Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Bill

The Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Bill was introduced on 13 December 2022. The Education, Children and Young People Committee is the designated lead committee and will be looking at the Bill alongside the Criminal Justice Committee.This briefing is to support Members’ consideration of the Bill by providing a short narrative of what the Bill seeks to do, a brief overview of the children's hearing system and the wider policy context.

Executive Summary

The Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Bill was introduced on 13 December 2022. The Education, Children and Young People Committee is the designated lead committee and will be looking at the Bill alongside the Criminal Justice Committee.

This briefing is to support Members’ consideration of the Bill by providing a short narrative of what the Bill seeks to do, a brief overview of the children’s hearing system and the wider policy context.

The Bill makes changes to the law in relation to the care of children and the involvement of children in the criminal justice system. This includes courts that hear cases relating to children and the places where children can be detained.

Intention of the Bill

According to the Policy Memorandum the main objective of the bill is to:

“Improve experiences and promote and advance outcomes for children, particularly those who come into contact with care and justice services. Building on Scotland’s progressive approach to children’s rights in line with the UNCRC, the Bill’s provisions aim to increase safeguards and support, especially to those who may need legal measures to secure their wellbeing and safety.”

The Programme for Government 2022/23 also states:

“Children also deserve extra care and protection in our justice system. The Children’s Care and Justice Bill will help us Keep The Promise by ensuring that children who come into contact with care and justice services are treated with trauma-informed and age-appropriate support and will put an end to placing under 18s in young offenders’ institutions. The Bill aims to improve experiences and outcomes for children in Scotland who interact with the children’s hearing and criminal justice systems, as well as care settings and those who are placed across borders in exceptional circumstances.”

Overview of the Bill

Part 1 changes the age of referral to a children's hearing from 16 years old to 18 years old and removes statutory barriers to 16- and 17-year-olds being referred to the Principal Reporter to access the children’s hearing system, both for welfare and on criminal grounds. It also contains some related measures, geared to assisting the raising of the age of referral.

Part 2 relates to children in the criminal justice system, including the framework on reporting of criminal proceedings involving children, remittal between the courts and children’s hearings, children in police custody, and looked after children status in relation to detained children. Part 2 also makes provision for ending under 18s being detained in young offenders’ institutions (YOIs), with secure accommodation services being the alternative where a child requires to be deprived of their liberty. There is also a regulation-making power around extending secure accommodation until the age of 19 in certain circumstances.

Part 3 changes the statutory definition of secure accommodation. It also legislates on the support, care and education that must be provided to children accommodated there. Moreover, it provides regulation-making powers regarding the approval framework of secure accommodation services by the Scottish Ministers. Part 3 also makes provision around regulation and recognition of cross- border care placements.

Part 4 makes two changes: it extends the meaning of child to under 18s in the Antisocial Behaviour etc. (Scotland) Act 2004;- and repeals Part 4 (provision of named persons) and Part 5 (Child’s Plan) of the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014. As Parts 4 and 5 have never been in force, the repeal does not affect the existing named person or child’s plan practice.

Current legislation

The Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 sets out actions to be taken in cases involving children and young people.

The Children (Scotland) Act 1995 is the primary piece of legislation relating to the care and welfare of children and young people in Scotland. It sets out local authority services for children and families in need of support. It also sets out parental responsibilities and rights of birth parents regarding how their child is brought up and situations in which these rights may be removed. Recent amendments to the 1995 Act via the Children (Scotland) Act 2020 introduced duties for the local authority, when making decisions about the care of a looked after child, to take the views of their siblings into account; and to promote direct contact and personal relations between a looked after child and any of their siblings.

The Looked After Children (Scotland) Regulations 2009 are an important operational piece of legislation in the Scottish looked after system. Through the revocation and amendment of much previous legislation, and the introduction of new provisions related to assessment and planning, ‘looked after at home’, kinship care, foster care and residential care, the regulations underpin many of the ‘looked after child’ processes in operation. They set out local authority duties and functions in relation to children in their care and are underpinned by three principles:

to give paramount consideration to the welfare of the child

to consider the views of the child

to avoid delay and to make the minimum intervention necessary to a child’s life.

A recent amendment to the 2009 Regulations introduced a duty for local authorities to place siblings together in care, as long as this is in their best interests.

The Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011 fundamentally overhauled legislation on the children's hearings system and sought to strengthen children's rights in the context of that system. It also provides the definition of child that is relied on for many other pieces of legislation, including criminal justice.

The Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 introduced a range of significant reforms across children's services. These include corporate parenting duties for certain publicly funded individuals and organisations to meet the needs of care experienced people. The Act also

sets out local authority duties to provide services and support for children at risk of becoming 'looked after' and assistance for kinship carers

extends the age of eligibility for aftercare support for young people leaving care to 26

introduces 'continuing care', providing care leavers up to the age of 21 with the opportunity to continue with accommodation and support they were provided with immediately before they ceased to be looked after.

The Act made amendments in relation to the withdrawal of Relevant Person status, and what required to be accepted at a grounds hearing.

The court structure in Scotland was streamlined by the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014, which (amongst other things) replaced the appellate jurisdiction of the sheriff principal with the new Sheriff Appeal Court which has since become a major and influential source of jurisprudence on the 2011 Act.

The Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2016 replaced all legislation regarding arrest for criminal offences. It also deals with children in police custody.

The Children (Equal Protection from Assault) (Scotland) Act 2019 removed the defence of reasonable chastisement, with the corporal punishment of children wholly criminalised.

Children’s Hearing System

Background to the current system

The Children’s Hearing System was introduced in 1971 following the Kilbrandon Report of 1964 and the Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968. Kilbrandon recommended a welfare-based system to provide an integrated approach to children who had committed offences and children in need of care and protection. In a children's hearing, there is an assumption that the child who has committed an offence is just as much in need of protection as the child who has been offended against. There is a lay tribunal which does not have the formality of the normal courts. The legislation was substantially revised in the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 but the key principles have remained constant.

The Children’s Hearing System is legislated for in the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011(referred to throughout as ‘the 2011 Act’). The 2011 Act consolidated existing legislation and made mostly structural changes to the Children’s Hearing System. This followed a period of review which started around 2004 and coincided with the development of the ‘Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC)’ approach to improving outcomes and supporting the wellbeing of children and young people.

Hearings are organised and administrated by the Scottish Children's Reporter Administration (SCRA) when children are referred for hearings.

