Getting the inactive active: Barriers to physical activity and their potential policy solutions

This briefing is the first output from a SPICe academic fellowship exploring barriers to physical activity in Scotland. It outlines the legislative landscape concerning physical activity funding in Scotland, summarises the current knowledge base concerning barriers to physical activity, identifies gaps in the evidence, and highlights potential policy solutions.

Summary

This evidence review is the first output from a SPICe academic fellowship exploring barriers to physical activity. It examines the evidence base regarding physical activity in Scotland to determine current barriers, identify knowledge gaps, and highlight potential policy solutions. A further briefing summarising the findings from the researchers' interviews with relevant stakeholders will be published in due course. Views expressed in this briefing are those of the authors and not those of SPICe or of the Scottish Parliament.

Summary of key findings from existing evidence base

The sporting landscape in Scotland is a complex field to navigate, which is further complicated by a series of external shocks and internal political challenges faced by the Scottish Government. Whilst many of the policy levers that shape decisions over where resources are focused, including for addressing physical inactivity, are held by the Scottish Government, the current financial climate means that significant increases to funding are unlikely, and existing real term reductions in local authority funding for sport and physical activity (PA) are expected to continue to have a negative impact upon participation1 . In this context realising the World Health Organisation's global target of a 15% relative reduction in physical inactivity amongst adults and adolescents by 2030 set out in the recent Framework for Physical Activity and Health2 is a major challenge. If a significant impact is not made towards this target, then the costs of physical inactivity will continue to rise and significantly impact the National Health Service, economic development, community well-being and quality of life for all34.

In consideration of the current political and financial landscape, the following points present what is currently known about the successes and challenges of raising participation in sport and PA in Scotland.

Universal access to sport and PA in Scotland remains challenging with issues of social class, poverty, gender, and geography as significant barriers to sport and PA participation5.

Inequalities in PA and sport participation levels remain stubbornly present regarding disparities in age, gender, and socioeconomic status6.

Poverty and material deprivation are experienced widely but unevenly across Scotland. People living in the most deprived areas of Scotland are much less likely to participate in sport. Ultimately, where we live shapes our health and our sport and PA opportunities.

Scotland has disproportionately poor health outcomes. Health inequalities are concentrated in particular areas and have been sustained over an extended period.

People facing deprivation experience greater benefit from taking part in sport and PA than those from less disadvantaged circumstances. Targeted and specific provision would increase sporting opportunities for people experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage7.

Despite policy intentions, rates of participation in sport and PA have remained relatively static alongside diversifying patterns of participation including the increase in fitness related activities6.

There is a growing disparity between children and young people who are physically active and those who are not9. Pupils living in the most deprived 20% areas in Scotland are most likely to be inactive - 35% of this group overall, compared to 23% for those in the 20% least deprived areas10.

For many young females, sport is a social activity which is about fun, friendship, family and foster social relationships.

There are considerable variations in participation across different local authorities in Scotland. Children from urban environments are often less active than children from rural communities11.

Poverty and deprivation negatively impact participation in sport by people with disabilities. Significant levels of sedentary behaviour have been noted amongst people with a disability, which negatively impacts general health12.

Scotland’s older population (65+ year-olds as a proportion of the total population) is estimated to grow from 19.4% to 25.5% by 20454.

55% of 65–74-year-olds meet the recommendations for PA with 29% having very low activity14.

The cost of physical inactivity to the NHS in Scotland is estimated at more than £77 million per year, or around £14.60 per person living in the country15.

Introduction

This review synthesises current evidence in relation to physical activity (PA) and the barriers to engagement. The review is informed by past and present PA policies within Scotland, recent reports that have addressed specific issues within sport and PA participation in Scotland including poverty, disability and recovery from COVID-19, and current academic literature. The review focuses on the elements of PA that positively influence engagement and the structural barriers that impact upon participation. Content is presented through a series of chapters that focus on specific aspects of PA and the challenges of addressing physical inactivity. These chapters explore issues around poverty; health and economic inequalities; equality, diversity and inclusion; gender disparities; geographical variations; age; demographics; disability and the economic impact of inactivity.

