Citizens' Assemblies - an international comparison

This briefing sets out the background to deliberative democracy and considers, in detail, the recent Citizens' Assembly of Scotland. The briefing also explores examples of citizens' assemblies, including climate assemblies, which have been used in other countries. The background to the assemblies; their make up, work and recommendations are all considered.

Executive Summary

On 24 April 2019, the First Minister announced plans to establish a Citizens’ Assembly of Scotland to consider the following broad questions:1

What kind of country are we seeking to build?

How can we best overcome the challenges we face, including those arising from Brexit?

What further work should be carried out to give people the information they need to make informed choices about the future of the country?

On 13 January 2021, the Citizen's Assembly published its report including its vision and recommendations.2

The Scottish Government published its response to the report by the Citizens' Assembly of Scotland on 23 November 2021.3 Many of the actions in the response had previously been announced in the Scottish Government's Shared Policy Programme with the Green Party and the Programme for Government 2021-22. The key announcements included:3

A commitment to future Citizens’ Assemblies.

A Citizens’ Assembly for under-16s.

Working with the Scottish Green Party to develop deliberative engagement and a citizens’ assembly on sources of local government funding.

The report of the Participatory Democracy Working Group setting out recommendations on making participatory processes routine and effective.

This briefing looks at the work of the Citizens' Assembly of Scotland and the Scottish Government's response. It then provides examples of citizens' assemblies used in Canada, Ireland, Belgium and France. The use of the citizens' assembly model to deliberate climate change policy in Scotland, and in the United Kingdom, is also discussed.

What is participatory and deliberative democracy?

Participatory and deliberative democracy aim to give citizens a role in governance at a national or local level.1 Participatory and deliberative democracy practices are used for both policy innovation and policy scrutiny, with the overall intention of using these practices to increase the democratic quality of policy making.1 These forms of direct democracy enable citizens to make recommendations about, or propose plans for public policy.3 They allow individual participation of citizens in political decisions which affect their lives, rather than democratic participation solely through elected representatives.3

Participatory and deliberative democracy have similar aims, but there is a difference in their approach:5

Participatory democracy allows for direct action with citizens having some element of decision making.

Deliberative democracy encourages citizens to reach a consensus view through discussion and deliberation of issues.

Forms of deliberative democracy, such as citizens' assemblies, have become increasingly popular in recent years at all levels of government and in countries around the world.3 The OECD described the trend in public authorities using representative deliberative and participative processes, like citizens’ assemblies, as “the deliberative wave”.3 Reflective of this growing popularity, organisations such as Participedia and The Sortition Foundation have begun tracking and mapping use of deliberative political processes around the world.

Aside from citizens' assemblies, there are also ‘citizen juries’, ‘consensus conferences’ and ‘deliberative polls’. All describe a form of deliberative democracy or engagement and have common principles, such as:8

using a random, or diverse, selection of participants to underpin the legitimacy of the process

facilitated discussions

experts providing evidence and advocacy of relevant information

the outcome of participants’ deliberations is reported.

The purpose, scope and subject matter of deliberative engagement and citizens' assemblies can be wide-ranging. Deliberative engagement and citizens' assemblies can be used as a form of constitutional convention to explore constitutional reform, to develop more nuanced positions on polarising issues, or to explore and generate ideas in a broadly defined policy area.9

What are citizens' assemblies?

The Electoral Reform Society describes Citizens’ Assemblies as:1

a form of deliberative democracy: a process through which citizens can engage in open, respectful and informed discussion and debate with their peers on a given issue.

Electoral Reform Society. (2019, June 28). What are Citizens' Assemblies?. Retrieved from https://www.electoral-reform.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/What-Are-Citizens%E2%80%99-Assemblies-Briefing-June-2019.pdf [accessed 19 March 2021]

A citizens’ assembly is made up of a representative group of around 50 to 200 citizens chosen at random from the general public.1 The selection of members is stratified to ensure that participants are as representative as possible of the general population according to certain criteria – usually gender, age, ethnicity, geographical location, and social background.1

The Electoral Reform Society’s briefing on citizens’ assemblies describes three typical phases:1

Learning phase: participants get to know each other, how the assembly works and what its aims are. Relevant facts about the issue at hand are presented to the participants, who get to ask questions of experts and access background and contextual information.

Consultation phase: campaigners from each side get to present their arguments and be questioned on them. Sometimes, the assembly might run a public consultation during this phase to understand what the broader public thinks about an issue.

Deliberation and discussion phase: the participants deliberate amongst themselves. Generally, assembly members will make recommendations to government or parliament at the end of this phase. In some cases, if these recommendations are taken up, they will be put to the people in a referendum (as in the case of Ireland). But it is usually up to elected politicians whether or not to follow the assembly's recommendations.

Citizens' assemblies (and deliberative engagement more generally) are distinguished from other forms of participation in policy by this process of informing, consulting and deliberating.6 Citizens' assemblies typically do not include representatives from organisations as participants (e.g. representatives of businesses, public authorities, non-governmental or third sector organisations, research institutes).7 Instead, the focus is on recruiting individual citizens without special interests to the citizens' assembly.7 However, representatives from such organisations may be invited to the citizens' assembly to provide expert opinion and clarification on specific issues.9 They may also be involved in the stewarding groups overseeing the assembly process (as was the case in Scotland's Climate Assembly).10

The use of random or stratified sampling avoids the issue of self-selection bias.11 Self-selecting participants for policy focus groups or consultations often have an interest in and prior engagement with the given subject matter.1 This can make it difficult to determine whether the findings from focus groups, consultations and other survey exercises reflect the public's position on the matter.13

The conclusions or recommendations of citizens' assemblies are usually communicated to the convening public authority to stimulate policy decisions and wider public dialogue about the issue under consideration.1 One of the main outcomes of this process is the signalling of informed public opinion.9 For example, the Citizens' Assembly of Ireland (discussed later in this briefing) is often credited with accurately signalling the state of public opinion on abortion to policymakers before the issue was brought to the public in a referendum.16

Criticisms of the citizens' assembly model include that there is no direct link between the recommendations of a citizens' assembly and the state of public opinion.17 One of the possible reasons for this is that each recommendation made by a citizens' assembly is often given the same weight whereas policymakers (or the electorate) may attribute greater importance to some recommendations over others.18 Similarly, citizens' assemblies are often used in an advisory capacity and there may be no requirement to commence further actions on the recommendations made.17 This criticism was raised by Gillian Mackay MSP in the Parliament on 23 November 2021 after Minister for Parliamentary Business George Adam MSP made a statement on the Government Response to the report of the Citizens' Assembly of Scotland:

One of the key weaknesses in participatory democracy is the lack of information about what will happen after the process, and there can be unclear assurances about how recommendations will be implemented.

Scottish Parliament Official Report. (2021, November 23). Report of the Citizens' Assembly of Scotland (Government Response). Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/chamber-and-committees/official-report/what-was-said-in-parliament/meeting-of-parliament-23-11-2021?meeting=13424&iob=121853 [accessed 24 November 2021]

The OECD Report on Deliberative Processes

The OECD published its report "Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave" on 10 June 2020. The report is one of the first empirical and comparative studies on the use of deliberative processes in countries around the world. The report made recommendations for designing successful deliberative processes and compiled the following:1

Good Practice Principles for Deliberative Processes for Public Decision Making1

"The principles are summarised as follows:

The task should be clearly defined as a question that is linked to a public problem.

The commissioning authority should publicly commit to responding to or acting on recommendations in a timely manner and should monitor and regularly report on the progress of their implementation.

Anyone should be able to easily find the following information about the process: its purpose, design, methodology, recruitment details, experts, recommendations, the authority’s response, and implementation follow-up. Better public communication should increase opportunities for public learning and encourage greater participation.

Participants should be a microcosm of the general public; this can be achieved through random sampling from which a representative selection is made to ensure the group matches the community’s demographic profile.

Efforts should be made to ensure inclusiveness, such as through remuneration, covering expenses, and/or providing/paying for childcare or eldercare.

Participants should have access to a wide range of accurate, relevant, and accessible evidence and expertise, and have the ability to request additional information.

Group deliberation entails finding common ground; this requires careful and active listening, weighing and considering multiple perspectives, every participant having an opportunity to speak, a mix of formats, and skilled facilitation.

For high-quality processes that result in informed recommendations, participants should meet for at least four full days in person, as deliberation requires adequate time for participants to learn, weigh evidence, and develop collective recommendations.

To help ensure the integrity of the process, it should be run by an arms’ length co-ordinating team.

There should be respect for participants’ privacy to protect them from unwanted attention and preserve their independence.

Deliberative processes should be evaluated against these principles to ensure learning, help improve future practice, and understand impact."

Citizens Assembly of Scotland 2019-2021

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon MSP announced plans for a citizens’ assembly in Scotland on 24 April 2019.1 This announcement was made amidst ongoing political and policy questions regarding the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union and wider constitutional issues.1

The Citizens’ Assembly of Scotland convened on 26 October 2019, and was tasked with considering three broad questions:3

What kind of country are we seeking to build?

How best can we overcome the challenges Scotland and the world face in the 21st century, including those arising from Brexit?

What further work should be carried out to give us the information we need to make informed choices about the future of the country?

The Citizens' Assembly of Scotland met four times in person and four times online (as an adaptation to Covid-19 restrictions) to deliberate on these questions and make their recommendations.3

Recommendations of the Citizens’ Assembly of Scotland

The Citizens’ Assembly of Scotland published its final recommendations in its report “Doing Politics Differently: The Report of the Citizens’ Assembly of Scotland” on 13 January 2021.1 The report of the Citizens’ Assembly of Scotland agreed a 10-point vision for the country and a set of 60 recommendations. The recommendations were grouped around the following broad topics:1

How decisions are taken (Recommendations 1-14).

Includes recommendations on citizens’ participation in decisions, behaviour standards and accountability of politicians, and provision of information to the public.

Incomes and Poverty (Recommendations 15-22).

Includes recommendations to increase incomes and tackle poverty (e.g. through universal basic income, living wage, abolition of zero hours contracts).

Tax and Economy (Recommendations 23-32).

Includes recommendations on measures to improve tax collection and investment in sustainable industries and green jobs for COVID-19 economic recovery.

Young People (Recommendations 33-37).

Includes recommendations to support young people’s mental health and wellbeing, access to affordable housing, skills development and increasing minimum wage.

Sustainability (Recommendations 38-42).

Includes recommendations on waste, recycling, renewable energy, energy efficiency in housing, a green recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, raising awareness of information on sustainable behaviours.

Health and Wellbeing (Recommendations 43-49).

Includes recommendations on services to improve wellbeing, matters relating to the NHS (e.g. pay and working conditions of NHS staff), and community health services.

Further Powers (Recommendations 50-54).

Includes changes to tax powers, the working week, trade agreements and immigration.

Mixed Group (Recommendations 55-60).

Includes recommendations on internet and technology access, pensions reform, social renewal, and criminal justice reform.

Scottish Government Response

On 23 November 2021, Minister for Parliamentary Business, George Adam MSP made a statement to the Parliament on the Scottish Government response to Doing Politics Differently – The Report of the Citizens’ Assembly of Scotland.1

The Scottish Government’s response linked its current policy actions and plans to recommendations from the Citizens’ Assembly of Scotland.2 Several of the key commitments the Scottish Government detailed in the response were previously announced in the Scottish Government’s Shared Policy Programme with the Green Party and the Programme for Government 2021-22:2

commitment to future Citizens’ Assemblies

a Citizens’ Assembly for under-16s.

working with the Scottish Green Party to develop deliberative engagement and a citizens’ assembly on sources of local government funding.

report of the Participatory Democracy Working Group (expected by the end of 2021) setting out recommendations on making participatory processes routine and effective.

The response was limited in its announcements of new policy and areas for further action where work was not currently underway2 A summary of policies mentioned in the response can be found in Annex 1. However, one of the areas of further action identified in the Scottish Government’s response was on ensuring standards and accountability within public institutions in Scotland. As part of the statement to the Parliament, George Adam MSP said:5

Given recent events in the Westminster Parliament, the importance of integrity in our political representatives can hardly be overstated. Those challenges should be of concern to everyone in the Parliament and in Government. We will be working with the Parliament to address them, and we will seek cross-party involvement in that.

Adam, G. (2021, November 23). Report of the Citizens Assembly of Scotland (Government Response). Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/chamber-and-committees/official-report/what-was-said-in-parliament/meeting-of-parliament-23-11-2021?meeting=13424&iob=121853 [accessed 25 November 2021]

The Scottish Government also set out a range of specific actions across the broad themes, including actions on sustainability and the environment, related to the work of Scotland’s Climate Assembly.2 Additionally, the response stated that recommendations from the Citizens’ Assembly of Scotland were used to inform the Scottish Government’s Covid Recovery Strategy.2

Commitment to Future Citizens Assemblies

As part of the statement to the Parliament by Minister for Parliamentary Business, George Adam MSP, gave a further indication of the Scottish Government's work on deliberative engagement and citizens' assemblies:1

The Government is committed to promoting not only citizens assemblies, but other forms of democracy and engagement, such as citizens juries, mini-publics and people’s panels. Later this year, an expert group will report to ministers with recommendations on institutionalising inclusive participation and democracy across Scotland’s democratic processes, including the future governance of and question setting for citizens assemblies.

As we have already spoken about, the working group will bring together experts from Scotland, England, the UK and international organisations to propose recommendations to make that routine and effective. It will identify methods of governance for delivering credible and trustworthy democratic processes.

Adam, G. (2021, November 23). Report of the Citizens Assembly of Scotland (Government Response). Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/chamber-and-committees/official-report/what-was-said-in-parliament/meeting-of-parliament-23-11-2021?meeting=13424&iob=121853 [accessed 25 November 2021]

Research Report on the Citizens' Assembly of Scotland

The Scottish Government led a research project to assess the operation of the Citizens' Assembly of Scotland and the reception of its recommendations. A report on the project, authored by independent academics and Scottish Government researchers, was published on 25 January 2022.

The report found that the member experience (including the transition from in-person to online proceedings) was positive.1 However, the breadth of the Assembly remit led to some challenges. For example, ensuring effective learning and evidence provision was difficult with such a broad Assembly remit.1 In addition, there was evidence that the breadth of knowledge required by the size of the remit may have hindered facilitation and deliberation.1 The report also found that public awareness of and engagement with the Assembly was low for the duration of the process.1

The report made the following recommendations for future assemblies:

"Assembly Remit

Decisions on remit must recognise the impact on design, delivery and governance. The broader the remit, the more time required.

Governance Framework

Roles and responsibilities must be collectively agreed and clearly defined with responsibilities for oversight, advice, design and delivery distinguished.

Assembly Phases

Sufficient time must be given to each stage of assemblies: 1) inception; 2) delivery; and 3) impact.

Assembly Impact

A clear mandate must be set out, including clear parameters for how the assembly will interact with the decision-making of other democratic institutions.

Public Engagement

Consideration must be given to how the assembly will interact with the wider public to build understanding, foster public deliberation and enhance legitimacy.

Capacity Building

Future action must include building capacity in skills, resources and infrastructure for delivering deliberative and participatory processes.

Research

Concurrent research should be embedded and used to inform the Assembly’s design and governance. The research should be fully funded and have a duration that enables an assessment of impact."

International Examples of Citizens' Assemblies

This section sets out international examples of Citizens' Assemblies, including:

Ontario Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform, Canada (2006)

Ontario's Citizens' Assembly examined the electoral system for returning members to the Ontario Legislative Assembly and deliberated on alternative electoral systems for the province.1 The Citizens' Assembly's final recommendation to adopt a mixed member proportional electoral system did not pass in a public referendum held in 2007.2

The design of Ontario's Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform was modelled on an earlier Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform in British Columbia during 2004.3 The box below provides a short summary of the 2004 British Columbia example.

Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform (British Columbia) 2004

The Citizens’ Assembly was a non-partisan and independent group consisting of 160 men and women (including two members from the indigenous community), chosen by random selection from the electoral register of British Columbia.4

The Citizens' Assembly underwent a three-stage process consisting of a "learning phase" for members of the assembly to develop knowledge on options for electoral reform, a "public hearings phase" to inform the public on the preliminary recommendations of the assembly, and finally a "deliberation phase" to review all options for electoral systems in British Columbia provincial elections.4

In October 2004, the Assembly recommended replacing the province's "First-Past-the-Post system" with a proportional "Single Transferable Vote" system.6

This recommendation was put to the electorate in a referendum held concurrently with the 17 May 2005 provincial election. The referendum required approval by 60% of votes and simple majorities in 60% of the 79 districts in order to pass. The proposal received majority support in 77 of 79 electoral districts but failed to pass by falling slightly short of the 60% threshold with 57.7% of votes in favour.7

The province of British Columbia has since had two further referendums (one in 2009, and the other in 2018) proposing to change the electoral system for elections to the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia.8 Both of these referendums saw the majority of voters supporting the incumbent first-past-the-post system over an alternative proportional voting system.8

While the initial 2005 referendum on electoral reform in British Columbia did not pass, the majority support for electoral reform indicated that support for electoral reform may be found in other provinces. As Ontario is the most populous province in Canada, advocates of federal electoral reform argued that the adoption of proportional representation in Ontario may encourage public interest and support for electoral reform in federal elections.10

Purpose of the Citizens' Assembly

The province of Ontario began reviewing its electoral system in 2005 with the appointment of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario's Select Committee on Electoral Reform. The committee reviewed several alternatives to the first-past-the-post system "with the knowledge that the government has committed to establishing a citizens’ assembly to consider electoral reform in Ontario."1

The committee's mandate also included considering the procedure for a referendum on reforming the electoral voting system following any recommendations made by the Citizens Assembly.1 The committee recommended similar arrangements to those used in the British Columbia electoral reform referendum of 2005.1 These included timing the referendum to be in conjunction with a provincial election and the level of support required for the referendum to pass.1

The regulation that established the Ontario Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform, Ontario Regulation 82/06, set the terms of reference for the assembly. The Regulation states:

The assembly,

(a) shall assess Ontario’s current electoral system and different electoral systems; and

(b) shall recommend whether Ontario should retain its current electoral system or adopt a different one.

Legislative Assembly of Ontario. (2006). O. Reg. 82/06: CITIZENS' ASSEMBLY ON ELECTORAL REFORM. Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/060082 [accessed 6 December 2021]

The Regulation also directed the assembly to consider eight principles and characteristics in its evaluation of different electoral systems.5

Eight Principles and Characteristics

Legitimacy

The electoral system should have the confidence of Ontarians and reflect their values.

Fairness of Representation

The Legislative Assembly should reflect the population of Ontario in accordance with demographic representation, proportionality and representation by population, among other factors.

Voter Choice

The electoral system should promote voter choice in terms of quantity and quality of options available to voters.

Effective Parties

Political parties should be able to structure public debate, mobilize and engage the electorate, and develop policy alternatives.

Stable and Effective Government

The electoral system should contribute to continuity of government, and governments should be able to develop and implement their agendas and take decisive action when required.

Effective Parliament

The Legislative Assembly should include a government and opposition, and should be able to perform its parliamentary functions successfully.

Stronger Voter Participation

Ontario’s electoral system should promote voter participation as well as engagement with the broader democratic process.

Accountability

Ontario voters should be able to identify decision-makers and hold them to account.

In addition, the Citizens' Assembly was invited to consider their own principles and characteristics which may direct the evaluation of electoral systems. The Citizens' Assembly added a ninth principle of "Simplicity and Practicality" and stated:

The Citizens' Assembly has also identified simplicity and practicality as principles that should be considered in assessing electoral systems. It believes the system should be understandable to the public. Simplicity may include how easy it is for voters to use the ballot and to understand the election results. Practicality involves looking at the feasibility of adopting a new system in Ontario.

Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform. (2006). Should Ontario keep its current electoral system or change to a new one?. Retrieved from http://www.citizensassembly.gov.on.ca/en-CA/About/Mandate.html [accessed 6 December 2021]

Composition and meetings of the Assembly

While the Ontario Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform was commissioned by the Government of Ontario, the assembly was independent of provincial Government. The Regulation 82/06 which established the assembly provided guidance on its composition. Every registered voter was eligible to participate with only certain individuals precluded from participating (e.g. elected officials or individuals convicted of contravening election law).1 The Citizens' Assembly consisted of 104 members, including a Chairperson, at least one person identifying themselves as an Aboriginal person and a gender split of 52 female participants and 51 male participants.1

The selection of members to the Ontario Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform members was conducted by the independent electoral office, Elections Ontario. Letters were sent to prospective Citizens' Assembly members from Election Ontario’s Register of Electors. Those recipients interested in participating were then invited to attend selection meetings across the province where one member for each electoral district and two alternate members were selected by random ballot.3

The Chairperson, George Thompson, facilitated the Citizens' Assembly process. The Citizens' Assembly met twice a month from 9 September 2006 to April 2007 to work through a three-stage process:4

Learning Phase (September 2006 - November 2006): The Citizens' Assembly met for six weekends to learn about Ontario’s electoral system and other systems used in the world.

Consultation Phase (October 2006 - January 2007): Assembly members undertook public consultations and outreach to inform deliberations.

Deliberation Phase (February 2007 - April 2007): The Citizens' Assembly revisited the findings from the previous phases and chose two electoral systems to design in detail: Mixed Member Proportional and Single Transferable Vote. In the final ballot, the Citizens' Assembly decided to recommend its Mixed Member Proportional system to the people of Ontario.

Recommendations and outcomes

The Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform completed its work with the publication of its final report on 15 May 2007. The report recommended a mixed-member proportional electoral system (similar to that used in Scottish Parliament elections) where voters have one vote for a local representative and another for a regional representative.1 The referendum on electoral reform in Ontario was held with the provincial election on 10 October 2007. The referendum result was binding if passed by 60% of the vote overall, and by 50% of the vote in 64 of the 107 electoral districts. This threshold was decided by the Ontario cabinet and diverged from the Select Committee which recommended a threshold of 50% support in 71 of the 107 electoral districts.23 The referendum failed to pass with 63% of voters rejecting the proposal.4

The divergence of the referendum result from the levels of support for electoral reform in the Citizens' Assembly was suggested to be the result of a limited public awareness campaign for the referendum, a lack of information available to voters, and the perceived complexity of the proposed mixed-member proportional system.56

Citizens' Assembly of Ireland (2016-2018)

Background: The Convention on the Constitution of 2012-14

The Convention on the Constitution, often called the Irish Constitutional Convention, was established by resolution of both Houses of the Oireachtas in 2012 to consider a number of possible changes to the constitution and make recommendations.1 The resolution committed the Government to providing a response to each recommendation.2

The Convention met over 18 months between 2012 and 2014.3 A slightly unusual feature of the Convention was that of the 100 members, 33 were representatives of political parties.3 It discussed ten topics in total.3 Several of its recommendations resulted in amendments to the constitution.6 The progress on the outcomes of the recommendations made by the Irish Constitutional Convention to the date of 12 November 2021 is shown in Annex 2.

In May 2015, referendums were held on two of the changes to the constitution that were recommended by the Irish Constitutional Convention.6 One referendum was to reduce the age threshold for candidacy in Presidential elections from 35 years of age to 21 years. This change to the constitution did not pass with 73% of voters voting against the proposal.6 The other referendum was on a change to the constitution which would enable marriage equality for single-sex couples. This change to the constitution passed with 62% of voters voting in favour of the extension of marriage rights to single-sex couples.6

In 2015, the then Taoiseach, Enda Kenny, speculated about the possibility for further meetings of bodies like the Irish Constitutional Convention.10 With growing calls by the political and civic community to review the Eighth Amendment of the Irish Constitution (that the State acknowledges the right to life of the unborn), the Citizens’ Assembly of Ireland in 2016 was set up as a successor to the 2012-14 Convention to deliberate the matter among other policy issues.11

Purpose of the Citizens' Assembly of Ireland

The Citizens' Assembly of Ireland was established, like the Convention before it, by resolution of both Houses of the Oireachtas. The resolution called for the Citizens’ Assembly to consider and to make "such recommendations as it sees fit and report to the Houses of the Oireachtas"1.

The assembly was asked to consider:1

the Eighth amendment of the constitution

how Ireland best responds to the challenges and opportunities of an ageing population

fixed-term parliaments

the manner in which referenda are held

how the state can make Ireland a leader in tackling climate change

The Citizens' Assembly convened for the first time on 15 October 2016.3

Composition and meetings of the Assembly

The assembly was made up of 100 members: 99 citizens and the Chair, the Honourable Mary Laffoy.1

The 99 members were chosen at random from those eligible to vote at a referendum.1 The Electoral (Amendment) Act 2016 provided that the information held on the electoral register could be used for the selection of candidates to the assembly. Certain individuals were automatically excluded from the Assembly, including those who worked as journalists or in the media; certain categories of politicians and members of political parties, and those campaigning on some aspects of gender equality.1 Those recruiting members were also unable to recruit family or friends together.1

Individuals who contacted the assembly wishing to be a member of it were also excluded to ensure a representative sample of participants recruited by the same process.1 The Citizen's Assembly 2016-18 website states the following on member selection:1

The recruitment was carried out by a team of highly professional recruiters from REDC Research and Marketing Ltd. across 15 broad regional areas throughout the country. The sampling points were selected on a random basis in accordance with Census 2011 data and QNHS population estimates to ensure that they were nationally representative in terms of geography. This did not mean however, that each county was necessarily represented. The process used by REDC was designed to ensure that the Members are broadly representative of Irish society including urban rural divide.

The Members were chosen at random and are broadly representative of demographic variables as reflected in the Census. The quotas each interviewer had to reach in their allocated District Electoral Division (DED), were based on a number of demographic variables – gender, age and social class.

Citizens' Assembly of Ireland. (n.d.) About the Citizens' Assembly. Retrieved from https://2016-2018.citizensassembly.ie/en/About-the-Citizens-Assembly/ [accessed 1 December 2021]

The Assembly met over twelve weekends. Five of the meetings focused on deliberations over the Eighth Amendment. Two meetings were held on the issue of the challenges and opportunities of an ageing population; two on climate change and one each on referendums and fixed-term parliaments. The schedule of meetings, as well as a full breakdown of what was discussed over each weekend can be found on the Assembly's website.

Recommendations and outcomes

The recommendations of the Citizens' Assembly were advisory. In accordance with the Resolution of the Houses of the Oireachtas approving establishment of the Assembly, all of the recommendations made by the Assembly were presented to the Houses of Oireachtas for further consideration.1

The Citizens' Assembly published reports on each of the topics deliberated on by the assembly:

The final report was laid in the Houses of the Oireachtas on 21 June 2018.2 The Citizens' Assembly of Ireland 2016-18 resulted in notable outcomes including legislating to change the constitution to allow for abortion access and declaring a "climate emergency".

The Eighth Amendment of the Constitution

The assembly recommended for a change to the eighth amendment and a constitutional provision that explicitly authorised the Oireachtas to legislate to address termination of pregnancy, any rights of the unborn, and any rights of the pregnant woman.1

The Oireachtas established a Joint Committee on the Eighth Amendment which produced its own report on 20 December 2017.2

The Houses of the Oireachtas passed the Thirty-sixth Amendment of the Constitution Act 2018 to allow for a referendum on amending the Constitution and repealing the Eighth Amendment.3

The Thirty-sixth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland which permits the Oireachtas to legislate for abortion was approved by referendum on 25 May 2018 with 66% of voters in favour.4

The subsequent Health (Regulation of Termination of Pregnancy) Act 2018 was signed into law by the President of Ireland on 20 December 2018.

Tackling Climate Change

The Citizens' Assembly made a series of highly supported recommendations with over 80% of support from the assembly. These included:1

empowering an independent body to address climate change.

Greenhouse gas (GHG) tax, including carbon tax and agricultural GHG tax.

encouragement of climate change mitigation measures including, electric vehicles, public transport, forests, organic farming, natural peat bogs, and ending subsidy of peat extraction.

reduction of food waste.

microgeneration of electricity.

increasing bus lanes, cycle lanes and park and ride facilities.

The Oireachtas established a Joint Committee on Climate Action which published its own report on 29 March 2019.2 On 9 May 2019, the Dáil endorsed the committee's report and declared a "climate and biodiversity emergency".3

The Government of Ireland Climate Action Plan 2019 which set out the Government of Ireland's proposals to reduce Ireland's greenhouse gas emissions followed the committee's report and the Dáil's declaration of a climate and biodiversity emergency.4

Public Reception of the Assembly's Recommendations

The consistency between the outcome of the deliberations of the assembly and the referendum results for marriage equality and legislating for abortion access has been seen as a measure of success for the representative nature of the assembly.1 However, the representative nature of citizens' assemblies and the route from deliberation to policy change has been questioned by some critics citing the presidential age referendums' failure despite the Irish Constitutional Convention's support for the matter.23

Citizens' assemblies have not been formally institutionalised in Ireland.4 However, the use of citizens' assemblies continue to be a popular method of deliberative engagement to address changes to the constitution and wider policy issues. Academics have noted that Ireland have been ‘systematizing’ the process of deliberation with the adoption of broadly similar processes for the establishment and operation of the Irish Constitutional Convention and subsequent Citizens' Assemblies of Ireland.4

The most recent Citizens' Assembly of Ireland 2019-21 convened on 25 January 2020 and published its final report on 2 June 2021.6 The citizens' assembly was tasked with making recommendations to advance gender equality in Ireland. A Citizens' Assembly of Ireland on elected mayors and local government structures for Dublin, biodiversity, matters relating to drug use and the future of education has also been proposed in the Government of Ireland's Programme for Government.7

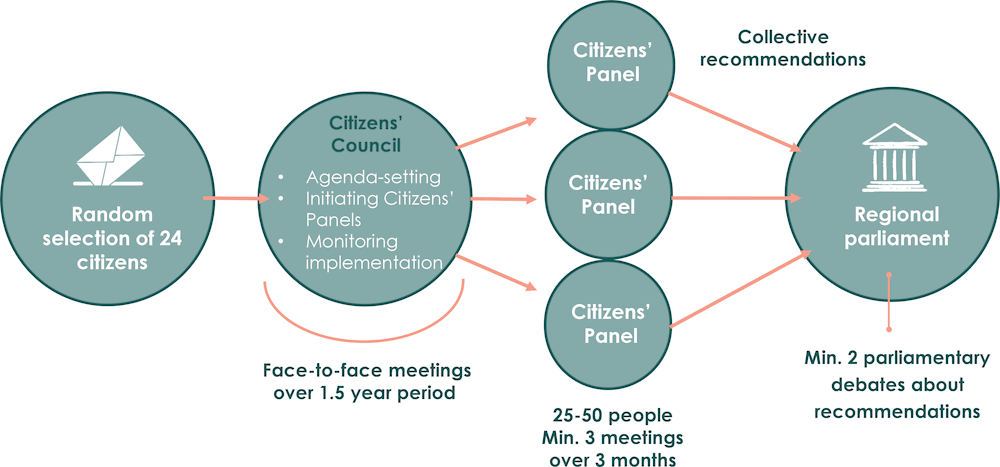

Institutionalising Citizen Participation - Ostbelgien, Belgium (2019)

The Parliament of Ostbelgien voted to establish a permanent Citizens’ Council on 25 February 2019.1 The role of the Citizens’ Council is to set the agenda for ad hoc and temporary citizens’ panels (akin to citizens’ assemblies) that then submit recommendations to the Parliament.2

This combined model of a permanent Citizens’ Council with temporary citizens’ panels was designed to ensure that the executive and legislature could be held accountable for acting on the recommendations of a citizens’ panel.3 The permanent Citizens' Council constitutes the third fundamental democratic institution together with the parliament and the executive.2

Background to the Citizens' Council

The Parliament of Ostbelgien (known as the PDG) is a small regional parliament in Belgium. It first used a citizens' assembly to debate childcare policy in September 2017.1 This citizens' assembly process gathered 26 randomly selected citizens to identify critical issues in childcare policy and formulate policy recommendations to address those issues.1 At the end of the process, the committee presented its agenda to the Parliament. The recommendations were then adopted as part of the "Childcare Masterplan for 2025".

The citizens assembly process was considered a successful initiative by then President of the PDG, Alexander Miesen, who approached G1000 (a civil society organisation) to develop a permanent citizen participation process for the PDG.1 The eventual output of this engagement with G1000 was the design of the "Ostbelgien Model" of a Citizens' Council.4 The PDG then instituted the Citizens' Council (Bürgerrat) by decree in February 2019. The first Citizens' Council and citizens' panel (akin to a citizens' assembly and known as Bürgerdialog) was held on 25 September 2019.5 There have so far been three Citizens' Councils convening citizens' panels on care, inclusive education and housing, respectively,

The Ostbelgien Model

The decree adopting the Ostbelgien Model created two new citizens' bodies within the PDG: the Citizens’ Council and citizens’ panels.1

Citizens' Council: The 24-person body in charge of setting the agenda for the Citizens' Panels. The Citizen Council comprises former Citizen Assembly participants, randomly selected by the Permanent Secretary (a PDG employee in charge of facilitating the Citizens' Council process and managing the budget). The restriction of membership in the Citizen Council to those who have participated in a citizens' panel before is to ensure participants have experience of the deliberative and participatory process.

Citizens' panel: A citizens’ panel is convened for each new policy area selected by the Citizen Council. Citizens' panel participants are recruited through a random selection process of citizens who do not hold public office and are over the age of 16. Participation in a citizens' panel is not compulsory and comprises only those who wish to participate. The size of a citizens' panel is determined by the Citizens' Council.

The Citizens' Council and citizens' panels carry out the deliberative and participatory policy making process through four steps:1

Topic Selection

The Citizens' Council initiates a call for topic proposals. Any citizen can submit a topic for consideration. The Citizens' Council can select any topic with over 100 signatures of support.

The Citizens’ Council determines the composition and reporting timescale for each Citizens’ Panel, which is then convened by the Permanent Secretary.

Deliberation

The Permanent Secretary provides the new Citizens’ Panel with relevant information, invites experts to deliver presentations on the topic of the panel, and selects an external moderator to lead the discussion.

Policy Recommendations

The citizens' panel compiles and agrees a set of policy recommendations which it discusses at an open meeting of a relevant parliamentary committee.

Implementation.

The recommendations of the Citizens' Council and citizens' panel are not legally binding and it is up to the legislature and relevant minister from the executive to implement the findings.

The Citizens’ Council and Permanent Secretary are in charge of monitoring the implementation of recommendations. To assist with this monitoring function, the Parliament is obliged to have two debates on the recommendations within one year of the report of the citizens' panel.

Climate Assemblies

Citizens' assemblies have also been proposed as a way of generating public policy innovation and consensus for global challenges such as the climate emergency. This section will briefly outline examples where the citizens' assembly model has been used to engage citizens in policy for addressing the climate emergency within the United Kingdom. A further international example on the Climate Assembly held in France between 2019 and 2020 is also discussed.

Scotland's Climate Assembly

The Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019 established Scotland's Climate Assembly. The Assembly consisted of over 100 members, representative of the wider population in Scotland, tasked with considering how to prevent or minimise the effects of climate change and make recommendations on measures to achieve emissions reduction targets. The recommendations made by the Assembly were laid before the Scottish Parliament in a report.

Scotland's Climate Assembly structured its recommendations around 16 goals.

Resources: Reduce consumption and waste by embracing society wide resource management and reuse practices.

Building Quality: Adopt and implement clear and future-proofed quality standards for assessing the carbon impacts of all buildings (public and private) using EnerPhit/Passivhaus standards (as a minimum) and integrating whole life carbon costs, environmental impact and operational carbon emissions.

Retrofit Homes: Retrofit the majority of existing homes in Scotland to be net zero by 2030, while establishing Scotland as a leader in retrofit technology, innovation and installation practice.

Standards and Regulation: Lead by example through government and the public sector implementing mandatory standards, regulations and business practices that meet the urgency and scale of the climate emergency.

Public Transport: Implement an integrated, accessible and affordable public transport system and improved local infrastructure throughout Scotland that reduces the need for private cars and supports active travel.

Travel Emissions: Lead the way in minimising the carbon emissions caused by necessary travel and transport by investing in the exploration and early adoption of alternative fuel sources across all travel modes.

Carbon Labelling: Provide clear and consistent, real and total carbon content labelling on produce, products and services (showing production; processing; transport; and usage emissions) to enable people to make informed choices.

Education: Provide everyone with accurate information, comprehensive education, and lifelong learning across Scotland to support behavioural, vocational and societal change to tackle the climate emergency, and ensure everyone can understand the environmental impact of different actions and choices.

Land Use: Balance the needs of the environment, landowners and communities across Scotland for sustainable land use that achieves emission reductions.

Communities: Empower communities to be able develop localised solutions to tackle climate change.

Circular Economy: Strive to be as self-sufficient as possible, with a competitive Scots circular economy that meets everyone’s needs in a fair way.

Work and Volunteering: Develop work, training and volunteering opportunities to support net zero targets, connect people with nature, rebuild depleted natural resources and increase biodiversity.

Business: Support long term, sustainable business models where people and the environment are considered before profit, and the carbon footprint of working practices are reduced.

20 Minute Communities: Realise the principles of a '20-minute community' in flexible ways across Scotland by reducing the need to travel for work, shopping, services and recreation in ways that support localised living.

Taxation: Develop and implement a fair, equitable and transparent tax system that drives carbon emission reductions, while recognising different abilities to pay, and generates revenue to enable energy transition.

Measuring Success: Reframe the national focus and vision for Scotland’s future away from economic growth and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in order to reflect climate change goals towards the prioritisation of a more person and community centred vision of thriving people, thriving communities and thriving climate.

The Scottish Government responded to Scotland's Climate Assembly in a report published on 16 December 2021. Furthermore, as described in the Scottish Government's response to the Citizens' Assembly of Scotland, many of Scotland's Climate Assembly recommendations were included in the Programme for Government 2021-22 or incorporated into long term plans such as the draft National Planning Framework (laid in the Parliament on 10 November 2021).

Climate Assembly UK

In June 2019, six select committees of the UK Parliament's House of Commons called a citizens’ assembly, Climate Assembly UK, to understand public preferences on how the UK can meet the UK Government’s legally binding target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050. The House of Commons contracted The Involve Foundation, Sortition Foundation and mySociety, to run Climate Assembly UK on its behalf. Climate Assembly UK consisted of 108 members considered to be representative of the UK population in terms of demographic variables and their level of concern about climate change. The work of Climate Assembly UK was intended to strengthen citizens participation in the UK’s parliamentary democracy by ensuring politicians and policy makers have accurate information about public preferences on reaching net zero targets.

The outcomes of Climate Assembly UK's discussions were presented to the six select committees in a report in September 2020. The UK Parliament (including the House of Commons select committees which commissioned Climate Assembly UK) intends to use the report to support its scrutiny work on the UK Government’s climate change policy and progress on net zero targets. The Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee also launched an inquiry on the findings of the Assembly's report. The committee reported on this inquiry on 8 July 2021 and recommended the UK Government provide a point-by-point response to the Climate Assembly UK's report, publish a net-zero strategy, and publish a net-zero public engagement strategy. The UK Government's response on 9 September 2021 declined to provide a point-by-point response to the Climate Assembly UK report but indicated public engagement plans would be included in its upcoming Net Zero Strategy. The UK Government published its "Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener" on 19 October 2021.

COP26: The Global Assembly

Citizens’ assemblies are also being developed by supranational organisations for global issues like the climate and biodiversity crises. The Global Assembly convened 100 people from the global North and South to learn about and deliberate on the climate and ecological crises. The Declaration prepared by the Global Assembly was presented at the United Nations COP26 conference in Glasgow in November 2021.

The Scottish Government provided £100,000 to support the Global Assembly ahead of COP26.1 In a speech to the Global Assembly at COP26, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon MSP, indicated the Scottish Government’s support for public engagement in climate action and citizens’ climate assemblies.

Citizens' Convention on Climate - France

The Citizens' Convention on Climate convened 150 randomly selected French citizens to deliberate on proposals for achieving a 40% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030.1

President of the Republic, Emmanuel Macron, announced the Citizens' Convention on Climate on 25 April 2019.1 This announcement was made amidst protests by the Gilets Jaunes movement and following the Grand Débat National (a town hall process seeking citizens' views on major issues like public spending and the environment).1 During this time, many French citizens were advocating for the public to be more involved in the policy making process.4

Membership and meetings of the Citizens' Convention

The Economic, Social and Environmental Council was mandated to organize the Citizens’ Convention on Climate.1 It installed an independent Governance Committee composed of experts in the fields of ecology, participatory democracy, and economics and social affairs to support the work of the Convention.1 Three guarantors from the members of the Convention were appointed to ensure the independence and quality of the process.3 The Citizens' Convention comprised of 150 randomly selected participants considered to be representative of the wider gender, age, education and geographical distribution in France.4

The Citizens' Convention was held over seven sessions across nine months and consisted of three phases. The first three sessions corresponded to the learning phase, the deliberative component took place during sessions four to six, and the decision-making phase took place in the final session. Initially planned for six sessions, the members requested an additional session to address emissions reduction as part of the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.4

For most of the sessions, members were randomly assigned to one of the five working groups addressing aspects of climate change policy. The five working groups deliberated on consumption, transport, food, production and work, respectively.4 Between sessions, members were encouraged to inform their communities and local stakeholders of the Citizens' Convention and its work.4 Unlike other examples of citizens' assemblies, members of the Citizens' Convention deliberated only on the topic assigned to their working group but could vote on all of the proposals devised by other working groups of the Citizens' Convention.8

The final report was submitted to the Government and shared with the public on 21 June 2020.

Proposals and Public Reception

The budget for the Citizens' Convention as well as the interaction between the French Government and some members of the Citizens' Convention on Climate in France has attracted considerable attention. The budget for the Citizens' Assembly was €5.4 million ($6.34 million).1 For comparison, the climate assembly arranged by the UK Parliament had a budget of £520,000 ($672,139), albeit for a smaller assembly of 108 citizens and meetings held over a shorter timescale of four rather than nine months.1 The investment in the Citizens' Convention on Climate generated significant public awareness of the work of the Citizens' Convention in France.1

Academics have noted that the Citizens' Convention on Climate highlights the importance of ensuring a mutual understanding between the Government (or commissioning public authority) and the Citizens' Assembly on how the proposals will be taken forward and implemented.4 During the convention, the members decided to submit their proposals directly to the Government with the expectation that the legislature would pass a law to enact each proposal.5 This expectation was due in part to President Macron indicating at the announcement of the Citizens Convention on Climate that recommendations would be enacted through referendum, legislation or executive powers.1 The intervening time between the publication of the Citizens' Convention report and the introduction of the Climate and Resilience Bill contributed to a public perception that the French Government was not acting on recommendations by the Citizens' Convention and led to tensions between members of the Convention and the French Government.7 A group advocating for the implementation of the Citizens' Convention proposals, called "Les 150", was also founded in this time.7

The Climate and Resilience Bill, introduced to the French Parliament in January 2021, was criticised by members of the Citizens' Convention for significantly weakening the majority of the Convention's proposals.7 An estimated 40% of the proposals from the Citizens' Convention were included in the Climate and Resilience Bill.10 The Bill passed in the National Assembly on 4 May 2021 and became law on 21 July 2021 after passing in the Senate.11

Annex 1: Citizens' Assembly of Scotland Recommendations and Outcomes

i

| Recommendation Group | Outcome |

|---|---|

| How decisions are taken |

|

| Incomes & Poverty |

|

| Tax and Economy |

|

| Young people |

|

| Sustainability |

|

| Health and wellbeing |

|

| Further powers |

|

| Mixed group |

|

Annex 2: Irish Constitutional Convention of 2012-14 Topics, Recommendations and Outcomes.

| Topic | Recommendation | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Presidential termReducing the President’s term of office to five years and aligning it with the local and European elections |

|

|

| Voting ageReducing the age at which people can vote in elections |

|

|

| Review of the Dáil electoral system |

|

|

| Right to voteIrish citizens living abroad to have the right to vote in presidential elections. |

|

|

| Provision for same-sex marriage |

|

|

| Role of womenAmending Article 41.2 on the role of women in the home and encouraging greater participation of women in public life. |

|

|

| Increasing the participation of women in politics. |

|

|

| Removal of the offence of blasphemy from the Constitution. |

|

|

| Dáil reform |

|

|

| Economic, social and cultural rights |

|

|

Annex 3: Further Research on Citizens' Assemblies

Further information on the background to deliberative democracy, the announcement of the Citizens’ Assembly for Scotland, and the actions on deliberative democracy set out by the Programme for Government 2021-22 can be found in previous SPICe blogs:

A Citizens’ Assembly for Scotland (28 June 2019)

Programme for Government 2021-22: A fairer, greener Scotland? (8 September 2021)

Are citizens' assemblies "here to stay"? (30 November 2021)