Exploring Employability Funding Allocation in Scotland

This report examines the impact of funding delays on employability services in Scotland, using survey data and qualitative interviews.Note: This presents the results of a research project carried out by Dr Seemab Farooqi (Lecture at University of Dundee Business School) as part of the SPICe Academic Fellowship programme. Views presented are those of the author, not of SPICe.

Executive Summary

Employability services in Scotland play a key role in supporting individuals into and sustaining employment, aligning with the Scottish Government’s National Strategy for Economic Transformation (NSET) and the Tackling Child Poverty Delivery Plan (2022-2026). The No One Left Behind (NOLB) strategy is the cornerstone of Scotland's employability framework, designed to promote local flexibility, person-centred support, and integration with wider public services. Under this model, Local Employability Partnerships (LEPs) led by local authorities coordinate funding and service provision, working collaboratively with third-sector organisations, private sector partners, and national agencies. The Employability Strategic Plan (2024-2027) sets out priorities for employability services, including increased awareness, partnership working, and streamlined funding mechanisms1.

Employability funding in Scotland has evolved through a combination of devolved and national funding streams, with the No One Left Behind (NOLB) strategy(2018-Present) at its core. Alongside NOLB, targeted funding streams such as the Parental Employability Support Fund(PESF) (2019-Present) and the Young Person's Guarantee (YPG) (2020-Present) have sought to address specific labour market needs. However, their ring-fenced nature and fluctuating availability have led to gaps in service delivery. The discontinuation of Fair Start Scotland (2018-2024) and the impending end of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF) in March 2025, which replaced the European Social Fund(ESF) in 2022, further underscore the fragility of the funding landscape.

The 2024-25 Scottish Budget saw a 23% reduction in employability funding, with allocations falling from £133.6 million in 2023-24 Scottish Budget to £102.9 million, following earlier reductions in the 2022-23 Emergency Budget Review. The Autumn Budget Revision (ABR) for 2024-25 provided £155.9 million in additional funding to local government, though it did not explicitly allocate further resources to employability-specific programmes such as PESF or YPG. The fragility of the funding landscape has exacerbated existing challenges within the sector raising concerns regarding delays in the allocation of funding to delivery organisations, which in turn has affected the overall effectiveness of employability programmes.

This research examines the impact of Scotland's employability funding model on service delivery, particularly in the context of a challenging budget settlement. It analyses funding flows from the Scottish Government to local authorities and delivery partners, identifying bottlenecks and assessing their implications for service provision. Additionally, the study explores how local authorities, third-sector organisations, and other delivery partners navigate these mechanisms, highlighting regional variations and the operational challenges posed by funding delays.

This report uses a mixed-methods approach, integrating survey data (n=156) with interviews across 19 local authorities, including 21 employability leads, 15 third-sector representatives, and 4 national organisations. It examines how funding delays disrupt staffing, programme delivery, and long-term planning, revealing barriers from short-term cycles, disbursement delays, and administrative complexities. Geographical variations further underscore the need for systemic reforms to improve service effectiveness.

Key Findings

Systemic Funding Challenges:

Funding Delays: All local authorities reported experiencing delays in accessing funding within the last two years, with 75% of these delays tied to Scottish Government funding streams. 85% cited delays in grant award letters as a significant issue, with allocation delays averaging 12–24 weeks in some areas.

Geographical variations: Rural councils face deeper funding cuts along with higher operational costs due to geographic isolation and dispersed populations, fewer providers making it difficult for these councils to absorb delays, leading to severe planning and staffing difficulties.

Impact on Service delivery:

Fragmented Procurement Processes: 78% highlighted issues with procurement timelines, with piecemeal or short-term contracts dominating. 68% reported post-procurement delays, due to internal processes, that further limited effective service implementation.

Staffing challenges: 97.2% of Local Authorities and 93.1% of Third Sector organisations reported difficulties in staff recruitment and retention caused by funding delays.

Program Disruptions: Delayed program start dates affected 91.7% of Local Authorities and 82.8% of Third Sector organisations, with reduced program duration cited by 83.3% and 75.9%, respectively.

Planning Barriers: 100% of Local Authorities and 93.1% of Third Sector organisations cited long-term planning challenges due to unpredictable funding timelines.

Poor Coordination: 72% of respondents noted ineffective communication between local authorities and the Scottish Government as a barrier to timely and transparent disbursement.

Sector-Specific Impacts:

Local Authorities face heightened accountability pressures, with 86.1% citing difficulties in meeting funders’ expectations.

Funding delays and annualised funding cycle disproportionately affect Parents and Disabled individuals. Only 28% believed current funding mechanisms effectively address the needs of marginalised groups, including disabled individuals and parents, underscoring systemic gaps in service provision.

Third Sector organisations reported greater variability in their ability to mitigate funding delays, reflecting resource and structural constraints.

Emerging Policy Recommendations For Scottish Government, Local Authorities and Third Sector Partners in Employability Service Provision

Emerging from survey responses and stakeholder interviews, these recommendations provide insights for the Scottish Government, Local Authorities, and Third Sector organisations on ways to strengthen the coordination, responsiveness, and sustainability of employability service delivery:

Adopt Multi-Year Funding Models:

The transition to multi-year funding is widely recognised as the most critical reform required for effective employability service provision. A significant 91.0% of respondents identified this as their most important recommendation, underscoring the urgent need for greater financial stability. This recommendation is aimed primarily at the Scottish Government, which sets funding cycles, but also at Local Authorities and third-sector organisations, which require longer-term financial commitments to plan and deliver sustainable services.

Address the Cascade Impact of Funding Delays:

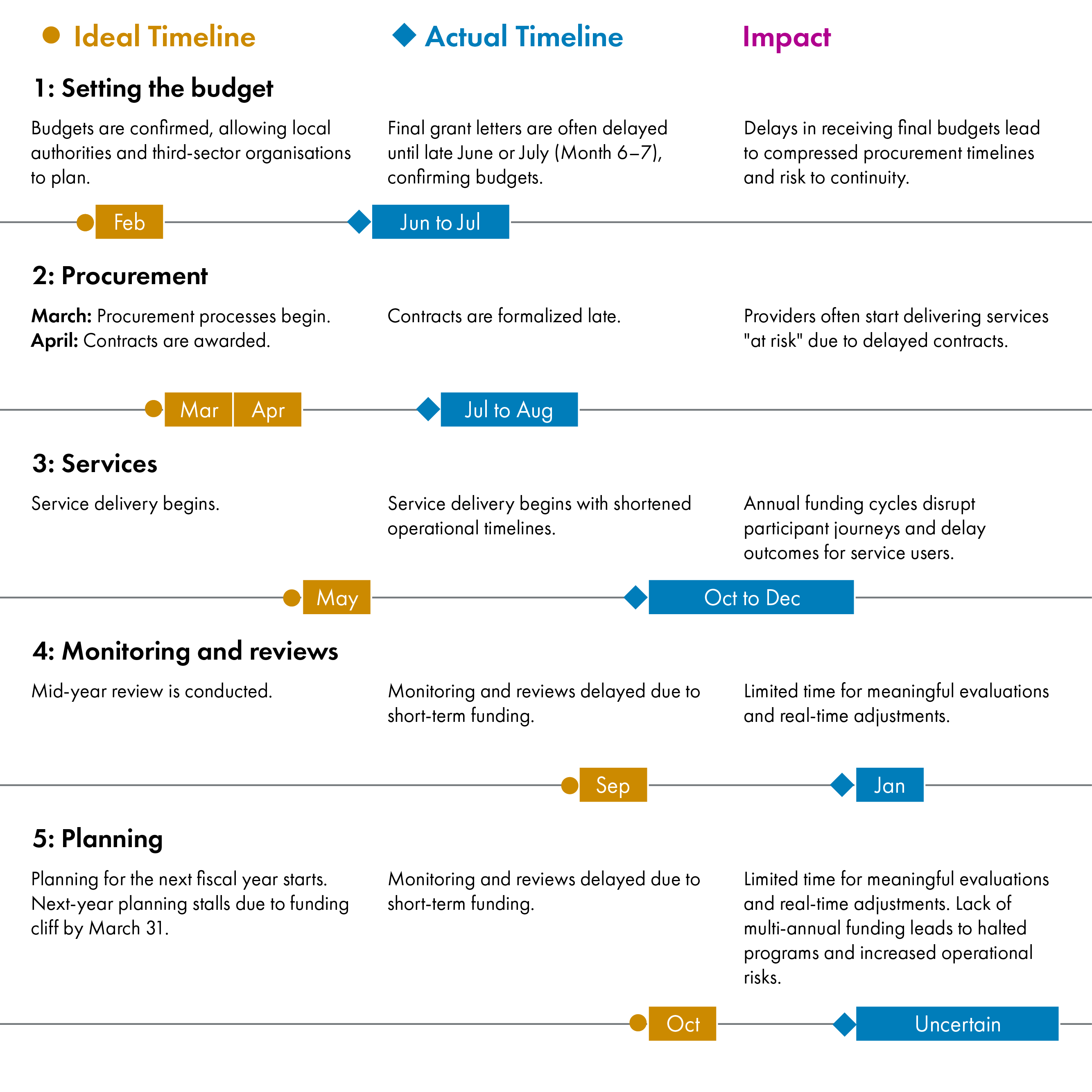

The misalignment between funding cycles and service delivery creates a knock-on effect that disrupts the entire employability ecosystem. Late grant allocations delay procurement and commissioning, preventing services from being properly mobilised and leaving providers with insufficient time to recruit staff, develop programmes, or engage participants. This results in fragmented support, service gaps, and reduced effectiveness in reaching those most in need. 88% of respondents highlighted the need to simplify administrative processes, reduce bureaucratic delays, and reform procurement practices to improve efficiency. Tackling these systemic delays requires the Scottish Government to ensure timely funding allocations and Local Authorities to develop more flexible commissioning processes that mitigate disruption to service users.

Enhance Communication Between Key Stakeholders:

Improved communication between Local Authorities and the Scottish Government is critical, with 85.3% of Local Authorities reporting neutral or ineffective experiences, highlighting significant gaps in clarity and timeliness. Establishing more structured engagement mechanisms, clear guidance on funding allocations, and consistent feedback loops will ensure that policy decisions are better aligned with on-the-ground service delivery needs.

Ensure Funding Reflects Regional and Demographic Needs:

There is strong consensus among Local Authorities, third-sector organisations, and other stakeholders that employability funding mechanisms must better reflect regional disparities. This is particularly crucial for rural and island communities, where higher costs and logistical challenges create additional barriers to service delivery. 76% of respondents advocated for funding models that incorporate regional cost adjustments and flexibility to address localised challenges. This requires policy adjustments from the Scottish Government, in collaboration with Local Authorities and regional economic development bodies.

Develop Streamlined, Strategic Commissioning Frameworks:

Fragmented procurement processes and funding delays significantly hinder employability service provision. Moving towards a more strategic commissioning model with longer contract durations, fewer piecemeal contracts, and reduced administrative burdens, would particularly benefit third-sector providers, who often face disproportionate challenges in securing and managing funding. This requires action from both the Scottish Government and Local Authorities, ensuring that commissioning processes align with service delivery needs and minimise bureaucratic inefficiencies.

Conclusion:

This report has examined the structure, distribution, and challenges of employability funding in Scotland, highlighting key findings from survey responses and stakeholder interviews. The No One Left Behind (NOLB) approach has introduced greater local flexibility, but findings suggest variation in implementation across local authorities, leading to inconsistencies in service delivery (Sections 1 & 2). While NOLB has streamlined funding structures, the transition from multi-stream funding to a localised model has raised concerns, particularly regarding the loss of the European Social Fund (ESF) and the forthcoming conclusion of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF) in 2025 (Section 2). These challenges are further compounded by delays in grant offer letters, which create additional financial uncertainty for service providers, affecting their ability to plan and sustain employability programs effectively (Section 3). Moreover, these funding constraints contribute to fragmented commissioning processes, where short-term contracts and misaligned procurement timelines disrupt service continuity and long-term workforce planning (Section 4).

One of the most prominent findings is the strong consensus on the need for multi-year funding, with 91% of respondents ranking it as the most critical reform (Table 6.1a, Section 6). Annualised budgets were identified as a key challenge, limiting long-term planning, staff retention, and program sustainability (Section 5.1). Additionally, funding delays and disbursement inefficiencies were reported across all sectors, impacting the timing and continuity of service delivery (Section 3.1& 3.2).

Coordination between Scottish Government, local authorities, and third-sector providers was another recurring theme, with respondents identifying communication and administrative burdens as barriers to effective employability service provision (Section 3 and 4). Administrative complexity and multiple funding streams were cited as increasing the workload for organisations, diverting resources away from front-line service delivery (Section 5.1).

While these challenges present ongoing concerns, the findings suggest that enhancing coordination, introducing greater funding flexibility, and addressing procedural inefficiencies could support a more sustainable employability funding model (Section 6). Moving forward, ensuring stability in funding cycles, improving engagement between funding bodies and service providers, and aligning funding structures with local labour market needs will be critical to enhancing Scotland's employability services.

About the Author

Dr. Seemab Farooqi is a Lecturer in Human Resource Management at the University of Dundee Business School and a Scottish Parliament Academic Fellow (SPICe), conducting research on employability funding and service provision in Scotland. Her expertise spans public policy, performance management, and inclusion, with a research focus on policy analysis, public sector management, and entrepreneurship.

Her current projects include Mapping Funding Flow and Support for Under-represented Social Entrepreneurship (PRME UK Charter Seed Funding), exploring the hidden cost of living with disability in Scotland (Royal Society of Edinburgh Funding), and research on the Circular Economy (Scotland Beyond Net Zero Funding Project). Her work contributes to policy discussions on funding structures, labour market inequalities, and sustainable economic development in Scotland.

Dr Seemab Farooqi has been working with the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) as part of its Academic Fellowship Scheme. This aims to build links between academic expertise and the work of the Scottish Parliament.

The views expressed in this briefing are the views of the author, not those of SPICe or the Scottish Parliament.

Methodology

This report employs a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative data to provide a comprehensive understanding of funding challenges in employability service delivery across Scotland. By integrating survey data with interview insights, the methodology captures both the breadth and depth of stakeholder experiences.

Data Collection

Quantitative Component:

Survey Design: Structured surveys were distributed to key stakeholders, including Local Authorities, Third Sector organisations, and other entities engaged in employability programs.

Sample Size: Responses were collected from 156 participants, representing diverse roles such as policy officers, delivery partners, and funding recipients.

Qualitative Component:

In-Depth Semi Structured Interviews: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with representatives from SLAED, TSI networks, and other key stakeholders. Table 1 presents the anonymised sampling framework, categorising local authorities based on their urban, semi-urban, rural, or island classification. A total of 19 local authorities were interviewed, comprising 21 initial interviews with employability leads, 15 interviews with third-sector representatives, and 4 interviews with national organisations. Additionally, 8 follow-up interviews were conducted with employability leads and 4 with third-sector representatives.

| Informant Group | Contextual Setting and Actors | Data Collection |

| Employability Leads (EL) | Local government representatives directly involved in formulating and implementing employability policies. | 21 initial interviews conducted across 19 local authorities:Urban: 7 interviews. Semi-Urban: 4 interviews. Rural: 7 interviews. Island: 3 interviews. 8 follow-up interviews conducted with Employability Leads from 8 local authorities. |

| Third-Sector Organisations (TSO) | organisations delivering employability services under public sector contracts. | 15 initial interviews conducted across local authorities: Urban: 5 interviews.Semi-Urban: 3 interviews. Rural: 4 interviews. Island: 2 interviews. 4 follow-up interviews conducted with representatives from third-sector organisations. |

| National Organisations | Representatives from national and coordinating organisations, such as SLAED and COSLA. | 4 interviews conducted: 2 with SLAED and 2 with COSLA. These organisations operate nationally and are not tied to specific local authority classifications. |

Analysis Strategy:

Quantitative Data Analysis:

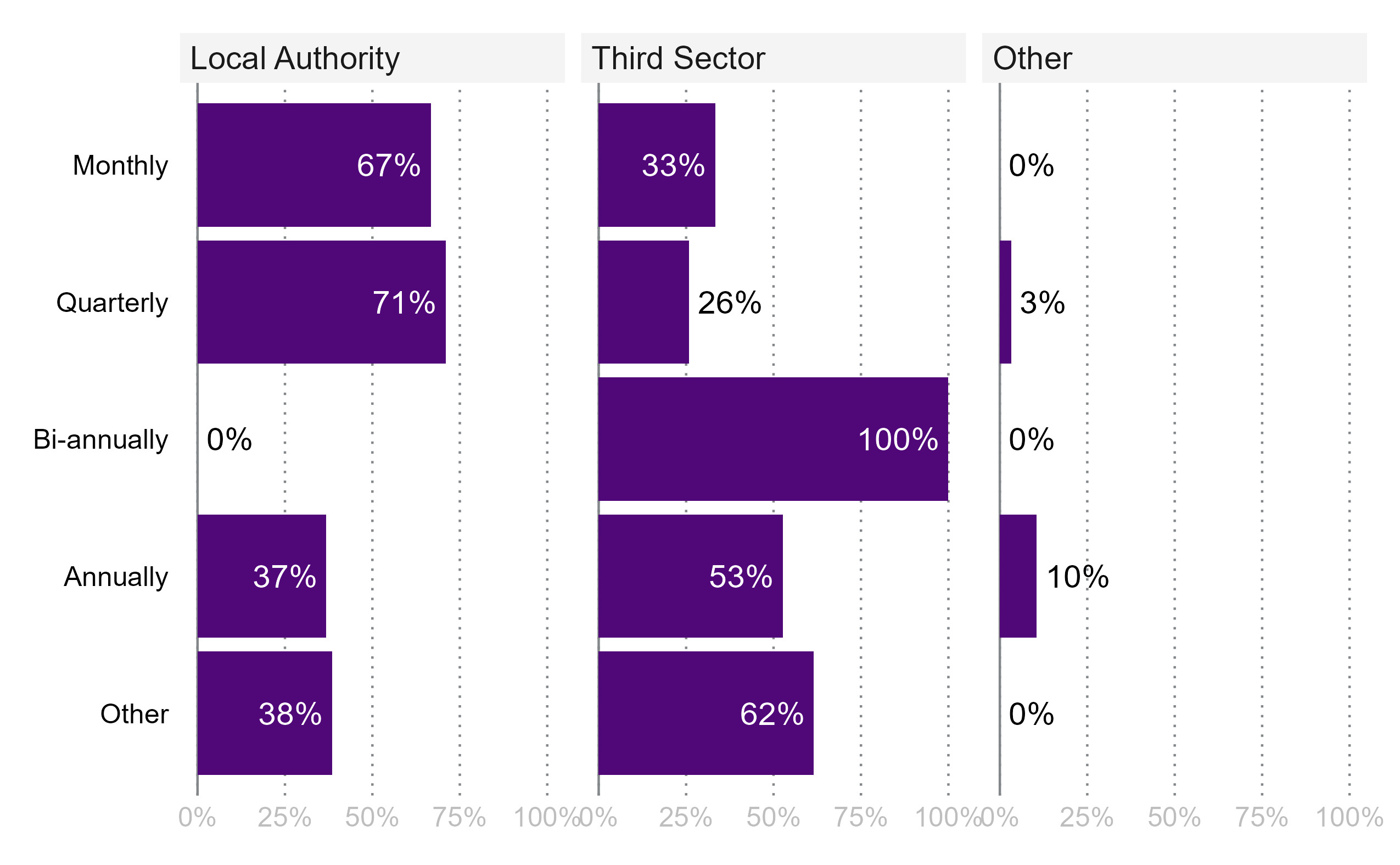

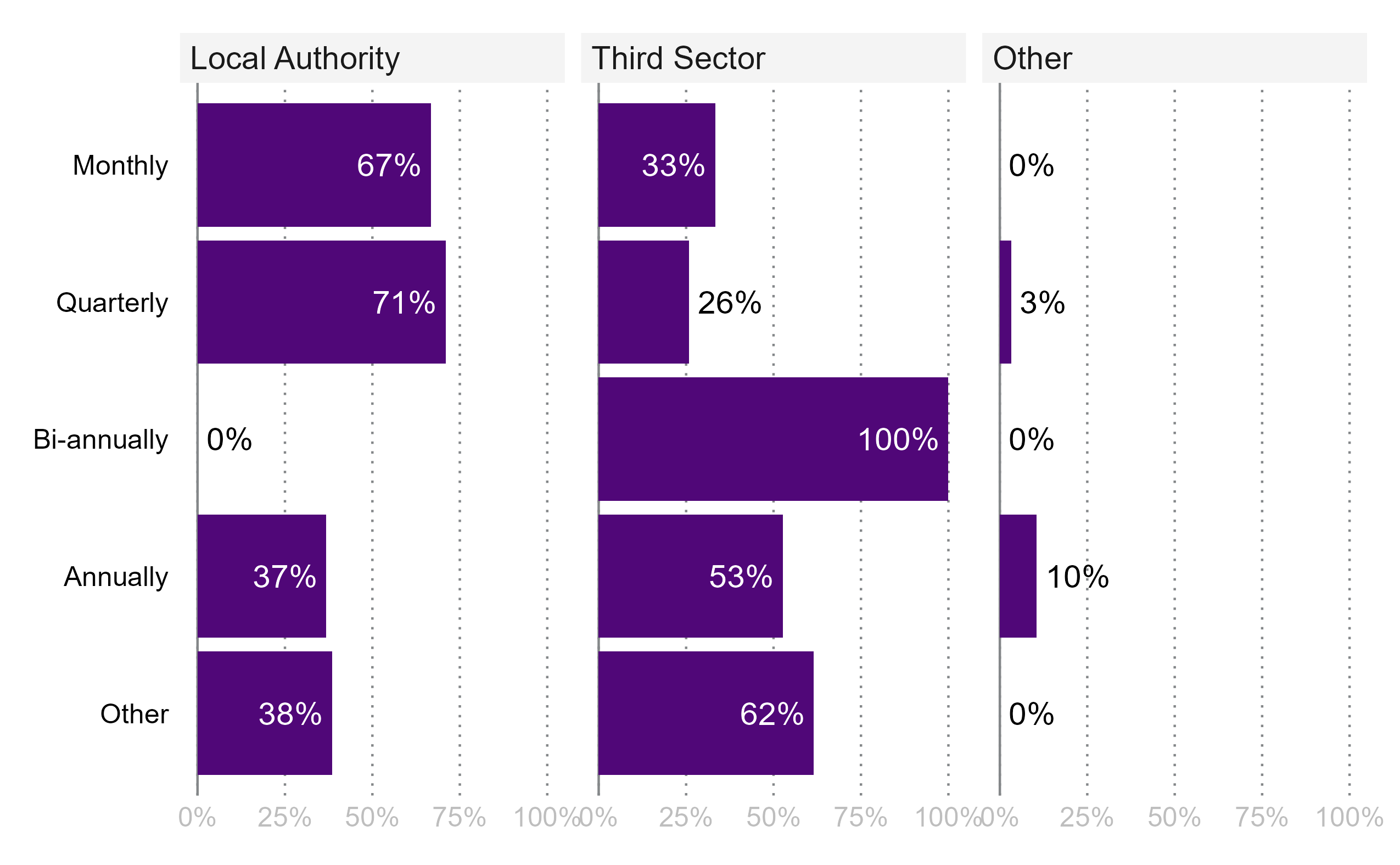

Descriptive statistics (means, percentages, standard deviations) and cross-sector comparisons (Local Authorities, Third Sector, and others) to identify funding challenges.

Qualitative Data Analysis:

Thematic Coding: Thematic coding of interviews and follow up interviews to capture recurring patterns and stakeholder priorities.

Integration with Quantitative Insights: Qualitative findings were used to contextualise quantitative trends, ensuring a holistic interpretation of the data.

Strengths & Limitations

Strengths:

Comprehensive Scope: Mixed-methods approach captures systemic trends and individual experiences, informing actionable recommendations.

Diverse Representation: Input from Local Authorities, Third Sector, and other stakeholders reflects the complexities of employability funding.

Limitations:

Sample Representation: A small sample size for "Other Organisations" limits generalisability.

Time Constraints: Limited participant availability may have reduced the depth of qualitative insights.

Introduction

Employability funding in Scotland is structured under the No One Left Behind (NOLB) approach, which prioritises person-centred, tailored, and responsive employment support that aligns with local labour market needs. No One Left Behind promotes flexibility, integration with wider services, and partnership driven delivery through Local Employability Partnerships (LEPs), ensuring that individuals of all ages receive support to enter and sustain employment. Funding is provided through a combination of Scottish Government allocations, including the Core Employability Budget, the Parental Employability Support Fund (PESF), and the Young Person’s Guarantee (YPG), alongside local authority budgets and UK Government contributions, such as the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF).

The 2023-24 Scottish Budget allocated £133.6 million to employability, primarily supporting local employability partnerships (LEPs) and third-sector delivery partners. However, in the 2024-25 Scottish Budget 1, funding was reduced by 23% to £102.9 million, reflecting broader fiscal pressures and spending realignments. The Autumn Budget Revision (ABR) for 2024-25 introduced adjustments, allocating £155.9 million in additional funding to local government 2, but it did not explicitly earmark further resources for employability-specific programmes such as PESF or YPG.

The funding landscape continues to evolve, with the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF) set to conclude in March 2025, introducing uncertainty around future funding streams. The current funding structure operates on annual cycles, which influences how local authorities and third-sector providers plan and manage employability programmes. While some areas have received increased allocations, stakeholders have highlighted service delivery considerations, including grant offer letter timings and programme funding structures. The funding landscape continues to evolve, with UKSPF scheduled to conclude in March 2025, introducing uncertainty regarding future funding streams. The annual funding cycle impacts service planning and delivery, with stakeholders emphasising grant offer delays and programme funding structures as key challenges.

Employability funding in Scotland, coordinated through the No One Left Behind Approach (NOLB), is primarily delivered by third sector organisations, and managed by Local Employability Partnerships (LEP), leading to variation across the country. This research explores Scotland's employability provision, funding flows, and outcomes for different user groups, while assessing regional variations in service delivery and funding experiences of providers. This will provide the stakeholders with insight into how the funding model impacts delivery of employability support across Scotland.

Key objectives of this report are:

Producing an overview of employability provision across Scotland, including the types of providers who deliver front-line services and the client groups being served.

Analysing and producing a summary of how funding flows from the Scottish Government to local authorities and then to delivery partners, and how this has changed over time.

Analysing the outcomes for different user groups and how these outcomes are defined and measured.

Section 1: Overview and Composition of Employability Funding

Overview and Composition of Employability Funding

The funding landscape for employability services in Scotland has evolved through a mix of devolved and national funding streams, with theNo One Left Behind(NOLB) strategy, introduced in 20181, at its core, aiming to create a more flexible and locally driven system. Over time, funding has shifted from rigid, centrally managed programmes to a model where local authorities have greater discretion in designing services to meet community needs. However, this has led to inconsistencies in provision across different regions, exacerbated by short-term annual funding cycles that limit long-term planning. The Parental Employability Support Fund (PESF)2, introduced in 2019, and the Young Person’s Guarantee (YPG)3, launched in 2020 and still operational, have sought to address specific challenges, yet their ring-fenced nature and fluctuating availability often result in gaps in service delivery. The discontinuation of Fair Start Scotland4, which began in 2018 and ceased taking new referrals in March 2024, and the uncertainty surrounding the UK Shared Prosperity Fund5, which replaced the European Social Fund6in 2022 but is set to end in March 2025, further highlight the fragility of the current system, which remains constrained by funding delays, a lack of multi-annual commitments, and challenges in integrating support for different client groups.

This section provides an overview of the structure and composition of employability funding in Scotland, examining key funding streams, their allocation mechanisms, and their impact on service delivery. It explores how different sources of funding interact, highlighting the complexities faced by local authorities, third-sector providers, and other stakeholders in navigating the employability funding landscape. Key findings explore the challenges of managing multiple funding streams, the administrative burdens associated with each source, and the alignment of funding structures with organisational needs. Insights from survey respondents and qualitative interviews highlight how funding sources shape innovation, flexibility, and long-term planning across organisation types.

Section 1.1: Funding Sources and Distribution

As outlined in the previous section on the funding landscape for employability services, the No One Left Behind strategy, Parental Employability Support Fund, and other government-led initiatives play a crucial role in shaping the overall funding structure. However, survey responses reveal significant variation in how different organisations experience and access these funding streams.

Table 1.1 presents respondents’ estimates of their funding composition, reflecting perceived reliance on different sources rather than verified financial data. This provides insight into the disparities in funding accessibility and dependence across Scotland's employability sector. This was a multiple-choice question, meaning that respondents could report receiving funding from several sources.

| Funding Source | Average Proportion (%) | Range (%) | Standard Deviation | Total Responses |

| Local Authority Core Budget | 21.84 | 0 – 100 | 30.18 | 108 |

| Additional Scottish Government Streams | 24.94 | 0 – 100 | 31.90 | 109 |

| UK Government (e.g., Shared Prosperity Fund) | 11.89 | 0 – 90 | 16.76 | 108 |

| Other Sources (e.g., private/philanthropic) | 8.13 | 0 – 100 | 22.12 | 108 |

Key Findings:

Local Authority Core Budget:

The proportion of funding from Local Authority budgets varies significantly, with some organisations reporting higher levels of reliance, while others receive little to no core budget support (Standard Deviation (SD) = 30.18).

Implication: Unequal access to core budgets highlights the need for more equitable distribution to reduce regional disparities and ensure consistent service delivery, aligning with concerns raised in the budget-to-budget comparison on funding stability.

2. Additional Scottish Government Streams:

These represent the largest single funding source, but with high variability (SD = 31.90), indicating that organisations experience inconsistent access and reliance on these funds.

Implication: The inconsistency underscores the need for more predictable allocation models, particularly given the £30.7 million decrease in the 2024-25 Employability Budget, which could further disrupt services.

3. UK Government Funding (e.g., Shared Prosperity Fund):

This funding has a lower average share and less variability (SD = 16.76), suggesting limited accessibility or lower importance within the sector.

Implication: Expanding access to UK Government funds could help diversify income streams, reducing over-reliance on Scottish Government and Local Authority budgets. Given the upcoming expiration of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (March 2025), there is an urgent need to consider alternative funding sources.

4. Other Sources (e.g., private/philanthropic):

Non-governmental sources contribute 8.13% on average, with wide variability (SD = 22.12), reflecting variable use across organisations.

Implications: Encouraging partnerships with private and philanthropic funders could provide innovative and flexible funding options, though this would require capacity-building support for organisations to access these streams effectively.

Qualitative Insights: Transition to No One Left Behind Approach

The funding landscape for employability in Scotland has undergone significant restructuring over recent years, shaped by the transition to the No One Left Behind (NOLB) approach, introduced in 2018. This transition aimed to create a more locally driven, flexible employability model, replacing fragmented and prescriptive funding streams with a cohesive, person-centred approach that aligns with local labour market needs.

While Scottish Government funding remains the primary source of employability support, allocated through NOLB and additional funding streams such as the Parental Employability Support Fund (PESF) (2019-Present) and the Young Person’s Guarantee (YPG) (2020-Present), UK Government funding has also historically played a role. Previously, employability programmes in Scotland benefited from the stability of the European Social Fund (ESF), which operated on a seven-year funding cycle (2014-2020), allowing local authorities and service providers to strategically plan and maintain service continuity.

Following Brexit in 2020, ESF funding was discontinued, leaving a gap in long-term employability investment. In response, the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF) was introduced in 2022 as a shorter-term replacement, allocated on a three-year cycle (2022-2025). However, unlike ESF, UKSPF does not provide multi-annual financial security, creating challenges in aligning with NOLB’s localised, long-term planning approach. With UKSPF set to conclude in March 2025, local authorities and service providers face uncertainties regarding staffing, service continuity, and the future of employability funding beyond 2025.

This section draws on interviews with local authority representatives and third-sector stakeholders to explore the transition to the No One Left Behind (NOLB) funding model.

Evolution of Employability Funding landscape

According to interviewees, the shift to a unified funding model under NOLB enabled local authorities to adopt more cohesive, locally tailored approaches, helping to reduce duplication in funding mechanisms and streamline service delivery. Stakeholders reflected that this transition allowed greater flexibility at the local level, aligning funding more closely with regional labour market needs.

As one employability lead noted:

“We’ve moved from five separate funding streams to one under No One Left Behind, simplifying the landscape but with less overall funding.” (Employability Lead 1, LA07_Urban)

This shift replaced siloed and prescriptive funding with an aligned, flexible vision at the local level:

“No One Left Behind brought a shift from silo and prescriptive funding to an aligned, local vision that allows greater flexibility.” (Employability Lead 1, LA15_Urban)

While NOLB aimed to reduce duplication in funding mechanisms and enhance local flexibility, interviewees highlighted that its implementation has varied across local authorities, resulting in differences in service availability and delivery structures.

“The biggest change really has been the introduction of No One Left Behind. Every single local authority has chosen to do it differently, which reflects flexibility but also inconsistency.” (Third Sector _12 Rural & Urban)

Scottish Government allocations remain the largest contributor to employability services, particularly in rural and island councils, where alternative funding sources are less accessible:

“For smaller authorities, NOLB is critical, but the annual nature of funding creates planning challenges.” (Employability Lead, LA29_Island)

“We only get No One Left Behind funding; there’s no UK Prosperity Fund support for us….We’ve seen reductions in funding this year…20% for us compared to 10% reductions for mainland councils.” (Employability Lead, LA22_Island)

Local Authority contributions vary significantly, ranging from 0% to 100%, creating disparities in financial capacity across regions:

“Our core budget is limited, so we rely on NOLB and other external funding to maintain service levels.” (Employability Lead, LA04_Rural)

“We don't have core funding or other funding streams; if NOLB doesn't come in, the service ends.” (Employability Lead, LA22_Island)

The UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF) is valued for providing flexibility to address funding delays, particularly in urban and some rural areas. However, access to this fund remains inconsistent, with rural and smaller councils often excluded.

"We only get No One Left Behind funding; there’s no UK Prosperity Fund support for us." (Employability Lead, LA22_Island)

For urban and larger local authorities, UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF) has been instrumental in bridging funding gaps caused by delays in Scottish Government streams:

"The flexibility of UKSPF allowed us to bridge gaps and maintain service delivery during periods of uncertainty." (Employability Lead, LA30_Urban)

"We’ve used [UK]SPF to extend contracts and run a grant program before the official grant offer letter came in. It gave us flexibility to cover staff and grants before other funds arrived.” (Employability Lead, LA10_Rural)

Despite its benefits, the conditions attached to UKSPF funding often limit its full utilisation:

"UK Shared Prosperity Fund was used where Scottish Government funding wasn’t eligible, but constitutionalities often dictate how it's used." (Employability Lead, LA13_Semi Urban)

Local authorities also emphasised the importance of integrating UKSPF with other funding streams, such as No One Left Behind, to avoid duplication and ensure coherence:

"We made sure that we linked the guidance very clearly to No One Left Behind funding, so there was complementarity and not duplication." (Employability Lead, LA04_Rural)

The end of UKSPF funding in March 2025 has raised concerns about a potential "cliff edge" in funding, threatening service delivery continuity and staff contracts:

“We’re just hoping something is announced in October, so everything doesn’t fall off a cliff edge come the end of March 2025.” (Employability Lead, LA10_Rural)

“Without clarity on UKSPF replacement, staff contracts and ongoing programs are at significant risk.” (Employability Lead, LA22_Island)

Private and Philanthropic Contributions are more prevalent in urban areas, these sources offer opportunities for innovation but remain underutilised in rural regions.

"We’ve partnered with private funders to address gaps in government funding." (Employability Lead, LA07_Urban)

Benefits of Streamlining under ‘No Left Behind Strategy’:

Reduced Duplication: By consolidating funding streams, NOLB minimised overlap and improved resource efficiency:

“Before NOLB, we had too many funding streams doing the same thing, which made service delivery overly complex.” (Employability Lead 2, LA15_Urban)

“Streamlining has enabled us to avoid duplicating efforts, ensuring more resources go directly to those who need them.” (Employability Lead, LA29_Island)

Increased Local Flexibility: Councils now have greater autonomy to adapt funding to regional needs, fostering innovation and co-production:

“Branding like Glasgow Futures ensures local identity while improving service integration and coherence.” (Employability Lead 2, LA15_Urban)

“NOLB allows us to tailor employability services to specific community needs, which was impossible under the old, rigid funding models.” (Third Sector 3, Urban and Rural)

Strategic Use of Partnerships: Local Employability Partnerships (LEPs) have emerged as critical structures for collaboration, enabling local authorities, third-sector providers, and other stakeholders to align resources and expertise. While larger councils use these partnerships to reduce service duplication, smaller authorities rely on them to share knowledge and overcome resource limitations:

"Collaboration within the LEPs ensures services align with local labour market needs and avoid duplication." Employability Lead, LA29_Semi Urban)

“Through our LEP, we’ve established communication channels that are open and transparent with our partners, even if information from the Scottish Government is limited.” (Employability Lead, LA10_Rural)

LEP effectiveness varies based on leadership and trust among partners. Third-sector interviews indicate that some LEPs lack engagement in key decisions, impacting their ability to address local needs comprehensively:

“Our head of learning and employability sits as a third sector rep on the LEP forum, but none of that [service planning] is discussed there” (Third Sector _12 Rural and Urban)

“They brought everybody around the table, began to think about what’s needed in different areas, and coordinated services through regular meetings. This approach allowed partners to leverage their strengths and address local needs effectively.” (Third Sector _12 Rural and Urban)

Challenges of the Transition to No One Left Behind (NOLB) strategy:

Despite its advantages, the implementation of NOLB has revealed systemic challenges:

Reduced Overall Funding:

While the policy has streamlined funding processes, it has reduced the overall funding available to the local authorities in that process:

"We had five or six funding streams, but NOLB merged them into one. This helped reduce duplication but also meant less total funding." (Employability Lead, LA07_Urban)

Some stakeholders also reflected on variability in funding distribution, with concerns that changes in funding structures do not always support service continuity across different regions:

"There’s much less funding than there ever was, and the challenge with No One Left Behind is that it doesn't always create consistency in service delivery.” (Third Sector _12 Rural & Urban)

2. Geographic Disparities:

The localised nature of No One Left Behind (NOLB) has led to diverse service models across Scotland, allowing councils to tailor employability support to local labour market needs. While this flexibility ensures responsiveness, it also creates variability in service availability, particularly for individuals moving between local authority areas:

"Every single local authority has chosen to do it differently. It really is a bit of a postcode lottery in terms of what’s available, what you can access, and when." (Third Sector _12 Rural & Urban)

While localised funding empowers councils to address their specific needs, systemic disparities and geographic constraints pose persistent challenges, particularly for smaller and rural authorities.

"Delivery in the Isles costs significantly more, with transport and time challenges amplifying the disparity.” Lindsey Johnson

“We are expected to do what Glasgow does, with significantly fewer resources and a much smaller team.” (Employability Lead, LA22_Island)

Smaller councils face additional hurdles as national funding formulas often fail to account for local disparities in needs and costs.

"Core budgets vary year by year, making it difficult to plan long-term. Allocations depend on regional needs and political priorities, which aren’t always transparent. " (Employability Lead LA32, Island)

3. Short-Term Funding Cycles and Misaligned Commissioning:

NOLB’s reliance on annualised funding has limited councils’ ability to plan strategically, affecting staff retention and long-term projects:

"We’re always working against the clock. By the time funding is confirmed, we’ve already lost crucial months.” (Employability Lead, LA32_Island)

4. Misalignment Between National and Local Priorities:

While NOLB promotes flexibility, its implementation is sometimes constrained by national priorities that do not align with local realities:

“We don’t have large numbers of priority groups like asylum seekers or young parents, but funding expects us to deliver the same targets as mainland councils.” (Employability Lead, LA22_Island

“Flexibility in funding allocation would allow us to address our real priorities more effectively.” (Employability Lead, LA29_Semi Urban)

Findings suggest that while NOLB has enhanced flexibility and local alignment, challenges remain due to reduced overall funding, short-term cycles, and regional variations. Councils have adjusted by integrating funding sources, but multi-annual funding is still seen as important for stability and effectiveness.

BOX 1.1: Additional Key Insights on Employability Provision and Funding

1. Types of Providers and Client Groups:

Providers: Employability services in Scotland are delivered through a mix of local authorities, third-sector organisations, private sector providers, and arm’s length organisations.

“We rely heavily on third-sector providers to ensure service delivery in rural areas.” (Employability Lead, LA04_Rural)

Client Groups: Employability support under No One Left Behind (NOLB) is designed to be person-centred and responsive to local labour market needs, reaching those facing the greatest barriers to work. Interviewees highlighted that services support young people, including school leavers and those transitioning into work, as well as low-income parents, aligning with child poverty reduction efforts. Support also extends to disabled individuals, those with long-term health conditions, minority ethnic groups, care-experienced young people, and individuals with lived experience of the justice system. The broad scope of client groups reflects the commitment to inclusive and adaptable employability services across Scotland.

“Our services target everyone from school leavers to those facing systemic barriers.” (Employability Lead, LA29_Island)

2. Funding Evolution:

Shift to No One Left Behind (NOLB): The transition from fragmented, multi-stream funding to a localised employability model under No One Left Behind (2018-Present) has simplified funding administration and given local authorities more flexibility. However, many respondents noted that this shift has also resulted in reduced overall funding, making it difficult to sustain service levels.

“We’ve moved from five funding streams to one, simplifying the process but with less funding.” (Employability Lead, LA07_Urban)

Loss of European Social Fund (ESF): Until 2020, ESF provided long-term, multi-annual funding on a seven-year cycle (2014-2020), offering stability and strategic investment for employability programmes. Following Brexit, ESF funding was discontinued, requiring a shift to short-term domestic funding models:

“The absence of ESF has forced us to operate on short-term funding cycles, limiting planning.” (Employability Lead, LA21_Urban)

End of UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF) in 2025: Introduced in 2022 as the UK Government’s domestic replacement for ESF, UKSPF operates on a three-year funding cycle (2022-2025), offering less long-term financial security compared to ESF. With UKSPF set to end in March 2025, local authorities have raised concerns about a funding cliff edge, with no clear successor programme announced.

“We’re just hoping something is announced in October, so everything doesn’t fall off a cliff edge come the end of March 2025.” (Employability Lead, LA10_Rural)

3. Key Challenges:

Costs and logistical challenges are significantly higher in rural and island councils.

"Transport and staffing costs in the Isles make service delivery disproportionately expensive.” (Employability Lead, LA29_Island))

Localised decision-making under NOLB has created a 'postcode lottery.'

“Every local authority has chosen to do it differently, resulting in significant inconsistencies.” (Third Sector _12 Rural & Urban)

Annualised funding limits long-term planning and staff retention:

“Short-term funding cycles create a cliff-edge effect, risking service continuity every year.” (Employability Lead, LA04_Rural)

Section 2: Perceptions of Employability Funding

This section examines respondents' perceptions of employability funding structures and is organised into three subsections, each focusing on a key aspect of funding effectiveness. The first subsection, Perceptions of Funding Structure's Efficiency and Flexibility, explores how funding mechanisms support or constrain local flexibility and financial sustainability, drawing on Chart 2.1 a and Chart 2.1 b. This analysis integrates survey responses and interview insights to assess administrative efficiency, funding accessibility, and the extent to which funding structures enable responsiveness at the local level.

The second subsection, Perception of Effectiveness of Funding Models, evaluates whether funding structures promote a holistic employability approach, foster long-term employer relationships, and allow programme adaptability, referencing Chart 1.4b. This section highlights variations in perception across local authorities, third-sector organisations, and other service providers, reflecting the differing challenges and opportunities they experience.

The final subsection, Operational Challenges in Managing Multiple Funding Streams, further explores the challenges associated with fragmented funding structures, short-term financial planning, and administrative burdens. Drawing on survey findings and qualitative insights, this section examines how organisations navigate funding complexity, service continuity risks, and the impact of annual budget cycles on employability provision.

Section 2.1: Perceptions of Funding Structure's Efficiency and Flexibility

Survey respondents identified systemic inefficiencies and limited flexibility in the funding framework. These issues impact collaboration, adaptability, and service delivery. Chart 2.1(a)highlight respondent perceptions of efficiency, flexibility, and related challenges.

Key Findings - Efficiency of Funding Models:

Efficiency of the Funding Structure:

As shown in Chart 2.1 (a), a majority of respondents from Local Authorities (83.3%) and Third Sector organisations (85.3%) disagree that the current funding structure is efficient.

Implication: These results indicate systemic inefficiencies and suggest structural issues rather than organisation-specific challenges.

Unnecessary Complexities:

Significant agreement from Local Authorities (70.7%) and Third Sector organisations (82.9%) highlights widespread frustration with the complexities of managing diverse funding streams.

Implication: Inefficiencies limit organisations' ability to deliver timely and effective employability services, compounding operational challenges.

Qualitative insight: Factors contributing to efficiency and/or inefficiency in Employability Provision:

Survey respondents widely view the funding structure as inefficient due to systemic delays and complexities. Interviews with local authority and third-sector stakeholders highlight key barriers, including fragmented reporting, delayed allocations, and geographic disparities.

Fragmentation in Processes and Reporting (Efficiency Issue): Stakeholders highlighted the challenges of managing multiple funding streams, each with distinct requirements and timelines, leading to excessive administrative work at the expense of service delivery.

Local Authority Perspectives: Local authority representatives emphasise that overlapping requirements across multiple funding sources create operational inefficiencies, particularly in smaller or rural councils with limited administrative capacity.

"Each funding stream comes with its own set of requirements, timelines, and conditions. Trying to align all of this while maintaining our services is exhausting.” (Employability Lead 1, LA15_Urban)

Third-Sector Perspectives: Third-sector organisations face additional challenges when working across multiple local authorities, as each council has different requirements and commissioning process.

"Each council has its own process, making it a logistical nightmare for organisations working in multiple areas.” (Third Sector 2_Rural)

"We’re spending far too much time on compliance and reporting. Smaller teams, especially in rural councils, don’t have the capacity to handle this level of bureaucracy." (Third Sector 3_Urban/Rural)

2. Urban-Rural Disparities in Resources and Costs: Geographic and demographic differences exacerbate funding inefficiencies. Urban councils benefit from economies of scale, while rural councils face higher costs and logistical constraints that are not reflected in funding allocations.

Local Authority Perspectives:

"Delivering services in the Isles costs significantly more, yet funding doesn’t reflect this reality."(Employability Lead, LA12- Urban)

"Employability is not a statutory service, so it’s vulnerable within local authorities… you might not have the infrastructure needed when there’s a downturn." (Employability Lead, LA11- Rural)

Local authorities highlighted several issues, stating:

"Employability is not a statutory service, so it’s vulnerable within local authorities… you might not have the infrastructure needed when there’s a downturn." (Employability Lead, LA11- Rural)

Rural councils struggle with higher service delivery costs, weaker infrastructure, and funding delays, making it difficult to plan and sustain employability programs effectively.

Third-Sector Perspectives: Funding delay disrupts critical planning processes, creating inefficiencies that ripple throughout the service delivery chain.

"We don’t necessarily know what the conditionality is within that grant until after the beginning of the delivery year. And we then have to start thinking about where is that money going to be missed, and where do we need to fill the gaps with our own core funding. You’re almost a quarter of the way through the year by the time you need to do some of that." (Third Sector 3_Rural)

Funding delays create significant planning disruptions for third-sector providers, who often must reallocate their own core funding to fill gaps while awaiting grant conditions and allocations.

3. Delays in Funding Flow:

Systemic delays in funding allocation and grant letters disrupt service delivery and hinder effective planning. Delays in issuing grant offer letters from the Scottish Government trigger a cascade of problems throughout the system. These delays create uncertainty, push the start of programmes later into the financial year, impacting staff retention and the ability to maintain critical programmes.

Local Authority Perspectives: Funding delays have a cascading impact on service provision, causing disruptions in commissioning processes and job security concerns for staff.

"When the funding is late, commissioning processes can't happen, redundancy notices may be issued, and staff start leaving because they feel their job isn't secure." (Employability Lead, LA11_Semi_Urban)

The timing of funding allocations remains a persistent challenge:

"The allocation, the grant offer letters, potentially delays with that... We’ve only once in the last six years had anything by the end of April." (Employability Lead, LA12_Semi_Urban)

These delays extend beyond administrative hurdles, affecting service continuity and workforce retention. Local authorities find it challenging to plan long-term, limiting their ability to provide stable and effective employability support.

Third-Sector Perspectives: The unpredictability of funding timelines creates instability for organisations, forcing them to operate on financial uncertainty.

"There’s no service that should be based on hope. Yet, we hope the money will arrive to keep our services running." (Third Sector 3_Rural)

Delays in disbursing funds directly impact programme implementation:

"This year, in June, we finally got the first quarter’s allocation, which wasn’t enough to start our third-sector grant process." (Employability Lead, LA25_Rural)

With services dependent on funding cycles, staff retention becomes increasingly difficult:

"Our ability to retain staff and sustain programs hinges entirely on timely grant letters. The uncertainty is unsustainable." (Third Sector 8_Rural)

This highlights the systemic inefficiencies respondents referenced, including the late timing of funding allocations.

4. Complexity and Administrative Burden: Procurement regulations and other administrative requirements introduce additional layers of complexity, delaying programme implementation and diverting resources from service delivery.

Local Authority Perspectives: Funding conditions are often unclear until well into the delivery year, making it difficult to plan effectively:

"We don't necessarily know the conditionality of the funding until after the delivery year starts, which delays planning and commissioning…We have to stick to the regulations around competitive procurement... where you have to re-score or re-tender because the bids aren’t up to standard, and you're now into the second or third quarter of the year." (Employability Lead, LA29_Semi-Urban )

Late funding announcements and allocation bottlenecks create inefficiencies, complicating efforts to align funding with local needs:

"This year, as an example, in June we got a letter—not April, but in June—telling us we would get the first quarter's allocation of the grant. Which still wasn't enough for me to put in place our third sector grant process. But then two weeks later, we got a subsequent communication telling us that the full award would be given. " (Employability Lead, L05_Rural )

Administrative delays place additional pressure on finance teams, particularly at critical points in the funding cycle:

"The grant letter can take a long time to come in, and that's when you're at the mercy of your finance director….At the beginning of the financial year and at the end of the financial year, because you're trying to get everything complete... so that, you know, the delivery has been done, the invoices have been out and back, and everything's paid." (Employability Lead, LA32_Island)

Key Findings- Flexibility of Funding Models:

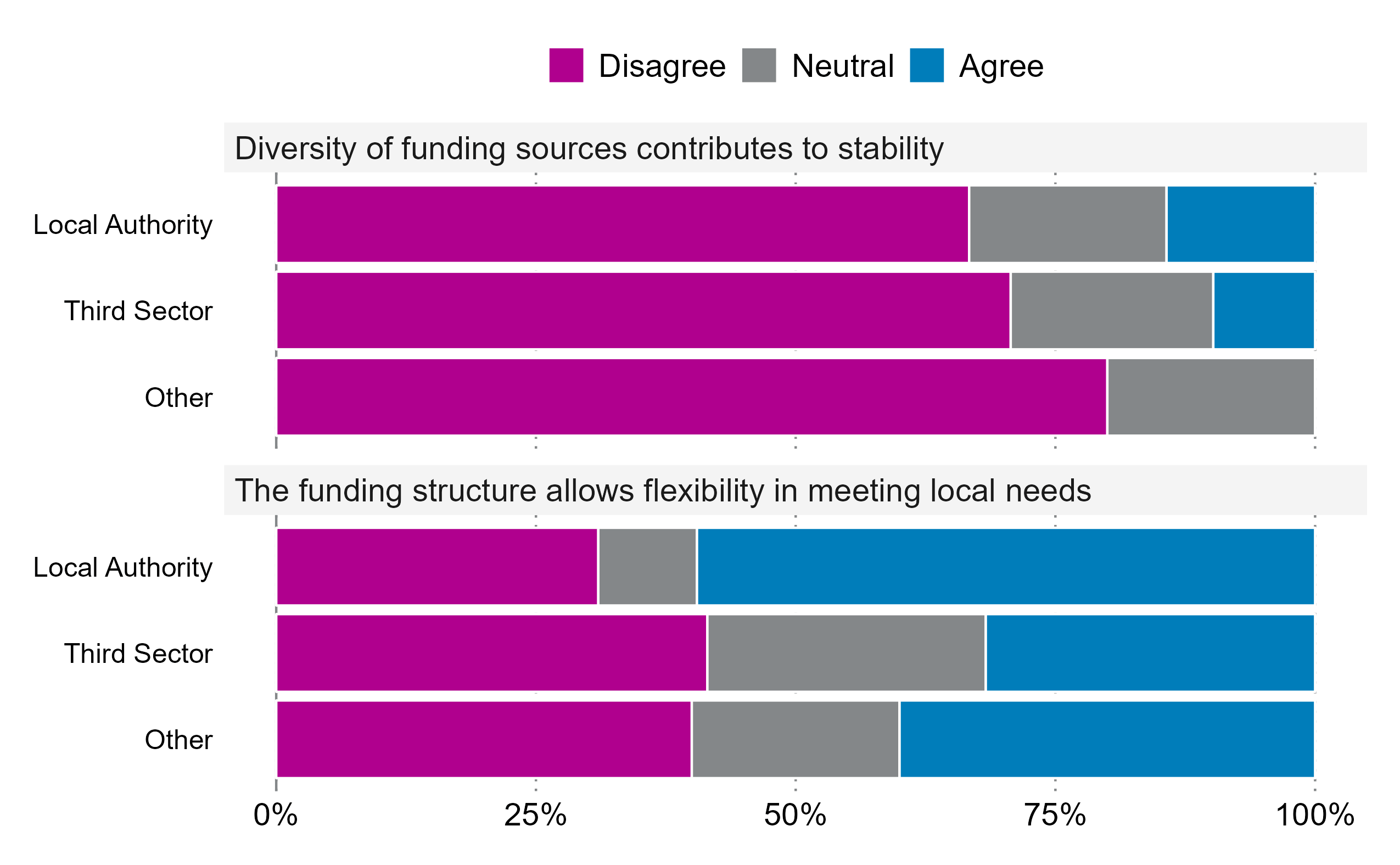

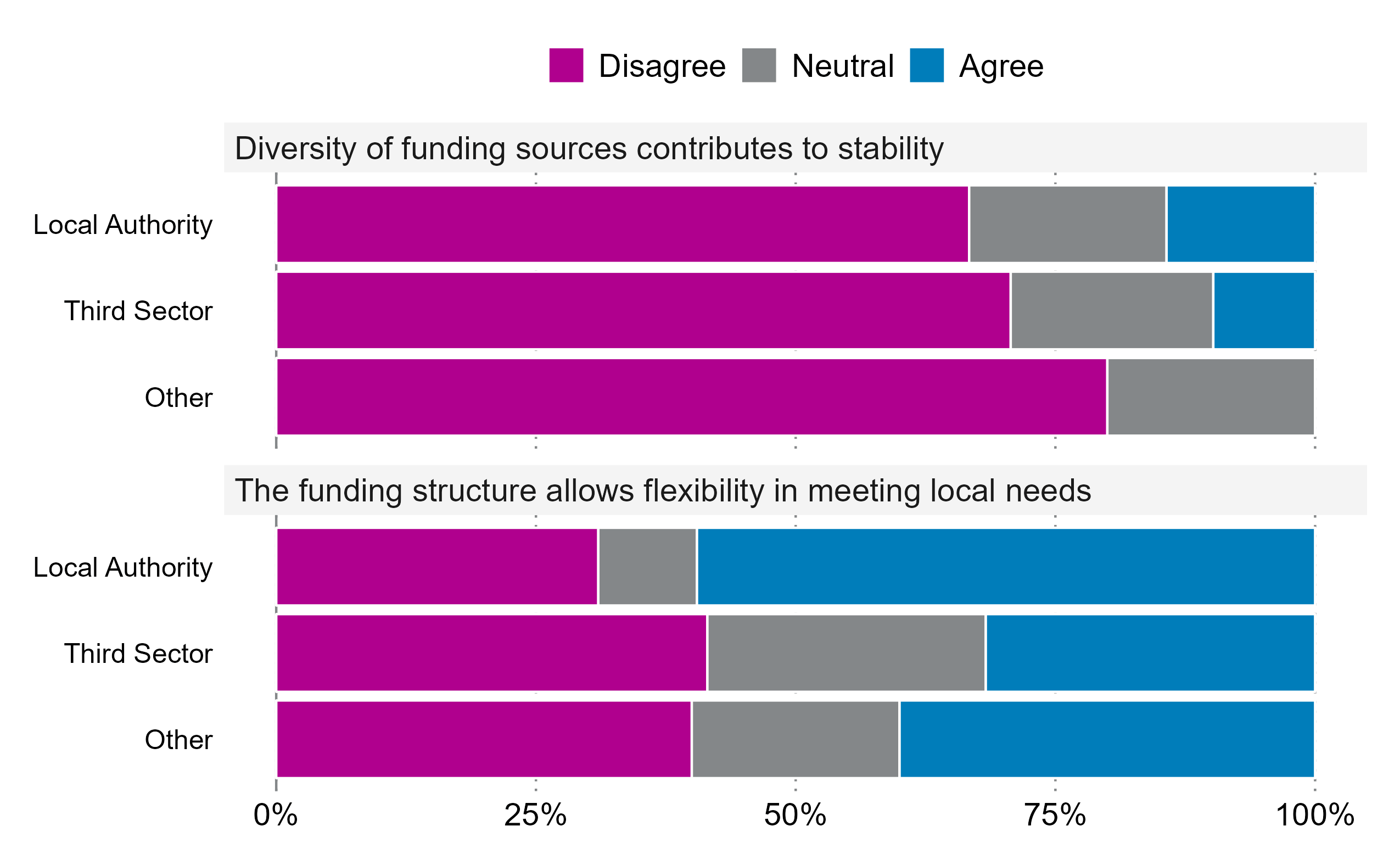

The extent to which employability funding structures support local flexibility and financial stability varies across organisations. Survey responses (Chart 2.1 (b)) highlight differences in perception between local authorities, third-sector organisations, and other providers regarding how funding mechanisms enable adaptability in meeting local needs and whether the diversity of funding sources enhances financial stability.

Key Findings:

Flexibility in Meeting Local Needs:

Chart 2.1 (b) suggests that perceptions of flexibility vary significantly between sectors, with 59.5% of Local Authorities agreeing that the funding structure allows flexibility, compared to only 31.7% of Third Sector organisations.

According to the survey data, Third Sector respondents highlighted rigid guidelines and short-term funding cycles as major barriers to adapting services to local priorities.

Implication: The rigidity of funding structures disproportionately affects Third Sector organisations, reducing their capacity to respond to evolving local needs.

Stability from Diverse Funding Sources

As illustrated in Chart 2.1 (b), both Local Authorities (66.7%) and Third Sector organisations (70.7%) expressed scepticism about the stabilising effects of diverse funding sources.

Implications: Fragmented and variable funding streams create financial uncertainty rather than stability, undermining long-term planning and operational effectiveness.

Qualitative Insights on the Flexibility of Employability Funding

This section presents findings from semi-structured interviews with local authority and third-sector representatives, complementing the survey findings, as illustrated in Chart 2.1 (a) & (b), on the flexibility of the No One Left Behind framework and other funding streams such as UK Shared Prosperity Fund, and parental employability. While the employability funding policies aims to offer adaptability, stakeholders highlighted significant inconsistencies in its application, conditionality in funding, and systemic barriers that limit its effectiveness.

Conditionality in Funding Allocations:

Funding is often tied to specific outcomes or target groups, such as young people or long-term unemployed individuals, limiting councils' ability to address localised needs.

"The flexibility we’re promised doesn’t exist in reality when the funding conditions are so prescriptive." (Employability Lead LA12_Urban)

Local authorities face limited discretion (15%) in reallocating Parental Employability funding, restricting their ability to adapt resources to local needs. Some councils may have different employability priorities, yet funding constraints prevent them from reallocating resources effectively.

"Parental employability funding allows only 15% discretion, but local authorities have unique contexts and priorities that don’t always align with rigid funding structures. Sometimes, a particular funding stream isn’t the top priority for a local authority, but the structure doesn’t allow much room for adaptation." (Employability Lead LA01_Urban)

2. Misalignment with Local Needs:

Respondents emphasised that funding formulas often fail to account for the unique challenges faced by rural councils, such as higher per capita costs, logistical barriers, and dispersed populations. Similarly, urban councils face difficulties addressing scale and complexity, further limiting the practical application of flexibility.

"In rural areas, flexibility is meaningless if the funding doesn’t account for transport costs or dispersed populations…. The funding doesn’t consider the realities of working in Island…it’s just not designed with us in mind." (Employability Lead, LA22_Island)

For example, rural councils face distinct challenges such as higher costs and limited access to services, while urban councils contend with scale and complexity.

"We appreciate the concept of flexibility, but the reality is we’re still expected to fit into one-size-fits-all funding models." (Employability Lead, LA24_Rural)

Urban councils also shared similar concerns that Scottish Government policies dictate priority group, limiting their ability to respond flexibly to local needs:

"Scottish Government policy drives who the priority group is, and I'm not sure that's particularly helpful. We should be able to respond to what our local need is." (Employability Lead LA01_Urban)

This lack of flexibility hinders local authorities from addressing emerging challenges, potentially leading to inefficiencies in service delivery and missed opportunities to tailor support for those who need it most.

3. Short-Term Funding Cycles:

Short-term funding cycles were identified as a significant barrier to operational flexibility. Annual funding timelines force councils and Third-sector organisations to prioritise immediate outcomes over strategic, long-term planning and innovation.

"Short-term funding forces us to operate reactively, which is the opposite of what flexibility should mean." (Employability Lead, LA 15_Urban)

"We barely have time to adjust or innovate before the funding cycle ends." (Employability Lead, LA 24_Rural)

Qualitative and quantitative data illustrate that the composition of employability funding includes a mix of flexible and restrictive funding streams, each with its own rules and limitations.

No One Left Behind (NOLB) provides significant flexibility for the council to design services tailored to local needs. While other funds, such as Parental Employability Fund (PEF) and UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF), are more restrictive and focused on specific groups or outcomes.

This mix of funding streams creates administrative complexity and limits the council's ability to reallocate resources across different target groups.

While there is some discretion in managing funds, the councils must also balance this with accountability measures and reporting requirements, ensuring that all funding is used in accordance with its intended purpose, creating administrative burden.

Barriers such as slow approvals, fragmented funding flows, and rigid guidelines hinder organisations' ability to meet local needs and adapt to changing priorities.

Additionally, scepticism regarding the stabilising effects of funding diversity highlights the financial risks and operational challenges faced by organisations across sectors.

Section 2.2: Perception of Effectiveness of Funding models

Chart 2.2 (a) summarises respondents’ views on how effectively current funding mechanisms support collaboration, adaptability, holistic approaches, long-term employer relationships, and funding flexibility. The data underscores significant discrepancies between Local Authorities and the Third Sector.

Key Findings and Analysis

Collaboration and Economic Responsiveness

Chart 2.2 (a) suggest that a majority of Local Authorities agree that funding mechanisms foster collaboration (57.8%) and allow effective responses to economic changes (71.4%). However, Third Sector organisations report significantly lower agreement levels (35.7% and 33.0%, respectively).

Implication: Structural barriers and fragmented funding streams may hinder Third Sector organisations from fostering collaboration and economic adaptability.

Qualitative Insights on Collaboration and Relationship Dynamics

Collaboration between local authorities and Third Sector organisations is a critical component of effective service delivery but varies significantly across regions. Interviews with key stakeholders revealed a spectrum of experiences, ranging from highly cooperative relationships to more transactional dynamics that hinder co-production and innovation.

Variability in Local Authority-Third Sector Collaboration: The Role of Local Employability Partnerships (LEP):

The collaborative approach within the Local Employability Partnership (LEP) is highly valued for ensuring that funding decisions align with local priorities and resources are efficiently allocated.

"Because the Scottish Government funding has to be approved by the LEP… we need to provide evidence that we've discussed it with the LEP and submit the minutes to Scottish Government, showing that the partnership has agreed on the priorities for that year." (Employability Lead, LA 05_Rural)

There is broad agreement among stakeholders about the value of LEPs in fostering collaboration and aligning services with local priorities.

"The LEP isn’t just about meeting targets—it’s about listening to our providers and participants, taking on board their feedback, and making changes where needed." (Employability Lead 2, LA 05_Rural)

However, the effectiveness of LEP varies across regions, particularly in rural and urban areas:

"In rural areas, the LEP's coordination is limited by geographic distance and the cost of delivering services." (Employability Lead, LA 26_Island)

Third-Sector organisations stress the importance of interpersonal relationships in fostering genuine collaboration. While some LEPs embrace co-production, others are perceived as overly bureaucratic and compliance-driven.

"Partnerships depend on people, and while statutory labels bring us together, real collaboration happens when there’s harmony and collective desire to help." (Third Sector 3_Urban)

"Collaboration is often superficial; we’re treated as service providers, not partners." (Third Sector 5_Urban)

Stakeholders highlight that collaboration between local authorities and third-sector organisations varies significantly. Some councils have fostered trust-based relationships, while others engage third-sector providers in a purely transactional manner, limiting the potential for meaningful cooperation.

"We’ve built strong relationships with some councils, but others treat us as purely transactional partners." (Third Sector 05_Rural)

"Open communication with local authorities has been key to resolving operational challenges." (Employability Lead 2, LA 15_Urban)

In island councils, partnerships are often strong due to their smaller scale and necessity for resource sharing. However, extending these collaborative practices to mainland councils poses challenges:

"Collaboration across island councils works well but extending that to mainland Scotland poses logistical and resource challenges." (Employability Lead, LA 26_Island)

By fostering genuine partnerships, LEPs can play a stronger role in delivering more effective and inclusive employability services across Scotland.

2. Inter-Authority Collaboration as a Strategy:

Collaboration between local authorities helps address resource constraints and enhances service delivery, particularly for smaller councils.

"Fair Start Scotland taught us the value of collaboration, leading to ongoing joint projects like specialist employability support." (Employability Lead, LA 29_SemiUrban)

"Strong partnerships help mitigate funding challenges by pooling in-kind contributions and aligning priorities." (Employability Lead, LA 13_SemiUrban)

With a limited pool of participants, cooperation becomes essential:

“You're almost... forced into working together because there's a limited pool of people... We're often working with the same individuals.” (Employability Lead, LA 22_Island)

3. Challenges in Inter-Authority Collaborations:

The effectiveness of collaboration varies significantly between urban and rural councils, driven by differences in resources, proximity to markets, and logistical constraints. Urban councils benefit from larger budgets and faster adaptability, while rural areas face delays and resource limitations.

Even with shared issues, geographic isolation and funding disparities hinder consistent joint initiatives." (Employability Lead, LA 29_SemiUrban)

Partnership models can enhance service equity but require sustained coordination:

"Partnership models ensure equitable service delivery across diverse geographies, but coordination requires constant effort." (Employability Lead, LA 05_Rural)

Local authority dynamics further influence collaboration:

"We’ve seen good examples of collaboration, but it often relies on personal connections rather than a clear framework." (Employability Lead, LA 12_Urban)

Geographical disparities also pose challenges:

"We communicate constantly with Orkney and the Western Isles, but geographic and resource differences make joint ventures hard." (Employability Lead, LA 26_Island)

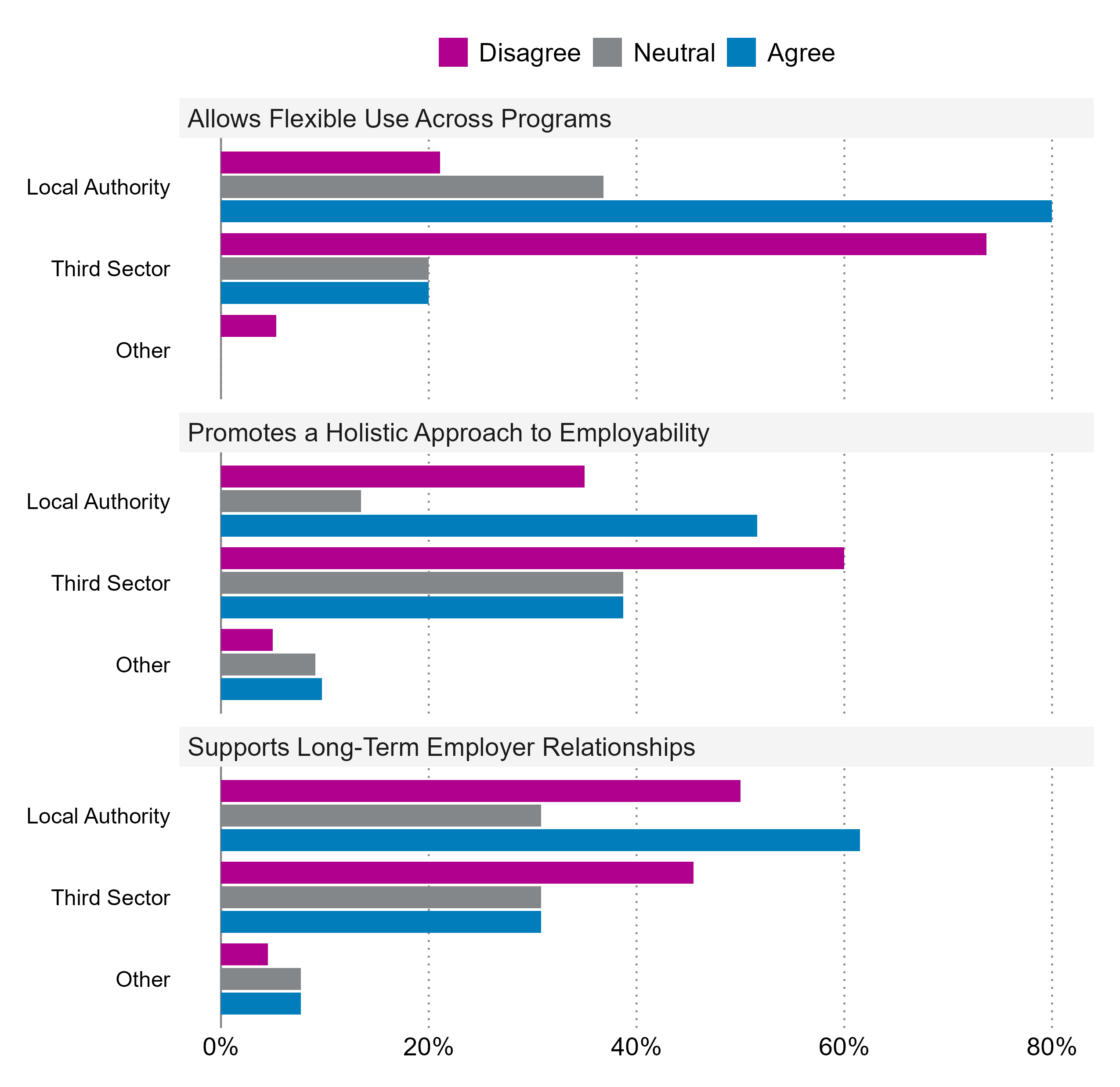

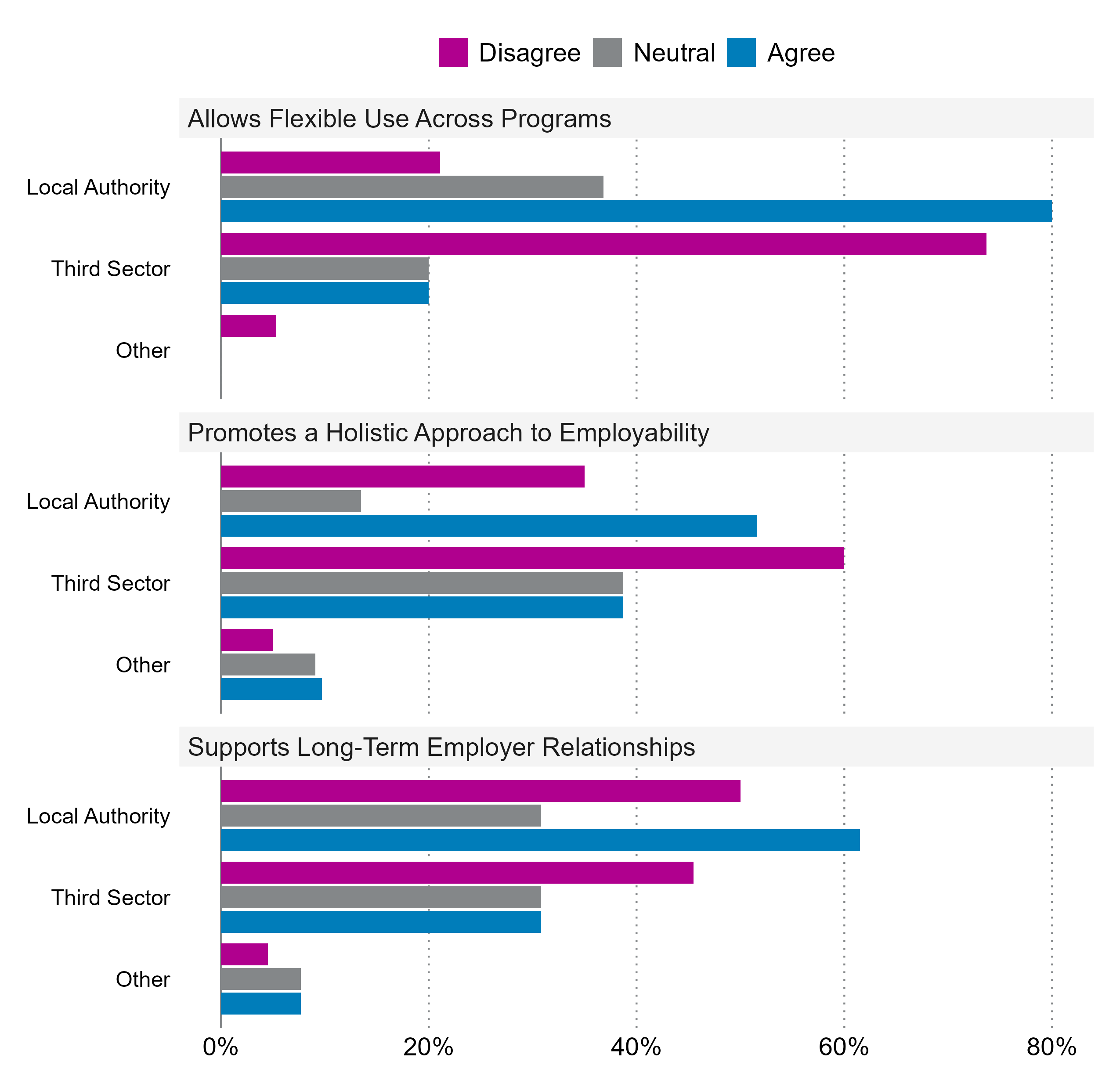

Expanding on earlier insights into funding flexibility, the survey assessed whether current funding structures promote a holistic employability approach, support long-term employer relationships, and allow flexibility across programmes. As shown in Chart 2.2 (b) responses varied across local authorities, Third-Sector organisations, and other providers, with local authorities reporting greater flexibility, while Third-Sector organisations highlighted challenges in adaptability and employer engagement.

Key Findings:

Holistic Approaches and Employer Relationships:

According to the survey findings, Chart 2.2 (b), 51.6% of Local Authorities agree that funding supports a holistic approach to employability, compared to only 38.7% of Third Sector organisations. Similarly, while 61.5% of Local Authorities agree that funding supports long-term employer relationships, just 30.8% of Third Sector respondents share this view.

Implication: Third Sector organisations face challenges in sustaining holistic strategies and long-term employer relationships, likely due to funding rigidity and short-term cycles.

Program Flexibility

As indicated in Chart 2.2 (b), 80.0% of Local Authorities agree that funding allows flexibility, while only 20.0% of Third Sector organisations concur.

Implication: The lack of flexibility limits the ability of Third Sector organisations to adapt to evolving local priorities and emerging needs.

Qualitative insight on how Employability Funding promotes a Holistic Approach to Employability Service Provision: As discussed above, the survey findings reveal that 51.6% of local authorities agree that current funding supports a holistic approach to employability, compared to only 38.7% of third-sector organisations. This disparity is reflected in their qualitative responses, highlighting differences in capacity, priorities, and the realities of implementing integrated services.

Local Authority Perspective:

Larger councils can align multiple funding streams but face significant administrative burdens, while smaller councils struggle with resource constraints.

"We have tried to integrate employability with mental health, housing, and education services, but aligning multiple funding streams is a logistical nightmare." (Employability Lead, LA 07_Urban)

There was also a recognition that although urban areas focus on integrated strategies, rural councils cite challenges in aligning fragmented funding streams with holistic goals.

"We strive for a wraparound approach, but fragmented reporting makes it hard to deliver on this promise." (Employability Lead, LA 22_Island)

"Smaller councils don’t have the resources to align funding for comprehensive services." (Employability Lead, LA 07_Urban)

Third-Sector Perspective:

Third-sector organisations often feel restricted by narrow funding conditions, which prevent them from addressing interconnected client needs comprehensively.

"We want to offer a holistic service—helping with employability, mental health, and childcare—but the funding is so specific we end up focusing on one thing and ignoring the rest." (Third Sector Provider_05 Urban)

Supports Long-Term Employer Relationships: Qualitative responses highlight that Local Authorities have greater access to employers and resources to sustain these relationships, whereas third-sector providers often feel excluded from strategic engagement.

Local Authority Perspective: Larger councils with dedicated employer engagement teams reported success in maintaining long-term relationships.

"We’ve been working with some employers for over a decade, building trust and ensuring they see value in the partnership." (Employability Lead 1, LA 15_Urban)

However, rural councils often lacked the scale or proximity to employers to replicate this success:

"In rural areas, we’re limited in the number of employers we can engage, and our geographic isolation makes sustaining relationships challenging….It’s hard to engage employers when we’re so far from major hubs." (Employability Lead, LA26_Island)

Third-Sector Perspective: Third-Sector organisations reported feeling disconnected from strategic employer engagement efforts, limiting their ability to connect clients with sustainable opportunities:

"We’re not part of the conversations with employers, so we’re left to pick up the pieces without the relationships to back us up." (Third Sector-06 Urban)

Allows Flexible Use Across Programs: The survey shows a stark difference in perceptions of flexibility, with 80.0% of Local Authorities agreeing that funding allows flexible use across programmes, compared to just 20.0% of third-sector organisations. This discrepancy stems from differences in autonomy and funding conditions.

Local Authority Perspective: Local Authorities appreciated the theoretical flexibility in funding but acknowledged that smaller councils struggle to exercise this flexibility due to resource constraints and higher costs:

"Flexibility is there in principle, but the administrative workload of reallocating funds can discourage smaller councils from using it effectively….. We don’t have as much flexibility as we’d like... the money comes with a lot of strings attached, and there’s not much room to manoeuvre."(Employability Lead, LA22_Island)

Third-Sector Perspective:Third-Sector providers consistently reported that funding conditions and timelines undermine flexibility, leaving them unable to adapt programmes to local needs.

"We’re told there’s flexibility, but every time we try to make a change, we’re met with resistance or delays." (Third Sector _ 03 Urban)

"Short funding cycles and rigid conditions mean we’re constantly firefighting rather than planning strategically." (Third Sector-03 Rural)

Findings reveal sectoral differences in funding perceptions, with Local Authorities reporting more positive experiences, while third-sector organisations struggle with flexibility and collaboration.

Section 2.3: Challenges in Managing Multiple Funding Streams

Building on the earlier findings that highlighted inefficiencies, rigid guidelines, and fragmented funding flows, survey respondents provided detailed insights into the operational challenges created by managing multiple funding streams. Table 2.3 summarises these challenges, highlighting significant concerns across organisation type.

| Statements | organisation Type | Disagree (%) | Neutral (%) | Agree (%) |

| Conflicting funding requirements | Local Authority | 16.7 | 11.9 | 71.4 |

| Third Sector | 2.4 | 7.3 | 90.2 | |

| Other | 0.0 | 20.0 | 80.0 | |

| Administrative burden | Local Authority | 4.8 | 4.8 | 90.5 |

| Third Sector | 2.4 | 9.8 | 87.8 | |

| Other | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | |

| Coordination of timelines | Local Authority | 7.2 | 14.3 | 78.6 |

| Third Sector | 0.0 | 19.5 | 80.5 | |

| Other | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

Key Findings:

Conflicting Funding Requirements

Challenge: Over 90% of Third Sector respondents and 71.4% of Local Authorities agree that conflicting requirements are a significant issue.

Implication: Conflicting requirements of multiple funding sources increase complexity and inefficiency, underscoring the need for standardised or harmonised funding criteria to reduce administrative strain.

Administrative Burden

Challenge: Administrative demands were identified as a major barrier, with over 90% agreement among Local Authorities and Third Sector respondents.

Implication: Excessive administrative burdens detract from the time and resources available for service delivery, necessitating streamlined processes and reduced compliance requirements.

Coordination of Timelines

Challenge: Multiple funding streams also increase the challenge to meet multiple timelines that affect program planning and delivery, with 80.5% of Third Sector respondents and 78.6% of Local Authorities highlighting this issue.

Implication: Aligning funding cycles across streams is crucial to improving programme implementation and reducing delays

Qualitative insights on Challenges in Managing Multiple Funding Streams

This section synthesises insights from semi-structured interviews with local authority representatives and third-sector stakeholders, complementing survey findings to explore how the funding model supports or undermines a holistic approach to employability.

Conflicting Funding Requirements: Stakeholders emphasised the challenges posed by conflicting priorities and conditions across funding sources, particularly between Scottish Government initiatives like No One Left Behind and UK-wide schemes like the UK Shared Prosperity Fund. These discrepancies lead to inefficiencies in planning and resource allocation.

Local Authority Perspective:

"We often have to balance priorities between the Scottish Government’s 'No One Left Behind' funding and the UK Shared Prosperity Fund, which leads to inefficiencies." (Employability Lead 1, LA 04_Rural)

"Reconciling funding streams is a constant challenge, as each comes with its own set of conditions and timelines." (Employability Lead 1, LA 21_Urban)

Third-Sector Perspective:

"It’s difficult to meet the varying expectations from different funders, especially when we lack the resources to do so effectively." (Third Sector_05 Urban)

Administrative Burden: Both local Authorities and Third-Sector organisations highlighted the significant administrative workload associated with compliance, which detracts from their capacity to focus on strategic planning and service delivery.

Local Authority Perspective:

"The administrative demands, especially around quarterly and monthly reporting, are overwhelming and detract from service delivery." (Employability Lead 1, LA 04_Rural)

"So we're all doing the same thing, but we're just using different pots of money, which then means more admin, more reporting, more meetings....taking us away from the day-to-day business."(Employability Lead 1, LA 05_Rural)

Third-Sector Perspective:

"We spend so much time proving how funds are used that it feels like we’re doing less actual work." Third Sector _03 Rural)

Stakeholders highlight the need for streamlined reporting processes that maintain accountability without hindering service efficiency.

Coordination of Timelines: Delays in grant offer letters and funding disbursements were a recurring concern, disrupting planning and creating financial instability for both local authorities and third-sector providers.

Local Authorities Perspective:

"We received the finalised grant offer letter in June, which meant losing a quarter of the financial year to delays." (Employability Lead 2, LA 04_Rural)

"Partners are often left in limbo, unable to plan or execute programs due to funding delays." (Employability Lead, LA 07_Urban)

Third Sector Perspective: Third-sector organisations face heightened risks due to funding unpredictability, which impacts their ability to commit to long-term staffing and service delivery.

"We’re constantly on the edge of a cliff, waiting for funding announcements that come too late to make any meaningful plans." (Third Sector _05 Urban)

“Every local authority is different... some have higher levels of poverty, some have different administrative hurdles, and it all affects how they can manage employability services.” (Third Sector _O8 Urban)

Geographic Challenges: Stakeholders identified additional barriers, such as geographic disparities which exacerbate operational difficulties, particularly for rural and Island councils.

"On average, it will cost someone in Island 30% more to live than on the mainland... If you go out to the aisles, it can cost up to 50% more….A caseload that may be 30 in Edinburgh is manageable, whereas here it could take us 3 hours to get in and out for one appointment…..The knock-on effect of that is everything that we're delivering, we might have to take an hour and a half on a ferry to reach somebody." (Employability Lead 1, LA 22_Island)

Section 3: Timing and Disbursement of Employability Funding

The effectiveness of employability services depends not only on the availability of funding but also on the timeliness and reliability of disbursement processes. This section examines how funding delays and disbursement timelines impact service delivery, drawing on survey responses and stakeholder insights.

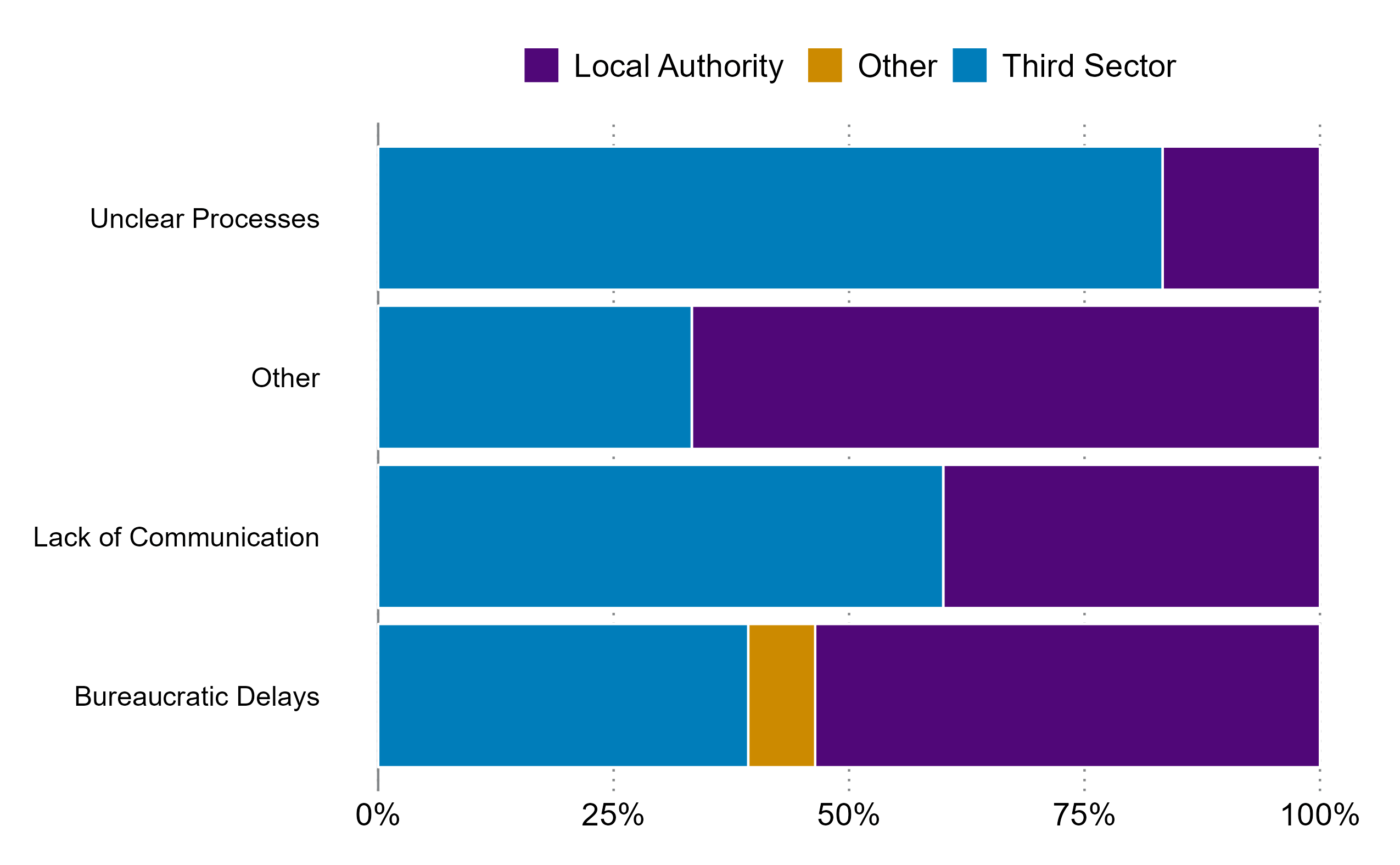

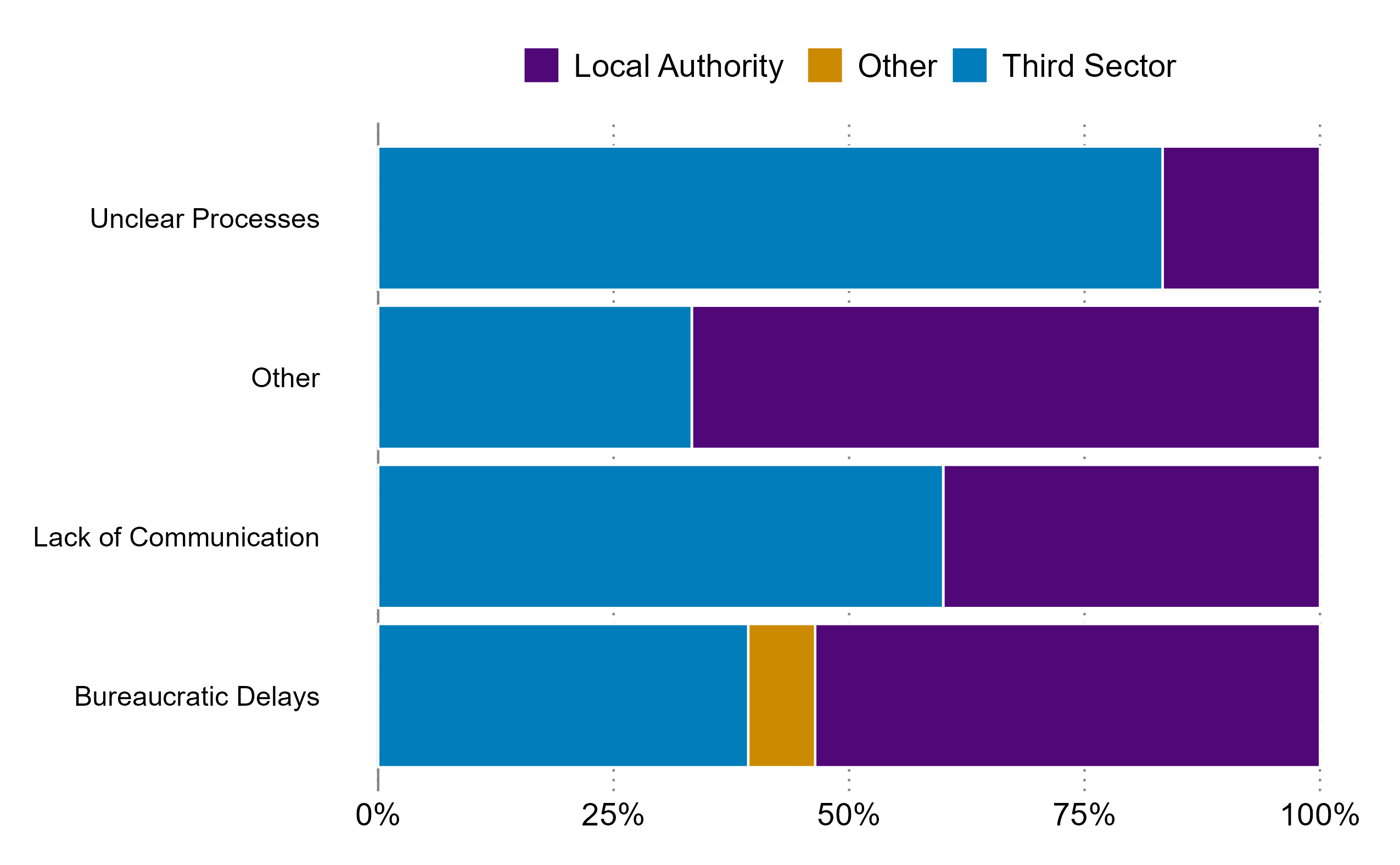

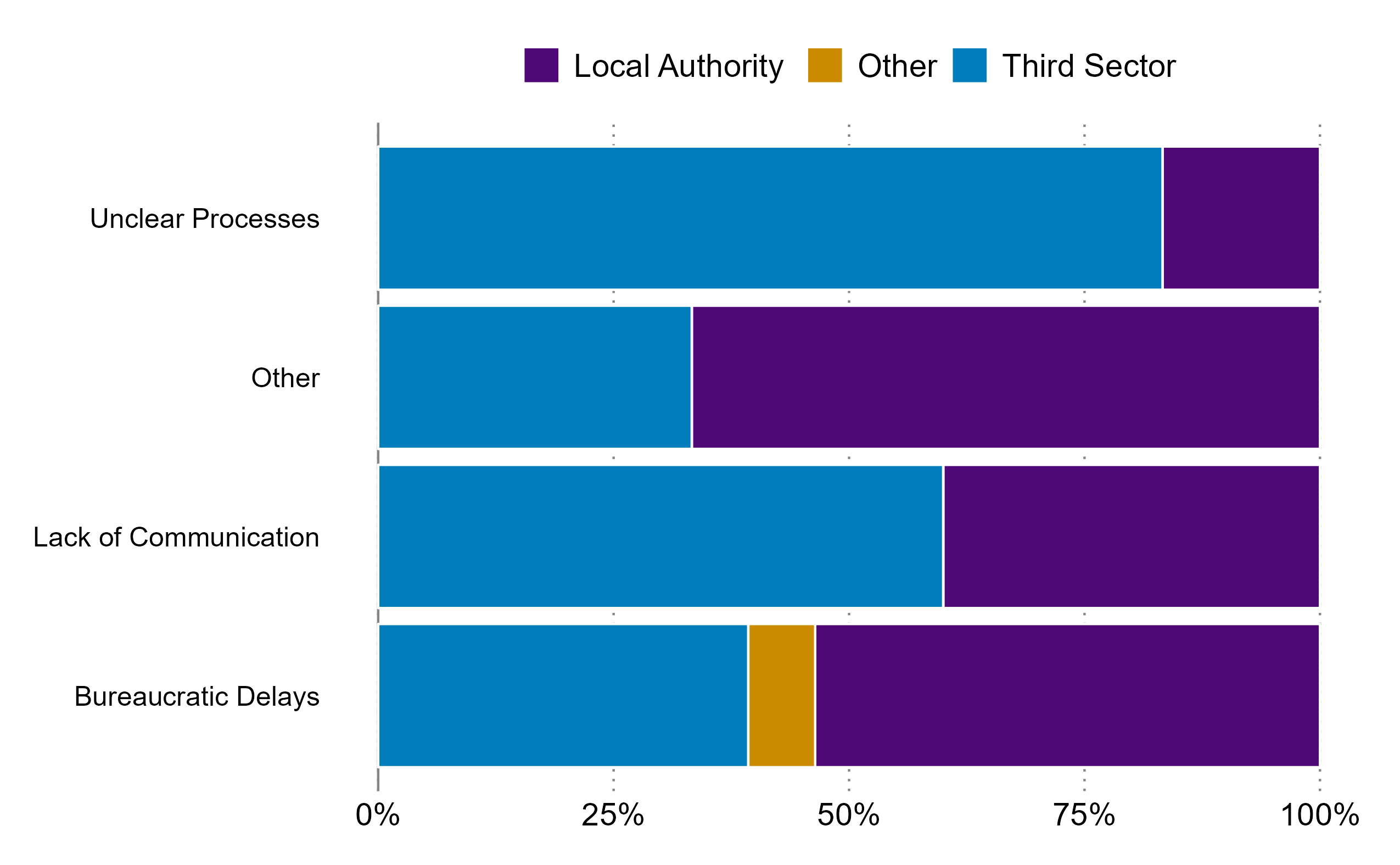

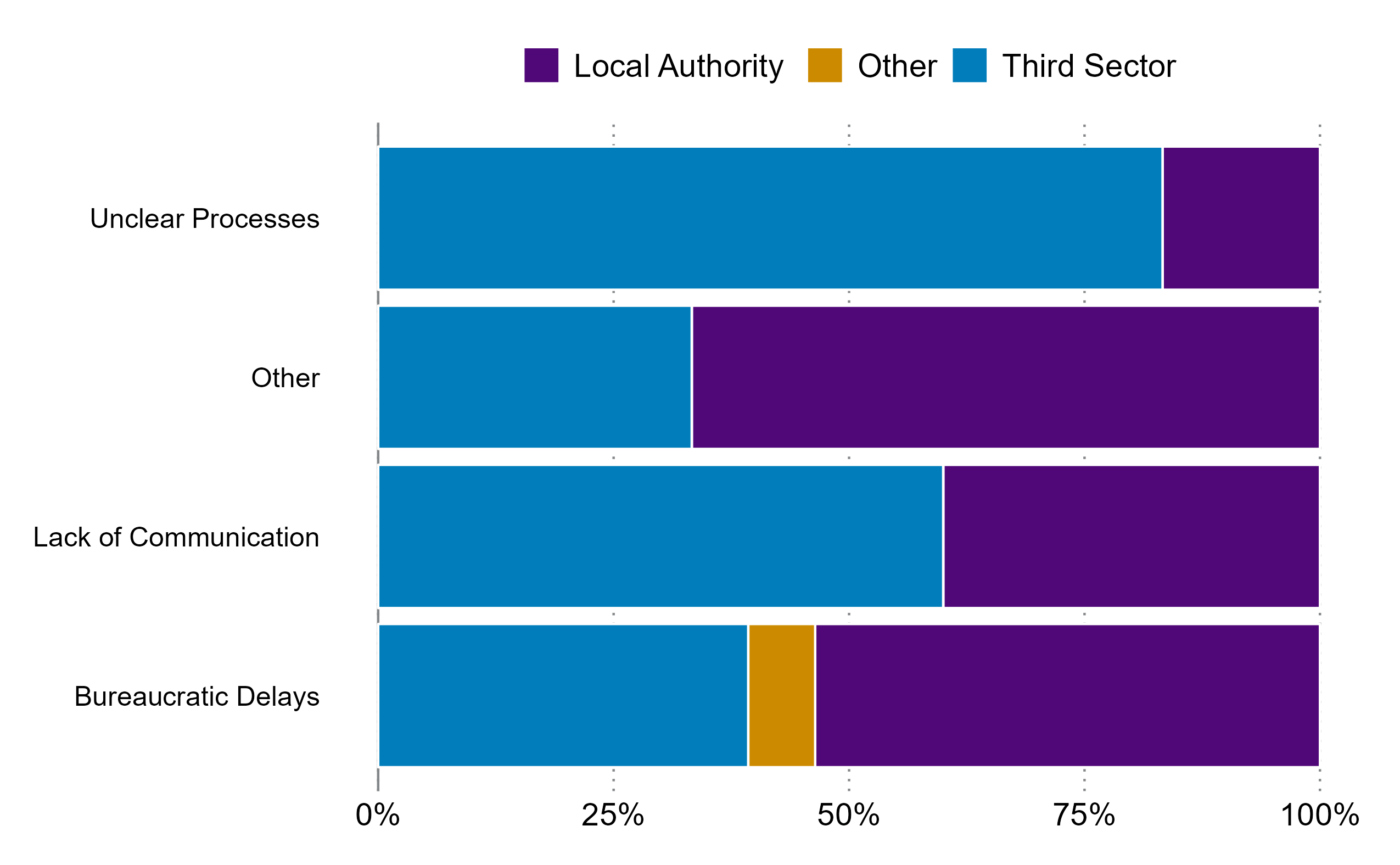

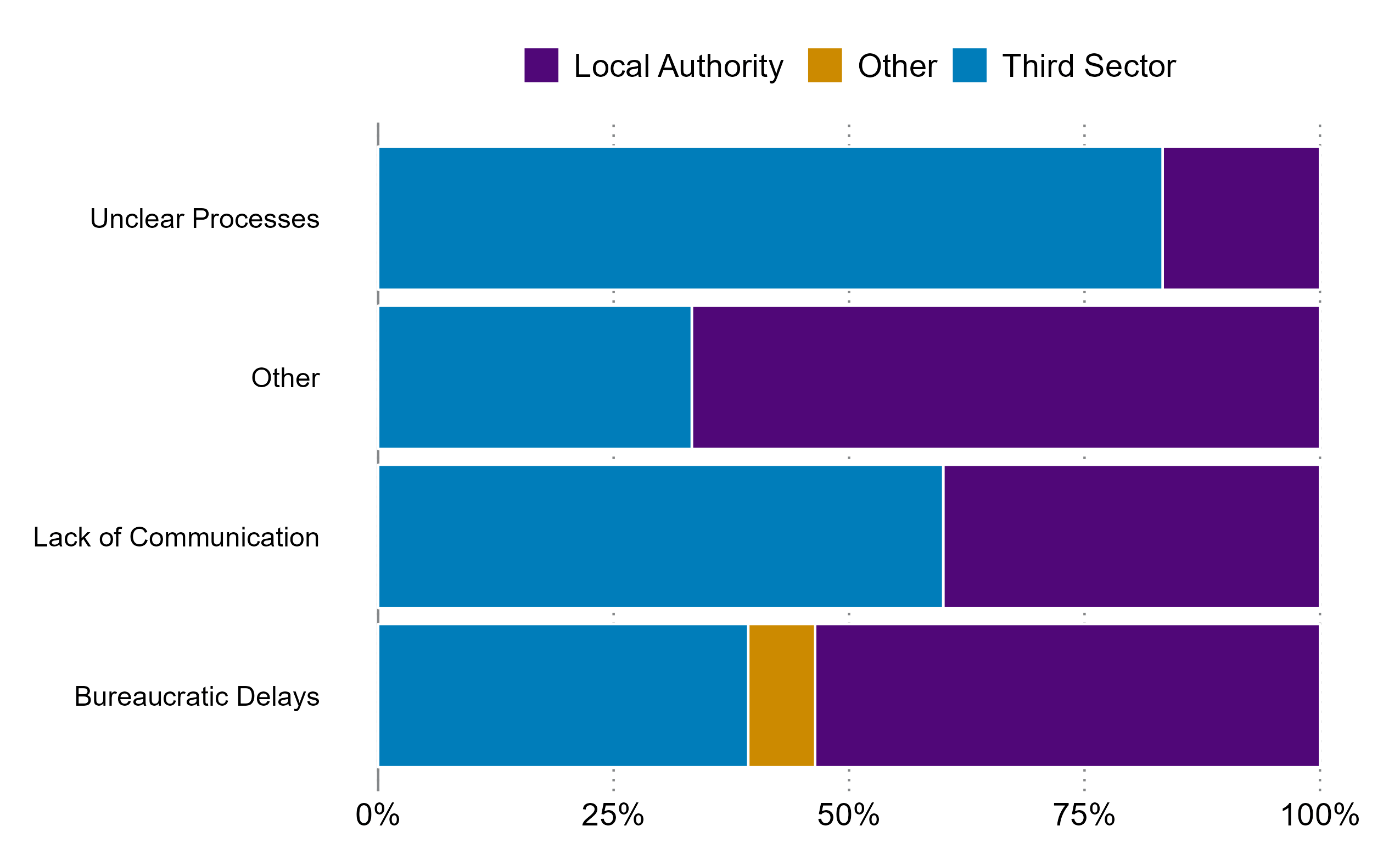

The first subsection, Funding Delays, explores the extent to which different organisation types experience delays, identifying which funding sources are most frequently associated with disruptions (Table 3.1). The second subsection, Timing and Disbursement of Employability Funding, assesses key stages in the funding process that are prone to delays, including funding announcements and payments to delivery partners. It also examines the underlying causes such as administrative inefficiencies, procedural challenges, and political decision making and their implications for service continuity and operational planning.

By analysing the timing and disbursement of employability funding, this section provides a detailed understanding of systemic challenges that affect the responsiveness and stability of employability programmes.

Section 3.1: Funding Delays

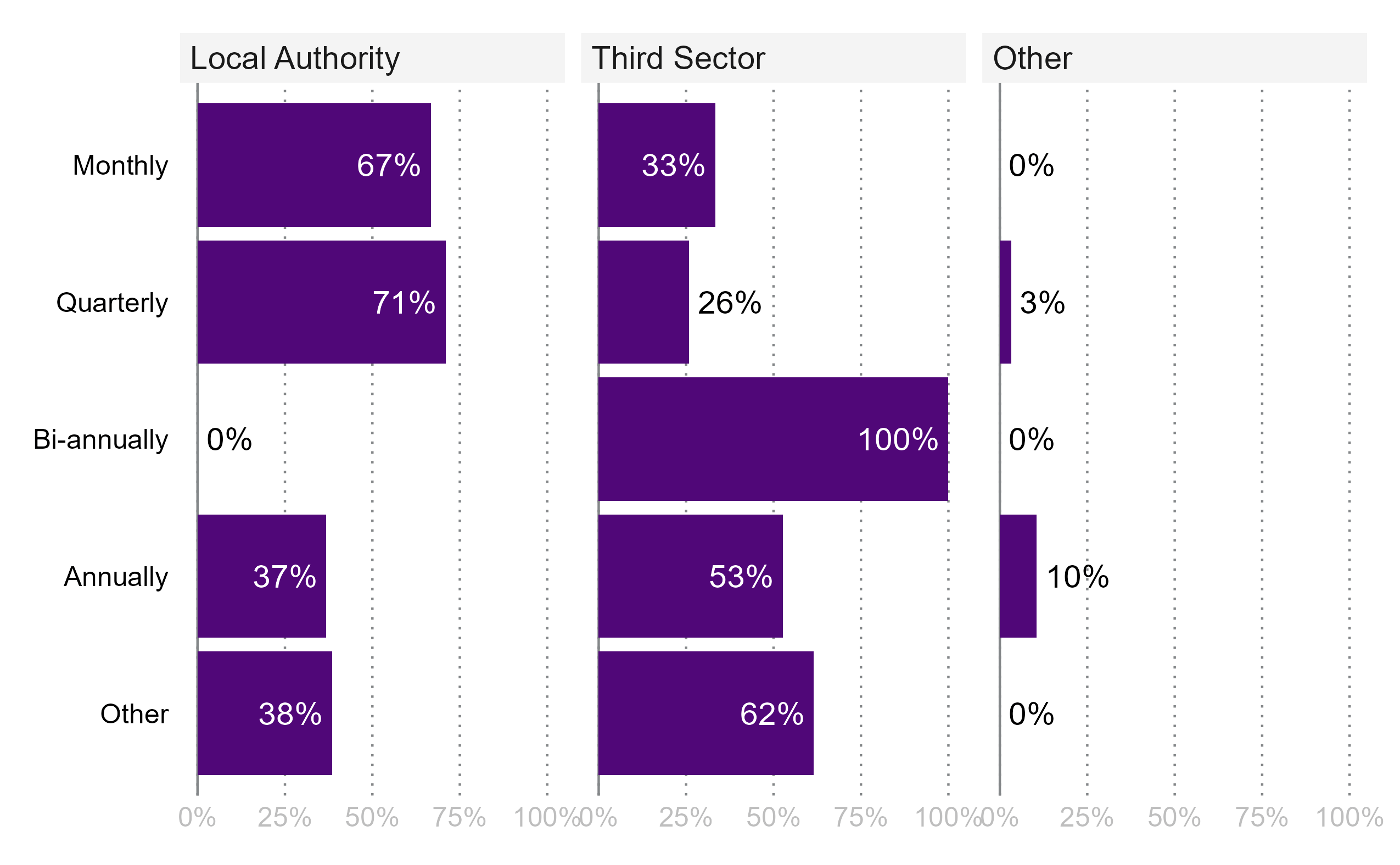

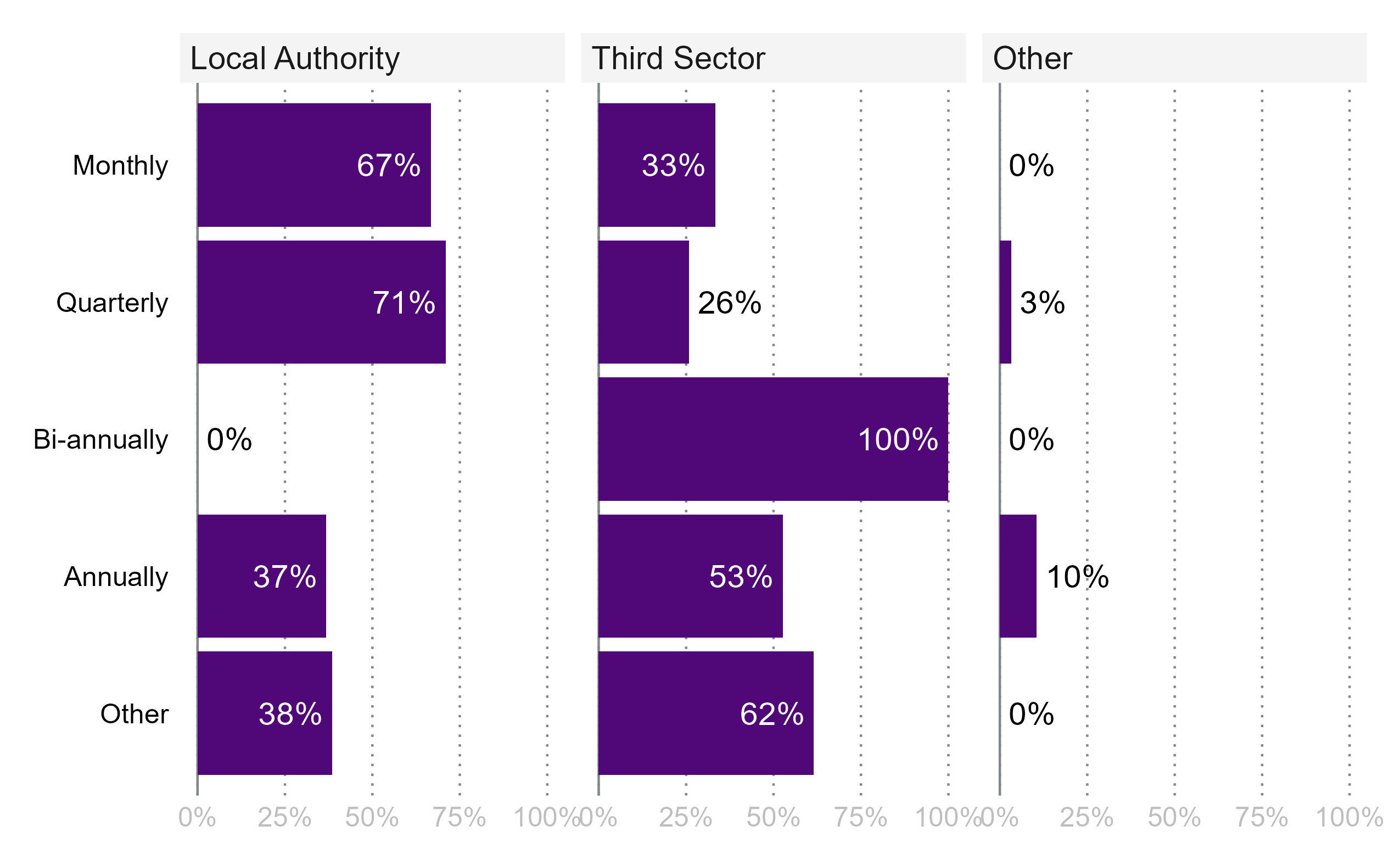

Funding delays pose a significant challenge to the timely delivery of employability services, with different organisation types experiencing delays from distinct funding sources. Table 3.1illustrates the survey responses regarding funding sources most frequently associated with delays, as reported by Local Authorities, Third Sector organisations, and other entities. These disparities reflect systemic inefficiencies and sector-specific challenges in accessing timely funding.

| Funding Source | Local Authority (%) | Third Sector (%) | Other (%) |

| Scottish Government Funding Streams | 75.0% | 20.0% | 5.0% |

| UK Government's Shared Prosperity Fund | 33.0% | 67.0% | 0.0% |

| Local Authority Core Budget | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% |