Scottish Languages Bill

A briefing on the Scottish Languages Bill. This briefing explores the current policy landscape for the support of Gaelic and Scots and then explores the provisions of the Bill.

Executive Summary

This briefing supports the scrutiny of the Scottish Languages Bill.

The Bill intends to build on existing policy and legislation. This paper briefly covers the current policy and legislative framework and some of the main features of the Bill.

Current Policy Framework

Since devolution there has been greater policy focus and more resources directed at supporting Gaelic than Scots.

Gaelic

Policy supporting Gaelic is underpinned by the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005. This made a number of provisions with the aim of “securing the status of the Gaelic language as an official language of Scotland commanding equal respect to the English language.” The 2005 Act established Bòrd na Gàidhlig.

The Bòrd has a number of functions, these include—

preparing and publishing the National Gaelic Plan

requiring certain public bodies to produce Gaelic Plans and to approve and monitor those plans

providing support and advice

producing statutory guidance on Gaelic education.

Gaelic education is a key aspect of policy to support the language. Gaelic education includes:

Gaelic Medium Education (GME) where teaching across the curriculum is primarily in the medium of the Gaelic language

Gaelic Learner Education (GLE) where the language is taught as a modern language in an English medium school.

In recent years, there has been additional policy activity in relation to the Gaelic language. In 2018, the Government established an initiative called Faster Rate of Progress. The Faster Rate of Progress initiative seeks to bring together a range of bodies to collaborate to support the Gaelic language.

In 2022, the then Cabinet Secretary for Finance and the Economy, Kate Forbes MSP, established a Short Life Working Group on Economic and Social Opportunities for Gaelic (the SLWG). The focus of this group’s work was to seek to “strengthen Gaelic by means of a focus on economic opportunities and to strengthen the economy by making the most of Gaelic opportunities”.

Scots

In 2015, the Scottish Government published its Scots language policy. This includes three aims for the policy—

to enhance the status of Scots in Scottish public and community life

to promote the acquisition, use and development of Scots in education, media, publishing and the arts

to encourage the increased use of Scots as a valid and visible means of communication in all aspects of Scottish life.

There is no Government agency with specific focus to support the Scots Language. There are, however, a number of organisations supported by the Scottish Government which promote and support Scots.

In 2010, a Ministerial Working Group on the Scots Language reported and made recommendations across a number of areas—

policy and strategy

education

broadcasting

literature and the arts

international contacts

public awareness

dialects.

European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages is a Council of Europe treaty. It was drawn up in 1992 with the aim to protect and promote regional or minority languages in Europe and give speakers of those languages the chance to use them in private and public life. The UK became a signatory in 2000 and ratified the Charter in 2001.

Both Gaelic and Scots are covered by the Charter.

Policy Outcomes

While the policy initiatives address a range of policy areas and domains where languages may be utilised, it is not always clear from the strategic documents what successful policy outcomes will look like or how they will be measured.

Data

There is a range of data on this policy area. There is more data in relation to Gaelic than Scots.

The most recent census data on language use is from the 2011 Census. The National Records of Scotland expects the data on languages from the 2022 census to be published later in 2024. In the 2011 census, more than 1.5 million people said they could speak Scots and just over 57,000 people said they could speak Gaelic.

In 2012 and 2021 questions were included in the annual Scottish Social Attitudes survey on Gaelic. Comparing the two surveys, there has been progress in the proportion of adults in Scotland with some knowledge of the Gaelic language and positive attitudes towards the language.

In the past ten years, there has been an increase in the proportion of pupils participating in both GME and GLE. There has also been an increase in the number of teachers currently teaching through Gaelic or who potentially could teach through Gaelic.

Taken together, direct Scottish Government funding for day to day spending on Scots and Gaelic has been relatively stable in cash terms over the past ten years. This represents a real terms cut. As well as resource funding, there is a Capital budget under Gaelic to support local authorities in providing Gaelic Medium Education. This has increased in recent years and currently stands at £4m per year.

Scottish Languages Bill

The Government undertook a consultation on Gaelic, Scots and a Scottish Languages Bill in 2022. The current Bill was developed following that consultation.

The Bill is in two substantive parts covering provisions relating to Gaelic and Scots. Within those two parts are Chapters covering support for the languages and education.

Part 1 – Chapter 1 of the Bill is on support for the Gaelic Language and the provisions in the chapter include:

Gaelic having official status in Scotland

changes to the functions of Bòrd na Gàidhlig

creating a power to designate geographical areas as “areas of linguistic significance”

putting a duty on the Scottish Government to prepare a National Gaelic Strategy, which replaces the National Gaelic Plans

giving Scottish Ministers (the Government) more powers to put duties on public bodies to promote, facilitate and support Gaelic.

Part 1 – Chapter 2 of the Bill is on Gaelic education and the provisions in the chapter include:

requiring Scottish Ministers to promote Gaelic education

providing Scottish Ministers with powers to set standards and produce guidance for local authorities in relation to Gaelic education

amending the statutory definition of school education

requiring local authorities to promote Gaelic education

making various other changes linked to GME including a process for parents to request Gaelic Medium Early Learning and Childcare.

Part 2 – Chapter 1 is on support for the Scots language. The provisions in the chapter include:

Scots having official status in Scotland

requiring Scottish Ministers to create a Scots language strategy and report on any progress made

providing that Scottish Ministers can produce guidance for public bodies in relation to promoting and supporting the Scots Language and the development of Scots culture

Part 2 – Chapter 2 is on school education in relation to Scots. This includes provisions which would—

require Scottish Ministers to promote and support Scots language education in schools

allow Scottish Ministers to produce guidance and set standards for local authorities relating to Scots language education in schools.

Financial Memorandum

The Financial Memorandum sets out the expected additional costs that will arise from the Bill. In total, the cost of the Bill is estimated to be around £700,000 over five years.

Introduction

The Scottish Languages Bill was introduced to Parliament on 29 November 2023.

The Bill gives the Gaelic and Scots languages official status in Scotland and makes changes to the support for the Gaelic and Scots languages in Scotland. This includes changes in relation to education.

The lead Committee at Stage 1 of the Bill will be the Education, Children and Young People Committee.

The Policy Memorandum states—

The provisions of this Bill are building on current policy priorities that are currently in place with the aim of making the new package of measures more effective for the progress that is needed for Gaelic and Scots.

PM Para 5

This briefing is two parts. The first part outlines the current policy frameworks supporting Gaelic and Scots. The second explores the provisions in the current Bill.

Current Policy Landscape

The Bill intends to build upon the current work to support Gaelic and Scots.

This section is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of this policy area. Rather it is intended to provide Members with an understanding of the current policy and legislative frameworks to support Gaelic and Scots.

Gaelic

Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005

The Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005 made a number of provisions with the aim of “securing the status of the Gaelic language as an official language of Scotland commanding equal respect to the English language.”

The 2005 Act established Bòrd na Gàidhlig. The Bòrd is the principal public body in Scotland responsible for promoting Gaelic development and providing advice to the Scottish Ministers on Gaelic issues.

Section 1 of the 2005 Act stated—

The functions conferred on the Bòrd by this Act are to be exercised with a view to securing the status of the Gaelic language as an official language of Scotland commanding equal respect to the English language through—

(a) increasing the number of persons who are able to use and understand the Gaelic language,

(b) encouraging the use and understanding of the Gaelic language, and

(c) facilitating access, in Scotland and elsewhere, to the Gaelic language and Gaelic culture.

The 2005 Act provided that the Bòrd “prepare and submit to the Scottish Ministers a national Gaelic language plan which must include proposals as to the exercise of its functions under this Act”.

The 2005 Act also provided for the Bòrd to have the power to require public bodies to prepare, publish and implement Gaelic Language plans. The Bòrd’s website lists 57 public bodies with approved Gaelic Plans.

The 2005 Act provided that the Bòrd may monitor the implementation of public bodies’ Gaelic plans. Under the 2005 Act, there are two ways in which the Bòrd can escalate issues with public bodies’ Gaelic plans. In the process of approving plans, the Bòrd can suggest amendments to the public body and, if agreement is not reached, the Bòrd may refer the matter to Ministers, who are able to decide whether the suggested changes should form part of the public body’s plan. If the Bòrd considers that a public body is failing to implement adequately measures in its plan, the Bòrd may submit to the Scottish Ministers a report setting out its reasons for that conclusion. Ministers may then direct the authority in question to implement any or all of the measures in its Gaelic language plan.

The 2005 Act also provided that the Bòrd issue statutory guidance on Gaelic education.

National Gaelic Language Plans

The 2005 Act provides that the Bòrd “prepare and submit to the Scottish Ministers a national Gaelic language plan which must include proposals as to the exercise of its functions”. The plan must include a strategy for promoting, and facilitating the promotion of—

the use and understanding of the Gaelic language, and

Gaelic education and Gaelic culture.

The current and fourth National Gaelic Plan covers the period 2023-2028. Its vision is for a measurable “increase in the numbers of people, speaking, learning, using and supporting Gaelic.” The main aim of the plan reflects this vision. The plan highlights a number of domains which have short lists of “priority areas” and “targets”. The domains are—

community

homes

creative industries

business and the economy

public authorities

education 0-18

post-school and adult learning.

The Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills’ foreword to the current plan said—

The promotion of Gaelic is a shared responsibility. A significant number of local authorities and public bodies can and do make an important contribution to support for Gaelic.

The intention is that public authorities’ Gaelic plans will reflect the national plan.

Gaelic Education

Gaelic education has two aspects. Gaelic Medium Education (GME) and Gaelic Learners Education (GLE). GME is where the education is through the medium of Gaelic. GLE is where the language is taught as any other modern language.

The Bòrd’s Statutory Guidance on Gaelic Education explains that in Gaelic medium primary education—

Only Gaelic should be used for learning, teaching and assessment from P1 to P3. From P4, English should be gradually introduced, with Gaelic remaining the predominant language of the classroom.

In Gaelic Medium Secondary Education, the guidance states “schools should aim to deliver a sufficient proportion of the secondary curriculum through the medium of Gaelic to enable young people to continue to develop their fluency in Gaelic.”

The Scottish Government’s consultation stated—

Gaelic medium primary education (GMPE) is currently available in 14 out of 32 education authority areas across Scotland. There are also a growing number of Gaelic medium schools in Scotland and dual stream (Gaelic and English) primary schools where GME is in the majority. There are also a number of Gaelic medium early years centres and cròileagain (playgroups) operating across Scotland. Gaelic medium secondary education (GMSE) is also available in 33 secondary schools in Scotland. In these schools, Gaelic is typically offered as a subject, with some schools delivering a further proportion of the curriculum through the medium of Gaelic.

The Education (Scotland) Act 2016 provides that parents and carers whose child is under school age and who has not yet started to attend a primary school, have the right to request an assessment of the need for GMPE from their local authority. The 2016 Act also sets out a statutory process for local authorities to undertake an initial assessment of the need for GMPE in a particular area and then, potentially, a full assessment.

Faster Rate of Progress

In 2018, the Government established an initiative called Faster Rate of Progress. The Scottish Government’s Gaelic Plan (not to be confused with the National Plan, developed by the Bòrd) states—

The Faster Rate of Progress initiative is a cornerstone to the Scottish Government's Gaelic policy and pulls together around 25 Public Bodies who are contributing to the sustained growth and support of the Gaelic language.

The National Plan describes Faster Rate of Progress as “a transformational initiative led by Scottish Ministers, has successfully brought together national organisations and key authorities, which have Gaelic language plans to progress workstreams and deliver key Gaelic commitments through collaboration.” These workstreams include—

community engagement

digital and media

teaching and learning

tourism

culture and heritage

economy and workforce.

There is no website or page on the Government’s website that provides details of this work. It is therefore difficult to assess activities that are taking place under this initiative, the resources directed at this work, or its outcomes.

Short Life Working Group on Economic and Social Opportunities for Gaelic

In 2022, the then Cabinet Secretary for Finance and the Economy, Kate Forbes MSP, established a Short Life Working Group on Economic and Social Opportunities for Gaelic (the SLWG). The focus of this group’s work was to seek to “strengthen Gaelic by means of a focus on economic opportunities and to strengthen the economy by making the most of Gaelic opportunities”.

The SLWG noted—

Economic and cultural activity cannot be viewed separately. Cultural events contribute significantly to Scotland's economy as well as offering social cohesion in communities and opportunities to use Gaelic. The language is of considerable interest to visitors coming to Scotland who also contribute to the economy. In language planning terms, the desire to use Gaelic is influenced by the language's status. Economic opportunities and social activities can often inspire people to acquire, or make more use of, Gaelic skills.

The SLWG noted the range of policy interventions but stated “the group is in no doubt that Gaelic remains in a fragile position and there must be a demonstration of urgency, across the range of bodies which can bring about positive change, to ensure the language's future.” It also said that the Scottish Government should increase its direct funding for Gaelic development “to stimulate economic growth and realise fully the social and wellbeing potential of Gaelic.”

The SLWG made recommendations under a wide range of headings, these were:

population and Infrastructure

public sector and Gaelic plans

communities

education

key sectors (including social care, creative industries, culture, heritage, tourism, sport, food & drink and the natural environment).

The SLWG had a particular, but not exclusive, focus on “Key Gaelic Communities”, which it defined as “all those in Na h-Eileanan Siar, Skye & some districts of Lochalsh, Tiree, Islay and Jura – places where, in the 2011 census, 20% or more of the population had Gaelic abilities”. The SLWG said—

Many of the challenges facing language use in Key Gaelic Communities are related to population attraction and retention. Without infrastructure such as adequate housing and reliable transport links, as well as digital connectivity, populations cannot be grown or retained. The viability of those communities is threatened and, with that, Gaelic as a community language.

The Scottish Government is yet to respond to the report of the SLWG. In answer to a parliamentary question in December 2023, the then Cabinet Secretary for Wellbeing Economy, Fair Work and Energy, Neil Gray MSP, said—

The Scottish Government welcomes the report of the short-life working group on economic and social opportunities for Gaelic and has set up an internal Scottish Government steering group to consider the wide-ranging recommendations. The Scottish Government expects to issue a response to the group in the early months of 2024. … The provisions in the [Scottish Languages Bill], including the drafting of a Gaelic strategy and Gaelic standards, the designation of areas of linguistic significance and improved Gaelic language plans all have the potential to make progress on the recommendations on the key sectors that are identified in the Gaelic economy report and are the basis from which Kate Forbes introduced the review in the first place.

Scots

The Scots language has less policy infrastructure dedicated to it than Gaelic.

In 2015, the Scottish Government published its Scots language policy. This includes three aims for the policy—

to enhance the status of Scots in Scottish public and community life

to promote the acquisition, use and development of Scots in education, media, publishing and the arts

to encourage the increased use of Scots as a valid and visible means of communication in all aspects of Scottish life.

There has not been an evaluation of the progress against these aims.

Scots Language Bodies

The Scottish Government’s 2022 consultation listed a number of Scots Bodies that the Government provided funding for in 2022. These were—

Scots Language Centre (SLC)

Dictionaries of the Scots Language

Association for Scottish Literature

Scots Hoose

Scots Radio/Doric Film Festival

Doric Board

Scottish Book Trust (Scots Publishing Grant & Scots Bookbug app)

YoungScot (Scottish Languages Panel).

The Scots Language Centre provides information and advice on Scots and promotes the use of the Scots language, culture and education. The Doric Board performs a similar function but focusing only on Doric. The Association of Scottish Literature, Scots Hoose and the Scottish Book Trust, along with the SLC, all (among other things) provide support for Scots education.

Unlike Bòrd na Gàidhlig, these bodies are not Government bodies. Also, unlike Gaelic, there currently aren’t regular updates to national strategies.

2010 Working Group on Scots

In 2010, a Ministerial Working Group on the Scots Language reported and made recommendations across a number of areas—

policy and strategy

education

broadcasting

literature and the arts

international contacts

public awareness

dialects.

The recommendations and analysis of the Working Group largely remain relevant. This paper will not replicate all the Working Group’s recommendations here, but it is worth highlighting a few in the context of the current Bill.

The Working Group recommended that the Government “develop a national Scots Language policy with reference to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages; and this should be enshrined in an Act of Parliament.” As noted above, a Scots language policy was published in 2015 and the current Bill intends to strengthen the policy framework in relation to Scots.

Under Education, the Working Group said—

This is one of the areas in which action is most urgently required, at all levels: pre-school, primary, secondary and tertiary (the latter including teacher training). The situation is particularly critical in that the current lack of resources and priority for Scots in education endangers all the ground-breaking progress made in recent years.

The Working Group made a number of recommendations to practically strengthen the resources for Scots education.

In relation to dialects, the Working Group stated—

Scots as a spoken language exists in a number of distinct forms, each of which is strongly identified with a particular area and several of which have been developed for flourishing traditions of local literature. The need to preserve the individual dialects and respect their distinctive identities, while at the same time developing the language as a whole, will require careful planning: in particular, the necessity of developing a standard form of Scots for official purposes must be presented so as to avoid any appearance of a threat to the dialects.

One of the recommendations of the Working Group was—

Local authorities should have not only a clear policy on Scots but a clear awareness of the dialects in their particular areas, and should tailor the application of the national policy to their own particular context.

European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languagesis a Council of Europe treaty. It was drawn up in 1992 with the aim to protect and promote regional or minority languages in Europe and give speakers of those languages the chance to use them in private and public life. The UK became a signatory in 2000 and ratified the Charter in 2001.

Both Gaelic and Scots are covered by the Charter, albeit in slightly different ways. The Charter allows for two levels of obligations. Part II of the Charter sets out a common core of principles in supporting regional or minority languages. These principles include—

the recognition of the regional or minority languages as an expression of cultural wealth

the need for resolute action to promote regional or minority languages in order to safeguard them

the facilitation and/or encouragement of the use of regional or minority languages, in speech and writing, in public and private life

the provision of appropriate forms and means for the teaching and study of regional or minority languages at all appropriate stages.

Part III contains a set of specific provisions concerning the use of the regional or minority language in a broad range of public or civic life, such as:

education

justice

administrative authorities and public services

media

cultural activities and facilities.

States can determine whether a language is covered by the provisions in only Part II or both Part II and Part III. Gaelic is covered by both parts and Scots is covered only by Part II.

The implementation of the Charter is monitored by a committee of independent experts. The most recent report of this Committee, published in 2021, made one ‘recommendation for immediate action’ on Scots and two on Gaelic.

In relation to Scots, it said the Scottish Governmenti should—

provide forms and means for the teaching and study of Scots at all appropriate stages.

In relation to Gaelic, it said the Scottish Government should—

take further measures to make pre-school, primary and secondary education available in Scottish Gaelic

continue taking measures to strengthen Scottish Gaelic education, especially through the training of teachers and the production of teaching and learning materials.

The committee of experts is currently working on the next report on the implementation of the Charter in the UK.

Language Shift, Maintenance and Revitalisation

The purpose of the Bill is to strengthen the policy framework to “support for Scotland’s indigenous languages, Gaelic and Scots”. This is part of a continuing effort to promote and support these languages.

The position of languages and changing patterns of usage is an area of both academic study and policy attention. The purpose of this section is to set out some of the main concepts in brief and general terms.

Language shift is when a “a community of users replaces one language by another, or ‘shifts’ to that other language” (Grenoble, 20211). Language maintenance can be described as the process or activities to uphold and maintain current usage; and language revitalisation is concerned with improving the position of a language. Both language maintenance and revitalisation would be considered to be responses to language shift. (Lewis & McLeod 20212)

Different authors in the field of language revitalisation have emphasised different approaches. Hinton (2011)3 argued that “School-based programmes include examples of the most successful cases of language revitalization” and she also highlighted the value of community summer camps and adult learning. She said that the “ultimate goal for language revitalization would be for it to regain its place as a language of daily communication within the speech community.” Fishman (1991)4 argued that the family structure was crucial to successful intergenerational transmission of languages. Romaine (2007)5 argued that one should take an ecological approach to protecting languages, that “the preservation of a language in its fullest sense ultimately entails the maintenance of the group who speaks it.” The role of government is also seen as important in developing supportive policy frameworks.

A recent UK research project, Revitalise, sought to reflect on the social, economic and political changes over the past decades and explore what this may mean for efforts to revitalise languages. This explored whether “changes in the nature of community life and in patterns of interaction among individuals have implications for the emphasis traditionally placed by language revitalization frameworks on the role of the local, territorially defined, community.” It also asked questions about “the way that families organize their day-to-day lives and care for their children” as well as looking at economic and governance changes.

Policy aims in Scotland and measures of success

To a degree, the policy aims reflect the breadth of areas of focus within language revitalisation literature. The current National Gaelic Plan covers: community, home, creative industries, business and the economy, public authorities, and education (both school and post-school).

The current National Plan highlighted the positive results from the Scottish Social Attitudes survey and the 2018-23 National Plan included the aim of “Promoting a positive image of Gaelic”. The 2018-23 National Plan did not however explain how this aim would be measured or that the Scottish Social Attitudes survey would be used as an indicator of success.

The Scottish Government’s Scots language policy aims—

to enhance the status of Scots in Scottish public and community life

to promote the acquisition, use and development of Scots in education, media, publishing and the arts

to encourage the increased use of Scots as a valid and visible means of communication in all aspects of Scottish life.

The policy outcomes in Scotland tend to be expressed in general and iterative terms. The aim is often “to enhance…” or “to increase…”, rather than measurable outcomes. Without clear policy aims and expected outcomes and measures, it is difficult to determine whether the policies and activities to support Scots and Gaelic are, on their own terms, successful.

There have been several frameworks developed to measure the health of languages. For example, a 2003 paper published by UNESCO identified six major factors to evaluate a language’s ‘vitality’. These were:

intergenerational language transmission

absolute number of speakers

proportion of speakers within the total population

shifts in domains of language use (i.e. the settings where the language is used)

response to new domains and media

availability of materials for language education and literacy.

The UNESCO paper also said “none of these factors should be used alone” (emphasis in the original text).

Data

There is a range of data on this policy area. There is more data in relation to Gaelic than Scots.

Census

The most recent census data on language use is from the 2011 Census. The National Records of Scotland (NRS) expects the data on languages from the 2022 census to be published later in 2024.

In relation to Scots and Gaelic in 2011, NRS reported—

More than 1.5 million people said they could speak Scots.

Another 267,000 people said they could understand Scots but not read, write or speak the language.

1.1% of adults said they spoke Scots at home. The Shetland Islands, Aberdeenshire, Moray and Orkney Islands had the highest proportions of Scots speakers at home.

Just over 57,000 people said they could speak Gaelic.

This was a fall from 9,000 in the 2001 census. 23,000 people said they could understand Gaelic, but not read, write, or speak it.