PA, in conjunction with eating well and maintaining a healthy weight, is one of the six Public Health Priorities for Scotland1 . Scotland’s capacity to realise this priority is currently well supported by national policies for PA that have created links between government and organisations with responsibility for enacting the policy across a variety of sectors234 . The political process of addressing inactivity began with the [then] Scottish Executive publishing a white paper entitled ‘Towards A Healthier Scotland’ in 1999 which led to the setting up of the National Physical Activity Task Force in 2001. Deriving from the task force, the national strategy, Let’s Make Scotland More Active (LMSMA) was published in 2003. Following a review of LMSMA and in line with the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) global plan on PA, the Active Scotland Delivery Plan (ASDP) was published in 2018. The ASDP aligned 7 cross-cutting guiding principles to the agenda set out in the WHO’s Global Action Plan on PA and with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals5. To realise these 7 principles the Physical Activity Delivery Plan produced the Active Scotland Outcomes Framework. The intention of the framework was to support, promote and enable people to become more physically active. For example, a specific aim of the framework was for Scotland to meet the WHO global target set in 2018 of a 15% relative reduction in physical inactivity amongst adults and adolescents by 2030. This target has been reinforced in the recent publication of the new Framework for PA and Health6 . To realise this aim the framework advocates for a systems-based approach and outlines a wide range of actions across multiple sectors and settings, including schools, healthcare, urban planning and communities .

Review aims and objectives

Our reflection upon PA policy and its impact is informed by a series of reports that have been written exploring the current state of play across Scottish sport and PA. These reports cover a wide variety of contexts and provide a strong evidence base for exploring current issues, concerns and areas of best practice. For example, Finch, Wilson & Bibby1explore the impact of health inequalities; Murray et al2explored the impact of COVID-19 on children’s sport; Davison et al3 analysed participation for people with a disability, and Kay4 critically explored the impact of poverty and inequality on participation. These reports, alongside work produced by the Health, Social Care & Sport Committee (HSCSC), such as its report into Female Participation in Sport and Physical Activity5, enable a broad analysis and help to determine specific aspects that can be utilised across the sector or which require further development and / or support to realise their objectives.

In building upon our understanding of the PA and sport participation landscape, the rationale for this study is to present what we currently know about PA in Scotland and to determine what we need to know to address concerns around levels of inactivity. In relation to participation in PA, current evidence shows a general increase. In 2021 for example, significantly more adults met the guidelines for moderate or vigorous physical activity (MVPA) than in previous years, continuing a general upwards trend since 20126. However, we also know that the position is far more nuanced and that universal access to sport and PA in Scotland remains a work in progress, with issues of social class, poverty, gender, and geography remaining significant barriers to sport and PA participation7. Inequalities in PA and sport participation levels remain stubbornly present regarding disparities in age, gender, and socioeconomic status. Structural inequalities in participation by social class, income, and neighbourhood remain entrenched at a young age and persistent into adulthood89 . Ultimately, there are significant disparities in how people of diverse backgrounds and demographics engage with sport and PA10. The Scottish Government is cognisant of these challenges and states that ‘addressing inequalities in opportunities is a priority. The barriers faced by too many people must be removed to allow everyone in Scotland to gain the health benefits of being active’11.

With these concerns in mind the aim of this review is to explore what can be done differently to address existing structural disadvantage and increase levels of participation in PA. The research seeks to realise this aim through the following objectives: (1) critically explore the current social, political, cultural, and economic barriers that limit engagement in sport and PA and, (2) provide informed recommendations for future policy. To address these objectives, we begin by exploring the current evidence base around physical inactivity across a wide variety of different areas and determine the key aspects that need to be enhanced or developed in any future policy development.

