Judicial Factors (Scotland) Bill

This briefing covers the Judicial Factors (Scotland) Bill. A judicial factor is a person appointed by the court to gather in, hold, safeguard and administer property belonging to someone else. The Bill aims to reform the existing law associated with judicial factors.

Executive Summary

The Judicial Factors (Scotland) Bill is a Scottish Government Bill. It is based on a law reform project by the Scottish Law Commission ('the Commission'), the independent body that makes recommendations for law reform to Scottish Ministers.

A judicial factor is a person the court can appoint to manage property which is not being appropriately managed, or otherwise would not be appropriately managed. At present, the majority of individuals appointed are legal and financial professionals.1

Depending on the circumstances, a judicial factor's role can include gathering in, holding, administering, protecting, and selling (or otherwise disposing of) the property.

For convenience, the property in question is referred to in this briefing as the estate.

Currently, individual statutes set out specific circumstances in which judicial factors can be appointed. For example, in certain situations, a judicial factor can be appointed to manage the estate of

However, there are also circumstances where legislation says it is not possible to appoint a judicial factor. For example, there are separate legal interventions, such as guardianship, for incapable adults (over 16s) under the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000.2

Appointments of judicial factors are currently relatively rare in practice.3 One Scottish Government policy aim is to make appointment of a judicial factor more attractive as an option in a wider range of circumstances.4

Under the Bill, it would be possible for the court to appoint a judicial factor in two alternative or coexisting sets of circumstances: a) it is not “possible, practicable or sensible” for the person who would otherwise do it to undertake that role; and b) it would be “to the advantage of” the estate.

Judicial factors are supervised by a public official called the Accountant of Court, who also sets judicial factors' rates of pay. With some changes to the detail, the Bill proposes both these arrangements will continue.

The Bill is split into six parts, as follows:

Part 1 coves a range of topics associated with the appointment of a judicial factor

Part 2 and schedule 1 cover the functions of a judicial factors, with the term 'function' covering both powers and duties

Part 3 covers some issues associated with the judicial factor's legal relationships with third parties, that is individuals and organisations not otherwise directly connected with the estate

Part 4 makes provision on topics associated with the end of the judicial factoring arrangement and a judicial factor's role in the estate

Part 5 covers the supervisory role of the Accountant of Court

Part 6 is a miscellaneous and general part of the Bill, which includes section 50, where some (but not all) of the legal terms used in the Bill are defined.

Introduction and overview

The Judicial Factors (Scotland) Bill, a Scottish Government Bill, was introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 5 December 2023. It was introduced by Angela Constance, Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs. The Bill originated in work carried out by the Scottish Law Commission ('the Commission').

Documents relating to the Bill are available on the Judicial Factors (Scotland) Bill page on the Scottish Parliament website. They include:

the Judicial Factors (Scotland) Bill,1 as introduced in Parliament

the Policy Memorandum to the Bill,2 ('the Policy Memorandum') which explains the overarching objectives which the Scottish Government aims to meet

the Explanatory Notes to the Bill,3 ('the Explanatory Notes') which explain the proposed purpose and effect of the individual provisions of the Bill.

The Bill is being considered under the Scottish Parliament's special procedure for dealing with certain Scottish Law Commission bills which have been classified as non-controversial.

Accordingly, the Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee ('DPLR Committee') is the lead committee for Stage 1 parliamentary scrutiny of the Bill. Stage 1 scrutiny looks at the general principles of a bill. The DPLR Committee issued a call for views on the Bill, which closed on 15 March 2024.

Previously, the Commission published a discussion paper4in 2010 (usually referred to as its consultation in this briefing) and then its final report5in 2013.

The responses to the Commission's consultation are not publicly available. SPICe would like to thank the Commission and the Scottish Government for making the submissions the Commission received (and had consent to pass on) available to SPICe.

The Scottish Government published its initial response6 to the Commission's report5 in 2015 and later consulted on the proposals itself in 2019.89

The two consultations, and the Committee's call for views on the Bill, had low response rates. The consultations, and the call for views, are one of a range of topics considered in more detail later in the briefing.

Most of the Bill's provisions will apply only in Scotland. However, there are certain provisions that the Commission and the Scottish Government consider should apply in the rest of the UK as well. The Scottish Government intends to discuss a section 104 order with the UK Government, with the aim of achieving this (Policy Memorandum, paras 9 and 10).10

The structure of the rest of the briefing

The remainder of this briefing is divided into the two main sections:

a section setting out the background to the Bill, including, among other things, a description of the current law and practice relating to judicial factors

a section discussing the substantive parts of the Bill in detail, which refers to individual responses to both the earlier consultations12 and the Committee's recent call for views.

Background to the Bill

This section provides an initial introduction to the Bill. It covers the following topics:

The policy objectives of the Bill

The Government's key policy objectives for the reforms include:1

clarifying the law, including the extent of a judicial factor's powers, an area where there appears to be particular uncertainty

creating a comprehensive regime in one piece of legislation, resolving the difficulties associated with having the relevant law spread over a number of different pieces of legislation

introducing a more efficient and flexible regime, which might make the solution of appointing a judicial factor an attractive one in a wider range of circumstances.

In relation to the second bullet point, note that, the Bill (if it becomes law) would consolidate much of the law relating to judicial factors. However, a number of existing pieces of legislation would remain in force allowing the appointment of judicial factors in specific circumstances.

In addition, it is anticipated that rules of court, made by the Court of Session, will be updated to flesh out the more detailed aspects of the procedure relating to the appointment of judicial factors.

The current law and practice relating to judicial factors

This sub-section of the briefing considers various aspects of the current law and practice relating to judicial factors. It covers the following topics:

Sources of law

The law applying to judicial factors comes from both legislation and the common law or case law, that is to say, the branch of law developed by judges reaching decisions in individual cases. There are also relevant powers in various Acts of Sederunt, also known as rules of court.

Judicial factors have a long history in Scots law, with mention of them in legislation pre-dating the Union of the Parliaments of Scotland and England in 1707.1 Legislation on judicial factors today includes legislation from the 19th Century.i This legislation, and a range of other relevant pieces of legislation, are discussed later in the briefing.

Key terms and features of the system

It is helpful to be aware of some key terms associated with, and the main features of, the existing system.

As already mentioned, the property for which the judicial factor is responsible is referred to in this briefing as the estate, although it is referred to in the Bill under a longer name, the factory estate.

The (slightly odd sounding) term, judicial factory, is the arrangement whereby a judicial factor has been appointed over an estate.

An estate can include heritable property, that is, land and buildings (including, for example, parts of buildings, such as flats). It can also include moveable property, as in, all property other than land and buildings. Examples of moveable property include:

physical objects (such as vehicles, furniture, artwork, jewellery)

money in a bank account

shares and other investments

rights to collect debts or other sums due.

As noted earlier, a judicial factor is appointed by the court. The general rule is this can either be (the Outer House of) the Court of Session in Edinburgh, or the local sheriff courts, with Edinburgh Sheriff Courtplaying a key role in some circumstances.i There are also some exceptions to that general rule discussed later in the briefing.ii

At present, all judicial factors must find caution (cay-shun, pronounced to rhyme with 'station'). A bond of caution is usually arranged via an insurance company to satisfy this requirement. In accordance with the terms of the bond, the insurance company will then make good any financial loss caused to the estate as a result of the judicial factor's mismanagement or other wrongdoing.

As alluded to earlier, the judicial factor may be appointed to do various things with the estate. It depends on the purpose of their appointment, and the person to whom the estate belongs.

For example, in the context of businesses and other organisations sometimes a judicial factor can be brought in to 'steady the ship'. The aim is that business or organisation can continue to operate as a going concern. On the other hand, there may be no prospect of that and the aim is to wind the business up and pay creditors.

Depending on the circumstances, the judicial factor may have to realise the estate, a process which (almost always) involves selling all the assets of the estate (or at least those which are worth selling).

Under the common law, judicial factors must comply with various fiduciary duties. These duties include the duty on the judicial factor (as the fiduciary) to put first the interests of another person (the beneficiary) over their own interests.1 Note that the term fiduciary is pronounced ‘fuh-do-shuh-ree’.

At present, and under the proposals in the Bill, judicial factors are supervised by a public official called the Accountant of Court ('the Accountant').

As well as judicial factors, the Accountant also supervises other types of official who are similar in function to judicial factors. For example, the Accountant supervises administrators who deal with property confiscated under the Proceeds of Crime (Scotland) Act 1995.iii

An interesting feature of the supervisory arrangements (both existing and proposed) for judicial factors is that the same person who is the Accountant is also the Public Guardian (Scotland).iv

The Public Guardian's responsibilities, in turn, include supervising separate legal interventions for incapable adults under the 2000 Act.

No formal merger of the offices is proposed in the Bill.

The statistics on judicial factors in practice

At present, appointments of judicial factors are relatively rare in practice. There have been an annual average of eight applications for such an appointment for the years 2019 to 2023.

As of 2022, there were 64 open cases where judicial factors were being supervised by the Accountant of Court. By 2023, the equivalent figure was 42 open cases.

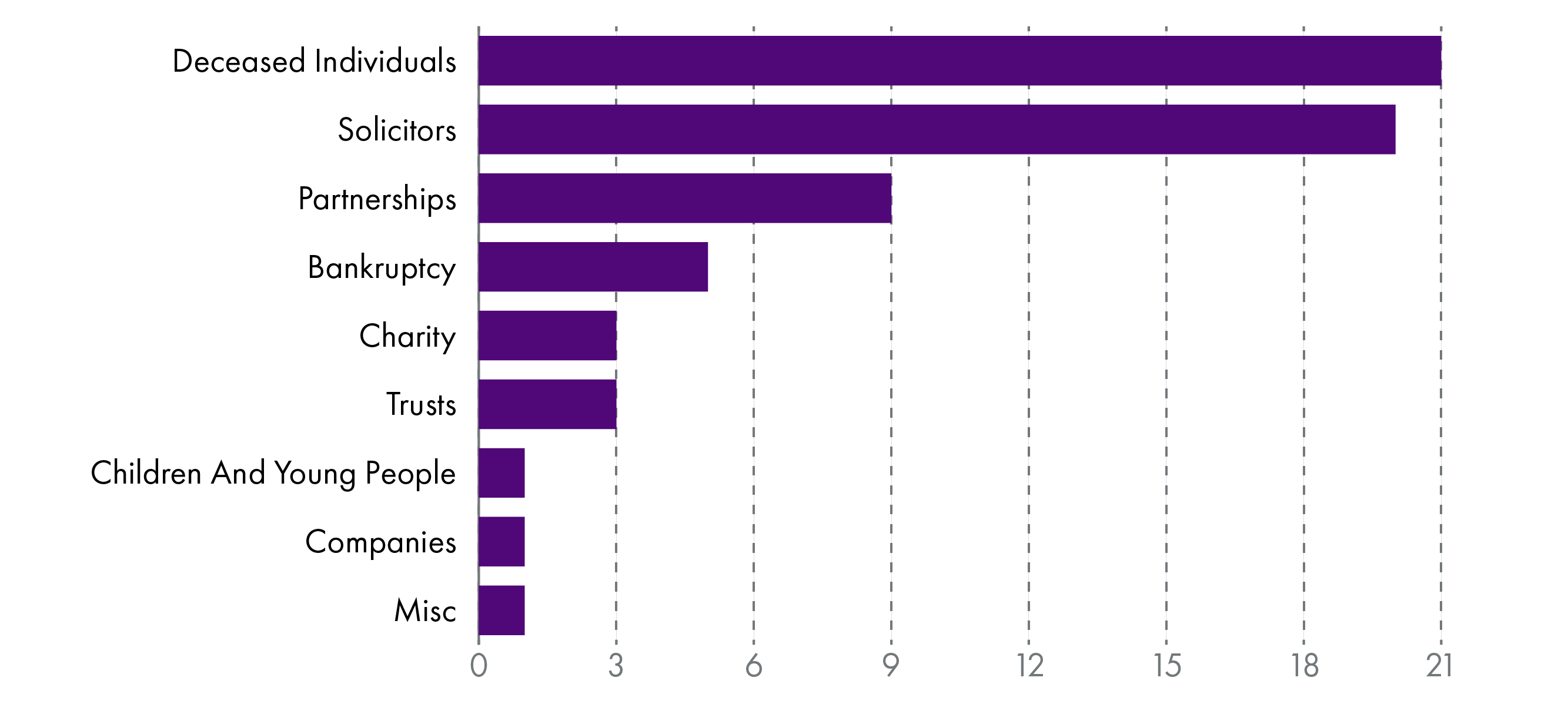

Figures 1 and 2 below shows the distribution of the caseload across different subject areas for the years 2022 and 2023, using statistics from the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service. Note its classification of the different categories is similar to, but not identical to, the one used by SPICe in the next section of this briefing. References to solicitors below include solicitors' firms.

.png)

When can a judicial factor be appointed?

As alluded to previously, factors can be appointed in a range of circumstances. These, in turn, are determined by specific pieces of legislation, and the common law.

The circumstances in which an appointment is possible are in more detail in this section of the briefing, under the following categories:

Note that, with a couple of exceptions, discussed in more detail later, the Bill proposes that the legislation discussed in this section of the briefing will remain in force.

Solicitors: section 41 of the Solicitors (Scotland) Act 1980

The Law Society of Scotland ('the Law Society') is the professional body for Scottish solicitors. Its Council (its principal decision-making body) may apply to the Inner House of the Court of Session for the appointment of a judicial factor under section 41 of the Solicitors (Scotland) Act 1980.i

The Law Society has an in-house judicial factor who also heads up its interventions team. This team has a key role where a solicitors' firm closes down or is otherwise in trouble. In practice, the interventions team appear to have an important role in the exercise of the statutory powers covered in this section of the briefing.

An appointment of a judicial factor under the 1980 Act can either relate to the estate of a solicitor or an incorporated practice. An incorporated practice includes a solicitors' firm taking the form of a company or a limited liability partnership.ii

The statutory power in the 1980 Act may be exercised where, under the Law Society's accounts rules or rules relating to money laundering compliance, the Council has carried out an investigation. If, after that investigation, it is satisfied that:

there has been a breach of those rules and

the solicitor or practice's liabilities exceed their assets or

the condition of their accounting records make it not possible to reasonably ascertain whether liabilities exceed assets or

it is likely there will be a claim on the Guarantee Fundiii

the Council may apply to (the Inner House of) the Court of Session for the appointment of a judicial factor.iiii

The Guarantee Fund, also known as the Client Protection Fund is paid for collectively by Scottish solicitors. It exists to protect a solicitor or firm's clients from the dishonesty of a solicitor or a member of their staff.

As noted earlier, appointments under the 1980 Act are a relatively common form of appointment in practice.

The Commission's report says that, under the 1980 Act, the judicial factor is traditionally tasked with the management and preservation of the property. It is carrying out that function primarily in order to protect the clients of the firm, and the Guarantee Fund, from the consequences of faulty administration (actual or anticipated) on the part of the solicitor or the firm.1

Note that the Law Society has said that it would like additional powers under the 1980 Act to address what it described in 2019 as a "serious problem" associated with its current powers under the 1980 Act in relation to incorporated practices. See later in the briefing on this issue.

Trusts: the common law

The court may appoint a judicial factor (instead of a trustee) over the estate of a trust under the common law.

A trust is a legal device for managing assets. A trust enables assets to be legally owned by one person or entity (the trustee) while a different individual, entity or section of the general public benefits from those assets in practice.

The purpose of the appointment may be to administer the estate, or to realise the estate and distribute it, depending on the purposes of the trust.1

The SCTS website reports that these normally represent the longest running types of Judicial Factory, with the oldest active case relating to a trust drawn up in 1826.

Charities: Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005

On application of OSCR, the Scottish charities regulator, the Court of Session may appoint a judicial factor under section 34 of the Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005.

This can happen where it appears that there has been misconduct in the management of a charity or where there have been unwarranted representations that an organisation is a charity.

Deceased individuals: section 11A of the Judicial Factors (Scotland) Act 1889 and the common law

A judicial factor can be appointed to the estate of a deceased person. Their role can be divided into three broad categories, discussed further in this sub-section of the briefing.

As mentioned earlier, judicial factors acting over the estate of a deceased person is a relatively common form of appointment in practice.

Partnerships: the Partnerships Act 1890, sections 35 and 39, and the common law

A judicial factor may be appointed over a partnership estate under statutei and under common law.1

In practice, a judicial factor might be appointed where the partners cannot agree on how the business should be run, or how the business should be wound up.2 A judicial factor could, for example, realise and distribute the assets of the partnership.24

Companies: the Companies Act 2006, sections 994-999, and the common law

A court may appoint a judicial factor to a limited company under statute (to protect members of the company from unfair prejudice)i and also under the common law.1

An appointment is normally sought by one of the directors, where the relationship between directors is detrimentally affecting the running of the company. It can also be sought by an aggrieved shareholder where there has been misconduct by the directors.2

A judicial factor is usually appointed in this instance to carry on the business of the company.34

Children and young people: the Children (Scotland) Act 1995

The Children (Scotland) Act 1995 ('the 1995 Act') sets out parental responsibilities and rights (PRRs) in respect of children and young people (under 16s) in Scotland.

In ordinary circumstances, a child or young person's parent or guardian will be responsible for the child or young person's money and property. However, a judicial factor can be appointed over the estate of a child or young person under three statutory provisions of 1995 Act, discussed in more detail in this sub-section of the briefing.

Missing persons: Presumption of Death (Scotland) Act 1977 and rules of court

Where a person goes missing for a long time, as well as the significant emotional impact, there can be practical implications for family members, such as having to deal with the person's property and financial affairs while they are missing.

A judicial factor can be appointed to manage the estate of a missing person. Such appointments are usually referred to as a judicial factor 'in loco absentis'.

Under statute this is after a person is declared dead by the courti and, separately, under rules of court, it can happen in a wider set of circumstances.ii

Note that schedule 3 of the Bill proposes revoking (that is, cancelling) the relevant Act of Sederunt.ii However, the general provisions of the Bill (sections 1 and 3) enabling the appointment of a judicial factor would, in effect, replace the function of this part of the rules of court.

On the use of judicial factors in relation to missing persons, the Scottish Government commented as follows in its 2019 consultation paper:1

It would seem that the powers are ... rarely used. Since 1985 the Accountant of Court has had to supervise only 12 in loco absentis cases. The last 2 cases were in 2007 and 2011 ...

It is not clear why there have been so few applications for this type of factory given that there are around 700 open cases of persons in Scotland classified as long-term missing.

Pending litigation: the common law

Under the common law, the court may appoint a judicial factor over property pending litigation. The principal duty of the factor under such an appointment is to preserve the property.1

At the discretion of the court

Finally, the Court of Session can appoint a judicial factor under the nobile officium, that is, this court's special fallback power.1 This power exists where this is necessary to afford protection against loss or injustice. It is designed to cover the situation where no other part of the law can assist.

Note that the term, nobile officium, is pronounced 'noh-billy-offick-ay-um.'

The consultation process on the Bill

As noted earlier, both the Commission1 and the Scottish Government2 consulted on the Bill. The (DPLR) Committee also issued a call for views. Key points about the consultations and the call for views are summarised in this section of the briefing.

Responses to the consultations and the call for views are also referred to throughout this briefing in relation to the individual parts and sections of the Bill.

The Commission's consultation (2010)

As noted earlier, the Commission published its consultation, a Discussion Paper1, in 2010. The Commission received fourteen responses to that paper, broken down as follows:

accountants (four responses)

legal bodies/lawyers (three responses)

public bodies (four responses), including the Accountant of Court

private individuals (one response).

A majority of those responding to the Discussion Paper supported (many of) the Commission's recommendations. A couple of the Commission's original policy ideas, discussed in more detail later, did not make it past this initial consultation stage.

The Scottish Government's consultation (2019)

In the latter half of 2019, the Scottish Government consulted separately on the recommendations in the Commission's final report:

In Part 1, the Scottish Government consulted on those Commission recommendations where the Government's desire was to implement them without changes.

Part 2 and Part 3 contained new policy ideas relating to missing persons and children and young people respectively.

Part 4 of its consultation focused on several areas where the Government wanted to test the Commission's recommendations further, including, for example, which court should be able to appoint judicial factors (now covered by section 1(5) of the Bill.)

The Scottish Government received nine responses, eight of which are available online. These can be broken down as follows:

legal bodies/lawyers (three responses)

public bodies (three reponses), namely OSCR, the Scottish charity regulator, HMRC, and a joint response from the Accountant of Court/the Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service (SCTS)

interest groups (one response), specifically, the charity, Missing People

private individuals (one response).

In August 2020, the Government also published an analysis of those consultation responses.

Subject to some specific policy points, all of those responding to the Scottish Government's consultation thought the recommendations in the Commission's report should be implemented.1

The Committee's call for views (2023-2024)

There were eleven responses to the Committee's recent call for views on the Bill, predominantly from those with a legal background. Responses can be divided into the following categories:

the judiciary: the Senators of the College of Justice; The Sheriffs and Summary Sheriffs Association

the legal profession: the Law Society of Scotland; the Charity Law Association; the Faculty of Advocates; the Faculty of Procurators of Caithness

academic lawyers: Professor Nicholas Grier (Abertay University); Dr Alisdair MacPherson, Professor Donna McKenzie Skene, Dr Euan West (Centre for Scots Law, University of Aberdeen)

interest groups/associations: Missing People (a charity supporting the families and friends of missing people); Propertymark (a professional body for the property sector); R3 (a trade association for insolvency professionals).

Respondents to the call for views were generally supportive of the Bill. Some specific policy points, as well as detailed drafting points, were raised by respondents.

For example, on the policy side, the organisation, Missing People, and the Law Society, both thought that the Bill could have done more to address the needs of families where people go missing. The Charity Law Association was keen that there is further consideration of the Bill as it applies to the charitable sector.

Some specific policy points were also made by the Law Society and the Faculty of Procurators of Caithness about the appointments of judicial factors to solicitors and solicitors’ firms. The Law Society also provided a detailed response on most of the provisions in the Bill.

What did not make it into the Bill

Some policy ideas which proposed by either the Commission or the Scottish Government on consultation did not make it into the Bill as introduced. Some examples of these are highlighted in this section of the briefing.

The Commission's ideas

A key policy idea which the Commission consulted on was that a new public office of judicial factor should be created, probably by expanding the role of an existing public office.1

The aim was to provide the required judicial factor service more efficiently and economically than under current arrangements (Policy Memorandum to the Bill, at para 114).2 If there was such a public office, the Commission thought there may then be no need for supervision of judicial factors by the Accountant of Court.3

The idea of a public office of judicial factor did not attract support on consultation, and so it was abandoned.4

The Commission also considered whether the existing term, judicial factor, was descriptive enough of its function and proposed alternative names.5Mixed views were expressed on this issue on consultation6 and ultimately, as is evident from the Bill, the existing name was retained.

Separately, the Committee also sought views on the terms judicial factor and Accountant of Court in its recent call for views, but there was virtually no support for change.

The Scottish Government's ideas

The Scottish Government's proposals which did not make it into the Bill included:

an alternative proposal to the Commission's on which court should have authority appoint judicial factors (discussed in more detail later in the briefing in relation to the relevant provision of the Bill)

the specific proposals relating to the safeguarding of children and young people's property the Children (Scotland) Act 1995, including how to take the views of those children and young people into account as part of the process

various proposals relating to missing persons, discussed in more detail in the next sub-section of the briefing.

Missing persons

In England and Wales, there is specific legislation allowing the appointment of guardians in respect of the estates of missing persons.i

In its consultation paper, the Scottish Government consulted on certain issues relating to missing persons which might have led to the creation of a specific regime in Scotland in this policy area.1

The respondents to this part of the Scottish Government's consultation expressed mixed views on the issues raised.2 However, the analysis of consultation responses summarises their collective view of the current system of judicial factors (as it applies to missing persons) as follows:

... the procedure was not widely known to the public or those within the professional sector and therefore not used. The process is viewed as complex, overly legalistic and costly.

It was suggested that the current system of judicial factors usually works to protect the interests of creditors, rather than protecting a missing person's estate and ensuring that their dependents are looked after.

Scottish Government. (2020). Judicial Factors: Analysis of responses to the Scottish Government consultation, p 8, paras 24 and 25. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/judicial-factors-analysis-responses-scottish-government-consultation/

Ultimately, the Scottish Government has decided not to create a special regime for missing persons in the Bill. It is relying on the proposed general reforms to the law of judicial factors to resolve outstanding issues (Policy Memorandum, paras 116-117).

As noted earlier in the briefing, in response to the Committee's recent call for views, the organisation, Missing People, has expressed some concerns about the suitability of the Bill's provisions for the needs of families of missing persons.

The Bill in more detail

The first five substantive parts of the Bill are considered in more detail in this section of the briefing, along with relevant responses to the consultations and the Committee's call for views.

Points to note about this section:

This section covers all the main proposals in the Bill, however, it does not include a description of every section of the Bill (for that purpose, see the Explanatory Notes)

This section mostly describes key provisions in chronological order, except in a few places where an alternative grouping is thought to make more sense.

Not all proposals in the Bill were the subject of a specific question in the consultations, or otherwise attracted comment on consultation or in response to the Committee's call for views.

Part 1: The appointment of a judicial factor

This section of the briefing considers Part 1 of the Bill, which cover a range of issues relating to the appointment of a judicial factor.

Proposals of particular policy significance in Part 1 are as follows:

which court can appoint a judicial factor (section 1(5))

the circumstances in which a judicial factor can be appointed (section 3)

who can be a judicial factor (section 4)

caution ('cay-shun'), broadly, a form of insurance for when things go wrong (section 5)

the payment of a judicial factor (section 9).

The court's power of appointment (section 1)

Under the current law, to make an application for the appointment of a judicial factor, the applicant must have a direct interest in the estate.

A neighbour of a missing person's semi-detached property, who is concerned about the state of a shared roof, is an example of a person who the Commission thought might fall outside the scope of direct interest.1

Section 1 of the Bill, in conjunction with section 3, would give a discretion to the court to appoint a judicial factor in respect of an estate.

The court would be able to make this appointment after an application to it by an interested person. This application may be made as a stand-alone application (section 1(1)) or during other court proceedings relating to the estate (section 1(3)(a)(ii)).

The Bill says an interested person is someone the court is satisfied has an interest in the appointment (section 1(4)). This would permit a broader group of people to apply than under the current law.

The court would also be able to appoint a judicial factor on its own initiative during other court proceedings relating to the estate (section 1(3)(a)(i)).

What was said on consultation

When it consulted, the Commission asked for views on widening the class of potential applicants for the appointment of a judicial factor.1 Those responding to the relevant consultation questions, were generally supportive of such an expansion.2

In its response to the Committee's recent call for views, the Faculty of Advocates commented on section 1's requirements to intimate (notify) interested individuals or entities in relation to an application to appoint a judicial factor.

The Faculty thought it was not desirable that the proposed requirement to notify is currently restricted to circumstances where a stand-alone application is made (section 1(2)). It does not apply where a factor is appointed as part of other court proceedings (section 1(3)).

A related point was made by the Faculty of Procurators of Caithness. It wanted to ensure there are distinct notification requirements associated with the appointment, or proposed appointment, of: a) an interim judicial factor (a temporary one) (section 2); and b) the appointment of a permanent judicial factor (section 1). The Faculty considered someone might not object to a temporary appointment but may have a different view or interest associated with the appointment of a permanent one.

The general conditions for appointment (section 3)

Under the Bill, the court's power of appointment would be available in two, alternative or coexisting, sets of circumstances (section 3(1)(b)):

it is not “possible, practicable or sensible” for the person who would otherwise do it to undertake that role

it would be “to the advantage of” the estate.

The key policy idea here is the introduction of a general set of conditions where a judicial factor can be appointed. This relates to the Scottish Government's objective of making the option of a judicial factor an attractive one in a wider set of circumstances.

The general conditions would sit alongside the remaining legislation allowing for the appointment of a judicial factor in specific sets of circumstances.

What was said on consultation

In response to the Committee's call for views, the Centre for Scots Law (University of Aberdeen) and R3 commented on the general conditions for appointment of a judicial factor. They said that the term ‘sensible’ is “ambiguous and implies a value judgement.” They would prefer ‘reasonable’ or ‘appropriate’.

Which court? (section 1(5))

Section 1(5) of the Bill covers the issue of which court can consider an application for the appointment of a judicial factor.

The current law and practice

As a reminder, the current law says, with some exceptions, either the Outer House of the Court of Session in Edinburgh or a sheriff court can appoint a judicial factor.i

Appointments of judicial factors to solicitors/solicitors' firms, and to charities, are two of the relevant exceptions. Only an application to the Court of Session (and, in the case of solicitor/solicitor's firm, to the Inner House of the Court of Session) is competent.ii

Edinburgh Sheriff Court is also the only competent sheriff court where the appointment relates to an estate held other than by an individual or by a trust.iii

This rule gives this court a significant role in relation to the estates of businesses, and where the person whose estate is to be managed lives overseas.

In practice though, most judicial factors are currently appointed by the Court of Session.1

What section 1(5) would do

Section 1(5) of the Bill proposes that it should still be possible for either the local sheriff court or the Court of Session to appoint a judicial factor (in most circumstances).

Section 1(5) also removes the special position of Edinburgh Sheriff Court in respect of applications over the estates of businesses. They would be able to be made instead in the sheriff court local to the business.

The Bill itself does not propose any specific alterations to the other exceptions to the general rule existing in the current law, and in rules of court,i meaning that these exceptions would remain.

What was said on consultation

Both the Commission's1 and the Scottish Government's consultations2 consider the issue of which court should be responsible for judicial factor appointments. The issue also attracted comment in the responses to the Committee's call for views.

Who can be a judicial factor (section 4)

Section 4 of the Bill sets out who can be appointed by the court as a judicial factor. The main qualification required is that the court considers the person 'suitable' for that role.

Section 4 largely restates the existing law, however, it also represents a policy choice not to be more prescriptive in the requirements. One motivation for this appears to be the desire on the part of the Scottish Government to allow family members to be appointed as judicial factors to the estates of missing persons.1

The Commission had also earlier noted that many tasks carried out by a judicial factor were administrative in nature and it was not clear they needed a legal or financial background to undertake them.23

There is a policy connection, explored later, between the decision to (continue to) permit a wide range of people to become judicial factors and provision in the Bill on:

any insurance requirements associated with the role (section 5)

provision on what judicial factors are to be paid (section 9).

What was said on consultation

The Commission consulted on the possible qualifications which should be required for a judicial factor role. However, this was only in the context of its (now abandoned) proposal to create a new public office.1

The Government's consultation, and the Committee's call for views, attracted wider commentary on the issue of who should be considered suitable for the role of a judicial factor.

Interim judicial factors (temporary appointments) (section 2)

As mentioned earlier, section 2 of the Bill says that it would be possible to appoint an interim judicial factor, that is, a temporary one. For the duration of their appointment, they would usually have the same powers and duties as a permanent judicial factor, unless the court to any extent restricted their powers (section 2(2)).

The Accountant of Court would be required to keep "under review" the progress of any interim arrangements (section 2(3)). No further details are provided on this point, such as, for example, a maximum permitted time period between reviews. Accordingly, the relevant time period would appear to fall within the discretion of the Accountant.

At present, such reviews are required monthly by the Accountant.1

Interim judicial factors might be suitable in circumstances where speed of action in appointing a judicial factor is important. For example, there may be cases where a relationship between business partners deteriorates to such an extent that no effective decision can be taken, putting the business owned by the partnership at risk (Policy Memorandum, para 27).

What was said on consultation

When it consulted, the Commission asked a number of questions relating to interim judicial factors.

The Commission asked for views on whether interim judicial factors should have the same powers and duties as a permanent judicial factor.1

On the duties, responses were mixed. However, there was majority support from those responding on this point for the interim factor having the same powers. Two respondents in favour here thought the court should have a discretion to limit powers in a particular case.2

The Accountant of Court was an example of a dissenting view on both powers and duties. She thought powers and duties should be more limited (compared to a permanent appointment). This is because, she said, interested parties don't have the opportunity to be heard by the court prior to the appointment.2

The Commission also asked whether the appointment of an interim judicial factor should have a time limit, with the possibility of the court approving an extension.4 There was strong support for this from among those responding on this point. STEP Scotland (a representative body for various professionals advising families), for example, thought a time limit of six months was appropriate. The Accountant of Court thought nine months, with the possibility of a further extension of three months.2

Finally, the Commission asked whether the Accountant should still be required to review the appointment, and whether the court should have a discretion to fix the time period between reviews.6

There was unanimous support for the first point, from those responding on this issue. A majority of those respondents also thought the current one month reporting requirement was excessive. They either made alternative suggestions for alternative time periods, or agreed that the court (or, for one respondent, the Accountant) should have discretion to fix time period for further reviews.2

Caution ('cay-shun'): insurance against risk (section 5)

Earlier in the briefing, the existing requirement on judicial factors to find caution ('cay-shun') was discussed. This is usually satisfied by taking out a bond of caution from an insurance company. The aim is to protect the estate from any financial risk associated with any mismanagement or wrongdoing by the judicial factor.

In a shift from the current position, section 5 of the Bill does not require caution to be routinely sought. Instead, it gives any court a discretion to require the judicial factor to find caution where there are exceptional circumstances which justify this.

What was said on consultation

The Commission's1 and the Scottish Government's consultations,2 and responses to the Committee's call for views, considered the proposal now contained in section 5 of the Bill.

Some consequences of the appointment (sections 6-8)

Sections 6-8 of the Bill set out some immediate consequences associated with the appointment of a judicial factor.

Section 7 of the Bill says that the estate vests in the judicial factor. In other words, they acquire legal rights to it, in their capacity as a judicial factor, as if they were owner of it.

Section 8 of the Bill gives the factor warrant to intromit. This is, very broadly, the capacity to access and use property in the estate.

Section 6 of the Bill creates a new requirement that the notice of appointment of a judicial factor must be registered in an existing public register. This register is called the Register of Inhibitions. It is overseen by the public body Registers of Scotland.

What was said on consultation

The issues covered by sections 6-8 of the Bill were considered at two main stages of the consultation process.

The payment of judicial factors (section 9)

Section 9 of the Bill coves the payment of judicial factors.

The current approach

In addition to their role in supervising judicial factors, the Accountant of Court currently sets the commission paid to judicial factors.

The Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service website says:

The hourly rate for the commission paid to a judicial factor takes account of their professional qualifications, experience and the hourly rate which would routinely be paid to them in the exercise of their normal duties (for example, as a solicitor or accountant).

Annual increases will reflect increases to this amount, as well as current rates of inflation.

The hourly rates payable (from 1 April 2022) are:

Partner - £252.50

Manager - £181.80

Support Staff - £90.90

What section 9 would do

Section 9 of the Bill says that:

judicial factors are to be paid for their work out of the estate

the rates are to be fixed by the Accountant of Court

there is a right of appeal for the judicial factor to the court in relation to a decision of the Accountant of Court, both on rate of pay and frequency of payment.

On the last bullet point, note that there is no equivalent right of appeal for a person or organisation with an interest in the estate.

What was said on consultation

Both the Commission's1 and the Scottish Government's consultations2 considered the issue of judicial factors' pay.

Part 2 and schedule 1: functions of the judicial factor

This section of the briefing considers Part 2 and schedule 1 of the Bill which cover the proposed functions of a judicial factor.

The term functions refers to both the powers and duties of a judicial factor.

The 'general function' (sections 10 and 11)

Section 10(1) of the Bill sets out the general function of a judicial factor. The general function is to hold, manage, administer, and protect the estate for the benefit of those with an interest in it.

The general function:

can be varied by the court, either at the time of the appointment or later (sections 10(2), 11(1) and (2))

is subject to any other legislation relating to a judicial factor's functions (sections 10(2))

must be exercised with "care, prudence and diligence" and, in its exercise, the judicial factor must take professional advice when appropriate (section 10(3)).

The 'standard powers' (sections 10 and 11, schedule 1)

When appointed, the judicial factor acquires the standard powers.

Broadly speaking, the standard powers are all the powers someone who owns the estate would have.

A (non-exhaustive) list of the standard powers is set out in schedule 1.

It is possible for the court to vary the standard powers, either at the time of the appointment or later (section 10(6),(7) and 11(1), (2)).

A key policy aim is to provide a more comprehensive list of standard powers than exists under the current law. The intention is to reduce the circumstances in which extra powers will be needed from the court.

What was said on consultation

The proposed powers of a judicial factor attracted commentary at the stage of the Commission's consultation,12and also in response to the Committee's call for views.

The power to request information (section 12)

With some exceptions, section 12 of the Bill gives the judicial factor the power to request information relating to the estate from both organisations and individuals. For example, financial information could be requested from banks.

The information requested must be that which the judicial factor reasonably considers relevant to the judicial factor’s functions.

The general rule is that the body or individual receiving the information notice is required to comply with it without delay (although what constitutes delay is not further specified) (section 12(3)).

Certain organisations and individuals, such as bodies exercising reserved functions, like HRMC, or UK Government department or ministers, are exempt from the obligation to comply and can choose whether to do so (section 12(4)). This differs from the approach in the Commission's draft Bill (also section 12).

What was said on consultation

In response to the Committee's call for views, the Sheriffs and Summary Sheriffs Association and the Law Society both referred to the exemption in section 12(4) from the general requirement.

Both organisations commented that the policy effect of the exemption would be to weaken the information-gathering powers and sought clarification from the Scottish Government as to the rationale for the exclusion. The Law Society also queried how information was to be gathered about funds held outside Scotland.

On the other hand, the Faculty of Advocates thought that section 12 is “somewhat draconian” as currently drafted. It said there should be provision for the situation in which a person who is required to provide information can appeal to the appointed court against the requirement on the basis that the provision of the information requested, would, for example, breach confidentiality; or where the cost of providing the information would be onerous.

Furthermore, the Faculty felt it was not clear what should happen if a person maintains they do not have the information sought.

The Faculty also commented that the section also currently lacks any sanction for non-compliance.

Duties of the judicial factor (sections 14-17)

Sections 14 to 17 of the Bill set out various duties of the judicial factor. These include:

a duty to gather in the assets of the estate and make an inventory of them (section 14)

a new duty to prepare a management plan relating to the estate, which must be approved by the Accountant of Court (section 15)

a duty to regularly report to the Accountant of Court, including by submitting accounts to that official at least once every two years (but not less than once a year, unless exceptional circumstances apply) (section 16)

a duty to consider whether it would be appropriate to invest the funds which form part of the estate and a duty then to make any such appropriate investments (section 17).

What was said on consultation

Various aspects of these proposals were explored when the Commission consulted, and in response to the Committee's call for views.

Solving disagreements (section 19)

Section 19 of the Bill applies if the judicial factor was appointed because people were unable to agree how an estate should be managed. For example, it might apply if partners in a partnership were unable to agree how the business should be run and this, of itself, was jeopardising the business.

A judicial factor appointed against the backdrop of a dispute must, by whatever methods they think appropriate “promote agreement” between the people concerned. The judicial factor may act as a mediator or arbitrator or appoint a person to act in this capacity (section 19).

Mediation: Mediation involves an independent and impartial person (the mediator) helping two or more individuals to negotiate a potential solution to a problem in a confidential setting. The people involved in the dispute must be willing to participate voluntarily. They, not the mediator, decide the terms of any subsequent agreement. The outcome is not legally binding, without further steps being taken by the people concerned.

Arbitration: In arbitration, a third party (the arbitrator), who often has specialist expertise or knowledge, will decide how the dispute should be resolved. The outcome is legally binding. The law relating to arbitration in Scotland was significantly reformed by the Arbitration (Scotland) Act 2010.

What was said on consultation

The Commission asked for views on whether a judicial factor should be under a duty to encourage and assist parties in settling a dispute.1

It received six responses on this point, with an even split of views on whether this was desirable.2 For example, in favour, the Accountant of Court thought it could save on court time to require this.2 Against such a move, for example, one accountant commented:

No – you can take a horse to water etc etc – generally a partner/shareholder seeks the appointment of a Judicial factor as a last resort – often after years of failing to reach a consensus with his fellow partners/shareholders.

Scottish Law Commission. (2023). Consolidated responses to: Discussion Paper No 146 on Judicial Factors.

In response to the Committee's call for views, the Faculty of Advocates argued that the current drafting (in section 19(3)) means that the judicial factor can compel those involved in the dispute to go mediation or arbitration. The Faculty commented that the intention instead was presumably to make it clear that, if those people did wish to go, then it is the factor's role to either conduct the process or appoint a mediator or arbitrator.

Other issues raised on consultation in relation to Part 2

Those participating in the consultation process made some wider points about the powers and duties of judicial factors found in Part 2 of the Bill.

Powers of a judicial factor

Some respondents in the consultation process suggested additional powers for the judicial factor.

In response to the Committee's call for views, the Faculty of Advocates said it would be appropriate to give the judicial factor the power to seek directions from the appointing court (as, for example, is available to insolvency practitioners).

Also in response to the call for views, the Faculty of the Procurators of Caithness had some specific proposals on judicial factors' powers where a judicial factor is appointed in respect of a solicitor/solicitors' firm. For example, in the case of a partnership or a “corporate practice", it proposed that the powers over the estate would only relate to the estate of the firm or company, not the personal estate of the individual partners.

The 1980 Act: additional powers relating to incorporated practices

In its response to the Scottish Government's 2019 consultation on the proposals in the Bill, the Law Society said that it would like additional powers under the 1980 Act to address a "serious problem" associated with its current powers and incorporated practices.

For such practices, only one person might be authorised to manage client funds. If that person drops out of the picture, for any reason, the Law Society said it cannot step in to manage these funds. This, it also said, contrasts with the Law Society's powers for solicitors who are either sole practitioners, or in a firm which is not incorporated.

Here the Law Society would like options additional to the appointment of a judicial factor. It thought this could be achieved by way of amendment to the Bill.

The point was also repeated (albeit more briefly) in the Law Society's response to the Committee's call for views.

Duties of a judicial factor

In response to the Committee's call for views, some respondents mentioned additional duties they thought could be expressly stated in the Bill. These included:

an explicit reference to the fiduciary nature of the judicial factor's duties (Professor Nicholas Grier (Abertay University); Centre for Scots Law (University of Aberdeen); R3)

a specific duty on judicial factors to not unduly delay in dealing with the estate under their control (The Faculty of the Procurators of Caithness)

in relation to appointments relating to solicitors/solicitors’ firms under the 1980 Act, a duty to report suspected criminal activity and to co-operate with the police/the Law Society in any associated investigations (The Faculty of the Procurators of Caithness).

Part 3: the judicial factor's legal relationships with other individuals or organisations

This section of the briefing considers Part 3 of the Bill.

Part 3 covers a range of specific issues associated with the judicial factor's legal relationships with third parties, that is individuals and organisations not otherwise directly connected with the estate.

Buyers of property from the estate (section 20)

Section 20 of the Bill contains certain protections for a buyer of property who buys that property from an estate managed by a judicial factor.

Debts and other obligations (section 21)

Section 21 of the Bill says that a judicial factor is liable (in their capacity as factor) for any debt or other obligation due to a third party.

Contracts (section 22)

Section 22 of the Bill sets out two rules relating to contracts entered into by a judicial factor in their capacity as factor.

These rules would apply as long as the other person or organisation who has entered into a contract ought to have been aware that the judicial factor was entering into their contract in their capacity as judicial factor.

Section 22 of the Bill says any contractual obligations (such as an obligation to pay money) will be enforceable out of the estate.

It also says that any court proceedings associated with the contract should be raised against the judicial factor (in their capacity as factor).

Legal costs (section 23)

During litigation, both sides will likely incur legal costs. At the end of litigation, a court typically makes an award of expenses, in other words, it stipulates who should pay the legal costs incurred. The rule it usually applies is that expenses follow success. In other words, the losing side pays the winning side's legal costs (as well as their own).

Section 23 of the Bill says that where the judicial factor is involved in court proceedings on behalf of the estate, there is a proposed rule that any legal costs (which the court orders the judicial factor must pay) would come out of the estate.

Financial damages (section 24)

Section 24 of the Bill covers the situation where a court decides a judicial factor must pay damages to someone (that is, financial compensation), for example, under the law of negligence.

Here the proposed general rule is that the damages (and any legal costs the court says the judicial factor must pay) will come out of the estate. However, there is discretion for the court to decide otherwise if a breach of duty by a judicial factor caused the loss (section 24).

Time limits on obligations (section 25)

Section 25 of the Bill covers the interaction between the law of prescription and the appointment of a judicial factor.

The law of prescription provides for the extinction of rights and obligations (such as an obligation to pay a debt) after the passage of a period of time.

Subject to one exception, section 25 sets out the rule that the appointment of a judicial factor does not affect the ticking of the clock on any prescriptive time period in respect of legal obligations due to, or by, the estate. It will continue as if no judicial factor had been appointed.

Judicial factors and trusts (section 26)

Section 26 of the Bill applies where the estate forms part of a trust. Furthermore, the judicial factor wishes to exercise a function which a trustee would ordinarily be entitled to exercise in relation to the estate, but the judicial factor considers that the terms or purposes of the trust do not allow for it.

Section 26 sets out a procedure for the judicial factor to get consent to exercise the function in question from the Accountant of Court.

What was said on consultation

Part 3 of the Bill attracted commentary at the stage of the Commission's consultation and in the the Committee's call for views.

The Commission's consultation

The Commission consulted on most of the proposals now contained in Part 3.

Commentary was relatively limited but those that responded were generally supportive, with some minor points made.1

The Commission consulted on a slightly different proposal2 than the one in section 23 of the Bill as introduced. To recap, section 23 says legal costs should always come out of the estate. The Commission's proposal, which was well-received on consultation,1 would have retained the basic rule. However, it would subsequently allow the estate to recover costs incurred from the judicial factor when the judicial factor had engaged in unnecessary litigation.2

The Committee's call for views

Part 3 of the Bill was generally well received by those who commented on it in response to the Committee's call for views. For example, both the Senators of the College of Justice ('the Senators') and the Charity Law Association described it as "sensible."

Several respondents (including the Senators; Centre for Scots Law (University of Aberdeen); Professor Grier, Abertay University) made suggestions relating to the drafting of this part of the Bill.

Separately, the Law Society flagged a couple of areas where the Bill as introduced differed from the Commission's draft bill and sought clarification of the policy rationale for this. For example, it noted that that the Commission's draft Bill (at section 30) made specific provision on judicial factors and unjustified enrichment, whereas the Bill as introduced does not.

Unjustified enrichment is the principle (enforceable by court action) that a person must not suffer a loss by giving another person a benefit which is unjustified and unfair.

The Scottish Government's position is that compensation payable for unjustified enrichment is now covered as part of the general rule on damages under section 24 (Explanatory Notes, para 46) rather than by a specific provision in the Bill.

Another legal remedy for unjustified enrichment is the return of the property concerned, which is not covered by section 24.

The Faculty of Advocates and the Sheriffs and Summary Sheriffs Association both thought section 23 of the Bill, which sets out the rule that legal costs should be borne from the estate, could be modified. This would be to deal with exceptional circumstances when a judicial factor was at fault and so should be found personally liable (out of their own pocket).

In relation to section 26 of the Bill, on trusts, where the Accountant must reach a decision, the Sheriffs and Summary Sheriffs Association noted that there was no express power for an objector to appeal the Accountant’s decision and wondered if one should be added.

Part 4: Distributing an estate and ending the judicial factor arrangement

This section of the briefing covers Part 4 of the Bill. It makes provision on topics associated with the end of the judicial factoring arrangement and ending a judicial factor's role in the estate.

A general overview

Currently, a judicial factor arrangement may be terminated by way of a formal procedure involving the court. In addition, in limited circumstances, it can be terminated by way of a less formal administrative procedure, involving the Accountant of Court.

Part 4 of the Bill contains both administrative procedures and court-based procedures.

A key policy approach is expanding the circumstances in which use of an administrative procedure is possible.

The administrative procedure (sections 27, 29 and 34)

Part 4 of the Bill contains administrative procedures which allow the Accountant of Court, on application by the judicial factor, to:

authorise the distribution of the estate (section 27)

end the situation where the estate is subject to a judicial factor arrangement (termination) (section 29(2)(a))

cancel (recall) the current judicial factor's appointment (section 29(2)(b))

free the judicial factor from legal liability (that is, discharge them) in respect of their acts or omissions associated with the estate from that point onwards (sections 29(2)(c)).

Section 34 of the Bill sets out the main rule that discharge frees the judicial factor from liability as factor under civil law (for example, under the law of contract or the law of negligence).

However, under section 34, the judicial factor is not freed from liability under criminal law, or any civil law liability associated with such criminal law liability.

The administrative procedure for distribution can be used in any of the following circumstances:

the purpose of the judicial factor appointment has been fulfilled, or no longer exists

there are insufficient funds for the judicial factor arrangement to continue

a judicial factor was appointed in the event of a disagreement that then cannot be resolved (sections 19(4) and 27(1)).

In any of these circumstances, if someone objects to the scheme for distribution proposed by the judicial factor as part of the application, the issue must be referred to the court to determine (section 27 (6)(7)(8) and (9)).

The court-based procedures (sections 28, 30 and 31)

Part 4 also contains court-based procedures.

For example, there is a procedure for someone with an interest in the distribution of the estate to apply to the court for distribution of it. If the court application is successful, the administrative procedure can then be used to the carry out the remaining legal steps of termination, recall and discharge (sections 28 and 29).

There is also a procedure for a judicial factor, or someone with an interest in distribution, to apply to the court to end the judicial factor's role in an estate (that is recall and discharge). This is in a broader set of circumstances than those covered by the administrative procedure (section 31).

There is also a duty on the Accountant of Court to apply to court in order that it can appoint a new judicial factor. This duty exists where the original factor has either died or is not performing their functions (and no application for a new appointment has otherwise been made) (section 30).

What was said on consultation

Part 4 of the Bill was mainly considered at the stage of the Commission's consultation and the Committee's call for views.

The Commission's consultation

The Commission's consultation contained some high-level questions on the approach now contained in Part 4 of the Bill.

Significantly, the Commission sought views on whether the procedure for administrative discharge should be extended to cover all circumstances.1 There was support for this from five out of the six respondents commenting on this issue. However, the Accountant of Court, who would be responsible for the administrative discharges, was opposed.2

The Committee's call for views

Those responding to the Committee's call for views were generally supportive of Part 4 of the Bill, with some specific points being made. For example, Professor Grier and the Senators both described Part 4 as "sensible."

For two provisions (sections 27(5) and section 29(6)), the Sheriffs and Summary Sheriffs Association argued that, where certain legal steps had to be taken within a specified time period, the court needed discretion to extend that time period. This, it said, was to cater for when the deadline was missed for a good reason.

In Part 4 there are obligations to notify those with an interest in the estate when certain things happen. For example, this is the case when the Accountant of Court approves a scheme for distribution of the estate. The Charity Law Association argued this obligation needed to better reflect the wider public interest associated with certain charities. It suggested a requirement to notify OSCR, the charities regulator, might satisfy that aim.

The organisation, Missing People, queried how Part 4 would work with the statutory powers under the Presumption of Death (Scotland) Act 1977 ('the 1977 Act'), specifically, the power of the court to declare that someone is dead.

For example, the organisation asked whether a judicial factor would be able to distribute an estate in a way that conflicts with a missing person's will. Separately, it wanted a judicial factor appointment to be immediately terminated if a missing person returns, rather than them having to apply to the court to achieve this aim.

The Centre for Scots Law, University of Aberdeen) wanted the interrelationship between section 34 (on the ending of a judicial factor’s accountability on discharge) and section 38 (in Part 5, on the misconduct or failure of a judicial factor) to be spelled out a bit more:

Presumably it is intended that if a judicial factor is discharged but certain forms of misconduct later come to light and are reported to the court, then the court 'may dispose of the matter in whatever manner it considers appropriate' and thereby hold the discharged judicial factor accountable/liable, perhaps most likely on an individual basis. If this is the intention, it should be made more express ...

Part 5: the Accountant of Court

This section of the briefing considers Part 5 of the Bill. Part 5 covers the supervisory role of the Accountant of Court ('the Accountant') over judicial factors.

The Accountant's role in relation to a judicial factor's pay is covered earlier in the briefing (section 9 of the Bill).

Background

The Accountant's supervisory role over judicial factors exists as part of her current role.

On the underlying policy here, the Commission commented in its report:

The importance of such a function is obvious. The judicial factor is given – by the court – sweeping powers in relation to the property of someone else, who may in many cases be in no position to scrutinise or monitor its management. It is essential that the conduct of such a factor should be properly supervised.

Scottish Law Commission . (2013). Report on Judicial Factors, Scot Law Com No 233, para 8.4. Retrieved from https://www.scotlawcom.gov.uk/files/2913/7776/7158/Report_233.pdf

The Accountant is currently appointed and employed by the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service (SCTS).

As noted earlier, the same person who holds the office of the Accountant also acts as the Public Guardian (Scotland) in respect of supervision of the (separate) legal interventions under the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000. The Scottish Government’s policy intention is that this overlap of roles will continue.2

The general approach in Part 5

As alluded to in earlier sections, the general approach in Part 5 of the Bill is that the Accountantshould continue to perform a supervisory role in respect of judicial factors.

In the Committee's call for views, it sought opinions on this general principle. The organisation, Missing People, was the only respondent who was unsure.

They said it would depend on the skill set of the person appointed, and the guidance they received, as to whether they could cater to the needs of the families of missing people.

There are also various specific proposals relating to the Accountant in Part 5. The briefing now considers the details of the arrangements proposed for the Accountant under Part 5.

Note that, in response to the Committee's recent call for views, while some policy points were raised, mainly by the Law Society, there was a good level of support for the details of the approach in Part 5.

Appointment, remuneration and fees (sections 35 and 36)

Section 35 of the Bill retains the power of SCTS to appoint the Accountant. The person appointed must be, in the opinion of SCTS "appropriately qualified or experienced" in law and accounting (section 35(1)).

The Policy Memorandum (at para 105) says that formal qualifications in these disciplines are not necessarily required.

The Accountant is to be paid for their role. The SCTS is to (continue to) determine their pay (section 35(3)). However, the Accountant must also charge fees relating to their work, to cover their reasonably incurred costs. These fees are to be met out of the estate managed by the judicial factor (section 35(4)(5)).

Section 36 of the Bill says that SCTS may also appoint a Depute Accountant, to carry out the functions of the Accountant during any period the Accountant is unable to do so. This is on such terms and conditions as SCTS may determine.

The Explanatory Notes (at para 78) note that in practice, a Depute Accountant is already appointed by SCTS. They say this provision gives the appointment a statutory underpinning.

What was said on consultation

The Sheriffs and Summary Sheriffs Association thought the appointment of the Accountant should be made not by SCTS directly but by the Lord President, as Head of the Judiciary, who is also the judicial head of SCTS.i

The Law Society commented on what it regards as "a significant departure" from the Commission's draft Bill. It considered there was a 'watering down' of the level of legal and accountancy knowledge required for the roles of the Accountant and the Depute Accountant. It thought this shouldn't happen because of the potential impact on the oversight of complex cases.

Supervision and investigations (sections 37-38)

The Bill says that the Accountant must supervise the performance of judicial factors, both those appointed under the proposed legislation, and any appointed under existing legislation or the common law. This function is described as the general function of the Accountant (section 37(1)).

The Accountant can issue instructions to judicial factors as to how they carry out their functions (section 37(2)).

The Accountant also would have an investigatory power. Specifically, if the Accountant has reason to believe that the judicial factor is engaging in misconduct or failing in certain other ways they can make such inquiries "as the Accountant considers appropriate" (section 38(1)(2)(a))). Here, the Accountant must give the judicial factor opportunity to make representations on the matter (section 38(2)(b)).

Where "serious misconduct or other material failures" are found, the Accountant must report them to the court. Furthermore, if the judicial factor is a member of a professional body, the Accountant must report the factor to that body (section 38(4)).

What was said on consultation

The Accountant's role in supervision and investigations attracted comment at the stage of the Committee's call for views.

On oversight of judicial factors, the Faculty of Procurators of Caithness said it thought there should be a specific provision for an interested person or organisation to raise concerns about the judicial factor's management of the estate. This, it proposed, would first be to the Accountant. If unsatisfied with the outcome, there would then be a role for the court.

The Commission's draft Bill required the Accountant to refer to the court or professional body where there had been "some appreciable" misconduct or failure (section 46(5)). The Law Society's response noted that this was lower than the threshold for referral now appearing in the Bill, as introduced.

The Law Society also highlighted that the report to the professional body must be made before the court had considered the issue. It questioned what would happen if the judicial factor was subsequently exonerated by the court.

The Law Society also queried how section 38 (including the reporting duty) would interact with the right of the judicial factor to require from the court a determination relating to a decision of the Accountant (section 45). Section 45 is considered later in the briefing.

More generally, the Law Society thought that this part of the Bill may dissuade individuals from accepting appointment as factor, given the often-contentious nature of the cases involved.

Power of the Accountant to require information (section 39)

Equivalent to the information-gathering power for a judicial factor under section 12 of the Bill, section 39 of the Bill gives the Accountant the power to require information relating to the estate from bodies, such as banks, and individuals. The information must be that which the Accountant reasonably considers relevant to the Accountant's functions.

As with section 12, certain individuals and bodies, such as bodies exercising reserved functions, like HRMC, or UK Government department or ministers, are exempt from the obligation to comply and can choose whether to do so (section 39(3)). Again, this differs from the approach in the Commission's draft Bill (section 47).

What was said on consultation

In response to the Committee's call for views, the Sheriffs and Summary Sheriffs Association and the Law Society both commented on the limits of the Accountant's information-gathering power (in relation to bodies exercising reserved functions, or UK Government departments/ministers).

The respondents' concerns were the same as those expressed in relation to the judicial factor's equivalent power. In order words, they thought that the relevant exceptions weakened the strength of the power.

Audit of accounts by the Accountant (sections 40-41)

Earlier in the briefing, it was explained that, under the Bill's proposals, a judicial factor must submit accounts to the Accountant periodically, at the Accountant's discretion, and at least once every two years (section 16). Section 40(1) of the Bill sets out a corresponding duty on the Accountant to audit the accounts received from judicial factors.

Section 40(2) gives the Accountant the power to examine further information, and to send the accounts to an external accountant for auditing if the Accountant considers that it is necessary, or would be beneficial, to do so.

Section 41 sets out the process which will apply when any objection or appeal is made by the judicial factor in relation to an audit carried out in accordance with section 40. As a final step of the process, the judicial factor can require the Accountant to ask the court to reach a decision.

What was said on consultation

In response to the Committee's call for views, the Law Society queried how the provisions passing the cost of external audit to the estate (section 40(6)) would work in practice, where the estate is unable to bear the costs (for example, because it is insolvent).

Annual review (section 42)

Section 42 of the Bill places the Accountant under an obligation to publish an annual review detailing the Accountant’s activities in relation to the relevant judicial factories, for the reporting year to which the report relates.

Inspection of records held by the Accountant (section 43)

Section 43 of the Bill places the Accountant under an obligation to make certain documents relating to an estate available for inspection, or to provide copies of the documents.

This obligation applies to a person with an interest in the estate who requests such copies or inspection. The documents are defined as being the management plan, the annual accounts, and the audit report in relation to the relevant estate.

What was said on consultation

In response to the Committee's call for views, the Law Society commented that the Bill as introduced differs from the terms of the Commission's draft Bill (section 51(1)) in that the inventory of the estate is omitted from the documents which must be made available for inspection.

Inconsistency in judgement or practice (section 44)

Section 44 of the Bill requires the Accountant to submit a report to the Lord President of the Court of Session (the Head of the Judiciary in Scotland). This section applies if the Accountant is of the view that the local sheriff courts in Scotland are not consistent in their dealings in relation to judicial factors or estates where a judicial factors have been appointed.

The Accountant must propose a rule of practice in relation to the inconsistency identified. The Lord President may take such action as the Lord President considers appropriate – which may include adopting the rule proposed by the Accountant.

Right of judicial factor to require a determination (section 45)

Section 45 of the Bill gives a judicial factor a right to apply to the court which appointed them for a determination in relation to any decision that the Accountant has made about the judicial factory. In effect, this gives a judicial factor a right of appeal to the court.