Council areas with the most Gaelic speakers were:

Eilean Siar (Western Isles), where 52.3% of the population could speak Gaelic

Highland, where 5.4% could speak Gaelic

Argyll and Bute, where 4.0% could speak Gaelic

These were also the areas were people most commonly spoke Gaelic at home. Overall, 0.5% of adults in Scotland said they spoke Gaelic at home.

The number of people able to speak Gaelic decreased between 2001 and 2011 for all age groups except in people under 20, which had an increase of 0.1 of a percentage point.

The figures above are shown as percentages of the population who could speak Gaelic in each local authority. A significant proportion of Gaelic speakers live in other local authority areas. For example, Glasgow City had the third highest number of Gaelic speakers reported in the 2011 Census.

Scottish Social Attitudes Survey

In 2012 and 2021, questions were included in the annual Scottish Social Attitudes survey on Gaelic. The report on this element of the survey found—

Overall, in the last decade there has been an increase in the proportion of adults in Scotland with some knowledge of the Gaelic language and in exposure to Gaelic public signage. The proportion of adults reporting exposure to Gaelic during childhood and recently in the media/online has remained stable since 2012, as has level of comfort with hearing the language spoken, views on bilingual signage and perceptions of the importance of Gaelic to the heritage of Scotland and the Highlands and Islands.

There has been a shift towards more positive attitudes regarding the language in a range of areas, including views on Gaelic education, the importance of Gaelic to one’s own cultural heritage, public spending on Gaelic, and the future of Gaelic.

Statistics on Gaelic Education

There are a range of statistics covering the provision and take up of Gaelic education. Bòrd na Gàidhlig produces annual statistics on Gaelic education; this is largely derived from the pupil and teacher censuses. Where applicable, the source used here is the Scottish Government’s publications rather than the Bòrd’s.

Pupils

The tables below show the number of pupils who have Gaelic education. As noted previously, there are two types of Gaelic education: Gaelic Medium Education and Gaelic Learner Education.

| Gaelic Medium Education | Gaelic learner classes | No Gaelic | |

| 2013 | 0.6% | 0.9% | 98.5% |

| 2023 | 1.0% | 1.2% | 97.8% |

| Some subjects other than Gaelic taught through Gaelic | Gaelic the only subject taught through Gaelic | Gaelic learner classes | No Gaelic | |

| 2013 | 0.2% | 0.2% | 1.1% | 98.5% |

| 2023 | 0.5% | 0.2% | 1.2% | 98.1% |

Between 2013 and 2023 there has been proportionally a large increase in pupils in GME. However, this remains a small percentage of pupils in Scotland. There is wide regional variation in the provision of GME.

The proportion of pupils experiencing Gaelic learner classes has also increased but at a slower rate than GME. Again, there are significant variations between local authorities in the statistics. It is notable that in 2023 some local authorities that have GME provision report that zero pupils are learning Gaelic as a second language in English medium education (e.g. Glasgow, Edinburgh).

Teachers

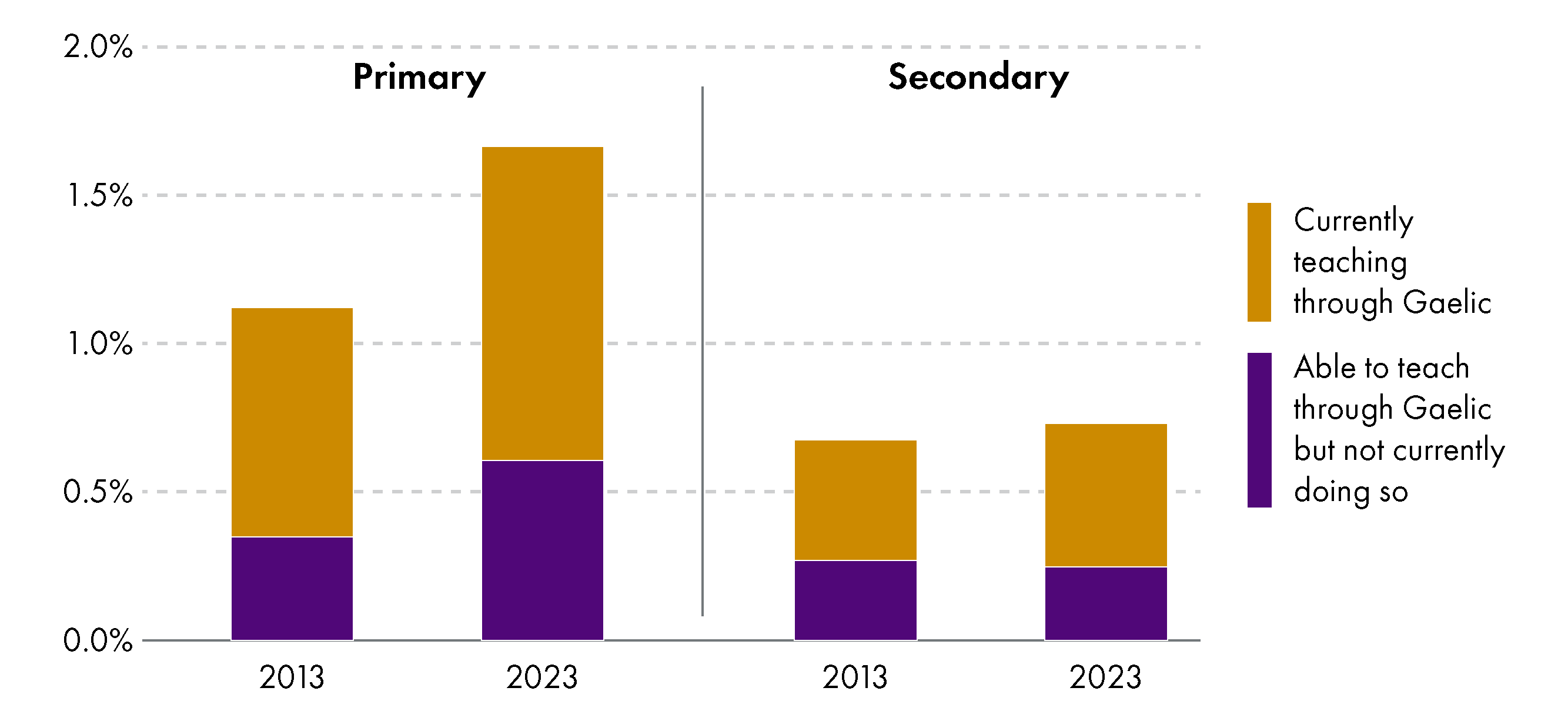

The chart below shows the percentage of teachers (FTE) in Scotland who are currently teaching through Gaelic or who potentially could teach through Gaelic.

The data mirrors that for pupils. There has been an increase in the percentage of teachers that teach in GME, particularly in primary school. However, the percentages are small and the potential to grow the number of GME teachers using the existing workforce appears limited.

