple layers of government, the private, and third sectors.

The main Scottish Government strategy relevant to halving the disability employment gap is the Fair Work Action Plan. This plan brings together ambitions around the gender pay gap, the disability employment gap, and the anti-racist employment strategy, “driving fair work practices for all”.1

This plan, however, does not include a detailed plan of how the disability employment gap target will be met. There is little detail on the expected impact of policy interventions, the outlook for funding these, and the timescales involved. Witnesses told the Committee that if the Scottish Government is to achieve its ambition by 2038, it is vital that a clear, concise, and tangible action plan be developed.

Linked to this lack of detail in the Fair Work Action Plan is the Review of Supported Employment, which was commissioned by the Scottish Government and reported in 2022.1

The review made several detailed recommendations which included a “Supported Employment Guarantee”, funding and targets for local authorities to deliver consistent access rates, the introduction of quality standards, and the “professionalisation” of the supported employment workforce.3 The Fair Work Action Plan notes that the Scottish Government will “work collaboratively to develop resources to support workers to access, remain and progress in fair work”, and as part of this, it will “draw upon the findings and recommendations” of the Review of Supported Employment.1

The review was welcomed by stakeholders, but frustrations were expressed that, to date, this has not led to any action. David Cameron (Scottish Union of Supported Employment) stated that—

There are many elements in it that we were very excited about. I had some conversations with senior civil servants in 2023 about some preliminary ideas for implementation. There has literally been nothing since. 5

The Minister for Employment and Investment indicated to the Committee that he would consider progress towards implementing the recommendations in the near future.6

The final relevant strategy is the forthcoming National Transitions to Adulthood Strategy. This is currently being developed, and many of the witnesses the Committee heard from had been involved in this process. The strategy has been designed with five key priorities—

Choice, control, and empowerment for the young person;

Clear and coherent information;

Co-ordination of individual support and communication across sectors;

Consistency of practice and support across Scotland; and

Collection of data to measure progress and improvements.7

The Committee heard that stakeholders are generally supportive of its current trajectory. Witnesses welcomed the way in which the Scottish Government has approached its development and generally agreed with the five priority areas selected.8

Throughout the inquiry however, there was an overall sense that there has been enough consultation and discussion on what needs to be done, and that concrete action is now vital. Joanna Panese (Scottish Autism) articulated this view well, stating that—

It feels as though we have all the ingredients to meet the target and to do the things that we are committed to doing. There is almost a sense that we have done the talking, and now we need to take action … I would like to say that I am optimistic that we will reach and even exceed the 2038 target, but if we keep doing what we are doing, we will not. The time is now—we need to strengthen our approach and get on with it.9

The Committee agrees that urgent and tangible intervention is necessary if the Scottish Government is to achieve its aim of halving the disability employment gap by 2038. Many of the stakeholders we heard from believe the target will not be met on the basis of current policy, and the Committee believes that the Scottish Government needs to listen to the voices of lived experience to ensure future actions are effective in meeting the Scottish Government's targets. The current strategy does not contain sufficient detail on how the targets will be achieved.

Given the scale of the barriers faced by disabled and neurodiverse people, and the scale of the Scottish Government's ambition to deliver one of the biggest transformations in Scotland's labour market in modern history, the Committee agrees that the Scottish Government must now deliver a concrete action plan at a scale and pace that the target demands.

This action plan must include a detailed implementation plan outlining exactly how it intends to achieve this goal, how any policy interventions will be funded, what improvements disabled people can expect to see, and a projected timescale for delivery of these improvements. A regular assessment of the impact of these policy interventions should also be published to monitor progress.

The Committee also calls on the Scottish Government to provide an update on the actions taken following the review of supported employment and to indicate when an implementation plan will be published for the National Transitions to Adulthood Strategy.

The Committee notes the Scottish Government has consulted on a Learning Disabilities, Autism and Neurodivergence Bill with the aim of “protecting, respecting and championing the rights of people with learning disabilities and neurodivergent people.”10

The Committee welcomes this work and notes that many of the findings of this inquiry could inform its development. The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to provide an update on the development of this legislation, when it intends to introduce it, and the expected impact it will have on employment.

Employers

The Committee has heard repeatedly, over several inquiries, about labour and skills shortages making it more difficult for businesses to expand and grow. It has also heard of the benefits a more diverse workforce can bring, allowing businesses to be “more productive, have better problem solving and make greater profits” (Ashley Ryan, Enable).1

Given the number of disabled people currently not in the labour market, and the benefits of having a more diverse workforce, the Committee agrees that more should be done to encourage and support employers to recruit and retain more disabled people.

Obligations under the Equality Act 2010

Employers have a legal obligation under the Equality Act 2010 to make “reasonable adjustments” to recruitment and working practises to make them more accessible for disabled people.1

The Committee heard of several adjustments employers could make, for example physical adjustments to workspaces, providing supportive equipment or software, changing working patterns, providing additional training and awareness raising (particularly on hidden disabilities) for staff and managers, changing workplace cultures, introducing more flexibility for employees, changing recruitment processes, and collecting and reporting more data on employees’ disability status and support needs.

The Committee also heard however, that the main barrier for many businesses in making, or even considering, these types of adjustments is fear of not implementing them correctly.

Witnesses stated that employers generally see the benefit to their business of having a diverse workforce that includes disabled people, and want to ‘do the right thing’, but that fears around ‘getting it wrong’ often stand in the way. Chirsty McFadyen (Fraser of Allander Institute) stated that—

Surveys have consistently found evidence of misplaced nervousness among employers in hiring disabled people, over fears about productivity or additional costs. However, we have also found in our research with employers that there is a fear of getting things wrong, and that sometimes it is easier not to hire people with learning disabilities than it is to risk causing further harm. That is where employers need extra support. 2

Heather Fisken (Inclusion Scotland) pointed out that “reasonable adjustments” is a legal term and people often do not fully understand what it means. She said that many think it means big, costly changes such as altering the fabric of a building, or drastically altering working arrangements, when in most cases only modest changes are required. 2

The Committee heard of many examples of good practice amongst employers across the country, but that these need to be shared more widely. Simple steps such as providing assistance with applications and support during interviews can really make a difference. The provision of this support, and publicising it to potential applicants, could encourage more disabled and neurodiverse people to apply for roles. Chirsty McFadyen (Fraser of Allander Institute) stated that—

We have seen lots of great simple things that can be done, but it is important that businesses are made aware of what can be done to make the process accessible for people. Some employers are not aware of what they could do, which again adds to the fear that we talked about. Better guidance would help with that.2

Witnesses told the Committee there is a lot of information and resources available for business owners and employers to support them in making their businesses more accessible to disabled people. Most, however, are not aware of the various types of support available, or where to access these. Additionally, many small and medium-sized business owners do not have the time or resources to properly investigate this support.

The Committee heard that when business owners and managers become aware of support resources, they are often confronted with lengthy and complex guidance that often does not seem to have been designed with busy business owners or managers in mind.

Angela Matthews (Business Disability Forum) pointed to the centrally available employment guidance on the UK Government website as an example of this. She stated that some of the guidance links to very lengthy documents, and that “no line manager has time to read that”.2 The presentation of information in this way creates a perception that the hiring of disabled people is more difficult and costly than it is. Vikki Manson (FSB Scotland) stated that—

Looking at adjustments to interview processes can feel like a huge challenge to SME owners, but the fact is that they can be just simple little things such as providing the questions prior to an interview or arranging an interview for a specific time of day. The question, then, is: how do we communicate that to small business owners?2

The Committee heard that clear and concise information must be made available in one central location for employers to access. Making this information easily accessible, and in a manageable format, is vital to eliminate the fears currently common amongst employers around the recruitment of disabled people.

The Scottish Government has committed to establishing a central ‘Fair Work resource’ for employers with advice and good practice guides, and is developing a communications strategy around the business case of fair work (including the benefits of supporting disabled employees).

The Committee notes the Scottish Government's commitment to establish a fair work resource for employers and asks for an update on this work. This should include—

a timescale for its launch;

how the lived experience of disabled and neurodiverse people has informed its development;

how it will address the perceptions amongst many SMEs around the recruitment and employment of disabled and neurodiverse people;

how many employers it expects to make use of this resource;

how it will maximise its reach;

what impact it is expected to have; and

how its effectiveness will be monitored taking account of the lived experience of disabled and neurodiverse people.

The Committee shares the views of witnesses that this resource must be easily accessible, concise, and must seek to minimise any resource burden on employers. It calls on the Scottish Government to take this into account when producing its forthcoming Fair Work resource for employers.

The Committee agrees that efforts to make progress in this area are not solely the responsibility of the Scottish Government. Employers themselves have a significant role to play. The Committee encourages all employers in Scotland to make use of the support currently available to them, as well as the forthcoming Fair Work resource, to make recruitment processes and roles as accessible as reasonably possible for disabled and neurodiverse people.

Access to Work scheme

One of the main avenues for support in making reasonable adjustments for disabled and neurodiverse people is the UK Government's Access to Work scheme. This has been in place since 1994. The scheme provides funded support to disabled people such as communication support for interviews, special aids and equipment, help with travel costs, support workers etc. Individuals must apply for this support directly, their employer (or prospective employer) cannot do it on their behalf.

The Committee heard that this scheme has been a great help to those successful in accessing it, providing them with good support to enter employment. Witnesses told the Committee however, that in many cases, the scheme can be too slow and restrictive. Specifically, witnesses pointed out that—

awards can take too long;

the application process can be cumbersome;

its scope is too restrictive (e.g. it will pay for equipment to support a disabled person in work but not for software updates);

claims should involve the employer (currently it is led by the employee, but it was questioned what happens if the employee is off sick, for example); and

the funding cap means that some potential employees miss out on support.

The Committee heard that the scheme is not agile enough to support workers in industries where work is insecure and piecemeal, such as creative industries and media, where freelance work is commonplace. Angela Matthews (Business Disability Forum) gave an example of a freelance worker being awarded a contract on a Friday, with a Monday start. Depending on the circumstances, that individual's support package may need to change, and the current scheme is not equipped to move at that pace.

Chirsty McFadyen (Fraser of Allander Institute) also stated that the Access to Work scheme is more relevant to those with a physical disability or those that require a support worker. It is not a solution for all disabled people, for example some people with a mental health condition, or where the adjustments required are complex.1

The Committee welcomes the support available via the Access to Work scheme and the intent behind it. It agrees with witnesses however that the scheme, in its current form, is too slow and restrictive, especially with regards to the lengthy application process and funding cap.

The Committee calls on the UK Government to set out when it intends to review the scheme to make it more streamlined and responsive. In particular, the Committee recommends to the UK Government that it considers removing the funding cap, which was suggested by witnesses as a major limitation of the scheme. The Committee further recommends that the establishment of a specific scheme for self-employed and freelance workers, who are currently not best served by it, be considered.

This section of the report, and the lived experience of those that contributed to it, is drawn to the attention of the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions and the Secretary of State for Scotland.

Employability services

No One Left Behind

Employability services that support disabled people into work is one of the key policy levers available to the Scottish Government to meet its target of halving the disability employment gap. In 2019, the Scottish Government began a gradual shift from its previous employability strategy, Fair Start Scotland, to its new strategy, No One Left Behind (NOLB).

NOLB is intended to de-clutter the employability support landscape and develop a more streamlined, consistent offer of support. The Scottish Government states that NOLB places—

people at the centre of the design and delivery of employability services, promotes a strengthened partnership approach where the spheres of government work more collaboratively with third and private sector to identify local needs and make informed, evidence-based decisions, flexing these to meet emerging labour market demands. 1

The strategy is intended to offer more flexible support to meet users’ individual needs (which are often complex) and to link support with other service areas, such as housing, justice, health and social care.

Under NOLB, the funding for the delivery of employability services has been transferred to local authorities, who are free to organise this provision in different ways, depending on local need. Some deliver these services in-house, whereas others commission external partners. Dundee City Council, for example, works with Enable and others to provide employability support to disabled people.

To assist local authorities in delivering this provision, Local Employability Partnerships (LEPs) have been established as forums to facilitate partnership working across the public and private sector.

There is no set eligibility criteria to access support via NOLB. People can self-refer to services in their area or be referred from a variety of sources, such as health services or the Department for Work and Pensions. Support can include things like training courses, access to further or higher education providers, job analysis and job coaching, supported employment placements, help in applying for jobs, and peer mentoring. Some schemes are tailored specifically for disabled people.

The new approach taken under NOLB was generally welcomed by witnesses. The Committee has heard throughout the inquiry of the array of different services that need to come together to support a disabled person into employment, and of the need to avoid siloed working. Alasdair Scott (Scottish Borders Local Employability Partnership) stated that the creation of LEPs under NOLB was helping to achieve this, and that the different services—

are more aligned now than we ever were through collaboration with other organisations and services to hopefully meet the demand and make more of an impact.2

Concerns were raised however around consistency and transparency across the different local authority areas, which some have described as a “postcode lottery.” Oxana MacGregor-Gunn (SAMH) for example, expressed the view that LEPs are working very well in some local authority areas, but not in others. It was also stated that having different approaches in all 32 local authority areas meant that, for third sector organisations like SAMH, it was “32 times harder to engage with them all.”2

The Committee did however also hear examples of good practice being shared across different local authorities. Ashley Ryan (Enable) told the Committee that local authorities in the Forth Valley area have been working well together—

They have commissioned us to deliver supported employment across the Forth Valley region. That allows us to deliver the principles of “No one left behind”, understanding the nuances between Clackmannanshire and Falkirk and Stirling, but also allowing us to deliver a real team around quality, with qualified staff. That is a good example of local authorities coming together to create that resource.4

One area of good practice that the Committee heard could be shared across Scotland was the provision of wrap-around support for disabled people such as that offered through programmes such as DFN Project Search, Enable Works, the National Autistic Society’s Moving Forward +, and SAMH's Individual Placement and Support (IPS). These programmes provide support to individuals to help prepare them for work, support them through the application process, then continue to work with them and their employers to provide support when needed.

Carmel McKeogh (DFN Project Search) told the Committee of the good results her programme was having in Scotland, with excellent outcomes for those taking part. Similarly, Oxana MacGregor-Gunn (SAMH) highlighted the benefit of providing support to individuals after they have secured a role, pointing to the confidence that support can give to both the individual and the employer.2

Frustrations were expressed however, that these programmes can only operate where there is access to an appropriate level of funding. The National Autistic Society for example, told Committee members during their visit to Glasgow that programmes such as theirs have proven results and that they would like to expand their reach, however funding limits them to a specific location. This leads to an uneven provision throughout the country where autistic people in other parts of Scotland (or even other parts of Glasgow) cannot access the same support.

Carmel McKeogh (DFN Project Search) expressed a similar view, and told the Committee that—

There is a real desire and wish to make sure that the programme is universally available to everybody in Scotland. We know that it works. Let us find a way to make that happen. It is partly a question of addressing those two issues of funding.2

Another area where good practice could be shared across Scotland is in the provision of job coaches. Organisations such as DFN Project Search and Enable spoke of the importance of job coaches in helping disabled people succeed in work. Job coaching often involves more intensive and hands-on in-work support, including support for employers and is part of the five-stage model of supported employment.

It was argued that there are insufficient numbers of job coaches to transform employment prospects for disabled people furthest from the labour market. The Committee also heard that funding for job coaches is “entirely reliant on the local authority.”2 This is another area where a more consistent approach would be welcomed.

Witnesses told the Committee however that progress is being made, and that the NOLB approach is relatively new and still being embedded across the country. Ashely Ryan (Enable) stated that—

in the last year or so we have seen real strides forward being made, in that LEPs are looking to engage the third sector a bit more closely to understand the needs on the ground … but they remain a little inconsistent in terms of how transparent they are, who is on the LEPs, how you can become a partner and engage with the LEPs more closely, and the purpose of what they are doing.2

The Minister told the Committee that, with any locally administered scheme, there will inevitably be variation in approach. He stated “what we want is variation that arises from a positive response to a location's particular challenges and opportunities rather than variation that occurs through lack of knowledge of best practice elsewhere.”

With regards to the funding of job coaches, the Minister noted that some funding for job coaches had previously been allocated from the workplace equality fund and that an independent evaluation would take place of that fund to inform future policy development.9

The Committee welcomes the No One Left Behind approach and the allocation of funding directly to local authorities, allowing them to tailor services to their specific needs.

The Committee however notes that reported statistics only currently illustrate headline outcomes, and that these numbers show little sign of improving for disabled people. There is, as yet, no quantifiable evidence that employability services for disabled people are helping to ‘shift the dial’ on disability employment overall.

Unlike other strategies, such as the Tackling Child Poverty Delivery Plan 2022-26, there appears to be no specific detail in the No One Left Behind strategy on the number of disabled and neurodiverse people it aims to help. Given the scale of the ambition, the Scottish Government is asked to set out how many disabled people it expects to support into work under No One Left Behind, over what timescale, and what the expected impact on the disability employment gap will be.

The Committee notes the examples of good practice across different local authorities, and that many are working well together, but also notes the criticisms of the lack of consistency and transparency in decision making across the country.

Given this lack of consistency, the Committee agrees it is vital that there is a mechanism for good practice to be shared across the 32 local authorities. This would allow each council to build on successes and develop the best bespoke models for their specific needs, such as a consistent provision of job coaches.

The Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government to outline how good practice will be shared across all local authorities so that they can learn from each other and accelerate progress towards reducing the disability employment gap.

Data reporting

The Committee heard that under NOLB, data collection on employability services had improved, with services in each local authority area now feeding data on delivery into a new Shared Measurement Framework.

This framework is intended to deliver a coherent view of how effective employability programmes are across Scotland in a way that captures information beyond headline job outcomes. The motivation behind this is that a successful intervention may leave a service user closer to the labour market, but not yet in a position to sustain employment. If only job outcomes are used to measure the impact of employability services, the incentive would be created to target support at those closest to the labour market, leaving those with the greatest need without support.

The Committee notes however that data is only currently collected on those already in the system and is not available for those with unmet need, particularly around people with learning disabilities. Chirsty McFadyen (Fraser of Allander Institute) told the Committee that although there is anecdotal evidence from various sources, that information is not captured in nationally representative data. This makes it more difficult to ensure policy is evidence-based. The Committee heard that data on the experience of people is also needed, not just whether they are still in a job after a set period.1

The Committee welcomes the establishment of the Shared Measurement Framework, but shares the concerns raised around data gaps on those not currently in the employability system.

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to outline how it will seek to develop a means to collect data on unmet need to better inform the allocation of resources.

Funding

Funding for employability services was raised by witnesses throughout the inquiry as an area of concern.

Given the scale of the Scottish Government’s ambition to close the disability employment gap, the Committee was surprised to note that the 2024-25 budget contained an overall 24.2% cut in real terms to employability services. It is unclear how the Scottish Government's overall ambition can be realised with such a large decrease in funding.

The Minister for Employment and Investment recognised this concern but stated that budget decisions had been taken “in the context of a very challenging set of public finances.”1

The Committee agrees that halving the disability employment gap by 2038 would significantly benefit the wider economy by supporting a larger, more diverse, and more resilient labour force.

It notes however the conflict between the scale of this ambition, and the 24.2% cut in real terms to employability budgets, which is much higher than cuts in other areas.

The Committee recognises the difficult fiscal circumstances which influence the Scottish Government's decision-making in relation to the Scottish Budget. However, given the Scottish Government's commitment to halve the disability employment gap by 2038, and the scale of the challenge in meeting this aim, the Committee has difficulty in understanding the rationale for such a significant reduction in funding for employability services.

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to set out how it will provide an appropriate level of funding for employability services moving forward so that the necessary support can be put in place to help achieve its aim of halving the disability employment gap by 2038.

Beyond the headline budget figures, uncertainty around the availability of funding on the ground, and often the late awarding of funding, for employability service providers was repeatedly raised by several stakeholders as a barrier to effective service delivery.

Elizabeth Baird (Inverclyde Local Employability Partnership) told the Committee that, despite the positive changes brought about by NOLB, and the bringing together of the different areas of the public and private sectors—

it is genuinely the case that the annual funding process makes it extremely difficult to improve the situation and achieve a good level of quality without feeling that the good work that we are doing will tail off and will have to be re-established because of the lack of cohesion in the funding stream.2

Alasdair Scott (Scottish Borders Local Employability Partnership) told the Committee of a three-month delay in being allocated funding last year. He stated that this lack of certainty makes planning very difficult—

all sectors, including the third sector, rely on staffing costs being met. That is core to ensuring continuity of delivery before we even look at individual projects. We cannot just stop a service on 31 March; we need to continue to work with the clients with whom we have built relationships and keep the support mechanisms in place. It is a real struggle just now, and it is quite a worry for a lot of people.2

The Committee heard, for example, that employment support for disabled people is not just about help with applications and interviews, but that continued wrap-around support once disabled people have secured a job is vital. This requires time for a relationship to develop with the individual and the employer, and crucially, long-term funding to ensure consistency of provision. Ashely Ryan (Enable) told the Committee that—

We need to have a multiyear structure for investment that allows us to heavily invest in things such as aftercare. We have seen some real shifts where local authorities understand the need for aftercare, but in an annual cycle of funding, the reality for them is that they cannot go beyond 12 months.2

Ashley Ryan also told the Committee that where longer-term funding has been secured, success rates have been excellent. She noted that the City of Edinburgh Council had committed to funding employability services provided by All in Edinburgh (a partnership of four charities) for the next six years. She stated that—

The City of Edinburgh Council has recognised that, although it does not have all the funding answers right now, there is a challenge that has to be supported and funded. That allows us, as a partnership, to retain staff, and it also allows those staff to become qualified. They are all qualified in supported employment; they understand the client group; and they are there to be a sustained presence for that group. That is key; it means that we are achieving higher rates of jobs in that client group than ever before.5

The Minister for Employment and Investment recognised these concerns and the benefit that longer-term funding can bring, and stated that—

We are all familiar with the fact that our broader funding landscape is dependent on various factors that are not within the direct control of the Scottish Government. That creates challenges with regard to our ability to provide multiyear financing. I want to work with colleagues to address the issue so that, when a budget is allocated, we ensure that the award goes out as swiftly as possible, to provide certainty to partners on the ground.1

In a follow up letter to the Committee dated 14 June, the Minister confirmed that the full employability budget allocation of up to £90million for 2024/25 had now been released and that updated grant offer letters would be issued shortly to local authorities. He also stated that—

The Scottish Budget also sets out a commitment to consider future multi-year funding arrangements. Officials will continue working to determine the detail underpinning this commitment in the coming months.7

The Committee recognises the constraints of current funding payment cycles. It notes however the benefits, as highlighted by local authorities, that increased certainty of funding (at least for each financial year, if not multi-year funding) could bring to provide these services in-house or to fund third sector providers.

The Committee welcomes the Minister's commitment to work with colleagues to ensure prompt allocation and payment of funding. Given the evidence heard around the amount of time needed to properly support disabled people into work, and the benefits of wrap-around support, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government to set out how it intends to provide long term certainty to providers of employability services to address the concerns raised.

Jobcentre Plus

Jobcentre Plus is part of the UK Government's Department of Work and Pensions. Its activities were not part of the inquiry remit, therefore formal evidence from Jobcentre Plus was not sought.

During one of the Committee's engagement sessions, members heard from some disabled young people of their experience of the Jobcentre Plus network.

Witnesses told the Committee that advice from Jobcentre Plus can often not be tailored to the specific needs of disabled people, and that for many , the job centre is associated with benefit sanctions rather than with employment support.1

The Committee also heard that the network is generally decoupled from the wider employability system in Scotland. Carmel McKeogh (DFN Project Search) talked of the benefits of having better links between Scottish employability services and the Jobcentre Plus network, especially around services for disabled and neurodiverse people—

we can bring them into existing services, such as a Project Search programme or The Usual Place, and link them with people who know what they are doing, we usually find them to be eternally grateful and quite helpful. Mostly, though, they operate apart from us; they do not know what they are doing with people and it all ends up being a bit of a horrible mess. Sometimes it is a relief to jobcentres if we can link with them, because they do not get any training and support in that area. It is also helpful to us, as they have access to a lot of jobs that we can tap into.1

The Committee did not hear directly from Jobcentre Plus during the inquiry but notes the concerns raised in evidence.

The Committee calls on the UK and Scottish governments to set out how they will better align the Jobcentre Plus network in Scotland with the devolved employability services, to allow them to work better together and provide better signposting to specialist organisations. The voices of lived experience must be at the heart of the formation of policy and service delivery.

The Committee also calls on the UK Government to outline what training is in place for Jobcentre Plus staff around the needs of disabled and neurodiverse people, and whether there are any plans to refresh this.

Transitions to adulthood

What are transitions?

As young people with additional support needs approach adulthood, they transition from childcare and support services to adult services. This process involves preparing them for adult life (including their future career) and is referred to as ‘transitions’.

Transitions support is often delivered in an education setting but links to multiple areas of public life, including higher and further education, employability support, and health and social care services.

Highlighting the importance of this stage, the Committee heard of a “cliff edge”, where young disabled people receive support throughout their childhood, which then disappears as they become an adult (Tracey Francis, Association for Real Change Scotland).1 This emphasises the need for effective transition support.

During the Committee's engagement event with young people from the Usual Place in Dumfries, participants spoke of their experience of this transition and of not feeling supported at school, that they often felt “forgotten”. It should be noted however, that this was not a representative group and that transition support in other areas/schools may be different.

Early intervention

Witnesses agreed that early intervention and support can make a significant difference to a disabled person’s future. Carmel McKeogh (DFN Project Search) argued that the final year of school or college for some disabled pupils should be entirely focused on practical preparation for work.1

Dr Charlotte Pearson (University of Glasgow) told the Committee that—

It is critical that we have conversations about employment expectations and aspiration, and that we have them really early in the process. From the young people whom we have spoken to in our research, it is very clear that that is not happening and that there is not a huge amount of support within school systems. There is an expectation that many of the young people whom we have spoken to will not be in employment—that it is not for them. The message is, “That will not be your life course.”2

The Committee heard that, for some, this lack of aspiration can often be compounded by parents being forced to ‘talk up’ their child's impairment(s) to secure the necessary support (Carmel McKeogh, DFN Project Search).1 This can contribute to a culture where many young disabled people do not expect to have a fulfilling career.

Tracey Francis (Association for Real Change Scotland) agreed, stating that a lot of the language used in this area is “deficit-led”, focussing on what disabled young people cannot do rather than on what they can. This impacts aspirations and limits their ability to “sell themselves” in applications or interviews.2

Evidence heard by the Committee suggested that, by intervening earlier in the process, this could be remedied, empowering disabled and neurodiverse young people to embrace their true potential and to secure sustained and fulfilling employment, if that is the best course for them.

Careers support

The Committee heard that many teachers felt they did not have the right training to best assist disabled young people during this transition phase, and that the focus is often on educational attainment rather than employment.

It was suggested that, given the pressures schools are already under, there is merit in bringing in qualified external support to complement existing provision. Ashley Ryan (Enable) stated that—

When a school and Enable can work closely together, we see the greatest success because it balances educational attainment with what comes next. It is very difficult to do it all—we have to be mindful of that. This is not about saying that schools are not doing it well.1

Similarly, witnesses told the Committee that careers advice is rarely tailored to the needs of disabled and neurodiverse young people, and that often, careers advisors are not given enough training to best support them.

The Committee heard that in many cases, disabled and neurodiverse young people are ‘funnelled’ into supported college courses as a positive destination, with little thought as to their future career.1 During one of the Committee's engagement events, one participant told members that he felt he was directed towards college “for something to do”.

Dave McCallum (Skills Development Scotland) however stated that SDS works closely with schools and guidance staff to “identify young people who may need that extra support” and that services are adapted to support individual needs—

the mechanism is there and we have a good, robust system in the 16+ data hub as we know that young people can fall out at that stage.1

One solution put forward by witnesses was to employ dedicated transitions coordinators in schools. Tracey Francis (Association for Real Change Scotland) told the Committee of one local authority that had found success with this approach. She stated that—

if the transition experience is smooth, it is a lot easier to have conversations about employment, because people have the bread and butter in place. They have the essentials.4

The Committee agrees with witnesses that the provision of transition coordinators in schools would greatly aid smoother transitions to further education or employment.

National Transitions to Adulthood Strategy

The Scottish Government is currently developing a National Transitions to Adulthood Strategy. Part of this will include the Principles of Good Transition, developed by the Scottish Transitions Forum.

As previously discussed, stakeholders are generally supportive of the current trajectory of this strategy and believe that the right policies and structures are now in place.

Witnesses told the Committee however that there has been enough discussion and that another high-level strategy won't make a difference unless it is backed up by sustained funding and a clear plan for implementation.

Much of the evidence heard during the inquiry comes under the remits of both this Committee and the Education, Children and Young People Committee. This report is therefore drawn to the attention of the Education, Children and Young People Committee to help inform any future work it may decide to undertake in this area.

Every young person in Scotland should be able to access support in their transition from education to employment. The Committee notes the Scottish Government's forthcoming National Transitions to Adulthood Strategy and seeks an update from the Scottish Government on when the final strategy will be published.

The Committee agrees that this strategy must include training for teaching staff and careers advisors on the specific needs of disabled and neurodiverse young people.

The Committee notes the evidence heard around the difference that transition co-ordinators can make to bring together different services and calls on the Scottish Government to consider the provision of transition co-ordinators as part of the National Transitions to Adulthood Strategy.

The Committee agrees with calls for a clear implementation plan and seeks confirmation from the Scottish Government that this will be included in the final strategy.

Social care budgets