Scotland's water industry: overview of regulation and key challenges

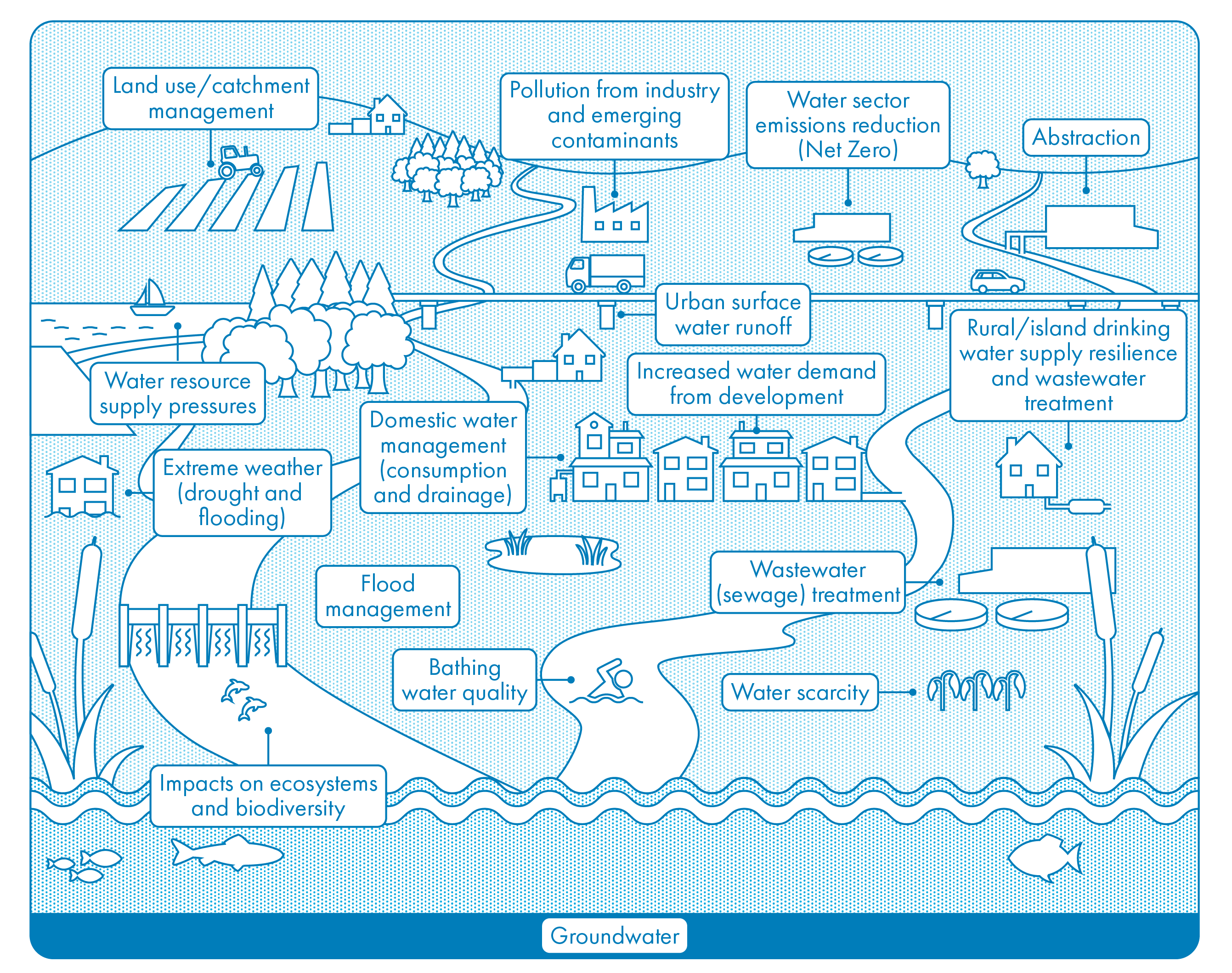

This briefing outlines the governance and regulation of Scotland's water industry, including public and private service provision. It highlights key challenges such as climate change, pollution, and infrastructure pressures.

Executive Summary

Background

Scotland's water sector plays a vital role in public health, environmental protection, and economic development. Over 90% of the population receives water and wastewater services from Scottish Water, a publicly owned company.

Water policy in Scotland is largely devolved and intersects with other policy areas such as agriculture, planning, and energy. The domestic sector has evolved from local provision to a nationally coordinated system, culminating in the establishment of Scottish Water by the Water Industry (Scotland) Act 2002 which replaced three regional water boards (covering north, west and east of Scotland). This historical trajectory informs current governance and regulatory arrangements.

Key challenges for Scotland's water sector

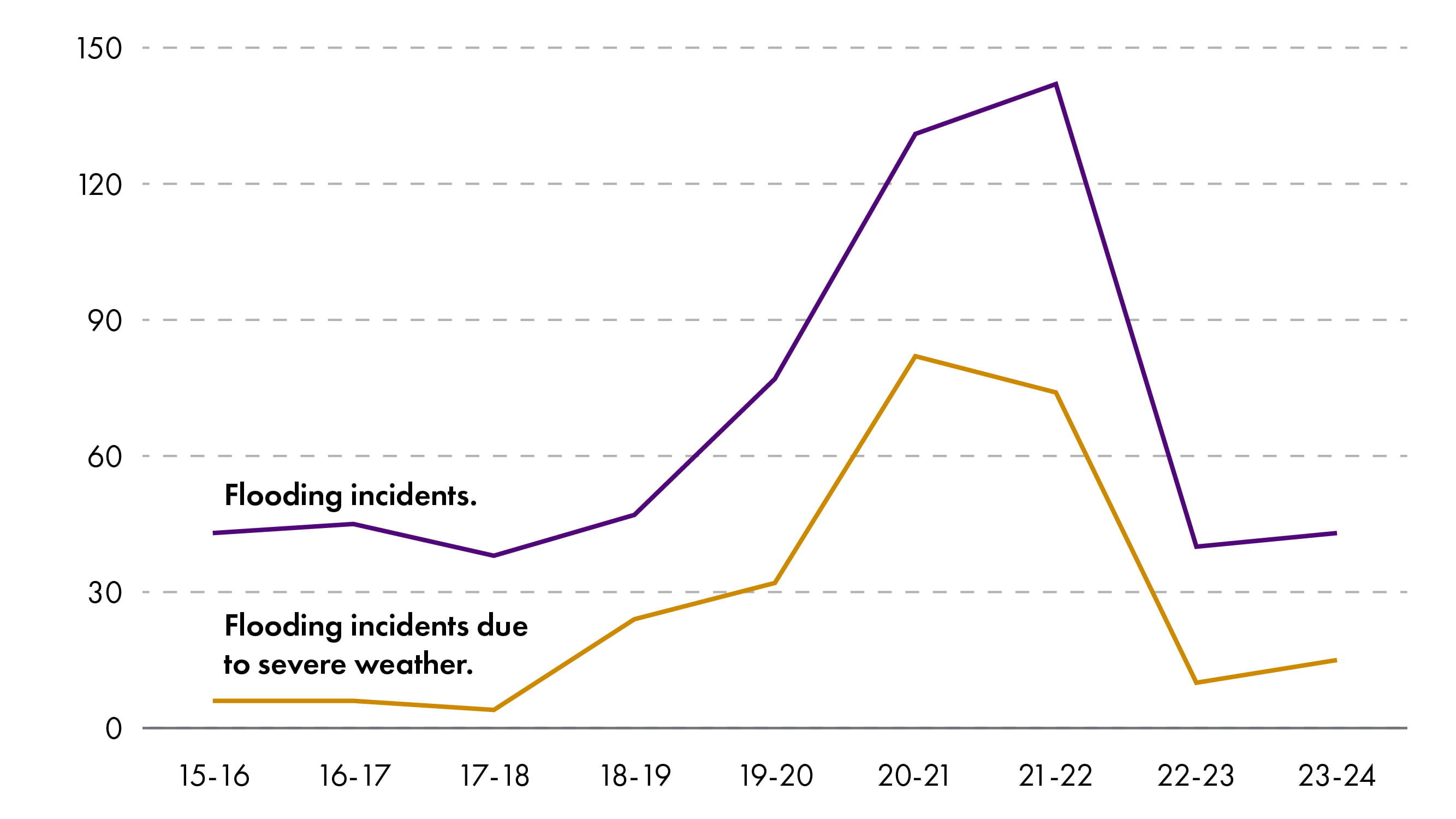

Scottish Water's long-term strategy recognises three major pressures: climate change, demographic shifts, and ageing infrastructure. Coordinated investment and policy reform are essential to address these systemic risks. The Scottish Government is currently reviewing water, wastewater and rainwater drainage policy.

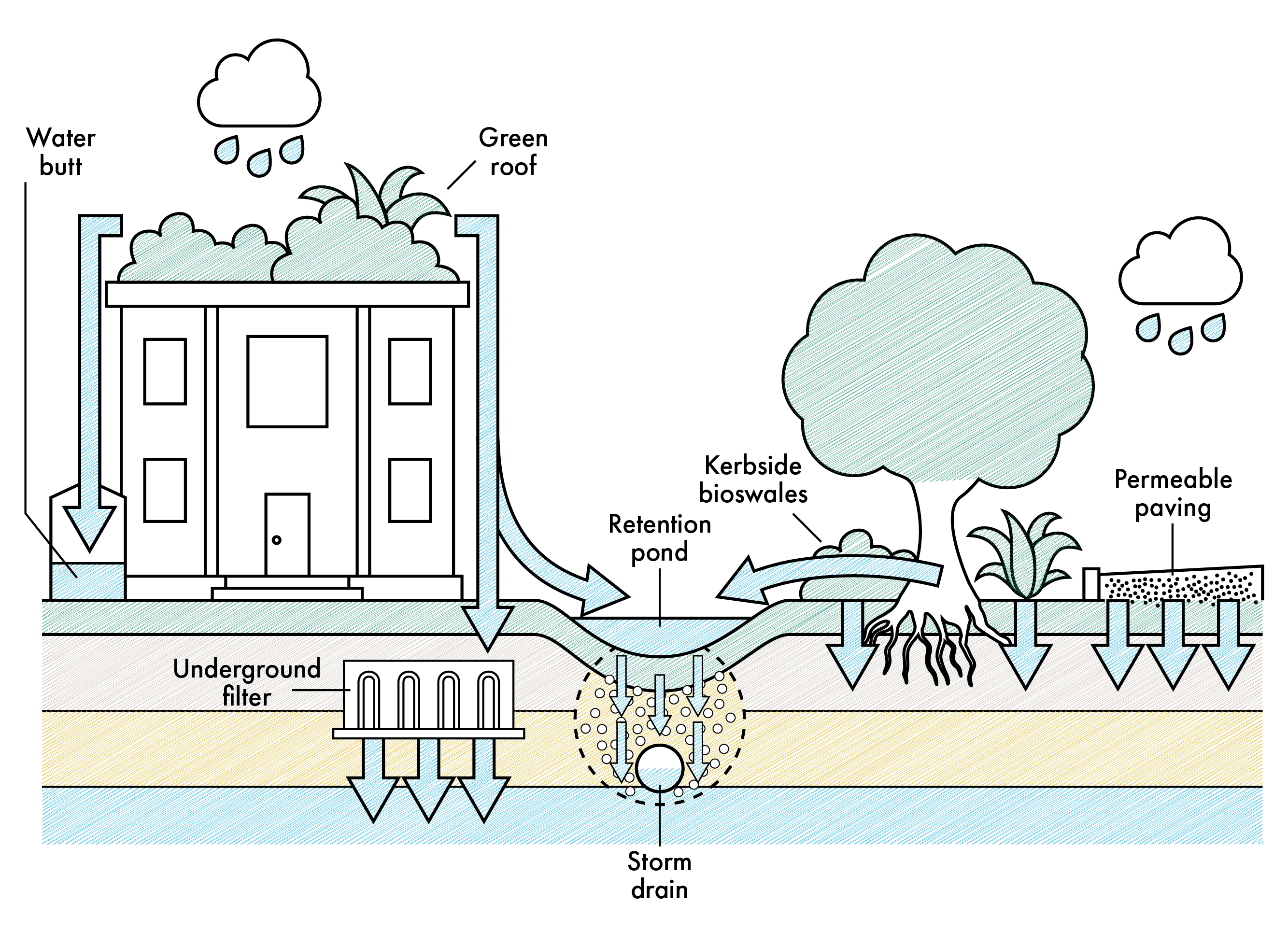

Climate change is increasing the frequency of extreme weather, impacting water resource resilience and infrastructure. Blue-green infrastructure, such as sustainable urban drainage systems (SuDS), is promoted to manage rainwater and reduce flood risk. Legislation and National Planning Framework 4 now requires integration of such infrastructure in development.

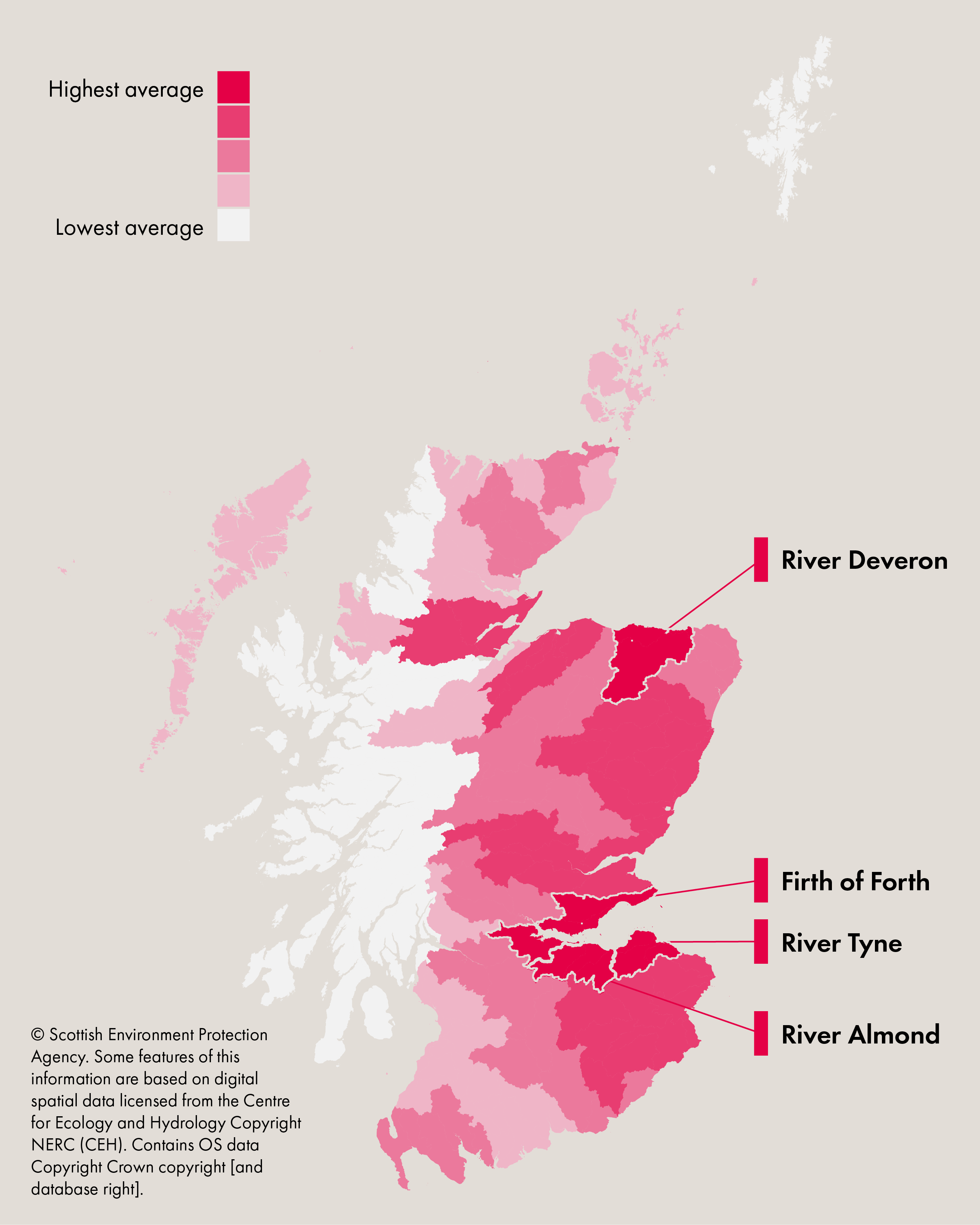

Catchment-based approaches are vital for protecting water quality and ensuring sustainable supply. Water scarcity is an emerging issue, particularly in eastern Scotland, driven by climate change and population growth. SEPA, Scottish Water and the Scottish Government are developing strategies to manage demand and support vulnerable users.

