Suicide and Self-Harm in Scotland

This briefing provides a brief overview of self-harm and suicide in Scotland. It presents some of the available data and evidence on the prevalence and rates of self-harm and suicide. It then provides information on Scottish Government policy and developments in these areas, ahead of the forthcoming publication of a new suicide prevention strategy and the development of a self-harm strategy for Scotland.

Executive Summary

The Scottish Government's current suicide prevention action plan was published in August 2018 and is due to be replaced by a new strategy in September 2022. In addition to the new strategy, the Scottish Government also announced in October 2021 that it would develop a self-harm strategy for Scotland.

The suicide rate in Scotland declined between 2002 and 2017, which coincided with the implementation of Scotland's previous suicide prevention plans (Choose Life, 2002-2013and the Suicide Prevention Strategy, 2013-2016). The suicide rate, however, increased in 2018 and 2019, before decreasing slightly in 2020.

Some individuals are at an increased risk of suicide, with certain population groups having a higher suicide rate than others in Scotland. Males have significantly higher rate than females. Males in the 35-44 and 45-54 age categories now have the highest suicide rates. Those living in Scotland's most deprived areas also have a higher suicide rate compared to those in the least deprived areas.

Although the suicide rate decreased slightly in 2020, there is some evidence to suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the prevalence of suicidal thoughts.

Evidence on the prevalence of self-harm in Scotland is limited. However, the Scottish Health Survey has collected some data on self-harm in Scotland since 2008. Younger age groups and, in particular, young women, are more likely to have reported ever self-harming.

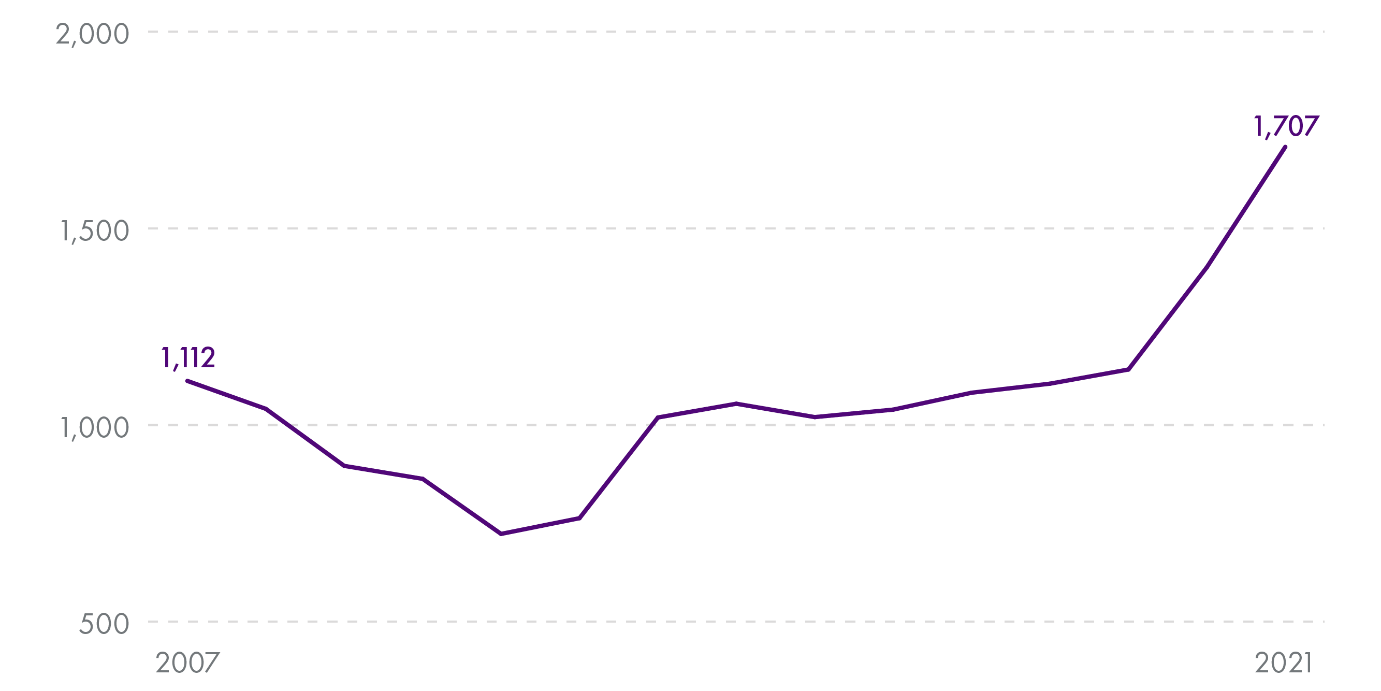

Research has also suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the prevalence of self-harm in the UK. In Scotland, the number of child (under 18) inpatients diagnosed with self-harm related injuries in Scottish NHS acute hospitals increased by 22.8% between 2019 and 2020 and by a further 21.8% between 2020 and 2021.

'Every Life Matters' contains 10 actions, which are at varying stages of completion. A review of the plan's progress was published in February 2021, which found “limited available evidence concerning whether and how the different actions, collectively or individually, may contribute to the ultimate goal of a reduction in suicidal behaviour”.

'Every Life Matters' has the overall aim of reducing the rate of suicide by 20% from a 2017 baseline, by 2022. The 2017 baseline was based on a five-year average (2013-2017) and will be compared to the five-year average for 2018-2022. Based on calculations by Public Health Scotland, the suicide rate (five-year rolling averages) has increased between 2013-2017 and 2016-2020.

In October 2021, the Scottish Government committed to developing a self-harm strategy for Scotland. This announcement followed the publication of a report by Samaritans Scotland in October 2020, which recommended that a Scottish self-harm strategy should be developed by summer 2021. At the time of writing, further information on the strategy has not been published by the Scottish Government.

Introduction

The Scottish Government published its current suicide prevention action plan – Every Life Matters – in August 2018. Every Life Matters followed Scotland’s previous suicide prevention action plans, Choose Life (2002-2013) and the Suicide Prevention Strategy (2013-2016). The suicide rate in Scotland (European age-sex-standardised rate per 100,000 population) fell by 20% between 2002-2006 and 2013-2017.1

‘Every Life Matters’ aims to reduce the rate of suicide in Scotland by 20%, from a 2017 baseline, by 2022.1'Every Life Matters' is due to be replaced by a new strategy in September 2022.

In October 2021, the Scottish Government also committed to developing a self-harm strategy for Scotland.3

Ahead of the end and replacement of 'Every Life Matters' and the development of the self-harm strategy, this briefing provides an overview of suicide and self-harm in Scotland. It firstly provides context on the prevalence of suicide and self-harm by outlining recent trends. It then looks at Scottish Government policy through its progress to implement the actions in 'Every Life Matters' and reduce the suicide rate by 20% by 2022. Finally, it provides some background to the Scottish Government's recent commitment to develop a self-harm strategy.

Definitions

Suicide:

Scotland’s national suicide prevention action plan defines suicide as ‘death resulting from an intentional, self-inflicted act’. Suicidal behaviour includes both ‘completed suicide attempts and acts of self-harm that do not have a fatal outcome, but which have suicidal intent.’1

Suicidal feelings:

Suicidal feelings can vary. They can include thoughts about ending your life, feeling that people would be better off without you, thinking about methods of suicides, or making plans to take your own life.5Suicidal feelings may also be referred to as suicidal thoughts, suicidal ideation, or suicidal ideas.

Self-harm:

Scotland’s national suicide prevention action plan defines non-fatal self-harm as ‘self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of motivation or extent of suicide intent (excluding accidents, substance misuse and eating disorders).’1

As a 2020 report by Samaritans Scotland, Hidden Too Long: uncovering self-harm in Scotland, notes, for many people, self-harm is distinct from suicidal thoughts and behaviour. Although research suggests that repeated self-harm is a “strong predication for future suicidal risk”, most people who self-harm will not attempt suicide.7

Prevalence of suicide in Scotland

The National Records of Scotland changed its coding rules for certain causes of death in 2011. Some deaths that were previously coded under 'mental and behavioural disorders' are now coded as 'self-poisoning of undetermined intent' and are now classified as suicides.1 When looking at longer-term trends, data from the old-coding rules has been used in this briefing.

The crude suicide rate per 100,000 population declined from 17.7 to 12.2 between 2002 and 2017 in Scotland.1 This decline coincided with the implementation of Scotland’s previous suicide prevention plans, Choose Life (2002-2013) and Suicide Prevention Strategy (2013-2016).

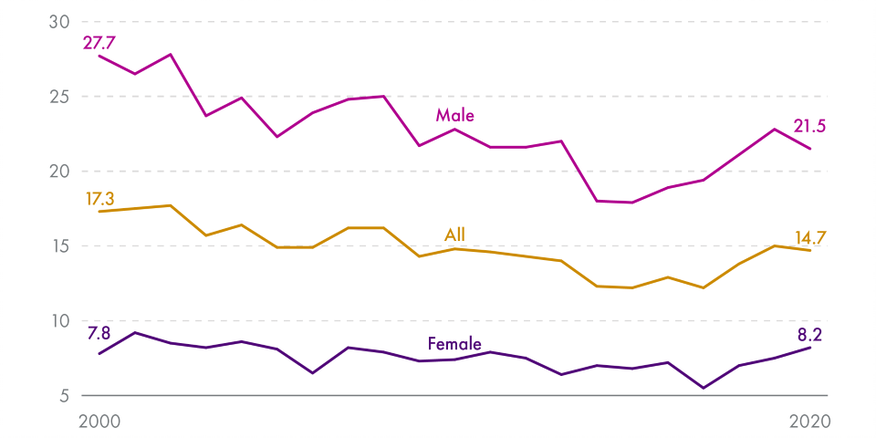

In 2018, however, the suicide rate increased to 13.8 and then again to 15.0 in 2019, before decreasing slightly to 14.7 in 2020 (Figure 1).1

The suicide rate for males remains significantly higher than for females. In 2020, the crude suicide rate per 100,000 population for males was 21.5, compared to 8.2 for females. Unlike the overall rate and male rate, the female suicide rate was higher in 2020 (8.2) than it was in 2000 (7.8).

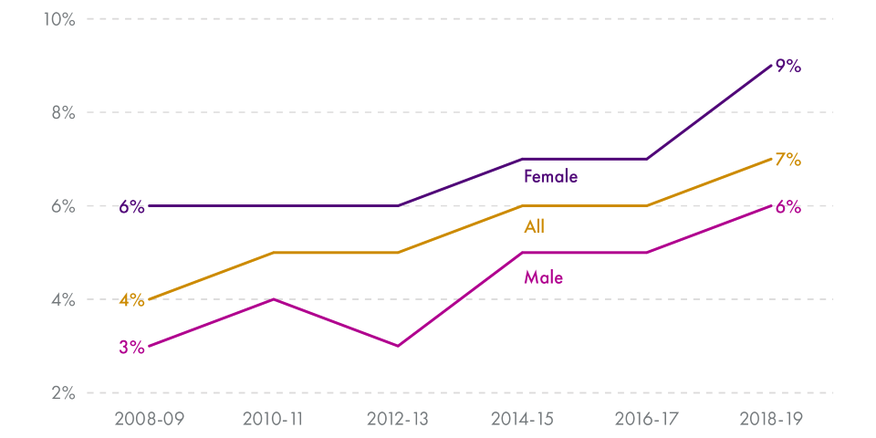

However, women were more likely than men to report ever having attempted suicide in the Scottish Health Survey (Figure 2). A 2021 research briefing by the Samaritans on gender and suicide explored some of the reasons why the suicide rate for men is higher than for women, despite women being more likely to experience suicidal thoughts and to attempt suicide. 4 The Samaritans note that the reasons for this are "complex and remain only partially understood".4 They include a difference in the choice of suicide method between men and women, the existence of a 'gendered stigma' (for example, when discussion of suicidal thoughts can be associated with weakness), and some risk-factors for suicide impacting men and women differently.4

In addition to males, certain other groups are at an increased risk of suicide. The Scottish Public Health Observatory (ScotPHO) identified four key groups of factors that put individuals at an increased risk of suicide:

Risks and pressures within society - such as poverty and inequalities, access to methods of suicide, and substance misuse.

Risks and pressures within communities – such as social exclusion, isolation, and inadequate access to local services.

Risks and pressures for individuals – such as socio-demographic characteristics, previous self-harm, and experience of abuse.

Quality of response from services (e.g. health and social care services) – such as the insufficient identification of those at risk.7

As ScotPHO has noted, the National Confidential Inquiry (NCI) into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health reported that approximately one quarter of the people who died by suicide in England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland had been in contact with mental health services in the year before their death.8 The NCI includes the collection of UK-wide data on suicides by people under the care of psychiatric services, which is defined as those who have had service contact with psychiatric services within the previous year.

In its analysis of deaths by suicide in Scotland from 2011 to 2019, Public Health Scotland found that 77.3% of people who had died by suicide had contact with at least one of nine healthcare services in the 12 months prior to death. These healthcare services included psychiatric inpatient care, psychiatric outpatient care, drug services, NHS 24, and GP Out of Hours. Females were more likely to contact healthcare services (90%) compared to males (73%) in the period before death.9

Age and sex

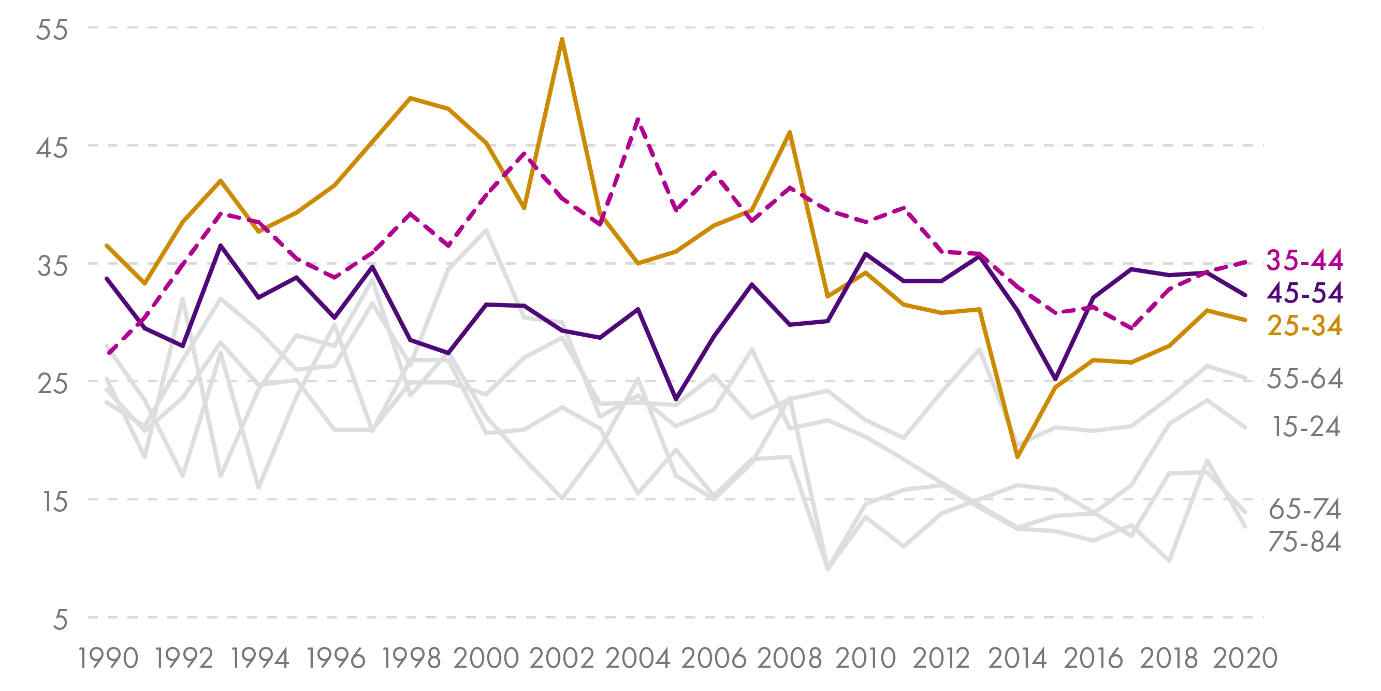

Between 1990 and 2003, the 25-34 age group generally had the highest suicide rate amongst males (Figure 3).1 While this shifted to the 35-44 age group for 2004-2006, it returned to the 25-34 age group for 2007 and 2008 (Figure 3).1

Since 2008, however, the 35-44 age group has generally had the highest suicide rate amongst males – except for 2016, 2017 and 2018, which saw the 45-54 age group with the highest rate (Figure 3).1 Since 2010, the 25-34 age group now has the third highest suicide rate amongst males (Figure 3).1

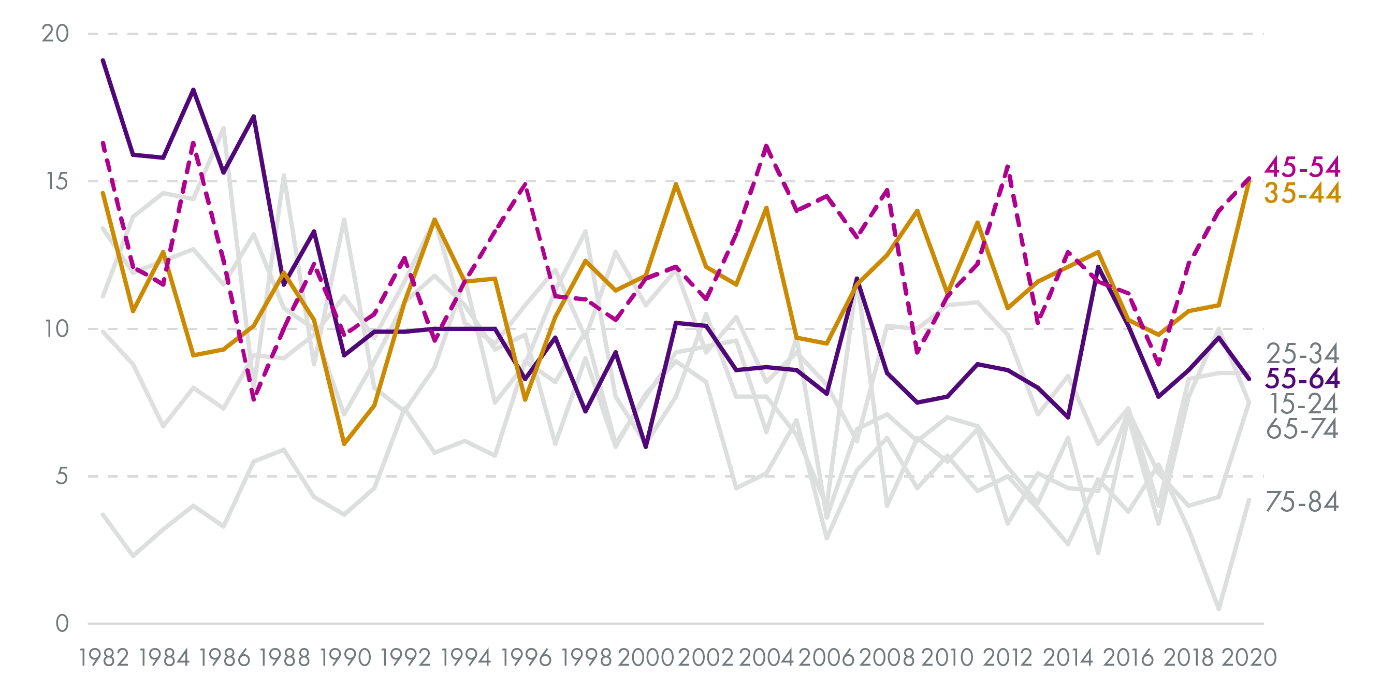

In females, the suicide rate was highest in the 55-64 and 65-74 age groups prior to 1990. The age group with the highest prevalence fluctuated between the 25-34, 35-44, 45-54 and 65-74 age groups in the 1990s (Figure 4).1 Since 2000, the suicide rate has been highest for females in either the 35-44 or the 45-54 age group (Figure 4).1

Deprivation

In its analysis of deaths by suicide in Scotland from 2011 to 2019, Public Health Scotland found that suicide deaths were approximately three times more likely among those living in the most deprived areas of Scotland compared to those living in the least deprived areas.1

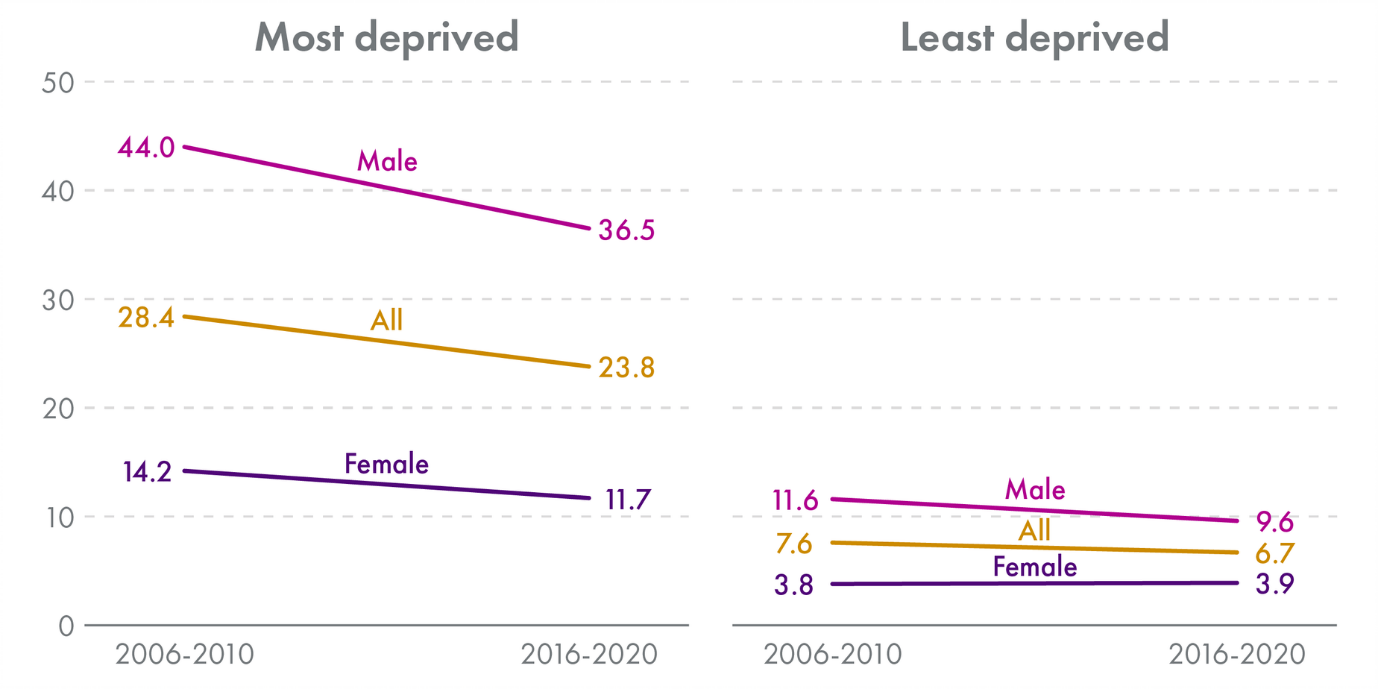

For the most recent five-year period (2016-2020), the overall crude suicide rate per 100,000 population in Scotland’s most deprived Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) decile was 23.8. This compares to 28.4 for 2006-2010 combined.2 In Scotland's least deprived SIMD decline, the overall crude suicide rate per 100,000 population was 6.7 for 2016-2020. This compares to 7.6 for 2006-2010 combined.2

The SIMD is a relative measure of deprivation across 6,976 small areas (called 'data zones'). The SIMD looks at the extent to which an area is deprived across income, employment, education, health, access to services, crime and housing. The SIMD ranks these areas from the most deprived to the least deprived using a certain rank (quintile, decile, vigintile).

For males, the suicide rate in the most deprived SIMD decile was 36.5 for 2016-2020 combined (compared to 44.0 for 2006-2010). In the least deprived decile, the rate for males was 9.6 in 2016-2020 (compared to 11.6 in 2006-2010).2

For females, the suicide rate in the most deprived decile was 11.7 for 2016-2020 combined (compared to 14.2 for 2006-2010). This compared to 3.9 in the least deprived decile for 2016-2020 and 3.8 for 2006-2010.2

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

In its COVID-19 statement (July 2020), the National Suicide Prevention Leadership Group (NSPLG), which has been established to deliver the actions within Every Life Matters, noted initial “anecdotal evidence” in the UK of an increase in mental health presentations and expressions of suicidal ideation.1In February 2022, the Wave 5 report of the Scottish COVID-19 Mental Health Tracker Study noted that, while their evidence related to suicidal thoughts or behaviour, “there has been no evidence of an increase in suicide rates in the UK or globally” so far.2

The Scottish COVID-19 Mental Health Tracker Study included the question ‘how often have you thought about taking your life in the last week?’, with the options:

‘Never’

‘One day’

‘Several days’

‘More than half the days’

‘Nearly every day’

‘I would rather not answer’.

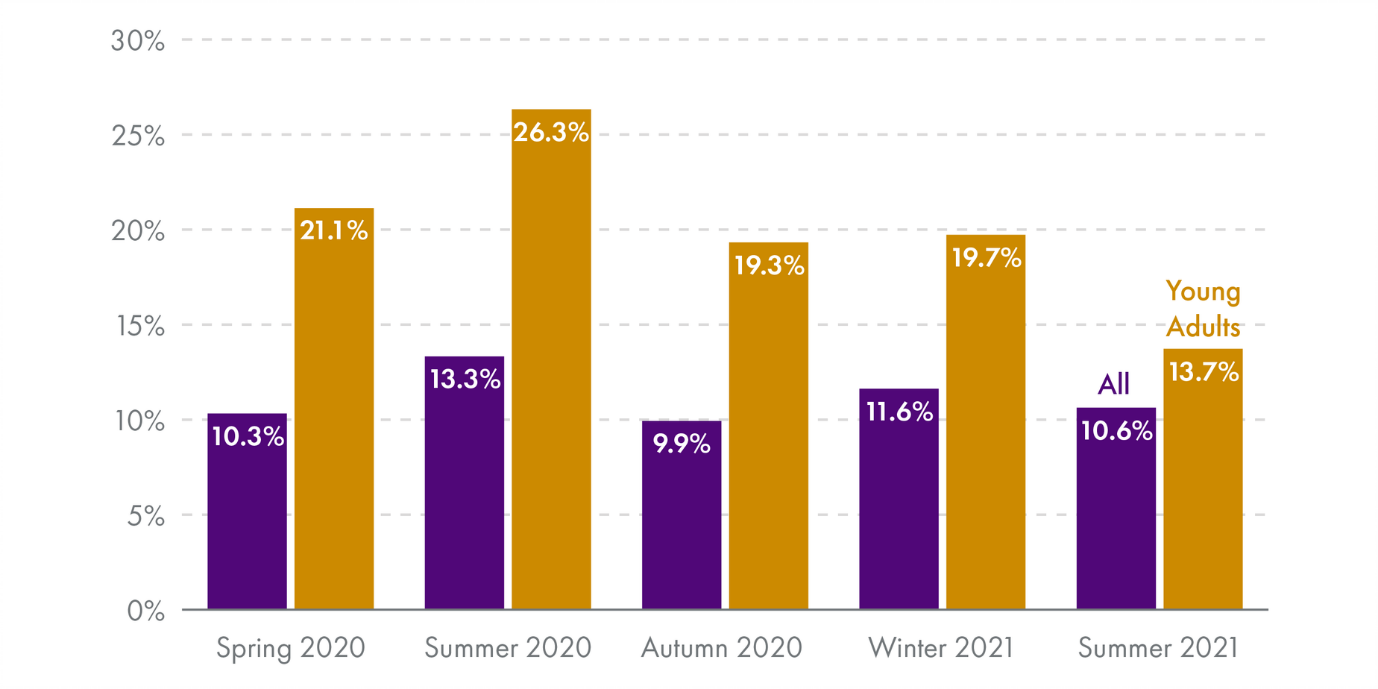

The final report (Wave 5) included a comparison of answers across waves.2Spring 2020 (Wave 1), Autumn 2020 (Wave 3), and Winter 2021 (Wave 4) coincided with periods of higher COVID-19 restrictions. Summer 2020 (Wave 2) and Summer 2021 (Wave 5) were periods of fewer restrictions.

Young adults (18-29 years) were more likely to report having suicidal thoughts.2

Prevalence of self-harm in Scotland

In its October 2020 report, Hidden Too Long: uncovering self-harm in Scotland, Samaritans Scotland noted that self-harm is “often hidden”. Limitations in data and evidence can make it difficult to measure its prevalence.

Stigma remains an issue and often prevents people from telling others how they are feeling and seeking help. Self-harm will be under-reported as a result.1 The survey commissioned by Samaritans Scotland in 2020 suggested that 1 in 4 adults in Scotland would not feel comfortable talking to their GP or another healthcare professional about self-harm.2Furthermore, a study published by The Lancet Psychiatry of people aged 16+ in England highlighted that although there was an increased prevalence in non-suicidal self-harm in England between 2000-2014, there was no “significant changed in the proportion of respondents who subsequently sought support from health services.”3

Samaritans Scotland's 2020 report stated that the Scottish Health Survey is the “most comprehensive picture of the prevalence of self-harm across the Scottish Population.”2

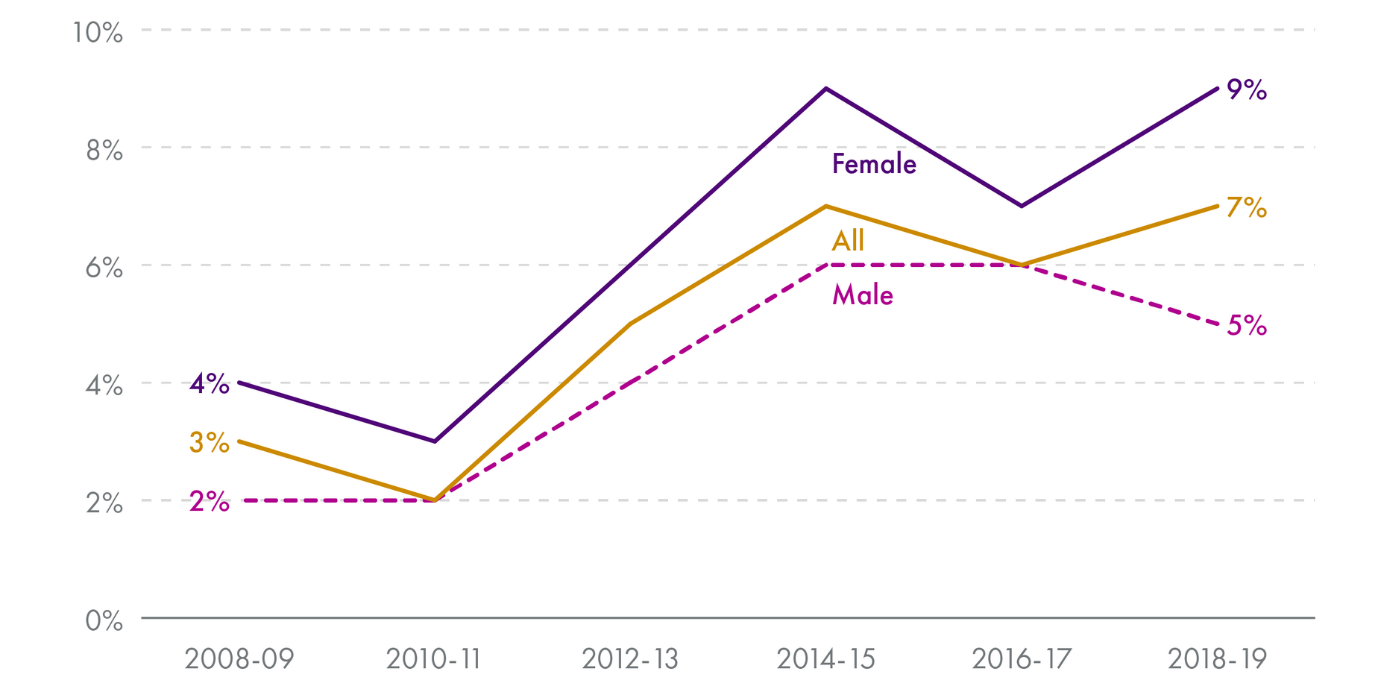

The Scottish Health Survey has recorded data on self-harm since 2008 (Figure 7), with participants asked whether they have deliberately harmed themselves in any way but not with the intention of killing themselves. Participants are also asked when this occurred (the past week, year, or at some other time).

There are multiple societal risk factors for self-harm. These include socio-economic deprivation, unemployment, substance misuse, social fragmentation in communities, and individual factors like Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs).5For 2018-2019 combined, 13% of people in the most deprived SIMD quintiles reported ever having self-harmed in Scottish Health Survey. This compared to 6% in the least deprived SIMD quintiles.6

Age and sex

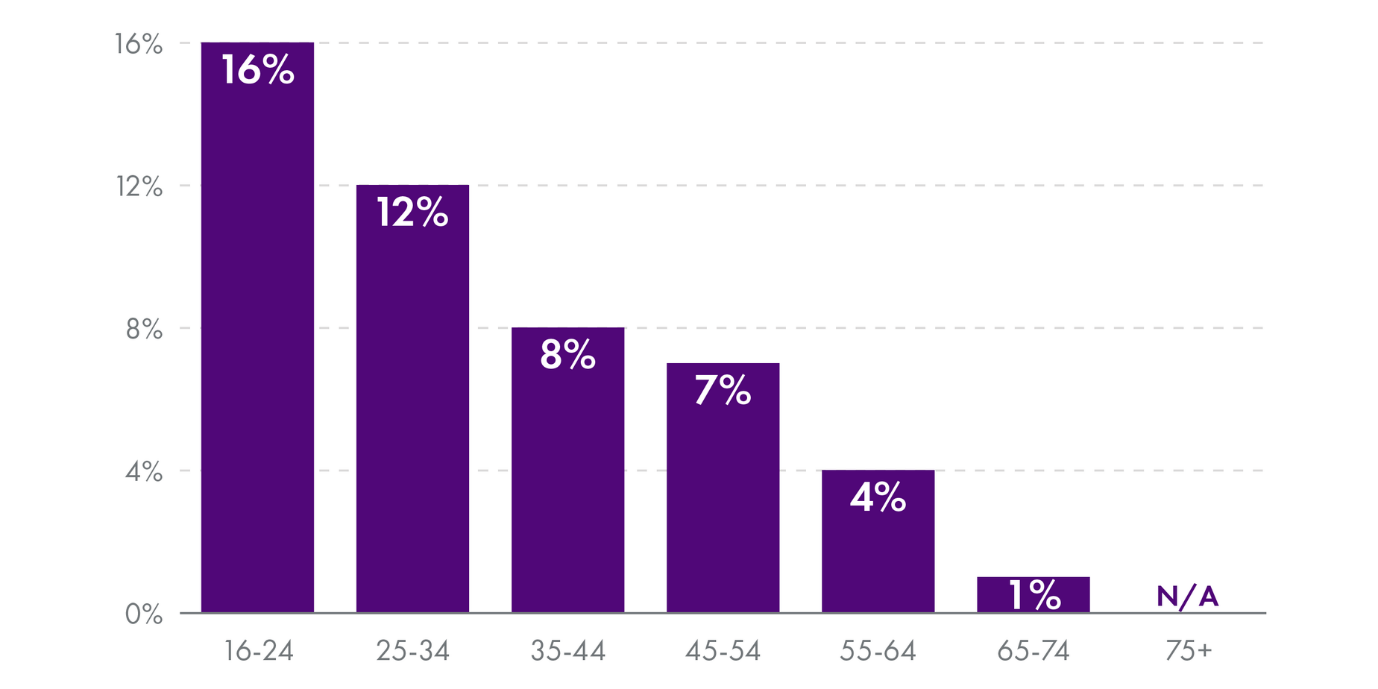

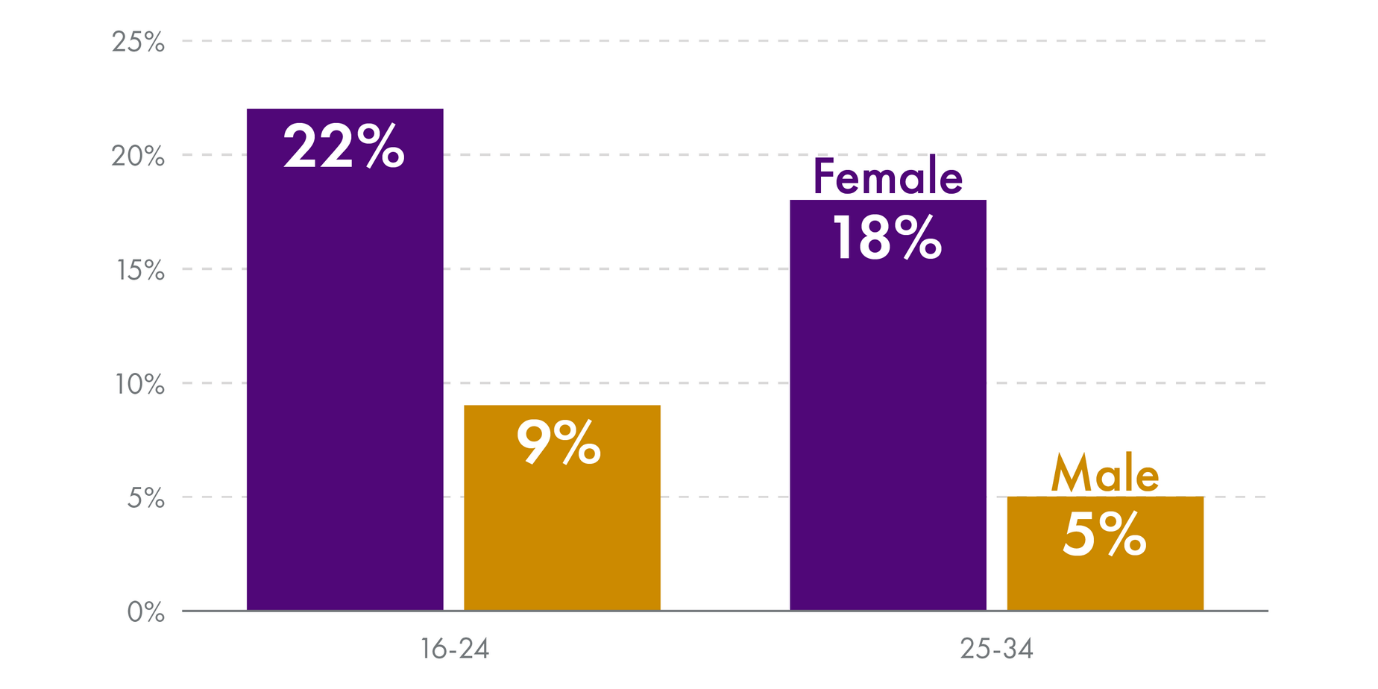

Younger age groups were also more likely to report having ever deliberately self-harmed to the Scottish Health Survey, for 2018-19 combined (Figure 8).1

Furthermore, women in the 16-24 and 25-34 age groups were much more likely than men in their age group (Figure 9) to have reported ever deliberately self-harming (compared to the gap between women and men in the older age groups).1

The Scottish Health Survey does not include information on self-harm in those under the age of 16. There have been reports of an increase in self-harming behaviours amongst adolescents, particularly teenage girls.3

A study examining the data of 16,192 patients aged 10-19 in the UK between 2001 and 2014 reported a 68% increase in self-harm incidence in girls aged between 13 and 16.4 The study’s definition of self-harm, however, uses the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s (NICE) current definition – any act of self-poisoning or self-injury, regardless of intention (NICE are due to publish updated guidance on self-harm in September 2022). The Scottish Health Survey’s questionnaire asks about acts of self-harm without suicidal intent.

Inpatients diagnosed with self-harm injuries

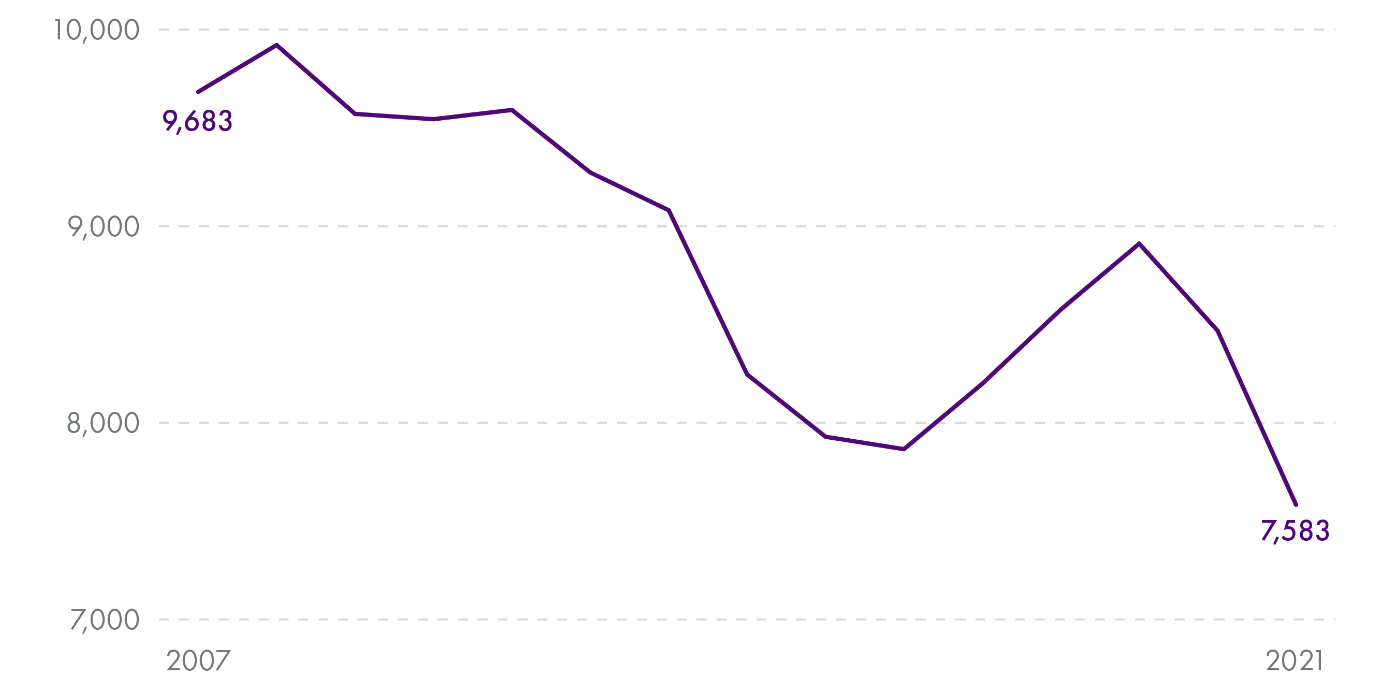

Public Health Scotland records data on the number of inpatients diagnosed with self-harm related injuries in Scottish NHS acute hospitals, for both adults (Figure 10) and children (Figure 11).i

This data should not be interpreted as the number of self-harm diagnoses in Scotland. Inpatient hospital data alone will not give an accurate picture of the number of people diagnosed with self-harm related injuries. These figures will only show a small proportion of the total of intentional self-harm in Scotland, which is unknown. Many people who have intentionally self-harmed will not attend services, as the physical consequences of the self-harm may not be severe enough to require medical intervention. Furthermore, given the nature of self-harm related injuries, it is likely that the main initial presentation of a patient attending hospital is to an accident and emergency (A&E) department. It is likely that most minor cases would be treated within A&E and will not require admission to an inpatient setting. The decision to record self-harm also lies with a clinician, so the decision can differ between clinicians.

These figures should therefore be read alongside other data, such as the Scottish Health Survey, while also considering Samaritans Scotland’s finding that self-harm is “often hidden” and limitations in data and evidence can make it difficult to measure its prevalence.1

An increase in the prevalence of self-harm amongst adolescents and young people has been attributed to multiple factors. Much of the focus has been on understanding the rise in self-harm amongst adolescent girls.

Self-harm is linked to the presence of anxiety disorders and depression and mental ill-health is becoming increasingly common for early-mid adolescent (13-16) girls.2 The rise in self-harm cases has also been attributed to the impact of the internet and digital media on young people.3In a 2010 report, the Royal College of Psychiatrists expressed concerns over an increase in websites that encourage or glamourise self-harm.3Adolescent girls have been viewed as at an increased risk of online harm.2

However, the same study by the Royal College of Psychiatrists suggests that the increased incidence of self-harm amongst early-mid teenage girls may be reflective of frontline services being more alert to and inquiring more about self-harming behaviour in this age group compared to boys at this age and teenage girls in other age groups.2

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Due to the suspension of face-to-face interviewing from March 2020, the Scottish Health Survey was only able to conduct the 2020 survey through a telephone survey format. Self-harm was not included in the questionnaire.1

Other available evidence, however, suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the prevalence of self-harm in the UK. 2 The COVID-19 pandemic increased the prevalence of exposure to violence and abuse through staying at home, economic adversity, unemployment, isolation and loneliness. These are all factors linked to higher rates of self-harm, in addition to suicide and poorer mental health outcomes.2

Wave 1 (Spring 2020) of the Scottish Government’s COVID-19 Mental Health Tracker Study did ask participants if they had self-harmed (separate to suicidal thoughts and attempts) in the past week.4 Young adults (18-29) were most likely to report having self-harmed in the last week (3% of those surveyed) compared to 30-59 year olds (1.5%) and 60+ year olds (nil). Women aged 18-29 (5.3%) were the most likely out of all age groups, for both men and women, to have reported self-harming.4 Although questions on suicide were included in the reports for Waves 2-5, self-harm was not included again as a separate question.

Scottish Government policy

Suicide

Every Life Matters

Every Life Matters was published in August 2018 and contains ten actions, which are at varying stages of completion. Actions 2, 3, 5, 6 and 9 were prioritised by the National Suicide Prevention Leadership Group (NSPLG) during the COVID-19 pandemic, while work on the other actions was paused or adapted due to the pandemic.1

| Action number | Action detail | Progress |

|---|---|---|

| Action 1 | The Scottish Government was to fund and establish a National Suicide Prevention Leadership Group (NSPLG) by September 2018. Action 1 also stated that the NSPLG’s remit should include making recommendations on supporting the development and delivery of local prevention action plans. | The NSPLG was established in 2018 and supports the delivery of the action plan.2Its initial delivery plan was published in December 2018, with updated versions published in 2019 and 2020.3Local area suicide prevention action plan guidance was published by the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA) in 20214, following a delay due to local pressures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.5The Scottish Government has funded implementation lead roles, based in Public Health Scotland, to help local areas develop their action plans.iThe work of the NSPLG and the delivery of local prevention action plans was supported by £3 million in funding over the course of the previous Parliament.5 |

| Action 2 | The Scottish Government was to fund the creation of and support the implementation of refreshed mental health and suicide prevention training by May 2019, which would be compulsory for all NHS staff who receive mandatory physical health training. | Resources on mental health improvement and prevention of self-harm and suicide have been developed by NHS Education for Scotland and Public Health Scotland. Furthermore, the Mental Health Improvement and Suicide Prevention in Scotland: Workforce Development Plan (2019-2021) was published by NHS Education for Scotland in May 2019.7This action was prioritised during the COVID-19 pandemic1 and resources were developed in response to the pandemic’s impact, such as NHS Education for Scotland’s ‘COVID-19: mental health and suicide prevention’.The Scottish Government has also funded learning and development lead roles, based in Public Health Scotland, to help support local areas promote and embed learning resources and awareness raising on suicide prevention.i |

| Action 3 | The Scottish Government is to work with the NSPLG and other partners in Scotland to encourage a coordinated approach to public awareness campaigns. | This is delivered by the on-going United to Prevent Suicide campaign, which launched in September 2020. As part of the campaign, FC United to Prevent Suicide was launched in August 2021. |

| Action 4 | The Scottish Government is to work with the NSPLG to develop a Scottish Crisis Care Agreement. A Scottish Crisis Care Agreement should ensure that “timely and effective” support is available for those affected by suicide. | A pilot service to support people bereaved by suicide was introduced in NHS Ayrshire and Arran and NHS Highland in August 2021.9 |

| Action 5 | The NSPLG is to assess different models of crisis support and make recommendations based on these assessments. | The NSPLG published its recommendations for improvements in suicidal crisis support in October 2021.10A National Lead for Suicidal Crisis Support was appointed in October 2021 to lead this work.11 |

| Action 6 | The NSPLG is to work with partners to develop and support the use of digital technology to improve suicide prevention. | This action is on-going, with the NSPLG stating in its third annual report (September 2021) that proposals for this action were approved by the Scottish Government in August 2021.12In 2022, a digital campaign, ‘Surviving Suicidal Thoughts’ was launched by NHS 24. |

| Action 7 | The NSPLG is to ensure the development of preventative actions that target at-risk groups. | This action is on-going, with the NSPLG receiving a report of a Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) study findings in May 2021.12Research on risk and protective factors has also recently been commissioned by the Scottish Government, which will inform its approach to Action 7.i |

| Action 8 | The NSPLG is to ensure that the actions of the Plan consider the needs of Scotland’s children and young people. | The NSPLG’s third annual report (September 2021) stated the NSPLG was in the process of starting up a Youth Advisory Group, which will sit alongside their Lived Experience Panel.12 A suicide prevention campaign aimed at young people is due to be launched by United to Prevent Suicide, which also contributes to Action 3.i |

| Action 9 | The Scottish Government is to work with partners to ensure that data, evidence and guidance is used to effectively maximise the plan’s impact. | The NSPLG’s third annual report (September 2021) stated Public Health Scotland (PHS) and Police Scotland had begun work to introduce a new system providing local areas with regular data on suspected suicides.12 This is now in place.i |

| Action 10 | The Scottish Government is to work with the NSPLG and others to develop appropriate reviews into all deaths by suicide and ensure that lessons from the reviews are shared with the NSPLG and partners and acted upon. | Work on involving families in pilot reviews began in July 2021.12Early reviews to test approaches have been undertaken in three areas and there is a plan in place for future implementation across Scotland.i |

COVID-19 pandemic

In addition to the prioritisation of certain actions, the NSPLG released its COVID-19 statement in July 2020. The NSPLG incorporated four priorities for pandemic-related suicide prevention actions:

Closer national and local monitoring of enhanced and more timely suicide and self-harm data.

Specific public suicide prevention campaigns, distinct from, but in partnership with, the ‘Clear Your Head’ mental health and wellbeing campaign.

Enhanced focus on specifically suicidal crisis intervention.

Restricting access to means of suicide.

Overall progress

The NSPLG commissioned a review of the plan’s progress between September 2018 and October 2020, which was published in February 2021. While momentum towards achieving the plan’s actions and its purpose had increased as a result of the “added urgency” created by the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on mental health, the report found that the pace of progressing actions has been slower than anticipated overall.1 This was partly due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to other barriers to implementing the actions.1

Notably, the report found “limited available evidence concerning whether and how the different actions, collectively or individually, may contribute to the ultimate goal of a reduction in suicidal behaviour”.1

Every Life Matters contained the target to reduce the rate of suicide by 20% by 2022, from a 2017 baseline. 4

The 2017 baseline was based on a five-year average (2013-2017) and will be compared to the five-year average for the period 2018-2022 as the end date.4 National Records of Scotland will publish this information in mid to late 2023. The rate will be calculated using the European Age-Sex-Standardised Rate (EASR). National Records Scotland uses the EASR as Age-Standardised rates account for population size and age structure, which provides more reliable comparisons between groups and/or over time.

Public Health Scotland have calculated the EASR per 100,000 population (five-year rolling averages) for 2013-2017 as 13.0 using old coding rules and 13.5 using new coding rules. For the most recent five-year period available (2016-2020), the suicide rate has increased.Public Health Scotland calculated the EASR as 13.9 using the old coding rules and 14.3 using the new coding rules.6

Upcoming suicide prevention strategy

The Scottish Government and COSLA are due to publish a new, long term suicide prevention strategy in September 2022. Engagement with stakeholders to shape the plan has been ongoing since 2021.1

The review of the national action plan’s progress between September 2018 and October 2020recommended that any subsequent suicide prevention strategies should be:

outcome focused

evidence-informed

clearly identifying how activities will influence long-term, intermediate, and short-term outcomes.2

The Programme for Government 2021-22 committed to doubling funding for suicide prevention to £2.8 million by the end of the current Parliament, with the aim of ensuring that the “right investment, policies and services are in place to underpin the new suicide prevention strategy.”3

Self-harm

In October 2021, the Scottish Government committed to developing a self-harm strategy for Scotland.1

Prior to this, a National Self-Harm Working Group was established in 2009 and the Scottish Government produced a report in 2011 outlining actions to improve responses to and support for self-harm in Scotland.2In its 2020 report, Hidden Too Long: uncovering self-harm in Scotland, Samaritans Scotland stated that it is “not clear to what extent recommendations from this report were implemented” and noted that the report was not mentioned in their engagement with relevant stakeholders on self-harm.1

The Scottish Government’s commitment to developing a self-harm strategy followed recommendations made by Samaritans Scotland in its 2020 report, which highlighted that self-harm was not significantly featured in any of the Scottish Government’s current strategies.1 It therefore recommended that, by summer 2021, a new Scottish self-harm strategy should be developed. Furthermore, the strategy should:

work in tandem with suicide prevention, mental health and public health policy

require a clear definition of self-harm and clearly outline the strategy’s aims

be collaborative and inclusive throughout its development and delivery; for example, ensuring that it is appropriate to the needs of different demographic groups

support cross-sector working to address the underlying causes of self-harm

ensure that the strategy’s successful delivery is informed by transparent accountability through clear actions, measures, and timeframes.1

The report also identified key themes that should be included in a new strategy, based on the key issues and areas identified in the report. These themes included:

developing data and evidence to inform self-harm policy and services

developing self-care tools and techniques that are evidence-based, safe, effective, and can work alongside other support services

realising the potential of education and youth services to support early intervention and mental health literacy

investing in sustainable community support and third sector services.1

Conclusion

Discussion of the Scottish Government's policy on suicide and self-harm is likely to be prominent during the second half of 2022 and throughout 2023.

In September 2022, the Scottish Government and COSLA are due to publish Scotland’s new suicide prevention strategy. The new strategy, and the Scottish Government’s suicide prevention efforts overall, will be supported by £2.8 million in funding by the end of this Parliament.

In addition to the new strategy, ‘Every Life Matters’ will conclude in mid-to-late 2023 when the National Records of Scotland will publish the suicide rate for 2018-2022 (five year average), which ‘Every Life Matters’ aimed to be 20% lower than the 2017 baseline.

Finally, although the Scottish Government has not announced further details on the self-harm strategy for Scotland, it is likely that work to develop the self-harm strategy will start over the next couple of years and could be included in the Programme for Government 2022-23.

Further information

Some resources for anyone affected by suicide and self-harm include: