Police (Ethics, Conduct and Scrutiny) (Scotland) Bill

The Police (Ethics, Conduct and Scrutiny) (Scotland) Bill seeks to make sure that there are robust, clear and transparent mechanisms in place for investigating complaints, allegations of misconduct, or other issues of concern in relation to the conduct of police officers and staff of policing bodies operating in Scotland.

Summary

The Police (Ethics, Conduct and Scrutiny) (Scotland) Bill ("the Bill") seeks to make amendments to the Police, Public Order and Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2006 and the Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Act 2012.

The Bill seeks to make changes in four areas.

Sections 2 and 3 of the Bill cover the ethics of the police. These sections:

create a statutory obligation for Police Scotland to have a code of ethics

place a statutory duty of candour on individual police officers and Police Scotland as an organisation.

Sections 4 to 8 of the Bill cover aspects of police conduct. These sections:

clarify that the Scottish Police Authority is liable for the unlawful conduct of the Chief Constable

amend the functions that can be conferred on the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner (PIRC)

provide a power to allow misconduct procedures to be applied to former police officers

introduce an advisory list for police officers under investigation for alleged gross misconduct, and a barred list for officers dismissed, or who would have been dismissed, due to gross misconduct

amend the misconduct procedures for senior police officers, including requiring an independent panel to determine such cases.

Sections 9 to 16 of the Bill refer to functions of the PIRC. These sections:

provide clearer definitions of a “person serving with the police” and “member of the public”

provide the PIRC with additional powers, including extra functions in the complaint handling review process; being able to call in complaints, review practices and policies; and having a role in investigating police officers from outwith Scotland who are carrying out policing functions in Scotland

enable the PIRC to have direct access to Police Scotland's complaints database.

Section 17 of the Bill covers the governance of the PIRC and requires there to be a statutory advisory board to the Commissioner.

Cover photograph is copyright of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. https://www.parliament.scot/about/copyright

Introduction

The Scottish Government introduced the Police (Ethics, Conduct and Scrutiny) (Scotland) Bill ("the Bill") in the Scottish Parliament on 6 June 2023.1 Documents published along with the Bill include Explanatory Notes2, a Policy Memorandum3, a Delegated Powers Memorandum4 and a Financial Memorandum5.

The Bill seeks to make amendments to the Police, Public Order and Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2006 (“the 2006 Act”) and the Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Act 2012 (“the 2012 Act”). It is an entirely amending Bill.

The Bill seeks to make changes in four areas:

ethics of the police

police conduct

functions of the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner (PIRC)

governance of the PIRC.

The Policy Memorandum states that the objective of the Scottish Government in introducing this Bill is to ensure there are robust, clear and transparent mechanisms in place for investigating complaints, allegations of misconduct, or other issues of concern in relation to the conduct of police officers in Scotland.

Whilst the Policy Memorandum refers to ‘police officers’, sections 2, 3 and 9 to 13 of the Bill also apply, to some extent, to civilian staff of policing bodies as well as police officers.

In terms of police officers, most of the Bill's provisions are concerned with Police Scotland. However, some provisions relating to the PIRC have the potential to apply to officers of other relevant policing bodies with remits covering both Scotland and other parts of the UK (for example, British Transport Police), subject to agreements being in place with the PIRC.

Section 14 of the Bill also means that officers from other UK police forces could, when carrying out policing functions in Scotland, be covered by provisions relating to investigation for potential criminality and involvement in serious incidents. There will also be the option of the PIRC investigating some deaths involving these officers where these are deaths that the procurator fiscal has to investigate under Scottish Law, such as some fatal accidents.

This briefing sets out the background to the Bill, provides information on the processes which led to its development, and considers its key provisions.

Background to the Bill

This section covers the context and background to the introduction of the Bill including:

Key policing organisations

Police Scotland

The Police Service of Scotland (generally referred to as Police Scotland) was established by the Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Act 2012 ("the 2012 Act"). It brought together the eight former police forces in Scotland and the Scottish Crime and Drug Enforcement Agency into a single force. Police Scotland is made up of police officers and police staff (civilian roles).

The technical term for police officers used in the legislation is ‘constables’. This covers all ranks of police officer, which range from Police Constable, through Sergeant, Inspector, Chief Inspector, Superintendent and Chief Superintendent, to the senior ranks of Assistant, Deputy and Chief Constables.

Police staff are civilian roles and can involve those working in a range of areas including Human Resources, Analysis and Performance, Custody, Business Support and the National Intelligence Bureau. As at 30 September 2023, there were 16,613 full-time equivalent (FTE) police officers in Scotland and 5,868 FTE police staff.1

The Scottish Police Authority

The Scottish Police Authority (SPA) was also established by the 2012 Act. It is responsible for the governance of Police Scotland and has the following areas of responsibility:

maintaining the Police Service

promoting the policing principles set out in the 2012 Act

supporting continuous improvement

keeping policing under review

holding the Chief Constable to account.

The SPA also manages and delivers forensic services across Scotland and is responsible for independent custody visiting, where it monitors the welfare of those in police custody.

All funding for Police Scotland goes through the SPA. The SPA is accountable to Scottish Ministers and the Scottish Parliament.

The Police Investigations and Review Commissioner

The Police Investigations and Review Commissioner (PIRC) was originally set up as the Police Complaints Commissioner under the Police, Public Order and Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2006 ("the 2006 Act") and was renamed by the 2012 Act. The PIRC provides independent oversight of policing in Scotland. The Commissioner is appointed by Scottish Ministers. The PIRC investigates incidents involving policing bodies in Scotland and reviews the way those bodies handle complaints from the public.

The two main policing bodies in Scotland are Police Scotland and the SPA. The Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Act 2012 (Consequential Provisions and Modifications) Order 2013 ("the 2013 Order") extended the PIRC’s remit to investigate serious incidents involving other policing bodies operating in Scotland.

The Police, Public Order and Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2006 (Consequential Provisions and Modifications) Order 2007 allowed the PIRC to review the handling of complaints by other bodies. These bodies are:

British Transport Police

Civil Nuclear Constabulary

Ministry of Defence Police

National Crime Agency

HM Revenue and Customs

certain UK borders, customs and immigration enforcement functions.

These extensions in remit were achieved through the PIRC entering into agreements with the individual organisations.

The 2013 Order also has provision which means that the PIRC can currently investigate allegations of criminality against police officers and civilian staff of all these policing bodies, in relation to offences in Scotland or where there is Scottish jurisdiction. These are referred to the PIRC from the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS). The PIRC also investigates serious incidents involving police officers or civilian staff. This includes serious injuries in police custody, the death or serious injury of someone following contact with the police, and the use of firearms by police officers. Requests to carry out these investigations come from Police Scotland, the SPA or other policing bodies operating in Scotland.

The PIRC has a role within the misconduct process in terms of allegations made against senior officers of Police Scotland (those at and above the rank of Assistant Chief Constable). See the Current police misconduct process section below for a diagram outlining this process and the role of different policing organisations within it.

The PIRC can also carry out complaint handling reviews where someone can request a review of how their complaint against Police Scotland, the SPA or other policing bodies operating in Scotland was handled. This can be in terms of the actions of police officers or civilian staff.

Post-legislative scrutiny

As noted earlier, Police Scotland was created through the 2012 Act.

In 2018, the Justice Committee undertook post-legislative scrutiny of this Act, publishing their report in March 2019.1 They looked at how the legislation was being put into practice, any unintended consequences, and any improvements that could be made.

The report identified a number of issues in relation to the police complaints system and concluded that the processes were not working as the 2012 Act had intended. There were concerns about the complexity of the system, around transparency, accountability and fairness, and the time taken to investigate complaints. This was said to be affecting public confidence in the system. The report also made recommendations in terms of improving oversight and audit functions within the complaints process.

Independent Review of Complaints Handling, Investigations and Misconduct Issues in Relation to Policing

In June 2018, the Scottish Government and the Lord Advocate jointly commissioned an independent review led by Dame Elish Angiolini (now Lady Angiolini) - the Independent Review of Complaints Handling, Investigations and Misconduct Issues in Relation to Policing (the Angiolini Review).

The Angiolini Review began in September 2018, a Preliminary Report1 was published in June 2019 and a Final Report2 in November 2020. There were 111 recommendations across both reports. They related to several organisations including Police Scotland, the SPA, the PIRC and the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS). The Scottish Government and Lord Advocate both broadly accepted the recommendations within it.

Many of the recommendations were similar to the findings in the Justice Committee's post-legislative scrutiny report. Thirty-four of the recommendations within the Angiolini Review required legislative change. These were arranged under the following themes when taken forward by the Scottish Government in their public consultation:

rights and ethics

governance, jurisdiction and powers

conduct and standards

liability for unlawful conduct.

Various thematic reports have been produced by the Scottish Government to outline the progress that is being made on the Angiolini Review recommendations. The latest is the fifth thematic progress report3, published in May 2023. The reports outline the progress made on the non-legislative recommendations. So far, 58 of these have been marked as complete, 12 are in progress and two are under review. They also list the recommendations which require legislative action to progress.

The Scottish Government's intention is that some of the recommendations requiring legislative action will be taken forward in this Bill and some will be taken forward through secondary legislation. Those that will be taken forward through secondary legislation include the following.

faster misconduct hearings in certain circumstances (Recommendation 51)

gross misconduct hearings to be heard in public (Recommendation 52)

statutory provision for joint misconduct hearings (Recommendation 55)

the outcome of gross misconduct proceedings to be made public (Recommendation 58)

provision for allegations against probationers to be dealt with more quickly in probation (Recommendation 56).

As outlined in the Scottish Government's response to a written parliamentary question (S6W-20855), powers to introduce secondary legislation to deliver on some of the recommendations within the Angiolini Review (numbers 51, 52, 53, 55, 56, 57 and 58) are already held by Scottish Ministers under the 2006 and 2012 Acts.

A background note by the clerk4 provides an overview of reform to police complaints in Scotland. The Annexes to this paper include the recommendations from the Angiolini Review, and for those which require legislative change, the related responses from the Scottish Government consultation on these. It also outlines the practice around police complaints in a range of other jurisdictions internationally.

Scottish Government consultation

In 2022, the Scottish Government ran a public consultation on the legislative recommendations of the Angiolini Review – Police Complaints, Investigations and Misconduct: A Consultation on Legislation. As noted above, the consultation covered themes of:

rights and ethics

governance, jurisdiction and powers

conduct and standards

liability for unlawful conduct (included here, though not covered within the Angiolini Review).

The Scottish Government commissioned an independent organisation to analyse the results of the consultation. They published the responses1 and an analysis2 of this consultation on 30 November 2022. The responses were broadly in support of the majority of the recommendations within the Angiolini Review that were consulted on. These responses are considered in more detail later in this briefing.

Current context of policing in Scotland

Police Scotland operates under the principle of policing by consent. This requires the force as a whole, and individual officers, to have the trust and respect of the public. Recent reports and incidents within the public domain across the UK may have contributed to an undermining of public confidence in the police and concerns around scrutiny of their behaviour, particularly in relation to the treatment of women and minorities.

In May 2023, the former Chief Constable of Police Scotland acknowledged there was discriminatory behaviour in policing1 in Scotland. He stated that “institutional racism, sexism, misogyny and discrimination exist” and that Police Scotland is “institutionally racist and discriminatory”. The new Chief Constable of the force has said that she agrees with this2; that Police Scotland is “institutionally discriminatory”.

There is currently an ongoing independent public inquiry into the death of Sheku Bayoh after an incident involving Police Scotland officers. It is looking at the events surrounding his death, the subsequent investigation and whether race was a factor.

An HMICS Assurance review of vetting policy and procedures within Police Scotland3 by HM Inspectorate of Constabulary in Scotland (HMICS) was published in October 2023. It found the following:

there is no legal requirement for police forces in Scotland to vet officers and staff

that not all serving police officers and police staff have a record held on the Police Scotland vetting system

there is currently no guidance or requirement for police officers or staff to inform the organisation of relevant changes in circumstances

there is no easily identifiable requirement or process requiring officers or staff to notify Police Scotland of any off-duty criminal conviction, offence or charge

Police Scotland has no process of reviewing a vetting clearance following misconduct.

HMICS made a number of recommendations in the report requiring action by Police Scotland. They also made the following recommendation in terms of legislative change:

The Scottish Government should place into legislation the requirement for all Police Scotland officers and staff to obtain and maintain a minimum standard of vetting clearance and the provision for the Chief Constable to dispense with the service of an officer or staff member who cannot maintain suitable vetting.

On 6 October 2023, the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs, Angela Constance MSP, wrote4 to the Convener of the Criminal Justice Committee, Audrey Nicol MSP, to state that the Scottish Government is considering options to place vetting on a legislative footing.

HMICS are also currently undertaking a Thematic Inspection of Organisational Culture in Police Scotland.5 Its aim is to “make an assessment as to whether Police Scotland has a healthy organisational culture and ethical framework and whether the appropriate values and behaviours are consistently lived across the organisation”.

In the UK more widely, crimes by serving Metropolitan Police officers, such as the murder of Sarah Everard by Wayne Couzens, and David Carrick's convictions for a series of rapes, as well as the recent findings from the Independent review into the standards of behaviour and internal culture of the Metropolitan Police Service by Baroness Casey6 may have contributed to a reduction in public confidence in the police and the processes in place to handle complaints and allegations of misconduct.

Current police misconduct process

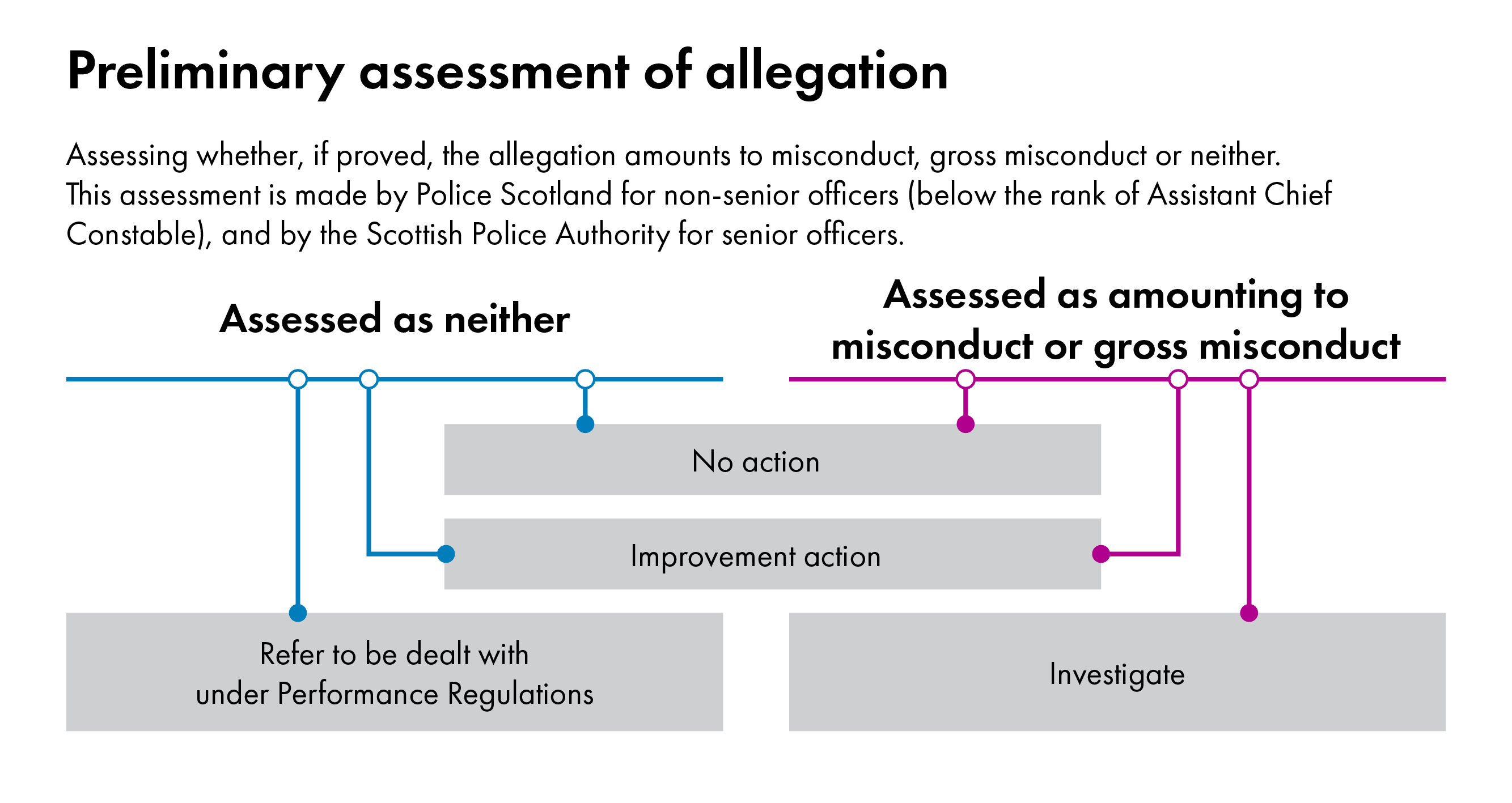

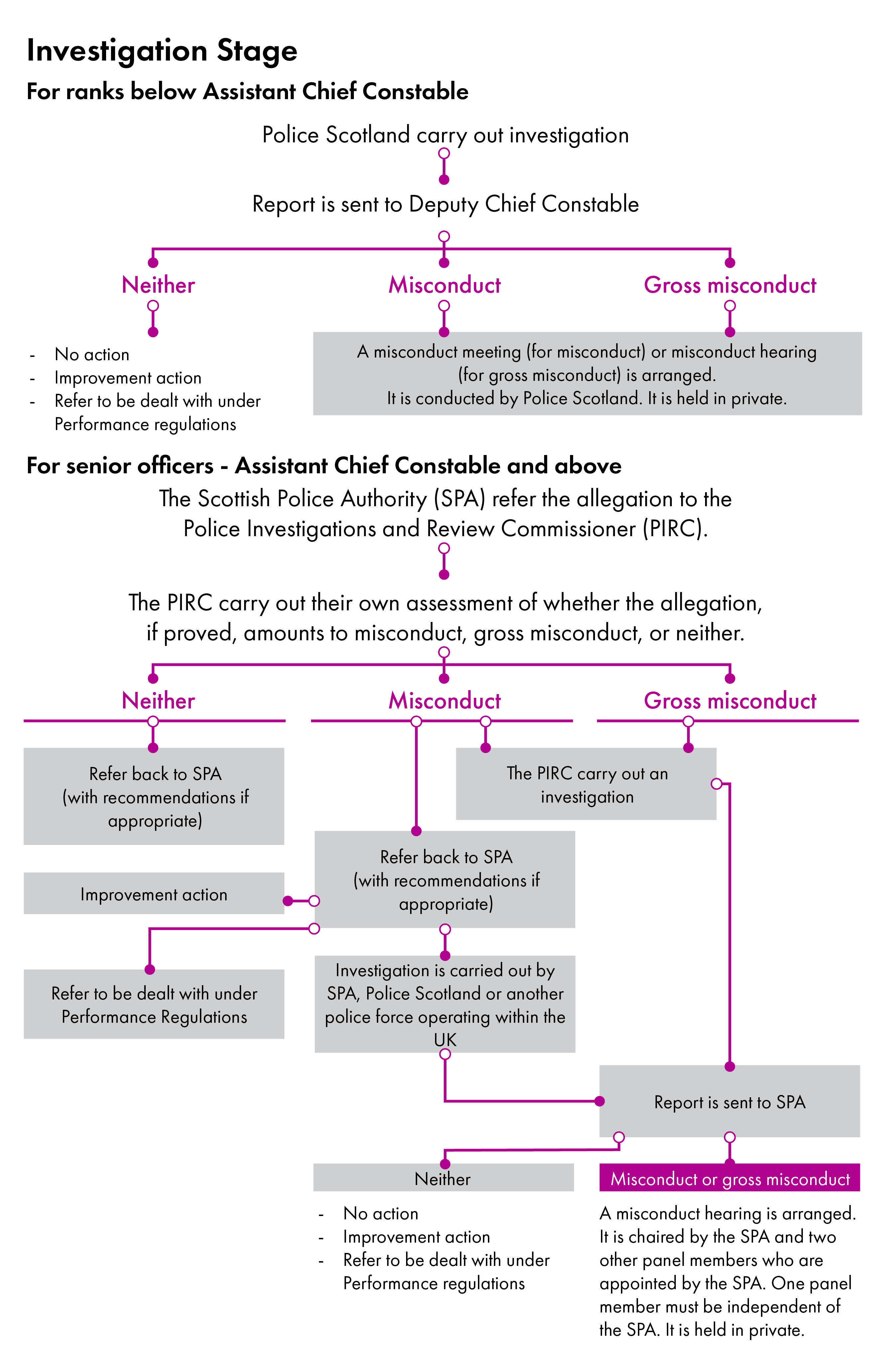

The current procedures for misconduct and gross misconduct differ depending on whether the allegation is against a senior officer (Assistant Chief Constable (ACC) or above) or police officers of ranks below this. The images below shows this process, and the current role of different organisations within it.

Issues relating to the performance of a police officer are dealt with separately under Performance Regulations. These are dealt with by the SPA (for senior officers) and Police Scotland (for those below the rank of ACC).

Image 1 below shows an overview of the preliminary assessment stage of the police misconduct process while Image 2 shows the process and organisations involved in the investigation stage.

Policy objectives of the Bill

The overarching policy objective of the Bill, as stated within the Policy Memorandum, is to ensure there are robust, clear and transparent mechanisms in place for investigating complaints, allegations of misconduct, or other issues of concern in relation to the conduct of police officers in Scotland.

While the aim is stated in respect of ‘police officers’, sections 2, 3 and 9 to 13 of the Bill also apply, to some extent, to civilian staff of policing bodies as well as police officers.

In terms of police officers, most of the Bill's provisions are concerned with Police Scotland. However, some provisions relating to the PIRC have the potential to apply to officers of other relevant policing bodies with remits covering both Scotland and other parts of the UK (for example, British Transport Police), subject to agreements being in place with the PIRC.

Section 14 of the Bill also means that officers from other UK territorial forces, when carrying out policing functions in Scotland, would be covered in certain circumstances. This would be through the ability for them to be investigated for potential criminality and involvement in serious incidents. There will also be the option of the PIRC investigating deaths involving these officers where these are deaths that the procurator fiscal has to investigate under Scottish Law, such as some fatal accidents.

The Bill seeks to achieve the policy objectives by doing the following:

placing a code of ethics and duty of candour, which already exist or are implicit expectations within policing, on a statutory footing

enhancing the levels of independent scrutiny within the misconduct process by providing the PIRC with additional powers or functions

doing the same for the complaints process by providing the PIRC with additional powers, including being able to call-in complaints, review practices and policies, and extra functions in the complaint handling review process

providing clarity to the process through clearer definitions (such as “person serving with the police” and “member of the public”)

improving public confidence in the process by outlining how misconduct procedures will be able to commence and continue against former officers, and introducing an advisory list for police officers under investigation for alleged gross misconduct, and a barred list for officers dismissed, or who would have been dismissed, due to gross misconduct.

The main provisions of the Bill are set out under the following headings:

ethics of the police

police conduct

functions of the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner

governance of the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner.

Each of these areas is considered below.

Ethics of the police

Sections 2 and 3 of the Bill would amend the Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Act 2012 ("the 2012 Act"). They would require the Chief Constable to prepare and maintain a Code of Ethics and would place an explicit duty of candour on both individual officers and the organisation as a whole.

Section 2 - Code of Ethics

Provision in the Bill

Section 2 of the Bill puts in to place a statutory obligation for there to be a Code of Ethics for Police Scotland. The Bill creates a duty on the Chief Constable of Police Scotland to prepare (and later review) this Code of Ethics, with the involvement of the SPA, and in consultation with a range of people and organisations as set out in the Bill.

As outlined in the Policy Memorandum (para 45):

In preparing the Code, the Chief Constable has to have regard to certain sources, including the policing principles, and rights contained in the European Convention on Human Rights.

This Code of Ethics would be referred to in a revised version of the Constable's Declaration:

I, do solemnly, sincerely and truly declare and affirm that I will faithfully discharge the duties of the office of constable with fairness, candour, integrity, diligence and impartiality, that I will follow the Code of Ethics for Policing in Scotland and that I will uphold fundamental human rights and accord equal respect to all people, according to law.

The Explanatory Notes (para 21) state that:

The Code will not have any particular legal effect. A failure to comply with the Code will not of itself give rise to grounds for any legal action. Neither will a breach necessarily constitute misconduct, which will continue to be measured by the standards of professional behaviour alone.

While the Explanatory Notes set out that the Code will have no particular legal effect, it is the role of the courts to decide this. They can look at the Explanatory Notes as an aid to interpreting the legislation in question but do not have to follow their direction.

Background

There are currently four sources of ethics for Police Scotland.

The policing principles (which apply to officers and police staff) and what is called the “constable's declaration”. This is a declaration made by all police officers joining Police Scotland. The principles and declaration are set out within the 2012 Act.

The Standards of Professional Behaviour for police officers below the rank of Assistant Chief Constable, which are contained within The Police Service of Scotland (Conduct) Regulations 2014.

The Standards of Professional Behaviour for senior officers, which are contained within The Police Service of Scotland (Senior Officers) (Conduct) Regulations 2013.

A Code of Ethics produced by Police Scotland, which covers both police officers and police staff.

The Angiolini Review made the following recommendation (Recommendation 1) in terms of ethics:

Police Scotland's Code of Ethics should be given a basis in statute. The Scottish Police Authority and the Chief Constable should have a duty jointly to prepare, consult widely on, and publish the Code of Ethics, and have a power to revise the Code when necessary.

This differs from the provision contained within the Bill in that the Chief Constable must involve SPA in the preparation process, but they will not “jointly” prepare the Code of Ethics as recommended in the Angiolini Review.

An analysis of the Scottish Government consultation showed there was broad support for there being a statutory requirement for there to be a Code of Ethics for Police Scotland. Respondents were split over who should prepare this. Organisations favoured the option of the Chief Constable and SPA jointly preparing the code. Individual respondents favoured this being done by a different organisation.

Of the policing organisations who responded to the consultation, the Scottish Police Federation (SPF) and Association of Scottish Police Superintendents (ASPS) disagreed that there needed to be a statutory requirement for Police Scotland to have a Code of Ethics. Both felt that the current arrangements were sufficient, with ASPS stating that this statutory requirement was “additional and unnecessary bureaucracy”.

Section 3 - Duty of candour

Provision of the Bill

Section 3 of the Bill establishes a statutory duty of candour. This includes a duty on police officers to attend interviews and to co-operate with proceedings, including against other officers. In addition, a statutory duty would be placed on the organisation as a whole to be candid and co-operative in proceedings, including investigations against police officers. The individual duty would not be placed on members of police staff, but they would be covered by the organisational duty of candour.

The individual duty would be recognised through inclusion within the constable's declaration.

Constables act with candour and are open and truthful in their dealings, without favour to their own interests or the interests of the Police Service.

And through the following being added to the Conduct Regulations for all police officers:

Constables attend interviews and assist and participate in proceedings (including investigations against constables) openly, promptly and professionally, in line with the expectations of a police constable.

To achieve the aim of an organisational duty of candour, an additional policing principle would be added by the Bill, requiring Police Scotland to be “candid and co-operative in proceedings, including against constables”.

The Bill generally makes no provision as to the legal effect of the duty of candour, its enforcement or sanction for breach. The exception to this is where the duty is placed within the standards of professional behaviour contained within both sets of Conduct Regulations. A breach could lead to a finding of misconduct, though would not necessarily do so.

The proposed duty of candour is subject to protections for those covered by it, including the right to silence and privilege against self-incrimination. In terms of this, the Angiolini Review concluded that “other than in very restrictive circumstances, any officer who is a witness to a serious incident should be under an obligation to assist”.

Background

Currently, a police officer's duty to assist in proceedings is expressed within section 20 of the 2012 Act solely in terms of them being required to attend court to give evidence. Their requirement to assist in the investigatory aspects of these proceedings is not directly expressed within the 2012 Act or elsewhere.

The Angiolini Review recommended (Recommendation 10) that a statutory duty of candour should be placed on the police to fully co-operate with all investigations, including those into allegations against its officers. It also recommended that the Scottish Government should consult on a statutory duty of co-operation, to be included in both sets of Conduct Regulations.

The Policy Memorandum (para 55) outlines that this would:

create a culture where constables are expected and encouraged to co-operate fully with investigations and answer questions based on their honestly held recollection of events. In doing so constables will uphold the values of policing by consent, maintaining the trust and faith of the public in the execution of their duties, and act at all times with fairness and integrity.

An analysis of the Scottish Government consultation showed there was broad support for introducing a duty of candour, with most respondents agreeing this should be placed on the organisation as well as individual officers (there is no mention of police staff in this question). Most respondents thought that this duty should extend to off-duty police officers, though the PIRC did not agree with this, and Police Scotland highlighted that there may be challenges in terms of this applying to incidents involving off-duty officers.

The Angiolini Review also recommended that the Scottish Government should consult on a statutory duty of co-operation (Recommendation 12). This was to be included in the Conduct Regulations so would have applied only to police officers and not police staff. It also recommended including a power for the PIRC to compel officers to attend for interview within a reasonable timescale (Preliminary Report Recommendation 15).

These recommendations have not been included within the Bill as the Scottish Government felt that a duty of co-operation is “a facet of the duty of candour and not a freestanding duty”, and that the duty of candour covers expectations on attending for an interview promptly.

Financial costs

The estimated costs arising from the proposed changes within sections 2 and 3 of the Bill are outlined in the Financial Memorandum. These relate to training costs and it is stated that they will be below £10,000 and would be absorbed by Police Scotland.

In Police Scotland's written response to the call for views on this Bill's Financial Memorandum by the Finance and Public Administration Committee, they state that the figures provided in the Financial Memorandum are "significantly underestimated".

Police conduct

Sections 4 to 8 of the Bill would amend the Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Act 2012 ("the 2012 Act"). They concern the procedures for dealing with, and the consequences of, certain conduct by police officers. They aim to ensure there is greater transparency and consistency within these procedures and improve public confidence in how misconduct allegations are dealt with.

One of the Angiolini Review recommendations which aims to ensure greater transparency and improve public confidence in the misconduct process is the holding of gross misconduct hearings in public (Recommendation 52). This is not dealt with directly in this Bill, but the Scottish Government has indicated their intention to take this forward through secondary legislation, which Scottish Ministers already hold the powers to implement.

There were divided views around this recommendation by organisational respondents within the Scottish Government consultation. A follow-up question of which ranks hearings should be held in public for, if this were to happen, saw most respondents agreeing that this should be for all ranks rather than only senior officers.

Several police organisations disagreed with the holding of gross misconduct hearings in public, including the Association of Scottish Police Superintendents (ASPS), Scottish Chief Police Officers Staff Association (SCPOSA), the Scottish Police Federation (SPF) and Police Scotland. The SPA stated they supported the recommendation but questioned if transparency could be achieved in another way, for example publishing the outcome of the hearing. In a response to a written parliamentary question (S6W-20884) around the holding of gross misconduct hearings in public, reference is made to section 8 of this Bill suggesting this would only apply to senior officers.

Section 4 – Liability of the Scottish Police Authority for unlawful conduct of the Chief Constable

Provision in the Bill

Section 4 clarifies that the liability of the Scottish Police Authority (SPA) for unlawful conduct includes the conduct of the Chief Constable. This means that the SPA would be obliged to pay out damages in the case of the Chief Constable acting unlawfully in carrying out their functions, as is currently the case for all other ranks of police officer.

Background

There was no recommendation within the Angiolini Review around this. It has been included within the Bill to ensure consistency of SPA liability for unlawful conduct across all ranks.

Analysis of the Scottish Government consultation showed a majority of respondents agreed with this recommendation.

Section 5 – Procedures for misconduct: functions of the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner

Provision in the Bill

Section 5 amends the functions that can be conferred on the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner (PIRC). Currently the PIRC is only able to carry out an investigation of whether a police officer has been engaged in misconduct. They are not involved in other aspects of the disciplinary process. For example, they do not carry out the preliminary assessment of the allegation and cannot present at any misconduct hearing following an investigation. The Bill would make the PIRC's power broader by allowing functions to be conferred on to them relating to any aspect of the procedures dealing with police officers whose standard of behaviour is unsatisfactory.

The Scottish Government intends to bring forward secondary legislation which would outline the details of these wider functions.

Background

Currently, while the 2012 Act allows functions to be conferred on the PIRC in relation to the investigation of whether any constable has been engaged in misconduct, this has only been done for senior officers (the rank of Assistant Chief Constable and above) through their Conduct Regulations. Misconduct investigations into lower ranks are carried out by Police Scotland.

The PIRC only has powers in relation to “investigation”, so does not, for example, carry out the initial preliminary assessment of an allegation to ascertain whether, if proved, it would amount to misconduct, gross misconduct or neither. Nor can it present cases at misconduct hearings following an investigation.

Images 1 and 2 in the Current police misconduct process section outline the current misconduct process and the role of different organisations within it.

The Angiolini Review made a number of recommendations, relating to senior officers only, in terms of the role of the PIRC in misconduct proceedings.

preliminary assessment to move from the SPA to the PIRC (Recommendation 25)

the PIRC to handle key stages of senior officer misconduct proceedings (Recommendation 39)

the PIRC to have a new statutory function to present cases in senior officer gross misconduct hearings (Recommendation 40)

the PIRC to have the power to recommend suspension of a senior officer (Recommendation 41).

The Policy Memorandum (para 71) acknowledges that the change made in this section of the Bill on its own “does not meet the policy aim to enhance independent scrutiny and remove any perception of familiarity in the conduct process”. The Scottish Government has stated that it intends to bring forward the changes required to meet the Angiolini Review recommendations through secondary legislation.

The Scottish Government consultation asked respondents about additional functions the PIRC could take on in respect of the misconduct process for senior officers that would be enabled through the changes made by this Bill.

The majority of respondents agreed that the PIRC should take over the preliminary assessment role from the SPA, as well as that they should be able to present cases at gross misconduct hearings for, and recommend the suspension of, a senior officer.

When asked about whether the PIRC should be able to take on responsibility for other key aspects of misconduct and gross misconduct proceedings for senior officers there was agreement, though at differing levels, with the following aspects:

for receipt of complaints and allegations, where appropriate, referral to an independent legally chaired panel

for preliminary assessment

for referral to COPFS of criminal allegations

for referral to an independent legally chaired panel where appropriate if there is a disciplinary hearing subsequent to referral to COPFS.

More respondents felt that the preliminary assessment powers should not take account of whether an allegation is made anonymously, is sufficiently specific in time and location, is malicious, or is vexatious for any police officers than agreed that these aspects should be taken account of for senior officers. In contrast to individual respondents, organisational respondents were slightly more likely to agree that all these aspects should be considered for senior officers. The consultation only allowed one response to this question and did not offer an option of ‘all ranks’. The options were, to agree for senior officers, agree for non-senior officers or disagree for all ranks. Therefore, the consultation responses may not accurately reflect respondents’ views about the ranks of officers they felt this should apply to.

The Scottish Government has advised that there have been changes made to the system by the SPA and the PIRC in terms of vexatious complaints following the preliminary report from the Angiolini Review. It is their intention to monitor this, and they may take forward these changes through secondary legislation if required.

Section 6 – Procedures for misconduct: former constables

Provision in the Bill

Section 6 enables procedures for misconduct which are set out in regulations made under section 48 of the 2012 Act to be applied, in certain circumstances, to former police officers where a preliminary assessment (made by the PIRC) decides the allegation is potentially at the level of gross misconduct.

The Bill also includes a power to set a period of time from any date of resignation after which no steps (or only certain steps) in the procedure can be applied unless additional criteria are met. The intention is that this period will be 12 months. It would, along with the additional criteria, be set out in secondary legislation.

Background

Currently, where police officers are subject to an allegation of misconduct or gross misconduct, any ongoing investigation or conduct proceeding concludes should they retire or resign.

The Angiolini Review made the following recommendation (Recommendation 23):

The Scottish Government should develop proposals for primary legislation that would allow, from the point of enactment, gross misconduct proceedings in respect of any police officer or former police officer to continue, or commence, after the individual ceases to hold the office of constable.

Gross misconduct is defined within The Police Service of Scotland (Senior Officers) (Conduct) Regulations 2013 and The Police Service of Scotland (Conduct) Regulations 2014. It is a breach of the Standards of Professional Behaviour contained within these Regulations which is so serious that dismissal may be justified, or for senior officers (the rank of ACC and above), dismissal or a demotion in rank.

The Policy Memorandum (para 72) states:

Ensuring that disciplinary proceedings can commence or continue to reach a conclusion even after a constable retires or resigns means officers cannot evade disciplinary proceedings.

Most respondents to the Scottish Government consultation agreed that it should be possible to commence or continue proceedings against former police officers, where the alleged behaviour is assessed to be at the level of gross misconduct. There was disagreement over who should be responsible for making the decision to continue or begin proceedings, with the most popular response being the PIRC, followed by the SPA, the Chief Constable and a different body than those included in the options given.

Most respondents agreed that it should be possible to take forward disciplinary proceedings where the allegations came to the attention of the relevant authorities more than 12 months after the person ceased to be a police officer, with the PIRC determining whether this was reasonable and proportionate (Recommendation 24). Both of the following conditions should also be met:

the case is serious and exceptional

the case is likely to damage public confidence in policing.

A minority of respondents disagreed with this recommendation, although notably Police Scotland disagreed, as did other police organisations (the Scottish Police Federation and the Scottish Chief Police Officers Staff Association). The absence of powers such as this for employees in other areas was highlighted, as well as the logistics around this and the lack of sanctions (where previously dismissal would have been the result) as reasons for disagreement.

Section 7 – Scottish police advisory list and Scottish police barred list

Provision in the Bill

Section 7 provides that the SPA must establish and maintain a Scottish police barred list and a Scottish police advisory list.

The consequences of an individual being on either of these lists will be provided for by Scottish Ministers within regulations. This could include the prevention of their employment if they are on a barred list; and the policing bodies that must consult advisory or barred lists before employing someone.

Individuals would be added to the advisory list where disciplinary proceedings have been brought against them for gross misconduct and they:

either ceased to be a police officer before the proceedings concluded

or ceased to be a police officer before these proceedings were brought.

They would be added to a barred list if they were dismissed for gross misconduct or would have been dismissed had they not already ceased to be a police officer at that point.

The framework around these lists will be set up in regulations, with this Bill giving Scottish Ministers regulation-making powers to allow this to be done.

Gross misconduct is a breach of the Conduct Regulations which is so serious that dismissal may be justified, or for senior officers (above the rank of ACC) dismissal or a demotion in rank.

Background

There is currently no list of individuals who have been dismissed from Police Scotland as a result of misconduct proceedings. Where this occurs in England and Wales, their names are currently added to a barred list which prevents them from being appointed by another police force or other policing body in England and Wales. Where they are subject to an allegation being investigated, they are added to an advisory list. This does not prevent them being employed by a policing body but is intended to act as a vetting tool to identify those who are currently under investigation. Individuals will remain on the advisory list until the outcome of proceedings.

As things stand, Police Scotland can access the publicly searchable elements of the England and Wales barred list only. Forces in England and Wales would not be aware of allegations of, or dismissal because of, gross misconduct by an officer with Police Scotland.

The Angiolini Review recommended (Recommendation 24) that:

The Scottish Government should engage with the UK Government with a view to adopting Police Barred and Advisory Lists, to learn from experience south of the border and to ensure compatibility and reciprocal arrangements across jurisdictions.

The Policy Memorandum (para 80) notes that these lists:

would strengthen those vetting processes and would make it possible to ensure English and Welsh policing bodies are made aware of the Scottish officer's gross misconduct and thereby effectively preventing those who do not meet the high standards required of the police service from being able to continue to work in policing throughout Great Britain.

Analysis of the Scottish Government consultation showed that most respondents agreed with the establishment of a Scottish police barred and advisory list and that the Scottish Government should work with the UK Government to adopt the barred and advisory list model.

Section 8 – Procedures for misconduct: senior officers

Provision in the Bill

Section 8 amends a requirement in the 2012 Act that stipulates that the SPA must determine cases against senior officers. Senior officers are those of the rank of Assistant Chief Constable (ACC) and above. It would allow an independent panel to determine a conduct case against a senior officer, removing the SPA from having a role in this process. The details outlining the composition of the independent panel would require to be taken forward through secondary legislation. The SPA will retain their role in terms of determining cases relating to performance (under The Police Service of Scotland (Senior Officers) (Performance) Regulations 2016).

The Bill does not provide detail around the make-up of the independent panel, nor who will appoint the members of it. This will be dealt with through secondary legislation.

The Bill would also provide senior officers with an additional right of appeal to the Police Appeals Tribunal (PAT) in cases of any disciplinary action against them in relation to conduct matters. This is currently restricted to cases where there is dismissal or demotion.

Background

The Angiolini Review made several recommendations in terms of misconduct procedures for senior officers. Some of these would be addressed by secondary legislation. This section of the Bill addresses recommendation 27 which states:

Gross misconduct hearings for all ranks should have 1) an independent legally qualified chair appointed by the Lord President, 2) an independent lay member appointed by the Lord President and 3) a policing member.

When asked about misconduct proceedings against senior officers, most respondents to the Scottish Government consultation felt that the Chair of any hearing should be an independent legally qualified person. When asked about the wider composition of the panel, most respondents felt that in addition there should be a senior expert on policing, followed by an independent lay person and an independent legally qualified person .

There was support by respondents for the Lord President appointing the Chair of a misconduct hearing for senior officers. In terms of whole panel appointments, there was less consensus around the Lord President being involved in these appointments, with slightly more respondents agreeing than disagreeing with this for senior officers. Organisational respondents, however, were almost evenly split.

HM Inspectorate of Constabulary in Scotland (HMICS) and the Association of Scottish Police Superintendents (ASPS) did not agree that the Lord President should make wider panel appointments for senior officers, but agreed they should only appoint the Chair. The Scottish Police Federation (SPF) and British Transport Police (BTP) did not agree the Lord President should make any of the appointments for senior officers' misconduct procedures. The BTP pointed out the delay that could be brought into the process if the Lord President were to appoint panels. The issue of delays was something identified by the Angiolini Review and by the former Justice Committee in its post-legislative scrutiny of the 2012 Act as a problem within the current system.

Most Scottish Government consultation respondents agreed that senior officer conduct regulations should be revised to ensure that where there has been a finding of gross misconduct there should be only one route of appeal, to the Police Appeals Tribunal (PAT). Around half agreed that the same process should be in place for misconduct findings, with all but one of the organisations agreeing with this. Slightly more individuals felt this should be managed by the independent legally-chaired panel rather than the PAT.

Similar questions to those outlined above were asked of respondents to the Scottish Government consultation in respect of all ranks of police officer, though only in terms of gross misconduct hearings. The provisions within this section of the Bill, however, relate solely to senior officers.

The Policy Memorandum (para 107) outlines the reasons for making these changes to the misconduct process for senior officers only, rather than all ranks. It notes that the introduction of a legally qualified chair for senior officer hearings would remove the perceptions of proximity bias between senior officers and the SPA. This is not an issue for non-senior officers. The greater numbers of cases involving non-senior officers would also see potential delays and larger costs should this change be introduced across all ranks.

Financial costs

The estimated costs arising from the proposed changes within sections 4 to 8 of the Bill are outlined in the Financial Memorandum. These apply to the increased costs related to allowing gross misconduct proceedings to commence and continue against former police officers which are estimated in the range of £103,000 if the officer retires after the investigation but before the hearing, and £211,000 if the officer retires or resigns before the investigation and the hearing, each year.

Where secondary legislation brings in changes to gross misconduct hearings (for example, being held in public), costs to accommodate this are estimated at £372,000 per year once this was in place, with estimates for former officers’ legal representation of £392,000. PAT contingency for two cases per year is estimated at £10,340.

This gives a total of £877,340 to £985,340 per annum.

In the Scottish Police Federation's and Police Scotland's written responses to the call for views on this Bill's Financial Memorandum by the Finance and Public Administration Committee, they raise concerns that the figures within the Financial Memorandum have not taken account of some costs and have underestimated others. This includes in terms of:

training costs, the cost of digital upgrades and project team costs to implement the provisions in the Bill around police conduct

an underestimate of the numbers of former officers who will be involved in misconduct procedures

an underestimate of costs to Police Scotland where figures used are prior to a 5% and 7% pay award to police officers since the figures were produced

an underestimate of the legal costs accrued during these processes

questioning who will be responsible for funding these legal costs for former officers.

Functions of the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner

Sections 9 to 16 of the Bill would amend the Police, Public Order and Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2006 ("the 2006 Act") in relation to the functions of the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner (PIRC).

There are a number of aspects to the PIRC's current role:

investigating allegations of criminality against police officers and civilian staff of policing bodies operating in Scotland

investigating on behalf of the procurator fiscal, deaths that the procurator fiscal is legally required to investigate and which involve a person serving with the police - this includes deaths in police custody

investigating serious incidents involving police officers or civilian staff - this includes serious injuries in police custody, the death or serious injury of someone following contact with the police and the use of firearms by police officers

within the misconduct process, in terms of allegations made against senior officers (the rank of Assistant Chief Constable and above)

carrying out complaint handling reviews where someone can request a review of how their complaint against Police Scotland, the SPA or other policing bodies operating in Scotland was handled

investigating other matters relating to the SPA or Police Scotland where the PIRC considers it would be in the public interest to do so.

The Key policing organisations in Scotland section contains more detail of when and how the PIRC was established and its functions. The Current police misconduct process section outlines the existing role of the PIRC in the misconduct process.

Section 9 – Investigations into matters involving persons serving with the police

Provision in the Bill

Section 9 of the Bill provides clarification that the PIRC can investigate allegations of criminality committed by a person serving with the police before they joined, during their time with, or after they have left, the relevant policing body. This is regardless of whether this criminality occurred when a police officer was on-duty, or for civilian staff when they were working. This is achieved by inserting into section 33A of the 2006 Act the following:

who is, or has been, a person serving with the police may have committed an offence (regardless of when those circumstances occurred)

In terms of the PIRC investigating a death that the procurator fiscal is legally obliged to investigate, and where a person serving with the police has been involved, this will apply “whether or not the circumstances occurred in the course of the person's duty, employment or appointment”.

A person serving with the police is defined under section 47 of the 2006 Act as “a constable of the Police Service of Scotland; a member of police staff; or a member of staff of the Scottish Police Authority”.

Background

The Angiolini Review recommended the need for clarity around the definition of a “person serving with the police” in terms of alleged criminality (Recommendation 8):

The Scottish Government should amend the relevant provisions at the earliest opportunity to put beyond doubt the definition of a ‘person serving with the police’.

This was to provide clarity over whether the PIRC has the power to investigate the alleged criminal offending of police officers and staff who have left the force since the time of the incident in question, or for officers, where they were off-duty when the incident occurred.

The Policy Memorandum (para 111) states that:

The Bill clarifies that the PIRC investigations into criminal conduct can continue and occur when the police officer concerned has since left the service, did not become an officer until subsequent to the conduct or was not on duty at the time of the relevant incident, by stating that the PIRC can be directed to investigate where a person “who is, or had been, a person serving with the police may have committed an offence (regardless of when those circumstances occurred).” This will put beyond doubt the definition of a “person serving with the police” and will clarify the PIRC's investigatory powers."

While this speaks about police officers only, the definition of “person serving with the police” means that amendments made by this Bill would apply to civilian staff as well as police officers.

There was general agreement from most of the respondents to the Scottish Government consultation with the recommendation to more clearly define “person serving with the police”. A subsequent question around this focused only on police officers, with agreement from respondents that officers who retired, resigned and were off-duty should be able to be investigated. No questions were asked about when this should also apply to civilian members of staff.

A further statement within the Angiolini Review was that:

The Review received evidence that this sub-section [section 33A(b)(ii) of the 2006 Act] is ambiguous in that it is not clear whether the provision encompasses the death of a serving police officer. The 2006 Act should be amended to put this beyond doubt.

Most respondents to the Scottish Government consultation agreed that this clarification was required, although there was less consensus among organisational respondents.

While not explicitly referenced within the Policy Memorandum or Explanatory Notes, the Scottish Government advised that there was not a need to change the legislation as it could already apply where the person who died was a person serving with the police. The Bill does clarify that this person serving with the police could have been on or off duty at the time of the death.

Section 10 – Complaints made by persons serving with the police

Provision in the Bill

Section 10 provides clarification around who can make a complaint to include those who are currently defined as people serving with the police (i.e. police officers and civilian members of staff with Police Scotland and the SPA) where the matter being complained of affected them in their personal capacity.

It also amends what is defined as a “relevant complaint”, adding that this does not cover any complaint which affected them in their capacity as someone serving with the police. It also clarifies that this does not cover something that they witnessed but did not directly affect them, whether in their personal capacity or not.

Background

The Angiolini Review recommended (Preliminary Report Recommendation 30) the need for clarity around the definition of “members of the public” in terms of who can make a complaint to the PIRC. This would provide clarity around those who are currently defined as people serving with the police being able to make complaints about incidents that adversely affect them in their personal capacity.

The majority of the respondents to the Scottish Government consultation agreed with this recommendation. Respondents also agreed that it should be made clear that it applies to officers who are off-duty at the time of the incident. No specific questions were asked about when it should apply to civilian members of staff.

Section 11 – Complaint handling reviews

Provision in the Bill

Section 11 amends the circumstances in which the PIRC can carry out a complaint-handling review. The amendments would allow the PIRC to do this without a request having to be made by the complainer, or by Police Scotland or the SPA, as long as it was in the public interest to carry out this review.

It also enables the PIRC to make recommendations in its review of a complaint and requires the SPA or Police Scotland to respond to these recommendations in terms of what they plan to do, have done, or explaining why nothing has been done.

Background

The Angiolini Review recommended (Preliminary Report Recommendation 22) that the PIRC should have the power to make recommendations following complaint-handling reviews, and that a duty should be placed on Police Scotland to comply with these. This was to address the concern as outlined in the Policy Memorandum (para 116):

Whilst the PIRC does make recommendations as set out above, there is no statutory basis for the making of these recommendations. Dame Elish stated that the PIRC has raised concerns that too many of these non-statutory recommendations were not being implemented, therefore the PIRC was increasing the use of reconsideration directions to attempt to encourage compliance. This, in turn, has resource implications for Police Scotland. To combat this, Dame Elish supported suggestions by the previous PIRC that the PIRC should have a statutory recommendation making power, with supporting obligations upon the Chief Constable.

While the Angiolini Review refers only to placing obligations on the Chief Constable, the Bill places this requirement on the “appropriate authority”, which could be Police Scotland or the SPA.

Most of the Scottish Government consultation respondents agreed with the recommendation in the Angiolini Review that the ability of the PIRC to make recommendations should be placed in statute. Half of the respondents felt this should follow both a review and an audit of police complaints. Of the other respondents, there was an almost even split between those who agreed it should only be following a review, those who disagreed with this recommendation entirely and those who didn't know. Organisations were mostly split between it following both a review and audit (including the SPA and the PIRC) and that they should not have this ability at all. Those who disagreed included the Scottish Police Federation, the Association of Scottish Police Superintendents and Police Scotland. Police Scotland responded that they felt the existing legislation and regulatory powers were sufficient and that any further statutory power for the PIRC “would adversely impact the operational independence of the Office of Chief Constable”.

The vast majority of survey respondents also agreed that there should be a duty on Police Scotland to respond to these recommendations, whether following a review or audit of police complaints handling. This question was only asked in terms of Police Scotland rather than also including the SPA.

When asked whether Police Scotland or other policing bodies should be required to act on the recommendations most respondents agreed, though these responses were split between whether this should be with no restrictions (most individuals agreed with this) or whether they should act unless there was an overriding operational or practical reason not to (most organisations agreed with this).

Section 12 – Call-in of relevant complaints

Provision in the Bill

Section 12 provides for the ability of the PIRC to call-in complaints in certain circumstances and outlines the processes around this.

Calling-in a complaint means the PIRC can take over the consideration of a complaint, rather than simply reviewing how it has been handled, with the option of issuing a reconsideration direction for the complaint to be looked at again by the policing body it relates to.

The PIRC would be able to call-in complaints in the following circumstances:

where the PIRC determines, following a complaint handling review (CHR) that the complaint is to be considered by the PIRC

when requested to do so by the authority to which the complaint was made

of the PIRC's own volition or at the request of the complainer, and following consultation with the authority which dealt with the complaint initially, if the Commissioner has reasonable grounds to believe that the appropriate authority is not handling, or has not handled, the complaint properly and it is in the public interest for the Commissioner to consider the complaint.

This section also outlines the steps the PIRC must take after calling-in and taking over the consideration of a complaint, which are similar to those outlined in the complaint-handling reviews section (for example, make statutory recommendations and place an obligation on the appropriate authority to respond to them).

Background

The Angiolini Review recommended that the PIRC be able to “call-in” complaints (Recommendation 37). The Review referred specifically to Police Scotland and that this would mean that the PIRC could take over the investigation of a complaint where there was sufficient evidence Police Scotland had not dealt with it properly, compelling evidence was provided of this failure, and where it was assessed to be in the public interest to re-investigate.

The Policy Memorandum (para 126) states that:

The Bill clarifies that PIRC can call in a complaint at any stage in the CHR, or reconsideration, and provides the Commissioner with the ability to review the complaint handling following a request from the complainer before deciding whether to call it in. This aims to address any concerns from the complainer around a lack of progress in the handling of their complaint and ultimately improve the efficiency of the process.

While the Angiolini Review referred to this change being in reference to Police Scotland only, the Bill covers complaints made to Police Scotland and the SPA. This ensures that the PIRC can call-in complaints against all ranks of police officer, and can call-in a complaint as well as carry out a complaint handling review for both Police Scotland and the SPA.

Most of the respondents to the Scottish Government consultation agreed that the PIRC should be given this extra power to call-in complaints.

When asked a subsequent question about the circumstances in which the PIRC should be able to investigate a complaint, this was in terms of Police Scotland only. Most respondents agreed that the PIRC should be able to investigate a complaint against Police Scotland given each of the circumstances outlined in the Angiolini Review recommendation:

if the complainer provides compelling evidence of a failure on the part of Police Scotland

if the PIRC assesses that it would be in the public interest to carry out an independent re-investigation

if there is sufficient evidence that Police Scotland has not dealt with a complaint properly.

Section 13 – Review of arrangements for investigation of whistleblowing complaints

Provision in the Bill

Section 13 requires the PIRC to audit the SPA and Chief Constable's arrangements for the investigation of information provided in whistleblowing complaints. The PIRC would also be able to make recommendations or give advice on the arrangements for handling such complaints.

Background

The Angiolini Review considered that the PIRC should have an audit role in relation to whistleblowing reports.

The vast majority of respondents to the Scottish Government consultation agreed that concerns which have been raised about wrongdoing within policing in Scotland should be audited by an independent organisation. Almost all also agreed that people working in Police Scotland and the SPA should be able to raise their “whistleblowing concerns” with an independent oversight organisation. For both questions, respondents were almost evenly split on whether this oversight organisation should be the PIRC or another independent organisation, with organisations mostly agreeing it should be the PIRC and individuals another body. Where further comments were provided, there were concerns that the PIRC is not sufficiently impartial for the audit role, including a concern that the PIRC employs people with a police background.

The Angiolini Review did not consider that the audit function alone would be sufficient to give whistleblowers confidence in reporting concerns. It also recommended that the PIRC should be added to the list of prescribed persons in The Public Interest Disclosure (Prescribed Persons) Order 2014 (Recommendation 20). This is a reserved piece of legislation and the Scottish Government do not address this point within the Policy Memorandum published along with the Bill.

Section 14 – Investigations involving constables from outwith Scotland

Provision in the Bill

Section 14 would extend the powers of the PIRC to allow them to investigate serious incidents or allegations of criminality involving police officers of forces from other parts of the UK who are carrying out policing functions in Scotland.

This would happen, depending on the situation, at the request of the Chief Constable or Chief Officer of either Police Scotland or the relevant force of the officer involved, or when directed by the appropriate prosecutor in respect of allegations of offending.

Background

The Angiolini Review recommended an extension of the PIRC's function in terms of being able to investigate officers from forces operating in the rest of the UK (Recommendation 81).

The Policy Memorandum (para 140) notes that:

Introducing a legislative solution to these cross-jurisdictional issues will help to ensure the integrity of independent investigation in line with the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) obligations and avoid the potential for double-handling.

Of those who provided views on this question in the Scottish Government consultation, most agreed with the recommendation to address the existing gap in cross-jurisdictional investigations. in the rest of the UK. Of the respondents that disagreed, some suggested that it should be the responsibility of the jurisdiction the officer is from rather than the PIRC having this power to investigate.

Section 15 – Review of, and recommendations about, practices and policies of the police

Provision in the Bill

Section 15 would extend the powers of the PIRC to enable them to review practices and policies of Police Scotland and the SPA generally, and not just in relation to a particular incident or audit function, if deemed to be in the public interest. It also makes new provision for the SPA and the Chief Constable to respond to recommendations made to them by the PIRC and the processes around this.

Section 15 further contains provision allowing the PIRC to make recommendations in relation to the arrangements for complaints handling and investigation of information in whistleblowing allegations, and for recipients to respond.

Background

The Angiolini Review recommended that the PIRC should be able to review Police Scotland's practices and policies if in the public interest (Recommendation 38).

The Policy Memorandum (para 150) states that:

This will reduce the previous PIRC practice of issuing statutory reconsideration directions to increase compliance, and the significant resource implications on Police Scotland to implement them.

A reconsideration direction requires the policing body to look at the complaint again in full.

While Police Scotland is referenced specifically here the amendments in the Bill would apply to Police Scotland and the SPA.

Respondents to the Scottish Government consultation were asked about whether they felt the PIRC should be able to review practices and policies of Police Scotland (the SPA was not mentioned). The majority felt they should, though some did feel there should be limits or restrictions to these powers.

A number of police organisations, including HM Inspectorate of Constabulary in Scotland (HMICS), Police Scotland and the SPA noted that the ability to review police practices and policies is already a function of HMICS. The Policy Memorandum addresses this issue by stating that the PIRC and HMICS must collaborate to decide who is the most appropriate body to review any practice or policy so that there is not unnecessary duplication.

Section 16 – Provision of information to the PIRC

Provision in the Bill

Section 16 provides for the Scottish Ministers to make regulations allowing the PIRC to access Police Scotland's conduct and complaints electronic storage system, or an SPA electronic storage system. This would be by creating a legal obligation on the SPA or the Chief Constable to provide access to the system.

Background

The Angiolini Review recommended that the PIRC should be able to access the Police Scotland conduct and complaints database (Recommendation 13).

The Policy Memorandum (para 155) outlines how this legislative change would address issues within the current complaints process and public confidence in the system.

Providing the PIRC with a power to have direct and supervisory access to the complaints database, as recommended in Dame Elish's Review, will allow the investigation process to be truly independent, with the intention of improving transparency and public confidence in the system. It will improve timeliness and efficiency as it will allow the PIRC staff instant access to the database at their own place of work, saving travel time and delays that are currently experienced to co-ordinate access in its current format.

Almost all of the respondents to the Scottish Government consultation agreed that the PIRC should be able to access the Police Scotland complaints and conduct database remotely. However, the Scottish Police Federation disagreed with this recommendation, stating that it was a Police Scotland database and access should not be given in this way. While Police Scotland did agree, they stated that they did not feel legislation needed to be put in place to achieve this.

Financial costs

The estimated costs arising from the changes within these sections of the Bill are outlined in the Financial Memorandum.

These apply to costs that will be incurred by the PIRC due to their increased powers to call-in complaints and carry out reviews of practices and policies which would require further staff. This is costed at a recurring cost of £376,384.

IT licences to enable the PIRC to access Police Scotland's complaints database are costed at £15,000 for a one-off set-up cost and an ongoing licence of £10,000.

In Police Scotland's written response to the call for views on this Bill's Financial Memorandum by the Finance and Public Administration Committee, they state that costs they believe they will incur in terms of the PIRC being able to investigate allegations of criminality where officers are off-duty have not been included. The Financial Memorandum states that the Scottish Government does not believe that this clarification around off-duty allegations will result in a significant change in the amount of cases the PIRC handles so does not expect significant additional costs as a result.

Governance of the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner

Section 17 – Advisory board to the Commissioner

Provision in the Bill

Section 17 of the Bill would amend the Police, Public Order and Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2006. It is concerned with improving the scrutiny, accountability and transparency within the PIRC through requiring them to establish a statutory advisory board.

The board would advise on the corporate governance and administration of the PIRC. Members of the advisory board would be appointed by Scottish Ministers.

Background

The Angiolini Review recommended that a statutory board be created for the PIRC (Recommendation 34).

Around two thirds of respondents to the Scottish Government consultation supported this recommendation, though responses from organisations were almost equally split on this question. The PIRC itself disagreed that this was necessary, stating: “Given the size and budgetary provision of the PIRC, it is submitted that the requirement for a Statutory Board would be disproportionate”, and citing the examples of the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service and the Scottish Prison Service who do not have statutory boards.

The Angiolini Review also recommended that the PIRC be re-designated as a Commission, with one Police Investigations and Review Commissioner and two Deputy Commissioners. Most respondents to the Scottish Government consultation agreed with this recommendation. This has not been taken forward in the Bill.

The Scottish Government outline their reasons for this in the Policy Memorandum (paras 171 and 172). They state that they believe that “the policy intention to ensure a greater degree of expert and balanced support for the Commissioner would be better met through the appointment of a Statutory Board that has relevant expertise”. The PIRC have also already appointed “new permanent staff members with relevant expertise, including legal expertise, to fulfil deputy functions, and to support the work of the Commissioner” following the preliminary report of the Angiolini Review.

The Policy Memorandum goes on to state that the Scottish Government will continue to monitor the structure of the PIRC and if required can make further changes through the Public Services Reform (Scotland) Act 2010.

The Angiolini Review also recommended that the PIRC should be accountable to the Parliament for non-criminal matters (Recommendation 35). This is not being taken forward in the Bill. In the Scottish Government's response to a written parliamentary question (S6W-20883) on whether there were any recommendations in the Angiolini Review that it anticipated would not be implemented, they advised that Recommendation 35 would not and stated the following:

This is because current provisions within the Police, Public Order and Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2006 already provide appropriate and proportionate lines of accountability to Scottish Ministers, and in turn to the Scottish Parliament. This is in line with the governance and accountability arrangements in place for other office-holders the Parliament oversees.

Financial costs

The estimated cost of this advisory board is outlined in the Financial Memorandum as £2,750 per annum.