Links between Climate Change and Health in Scotland.

This briefing summarises the links between climate change and health in Scotland. It gives an overview of direct and indirect impacts on physical and mental health, outlines some key approaches and describes responses to reduce the impact of climate change on health and wellbeing. The briefing addresses the ways in which socio-economic and health inequalities intersect with climate risks by discussing how climate change undermines the building blocks of health. As well as the impacts of climate change on health and the healthcare system, it outlines how healthcare contributes to greenhouse gas emissions as well as efforts to reduce this.

Executive Summary

Annual temperatures in Scotland are expected to rise by around 1.1°C in 2050, compared to a 1981-2000 baseline. Over the next few decades and beyond, climate change will continue to affect Scotland's weather, with more extreme temperatures, changes in rainfall, droughts and wildfires. The sea level will rise and flooding will be a particular threat.

This briefing outlines some of the most relevant impacts of climate change on health in Scotland. As well as risks from injury, damage to property, spread of infectious diseases and mental health impacts, the changing climate will affect food security, water availability and access to services and resources including health and social care. This the final output from a SPICe academic fellowship exploring these themes. Views expressed in this briefing are those of the author's and not those of SPICe or of the Scottish Parliament.

Climate change therefore threatens and undermines the building blocks of good health, like decent housing, mobility, nutritious food, access to green space, secure employment and strong social networks. Vulnerable groups will be worst affected. Action to mitigate climate change and to adapt to its effects can therefore create more resilient communities and help improve equity.

Climate change will add pressures onto health and social care systems. As well as creating greater need for care and support, extreme weather events and other climate effects can damage buildings and infrastructure, disrupt transport and lead to closures of health and social care settings, affecting access to and provision of care. Proactively planning for the effects of climate change while also reducing emissions, including in health and social care, can therefore relieve pressure on the NHS and social care providers and protect public health.

There are many examples of inspiring plans and exemplary actions within the health system in Scotland. These include the attention paid to the health risks of the planetary crisis by the Chief Medical Officer, NHS Scotland's Climate Emergency and Sustainability Strategy, Public Health Scotland's strategic approach to climate change and population health and their adverse weather plan. There are also specific initiatives such as reducing the use of greenhouse gas-emitting anaesthetics, using design to make hospitals greener, trialling blue-green prescribing and incremental dialysis. There has also been a proposal to add a 'climate action' outcome to the National Performance Framework: 'We live sustainably, achieve a just transition to net zero and build Scotland’s resilience to climate change'.

As this briefing shows, there is increasing evidence of the risks to health posed by climate change in Scotland. There is also a good understanding about how we can best respond to them by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases while also adapting to climate change's effects. Climate adaption and climate mitigation will help prevent the worst anticipated impacts of climate change on population health. They also have the potential to deliver health benefits by strengthening the building blocks of health1. Gaps in the research remain, yet the evidence we have of the risk to physical and mental health that climate change represents, provides a compelling reason to act to protect individuals' and public health - and the health and social care systems that serve them.

Glossary

Climate change mitigation

Mitigating climate change refers to any efforts to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. In practical terms, this means actions including replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy and more energy-efficient technologies, preventing deforestation and restoring natural habitats, rethinking the way we produce food and use land and changing our behaviours to use less energy.

Climate change adaptation

Adaptation is the process of understanding and planning for the effects of climate change and putting in place measures to cope with them. These include infrastructural ones like improving flood defences, changing the crops we grow so they are more suitable for the changing climate, reducing water usage and improving greenspace to boost cooling. More information about what this means for Scotland can be found here: https://adaptation.scot/.

Climate change resilience

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)1 defines resilience as 'the capacity of social, economic and ecosystems to cope with a hazardous event or trend or disturbance, responding or reorganising in ways that maintain their essential function, identity and structure as well as biodiversity in case of ecosystems while also maintaining the capacity for adaptation, learning and transformation'. The Union of Concerned Scientists adds that a fully resilient approach would also take climate justice into account, by ensuring that vulnerable populations are prioritised in adaptation measures and that mitigation efforts help rather than harm those who are likely to be most affected by climate change and least able to cope with it.2

Net zero

Many countries and organisations have now adopted net zero targets, which put aspirations to mitigate climate change into targeted, often legally-binding, practical actions. Scotland has a target to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045 and the UK aims to reach net zero by 2050. Much of the effort to reach net zero will be achieved through reducing emissions through technologies and behaviour change, but some emissions that are hard to abate with current technologies and societal needs will be removed and stored through a range of measures from planting more trees to using carbon capture and storage technologies. More information can be found here: https://netzeronation.scot/.

Introduction

In June 2022, the Conveners Group (made up of all committee conveners) agreed a package of proposals to strengthen cross-cutting scrutiny of climate change in the Scottish Parliament. This briefing is one outcome of this agreement and part of a package of work to highlight the links between climate change and the remits of the different committees. It outlines evidence about some of the most relevant impacts of climate change on physical and mental health in Scotland. This briefing is the final output from a SPICe academic fellowship exploring these themes. Views expressed in this briefing are those of the authors and not those of SPICe or of the Scottish Parliament.

The projected effects of climate change in Scotland in the 2050s include1i:

Annual temperatures in Scotland are expected to rise by around 1.1°C compared to a 1981-2000 baseline, though this will depend on global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the meantime.

Winter rainfall is expected to increase by 7%, with a likely increased flood risk. Summer rainfall is predicted to decrease by 7%, bringing more periods of water scarcity and consequent implications for agriculture. When it does rain in summer, it is likely to be more intense.

Extreme weather events including heatwaves, drought and wildfires will increase in frequency and intensity.

Sea level will rise. For example, in Edinburgh, it is expected to rise by 12-18cm compared to a 1981-2000 baseline by the 2050s.

Evidence is less certain about whether storms will increase, and this has been identified as an area for further investigation.

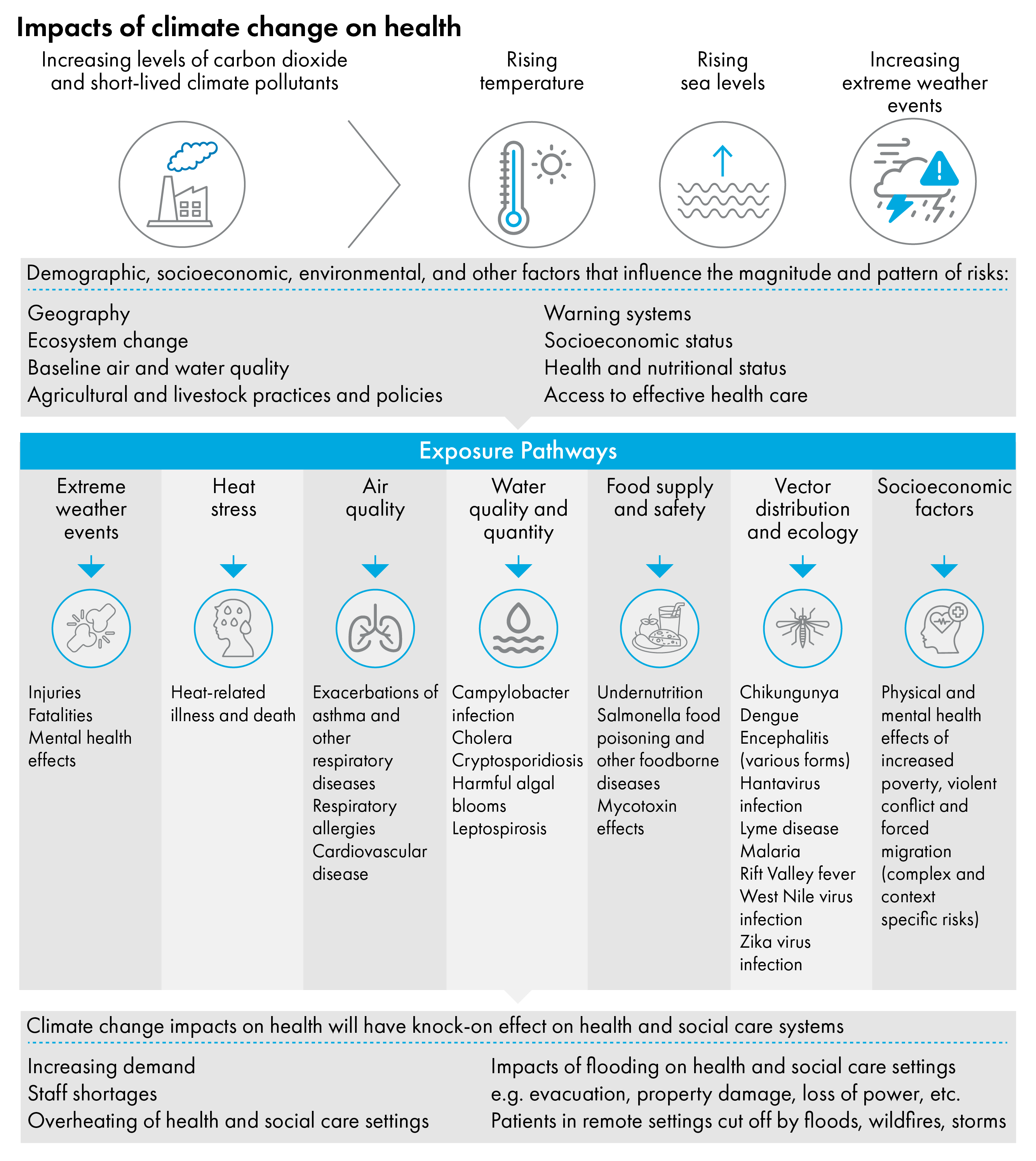

It is important to remember that climate change has direct and indirect effects on health. For example, flooding can have direct impacts like injuries, but it can also have indirect impacts on mental health as a result of displacement, financial losses and loss of social connections. Climate change therefore impacts people across different pathways and can undermine what are sometimes referred to as the building blocks of good health, like decent housing, mobility, nutritious food, access to green space, secure employment and strong social networks.

