Scotland's Commissioner Landscape - A Strategic Approach

Scotland has seven commissioners accountable to Parliament, with an eighth approved in September 2023 and six more proposed. Due to the rise in the number, and therefore cost, the Finance and Public Administration Committee has begun an inquiry into Scotland's Commissioner Landscape. This briefing provides insight into the Commissioner landscape in Scotland and in other countries across the UK and internationally.

Summary

Scotland is home to seven independent officeholders, often referred to as commissioners, with an eighth approved in September 2023 and six more proposed. With the rise in the number, and therefore cost, of commissioners the Finance and Public Administration Committee has begun an inquiry into Scotland's Commissioner Landscape. This briefing provides insight into the Commissioner landscape in Scotland and in other countries across the UK (England, Wales, and Northern Ireland) and internationally (Canada and New Zealand).

The complexity of the commissioner landscape

The commissioner landscape is intricate, not just in Scotland, but also across the UK and globally. This complexity can be attributed to several factors, including diverse historical contexts, the powers devolved to individual Parliaments/Assemblies, political systems, and political cultures.

International perspectives and learning

It is crucial to consider the broader international commissioner landscape and draw insights from various models. While doing so, it's important to recognise that these models may not seamlessly apply to all political systems. Nonetheless, given the relatively recent establishment of the Scottish Parliament, there is an opportunity for it to evolve and adopt best practices effectively.

Remit and budget creep

A common occurrence across the countries analysed in this report was commissioners with an increasing remit and budget. In many ways this is unsurprising given many commissioners were created decades previously and even recently there have been far reaching global events.In New Zealand, for example, Covid-19 was raised by the Controller and Auditor General, Ombudsman and Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment as a reason for delayed projects, to extend mandates and increase staffing, and therefore an increased forecast in spending. In Wales, a similar remit creep can be seen, conversely in this case the funding received from the Welsh Government has not been uplifted to reflect the additional roles and responsibilities and/or has not kept pace with inflation. This demonstrates the potential for there to be an effective challenge function in place to ensure that bodies can adequately undertake their required roles, without an assumption that their budgets will increase incrementally year-on-year.

Independence of commissioners

The commissioner model in England highlights the potential compromise of commissioner independence due to their reliance on sponsor departments for budget support, which could hinder their ability to act independently. Additionally, whilst acts for commissioners outline their functions to request cooperation from specified public authorities, a lack of detail on the practical implementation along with a potential lack of public or effective scrutiny raises further questions about their autonomy.

Effective sustainable development models

The Future Generations Commissioner in Wales actively demonstrates how a commissioner can promote sustainable development and encourage long-term decision-making through various key actions and initiatives. This includes championing public participation, challenging the status quo, and supporting improvements in assessing and planning for well-being, as well as providing advice and support to public bodies and public services boards on well-being planning, emphasising the need for an integrated, long-term approach. The commissioner also serves as a guardian for future generations, engages with stakeholders to identify emerging priorities, and chairs a network of institutions for future generations, fostering collaboration and sharing best practices on sustainable development. These efforts collectively highlight the active promotion of sustainable development, encouragement of long-term decision-making, and support for the implementation of the Well-being of Future Generations Act in Wales. The effectiveness of this model, however, may vary across differing political and governance systems due to the potential complexity arising from tailoring structures to Wales' specific context.

Funding mechanisms and accountability

In Canada, ongoing discussions for an independent funding mechanism for the Auditor General underscores the importance of a stable funding mechanism to preserve independence and capacity to respond to an evolving environment. Meanwhile, New Zealand's Crown Entities Act 2004 provides a unique approach to the commissioner landscape by establishing a consistent framework for the establishment, governance, and operation of Crown entities, and clarifying accountability relationships. Similarly, commissioners in Northern Ireland are sponsored by departments, with the Minister and their Department playing a pivotal role in setting the legal and financial framework, including the structure of the commissioner’s funding and governance.

Establishment of new commissioners in Scotland

The interviews carried out by Research Scotland revealed mixed views on whether a new commissioner would be the most effective way to address issues ‘on the ground’ for those with learning disabilities, autism, or neurodiversity. Concerns were raised regarding the potential complexity and confusion that the creation of new commissioners might introduce to an already crowded landscape. Moreover, there were apprehensions about potential overlaps between the functions of existing commissioners if the number of commissioners continued to increase. This is explored in the context of the commissioners with overlapping human rights remits, of which there are several. The responses received to the Committee’s call for views also highlighted that often a commissioner is needed due to a failure of national or local government and that there is a need for a review of the criteria for creating new commissioners to align with the changing public sector delivery landscape.

Governance and oversight in Scotland

The Committee's call for views responses recommended that new bodies undergo explicit scrutiny of costs and potential efficiencies. It was stressed that any new role should align with existing responsibilities and be integrated into current organisational structures. Additionally, there is a need to enhance collaboration and joint working approaches among commissioners with intersecting responsibilities. Furthermore, the responses received to the call for views highlighted the importance of reporting directly to Parliament and the public, ensuring effective and transparent financial planning, and addressing concerns about the value for money of what the commissioners deliver. This will be especially important with the potential addition of new commissioners in future.

Resource allocation and independence in Scotland

A predominant theme was the crucial importance of ensuring that any new commissioner has adequate resources and powers to fulfil their remit. There were concerns raised in the responses to the call for views about the potential lack of resources in a time of tight public resources, possibly affecting the effectiveness of future commissioners. Furthermore, the call for views and a Research Scotland report highlighted the independence of commissioners as being crucial, with the need for a clear remit, adequate resources, and a well-defined induction to enable them to define their role, effectively engage with affected groups, and influence from within the organisation.

In conclusion, the analysis in this briefing presents a diverse range of themes, including the challenges to commissioner independence, the effectiveness of governance models, the importance of stable funding mechanisms, and the accountability relationships within different commissioner systems. These themes underscore the complex and nuanced nature of commissioner governance, emphasising the need for careful consideration and tailored approaches to address the specific challenges and opportunities within each system. In Scotland specifically, there is a potential need for careful consideration in the establishment of new commissioners, effective governance, resource allocation, and the importance of independence to ensure the effectiveness and credibility of commissioners. Additionally, the need for strategic oversight and collaboration among commissioners with intersecting responsibilities is pivotal for their successful operation.

Introduction

Scotland is home to seven independent officeholders, often referred to as commissioners.1

The current seven officeholders are:

Additionally, there are seven new proposed commissioners, including one that has recently been approved:1

Patient Safety Commissioner(Bill passed September 2023)

Victims and Witnesses Commissioner(Bill at stage 1)

Disability Commissioner(Bill at stage 1)

Older People's Commissioner

Wellbeing and Sustainable Development Commissioner

Future Generations Commissioner

Learning Disability, Autism and Neurodiversity Commissioner / Commission

The Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body (SPCB) supports these independent officeholders and sets the terms and conditions of their appointment and annual budget. The SPCB Budget Bid for 2024-25 included £18.296 million for Commissioners and Ombudsman, with individual officeholder budgets ranging from the smallest at £363,000 to £6,708,000.3 This is a 10% increase from the 2023-24 Budget to the 2024-25 budget bid (8.15% in real terms); the main changes in these budgets from 2023-24 reflect changes in the Electoral Commission (EC) and the Scottish Public Services Ombudsmen (SPSO).

This briefing will explore the Commissioner model in Scotland and internationally to support the Finance and Public Administration Committee’s inquiry into Scotland’s Commissioner Landscape.

The Scottish Government defines Parliamentary commissioners and ombudsmen as the following:4

"Parliamentary commissioners and ombudsmen are typically responsible for safeguarding the rights of individuals, monitoring and reporting on the handling of complaints about public bodies, providing an adjudicatory role in disputes and reporting on the activities and conduct of public boards and their members. The jurisdictions of these officeholders usually cover Scottish Government activity, so it is important to ensure independence from the Scottish Ministers.

Parliamentary Commissioners and Ombudsmen are appointed by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body (SPCB) with the approval of the Scottish Parliament. Each office holder is responsible for employing their own staff, who are not civil servants, and managing their own budgets from funding provided by the Scottish Parliament. Whilst these officeholders are independent in function (i.e., in undertaking their respective regulatory responsibilities), they are accountable to and report directly to the Scottish Parliament on the day-to-day operation of their offices (i.e., funding, accounts, staffing arrangements etc.)."

It is worth noting that differing political and government systems, conflicting and overlapping definitions lead to a complex comparison of the commissioner landscape both nationally and internationally. There is no clear definition of what a commissioner is, and other countries covered in this research often use different definitions, different terms, i.e., officeholder, and many do not distinguish commissioners from a wider subsection of independent organisational types such as ombudsman, Auditor-Generals, or other independent statutory entities. Furthermore, the terms 'commissioner' and 'commission' are utilised in various countries to denote a variety of roles distinct from the specific officeholder relevant to the Committee, including regulatory bodies such as the Scottish Water Industry Commission and inquiries on significant public matters like royal commissions/commissions of inquiry, as observed in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. It is important to learn from these other systems whilst bearing in mind their models may not be directly comparable or able to be mapped onto Scotland’s commissioner model.

This briefing will use the following themes as laid out in the Institute for Government Report “How to be an effective Commissioner” and The Scottish Government commissioned report “The role of commissions and commissioners in Scotland and the UK” to determine what ‘commissioners’ and ‘commissioner models’ to use as evidence.56

A commission is an independent public body which functions independently of the government. Commissions are independent, arm's length bodies which scrutinise a particular issue or work to secure the rights of a particular group of people, or in relation to a particular theme.

A commissioner is an individual who advocates for a certain group, generally supported by a team of staff. These are very individual roles, and the individual appointed can make quite a difference to how the role is undertaken.

Often these models can be combined. For example, commissions often have groups of commissioners who serve on their Board.

The roles and responsibilities of commissions and commissioners are generally set out in the law, and the powers commissions have can vary.

A commissioner is not an ombudsman, tsar, regulatory body, or inspectorate, but can have cross-over with some of these roles.5

Research aims and objectives

Detailed objectives of the proposed research

The Finance and Public Administration Committee has launched an inquiry into Scotland’s Commissioner Landscape: A Strategic Approach to better understand how the current model has evolved since devolution, the governance, scrutiny and budget-setting arrangements in place, relationships with government and parliament and whether a more coherent approach to the creation of commissions and commissioners is required.1

This research is intended to support the Committee’s inquiry by looking at the different Commissioner Models in operation in other countries in both the UK and internationally. It considers the following questions for each country.

What is the Commissioner model and is it coherent?

How and why were these roles created?

What are their role and what functions do they fulfil?

How well do they work in practice, including their governance, accountability, scrutiny, funding, and reporting arrangements?

What is their relationship with Parliament and Government?

What are the costs and budget-setting arrangements?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of these Commissioner models?

Importance of identifying international Commissioner models

The research also involves mapping the existing Scottish Commissioners’ functions and duties to identify where duplication exists which the Committee can draw on when considering the coherence of Scotland’s Commissioner model.

Evolution of Commissioner landscape in Scotland

The commissioner landscape in Scotland has significantly evolved since devolution, with the establishment of seven independent commissioners, and the Parliament's recent approval of an additional commissioner. Furthermore, there are six further proposed commissioners being considered, potentially bringing the total to 14 by the end of the current parliamentary session, if approved by Parliament. As such, the Finance and Public Administration Committee states the evaluation of how commissioners work in Scotland is both “timely and necessary” and is needed to “investigate whether a more coherent and strategic approach is needed for the creation of such commissioners in Scotland”.1

Additionally, research carried out by Research Scotland on behalf of the Scottish Government on the establishment of a potential new commission or commissioner for learning disability, autism and neurodiversity found that there was concern from current commissioners, commissions, and their partners about the focus on creating more bodies for specific groups, suggesting that a broader approach focusing on human rights and equality for everyone might be more effective. Furthermore, there were reservations about the potential complexity and ‘busyness’ of the landscape, with a few interviewees highlighting the importance of adhering to the Paris Principles, which establish minimum standards for national human rights institutions.2

In 2006 an independent review by Audit Scotland commissioned by the SPCB was carried out to scrutinise the budgets, the existing lines of accountability and how the current Commissioner/Ombudsman work in practice. Considering the resources available in the offices of those commissioners and ombudsman already established, the review concluded that Parliament (and the Executive as appropriate) should consider "…whether the role being created is complementary to the responsibilities of existing office holders and could therefore potentially be subsumed into existing organisational structures."3

The Deputy First Minister's letter to the Committee on 7 March 2024 outlines the Scottish Government's Ministerial Control Framework (MCF), which aims to ensure evidence-based and cost-effective decision-making in the establishment of new public bodies amid significant pressure on public spending. The MCF is guided by three key principles:

Last Resort: New public bodies should only be established as a last resort according to the Scottish Government's policy.

Exhaustion of Other Delivery Mechanisms: The approval process for setting up a new public body through the MCF should only follow after considering all other delivery mechanisms.

Formal Cabinet Approval: Formal approval from the Cabinet must be sought before any decision or announcement regarding the establishment of a new public body.4

Additionally, a 2006 report on Accountability and Governance by the former Finance Committee in Session 2 also recommended that MSPs should follow specific criteria when deciding whether to propose the creation of a Commissioner:

Clarity of remit: a clear understanding of the officeholder's specific remit.

Distinction between functions: a clear distinction between different functions, roles and responsibilities including audit, inspection, regulation, complaint handling, advocacy.

Complementarity: a dovetailing of jurisdictions creating a coherent system with appropriate linkages with no gaps, overlaps or duplication.

Simplicity and Accessibility: simplicity and access for the public to maximise the 'single gateway'/'one-stop-shop' approach.

Shared Services: shared services and organisational efficiencies built in from the outset.

Accountability: the establishment of clear, simple, robust, and transparent lines of accountability appropriate to the nature of the office. 5

Mapping of existing Commissioner functions and duties in Scotland

Current Commissioner model

In Scotland, commissioners are created through a process involving legislation and parliamentary approval.1 The creation of commissioners is a significant aspect of the devolved powers of the Scottish Parliament, and it follows a structured and transparent procedure.

Legislative Process

Committee Consideration

Consultation and Stakeholder Engagement

Parliamentary Debates and Voting

Royal Assent

Implementation and Operationalisation

Ongoing Scrutiny and Evaluation

This process reflects the democratic and transparent approach to the establishment of commissioners. Detail on the individual roles, responsibility, and scrutiny (where applicable) of the Scottish Commissioners can be found in Annex A.

Current Commissioners & budgets

*2024-25 budget bid vs 2023-24 approved budget

**Calculated using the Real Terms Calculator. The 23-24 budget is put in 24-25 terms.

***Co-location accommodation costs for SPSO, CYPCS, SHRC and SBC are accounted for through the SPSO's budget and annual accounts.

Proposed Commissioners

In addition to the current seven commissioners, an eighth commissioner, the Patient Safety Commissioner, was agreed by Parliament in September 2023. Moreover, there are proposals for both Members Bills and Scottish Government Bills that could see the creation of additional commissioners. They are as follows.

Victims and Witnesses Commissioner (Bill in stage 1)

Disability Commissioner – (Bill in stage 1)

Older People's Commissioner – Member

Future Generations Commissioner - Scottish Government

Learning Disability, Autism and Neurodiversity Commissioner / Commission – Scottish Government

Identification of duplication in functions and duties

Duplication in functions and duties of commissioners in Scotland has been a topic of concern, prompting the need for a strategic and coordinated approach to commissioning. One of the key concerns raised is the potential for overlap and duplication of functions among different commissioners and across other organisations in Scotland. This concern is particularly relevant as the number of commissioners continues to grow, potentially increasing the risk of duplication.

In addition to the risk of duplication, there is a need to ensure that commissioners deliver value for money and effectively address the needs of the population. This involves addressing the potential risks associated with duplication and working towards enhancing the efficiency, effectiveness, and impact of commissioners in addressing critical societal issues.

Furthermore, the call for greater accountability and oversight emerged as a critical aspect of addressing duplication in functions and duties. Establishing robust governance structures and mechanisms for evaluating the performance and impact of commissioners can help enhance transparency and accountability. This, in turn, enables the identification and resolution of instances of duplication, thereby improving the overall effectiveness of commissioners.

The following tables show the current and proposed commissioners, their remits, and their potential overlap with other commissioner and public bodies. In some cases, there may be a duplication of duties however in others there may be potential for commissioners to work in tandem and with other organisations to deliver their functions more efficiently and effectively.

| Officeholder | Remit | Potential Overlap -Commissioners | Potential Overlap -Public Bodies |

| Commissioner for Children and Young People in Scotland | The Commissioner protects and promotes the human rights of children and young people. This includes reviewing law, policy, and practise in relation to the rights of children and young people, promoting best practise, researching issues around children and young people's human rights, investigating issues affecting children's human rights, and reporting to the Scottish Parliament on their work. | Scottish Commission for Human Rights | Children's Hearings Scotland (CHS)Independent Living Fund ScotlandPoverty and Inequality Commission |

| Scottish Commission for Human Rights | The Commission promotes awareness, understanding and respect for all human rights – economic, social, cultural, civil, and political – to everyone, everywhere in Scotland, and to encourage best practice in relation to human rights. The Commission has powers to recommend changes to law, policy, and practice; promote human rights through education, training, and publishing research; and to conduct inquiries into the policies and practices of Scottish public authorities. The Commission is the only Scottish organisation that can make direct contributions to the UN Human Rights Council. | Equality and Human Rights CommissionDisability CommissionerCommissioner for Children and Young People in ScotlandOlder People’s CommissionerLearning Disability, Autism and Neurodiversity Commissioner / CommissionThe Independent Anti-Slavery CommissionerSocial Mobility Commission | The Mental Welfare Commission for ScotlandPoverty and Inequality Commission |

| Scottish Public Services Ombudsman | The role of the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman is to investigate complaints about public services in Scotland, including government agencies, local councils, the National Health Service, and a range of other public bodies, to ensure fair and transparent resolution, thereby upholding standards and promoting trust in public services. The Ombudsman also works to drive improvements in public service delivery by identifying and addressing systematic issues and contributing to the enhancement of administrative justice in Scotland. | Victims and Witnesses CommissionerPatient Safety Commissioner |

| Officeholder | Remit* | Potential Overlap -Commissioners | Potential Overlap -Public Bodies |

| Patient Safety Commissioner | The commissioner's role is to advocate for systemic improvements in healthcare safety and to promote the importance of patient and public input, including gathering information, making recommendations, and fostering coordination among healthcare providers. | Scottish Public Services OmbudsmanEquality and Human Rights Commission | Healthcare Improvement Scotland |

| Victims and Witnesses Commissioner | The commissioner's role is to protect and promote the rights of victims and witnesses, advance their voices, influence change, ensure that criminal justice agencies meet their responsibilities under the Victims' Code, and abstain from championing or intervening in individual cases. | Scottish Public Services Ombudsman | Community Justice ScotlandPolice Investigations & Review CommissionerScottish Police AuthorityScottish Criminal Cases Review Commission |

| Disability Commissioner | The commissioner's role is to promote and safeguard the rights of disabled people, advocate for them at a national level, review laws, policies, and practices related to their rights, promote best practices among service providers, and conduct investigations into service providers related to matters within the remit of the devolved institutions, focusing on how they have addressed the rights, views, and interests of disabled people. | Scottish Commission for Human RightsLearning Disability, Autism and Neurodiversity Commissioner / CommissionEquality and Human Rights Commission | Independent Living Fund ScotlandThe Mental Welfare Commission for ScotlandPoverty and Inequality CommissionMobility and Access Committee |

| Older People’s Commissioner | The commissioner's role is to raise awareness of the interests of older people in Scotland, promote opportunities for, and eliminate discrimination against, older people, encourage best practice in their treatment, review the adequacy and effectiveness of laws affecting their interests, and undertake investigations into how service providers consider the rights, interests, and views of older people in decisions and work related to devolved matters. | Scottish Commission for Human RightsEquality and Human Rights Commission | Independent Living Fund ScotlandPoverty and Inequality Commission |

| Wellbeing and Sustainable Development Commissioner | The role of the Commissioner is to ensure compliance with the proposed Bill, hold public bodies accountable, oversee relevant Acts, provide advice, make recommendations, and contribute to legislative reviews and reform, with a focus on achieving the National Outcomes and meeting the values and aspirations of the people of Scotland. | Future Generations Commissioner | Highlands and Island EnterpriseScottish Law CommissionPoverty and Inequality CommissionScottish Futures Trust |

| Future Generations Commissioner | The role of the commissioner, who acting on behalf of future generations would be empowered to hold public bodies, including Ministers, to account as well as provide support in relation to the delivery of wellbeing, sustainable development, and future generations outcomes. | Wellbeing and Sustainable Development Commissioner | Highlands and Island EnterprisePoverty and Inequality CommissionScottish Futures Trust |

| Learning Disability, Autism and Neurodiversity Commissioner / Commission | The role of the Commissioner is to oversee the protection of the rights of individuals with learning disabilities and autism, ensure compliance with new laws, and address concerns related to policy implementation, thereby promoting inclusivity and support for neurodivergent individuals in Scotland. | Scottish Commission for Human RightsDisability Commissioner | Independent Living Fund ScotlandThe Mental Welfare Commission for ScotlandPoverty and Inequality CommissionMobility and Access Committee for Scotland |

* The list is not exhaustive of the activities in which the Commissioner might engage.

The potential overlap between commissioners as well as other public bodies is most prominent in commissioners with roles related to human rights. This is due to the broad nature of human rights and the defining legislation. The Equality and Human Rights Commission protects those rights set out in the Human Rights Act 1998 and the Equality Act and the Scottish Human Rights Commission protects those rights set out in the Human Rights Act 1998. A non-exhaustive list of rights in both acts is listed below.

| Rights listed in the Human Rights Act 1998: | Protected Characteristics listed in the Equality Act: |

|

|

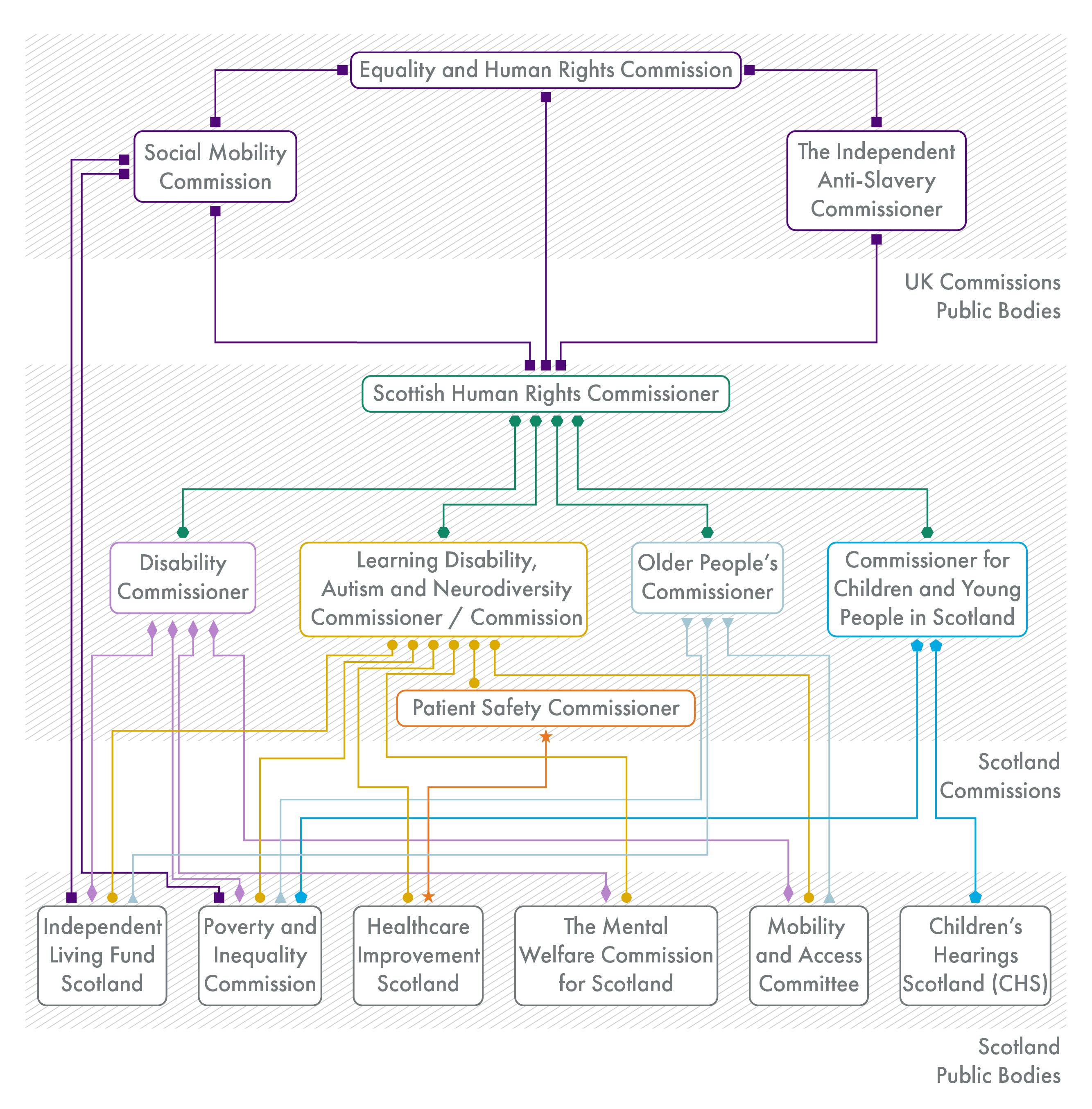

Several of the rights and protected characteristics covered by the Equality and Human Rights Commission and Scottish Human Rights Commission can be seen in the functions of current and proposed commissioners as well as other public bodies that work in Scotland. The figure below details the potential overlap between the commissioners and other public bodies as well as the complexity of the landscape. Please note that that this figure is not exhaustive.

Considerations for the coherence of Scotland's Commissioner model

Research commissioned by the Scottish Government included interviews with commissions, commissioners and partners which provided some insight into the potential implications of additional commissioners in Scotland. Although the interviewees were asked in the context of a potential new commission or commissioner for learning disability, autism and neurodiversity, their insights can be considered more broadly.1

Interviewees welcomed additional resources however, there were mixed views on whether a commissioner was the best way to address the issues. A few said it was important to think about what difference having a commission or commissioner would make tangibly, on the ground for people with lived experience.

Interviewees highlighted that the landscape was already quite complicated and busy, and the creation of more commissioners could further complicate the situation.

There were also concerns about potential confusion and uncertainty among the public regarding which commissioner applies to them, as well as the possibility of individuals being pushed between commissioners.

Interviewees stressed the importance of ensuring that any new commissioner complements existing activity and does not duplicate powers or take away powers from existing commissioners. There were concerns that having more commissioners could lead to issues with investigating cases that fall under the remit of another body, potentially creating more challenges in this regard.

Furthermore, interviewees underscored the need to consider other options for strengthening human rights for people with autism, learning disability, and neurodiversity, such as better resourcing existing organisations, supporting good practice through standards and guidance, and investing in co-production of policy and practice with the affected communities. Some interviewees suggested that adding resources to existing human rights organisations equivalent to establishing a new commissioner could be transformative.

The Institute for Government’s report “How to be an effective commissioner” lays out several recommendations that are relevant when it comes to Scotland’s commissioner model and specifically setting up or recruiting new commissioners. The following is directly taken from their report.

Give the commissioner a well-defined but not overly restrictive remit, be clear where they fit in and organise a proper induction. A clear remit will allow the appointee to define the role and be able to respond to emerging concerns while avoiding overstretch and conflict with other bodies. A well thought through induction, which draws on the experience of previous commissioners, should enable them to hit the ground running, help someone coming in with little experience of government understand better how government works and how to make an impact and help them understand their formal responsibilities as Accounting Officer.

Ensure that the role has adequate resources and powers to fulfil its remit. There is nothing more frustrating for external groups than raising expectations that the role will make a difference and then under-resourcing it to perform its functions. So, the powers of a commissioner – particularly in relation to co-operation from public bodies, and information provision – and their statutory basis are important, as is staff resource, the ability to commission independent research and to publicise the role and reach out to involve affected groups. Assurance on future budgets may be an important element of this – to avoid any suggestion that a department might seek to curb a critical commissioner by reining in their budget.

Appoint an individual who has credibility with represented groups and can manage complicated relationships. These are highly individual appointments – very different from chair/chief executive roles. The appointee needs to be able to hold their own with campaign groups but also be seen as a credible voice for their concerns. They also need to be politically savvy enough to manage the complicated web of relationships and know when to influence from the inside and when to go public.

Reinforce the independence of the commissioner. Commissioners are effective only if they are genuinely independent of government. That means they must be able to investigate without needing to seek permission or resource from the department; be able to publish reports under their own authority, rather than going through the department; and have a direct link to parliament, particularly relevant select committees. There may also be a case for considering which department acts as sponsor – to make it a department that will not be the prime focus of the commissioner’s work and consider a single, longer-term appointment to allow them to do the job unhindered by the need to consider reappointment.

Take commissioner recommendations and input seriously – and be seen to do so. There is no point in establishing a commissioner to give voice to under-represented groups if government is not committed to responding to recommendations and listening to what they say. That means there should be a formal commitment to respond to reports within a limited time period, as well as to involve the commissioner in advance in relevant policy discussions. If the department – particularly the sponsor department for the commissioner – does not take them seriously they will rapidly lose credibility in the role.

The Finance and Public Administration Committee launched a call for views for this inquiry which offered valuable perspectives on the present and evolving commissioner model in Scotland. The Committee received 23 submissions to the call for views, all of which were from organisations. A full summary is being published separately; the submissions contained the following key themes.

Commissioners are used to hold those with power accountable due to an accountability gap in Scotland.

Independence is a crucial aspect of why commissioners are preferred over government ministers or departments.

Commissioners are created to address the perceived failing of authorities and public bodies to deliver functions.

Future commissioners may lack resources in a time of tight public resources, potentially affecting their effectiveness.

Reporting directly to Parliament is preferred, but it may also be preferable for commissioners to report to the public.

The current approach to commissioning in Scotland is not coherent and needs improvement.

The criteria for creating new commissioners should be reviewed to meet a much-changed public sector delivery landscape.

It is difficult to determine the value for money of what the commissioners deliver.

The annual budget process is problematic, making medium to longer-term financial planning difficult.

Concerns were raised about potential overlaps between the functions of existing Commissioners if the number of Commissioners continues to increase.

There is a potential need for enhancing collaboration and joint working approaches among commissioners with intersecting responsibilities.

An independent review of Commissioners and Ombudsman was carried out by Audit Scotland commissioned by the SPCB in 2006. Despite the commissioner landscape changing in Scotland since the date of this review, its recommendations remain relevant especially with the potential overlap in remits of proposed Commissioners.2

During the establishment of new bodies, ensure that explicit scrutiny of costs and potential efficiencies from shared services is an integral part of the pre-legislative phase, including assessing if the new role aligns with existing responsibilities and can be integrated into current organisational structures.

Utilise existing structures and processes where feasible to minimise bureaucracy and unnecessary organisational complexity.

Grant the SPCB the explicit responsibility, powers, and resources to strategically oversee the business operations of the Ombudsman and Commissioners, while safeguarding the independence of office holders and minimising any perception of compromise.

Assess the need for amending the legislation that established the Ombudsman and Commissioners.

Comparative analysis of international Commissioner models

This section introduces an international comparative analysis of Commissioner models across various countries, supplemented by a case study to enrich the understanding of their structures and functions. By examining the diverse approaches employed to fulfil regulatory and investigative roles in nations including England, Wales, Northern Ireland, Canada, and New Zealand, this analysis seeks to identify commonalities, disparities, and best practices in international commissioner models. The inclusion of a specific case study example of the human rights commissioner, ahead of looking at country models in detail, aims to provide practical insights into the application of these models in real-world contexts, fostering a comprehensive understanding of their efficacy and adaptability across different jurisdictions.

Comparative case study – Human Rights Commissioner

Human rights are an important issue for all the countries examined in this paper, and all had a Human Rights Commission or Commissioner. However, the power, roles, and remits have differences. Additionally, there are also differences between them relating to their governance, accountability, scrutiny, funding, and reporting. The table below illustrates the commonalities and variations between countries’ commissioner models.

The Commissioners in all countries listed are independent and have similar remits centred around promoting and protecting human rights with some also including equality. Their roles also include the power to investigate and resolve complaints related to human rights and discrimination. The Commissioners for all countries are funded by their respective government and accountable to their respective parliament, however some are governed by boards. Their budgets are set by their respective Parliaments, and they are all required to submit annual reports. These reports vary somewhat in what they include, some containing reporting on the commissioner’s activities, the state of human rights in their country, and recommendations to the government.

| Country | Powers and Role | Governance, Accountability, and Funding | Reporting and Scrutiny | Budget Setting Arrangements |

| New Zealand Human Rights Commission | Promotes and protects human rights, resolves complaints of discrimination and breaches of human rights. | Accountable to the New Zealand Parliament, the commission is funded by the government. | It reports annually on the state of human rights in New Zealand and its activities. | Set by the New Zealand Parliament. |

| Canadian Human Rights Commission | Investigates and tries to settle complaints of discrimination, is accountable to the Parliament of Canada. | Accountable to the Parliament of Canada, the commission is funded by the federal government. | It reports on its activities and the state of human rights in Canada annually. | Set by the Parliament of Canada. |

| Northern Ireland Human Rights Commissioner | Promotes awareness and understanding of rights, reviews legislation, and operates independently. | The Commission is a non-departmental public body and receives grant-in-aid from the United Kingdom government through the Northern Ireland Office. It reports to Parliament through the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. | The commissioner submits an annual report to the Northern Ireland Assembly. | Allocated by the UK Government through the Northern Ireland Office, with the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland passing the agreed funding to the Commission as approved by the Westminster Parliament. |

| England, Scotland & Wales Equality and Human Rights Commission | Enforces equality legislation, promotes, and monitors human rights, and has the authority to scrutinise public authorities’ compliance with human rights laws. | Governed by a board, the commission is accountable to the UK Parliament and receives funding from the government. | It is required to report on its activities and make recommendations to the government. | Set by the UK Parliament. |

| Scottish Human Rights Commission | Holds the power to review the compatibility of Scottish Parliament legislation with human rights, and it plays a significant role in promoting human rights and offering advice and guidance. | Governed to ensure its independence and effectiveness, the commission is funded by the Scottish Government, and it is required to report annually on its activities and the state of human rights in Scotland. | The commission is mandated to report annually on its activities and the state of human rights in Scotland. | Set by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body (SPCB). |

Commissioner models in the UK

England/UK-wide

There are several commissioners and other similar bodies that have remits specific to England or that operate across the whole of the UK. Those that function in a similar way to officeholders in Scotland are set out in the Table below. Some also have equivalents with similar remits in Scotland.

| Office | Created | Legislation | Role |

| Electoral Commission | 2001 | Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 | The role of the Electoral Commission is to oversee and regulate elections and referendums in the United Kingdom, ensuring their fairness, transparency, and integrity. |

| Children’s Commissioner for England | 2004 | Children Act 2004Children and Families Act 2014 | The Children’s Commissioner for England is responsible for promoting and protecting the rights of children, including advocating for their interests to be considered in policies and decisions. |

| Victims’ Commissioner for England and Wales | 2004 | Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004 | The role of the Victims’ Commissioner for England and Wales is to promote the interests of victims and witnesses of crime, ensuring that their needs are recognised and addressed within the criminal justice system. |

| Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner | 2015 | Modern Slavery Act 2015 | The role of the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner is to encourage good practice in the prevention, detection, investigation, and prosecution of modern slavery offenses, and to work closely with various agencies to ensure the coordinated and effective handling of modern slavery issues across the UK. |

| Domestic Abuse Commissioner | 2019* | Domestic Abuse Act 2021 | The role of the Domestic Abuse Commissioner is to champion the rights and interests of victims and survivors of domestic abuse, and to hold the government and relevant authorities accountable for their response to domestic abuse issues in England and Wales. |

| Equality and Human Rights Commission | 2007 | Equality Act 2006 | The Equality and Human Rights Commission is responsible for enforcing equality and non-discrimination laws in the UK, as well as promoting and protecting human rights. It also provides guidance and support to individuals and organisations to ensure compliance with equality and human rights legislation. |

*On 18 September 2019, Nicole Jacobs was appointed as the Designate Domestic Abuse Commissioner and her powers came into force in 2021, and in 2022.

Governance, accountability, scrutiny, funding, and reporting

The Commissioners operate as autonomous non-departmental public bodies (NDPB). The parameters for accountability and governance of NDPBs are established in framework agreement documents, which outline the relationship between these bodies and their respective sponsor departments.

In the case of the Equality and Human Rights Commission the governance and accountability is as follows. Its sponsor department is the Department for Education (DfE) (since 2015) The Permanent Secretary of the Department for Education serves as the accountable officer to the Parliament and oversees the allocation of funds to the Commission, ensuring regular oversight. The Government Equalities Office acts as the government sponsor for the Commission, with the director holding formal lead responsibility for the relationship with the Commission's CEO and accounting officer. The Commission's Board, comprising 10-15 commissioners, is responsible for strategic direction and oversight, with the CEO being accountable to various stakeholders and responsible for the day-to-day operations.1

The establishing Acts for the Children’s Commissioner, Victim’s Commissioner, Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner and Domestic Abuse Commissioner set out that the Secretary of State is responsible for making “payments to the … Commissioner of such amounts, at such times and on such conditions (if any) as the Secretary of State considers appropriate”. 2In the case of the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, before the beginning of each financial year the Secretary of State must specify a maximum sum which the Commissioner may spend that year.3

Commissioners are responsible for providing annual accounts to the Secretary of State and the Comptroller and Auditor General.

The Victims Commissioner, Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner and Domestic Abuse Commissioner are also responsible for providing an annual report on the carrying out of its functions.35 The Victim’s Commissioner to the Secretary of State for Justice, the Attorney General, and the Secretary of State for the Home Department, the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner to the Secretary of State, the Scottish Ministers and the Department of Justice in Northern Ireland and the Domestic Abuse Commissioner to the Secretary of State. The Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner and Domestic Abuse Commissioner must also prepare a strategic plan and submit it to the Secretary of State and have it approved by the Secretary of State. In the case of the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, the plan must:

State the Commissioner’s objectives and priorities for the period to which the plan relates.

State any matters on which the Commissioner proposes to report during that period.

State any other activities the Commissioner proposes to undertake during that period in the exercise of the Commissioner’s functions.3

The creating Acts for the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner and Domestic Abuse Commissioner also state that the Commissioners may request a specified public authority to co-operate with the Commissioner in any way that the Commissioner considers necessary for the purposes of the Commissioner’s functions however it does not detail how this should be done.

The funding of UK wide commissioners is somewhat more complicated. For example, the electoral commission can receive funding from UK Parliament, Secretary of State, Scottish Ministers, Welsh Consolidated Fund, Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body, Welsh Ministers, and Senedd.7

Considerations

The use of sponsor departments has the potential to compromise the independence of a commissioner. An Institute for Government report explains:8

The ability of commissioners to act independently can be hampered by the fact that they often rely on the department they are supposed to challenge for budget support. Some have to go through their sponsor departments before they can lay their reports through parliament, something they would prefer to be able to do under their own authority. In his resignation letter, the previous Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner cited Home Office interference, commenting that ‘at times independence has felt somewhat discretionary from the Home Office, rather than legally bestowed’.

Although several of the creating Acts for commissioners include sections on the functions commissioners have to request a specified public authority to co-operate with the Commissioner, there is a lack of detail on how this would work in practice.

Wales

In Wales, there are four commissioners:

Children's Commissioner for Wales: The Children's Commissioner for Wales is responsible for promoting and safeguarding the rights and welfare of children in Wales, as well as ensuring that their voices are heard, and their interests are represented.

Older People’s Commissioner for Wales: The Older People’s Commissioner for Wales works to promote and protect the rights and interests of older people in Wales, addressing issues that affect their well-being and quality of life.

Welsh Language Commissioner: The Welsh Language Commissioner promotes and facilitates the use of the Welsh language, ensuring that organisations and public bodies comply with Welsh language standards and that the rights of Welsh speakers are protected.

Future Generations Commissioner for Wales:The Future Generations Commissioner for Wales focuses on ensuring that the interests of future generations are considered in decision-making processes, promoting sustainable development and the well-being of future generations.

These commissioners were created through the following process, which is similar to the approach that has been followed in Scotland:

Identify the need: Identify a specific area where a commissioner is needed to oversee and advocate for rights or interests. This could arise from social, legal, or political concerns within Wales, similar to how commissioners are proposed in Scotland.

Legislative proposal: Develop a legislative proposal outlining the establishment of the commissioner's office, including their role, powers, and responsibilities. This proposal is typically drafted by the Welsh Government or a Member of the Senedd (MS).

Introduction to Senedd: The legislative proposal is introduced to the Senedd, Wales' parliament, as a bill. The bill is assigned to a relevant committee for scrutiny and examination.

Committee review: The committee examines the bill in detail, holds consultations, gathers evidence, and may make amendments to the proposed legislation based on feedback and expert opinions.

Debate and vote: Following committee review, the bill is presented to the full Senedd for debate and voting. Members of the Senedd discuss the bill's merits, potential impacts, and any proposed amendments before voting on its approval.

Passage of legislation: If the bill receives majority support in the Senedd, it is passed into law. This legislation formally establishes the commissioner's office and outlines their mandate.

Appointment process: The Welsh Government initiates the process of appointing the commissioner as outlined in the newly passed legislation. This typically involves a selection process based on specified criteria and may include public consultations or interviews.

Commissioner takes office: Once appointed, the commissioner assumes office and begins fulfilling their duties as outlined in the legislation. They may engage in advocacy, oversight, investigation, and other activities related to their mandate.

Governance, accountability, scrutiny, funding, and reporting

In Wales, oversight of commissioners is primarily provided by the Welsh Government. The Welsh Government ensures that commissioners operate within their defined mandates, adhere to relevant legislation, and effectively utilise allocated budgets. Additionally, oversight may come from specific government departments or bodies responsible for the respective areas covered by the commissioners, such as the Ministry for Children, Young People and Families for the Children's Commissioner or the Welsh Language Board for the Language Commissioner. Furthermore, the Welsh Parliament may provide scrutiny and oversight through committees and inquiries to ensure accountability and transparency in the commissioners' activities.

Future Generations Commissioner for Wales – A holistic approach

The Future Generations Commissioner in Wales demonstrates how a commissioner can promote sustainable development and encourage long-term decision-making through several key actions and initiatives:

Advocacy for sustainable development: The commissioner champions public participation, involvement in decision-making, and challenges the status quo within the public sector to support improvements in assessing and planning for well-being.

Support for public bodies: The commissioner provides advice and support to public bodies and public services boards on well-being planning, emphasising the need for an integrated, long-term approach to effectively assess and challenge public bodies on their contribution to the Well-being of Future Generations Act.

Guardian for future generations: The commissioner serves as a guardian for future generations, highlighting the risks they face and challenging short-term policymaking. This includes producing the first Future Generations Report, setting out how public bodies can think and plan for the future.

Engagement and priorities: The commissioner engages with various stakeholders, identifying emerging priorities such as climate change, economic change, population change, and citizen disengagement. This engagement facilitates a deeper understanding of the needs of communities and individuals, influencing long-term decision-making.

Networking and collaboration: The commissioner chairs a network of institutions for future generations, providing a platform for sharing knowledge, experience, and best practices on sustainable development. This collaboration fosters long-term approaches to decision-making and policy formulation.1

These actions and initiatives demonstrate how the Future Generations Commissioner actively promotes sustainable development, encourages long-term decision-making, and supports the implementation of the Well-being of Future Generations Act in Wales.2

Costs and budget-setting arrangements

The process for costs and budget-setting arrangements for the Commissioners is governed by the relevant creating Act which outlines the funding arrangements, budget setting, and allocation of resources for the office. The Commissioners are funded independently of Welsh Ministers but are accountable to the Welsh Parliament for the use of resources made available to the organisation. The Commissioner is required to submit an annual budget to Welsh Ministers, setting out the estimated financing needed from the Welsh Government to fulfil statutory functions. Welsh Ministers are required to then lay the Estimate, with or without modifications before the Welsh Parliament. Additionally, the Commissioner must prepare a statement of accounts for each financial year, which is then audited by the Wales Audit Office and laid before the Welsh Parliament. The Commissioner's salary is set by the Welsh Ministers, and the salaries of directly employed staff are reviewed annually.

| Office | Created | Legislation | Indicative 24-25*£’000 | Draft Budget 24-25£’000 | Changes£’000 | Change**% |

| Children's Commissioner for Wales | 2000 | Care Standards Act 2000;Children's Commissioner for Wales Act 2001 | 1,675 | 1,591 | -84 | -5.01 |

| Older People's Commissioner for Wales | 2006 | Commissioner for Older People (Wales) Act 2006 | 1,701 | 1,616 | -85 | -5.00 |

| Welsh Language Commissioner | 2011 | Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011 | 3,357 | 3,189 | -168 | -5.00 |

| Future Generations Commissioner for Wales | 2015 | Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 | 1,695 | 1,610 | -85 | -5.01 |

| Total | 8,428 | 3,006 | -422 | -5.00 |

*Each Commissioner has submitted their statutory estimate for 2024 to 2025 as required by the respective Acts by the end of October before the next financial year.

In practice this has shown varying levels of success. In a recent report published by the Welsh Parliament Public Accounts and Public Administration Committee the following was highlighted:

All Commissioners note changes to their roles and responsibilities since the posts were established. However, they report the funding they receive from the Welsh Government has not been uplifted to reflect the additional roles and responsibilities and/or has not kept pace with inflation, changes to the demographic and Welsh Government strategies.

As noted in the table above, budgets have reduced as “a cross-government decision has resulted in a reshaping of indicative spending allocations to provide extra funding and protection for the services which matter most to people and communities across Wales – the NHS and the core local government settlement, which funds schools, social services and social care and other everyday services. Spending more in some areas means that there is less to spend in other areas. This has led to a 5% budget reduction for all four statutory Commissioners in Wales.”3

Considerations

The commissioner model in Wales, exemplified by institutions such as the Welsh Language, Older Persons, and Children's Commissioners, serves as a clear governance approach. This model enables the promotion of sustainable development and encourages public bodies to consider the long-term impacts of their actions, fostering an environment that supports decision-making for the long term. The Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, for instance, is tasked by statute with producing a Future Generations Report every five years, providing an assessment of improvements public bodies should make to meet well-being objectives.4 This approach allows for monitoring and assessment of the extent to which public bodies are meeting their well-being objectives, promoting awareness, encouraging best practices, and providing advice and assistance to public bodies. Additionally, the creating Acts for the commissioners in Wales specify how the new commissioner should work with relevant ombudsman and commissioners and public service boards.

However, one of the potential disadvantages of this model is the potential complexity arising from the need to build structures tailored to Wales' specific context, which may not be directly applicable to other countries or even other parts of the UK.5 While the commissioner model emphasises long-term decision-making and public participation, its effectiveness may vary across different regions and governance systems, necessitating a nuanced approach to its implementation.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland has several non-departmental public bodies (NDPB). An NDPB is a national or regional public body that operates independently but is still answerable to ministers and is not staffed by civil servants. There are two main types of NDPBs: Executive NDPBs, which carry out executive, administrative, commercial, or regulatory functions within a government framework with varying degrees of operational independence, and Advisory NDPBs, established by ministers to provide counsel on specific matters to them and their departments.

The NDPBs that function in a similar way or have a similar remit to commissioners in Scotland are seen below.

| Office | Created | Legislation | Sponsoring Department | Role |

| Northern Ireland Human Rights Commissioner | 1999 | Belfast (Good Friday) AgreementNorthern Ireland Act 1998Justice and Security (Northern Ireland) Act 2007European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 | UK Government Department, The Northern Ireland Office | The Commission's primary role is to make sure government and public authorities protect, respect, and fulfil the human rights of everyone in Northern Ireland. |

| Commissioner for Older People | 2011 | Commissioner for Older People Act (Northern Ireland) 2011 | Department for Communities | Safeguard and promote the interests of older people. |

| Commissioner for Children and Young People | 2003 | The Commissioner for Children and Young People (Northern Ireland) Order 2003 | Department for Communities | Safeguard and promote the interests of children and young persons |

| The Equality Commission for Northern Ireland | 1998 | Northern Ireland Act 1998 | The Executive Office | Provide protection against discrimination on the grounds of age, disability, race, religion and political opinion, sex, and sexual orientation. |

| Commission for Victims and Survivors for Northern Ireland | 2006 | The Victims and Survivors (Northern Ireland) Order 2006 | The Executive Office | Promote the interests of victims and survivors. |

Governance, accountability, scrutiny, funding, and reporting

The above commissions are NDPBs and receive grant-in-aid from the UK government through the Northern Ireland Office. They report to Parliament through the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. The Secretary of State for Northern Ireland is responsible for passing to the Commission the funding agreed by the UK Parliament. The Northern Ireland Office is also responsible for laying annual reports and financial accounts before Parliament.1

Additionally, the commission/er can establish an Audit and Risk Assurance Committee (ARAC) to advise and support the Commissioner as Accounting Officer in the discharge of responsibilities for issues of risk, control and governance and associated assurance.

As stated in their founding legislation, all commissioners are responsible for reporting each year. This includes sending copies of the statement of accounts relating to that year and a report on the carrying out of the functions of the Commissioner during that year. The statement of accounts must be sent to the Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister (the Office), and the Comptroller and Auditor General. The Comptroller and Auditor General must examine, certify, and report on every statement of accounts sent to the Comptroller and Auditor General by the Commissioner under this paragraph, and send a copy of the Comptroller and Auditor General's report to the Office. The Office must lay a copy of the statement of accounts and of the Comptroller and Auditor General's report before the Assembly.

The report on the carrying out of the functions of the Commissioner during that year must be sent as soon as practicable after the end of each financial year. The Commissioner must send to the Office a report giving details of the steps taken by the Commissioner in that year for the purpose of complying with the Commissioner's duty. The Office must then lay a copy of every report sent to it before the Assembly; and send a copy of every such report to the Secretary of State.

Costs and budget-setting arrangements

Although the commissioners are NDPBs, they are sponsored by Departments who provide their budget allocation. For example the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commissioner is sponsored by the UK Government Department and the Northern Ireland Office and the Commissioner for Older People (COPNI) is sponsored by the Department for Communities who provide COPNI with a budget allocation. The relationships between COPNI, the Minister and her Department are governed by the “arm’s length” principle, wherein the primary role of the Minister is to set COPNI’s legal and financial framework including the structure of its funding and governance. These responsibilities are discharged on a day to-day basis on the Ministers’ behalf by the Sponsoring Department, the Department for Communities.23

Considerations

Commissioners in Northern Ireland are sponsored by Departments who provide their budget allocation. Although this relationship is described as ‘arm’s length’ the primary role of the Minister and their Department is to set the legal and financial framework including the structure of the commissioner's funding and governance.

Commissioner models in international contexts

The comparison of commissioner systems internationally is complex due to differing political and government systems and conflicting definitions. The term "commissioner" lacks a clear, universal definition, with different countries using varying terms and often failing to distinguish commissioners from other independent organisational types. Moreover, the use of "commissioner" and "commission" in different countries denotes a wide range of roles, from regulatory bodies to inquiries on public matters. While it's important to learn from these systems, it's crucial to recognise that their models may not be directly comparable or suitable for Scotland's commissioner model.

Canada

There are nine officers responsible directly to Parliament rather than to the government or a federal minister however there is no statutory definition of what constitutes an officer of the Parliament.12Additionally, several Canadian provinces have established their own commissioners, such as the Human Rights Commissioners in Quebec and British Columbia. For consistency, only national commissioners have been included in this research.

| Office | Created | Legislation | Role |

| Auditor General of Canada | 1878 | Auditor General Act Financial Administration Act | Oversees federal government operations and provides independent advice to Parliament. |

| Chief Electoral Officer of Canada | 1920 | Canada Elections Act Referendum Act | Ensures fairness and efficiency in federal elections. |

| Commissioner of Official Languages | 1970 | Official Languages Act | Ensures federal offices comply with the Official Languages Act. |

| Information Commissioner of Canada | 1983 | Access to Information Act | Oversees compliance with the Access to Information Act. |

| Privacy Commissioner of Canada | 1983 | Privacy Act Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act | Protects and promotes privacy rights of individuals. |

| Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner | 2007 | Parliament of Canada Act | Ensures public office holders adhere to high ethical standards. |

| Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada | 1985 | Conflict of Interest Act | Oversees lobbying activities and promotes transparency. |

| Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada | 2007 | Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act | Addresses disclosures of wrongdoing in the federal public sector. |

| Parliamentary Budget Officer | 2006* | Parliament of Canada Act | Provides independent financial and economic analysis to Parliament. |

