Initial Teacher Education

It is over ten years since the publication of Teaching Scotland’s Future, the report by Graham Donaldson on his review of teacher education in Scotland. That review was important in the development of Initial Teacher Education (ITE) in the past decade. This paper explores the current provision of and debates around ITE in Scotland and elsewhere.

About the author

Dr Paul Adams is a Senior Lecturer (Curriculum and Pedagogy Policy) at the University of Strathclyde. Dr Adams' broad research areas are in the policy and politics of education. Dr Adams was a co-Principal Investigator on a Scottish Government funded project Measuring Quality in Initial Teacher Education (MQuITE), which is discussed in this briefing.

Dr Adams has been working with the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) as part of its Academic Fellowship programme. This aims to build links between academic expertise and the work of the Scottish Parliament.

The views expressed in this briefing are the views of the author, not those of SPICe or the Scottish Parliament.

Introduction

Teachers must meet the General Teaching Council for Scotland’s (GTCS) Standards for Registration to work in schools in Scotland. Part of these standards is to have a teaching qualification. These qualifications are awarded after a period of Initial Teacher Education (ITE) in a Scottish Higher Education Institute. ITE is a mix of academic-focused work in university departments and practical experience in classrooms.

The GTCS has developed Guidelines for ITE Programmes in Scotland.1 These state that the overall aim of such programmes is to prepare student teachers to become competent, thoughtful, reflective and innovative practitioners, committed to providing high quality teaching and learning for every learner.

ITE is the start of the pipeline for teachers. It is therefore a key element of workforce planning to ensure that Scotland has sufficient numbers of suitably qualified teachers in schools.

School education more broadly is set for a further period of reform and change this parliamentary session. Teachers, along with pupils and parents/carers, sit at the heart of the education system and high-quality teaching and learning are crucial to improving outcomes in our education system. It would be natural that some of the changes and aspirations of a renewed approach to school education may lead to calls for changes to the initial education of teachers.

The last comprehensive review of Initial Teacher Education in Scotland was undertaken by Graham Donaldson over ten years ago. His report Teaching Scotland’s Future was published in 2011 (although it is dated December 2010). That report concluded that "the two most important and achievable ways in which school education can realise the high aspirations Scotland has for its young people are through supporting and strengthening, firstly, the quality of teaching, and secondly, the quality of leadership".

This briefing is intended to sketch how the Donaldson Report has influenced ITE along with the broader debates around ITE. The briefing is in four parts:

an overview of the Donaldson Report’s main sections and a selection of the recommendations pertinent to ITE

current ITE structures and organisation

discussion and debate regarding current provision

possible developments in ITE provision across Scotland.

The Donaldson Report 2011

In December 2010, Graham Donaldson completed his report Teaching Scotland’s Future.1 This report was underpinned by five ‘almost axiomatic’ (p. 2) ideas:

high aspirations for young people are best realised through supporting and strengthening the quality of teaching and the quality of leadership

teaching is both complex and challenging and requires high standards of professional competence and commitment

leadership must be acquired and fostered from entry into the teaching profession

Curriculum for Excellence is potentially powerful and yet the implications for the teaching profession and its leadership had not been fully addressed

career-long teacher education is too fragmented and haphazard and should be at the heart of teacher learning.

The conclusions and recommendations of the report consisted of fifty proposals all of which were accepted by the Scottish Government in full, partly, or in principle. Many of these proposals related to ITE and covered areas such as:

entry into ITE programmes

the deployment and training of mentors, school, and university staff

rolling ITE in with the induction year to provide seamless transitions into the profession

partnership working between universities, schools, and local authorities

mechanisms for the accreditation and re-accreditation of programmes.

To reduce often ‘fragmented and haphazard’ (p. 2) teacher education methods, the report recommended an overhaul of ITE including:

the replacement of Bachelor of Education (BEd) courses with wider-university oriented undergraduate BA/MA programmes

Masters learning (level 11) as an outcome from one-year professional graduate courses (PGDE)

strengthening partnership working between schools, local authorities, and universities.

Chapter two of the report sought to describe what 21st century teachers and education leaders should know and be able to do. This chapter noted (p. 14) that

The most successful education systems invest in developing their teachers as reflective, accomplished and enquiring professionals who are able, not simply to teach successfully in relation to current external expectations, but who have the capacity to engage fully with the complexities of education and to be key actors in shaping and leading educational change.

The report (p. 14) argued that teachers ‘must be able to go well beyond recreating the best of current or past practice’. This implies ‘a teaching profession which, like other major professions, is not driven largely by external forces of change but which sees its members as prime agents in that change process.’ Citing Eric Hoyles’ work on professionalism, Donaldson suggested that the 21st century teacher is not only ‘highly proficient in the classroom’ (p. 15) but is also ‘reflective and enquiring … about those wider issues which set the context for what should be taught and why’ (p. 15). The Report endorsed a vision for teaching which recognised that teachers:

are expert practitioners rooted in strong values

take responsibility for their own development

contribute to their own development and the development of others.

It identified the need for well-planned and well-researched innovation to be at the heart of professional learning for educational change. These elements formed the basis for the report which sought to expand teacher education to incorporate career long professional learning (CLPL). Citing historical high levels of teacher unemployment and the need to ensure CLPL, Donaldson was clear about the need for careful workforce planning and integrated and collaborative professional development arrangements.