The impacts of climate change on health

Climate change will have wide ranging effects on our health and wellbeing. These may be direct, for example an increase in injuries due to flooding or deaths from heart disease due to high temperatures. They may be indirect, by reducing access to the building blocks of health and wellbeing in local places. For example, flooding events may cause people to lose their belongings and be displaced from home leaving them unable to connect with friends and family, unable to access school, work or vital goods or services such as healthcare, with profound and lasting impacts on mental health and wellbeing (p.61).1

Climate change will have many negative consequences for Scotland, including in relation to health. With climate change, there will be more adverse weather events such as floods, heat waves, extreme cold and droughts, all of which have negative impacts on individuals, communities and the agencies with responsibility for supporting them, including the NHS and social care providers2. These events can have long-lasting effects on physical and mental health.

Global greenhouse gas emissions to date mean that we are already experiencing impacts to which we will need to adapt. The scale and severity of these in the future will, in part, be determined by global progress in cutting emissions, however we will still need to plan for the changes that have already happened to the climate3 and their effects into the future. Adaptation means changing the way we do things and how we use resources so that, for example, we use water more efficiently, make buildings more resilient to extreme temperatures, storms, wildfires and floods and grow different crops that can withstand drought and new pests (see more at: Adaptation Scotland). The specific measures will vary in different places, but successful adaptation will have positive effects for human health and wellbeing by reducing the risks from climate change and, if carefully planned, reducing health inequalities as well.

It is understandable that many minds will be focused on conserving financial resources and concerned about more apparently immediate problems within health and social care. However, mitigating the worst effects of climate change through reducing emissions and adapting to these effects will in fact alleviate pressure on health and social care services.

As people's health is increasingly impacted by the effects of climate change, this will have a knock-on effect on health and social care systems by increasing demand and potentially leading to staff shortages since health and social care professionals may also be affected.4 While the literature tends to focus more on healthcare settings than social care, the most recent Climate Change Risk Assessment for Scotland (CCRA3) points out that these risks are also relevant to social care, noting that care homes may become overheated in heatwaves or need to be evacuated in floods and that it may become harder for care workers to reach patients in remote settings.56

As with any health issue, preventing the problem - in this case, unchecked climate change - is better than curing its effects. The UCL Institute of Health Equity states that, 'Actions to combat climate change, done in the right way, could improve health and health equity. Conversely, actions to improve health and health equity have the potential to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions' (p.3). 78

The impact of healthcare on climate change

Health and social care systems deal with the effects of climate change, but also contribute to them through carbon emissions. As a public body, NHS Scotland also has a legal duty to act sustainably, as outlined in the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009. This includes reducing greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to the Scottish National Adaptation Plan, and ensuring it is resilient to future climate impacts. NHS Scotland's Climate Emergency and Sustainability Strategy summarises the rationale for action: 'We all want Scotland to be a place where everybody thrives and has a better quality of life. Vibrant, healthy, safe and sustainable places are key to improving health and wellbeing and reducing inequalities. The growing threat to public health from the climate emergency increases the need for action. We all have a clear responsibility to respond in a way that nurtures good health for the population and the planet' (p.70).1

The co-benefits of acting to prevent the impacts of climate change

'Co-benefits' is a term used to describe the range of positive or beneficial outcomes that result from an intervention, including indirect ones. In the sphere of climate change, examples would include policies which aim to reduce carbon emissions but also have beneficial effects for public health or the economy.1

A co-benefits approach puts forward policies and strategies that advance other policy goals, including improving health and wellbeing, in addition to mitigating climate change.2 Many of the actions needed to adapt to climate change and reduce greenhouse gas emissions can have co-benefits if they are designed with these outcomes in mind. If climate action is planned to strengthen the building blocks of health, this could also lead to savings in the healthcare sector. For example, one study calculated that increasing walking and cycling and reducing use of private cars in urban areas of England and Wales would save the NHS £17 billion over 20 years by reducing rates of type 2 diabetes, dementia, ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and cancer (even after adjusting for an increased risk of road traffic injuries) .3

The Water Environment Fund supports urban river restoration in ways that both reduce flood risk and encourage more walking and cycling, thereby benefiting public health, increasing time spent in nature, improving air quality and reducing emissions. Similarly, many behavioural changes that are beneficial for individual health are also effective at reducing carbon emissions. For instance, reducing meat and dairy products and increasing plant-based products in diets can improve people’s health as well as lower their carbon footprint (though care would need to be taken to ensure sufficient nutrients were taken in, especially amongst vulnerable populations).45

Identifying the co-benefits of climate mitigation policies can give a broader sense of their range of potential positive impacts. If these are health-related benefits, they may seem more relatable and closer in time and space for members of the public compared to global emissions targets, which may seem quite abstract and less immediate. Increasing evidence also shows that climate action can have economic and social benefits. For example, Sudmant et al. report that, 'meeting the UK’s 2033–2037 climate targets could yield £164 billion in total benefits', though, 'Notably, only 13% of these benefits are financial, in contrast to the 79% of which are social benefits. These social benefits include improvements in public health, reduced traffic congestion, and increased thermal comfort in homes'6 - which as noted are the building blocks of good health and so can lead to improved health and, therefore, potential savings for healthcare.

Taking a co-benefits approach can be a way of making the case for policies that reduce carbon emissions that is convincing even to those who are not concerned about climate change .78 However, Karlsson et al. write, ‘co-benefits are commonly not considered in policy-making. One reason may be that decision-making still often takes place in silos, where single ministries or committees focus on their core issues and often overlook other important dimensions, including co-benefits in other areas’ (p.307). 110

Climate change mitigation measures have significant health co-benefits. Hence, these measures not only contribute to a liveable planet for current and future generations, but they also benefit human health immediately by addressing long-standing public health problems such as air pollution, lack of physical activity unhealthy diets, and poverty (p.2).11

The Climate Change Committee’s 2025 progress report found plans to prepare health and social care systems for the impacts of climate change 'insufficient'.12 Becoming resilient to climate change offers many benefits for Scotland, not least in improving health and reducing inequalities. By reducing emissions and putting in place measures to adapt to climate change which take health and equity into consideration, we can take a preventive approach to protecting health and improving people's wellbeing.

The impacts of climate change are broad and multifaceted, so measures to address it can also be wide-ranging, as can their positive outcomes. For example, increasing the amount that people walk, wheel and cycle to work, school or to visit their GP will reduce the emissions associated with taking a car for each of those journeys. It will improve people's health by increasing rates of exercise. Having fewer cars on the road will reduce air pollution and road-traffic accidents and potentially improve the environments in which people live, work and spend time together.

Similarly, by reducing its greenhouse gas emissions and waste and restoring nature on its estate, NHS Scotland can not only make a significant contribution to reducing Scotland's overall emissions, but also act as an anchor institution, demonstrating how to create a climate resilient society. For example, greening the NHS Scotland estate will help store carbon and improve biodiversity, as well as creating more pleasant environments for patients, staff and visitors, thereby improving wellbeing, including amongst those with chronic health conditions, the elderly and others who visit NHS buildings more frequently.

The planetary crisis is the single biggest threat facing our collective wellbeing across the world. As health and care professionals, we have a duty to practise sustainably, to use resources wisely. We must leverage our expertise, insight and humanity to help set the natural world on the road to recovery.

But progress can be slow, and action is not keeping pace with aspiration or with need. We must accelerate our efforts towards a more sustainable system that will benefit the people we care for, our population and our planet (p.32).13

One Health and Planetary Health

Scotland's Chief Medical Officer has written that, 'the most significant long-term threat to human health remains the climate emergency and its impact on planetary health' (p.4).i1 In the face of health inequalities, which he links directly with planetary and public health, he argues for centring careful and kind care which goes beyond paternalistic efforts to protect people, by looking after the worlds in which we all live, to foster people's wellbeing and agency without harming the planet on which we depend.

One Health emerged in the early 2000s and is closely associated with approaches to zoonotic (spread from animals to humans) diseases, with the Covid-19 pandemic sparking a resurgence of interest in the concept .23

One Health is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals and ecosystems.

It recognizes that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are closely linked and interdependent.

While health, food, water, energy and environment are all wider topics with sector-specific concerns, the collaboration across sectors and disciplines contributes to protect health, address health challenges such as the emergence of infectious diseases, antimicrobial resistance, and food safety and promote the health and integrity of our ecosystems.

