Digital assets in Scots law

This briefing examines the law relating to 'digital assets' in Scotland, including with reference to developments in other jurisdictions and internationally. It also reviews proposals for reform of Scots law in anticipation of the introduction of a bill on digital assets.

About the authors

Dr Alisdair MacPherson is a Senior Lecturer in Commercial Law and Professor Burcu Yüksel Ripley is a Professor of Law at the University of Aberdeen.

Dr MacPherson and Professor Yüksel Ripley have been working with the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) as part of its Academic Fellowship programme. This aims to build links between academic expertise and the work of the Scottish Parliament. The views expressed in this briefing are the views of the authors, not those of SPICe or the Scottish Parliament or any other organisation or group with which the authors are affiliated.

Summary

In recent decades, digital assets have become widespread, important and frequently valuable. Particular types of digital assets, including cryptocurrencies, have emerged through the use of distributed ledger technology and raised challenges regarding how they can be accommodated in law. This is true for Scots law, as well as for other legal systems around the world.

There is, however, minimal legal authority in Scotland regarding the law relating to new forms of digital assets. As such, legislative reform has been proposed to better accommodate such assets and provide greater legal clarity.

This briefing provides background, concepts and terminology relating to digital assets, so that they can be better understood in the wider context of the law and possible reform. In this context, relevant forms of technology and examples of digital assets are discussed. This is followed by coverage of how digital assets are defined in the UK and by international organisations. The briefing then highlights international initiatives involving digital assets and related subjects, as well as reform developments in selected countries, including England and Wales.

The next section focuses on the current law relating to digital assets in Scotland, with particular reference to what is known as private law (encompassing areas such as property law, contract law and family law). It shows that while in some ways existing Scots law can deal with digital assets, there are various points of uncertainty including in relation to aspects of property law, the law of debt enforcement and insolvency, civil procedure and private international law.

The final part of the briefing examines recent law reform proposals for digital assets in Scotland. This mainly involves consideration of the proposals in the Scottish Government's Consultation on Digital Assets in Scots Private Law (2024-2025). These proposals are likely to form the basis for a Bill on digital assets that is expected imminently. They primarily concentrate on property law aspects of digital assets, including issues of definition, property categorisation and transfer of ownership.

Various other matters regarding digital assets in Scots private law are not expected to be covered in the forthcoming legislation, including within the challenging areas identified above (such as debt enforcement and insolvency law). It is unknown how the Scottish Government intends to proceed in relation to such areas, and whether further reform is anticipated.

Cover image (cropped) licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-ND 4.0). No attribution available.

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Bill of exchange | An unconditional written order to pay a certain sum of money. It is addressed by one party to another and requires the party to whom it is addressed to pay a specified person (or to their order), or the bill's bearer. The term is defined in the UK-wide Bills of Exchange Act 1882, section 3(1). |

| Bill of lading | A document used in the transportation of goods by sea. It serves different functions, including being a receipt for the goods taken by the carrier; evidence of the contract of carriage; and can also be a document of title for the goods. |

| Blockchain | A type of distributed ledger technology (DLT) that records data using time-stamped 'blocks' that are linked (chained) to previous blocks. |

| Carbon credit | A unit or permit that can be acquired to 'offset' carbon emissions and is intended to help reduce such emissions. It can subsequently be traded by its holder. There are different varieties of carbon credit with their own characteristics. |

| Central bank digital currency (CBDC) | A digital form of (fiat) currency issued by a state's (or monetary union's) central bank, e.g. the concept of a 'digital pound' being explored in the UK. |

| Collateral | The property used as security for a debt. For example, if a borrower (debtor) grants a security right over a digital asset to a lender (creditor) to obtain a loan, the digital asset is the collateral. |

| Cryptocurrency | A type of cryptoasset, issued privately (not by a state's central bank), that enables the transfer and storing of value electronically on a decentralised system using cryptography. The most well-known cryptocurrency is Bitcoin. |

| Decentralised autonomous organisation (DAO) | This describes a form of online organisation that uses rules set out in computer code. The participants in a DAO will usually seek to achieve a shared goal, e.g. making profit or a charitable endeavour. |

| Delict | The law of delict is part of the law of obligations and is concerned with liability for wrongful acts, including due to negligence or intentional acts. The equivalent term in England and Wales is tort law. |

| Distributed ledger technology (DLT) | A type of technology that enables the operation and use of a distributed ledger, which is a digital store of information or data. The ledger is shared (distributed) among a computer network. Participants validate and approve additions to the ledger through a consensus mechanism and update the ledger in a synchronised manner. |

| Estate | All of a person's property of whatever type (with some exceptions), usually with reference to bankruptcy or upon the person's death. |

| Fiat currency | A currency, like the Pound, which derives its value from the fact it is issued by a government, rather than being based on a commodity (such as gold). |

| Floating charge | A form of security right that can be granted by companies and some other corporate entities. It covers a class of property, potentially encompassing all of a company's property (both present and future property). It is enforced in the context of administration, liquidation or, less commonly nowadays, receivership. |

| Non-Fungible Token (NFT) | A type of digital asset that represents proof of title of a unique digital item, for example, artwork. |

| Obligations | An area of private law dealing with binding legal relationships between individuals and/or legal persons. It has various sub-branches including contract law (i.e. voluntary obligations), delict and unjustified enrichment. |

| Off-chain | Actions or transactions that are external to the relevant system. |

| On-chain | Actions or transactions that are executed and recorded within the relevant system. |

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Pledge | A form of security right which traditionally depended on delivery of the collateral to the creditor. This (possessory) pledge is still available, but a non-possessory statutory pledge has also been introduced by the Moveable Transactions (Scotland) Act 2023. |

| Private international law (or international private law or conflict of laws) | Where there is a cross-border element to a dispute, private international law determines the questions of international jurisdiction (which country's courts have jurisdiction to deal with the case); applicable law (which country's law applies to the issue(s) before the court); and recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments (whether a judgment given by the courts of one country can be recognised or enforced in another country). |

| Private key and public key | Many digital assets depend upon an encryption scheme that uses two paired keys (normally consisting of long data strings) – i.e. a public key and a private key. The public key is used for encryption purposes, and the private key is used for decryption. |

| Private law | A large branch of law involving relationships among or between individuals or legal persons (e.g. companies). It includes areas such as contract law, delict, property law, debt enforcement and family law. Private law can be contrasted with public law, which involves relationships between individuals (or legal persons) and the state (when not acting as a private party), including criminal law, constitutional law and tax law. |

| Pseudonymity | Where a participant in a system has an identifier, but it cannot be used to confirm the person's true identity. Pseudonymity is associated with some distributed ledger technology-based systems and other systems that give rise to digital assets. Transactions in such systems therefore usually happen among persons unknown to one another. |

| Secured transaction | A legal arrangement in which a borrower (debtor) grants a security right over collateral to a lender (creditor) to obtain and secure a loan or other debt. In comparison to unsecured lending, a secured transaction may enable the borrower to access finance that would otherwise be unavailable or to access it on better terms (such as lower interest rates). |

| Securities | Company shares, bonds and other financial instruments (other than cash). These should not be confused with security rights; however, they can be used as collateral. |

| Security right | A type of property right that a secured creditor holds over collateral to secure a debt. There are various different types of security right in Scots law, including pledges (possessory and statutory), floating charges, and standard securities (for land). Upon default by a debtor, security rights are usually exercised by selling the collateral and using the proceeds to pay off the debt owed. |

| Stablecoin | A type of digital asset, the value of which can be pegged to one or more reference assets, such as a fiat currency or commodity, in order to maintain a relatively stable value. |

| Tokenisation | The creation of a digital representation of property or rights relating to property (such as rights relating to land, artwork or securities) by using DLT or similar technology, which can facilitate dividing rights and the ease of transferability of those rights. |

| Trust | A legal arrangement in which property is held by one party (trustee(s)) for the benefit of another party (one or more beneficiaries). The party who establishes the trust is the truster (or settlor). |

| Unjustified enrichment | A form of involuntary obligation that provides a remedy where one party has been unjustifiably enriched at the expense of another. For example, Alex owes Bashir £1,000 but accidentally transfers £2,000 to him when seeking to pay off the debt. Bashir has no legal basis to retain the extra £1,000 and has an obligation to pay it back to Alex. |

* Some of the terms in this glossary contain modified versions of the definitions in the Scottish Government's Consultation on Digital Assets in Scots Private Law and the Law Commission of England and Wales's Digital Assets: Final Report, Digital Assets and (Electronic) Trade Documents in Private International Law Including Section 72 of the Bills of Exchange Act 1882: Consultation Paper, and Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs): A Scoping Paper.

Digital assets: background, concepts and terminology

‘Digital asset’ is usually used as a broad term to refer to an asset in electronic or digital form. There are many sub-types of assets, with different features and characteristics, captured under the umbrella term of digital assets. However, the emergence of digital assets using distributed ledger technology (DLT) is relatively recent, starting with the introduction of the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, in 2009.

This part of the briefing covers:

Bitcoin and DLT

Bitcoin, underpinned by blockchain (a type of DLT), was introduced by its pseudonymous founder, Satoshi Nakamoto, as “a peer-to-peer electronic system” to make payments without the involvement of central authorities or intermediaries (such as banks or financial institutions).1 In the traditional sense, it is not money or currency and has no intrinsic value. It is privately issued, not by a state. It does not have a physical existence and is not backed by a physical asset. It is essentially data, strings of code, and its market value depends on what people are willing to pay for it, which makes it highly volatile.

However, the introduction of Bitcoin underpinned by blockchain represented a fundamental change to the traditional way of making payments. It has enabled non-cash payments to be made outside the banking system directly from payer to payee and secure digital records can be held by parties, independently of the usual central authorities.2

Bitcoin has been influential in the creation of other types of digital assets and systems using DLT that allow for transactions with such assets.

Traditional systems vs DLT-based systems

DLT-based systems are fundamentally different from traditional systems. Traditional systems, including banking and financial systems, are centralised and intermediated. Transactions are executed by central authorities acting as intermediaries between parties and are recorded by those authorities on central ledgers. On the other hand, DLT-based systems are decentralised and disintermediated. Participants can transact peer-to-peer by using their public key (which encrypts data) and private key (which decrypts data).

Types of transactions and the importance of the private key

A transaction can be ‘on-chain’, executed and recorded on the ledger within the relevant system; or ‘off-chain’ taking place outside of the system, with no ledger recording in the system, for example, by the passing of the private key from one person to another. A private key is crucial in this context as many digital assets can only be accessed by private keys.

Whoever has the private key to a digital asset is the only one who can deal with that asset. If the private key is lost, the asset cannot be accessed or recovered. This is seen in an ongoing battle for the recovery of Bitcoin involving an early adopter in Wales, where there was accidental disposal of a hard drive containing the private key for approximately 7,500 Bitcoin in 2013, valued at around £500,000 when acquired and worth around £625 million at the time of writing.1

How distributed ledger technology operates

Unlike the traditional centralised and intermediated systems, in DLT-based systems, transactions are validated and recorded on ledgers by participants in accordance with consensus mechanisms. A distributed ledger functions like a synchronised database, which includes the entire history of all the transactions that have ever occurred within the system. It is distributed and shared across the system among participants, and it cannot be modified by a participant secretly.2

This technology brings certain potential benefits to transactions, such as traceability and integrity of records, verification of receipt, and direct peer-to-peer real-time transaction removing the need for a trusted third-party or intermediary. However, because of the ever-growing size of the ledger and associated scalability issues, third-party intermediaries, such as digital wallet providers or exchanges, have now become a notable feature in the market. Many participants access and manage their digital asset holdings through them.

Many of the systems involving digital assets are open to anyone to participate. For example ‘permissionless’ systems operate among pseudonymous participants whose true identities are not disclosed or known, and they typically have a public ledger updated by consensus among the participants.3 DLT-based systems allow participants to transact peer-to-peer without any need for them to trust each other. Therefore, disclosure of the true identities of participants does not matter from the perspective of the technology. Pseudonymity also enables participants to maintain privacy.

Other systems are open to a defined group only, for example ‘permissioned’ systems which operate among participants known to each other and which usually have a private ledger updated by trusted participants. Hybrid models are also possible.3

Use cases of digital assets and DLT beyond Bitcoin

The types of digital assets and use cases of DLT are expanding and evolving across different sectors and industries. There are various examples, including the following:

Stablecoins: Unlike Bitcoin-like cryptocurrencies that are highly volatile, stablecoins can maintain their value against one or more reference assets, such as a fiat currency or commodity. Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC) are among stablecoins which are pegged to the United States (US) dollar as fiat currency.

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs): CBDCs are being introduced or explored in various countries (including the UK) as a digital form of money issued by central banks. They therefore differ from privately-issued cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin.

Tokenised securities: These are digital representations of traditional securities and can facilitate transactions relating to such assets.

Electronic trade documents: In international trade, DLT has facilitated a growing transition to paperless trade and the use of electronic trade documents.

Digital assets are being used and invested in by individuals as well as businesses. In spite of their increased use, digital assets, particularly cryptoassets, are also controversial. There are concerns around the high volatility and energy consumption of some types of digital assets, such as Bitcoin, and their association with fraud and other forms of illegal activity.1

However, digital assets have become increasingly important globally, impacting on trade, finance and law. It is therefore important that relevant areas of law are well-equipped to deal with the implications of digital assets.

Accommodating digital assets in law

As mentioned in the background, concepts and terminology section, a broad usage of the term digital assets can capture any assets in an electronic or digital form. An email account, for example, can be regarded as a digital asset in a broad sense. However, not all types of digital assets pose difficulties for the law, because the existing law already provides relevant solutions for some of them. Currently, what is challenging for the law is to accommodate the novel types of digital assets which have emerged with the use of DLT, most notably cryptoassets.

As will be seen in the section dealing with Legal approaches to digital assets beyond Scotland, there are countries which have reformed their laws or are seeking to do so, to adequately respond to the challenges raised by digital assets. At the international level, digital assets and related subjects are also under consideration by international organisations with a view to developing widely accepted legal solutions.

Digital assets pose challenges in Scots law too, as discussed in the Current law relating to digital assets section. The ongoing law reform work in Scotland, which aims to address some of these challenges by clarifying the status of digital assets as objects of property in Scots private law, is timely and desirable, and is the principal focus of this briefing.

Defining digital assets

There is no universally agreed terminology in this area. The definitions of ‘digital asset’ and other related concepts vary, and the definitions that do exist are often specific to a particular context. Different definitions and understandings are also seen across legal instruments and ongoing initiatives among countries and international organisations.

This part of the briefing covers:

Definitions in Scotland and the UK

There is no definition of ‘digital asset’ in Scots law.

In England and Wales, the Law Commission of England and Wales, in its final report on digital assets, defined a digital asset in a broad sense as “any asset that is represented digitally or electronically”, and considered that “it captures a huge variety of things including digital files, digital records, email accounts, domain names, in-game digital assets, digital carbon credits, crypto-tokens and NFTs”.1

Cryptoassets are defined in financial regulation legislation

In the UK, the term ‘cryptoasset’ is defined in the context of financial regulation. The Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 section 417(1), as introduced by section 69 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2023, provides that:

any cryptographically secured digital representation of value or contractual rights that- (a) can be transferred, stored or traded electronically, and (b) that uses technology supporting the recording or storage of data (which may include distributed ledger technology).

A similar definition of ‘cryptoasset’ is also used in the UK concerning money laundering and terrorist financing (see Regulation 14A(3)(a) of the Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing and Transfer of Funds (Information on the Payer) Regulations 2017 (SI 2017/692) as inserted by Regulation 4(7) of the Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (Amendment) Regulations 2019 (SI 2019/1511)).

UNCITRAL definition

The United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) is a subsidiary body of the General Assembly of the United Nations (UN), with a mandate to further the progressive harmonisation and unification of the law of international trade. The UK is a member of UNCITRAL.

The Taxonomy of Legal Issues Related to the Digital Economy, prepared by the secretariat of UNCITRAL in 2023, recognised that there is no widely accepted definition of a digital asset. Instead, various different names exist for such assets, for example ‘cryptoassets’ or ‘tokens’.1 It was further provided that “[i]n its ordinary meaning, the term “digital asset” connotes a collection of data, stored electronically, that is of use or value”, a concept noted in the Taxonomy as being already well known to UNCITRAL texts on electronic commerce (paragraphs 82-83).

In 2025, UNCITRAL published a draft Guidance Document on Legal Issues relating to the Use of Distributed Ledger Technology in Trade.2 The existence of different definitions of ‘digital assets’ was noted in that Guidance too (paragraphs 86-87). The Guidance further noted that some assets, which may fall under the definition of digital asset, may also fall under other legally relevant definitions. A potential example of this is electronic trade documents and, as stated in the Guidance, the law should determine which legal regime will prevail in such cases.

UNIDROIT definition

The International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT) is an independent intergovernmental organisation, which studies the need and methods for modernising, harmonising and co-ordinating private law between states. It formulates uniform law instruments, principles and rules to achieve those objectives. The UK is a member of UNIDROIT.

As will be discussed further in the section relating to international initiatives, the UNIDROIT Principles on Digital Assets and Private Law (DAPL Principles), adopted in 2023, define a digital asset as “an electronic record which is capable of being subject to control” under Principle 2(2). The Commentary considers various types of asset and provides in paragraphs 2.8-2.17 that:

virtual (crypto) currency on a public blockchain (e.g. Bitcoin) is a digital asset

a central bank digital currency may be a digital asset

a social media page with password for access is not a digital asset

an Excel or Word file with password protection could be a digital asset.

HCCH definition

The Hague Conference on Private International Law (HCCH) is an intergovernmental organisation, working for the progressive unification of the rules of private international law. The UK is a member of the HCCH.

As will be discussed further in the section about international initiatives, the HCCH is using the term ‘digital token’ in its ongoing Digital Tokens Project. This term was described in paragraph 8 of Prel. Doc. 5B REV of March 2024 as “virtual representations, stored electronically on decentralised or distributed storage mechanisms”.1

Difficulties in defining digital assets in law

The absence of uniform terminology and definitions in the area poses difficulties for any law reform work. As mentioned, digital asset is often used as a broad umbrella term which can capture various assets with different characteristics and features. However, the current legal challenges primarily relate to only the novel types of digital assets which have emerged with the use of DLT.

At the same time, there is rapid technological development and emergence of further types of assets and systems. These all make it challenging to formulate precise definitions in the area.1

On the one hand, it is important that law reform captures the intended categories of digital assets and not others. On the other hand, definitions or tests to be used for that purpose should be sufficiently flexible and future-proof to be able to accommodate equivalent assets that may emerge in the future with technological developments and innovation.2 Technological neutrality is emerging as an important consideration in national and international legal frameworks in this area.

Legal approaches to digital assets beyond Scotland

Before considering Scotland, it is useful to look at what legal approaches exist elsewhere, and whether and to what extent Scotland can benefit from these approaches in reforming its laws. In general, there is no single or uniform legal approach to digital assets at national or international levels. However, as will be seen, some concepts (such as control) and principles (such as technological neutrality) are commonly encountered in different legal frameworks in this area.

At the international level, UNCITRAL, UNIDROIT and the HCCH have been undertaking projects on digital assets and related subjects. They endeavour to do this in a coordinated way to avoid fragmentation among their legal instruments and initiatives. However, full uniformity in approaches across their projects seems to be difficult to achieve through international collaboration. This is because their membership is not identical. Their mandates and the timelines for their proposed outputs are also different.1

These developments are discussed in more detail in the International initiatives section of the briefing.

At the national level, various countries have been considering digital assets and related subject matter under the reform agenda. Reform projects are being shaped based on countries’ needs, their legal traditions and legal systems. Some of these reform projects have already resulted in the enactment of new acts or legal frameworks, such as in Liechtenstein, Switzerland and the US. Others are at an advanced stage with legislative proposals, for example in England and Wales.

These developments are discussed in more detail in the section of the briefing on Law reform developments in selected countries.

International initiatives

There are various international initiatives on digital assets and related subjects undertaken by international institutions, including, for example, the European Law Institute (ELI) concerning the use of and enforcement against digital assets, and intergovernmental organisations. This part of the briefing provides an overview of some of the completed and work-in-progress projects of UNCITRAL, UNIDROIT and the HCCH.

UNCITRAL

UNCITRAL adopted a Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records (MLETR) in 2017 to facilitate paperless trade in both domestic and cross-border contexts. The MLETR applies to electronic transferable records which are functionally equivalent to transferable documents or instruments issued in paper, such as bills of lading and bills of exchange. Non-discrimination against the use of electronic means, functional equivalence, and technology neutrality are key principles underlying the MLETR.

The UK's Electronic Trade Documents Act (ETDA) 2023, which will be discussed in the section covering the law relating to electronic trade documents, was influenced by the MLETR.

UNIDROIT

As mentioned in the section about definitions, UNIDROIT adopted the DAPL Principles in 2023 to facilitate transactions in types of digital assets often used in commerce and to provide guidance to different parties dealing with digital assets. It is a technology neutral instrument and is also jurisdiction neutral (see Commentary, paragraphs 0.5 and 0.6). It consists of a set of principles, each accompanied by commentary, and its scope of application is limited to certain private law issues, particularly proprietary rights. On a related note, UNIDROIT is also undertaking a project on the legal nature of verified carbon credits.

The Principles do not address whether a digital asset falling within the scope is considered property, but they provide under Principle 3(1) that such a digital asset can be the subject of proprietary rights (see Commentary, paragraph 0.13).

Control as a key factor in defining digital assets

The DAPL Principles apply only to a subset of digital assets (see Commentary, paragraph 0.11), namely those which are “capable of being subject to control” as per Principle 2(2). This definition seems to have been inspired by the definition of ‘controllable electronic record’ in Article 12 of the US Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), as will be seen in the section dealing with law reform in the United States.

‘Control’ is defined in DAPL Principle 6, with reference to (Principle 6(1)(a)):

(i) the exclusive ability to prevent others from obtaining substantially all of the benefit from the digital asset,

(ii) the ability to obtain substantially all the benefit from the digital asset, and

(iii) the exclusive ability to transfer these abilities to another person

Under these ‘exclusive ability’ requirements, ‘control’ assumes a role for digital assets which is functionally equivalent to what ‘possession’ assumes for movables (or moveable property) as a factual matter (see Commentary, paragraphs 6.2 and 6.3). In Principle 6(3), there is, however, a relaxation of the ‘exclusive ability’ requirements for situations (see Commentary 6.11):

a) where the inherent attributes of a digital asset or the relevant system may result in changes, including a change of control of the digital assets, or

b) where the person in control wishes to share its abilities with one or more other persons.

The concept of ‘control’ has a central role under the DAPL Principles, and is relevant to various rules, for example, on innocent acquisition of digital assets under Principle 8, and on achieving third-party effectiveness of a security right under Principle 15 (see Commentary, paragraph 0.15).

HCCH

The HCCH has been undertaking several projects examining private international law matters concerning different aspects of the digital economy. As mentioned in the definitions section, one of them is the Digital Tokens project.

Following the Exploratory Stage (2024-2025), the project progressed to the Experts’ Group Stage.1 An Experts’ Group was established and the work continues with the study of private international law issues relating to digital tokens by focusing on representative, concrete use cases. The project includes a separate workstream on the Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records as a use case, with work being done in coordination with UNCITRAL.

The project aims to take a holistic approach by considering matters relating to jurisdiction, applicable law, recognition and enforcement, and international cooperation mechanisms concerning digital assets.1 The project excludes securities, central bank digital currencies, and carbon credits, due to separate projects the HCCH is undertaking or is involved with regarding them.

This project and other related international projects are timely and of global importance. Therefore, they should be monitored closely in Scotland to help shape the country's private international law reform agenda for the future.3

Law reform developments in selected countries

Country approaches differ regarding the reform of laws concerning digital assets and related subject matter. This part of the briefing provides an overview of some of the completed and work-in-progress law reform work in the selected countries of Liechtenstein, Switzerland, the United States and England and Wales, as representative early adopters of relevant legal reforms.

Liechtenstein

In 2019, Liechtenstein enacted the Act on Tokens and Trustworthy Technology Service Providers (TVTG). The TVTG, which entered into force on 1 January 2020, includes a section on private law issues as well as a regulatory section.

The TVTG aims to provide a comprehensive and technology-neutral legal framework for transaction systems based on what it calls ‘Trustworthy Technology (TT)’. This is defined in Article 2(1)(a) as “technologies through which the integrity of Tokens, the clear assignment of Tokens to TT Identifiers and the disposal over Tokens is ensured”. It can include DLT (or blockchain technology) but is not limited to it.

Token, in the context of the TVTG, is defined in Article 2(1)(c) as “a piece of information on a TT System, which 1) can represent claims or rights of memberships against a person, rights to property or other absolute or relative rights; and 2) is assigned to one or more TT Identifiers”.

There is no token classification in the TVTG. Instead, the TVTG introduces and adopts a ‘Token-Container-Model’ under Article 2(1)(c) according to which all kinds of rights can be represented by tokens.1 The transfer of the token results in the transfer of the right represented by the token under Article 7(1).

Switzerland

In 2020, Switzerland adopted the Federal Act on the Adaptation of Federal Law to Developments in Distributed Ledger Technology to amend its law to respond to the developments of DLT. It did so through a framework amending and incorporating provisions into the existing federal acts in various areas of laws, including private law, financial regulation, debt enforcement and bankruptcy.1

Although it is known as the DLT Act, it aims to be technologically neutral. The private law adaptations included enabling tokenisation of rights, claims, and financial instruments through ‘ledger-based securities’ in Article 973 onwards of the Code of Obligations, which have been in force since 1 February 2021.

