Charities (Regulation and Administration) (Scotland) Bill

This briefing summarises the Charities (Regulation and Administration) (Scotland) Bill, which would amend existing Scottish charity law and provide further powers for the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator (OSCR). The Bill's provisions aim to increase transparency and accountability in the charity sector and also bring aspects of existing legislation in line with the law in other parts of the UK.

Summary

There are over 25,000 charities in Scotland, including 1,179 cross-border charities that also operate in other parts of the UK. The charitable sector includes a wide variety of different types of organisations, including community groups, care providers, health research organisations, training providers, environmental groups, village halls, leisure facilities, museums, universities, independent schools and churches.

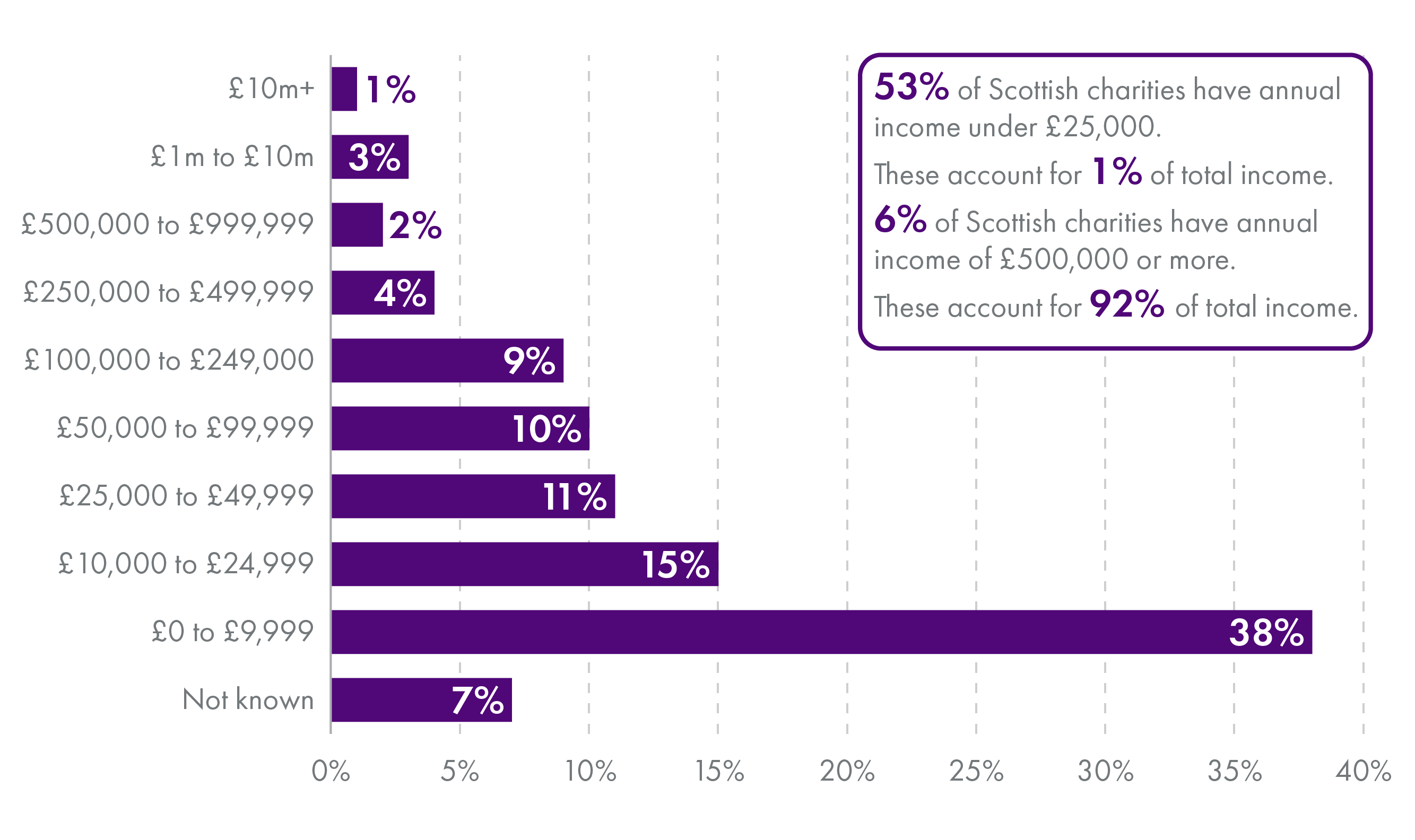

Just over half of Scottish charities are small organisations with annual income of less than £25,000. However, the very large charities account for the vast majority of income.

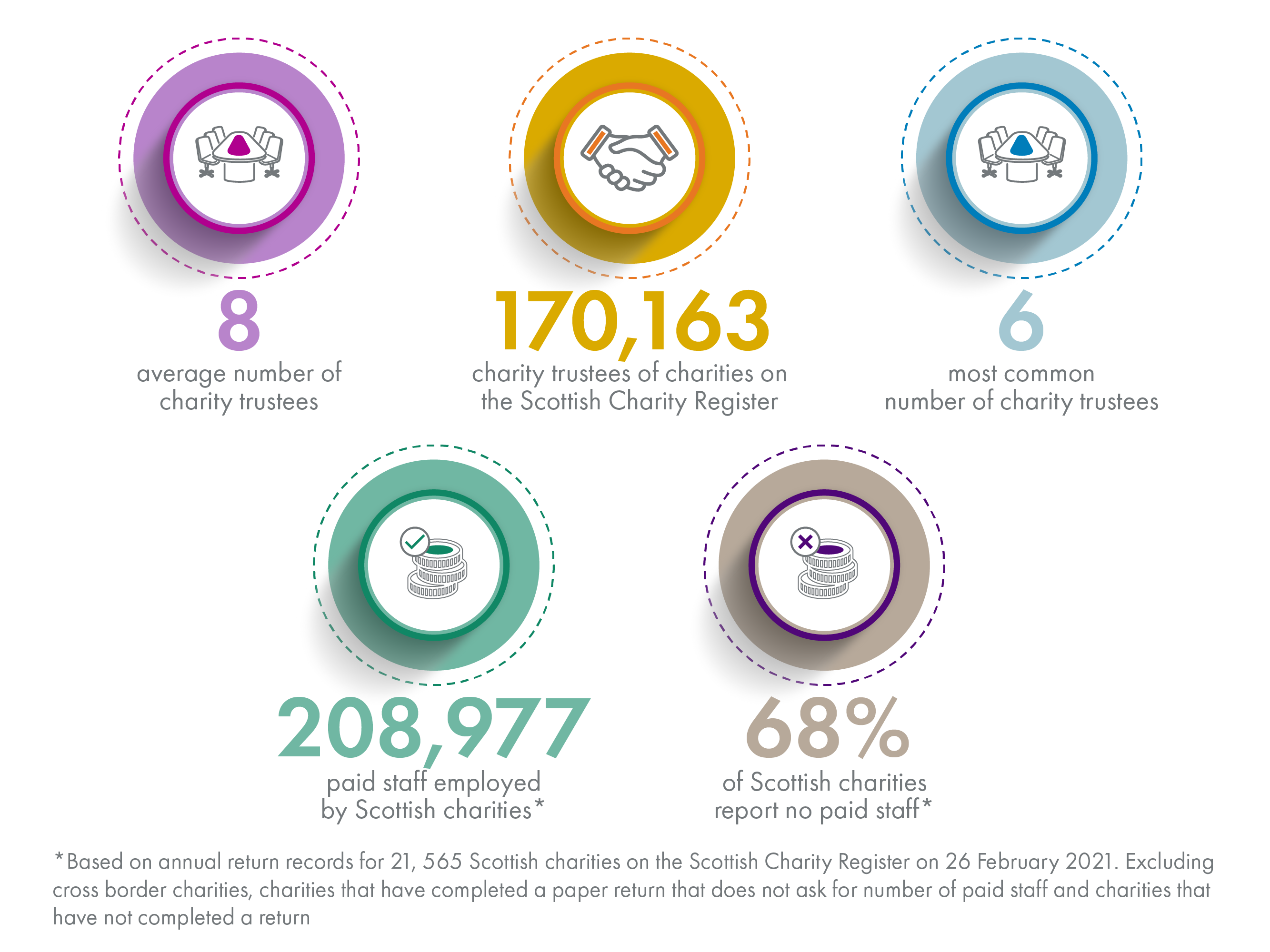

Charity trustees are the persons legally responsible for the charity, although they might not always be involved in the day-to-day running of the charity. Some charities only have trustees, while others may have employed staff and/or volunteers. On average, Scottish charities have eight trustees.

The Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator (OSCR) is responsible for regulating the Scottish charitable sector. All Scottish charities must be registered on the Scottish Charity Register and must submit annual accounts to OSCR.

The Charities (Regulation and Administration)(Scotland) Bill was introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 15 November 2022, following two consultation exercises in 2019 and 2021. The Bill aims to strengthen and update the current legislative framework for charities by:

increasing transparency and accountability in charities

making improvements to OSCR’s powers

bringing Scottish charity legislation up to date with certain key aspects of charity regulation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Scottish Government considers the Bill proposals to be "generally regulatory in nature as opposed to anything more fundamental about charities". Acknowledging that there have been calls for a more fundamental review of the charitable sector, the Scottish Government intends to consult further with the sector following the passage of this Bill.

If passed, the Bill would:

require OSCR to publish names of trustees on the public Scottish Charity Register

require OSCR to maintain an internal database of trustee contact details

update the range of offences and situations that result in disqualification of charity trustees

extend the criteria for disqualification to apply to senior management positions as well as trustees

require OSCR to create a searchable record of charity trustees who have been barred by the courts from acting as trustees

allow OSCR to appoint interim trustees in specific circumstances

require OSCR to publish annual accounts for all charities on the Register

allow OSCR to remove charities from the Register if they fail to submit accounts and fails to respond to subsequent communication from OSCR

require OSCR to keep a record of charity mergers to assist with the transfer of legacies

allow OSCR to undertake inquiries into former charities and their trustees

enable OSCR to issue positive directions to charities following inquiry work

require charities to demonstrate a connection to Scotland if they are to be registered by OSCR.

Where charities or trustees have concerns regarding the publication of names or other details, the Bill provides a mechanism for them to request that information is withheld. OSCR will consider such requests and, if refused, there are channels for review of these decisions.

In addition to the above, the Bill includes a range of minor and technical amendments to existing legislation.

In total, the Bill's provisions are expected to cost between £0.6 million and £1 million across the first three years following implementation. Costs are expected to fall on the Scottish Administration (which includes OSCR), with no anticipated costs for local authorities.

The Scottish Government does not estimate that the Bill would require significant additional activity on the part of individual charities, so has not included any costs for these bodies in the Bill documents. However, it should be noted that even very minor additional costs could have an impact on smaller charities. Also, with over 25,000 charities in Scotland, even minor additional costs for each of these charities would imply a significant additional cost across the sector.

Introduction

The Charities (Regulation and Administration)(Scotland) Bill ("the Bill") was introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 15 November 2022.1The Scottish Parliament's Social Justice and Social Security Committee has been assigned as the lead committee for scrutiny of the Bill at Stage 1.

The Bill's aims, as set out in the accompanying Policy Memorandum, are to strengthen and update the current legislative framework for charities by:

increasing transparency and accountability in charities

making improvements to OSCR’s powers

bringing Scottish charity legislation up to date with certain key aspects of charity regulation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Scottish Government considers the Bill proposals to be "generally regulatory in nature as opposed to anything more fundamental about charities".2

The Bill is accompanied by a range of standard documents that accompany all Bills:

Explanatory notes that set out the purpose of each aspect of the Bill proposals.

A Policy Memorandum that explains the rationale for the proposals.

A Financial Memorandum that sets out the anticipated costs of the Bill proposals.

The Scottish Government has published an equalities impact assessment, a data protection impact assessment, a business and regulatory impact assessment, and an island communities impact assessment to accompany the Bill.

There is also a Keeling Schedule accompanying the Bill, which sets out how the proposals would amend the Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005.3 The vast majority of the provisions in the Bill make modifications to the 2005 Act (referred to throughout this briefing as "the 2005 Act").

The charity sector in Scotland

This section sets out some facts and figures on the Scottish charity sector.

Context for the Bill

Following devolution and the establishment of the Scottish Parliament, work began to reform the law around charities in Scotland.

In April 2000, the Scottish Charity Law Review Commission, also known as the McFadden Commission, was tasked with reviewing the law relating to charities in Scotland and to make recommendations on whether reform was necessary. The McFadden Commission reported in May 2001, and their report helped shape what would later become the Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005 (“the 2005 Act”).

Prior to the 2005 Act, most of the provisions governing Scottish charities were found in the Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Scotland) Act 1990. However, during the 1990s, it was felt that Scottish charities legislation was inadequate.

In particular, there were a number of different agencies involved in the regulation of charities, but there was no central regulatory or support body, there was no register of charities in Scotland, and charitable status was effectively conferred by the Inland Revenue for tax purposes. As a result, there were very few obligations on charities and the sector was perceived to be suffering from a lack of oversight.

The Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005

The 2005 Act introduced a unique Scottish charity test for a body to be entered on to the newly established Scottish Charity Register (“the Register”). Entry on to the Register would then entitle a body to call itself a “charity”, “charitable body”, “registered charity”, or “a charity registered in Scotland”. The 2005 Act also established the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator (“OSCR”), which is discussed further in the section on the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator.

Scottish charities that existed prior to the 2005 Act and still operating in Scotland were automatically enrolled on the Register. Unlike arrangements prior to the 2005 Act, they were now also subject to a new, continuous obligation to ensure they were meeting the requirements of the charity test. Failure to meet the requirements of the charity test, at any point, could result in removal from the Register.

The charity test is met if its purposes consist solely of one or more of the definitive list of charitable purposes defined in the 2005 Act. This list, as defined in Section 7(2) of the 2005 Act, includes:

the prevention or relief of poverty

the advancement of education

the advancement of religion

the advancement of health

the saving of lives

the advancement of citizenship or community development

the advancement of the arts, heritage, culture or science

the advancement of public participation in sport

the provision of recreational facilities, or the organisation of recreational activities, with the object of improving the conditions of life for the persons whom the facilities or activities are primarily intended

the advancement of human rights, conflict resolution or reconciliation

the promotion of religious or racial harmony

the promotion of equality and diversity

the advancement of environmental protection or improvement

the relief of those in need by reason of age, ill-health, disability, financial hardship or other disadvantage

the advancement of animal welfare

any other purpose that may reasonably be regarded as analogous to any of the preceding purposes.

It also must provide (or in the case of an applicant, intend to provide) public benefit in Scotland or elsewhere. Public benefit is defined in Section 8 of the 2005 Act and OSCR also provide further information on interpretation of public benefit on their website.1

Developments in charity law in England and Wales

Charity law in Scotland is devolved and therefore distinct from the rest of the UK. The principal regulator (and OSCR equivalent) for charities in England and Wales is The Charity Commission (“the Commission”). This was established by the Charities Act 2006, which amended the Charities Acts 1992 and 1993, with the 2006 Act also codifying 300 years of case law on “charitable purposes”. A Charity Tribunal was also established, providing an avenue for appealing decisions of the Charity Commission.

Effectively all provisions contained within these Acts were consolidated in the Charities Act 2011, which did not seek to change existing law or introduce new policies, but instead aimed to simplify the structure of existing legislation for England and Wales.

Despite this consolidation, it was felt that numerous gaps remained in the law. Following Lord Hodgson’s review of the Charities Act 2006 in 2012, the Law Commission began investigating some of the “technical issues” in charity law. It published recommendations as part of their 2017 Technical Issues in Charity Law report.

The most recent piece of legislation governing charities in England and Wales is the Charities Act 2022 – with the majority of the recommendations made by the Law Commission being accepted by Government and enacted in the legislation.

Consultation on the proposals

Reform of charity law has been on the Scottish Government’s agenda for some time. It was felt that reform was needed given the framework had not been updated since the 2005 Act, and given that corresponding legislation in England and Wales had been updated since 2005.

OSCR put forward several proposals for change in a paper to Scottish Ministers, which broadly focused on improvements to the law aimed at increasing transparency and accountability, in order to maintain public trust in both Scottish charities and OSCR.1 On 7 January 2019, the Scottish Government launched a consultation based on OSCR’s proposals, seeking views on potential improvements to the statutory charity regulation framework in Scotland.2

OSCR suggested a number of further changes during the 2019 consultation process. First, they felt focus should be given to promote greater transparency and accountability in the charity sector. Their research, through various surveys conducted across the sector, showed that public trust in charities is closely linked to understanding what charities have achieved, knowing how well it is run, knowing charities are independently regulated, and knowing how much of donations are spent on causes.

Second, their proposals identified areas where practical experience showed gaps in OSCR powers. They felt reform in these areas was needed in order to take quick and decisive action, when necessary, which they stated is vital to maintaining public trust in both the sector and OSCR as a regulatory body.

Finally, OSCR sought changes aimed at streamlining operations and introducing efficiencies – clarifying the law and OSCR’s powers of reorganisation.

The Scottish Government’s consultation closed on 1 April 2019 after receiving 307 responses from individuals, charities and other groups with an interest in charity law. Most respondents broadly supported the proposals outlined.

However, the analysis report highlighted that more policy development work and stakeholder engagement would be required before any legislative changes could be brought forward.3 There were also some concerns as to the impact the proposals would have on data protection, requiring further formal consultation with the Information Commissioner’s Office.

The Scottish Government further stated, following conclusion of the 2019 consultation, that they would consider all points raised and engage with those who called for wider changes to the regulation. They also committed to:

continuing to work with the third sector and other key stakeholders to develop and refine the proposals

working more closely with OSCR, specifically to establish a working group to address outstanding issues with The Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organisations (Removal from Register and Dissolution) Regulations 2011.

However, progress on further engagement with the sector was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Engagement with the sector then re-started in December 2020 and January 2021, with a number of targeted stakeholder events taking place to help define and refine the proposals. A mix of charity professionals, trustees, charity staff, volunteers and practitioners were represented at these events from a variety of organisations – including the Law Society of Scotland, OSCR, Scottish Council for Voluntary Organisations (SCVO), and smaller third sector organisations.

A Citizen Space survey was also launched called “Strengthening Scottish Charity Law”.4 This ran between December 2020 and February 2021, with a total of 100 responses received. While the more technical proposals impacting specific charitable bodies was not considered in this engagement, the more general proposed changes impacting the wider sector again received a high level of support. One proposal that was included in the 2019 consultation but not in the 2021 consultation related to amendments to the process for reorganisation for certain charities established by Royal warrant, Royal charter or enactment. Although there was broad support in the 2019 consultation for proposals for change, there was not clarity around the best way forward. The Policy Memorandum notes that the Scottish Government will continue to consider this proposal.

The proposals put forward in the 2021 consultation, which build on OSCR’s recommendations from the 2019 consultation, were generally regulatory in nature. While these received broad support, there were also calls for a wider review and reform of charity law. The Scottish Government has therefore committed to carrying out a wider review following the passage of the Bill, stating in the Policy Memorandum:

The Scottish Government is aware that some in the sector wish to see a broader review of charity regulation. However, this requires further consideration and comprehensive consultation. Following the passage of this Bill, the Scottish Government will engage with the charity sector on the wider questions for review.

The Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator (OSCR)

The 2005 Act established the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator (“OSCR”). OSCR acts as the independent regulator and registrar for Scottish charities, and reports directly to the Scottish Parliament every year. OSCR is a Non-Ministerial Office and is part of the Scottish Administration. As such, the Scottish Government provides funding to support OSCR’s activities. The latest Scottish Government budget provides £3.3 million for OSCR in 2023-24 .1

OSCR oversees charities in Scotland. Specifically, their general functions are as follows:

determining whether bodies are charities and granting charitable status

keeping a public register of charities

encouraging, facilitating and monitoring compliance by charities with regulatory requirements under charity law

identifying and investigating apparent misconduct and taking necessary remedial or protective action

giving information, advice, or making proposals to Scottish Ministers

principal authority for approval of reorganisation schemes, restricted funds, and conversions for charities.

In its role as a regulator, OSCR also operates with a core aim of encouraging transparency within charities. This is seen by OSCR as integral to public confidence in the charities sector, as encouraging transparent administration is seen to help maintain integrity and ensure accountability of charities on the Register.

In addition to directly engaging with the Scottish Government, OSCR also commissions extensive survey reports of the Scottish charities sector and the public to gain further knowledge of charity life and public confidence. These reports are generally produced biennially, with their latest survey results being published on 16 June 2022.2

OSCR is comprised of board members appointed by Scottish Ministers, along with a chief executive and staff of around 45 full-time equivalents. With over 25,000 charities registered in Scotland, the 2005 Act gave OSCR a number of powers to carry out its supervisory, overseeing, and regulatory role, namely:

review of entries in the Register

direct a charity to change its name and remove it where non-compliant

direct a charity not to take action in a consent matter, pending further inquiry

obtain information for Register entry purposes

make inquiries, either generally or for a particular purpose

direct any charity, body or person from undertaking activities for a period of six months while making inquiries

obtain information for inquiries

direct a charity to take action to meet the charity test within a specified period

remove a charity from the Register in specific circumstances

suspend any person concerned in the management and control of a charity for a period of six months

direct any body misrepresenting itself as a charity to stop doing so

restrict transactions of a charity

direct that property not be parted with

direct a person to cease acting on behalf of a charity

publish a report of the subject matter of an inquiry

appoint a suitable person to prepare accounts

direct a charity to recover remuneration in contravention of section 67 of the 2005 Act.

The 2005 Act also gave various powers in relation to charities to the Court of Session, on application by OSCR. For example, OSCR can apply to the Court of Session for certain actions to be taken in cases of misconduct.

OSCR also produces guidance and forms for charities, acting as a point of contact for trustees should they require assistance about any of the technical aspects regarding becoming or managing a charity.

The role of charity trustees

All charities must have charity trustees and several of the Bill provisions relate to trustees.

Charity trustees are the persons legally responsible for the charity, although they might not always be involved in the day-to-day running of the charity. Some charities only have trustees, while others may have employed staff and/or volunteers. According to OSCR, Scottish charities have, on average, eight trustees, and there are just over 170,000 charity trustees across the Scottish charitable sector as a whole, although some individuals will act as trustees for more than one charity. These figures include cross-border charities that also operate in England and Wales. 1

The duties of charity trustees are set out in the 2005 Act. Charity trustees have an overarching duty to act in the interests of the charity and comply with specific duties, such as providing details to OSCR for the Register, preparing and reporting financial accounts, and providing information to the public. Further details are set out on OSCR's website and OSCR provides guidance to help trustees fulfil their legal duties and ensure good governance of charities.2

The Bill's provisions

This section of the briefing considers the various provisions set out in the Bill, looking at their purpose, how they would impact on charities and the feedback received on the proposals during the consultation phase.

Information about charity trustees

Sections 2 and 3 of the Bill propose changes to the information that OSCR is required to hold on charity trustees.

Section 2 of the Bill requires that OSCR publishes the names of all charity trustees on the public Scottish Charity Register ("the Register"). At present, the Register is only required to include details of the principal office of the charity or (where there is no office), the name and address of one of its trustees. Under the changes proposed, details of the names of all trustees would be included on the Register. The Register would not include address details of trustees (other than, as at present, the address of one trustee if there is no principal office address). The Scottish Government believes that this will improve accountability and transparency and also mirrors the position in England and Wales, and that of Companies House.

If a charity has any concerns about the publication of names of trustees, the charity can apply to OSCR for a name (or names) to be withheld from the Register. This might be considered necessary to protect the safety or security of particular individuals or property. OSCR will have responsibility for determining whether such a dispensation will be allowed, including granting dispensations of its own accord, rather than in response to requests. For example, OSCR might choose to apply dispensations to particular types of charity, such as women's refuge charities. In the event that a dispensation request is refused by OSCR, the charity in question has the right to ask for a review of the decision. These rights of review are already included in the 2005 Act in relation to requests to withhold a charity's address (or name/address of one trustee). The Bill provisions extend this existing review mechanism to decisions on withholding details of names of all trustees.

There was broad support for this proposal in the 2019 consultation, with 71% supporting the publication of trustees' names on the public Register, provided this was limited to trustee names only. A smaller proportion (58%) felt that trustees should be allowed to request that their names are withheld.

Some concerns were raised around data protection issues and the impact that publication of trustee names might have on the ability of charities to recruit trustees. In its response to the 2019 consultation, the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) said1:

"...there are significant risks associated with the establishment of a freely, accessible external trustee register...and in particular the proposal to publish the names of removed trustees."

The ICO particularly highlighted:

potential risks to vulnerable individuals

risks associated with publishing details of removed trustees (discussed in section on disqualification from being a charity trustee)

the "right to be forgotten" whereby individuals convicted of criminal offences with sentences of less than four years can be considered rehabilitated after a specified period of time.

In line with the ICO's recommendation, the Scottish Government has conducted a data protection impact assessment (DPIA), which is published alongside the Bill.2 The DPIA notes that a meeting was held with ICO on 12 February 2020. Some of the concerns around the proposals for including trustee names on the external Register are highlighted in the DPIA:

It has been highlighted by the Church of Scotland, in their response to the 2019 consultation, and reiterated in 2021, that particularly with regard to Designated Religious Charities (DRCs) any publication of names of trustees would allow the public to infer an individual’s religion or belief and could therefore put them at risk of discrimination. This could also be true of certain charities where in order to be a trustee a person must have lived experience of certain criteria (i.e., addiction recovery, domestic abuse, disability).

As noted above, there is scope for individuals and charities to apply for trustee names to be withheld, and to appeal any subsequent decisions by OSCR.

Section 3 of the Bill requires that OSCR collects and holds details of all trustees on an internal database. This would include names, addresses and contact information. The purpose of this is to assist OSCR in its compliance, inquiry and engagement work, which is currently sometimes hampered by a lack of up-to-date contact information for charity trustees. Note that this information is for internal use by OSCR only and will not be included on the public Register.

At present, OSCR gathers information on trustees when a charity is first established, but this can quickly become out-of-date. While a charity's accounts will include names of trustees, this does not include contact details and the information is redacted by OSCR before the accounts are made available (if they are being directly published by OSCR rather than being available via Companies House). OSCR has contact details for a "principal contact" for each charity which is requested each year as part of the annual return that a charity is required to complete. However, this individual is not always a trustee (it could, for example, be an employee or professional adviser), and this information could also become out-of-date if details change between annual return submissions. According to the Policy Memorandum "OSCR currently holds limited information on the over 180,000 charity trustees involved in over 25,000 charities in Scotland".

Given the importance of trustees in the governance of charities, the Scottish Government considers that it is important that OSCR, as the regulator, has up-to-date information on trustees to support effective regulation. The Bill provisions require OSCR to hold this information, and also require that charities ensure that the information on their trustees is kept up-to-date.

In the 2019 consultation, 79% of respondents agreed with the proposal for OSCR to hold an internal database. Some concerns were raised with respect to data protection requirements and the challenges of maintaining the database.

In its 2019 submission, the ICO noted:1

A legal obligation to establish an internal trustee database would provide OSCR with a clear legal gateway for processing under the GDPR [General Data Protection Regulation] however the Scottish Government should still satisfy itself that this processing is necessary and proportionate for more effective regulation.

In its DPIA, the Scottish Government note that:

OSCR have a power of inquiry over trustees but no easy way of knowing who they are or how to contact them... This power will introduce efficiencies for compliance, investigation, and engagement work, and make it easier to identify who is in control and management of charities. It will enable OSCR to act more quickly and decisively where vulnerable beneficiaries or charitable assets may be at risk.

Disqualification from being a charity trustee

Sections 4-7 of the Bill make amendments to the current law surrounding the disqualification of charity trustees.

At present, individuals are disqualified from being a charity trustee if they have been convicted of certain offences (and the conviction is not legally spent under the terms of the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974). The proposals in Section 4 of the Bill would extend the list of offences for which an individual is disqualified from being a trustee, to include offences such as bribery, acts of terrorism, money laundering and perjury. At present, the individual offences resulting in disqualification are not detailed in the legislation, which currently just refers to an offence involving dishonesty or an offence under the 2005 Act. The proposals in Section 4 would introduce a list of specified offences. This list can be subsequently amended via secondary legislation.

The proposals in Section 5 would also add some descriptions of situations that would result in disqualification, such as being a designated person under terrorist asset freezing orders. Again, the list can be modified via secondary legislation.

In its report to the lead committee, the Scottish Parliament's Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee queried whether it was appropriate for modification of the detailed lists of offences and situations leading to disqualification to be possible via secondary legislation.1 In its response, the Scottish Government argued that this was necessary in order to allow for flexibility, should new offences emerge which are not currently captured by the legislation.2

In addition, Section 6 of the Bill proposes that these criteria for disqualification be extended to senior management positions in charities, rather than just trustees. The Bill includes a description of the type of positions that would be considered to be "senior management positions", which is defined by the seniority and responsibilities of the position and degree of control over finances.

The changes proposed by Sections 4-6 will bring the Scottish law into line with that of England and Wales, meaning that if an individual is disqualified from being a charity trustee in England and Wales they will also be disqualified in Scotland. Those responding to the 2019 consultation on these proposals were widely supportive of the proposals, with 84% supporting the extension of disqualification criteria and 79% supporting the extension of these criteria to senior management.

Section 7 of the Bill proposes that the names of any individuals disqualified as trustees by the Court of Session would be held on a public record which is searchable by reference to a specific name. There would be exceptions where OSCR has granted a waiver to a disqualified individual to allow them to act as a trustee.

Sections 4 to 6 deal with the grounds for a person being automatically disqualified from acting as a charity trustee or senior manager due to their having committed a specified offence or because they an undischarged bankrupt, etc – i.e. something that has happened in their life generally rather than because of their involvement with a charity. In contrast, Section 7 of the Bill relates to a small number of individuals who have been permanently disqualified or removed from acting as a charity trustee by the Court of Session either on application by OSCR or under the preceding Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Scotland) Act 1990.3 These individuals have been removed as trustees by the Court of Session due to their actions when involved with a charity (as opposed to them falling within any of the automatic disqualification criteria, such as bankruptcy). The record will not contain details of trustees who have been disqualified by means other than the Court of Session.

As with the disclosure of trustees' names, individuals who have been disqualified in this way can apply to have their names withheld from the public record if there are safety or security concerns. OSCR will determine whether the request is reasonable and the individual will be able to appeal if they disagree with OSCR's decision.

The majority (79%) of respondents to the 2019 consultation felt that the disclosure of the names of disqualified individuals was appropriate. However, the ICO noted some concerns in its submission.4 In particular, it highlighted that:

This is sensitive information that could be used to infringe the rights and freedoms of the named trustees now and in the future. Once published OSCR will have no control over how this information will be used. For example, future employers could use this information to vet potential employees.

ICO also highlighted the "right to be forgotten":

Currently in Scotland anyone convicted of a criminal offence of less than two and a half years can be regarded as rehabilitated after a specified period of time and do not have to disclose their offending history.....There appears however, to be no equivalent to rehabilitation for removed trustees.

In its DPIA, the Scottish Government stated that:5

Consideration has been given to the ‘right to be forgotten’ regarding the names of removed or disqualified trustees being published as part of this proposal. It was concluded that once a trustee has been removed (by OSCR/Courts) the disqualification is permanent, unless or until a disqualification is waived by OSCR – the right to be forgotten does not apply where the data controller has a legal obligation to process the information or for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority.

The Charity Commission for England & Wales (CCEW) has a search facility on their website that allows for a search on a person’s name to check if they have been removed by an Order of the High Court. Note that this is a search function opposed to a list of names in one place, which allows trustees to do due diligence whilst minimising the amount of information that is publicly available about individuals. It is this model that the Bill follows.

Appointment of interim charity trustees

Section 8 of thae Bill provides OSCR with a power to appoint interim trustees. OSCR already has such a power under the 2005 Act, where a charity does not have enough trustees to form a quorum to appoint further trustees under the terms of its governing document, and where the governing document does not specify a mechanism for appointing trustees in these circumstances. This intervention must be at the request of the charity concerned.

However, at present, OSCR does not have powers to appoint interim charity trustees when it is not requested by the charity. There may be situations where a charity has no trustees, or where the existing trustees cannot be located or refuse to act. At present, the only option available to OSCR is to apply to the Court of Session for the appointment of a trustee or judicial factor. This is a costly process that is only used where a charity has significant assets. The Bill proposals would allow OSCR to appoint interim trustees directly, which would enable the charitable assets to continue to be used for the purpose intended. These interim trustees would then appoint trustees in line with the charity's constitution. The 2005 Act specifies that interim trustees are appointed for 12 months (although it can be for a shorter period, and the period can also be extended by 3 months). There is no mechanism in the Bill or the 2005 Act for the charity to dispute the appointment of interim trustees.

This provision in the Bill came as a result of OSCR's response to the Scottish Government's 2019 consultation.1 As a result, it was not consulted on as part of the 2019 consultation. The second phase of consultation (December 2020-February 2021) did not cover this proposal. In the Policy Memorandum for the Bill, the Scottish Government states that:

The remaining proposals [which include the proposal for appointment of interim trustees] were not considered appropriate for this strand of engagement due to their technical nature and/or limited application to the wider sector.

Charity accounts

Sections 9-11 of the Bill set out proposals in relation to charity accounts.

Section 9 introduces a duty on OSCR to publish accounts for all charities on the Register, which is a public register. At present, all charities are legally required to submit accounts to OSCR within nine months of the end of their financial year. However, OSCR only publishes the accounts for charities with annual income of over £25,000 or those that are Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organisations (SCIOs). Under the current legislation, OSCR is not required to publish accounts, but it has chosen to adopt this approach. Smaller charities are still required to submit accounts to OSCR, but these are not published by OSCR. However, they are provided on request, provided that the request is deemed by OSCR to be reasonable. Currently, OSCR also links to accounts that are published directly by the charities or that are published elsewhere e.g. Companies House. According to the Policy Memorandum, the current arrangements mean that accounts are currently in the public domain for just over half of charities on the Register.

The Bill proposals would mean that accounts would be available for all charities, regardless of size. However, as noted above, this does not require the charities to prepare any additional information as there is already a legal duty for charities to prepare annual accounts and submit these to OSCR. The Bill proposals will just make that financial information publicly available, where it would not currently be so readily available for smaller charities. According to the Policy Memorandum, the intention is to increase transparency and accountability in the sector.

At present, in order to comply with data protection legislation, OSCR redacts all personal information from the accounts before publishing. This would no longer be required if this Bill is passed as the Bill would provide a basis in statute for publishing the accounts in full. OSCR does not currently have a statutory duty to make the information it holds in charities' accounts available for public inspection.

As with the proposals for publication of trustee names, there will be scope for charities to request that certain details are withheld from the published accounts if this is considered to jeopardise the safety or security or a person or property. OSCR will determine whether any such request is upheld and the charity can request a review of this decision under mechanisms already in place under Section 74 of the 2005 Act.

Respondents to the 2019 consultation were strongly in favour of this proposal, with 82% supporting the measure. Those that were not in favour generally cited concerns about release of sensitive personal or commercial information. The second phase of consultation (2021) focused on the scope for dispensation from release of certain data in the accounts. The majority (72%) felt that, where dispensations were made, a redacted or abbreviated set of accounts should still be published. Just over half of respondents did not feel that any dispensation for withholding information should be available.

However, the ICO had noted some concerns with the publication of all accounts in its response to the 2019 consultation:1

The Scottish Government should consider what kind of risks blanket, online publication could present, particularly to vulnerable individuals identified in these reports....Our view is that the evidence and analysis presented in the [2019] consultation paper does not make a strong enough case.

In its DPIA, the Scottish Government noted:

The proposal will enable OSCR to publish statement of accounts for all charities in Scotland, in full as a default. This increases transparency and accountability in the sector and is consistent with legislation elsewhere in the UK and the powers given to other charity regulators and registrars of corporate bodies.

The DPIA also notes that this approach will free up resources in OSCR (who will no longer need to redact accounts) and also notes that charities will have the right to apply for dispensation from certain information being published.

Section 10 of the Bill makes minor and consequential modifications in relation to charity accounts, including to change references to "account" in the 2005 Act to refer to "account and independent report on accounts".

Section 11 of the Bill provides OSCR with powers to remove a charity from the Register if it has failed to submit accounts, and has also failed to engage with OSCR in relation to requests for accounts. OSCR classifies a charity as "defaulting" if it has failed to submit a set of accounts to OSCR within nine months of the end of its financial year and has then failed to respond to reminder emails from OSCR for 10 weeks after this deadline.

According to the Policy Memorandum, at September 2022, 11% of Scottish charities are classified as defaulting. This represents 2,849 charities in Scotland. Within that total, 352 (or 12% of defaulting charities) have never submitted a complete statement of account. The Bill would give OSCR powers to remove defaulting charities from the Register and they would no longer be recognised as a charity in Scotland. Charities would be notified that OSCR intends to remove them from the Register and if there is still no contact from the charity within threemonths of that notification, they can be removed from the Register.

In the 2019 consultation there was widespread support for this proposal, with 87% of respondents in favour.

Charity mergers

Section 12 of the Bill relates to the recording of charity mergers and the treatment of legacies affected by charity mergers.

The current charity legislation does not allow a charity on the Register to change its legal form while retaining a continuous identity as a charity. The Policy Memorandum lists some examples of situations where a charity might consider changing its legal form:

Where a trust or unincorporated association becomes a Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organisation (SCIO) or a charitable company.

Where one or more charities are winding up their activities and transferring all property, rights and liabilities to another charity.

Where two or more charities are merging and continuing to provide benefit under a new charity with the name of one of the previous charities, or under a new name.

In these situations, or other situations involving a change of legal status, a merger, or name change, there is a risk that any legacies to the original charity will be lost because the charity named in the will no longer exists. According to a 2021 report on the Scottish legacy market1, legacies in wills raise over £90 million annually for Scottish charities. The same report highlights that 500 Scottish charities are named in wills each year, of which 64% are smaller charities. The potential loss of legacy income to charities that change their legal form or merge with another charity and change their name is therefore significant.

The risk of loss of legacy income could lead charities to put off changing their legal status or merging, which could be less beneficial in terms of governance, or they might choose to retain a "shell" charity only to collect legacy income. Neither of these are optimal arrangements, as preserving shell charities creates additional administrative burdens both for the charities and for OSCR, and is less transparent for the public.

The Bill would require OSCR to create a record of charity mergers and, where a merger is recorded, the new charity will be entitled to any legacies bequeathed to charity that has merged with it (the "transferor" charity). The legacy would transfer to the new charity unless it is clear that the person who made the will intended otherwise. The definition of a merger in the Bill includes where all the property, rights and liabilities of one charity are transferred to another charity, so would encompass changes in legal form e.g. when a trust or unincorporated association register a SCIO, transfer its property, rights and liabilities to the SCIO and then winds up the original charity.

In England and Wales, the equivalent provisions relate to all gifts to charities, not just legacies. The Scottish Government decided to opt for a narrower option specifically in relation to legacies as this is where the most significant issues are considered to arise. Where lifetime gifts are concerned, the individual is still alive and so can make arrangements themselves to direct their charitable giving appropriately. Where legacies are involved, this option is not available as, by definition, the individual involved is no longer alive.

As this proposal came from the Law Society of Scotland in their response to the 2021 consultation2, it has not been publicly consulted on.

OSCR inquiries

Sections 13 to 15 of the Bill provide OSCR with new powers to support it in conducting inquiries into charities where concerns have been raised. Any individual can report a concern about a charity to OSCR. In 2021-22, a total of 563 concerns were raised with OSCR. Following assessment of the issues, OSCR determined that an inquiry was appropriate for 60 of these cases.1 The 2005 Act that created OSCR requires it to act in a manner which is "proportionate, accountable, consistent, transparent and targeted only at cases in which action is needed".

The provisions in Sections 13-14 of the Bill are designed to make it easier for OSCR to access the information it needs in order to conduct its inquiry work effectively, while Section 15 provides further powers for OSCR in response to these inquiries.

Section 13 provides OSCR with a power to conduct inquiries into former charities and their trustees. At present, OSCR can only conduct inquiries into existing charities. This means that if concerns are raised about charities that have ceased to exist (or bodies that still exist, but are no longer charities), OSCR cannot investigate. As highlighted in the Policy Memorandum (paragraph 71)2:

If OSCR cannot open an inquiry, it cannot gather the necessary evidence to allow it to make an application to the Court of Session. This poses a risk that charity trustees who are guilty of serious misconduct could go on to be charity trustees of other charities, in cases where the misconduct was only discovered after the body in question ceased to exist or ceased to be a charity.

This proposal received widespread support in the 2019 consultation, with 83% of respondents agreeing that OSCR should have powers to make inquiries into former charities and their trustees. Of the small number who disagreed, it was noted that there must always be OSCR should have robust evidence of misconduct before conducting an inquiry. Some also made the point that, where criminal offences are involved, matters should be re-directed to the police or other relevant agency. The Policy Memorandum notes that this is already the approach taken with OSCR inquiries into existing charities and trustees, but that it was not felt appropriate or sufficiently flexible to use primary legislation to prescribe the cases where OSCR could and could not act.

Section 14 of the Bill clarifies existing provisions around the gathering of information by OSCR for inquiries, with the intention being to improve the speed and efficiency of the information gathering.

There are two aspects to this:

Where a charity no longer exists, the Bill's provisions mean that OSCR would no longer be required to give notice to the non-existent charity before requesting information from a third party. Instead, OSCR will be able to notify former trustees. At present, a requirement for OSCR to notify the charity means that if the charity no longer exists, OSCR is unable to contact them to give the required notice and is therefore unable to request information from third parties.

The Bill also seeks to clarify the notice periods and time limits for information requests connected with OSCR's inquiry work as there is currently some confusion as to how they interact.

These proposals were widely supported in the 2019 consultation, with 87% of respondents being supportive of the plans.

Section 15 of the Bill allows OSCR to make positive directions to charities following inquiry work. The 2005 Act sets out the current direction-giving powers, but these largely involve negative directions i.e. requiring a charity not to do certain things, or to stop doing certain things. The Bill provisions would provide more general direction-giving powers, including positive directions e.g. directing a charity to ensure a conflict of interest is properly managed.

Under the Bill's proposals, a failure to comply with a positive direction issued by OSCR will be classified as trustee misconduct. This contrasts with the penalties for failing to comply with negative directions, which are classified as both trustee misconduct and also as a criminal offence. As noted above, all OSCR's activities are required under the 2005 Act to be "proportionate, accountable, consistent, transparent and targeted only at cases in which action is needed". This applies to any inquiry work, as well as any directions issued as a result.

Some of the current direction-giving provisions in the 2005 Act do not apply to "Designated Religious Charities" (DRCs) and the Bill proposes that exemptions will also apply to the new proposed direction-giving powers. The rationale for excluding DRCs from some of the existing direction-giving powers is that DRCs are expected to have internal supervisory and disciplinary functions of their own (and will only be designated as a DRC if they have such functions).

It should be emphasised that not all charities with religious purposes are DRCs. According to the 2005 Act, in order to be classified as a DRC by OSCR, a charity must:

have the advancement of religion as its main purpose

have as its main activity the regular holding of public worship

have been established in Scotland for at least 10 years

have a membership of at least 3,000 persons aged at least 16 and resident in Scotland

have an internal organisation with supervisory and disciplinary functions over all its component parts

have a regime for keeping accounting records which OSCR considers to correspond to those for other charities.

As such, it is only larger religious organisations (such as the central body of a religious denomination) that are likely to be DRCs and, even then, not all denominations are DRCs. For example, the Church of Scotland is a DRC, but the Scottish Episcopal Church is not.34 Note that this classification refers to the central organisation and different denominations take different approaches to their constitution. For example, in the Church of Scotland, individual parishes are set up as charities in their own right. However, in the Roman Catholic church the diocese are registered as DRCs but individual churches are not registered separately as charities. In the example of the Church of Scotland, although individual churches are registered as charities in their own right, they are exempt from specified directions by OSCR as they are component elements of and governed by the Church of Scotland as a DRC.

The Scottish Government believes that these proposals for positive direction-giving powers will enhance OSCR's effectiveness as a regulator and support it in promoting good governance across the charitable sector. This change would also bring Scotland into line with other UK charity regulators.

In the 2019 consultation, 83% of respondents supported giving OSCR powers to issue positive directions to charities following an inquiry. However, views were more mixed as to whether this new power should be specific or wide-ranging i.e. whether the legislation should specify the types of positive directions that could be issued. The 2005 Act is specific in relation to the types of negative directions that can be issued by OSCR. However, the Bill proposals in respect of positive directions are more general in scope. The Policy Memorandum explains that:

It is considered that the different situations in which a positive direction may be needed cannot be exhaustively defined. Accordingly, a general power avoids the need for future legislative changes as new circumstances emerge which require OSCR’s intervention.

Charity connection to Scotland

Section 16 of the Bill specifies that OSCR should not be required to register a charity that has no connection with Scotland (or only a negligible connection). Under the current legislation, only Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organisations (SCIOs) are required to demonstrate a link with Scotland. Other types of charities do not have to demonstrate such a link (although in practice, according to OSCR, the vast majority of charities currently on the Register do have a connection to Scotland).

Under the Bill provisions, OSCR can refuse to register a charity if it cannot demonstrate a link with Scotland. If an existing Scottish charity is no longer considered to demonstrate such a link with Scotland, OSCR can instruct it to take action to establish such a link. If the charity fails to do so, OSCR can remove the charity from the Scottish Charity Register. Affected charities can appeal any decision by OSCR to issue a direction or remove a charity from the Register.

The Policy Memorandum notes that:

The intention is not to preclude the registration of cross-border charities, which should continue being able to register with both the CCEW, and the Charity Commission for Northern Ireland (CCNI), and OSCR, where such charities have a connection to Scotland. Similarly, the policy is not to exclude charities operating in Scotland for the benefit of those outwith Scotland (e.g. overseas aid charities).

Rather, the intention is to ensure that OSCR can act as an effective regulator and take necessary enforcement action where appropriate, which is difficult where a charity has no clear connection with Scotland e.g. has no Scottish premises, or no trustees resident in Scotland.

The Bill proposes that OSCR should take the following factors into consideration when considering whether a charity has a connection with Scotland:

whether the charity has (or intends to have) a principal office in Scotland

whether the charity occupies (or intends to occupy) any land or premises in Scotland

whether the charity carries out (or intends to carry out) activities in any office, shop or similar premises in Scotland

whether the charity is established under the law of Scotland (for example, as a SCIO)

whether any of the persons who are (or are to be) concerned in the management or control of the charity are resident in Scotland

any other relevant factor.

The Bill allows for these criteria to be modified via secondary legislation. This was highlighted by the Scottish Parliament's Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee, who questioned whether it was appropriate for this power to be delegated to secondary legislation.1 In its response to the Committee, the Scottish Government argued that allowing for the list to be modified by secondary legislation would permit flexibility in response to changing circumstances (for example, highlighting that the pandemic had led to changed working practices, with many more charities operating remote working without a physical base).2

In the 2019 consultation, 82% of respondents supported the proposal that charities registered in Scotland should be able to demonstrate a connection with Scotland. The 2021 consultation was also supportive of these proposals.

Other minor and technical amendments to the 2005 Act

Section 17 of the Bill refers to the schedule included in the Bill, which sets out a range of minor and technical amendments to the Bill. These proposed changes in the schedule result from proposals put forward by OSCR, primarily as part of their response to the 2019 consultation. Many of the issues addressed were also highlighted by the Law Society of Scotland in their response to the 2019 consultation. Largely due to their technical nature, these proposals were not included as part of the 2021 consultation and, as such, have not been part of any public consultation prior to the publication of the Bill.

In summary, the proposals in the schedule:

Modify the statutory duty for OSCR to review the Scottish Charity Register to give OSCR more discretion over its approach to reviewing entries in the Register and allow it to act in a more targeted and proportionate way. Essentially, this involves softening some of the language associated with the statutory review duties, so that it "may review any entry", rather than "must review each entry".

Clarify OSCR's powers to remove charities from the Register where it has information to demonstrate that the charity no longer exists.

Allow OSCR discretion to include duplicate names on the Scottish Charity Register where this is part of a merger process, to avoid charities involved in mergers from having to be temporarily re-named in order to preserve an existing name.

Clarify arrangements for OSCR giving consent for a charity name to allow for situations where further information is required but cannot be obtained within the current 28 day period. Under current arrangements, if OSCR cannot get the information needed to inform its decision on whether a proposed name is appropriate, its only option is to refuse consent. The changes allow for an extension to the current period to allow for further information to be gathered and considered. This situation might arise if OSCR is considering whether a proposed name is objectionable (as defined under Section 10 of the 2005 Act). The Bill also provides for OSCR to refuse consent to a proposed name if they cannot satisfy themselves that it is not objectionable, even when it does not fall within the definitions set out in Section 10 of the 2005 Act.

Provide OSCR with powers over the use and appropriateness of "working names" for charities, where these differ from the name on the Scottish Charity Register.

Clarify that the assets of de-registered charities must continue to be used to provide public benefit (as defined in Section 8 of the 2005 Act).

Clarify the wording around requirements for charities to notify OSCR of certain changes, to correct for an inconsistency in the current legislation

Specify that charities must provide copies of constitutions and/or accounts within 28 days (there is currently no specified time period in the legislation).

Clarify the period for which charities must retain accounting records for situations where the preparation of the accounts covers two financial years.

Clarify that any concerns raised with OSCR by auditors or independent examiners under Section 46(2) of the 2005 Act should be made in writing.

Introduce a statutory requirement for charities to complete annual returns and submit to OSCR. Annual returns are different from the annual accounts and include information such as the charity address and contact information, which is important for OSCR in maintaining the accuracy of the Register and conducting regulatory functions. At present, OSCR requests that charities complete these returns, but there is no statutory obligation to do so.

Introduce a mechanism to require (via regulations) that SCIOs state their charity number on specified documents. At present, all charities other than SCIOs are required to do so, and this corrects an apparent oversight in the existing regulations.

Clarify the scope of "connected persons" in the context of remuneration of trustees. At present, the number of charity trustees being renumerated (directly or indirectly) must be less than half of the total number of trustees. The changes proposed broaden the definitions so as to prevent some situations where more than half of trustees might be benefitting indirectly.

Provide scope for OSCR to formally communicate with an address other than the main address on the Register, where it does not consider that correspondence to the main address will be received.

The Financial Memorandum

The Financial Memorandum (FM) for the Bill considers the costs (and/or savings) that might be expected to arise as a result of the proposals set out in the Bill. As required by the Parliament's Standing Orders, costs are assessed separately for:

the Scottish Administration (which includes OSCR)

local authorities

other bodies, individuals, businesses and third sector organisations.

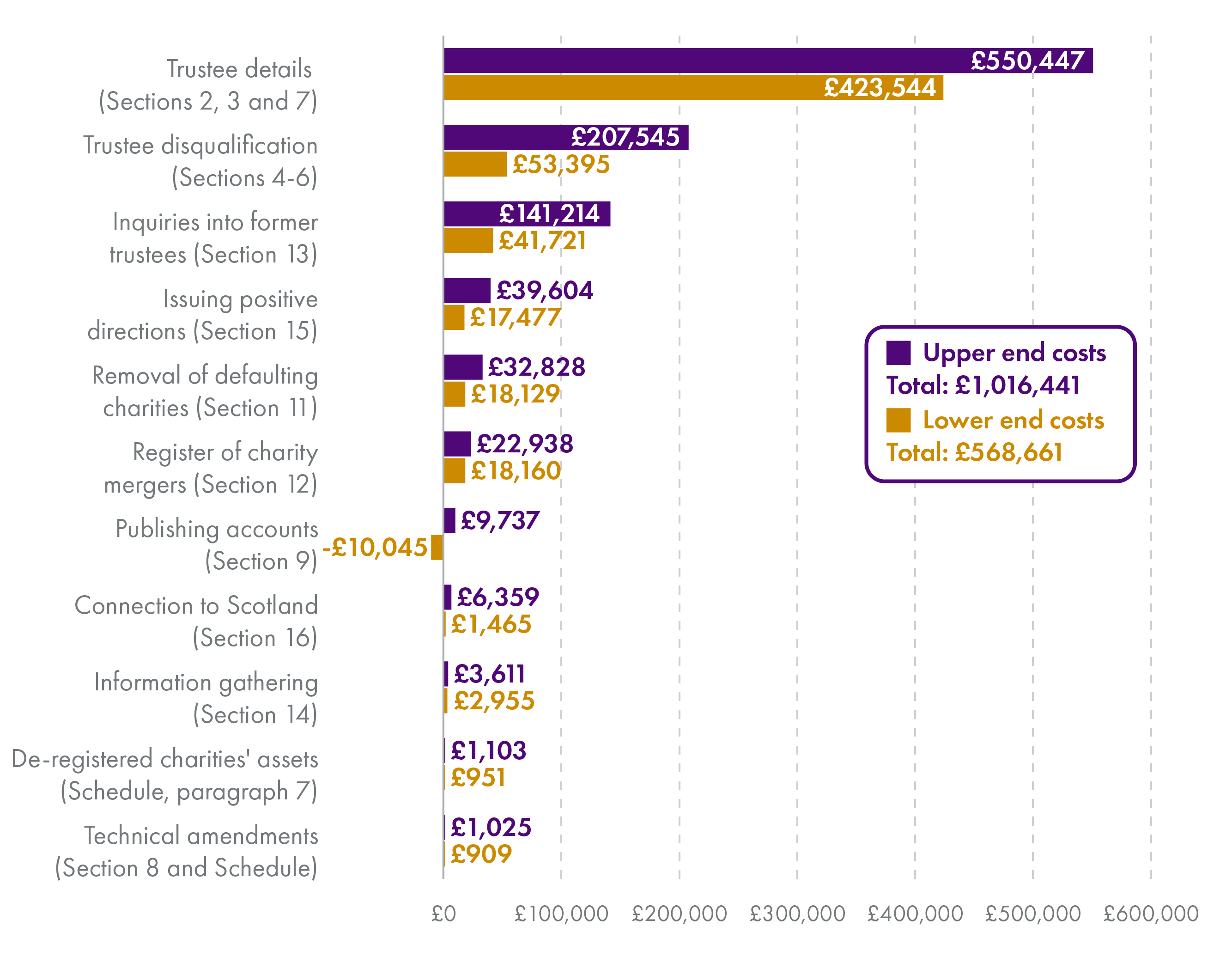

Figure 6 sets out the total estimated costs associated with the Bill over a three year period according to the section of the Bill to which they relate. The FM provides a breakdown for individual years. The three years are not specified, but are the first three years post- implementation. The FM states that costs have been projected to 2024-25 "to provide the best estimate likely costs at implementation", indicating that implementation is likely to be in 2024-25.

As required by the Parliament's Standing Orders, a range is shown to reflect any uncertainties in the costings. Where savings are anticipated, these are shown in brackets.

In total, over a three year period, the Bill is expected to result in costs of between £0.6 - 1.0 million.

Costs to the Scottish Administration

All of the costs identified in the FM are expected to fall to the Scottish Administration. The FM states that the costs identified for the Scottish Administration relate to the running costs of OSCR, but goes on to note that:

These figures are not spending commitments and should not be used as a tool for future budgeting, as costs may be affected by other factors in addition to the changes made by the Bill. Funding for OSCR will be negotiated in the usual way, taking into account the projected costs of its functions at the time.

The FM acknowledges that there could be additional costs for the Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service (SCTS) as a result of proposals in the Bill that could potentially lead to review and appeal. Any associated costs have not been estimated in the FM, which notes that these are difficult to estimate due to the uncertainty around numbers and complexity of cases. The FM does note that, since implementation of the 2005 Act, there have been only 12 appeals suggesting that numbers of appeal cases are likely to be relatively low. However, the FM also notes that numbers of appeals could increase as a result of the Bill provisions. The FM also notes that a lengthy case (10-11 days) involving appeal to both the First-tier Tribunal and the Upper-tier Tribunal could cost up to £30,000.

The FM states that costs have been estimated by OSCR, reflecting their own experience of casework, or (where provisions represent new areas of activity for OSCR) the experience of the Charity Commission for England and Wales. The FM further notes the following general points in relation to the costings:

Costs have been projected forward to 2024-25, reflecting likely timescales for implementation.

Staff costs have been increased by 3% per year using 2021-22 as a baseline, with the majority of costs identified relating to OSCR staff costs.

Hourly rates for relevant grades have been calculated and applied to the estimated number of hours associated with each task.

IT costs have been estimated with reference to quotes from IT contractors, adjusted to implementation date using Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts for the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) deflator and also adjusted to allow for contingency costs of 15-25%.

VAT has been included where this is not recoverable.

Three areas of costs are expected to account for around 90% of the total costs over three years:

gathering information on trustees and creating a public record (including details of disqualified trustees)

updating criteria for disqualification of trustees and extension to senior management positions

providing a power for OSCR to undertake inquiries into former trustees.

These three areas of costs are examined in further detail below. Costs associated with other areas of the Bill are expected to be modest. In relation to the publishing of accounts, the FM anticipates that there could be cost savings due to OSCR no longer needing to redact personal information from the published accounts.

Gathering and publishing trustee details

The biggest element of costs relates to the changes proposed in relation to gathering and publishing information on charity trustees, including maintaining a register of those removed from office. These aspects of the Bill provisions (Sections 2, 3 and 7) are expected to account for between half and three-quarters of the total estimated costs (£0.4-£0.6 million over a three year period).

Most of the estimated costs fall in the first year of implementation and are associated with database development costs, with associated project team support, communication and engagement costs and costs for stakeholder support and guidance. Together, these aspects are expected to cost between £280,000 and £360,000.

Ongoing recurring costs are set out separately and are expected to range between £48,000 and £65,000 per year. Although the introduction to the FM states that costs are based on uprated staff salaries combined with estimated hours required, the detail of assumptions around the hours of work or grades of staff are not set out in the FM.

Updating criteria for disqualification of trustees and extending to senior management

Sections 4-6 of the Bill relate to proposals to extend the criteria for disqualification of trustees and extend these criteria to senior management. The costs associated with these aspects of the Bill are estimated at between £53,000 and £208,000 over three years. The large range in potential costs reflects uncertainty around the range of casework for OSCR that might result from these provisions. Casework costs relate primarily to cases where an individual or charity applies to OSCR for a waiver (which would allow an individual disqualified from acting as a trustee by the Court of Session to continue to act as a trustee). OSCR would then be required to consider this application and (if it refuses the waiver) could be subject to appeal. OSCR has taken account of the experience of the Charity Commission for England and Wales (CCEW) in estimating potential caseloads, as similar changes have recently been introduced in England and Wales.

Inquiries into former trustees

Section 13 of the Bill introduces changes that would allow OSCR to conduct inquiries into former trustees of charities. The costs associated with these changes are estimated to cost between £42,000 and £141,000 over three years. OSCR has estimated costs based on conducting between three and five such inquiries per year, with the expectation that some might involve court action. The range in costs reflects the potential number and complexity of inquiries, although details on legal costs and staff time assumptions are not set out in the FM.

Costs to local authorities

No costs to local authorities are included in the FM. The FM acknowledges that there might be some costs associated with the charitable interests of local authorities, such as historic trusts that are managed by a local authority. For example, OSCR might decide to investigate a historic trust managed by a local authority and the local authority might then incur legal costs, but the uncertainty associated with the scale of such activity and the resulting costs mean they have not been estimated in the FM. Or, a local authority might decide to apply for (or appeal a decision relating to) a dispensation for disclosure of charity details and these costs would fall to the local authority. Again, these costs are not estimated in the FM but are not expected to be significant in scale.

Many local authorities use Arm's Length External Organisations (ALEOs) to deliver certain activities such as leisure services. These ALEOs are often set up as charities. However, the FM notes that, as ALEOs are independent of local authorities, any costs associated with the Bill would fall to the ALEO and not the local authority.

Costs to other bodies (including charities)

The FM does not incorporate any estimated additional costs for other bodies, including charities. The FM notes that:

The Scottish Government approached a small representative sample of charities to ascertain estimated costs and savings of the Bill provisions which will directly impact all charities (proposals 1 to 5).... Overall the charities who fed back did not anticipate incurring anything other than minor costs and were supportive of the proposals set out.

The Bill provisions will require some additional administrative time from charities e.g. in submitting and updating trustee details, but the FM states that these are not expected to result in significant additional costs for charities. The FM does acknowledge, however, that there would be some circumstances where additional costs would be incurred. For example, if a charity chose to apply for a dispensation in relation to disclosure of information, or appealed a decision by OSCR there would be additional administrative time and associated costs involved.

There FM also acknowledges that extending disqualification criteria to senior management could require charities to review recruitment processes and pre-employment checks.

There could also be costs for a charity if, following an OSCR inquiry, a positive direction was issued requiring the charity to take action, or seek legal advice. However, the uncertainty around the scope of such directions makes estimating such costs difficult.

It is clear from the FM that there are circumstances where additional costs might arise for charities as a result of the Bill provisions. The nature of the impacts mean that they are difficult to cost due to the unpredictable scale and scope of the effects. However, it should be noted that, with over 25,000 registered charities in Scotland, even small changes to their administrative costs could, in aggregate, result in significant costs across the sector. For example, if each of the 25,000 charities incurred additional administrative costs of £100 per year in order to ensure compliance with the legislation, this would represent total costs across the sector of £2.5 million. A sum of £100 would represent roughly one day's work for an individual on an annual salary of £25,000. While smaller charities might not have paid staff, there would still be an additional burden on volunteers e.g. in ensuring trustee details are kept up-to-date.

On the other hand, the FM notes that the Bill provisions relating to charity mergers could lead to a positive gain for charities as they could benefit from legacy income that might otherwise have been lost. Again, the FM does not quantify potential gains, but notes that a 2021 report estimated that gifts in wills raise over £90 million annually for Scottish charities.1 The FM also notes that there could be savings resulting from fewer court cases disputing legacies, although also notes that individuals who might have benefited under the existing law from legacies to charities would no longer benefit.