A list of reasons, known as ‘grounds’, outline why a child may be considered to be at risk and form the basis of a referral to a children’s hearing. Any person (private individuals, teachers, social workers, health professionals, police etc.) can refer a child to SCRA, who will consider whether grounds exist for a hearing. Section 67 of the 2011 Act sets out the grounds on which a Reporter may refer a child to a children’s hearing.

Children’s Hearing Improvement Partnership (CHIP) guidance summarises the statutory criteria for referrals set out in the 2011 Act as follows:

“(a) the child is in need of protection,’ guidance, treatment or control; and (b) it might be necessary for a Compulsory Supervision Order to be made in relation to the child. The Local Authority and the Police must refer a child when the criteria apply. Any other person may do so.”

Once a referral is made to the Children’s Reporter, the Reporter must decide whether there is enough evidence to establish the ground and consider whether a Compulsory Supervision Order is necessary. Only if both are met will a hearing be called.

The Children’s Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011 sets out who may attend a children’s hearing in relation to a child as a ‘Relevant Person’. People automatically considered to be Relevant Persons are:

any parent, whether or not they have parental rights or responsibilities

any person who has court-appointed parental rights or responsibilities relating to the child.

Other people, such as foster carers and kinship carers, are not automatically considered to be Relevant Persons. However, a Pre-Hearing Panel or a children's hearing can decide whether someone can be deemed as a Relevant Person. This is done by taking into consideration whether the person has had significant involvement in the upbringing of the child.

Children's Hearings Scotland

The 2011 Act established a new non-departmental public body ‘Children's Hearings Scotland’ with five to eight board members, headed by a National Convener. Children's Hearings Scotland recruits, trains and supports around 3,000 volunteer panel members across Scotland.

The National Convener is appointed by members of Children's Hearings Scotland, with the approval of Scottish Ministers, and has the following functions:

to recruit and appoint panel members, publish a list of panel members and select members for hearings, who among them must be from all 32 local authority areas

to train, monitor and quality assure the performance of and pay allowances to panel members

to appoint committees known as Area Support Teams

to give advice at hearings.

How does the Children's Hearing System work?

The following gives a very brief overview of the main stages of a hearing. Throughout, the procedures are informed by the key principles of the system which are:

the welfare of the child is the paramount consideration

an order will only be made if it is necessary (i.e. the state should not interfere in a child's life any more than is strictly necessary)

the views of the child will be considered, with due regard for age and maturity.

The hearing should have the character of a discussion about the child's needs. A sheriff court is generally only involved if grounds of referral are in dispute or not understood, a child protection or child assessment order is required, or there is an appeal against a decision of a hearing. The aim is to balance the ‘lay’ character of the system with the guarantees of individual rights afforded by a court system.

Anyone can make a referral to the Reporter, but in practice most referrals are made by the policei. The Reporter investigates and decides whether a hearing is required. This decision is based on whether there is sufficient evidence that a statutory ground for referral has been met and, if so, whether compulsory measures of supervision are needed.

If a hearing is required, the Reporter arranges one and three members of the local children's panel ‘as far as practicable’ are selected to form the hearing. The child and Relevant Persons have a duty to attend a hearing unless they are excused. They also have a right to attend (although the Relevant Person can be excluded temporarily from a hearing).

At the hearing, the grounds for the referral must either be accepted by the Relevant Persons and child or established by the sheriff in order to proceed. In considering the case, everyone should have the opportunity to participate freely. If necessary, a Relevant Person can be temporarily excluded if this is needed to allow the child to express his or her views or to prevent distress to the child, along with other grounds outlined in Section 20D of the 2011 Act. A safeguarder, whose role is to protect the child's interests, can be appointed at any time during the hearings process. A child or Relevant Person can be represented at a hearing and there is state funding available in particular circumstances for legal representation. A scheme for children has been available since 2002 and this was extended to Relevant Persons in June 2009.

Once the case has been considered the hearing can

continue the case (i.e. defer decision to a later hearing)

discharge the referral

refer for voluntary support including restorative justice (if the child is aged 8 to 17 and referred on an offence ground)

make a Compulsory Supervision Order and an interim CSO.

A Compulsory Supervision Order can set out where the child is to live and with whom he or she will have contact. It can have any condition attached to it, including authorising placement in secure accommodation, requiring a medical examination or a ‘movement restriction condition’ (electronic tagging) and imposing duties on the relevant local authority. It can be reviewed at any time and will cease to have effect unless it is reviewed within a year.

The local authority must implement a Compulsory Supervision Order. If it does not do so, the hearing can ask the National Convener to apply to the sheriff principal for an enforcement order.

Appeals can be made by the child (where considered to have the capacity) or Relevant Person to the sheriff and then to the Sheriff Appeal Court or Court of Session.

Although the above gives an outline, the detail of the hearings system is quite complex. For example, in addition to the above, it provides for the emergency protection of children through consideration of child protection orders, and for various warrants and orders for the removal of children to a place of safety or for a medical assessment. There are strict time limits with regard to the detention of children which vary according to the circumstances in which an order is sought. Part of the complexity is a result of the need to ensure that emergency protection, or any detention of a child, is followed up timeously with full consideration of the child's needs.

Offences

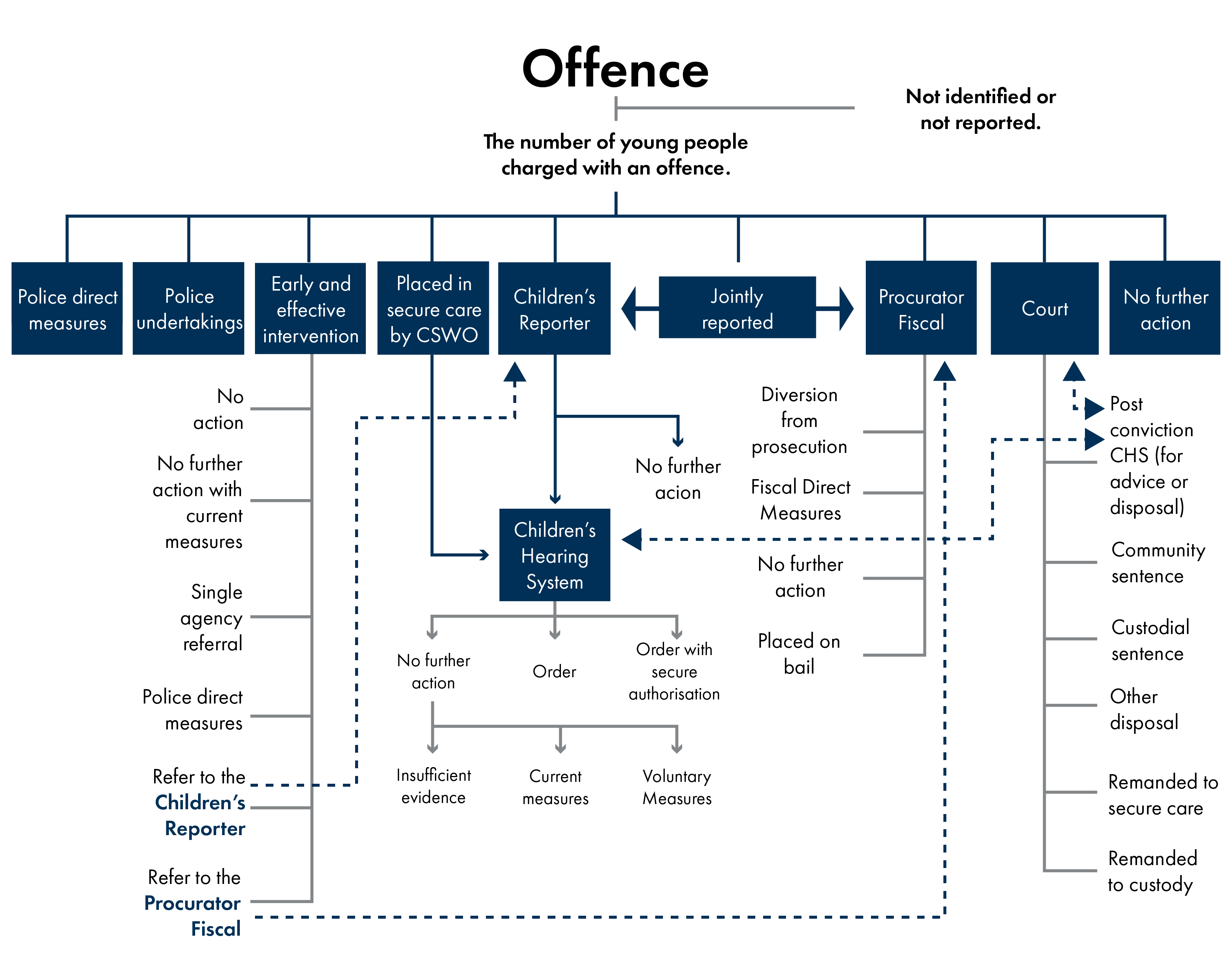

Where a child over the age of prosecution is reported to the police, the Lord Advocate’s Guidelines to the Chief Constable on the Reporting to Procurators Fiscal of offences alleged to have been committed by children applies. This requires the police to jointly report certain cases to the Procurator Fiscal and the Principal Reporter.

If the child is not jointly reported, the police will deal with the child in the most appropriate way, for example, through police direct measures, by reference to Early and Effective Intervention, or by referring to the Principal Reporter if it is considered that compulsory measures may be required.

Source: Children and Young People's Centre for Justice, Journey through Justice.

Offences reported to have been committed by 16- and 17-year-olds

Under the Lord Advocates Guidelines to the Chief Constable on the Reporting to Procurators Fiscal of offences alleged to have been committed by children, certain offences alleged to have been committed by 16- and 17-year-olds are currently jointly reported to the Procurator Fiscal and the Children's Reporter if:

they are subject to a CSO or

where they were referred to the Principal Reporter before their 16th birthday, but where a decision has not yet been made either to make them subject to a CSO, nor to refer them to a Children's Hearing nor to discharge the referral.

The 16- or 17-year-olds who fall outwith the Lord Advocates guidelines are either reported to the Procurator Fiscal only, or are dealt with through local Early and Effective Intervention arrangements as part of police direct measures.

This currently has the effect that two 16-year-olds may be treated differently at reporting simply as a result of their prior involvement with the Children's Hearing system.

In all jointly reported cases, the decision as to whether the case will be prosecuted or referred to the Children's Reporter is made in consultation between the Procurator Fiscal and Children's Reporter, with the Procurator Fiscal making the final decision.

In jointly reported cases, there is a presumption in favour of referral to the Children's Reporter. This presumption can be set aside where it is in the public interest to prosecute.

In assessing whether the public interest resides in prosecution, the Procurator Fiscal may consider the following factors including:

whether the gravity of the offence is such that solemn proceedings may be justified

the impact of the offence on the victim

any pattern of serious offending by the child.

Statistics

In 2021/22, 10,494 children in Scotland were referred to the Children's Reporter:

8,691 on non-offence grounds

2,398 on offence grounds.

The figure of 10,494 children referred to the Reporter in 2021/22 equates to 1.2% of all children in Scotland.

Within this, 1.0% of all children were referred on non-offence grounds and 0.5% of all children aged between 8/12 and 16 years were referred on offence groundsi.

The number of children referred to the Reporter has increased for the first time since 2006/07, following 14 consecutive years of decrease. The Reporter suggests that this is most likely an impact of Coronavirus and lockdowns rather than any wider system trend. Therefore, any conclusions drawn from this data should be treated with caution.

In 2020/21, 595 children aged 16 and 17 were proceeded against in a criminal court.

Statistics on children under 18 remanded or sentenced to detention in young offenders’ institutions are set out later in this briefing when considering relevant proposals in Part 2 of the Bill.

Part 1: Children's Hearing System

Age of referral to children's hearings

Part 1 of the Bill changes the age of referral to a children's hearing from 16 years old to 18 years old and removes statutory barriers to 16- and 17-year-olds being referred to the Principal Reporter. This change will extend to all under 18s, both those on welfare grounds and criminal grounds.

Section 1 will amend section 199 of the Children's Hearing (Scotland) Act 2011 which currently defines a “child” as anyone under the age of 16 or over who has been referred to the hearings system before they turn 16 in order for the hearings system to deal with them, or 16- and 17-year-olds if they are already subject to a CSO.

This would provide the opportunity for children to be referred or remitted to a children's hearing up to age 18; it also covers non-offence referrals. The Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service will however continue to have discretion to prosecute.

Currently if a child has not had prior involvement in the children's hearing system, then the child can only be referred to the Principal Reporter if they are under 16.

The hearings system can still deal with some 16-year-olds provided they were referred to the system before turning 16, and those aged 16-17 who are already subject to a Compulsory Supervision Order as outlined earlier in this briefing, as well as children who are remitted from court.

In practice this means that two young people both aged 16 can commit the same crime but will be dealt with differently. While one could have their case heard by the children's hearing system in a welfare-based system, the other may need to be heard by the courts.

The SCRA forecasts an additional 3,900-5,300 referrals of between 2,600-3,400 children as a result of extending the age of referral as proposed. Referrals do not always lead to a hearing being convened. In terms of hearings, the forecast is for an additional 80 to 150 hearings on offence grounds and 650 to 1,200 on non-offence grounds annually, equating to 730-1,350 additional hearings per year.

The Bill consultation also considered whether the children's hearing system should have a scope post-18 to prevent ‘cliff-edges’ where a young person transitions from one forum to another. However, analysis from the Scottish Government highlighted barriers to taking such an approach, including maintaining the hearings system as a model solely pertaining to children, and in terms of the rights of adults.

Compulsory Supervision Orders (CSOs)

A CSO is a formal order made by a Children's Hearing or, less commonly, by a sheriff for children who need additional protection or support.

When a CSO is made, it means a child's local authority must perform duties in relation to the child's needs and support their family as set out in section 83 of the 2011 Act. It also means there are certain rules the child may have enforced, such as living in secure care or away from their family.

Prior to a child's hearing, Reporters prepare a statement of grounds, setting out the grounds for a CSO and supporting facts. CHIP guidance explains:

“The Hearing may only proceed to consider whether to make a Compulsory Supervision Order if the child, and relevant persons present at the Hearing, accept a ground, or a ground is found established by the Sheriff.”

Children have the right to attend court, though the sheriff may decide they do not have to. The child or young person and their parents or carers have the right to have a lawyer represent them in court.

The Policy Memorandum to the Bill states that the measures in Part 1 of the Bill do not affect the constitutional independence of the Lord Advocate and Procurators Fiscal who will retain the discretion to begin criminal proceedings and to prosecute children in court, where appropriate. The Bill takes forward measures to enhance the ability for protective and preventative measures to be made available through this system, as well as to promote information to those who have been harmed.

One of the measures currently in a CSO is a requirement that the child reside at a specified place. Section 2 and 5 amends section 83 of the 2011 Act to make it clear that an authorisation to the person in charge of a place in which a child is required to reside to restrict the liberty of the child, does not include an authorisation to deprive the child of their liberty.

Section 5 of the Bill amends the secure accommodation authorisation criteria so that if a children's hearing considers it necessary to deprive a child of their liberty it would need to include in the CSO a secure accommodation authorisation. That measure attracts special legal safeguards for the child's protection.

Movement restriction conditions (MRC) are a measure on a CSO restricting a child's movements and requiring the restrictions to be monitored by way of an electronic monitoring device. MRC can be included in a CSO only where certain criteria are meti:

The hearing or the sheriff is satisfied that it is necessary to include an MRC in the order, AND

The child has previously absconded and is likely to abscond again, and if the child were to abscond it is likely that the child's physical, mental or moral welfare would be at risk, and/ or

The child is likely to engage in self-harming conduct, and/or

The child is likely to cause injury to another person.

The provisions in the Bill decouple the MRC criteria from that of secure accommodation authorisations and can apply without the prerequisite of absconding.

In addition, the new test for MRC moves to consideration of ‘harm’ rather than ‘injury’ and also makes it clear that it can be applied where it is necessary to help the child to avoid causing physical or psychological harm to others.

The Policy Memorandum states:

“The new test would mean the MRC would be available as an option for panel members to protect both the child and others from harm where the child's physical, mental or moral welfare is at risk. This would cover situations to stop the child self-harming as well as to stop putting themselves at risk of further conflict with the law by approaching a specified person or place.” (Page 14).

MRCs involve giving a child intensive support and monitoring the child's compliance by means of an electronic monitoring device which uses radio frequency technology.

Section 4 amends section 83 of the 2011 Act to apply a new set of conditions for the purpose of including MRCs in a CSO where:

a child's physical, mental or moral welfare is at risk

a child is likely to cause physical or psychological harm to another person.

These conditions cover a broader range of circumstances than the current conditions. For example, they might limit a child's movement to a certain address where a known abuser lives, a place where there is a risk of sexual exploitation, or a locale where the child is known to buy drugs.

Information sharing

Another key issue for the parliament to consider is around information sharing with victims, balanced with the rights of the child.

Article 16 of the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) states:

“No child shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his or her privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his or her honour and reputation. The child has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.”

The Bill creates a statutory obligation for the Children’s Reporter to inform a person entitled to receive information of their right to that information subject to certain exceptions.

The Policy Memorandum states:

“This reframes the existing provisions which give the Children’s Reporter the discretion to advise a person entitled to information of that right. The Scottish Government understands that under current practice the Children’s Reporter writes where possible to a person entitled to information under the 2011 Act now to advise them of their right. Accordingly, these provisions simply seek to place that current practice on a statutory footing.”

Part 2: Criminal justice and criminal procedure

This section of the briefing sets out the provisions in Part 2 of the Bill, which deal with criminal justice and criminal procedure involving children.

The Policy Memorandum to the Bill states that the measures in this part of the Bill aim to enhance the rights of all children aged under 18 in the criminal justice system, recognising that their treatment requires to be distinct from adults, whilst retaining the constitutional autonomy of the courts and judiciary.

In Part 2, provisions have been introduced to reflect the updated definition of a child (i.e. under 18) in criminal proceedings. A number of safeguards are enhanced through further development of responses to children in police custody; the framework for reporting on criminal proceedings involving children; and for children at court. There are also provisions which seek to maximise the ability of the courts to remit the cases of children who have pleaded or been found guilty of an offence to the children's hearings system for advice or disposal.

Further provisions relate to the remand, committal, and detention of children. These include removing the ability for children under 18 to be remanded or sentenced to detention in young offenders’ institutions (YOIs) or prisons, instead requiring that where a child is to be deprived of their liberty, this should normally be in secure accommodation. Finally, local authority duties in relation to children deprived of their liberty in secure accommodation, and cross-border placements of children in secure accommodation are also covered.

The following sections in this part of the briefing set out and summarise some of the key policy objectives and provisions in Part 2 of the Bill.

Involvement of children in criminal proceedings

The Policy Memorandum to the Bill points out that the meaning of “child” for the purposes of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 (“the 1995 Act”) is currently defined by reference to section 199 of the 2011 Act. Currently, in the context of the children's hearings system, while all under 16s will be children for the purposes of the 1995 Act, some 16- and 17-year-olds will also be children if they are already involved with the children's hearings system.

The Bill will amend the definition of “child” in the 1995 Act meaning that “child” will generally now mean the same in both the children's hearings system and the criminal justice system, namely a person under 18.

Prosecution of children

In Scotland, the age of criminal responsibility is currently 12. Section 42 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 currently provides that children aged 12 to 15 who commit an offence may only be prosecuted if the Lord Advocate authorises the prosecution. Children aged 16 or over can be prosecuted without this authorisation, although a child of this age who offends while already subject to a Compulsory Supervision Order may be remitted back to a children's hearing.

Section 10 of the Bill will amend section 42 of the 1995 Act so that all children over the age of criminal responsibility (all those aged over 12 and under 18) may be prosecuted only if the Lord Advocate authorises it.

Safeguards for children involved in criminal proceedings

Children in police custody

The Scottish Government has stated that its policy in this area has been developed to ensure that there is a more consistent approach to the upholding of children's rights when in police custody. With the amended definition of ‘child’ as proposed in the Bill, the intention of the changes regarding safeguards in the Bill would mean that all children under age 18 will have enhanced rights when in police custody.

The Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2016 (“the 2016 Act”) makes provision for what happens if a child is arrested and taken into police custody.

Under the 2016 Act, a child who the police believe is under 16 or one who is subject to a CSO, must be kept in a place of safety until they can be brought to court. While every effort is made to avoid detaining children in police stations, which can be frightening and intimidating, it is sometimes not practicable to hold a child anywhere else. In taking a decision to hold a child in police custody, the wellbeing of the child is a primary consideration. Guidelines issued by the Lord Advocate set out a presumption of liberty, unless factors such as the seriousness of the offence, a significant risk to victims or witnesses, and the nature and timescale of further enquiries, justify police custody.

Where a child is being prosecuted for an offence and is in police custody and is not to be liberated, the place of safety where they are to be held must not be a police station unless it would be impracticable, unsafe, or not advisable for reasons of the child's health to be kept anywhere else. The provisions in the Bill extend these considerations to all under 18s, and, except in the limited circumstances described, children should not be kept in police stations.

The 2016 Act also currently provides that where a child under 16 is brought into police custody, a parent of the child must be informed (if one can be found) and the relevant local authority must also be informed. Where the person is 16 or over, the intimation will be sent only on the person requesting it and only to an adult named by the person making the request.

A key change proposed by the Bill is that the relevant local authority will now be informed when any child under 18 is in police custody. This is to ensure that the local authority can visit the child if it decides that this would best safeguard and promote the child's wellbeing. It is clear that being brought into police custody under any circumstances can be an intimidating experience and, for many children, they may also be vulnerable and require appropriate support. The local authority may also be able to provide information as to the child's wider needs including who may be an appropriate person to be informed of the child being in police custody or in respect of their care status.

With regard to parents of a child in custody being informed, for those children under 16, their parents will always be informed and asked to attend unless the local authority advises that this would be detrimental to the best interests and well-being of the child. The Policy Memorandum points out that from age 16, and respecting the evolving capabilities of the child, the Bill will ensure that a child will have the choice to nominate that another adult other than a parent is notified of their being in custody (subject to the possible intervention of the local authority as noted above). The child can also request that no notice is sent or ask that no adults attend the police station. In such circumstances, the local authority would be informed to ensure that every child has someone notified of their situation. Likewise, in any case, should parental or another adult access to the child be refused or restricted, the local authority should be notified.

Other provisions in the 2016 Act include the right to have a solicitor present while being interviewed by the police. In certain circumstances, the right to have a solicitor present can be waived. However, this is deemed to be an important right by the Scottish Government and an important safeguard for children in such circumstances. Therefore, the Bill amends the relevant provisions in the 2016 Act so that no child under 18 can waive the right to have a solicitor present at a police interview.

Restrictions on reporting

The Bill includes a number of provisions relating to the reporting of suspected offences or proceedings involving children.

In Scotland, the identification of a child either as an accused person or as a witness is relatively rare. This is in line with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) where a child's general right to privacy is given additional attention where a child is in conflict with the law.

The Policy Memorandum states that there are arguments surrounding the public identification of children who commit offences in childhood. On the one hand, there are those that suggest that identification relates to the principles of open and transparent justice, which are important in ensuring the integrity of and accountability of the justice system and upholding public confidence. Others point to identification as being at odds with children's rights, arguing that this should never be permitted, and that anonymity should be lifelong. It is also acknowledged that stigmatisation is entirely detrimental to the promotion of rehabilitation and can have severe consequences with regard to a child's future development and life chances.

Currently, provisions in the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 govern reporting restrictions where proceedings involve children where a child (under 18) is the accused. In such cases, there is an automatic prohibition on newspaper reports or sound and television programmes revealing the identity of the child or any other child involved in the proceedings. These restrictions also apply to a witness under 18 years old where the accused party is a child. However, where the accused is not a child, the reporting restrictions apply to any other child involved in the proceedings only if directed by the court.

Whether a child appearing in court is the accused or a witness, the court has the power to dispense with reporting restrictions at any point in the proceedings, and the Scottish Ministers have the same power but only when proceedings have concluded.

The Bill includes provisions which deal with restrictions on the reporting of (a) suspected offences involving children, and (b) proceedings involving children.

With regard to the restriction on reporting of suspected offences involving children, the Bill makes it an offence to publish information that is likely to lead to the identification of a person suspected of committing an offence at a time when they were under 18. The same offence applies with regard to the likely identification of a person under 18 who is a victim or witness to such an offence. The restrictions imposed will only apply if there are no proceedings in a court in respect of a suspected offence. If proceedings are raised at court, the restrictions in the Bill cease to apply and the restrictions contained in the 1995 Act, as amended by the provisions in the Bill, become relevant.

The Bill also includes provisions which deal with applications to dispense with the restrictions imposed by the Bill. Applications to have the restrictions dispensed with can be made to a sheriff by the police, a prosecutor, the person whose information is the subject of the restrictions, or by a media representative. A sheriff may dispense with the restrictions if they are satisfied that it would be in the interests of justice to do so. Before dispensing with restrictions, the sheriff must have regard to the wellbeing of the person whose information is restricted and also whether any persons should, as detailed in the Bill, be given the opportunity to make representations.

With regard to restrictions on reporting of proceedings involving children, the Bill makes a number of amendments to the 1995 Act.

It is currently an offence under the 1995 Act to include information in a newspaper report, or in a sound or television programme that would be likely to lead to the identification of a child involved in criminal proceedings. The Bill, taking into account advances in technology and other forms of media, includes other forms of speech, writing or communication which are addressed to a section of the public.

The Bill also provides that identifying information about an accused person must not be published if the person was under 18 at the alleged date of the commission of the offence. The restrictions apply until the date on which the person whose information is protected reaches the age of 18 or the proceedings are concluded, whichever is the later, unless the person was the accused, and the proceedings end with an acquittal or are otherwise discontinued. In that case, the reporting restrictions apply for the lifetime of the person.

The Bill also makes provision, with regard to an accused person, that the court must not dispense with restrictions unless it has taken into account a report from a relevant local authority regarding the person's circumstances and only at the conclusion of proceedings. The Bill also provides for appeals against decisions to dispense with restrictions.

Remit to children's hearing from criminal courts

The Policy Memorandum to the Bill points out that the children's hearings system and criminal justice system currently interact in certain limited circumstances, including the ability of the court, where considered appropriate, to remit a child's case to the hearings system for advice and/or disposal where a child has pleaded or been found guilty. The circumstances in which a child's case can be remitted vary depending on the child's legal status, age (if not already subject to measures through the hearings system), court and proceeding type. As a result, not all children can benefit from the option of remittal to the hearing system, where more age and stage appropriate, welfare-based, and holistic support could be provided to meet the child's needs.

Section 49 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 on remittal outlines what the courts may do when a child pleads or is found guilty of an offence. It provides that, in certain circumstances, the court may seek advice from a children's hearing as to the appropriate disposal to make in a child's case; may remit the child's case to a children's hearing for that hearing to dispose of the case; or can dispose of the case itself, either immediately or after getting advice from a children's hearing. These options depend on the age of the child, whether the child is subject a CSO, whether the court is a Justice of the Peace Court, the sheriff court, or the High Court, and whether the proceedings are solemn proceedings or summary proceedings. For example, where a child is subject to a CSO or Interim Compulsory Supervision Order (ICSO), section 49(3)(b) of the 1995 Act currently provides that the sheriff court must seek advice from a children's hearing before it can dispose of the child's case.

The Bill makes a number of changes to the 1995 Act, with the main one being that no distinction is made between a child subject to a CSO/ICSO and a child who is not. In this regard, under 18s will now be treated the same way whether they are subject to a CSO/ICSO or not. Summary cases and solemn cases continue to be treated differently, and solemn cases in the sheriff court are treated differently from High Court cases.

With regard to court procedures, the High Court hears the most serious cases, including all cases of rape and murder. There are no limits on the length of prison sentence or fine which the High Court can impose. Trials are heard by a judge and jury and the judge decides the sentence. These cases are subject to solemn procedure. The High Court also deals with all criminal appeal cases.

Sheriff courts deal with other criminal cases which are heard either by a sheriff and jury (these are also called solemn proceedings), or by a sheriff sitting alone (such cases are subject to summary procedure and are called summary cases). In a solemn case, the court can impose a prison sentence of up to five years or impose a fine of any amount. In a summary case, the court can impose a prison sentence of up to 12 months or impose a fine of up to a maximum of £10,000. Examples of cases which the sheriff court may hear include assault, breach of the peace or driving under the influence of drink or drugs.

Justice of the Peace courts (JP courts) deal with less serious offences, including more minor road traffic offences. The judge in a JP court is called a justice of the peace and there is jury involvement. The maximum sentences which the JP court can impose are a prison sentence of up to 60 days or a fine of up to £2,500.

With regard to the provisions in the Bill, in summary cases, the court will be required to either request advice on the disposal of the child's case from a children's hearing or to remit the case to the hearing for disposal. The court can also proceed straight to remitting the case to a children's hearing for disposal without first requesting advice, but it cannot generally dispose of the case itself without first requesting advice. The exception is where the child is within six months of turning 18. Where that is the case, and the court considers that it would not be practicable to either seek advice or remit the case for disposal, the court may dispose of the case itself. There are also exceptions for certain offences, such as where section 51A of the Firearms Act 1968 or section 29 of the Violent Crime Reduction Act 2006 applies, where the court must dispose of the case itself.

In sheriff court solemn cases, the Bill provides that the sheriff has a choice: to request advice for a children's hearing, to remit the case to a hearing for disposal, or to dispose of the case without remitting it. However, before disposing a case without remitting it, the sheriff must request advice from a children's hearing. The sheriff can move to dispose of the case without requesting advice in two circumstances: (a) either where the sheriff determines that it would not be in the interests of justice to do so, or (b) where the child is within six months of turning 18 and the sheriff considers that it would not be practicable to request advice before disposing of the case.

Where a child pleads guilty to, or is found guilty of, an offence in solemn proceedings in the High Court, the court may request advice before deciding how to dispose of the case or remit the case to a children's hearing (with or without first requesting advice), or dispose of the case itself (again, with or without first requesting advice).

Remand, committal, and detention of children

The Policy Memorandum to the Bill states that significant progress has been made in reducing the number of children who required to be deprived of their liberty, including being held in custody. This builds on the Whole System Approach under the Youth Justice Vision that wherever possible, no under-18s should be detained in young offenders’ institutions (YOIs), including those on remand.

The policy approach adopted by the Scottish Government is that, instead, secure accommodation and intensive residential and community-based alternatives should be used where trauma informed approaches are required for the safety of the child and those around them.

As such, the relevant provisions in the Bill are intended to ensure that any child who is to be deprived of their liberty will receive rights-based psychological and trauma informed responses in age appropriate and therapeutic environments, which will normally be secure accommodation. The Bill is also seeking to end the use of YOIs (and prisons) for all children aged under 18.

It is important to point out that where a child is to be considered for placement in secure accommodation, there needs to be a significant level of concern about any risks that the child's behaviour may present either to themselves or others and, as such, all alternative options to meet the child's needs must have been considered.

Current use of YOIs and prisons for children under 18

Under current arrangements, some children aged 16 and 17 who are prosecuted in the criminal courts are held in young offenders’ institutions (YOIs). This may be as:

remand prisoners – those held in custody prior to trial (untried) or convicted awaiting sentence (CAS)

sentenced prisoners – those serving a custodial sentence.

The following two tables provide information on the number of prisoners aged 16 or 17 during the years 2016-17 to 2021-22. No children under that age were held as prisoners during the period. The figures are taken from the Scottish Government statistical bulletin Scottish Prison Population Statistics 2021-22. They are broken down into:

number of individuals – the number of 16- and 17-year-olds who spent any time being held in custody during the year i

average daily population – the average daily number of 16- and 17-year-old prisoners during the year.

Table 1: prisoners aged 16 to 17 – number of individuals

| Year | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 |

| Remand – untried | 155 | 105 | 108 | 75 | 56 | 54 |

| Remand – CAS | 116 | 88 | 84 | 57 | 26 | 22 |

| Sentenced | 106 | 77 | 75 | 39 | 17 | 8 |

Table 2: prisoners aged 16 to 17 – average daily population

| Year | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 |

| Remand – untried | 16 | 12 | 13 | 10 | 12 | 10 |

| Remand – CAS | 9 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Sentenced | 37 | 24 | 28 | 16 | 7 | 3 |

Although prisoners aged 16 and 17 were generally held in YOIs rather than adult prisons, there have been occasions where individuals have been held in adult prisons. For example, the Scottish Government has advised that one under-18 prisoner was held on remand in HMP Inverness during 2021-22.

Remand and committal of children before trial or sentence and detention of children on conviction

The Bill makes a number of amendments to the 1995 Act in these areas.

Section 16 and 17 of the Bill make two main changes. The first, which is consequential to the change made to the meaning of ‘child’ for the purposes of the 1995 Act, is to ensure that the provisions that apply to children apply to all persons under 18, regardless of whether they are subject to a Compulsory Supervision Order or not.

The Explanatory Notes to the Bill point out that currently, some provisions of the 1995 Act refer to a person under 16 rather than to a ‘child’ and distinguish between children aged 16 and above subject to CSOs and those not subject to CSOs. The other main change in the Bill is to provide that a child cannot be held on remand or sentenced to detention in a young offenders’ institution. Generally, as a result of these amendments, children will be held in secure accommodation.

The Policy Memorandum to the Bill points out that these provisions do not interfere with a court's ability to deprive children of their liberty where this is deemed to be necessary; they simply change where a child can be detained. In cases of remand, the place of detention would either be secure accommodation, if the court requires this, or a place of safety to be determined by the local authority, which could include secure accommodation. Essentially, children under 18 can no longer be committed to a prison or YOI.

Also, where a child is sentenced to detention under summary proceedings, this will be in a residential establishment chosen by the local authority, which, again, could include secure accommodation. Where a child is sentenced under solemn proceedings, the Scottish Ministers will direct where the child is to be placed – this may not be a prison or YOI but may be secure accommodation.

The Bill also provides that the Scottish Ministers may make regulations relating to children detained in secure accommodation through a criminal justice route, which may include providing that a child may remain in secure accommodation up to a maximum age of 19. This will remove the current requirement for children to automatically leave secure accommodation when they turn 18 and is intended to provide support, stability, continuity of care and maintain relationships which will be essential for rehabilitation and gradual transitions from secure accommodation.

Although a young person may subsequently transfer to a YOI as part of their sentence, it is considered that the period spent in secure accommodation will enable them to benefit from the support and stability required to assist them in preparing for adulthood and any future transitions to a YOI.

The Bill also includes provision to make amendments which will change the definition of “young offenders’ institution” and “young offender”.

Under section 19 of the Prisons (Scotland) Act 1989 (“the 1989 Act”), the Scottish Ministers have a duty to provide young offenders’ institutions (YOIs) - places where offenders sentenced to detention in a YOI, and those aged at least 14 but under 21 who are remanded in custody for trial or awaiting sentence, can be held. As a result of the provisions in the Bill no one under 18 will now be held in in a YOI. Consequently, the Bill amends the 1989 Act so that YOIs are defined as places for the detention of those aged 18 but under 21. The Bill also amends the Prisons and Young Offenders Institutions (Scotland) Rules 2011 which defines a “young offender” as someone who is aged at least 16 but under 21. The Bill ensures that “young offender” will now mean a person aged at least 18 but under 21.

The 1989 Act also provides that the Scottish Ministers have a duty to provide remand centres, i.e. places where those aged at least 14 but under 21 and remanded in custody either for trial or to await sentence can be held. As there are no such centres in Scotland, amendments in the Bill will remove the duty to provide them. The Bill also repeals any other redundant and unnecessary references to remand centres in legislation.

Local authority duties in relation to detained children

The Policy Memorandum to the Bill states that local authorities already have duties to assess the wellbeing of children where there may be concerns about their welfare, and to work in co-operation with other service providers to assess their needs and provide coordinated support as necessary.

Where a child is a looked after child, there are additional duties on corporate parents. If the child ceases to be looked after on or after their 16th birthday, they will have additional entitlements to support as care leavers, including aftercare potentially up to the age of 26. The Policy Memorandum points out that, currently, most children in secure accommodation are looked after children and, on leaving secure accommodation, could be care leavers. However, if they are not regarded as care leavers, they would not benefit from such entitlements.

In enabling any child to be detained in secure accommodation, whether on remand or following sentence, it is likely that more children will be placed in secure accommodation who are not regarded as looked after children and therefore would not have corporate parenting or aftercare entitlements. Many of these children will be vulnerable and will, more often than not, have been subject to trauma and adverse childhood experiences. It follows that they will require support at all points in their journey through the criminal justice system whether at the point of remand, sentence and on their return to their families and communities.

To that end, the Bill is seeking to provide parity by enabling any child who is sentenced or remanded to secure accommodation to be treated as if they were a looked after child for the duration of their placement. It also provides that children who are detained will be afforded the same aftercare and support as these apply to former looked after children.

Part 3: Secure accommodation and cross-border placements

Children and young people can currently be placed in residential care settings in Scotland from other UK jurisdictions. These are known as cross-border placements and can often occur without Scottish authorities being aware that the children are in Scotland.

The Policy Memorandum to the Bill points out that The Promise stated that the acceptance of children from other parts of the UK cannot be sustained when it is not demonstrably in those children's best interests to be taken to a place with no connections or relationships. These placements can result in children and young people being separated from their families, and community support and services. This can impact on planning for the child and may also impact on their human rights. The Promise is also clear that current commercial practices regarding cross-border placements, where they are purchased by a local authority in another UK jurisdiction, must end. The Scottish Government's position is that cross-border placements should only occur in exceptional circumstances where the placement is in the best interests of an individual child.

In order to manage issues of increasing capacity for cross-border placements, the Bill provides that any new care service providers must tailor provision to Scotland's particular needs, for example, by increasing scrutiny and communication around proposed new services. The Bill will also amend the powers of the Care Inspectorate to have an increased role in relation to the registration, regulation, and oversight of care settings where cross-border children are accommodated.

Part 4: Child's plan and named persons

Part 4 makes two changes; it extends the meaning of child to under 18s in the Antisocial Behaviour etc. (Scotland) Act 2004 and repeals Part 4 (provision of named persons) and Part 5 (Child's Plan) of the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014. As Parts 4 and 5 have never been in force, the repeal does not affect the existing named person or child's plan practice.

Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC) principles mean that decisions about a child or young person should be based on an understanding of needs and wellbeing, with co-ordination between services and a focus on early intervention. Each child in need of extra support should have a child's plan. This keeps a record of why the plan is in place, what needs to improve for the child, and planned actions. Multi-agency activity is co-ordinated by a Lead Professional; for children in need of care and protection, this is usually a social worker.

Part 4 of the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 makes provision for every child in Scotland to have a 'named person' to act as a first point of contact for children and families seeking information or advice about a child or young person's wellbeing.

Following a successful legal challenge, the provisions have not been brought into force and the provisions in this Bill repeal the relevant legislation. However, as a key element of the national GIRFEC approach, in many local authorities, children under 18 do have a non-statutory key point of contact known as the 'named person'. For pre-school children, the named person will usually be a health visitor and for school aged children it will likely be a senior, deputy or head teacher.

Policy context

Two key policy objectives of the Bill are to place children's rights at the heart of the system and to ensure that the Bill meets human rights requirements now and in the future. The two most relevant conventions are the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

The Bill is also set in the context of the Scottish Government's commitment to Keeping the Promise, Getting it Right for Every Child and the Whole System Approach to Youth Justice.

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)

The UNCRC is a wide-ranging convention including civil, social and economic rights. While there are specific provisions relating to juvenile justice and state protection of children, the key principles relate to the best interests of the child (article 3) and the views of the child (article 12).

3(1). In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.

12(1). States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.

12(2). For this purpose, the child shall in particular be provided the opportunity to be heard in any judicial and administrative proceedings affecting the child, either directly, or through a representative or an appropriate body, in a manner consistent with the procedural rules of national law.

The Scottish Government intends to fully incorporate the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) into law. The UNCRC Incorporation (Scotland) Bill was passed in March 2021, but cannot be enacted following the Supreme Court's judgement that it goes beyond the powers of the Scottish Parliament. The Scottish Government has restated its commitment to full incorporation but the timescale and process for this is not yet clear.

Full incorporation of UNCRC would ensure rights-based approaches are taken, and rights breaches are prevented, giving children access to legal redress if their rights are breached. While full incorporation of UNCRC has not yet been achieved, it remains the case that recent policy and legislation for children’s care and protection in Scotland have been informed by UNCRC.

Article 1 of the UNCRC states that “for the purposes of the present Convention, a child means every human being below the age of 18 years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier.”

European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

The Bill also seeks to ensure that legislation is in line with the European Convention on Human Rights.

This includes Article 5 which ensures the right to liberty and security – protecting citizens from having freedom arbitrarily taken away. This right is particularly important for children and young people held in the criminal justice system.

Article 6 is about procedural fairness in courts, guaranteeing a right to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal. In S v Miller 2001 SLT 531, the court found that a children's hearing constituted civil proceedings which engage article 6(1) rights.

The concept of a fair trial includes that:

the system must be and appear to be independent and impartial

cases must be progressed within a reasonable time, although what is reasonable will depend on the circumstances of the case

in some cases there should be access to legal representation in order to ensure effective participation in the process. While generally the choice of how to ensure practical and effective access to a court is left to states, state funded legal representation has been found to be required in relation to both children and Relevant Persons in children's hearings, where certain criteria are met (S v Miller and SK v Paterson [2009] CSIH)

parties must be able to participate effectively in proceedings. This can include access to documents and a right to be present at a hearing.

failure of a hearing to provide copies of expert reports to parents was found to breach article 6 (McMichael v United Kingdom (1995) EHRR 205).

depending on the seriousness of the issue, there is a right to be present in civil proceedings (X v Sweden 1959 TB 354)

a reasoned judgement should be given so that it can be challenged (Hadjianastassiou v Greece (1993) 16 EHRR 219).

Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC)

GIRFEC underpins the public sector approach to all children's services, from early years to school education to child protection arrangements. Developed in pathfinder areas since 2006, GIRFEC was implemented as a national approach to supporting children's wellbeing across Scotland in 2011. The Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 gave certain elements a statutory basis.

GIRFEC aims to bring a child-centred approach to children's service provision and decision making, reflecting the principles of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. The GIRFEC approach is:

child-focused, ensuring the child and their family is at the centre of decision-making and support

based on understanding of the child's wellbeing in their current situation

built on early identification of need

reliant on joined-up working.

In terms of child protection, GIRFEC principles mean that decisions about a child or young person should be based on an understanding of needs and wellbeing, with co-ordination between services and a focus on early intervention.

Each child in need of extra support should have a child's plan. This keeps record of why the plan is in place, what needs to improve for the child, and planned actions.

Multi-agency activity is co-ordinated by a Lead Professional; for children in need of care and protection, this is usually a social worker. In many local authorities, children under 18 do have a non-statutory key point of contact known as the 'named person'. For pre-school children, the named person will usually be a health visitor and for school aged children it will likely be a senior, deputy or head teacher. GIRFEC also incorporates national wellbeing indicators known as SHANARRI. These indicators consider whether a child is Safe; Healthy; Achieving; Nurtured; Active; Respected; Responsible; and Included. The Scottish Government states that these wellbeing indicators help to aid discussions around how a child is doing and are influenced by each child's experiences and needs.

The Promise

An Independent Care Review (Care Review) was commissioned in 2017 and reported in 2020. This was a root and branch review of the care system which listened to the voices of over 5,500 people with experience of the care system or who work within it.

The review findings were published in February 2020, setting out the steps toward significant reform to the care system for children and young people. The main findings were set out in the main report The Promise.

The Promise called for a new approach to youth justice, as summarised below:

a new approach to youth justice is needed that holds true to the Kilbrandon principles

the rights of children and young people in conflict with the law must be upheld, ensuring they have access to all they need for health, education and participation

children must be able to participate in all decisions about them in appropriate environments - not traditional criminal courts

under 18s are children: there should be no 16- or 17-year-olds in YOIs; being placed in prison-like settings is deeply inappropriate for children

yhe importance of relationships cannot be overstated - every effort must be made to nurture and sustain positive and important relationships for care experienced children

there must be a significant, ongoing and persistent commitment to ending poverty and mitigating its impacts for Scotland's children, families and communities

there must be more universal and intensive support for families who are struggling, whatever issues they face

Scotland must improve support for children affected by parental imprisonment, ensuring wraparound support for families

more must be done to avoid imprisoning pregnant mothers, and better support provided to those who are in prison.