The sport and physical activity landscape in Scotland

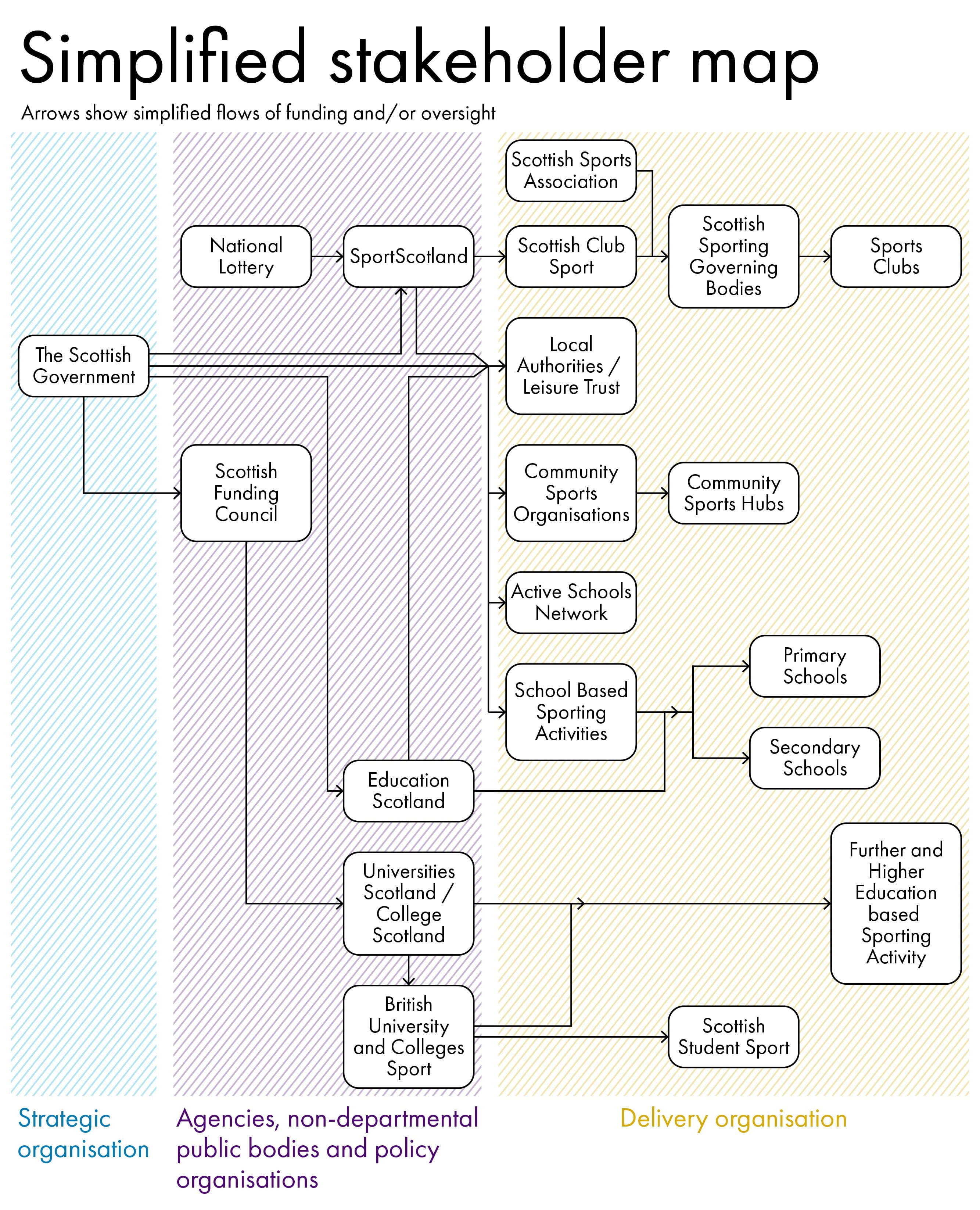

As Jarvie1 states, sport and PA in Scotland sit within a complex landscape, with responsibility shared across a range of organisations at both a national and local level (see figure 1).

Figure 1: simplified organisational map of sport stakeholders in Scotland (adapted from Murray et al., 20242)

For example, local authorities, often via arms-length leisure trusts, are responsible for the provision of public local sports facilities. The role of local authorities is significant, and it is often suggested that more than 90% of publicly funded sport in Scotland is provided through Trusts and local authorities1. Other sport and PA facilities are owned and operated by a wide range of private and third sector organisations5. Within this landscape the Scottish Government acts as a provider of funding and investment, but also as a leader of policy and change6. The Active Scotland Division of the Scottish Government has overarching responsibility for the delivery of policy for sport and PA. However, this is predominantly realised through Sportscotland, a non-governmental organisation which retains a certain amount of independence when it comes to organising sport policy and funding, albeit still having to ensure governmental targets and value for money are being achieved7. For example, across 2023/2024 there was an increase in investment with Sportscotland investing ‘up to’ £36.7 million in Scottish Governing Bodies of Sport (SGBs), local authorities and wider national partners. This would be an 8.6% increase on the previous year and a record investment in core activities5. Alongside Sportscotland, there are many other organisations, agencies, and delivery partners who bear responsibilities in enacting government policy, making it a complex field to navigate.

A key example of this is in the significant levels of financial investment that have taken place in developing the school estate. In seeking to develop the school estate to support the needs of the communities in which they reside, the Scottish Government (2019) published Scotland’s Learning Estate Strategy: Connecting People, Places and Learning. The strategy provided a series of guiding principles for the development of the school estate. The guiding principles that related directly to sport and PA were:

The learning estate should be well-managed and maintained, making the best of existing resources, maximising occupancy and representing and delivering best value.

