Bail and Release from Custody (Scotland) Bill

The Bail and Release from Custody (Scotland) Bill seeks to make changes in relation to bail for people who have been accused of a crime, as well as arrangements for the release of prisoners.

Summary

Part 1 of the Bail and Release from Custody (Scotland) Bill deals with bail. It sets out:

a range of measures aimed at increasing the likelihood of accused persons being granted pre-trial bail, as opposed to being held (remanded) in custody, where this can be done safely

provisions on what account should be taken of any period a person has spent on bail subject to a curfew condition when a court is imposing a custodial sentence in the case.

Part 2 of the Bill deals with the release of prisoners from custody. It sets out:

a range of measures aimed at improving the transition of prisoners back into the community – including release planning, prisoner throughcare, information on prisoner release to support victims, and a new form of temporary release for certain long-term prisoners

provision for a Scottish Government regulation-making power to release groups of prisoners early in emergency situations.

In addition to looking at the proposals set out in the Bill, this briefing provides information on:

the current approach to decisions on bail and remand

how the average remand population has changed over time (including how it compares to the sentenced population), the number of people being remanded and the length of time spent on remand

the process of preparing prisoners for release into the community and supporting their reintegration once released.

Introduction

The Scottish Government introduced the Bail and Release from Custody (Scotland) Bill in the Scottish Parliament on 8 June 2022.1 Documents published along with the Bill include explanatory notes,2 a policy memorandum3 and a financial memorandum.4

The Bill seeks to make changes in relation to:

the granting of bail by the criminal courts, as opposed to being remanded in custody, for people who have been accused of a crime

arrangements for the release of certain prisoners from prisons (including young offenders institutions).

The Bill is not concerned with the circumstances in which the police may hold people in custody, or release them on conditions, pending an appearance in court.

Potential reforms in the areas covered by the Bill were included in a Scottish Government consultation on bail and release from custody5 published in November 2021. Consultation responses6 are published online, along with a consultation analysis.7

In January 2020, the Scottish Government commissioned research into the reasons behind decisions on bail and remand. It noted that this was intended to "support work to reduce the number of people on pre-trial and pre-sentencing remand in the prison system".8 The research was paused due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but an interim findings report was published in July 2022.9 Relevant findings are outlined below when looking at the current approach to decisions on bail and remand.

Other work on bail and remand includes an inquiry into the use of remand10 (report published June 2018) carried out by the then Justice Committee of the Scottish Parliament. In January 2022, the current Criminal Justice Committee stated that:11

A priority issue this parliamentary session for organisations in the justice sector must be addressing the high numbers of prisoners on remand and improving the experience of those prisoners who must be held on remand. Our predecessor committee reviewed the situation back in 2018 and, over three years on, there is no discernible sign of substantive progress on the numbers being held despite the concern of many. That cannot continue.

Whilst at Westminster, in March 2022 the House of Commons Justice Committee launched an inquiry into the role of remand.12

Bail

In many situations, people who are accused of crimes remain in the community whilst waiting for the trial in the case. In some, generally less serious cases, an accused is simply ordained to appear at relevant court hearings - the accused is ordered to appear without being subject to other conditions.

In other cases, the court will decide whether the accused should be released subject to bail conditions or remanded in custody pending trial.

Part 1 of the Bill deals with bail. It sets out:

a range of measures aimed at increasing the likelihood of an accused being granted pre-trial bail, as opposed to being held (remanded) in custody, where this can be done safely

provisions on what account should be taken of any period a person has spent on bail subject to a curfew condition when a court is imposing a custodial sentence in the case.

In relation to bail, the Bill would amend existing provisions in the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 and, to a lesser extent, the Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968.

Current approach to decisions on bail and remand

The criminal courts may have to consider whether or not to grant a person bail at various points of a case. The issue can arise during the initial stages, in relation to pre-trial bail, and following conviction where sentencing is not immediate. There is also the possibility of bail reviews and bail appeals.

Given that the Bill seeks to make changes to the consideration of pre-trial bail, this section also focuses on that area.

Relevant legislative provisions are mainly set out in Part III of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995. Section 23B states that bail is to be granted to an accused except where, by reference to section 23C and having regard to the public interest, there is good reason for refusing bail. The section goes on to state that the ‘public interest’ includes the interests of public safety. It also provides that in deciding whether to grant bail, the court is to consider the extent to which the public interest could be safeguarded by imposing bail conditions.

Section 23C of the 1995 Act sets out various grounds which may lead to the refusal of bail. The stated grounds are, any substantial risk that the accused might if granted bail:

abscond or fail to appear at a court hearing when required to do so

commit further offences

interfere with witnesses or otherwise obstruct the course of justice.

Or, any other substantial factor which appears to the court to justify keeping the person in custody.

The section goes on to provide examples of points which may be relevant in assessing those grounds. These include:

the nature of the alleged offences and probable sentence if convicted

whether an accused was already on bail at the time of the alleged offences

the nature of any previous convictions the accused has

the associations and community ties of the accused.

The general approach to decisions on bail set out in sections 23B and 23C is subject to section 23D of the 1995 Act. Its provisions apply to certain cases prosecuted under solemn procedure. Solemn procedure, as opposed to summary procedure, is used to prosecute more serious offences. Section 23D provides that bail is only to be granted in exceptional cases if the accused is being prosecuted under solemn procedure for either:

a violent, sexual or domestic abuse offence and has a previous conviction under solemn procedure for any such offence

a drug trafficking offence and has a previous conviction under solemn procedure for such an offence.

Any person released on bail is subject to standard bail conditions (e.g. to appear at court as required, not commit any offence and not interfere with witnesses). The court can also impose additional special conditions to help ensure that that the standard conditions are complied with (e.g. conditions prohibiting an accused going to a particular address or approaching a specific person).

In April 2022, the Scottish Government published a research paper looking at some key trends in bail and remand decisions in the sheriff courts.1 It uses data covering the period April 2016 to March 2021. The sheriff courts deal with a very wide range of criminal cases under both summary and solemn procedure. In relation to the issue of bail, they include cases which go on to be dealt with in the High Court. The research paper (p 8) states that:

Across the five years of hearings data from April 2016 to March 2021 analysed, the most likely outcome for the accused when their case calls for the first time in sheriff court is that they will be bailed (45%). The next most likely outcome is that they will be ordained (27%), followed by being remanded in prison (12%).

Other outcomes included the case not proceeding or a warrant being issued for the arrest of the accused.

In relation to the use of remand, the research paper notes that this was more likely in solemn procedure cases - 40% compared to 7.7% of relevant summary cases. This may be expected given that more serious offences are dealt with under solemn procedure. It is, however, worth noting that many more sheriff court cases are dealt with under summary procedure. Because of this, the smaller proportion of remands in summary cases resulted in more instances of people being on remand during the five-year period - approximately 25,000 compared to 19,000 in solemn cases.

In addition to the point about remand being a more likely outcome in solemn cases, key messages highlighted in the research paper include that:

the way in which a person appears in court (e.g. from police custody) is strongly correlated with the likelihood of bail and remand outcomes

people who have previously breached bail are far more likely to be remanded

an increase in the number of decisions to remand in solemn cases was driven by an increase in the number of solemn petitions rather than the likelihood of being remanded.

In July 2022, the Scottish Government published an interim findings report about decision making on bail and remand.2 The report outlines findings of two online surveys - one with prosecution staff (Crown Office & Procurator Fiscal Service) and one with members of the judiciary. Findings included the following.

Prosecution staff:

decisions to oppose bail usually resulted from a combination of factors

important factors in deciding whether to oppose bail included - the risk of the accused committing further offences; previous breaches of bail; the nature of any previous convictions; the seriousness of the offence; and the importance of protecting victims, witnesses and the general public

the most common special bail conditions requested included - having no contact with named individuals; staying away from specific locations; being subject to a curfew; and needing to sign on at a police station

awareness of bail supervision services was variable and such services were perceived as perhaps not being used to maximum effect.

Members of the judiciary:

there was a focus on the past behaviour of the accused as the best predictor of future behaviour, with previous analogous offending and breaches of previous court orders featuring strongly in decisions to refuse bail

a history of no/low risk offending, previous compliance with bail and/or the likelihood of a non-custodial sentence were likely to feature in decisions to grant bail

there was little evidence of the age or gender of the accused influencing decisions, with caring responsibilities, employment and housing stability instead appearing to feature more in considerations

respondents felt largely unassisted in their assessment of risk, and commented that professional risk assessments, especially in cases involving vulnerable accused, would be welcomed

there was reasonably strong support for alternatives to remand, including electronic monitoring in particular

a perceived lack of resources (practical and financial) was seen as the single biggest barrier to greater use of alternatives to remand.

The Bill - consideration of bail and remand

Section 1

Section 1 of the Bill seeks to enhance the role of justice social work where bail is being considered. It would require a court to give justice social work the opportunity to provide relevant information when the court is considering bail for the first time, and separately would allow the court to request further information from justice social work when considering bail on other occasions throughout the life of a case. The change seeks to support better informed decisions on bail at the pre-conviction stage of proceedings.

The Bill's policy memorandum (para 159) notes that the courts may already seek relevant information from justice social work, but that:

this practice is inconsistent and can be dependent on certain factors, such as the availability of a justice social worker in the court (linked to the resources of the local authority), and the culture and relationships between the court and justice social work.

It is intended that the Bill would encourage more consistent input from justice social work. The policy memorandum (para 164) goes on to say that:

Relevant information which justice social work may be able to provide, or which the court may proactively request from justice social work, could include matters about the accused, such as addiction issues, home life, what a remand decision might mean for parental responsibilities etc. Elevating the role of justice social work better empowers the court to receive a more holistic picture of the accused person prior to fundamental questions being determined that impact on an accused person's liberty.

In addition to whether or not bail should be granted, the policy memorandum notes that information from justice social work could help the courts decide whether special bail conditions (over and above the standard ones) should be imposed.

One potential special bail condition is the electronic monitoring of the accused. This was provided for in the Management of Offenders (Scotland) Bill 2019 and has been available since May 2022. Electronic monitoring was already used in various other contexts (mainly to monitor compliance with a curfew).

In relation to the possible use of electronic monitoring (EM) as a condition of bail, the Scottish Government's consultation on bail and release from custody1 noted that obtaining information on the suitability of an accused could require greater input from justice social work. The consultation (p 26) went on to state that:

As such, it is considered some additional time to assess suitability may be beneficial if that is considered necessary in a case. There is work being progressed through the implementation project for EM [electronic monitoring] bail whereby justice social work offers an assessment of suitability for EM bail in cases where the prosecution intend to oppose bail. This work will benefit the court in having as much relevant information as possible available when ultimately determining whether to make use of EM bail when releasing an accused person on bail.

Section 2

Section 2 of the Bill seeks to narrow the grounds upon which a court may decide to refuse bail. It does this in two ways:

Solemn and summary cases - adding a specific requirement that reasons for refusing bail must include a determination that this is necessary in the interests of public safety, including the safety of the complainer, or to prevent a significant risk of prejudice to the interests of justice.

Summary cases - limiting the circumstances in which a risk that the accused might abscond or fail to appear can be used as a ground for the refusal of bail.

The way in which the first of these changes would operate to limit the circumstances in which a court may refuse bail might not be wholly obvious on reading the Bill. Although restructured, many of the elements of the current test for considering bail, as set out in sections 23B and 23C of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 (outlined above), would remain the same. In addition, the courts can already take account of issues relating to public safety and the interests of justice when considering bail and remand. However, the Bill seeks to emphasise the importance of these two areas by making at least one of them a requirement for refusing bail. The Bill's policy memorandum (para 96) notes that:

the Bill makes provision to refocus the legal framework within which bail decisions are made by a criminal court, so that the use of custody is limited to those accused persons who pose a risk to public safety, which includes victim safety, or to when it is necessary to prevent a significant risk of prejudice to the interests of justice in a given case. Accused persons who do not pose a risk to public safety or the delivery of justice should be admitted to bail as the criminal justice process proceeds.

The policy memorandum also notes that the Scottish Government's consultation on bail and release from custody1 had looked at the possibility of making public safety an essential reason for refusing bail - without the alternative of preventing a significant risk of prejudice to the interests of justice. The policy memorandum (para 129) states:

While just under two thirds of respondents supported proposals that a need to protect public safety must be present to justify refusal of bail, some respondents highlighted that flexibility would be needed in the system to allow those with repeated breaches of bail/failures to appear to be remanded in order to maintain confidence in and the proper functioning of the justice system as a whole.

And that (para 130):

It was recognised, particularly amongst legal and justice sector respondents, that there are those accused persons who pose no or low public safety risks but habitually fail to cooperate with orders of the court through deliberate failures to appear. The Scottish Government recognises the ability of accused persons to deliberately evade justice is not in the interests of complainers, witnesses nor the wider public interest and it is important a limited discretion is retained by the courts to remand on non-public safety grounds, as part of the wider package of bail reforms in the Bill.

The second way in which the Bill seeks to limit the grounds for refusing bail applies to summary cases (less serious offences) only. In such cases, a risk of an accused absconding or failing to appear at court, if granted bail, would only be allowed as a legitimate ground for remanding the accused in two situations:

the accused has failed to appear at a previous court hearing in the case

the case against the accused includes a charge of failing to appear in court.

The policy memorandum (para 125) argues that:

The distinction in approach here between summary and solemn proceedings recognises that the nature and gravity of offences under solemn procedure are more serious, where it may be appropriate in the public interest to remand on the section 23C(1)(a) ground (failure to appear) to secure the continued delivery of justice from the outset of a case.

Section 3

Section 3 of the Bill seeks to repeal section 23D of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 which restricts the granting of bail in certain solemn cases. As outlined above, section 23D currently provides that bail is only to be granted in exceptional cases if the accused is being prosecuted under solemn procedure for:

a violent, sexual or domestic abuse offence and has a previous conviction under solemn procedure for any such offence; or

a drug trafficking offence and has a previous conviction under solemn procedure for such an offence.

With the repeal of section 23D, the courts would instead apply the general rules for decisions on bail and remand which are used in other cases. The Bill's policy memorandum (para 145) argues that:

The benefits of this change will be to simplify the legal framework on bail so as to aid decision-making of the court and wider understanding as to how decisions of bail are made in each and every case before the court.

Section 4

Section 4 of the Bill seeks to expand the current requirements for a court to state its reasons for refusing bail and to require the recording of those reasons.

The courts would need to address certain issues when explaining their reasons for refusing bail. This would include, amongst others, stating why concerns about release on bail could not be adequately addressed by requiring the accused to be electronically monitored as part of a special bail condition. As noted earlier, electronic monitoring as a condition of bail was provided for in the Management of Offenders (Scotland) Bill 2019 and has been available since May 2022.

In seeking to justify the proposed changes, the Bill's policy memorandum (para 177) says:

The benefits of these changes are to reflect the seriousness of a decision to place an accused person in custody at the pre-conviction stage of the criminal justice process and emphasise the measures available to help support accused persons remaining in the community. Over time, the recording of reasons will also improve transparency and general understanding of this part of the court's decision-making process at a critical point when a person not convicted of any offence loses their liberty.

The Bill - sentencing where a person was on electronically monitored bail

Section 5

Section 5 of the Bill would require a court, when imposing a custodial sentence, to have regard to any period the person spent on bail subject to an electronically monitored curfew condition. This could be pre-trial bail or bail whilst awaiting sentence.

It generally provides for one-half of that period to be deducted from the proposed sentence, whilst allowing a court to disregard some (or all) of the time spent on such bail where it considers this appropriate. Where the sentencing court does disregard any part of the period on such bail, it would need to state its reasons for doing so. The Bill does not seek to provide any guidance on what might amount to a valid reason.

Currently, section 210 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 includes measures providing that any period spent on remand (awaiting trial or sentence) should be taken into account where a court is imposing a custodial sentence in the case.

The Bill's policy memorandum argues that bail subject to an electronically monitored curfew condition is more restrictive of a person's liberty than bail without such a condition. It notes that some other countries, including England and Wales, already have statutory provisions on what account should be taken of time spent on bail, subject to this type of condition, when a court is passing sentence. It goes on to say (para 197):

The Scottish Government recognises that while there is a restriction on movement and impact on a person's liberty by virtue of being on electronically monitored bail, this does not involve the same degree of deprivation of liberty as being on remand in custody. To acknowledge the difference in impact on a person's life, the Bill provides a conversion of electronically monitored bail days to custody days on a two to one ratio, so that two days on an electronically monitored curfew condition equates to one day spent in custody.

The policy memorandum acknowledges that the Scottish courts may already have a limited ability to take account of time spent on bail subject to an electronically monitored curfew condition when determining sentence. However, it argues that the proposed statutory provision would help support consistency of approach by the courts.

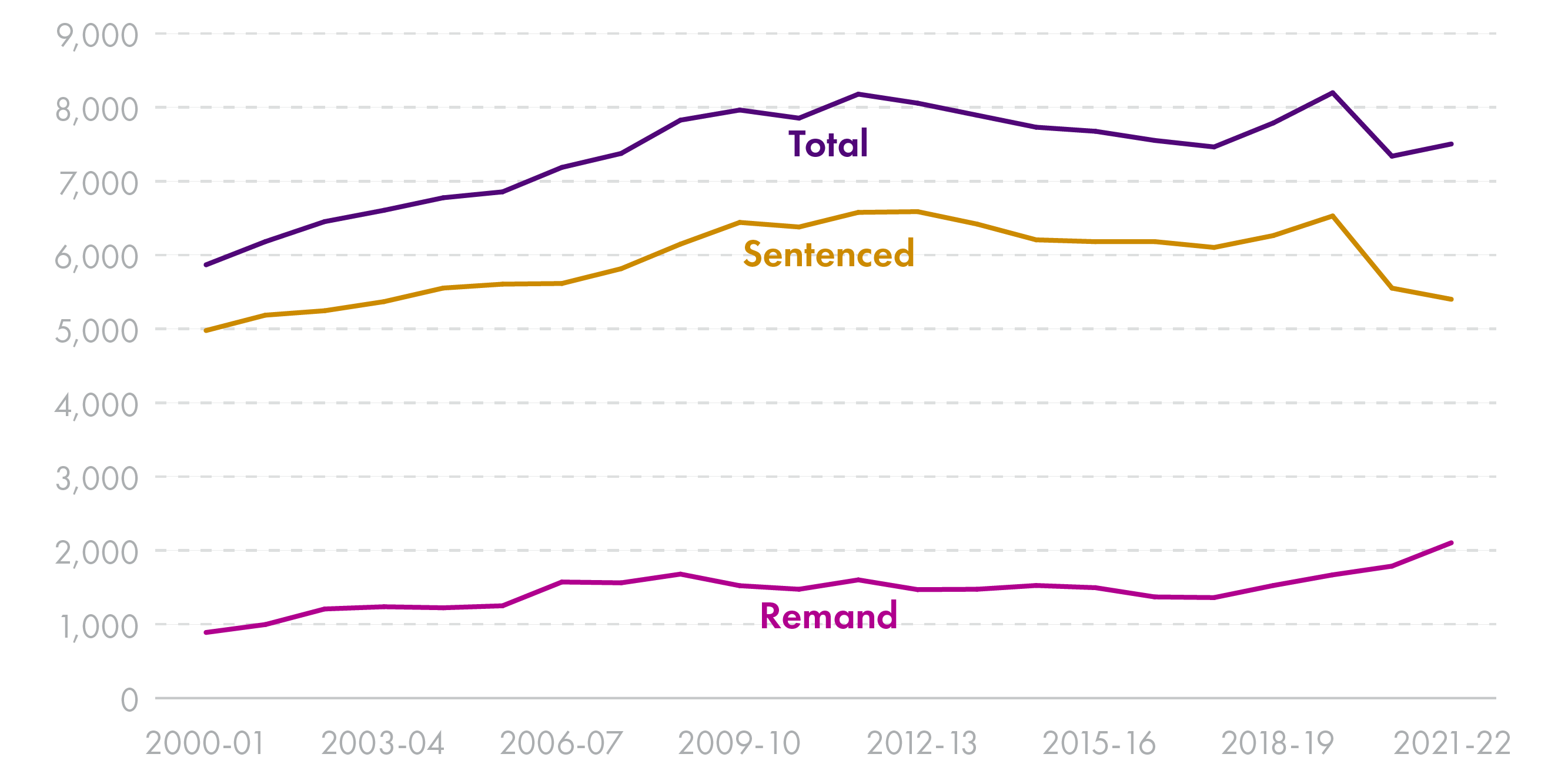

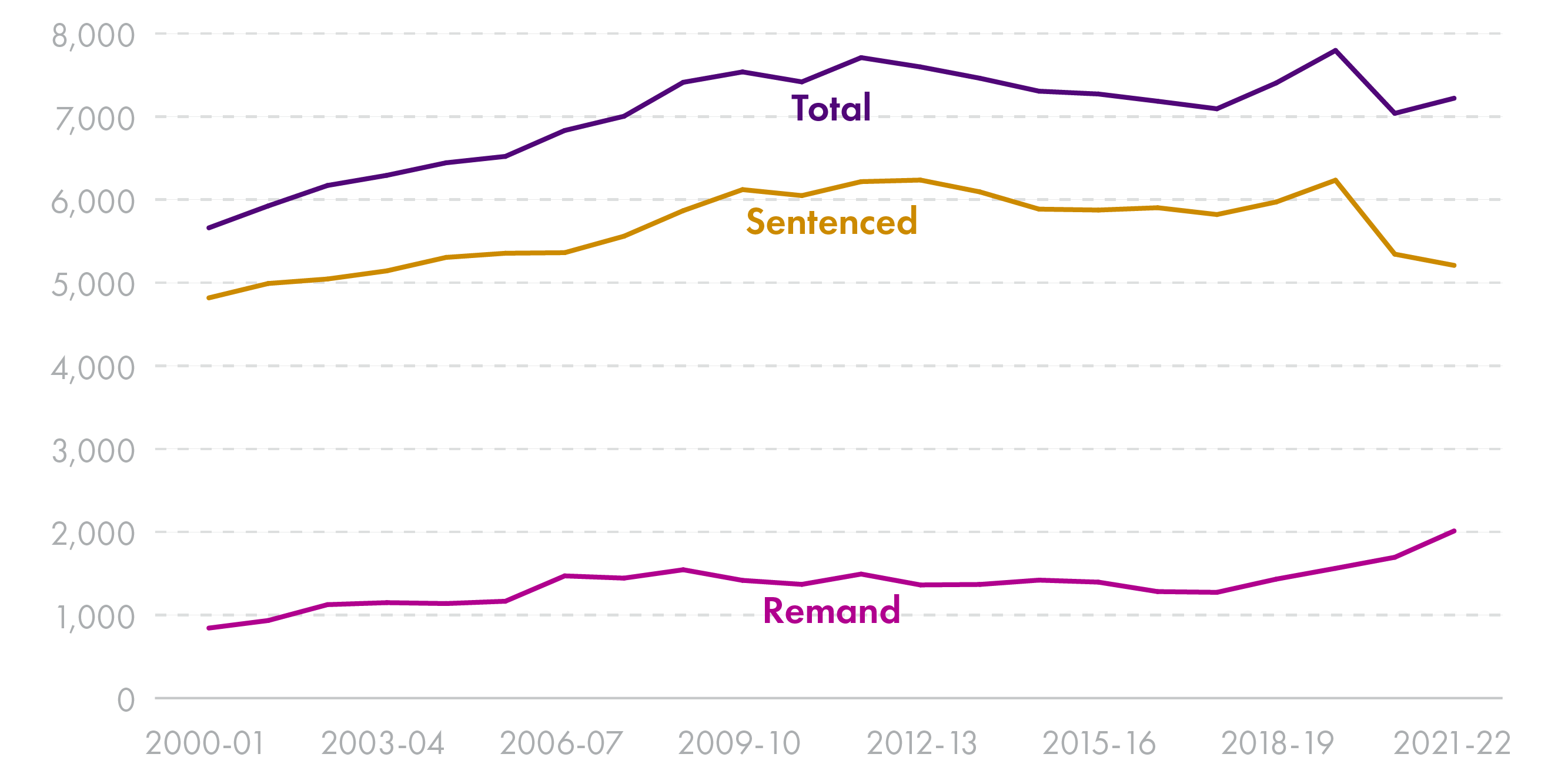

Remand prison statistics

As noted in the introduction to this briefing, the number of people being held on remand in Scottish prisons has given rise to concern. The following four charts set out data on:

how the average remand population has changed over time (including how it compares to the sentenced population)

the number of people being remanded and the length of time spent on remand.

The figures include young people (under 21) held in young offenders institutions, as well as adult prisoners. They also include both male and female prisoners. Additional charts set out in the appendix to this briefing, provide data broken down into male, female and under 21 prisoners.

The charts in this section use figures published on the Scottish Prison Service (SPS) website under the heading of SPS Prison Population1 along with some used in the Scottish Government's statistical bulletin Scottish Prison Population Statistics 2020-21.2

The figures used for the charts are reproduced in the appendix - see tables 1 to 4.

Chart 1 shows how the remand, sentenced and total prison population has changed over the period 2000-01 to 2021-22.

The remand population rose from 889 in 2000-01 to a high of 2,103 in 2021-22 (an increase of 137%). The sentenced population rose from 4,978 in 2000-01 to a high of 6,588 in 2012-13 (an increase of 32%). There was a significant fall in the sentenced population between 2019-20 and 2021-22 - down from 6,529 to 5,401 (a decrease of 17%).

This recent fall in the sentenced population was linked to the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. as a result of restrictions on the carrying out of criminal court business). The Scottish Government's statistical bulletin Scottish Prison Population Statistics 2020-21 (p 10-12) provides some analysis of the impact.2

Unlike the position for sentenced prisoners, the remand population rose during the pandemic. Although delays in concluding cases meant fewer people receiving custodial sentences, such delays also made it more difficult to keep periods of remand within normal statutory time limits. This was reflected in the temporary (still ongoing) extension of those time limits by COVID-19 legislation.

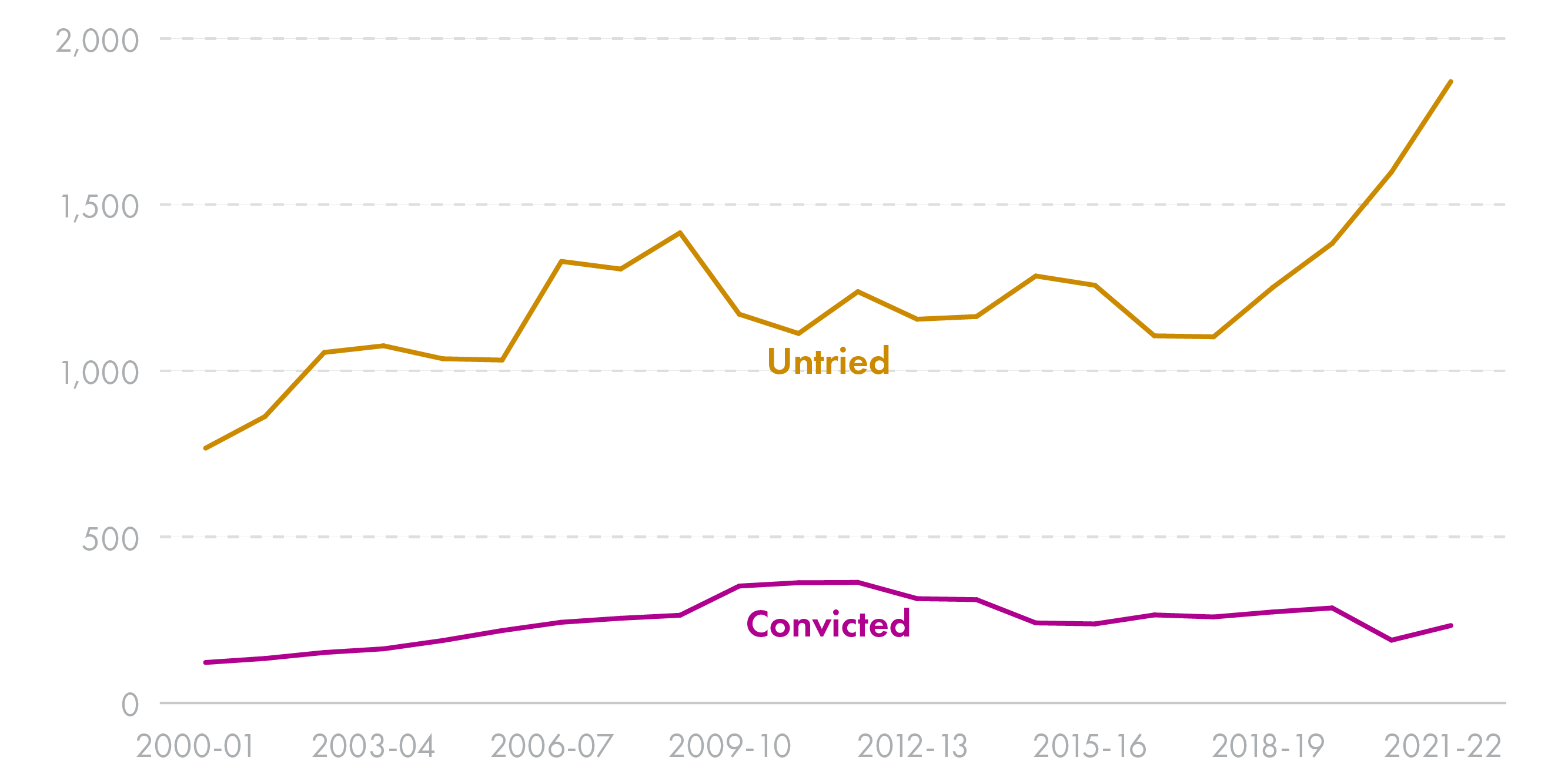

Chart 2 also covers the period 2000-01 to 2021-22. It looks in more detail at the remand population - splitting it into untried prisoners (those remanded pending trial) and those who have been convicted but are awaiting sentence (referred to below as 'convicted').

The untried remand population rose from 767 in 2000-01 to a high of 1,870 in 2021-22 (an increase of 144%). The convicted remand population rose from 122 in 2000-01 to a high of 363 in 2011-12, before falling back to 233 in 2021-22 (still 91% more than in 2000-01).

The untried remand population rose sharply between 2017-18 and 2021-22 -up from 1,102 to 1,870 (an increase of 70%). Some of this will reflect the significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the criminal justice system since March 2020. However, it would appear that the pandemic might have exacerbated or continued an existing trend rather than creating an entirely new one.

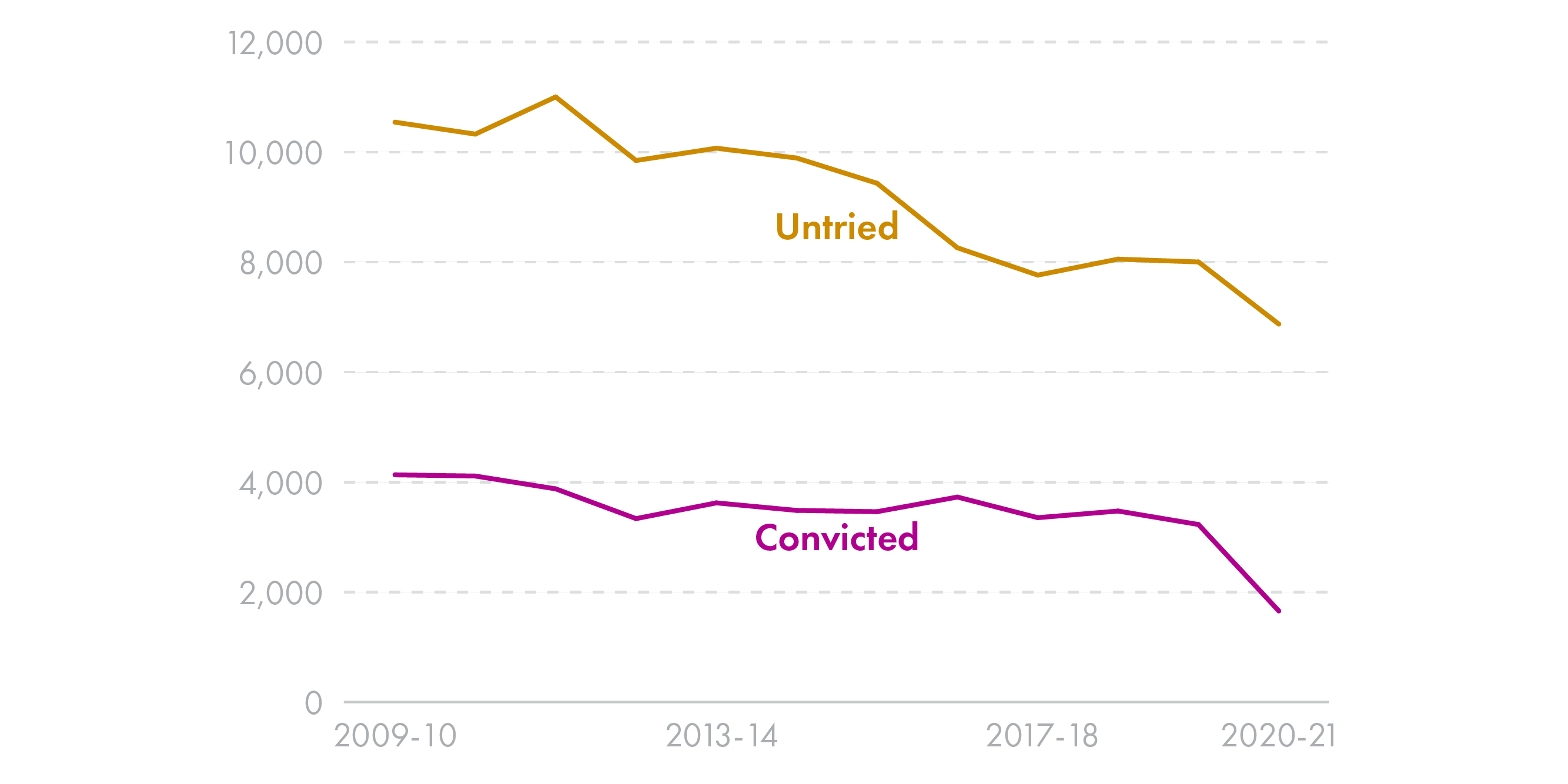

Chart 3 covers a shorter period, from 2009-10 to 2020-21 (due to availability of data). It sets out information on the number of people being remanded in custody. Again, it distinguishes between untried remand prisoners and those who have been convicted but are awaiting sentence.

The chart shows that the number of people arriving to remand, both untried and convicted, has fallen since 2009-10. This includes a significant reduction between 2019-20 and 2020-21 (when the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is seen in the data).

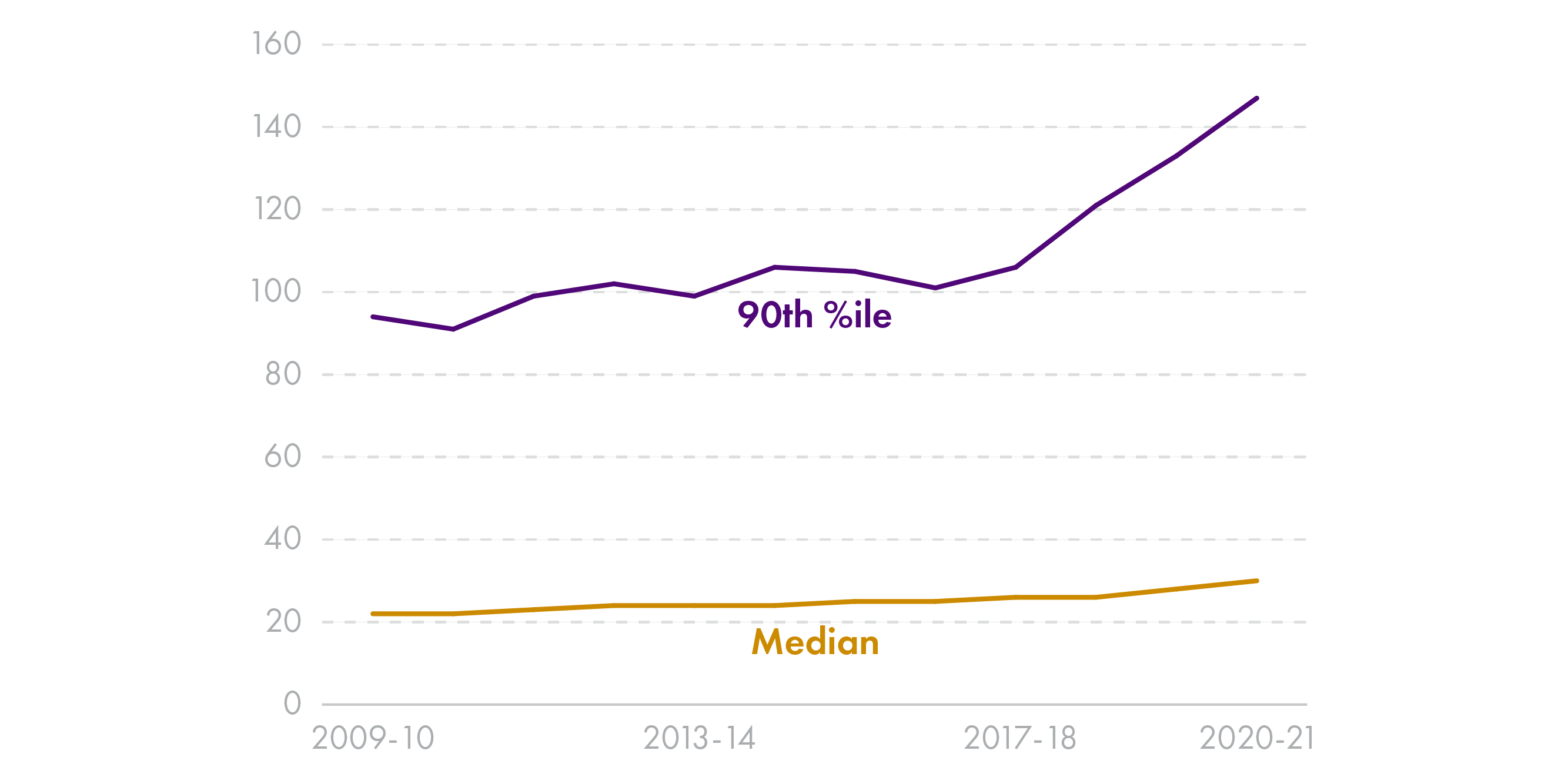

Chart 4 also covers the shorter period from 2009-10 to 2020-21. It sets out information on the length of time prisoners spent on remand, combining data for untried and convicted prisoners. To provide a better measure of where the centre of the data set lies, median values are shown rather than averages.i The median figure rose from 22 days in 2009-10 to 30 days in 2020-21 (an increase of 36%).

The chart also sets out 90th percentile figures - the time taken for 90% of periods on remand to come to an end (e.g. on release or the start of a custodial sentence). This figure rose from 94 days in 2009-10 to 147 days in 2020-21 (an increase of 56%), with a particularly steep rise between 2017-18 and 2020-21 (up 39%).

Looking at the picture presented in the four charts, it would appear that a major driver for a rising remand population since 2017-18 has been an increase in the length of time spent on remand for a segment of untried prisoners. And that, whilst the COVID-19 pandemic is most likely to be a factor, it is not the only one. Detailed consideration of what factors might have led to an increase in the length of time some accused are spending on remand is beyond the scope of this briefing. However, they may include some changes in the profile of cases being dealt with by the courts, such as an increase in the number of more serious and complex cases where a longer period of remand is more likely. On this point, the Scottish Government's research paper looking at some key trends in bail and remand decisions in the sheriff courts,4 noted that (p 2):

There was an increase in the number of decisions to remand in Solemn – which was driven by an increase in the total number of solemn petitions rather than the likelihood of being remanded.

Release from Custody

Part 2 of the Bill deals with the release of prisoners from custody. It sets out:

a range of measures aimed at improving the transition of prisoners back into the community – including release planning, prisoner throughcare, information on prisoner release to support victims, and a new form of temporary release for certain long-term prisoners

provision for a Scottish Government regulation-making power to release groups of prisoners early in emergency situations.

In relation to arrangements for the release of prisoners, the Bill would amend a fairly long list of existing statutes - Prisons (Scotland) Act 1989; Prisoners and Criminal Proceedings (Scotland) Act 1993; Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2003; Victims and Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2014; Community Justice (Scotland) Act 2016; and Management of Offenders (Scotland) Act 2019.

Reintegration and throughcare

The successful reintegration of prisoners back into the community may depend upon a range of measures aimed at tackling existing problems and avoiding the creation of new ones. These include:

programmes to address offending behaviour and the underlying causes (e.g. addiction issues)

support for prisoners in maintaining positive relationships with family and friends in the community

support for prisoners in obtaining stable accommodation, access to healthcare, social security benefits and employability support/work upon release.

Some of this may be spread across a person's time in prison, whilst other aspects may be focused during a period before and following release. Various elements of the above are sometimes referred to as 'throughcare'.

In addition to prison personnel, throughcare may involve:

central, local government and NHS services - including ones with a criminal justice focus (e.g. justice social work) and more general ones (e.g. dealing with health, housing and social security)

third sector providers of services (e.g. the Wise Group - a social enterprise providing mentoring and other services)1

private sector organisations (e.g. the Scottish Prison Service seeks to develop partnerships with businesses which are looking to offer employment opportunities to people with convictions).

The importance of both criminal justice bodies and other organisations working effectively in combination was highlighted in a 2015 Scottish Government report of a Ministerial Group on Offender Reintegration.2 It noted that:

The work of this group has found that re-offending is a complex social issue and there are well established links between persistent offending, poverty, homelessness, addiction and mental illness. When transitioning from custody to the community, gaps in access to vital support services and basic needs can hamper attempts to desist from offending. Not all structural factors and social factors are amenable to change by the criminal justice system, but it is important to note that many different bodies and agencies must work effectively and collaboratively to support those in our criminal justice system who may face challenges in multiple areas of their lives.

It is not only those serving custodial sentences who can face problems upon release from prison. People held on remand, for even relatively short periods, may be affected by similar issues (e.g. loss of housing, work or welfare benefits).

The Bill - transition of prisoners into the community

Section 6

Section 6 of the Bill seeks to improve access to services for prisoners upon release. It does this by further restricting the days on which prisoners are released from custody – thereby bringing forward the release dates of affected prisoners to days on which accessing services may be easier.

Current provisions, in the Prisoners and Criminal Proceedings (Scotland) Act 1993, on the timing of the release of prisoners:

Require release to be brought forward where it would fall on a weekend or a public holiday (e.g. meaning that a prisoner whose release date would fall on a Saturday or Sunday is released on the preceding Friday, or earlier if the Friday is a public holiday).

Allow for the release date of a prisoner to be brought forward by up to two working days where this would be better for the prisoner's reintegration into the community. Unlike the first provision, this is not automatic. It involves an assessment in relation to the individual prisoner following an application.

In relation to the current possibility of bringing forward the release date of individual prisoners by up to two working days, the Scottish Government's consultation on bail and release from custody said (p 40):1

In practice, this is used infrequently and there have been calls, from the Drugs Deaths Taskforce amongst others, to expand the use of this approach by imposing a blanket ban on release on a Friday or the day before a public holiday in order that people leaving prison can access the services they need at the point of release. This recognises the vulnerability of people leaving custody which can manifest in a number of ways, from difficulty accessing accommodation or benefits to drug related or other harms.

The Bill proposes to add Fridays and the day before a public holiday to the list of days where release must be brought forward (i.e. this would apply automatically without any process of application or assessment).

It would also bring forward Thursday releases by a day for those prisoners who, before the application of the above rules, were due to be released on a Thursday. This is intended to help avoid too great a bulge of Thursday releases (which might overload relevant services on that day).

Section 7

Section 7 of the Bill seeks to replace the possibility of release on home detention curfew (HDC) for long-term prisoners with a new system of temporary release under what the policy memorandum refers to as a ‘reintegration licence’ (the term is not used in the Bill).

The proposed change would not affect short-term prisoners, who would still be covered by rules allowing for release on HDC.

Existing provisions allowing for the release of prisoners on HDC can be used in relation to both:

short-term prisoners - custodial sentences of less than four years

long-term prisoners - custodial sentences of four years or more (not including life sentences), provided that release at the parole qualifying date has been recommended by the Parole Board for Scotland.

They allow prisoners to spend up to a quarter of their sentence on licence in the community (with a maximum of six months) while wearing an electronic tag. HDC release conditions include a curfew, monitored using the tag, under which the prisoner must remain at a particular place for a set period each day. Breach of licence conditions can result in recall to custody. Further information about HDC is included in a SPICe briefing on the prison service.1

In practice, release on HDC is mainly used for short-term prisoners. During Stage 2 scrutiny of the Management of Offenders (Scotland) Bill, in April 2019, the then Cabinet Secretary for Justice, Humza Yousaf MSP, noted that long-term prisoners comprise around 0.5% of those on HDC.2

Under the provisions in the Bill, release of long-term prisoners on the proposed reintegration licence:

would include a curfew condition and be subject to supervision by justice social work

could not happen earlier than 180 days before the half-way point of the sentence (the latter being the earliest point at which a person may be released on parole)

could last for up to a maximum of 180 days on any one occasion.

The Bill's proposals cover two situations outlined below.

1. Prior to the Parole Board for Scotland deciding whether to recommend release on parole

The Scottish Prison Service (on behalf of the Scottish Ministers) would be able to release long-term prisoners on reintegration licence prior to the Parole Board deciding whether to recommend release on parole. Some long-term prisoners would be excluded from release under these provisions (e.g. where convicted of terrorist offences).

The Bill provides for the return of the released prisoner to custody where the period of reintegration licence expires without the Parole Board recommending release on parole, or earlier if the Parole Board comes to a decision not to recommend it. A prisoner could also be recalled to custody if the conditions of release on reintegration licence are not complied with. Failure to return to prison when required would be a criminal offence.

In relation to release granted by the Scottish Prison Service, the Bill's policy memorandum (para 229) states that:

This approach is intended to better support the reintegration of certain long-term prisoners, for example by providing the individual with the opportunity to make positive connections in their community, including links to community-based support services. It is also intended to provide further evidence to the Parole Board to inform decisions on whether to recommend release of a long-term prisoner under section 1(3) of the 1993 Act.i

2. Where the Parole Board for Scotland has recommended release on parole

The Parole Board would be able to direct the Scottish Prison Service to release a prisoner on reintegration licence where it has recommended that the prisoner should be granted parole at their parole qualifying date (but in advance of that date). The period of release on reintegration licence would would take place in the run-up to the start of parole. The policy memorandum (para 229) states that:

This is intended to better support the reintegration of certain long-term prisoners by providing them with a managed return to their communities.

In relation to both of the above scenarios, the policy memorandum (para 235) goes on to say:

The approach under this Bill is intended to provide increased opportunities for long-term prisoners to access structured and monitored temporary release as part of the support for their reintegration. This will be subject to different risk assessment processes to HDC and the Parole Board will be consulted on the individual's suitability, given the Board's expertise in risk-based decision making in relation to long-term prisoners.

Section 9

Section 9 of the Bill seeks to facilitate the development, management and delivery of personal release plans for prisoners. A release plan would deal with elements of reintegration and throughcare for both remand and sentenced prisoners:

the preparation of the prisoner for release

measures to facilitate the prisoner's reintegration into the community and access to relevant general services (e.g. housing, employment, health and social welfare).

The Scottish Ministers (in practice the Scottish Prison Service) would be able to require various organisations to engage in this work (e.g. local authorities and health boards).

The Bill's policy memorandum notes that the Community Justice (Scotland) Act 2016 already requires a range of bodies to cooperate in preparing prisoners serving custodial sentences for release, and in the provision of services following release. However, it states that (para 272):

The picture across Scotland on release planning is mixed, with differing approaches and levels of co-ordination depending on the type of prisoner, and different service offers for individuals seeking voluntary assistance.

And that the proposed reforms will (para 270):

have the benefit of supporting a more consistent approach to release planning and ensuring that the key role of the third sector in providing support to people leaving prison is recognised.

Section 10

Section 10 of the Bill deals with throughcare support for both remand and sentenced prisoners.

It would require the Scottish Government to publish, and keep under review, minimum standards applying to throughcare support. In doing so, the Scottish Government would be required to consult the following:

Community Justice Scotland

local authorities

health boards

integration joint boards (where established by local authorities and health boards to plan health and social care services)

Police Scotland

Skills Development Scotland

third sector bodies involved in community justice and the provision of throughcare support

such other persons as the Scottish Ministers consider appropriate.

It would also require various bodies (including the Scottish Government) to comply with those standards when providing throughcare support.

The Bill's policy memorandum (para 292) states that:

This is intended to promote a consistent approach to the provision of throughcare support across Scotland.

The policy memorandum notes that the proposed minimum standards would replace existing national standards for the provision of throughcare published in 2004,1 which are more narrowly focused on the role of justice social work.

Section 11

Section 11 of the Bill seeks to provide that information about a prisoner's release, that can already be given to a victim of that prisoner, can also be given to a victim support organisation to inform the support it provides to the victim. It would also allow such an organisation to request that information.

The new provisions will operate in conjunction with the current Victim Notification Scheme,1 allowing a victim to nominate a victim support organisation to receive information about the release of the prisoner in their case.

The policy memorandum argues that (para 324):

Providing victims with the option of using VSOs [victim support organisations] to request and receive the information that victims are currently entitled to is a way of allowing that information to be delivered to the victim in a more trauma-informed manner, and as part of an immediate conversation or series of conversations between the VSO and the victim about ways in which that VSO can proactively support the victim.

Separately from the proposed reforms in the Bill, the Scottish Government has established an independent review of the Victim Notification Scheme:2

The review was launched in April 2022 and should run for around a year. The review will take evidence from voluntary support organisations, people with experience of the system and the statutory organisations with responsibility for administering the scheme. The review team would also welcome comments from the general public.

The Bill's policy memorandum notes that the review may lead to it considering other changes to the operation of the Victim Notification Scheme.

The Bill - emergency power to release prisoners

Section 8

Section 8 of the Bill seeks to give the Scottish Government a regulation making power to release groups of prisoners earlier than would be the case under normal rules on early release. Use of the proposed power would be restricted to situations where the Scottish Government is satisfied that it is a necessary and proportionate response to the impact of an emergency situation on prisons.

The Bill provides some examples of what is meant by an emergency situation, including:

the spread of an infection which could present significant harm to human health

an event which has resulted in part of a prison becoming unusable.

Relevant regulations would detail who qualifies for release in the particular emergency situation. However, various types of prisoners would be excluded from release under any regulations. These exclusions include:

prisoners held in custody on remand

prisoners serving life sentences

prisoners serving sentences for domestic abuse offences or who will be covered by sex offender notification requirements upon release.

In relation to long-term prisoners, any regulations would only be able to provide for the release of individuals who have already been recommended for release by the Parole Board.

In addition, prison governors would have the power to prevent the release of any individual prisoner who is considered to pose an immediate risk of harm to an identified person.

In explaining the reasons for seeking the power, the Bill's policy memorandum (para 254) states:

The Scottish Ministers do not currently have a general executive release power to release groups of prisoners should the need arise. Existing executive release powers such as compassionate release relate to the consideration of specific individual cases. This means should an operational emergency arise within Scottish prisons which places the security and good order of prisons or the health, safety and welfare of prisoners and prison staff at risk, new emergency legislation would be required to facilitate the release of groups of prisoners, which has resource and time implications, potentially exacerbating the issues related to the operational emergency.

The Scottish Government does currently have a narrower regulation-making power to release groups of prisoners - the power is temporary and can only be used where it is a necessary and proportionate response to the impact of COVID-19 on prisons. It was initially set out in the Coronavirus (Scotland) Act 2020 and has been used once, in relation to the Release of Prisoners (Coronavirus) (Scotland) Regulations 2020. The regulations set out time-limited measures, applying to a period in 2020, providing for the release of some short-term prisoners before the half-way point of their sentence.

The temporary power in the Coronavirus (Scotland) Act 2020 is due to expire at the end of September 2022. However, the Coronavirus (Recovery and Reform) (Scotland) Act 2022 includes a similar COVID-19 related power - again on a temporary basis.

Appendix: Additional Prison Statistics

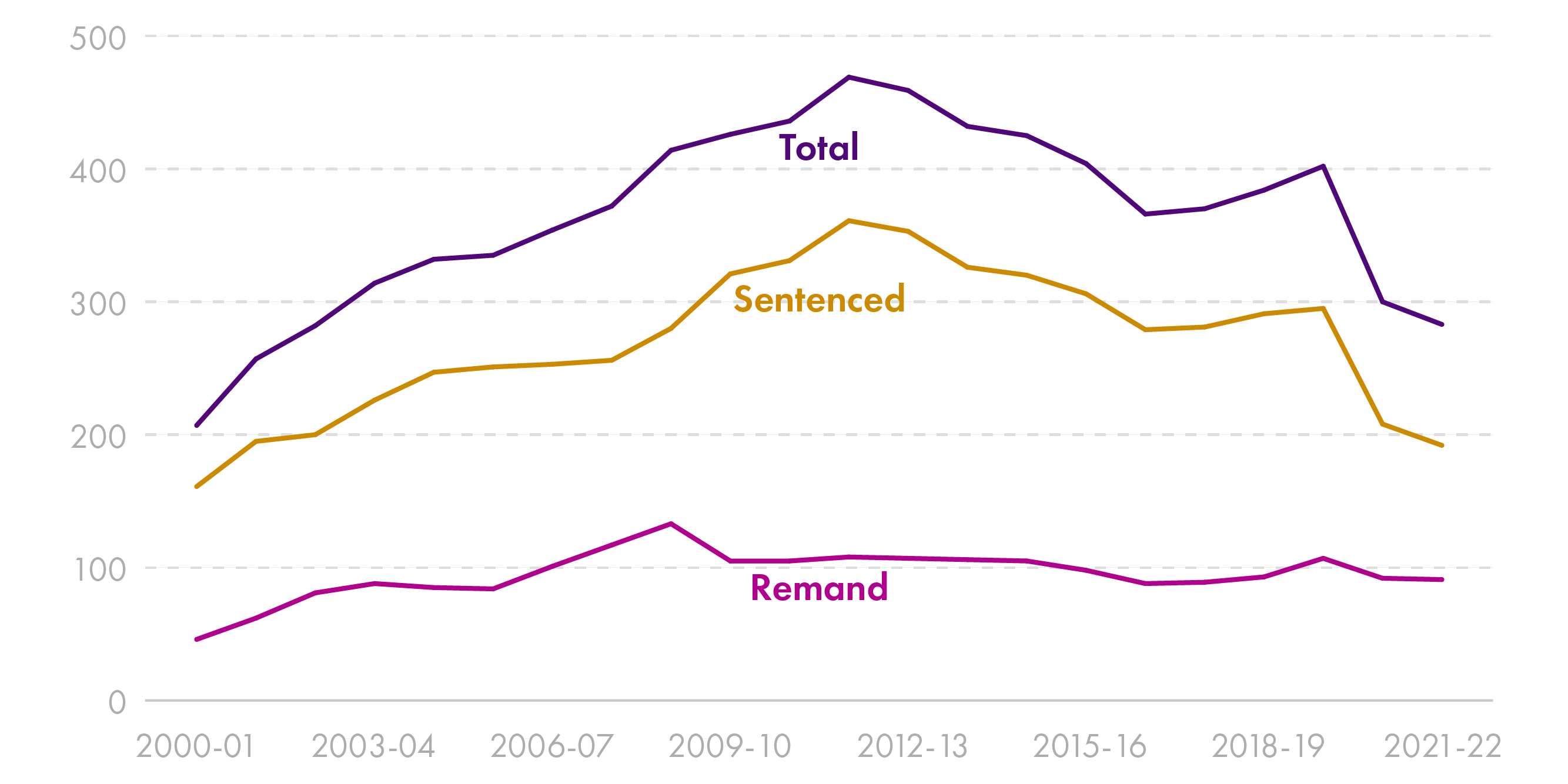

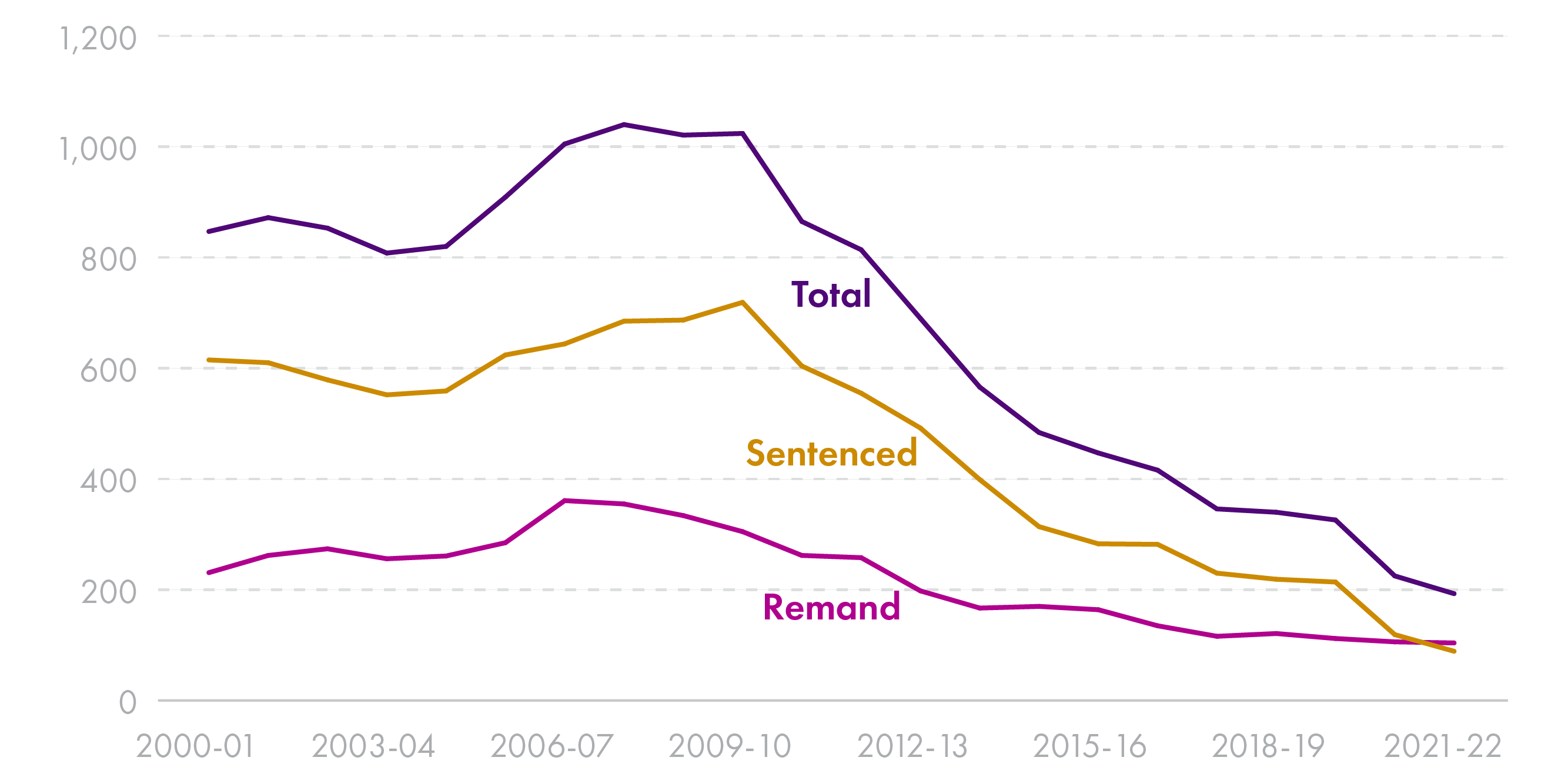

The three charts set out in this appendix show how the remand population has changed over time, including how this compares to the sentenced population, broken down into male, female and under 21 prisoners. They use figures published on the Scottish Prison Service (SPS) website under the heading of SPS Prison Population.1

The tables reproduce the figures used in the charts - those charts set out earlier under the heading of Remand prison statistics as well as the additional charts in this appendix.

Charts

The following three charts cover the period 2000-01 to 2021-22, setting out information on how the average daily prison population has changed.

Chart 5 provides a breakdown into remand, sentenced and total prison population for male prisoners. Given that most prisoners are male, the changes in population illustrated in this chart follow a similar profile to those in Chart 1 (male plus female prisoners).

Chart 6 provides the same breakdown for female prisoners. The remand population rose from 46 in 2000-01 to a high of 133 in 2008-09 (an increase of 189%). It fell back to 105 the following year and has, since then, fluctuated between 88 and 108.

The sentenced population rose from 161 in 2000-01 to a high of 361 in 2011-12 (an increase of 124%). By 2021-22 this had fallen to 192 (19% higher than the 2000-01 figure).

Finally, Chart 7 provides the same breakdown for prisoners under the age of 21. The remand population peaked in 2006-07 at 361. The sentenced population peaked in 2009-10 at 719. Since those peaks, both have reduced significantly. However, a very large fall in the sentenced population meant that by 2021-22 it was, for the first time, lower than the remand population (remand 104 and sentenced 89).

Tables

| Year | Total | Sentenced | Remand |

| 2000-01 | 5,868 | 4,978 | 889 |

| 2001-02 | 6,182 | 5,186 | 996 |

| 2002-03 | 6,453 | 5,246 | 1,207 |

| 2003-04 | 6,606 | 5,369 | 1,237 |

| 2004-05 | 6,776 | 5,553 | 1,223 |

| 2005-06 | 6,856 | 5,606 | 1,250 |

| 2006-07 | 7,187 | 5,615 | 1,572 |

| 2007-08 | 7,376 | 5,815 | 1,561 |

| 2008-09 | 7,827 | 6,148 | 1,679 |

| 2009-10 | 7,964 | 6,442 | 1,522 |

| 2010-11 | 7,854 | 6,380 | 1,474 |

| 2011-12 | 8,179 | 6,578 | 1,601 |

| 2012-13 | 8,057 | 6,588 | 1,469 |

| 2013-14 | 7,894 | 6,420 | 1,474 |

| 2014-15 | 7,731 | 6,206 | 1,525 |

| 2015-16 | 7,676 | 6,181 | 1,495 |

| 2016-17 | 7,552 | 6,182 | 1,370 |

| 2017-18 | 7,464 | 6,103 | 1,361 |

| 2018-19 | 7,789 | 6,264 | 1,525 |

| 2019-20 | 8,198 | 6,529 | 1,669 |

| 2020-21 | 7,339 | 5,552 | 1,787 |

| 2021-22 | 7,504 | 5,401 | 2,103 |

| Year | Untried | Convicted Awaiting Sentence |

| 2000-01 | 767 | 122 |

| 2001-02 | 862 | 134 |

| 2002-03 | 1,055 | 152 |

| 2003-04 | 1,075 | 163 |

| 2004-05 | 1,036 | 188 |

| 2005-06 | 1,032 | 218 |

| 2006-07 | 1,329 | 243 |

| 2007-08 | 1,306 | 255 |

| 2008-09 | 1,415 | 264 |

| 2009-10 | 1,170 | 352 |

| 2010-11 | 1,112 | 362 |

| 2011-12 | 1,238 | 363 |

| 2012-13 | 1,155 | 314 |

| 2013-14 | 1,163 | 311 |

| 2014-15 | 1,285 | 241 |

| 2015-16 | 1,257 | 238 |

| 2016-17 | 1,105 | 265 |

| 2017-18 | 1,102 | 259 |

| 2018-19 | 1,251 | 274 |

| 2019-20 | 1,383 | 286 |

| 2020-21 | 1,598 | 189 |

| 2021-22 | 1,870 | 233 |

| Year | Untried | Convicted Awaiting Sentence |

| 2009-10 | 10,544 | 4,132 |

| 2010-11 | 10,327 | 4,110 |

| 2011-12 | 11,003 | 3,877 |

| 2012-13 | 9,847 | 3,336 |

| 2013-14 | 10,071 | 3,622 |

| 2014-15 | 9,892 | 3,485 |

| 2015-16 | 9,433 | 3,462 |

| 2016-17 | 8,260 | 3,728 |

| 2017-18 | 7,763 | 3,353 |

| 2018-19 | 8,054 | 3,474 |

| 2019-20 | 8,003 | 3,229 |

| 2020-21 | 6,873 | 1,657 |

| Year | Median | 90th %ile |

| 2009-10 | 22 | 94 |

| 2010-11 | 22 | 91 |

| 2011-12 | 23 | 99 |

| 2012-13 | 24 | 102 |

| 2013-14 | 24 | 99 |

| 2014-15 | 24 | 106 |

| 2015-16 | 25 | 105 |

| 2016-17 | 25 | 101 |

| 2017-18 | 26 | 106 |

| 2018-19 | 26 | 121 |

| 2019-20 | 28 | 133 |

| 2020-21 | 30 | 147 |

| Year | Total | Sentenced | Remand |

| 2000-01 | 5,661 | 4,818 | 843 |

| 2001-02 | 5,925 | 4,991 | 934 |

| 2002-03 | 6,171 | 5,045 | 1,125 |

| 2003-04 | 6,293 | 5,143 | 1,149 |

| 2004-05 | 6,444 | 5,305 | 1,138 |

| 2005-06 | 6,521 | 5,355 | 1,166 |

| 2006-07 | 6,833 | 5,362 | 1,471 |

| 2007-08 | 7,004 | 5,560 | 1,444 |

| 2008-09 | 7,413 | 5,868 | 1,545 |

| 2009-10 | 7,538 | 6,121 | 1,417 |

| 2010-11 | 7,418 | 6,049 | 1,369 |

| 2011-12 | 7,710 | 6,217 | 1,493 |

| 2012-13 | 7,598 | 6,236 | 1,362 |

| 2013-14 | 7,462 | 6,094 | 1,368 |

| 2014-15 | 7,306 | 5,886 | 1,420 |

| 2015-16 | 7,272 | 5,875 | 1,396 |

| 2016-17 | 7,185 | 5,903 | 1,282 |

| 2017-18 | 7,094 | 5,821 | 1,273 |

| 2018-19 | 7,405 | 5,972 | 1,432 |

| 2019-20 | 7,796 | 6,234 | 1,562 |

| 2020-21 | 7,039 | 5,344 | 1,695 |

| 2021-22 | 7,221 | 5,209 | 2,012 |

| Year | Total | Sentenced | Remand |

| 2000-01 | 207 | 161 | 46 |

| 2001-02 | 257 | 195 | 62 |

| 2002-03 | 282 | 200 | 81 |

| 2003-04 | 314 | 226 | 88 |

| 2004-05 | 332 | 247 | 85 |

| 2005-06 | 335 | 251 | 84 |

| 2006-07 | 354 | 253 | 101 |

| 2007-08 | 372 | 256 | 117 |

| 2008-09 | 414 | 280 | 133 |

| 2009-10 | 426 | 321 | 105 |

| 2010-11 | 436 | 331 | 105 |

| 2011-12 | 469 | 361 | 108 |

| 2012-13 | 459 | 353 | 107 |

| 2013-14 | 432 | 326 | 106 |

| 2014-15 | 425 | 320 | 105 |

| 2015-16 | 404 | 306 | 98 |

| 2016-17 | 366 | 279 | 88 |

| 2017-18 | 370 | 281 | 89 |

| 2018-19 | 384 | 291 | 93 |

| 2019-20 | 402 | 295 | 107 |

| 2020-21 | 300 | 208 | 92 |

| 2021-22 | 283 | 192 | 91 |

| Year | Total | Sentenced | Remand |

| 2000-01 | 847 | 615 | 231 |

| 2001-02 | 872 | 610 | 262 |

| 2002-03 | 853 | 579 | 274 |

| 2003-04 | 808 | 552 | 256 |

| 2004-05 | 820 | 559 | 261 |

| 2005-06 | 909 | 624 | 285 |

| 2006-07 | 1,005 | 644 | 361 |

| 2007-08 | 1,040 | 685 | 355 |

| 2008-09 | 1,021 | 687 | 334 |

| 2009-10 | 1,024 | 719 | 305 |

| 2010-11 | 865 | 604 | 262 |

| 2011-12 | 814 | 555 | 258 |

| 2012-13 | 690 | 492 | 198 |

| 2013-14 | 566 | 399 | 167 |

| 2014-15 | 484 | 314 | 170 |

| 2015-16 | 447 | 283 | 164 |

| 2016-17 | 416 | 282 | 135 |

| 2017-18 | 346 | 230 | 116 |

| 2018-19 | 340 | 219 | 121 |

| 2019-20 | 326 | 214 | 112 |

| 2020-21 | 225 | 119 | 106 |

| 2021-22 | 193 | 89 | 104 |