The report highlighted how workforce planning needs to ensure sufficient teaching staff and how teacher demographics provide the backdrop for further development. The report also highlighted the significant time-lag between setting intakes for university courses and those students becoming fully registered teachers. Donaldson recommended that Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) and local authorities should work more closely to ensure accurate workforce planning.

To support a diversity of applicants, the report proposed that part-time courses should be developed alongside consideration of other models for ITE.

The report placed ITE within a wider early phase of a teacher’s learning and career. Indeed, Donaldson argued that ITE should be “seen as and should operate as a continuum, spanning a career and requiring much better alignment across and much closer working amongst schools, authorities, universities and national organisations.”

The report noted that mostly, ITE, the induction year and subsequent early career development (ECD) operated independently but that the period covering initial teacher education, induction and the early years of employment lays the foundations of professional values, knowledge and expertise of those who will be our teachers and educational leaders (p. 28).

Teacher Induction Scheme and Early Career Development

The Teacher Induction Scheme was introduced in 2002. This offers all new teachers qualifying from Scottish universities a paid year-long placement in a mainstream school, giving them support to achieve the GTCS Standard for Full Registration. Donaldson acknowledged that this development, which replaced the often ad hoc two year probationary period, marked a significant positive development in the education of new teachers. Similarly, the report identified university-based provision for ITE as a strength of the system. The competitive nature of entry to the profession and the then emerging diversity of ITE routes were also considered positive features.

Upon qualification, Donaldson praised the fact that new teachers seemed to adopt a reflective, enquiring approach to their work and were often reported as making considerable impact in schools. Surveys for the Donaldson Report concluded that recently qualified teachers, probationers, and students were generally happy with the education they had received on their ITE course. This finding was replicated ten years later by the MQuITE Project, which seeks to identify and develop approaches to measuring quality in initial teacher education (the author of this paper is a Co-Principle Investigator on MQuITE).

Respondents to surveys informing Professor Donaldson’s report noted the range of experiences to which student teachers were subject and how this led to variability in depth and quality between courses; however, this was not identified as problematic.

The report highlighted six areas for development:

coherence and progression

variability in quality

preparing for becoming a teacher, including addressing gaps

gaining more from placements

capitalising more fully on expertise

beginning to develop extended professionalism, including preparation for distributive leadership roles and partnership working.

Content of ITE

Donaldson asked the question ‘Initial teacher education – what should it contain?’ (p. 34). In response, the report was clear ‘Any expectation that initial teacher education will cover all that a new teacher needs to know and do is clearly unrealistic’ (p. 34). HEI staff strongly referenced ‘the impossibility of including in an initial teacher education programme all that would ever be required of teachers’ (p. 34) and highlighted the increasing external demands and expectations placed upon ITE to increase breadth often at the expense of depth. Donaldson referenced the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) who stated that ‘initial education cannot provide teachers with the knowledge and skills necessary for a life-time of teaching’ (OECD, 2007). The report further quoted the OECD stating ‘the education and professional development of every teacher needs to be seen as a lifelong task, and be structured and resourced accordingly’ (OECD, 2007).

In the Report's survey, newly qualified teachers, students and early career teachers identified three aspects of their ITE provision as most useful: classroom management, pedagogy, and subject content. These might be described as ‘technical’ but here it should be remembered that such aspects always have a basis in theoretical underpinnings and research, a perspective once again endorsed by the MQuITE Project.

Placement was seen by most Donaldson respondents to be one of the most significant elements of their ITE course, followed by face-to-face provision with ITE tutors and other students. Self-study was also acknowledged as important.

Donaldson’s position was that, while a core for ITE might be valuable, personalisation and flexibility remain key to producing world-class teachers.

The report also discussed the place of undergraduate learning and the length of time taken to reach the standards for provisional, and then full, registration. On the former, as indicated above, Donaldson proposed to phase out the BEd and replace it with degrees that made better use of wider university knowledge and skills. On the latter, Donaldson suggested a range of measures to lengthen the 10-month PGDE to one that both made better use of time available before, during, and after an ITE course and an undergraduate experience better tied to the induction year so that the whole experience is seen as a five-year ITE programme.

In all cases Donaldson noted the range of experiences students have while on placement in educational establishments. Here, 77% of survey respondents suggested that their placement experience was at least of consistent medium quality and 51% highlighted that the support they received from HEI staff was at least effective. In response, Donaldson proposed that placements occur in schools that meet quality standards and with the capacity to mentor and assess student teachers judged by HMI Inspections. The idea of ‘hub schools’ for ITE was also proposed.

The assessment of students on placement and in the induction year was also scrutinised. Here, Donaldson discussed the role school-based and HEI-based ITE tutors might have. Ten years later, the MQuITE project surveyed both groups at the start of the project in 2018. Responses were mixed. HEI tutors acknowledged the important role school-based staff undertake but with reservations about the time, capacity, ability, and remuneration allowed for such professionals to adequately undertake their duties (Adams, Carver, & Beck, forthcoming). School-based staff were similarly keen to undertake such duties and also recognised the expertise of HEI-based staff, but here there was disagreement as to their role based on similar concerns to those above.1 Donaldson floated the idea of joint appointments between HEIs and local authorities as a possible mechanism for improvement, with such individuals shifting their focus from administrative functions to the quality improvement of ITE and partnership. Mentoring was highlighted as a key feature for the development of teachers, not only in the early career phase; in the main, support for inductees and ECD teachers was identified as requiring improvement. Alongside these proposals were those that signalled the need to treat ITE, induction and ECD more seamlessly.

As described above, Donaldson conceived teacher education as being a career-long endeavour. Donaldson highlighted the need for teachers to engage with ongoing professional development that meets personal, school and community need in a wide variety of ways. Citing the international literature, Donaldson highlighted how the most effective CLPL is ‘‘site-based’, fits with an existing school culture and ethos, addresses the needs of different groups of teachers, is peer-led, collaborative and sustained (p. 64).

Donaldson identified that who a teacher is, where they work, and the quality of leadership significantly impact on professional learning and development. The report stated that CLPL often lacked coherence and progression. In response, the report identified core knowledge and skills that required development over time, starting in ITE, progressing through the induction year, into ECD and beyond using GTCS standards as benchmarks. The report suggested that tailoring CLPL to the needs of schools and individual teachers through a combination of specialist input and an ongoing programme of school-based support was often cited by respondents and the literature as the most effective means for professional development.

Professional Review and Development (PRD) arrangements were noted as of most impact when both supportive and challenging. Problematically, the quality and impact of PRD was, at best, variable, a position reinforced by Adams & Mann (2021).2 While accreditation of learning was not highlighted as essential, 39% of respondents to Donaldson maintained that they would be more likely to engage with CLPL should their efforts glean awards. Despite acknowledging that evidence for a Masters level profession was growing, Donaldson did not suggest this should be the norm but rather that ITE, ECD, and CLPL should look to accredit professional learning at Masters level where possible.

2016 evaluation

In 2016, the Scottish Government published an Evaluation of the Impact of the Implementation of Teaching Scotland's Future. This found that:

The teaching profession has risen to the challenge set out in [Teaching Scotland’s Future]. The evaluation found evidence of real progress in many areas of teacher education and, above all, there has been a significant shift in the culture of professional learning.

Specifically in relation to ITE, the 2016 evaluation found that the partnerships between universities and local authorities had progressed and the support for students on placement and teachers in the induction year had improved. Indeed, the products of ITE were seen to be influential in supporting wider culture change; the evaluation stated:

There was also a widespread view that the 'new generation' of teachers emerging from Initial Teacher Education in recent years had helped change the culture. It was felt that it was 'ingrained' in these teachers from the start that they should be self-reflective, engage in professional dialogue, share practice and work collaboratively. Not only did this help change the culture simply because the new generation were gradually replacing the older generation, but it also forced more experienced staff to 'raise their game'.

In terms of ITE, the evaluation identified further areas for improvement. These were:

further clarification and agreement of the respective roles of the school and the university in relation to joint assessment

improved communication between the university and the school on aspects of student placements

the provision of additional support for probationers to further develop key pedagogical skills.

The evaluation reported that fewer teachers reported barriers to accessing Career-long Professional Learning in 2015 compared to 2010.

Measuring Quality in ITE (MQuITE)

In January 2017, the Scottish Government funded a six year project, Measuring Quality in Initial Teacher Education (MQuITE). The project was co-led by Professor Aileen Kennedy and Dr Paul Adams, but worked with representatives from all higher education institutions that offer ITE in Scotland. The project surveyed two cohorts of ITE students (2018 and 2019) following graduation from their ITE course. The project surveyed these students for their views on:

their programmes

their time in the induction year

subsequent career long professional learning opportunities and needs.

Survey data were augmented by data gathered from interviews. Overall, the project identified considerable satisfaction with many elements of ITE and the induction year. Areas for development, such as further work on Additional Support Needs (ASN), was identified, but such matters are in keeping with other research undertaken in other countries. Papers and blog posts have been written and presentations have been made to a range of audiences including academic, professional, and to policy-makers. The project is due to complete in December 2022, after which knowledge exchange work will continue.

Current Scottish ITE provision

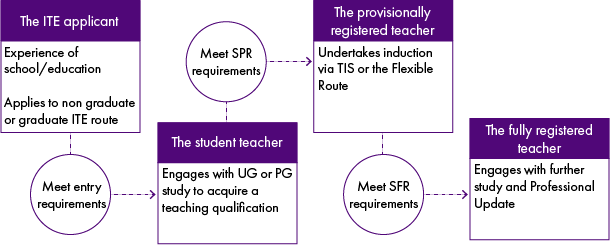

Scotland’s current ITE structures and approaches largely reflect the recommendations in Teaching Scotland’s Future. The current process for qualifying as a teacher in Scotland is described in the graphic below.

Those who wish to become a teacher in Scotland and who do not already possess a teaching qualification must successfully complete an ITE course offered by one of eleven Scottish Higher Education institutions (HEIs). Successfully completing an ITE course allows for Provisional Registration with the General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS). There are a variety of ITE courses offered in Scotland:

undergraduate, four year BA/MA degrees, predominantly for primary teachers - these are different in structure to the traditional BEd that existed prior to Donaldson in that they seek to utilise the knowledge, expertise and experience of areas of the university wider than just departments of education

undergraduate, four year combined degrees that offer subject study and study of teaching; as with BA/MA courses, such degrees use the support of departments outwith education

undergraduate top-up degrees for those students with qualifications such as HNC/HND

ten-month, professional graduate diplomas in education (PGDEs) devoted to the study of education (some of these vary in their relationship to the induction year and Masters level learning)

a small number of other routes sometimes developed following calls for variation in the system in 2016, such as the two-year Masters (MSc) offered by Edinburgh University or the five-year MEDUC offered by Glasgow University.

Funding for ITE courses is channelled through HEIs. However, responsibility for Scottish ITE provision is managed through partnership mechanisms shared between the GTCS, local authorities, schools, and HEIs. Education Scotland provide opportunities for the audit of courses. Each ITE partnership must:

assess applicant suitability, devise and deliver the HEI component of courses

supervise, support and assess student teachers whilst on school placement

advise on student suitability for the conferment of the Standard for Provisional Registration.

Additional post-ITE partnership working does take place, particularly following recent Scottish Government funding for Masters level learning, but this is limited. ITE changes since 2011 have led to variable programme iterations in the intervening years in response to HEI quality enhancement mechanisms, such as reviews every five years and changes to GTCS standards.

Placements

Each ITE course has its own mechanisms and organisational structure designed to meet student need and the requirements of local schools. Courses must adhere to the GTCS guidelines and include professional learning placement opportunities. For undergraduate courses, students must spend at least 30 weeks on placement. For PGDE, placement must make up 50% of the course.

Teaching placements are mostly operated via the GTCS-run Student Placement System (SPS). Universities and local authorities negotiate placement opportunities for ITE students. Local schools may ‘opt out’ of being included in negotiations for operational and educational reasons. Students are allocated placement schools. Occasionally, students may wish to request a certain placement, for example in a rural school. This can be managed by SPS but sometimes involves other negotiations. The GTCS manage the operation of SPS and seeks to ensure that:

student journey times are not excessive

HEI programme criteria are met

Local Authority Coordinators maintain control and management of their placement opportunities

communication between partners is transparent and efficient

statistical reporting can take place.

Many state schools offer ITE student placement opportunities through the SPS. Each school has a range of personnel to support student teachers, such as:

regents, who plan induction programmes for student teachers and are responsible for the oversight of ITE students’ experience

mentors (sometimes principal teachers) who organise students’ day-to-day classroom experiences. They provide explicit feedback to students on progress towards the Standard for Provisional Registration. In secondary schools, mentors may not follow student teachers for all their time in school. In primary schools, as teachers are mostly allocated to one class, it is likely that the mentor will also be the class teacher

class teachers sometimes work with and support student teachers outwith the role of mentor. This is more likely in secondary schools.

Teacher Induction Scheme

Upon graduation, newly qualified teachers enter an induction period, either the guaranteed employment Teacher Induction Scheme (TIS) or the Flexible Route and have up to three years to achieve the Standards for Full Registration. In the former, this is mostly achieved whilst employed as a Newly Qualified Teacher (NQT) for their induction in a local authority maintained school, usually over one school year. On the latter route, the Standards for Full Registration are achieved mainly through part-time and supply work. Most NQTs opt to complete induction via TIS. HEI involvement in the induction year is highly variable and subject to available funding and synergy between HEI expertise and local authority need.

Local authorities are also responsible for supporting induction year teachers working within the Teacher Induction Scheme towards the Standards for Full Registration. Support is organised differently across local authorities but meets contractual obligations for each inductee’s working week:

reduced classroom contact time (18 hours)

4.5 hours of professional development

an induction supporter/mentor to guide the inductee through their induction year.

ITE students nearing the end of their programme and who wish to enter TIS, specify five first-choice local authorities. There is the option to ‘tick the box’ thereby indicating that the student is willing to teach anywhere in the country – those that do so currently receive an additional £6,000 (primary) or £8,000 (secondary). Local authorities have no quotas for the number of inductees they take, rather students are matched according to their preferences and local authority opportunities. Student teachers are matched to a school in the authority in which they have been placed. GTCS is clear that personal matters will not be considered for the initial placement with a local authority. This and other reasons have led to variability in the quality of the TIS:

those supporting inductees may or may not have experience and/or formal mentoring qualifications

staff may or may not be in a strong position to engage with the mentoring process

the school may or may not be in a strong position to support the inductee.

Funding for the first 1,800 probationers is included in the General Revenue Grant from the Scottish Government to local authorities. The Scottish Government provides additional funding for probationers over the first 1,800. In 2022-23, this additional funding was £37.6m.1

Roles and responsibilities

ITE is intended to be a partnership between a number of bodies. Each partnership member has distinct and complementary roles in Scottish ITE. These roles are explored in the following sections.

General Teaching Council for Scotland

The GTCS is responsible for:

accrediting ITE programmes

devising Standards for Provisional Registration and Standards for Full Registration; achievement of the former permits ITE graduates to take part in the Teacher Induction Scheme or the Flexible Route to achieving the Standards for Full Registration

supporting the Teacher Induction Scheme

administering the Student Placement System.

Education Scotland

Education Scotland is a ‘Scottish Government executive agency charged with supporting quality and improvement in Scottish education’. Education Scotland monitor ITE partnership self-evaluation reports through mechanisms drawn up in the document Self-evaluation framework for Initial Teacher Education (Education Scotland, 2018).

Self-evaluation sits within a framework of professional learning and partnership working provided by Education Scotland resulting from the Aspect Review of the Education Authority and University ITE Partnership Arrangements (phase one).1

Higher Education Institutions

Currently, eleven Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) offer ITE courses that confer teaching qualifications and recommend students for Provisional Registration status. Students on designated undergraduate courses mostly graduate with an award at level 10 of the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (an Honours degree). Professional Graduate Diplomas (PGDEs) often offer a mix of level 10 and level 11 qualifications, increasingly the latter. Entry into and qualification from all HEI courses is governed by GTCS1, individual HEI regulations, and advice from ITE partners.

Local authorities

All 32 Scottish local authorities have a responsibility to ensure that education provision in their area is adequate and efficient. Although each local authority operates different structures, they must ensure continuous good service and improvement.

Largely, local authority involvement in ITE centres on planning for students’ placement provision in local schools and supporting the teacher induction scheme.

As employers, local authorities are also largely responsible for their staff’s professional development.

Schools

Most Scottish state schools are under local authority control and work with appointed local authority staff to provide for student teachers.

Debates about ITE

Discourse in Scotland around ITE can identify the content of university ITE courses as a lever to achieve changes in teaching and learning in school education. This briefing does not address these issues. However, there are wider debates around ITE provision which are explored in this section.

Donaldson discussed a number of debates around ITE. These included:

the purpose of ITE

the role for various organisations in ITE partnerships

the links between ITE, early career and career long professional learning (CLPL).

Recent debates around ITE in Scotland can be framed by what is or is not covered in universities’ ITE courses. For example, Angela Morgan’s review of the implementation of additional support for learning recommended that “all teacher education and development includes nationally specified practice and skill development in supporting learners with ASL needs as a core element.” The report of the LGBTI Inclusive Education Working Group also recommended that the Scottish Government work to “ensure a long term, sustainable approach to LGBTI inclusive education within ITE provision.”

Purpose of ITE

Throughout the 20th century, Scottish ITE moved towards HEI involvement and, along with other parts of the UK, to the creation of undergraduate routes for teacher preparation.1 In many instances, ITE was the subject of social, cultural, and political debates questioning HEI involvement. In her 2020 chapter on the development of ITE in Scotland, Professor Moira Hulme quotes John Young’s (President of the Educational Institute of Scotland in 1893) view that while universities should ensure teachers are well-prepared academically, experience ‘under an experienced teacher is the best preparation’ for becoming a teacher .2 The redesignation of Scottish teacher training colleges into colleges of education and their subsequent expansion in number developed throughout the 1960s and 1970s to keep abreast of curricular and organisational changes in Scottish education including comprehensivisation.1 However, social, political, and funding changes throughout the 1980s and 1990s eventually required college incorporation into wider HEI provision. Incorporation was not straightforward and was often stymied by university concerns about research and intellectual standing and college concerns about alterations to mission. Incorporation further steered Scottish ITE towards HEI provision as the means to meet the preparatory needs of a professionally educated community.

The Donaldson Report explored this issue. It stated:

the period covering initial teacher education, induction and the early years of employment lays the foundations of professional values, knowledge and expertise of those who will be our teachers and educational leaders. (p. 26)

Furthermore, as noted previously, Donaldson saw professional learning holistically. Recommendation 3 stated:

Teacher education should be seen as and should operate as a continuum, spanning a career and requiring much better alignment across and much closer working amongst schools, authorities, universities and national organisations. (p.85)

One ITE debate centres on whether HEIs should lead ITE with schools in supporting roles or, conversely, whether ITE should be delivered and managed by schools either alone or with some HEI input. Notably, the Donaldson Report highlighted these as stemming from 30 years of effectiveness drives and cost-cutting exercises which place heavy emphasis on ‘practical competence’ (p. 4). Donaldson challenged such interpretations ‘…which have created unhelpful philosophical and structural divides and have led to sharp separations of function amongst teachers, teacher educators and researchers’ (p. 5).

However, the report also noted an

over-emphasis on preparation for the first post and less focus upon the potential of the initial and early period of a teacher’s career to develop the values, skills and understandings which will provide the basis of career-long growth and in so doing create a broader and deeper leadership pool. (p. 5)

As noted above, Donaldson identifies that ITE cannot cover all that a new teacher needs to know and be able to do. However, the report did highlight areas of ITE deemed useful and culminated in the following as aspects with which new teachers should be comfortable:

address underachievement, including the potential effects of social disadvantage

teach the essential skills of literacy and numeracy

address Additional Support Needs (particularly dyslexia and Autism Spectrum Disorders)

assess effectively in the context of the deep learning required by Curriculum for Excellence

know how to manage challenging behaviour.

Key here is balance between the need for knowledge and skills that can be immediately set to work during ITE placement and beyond, and the knowledge and skills needed to understand wider social, cultural, and political contexts and their impact on schooling. Such an approach requires synergistic relationships between theory and practice that emphasise ‘…effective professional practice, reflection, critical analysis and evidence-based decision making’ (p. 42).

A case is made by Donaldson and the MQuITE Project for the significant role of HEIs in partnership with other agencies. In a 2017 paper commissioned by the Scottish Council of Deans of Education, Professor Ian Menter noted how universities are either seen as a place to prepare students for work or as places to develop the rational mind. This dichotomy rarely features in discussions of the education of lawyers, doctors, engineers, etc., but can be the topic of discussions on the preparation of teachers, social workers, or nurses. Reasons for this are complex but often stem from views that person-centred professions are better prepared for through apprenticeship-style formative periods.

Teaching: a craft or a profession?

Most countries organise ITE so as to balance immediate practical relevance with theoretical issues about what teachers should be able to do and should know. Accordingly, across the globe ITE varies in form, function, and intent. Some countries, such as the United States, Australia and Canada, organise ITE systems regionally within national frameworks. International differences often stem from geography but also in-county pressures to credentialise teachers and meet workforce demand. While HEI involvement in ITE remains a contested area across the globe, Professor Menter’s paper for the SCDE noted the arguments that:

the complexities of teaching require HEI input

globally the most effective approaches to ITE have been shown to be those that seek to integrate theory and practice

the ‘university turn’ is associated with higher performing education systems.

Scottish ITE adopts the position that teacher preparation must take place with significant HEI input and must lead to a teaching qualification. This position is based on the understanding that teaching is a research-informed, research-focused, and research-led profession. This is reinforced through the GTCS standards for provisional and full registration and is similar to the approaches of countries such as Norway and Finland. Conversely, other countries, such as England, have a greater emphasis on teaching as a craft-based profession, best learnt under apprenticeship-type activities supported by teaching standards that allude predominantly to activity and the technicalities of teaching.1

There are notable debates that highlight questions about clarity of purpose for ITE:

the role played by differing organisations in teacher preparation

whether teachers require a teaching qualification or whether they just need to meet professional standards

whether teaching is a craft-based job of work or a vocation-based profession.

Research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has considered the financial element to teacher preparation provision in England.2 The IFS calculated that the total average costs for Initial Teacher Training whether school- or HEI-based are comparable. Notably, the costs for Teach First (highlighted in the Donaldson Report as a programme to consider in Scotland), a charity established to train graduates from prestigious universities for placements in schools in challenging circumstances, were considerably higher.

Engaging with initial teacher preparation has been found to benefit schools and teachers in areas such as:

teaching capacity

staff learning

professional growth of existing staff

fresh thinking.

The IFS report found that around 30% of primary head teachers in England surveyed felt that the costs of involvement with school-led approaches outweigh the benefits.

Donaldson cited strong international evidence that the most successful education systems seek much more than competence through prescription; rather they seek to develop teachers as ‘reflective, accomplished and enquiring professionals’ who ‘have the capacity to engage fully with the complexities of education and to be key actors in shaping and leading educational change’ (p. 4). Regarding the Scottish system, Donaldson did not advocate conformity or uniformity as this may negate local need. However, the report did state that improvements in quality were required.

Retention and recruitment

ITE can be considered the beginning of the pipeline for ensuring there are sufficient teachers to meet the needs of learners or to meet policy goals. The current Scottish Government has committed to additional recruitment of at least 3,500 teachers and 500 classroom assistants over the course of this Parliament (i.e. by 2026).

The Scottish Government co-chairs the Teacher Workforce Planning Advisory Group. This group advises on the annual intake targets for Scottish ITE courses. In March 2022, the group also set out its modelling to meet the Scottish Government’s 2025 targets.

Applications to ITE courses ebb and flow. During times of economic growth, it is not unusual for ITE applications to reduce in number while during times of economic hardship many providers note an upsurge in those applying to enter the profession.

Recruitment and retention rates across Scotland vary considerably region by region. Teacher mobility, local access to ITE students and relative local pay are all significant issues that impact on Scottish ITE recruitment.

The willingness of newly qualified or experienced teachers to relocate impacts on local recruitment and retention rates. ITE traditionally attracts younger entrants, but increasingly older applicants and those undertaking a career change now enter the profession. Mobility is related to myriad factors such as family ties, financial situation, caring responsibilities, or sense of community. Significant geographical relocation is not always possible. Scottish schools in areas of low teacher mobility are less likely to experience high staff turnover. The need to replace staff in such schools is most often associated with life changes and these schools have limited need for newly qualified teachers. Schools in high areas of staff turnover are more likely to require increased numbers of newly qualified teachers. In such instances, links with ITE partnerships form an important part of the recruitment cycle.

Across some areas, opportunities for ITE students are more difficult due to matters such as rural or remote locations, housing availability and affordability, transport links, or amenities. In addition, a lack of available ITE courses mean that some schools can be unable to present themselves as viable options for placement thus exacerbating recruitment issues.

The IFS report noted above highlighted that higher local pay is associated with poorer teacher retention; for a five-year period of 10% total increase in local wages over that for teachers, teacher retention decreases by 5 percentage points.

There are relatively few routes into teaching in Scotland compared to, say, England. Data from elsewhere suggests that the introduction of additional ITE routes does not consistently solve recruitment and retention issues. A variety of factors influence the extent to which local authorities and schools can and do recruit and retain staff.

Across Scotland, all routes into teaching attract school-leavers, graduates, and career-changers. Glasgow and Edinburgh have higher application rates but given their geographical location, the fact that they are in high population areas and that more ITE places are available in their HEIs this is unsurprising. In addition, as most of the Scottish population live in the central belt with its good transport links, it is also unsurprising that local authorities in this area have traditionally attracted higher numbers of applications for the Teacher Induction Scheme and can retain staff.

Undergraduate or postgraduate

In Scotland, a minority of the intake into ITE courses are undergraduate courses. The majority take the one year Post Graduate Diploma in Education (PGDE), having attained a degree in another discipline related to the school curriculum. A small number of ITE students take Masters/doctoral degrees prior to entry to the profession

Some countries, such as Norway and Finland, have designated their initial teacher preparation courses as five year courses that culminate in a postgraduate qualification. The countries do retain one year postgraduate courses for graduates as well, particularly for the secondary sector. Approaches and content can differ both within and between the two countries but the direction here is that teachers should be educated to postgraduate degree level.

While there is little research on the undergraduate/postgraduate distinction in teaching, there is a general global trend towards the latter. Increasingly, providers and students value postgraduate awards for initial teacher learning, later professional development, and career prospects. Teachers may feel the need to differentiate themselves from others both in the profession and in other careers.1 The acquisition of status conferred by Masters level learning is endorsed by some as a key feature in the drive to improve teacher standing. This level of learning requires learners to engage with more in-depth knowledge, demonstrate complex practice, show enhanced skill levels, communicate more effectively, and accept higher levels of accountability and autonomy. In ITE partnerships, this increase in expectations is tied to more complex assessments regarding written work and presentations in the courses.

Partnership

Partnership working is an integral feature of ITE but understandings of what this means in practice can vary. This can be explained by considering varying approaches to partnership working.

Institution-led approaches where one organisation takes overall responsibility for ITE and staff therein either singularly assess student teachers or ‘legitimise’ the assessments of student teachers made by others.1

Co-operative approaches premised on each partner having distinct roles and responsibilities, with the aim to expose student teachers to different theoretical and practical knowledge forms.2

Collaborative approaches where partners plan and work together to support the development and legitimation of different forms of ITE theory and student understanding and practice.1

School-based routes predominately follow an institution-led approach, particularly where no HEI is involved or where there is no ensuing qualification. Co-operative approaches tightly define partners’ roles and responsibilities but attempt to distribute power and control. Collaborative approaches seek to cut across organisational barriers. Here, roles and responsibilities are loosely defined and it is important to accept that partners work differently. Collaborative approaches use these differences to help students understand that teaching can be viewed from a variety of standpoints (e.g. university and school).4

The Scottish Government encourages collaborative approaches across all aspects of school education and Education Scotland encourages ITE programmes to engage with partnership as a core feature of their work.5

The Scottish Council of Deans of Education commissioned Professor Ian Menter, Emeritus Professor, University of Oxford, to "draw on lessons from other parts of the UK and across the world about the contribution of universities to teacher education." His paper The Role and Contribution of Higher Education in Contemporary Teacher Education was published in 2017 and it noted that to meet the complexities of the 21st century

The Scottish Government has [supported] the formation of university and local authority partnerships. These partnerships across Scotland are excellent examples of collaboration envisaged by Teaching Scotland’s Future at strategic and operational levels.

Menter, I. (2017). The Role and Contribution of Higher Education in Contemporary Teacher Education. Retrieved from http://www.scde.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Report-Ian-Menter-2017-05-25.pdf

Professor Menter’s paper also noted that across Scotland, while there is an intent to develop partnership working, there have been difficulties in its practical realisation. Although partnership working serves many functions it is most obviously seen through the student placement system. Comments from school- and HEI-staff made to the MQuITE project noted that while personal relationships between HEI-tutors and school-based staff often developed throughout student placements, these could be stymied by formal partnership arrangements and bureaucracy. Respondents signalled clear desire for partnership to develop further but both groups expressed an understanding of the complexities and difficulties to do so.

Education Scotland’s Aspect Review Education Authority and University ITE Partnership Arrangements considered relationships between ITE and induction. Donaldson called for greater synergy between the two. Recent funding allocations for level 11 learning, part of which were specifically earmarked for PGDE-graduates to top-up their credits to a full Masters degree, indicates Scottish Government intent to support university involvement in teachers’ development beyond ITE. This also illustrates that partnerships between universities and local authorities are developing beyond collaboration focused solely on ITE.

While there are strongly held desires for ITE to be delivered through partnership mechanisms, Beck & Adams (2020) and Mackie (2020) note that how partnerships ought to work in practice is still a matter for debate.78

Possibilities for the future

The historical development of Scottish ITE reflects the belief that teaching is a professional endeavour supported by systems to promote practice, theory, and research. Universities have, for many years, played a significant role.

As we have seen, a partnership approach has also been in place for a significant time, and, although this has faced challenges, it is valued by the partners involved. However, while universities play a large role in ITE, their position in the induction year and career long professional learning (CLPL) is limited - there local authorities or Education Scotland tend to take the lead.

Scotland’s geography presents challenges to the development of a single approach to ITE across the country.

Research indicates five messages that should inform any Scottish ITE system:

internationally, some of the most successful education systems have high levels of HEI involvement in ITE and support teachers to become qualified to higher degree level

entry route diversity does not, in itself, necessarily reduce tensions in recruitment, retention, or mobility

as teaching is a multi-faceted role involving many social and cultural matters, it is important to ensure that ITE utilises the strengths and talents of a wide variety of organisations and people, in partnership

professional development from ITE to induction to Early Career Development (ECD) has occupied space and time in debate but, to date, provision and thinking remains inconclusive and patchy.

Questions

There are two key questions to be considered in formulating the development of Scottish ITE.

What is the role for ITE?

The literature review which supported Professor Donaldson’s review of ITE identified four models of teacher education all of which have relevance. In turn these relate to:

the effective teacher: the dominant, global discourse in ITE that elevates the teacher’s role in contributing to improvement in measurable learning which is tied to economic success

the reflective teacher: stresses the significance of values and theory informing decision-making to support teachers to become active decision-makers through practice-based personal professional development

the enquiring teacher: promotes teaching as a process of active systematic enquiry in teachers’ own classrooms

the transformative teacher: combines features of the reflective and enquiring teacher in bringing forth an ‘activist’ dimension to challenge the status quo and address matters of social and educational inequality.

Each of these four types can be seen across Scotland but CfE mostly promotes the reflective teacher, the enquiring teacher and the transformative teacher. ITE must address a variety of concerns:

should ITE for teachers of all ages and stages be the same?

is the current primary/secondary qualification demarcation still applicable?

should the focus for ITE be on one or more of the four types above?

How does ITE fit within provision for induction/CLPL?

Conditions of service require teachers to engage with at least 35 hours of CLPL per academic year. Identifying CLPL that supports teacher learning and local authority based development is a positive feature that both notes the need for systemic provision while at the same time offering a personalised professional development agenda. Key here is to enable a coherent follow on from ITE into the induction year and beyond. ITE courses differ, and local authorities can employ induction year teachers from any ITE provider. This, and the fact that each induction year teacher will have specific strengths and weaknesses, suggests the need for a flexible process that offers opportunities for new teachers to develop within their schools, gain experience in other establishments, and learn from both peers and others. The GTCS has standards for CLPL and middle leadership that identify key knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes pertinent to ongoing professional learning, and local authorities, Education Scotland, and others offer programmes in support of this.

A question remains however as to the role for universities in such provision. Given that universities are quasi-autonomous business institutions, if local or central government do not contribute to costs then individual teachers will have to provide for themselves. In part, government funding for Masters level learning has mitigated individual teacher contribution but in such a scenario HEIs are only able to offer that which is on their portfolio unless significant resource is provided either from the institution itself, government, local authorities, or other sources. It may be that other organisations can take up the slack, but given the need for research informed professional development it may be best to deploy the knowledge and skills of those for whom research forms a significant part of their work.

One alternative is offered by Donaldson: to see ITE, induction and ECD as part of a continuum. Considering the first five years following entry into a teacher education course as one continuous phase of teacher education and development, rather than the somewhat fragmentary approach taken now, may provide opportunities for greater clarity of provision, collaborative working, and flexibility.

Conclusion

Like preparation for other professions, ITE is most suitably supported by a range of actors. In Scotland, this includes universities, local government, schools, and others in the education field. Debates can centre around the location for ITE provision often based on underlying beliefs about how to educate or train teachers. Debate and research across Scotland have mostly supported provision enacted through partnership mechanisms with universities as lead. The Donaldson Report was a watershed moment, but it is debatable whether its conclusions and recommendations have led to a demonstrable sea change in the preparation of teachers. The partnership endeavours highlighted by Education Scotland’s 2015 Aspect Review and recent provision for Masters level funding are all too often governed by time-limited approaches that are difficult to maintain or replicate. Wider issues of partnership have remained, but data gathered by the MQuITE Project indicates, at best, slight satisfaction with arrangements and approaches by school-based and university-based teacher educators but a desire for more. The landscape can feel cluttered and while it can be argued that support from a wide variety of agencies and personnel can enrich provision, it is also the case that those working in ITE feel some concerns about having to work to many aims within myriad governance procedures. Alternatively, there could be potential issues should one, or a small number of organisations dominate the governance of ITE provision.

In considering the future of ITE, policy makers could consider the following five debates:

What should the early phase of teacher education seek to achieve? Should it concentrate on developing skills such as classroom management, curriculum understanding, and simple pedagogic functions, or should it spend time developing an understanding of teaching’s wider role in the development of the country, society, young people, and professional development. It may be that both should feature strongly, but questions must then be asked as to whether this can be achieved in as short a time as a PGDE and an intensive induction year.

Is the separation of ITE from induction from ECD appropriate or would it make more sense to encapsulate all three within seamless provision? This leads to questions concerning the level of education required of probationary teachers and the role for postgraduate learning opportunities throughout teachers’ careers.

What should be the relationship between different actors in partnership arrangements and how can they best work together to effect meaningful change and teacher education, and should these arrangements be similar across the whole of the country?

What governance arrangements should be established to support ITE? Questions as to whether ITE should be ‘school-centred’ or ‘HEI-led’ often miss the important point that in a true collaboration, different elements can be led by different partners but working with all members of the partnership.

How can funding be arranged, distributed, and managed to best support ITE?

After more than a decade since the publication of Donaldson’s Report, coupled with current need for teachers, wider reforms across school education, and international ITE shifts, there is an opportunity for reappraisal of ITE and its content, organisation, and governance.