Eating Disorders in Scotland

This briefing provides an overview of eating disorders in Scotland. It covers their prevalence, recent reviews on the services and support available in Scotland, and developments in Scottish Government policy in this area. It also identifies the key issues that have been raised around eating disorder services and care in Scotland, such as the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the role of the third sector, and the availability of services.

Executive Summary

Eating disorders are complex mental illnesses. There is currently a lack of firm evidence on the number of people with an eating disorder in the UK, with the eating disorder charity, Beat, estimating 1.25 million.

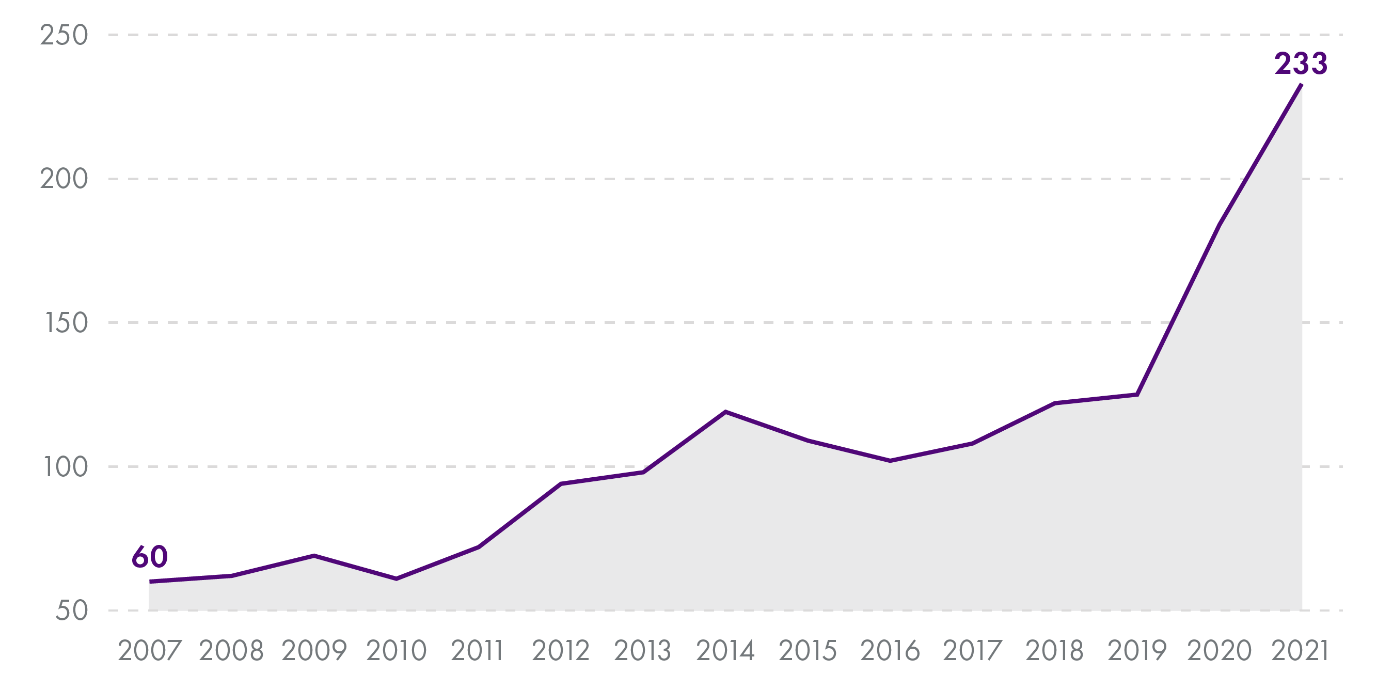

Current evidence indicates that the Covid-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the prevalence and severity of eating disorders, particularly amongst children and adolescents. The number of children under 18 admitted to a mental health or general/acute speciality, either as an inpatient or day case, with an eating disorder in Scotland increased by 47% between 2019 (125) and 2020 (184) and then again by 27% between 2020 (184) and 2021 (233). Between 2019 (125) and 2021 (233), there has been an overall increase of 86%.i

Eating disorders were specifically included in Action 22 of the Scottish Government’s Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 (for the Scottish Government to help the development of a digital tool that would support young people with an eating disorder)1, which has been delivered.2 Other general actions (i.e. those not related to specific mental health conditions or disorders) in the Mental Health Strategy are also relevant to eating disorder services in Scotland.

The Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland (MWC) undertook a national visit of eating disorder services in 2018 and 2019. The MWC published its report in September 2020.3The MWC mapped the services available in Scotland, outlining key issues such as a lack of support available across all of Scotland and delays in accessing support.

The Scottish Government announced a review into eating disorder services in March 2020. The recommendations of the National Review of Eating Disorder Services were published in March 2021, with the full report published in June 2021.4 An Implementation Group was established in 2021 to oversee the short-term implementation of the 15 recommendations outlined in the report. £5 million of the £120 million Mental Health Recovery and Renewal Fund has been allocated towards implementing the recommendations.

The third sector plays a significant role in the delivery of eating disorder support in Scotland. The Scottish Government provided £42,963 to the eating disorder charity Beat in June 2020 and a further £400,000 in July 2021, from the £5 million allocated to eating disorder services from the Mental Health Recovery and Renewal Fund.

The MWC’s report, the Scottish Government’s review, and research by organisations such as Beat have highlighted continued concerns from patients, their families and carers around the level of training on eating disorders provided to the general health workforce.

Introduction

This briefing provides context on eating disorders, their prevalence, and outlines recent policy developments and key issues in Scotland.

It begins with brief context on what eating disorders are, some examples of types of eating disorders, and an overview of current evidence around their prevalence in the UK and in Scotland specifically. It then provides an overview of developments in Scotland, such as the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland's report on eating disorder services, relevant Scottish Government policy and funding -including the Scottish Government's National Review of Eating Disorder Services - and current clinical guidelines.

This briefing finally identifies some of the key issues around eating disorder policy and the delivery of services in Scotland, which may be significant to the implementation of the recommendations outlined in the Scottish Government's National Review.

Eating disorders and their prevalence

Eating disorders are complex mental illnesses characterised by a preoccupation with weight, shape and calorie balance.1People with eating disorders use disordered eating behaviour as a way to cope with difficult situations or feelings.

Eating disorders can emerge at any age, but typically develop during early to mid-adolescence. There is often a gap between the emergence of symptoms and a person seeking help, with the Scottish Government’s National Review of Eating Disorder Services noting that half of all first presentations are to adult services.2

There are different types of eating disorders. These include:

Anorexia nervosa: Where a person tries to keep their weight low by limiting how much they eat or drink. Anorexia nervosa has a higher mortality rate than any other mental health disorder and NICE estimates that 20% of deaths in people with anorexia nervosa are due to suicide.3

Bulimia nervosa: Where a person is in a cycle of eating large quantities of food (‘bingeing’) and then trying to avoid gaining weight by vomiting, taking laxatives or diuretics, fasting, or exercising excessively (‘purging’).

Binge eating disorders (BED): Where a person eats very large quantities of food (bingeing) without feeling in control of what they are doing. Unlike bulimia, people with BED do not usually follow overeating with getting rid of the food.

Other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED): This is an umbrella term, used in circumstances where a person’s symptoms do not exactly fit the expected symptoms for anorexia, bulimia, and BED.

Prevalence

The UK eating disorder charity, Beat, estimates that around 1.25 million people in the UK have an eating disorder. Beat notes, however, that “there has not been sufficient research to draw firm conclusions about the prevalence of eating disorders in the UK”. Its estimate is based predominately on research conducted in other countries. Beat looked at a series of studies investigating the prevalence of eating disorders among different genders, age ranges, and diagnoses, and applied these to recent data on the UK population to reach a total estimate of 1.25 million.

It is also difficult to determine the exact prevalence of specific disorders. NICE estimates that OSFED cases account for the highest percentage of eating disorders, followed by binge eating disorders and bulimia nervosa. Anorexia nervosa is the least common eating disorder.1

Scottish data

The number of people diagnosed with an eating disorder is not centrally held in Scotland. However, Public Health Scotland (PHS) collects data on inpatients admitted with an eating disorder diagnosis. Updated figures from 2007-2021 (Figures 1 and 2) have been provided by Public Health Scotland via personal correspondence in June 2022.

The data only shows those who have been admitted to hospital and do not include those diagnosed in other settings. Patients will be counted multiple times if they have been admitted within the same board in different years, or different boards in the same year, or both. A patient will be counted as both an adult and a child in the year they turn 18 if they had an episode when they were 17 and a subsequent episode that year aged 18.

The number of child patients admitted as an inpatient with an eating disorder diagnosis has increased significantly since 2019 (Figure 1), rising by 47% between 2019 (125) and 2020 (184) and by a further 27% between 2020 and 2021 (233). In total, eating disorder admissions for child patients have increased by 86% between 2019 and 2021.

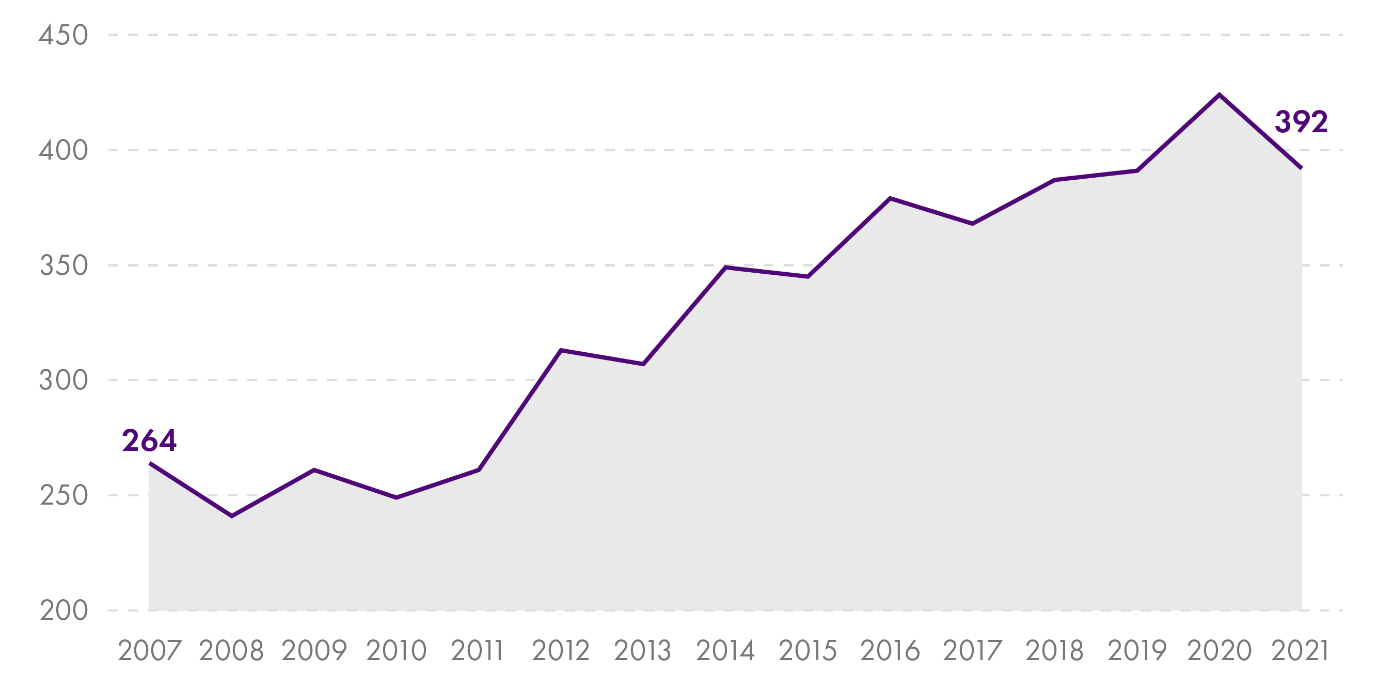

In adults, the number of inpatient admissions increased by 8% between 2019 (391) and 2020 (424), before decreasing to 392 in 2021.

The Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland's report

The Mental Welfare Commission (MWC) for Scotland undertook a national themed visit of eating disorder services across two phases in 2018 and 2019. Its report, ‘Hope for the Future’, was published in September 2020.1

The MWC outlined recommendations for Integration Authorities, the Scottish Government, and Healthcare Improvement Scotland. 1These included:

That Integration Authorities ensure a comprehensive range of services are available, across all ages, and that gaps in provision are “identified and addressed”. This should include clearly defined access to inpatient mental health beds for people with eating disorders, across all ages.

That Integration Authorities ensure support is maintained following discharge from hospital and specialist community services, including the provision of support for families and carers during this transition.

That Integration Authorities ensure there is access to the appropriate level of training in eating disorders for their staff.

That, in its National Review, the Scottish Government use the report to help inform their work and look to establish a managed clinical network in relation to eating disorders. The National Review of Eating Disorder Services, published in June 2021, explicitly states that the review will “build on the findings” of and cross-reference the MWC’s review.3

That Healthcare Improvement Scotland prioritise a review of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), which requires review, revision, and an update of the efficacy of treatment and therapies to support people with eating disorders. Updated guidelines were published in January 2022.4

Scottish Government policy

Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027

Eating disorders were mentioned specifically in the Scottish Government’s Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 under Action 22, which was for the Scottish Government to help develop a digital tool that would support young people with an eating disorder.1

This action was implemented in 2018, with the delivery of an online peer support tool that pairs young people with a trained volunteer who has recovered from an eating disorder. NHS Lothian and Beat co-delivered this resource.2A website for parents and carers of young people (up to the age of 25) who have recently received an eating disorder diagnosis and are due to start, or have recently started, treatment was also created.These resources were supported by an investment of £129,187 over two years.2

Other general actions within the Strategy were also relevant to eating disorders. These include actions related to prevention and early intervention, access to treatment, patient rights, and the physical wellbeing of people with a mental health problem.1

National Review of Eating Disorder Services

A review into eating disorder services was announced by the Scottish Government in March 2020 and formally launched in October 2020. Its purpose was to provide a full picture of the current support available in Scotland and detailed recommendations as to how services, as well as the wider support system in Scotland, should be constructed.1

The Review outlined the fifteen recommendations in March 2021,2 prior to the publication of the full report in June 2021.1 Recommendations from the full report included:

The Scottish Government should set up an Implementation Group which is, in the short-term, responsible for the implementation of the service review recommendations, in addition to planning for and setting the strategic direction, vision, and ethos for the improvement and delivery of eating disorder services over the next 10 years. The Implementation Group was established in July 2021.4

A National Eating Disorder Network should be established and funded by the Scottish Government, which will then take over from the Implementation Group in supporting the delivery of the review’s recommendations. The Network will also be responsible for national activity (such as training and service development) and data collection. It is unclear when the National Eating Disorder Network will be established to take over from the Implementation Group.

A lived experience panel should be set up to advise the Implementation Group and work alongside the National Eating Disorder Network, advising on all national changes related to eating disorders. A lived experience panel is in the process of being established.i

The Scottish Government should provide funding to the Third Sector for the development of platforms and community services that will allow for free, evidence-based self-help resources to be available to everyone in Scotland. Funding was provided by the Scottish Government to Beat in 2020 and 2021.

The Scottish Government should commission and fund equitable provision of high-quality, accessible specialist community-based services for eating disorders that are available across Scotland, for all ages, and for all types of eating disorders. At the member's debate for Eating Disorders Awareness Week 2022, the Minister for Mental Wellbeing and Social Care, Kevin Stewart MSP, stated that the majority of the £5 million provided to implement the recommendations of the review in 2021-22 will be "provided to NHS boards to support them to respond to the increase in eating disorder referrals." 5

The development of a comprehensive training plan to equip the healthcare workforce to deliver high-quality care in all settings. There should also be appropriate education and awareness training for other relevant professionals, such as youth workers and counsellors. The timeframe for this is currently unclear, although the Scottish Government has committed to developing a mental heath workforce plan in the first of this parliament.NHS Scotland previously developed, and still offers, Eating Disorders Education and Training Scotland (EEATS), an accredited programme of training and theoretical knowledge on the assessment and management of eating disorders.

Health Boards should work together to ensure that there is equitable access to in-patient services across Scotland – including a further recommendation for a smaller review, specifically on national inpatient provision across all ages, in 5 years’ time. The full report and recommendations stated that this review should take place after community service improvements have been implemented.1

Recent funding

The Scottish Government announced in June 2021 that £5 million of the £120 million Mental Health Recovery and Renewal Fund will go towards implementing the recommendations of the National Review of Eating Disorder Services in 2021-22.1£400,000 of this funding has been allocated to Beat.

At the members’ debate for Eating Disorders Awareness Week 2022, the Minister for Mental Wellbeing and Social Care, Kevin Stewart MSP, provided an update that NHS Health Boards have initially used the investment to ensure staff have access to eating disorder training, to expand clinician time, and recruit additional staff.2

Clinical guidelines

The National Review of Eating Disorder Services also noted concerns from clinicians around the applicability of NICE’s updated guidelines (published in 2017 and revised in July 2019) to the specific context of eating disorder services in Scotland, with clinicians agreeing that Scottish intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines would therefore be appropriate. HIS previously published recommendations on the identification, management, and treatment of eating disorders in 2006.2

New guidelines were published in January 2022 by SIGN, following a delay caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and will be reviewed in 2025.3

Key issues

This section identifies some of the key issues around eating disorder policy and the delivery of services in Scotland. These issues are varied, ranging from recent developments (such as the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic), long-standing issues (such as access to services, early intervention and waiting times, workforce training, and the ability of services to work together), and the role of the third sector in Scotland.

Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic

The current evidence suggests that the Covid-19 pandemic has significantly increased the prevalence of eating disorders, as well as their severity.

As noted by the Scottish Government in its National Review, services across Scotland have seen increased numbers of referrals for people with eating disorders since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.1 The review stated that “eating disorders thrive on isolation”1, with the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland also stating separately that “loss of support structures” has contributed to the increase in children and adolescents presenting with eating disorders.

Another study of adult patients in Scotland and England with an eating disorder during the pandemic highlighted that reduced social interactions and activities could increase the “time and mental space” spent by an individual on food and their eating behaviours, which was previously taken up by social interactions and activities.3Restricted access to community services, due to Covid-19 restrictions, has also been raised as another factor by the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland. Furthermore, national restrictions created a lack of routine and structure for many people. For individuals with disordered eating, routine and structure is particularly important in order to cope with dysfunctional thoughts and behaviours.3

In July 2021, Beat published that demand for its eating disorder services had increased by 283% over 18 months in comparison to the previous year.528% of people contacting Beat’s helpline services between May and June 2020 linked the possible trigger for relapsing or developing symptoms to the pandemic.6

The Scottish Government’s National Review of Eating Disorder Services also cited reports from inpatient colleagues of an increase in the complexity and severity of illness in people being referred.1

The impact appears to be particularly significant for children and young people. The summary recommendations report of the National Review of Eating Disorder Services stated that CAMHS eating disorder staff in Scotland were reporting an “unprecedented” increase in the number of children and young people presenting with eating disorders, as well as in the severity of cases.8

In June 2021, an FOI by the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland found referrals for eating disorders in children and young people under 18 to have increased from 217 in 2018-19 to 456 in 2019-20 and then to 615 in 2020-21.

As discussed in the section on Scottish data, the number of child patients admitted to a mental health or general/acute specialist for an eating disorder in Scotland has increased significantly since 2019. Between 2019 and 2020, the number of admissions increased by 47% from 125 to 184. There was a further 27% increase between 2020 (184) and 2021 (233). Between 2019 and 2021, the number of admissions has increased by 86%. Adult admissions also increased by 8% between 2019 (391) and 2020 (424), before decreasing in 2021.i

Furthermore, the Covid-19 pandemic presented some specific challenges for eating disorder treatment and care. While the use of technology in healthcare settings can be beneficial, the Scottish Government’s summary recommendations report suggested that, for eating disorder services, these benefits will need to be balanced against the necessity of physical monitoring and maintaining the medical safety of patients.8

Services in Scotland

The most recent mapping of eating disorder services in Scotland was undertaken by the MWC as part of their national review of eating disorder services.1 A report summarising the eating disorder services available in each NHS Health Board was published separately.2

Information on both specialist services (those which specialise solely in the care of individuals with an eating disorder as the primary difficulty) and generic services (those designed to look after individuals with a range of mental health difficulties and do not specialise in providing care for eating disorders alone) was provided for each Health Board. This information covered mental health inpatient facilities, medical inpatient facilities, and community facilities.

There are three adult specialist inpatient units in Scotland for eating disorders:

The Regional Eating Disorder Unit at St John’s Hospital, Livingston (12 beds).

The North of Scotland Eating Disorder Unit (Eden Unit) at Royal Cornhill Hospital, Aberdeen (10 beds).

Four specialist eating disorder beds within the general adult psychiatry ward at Stobhill Hospital, Glasgow.

There are no specialist inpatient eating disorder units for children and young people in Scotland. Children and adolescents (generally those between the ages of 12-18) who require inpatient admission for an eating disorder will be admitted to a paediatric ward or to one of the three CAMHS adolescent inpatient units:

Skye House at Stobhill Hospital, Glasgow (24 beds).

The Melville Young People’s Mental Health Unit at the Royal Hospital for Children and Young People, Edinburgh (12 beds).

The Dudhope Young People’s Inpatient Unit in Dundee (12 beds).

Additionally, children aged 5-11 can receive inpatient care from the Child Inpatient Psychiatry Unit inside the Royal Hospital for Children in Glasgow (6 beds).

A briefing published by the Royal College of Psychiatrists in 2014 had stated that, although Scotland had made “strong improvements in the provision of specialist eating disorders over the past decade”, there still remained a “lack of services, or at least very inadequate provision within existing services,” for the management of eating disorders in Scotland.3

The MWC found that most people with eating disorders are treated in their community. Patients, however, often found it difficult to access this support. A lack of resources existed in some areas, with some treatments only available in specialist inpatient services and not in the community. The MWC noted incidences of people choosing to seek private care due to the lack of NHS services available in their area.1

Furthermore, the community support available can vary across Scotland. For example, the MWC’s mapping highlights that only NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde has a clinical specialist eating disorder service for children and young people. While NHS Lothian does have a separate CAMHS eating disorder team, this is non-clinical and focuses on increasing skills, education, and undertaking research.2

The Scottish Government’s National Review of Eating Disorder Services came to a similar conclusion, finding that there remains a “lack of adequate service provision”6 to ensure that anyone with an eating disorder can access the timely, safe, person-centred, effective, efficient and equitable care outlined in the Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027.7

Early intervention and waiting times for treatment

SIGN notes in its guidelines that “harms can accumulate” when eating disorders are left untreated. This is particularly significant in cases of anorexia nervosa as prolonged starvation can damage brain structure and function.1

Waiting times for patients with an eating disorder are not separately recorded. They are included either in the CAMHS or (adult) psychological therapies waiting times. For the most recent quarter ending March 2022, 73.2% of children and young people2 and 83.1% of adults started treatment within 18 weeks of a referral.3

In 2017, Beat undertook a UK-wide research programme around the impact of delaying treatment for eating disorders.A separate report on the experiences of respondents who were resident in Scotland when they first referred for treatment was published.4 It found that the average waitbetween a person’s eating disorder emerging and the decision to seek medical help was 162 weeks. After seeking help, the average wait between the first GP visit and the start of treatment was 30 weeks.4

In particular, the MWC found a perception from patients, their families, and carers that services concentrated too heavily on weight alone as a threshold for accessing treatment. This made some people with eating disorders concentrate on their weight, viewing it as a “target to achieve” to access services. As such, the MWC identified a perception from patients, families, and carers that patients had been prevented or delayed from accessing support until their weight was “dangerously low.”

In its response to the Scottish Government’s Mental Health Strategy, Beat recommended eating disorder specific waiting time standards for both CAMHS and adult patients.6Beat noted that waiting times for children and young people with an eating disorder are collected in England.6

Joined-up services and transitions

Eating disorders require assessment, treatment, and monitoring in relation to both mental and physical health. It is necessary for several services to therefore work together in managing a patient’s care. Joined-up health services and managing transitions across services were identified as areas for improvement by the MWC in its report.1

The physical monitoring of patients looked after by mental health services was a “significant difficulty” for all respondents to the MWC’s survey. Responsibility for the physical health monitoring of patients with anorexia nervosa, in particular, seemed “largely uncertain.”1

Managing transitions for young patients, particularly from CAMHS to adult services, was also raised. While the GPs and psychiatrists engaged by the MWC returned mixed views around the planning of transitions, the process from CAMHS to adult services was “universally felt to be unsatisfactory” by the families and carers surveyed.1

Part of Action 21 of the Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 aimed to improve the "quality of anticipatory care planning approaches" for those transitioning from CAMHS to Adult Mental Health Services.4Transition Care Plans (TCPs) were launched in August 2018. A TCP is a document that young people receiving treatment from CAMHS will complete as part of their transition to adult services. There is now an expectation that TCPs will be used as a standard in every transition between CAMHS and adult services.5

Additionally, the SIGN guidelines include a section on transitions, with recommendations for managing instances when a patient’s age or geographical location necessitates a change of clinical team.6

Role of the third sector in Scotland

The Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland acknowledged the role of the third sector in its 2014 briefing on eating disorders, suggesting that it could have an effective role in delivering guided self-help to those with bulimia and binge eating disorders and in providing addition care, alongside NHS treatments, for patients with severe anorexia nervosa.1

In its report, the MWC looked at the different activities offered to patients in specialist adult and CAMHS inpatient and community services.It found that “more than half of the services had, or had previously had, input from outside organisations such as Beat.”2

A recommendation in the National Review of Eating Disorder Services was for the Scottish Government to provide funding to the Third Sector for the development of platforms and community services that will allow for free, evidence-based self-help resources to be available to everyone in Scotland.3

The Scottish Government provided funding to Beat in 2020 and in 2021.A £42,963 grant was announced in June 2020 in response to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.4 In July 2021, Beat received £400,000 in funding to support those with eating disorders and their families in Scotland.5This investment is from the £5 million allocated to eating disorders from the Mental Health Recovery and Renewal Fund.6

Beat has a dedicated Scottish helpline, in addition to its UK-wide support services.

Workforce in Scotland

The 2014 briefing on eating disorders by the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland raised concerns around the eating disorder workforce and its training. In addition to attracting young clinicians to eating disorders as a psychiatric speciality, it was also felt “essential” to provide “basic grounding” to those specialising in general adult, child and adolescent, and liaison psychiatry.1

In its report, the MWC referred toEating Disorders Education and Training Scotland (EEATS), which was developed by NHS Education Scotland. EEATS offers an accredited programme of training and theoretical knowledge of the assessment and management of eating disorders. The MWC found that half of the Health Board areas involved in their survey had undertaken further accredited training on eating disorders via EEATS and NHS Education Scotland.2

Beat currently calls for all Scotland-based medical students and junior doctors to have more training in eating disorders. Research conducted by Beat shows that the average GP receives less than two hours of training on eating disorders during their entire medical degree. 20% of UK medical schools do not provide any training on eating disorders.3

The impact of clinicians not receiving sufficient training was highlighted by a survey conducted by Beat during September and October 2021, of which Scottish results were published separately.4Of the 96 participants with an eating disorder who had sought help from healthcare professionals:

46% felt that their GP did not understand eating disorders.

67% felt that their GP did not know how to help them with their eating disorder.

92% felt that their GP would benefit from more eating disorder training.4

People with eating disorders, their families, and carers reported to the MWC that they did not always feel the professionals working with them had “sufficient knowledge and expertise” on eating disorders. Additionally, the GPs who responded to the MWC’s survey did not express “high confidence” in managing patients with eating disorders.2

At the members’ debate for Eating Disorders Awareness Week 2022,the Minister for Mental Wellbeing and Social Care, Kevin Stewart MSP, provided an update that all medical schools in Scotland were in discussion with Beat around delivering eating disorder training or were already delivering training.7

It was also highlighted by the Minister in March 2022 that the £400,000 in funding for Beat will be used towards its training for GPs and healthcare professionals.8

The Scottish Government published its national workforce strategy for health and social care in March 2022. The strategy commits to developing a mental health workforce plan in the first half of this parliament, following the refresh and refocus on the Mental Health Strategy in 2022.9

Conclusions

The Scottish Government’s National Review of Eating Disorder Services outlined 15 recommendations to be delivered. An Implementation Group, established in 2021, is now due to implement the recommendations in the short-term and to set the strategic direction, vision, and ethos for the improvement and delivery of eating disorder services over the next 10 years.

Key policy issues for eating disorder services, as well as the delivery of the Review’s recommendations, may include:

The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the increased prevalence and severity of eating disorders in Scotland, particularly amongst children and adolescents.

Implementing the report’s actions to improve the provision of eating disorder services in Scotland, ensuring that they meet the six quality dimensions (person-centred, safe, effective, efficient, equitable and timely) outlined in the Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027.

The role of the third sector in continuing to deliver support and services, including the measuring the impact of the £400,000 provided in July 2021 to Beat.

Ensuring sufficient training and knowledge of the assessment and management of eating disorders in Scotland, particularly the use of new SIGN guidelines and external developments in relation to the training provided at universities.

Further resources

Resources for those affected by an eating disorder include: