Children and the Scottish Criminal Justice System (October 2024)

This subject profile outlines how the criminal justice system treats and interacts with children in conflict with the law.

Introduction

This subject profile is one of six covering various aspects of the Scottish criminal justice system. It outlines how the criminal justice system treats and interacts with children in conflict with the law.

It looks at the background and history of how children who offend have been dealt with in Scotland and outlines the law and practice in terms of the age of criminal responsibility.

It then looks at the systems children in conflict with the law can come into contact with - the children's hearings system, the criminal courts, and both secure accommodation and young offenders institutions.

It finishes by outlining the rules and processes around the retention and disclosure of information in terms of offending behaviour by children.

The other five briefings in this series deal with:

Cover image © Open Aye.

Dealing with children in conflict with the law

The impact of the Kilbrandon Report

The children's hearings system has, since it began operating in 1971, played a central role in dealing with children who are accused of committing offences.

Prior to the establishment of the children's hearings system, child offenders who had reached the age of criminal responsibility were dealt with through the court system (which included juvenile courts).

Concern about how the court system affected children led, in 1961, to the appointment by the Secretary of State for Scotland of a Committee on Children and Young Persons chaired by Lord Kilbrandon (the Kilbrandon Committee) to:

consider the provisions of the law of Scotland relating to the treatment of juvenile delinquents and juveniles in need of care or protection or beyond parental control and, in particular, the constitution, powers and procedures of the courts dealing with such juveniles.1

The Kilbrandon Committee's ethos was that children who appeared before the courts because they had committed an offence, and those who appeared because they were in need of protection, had common needs. Its report was published in 1964 - the Kilbrandon Report1. The approach put forward in the report was based on:

a focus on the needs of the child

the adoption of a preventative and educational approach to children's problems

an emphasis on the importance of the family in tackling children's problems

separating the establishment of disputed facts (through the court system) from decisions on the treatment of children (through a system of lay panels).

The general approach put forward by the Kilbrandon Committee was accepted by the UK Government and led to the abolition of juvenile courts and the establishment of the children's hearings system in Scotland. The hearings system took over from the courts most of the responsibility for dealing with children under the age of 16 who commit offences, or are in need of care or protection. However, provided they have reached the age of criminal responsibility, the power to prosecute children under 16 in the criminal courts for serious offences was retained, and still exists.

The statutory framework for the children's hearings system was originally set out in the Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968. Relevant provisions were, with some changes, re-enacted in the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 and are now contained in the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011. The rules governing the children's hearings system are outlined later in this briefing.

Wider developments in the approach to legal issues (in particular, human rights law) and in society more generally have, since the creation of the children's hearings system, led to some important changes. Nevertheless, the strength of continuing support for the general principles underlying the hearings system has been highlighted. For example, by Professor Kenneth Norrie in 2013:

A feature of this history, as noticeable as it is remarkable, is the commitment from across the political spectrum to the essential characteristics of the Scottish system for dealing with children who are at risk, either from their own actions or from the acts or neglects of others. The 1968 Act was passed by a UK Labour Government; the 1995 Act by a UK Conservative Government; and the 2011 Act by a Scottish Nationalist Government. These essential characteristics remain, without serious political challenge, at the heart of the system notwithstanding that the structures within which it operates today are very different from those envisaged by either the Kilbrandon Committee or the drafters of the 1968 Act. Both the structures and the approach to legal argument have evolved over the past half-century, but the philosophy underpinning the system has proved itself remarkably robust.3

And in the 2010 Stage 1 report on the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Bill produced by the Scottish Parliament's Education, Lifelong Learning and Culture Committee:

The Committee believes that the children's hearings system is vital to support the needs of some of Scotland's most vulnerable children and young people. The system rests on key principles which focus on the needs of the child and achieving the best outcome for him or her rather than on behaviour.4

Going on to say:

The Committee also recognises, however, that the children's hearings system is not perfect. It has to be modernised to ensure that it can provide a consistent service across and respond to the needs of modern society. Throughout its consideration of the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Bill at Stage 1, the Committee has scrutinised the Bill's proposals according to how they meet the twin challenges of updating the system without compromising any of its key principles.5

This welfare approach to dealing with children in conflict with the law was challenged during a more punitive phase in Scottish youth justice during the early 2000s. This period saw a move towards more of a focus on individual responsibility and the accountability of both children and young people, and their parents, for their behaviour6. Youth courts were reintroduced during this period and the Antisocial Behaviour etc. (Scotland) Act 2004 saw the introduction of Antisocial Behaviour Orders and Dispersal Orders for children, contradicting the Kilbrandon philosophy7.

The introduction of the Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC) framework in 2006; the National Performance Framework8 in 2007; and the piloting in 2008, and then national roll out in 2011, of the Whole System Approach saw a move back towards the welfare ethos of Kilbrandon7. From this period to date, there has been a significant reduction in the number of criminal court proceedings against children under the age of 16, as well as 16 and 17 year olds, alongside a significant drop in the number of such cases resulting in custodial sentences. The figures for these reductions are outlined in more detail later in this briefing in the Criminal proceedings and outcomes section.

The Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Act 2024 reinforces the welfare approach to youth justice in Scotland. It will, once relevant provisions are in force, raise the age children can be referred into the children's hearings system to include all those under the age of 18. It will also change the definition of 'child' within the criminal justice system, meaning all those under the age of 18 are classed, and treated, as children. Since 28 August 2024, when sections 18, 19 and 21-24 of the Act were brought into force, it has meant that children are no longer held within Young Offenders Institutions or prisons in Scotland. These changes are covered in more detail in the relevant sections later in this briefing.

Current approach to dealing with offending

The Scottish Government's website for Youth Justice states that:

Preventing offending is key to our vision of Scotland as the best place to grow up. We focus on tackling the causes of offending by young people and supporting them to change their behaviour, with the aim of avoiding them entering the criminal justice system.

There are four policy actions listed:

whole system approach to young offending

secure care

age of criminal responsibility

children's hearings.

The elements around secure care, age of criminal responsibility and children's hearings are dealt with in separate sections in this briefing.

The Whole System Approach (WSA) was introduced nationally in 2011. On the Scottish Government website, it says:

The Whole System Approach (WSA) is our programme for addressing the needs of young people involved in offending. It's underpinned by Getting it Right for Every Child, which aims to ensure that support for children and young people puts their – and their family's – needs first. Practitioners need to work together to support families, and take early action at the first signs of any difficulty. So they're not getting involved after a situation has already reached crisis point.

There are multiple policy strands to the Whole System Approach, including Early and Effective Intervention and Diversion from Prosecution.

In relation to the policy of Early and Effective Intervention (EEI), a Guide for Children and Young People in Conflict with the Law, published by the Children and Young People's Centre for Justice in 2023, states that:

EEI is a voluntary process where concerns regarding a child's wellbeing have arisen in response to their alleged involvement in an incident which has brought them into conflict with the law, or where their behaviour raises concerns. It is a response to allegations of offending or concerning behaviour as potential indicators of wellbeing needs that may benefit from proportionate and appropriate support. 1

It is the responsibility of Police Scotland to identify cases suitable for discussion/referral to EEI. Decisions about whether EEI is suitable are primarily based on the seriousness of the offence and whether compulsory measures of supervision are required. All offences should be considered for EEI unless they are excluded under:

the Lord Advocate’s Guidelines: Offences committed by children

the Crown Office Framework on the Use of Police Direct Measures and Early and Effective Intervention for 16 and 17 year olds; or

the police deeming a referral to the Scottish Children's Reporter Administration is necessary as compulsory measures may be required.1

In relation to Diversion from Prosecution, the Guide states that it is:

the mechanism by which prosecutors are able to refer an individual to social work or other identified agency in lieu of the individual being prosecuted, or facing other prosecutorial proceedings. It is a decision that can be taken when it is deemed an appropriate means of addressing the underlying causes of alleged offending. As a prosecutorial option it has the twin aims of providing an appropriate person-centred response (based on the circumstances of the individual and the alleged offence) without the need to enter formal judicial proceedings, whilst also delivering a swift response to said behaviour and thus attempting to prevent further conflict with the law.1

The current Scottish Government youth justice strategy, published in 2021, Justice for children and young people - a rights-respecting approach: vision and priorities4, builds on the previous strategy which ran from 2015-2020, Preventing Offending: Getting it Right for Children and Young People5. It continues to support the agenda to keep children out of the criminal justice system and promote the use of the Whole System Approach. The current strategy states that:

A new approach to youth justice in Scotland is required, which continues to align with UNCRC [United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child], proceeds from a rights-respecting approach, supports all children under the age of 18 and young people up to age 26 to participate in decisions about them, directs positive support to families, and offers that support through safe and caring relationships.4

This rights-respecting approach reflects the findings of the report following the independent review of the care system in Scotland, The Promise7 and their specific Youth Justice publication8. It also reflects the report by the Children and Young People's Centre for Justice, Rights Respecting?: Scotland's approach to children in conflict with the law, which concludes that:

... Scotland would benefit from thinking about children in conflict with the law from the perspective of rights. This represents a shift from focusing on children as troubled, challenged, vulnerable and challenging, which whilst often well-meaning and containing a partial truth, can encourage negative unintended consequences which disproportionately affect and stigmatise the most disadvantaged children. Children in conflict with the law, like all children, are rights holders. They are entitled to their rights and should have their rights upheld.9

This approach can also be seen in the language used within, and the stated purpose of, the Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Act 2024. The Policy Memorandum for the Bill stated that:

The Bill also supports the achievement of a Rights Respecting Approach to Justice for Children and Young People: Scotland's Visions and Priorities. The Vision represents a shared foundation between the Scottish Government and partners to keep children out of the criminal justice system, and promote the Whole System Approach (WSA) to preventing offending by children and young people focused on early intervention, diversion from prosecution and alternatives to secure accommodation and custody10.

16 and 17 year olds

Historically in Scotland, children in the context of youth justice have been viewed as those aged under 16, with exceptions for 16 and 17 year olds in some cases. For example:

section 199 of the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011 generally defined a child as a person under the age of 16, but extended the definition in a number of circumstances (for example, to any person under 18 who is subject to a Compulsory Supervision Order)i

the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2016 included provisions on police powers setting out a number of additional safeguards for any child, under the age of 18, suspected of committing an offence. Some provisions distinguished between children aged 16/17 and younger children (for example, section 33), whilst others do not (for example, section 51).

This meant there was disparity between how children were dealt with both within the children's hearings system and the criminal justice system. There was also disparity with the definition of a child as set out in article 1 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)1. This article defines a child as a person “below the age of eighteen years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier".

These differences meant that, while all those under the age of 18 were covered by the Whole System Approach outlined earlier in the briefing, the likelihood of being dealt with through the adult criminal justice system was significantly greater for 16 and 17 year olds than for children under 16. It also saw 16 and 17 year olds being treated differently when within the adult court system and in the use of Early and Effective Intervention2 if they were subject to a Compulsory Supervision Order (CSO).

The Scottish Government aimed to address this disparity firstly by incorporating the UNCRC into domestic law and secondly through the introduction of the Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Act 2024.

The Scottish Government began the process of incorporating the UNCRC into domestic law through the introduction of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill on 1 September 2020. This was passed by the Parliament on 7 December 2023. It applies only to laws passed by the Scottish and not the UK Parliament.

When the Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Act 2024 comes in to force, it will deal with the disparity between definitions of who is a child within both children's hearings and criminal justice legislation, recognising the UNCRC definition of a child as being anyone below the age of 18. It amends Section 199 of the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011 to define a child as anyone under the age of 18. It also amends the definition of a child within the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 by referring to this new definition within the 2011 Act; and amends the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2016 so that any references to 'child' are to those under the age of 18.

Age of criminal responsibility

Law and practice

The age of criminal responsibility in Scotland is 12, with section 41 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 providing that:

A child under the age of 12 years cannot commit an offence.

Until quite recently, it provided that no child under the age of eight could commit an offence. This was raised, with effect from December 2021, through changes made by the Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Act 2019.

In addition, section 42(1) of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 restricts the use of prosecution through the criminal courts for children who have reached the age of criminal responsibility. The section currently states:

A child aged 12 years or more but under 16 years may not be prosecuted for any offence except on the instructions of the Lord Advocate, or at the instance of the Lord Advocate; and no court other than the High Court and the sheriff court shall have jurisdiction over such a child for an offence.

The Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Act 2024 amends this text by removing the words "but under 16 years". This means that when this Act is in force that 'child' will mean anyone under the age of 18.

The Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS) has published a Prosecution Code1 setting out general criteria for prosecution decision making. It states that "the youth of an accused may, depending on other circumstances, be a factor which influences a prosecutor in favour of action other than prosecution".

Information relating to cases jointly reported to the Procurator Fiscal, for possible prosecution in the criminal courts, and to the children's hearings system is set out in:

guidance for the police on offences which should be jointly reported2

an agreement between the COPFS and the Scottish Children's Reporter Administration on cases which are jointly reported.3

The current guidelines for the police note the categories of case where a child, aged at least 12 but under 16, will be considered for prosecution include:

very serious offences - those which must be prosecuted under solemn procedure or which are so serious as normally to give rise to solemn proceedingsi

road traffic offences - those alleged to have been committed by children aged 15 years or over which in the event of a conviction oblige or permit a court to order disqualification from driving.

Cases should also be jointly reported where:

a child is aged 16 or 17 and is subject to a Compulsory Supervision Order

they were referred to the Scottish Children's Reporter Administration before the age of 16 and a decision is outstanding on that referral.

A review of these guidelines is taking place in light of the Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Act 2024 - it sees a change in the definition of 'children' to anyone under the age of 18. Once in force this will change how those aged under 18 will be dealt with. Children aged between 12 and 17 could only be prosecuted in the criminal courts subject to the guidance of the Lord Advocate, and could be referred to the children's hearings system on both offence and non-offence grounds. Children under the age of 12 lack the legal capacity to commit an offence. They therefore cannot be prosecuted in the criminal courts and can only be referred to the children's hearings system on non-offence grounds.

During 2022-23:

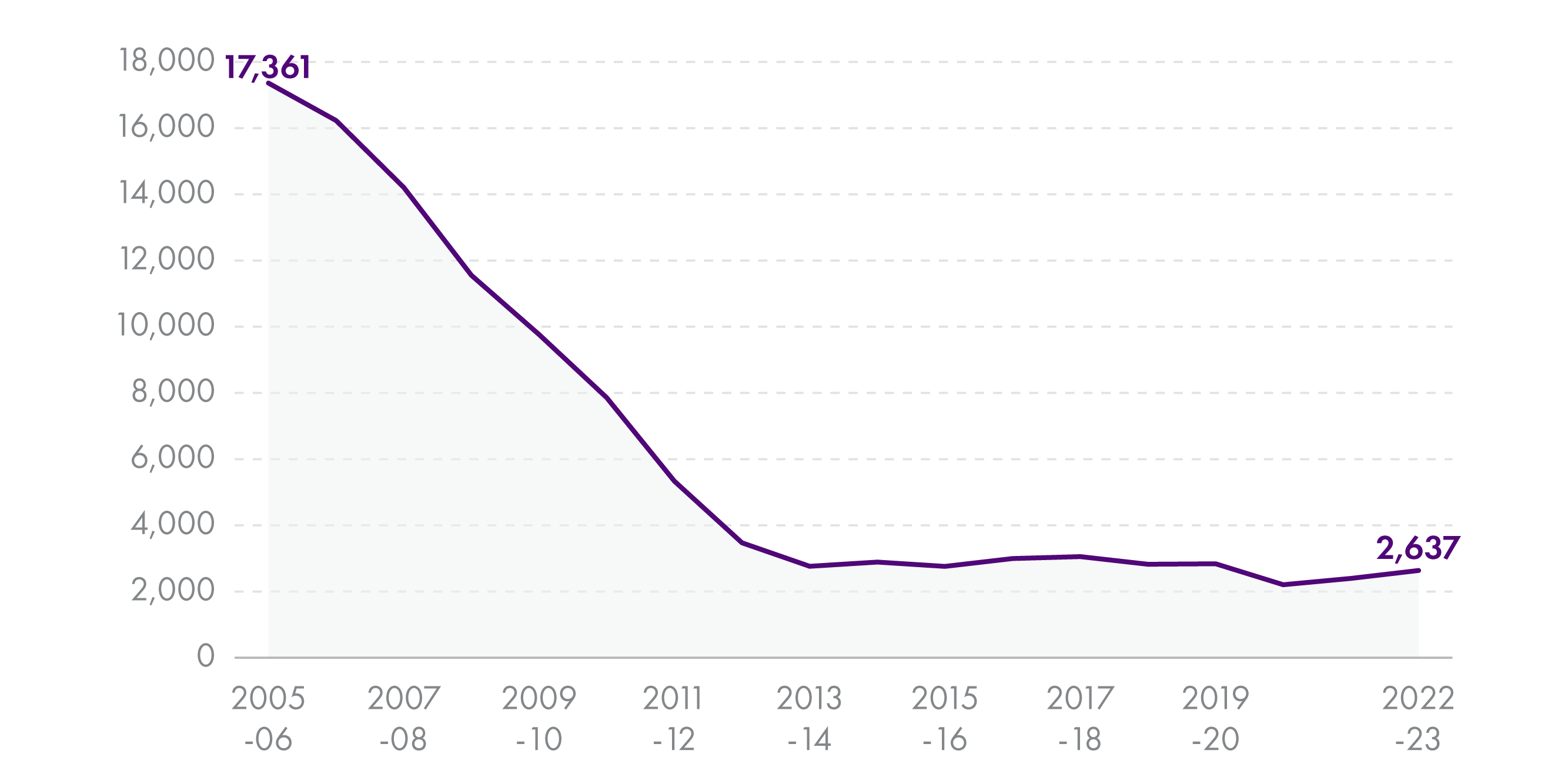

a total of 2,637 children were referred to the children's hearings system on offence groundsii4

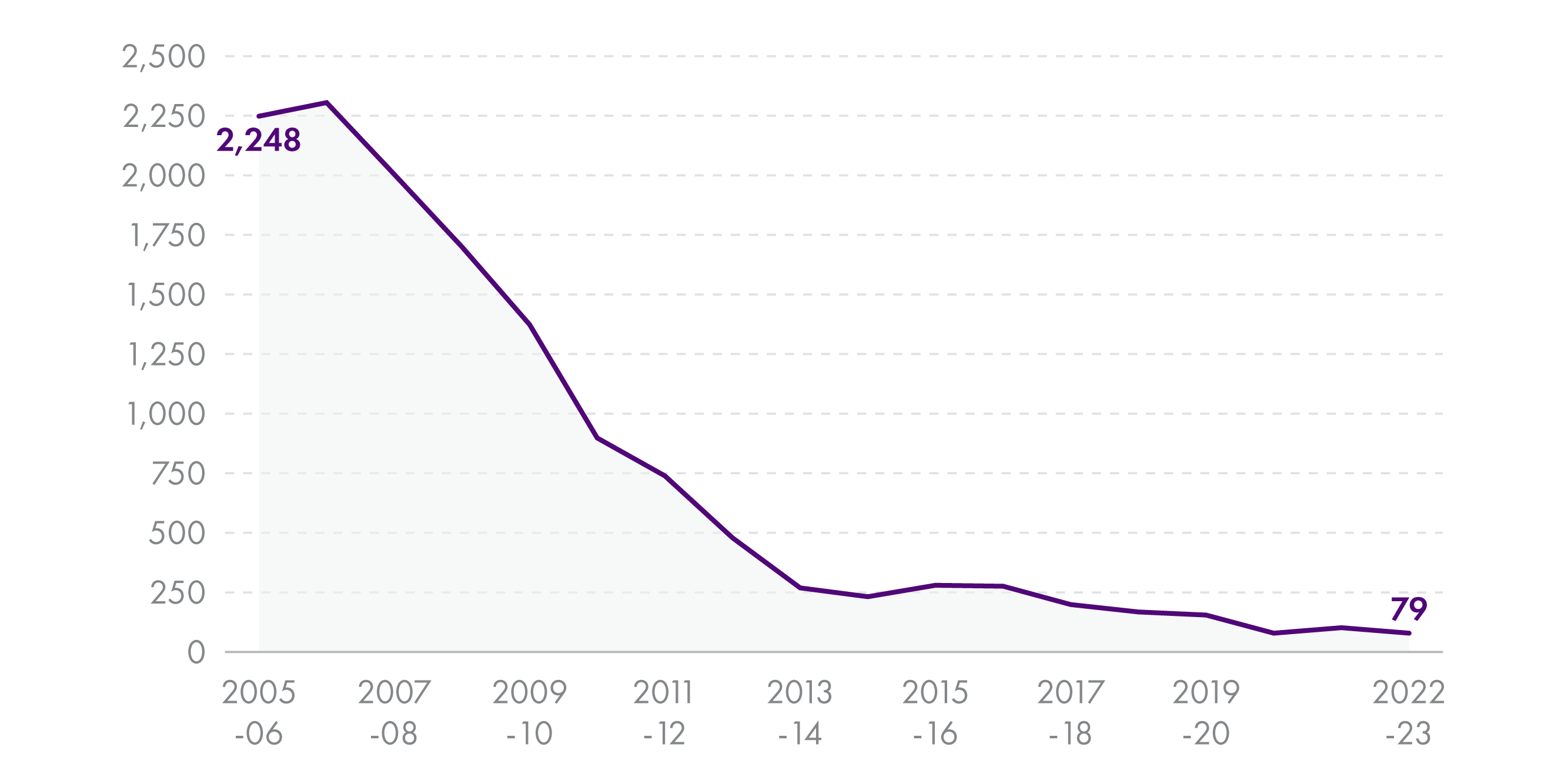

a decision was taken to arrange a children's hearing, dealing with offence grounds, in relation to 79 childreniii4. Reasons for not arranging a hearing included an assessment that there was no need for compulsory measures, that suitable measures were already in place, or that there was insufficient evidence to proceed.

During 2021-22:

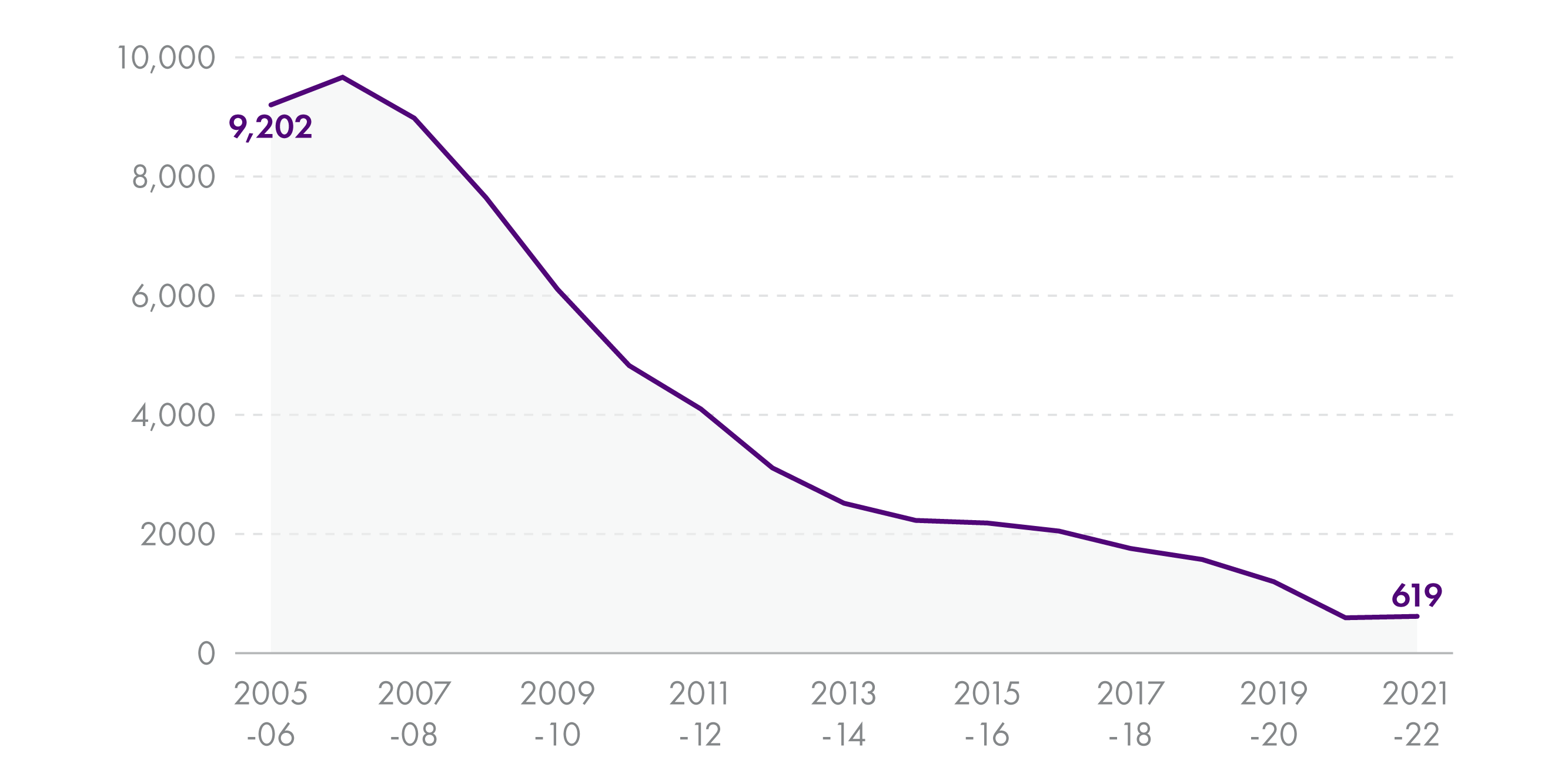

there were 621 cases against children under the age of 18 in the criminal courts. Almost all of these (619) concerned children aged 16 or 17.iv While the numbers of cases had been falling significantly over the previous five years (a reduction of 45% from 2,206 in 2015-16 to 1,218 in 2019-20), this figure must be considered in the context of the significant impact of COVID-19 on the courts system.

Debate on appropriate age

The question of whether relevant reforms to Scots law in relation to the age of criminal responsibility should go further has remained a live issue. In 2019, the Scottish Government established an Age of Criminal Responsibility Advisory Group1. This was to assist Scottish Ministers to undertake a statutory review to evaluate the operation of the Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Act 2019, as well as to consider a future age of criminal responsibility.

Article 40 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child2 includes provisions requiring states to seek to promote the establishment of “a minimum age below which children shall be presumed not to have the capacity to infringe the penal law”. The article does not specify a minimum age, but the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child3 has recommended 14 as an absolute minimum stating that:

In the original general comment No. 10 (2007), the Committee had considered 12 years as the absolute minimum age. However, the Committee finds that this age indication is still low. States parties are encouraged to increase their minimum age to at least 14 years of age. At the same time, the Committee commends State parties that have a higher minimum age, for instance 15 or 16 years of age.

Children's Hearings System

Introduction

The purpose of the children's hearings system is to determine what measures may be required to address the behaviour and welfare of children. It seeks to ensure that appropriate care, protection and supervision is implemented.

Children may be referred to the hearings system in relation to situations where they have been or may be harmed by others, or where their own behaviour causes concern. This includes situations where it is alleged that they have committed an offence, though most referrals to the hearings system are on non-offence grounds.

In relation to offending behaviour, where some form of compulsory intervention is considered necessary, the majority of children under the age of 16 are dealt with through the hearings system rather than the criminal courts. This briefing focuses on referrals on offence grounds. Children may only be referred on offence grounds where they had the legal capacity to commit the alleged offence (i.e. where they were aged 12 or over at the time).

Currently, the children's hearings system mainly deals with children under the age of 16. However, some young people aged 16 and 17 are also dealt with through the hearings system. This may happen where they are still subject to supervision requirements imposed by a children's hearing, or where their case is remitted to the hearings system for disposal following conviction by a criminal court.

The statutory framework for the children's hearings system is set out in the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011. It restates much of the previous law with the main changes concerning how the children's hearings system is administered. These include:

the establishment of a new national body called Children's Hearings Scotland with responsibility for the recruitment, appointment and training of the members of children's panels

the replacement of separate children's panels for each local authority with a single national panel.

When in force, the Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Act 2024 will make a number of amendments to the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011 including:

the possibility of referral to the children's hearings system will include all children under the age of 18

additional measures that can be included within a Compulsory Supervision Order

providing for continued supervision and guidance for young people, where they have been dealt with under the children's hearings system, after they turn 18 up to age 19.

The Bill also amended the circumstances where children found guilty of an offence within a criminal court can be remitted to the children's hearings system for advice or disposal. For cases in the High Court and solemn cases in the Sheriff Court, the court may refer for advice. In summary cases, the court must seek advice, as must the court in solemn cases before they are disposed of. This would apply to all those under 18, though the court need not do this for those who are within six months of their 18th birthday. All courts are able to refer a case to the children's hearings system for disposal.

Key elements of the system

The children's hearings system, as provided for in the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011, includes the following elements.

Scottish Children's Reporter Administration and Children's Reporters

The Scottish Children's Reporter Administration (SCRA) is a non-departmental public body whose responsibilities include facilitating the work of children's reporters, providing suitable accommodation for children's hearings and disseminating information on the hearings system.

Reporters are officials employed by SCRA to consider the circumstances of children referred to the hearings system. Most referrals are made by the police although other agencies, for example, social work, and members of the general public, may also make referrals. On receipt of a referral, the local reporter will undertake initial investigations before deciding what action, if any, is necessary in the child's interests.

A reporter will consider whether there is sufficient evidence supporting the ground(s) of referral and, if so, whether compulsory measures of supervision are needed. Where the answer to both questions is yes, the reporter will arrange a children's hearing. The reporter does not participate in the decision-making process of the hearing, with decisions being made by children's panel members.

In other cases, the child may be referred to the local authority so that advice, guidance and assistance can be given on an informal and voluntary basis (often involving support from a social worker).

Children's Hearings Scotland and the Children's Panel

Children's Hearings Scotland (CHS) is a non-departmental public body providing support for the Children's Panel (e.g. in relation to recruitment, training and support of panel members).

Following reforms made by the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011, there is now a national Children's Panel (replacing separate panels for each local authority) with a National Convener providing leadership for all panel members. The latter are trained volunteers (around 2,500 in number) who make the decisions in children's hearings. The National Convener is also Chief Executive Officer of CHS.

Children's hearings

Children's hearings are lay tribunals, which consist of three children's panel members. They consider and make decisions on what measures may be required for the welfare of a child, taking into account all of the circumstances, including any offending behaviour. They take place in private and do not determine the facts of a case.

Where the grounds of referral are not accepted, or the child does not understand the grounds, the case is referred to a sheriff court to decide whether the grounds are established. If the court determines that the grounds of referral are established, the case is sent back to a hearing to decide whether compulsory measures of care are necessary.

Local authorities are responsible for implementing the decisions of children's hearings where such measures are deemed necessary.

Legal aid

The Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011 also extended the scope and availability of legal aid within the children's hearings system. There is now a permanent scheme of state-funded legal representation in relation to the hearings system, replacing an interim scheme first introduced in 2002.

Parliamentary scrutiny of the proposed reforms set out in the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011 included consideration of how the hearings system should balance a desire for retaining a relatively informal approach to proceedings (compared to the more legalistic adversarial approach generally associated with court proceedings) with the need to protect the legal rights of those involved. The 2010 Stage 1 report on the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Bill stated (paras 168-170) that:

It is the Committee's view that [it] is unlikely that extending legal aid to hearings will alter radically the nature of the hearings system in Scotland. However, this will depend on panel chairs being effectively trained to manage legal representatives’ participation within the hearing and on family lawyers being appropriately trained in the ethos and aims of the children's hearings system. The Committee considers it essential that measures be put in place to ensure that such training takes place.1

In this context, a registration scheme and code of practice were established with the aim of ensuring that solicitors appearing at hearings delivered an appropriate level of service.

Possible changes to the children's hearings system

The Children (Care and Justice) Act 2024 provides for important changes to the children's hearings system. These are outlined in the Dealing with Children in Conflict with the Law and Age of Criminal Responsibility sections above as well as in the Introduction to this section.

There may be further changes to the children's hearings system as a result of The Promise.1 In 2016, the Scottish Government commissioned an independent review of the care system in Scotland. Its final report, entitled The Promise, was published in 2020 and recommended a redesign of the children's hearings system.

Following this, a Hearings Systems Working Group, made up of Children's Hearings Scotland (CHS), the Scottish Children's Reporter Administration (SCRA) and The Promise Scotland, was established and published its report, Hearings for Children: Hearing System Working Group's Redesign Report, in May 2023.2 It contained several recommendations which would change some of the key elements of the system as outlined above, including:

there must be a review of the current functions of CHS and SCRA to ensure that the redesigned system operates effectively and efficiently for children and families and adequately supports and resources the discrete legal functions of the National Convener and Principal Reporter

children should be fully informed of their right to legal representation; and there should be a review of whether the current mechanisms for them to access legal aid and support are sufficient

there must be a review of the existing Code of Practice that lawyers are required to adhere to, and of the register of solicitors eligible to provide legal assistance to children

the programme for delivery and implementation put in place to oversee the implementation of these recommendations should consider whether there is a role for a new accountability body to ensure ongoing quality assurance, continuous improvement and oversight of a redesigned children's hearings system.

The Scottish Government published their response to this Hearings for Children report3 in December 2023. They accepted 63 of the report's recommendations entirely, 26 were accepted with conditions and 42 were said to require consultation or exploration. They also declined seven of the recommendations. This included the recommendation that the panel chair would become a salaried position, with the accompanying panel members also being remunerated at a daily rate.

A Children's Hearings Redesign Board has been set up to oversee the delivery of the changes to the children's hearings system. The Board held their first meeting on 18 January 2024 and has a time-frame for completion of their work of 2030.

Referrals and hearings

The Scottish Children's Reporter Administration's Statistical Analysis 2022-231 notes that:

In 2022/23, 2,637 children aged between twelve and seventeen years were referred to the Reporter on offence grounds. These children were referred for 11,702 alleged offences on 6,498 referrals.i The most common types of alleged offences were assault, threatening or abusive behaviour and vandalism.

A referral will not necessarily lead to a children's hearing. The above analysis of figures for 2022-23 goes on to note that a decision was taken to arrange a children's hearing, dealing with offence grounds, in relation to 79 children. In other cases relating to offence grounds, children's reporters decided not to arrange a hearing for the following reasons:

no indication of a need for compulsory measures (990)

relevant measures already in place (882)

Compulsory Supervision Order not necessary and referral to local authority (792)

insufficient evidence to proceed (192)

no jurisdiction (29).ii

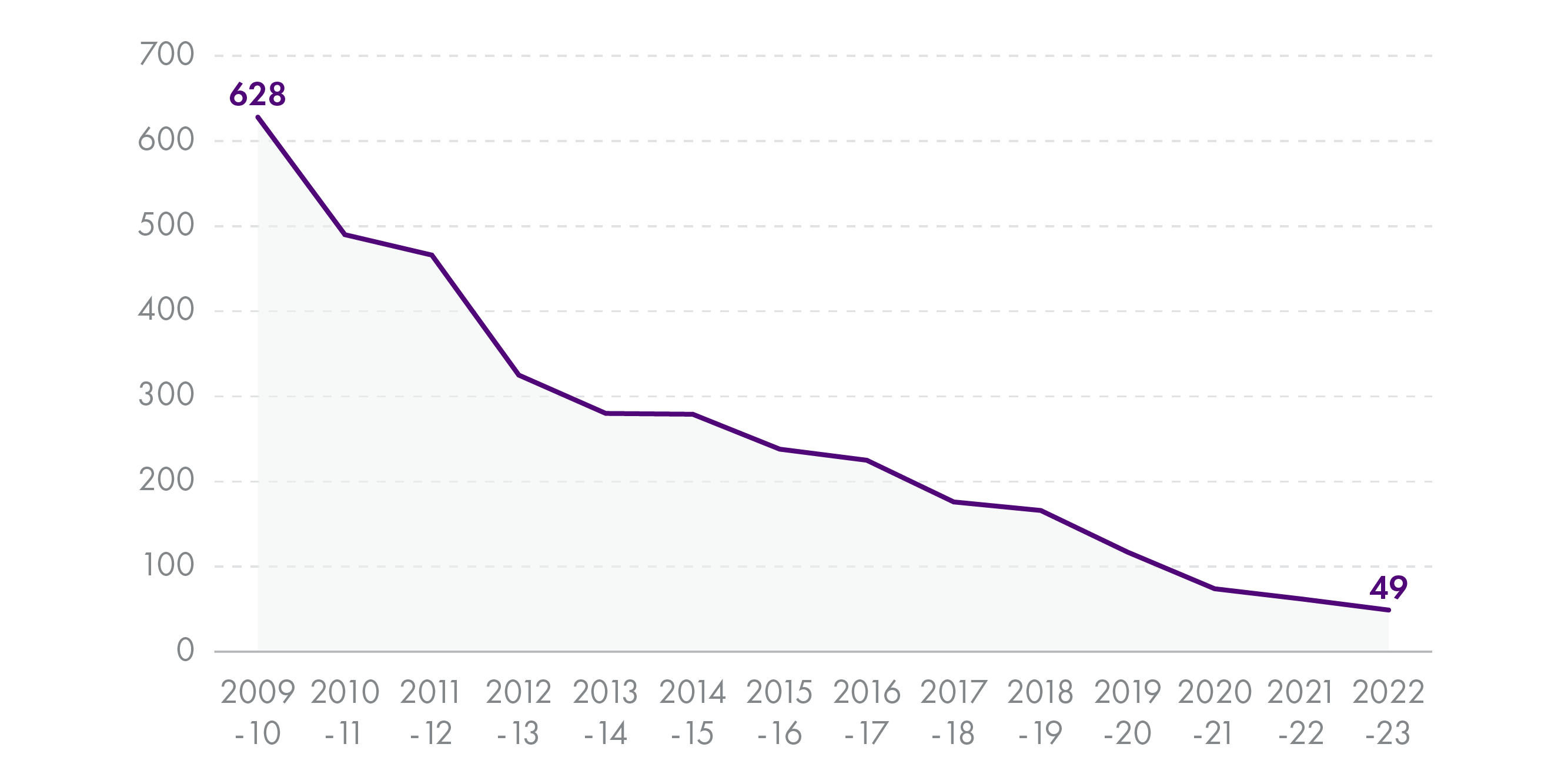

Following the Scottish Government's introduction of the Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC) framework in 2006 and the Whole System Approach in 2011, the number of children referred on offence grounds, and decisions made to arrange a children's hearing on offence grounds, dropped significantly.iii

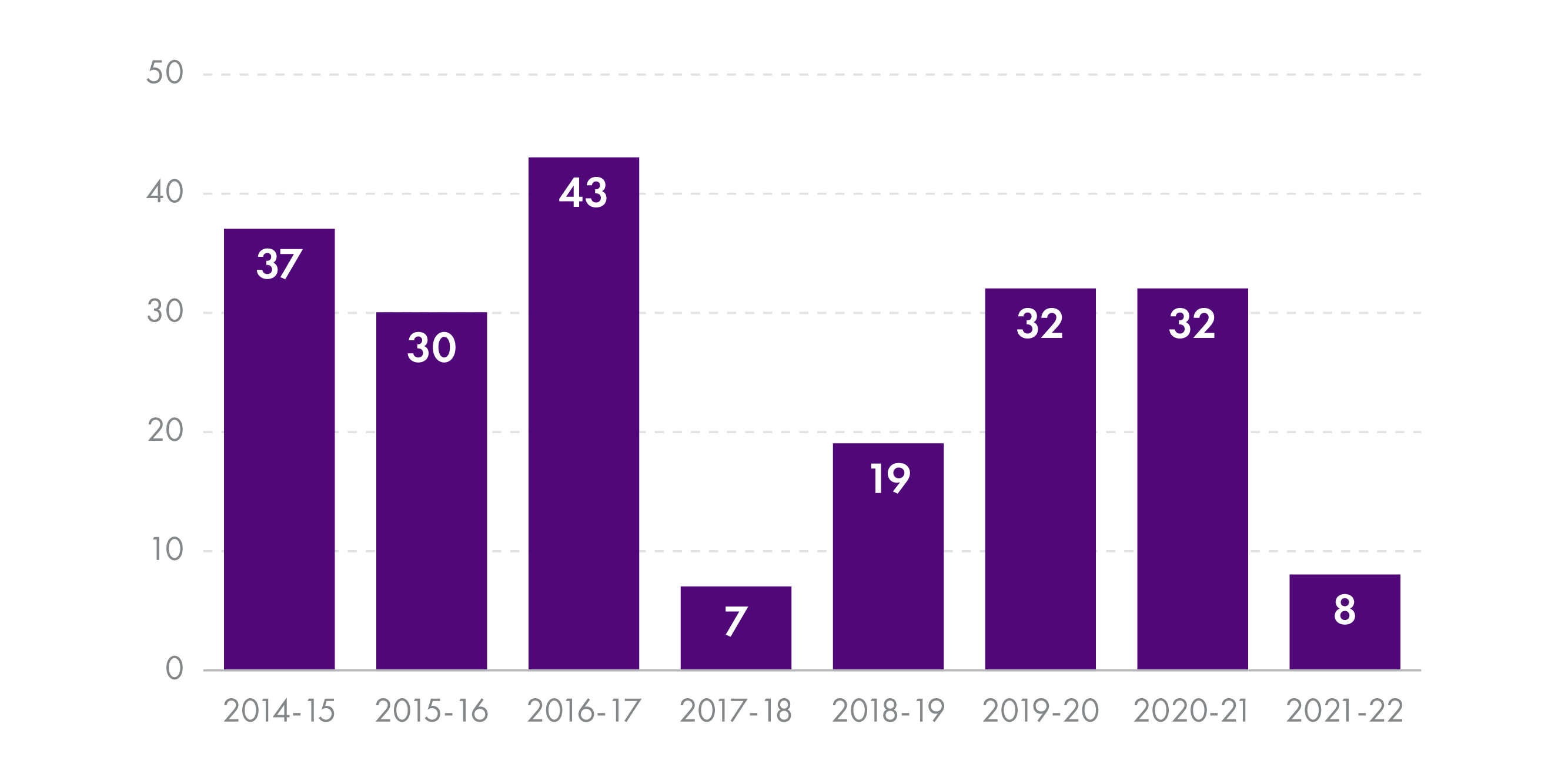

The figures for years 2020-21 and 2021-22 in charts 1 and 2 below should be read in the context of the impact of COVID-19 lockdown restrictions on children and young people's behaviour and subsequent referrals. The charts should also be read in the context of the Age of Criminal Responsibility Act (Scotland) Act 2019, which means that, as of 17 December 2021, children under 12 could no longer be referred to the Children's Reporter on offence grounds and, as of 29 November 2019, children under 12 were no longer referred to a hearing on offence grounds.

Table 1 below shows the breakdown of the children referred to the Children's Reporter on offence grounds by age over the same period as the charts above. It is based on SCRA live operational data so may differ from other published data. Children can be referred more than once in each year and hence at different ages in the year. The total figures show the unique total of children referred each year rather than the sum of constituent rows.

As above, the figures for years 2020-21 and 2021-22 should be read in the context of the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, and that, as of 17 December 2021, no children under 12 could be referred on offence grounds.

| Age | Year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | |

| 8 | 210 | 144 | 136 | 105 | 68 | 60 | 38 | 16 | 10 |

| 9 | 382 | 370 | 287 | 233 | 161 | 143 | 79 | 41 | 48 |

| 10 | 566 | 554 | 437 | 367 | 287 | 224 | 135 | 74 | 66 |

| 11 | 892 | 848 | 738 | 659 | 499 | 372 | 228 | 172 | 101 |

| 12 | 1,808 | 1,678 | 1,458 | 1,199 | 1,002 | 735 | 503 | 297 | 234 |

| 13 | 3,241 | 3,009 | 2,648 | 2,175 | 1,810 | 1,478 | 913 | 597 | 458 |

| 14 | 5,263 | 4,838 | 4,263 | 3,445 | 2,931 | 2,326 | 1,677 | 926 | 800 |

| 15 | 6,737 | 6,407 | 5,535 | 4,399 | 3,762 | 2,986 | 2,050 | 1,416 | 1,088 |

| 16 | 607 | 667 | 590 | 565 | 543 | 466 | 334 | 372 | 271 |

| 17 | 108 | 88 | 119 | 98 | 133 | 93 | 80 | 79 | 90 |

| Total | 17,361 | 16,229 | 14,209 | 11,554 | 9,765 | 7,857 | 5,336 | 3,473 | 2,764 |

| Age | Year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23** | |

| 8 | 15 | 21 | 14 | 15 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 14 | <5 |

| 9 | 34 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 32 | 18 | 13 | 17 | 0 |

| 10 | 60 | 61 | 64 | 77 | 52 | 44 | 24 | 35 | <5 |

| 11 | 116 | 92 | 99 | 109 | 92 | 104 | 59 | 58 | 0 |

| 12 | 224 | 226 | 301 | 306 | 233 | 273 | 186 | 210 | 257 |

| 13 | 440 | 459 | 566 | 624 | 474 | 497 | 368 | 469 | 576 |

| 14 | 787 | 788 | 860 | 919 | 890 | 829 | 577 | 716 | 854 |

| 15 | 1,168 | 1,075 | 1,106 | 1,095 | 1,143 | 1,116 | 872 | 845 | 1,007 |

| 16 | 350 | 384 *** | 294 | 307 | 273 | 288 | 289 | 255 | 245 |

| 17 | 110 | 99 | 92 | 109 | 106 | 117 | 123 | 119 | |

| Total | 2,891 | 2,761 | 2,998 | 3.056 | 2,825 | 2,840 | 2,207 | 2,398 | 2,637 |

* Based on SCRA live operational data (may differ from other published data). Children can be referred more than once in each year and hence at different ages in the year. The total figures show the unique total of children referred each year rather than the sum of constituent rows

** In 2022-23, <5 children were referred on offence grounds under the age of 12. This was due to delay between the offence occurring and the child being charged.

*** 16/17 individual age split unable to be provided.

A reduction in the number of children referred on offence grounds can be seen across all ages, except for 17 year olds, which increased slightly over this period. The greatest drop is for those aged between eight and eleven, who are now no longer able to be referred on offence grounds. Significant reductions in offence referrals for those aged 12-15 years old can also be seen, with a slightly smaller reduction in referrals for 16 year olds over this period.

Criminal courts

Criminal proceedings and outcomes

As noted above, Scots law now provides that children under the age of 12 do not have the capacity to commit a crime. Previously, while the age of criminal responsibility was set at eight, reforms set out in the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 meant that children under the age of 12 could still not be prosecuted in the criminal courts.

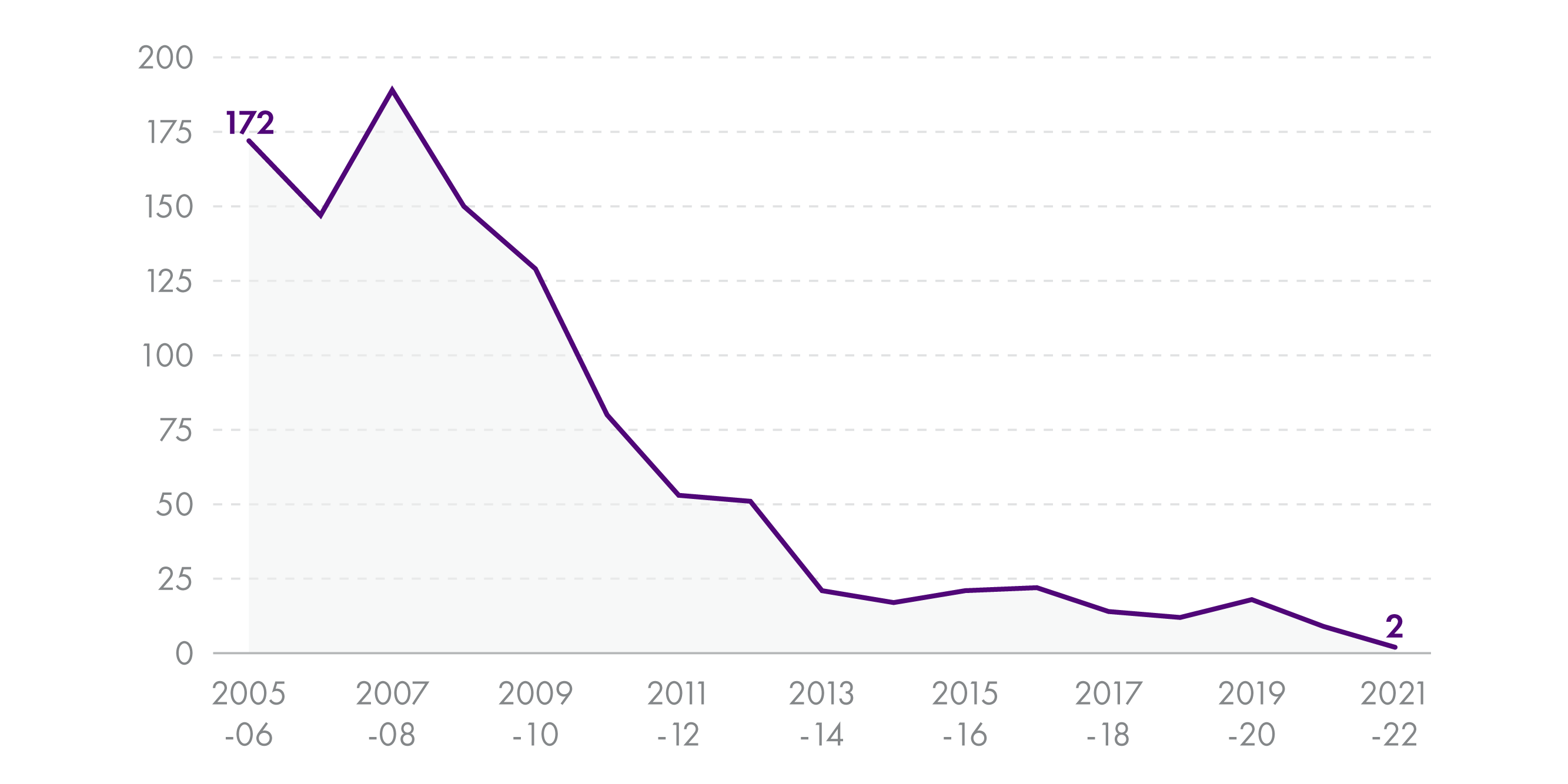

Similar to data on offence referrals to SCRA and decisions made to hold a children's hearing on offence grounds, a significant drop in the number of cases against children aged under 16, and those aged 16 and 17 in the criminal courts can be seen during the period 2005-06 to 2021-22.i The figures for years 2020-21 and 2021-22 should be read in the context of reductions and limitations on court business due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2 below shows a breakdown of these proceedings against children in the criminal courts by age. As above, the figures for 2020-21 and 2021-22 should be read in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Age | Year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | |

| 8-11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 25 | 16 | 21 | 31 | 26 | 15 | 9 | 9 | 1 |

| 15 | 143 | 129 | 158 | 118 | 97 | 62 | 42 | 42 | 20 |

| 16 | 2,822 | 2,870 | 2,587 | 2,244 | 1,739 | 1,271 | 1,157 | 846 | 637 |

| 17 | 6,380 | 6,796 | 6,393 | 5,404 | 4,369 | 3,557 | 2,943 | 2,264 | 1,880 |

| Total | 9,374 | 9,813 | 9,169 | 7,798 | 6,237 | 4,908 | 4,153 | 3,161 | 2,568 |

| Age | Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | |

| 8-11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 15 | 15 | 19 | 19 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 8 | 1 |

| 16 | 524 | 559 | 484 | 380 | 366 | 281 | 101 | 118 |

| 17 | 1,705 | 1,626 | 1,566 | 1,378 | 1,237 | 919 | 494 | 501 |

| Total | 2,246 | 2,206 | 2,072 | 1,772 | 1,585 | 1,218 | 604 | 621 |

The fact that a child has been prosecuted in the criminal courts does not necessarily mean that the child will be treated in the same way as an adult following a conviction for a similar offence. In addition to what it says about establishing a minimum age of criminal responsibility, article 40 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child includes provisions relevant to the treatment of children who are convicted of committing an offence:

A variety of dispositions, such as care, guidance and supervision orders; counselling; probation; foster care; education and vocational training programmes and other alternatives to institutional care shall be available to ensure that children are dealt with in a manner appropriate to their well-being and proportionate both to their circumstances and the offence.

As well as the possibility of remitting a case to a children's hearing for disposal, a court may seek advice from a hearing on the treatment of a child.

Table 3 provides information on the outcomes of cases against children under the age of 16 in the criminal courts. Table 4 provides the same information for children aged 16 and 17.

| Outcome | Year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | |

| Charge not proved | 31 | 17 | 30 | 26 | 23 | 13 | 6 | 15 | 5 |

| Custodial sentence | 24 | 24 | 26 | 21 | 22 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 5 |

| Community sentence | 15 | 26 | 20 | 13 | 17 | 17 | 9 | 7 | 3 |

| Financial penalty | 19 | 10 | 32 | 16 | 10 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Remit to children's hearing | 57 | 45 | 56 | 59 | 42 | 15 | 20 | 13 | 7 |

| Admonished | 26 | 24 | 23 | 14 | 15 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 0 |

| Other sentence | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 172 | 147 | 189 | 150 | 129 | 80 | 53 | 51 | 21 |

| Outcome | Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | |

| Charge not proved | 5 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Custodial sentence | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Community sentence | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Financial penalty | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Remit to children's hearing | 3 | 1 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Admonished | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Other sentence | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 17 | 21 | 22 | 14 | 12 | 18 | 9 | 2 |

| Outcome | Year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | |

| Charge not proved | 1,275 | 1,256 | 1,215 | 1,094 | 934 | 775 | 753 | 576 | 490 |

| Custodial sentence | 752 | 900 | 834 | 742 | 642 | 438 | 455 | 317 | 184 |

| Community sentence | 1,836 | 1,893 | 1,881 | 2,024 | 1,546 | 1,235 | 1,061 | 881 | 772 |

| Financial penalty | 3,830 | 3,946 | 3,441 | 2,289 | 1,811 | 1,267 | 871 | 588 | 470 |

| Remit to children's hearing | 202 | 263 | 200 | 146 | 131 | 152 | 119 | 120 | 85 |

| Admonished | 1,239 | 1,348 | 1,349 | 1,304 | 988 | 928 | 797 | 606 | 481 |

| Other sentence | 68 | 60 | 60 | 49 | 56 | 33 | 44 | 22 | 35 |

| Total | 9,202 | 9,666 | 8,980 | 7,648 | 6,108 | 4,828 | 4,100 | 3,110 | 2,517 |

| Outcome | Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | |

| Charge not proved | 398 | 398 | 337 | 280 | 252 | 196 | 59 | 86 |

| Custodial sentence | 171 | 214 | 195 | 130 | 178 | 54 | 40 | 21 |

| Community sentence | 678 | 695 | 678 | 568 | 447 | 397 | 199 | 191 |

| Financial penalty | 431 | 340 | 334 | 298 | 243 | 186 | 108 | 114 |

| Remit to children's hearing | 62 | 73 | 89 | 82 | 79 | 84 | 29 | 23 |

| Admonished | 454 | 427 | 391 | 370 | 348 | 251 | 152 | 163 |

| Other sentence | 35 | 38 | 26 | 30 | 26 | 32 | 8 | 21 |

| Total | 2,229 | 2,185 | 2,050 | 1,758 | 1,573 | 1,200 | 595 | 619 |

Youth courts and structured deferred sentencing

Two youth courts were established on a pilot basis in 2003 and 2004 – at Hamilton and Airdrie sheriff courts. They were aimed primarily at persistent offenders aged 16 and 17, with the intention of providing transitional arrangements between the children's hearings system and the full adult criminal justice system. The two youth courts ceased to operate in March 2014.

Information on the former courts is set out in an Evaluation of the Airdrie and Hamilton Youth Court Pilots1 and a Review of the Hamilton and Airdrie Youth Courts2.

The decision to close the pilot courts was taken in the context of the falling number of cases dealt with by the pilot courts as young people were increasingly diverted away from statutory measures and prosecution in favour of early intervention. The Evaluation of the Youth Court Pilots also raised the issue of potential "net-widening" where young people are drawn into a court system where previously they would have been dealt with by alternative measures .1

A youth court has been operational in Glasgow Sheriff Court since June 2021. It was developed using the context of Drug and Alcohol Problem-Solving Courts which were already operating in the city. The youth court was originally for those aged 16-21 years old but this was increased to include those up to age 24. It involves the use of Structured Deferred Sentences4 (SDS). This is an approach which involves multi-agency intervention and the provision of support along with regular court reviews to monitor progress. An Evaluation of the Glasgow Youth Court5 contains more information.

Other courts have used Structured Deferred Sentences as an interim disposal specifically for children and young people. These include in the following local authority areas:

Aberdeenshire (generally 16-26 year olds, though not exclusively)

East Lothian (up to the age of 18)

East Renfrewshire (16-26 year olds)

North Lanarkshire (16-21 year olds)

Perth and Kinross (16-26 year olds)

Shetland (16+ but generally reserved for young people)

South Lanarkshire (16-21 year olds at Hamilton, Airdrie or Glasgow Sheriff Courts and 16-25 year olds at Lanark Sheriff Court).

Children as victims and witnesses

Children can also be victims and witnesses within the criminal court system. There are a number of special measures already in place to support children giving evidence set out in Part 1 of the Vulnerable Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2004. For example, the taking of evidence by a commissioner, use of a live television link or screen, or giving evidence in chief in the form of a prior statement. The Act also states that all of a child witness' evidence in certain offences must be able to be given in advance of the hearing unless there are exceptional circumstances. Further protections for child witnesses under the age of 12 at the trials for certain offences also ensure they are not required to be present in the court to give evidence, should they not wish to be, unless specific criteria are met.

The Vulnerable Witnesses (Criminal Evidence) (Scotland) Act 2019 introduced a right for children giving evidence in the most serious criminal cases to have this pre-recorded instead of testifying in court. This is currently in place for those giving evidence in the High Court only. The Scottish Government's implementation plan for this Act, published in April 2024, sets out future dates for implementation across other courts.

To further support children who have been victims or witnesses of abuse and violence, as well as children who are under the age of criminal responsibility and whose behaviour has caused harm, Scotland is introducing the Bairns’ Hoose model (based on the Icelandic Barnahus, which means children's house). In their Programme for Government 2021-221, the Scottish Government stated that:

…all children in Scotland who have been victims or witnesses of abuse or violence, as well as children under the minimum age of criminal responsibility whose behaviour has caused significant harm, will have access to a “Bairns’ Hoose” by 2025.

The four rooms within a Bairns’ Hoose offer the opportunity for children to be interviewed, as well as for these interviews to be recorded and for there to be live links to courts. Further rooms allow children to take part in non-acute forensic examinations and for the child and their family members to access therapeutic support. It provides a single location alternative to courts, social work offices and police stations, and aims to allow children to have access to trauma informed recovery, support and justice all under one roof, while reducing the number of times children are asked to tell their story.

The Bairns' Hoose Project Plan2 was published in February 2022, with the Bairns' Hoose Standards3 published in May 2023. There is a three-phased approach to its introduction in Scotland – a pathfinder phase (2023-25), leading into a pilot phase (2025-26) and then a national roll-out (2027). The first Bairns’ Hoose was opened in North Strathclyde on 29 August 2023. An evaluation, The story so far: North Strathclyde Bairns Hoose Phase two evaluation report (August 2023 - September 2024), was published in September 2024.

Children in custody

Introduction

Children can be placed into custody by a court either through the imposition of a period of remand or a custodial sentence. They can either be placed within secure accommodation or a Young Offenders Institution (YOI).

Children can also be placed in secure accommodation by the children's hearings system. This can be as a result of a child being referred to a hearing on offence or non-offence grounds. A children's hearing is not able to either remand or sentence a child, this can only be imposed by a court.

Since 28 August 2024, when sections 18, 19 and 21-24 of the Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Act 2024 were brought into force, it has meant that, where a criminal court decides that it is necessary to place a child in custody, this will no longer be within a YOI or prison.

There are four secure care centres providing secure accommodation within Scotland. These are run by independent charitable organisations: the Good Shepherd Centre, Kibble Safe Centre, Rossie Secure Accommodation Services, and St Mary's Kenmure. There are 78 beds available across these four centres.1

HMP & YOI Polmont is, as of the implementation of the relevant sections of the Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Act 2024 on 28 August 2024, the national facility for holding young people aged 18 to 21 years old in Scotland (previously it was for 16-21 year olds). There is also availability for young adult women up to the age of 21 to be held in YOIs within the prison estate in Grampian and Stirling, where there is also a Mother and Baby Unit.

There have been no children under 16 held within a YOI since 2009-10. The prison population of 16 and 17 year olds has also dropped significantly since then.

Children's Social Work statistics show that, since 2019-20, no children have been within secure accommodation due to being sentenced in summary court proceedings. The numbers sentenced under solemn proceedings have been published since 2014-15 but due to the low numbers of these cases have been suppressed to maintain confidentiality.2

Chart 6 below shows the numbers of children within secure accommodation due to being remanded or committed for sentencing by a court under Section 51 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 since 2014-15.2

Children in custody on remand

Section 51 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 covers the remand and committal of children by the courts. This is where children are held before trial or after a finding of guilt but before sentencing, having not been given bail. Previously, how children were treated when they were remanded by a court was dependent on their age, and in some cases whether or not they were subject to a Compulsory Supervision Order (CSO).

The Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Act 2024 amended Section 51 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995. Since the implementation of this part of the Act on 28 August 2024, in cases of remand or committal, those under the age of 18 will either be detained in secure accommodation, if the court requires that, or a place of safety as determined by the local authority. This could include secure accommodation. They will no longer be held within a YOI or prison.

Children in custody having been sentenced

Sections 44, 205 and 208 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 deal with custodial sentences for children convicted in a criminal court. How children were treated previously was dependent on their age, and in some cases whether they were subject to a Compulsory Supervision Order (CSO), as well as whether they were subject to summary or solemn proceedings.

The Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Act 2024 amended the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 in terms of the detention of children. Since the implementation of the relevant parts of the Act on 28 August 2024, children will no longer be able to placed in a YOI or prison. Depending on whether they are subject to summary or solemn proceedings they will be dealt with as follows:

summary proceedings (less serious offences) – they will be detained in a residential establishment determined by the local authority, which could include secure accommodation

solemn proceedings (more serious offences) – Scottish Ministers will direct where the child is to be placed, which may be secure accommodation.

The Act also allows Scottish Ministers to make regulations which would mean that, under conditions which they are able to specify, children may remain in secure accommodation up to the age of 19.

Retention and disclosure of information

Introduction

The police may hold various types of information about both children and adults:

criminal convictions and alternatives to prosecution (e.g. fixed penalty notices and fiscal fines)

matters dealt with on offence grounds through the children's hearings system

non-conviction information (e.g. allegations that do not progress to formal criminal proceedings)

forensic information (e.g. fingerprint and DNA data).

This information may be used as part of future criminal investigations (e.g. fingerprint and DNA data). It may also be disclosed to third parties (e.g. the provision of information about previous convictions to potential employers).

The following outlines the rules under which such information is retained and disclosed.

Retention of information

The police have various powers to take forensic information (in particular fingerprint and DNA data) from people, including children, suspected of committing criminal offences. Such information can be analysed, checked against existing records and added to databases for future reference.

There are limitations to these powers for children under the age of criminal responsibility (i.e. under twelve). The Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Act 2019 provides that generally no prints or samples may be taken from a child under 12 except where authorised by an order of a sheriff, by a senior police officer in urgent cases, or by any other statutory provision. For children over the age of 12, and relating to an incident which occurred when they were under 12, police can apply to a sheriff if the child does not consent to this information being taken. The incident must involve violent or dangerous, or sexually violent or coercive behaviour.

Where the offence is dealt with in a court and there is a criminal conviction, any fingerprint and DNA data taken from the convicted person can be retained indefinitely, subject to data protection legislation. This is dealt with under police operating procedures. Where a suspect is not convicted in a criminal court, the general rule is that it must be deleted from databases and destroyed. However, where the suspect was prosecuted for a range of sexual or violent offences, such information may be retained for a period of three years after the conclusion of criminal court proceedings (with the ability to extend this for two years on application to a Sheriff), even if the suspect is not convicted.

There is also provision for the temporary retention of forensic information where alternatives to prosecution have been used.

Where samples have been taken from a child under 12 and/or relating to an incident which occurred when they were under 12, the Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Act 2019 states that the data must be destroyed "as soon as possible" should the child not be referred to the children's hearings system, or following the conclusion of any children's hearing proceedings to which they relate.

Where a child is aged 12 or above and the incident also occurred when they were over the age of 12, samples can be taken under the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995. In this case, where the offence is dealt with by the children's hearings system, fingerprint and DNA data can be retained for a period following the acceptance or establishment of grounds only where it relates to certain sexual or violent offences.

In addition to forensic information, the police may hold criminal conviction, children's hearing (offence grounds) and non-conviction information. Retention of this type of information is subject to police guidance – Recording, Weeding and Retention of Information on Criminal History System (CHS) Guidance.1 The guidance sets out rules on how long such information will be held on databases before removal (weeding). For example, information on:

criminal court convictions is generally retained for between 20 years and the lifetime of the person (depending on the nature of the offence/disposal)

offence grounds established/accepted at children's hearings is retained for two years (three years with a review annually thereafter for sexual and serious violent offences)

alternatives to prosecution is retained for two or three years (depending on the nature of the offence and type of alternative)

prosecutions which have not been proceeded with or have resulted in an acquittal is retained for six months (three years for certain sexual or violent offences).

The weeding of information precludes its future disclosure by Disclosure Scotland (which relies on the contents of such databases).

Disclosure of information

Individuals may, in some circumstances, be under a legal obligation to self-disclose the fact that they have criminal convictions (e.g. where asked by potential employers or when applying for certain university courses). A failure to do so may, for example, lead to the withdrawal of an offer of employment.

In addition, Disclosure Scotland (an executive agency of the Scottish Government) provides a formal disclosure service to third parties, using information held in police databases. This can cover both previous convictions and non-conviction information. Offence grounds established/accepted at children's hearings are treated as previous convictions for these purposes.

Whether or not disclosure is required depends on the following factors:

the nature of the information (e.g. a previous criminal conviction or non-conviction information)

whether a previous criminal conviction has become ‘spent’ - this is discussed below under Previous Criminal Convictions

the nature of the work being sought (e.g. whether a post involves working with vulnerable people).

These factors are reflected in the work of Disclosure Scotland which manages the Protecting Vulnerable Groups Scheme (PVG Scheme) as well as providing different levels of disclosure certificate. For example, the following forms of disclosure include the stated information:

basic disclosures – unspent convictions

standard disclosures – convictions (including relevant spent ones) and sex offender notification requirements

enhanced disclosures – as for standard disclosures plus non-conviction information which is reasonably believed to be relevant by the police (or other Government bodies)

PVG Scheme – as for enhanced disclosures.

The PVG Scheme differs from the arrangements for basic, standard and enhanced disclosure certificates in that scheme members are subject to ongoing monitoring, meaning that their vetting information is kept up-to-date.

Further details of the information provided by Disclosure Scotland under these different levels is set out on its website under Types of Disclosure.

Anyone can apply for a basic disclosure relating to themself. Standard and enhanced disclosures as well as a check through the PVG scheme must be applied for by employers or organisations rather than individuals. Standard and enhanced disclosures may be sought where people are working in specific roles. The PVG scheme is for people doing regulated work with children and protected adults. While the basic, standard and enhanced disclosures are one-off checks, Disclosure Scotland continuously monitors PVG members' records.1

The Disclosure (Scotland) Act 2020 will reduce the four levels of disclosure above to two:

Level 1 - replaces basic disclosure

Level 2 - replaces standard and enhanced disclosures and PVG Scheme Records

It received Royal Assent on 14 July 2020 but is not fully in force, including the sections which cover the implementation of Level 1 and Level 2 disclosure processes. Disclosure Scotland has provided a summary of how the disclosure process will change. They also state that they will implement the changes by April 2025.

Apart from basic disclosures, all of the above forms of disclosure include information about relevant spent convictions. Until 2015, this meant all spent conviction information held on police databases. However, changes to the law mean that some very old or less serious spent convictions are no longer disclosed. The purpose of the reform was to allow people with such convictions to put past offending behaviour behind them. Different rules apply to people convicted whilst under the age of 18.

The Disclosure Scotland website provides further information under Spent and Unspent Convictions. The Scottish Government also provides information on Disclosure periods of previous convictions & alternatives to prosecution in Scotland under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974.

The Disclosure (Scotland) Act 2020 also provides for changes to the specific rules around the disclosure of convictions for those under the age of 18. Again, however, relevant provisions are not yet in force. Once they are, Disclosure Scotland will make the initial decision of whether a spent or unspent childhood conviction or children's hearings outcome should be disclosed under a Level 2 disclosure, and an unspent childhood conviction disclosed under Level 1. The subject of the disclosure has a right to appeal this decision with it then being referred to an independent reviewer.

The Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Act 2019 means that those under the age of 12 cannot commit an offence. The Disclosure Scotland website contains information on Behaviour under the age of 12 and disclosure stating that information about behaviour before the age of 12 will not appear on a basic or standard disclosure but may be included on an enhanced disclosure or PVG Scheme Record, but only after an independent review of the information has taken place.

Previous criminal convictions

The Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974 provides that, following specified rehabilitation periods based on the sentence imposed (not the offence), convictions may become ‘spent’ for certain purposes. The 1974 Act was passed by the UK Parliament and applies to England and Wales as well as Scotland. However, its subject matter is, for the purposes of Scots law, devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

The general rule is that an ex-offender does not have to reveal a spent conviction (or alternative to prosecution) and cannot be prejudiced by it. For example, ex-offenders do not have to declare spent convictions when applying for most jobs or for insurance. As discussed above, certain types of work are exempted from these provisions, so that relevant spent convictions are disclosed. These exemptions are intended to strike an appropriate balance between supporting the rehabilitation of ex-offenders and public protection.

In relation to Scotland, changes were made to the 1974 Act by the Management of Offenders (Scotland) Act 2019. These included changes affecting the time taken for an offence committed by a child to become spent. As a result, convictions for those under the age of 18 at the date of conviction which result in the following criminal court sentences currently become spent after the period indicated (from the date of conviction):

an absolute discharge – immediately spent

a fine or community sentence – six months

a custodial sentence not exceeding 12 months – term of sentence plus one year

a custodial sentence exceeding 12 months but not exceeding two and a half years – term of sentence plus two years

a custodial sentence exceeding two and a half years but not exceeding four years – term of sentence plus three years.

In relation to alternatives to prosecution, the 1974 Act provides that some are treated as spent immediately whilst others become spent after three months.

The Disclosure (Scotland) Act 2020 provides for further changes to the periods of disclosure for criminal convictions for offences committed while under the age of 18 and resulting in the imposition of a fine or custodial sentence not exceeding 12 months. Once the relevant provisions are in force, such convictions will become spent immediately. This Act also amends section 5J of the 1974 Act, providing that when this provision is in force, no disclosure period will apply for any sentence other than an excepted sentence (those of more than four years) and custodial sentences of over 12 months where imposed for sexual offences where the offence was committed under the age of 18.

Convictions for children resulting in a custodial sentence of more than four years do not currently become spent in Scotland. The Scottish Government website, Previous convictions and alternatives to prosecution: disclosure periods, advises that "a review mechanism will be available in due course for relevant sentences over 48 months". The Scottish Government has advised that the power to provide a system of review for the requirement to disclose a conviction resulting in a sentence of greater than 48 months is a discretionary power for Scottish Ministers and that there are no current plans for the use of this power.

Children's hearings

Disposals by children's hearings are not the same as criminal convictions. However, where offence grounds are accepted or established at a children's hearing, the disposal of the hearing is treated as a criminal conviction for the purposes of disclosure and the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974 (see section 3 of this Act).

The amendment of section 5J of the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974 by the Management of Offenders (Scotland) Act 2019 means that all disposals by a children's hearing are now treated as sentences to which no disclosure period applies. Enhanced disclosures, as discussed above, will still include children's hearings outcomes.