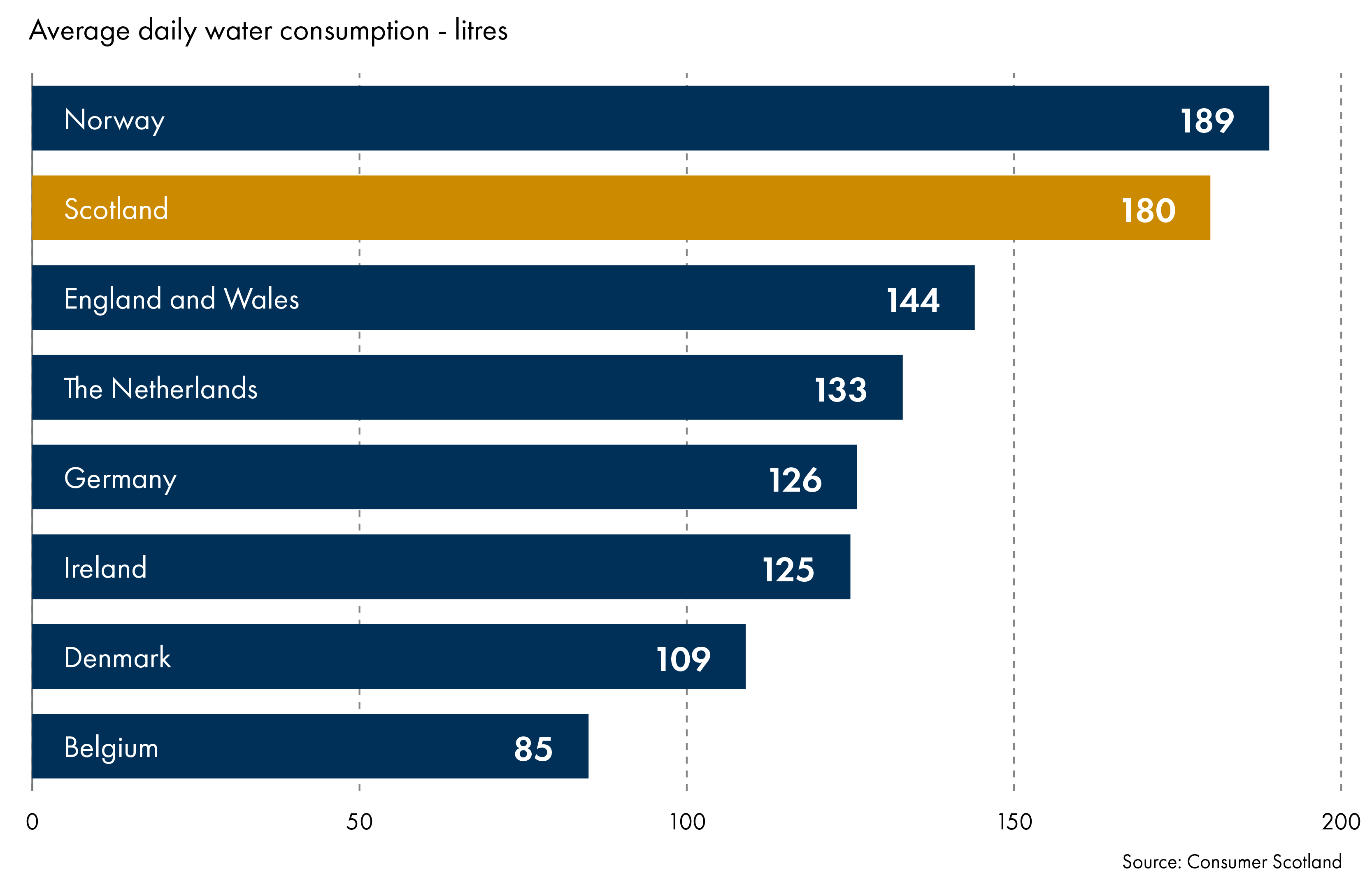

Per capita water use in Scotland is high compared to other European and UK countries due to a perception of abundance and because most people do not pay according to the volume of water they consume. Consumer education, smart metering, and more efficient appliances may help reduce demand. Policy measures and incentives are being explored to promote sustainable consumption.

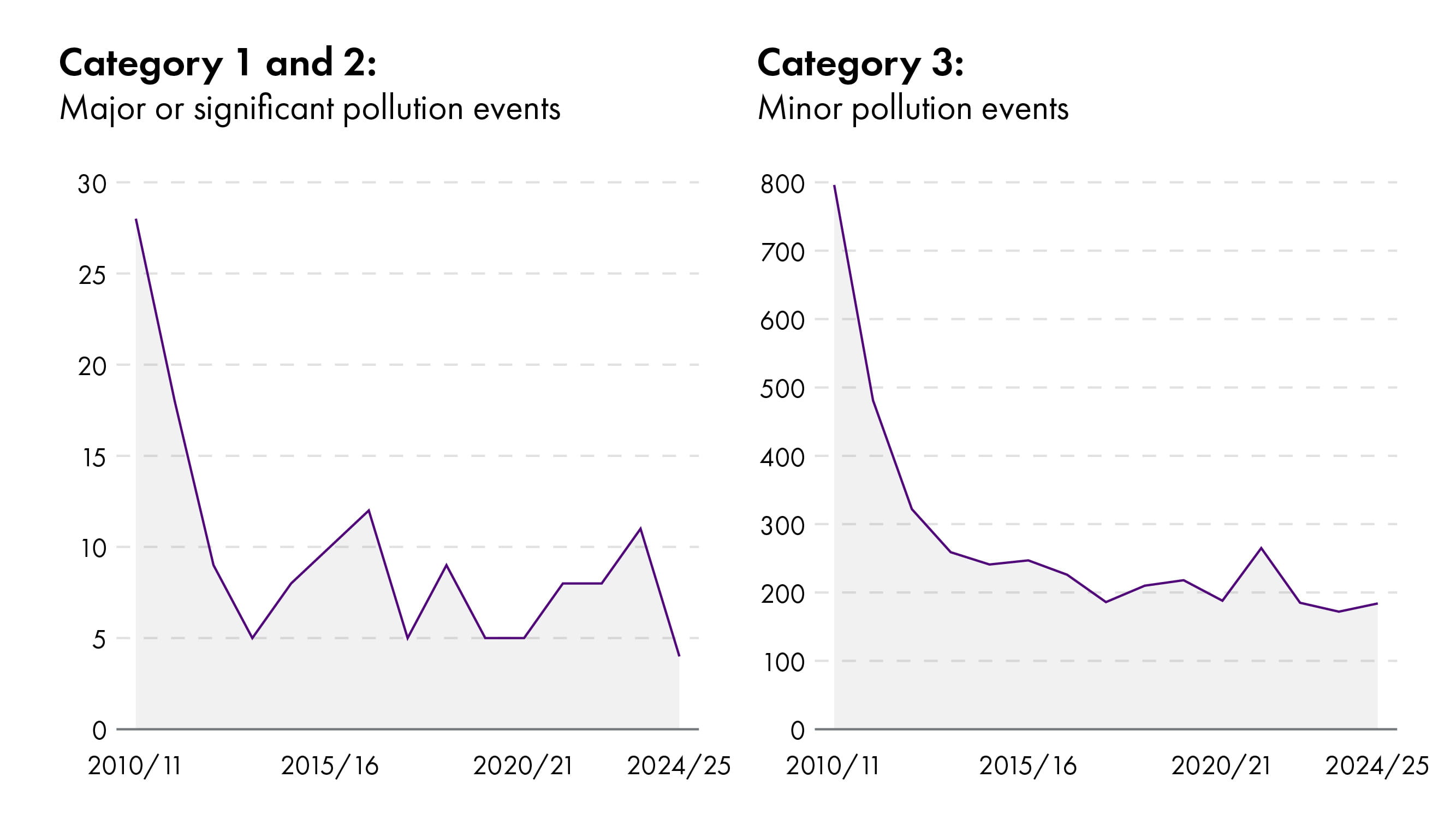

Awareness of sewage pollution issues may be associated with the rise in participation in outdoor recreation in inland and coastal waters. Monitoring is being expanded, and investment is targeted at high-risk areas. Data and monitoring transparency and public engagement are increasing, but further action is needed to address outdated infrastructure and pollution risks.

Pollutants such as 'forever chemicals' and microplastics in drinking water and water bodies pose new risks to health and the environment. Making producers of products responsible for pollution they may cause and improved product standards are being considered to manage these risks.

Policy and legislative framework

The Scottish Government's Hydro Nation initiative, launched in 2010, aims to maximise the economic and environmental value of Scotland's water resources. It is underpinned by the Water Resources (Scotland) Act 2013 and supported by research, international collaboration, and stakeholder engagement.

Management of Scotland's water resources is underpinned by the EU Water Framework Directive through River Basin Management Plans (RBMPs). SEPA leads this process, aiming for 81% of water bodies to achieve ‘good’ status by 2027.

Scottish Water and regulation

Scottish Water is publicly owned and the sole provider of household water and wastewater services in Scotland, regulated by a range of bodies including the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), Water Industry Commission for Scotland (WICS) and Drinking Water Quality Regulator (DWQR). Over 90% of Scotland's population get their water and wastewater services from Scottish Water. The remainder of Scotland's population which is not served by the public network, mostly in more remote rural areas, are served by small private systems.

The Scottish Government and WICS set strategic objectives and funding parameters for Scottish Water through regulatory periods. Economic regulation seeks to ensure affordability, efficiency, and long-term sustainability of services provided by Scottish Water.

Scottish Water operates as a public corporation with subsidiaries for commercial and retail services. It is funded primarily through customer charges and government borrowing, with economic oversight by WICS. The current regulatory period (2021–27) includes a customer charge cap of 12.6% above the rate of inflation, though actual increases have been moderated in recent years in response to cost-of-living pressures.

Drinking water standards are derived from EU legislation and implemented in domestic law, regulated by the Drinking Water Regulator (DWQR). The regulator monitors compliance, investigates incidents, and advises on investment priorities. Enforcement powers include issuing notices and penalties to ensure public health protection.

Domestic charges are largely unmetered and linked to council tax bands, with discounts for low-income households. Metered households are rare, while non-domestic customers operate in a competitive retail market.

Wastewater treatment and pollution control

Scottish Water operates over 1,800 treatment works, with high compliance rates with pollution control regulations. Pollution control is governed by EU-derived directives implemented in domestic law. These regulations cover discharges, abstractions, and engineering activities which may harm the water environment. SEPA is the lead regulator for issuing authorisations and monitoring compliance with environmental legislation.

Private water and wastewater systems

Around 3.5% of Scotland's population relies on private water supplies, which face challenges related to quality, resilience, and climate impacts. Regulation varies by supply type, with grants available for improvements. Private wastewater systems, including septic tanks, are regulated by SEPA but lack dedicated funding for upgrades and comprehensive data on their location.

Cover image credit: Scottish Water

1. Background

1.1 Why water policy matters in Scotland

Water is used in all aspects of modern life, and is critical to the survival of all life on earth. The way we collect, treat, consume and dispose of water is regulated through laws, cultural practices and everyday habits. These all impact on the wider health of people and the natural environment and can have wide ranging socio-economic impacts.

Water policy in Scotland is mainly devolved. The quality and availability of Scotland's water resources is heavily influenced and impacted by other devolved policy areas such as agriculture, forestry, food, transport, planning and infrastructure.

Devolved responsibility for water can also interact with reserved areas such as aspects of chemicals regulation, health and safety and energy generation.

This briefing sets out the policy, governance and regulation and legal framework regarding the management of Scotland's water resources. It also highlights some key challenges facing Scotland's water sector and wider water policy.

To understand the current structure and governance of Scotland's water sector, it is helpful to first explore how it has evolved over time.

1.2 A brief history of Scotland's water sector

Scottish Water was established by The Water Industry (Scotland) Act 2002. Subsequently, the Water Services etc. (Scotland) Act 2005 amended the 2002 Act to establish the governance and regulatory framework of the water sector as we know it today. Over the years, Scotland's water sector has existed in many different forms, with duties and responsibilities moving between a range of public bodies and institutions.

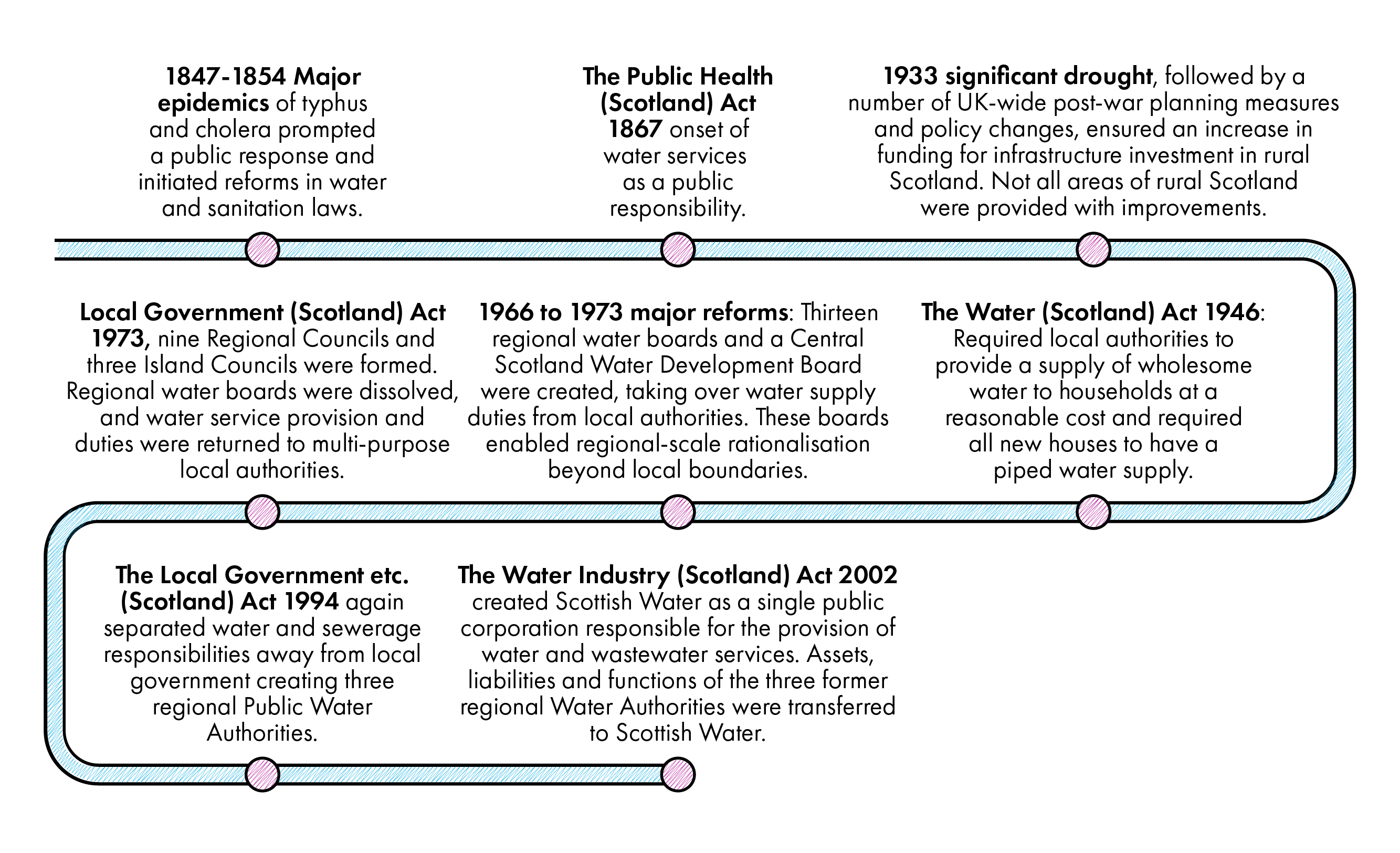

This historical context helps inform how and why today's sector operates as it does. Key events in the historic development of Scotland's water industry are depicted in Figure 1 and discussed further below. A summary of key legislation is provided in Annex A.