Learning environments should serve the wider community and where appropriate be integrated with the delivery of other public services in line with the place principle.

Outdoor learning and the use of outdoor learning environments should be maximised.

Collaboration across the learning estate, and collaboration with partners in localities, should support maximising its full potential.

Further to the development of the school estate for PA and sport, the Minister for Social Care, Mental Wellbeing and Sport highlighted to the Scottish Parliament's Health, Social Care, and Sport Committee that when investing in facilities through their Sports Facilities Fund, Sportscotland prioritise projects that have a strong, clear, and embedded focus on the promotion of equality, diversity and inclusion in sport and PA5. The Minister also highlighted School Community Hubs which offer PA and sport programmes in evenings out of school buildings to create opportunities for children, young people and their families to access opportunities. Whilst the development and utilisation of the school estate to support the delivery of community sport and PA is a logical way to ensure efficiency, the data on its impact on participation and engagement is currently limited.

External factors affecting physical activity provision in Scotland

Along with the complexities of the sporting landscape, the Scottish Government has had to contend with a series of external shocks which have affected its overall approach to funding and policy. These include the 2008 financial crisis and prolonged period of real wage growth stagnation that has followed and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic, alarming rises in the cost of living, and substantial price rises for energy supplies1. Further to these shocks, the Scottish Government's approach to funding and policy is being complicated by significant areas of change that are occurring across the sporting landscape. For example, reduced participation trends in sport have occurred despite heightened public policy concern and political consensus. Reinforcing this concern are changing patterns of participation including fitness related activities such as weight training and yoga overtaking individual sports such as golf and martial arts as the sport of choice for 16 to 25-year-olds2. Alongside diversifying patterns of participation lie broader social and health concerns around physical inactivity that require collaboration with local and national decision-makers within healthcare, transport, planning, education, environment, and many other sectors3 . These concerns are further reinforced through the following three issues:

The places and neighbourhoods where people live and grow up shape their opportunities and influence their life course4.

PA levels are influenced by (1) transport and planning systems (2) access to affordable and attractive sports facilities and clubs (3) stigma and, (4) social expectations amongst numerous other social, political and economic factors3.

Cuts to local authority funding for sport and PA over recent years and the negative impact this will have had on participation6.

Devolved powers available to support physical activity provision in Scotland

Whilst significant challenges exist in addressing such issues in the 25 years since devolution, the powers available to the Scottish Government have gradually increased. Many of the policy levers that shape the determinants of health, and decisions over where resources are focused, including for addressing physical inactivity and reduced participation in sport, are now held by the Scottish government1. These levers include the setting of income tax rates and thresholds; decisions on certain social security benefits; and the capacity to incorporate approaches to the development of PA through wider policy portfolios such as transport, health, and housing. This increased autonomy over policy development and funding provides clear opportunities for the Scottish Government to develop policy that utilises PA and sport to contribute to resolving wider concerns such as poverty and economic inequality. The choices made regarding investment are particularly pertinent considering that Scotland’s population is expected to fall by 2043, but the level of illness is expected to increase by 21%2.

Poverty and economic inequality

Poverty and material deprivation are experienced widely but unevenly across Scotland. People living in the most deprived areas of Scotland are much less likely to participate in sport (37%, excluding walking) compared with those living in the least deprived areas (64%). Further to this, 57% of people in the most deprived areas of Scotland meet the recommendations for MVPA with 31% having very low activity. When looking at the least deprived areas, 73% of people are meeting the recommendations and only 13% have very low activity1. It is fundamental therefore that any initiatives that promote PA and sport participation address the role that poverty and material deprivation may play in their situation2.

A recent report by the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee3 looked specifically at the issue of tackling health inequalities in Scotland. In a summary of responses to the report, respondents argued that people facing deprivation experienced greater benefit from taking part in sport and PA than those from less disadvantaged circumstances, and that increased provision should therefore be made to create sporting opportunities for people experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage. Within the report the Committee highlighted four key aspects in relation to physical inactivity, health, funding and policy:

(1) They were struck by the volume of evidence they received that showed the overriding impact poverty and deprivation has on the health and wellbeing of children and young people.

(2) A reduction in sport and PA from age 11 upwards disproportionately affects those from more disadvantaged backgrounds as well as girls, disabled children and young people.

(3) A requirement for the Scottish Government to ensure any additional funding committed over the course of this Parliament is channelled towards breaking down barriers to accessing sport and PA for children and young people living in poverty.

(4) Sportscotland, and any other provider of sport and PA services, should be collecting data on participants’ socioeconomic backgrounds and whether they were previously inactive.

Health inequalities

In building upon our understanding of the relationship between economic deprivation and physical inactivity, it is important to understanding the impact of health inequalities in these contexts. Scotland has demonstrated over time disproportionately poor health outcomes compared to countries of similar political and economic status and has the lowest life expectancy and the widest mortalities inequalities in Europe1. Health inequalities in Scotland are concentrated in particular areas, sustained over a long period of time and ‘are a consequence of historical socioeconomic inequalities and deindustrialisation’2.

There are significant differences in the life expectancy and health of people across Scotland, depending on factors such as where they live, their age and gender, and their ethnic group. People living in less affluent areas of Scotland have a shorter life expectancy than those living in wealthier areas3 . As the Scottish Household Survey 20224highlighted, health has a significant impact on sport and exercise participation. Of people with limiting long-term conditions, 51% meet recommended activity levels and 34% have very low activity. By way of comparison, 69% of people with a non-limiting long-term condition meet the recommendations and 15% have very low activity. These concerns are reinforced by statistics showing on average a twelve-year gap in life expectancy between people living in the most and least deprived areas5. Furthermore, in 2018–20, there was a 24-year gap in healthy life expectancy between people living in the least and most deprived areas of Scotland2 .

Barriers to participation in physical activity

Despite policy intentions, rates of participation in sport and PA have remained relatively static. Data from the Scottish Health Survey highlight the static nature of participation. In 2016, 65% of adults met the guidelines for MVPA, in 2018 and 2019, 66% of adults met the guidelines . The most recent available data shows that when taken as an average, 65% of the population meet PA recommendation with 22% of the population having very low activity. 70% of men meet recommendations with 19% having very low activity and 60% of women meet recommendations with 25% having very low activity1. In 2017 the Health and Sport Committee highlighted that many of the issues raised about this stagnation were raised in the Committees previous two sport/PA inquiries2. As Rowe3states, we need to question whether static is acceptable considering that Scotland rates amongst the highest in the world for levels of obesity and sedentary behaviour. There are several key groups where participation remains significantly challenging, each of which will be addressed in turn.

Young people

There are significant concerns when analysing the current participation rates of young people. For example, only a small minority of children and young people are currently meeting daily PA recommendations. There is a growing disparity between children and young people who are physically active and those who are not1. This has been exacerbated by many activities not returning to pre-COVID-19 patterns2. Fewer than one in five (17%) of adolescents in Scotland meet the current physical activity recommendations for 60 minutes a day of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA), as highlighted by the Scottish Parliament Health, Social Care, and Sport Committee's inquiry into the health and wellbeing of children and young people3. These concerns are further reinforced through the data presented below:

Less than half of adolescents in Scotland usually walk to school and very few pupils cycle4.

Pupils living in the most deprived 20% areas in Scotland are most likely to be inactive - 35% of this group overall, compared to 23% for those in the 20% least deprived areas5

Young people who are already active are more likely to become involved in in programmes such as Active Schools than those who are not. If the focus on increasing collective participant numbers as opposed to targeted interventions remains, the gaps between those who are active and those who are not will inevitably increase6.

Gender disparity

Increasing participation rates for women and girls is important for equality in sport. Participation in sport can have a positive impact on their health and wellbeing, self-esteem and self-empowerment, social inclusion and integration, and opportunities to develop leadership and other skills1. Whilst more women than men participate in recreational walking, dance, keep fit/aerobics and swimming, this is not the case for all other sports where men significantly outnumber women2. However, in the 2022-23 academic year over 124,000 girls and young women made over two million visits to Active Schools sport and PA sessions, making up 46% of participants in the Active Schools programme, which demonstrates that the desire for PA participation amongst this demographic exists and was successfully enabled. The highest participation activities were netball, football, multisport, dance and movement, and basketball3.

The 'gender gap' in sports participation starts very young and girls’ participation drops markedly as they move into their teenage years, so that by the age of 13-15 years more girls do not participate in sport (55%) than do (45%)2. Traditionally, girls have been less positive about sport than PA and were more concerned about having fun and being with their friends, rather than the competitive element of sport. This position was reinforced by the Health and Sport Committee's Sport for Everyone inquiry report5, which found that for young females in general, sport is a social activity which is about fun, friendship and family. Whilst there are numerous girls and women who enjoy the competitive element of sport and PA, many prefer to focus on enjoyment and should be offered ample opportunities to do so with like-minded participants6.

