Report from a partial evaluation of the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016

This report comprises a partial evaluation of the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016. It was commissioned by the Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments (SPPA) Committee and undertaken by the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe). The report provides background on the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016, sets out the findings of the evaluation, and suggests areas for further consideration based on those findings.

Executive Summary

This partial evaluation of the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016 was commissioned by the Scottish Parliament Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments (SPPA) Committee (Session 6), and undertaken by the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) between March and September 2023. The aim of this partial evaluation is to support the SPPA Committee's consideration of whether the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016 is fulfilling its policy objectives of increasing the transparency of lobbying activity.

The partial evaluation was structured around three research questions agreed by the SPPA Committee.

1. How does the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016 compare with international best practice and comparator countries?

2. How is the reporting duty under the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016 operating?

3. How is the Lobbying Register used and by whom?

In support of the three research questions, SPICe analysed the statutes governing lobbying in Scotland to assess how the provisions for lobbying disclosure compare with best practice standards. A full analysis of returns on the Lobbying Register and a survey of registered organisations was conducted to assess how the reporting duty in the Act is operating. Finally, SPICe surveyed users of the Lobbying Register to understand who uses the Lobbying Register and for what purposes.

The findings of the partial evaluation indicate there is sufficient evidence to suggest that the Act is delivering on its policy objectives of increasing the transparency of lobbying activity. However, the evidence in favour of increased awareness of lobbying activity is more limited.

The findings in support of increased transparency include the following.

Scotland was rated higher than average for its provisions for lobbying disclosure and public sector transparency. The lobbying disclosure system on its own, as provided for by the Act, was rated as a medium-robustness system.

The assessments of the provisions of the Act, text analysis of the Lobbying Register content, and responses to a survey of registered organisations, indicate that the Lobbying Register allows substantive information on regulated lobbying activities to be recorded and completed to a consistent standard.

A range of organisations in different sectors can access legislators and are increasing their engagement with legislators. There is no suggestion that the Act has deterred organisations from sharing expertise, seeking support for causes, and engaging in a wide range of activities that could be considered regulated lobbying.

A survey of Lobbying Register users indicated that registered organisations, members of the public and members of the media all use the Lobbying Register to varying extents.

The findings from across the three research questions indicate areas of the Act - in its provisions and operation in practice - where the delivery of transparency outcomes could be improved. These areas are summarised as follows.

The provisions are manageable for most organisations but the definition of regulated lobbying may be biased towards capturing the activity of campaigning and public awareness organisations. The extent to which broader information on lobbyist contacts with elected representatives and public officials is captured may warrant further consideration.

The reporting period of six months is longer than time periods considered best practice for disclosing lobbying activities. The shortening of the timescale and moving to harmonised reporting dates may improve the transparency outcomes of the Act by making it easier to identify the lobbying meetings that may have affected policy and legislation.

There may be an imbalance between the extent to which the provisions allow for transparency, and the eventual engagement with the Lobbying Register by members of the public. Public awareness of, and public engagement with, the Lobbying Register may warrant consideration in order to ensure that the Act's transparency outcomes realise the secondary objectives of facilitating understanding of lobbying activity and improved public scrutiny of the Government and Parliament.

Background to the partial evaluation of the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016

Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016

The Scottish Government introduced the then Lobbying (Scotland) Bill in the Parliament on 29 October 2015.1 The Scottish Government’s stated aim for the Bill (as put forward in the Policy Memorandum to the Bill) was:

to increase transparency of direct face to face paid lobbying (communication) with MSPs and Ministers. Improved transparency will facilitate improved awareness and understanding of lobbying activity, improved public scrutiny of the work of the Parliament and Government, improved public accountability and trust in that work and improved outcomes. In this context paid lobbying is used in the sense of a consultant paid to lobby or individuals in commercial or other organisations who lobby as part of their paid work.

The Scottish Parliament. (2015, October 29). Lobbying (Scotland) Bill. Retrieved from https://archive2021.parliament.scot/S4_Bills/Lobbying%20(Scotland)%20Bill/SPBill82PMS042015.pdf [accessed 4 September 2023]

The Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016 (“the Act”) received Royal Assent on 14 April 2016 and came into force on 12 March 2018.3 The Act provides for a public lobbying register in which all instances of regulated lobbying can be recorded.

Section 1 of the Act sets out that a person is engaging in regulated lobbying if they make a face-to-face oral communication (including by British Sign Language or 'otherwise made by signs') on a matter of Government or Parliamentary functions, and for which they are paid, to any of the following persons:3

Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs);

members of the Scottish Government (including Scottish Law Officers and junior Scottish Ministers);

Scottish Government special advisers; and

the Permanent Secretary to the Scottish Government.

Any communication that is not made face-to-face (or on a video-conferencing platformi) is not regulated lobbying.3 Written correspondence, phone calls (without video-conference functionality), and direct messages on social media are not regulated lobbying in accordance with the Act.3

Some in-person oral communications are not lobbying for the purposes of the Act. These exemptions are listed in the Schedule to the Act. An exemption applies when:8

an individual is raising an issue on their own behalf;

the face-to-face lobbying was with an MSP who is not a member of the Scottish Government but represents the constituency or region in which the registered organisation is ordinarily based or operating;

the individual is unpaid by the registered organisation;

the registered organisation has fewer than 10 full-time employees, and the individual conducting the face-to-face lobbying is not communicating on behalf of a third party;

the face-to-face lobbying takes place during formal parliamentary proceedings or as communication required by statute or another rule of law;

the communication is made in response to requests for factual information or views on a topic from MSPs, the Scottish Government, Law Officers, Permanent Secretary, or Special Advisers;

the communication is made by a political party, for the purposes of journalism, or for discussing terms and conditions of employment;

the individual making the communication is exempt due to their public role or the role of the organisation that they represent.

Part 2 of the Act provides that the Clerk of the Scottish Parliament must establish and maintain a lobbying register.3 The 'Lobbying Register' is a public register of lobbying activity. It is operated by the Scottish Parliament.

The Clerk of the Scottish Parliament along with the Commissioner for Ethical Standards in Public Life in Scotland have responsibilities for oversight and enforcement of the Act.3 The Clerk of the Scottish Parliament has delegated the requirement to monitor compliance to the Lobbying Registrar (and the Registrar's team, referred to as the 'Lobbying Register team').8

The Lobbying Register must contain information on three categories of persons - active registrants, inactive registrants and voluntary registrantsii.

Any organisation which lobbies, within the section 1 definition of “regulated lobbying”, those individuals holding the offices covered by the Act (e.g., MSPs and Scottish Government Ministers) must register and make returns to the Lobbying Register.3 Registered organisations are required to detail certain information by making an information return on each instance of regulated lobbying undertaken in a six month period.3 Information returns must include:

the details of who was lobbied and their role (e.g., Minister, MSP);

the individual who carried out the lobbying activity;

when and where the regulated lobbying took place; and

a description of the lobbying and the intended purpose.3

The Lobbying Register team can ask for further information or clarification on submitted returns. If a registered organisation has not undertaken regulated lobbying in a six month period, then it must make a "nil" return.3

Where an organisation decides to stop engaging in regulated lobbying and wishes to be labelled as 'inactive,' it must formally apply to the Lobbying Register to be granted this status.3 Any outstanding returns (including nil returns) must be submitted to the Lobbying Register up to the date of the request before an organisation is granted inactive status. Returns submitted to the Lobbying Register before the organisation is made inactive remain published on the Lobbying Register.

If an organisation is reported for failing to register when it has engaged in regulated lobbying, then the Lobbying Registrar can ask for information and issue an Information Notice.3 The Commissioner for Ethical Standards in Public Life in Scotland ("the Ethical Standards Commissioner") is responsible for investigating complaints of alleged breaches.3 The Act also makes provision for penalties, fines, and criminal offences where there is a failure to provide accurate information or a failure to register.3

Part 4 of the Act makes provision for Parliamentary guidance on the operation of the Lobbying Register, public awareness of the Act, and a code of conduct for registered lobbyists.3 The Act also requires that guidance on the communications that are exempt from the Act (as listed in the Schedule and explained above) is provided.8

Section 50 review of the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016

Section 50 of the Act provides that a committee of the Parliament must carry out a review of the operation of the Act during the two-year period after the provision on the duty to register came into force.1 This review was carried out by the Session 5 Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny (PAPLS) Committee. The Act provides that the Committee must:

The Scottish Parliament Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny Committee (Session 5). (2021). Post-legislative scrutiny: The Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016. Retrieved from https://bprcdn.parliament.scot/published/PAPLS/2021/3/22/79252553-8fd1-49af-acc0-66899fb52338/PAPLSS052021R3.pdf [accessed 16 October 2023]

take evidence from such persons as it considers appropriate;

draft a report;

consult on the draft report and any recommendations it makes; and

prior to publishing its final report, have regard to any representations made to the committee on the draft report, and its recommendations.

The PAPLS Committee published its final report 'Post-legislative scrutiny: The Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016' (“the PAPLS report”) on 22 March 2021.2

Section 50 of the Act sets out several areas that the review should consider and make recommendations on.1 The PAPLS report summarised those provisions of the Act:

It provides that a final report may, in particular, make a recommendation to extend the circumstances in which regulated lobbying is deemed to have taken place. This can be done by changing:

the list of people who are considered to be lobbied in a regulated way;

the way in which a communication considered to be regulated lobbying is made.

The Act provides that the Committee may also recommend whether there should be changes to the circumstances in which a person undertaking regulated lobbying is required to provide information, to be included on the Lobbying Register, about costs incurred by the person when engaging in regulated lobbying.

The Scottish Parliament Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny Committee (Session 5). (2021). Post-legislative scrutiny: The Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016. Retrieved from https://bprcdn.parliament.scot/published/PAPLS/2021/3/22/79252553-8fd1-49af-acc0-66899fb52338/PAPLSS052021R3.pdf [accessed 16 October 2023]

The PAPLS Committee section 50 review looked at the operation and impact of the Act to date, options for legislative reform, and whether non-legislative changes could improve the operation of the Act.2 The PAPLS Committee’s final report recommended that the Scottish Government undertake a full and independent impact assessment examining the operation of the Act to inform a consultation on proposed legislative changes.2

The PAPLS Committee’s conclusions, summary of evidence, and recommendations for an impact assessment are set out in paragraphs 59 to 66 of its report.2 The Committee's conclusions indicated there was:2

diversity of opinion on the necessity of the legislation, the scope of the legislation, the accessibility of the Lobbying Register, and whether the Act has achieved its transparency objectives;

differing views on the administrative burden for registered organisations to record lobbying activity; and

positive reception that compliance with the Act appears to be high but uncertainty over whether it could unearth instances of poor practice and undue influence.

The PAPLS Committee report also recommended that an impact assessment should be able to inform any further extension of the scope of the Act.2 In addition, the Committee recommended that the impact assessment includes the following objectives:2

an examination, through the collection and analysis of appropriate data and engagement with end users of the Lobbying Register, of whether the Act has delivered its broader transparency and public accountability objectives as set in the Policy Memorandum;

full analysis of lobbying returns with identification of any variations in the way in which organisations are undertaking their reporting duties (and the reasons for this); and

full and comprehensive analysis of the impact of the Act on registered organisations.

The then Minister for Parliamentary Business and Veterans, Graeme Dey MSP, indicated the Scottish Government's view that it was for the Parliament to undertake or commission the impact assessment and make any recommendations for changes to the Act by means of a Committee Bill. 12

The Convenor of the Session 6 Public Audit Committee wrote to the Convenor of the Session 6 Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments (SPPA) Committee to highlight the post-legislative scrutiny of the Act.13 The Convenor of the Public Audit Committee asked that the SPPA Committee consider following up on the recommendations from the post-legislative scrutiny since lobbying falls within the remit of the SPPA Committee.13

Scope of the evaluation

The Session 6 SPPA Committee agreed to ask the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) to undertake a partial evaluation study of the Act on 23 March 2023.1

The PAPLS report set out that the aim of the evaluation study should be to establish whether the Act has delivered its transparency and public accountability objectives (as articulated in the Policy Memorandum to the Bill).2 The SPPA Committee agreed a mixed-methods research approach in support of this aim structured around three research questions.

1. How does the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016 compare with international best practice and comparator countries?

2. How is the reporting duty under the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016 operating?

3. How is the Lobbying Register used and by whom?

To address the first research question, SPICe analysed the statutes governing lobbying in Scotland using two published questionnaires. The scores from these questionnaires were then used to quantitatively appraise the statutes across various metrics, including transparency, public access, and oversight of registration systems. The resultant scores from this analysis are compared with published scores from the respective systems in the United Kingdom and Ireland to gauge how the Scottish Act compares to countries with similar standards and transparency systems.

To address the second question, a full analysis of returns on the Lobbying Register was conducted to assess how the reporting duty in the Act is operating. This was supported by a text analysis of lobbying returns to assess common topics and themes present in regulated lobbying activity. Representatives from registered organisations were also surveyed for their assessments of the administrative effort involved in complying with the reporting duty.