State involvement in water service provision in Scotland was limited before the mid-nineteenth century.1 Water management was typically considered a local issue, to be addressed at the local level.2

Major epidemics of typhus and cholera between 1847-1854 prompted a public response. This marked the start of co-ordinated reforms in water and sanitation laws in Scotland.1,2The Public Health (Scotland) Act 1867 marked the onset of water services as a public responsibility. A significant drought in 1933, followed by a number of UK-wide post-war planning measures and policy changes, ensured an increase in funding for infrastructure investment in rural Scotland.5 However not all areas of rural Scotland were provided with improvements.

The Water (Scotland) Act 1946 required local authorities 'to provide a supply of wholesome water to every part of their district where a supply of water is required for domestic purposes and can be provided at a reasonable cost'. It promoted the amalgamation of water supplies to improve efficiency and empowered authorities to collaborate. The Act also provided that from May 1946, all new houses were required to have a piped water supply.

From 1966 to 1973 Scotland underwent major water governance reforms. Thirteen regional water boards and a Central Scotland Water Development Board were created, taking over water supply duties from local authorities. These boards enabled regional-scale rationalisation beyond local boundaries. 1

Following local authority reforms under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973, nine Regional Councils and three Island Councils were formed. The regional water boards were dissolved and water service provision and duties were returned to multi-purpose local authorities. Responsibility for sewerage remained with Local Authorities.

At the time it was considered that water and wastewater services were a core responsibility of local government. The Water Scotland Act 1980 made provisions for the establishment and duties of the water authorities based on the then nine Regional Councils and three Island Councils. However, The Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994 again separated water and sewerage responsibilities away from local government creating three regional Public Water Authorities:

The North of Scotland Water Authority

West of Scotland Water Authority

East of Scotland Water Authority

In 2002 these Public Water Authorities were merged. The Water Industry (Scotland) Act 2002 created Scottish Water as a single public corporation responsible for the provision of water and wastewater (also referred to as 'sewerage') services.

The 2002 Act transferred existing assets, liabilities and functions of the three former regional Water Authorities to Scottish Water.

Building on the historical evolution of Scotland's water governance, the next section explores the strategic direction set by the Scottish Government through the Hydro Nation initiative.

2. Policy Framework: Scotland's Hydro-Nation

In 2010, the Scottish Government launched its ‘Hydro Nation’ initiative. Its purpose was to combine different aspects of the management of Scotland's water resources to bring the maximum benefit to the Scottish economy from Scotland's water resources.1,2

In February 2012, the Scottish Government published 'Scotland The Hydro Nation: Prospectus and Proposals for Legislation'. This consultation informed legislation to underpin the Hydro Nation agenda leading to the Water Resources (Scotland) Act 2013.

The 2013 Act placed a general duty on the Scottish Ministers to take appropriate steps for the purpose of ensuring the development of the value of Scotland's water resources. It also provided for Ministers to direct designated public bodies regarding their involvement in this development and placed a requirement on Ministers to report to the Scottish Parliament on the fulfilment of the duty.

Delivery of the Hydro Nation agenda is also achieved through the following mechanisms:

The Hydro Nation Chair: established by Scottish Water to bring the research and innovation community together to support its Net Zero ambitions and addressing climate change mitigation and adaptation challenges. Following a formal tender process Stirling University was selected to lead the Hydro Nation Chair. Prof Andrew Tyler was appointed at Scotland Hydro Nation Chair in June 2021. It operates independently from the Hydro Nation Scholars programme and Scotland's Centre of Expertise for Waters (CREW).

The Hydro Nation Forum: a group of water experts from industry, academia and public sector established by the Scottish Government to advise Scottish Ministers on the overall direction and focus of the Hydro Nation agenda.

The Hydro Nation Scholars programme: funds PhD research undertaking approved water resource projects hosted within Scottish Universities and Research Institutes. The programme is managed by CREW on behalf of the Scottish Government.

The Hydro Nation International Programme: aims to share knowledge and collaborate with other countries to grow the international water economy.

While Hydro Nation sets the overarching vision, effective water policy also depends on how Scotland's natural water resources are managed and protected.

3. Managing Scotland's water resources

Effective management of Scotland's water resources is essential to ensure their long-term sustainability and resilience. Scotland has more than 125,000 km of rivers, burns and streams, over 30,000 freshwater lochs and over 650 reservoirs.1,2

Groundwater is also a valuable resource used to supply drinking water, agriculture and industry. It is also particularly important to communities in rural Scotland, providing 75% of private drinking water supplies. Groundwater also feeds wetlands and river flows during dry spells and is vital to the maintenance of their rich ecology and biodiversity.1,4

Legislation and strategic planning

The EU Water Framework Directive (Directive 2000/60/EC) underpins the management of Scotland's water resources. It established a framework for the protection and sustainable management of all surface and groundwater bodies across Member States.

Its primary objective is to achieve "good status"—both ecological and chemical—for all water bodies by 2027, through integrated river basin management, pollution control, and ecosystem restoration. The Directive mandates the development of River Basin Management Plans (RBMPs) and Programmes of Measures (PoMs), updated every six years, and promotes cross-border cooperation, public participation, and the use of economic instruments to support water conservation.5,6,7

In Scotland, the Water Framework Directive was primarily implemented by the Water Environment and Water Services (Scotland) Act 2003 and its amendment of the Sewerage (Scotland) Act 1968.

River Basin Management Planning

Every six years Scotland produces a river basin management plan. This describes the condition of surface waters and groundwaters, the pressures affecting them, and actions planned to alleviate the pressures.

The Water Environment and Water Services (Scotland) Act 2003 introduced a River Basin Management Plan (RBMP) regime. RBMP objectives and action programmes are set on a six-year cycle which aligns with the current regulatory period for economic regulation of Scottish Water (2021-2027).

There are currently two RBMPs in Scotland. One for the Scotland river basin district (RBD) and one prepared jointly with the Environment Agency for the cross-border Solway Tweed RBD. The Scottish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA) has responsibility for coordinating Scotland's two RBMPs. The Scottish Government, other public bodies, and stakeholders are also responsible for RBMP delivery.

The first RBMP cycle ran from 2009 –2015, and the second series of RBMPs ran from 2015-2021. The central target of RBMPs is for 81% of water bodies to reach 'good' status by 2027.

The next report on Significant Water Management Issues in Scotland is due to be laid by 25 December 2025.

Reservoirs

Scotland's reservoirs are used for a variety of purposes, with a wide range of owners from large national companies such as Scottish Water and energy companies to individuals. They are regulated under the Reservoirs (Scotland) Act 2011. The Act takes a risk-based approach to the regulation of reservoirs by considering the consequences of an uncontrolled release of water.

Under the Act, all reservoirs that have the capacity to hold 25,000m3 or more of water above the natural level of the surrounding land are required to be registered with SEPA. Reservoir managers are the operators, users or owners of a reservoir and have ultimate responsibility for its safety.

Scottish Water manages around 300 of Scotland's reservoirs with many of them being sources of drinking water. Scottish Water provides weekly updates on its water resource levels on its website page - Scotland's Water Resource Levels.

Having outlined how Scotland's water resources are managed, the next section examines how water and wastewater services are delivered to the public and regulated.

4. Public water and wastewater services

Over 90% of Scotland's population get their water and wastewater services from Scottish Water, Scotland's publicly owned and sole provider of household public water and wastewater services.1

This section covers the regulation and governance of public water and wastewater services. However, the remainder of Scotland's population which is not served by the public network, mostly in remote rural areas, are served by small private systems. This is covered in Section 5.

4.1 Who oversees Scotland's public water sector

Scottish Ministers are responsible for national governance of the water sector. Key responsibilities include:

Setting the objectives for the water industry, as set out in ministerial directions.

Determining the length of each regulatory period (see further information below).

Determining the principles that should underpin household customer charges, as set out in the principles of charging statement.

Providing funding to Scottish Water for capital investment in the form of loans.

Appointing the chairs and members of the boards of both Scottish Water and the Water Industry Commission for Scotland (WICS).

Endorsing WICS' terms and conditions, including remuneration of its board members, senior executives and staff.1

For Scottish Water, the Scottish Ministers appoint non-executive board members only. Scottish Water appoints executive members.

The Scottish Parliament holds Scottish Water and Scottish Ministers to account on overall performance of the water sector.

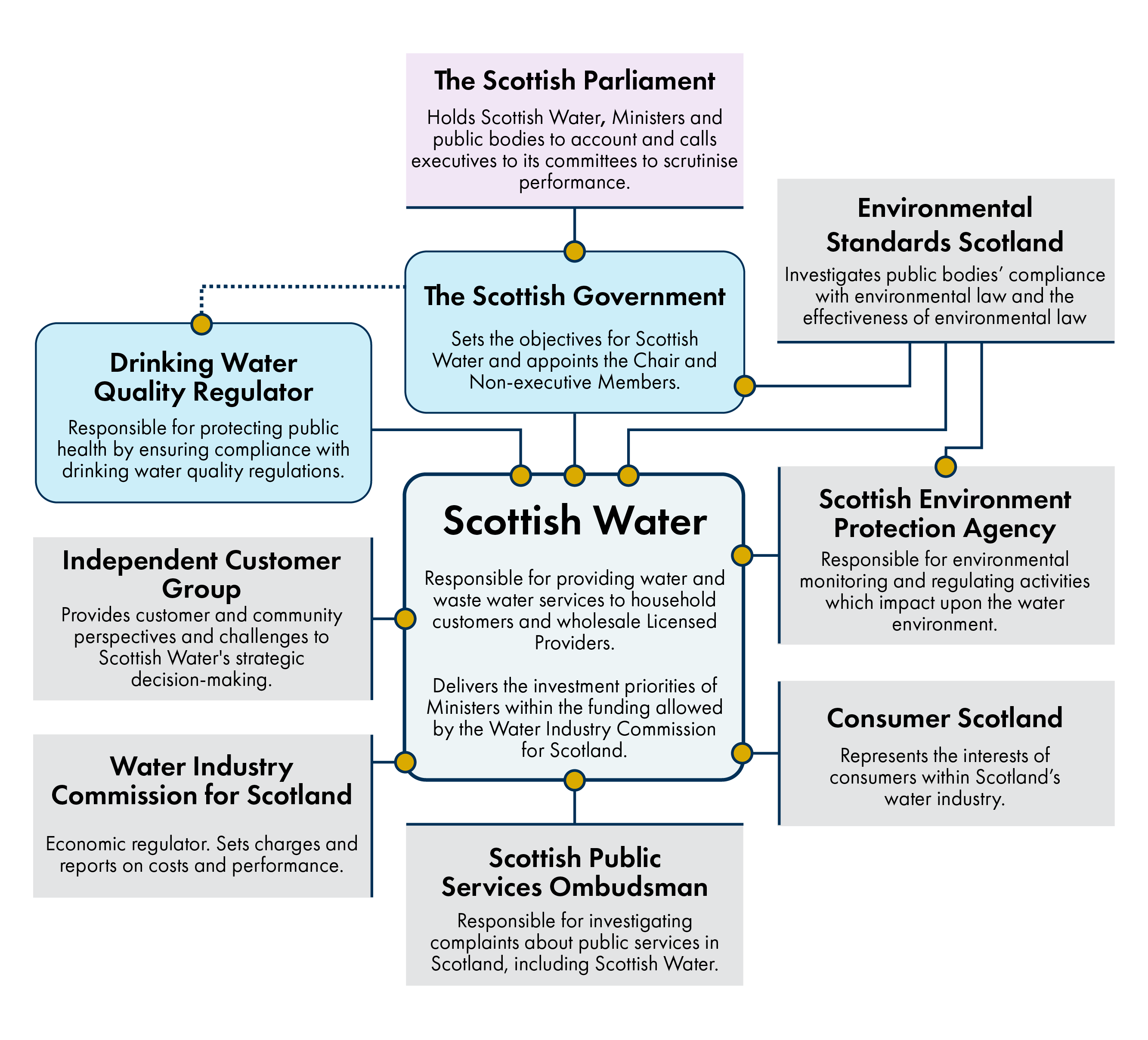

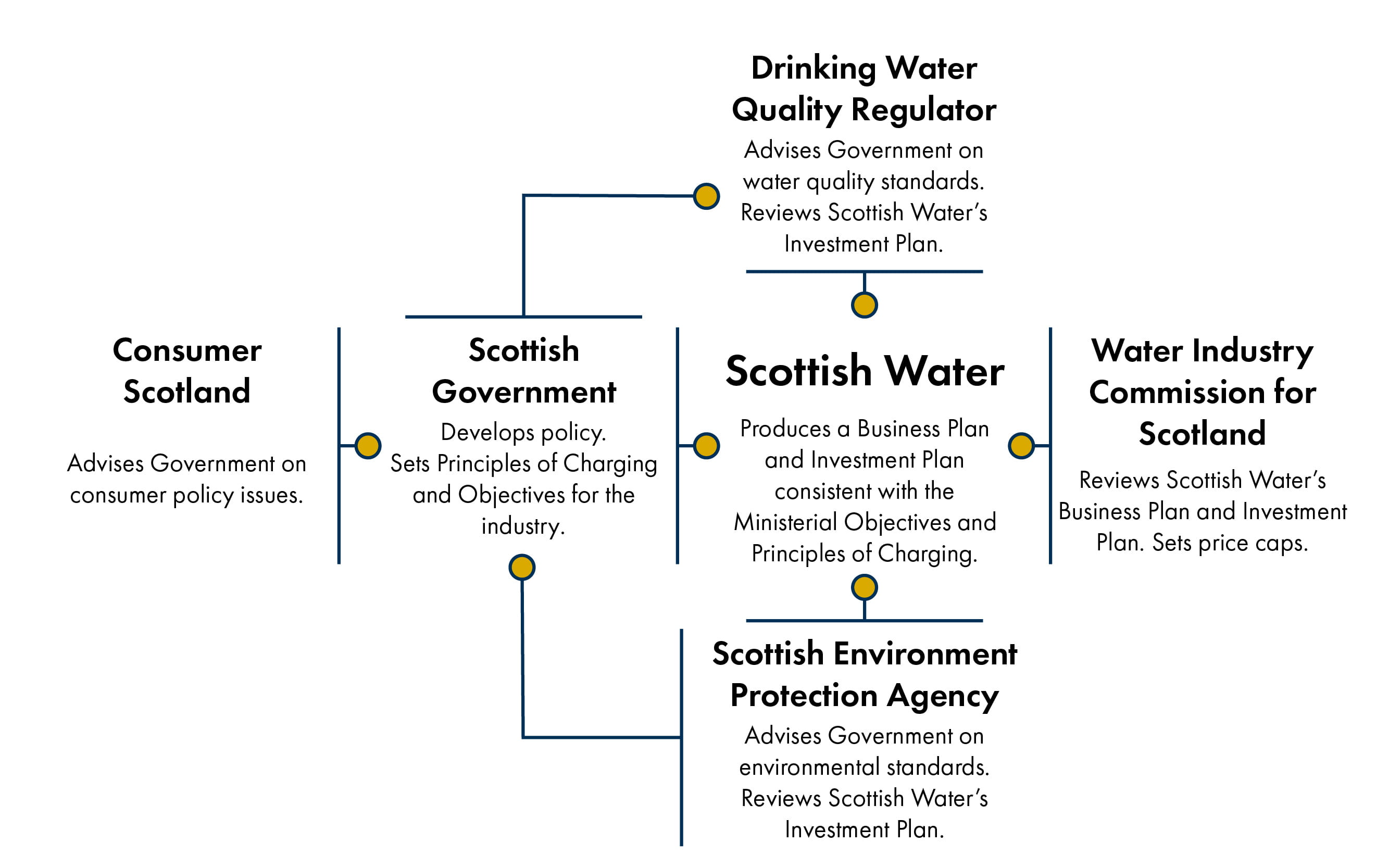

The regulatory framework for Scotland's water industry is visualised in Figure 2 below which sets out the roles and responsibilities of regulatory authorities. Further details of regulatory responsibilities are provided in Table 1 below.