*Did not become an officer of Parliament until 2017

Additionally, the following do not fall under the same designation as an officer of the parliament however are empowered under an Act and operate independently from government. Both the Accessibility Commissioner and Pay Equity Commissioner sit within the Canadian Human Rights Commission.

| Office | Created | Legislation | Role |

| Canadian Human Rights Commission | 1977 | Canadian Human Rights Act Employment Equity Act 1995 | Administers the law, which protects people in Canada from discrimination when based on any of the 13 grounds such as race, sex, and disability. |

| Accessibility Commissioner | 2019 | Accessible Canada Act | Ensuring that organisations are fulfilling their obligations set out in the Accessible Canada Act and the Accessible Canada Regulations. |

| Pay Equity Commissioner | 2018 | Pay Equity Act | Administers and enforces the Pay Equity Act by leading the Pay Equity Unit, within the Canadian Human Rights Commission |

Governance, accountability, scrutiny, funding, and reporting

The officers of Parliament as well as the Human Rights Commission are responsible directly to Parliament, reinforcing their independence from the government of the day. These officers carry out duties assigned by statute and report to one or both chambers of Parliament.2

These officers are appointed by the Governor in Council by commission under the Great Seal, and their appointment is approved by one or both houses of Parliament through a resolution. They hold office for a guaranteed term as per statute and can be removed from office by a resolution of one or both houses. They report directly to Parliament, maintaining independence from the government.

The officers support both houses in their accountability and scrutiny functions by carrying out independent oversight responsibilities assigned to them by statute. They are responsible for providing analysis and reports to the Senate and the House of Commons on various matters of national significance, such as government estimates, national finances, and election campaign proposals.

The Officers of Parliament seek funding from the government for their operations. The funding is allocated through the Budget process and Treasury Board and is subject to approval by Parliament. This process involves seeking authority from Parliament for the supply of funding, either through a supply bill, which becomes an appropriation act upon royal assent, or through separate enabling legislation. The authority sought in a supply bill is scrutinised by parliamentary committees, with appropriations allotted by a departmental vote structure. Officers of Parliament, such as the Auditor General and the Parliamentary Budget Officer, support parliamentary scrutiny of government spending. The entire process, from policy approval by Cabinet through to consideration by Parliament, involves various stages, including Treasury Board approval, Budget decision, and parliamentary approval of funding through an appropriation act or separate legislation.4

This established funding mechanism ensures that the Officers of Parliament have the necessary financial resources to carry out their mandated responsibilities while upholding their independence and accountability. However, there have been discussions and efforts to establish an independent funding mechanism that reflects the independent role played by these officers, ensuring their financial independence and impartiality. This call for independence in funding has garnered support from other parliamentary watchdogs, emphasising the need for an independent process for funding, although the exact model is yet to be defined. The ongoing discussions and advocacy for independent funding mechanisms for Officers of Parliament underscore the importance of maintaining their independence and impartiality in fulfilling their oversight and accountability functions.5

Costs and budget-setting arrangements

Each year, each Officer of Parliament presents a Departmental Plan as part of the budget process. It includes budgetary spending for the current year as well as planned spending for current year and two following years. The table below shows the spending of a subsection of Officers of Parliament. Numbers are presented in Canadian Dollars (CAD).

| Office | 2024-25 Budgetary spending (Main Estimates) CAD | 2024-25 planned spending CAD | 2025-26 planned spending CAD | 2026-27 planned spending CAD |

| Auditor General of Canada | 127,415,620 | 127,534,214 | 128,234,214 | 126,230,714 |

| Chief Electoral Officer of Canada* | 259,288,288 | 259,288,288 | 195,833,290 | 152,170,542 |

| Commissioner of Official Languages | 25,354,225 | 25,354,225 | 24,423,802 | 24,452,644 |

| Information Commissioner of Canada | 17,169,646 | 17,169,646 | 17,239,478 | 17,249,272 |

| Privacy Commissioner of Canada | 33,981,300 | 33,981,300 | 31,752,904 | 31,780,347 |

| Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada | 5,956,000 | 6,154,000 | 5,978,000 | 5,982,000 |

| Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada | 6,066,353 | 6,066,353 | 6,103,397 | 6,110,699 |

| Canadian Human Rights Commission | 37,757,130 | 37,757,130 | 37,066,882 | 37,098,502 |

*During the period the agency will be getting ready to deliver an election under the new representation orders in 343 electoral districts and maintaining a high level of readiness under a minority government context until the latest date that the 45th general election can be called (fall 2025). Investments in digital transformation priorities will also continue. These variations affect only the statutory portion of the funding. As noted in the Financial Framework section, Elections Canada does not forecast planned spending in its Main Estimates related to election delivery activities until the fiscal year of a fixed-date election.

Considerations

The ongoing discussions and advocacy for an independent funding mechanism for the Auditor General of Canada highlight the need for consideration of a long-term, stable funding mechanism to preserve its independence and capacity to respond to an evolving environment.

New Zealand

New Zealand has Crown entities which are an important part of government, set up at ‘arm’s length’ from ministers to deliver a range of government services and make some decisions independently. The New Zealand Public Service Commission explains Crown entities in the following way:1

The legal basis for the way that Crown entities operate is set out in the Crown Entities Act 2004, with further requirements in other legislation including the Public Finance Act 1989 and Public Service Act 2020. In addition, each Crown entity is subject to its own founding legislation.

There are several different types of Crown entity as described in Section 7 of the Crown Entities Act 2004.

Statutory Crown entities must deliver services and functions in accordance with their establishment legislation. They are generally funded to do so through a combination of taxpayer funding, in some cases from fees, charges and levies on users, and in some cases from other sources.

Most statutory Crown entities are governed by boards appointed by a responsible minister. A small number of ‘corporation sole’ Crown entities have a sole member acting as the board and chief executive.

Statutory Crown entity ‘independence’ relates to their statutorily independent functions defined in their establishment legislation. They are not ‘independent’ of the Crown’s ownership interest and may have to give effect to or have regard to a range of directions and policies and whole-of-government directions.

Specifically, statutory Crown entities are expected to respond to priorities and expectations set for them by their responsible minister. They are also subject to a wider range of policies, standards, requirements, and expectations that apply to core government departments, including in areas such as integrity, employment relations and working across organisational boundaries in the delivery of services. These requirements and expectations may vary slightly, dependent on the type of statutory Crown entity.

Statutory Crown entity boards are accountable both to their responsible ministers, and to Parliament, for their performance and use of funds.

The following are the 3 key players in the operation of each statutory Crown entity. An operating expectations framework is set out in the Commission's guidance document ‘It Takes Three’.2

The responsible minister — appoints statutory Crown entity boards (or in the case of independent Crown entities, makes recommendations to the Governor-General to appoint). The responsible minister also sets expectations on delivery priorities and performance, holds the board to account, and is answerable to Parliament for the performance of the statutory Crown entity. Decisions on funding a statutory Crown entity, including the amount of taxpayer funding they receive and the level of any fees, charges, or levies, are generally set by Cabinet or (in some cases) by Parliament.

The statutory Crown entity board — governs the statutory Crown entity to deliver against legal requirements and ministerial expectations, within the budget that has been made available to it. The board appoints and holds their chief executive to account and makes specific decisions for which it has statutory independence. The board is also responsible for monitoring and reporting on the statutory Crown entity’s performance and its use of funds and is accountable to the responsible minister and Parliament.

The monitoring department — provides advice to the responsible minister on the statutory Crown entity's performance. Statutory powers of the monitor (if delegated by minister) are generally limited to requesting information from the board. The monitor also assists the responsible minister in making board appointments and conducts other tasks such as administering the relevant funding appropriation.

Independent Crown entities