Education, Children and Young People Committee

Additional Support for Learning inquiry

Introduction

The Committee launched this inquiry to consider how the 2004 Act is working in practice and to look at how successful the implementation of the presumption of mainstreaming, as introduced by the Standards in Scotland’s Schools etc. Act 2000 (the 2000 Act) has been. This inquiry can be considered as post legislative scrutiny of both those Acts.

The Committee was aware of concerns around the very low number of Co-ordinated Support Plans being put in place and was also keen to explore what a presumption of mainstreaming meant in practice for pupils with complex needs, as well as examining the mechanisms pupils and parents and carers can use to challenge decisions around the provision (or lack of provision) of additional support.

According to the latest Scottish Government figures, in 2023, 37% of all pupils (259,036 individuals) had an additional support need (ASN). This is 2.8 percentage points higher than 2022 when 34.2% of pupils had an additional support need.1

This inquiry focused on the following themes—

the implementation of the presumption of mainstreaming

the impact of COVID-19 on additional support for learning

the use of remedies as set out in the 2004 Act

The Committee issued a call for views based on these themes and received 590 responses to the English language version of the call for views, 29 responses to the British Sign Language version and one response to the easy read version. Many of the responses were from individuals with personal experience of ASL provision and a summary of responses was produced by SPICe and published on the website.2

The Committee took evidence from witnesses during five evidence sessions at its meetings on 21 February 2024; 28 February 2024; 6 March 2024; 13 March 2024; and 20 March 2024. A list of the additional written evidence that was submitted following these sessions is provided in the annexe to this report.

In advance of launching the inquiry, the Committee wrote to all local authorities across Scotland seeking a response to a number of questions. Responses were received from 25 local authorities, which are published on the website.

The Scottish Parliament's Information Centre (SPICe) produced a summary of these responses, which includes a list of those who responded, outlining the main themes emerging from the responses. This included the following—

In the main, local authorities thought that support for additional support needs (ASN) is working well in both mainstream and specialist settings;

There is both an increase in the numbers of pupils with ASN and an increase in complex needs;

Mainstreaming is considered a positive in the delivery of ASL, however resourcing was seen as a challenge including the availability and retention of specialist staff;

The importance of supporting good relationships with families and pupils; and

The importance of training for teaching and support staff.

The Committee was keen to speak with people with personal experience of additional support for learning to hear directly of the issues they faced and any areas where more could be done to support them. The Committee met with young people, Inclusion Ambassadors, parents and carers and teachers at informal participation sessions on 19 February 2024 and 4 March 2024. Notes of the discussions from these engagement activities are provided in the annexe to this report and published on the website.

The Committee would like to thank everyone who participated in this inquiry, in particular, those with personal experience of using the current additional support needs legislation in Scotland. The discussions it held and the evidence it received helped shape this inquiry and the Committee's recommendations to the Scottish Government. It should be noted that throughout this inquiry, many of the issues related to each theme, particularly the first two themes, overlapped and this report reflects this overlap.

The Committee welcomes the commitment from the Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills to “learn from the Committee's output and use that learning to inform that process."3

Background

Legislative landscape

The Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Bill 2004 was passed by the Scottish Parliament in April 2004. The main provisions of the resulting Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004 (the 2004 Act) came into force on various dates from May 2004. The 2004 Act was subsequently amended by the Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2009 and the Education (Scotland) Act 2016. The 2009 Act allowed parents and carers of children with additional support needs (ASN) to make out of area placing requests. These included those with co-ordinated support plans (CSPs) and placed a presumption that a child in care has ASN (i.e. a local authority would have to determine whether the child does not have ASN). The 2016 Act clarified the provisions around determining when a child has the capacity to make their own decisions.

As set out in the Explanatory Notes to the 2004 Act, the Act introduced the legal framework for the provision of additional support for learning. It replaced the system for assessment and recording of children and young people with special educational needs with a new system for identifying and addressing the additional support needs of children and young people who face a barrier to learning. It placed duties on education authorities in Scotland, local authorities for the purposes of the Act, and required other bodies and organisations to help. In providing school education, local authorities are required to identify and then make adequate and efficient provision for the additional support needs of children and young people.

Under the Act, parents and carers can request a local authority to establish whether their child has ASN and whether they require a CSP. A CSP must be prepared for those with enduring complex or multiple needs that require support from outwith education services. The plan focuses on supporting the child to achieve learning outcomes and assists the co-ordination of services from a range of providers. Additional Support Needs Tribunals were also established to hear appeals relating to co-ordinated support plans. The Act provides that mediation services must be made available to assist in dealing with disagreements between parents and carers and local authorities or schools and authorities may be required to put in place arrangements for dispute resolution.

The Act also defines what is meant by the term “additional support needs” and describes its context. The need for additional support is related to the ability to benefit from school education. Support is considered as additional if it is provision that is different in some way from that generally provided for children of the same age in pre-school centres and schools.

Section 15 of the Standards in Scotland’s Schools etc. Act 2000 Act (the 2000 Act) states that education authorities will provide school education to all pupils “in a school other than a special school” unless one (or more) of the following circumstances arises—

(a) would not be suited to the ability or aptitude of the child;

(b) would be incompatible with the provision of efficient education for the children with whom the child would be educated; or

(c) would result in unreasonable public expenditure being incurred which would not ordinarily be incurred.

The 2000 Act says that “it shall be presumed that those circumstances arise only exceptionally”. If one of the circumstances listed above is true, the education authority may provide education to child in mainstream education, but it “shall not do so without taking into account the views of the child and of the child’s parents in that regard”.

The 2000 Act applies to all children for whom the education authority is providing school education. The policy intention as set out in the Explanatory Notes was to “strengthen the rights of children with special educational needs to be included alongside their peers in mainstream schools.”

In 2019, the Scottish Government published guidance on the presumption to provide education in a mainstream setting. This guidance says that mainstreaming “must be delivered within an inclusive approach.”

The Scottish Government also published statutory guidance on the 2004 Act which was updated in 2017, often referred to as the Code of Practice. The Code of Practice states that it should be read alongside other legislation and policy where appropriate such as theCurriculum for Excellence, Getting it right for every child, Developing the Young Workforce, Hall 4 and the Universal Health Visiting Pathway.

Morgan Review

In 2020, the Scottish Government published Angela Morgan’s review of the implementation of additional support for learning (The Morgan Review), which is a key document in this policy area. The Morgan Review was intended to explore how ASL works in practice, across early learning and childcare centres, primary, secondary and special schools (including enhanced provision, services and units).

The Review highlighted the importance of public services working collaboratively with parents and carers who advocate for support for their children. The remit of the Review made clear that it excluded consideration of the principle of presumption of mainstreaming and the sufficiency of resources.

The Review set out the following four key conditions for delivery—

Values driven leadership;

An open and robust culture of communication, support and challenge – underpinned by trust, respect and positive relationships;

Resource alignment, including time for communication and planning processes; and

Methodology for delivery of knowledge learning and practice development, which incorporates time for coaching, mentoring, reflection and embedding into practice.

The Scottish Government and COSLA accepted all the recommendations of the review and the Scottish Government published an ASL Action Plan which set out how the recommendations would be taken forward.

The Additional Support for Learning Project Board was set up to “support the monitoring of implementation and oversee delivery of additional support for learning and inclusion policy, including through delivery of the Additional Support for Learning (ASL) Action Plan (updated November 2022) and its associated workstreams.”

Getting it right for every child (GIRFEC)

GIRFEC is intended to provide all children, young people and their families with the right support at the right time in order that every child and young person in Scotland can reach their full potential. It provides a “consistent framework and shared language for promoting, supporting, and safeguarding the wellbeing of all children and young people.” It is intended to use an ecological model which says that child development “is influenced by the relationships they have with their parents, then by school and community environment, then by wider society and culture.”1

GIRFEC is intended to support different services to work together to support the child and their family. GIRFEC principles will inform schools’ considerations of how to support a child or young person. This may be support provided only by the school or by other statutory or third sector services. Schools may also use GIRFEC planning mechanisms – normally a Child’s Plan – although other plans may be used instead or in addition to a Child's Plan.

Personal experience

At the outset of this inquiry, the Committee was keen to hear directly from those with personal experience of how the 2004 Act was working in practice and how the presumption of mainstreaming was being implemented. The voices of those children and young people, their parents and carers and teachers involved in providing ASL were uppermost in the Committee's mind when taking evidence from stakeholders. As many witnesses and respondents to the call for views said, it is imperative that the children and young people are put at the heart of this inquiry and that issues which have been raised throughout the inquiry are addressed.

Many responses to the call for views contained details of negative personal experiences, including parents and carers having to "fight" to get support for their child and some disturbing accounts of the impact on children and young people with ASN's health and mental wellbeing.

In many written responses, the Committee heard of the anger and frustration that parents and carers are experiencing in trying to get what they feel is the best support for their child. The Committee also heard from teachers who felt they are being left to struggle with a lack of support and time to allow them to do their job.

Concerns were raised around a lack of inclusion and the distinction was made between pupils being present in a mainstream setting and them receiving an inclusive education. Aberlour said that families have commonly highlighted experiences of “isolation, lack of inclusion and inequality.” 1

The Committee was fortunate to hear directly from the Inclusion Ambassadors, who were supported by Children in Scotland, on how it feels when their school gets their support right. The Inclusion Ambassadors is a group of secondary school-aged pupils who each have a range of additional support needs and attend a variety of school provision. The group was established to ensure the views of young people with additional support needs are heard in discussions about education policy.

The Inclusion Ambassadors spoke openly of their experience of being a pupil with additional support needs, including what works and what could be done to make things better. They told the Committee that pupils feel really good when the support provided is correct and suits their needs; however, it can be hard to understand when someone does not give them the support they need. They highlighted that it does not work well when there are not enough support staff to cope with the number of pupils who need support which can lead to pupils feeling frustrated. Some of the comments included 2—

It makes you feel special when teachers and staff check in with you to see if you are ok

Teachers are very kind and understand when you are upset which makes me feel supported and happy

It is important that teachers take time to ask you what you need rather than assuming what you need as sometimes your needs are not obvious

It is really good when all staff make a connection and you have a relationship with all staff, not just support staff

However, when the Committee spoke with parents and carers, the picture was very different. The Committee heard of the difficulties experienced by parents and carers in getting the correct support for their child including long delays in diagnosis and access to support services such as mental health services and speech and language therapy. Parents and carers spoke of not being listened to particularly where they felt that the presumption of mainstreaming was not meeting the needs of their child. Comments included3—

Children were commonly left on their own without support, outside of the classroom. Others raised concerns about part-time timetables and informal exclusions.

One parent spoke of their child who could not attend the mainstream school due to their additional support needs and, despite being happy in a specialist school 1 day a week, they were still not being referred to a full-time specialist school so this decision was being appealed.

Parents said that local authorities making an assessment of their parenting skills could sometimes delay their children’s ASN needs being met. For example, some said they were told they must attend a parenting programme before assessments for their child’s neurodiversity could be considered.

They made the point that not all pupils can attend a mainstream school and this should be better understood by schools and local authorities. They said the presumption of mainstreaming means the presumption of a right to mainstream school; however it was increasingly being interpreted as a presumption that all children are capable of attending a mainstream school without the appropriate accommodations needed for each individual child. They argued that when the needs of a pupil are not being met in a mainstream school it can be a very negative and damaging experience for that pupil and for the parents and carers witnessing this.3

When the Committee spoke to teachers, the picture painted was also very concerning. They spoke of a significant decline in support resources for pupils with ASN and a huge increase in the number of pupils with ASN in mainstream classes since the presumption of mainstreaming was introduced.5

The Committee heard of numerous cases where parents and carers had to fight for their children to receive the support they needed. One parent said6—

It is unhelpful where schools do not listen to parents on what additional support needs are required, or where a request is made to place the child in a specialist school.

Vivienne Sutherland representing Fife Council said that, although this was a theme which emerged from the Morgan Review, from her experience, she did not feel that all families needed to battle and that when working with families, in the vast majority of cases things can be resolved before reaching a crisis point. 7

Dr Lynne Binnie representing the Association of Directors of Education in Scotland (ADES) echoed this point and said in the majority of cases, local authorities listen to concerns from parents and carers and try to resolve their concerns as early as possible. She said8—

Of course, a small number of parents and carers do not feel that their concerns are listened to, and local authorities have in place a number of staged interventions that parents can access to have their concerns raised. In my experience, when listening to some of the complaints and tribunal cases that come over my desk day to day, what is often at the heart of the issue is a breakdown in communication and relationships.

Jenny Gilruth, Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills (the Cabinet Secretary) acknowledged that, in the 20 years since the 2004 Act was passed, the experiences of young people and their families have not progressed in the way and at the pace they should have.9 She said10—

Parents often feel that they have to fight against the system to get their voices heard and their young person diagnosed, and that does not reflect the intention behind the 2004 act.

The Committee is grateful to the Inclusion Ambassadors for sharing their views and experiences in education.

The Committee values the work being done by Children in Scotland on positive inclusion experiences.

The Committee recognises that where systems need to improve it is as important to understand where things are working as well as where there are challenges and, as such, recommends the Scottish Government continues to fund this work.

The Committee was extremely concerned by what it heard regarding the negative personal experiences of ASL provision, the implementation of presumption of mainstreaming and the detrimental impact this has had on some pupils with ASN, their parents and carers and teachers and support staff. The Committee commends the work done by teachers and support staff in providing support for pupils with ASN but was concerned to hear of the pressures they faced, leaving them feeling overwhelmed and 'burnt out'.

The Committee notes that ASN-related issues between families and the local authority can often be resolved at an early stage. However, it is clear that there are still many occasions where disputes are protracted. Parents and carers describe themselves as “fighting” for the right resources to be put in place for their children. Work carried out by our predecessor Committee in Session 5 suggested similar outcomes, indicating that significant issues in relation to meeting pupils’ ASN needs remain. The Committee finds this wholly unacceptable and it should not be allowed to continue.

The Committee considers the issues raised by witnesses and respondents to the call for views must be addressed as a matter of urgency to ensure the effective inclusion and appropriate support provision for all pupils with ASN in Scotland's schools. This report sets out the Committee's recommendations on how these issues can be addressed.

The implementation of the presumption of mainstreaming

In 2019, the Scottish Government published guidance on the presumption to provide education in a mainstream setting. This guidance says that mainstreaming “must be delivered within an inclusive approach.” The guidance reiterates the “four key features of inclusion” which are—

Present

Participating

Achieving

Supported

Principle of the presumption of mainstreaming

The overwhelming view both in written and oral evidence was that the principle of the presumption of mainstreaming is laudable and should be supported. However, concerns were raised around the implementation of this policy and the barriers faced in practice when mainstreaming was in place. The Committee heard that this has led to many pupils not being included in a meaningful way.

Matthew Cavanagh representing Scottish Secondary Teachers Association (SSTA), on social inclusion being one of the intended benefits of the presumption, said1—

Improving learning through diverse provision for our young people is a massive part of the benefits that can happen through schools. Having young people learning together across society, learning about one another and about themselves within that society, remains a common goal that we must pursue.

In written evidence, 2 the majority of organisations said that the presumption of mainstream education was correct one on a moral and philosophical level. However, often respondents including the Commission on School Reform3 (CSR), Govan Law Centre4, UNISON Scotland5 and AHDS6suggested that there was a gap between policy intention and delivery.

One parent’s submission said7—

The presumption of mainstreaming is a wise one as this means less segregation and more acceptance of those with additional learning needs not only in school but beyond.

The parent continued to say however that in practice there had not been enough support for their child and that due to lack of funding and lack of classroom support, their child can only attend school for half days.

The Children and Young People’s Commissioner Scotland (CYPCS) stated that the presumption of mainstreaming was a positive step towards delivering on international human rights treaty obligations and creating a more inclusive education system. However, she said8—

Disabled children and young people and children with additional support needs continue to be unfairly subjected to practices that impact negatively on their education, as well as their personal and social development. Because their needs are not being met, they are not always able to access a full curriculum, experiencing part time timetabling and informal school exclusion practices.

A number of respondents, including parents and carers, said that while in support of the presumption, it should be acknowledged that being educated in a mainstream setting is not appropriate for all pupils with ASN. Salvesen Mindroom Centre commented9 —

The presumption can add positively to the creation of an inclusive school community, where difference is fully accepted: this brings benefits for all of the children in school. The presumption has meant that families do not have to fight for the inclusion of their child in the catchment school, or parental choice school. The converse is also true, however - where children and families find the local mainstream school cannot provide adequate support it is more of a struggle to make the argument for specialist provision, even where this is clearly in the best interests of the child.

Govan Law Centre made the point that, while efforts should be made to ensure that a mainstream environment is inclusive for all children, there are occasions where this is not the best option for the pupil. It commented10—

There is a distinct gap in terms of how the presumption of mainstream model marries itself with children who are neurodivergent with a significant sensory profile and are unable to engage in a mainstream environment. Too often, we have seen the fruits of presumption of mainstream meaning that a child is on the face of it accessing a mainstream school but the reality is they are accessing a separate space alone for a significant portion of their education. This concerns us from both a wellbeing perspective and an inclusion perspective.

Moray Council went further saying that presumption of mainstreaming does not work for the majority of pupils with ASN or with no identified need.11

This point was echoed by Aberlour who said “mainstream settings can provide positive and meaningful learning experiences for children who require additional support. However, in our experience this is the exception rather than the rule.” It said that good practice is when there is “effective partnership working between schools and third sector services supporting the child and their family” and where there is the necessary investment to “to deliver additional capacity to focus on children and families’ wider needs”.12

The Tribunal commented on the interpretation of the 2000 Act’s provision that the circumstances where a presumption of mainstreaming should apply only exceptionally. It said that the exceptions in the 2000 Act “are tightly defined already, and another overall test seems misplaced … it is not clear how to apply the exceptionality requirement.” Overall, the Tribunal argued13—

An inclusive education for those who have additional support needs would be best served by the removal of a bias in favour of a particular type of education. A bias of this type is the reverse of an inclusive approach.

Suzi Martin, representing National Autistic Society Scotland (NASS) referred to the vision set out in the Scottish Government's Action plan where "school is a place where children and young people learn, socialise and become prepared for life beyond school". She highlighted that, although the plan was welcomed, progress had been slow and had not created the change required saying 14—

We see continually that autistic children and young people are forced to “fail” in mainstream settings before any other option or support is offered, and families are still forced to fight the system to get that support, with many being forced into legal action and having to engage a solicitor before a solution is found.

She suggested the following three areas for improvement—

The school environment

Training

Specialist provision within the mainstream setting14

Enquire said the key factors in determining the success of a pupil's school placement are not necessarily whether it is a mainstream or specialist provision, but rather it is whether "the child feels truly included, listened to and supported.”16

The Committee was alarmed to hear there was strong evidence to suggest that the majority of ASN pupils are not having their needs met.

The Committee agrees with the policy intention behind the 2000 Act's presumption of mainstreaming. However, the gap between the policy intention and how this has been implemented in practice is intolerable.

The Scottish Government, working alongside Education Scotland and COSLA, should act as a matter of urgency to address the issues highlighted via this inquiry to ensure that all pupils with ASN can enjoy their right to an education and have a positive experience at school. The Committee recommends that all those responsible for the delivery of education in Scotland should, at pace, outline how they will address this with clear action points and timelines.

The Committee was concerned about the practice highlighted by the Tribunal, where the use of the exceptional circumstances with regards to placements in mainstream are confused and not always working well. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government, working with Education Scotland, ADES and COSLA, should review the implementation of the grounds on which a request to be placed outwith mainstream are being used.

Identification of needs, diagnosis and support

As set out in the Code of Practice, the 2004 Act requires that the education authority "must make adequate and efficient provision for such additional support as is required by each child or young person with additional support needs, for whose school education the authority are responsible."1 There is no requirement in the 2004 Act that a diagnosis must be made before support is provided.

Many individual responses to the call for views from parents and carers spoke of long delays in recognising and providing additional support needed for their child. They expressed frustration at the processes involved in identifying and diagnosing ASN. For example, one parent said2—

My child's additional support needs were not recognised nor identified for over 5 years despite numerous requests to the mainstream school to assess and support my child. …. Before a formal diagnosis no reasonable adjustments were put in place. … I asked for my child to be referred to Speech and Language – they didn't do it despite saying they would. … It took 10 months to get them to do this. I asked for an OT referral on a number of occasions. … Every support my child has, has been due to a fight to get school to do anything. They have never offered support or made a suggestion of any support they could do. It is a constant battle, every day.

Long delays in the identification of needs and diagnosis for pupils with ASN was also raised by a number of educators and teaching unions. One educator commented3—

Some children come into school with a formal diagnosis in place and in most cases some support is provided particularly if the child is a flight risk, aggressive or has a range of conditions requiring personal support. However, I have also seen children who are diagnosed as ASD get very little extra support because they are amiable and not deemed a risk or at risk. Where a child starts school with no diagnosis, it can take a long time (about 3 years) to get a formal diagnosis made. Where I work provision/support will still be given to undiagnosed children if they are struggling in the mainstream setting.

The EIS stated that the delays between referral, diagnosis and post diagnostic support is caused in part by the shortage in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) and Educational Psychology Services and that this is unhelpful to the child or young person, their family and teachers and school staff.4

Salvesen Mindroom Centre argued that it was contrary to the ASL Act that in some cases education authorities are waiting for formal diagnoses before putting support in place.5

Mike Corbett representing NASUWT also spoke of the misconception that a diagnosis is required before support can be provided saying6—

...there is a perception among many parents and carers that having a diagnosis impacts on the level of support that a child or young person can access. In other words, there is a perception among many parents and carers that getting a label somehow brings more funding and more support.

Vivienne Sutherland, representing Fife Council, also argued that it is not necessary to have a diagnosis in order to access support and that support will be put in place when a need is identified. She explained that the council would support parents and carers in seeking a diagnosis but reiterated the fact that support would be provided without this. She said7—

Some parents are very keen on diagnosis because it helps them to understand their child’s difficulty. That is great, and we will support them along that pathway. Some parents are very resistant to diagnosis because they do not want their child to be labelled. We are also fine with that and will support the parents and the child through their journey regardless.

Susan Quinn, representing the Educational Institute of Scotland (EIS), reiterated the point that even if no diagnosis has been confirmed, staff still provide support for pupils; 8 however Peter Bain, representing School Leaders Scotland (SLS) made the point that local authorities will focus resources into ensuring that those who have a diagnosis are supported as outlined by the medical professionals.9

Dr Binnie however made the point that, although schools will provide support without a diagnosis, this is not always the case for partner agencies, who will require a diagnosis in order for people to access specific post-school services.7

Masking

A guide produced by Enquire and the National Autistic Implementation Team, a practitioner researcher partnership based at Queen Margaret University and funded by the Scottish Government, explains that masking is where a person covers up natural feelings, preferences and reactions to the world around them. It explains that masking can be tiring and can affect a person's wellbeing and that not all autistic children will be aware that they are masking.1

A number of written responses referred to difficulties associated with masking and how it affected children's mental wellbeing and made it difficult for schools to see there were additional support needs not being addressed. Some responses spoke of a lack of understanding of the issues surrounding masking. A psychologist working in CAMHS spoke of the difficulty in providing support where masking is a feature. She stated2—

This means schools are being asked to provide support on the basis of need not diagnosis which is in line with GIRFEC but can be difficult for those families where able children are masking their difficulties in school and appear not to need help there but then manifest significant emotional and behavioural issues at home, impacting both child and parent mental health.

Parents and carers raised the issue of masking as a concern causing delays in diagnosis. They suggested that with neurodivergent pupils, girls were often better at masking than boys resulting in greater delays in diagnosis for girls.3

May Dunsmuir, president of the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland, highlighted that masking was a common feature of tribunal hearings where there are two completely different pictures from the parties’ perspectives. She commented4—

Masking, which is a very common theme in our cases that involve neurodivergent children, is when a child puts in so much effort to be who they think they are supposed to be in school that, when they get home to their safe environment, the cost is enormous...We see a great deal more evidence of masking—it is almost common now.

She highlighted that the disruptive effect of masking when pupils return home to a safe place from school affects the relationship between the parent and the child and called for a better understanding of the issue saying5—

I know that a better understanding of masking is called for, because we are learning that from our cases and because we have been taught by experts that there needs to be better understanding of what masking is.

Chloe Minto representing Govan Law Centre said that masking was a central feature in almost every tribunal case it deals with and argued that education authorities need to take more responsibility in this area. She explained6—

We have questions about why the child is so different at home from the way that they are in school. Why are they stimming at home and not in school? What is the root cause of that? Not enough questions are being asked about that by the education system, which leaves parents feeling very failed.

Dr Binnie commented that schools are becoming more aware of masking and are trying to understand more about pupils' lives outwith school in order to try and help with adaptations which could help reduce distress at home.7 Kerry Drinnan representing Falkirk Council, also spoke of the support schools can provide for pupils who mask, such as building in a break before the pupil goes home to allow time for deregulation and offering advice and support to parents and carers. She emphasised the importance of listening to parents and carers who say their child is masking. 8

The Committee notes that there is no requirement under the 2004 Act for a diagnosis to be made before the local authority can provide support to a pupil with ASN; however, the Committee has been told that this is often a requirement when seeking support from other agencies.

The Committee was saddened to hear of the difficulties experienced by parents and carers in getting the correct support for their child and the misconception that a formal diagnosis was not only desirable, but necessary in order to obtain support. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government provides clarity in the Code of Practice on how support should be provided to pupils with ASN whether or not they have a formal diagnosis, including from agencies other than education.

The Committee notes the concerning evidence it heard in relation to neurodivergent pupils masking at school and believes that more must be done to understand its prevalence and the effect it is having on pupils’ school and home lives, in particular the impact on parents and carers and the ability for their children to obtain appropriate support.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government and COSLA undertake targeted research to understand the impacts of masking more fully and that the findings of this should be incorporated into the Scottish Government’s updated Code of Practice.

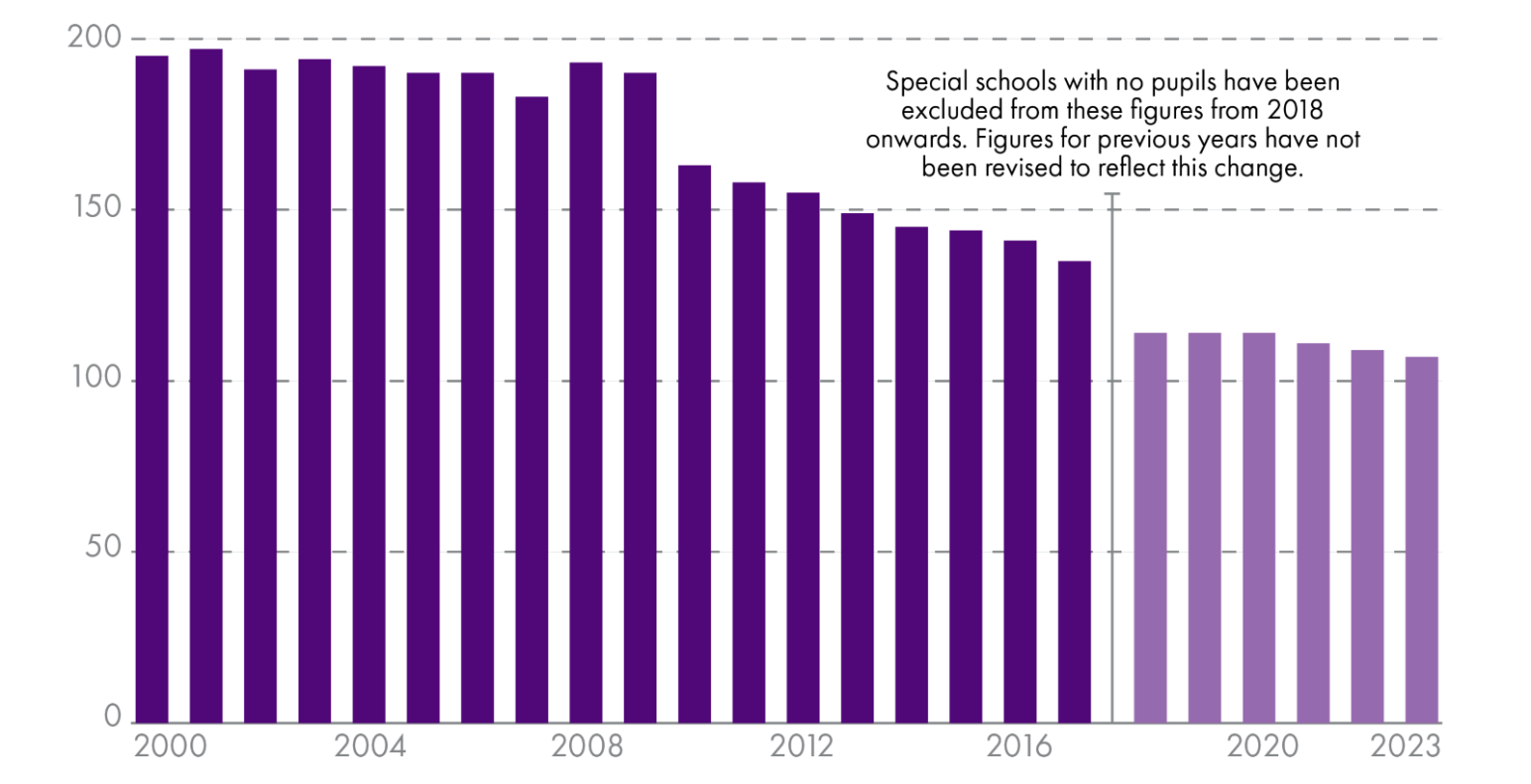

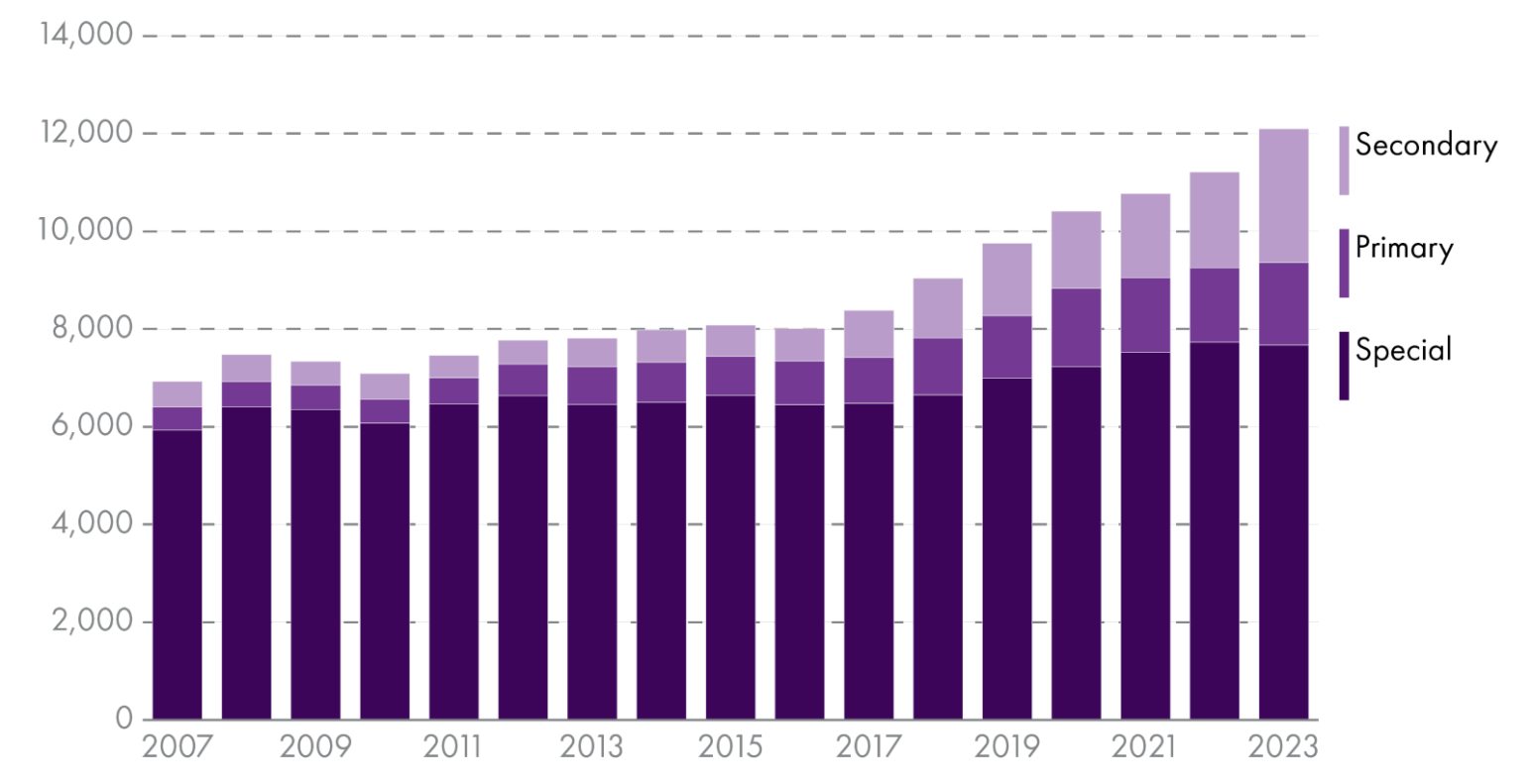

Special schools, units and support

The Scottish Government Pupil Census 20231 states that the total school roll across primary, secondary and special sectors in 2023 was around 706,000. Around 1.7% of pupils are reported as spending no time in mainstream classes. 36.7% of all pupils in 2023 had at least one identified additional support need. A small number of special school pupils spend part of the time in mainstream classes. In the secondary sector, the number of pupils with an identified additional support need who spend part of the time in mainstream settings has increased substantially since 2016: from 1,603 to 5,661 in 2023. There has also been a large increase in the number of secondary pupils spending no time in mainstream classes in that period: from 668 in 2016 to 2,739 in 2023. The charts below show the number of special schools2 in Scotland and the number of pupils who spend none of their time in mainstream classes.

Special Schools in Scotland

Scottish Government (2024), Pupil census supplementary statistics 2023,https://www.gov.scot/publications/pupil-census-supplementary-statistics/

Pupils who spend no time in mainstream classes, by sector  Scottish Government (2024), Pupil census supplementary statistics 2023,https://www.gov.scot/publications/pupil-census-supplementary-statistics/

Scottish Government (2024), Pupil census supplementary statistics 2023,https://www.gov.scot/publications/pupil-census-supplementary-statistics/

The Code of Practice section on school years states that all children and young people are entitled to receive the support they need to become successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens and effective contributors. It states3—

Where difficulties persist, a progressive process of assessment and support will inform next steps in learning. Consultation with parents and the child or young person, support staff and agencies outwith the school may be necessary. Additional support may be given within or outwith a classroom or mainstream school context. For example, some children may benefit from attending a specialist unit within the school on a full or part-time basis. Others may benefit from provision in a special school or a shared placement between schools. Others may benefit from attending a health, social work or voluntary agency facility.

The Committee considered the role played by specialist settings in the presumption of mainstreaming and the criteria for deciding when a specialist setting is appropriate or whether specialist support within a mainstream setting is more appropriate.

Salvesen Mindroom Centre set out some of the positives and negatives of specialist schools or units. It said that some positives included: the daily routine and structure better suited some pupils; small groups and 1-to-1 support is more likely; and that there appears to be better access to health professionals for those settings. Some negatives identified included: options for post-school transitions; high staff turnover and absence; and lack of a consistent national curriculum.4

Enquire made the point that “many still see a hard line between ‘mainstream’ and ‘specialist’ provision, and the presumption of mainstreaming legislation seems set up with this clear division in mind. In reality, this has become more and more blurred.” ASL units, bases or hubs in mainstream schools are now more common.5

Susan Quinn highlighted that the needs in relation to specialist provision have become more complex and more challenging to address. She said6—

Children who, historically, would have attended a complex needs school are now attending an additional support needs establishment, and those children who would have attended an additional support needs establishment are now attending a mainstream school, alongside those young people whose needs we would have expected to be addressed through the presumption of mainstreaming. In other words, there is still a level of tiering, which we would have expected the presumption of mainstreaming to address.

Deborah Best, representing Differabled Scotland, quoted one of the parents from her organisation who said some pupils fall between mainstreaming education and specialist placement education saying 7—

The first of the young people who were thrust into mainstream education were allowed to fail due to inconsistency or lack of support, especially in the early years, despite strong evidence of need and promises of support. It seems that it is now almost a requirement that a child must first fail badly before they are seriously considered for a specialist placement.

Chloe Minto also made the point that the legislation does not allow for split placements to be applied for. She said8—

If you are looking for a place for your child in a mainstream school for half the time and a special school for the other half, the legislation does not allow parents to do that and have the remedy of the tribunal placing request process. You can try to get that through a coordinated support plan.

Specialist support within mainstream settings

Section 23 of the 2004 Act provides that education authorities may seek assistance from other agencies (e.g. a local health board) in supporting pupils with ASN; examples of this could be speech and language therapy or occupational therapy. The other agency must comply with this request unless the request is “incompatible with its own statutory or other duties, or unduly prejudices the discharge of any of its functions”.

The Committee heard that access to a range of services outwith education has diminished over time and that services are often delivered within schools by school staff without appropriate back-up and support. Access to specialist services such as CAHMS and the length of waiting lists was regularly mentioned by many respondents to the call for views. Enable highlighted concern among parents and carers about the continuity and consistency of support and lack of access to specialist teaching support. It stated1—

Many young people continue to face long waiting times not only to services such as CAMHS but also for support such as speech and language therapy. There continues to be a need for increased and more timely access to these important supports which are vital for the wellbeing of the pupil and inclusion in their educational setting.

David Mackay, representing Children in Scotland, made the point that there is not always a consistent approach to the operation of ASL hubs within mainstream school settings and that this can lead to confusion for parents and carers who are not always aware of the available provision within mainstream schools. Marie Harrison, also representing Children in Scotland agreed telling the Committee2—

We quite often hear that parents have made a placing request for a mainstream school that has an ASL hub attached to it, because they feel that that will give their child the chance to do mainstream but get support from the ASL provision. However, that is not how it works. A placing request often has to be for the ASL provision. On top of that, there are learning hubs that are not necessarily ASL provision. Parents sometimes think that they can make a placing request for those, but they are readily available for all children.

A number of respondents to the call for views commented that the pressure on certain services such as CAMHS had increased since the pandemic. Cyrenians suggested that the service is now at “breaking point” and reported that “many families have said their children have been waiting for over 2 years to receive an assessment.”3

An individual response from a psychologist working in CAMHS said4—

The pandemic has led to a huge increase in the demand for neurodevelopmental assessments in CAMHS in Lothian. This far outstrips the capacity of the service to meet that demand, as there have also been significant increases in demand for mental health treatment, particularly for eating disorders which has to be the service priority where there isn't enough capacity to cover all needs. Consequently waiting times are 3 years approximately in Lothian at present.

The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT) agreed: "The clearest indicator of the impact of the pandemic on meeting the communication needs of children and young people has been the increased waiting times for speech and language therapy."5

A number of respondents to the call for views spoke of the challenges in recruitment of pupil support workers, teachers and other specialist staff which had an impact on providing additional support for pupils.

Kerry Drinnan highlighted how the council adopted a multi-agency approach for pupils with ASN which had reduced waiting times and increased the expertise of school staff. She explained that they have clusters where a high school and all its associated primaries has a named person in an agency to go to and the council has ASN advisers who each have two clusters which they support. She stated6—

We have a model in which we have a service level agreement with our allied health professionals for speech and language services and physiotherapy. We have named clinicians who are mapped to each cluster, who are there as a first point of call. If a school needs advice, it has a named person whom it can contact immediately, as do the families. We also extend that to educational psychology.

Vivienne Sutherland also spoke of the multi-agency approach adopted by Fife Council and highlighted the difficulties for schools in streamlining referral paperwork for pupils with ASN as it involves multiple referrals for multiple services. 7

Special schools

The statutory definition of a “special school” includes either a school or “any class or other unit forming part of a public school which is not itself a special school” but is especially suited to the additional support needs of pupils. The Enquire/My Rights My Say joint submission noted the interpretation section of the 2004 Act, which includes ASL units as part of the definition of a special school. This can lead to complexity when considering the legal position around, for example, placing requests.

The EIS argued that special schools and special units have an important and valuable role to play in more appropriately meeting the needs of pupils for whom mainstream provision may not be a suitable setting. It said that both mainstream and specialist provision must be adequately resourced if they are to be effective.1

The EIS noted that there has been a reduction of special schools in recent years, from 141 settings in 2016 to 109 in 2022. It said that some of its branches have2—

highlighted the impact which the reduction in the number of special schools and support-based units in mainstream settings is having on the delivery of inclusive education for children and young people who are now having to spend significant periods of time in mainstream without the support they were previously getting.

In written evidence, a number of individual parents and carers expressed frustration at the reluctance to provide specialist education provision, despite the parents and carers believing this would be the best option for their child. One parent/carer told the Committee3—

In our area there is no special school. Therefore no choice for parents. My daughter absolutely meets the criteria for a special school and we feel let down completely that this isn’t even an option for us.

Sylvia Haughney representing Unison Scotland echoed this point. She told the Committee that, although some parents or carers are happy to have their child in a mainstream school, where this is not the case and the parent or carer believes the child will be better suited to a specialist school then this can be very difficult. She said4—

They absolutely have to involve their local MP and go to their health visitor and their general practitioner to try to get their child where they need to be. That is only the parents who know that they have a voice. The parents who know that they have a voice will get their children into the ASN establishments, but those establishments are then full to capacity, so there is nowhere for children to go other than a co-located unit within a mainstream school where staff are not trained in the complex needs of the children who come to them.

Researchers from the University of Glasgow Researcher Project: Exploring the Inequalities and Diversities in Disabled Young Adult Transitions said that for participants in their research "most experiences of exclusively specialist settings were positive … specialist environments meant smaller classrooms and a quieter, more customised educational experience.” 5 Aberlour also said commented that “environmental needs can often best be met for children with additional learning needs within specialist provision.”6

The Committee heard that specialist provision will always be required for those pupils with the most complex disabilities and medical conditions with children surviving certain medical conditions and living into adulthood, where in the past this was not possible.

Matthew Cavanagh argued there was a lack of specialist support in general mainstream secondary schools and highlighted the increase in the number of pupils with emotionally based school non-attendance. He said7—

It is important to remember that specialist provisions, such as the one that I work in, have staff who work with partners every day and who have greater ability to meet the needs of individual pupils, whom they know better. In a mainstream secondary school, primary school or nursery there is not the ability to provide support to that extent, but that is the strength of settings outside the mainstream. Sadly, that is one of the unexpected consequences of the presumption of mainstreaming.

Placement requests

As set out in the Code of Practice, the 2004 Act enables parents and carers to make a placing request for their child to attend a school managed by an education authority, other than the authority for the area in which the child lives.1

Local authorities can refuse placing requests from pupils with ASN on a number of grounds as set out in schedule 2 of the 2004 Act.

As noted above, Enquire said that the interpretation section of the 2004 Act includes ASL units as part of the definition of a special school which can lead to complexity when considering the legal position around placing requests.2

The Health and Education Chamber of the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland (the Tribunal) considers (among other things) placing requests for specialist schools or units. The Tribunal commented on the legislation which it must interpret when making decisions in relation to placing requests. It said that the presumption of mainstreaming should not be a ground for refusing a placing request to a specialist school and highlighted twelve other legal grounds to refuse a placing request to a specialist school, for example, relating to the impact on other pupils at the school and the capacity of the school. 3

May Dunsmuir argued that there was duplication in the mainstreaming grounds for refusal of placing requests and that a bias in favour of one type of education would not represent an inclusive approach. She commented4—

I do not think that the presumption of mainstreaming is a necessary ground of refusal, because the three parts to that mainstream ground appear elsewhere, in the other 12 grounds that are set out in the 2004 act. It is an unnecessary ground, but we now see a number of education authorities refusing placing requests on that basis. They are clearly attaching that ground to their reasoning when they could just as easily use the three strands from the other areas.

The Cabinet Secretary appeared to be sympathetic with this position and made the point that legislation relating to the presumption of mainstreaming predates the 2004 Act. She referred to the revised guidance published in 2019 on the presumption of mainstreaming and said5—

If there is any doubt about the suitability of mainstream provision, it is the role of the local authority to use the legislation to weigh up the measures. I was quite taken with the evidence that the committee took from the tribunal president, and we will seek to engage with her directly on the matter, particularly with regard to updating the 2004 Act.

The Committee heard that the suitability of a placing request could sometimes be weighed against the cost implications of granting it.

May Dunsmuir acknowledged the criticisms made of the Act and how it was difficult to navigate; however she said the statutory grounds for refusal of placing requests are relatively clear. She went on to say6—

Some people would say that even the very basics are complex, and I think that that is probably true—you need only look at the CSP... if you were to ask me, “Is the legislation clear enough on CSPs?”, I would say, “Absolutely not.”

Chloe Minto said that where the education authority has deemed that specialist provision was not appropriate, it has 12 grounds on which to base its refusal. She said7—

That can include things such as capacity or the fact that the school is not suited to the ability and aptitude of the child. All those grounds are on top of the presumption of mainstream education, which is one of the reasons why a request can be refused.

She highlighted the lack of information in refusal letters and said that it would be helpful local authorities provided more information on why they came to their decision and what criteria they used for making that decision. 8

When asked if there is the correct balance between mainstream provision and the number and types of specialist places available for pupils with ASN, the Cabinet Secretary said9—

Having looked at some of the evidence that the committee has taken on that, I would have to say no, I am not convinced that we have it right, and we need to reflect that in the ASL action plan update.

The Cabinet Secretary acknowledged there was variance across local authorities regarding the level of specialist provision giving the following example10—

...some schools might have excellent speech and language provision, while in others that provision might have been reduced. The Government needs to reflect on that. If a local authority has made that decision, we need to ask where the support for children and young people will be provided.

She also spoke of the specialist provision being put in place by local authorities in responding to local needs and said this needs to be considered at a national level. She stated11—

Again, I highlight that there are opportunities through the ASL action plan for us to work with local authorities. I do not want to dictate to local authorities, but I see an opportunity for us to firm up some of the guidance on how mainstream support might look.

The Cabinet Secretary also acknowledged the need to embed substantive specialist provision to support teachers and highlighted the example of counselling services now being available in schools. She commented that the Scottish Government will do further work with COSLA in this area. She said12—

...we need to take leadership at the national level. My setting out expectations of the use of specialists is helpful in giving some of that direction, but we can get change at the local level by working with COSLA, whether that is on behaviour, attendance or supporting additional support needs.

The Committee was concerned to hear that pupils with ASN do not always have access to adequate specialist school provision near them. Pupils with ASN should be able to obtain appropriate support, ideally in their local area, without the need to travel long distances to and from school each day. The Committee urges local authorities to assess what specialist provision is currently in place and to address any gaps in provision as a matter of urgency. This will ensure that the needs of all pupils can be met.

The Committee was concerned to hear of long delays some pupils were experiencing when attempting to access specialist provision within a mainstream setting. This included, for example, accessing CAMHS support and/or speech and language therapy. The Committee considers that such delays are unacceptable. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government work closely with bodies such as NHS Scotland, the Royal College of Speech & Language Therapists, CAMHS and COSLA, to identify the causes of such lengthy delays and ensure that a more joined up approach to providing specialist support within mainstream settings is adopted in future.

The Committee acknowledges challenges around the recruitment of pupil support workers, teachers and other specialist staff and asks the Scottish Government what actions are being taken to address this.

The Committee notes the lack of clarity in relation to placement requests to specialist schools and specialist units within mainstream schools and recommends that the Scottish Government works with COSLA to update the Code of Practice and ASL Action Plan to provide greater clarity on the support available to families. In addition, the Committee recommends that the Code of Practice states that local authorities should clearly set out to parents and carers the grounds for refusal of placing requests and that information on how to appeal any decision must be signposted.

The Committee is concerned that there is not clarity for parents and carers in relation to ASL provision and what is available for their children both within mainstream and specialist settings. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government and COSLA update the ASL Action Plan to address these communication issues, to ensure that pupils, parents and carers are able to fully understand what support is being made available to their child, ahead of any placing request for specialist provision being made and that local authorities provide information to families in an accessible format.

Given the increase in the number of ASL bases and units within schools in the 20 years since the 2004 Act was passed, the Committee recommends that the Scottish Government undertakes a full review of placing requests to specialist services to consider how the current regime is working in practice, which would include reviewing the grounds for refusal for placing requests to specialist services.

Physical environment

The learning environment is listed in the Code of Practice as one of the factors giving rise to ASN. It states that1—

A need for additional support may arise where the learning environment is a factor. For example, pupils may experience barriers to their learning, achievement and full participation in the life of the school. These barriers may be created as the result of factors such as the ethos and relationships in the school, inflexible curricular arrangements and approaches to learning and teaching which are inappropriate because they fail to take account of additional support needs.

A number of respondents to the call for views pointed out that the physical environment of mainstream schools is not appropriate for all pupils with ASN, particularly neurodivergent pupils with conditions such as Autism Spectrum Conditions and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. The National Autistic Society Scotland said2—

One of the biggest barriers to attending school for autistic pupils is the social, and built, environment. … the built environment (for example, a large, open- 13 plan school or classrooms) can adversely impact an autistic pupil’s experiences. Most traditional school settings come with environmental challenges for autistic young people, from noisy canteens to busy corridors. In particular, the trend towards the ‘super-schools’ we now see across Scotland creates an environment that conflicts with sensory differences experienced by autistic people.

Moray Council echoed this point saying traditional school buildings with large classrooms or open plan settings are not conducive to supporting children with neurodiversity. 3

Govan Law Centre commented that, although many pupils have the academic ability to access a mainstream environment, "it is the architectural, sensory and social stimuli that they are exposed to that creates a barrier." It said4—

If the presumption of mainstream is to be successful it perplexes us as to why schools are becoming bigger, meaning more sensory and social stimuli to navigate...In many cases, for those with autism and other neurodivergent profiles, the loud and busy mainstream environment can lead to high levels of dysregulation, this dysregulation means that they are not in a ready to learn state and are significantly disadvantaged as a result - this cannot be considered meaningful inclusion in our large schools.

Dr Hannah Grainger Clemson outlined research she had undertaken on physical spaces in education settings in Edinburgh which found various architectural features, décor, furniture and other resources had a positive impact on children with ASN in mainstream settings. She said—

Educators describe the positive impact of particular elements of learning spaces on *all* pupil engagement and wellbeing, including that of Additional Support Needs (ASN) pupils. These elements include the learning environment - the buildings, and the style and functioning of the décor, light and sound, as well as the outdoor environment – and the learning tools: the furniture and its layout, and the portable items that are used in learning tasks.

Deborah Best highlighted the importance of school design for pupils with ASN and the problems open plan formats pose for pupils with ASN. She said5—

We are seeing more people struggling with open-plan formats. When children run, there is a fight-or-flight response and they are running through the whole school. We also need to think about the sensory aspect and noise coming from other rooms...When there are lots of children with additional support needs, it is not ideal to have no doors on classrooms.

Existing school estate

Witnesses made a number of suggestions on how schools' physical spaces could be adapted to support pupils with ASN without major resource. In relation to sensory integration, Deborah Best suggested the simple solution of moving a pupil to a small room with headphones to allow them to de-escalate, and then they can re-engage with education.1 Irene Stove representing the Scottish Guidance Association (SGA) argued for adaptable spaces in school buildings so they can be used as sensory rooms or "low arousal rooms" and agreed with Deborah Best that small spaces for pupils to de-stress and de-regulate must be available.1

Suzi Martin made the point that adapting the school estate to address the needs of pupils with ASN may not necessarily require a lot or resource. She gave simple examples such as providing high-backed chairs in a particular part of the school where an autistic pupil could go to feel enclosed and private, and allow them to regulate. She also gave the example of having a desk at the back of the classroom with some sensory toys or putting paper over glass panels. She did say however3—

I would add the caveat that that should not be a reason not to fund appropriate adaptations to schools, although we recognise that resources are not readily available for what we might call ideal adaptations.

Dinah Aitken, representing Salvesen Mindroom Centre, agreed with the need for adaptable spaces saying4—

The principle of universal design is that we should build a more flexible and adaptable environment from the ground upwards, so that, when someone needs individual specialisation, we can make minimal adjustments instead of having to start from scratch to make adjustments for that person.

Dr Binnie acknowledged that there were significant barriers in existing school estates and suggested that more research could be done nationally, through ADES, to look at making school buildings more inclusive and meet the needs of ASN pupils which would benefit all children and young people. 5

Kerry Drinnan also spoke of things which could be done to the existing estate to reduce barriers for ASN pupils without significant resource. She explained6—

If you were to walk into a primary school classroom now, you would see little nooks and crannies and safe areas, and there would be children with weighted blankets. It is all very soft and sensory. Our educational psychology service will do what is called an environmental audit. If a teacher has young people with more neurodivergent needs in their classroom, the service will come to support them and say, “This is how you should reduce your wall decorations,” “These are the colours that you should use,” and “This is what your displays can look like.” They try to reduce sensory overload, transitions and unpredictability.

She advocated that it should be a minimum requirement for all schools to have reduced sensory stimulation spaces that are accessible throughout the school days for pupils to be able to go to when needed.