Non-competitive and informal sport is even more likely to play a role in the older age groups particularly for women. For many girls and women, sport and PA become more relevant when they create involvement and foster social relationships. There is a need for further diversification to promote sport and PA’s more pleasurable and social aspects, widening the chances to participate in and create diverse, informal and non-standardised opportunities to be physically active7. As it stands however, there is not a clear picture on this relationship between gender and competitive/non-competitive sport in Scotland due to a lack of data8.

Further to the issue of competitive/non-competitive sport are barriers to participation in sport and PA because of a lack of understanding and education about the impacts of pregnancy, periods, menopause and other women's health factors on participation. Alongside this concern is the impact of negative and marginalising experiences in physical education and a lack of female-only sporting opportunities. To address such concerns requires alternative provision that takes account of women's health factors, with a view to increasing rates of female participation6.

Equality, diversity, and inclusion

There remain some significant concerns regarding the development of an equal, diverse and inclusive sporting system within Scotland. A strong focus on equalities is not always coming from the top and there remain some concerning attitudes towards equality, particularly from some of those involved in some Scottish Governing Bodies for Sport1. Consistent, positive messaging and actions around expected behaviours and values within any organisation are essential to creating an inclusive culture2. The Scottish Household Survey3 reports that participation trends within Minority Ethnic groups are equal to that of the overall population (82% including walking, 51% excluding walking). There is a recognition that the development of more single sex opportunities for women from ethnically diverse communities and a range of religions would increase their engagement with sport and PA opportunities4. However, intersectional analyses from wider sources suggest that these figures overlook several issues if taken at face value; for instance, Sport Wales5 reported a longstanding pattern of those children from Asian, Black, and Other ethnic backgrounds being less likely to be active than any other category, while Sport England6 has consistently noted the lack of Asian female sport and PA participation. This is a key area where more information and data are required to understand the underlying issues and barriers which exist.

Further to these concerns surrounding disparities in participation is the impact of direct and institutional racism. Cricket Scotland failed against 29 of the 31 indicators in the Plan4Sport Indicators of Institutional Racism Framework. The review concluded that the processes, attitudes, and behaviours of Cricket Scotland met the MacPherson definition of institutional racism2. Whilst cricket may be considered an outlier, we would argue that it would be wrong to view Scottish sport in these terms and naïve to assume that racism does not exist elsewhere across the Scottish sporting landscape.

Geographical variations

With regard to participation in sport and PA, there are contrasting demands and issues between rural and urban areas. For example, children from urban environments are often less active than children from rural communities1. Further to this, the cost of participation in sports clubs and activities such as gyms, the availability of sporting facilities in deprived areas, and the cost of equipment, and the time cost associated with participation in physical activities, were considered to disproportionately impact upon women and girls experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage2. Ultimately, there are considerable variations across different local authorities in Scotland. The extent of the variation is shown by comparing the average of sports participation rates (for 2015-17) for the top 'performing' local authorities (58%) with that of the lowest performing (42%)3. To widen access to sport across Scotland, therefore, requires the complexities associated with socio-economic disadvantage and the exclusion that can be experienced across geographic regions to be addressed4.

Disability

Davison et al's1 recent report on disability and sport in Scotland stated that 83.4% of people with a disability currently engage in sport and PA, primarily for non-competitive recreational purposes (43.5%). Taken at face value, this figure indicates a successful aspect of sport policy within Scotland. There are however some more worrying aspects of participation in sport and PA for people with a disability. For example, the knowledge of opportunities and the range of adapted and inclusive sports and PA available remains a significant barrier for people with disabilities. Further to this concern, Davison and McPherson2 highlighted that data within the 2018 Scottish Health Survey3 suggested that poverty and deprivation negatively impacts participation in sport for people with disabilities. The combination of having a disability and living in poverty creates ‘significant challenges in terms of sports participation that may influence motivation levels for people with disabilities living in Scotland’ (Davison et al, 2023, p.11)4. The issue of poverty is further reinforced by individuals expressing a fear of losing benefits. Whilst they express a strong desire to improve their physical health, they were concerned that if their participation led to improvements in physical function, they would be reassessed for their benefit entitlement. Alongside poverty there are three other areas of concern regarding disability participation. These are:

Significant levels of sedentary behaviour amongst people with a disability, which negatively impacts general health.1

Barriers faced by disabled girls and women, relating to a lack of accessible and suitably adapted facilities and infrastructure6.

A lack of Scotland-specific data on individuals’ lived experience of participation in sport and PA1.

An ageing population

Scotland, like many of its European counterparts is an ageing country. Scotland’s older population (65+ year-olds as a proportion of the total population) is estimated to grow from 19.4% to 25.5% by 20451 . This growth will have significant impacts on health provision and the welfare state over the next two decades and reinforces the need for older adults to be as active as possible. There is though, a clear pattern of declining rates of participation in PA as adults get older. This is evidenced through summary activity data from SHS2presented below:

74% of 45–54-year-olds meet the recommendations for PA with 20% having very low activity.

58% of 55–64-year-olds meet the recommendations for PA with 26% having very low activity.

55% of 65–74-year-olds meet the recommendations for PA with 29% having very low activity.

37% of 75-year-olds meet the recommendations for PA with 49% having very low activity.

In terms of being active for older adults, walking is by far the most popular activity. According to the 2022 Scottish Household Survey2, 70% of adults aged 60 or over regularly participated in physical activity including walking. When walking was excluded from this data, the percentage fell to 35%. Although there was a decline in physical activity participation between 2007 and 2016 for people under 65, there was a very slight increase for those aged 66 and above. To build upon this increase requires a shift in policy and practice. Currently, the majority of sport development initiatives are targeted at younger generations. There are also cursory mentions of older adults in policy documents in Scotland4.

Building a coherent and comprehensive evidence base

A significant concern across the sporting landscape in Scotland is the lack of a coherent and comprehensive evidence base. Whilst data exists, it does so across numerous organisations who each use their own reports, surveys and formats. Access to these raw datasets is also often restricted and unavailable for public or academic use. For example, Scotland is the only nation not to collect any data on sport and PA participation directly from children and young people, which leads to significant gaps in our ability to understand children’s sport in Scotland1. Further to this is the lack of data on Sportscotland’s flagship programme, Active Schools, where there has not been a full evaluation of the programme since 2018.

To address this concern the Health, Social Care, and Sport Committee recently highlighted the critical importance of creating an accurate and comprehensive benchmark to measure the effectiveness of future policy interventions. Rowe and Brown2 reinforce this concern through the following points:

In relation to the National Outcomes Framework and Active Scotland Outcomes Framework, Sportscotland report a relatively narrow set of measures confined to their own programme impact as opposed to a wider, national picture of sport participation.

In the absence of a current national strategy for sport in Scotland there is an absence of an accountability framework for sport outcomes that focus on participation in the population, drop out or sustained engagement in sport, club membership and volunteering.

Relatively little research has been commissioned by the Scottish Government and Sportscotland in the last 20 years, and so Scotland now lags behind its European neighbours in its commitment to and co-ordination of research, and available data and insight.

The Health, Social Care, and Sport Committee also urged the Scottish Government, as a matter of priority, to commission a population-level survey to measure current rates of participation in sport and PA, broken down by age, gender, socio-economic backgrounds, disability, sexuality, ethnic and religious background and other inequalities3. Whilst we support the collection of a national survey, we would also call for this to be combined with qualitative, participatory, and collective bottom-up approaches to data collection and the development of practice. Incorporating alternative methodological approaches would allow people to engage with new and personally meaningful ways to be physically active. They would also facilitate opportunities for the co-design of sport and PA opportunities that would meet different individual and community needs related to PA and enhance an individual's and/or community’s ability to act collectively towards tackling structural inequalities4. Finally, we concur with Rowe and Brown5 who call for a National Sport Research Strategy underpinned by secure funding commitment for at least five years, to allow it to develop credible understanding of the landscape and to contribute to the development of a new national sport strategy. Such a research strategy would ‘require national co-ordination with incentivisation of capacity building in academia; bridges built between policy, practice and academic research communities; promotion and facilitation of institutional and disciplinary collaboration around a shared strategic ambition; and networks for sharing and collaborating internationally’ (Rowe & Brown, 2023, p.35).

The economic impact of inactivity

Evidencing the economic impact of inactivity is a significant challenge. We know the correlation between inactivity and poor health, and we also know the correlation between poverty and health. The most recent analysis in 2015 estimated the cost of inactivity to the NHS in Scotland as more than £77 million per year or around £14.60 per person living in the country12. Further to this are concerns around the public health imperative to help individuals with a disability to participate in appropriate sport and PA to enhance their quality of life3 .

It is though important to note that whilst understanding the economic return on investment in sport and PA is important there is also a requirement to better understand the social return on investment (SROI). Evidence of the social and economic impact to support policies and interventions that encourage more participation would further enhance the value of PA and sport in Scotland4. The evidence that is currently available on the economic importance of sport only ‘quantifies part of the overall value of sport to society and in Scotland therefore the value of sport is currently underestimated’4(p.21). The evidence base around such correlations needs to be stronger with more work required to measure the impact sport can have as a preventative measure that reduces the societal costs of poor health and wellbeing2. Investing in preventative measures in relation to sport and PA is a matter of proving that they can enhance health and wellbeing. It is not a zero-sum game; rather, it is an opportunity to showcase measurable outcomes that would better inform budget-holders and decision-makers, both within and beyond sport7.

One significant area where we can clearly measure economic impact is volunteering. The social and economic value of volunteering is significant, with the annual value of volunteering in Scotland estimated at £2.26 billion8.

Evidence gaps and future recommendations

Whilst we know a great deal about the current circumstances of participation and inactivity, there are also significant gaps in our knowledge. The primary reason for this is a lack of a cohesive, detailed, and centralised evidence base. Significant gaps in our knowledge and understanding include but are not limited to:

Why rates of participation in sport are stagnating considering the levels of investments and policy development.

We have no current understanding of the impact of investment in the school estate on participation and engagement in sport and PA.

Whilst participation trends within minority ethnic groups are equal to that of the overall population it is likely that the real picture is more nuanced than this.

We do not have a clear picture on the relationship between gender and competitive/non-competitive sport in Scotland due to a lack of data1.

There is a lack of understanding and education about the impacts of pregnancy, periods, menopause, and other women's health factors on participation in sport and PA2.

Due to limited engagement with older adults in Scotland we are limited in our understanding of how to increase activity with this age group1.

Relatively little research has been commissioned by the Scottish Government and Sportscotland in the last 20 years, and so Scotland now lags its European neighbours in its commitment to and co-ordination of research, and available data and insight4.

There is no current data capture process to measure current rates of participation in sport and PA, broken down by age, gender, socio-economic backgrounds, disability, sexuality, ethnic and religious background, and other inequalities2.

We have limited understanding of the impact of Active Schools in engaging those who are currently inactive6.

Conclusion

As we have evidenced within this review, the aim of increasing participation in sport and PA is facing several complex challenges. Many participation trends affecting sport are working in the direction of pushing participation down in Scotland rather than up, increasing inequalities as opposed to reducing them. Structural inequalities such as gender and class in sports participation appear to be entrenched in Scottish society despite public policy priorities targeting these groups. The causes of inequalities are deep rooted and structural and, can be resolved by (1) a holistic and sustained approach to understanding the physical, social, structural, and environmental landscape; (2) a cross governmental commitment to the realisation of a systems based approach and, (3) for social inequality and material deprivation to be treated as a priority at national policy level.

There remains, however, a significant opportunity for sport and PA to be more collaborative and effective through a clear common agreed purpose across the Scottish sporting landscape and all levels of government. To realise this opportunity requires initial engagement with the new PA and Health Framework from local authorities followed by a renewed policy focus. Several significant bodies and researchers have called for new national strategies for sport and PA. Firstly, the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee (HSCSC) called for an overarching national strategy with clear and measurable goals for achieving increased physical activity and improved physical health of Scotland's children and young people. Secondly, the Observatory for Sport in Scotland (OSS) has called for a national strategy for sport and recreation, to address concerns around inactivity and its associated health impact, and create long-lasting health and wellbeing improvements across the population. Thirdly, the OSS1 has recommended a new vision of ‘sport as society’ driven by a new national strategy for sport that would engage widely across health, education, and communities, and be underpinned by investment in research capacity and evidence building. To deliver a successful new national strategy for sport and PA requires policymakers to be more informed of how participation in Scotland varies significantly according to deprivation if they are to develop and deliver approaches that help to raise participation among those who require it most. The last point to address is that of the limited evidence base and the subsequent difficulty in presenting a full evidence review. We do not have a full picture, and this will have considerable impact on the development of informed policy development. In addressing this concern, we echo calls for a National Sport Research Strategy to be underpinned by a secure funding commitment for at least five years. The intention would be to allow the strategy to develop credible understanding of the landscape and to contribute to the development of a new national sport strategy.