To assess the final question - how the Lobbying Register is used - SPICe administered a short survey on the Lobbying Register homepage. This was to gain an understanding of the types of people accessing the Register and for what purposes. One of the secondary aims of this exercise was to assess the extent to which members of the public access the Lobbying Register.

How does the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016 compare with international best practice?

Key findings: How does the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016 compare with international best practice?

The Act demonstrates moderate performance in enhancing lobbying transparency.

Provisions supporting the potential accessibility of the Lobbying Register and effective oversight by the Lobbying Register team taken to be strengths of the lobbying disclosure system.

The broader public transparency framework in Scotland, including the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 and the Scottish Ministerial Code, contributes positively to fostering transparency of public sector contact with lobbyists.

Statutory and voluntary codes of conduct for various stakeholders support a positive culture of lobbying and public transparency in Scotland.

Areas for consideration

Expansion of the definition of regulated lobbying to encompass written and oral communications in line with international standards.

Proactive disclosure of senior public officials' and elected representatives' contacts with lobbyists.

The absence of requirements to record lobbying expenditure on the Lobbying Register.

Changes to reporting requirements including shorter reporting intervals and harmonisation of reporting dates across registered organisations.

The absence of revolving door provisions and statutory cooling-off periods in the Act.

Assessments of lobbying and transparency provisions

SPICe selected two assessments to quantitatively measure the performance of regulations governing lobbying and related transparency mechanisms in Scotland.i The two indexes were:

The Transparency International Assessment Questionnaire ("the TI Assessment")1

The Center for Public Integrity Lobbying Index (also known as the CPI Index or “Hired Guns” Index).2

The TI Assessment is based on 19 countries in the European Union (including the UK as the assessment predates EU Exit).3 The CPI Index is based on state legislatures in the United States and has been extended to various jurisdictions globally to assess, improve and scrutinise lobbying regulations.2

The aim of this analysis is to identify the Act's relative strengths and areas where the transparency outcomes of the legislation could be enhanced. Each assessment provides an overall score of the strength and stringency of the law (or laws) that govern regulated lobbying. Individual questions, referred to as indicators, mark where specific aspects of a lobbying system sit relative to the assessment's view of best practice.ii A secondary objective of this analysis is to evaluate specific areas where the PAPLS Committee indicated further consultation and exploration was desired. These areas include:5

expanding the scope of regulated lobbying to encompass additional types of communications (e.g., including all written and oral communications);

extending regulatory coverage to other groups (e.g., senior civil servants);

enhancing transparency through the publication of diaries and calendars of those who are lobbied;

inclusion of expenditure or costs of lobbying on the Lobbying Register;

making revisions to the exemptions related to "regulated lobbying"; and

amending reporting timescales (e.g., to report on a quarterly basis).

Comparative rating of Scotland, the United Kingdom and Ireland's lobbying and transparency provisions

To provide further context on the transparency outcomes of the Act, summaries and assessment scores of the lobbying laws in the United Kingdom and Ireland are included in this evaluation report. The UK, Ireland and Scotland have similar governance structures for ensuring standards in public life. More specifically, all three have legislation (or related non-legislative mechanisms) overseeing:

standards of conduct for elected and appointed public officials;123

regulation of political parties and elections;45

regulation of expenditure of public funds to political parties;45

freedom of information;8910

transparency of lobbying of elected representatives or public officials.11121314

The aim of this comparative rating is to assess how Scotland's system for lobbying transparency compares to similar legal and political systems. The following publications were used to obtain comparison scores for UK and Ireland on the selected measures of lobbying transparency:i

The Transparency International Assessment Questionnaire

Mulcahy, S. (2015) Lobbying in Europe: Hidden influence, privileged access.15

The Center for Public Integrity Lobbying Index

Keeling, S., Feeney, S. & Hogan, J. (2017). Transparency, transparency: comparing the new lobbying legislation in Ireland and the UK.16

Lobbying laws in the United Kingdom and Ireland

This section provides an overview of the lobbying transparency mechanisms in the UK and Ireland.

Transparency International assessment for lobbying transparency

The Transparency International (TI) Assessment provides a framework to examine the current landscape of lobbying regulations, policies, and practices in national and sub-state regions. It comprises of 65 indicator questions categorised into three dimensions (or themes): transparency, integrity, and equality of access. These dimensions are nuanced further by 10 sub-dimensions (see Table 1). A score of 0 (no points), 1 (partial points), or 2 (full points) is assigned to each indicator depending on the available legislation and practices in the country being assessed (in this case, Scotland). The scores from each indicator can then be added together to obtain an overall score and a breakdown of performance on the three dimensions and 10 sub-dimensions. Percentage scores are presented to allow for comparison of overall scores, dimension scores, and sub-dimension scores.

| Transparency | Integrity | Equality of Access |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Access to public information, via freedom of information (FOI) regimes | 5. Pre and post-employment restrictions to reduce risks associated with the revolving door between the public and private sector | 9. Consultation and public participation mechanisms |

| 2. Lobbyist registration systems | 6. Codes of conduct for public sector employees | 10. Expert and advisory group composition and policies |

| 3. Oversight of registration system and sanctions for non-compliance | 7. Codes of ethics for lobbyists | |

| 4. Pro-active disclosure by public officials, including legislative footprint | 8. Self-regulation by lobbyist associations |

Summary of scores from the Transparency International Assessment

The Act and the public transparency framework in Scotland obtained an overall score of 64% (or 78 out of 122 points) on the TI Assessment. TI reported in 2015 that countries assessed on this measure had an average score of 31%.1i

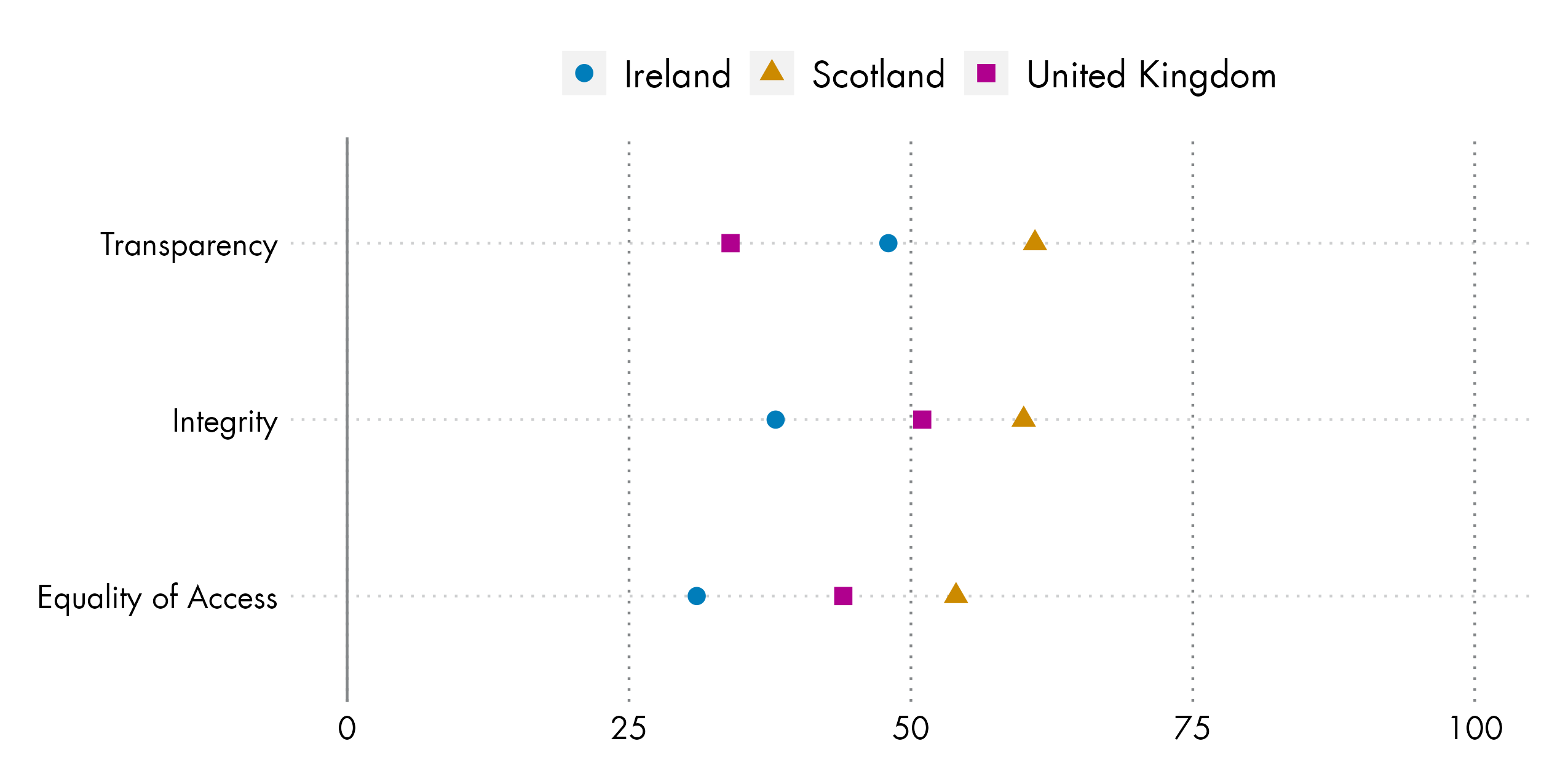

Figure 1 shows the percentage score given for Scotland on each dimension of the TI Assessment. The regulatory and standards framework for lobbying disclosure in Scotland was assessed as better than comparator countries, the UK and Ireland, on transparency, integrity, and equality of access.

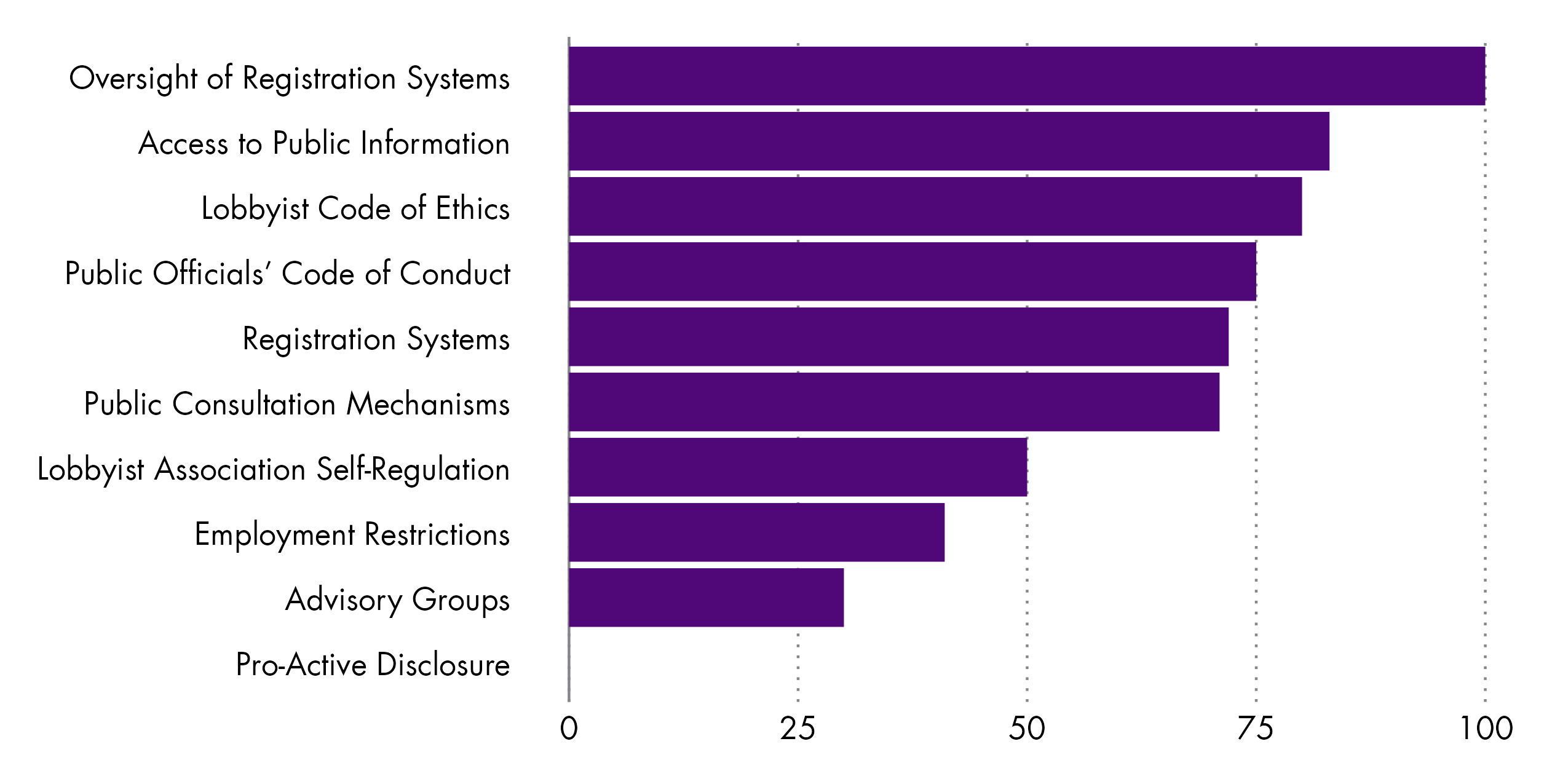

Figure 2 shows the percentage score given for the regulatory framework in Scotland on each sub-dimension of the TI Assessment. The Act and related legislation performs particularly well on indicators assessing the oversight of registration systems (i.e., the Lobbying Register) and indicators assessing access to public information (e.g., Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002). The Act performs poorly on the sub-dimension assessing the extent to which elected representatives and public officials (e.g., civil servants, parliamentary officials) are required to pro-actively disclose lobbying and stakeholder contacts. For example, the dimension assessed whether there are requirements for legislators to publish diaries and whether there are requirements for public officials to produce annexes to legislation on the stakeholder engagement undertaken in the legislative process.