By linking humans, animals and the environment, One Health can help to address the full spectrum of disease control – from prevention to detection, preparedness, response and management – and contribute to global health security.4

NHS Scotland adopted a One Health approach to tackling antimicrobial resistance in 2016 and a One Health approach is taken in several Scottish research and policy programmes. For example, the OneHealth Breakthrough Partnership brings together health and environmental researchers with representatives from the Scottish Environment Protection Agency, water providers and regulators and public health specialists to reduce pharmaceutical pollution in the environment. NHS Highland and the One Health Breakthrough Partnership delivered an award-winning project at Caithness General Hospital. It aimed to monitor pollution from medicines and micro-plastics in waste water and thereby reduce its effects on aquatic ecosystems.5

Planetary Health overlaps with and complements One Health in many ways. It has been promoted as a new science that develops public and global health by focusing not only on improving equity, but also taking into account the health of the environment in which we live and on which human health depends.678 One Health research increasingly considers climate change, but continues to focus on animal health and zoonotic disease, while Planetary Health focuses on the environment and human health.9

Our objectives are to protect and promote health and wellbeing, to prevent disease and disability, to eliminate conditions that harm health and wellbeing, and to foster resilience and adaptation. In achieving these objectives, our actions must respond to the fragility of our planet and our obligation to safeguard the physical and human environments within which we exist. Planetary health is an attitude towards life and a philosophy for living. It emphasises people, not diseases, and equity, not the creation of unjust societies (p.847).10

Planetary Health focuses on understanding the links and dependencies between climate change and other human-caused environmental problems and public health, with the aim of developing solutions that will protect both people and the planet. One highly significant way that this could be achieved is through reducing the carbon emissions of healthcare11. Other researchers have proposed embedding Planetary Health in the medical curriculum and integrating it into clinical guidelines.12 Herrmann et al. argue that this needs to be supported by greater evidence about the health effects of climate change which can be used to inform healthcare adaptation and mitigation, and transdisciplinary committees that can share and integrate knowledge about climate change and sustainability into clinical guidelines.13

Health, Climate Change and Inequalities

Factors like age, pre-existing medical conditions, housing tenure, socio-economic deprivation and homelessness can exacerbate a person's risk to the effects of climate change on health.123 Addressing climate change is therefore also a matter of equity.

It is well known that Scotland’s, and particularly Glasgow’s, life expectancy is lower than the rest of the UK and has been one of the lowest in Western Europe since the 1950s.4 A review of health inequalities in Scotland reports that there are two striking trends over the last quarter of a century. Firstly, there have been large and persistent inequalities in health for those living in the least and most deprived areas of Scotland. Only a little improvement has been made to this despite the efforts of policymakers. Secondly, life expectancy has not been improving as would be expected, with life expectancy stalling between 2014 and 2019 and healthy life expectancy decreasing by two years between 2011 and 2019 (after many years of steady improvement).5

The Chief Medical Officer for Scotland reports that socio-economic deprivation is a key driver of poor health outcomes in Scotland.6 A quarter of the population live with two or more health conditions, with these conditions starting earlier for those who live in the most deprived areas. Compared to comparable European countries, Scotland has a higher prevalence of largely preventable non-communicable diseases (such as cancer, heart disease and diabetes). Further health risks from climate change will only add pressure onto health services and exacerbate existing inequalities, including in access to services.

Climate change impacts people and places in multiple ways, and communities with less capacity to adapt because of existing inequalities will need support (p.7).7

Communities that are already disadvantaged are among the most vulnerable to the effects of systemic shocks and extreme events and climate change has the potential to widen existing health inequalities within the UK (p.3).8

One study held a roundtable event on climate change and health inequalities with 10 GPs from 'Deep End' (i.e. with the highest percentage of registered patients living in the most socio-economically deprived postcodes) practices in Scotland. It found that participants recognised the complex connections between the climate crisis and health inequalities:

The group recognized that when our patients are malnourished because of damaging food systems, or when patients struggle with weight, inactivity, and chronic respiratory and cardiovascular conditions because of unhealthy transport systems and environments, or when stressed patients use cigarettes, alcohol, drugs, and violence to cope with economic and social injustices, these are the drivers of climate change intersecting within the communities we serve (p.498).9

The researchers note that preventive medicine is the most sustainable way to practice and make some recommendations based on the views expressed by the GP research participants, including taking the carbon impact of different medications into account when prescribing and including sustainability in medical education and training.

Climate change impacts and social vulnerability

The extent to which people are adversely affected by climate change impacts is related to their social vulnerability. Social vulnerability to climate change impacts can be broken down into three categories:

Exposure to climate impacts is influenced by factors like housing tenure and building conditions which are likely to be worse affected by extreme weather and to be more prone to overheating, cold and damp.

Adaptive capacity refers to an individual's resources that can help them adapt to the changing climate, such as renters who are limited from adapting heating and ventilation systems in their homes, those who live remotely and may be cut off in a storm and people who cannot afford to insure their property against flood damage.

Sensitivity to climate impacts relates to people's existing health conditions which are typically associated with deprivation, which makes them more vulnerable to the health impacts of climate change.1

A ClimateXChange study of the impact of flooding, high temperatures and poor air quality on different population groups in Scotland highlights several important findings.2 In relation to exposure to climate impacts, they found that:

In rural areas, the risk of being impacted by climate change is higher than for those in urban areas, though the greater population density in urban areas means that more people in urban areas will be affected.

Vulnerability is heightened in rural areas because of isolation and less access to the internet.

Poor health, lower incomes, greater numbers in social and private rented accommodation, lack of local knowledge and limited mobility contribute to greater vulnerability in urban areas.

The more disadvantaged local authorities today are likely to continue to experience disadvantage in future.

The most socially vulnerable neighbourhoods in cities are three times more likely to be exposed to high temperatures compared to the rest of Scotland.

Black ethnic groups tend to experience higher risks of exposure to climate impacts, especially in relation to poor air quality.

The greatest disparity in risks for those in the most socially vulnerable neighbourhoods compared to others in the same ethnic group is amongst white ethnic groups.

Given these multiple and intersecting links between climate change, health and inequality, the UCL Institute for Health Equity has called for a health-equity-in-all-policies approach, which avoids increasing economic and health inequalities and ensures that climate change mitigation measures are implemented equitably so that their benefits reach those with the potential to be most positively impacted.3

.png)

Emissions from Healthcare

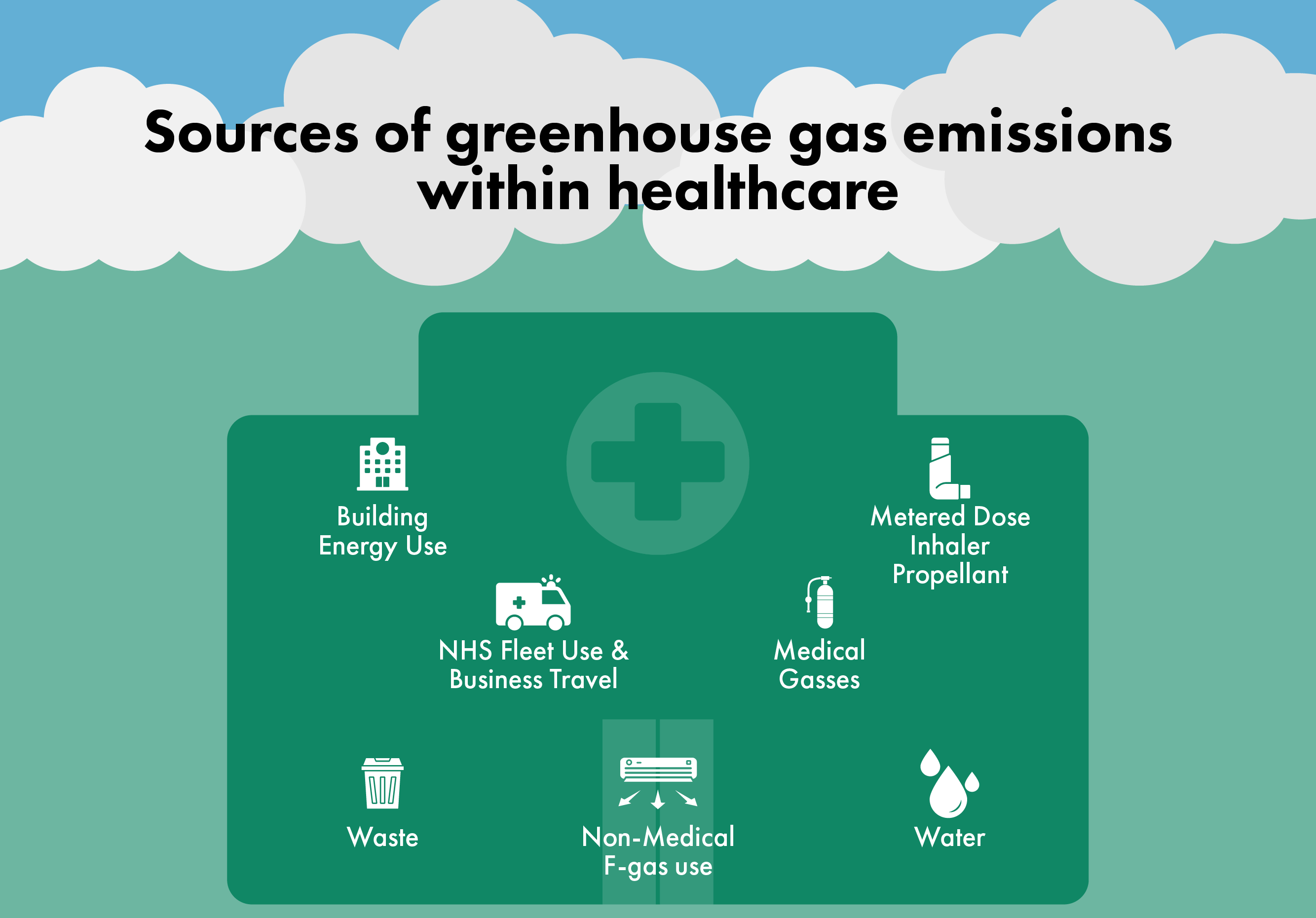

Globally, healthcare’s climate footprint is equivalent to 4.4% of net emissions (2 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent). Scotland's greenhouse gas emissions were 39.6 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO₂e) in 2022. Emissions from healthcare are falling in Scotland, but remained at 570,455 tonnes of carbon equivalent (tCO2e) in 2022-23.1

NGO Health Care Without Harm has found that, globally, 'If the health sector were a country, it would be the fifth-largest emitter on the planet' (p.4) and that '71% [of emissions] are primarily derived from the health care supply chain through the production, transport, and disposal of goods and services, such as pharmaceuticals and other chemicals, food and agricultural products, medical devices, hospital equipment, and instruments' (p.5).2

It is difficult to fully calculate healthcare emissions, and especially challenging to capture indirect emissions such as the manufacturing of drugs and the car journeys of people visiting NHS patients in hospital. However, NHS England has developed a carbon footprint tool that is judged to be world-leading by the Lancet Countdown (p.12).3 Using this tool, NHS England report that their carbon emissions represent 4% of England's emissions. Their Scope 1 (i.e. direct) emissions primarily come from the use of fossil fuels, NHS facilities, anaesthetics and the NHS vehicle fleet.