Scottish Government Funding

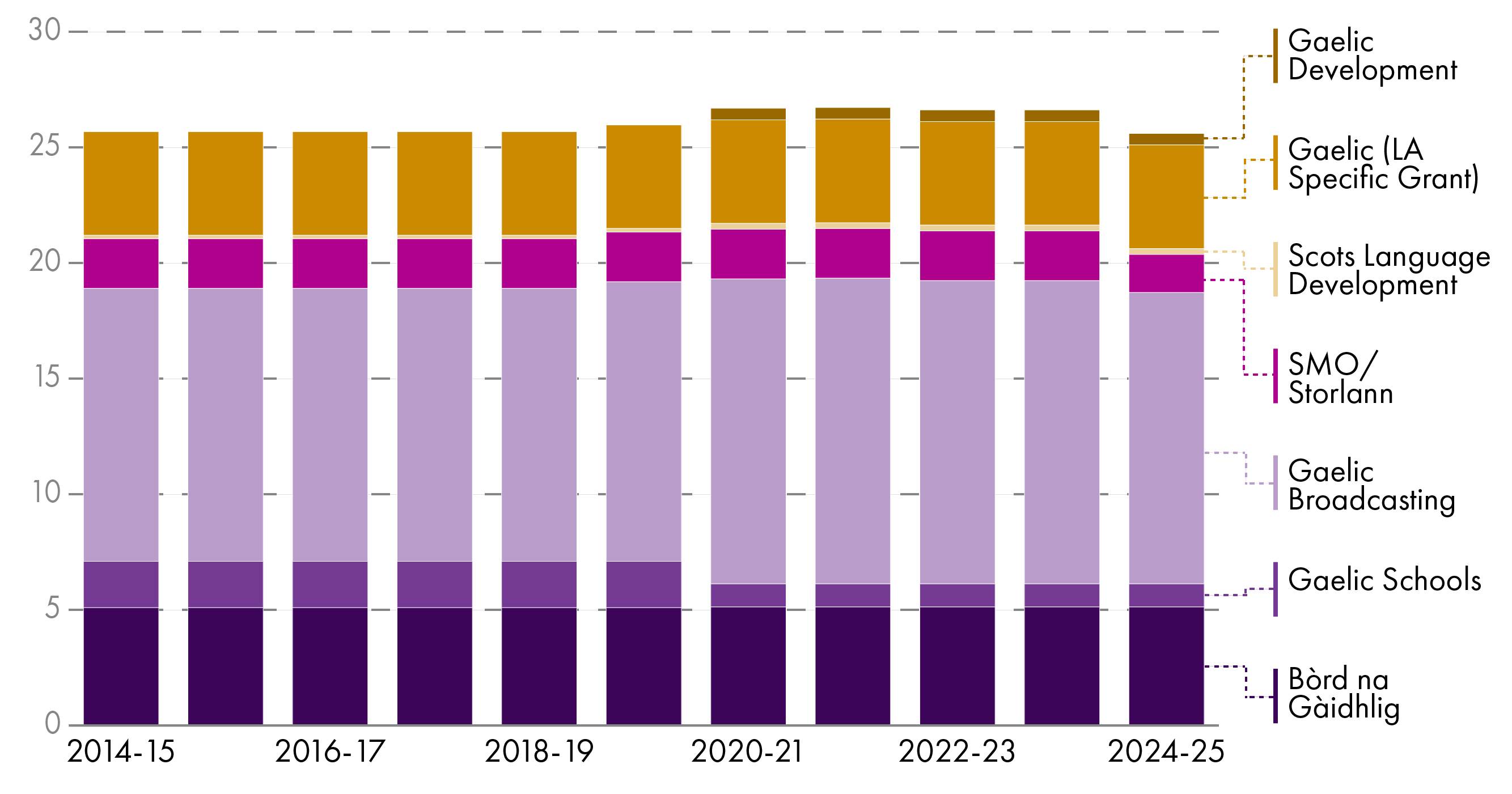

There are several lines in the Scottish Government’s budget which relate directly to supporting Scots and Gaelic. Resource funding (which supports day-to-day expenditure) has been around £26 million a year for the past ten years.

In 2024-25, of the £25.6 million of resource funding in the Scottish Government’s resource budget for Gaelic, around half of this budget, £12.6 million, goes to Gaelic Broadcasting – which is the Scottish Government’s contribution to MG Alba. The funding for Bòrd na Gàidhlig is £5.1 million.

The 2024-25 budget included provision of £250,000 to support the activities of the Scots Language Centre and Dictionaries of the Scots Language and their support of Scots language. The Government reports that it has increased its funding for Scots to around £550,000 per annum – this is not reflected in the annual budgets and comes from elsewhere in the Gaelic and Scots resource funding.1

The chart below shows the funding for Gaelic and Scots over the past 11 budgets.

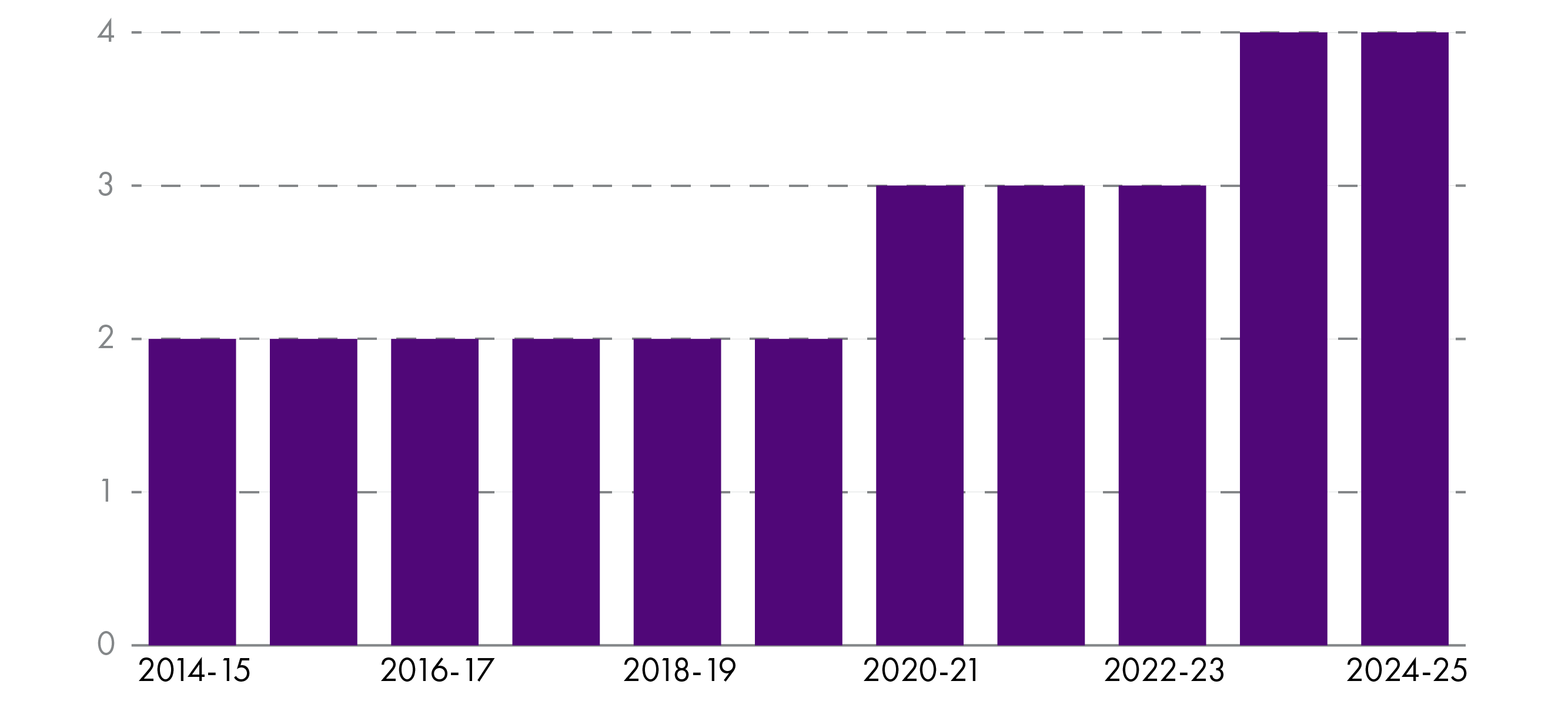

As well as resource funding, there is a Capital budget under Gaelic. This is to support local authorities in providing Gaelic Medium Education. The chart below shows how the funding for this has increased over the past 11 budgets.

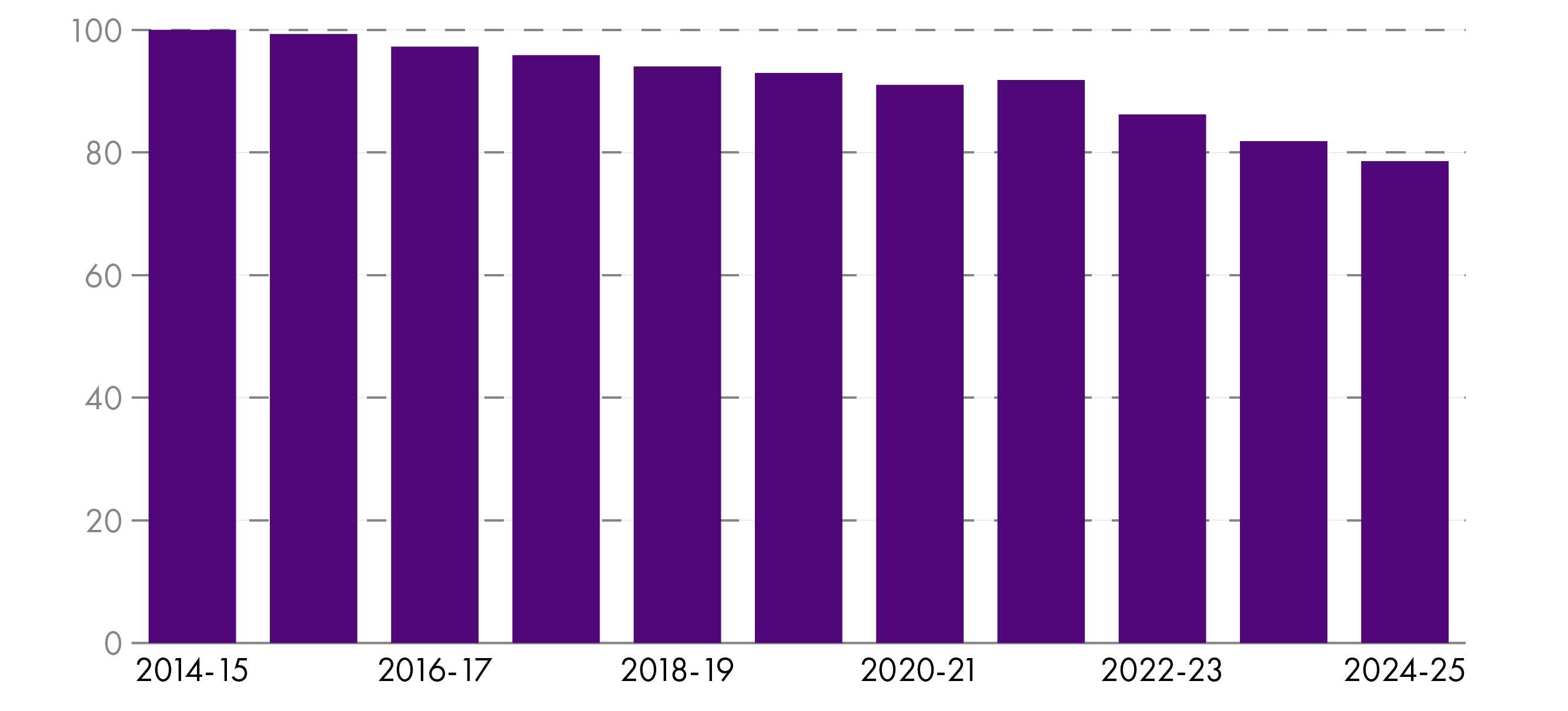

While the resource funding over the past decade is fairly flat in cash terms, there has been an increase in the capital budgets. Taken together there has been a real terms fall during that period. The chart below shows the real terms budgets for Gaelic (and Scots) over the past 11 budgets. The chart is an index where 2014-15 is 100.

On this index, 2024-25 is 78.6. This means that we can estimate that the spending power of these budgets in 2024-25 is around 21.4% lower than the equivalent budgets in 2014-15.

Funding for Gaelic will also come from other sources such as local authorities and national agencies (e.g. Creative Scotland, Education Scotland).

CMS Select Committee inquiry into Minority Languages

The Commons’ CMS Select Committee is currently undertaking an inquiry into Minority Languages. The purpose is to “consider the key factors determining whether a minority language thrives, what the criteria should be for determining official status, and whether there are lessons to be learnt from other countries where there is widespread fluency in more than one language.”

Provisions of the Bill

The SNP’s manifesto in 2021 made a number of commitments in relation to Gaelic and Scots. These included—

supporting more provision of Gaelic Medium Education

continuing to support e-Sgoil, Stòrlann and Sabhal Mòr Ostaig

exploring the creation of “a recognised Gàidhealtachd to raise levels of language competence and the provision of more services through the medium of Gaelic and extend opportunities to use Gaelic in every-day situations and formal settings”

reviewing the functions and structures of Bòrd na Gàidhlig

bringing forward a new Scottish Languages Bill covering both Scots and Gaelic.

The Government undertook a consultation on Gaelic, Scots and a Scottish Languages Bill in 2022. The consultation was broadly drafted and did not contain specific legislative proposals. The current Bill was developed following that consultation.

The Bill is in two substantive parts covering provisions relating to Gaelic and Scots. Within those two parts are Chapters covering support for the languages and education.

The Policy Memorandum that accompanies the Bill states—

The policy objective of this Bill is to provide further support for Scotland’s indigenous languages, Gaelic and Scots … The Bill will strengthen the support for and promotion of Gaelic and Scots by introducing a range of measures that will have implications in a number of sectors in Scottish public life.

(PM Paras 4-5)

The Policy Memorandum provided more detail on the provisions of the Bill and their intended purposes. This paper will briefly set out and discuss the main provisions of the Bill, rather than seek to replicate the Policy Memorandum.

Support for the Gaelic language

Part 1, Chapter 1 of the Bill focuses on the support for the Gaelic language.

Official Status

The purpose of the first section is to declare that Gaelic has official status in Scotland. The Bill states that this will be given effect by:

provisions in the 2005 Act (as amended by the present Bill) in relation to the functions of Bòrd na Gàidhlig, the Scottish Government and others in relation to promoting, facilitating and supporting the language; and

enactments in relation to Gaelic education.

In relation to this provision, the Financial Memorandum states—

The statement is valuable for the prestige and the esteem of the language and value and importance that is placed on the language. However, no financial costs arise for the making of the statement in and of itself.

FM Para 20

National Strategy and Gaelic Plans

A key change to the Gaelic policy landscape that Section 5 of the Bill proposes is that the Bòrd will no longer produce the National Gaelic Plan, rather the Government will produce a National Gaelic Strategy. The Financial Memorandum indicates that the first National Gaelic Strategy will be issued around 2028, at the end of the period covered by the current National Plan.

The Policy Memorandum comments that—

In order to make progress with Gaelic it is essential that there is an agreed set of priorities for the language and that the provision of a Gaelic language strategy will be given increased status by being issued directly from Ministers.

PM Para 19

The Bill provides that both Scottish Ministers and public bodies will be required to have regard to the National Strategy when exercising their functions. Public authorities will be required to have regard to the National Strategy when developing their Gaelic Plans – currently they would have regard to the National Gaelic Plan.

Section 6 of the Bill provides that Ministers can make regulations which set standards for public bodies. The Financial Memorandum states that initially these powers will be used to “move content and requirements that have appeared in statutory guidance and Gaelic language plans into regulations.” (FM para 42)

Section 7 provides for a general duty on public authorities to “have regard to the desirability” of supporting Gaelic and Gaelic culture.

The Bill provides that Ministers can issue guidance on this general duty or on the production of plans. Ministers may also give directions to specific public bodies on their Gaelic Plans or the general duty to consider supporting Gaelic.

The move away from the Bòrd producing National Gaelic Plans to the Government producing a National Strategy may make accountability for outcomes for the language clearer. The Scottish Government sets budgets and having the strategy sitting with the budget-setters may also provide for greater policy coherence. In addition, the powers in the Bill provide the Government with more tools to ensure that public authorities are focusing on the support of Gaelic.

The Role of Bòrd na Gàidhlig

The Bill would change the role of the Bòrd.

As noted previously, the Bill would remove the responsibility to produce the national strategic document. It will also shift the duty to prepare and publish statutory guidance on Gaelic education from the Bòrd to Scottish Ministers

The Bill would also create additional duties on the Bòrd. These include:

reporting on progress on the objectives of the National Strategy

reporting on the compliance with any standards set by Ministers and agreed by Parliament

reporting on public bodies’ fulfilling the general duty to “have regard to the desirability” of supporting Gaelic and Gaelic culture.

The Bòrd would have duties to advise or assist public bodies, or “any person”, on matters relating to the language, Gaelic education, or Gaelic culture. The Bòrd will retain its powers to require public bodies to develop Gaelic language plans.

On 13 December 2019, Audit Scotland published a report under Section 22 of the Public Finance and Accountability (Scotland) Act 2000 on the performance of the Bòrd. The Section 22 report highlighted a number of areas for improvement, particularly relating to governance and transparency.In 2021, Audit Scotland reported that the Bòrd had “tackled weaknesses in its leadership and governance”. The Bill seeks to provide for greater accountability of the Bòrd to Ministers and Parliament through a new duty to prepare a corporate plan.

The Scottish Government’s 2022 consultation found mixed opinions about the Bòrd and its functions. The summary of responses said—

There were mixed views on the duties, functions, and structure of Bòrd na Gàidhlig. Respondents suggested that Bòrd na Gàidhlig requires more funding for its duties. Some stated that the organisation needs to be restructured. A few emphasised the imperative aspect of engaging with communities more to identify the best ways to promote Gaelic. Finally, some respondents were not satisfied with the current operations of Bòrd na Gàidhlig and suggested that it should be disbanded.

Areas of Linguistic Significance

One of the ideas explored in the Government’s 2022 consultation was the creation of a Gàidhealtachd. In this context, this would be a recognised area where there is enhanced support for Gaelic. The SNP’s manifesto stated that a recognised Gàidhealtachd could be used to “raise levels of language competence and the provision of more services through the medium of Gaelic and extend opportunities to use Gaelic in every-day situations and formal settings.”

The Government’s 2022 consultation document noted possible tensions around this suggestion. It stated—

Some regard the term Gàidhealtachd as a specific location to be geographically designated. They would see the aim of this commitment to be to strengthen Gaelic in geographical areas where it is spoken by a significant percentage of the population. The presumption being that there are certain areas where the Gaelic language has a higher profile and that certain language support initiatives should happen in these areas.

At the same time a number of interest groups did not view the delivery of this commitment as a straightforward task. There were questions raised about how this commitment sat with the concept that Gaelic should be for all of Scotland and should be a national language. This was linked to the concern about ongoing support for Gaelic in other areas, such as Glasgow or Edinburgh, that might be defined as non-Gàidhealtachd. There were suggestions that this approach might be divisive, might be difficult for the allocation of grants and if a line was to be drawn on a map it would be difficult to reach agreement on the criteria for this decision.

The analysis of responses to the consultation highlighted the variety of opinions around this proposal and the Bill has taken a different approach. Rather than a nationally defined Gàidhealtachd, the Bill provides local authorities the power to designate part or all of their area as “areas of linguistic significance”. This designation is subject to a consultation and approval by Ministers. The Policy Memorandum said that this approach would ensure that there be support for Gaelic across Scotland while including “the possibility of proportionate support, dependant on the profile of the language in differing areas” (para 35)

The Bill proposes that areas that meet either of the following criteria could be designated an area of linguistic significance:

at least 20% of the population of the area have “Gaelic language skills”

the area:

“is historically connected with the use of Gaelic”

has GME provision, or

has “significant activity relating to the Gaelic language or Gaelic culture”.

One could argue that a very large proportion of Scotland would meet one of those tests.

At this point, it is not clear what a designation would mean for a local authority, or other public authorities, in relation to any additional duties or resources. The Policy Memorandum stated that “designating areas of linguistic significance provides a community framework within which Gaelic language planning activity can take place.” (PM para 49). The Financial Memorandum identifies costs of the designation process but identifies no additional costs to improve the support for Gaelic in those areas.

Gaelic education

The Bill makes a number of changes to the provision of Gaelic education. These include—

expanding rights of parents to seek Gaelic Medium Education in Early Learning and Childcare

including Gaelic education as part of the statutory definition of school education across Scotland.

The Bill would provide for a duty on Ministers to “promote, facilitate and support” Gaelic education. It also would give Ministers a range of powers to set standards and provide guidance on Gaelic education.

Taken together, the Bill seeks to increase local authorities’ focus on the provision of Gaelic education and provides the Scottish Government more tools in which to shape or direct the provision of Gaelic education across Scotland or in local areas.

Access to and Assessment of Gaelic Medium Education

The Bill would extend the process for parents/carers to request an assessment of the need for Gaelic medium primary education from their local authority. This process is set out in the Education (Scotland) Act 2016 and the Bill makes a number of amendments to that Act which extends the process to include Gaelic Medium Early Learning and Childcare.

Section 14 of the 2016 Act provided a power for Ministers to achieve this aim through regulations. It is not clear why the Government have not chosen to use the existing power in the 2016 Act. The Bill would repeal Section 14 of the 2016 Act.

Change to the Definition of School Education

Section 15 of the Bill is titled “General duty to provide education includes Gaelic education”. This section will amend Section 1 of the Education (Scotland) Act 1980 – specifically the subsection which defines “school education” in that Act.

The statutory definition of school education is generally quite broad. On the whole legislation does not specify subjects nor the method of teaching. There are two exceptions – one is the “teaching of Gaelic in Gaelic speaking areas” (the other is Religious Instruction/Observance). The teaching of Science, Maths, Literacy etc is not set out explicitly in statute. The teaching of Gaelic, either GLE or GME, outside of “Gaelic speaking areas” is currently something that any education authority can include as part of the school education for their area.

Section 1(1) of the 1980 Act states—

…it shall be the duty of every education authority to secure that there is made for their area adequate and efficient provision of school education and further education.

Much of the text of Section 1 qualifies this duty, for example, that further education is not education a college might normally deliver which leads to a qualification. The Bill seeks to amend section 1(5). This sub-section defines school education and further education within the 1980 Act; other legislation also refers to definitions within the 1980 Act. Section 1(5) currently reads—

In this Act—

(a) “school education” means progressive education appropriate to the requirements of pupils, regard being had to the age, ability and aptitude of such pupils, and includes—

(i) early learning and childcare;

(ii) provision for special educational needs;

(iii) the teaching of Gaelic in Gaelic-speaking areas;

(b) further education includes—

(i) …

(ii) voluntary part-time and full-time courses of instruction for persons over school age;

(iii) social, cultural and recreative activities and physical education and training, either as voluntary organised activities designed to promote the educational development of persons taking part therein or as part of a course of instruction

(iv) the teaching of Gaelic in Gaelic-speaking areas

The duties on local authorities contained in education law in Scotland are often broadly drawn and open to interpretation. In one of the key textbooks on Education Law in Scotland, Janys Scott KC, reflecting on this subsection, says “as part of ‘school education’, authorities should provide Gaelic in Gaelic-speaking areas.” (Scott 20031). The Bill would amend section 1(5)(a)(iii) to read “Gaelic learner education and Gaelic medium education”; it would amend Section 1(5)(b)(iv) to read “the Gaelic language”.