On the adaptations that have been made to existing school buildings to meet the needs of pupils with ASN, Dr Binnie suggested that more work needs to be done on sharing these adaptations and modifications and that these measures should be replicated across all local authorities.7

New-build schools

The Committee heard concerns regarding new-build schools and how they provided barriers to pupils with ASN. Irene Stove spoke of the difficulties some pupils have with the school environment and made the point that when building new schools, environmental aspects of both indoor and outdoor spaces must be considered in consultation with teachers and partners who work with pupils with ASN and understand their needs to ensure they are fit for purpose. She gave examples such as loud noisy buildings with glass panels on doors as being very difficult for pupils with hearing impairments and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder to focus on learning in these environments. She said1—

For many children, a way for them to be co-regulated or to regulate themselves is to get outdoors, but that needs to be done in a safe outdoor space. If we have a young person whom we might describe as a “runner”—I think that someone used that term earlier, and it is also how I would describe some young people—we need to know about that so that we can keep them safe. Many schools are community areas where the gates are not locked, which means that children can run out into busy roads. We need to consider how we keep everyone safe in our schools.

Marie Harrison, representing Children in Scotland and Megan Farr, representing the CYPCS, both also highlighted the difficulties associated with new-build schools for pupils with ASN, particularly in relation to them being large, open spaces, noisy and bright. Megan Farr said2—

Children with an autistic spectrum disorder in particular can find that extremely overwhelming and sometimes the adaptation aid is very small, such as taking a child out of the busier bit of the room. However, schools are still being designed like that. A number of primary schools were built around four-class clusters in a block with no walls; those are also difficult environments.

Dr Binnie told the Committee that the design of school buildings is often determined at local authority level which may involve professionals such as architects, who might not always understand or know about the complex needs of the children attending the school. 3

The Committee wrote to the Scottish Futures Trust (SFT) who work with the Scottish Government to deliver the Learning Estate Investment Programme (LEIP) and similar programmes on the evidence it heard regarding the design of the school estate not always supporting the delivery of inclusive education. It asked how the SFT supported local authorities to ensure that any new schools or refurbishments are designed to support the learning for pupils with additional support needs, particularly those children and young people with sensory needs.4

The SFT stated that the provision of schools in Scotland is the responsibility of local authorities who assess, plan and deliver infrastructure in response to the specific needs of communities. It highlighted that while there are overarching national statutory requirements covering basic parameters related to the learning estate, "local factors such as demographics, employment needs, approach to pedagogy and environment are decided by local authorities."5

The SFT referred to the guiding principles of the Learning Estate Strategy which was co-published by the Scottish Government and COSLA in 2009 and updated in 2019 which states—

Learning environments should support and facilitate excellent joined up learning and teaching to meet the needs of all learners

Learning environments should support the wellbeing of all learners, meet varying needs to support inclusion and support transitions for all learners

The SFT highlighted a number of projects it supported relating to standalone specialist schools, specialist facilities alongside mainstream and nurture spaces within mainstream. It stated6—

The programme approach managed by SFT encourages knowledge sharing across local authorities, and we have facilitated discussions between specific projects, across all authorities through Shared Learning Events and nationally through the annual Learning Places Scotland Conference. We will continue to learn from these and other projects and seek feedback from users to help inform the design of future learning spaces to support the needs of every learner.

Laura Meikle commented on the work being done as part of the update to the ASL Action Plan and the Code of Practice and said that there are opportunities to make connections with ASN and the importance of the design of the learning environment to reflect the recent changes in the educational experiences of children and young people. 7

The Cabinet Secretary acknowledged the issues relating to the physical environment and said "I have looked at some of the evidence that the committee has taken on school design, and I am pretty sympathetic to it." 8

She referred to the work of the SFT in providing guidance on the design of school buildings and work with local authorities on design specifications.9 She also highlighted the funding announced in December 2023 for phase 3 of the learning estate investment programme saying the Scottish Government is working with SFT on its approach to this.7

The Cabinet Secretary confirmed that the Scottish Government funds local authorities to improve the quality of the school estate and the design of school buildings comes from the local authorities. On the size of some schools, she agreed they were too big and admitted that further advice from the SFT was needed on school design. She said8—

They are too big for children with additional support needs, but they are also too big for our pupils and our staff—full stop. In big schools, teachers do not get to know their children and young people.

The Committee was disappointed to hear in evidence that many recently built schools have been designed in a way that is not accessible to all. Current open plan designs can act as a barrier to learning for pupils with ASN, and in particular for pupils who are neurodivergent. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government and the Scottish Futures Trust should reassess the support and advice provided to local authorities to ensure that schools are designed as accessible and welcoming environments for all, and that the Scottish Government should also give consideration to whether further regulation in this area is required. The Committee understands that this work will take time; however, it expects a full response to these two recommendations by the end of 2024.

The Committee recognises that much of the existing school estate will continue to be in use for many years to come. The Committee notes the evidence in relation to effective and relatively inexpensive adaptations which can be made to improve accessibility for pupils with ASN and considers that these low cost options should be collated and shared across local authorities. The Committee therefore recommends that the Scottish Government work with colleagues in local government, and relevant third sector organisations, and pupils themselves, to develop a suite of guidance to make existing schools as accessible as possible to those with sensory needs. Given the urgency, the Committee recommends that this guidance be published by the end of the year and that implementation of this guidance should appear in National and Local Improvement Plans as soon as possible thereafter.

Training

Training and skills is one of the four themes of the ASL Action Plan. It includes actions around the role of pupil support workers, the support provided by Education Scotland, and teachers’ education and continuing professional development.

COSLA, in relation to ensuring adequate training for staff on ASN, highlighted the resources available in relation to both the initial teacher education (ITE) and for qualified staff through Continuous Professional Learning and Development (CPLD). These included the delivery of the We were Expecting You Module in ITE, the Dyslexia Toolbox and the Autism Toolkit and a document entitled Introduction to Inclusive Education.1

The Committee heard from many witnesses of the need for better training for all staff on ASN, including Susan Quinn who made the point that all staff need ongoing professional training to ensure they are fully aware of pupils' ASN. She said2—

They need to be aware of the complexity of need but, at different points in all our careers, we will require specialist training to support the young people with whom we are directly working.

Dinah Aitken, Irene Stove and Suzi Martin all argued for more training for all staff on ASN; however there were mixed views on whether this training should be mandatory. For example, Susan Quinn said the EIS was not in favour due to the negative connotations associated with mandatory training3 and Peter Bain agreed that universal training should not be mandatory; however others including Sylvia Haughey said that there should be some elements of training in supporting additional needs that are mandatory.

Glenn Carter advocated a coaching approach to supporting staff in providing ASL saying4—

We need good-quality training, which is important, but the thing that facilitates behaviour change and a shift in how we facilitate kids’ communication is being in there and coaching and modelling with other people, rather than just throwing training at them and then walking away. We know that throwing training at people rarely works without follow-up and without coaching and modelling. We need to be brave.

Marie Harrison suggested that good practice in specialist schools could be shared with mainstream schools through learning exchange opportunities. She said5—

That is about supporting mainstream schools to learn from specialist settings about what it is that they do and what works really well for them, and looking at how we can transfer some of that good learning into mainstream settings as far as that is possible. We could look at whether there is scope to deliver some kind of continuous professional learning in that regard.

The Cabinet Secretary suggested that there may be a role for Education Scotland in exemplifying good practice in relation to ASL provision and sharing it across local authorities.6

Teachers

The ASL Action Plan includes the following action which is ongoing1—

The Scottish Government and COSLA/ADES will work with the Scottish Negotiating Committee for Teachers (SNCT) to ensure there is appropriate career progression and pathways for teachers looking to specialise in Additional Support for Learning, with the intention that this will result in an overall increase to the number of teachers who specialise in ASL in Scotland’s schools, with particular emphasis on ensuring that the Lead Teacher structure delivers on this outcome.

The progress update for this action stated1—

The Scottish Government will engage with the Project Board to understand current local authority planning in this area. The Scottish Government and partners, including professional associations, will consider how any barriers to specialising can be addressed and how uptake of this pathway can be incentivised. The Scottish Government is also working with partners to update existing guidance on the qualifications required to teach children and young people with sensory impairments.