Taylor and Mackie write that, while measuring the carbon footprint of healthcare is important, 'It is no longer sufficient to simply quantify the problems we face; health-care systems need to be much more effective stewards of the resources placed at their disposal' (p.e358).4 As Health Care Without Harm writes, the Hippocratic Oath provides one rationale for the health and social care sector to tackle climate change, given the harms that it represents and medics' responsibility to 'first, do no harm'.2

A survey of 100 NHS staff in England found that 90% of respondents were concerned about climate change and waste in the NHS, but also largely unaware of NHS initiatives around climate change.6 There is also public support for the idea that NHS Scotland has a responsibility to reduce its climate impact.7 While addressing climate change may seem like yet another demand on healthcare systems that are already stretched following the pandemic and other pressures, the co-benefits it can bring can in fact lessen the burden on healthcare systems in the long term, through increasing energy and financial efficiency, improving patient choice and reducing the health effects of climate change, for example by reducing air pollution that results from combustion of fossil fuels.4

Public health approaches promote the value of preventive medicine as it can reduce the need for medical treatment and address health inequities. Preventive medicine has great relevance for climate change as well, since as Maria Gaden, from the Centre for Sustainable Hospitals in Denmark remarks, 'the greenest care is the care we don't provide at all'. Preventing ill health has multiple benefits - most importantly, it improves people's lives, but it also reduces the need for care, freeing up healthcare resources and reducing the direct and indirect emissions associated with that care.9

NHS Scotland Climate Emergency & Sustainability Strategy 2022-2026

NHS Scotland's Climate Emergency and Sustainability Strategy notes that healthcare providers including the NHS have a responsibility and an opportunity to take climate change seriously, not only because of the substantial contribution to emissions that healthcare makes, but also because of the role that the NHS has as an anchor organisation and as a major employer, buyer and brand.1The strategy focuses on five areas: Sustainable Goods and services; Sustainable Land and buildings; Sustainable travel; Sustainable Care and Sustainable Communities.

NHS Scotland was the UK's first national health service to commit to becoming a net zero organisation and it aims to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2040 and achieve net-zero emissions from its supply chain by 2045.2 In particular, it aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from its buildings by at least 75% by 2030 compared to a 1990 baseline, to use renewable heating systems by 2038 for all NHS-owned buildings and for all its estate to have net-zero emissions by 2040 or earlier. Several key points from NHS Scotland's Climate Emergency and Sustainability Strategy are summarised here to give a sense of the scale of the issue in the Scottish context and the responses in place.

NHS Scotland's direct emissions are largely from heating and powering its one thousand buildings. Between 1990 and 2020/21, NHS Scotland reduced greenhouse gas emissions associated with energy use in buildings by nearly 64%. This was largely achieved through decarbonisation of the grid and switching from oil and coal to gas, so further reductions in the use of fossil fuels will be more challenging, though the buildings with the highest emissions are being prioritised for reductions.2 The predicted rise in number and length of heatwaves mean that overheating is a key risk for hospitals in Scotland and the UK more broadly. The Scottish Government has committed £10 billion to renew and refurbish the NHS estate over the next decade, with the aim of creating sustainable healthcare facilities that reduce fossil fuel use, are resilient to climate change and which provide healthy and inclusive internal environments and external environments, maximising the benefits of the green space in NHS Scotland's estate.1

Some medications contribute substantial carbon emissions, in particular metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) treatment and anaesthetic gases. Around 4.5 million MDIs were dispensed in Scotland in 2020/21, representing an estimated 79,000 tonnes of CO2e, which is more than the emissions from the NHS fleet and waste combined.1 NHS Scotland has committed to reducing emissions from inhaler propellant by 70% by 2028, for example by switching to dry powder inhalers (which have a lower carbon footprint) and supporting the disposal of MDIs in more environmentally friendly ways.1 Anaesthetic gases have a higher global warming impact than carbon dioxide and reducing their environmental impact is a priority for NHS Scotland. The use of these gases by NHS Scotland contributed 34,000 tonnes of CO2e in 2018/19, but this had fallen to 26,000 tonnes CO2e by 2020/21, which NHS Scotland attributes (aside from potential effects of the pandemic) to rapid reductions in the use of desflurane, which has the highest global warming potential of anaesthetic gases.1

Transport is another substantial contributor to NHS Scotland's greenhouse gas emissions. The Scottish Government is aiming to switch Scotland's transport system away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy and active travel. NHS Scotland has pledged to support this move in its own transport system:

By making it easier to walk, wheel, cycle and take public transport to NHS services, we will improve access for all (particularly those with low incomes), improve physical and mental health and encourage safer and more pleasant communities. By reducing the need to travel and supporting the shift to active travel, public transport, shared transport and vehicles powered by renewables, we will help improve air quality and cut transport related emissions.1

The 2024 NHS Scotland Climate Emergency & Sustainability Report finds that emissions from energy in buildings continued to fall, while the switch to electric vehicles increased and NHS Scotland was awarded European Sustainable Healthcare Project of the Year for its work on reducing emissions from medical gases.

Impacts of Climate Change on Health and Wellbeing

A quarter of a million additional deaths will occur globally every year between 2030 and 2050 as a result of humanity-driven changes to the climate. This is because climate change affects most of the basic building blocks of health by influencing the day-to-day weather conditions that we experience. How severely this impacts us depends on how much warming occurs.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change established an upper limit of 2° Celsius warming above pre-industrial level. Beyond this, we are likely to experience rapidly escalating, irreversible and unacceptable effects – on everything from water security to healthcare. But even today, as we approach 1.5° Celsius of warming, the changing climate is already affecting our health in Scotland (p.20).1

The following sections summarise the evidence about some of the direct and indirect impacts of climate change on health and wellbeing in Scotland: flooding, mental health, extreme temperatures and vector-borne diseases. These topics have been selected for their relevance to Scotland and to give a sense of the range of predicted impacts. Other important impacts include food insecurity with risks in malnutrition and under-nutrition, infections resulting from poor water quality and respiratory, cardiovascular and mental health impacts from poor air quality.234

Flooding

Flooding represents the most impactful and costliest climate hazard for Scotland. Climate change will lead to sea level rise and more frequent heavy rain events, which will exacerbate flooding in Scotland. NHS Scotland reports that, '19% of Scotland’s coastline is at risk of erosion within the next 30 years with between half and a third of all coastal buildings, roads, rail and water networks located in these erodible sections' (p.47).1

A 2022 study of public awareness of climate risks and opportunities found that flooding, heavy rain and storms were perceived as the most pressing of the weather-related problems associated with climate change. Half surveyed said these were already a serious problem for Scotland and more than a third saw them as likely future problems (p.15).2 This suggests that there is relatively good awareness of the risks and effects of flooding amongst members of the public in Scotland; this may be even greater following the severe storms that have occurred since the survey was taken.

The CMO's annual report notes that floods and storms will become increasingly common with climate change and that, 'By 2050 winter rainfall is expected to increase by 8-12% and sea levels in Edinburgh are expected to rise by 12-18cm' (p.20).34 Further, increased flooding in winters will be combined with higher temperatures and more heatwaves in the spring and summer, leading to droughts that will exacerbate flooding and food insecurity. As with the direct effects of flooding, climate shocks to the domestic and international food system are likely to affect those on lower incomes more severely, as they will struggle to access and afford healthy, nutritious food, thus undermining their overall health and wellbeing.

A Centre of Expertise for Waters (CREW) report on fluvial (river-based) flooding in Scotland states that, 'Climate change is increasing our exposure to fluvial flooding in Scotland. ... UK-wide, fluvial flood exposure is the dominant source of flood exposure today (compared to coastal, groundwater and surface water) and remains so in the future. Flooding poses a significant risk to people, communities and the built environment, with approximately 1.9 million people across the UK currently living in areas at significant exposure from either river, coastal or surface water flooding. The number of people at risk could double as early as the 2050s' (p.2).5 It quotes a hydrological modelling study which predicts that if carbon continues to be emitted at high levels, the peak flows for some river catchments in Scotland could increase by over half by the 2080s.5

Beyond its effects on individuals and communities, flooding represents a risk to infrastructure, as we saw with storms Arwen, Ciara and Dennis at the beginning of this decade. Emergency services are vulnerable to surface water flooding and NHS services, buildings and transport will all also be affected by flooding and other extreme weather events.1 NHS Scotland needs to be prepared and resilient in the face of increasing extreme weather events. The increasing frequency and severity of these events with climate change may mean that current approaches need to be updated and strengthened.

There is a legal duty under the Civil Contingencies Act (2004) for NHS organisations to maintain service during incidents and Health Boards use various tools and standards to monitor threats from climate change. The negative effects of flooding on healthcare services have already been seen in recent flooding events. The Climate Emergency and Sustainability Strategy reports that, 'Over 400 health and social care assets in Scotland are at risk of frequent flooding, and this number is likely to increase in the future even if global warming is kept to below 2oC' (p.28).1 Flooding and other extreme weather effects of climate change will strain NHS resources in terms of damage to buildings, reduced mobility and access to care and greater demand for services.

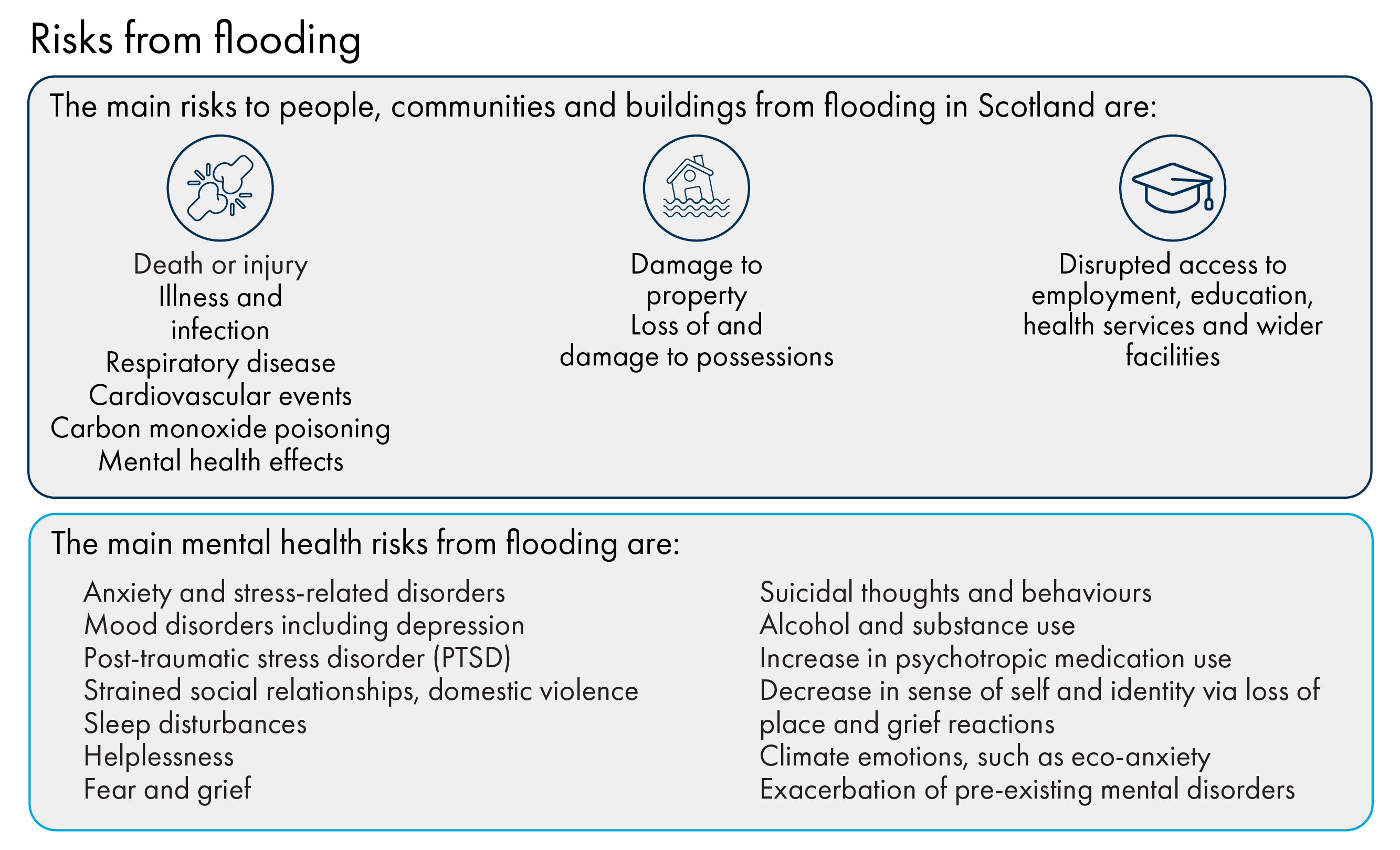

Risks to people, communities and buildings from flooding in Scotland include:

• Death or injury (including from drowning and electrocution)

• Illness and infection from water-borne pathogens, rodent-borne disease or chemical and/or biological contaminants in flood water

• Long term and severe impacts on mental health and wellbeing

• Damage to property - including the stress, upheaval and financial implications of cleaning up, repairing and rebuilding and/or moving to temporary accommodation

• Loss of and damage to possessions

• Respiratory disease from exposure to mould and damp

• Cardiovascular events

• Carbon monoxide poisoning in clean-up phase from inappropriate generator use

• Disrupted access to employment, education, health services and wider facilities45

While flooding represents one of the main adverse effects of climate change across the UK, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland will experience worse damage from floods than England (p.25).11 Flooding has a wide range of effects, from physical and mental health to social and economic impacts. As well as being the most impactful climate risk for Scotland, it illustrates the multifaceted nature of climate change's effects, and how they are interconnected. Most starkly, as we saw with Storm Babet in October 2023, flooding can lead to loss of life.

Mental health impacts of flooding

Evidence suggests that the largest impact on health resulting from flooding will be on mental health, as a result of displacement from homes, disruption to work and education and problems accessing essential services and utilities.1234 These impacts can be complex, and range from specific conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder to a sense of anxiety or dread about the future in a world experiencing the full effects of a global rise in temperature. While they range in severity, these will have implications for health and social care, as well as society more broadly.

The main mental health risks from flooding are:

• Anxiety and stress-related disorders

• Mood disorders including depression

• Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

• Strained social relationships, domestic violence

• Sleep disturbances

• Helplessness

• Fear and grief

• Suicidal thoughts and behaviours

• Alcohol and substance use

• Increase in psychotropic medication use

• Decrease in sense of self and identity via loss of place and grief reactions

• Climate emotions, such as eco-anxietyi

• Exacerbation of pre-existing mental disorders

Poor mental health can affect people's ability to cope with physical health impacts of flooding through the effect of stress on the immune system.4

Inequalities and vulnerability to flood risk

As with other climate risks, those experiencing social and economic disadvantage are likely to be most vulnerable and to find it hardest to recover from flooding.12 These vulnerabilities particularly relate to health conditions, financial insecurity and housing tenure, location and condition. Residents and businesses in flood and coastal erosion risk areas are most exposed to flood risk. The most sensitive groups to flood risk are: elderly and young people; people with health conditions; residents of poor-quality housing (e.g. mobile homes) or people with nomadic lifestyles; residents of areas with limited community flood response services; and uninsured or under-insured householders. Those least able to adapt are people on lower incomes, those with limited information about or experience of flood risk and those subject to restrictive property tenure.34

The third Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA3) identified that 'Flood disadvantage (the combination of living in an area at flood risk and the degree to which socially vulnerable communities are disproportionately affected by flooding) is highlighted as being greater in coastal areas, declining urban cities and dispersed rural communities' (2023: 83).5 While coastal areas are at particular risk, Glasgow and the wider City Region has a significant concentration of flood risk. Glasgow is one of ten UK local authorities that account for half of socially vulnerable people living in flood risks areas.5

Thomas and Niedzwiedz identify Scotland's ageing population, lower life expectancy, higher rates of deprivation and proportion of people living in rural areas as specific challenges for public health. Like others, they note that existing vulnerabilities may exacerbate flood impacts, though they remark that, 'It should also not be assumed that having a risk factor or factors automatically implies vulnerability – a person with a risk factor may also have resilience if they are prepared and have the appropriate support'.7

Proposed responses

The CREW report on fluvial flooding makes several recommendations to enhance community resilience and argues for greater incorporation of a public health perspective.1 Ultimately, such an approach may lead to a broad range of benefits. For example, building and maintaining homes to be resilient to the different weather conditions associated with climate change will also improve public health and better enable people to cope with flooding and other incidents. Public Health Scotland also argues that nature-based solutions will help manage flood risk and moderate extreme temperatures, but also nurture healthier natural environments.2 These will provide greater opportunities for people to experience the mental and physical health benefits associated with spending time in nature.

The Climate Change Committee states on flooding: 'Lack of action today stores up negative impacts for future generations, creating intergenerational inequalities'.3 The third Climate Change Risk Assessment states that, while Scotland has improved its strategic flood risk management at national and local levels, more action is required given the scale of the current and future risk.4

PHS has produced an adverse weather plan that focuses on heat, cold, flooding and drought, with the overarching aim of reducing the burden of disease and health inequalities associated with adverse weather events in Scotland. Its objectives are to:

Ensure knowledge and understanding of the current and projected burden of illness and disease associated with adverse weather events in Scotland through the development of epidemiological analysis and a surveillance system.

Support an improvement in preparedness, resilience, response, and recovery to adverse weather events from a public health perspective.

Increase knowledge and understanding of the health impacts of adverse weather events for the public and professionals by collaborating with key stakeholders to develop relevant tools and resources.

Contribute to long-term adaptation planning to ensure that a long-term perspective is taken to protecting health during periods of adverse weather.5

As PHS points out, effective adaptation planning should limit the impacts of adverse weather events in the long-term, thereby protecting and promoting health and wellbeing.5

Mental Health

A recently published ClimateXChange review defines mental health as 'A part of our overall health, alongside physical health, experienced daily; good mental health means realizing our full potential, feeling safe, secure, and thriving in everyday life'.1 The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has stated with very high confidence that climate change will have negative impacts on wellbeing and lead to poorer mental health. The authors note that this will particularly affect children and adolescents (especially girls), elderly people and those with existing mental and physical health challenges.2 They also point out that most health systems are under-equipped to deal with climate change impacts and that this is especially true for mental health. This leads them to argue for transformational change to health systems and to highlight 'an urgent and immediate need to address the wider interactions between environmental change, socioeconomic development and human health and well-being' (p.1047).2

Mental health and wellbeing are impacted by climate change in complex and sometimes subtle ways, which may change through an individual's life course. Several researchers describe climate change as a risk multiplier for mental health.4 Mental health effects of climate change have been less studied than physical health impacts, but this is an emerging area of research. The authors of one scoping review point out that research has so far tended to focus on direct impacts of extreme temperatures and less on understanding coping mechanisms which could help inform policies to adapt to and deal with these impacts.5

As with physical health, climate change can have direct and indirect effects on mental health, with the indirect effects resulting from the building blocks of health being undermined. The impacts of climate change on mental health tend to be categorised as follows:

Direct impacts - exposure to extremes in temperature and extreme weather events, displacement, malnutrition from food insecurity. These can trigger acute stress reactions, adjustment disorder, PTSD, insomnia and contribute to depression and anxiety. These impacts may be long-term.

Indirect impacts - resulting from economic, social, environmental and political determinants of health such as loss of livelihood, adverse working conditions, forced migration, conflict and civil unrest, exposure to air pollution, homelessness.

Overarching impactsi- these relate to the worries and anxieties that knowledge about climate change and its effects can generate.278

Niedzwiedz et al. note that, 'These impacts are unequally distributed according to long-standing structural inequities which are exacerbated by climate change' (p.1).9

An important point that emerges from the literature discussed in this section is that, while many of the effects of climate change can lead to specific mental health conditions, for many, climate change represents a change in outlook, a shift in perceptions of what the future will bring and about their and society's ability to cope with these changes, rather than a specific condition.

Polling shows that many Scottish people are highly, and increasingly, concerned about climate change and a majority feel that Scotland is already experiencing its effects. Millar et al. found that, 'Concern about climate change was high, with the majority (82%) saying they were either very (41%) or fairly (41%) concerned at the moment. When thinking about the impact of climate change on Scotland specifically, concern was also high but slightly less so than in relation to climate change generally: 76% were either very (28%) or fairly (48%) concerned' (p.8).10

As Andrews points out, understanding climate change and its likely effects can trigger stress.11 The stress that climate change induces may also lead to maladaptive coping, inhibiting the ability to deal with the threat it poses. Climate emotions will be discussed in further detail later in this section, but it is worth remembering that climate change may produce 'negative' emotions that are in many ways a reasonable and proportionate response to the complex threat of this global ecological crisis. This raises questions about how people are able to respond and cope with these feelings and what their long-term effects will be.

There are knowledge gaps about the mental health impacts of climate change in the UK , but given that climate change is a risk multiplier, it will be important to better understand how it will impact mental health in Scotland and the UK.12 The ClimateXChange evidence review on climate change and mental wellbeing in Scotland found that climate change is already impacting Scottish people's mental health, through direct, indirect and overarching effects and that these are likely to increase in future. It also found that these effects are unevenly distributed, with three main factors worsening someone's risk of poor mental health outcomes: exposure to climate change-related hazards; susceptibility to poor mental health; and access to resources and support to help with recovery.114

Climate emotions

In recent years, there have been increasing public conversations and research about people's emotional responses to the threat of climate change. Climate emotions are often related to distress, but can also refer to feelings like hope and empowerment. Terms like 'eco-anxiety', 'climate anxiety', 'climate worry', 'climate grief' and 'climate trauma' have been used but not systematically defined, which may reflect the fact that they are not intended to be clinical terms or diagnoses. As Niedzwiedz et al. note, choice of terminology is important in avoiding stigmatising or trivialising people's feelings, but also to avoid unnecessarily pathologising these experiences.1

Much research and commentary focuses on eco- and climate anxiety which, although not formally defined, is often characterised by feelings of uncertainty, unpredictability, uncontrollability and being overwhelmed. Eco-anxiety can also provoke emotions like guilt, shame, anger and despair. The review from ClimateXChange points out that the impact of eco-anxiety may be more severe for young people and those from other vulnerable or marginalised groups. This reflects the fact that the ability to cope with eco-anxiety is associated with a sense of agency about taking action to prevent climate change.2

Many agree that these emotions are rational responses to the existential threat of climate change.34 Anxiety is usually a response to danger and so, while it can be overwhelming, it can also inspire positive actions and pro-environmental behaviours.56 Climate emotions can be interpreted as a sign that someone understands the severity and scale of the climate crisis, which can motivate meaningful action. As Andrews argues, the key point is less about defining climate emotions and more about how people regulate them in the long-term - whether they provoke constructive adaptive coping responses or maladaptive coping responses that can exacerbate mental health issues.3

There is some evidence that engaging in climate action can help people manage eco-anxiety, though it may also risk exposure to stress and burn-out - this is a relationship that would benefit from further research.1 Beyond the individual level, climate emotions can lead to benefits for communities by inspiring civic engagement and action, collective responses and positive group identity, but this may be negated if the community is overwhelmed or has low social cohesion.

Young people, mental health and climate change

Although research on climate emotions and links between climate and mental health is a relatively new field, much of the existing evidence focuses on young people. For example, a survey of young people from 10 countries including the UK found that, 'Respondents across all countries were worried about climate change (59% were very or extremely worried and 84% were at least moderately worried). More than 50% reported each of the following emotions: sad, anxious, angry, powerless, helpless, and guilty. More than 45% of respondents said their feelings about climate change negatively affected their daily life and functioning' (p.e863).1

Scotland's National Adaptation Plan reports a survey by BBC Newsround, which found that 62% of 8-16-year-olds in Scotland were worried about climate change. Research by the Mental Health Foundation found that two fifths of British young people reported that their thoughts and feelings about climate change are negatively impacting their mental health.23

Children will face much harsher environmental conditions in the future, with the current generation predicted to experience seven times more heatwaves than their grandparents, for example. This will have consequences not only for physical health, but also mental health and wellbeing.4

Younger people will face the worse results of climate change because its effects will worsen over time. Exposure to chronic stress in childhood can have long-term impacts and lead to mental health problems and this may be exacerbated by the relative powerlessness that children and young people have to mitigate climate change. Hickman et al. predict that, 'As severe weather events linked with climate change persist, intensify, and accelerate, it follows that, in the absence of mitigating factors, mental health impacts will follow the same pattern' (p.e871).1

Interestingly, emerging research suggests that the relationship between socio-economic position and eco-anxiety is not straightforward:

Individuals from disadvantaged and low-income communities potentially face additional stressors related to eco-anxiety, such as limited access to essential resources, inadequate infrastructure, and heightened exposure to environmental risks. However, eco-anxiety appears to be shaped by awareness and knowledge of climate change, which is often higher amongst people with more advanced levels of education. Thus, it is possible that the relationship between socioeconomic position and eco-anxiety may differ depending on the indicator used (e.g. education level, individual/household income or wealth, and area-level deprivation) (p.28).4

This demonstrates the importance of how messages are framed - for example one qualitative study of adolescents in the UK found that news about environmental issues from a range of sources worsened feelings of stress, particularly when the storylines were catastrophic and not solution-focused.4

The importance of coping mechanisms becomes all the more acute in relation to young people, since chronic eco-anxiety may lead them to become burnt out, hopeless and unable to work towards constructive climate action. Understanding and addressing this issue is therefore important not only for helping individuals, but also for maintaining the health of communities and society more broadly. Eco-anxiety could have cascading effects on social resilience and cohesion, family relationships, health and social care systems, educational and economic outcomes. Kankawale and Niedzwiedz therefore call for it to be recognised as a growing public health issue.4

Climate emotions, power and agency

Some researchers have found that experiences of eco-anxiety and other climate emotions are related to whether and how governments have responded to climate change. Based on their international research, Hickman et al. write that, 'climate anxiety in children and young people should not be seen as simply caused by ecological disaster, it is also correlated with more powerful others (in this case, governments) failing to act on the threats being faced' (p.e871).1 In another recent article, Kankawale and Niedzwiedz report that, 'Studies consistently revealed concern from children and young people regarding their lack of inclusion and representation in decision-making processes, inducing a sense of disempowerment and betrayal which exacerbated eco-anxiety' (p.31).23

Building on this insight, researchers caution against individualising climate emotions and warn that, while taking climate action can be beneficial for some in addressing their concerns about climate change, this can also turn to disillusionment if they do not see others, including especially governments, also taking meaningful action. Hickman et al. argue that, 'To protect the mental health and wellbeing of young people, those in power can act to reduce stress and distress by recognising, understanding, and validating the fears and pain of young people, acknowledging their rights, and placing them at the centre of policy making' (p.e871).1

In a study of the emotional experiences of members of Scotland's citizens' assembly on climate change, which met in 2020-2021, Andrews found that, during the process, assembly members had higher levels of hopefulness and optimism compared to the general population.5 However, after receiving the Scottish Government's response to their recommendations, their optimism reduced and levels of worry increased. This finding underlines the reactive and dynamic nature of climate emotions and the critical importance of visible and tangible evidence that governments are acting to try and prevent the worst effects of climate change.

Researchers propose that governments, journalists, teachers and healthcare providers can all play a part in preventing climate emotions leading to long-lasting ill effects and empowering young people to cope with the effects of climate change. Examples of this would be schools providing climate education, healthcare providers making visible efforts to reduce carbon emissions, mental health practitioners recognising climate emotions and offering appropriate (but not over-medicalised) support, journalists being careful in their framing and targeting of climate news and governments leading the way by prioritising climate change as a cross-cutting issue.123 As the IPCC points out, this is not only a matter of mitigating climate change by reducing emissions, but also about adaptation: 'With proactive, timely and effective adaptation, many risks for human health and well-being could be reduced and some potentially avoided' (p.1044).9

Extreme Temperatures

While around three quarters of Scottish people are concerned about climate change, there is a common perception that it will not have severe effects in Scotland and that it is an issue of the far future. Yet, ‘Climate change means that Scotland will be wetter in winters, drier in summers, sea level rise will continue, and our weather will become more variable and unpredictable. Extremes will be more common. However, the impact of climate change is already being felt now both around the world and here at home’ (p.6).1

.png)

The Climate Change Committee (CCC) warns that current plans to adapt Scotland to the impacts of adverse weather need improvement.2 Similarly, the UCL Institute for Health Equity argues that policies around climate change must factor in adaptation to the unavoidable impacts of climate change in order to try and build a climate change resilient society (p.48).3

Without adaptation, heat and cold-related deaths are projected to increase in the UK due to a combination of climate change and sociodemographic factors. Mortality risk due to heat and cold increases with age. In the future, therefore, although we expect fewer very cold days in the UK, mortality due to moderate cold is actually projected to increase as we have an ageing population. Heat-related deaths – with no additional adaptation and limited global decarbonisation – could increase nearly 6-fold from a 2007 to 2018 baseline average estimate of 1,602 deaths per year, to 10,889 in the 2050s. We can expect both heat- and cold-related deaths to rise until the second half of the century when cold-related deaths would begin to fall. In the first half of the century, cold-related deaths will continue to dominate, despite increasing heat risks, with heat-related mortality increasing over time (p.2).4

As with other health issues, inequalities and social vulnerabilities can exacerbate the risks of extreme weather and limit more vulnerable people’s capacity to prepare for and recover from hazards. Therefore, supporting the most vulnerable and the most at risk would be highly effective.5 A study in England has found that, 'even though the most deprived areas may have a lower projected total number of hot and extreme summer days [with climate change], their greater vulnerability and reduced capacity to adapt suggest they will likely face worse health outcomes' (p.6).6 Southern England is both generally wealthier than northern England and likely to experience the highest temperatures and largest numbers of days of extreme heat. However, more northerly regions may in fact experience worse impacts because of existing stresses on people's physical and mental health as a result of inequalities and because they have fewer resources to adapt and cope.

Wan et al. report that extreme cold and extreme heat are expected to increase mortality by 9% and 4% respectively in Scotland, though cold effects have improved in the last 15 years. They write that, ‘Deaths from respiratory diseases were most sensitive to both cold and heat exposures, although mortality risk for cardiovascular diseases was also heightened, particularly in the elderly' (p.1).7 The worst effects from extreme temperatures are projected for the elderly. Also, younger people living in the most deprived areas are more vulnerable than those living in less deprived areas. This is important to note given Scotland’s ageing population and the extent to which inequalities already shape health outcomes.

In 2018, the UK, along with other countries in the northern hemisphere, experienced a summer heatwave that resulted in record temperatures, wildfires, crop failures, water shortages, overheating of buildings and roads and algal blooms. Undorf et al. write,

Climate projections suggest further substantial increases in the likelihood of 2018 temperatures between now and 2050, and that towards the end of the century every summer might be as hot as 2018. … Overall, Scotland could cope with the impacts of the 2018 heatwave. However, given the likelihood [sic] increase of high-temperature extremes, uncertainty about consequences of even higher temperatures and/or repeated heatwaves, and substantial costs of preventing negative impacts, we conclude that despite its cool climate, high-temperature extremes are important to consider for climate change adaptation in Scotland (p.1).8

Overheating and heat waves

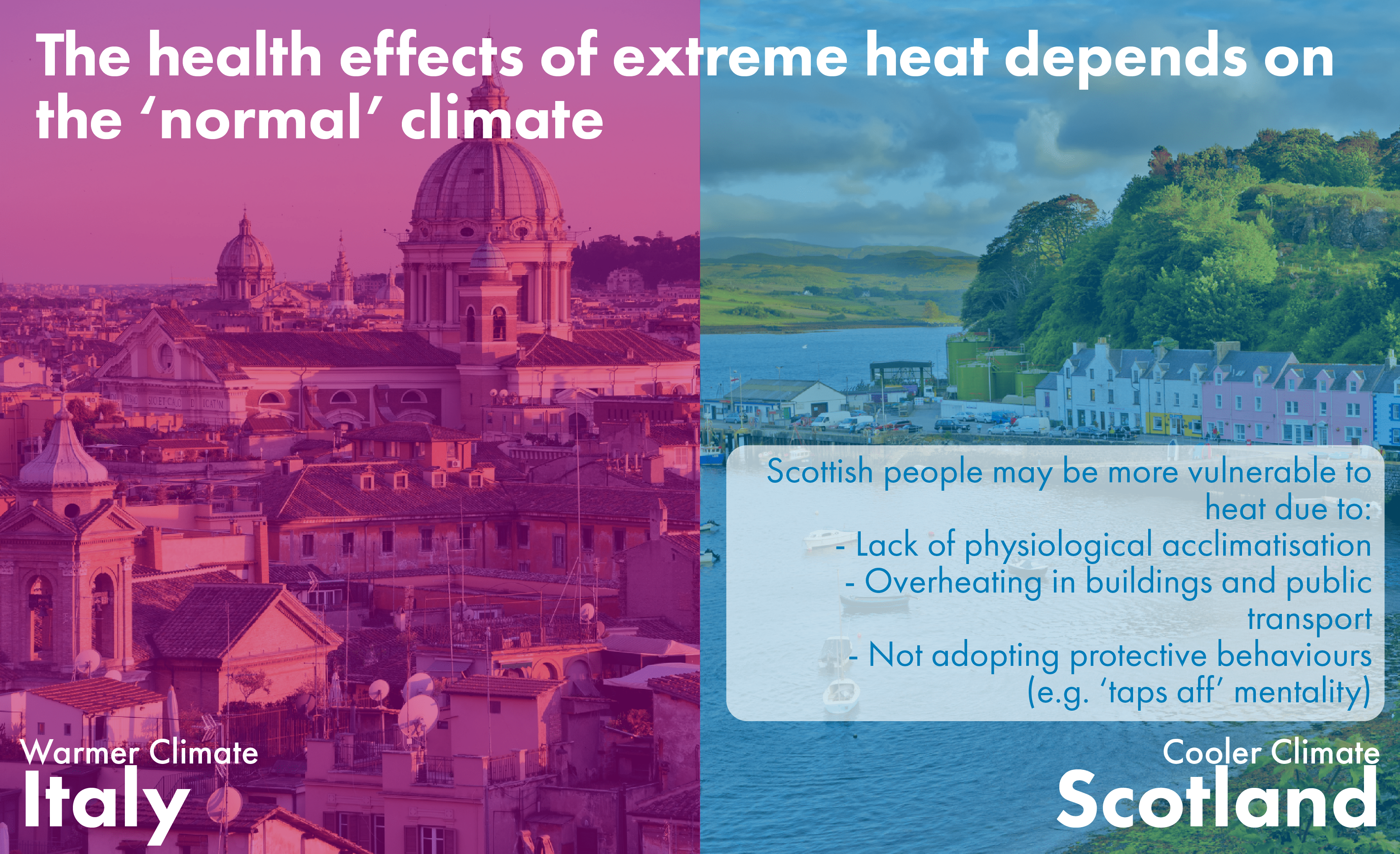

There is a perception that overheating is not a serious problem for Scotland because of its cool climate, but increasing evidence suggests this is too simplistic.1 The Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA3) shows that there could be some benefits from higher temperatures in Scotland, for example if it increases physical activity and contact with nature, both of which are known to improve physical and mental health. Nonetheless, climate change is likely to bring heatwaves and extremes of heat, which represent a risk to health and wellbeing even though the actual temperatures in Scotland may be lower than elsewhere.

The Met Office defines a heatwave as when a location records a period of at least three consecutive days with daily maximum temperatures meeting or exceeding the heatwave temperature threshold. The threshold varies according to region and Scotland's is 25◦C. Between 2011 and 2020, annual mean temperature in Scotland rose by 0.9◦C. With climate change, temperatures will continue to increase, and extreme heat events are expected to be both more frequent and more intense (Wan et al. 2023). Mortality increases by 1-3% with each degree of rise in high temperature, so effective interventions are needed to plan for this.2

Climate change is expected to increase heat-related mortality in Scotland, with projections estimating that heat related deaths will increase to around 70-285 per year by 2050 and 140-390 per year by the 2080s assuming no population growth. Although there is uncertainty about future impacts for Scotland, a study of future heatwaves in Glasgow shows an increase from 0 heatwave days per decade to 5-10 heatwave days per decade in the 2050s, and 10- 50 heatwave days per decade in the 2070s, from the baseline period 1981-2010 (p.80).34

As researchers note, hot weather tends to be viewed as positive and benign in Scotland, yet 'Scottish people may be more vulnerable to heat because buildings, public transport, and people’s behaviours are not adapted to heat’ (p.61).5 Most research on the effects of high temperatures on health has been conducted in hotter climates, but the evidence suggests that the temperature at which mortality risk rises is higher in warmer areas – for example, around 30°C in Athens and Rome compared to around 20°C in Helsinki and Stockholm. This indicates that local populations have adapted to higher temperatures while those in cooler countries like Scotland may be more vulnerable to higher temperature.6 This may be due to a range of factors including physiological acclimatisation, effective cooling systems in buildings and the adoption of protective behaviours.5

Besides mortality, high temperatures have a range of social and health outcomes and negative effects include poor sleep, sunburn, dehydration, lower productivity and violent crime and there is limited capacity to deal with these effects in the healthcare system.1 There is also increasing evidence that high temperatures interact with other environmental risks to health including air pollution, drought and wildfires and vector-borne diseases.3

One important factor that emerges from the research is a concern about overheating, as an unintended consequence of reducing exposure to cold.1 New buildings in Scotland have been designed to improve insulation and reduce heat loss, with many positive effects. However, the type of insulation used, occupant behaviours and lack of shading can all contribute to overheating and insufficient ventilation, which can become dangerous in high temperatures. With higher temperatures, there may also be greater demand for air conditioning, which would increase energy consumption and costs for consumers.

Proposed responses

Adapting to climate change in Scotland therefore requires planning for buildings, including hospitals and care settings, which can be kept cool in high temperatures and warm in cold temperatures, with minimal energy use. As well as building design that takes a full range of possible temperatures and user needs into account, planning green space effectively can help protect people from extremes of temperature, as well as improving outdoor spaces and thereby contributing to people’s wellbeing and opportunities for active travel. This resonates with a key recommendation from the UCL Institute for Health Equity, to 'design and retrofit homes to be energy efficient, climate resilient and healthy' (p.4) as a means of protecting health, reducing inequalities and mitigating climate change.12

While research on extreme temperatures in Scotland is a nascent field, the evidence suggests it is an important area to monitor and that we would benefit from further research, including on the effects of high temperatures and heatwaves, especially in an ageing population. Some researchers recommend that a heat-health strategy is drawn up for Scotland and that policymakers in health and social care, as well as other sectors, need to think of extreme temperatures in a more holistic manner, rather than assuming Scotland will only ever be affected by cold due to its current cool climate.3

Given the low awareness about risks from heat in Scotland, a first step will be to communicate the risks and strategies for coping with high temperatures to the public. Wan et al. suggest that, since people do not perceive themselves to be at risk from heat, an effective way of doing this may be to frame advice as a way of helping vulnerable neighbours and relatives.3 Such strategies will of course work best if health and social care professionals are also equipped to understand and prevent risks from extreme temperatures. This resonates with PHS' adverse weather plan, which emphasises public messaging about risks from extreme weather and increasing the knowledge of healthcare professionals on this issue and providing guidance on how to respond and plan.5.

Vector-Borne Diseases

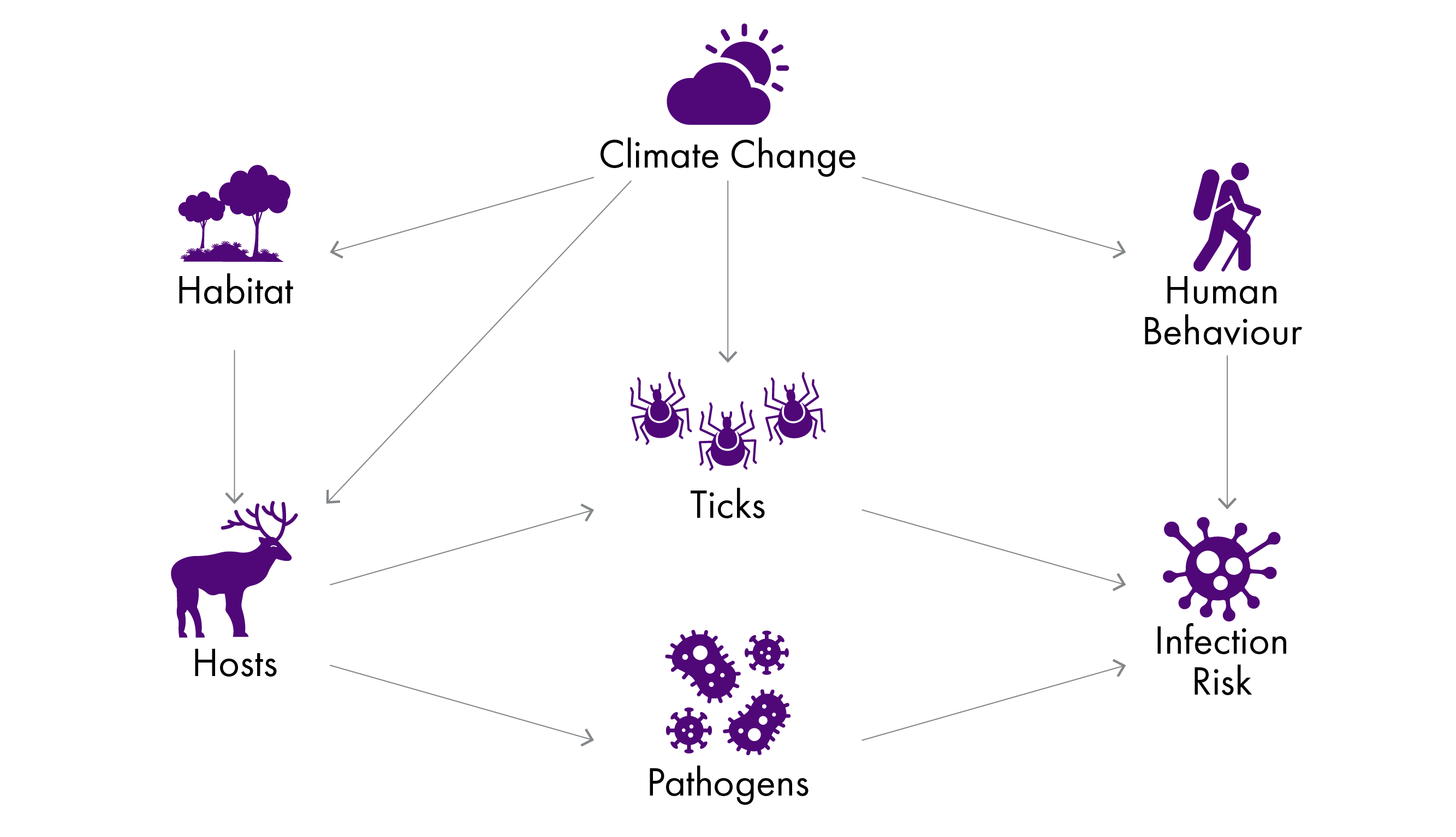

Climate change is predicted to lead to greater incidence of vector-borne diseases - that is, human illnesses that are caused by parasites, viruses and bacteria spread by animals such as blood-sucking insects. The IPCC's 6th assessment report states that, 'The burdens of several climate-sensitive food-borne, waterborne, and vector-borne diseases (VBDs) are projected to increase under climate change, assuming no additional adaptation (very high confidence)' and 'Higher incidence rates are projected for Lyme disease in the Northern Hemisphere (high confidence)' (p.1046).1 It also shows that in a low-adaptation scenario and with increasing rises in temperature, risks for both Lyme disease and West Nile Virus increase (p.1090). Climatic suitability for tick-borne disease has recently been added to the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change Europe's list tracking the negative impacts of climate change on human health, indicating experts' agreement that it is an important area to monitor.2

Lyme disease

Climate-sensitive pathogens and vectors, including the ticks that carry Lyme disease, are increasing their range within Europe. Higher temperatures lead to greater activity and higher rates of fertility and survival for ticks. Warmer habitats are also more suitable for many host species of ticks.1 Research which modelled future Lyme disease risk in Scotland nearly a decade ago predicted that a warming climate in Scotland would expand ticks' range, including to areas of higher altitude and northern regions such as Thurso and Golspie, and the length of the season in which they could transmit pathogens.1 While these researchers note that temperature will never be an isolated factor and real-world scenarios will be more complex, several researchers agree that we need to be vigilant to the risk of tick-borne diseases as the temperature warms.

Gilbert notes that determining whether climate change is the cause of increases in the population or range of ticks is difficult and that the increase in cases of Lyme disease in Scotland may not be due to climate change since the ticks that transmit it are already within their 'climate envelope' within Scotland.3 However, climate change could be an indirect cause since the milder winters it has brought are thought to be a factor in increasing deer populations, which are the primary reproductive hosts of the ticks that spread Lyme disease3.

Johnson et al. note that the increase in tick distribution and disease transmission that has been observed in other parts of Europe is likely to also be occurring in the UK, though evidence is limited. However, 'Climate change has resulted in milder winter temperatures at temperate latitudes, leading to an increase in tick survival and triggering tick activity earlier in the year' .5 The CCRA3 gives vector-borne diseases an urgency score of 'further investigation', indicating the Climate Change Committee's assessment that it is an area which would benefit from urgent research, as action may be required to adapt to this risk. The technical report notes that, 'Scotland has more reported cases of Lyme disease compared to other parts of the UK, due to higher humidity and high rates of outdoor tourism, both of which are likely to increase with climate change’ (p.96).6

Researchers agree that surveillance is critical for understanding and determining the threat of increased vector-borne disease that may come with climate change5.

There would be direct benefits from improving disease and vector surveillance in Scotland and across the UK, given the very large benefits of catching vectors and pathogens before they become established. The main benefits of further action are in enhanced monitoring and surveillance systems, including early warning, which can be considered a low-regret option. Surveillance programs are highly cost effective. There are also studies that show that vaccination for tick-borne encephalitis may be cost-effective, for people who may be exposed through work, although there is currently no vaccine for Lyme disease (p.96).6

Other vector-borne diseases and future risks