The Explanatory Notes accompanying the Bill state—

Section 15 of the Bill modifies the 1980 Act so it is clear that the provision of Gaelic learner education and Gaelic medium education comes within the definition of school education, and that therefore an education authority’s duty to secure the provision of adequate and efficient school education for the authority’s area may include Gaelic learner education and Gaelic medium education (inserting definitions of those terms into the 1980 Act to be consistent with the 2016 Act). This no longer applies only in Gaelic speaking areas (which was not defined in the 1980 Act, resulting in potential uncertainty). The teaching of the Gaelic language as part of an education authority’s duty to provide further education also no longer applies only in Gaelic speaking areas.

EN Para 54

The Policy Memorandum further explains—

This section recognises that the geography of Scotland’s Gaelic speaking communities has changed significantly since the Education (Scotland) Act 1980. The Gaelic speaking population is now almost evenly divided between the traditional Gaelic speaking areas within Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Highland Council and Argyll & Bute Council and the Gaelic communities of Glasgow City Council and Edinburgh City Council among other local authorities. The latter areas also constitute some of the language’s greatest areas of growth and the ability to access each form of Gaelic education within them is vital to its sustainability. This provision contributes to the aim of widening the areas in which Gaelic is considered.

PM Para 68

While there have been calls for a right to access GME, it is not the Government’s stated intention that school education must include Gaelic education for all education authorities. Both the Explanatory Notes and the Policy Memorandum state that the duty as amended “may include” the teaching of Gaelic. However, the Bill does not insert the word “may” in relation to the teaching of Gaelic.

If the Government’s intention was to clarify that school education “may include”, rather than “includes”, the teaching of Gaelic, the drafting of the Bill could have more closely matched the wording in the accompanying documents.

The Bill provides that every local authority must “promote, facilitate and support” Gaelic education in school education and adult education provided by local authorities. This creates a broader duty on local authorities than currently. Section 15 of the 2016 Act provides that local authorities must “promote the potential provision” of Gaelic education. Those authorities that provide Gaelic education must “so far as reasonably practicable, promote and support” that provision.

The Bill provides that local authorities must establish catchment areas for schools under their management that provide GME. These catchment areas can differ and overlap from catchment areas for English medium education schools. This provision reflects current statutory guidance.

Ministers' Duties and Powers

Section 11 provides a new duty on Scottish Ministers to “promote, facilitate and support” Gaelic education in school education and adult education provided by local authorities.

Section 12 would provide that Ministers may make regulations which “specify the standards and requirements” for local authorities providing Gaelic education. These regulations may set standards which apply differently to different areas. The Policy Memorandum stated—

Although good progress has been seen in Gaelic education, the provision of standards will address a number of the issues which are still viewed as obstacles in Gaelic medium education and will make clear to parents what can be expected when a young person commences Gaelic medium education. In general, the issues that would be considered as areas that need to be addressed in GME/GLE include the following. GME access to provision and local authority promotion of GME, GME as a 3-18 experience and GME continuity, GME subject choice, curriculum and assessment arrangements, GME teacher recruitment, placement, retention and professional learning, Teacher and pupil support and resources, O-3, early years provision and linguistic acquisition, Class sizes, language assistants, immersion and fluency, Taking account of GME when setting national expectations, Inclusion of GME in the planning for and reporting by schools where GME is provided, Gaelic learner education at all levels and establishing how national bodies and agencies can better work together to support GME and GLE. Some of these have been included in the Statutory Guidance on Gaelic education and will also be addressed in Standards and Strategy.

PM Para 62

The Bill also provides Ministers with the power to issue guidance on Gaelic education to public authorities and to make directions for individual local authorities in relation to their provision of Gaelic education.

Section 2 of the Education (Scotland) Act 1980 provides that Ministers can make regulations “prescribing the standards and to all local authorities in requirements to which every education authority shall conform in” securing school education. The Explanatory Notes argue that specific powers are needed in relation to Gaelic education to allow for differentiation between areas.

Support for the Scots language

Part 2 of the Bill is structured similarly to Part 1.

Under Chapter 1 of the Bill, the Bill declares that Scots “has official status within Scotland”. This is to be given effect “by the provisions in this Act conferring functions on the Scottish Ministers and other persons in relation to promoting, supporting and facilitating the use of the Scots language.” The Bill defines Scots as “the Scots language as used in Scotland”. In relation to declaring that Scots has official status, the Financial Memorandum states—

The statement is valuable for the prestige and the esteem of the language and value and importance that is placed on the language. However, no financial costs arise for the making of the statement in and of itself.

FM Para 103

The Bill provides that Ministers must produce a Scots language strategy. Ministers and Scottish public authorities will have to “have regard to” the strategy in performing their functions. Ministers may also issue guidance. Again, Scottish public authorities will have to “have regard to” this guidance.

Ministers will report on progress of the strategy. Here is a difference between the Scots and Gaelic strategy proposed in the Bill. Progress in the Gaelic strategy will be reported on by Bòrd na Gàidhlig rather than the Government.

The Policy Memorandum noted that the Government had considered establishing a Scots Language public body but had decided against doing so. It said—

There are a number of small Scots bodies operating with support from the Scottish Government. These bodies have considerable expertise and good community links and as a result will be well placed to support and take forward the provisions of this Bill. The Scots bodies also have good working relations with Scottish public authorities in relation to support for Scots.

PM Para 100

Scots Education

The Bill defines Scots language education as “education consisting of teaching and learning in the use and understanding of the Scots language”.

Similar to the chapter on Gaelic education, the Bill provides that Ministers and local authorities have a duty to “promote, facilitate and support” Scots language education. Ministers will also have the power, by regulations, to specify standards and requirements in relation to Scots language education. These regulations may apply differently in different areas. The Bill provides that Ministers may also issue guidance on Scots language education.

The Bill provides for a duty on Ministers to ensure that the “progress made in the delivery of Scots language education in schools” is reported on.

Finance

The Financial Memorandum (FM) sets out the expected additional costs that will arise from the Bill. There is an important distinction to be made here – the FM sets out the costs of taking forward the provisions in the Bill, not the costs of the consequences of those actions. For example, it provides estimates of the costs to develop strategies, but not costs of delivering on those strategies.

The FM states—

The main impact of the Bill provisions is a shift in activity, a repurposing of resources in terms of effort and attention. The Scottish Government considers that provisions do not create wholly new costs or a requirement for wholly new spend.

FM Para 13

The table below shows the expected costs up to 2029-30.

| 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | 2029-30 | Total | |

| Gaelic | 180,500 | 116,000 | 149,000 | 51,000 | 23,000 | 519,500 | |

| Scots | 175,000 | 175,000 | |||||

| Total | 355,500 | 116,000 | 149,000 | 51,000 | 23,000 | 694,500 |

In total, the cost of the Bill is estimated to be around £700,000 over five years. The majority of this funding is additional work for existing public servants. This would be, for example, contributing to national strategies.

The FM also provides an insight into how the Government expects provisions of the Bill to be utilised and sequenced over the first five years of operation. These include—

around five local authorities are expected seek to designate an Area of Linguistic Significance in the first five years

the National Gaelic Strategy is expected to cover the five-year period from 2028

the National Scots Strategy and the statutory guidance will be developed in 2025/26

regulations setting education standards for both Gaelic and Scots are expected around 2025-26.