The complete set of scores on each question sorted by dimension and sub-dimension can be found in Annex 1.1.2.

Analysis of dimensions: transparency, integrity and equality of access

The analysis of dimensions identifies and explains the legislation, policies and practices (or lack thereof) underpinning the scores for Scotland on each dimension and sub-dimension of the TI Assessment.

Transparency

The transparency dimension assesses the extent to which members of the public can access information held by public bodies and information held about lobbying activities.1 The regulatory environment in Scotland received a score of 61% on this dimension compared to an average (based on 19 other European countries) of 26%. The UK and Ireland received transparency scores of 34% and 48%, respectively.1

The following sections appraise and explain the scores given for each transparency sub-dimension. The four transparency sub-dimensions are:

access to public information;

lobbyist registration systems;

oversight of registration systems;

pro-active disclosure and legislative footprint.

Integrity

The integrity dimension assesses the extent to which the lobbying transparency system sets and enforces behavioural standards for lobbyists and lobbying targets.1 Scotland received a score of 60% on this dimension compared to an average (based on 19 other European countries) of 33%. The UK and Ireland received integrity scores of 51% and 38%, respectively.1

The following sections appraise and explain the scores given for each integrity sub-dimension. The four integrity sub-dimensions are:

employment restrictions;

public officials' code of conduct;

lobbyist code of ethics;

self-regulation by lobbyist associations.

Equality of access

The equality of access dimension assesses the extent to which there is diverse participation in the policymaking process and whether there is evidence that ideas are contributed by a wide range of interests.1 Scotland received a score of 54% on this dimension compared to an average (based on 19 other European countries) of 33%.1

The following sections appraise and explain the scores given for each equality of access sub-dimension. The two sub-dimensions are:1

public consultation mechanisms

advisory groups.

Center for Public Integrity Analysis of Lobbying Disclosure Laws

The CPI Index covers similar dimensions to the TI Assessment. However, there are key differences. The share of scores in the CPI Index places more emphasis on disclosing spending on lobbying and less emphasis on the wider standards systems (e.g., codes of conduct for public officials and the composition of advisory groups). The CPI comprises of 48 indicators categorised into eight dimensions:

definition of lobbyist;

individual registration (i.e., whether lobbyists have to register and submit returns);

individual spending disclosure (i.e., whether individual lobbyists have to disclose spending on lobbying);

employer spending disclosure (i.e., whether consultant lobbyists have to disclose spending on lobbying);

electronic filing of lobbying activity;

public access to a registry of lobbyists;

enforcement of lobbying disclosure laws;

revolving door provisions (i.e., restrictions on public officials seeking to carry out lobbying activities following vacation from office).

Summary of scores from the Center for Public Integrity Analysis of Lobbying Disclosure Laws

The Act obtained an overall score of 35% on the CPI Index. This means the provisions of the Act are categorised as a lobbying system with medium robustness.i1 The overall scores for the UK and Ireland are 33% and 37%, respectively.3

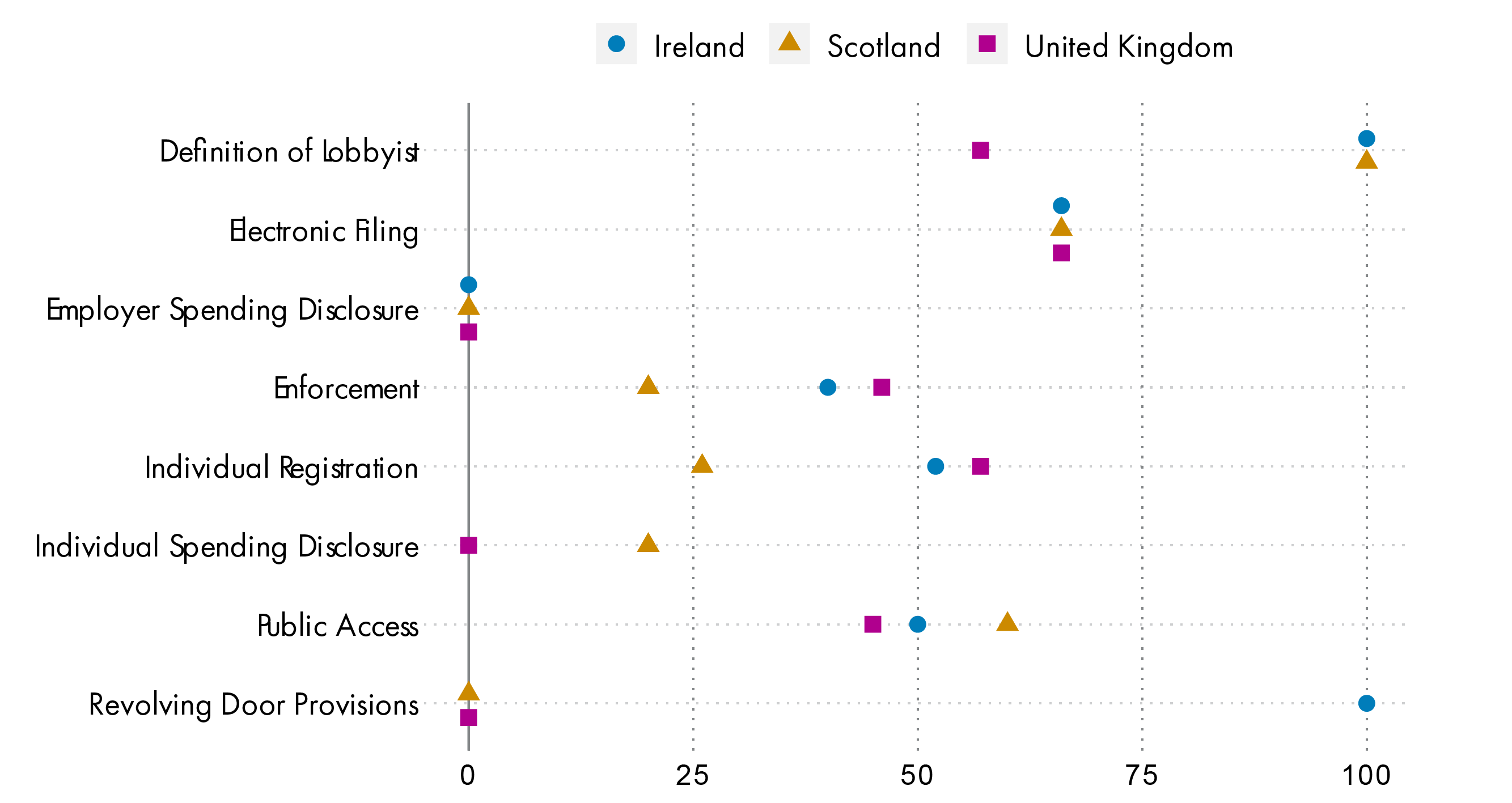

Figure 3 shows the percentage score given for Scotland on each dimension of the CPI Index. The regulatory framework for lobbying disclosure in Scotland performs well on indicators assessing the definition of lobbyist and was assessed as better than comparator countries, the UK and Ireland, on measures of public access.

Analysis of dimensions: essentials of lobbying disclosure laws

The following sections provide a complete analysis of the scores on each dimension of the CPI Index. The analysis identifies and explains the legislation, policies and practices (or lack thereof) underpinning the score for Scotland on each dimension.

Definition of lobbyist

The Act received a score of 100% on the dimension assessing the definition of lobbyist. The Act does not have a definition of lobbyist.1 However, full points were awarded because the indicator was relatively flexible and could be applied to the definition of regulated lobbying in the Act. Specifically, the indicators required the definition to apply when the lobbying target is a member of the Scottish Government and when the lobbying target is a member of the Scottish Parliament. Full points were also awarded because there is no exemption to the definition based on how much the lobbyist spends. Lobbyists must register and submit returns regardless of how much money is spent and regardless of whether any money is made from lobbying activities.1

Individual registration

The Act received a score of 26% for its provisions on registration of individual lobbyists.

The lower score on this dimension can be attributed to the practice of registering organisations on the Lobbying Register rather than registering all of the individuals conducting lobbying activities within an organisation. The registration and reporting timescales in the Act also did not meet the CPI Index standards. The CPI Index suggests that registration of a lobbyist (and any changes to registration) should happen within 15 days of the first instance of regulated lobbying and ideally before the lobbyist conducts any lobbying activities.1 This is in contrast to the Act which requires that individuals or organisations are registered within 30 days of conducting regulated lobbying.2

Areas where the Act performed well on this sub-dimension were:2

the lack of expiry date for registration on the Lobbying Register;

the requirement for lobbyists to apply to be made inactive if they stop engaging in regulated lobbying;

the use of nil returns to confirm no regulated lobbying took place;

the requirement to identify the type of lobbyists (e.g., consultant lobbyist) and the third party they are lobbying for.2

Partial points were awarded on an indicator assessing whether the subject matter of the lobbying communication is required in a return to the Lobbying Register. The inclusion of both a Bill number and a description of the subject matter in the communication is regarded as best practice on the CPI Index.5 There are many examples on the Lobbying Register where the names of Bills and Scottish Statutory Instruments are included in returns. However, this is not a mandated requirement and thus did not meet the full criteria for tracing legislative footprints.

The Act received no points for an indicator assessing whether photographs of lobbyists are available on the Lobbying Register. This may be an example where the scoring does not reflect the stringency of the provisions in Scotland. The requirement for photographs in the assessment is because some jurisdictions distribute sponsored access passes to lobbyists.1 There are arrangements for access passes to the Scottish Parliament for the media but this scheme is not available to lobbyists.7 The Association for Scottish Public Affairs also do not approve of such access, with its code of conduct stating that its members:

shall not allow any member of their organisation involved in public affairs work to hold a pass entitling them to gain access to local, national or devolved governments or parliaments, other than the holding of a temporary visitor’s pass.

Association for Scottish Public Affairs. (2023). Code of Conduct. Retrieved from https://aspa.scot/code-of-conduct/ [accessed 19 September 2023]

Individual spending disclosure

The individual spending disclosure dimension assessed whether individual lobbyists have to file lobbying expenditure reports and whether there are statutory provisions for reporting campaign donations. This dimension received a score of 21%.

This score was limited by the lack of provisions in the Act for disclosing spending on lobbying. Most of the points available came from provisions in other legislation (e.g., Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 and the Interests of Members of the Scottish Parliament Act 2006) where there are substantive requirements on the disclosure of gifts, donations, and hospitality.12 However, it should be noted that the lobbyist is not required to disclose the gifts, donations and hospitality they they provide. Instead, the responsibility to disclose falls on the political party or MSP receiving the gifts, donations, or hospitality.12

The Act received no points for indicators assessing:

requirements to file spending reports;

regularity and itemisation of spending reports;

disclosure of spending on specific subject matter (e.g., lobbying for provisions in a Bill);

reporting of lobbyist salaries;

spending on household members of elected representatives and public officials;

disclosure of business associations with elected representatives and political candidates.

Employer spending disclosure

The employer spending disclosure dimension received a score of 0%. The indicators in this dimension assessed whether employers of consultant lobbyists are required to file a spending report that contains the salary or fees paid out to the individual lobbyist. There are no such provisions in the Act.

Electronic filing

The electronic filing dimension assessed the extent to which online registration and reporting was facilitated by the oversight agency (in this case the Lobbying Register).1 This dimension received a score of 67%.

The Lobbying Register received full points for:

providing lobbyists with online registration;

keeping the register available in a searchable and electronic format available to all members of the public;

providing registrants with support and guidance on how to file registrations and returns.

The indicator on which the Lobbying Register received no points related to lobbyists spending reports being online as there are no provisions for disclosing spending under the Act.

Public access

The Lobbying Register received a score of 60% for its public access provisions.

Areas where the Lobbying Register performed to the CPI Index standards included the means of access and the publication schedule. The Lobbying Register is free to access, located online and in a searchable format with downloading functionality. The Lobbying Register also publishes returns and information on registrants as soon as that information is complete. A related indicator assessing access to registration forms (including sample registration forms and suitable guidance) also met the CPI Index standards.

There were three indicators assessing the extent to which the oversight agency (i.e., the Lobbying Register) publish spending data by reporting deadlines, by year-end, and spending totals by industries. As spending disclosure is not provided for in the Act, no points were awarded on these indicators.

Enforcement

The enforcement dimension assessed whether there are audits of lobbying returns by the oversight agency and whether there are penalties for breaching the reporting requirements of the Act.1 The overall score on this dimension was 20%. The indicators in this section (particularly those relating to auditing of lobbying returns) may be biased towards the legislative culture of the United States where there is a greater focus on lobbying expenditure.

Indicators relating to spending provisions could not be awarded points because there are no spending disclosure requirements in the Act. There is no body that has been granted the authority to audit returns on the Lobbying Register. There is also no mandatory audit of lobbying returns. The Lobbying Register does produce an annual report and a review was required two years after commencement by the provisions in section 50 of the Act.2 However, these provisions did not meet the CPI Index criteria for a regular mandatory audit of lobbying returns.

The Lobbying Register has the power to serve information notices and there are statutory penalties for not filing returns.2 This meant full points were granted for indicators assessing incomplete and incorrect filing. There was also an indicator assessing whether there is transparency on repeat non-compliance. This information is published in the Lobbying Register's annual report data.4 It is also likely that if a complaint were to be made about a lobbyist that the name of the organisation would be included in the Ethical Standards Commissioner's report given the requirement to provide details of the complaint in that report.2

Revolving door provisions

The Act does not contain any revolving door provisions or specify cooling off periods before legislators can register as lobbyists.1 Therefore, no points were awarded on the dimension assessing revolving door provisions.

Summary: How does the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016 compare with international best practice?

The aim of this chapter was to assess whether the Act met published standards for lobbying transparency systems. This chapter also assessed how the Act (and related transparency legislation) compares to countries with similar public transparency frameworks. The findings reported in this chapter indicate that the Act performs well against measures assessing the transparency outcomes of lobbying statutes. The comparative ratings found that the Act and the broader transparency framework in Scotland performs better than the UK and Ireland on the TI Assessment. The Act was rated as a medium-robustness lobbying system on the CPI Index. The comparative scores from the CPI Index indicated lobbying disclosure laws are better than the UK but not as stringent as those in Ireland.

Although the TI Assessment and CPI Index differ in the weight given to aspects of a lobbying transparency system, there was convergence between the two assessments on where Scotland performs well and where there is scope for increased stringency. Areas where the Act and the broader transparency framework perform well are the accessibility of the Lobbying Register, the oversight of lobbying disclosure by the Lobbying Register team, and the provisions for enforcement of lobbying regulations.

The Lobbying Register met the assessment standards for comprising a fully mandated and resourced body that is able to provide meaningful oversight of the lobbying disclosure system. The active role undertaken by the Lobbying Register in clarifying the subject matter of lobbying activity and the existence of a complaints mechanism (overseen by the Ethical Standards Commissioner) were often cited in support of high enforcement performance. There have been no complaints to the Ethical Standards Commissioner (as of the end of the 2022 Annual Report period) suggesting the strength of the oversight by the Lobbying Register may play a role in the enduring high compliance with the Act.

The broader public transparency framework was also a significant factor underpinning high scores on various indicators. The provision of information under FOISA and its application to information about meetings with external groups meant that lobbying activity that does not fall within the scope of the Act has an avenue to be brought into the public domain. The publication of meetings with external groups required by the Scottish Ministerial Code was also identified as good practice relating to pro-active disclosure of lobbying activity and stakeholder engagement. Disclosure of gifts, hospitality and donations is also captured through the broader transparency framework by legislation such as the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 and Interests of Members of the Scottish Parliament Act 2006. The culture surrounding lobbying and public transparency in Scotland was also rated favourably on the assessments. Common reasons cited for high scores were the presence of statutory and voluntary codes of conducts for elected representatives, public officials, civil servants, parliamentary officials and lobbyist membership associations.

Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny Committee consideration of legislative reform to the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016

Areas highlighted as gaps in the lobbying transparency framework often converged with areas considered for reform during the post-legislative scrutiny conducted by the Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny (PAPLS) Committee in Session 5. This section discusses each of the areas that PAPLS Committee identified in the context of the findings from the lobbying transparency assessments.

Types of communication

The PAPLS Committee considered whether the definition of regulated lobbying should be extended to other communications (e.g., all written and oral communications).1 The PAPLS Committee report sets out its view on the extension of communications and states:

The Scottish Parliament Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny Committee (Session 5). (2021). Post-legislative scrutiny: The Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016. Retrieved from https://bprcdn.parliament.scot/published/PAPLS/2021/3/22/79252553-8fd1-49af-acc0-66899fb52338/PAPLSS052021R3.pdf [accessed 16 October 2023]

110. The Committee understands those who argue that the information contained on the register provides only a partial view of lobbying activity carried out in Scotland given that the current definition of regulated lobbying is limited to face-to-face communications. The Committee recognises that lobbying activities take place in multiple forms, including face-to-face meetings, phone calls, emails and, increasingly, through videoconferencing. While it received no evidence to suggest that organisations were deliberately using other forms of communication to avoid having to register instances of lobbying activity, the Committee acknowledges that there is a body of communication and influencing being carried on that is not on the register and is not being seen.

111. The Committee notes, in particular, the evidence provided in response to its draft report which pointed to an increased number of phone calls made by Ministers with organisations which could conceivably be carrying out lobbying activity as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. As such, the Committee considers that in order to increase openness and transparency, subject to the findings of the impact assessment, there may be grounds for extending the Act to phone calls.

The restriction of regulated lobbying in the Act to communications made face-to-face (or on a videoconferencing platform) was one area identified by the TI Assessment as not meeting international standards. The TI Assessment regards the international standard as:

any contact (written or oral communication, including electronic communication) with lobbying targets for the purpose of influencing the formulation, modification, adoption, or administration of legislation, rules, spending decisions, or any other government program, policy, or position.

Transparency International. (2015, April 15). LOBBYING IN EUROPE: HIDDEN INFLUENCE, PRIVILEGED ACCESS. Retrieved from https://www.transparency.org/files/content/feature/2015_LobbyingEurope_Methodology_EN.pdf [accessed 15 June 2023]

The Irish Lobbying Act is similar to the Scottish legislation in how it defines regulated lobbying. However, the Irish Lobbying Act accounts for all written and oral communications meaning both phone calls and correspondence are accommodated on the Irish Lobbying Register.4 As such, this is one area where the Irish Lobbying Act aligns more closely than the Scottish Act to international standards.

Extension of the people considered lobbying targets

The inclusion of both members of the Scottish Government and members of the Scottish Parliament as targets of lobbying was identified as best practice by both the TI Assessment and the CPI Index. It was also an area where the Act was assessed as more stringent than the UK Lobbying Act because it included both the Executive and the Legislature.

The PAPLS Committee considered the extension of people considered lobbying targets under the Act during its post-legislative scrutiny.1 The Committee indicated additional information on the inclusion of civil servants was required in order to make a conclusive recommendation.1 The PAPLS Committee report states:

The Scottish Parliament Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny Committee (Session 5). (2021). Post-legislative scrutiny: The Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016. Retrieved from https://bprcdn.parliament.scot/published/PAPLS/2021/3/22/79252553-8fd1-49af-acc0-66899fb52338/PAPLSS052021R3.pdf [accessed 16 October 2023]

173. The Committee notes the evidence suggesting that civil servants can have a significant impact and influence on policy development, particularly at a senior level, and that, as such, the Act should be extended to communications to this category of individuals. Whilst the Committee is not necessarily persuaded by those who suggest that extending the Act to cover civil servants would risk politicising them, it considers that more information is required through the impact assessment before a conclusion is reached on whether an extension to this kind of decision maker is required.

With regards to civil servants, the TI Assessment only requires "high level public officials" to be included in the lobbying statutes in order to be assessed as good or best practice.4 The inclusion of the Permanent Secretary of the Scottish Government in the Act means this criteria was fulfilled. The TI Assessment placed more weight in its scoring rubric on the existence of civil service codes of conduct and behavioural standards for civil servants in managing contacts with lobbyists.4 Therefore, the extension to civil servants may not necessarily improve the transparency outcomes measured by TI Assessment and CPI Index.

That said, there are examples of where more categories of civil servant are included in lobbying statutes as potential lobbying targets. For example, the Irish Lobbying Act includes the most senior and second most senior grades of civil servants in departments of the Government of Ireland.6 This is supported by an additional transparency provision in the Irish Lobbying Act where civil servants' names and contact details are published online if they are a designated public official (i.e., a lobbying target under the Irish Lobbying Act).6

Proactive disclosure and publication of diaries

The TI Assessment highlighted proactive disclosure of contacts with lobbyists by senior public officials and elected representatives as an area for consideration. The Act places the requirements to disclose lobbying communications on registered organisations rather than elected representatives and public officials.1 However, the TI Assessment suggests that requirements to proactively disclose lobbying contacts should also apply to senior public officials and elected representatives.2 Transparency International set out its reasoning in its report on the lobbying statutes of 19 European countries.2 The report states:

It is increasingly recognised that access to information in a reactive form is not enough to build a culture of openness about public decision-making. Few dispute that, while lobbyists bear responsibility for their actions, the primary onus for transparency is on public officials and representatives: those who are accountable to the citizenry and have a duty to act, and be seen to act, in the open and with integrity. Public officials and institutions should, therefore, be required to pro-actively publish information on how decisions are made, which meetings they hold with various individuals and groups, what documentation is submitted in attempts to influence them, and who they invite to sit in an advisory capacity on various expert groups.

Mulcahy, S. (2015, April 15). Lobbying in Europe: Hidden Influence, Priveliged Access. Retrieved from https://www.transparency.org/en/publications/lobbying-in-europe [accessed 14 September 2023]

The publication of diaries was also considered by the PAPLS Committee during its post-legislative scrutiny. The Committee indicated that it did not support the publication of elected representatives' diaries. The PAPLS Committee report states:

117. A number of respondents suggested that, in addition to the Lobbying Register, MSPs and Ministers should be required to publish their diaries and calendars. The Committee notes that information about ministerial engagements is published on the Scottish Government’s website. The Committee further notes the responses to its draft report on this matter. However, it remains of the view that publication of diaries raises potential issues in relation to data protection. Therefore, the publication of MSPs’ diaries and calendars is not something that the Committee supports given its concerns about breaching the confidentiality of constituents and the disclosure of third party data.

The TI Assessment indicates that disclosure requirements on public officials and elected representatives need only pertain to meetings with lobbyists in order to be assessed as good or best practice.5 Therefore, a more limited provision than publication of MSPs' diaries in their entirety could be considered to improve transparency outcomes of the Act.

The accessibility of information under FOISA is another area for consideration with regards to proactive disclosure. MSPs are not public authorities under FOISA.6 However, information about the meetings of civil servants and senior public officials with external parties could be accessible in this way (if a relevant exemption under FOISA does not apply).6 In addition, civil servants are regularly listed by name in proactive transparency publications relating to the secretariat, attendance and minutes of advisory groups and Ministerial meetings with external parties.

Including lobbying expenditure on the Lobbying Register

The lack of requirements to record lobbying expenditure on the Lobbying Register was identified as a significant gap in transparency provisions by both assessments. There are no provisions for disclosing lobbying expenditure in the Lobbying Register.1 However, certain lobbying activities (e.g., gifts, donations and hospitality) may be disclosed under other legislation (e.g., the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act and the Interests of Members of the Scottish Parliament Act).23

Benchmark assessments (such as the TI Assessment and CPI Index) do not tend to be prescriptive in how lobbying expenditure should be disclosed. For example, reporting of lobbyist salaries and reporting estimates of lobbying expenditure in the financial year are both suggested in indicators assessing lobbying expenditure.45 The PAPLS Committee also gave its view on how lobbying expenditure could be disclosed and indicated that inclusion of information on lobbying expenditure should be explored following the evaluation.6 The PAPLS Committee report states:

The Scottish Parliament Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny Committee (Session 5). (2021). Post-legislative scrutiny: The Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016. Retrieved from https://bprcdn.parliament.scot/published/PAPLS/2021/3/22/79252553-8fd1-49af-acc0-66899fb52338/PAPLSS052021R3.pdf [accessed 16 October 2023]

134. Whilst the Committee is aware that money does not necessarily equate to access and influence, the Committee acknowledges the calls from witnesses who indicated that information about expenditure on lobbying activity should be included in the register.

135. The Committee recognises that any such mechanism should be proportionate and not overly burdensome and take account of potential commercial sensitivities in recording such information. The Committee notes options such as using a minimum threshold and a banding system. It is also attracted to the system whereby organisations submit a good faith estimate of their lobbying expenditure in line with the regimes in the EU and US. The Committee recommends that these options are explored following the impact assessment.

