Budget 2023-24

This briefing considers the Scottish Government's spending and tax plans for 2023-24. More detailed presentation of the budget figures can be found in our budget spreadsheets. Infographics produced by Andrew Aiton, Kayleigh Finnigan, and Fraser Murray.

Summary

Inflation wraps its tentacles around all aspects of economic life

The 2023-24 Scottish Budget comes at a time of dramatic increases in inflation which have impacted on many areas of economic life, here and beyond these shores.

Indeed the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC), whose forecasts underpin the size of the Scottish budgetary envelope, makes the point that inflation impacts on all areas they forecast, from growth, to tax receipts to living standards.

On living standards, the SFC forecasts that this year we’ll see the biggest fall (-3.3%) in living standards since Scottish records began in 1998. On the overall economy, the SFC, like its equivalent in the UK, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), now judges that Scotland has entered recession. This will see a “peak to trough” fall of 1.8%, and a slow recovery, with the Scottish economy not expected to return to pre-pandemic levels until Q3 2025.

It’s important to note that, when considering the Scottish Budget as we do in this briefing, inflationary pressures feed through into all areas of government spending. We have seen the effects of this already in the current financial year, with the Scottish Government’s Emergency Budget Review (EBR) last month, which reallocated £1.2 billion from within existing spending plans, primarily for improved public sector pay deals and cost of living support.

There have also been various additions for the current financial year’s budget (2022-23) from the UK government, and other adjustments which increase the Scottish spending envelope. Indeed the SFC in two recent reports have revealed that a total of £1.3 billion has been added to this year’s spending plans from a mix of Barnett consequentials, Scotland Reserve drawdowns, updated tax forecasts and other movements.

The effect of these in-year 2022-23 additions means that the usual “budget to budget” basis for presenting 2023-24 spend could be seen to be misleading, when trying to understand the year-to-year changes in budgets. For the purposes of this briefing, we present the numbers as published by the Scottish Government in the documentation. However, our briefing highlights where some of these comparisons might need further interpretation and explanation, for example in local government.

Spending choices

Local government spend is always a contested area and this year is no different.

The Budget shows the total local government allocation for 2023-24 increasing by £637 million in cash terms, or £223 million in “real” terms, when compared to Budget 2022-23. COSLA argues that the actual cash increase announced by the Deputy First Minister will be much smaller once existing policy commitments are taken into account.

COSLA’s news release focuses on “core” budget, which is the combination of general and specific revenue grants and income from non-domestic rates. This core revenue budget sees a real terms reduction of 0.2% between Budget 2022-23 and Budget 2023-24.

Health is again a budget priority, as it has been throughout the devolution years. The Health and Social Care portfolio grows by 6.2% (2.8% in real terms) in 2023-24. This represents over £1 billion in additional funding and goes beyond the Scottish Government’s commitment to pass on any additional funds that it receives as a result of increased UK government spending on health. With the pay offer currently on the table for 2022-23 costing an additional £515 million relative to the initial plans for 2022-23, a significant proportion of this extra funding will be absorbed by additional pay costs. There is also a commitment to increase pay for adult social care workers to £10.90 per hour, which comes at an estimated cost of £100 million.