United States

In 2022, the Uniform Law Commission (ULC) and American Law Institute (ALI) adopted amendments to the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) to address emerging technologies. The UCC is a model code with default rules that are uniformly adopted by US states. It provides a comprehensive set of laws governing all commercial transactions in the US and therefore is described as “the backbone of American commerce”.

The 2022 Amendments included a new Article 12 that governs the transfer of property rights in particular types of digital assets called ‘controllable electronic records (CERs)’. The legal regime provided by Article 12 is designed to work for not only existing technologies such as DLT, but also technologies that have “yet to be developed, or even imagined” (see Prefatory Note to Article 12). This reflects technological neutrality as an underpinning principle of Article 12.

Under UCC Section 12-102(a)(1)), CER is a “record stored in an electronic medium that can be subjected to control under Section 12-105”. The term however does not include “a controllable account, a controllable payment intangible, a deposit account, an electronic copy of a record evidencing chattel paper, an electronic document of title, electronic money, investment property, or a transferable record.”

The concept of ‘control’ is further defined under Section 12-105. The general rule (Section in 12-105(a)) is that the person has the control of a CER if the electronic record or the system:

(1) gives the person:

(A) power to avail itself of substantially all the benefit from the electronic record; and

(B) the exclusive power:

(i) to prevent others from availing themselves of substantially all the benefit of the electronic record,

(ii) to transfer control of the electronic record to another person or cause another person to obtain control of another CERs as a result of the transfer

(2) enables the person readily to identify itself in any way, including by name, number, cryptographic key, account number, as the person having the powers specified above

There is a presumption of exclusivity in section 12-105(d). Therefore, if control is established, there is no need to prove exclusivity (see the Official Comment on section 12-105, paragraph 5). There is also a relaxation of the exclusivity requirement in certain situations where the inherent attributes of CER or the system limit the use of the CER or cause a change, including a transfer or loss of control; or where the power is shared with another person (section 12-105(b)). Those situations do not impair exclusivity.

England and Wales

The Law Commission of England and Wales has various completed or work-in-progress law reform projects focusing on matters concerning emerging technologies, including smart legal contracts, electronic trade documents, digital assets, and decentralised autonomous organisations (DAOs). This briefing provides further details on three of them given their direct relevance to digital assets.

Electronic trade documents project

The law reform project on ‘electronic trade documents’ was completed and led to the enactment of the Electronic Trade Documents Act 2023. This legislation applies to the whole of the UK, with some provisions applicable only to Scotland (see further in the current law relating to digital assets section). The 2023 Act provides for equivalence between 'paper trade documents' and 'electronic trade documents' if the technological requirements set out in section 2 of the Act are met.

These terms are defined in the 2023 Act (sections 1(1) and 2(2)) and the documents intended to be captured by the legislation include bills of exchange and bills of lading (section 1(2)). The 2023 Act states that an electronic trade document can be possessed (section 3(1)), and “has the same effect as an equivalent paper trade document” (section 3(2)), with a similar equivalence provision for anything done in relation to such documents (section 3(3)).

Digital assets project

The final report for the project on ‘digital assets’ was published in 2023, with a supplementary report following in 2024. The supplementary report included a draft bill aiming to confirm the existence of a ‘third category’ of personal property rights, capable of accommodating certain digital assets including crypto-tokens under property law.1 Some of the concepts that the Law Commission of England and Wales examined in its consultation paper, such as ‘rivalrousness’ and ‘independent existence of persons and of the legal system’ seem to have been a source of inspiration in shaping the proposals in the Scottish Government's consultation.

At the time of writing, the Property (Digital Assets etc.) Bill, extending to England and Wales and Northern Ireland, is being considered by the House of Commons in the UK Parliament, having already passed through the House of Lords. It only has two sections, on ‘Objects of personal property rights’ and on ‘Extent, commencement and short title’. Section 1 on ‘objects of personal property rights’ provides that “A thing (including a thing that is digital or electronic in nature) is not prevented from being the object of personal property rights merely because it is neither— (a) a thing in possession, nor (b) a thing in action.”

Digital assets and electronic trade documents in private international law project

The law reform project on ‘digital assets and electronic trade documents in private international law’ is currently at the consultation stage. It aims to examine how private international law operates in the context of digital assets and electronic trade documents. This includes questions of which country's courts have jurisdiction to deal with these cases and which country's law applies to the issue(s) before the courts.

The Law Commission of England and Wales can only make law reform recommendations for England and Wales, and not for Scotland (nor Northern Ireland). However, as will be discussed further in the current law relating to digital assets section, some of the key sources of private international law alongside other legislation relevant to this project (such as the Electronic Trade Documents Act 2023 and the Bills of Exchange Act 1882) apply to the whole of the UK. Consequently, there are benefits of UK-wide law reform regarding private international law matters in this area, where possible and appropriate, and specifically to ensure alignment among the pieces of legislation which apply across the UK.2

This project of the Law Commission of England and Wales offers a valuable basis for possible UK-wide law reform and collaboration in this area.3 Consequently, engagement and close cooperation between the Scottish Law Commission (or another suitable body) and the Law Commission of England and Wales, as well as further expert input to the project from key Scottish stakeholders, will be beneficial and important as the project develops.4

Current law relating to digital assets in Scotland

Before considering possible reforms concerning digital assets in Scotland, it is helpful to assess the extent to which digital assets are currently accommodated in Scots law. This will be done with reference to various key areas of law:

trusts, inheritance (succession) law, and family law (especially divorce)

the law of obligations (such as those relating to contract and delict)

Brief reference will also be made to other areas, such as criminal law and financial regulation and tax law, which are generally beyond the scope of this briefing.

Property law

An important area for the accommodation of digital assets in Scots law is property law. That is because property law provides a framework or infrastructure, on which other areas of law depend, including the law of inheritance and trusts, family law, secured transactions and insolvency law. Consequently, if clarity is obtained regarding the property status and categorisation of digital assets (and related issues such as how ownership is transferred), this will also help to resolve issues in adjacent areas of law. As a result, it may avoid the need for separate reform of some of those areas.

A leading scholar, Professor Kenneth Reid, succinctly describes property law as “the law of things, and of rights in things (real rights)”.1 A real right is generally enforceable against anyone, in contrast with a personal right, which is a right against a particular person or persons. For example, if Charlie enters a contract with Deborah to buy Deborah's house, Charlie has a personal right that will usually only be enforceable against Deborah, and not against others who may claim to have rights in the house. However, if Charlie acquires the house from Deborah, then he has the real right of ownership, and this allows for enforcement of his right in the property against anyone.

A key question in relation to digital assets is whether they can qualify as things in which persons can have real (property) rights, such as ownership and security rights (i.e. whether digital assets can be “property objects”).

There seems to be little doubt that digital assets can be property objects in Scots law. Property law in Scotland is expansive and recognises a wide range of property objects. But there is currently an absence of legislation and case law confirming the property status of digital assets, including the criteria to be met for digital assets to be property objects.2

While some digital items will be considered valid property objects in Scots law, that will not be true for all examples of what may be considered digital assets in a broader sense. There is some uncertainty as to where the current law would draw the boundary between digital assets that can be property objects and those that cannot.

This part of the briefing covers:

How should digital assets be categorised within property law?

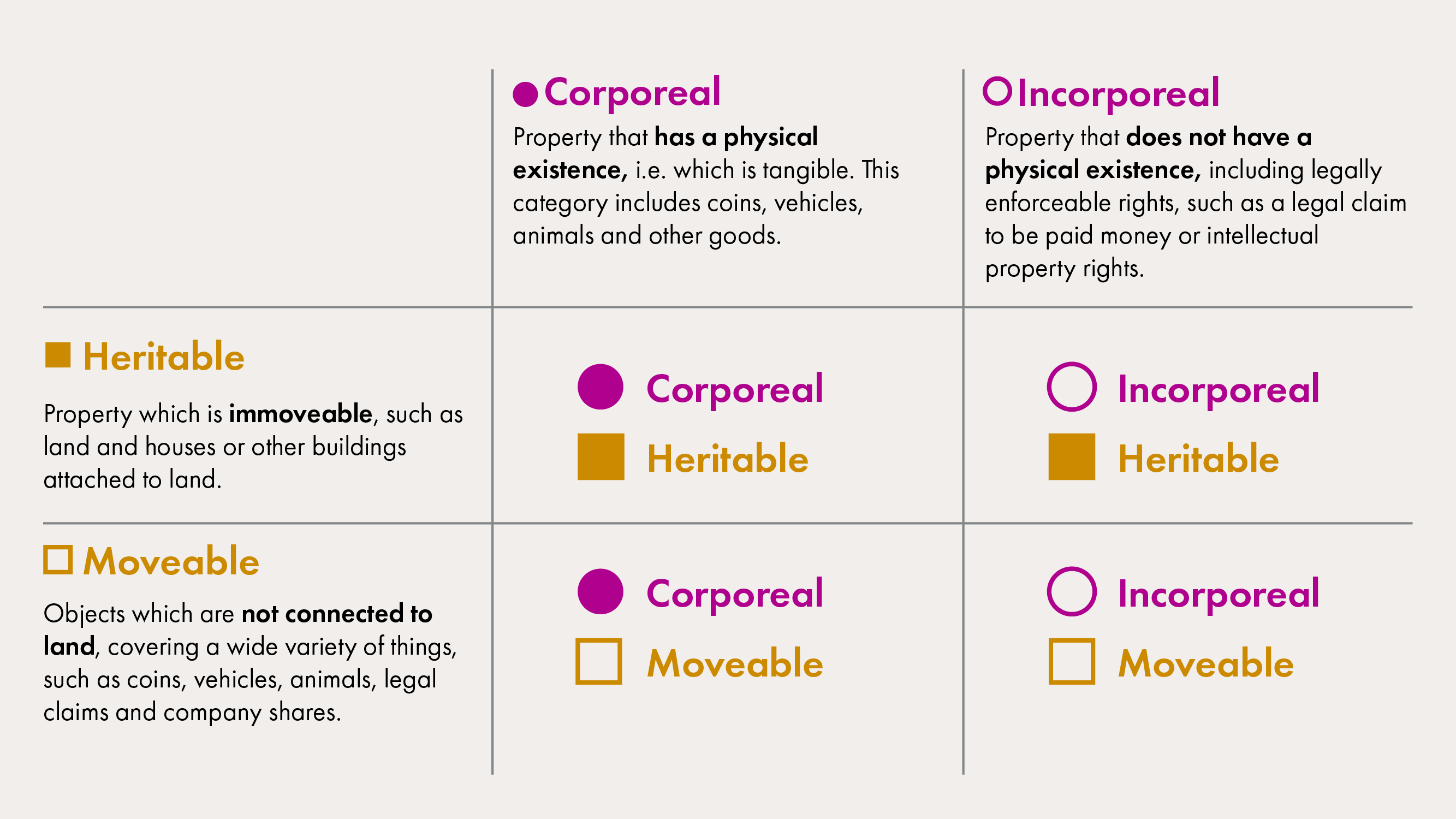

Assuming that some digital assets are property objects, the next matter to consider is what type of property they are. There are various ways in which property can be divided in Scots law.

Amongst the most common and significant of these are the divisions between: (1) heritable property and moveable property; and (2) corporeal property and incorporeal property. If these two forms of division are combined, there are four broad categories of property, as indicated in the table below – (a) corporeal heritable; (b) incorporeal heritable; (c) corporeal moveable; and (d) incorporeal moveable.1

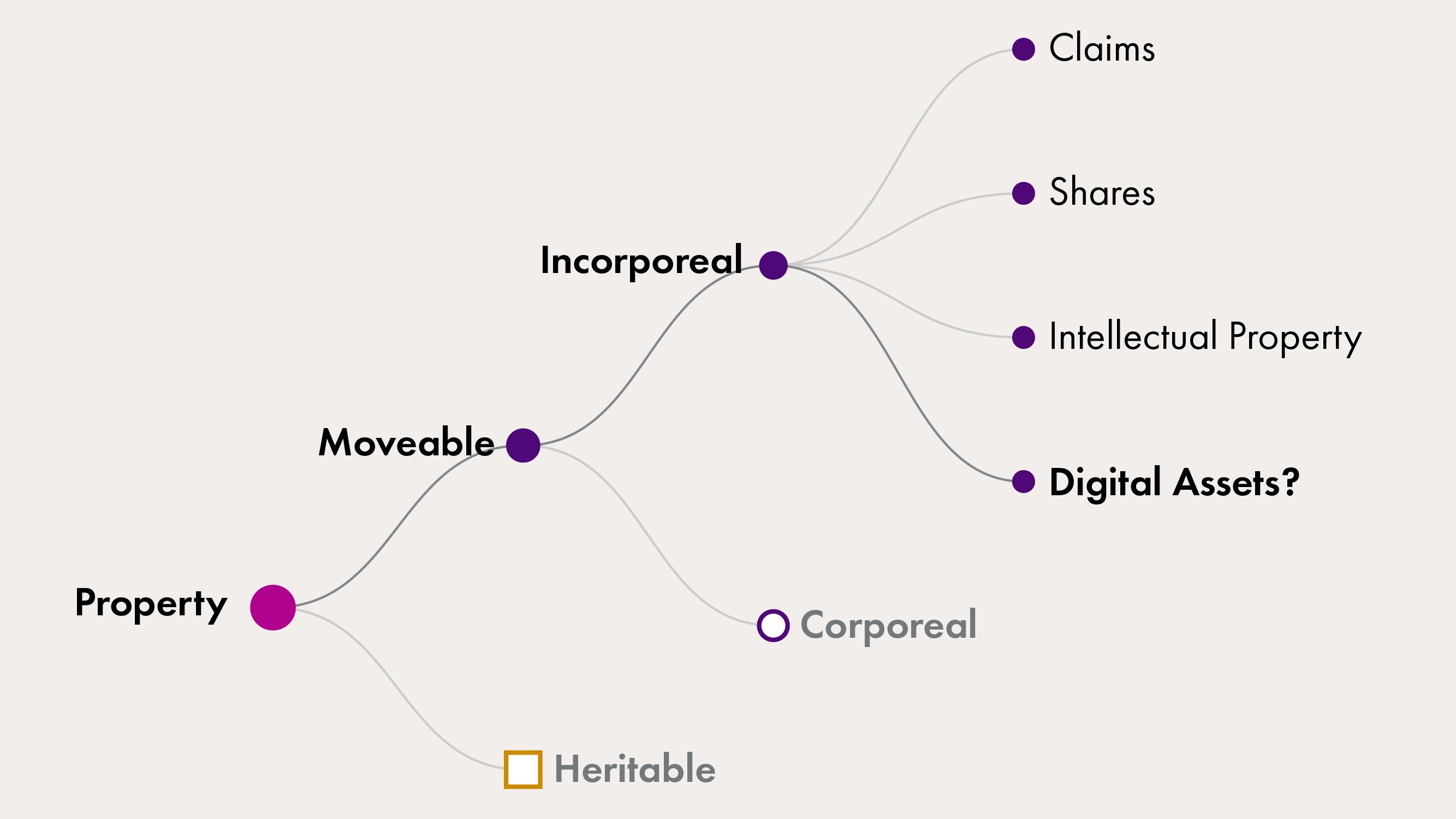

As digital assets are not land and are not (directly) connected to land, at least in most circumstances,i there seems to be no doubt that they are ordinarily moveable property. Their intangibility leads intuitively to the conclusion that they are to be categorised as incorporeal moveable property.

However, they differ from other forms of property in that category and share some characteristics with corporeal moveable property. Certain digital assets are intangible property objects that differ from rights created by law (such as legal claims) and they can be subject to control, which is similar to possession.

Digital assets as "intangible" corporeal moveable property

Such features have led some to suggest that digital assets could be considered intangible, corporeal moveable property.2 Yet the intangibility of digital assets means that they are not a neat fit with corporeal moveables, and their inclusion would undermine a definitive feature of that category, namely physical existence. Various aspects of the law relating to corporeal moveables are premised on the possibility of physical possession, including under the Sale of Goods Act 1979 and with reference to the debt enforcement mechanism of attachment in Part 2 of the Debt Arrangement and Attachment (Scotland) Act 2002. Control of a digital asset is also not an exact equivalent of possession.

Digital assets as incorporeal moveable property

The general body of opinion seems to be in favour of categorising digital assets as incorporeal moveable property .3 Nevertheless, there is widespread recognition that they are a novel sub-type of incorporeal moveable property, and that the rules for existing forms of incorporeal moveables cannot apply to digital assets in the same way, including with respect to transfer of the assets.

The category of incorporeal moveables is the residual category in Scots law (i.e. if something is not corporeal, it is automatically incorporeal) and already encompasses a range of different types of property, each with their own particular rules. As such, digital assets may simply be accommodated as an additional category alongside sub-categories such as legal claims, shares and intellectual property.

The following diagram highlights this categorisation:

Notes for Figure 2:

Heritable property (i.e. immoveable property such as land) is also either corporeal or incorporeal.

There are also ways in which heritable property and corporeal moveable property can be sub-divided further.

The sub-categories included within incorporeal moveable property are not exhaustive.

Intellectual property includes e.g. copyright, trademarks and patents, which all have their own distinguishing features.

Transferring ownership of digital assets

In any event, there remains some uncertainty as to the precise categorisation of digital assets and the relevant applicable rules. For example, it is not currently clear what the requirements are for the transfer of ownership of digital assets.

A transfer from A to B will almost certainly be recognised where the parties intend for ownership to pass and where the transfer is “on-chain”, i.e. by taking place within the relevant system and recorded on the ledger, so that the system recognises B as the holder of the asset. However, it is uncertain whether the law would accept a transfer of ownership where the purported transfer is “off-chain” through, for example, A giving B control of the asset via a private key.1

The publicity principle

Conferring ownership on B in this scenario may be reflective of what parties expect when dealing with digital assets but it is at odds with the so-called “publicity principle” of Scots law. This principle provides that “acts that can affect third parties should be made public, so that third parties can know of them”.2 Since ownership of property is effective against third parties, it may be expected that the transfer of ownership of digital assets should be accompanied by a publicity step, such as a new entry on the relevant system, albeit that this is an unusual form of publicity due to pseudonymity. In any event, the law is uncertain on this point.

Transfer of control

There are also questions about what precisely would be required for control to transfer to B, and thus potentially also the transfer of ownership. For example, even if B was given private key information, if A retained a copy of it or also gave it to someone else, would that stop ownership from passing to B?

Acquiring digital assets from a non-owner

A further question is whether B could acquire ownership where A is not the owner of the digital asset. Ordinarily, it is not possible to obtain ownership from a non-owner in Scots law. This is known as the “nemo plus” (or “nemo dat”) principle (or rule) and means that “no one can give that which he does not have”.3 However, there are some exceptions to this.4 For instance, Professors Gretton and Steven note that: “[f]or reasons of commerce, special rules enable the acquirers of money (legal tender) and negotiable instruments to acquire an original rather than a derivative title”.5

In other words, a “good faith” acquirer of a bank coin or an acquirer of a bill of exchange in good faith and for value can acquire ownership from a non-owner.

An exception may also be justified for digital assets, particularly where B is unaware that A is not the owner (i.e. is in good faith) and pays for the asset. The alternative, even where A has stolen an asset from the owner (perhaps through hacking), would be difficult to give effect to due to the nature of digital assets and how transactions take place.

This is discussed further in the section looking at consultation proposals on protection for purchasers acting in good faith.

Trusts, inheritance (succession) law and family law

This part of the briefing covers how digital assets might interact with:

the law of trusts (holding assets for the benefit of a third party)

family law (particularly divorce).

Trust law and digital assets

If it is accepted that digital assets can be property objects, then they can be held in trust.1 A trust is a versatile mechanism widely used by businesses and individuals to protect assets or to otherwise separate the management and benefit of property. Given the widespread use of digital wallets, exchanges and other platforms for the holding of digital assets, there will often be a need to consider whether a trust arrangement is involved.

The precise nature of how an asset is being held may have considerable implications, given that trust assets are ring-fenced from other assets and are protected from enforcement by a trustee's creditors.2 Consequently, if a trustee enters an insolvency procedure due to indebtedness outside their role as a trustee, assets they hold in trust, including digital assets, are protected from creditors by being excluded from the insolvent estate.i

Inheritance (succession) law and digital assets

Digital assets also interact with the rules of inheritance law, if they are property objects. They can form part of a deceased person's estate and provision may be made for them in a will. If there is no will, rules for “intestate succession” will apply, in the same way as for other moveable property. This includes the application of sections 2, 8 and 9 of the Succession (Scotland) Act 1964.

The challenges that exist for digital assets in succession law are mainly practical ones. For example, there are difficulties in providing sufficient information about relevant assets within a will, without giving so much information that would enable third parties to take control of the assets. Beyond this, an executor is likely to have problems identifying the existence of digital assets in an estate and accessing and transferring them, even if aware of their existence.1

However, because these are principally practical challenges, and are largely the result of the nature of digital assets, it is not obvious how they could be addressed through legal reform. There are other types of digital assets, broadly defined, including social media accounts and digital photographs.2 But these are generally beyond the scope of this briefing.

Family law and digital assets

Another related context in which digital assets may feature is family law. This is most notably the case in the context of divorce and dissolution of civil partnerships. The courts take account of “matrimonial property” in determining financial provision upon divorce, and such property could include digital assets. There are various orders available to a court, including for the transfer of property under section 8 of the Family Law (Scotland) Act 1985.

As with other assets, attempts may be made to conceal digital assets to avoid them being taken into account as part of a divorce. Given their nature, it may be easier to hide digital assets than is the case for other property. However, courts may seek to compel a party to disclose such assets or order them not to transfer or otherwise deal with the assets (by using an interdict).i

Security rights, debt enforcement and insolvency law

This part of the briefing looks at digital assets in relation to:

Security for loans and digital assets

It is important for businesses to be able to raise sufficient finance. The use of security rights helps to achieve this. Taking security minimises the risk to the lender, which will usually be reflected in a lower cost of the arrangement for the borrower.

Assuming that digital assets are property objects, they can also be used as collateral in secured transactions. For example, X Ltd owns digital assets and seeks funding for a new business venture from Y Ltd. Y Ltd may agree to provide a loan, as long as the digital assets are used as collateral (i.e. for security purposes) to help ensure repayment of the debt. Ownership could be transferred to Y Ltd for security purposes, or X Ltd could grant a floating charge covering some or all of its property (including the digital assets). There may be other forms of security available, with their own advantages and disadvantages.1

However, it is uncertain whether Y Ltd would acquire a security right if control is given to them but there is no intention to transfer ownership.2 While this may be viewed as akin to the pledge of corporeal moveable property, with control replacing possession, there are also differences and Scots law is restrictive regarding the creation of security rights.

Enforcing payment of a debt against digital assets

One of the most challenging areas for the accommodation of digital assets is the law of debt enforcement.1

In Scots law, debt enforcement mechanisms and rights that creditors obtain from these mechanisms are known as 'diligence'. By way of example, A has £10,000 worth of digital assets and owes B £10,000. B obtains a court decree (order) for payment against A. However, A continues to refuse to pay. B wishes to use diligence against A's property to enforce payment of the debt.

Unfortunately for B, there are considerable challenges to effectively use diligence against digital assets. B does not have the legal tools to discover the existence of A's digital assets, if B is not already aware of them. Even if B is aware, the existing forms of diligence are unsuitable.

For instance, the diligence of “attachment” (which allows goods belonging to a debtor to be seized and sold) is limited to corporeal moveable property under section 10 of the Debt Arrangement and Attachment (Scotland) Act 2002. “Inhibition” is a diligence for heritable property only (and freezes the debtor's ability to sell or otherwise deal with such property).

The principal form of diligence for incorporeal moveables, “arrestment” (usually used for bank accounts or other claims), requires a third party to be holding the assets rather than the debtor doing so. While digital assets may be held for the debtor by a third party, arrestment will be ineffective if the third-party arrestee is based outside Scotland.1 In addition, an earnings (wage) arrestment is an unsuitable diligence, as digital assets are unlikely to be earnings deriving from employment.

The final diligence to mention is “adjudication for debt”. While primarily associated with heritable property, it is also the residual diligence in Scots law, i.e. the diligence to be used where no other diligence is available.3 However, it is considered outdated, with expensive and drawn-out procedures, and is especially unsuited to digital assets. In particular, it is not possible for the enforcing creditor to sell the asset until they can become owner. This requires a wait of ten years.1

Insolvency law and digital assets

As property, digital assets could fall within a debtor's estate if the debtor were to enter an insolvency procedure. This is true for both corporate and non-corporate insolvency. Insolvency officeholders, such as trustees in sequestration and liquidators, have mechanisms to discover property in the estate and the debtor has a duty to cooperate with the relevant officeholder.i

Nevertheless, there are still risks that a debtor might conceal digital assets and an insolvency officeholder may have difficulties obtaining control of digital assets from the debtor or compelling a third party to cooperate, particularly if they are based in another jurisdiction.1

Law of obligations

This part of the briefing covers digital assets in relation to:

Contract law and digital assets

Digital assets will frequently feature various contractual relationships, involving issuers (where relevant), acquirers, transferors, transferees, intermediaries and customers. This potentially gives rise to a contractual web.1 There is likely to be a mixture of express and implied contractual terms for such property.

While there might be a need to determine what the applicable terms are in a given context and how the law applies to the facts, digital assets themselves do not seem to have generated the degree of substantive contract law problems that would justify statutory intervention at this stage.1

Delict, unjustified enrichment and digital assets

As regards delictual liability (i.e. liability arising from wrongful acts including due to fraud and negligence), parties will need to determine how legal rules apply to particular circumstances concerning digital assets. This is true for the type(s) of liability and the specific losses involved.

It appears that the law of delict is generally able to cope with such assets. However, there may be questions regarding the basis of liability where hacking is involved, for example, whether fraud provides the relevant ground or if there is an analogy with theft or other wrongful interference with property giving rise to delictual liability.

If a third party sought to purchase the “stolen” asset from the hacker, they might be able to become owner, depending upon whether a good faith acquisition rule applies. There are also questions as to whether developers or other third parties could be liable to the owners of “stolen” digital assets in some circumstances.1

The law of unjustified enrichment may be relied upon in some circumstances if a party has been enriched at the expense of another by obtaining digital assets without any legal basis for doing so.

The volatility of the value of digital assets may also create difficulties for litigation concerning digital assets, whether for contractual, delictual or unjustified enrichment actions.

Civil procedure

Pseudonymity is one of the greatest challenges created by digital assets for the law relating to civil procedure and evidence.

Pseudonymity means that it might not be possible to suitably identify a wrongdoer/potential defender for litigation. Tracing ownership and custody of digital assets will also be difficult.1 In addition, there are significant obstacles to service of an action in digital assets court cases, as it is not generally possible in Scots law to serve against persons unknown (Lord Advocate v Scotsman Publications Ltd 1989 SC (HL) 122).1

Private international law

Digital assets have cross-border dimensions. Digital asset systems underpinned by DLT or similar technologies have a global nature and reach and typically involve participants from across the world. There are also various cross-border use cases of digital assets, for example in international payments or in international trade.

Because of their cross-border dimensions, digital assets inevitably give rise to questions in private international law,1 which is an area of private law that deals with matters involving a foreign (or international) element. Private international law determines matters such as which country's courts have jurisdiction to deal with relevant cases and which country's law applies to the issue(s) before the court.

To do so, this branch of law uses techniques based on localisation, which requires identification of the location of, for example, particular assets or parties. Ascribing a real-world location (situs) to digital assets or systems with a global reach is challenging in decentralised contexts and somehow artificial. For example, where is Bitcoin located? As already mentioned in the section dealing with traditional systems vs DLT-based systems, identification of parties or their location is also difficult given that parties’ identities and locations are unknown due to pseudonymity.1

There is no specific private international law provision for digital assets in Scotland. The existing rules in legislation (such as the assimilated Rome I Regulation on the law applicable to contractual obligations and the assimilated Rome II Regulation on the law applicable to non-contractual obligations) and in the common law of Scotland remain relevant to the extent that they can be applied to digital assets.

Some existing legal tools, such as party autonomy (for example, through which parties can choose the applicable law) are helpful, to an extent, for determining private international questions arising from digital assets.3 However, they will not be able to resolve all questions satisfactorily that may arise in this area and therefore private international law reform would be desirable. As part of Scots private law in terms of section 126(4) of the Scotland Act 1998, private international law generally is devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

As discussed in the section dealing with law reform in England and Wales, the Law Commission of England and Wales is currently examining private international law issues concerning digital assets and electronic trade documents. The consultation paper, with provisional reform proposals, was published in June 2025.4 Some of these proposals concern legislation which applies to the whole of the UK.

In relation to (electronic) trade documents, the provisional proposals of the Law Commission of England and Wales include reforming private international law provisions in section 72 the UK-wide Bills of Exchange Act 1882 for England and Wales (see chapter 7 of the consultation paper). Such reform would be desirable for Scotland too.5

Regarding digital assets, the provisional proposals of the Law Commission of England and Wales include searching for alternative approaches for applicable law, including regarding the assimilated Rome I Regulation (see chapter 6 of the consultation paper). The other provisional proposals concern matters of civil procedure in England and Wales that are not applicable in Scotland (see chapter 4 of the consultation paper).

It would be beneficial if Scottish civil procedure issues relating to digital assets were separately considered, given the differences between the laws in the two systems and the specific challenges in Scotland that may necessitate reform.

As emphasised in the law reform in England and Wales section, there are benefits of UK-wide law reform regarding private international law matters in this area, where possible and appropriate, and specifically in relation to the UK-wide pieces of legislation. It would therefore be desirable for Scotland-specific expert input to be provided to the ongoing law reform project of the Law Commission of England and Wales, prior to the finalisation of the reform proposals.6

Similarly, at the international level, relevant international projects, particularly the HCCH Digital Tokens Project, are timely and of global importance and Scotland would benefit from monitoring them closely and contributing to these projects for its private international law reform agenda in the future.

Law relating to electronic trade documents

As discussed in the section dealing with law reform in England and Wales, there has been some recent UK legislation in relation to electronic trade documents (which may or may not fall within the definition of digital assets). The Electronic Trade Documents Act 2023 extends to the whole of the UK, but section 3(4) applies only to Scotland.

Section 3(4) states that an electronic trade document is “to be treated as corporeal moveable property for the purposes of any Act of the Scottish Parliament relating to the creation of a security in the form of a pledge over moveable property”.i This allows for an electronic trade document to be dealt with under the Moveable Transactions (Scotland) Act 2023, sections 42(5) and 44(1)(d), like its paper equivalent, enabling a pledge to be created over some types of electronic trade document, including bills of lading.1

The reforms enacted by the Electronic Trade Documents Act 2023 are commercially important. However, the legislation applies to a relatively small category of what may be considered digital assets and only affects Scots law in a limited way. Even so, it is important to consider the potential interaction between any future legislation on digital assets and the 2023 Act. There would be value in clarifying which of those pieces of legislation will prevail for electronic trade documents that may fall under the scope of both of them.

Given the functional equivalence between paper and electronic forms of trade documents established in the Electronic Trade Documents Act 2023 and the possibility of change of form from electronic to paper (or vice versa) for trade documents, it would be desirable for electronic trade documents to remain unaffected by any future substantive law provisions on digital assets. Electronic trade documents are substantially different from (other types of) digital assets and it is more appropriate to consider them (and any future law reform concerning them) under the law relating to trade documents, rather than digital assets.

Proposals for the reform of the law relating to digital assets more generally are discussed in the section looking at law reform proposals for Scotland.

Criminal law

As with Scots private law, there is a lack of authority regarding digital assets in criminal law. However, in one case resulting in a conviction, Bitcoin was seemingly treated as property for the crime of reset (possession of stolen goods). This case also apparently resulted in the use of proceeds of crime legislation to seize cryptocurrency and convert it into cash. The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, as amended by the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023, provides for confiscation orders and a civil recovery regime for cryptoassets. Criminal law is generally beyond the scope of the present briefing.

Financial regulation and tax law

There is UK legislation that provides for some financial regulation of a sub-type of digital assets, namely cryptoassets. As mentioned in the definitions in Scotland and the UK section, a cryptoasset is defined in the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, section 417(1) (as amended), as “any cryptographically secured digital representation of value or contractual rights that– (a) can be transferred, stored or traded electronically, and (b) that uses technology supporting the recording or storage of data (which may include distributed ledger technology)”. A similar definition is used in the Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing and Transfer of Funds (Information on the Payer) Regulations 2017 (SI 2017/692) reg 14A(3)(a).

The special rules applicable to cryptoassets in the context of financial regulation are beyond the scope of this briefing paper.1 This is also true of the treatment of the wider category of digital assets within financial regulation more generally. There is no bespoke regime for such assets, with the relevant regulation ordinarily depending upon whether and how the digital asset fits within the existing framework.

In the law of taxation, digital assets are dealt with under existing rules for relevant taxes (including income tax, capital gains tax, inheritance tax, value added tax and corporation tax).2 The tax treatment of cryptoassets and other digital assets will not be considered further here.

Law reform proposals for digital assets in Scotland

Expert Reference Group work with recommendations (2019-2023)

The emergence of digital assets and the need to consider legal issues regarding them, led to the Scottish Government establishing an Expert Reference Group (ERG) in 2019. The ERG was chaired by Rt Hon Lord Patrick Hodge, Justice of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, and included members from academia, legal practice, the Law Society of Scotland, the Law Commission of England and Wales, FinTech Scotland and the Scottish Government.

The remit of the ERG was to:

provide legal clarification on Scotland's path to accommodate digital assets within Scots private law which includes the status and treatment of cryptoassets and related technologies;

in so doing, take into account wider UK initiatives which may impact Scotland and the Scottish fintech sector; and

provide advice to the Scottish Government on whether there is a need for legislation to accommodate digital assets in Scots private law and to communicate with the Scottish Government on consequential work.

The ERG undertook a targeted consultation with stakeholders in May 2022,i and reported its findings and recommendations to the Scottish Government in November 2023.1 It recommended the enactment of primary legislation by the Scottish Parliament “to clarify the status of digital assets as property in Scots private law”.1

This part of the briefing looks at:

Commercial and legal reasons for legislating

The ERG proposed that the framing of such legislation should build on the Law Commission's Digital Assets: Final Report,1 the recommendations of which were restricted to the law of England and Wales. The ERG considered that the Law Commission's reasons for enacting “clarificatory” legislation for England and Wales also applied in Scotland.

In fact, they noted that the reasons are stronger in Scotland. This is because it is more challenging for Scotland to rely on court decisions to develop the law. Scottish litigation on the status of digital assets as property was described as “rare to non-existent”.2

The ERG asserted that there is a legal need for legislation, as well as commercial and economic justifications. Regarding the latter, they noted that large sums have been invested in digital asset technology and pointed to the existence of fintech start-ups in Scotland. Reference was made to an estimate by “Scottish Development International” that the value of the blockchain market in Scotland in 2030 could be £4.48 billion.2 The likelihood of this valuation being realised is unknown. The ERG noted the desirability of certainty for businesses and that, without legislation, they might use the law of another system or establish themselves outside Scotland.

Regarding the current law, the ERG stated that:2

On an expansive view of the existing law, digital assets may well be recognised as a kind of property in Scots law. Nonetheless, there is a real risk that they would not or that the law would develop unsatisfactorily in a piecemeal way. The difficulty is that existing definitions of the kind of thing that can be objects of property were formulated long before digital technology was invented. They may now be out of date.

The ERG pointed to Scots law's traditional recognition of only corporeal things and incorporeal rights as property objects, contending that digital assets “are neither one kind of thing nor the other”.2 There is a perceived risk that digital assets “fall outside the legal definition of property, which could deprive businesses of the fruits of their enterprise and their creditors of the means of obtaining payment of their debts”.2

As discussed in the section looking at the current law relating to digital assets in Scotland, it seems that Scots law can largely accommodate digital assets, with a high likelihood that they will be recognised as property objects. Yet the absence of existing authority means that some matters are unclear, including in property law, while other issues need to be addressed to make the law function effectively.

Reform to address the lack of clarity for individuals and businesses around digital assets

Many individuals and businesses in Scotland are using and investing in digital assets.i However, without legislation or judicial confirmation, they might have problems in determining and enforcing their rights or may have to rely on uncertain law.

Law reform relating to digital assets will be useful for various parties, including consumers, investors, creditors and family members of those who have these assets or are considering investing in them. For example, a consumer or investor will wish to know whether and how they can acquire ownership, a creditor would expect to have the ability to enforce against their debtor's digital assets, a married individual will want clarity as to whether they have any entitlement to their spouse's digital assets, and the children of a deceased individual will wish to know if they can inherit such assets from their parent.

The ERG also noted that the risks of non-recognition as property “might also mean that the usual forms of civil recovery of misapplied property would not apply to digital assets” and that it would be “unsatisfactory if, for example, the victim of hack [sic] had no means in private law of recovering their digital assets from the hacker”.1

The ERG consequently recommended the introduction of a short bill to the Scottish Parliament. This would provide clarification regarding aspects of property law, drawing upon and recognising “the existing general practices in the tech industry”.1 The proposed bill would cover the following:1

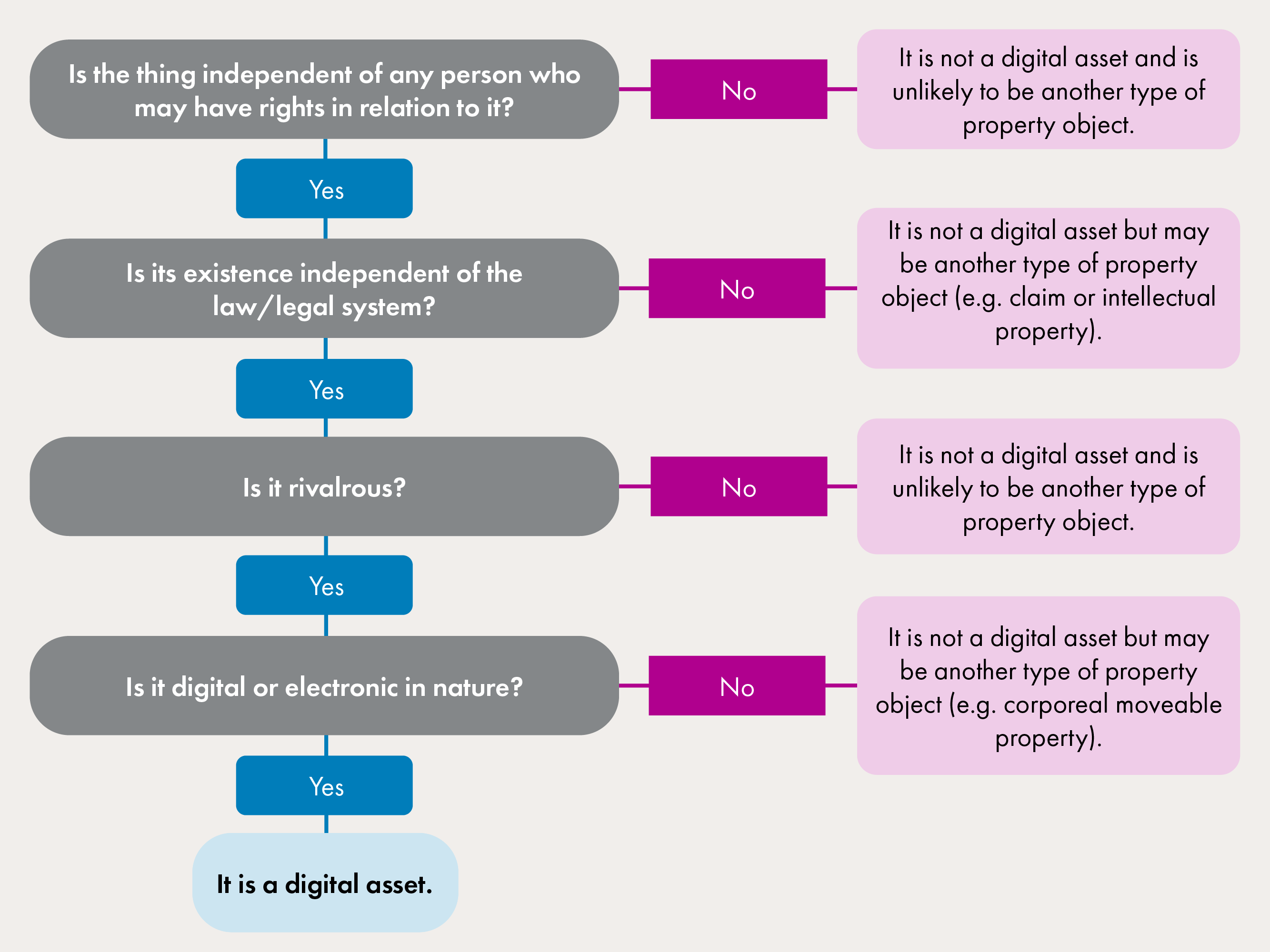

the use of a technologically neutral term to describe assets that would be called “digital objects” (the bill would apply only to those digital assets having an independent existence and capable of rivalrous use), which would accommodate future technological developments, and a statement that they are moveable property;

rules to govern the transfer of ownership of digital objects; and

the preservation of important rules of Scots private law, including a statement that digital objects can be the objects of a trust, and the application to digital assets of the principles of the laws of property, contract, and unjustified enrichment.

Further details about each of these are provided in the ERG's letter to the Minister and some of them will also be referred to in the next section.

The ERG also made secondary recommendations relating to Law Commission recommendations “in which Scottish interests will be engaged”.1 These ERG recommendations would not require legislation by the Scottish Parliament. The details are as follows and they are included here for completeness and as an indicator of possible future work in the area of digital assets:1

the establishment of a panel of industry and academic experts to provide non-binding guidance on the factual and legal issues relating to the control of digital assets - the ERG “considers that this recommendation would be directly beneficial to legal and judicial practice in Scotland” and would seek Scottish representation on the panel to take into account differences between private law in Scotland and elsewhere in the UK.

amendments to the Financial Collateral Arrangement Regulations (No. 2) 2003 (SI 2003/3226) - as the Regulations apply across the UK, and include references to Scottish insolvency legislation, the expectation is that specialists in the law of security rights in Scotland would contribute to amendments to ensure they fit with Scottish legislation. It was suggested that the ERG could help to identify relevant specialists.

a project to formulate a bespoke statutory framework that better and more clearly facilitates the entering into, operation and enforcement of certain crypto-token and cryptoasset collateral arrangements - the ERG stated that this approach also has merit for Scots law, and the ERG could assist in identifying specialists in the law of security rights in Scotland.

Scottish Government's consultation on reform