| Stakeholder | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Scottish Water |

|

| The Water Industry Commission for Scotland (WICS) | The economic regulator of the Scottish water industry. It is responsible for setting charge caps, monitoring Scottish Water's performance and overseeing the orderly functioning of the non-household retail market. |

| The Drinking Water Quality Regulator for Scotland (DWQR) | Ensures that Scottish Water complies with its duties in respect of public drinking water supplies in Scotland. It does this through monitoring Scottish Water's compliance with drinking water quality standards and advising on future investment priorities in respect of public supplies. It also supervises Local Authorities' enforcement of regulations over private water supplies in Scotland, which serve around 3% of the population. |

| The Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) | Environmental regulator in Scotland with a remit that goes beyond the water sector. Within the water sector, it has a wide-ranging role that involves monitoring, reporting and enforcement in relation to the quality of the water environment in Scotland and advising WICS and Scottish Water on future investment priorities. It also has a role in setting regulatory policy and regulations and advising on national policy. It is the lead authority for producing River Basin Management Plans for Scotland. |

| Consumer Scotland | The statutory, independent body for consumers in Scotland, established by the Scottish Parliament under the Consumer Scotland Act 2020 to advocate on behalf of consumers and represent consumer interests.It works to embed positive consumer outcomes and engagement with consumers across all aspects of service delivery in the water industry, across both the household and non-household markets. This includes affordability of services, how water and wastewater services can contribute to a transition to net zero and how services should be adapted to mitigate the impacts of climate change. |

| The Scottish Public Sector Ombudsman (SPSO) | Acts as the final stage for handling customer complaints for public sector bodies and departments. |

| Independent Customer Group | Hosted by Scottish Water and is operationally independent. Its purpose is to ensure customers, communities and the environment are at the heart of Scottish Water's strategy and service delivery, investment priorities reflect customers' expectations of the sector, and the resultant charges are affordable and represent value for money. |

| Environmental Standards Scotland | Public body responsible for ensuring public authorities, including the Scottish Government, public bodies and local authorities, comply with environmental law. Monitors and takes action to improve the effectiveness of environmental law and its implementation. Has a strategic aim to consider if Scotland is 'keeping pace' with environmental standards in the European Union. |

4.2 Planning and funding water investment: the regulatory period

Scottish Ministers determine the length of Scottish Water's investment programme sometimes referred to as the ‘regulatory period’. The current period is set over six-years from 2021 to 2027 and the next regulatory period has also been commissioned to run for a six-year period from 2027-2033.

At the beginning of each regulatory period, Scottish Ministers set out Ministerial objectives for Scottish Water in line with its legal commitments under the Water Industry (Scotland) Act 2002 (section 56(1)(a),(b)).

This process also initiates the Strategic Review of Charges undertaken by the Water Industry Commission for Scotland which involves setting charge caps for the regulatory period (the maximum amount Scottish Water can legally charge its household customers). Details on how charges are recovered from customers is set out in Section 4.3.5.

Key Ministerial objectives for the 2021-27 regulatory period are summarised in Box 1 below.

Box 1: Key Ministerial Objectives for Scottish Water for the 2021-27 regulatory period

Take an integrated and collaborative approach to decisions to maximise the impact of resources and to achieve better outcomes for people and communities.

Maintain or improve current levels of service, engaging to establish appropriate standards for the 2021-27 period and beyond.

Prepare a strategy to inform the long-term asset replacement needs ensuring asset maintenance is fully integrated in the investment programme.

Identify and provide new strategic capacity to meet the demand of all new housing development and domestic requirements of commercial and industrial development.

Align with the Scottish Government's circular economy strategy and assess the potential for resource recovery from sewerage.

Comply with drinking water quality duties and address failures to ensure compliance with drinking water quality standards, taking steps to improve resilience and remove lead from the network.

Improve compliance with environmental licences and limit the amount of plastics reaching the water environment through the sewer network.

Work with stakeholders to transform how rainwater and sewerage are managed to improve flooding and surface water management.

Maintain and improve the security of its network and systems, to protect them from malicious attack.

Make substantive progress in the 2021-27 period towards climate change targets.

Prepare and implement plans to manage its private finance initiative contracts which end in the 2021-27 period. 1

4.3 Scottish Water: structure, role and accountability

Scottish Water was established by the Water Industry (Scotland) Act 2002. It is responsible for providing water and wastewater (sewerage) services to household customers and wholesale licensed providers.

Scottish Water exercises statutory water and sewerage functions under the provisions of the Sewerage (Scotland) Act 1968 and the Water (Scotland) Act 1980. As set out above, the 2002 Act requires Scottish Ministers to issue directions to Scottish Water on how to exercise its functions.

Scottish Water is governed by a Board which comprises:

Chair and Non-Executive Members, who are appointed by the Scottish Ministers.

Executive Members including the Chief Executive, who are appointed by Scottish Water.

Scottish Water states that the key role of the Board is to:

Provide strategic guidance and direction to Scottish Water.

Demonstrate high standards of corporate governance.

Oversee the delivery of Scottish Waters Regulatory outputs.

Ensure statutory requirements in relation to the use of public funds are complied with.

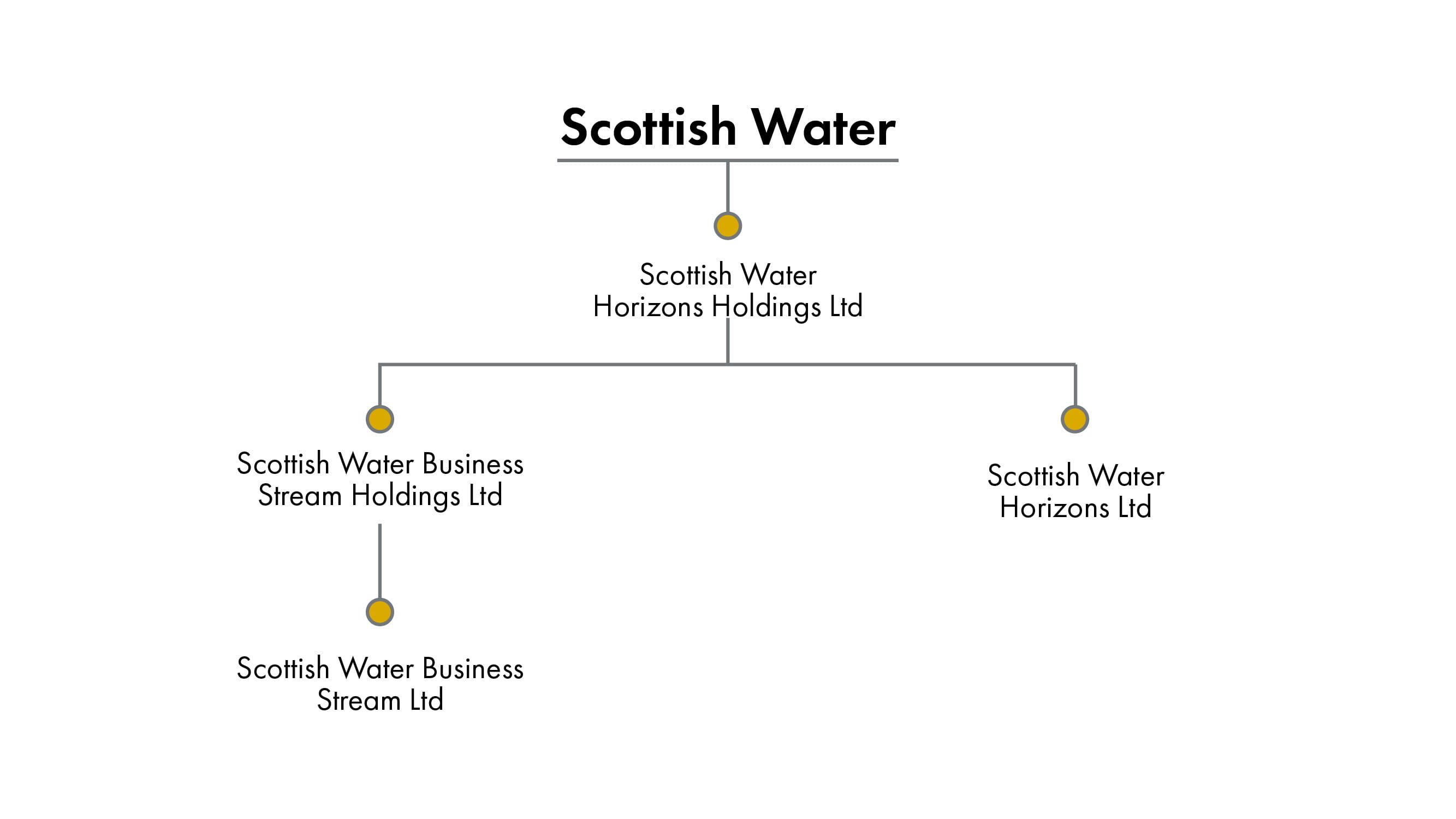

Scottish Water operates a group business model which is set out in Figure 3 below.

The Scottish Water Group consists of:

Scottish Water: a public corporation, supplies households with regulated water and wastewater services and wholesale services to Licensed Providers (see Section 4.3.6) serving non-domestic customers.

Business Stream: licensed retail subsidiary which supplies water and wastewater services to business customers.

Scottish Water Horizons: Scottish Water Horizons is a commercial subsidiary wholly owned by Scottish Water. In addition to water services its activities include renewable energy, broadband internet infrastructure and food waste recycling.

4.3.1 How public water services are funded

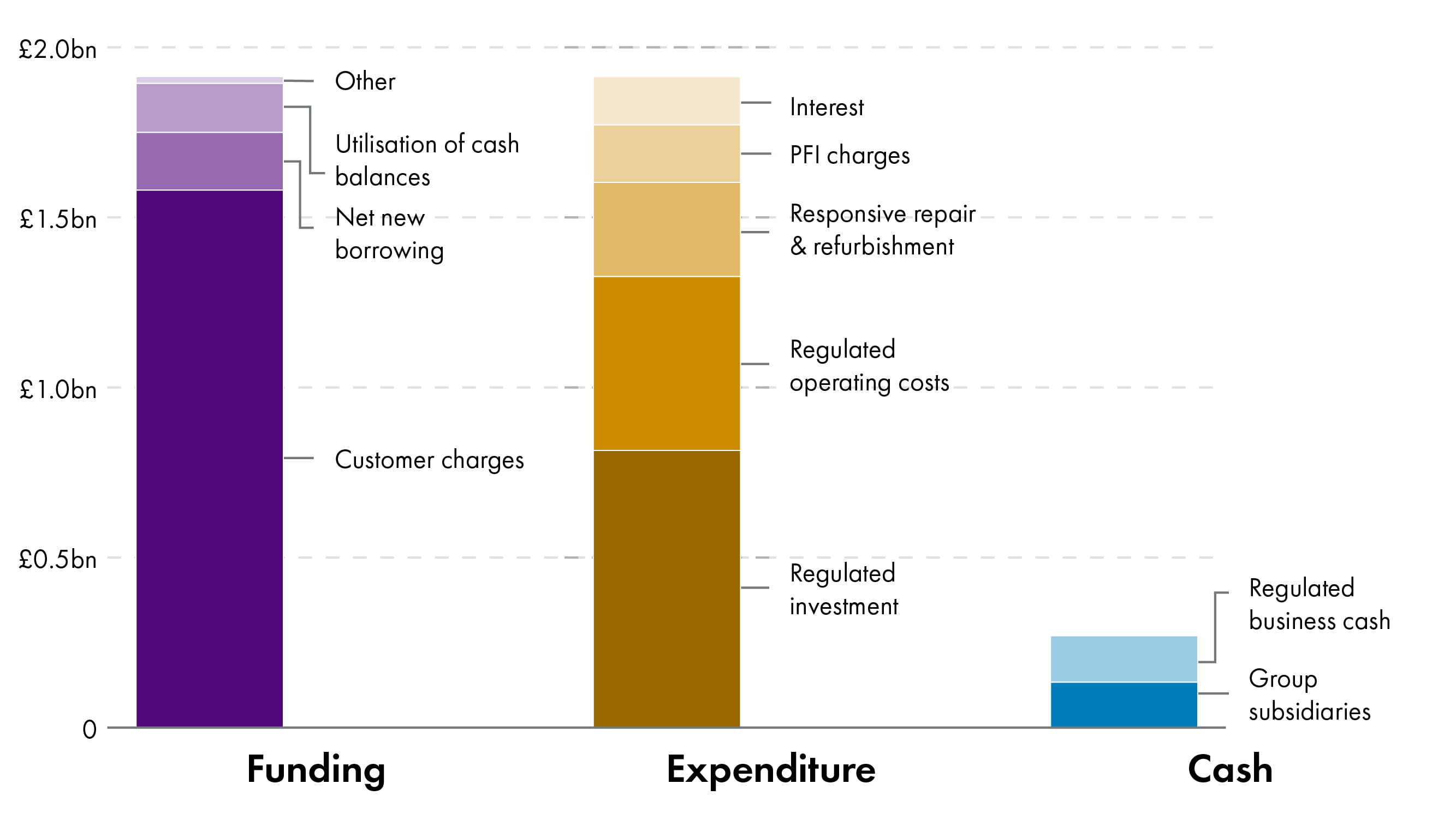

Scottish Water has a total revenue of around £1.6bn every year to provide water, sewerage and drainage services. This is required to operate water, wastewater and drainage networks, to maintain its current assets, and to invest in improvements and expansions of the infrastructure to meet new demand.1

The Water Industry Commission for Scotland (WICS) explains how Scottish Water's borrowing works:

The maximum amount of borrowing available to Scottish Water is set by Scottish Ministers in their Principles of Charging for the industry. To pay for investment, Scottish Water is free to borrow within the public sector allowance that has been granted in the Scottish Government's Budget. Scottish Water and the Scottish Government agree on the timing of this borrowing within the financial year and the duration of the borrowing. Each year, Scottish Water pays interest on this borrowing, and on the maturity of the loan, it repays the principal, currently through refinancing the debt. As such, Scottish Water effectively rolls over maturing debt at prevailing interest rates, and [WICS] refer to the new borrowing in the year less the borrowing repaid in the year as net new borrowing.

Scottish Water must comply with public expenditure rules. While it can borrow from any source, it must be able to demonstrate that it is accessing the cheapest source available. This has the effect of ensuring that all medium and longer term borrowing is provided by the Scottish Government.

Water Industry Commission for Scotland. (2024, December 12). STRATEGIC REVIEW OF CHARGES 2027-2033: FINAL METHODOLOGY. Retrieved from https://wics.scot/system/files/2024-12/SRC27-Final-Methodology.pdf [accessed 24 February 2025]

An overview of Scottish Water's regulated funding and expenditure is shown in Figure 4 below. 'Regulated' refers to any funding or expenditure covered by economic regulation (see Section 4.3.2).

Scottish Water's revenue comes from:

Household customer charges: charges to household customers charged according to property council tax bands (see Section 4.3.5). This accounts for around 90% of regulated revenue.

Wholesale customer charges: wholesale charges (e.g. network connections and new infrastructure) to licensed retailers of business customer services.

Borrowing: loans from the Scottish Government for capital investment. The amount that Scottish Water can borrow in a given financial year cannot exceed limits set out in an annual Budget Act. Interest rates are set by the UK Government.

Utilisation of cash reserves: cash held to support its investment programme expenditure. Scottish Water states any large infrastructure organisation that provides an essential service requires access to sufficient cash to maintain its activities and to respond to unforeseen events. Scottish Water's risk policy determines that the regulated business should always have access to approximately four weeks expenditure.

Other: charges for 'secondary services' which is everything else except Scottish Water's main water and waste water services.

In the most recent financial year 2024/25, Scottish Water's total regulated revenue from customer charges was £1,579 million, of which £1,154 million (73%) was from household customer charges.

The remainder of total regulated revenue from customer charges is from wholesale customer charges to licensed retailers for business customers.3 Total funding encompasses utilisation of cash reserves and new borrowing from the Scottish Government for capital investment.

Scottish Water spends money in the following areas to providing essential water and wastewater services:

Capital investment: spending on maintaining, upgrading and building new water sources, treatment plants, pipes, and other equipment required to provide water and wastewater services.

Operating expenditure: spending on ongoing, day-to-day activities required to provide water and wastewater services.

Private Finance Initiative (PFI) expenditure: regular payments to third-party organisations providing wastewater assets and services on behalf of Scottish Water under legacy contracts.

Taxation and interest payments on borrowing.4

In 2024/25 total regulated operating costs were £1,364 million leaving a total regulated operating surplus of £215 million. Total regulated investment was £815 million.3

WICS' Final Determination for the 2021-27 regulatory period set a charge cap of Consumer Price Index (CPI) plus 12.6% over the six-year regulatory period. CPI is a measure of inflation. This means that Scottish Water can only charge its household customers 12.6% above the rate of inflation in total over the six-year period. This equates to an annual household charge cap of CPI plus 2% on average in each year of the regulatory period.

By the end of the first three years of the regulatory period, Scottish Water had raised charges by CPI minus 4.4%. WICS states that this is 10.5% below the assumed position from the Final Determination, largely because Scottish Water responded to the cost-of-living crisis during 2021 and 2022. As a result of the profiling of charges, WICS expect Scottish Water to have £500m less funding available for investment than was assumed in its Final Determination.4

4.3.2 Economic regulation

Because Scottish Water is the only provider of household water services, it does not face competition. Economic regulation therefore seeks to mimic a competitive environment to ensure Scottish Water operates efficiently and in the interests of customers. The rationale for economic regulation is explained further in Box 2.

Box 2: Why is there a need for economic regulation of Scottish Water?

The development of the water industry in Scotland has given rise to Scottish Water as a 'natural monopoly'. A ‘natural monopoly’ refers to the situation where there is only one organisation supplying a product in the market, but this is not the result of the organisation's behaviour. Instead, it arises as it is the sensible way to organise the industry and it is in the best interests of customers to do so. This is not unique to Scotland. All household water services in the UK are natural monopolies (households can only get water from the service provider that covers their region).

The behaviour of natural monopolies may work against the customer interest if unchecked. WICS sets out two ways in which this might happen:

First, if the service is essential and the customer has no choice about where to purchase it, the monopoly has an incentive to charge an excessive price and to make excessive profits. This type of behaviour is known as monopoly pricing.

Second, in the absence of competition the monopoly faces no incentive to innovate and improve its efficiency over time. From the point of view of the firm, a failure to innovate and improve efficiency will have little or no implication for the size of the market that it serves or the level of profit that it earns. Compared with a competitive market, the industry will tend to stagnate.1

In a competitive market, companies face tight budgetary constraints in that they have to match their costs to the revenue they can win from customers. In the case of Scottish Water as a natural monopoly, regulation seeks to mimic the discipline and pressures of operating in a competitive market.

WICS provides the following explanation of how this works:

The annual process of approving Scottish Water's scheme of charges is a central part of providing this discipline in the Scottish water and sewerage industry. In the approval process the revenues that would be generated by Scottish Water's proposed charges are compared with the revenues that are allowed by the Strategic Review of Charges limits. The Strategic Review of Charges limits, or revenue caps, represent the revenue that an efficiently run Scottish Water would require in order to provide water and sewerage services. If the charges proposed by Scottish Water were to generate more revenue than is allowed by the Strategic Review of Charges revenue cap, this would indicate monopoly pricing. The regulatory process ensures that Scottish Water's charges are consistent with the revenue cap and so do not contain a monopoly pricing element.1

Water Industry Commission for Scotland

The Water Industry Commission for Scotland (WICS) is the economic regulator of Scottish Water. WICS regulates Scottish Water's domestic customer charges through a process know as the Strategic Review of Charges within the parameters set out in the Ministerial Objectives and Principles of Charging.

WICS engages in a Strategic Review of Charges process following the Commissioning letters from Scottish Ministers. This process is completed with the Final Determination unless Scottish Water chooses to appeal. WICS also has the statutory remit to monitor and report on Scottish Water's performance during the regulatory period.

Key milestones for the Strategic Review of Charges include:

A Commissioning letter from Scottish Ministers that commences the Strategic Review of Charges process and sets the duration of the regulatory period.

A Statement of Objectives and Principles of Charging from Scottish Ministers that confirms the overall policy objectives for the water industry in Scotland.

A methodology from WICS that sets out how it will set charge caps for the regulatory period.

A proposal from Scottish Water for charge caps and investment for the regulatory period.

A draft and Final Determinations of charges from WICS which sets charge caps for the regulatory period.3

The roles of various public bodies in the strategic review process are shown in Figure 5 below.

Through the Strategic Review of Charges process, WICS set charge caps consistent with the lowest reasonable overall cost incurred by Scottish Water in delivering Scottish Ministers' objectives. WICS states that these caps are "consistent with its assessment of the revenue that Scottish Water requires to cover the efficient cost of providing water and wastewater services and delivering the investment required".4

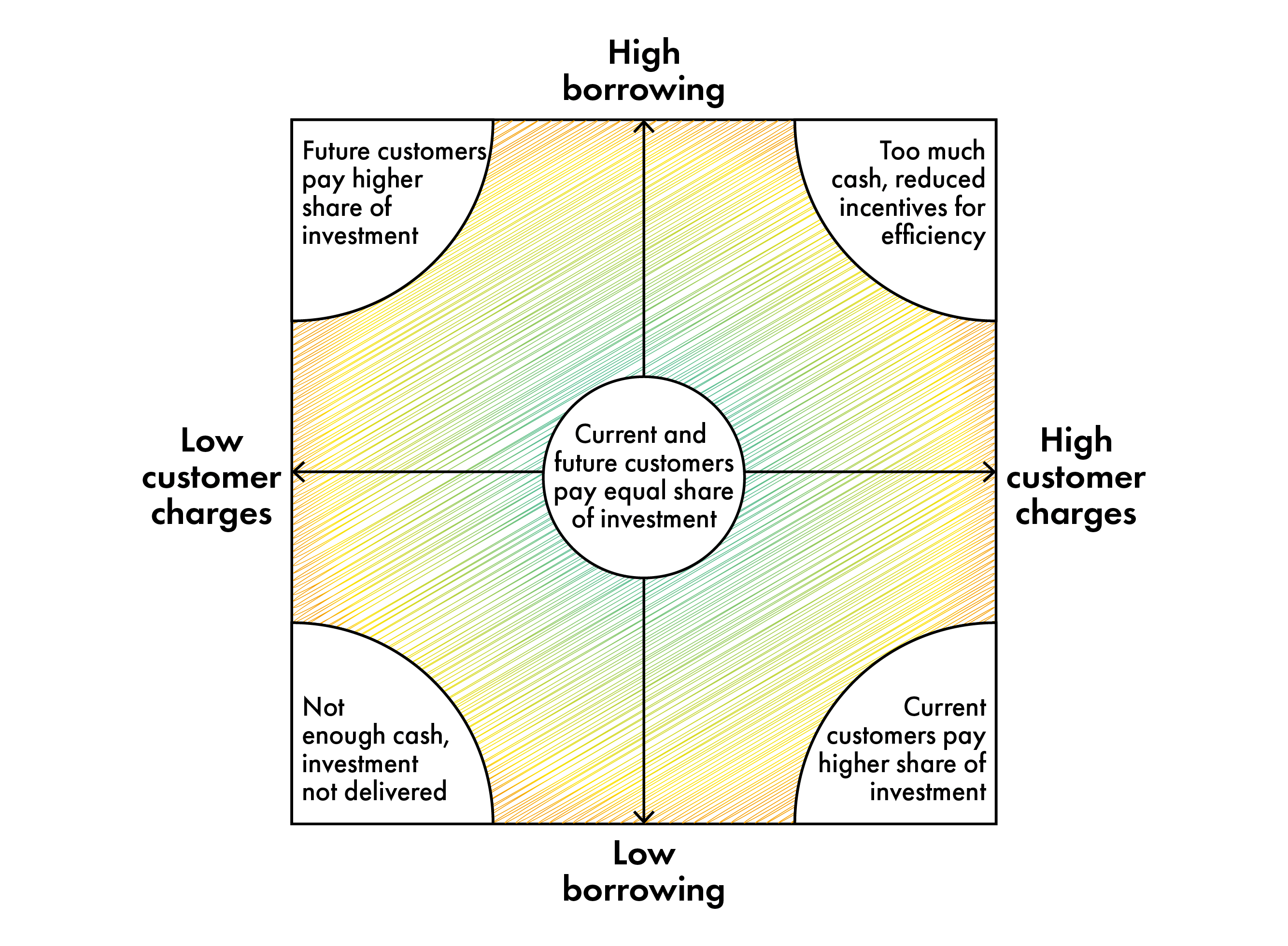

WICS must balance the cost to current and future customers when considering customer charges and borrowing that Scottish Water needs to deliver its services. This is key to ensuring financial sustainability and intergenerational equity.

WICS explains two key challenges associated with this:

The use of borrowing: Only customers or the taxpayer (in the form of Government borrowing) can meet the cost of any new investment Scottish Water undertakes. Borrowing is used to spread costs between current and future customers given the investment and the service improvements it provides for years into the future. While borrowing reduces the need for significant increases in customer charges in any given year, it is not a substitute for raising revenue over the medium to long term. For the water industry to be financially sustainable new borrowing should only be used for incremental expenditure. Ultimately if new borrowing is systematically used to cover the cost of anything other than true increments to Scottish Water's assets, future customers would be left paying for more than their appropriate share of the costs.

Charging for asset maintenance: WICS explains that how and when asset maintenance investment (the investment that Scottish Water undertakes to maintain its existing assets) should be paid for presents two key risks:

under-provisioning for the full replacement costs of assets, effectively undercharging current customers for the use of the assets and transferring costs to future generations

placing pressures on future charges, recognising that assets reaching the end of their life incur higher costs associated with their repair, refurbishment and, ultimately, replacement.

These challenges are conceptualised in Figure 6 below:

4.3.3 Public drinking water supplies

Historically, the overarching regulatory framework for drinking water quality in Scotland has been provided by standards set within EU legislation informed by the World Health Organisation.

The EU's Drinking Water Directive (98/83/EC) underpins quality standards for drinking water which have been implemented in domestic law in Scotland. The Directive was introduced in 1998 with the key objective of protecting human health from the adverse effects of any contamination of water intended for human consumption.1

The Directive requires that EU Member States must:

take the necessary measures to ensure the water does not contain concentrations of microorganisms, parasites or harmful substances that could be a danger to human health, and meets minimum microbiological and chemical standards

ensure the standards are met when the water comes out of a tap or tanker

monitor the water regularly at agreed sampling points in order to check that the microbiological, chemical and indicator parameter values are met

investigate immediately when the standards are not met and take the necessary corrective action

ban or restrict a water supply if it is considered to be a potential threat to public health

inform the public when corrective action is taken

publish a report every three years on drinking water quality.

The 1998 Directive was implemented in the UK through various domestic primary and secondary legislation and remains part of assimilated law (law that was kept from the period of the UK's membership of the EU). There are separate regulations covering public and private drinking water supplies but both are underpinned by the 1998 Directive:

Public Water Supplies (Scotland) Regulations 2014 (as amended).

The Water Intended for Human Consumption (Private Supplies) (Scotland) Regulations 2017.

The EU updated the 1998 Directive through the recast Drinking Water Directive in December 2020 which came into force in January 2021. The recast Directive was a response by the European Commission to the European Citizens' Initiative 'Right2Water'. Recent developments in EU law and the Scottish Government's alignment with these developments are discussed further in Section 6.5.

Drinking Water Quality Regulator

Drinking water quality in Scotland is regulated by the Drinking Water Quality Regulator (DWQR). DWQR is responsible for monitoring water quality and enforcing regulations on behalf of Scottish Ministers.2 It was established at the same time as Scottish Water under the Water Industry (Scotland) Act 2002.

DWQR enforces the requirements of The Public Water Supplies (Scotland) Regulations 2014 (as amended) to ensure the quality of public drinking water supplies, and takes action where these requirements are not met. It does this by:

Investigating Scottish Water's response to events and incidents that could affect drinking water quality.

Receiving, interpreting and presenting data on water quality throughout Scotland.

Participating in the investment planning process to ensure that any necessary improvements to water quality are delivered.

Checking that Scottish Water responds appropriately to any concerns from consumers about drinking water quality and that information it publishes on the subject is accurate and appropriate.

Ensuring future issues that may affect drinking water quality in Scotland are adequately understood, and that any knowledge gaps are filled through research.

Providing Scottish Ministers with an annual report on the quality of drinking water in Scotland.

Enforcement powers

The DWQR has three main powers under the Water Industry (Scotland) Act 2002:

The power to obtain information.

The power of entry or inspection.

The power of enforcement.

Emergency powers to require a water supplier to carry out works to ensure quality of water supplied is safe for public consumption.

Power to require information from local authorities.

The DWQR can initiate enforcement where non compliance has occurred or is likely to occur. Non compliance may be highlighted in a number of ways, such as:

By assessment of data and information supplied by Scottish Water.

During audit or inspection.

During an investigation following a drinking water quality or supply incident.

Following a consumer complaint.

Following notification or awareness of a significant risk to water quality.

The DWQR states that it seeks to secure compliance with legislation through cooperation, discussion and offering advice. This may include written recommendations, an advisory letter or 'Letters of Commitment' agreed with Scottish Water detailing delivery projects to make improvements.

Where resolution is not possible using the approach described above then the DWQR may use enforcement options available which are:

Information Notice: allows the DWQR or any authorised person, by notice, in writing to require the provision of water quality data or such documents that are considered to be relevant.

Enforcement Notice: setting out specific actions to be taken by Scottish Water within specified timescales. Failure to complete such actions by the due date is a criminal offence.

Emergency Notice: setting out specific actions to be taken by Scottish Water to reduce or remove the risk. Failure to complete such actions by the due date is a criminal offence.

Penalty Notice: specifying the reason for the notice, the size of the penalty imposed and details of the appeal mechanism. The sum imposed may be up to £17 million but must be appropriate and proportionate to the reason for the failure of a regulatory duty. Scottish Water may appeal to the First-Tier Tribunal should it disagree with the grounds upon which the Penalty notice is served.3

The DWQR also supervises local authorities' enforcement of the regulations governing the quality of private water supplies in Scotland and has the power to request information from local authorities as well as from Scottish Water.3 Private water supplies are discussed further in Section 5 of this briefing.

4.3.4 Public wastewater treatment

In 2022/23, Scottish households and businesses produced over a billion litres of wastewater every day. 1 The sewer network is designed so that the majority of the wastewater should be collected then treated at a treatment works before it is discharged to the natural environment. Wastewater in Scottish Water's network is treated at 1,838 wastewater treatment works across the country.2Scottish Water's wastewater assets include:

Sewers and sewage pumping stations: Underground networks and mechanical stations that transport wastewater from homes and businesses to treatment facilities.

Wastewater treatment works: Facilities that clean and process sewage to remove contaminants before releasing treated water back into the environment.

Sludge treatment facilities: Specialised plants that process the solid by-products of wastewater treatment to reduce volume and recover energy or nutrients.

Combined sewer and emergency overflows: Safety mechanisms that release excess wastewater during heavy rainfall to prevent flooding and system overload.

Sea outfalls: Engineered discharge points that release treated or partially treated wastewater into the sea.

Over the last 20 years, Scottish Water has invested over £2 billion in improving wastewater treatment quality. Wastewater discharge compliance from Scottish Water assets is generally high at around 96% of sites complying with regulatory standards in wastewater discharge licenses.

Despite this investment, Scottish Water has identified ageing assets as a major key long-term challenge. Scottish Water explains that many assets are over 100 years old and reform of legislation for water and wastewater treatment meant a boom in the number of assets which were installed in the 1950s and 1990s. It states that these assets are reaching a point where they need to be upgraded or replaced.3

Issues with sewage pollution are often associated with a combination of factors such as ageing assets and the increased frequency of extreme weather with climate change. These issues are explore further in Section 6.2

Controlling pollution from treatment facilities

Pollution control from wastewater treatment works in Scotland is underpinned by EU Directives that have been transposed into domestic legislation. Two key EU instruments established the regulatory framework for sewage discharge:

These directives aim to protect water bodies from pollution and ensure sustainable water management across the EU. In Scotland, the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive (UWWTD) is implemented through the Urban Waste Water Treatment (Scotland) Regulations 1994, as amended, and supported by duties under the Sewerage (Scotland) Act 1968.

Additionally, there are a range of regulations which provide a framework for controlling discharges and pollution to the water environment which apply to wastewater treatment works.

Environmental Authorisation Regulations

In Scotland, activities which may have an impact on the water environment will be managed by an integrated system for environmental authorisations under the Environmental Authorisation (Scotland) Regulations 2018 (as amended) or 'EASR'.

EASR brings together the processes for authorising, enforcing, and managing activities that may impact the environment. From 1 November 2025 (with some provisions coming into force earlier on 1 June 2025), water, waste management and industrial activities will be regulated under the new EASR regime.

Key regulated activities relevant to the water sector which require authorisations include:

Abstraction of water from the water environment, including for the operation of a hydropower scheme and any associated impoundments. It also covers the construction, extension or operation of any borehole.

Discharges to the water environment of sewage effluent, sewage from overflows, other effluents and water run-off.

Engineering activities that involve the building or engineering works in inland surface waters or wetlands, or in the vicinity of these waters, which have or are likely to have an impact on the water environment.

Impoundments (dam, weir or other structure that can raise the water level of a water body above its natural level). Uses of impoundments include the creation of a new reservoir, flood storage, maintaining or raising water levels within a wetland, raising the water level of a natural loch, estuary or even coastal waters.

Pollution control for activities that may cause the introduction of substances into the water environment.

Any other water activity that causes adverse impact. This applies to other water activities, not otherwise described by another activity, that have, or are likely to have, a significant adverse impact on the water environment.

Existing authorisations will be ‘sunset’ (expire) and migrate into the new regime. These include authorisations issued under the following regulations:

The Pollution Prevention and Control (Scotland) Regulations 2012 (or 'PPC regime'), which implement the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED) (2010/75/EU), provide a regulatory framework for certain industrial activities to ensure a high level of environmental protection. The regime adopts an integrated approach, considering emissions to air, water (including discharges to sewer), and land collectively.

The Water Environment (Controlled Activities) (Scotland) Regulations 2011 (as amended) – more commonly known as the Controlled Activity Regulations (or 'CAR regime') apply regulatory controls over activities which have the potential to be harmful to Scotland's water environment.

In practice, discharges from waste water treatment works and sewer networks must have a licence authorised under the EASR regime. The licence will contain conditions regulating activities at the site and will identify a ‘responsible person’ who must ensure compliance with the conditions of the licence. SEPA is responsible for monitoring and enforcing license conditions.

SEPA has provided guidance on how activities previously authorised and regulated under the regulations listed above will move to EASR.5

4.3.5 Domestic customer charges

Domestic customer water and wastewater charges are set by an annual charges scheme which must be approved by the Water Industry Commission for Scotland. This is set out in Section 4.3.2. This section sets out how charges are recovered and recent trends in customer charges.

Unmetered charges

Unmetered household charges are collected by local authorities along with council tax. These charges are based on the council tax banding of the customer's home.

Households that receive 100% Council Tax Reduction (CTR) due to their financial circumstances (they do not pay any council tax), are still required to pay water and wastewater charges for the services they have. However, households that receive CTR also qualify for a reduction of up to 35% on the public water and sewerage charges. The amount of the reduction depends on how much CTR the customer is receiving. Local Authorities apply this automatically to customer bills.

If a property connected to the water supply is exempt from council tax, it will usually also be exempt from water and sewerage charges. A property can be exempt from council tax for a number of different reasons such as:

the owner has died or moved into a care home (there might be a limit on how long the exemption lasts)

the property is inhabited by full-time students

the property is inhabited by someone who is severely mentally impaired.

The property is exempt from paying council tax and water and sewerage charges only if everyone in the property is exempt from paying council tax.1

A single occupant who qualifies to pay for council tax can receive a discount on their annual water and sewerage charge as part of their council tax discount up to a maximum discount of 25%. This includes single parent households and a single non-student adult in a student household.

The average annual household combined water and sewerage bill in 2025/26 is around £474.50 (£1.30 per day), although there is considerable variation between the charges of the lowest and highest council tax bands (charges in 2025/26 range from £400.26 in Band A to £1,200.78 in Band H).2

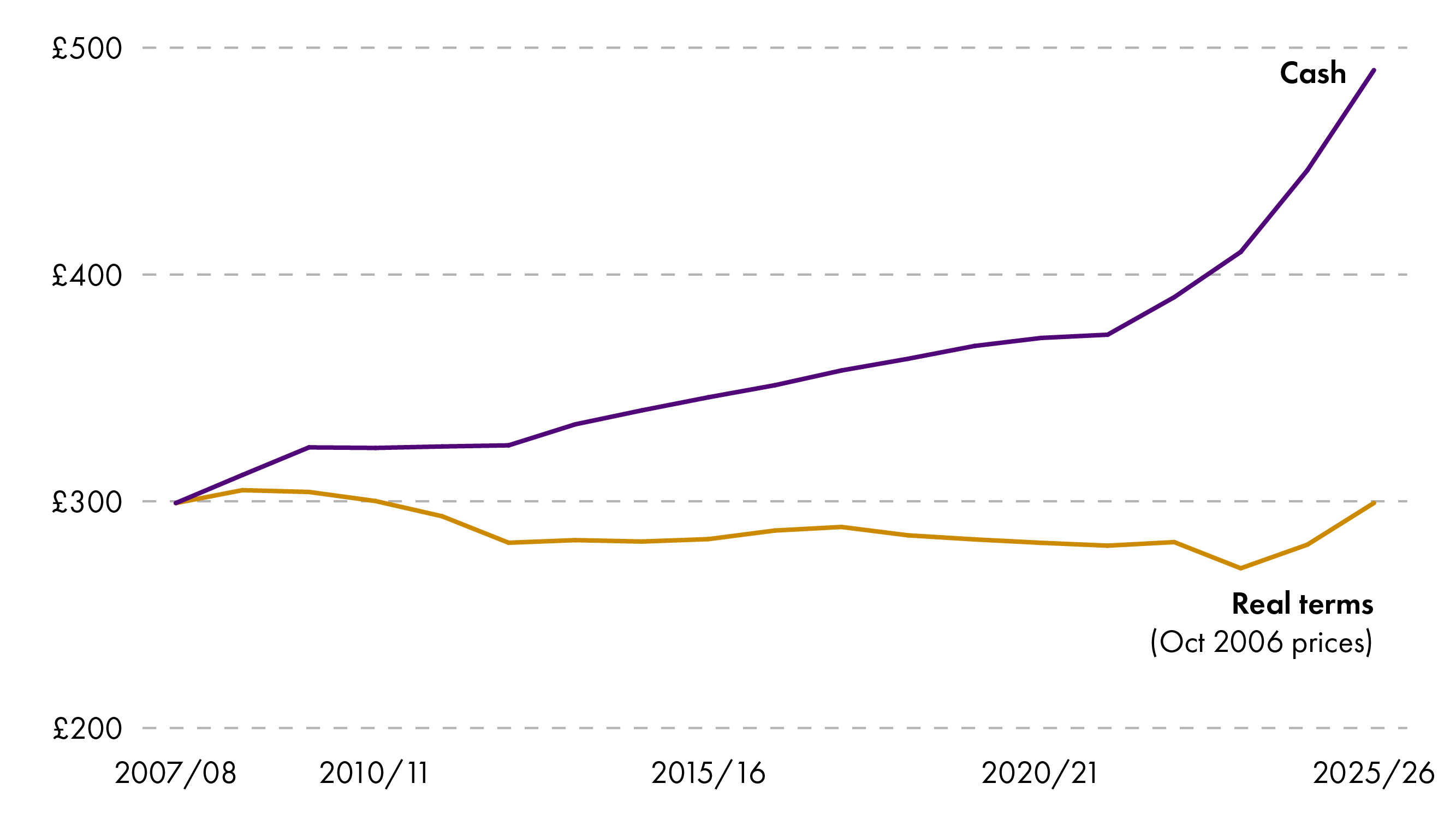

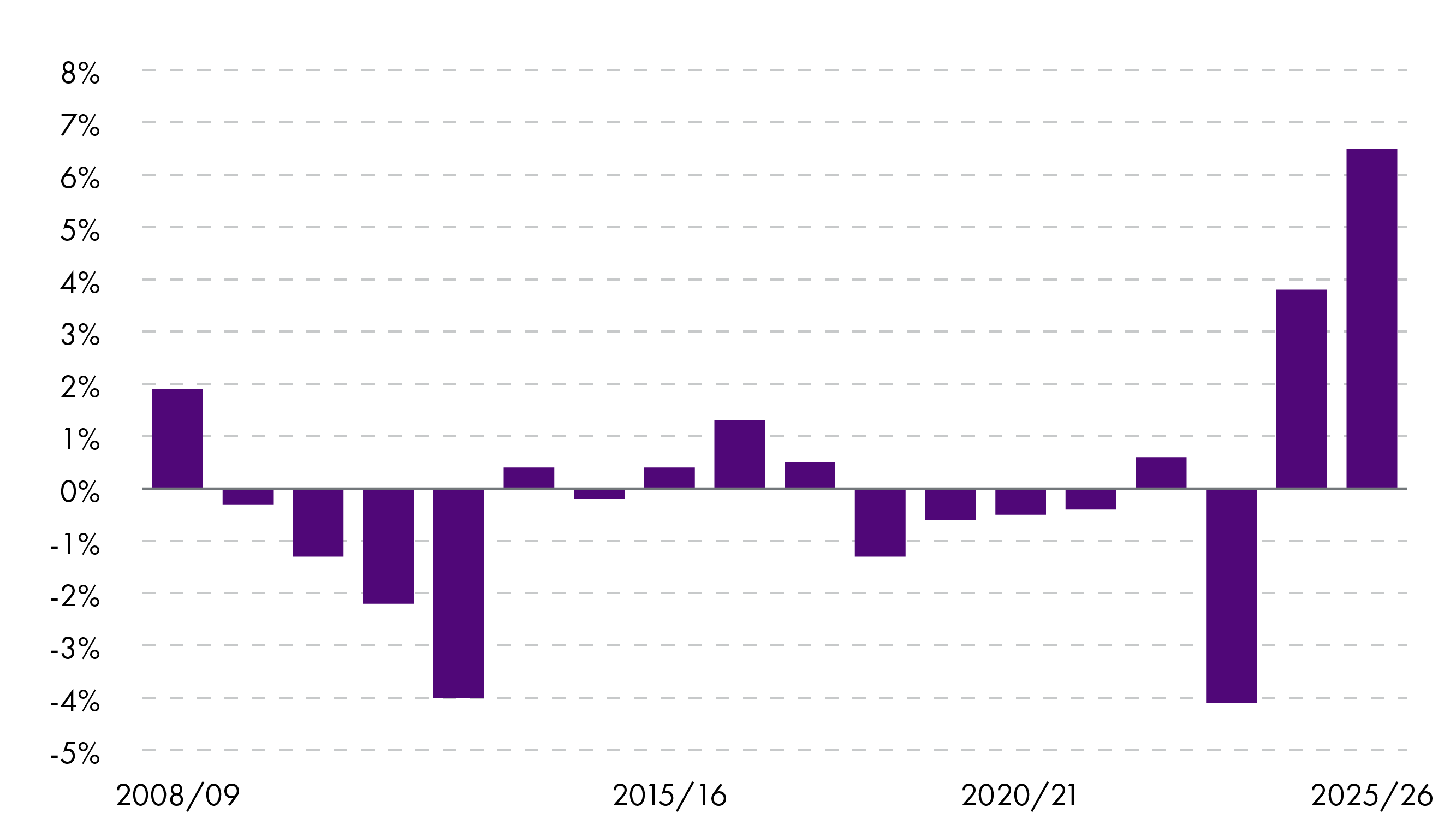

Average household bills over the past decade are shown in Figures 7 and 8 below. Figure 7 shows that although combined household water and sewerage charges have steadily increased since 2007/08 in cash terms, the cost to household customers in real terms in 2025/26 is broadly similar to 2007/08.

Annual customer charges vary from year-to-year within the regulated cap set by WICS for the regulatory period (see Section 4.2). The chart below shows the average percentage increase or decrease in household combined water and sewerage bills for each year compared to how much customers paid the previous year in real terms.

For example, household bills decreased by just over 4% in real terms in 2023/24 compared to the previous year in 2022/23. This was likely due to Scottish Water choosing not to increase customer charges in line with the high inflation rates during this period and in recognition of wider increased household living costs.

In contrast, in 2024/25 and 2025/26, household bills have increased compared to previous years. This increase may be required to ensure funding available for investment recovers to a level assumed in WICS' Final Determination for the 2021-2027 regulatory period (see Section 4.3.1).

Metered charges

There are fewer than 400 households in Scotland which pay by reference to a water meter. Metered household customers are billed directly by Scottish Water for the water and wastewater services. Metered bills may consist of the following elements, depending on which Scottish Water services the household has:

Water and sewer annual fixed charges: based on the size of the meter serving the house or property. Standard metered household supplies should only require a 15mm or a 20mm water meter unless there are unusually high water-use requirements.

Water and sewer volumetric charges: based on the size of the meter and the volume of water recorded on the meter serving the property.

Property drainage charges: applied if rainwater drains to the public sewer from the property. Charges are based on the Council Tax Band for the home/property.3

No discounts or reductions in water, sewage or drainage charges are applied to second homes or homes supplied through a water meter.4

4.3.6 Non-domestic customers

Within Scotland, there is retail competition for non-domestic customers for water and wastewater services. Since 1 April 2008, all non-household and public sector customers have been able to choose their retailer.

The Water Services etc. (Scotland) Act 2005 introduced the licensing framework for the water industry in Scotland. It requires that water services and sewerage services providers be licensed and that applications for licences be made to the Water Industry Commission for Scotland.

Scottish Water, as the wholesaler, continues to operate and maintain the water and sewerage network whilst providing wholesale services to licensed retailers. Retailers purchase wholesale water and sewerage services from Scottish Water. They then sell them along with retail services on to non-household customers. Retail services include all customer facing activities such as:

meter reading

billing arrangements

payment collection

customer enquiries and complaints

bad debt management.

All retailers are required to comply with the terms and conditions included in licences for water and/or sewerage services and with any associated direction and market codes.

Some retailers provide additional services such as advice on water efficiency and management of wastewater discharges. 1,2

4.3.7 Pipework responsibilities

It is common for MSPs to receive enquiries from constituents regarding the responsibility for maintenance and repair of domestic water pipework. Responsibility depends on the type and location of the pipework in relation to the property boundaries. Responsibility will fall on either the owner/landlord or Scottish Water. Responsibility may be shared by neighbours where pipework supplies multiple properties or crosses property boundaries.

Table 2 below summarises the responsibilities for different pipework elements. Further information is provided in a Scottish Water information sheet - Your guide to water pipework

| Pipework Element | Location / Description | Responsible Party | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water supply pipe | From property boundary to internal stop valve | Homeowner | Joint responsibility if shared with neighbours; includes pipes beyond boundary in some cases |

| Shared water supply pipe | One pipe serving multiple properties | Homeowner (jointly) | Common in older/terraced houses; responsibility depends on leak location |

| Stop valve | Inside property (e.g., under kitchen sink or in garage) | Homeowner | Used to shut off water supply during plumbing work or emergencies |

| Internal Plumbing | All pipework and plumbing within the home | Homeowner | Includes installation and maintenance; tenants should contact their landlord or Council |

| Stopcock | At the end of the communication pipe, near property boundary | Scottish Water | Used by Scottish Water to access water supply; may be within property boundary in some cases |

| Water Meter | Located with the stopcock | Scottish Water | Measures water entering the property; maintained by Scottish Water. Most properties in Scotland are not metered. |

| Communication pipe | From water main to stopcock | Scottish Water | Connects public supply to property; Scottish Water maintains up to and including the stopcock |

| Water main | Public water supply pipe in the street or local area | Scottish Water | May vary in size; includes strategic or trunk mains |

| Road-Located Supply Pipe | Supply pipe located in the road, serving properties fronting main roads | Homeowner | Scottish Water may repair, but costs may be passed to the owner |

| Leaks on Supply Pipe | Anywhere on the homeowner's supply pipe | Homeowner | Scottish Water may offer subsidised repair or replacement following assessment |

| Leaks in Rented Property | Internal or supply pipe leaks in rented accommodation | Landlord / Homeowner | Tenants may escalate unresolved issues to Scottish Water or Private Rented Housing Panel |

5.0 Private water supplies and wastewater treatment

While most people in Scotland are served by public services provided by Scottish Water, a significant minority depend on private systems, which face distinct challenges.

5.1 Private drinking water supplies

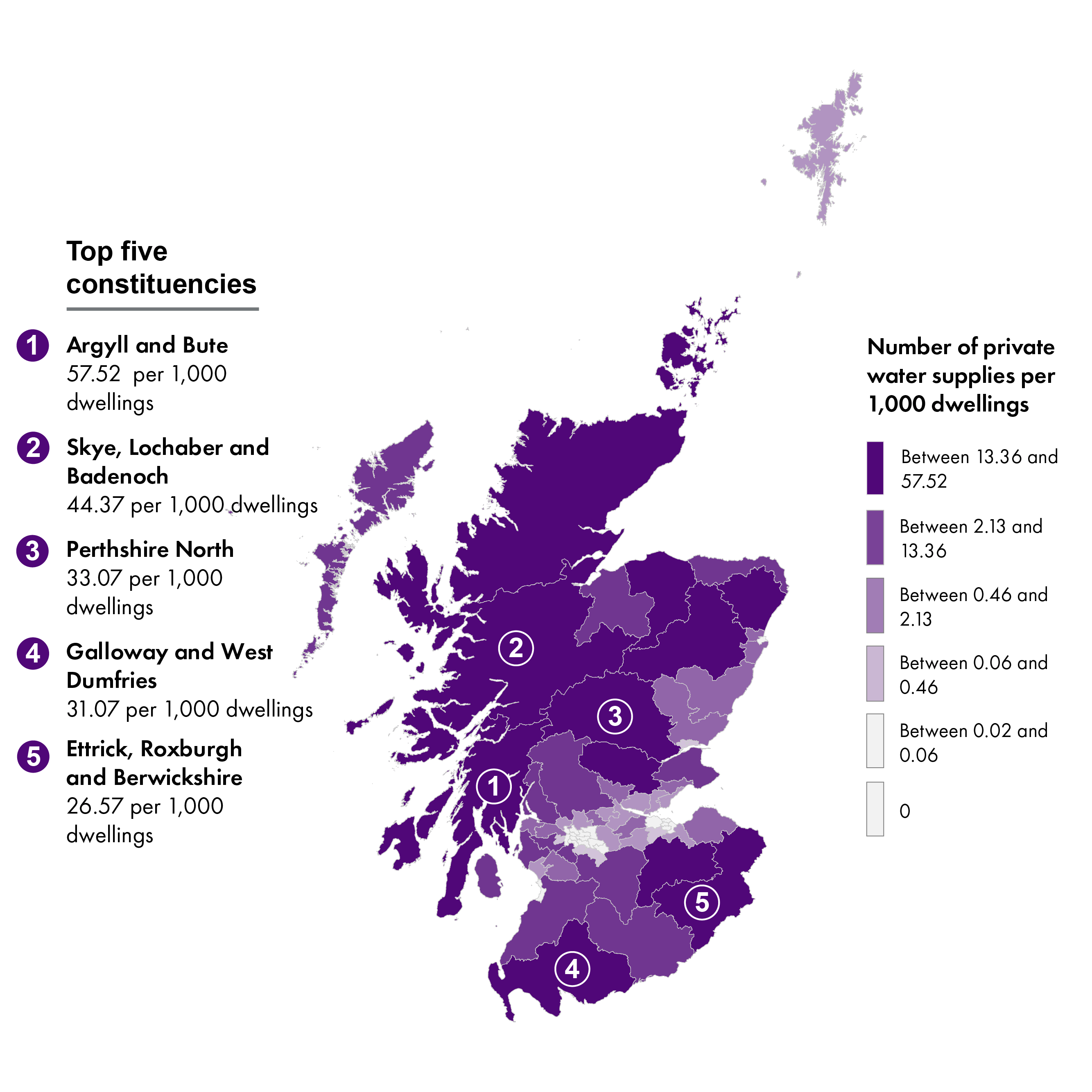

In Scotland, private water supplies (PWS) are defined as drinking water supplies which are not provided by Scottish Water, and are instead the responsibility of the owners and users. 1 Approximately 3.5% of the Scottish population use a PWS for their drinking water. This equates to 23,034 supplies which serve just over 190,000 people.1Figure 9 below shows the estimated concentration of private water supplies in each Scottish Parliament constituency.

The Drinking Water Quality Regulator (DWQR) state that the figure of 23,034 supplies is an underestimate of the population served, as it does not include the large numbers of people e.g. tourists, who interact with commercial premises that are supplied by private water supplies. 1

There are two key sets of regulations in place for PWS:

The Water Intended for Human Consumption (Private Supplies) (Scotland) Regulations 2017 which aim to protect human health from the adverse effects of any contamination of water intended for human consumption by ensuring that the water meets water quality standards.

The Private Water Supplies (Scotland) Regulations 2006 which implement the Drinking Water Directive in respect of private water supplies and enhance existing domestic regulatory provision regarding such supplies, to ensure the provision of clean and wholesome drinking water.

PWS in Scotland are split into two categories.

Regulated supplies (22.4% of PWS) (formerly Type A supplies) supply 50 or more people; provide 10 cubic meters or more of water per day; or supply premises that are part of a commercial or public activity. An example of premises served by Regulated supplies include schools, community halls, food premises, holiday lets, B&Bs, hotels and caravan parks.

Type B supplies (77.6% of PWS) are all other domestic supplies, the majority of which serve single properties.1

Local authorities are required to test Regulated supplies annually and conduct a risk assessment every five years, under The Water Intended for Human Consumption (Private Supplies) (Scotland) Regulations 2017.

Local authorities do not have a duty to test or carry out risk assessments on Type B supplies. Owners and users of Type B supplies can request a test from the environmental health department of their local authority for a fee. Local authorities must collect a sample within 28 days of the request. Although risk assessments are not required for Type B supplies under The Private Water Supplies (Scotland) 2006 regulations, local authorities must provide advice and assistance on risk assessments to those responsible.

Scotland's private water supply users are more vulnerable to water scarcity due to a high reliance on small scale groundwater and surface water sources, and limited storage options1, Supplies from springs and shallow wells are considered to be more vulnerable than boreholes.6

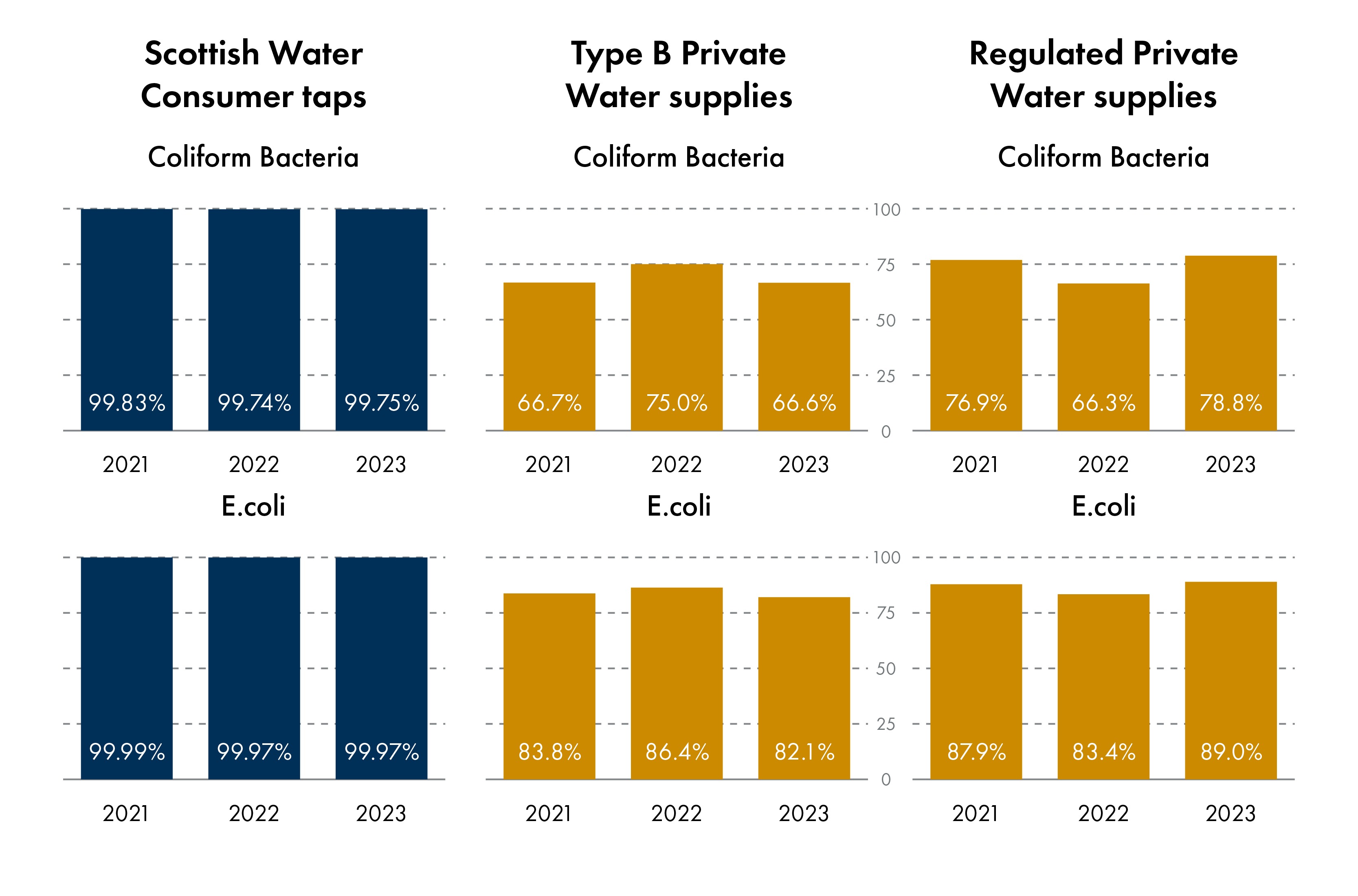

A 2020 report by the Centre for Expertise for Waters (CREW) investigating the impacts of climate change and resilience of private water supplies highlights a growing evidence-base for water quality issues regarding small supplies which are often associated with non-compliances with microbiological and chemical quality standards.6Figure 10 below demonstrates there is typically lower compliance rates with legal water quality standards in private water supplies compared to Scottish Water supplies.

The CREW report further identifies that these water quality problems may be exacerbated by a number of factors related to both water shortage and water quality, including low water table levels due to resuspension of sediments with falling water levels, and decreased dilution of sewage discharged to rivers.

The report made 11 recommendations including:

extending private water supply risk assessments to address climate change

improving drought risk indicators and early-warning systems

developing household water storage and cost-effective connections to mains water.

Owners and users of private water supplies do not pay water charges through their council tax. However, they are required to pay for any testing of their supply that they request through their local authority, as well as all installation and maintenance costs of any collection, distribution and treatment infrastructure they may have. The cost of testing is variable and based on individual local authority pricing. For example, Argyll and Bute Council charges range from £145 for a domestic sample to £266.05 for a compliance sample.8

Through The Private Water Supplies (Grants) (Scotland) Regulations 2006, private water supply owners can apply for a grant of up to £800 per property for improvements such as installing treatment systems, replacing lead pipes or installation of new water tanks. The grant cannot be used for ongoing maintenance costs or towards costs for connection to the mains water network. Local authorities manage the applications process and may be able to provide additional funding in the case of low income. The value of the grant has not changed since its introduction.

The Drinking Water Quality Regulator (DWQR) supervises local authorities' enforcement of the regulations governing the quality of private water supplies in Scotland. It does this by:

Providing guidance to local authorities on the private water supplies regulations and the role of the local authority.

Monitoring local authorities’ progress with evaluating and improving the quality of private water supplies.

Receiving, interpreting and presenting data on water quality from private supplies throughout Scotland.

There is no single, comprehensive source of information for private water supply users to access. 9 Advice and information is split across local authorities, the DWQR and the Scottish Government. The DWQR receives information from local authorities on private water supplies. However, there are gaps in the provision of this information (e.g. location) and data collection varies between local authorities.

Additionally there is no requirement to assess the risk of interruption to supply at type B supplies. Therefore there is no comprehensive dataset of PWS users most at risk from interruption of water supply.

Local authorities will have received contacts from some individuals on private water supplies that have experienced interruptions to their supplies, particularly where individuals are seeking emergency water supplies. However some PWS users may meet their water needs independently by purchasing bottled water during supply interruptions without contacting their local authority.

5.2 Private wastewater treatment

Within Scotland, those not on the public sewer network are usually served by private sewage treatment, most commonly a septic tank which offer a base-level of appropriate treatment to protect the water environment. Other small sewage systems offering more sophisticated treatment technology may be in place where required to protect more sensitive water environments.

With regards to wastewater and sewage discharges, a domestic property is a private dwelling including a caravan. Non domestic properties can include cafes, caravan sites, offices, holiday lets and hotels.