136. While the Committee understands that information about Government funding to individual organisations is currently publicly accessible, it recognises that there are good arguments why, in the interests of transparency, this information should also be included in the Lobbying Register. The Committee recommends that this potential development is explored at the same time as options are considered for including information in the register about lobbying expenditure.

Exemptions to regulated lobbying

The Act includes provisions for several exemptions that define activities not considered as "regulated lobbying".1 The PAPLS Committee conducted an examination of four specific exemptions that had been identified in the Lobbying Register Annual Report 2019 as needing further clarification or guidance on their interpretation and practical application.2 These exemptions are as follows:1

Communications to constituency or regional MSPs: the exemption applies when a communication is directed towards a constituency or regional Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) representing the area where the person or organisation's activities are ordinarily conducted.

Communications for factual information or views: under this exemption, a communication is not classified as "regulated lobbying" if the decision-maker initiates the request for factual information.

Communications by small organisations: this exemption is applicable to small organisations with ten or fewer full-time staff members, unless their primary purpose is third-party lobbying.

Unremunerated communications: a communication is not considered regulated lobbying if it is made without receiving payment. In essence, individuals who are unpaid for their work, such as volunteers, cannot undertake regulated lobbying within the terms of the Act.

The PAPLS Committee gave its view on legislative changes to the exemptions and stated in its report:

The Scottish Parliament Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny Committee (Session 5). (2021). Post-legislative scrutiny: The Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016. Retrieved from https://bprcdn.parliament.scot/published/PAPLS/2021/3/22/79252553-8fd1-49af-acc0-66899fb52338/PAPLSS052021R3.pdf [accessed 16 October 2023]

159. In general, the Committee does not take a view on the legislative changes that should be made to each of the exemptions above in order that their meaning is clear. However, the Committee does consider that there are good arguments for reconsidering whether there should be an exemption excluding communications which are made on request. In particular, it notes that a number of the organisations which submitted written evidence to the Committee found this exemption difficult to apply in practice because conversations can stray into topics that would constitute regulated lobbying under the Act even when conducted in response to an invite requesting information and that such conversations rarely remain contained.

The indicators of the TI Assessment and CPI Index on best practice do not discourage informal consultation (and other activities that may fall under the communications made on request category) so long as public consultation mechanisms are sufficient to document the different views and interests that have been taken into account during the legislative process.5 Public consultation mechanisms and equality of access was an area where the regulatory framework scored well on the assessments.

There were no exemptions provided for in the Act that were directly evaluated by the assessments. However, there was an indication in the assessments that exemptions based on lobbying expenditure (e.g., only activity above a certain expenditure threshold is registrable) were generally seen as inadequate transparency practice.6 The recent changes to the Irish Lobbying Act may also be of interest with respect to assessing exemptions for small organisations and unremunerated communications. The 2023 Irish Lobbying Act amends the 2015 Irish Lobbying Act to include representative bodies with no employees within the scope of lobbying requirements.7 Similarly, an exemption that previously applied to unremunerated office holders (e.g., volunteer board members within an organisation) has been removed, making such communications registrable as lobbying.7

Reporting timescales

The PAPLS Committee indicated that it was supportive of changes to the reporting requirements under the Act. The PAPLS Committee report states:

The Scottish Parliament Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny Committee (Session 5). (2021). Post-legislative scrutiny: The Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016. Retrieved from https://bprcdn.parliament.scot/published/PAPLS/2021/3/22/79252553-8fd1-49af-acc0-66899fb52338/PAPLSS052021R3.pdf [accessed 16 October 2023]

172. A key objective of the Lobbying Act is to increase transparency in lobbying activity and to demonstrate the integrity and probity of policy and political decision-making processes. In order to achieve this objective, it is clearly important that the registration of lobbying activity is undertaken timeously to ensure that the information it contains is topical. However, witnesses pointed to a number of weaknesses in the Act in this regard indicating that the six-month reporting period may result in lobbying activity being submitted after the passage of a Bill and potentially allowing more ‘controversial’ lobbying activities to effectively lie unreported...

175. The Committee is therefore supportive of shortening the reporting timetable to a quarterly basis in line with international best practice. It is also supportive of reporting requirements being harmonised as proposed by the Lobbying Registrar and for the starting point for reporting requirements to be from the date at which the lobbying activity took place. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government initially consult on these changes and then bring forward the necessary legislation as early as possible in the new session.

The assessment findings supported the view of the PAPLS Committee that:

reporting requirements should start from the first day regulated lobbying takes place (rather than 30 days after);

lobbying reporting intervals should be shortened from every 6-months to quarterly;

the reporting schedule should be harmonised across registered organisations (rather than each registrant having a unique reporting date).

Additional areas for consideration

The lack of revolving door provisions in the Act was identified by both assessments as an area of inadequate practice and an area where the provisions differed significantly to one of its comparators (Ireland).1 One of the significant shortcomings identified was the absence of statutory cooling off periods following the departure from public office. As Ireland recently strengthened its revolving door provisions, the consideration of statutory cooling off and revolving door provisions may be warranted if this is an area where best practice is desired.2

The indicators on these assessments provide estimates of the transparency outcomes of a lobbying disclosure system but they do not necessarily transfer to how those provisions work in practice. The next chapter reports the findings of the analysis of the contents of the Lobbying Register to obtain an understanding of how the reporting duty is working in practice and how the reporting duty is experienced by registered organisations.

How is the reporting duty under the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016 operating?

Key findings: How is the reporting duty under the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016 operating?

Analysis of the Lobbying Register

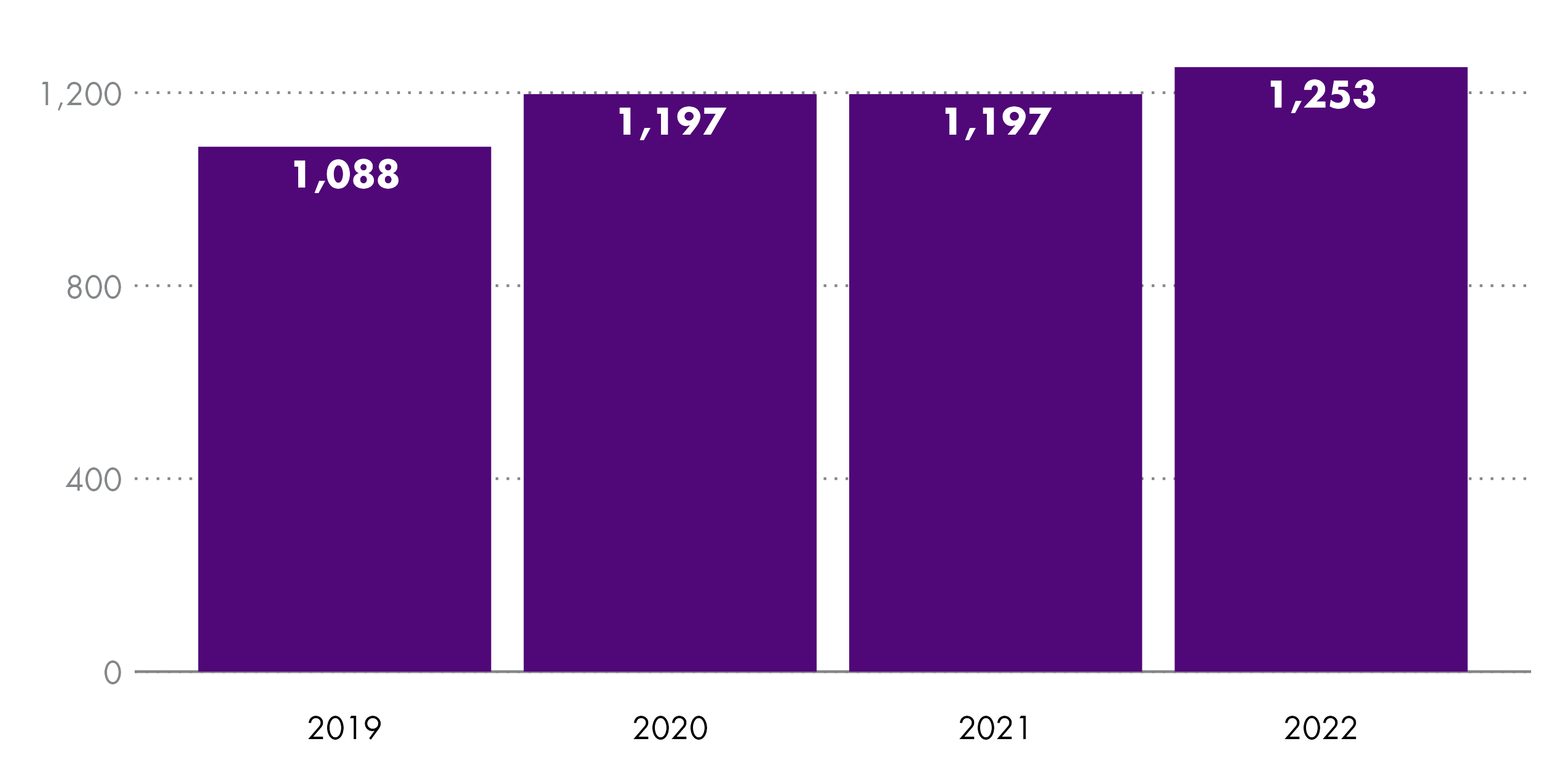

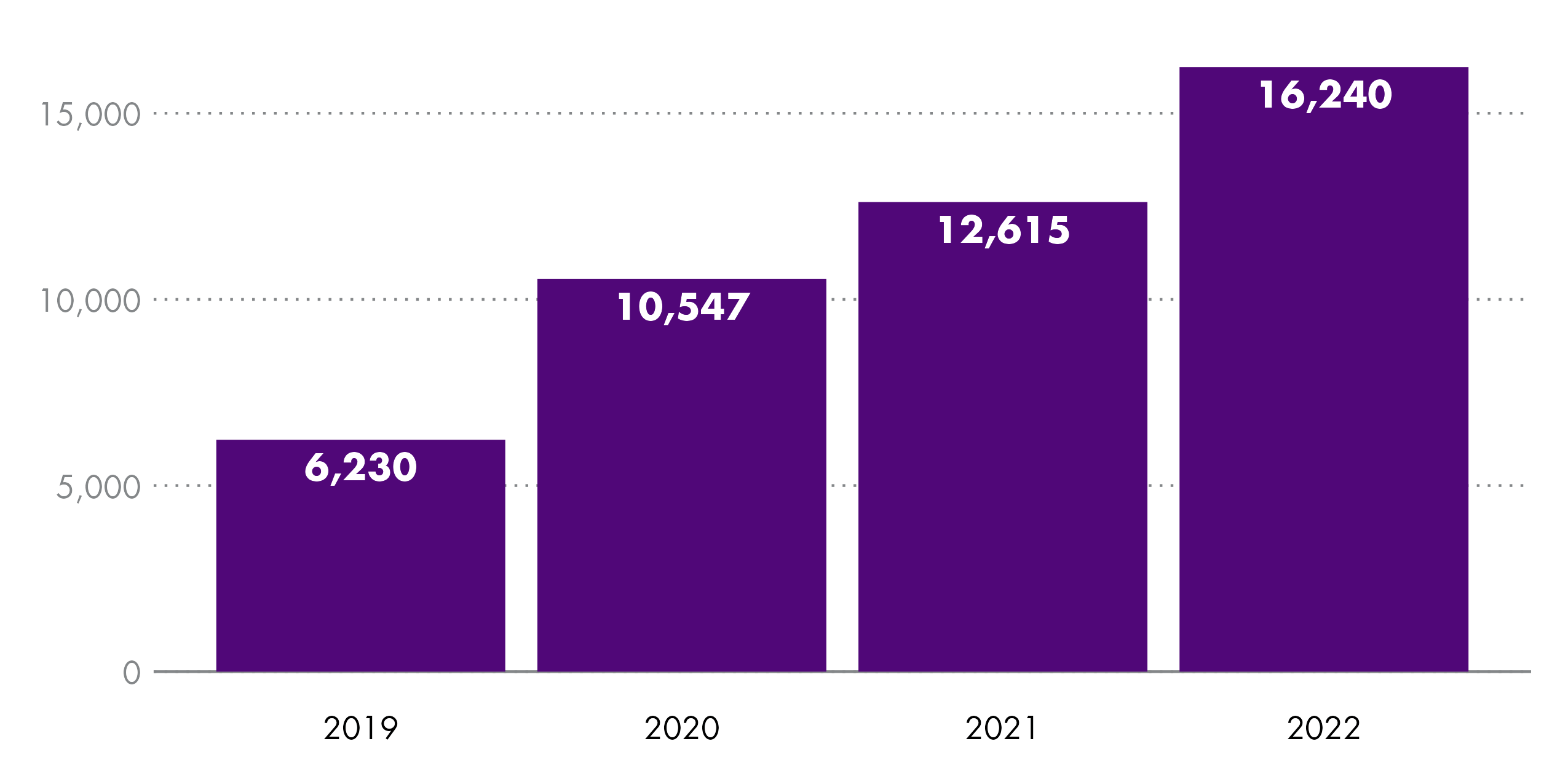

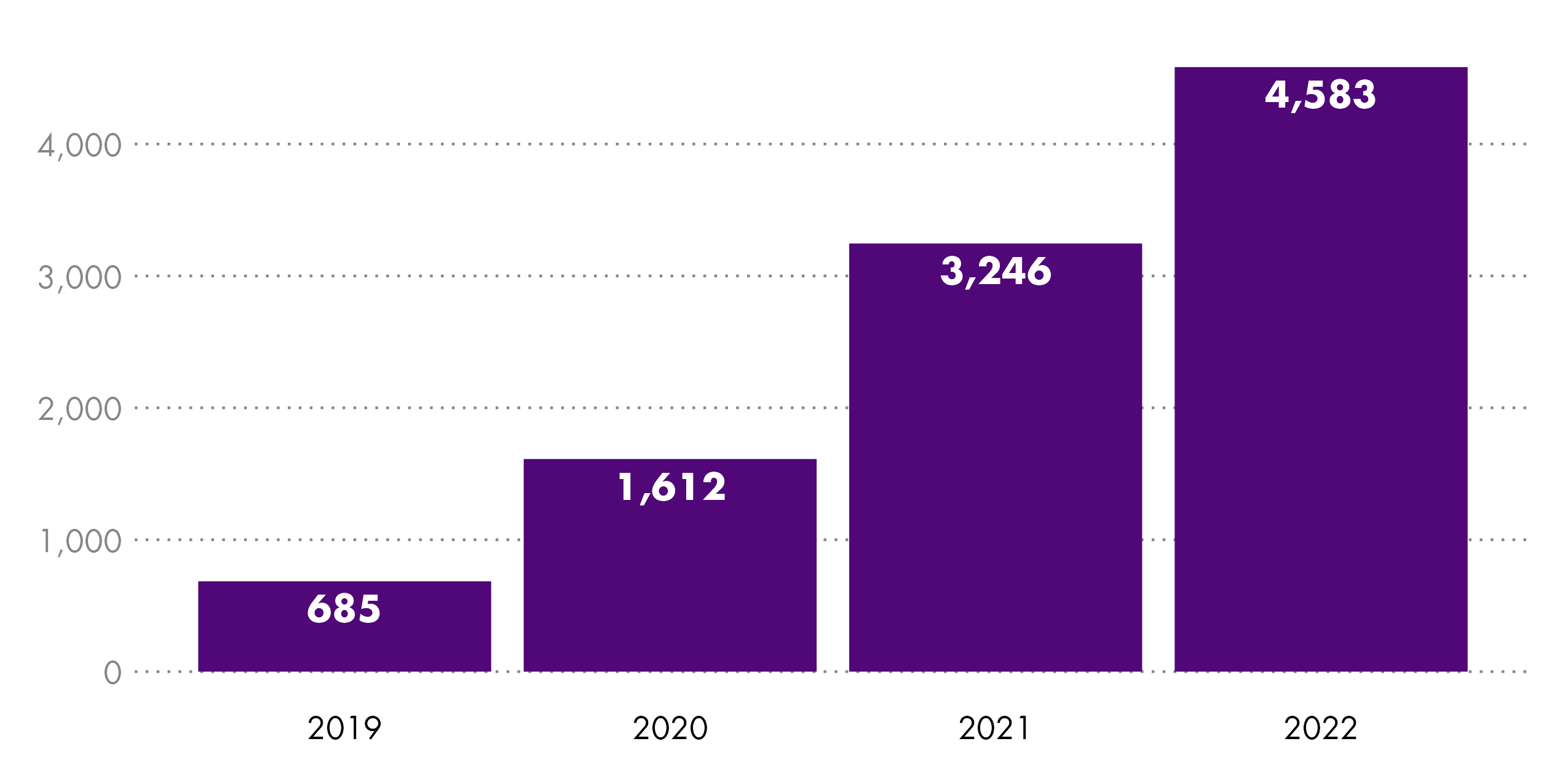

The number of registrants on the Lobbying Register, the number of returns on the Lobbying Register, and the intensity at which registered organisations are engaging in regulated lobbying has increased every year since the Act came into force in 2018.

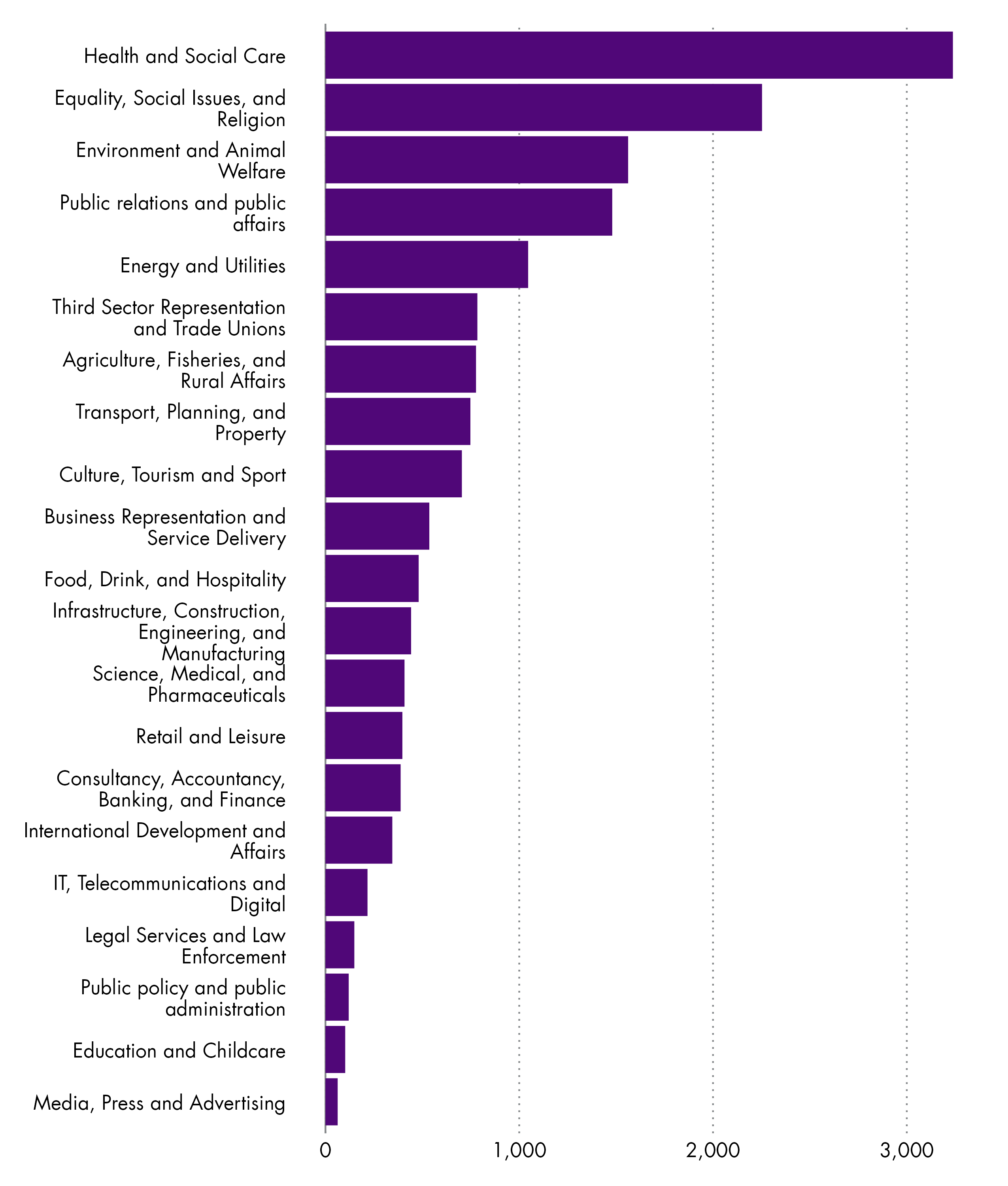

The following sectors produce the highest number of returns:

health and social care

equality, social issues, and religion

environment and animal welfare

public relations and public affairs

energy and utilities.

Most registrants representing charities, trusts and advocacy bodies lobby in the equality, social issues, and religion sector and the health and social care sector.

Companies were the dominant registrant type in the public relations and public affairs sector, the transport, planning and property sector, and the energy and utilities sector.

Sole traders and paid individuals could only be associated with the public relations and public affairs sector.

Individual registrants produce more returns on average in the following sectors:

environment and animal welfare

agriculture, fisheries, and rural affairs

trade unions and third sector representation.

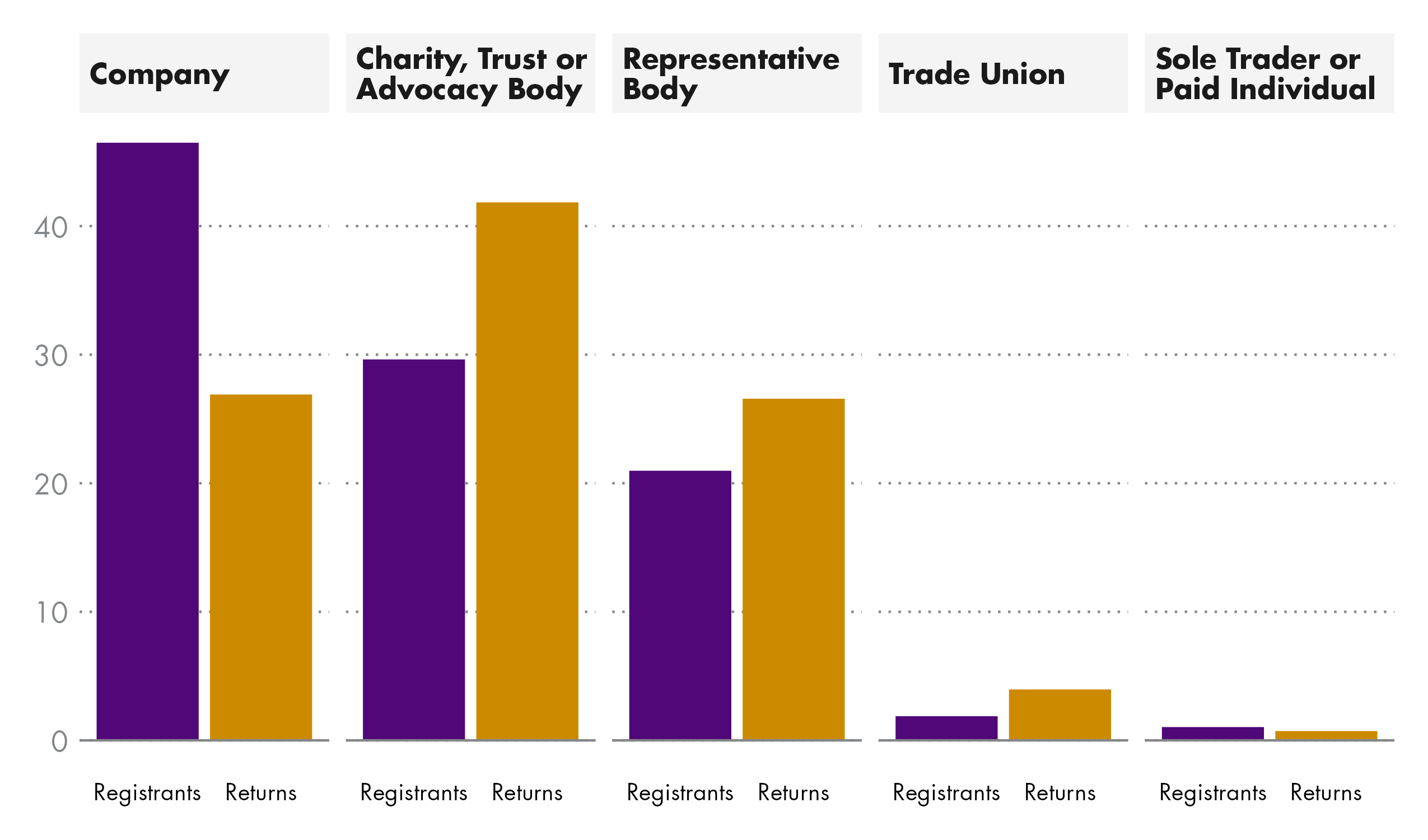

Charities, trusts and advocacy bodies, representative bodies, and trade unions all produce proportionately more returns relative to their share of registrants on the Lobbying Register.

Companies and sole traders and paid individuals produce proportionately less returns relative to their share of registrants on the Lobbying Register.

Compliance with the reporting duty

Compliance with the Act is high. Most registrants either comply or have a low incidence of repeated breaches.

No evidence of significant variations in the way in which different types of registered organisations are undertaking their reporting of regulated lobbying could be identified from the contents of the Lobbying Register.

No evidence of consistently untoward or unscrupulous lobbying could be identified from the contents of the Lobbying Register.

The impact of the reporting duty on registered organisations

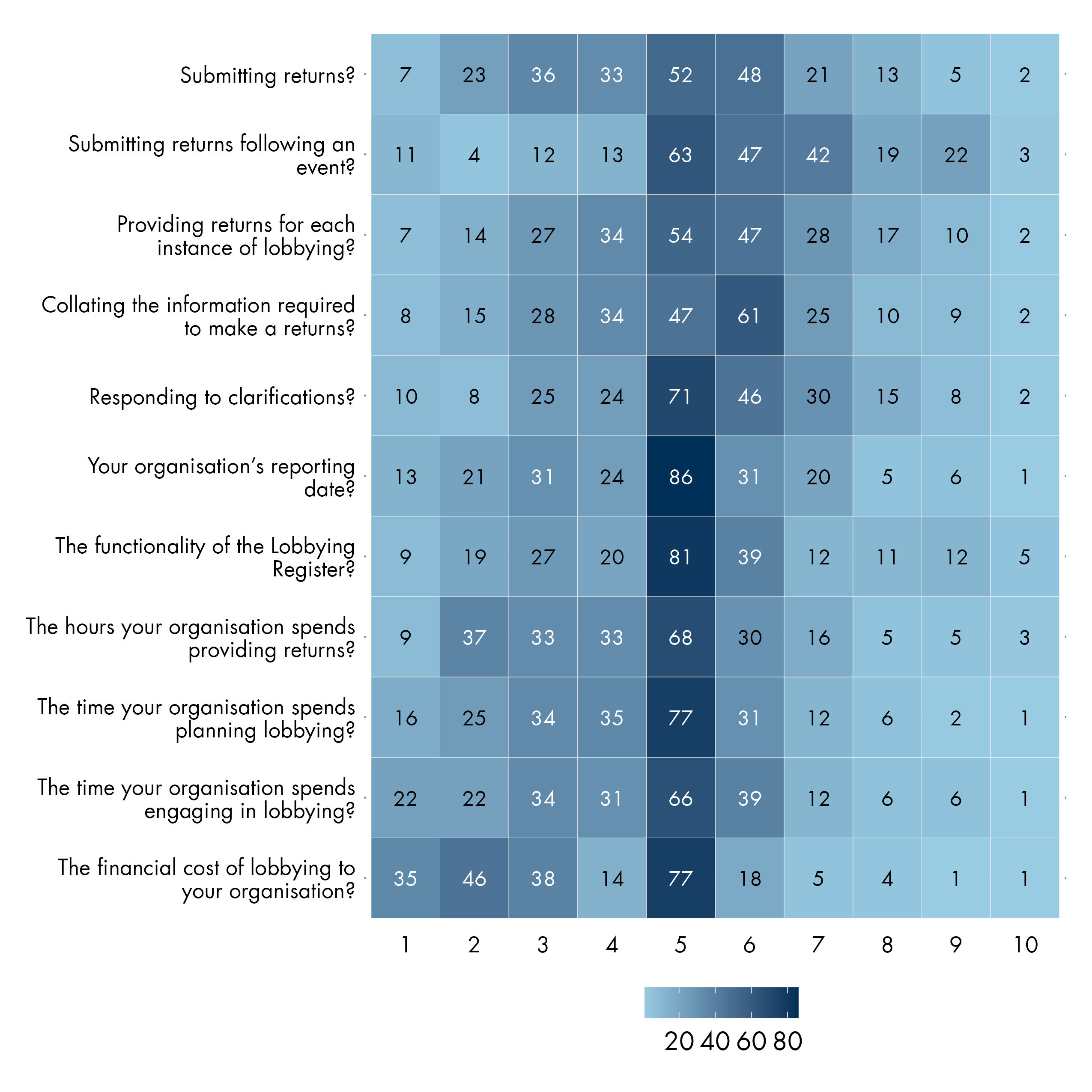

Registered organisations spend 3.7 hours on average in each reporting period submitting returns and responding to clarifications.

Charities spend the most time submitting returns to the Lobbying Register compared to other organisation types.

The majority of registered organisations indicated that the reporting duty is appropriate. Areas where administrative effort is required are largely reported to be in the organisation's internal management of lobbying information.

Submitting lobbying returns for each instance of regulated lobbying after an event is seen as high effort by a majority of registered organisations.

Analysis of registrants and returns on the Lobbying Register

A full analysis of registrants and returns was conducted to support an assessment of how the Act reporting duty is operating. The findings are set out in four sections:

registrants on the Lobbying Register;

returns on the Lobbying Register;

compliance with the reporting duty;

content of the Lobbying Register.

The Lobbying Register launched on 12 March 2018. This returns analysis covers data from that start date to the 12 June 2022. The annual report periods refer to the following dates:

2019: 12 March 2018 - 12 June 20191

2020: 13 June 2019 - 12 June 20202

2021: 13 June 2020 - 12 June 20213

2022: 13 June 2021 - 12 June 20224

The 2019 period is longer than the other periods as it includes the three months during which the Act was in operation before the annual report cycle commenced.

Registrants on the Lobbying Register

SPICe categorised registrants into fewer registrant types and registrant sectors than those typically reported in Lobbying Register annual reports to provide for a clearer summary of the Lobbying Register's composition. The list of registrant types and sectors that is used by the Lobbying Register for annual reporting can be found in Annex 2.1.

Definitions

Registrants refers to active registrants on the Lobbying Register unless voluntary or inactive registrants are specified.

Returns refer to substantive returns unless nil returns are specified.

Registrant sector refers to the most relevant primary subject area that the registrant lobbies in or for.

Registrant type refers to whether a registrant is a:

charity, trust or advocacy body;

company;

representative body (i.e., an organisation which represents a collective or organisations);

sole trader or paid individual; or

a trade union.

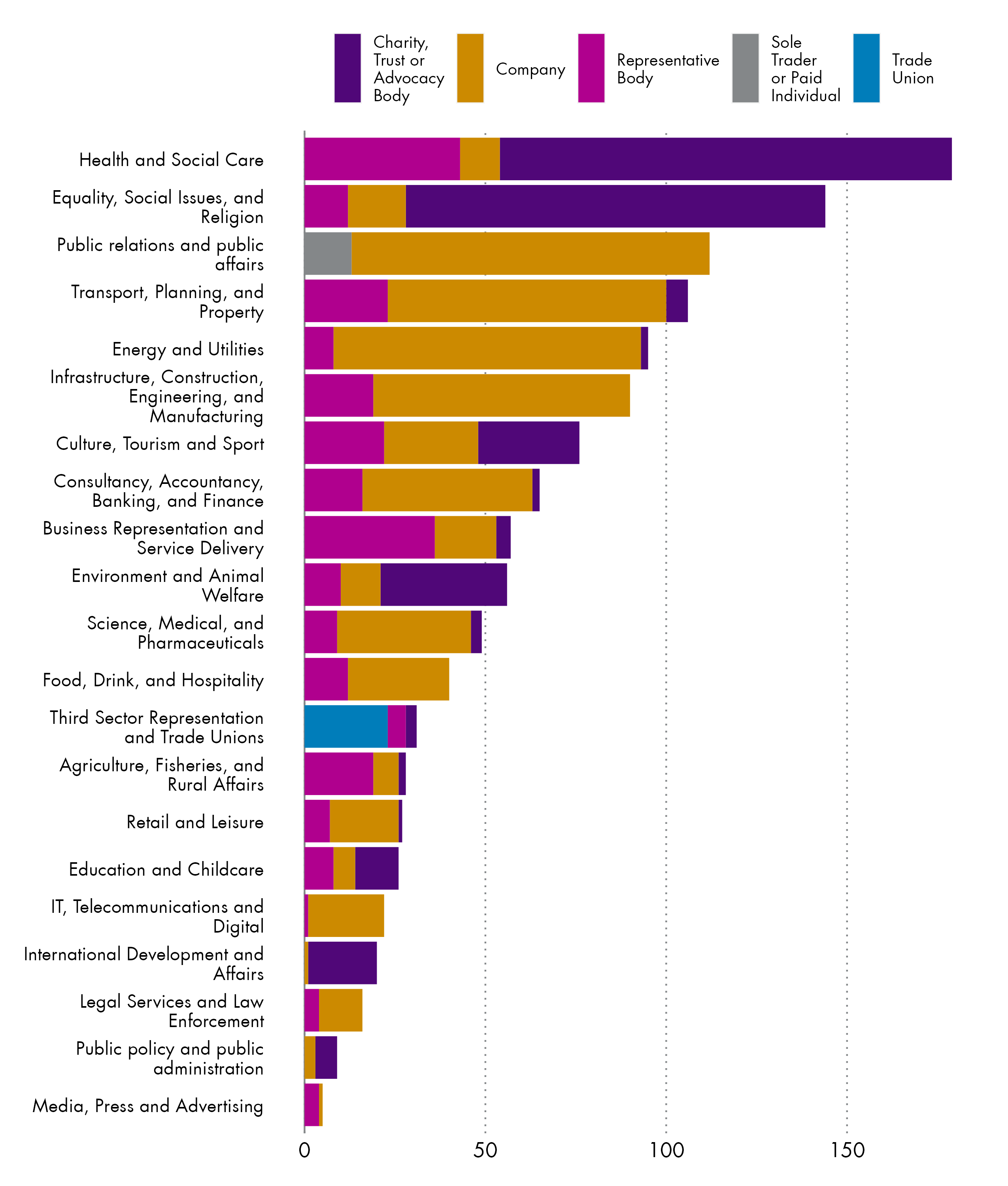

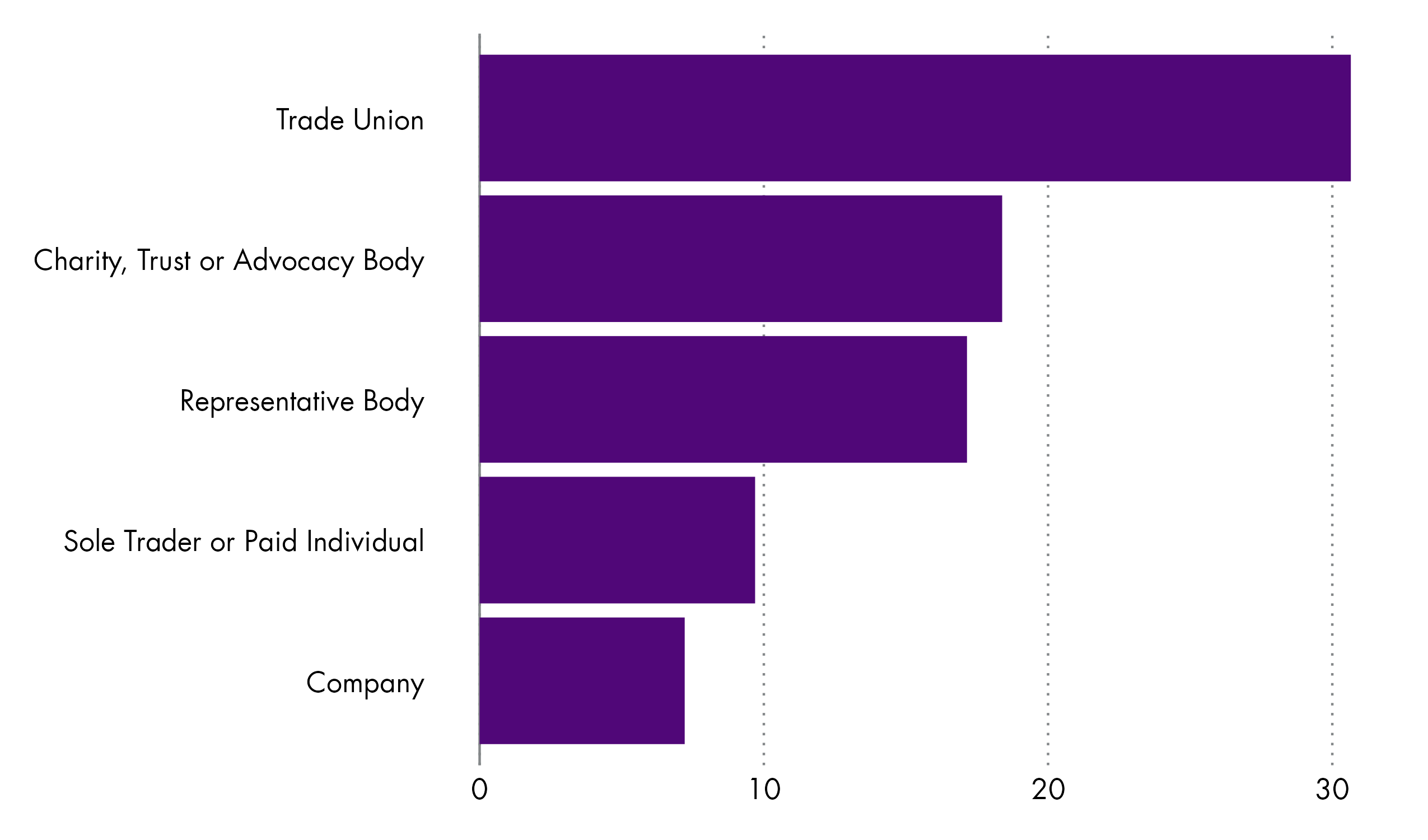

The complete data for the number of registrants associated with each registrant sector and registrant type across annual report periods is shown in Annex 2.2. This analysis indicated that most registrants in the charity, trust and advocacy body group file returns in the equality, social issues, and religion and the health and social care sectors. Companies were the dominant registrant type in the public relations and public affairs sector, the transport, planning and property sector, and energy and utilities sector. Sole traders and paid individuals could only be associated with the public relations and public affairs sector. The breakdown of registrants for each registrant sector and registrant type during the 2022 annual report period is shown in the following graph.

Inactive and voluntary registrants

Section 12 of the Act permits registrants to become an "inactive registrant" on the Lobbying Register if the registrant determines it is no longer going to engage in regulated lobbying.1 A total of 113 registrants have been made inactive between 12 March 2018 and 12 June 2022.

| Registrant type | Number of inactive registrants |

|---|---|

| Charity, trust or advocacy body | 26 |

| Company | 75 |

| Representative body | 9 |

| Sole trader or paid individual | 3 |

Organisations may register as a voluntary registrant under section 14 of the Act after becoming an inactive registrants.1 Voluntary registrants tend to be small organisations of less than 10 people who provide returns on a non-statutory basis. A total of 10 registrants have been granted voluntary registrant status between 12 March 2018 and 12 June 2022.

Returns on the Lobbying Register

Registrants must submit substantive returns on the Lobbying Register every six months when they have undertaken registered lobbying.1 Registrants must make a nil return when they have not undertaken registered lobbying within the six month reporting period.1 The following section reports analyses conducted to assess trends in the number of substantive and nil returns recorded on the Lobbying Register.

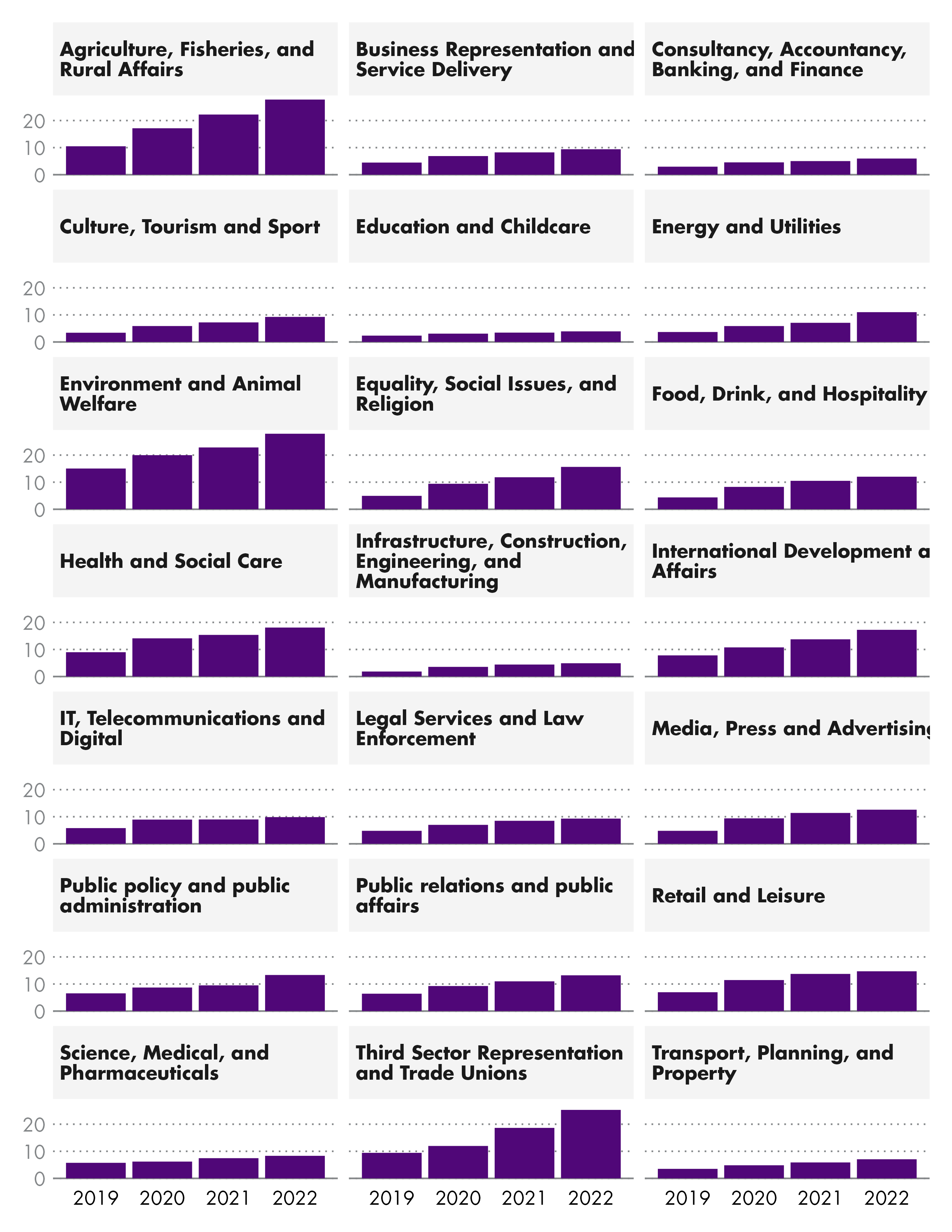

Volume of regulated lobbying

The distribution of returns across sectors analysis indicates that regulated lobbying takes place in every sector and during each annual reporting period to some extent (see Annex 2.3). The number of returns also increases every annual reporting period in every sector. The following sectors exhibit consistently higher numbers of returns over the annual reporting periods:

health and social care;

equality, social care, and religion;

environment and animal welfare;

public relations and public affairs;

energy and utilities.

The following sectors have consistently lower numbers of returns over the annual reporting periods:

media, press and advertising;

education and childcare;

public policy and public administration;

legal services and law enforcement.

The same analysis was performed to assess the number of nil returns by registrant sector and annual report period (see Annex 2.4). The distribution of nil returns across sectors analysis indicates that nil returns are being made in every sector and annual reporting period to some extent, but at much a lower frequency than substantive returns. The number of nil returns also increases every annual reporting period in every sector. Those sectors with the most substantive returns also tended to have the most nil returns.

Intensity of regulated lobbying

The analyses thus far have looked at total returns which provides an assessment of the volume of regulated lobbying taking place. The next set of analyses calculate average returns to assess the intensity of regulated lobbying.

The average number of returns made by each registrant increases over every annual report period across all registrant types and sectors. Overall, this suggests that engagement in regulated lobbying by individual registrants is increasing over time. Several other insights were gained from calculating average returns, including, that trade unions are the registrant type with the highest average returns and companies produce the lowest average returns.

The sectors with the highest number of average returns are:

environment and animal welfare;

agriculture, fisheries, and rural affairs;

trade unions and third sector representation.

The sectors with the lowest number of average returns are:

education and childcare;

consultancy, accountancy, banking and finance;

infrastructure, construction, engineering, and manufacturing.

The numerical breakdowns of average returns for registrant type and registrant sector can be found in Annex 2.5 and 2.6, respectively.

Proportionality of regulated lobbying

The next set of analyses plot the proportion of registrants associated with a registrant type or registrant sector against the respective proportion of returns they contribute to the Lobbying Register. This is to assess whether there are any sectors or organisation types that can be considered relatively high or relatively low contributors to the Lobbying Register.

Numerical data supporting the visualisation can be found in Annex 2.7. The analysis indicated that charities, trusts and advocacy bodies, representative bodies, and trade unions all produce proportionately more returns relative to proportion of registrants on the Lobbying Register. Companies and sole traders/paid individuals produce proportionately less returns relative to proportion of registrants on the Lobbying Register.

To further assess proportionality between registrants and returns, the difference between proportion of registrants and returns was examined (see Table 3). The difference, expressed as a percentage points difference, provides a measure of the disparity between the proportions of registrants and returns. Charities, trusts, and advocacy bodies are producing a disproportionately high number of returns. This is also the case to a lesser degree for representative bodies and trade unions. Conversely, sole traders and paid individuals, and companies are producing a disproportionately low number of returns.

| Registrant type | Percentage point difference |

|---|---|

| Charity, trust or advocacy body | 12.2 |

| Representative body | 5.6 |

| Trade union | 2.1 |

| Sole trader or paid individual | -0.3 |

| Company | -19.6 |

Differences in proportion of registrants and returns for each registrant sector were also calculated (see Table 4 and Annex 2.8).

| Registrant sector | Percentage of registrants | Percentage of returns | Percentage point difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sectors where there are proportionately more returns than registrants | Health and social care | 14% | 21% | 7.0 |

| Environment and animal welfare | 4% | 10% | 6.0 | |

| Agriculture, fisheries, and rural affairs | 2% | 5% | 3.0 | |

| Equality, social issues, and religion | 12% | 13% | 1.0 | |

| Third sector representation and trade unions | 3% | 4% | 1.0 | |

| Retail and leisure | 2% | 3% | 1.0 | |

| Sectors where returns and registrants are proportionate | International development and affairs | 2% | 2% | 0.0 |

| Public relations and public affairs | 9% | 9% | 0.0 | |

| Media, press and advertising | 1% | 1% | 0.0 | |

| Public policy and public administration | 1% | 1% | 0.0 | |

| Food, drink, and hospitality | 3% | 3% | 0.0 | |

| Legal services and law enforcement | 1% | 1% | 0.0 | |

| Sectors where there are proportionately fewer returns than registrants | IT, telecommunications and digital | 2% | 1% | -1.0 |

| Education and childcare | 2% | 1% | -1.0 | |

| Business representation and service delivery | 4% | 3% | -1.0 | |

| Science, medical, and pharmaceuticals | 4% | 3% | -1.0 | |

| Energy and utilities | 7% | 5% | -2.0 | |

| Consultancy, accountancy, banking, and finance | 5% | 3% | -2.0 | |

| Culture, tourism and sport | 6% | 4% | -2.0 | |

| Transport, planning, and property | 9% | 5% | -4.0 | |

| Infrastructure, construction, engineering, and manufacturing | 7% | 3% | -4.0 |

Compliance with the reporting duty

The Act provides for a system of oversight and compliance.1 The duty to monitor compliance with the Act has been delegated by the Clerk of the Scottish Parliament to the Lobbying Register Team.2 Possible and alleged breaches of the Act can be investigated by the Commissioner for Ethical Standards for Public Life in Scotland.1 There have been no instances to date where such an investigation has taken place. The Parliament's powers to censure lobbyists have also not been used since the Act came into force. There are also provisions for criminal offences and penalties in the Act, which likewise, have not been used to date.

Instances of non-compliance with the Act (i.e., failure to submit a return by the reporting deadline) are routinely addressed by the Lobbying Register Team and result in non-compliance emails being issued to conclude a registrant's returns for the reporting period.4 The Lobbying Register Annual Report for 2021-22 provides the data for number of non-compliance emails issued to each registrant since the Act came into force.4 This data indicates that a total of 2089 non-compliance emails have been sent to 850 registrants (i.e., 68% of registrants have received at least one non-compliance email since the Act came into force).

By the end of the 2022 Annual Report period, there had been a total of 9 statutory reporting periods (each of six months). Therefore, an organisation in this dataset can only be classified as having breached the Act a maximum of 9 times. The following table provides the percentage of registrants associated with the available number of breaches.

| Breaches of reporting period | Number of registrants within breach category | Percent of registrants within breach category (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 403 | 32.16 |

| 1 | 280 | 22.35 |

| 2 | 229 | 18.28 |

| 3 | 145 | 11.57 |

| 4 | 106 | 8.46 |

| 5 | 61 | 4.87 |

| 6 | 18 | 1.44 |

| 7 | 10 | 0.79 |

| 8 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 9 | 1 | 0.08 |

The data shows that approximately one third of registrants have not received a non-compliance email by the end of any of their reporting periods. This indicates that a substantial proportion of registrants complied with the Act without any breach. There is also an indication of a low incidence of multiple non-compliance with the percentages declining quickly for registrants receiving more than one non-compliance email over their reporting periods. It suggests that most registrants either comply or have a low incidence of repeated violations.

Content of returns on the Lobbying Register

SPICe used quantitative text analysis techniques to guide the assessment of the Lobbying Register's content. These included a word frequency analysis to identify the most common topics being discussed and a topic modelling analysis to identify themes from across the entries on the Lobbying Register.

The dataset downloaded from the Lobbying Register consisted of 17,221 substantive returns published between 23 March 2018 to 12 August 2022.i The extract of returns was processed prior to text analysis. Processing involved removing special characters and "stopwords" (i.e., common words that are not informative on their own such as "it", "the", "an").

Accessibility of Lobbying Register entries