Education, Children and Young People Committee

Scottish Attainment Challenge

Executive summary

The Committee recognises and commends the excellent work being done by individual schools and local authorities. The commitment of teachers and headteachers who spoke to the Committee was striking and inspirational. In this report, despite the challenges that were set out in evidence, the Committee wants to highlight this work as well as making some recommendations aimed at improving the attainment challenge policy.

The Committee notes the conclusion from Audit Scotland that the poverty-related attainment gap remains wide with limited progress on closing the gap and that inequalities have been exacerbated by Covid-19.

Whilst work to tackle the impact of poverty on educational outcomes was being done in some schools and local authorities before the start of the attainment challenge, the Committee notes evidence that the attainment challenge has heightened knowledge and awareness of the barriers faced by children and young people living in poverty and what works in trying to tackle them.

It is important to understand the full extent to which the pandemic has impacted on closing the poverty-related attainment gap. There is a need to establish a national baseline on which to base post-pandemic targets. The Committee asks the Scottish Government to set out how it will, as a matter of urgency, establish a national baseline for measuring progress in closing the attainment gap following the pandemic.

The Committee recognises that there is poverty everywhere in Scotland, including in rural and less deprived areas. The Committee supports the policy of funding local authorities through the Strategic Equity Fund to ensure that targeted support is available to all children and young people living in poverty in Scotland.

However, the Committee acknowledges the evidence received on the impact of the reduction in funding to the challenge authorities. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government works with local authorities to examine and monitor the impact of the tapered reduction in funding on the challenge authorities and reports its findings to the Committee, along with any proposed action to mitigate any detrimental impact.

The Committee notes the role played by headteachers in the deployment of the Pupil Equity Fund (PEF) in schools. Headteachers' capacity is the key factor in the performance of the attainment challenge. The Committee notes concerns about current challenges with recruitment and retention of headteachers. Given the critical role headteachers play in delivery and accountability for PEF spending, the Committee asks the Scottish Government to set out what steps it is taking to address recruitment and retention issues.

The Committee supports the emphasis on the need for meaningful engagement of teachers, parents and carers, children and young people and other key stakeholders throughout the processes of planning, implementing and evaluating approaches for spending PEF. Protected time for headteachers and teachers is key to creating space for such engagement. The Committee asks the Scottish Government what steps it is taking to ensure that headteachers have the capacity to work with teachers, parents, carers and pupils to consult them in a meaningful way on the deployment of PEF within their schools.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government tasks Education Scotland with monitoring practices in schools and local authorities to ensure that the voices of classroom teachers, parents, carers and children and young people are at the centre of plans for attainment challenge spending.

The Committee notes with concern evidence on variation in education performance across local authorities in Scotland. It is important that children and young people's outcomes are not dependent on where they live. There is a key role for Education Scotland to play in tackling these variations. The Committee recommends that Education Scotland is tasked with undertaking urgent work to investigate the reasons for these variations and with setting out the action it is taking to achieve consistency across the country. The Committee recommends that Education Scotland reports back to the Committee on progress with this work within 6 months of the publication of this report.

The Committee notes that the attainment challenge has been in place since 2015 and during that time many new interventions have been adopted, adapted and, in some cases, abandoned. With the introduction of the refreshed approach, it is vital that lessons learned during that period are shared widely and systematically. Given the mixed evidence on whether this is happening on the ground, the Committee asks the Scottish Government to closely monitor how effectively and consistently best practice is being shared by Education Scotland.

The Committee notes the role of Regional Improvement Collaboratives (RICs) in supporting local authorities and schools and promoting consistency in outcomes. The role of HM Inspectorate of Education is explored later in this report; the Committee recommends that the performance of RICs is evaluated by HM Inspectorate of Education as part of its ongoing work.

The Committee notes that the poverty-related attainment gap cannot be tackled by schools alone. There is a need for strong collaboration with stakeholders, including third sector organisations which can often facilitate the vital link between school and home. The Committee is aware that the short-term nature of funding is a long-standing problem for many third sector organisations. The Committee invites local authorities to consider how multi-year funding can be offered to third sector organisations within the parameters of the Framework. The Committee recommends that Education Scotland monitors how local authorities are, where appropriate, ensuring stability of funding for third sector partners and evaluating how such longer-term relationships impact on outcomes for children, young people and their families.

The Committee notes evidence that free school meals is not a reliable metric for calculating PEF allocation to schools and that this formula excludes a number of schools from receipt of PEF. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government make an early start in considering what metric it may use to determine any future allocation of school-level national funding. The Committee would welcome details of the timescales of this work and what form it will take.

The Committee considers that greater clarity on the level of discretion available in relation to additionality would be helpful for school leaders in determining how to spend these funds. Such clarity would also be helpful to those who ought to be part of the decision-making process at the school level, i.e. pupils, parents/carers and teachers.

There is an active role for Education Scotland to make sure that the needs of rural schools are taken into account as part of the attainment challenge. The Committee was not convinced by the response from Education Scotland when asked what steps it takes to tackle the specific barriers faced by rural schools in closing the attainment gap. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government sets out how barriers to progress in rural schools will be tackled through the Framework and reports back to the Committee with proposals for ensuring that these schools have the same opportunities to improve outcomes for disadvantaged pupils as their urban counterparts.

Closing the attainment gap is a complex endeavour. The Committee notes the plan for stretch aims to be set at local authority level and for this to be aggregated into national targets. The Committee seeks assurances from the Scottish Government that there will be sufficient challenge in this process to ensure that both local and national targets are ambitious and that appropriate milestones are set. The Committee also asks the Scottish Government to set out how robust national data will be produced on outcomes when local authorities may use different metrics within the 'core-plus' model of setting stretch aims.

The Committee heard evidence that it can be challenging to attribute an improvement in attainment to specific interventions. The Committee is concerned that this makes measuring outcomes from the large investment in the attainment challenge difficult. The Committee notes the work ongoing in improving measurement of outcomes and considers that this work is vital to enable the impact of the attainment challenge to be properly measured. The Committee recommends that Education Scotland is tasked with ensuring that every local authority has access to relevant external expertise to enable them to measure the effectiveness of interventions.

The Committee heard in evidence that there is a lack of transparency and accessibility to data on the outcomes of the attainment challenge. The Committee notes that the Scottish Government publishes a National Improvement Framework Evidence Report which provides data on education performance and closing the attainment gap nationally and at a local authority level. The Committee would welcome details of how the Scottish Government will present this data alongside local stretch aims and how parents/carers will be supported to use this tool to better understand their local authority's performance.

There is an opportunity with the forthcoming education reforms to ensure that the schools inspectorate plays a full role in monitoring the effectiveness of the implementation of plans to close the poverty-related attainment gap. The Committee believes it is essential that this is factored into the design of the new education agencies, which is currently ongoing.

Given the size of the budget and scale of ambition, it is vital that the long-term impact of the attainment challenge funding is measured. Evaluating what types of interventions and policy approaches create better outcomes in the long-run is a vital part of any policy approach, be that at a local or national level. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government commissions a longitudinal study into the impact of the attainment challenge policy. The study should cover the impact of the policy at a national, regional and school level.

The Committee welcomes the good work being carried out by teachers, schools and local authorities to assist young people in finding positive destinations on leaving school.i The Committee notes the evidence from the Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills on the narrowing of the gap between young people from the most and least deprived areas participating in education, training, and employment on leaving school. There were mixed views in the Committee regarding the value of positive destinations as they are currently defined. The Committee did not examine the details of the types of destinations being counted under this measurement as part of this inquiry.

The Committee believes that it is important to consider outcomes of the attainment challenge in terms of sustainable post-16 positive destinations and the life long learning agenda. The Committee notes evidence that the use of the system varies across the country and the current measure of positive destinations is not always capable of following a young person when their location changes. The Committee recommends that Education Scotland takes steps to address these issues so that the long-term sustainability of positive destinations can be fully tracked and measured.

Education Scotland has a key role in the Framework to provide challenge and support to local authorities, headteachers and classroom teachers. Given the number of stakeholders involved in delivering the attainment challenge, it is crucial that the education agency takes ownership and demonstrates accountability for outcomes. This must be incorporated into the design of the new education agency.

Introduction

This report sets out the Education, Children and Young People Committee's findings on its inquiry into the Scottish Government's policy commitment to close the poverty-related attainment gap. The Committee has gathered written and oral evidence from a wide range of people and organisations and is grateful to all those who contributed to the inquiry. The Committee would particularly like to thank the children and young people, teachers, parents and carers who took the time to talk to Members about their experiences. Details of evidence received during this inquiry are set out in the annexes.

The Committee wishes to highlight the commitment and dedication to closing the poverty-related attainment gap which Members have witnessed among teachers during the inquiry. The passion of teachers and headteachers and genuine care with which they approach their work has been striking. Whilst this report highlights certain issues which the Committee has identified through this inquiry, the Committee is keen to state its appreciation of the work going on across Scotland aimed at improving outcomes for children and young people. Some examples of work carried out as part of the attainment challenge are set out below:

Numeracy intervention in primary schools

One teacher was seconded to a post to provide support to teachers in mathematics and numeracy across a number of primary schools. The training was developed and funded by the local authority and seeks to build the capacity of teachers to improve numeracy and literacy outcomes. The project was focused on schools with higher levels of deprivation and lower achievement in numeracy and mathematics. The project was able to show demonstrable improvement in attainment and this helped to ensure that teachers saw it as a credible and useful intervention.

English as a second language

One headteacher told Members that 99% of students in their school community are from an ethnic minority group, 85% of whom speak English as an additional language. The sizeable funds provided to the school through the attainment challenge have given them freedom to seek to address the many challenges which come from outside the school.

Additional teachers

One headteacher told Members that extra teachers are the ‘best resource you can ever have for raising attainment’. They have very small primary one classes (three teachers work across two classes); the difference this has made has been ‘phenomenal’. Some children will not attain to the expected level but the increase in levels of attainment with an extra person working with them and their parents is ‘amazing’.

It is important that the attainment challenge is considered in the wider context. The Child Poverty Action Group in Scotland referred to a backdrop of 'unacceptable high levels of child poverty' in Scotland, with one in four children in Scotland living in poverty in 2019/20. The impact of poverty on children and young people is stark and creates barriers to their attainment at school. The cost of living crisis is increasing the pressure on families in poverty who are being worst hit by rising supermarket prices and energy bills.

Research by the Poverty Alliance shows that the mental health of parents and young people living in poverty is 'a massive issue at the moment'. The Committee has heard about the devastating effect poverty can have on the mental health of children, young people and their families. Members also heard that health and wellbeing is fundamental to academic success. Many schools in Scotland have used attainment challenge funding to embed nurturing approaches, focused on health and wellbeing. Teachers, parents and carers highlighted the value of such interventions, including measures aimed at improving mental health for both pupils and parents.

The Committee recognises that the poverty-related attainment gap cannot be solved by school-based interventions alone. The attainment challenge does not exist in a vacuum; child poverty is a complex issue and there are many other policies and initiatives across government aimed at tackling it. Poverty and its impact must be tackled at source. However, in this inquiry, the Committee has maintained its focus on the role of the Scottish Attainment Challenge in addressing the poverty related attainment gap.

The Committee recognises and commends the excellent work being done by individual schools and local authorities. The commitment of teachers and headteachers who spoke to the Committee was striking and inspirational. In this report, despite the challenges that were set out in evidence, the Committee wants to highlight this work as well as making some recommendations aimed at improving the attainment challenge policy.

Scottish Attainment Challenge

The 2016-17 Programme for Government set out the Government’s ambition to close the poverty-related attainment gap. It said:

It is the defining mission of this Government to close the poverty-related attainment gap. We intend to make significant progress within the lifetime of this Parliament and substantially eliminate the gap over the course of the next decade. That is a yardstick by which the people of Scotland can measure our success.

To this end, the Scottish Government established a number of policies under the banner of the Attainment Scotland Fund (ASF):

From 2015-16, Challenge Authorities and Challenge Schools: selected on the basis of the proportion of children living in Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) 20 areas (the fifth most deprived areas based on SIMD methodology);

From 2017 -18, Pupil Equity Funding (PEF), based on the proportion of children eligible for free school meals;

From 2018-19, the Care Experienced Children and Young People Fund, aimed at improving outcomes for care experienced young people up to the age of 26;

A range of national programmes which include support for staffing supply and capacity, professional learning and school leadership, Regional Improvement Collaboratives (RICs), and some third sector organisations.

In the previous parliamentary session, £488 million of the ASF funding was allocated to the Pupil Equity Fund (PEF) between 2017/18 and 2020/21. Nine challenge authorities received £212 million and a further £36 million was allocated to schools with high levels of deprivation across all council areas. The remainder was allocated to national programmes (£39 million) and specific targeted funding for care experienced children and young people (£29 million).

After the initial closure of schools due to Covid-19 in March 2020, the Scottish Government issued guidance to councils that use of the ASF could be more flexible, citing examples where funding had already been used to provide digital devices, books and other learning material, transport for children to attend school hubs and supporting home-school link workers to maintain contact with children.

As well as the targeted programmes or funding streams, closing the attainment gap is an overall aim of the education system. As such, the universal school education offer is intended to support the goal. In addition, one of the aims of the expansion of funded Early Learning and Children provision to 1,140 hours is to improve children’s outcomes and help close the poverty-related attainment gap.

The attainment gap

The focus of the Scottish Government is on closing the gap in attainment between children from the most deprived areas and the children in the least deprived areas, attending publicly funded schools. The poverty-related attainment gap is a long-standing and complex issue. The Poverty Alliance said that it starts in the early years and widens as children and young people move through the education system:

From the early years, the attainment gap is stark: in 2019/20, there was a 13.9 percentage point gap in records of development concerns for infants aged 27-30 months between the least and most deprived areas in Scotland. Upon leaving school, just over two in five living in the most deprived areas achieve one or more highers (43.5%) compared to almost four in five young people living in the least deprived areas (79.3%) (2018/19).

Several of the National Improvement Framework measures have not been published since Covid. However, 2020/21 data on primary school achievement of Curriculum for Excellence levels shows that gaps in numeracy and literacy between primary pupils living in the most and least deprived areas has widened since 2018/19 and is now wider than at any point since 2016/17.

Audit Scotland published its report 'Improving outcomes for young people through school education' in March 2021 ('the Audit Scotland report'). It stated:

The poverty-related attainment gap remains wide and inequalities have been exacerbated by Covid-19. Progress on closing the gap has been limited and falls short of the Scottish Government’s aims. Improvement needs to happen more quickly and there needs to be greater consistency across the country. The government and councils recognise that addressing inequalities must be at the heart of the response to Covid-19, longer-term recovery and improving education.

The Scottish Government's 'Fourth evaluation report of the Attainment Scotland Fund', published in March 2021, highlighted a mixed picture in terms of the quantitative data. It said:

For the majority of measures, attainment of those from the most deprived areas has increased, although in some cases not at the same rate as those in least deprived areas.

The Robert Owen Institute for Educational Change said that over the last eight years they have worked alongside a range of partners across the Scottish education system to explore how greater equity can be achieved in schools:

This has revealed how, despite the serious national commitment to enhancing excellence and equity and a huge range of well-intentioned initiatives, the most vulnerable children and young people still lose out, and that the established links between education and disadvantage have yet to be broken.

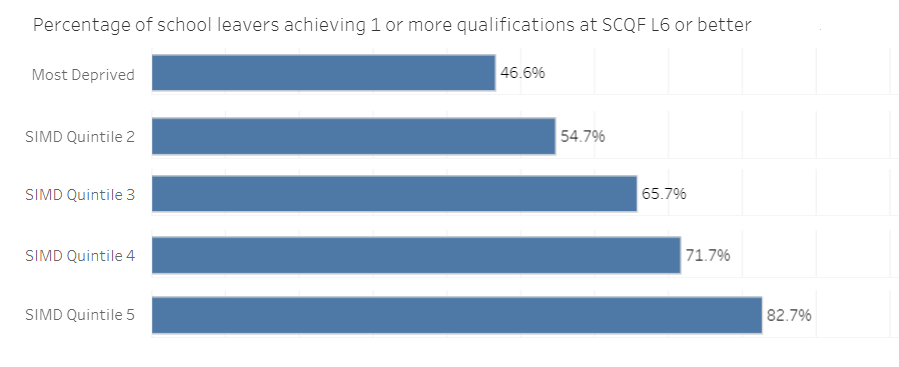

It is important to note that the relationship between household income and outcomes in schools continues up the socio-economic status scale. For example, one measure the Scottish Government currently uses to assess progress in Scottish Education is the percentage of school leavers with at least one qualification at Level 6 – that is, a Higher or equivalent (both in level and size). The table below shows the outcomes after the 2020 diet with those percentages for each of the SIMD quintiles:

While progress on national or local measures has been reported as slow or mixed, other areas of progress achieved through the work of the Scottish Attainment Challenge have been highlighted in evidence. This includes a heightened focus on equity, greater capacity and improvements of pedagogy, better collaboration within and outwith the profession and the use of data.

The Committee notes the conclusion from Audit Scotland that the poverty-related attainment gap remains wide with limited progress on closing the gap and that inequalities have been exacerbated by Covid-19.

Focus on equity

In this inquiry, the Committee agreed to take evidence from case-study local authority areas involving witnesses from primary schools, secondary schools, and local authority representatives from selected areas. The Scottish Attainment Challenge is intended to provide significant autonomy to local authorities and schools and there are a multitude of approaches within localities. Local authorities are grouped regionally in ‘Regional Improvement Collaboratives’ (RICs). It was agreed that scrutiny of the Scottish Attainment Challenge at the level of a RIC would allow the Committee to compare different local authorities and how they work together and with Education Scotland.

The Committee agreed that the West Partnership RIC, which consists of eight local authorities across the west of Scotland: East Dunbartonshire, East Renfrewshire, Glasgow City, Inverclyde, North Lanarkshire, Renfrewshire, South Lanarkshire, and West Dunbartonshire, form the case study area for this inquiry. Thirty-five percent of Scotland’s school population attend a West Partnership school. There are over 1000 nurseries, primary, secondary and special schools in the West Partnership, serving mainly urban but also many rural communities.

Evidence set out in this report from local authority Directors of Education and engagement with parents, carers, headteachers and teachers should be considered in the context of these views being from within the West Partnership RIC, rather than representing the position across the whole of Scotland. Some of the evidence from Education Scotland also focused on work being undertaken within the West Partnership RIC.

Education Scotland said that RICs operate within different contexts and face different challenges; they highlighted the levels of deprivation within the West Partnership RIC:

when we look at the local authorities in the West Partnership, we should remember that it contains five of the most deprived local authorities in Scotland. South Lanarkshire, which was originally involved in a schools programme, has significant levels of deprivation.

The Committee heard in evidence that, in some areas, work was already being done in schools to address poverty related issues before the attainment challenge was launched. Gerry Lyons, Director of Education at Glasgow City Council, told the Committee that they have always had a focus on improving outcomes for young people in poverty; that focus was heightened by the attainment challenge. The Committee also heard from teachers and parents that, since the start of the attainment challenge, there has been progress in developing the culture of focusing on equity in schools, including a greater awareness and understanding of the barriers facing children and young people. Professor Ainscow of the University of Glasgow said:

One of the major achievements, which should not be underestimated, is that, as far as I can see, everyone in the Scottish education system is clear on the agenda. They are clear that the push for equity and the concern for excellence are central to everything.

In its 'Closing the poverty-related attainment gap: progress report 2016 to 2021', the Scottish Government said:

Over the 5-year time period a number of key elements have been put in place that provide strong foundations for on-going progress. Important strengths of the Scottish approach include: a systemic change in terms of culture, ethos and leadership; a strengthened awareness of the barriers facing children and young people adversely affected by socio-economic disadvantage; the significant role of local authorities in driving forward a strategic vision for equity at local level.

Tony McDaid, Director of Education for South Lanarkshire Council, described the 'huge impact' of the work of organisations such as the Child Poverty Action Group in Scotland leading to schools being sensitive to the issues, including the importance of removing barriers to participation in extra-curricular and residential activities.

As well as heightened knowledge of the barriers faced by children and young people living in poverty, the Committee heard that work carried out through the attainment challenge has led to schools and teachers identifying which interventions make a difference, including reaching out to families. Education Scotland referred to professional learning which has taken place since the attainment challenge began, with schools and teachers finding out 'what works'.

Whilst work to tackle the impact of poverty on educational outcomes was being done in some schools and local authorities before the start of the attainment challenge, the Committee notes evidence that the attainment challenge has heightened knowledge and awareness of the barriers faced by children and young people living in poverty and what works in trying to tackle them.

Impact of the pandemic

Education Scotland's 'Equity Audit' set out the position in relation to the attainment gap prior to the pandemic. It said:

The Scottish Government’s third interim evaluation report of the Attainment Scotland Fund which covered the 2018/19 academic year, indicated that whilst there is some progress in closing the attainment gap on a number of National Improvement Framework attainment measures, this is a varied picture depending on the measure under consideration. The report concludes that ‘overall, quantitative measures of the attainment gap do not yet show a consistent pattern of improvement’.

The pandemic is considered to have made existing inequalities in educational outcomes worse. According to the 'Achievement of Curriculum for Excellence Level (ACEL) statistics' (which only covered primary schools in 20-21) the gap between those living in the most and least deprived communities grew during the pandemic. In literacy, the gap between primary pupils from the 20% most and least deprived areas was 24.7 percentage points in 2020/21 (up from 20.7 percentage points in 2018/19). The equivalent gap in numeracy was 21.4 percentage points in 2020/21 (up from 16.8 percentage points in 2018/19).

There was wide agreement in evidence that the pandemic has been a set back in the work to close the poverty-related attainment gap, with the cost of living crisis adding to the difficulties faced by families. Emma Congreve of the Fraser of Allander Institute said:

Overall poverty and child poverty are not falling in Scotland. The pandemic has put an enormous amount of pressure on low income households, and the cost of living crisis is putting even more pressure on. We need to try to think about why we are not making the progress that we wish to. That side of the equation is incredibly important to understanding why we are in the position that we are in and are having this inquiry.

The Poverty Alliance highlighted that before the pandemic, over one million people in Scotland, including one in four children, were living in poverty. They said that Covid-19 has increased levels of poverty in Scotland, resulting in precarious household circumstances for low-income families including not being able to afford regular, basic needs such as food and clothing. They described the impact on children and young people and their families:

Covid has presented significant digital exclusion barriers for low-income families, and has negatively impacted on children and young people’s mental health. As well as the closure of schools impacting on children and young people’s attainment, the removal of many different forms of ‘out of school’ provision was felt acutely by priority family groups, particularly lone parent families.

Teachers described a changed landscape post-pandemic. There was general agreement that Covid-19 has given rise to different needs; therefore, schools have had to update their improvement plans to reflect this. Teachers told Members that financial struggles have become much worse for the children and young people in their schools since the pandemic. One said that teachers are now tasked with repairing the damage of the Covid-19 pandemic. In addition, Members heard that teachers were already witnessing the negative impact of the cost of living crisis on children.

There was a concern among some teachers that the impact of the pandemic may mask progress being made by some children and young people before the school closures. Several teachers expressed frustration at the loss in attainment after making head-way before the Covid-19 disruption. Some teachers said that, given the considerable impact of Covid-19, any expectation of improvement in attainment between March 2020 and now is 'completely unrealistic'. In the circumstances, maintaining levels was viewed by some as a 'great success'.

Some of the positive outcomes of the pandemic were highlighted by teachers. One teacher reflected that a continued emphasis on children’s health and wellbeing was a positive change. In addition, since the beginning of the pandemic, many teachers felt that their digital skills had improved significantly; the digital curriculum has also been accelerated.

However, teaching unions told the Committee that, since the pandemic, there has been a rise in challenging behaviour, mental health issues and staff absences which have greatly increased the workload of teachers.

There is a gap in robust evidence on the impact of the pandemic on closing the attainment gap. The Audit Scotland report stated that data collection on national performance for primary and early secondary pupils was cancelled in 2020 due to the pandemic and that this will affect performance tracking over time.

NSPCC pointed to gaps in evidence on children and young people’s educational experiences during the pandemic. They would welcome further disaggregation of data to understand which groups of children, and in which geographical areas, have been affected by the disruption to schooling and wider community support services. A lack of evidence on marginalised groups including refugee and asylum seekers, black and ethnic minority children and young people has also been identified.

The Scottish Government's response to the Committee's report on its inquiry into the Impact of Covid-19 on Children and Young People said:

the Scottish Government has published a substantial body of quantitative and qualitative evidence of the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on a range of different groups of learners.

However, there is a need to establish a baseline from which to measure progress in narrowing the attainment gap post-pandemic. Emma Congreve of the Fraser of Allander Institute said:

We cannot simply say that the targets are not achievable because of Covid and that we should forget about them. Things have got worse, so it is not an excuse. If the targets are missed, we need to know why and we need to know how to get back on track. Therefore, evidence is incredibly important.

Professor Francis of the Education Endowment Foundation spoke of the urgent need to respond to the impact of Covid-19 on attainment:

it is right to say that there is an emergency in relation to the widening gaps. We need to diagnose where there has been learning loss during the pandemic and then think of short-term means to address the gap.

The 'Scottish Government's Recovery Plan' sets out the work being carried out as part of the attainment challenge, including a 'Covid-19 premium' injection of funds. However, the EIS said that there is a need for significantly greater overall funding in education to enable class-size reduction, more specialist additional support and the services of external agencies, such as Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). Andrea Bradley of the EIS said:

we do not think that the plans that are being put in place for recovery are realistic or ambitious enough, given the impacts of the pandemic.

Education Scotland said that they are able to quantify the impact of the pandemic on the attainment gap to an extent with the national improvement framework data that was published in December. However, they said, ‘it is difficult to quantify it in a single figure’ and that it has to be examined at local authority level and school level.

The 'Audit Scotland report' said that the Scottish Government should work with stakeholders to agree an approach to dealing with the challenges created by data disruption in 2020 and 2021 which will affect monitoring of progress in achieving policy ambitions relating to outcomes and the attainment gap. The Scottish Government responded by saying that there is reliable data in the 2022 National Improvement Framework which sets out how children and young people are faring following the pandemic:

The National Qualification results in 2020 and 2021 provide an accurate picture of the qualifications awarded to learners in those years. Comparisons with previous and future years is possible, provided it is done with an understanding of the different underlying assessment methodologies.

The 2021 data for Insight – the tool used by schools for improvement in the senior phase – was released as usual in September, therefore schools and local authorities continue to have the same data available to them as in a “normal” year to enable them to drive forward improvement activity tailored to their own context.

ACEL data for primary schools has been collected for 2020/21 and it is possible to compare this with data from previous years.

The Scottish Government said that any data gaps relate to national gathering of these data but that teachers and schools routinely assess progress in literacy and numeracy, which means that the key actors have access to the information they need to inform learning and teaching.

It is important to understand the full extent to which the pandemic has impacted on closing the poverty-related attainment gap. There is a need to establish a national baseline on which to base post-pandemic targets. The Committee asks the Scottish Government to set out how it will, as a matter of urgency, establish a national baseline for measuring progress in closing the attainment gap following the pandemic.

Refreshed approach to the attainment challenge

On 30 March 2022, the Scottish Government published a number of documents setting out its new approach to closing the poverty-related attainment gap, including:

The Framework began by acknowledging that more progress is needed. It said:

The pandemic disrupted the learning of our children and young people and had a disproportionate impact on children affected by poverty. The refreshed Scottish Attainment Challenge programme, backed by a further commitment of £1 billion from Scottish Government through the Attainment Scotland Fund, aims to address these challenges and ensure that equity lies at the heart of the education experience for all.

The Framework sets out the overall approach. It states that the refreshed challenge will have a new mission:

to use education to improve outcomes for children and young people impacted by poverty, with a focus on tackling the poverty-related attainment gap.

The Framework contextualises the continuing work of the Scottish Attainment Challenge within:

A need to continue progress, and to speed up progress and to tackle variation in outcomes between and within local authority areas and

A need to address the negative impact of Covid-19 on children’s health and wellbeing and learning.

It also states:

Improving leadership, learning and teaching and the quality of support for families and communities and targeted support for those impacted by poverty remain the key levers to improve outcomes for children and young people.

Funding streams

The new approach changes the funding streams of the Scottish Attainment Challenge. Compared to the previous model, the key changes are the removal of the Challenge Authority and Challenge School programmes.

The Strategic Equity Fund (SEF) has replaced the Challenge Authority funding, whilst Pupil Equity Funding (PEF) remains. PEF and SEF Allocations to schools and local authorities have been set out for 2022-23 to 2025-26. Allocations for the other two aspects of the Attainment Scotland Fund, the Care Experienced Children and Young People Fund and the National Programmes, have not been confirmed. The totality of the spending is due to be around £200m per year in the coming five years.The table below shows the Attainment Scotland Fund in 2021-22 and the allocated funding in 2022-23:

| 2021-22 | 2022-23 | |

| Challenge Authority Funding | £42,923,109 | - |

| SEF | - | £44,743,505 |

| PEF | £127,797,059 | £130,490,760 |

| Challenge Schools Funding | £7,033,543 | - |

| CECYPF* | £11,500,000 | £11,500,000 |

| National Programmes* | £6,161,000 | £13,300,000 |

| Total | £195,414,711 | £200,034,265 |

| Covid-19 PEF Top up | £19,169,559 | - |

| *2022-23 figures are likely estimates | ||

The PEF allocation, not including the Covid-related top up in 2021, will increase by around £3m compared to 2021-22 and is intended to remain the same up to 2025-26. It is worth noting that PEF began as a £120m fund in 2017-18. Taking last year as a baseline, the increase in PEF does not match the loss in funding through the Schools Programme. The greatest increase has come under the National Programmes. 2022-23 is the first year of SEF and there are transitional funding arrangements through to 2025-26. The table below sets out the SEF allocation from 2022-23 to 2025-26:

2022-23 2023-24 2024-25 2025-26 SEF £44,743,505 £43,366,147 £43,020,675 £43,000,000

Any future allocations are subject to annual budget processes. Flat-cash funding over four years is likely to translate as real terms cuts. However, the refreshed approach confirms allocations for PEF and SEF until the end of the parliamentary term, aimed at giving local authorities and schools certainty to support long-term planning.

The move to multi-year funding was broadly welcomed in evidence. Moving to more stable, multi-year funding approach was a key ask from COSLA in terms of improving service delivery and supporting greater partnership working. Similarly, Jim Thewliss of School Leaders Scotland described the three-year funding element as 'absolutely fundamental'.

Strategic Equity Fund

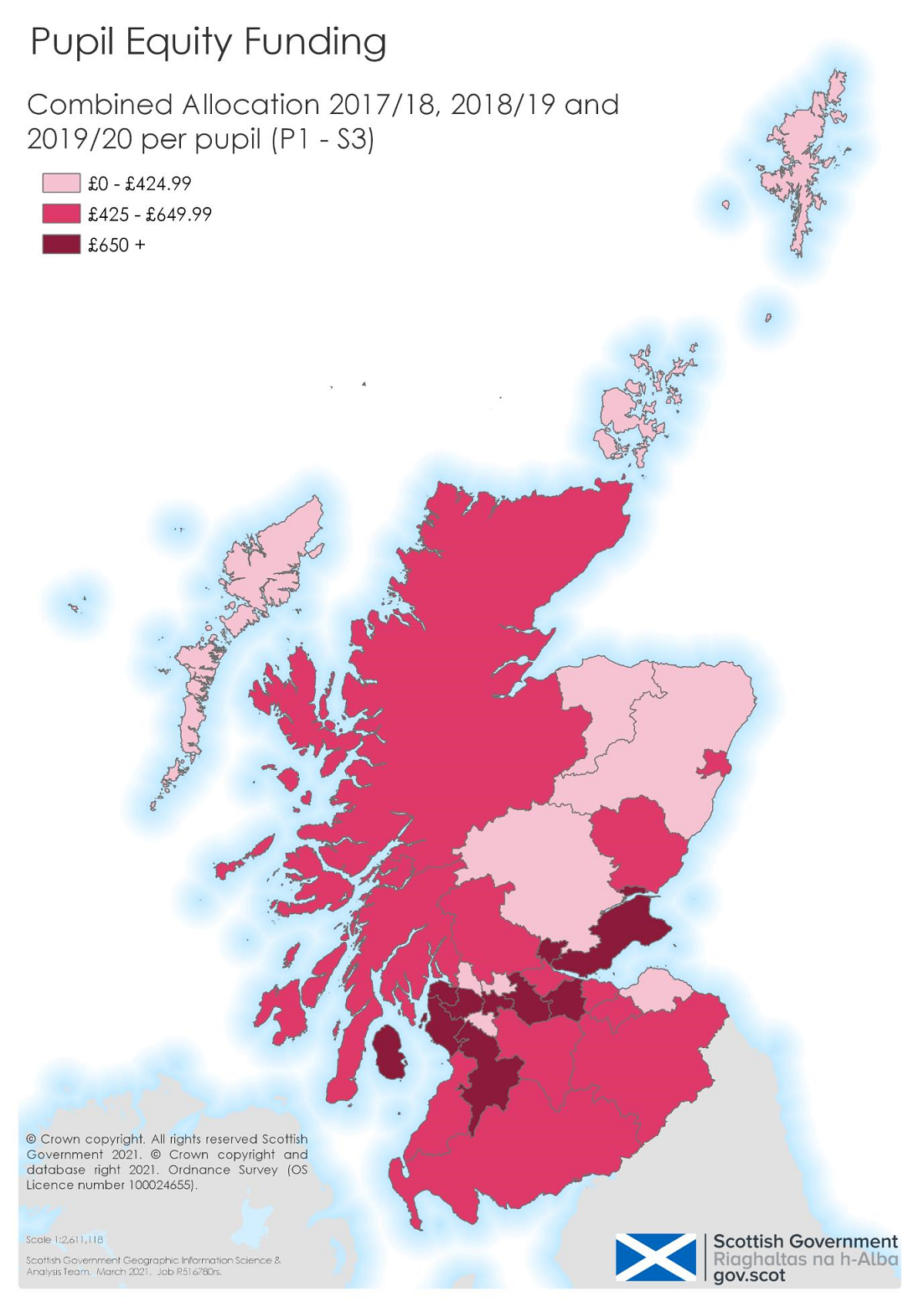

As part of the refreshed attainment challenge, the Scottish Government announced that from the next financial year funding previously allocated to nine challenge authorities (with the highest concentrations of deprivation based on SIMD) will be distributed equitably between 32 local authorities based on Children in Low Income Families (CILIF) data for the 2019/20 financial year. By directly measuring household income at the individual level, CILIF provides data on the number of deprived children in each local authority.

A criticism of SIMD20 is that, as a community or small neighbourhood-based measure, it does not capture individual families who are materially deprived living in areas where this is less common. In addition, the datazones in rural areas can be quite large, which could mask pockets of deprivation using this measure.

The Challenge Schools funding was previously available to schools outwith those nine authorities with the highest densities of pupils from SIMD20 areas. The Challenge Schools Programme has also stopped, with some of the funding from that programme supporting the increased funding of PEF.

There is a taper in the funding to 2025-26 which is intended to support the transition for the nine Challenge Authorities and to allow the other 23 local authorities to develop and scale up their approaches. Some of the challenge authorities will lose significant amounts of funding.

The Strategic Equity Funding allocations for all local authorities from 2022-26 are set out below:

| Local authorities | 2022/2023 | 2023/2024 | 2024/2025 | 2025/2026 final |

| Aberdeen City | £473,825 | £638,079 | £955,190 | £1,272,300 |

| Aberdeenshire | £341,052 | £678,005 | £1,014,957 | £1,351,910 |

| Angus | £221,234 | £439,809 | £658,385 | £876,960 |

| Argyll & Bute | £142,162 | £282,615 | £423,068 | £563,522 |

| Clackmannanshire | £1,303,282 | £1,034,744 | £766,205 | £497,666 |

| Dumfries & Galloway | £324,859 | £645,813 | £966,768 | £1,287,722 |

| Dundee City | £4,993,490 | £3,763,513 | £2,533,537 | £1,303,561 |

| East Ayrshire | £3,127,507 | £2,492,224 | £1,856,941 | £1,221,658 |

| East Dunbartonshire | £133,802 | £265,997 | £398,191 | £530,386 |

| East Lothian | £200,099 | £397,793 | £595,488 | £793,182 |

| East Renfrewshire | £134,591 | £267,565 | £400,538 | £533,512 |

| Edinburgh City | £641,043 | £1,274,381 | £1,907,719 | £2,541,058 |

| Eilean Siar | £100,000 | £100,000 | £117,345 | £156,302 |

| Falkirk | £332,745 | £661,491 | £990,237 | £1,318,983 |

| Fife | £859,490 | £1,708,651 | £2,557,812 | £3,406,972 |

| Glasgow City | £7,806,164 | £7,562,328 | £7,318,493 | £7,074,657 |

| Highland | £895,005 | £895,005 | £1,280,783 | £1,705,987 |

| Inverclyde | £2,748,713 | £2,030,319 | £1,311,926 | £593,532 |

| Midlothian | £174,180 | £346,266 | £518,353 | £690,439 |

| Moray | £170,500 | £338,950 | £507,400 | £675,851 |

| North Ayrshire | £4,672,951 | £3,578,650 | £2,484,349 | £1,390,048 |

| North Lanarkshire | £6,454,948 | £5,431,037 | £4,407,126 | £3,383,214 |

| Orkney Islands | £100,000 | £100,000 | £109,992 | £146,507 |

| Perth & Kinross | £251,412 | £499,802 | £748,193 | £996,583 |

| Renfrewshire | £3,749,496 | £2,940,992 | £2,132,488 | £1,323,984 |

| Scottish Borders | £225,440 | £448,171 | £670,901 | £893,632 |

| Shetland Islands | £100,000 | £100,000 | £100,000 | £105,660 |

| South Ayrshire | £299,642 | £435,211 | £651,500 | £867,790 |

| South Lanarkshire | £1,472,616 | £1,472,616 | £1,857,809 | £2,474,577 |

| Stirling | £147,735 | £293,694 | £439,653 | £585,612 |

| West Dunbarton-shire | £1,745,797 | £1,447,779 | £1,149,761 | £851,743 |

| West Lothian | £399,725 | £794,646 | £1,189,567 | £1,584,488 |

| Total LA allocations | £44,743,505 | £43,366,147 | £43,020,675 | £43,000,000 |

New funding approach

As set out above, the Scottish Government is moving away from the rationale of increased support for communities with severe multiple deprivation towards support for those living with poverty across the country. The impact of the reduction of funding to the nine challenge authorities was highlighted in evidence. COSLA is supportive of the new approach:

Poverty exists across all of Scotland and, unfortunately, every local authority has children and young people living in poverty within their boundaries. Therefore, we felt the delineation of Challenge Authorities and ‘non-Challenge Authorities’ was unhelpful, and that all authorities should receive additional funding to help close the poverty-related attainment gap. Moreover it was key that SAC funding was distributed on a need-basis taking into account both urban and rural poverty.

The education unions argued that core budgets are insufficient and should be increased in all areas, rather than cutting the funding for the nine challenge authorities. Jim Thewliss School Leaders Scotland said:

We should know—the Government statisticians will know—the number of young people who are impacted by deprivation within those nine areas. We have had a discussion around how we define deprivation, but let us take it that there is a definition there. It is a reasonably straightforward statistician’s exercise to look at how much core funding per capita was allocated across those nine areas and reallocate that per capita into the other remaining areas. I know that there is a financial aspect to this, but in terms of equity and fairness to the young people who are in the areas who have been supported in a certain way, it is surely immoral to take away that funding. We should allocate the money on a per capita basis across all the areas, working out how much was allocated per capita to the nine areas in the first place.

The EIS agreed that the attainment challenge should be reframed to take account of the fact that poverty exists in every local authority area and school community. However, they do not believe that this should be at the expense of budgets for local authorities originally considered to be in high need of additional support; they called for a reversal of the cuts to funding for the challenge authorities. Andrea Bradley from the EIS said:

I have to say that we have been absolutely appalled at the levels of funding cuts to six of the original challenge authorities. It beggars belief. We do not understand why those cuts would be made at a time when we know that poverty levels are rising, when the pandemic has absolutely bludgeoned some communities and we know that individual families and the young people within those families are struggling as a result of Covid.

The EIS also highlighted the transition that the local authorities not previously in receipt of challenge authority money will have to make; this will require 'quite a sizeable piece of work' around professional learning.

The Committee heard evidence from teachers who do not believe that their schools are ready to lose the challenge authority funding. Several teachers in senior management roles in primary schools were concerned about losing funding and said that the cut would have a significant impact. One headteacher said that staffing is critical, and some positions are only possible because of this funding. Some headteachers referred to an element of panic setting in about what the next year would look like. Several teachers said that, whilst they understand the reasons for the change, the answer is not to take away money from the schools that had and needed it, but to add more money into the fund.

In one engagement session, teachers were asked about the impact of the reduction in funding for challenge authorities. In response, one teacher, who worked for a challenge authority which was dealing with a 78% phased reduction in funding due to the change in policy, said that their teacher colleagues are ‘raging’ about this. Another teacher believed that the additional funding should be made permanent; they spoke about the need for a generational change which cannot happen in only five years.

Laura Robertson of the Poverty Alliance agreed that all local authorities should have access to resources, with the allocation based on young people living in poverty. Professor Francis of the Education Endowment Foundation said that the impact of deep poverty, and the persistent disadvantage that can engender, is a key predictor of educational outcomes. However, she believes that the issue of having equity across the board remains fundamental to social justice:

I would argue that we must not be dragged away to focus only on the challenge of deep poverty and persistent disadvantage, important and urgent though it is.

Sustained and embedded practice is one of the long-term ambitions for the Scottish Attainment Challenge. The Committee heard evidence that the challenge authorities were told that they were pathfinders and that the funding has led to finding out what works. The Cabinet Secretary said:

The pathfinders were very successful in trying out different models, looking at what worked in their systems and ensuring that the learning was shared not only in their local authority, but with others.

The Committee heard evidence of work being done to embed these new approaches. When asked about the move away from challenge authorities, Elizabeth Somerville, an Education Scotland Attainment Advisor, spoke of a ‘motorway of sustainability and intervention that brings us to a place where we have a solid and embedded approach.’ She said that there is a need to look at a sustainability strategy that might involve exiting certain aspects, maintaining them in a different way or a transfer of responsibilities.

Inverclyde is one of those areas which will lose Scottish Attainment Challenge funding under the new approach compared to the previous model. However, Ruth Binks from that local authority stated:

I am not saying that I welcome it; I think that it was a fair thing to do. We needed to look altruistically across Scotland. When we started as attainment challenge authorities we were very much told that we were the pathfinders, looking at how to make things work. We were asked to adopt, adapt and abandon initiatives, which we certainly did. It is very helpful to see that many of the initiatives that the attainment challenge authorities took forward in the early days are now being rolled out more widely. I started my answer by saying that if I could keep the £2.8 million I would absolutely welcome that. It is a big cut for Inverclyde, but it is one that we always knew could and would happen …

Let us look at the totality of the system and the learning that has taken place. I hope that the experience of our young people will very much benefit from the attainment challenge work that has been done to date.

Ruth Binks also highlighted particular challenges her authority will face:

We are worried about whole-family wellbeing and our partnership with the third sector. We have a very good partnership with the third sector, but we will probably not be able to keep that going, given the amount of money that we will end up with in 2024-25. However, there are opportunities now for us to revise our approach by working across children’s services to look at whole-family wellbeing.

South Lanarkshire was not a challenge authority although twenty of its schools received £1.9m in 2021-22 through the schools programme. Tony McDaid from South Lanarkshire stated:

We would not necessarily have picked those 20 schools. Those schools were picked on the basis of a particular profile, but that did not take into account rural poverty or the concentration of poverty in a couple of our schools. The bulk of the money still goes through PEF, but there is also the strategic equity fund, which comes to just over £2 million for us [£2.5m by 2025-26]. We will be able to redirect that resource to more concerted activity around the 124 primary schools and, indeed, across our 20 secondary schools as well. We can take some of the learning that has happened with the schools.

Education Scotland said that the refresh of the challenge is the result of looking at evidence from the past six years of the challenge, which pointed to a need to accelerate progress:

The OECD report [also] asked us to look at more universal support and hidden poverty, and to take account of the pandemic, to make sure that we were really recognising that poverty exists everywhere in Scotland.

We are looking at a redistribution of the funding, not a cut to it. We should remember that the overall attainment Scotland fund has actually increased, from £750 million to £1 billion. That was the Cabinet Secretary’s decision. It is not a cut to funding; it is a redistribution, and it is a different model.

The Cabinet Secretary stated that 59% of children in relative poverty live outside the challenge authorities and that the new funding model recognised that poverty exists in all local authorities. She highlighted that funding will go to all local authorities, thereby supporting them to develop strategic approaches to working with schools, wider local authority services and national community partners. The Cabinet Secretary said:

Through our allocations, we have attempted to ensure that there is a fair funding formula right across Scotland. There was an understanding, as was shown in the evidence from the directors of education, that we needed to look for a fair funding formula right across Scotland.

When pressed on maintaining the current funding levels for challenge authorities, the Cabinet Secretary said that the money would have to be found within other budgets:

The importance of recognising that poverty exists across all local authority areas, of dealing with that and of addressing the impact of the Covid pandemic across all 32 local authorities led us to change the funding formula. There is no additional money in my portfolio that is not being spent, so money would have to come from somewhere else within my portfolio.

The Committee recognises that there is poverty everywhere in Scotland, including in rural and less deprived areas. The Committee supports the policy of funding local authorities through the Strategic Equity Fund to ensure that targeted support is available to all children and young people living in poverty in Scotland.

However, the Committee acknowledges the evidence received on the impact of the reduction in funding to the challenge authorities. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government works with local authorities to examine and monitor the impact of the tapered reduction in funding on the challenge authorities and reports its findings to the Committee, along with any proposed action to mitigate any detrimental impact.

Freedom within a framework

One of the shifts under the new model is a clearer emphasis on the roles of all local authorities in supporting how Attainment Scotland Fund monies are spent at school and local authority levels. The Framework provides details on the expected role of the central local authority in setting the local strategic plans and aims, supporting schools in developing their improvement plans (including the attainment challenge aspects of those) in a two-way process.

PEF is allocated directly to schools and targeted at closing the poverty related attainment gap. The funding is spent at the discretion of headteachers working in partnership with each other and their local authority, with PEF national operational guidance designed to help support those plans.i

It should be noted that around 3% of schools are not in receipt of PEF, including rural schools. Headteachers in these schools do not have experience of being part of the process of allocating attainment challenge funding within their schools. This issue is covered later in the report.

The Framework envisages 'freedom within a framework' for headteachers and their schools, with a strong emphasis on consulting teachers, parents, carers and pupils. It retains the role of the headteacher in determining approaches to using PEF in their schools. However, local authorities remain accountable for the use of Attainment Scotland Funding, including PEF. Therefore, local authorities should support headteachers and have processes in place to ensure plans are targeted and evidence based.

Autonomy of school leaders and involvement of teachers in decision making were key themes in the inquiry. Professor Mel Ainscow of the University of Glasgow said:

Educational change is about implementation; you can have the best policies in the world.... but the real challenge is implementation down the levels. As I keep reiterating, teachers are policy makers, and we have not only to engage and support them but to give them freedom. We have to give teaching back to teachers.

COSLA agrees that individual schools should be empowered through the Framework:

We believe there are tensions that need to be considered and resolved as part of this work. This will include ensuring that we avoid top-down setting of expectations and determining where the refreshed SAC fits the ongoing commitment to the school empowerment agenda.

The concern that the central local authority’s role can impinge too much upon the professional autonomy of headteachers in their schools has been raised by witnesses during this inquiry. The Robert Owen Centre for Educational Change said that a tradition of rigid local authority line management can constrain decision-making amongst school leaders. Jim Thewliss of School Leaders Scotland agreed that local authorities should operate as an agency to support schools. He said:

If the strategy is driven from the ground up and local authorities look to support the strategies that schools are devising, we are in a much better place to enable and empower schools to respond to young people’s needs...Schools are more than happy to be held accountable for the strategies that they put in place if they are empowered to develop the strategies in the first place, as opposed to having them imposed on them within a local authority wide structure.

However, Emma Congreve of the Fraser of Allander Institute referred to difficulties in articulating the needs of individual schools at local authority level:

Often, it can feel as though there is a disconnect between what local authorities are saying and doing and what teachers on the ground think is necessary. Part of the reason for that is that it is very difficult for everyone to get the full picture of the situations that need to be addressed at school, local authority and Scotland levels.

Professor Ainscow said that headteachers want more control over funding; there is a need to trust them to understand their school and context. He spoke of frustration among headteachers because they cannot design their staffing profile in order to deliver programmes that they think their children and their community need. In contrast, Greg Dempster of AHDS said that most school leaders do not feel that they are being directed on attainment challenge spend.

The Poverty Alliance also said that much of the evidence about PEF has been extremely positive:

Evaluations of the pupil equity fund by headteachers and schools have been very positive about the empowerment that the funding gives to local schools. It gives them autonomy with local services, and they can offer bespoke support to young people who are living in poverty or who might be at risk of being excluded.

Tony McDaid of South Lanarkshire Council illustrated this by saying that children in schools in his area know that they can ask for help with costs of residential activities or uniforms; this confidence is built on relationships and staff knowing the individual children. Ruth Binks of Inverclyde Council said that headteachers now feel that they are 'not alone', and are empowered to put interventions in place that will help individual families.

The role of headteachers is key to the effective use of PEF. Witnesses told the Committee that headteachers need time and practical support in deciding how to deploy PEF within their schools. Greg Dempster of AHDS identified the lack of protected time for school leaders as a problem his members are concerned about. He said:

If you are being pulled away to give one-to-one support to individual pupils or cover classes, that will obviously swallow up time that could be used to consider more strategic interventions, to look at your school’s data, to pinpoint areas for action and improvement or to examine research and evidence on what you might be able to do to address gaps.

Mike Corbett of NASUWT spoke of a 'looming recruitment and retention crisis' as teachers consider leaving the profession, and Greg Dempster referred to a decrease in the number of people seeking to apply for school leadership roles:

There have already been problems with recruitment into headships, particularly in some areas, but across the board there is an issue with recruiting heads in the primary sector in particular. We asked members who are depute heads to respond to the statement, “I am a depute headteacher and I am keen to become a headteacher,” and 18 per cent of those who responded were positive. To me, that would be an implication. The first time we did the survey was in 2016, when 35.7 per cent were positive. That represents a significant drop-off over time.

Gerry Lyons, Director of Education at Glasgow City Council, confirmed that they have had challenges with recruitment, with some newly appointed headteachers having no experience of running a school pre-covid:

there have been some challenges around the legislative requirement with regard to the into headship qualification. It is right that we want highly qualified people, but there has been a bit of a time lag between people getting that qualification and their being ready to take on the posts, and then a lag between that and getting the number of people we need. There is a bit of work to be done to improve that.

Headteachers told the Committee that they receive support from the local authority in managing financial and administrative aspects of PEF. They also said that they felt supported by their local authorities to make difficult decisions on competing demands and priorities. Professor Ainscow of the University of Glasgow said that headteachers need to have different kinds of expertise in their school offices to deal with these issues and recommended collaborative governance arrangements.

The Committee notes the role played by headteachers in the deployment of PEF in schools. Headteachers' capacity is the key factor in the performance of the attainment challenge. The Committee notes concerns about current challenges with recruitment and retention of headteachers. Given the critical role headteachers play in delivery and accountability for PEF spending, the Committee asks the Scottish Government to set out what steps it is taking to address recruitment and retention issues.

Involvement of parents, carers, children, young people and teachers

Meaningful involvement of teachers, parents and carers, children and young people is one of the key principles of PEF guidance. The Committee heard mixed evidence on how involved teachers and parents feel in planning for the use of PEF in their schools. Some teachers said that they were consulted on decisions on how to spend PEF in schools, whilst others said that this depended on the management style of the headteacher. The EIS said:

There could be efforts made in the context of the empowerment agenda to encourage properly collegiate dialogue and decision-making at school level as to how PEF money and/or any other funds disbursed individually to schools through SAC should be spent. The 2018-19 EIS research found that teachers are not universally involved in such discussions, this is underlined by the fact that more than 10% were not only excluded from discussions but unaware of how PEF was being spent in their schools.

Mike Corbett of the NASUWT also described a 'patchwork picture' of teacher involvement in PEF planning and said that teachers need time to engage with PEF plans and outside agencies to deliver the collective agency approach.

Generally, the parents reported that headteachers were consulting and informing parents about how the PEF funds were being used, often through parent councils. Some parents stated that headteachers listened to and acted on feedback from parent councils, whilst others said that they were not involved in decisions on how to use PEF in their child's school. Connect also reported patchy engagement with parents and carers in planning PEF interventions.

Children and young people should also have a voice in relation to how attainment challenge funding is spent in their schools. The Child Poverty Action Group said that pupil voice could be built on and further developed:

At all levels, school, locally and nationally, we need to keep children’s and parent’s involvement, voices and lived experiences central to how we proceed and, alongside this, make the most of opportunities to have children and young people taking the lead on equity in their schools and communities.

The Committee supports the emphasis on the need for meaningful engagement of teachers, parents and carers, children and young people and other key stakeholders throughout the processes of planning, implementing and evaluating approaches for spending PEF. Protected time for headteachers and teachers is key to creating space for such engagement. The Committee asks the Scottish Government what steps it is taking to ensure that headteachers have the capacity to work with teachers, parents, carers and pupils to consult them in a meaningful way on the deployment of PEF within their schools.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government tasks Education Scotland with monitoring practices in schools and local authorities to ensure that the voices of classroom teachers, parents, carers and children and young people are at the centre of plans for attainment challenge spending.

Consistency and sharing best practice

The importance of sharing best practice as part of the attainment challenge was highlighted by many witnesses. However, the Committee heard mixed evidence about the extent to which this is happening on the ground. NASUWT and others told the Committee that more could be done in sharing best practice in using the attainment challenge funding:

There have been isolated examples of good practice from individual schools utilising the SAC funding streams; however, these are often isolated, and insufficient opportunity has been taken to share these successes and facilitate any learning where the results have been disappointing.

The Committee notes that there are varying levels of experience in local authorities and schools across the country in allocating attainment challenge funding. Laura Robertson of the Poverty Alliance said that whilst some work is being done in sharing best practice, local authorities need more support, especially since some interventions are not available across the country:

The recent evaluation of the Scottish attainment challenge showed that schools widely are using the Education Endowment Foundation’s learning and teaching toolkit to give them access to evidence on the types of initiatives and interventions that have worked well. There is a lot of good practice in Scotland. For example, attainment advisers have been specifically created to find and share such evidence, but local authorities need more support in carrying out that role of finding the evidence and seeing what works. On top of that, although there is a lot of evidence out there on what works, those kinds of initiatives might not be available in certain local authorities.

Education Scotland recently published 'Pupil Equity Funding: Looking inwards, outwards, forwards'. This was based on field work across the country and is intended to share practice and to help staff involved in the planning, implementation and monitoring of PEF to reflect and build on their current practice. Education Scotland said that this document provides 'strong examples of what is working well'.

The Cabinet Secretary said that there are roles for Education Scotland and RICs in promoting and sharing best practice. The Framework also sets out the role of HM Inspectorate of Education in gathering and sharing evidence of what is working well and where further development is needed.

One of the aims of the Framework is to address inconsistencies in outcomes across local authorities. The Audit Scotland report found variation in education performance across councils and in councils’ spending per pupil:

There is wide variation in education performance across councils, with evidence of worsening performance on some indicators in some councils. At the national level, exam performance and other attainment measures have improved. But the rate of improvement up until 2018–19 has been inconsistent across different measures.

The Cabinet Secretary acknowledged that there is variation in outcomes within and across local authorities:

The data that we have suggests that that variation is marked, and if we can tackle that, we should do so. That is another lens for looking at the poverty-related attainment gap, because it cannot all be explained by different poverty levels in different parts of Scotland.

Audit Scotland recommended that Education Scotland should work with schools, councils and RICs to understand the factors that cause variation in performance across schools and councils. It said that councils face different pressures and challenges, for example due to their geography, levels of deprivation, staffing levels, funding levels and local priorities. These factors need to be considered when comparing performance across councils.

Education Scotland highlighted the role of RICs in tackling variation of outcomes across local authorities. Improvement work can be taken from school level to local level to RICs level; Education Scotland said that these structures can minimise variation. In 2021-22 national programmes funded under the ASF totalled £6.6m; RICs received £2 million to fund their work.

The Cabinet Secretary highlighted the role of RICs in sharing best practice:

The RICs are perhaps a part of the system that does not get much discussion. It is perhaps understandable that national Government, its agencies and local government get more attention, but the RICs form an important part of the information sharing and collaborative working. That was absolutely the intent when the RICs were established.

The Audit Scotland report found that whilst schools and councils are getting better at identifying needs, reviewing what works, and determining the impact on closing the poverty-related attainment gap, there is scope to achieve greater consistency and impact across the system through evaluation and transfer of learning. Audit Scotland said that schools are being supported in this by RICs and Education Scotland; however, the Committee is not clear on who assesses the performance of RICs.

The Framework sets out the role of Education Scotland in challenging this variation and areas where there is limited progress. The Cabinet Secretary highlighted the key role of Education Scotland in providing universal support. She also emphasised the role of new 'stretch aims' in addressing variation of outcomes:

One of the reasons behind the introduction of the stretch aims is to tackle the unwarranted variation between local authorities. We hope that the transparent mechanism that we are putting into the system will give a clear understanding of local ambitions.

The Committee notes with concern evidence on variation in education performance across local authorities in Scotland. It is important that children and young people's outcomes are not dependent on where they live. There is a key role for Education Scotland to play in tackling these variations. The Committee recommends that Education Scotland is tasked with undertaking urgent work to investigate the reasons for these variations and with setting out the action it is taking to achieve consistency across the country. The Committee recommends that Education Scotland reports back to the Committee on progress with this work within 6 months of the publication of this report.

The Committee notes that the attainment challenge has been in place since 2015 and during that time many new interventions have been adopted, adapted and, in some cases, abandoned. With the introduction of the refreshed approach, it is vital that lessons learned during that period are shared widely and systematically. Given the mixed evidence on whether this is happening on the ground, the Committee asks the Scottish Government to closely monitor how effectively and consistently best practice is being shared by Education Scotland.

The Committee notes the role of RICs in supporting local authorities and schools and promoting consistency in outcomes. The role of HM Inspectorate of Education is explored later in this report; the Committee recommends that the performance of RICs is evaluated by HM Inspectorate of Education as part of its ongoing work.

Life outside school and the role of the third sector

A theme in evidence to the Committee was that inequality and poverty are the key drivers for the attainment gap and therefore policies to reduce child poverty and the attainment gap should be better aligned. COSLA’s submission stated:

Fundamental to the attainment gap is tackling child poverty, and its symptoms, directly. The original SAC had placed schools at the centre of tackling the attainment gap, and our view was that there were not sufficient links made between the strategic approach to tackling child poverty, and tackling the attainment gap. This would have included the flexibility for councils and schools to use SAC resources across a wider range of services which support children and families.

The Cabinet Secretary stressed the importance of a whole-child approach. The Framework states that work in support of improving outcomes for children and young people will not be achieved by schools alone. It said:

Prior learning and research evidence shows us that schools and education services alone will not reduce the poverty-related attainment gap. The mission of the Scottish Attainment Challenge is one that must be supported by ‘collective agency’ – the range of services, third sector organisations and community partners working together with families, with a clear focus on improving the educational experiences, health and wellbeing and outcomes of children and young people. In this way educators, who are at the heart of these collaborations, will play a vital role in breaking the cycle of poverty and make a long-term contribution to Scotland’s national mission to tackle child poverty.

The Committee heard that children's learning is significantly impacted by what happens away from school and that to improve learning, there is a need to understand the wider issues impacting on a child or young person's attainment. Maureen McAteer from Barnardo’s Scotland said:

I am interested in the interface between the work on the attainment challenge fund and other Scottish Government funding streams. From our perspective, fragmentation can be challenging. A family’s needs are not cut into chunks, with some being attainment issues, some being family support issues and some being early years issues. Those things are all connected, which is why a more holistic approach, rather than a school-centric approach, is essential for getting good outcomes for children, young people and families.

Teachers highlighted the importance of the family environment and the limits of what schools might be able to achieve to militate against the impacts of poverty. They also noted both the importance, and sometimes the difficulty, of building positive relationships with parents and argued for a holistic approach to supporting families. This included considering what barriers may exist to families accessing a wide range of support. An example of how one school worked with families is set out below:

Working with families

A teacher explained to Members that they were taken out of class for attainment challenge work; they were a ‘protected teacher’ working on attainment and led project work, including organising literacy and numeracy support for parents. They organised a ‘really successful’ film literacy club for parents; it is sometimes challenging to get parents into schools and being able to work on literacy skills with them through film was ‘fun and relaxed’. This was only possible through attainment challenge funding and having the extra teacher whose sole purpose was to focus on such projects. The funding was there to sustain the project throughout the year. Parents were then able to take those skills back home.

Save the Children agreed that the role of the family is key:

While parental engagement has been recognised as a key driver for closing the attainment gap, and there are some signs of progress, this is not yet translated into consistent good parental engagement practice and improved outcomes for children.