5.2.1 Septic tanks

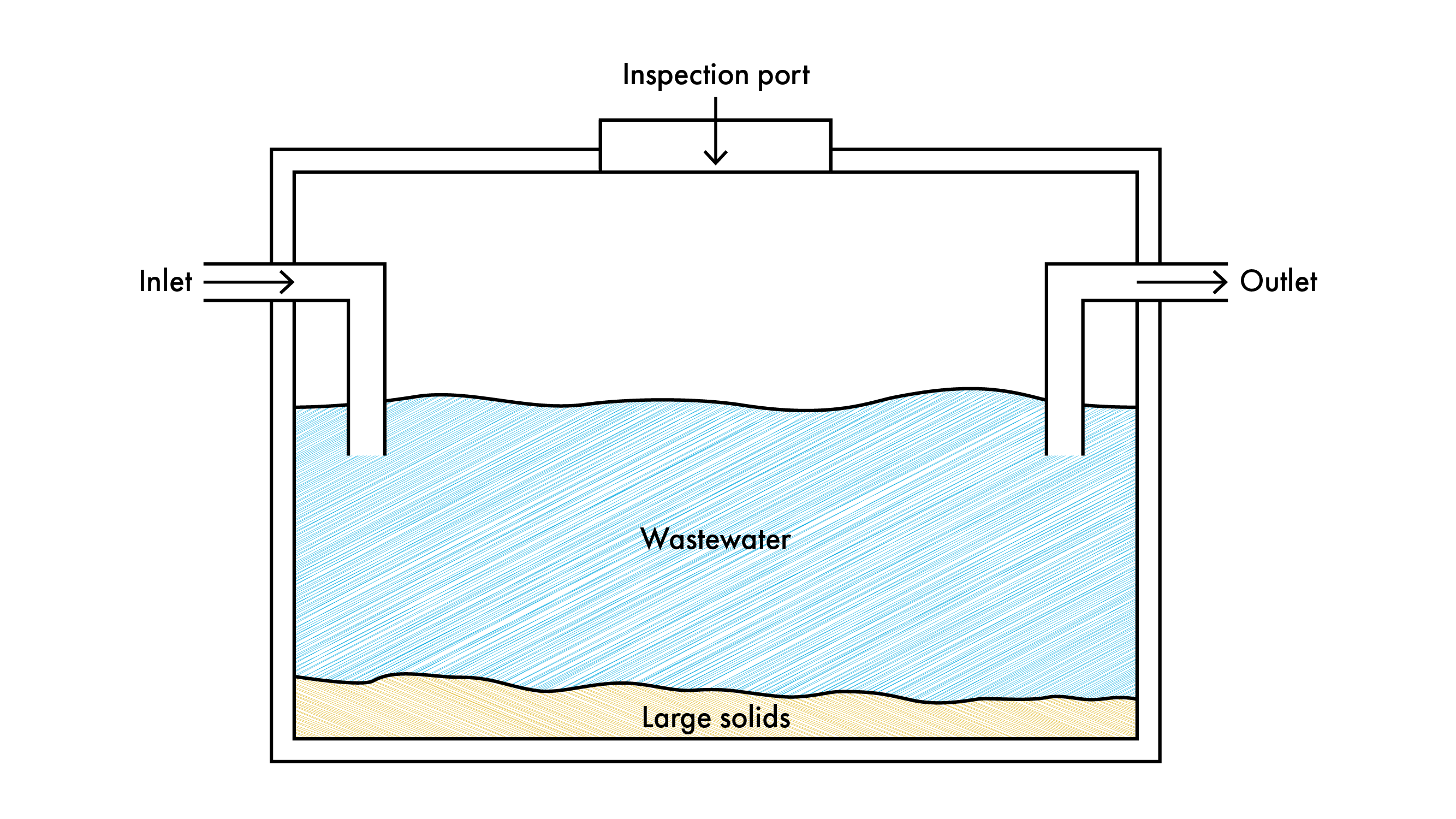

Septic tanks are a type of small sewage system broadly known as a 'settlement system'. Septic tanks are typically underground structures that work by using gravity to settle and separate solids from liquids (see Figure 11 below).

Solids that build up over time are required to be removed (a process referred to as 'de-sludging') by a specialist contractor. Liquids drain away from the tank via a soak-away. Effluent from septic tanks are sometimes discharged to surface waters. Septic tanks may be installed subject to planning permission, building control and SEPA authorisation.

There are a variety of settlement tanks available on the UK market. Some provide basic treatment of small solids (septic tanks and baffled reactors) through limited biological processes.

The treatment system (or combination of treatment systems) installed must treat wastewater to a satisfactory level established by SEPA. Depending on type of system, it can provide:

Primary treatment of wastewater – which removes solids that will either settle or float.

Secondary or biological treatment of wastewater – which, by the action of microorganisms, removes organic materials that will not settle or which are dissolved in the wastewater.

Tertiary treatment of wastewater - which achieves further refinement of the effluent by either mechanical, chemical or biological means.2

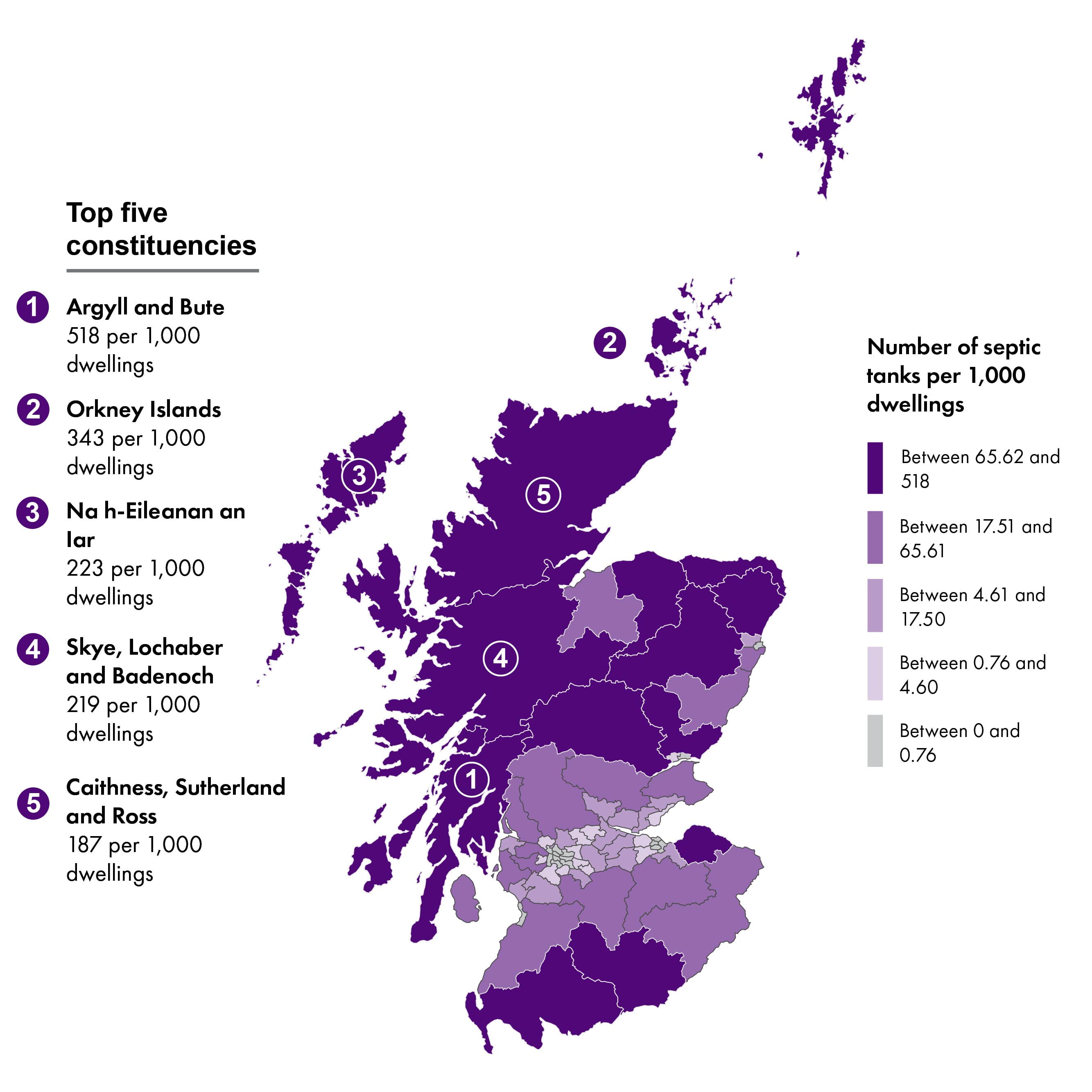

The exact number of private septic tanks in Scotland is unknown. A 2022 report by CREW used modelling to estimate the total number of unique Private Sewage System locations. It estimated a total of around 169,000 serving 173,000 properties.1

A map of the known concentration of septic tanks according to available SEPA data by Scottish Parliament constituency is shown in the map in Figure 12 below. Note that the data in the map below is not complete because not all household discharges are currently authorised, meaning that SEPA does not have a complete record of all small-scale sewage discharges.

The quality of treatment that occurs by a septic tank is largely dependent on the management and maintenance of the infrastructure. For example, as sewage sludge builds up in a septic tank, if the excess sludge is not removed, then the ability for settlement is diminished. Non-wastewater items (e.g. wet wipes, sanitary products, grease, fats and oils) may cause the system to be clogged.2 The cost of de-sludging of septic tanks in Scotland can differ due to location, size of tank and whether or not it is considered a scheduled visit.

Under the Sewerage (Scotland) Act 1968 (s.10), Scottish Water has a duty to empty a septic tank when requested to do so by the property owner if "reasonably practical" and can recover the cost of this service through charges. 5 In 2025/26, standard charges that apply to a single household, serving up to 5 houses and up to a capacity of 9m3 are £245.60 for a scheduled visit, £340.90 for unscheduled or £492.00 (or actual cost if this is more) for an urgent response visit.6 Additional charges can apply to business owned septic tanks and those with tanks larger than 9m3.

Scottish Water's ability to empty a tank is dependent on household location and providing that the property meets access requirements. In addition to Scottish Water, there are a number of private companies that offer services to empty tanks. The price for these services is again dependent on location and local competition.

Scottish Water provides a septic tank emptying service to a number of islands including some very small islands with few inhabitants. This requires careful scheduling to provide this service. For some of Scotland's islands, and some mainland remote rural areas, it may be impractical and/or cost prohibitive for Scottish Water or other private companies to offer de-sludging services.

Pollution issues

A recent study has identified community septic tanks within Scotland to be a pathway for emerging contaminants entering river courses. The study highlights no or limited removal of emerging contaminants within Scottish Water owned and operated community septic tanks.

However, it found that the risk to receiving rivers was "generally low, indicating small risk for the environment" but that alternative technological or non-technological approaches to reduce emerging contaminants pollution may be needed where septic tank discharges have low dilution. 7 The potential risks and concerns relating to emerging contaminants is discussed in Section 6.4 of this report.

SEPA has stated that every year it receives hundreds of enquiries and complaints about small-scale private sewage treatment systems. Most complaints are about "ponding", when wastewater or sewage forms puddles on the ground, or about sewage related solids in rivers or being washed up on beaches.

SEPA has also stated that many of the problems caused by private sewage treatment systems are because systems are not looked after properly or maintained. 8SEPA's response to these problems is to provide advice on any remedial action required, with potential use of enforcement tools such as fixed monetary penalties "to change behaviours of those who persistently fail to comply, and where improvements are necessary to limit localised environmental harm or nuisance". 8Details of SEPA's approach to complaints regarding septic tanks can be found in its service level statement for small-scale private sewage treatment systems.

Enforcement may be challenging where the impact on a water body is the cumulative effect of multiple private wastewater discharges and/or wider pollution sources within a catchment. This makes it difficult to identify and attribute the pollution to a single source for enforcement action. 10 Unlike private water supplies, there is currently no grant funding available to households for upgrades to private wastewater systems.

5.2.2 Regulation of private sewage systems

As with public wastewater treatment, private sewage system discharges are regulated by SEPA. Any sewage discharge to the water environment must be authorised by SEPA.

Up until 1 November 2025, this has been regulated under the Water Environment (Controlled Activities) (Scotland) Regulations 2011 (the 'CAR regulations'). Section 37 of the CAR regulations requires SEPA to maintain a public register of authorisations. Registration of a septic tank or other small sewage treatment systems has a one off fee of £190.1

As with the wider regulation of activities impacting on the water environment, regulation in this area will fall under the EASR regime from 1 November 2025 (see Section 4.3.4), with CAR registrations automatically migrating over into the new system. Standard conditions apply to different scales and types of discharge which are similar to those in place under the CAR regime.

Conveyancers check whether a septic tank is registered as part of the house purchase process (see Section 6.3.4 regarding house purchases), but otherwise voluntary registration is slow. SEPA receives around 2,500 registrations for private sewage systems per year. SEPA reports that approximately 75,000 private sewage systems are authorised in Scotland as of April 2023, including those vested in Scottish Water. This accounts for approximately 44% of the number of Private Sewage Systems estimated by CREW.2

5.2.3 Connecting to the public network

Under the Water (Scotland) Act 1980 (s.6) and Sewerage (Scotland) Act 1968 (s.1), Scottish Water is required to provide every property within its area with a domestic water and wastewater connection, provided it is practical at ‘reasonable cost’ to do so. 1

Households currently on a private water supply or private sewerage system can contact Scottish Water to connect to the public mains water network. However, this may not always be feasible or may be too expensive for the owner due to the distances of some properties from the mains water supply/sewer network.2

In June 2022, the Scottish Government announced £20 million of funding to be allocated during the remainder of Session 6 of the Scottish Parliament to a pilot project to extend the public water networks to connect with households reliant on private water supplies. The project is working with the assistance of Scottish Water, Aberdeenshire Council and Consumer Scotland.

This Scottish Government states the project will examine "communities that are in close proximity of existing water mains and that have experienced loss of water due to water scarcity".3

Reasonable Cost Contribution

There is no current strategic plan for connecting private water supplies or wastewater to Scottish Water's network. Requests are managed on a case-by-case basis.

Scottish Water may pay a ‘Reasonable Cost Contribution’ for connecting new local network infrastructure to existing network assets. Calculations for reasonable cost contributions are determined by regulations under the Sewerage (Scotland) Act 1968 and the Water (Scotland) Act 1980 (as amended) - the most recent being The Provision of Water and Sewerage Services (Reasonable Cost) (Scotland) Regulations 2015. This only applies in instances where infrastructure is being vested with (adopted by) Scottish Water.

The Reasonable Cost Contribution regulations provide for the maximum Scottish Water contribution to assets that can be vested. Customers pay the non-vestable assets (i.e. connection pipes and sewers). Where the costs of the vestable assets is beyond the Reasonable Cost Contribution, and the customer is prepared to pay the cost differential, the connection will proceed.

Connection costs are reviewed every year through Scottish Water's scheme of charges, however there is no maximum cap on what it may cost a customer. Costs are dependent on the length and complexity of the connection, and this is particularly relevant in instances when there are non-standard connections. Reasonable Cost Contributions do not typically apply to single domestic property connections.4

Access to private land for connecting to the public network (servitude)

Connections to Scottish Water's main supply network can be complicated when service pipes need to cross private land owned by a neighbour.

On this point, Scottish Water’s guide to connecting to its network states:

Should you need to lay your pipework across land which is not in your ownership, to gain a connection to our network, you must obtain permission from the owner of the affected land prior to commencing work. We will request a copy of this documentation for our reference and review.

Scottish Water. (n.d.) Your guide on how to connect to our network. Retrieved from https://www.scottishwater.co.uk/-/media/ScottishWater/Document-Hub/Business-and-Developers/Connecting-to-our-network/All-connections-information/31823SW_SH_GuidancePack.pdf [accessed 8 2025]

Access to private land for connecting to the public network (servitude) In some cases, there can be existing legal rights (known as servitudes) which can be relevant to a person's water supply.

A servitude relates to how land and property is used. In simple terms, it imposes a legal obligation on one property for the benefit of a neighbouring property. For example, one recognised type of servitude allows one owner to lead a pipe over another person's land. Another type of servitude gives a property owner the right to access a neighbour's land, such as for repairing a pipe.

Properly created, servitudes survive changes of ownership of the affected land or property.

Servitudes can be created in writing in the official ownership documents relating to land or property, that is, the title deeds (also sometimes referred to as the title documents). However, they can also be formed by: