Intergovernmental relations

This briefing is about intergovernmental relations in the UK. It describes the UK's intergovernmental architecture and discusses reforms proposed as part of a recent joint review of intergovernmental relations by the UK Government and devolved governments.

Summary

Intergovernmental relations (IGR) in the UK primarily concern relationships between the UK Government and the devolved governments of Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales. Since 1999, the main forum for intergovernmental discussion in the UK was the Joint Ministerial Committee (JMC), which was designed to facilitate communication and cooperation between the UK Government and devolved governments.

IGR mechanisms in the UK, including the JMC, have been widely criticised by parliamentary committees, academics, government reviews, and independent commissions, including for its ad-hoc nature, lack of transparency, and ineffective dispute resolution process. Such criticisms led the UK Government and devolved governments to agree to a joint review of IGR in 2018. The conclusions of this review, including a list of proposals, were published on 13 January 2022 and the UK Government and devolved governments have agreed to implement them.1

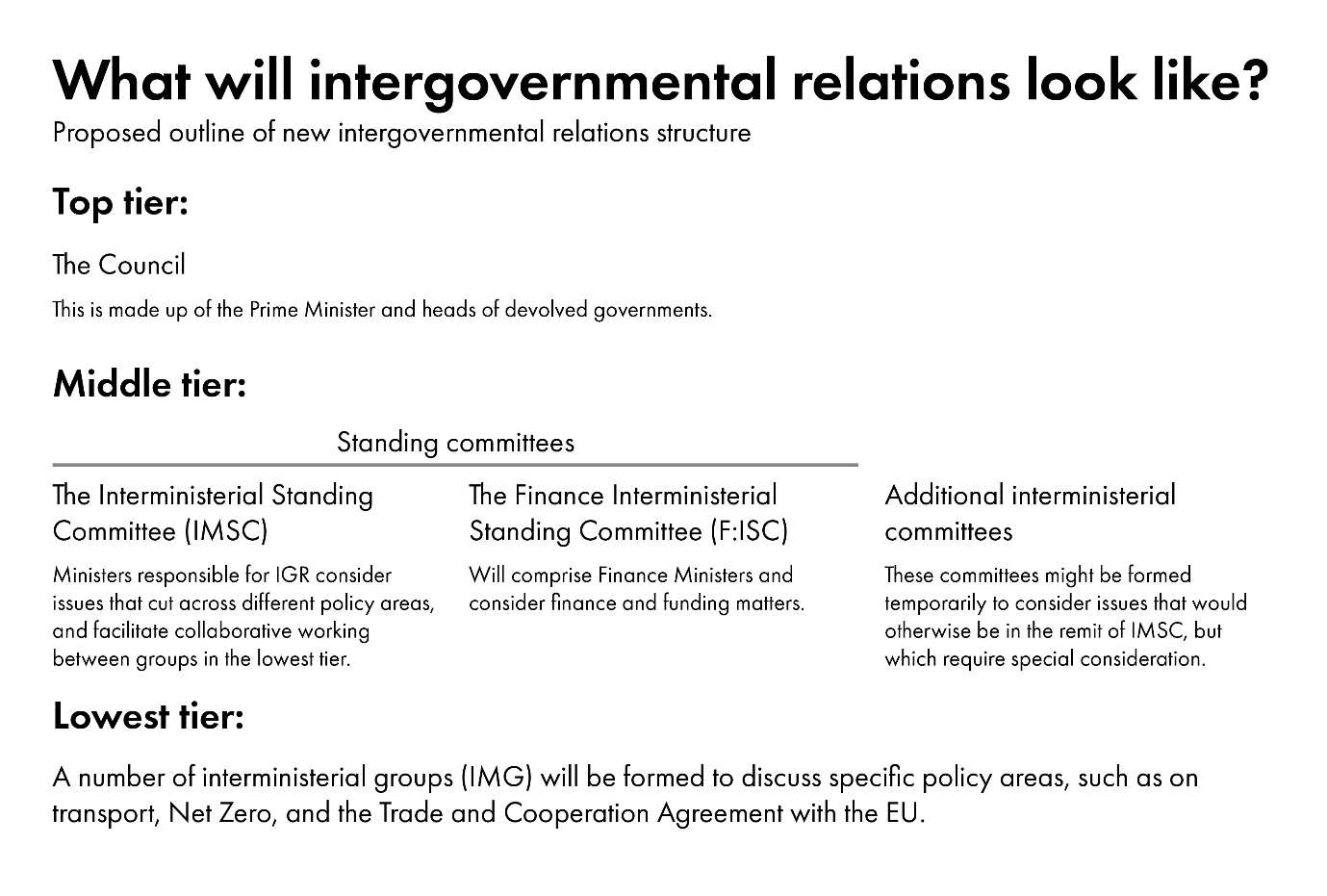

The proposals include replacing the JMC with a three-tiered alternative structure and set out ways of working, dispute resolution, and reporting requirements. This briefing describes the new proposals and how they have been received. It then considers the extent to which the proposals address core criticisms made about the previous IGR architecture and how they may shape intergovernmental relations in the UK in the future.

Intergovernmental relations

The term ‘Intergovernmental Relations’ (IGR) refers to relationships between different governments within the same country. In the UK, these are primarily the UK Government and the devolved governments of Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales. The term can be used to describe relations between devolved governments, such as the Scottish and Welsh governments, but also between devolved governments and the UK Government. This briefing does not cover engagement involving local forms of government.

Intergovernmental relations since 1999

Devolution in the UK is the decentralisation of powers from London. In the case of Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales, both legislative and executive powers were transferred. The Scotland Act 1998, the Northern Ireland Act 1998, and Government of Wales Acts 1998 led to the establishment of three new governments/executives in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales.

Since 1999, the main forum for intergovernmental discussion in the UK was the Joint Ministerial Committee (JMC) - this was established by a Memorandum of Understanding, which was amended most recently in 2012.1 The JMC considered reserved matters that impinged on devolved responsibilities and vice versa. It was designed to facilitate communication and cooperation between the UK Government and devolved governments.

The JMC met in different configurations, in plenary sessions or through various sub-committees. Plenary sessions were attended by the prime minister, heads of devolved governments, the relevant secretaries of state, and, sometimes, other government ministers. The JMC did not meet in its plenary form between 2003 and 2008.2 A report by Akash Paun and Robyn Munro for the Institute for Government says:

With Labour in power in Scotland, Wales and Westminster, and devolution suspended in Northern Ireland for much of the period up to 2007, there was little need to use these formal intergovernmental structures. Instead intergovernmental relations were managed more informally (and often bilaterally) between officials or through party machinery.3

After the Scottish National Party formed a minority government in Scotland in 2007, the Scottish Government pushed for a revival of the JMC (Plenary). In a speech, Alex Salmond, then First Minister, said:

Those joint ministerial committees, certainly in plenary session, have not met since 2002. In terms of the sub-committees, which are part of that process, only one strand of four sub-committees has met over the past five years, and that is the sub-committee on Europe. An arrangement that was brought into being—presumably, because it envisaged a situation in which the same party would not be in government in Westminster as was in government in Scotland or Wales—has fallen into total disrepair. It is important that that instrument, or something like it, is brought back into being very quickly.4

The JMC (Plenary) subsequently met again in 2008 and continued to meet yearly until 2018, with the exception of 2015.2

The JMC also comprised a number of sub-committees which met during different periods of its existence:

JMC (Europe): 2001-2019

JMC (Domestic): 2009-2014

JMC (Poverty): 1999-2002

JMC (Knowledge Economy): 2000

JMC (Health): 2000-2001

JMC (EU Negotiations): 2016-2020

In its plenary form, the JMC did not meet after 2018. The last meeting of a JMC sub-committee, the JMC EU Negotiations, took place in 2020.6

The JMC will be replaced by a new IGR structure that is being established as a result of the joint review of IGR.

The JMC EU Negotiations

The most active JMC sub-committee in recent years was the JMC EU Negotiations (JMC EN), which was established in 2016 to:

"discuss each government‘s requirements of the future relationship with the EU;

seek to agree a UK approach to, and objectives for, Article 50 negotiations; and

provide oversight of negotiations with the EU, to ensure, as far as possible, that outcomes agreed by all four governments are secured from these negotiations; and,

discuss issues stemming from the negotiation process which may impact upon or have consequences for the UK Government, the Scottish Government, the Welsh Government or the Northern Ireland Executive."1

While the JMC (EN) met more frequently than the JMC (Plenary), some participants expressed dissatisfaction which the way it operated. For example, giving evidence to the House of Commons Committee on Exiting the European Union in 2017, Mark Drakeford, then Welsh Minister for Brexit, said:

It needs to be better run. It is not encouraging when agendas arrive less than 24 hours before the meeting takes place. When you leave Cardiff to attend a meeting, there is not even a room identified where the meeting is going to happen. Minutes are not produced, so we are unable to track progress against things that have been agreed. So there is the basic business about putting more effort into giving these meetings the sort of administrative back-up that they need if they are going to be able to do the job. It needs a proper work programme. There is a constant frustration at the JMC (EN) that we never seem to manage to get a clear sense of what that forum needs to tackle next. We have never had on our agenda an item that is actually about triggering Article 50. That seems fairly extraordinary, really.2

In its committee report, the House of Commons Committee on Exiting the European Union concluded:

We therefore endorse the view of most of our witnesses that the UK Government needs to raise its game to make the JMC (EN) effective.3

Intergovernmental relations in the UK came under particular strain during the UK's exit from the EU. While the UK as a whole voted to leave the European Union, Northern Ireland and Scotland voted to remain. During the UK's exit from the European Union, the devolved parliaments withheld consent for core pieces of EU exit legislation, which were nevertheless passed by the UK Parliament. Examples of this are the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 which passed without the consent of the Scottish Parliament, and the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 which was passed despite all of the devolved legislatures withholding consent.

Case Study: Intergovernmental work during the pandemic

The Covid-19 pandemic brought renewed focus on intergovernmental work. Health is a devolved matter in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. As the virus didn't halt at national borders, effective intergovernmental cooperation between governments responsible for health in different parts of the UK thus became an important part of the pandemic response.

There was a lot of intergovernmental engagement from the onset of the pandemic.1Describing this engagement, Michael Gove, Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities and Minister for Intergovernmental Relations, stated that there "is no better example of collaboration between the UK government and devolved administrations than the response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic."2

Intergovernmental work during the pandemic was coordinated through the Civil Contingencies Committee (COBR), and newly created interministerial groups rather than the JMC, and this has raised questions about the role of the JMC in a crisis. The House of Commons Select Committee on Scottish Affairs noted that this use of other structures:

raises further questions about the resilience and suitability of existing intergovernmental structures in crisis situations and what it means for the future of intergovernmental relations.1

Examples of intergovernmental cooperation were discussed in a report by the Institute for Government.4 These include the Coronavirus Act 2020, which was developed in close intergovernmental cooperation and subsequently quickly given consent by all devolved legislatures, avoiding delays in taking action. The mechanisms of intergovernmental engagement have also been credited with facilitating the coordination of announcements - for example the closure of schools and lock downs.4

Professor Nicola McEwen of the University of Edinburgh, giving evidence to a House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee inquiry examining intergovernmental work during the pandemic, stated:

If you look back to the early phase and the action plan document of 3 March, that looks to me very much like an intergovernmental document. It speaks in the language of intergovernmental relations and seems to be something that has been co-determined and shaped by all of the Administrations.6

One potential reason for such close intergovernmental work during the pandemic was that governments across the UK agreed on the general approach to the pandemic response, especially during the first few months. This consideration will be discussed in more detail in the section on intergovernmental decision-making. Closer intergovernmental work also appears to have been encouraged by a shared desire to have clear and consistent messaging, and recognition of the overlapping responsibilities sitting with different governments as described in the House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee 2020 report on intergovernmental work during the pandemic.1

Assessments of IGR during the pandemic have not been wholly positive and one particular piece of criticism, concerning the role of the UK Government, will be discussed further in the section on representation of England.1

The IGR review and new structure

IGR structures in the UK, in particular the JMC, have been widely criticised by parliamentary committees12345, academics67, the Dunlop Review8, and independent commissions91011 on the basis of a number of reasons, including ineffective dispute resolution, the role of the UK Government, and a lack of transparency.

In 2018, the UK Government and devolved governments agreed to conduct a joint review of IGR in the UK.12 Principles for the review were agreed by all four governments in 2019:

Maintaining positive and constructive relations, based on mutual respect for the responsibilities of governments across the UK and their shared role in the governance of the UK

Building and maintaining trust, based on effective communication

Sharing information and respecting confidentiality

Promoting understanding of, and accountability for, their intergovernmental activity

Resolving disputes according to a clear and agreed process13

Then Prime Minister Theresa May commissioned a separate review of UK Government Union Capability, which included a chapter on intergovernmental relations.14 This review was undertaken by Lord Dunlop who described its objectives as follows:

Following an announcement in July 2019 this Review has considered, within the context of the existing devolution settlements, how the UK Government can work to most effectively realise the benefits of being a United Kingdom and how institutional structures can be configured to strengthen the working of the Union. The objective is to articulate a coherent plan to deliver better governance for the UK as a whole, guided by the core principles of trust, respect and co-operation.8

In his report, which was finalised in November 2019 but not published until March 2021, Lord Dunlop concluded that "the IGR machinery is no longer fit for purpose and is in urgent need for reform".8 On the same day the Dunlop Review was published, the Cabinet Office published a response letter to the Dunlop Review as well as a progress update on the IGR review, which Michael Gove, then UK Minister for the Constitution, described as "align[ing] closely with [Dunlop's] recommendations"1718

A document described as the 'conclusions' of the joint review on IGR by the UK Government and devolved governments was published on 13 January 2022.19 It is worth noting that no full review was published, but the conclusions document sets out a range of proposals for new IGR structures. All four governments have agreed to work to the new arrangements.19

The review promises the introduction of:

a new era for IGR with improved reporting on intergovernmental activity, providing greater transparency, accountability and the opportunity for improved scrutiny from each government’s respective legislatures.19

The biggest change is that the Joint Ministerial Committee is being replaced by an alternative structure. The new structure comprises three tiers:

In contrast to the JMC, which met only when called by the UK Government, engagement within the new structure is to take place regularly. The Council will meet once a year or more frequently if needed. The IMSC is expected to meet every two months and the F:ISC quarterly, though they may meet more or less frequently if agreed unanimously. The proposals state that further guidance will be issued on IMGs that includes recommendations on the frequency of meetings, but that the final decision will be taken between governments.

The document includes a list of IMGs already or likely to be established, but also states that this list is not exhaustive or definitive and may be adapted according to need. The list includes:

IMG (Engagement on science and research)

IMG (Business and Industry)

IMG (Net Zero)

IMG (Elections)

IMG (UK-EU TCA)

IMG (Culture)

IMG (Sports Cabinet)

IMG (Tourism)

IMG (Efra)

IMG (Education)

IMG (Higher Education)

IMG (Transport)

IMG (Trade)

IMG (Covenant Veterans)

The proposals also list a number of UK Government departments which will be assigned further IMGs, including the Home Office, Ministry of Justice, and Department for Education.

The secretariat that provided support to the JMC was, at times, not seen as independent by devolved governments because it was provided by the UK Government.8 The review proposes that a new standing secretariat be established, which will be accountable to the Council, not the UK Government's Cabinet Office, and staffed by members of all four governments. The secretariat will be tasked with producing and publishing an annual report on intergovernmental engagement and is intended to play an important role in the dispute resolution process.

Responses by the governments

Announcing the publication of the IGR review conclusions, UK Government Minister for Intergovernmental Relations, Michael Gove, said that the:

landmark agreement [...] will build on the incredible amount of collaboration already taking place between the UK government and the devolved administrations. By working together even more effectively, we can better overcome the challenges we face, create greater opportunities and improve people’s lives for the better.1

However, the devolved governments struck a more cautious tone. For example, First Minister of Wales, Mark Drakeford, stated:

Overall, the package has the potential to deliver significant improvements, if the spirit and content as set out in the package is translated through into consistent approaches and actions, based on respect, parity of participation and parity of esteem, and a desire to reach agreement through discussion (and indeed compromise) not imposition. All 4 governments have a responsibility to live up to these principles.2

Deputy First Minister of Scotland, John Swinney, said that:

re-branding of existing structures will not deliver the step change in attitude and behaviour from the UK government that is needed if there is to be a genuine improvement in intergovernmental relations.3

Nichola Mallon, then Minister for Infrastructure in the Northern Ireland Executive and member of the SDLP, voiced even stronger concern:

Obviously the SDLP will take part in initiatives designed to strengthen collaboration across these islands but the track record of British government ministers tells us that they're interested in undermining, overriding and obstructing locally elected political leaders – if that's what this is about, or what it becomes, then it won't be acceptable to us.4

Implementation

The Cabinet Office's website, on which the IGR review document is hosted states that all "4 administrations have agreed to work under these new arrangements".1 It is unclear what practically will be required to implement the outcomes from the review, the time frame for implementation, or to what extent the processes are already in operation.

Common framework documents published after the review conclusions include standard text about how they relate to the IGR review:

The outcomes of the intergovernmental relations review are in the process of being implemented. Once confirmation has been provided from each government, the outcomes of the review and appropriate intergovernmental structures will be reflected in this Common Framework. 233567891011121314

A communiqué for the first meeting of the Interministerial Standing Committee, which took place in March 2022, outlined discussion about the implementation of the new IGR arrangements but gave no further details.15It does not appear that the Council has met yet.

The rest of this briefing discusses the new proposals by considering the extent to which they address core strands of criticism made about the previous structures that supported intergovernmental work in the UK. An argument map illustrates the structure of issues discussed. The map shows core reasons for reform made by critics of the old IGR system, which are labelled 'because'. It also shows effective intergovernmental work during the pandemic, as a counter-point, labelled 'but'.

.png)

Discussion

Statutory basis

.png)

In contrast to intergovernmental structures in some other countries such as Belgium or Spain, the JMC lacked a statutory basis and was underpinned by a Memorandum of Understanding only.12 This meant that the frequency and form of intergovernmental engagement was not mandated by legal requirements. Connections have been drawn between this and the fact that intergovernmental engagement through the JMC took place irregularly and only when deemed necessary by the UK Government. For example, during an evidence session for the House of Commons' Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee report on Devolution and Exiting the EU, Professor Alan Page, formerly of the University of Dundee, said:

the basic machinery has to be put on a statutory footing so that the Parliaments are making it clear, “This is our expectation as to the way these relations will be conducted,” rather than leaving it to the discretion of individual Administrations.3

Concurring, Professor Richard Rawlings of University College London and Cardiff University, said:

I suggested that we should be thinking about a statutory base for [a new intergovernmental body]. I don’t want to be too prescriptive, but it seems to me that it should be on a statutory base. There should be an independent secretariat and, if there is one thing that we have learned in the last year, there really should be entitlements for all the Administrations of the UK to say, 'We want a meeting.' It just cannot be in the gift of one Government to say, 'Well, all right, when we feel like it.'3

A statutory underpinning that regulates IGR in the UK has also been advocated by the 2018 House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee report on Devolution and Exiting the EU, the 2015 House of Lords Constitutional Committee's report on Intergovernmental Relations in the UK, and the 2018 report from the National Assembly for Wales Constitutional and Legislative Affairs Committee, although their recommendations differ with regards to what aspects of IGR engagement such legislation should apply to.567

However, others have argued that the lack of statutory basis for IGR has its advantages. For example, McEwen et al (2018) suggest that the JMC's lack of statutory basis has given it the ability to maintain "a flexible approach which can allow governments to adapt intergovernmental forums to new challenges as they arise."1

Statutory basis in the new structure

The new proposed IGR system does not include a statutory basis. The report states that reforms will not be brought about through new legislation, but instead are "a statement of political intent [...] that do not create new, or override existing, legal relations or obligations, or to be justiciable."1 The governments' commitments to more regular meetings and the form those meetings take are thus not legally enforceable.

However, a recent letter to the Welsh Senedd's Legislation, Justice and Constitution Committee from the Welsh Government suggests that further changes may be being considered.2 The letter responds to questions from the Committee, including one about a possible update to the Memorandum of Understanding that sets out how the UK Government and devolved governments work together.3 In the letter, Mick Antoniw, Welsh Counsel General and Minister for the Constitution states:

In January 2022, the Welsh Government, along with the UK Government, the Scottish Government, and the Northern Ireland Executive, agreed to use the package of reforms which emerged from the joint IGR Review as the basis for the conduct of intergovernmental relations. [...] we hope that the Review and the package of reforms will be codified in a new MoU and, if all governments agree, underpinned in statute.2

It is unclear in this quote, whether 'we' refers to the Welsh Government's position or that of all governments in the UK. The preceding sentences refer to collective agreement by all UK governments, but the second part of the sentence, 'if all governments agree' suggests his statement may just be made on behalf of the Welsh Government. In either case, the letter suggests that at least some governments may want to further pursue the question of putting intergovernmental structures on a statutory basis in the future, even if the current proposals do not do so.

Decision-making

.png)

Scottish Parliament Information Centre Data Visualisation Team

The Memorandum of Understanding that set out the workings of the JMC stated explicitly that it was not a decision-making body whose business was not to impose solutions on any UK nation other than where all parties agreed to them. It says:

The JMC is a consultative body rather than an executive body, and so will reach agreements rather than decisions.1

This led, in the eyes of some, to the JMC's being seen as, in the words of a 2017 Welsh Government report, a ‘talking shop’.2

In a 2015 evidence session for a House of Lords inquiry on intergovernmental relations in the UK, Peter Robinson, then First Minister of Northern Ireland described the JMC:

I suppose I had best explain the culture of the JMC. We will have an agenda. It will be made evident early on that we are going to spend 20 minutes on this one and 10 minutes on that one. We will go round the room. We will ask each of the devolved regions, plus whoever is the departmental Minister who is dealing with the issue to make their comments, and that is the end of it. It is not a case of trying to reach any agreement, it is just a stating of positions.3

One way of understanding how the JMC may not have been considered a decision-making body relates to a point made in the section of intergovernmental work during the pandemic. While intergovernmental work on the pandemic response wasn't conducted through the JMC, at least at the beginning governments across the UK agreed on the general approach and hence were able to make decisions together. In contrast, most other recent intergovernmental work conducted through the JMC, has focussed on issues such as EU exit where there was little agreement. As decisions made by the JMC can only be taken by consensus, the lack of agreement between governments on such issues meant that there were few decisions governments could take together through the JMC.

It has been suggested that intergovernmental decision-making in the UK should not be limited to decision-making by consensus. However, any such proposal faces the question of how decisions where there is no consensus should be made. In 2017, the Welsh Government proposed that such decisions should be made through qualified majority voting if the UK Government and at least one devolved government agreed.2 This approach was also discussed by witnesses in a 2018 session held by the House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs committee on Devolution and Brexit.5 However, as McEwen et al (2020) put it, "None of the other administrations have embraced this proposal and it would likely be met with considerable resistance."6

Decision-making in the new structure

The review does explicitly say that joint decisions can be taken, but only by consensus. So it does not appear that what will be changing is the way decisions are made -but rather what kinds of decisions, and perhaps their volume.

Writing for the Bennett Institute for Public Policy, Professor Michael Kenny and Jack Sheldon of the University of Cambridge suggest that the new proposals signals that IGR processes will be used for "more substantive purposes than previously", specifically "policy challenges that cut across devolved and reserved competences such as pandemic recovery, tackling the climate crisis and delivering sustainable growth."1

Common frameworks

Common frameworks are agreements between governments to work together on specific devolved policy areas. You can read more about what common frameworks are and why they are being developed on our SPICe common frameworks hub. In many policy areas, EU laws previously ensured that there was a consistent approach across the UK, even where these areas were devolved. This is because the UK and all of its governments had to comply with EU law. In effect, this compliance has meant that the same overarching policy was followed. Now that the UK, with the exception of Northern Ireland as a result of the Protocol on Ireland/ Northern Ireland, is no longer required to comply with EU law, there is the possibility that different governments within the UK may choose to diverge in their approaches in these policy areas. If divergence is thought to be undesirable then avoiding it necessitates effective intergovernmental work and hence the infrastructure to support such work. Common frameworks form part of this infrastructure as agreements to work together in some of these policy areas to manage potential divergence.

At the time of writing, common frameworks are making their way through legislatures for scrutiny before they are confirmed and implemented. However, most frameworks have actually been operational on an interim basis for over a year as they are being scrutinised and confirmed.1 This means that officials and ministers have been meeting regularly to operate frameworks on an interim basis and to develop finalised versions.2 The increased intergovernmental engagement that developing common frameworks has necessitated is seen by some as an important part of expanding IGR in the UK. For example, Dr Marius Guderjan of Humboldt University of Berlin describes common frameworks as a "web of intergovernmental arrangements [that] has evolved below the constitutional arrangements"3 and McEwen et al (2020) as a "bottom-up approach to IGR."4

The new IGR proposals include an oversight structure for common frameworks. At the lowest tier, interministerial groups have responsibility for specific frameworks within their remit. This responsibility is reflected in many of the more recently published framework documents which make reference to interministerial groups.5678910111213 At the middle tier, the Interministerial Standing Committee has responsibility for overseeing the frameworks programme as a whole.

Common frameworks explicitly provide decision-making mechanisms. Framework documents set out which groups take what kinds of decisions and what should happen if they disagree. However, it is worth noting that the decision-making processes in frameworks also rely on consensus and do not facilitate decisions being taken on, e.g. a majority basis. In that sense, the new IGR proposals and common frameworks programme do suggest that while decisions will continue to be made by consensus, there is likely to be an increased amount of intergovernmental decision-making in devolved areas previously governed by EU laws.

Dispute resolution

.png)

A central point of criticism of the old IGR structure was its dispute resolution process. One particular point of criticism was that any party to a disagreement had the power to veto the decision to take a disagreement to the formal dispute resolution process.1 This included the UK Government. This led to cases in which devolved governments attempted to raise disputes, but these were vetoed by the UK Government.2 This issue has likely played a role in the fact that the dispute resolution process has been used infrequently and was, at least at times, not trusted by devolved governments.1 Surveying these issues and their effects, the 2019 Dunlop Review noted "the strong case for the creation of a more robust and trusted dispute handling process."2

Dispute resolution in the new structure

In the proposed new dispute resolution process, the IGR Secretariat takes a central role. The secretariat, not parties to the disagreement, will decide whether a disagreement is to enter the formal dispute resolution process, based on criteria, such as whether the disagreement has previously been discussed by officials and whether it has implications beyond its policy area.

One other aspect of the previous dispute resolution process that was contentious was that the UK Government chaired discussions. In contrast to this, the new process requires that no party to a disagreement can be appointed to chair at stage 1 or 2 of the dispute resolution process, and thus must either represent a government not party to the dispute or be an independent chair agreed to by all parties to the dispute. The chair will not have decision-making powers.

The new process also includes more extensive reporting requirements about disputes. The IGR secretariat is required to report on the outcome of disputes at the final escalation stage, including on any third-party advice received. Each government is also required to lay this report before its legislature. In addition, if a dispute cannot be resolved at the highest level, each government is required to make a statement to their legislatures about why they were unable to reach a solution.

However, in a blog article on the review, Professor Nicola McEwen notes that one component of the new structure, the middle-tier Financial Interministerial Standing Committee, differs from the rest of the new structure in its dispute resolution process.1 As Professor McEwen points out, the dispute resolution process for this committee states that disagreements on funding may only legitimately be escalated "where there is reason to believe a principle of the Statement of Funding Policy may have been breached" and further, that "policy decisions on funding are strictly reserved to Treasury ministers, with engagement with the devolved administrations as appropriate". This is particularly significant given that most intergovernmental disputes in the past have been about funding.2 These provisions appear to afford the UK Government, through the Treasury, a continued, more central, role in the new IGR machinery with regards to financial matters than the rest of the document would suggest.

Of this difference in the F:ISC, Dr Paul Anderson of Liverpool John Moores University and Dr Johanna Schnabel of the Free University of Berlin write:

That the Prime Minister and the Treasury preside over the Council and the Finance: Interministerial Committee respectively, underlines these concerns. It is not surprising that the UK government wants to keep its hand on the new arrangements. The experience of countries like Australia, Canada, and Spain shows, however, that it is a bad idea – one that undermines the message of collaboration and cooperation the UK government is seemingly trying to convey.3

Transparency

.png)

Intergovernmental work in the old IGR structures had long been criticised for its lack of transparency. There were some limited reporting requirements, for example an annual report on activities of the JMC, but as McEwen et al (2020) put it, it was "not always published annually" and "[n]either the post-meeting communiques nor the annual report offer[ed] much insight into the substance of discussions or disputes."1This, in turn, made it difficult for parliaments to scrutinise decision-making.

Giving evidence to the Scottish Parliament Devolution Committee in 2015, Professor Michael Keating of the University of Aberdeen and University of Edinburgh said:

Whenever there is intergovernmental working, things disappear into rather opaque arenas. That is really not necessary. It is a peculiarly British habit that we like to have our arguments in private before presenting things to the public, and Governments will sometimes exploit that in order to stay away from the public gaze.2

and

There is a broad negative experience, which is that, whenever things are taken into intergovernmental relations, there is a loss of parliamentary accountability.2

The Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament have since agreed to slightly more substantial reporting requirements to facilitate greater parliamentary scrutiny, as have the Welsh Government and Senedd, but given the increased importance of intergovernmental work post EU-exit on devolved matters, concerns about transparency may become increasingly urgent.45

For example, the Scottish Parliament's Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee noted in a recent inquiry on the UK internal market that there:

is a risk that the emphasis on managing regulatory divergence at an intergovernmental level leads to less transparency and Ministerial accountability and tension in the balance of relations between the Executive and the Legislature.6

Transparency in the new structure

The proposals for new IGR structures do respond to some concerns about the lack of transparency in intergovernmental engagements and their effects on parliamentary scrutiny. The new structure will include a requirement for the independent secretariat to produce yearly reports on intergovernmental engagement and produce additional information on disputes. The dispute resolution process itself also requires governments to make statements to legislatures if they are unable to resolve disagreements at higher levels of engagement. However, there is no general requirement for parliamentary engagement or oversight.

Writing for the Bennett Institute, Professor Michael Kenny and Jack Sheldon note:

The report commits to transparency and enhanced reporting of information about meetings to the respective legislatures. One of the benefits of doing this is that it helps address one of the most difficult aspects of IGR processes in democratic systems – the problem of how to ensure parliamentary scrutiny for deals done between heads of government and their ministers. The onus is on the legislatures to establish appropriate arrangements for this, and just as importantly to consider the viability of developing an interparliamentary dimension to this system, involving joint work between members of Westminster and the devolved legislatures.1

This comment echoes proposals made by McEwen et al (2015), who suggest that legislatures themselves should expand their scrutiny role, for example by establishing permanent scrutiny committees and strengthening interparliamentary working.2 Such proposals are currently being considered by the Scottish Parliament Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee.

Representation of England

.png)

A central criticism of of the IGR system in the UK arises from issues concerning representation of England. The underlying issue is that England as a whole lacks a formal representative in intergovernmental forums.1 As a result, it is unclear whose interest the UK Government is meant to represent in intergovernmental engagements, which leads to the following dilemma. If the UK Government represented England's interests, this would lead to conflicts with the devolved governments, especially in light of the UK Government's historically dominant role in hosting and chairing intergovernmental engagements. However, if the UK Government did not represent England's interests and instead only the interests of the UK as a whole this would leave England without representation.

Some of the recent intergovernmental work during the pandemic provides a good illustration of this issue. A concern that has been voiced about the later stages of the pandemic in particular, is that as more divergent approaches emerged between different governments, coordination of these and in particular the messaging around them, was less successful. This confusion reflects the lack of clarity about the role of the UK Government in intergovernmental work.

As Professor Nicola McEwen put it in evidence to the House of Commons Select Committee on Scottish Affairs:

The UK Government are simultaneously speaking for the UK as a whole and also acting as the Government of England. That has been at the source of some of the confusion in the public health messages, where it is not always clear, and it has not always been made clear when the messages are directed at England alone and when they are directed at the UK as whole.2

One example of this was when Prime Minister Boris Johnson, changed the public health slogan from 'Stay at Home' to 'Stay Alert', a change which he did not clarify only applied to England, leading to confusion for those in other UK nations.32

McEwen et al (2018) suggest some options for remedying the situation, which consist of appointing separate representatives for England and the UK as a whole. For example, they consider appointing a minister as a general representative for England in intergovernmental engagements, or appointing sectoral ministers as representatives for particular English interests. 5

Representation of England in the new structure

As the review conclusions don't engage with the wider question of English devolution, they also don't address concerns about English representation in intergovernmental work directly. The changes that afford the UK Government a less central position, for example through the role of the independent secretariat in dispute resolution, may lessen the worries of at least the devolved governments. However, they do not address the wider question of whose interests the UK Government represents in intergovernmental engagements, and if the answer isn't England's, who is there to represent English interests?

Of this, Professor Michael Kenny and Jack Sheldon write in their blog article:

It is perhaps not surprising that the governments have dodged an issue that cannot be fully addressed without opening up fundamental questions about the UK’s asymmetrical devolution arrangements. Nevertheless, an opportunity to explain how UK government ministers interpret their territorial remits when participating in IGR forums has been missed here.1

Culture

.png)

This briefing has focussed mainly on issues with structural features of the IGR system and the extent to which the new proposals address them. However, it's not just the structural feature of intergovernmental work that determine how successful it is. Just as important are the attitudes of participants and the culture that guides their interactions with one another.

As Professor McEwan notes in her blog article on the new proposals:

Machinery matters. Process and organisation matter. But the culture and conduct of intergovernmental relations matters more.1

There have been concerns about the culture of intergovernmental relations and the conduct of different participants. Giving evidence to the Constitutional and Legislative Affairs Committee in 2017, Elfyn Llwyd, former parliamentary group leader for Plaid Cymru in the House of Commons, said in response to a question about the levels of respect between the UK Governments and devolved governments:

It’s nothing like equality of respect, and that’s what it should be. After all’s said and done, it’s a form of partnership. Devolution is a form of partnership, isn’t it?2

Speaking of current IGR structures to the House of Lords Constitution Committee in 2021, Angus Robertson, Scottish Cabinet Secretary for the Constitution, External Affairs and Culture, criticised the conduct of the UK Government in response to a metaphor about the UK Government and devolved governments forming a family:

Going back to [...] your family comparison, though, I do not know of a workable family model where one member of the family effectively dictates what the family does as a whole and thinks that that is a normal family. It is not. If a family is based on respect, when really big things come along, such as your relationship with the rest of Europe, and two of the four say, “We don’t want this to happen”, it is not a normal reaction to say, “I’m the biggest, so it’s going to happen anyway”.3

This comment was made in reference to incidents during the UK's exit from the EU, in particular in relation to issues related to the Sewel Convention such as the UK Parliament's decision to pass the European Union Withdrawal Bill (2018) despite a lack of consent from the Scottish Parliament, and the European Union Withdrawal Agreement Bill (2020) despite all of the devolved legislatures withholding consent.

However, the Scottish Government's conduct in intergovernmental forums has also been criticised. In an evidence session to a Select Committee on the Constitution in 2021, Michael Gove, then Minister for the Cabinet Office, said that:

While on a day-to-day and week-to-week basis ministers have very good relationship with their counterparts in the devolved administrations, it is necessarily the case that ministers in the Scottish Government have a different constitutional vision, so there is an incentive for them, when a political platform is provided, to try to amplify what they perceive to be weaknesses in the constitutional settlement and to downplay the day-today effectiveness of our arrangements.4

The 2019 Dunlop Review acknowledged some of these difficulties, but also reiterated the need for respectful working relationships and greater levels of trust:

It is important to be realistic about what this reform can achieve. No IGR machinery, however perfect, is capable of resolving fundamentally different political objectives of the respective administrations, particularly where these involve very different visions for the UK’s constitutional future, and nor should it. It is, however, realistic to expect that serviceable and resilient working relationships, based on mutual respect and far greater levels of trust, can be established between the governments across the UK.5

The structural features of IGR systems and its culture are not unrelated as structures can engender respectful culture or provide barriers to it. With regards to the new proposals, the less dominant role for the UK Government has the potential to lessen distrust in intergovernmental engagement by the devolved governments, and more regular contact, including at lower levels, could help build relationships.

In addition, several commentators have noted that the IGR review conveys a change in tone that seems intended to signal a change in culture. For one, the language used in it differs to the language used in previous, similar documents, for instance, the report speaks of 'devolved governments' instead of 'devolved administrations'.17 Further, it lists among the core principles guiding future intergovernmental engagement a commitment to "positive and constructive relations, based on mutual respect for the responsibilities of the governments" on its first page and reiterates the objective to build trust between governments at different points in the document.

Summarising the proposals, Professor Dan Wincott of Cardiff University wrote:

These arrangements emerged from long negotiations with the devolved governments while relations among them were tense; some participants want the UK to break up. The ‘cultural’ aspect of IGR is at least as important as its structures: the proposals embody the cultural changes they need to generate, at least to some extent.7

However, Professor Nicola McEwen points out that this change in tone doesn't occur in all parts of the document. Crucially, those about the Financial Interministerial Standing Committee, continue to speak about 'devolved administrations'.1 As this committee may be a locus of future disputes, the culture surrounding it could be particularly critical in influencing relationships more widely.

The project of building trust between the UK Government and devolved governments was off to a rocky start with the announcement of a 'Brexit Freedoms Bill' by the UK Government two weeks after the IGR proposals were published, which sparked animosity from devolved governments. Speaking to BBC Radio Scotland, Deputy First Minister for Scotland, John Swinney, said :

No prior consultation, no engagement, no dialogue, no enhancement of the way in which the administrations work together. So the stories that were run a couple of weeks ago [about the new IGR structures] are totally meaningless.10

Positive conduct by participants in intergovernmental relations, and the culture which influences that conduct, is a long-term goal and changes may not be seen immediately. We will have to wait and see to what extent the new proposals may help bring about culture change and whether such a change can take place in an environment where there is likely to be disagreement between governments across the UK about the direction of policies following EU exit.

Conclusion

At first sight, the proposals contained in the IGR review have the potential to re-shape relations between the governments of the UK. The replacement of the JMC with a three-tiered engagement structure and independent secretariat provides for an expanded and more structured IGR system in the UK. Proposals for increased contact and a more transparent dispute resolution process address some central criticisms of the old system and might help build trust between governments in the UK and improve the way they work together in the future.

However, the different governance arrangements and dispute resolution process for the Financial Interministerial Standing Committee mean that we will have to wait and see how different the new structures are in practice, and whether they lead to differences in the culture of IGR in the UK. It is only when the new proposals are in place and operating will we know how effective they are in addressing previous concerns about the operation of IGR in the UK.