Children and young people's mental health in Scotland

This briefing looks at recent developments in children and young people's mental health services. It covers both the universal and specialist levels of support available in Scotland. It also contextualises Scottish Government policy within the worsening mental health of children and young people over the last decade and considers the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Executive summary

Child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) are delivered by a four-tier system in Scotland. The four-tiers provide support across general mental health wellbeing at Tier 1, less severe mental health difficulties at Tier 2, greater difficulties or mental health conditions requiring out-patient services at Tier 3, and severe difficulties requiring inpatient and/or intensive community treatment services at Tier 4.

Audit Scotland's 2018 report

Audit Scotland published a major report into children and young people's mental health services in 2018. It suggested that Scotland's child and adolescent mental health services were facing significant challenges, such as:

increased number of referrals to specialist services

longer waiting-times to start treatment

increasing number of rejected referrals

weak non-specialist support.

Audit Scotland highlighted how some of these issues continue to persist, as well as the key developments since 2018, in a blog published in August 2021.

Scottish Government policy

In its National Performance Framework, the Scottish Government states that good mental health and wellbeing is central to ensuring that all of Scotland's children and young people grow up loved, safe, and respected so that they can realise their full potential.

Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027

The Scottish Government's Mental Health Strategy 2017-2017 included multiple specific actions for CAMHS in Scotland, with a particular focus on prevention and early intervention.

Audit into rejected referrals to CAMHS

Delivery of policies

Following the publication of Audit Scotland's 2018 report and the audit into rejected referrals, the Children and Young People's Mental Health Taskforce was set up to support the delivery of Scottish Government policy for child and adolescent mental health. The Taskforce published its Delivery Plan in December 2018.The Children and Young People's Mental Health and Wellbeing Programme Board was responsible for the actions outlined in the Delivery Plan until December 2020. This work is now being progressed by Children and Young People's Mental Health and Wellbeing Joint Delivery Board, which is due to run until December 2022.

COVID-19 response

In October 2020, the Scottish Government published its Coronavirus (COVID-19): mental health - transition and recovery plan in response to the pandemic's impact on mental healthcare services, including CAMHS. The plan built on previous commitments, in addition to introducing new actions. The Scottish Government allocated £11.25 million to services in November 2020 to respond to the mental health and emotional wellbeing issues arising as a result of the pandemic.

Parliamentary scrutiny

Scottish Government policy has been scrutinised by various committees in the Scottish Parliament. Most recently, the Health, Social Care, and Sport Committee (HSCS) undertook an inquiry into the health and wellbeing of Scotland's children and young people. Mental health featured as one of the key themes within the inquiry, with the Committee hearing evidence specifically on mental health and CAMHS in January 2022.

Trends in child and adolescent mental wellbeing

There has been a decline in the mental wellbeing of children and adolescents in the past decade, which is reflected in the significant increase in referrals to CAMHS highlighted by Audit Scotland in 2018.

Inequalities

Some groups are at an increased risk of poor mental wellbeing, including:

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a particularly negative impact on children and young people's mental health and wellbeing, with the impact exacerbated for those groups already at-risk of poorer mental wellbeing. The extent of longer-team impacts of the pandemic are still to be fully understood.

Key issues

Funding

There has been an increased emphasis on prevention and early intervention in Scottish Government funding for child and adolescent mental health. However, funding for Tier 1 and Tier 2 supports and services will need to be balanced against the consistent demand for specialist CAMHS services and the continuing challenges facing CAMHS, such as long waiting-times.

Prevention

The Scottish Government aims to have a preventative approach to child and adolescent mental health and views this as an important way to decrease referrals to specialist CAMHS in the longer-term.

General

There has been continued work around encouraging good mental health and wellbeing amongst all children and young people in Scotland, especially within a school context through the review of Personal and Social Education (2019) and a 'whole school approach' to mental wellbeing.

At-risk groups

In addition to the general encouragement of good mental wellbeing amongst children and young people, the Scottish Government also aims to ensure that support for at-risk children and young people is available in Scotland. This has included a focus on mitigating the impact of and supporting children who have experienced trauma and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs).

The third sector

The third sector plays a significant role in the delivery of Tier 1 and Tier 2 services in Scotland, delivering a range of support and services. These include providing direct support (like as counselling) to children and young people, providing online resources, and supporting the Scottish Government with research.

School counselling

The provision of school counsellors was identified as a weakness by Audit Scotland in 2018. The Programme for Government 2018-19 committed to investing over £60 million in additional school counselling services, with the aim of creating around 350 counsellors. £12 million was provided to local authorities in 2019-20 for the delivery of this commitment and a further £16 million has been provided for 2020-21, 2021-22, and 2022-23. The Scottish Government has stated that every secondary school in Scotland now has access to a counsellor.

Community support

Progress has also been made in recent years to deliver community mental health and wellbeing support services for children and young people, which was identified as a key issue by the Children and Young People's Mental Health Taskforce in 2019. The delivery of new and enhanced community mental health and wellbeing services for 5-24 year olds in Scotland has been supported by a £15 million investment in 2021-22. An additional £15 million is allocated for 2022-23. 200 community support services have been established since January 2021. The implementation of these supports and services are guided by a Framework, which was published in February 2021. Audit Scotland raised some possible challenges that the implementation of these supports and services may face in its August 2021 blog.

Recruitment and workforce

The workforce responsible for children and young people's mental health and wellbeing is large, including both non-specialists (for example, teachers) and specialist healthcare professionals.

Delivery of prevention and early intervention supports

The Scottish Government has emphasised the need to upskill school staff on mental health and wellbeing, with schools encouraged to take a 'whole school approach'. Previous research suggested that teachers were not confident in supporting pupil mental health and wellbeing and the Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 included an action to improve the mental health training available to those supporting children in an educational setting. A number of resources and training materials have been developed and offered to teachers since 2017. Concerns have been raised, however, around the capability of the workforce to deliver the Scottish Government's commitments on school counsellors.

Specialist CAMHS workforce

In specialist CAMHS, the most recent workforce figures reflected a 68.2% increase in Whole Time Equivalent (WTE) staff in post since 2006. The Programme for Government 2021-22 stated that the £40 million allocated from the Mental Health Recovery and Renewal Fund to CAMHS will be used towards funding around 320 additional CAMHS staff over the next 5 years. However, a recent survey by the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland has highlighted continuing concerns around the CAMHS workforce from its members.

Specialist CAMHS services

Accessing CAMHS services was identified as an issue by Audit Scotland in 2018 and specialist CAMHS services continue to face challenges around high numbers of referrals, steady numbers of rejected referrals, and long waiting times.

Accessing services

Audit Scotland stated in 2018 that navigating mental health services, especially specialist services, can be confusing for children and young people and are hard to access due to a number of factors. Children and young people often do not know what support is available or where to get that support. Furthermore, the audit into rejected referrals identified a perception from children and young people that the threshold to be accepted by CAMHS was very high. The CAMHS national service specification was published in February 2020.It outlines what children, young people and their families can expect from Tier 3 and Tier 4 support. The delivery and impact of the national service specification in improving children and young people's understanding and knowledge of CAMHS will need to be evaluated over the long-term.

Referrals

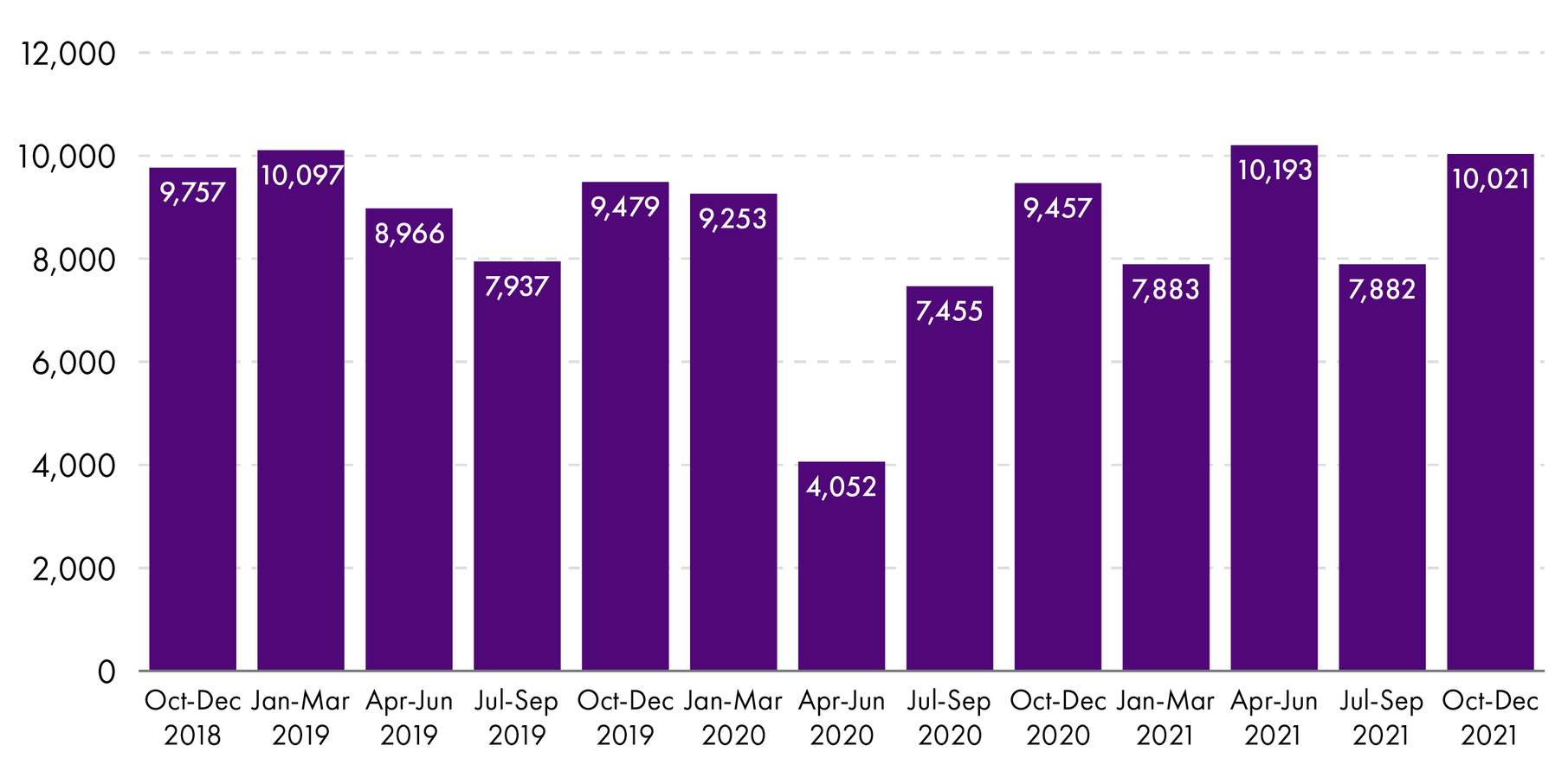

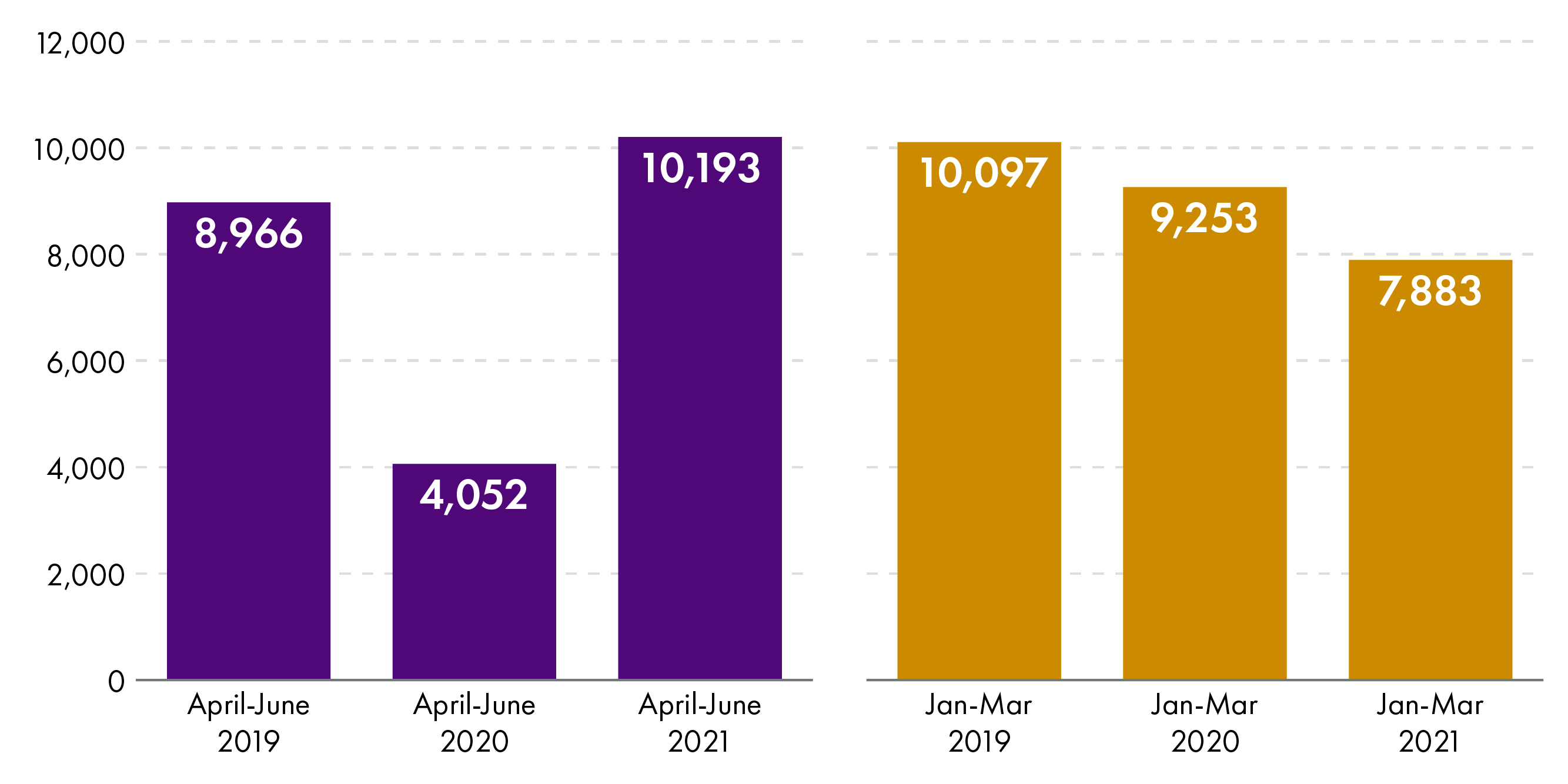

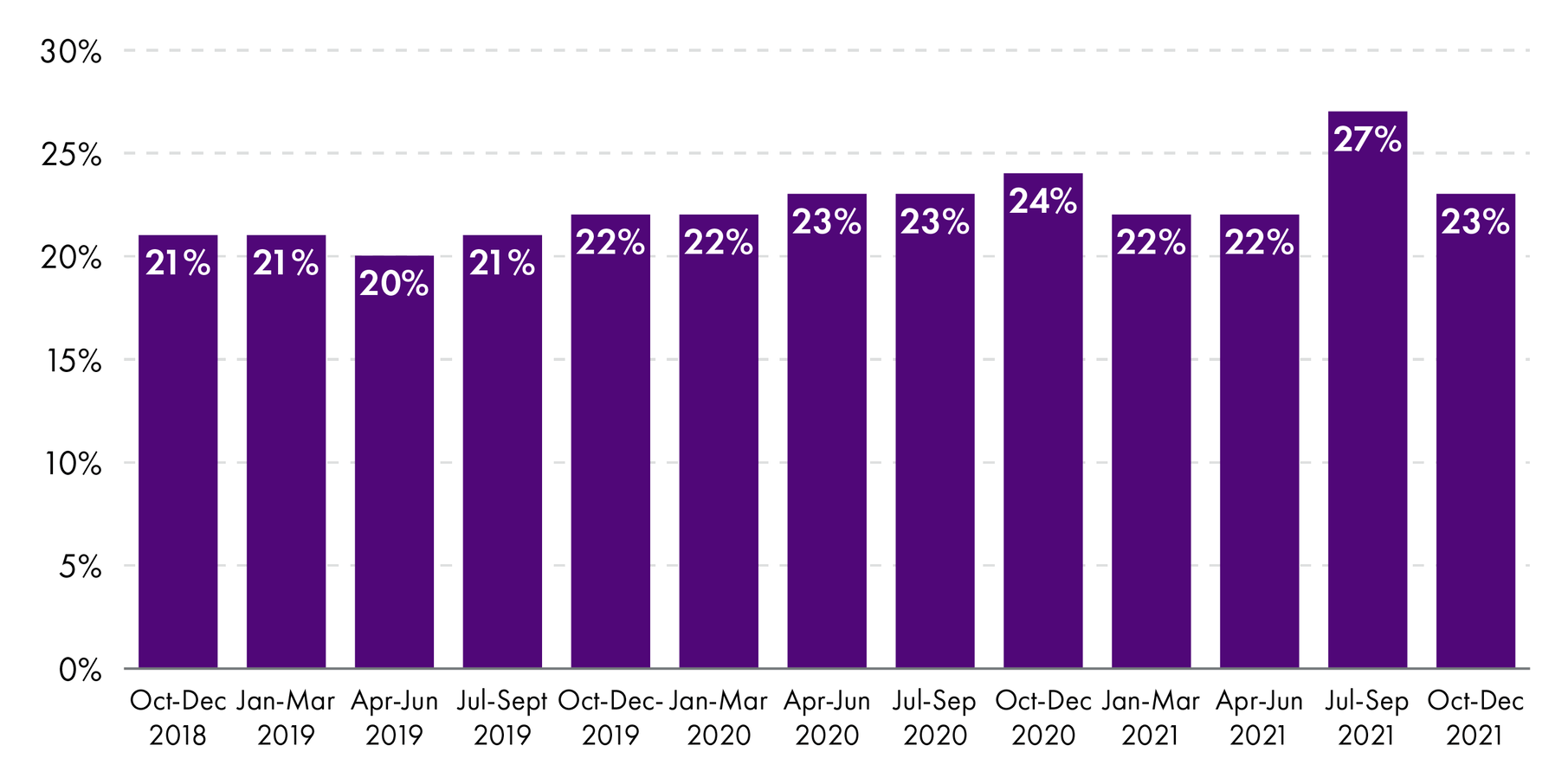

Referrals to CAMHS have remained consistent since 2018, with the exception of quarters that overlapped with school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Referrals to CAMHS saw a significant drop during these months.

Rejected referrals

The percentage of referrals not accepted by CAMHS has not significantly decreased since the publication of the 2018 audit into rejected referrals. The quarter ending 30 September 2021 saw the highest percentage (27%) of referrals rejected by CAMHS since data has been collected. The Scottish Government accepted the recommendations contained in the audit into rejected referrals in full. Progress has been made to deliver some of these recommendations, such as enhanced data collection. While the CAMHS National Service Specification is aimed to deliver multiple recommendations within the report, it is unclear how its impact will be monitored.

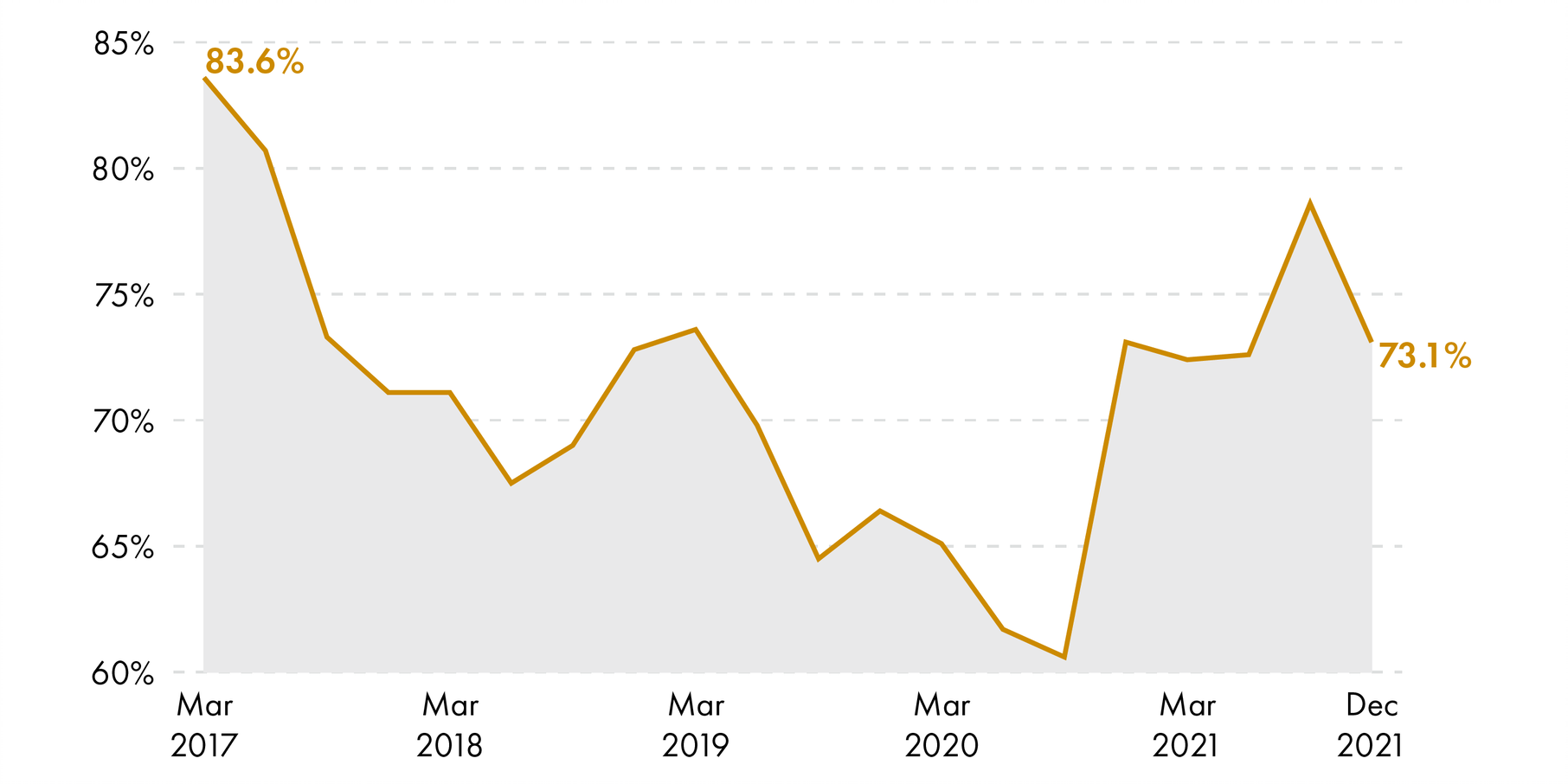

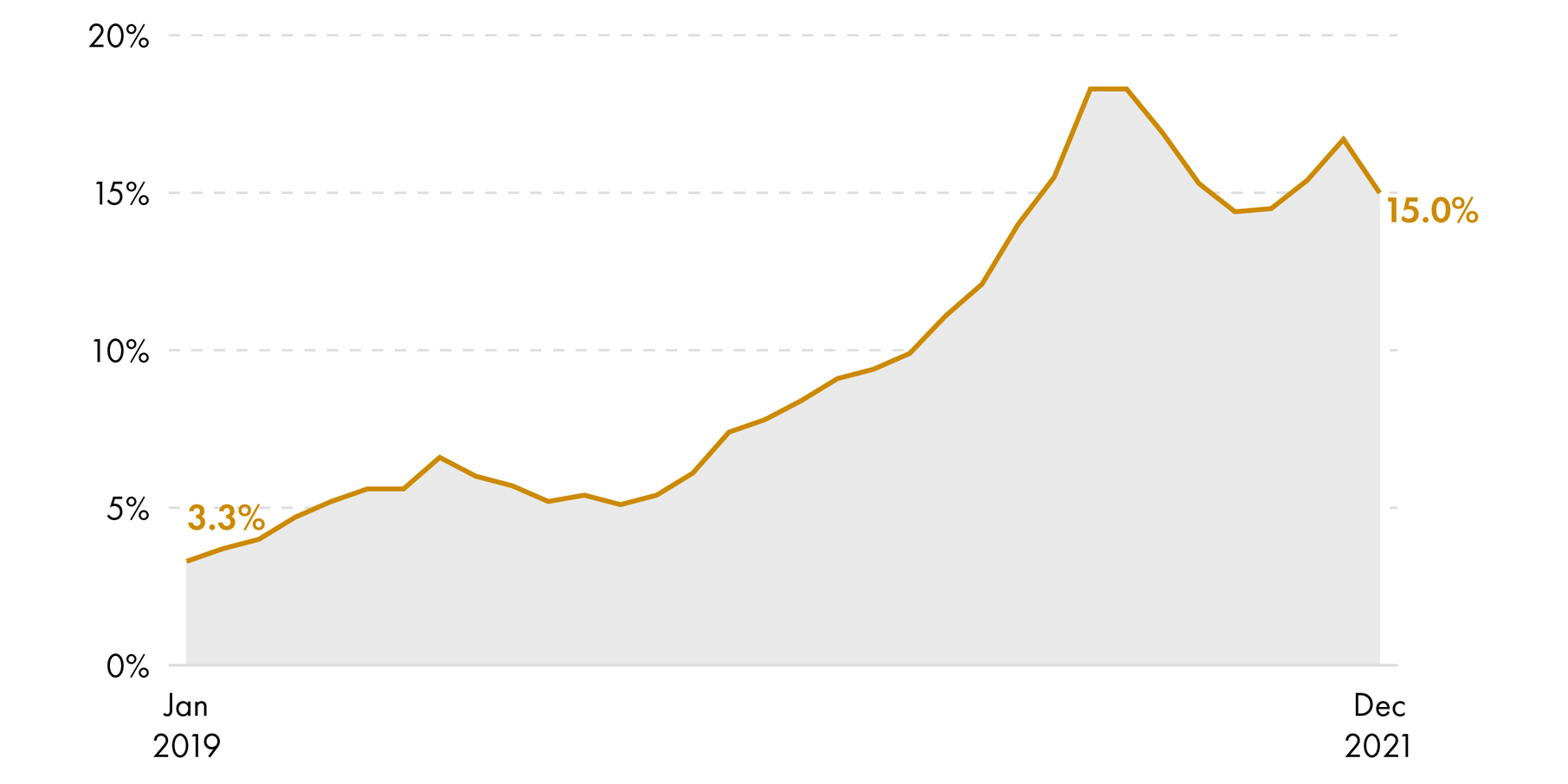

Waiting times

Waiting times remain a challenge. The target that 90% of CAMHS patients should start treatment within 18 weeks of a referral is not being met. The most recent highest percentage (83.6%) was seen in the quarter ending 31 March 2017. 70.3% of patients started treatment within 18 weeks of referral for the most recent quarter (31 December 2021).Furthermore, the number of patients waiting more than 53 weeks to start treatment has increased. Fifteen percent of the 10,452 patients waiting to start treatment in December 2021 had been waiting 53+ weeks, compared to 3.3% in January 2019.

Crisis support

The Programme for Government 2018-19 committed to developing 24/7 crisis support for children and young people. This action is still in development, with the Children and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Joint Delivery Board now responsible for taking this action forward. The Distress Brief Intervention (DBI) pilot is also due to expand across Scotland by 2024.

In-patient care

The number of children and young people admitted to non-specialist inpatient wards has decreased since 2015 and, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Scottish Government prioritised the delivery of guidance and protocol for admissions to non-specialist wards. The development of multiple specialist inpatient services is also underway.

Monitoring progress and outcomes

The impact of recent policy developments is not likely to be immediate.For example, the impact of enhanced and new supports, such as school counsellors and community services, on referrals to specialist CAMHS services will need to be tracked over the long-term. Having the appropriate data to measure progress will be important going forward.

Introduction

In August 2021, Audit Scotland published a blog on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services.1 It found that, despite "significant investment", the issues outlined in its 2018 report - such as long waiting times to start treatment, gaps in national data, and high numbers of rejected referrals2 - still remain. The Scottish Government's Programme for Government 2020-21 had previously acknowledged that these challenges continue to persist in Scotland:

Spend on CAMHS in Scotland has increased year‑on‑year since 2011 and by 182.7% since 2006. Despite this, we know that too few Boards are meeting their required targets and too many children and young people (...) are waiting an unacceptably long time to start treatment. Our investments have helped to substantially increase the CAMHS and psychological therapies workforce but the impact on performance has been slower and less comprehensive than expected and needed.3

This briefing looks at Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) in Scotland across its four tiers, covering both general support offered to all of Scotland's children and young people and more specialist services for severe mental wellbeing issues.

Specifically, it explores the recent developments within CAMHS following the publication of theMental Health Strategy 2017-2027, Audit Scotland's 2018 report, and the audit into rejected referrals to CAMHS and outlines what progress has been made on key issues.

The briefing first outlines the current context for CAMHS: a decline in good mental wellbeing amongst children and young people. It then explores the key policy issues, beginning with the Scottish Government's ambitions to shift funding for children and young people's mental health towards preventative and early intervention approaches.

Progress in Tier 1 and Tier 2 CAMHS is examined, looking at developments around the prevention of poor mental wellbeing, the delivery of school counsellors, and community wellbeing services for children and young people. The role of the third sector in the delivery of some Tier 1 and Tier 2 services is also explored.

This briefing then covers workforce and recruitment, looking at progress around training and recruitment within both the general workforce supporting children and young people and the specialist CAMHS workforce.

Following this, the briefing moves onto specialist CAMHS services. It first looks at the challenges that some children and young people have faced in trying to access these services, recent trends in the number of referrals to CAMHS, progress made following the audit into rejected referrals, and waiting times figures. It then outlines the more intensive support available, looking at developments in crisis support and in-patient psychiatric care for children and young people.

Finally, the key issues conclude with a discussion on how developments and outcomes may be monitored by the Scottish Government, NHS Health Boards, and Local Authorities.

Definitions

Mental health and wellbeing

This briefing uses the World Health Organisation's definition of mental health:

Mental health is a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.1

Mental illness

All children and young people have a general mental health. Mental illness and disorders, however, are diagnosable health disorders - like eating disorders, severe depression or anxiety, and personality disorders - that significantly impact a person's thinking, feelings, behaviours or mood.

Children and young people

The definition of a child or a young person can differ in Scotland depending on the context. The Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 includes all children and young people up to the age of 18. 1 To narrow the scope of this briefing, it focuses on children and young people from primary age (aged 4/5) to those aged 18. It does not include infant health and wellbeing or young people aged 18-24, who can have distinct and separate wellbeing concerns.

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) tiers

Children and adolescent mental health services in Scotland are delivered by a four-tier system. The tiers depend on the needs and severity of the child or adolescent's mental health difficulty or condition.

Tier 1: Universal services

Tier 1 services promote positive emotional health and wellbeing for all children and young people. They also provide general advice and support for less severe mental health problems or emotional difficulties. Additionally, Tier 1 services can identify a child or adolescent's problems at an early-stage and provide an onward referral to more specialist services where necessary. Tier 1 services are delivered by practitioners working with children and young people across universal services - like GPs, teachers, school nurses, social workers, youth workers, and third sector organisations.

Tier 2: A combination of specialist children and adolescent mental health services and some community-based services

Tier 2 services provide more specialist support for children and young people who are experiencing less severe mental health problems, such as mild to moderate anxiety and depression. Tier 2 practitioners can also provide consultation and training to those delivering Tier 1 services. Tier 2 is delivered by practitioners who work in primary care and/or the community - like child and adolescent psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, educational psychologists, and school counsellors.

Tier 3: Specialist multidisciplinary outpatient children and adolescent mental health teams

Tier 3 services are for people who are experiencing significant mental health problems. Tier 3 services are delivered by multi-disciplinary teams, based in a local area, who work in a community health setting or in a child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient service. Nurses, clinical and applied psychologists, social workers, psychiatrists and occupational therapists form the main professions in Tier 3. Tier 3 services also have access to systemic and family psychotherapists, child and adolescent psychotherapists, speech and language therapists, and dieticians, where required.

The CAMHS Service Specification outlines that CAMHS locality teams in Tier 3 will provide services for:

severe depression and anxiety

moderate to severe emotional and behavioural problems, including severe conduct, impulsivity, and attention disorders

psychosis

obsessive-compulsive disorders

eating disorders

self-harm

suicidal behaviours

mental health problems with comorbid drug and alcohol use

neuropsychiatric conditions

attachment disorders

post-traumatic stress disorders

mental health problems comorbid with neurodevelopmental problems

mental health problems where there is comorbidity with mild/moderate intellectual disabilities and/ or comorbid physical health conditions, additional support needs and disabilities, including sensory impairments

children and young people in the above categories and who require Intensive Home Treatment and Support.

Tier 4: Highly specialised inpatient children and adolescent mental health units and intensive community treatment services

Tier 4 services are for children and young people who are deemed to be at greatest risk of rapidly declining mental health and serious self-harm or who require a period of intensive input for assessment and/or treatment. Tier 4 services are delivered by community treatment teams, in-day units, or inpatient units. The patient's treatment is usually overseen by a consultant child and adolescent psychiatrist or a clinical psychologist.

Tier 3 and Tier 4 are supported by CAMHS services that provide additional and specific expertise to children and young people who also have more complex and/or specific difficulties, such as:

substance misuse service

eating disorders service

intensive home treatment service

crisis service

gender identify service

forensic CAMHS

learning disability/Intellectual disability CAMHS service.1

Audit Scotland's 2018 report

Audit Scotland published its report, 'Children and young people's mental health', in September 2018. It examined CAMHS services in Scotland. The report looked at the accessibility of services, the support offered to children and young people, the resources supporting these services (including funding and the workforce) and the Scottish Government's policy and strategic direction.

The report concluded that mental health services for children and young people in Scotland were under "significant pressure". The number of referrals to specialist CAMHS had increased by 22% between 2013-14 and 2017-18. In addition, there were more rejected referrals and longer waits for treatment. Twenty six percent of those who started treatment in 2017-18 waited over 18 weeks, compared to 15% in 2013-14.1

Key findings from Audit Scotland included:

CAMHS is "complex and fragmented, and access to services varies throughout the country."

The current system "makes it difficult for children, young people, and their families and carers to get the support they need."

A need for funding to be directed towards intervention and prevention, whilst also balancing the need for specialist and acute services.

A need for "effective multi-agency working" between specialist CAMHS services, primary care, social work, schools, and the voluntary sector.1

2021 Blog

In August 2021, Audit Scotland published a blog on the progress made since 2018. It found that, ultimately, despite "significant investment", the situation in 2021 remains similar to the one outlined in 2018.1 Waiting times were identified as a key issue, in addition to a continued lack of data on CAMHS patients. Audit Scotland also outlined how new developments, such as the CAMHS service specification and community wellbeing services, may face challenges during their implementation.1

Scottish Government policy

The Scottish Government has the ambition that all of Scotland's children and young people will grow up "loved, safe and respected" so that they can realise their full potential.

Getting it right for every child

Getting it right for every child (GIRFEC) underpins Scottish Government's policies that support children, young people, and their families. GIRFEC has the following principles and values for Scotland's approach to children and young people:

Child-focused, ensuring that the child or young-person, and their family, is at the centre of decision-making and available support.

Based on an understanding of the child in their current situation, taking into consideration the wider influences on a child or young person and their developmental needs when thinking about their wellbeing.

Based on tackling needs early, so that needs are identified as early as possible to avoid bigger concerns and problems from developing.

Requires joined-up working, where children, young people, parents, and services work together in a coordinated way to meet specific needs and improve wellbeing.

GIRFEC has eight wellbeing indicators (SHANARRI). At home, in school, or the wider community, every child and young person should be:

safe

healthy

achieving

nurtured

active

respected

responsible

included.

Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027

In 2017, the Scottish Government published its 10-year Mental Health Strategy with specific actions for children and young people's services - especially within the context of early intervention and prevention. It included:

Action 1: Review Personal and Social Education (PSE), the role of pastoral guidance in local authority schools, and services for counselling for children and young people.

Action 2: Roll out improved mental health training for those who support young people in educational settings.

Action 3: Commission the development of a matrix of evidence-based interventions to improve the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people.

Action 5: Ensure the care pathway includes mental and emotional health and wellbeing, for young people on the edges of, and in, secure care.

Action 6: Determine and implement the additional support needed for practitioners assessing and managing complex needs among children who present a high risk to themselves or others.

Action 8: Work with partners to develop systems and multi-agency pathways that work in a co-ordinated way to support children's mental health and wellbeing

Action 18: Commission an audit of CAMHS rejected referrals, and act upon its findings.

Action 19: Commission lead clinicians in CAMHS to help develop a protocol for admissions to non-specialist wards for young people with mental health problems.

Action 20: Scope the required level of highly specialist mental health inpatient services for young people, and act on its findings.

Action 21: Improve quality of anticipatory care planning approaches for children and young people leaving the mental health system entirely, and for children and young people transitioning from CAMHS to Adult Mental Health Services.1

Action 40 of the Mental Health Strategy committed the Scottish Government to reviewing the strategy in 2022 (its halfway point). The Programme for Government 2021-22 committed to a "review and refresh" of the Mental Health Strategy in 2022.2

Rejected referrals to child and adolescent mental health services: audit

Action 18 of the Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 was completed in June 2018, through the publication of the audit into rejected referrals to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). The term ‘rejected referrals’ refers to referrals made to CAMHS Tier 2, 3, or 4 services that are not accepted for treatment.1 Concerns had been raised over the increasing number of rejected referrals, with Audit Scotland highlighting in 2018 that there had been a 24% increase in the number of referrals not accepted by specialist services since 2013-14.2

The audit contained 29 recommendations, which the Scottish Government accepted in full.3 From the evidence and experiences provided by the children, young people, and their families who participated in the audit's research, the audit identified CAMHS being 'unsuitable' as the main reason why a patient's referral was not accepted. A child or young person may be 'unsuitable' for specialist services based on the seriousness and nature of their condition or by not meeting other aspects of the health board's referral criteria.

The audit also highlighted issues around children, young people, and their families not understanding the referrals process, feeling that signposting to other resources was unhelpful, and dissatisfaction with the assessment process (for example, the absence of a face-to-face assessment and CAMHS not adequately detailing the reasons why a referral had not been accepted).

The audit’s recommendations were grouped into four themes:

further research

meeting the needs of children, young people, and their families

making immediate changes to CAMHS

data collection.

Delivery of mental health and wellbeing policies

The Children and Young People's Mental Health Taskforce was jointly commissioned by the Scottish Government and the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA) in June 2018. The Taskforce published a Delivery Plan in December 2018 and sought to "ensure that the mental health needs of children and young people receive the attention and priority agreed by the Government and COSLA" following Audit Scotland's 2018 report and the audit on rejected referrals.1The Children and Young People's Mental Health Taskforce made its final recommendations to the Scottish Government and COSLA on 4 July 2019.

Delivery of the recommendations made by the Children and Young People's Taskforce was overseen by the Children and Young People's Mental Health and Wellbeing Programme Board, which was jointly chaired by the Scottish Government and COSLA. The Board met for the first time in August 2019 and concluded in December 2020. The Programme Board outlined nine planned aims, including:

Enhancing existing community based supports and developing innovative new approaches for emotional/mental distress.

Enhancing the crisis support available to children and young people.

Developing a CAMHS Service Specification for use across services in Scotland.

Developing a Neurodevelopmental Service Specification for use across services in Scotland.

Developing a programme of education and training to increase the skills and knowledge required by all staff to support children and young people's mental health.

The Children and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Joint Delivery Board, chaired by COSLA and the Scottish Government, was formed to progress the aims of the Programme Board. It anticipates to run until December 2022. The Joint Delivery Board's aims include:

Continuing to enhance community based support for emotional wellbeing/mental distress through ongoing investment and support for local partnerships.

Ensuring crisis support is available 24/7 to children and young people.

Supporting mental health pathways and services for vulnerable children and young people, aligned to the work of The Promise.

Developing a support programme to enable the implementation of the CAMHS service specifications.

Developing a programme of education and training to increase the skills and knowledge required by all staff to support children and young people's mental health.

COVID-19 response

The Scottish Government published the Coronavirus (COVID-19): mental health - transition and recovery plan in October 2020. The plan includes specific commitments for children, young people and families, centred around four themes:

Developing a population health response to the issues affecting the mental health and wellbeing of children, young people and their families.

Continuing to develop mental health and wellbeing support in education and schools.

Developing a response to support children, young people, and families experiencing heightened distress.

Maintaining safe and effective treatment for children, young people, and perinatal women experiencing mental illness.1

Many of the actions expanded on the Scottish Government's previous commitments for children and young people's mental health services, as well as introducing new areas of work. These included:

Continuing work to establish community health and wellbeing services and supports for children and young people.

Developing a mental health training and learning resource for staff in schools, including guidance on how to respond to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental wellbeing of pupils.

Ensuring further research on the factors that have impacted children and young people's emotional wellbeing during the pandemic - such as worries about education, increased screen time, and disrupted sleep - and implementing findings into the Scottish Government's policy and actions.

Continuing progress to ensure that all secondary schools have access to a counselling service.1

The Coronavirus (COVID-19): mental health - transition and recovery plan made further commitments for specialist CAMHS. In particular, the plan acknowledged the importance of factoring the increased demand for CAMHS into the Scottish Government's longer term renewal programme for services and ensuring that they are sustainable and committed to "improving the quality and accessibility" of CAMHS services as Scotland moves forward from the pandemic.1

In November 2020, £11.25 million in funding was allocated to local authorities for community health and wellbeing services supporting children, young people, and their families impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. This funding was separate to the £3.75 million allocated for new and enhanced community health and wellbeing services and was aimed at responding specifically to the pandemic's impact.

The third annual progress report for the Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027, published in March 2021, outlined the Strategy's Actions that were prioritised during the COVID-19 pandemic. Two of these six actions (Action 19: Publication of protocol for admissions of young people to adult wards and Action 22: Support for young people with eating disorders) were specifically related to children and young people.4

Parliamentary scrutiny

The Health, Social Care, and Sport Committee (HSCS Committee) recently undertook an inquiry into the health and wellbeing of children and young people in Scotland. Mental health, access to CAMHS, and the importance of early intervention have been specific themes within the inquiry. The Committee heard evidence regarding mental health and CAMHS during the meeting on Tuesday 18 January 2022. Prior to the Committee's current inquiry, the Session 5 Health and Sport Committee (predecessor to the HSCS Committee) completed inquiries into mental health, including CAMHS, in Session 5 and the equivalent Session 3 Committee undertook an inquiry into child and adolescent mental health and wellbeing.

The Public Petitions Committee received evidence in Session 5 for its consideration of PE01627: Consent for mental health treatment for people under 18 years of age. The evidence received highlighted "serious concerns about the experiences of young people seeking help for their mental health". The Committee established an inquiry into mental health support for young people in Scotland. The inquiry focused specifically on Tier One support. The Public Petitions Committee published its report in June 2020.1

In Session 5, the Public Audit and Post-Legislative Scrutiny Committee received evidence on Audit Scotland's 2018 report, and the committee published its report on children and young people's mental health in March 2019. Following the publication of Audit Scotland's blog into child and adolescent mental health services in August 2021, the Public Audit Committee took evidence on child and adolescent mental health services at its meeting on 7 October 2021.

There is also a Cross Party Group on Mental Health, which is undertaking a two-year long inquiry into the Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027. While the group's remit covers all age groups, two of their recent reports (Priorities for Access to Treatment and Joined Up Accessible Services and Priorities for Prevention and Early Intervention) cover issues relating to children and young people's mental health and wellbeing.

Trends in children and young people's mental health and wellbeing

The mental health and wellbeing of children and young people has been measured in a variety of ways.

National mental health indicators for children and young people were introduced by Public Health Scotland in 2011, covering both the state of a child or young person's mental health and associated contextual factors.1 Various data sources were used depending on the indicator; in particular, data from the Scottish Schools Adolescent Lifestyle and Substance Use Survey (SALSUS), the Scottish Health Survey, and the Health Behaviour in School Aged Children (HBSC) survey were used.

Public Health Scotland have developed new mental health indicator sets for children and young people, which refreshes and builds on the 2011 indicators. The first phase of resources - the indicator set and a rationale document - was published in March 2022, with trend data due to be published later in the year. Public Health Scotland states that it will publish detailed analysis in the future to highlight "inequalities and the challenges faced by different population groups." The Health and Wellbeing Census is a core data source for the indicators.2 The census is being conducted during the current academic year (2021-22). As of February 2022, 23 local authorities have signed up to participate in the census.3

For secondary school pupils, the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) has frequently been used to measure mental wellbeing. The WEMWBS was added to the SALSUS in 2010; the SALSUS is conducted every two years and surveys S2 (around age 13) and S4 (around age 15) pupils. A WEMWBS score of 41-44 suggests 'possible depression.' The use of the WEMWBS has highlighted a possible decline in good mental wellbeing for this age group over the last decade:

Between 2010 and 2013, the WEMWBS score for pupils surveyed by the SALSUS fell from 50 to 48.7.4

The WEMBS score decreased slightly from 48.7 to 48.4 between 2013 and 2015.5

The WEMWBS score for pupils surveyed in the SALSUS: mental wellbeing report 2018 fell from 48.4 to 46.9 between 2015 and 2018. 6The 2018 survey was the last SALSUS in its existing format.

In December 2021, the Scottish Government published a report on Ipsos MORI’s Young People in Scotland (YPIS) 2021 survey. Between 8 February 2021 and 2 April 2021, 1361 pupils from 50 secondary local authority secondary schools completed the survey. The mean WEMWBS score was 44.8.7

The WEMWBS is only suitable for children aged 13 and above. For children aged 4-12, the Scottish Health Survey has asked participating parents to complete the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SQD). The Scottish Government has used this data to measure child wellbeing and happiness as a National Performance Framework (NPF) Indicator. The SDQ includes an emotional symptoms score:

The percentage of children aged 4-6 reporting an "abnormal" or "borderline" emotional symptoms score remained at 12% for 2013-2016 and 2016-2019.

The percentage of children aged 7-9 reporting an "abnormal" or "borderline" score increased from 14% for 2013-2016 to 18% for 2016-2019.

The percentage of children aged 10-12 reporting an "abnormal" or "borderline" score increased from 17% for 2013-2016 to 19% for 2016-2019.

Children and young people's mental health and wellbeing may also be measured via the demand for specialist services. Referrals to specialist CAMHS in Scotland have risen over the past decade, with Audit Scotland noting a 22% increase between 2013-14 and 2017-18.8 The first progress report for the Scottish Government's Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 stated that increased demand and more people coming forward for treatment has partially been driven by decreased stigma and more awareness about mental health problems.9

A 2016 report by the Scottish Youth Parliament included a survey of 1453 young people (aged 12-26) and suggested that stigma around mental health issues still prevented children and young people from talking about their mental health and seeking support.10 Furthermore, 74% of those surveyed did not know what mental health information, support, and services were available in their local area.10 The factors driving increased demand for CAMHS are complex and cannot be explained alone by de-stigmatisation and an increasing willingness by children and young people to seek support.

Children and young people's mental health in 2022 is impacted by a variety of issues. The most recent reports submitted by local authorities highlight some of the issues that over 12,000 children and young people sought school counselling for between July and December 2021. The full list of issues was lengthy, including: bullying, eating disorders, academic and school pressures, relationships, parental issues, gender identity and LGBTQIA issues, anger and self-esteem.i

Health inequalities

Children and young people's mental health and wellbeing can differ depending on the population group looked at. For age groups, for example, this is normal and to be expected; the mental health concerns of a 4 year old will be different from an 18 year old.

However, some differences in experience reflect wider health inequalities in Scotland. Public Health Scotland defines health inequalities as the “unjust and avoidable differences in people’s health across the population and between population groups.”Public Health Scotland has listed some of the inequalities in children and young people's mental health. This briefing has included four examples.

Low income and deprivation

In 2018, NHS Health Scotland published a briefing on the health impacts and health inequalities linked to child poverty in Scotland. It highlighted that children aged 4-14 in Scotland's lowest income households were four times as likely to have poorer mental wellbeing than those in the highest income households.1

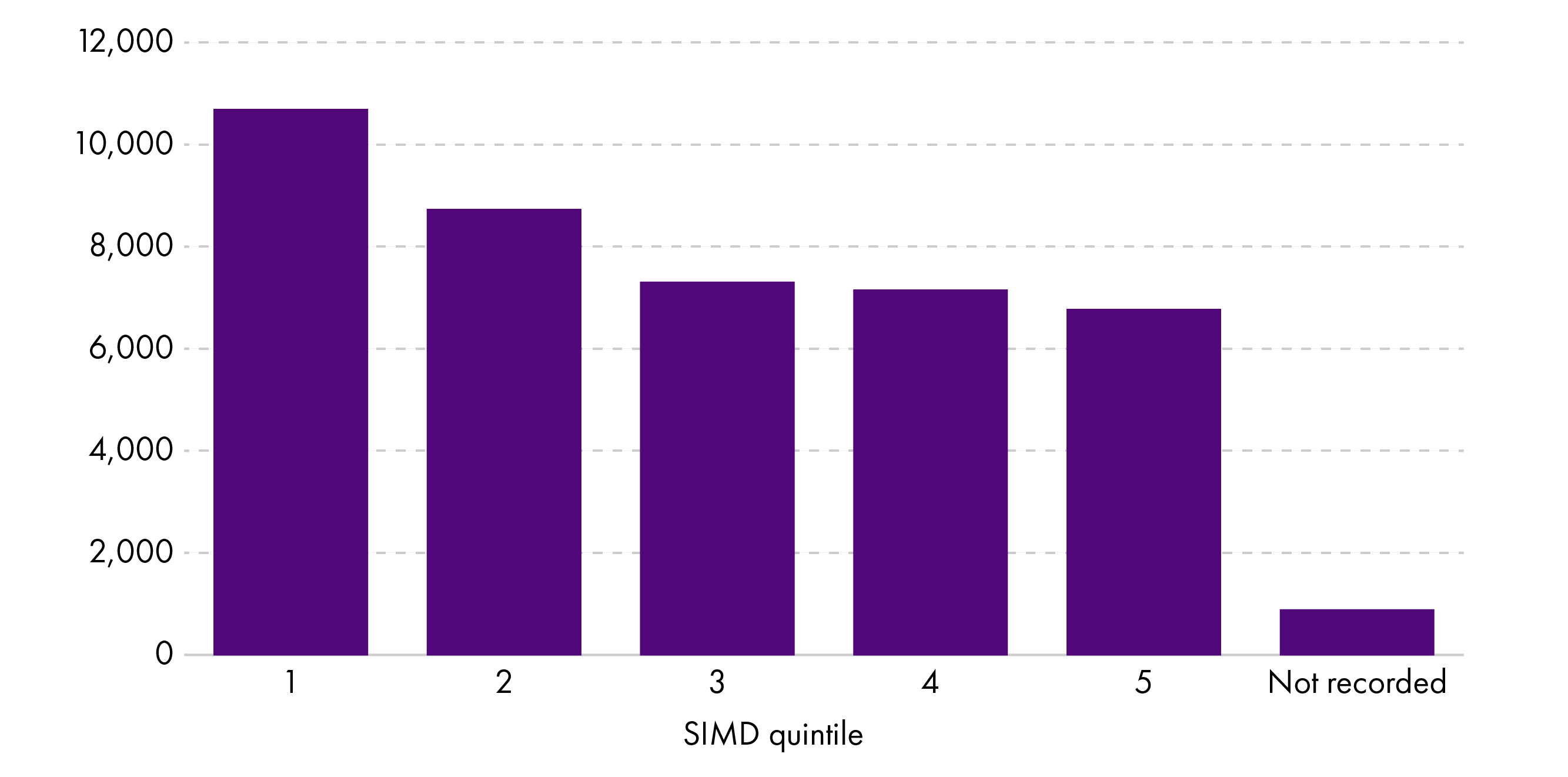

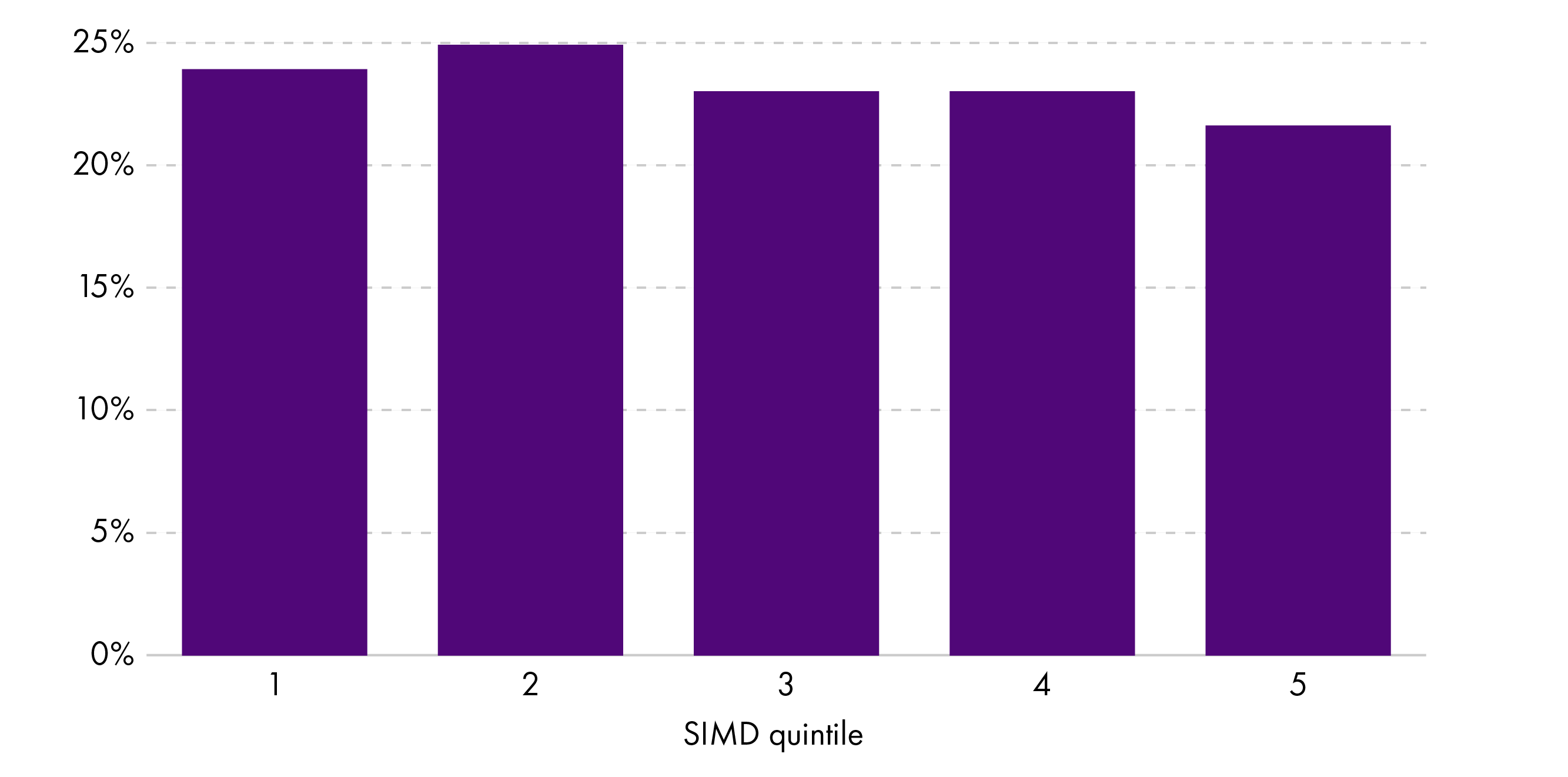

The CAMHS and Psychological Therapies National Dataset (CAPTND) first reported data as part of Public Health Scotland's publication on CAMHS waiting times for the quarter ending 31 March 2021 (Appendix 1).

For September 2020 to September 2021, CAPTND recorded 41,536 first referrals in total.i Referrals by Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) quintile were provided. The SIMD is a relative measure of deprivation across 6,976 small areas (called 'data zones'). The SIMD looks at the extent to which an area is deprived across income, employment, education, health, access to services, crime and housing. The SIMD ranks these areas from the most deprived to the least deprived using a certain rank. SIMD quintiles rank areas from the 20% most deprived (1) to the 20% least deprived (5).

Care experienced children and young people

Research by the University of Glasgow on the health outcomes of care experienced children has also highlighted that care experienced children had a higher rate of prescriptions for depression, psychiatric outpatient clinic attendances, and acute inpatient admissions due to mental and behavioural disorders.1

LGBTI

Young people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) have been found to be at an increased risk of reporting poorer mental health and wellbeing. The most recent Life in Scotland for LGBT Young People report by LGBT Youth Scotland saw that, of those surveyed, 40% of LGBT young people considered themselves to have a mental health problem. With the exception of stress, transgender young people had higher rates of mental health challenges compared to LGBT young people overall:

74% of transgender people said that they experienced depression, compared to 63% of LGBT young people overall.

63% of transgender young people experienced suicidal thoughts or behaviours, compared to 50% of LGBT young people overall.

59% of transgender young people reported that they self-harmed, compared to 43% of LGBT young people overall.1

Adolescent girls

Over the last decade, significant concerns have been raised over evidence suggesting a decline in the mental health of adolescent girls, with the First Annual Progress Report for the Scottish Government's Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 stating that this was a "major public policy" challenge for Scotland.1

In the reports submitted on access to counselling in secondary schools, more girls than boys were recorded as accessing counselling provisions between July and December 2021.i

.png)

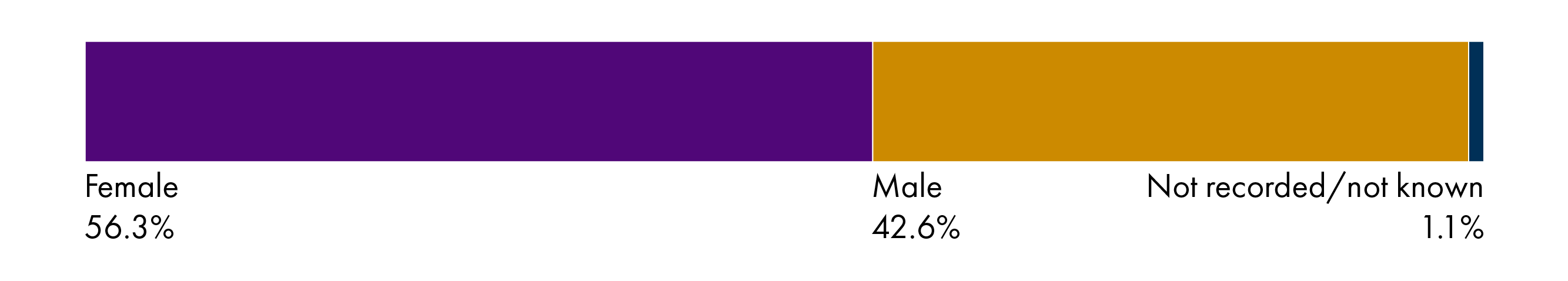

The Scottish Government's report on Ipsos MORI’s Young People in Scotland (YPIS) 2021 survey found that, overall, female pupils reported lower mental wellbeing, more often felt lonely, and were less likely to report feeling optimistic than male pupils.2 CAPTND information for first referrals to CAMHS, for September 2020 to September 2021, showed that 56.3% of referrals were for females, compared to 42.6% for males.ii

Public Health Scotland's most recent report on mental health inpatient activity also showed that, for all age groups, 54% of patients who experienced mental health inpatient care in 2020-21 were male. When taking the under-18 age category alone, 65% were female.3 However, as with other age groups, the number of suicides registered for 15-24 year olds in Scotland has consistently been higher for males. Public Health Scotland's latest release on suicide statistics for Scotland detailed that, in 2020, 68 suicides registered for the 15-24 age group were male compared to 23 females.4

The COVID-19 Pandemic

The Coronavirus (COVID-19): mental health - transition and recovery plan acknowledged growing evidence that interventions to control the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic had a particularly negative impact on the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people. Vulnerable children and young people and those with challenging home environments were thought to be more likely than others to have experienced poor mental health during the pandemic.1

The Scottish Government publishes regular evidence summaries on the impact of COVID-19 on children, young people, and families. The sixth report was published in June 2021 and covers research published between October 2020 and May 2021.2 The evidence examined included both UK-wide research and research specific to Scotland.

In particular, the review covered the research conducted by the Scottish Youth Parliament, Youth Link Scotland, and Youth Scot for LockdownLowdown: what young people in Scotland are thinking about COVID-19.3 Its November 2020 publication, which surveyed over 6,000 young people (11-26) from across Scotland between September and November 2020, reported that 42% of respondents felt good about their mental health and wellbeing. This compared to 60% of respondents feeling good about their physical health and wellbeing.3

A separate demographic exploration of the November 2020 survey was published in January 2021. In particular, mental wellbeing seemed to decrease by age: 69% of respondents aged 11-12 felt good about their mental health and wellbeing, compared to 20% of respondents over 18. Furthermore, 59% of male respondents reported feeling good about their mental health - compared to 34% of female respondents and 18% of respondents who identified as non-binary or in a different way.3

Although the longer-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic will become clearer in future years, some studies have observed that, at least in the short-term, children and young people's mental health and wellbeing appeared to improve during periods when restrictions were lifted. For example, the Children's Parliament undertook a survey of 8-14 year olds during September and early October 2020. Results were compared to previous surveys (April, May, and June 2020) and found "significant improvements when it comes to children reporting that they often feel lonely".6 20% agreed that they often feel lonely, compared to 26% across the April-June 2020 surveys.6

It is unclear if rates of positive mental health and wellbeing will return to pre-pandemic levels. This was highlighted by two surveys conducted by the Schools Health and Wellbeing Improvement Research Network (SHINE) and Generation Scotland on the health and wellbeing of young people during COVID-19. Survey 1 ran from 22 May 2020 to 1 July 2020 and was aimed at young people in Scotland aged 12-17. Survey 2 ran from 18 August 2020 to 10 October 2020 and included the same age group.8 20% of those responding to Survey 2 reported feeling lonely most or all of the time, compared to 28% in Survey 1. SHINE and Generation Scotland noted, however, that levels of loneliness still remained higher than pre-lockdown levels.8

Neurodevelopmental disorders

This briefing is concerned with mental health and mental illness in children and young people, rather than neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurodevelopmental disorders include intellectual disability (ID), Communication Disorders, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Neurodevelopmental Motor Disorders, and Specific Learning Disorders.

The Children’s Neurodevelopmental Pathway – Practical Framework, published in May 2021, was developed by the Scottish Government-funded National Autism Implementation Team (NAIT). It is aimed to support practitioners in local health boards to develop and implement a local neurodevelopmental pathway for children and young people. It clarifies that neurodevelopmental differences “are not considered to be mental health conditions”.1

The National Neurodevelopmental Service Specification for Children and Young People in Scotland (September 2021) is intended to sit alongside the CAMHS National Service Specification. It is for children and young people who have neurodevelopmental profiles with support needs and require more support than what is currently available. The National Neurodevelopmental Service Specification notes that “these children are often referred to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) but do not always meet the mental health criteria described in the CAMHS national service specification criteria.”2

Like all children and young people, those with neurodevelopmental disorders can experience mental ill-health and have mental illness. This briefing discusses some of the supports available for this group. The National Neurodevelopmental Service Specification includes guidance on provisions for children and young people with both neurodevelopmental disorders and mental ill-health, stating that professionals working in neurodevelopmental services, health and social care services, and education services, should be “linked with CAMHS so that children and young people with both neurodevelopmental and mental health support needs can get the additional support they require.”2

The CAMHS National Service Specification states that CAMHS Locality Teams (Tier 3) will include services for children and young people with:

moderate to severe emotional and behavioural problems, including severe conduct, impulsivity, and attention disorders

mental health problems comorbid with neurodevelopmental problems

mental health problems where there is comorbidity with mild/moderate intellectual disabilities and/ or comorbid physical health conditions, additional support needs and disabilities including sensory impairments.4

As outlined, these services are supported by CAMHS services that provide “additional and specific expertise to children and young people who also have more complex and/or specific difficulties.” This includes the LD/Intellectual Disability CAMHS Service.

LD/Intellectual Disability CAMHS Service

This service works with children and young people with Intellectual Disabilities/Learning Disabilities (ID/LD) and mental health difficulties or complex behavioural difficulties. It provides comprehensive assessment and specialist, multidisciplinary, therapeutic interventions, broadly similar to mainstream CAMHS, with additional interventions/treatment approaches tailored to the needs of children young people with ID/LD e.g. behavioural and communication interventions. ID/LD CAMHS understands the complex genetic, neurological or physical health difficulties which often impact on the mental health and development of children and young people with ID/LD and tailor their approach accordingly.4

In the most recent release for CAMHS waiting times (quarter ending 31 December 2021), Public Health Scotland explained on-going changes to how waiting times for some CAMHS Neurodevelopmental Services are recorded:

A number of NHS health boards have implemented the national CAMHS service specification and submit to Public Health Scotland data on the subset of patients that meet the CAMHS criteria (“clear symptoms of mental ill health which place them or others at risk and/or are having a significant and persistent impact on day-to-day functioning”) rather than the full caseload of child and young people services, which can include for example those awaiting ADHD and ASD assessments in the Neurodevelopmental Service (though where Neurodevelopmental Service patients do also fit the CAMHS service specification they should not be excluded from reporting).6

Key issues

There are many key policy issues around children and young people's mental health in Scotland. Many of these are related to the delivery of the commitments made in the Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 and the recommendations from Audit Scotland's 2018 report and the audit into rejected referrals to CAMHS, in addition to longer-standing issues like CAMHS waiting-times. There are four overall themes:

An increased focus on and funding towards the prevention of poor mental health and ensuring support can be offered at the early stage of a mental health difficulty, especially in schools and in local communities.

The accessibility of specialist CAMHS services, including the Scottish Government's target that 90% of children and young people should start treatment within 18 weeks of a referral.

The supports and services offered beyond Tiers 1-3 for those in crisis or who require in-patient psychiatric services.

How the impact of these developments will be monitored and evaluated over the longer-term.

Funding

Action 17 of the Mental Health Strategy 2017-2017 committed to funding "improved provision of services to treat child and adolescent mental health problems".1 In the future, a key challenge will be balancing demand for specialist services with the Scottish Government's shift towards prioritising prevention and early intervention.

The Scottish Government's Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 acknowledged the importance of early intervention and prevention in mitigating mental health problems in children and young people. It outlined that improved support at Tier 1 and Tier 2 has the potential to "tackle such issues earlier and stem the flow of referrals" to Tier 3 and Tier 4.1

Audit Scotland raised concerns about the Scottish Government's approach to early intervention and prevention in 2018. 3While the Scottish Government's mental health strategy focused on early intervention and prevention, this was "limited" in practice. Mental health services for children and young people were "largely focused on specialist care and responding to crisis" and mental health funding had primarily been used for specialist services.

Furthermore, the availability of these services, such as school counsellors and primary mental health workers, were described as being "patchy" across Scotland. These Tier 1 and Tier 2 services are funded by councils, integration authorities, and the voluntary sector. The availability of these services can therefore vary depending on the local area, which is influenced by perceived local need and if children and young people's mental health and wellbeing services are considered to be a local investment priority.3

Audit Scotland's report recommended that the Scottish Government, COSLA, NHS Boards, councils, Integration Authorities, and their partners "develop local plans for how the balance of spending and activity will be shifted towards early intervention and prevention over the longer term."3 The Children and Young People's Mental Health Taskforce recommended that the Scottish Government and COSLA "support future investments in children and young people's mental health that prioritises early intervention and prevention approaches."6

The Programme for Government 2018-19 announced a £250 million investment over 5 years in mental health services for children, young people, and adults. The Programme for Government stated that long waits for CAMHS and rejected referrals required a change in the approach to services. with a focus on early intervention and ensuring support is available as close to children and their families as possible.7

£60 million from this investment was allocated to deliver the provision of school counselling services, with £12 million in 2019-20 and £16 million in 2020-21, 2021-22, and 2022-23.

£2 million was also allocated to local authorities in March 2020 to plan the development of new and enhanced community mental health and wellbeing supports for children and young people. A further £3.75 million was then allocated to local authorities to establish and fund community mental health and wellbeing supports for children and young people from January to March 2021.

Work to develop community services is now supported by a £15 million allocation to local authorities from the Mental Health Recovery and Renewal Fund in 2021-22, with a further £15 million allocated for the continuation of these services in 2022-23. The Programme for Government 2021-22 has committed to doubling the budget for children and young people's community based mental wellbeing services to £30 million per annum.8Scottish Government ministers are now considering options to take this forward.

While the importance of prioritising prevention and early intervention has been highlighted in recent years, demand for specialist CAMHS services remains high. Persistent challenges remain around key areas, like long waiting times.

In 2016, the Scottish Government announced £54 million in funding over four years (2016-2020) for Scotland's mental health services (children, young people, and adults). £4 million of further funding was provided in December 2018 in order to specifically support the additional workforce capacity of CAMHS. The Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027: Second Annual Progress Report, published in November 2019, stated that this funding, then in its final year, had been used to assist Health Boards with improving CAMHS waiting times by supporting workforce development, recruitment and retention, and service improvement.9

In February 2021, a £120 million investment was pledged towards the Mental Health Recovery and Renewal Fund for 2020-21.10 This investment is aimed at implementing the actions outlined in the COVID-19: mental health - transition and recovery plan.11 £40 million has been allocated to CAMHS for 2021-22. The Scottish Government has stated funding will be used to:

Offer treatment to those already on CAMHS waiting lists this year, with the intention of clearing all backlogs by March 2023 (£4.24 million)

Implement the National CAMHS Service Specification (£16.4 million)

Build the professional capacity in NHS Boards to ensure that children and young people with neurodevelopmental support needs can receive the advice, support and treatment needed (almost £3.06 million part-year funding this year)

Improve community CAMHS (£8.5 million)

Provide access to out of hours assessment, intensive and specialist CAMHS services (£4.9 million part-year funding this year)

Funding to establish 3 regional CAMHS Intensive Psychiatric Care Unit (IPCU) services (£1.65 million part-year funding this year)

A national data and information programme to support and evidence improvement for children and young people (£500,000).

The Scottish Government's Programme for Government 2021-22 committed to increasing investment in mental health by at least 25% over the course of this Parliament.Ten per cent of front line NHS spend is aimed to go towards mental health by the end of this Parliament, with 1% on child and adolescent services.8

Prevention

Preventing poor mental health and wellbeing, both from developing or escalating, has increased as a priority in recent years. This has included ensuring that general wellbeing education is able to encourage good mental wellbeing, in addition to more targeted support for groups who are identified as at an increased risk of developing poor mental health and wellbeing.

Encouraging good mental health and wellbeing

The actions within the Scottish Government's Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 included a review of Personal and Social Education (PSE), which was delivered through the publication of Review of Personal and Social Education: preparing Scotland's children and young people for learning, work and life in January 2019.1 PSE is the term used to deliver health and wellbeing education in school and is one of the eight areas of focus in Scotland's curriculum.

As the review of PSE stated:

Learning in HWB/PSE is designed to ensure that children and young people develop the knowledge and understanding, skills, resilience, capabilities and attributes which they need for mental, emotional, social and physical wellbeing.1

The review of PSE encompassed a thematic inspection of delivery of PSE in schools and early learning and childcare settings across Scotland, which was delivered by Education Scotland in August 2018. Regarding education on mental health and wellbeing, Education Scotland reported positive developments:

Secondary school staff noted an increase in stress and mental health issues for young people. As a result, PSE/HWB programmes now include an increased emphasis on mental health, and staff are giving high priority to ensuring that vulnerable young people receive the support they require. For example, secondary schools are using an increasing range of approaches to supporting mental health and building resilience, such as providing increased specialist input from partners, anxiety workshops, stress management, dealing with bereavement and loss, whole school approaches to nurture, restorative approaches and raising awareness of mental health.3

The Scottish Government published its framework for a whole school approach to mental health and wellbeing in August 2021.4 The framework states that schools will need to take a whole school approach in order to promote mental health effectively and ensure that pupils can "flourish and sustain a state of being mentally health."4 A whole-school approach should involve:

community leadership and management

community ethos and environment

effective curriculum and learning and teaching

the voices and participation of children and young people

professional learning and development for staff

identifying need and monitoring impact

engagement with parents, carers and the wider community

targeted support.4

Outside of a school context, the Scottish Government has supported Aye Feel and Mind Yer Time. Aye Feel is delivered by Young Scot and provides online information on how children and young people can look after their emotional wellbeing. Mind Yer Time has been designed by the Children's Parliament and the Scottish Youth Parliament and offers support and guidance on how to maintain a positive relationship with social media and screen use.

At-risk children and young people

Audit Scotland’s 2018 report acknowledged that some children and young people are at increased risk of experiencing poor mental health and wellbeing. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and trauma, in particular, are major contributors to mental ill health.1 ACEs are stressful or traumatic events that occur between the ages of 0 to 18 years, such as physical and emotional abuse and neglect.

The Scottish Government has implemented multiple policies aimed at reducing the overall negative impacts of ACEs and trauma. For example, the Programme for Government 2021-22 committed to ensuring that all eligible children who are victims or witnesses to abuse or violence and children below the age of criminal responsibility, whose behaviour has caused harm, will have access to a ‘Bairns’ Hoose’ by 2025, where child protection, health, justice, and recovery services will be available in one physical setting for children. A project plan was published in February 2022. Furthermore, the Scottish Government, COSLA, and other bodies aim to have a trauma-informed and trauma-responsible workforce across Scotland. This work has been supported by likes of the National Trauma Training Programme, which has been developed by NHS Education for Scotland.

Audit Scotland noted in 2018 that care experienced children and young people may experience multiple ACEs that can lead to a range of mental health difficulties.1 In February 2020, the Scottish Government accepted the conclusions of all the reports produced by the Independent Care Review into care experienced children and young people. The Promise Scotland is responsible for driving the work of change demanded by the conclusions. Work to #KeepThePromise between 2021 and 2030 will be shaped by a series of three plans, with Plan 21-24 covering the period 1 April 2021 to 31 March 2024. One of the priority areas of Plan 21-24 is ensuring that all children and young people can have a good childhood. By 2024:

Every child that is ‘in care’ in Scotland will have access to intensive support that ensures their educational and health needs are fully met.

Local Authorities and Health Boards will take active responsibility towards care experienced children and young people, whatever their setting of care, so they have what they need to thrive.3

Change Programme ONE outlines progress towards the actions contained in Plan 21-24. It found that, despite a strong commitment to ensuring that children and young people living in care can access the supports that they need, the current context is “extremely challenging”.4 The full impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on these children and young people, as well as the support available to them, is not fully known. However, Change Programme ONE stated that the increased referrals to mental health services “demonstrate the extent of current unmet need.” Furthermore, it made the suggestion that:

There are difficulties monitoring whether children and young people living in and around the ‘care system’ have access to what they need, and organisations reported that a better understanding and use of data would promote better decision making and improve understanding of local resourcing needs.4

The Programme for Government 2021-22 has committed to investing at least £500 million over this Parliamentary term to create a Whole Family Wellbeing Fund.6 The Whole Family Wellbeing Fund aims to keep children and young people with their families and reduce the need for family crisis intervention. This will be achieved by building support that is universal and holistic across Scotland. The areas that the Fund hopes to impact are varied and includes children and adolescent’s mental health.

The third sector

Third sector organisations help to deliver Tier 1 and Tier 2 services in Scotland, in addition to other work that progresses Scottish Government policies relating to children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. Its role was recognised by the Children and Young People’s Mental Health Taskforce in its recommendations to the Scottish Government and COSLA, with Recommendation 3 stating:

The Scottish Government and COSLA should recognise the vital and increasing role the third sector performs in supporting and improving the mental health of children and young people and should ensure they are fully involved and represented in strategic partnerships at a local and national level.1

Recommendation 24 of the audit into rejected referrals to CAMHS was that the Information Services Division (ISD) of NHS Scotland should:

work with third sector organisations to understand the services they provide to children and young people and explore sharing data between these organisation and statutory services to ensure full pathway information is available and used for improving services and experience.2

The Mental Health Strategy 2017-27: Second Annual Progress Report outlined the Scottish Government action's following the audit’s recommendations; the Scottish Government stated that ISD was already part of a Sharing Intelligence for Health and Care Group, alongside six other national organisations.3

The HSCS Committee received evidence from third sector organisations during the course of its inquiry into children and young people's health and wellbeing. At its meeting on 11 January 2022,Children 1st, which provide a range of services to support families (such as its Parentline support service), told Members that the current structure and delivery of funding to the third sector can be problematic when delivering support:

One of the challenges that we have is that these test, learn and develop initiatives, which can produce good evidence, are really difficult to take to scale because of a lack of funding or because funding is very short term. We need to fill that gap between universal services and very specialist services such as CAMHS with that whole-family support and community-based offer that any parent or carer, without stigma or shame, can reach out to and access quickly to get the support that they need.4

Scope of the third sector's work

Third sector organisations provide a range of services in Scotland – such as direct support to children and young people, resources to encourage good mental wellbeing, and conducting research on the topic. In recent years, this has included:

Young Scot and the Scottish Association for Mental Health (SAMH) working together to deliver the Youth Commission on Mental Health Services. Young people aged 15-25 worked on the Youth Commission for 16 months and its final report and recommendations was published in May 2019.

In-school mental health support, training, and resources delivered by Place2Be in Scotland.

Public campaigns delivered for young people by See Me Scotland and its Young Championsprogramme, which involves 16-25 year olds assisting with the delivery of See Me materials, delivering training to pupils in schools and speaking about their own experiences with mental health.

Online resources for teachers, developed by SAMH to improve the mental health training of teachers in Scotland, and the SAMH’s ‘Connect Project’ which delivers workshops, training, and direct support to children, young people, parents, carers and school staff in Scotland.

Aye Feel is delivered by Young Scot and provides online information on how children and young people can look after their emotional wellbeing.

YouthLink Scotland, Young Scot, the Scottish Youth Parliament, and the Children’s Parliament are also currently undertaking research on children and young people’s experiences and views of mental health support in Scotland. This research will support the work of the Children and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Joint Delivery Board and is intended to shape how services and supports are delivered.

School counselling

Audit Scotland's 2018 report on children and young people's mental health found that support for mental health and wellbeing within schools is varied.1 The support available is often dependent on the allocation of additional funding schemes, such as the Pupil Equity Fund.

The Mental Health Strategy, 2017-2027 aimed for every child and young person to have "appropriate access to emotional and mental wellbeing support at school."2 The Review of Personal and Social Education: preparing Scotland's children and young people for learning, work and life identified "access to professional counselling services" as an area for improvement in Scotland's schools.3

The Scottish Government's Programme for Government 2018-19 committed to investing over £60 million in additional school counselling services across all of Scotland, with the aim of creating around 350 counsellors.4 The Scottish Government stated that this investment should "ensure that every secondary school has counselling services." £12 million was provided to Local Authorities in 2019/20 and £16 million has been provided in each year for 2020-21, 2021-22 and 2022-3 (£60 million in total).

At the meeting of the Education and Skills Committee on 5 February 2020, Laura Meikle, Unit Head at the Support and Wellbeing Unit of the Scottish Government, explained that the commitment of around 350 counsellors related to 1 per school (Scotland has 357 secondary schools). Furthermore, Laura Meikle detailed the planned distribution of counsellors:

A number of schools have quite small pupil populations. When we were considering how the policy would work, we looked to balance larger schools that would have more than one counsellor and smaller areas that would have fewer than one. Every school will have access to someone; the balancing arrangement is because we do not want underprovision and we cannot have overprovision.5

The Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027: Second Annual Progress Report provided an initial update on this commitment in November 2019. In addition to the aim of ensuring that every secondary school has access to counselling services, this funding is intended to improve the ability of local primary and special schools to access counsellors. The first cohort of counsellors was due to be in-place by the end of that academic year (Summer 2020).6

The Programme for Government 2020-21 stated that the Scottish Government would continue to implement previous commitments on the provision of school counsellors.7 All education authorities had an implementation plan in place for providing school counsellors and many had "accelerated" implementation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In March 2021, Beatrice Wishart MSP lodged a question in the Scottish Parliament asking the Scottish Government "whether it has met its commitment to create around 350 counsellors in school education and to ensure that every secondary school has counselling services." John Swinney MSP, then the Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills, responded on 15 March 2021:

The approximate figure of 350 counsellors is the commitment related to the number of secondary schools in Scotland. The Scottish Government is confident it has met the commitment in full and that all secondary schools in Scotland now have access to counselling services.

In November 2021, Shirley-Anne Somerville MSP, the Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills, provided an update on school counsellors in her answer to a written question from Willie Rennie MSP that asked how many counsellors are currently in place to provide services in schools:

Access to counselling support services through secondary schools are in place across Scotland. As highlighted in the answer to S5W-35805, there is variation in how the counselling service is being delivered across authorities. Twenty four authorities are providing a specific resource in schools and eight authorities are providing an authority wide service according to need across their region.

12,149 children and young people were recorded as having accessed counselling services between July and December 2021, with demand peaking between S2 and S4.

The Programme for Government 2021-22 stated that the Scottish Government "will continue work to establish a guarantee of access in school to the mental health and wellbeing support that young people need, including counselling services."8

Community support

The Scottish Government has acknowledged the value of community mental health and wellbeing services in supporting early intervention and prevention, including how these supports can mitigate mental health problems in children and young people and reduce the number of referrals needed to more specialist services.1

Action 17 of the Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 committed the Scottish Government to funding "improved provision of services to treat child and adolescent mental health problems." In addition to CAMHS services in Tiers 2, 3, and 4, the Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027: Second Annual Progress Report outlined that the development of a community mental wellbeing service would contribute towards Action 17.2

The Programme for Government 2018-19 committed to developing community mental wellbeing services for 5-24 year olds and their parents. 3 In December 2018, the Children and Young People's Mental Health Taskforce stated in its Delivery Plan that there were "gaps" in community services to support children and young people with milder mental health problems.4How community services should be developed was included in the Taskforce's recommendations, which were published in July 2019.

Work to develop these services is on-going. The Children and Young People's Mental Health and Wellbeing Programme Board was originally responsible for its delivery.An initial £2 million was allocated to local authorities in March 2020 to plan the development of these services. Due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on local authorities in 2020, the first services were in place from January 2021.5£3.75 million in funding was allocated to the development of these services from January to March 2021.A further £15 million was provided to local authorities for 2021-22. The Programme for Government 2021-22 stated that around 200 community based mental health and wellbeing services for children and young people had been developed in the last year.

The Children and Young People's Mental Health and Wellbeing Joint Programme Board is now responsible for continuing the development of these services. £15 million will be provided to Local Authorities in 2022-23, which the Programme for Government 2021-22 committed to doubling thereafter.

Community support services are available to children and young people aged 5-24 years, with care experienced young people able to access services up until the age of 26.

The Scottish Government published Community mental health and wellbeing supports and services: framework in February 2021. The framework assists local children's services and community planning partnerships with commissioning and establishing new community supports and services for children and young people, as well as the development of existing services and supports.

Ultimately, every child and young person in Scotland should be "able to access local community services which support and improve their mental health and emotional wellbeing."6 These community supports and services target issues of mental and emotional distress and wellbeing - rather than mental illness and other mental health needs that may require CAMHS.6

The framework takes a whole system approach. Developments in community mental health and wellbeing supports and services should complement existing local support and the services provided by education, universal children's services, social work, health and care services, and other relevant services that work with children and young people.6