The Alcohol (Minimum Pricing)(Scotland) Act 2012 (Continuation) Order 2024

The legislation that introduced minimum unit pricing for alcohol contained a 'sunset clause'. This means the policy will expire on 30 April 2024 unless the Scottish Parliament votes for it to continue. This briefing examines the background to the policy, key areas of debate, the findings of the evaluation and the response of stakeholders.

Summary

Background

The Alcohol (Minimum Pricing)(Scotland) Act 2012 was the Scottish Parliament's second attempt to legislate for the policy of setting a minimum price for a unit of alcohol sold in Scotland. It came into effect on 1 May 2018 and will expire on 30 April 2024 unless the Scottish Parliament votes for it to continue.

Origins of minimum unit pricing

Minimum unit pricing (MUP) draws together research on (a) the relationship between price and consumption of alcohol, with (b) research on the link between consumption and harm.

The idea for MUP came from Swedish research which showed a floor price prevented drinkers from 'trading down' to maintain their overall level of alcohol consumption when prices increased.

Sheffield modelling

Due to the novel nature of the policy, the case for MUP was underpinned by modelling from the University of Sheffield.

This modelling estimated that a 50p unit price would result in a 5.7% reduction in consumption, 60 fewer deaths per year and 1,600 fewer hospital admissions per year.

Passage through the Scottish Parliament

In order to address remaining doubts about the policy, the legislation included a 'sunset clause' and the requirement for the Scottish Government to publish a report on the operation and effect of MUP.

To inform this report, Public Health Scotland (PHS) was commissioned to undertake a comprehensive evaluation of the policy and its impact. The final evaluation report was published in June 2023 and the Scottish Government produced its report in September 2023. This found that there was enough evidence to conclude that MUP had achieved its policy aim.

Evaluation

The evaluation by PHS examined 7 outcomes, including the effect on consumption, health harms, social outcomes and the alcohol industry. PHS concluded that, overall, MUP had a positive impact on health outcomes by reducing alcohol attributable deaths and hospital admissions in men and those living in deprived areas.

It found no clear evidence of substantial negative effects on the alcohol industry, or on social outcomes at a population level.

The link between price, consumption and harm

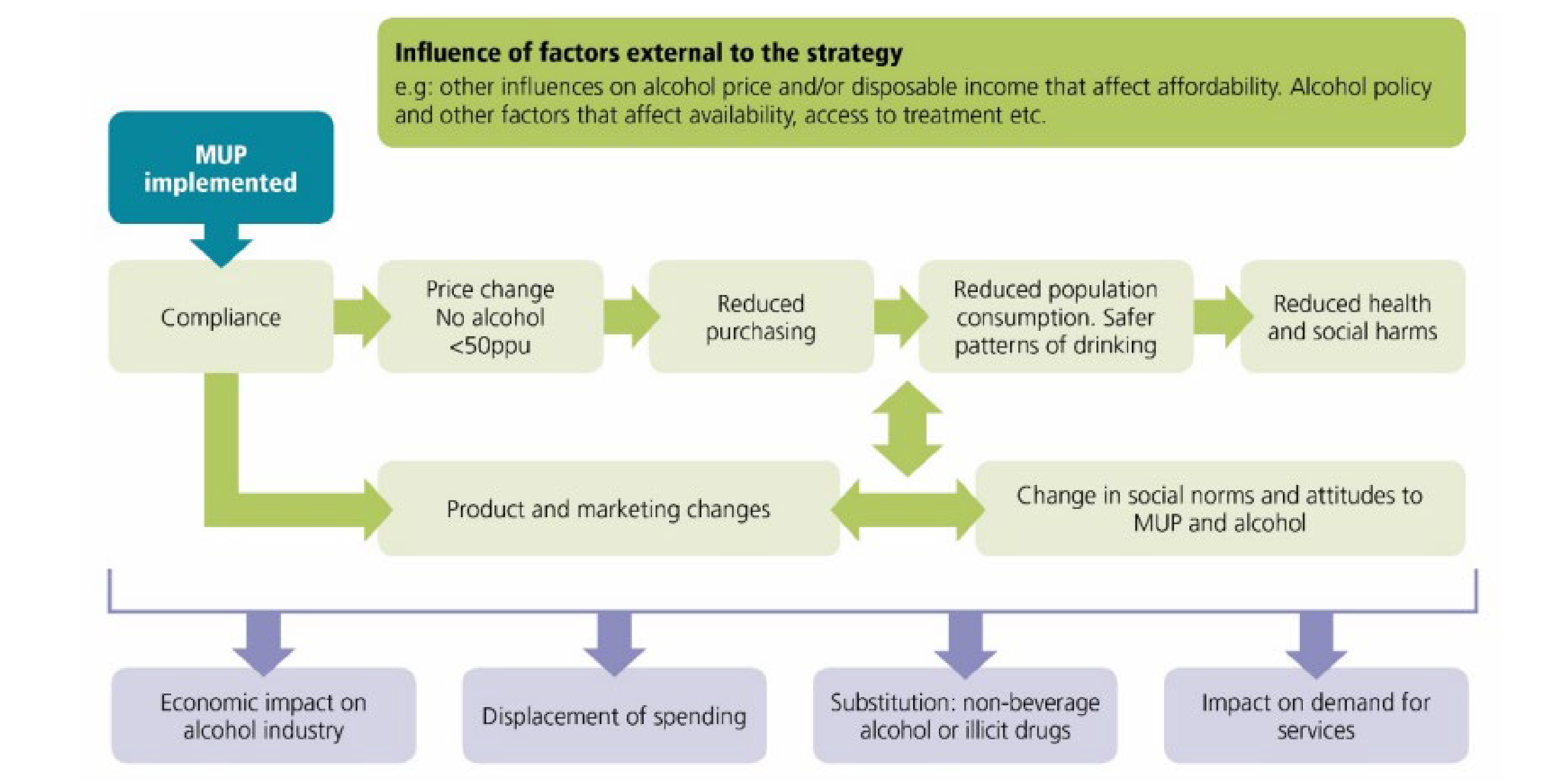

The link between price, consumption and harm forms the basis of the 'theory of change' that underpins MUP. It was also the focus of much debate during scrutiny of the legislation, with some calling into question how straightforward the relationship is.

The PHS evaluation found strong and consistent evidence of a reduction in alcohol consumption in Scotland relative to other areas of Great Britain.

In relation to health harms, the evaluation found a reduction in alcohol attributable deaths relative to England. It also reports a smaller, and less certain, decrease in alcohol attributable hospital admissions.

For other types of health harm (e.g. ambulance call-outs, emergency department attendance) there was no consistent evidence, positive or negative, of a population level effect.

In relation to other social outcomes, such as crime and illicit drug use, the evaluation concluded there is a lack of evidence of an impact at a population level.

These results have led to a continued debate about the effectiveness of MUP.

Those in favour of MUP claim the evaluation provides sufficient evidence that the policy works. Those opposed to MUP criticise the evaluation findings as selective and claim the evidence is not conclusive.

These criticisms centre on the conclusions around deaths and hospital admissions being based on one study and they allege that PHS ignores the findings of the others. This one study was also criticised for carrying a level of uncertainty.

A targeted intervention?

During scrutiny of the 2012 legislation, there were opposing views about how targeted the policy is.

Those in favour believed it to be a targeted intervention as it only affects low-price, high-strength products favoured by more harmful drinkers.

Those opposed claimed MUP was a blunt tool which would have no effect on the heaviest drinkers, while punishing moderate drinkers and those on low incomes.

The evaluation found MUP had no effect on dependent drinkers and may have increased existing harmful coping strategies in order to absorb price increases (e.g. reducing spending on food). Results were mixed for the broader category of harmful, non-dependent drinkers.

Supporters of MUP have argued that it was never expected to target dependent drinkers, while opponents have claimed the findings prove the point that it is not a targeted policy.

Unintended consequences

Several unintended consequences from MUP were suggested during scrutiny of the legislation. These included a negative impact on the alcohol industry, children and families, and an increase in cross-border trade.

The evaluation found no consistent evidence that MUP impacted positively or negatively on the drinks industry as a whole. There was an increase in the value of off-trade sales and a minor reduction in producer revenues. It was not possible to determine the impact on profits.

The evaluation could not say whether children and families were positively or negatively affected. There was no evidence of change in parenting outcomes and concerns persisted about the effect the policy might have on household budgets and the risk of domestic violence.

There was some evidence of cross-border purchases increasing after MUP came into effect but these tended to be among those who lived near the border with England. There was insufficient evidence to make any conclusions about the effect of MUP on online sales.

Changing the unit price

The Scottish Government has also laid an order proposing to increase the unit price from 50p to 65p. Those in support of MUP argue this is necessary to maintain the effect on reducing consumption because the unit price has been eroded by inflation since introduction.

Those opposed to increasing the price also cite inflation as a reason not to, often referring to the cost-of-living crisis.

Background

In 2007, the newly elected SNP Government announced its intention to implement a minimum unit price for alcohol. The intention at the time was to do this via subordinate legislation by adding to the mandatory conditions of alcohol licences.

Following objections from opposition parties, the Scottish Government decided to introduce primary legislation to implement Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP).

This resulted in the Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill being introduced in 2009.1

The Bill was passed on 10 November 2009 but without the flagship MUP policy.

Nevertheless, MUP was brought back for a second time in 2011 and the Alcohol (Minimum Pricing)(Scotland) Act 2012 was passed on 24 May 2012.

Notably this time, the Act contained a ‘sunset clause’ which meant that MUP would cease after six years of operation unless the Scottish Parliament voted for it to continue.

The Act came into force on 1 May 2018 and so MUP will expire on 30 April 2024 unless extended.

The Act also contained a review clause requiring Ministers to lay a report before the Scottish Parliament on the operation and effects of MUP after being in place for 5 years.

In accordance with the legislation, the review report should detail the effect of MUP on:

The five licensing objectives

Producers of alcoholic drinks and licence holders in Scotland

Other appropriate categories of person, determined with reference to certain characteristics such as age, gender, socioeconomic status and alcohol consumption.

In order to inform the report, the Scottish Government commissioned Public Health Scotland (PHS) to oversee an evaluation of the policy.

In June 2023, PHS published a final report which synthesised all of the evidence from the evaluation.

The Scottish Government subsequently published its report on the operation of MUP on 20 September 2023 which concluded:2

Scottish Ministers have considered all the information presented in this report and conclude that there is sufficient evidence that Minimum Unit Pricing has achieved its policy aim.

Origins of minimum unit pricing

When MUP was first proposed, there were no countries which had implemented the policy. Instead, the rationale for the policy drew together existing research which had examined:

the effect of price on alcohol consumption, and

the effect of alcohol consumption on health and social harms.

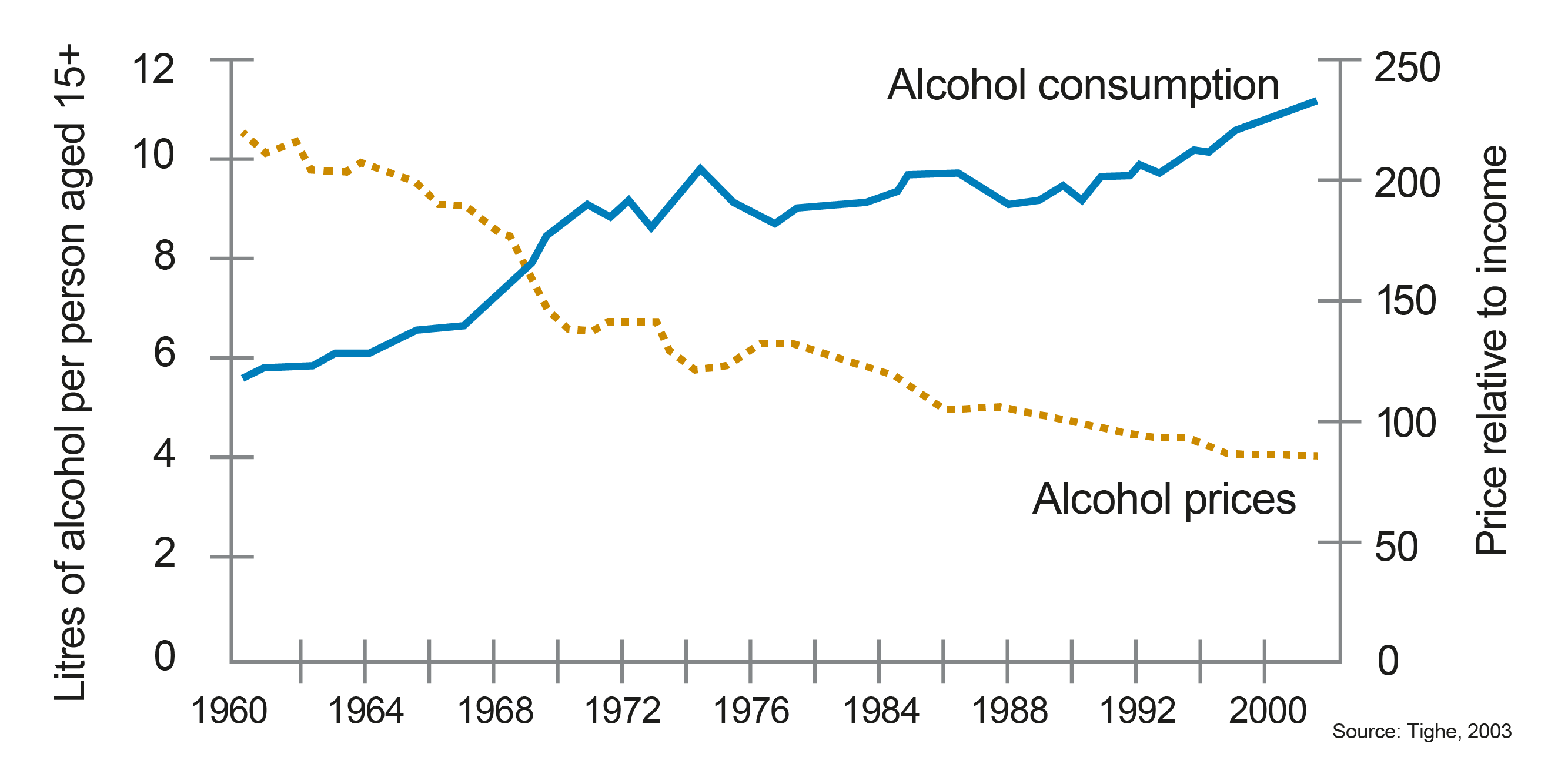

In relation to the first point, research has shown that alcohol behaves like other commodities in that the amount consumed is influenced by the price. This relationship was memorably illustrated in the following graph:

Second to this, there is a body of evidence showing that alcohol consumption is linked to health and social harms.

The resulting theory combines these two relationships i.e. price changes would change consumption, which would in turn affect health and social harms.

This link has underpinned alcohol pricing and taxation policies throughout the world. However, MUP takes this relationship one step further and has its origins in research that was conducted in Sweden.1

This research found that changes in price influenced the types of alcohol that people were consuming. For example, it found that when prices rose, people would ‘trade down’ and purchase beverages which were cheaper while maintaining the overall alcohol content.

As a result, the authors suggested that a floor price would be a more effective pricing mechanism than taxation if the goal was to reduce alcohol consumption, as this would prevent people from choosing cheaper, higher strength alternatives.

Shortly after the publication of the Swedish research, the idea of minimum pricing began to gain traction. Other influential publications at that time included:

Modelling by the University of Sheffield which was commissioned by the UK Department of Health. This was the first of many iterations of the model which came to form a key part of the debate.

The RAND Europe report on the 'The affordability of alcoholic beverages in the European Union: Understanding the link between alcohol affordability, consumption and harms.'2

In 2008, the Department of Health in England commissioned the University of Sheffield to undertake research examining the link between alcohol price, advertising and consumption. The project consisted of 2 parts: a systematic review of the literature3; and a modelling exercise using domestic data4. A subsequent version of the modelling was carried out on behalf of the Scottish Government using Scottish data5.

Sheffield modelling

The modelling by Sheffield University's School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) became pivotal in the debate around MUP.

This modelling combined research on price and consumption, with research on consumption and harms, to model the effect of MUP on outcomes such as death and illness. It also estimated outcomes for different types of drinker.

The main categories of drinker used were:

Moderate drinkers - those drinking less than 14 units per week

Hazardous drinkers - those drinking between 14-35 units a week (for women) or between 14-50 units a week for men

Harmful drinkers - those drinking more than 35 units a week (for women) or 50 units a week (for men).

There were various versions of the modelling but the final version prior to the Bill being passed included the following estimates for a 50p unit price:1

5.7% drop in consumption per annum

60 fewer deaths in the first year

1,600 fewer hospital admissions in the first year

The modelling also estimated the effect on other social harms such as crime and unemployment. Some of the modelled outcomes for a 50p unit price included:

3,500 fewer crimes per annum

32,300 fewer days absence from work

1,300 fewer unemployed people

For all unit prices, consumer spending was expected to increase, with a 50p unit price (plus discount ban) resulting in increased consumer spending of 5.2%.

Retailer revenue was also expected to increase under all unit prices across both the off-trade (shops, supermarkets etc.) and the on-trade (pubs, bars, restaurants etc.). It was expected that the higher the unit price, the higher the revenue, although the model could not provide a breakdown across the supply chain.

For a 50p unit price (plus discount ban) the model estimated an additional £125 million in retailer revenue per annum.

An updated version of the modelling was produced in 2016.2

Passage through the Scottish Parliament

MUP was scrutinised by the Scottish Parliament twice:

In 2009/10 during the passage of the Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Act 2010

In 2011/12 during the passage of the Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) 2012

As a result, the policy has been subject to extensive scrutiny. However, in order to address remaining doubts, the Scottish Government included the sunset clause making its continuation dependant on the will of the Scottish Parliament. This vote would be informed by the publication of an evaluation and a report from the Scottish Government on its findings.

Public Health Scotland (PHS) was in charge of the evaluation and published its final evaluation report in June 2023.1 This report was a synthesis of the research conducted on MUP. Some of this research was commissioned by PHS and some was undertaken by others who were independent of the evaluation.

In addition to this, the Scottish Parliament's Health, Social Care and Sport Committee also took evidence from key stakeholders in November 2023 and February 2024.

During stage 1 of the 2012 Bill, the main issues raised with the Health and Sport Committee could be categorised under the following 4 themes:

the evidence base,

how targeted an intervention it would be,

the unintended consequences, and

the legality of the policy.

The legality of the policy was determined by the Supreme Court in a judicial review lodged by the Scotch Whisky Association. The court ruled2 in 2017 that the 2012 Act did not breach EU law and was 'a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim'. The UK has also left the European Union since this time.

This briefing examines the remaining 3 issues raised during the passage of the Bill and pulls out what can be learned from the evaluation in relation to them. It also highlights relevant responses to the Scottish Government's consultation and from those who gave evidence to the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee.

Evaluation

The final report from Public Health Scotland (PHS) synthesises the evidence on MUP since its introduction.1 The evaluation was designed to answer two key questions:

To what extent has implementing MUP in Scotland contributed to reducing alcohol-related health and social harms?

Are some people and businesses more affected (positively or negatively) than others?

In order to answer these questions, PHS examined 7 separate outcomes:

Alcohol related health outcomes

Compliance

Price

Consumption

Social outcomes

Alcoholic drinks industry

Attitudes to MUP

In evaluating the evidence, PHS commissioned research but also reviewed research commissioned by others. This included peer reviewed papers and unpublished literature. In total, the final report included 40 studies across the range of outcomes.

The conclusion of PHS was:

Overall, the evidence supports that MUP has had a positive impact on health outcomes, namely a reduction in alcohol-attributable deaths and hospital admissions, particularly in men and those living in the most deprived areas, and therefore contributes to addressing alcohol-related health inequalities. There was no clear evidence of substantial negative impacts on the alcoholic drinks industry, or of social harms at the population level.

Key Issue - The link between price, consumption and harms

Overview of previous debate

The link between price, consumption and harm forms the basis of the 'theory of change' that underpins MUP. That is, it is theorised that price influences consumption, which then influences harms from alcohol. This is depicted by PHS in the following way:

The validity of this theory was also a theme that ran through scrutiny of both Bills.

At that time, some commentators called the link in to question and highlighted the lack of empirical evidence. They argued that the link was not straightforward and utilised international examples to illustrate this point.

These examples usually centred on countries where it was perceived that alcohol was expensive but harms from alcohol still significant (e.g. Scandinavian countries), or conversely, where alcohol was cheap but harms not as significant (e.g. Southern European countries).

It was also frequently highlighted that prices were the same across the UK, but consumption and harms were higher in Scotland.

In contrast, proponents of MUP argued that there were many other influences on consumption and harm so a simple comparison between places was not straightforward.

The final synthesis of the evidence examines the effect of MUP on consumption, health harms and social harms separately. The findings for each are summarised below, followed by the response from stakeholders.

Consumption

Evaluation findings

The evaluation's summary of the findings on consumption was:

There is strong and consistent quantitative evidence of a reduction in alcohol consumption, as measured by alcohol sales or purchasing data, in Scotland relative to other areas in Great Britain. The overall reduction in consumption was driven by a reduction in consumption of alcohol sold through the off-trade. The evidence consistently shows that the greatest reductions were seen for cider and spirits with mixed evidence of the impact on beer and wine.

There is consistent quantitative evidence that the greatest reductions in alcohol purchases were seen among those households purchasing the most alcohol prior to MUP implementation, with negligible impact on those that typically purchase less.

Some evidence of cross-border purchasing was identified, but its extent was observed to be minimal, most likely to occur among those living near the Scotland–England border and unlikely to undermine the overall impact of MUP on consumption.

Qualitative evidence identified a range of effects of MUP on consumption behaviour including changes in the quantity and type of alcohol consumed. Those working with families affected by alcohol reported that they thought MUP helped reduce consumption in those drinking at hazardous or harmful levels but not those with alcohol dependence.

19 studies with a quality score of 'strong' (13 studies) or 'moderate' (6 studies) were included in the final evaluation report. Some of these studies used sales and purchasing data as a proxy for consumption and others used reported drinking behaviour.

The main findings of the studies with a strong rating are detailed in the following table.

| Author | Key findings relating to individual consumption levels |

|---|---|

| Anderson et al (2021) | MUP led to an immediate reduction of 7.063 (95% Confidence Intervali (CI): -6.656 to -7.470) purchased grams of alcohol per person in Scotland (relative to northern England), and reduced consumption was maintained throughout 2020 (7.570g; 95% CI: -7.262 to -7.878).The researchers conclude that MUP is a ‘powerful’ and ‘highly targeted’ policy that led to decreases in purchasing of alcohol, particularly in the households that purchase the most alcohol. |

| Anderson et al (2022) | The researchers conclude that MUP is associated with an 8% reduction in purchases of grams of alcohol within beer, and with shifts in purchasing from higher-strength beer products towards lower-strength beer products. |

| Dimova et al (2022) | Service providers that work with people experiencing homelessness typically did not report any change in service users’ alcohol consumption post-MUP. However, some reported reductions in consumption among service users that drink high-strength, low-cost cider, who either switched to lower-strength ciders or higher-strength spirits or fortified wines.The researchers conclude that their study found some evidence of shifts away from high-strength, low-cost ciders among people experiencing homelessness. |

| Emslie et al (2023) | For some with experience of homelessness, their alcohol consumption was not affected by MUP as their preferred drinks had not previously been sold below £0.50 per unit. Others reduced their alcohol consumption and/or changed from drinking strong white cider to drinking other categories of alcoholic drinks. The researchers conclude that, from the perspectives of people with experience of homelessness, MUP had worked as intended for some, but had had negative impacts on a minority of people. |

| Ford et al (2020) | Participants from organisations working with families affected by harmful alcohol use suggested some people changed their purchasing patterns to attempt to continue consuming the same amount of alcohol, for example by shopping at supermarkets rather than smaller retailers.Participants noted that price increases helped some parents and carers to reduce their consumption.The researchers concluded that service providers felt that the intervention may support some of those drinking at hazardous or harmful levels to reduce their consumption, although the impacts of MUP on those with alcohol dependence were anticipated to be limited. |

| Giles et al (2022) | After three years, MUP was associated with a relative reduction in sales of pure alcohol per adult in Scotland of 3.0% (95% CI: -4.2% to -1.8%). The net reduction in off-trade sales reflects a 1.3% reduction in Scotland and a 2.5% increase in England & Wales over the same time period. |

| Holmes et al (2022) | No statistically significant evidence that the proportion of drinkers in Scotland consuming at harmful levels (>35/50 units female/male) changed relative to England (p=0.500)ii after the introduction of MUP.Strong evidence that the proportion of drinkers consuming at hazardous levels (14–35/14–50 units female/male) in Scotland decreased significantly by 3.5 percentage points relative to England after the introduction of MUP (p<0.0005), but no statistically significant evidence of a change in the proportion consuming at moderate levels (<14 units) changed (p=0.269).No statistically significant difference pre-post MUP in average number of units consumed in Scotland, relative to England. |

| Iconic Consulting (2020) | Participants gave examples of children and young people's consumption changing (both increasing and decreasing) post-MUP, although participants typically did not view price as a major contributor to purchasing and consumption decisions. |

| O'Donnell et al (2019) | MUP associated with a reduction in Scotland of 9.5g (95% CI: -5.1 to -13.9; 1.2 UK units; 7.6% decrease) in weekly purchased grams of alcohol per adult per household. |

| Robinson et al (2021)Giles et al (2021) | Strong evidence that MUP was associated with a reduction in total off-trade sales in Scotland, when controlling for sales in England & Wales, in both the unadjusted (-3.5%; 95% CI: -2.1% to -4.4%, p<0.001) and adjusted (-3.5%, 95% CI: -2.2% to -4.9%, P < 0.001) analyses.Strong evidence that MUP was associated with a 2.0% (95% CI: -0.4% to -3.6%, p=0.014) reduction in off-trade sales per adult in Scotland, and a 2.4% (95% CI: +0.8% to +4.0%, p=0.004) increase in England & Wales. |

| So et al (2021) | No statistically significant evidence that the odds of binge drinking among current drinkers changed relative to England post-MUP (OR 1.13; 95% CI: +0.96 to +1.34; p=0.139). When disaggregating this analysis by age, sex, employment status and level of education, no subgroup saw a significant difference. Among current drinkers attending a sexual health clinic, there was strong evidence of a large (22%) increase in the odds of ‘alcohol misuse’ relative to England post-MUP (OR 1.22; 95% CI: +1.04 to +1.42; p=0.012). This was driven by both an increase in the prevalence of alcohol use in Scotland and a decrease in England. When disaggregating by age, sex, employment status and level of education, no subgroup exhibited a significant difference after. |

Of these studies, PHS concluded that two in particular provided strong quantitative evidence that MUP was associated with a reduction in alcohol sales 1 year1 and 3 years2 after implementation.

Both studies use interrupted time series analysisiii to estimate changes in alcohol sales following the implementation of MUP in Scotland, with alcohol sales in England & Wales incorporated as a control.

After one year of implementation, there was strong evidence that MUP was associated with a 2.0% reduction (95% CI: -3.6% to -0.4%, p=0.014) in the total volume of pure alcohol sold per adult through the off-trade in Scotland. There was strong evidence that England & Wales saw a 2.4% (95% CI: +0.8% to +4.0%, p=0.004) increase over the same period. When controlling for England & Wales and adjusting for changes in disposable income and substitution between drink types, there was strong evidence that MUP was associated with a net reduction of 3.5% (-4.9% to -2.2%, p<0.001) in total off-trade alcohol sales in Scotland[.]

The time-series analysis found that, although alcohol consumption was already declining in Scotland, MUP increased the rate of decline.

There was very little evidence of any change to per-adult sales of alcohol through the on-trade.

Stakeholder response

The impact of MUP on consumption was raised by respondents to the Scottish Government's consultation3. Those supportive of MUP accepted that the policy had reduced consumption, in particular by reducing consumption in hazardous and harmful drinkers down to more moderate levels.

During the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee's evidence sessions, Alison Douglas from Alcohol Focus Scotland said:

The Sheffield modelling predicted that there would be a 3.5 per cent decrease in consumption, or a three-year 3.5 per cent decrease in consumption, which is pretty much what we have seen in practice. With regard to the effect on consumption, it has been pretty accurate.

However, the consultation analysis reports that some questioned whether a drop in consumption could be attributed to MUP as people were already drinking less in Scotland. They felt this was the continuation of an existing trend. Others highlighted that this is also a trend amongst particular groups such as young people.

Others highlighted the potential distortive effect MUP may have had on drinking habits, with an apparent shift in consumption towards higher strength products such as spirits. These responses called for more research into changing consumption patterns before MUP is continued or amended.

Health harms

Evaluation findings

The PHS evaluation summarised the findings on health harms as follows:

There is strong quantitative evidence that MUP was associated with a reduction in deaths wholly attributable to alcohol consumption, relative to England. A smaller, and less certain, relative decrease was seen in hospital admissions wholly attributable to alcohol. The estimated reductions in deaths and admissions were largest among men and those living in the 40% most deprived areas in Scotland. Strong evidence was found that MUP was associated with reductions in deaths and hospitalisations due to chronic conditions, with less certain evidence that MUP was associated with an increase in deaths and hospitalisations due to acute causes.

There is no consistent evidence of a population-level effect, either positive or negative, on alcohol-related ambulance callouts, prescriptions for treatment of alcohol dependence, emergency department attendance or the level of alcohol dependence or self-reported health status in drinkers recruited through alcohol treatment services in Scotland, relative to England.

There is some qualitative evidence that MUP may have had some negative health consequences, particularly for those with alcohol dependence. These included increased withdrawal in homeless and street drinkers, an increase in the consumption of stronger alcohol types and concern about switching from weaker to stronger alcohol drinks. Some professionals reflected that reduced affordability was driving individuals to seek treatment.

The final evaluation analysis drew upon 8 studies that looked at health outcomes and were deemed robust enough.

Six of these papers provided quantitative evidence and, of these, PHS concluded that one study1 provided strong evidence that MUP was associated with a reduction in deaths and hospital admissions due to chronic alcohol conditions, compared to England.

PHS concluded that the other studies did not provide any evidence, either positive or negative, as to the impact of MUP on alcohol-related health outcomes.

From this evaluation, PHS reached the overall conclusion that there was strong evidence that MUP reduced chronic alcohol deaths and hospital admissions caused wholly by alcohol consumption.

Stakeholder response

The robustness of the findings on the health outcomes formed a key focus of the Scottish Government consultation and the evidence to the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee.

Supporters of MUP are satisfied that the evaluation provides enough evidence to conclude that MUP has reduced deaths and hospital admissions which are wholly attributable to alcohol. For others though, there are still questions about the sufficiency of the evidence.

For example, Dr Sandesh Gulhane MSP raised several concerns about the evaluation report in a letter to the UK Statistics Authority:2

I am concerned the report and associated publicity and ministerial statements significantly overstate the health impact of MUP, and under-represent the significant uncertainty in the wider body of research and among the scientific community.

In response to Dr Gulhane's concerns, the UK Statistics Authority (UKSA), acknowledged that the Scottish Government’s press release and the PHS ‘at-a-glance’ summary failed to report levels of uncertainty related to the results. This response also noted that these communications failed to make it clear that only 8 of the 40 studies considered as part of the evaluation looked at health outcomes. In relation to levels of uncertainty related to the study, the UKSA said:

The Scottish Government press release and the PHS ‘at a glance’ document both referred to the results of the PHS/Glasgow/Queensland study. However, information about the level of uncertainty associated with the reduction in hospitalisations and deaths was not included in either output, despite being emphasised in the study. For example, the figures are estimates based on statistical modelling and the reduction in hospital admissions was not found to be statistically significant.

In the Scottish Government consultation analysis, opinion was divided around the impact on health outcomes.

Many responses felt the evidence was still insufficient and that the PHS conclusion of 'strong evidence' of a positive impact on health outcomes was not reflective of all the evidence. Some highlighted that just 1 of the 8 relevant studies found a positive impact and described the evaluation as 'selective, biased, misleading or flawed'.3

It was also highlighted that the one study which did show a positive impact was based on estimates and modelling.

In our view, the study does not provide enough evidence that the introduction of MUP ‘saved lives’, it simply provides a theoretical illustration of what might have happened had MUP not been introduced. All of the other studies relevant to this area found no evidence to support the hypotheses that the introduction of MUP would reduce alcohol-related health harms. Despite the overwhelming message from these studies being that MUP has had no real impact on these health outcomes, the Public Health Scotland report still claims that there is “strong evidence” to support that MUP has led to reductions in alcohol-related morbidity and mortality levels. - The Law Society4

In contrast, those who were supportive of MUP were convinced the available evidence had shown that MUP was effective. These responses tended to come from organisations.

In oral evidence to the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee, Alison Douglas of Alcohol Focus Scotland said:

With regard to the effect on health outcomes, the estimate was a very conservative one. The effect that we have seen in the real world has been significantly higher. The modellers were probably quite deliberate in being cautious about the expected health benefits. As you know, minimum unit pricing was predicted to save 60 lives in the first year of operation. In practice, it has saved 156 lives. That is a significantly greater number than was predicted.

Other social outcomes

Evaluation findings

The PHS evaluation summarised the findings on social harms as follows:

Overall, there is a lack of evidence of MUP having an impact on social outcomes at a population level. For people who already used illicit drugs before MUP was implemented, quantitative analyses from four studies found no effect of MUP on illicit drug behaviours and, while there were qualitative reports of increased illicit drug use, these were often difficult to attribute to MUP. There was no evidence that participants who did not use illicit drugs prior to MUP began using illicit drugs after implementation, meaning there was no suggestion that people started to use illicit drugs because alcohol increased in price.

There was little indication of increased use of non-beverage or illicit alcohol. Quantitative studies on crime, including drug crime, switching to non-beverage alcohol and spend on food and the nutritional value of food all found no positive or negative impact, and quantitative evidence on the impact of road traffic accidents was mixed.

There were some qualitative insights that suggest that for some drinkers, especially those with probable alcohol dependence and particularly the financially vulnerable, existing social harms, particularly those related to financial pressures, may have been exacerbated, but there is no evidence of those experiences being prevalent or typical. It is not possible to say whether children and young people in families affected by alcohol use were positively or negatively affected.

The social outcomes reviewed in the PHS evaluation were:

Illicit drugs

Individual and household budgets

Food purchasing and nutritional quality

Crime and disorder

Road traffic accidents

Children and families

Non-beverage and illicit alcohol

The potential impact of MUP on these outcomes may be beneficial or detrimental. For example, MUP may reduce crime by lessening anti-social behaviour. Conversely, it may increase some crimes such as theft or illicit drug use.

Stakeholder response

In the Scottish Government consultation, those supportive of MUP referred to the lack of evidence that MUP had a negative impact on social outcomes like increased illicit drug use or crimes like theft.

Conversely, those in opposition to MUP cited the evidence as showing that MUP had no beneficial effect on social outcomes like reductions in crime or improvements in child welfare.

Some respondents also highlighted the negative effect reported for dependent drinkers. At times, this included those supportive of the policy, and were usually accompanied with a plea to increase support for these people should MUP continue:

While we agree that MUP has had a positive impact on the wider population and should continue, we are not willing to overlook the harm it causes to a particularly vulnerable group of people in order to benefit the greater good. Secondly, future consideration and discussion of MUP should include consideration of this population who do not benefit from it. We cannot push ahead with a policy that delivers such positive impact for most while causing harm for some without connecting our thinking and our investment to ensure that harm is mitigated. – Turning Point Scotland

This was also picked up in one of the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee's evidence session:

Perhaps one of the lessons that we have learned compared with when MUP was first introduced, relates to concerns about the effect on dependent drinkers—that 1 per cent of the population—and how we need to support them. Continuing MUP and, I hope, uprating it to an appropriate level, is the ideal time to focus on improving services for treatments. That takes money and resources, so it is a win-win situation to plough that windfall or increased revenue into the public purse and for that to be put into alcohol services. - Dr MacGilchrist

The potential negative effect on dependent drinkers and their families is discussed in more detail in the sections on 'Heavy drinkers' and 'Unintended consequences'.

Key Issue - A targeted intervention?

A common theme throughout the scrutiny of both Bills, was that MUP would ‘punish the many for the sins of the few’ and not target those that need to reduce their drinking the most.

In contrast, the Scottish Government argued that it would be a targeted intervention as it would affect the price of the the cheapest drinks which tend to be drunk by the heaviest drinkers.

Debate around targeting centred on 3 key areas:

Effect on heavy drinkers

Effect on moderate or 'responsible' drinkers

Effect on low income groups.

These are examined in more detail in the following sections.

Heavy drinkers

Overview of previous debate

Despite the modelling predicting a larger response in hazardous and harmful drinkers, whether they would be this responsive in reality became a central dispute during the scrutiny of both Bills and led to questions about the potential effectiveness of the policy.

Research shows that consumers of alcohol increase their drinking when prices are lowered, and decrease their consumption when prices rise1. However, opponents to MUP contended that the modelling had failed to take account of the evidence that heavier drinkers are the least responsive to price changes.

[T]he key problem for us is that the idea that harmful drinkers are more responsive to price changes than moderate drinkers are seems counter-intuitive. We took a number of studies…which showed that binge-drinking types—harmful drinkers—are the least responsive to price changes. - Benjamin Williamson, Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR)

In response, the Scottish Government highlighted that the modelling did account for the lower responsiveness of heavy drinkers but differentiated that – while less responsive to price changes in general – heavy drinkers would be more responsive to minimum pricing. This is because they are more likely to drink the cheapest alcohol and MUP would be prevent them from choosing cheaper alternatives.

The policy memorandum to the Bill said:

Minimum pricing targets price increases at alcohol that is sold cheaply. Cheaper alcohol tends to be bought more by harmful drinkers than moderate drinkers. So a minimum pricing policy might be seen as beneficial in that it targets the drinkers causing most harm to themselves and society.

The targeted nature of MUP was asserted by many stakeholders throughout the passage of the Bill, for example:

All pricing strategies have the most impact on heavy drinkers, but minimum pricing especially targets heavier and younger drinkers, because they mostly prefer cheaper drinks. - Prof Tim Stockwell, University of Victoria, British Columbia

Scottish Parliament. (2012). Stage 1 Report on the Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) Scotland Bill. Retrieved from https://archive2021.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/CurrentCommittees/48155.aspx [accessed 1 February 2023]

Evaluation findings

It is important to note that, while terms like 'heavy drinkers' and 'alcoholics' are used in the debate around the policy, the Sheffield modelling and the evaluation are much more specific in categorising drinkers.

The categories used are:

Moderate drinkers - those drinking less than 14 units per week

Hazardous drinkers - those drinking between 14-35 units a week (for women) or between 14-50 units a week for men

Harmful drinkers - those drinking more than 35 units a week (for women) or 50 units a week (for men)

Dependent drinkers - a subset of harmful drinkers, whose drinking is characterised by craving, tolerance, a preoccupation with alcohol, and continued drinking in spite of harmful consequences (for example, liver disease or depression caused by drinking). An estimated 1 in 5 harmful drinkers are believed to be dependant on alcohol).i

This difference in terminology means it can be difficult to know whether those on either side of the debate are referring to the same type of drinker.

This is further complicated by the fact that the evaluation was structured in such a way that it did not specifically look at all of the outcomes by different type of drinker.

Nevertheless, research from Holmes et al (2021) did provide some insights into the effect on those who drink at harmful levels:

There is no clear evidence that MUP led to an overall reduction in alcohol consumption among people drinking at harmful levels or those with alcohol dependence, although some individuals did report reducing their consumption.

There is also no clear evidence that MUP led to a change in the severity of alcohol dependence symptoms among those presenting for treatment.3

Other relevant research findings show mixed results in relation to the impact on harmful drinkers. For example:

Analysis of national population survey data on self-reported consumption found decreases in a number of measurements on consumption in Scotland relative to Wales for those drinking at harmful levels, with little evidence of impact on those drinking at hazardous levels.4

...a separate study found the prevalence of drinking at harmful and moderate levels did not change, but there was a reduction in the prevalence of drinking at hazardous levels.3

Overall, there was no clear evidence of change in the amount, pattern or type of drinking self-reported by drinkers under 18 in response to MUP, adults who engage in binge or harmful drinking,6 people with probable alcohol dependence recruited through alcohol services or the community 73and people with current or recent experience of homelessness.9

In relation to dependent drinkers, PHS concluded:10

There is limited evidence to suggest that MUP was effective in reducing consumption for those people with alcohol dependence. Those with alcohol dependence are a particular subgroup of those who drink at harmful levels and have specific needs. People with alcohol dependence need timely and evidence-based treatment and wider support that addresses the root cause of their dependence.

The evaluation also highlighted that there is some evidence people with alcohol dependence, who have limited financial support, may experience increased financial pressure as a result of MUP:10

Others, especially those with alcohol dependence who were also financially vulnerable, reported needing to use pre-existing harmful strategies more often, such as reducing spending on food and, for those who were also homeless, begging or stealing to cope with the price increase. Substituting illicit drugs appeared to be uncommon and confined to those who already used such substances.

In relation to the larger group of harmful drinkers , the PHS final evaluation report did not reach an overall conclusion.

Stakeholder response

The impact of MUP on heavy and harmful drinkers continues to form a key focus in the debate.

During oral evidence to the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee, Members questioned PHS and other stakeholders on the findings of the evaluation in relation to dependent drinkers. During the evidence session PHS stated:

The patterns of spend in people who are the heaviest drinkers tend to involve the lowest and strongest alcohols, and their purchases tend to be from off-sales. We would therefore have expected minimum unit pricing to have had a particular impact on purchasing decisions in that group. However, we see in the broader context that dependence is quite a complex phenomenon, and we saw reports of individuals prioritising their spend on alcohol over other commodities where household budgets were finite. - Tara Shivaji, Public Health Scotland

At the evidence session with health organisations, it was argued that dependent drinkers were a complex sub-group of harmful drinkers and the policy was never expected to impact on their drinking:

To come back to the question about whether minimum unit pricing has worked for dependent drinkers, I make it absolutely clear that it was not the purpose of minimum unit pricing to change the drinking of dependent drinkers. The purpose was to reduce consumption among people who drink above the low-risk guidelines. - Alison Douglas, Alcohol Focus Scotland

Alison Douglas went on to argue that the intention was to prevent people becoming dependent in the first place and MUP was a part of that. This argument was also repeated in the Scottish Government consultation12:

While some dependent drinkers reported reducing their consumption due to MUP, the policy’s greatest contribution to reducing alcohol dependence is by helping to reduce the risk of others becoming dependent in future. – NCD Alliance

In contrast, those opposed to MUP state that the evidence illustrates MUP has not worked and does not deter people with alcohol dependence as the cost of alcohol is not a consideration.13

Moderate drinkers

Overview of previous debate

Many contended that the vast majority of people drink responsibly and would therefore be unfairly penalised by MUP.

The modelling at the time predicted that the drop in consumption at a population level would be made up of a small reduction spread across the bulk of moderate drinkers, and a larger reduction across the smaller group of hazardous and harmful drinkers. However, the drop in consumption in the hazardous and harmful drinkers was predicted to make up the largest proportion of the overall reduction (-60.5 million units compared to -7.4 million units in moderate drinkers).

For a 50p minimum price combined with a discount ban, the modelling estimated spending for moderate, hazardous and harmful drinkers at £11, £65 and £148 per week respectively which equated to an additional spend per week of £0.22, £1.25 and £2.83.1

Evaluation findings

The final evaluation report did not contain a summary or conclusion on the effect of MUP on moderate drinkers and their consumption or expenditure.

However, the report did highlight research which provides glimpses into changes in sales, expenditure and consumption among moderate drinkers, including the following:

Strong evidence that the proportion of drinkers consuming at hazardous levels (14–35/14–50 units f/m) in Scotland decreased significantly by 3.5 percentage points relative to England after the introduction of MUP (p<0.0005), but no statistically significant evidence of a change in the proportion consuming at moderate levels (<14 units) changed (p=0.269).2

One paper found there was little or no increase in expenditure on alcohol in households that generally bought small amounts of alcohol.3

Moderate drinkers (defined as <14 units per week) were found to be less likely to have consumed alcohol in the previous seven days in Scotland post-MUP, relative to Wales. 4

...a separate study found the prevalence of drinking at harmful and moderate levels did not change, but there was a reduction in the prevalence of drinking at hazardous levels.2

Increases in household expenditure on alcohol were predominantly in households that purchased the greatest quantity of alcohol, with no pattern associated with income.6

Stakeholder response

The Scottish Government consultation analysis shows that there is still a belief among some that MUP penalises moderate drinkers. These responses tended to come from individuals who believed that those who drink responsibly should simply not have to pay more for alcohol. These comments also overlapped with the theme that MUP adds an increased financial burden during a cost of living crisis.

There's absolutely nothing wrong with having a glass of wine to relax over a meal. Personally, I drink around 12 units a week, but I get annoyed when I've got to shell out more.” – Individual

Those in support of MUP argued that the policy has not harmed moderate drinkers as it has had no or little impact on the products consumed by most moderate drinkers.

Low income groups

Overview of previous debate

Another issue regarding how targeted the policy is, concerned how it might impact on low income groups.

The original modelling from Sheffield did not estimate the effect of MUP on different socio-economic groups due to a lack of adequate data. This led to concerns that MUP would unfairly impact on lower income groups and be 'regressive'i in nature.

Questions were also raised about how effective MUP would be in relation to higher income groups who may be able to absorb any price increases. Research at the time showed that higher income groups were more likely to exceed drinking guidelines than those in lower income groups.1

During the first Bill, analysis from supporters of the policy tried to ease concerns by highlighting that the drinking habits of people in low-income groups tends to be quite polarised i.e. they drink either little/nothing at all, or they are heavy drinkers.2 As a result, it was argued that the policy would help target heavy drinkers in low-income groups while not affecting those who do not drink or who drank little.

In response to concerns about low income groups during the previous alcohol bill, the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Wellbeing provided the Health and Sport Committee with an analysis of existing data3.

This was also supplemented by additional evidence from Prof Ludbrook of Aberdeen University2. The key findings from the Government analysis and the evidence from Prof Ludbrook included:

People in low income groups were more likely to drink nothing, very little or very heavily (i.e. their drinking pattern is fairly polarised)

23% of the lowest income decile do not drink so will not be affected by minimum pricing

57% drink at very low levels (averaging 4.9 units per week) so will be slightly affected by minimum pricing

Harmful drinkers in low income groups tend to drink more than harmful drinkers in higher income households and are more likely to be admitted to hospital or to die from an alcohol related cause

Purchasing of low priced alcohol occurs across the income distribution. The Government concluded that when propensity to purchase alcohol is taken into account the lowest groups are among the least likely to buy cheap alcohol.

However, further analysis by the Institute for Fiscal Studies5 found that although poorer households drink less, they tend to pay less per unit than richer households.

Evaluation findings

The final report from the evaluation did not specifically examine the findings in relation to people on low incomes. However, it did include some details of research with relevant findings:

Increases in household expenditure on alcohol following MUP were predominantly within the households that purchased the most alcohol, with no particular pattern associated with household income. 6

Changes in expenditure on alcohol were not systematically associated with household income, but were greater for those households that purchased the largest quantity of alcohol.78

Households that generally bought small amounts of alcohol following MUP saw negligible increases in expenditure on alcohol, particularly lower-income households.7

...after secondary before and after analyses, the size of the associated drop in consumption for men became smaller with increasing deprivation, with men living in the most deprived areas having no associated decrease in consumption. For women, the associated drop in consumption also decreased slightly with decreasing deprivation score, although less so than for men.10

However, attitudes to MUP among lower income households were more negative, with 44% of those in the most deprived 20% in support of MUP, compared to 60% in the least deprived 20%.11

It is also worth noting that PHS came to the overall conclusion that MUP has reduced alcohol attributable deaths and hospital admissions particularly in those living in deprived areas. It therefore came to the conclusion that MUP has had a positive effect on deprivation based health inequalities from alcohol harms.

Stakeholder response

The Scottish Government's consultation analysis reported that the most common reason for opposing MUP was that it would increase the financial burden on people, particularly those living on low incomes.

As before, it was seen by those opposed to MUP as a regressive, stealth tax which added to the already higher tax burden in Scotland compared to the rest of the UK.

However, for some in support of MUP, they argued that poverty and income inequality should be addressed rather than changing MUP.

Key Issue - Unintended consequences

Overview of previous debate

Throughout the scrutiny of the legislation, it was suggested that MUP could lead to several unintended consequences. These mainly centred on:

a negative impact on the alcohol industry

a negative impact on the children and families of harmful drinkers

an increase in cross-border trade.

These are examined in more detail in the following sections.

Alcohol industry

Overview of previous debate

During the passage of the Bill, industry representatives made several claims about the detrimental effect the policy could have on the alcohol industry. These included:

Manufacturers would experience a fall in sales and, although the lower volume would be offset by the higher price, this extra revenue would go to retailers and be to the detriment of manufacturers.

Demand for some drinks would disappear entirely resulting in a cost to the economy and lost jobs.

MUP would be a trade barrier which would result in retaliatory barriers to trade in new and existing markets. This could affect exports and Scottish jobs.

In response, the Scottish Government asserted that the policy would benefit the industry as the increase in price would result in increased revenue.

In line with the 2012 version of the modelling , it was estimated that the industry would benefit from an additional £125 million in revenue, with around 70% of this going to the off-trade and the remaining 30% to the on-trade.

In addition, a perceived benefit by some was that MUP would 'level the playing field' between the off-trade and the on-trade.

Evaluation findings

The PHS evaluation concluded that there was no consistent evidence that MUP had a positive or negative impact on the industry:

Overall, there is no consistent evidence that MUP impacted either positively or negatively on the alcoholic drinks industry as a whole. Sales data identified that an overall increase in the value of off-trade alcohol sales was seen, with increases in retail price offsetting declines in volume sales. While a reduction in producers’ revenues was observed, this was considered in qualitative interviews to be minor. Little evidence was found of MUP having had an impact on key business performance metrics. There is some evidence that the industry responded to MUP by introducing new formats and packaging sizes. (Pg 58)

However, it did find that retailers reported a loss in sales, offset by an increase in price.

Ciders, perries and own-brand spirits experienced the greatest reduction in sales.

The effect on producers’ revenues was negative, but was considered by some, although not all, to be small. There was limited evidence that increased revenues for retailers had been passed on to producers.1

No changes in employment or facilities was reported due to MUP but some individual retailers were adversely affected. 13

The evaluation did not place a specific figure on any additional revenue to the industry. However, one study estimated retailers had benefited from additional revenue of £270 million over 4 years (£67.5 million per year).4 It was not possible to determine the impact on profit.3

Stakeholder response

In the Scottish Government consultation on the continuation of MUP, 83% of alcohol industry representatives, 60% of alcohol producers and 50% of retailers were opposed to the policy.

Reasons for opposition included the difficulties facing the sector being compounded by MUP:

I own a tiny brewery in Glasgow… Our industry has been subject to horrifying increases in costs over the last years combined with an increasing inability of consumers to meet those costs. We are still facing the fallout of Brexit, Covid, and the Ukrainian conflict. Westminster has recently enacted the most punishing duty increases in decades and is promising further increases imminently. Businesses are closing and people are losing their jobs with alarming frequency. In circumstances like these, the need to be proportionate, pragmatic and evidence-constrained in the burdens we place on businesses is even more acute than usual.6

However, those in support of MUP claimed the evaluation shows there is no evidence of a negative impact on the industry and it may actually have been beneficial to smaller retailers as they could compete more with the large stores.

The increase in revenue was also highlighted as a benefit to the industry and there were renewed calls for the imposition of a levy to recoup the additional revenue so that retailers do not profit from MUP.

Alcohol Focus Scotland’s submission to the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee highlights a study which puts the windfall gains to the industry resulting from MUP at £383 million per year.

However, some in the industry contended that extra revenue did not necessarily translate into profit. For example, the consultation response from the Wine and Spirit Trade Association to the Scottish Government states:

There is no general evidence of extra profit accruing to retailers, wholesalers, importers or producers, although turnover, pricing and cost data is hard to analyse and there may be some examples of extra profit being generated.

Children and families

Overview of previous debate

Concerns were raised that if alcohol prices increase, problem drinkers may use spending from elsewhere in their budget to maintain their consumption levels. It was feared that this could be to the detriment of their families.

Those in favour of MUP argued that ultimately, low-income families would benefit from the policy, because they disproportionately experience many of the harms arising from alcohol misuse.

At the time, there was no research on the effect of alcohol consumption on family spending.

Evaluation findings

The PHS evaluation concluded:

It is not possible to say whether children and young people in families affected by alcohol use were positively or negatively affected. (p55)

The evaluation report highlighted the following from the 3 qualitative papers which looked at the effect of problem drinking on children and families:

Researchers felt unable to determine if MUP had a positive or negative impact on the lives of children and young people affected by other people’s drinking.1

There was no evidence of change in any parenting outcomes after the introduction of MUP.2

There were some accounts of concerns about the impact the policy might have on household budgets and the potential for increased domestic violence.2

Analysis of survey data also suggested that sharing a home with a partner or children had no impact on the consumption of people who drink at harmful levels.2

Stakeholder response

The harm to children and families was raised by stakeholders as an area where interventions still need to be put in place to mitigate against the effect of harmful drinking:

A wider range of interventions are necessary, including support for dependent drinkers and recognition of the impact on their families and those around them. Those are key interventions that we would want to see. (Tara Shivaji, Public Health Scotland)

Cross border trade

Overview of previous debate

One of the feared effects of MUP was that it may fuel cross-border and illicit trade and therefore undermine the effectiveness of the policy.

Another fear was that the policy could be undermined by shoppers ordering alcohol online from retailers which dispatch from England or elsewhere.

Evaluation findings

The evaluation included 6 studies which looked at the effect of MUP on in-person cross-border purchases. These studies found that cross-border purchases were most likely by those living near the border and were likely to be for individual purchases rather than bulk-buying with the intention of supplying to others.

Frontier Economics found some evidence of Scottish consumers increasing cross-border purchasing, primarily within 15km of the border and close to major English towns, but no evidence of a substantial impact on profitability, turnover or employment of retailers in Scotland close to the border1.

Patterson et al concluded that for the majority of the population, distance from the border means there is limited financial incentive for cross-border purchase23.

In relation to online sales outwith Scotland, the research findings in the evaluation were relatively limited.

One study found the introduction of MUP coincided with an increase in Scottish internet searches for cheap alcohol and online outlets compared with England.4

Another study found a 14% increase in people buying alcohol online. However, the authors suggest the finding may have been inflated due to the 'stay-at-home order' which was in place as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.5

Stakeholder response

An increase in cross-border and online sales continued to be mentioned as a potential consequence of the policy in the Scottish Government's consultation.

Some individuals stated they knew people who already bought alcohol in this way and said they would also do this if MUP was to continue.

The impact on Scottish businesses was raised by both individuals and organisations, and some called for better monitoring or further research on this issue.

The European Health Policy Alliance and some of its members also felt the evaluation did not have enough detail on this issue. Their reasoning for this was they felt it was a missed opportunity to put to rest the claims that cross-border and online sales are a reason not to implement MUP.

Changing the unit price

In addition to continuing MUP, the Scottish Government also recently consulted on proposals for a new unit price and the Alcohol (Minimum Price per Unit) (Scotland) Amendment Order 2024 was laid on 19 February 2024. This order seeks to amend the unit price from 50p to 65p.

The unit price of 50p was initially proposed back in 2012 but did not come into effect until 2018.

The lack of change has been criticised for undermining the effectiveness of the policy in light of inflation over that time.

In its submission to the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee, Alcohol Focus Scotland wrote:

Inflation has eroded the value and effect of MUP since it was set at 50p per unit in 2018. Today, the MUP would have to be 62.5p to have the same effective value as 50p had in May 2018. As a consequence, alcohol consumption in Scotland was an estimated 2.2% higher in 2023 that it would have been had the MUP risen in line with inflation. Continuing MUP without increasing the price would, in effect, be a choice to decrease the price in real terms, which will lead to increased alcohol consumption and harms. Should the level remain at 50p, it is estimated that consumption will be 3.4% higher by 2040, leading to 1,076 additional deaths, 14,532 additional hospital admissions, and £17.4million in additional NHS hospital costs over this period.

Uprating mechanism

There is no mechanism within the 2012 Act for routine amendment of the unit price. Some commentators have suggested linking it in future to an inflationary index such as the Retail Price Index (RPI).

The original proposal for MUP drew upon an ‘affordability index’3 to argue the case for increasing the cost of alcohol.4 This index compared the price of alcohol with disposable incomes over time to show how alcohol had become more affordable. The report noted that real disposable income can alter due to changes in total household income, tax and social contributions, as well as inflation/deflation.

The Scottish Government policy note on the Order details that the 50p unit price was adjusted using the Consumer Price Index with Housing Costs (CPIH) to get an equivalent unit price for the present day.

It then details that the following factors were also taken into account:

Affordability of alcohol

Alcohol prices including price distribution

Cost crisis

Impact of COVID-19 restrictions on alcohol consumption and harms

Covid-19 recovery

Following this, the Scottish Government decided on a proposed price of 65p per unit.

Stakeholder response

Many of the responses to the Scottish Government’s consultation argued that the new price should be ‘at least’ 65p. This was argued on the basis that the price was actually set in 2012, not 2018, and that, over the intervening time period, the rate of inflation has been persistently high.

Some respondents argued in favour of a per unit price ranging from 70-85p.

In contrast, industry stakeholders who gave evidence to the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee argued for the price per unit to remain at 50p. If the unit price were to increase, they suggested that the alcohol industry should be given a period of notice to prepare and adjust, prior to it coming into force.

Some stakeholders also used inflation and the cost-of-living crisis as a reason not to increase the unit price:

The higher MUP goes (from 50p to 65p), the worse this economic impact will be. During a cost of living crisis, consumers – but also businesses - are already struggling with escalating costs. - Wine and Spirit Trade Association

Another concern about raising the unit price centred on the potential for a further windfall to the industry. A commonly held view was that any additional revenue should go to treatment services and there was support for the introduction of a levy to recoup any windfall.

The Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Act 2010 already contains a power for Ministers to introduce a Social Responsibility Levy on licence holders but this power was never used.

In the recent Scottish Budget, the Deputy First Minister announced the intention to consider the reintroduction of a public health supplement.

The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee recommended (by division) to the Scottish Parliament that both the Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act 2012 (Continuation) Order 2024 [draft] and the Alcohol (Minimum Price per Unit) (Scotland) Act 2012 (Amendment) Order 2024 [draft] be approved.