Prisoners (Early Release) (Scotland) Bill

The Prisoners (Early Release) (Scotland) Bill sets out provisions which amend the rules relating to the automatic early release of certain short-term prisoners. It also grants Scottish Ministers powers to make future changes to automatic early release points for both short and long-term prisoners.

Summary

The Prisoners (Early Release) (Scotland) Bill ("the Bill") seeks to amend the rules relating to the automatic early release of prisoners serving short-term sentences. This would include children under the age of 18 serving sentences of less than four years in secure accommodation following criminal proceedings. It also grants Scottish Ministers powers to make future changes to automatic early release points for both short and long-term prisoners.

Short-term prisoners are those sentenced to less than four years.

Long-term prisoners are those sentenced to four years or more, but excluding those serving indeterminate sentences (e.g. life sentences).

The Bill does two things in relation to automatic early release:

Sections 1 and 2 of the Bill change the automatic early release point for some short-term prisoners, including children detained for less than four years following criminal proceedings. This will now apply at the point of them having served 40%, rather than the current 50%, of the sentence. This excludes those serving sentences for sexual offences, domestic abuse or terrorism offences.

The changes will apply retrospectively, and the Bill makes transitional provision so that those immediately eligible for release will be released in tranches.

Section 3 of the Bill grants Scottish Ministers a power to make future changes to automatic early release points for both short and long-term prisoners, including children detained in secure accommodation, by subordinate legislation. These regulations would be subject to parliamentary approval via affirmative procedure.

The Bill will not affect remand prisoners or those serving an indeterminate sentence.

Cover photograph of HMP Edinburgh by Thomas Nugent licensed under CC-BY-SA-2.0.

Introduction

The Scottish Government introduced the Prisoners (Early Release) (Scotland) Bill1 (“the Bill”) in the Scottish Parliament on 18 November 2024. Documents published along with the Bill include Explanatory Notes2, a Policy Memorandum3, Delegated Powers Memorandum4, Financial Memorandum5 and statements on legislative competence6.

The Prisoners (Early Release) (Scotland) Bill: Emergency Bill Motion is due to be moved on 20 November 2024, with the Stage 1 debate due to take place on 21 November 2024.

The Bill seeks to amend the rules relating to the automatic early release of prisoners from prison, and of children under the age of 18 from detention in secure accommodation, who are serving short-term sentences. It also grants Scottish Ministers powers to make future changes to automatic early release points for both short and long-term prisoners.

The Bill seeks to make changes in two areas:

Sections 1 and 2 of the Bill change the automatic early release point for some short-term prisoners, from the halfway point in the sentence to when 40% of the sentence has been served. This includes children detained for less than four years following criminal proceedings. It excludes those serving sentences for sexual offences, domestic abuse or terrorism offences.

The changes will apply retrospectively, and the Bill makes transitional provision so that those immediately eligible for release will be released in tranches.

Section 3 of the Bill grants Scottish Ministers a power to make future changes to automatic early release points for both short and long-term prisoners by subordinate legislation, subject to parliamentary approval via affirmative procedure.

The Bill will not affect remand prisoners or those serving an indeterminate sentence.

In terms of the objective of the Scottish Government in introducing this Bill, the Policy Memorandum (paras 4 and 6) states that:

This Bill forms part of a range of measures designed to respond to the rising prison population [...] The changes will apply retrospectively, meaning they apply to those serving a short-term sentence on the date when the legislation comes into force as well as those sentenced to a short-term sentence following that date. This will result in both an immediate and sustained impact on the prison population.

While the Policy Memorandum does not explicitly outline the objective of including children within the provision, this is likely to ensure an equivalence of treatment with adult prisoners rather than being a response to rising numbers within secure accommodation. Capacity across the secure accommodation providers is updated daily. As at 18 November 2024, there were 7 vacant beds out of a capacity of 76. The Financial Memorandum (para 45) notes that on 6 November 2024 there were only 7 sentenced children in Scotland.

The Policy Memorandum estimates the eligible population, as a proportion of the sentenced population, would be around 5%. Accordingly, the expected reduction on the projected sentenced (and total) population in January 20257 would be around 260 to 390. The number of individuals eligible will vary depending on the size and make-up of the short-term sentenced population at the time of commencement. Once fully implemented, it notes that these changes are likely to result in this reduction being sustained over time.

This briefing sets out the background to the Bill, provides information on the processes which led to its development and considers its key provisions.

Background to the Bill

The size of the prison population in Scotland has been a concern of both the Scottish Government and a range of organisations within the criminal justice system. This is in respect of the current size of the population and the fact it is projected that, without intervention, the population will continue to rise. The Scottish Government produces prison population projections, with the latest version being published in October 2024.1

The Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs, Angela Constance MSP, wrote to the Criminal Justice Committee on 13 September 2023, highlighting issues around the prison population.

The Prison Governors Association Scotland also wrote to the Criminal Justice Committee on 30 April 2024, raising their concerns around the prison population pressures and predicted increasing trajectory of the population. They noted that “continuation on this path, at best, provides humane containment, albeit even this may be at a stretch”. They went on to state that:

Our members are working in a state of ‘permacrisis’, working with constant pressures due to the mix of population complexity and physical numbers. We are operating with a prevailing sense of ‘only just coping’ and remain concerned that emergency action will only be taken when something goes significantly wrong.

HM Inspectorate of Prisons in Scotland (HMIPS) wrote to the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs about the overcrowding in Scottish prisons on 12 September 2023. They raised the issue again in their Annual Report 2023-2024,2 published in August 2024, stating:

In 2024, we see the crisis has deepened and in the context of economic, environmental, and political challenges I am forced to raise this issue again as a matter of urgency. Overcrowding in Scottish prisons not only undermines the welfare and human rights of prisoners but also poses substantial risks to prison staff, public safety, and the overall criminal justice system. Inevitably, reduced access to essential services such as healthcare, mental health support, education, and rehabilitation programmes increases the likelihood of exacerbating existing issues, hindering the potential for successful reintegration into society upon release.

The Public Audit Committee's scrutiny of the 2022/23 audit of the Scottish Prison Service by the Auditor General for Scotland, published on 10 June 20243, also raised issues relating to the impact of increasing prisoner numbers.

The Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs made a ministerial statement to the Scottish Parliament regarding the prison population on 16 May 2024. The Scottish Government also published a prison population position paper4 along with this statement, outlining a significant rise in the prison population over the previous two months – a rise of 400 to a total of 8,348 on 16 May 2024.

At this time, the Scottish Prison Service (SPS) were reporting that six prisons – over a third of the estate – had a red risk rating. This rating takes into account factors including the daily population compared to the design capacity, the prevalence of double occupancy in cells, the protection of individuals, staffing levels and other factors affecting the overall safe running of the prison.

In response to this rising prison population, the Scottish Government brought into force section 11 of the Bail and Release from Custody (Scotland) Act 2023 on 26 May 2024. This gave Ministers the power to release prisoners in emergency situations. This power was used between June and July 2024, with a total of 477 prisoners released up to 180 days early from their original sentence. Further information on this can be found in the Emergency early release section below.

The Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs made a further ministerial statement to the Scottish Parliament regarding the prison population on 10 October 2024. The Scottish Government also published an information note at this time - Prison population - proposed bill on release point for short term prisoners: information note.5

A statement, Prosecution guidance on public safety and prison population, was also made to the Scottish Parliament on this date by the Lord Advocate, Dorothy Bain KC.

The Policy Memorandum (para 9) accompanying the Bill outlined the following in terms of the prison population:

The prison population has risen by around 14% since the start of 2023, with a particularly sharp rise between March and May 2024. That rise has been driven by a complex set of factors, including: the court backlog, caused by reduced court capacity over the pandemic; an increase in the sentenced population; and the remand population remaining at a high level. In addition, the prison population is increasingly complex, and many groups are required to be accommodated separately from others. Modelling indicates the overall prison population will likely increase between September 2024 and January 2025. If the population follows current trends, the average daily prison population could be between 7,750 and 9,250 in January 2025.

Current legislative position

There are currently two Acts which govern arrangements relating to the release of adult prisoners in Scotland:

These Acts also govern the arrangements relating to the release of children who have been detained in solemn proceedings (dealing with more serious offences). The Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 governs the release of children in summary proceedings (less serious offences).

Automatic early release

The arrangements for automatic early release are different depending on whether a prisoner is a:

short-term prisoner – serving a determinate (fixed term) custodial sentence of less than four years

long-term prisoner – serving a determinate custodial sentence of four or more years

extended sentence prisoner - serving a combined period in prison with a further set time of supervision in the community

indeterminate sentence prisoner – serving a life sentence or order for lifelong restriction where there is a fixed punishment part but no set end point to the sentence.

While information is provided here in relation to the release arrangements for indeterminate sentence prisoners for context, the Bill only applies directly to short-term prisoners, with the ability to introduce subordinate legislation relating to long-term prisoners.

Short-term prisoners

Short-term prisoners are those sentenced to less than four years.

All short-term prisoners (excluding those convicted of certain terrorism offences) must currently be released after serving half of their sentence. For most prisoners, this release is unconditional and they are not subject to supervision by criminal justice social work.

There are exceptions to this unconditional release.

Where a court has directed statutory supervision to form part of their release (e.g. through a supervised release order (SRO) or extended sentence). Those prisoners subject to an SRO will be released subject to licence conditions and under the supervision of a justice social worker for up to 12 months after their release. Further information on extended sentence prisoners is found in the section below.

Sex offenders receiving sentences of between six months and four years, and who are subject to notification requirements under Part 2 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003, are also released on licence, which lasts until the end of the period of their sentence.

Those convicted of certain terrorism offences will have their case referred to the Parole Board for Scotland at the two-thirds point of their sentence rather than obtain automatic release at the halfway point.

Where a prisoner is released on licence conditions, if they breach these during the period when they would have been in prison if not for their release, they can be recalled to prison. This decision is made by Scottish Ministers following a recommendation by the Parole Board for Scotland.

Where someone commits an offence punishable by imprisonment following their release but prior to the end date of their sentence, the court can also re-impose all or part of the ‘unexpired portion’ of the original prison sentence. This applies to all short-term prisoners and not only those released on licence.

Long-term prisoners

Long-term prisoners are those sentenced to four years or more, but excluding those serving indeterminate sentences (e.g. life sentences).

Long-term prisoners are eligible to apply for parole at the halfway point in their sentence. If successful, they are released on what is known as a 'parole licence'. This decision is taken by Scottish Ministers following a recommendation by the Parole Board for Scotland, following their assessment of whether a prisoner is likely to present a risk to the public if released. Should they be unsuccessful with their parole application, their case will return periodically to the Parole Board for re-consideration.

Long-term prisoners sentenced before 1 February 2016 who have not already been released, must be released automatically after serving two-thirds of their sentence, on what is known as a 'non-parole licence'. Those serving sentences imposed on or after 1 February 2016 will, if not released on parole earlier, generally qualify for automatic early release when they have six months (rather than a third) of their sentence left to serve. This is due to changes made by the Prisoners (Control of Release) (Scotland) Act 2015. This does not apply to prisoners given an extended sentence.

Long-term prisoners are, irrespective of the proportion of sentence served in custody and when they were sentenced, released on licence under conditions set by the Parole Board and subject to supervision by criminal justice social work. The licence, unless previously revoked, continues until the end of the whole sentence.

There is restricted eligibility for release on licence of certain terrorist prisoners with sentences imposed both before and after 1 February 2016. They will have their case referred to the Parole Board for Scotland at the two-thirds point of their sentence but do not qualify for automatic release.

Where long-term prisoners are released early and they breach their licence conditions, they could be recalled to prison to serve the remainder of their sentence. This decision is made by Scottish Ministers following a recommendation by the Parole Board for Scotland. Where they breach the conditions by committing an offence punishable by imprisonment, the court can also re-impose all or part of the ‘unexpired portion’ of the original prison sentence. Where someone has previously been released on a parole licence and are subsequently recalled they are then not eligible for automatic early release on a non-parole licence. They can, however, be released on parole licence again if recommended by the Parole Board.

Extended sentence prisoners

An extended sentence combines a period in prison with a further set time of supervision (the extension part) in the community. These sentences can be given to individuals who have committed a sexual or violent crime or abduction on indictment (more serious crimes).

For a violent crime or abduction, the custodial term of the sentence must be four years or more, so, as with long-term determinate sentences, the person can be considered for parole from the halfway point of the prison part of their sentence.

Where the custodial part of the sentence is below four years but the extended part of the sentence takes the period beyond this, the person will be referred to the Parole Board for Scotland for licence conditions only. If the custodial part of their sentence is more than four years they will be considered in the same way as long-term determinate prisoners.

When released, the individual is on licence until the end of the extension part of their sentence and they can be recalled to prison if they breach the terms of their licence.

Since anyone given an extended sentence where the custodial term is less than four years will have committed sexual offences, they will not be affected by the changes made in this Bill.

Those with an extended sentence with a custodial term of four years or more will NOT be affected by future changes to long-term prisoners brought in under the subordinate legislation powers brought in by this Bill.

Indeterminate sentence prisoners

Life sentence prisoners and those given an Order for Lifelong Restriction (OLR) have a punishment part set by the court when imposing the sentence. The prisoner serves the whole of the punishment part in custody. Once this part of the sentence has been served the prisoner may be released if the Parole Board of Scotland considers that continued incarceration is not required for the protection of the public. The possibility of release is considered again periodically where the Parole Board does not initially order the release of the prisoner. On release, those subject to a life sentence remain on licence until their death while those subject to an OLR remain subject to a risk management plan while in the community.

There are no automatic early release provisions for individuals serving indeterminate sentences. This Bill would not make any changes to the arrangements for indeterminate sentence prisoners.

Prison population

The Scottish Government publishes the Scottish Prison Population Statistics1 annually. These show the prison population trends over the longer term. The latest data available is from 2022-23, with the 2023-24 data due to be published in December 2024.

Key points from this publication are that:

there was a decline from an average daily population of 8,133 in 2011-12 to 7,464 in 2017-18, followed by an increase to a population of 8,197 in 2019-20

there was then a significant fall in the average prison population to 7,339 in 2020-21 due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was linked to temporary measures taken in response to the pandemic, with additional powers introduced to release prisoners before the end of their sentence and restrictions on the carrying out of criminal court business

the population then remained fairly stable up to 2022-23.

The Scottish Government also publishes data on the prison population on the first of each month in their Safer communities and justice statistics monthly reports. This shows the more recent trends in the prison population.

