A review of inter-governmental cooperation and communication during Ukraine resettlement efforts in Scotland

This briefing examines the collaboration and communication that took place between the Government of the United Kingdom, the Scottish Government, the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (CoSLA) and Local Authorities in the implementation of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme and the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme. It draws together the learnings to inform the response to future migration crises that require inter-governmental cooperation.

Glossary

Afghan Citizen Resettlement Scheme (ACRS): A resettlement scheme with three pathways for at-risk individuals from Afghanistan.

Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy (ARAP): The UK Government's relocation policy for former employees of the UK Government in Afghanistan.

Afghan Resettlement Local Authority Network (ARLAN): Regular forum organised by the UK Government for Local Authorities with people resettled under the Afghan schemes. Latterly used to also discuss Ukraine issues.

Association of Ukrainians in Great Britain (AUGB): Representative body for Ukrainians and those of Ukrainian descent in the UK.

Border Force: A law enforcement command within the Home Office that operates immigration and customs controls.

Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (CoSLA): The national association of Scottish councils, acting as the voice of Scottish local government and partner in the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy.

Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC): Now the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government. DLUHC was responsible for administering the UK Government's Ukraine visa schemes beyond the visa application process.

Foundry Case Management System: The software tool procured by the UK Government and developed by the company Palantir. Foundry contains case file data concerning Homes for Ukraine applicants and sponsorship arrangements.

Homes for Ukraine Scheme: The main visa route for people from Ukraine administered by the UK Government. Visas were issued once a person or family had matched with a private sponsor in the UK able to provide safe housing for a minimum of six months.

JIRA Service Management System: The software tool utilised by the UK Government for councils to raise online helpdesk issues with the Foundry Case Management System.

Leave to Remain: A general term for various forms of permission to live in the UK with various rights and entitlements.

Local Government Association (LGA): The national membership body for Local Authorities in England and Wales.

New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy (NSRIS): A Scottish Government Strategy - in partnership with the Scottish Refugee Council and the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities - supporting the integration of refugees, people seeking asylum and other forced migrants in Scotland.

No Recourse to Public Funds: When a person is ineligible to claim most benefits, tax credits or housing assistance paid for by the state.

Objective Connect: A secure digital workspace owned by Social Security Scotland and utilised by the Scottish Government as a means of securely sharing files.

Registered Social Landlord (RSL): A society or company that provides, constructs, improves or manages housing accommodation without seeking to profit.

Scottish Refugee Council: Scotland's national refugee charity and partner organisation in the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy.

Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme: The Super Sponsor scheme removed the need for applicants to be matched with a host before applying for a UK visa.

Strategic Migration Partnerships (SMPs): Local Government led partnerships funded by, but independent from, the Home Office. Their role is to coordinate and support delivery of national programmes in asylum and refugee schemes, as well as agreed regional and devolved migration priorities.

Surge team: An emergency response team deployed within the civil service.

Tariff funding: The UK Government committed to provide one-off funding for Local Authorities to provide wrap-around support for individuals arriving under the Homes for Ukraine Scheme and the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme. Tariff funding was initially set at £10,500 for individuals arriving on or prior to the 31st of December 2022, and was reduced to £5,900 for those arriving on or after the 1st of January 2023.

UK Resettlement Scheme (UKRS): Successor to the Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme, removing the geographical limits of the scheme.

Ukraine Extension Scheme: UK Government scheme to extend the visas of people from Ukraine who were already living in the UK at the time of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Ukraine Family Scheme: UK scheme for people from Ukraine intending to join a close family member already living in the UK.

Ukraine Longer Term Resettlement Fund (ULTRF): A Scottish Government fund established to bring back into use void accommodation of Local Authorities and Registered Social Landlords for the purpose of providing accommodation for Ukrainian Displaced Persons.

Ukraine Permission Extension (UPE) scheme: A UK Government scheme for people who arrived on all the Ukraine schemes operated in the UK to extend their visas by a further 18 months.

Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme (VPRS): A UK Government scheme which was established with the intention of resettling 20,000 refugees from Syria.

Warm Scots Welcome app: The digital platform designed by the Scottish Government and used by Local Authorities and the Scottish Government's surge team to match people in temporary accommodation to hosts or suitable accommodation in Scotland.

Welcome Accommodation: The temporary accommodation offered to displaced persons from Ukraine by the Scottish Government while long-term housing could be found.

Welcome Hubs: Spaces created by the Scottish Government for those arriving under the Super Sponsor Scheme where could receive advice and initial triage of requirements.

Welsh Local Government Association: The representative body of Local Government in Wales.

Executive Summary

This briefing presents the results of research into the development and implementation of the resettlement schemes in the United Kingdom for people from Ukraine following Russia's illegal invasion. The research has been undertaken by Dr Dan Fisher from the Centre for Public Policy at the University of Glasgow and has been informed by interviews with senior actors and decision-makers in the Scottish Government, CoSLA and Local Authorities who were involved in the resettlement of people from Ukraine in Scotland. The views expressed in this briefing are the views of the author, not those of SPICe or the Scottish Parliament.

On 24 February 2022, Russian forces launched an illegal invasion of Ukraine. As a result of the invasion and ongoing fighting, figures from the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) show that over 5 million people from Ukraine had sought refuge outside the country as of 2024.1

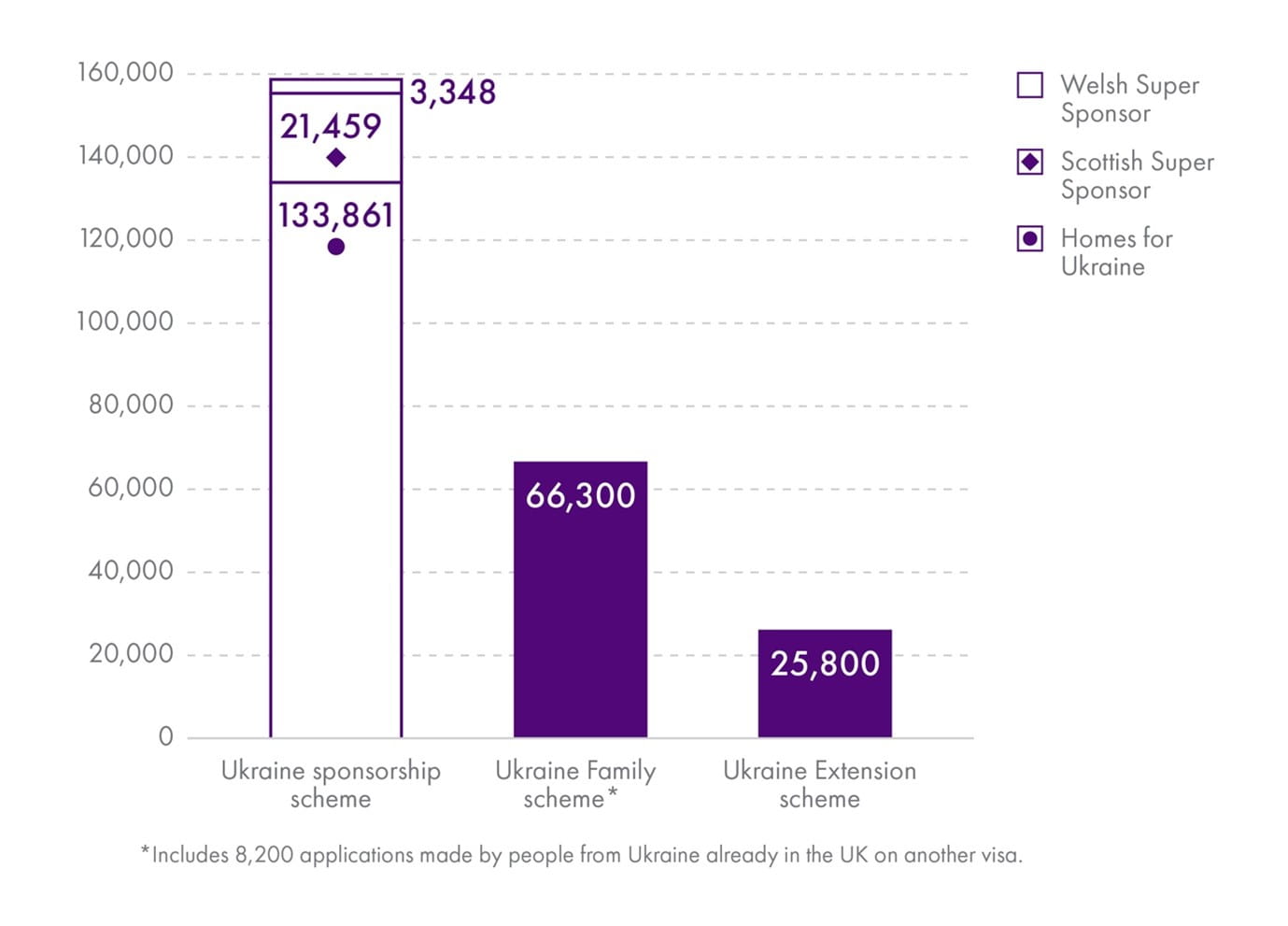

Following the Russian invasion, the UK Government launched the Homes for Ukraine Scheme and the Ukraine Family Scheme. The Homes for Ukraine scheme (also referred to as the Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme) allowed UK residents to sponsor displaced people from Ukraine to live with them while the Ukraine Family Scheme permitted Ukrainian nationals to join or stay with their relatives in the UK. A Ukraine Extension Scheme was also introduced for persons from Ukraine who held a valid UK visa on or after 1 January 2022.

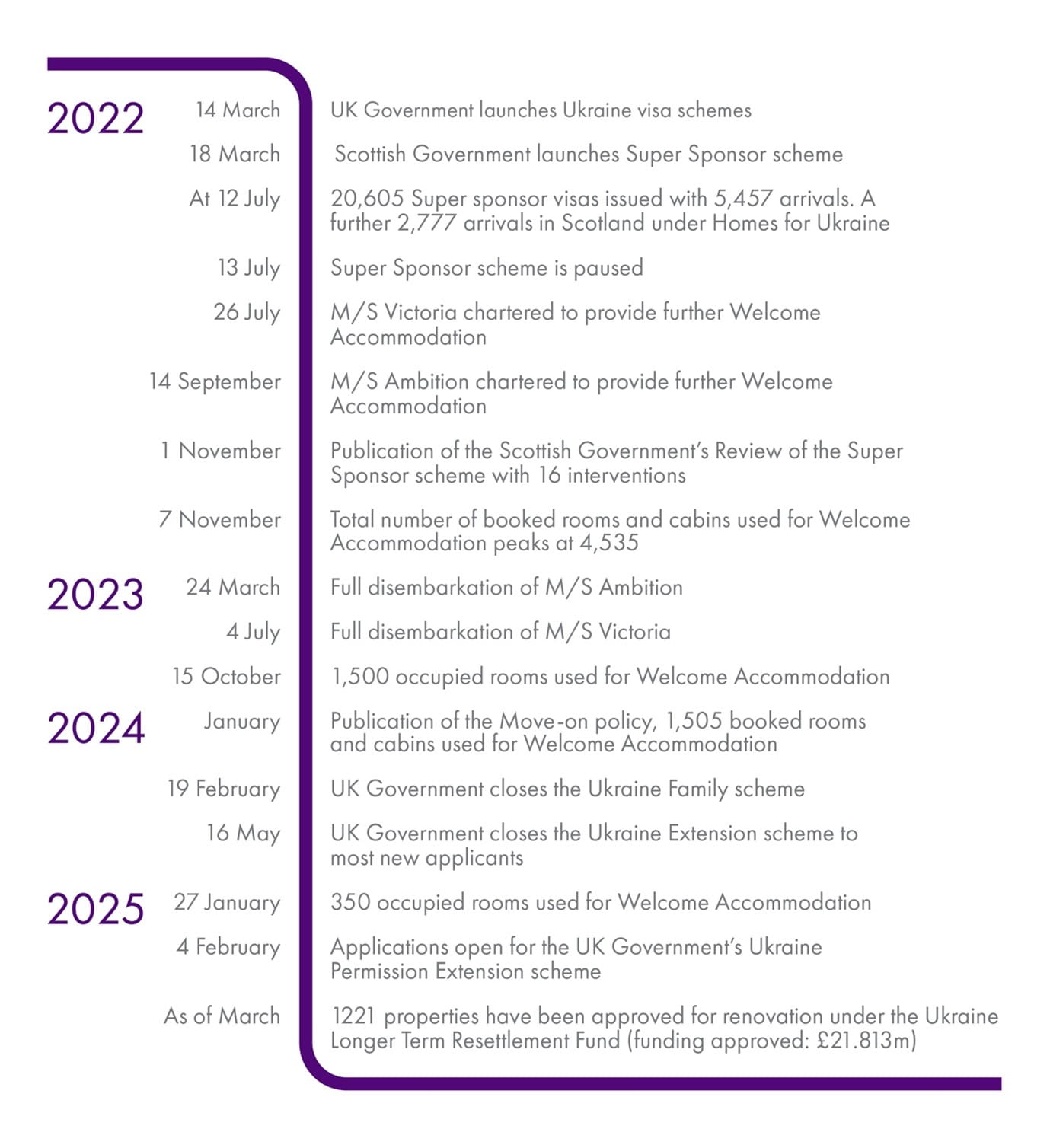

The Scottish Government introduced the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme, which sits within the Homes for Ukraine Scheme. The Super Sponsor Scheme allowed people from Ukraine to apply for a Homes for Ukraine Scheme visa by naming the Scottish Government as their sponsor. This meant that people did not need a pre-arranged host, thereby simplifying the visa process and improving safeguarding. Under the scheme, the Scottish Government provided temporary accommodation (known as Welcome Accommodation) to people from Ukraine, followed by support to secure future housing. As it sits within the Homes for Ukraine Scheme, certain aspects of the Super Sponsor Scheme were the responsibility of the UK Government - most notably the visa approval process. Other elements of the scheme - such as the provision of Welcome Accommodation - were administered by the Scottish Government. As a result, the Super Sponsor Scheme element of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme was administered differently in Scotland compared to the rest of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme. The Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme is currently paused for new applications.

There were just 32 days between the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and people from Ukraine being able to apply for both the Homes for Ukraine Scheme and the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme. Therefore, both schemes were developed and implemented more quickly than other comparable resettlement schemes due to time limitations. It is also worth noting that the governmental departments responsible for operating both schemes - the UK Government’s Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities (DLUHC) and the Scottish Government’s Equality, Inclusion and Human Rights Directorate had not previously led on the design and implementation of refugee resettlement schemes.

This briefing offers learnings that can be gained from the implementation of both the Homes for Ukraine Scheme and the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme in Scotland. It provides an in-depth analysis of the collaboration and communication that took place between the UK Government, the Scottish Government, the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (CoSLA) and Local Authorities in Scotland. It has been informed by qualitative interviews with senior actors and decision-makers in the Scottish Government, CoSLA and Local Authorities who were involved in the resettlement of people from Ukraine in Scotland. Conclusions drawn in this briefing are based on those interviews which were conducted on the understanding that direct quotes would be used in the briefing. The UK Government’s Ministry for Local Government, Housing and Communities was directly approached for input for this briefing, however these requests for participation were refused citing resource pressures.

The use of qualitative data and direct interview quotes sets this briefing apart from a normal SPICe briefing. This approach is as a result of the briefing being the main output of a SPICe academic fellowship conducted by Dr Dan Fisher (Centre for Public Policy, University of Glasgow). Academic fellowships allow authors time to research issues in greater depth including where appropriate to undertake qualitative interviews.

The Homes for Ukraine Scheme

Under the Homes for Ukraine Scheme, 7,093 individuals arrived in the UK through visas that were sponsored by individuals or households based in Scotland.i This figure represents almost 4.3% of the total number of people resettled to the UK through sponsorship. The Scottish Government was kept abreast of the UK Government’s plans, though it sought less involvement in the design of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme once it had been decided that the Scottish Government would launch its own Super Sponsor Scheme.

During the design of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme, CoSLA interviewees described an under-utilisation by DLUHC of the existing Strategic Migration Partnerships (Local Government led partnerships that coordinate and support the delivery of asylum and refugee schemes) – although this was mitigated by the initial involvement of the Local Government Associations (LGAs). Local Authority resettlement lead officials were not included in the policy design of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme.

At the outset, Scottish Ministers had significant concerns regarding the visa application process for the Homes for Ukraine Scheme – these concerns were also expressed in an open letter co-signed by the then Scottish party leaders Nicola Sturgeon MSP (SNP), Anas Sarwar MSP (Scottish Labour Party), Patrick Harvie MSP and Lorna Slater MSP (Scottish Green Party) and Alex Cole-Hamilton MSP (Liberal Democrats), which was sent to then Prime Minister Boris Johnson MP. Across the Scottish Government, CoSLA and Local Authorities, interviewees were concerned with the potential for safeguarding issues to arise with the sponsorship model of refugee resettlement to be adopted by the Homes for Ukraine Scheme.

Local Authority resettlement teams experienced significant challenges in implementing the Homes for Ukraine Scheme, in particular as a result of the fast pace of arrivals from Ukraine and the slow means by which data was shared with Local Authorities by the Home Office. This issue was compounded by Scottish Local Authorities’ lack of access to the data management system procured by the UK Government (known as ‘Foundry’), which contains case file data concerning applicants to the scheme and sponsorship arrangements. These challenges exacerbated the risk of safeguarding issues arising, as people were routinely arriving before property and disclosure checks had taken place.

CoSLA and Local Authority interviewees continue to express reservations about the temporary nature of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme’s funding model, which provided Local Authorities with one year of funding per displaced person to provide wraparound support. Local Authority interviewees also expressed concern at the lack of consideration by the UK Government of the role of Local Authorities in managing hosts and engaging with local communities. Managing hosts was an aspect of refugee resettlement that had not previously been required in Scotland at such a scale – and there were challenges in managing hosts’ expectations of the scheme and what housing would be available for their guests after the initial sponsorship period had ended.

Despite the concerns set out above, the Homes for Ukraine Scheme was viewed positively by Local Authority interviewees as, after the scheme was fully established, it was considered less ‘hands-on’ than the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme (albeit with fewer people resettled per capita). In addition, the Homes for Ukraine Scheme was viewed by Local Authority interviewees as being beneficial for rural areas with available jobs and sponsorship accommodation.

There was a mix of views expressed about the UK Government’s communication with stakeholders in Scotland in relation to the development and operation of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme. Following the scheme’s establishment, Scottish Government respondents reported good communication with the UK Government regarding the scheme and, in particular how scheme guidance was adapted to fit Scotland-specific legislation and the Scottish context. However, CoSLA interviewees noted that they were not included in strategic discussions with the UK Government, in contrast to their involvement in other refugee resettlement schemes.

Local Authority interviewees reported limited discussion and information-sharing about the Homes for Ukraine Scheme with the UK Government. While a forum for discussing the scheme with Local Authorities was later established, this provided limited space to discuss the specificities of the scheme’s implementation in Scotland. There are ongoing concerns amongst Local Authorities regarding the Ukraine Permission Extension Scheme, the lack of support provided to ensure it is correctly implemented, and the potential for people's visas to expire without their knowledge and without Local Authorities' knowledge given the issues of data management and data sharing.

The Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme

In total 21,702 individuals arrived in the UK through the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme (i.e. by naming the Scottish Government as their sponsor on their Homes for Ukraine visa application). This figure represents 13.1% of the total number of people resettled to the UK through sponsorship and 75% of the total number of arrivals of displaced persons from Ukraine to Scotland through sponsorship.

The Super Sponsor Scheme was originally envisaged as an approach to resettling an initial 3,000 people. It was on this basis that an agreement was reached between the Scottish Government and CoSLA for a Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme. Despite this initial agreement and the inclusion of CoSLA representatives and three Local Authority Chief Executives in planning meetings, there appears to have been a lack of alignment between the Scottish Government, CoSLA and Local Authorities concerning key aspects of the Super Sponsor Scheme, namely; the decision not to cap the scheme and the decision to use short-term accommodation such as hotels (referred to as Welcome Accommodation) to temporarily house new arrivals until longer-term housing arrangements could be found.

It was suggested in some interviews with CoSLA and Local Authority research participants that there had been an over-estimation of the housing capacity within Scotland to support an uncapped scheme, as well as an underestimation of the resource required in the Scottish Government and Local Authority resettlement teams to manage it. When the scheme was launched, the teams within the Scottish Government’s Equality, Inclusion and Human Rights Directorate and CoSLA’s Migration, Population and Diversity team initially consisted of a small number of people relative to the eventual scale of the Super Sponsor Scheme. Similarly, Local Authority resettlement teams would (prior to Ukraine) have consisted of a handful of people depending on the size of the Local Authority. Therefore, although there was significant experience of refugee resettlement within Scotland prior to the war in Ukraine, the initial burden of the challenge fell on a small number of people who worked long hours to deliver the scheme.

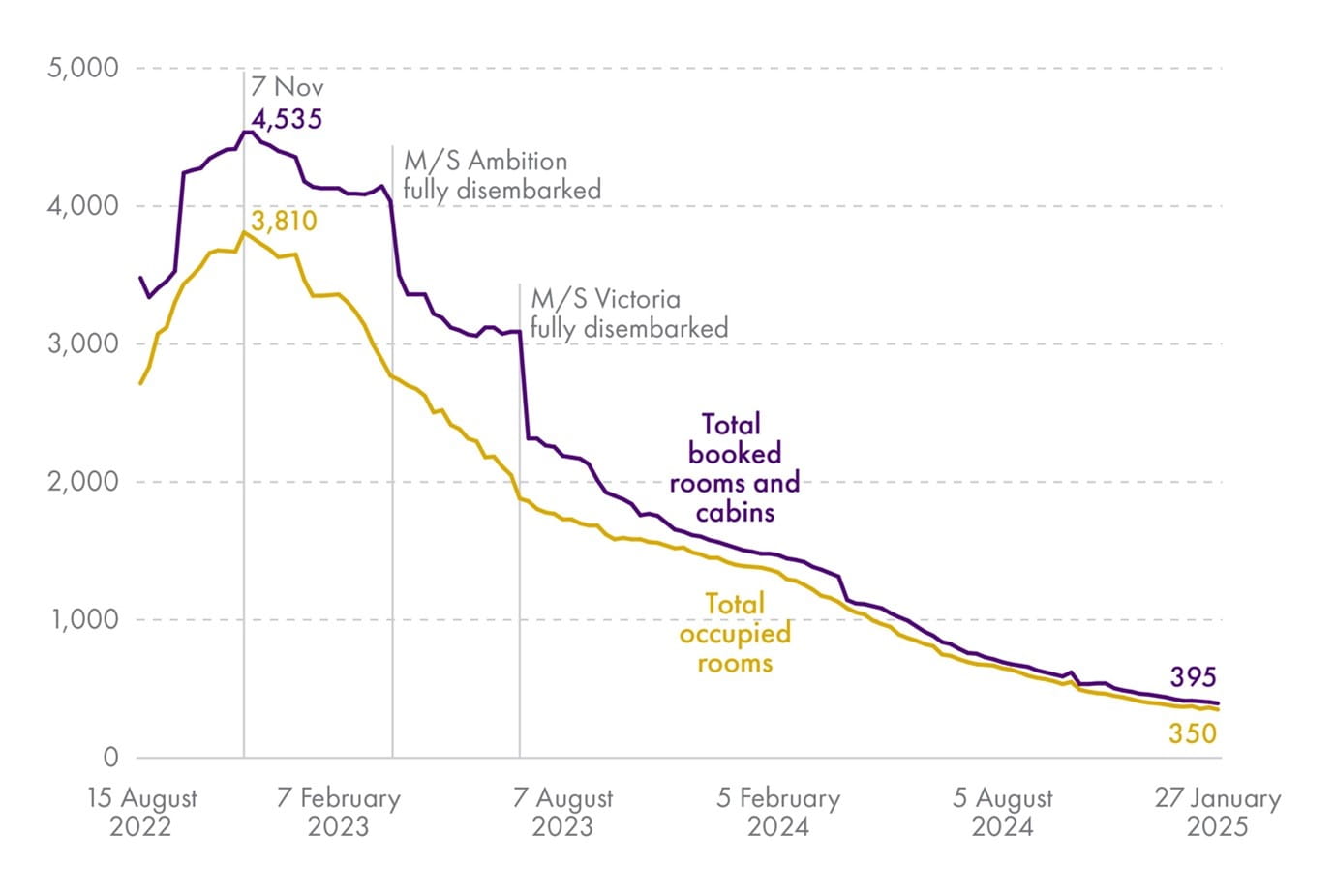

Challenges around data management and data sharing between the UK Government and the Scottish Government were significant issues in the implementation of the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme. The Scottish Government had limited oversight of the backlog of visa applications that the Home Office were working through once the Super Sponsor Scheme was launched. Scottish Government interviewees noted that the lack of Scottish Government oversight of visa approvals affected planning for the procurement of Welcome Accommodation. Following the establishment of the Super Sponsor Scheme, some collaborative challenges between the UK Government and the Scottish Government emerged. These centred on the funding for the scheme and the procurement of vessels M/S Ambition and M/S Victoria for use as Welcome Accommodation, where Home Office concerns regarding the visas of crew members slowed procurement.

The Super Sponsor Scheme proved to be more popular than expected and it was paused after a spike in applications in July 2022. However, even before this point was reached, Local Authorities had been calling for the scheme to be paused due to concerns regarding the number of arrivals and their capacity to deliver the scheme safely. In addition, moving people out of Welcome Accommodation became a major challenge for the scheme; as many of those arriving did not subsequently accept longer-term offers of accommodation – especially once parents had registered children in schools and adults had become locally employed. A bottleneck therefore emerged in the Welcome Accommodation which became difficult to unpick. While some Local Authorities advocated for a firmer approach to the provision of offers of accommodation, others were concerned of a potential rise in homeless presentations occurring in areas with existing housing pressures if such offers were nevertheless refused.

Prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Scotland had established an internationally renowned New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy (NSRIS), which includes principles of refugee integration and working group structures around key issues such as housing, employability and welfare rights, language, and health and wellbeing. While the Strategy was considered to have been acknowledged by the Scottish Government in the planning process and throughout the evolution of the scheme’s implementation, Local Authority and CoSLA interviewees expressed concern that the Strategy’s principles were not being adhered to in the implementation of the Super Sponsor Scheme. These concerns centred on the incompatibility between the Strategy’s principle of “integration from day one” and the fact that people resettled under the scheme were living for extended periods in temporary Welcome Accommodation. CoSLA and Local Authority interviewees also discussed how the existing NSRIS working group structures had not been adopted in the implementation of the scheme, noting challenges arising from the Scottish Government’s involvement in the scheme’s operational activities while overarching issues concerning the scheme remained unresolved for long periods of time.

Despite the challenges discussed in this briefing, the resettlement of people from Ukraine to Scotland was a positive demonstration of the UK Government, Scottish Government, CoSLA and Local Authorities cooperating in the face of a crisis. The Ukraine response emphasised the value of trust and regular communication between Scottish Government departments and their UK Government counterparts – especially where these departments do not routinely work together outside of crisis situations. The need to respond quickly to the war in Ukraine also provided opportunities for innovation to occur in the context of resettlement and housing. Building on this positive cooperation, this briefing offers learnings that can be gained from the implementation of both the Homes for Ukraine Scheme and the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme in Scotland.

1. Introduction

This briefing provides an in-depth analysis of the collaboration and communication that took place between the Government of the United Kingdom (UK), the Scottish Government the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (CoSLA) and Local Authorities in Scotland in the context of the humanitarian response to the war in Ukraine. Efforts to evacuate and resettle displaced persons from Ukraine to Scotland were designed and delivered at pace. The Ukraine schemes therefore diverged from previous refugee resettlement schemes where Local Authorities volunteered to resettle individuals and families in return for a pre-determined funding package.i This briefing presents the experiences of some of those involved in this resettlement work and draws together the learnings to inform the response to future migration crises that require inter-governmental cooperation.

On 24 February 2022, Russian forces launched an illegal invasion of Ukraine. Information on the background to the conflict can be found in a previous SPICe blog.1 As a result of the invasion and ongoing fighting, figures from the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) show that over 5 million people from Ukraine had sought refuge outside the country as of 2024.2 Following the Russian invasion, the UK Government launched the Homes for Ukraine scheme and the Ukraine Family Scheme. The Homes for Ukraine Scheme (formally referred to as the Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme) allowed UK residents to sponsor displaced people from Ukraine to live with them while the Ukraine Family Scheme permitted Ukrainian nationals to join or stay with their relatives in the UK. A Ukraine Extension scheme was also introduced for persons from Ukraine who held a valid UK visa on or after January 1, 2022. Displaced persons from Ukraine sponsored by individuals in Scotland were eligible for homeless support from councils in Scotland where sponsorship breakdowns occurred or when their sponsorship came to an end.

The Scottish Government introduced the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme to sit within the Homes for Ukraine Scheme (see Figure 1). The Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme allowed people to apply for Homes for Ukraine visas without needing a pre-arranged host, thereby simplifying the visa process. Under this scheme, the Scottish Government served as the sponsor and provided temporary Welcome Accommodation to people from Ukraine, followed by support to secure future housing. The visa did not require persons to stay in Scotland for the duration of their visa and people were free to move throughout the UK though, as with the UK Homes for Ukraine Scheme, they would not have been eligible for homeless support outwith Scotland.ii

As of March 2025, 165,390 people had arrived in the UK through the Homes for Ukraine Scheme (including individual sponsors and sponsorship by the Scottish and Welsh Governments). A further 66,300 people arrived in the UK under the Ukraine Family Scheme and 25,800 extended their existing visas under the Ukraine Extension Scheme.3 A breakdown of the number of people that arrived through the Homes for Ukraine Scheme is provided in Section 3 of this briefing.

Displaced persons from Ukraine therefore arrived in Scotland under all three UK Government schemes; including Homes for Ukraine Scheme visa applications where the Scottish Government acted as the sponsor. This briefing is specifically focused on the Homes for Ukraine scheme and the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme. While the Homes for Ukraine scheme was administered by the UK Government, the Scottish Government published guidance for hosts in Scotland for both schemes and a bespoke safeguarding process for sponsorship was developed by the Scottish Government with its partners. Occasionally, people arriving under the Homes for Ukraine Scheme through private sponsorship arrangements could also be housed in Welcome Accommodation in the event of sponsorship breakdowns.

This briefing is structured into 6 Sections. The establishment and implementation of the Homes for Ukraine scheme is discussed first, followed by the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme. It is important to bear in mind, however, the near-simultaneous implementation of both schemes (see Figure 2). The briefing is structured as follows:

Section 2 sets out the methodology that underpins the briefing's findings.

Section 3 provides an overview of the total number of people that arrived in the UK through the Homes for Ukraine Scheme, including the number of people sponsored by the Scottish Government through the Super Sponsor Scheme. It also provides a high-level summary of the funding that was provided by the UK Government and the Scottish Government to run both schemes.

Section 4 discusses the Homes for Ukraine Scheme in Scotland and is split into three parts: i) cooperation concerning its establishment, ii) the reaction to the scheme from the Scottish Government, CoSLA and Local Authorities, iii) the implementation of the scheme in Scotland, and iv) the ongoing inter-governmental collaboration that then took place.

Section 5 discusses the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme and is split into five parts: i) collaboration concerning its establishment, ii) the design of the scheme, iii) the visa processing and pause of the scheme, iv) the ongoing inter-governmental collaboration that took place, and v) the long-term challenge of moving people out of Welcome Accommodation.

The concluding section considers the learnings that can be gained from this work.

2. Methodology

The briefing is informed by qualitative interviews with 29 senior actors and decision-makers involved in the evacuation and resettlement of people from Ukraine to Scotland. Broken down into sub-groups; nine individuals were interviewed that could provide a perspective from the Scottish Government,i five interviews were conducted with those that could provide a perspective from CoSLA and fifteen interviews were conducted with staff from eleven Scottish Local Authorities.ii Given the need to maintain the anonymity of those interviewed, the briefing makes no distinctions between elected officials and civil servants when quoting interviewees. Similarly, no distinction is made between CoSLA staff and elected officials.

Interviews were conducted on the understanding that direct quotes would be used for this briefing. Given the complexity of the topic, many quotes were checked with interviewees to ensure the accuracy of both their statements and their interpretation by the researcher. Occasionally statements are made concerning interviewees’ views without a quote being provided. This occurs where quotes would likely lead to the interviewee being recognised or where the interview was conducted without recording.

The UK Government’s Ministry for Local Government, Housing and Communities was directly approached for input for this briefing, however these requests for participation were refused citing resource pressures.

Interviews followed a semi-structured interview schedule which focused on the:

Design of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme

Design of the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme

Challenges and experiences of implementation across both schemes

Current concerns

Lessons learned and/or lessons that respondents hoped others might learn

Recurring themes in the interviews, which are also reflected in the findings of this report, include discussions concerning data management and data sharing; the challenge of matching people in temporary accommodation to long-term housing; the vulnerability of displaced persons from Ukraine; and the novelty of not only the resettlement schemes but also of the connections that needed to be made between UK Government and Scottish Government departments, as well as between both governments’ departments, CoSLA and Local Authorities.

A consistent challenge when conducting the interviews was that of maintaining a separation between the Homes for Ukraine Scheme and the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme when discussing the implementation of both by local actors. The ways in which the schemes blended and created difficulties for Scotland’s Local Authorities will be discussed, but it is important to acknowledge that research participants did occasionally struggle to separate the schemes during the interviews. A further challenge to be acknowledged is that of the speed at which decisions were being made at the start of the war and the time that has passed since those initial months, during which the schemes were being established.

While the briefing is intended to be a resource to capture peoples’ learnings and experiences of this time, interviewees would often state that their memories were unclear regarding certain events and timelines. Interviewees were therefore not quoted on matters that they were uncertain on. In addition, this briefing teases out the discussions surrounding the establishment of both the Homes for Ukraine Scheme and the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme, and subsequent planning discussions surrounding their implementation. It is important to acknowledge that these events occurred so quickly that, for some research participants, there would be very little time between these two stages.

All interviewees have been anonymised for the purpose of this publication and quotes have been edited and/or redacted to preserve the anonymity of the speakers and, where relevant, other actors they discussed in their quotes.

As with all briefings, there are certain limitations and elements that have fallen outwith the scope of this work. Future work will be required to capture the experiences of UK Government officials, representatives of the third sector and displaced persons from Ukraine. In addition, multiple respondents mentioned the importance of the Welsh Government and Welsh Local Government Association in terms of complementing Scottish Government’s communications with the UK Government and providing learnings for use in the Scottish context. For the most part, this is a topic that falls outwith the scope of this report, although there are occasions when these links with the Welsh experience are discussed.

3. The Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme: people resettled and funding provided

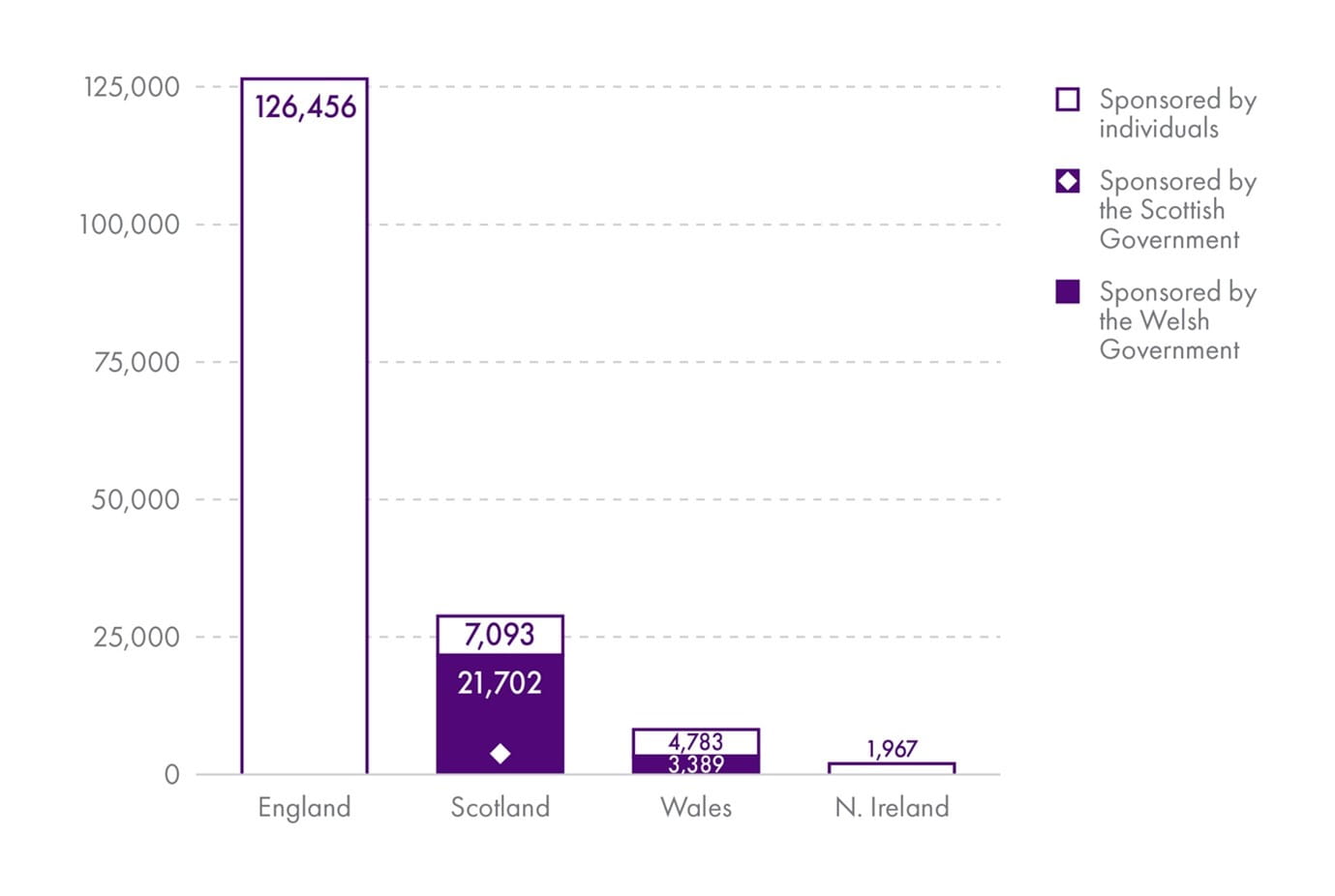

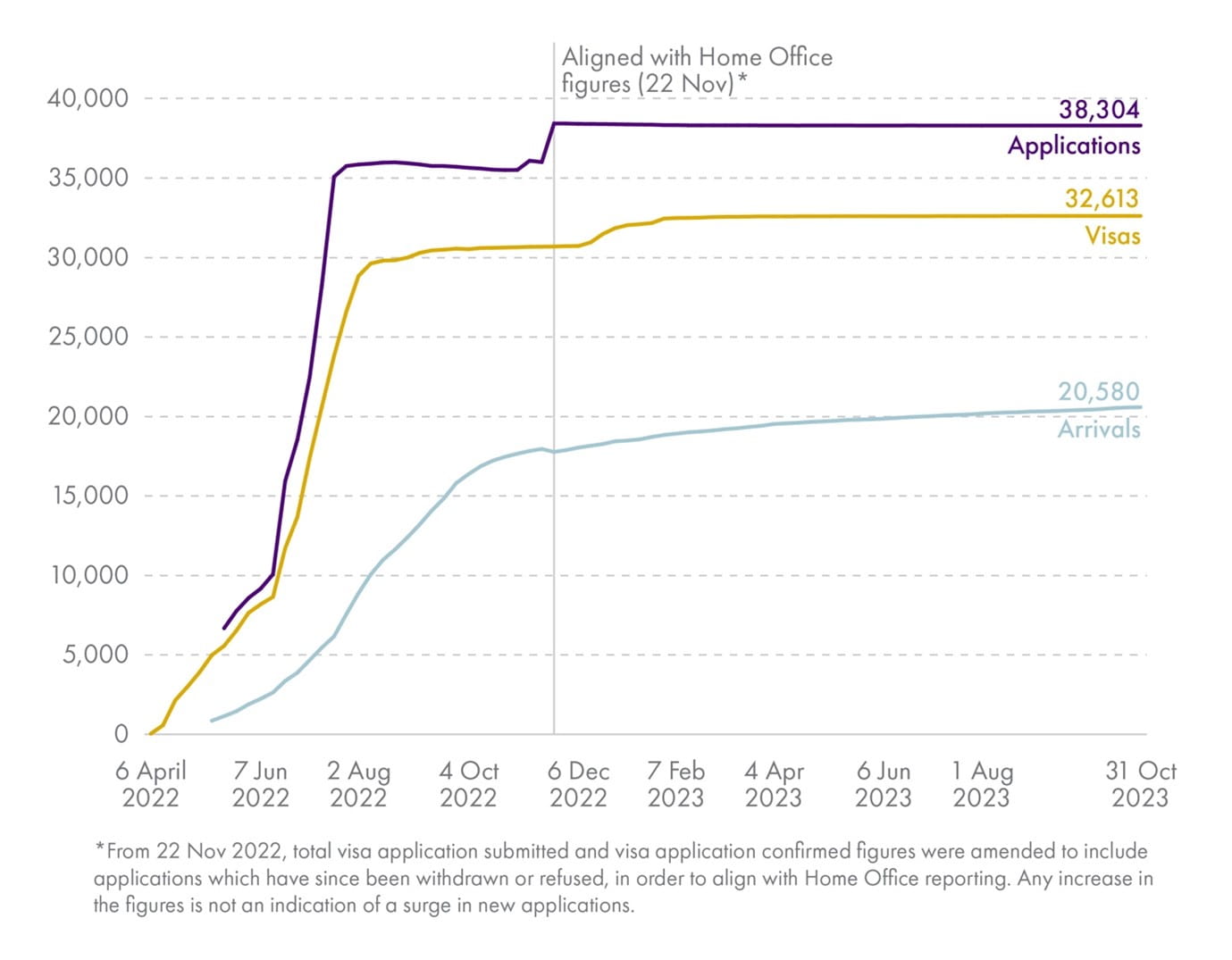

The collective efforts of governments across the UK to introduce sponsorship schemes to bring people to the UK (and of households to provide hosting arrangements) helped provide a significant number of people with a place of safety. As of March 2025, 165,390 people have arrived in the UK through sponsorship arrangements.1 As data is not collected on people's movements following their arrival in the UK, it is not possible to state how many displaced persons from Ukraine were resettled in Scotland specifically. Through sponsorship in Scotland (i.e. by combining private hosting arrangements for Homes for Ukraine visas and applications with the Scottish Government as the host), 28,795 people have arrived in the UK– representing 17.4% of the total number of arrivals through sponsorship (see Figure 3).2

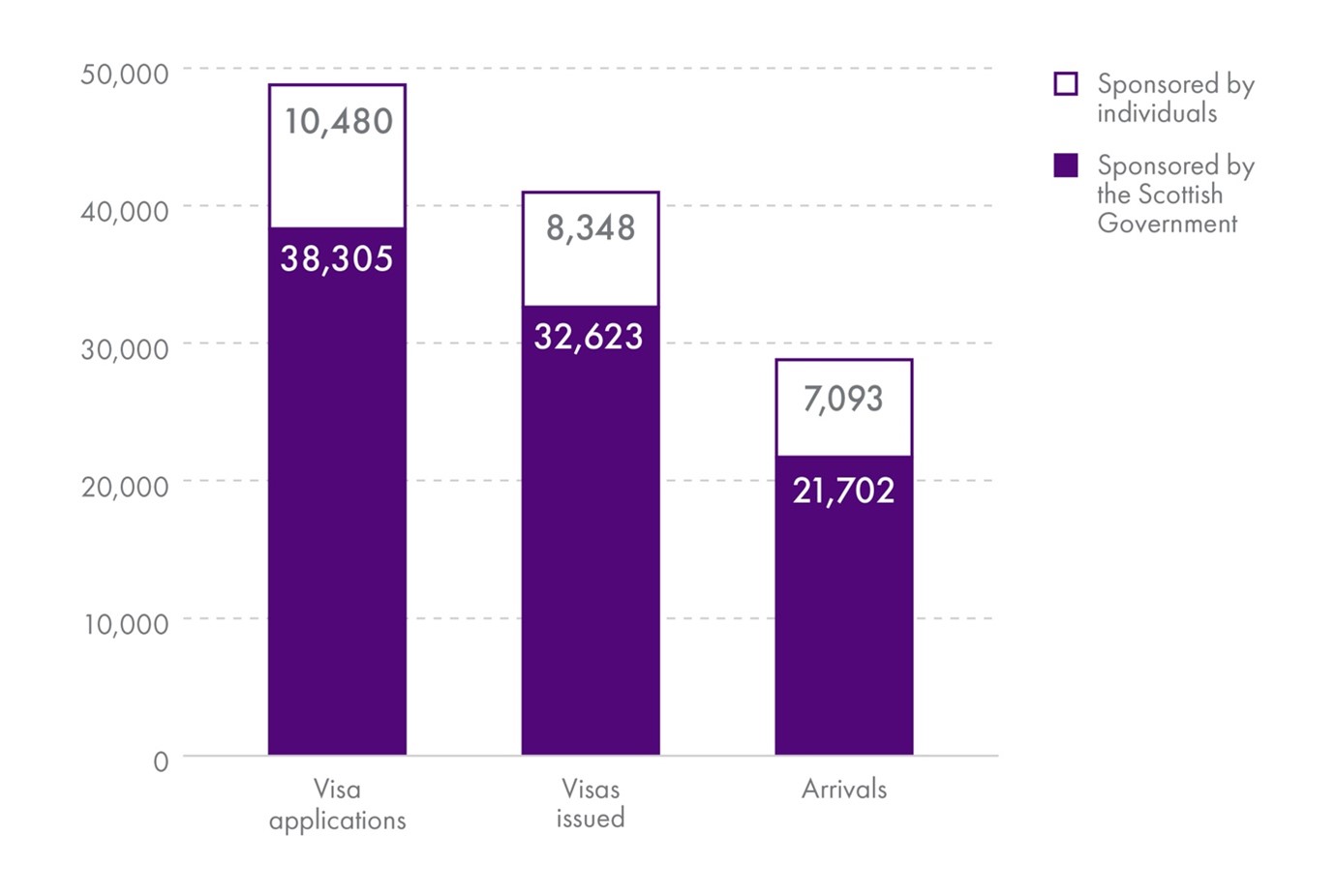

The Scottish Government has acted as sponsor for 21,702 displaced persons from Ukraine, which represents 75% of the total number of arrivals of people to the UK through a Scotland-based sponsorship arrangement (see Figure 4).2 At the time of writing, there are a further 11,164 Scottish Super Sponsor visa holders that could yet travel to Scotland.2

The UK Government committed to provide one year's worth of funding for Local Authorities to provide wrap-around support for individuals arriving under the Homes for Ukraine Scheme (referred to as tariff funds). After discussion (see Section 5.4), it was also agreed that the UK Government would provide the same tariff funding to Local Authorities for those arriving under the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme. Tariff funding was initially set at £10,500 for individuals arriving on or prior to 31 December 2022, and was reduced to £5,900 for those arriving on or after 1 January 2023.5

In addition to the tariff funds, hosts were given £350 per month ‘thank you’ payments from the UK Government as a gesture of support for providing free accommodation.i At the end of September 2023, the National Audit Office calculated that the UK Government had provided £2.1 billion in funding through tariff payments and ‘thank you’ payments.6

Data published by the Scottish Government in January 2024 show that the Scottish Government contributed £231 million to support people from Ukraine through its overarching Warm Scots Welcome programme.7 This included £196.9 million to fund the provision of free Welcome Accommodation for those arriving from Ukraine under the Super Sponsor Scheme (the Scottish Government claimed £5.5 million from the UK Government in ‘thank you’ payments to partially offset this cost).7 In addition, the Scottish Government funded third sector grants, Local Authority grants and direct running costs of the Ukraine resettlement efforts in Scotland.

Separate research is required to explore the funding that was provided as part of the sponsorship schemes in more detail. For the purposes of this briefing it is noteworthy that Local Authorities were able to use tariff funding for aspects of their work in Welcome Accommodation, yet the limiting of the tariff to one year meant that in many cases these funds had been claimed before a person on the Super Sponsor Scheme was moved to the Local Authority in which they would eventually settle. Local Authorities were also able to claim funds from the Scottish Government for their provision of support to people in Welcome Accommodation, although respondents noted that the specifics of what could be claimed for had to be discussed in retrospect.

4. The Homes for Ukraine Scheme in Scotland

4.1 Cooperation concerning the Homes for Ukraine scheme

On Monday 14 March 2022, the UK Government announced its Homes for Ukraine Scheme, through which households in the UK could sponsor a displaced person in Ukraine to travel to the UK. The scheme was subsequently launched on Friday 18 March 2022. Hosts would receive £350 per month in the form of ‘thank you’ payments from the UK Government, which would be administered by the Local Authority. Hosting arrangements were expected to last for at least six months. Local Authorities were initially provided with 1-year tariff funding to support their ‘wrap-around’ integration services of £10,500 (per sponsored person). This tariff was reduced to £5,900 for new arrivals from 1 January 2023 onwards.1

Unlike the European Union (EU), which issued a Temporary Protection Directive through which displaced persons from Ukraine could enter the EU without a visa, the UK Government’s Scheme required displaced persons to make contact with households in the UK in order to apply for a Homes for Ukraine visa. In line with the wishes of the Ukrainian Government, displaced persons from the Ukraine who were granted a visa were not granted refugee status and were initially offered three years’ Leave to Remain (LtR) in the UK.i

According to those interviewed, the Scottish Government was able to hold close conversations with the UK Government regarding the policy directions being taken by the UK Government for its Homes for Ukraine Scheme. As recollected by a Scottish Government interviewee,

“We were involved in at least some of the [early] discussions [regarding Homes for Ukraine]. From my experience, there was always a risk that conversations that were happening at a UK Government level would not be sufficiently inclusive. […] We had been working together well all through the pandemic, so there were quite good relationships with, for example, the Cabinet Office. There were less well-developed relationships […] with the Home Office and with […] the Department for Communities and Local Government. […] What we did was seek to ensure very good, frequent engagement to understand the policy direction that was being taken at a UK Government level.”

Other interviewees also recalled there being good levels of communication at both the Ministerial level and between civil servants serving the Scottish and UK governments, yet recalled the fact that everyone involved was dealing with limited information. As stated by a Scottish Government interviewee,

“Nobody really knew what was happening, what would happen, what the scale of the [Russian] invasion would be, what it would mean in terms of refugees, what role we would play in that. So huge levels of uncertainty throughout actually. But the channels of communication were put in place fairly early on and very quickly. And the UK Government quite quickly started talking about their Homes for Ukraine Scheme [… and] we were trying to establish information about the Homes for Ukraine Scheme and what that would mean [for Scotland].”

It became clear from an early stage, however, that the Scottish Government would have the opportunity to develop its own Super Sponsor Scheme (discussed in Section 5). As a result, attention in the Scottish Government turned to the latter’s design. As mentioned by a Scottish Government source,

“In the Scottish Government we probably saw [Scottish Super Sponsorship] as sitting alongside the Homes for Ukraine Scheme and that most of our focus […] was put into making sure the Super Sponsor Scheme worked after we had obtained, really quite rapidly, agreement from the UK Government to go ahead and do it.”

Although there were meetings between the UK Government, Scottish Government and Local Authority leads from areas where it was anticipated that most people would arrive, Scottish Local Authorities and CoSLA reported that they were not meaningfully included in discussions regarding the initial design of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme. Local Authority interviewees reflected that this lack of consultation was not wholly unlike their existing relationship with the UK Government through the Home Office. As one source stated,

“I find that with the UK Government, they don't check in with us to say, ‘Do you agree with this, do you think this looks right?’ It's more like, ‘ This is what we're doing, you will need to come along with it.’”

Representatives of CoSLA noted a distinct lack of engagement with local government concerning the design of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme. They attributed this lack of engagement to the fact that the scheme was led by DLUHC instead of the Home Office, which traditionally leads on refugee resettlement programmes and with whom they had existing working relationships. According to a CoSLA interviewee, the Strategic Migration Partnerships (local government led partnerships that coordinate the delivery of refugee schemes), were insufficiently included in the discussions regarding Homes for Ukraine.

“There was very little engagement with local government across the UK around Homes for Ukraine. And it was established without meaningful discussions with us […] Part of that, I think, was because DLUHC were kind of entering a new space for themselves and they didn’t get the role of Strategic Migration Partnerships (even though they are a local government-facing department). They didn’t understand that world [of migration and resettlement]. And therefore, I think, they […did] their own thing and had their own ideas without tapping into the [existing] expertise that was out there.”

A key factor that the interviews have highlighted is how important trust and pre-existing relationships are to designing effective policies at speed. However, in some cases, existing relationships were nevertheless able to support the development of the Homes for Ukraine scheme, as demonstrated in the following CoSLA interview excerpt concerning discussions of the necessary disclosure checks on sponsors and environmental checks on their properties that needed to take place:

“I definitely think the local government perspective was taken on board [by the UK Government] because there were so many questions around the safeguarding and the checking of all the homes and the hosts etc […] The conversations where [those issues] were framed were when we sat with the other two Local Government Associationsii […] Those [meetings] were much more influential than [meetings] with the Strategic Migration Partnership leads.”

CoSLA interviewees noted the need to consider how the scheme’s implementation would differ between the four nations and how the scheme would require new teams within Local Authorities to work together. Rather than being communicated through the Strategic Migration Partnerships, CoSLA research participants stated that such concerns were discussed through meetings between DLUHC, CoSLA, the Local Government Association (LGA) and the Welsh Local Government Association (WLGA). They noted that,

“The LGAs probably were really quite useful to DLUHC at that point because all three of us worked really hard to give them context and understanding - not only of Local Authority processes in all three nations - but also that kind of [local] immigration context […] I think the biggest thing was about really knowing what was required around home checks and safeguarding and what was feasible for a Local Authority to do within the time frames. What safeguarding was it [actually] bringing? […] which teams needed to be doing that in a local authority? Originally it had been, ‘Oh, community development workers can go out’ and it ended up being environmental health officers and social workers banding together to do that kind of work. [But] the environmental health teams and planning teams had never ever been involved in any kind of humanitarian protection work [previously].”

Across all levels of government, the response to the war in Ukraine required departments that had rarely worked together previously to quickly establish connections and trust in order to collaborate on the establishment of the UK Government’s Homes for Ukraine Scheme. The Scottish Government was kept abreast of the UK Government’s plans, though it sought less involvement in the design of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme once it had been decided that the Scottish Government would launch its own scheme. At this stage, CoSLA interviewees described an under-utilisation of the Strategic Migration Partnerships by the UK Government Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) – although this was mitigated by the initial involvement of the Local Government Associations (LGAs). Local Authority resettlement lead officials were not included in the policy design of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme.

4.2 Reaction to the Homes for Ukraine Scheme

From the outset of the discussions surrounding the Homes for Ukraine Scheme, Scottish Government Ministers – including the then First Minister Nicola Sturgeon MSP – had strong reservations regarding the UK Government’s scheme. Such reservations were predominantly centred on the need for displaced persons to obtain a visa - thereby slowing the evacuation - and the need to obtain such a visa through a sponsor, which could result in safeguarding issues.i These reservations were, in part, what led to the Scottish Government developing its Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme and were published in an open letter from the then First Minister Nicola Sturgeon MSP to the then Prime Minister Boris Johnson MP.1 A second open letter, co-signed by then party leaders Nicola Sturgeon MSP (Scottish National Party), Anas Sarwar MSP (Scottish Labour Party), Patrick Harvie MSP and Lorna Slater MSP (Scottish Green Party) and Alex Cole-Hamilton MSP (Liberal Democrats), was also sent to Prime Minister Boris Johnson MP – indicating cross-party concerns regarding the need to require “people fleeing war to go through complex bureaucratic processes in order to reach safety within the UK.”2

Local Authority interviewees also had concerns regarding the UK Government’s Homes for Ukraine Scheme and potential issues around safeguarding of people arriving and living in sponsors’ homes. As one Local Authority source stated,

“When more information came out [about the fact] they were going to be paying out £350 a month […] that sent alarm bells ringing. […] And then [the concern was], ‘How are they going to vet this? How are they going to do the checks?’ And then it came back that we were doing the checks [laughs]. OK great, we're doing the checks. Because the Home Office were saying that they were doing the checks on the people arriving and we were doing the checks on the people at our end. And then I thought, ‘OK, this is going to grow arms and legs.’”

Local Authorities also had other concerns regarding the Homes for Ukraine Scheme; including, the novelty of the scheme’s sponsorship model in the UK context, a perceived lack of understanding from DLUHC and civil servants being drafted into the Homes for Ukraine Scheme concerning what refugee resettlement would entail and the need to determine the role of Local Authorities in the scheme.

“There was a lot of frustration along the way with how the scheme would develop because it was new to everybody […] and there were a lot of [UK Government] people who'd been pulled in to run Homes for Ukraine, and they'd never done anything like that before. [… In standard resettlement procedure] we go out to the local community [...] to inform them [that], ‘We've got a new resettlement scheme coming to your area.’ But we weren't in a position to do this with Homes for Ukraine. That whole element of resettlement we felt wasn't being tapped into [...] we felt that was missing from the UK Government. They were very functional: ‘We've designed a scheme that brings people over [and] allows them to be safe [...] After that, it’s up to you guys. It's up to the host.’ We were [saying], ‘That's not enough because Local Authorities will have to be a part of this. [People] will need our support. Hosts will be coming to us for questions, hosts. So maybe clarity on our role in it we felt was being ignored.”

CoSLA interviewees were also concerned with the Homes for Ukraine model of refugee resettlement. In particular they noted the insecurity into which hosting arrangements place people and the lack of long-term funding to support Local Authorities in the event that sponsorships fail and/or if people later rely on homeless support after the end of their sponsorship. As referenced above, under the Homes for Ukraine and the Scottish Super Sponsor scheme, the UK Government provided funding for one year to Local Authorities to provide wrap-around support to individuals and families. This tariff funding was set at £10,500 for individuals arriving on or prior to the 31st of December 2022, and £5,900 for those arriving on or after the 1st of January 2023.3 As one CoSLA interviewee stated,

“We were concerned about the sponsorship model. We’re not saying that there isn’t a place for it, but for that to be the core model where it creates [a] kind of instability for the individuals and families concerned – as opposed to resettlement – […] and that remains [our] concern around Homes for Ukraine and sponsorship. [...] Ultimately, sponsorship arrangements will end and have ended. And then you hope that the majority of people have got on their feet by then and got a job and they’ve got their own agency and ability to find accommodation, but others don’t. And, you know, they require support from local services and the third sector as well, [but] that’s entirely unfunded.”

It is worth noting that under standard resettlement programmes in the UK, accommodation would be sourced directly for families by Local Authorities with a longer-term funding package agreed to support integration, thereby negating the need for disclosure and property checks but also creating a more sustainable setting into which people arrive. From the perspective of Local Authorities, therefore, neither the Homes for Ukraine Scheme nor the Super Sponsor Scheme fall under the rubric of ‘resettlement’ as it is commonly understood in Scotland. Both schemes differ to standard resettlement due to the aforementioned lack of long-term housing, clear pathways to integration, or focus on those with the greatest need (discussed further in Section 5). Combining their thoughts regarding both schemes in this regard, one Local Authority respondent forcefully stated that,

“Neither government consulted with local authorities before launching, which infuriated us. We had to evacuate a country. I completely understand that [and] people were absolutely terrified. But we created a scheme with no humanitarian principles at its core. And we've shoehorned it into other humanitarian resettlement work. It's not the same. It's not the same for so many reasons.”

While the temporary support offered by sponsors amidst the uncertainty of the war created the opportunity for thousands to be hosted, it also created the conditions in which Local Authorities feared significant numbers of homelessness presentations by people from Ukraine in the event of sponsorship breakdowns or at the end of the initial six-month sponsorships.ii It is also worth noting that, in Scotland, under the Housing (Scotland) Act 1987, people can apply as homeless in any local authority without requiring a ‘local connection'.4iii Without this need for a local connection, Local Authority interviewees in areas with already-acute housing and homeless pressures were therefore concerned that they might receive high numbers of people from Ukraine presenting as homeless at the end of their periods of sponsorship.

Interviewees noted that these concerns were somewhat alleviated in Scotland as, initially, people who had arrived through Homes for Ukraine could be placed in Welcome Accommodation (funded by the Scottish Government) in the event of sponsorship breakdowns, whereas in England such breakdowns would more likely have resulted in homeless presentations to Local Authorities. In such cases, homeless presentations would be the responsibility of Local Authorities and their existing funding.

Scottish Ministers had significant concerns regarding the visa application process for the Homes for Ukraine Scheme – these concerns were expressed in an open letter co-signed by party leaders Nicola Sturgeon MSP (SNP), Anas Sarwar MSP (Scottish Labour Party), Patrick Harvie MSP and Lorna Slater MSP (Scottish Green Party) and Alex Cole-Hamilton MSP (Liberal Democrats), which was sent to then Prime Minister Boris Johnson MP. Across the Scottish Government, CoSLA and Local Authorities, interviewees had been concerned with the potential for safeguarding issues to arise with the sponsorship model of refugee resettlement. CoSLA and Local Authority interviewees maintain reservations concerning the temporariness of the scheme’s funding model. Local Authority interviewees expressed concern at the lack of consideration by the UK Government of the role of Local Authorities in managing hosts and engaging with local communities.

4.3 Implementing the Homes for Ukraine Scheme

Displaced people from Ukraine began arriving very quickly after the launch of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme. However, Local Authority interviewees reported there being a time lag between the UK Government approving peoples’ visas and Local Authorities in Scotland being able to conduct the disclosure and property checks. In part this lag was attributed by Local Authority interviewees to the fact that they did not have access to the case management system that had been procured by the UK Government for the Homes for Ukraine Scheme1 – Palantir’s Foundry Case Management System (referred to as ‘Foundry’).[1]

While the UK Government opted to procure the Foundry system, the Scottish Government took a decision early on not to use it. The view from Scottish Government sources was that Foundry was under-developed and had limited functionality in relation to the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme. As a result, some Scottish Government sources commented that there could have been better collaboration between the Scottish Government and the UK Government to procure a case management system that would have suited both schemes’ needs.

Local Authorities in Scotland did not have direct access to Foundry in order to manage their Homes for Ukraine arrivals, meaning that a separate process had to be established for the transfer of data from the UK Government to Local Authorities in Scotland concerning Homes for Ukraine arrivals. Why Scottish Local Authorities were unable to directly access Foundry for the Homes for Ukraine Scheme is a matter that would have been discussed with the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government had an interview been organised (see Section 2).

With Local Authorities not having direct access to Foundry, an approach was required to ensure relevant sponsorship details and visa data for the Homes for Ukraine Scheme was shared with them. This information was sent by the UK Government to the Scottish Government, which then provided access to the data to Local Authorities through the Scottish Government’s Objective Connect system in the form of large spreadsheets.

As will be discussed below, the view from Local Authority interviewees was that this format of transferring data significantly slowed the sharing of data by the UK Government with local authorities. While Local Authorities do have access to Foundry for the purpose of managing cases of Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children, Local Authority interviewees reported still not having access to Foundry for the Homes for Ukraine Scheme at the time of writing – with the consequences of this lack of access discussed in Section 4.4.

In part as a result of the issues with the transfer of data, following the implementation of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme, Local Authorities would often only find out about a sponsoring arrangement after a person had arrived and the host made contact with them to claim their ‘thank you’ payments. As one Local Authority interviewee explained,

“That was a nightmare, trying to keep track of who was here. Who wasn't here. Who was still to arrive. A lot of people had guests living with them where no checks all at all had been done. They would contact us and go, ‘Picked up my guest yesterday from the airport’ and you're like, […] ‘Oh, really? So what's your address again?’ […] So retrospective inspections were going on - not all the time. But I mean that's still happening now, that hasn't changed. […] Getting up to date data that we trusted [was a] big challenge, big, big challenge for us.”

In the initial period after the launch of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme, therefore, Local Authorities were extremely concerned regarding safeguarding gaps despite the procedures that had been put in place. As one Local Authority source stated,

“The issue with the UK Government’s [Homes for Ukraine] Scheme was that there was no safeguarding. So that absolutely concerned us. People were coming straight off planes [and] being picked up by hosts who we had neither verified (because this was happening so quickly) [nor] done the property checks [for]. We had some really dicey hosting arrangements […] and the visas were being issued anyway, regardless of Local Authorities having the time and the information to do any of the background checks.”

Another Local Authority interviewee similarly recounted the issue of safeguarding, noting how this issue formed part of what was a frenetic period for all those involved in Ukraine resettlement.

“[Homes for Ukraine] had obviously been developed at pace. And people were arriving before the Local Authorities were fully informed. And so that added another dimension to an already frantic time.”

While respondents stated that the process of receiving information about new sponsorships improved over time, another Local Authority source noted that the issue has nevertheless persisted.

"But we are also aware – and continue to be aware – [of the fact that] there's a lot of host arrangements that you only find out about when they go wrong. No one's claiming payment, so no checks have taken place. They're privately organised on social media. You only find out when something goes wrong - and that continues to be the case.”

A further problem encountered by Local Authorities was that, when hosts did fail their checks, there was no means for them to quickly flag this issue. Instead, Local Authorities in Scotland could only use the Jira Service Management system to raise a ‘ticket’ to alert UK Government civil servants, but this was often too slow a means of registering an issue before people arrived. The following quote from a Local Authority interviewee highlights the sluggishness of the process as a result of Scottish Local Authorities not having access to the data management system used by the UK Government and Local Authorities in England.

“Local Authorities in England use Foundry as their database. They can go on, they can make changes, they can add people […] I certainly can't. […] We had to raise a ticket with Jira to say, ‘This host has withdrawn’, for example or ‘the family are no longer coming.’ […] We had homes and hosts that were not suitable […] or hosts that said, ‘I was only sponsoring them. They're not coming to live here.’ […] The first year was a nightmare with people arriving to nowhere. Because we had to raise a ticket with Jira. And Jira would take five days to come back to say, ‘What's the problem?’ Then […] it would take another three weeks before the visa information was updated. By that time visas were being approved, people were arriving at Edinburgh Airport and I'm quite sure the Gogarburni staff were really cheesed off because they were trying to deal with the Super Sponsorship Scheme. And [they would say] the onus [was on us]: ‘You need to find another host for them. We'll put them in a hotel just now, but you need to find another host.' And that was really quite difficult.”

The issues discussed above regarding access to the UK Government’s information management systems highlights the challenges that Scottish Local Authorities faced when trying to support the implementation of a UK Government scheme. Aside from the challenges regarding data management and the transfer of data, the above quote indicates a new aspect of resettlement that Local Authorities had hitherto not engaged with before, namely hosting arrangements. Many sponsors signed up during the initial calls for hosts and later decided to rescind their offers (for understandable reasons), but often this happened when Local Authorities contacted them to complete the required checks – thereby further stretching existing resources.

Sponsors were a key aspect of the scheme’s delivery, yet there was very little time to deliver training and communicate with sponsors what the resettlement journey would look like for guests following their arrival and, importantly, what would happen following the agreed upon six months sponsorship. As a Local Authority research participant noted, this lack of information and knowledge could lead to people from Ukraine being misinformed or misguided, hosts often expected guests to find accommodation nearby following the six months.

“A lot of hosts were [staying in affluent areas…] so they would say to us, ‘But they’ve stayed here for six months, the kids go to school here, they’ve found a job here, so you'll find them a house here.’ […] So they didn’t understand how social housing worked [and] if we were offering somebody a Council house, it was like, ‘Well why has it not got carpets, why is not fully furnished? They just didn’t have an understanding of what social housing was. And, you know, if you're wanting a house in [redacted affluent area], you're going to be waiting ten years for it.”

Managing hosts as well as organising the support for displaced persons resettled under the Homes for Ukraine Scheme therefore became a large aspect of the work conducted by Local Authorities. Occasionally resettlement officers could feel caught between sponsors and the UK Government, with whom sponsors had no contact. Yet Local Authority sources discussed being able to apply their existing models of integration to the Homes for Ukraine Scheme.

“It was fortunate in Scotland, that all 32 Local Authorities were already doing [refugee] resettlement, and I think that’s what saved the Homes for Ukraine Scheme. [The scheme] worked well in that people knew where they were going, that they were going to a sponsor - and we quickly got our head round how we were doing it [...and applied] our normal model of getting national insurance in place, benefits, bank accounts opened, GP places, schools.”

Aside from concerns regarding safeguarding, the limited time period of tariff funding, and the scale of the Super Sponsor Scheme that influenced the implementation of Homes for Ukraine (discussed in Section 5), Local Authority interviewees felt that they had largely been able to cope with the Homes for Ukraine Scheme – to the extent that some were surprised by its level of success. The scheme was viewed as being particularly successful in Local Authorities with rural areas, where it benefitted local communities by plugging labour gaps. As one source stated,

“Had you told me back in March 2022, ‘if they were to set up a scheme of this type, would we be able to cope?’ I would have said, ‘Absolutely not.’ [...] I would have been too nervous about the rate of failure of sponsorship to agree that it should happen. And I was wrong about that. [Homes for Ukraine] has been really good [in our Local Authority]. So that model of sponsorship has worked really, really well. We've managed to welcome far more Ukrainians and give them a much better quality of support than I ever thought we could.”

Local Authority resettlement teams experienced significant challenges in implementing the Homes for Ukraine Scheme, in particular concerning the fast pace of arrivals from Ukraine and the slow means of sharing Home Office data with Local Authorities. According to interviews with Local Authorities, this issue was compounded by their lack of access to the UK Government’s Foundry data management system. The risk of safeguarding issues was therefore high, as people were routinely arriving before property and disclosure checks had taken place. Managing hosts was an aspect of refugee resettlement that had not been required in Scotland at such a scale previously and there were challenges in managing hosts’ expectations concerning what housing would be available for their guests after the initial sponsorship period had ended. Nevertheless, the Homes for Ukraine Scheme was viewed positively by Local Authority interviewees as, after the scheme was fully established, it was considered less ‘hands-on’ than the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme. In addition, the Homes for Ukraine Scheme was viewed by Local Authority interviewees as being beneficial for rural areas with available jobs and sponsorship accommodation.

4.4 Homes for Ukraine ongoing inter-governmental collaboration

At Ministerial level, relationships were considered to be good between the Scottish Government and the UK Government concerning the Homes for Ukraine Scheme. Relationships were particularly well-established while Lord Harrington (Minister for Refugees) was in post, but then communications with the UK Government dropped off following his resignation from the temporary post after stating that his task was essentially complete (and no new Minister was appointed). Interviewees reflected on the fact that, under the 2019-2024 UK Government, inter-ministerial communication was reliant on personal relationships rather than a systematic process. Whilst relationships were considered by interviewed stakeholders to have improved following the change of Government in Westminster after the 2024 General Election, there were still unresolved issues in terms of the development of a systematic process for inter-ministerial communication.

Beyond Ministerial meetings, Scottish Government interviewees discussed having good working relations with civil servants in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in which information and lessons could be shared concerning both the Homes for Ukraine Scheme and the Super Sponsor Scheme. As one Scottish Government interviewee noted,

“We were having weekly meetings, which was bringing together the senior leaders for the four nations [...] to discuss what the key challenges were, funding, and how we were having people moving around the country. [...] And then we would have working groups that were kind of focused into the key things, that might be a policy area, or it might be around the kind of visa scheme itself and looking at how we were getting our data and what we needed as part of the [Super Sponsor] Scheme. So we would have that dedicated line that we could just do that with them. [...] We had common ground as to what we were trying to look at, so the communication was good. Our colleagues in Wales probably were facing more similar [situation] to what we were facing, because they were also providing [Welcome] Accommodation [...] so that brought us together even more with them. And as time went on, even increased that work of what we did around looking at housing and how we’d work together, and our Welsh colleagues came up to see what we were doing, our English colleagues came up to see what we were doing, so we kept that collaboration really going between us.”

Another important area of work where Scottish Government respondents felt there was good communication was around cooperation with the UK Government regarding its guidance for the Homes for Ukraine Scheme and how this needed to be adapted to fit Scotland-specific legislation and the Scottish context.

“The collaboration [with the UK Government regarding] the Homes for Ukraine Scheme was very good because every part of the UK was doing the same thing. So we were able to share and make sure we were delivering policies that were fit for Scotland but aligned with the overall UK scheme. UK Government were good at sharing their draft guidance, they were good at sending on documentation that they were working on. So I think that side of it actually worked well. And in Scotland we were able to adapt that by working through our governance arrangements to think about what Local Authorities in Scotland needed in order to be compliant with their statutory obligations. So I think that kind of intergovernmental relations worked well and that continued.”

It is worth noting, however, that such communication channels differed from the standard communication practices for refugee resettlement – where there is a direct link between the Home Office and CoSLA. While the establishment of the Super Sponsor Scheme meant that there were bilateral discussions that needed to happen between the Scottish Government and the UK Government, the experience of CoSLA participants interviewed for this briefing was that such discussions included strategic discussions concerning the implementation of the Homes for Ukraine Scheme in Scotland – yet those discussions took place without CoSLA, which was a source of CoSLA’s frustration with both the UK and Scottish governments. For example, CoSLA sources discussed not being involved in discussions concerning Local Authorities’ access to the UK’s Foundry system for the Homes for Ukraine Scheme (see Section 4.3). As a CoSLA interviewee set out,

“In all of the other [refugee] schemes, local government in Scotland has a direct relationship with UK Government. The local government role in Homes for Ukraine was diminished anyway, just by the nature of the scheme. But the Scottish Government [...] had bilateral conversations with DLUHC in a Scottish context that didn’t involve us. [...] And that, therefore, meant again that people that weren’t experts in this area [of refugee resettlement], were speaking to DLUHC and projecting the view as they saw it as to what would work well with the Homes for Ukraine [Scheme in Scotland]. And we repeatedly sought to engage in that conversation in a more meaningful way, and it didn’t happen.”

From the perspective of those in the Scottish Government, it was acknowledged that the communication structure was different to the asylum context. However, their view was that it was a DLUHC decision to communicate directly with the Scottish Government and that this decision was likely as a result of their challenges regarding direct communication and planning with Local Authorities in England concerning the Homes for Ukraine Scheme. As one Scottish Government interviewee stated,

“The UK Government preferred to limit their engagement to the Scottish Government […] I think what was happening was [that] our English counterparts in the UK Government were so consumed with what they were trying to do and deliver that actually they were thinking, ‘Well if we can get the message to the Scottish Government and deal with the Scottish Government [that would be more preferable] than trying to [manage too] many stakeholders.”

CoSLA research participants did, however, also consider that their strategic involvement was less required for the Homes for Ukraine Scheme – especially after its inception and the subsequent launch of the Scottish Super Sponsor Scheme. As a CoSLA source noted,

“Local Authorities were still getting the Homes for Ukraine information that they needed to, so that didn't change. It was more [CoSLA’s involvement in] the kind of policy strategic discussions that were stymied [...] Because also then at that point we were in a slightly better place with Homes for Ukraine because, whether we liked it or not, we knew what was happening.”

In addition to the lack of strategic discussions with CoSLA, the creation of the Super Sponsor Scheme alongside the Homes for Ukraine Scheme in Scotland created communication issues for Local Authorities regarding tariff funding for both schemes (as both came under the Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme – discussed in Section 4.2). The UK Government did not initially establish a forum to which Scottish Local Authorities were invited to discuss issues or raise queries. A Local Authority source questioned whether the UK Government’s expectation was that such queries could be handled by the Scottish Government, especially as guidance diverged between Scotland and the rest of the UK, and tariff funding was adapted in Scotland with the Super Sponsor Scheme. Yet Local Authority interviewees critiqued that such discussions did not take place with the Scottish Government, given its focus on the Super Sponsor Scheme (see Section 5). As one Local Authority source outlined,

“[Regarding] Homes for Ukraine, the host sidei was always brushed under the carpet by the Scottish Government as it wasn't their issue. It was never discussed. And when statistics were presented to delivery board and programme board, host numbers were never in the stats. Whereas, from a Local Authority point of view, that is probably the biggest risk to the Local Authority, is those [hosting arrangements] ending. So there was constant back and forth – and it continues to be [the case] that for some reason the host numbers were never part of the data sets. It might be that [the Scottish Government] don't have the data.”

There was understanding amongst Local Authority research participants that, outside of the Scottish context, there was less of a need for the UK Government to communicate directly with Local Authorities regarding Homes for Ukraine given the lower numbers of guests per capita. This reduced level of importance is demonstrated by the fact that Homes for Ukraine was added to an existing series of meetings concerning the Afghan resettlement schemes and other resettlement schemes (ARLAN meetingsii). Scottish Local Authorities were not initially aware of Ukraine being discussed at the ARLAN meetings, with interviewees mentioning being initially invited by Local Authority resettlement leads in England rather than the UK Government.

Interviewees found the ARLAN meetings to be a somewhat useful resource to receive updates from the UK Government regarding Ukraine visas, tariffs and as a forum to ask questions of the UK Government, but were frustrated at Ukraine resettlement frequently being an element tacked on to the final section of the meeting with time often running out before questions could be raised. Local Authority resettlement leads discussed the challenge of requesting Scotland-specific questions of the UK Government at ARLAN meetings, which are intended to be focused on the UK as a whole. For example, Local Authorities with large numbers of persons in Welcome Accommodation discussed the challenge of raising specific questions with the UK Government concerning how they could spend tariff funding. Meanwhile only one Local Authority team discussed having utilised contacts in the Scotland Office to communicate with the UK Government regarding the Homes for Ukraine Scheme.

There were also frustrations amongst Local Authority interviewees regarding the UK Government’s process for handling the extension of people’s visas for another 18 months (through the Ukraine Permission Extension scheme) with limited opportunities for Local Authorities to provide input. Instead, interviewees spoke of their frustration at the process going live without them having seen the full guidance, the lack of clarity regarding the amount of support Local Authorities are permitted to give to people completing the extension form, the lack of a third party engaged to support the submission of extension forms,iii and the limited time permitted to apply for the extension and concerns regarding unforeseen issues leading to people potentially losing their right to public funds (NRPF).iv On ensuring that all visa holders apply for the extension scheme, one Local Authority source stated,

“[Visa holders] were supposed to have applied by the 31st of December 2024. So, the date of your visa expiry will be on your e-visa. But that is really putting the onus entirely on the guest to check that, to apply within the window, you know. But there are a lot of potential issues around that. Some of our guests don't even speak English well enough to be able to read an application. [...] So there is potential for issues around that with the short window. And there's also some stipulations that if you've been out of the UK for a certain period of time [that the extension might not be granted]. But they have not stated what time period is acceptable.”

Regarding the risk of Ukrainians losing their right to public funds and whether or not Local Authorities should assist them with the forms, another Local Authority source remarked,

“We should not be giving immigration advice, but we will need to get involved [with the Extension Scheme applications] to a certain extent because it's in our interests [...] We have put a lot of Ukrainians in tenancies. If they don't do their application right, they could fall into [risk of having] NRPF, and then they have no way of paying the tenancy, you know. And then, we end up with a whole pile of rent arrears on all the Registered Social Landlord properties [... and then people will] maybe have to claim asylum.”

The issues recounted in this section again point to the challenges being experienced by Local Authorities as a result of issues of data sharing between Scottish Local Authorities and the UK Government. While the UK Government’s Foundry system records the date of people's original Homes for Ukraine application, for example, Scottish Local Authorities will not be able to see this unless they recorded it when the person originally arrived. At the time of writing, Local Authorities similarly do not have exact visa data for those on the Super Sponsor Scheme either, meaning that there is uncertainty concerning when displaced people from Ukraine living in their authority will need to apply for the extension.

A wider issue discussed was the perceived siloed approach in the UK Government concerning the broader challenge of forced migration and resettlement, highlighted by the creation of multiple resettlement schemes with different funding instructions, rights and responsibilities for Local Authorities. The multiple Ukraine schemes added to the many existing forced migration schemes and routes that operate in the UK. As a CoSLA interviewee stated,