Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee

Inquiry into the use of the made affirmative procedure during the coronavirus pandemic

Summary of evidence

Clarity and accessibility of law

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to outline its internal checks and balances for ensuring that secondary legislation, even when drafted at speed, meets the high standard of drafting required for making changes to the law.

The law should be clear and accessible to all. The Committee considers that this is especially true where the law is continually changing and coming into force within a matter of days and on occasion with immediate effect, such as has been the case during the pandemic.

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to ensure that regulations relating to the pandemic, and particularly those subject to the made affirmative procedure, that have been frequently amended are regularly consolidated.

It also calls on the Scottish Government to:

publish as soon as possible, and prior to them coming into force, any relevant consolidated regulations;

clearly signpost to the public where the most up-to-date and consolidated regulations dealing with the pandemic might be read. In the short term, this could be a clear link on the Scottish Government's main coronavirus website and to the relevant consolidated regulations on www.legislation.gov.uk; and

ensure that the policy note and explanatory note accompanying each SSI is written in plain English and is sufficiently detailed so those affected can clearly understand the law and how it impacts them.

Changes to how made affirmative instruments are brought forward

Test of urgency

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to:

publish its criteria for determining whether a situation is suitably urgent in responding to the Coronavirus pandemic to require the use of the made affirmative procedure;

provide a written statement prior to the instrument coming into force (which in any event should accompany the laid instrument) for any future made affirmative instrument that provides a consistent level of detailed justification and evidence as to why the Scottish Ministers consider the regulations need to be made urgently; and

ensure that any such regulations are published as quickly as possible following any Scottish Government announcement so that all those impacted might fully understand the detailed changes being made to the law.

If the Committee considers that the Scottish Government has not sufficiently justified its choice of the made affirmative procedure for reasons of urgency, it reserves the right to seek to raise this matter in the Chamber and to do so quickly. There is no obvious current parliamentary process by which Members could debate the issue with sufficient speed. Current available routes include requesting:

a committee announcement to be made on a Tuesday afternoon (albeit there is no requirement for a Minister to respond);

an urgent question; or

a supplementary question during a question time such as First Minister’s Questions.

The Committee acknowledges that using these current Chamber options would mainly serve to highlight the Committee’s concerns but that there would be limited opportunities for other Members to contribute. The Committee considers that any discussion of this issue should not be confined to contributions from the Convener of the Committee and the Minister. The Committee will therefore write to the Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments (SPPA) Committee to invite it to explore options for further debate in cases where the Committee considers that the Scottish Government has not sufficiently justified its choice of the made affirmative procedure as part of the SPPA Committee's inquiry into 'shaping parliamentary procedures and practices for the future’.

Furthermore, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government, in discussion with the Parliamentary Bureau, to provide a note containing a summary of all statutory instruments to be considered in the Chamber, which should be sent to Members sufficiently far enough in advance of the motion being taken.

Future made affirmative powers

The Committee considers there should be a set of principles that underpin the Scottish Government’s approach when it is contemplating inclusion of provision for the made affirmative procedure in future legislation.

While the Committee will consider each proposed delegation of power on a case by case basis, the Committee has developed the following four principles as the basis of its scrutiny where legislation includes such provision. The Committee will be looking for evidence that the Scottish Government had regard to these principles in developing the legislation:

Given the lack of prior parliamentary scrutiny and risks to legislative clarity and transparency in the made affirmative procedure, use of the affirmative procedure should be the default position in all but exceptional and urgent circumstances. Legislation making provision for the made affirmative procedure must be very closely framed and its exercise tightly limited.

The Parliament will require an assurance that a situation is urgent. Provision in primary legislation will need to encompass a requirement to provide an explanation and evidence for the reasons for urgency in each case where the procedure is being used. There should be an opportunity for debate in a timely fashion and open to Members to seek to contribute.

Any explanation provided by Scottish Ministers should also include an assessment of the impact of the instrument on those affected by it and Ministers’ plans to publicise its contents and implications. This could include details of the relevant Scottish Government website where links to the instrument, including where relevant any consolidated version of the instrument it amends, as well as any associated guidance, can be found.

There will be a general expectation that legislation containing provision for the made affirmative procedure will include provision for sunset clauses to the effect that (a) Ministers’ ability to use the power will expire at a specified date and that (b) any instrument made under the power will be time-limited.

An expedited affirmative procedure

The Committee would be happy to consider with the Scottish Government, alongside the COVID-19 Committee (or relevant lead committee) and the Parliamentary Bureau (which manages the business in the Chamber), on a case-by-case basis for when the use of an expedited affirmative procedure as an alternative to the use of the made affirmative procedure might be appropriate and the parliamentary timescales for such scrutiny.

The Committee considers that, in the meantime, it may be helpful for the Parliament and Scottish Government to agree the process (perhaps in the form of a protocol) that should be followed to aid the decision making in such cases.

The Committee considers that any such expedited affirmative procedure must allow for robust scrutiny. The desire to consider legislation prior to it coming into force should not come at any cost, nor should it become habitual.

The Committee also notes that the advances in technology brought in by the Parliament during the pandemic allowing virtual or hybrid proceedings in committees and the Chamber may facilitate greater flexibility when considering any instances of an expedited affirmative procedure but should be cognisant of the founding principles at the establishment of the Scottish Parliament.

Introduction

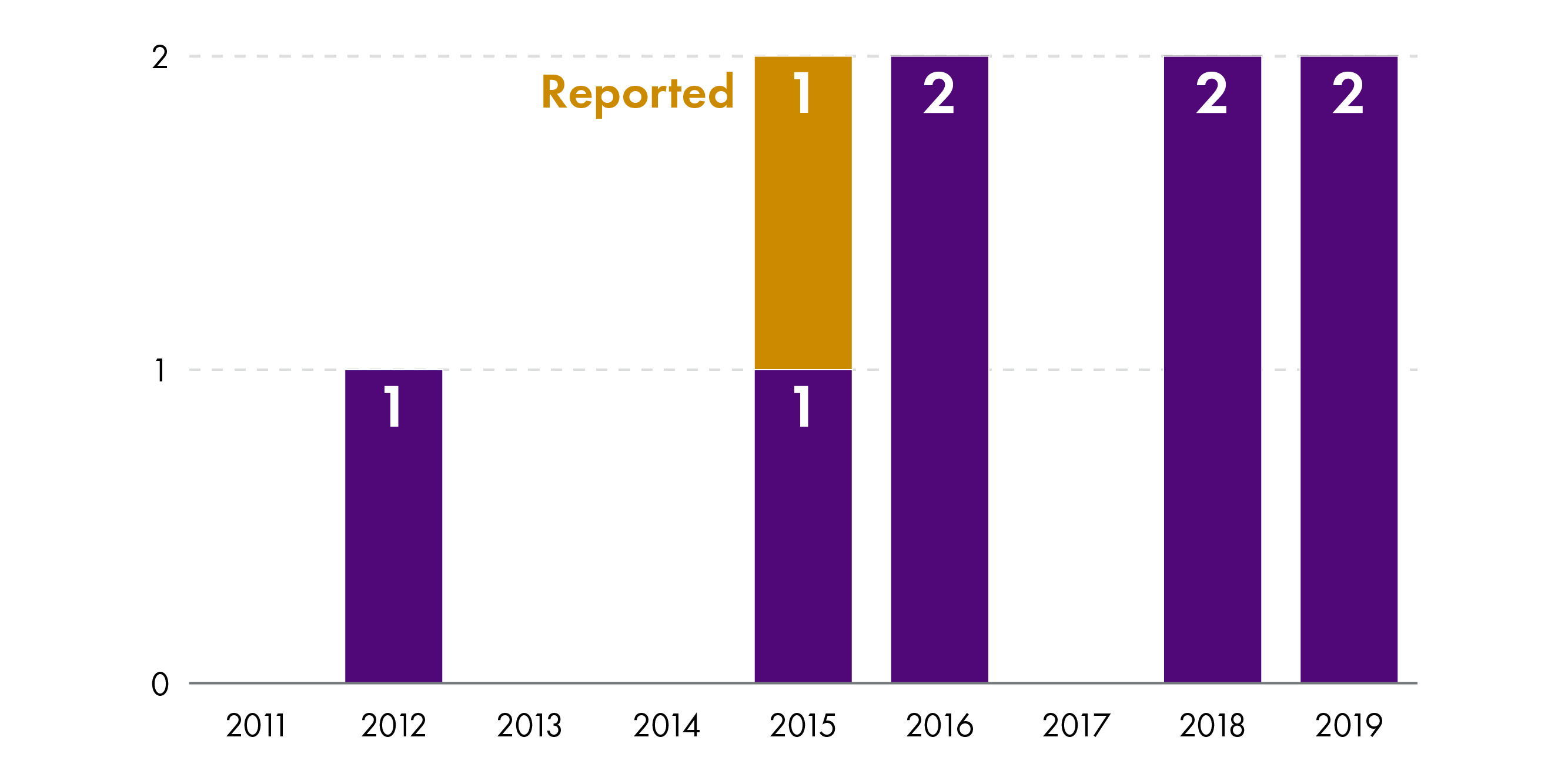

Up until the start of the pandemic, the made affirmative procedure was a rarely used and little known parliamentary mechanism for the laying of SSIs (Scottish Statutory Instruments). The Scottish Parliament considered roughly one or two a year. This was primarily due to rarity of provisions to allow the use of the made affirmative procedure in primary legislation.

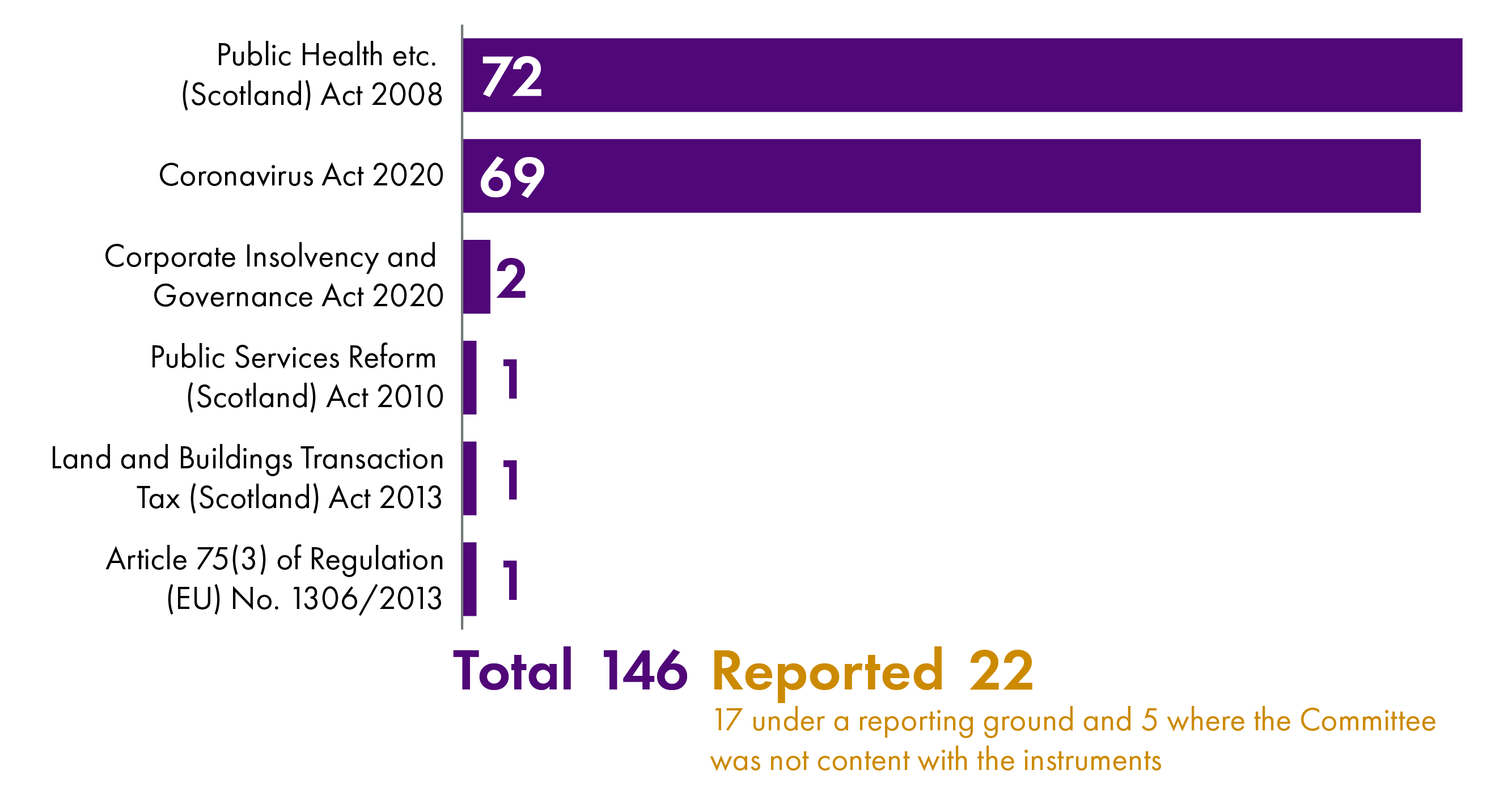

Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, over 120 made affirmatives have been laid by the Scottish Government. The vast majority of these have been made using the provisions in schedule 19 of the UK Coronavirus Act 2020 Act (restrictions, local levels and current requirements) and sections 94(1) and 122 of the Public Health etc. (Scotland) Act 2008 (International Travel Regulations).

The Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee ("the Committee"), has regularly acknowledged the requirement for made affirmative instruments during the pandemic so as to allow the Scottish Government to respond quickly to the many challenges presented by coronavirus. Nevertheless, the Committee has also said that bringing such substantial changes into force immediately, before any parliamentary scrutiny, should only be used when essential and should not become standard practice when time would allow the affirmative procedure to be used.

Given the rapid increase in the use of the made affirmative procedure since March 2020, the Committee agreed at its meeting on 9 November 2021 to hold a short and focused inquiry to consider how the made affirmative procedure has been used by the Scottish Government during the coronavirus pandemic. The Committee's objective for this work was to:

help inform the Parliament’s consideration of the made affirmative procedure in future legislation; and

help ensure there is an appropriate balance between flexibility for the Government in responding to an emergency situation while still ensuring appropriate parliamentary scrutiny and oversight.

The Committee heard from witnesses across three evidence sessions and received a number of written submissions and correspondence on its inquiry. A full list of witnesses and those who contributed written submissions is available in Annex A. The Committee is grateful for all those who took time to contribute to the Committee's work.

The Committee has also used its experience of considering made affirmative instruments and its scrutiny of proposed delegated powers in Bills to inform this report.

What is the made affirmative procedure?

The made affirmative procedure allows an SSI to be made and come into force even though it has not yet been approved by the Parliament. However, it cannot remain in force beyond a specified period of time (often 28 days in the case of coronavirus instruments) unless it is subsequently approved by the Parliament.

The primary difference between the made affirmative and affirmative procedures is that an SSI laid under the affirmative procedure cannot be made and come into force unless and until the Parliament has voted to approve it. The lead committee has up to 40 days from when an affirmative instrument is laid to publish its report.

Made affirmative SSIs were not, until 2020, very common. These are only used for time-limited situations because they can make changes to the law immediately before the Parliament has looked at an SSI that would otherwise be subject to the affirmative procedure.

Both a made affirmative and affirmative instrument will firstly be considered by the Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee as a matter of law. It will then be considered by the relevant subject committee (known as the lead committee) as a matter of policy before being voted on in the Chamber.

Clarity and accessibility of law

The Committee heard evidence on the tension between needing to respond quickly to changing circumstances and ensuring appropriate parliamentary scrutiny.

The test for using the made affirmative procedure

The Scottish Government can only use the made affirmative procedure where primary legislation has made provision for such a procedure to be used. Such provisions can be found in a number of Bills, including both the Public Health etc. (Scotland) Act 2008 and the Coronavirus Act 2020.

There is usually a legal test for whether the made affirmative procedure can be used in place of the affirmative procedure. The Scottish Government has used the made affirmative procedure provided for in paragraph 6 of schedule 19 of the Coronavirus Act 2020 for over 60 made affirmative SSIs. These regulations have primarily dealt with coronavirus restrictions, requirements and the setting of local levels.

The relevant text of paragraph 6 of schedule 19 of the Coronavirus Act 2020 is outlined below:

Health protection regulations: procedure

6 (1) Regulations under paragraph 1(1) are subject to the affirmative procedure (see section 29 of the Interpretation and Legislative Reform (Scotland) Act 2010).

(2) Sub-paragraph (1) does not apply if the Scottish Ministers consider that the regulations need to be made urgently.

(3) Where sub-paragraph (2) applies, the regulations (the “emergency regulations”)—

(a) must be laid before the Scottish Parliament; and

(b) cease to have effect on the expiry of the period of 28 days beginning with the date on which the regulations were made unless, before the expiry of that period, the regulations have been approved by a resolution of the Parliament.

A similar test is provided in section 122 of the Public Health etc. (Scotland) Act 2008. The relevant text is provided below:

Regulations and orders

(5) No statutory instrument containing regulations made under section 25(3), 94(1), 99(1) or 105(11) may be made unless a draft of it has been laid before, and approved by resolution of, the Scottish Parliament.

(6) Subsection (5) does not apply to regulations made under section 25(3) or 94(1) if the Scottish Ministers consider that the regulations need to be made urgently.

(7) Where subsection (6) applies, the regulations (the “emergency regulations”)—

(a) must be laid before the Scottish Parliament; and

(b) cease to have effect at the expiry of the period of 28 days beginning with the date on which the regulations were made unless, before the expiry of that period, the regulations have been approved by a resolution of the Parliament.

The regulations laid under the 2008 Act during the pandemic have mainly dealt with international travel restrictions.

In each Act, the Minister is not required by law to provide evidence or an explanation as to why they consider the regulations require to be made urgently.

Made affirmative instruments reported by the Committee under its remit

Rule 10.3 of the Scottish Parliament's Standing Orders (the full list is provided in Annex B) outlines 11 grounds on which the Committee might draw the attention of the Parliament on any instrument it considers under its technical remit.

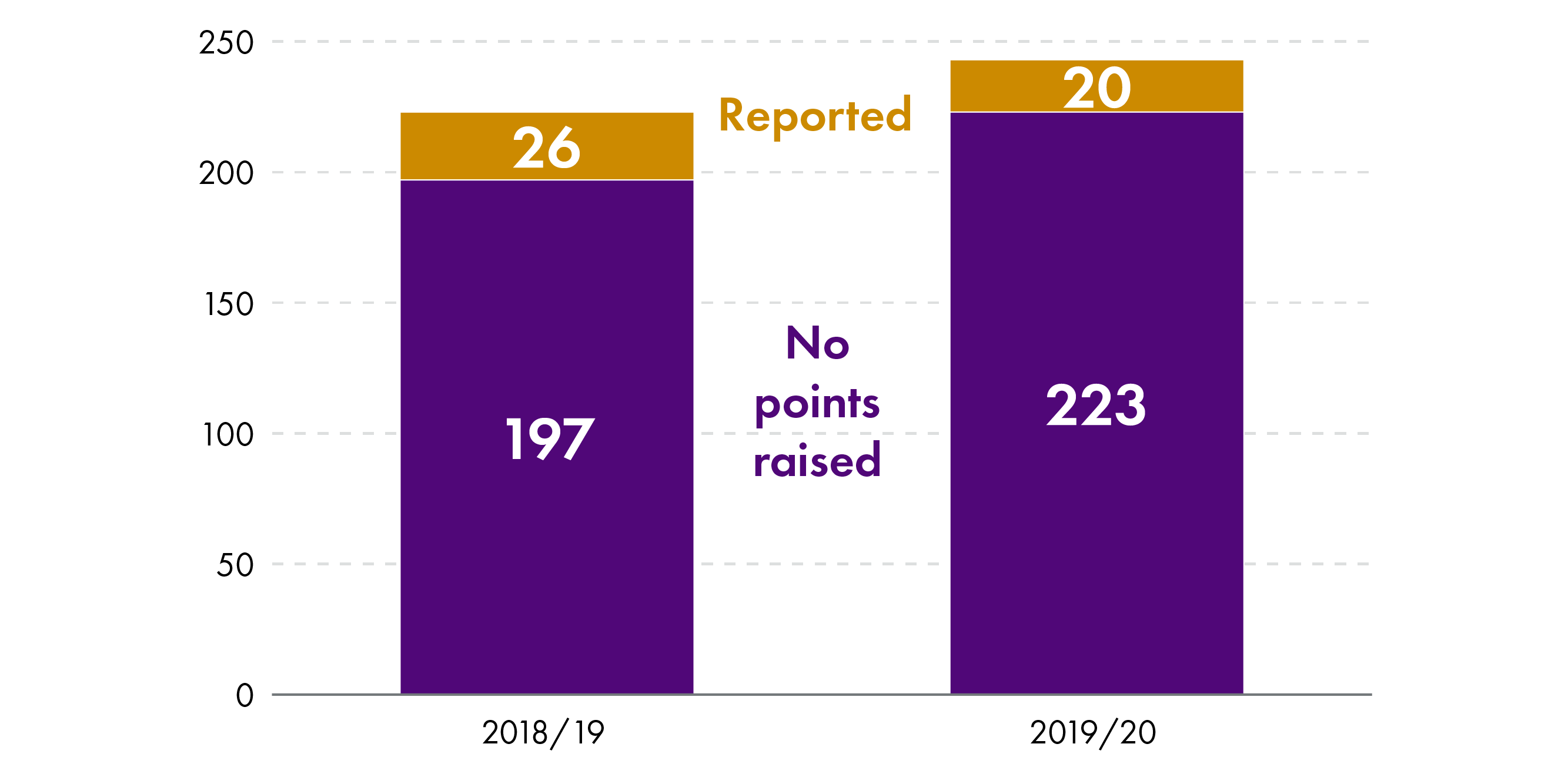

Between 20 March 2020 and 1 February 2022, (a period of just over 22 months) the Committee reported 22 made affirmative coronavirus instruments out of a total of 146 (or 15.1%). Of those, 17 were drawn to the Parliament's attention under at least one of the 11 reporting grounds (or 11.6%). This is similar to the percentage of overall instruments the Committee reports under the reporting grounds over the course of a parliamentary year.

Four of the reported instruments laid during the pandemic have contained serious errors which the Committee reported under ground (i) - that the drafting appears to be defective. Full details of each of these instruments can be found in Annex C.

Of the other 13 made affirmatives reported under a reporting ground, they were either under the general reporting ground (8) or reporting ground (h) - that the meaning could be clearer (5).

For the remaining five SSIs (SSIs 2021 349, 475, 496, 497 and 498) the Committee considered in each case that the affirmative procedure would have instead been the more appropriate choice of procedure for each set of regulations.

For example, the Health Protection (Coronavirus) (Requirements) (Scotland) Amendment (No.2) Regulations 2021 (SSI 2021/349) provided for the introduction of a vaccine certification scheme. The Committee noted that the Scottish Government had announced its intention to bring forward the scheme in early September. However, the instrument was not made until 11.39 am on 30 September 2021 and laid before the Parliament at 3.30 pm the same day. It came into force at 5.00am on 1 October 2021. The requirement to implement a reasonable system for checking a person’s vaccination status and the requirement to prepare and maintain a compliance plan would not be enforced until 5.00am on 18 October 2021.

Clarity and accessibility of law - evidence

The link between clarity in legislation and accessibility of law was widely discussed in evidence, particularly given that made affirmative regulations often need to be drafted and laid very quickly.

Morag Ross QC, who gave evidence on behalf of the Faculty of Advocates, considered that clarity was fundamental to good legislation and consistent application. Ms Ross QC highlighted the risk of errors in instruments which are drafted quickly, pointing out:

In general, legislation that is made in a hurry is unlikely to be of the same quality as legislation to which great thought has been given and for which preparation has been undertaken.i

Morag Ross QC nevertheless highlighted the work of those drafting legislation:

I do not criticise those who draft legislation; drafting is a tremendous skill, and doing it at speed and accurately is a valuable skill. A great deal of respect is due to those who work in pressing circumstances. However, it is inevitable that there is room for mistakes to be made.i

Dr Ruth Fox, Director of the Hansard Society, spoke of a number of instruments laid at Westminster (known as SIs - Statutory Instruments) which had been made and quickly revoked at the UK Parliament during the COVID-19 pandemic to highlight the effect that urgent, repeated delegated legislation can have on clarity and therefore accessibility. She indicated that where legislation is pushed through quickly the scrutiny and technical checks are missing so that “the drafting problems get through, and you have to either amend the regulations, which adds to their complexity, or revoke them.”iii

Sir Jonathan Jones QC, former head of the UK Government's Legal Department and who now works for Linklaters LLP, highlighted the balance between clear legislation and time, arguing that the balance has been lost with urgency being considered above other matters:

In recent times, over the course of the pandemic, we have prioritised, and we are continuing to prioritise, extreme urgency over the quality and comprehensibility of legislation.iv

Sir Jonathan noted that the cumulative effect of amendments can negatively impact the clarity and accessibility of law and suggested an answer to this challenge:

One solution which I and others have suggested-it is not a new idea-is that, when you are amending an instrument, you should at the same time produce a consolidated amended version of the whole instrument so that the people can see what the law as amended now looks like in one place.v

In its written evidence to the Committee, the Law Society of Scotland echoed concerns about the clarity and accessibility of made affirmative instruments which are subject to frequent and significant amendment. It highlighted that the Health Protection (Coronavirus) (International Travel) (Scotland) Regulations 2020 (SSI 2020/169) (now revoked) were amended 25 times. The Law Society suggested that, when amending an instrument, the Government should produce a consolidated version showing the whole instrument as amended, pointing out that the drafter and policy team must be working with a marked up consolidated version and that therefore “it ought not to take extra time to produce a consolidation instrument.”vi

Morag Ross QC also spoke of the need for law to be accessible for all- both for individuals and lawyers who advise on legislation, Ms Ross QC said that if the made affirmative procedure is used repeatedly, there is a risk of "accumulating rapidly changing regulation, which becomes confusing."vii

In evidence to the Committee, the Deputy First Minister and Cabinet Secretary for Covid Recovery, John Swinney MSP, noted that the requirement to deal with the pandemic was not the "ideal model for how we should legislate" and "We should always take care and time over legislation".viii Mr Swinney also said:

The procedure should not be used in the ordinary run of life but, when we are dealing with a global pandemic with serious material threats to the lives of our individual citizens, we must act. There are opportunities for Parliament to challenge such questions, and there has been no lack of opportunity for people to raise their concerns in Parliament about issues since March 2020—the First Minister has made statements almost weekly since March 2020; members have had the ability to raise issues; committees have met; and a bespoke Covid committee has been created. There have been endless opportunities for members to raise issues.ix

Mr Swinney highlighted the quality of drafting skills among officials in the Government which enables it to prepare legislation of this type. While noting that there is the potential for errors to be made when things are done at pace, the Deputy First Minister said that the Scottish Government seek to minimise such errors.x

Rachel Raynor, Deputy Legislation Co-ordinator in the Scottish Government Legal Directorate added that there is a checking process to "ensure that a high standard of drafting is maintained" and if issues do arise "we consider and reflect carefully on the issue and on what can be done to avoid it happening in the future."xi

In relation to the accessibility of legislation, the Deputy First Minister said he would consider whether any improvements could be made to the publication of Covid-19 regulations. Mr Swinney added that regulations are updated as soon as possible on the legislation.gov.uk website but is "willing to consider further the points that witnesses have raised."xii

Conclusions and recommendations

Clear and accessible legislation is crucial to good law which can be consistently interpreted and applied.

The Committee acknowledges that responding to the many complex and shifting challenges of the pandemic at times necessitated legislation being drafted and made at speed. The made affirmative procedure enabled the Government to respond quickly to these challenges.

However, such swift changes to legislation bring with it challenges, including ensuring that:

it is properly and clearly drafted, so it is legally accurate; and

it is easy to find and can be interpreted by all, given many regulations made during the pandemic placed often significant restrictions and potential criminal sanctions on individuals and businesses.

The Committee recognises the difficulties in drafting legislation at pace in often challenging circumstances and so recognises the work of Scottish Government officials.

The Committee acknowledges that legislation.gov.uk is a free to use and, as the Deputy First Minister said, regularly updated source of information on the most recent regulations. However, there is a responsibility on the Scottish Government to signpost the public to the website and where to find within it the most up-to-date, consolidated regulations. While the Coronavirus in Scotland website links to multiple pieces of guidance, there are currently no links to the relevant regulations.

The Committee welcomes the Deputy First Minister's commitment to consider ways to improve and enhance the current arrangements.

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to outline its internal checks and balances for ensuring that secondary legislation, even when drafted at speed, meets the high standard of drafting required for making changes to the law.

The law should be clear and accessible to all. The Committee considers that this is especially true where the law is continually changing and coming into force within a matter of days and on occasion with immediate effect, such as has been the case during the pandemic.

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to ensure that regulations relating to the pandemic, and particularly those subject to the made affirmative procedure, that have been frequently amended are regularly consolidated.

It also calls on the Scottish Government to:

publish as soon as possible, and prior to them coming into force, any relevant consolidated regulations;

clearly signpost to the public where the most up-to-date and consolidated regulations dealing with the pandemic might be read. In the short term, this could be a clear link on the Scottish Government's main coronavirus website and to the relevant consolidated regulations on www.legislation.gov.uk; and

ensure that the policy note and explanatory note accompanying each SSI is written in plain English and is sufficiently detailed so those affected can clearly understand the law and how it impacts them.

Changes to how made affirmative instruments are brought forward

The made affirmative process has brought challenges to the Parliament's ability to properly scrutinise changes to the law because of the speed, complexity and significance of the changes made by delegated legislation. As such, the Committee explored with witnesses the importance of transparency in law making and how that links with robust procedure. This section of the report explores:

the tension between urgency and scrutiny of law; and

how the Parliament can determine the urgency of made affirmative instruments:

under current legislation; and

and when scrutinising primary legislation which creates future delegated powers with the option of the made affirmative procedure.

Test of urgency - evidence

As outlined earlier in the report, under the Public Health etc. (Scotland) Act 2008 and the Coronavirus Act 2020, it is for the Scottish Government to consider whether regulations need to be made urgently and so it is for the Scottish Ministers to determine what ‘urgently’ means on a case by case basis.

Morag Ross QC said that the scrutiny of legislation already in force and that which is prospective is likely to differ. Ms Ross QC provided the following analysis:

It is important to remember that anybody who is looking at something that is already in force and is effectively a fait accompli will approach the matter in a particular way, and that way is likely to be different from the way in which the person applying scrutiny approaches legislation that is prospective. If there are two instruments, one of which has already been made, you are likely to look at it in a different way from how you would consider an instrument that will come into force in 28 days’ time.i

It was noted in evidence that the Scottish Government might provide advance notice to Parliament and the public of its plans for changing restrictions, such as the First Minister's regular statement to the Chamber on Tuesday afternoons, but that this is not a substitute for proper parliamentary scrutiny.

Dr Ruth Fox of the Hansard Society noted that one of the "lessons of the pandemic experience" was that difficulties arose when there is communication from the Government for several days prior to regulations being laid about what they will do, yet "no one actually has access to the legal text to enable them to know explicitly what those regulations say."ii

The Children and Young People's Commissioner Scotland commented that:

While we appreciate the urgency of the situation and the pressures on Scottish Government, too often the text of regulations were published scant hours before they came into force.iii

Professor Tierney, while accepting that considering and debating policy is "difficult to do at the height of an emergency", believed that where that does not happen could lead to problems with comprehension and enforcement:

You will certainly get the position in which parliamentarians, the public, businesses and the people whose job it is to enforce the law will not really understand the law and will not necessarily buy into it.iv

In July 2021, the UK Parliament's Joint Committee on Statutory Instruments (JCSI) published a report entitled: Rule of Law Themes from COVID-19 Regulations. This was based on the UK Parliament’s scrutiny during the pandemic. On the timing of commencement, laying and publication of coronavirus SIs, the JCSI said it was concerned that a trend had developed, since the first coronavirus legislation was made in March 2020, of "legislation being made, published and brought into force with almost no time either for Parliament to scrutinise it or for the public to prepare for it." It added that while this "was only to be expected in the early days of the pandemic...the Committee has observed with mounting unease that better knowledge of the virus and its impact has not been reflected in decreased reliance on last minute legislation. Some examples are particularly egregious."

In its written evidence, the University of Birmingham COVID-19 Review Observatory commented that the frequent use of the made affirmative procedure since the start of the pandemic raised questions about how that urgency threshold is operating as a constraint. This, said the COVID-19 Review Observatory, suggests that the urgency requirement is not an "effective constraint" on the use of the made affirmative procedure. It added that the use of the made affirmative procedure should be justified to ensure that all such SSIs are treated as exceptional.v

Dr Fox highlighted the use of urgent procedure at the UK Parliament and questioned whether in the time available normal procedure could, in fact, be used, saying:

The question of the extent to which that is partly a product of the developing nature of policy during the pandemic, and the extent to which it is about the way in which ministers have been able, for reasons of political and administrative convenience, to push these things to the wire and get away, if you like, without producing information and doing substantive policy work, because they have had the option of resorting to the made affirmative procedure, is hotly debated. At Westminster, there is a concern—as I know there is in this committee—that ministers are using that power rather than doing some of the policy work in order to provide the information when the regulations are brought forward.vi

Sir Jonathan Jones QC spoke of the challenges of the use of the made affirmative procedure becoming a habit:

We are 18 months or so into the pandemic and admittedly still face huge challenges. Nonetheless, the default position for the legislative response has continued to be to legislate at speed, use the made affirmative procedure or its equivalents and let any scrutiny that happens—if there is any at all—happen only after the event. That becomes a habit, and I have suggested that it is a bad one. It might be necessary to act in that way in real emergency circumstances but it should not become the default way of legislating when there is, or should be, more time and space to consider the right policy and legal response. My fear is that it has become a habit.vii

When the Deputy First Minister gave evidence to the Committee, he said that he recognised the concerns that the made affirmative procedure should not be viewed as a "normal approach to legislating"viii and assured the Committee that the Scottish Government shared that view. Mr Swinney added:

The Government has used the made affirmative procedure as much as we have only because of the global pandemic. It is not a default view of the Government that that is the approach to legislating; using the made affirmative procedure has been a necessity because of the incredibly difficult circumstances that we have faced and the need for us to act with urgency to protect the public. Substantial numbers of the orders that are put in place through the made affirmative procedure lapse and are not renewed simply because of the temporary nature of the provisions that are put in place.ix

Mr Swinney also responded to some of the evidence suggesting a definition of 'urgency' and said that "a reasonable point has been made". He said that if the Committee considered that made affirmatives would be "enhanced by the provision of a statement of urgency, I would be very pleased to think about that."x

Conclusions and recommendations

The Committee again restates its view that there was a requirement for made affirmative instruments to allow the Government to respond quickly to these challenges posed by the pandemic. Yet retrospective scrutiny of significant changes of the law is always second best. Like the COVID-19 Recovery Committee it considers that the affirmative procedure, which is a well established scrutiny measure for more significant powers delegated in primary legislation, should be the Scottish Government's default option.

The Committee acknowledges that primary legislation has previously been passed both in Holyrood and Westminster which gives the Scottish Government the option of using the made affirmative procedure if Scottish Ministers consider that the regulations need to be made urgently. While an explanation for the use of the made affirmative procedure is sometimes provided in a letter to the Presiding Officer when a made affirmative instrument is laid, provision of the level of detail required to allow the Committee to reach an informed view of urgency can be inconsistent. The Committee therefore considers that to aid transparency in the process, further justification from the Scottish Government is required where it opts to apply the made affirmative procedure to an instrument on the grounds of urgency.

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to:

publish its criteria for determining whether a situation is suitably urgent in responding to the Coronavirus pandemic to require the use of the made affirmative procedure;

provide a written statement prior to the instrument coming into force (which in any event should accompany the laid instrument) for any future made affirmative instrument that provides a consistent level of detailed justification and evidence as to why the Scottish Ministers consider the regulations need to be made urgently; and

ensure that any such regulations are published as quickly as possible following any Scottish Government announcement so that all those impacted might fully understand the detailed changes being made to the law.

If the Committee considers that the Scottish Government has not sufficiently justified its choice of the made affirmative procedure for reasons of urgency, it reserves the right to seek to raise this matter in the Chamber and to do so quickly. There is no obvious current parliamentary process by which Members could debate the issue with sufficient speed. Current available routes include requesting:

a committee announcement to be made on a Tuesday afternoon (albeit there is no requirement for a Minister to respond);

an urgent question; or

a supplementary question during a question time such as First Minister’s Questions.

The Committee acknowledges that using these current Chamber options would mainly serve to highlight the Committee’s concerns but that there would be limited opportunities for other Members to contribute. The Committee considers that any discussion of this issue should not be confined to contributions from the Convener of the Committee and the Minister. The Committee will therefore write to the Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments (SPPA) Committee to invite it to explore options for further debate in cases where the Committee considers that the Scottish Government has not sufficiently justified its choice of the made affirmative procedure as part of the SPPA Committee's inquiry into 'shaping parliamentary procedures and practices for the future’.

Furthermore, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government, in discussion with the Parliamentary Bureau, to provide a note containing a summary of all statutory instruments to be considered in the Chamber, which should be sent to Members sufficiently far enough in advance of the motion being taken.

Future made affirmative powers - evidence

The Coronavirus Act 2020, which makes provision under paragraph 6 of schedule 19 for the Scottish Government to use the made affirmative procedure if Scottish Ministers consider that the regulations need to be made urgently, was passed in response to the pandemic. However, the option to use the made affirmative procedure in section 122(6) and (7) of the Public Health etc. (Scotland) Act 2008 was passed over a decade before it was used to legislate in relation to the pandemic.

Professor Stephen Tierney said that adequate scrutiny of the primary legislation which creates delegated powers is a key part of the robustness which good law making requires. Professor Tierney suggested that:

The real problems are not simply with the made affirmative procedure downstream but with the fact that the primary legislation that created the powers was itself drafted and passed very quickly without adequate scrutiny.i

The Covid-19 Review Observatory at the University of Birmingham suggested a number of changes:

...any new primary legislation pertaining to public health emergencies might be designed so that different available ‘levels’ of foreseeable elements of a public heath response (like lockdowns, restrictions on international travel, closure of schools, requirements for vaccine status certification etc) are outlined within primary legislation, with powers to trigger these powers and tailor them according to level, extent, duration etc being exercisable through secondary legislation. Such a legislative design would strike an appropriate balance between flexibility and urgency in response to an evolving situation, and democratic legitimacy for and parliamentary oversight of government powers. Furthermore, this would allow bodies involved in delivering and enforcing public heath responses, like police forces, local authorities and NHS services, to have delivery plans in place and be prepared according to a known general framework of response.ii

A number of witnesses considered that sunset provisions are helpful.i Professor Tierney explained that sunset clauses can serve two purposes.

they may be included in primary legislation, which means that Ministers’ ability to use powers will expire at a specified date; and

they can be included in instruments themselves, meaning that measures contained in those instruments are also time-limited.iii

The Deputy First Minister said that it is ultimately for the Parliament to decide on the "appropriate content of legislation."iv He later added:

We wrestle at all times with the question of what approach it is right to take. In general, the arrangements that the Parliament has in place habitually are the appropriate measures to take. In the circumstances of a global pandemic that requires swift action, the measures that have been taken are appropriate. However, we should always be open to learning lessons from the situation and the Government will consider with care any output from the committee’s inquiry.v

On sunset provisions, Mr Swinney said:

Obviously, in relation to primary legislation, Parliament is at liberty to apply sunset provisions if it judges them to be appropriate. By their nature, many of the statutory instruments in relation to the handling of Covid that have been introduced through the made affirmative procedure have sunset provisions in them already. Indeed, a large number of those instruments have expired as a result of such provision. There is a role for sunset provisions. There is sunsetting provision implicit in the made affirmative procedure, in that if the Parliament does not vote for the legislation within 28 days, it lapses. There is a role for sunset provisions and the Government would be happy to consider those measures and possibilities as part of the legislative process.vi

Conclusions and recommendations

The Committee recognises the need for effective and robust scrutiny of primary legislation which creates future delegated powers with the option of the made affirmative procedure. The following recommendations are proposed to ensure there is an appropriate balance of power between the Parliament and Government.

The Committee considers there should be a set of principles that underpin the Scottish Government’s approach when it is contemplating inclusion of provision for the made affirmative procedure in future legislation.

While the Committee will consider each proposed delegation of power on a case by case basis, the Committee has developed the following four principles as the basis of its scrutiny where legislation includes such provision. The Committee will be looking for evidence that the Scottish Government had regard to these principles in developing the legislation:

Given the lack of prior parliamentary scrutiny and risks to legislative clarity and transparency in the made affirmative procedure, use of the affirmative procedure should be the default position in all but exceptional and urgent circumstances. Legislation making provision for the made affirmative procedure must be very closely framed and its exercise tightly limited.

The Parliament will require an assurance that a situation is urgent. Provision in primary legislation will need to encompass a requirement to provide an explanation and evidence for the reasons for urgency in each case where the procedure is being used. There should be an opportunity for debate in a timely fashion and open to Members to seek to contribute.

Any explanation provided by Scottish Ministers should also include an assessment of the impact of the instrument on those affected by it and Ministers’ plans to publicise its contents and implications. This could include details of the relevant Scottish Government website where links to the instrument, including where relevant any consolidated version of the instrument it amends, as well as any associated guidance, can be found.

There will be a general expectation that legislation containing provision for the made affirmative procedure will include provision for sunset clauses to the effect that (a) Ministers’ ability to use the power will expire at a specified date and that (b) any instrument made under the power will be time-limited.

An expedited affirmative procedure - background

At its meeting on 29 November 2021, the Committee considered the Health Protection (Coronavirus) (Requirements) (Scotland) Amendment (No. 4) Regulations 2021. This SSI amended the principal Requirements Regulations to provide that a negative test for Covid-19 is an alternative to vaccination for the purposes of permitted attendance at certain premises under the vaccine certification scheme.

The Regulations were laid under the affirmative procedure. The Convener said at the meeting that the Scottish Government had chosen to use the affirmative procedure rather than the made affirmative procedure on this occasion. However, the timescale - 4 days for the parliament to consider and vote on the Regulations - did not allow for the normal scrutiny timescale for affirmative instruments (up to 40 days for the lead committee to report on the instrument followed by a vote in the Chamber). The Convener added that on this occasion, the Committee and the COVID-19 Recovery Committee agreed that an expedited timescale was permissible.

In a subsequent letter to the COVID-19 Recovery Committee, the Convener said that allowing 4 days for the Parliament to consider the instrument rather than 40 days as would normally be the case for an affirmative SSI was "far from ideal." The Convener added:

...while the Committee has in the past called for the affirmative rather than made affirmative procedure to be used, this should not be at the cost of proper parliamentary scrutiny. I agreed to the timetable set out by the Scottish Government on this occasion, but I am clear that this does not set a precedent for consideration of future regulations.

The advantage of being able to consider an affirmative instrument, even one using an expedited procedure, is that the Parliament can scrutinise any proposed changes to the law before the regulations come into force. However, the risk of using an expedited procedure is that it reduces overall parliamentary scrutiny and could, if checks and balances were not in place, potentially risk becoming habitual (not only in relation to perceived urgent situations).

Scrutiny by the Committee and the lead committee provide two different and distinct opportunities to ensure that the law works as intended. The Committee's scrutiny of the “technical elements” of each and every SSI help to ensure validity, accuracy, clarity and accessibility of the law. Good technical scrutiny takes time but is valuable as errors and other technical drafting deficiencies can in the worst case scenario result in businesses and people being caught by restrictions unintentionally, affecting individual freedoms, livelihoods and the economy. In other cases, seeking early clarification from the Government can make it easier for businesses and individuals to understand and adapt successfully to what is required of them and limit the impact on their operations.

An expedited affirmative procedure - evidence

In a letter to the Committee contributing to the inquiry, the COVID-19 Recovery Committee said that the affirmative procedure enabled it to gather views from affected stakeholders before proposed policy changes are made into the law. This process it believed was "an essential part of the Committee’s role in delivering the Scottish Parliament’s mission statement to create good quality, effective and accessible legislation." Nevertheless, the COVID-19 Recovery Committee considered that:

In circumstances where it is not possible to allow the full 40 days for parliamentary scrutiny, the Committee would be content to consider proposals for a compressed period of scrutiny on a case-by-case basis.i

The Deputy First Minister said in evidence that the Scottish Government "budgets on requiring 54 daysi to be confident that legislation can be enacted under the affirmative procedure."ii Mr Swinney later added that he does not "have the luxury of having lots of time on my hands when dealing with these difficult issues."iii

Conclusions and recommendations

The affirmative procedure enables the Committee and the lead committee to conduct their respective technical and policy scrutiny roles before proposed changes are made into law. This process is an essential part of delivering the Scottish Parliament’s mission statement to create good quality, effective and accessible legislation. Nevertheless, in circumstances where it is not possible to allow the full 40 days for parliamentary scrutiny, the Committee would be content to consider proposals for a compressed period of scrutiny on a case-by-case basis where there is a choice to apply made affirmative procedure so as to enable scrutiny prior to the changes to the law coming into force.

The Committee would be happy to consider with the Scottish Government, alongside the COVID-19 Committee (or relevant lead committee) and the Parliamentary Bureau (which manages the business in the Chamber), on a case-by-case basis for when the use of an expedited affirmative procedure as an alternative to the use of the made affirmative procedure might be appropriate and the parliamentary timescales for such scrutiny.

The Committee considers that, in the meantime, it may be helpful for the Parliament and Scottish Government to agree the process (perhaps in the form of a protocol) that should be followed to aid the decision making in such cases.

The Committee considers that any such expedited affirmative procedure must allow for robust scrutiny. The desire to consider legislation prior to it coming into force should not come at any cost, nor should it become habitual.

The Committee also notes that the advances in technology brought in by the Parliament during the pandemic allowing virtual or hybrid proceedings in committees and the Chamber may facilitate greater flexibility when considering any instances of an expedited affirmative procedure but should be cognisant of the founding principles at the establishment of the Scottish Parliament.

Broader themes - evidence

The Committee heard views from a number of witnesses indicating that the trends in the use of the made affirmative procedure should be seen as part of a broader context with a shift in the balance of power between Parliament and the Government over generations. This trend is reflected in an increased use and reliance on subordinate legislation to bring about changes in the law.

Dr Ruth Fox provided some historical context:

One of the features of the debate about delegated legislation in general—not just the made affirmative procedure, but how statutory instruments are laid and scrutinised—is that people were having exactly the same debates in the 1930s. Books were being published about government by diktat and the use of emergency provisions setting a precedent for the future in the aftermath of the second world war. The Donoughmore Committee on the Powers of Ministers in the early 1930s had almost exactly these same debates… History suggests that concern about the concentration of legislative power with the Executive, the shift of influence away from Parliament and the balance of power between the institutions has been a long-running sore. The suggestion is that that has got worse, because over the past 25 to 30 years there has been greater use of skeleton billsi with broad powers and, when policy is ill-defined, ministers are given considerable scope in the way that they choose to exercise those powers through regulations at a later date. The sheer breadth and volume of the powers gives ministers more power to exercise in the future.”i

Professor Tierney said that use of the made affirmative procedure was part of a wider challenge of the increased exercise of executive powers. He considered that:

the made affirmative procedure can, to some extent, become a bit of a straw man…the issue is much broader. It is really about executive power constantly expanding through the use of wider delegated powers; the increased use of Henry VIII powers, or powers to amend primary legislation; and the use, which we are now seeing, of what we could call super-Henry VIII powers, which involve the power to amend the parent statute itself.ii

Speaking about how to address the challenges, Sir Jonathan Jones QC said:

Change will need a whole combination of things: political leadership, behavioural change and members of all the Parliaments…asserting themselves, as parliamentarians are starting to do and as scrutiny committees are doing. It will take all those things.iii

Mr Swinney did not consider that there was an increasing trend towards skeleton legislation. Instead, he said that there is always a debate about the appropriate level of detail in a Bill, adding:

Some voices will say that there is far too much detail because it runs the risk of becoming inflexible and other voices will say that there is far too little detail and it therefore remains vague and gives far too much power to ministers. Parliament has to wrestle with that spectrum on a case-by-case basis.iv

Conclusions

The Committee notes the broader discussions and concerns raised on the balance between parliamentary and executive power during the pandemic and the potential for skeleton bills to lead to more laws being made using secondary legislation. It also notes the Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments Committee's debate on Thursday 16 December 2021 on 'shaping parliamentary procedures and practices for the future' and how the broader points drawn out from this inquiry might be reflected in future parliamentary work.

Final thoughts

The Committee readily acknowledges that the Government did not enter 2020 with the desire to use the made affirmative procedure over 146 times in 22 months. As the Deputy First Minister reflected in his evidence, urgent intervention was at numerous times necessitated by events that had not been envisaged even a few days earlier.

The Committee nevertheless embarked on this inquiry because of the importance of proper parliamentary scrutiny that leads to good law which is accessible to all.

While the made affirmative procedure has been a vital tool in the handling of the pandemic, the Committee is keenly aware of its downsides and does not wish its use to become the norm. The recommendations in this report are not to remove this important tool but rather to reflect on how the procedure has been used during the pandemic and make proposals for how the Parliament responds to its potential use in the future.

Finally, the Committee recognises that this report is only the first step in this work. It hopes that these recommendations will help guide the Parliament's scrutiny of future primary and secondary legislation in the coming months and years.

Annex A - witnesses and those who contributed written submissions

Evidence sessions

Dr Ruth Fox, Director, Hansard Society

Morag Ross QC, Faculty of Advocates

Professor Stephen Tierney, Professor of Constitutional Theory, School of Law, University of Edinburgh

Sir Jonathan Jones QC, Linklaters LLP

John Swinney, Deputy First Minister and Cabinet Secretary for COVID Recovery, Rachel Rayner, SGLD Deputy Legislation Co-ordinator, Elizabeth Blair, Unit Head, Covid Co-ordination and Steven Macgregor, Head of Parliament and Legislation Unit, Scottish Government

Bill Bowman

Campbell Wilson

Children and Young People's Commissioner Scotland

Ian Davidson

NASUWT

The Law Society of Scotland

University of Birmingham COVID-19 Review Observatory

University of Birmingham COVID-19 Review Observatory - supplementary evidence

COVID-19 Recovery Committee (Scottish Parliament)

Legislation, Justice and Constitution Committee (Welsh Parliament)

Joint Committee on Statutory Instruments (UK Parliament)

Annex B - Relevant extract of Rule 10.3 of the Scottish Parliament's Standing Orders

Rule 10.3 Subordinate legislation scrutiny

1. In considering the instrument or draft instrument, the committee mentioned in Rule 6.11 shall determine whether the attention of the Parliament should be drawn to the instrument on the grounds—

(a) that it imposes a charge on the Scottish Consolidated Fund or contains provisions requiring payments to be made to that Fund or any part of the Scottish Administration or to any local or public authority in consideration of any licence or consent or of any services to be rendered, or prescribes the amount of any such charge or payment;

(b) that it is made in pursuance of any enactment containing specific provisions excluding it from challenge in the courts, on all or certain grounds, either at all times or after the expiration of a specific period or that it contains such provisions;

(c) that it purports to have retrospective effect where the parent statute confers no express authority so to provide;

(d) that there appears to have been unjustifiable delay in the publication or in the laying of it before the Parliament;

(e) that there appears to be a doubt whether it is intra vires;

(f) that it raises a devolution issue;

(g) that it has been made by what appears to be an unusual or unexpected use of the powers conferred by the parent statute;

(h) that for any special reason its form or meaning could be clearer;

(i) that its drafting appears to be defective;

(j) that there appears to have been a failure to lay the instrument in accordance with section 28(2), 30(2) or 31 of the 2010 Act.

or on any other ground which does not impinge on its substance or on the policy behind it.

Annex C - Made affirmative instruments reported under ground (i): that the drafting appears to be defective

The Health Protection (Coronavirus) (Restrictions and Requirements) (Local Levels) (Scotland) Regulations 2020 (now revoked) (SSI 2020/344) was reported on three counts of defective drafting. The policy intention was that contravention of the requirement on those responsible for a place of worship, carrying on a business or providing a service to take measures to ensure that a distance of 2 metres was maintained on their premises should be a criminal offence in each local level area. Cross referencing errors meant that a criminal offence was not created in respect of level 2 or level 3 areas. The instrument also failed to make provision as intended for those aged 18 and over to gather outdoors in a private dwelling in a level 0 area. Further, the instrument stated that the permitted maximum size of a gathering of people aged 12-17 in a level 0 area was 8, whereas the policy intention was to set this limit at 15.

The Health Protection (Coronavirus) (International Travel) (Managed Accommodation and Testing) (Scotland) Regulations 2021 (now revoked) (SSI 2021/74) was also reported on two counts of defective drafting. The policy intention had been to create an offence in respect of a responsible adult who failed to ensure that a child undertook tests following international travel, but drafting errors meant that an offence was not created. Further, it was intended that a reasonable excuse was created in respect of a person failing to undertake tests on account that their failure to do so was due to them travelling in order to leave Scotland, but similarly drafting errors meant this reasonable excuse was not created.

The Health Protection (Coronavirus) (Restrictions and Requirements) (Local Levels) (Scotland) Amendment (No. 21) Regulations 2021 (SSI 2021/193) was again reported on two counts of defective drafting. The instrument restricted the number of 12-17 year olds who could gather in a group outdoors in Level 2 areas further than intended. It meant that groups of people over 18 could gather in larger groups than those aged 12-17, which was not the policy intention. The instrument also erroneously removed curfew restrictions relating to the exemptions in respect of businesses providing services in connection with a marriage ceremony, civil partnership or funeral. This resulted in there being no restriction on the time that those businesses could remain open when providing such services in a Level 3 area, which was not the policy intention.

The Health Protection (Coronavirus) (International Travel and Operator Liability) (Scotland) Amendment Regulations 2022 (SSI 2022/2) was reported on the defective drafting ground as the change in the definition of “WHO List vaccine” in regulation 3 was intended to come into force on 10 January 2022 at the same time as the equivalent change was made in England and Wales by the UK Government, rather than on 7 January 2022 as provided for in regulation 1 of the instrument.