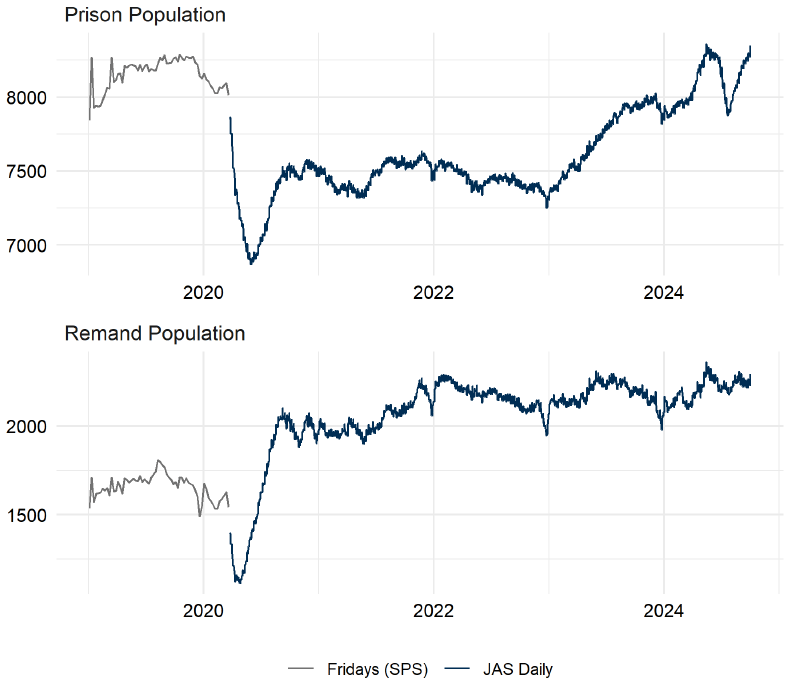

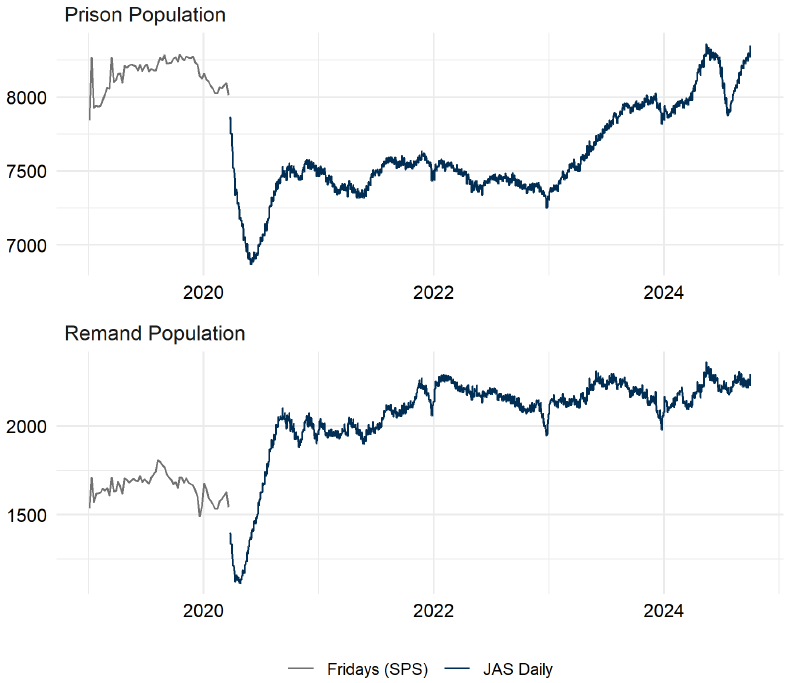

Chart 1 below shows the changing total prison population from January 2019.

As can be seen from this chart, the prison population has generally been increasing since the beginning of 2023. There was a drop of 4.25% from 8,232 on 21 June to 7,882 on 19 July 20242 as a result of emergency release measures (as outlined in more detail in the relevant section below), before the population began rising again.

The latest Safer communities and justice statistics monthly report was published on 31 October 20243. As at 1 October the total prison population was 8,347.

The current prison population is 8,273 as at 8 November 20242.

Short-term prisoner population

The Scottish Government's Scottish Prison Population Statistics1 is published annually and shows prison population trends over the longer term. This data is based on the index sentence, which is the longest single sentence being served by the person in prison.

Key points from this publication are that:

the short-term prisoner population remained fairly stable for the five years prior to the pandemic (sitting at an average daily population of just below 3,500)

as seen in the prison population as a whole, there was then a significant fall in the average short-term prison population to 2,530 in 2020-21 due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

the population then remained fairly stable.

The Scottish Government also publishes data on the prison population on the first of each month in their Safer communities and justice statistics monthly reports. This shows the more recent trends in the prison population, and is based on overall sentence length rather than index sentence.

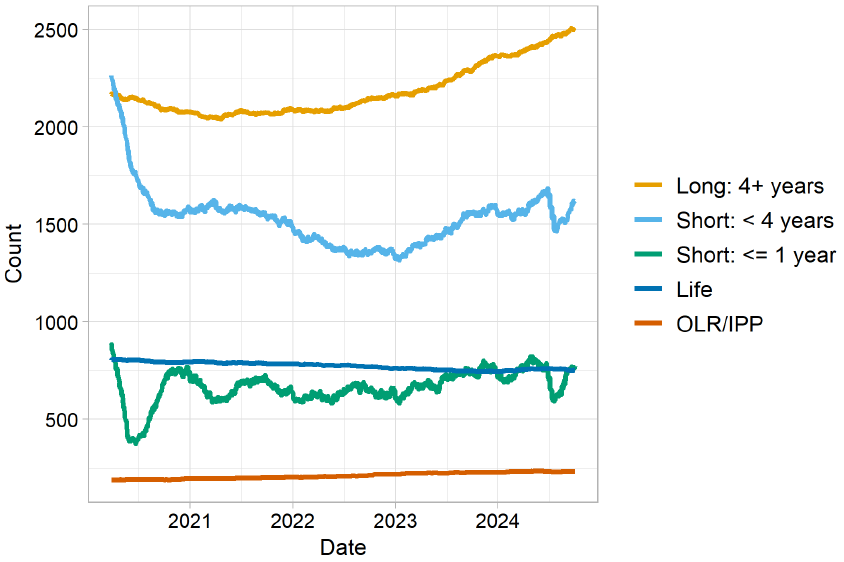

Chart 2 below shows the changing short-term prison population from 26 March 2020.

* Total short-term prisoners in this chart includes those under "Short: < 4 years" and "Short: <= 1 year".

The latest Safer communities and justice statistics monthly report was published on 31 October 20242. As at 1 October there were 2,396 prisoners with an overall sentence length of less than four years (approximately 29% of the total prison population as at 4 October 2024).

The weekly population figures provided by the Scottish Prison Service do not break the data down to this level of detail on sentence length.

Long-term prisoner population

The Scottish Government's Scottish Prison Population Statistics1 is published annually and shows prison population trends over the longer term. This data is based on the index sentence, which is the longest single sentence being served by the person in prison.

Key points from this publication are that:

the long-term prisoner population remained fairly stable from 2009-10 to 2017-18 (an average daily population of between approximately 1,350 and 1,400)

there was then a rise to 1,606 in 2019-20 and a continued increase to 1,749 in 2022-23 .

The Scottish Government also publishes data on the prison population on the first of each month in their Safer communities and justice statistics monthly reports. This shows the more recent trends in the prison population, and is based on overall sentence length rather than index sentence.

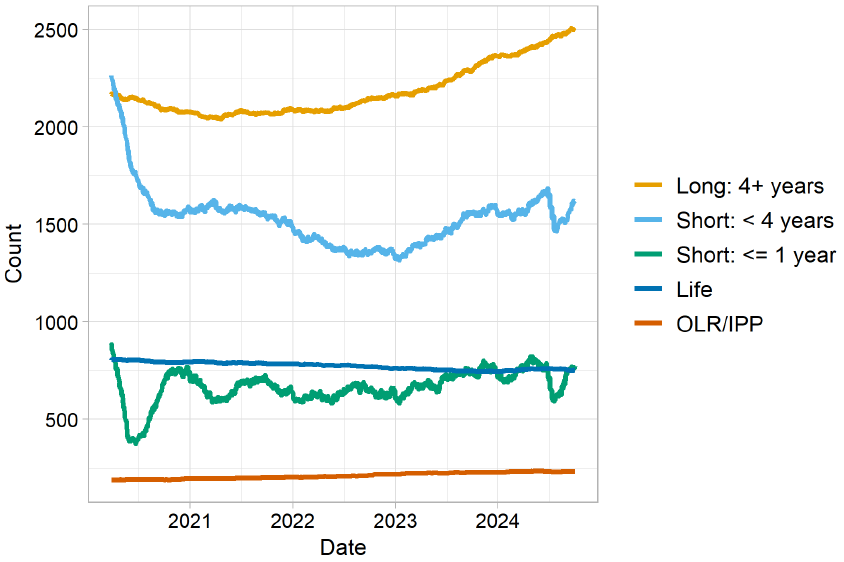

Chart 3 below shows the changing long-term prison population from 26 March 2020.

* Total short-term prisoners in this chart includes those under "Short: < 4 years" and "Short: <= 1 year".

The latest Safer communities and justice statistics monthly report was published on 31 October 20242. As at 1 October there were 2,497 prisoners with an overall sentence length of 4+ years (approximately 30% of the total prison population as at 4 October 2024).

The weekly population figures provided by the Scottish Prison Service do not break the data down to this level of detail on sentence length.

The Bill does not initially focus on reducing the long-term prisoner population, despite the fact there has been a significant increase in this population over recent years.

Indeterminate sentence prisoners

The Scottish Government's Scottish Prison Population Statistics1 is published annually and show prison population trends over the longer term.

Key points from this publication are that:

the number of life sentence prisoners increased steadily from an average daily population of 841 in 2009-10 to 967 in 2020-21. This then fell to 928 in 2022-23.

the number of indeterminate prisoners increased from an average daily population of 60 in 2009-10 to 197 in 2019-20. This then fell to 187 in 2022-23.

The Scottish Government also publishes data on the prison population on the first of each month in their Safer communities and justice statistics monthly reports. This shows the more recent trends in the prison population.

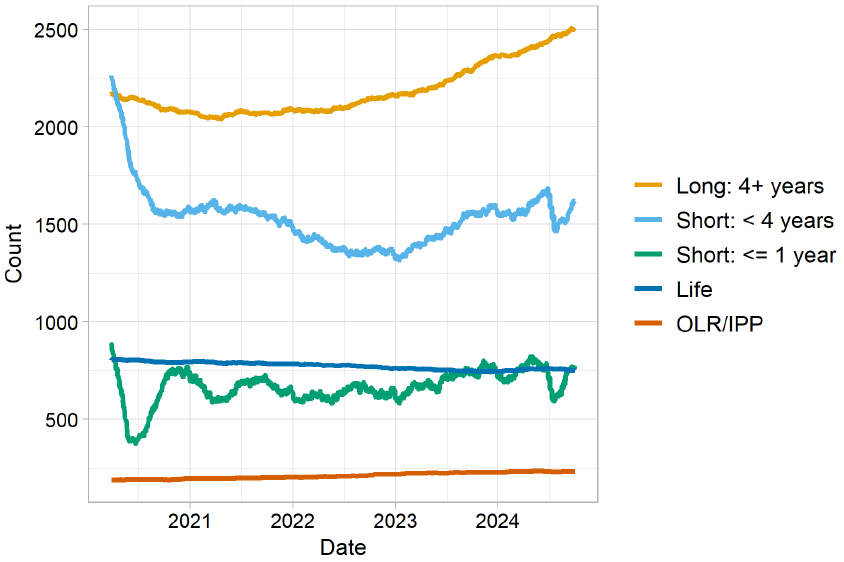

Chart 4 below shows the changing indeterminate (OLR/IPP) and life sentence prison populations from 26 March 2020.

The latest Safer communities and justice statistics monthly report was published on 31 October 20242. As at 1 October there were 751 life sentence prisoners (approximately 9% of the total prison population as at 4 October 2024) and 232 OLR/IPP prisoners (approximately 3% of the population).

This Bill makes no changes to the release point for indeterminate prisoners.

Remand population

The Scottish Government's Scottish Prison Population Statistics1 are published annually and show prison population trends over the longer term. Remand prisoners are made up of those who are untried, as well as those who are convicted and awaiting sentence. The vast majority of the remand population are untried.

Key points from this publication are that:

the remand population remained fairly stable in the ten years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (sitting between approximately 1,250 and 1,525 over this period)

there was then a rise to 1,634 in 2020-21 where the pandemic saw restrictions on court business which made it more difficult to keep periods of remand within normal statutory time limits. This was reflected in the temporary extension of those limits by COVID-19 related legislation. While most extended time limits have now returned to the pre-pandemic position, the longer time limits for holding prisoners on pre-trial remand in solemn procedure cases have been extended to 30 November 2025.

the remand population continued to rise to a figure of 1,804 in 2022-23.

The Scottish Government also publish data on the prison population on the first of each month in their Safer communities and justice statistics monthly reports. This shows the more recent trends in the prison population.

Chart 5 below shows the changing remand prison populations from January 2019.

The latest Safer communities and justice statistics monthly report was published on 31 October 20242. As at 1 October there were 2,293 prisoners on remand (approximately 28% of the total prison population as at 4 October 2024).

Currently, as at 8 November 2024, those who are on remand make up 26% (2,136) of the total prison population3.

This Bill makes no changes to prisoners serving a period of remand.

Other actions to manage the rising prison population

The Policy Memorandum published along with this Bill outlines a range of actions which the Scottish Government and the Scottish Prison Service (SPS) have taken to reduce the prison population. These include:

encouraging more widespread use of community sentences and diversion from prosecution

extending the presumption against short sentences

introducing electronically monitored bail and enabling that time to be taken into account at sentencing

confirming plans for an independent review of sentencing and penal policy

strengthening alternatives to remand

indicating future plans to adapt the use of Home Detention Curfew (HDC) to increase the period of time individuals can be granted release under licence conditions

transferring prisoners to HMP Polmont following the end of placement of those under 18 in Young Offenders Institutions (YOI)

investment in the construction of HMP Highland and HMP Glasgow

increasing funding for community justice

further implementation of provisions in the Bail and Release from Custody (Scotland) Act 2023

emergency early release of prisoners.

Further details are provided below on two of these measures:

Emergency early release

Following the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs' ministerial statement to the Scottish Parliament regarding the prison population on 16 May 2024, the Scottish Government brought into force section 11 of the Bail and Release from Custody (Scotland) Act 2023 on 26 May 2024. This gave Ministers the power to release prisoners in emergency situations, where it is deemed necessary and proportionate to do so, in order to protect the security and good order of prisons, or to protect the health and welfare of prison staff and prisoners.

The Cabinet Secretary acknowledged in her ministerial statement that "emergency release will not solve the problem in the longer term", with this measure being capable of only having a short-term impact on the prison population.

The Criminal Justice Committee took evidence on the Early Release of Prisoners and Prescribed Victim Supporters (Scotland) Regulations 2024 from a range of witnesses, including the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs and her officials, on the following dates:

The Committee agreed the motion to approve these regulations by division (For 4, Against 4; agreed on the casting vote of the Convener).

The Regulations were approved by Parliament on 12 June 2024 (For 66, Against 47, Abstained 5, Did not vote 11).

Subsequently, 477 prisoners were released under these regulations between 26 June and 18 July 2024. Those that were eligible for release were short-term prisoners (serving a sentence of under four years) who had 180 days or less of their sentence left to serve. Those serving the following sentences were not eligible for early release:

life sentences

sentences for terrorism offences

sentences for domestic abuse

sentences for sexual offences.

Those with previous convictions for domestic abuse which had not become spent or who were subject to a non-harassment order were also ineligible for early release.

Under the Bail and Release from Custody (Scotland) Act 2023, it was possible for a prison Governor to veto the emergency release of a prisoner otherwise deemed as eligible (where they deemed that their release would pose an immediate risk of harm to an identified person or group). The Scottish Government published Prison emergency early release: veto guidance for governors1 on 11 June 2024.

The Scottish Prison Service also published Operational Guidance – Emergency Release2 in June 2024.

Victims registered with the Victim Notification Scheme (VNS) received notification if the prisoner registered in their case was to be released early under the process, and the emergency release regulations also set out which victim support organisations could receive this information on behalf of victims. Further arrangements were made to allow victims to contact SPS directly to request information about the release of the prisoner in their case. All the victims registered on VNS in regard to prisoners granted early release were notified before the release took place. On 24 September 2024, Katy Clark MSP asked a topical question in the Chamber (S6T-02115) in which she referenced the fact only five victims had received notifications through the VNS.

The Scottish Prison Service carried out an analysis of those who had been released as part of this early release programme and had returned to custody up to and including 18 September 2024. They plan to publish a further update in January 2025. As at this date, 57 people had returned to custody before the date they would originally have been liberated had they not been released early. This equates to approximately 12% of the 477 individuals released.

To place this figure in some kind of context, the reconviction rate for short sentences (for those reconvicted within one year from release) are outlined in the table below.

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One year or less | 48.9% | 52.1% | 47.5% | 50.2% |

| Over one year to two years | 29.7% | 33.0% | 27.3% | 30.4% |

| Over two years to less than four years | 26.8% | 29.7% | 24.5% | 19.7% |

Source: Reconviction Rates in Scotland: 2020-21 Offender Cohort3

It should be noted that the figures for 2019-20 and 2020-21 will have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and caution should be taken when comparing these figures with previous, or future, years.

Home Detention Curfew

Currently, under Section 3AA of the Prisoners and Criminal Proceedings (Scotland) Act 1993, the Scottish Prison Service (on behalf of Scottish Ministers) has the power to release some prisoners earlier than would otherwise be the case on what is known as home detention curfew (HDC). HDC release is not automatic, and the legislation excludes certain prisoners from being eligible, including those convicted for sexual offences. HDC release is underpinned by an individualised risk assessment process, which includes a community assessment. Where an eligible individual is released on HDC, they are required to adhere to a curfew (which is electronically monitored) and other licence conditions. Where these conditions are breached an individual can be returned to custody.

This means that individuals that are eligible and assessed as suitable can be released on HDC before their scheduled release point, and spend up to a maximum period of 180 days under HDC. This is mainly used in relation to short-term prisoners, where the period of release on HDC allows an element of controlled release for a period before the prisoner qualifies for automatic early release (currently at the halfway point of their sentence). HDC can also be used for long-term prisoners, but they can only be granted HDC after the individual has been approved for parole by the Parole Board for Scotland.

Section 9 of the Bail and Release from Custody (Scotland) Act 2023 includes provision for a new temporary release licence for long-term prisoners which is intended to permit selected individuals with more opportunities to make positive connections in their community and provide further evidence to the Parole Board to support their decision-making, and facilitate the individual's reintegration into the community. This section of the Bill is not yet in force and the operation of this provision will be devised in co-operation with justice stakeholders, before it is brought into force.

When in force, it would allow the SPS (on behalf of Scottish Ministers) to release long-term prisoners for up to a maximum of 180 days, starting no earlier than 180 days before the earliest possible release point (the halfway point of their sentence). If the Parole Board then decides not to release the person on parole at the halfway point of their sentence, they can be recalled. They can also be recalled if they breach the conditions of this licence. Some long-term prisoners would be exempt from this provision (e.g. those convicted of certain terrorist offences).

In the information provided by the Scottish Government in its public consultation on the long-term prisoner release process, the Government states that the:

planning for the commencement and implementation of [this provision] is underway. This includes working with our justice partners on the implementation plans for the Act to consider resource requirements, workforce implications and timescales for commencement of each section.

In the information note published by the Scottish Government1 on 10 October 2024, the Government states that:

We plan to introduce Regulations to Parliament that would enable GPS technology to be used to further monitor individuals being released on HDC. We are also considering options for expanding the time that prisoners who have passed the necessary risk assessments can be granted HDC.

This Bill does not make any changes to the substantive legislative position on home detention curfew. It does, however, make changes to when the 180 day limit can apply, for those assessed as suitable for release, so it will cover eligible short-term prisoners released at both the 50% and 40% stage of their sentence, should they be deemed suitable for release following completion of the HDC assessment process. It will also allow a recalculation of licence periods based on earlier release dates (if applicable) for those on HDC when the changes in this Bill come into force.

Scottish Government consultation

The Scottish Government ran a public consultation on the long-term prisoner release process from 8 July until 19 August 2024. It sought views generally on changing the law to allow for the automatic early release of long-term prisoners at an earlier point, along with views on a specific proposal that this point would be at the two-thirds point of a sentence.

In the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs' ministerial statement on 10 October 2024, she stated that in light of concerns expressed during this consultation that "changing the long-term prisoner release point at pace would present significant practical difficulties" (e.g. services being able to safely manage risk within current resources) and "the need for any changes to take effect quickly prompted an exploration of alternative approaches". The Scottish Government would instead introduce changes to the automatic early release point for short-term prisoners through a Bill. They also said they would include provision in the Bill to change the release of long-term prisoners at some future point through subordinate legislation.

There was no public consultation on the proposals relating to short-term prisoners contained in this Bill due to it being developed on an emergency basis.

A summary of the long-term prisoner consultation, and consultation work with stakeholders that has taken place in relation to short-term prisoners are in the sections below.

Long-term prisoners

In its prison population position paper,1 the Scottish Government notes that one of the drivers of the increased prison population has been:

… the ending of automatic early release at the two thirds point for long term prisoners (sentences of 4 years or more) in 2016. Release now takes place six months before the end of the sentence for those not already granted parole.

The Scottish Government's consultation on the release of long-term prisoners sought:

views on the general proposal that the point of automatic release on non-parole licence for long-term prisoners should be at an earlier point

views on the general proposal that the point of automatic release on non-parole licence should be proportionate to sentence length (as opposed to a fixed period of time before the end of the whole sentence)

views on the specific proposal to release most long-term prisoners on non-parole licence following two thirds of their sentence

any additional views or evidence in relation to the proposals (e.g. operational impact of the proposals).

There were 161 responses to the consultation - 119 from individuals and 42 from organisations. Two virtual workshops were also held for relevant stakeholders on 26 July and 6 August 2024.

The Scottish Government published the responses to the consultation alongside an analysis of the findings on 10 October 2024, which includes an overview of the two workshops.

While there was found to be notable support for increasing the time some long-term prisoners spend in the community as part of a sentence, respondents also expressed concerns about how quickly this change could safely be made and the pressure it may place on community resources.

Some respondents, particularly those representing victims' interests, were not supportive of early release in principle, including current arrangements.

Twelve thematic operational issues were identified amongst the responses which respondents felt required to be considered should changes to the release point for long-term prisoners be made. These included:

the consideration of risk in the process

support and provision in the community

housing

victims

families

the possibility of exclusions

re-offending and recall

operational resources.

In the Policy Memorandum (para 38) published along with the Bill, the Scottish Government states:

Taking into account the responses to the consultation exercise, the Scottish Government's view is that any change to the release point for long-term prisoners would require further consideration in collaboration with stakeholders and delivery organisations, and as such is not suitable as an immediate response to the rising prison population.

Short-term prisoners

The Policy Memorandum notes that while there has been no public consultation on the specific proposals relating to short-term prisoners contained in this Bill, they have taken account of other public consultations in relation to the release processes for prisoners, for example, on the Bail and Release from Custody (Scotland) Act 2023.

It also outlines the stakeholders with whom targeted engagement has taken place, including:

the Scottish Prison Service

COSLA

Social Work Scotland

Association of Local Authority Chief Housing Officers (ALACHO)

Community Justice Scotland

Criminal Justice Voluntary Sector Forum

victim support organisations.

Criminal Justice Committee - written evidence

Prior to the introduction of the Bill, the Criminal Justice Committee wrote to a range of organisations within the criminal justice system looking for their views in respect of both the ministerial statement made by the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs, Angela Constance MSP, on 10 October 2024, and the statement on Prosecution guidance on public safety and prison population made by the Lord Advocate, Dorothy Bain KC, on the same date. These responses have been published by the Committee .

In general, most organisations were supportive of the proposed change to the reduction in the automatic early release point from 50% to 40% of the sentence for most short-term prisoners. They did, however, raise a range of issues relating to the implementation of any changes brought in by the proposed Bill. Key points from the responses relative to the provisions for short-term prisoners in this Bill cover the following themes:

These are outlined in more detail below.

A summary of the responses to questions on long-term prisoners has not been included here as it is unknown what provisions may be brought in through any subordinate legislation, and wider views are likely to be represented in the Scottish Government's consultation which took place over the summer and is outlined above.

As well as these themes, a number of organisations also emphasised that the changes within the Bill must only be one element of a broader range of measures, including a move away from custody and to community justice alternatives. The Risk Management Authority (RMA) noted that "a safe and sustained reduction in the prison population will only be achieved by reducing the number of individuals receiving a custodial sentence". The Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research (SCCJR) conveyed similar sentiments, stating:

As criminologists in our Centre have been saying for a long time, across-the-board changes to ensure that Scotland criminalises fewer people and sends fewer people to prison need to be pursued, alongside action to address sentence inflation.

Resources

A number of respondents highlighted the need for support, including additional finances, for both statutory and third sector services which will be impacted by the introduction of the Bill, and already faced additional pressures during the emergency early release over the summer. Families Outside stated that the workforce should not experience unnecessary additional pressures and the Criminal Justice Voluntary Sector Forum (CJVSF) stated that pressures cannot simply be transferred from the prison on to community services, which are already stretched. The SCCJR called for "more sustained investment in small charities, which do the bulk of the work of supporting both people after prison and the communities to which they return".

COSLA noted that while the short-term prison population may be less likely to be high-risk, they are more likely to be in the high-need category, requiring input from key services such as housing, drug and alcohol support and mental health. The CJVSF spoke of there being a need for transparency about how any community justice funding for the third sector will be administered via local authorities.

The Wise Group spoke of resources in terms of voluntary throughcare support in particular, stating that in order to support these early release proposals recruitment would need to begin by November 2024 at the latest to prepare staff for the increased demand expected between February and March. More information is available on throughcare support services in the section below.

Planning

The importance of planning was raised as an issue by several respondent organisations. HM Inspectorate of Prisons for Scotland (HMIPS) stated that it was essential that:

implementation plans and the timing of releases are staged at a pace that takes account of the need for community partners to plan safe and effective reintegration into local communities. A rushed implementation risks failure and potentially further victimisation.

The CJVSF highlighted the importance of planning not just for organisations but also the individual being released, stating that people must have time to mentally prepare and work with support services and that being able to do so reduces risks on release (e.g. drug-related deaths, homelessness, re-offending).

They called for lessons to be learned from the emergency release programme, including on information sharing, adequacy of support on release, recidivism rates, and from the experiences of third sector and statutory organisations, as well as those who were released. They also requested meaningful engagement with the third sector at a national level around the crisis response and urged "the Scottish Government to work with third sector partners, as well as statutory partners, to plan for different scenarios".

The Risk Management Authority (RMA) response advocated that any proposals and measures surrounding the point of automatic early release "adopt a risk based approach in accordance with the values, principles and standards outlined in Framework for Risk Assessment, Management & Evaluation (FRAME, 2011)".

Victims

Multiple organisations raised the issue of these changes potentially deterring victims from coming forward and risking them losing confidence in the criminal justice system.

The importance of further investment in victim support services, expediting reform of the Victim Notification Scheme (VNS), as well as the importance of appropriate communication with victims and/or victim support services were also raised.

Victim Support Scotland (VSS) stated that:

all victims should be automatically notified when emergency release measures are put in place and that all victims affected should be offered support and safety plans to run alongside release planning for prisoners in their case.

VSS went on to ask for legislative reform to consider how victims can be contacted if they are not part of the VNS.

Families of prisoners

The response from Families Outside raised the role of, and impact on, families when someone is released. They advocate for families to be involved in pre-release planning, and that there needs to be improved communication and information sharing with families. One way of doing this is the use of family and child impact assessments, for example, the ‘This Is Me’ toolkit developed by the Prison Reform Trust.

Exclusions and risk management

Some organisations wished to see further groups of short-term prisoners excluded from the changes made in the Bill. The Wise Group suggested violent offenders and high-risk or repeat offenders. Victim Support Scotland (VSS) called for the use of the governor's veto, as was available in the emergency early release which took place in the summer. VSS also called for greater use of Non-Harassment Orders, to provide an additional layer of protection for victims who may still be at risk.

HMIPS stated in their response that it should be noted that the individuals being released at the 40% point of their sentence would have been released at the 50% point with no supervision, unless requested as part of voluntary throughcare, or those subject to a short-term sex offender licence. They suggest that the use of curfews, electronic monitoring and GPS may mitigate some of the risk of not excluding those with previous convictions for domestic abuse or sexual offences whose current index offence would not see them excluded.

Throughcare support services

Throughcare services are services that are provided to prisoners both during and after their sentence to support them on their release. Local authorities (via justice social work) have a duty to provide statutory supervision to long-term prisoners and certain short-term prisoners convicted of sexual offences. They also have a duty to provide voluntary support to other short-term prisoners or those leaving custody following a period of remand, where it is requested. Short-term prisoners can also access voluntary throughcare from a range of third sector services.

The planned implementation period of the Bill coincides with the transition period from the current provision of third sector voluntary throughcare services delivered by the Public Social Partnerships (PSPs), 'New Routes' and 'Shine', to the new National Voluntary Throughcare Service, which will be in place for 1 April 2025. Some organisations raised concerns around this and the additional unexpected demand which will fall to either the PSPs or the new service, depending on when the legislation is implemented. This is noted as creating additional challenges for the sector by the CJVSF, which goes on to call for clarity over the new arrangements as soon as possible.

The Wise Group advised in their submission that their projected profile for the 2024-25 national throughcare mentoring service already anticipated a customer start limit close to the 1,200 threshold by February 2025. They asked for clarity on how any release schedule included in the Bill would align with this capacity and of any contingency planning for handling an increase beyond planned limits. They go on to note that an additional influx of cases "may complicate data migration and customer transitions, impacting customer experience and continuity of support".

The importance of the circumstances in place surrounding someone's release was emphasised by the SCCJR in its response:

We are not aware of empirical evidence (in Scotland or internationally) that this small change in the timing of release will have a significant adverse effect in terms of reoffending. Rather, the weight of criminological evidence suggests that risk of reoffending is much more likely to be affected by the condition in which people are released and the circumstances to which they are released [...] Opportunities for rehabilitation-oriented and desistance-oriented activities for adult men on short-term sentences are severely limited in what is a challenging environment in prisons. In this context, moving their release forward by a matter of weeks or months (e.g., being released at 10 months or the 40% point of a two-year prison sentence, instead of at 12 months or 50% point) is not likely to be the largest influencing factor of either reoffending or desistance.

Public confidence / knowledge

Concerns were raised by some respondents that the changes made in this Bill could risk a reduction in public confidence in the criminal justice system and deter victims from coming forward.

In terms of awareness, VSS highlighted their concern that there is limited awareness among the public, including victims, that currently prisoners may only serve 50% of a sentence. They highlight the importance of communication with victims and witnesses around the proportion of sentences that are served and why, as well as any changes to the release date.

The Scottish Sentencing Council stated that "a credible framework for release, and effective arrangements for its operation in practice, are essential to ensuring public confidence in the criminal justice system". Going on to note that the reasons for releasing prisoners before the end of their sentence are "opaque to members of the public, as well as to those affected by offending behaviour".

The SCCJR also raised the importance of communication in this area, and the role of politicians. It noted that:

Where politicians stoke what sociologists term ‘populist punitiveness’, they can make the climate for rehabilitation, desistance and reintegration much less favourable. In the long term, this can affect public safety and public fear of crime.

They went on to advise that in countries where "there has been a significant and sustained drop in prison population [they] are not associated with rising crime trends and increased threats to public safety".

Presumption against short sentences

Social Work Scotland and the Scottish Sentencing Council (SSC) raised the fact these changes were taking place in the context of a presumption against short sentences, with the SSC stating:

A natural consequence of bringing forward the point of early release for short-term prisoners might be an increase in the number of prisoners serving sentences of periods which would otherwise have been captured by the presumption against short-term sentences of 12 months or less. Given that the presumption was introduced, among other things, on the basis that sentences of such periods increase the risk of re-offending the Council will be particularly interested to learn of any further measures to enhance efforts to support rehabilitation and desistance alongside the measures proposed within the forthcoming bill.

Permanence of provisions

In the request for written evidence, the Criminal Justice Committee included a question on whether any legislative changes to bring forward the date on which short-term prisoners qualify for automatic early release should be permanent or temporary. Not all organisations who responded addressed this point.

Of those who did, the Wise Group suggested a temporary change to allow an evaluation before any adjustment was made permanent. VSS also believed the changes should be temporary until the prison population was at a safe and sustained level. While the CJVSF did not offer a view on whether the change should be permanent, it said it wished to see information and analysis before doing so, suggesting a temporary introduction of the provisions to allow an evaluation to take place.

COSLA stated that "broadly a permanent change to automatic early release for short-term sentences would be welcomed", with Families Outside also in favour of the change being made on a permanent basis.

The crisis in prisons report / UK Government response

The Institute for Government is an independent think tank which seeks to make government more effective. It produced a short paper, The crisis in prisons1, on 3 July 2024. It looked at the current state of the prison population in England and Wales and how the UK government could begin to address issues with the prison population.

Lowering the point of automatic release for most offenders from 50% of their sentence to 40-45% was noted as being "the lever that delivers the greatest capacity the quickest". Though the report does also note that this "would likely damage public confidence in the system". By moderating the release, where it would not apply to the most serious violent and sexual offenders, the report notes that this would "limit the public safety risk".

Those who would be released under their suggested scheme, would be supervised by the probation service (a role covered by criminal justice social work in Scotland) and recalled to prison if they committed further offences or breached conditions. This was noted as placing a strain on the probation system and could see some freed up capacity having to be used for those who are recalled.

The UK Government made changes to the law on automatic early release for those serving determinate (fixed term) sentences in England and Wales in July 2024. The release point was changed from the half-way point in the sentence to prisoners being released on licence after 40% of the sentence had been served. Those serving sentences for certain sexual, violent, domestic abuse, terrorism and national security offences were excluded.

The law change came into force on 10 September 2024 for those serving sentences of less than five years, and 22 October 2024 for those serving sentences of five years or more. The UK Justice Secretary stated that the new release scheme was only a temporary measure and would be reviewed within 18 months.

This change in England and Wales differs from the provisions within this Bill as it applies to all determinate sentenced prisoners (with offence exclusions) and is also only a temporary measure.

Provisions of the Bill

The Bill seeks to amend the rules relating to the automatic early release of short-term prisoners, including children sentenced to less than four years in secure accommodation following criminal proceedings. It will change the automatic early release point for some prisoners from the halfway point in the sentence to when 40% of the sentence has been served. This excludes those serving sentences for sexual offences, domestic abuse or terrorism offences. The changes will apply retrospectively, and the Bill makes transitional provision so that those immediately eligible for release will be released in tranches.

It also grants Scottish Ministers a power to make future changes to automatic early release points for both short and long-term prisoners by subordinate legislation, subject to parliamentary approval via affirmative procedure.

Further information on these provisions, including the financial costs, is outlined below.

While the Bill does not make any changes to the victim notification provisions that are currently in place, details of the current position are also included below for information.

Extension of early automatic release for certain short-term prisoners and certain detained children

Section 1 of the Bill sets out a new automatic release point at 40% of the sentence, rather than the current 50%, for some short-term prisoners. Section 2 of the Bill makes similar provisions for children sentenced to detention for less than four years following proceedings in a criminal court.

The changes made under these sections apply retrospectively, meaning they will apply to those currently serving short-term sentences as well as to those sentenced in future.

The provision in the Bill under each section is outlined in more detail below. Some alternative approaches which were in place during the emergency early release provisions over the summer, but are not contained within this Bill, are also commented on below.

Section 1

Section 1 of the Bill modifies section 1 of the Prisoners and Criminal Proceedings (Scotland) Act 1993 ("the 1993 Act"). It imposes a new automatic release point at 40% of the sentence, rather than the current 50%, for some short-term prisoners. These changes will apply retrospectively, meaning they will apply to those currently serving short-term sentences as well as to those sentenced in future.

The Policy Memorandum (para 44) published along with the introduction of the Bill states that:

The Scottish Government considers this new point of release (40%) to be a proportionate change as it will result in a sustained reduction in the overall prison population, while ongoing and further actions are progressed.

The change would not apply to prisoners serving a sentence for:

terrorist offences

listed sexual offences (i.e. one where sex offender notification requirements apply upon conviction)

domestic abuse.

Where short-term prisoners are serving two or more sentences, either consecutively or concurrently, and at least one of those terms is for a domestic abuse or sexual offence, they will continue to be released at the 50% point of their sentence.

In respect of why these exclusions to the changes made by the Bill have been included, the Policy Memorandum (para 47) notes that:

the Scottish Government considers that there are specific issues in relation to domestic abuse and sexual offences that are not necessarily as prevalent in relation to other offences. For example, there is evidence of particular barriers to reporting sexual and domestic abuse offences. Domestic abuse is known to inflict long-term trauma on victims. It is rarely a one-off incident and has a particular damaging effect on victims and those around them.

It goes on to state (para 50):

It remains imperative that victims of these offences retain confidence in the justice system when reporting and therefore the Scottish Government considers that changes should not apply to short-term prisoners serving a sentence for domestic abuse or sexual offences.

The Policy Memorandum goes on to recognise the differential impact on categories of prisoner and the impact of that on their Article 14 rights under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), given that changes in the Bill will not apply to those serving a sentence for domestic abuse or a sexual offence. The Policy Memorandum (para 119) states:

To the extent that such provisions engage article 14, the Scottish Government considers that such differential treatment is justified for the preservation of public confidence and in particular, victim confidence and the impact on the incidence of reporting of such crimes if such prisoners were to be released earlier than they already are under the current regime.

The changes made to the 1993 Act will not make any changes to the conditions placed on prisoners who are now released at the earlier 40% point. They will continue to be released unconditionally, subject to the exceptions as already contained in the 1993 Act (see the short-term prisoners section above for more details).

The Bill also alters the automatic early release point from 50% to 40% separately for short-term prisoners who are in custody for defaulting on a fine or imprisoned for contempt of court.

Section 2

Section 2 of the Bill makes similar provision as that in Section 1 for children sentenced to four years or less in secure accommodation following proceedings by a criminal court.

Children may be detained in secure accommodation either following a conviction on indictment (for more serious offences) or in summary proceedings (for less serious offences). This section of the Bill means that where these children are serving sentences of less than four years they will now be released at the 40%, rather than 50%, point of their sentence. Those who were convicted on indictment will be released on licence, while those detained in summary proceedings can be released on supervision.

The same exceptions apply to children as with adult prisoners under section 1 of the Bill, i.e. those sentenced for sexual or domestic abuse offences will continue to be released at the 50% point of their sentence.

Alternative approaches

During the emergency early release of prisoners which took place this summer, more groups were excluded from eligibility than are covered by exclusions from the changes in Bill. There was also a power for prison governors to veto an individual's early release.

The Policy Memorandum (para 83) sets out the reasons for not taking account of previous convictions in this Bill:

Consideration was given to whether previous convictions should be taken into account, as was the case in relation to the emergency early release process undertaken earlier in 2024. However, while this was considered an appropriate and workable safeguard in relation to emergency early release, given the focus on quickly identifying and releasing a cohort of prisoners within a short period of time, the Scottish Government does not consider that this should be part of the standard release process. Given the relatively small changes to release dates and the need to ensure operational sustainability, the approach set out is considered to be an appropriate way of ensuring that certain prisoners are not released any earlier than at present, while not making significant and resource intensive changes (which would be necessary if previous convictions were to be considered in all cases) to the standard release processes.

It goes on to outline the reason for not including a governor veto (para 84):

Consideration was also given to whether a 'governor veto' should exist, enabling prison governors to prevent the release of certain individuals. The availability of the governor veto in relation to emergency early release reflects the fact that those powers are likely to be used at extremely short notice, in an emergency, to select a specific group of prisoners that will be released early. In those circumstances, governors could prevent the release of an eligible individual, where there is evidence of an immediate risk of harm to an individual or a group. The process associated with operating the governor veto is extremely resource intensive for SPS and Police Scotland in particular, as well as both prison based and community based justice social work, the Risk Management Authority (RMA), and other community partners. Applying such an assessment to every eligible short-term prisoner would involve significant workforce planning and additional resource. To establish this process on a permanent basis would threaten resource availability within these services.

Financial costs

The estimated costs arising from the proposed changes within sections 1 and 2 of the Bill are outlined in the Financial Memorandum. These include additional one-off implementation costs borne by the Scottish Prison Service, the Scottish Government, and those relating to housing costs. It is stated that these one-off costs will be between £1,526,698 and £2,029,372, and there will be a recurring cost of £131,383 for SPS and for local authorities due to the transfer of social care provision from prison to the community. This is based on estimates of between 260 and 390 prisoners being released.

The Financial Memorandum outlines that it has not been possible to estimate the implementation costs for the following, so these have not been included in the above figures:

claims for devolved benefits issued by Social Security Scotland or payments made for benefits administered by the UK Government

costs relating to the impact of any additional demand for voluntary throughcare support services - met by either justice social work or third sector organisations

costs relating to the impact of any additional demand for services of victim support organisations.

In respect of voluntary throughcare services, these can be provided by either local authorities or third sector organisations. The Scottish Government funds two national third sector voluntary throughcare services at a total of around £3.4 million per year (in 2024-25). They have commissioned a new single national third sector throughcare service which will provide support to those leaving custody after a period of remand or a short-term prison sentence. This new service will replace the two existing services and will be in place for 1 April 2025. The intended timescales for the legislation therefore mean that it will come into force during the transition period to the new service. The Scottish Government state in the Financial Memorandum (para 83)that they:

will continue to work with the existing national third sector services and the approved national provider, once confirmed, to determine the resource implications for this transitional period.

Issues around this transition period are raised within submissions to the Criminal Justice Committee in response to the ministerial statement made by the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs, Angela Constance MSP, on 10 October 2024. These can be found in the Criminal Justice Committee - written evidence section above.

Power to modify timing of automatic early release

While the Scottish Ministers already have some powers under the 1993 Act to make changes to the automatic early release point for prisoners serving short and long-term sentences, this Bill provides them with more flexible powers to make regulations in this area. These are set out in Section 3 of the Bill.

Section 3

The 1993 Act currently contains provision which allows Scottish Ministers to make some changes to the automatic early release point for prisoners serving short-term and long-term sentences. There are, however, limitations to this power.

it can only change the proportion of the sentence, so does not allow this to be changed to a fixed period of time

any changes would not appear on the face of the 1993 Act

it does not allow different provision to be made for different circumstances, e.g. for prisoners convicted of different offences

it cannot be used for long-term prisoners sentenced after 1 February 2016 (as their automatic early release is a fixed period of time before the end of their sentence).

This section of the Bill provides Scottish Ministers with a more flexible power to make regulations which adjust when the automatic early release of prisoners (or of those detained as children) takes place.

It will allow regulations to be made that provide for a different automatic early release point for both short-term and long-term prisoners. It would not, however, apply to prisoners released on licence after imprisonment for 6 months or more for a sexual offence. The release point could be expressed as either a period of time, or as a proportion of the sentence. These changes would be made on the face of the 1993 Act and would apply to adult prisoners as well as those detained as children. They could apply retrospectively, so to those sentenced prior to the introduction of the regulations as well as those sentenced following their introduction.

This section of the Bill provides that the regulations may make different provision for different purposes. For example, different release points could be imposed based on the offences committed, whether they have an extended sentence, or what date the sentence was imposed. This ability is limited for long-term prisoners and those detained as children for a period of four years or more. In these cases it is only possible to make different provision based on when they were imprisoned or detained. This would therefore allow a change to be made which was not retrospective and which affected only future prisoners/detained children, but would not allow different rules to be applied based on other distinguishing features.

These regulations would be subject to parliamentary approval via affirmative procedure.

Financial costs

The estimated costs arising from the proposed changes within section 3 of the Bill are outlined in the Financial Memorandum. This is split into costs should further changes be made to the automatic early release point for short-term prisoners and for where subordinate legislation is introduced to modify the automatic early release point for long-term prisoners. These are outlined separately below.

Power to modify timing of automatic early release - short-term prisoners

The Scottish Government note in the Financial Memorandum (para 88) that they have "no plans to change the release point for short-term prisoners beyond the changes proposed on the face of the Bill". However, they include costs based on a scenario of a change resulting in 100 short-term prisoners becoming eligible for earlier release, while noting that costs would vary depending on the nature and extent of any change in the release point and the number of prisoners affected.

The costs outlined include one-off implementation costs borne by the Scottish Prison Service, Scottish Government and relating to housing costs. It is stated that these one-off costs will be between £910,661 and £947,290. Recurring costs of £86,667 will be borne by local authorities for the transfer of social care provision from the prison to the community.

The Financial Memorandum outlines that it has not been possible to estimate the implementation costs for the following, so these have not been included in the above figures:

claims for devolved benefits issued by Social Security Scotland or payments made for benefits administered by the UK Government

costs relating to the impact of any additional demand for voluntary throughcare support services - met by either justice social work or third sector organisations

costs relating to the impact of any additional demand for services of victim support organisations.

Power to modify timing of automatic early release - long-term prisoners

The Scottish Government note in the Financial Memorandum that no decisions have yet been made on what any future changes would be for long-term prisoners, and that "it is not possible to predict the resulting workloads and costs with the same degree of confidence that has been provided for the proposals relating to short-term prisoners" (para 91). The figures provided should therefore be read in this context. The costs provided are based on a scenario of a change resulting in 100 long-term prisoners becoming eligible for earlier release.

The costs outlined in the Financial Memorandum include additional one-off implementation costs borne by the Scottish Prison Service, the Parole Board for Scotland and relating to housing costs. It is stated that these one-off costs will be between £1,573,220 and £1,585,352. Recurring costs of £317,468 to £348,968 will be borne by the Scottish Government and local authorities (through justice social work and for the transfer of social care provision from prison to the community).

The Financial Memorandum outlines that it has not been possible to estimate the implementation costs for the following, so these have not been included in the above figures:

costs falling on the National Health Service and Police Scotland relating to the undertaking of MAPPA (multi-agency public protection arrangements) activities as a responsible authority for a longer period

advice and assistance costs for non-parole licence cases met by the Scottish Legal Aid Board (however, for indicative purposes, information was provided that the average payment made for advice and assistance applications for parole matters in the 12 months to September 2024 was £274)

costs relating to the impact of any additional demand for services of victim support organisations.

Consequential, transitional and transitory provision

Section 4 of the Bill introduces the schedule, which makes consequential and transitional provisions.

Part 1 of the Schedule

Part 1 of the Schedule makes a change to the 1993 Act in relation to release under home detention curfew (HDC) to ensure that someone is able to be released up to 180 days prior to the point they are eligible for automatic early release - regardless of whether this will now take place at the 40% or 50% point of the sentence.

Part 2 of the Schedule

Part 2 of the Schedule contains transitional and transitory provisions which are necessary to manage the release of individuals who would immediately qualify for earlier release following the commencement of section 1 of this Bill (bearing in mind that the provisions would apply to those already serving sentences). It outlines the three tranches in which these prisoners will be released, and who will fall into each tranche.

The Policy Memorandum (para 64) states that:

If the relevant provisions were commenced fully on a specified date, this would necessitate the immediate release of all eligible short-term prisoners who have already served two-fifths (40%) or more of their sentence. If commenced in this way, there would be a risk that community services would be overwhelmed, individuals would not be suitably prepared for their release and victims who wish to be would not be informed.

These tranches do not apply to children at the date of commencement and whose automatic early release date has been changed due to the provisions within this Bill. They will be released immediately on the commencement date if they have already served 40% of their sentence at this point. This is due to the significantly smaller numbers of children involved in any release.

Paragraphs 4 and 5 lay out transitional provisions to ensure that HDC continues to operate as set out in the legislation, taking account of changes made to short-term prisoners' automatic early release by this Bill and in preparation for changes which will be made when section 9 of the Bail and Release from Custody (Scotland) Act 2023 is implemented.

Individuals who are on licence (including those on HDC or who have received compassionate release) at the point short-term prisoners' automatic early release provisions are changed will automatically have their licence period recalculated to reflect their earlier release date, if applicable. This Schedule, however, will ensure that the person's licence will end (unless revoked earlier) on the date on which section 1 of the Bill comes into force or the date on which the licence would otherwise have ended, whichever is later. Therefore avoiding retrospective changes. The Explanatory Notes (para 69) sets out an example of why this provision is necessary.