Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee

Culture in Communities: The challenges and opportunities in delivering a place-based approach

Introduction

This report details the findings and recommendations of the Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee (‘the Committee’) following its inquiry on culture in communities, with a focus on the challenges and opportunities in delivering a ‘place-based’ approach to cultural policy.

The call for views on the inquiry was issued on 17 February 2023 and closed on 7 April 2023. It received 58 written submissions, which were summarised by the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe). The Committee held a series of evidence sessions between April and June 2023.

To gather further evidence on good practice and barriers to place-based cultural policy and cultural participation within different communities across Scotland, the Committee also undertook visits to Wester Hailes and Craigmillar in Edinburgh, Dumfries, and Orkney. A note of each visit has been published.

The Committee thanks all those organisations and individuals who provided the written and oral evidence and facilitated and participated in the engagement visits that have helped to inform the inquiry and the findings which follow.

Overview of a place-based approach to culture

A Culture Strategy for Scotland

The idea of taking a ‘place-based’ approach to culture is a key focus of 'A Culture Strategy for Scotland', published in February 2020 by the Scottish Government. The importance of place is listed as one of its ‘guiding principles’.

The culture strategy outlines that “place-based approaches enable local communities to influence, shape, and where there is an appetite, deliver long term solutions because it is easier for people and communities to identify with, relate to and feel connected with their place”.1

In relation to a place-based approach to culture, the strategy states that “giving people a greater say in shaping the cultural life of their communities and community ownership can help protect Scotland’s rich cultural heritage and provide inspiration for the cultural expression of the future.”1

In the Programme for Government 2023-24, the Scottish Government set out that in the coming year it would “publish, and begin implementing” its “Culture Strategy Action Plan Refresh, to support the recovery and renewal of the culture sector with a focus on empowering individuals and communities to further develop their own cultural activity”.3

The Place Principle

This followed the adoption of the Place Principle by the Scottish Government and COSLA in 2019, which committed them to taking “a collaborative, place-based approach with a shared purpose to support a clear way forward for all services, assets and investments which will maximise the impact of their combined resources”.4

The Scottish Government’s culture strategy outlined that the “adoption of the Place Principle can help realise our vision of an inclusive and extended view of culture which recognises and celebrates the value and importance of the emerging, the everyday and grassroots culture and creativity.”1

The Scottish Government recognised that “a collaborative, place-based approach can help create the right conditions for culture to thrive”, and highlighted that “partnerships between local government, cultural and creative organisations, businesses and organisations in Scotland’s most deprived communities can and do realise a wide range of outcomes for people including improved health and wellbeing, social cohesion and reducing inequality.”1

Planning Aid Scotland agreed that to “deliver on the ‘Place Principle’, a place-based cultural approach needs a decentralised, local approach that is agile and responsive to the needs of individual communities”. It outlined that “a place-based approach can only achieve positive outcomes when all partners are involved, such as different arms of the local authority, as well as relevant public bodies and agencies.”7

Background

The wider principle of taking a community-led approach to the delivery of public services was set out by the Christie Commission report in 2011. It identified “recognising that effective services must be designed with and for people and communities” and “working closely with individuals and communities to understand their needs” as priorities for future service delivery, and recommended “making provision in the [then] proposed Community Empowerment and Renewal Bill to embed community participation in the design and delivery of services”.8 The report also emphasised the importance of local partnership working and collaboration between public service providers.

Thereafter, the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act was passed in 2015, with the aim to “help to empower community bodies through the ownership or control of land and buildings, and by strengthening their voices in decisions about public services.”9The Act is referenced throughout this report in relation to the extent to which its provisions on community planning and community asset transfer support the delivery of a place-based approach to culture.

Ten years on from the Christie report, the Auditor General for Scotland (AGS) outlined that there had been “progress” made on Christie’s call for “more recognition” to be given to “the role that the third sector and local communities play in improving lives in their local area”, for example through the Community Empowerment Act, which the AGS said, “has given individuals and communities important new powers to influence the services they need”. However, the AGS also recognised “the third sector can feel like a poor relation to mainstream public services. And many community groups also still feel that barriers are put in their way to taking part in changing services for the better.”10

Initiatives to support place-based and community-led approaches to culture have also been taken forward for several years, such as Creative Scotland’s Place Partnership Programme. It told the Committee that this is a “strategic programme designed to encourage and support local partners to work together with their creative communities and Creative Scotland” and that it “supports local groups to come together to spark ideas, promote collaborative working, build capacity and ultimately deliver creative activity which responds to the distinct opportunities and challenges within different localities”.11

The programme was commended by the Culture, Tourism, Europe, and External Affairs Committee in Session 5 in its 2019 report, Putting Artists in the Picture: A Sustainable Arts Funding System for Scotland, which recommended that it should be delivered with more local authorities and its implementation strengthened to embed the benefits of the investment for the long-term. We draw upon the Session 5 committee report throughout our report.

What does 'good' place-based cultural policy look like in practice?

The Committee heard that ‘good’ place-based cultural policy “involves empowering the local community to create a cultural offering that caters to their specific needs”, and “requires co-production, where cultural institutions and communities work together as equal partners, so that communities have ownership over the cultural offering”.12

Creative Scotland, the national body which supports the arts, screen, and creative industries across Scotland, described ‘good’ place-based cultural policy as that which “recognises the individual needs of people, communities and places, recognises unique culture and heritage of individuals and communities, and responds to the ambition, need and challenges of each place”.11

In relation to the importance of empowering communities as part of a place-based approach, Traditional Arts and Culture Scotland drew a distinction between the so-called ‘democratisation of culture’ and ‘cultural democracy’—

“The democratisation of culture refers to a policy of making accessible already existing cultural opportunities that have hitherto been taken by a restricted range of the population: cut-price tickets for the opera for example, or the opening of arts centres in communities where such facilities were unheard of.

Cultural democracy on the other hand is a state in which everyone feels empowered to actively participate in the broadest range of cultural activity, what the Culture Strategy for Scotland describes as ‘everyday culture’.”14

An Arts Council England report from 2018 suggested that arts and cultural organisations looking to work towards ‘cultural democracy’ might shift from, for example, employing professional artists to come up with ideas for community programmes, to having those artists work with communities to co-create ideas, or from selling cheaper tickets to encourage broader audiences to attend, to connecting with those broader audiences to understand what they might want.15

The National Theatre of Scotland summarised that this “is about having conversations with organisations about what they need, as opposed to our imposing things on them”.16

Dumfries and Galloway Council was of the view that, in order to overcome barriers to cultural participation, it is important to support communities to grow the cultural activities they want to see, rather than taking a “topdown” approach of giving communities access to culture that it is decided they should have.17

Glasgow Life agreed that co-production of cultural interventions was “key”. Through such an approach, instead of “forming a view of what people want, where they want it and how they want to access it”, this can be identified “in partnership with citizens and communities”.17

The Committee heard that it was important to recognise the cultural activity that already takes place in and is valued by communities, including that which may fall under a wider definition of ‘culture’.

In Professor David Stevenson’s view, good place-based cultural policy “should be responsive to different groups, communities, people and places”, with “meaningful cultural participation” able to look “very different for different groups and communities of people”. He identified that a challenge with cultural policy can be that “we fall into thinking that there is a one-size-fits-all model and that we can invite people into a universal shared culture”.16

Professor Andrew Miles suggested that “we should be supporting what people already do” and emphasised that “we have to start with what people themselves want to participate in”, questioning “how far we want people to go in moving into different cultural spheres, and why”.16

Professor Stevenson warned that policymakers can fall into a “danger” of only helping individuals overcome barriers to cultural participation where these are “barriers to the type of culture that we feel is valuable for them to take part in”, and identified that “we tend to challenge those who have the least amount of influence in society to diversify their cultural interests the most”.16

Creative Scotland considered it “important that local and national government and national bodies recognise the individual needs and requirements of different communities and places” and “recognise that a lack of established traditional artistic infrastructure does not mean that there is a lack of creative or cultural activity or expression”.11

However, the Committee also heard a view that some larger cultural organisations can “parachute” into communities and use community-based arts organisations and their connections, including to secure funding. There was a sense that the manner in which some larger organisations worked in communities for a short period of time—for example, through ‘gifting culture’ and providing free tickets to cultural performances—was often on the terms of those organisations and that communities did not have the agency to choose how they wanted to participate.23

The Federation of Scottish Theatre noted its concern regarding the “pitfalls of an approach that takes a narrow view of culture or cultural provision and ‘redistributes’ it according to this view, without the genuine needs and tastes of communities being taken into consideration, or thorough mapping taking place that respects existing provision in whatever form that takes”. It considered that “cultural need can be defined by what the funding priorities or available resources are”.24

Creative Scotland acknowledged that “there are cases of what might be felt as, ‘We are doing good to communities—we are offering you something, so come and see it,’ without understanding what it can mean to the people and what the unmet need is in that community”.25 It said it was “very vigilant in regard to projects and applications that we parachute into areas or where that relationship is imbalanced—when it is about an organisation coming into a community and saying, ‘Here is an offer for you,’ instead of saying, ‘What does your community want or need, and how can we work together to deliver that?’.25

The Committee recognises that the idea of taking place-based and community-led approaches to service delivery, including in relation to cultural provision, is not new, and that there is a strong evidence base supporting such an approach. We note the comments made by the Auditor General for Scotland in 2021 that while progress has been made on empowering local communities to influence service delivery, barriers remain, and further progress is still required.

Our inquiry examined the application of this approach to cultural policy. We note that there was a clear consensus in the evidence received from a wide range of stakeholders on what a place-based approach to culture should look like in practice, for example in empowering communities to shape the cultural life of their place, and for organisations delivering cultural activities or interventions to understand and respond to the needs of communities.

Within this context, our report considers the following challenges we have identified for national public bodies and local government in delivering a place-based approach to culture where communities are central to shaping the cultural life of their place—

Supporting community-based cultural activity;

Funding culture in communities;

Providing and supporting local cultural services; and

Providing and protecting physical spaces in communities for cultural activity to take place in.

Supporting community-led cultural activity

Throughout its inquiry, the Committee was told that local networks of community-based organisations and volunteers were vital to the local cultural ecology, and to supporting the delivery of a place-based approach where communities are central to shaping the cultural life of their place and to growing and sustaining the cultural activity which meets their needs.

Professor Stevenson considered that this “infrastructure—that local network—needs to be sustained. It will not necessarily have outputs constantly, but its presence—the sense of people being there, having the time and being able to contribute—is part of our infrastructure, along with those small spaces and small bits of equipment”.1

The Committee also heard that this infrastructure, in addition to supporting community-led culture, supports national agencies to deliver cultural performances in communities. In Professor Stevenson’s view, having local networks “maximises the investment that we put into our nationals. Otherwise, the nationals do not have a local infrastructure to build on when they go out touring”. And therefore, “even if you want to democratise culture in the sense of democratising those high arts organisations, the best way to do that is through having a strong cultural democracy whereby there is a localised, grounded network that can be connected into”.1

The National Partnership for Culture considered that “the aspirations of the Culture Strategy cannot be delivered without a vibrant and flourishing cultural ecology that supports the creation, presentation, and enjoyment of creative and cultural activity in every part of Scotland”.3

Below, we consider the role of volunteer networks and community-based cultural organisations in delivering a place-based approach, and the challenges and opportunities facing these networks within the local cultural ecology.

Volunteer networks

The Committee heard that the “vast majority” of cultural activities in communities is “dependent on the efforts of volunteers”.1 According to Volunteer Scotland, “culture in communities would be significantly reduced without volunteers”,1 however it said that much of this activity is “unseen”.3

Creative Lives illustrated what is meant by ‘volunteers’ in this context using the example of a community choir—

“The people who turn up to sing for the joy of singing, who are often from professional, community or amateur backgrounds, do so in a participatory sense. The volunteers are the ones who set up and run things and keep the choir going. They may also bring in paid support for tutoring, recording and so on.”3

Making Music considered that many volunteers within its member groups would not consider themselves as such, with the “driver” for their volunteering being their own participation in a leisure activity—“they take part in their choir, they sing and they organise the rota for the tea or organise ticket sales at the door, so they do not count themselves as volunteers”.3

The role of volunteers in sustaining local culture was recognised by local authorities. Orkney Islands Council said that “most activity in Orkney is entirely grassroots, home-grown and volunteer managed”,6 while Moray Council reflected that “a large percentage” of cultural activities in Moray are “managed, operated and created” by the voluntary sector.7

While volunteer-led, locally based creative groups “represent the true backbone of culture in Scotland”, Creative Lives considered that it is “one of the most overlooked parts of our cultural landscape”.8

Time and resource challenges

The Committee heard concerns that there could be inequalities between communities who have greater time and resources to volunteer and those who do not, and, given the vital role of volunteering in sustaining culture in communities, how this could impact on access to opportunities for cultural participation across communities in Scotland.

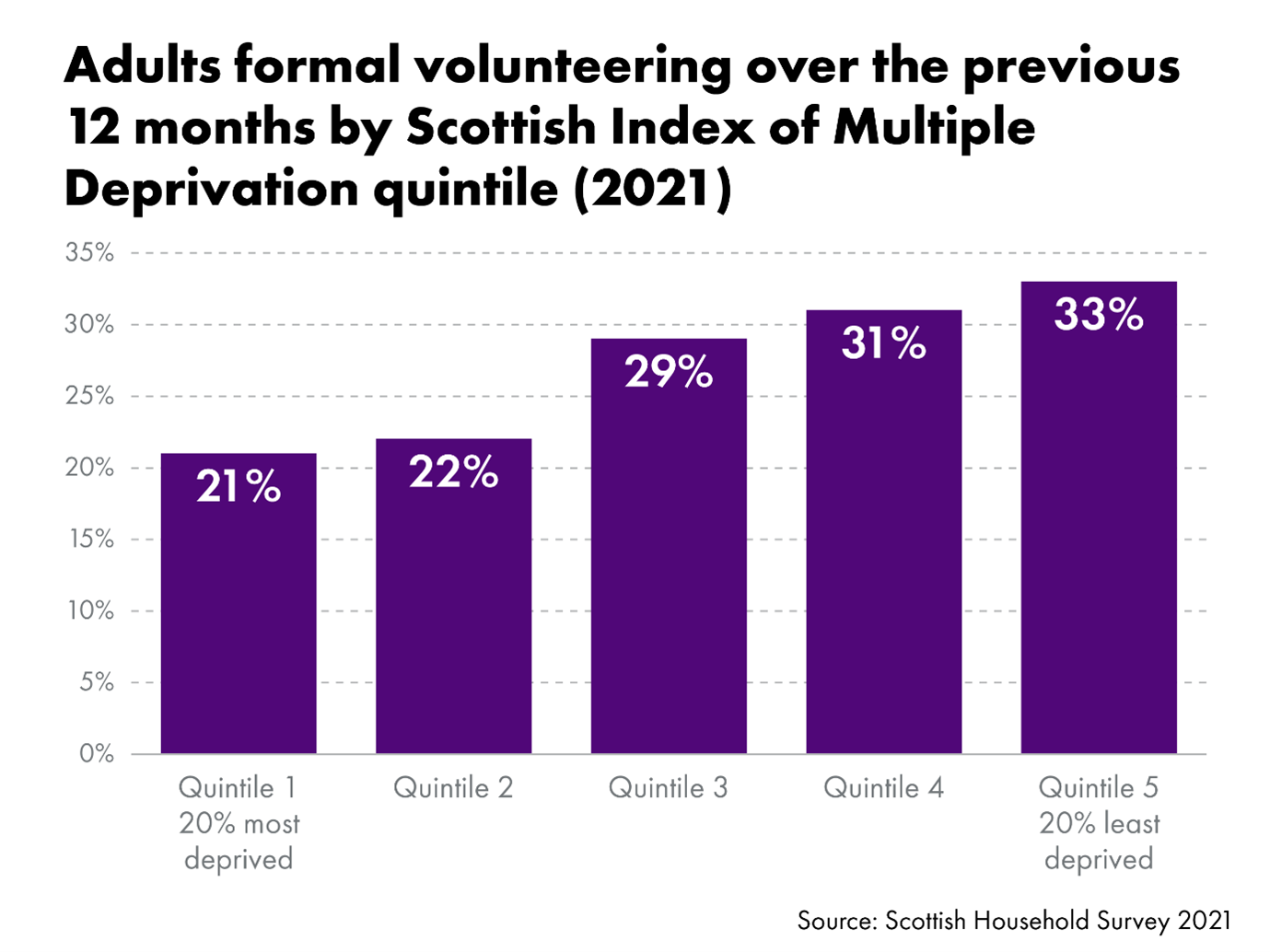

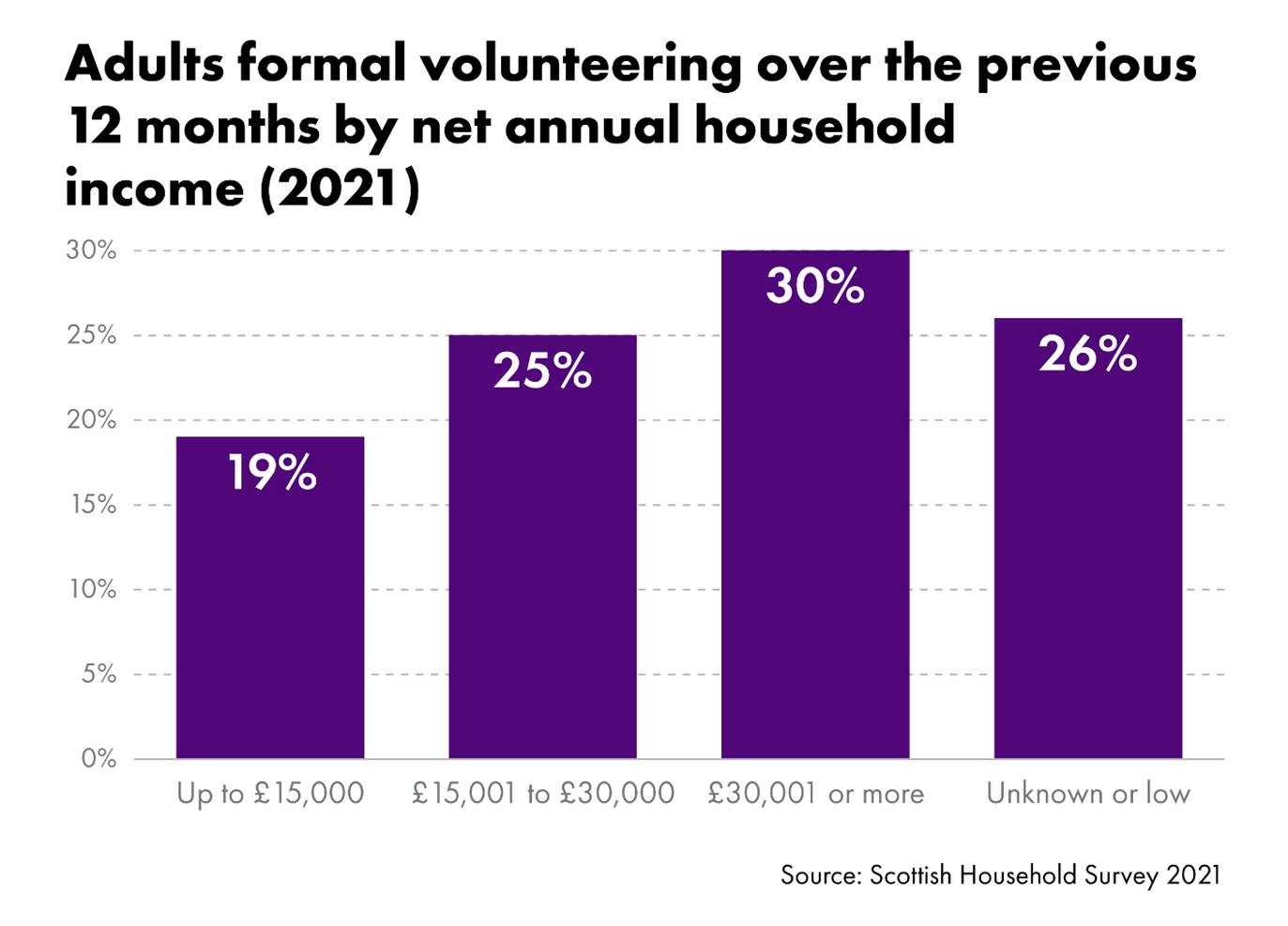

The Scottish Household Survey for 2021 found that adults who participated in formal volunteering were less likely to live in areas of multiple deprivation, and more likely to have higher incomes (see Figures 1 and 2).

Professor Andrew Miles said that it is “very clearly the case that better resourced people have more time”, including for volunteering and organising cultural activities, while Professor Stevenson posed the question of “who has the time to set up a new organisation?”9

Professor Stevenson also noted that there was a “significant challenge regarding diversity on the boards” of both voluntary organisations and major cultural organisations in relation to age, ethnic background, and class. He suggested that more representative boards could lead to a “diversity of programming” which results in more diverse audiences.9

On the Committee’s visit to Orkney, the Committee heard that there was an immense commitment from the community to make cultural activity happen, with high levels of volunteering and the vast majority of cultural activity run by small organisations. There was seen to be a greater onus on the community to be self-starting and sustaining in providing cultural opportunities.11

However, the reliance on the community to sustain cultural activity was recognised as a challenge for Orkney as well as a strength, with volunteer fatigue and burn-out identified as key concerns. The Committee heard that there was an ageing population, including among volunteers, with concerns raised about the sustainability of volunteer-led culture in Orkney.11

Professor Stevenson illustrated the delicate nature of relying on voluntary networks to sustain cultural activity with the example of the Touring Network, which supports professional music, dance, theatre and children's events to be staged across the Highlands and Islands—“It is an ageing network of, essentially, voluntary producers who do the work of connecting: opening up the halls, making sure that someone has somewhere to stay and ferrying people in cars where there are no buses. However, it faces a challenge in that a lot of those people are saying, ‘I am too old’, or ‘It is time for someone else to pick this up’, and moving on. If there are no young people with the time, because they are too busy trying to find work or their work is very short term, we lose that network, which is part of the infrastructure.”9

Volunteer Scotland called on Creative Scotland to take on “a bigger role in acknowledgement of the capacity that is required in order for volunteers to support community-based cultural activity”.3

Creative Lives said that voluntary groups “need support from infrastructure bodies” in terms of skills development and networking opportunities, while Making Music noted that there was “not the same professional development support for volunteer-led arts activities as there is for professional arts”.3

Financial challenges facing voluntary groups

Similar challenges were raised in relation to the inequality between those who greater time and resources to attend or participate in cultural activity and those who do not. Professor Miles assessed that “the only people who are increasing their [cultural] participation” are those who are “economically capital-rich”. He highlighted that those who have more disposable income to spend on participating in culture also tend to have more time to spend on culture.9

Furthermore, the Committee heard that as many voluntary arts groups are “self-sustaining and rely on charging for some of their services”, this presents a challenge for those who “do not have the money to pay to access culture in their community”.

Creative Lives said that the cost-of-living crisis was a “major concern” for the voluntary arts sector and warned that it “may result in less availability of creative activities as the cost of materials, utilities and venue hire charges increase”. It also highlighted the impact on “the cost of transport and digital connectivity which are also essential in allowing more people to participate in creative activity alongside others”.8

Making Music noted the financial challenges faced by voluntary groups due to the cost-of-living crisis who are “very reluctant” to raise their fees due to members “experiencing challenges with their own incomes”.3

Volunteer Scotland said there was a “catch-22 situation” where costs for cultural organisations were rising, for example charges for hiring community halls, but where those “who usually access their cultural services cannot afford to pay more”. It considered that there is “a need for funding to support equality of access to culture”.3

Creative Lives encouraged the exploration of “a regular funded micro-grant programme for community-based and volunteer-led groups” which would enable voluntary arts groups “to both thrive and survive, providing true value for money and a major social return on a small investment”.8 Creative Scotland recognised that “small grants can make a big difference for community led organisations”.21

The Committee recognises the vital role of volunteers in sustaining grassroots cultural activity in many communities, and that without these networks, the delivery of a place-based approach to culture—where communities are central to shaping the cultural life of their place and to growing and sustaining the cultural activity which meets their needs—would be significantly more challenging.

However, we also recognise that volunteering in the community is time and resource intensive. We are concerned by the evidence received that there could be disparities between communities who have greater time and resources to volunteer and those who do not, and, given the vital role of volunteering in sustaining culture in communities, that this is likely to impact on access to opportunities for cultural participation across communities in Scotland. The Committee’s view is that it is crucial for all communities across Scotland to have the opportunity to shape the cultural life of their places, and to be able to grow and sustain the cultural activity which meets their needs.

The Committee therefore notes the calls from organisations representing the voluntary sector for there to be greater support for voluntary arts, both in terms of capacity-building for volunteers and regular micro-grant funding for voluntary groups, in response to some of the resource challenges we have highlighted above; and invites the Scottish Government and Creative Scotland to explore whether further support can be provided to protect and encourage the vital contribution of volunteers to culture in communities, including in communities with fewer resources.

Community-based cultural organisations

Through its inquiry, the Committee also heard from a range of organisations working within communities across Scotland on the opportunities they provide for communities to participate in cultural activity, including national cultural organisations delivering participatory projects across communities, those embedded in specific communities, and community organisations with a cultural arm. We consider the role of community-based groups below.

The Committee heard evidence that well-established community-based arts organisations which had been embedded within communities longer-term were effective in supporting cultural participation and engagement in their areas. Instead of getting communities engaged through a specific project which ends due to the funding concluding, and there being nothing for them to move on to, it was important to continue to support participation through other projects and groups.1 Station House Media Unit said that taking a place-based approach to culture “is about long-term engagement”, as opposed to “a cultural organisation swooping in and delivering 12 weeks of a programme and then disappearing”.2

As discussed above, the Committee was told that it was important to understand the unmet needs of the community, and co-produce the cultural activity that can meet those needs, and that community-based organisations were well placed to deliver this work. Instead of ‘doing the arts’ to people or seeing them as ‘targets’, it was said to be important for organisations delivering this work to be ‘in and of’ the community.1

Culture Collective

The Committee heard that one example of how cultural organisations, artists and communities have been supported to develop local cultural projects is the Culture Collective programme, funded by Scottish Government emergency COVID-19 funds through Creative Scotland. It is a network of 26 participatory arts projects, which are shaped by local communities alongside artists and creative organisations.

Professor Stevenson said the programme had been “so powerful” as a result of “recognising the need for strong networks locally”.4 The Culture Collective told the Committee that the programme had provided a national network between the projects, with “opportunities to share resources, learning and experiences”, but that it had also “been able to create small, informal networks with the projects and the practitioners within them” more locally.2

Creative Scotland told the Committee that the programme offers “a strong example of how to address unmet need, through place-based and people-centred processes” with each project “designed and driven by the community in which it is rooted”.6 It “did not want to see predetermined outcomes, because the outcomes should be determined through working with the communities”.7

Traditional Arts and Culture Scotland said that it had given them “the space, flexibility and freedom to be in a place for a year of more”,2 with this longer-term engagement and embedding within communities, as discussed above, seen to be beneficial to the delivery of a place-based approach.

Stellar Quines thought that it had enabled them to show “how it could be and what might be possible” if the necessary funding was available.2 The Culture Collective commented that while community work has thus far existed with “dregs of funding”, this programme being “funded at scale” had enabled the projects to “shift the question” from “How can we do this cheaply because that’s all we’ve got?” to “How can we be most effective and most brilliant?”2

The funding for the Culture Collective is coming to an end, with projects concluding in October 2023. It is not clear whether the initiative will be replaced.

In evidence to the Committee, a representative of the Culture Collective project lead team said: “we are trying to build a sustainable network that can exist beyond our contract and the known lifetime of the Culture Collective, while at the same time knowing that it will never be enough and that this should not be a short-term initiative… Trying to wind down in a healthy and sustainable way is not what we want to be doing, but it is the best that we can do with the resources that we know we have.” On the Culture Collective’s legacy, they added that “we are focusing on building a network that exists sustainably without our support”.2

The National Partnership for Culture noted that “important national initiatives such as the Culture Collective and Creative Communities have already grown from the Culture Strategy but embedding these ways of working will require long term commitments and further changes to how culture is supported.” It considered that these such initiatives can be used “as foundations” to be built upon.12

The Committee consistently heard throughout its inquiry that the Culture Collective programme had been a powerful example of a national place-based initiative which had supported cultural organisations to work in partnership with artists and communities to develop local cultural projects.

Given that the funding for the programme and its projects will soon conclude, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government and Creative Scotland to set out how the foundation and legacy of Culture Collective will be built upon through future place-based initiatives. We further consider the role of funding to support community-based cultural activity below.

Funding for culture in communities

In this section, we consider the challenges to the delivery of a place-based approach posed by the wider budgetary challenges faced by the culture sector and the challenges of project funding for place-based cultural activity, as well as opportunities for the future funding of community-based cultural activity.

Impact of wider budgetary challenges on place-based culture

The Committee has taken considerable evidence to date on the budgetary challenges facing the culture sector. In its pre-budget scrutiny report last year, the Committee concluded that the sector was facing significant financial pressures, contributed to by a “perfect storm” of long-term budget pressures, reduced income generation, and increased operating costs.1

Through the course of this inquiry, the Committee heard that the ongoing impact of the wider budgetary challenges facing the culture sector placed limits on what was possible in the extent to which cultural organisations are able to deliver place-based and participatory cultural projects with communities, and on the ability of voluntary groups to source funding for their activities.

Several organisations highlighted, as the Committee has heard previously through its budget scrutiny, that they have been in receipt of ‘standstill’ funding for several years. Creative Scotland previously told the Committee that many organisations it funds on a regular, multi-year basis “have received unchanged levels of funding, for a number of years” and that this is “increasingly unviable” as it represents “an increasing year-on-year cut for organisations”.1

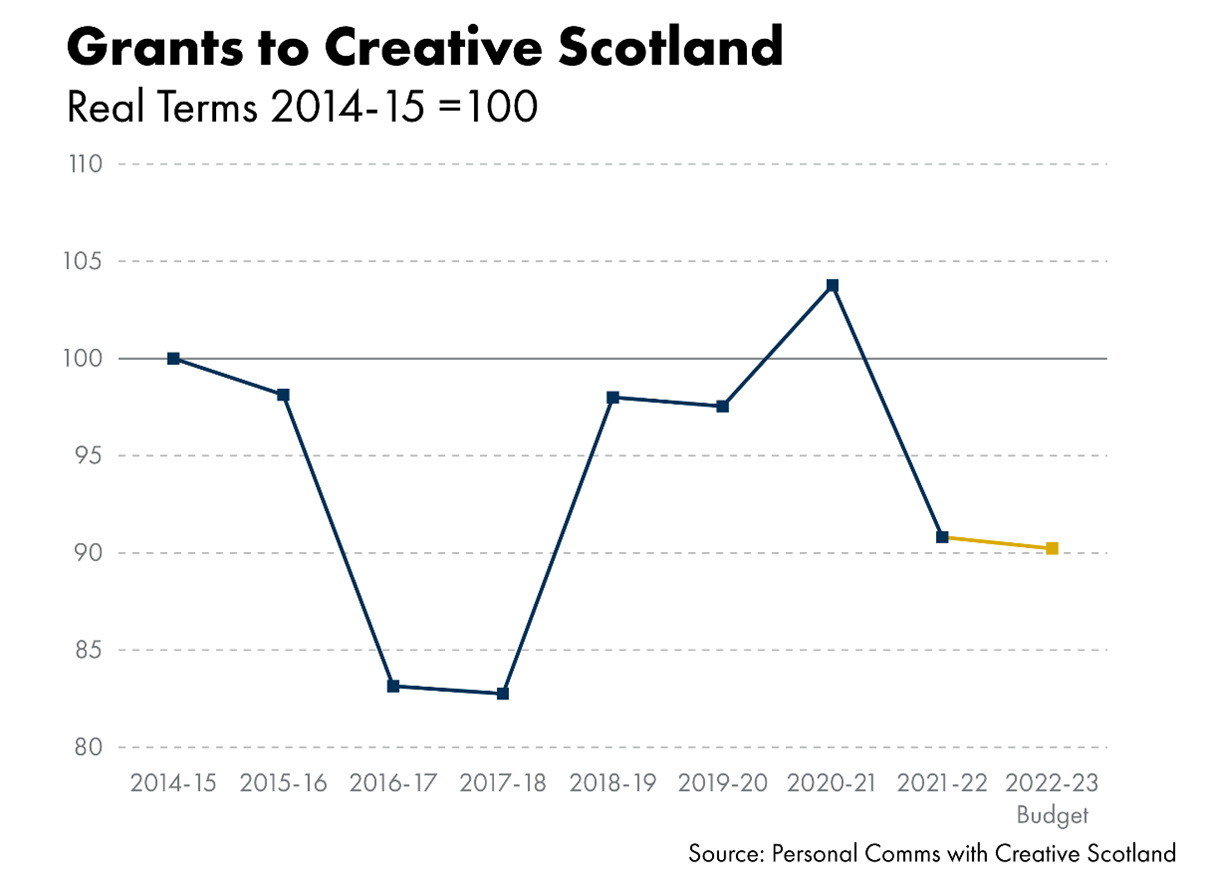

SPICe analysed the funding received by Creative Scotland from 2014-15 to 2022-23 from both the Scottish Government and the National Lottery. Figure 3 illustrates the relative real terms changes in the sum of grant-in aid funding from the Scottish Government (not including emergency COVID-19 funding) and National Lottery funding.

SPICe assessed that the total grant funding for Creative Scotland in 2021-22 (excluding emergency COVID-19 funding) was approximately 10% lower in real terms than in 2014-15. It noted that this is despite the Scottish Government providing increased funding for Screen Scotland, part of Creative Scotland, since 2018-19 and that therefore, the real terms cuts to the areas of Creative Scotland that are not screen related since 2014-15 will be substantially more than 10%.3

The Federation of Scottish Theatre noted that, as a result, organisations that are needed to deliver cultural work in communities “are in an extremely precarious financial position”. It said that “inconsistency of funding” puts place-based cultural work “seriously at risk” and that place-based cultural policy needed to be “sufficiently and effectively resourced”.4

YDance highlighted that it is “increasingly difficult to source a reasonable level of funding for participatory dance programmes in local communities”, noting that its Creative Scotland funding has been “standstill for 8 years” and “local authority culture and education budgets are cut to the bone”.5

Stellar Quines agreed that the arts having been “chronically underfunded and on standstill for so long creates a limit on what is possible”.6 Fèisean nan Gàidheal highlighted that standstill funding is having a “real effect” on its ability to “even sustain” the work it is currently delivering, “never mind develop it”6

Findhorn Bay Arts noted that “not only has there been standstill funding within Creative Scotland, but that is coupled with local authority budget cuts, and with services being picked up by the third sector and the cultural sector.” It highlighted that this “presents an unprecedented challenge” for trusts and foundations.6 The Royal Scottish National Orchestra also commented that the reduction in its local authority income had put “increasing pressure on trust and foundation income” and that this would be “very difficult to sustain”.9

Scottish Chamber Orchestra on the other hand spoke to the delivery of their five-year community residency in Craigmillar supported by funding from City of Edinburgh Council. It said this project was “a model for how it could work in other places, if that level of funding was available”.9

The challenges of project funding for place-based culture

The Committee heard that organisations often have to source project funding for this community-based work, however that it is often short-term and volatile, and unable to cover essential core costs.

Short-term nature of funding

Professor Stevenson’s view was that the “biggest challenge” the sector faces is a “persistent and pernicious obsession with short-term project funding”.1 Scottish Ballet said that this approach created a “stop-start mechanism” where funds are raised for piloting a project “and then that funding may drop away”.1

The Committee has previously recognised that multi-year funding has been a consistent ask from the culture sector and set out its view that the shift towards increased multi-year funding should allow much greater progress in delivering the mainstreaming of culture across all policy areas.3 In response to a letter from the Committee, the Cabinet Secretary for the Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture, Angus Robertson MSP, (‘the Cabinet Secretary’) said in March 2023 that he remained “keen to conclude some work on multiyear funding, even if economic uncertainty means that the figures for later years can be at most only indicative.”4

Scottish Opera outlined that “the need for consistency” and “taking a long-term approach” are key characteristics of a place-based approach.1 Art27 highlighted that “short term and underfunded work disrupts trust” with communities,6 while Findhorn Bay Arts said that “embedding artists in communities and building long, robust and meaningful relationships” helps to overcome barriers to participation.7

Station House Media Unit considered that “enabling and supporting creative community anchor organisations to run long-term interventions, co-designed and developed alongside those who benefit from them, creates long-term lasting change”. It said that this impact is “almost impossible to replicate with short-term funded project work, where city centre based, regional, or national cultural organisations parachute in with 'outreach' course for a number of weeks and then have to pull out again when the funding comes to an end.”8

But the Federation of Scottish Theatre recognised that “sustaining activity over time to evidence the real benefits of the intervention is less attractive [to funders] than new projects”.9 Alchemy Film and Arts said that funding applications “always need new ideas”.7

The Committee heard that continually seeking small, short-term pots of funding, requiring new ideas, takes up significant time and resource of staff members and volunteers, which drives energy away from delivery.11 The Cabinet Secretary said that this “goes to the heart of why a multi-annual approach to the funding of cultural organisations” is a “priority” for the Scottish Government and Creative Scotland. He said he was “very keen to support Creative Scotland as it moves towards a new funding model” which he hoped would “obviate some of the issues around annual applications for funding”.12

Who covers the overheads?

Members heard that securing core funding for community-based cultural activity was a major challenge, with there being a persistent problem of what was referred to by stakeholders as “donut funding”, where funding supports project delivery, such as material costs and freelancers, but not core costs such as the infrastructure, overheads of running a premises, and management staff costs. There was said to be an assumption from some non-government funders that core funding is met by local or central government.11

However, it was outlined that without these core functions of community organisations, the organisations would not be able to operate, and therefore, the projects they run for communities would not be able to be delivered.11

Built Environment Forum Scotland (BEFS) reflected that “there is a trope that nobody will pay to fix the roof but that, if you tell them what is happening underneath it, you might get some money for the activity”, and that funding mechanisms can “inhibit” such cultural activity “if they are focused too narrowly”.15

Professor Stevenson considered that in a “fractured funding landscape”, “we have a big challenge in determining who covers the overheads, whether they are the overheads of a major theatre space or those of keeping the heating on in a village hall”, and noted that in other countries, there is a “much clearer understanding of how different elements of the funding landscape support different things”.1

He said “we could take a much bolder overview by asking, ‘What is national funding looking to support? Is that there to provide the infrastructure? Is the local authority there to provide the activity?’ and considered that such a funding model would mean “individual organisations not having to spend time navigating a very complex landscape in order to piece together bits of funding to support the infrastructure.”1

We also note the conclusion of our predecessor committee in 2019 that the “existing policy framework for establishing the respective roles of local and national government in funding the arts, including opportunities for co-funding, is not working well.”18

A specific funding stream

The Committee heard that for many people, participation in culture in the community “is what their cultural life looks like”. Therefore, the Culture Collective thought there was a need to consider “how we prioritise culture and community”, “how we recognise that as more than just a nice add-on for the culture sector”, and “how to shift the current balance to recognise the community element as the heart of the culture sector”.1

It considered that “for far too long, there has been deeply embedded inequity in the cultural sector, whereby one form of culture” is “put on a pedestal above other forms of culture”.1 Members were told that community-based organisations, particularly in more deprived areas, were not equally funded with other arts organisations, and that it was important to consider who is able to access the culture provided by organisations in receipt of public funding.3

Creative Lives added that governments “must acknowledge that creativity extends far beyond the boundaries of the professional and publicly funded arts sector”.4

The founding ethos of the first Arts Council of Great Britain that “it is about the best not the most” was said to still inform Creative Scotland’s approach.3 In relation to how community culture could be better prioritised, Art27 reported that “in other countries the complex and multifaceted community arts sector is recognised through its own sector development agencies”.6

On the Committee's visit to Dumfries, Members heard comparisons made with Ireland, where national government makes distinctions about how it supports different types of culture, and where there were three core agencies supporting culture: the Arts Council (the equivalent of Creative Scotland), Create (an independent agency but one directly funded by the Arts Council, and supporting community-based creative practice), and Creative Ireland (which was understood to run mostly national initiatives for grassroots participation in culture).3

The Committee also heard that community-based culture should be better prioritised through funding. Professor Miles said that there needed to be “structural funding into communities”.8

Members heard that community-based arts organisations often support the fulfilment of national outcomes in areas such as health and wellbeing, as well as the delivery of cultural opportunities to a wider breadth of people, and that this should be reflected in funding envelopes.3

An argument was made that there should be a specific funding stream for community-based culture, alongside funding for professional arts. The Stove Network considered that “culture funding is for professionally created culture”, while conversely its “type of work is forced to compete for 'communities' funding and 'wellbeing' funding where it is judged against projects like foodbanks”, and therefore “cultural participation projects often lose out in competitive funding environments”.10

The Federation of Scottish Theatre echoed that this cultural activity can be often forced “into direct competition” for funding “with more traditional ‘front line’ services”, with the wider value of culture not “always recognised by funders or key decision-makers when making choices between different activities”.11

The Committee was told that “dedicated funding streams” for cultural participation projects were required to better support this activity.10 The Stove Network suggested that this could be provided through portfolios such as health, education, and justice spending a percentage of their budget “on activities that support participation in culture towards their own portfolio objectives”.10

The Cabinet Secretary told the Committee that “culture is agreed to be a priority across government because of what it can offer to the outcomes for which various government departments are responsible”, however that the Scottish Government is still “in the foothills” of making the process of cross-portfolio funding work.14

The Committee also heard distinctions drawn between funding for sport and funding for culture, with it viewed that the funding of participation in sport, alongside funding for elite sport, could provide a model for funding for participation in culture. Professor Stevenson thought that “the challenge for arts and culture, which sport does not have, is that we are trying to service both with the same policy interventions; whereas, in sport, it is recognised that elite-level sport requires different interventions from those that support local-level movement and sport activity.”8

However, Creative Lives’ view was that it would be a “mistake to separate so-called professional creative practice and community-led creative practice” in funding streams, as it said this is “an ecology in which things are inherently linked”. It said that “we run into muddy water if we start to have a false dichotomy involving professional, amateur and community arts” as they are “all interrelated”. Instead, its view was that “funding streams in the creative sector work best when there is scope for collaboration and flexibility”.16

The Committee concluded in its pre-budget scrutiny report last year that the budgetary challenges facing the culture sector had become “much more acute”, contributed to by a “perfect storm”of long-term budget pressures, reduced income generation, and increased operating costs, as noted at paragraph 78 above. Our view was that these challenges meant there was now “an increased urgency for the Scottish Government to accelerate consideration and implementation of an innovative approach to the funding of the culture sector,” including “progressing additional revenue streams such as the Percentage for the Arts scheme”, for “consideration” to “be given to how the sector could benefit” from a Transient Visitor Levy scheme, and “consideration of investment from budget lines beyond the culture portfolio”.17

Through this inquiry, the Committee heard that these long-standing financial challenges facing the culture sector, which have intensified in recent years, places limits on what is possible in the delivery of place-based and participatory cultural projects with communities.

We also heard that the reliance on project funding—which is short-term, volatile, requires resource-intensive applications, and does not cover core costs—presented significant challenges for community-based cultural organisations in supporting the delivery of a place-based approach to culture, as this requires greater consistency and a longer-term embedding within communities to be successful.

The Committee’s view is that the current funding environment poses a significant challenge to the successful delivery of place-based cultural policy, and we re-affirm our call for the consideration and implementation of innovative approaches to the funding of the culture sector to be accelerated in response. A multi-annual approach to funding, which the Cabinet Secretary said the Scottish Government considers a “priority”, is at the heart of this. Recognising the immediacy of the challenges facing the culture sector, the Committee is of the view that the Scottish Government should set out, in the context of Budget 2024-25 and the publication of the refreshed Culture Strategy Action Plan, how it will accelerate the implementation of innovative approaches to the funding of the culture sector. We will consider this further in our forthcoming pre-budget scrutiny.

Given the evidence received that place-based cultural activity often relies on project funding which does not cover core costs, we also acknowledge that there is a challenge in determining ‘who covers the overheads’ within the funding landscape, and that there needs to be a clearer understanding of the respective roles of national and local government funding for community-based culture in supporting cultural activity as well as the infrastructure underpinning it.

The Committee’s view, therefore, is that the Scottish Government, Creative Scotland, COSLA and local authorities should consider how it can take a strategic, joined-up and complementary approach to funding for cultural activity in communities, what the respective roles of national agencies and local government are, and where external funders are able to fill any gaps, noting the evidence we received that a reliance on trusts and foundations as a result of reduced public funding for culture is unsustainable. We further consider collaboration between local and national government as part of the next section of this report.

We will also write to key non-government funders of cultural activity in communities to invite their views on the evidence and conclusions of this report, including on the challenges raised by stakeholders in relation to short-term project funding, and on the roles of non-government funders within the funding landscape, given the financial challenges facing national agencies and local government.

Lastly, the Committee acknowledges that there was a strong view expressed in the evidence we received that there needs to be a greater prioritisation of the role of community-based and place-based culture as being central to the cultural sector and the delivery of cultural outcomes, with the recognition that, for many people, their cultural participation is within their communities. We therefore invite the Scottish Government to explore the model suggested by some witnesses for community-based culture to be considered and funded separately from professional arts.

Stakeholders suggested that this could be supported by funding from across different portfolios for activities that support participation in culture towards their respective objectives. We note the comments of the Cabinet Secretary that while culture is agreed to be a priority across government, the Scottish Government is still in the “foothills” of making cross-portfolio funding work. As noted above, our view is that the Scottish Government should now set out how it will accelerate this work.

The Committee has recommended through our scrutiny of the Resource Spending Review Framework and our pre-budget scrutiny for Budget 2023-24 that consideration should be given to investment in culture from budget lines beyond the culture portfolio. We reiterate this view again, and that the contribution that community-based cultural activity in particular makes to wider local outcomes should be considered as part of this discussion.

Local cultural provision

A key consideration of the Committee’s inquiry was the role of local government, alongside national government, in ensuring that communities have opportunities for cultural participation. We address the challenges and opportunities facing local cultural provision below.

Challenges to local cultural services

Local authorities are required to “ensure that there is adequate provision of facilities for the inhabitants of their area for recreational, sporting, cultural and social activities”, though “adequate” is not defined. Some local authorities have arms-length external organisations run their culture services.

However, the Committee heard that funding challenges facing local government were impacting on the provision of cultural services in communities by local authorities and arms-length culture trusts.

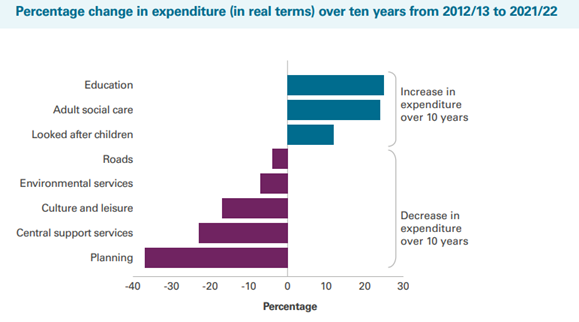

The Local Government in Scotland: Overview 2023 report from the Accounts Commission assessed that, with “little resilience” in local culture and leisure services “owing to long-term funding reductions”, future challenges to these services are “significant”.Figure 4 illustrates the percentage change in local government expenditure on culture and leisure services from 2012-13 to 2021-22 compared to other services.

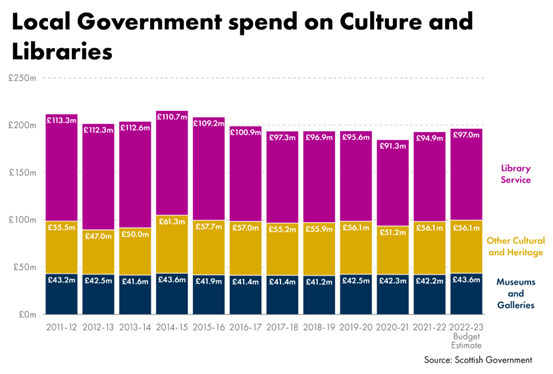

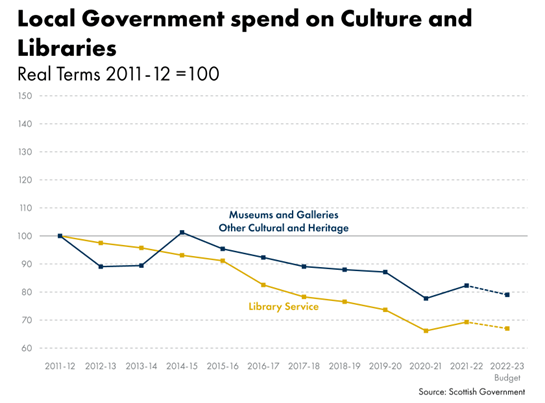

SPICe analysed local government spend on Museums and Galleries, Other Culture and Heritage, and Library Services from 2011-12 to 2022-23 with financial data based on collations of individual local authority outturns (Scottish Local Government Finance Statistics workbooks and 2022-23 Provisional Outturn and Budget Estimates). The data for 2022-23 is a budget estimate.1

Spend in cash terms is shown in Figure 5 below. SPICe notes that this demonstrates a clearer trend of reduced spend in cash terms on library services. Figure 6 shows the relative real terms changes of local government spending on: the sum of museums and galleries and other cultural and heritage activities; and libraries. SPICe stated that this shows significant real terms reductions in spend by local government in these areas.1

The Federation of Scottish Theatre noted that the “scarcity of specific local authority cultural funding over the last decade, and recent cuts across local authorities in Scotland, is keenly felt”.3 The Museums Association said that such reductions in spend “will result in some local authorities limiting cultural provision or removing free access to culture”.4

Glasgow Life said “the health of local government finances” is having a “direct impact on the funding available” for the services it provides. It urged the Committee to understand the “increasingly impossible tasks of balancing the cost of running venues alongside the costs of providing cultural programmes” and noted that “the current funding context must be addressed at national and local levels to provide strategic, sustainable place-based cultural activity”.5

Community Leisure told the Committee that, as of March 2023, 95% of the arms-length culture trusts in its membership were “at risk”, with management fees from local authorities having been “steadily decreasing over a number of years”. It said that “any reductions will now result in reductions in provision”.6

Creative Scotland expressed concern that “the pressure on local authority services due to constrained budgets, rising costs of living and non-statutory nature of some cultural services has seen threats to arts development, as well as library and museum services, and an overall reduction in the provision of grant funding and specialist services, like arts development officers”.7 Creative Lives referred to there having been a “decimation of local arts development officers” across Scotland.8

The Committee also heard of the impact of the reduction in local authority funding for culture on the provision of cultural activities by cultural organisations. For example, Scottish Ballet said that it was previously funded in each local authority area where it performed to do outreach programmes with organisations in those areas, however that this funding “has eroded to zero” over the last decade, while the Royal Scottish National Orchestra said that local authority funding had “decreased enormously”, and while it is committed to work in every local authority, “the funding for that now comes from trusts and foundations”.9

Given the reduction in spend on cultural services by local authorities, the Museums Association considered that national government should work with local government together with the third sector “to ensure that each local authority in Scotland has a strong cultural offering to avoid access to culture becoming a postcode lottery”.4

Traditional Arts and Culture Scotland said that there is an “inconsistency in cultural provision at the local level”.11 The Independent Report of the National Partnership for Culture was also of the view that “there is currently significant disparity in the role culture plays within local authorities across Scotland, which is a significant barrier to realising the aspirations of the Culture Strategy across every part of Scotland”.12

The Cabinet Secretary expressed concerns that in some local authorities there may have been a “diminution” of local cultural provision, noting that “decisions have been made in localities that relegate the importance of culture and the arts in decision making and delivery”.13

He told the Committee that national and local government have “co-responsibility” for delivering on culture and that he wanted to work in partnership with local government “to underline the importance of mainstreaming culture and arts priorities in local decision making”, noting that there could be more done to protect local cultural provision.13

The Cabinet Secretary noted the importance of empowering local authorities to make decisions about local priorities, however at the same time acknowledged the concern that this “might lead to culture and the arts being less supported in some parts of the country”. He told the Committee that he was keen to work with partners in local government to ensure that culture is not the first thing to be economised in favour of other priorities, given the current financial constraints.13

He added that the Scottish Government was “very alive” to the fact that if there has been a “diminution” of the cultural provision being delivered by local authorities, “there is potential for displacement and for the costs needing to be borne by others, whether that is Creative Scotland or the Scottish Government directly”.13

The Committee notes the essential role of local government in the delivery of a place-based approach to culture, including through the delivery of cultural services, the provision of spaces for cultural activity to take place in, and the provision of grant funding for cultural activity, at a local and more decentralised level; as well as through empowering communities to grow cultural activities and shape cultural services which meet their needs.

The Committee also recognises the funding challenges facing local government and echoes the concerns raised by witnesses about the impact that reductions in spend on cultural services by local authorities could have on their ability to deliver those services for communities.

There is also an outstanding question for the Committee in relation to the impact that the reduction of local authority funding for culture and reduction in services in some cases may have on other actors within the cultural ecosystem to fill any gaps in provision, noting the wider funding challenges for culture discussed above.

The Committee’s view is that the Scottish Government, Creative Scotland, COSLA and local authorities should work in partnership to assess the ongoing impact of the fiscal environment on local cultural provision, and in line with the Place Principle approach, support a clear way forward for services which will maximise the impact of combined resources. We further consider the collaboration necessary within local authorities, and between local and national governments, to deliver a place-based approach, and the opportunities provided by Community Planning Partnerships to facilitate this collaboration below.

A whole system approach

As outlined above, the culture strategy recognised that “a collaborative, place-based approach can help create the right conditions for culture to thrive”, and committed to work with local government to realise local outcomes.1

Throughout its scrutiny of the culture portfolio this session, the Committee has reported on the value of taking a ‘whole system’ approach, between and across different layers of government, to realise the wider benefits of culture for communities. In reporting on the Resource Spending Review Framework, the Committee agreed with COSLA that “a ‘whole system’ approach is essential to the spending review and that this is consistent with an outcomes-focused and collaborative approach”.2 In response, the Scottish Government recognised the need to “collaborate, both across Scottish Government and the wider public sector to achieve the outcomes we seek”.3

Through this inquiry, the Committee considered how national and local layers of government work together and complement each other in line with the Place Principle to support the provision of cultural services, ensure that communities have opportunities to take part in cultural activities locally, and support local outcomes to be met through culture.

On 30 June 2023, after the Committee had concluded taking evidence on this inquiry, the Scottish Government and COSLA announced a new Partnership Agreement (the Verity House Agreement), setting out their “vision for a more collaborative approach” to delivering “shared priorities for the people of Scotland”.

Local-national co-ordination

As mentioned above, the culture strategy outlined that the adoption of the Place Principle by the Scottish Government and COSLA—which committed them to taking a “collaborative, place-based approach with a shared purpose to support a clear way forward for all services, assets and investments which will maximise the impact of their combined resources”—could help realise the strategy’s “vision of an inclusive and extended view of culture which recognises and celebrates the value and importance of the emerging, the everyday and grassroots culture and creativity.”1

There are a number of actions in the culture strategy which relate to local authorities, including for the Scottish Government to—

Work with Creative Scotland to map local authority support for culture and to explore future models of collaboration between national and local bodies;

Launch a Creative Communities programme in partnership with Inspiring Scotland and with support from Creative Scotland – a new initiative to support and empower individuals and communities to further develop their own cultural activity;

Work in partnership with culture trusts and local authorities, including in Community Planning Partnerships local networks and COSLA to realise local outcomes across Scotland;

Work with Culture Conveners from Scottish local government and culture trusts including through establishing a joint meeting of arts and culture conveners;

Work with national organisations to help them plan their community activities to ensure the widest possible reach across Scotland.

As it has not been reported how much progress has been made on these actions aside from on the Creative Communities programme, SPICe outlined that the extent to which local authorities have engaged with these actions is not clear. The extent to which local authorities refer to the national culture strategy or use it to influence local plans or strategies is also unclear.5

Community Leisure previously told the Committee that there are “opportunities for closer alignments, particularly in how the culture strategy at a national level is adopted and embedded at local authority level and in how local authority approaches to provision feed into a national strategy.”6 In evidence to this inquiry, it said that “the picture is perhaps a bit mixed across the country” in relation to how the culture strategy has influenced delivery at a local level, and that this “depends very much on local authorities’ priorities and how they implement and embed the strategy”.7

Glasgow Life said that the national culture strategy “significantly influences how we conceive, deliver and conceptualise culture in Glasgow” and that it provided a “platform on which conversations with national agencies take place”.7

COSLA also previously told the Committee that while the culture strategy had been “well received”, in its view, “without joint political ownership and investment it is difficult to see how the strategy will positively influence provision at a local level in the tight financial climate.”9

The Culture, Tourism, Europe, and External Affairs Committee in Session 5 recommended in 2019 that there should be an “intergovernmental policy framework between local and national government to support the arts as part of its [then] forthcoming culture strategy”, with “a requirement for local authorities to plan for culture and to take account of local and national priorities in doing so.”10

The response from the then Cabinet Secretary with responsibility for culture noted that as set out in the culture strategy, the Scottish Government along with COSLA was establishing a joint meeting of the Culture Conveners from Scottish local government and culture trusts, which it said would be “a critical first step in giving due consideration to the Committee’s recommendation for a new intergovernmental policy framework between local and national government to support the arts.”11

Community Leisure told this Committee that it had held “discussions with COSLA on the culture conveners initiative with regard to how that works and what its purpose is.” It added: “we want to think about shaping that a little bit more so that there is more value and a clear purpose there.”7

The National Partnership for Culture, established by the Scottish Government to advise Ministers on the delivery of the culture strategy, made the following recommendations on ‘Community and Place’ when it reported in March 2022 which stressed the importance of effective collaboration between approaches at national and local levels—

National initiatives should be joined up and both inform and be influenced by local and regional initiatives;

Equity of access to culture should be prioritised at a national level to support local, grassroots delivery; and

Local authorities should use culture as part of their delivery across wider local authority services.13

The Scottish Government responded in September 2022 that while “setting the strategic direction of local authorities is not facilitated by the Scottish Government, nor does the Scottish Government provide direct funding for local authority culture facilities”, it was “working with partners to develop actions that support national and local organisations working together to support culture, which will be captured in the forthcoming Culture Strategy Action Plan”.14

It said that “this work will complement meetings between Ministers and the Culture Conveners group, to identify ways to strengthen and review models of co-operation around the principals of recovery and renewal and through key workstreams such as education, health and wellbeing.14

The Committee asked for an update on the action within the culture strategy for the Scottish Government to “work with Creative Scotland to map local authority support for culture and to explore future models of collaboration between national and local bodies”.

Creative Scotland told the Committee that while work had been undertaken to “map the structures and financial channels in the sector and to look at how national bodies work with public bodies”, this had been paused due to the pandemic. It said it planned to revisit this work later in the year.16

It also recognised that since the work it had undertaken on the mapping exercise prior to the pandemic, “the financial context has changed considerably”, stating that the “significant pressure” on local authorities and cultural trusts had not provided “a gap” for Creative Scotland to meet with local authority partners to map out how they wanted to work together.16

Creative Scotland also said that the loss of arts development services in some local authorities “creates barriers and a lack of consistent provision across Scotland” and “can result in significant challenges for national and local government, and national bodies, to work collaboratively for the benefit of communities.”18 The Cabinet Secretary also recognised that where there is a loss of arts development officers, the local authority and, by extension, national organisations, lose the “interlocutor” which they rely on to know what is happening culturally in communities.19

Community Leisure assessed that “the national-local dynamic needs a bit more co-ordination” however that there had been increased partnership working since the pandemic.7 Glasgow Life concluded that a “more joined-up approach between local and national agencies” was “urgently required to address barriers to creating sustainable place-based programmes of cultural activity”.21 It described “the connection between national, metropolitan, regional and local levels” as not “completely coherent”.7

The Committee recognises that while there is an appetite for a more joined-up approach between local government and national agencies, and that this vision has been supported by the culture strategy and the Place Principle, the evidence we received would suggest that further progress is required to improve collaboration.

The Committee would therefore welcome a further update before the end of 2023 on what progress has been made on the commitment in the culture strategy for the Scottish Government to work with Creative Scotland to map local authority support for culture and explore future models of collaboration between national and local bodies.

The Committee is cognisant that, if local authority support for culture is not understood at a national level, it may be challenging to assess where there is unmet cultural need across Scotland and direct resources. This is particularly pertinent in the context of reductions in spend on cultural services by local authorities.

We also note the evidence received in relation to the loss of arts development services across several local authorities and the impact that this could have on collaboration between national and local government, as well as on the level of support provided to communities to develop cultural activity.

The Committee invites the Scottish Government to set out as part of its refreshed Culture Strategy Action Plan how it will respond to the recommendations of the National Partnership for Culture and how it will seek to improve collaboration and connection between local government and national agencies in the delivery of place-based culture. Below, we consider the role of Community Planning Partnerships as a vehicle through which this collaboration can take place.

Community planning

As mentioned at the outset of this report, the passage of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 (‘the 2015 Act’) was an important step in making progress towards a community-led and collaborative approach to the delivery of public services. The 2015 Act made significant changes to community planning legislation in response to recommendations of the Christie Commission, with the reforms recognising that public bodies need to work closely in partnership with each other and their local communities in order to make the biggest difference in the outcomes for which they are responsible.1

The culture strategy committed the Scottish Government to “support Creative Scotland and other national cultural organisations to realise the potential that culture has to achieve local outcomes”, and also to “work in partnership with culture trusts and local authorities, including in Community Planning Partnerships local networks and COSLA to realise local outcomes”.2

In particular, the role that Community Planning Partnerships (CPPs) can play in providing a forum for public services, including national and local layers of government, and communities to work together to meet local outcomes through culture was raised by several witnesses in evidence to this inquiry, and we consider this below.

CPPs are intended to enable public bodies to work together along with local communities to design and deliver better services. Each CPP focuses on where partners’ collective efforts and resources can add the most value to their local communities, with particular emphasis on reducing inequality.3

CPPs are required by the 2015 Act to prepare and publish a Local Outcomes Improvement Plan (LOIP) which SPICe advise should be clearly based on active participation by communities and community bodies and on a good understanding of the needs of the communities in the local area.4 The Session 5 Committee highlighted that 2015 Act did not provide any role for the Scottish Government to require LOIPs to reflect nationally imposed priorities.5

The culture strategy suggests that “arts and culture can contribute to many of the often deep-rooted and complex themes that [CPPs] typically prioritise in their Local Outcomes Improvement Plans, such as around inclusive growth and improving employment prospects, positive physical and mental health, children’s wellbeing and sustaining fragile communities.2

SPICe suggest that one might expect CPPs to consider both how a range of services could impact on the availability of cultural activities across local communities and how cultural activities could contribute to a range of outcomes.4

Community Leisure highlighted the benefits that its members have seen from sitting on CPPs—

“They can understand the discussions about community and they have opportunities to be involved: for example, if there is a discussion about health and wellbeing, they can offer a service. Such a connection is made much more fluidly than it would be if they were sitting outside the community planning partnership and trying to understand what was happening within it.”8

Glasgow Life said that CPPs are “important for presenting an opportunity for culture to build coalitions and consensus and to develop relationships and move things forward.8

Creative Scotland said that “the role that culture and creative practitioners can play in creating vibrant, diverse and resilient places has been demonstrated through the many regeneration and development projects which are culture-led or centred around culture, which demonstrate that including culture from the very start in planning can help to rejuvenate places and communities.”10

Within local authorities, the Committee heard that it was important for culture to be “embedded across services” and taken “out of the silo that it has perhaps traditionally been in”. However, Community Leisure said that “there are challenges where culture does not have a high profile at a local level”.8

It explained: “With some of the changes across local authorities, we are seeing that there are not necessarily people with a cultural remit in the local authority. That expertise is lost somewhere. Where there is a culture trust, there is not necessarily a connection to the local authority with the expertise to really understand and embed some of the issues.”8

BEFS noted that CPPs have “lots of competing demands” and that there is a challenge in “how culture finds its voice within that when there are health and education priorities”.13Glasgow Life noted that, with “competing priorities for the public pound”, “culture always has to make its case”.8

Community Leisure told that the “voice of culture” in community planning partnerships is “not consistent across the country”. It commented that there are “significant issues around the value of culture coming through” where there is “no connection to community planning partnerships and health and social care partnerships, or to the local authorities”. It said it was important to have the “right flags in the ground” to “connect the different agencies”.8

This inconsistency was highlighted by varying experiences across the local authorities that the Committee heard from.

In Renfrewshire, the CPP is “part of the discussion” in how the investment associated with Paisley’s UK City of Culture 2021 bid and its legacy plan is being spent.8 While Glasgow Life is “heavily engaged” in the community planning partnership process in Glasgow, its view was that “the priority that community planning partnerships attach to culture could, possibly, be better”.8

Moray Council agreed that the connection of culture with the CPP could be improved. It said that culture is connected to the CPP in Moray and in its LOIP, however that this was focused solely on how culture supports economic development, rather than wellbeing.8

Dumfries and Galloway Council said “culture does not feature” in the CPP at present however it hoped this would change. Cultural voices however were represented on the community learning and development partnership and the place partnership.8

The Stove Network said that there needed to be “joined up working” between community organisations, local authorities, and local cultural organisations. It suggested that “this could be facilitated through appointing cultural representatives to community planning partnerships, local health boards, and regional economic partnerships”.20

Glasgow Life regarded the inclusion of culture in forums such as community learning and development partnerships, community planning partnerships, and health and social care partnerships as a “no brainer”.8

The 2015 Act expanded the number of public sector bodies that are subject to community planning duties, and placed specific duties on those community planning partners, including to co-operate with other partners in carrying out community planning.22 Schedule 1 sets out the statutory community planning partners. This includes bodies such as sportscotland, however Creative Scotland is not listed.

Creative Scotland told the Committee that it was “on record” as saying it “would be positive about being a statutory partner in community planning.” At present, it felt as though it often needs to “knock on the door from the outside just to get into conversations at local level.”23

While not being a statutory partner does not stop it “working effectively with all local authorities and helping them to develop their strategies and plans”, Creative Scotland’s concern was that “it gives rise to the potential for an uneven strategic locus across the country.”23

It added that LOIPs “do not always mention culture. Councils might have cultural strategies sitting to the side of those plans, but we want to see them in the centre—the more central we can be to local planning protocols, the better.”23

The Cabinet Secretary noted that “sometimes culture and the arts are not afforded the prominence they should have in terms of planning”, and said that it would be an “entirely sensible approach” to have cultural organisations embedded in CPPs.26

The Committee recognises that CPPs can provide an important mechanism for collaboration between local and national bodies and with communities more broadly. However, it is clear from the evidence we received that CPPs could be better utilised with respect to culture.

The Committee heard that, where there is a cultural voice in CPPs and other forums, this can be beneficial in giving culture a greater platform and providing opportunities to facilitate interventions which use culture as means to improve local outcomes across portfolios. However, that the extent of this cultural voice in community planning is inconsistent across Scotland.