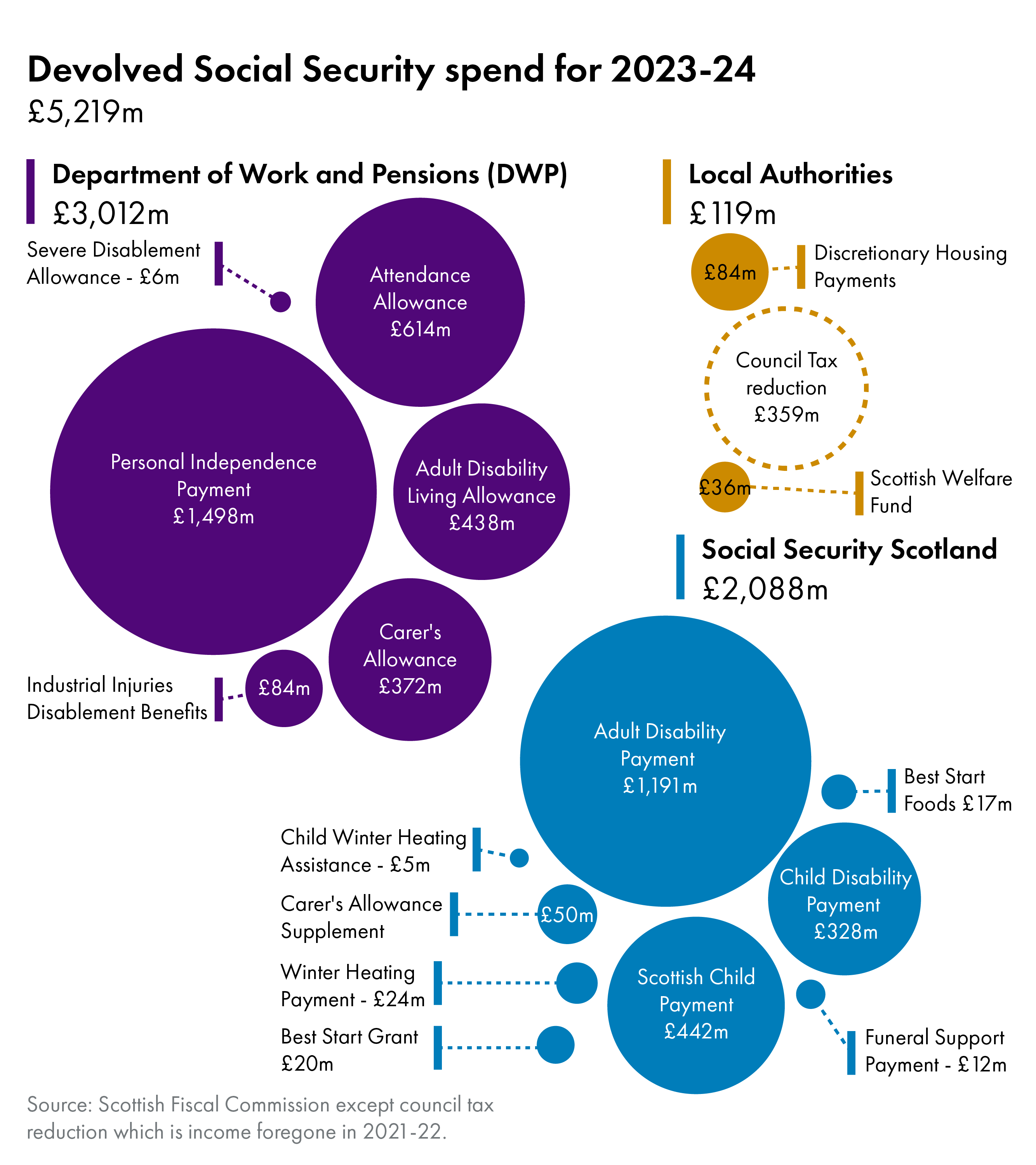

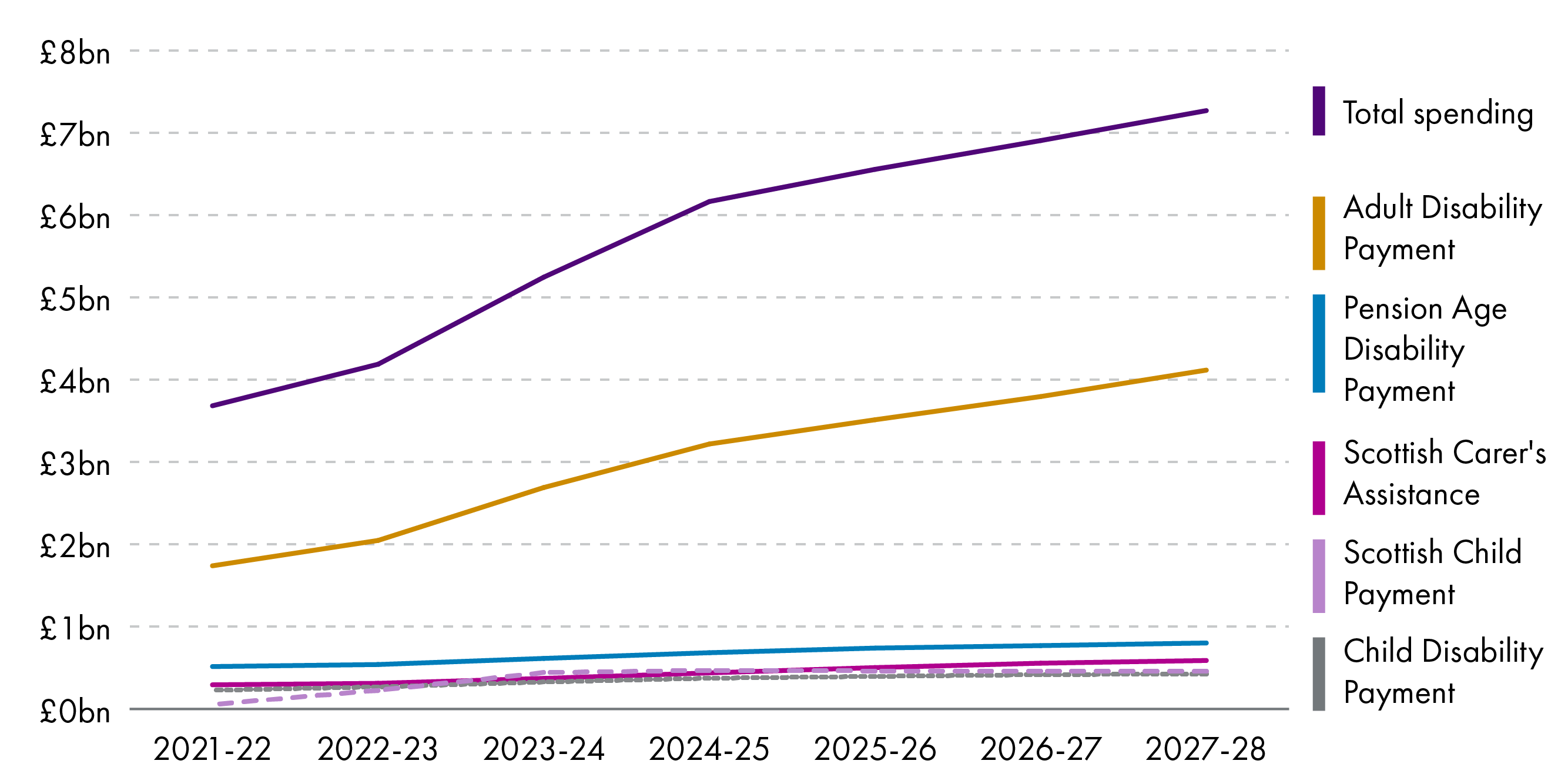

Social security again will see spending increases which exceed the size of the Block Grant Adjustment (BGA) added to the Scottish budget from the UK government’s equivalent spend in 2023-24. The SFC forecasts that this will increase in subsequent years of the forecast period. This reflects policy decisions around disability benefits and the increase in both the payment amount and eligibility for the Scottish Child Payment.

The SFC expects social security spend to be £0.8 billion above the BGA next year and rise to £1.4 billion more than the BGA by the end of the forecast period in 2027-28. By prioritising social security in this way, the implication is that other ‘non-prioritised’ areas of spend will be squeezed.

In line with the approach taken by the UK government, the Scottish Government will increase all social security benefits over which it has control by the rate of inflation in September of 10.1%.

There has been much criticism of the lack of clarity around the potential costs of the proposed National Care Service (NCS), including from the Parliament’s Finance and Public Administration Committee. The budget document states that funding has been included in the budget for 2023-24, but it is not clear how much has been set aside for the NCS, as NCS funding is included under the broader heading of "National Care Service / Adult Social Care". This adds further to the lack of clarity around funding for this flagship policy.

When budgets are tight, historically infrastructure spending can suffer. Inflation is eroding the spending power of the capital budget, and the interim Cabinet Secretary warned in his speech that the Capital budget won’t be able to deliver as much as planned. However, the document is short on specifics around which projects might be impacted.

Tax policy – continuing divergence from rest of UK on income tax

Budget 2023-24 extended the income tax policy divergence between Scotland and the rest of the UK. The Scottish Government proposes to keep all thresholds frozen except the top rate threshold, which is reduced to £125,140 in line with the UK government plans. However, the higher and top rates are to be increased to 42p and 47p respectively. The combined impact of all these changes, according to the SFC, is an additional £129 million in income tax revenues next year (after taking account of any behavioural changes that might result).

These decisions widen the gap between Scottish Government policy and policy in the rest of the UK, with higher earners now facing tax rates of 42p (above £43,662) and 47p (above £125,140)

Scottish taxpayers earning less than £27,850 will pay £22 less income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK. This accounts for 52% of all Scottish taxpayers. Above this earnings level, Scottish taxpayers pay more tax than they would in the rest of the UK, and the gap widens rapidly for those earning above £44,000. Those earning more than £50,000 will be paying at least £1,500 more income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK.

The difference between the two income tax policies mean that Scottish taxpayers are paying £1 billion more in income tax than they would do under income tax policy in the rest of the UK.

But, because of how the funding settlement works, the Scottish budget does not see the full benefit. The additional income tax raised is only £325m more than the amount taken away from the Scottish budget (the “block grant adjustment”) due to the devolution of income tax powers. This differential results from slower growth in income tax revenues per head in Scotland when compared with the rest of the UK. This in turn reflects a range of factors, such as a different mix of lower and higher rate taxpayers and different rates of earnings growth.

Areas for ongoing Parliamentary scrutiny

In a departure from the norm, no public sector pay policy was published for 2023-24 alongside the Budget and is now expected at an “appropriate time in the new year”. With negotiations ongoing across different sectors, it is possible costs will increase above what had initially been indicated in the EBR for this year, pushing the baseline up for next year.

Given that public sector pay accounts for over £22 billion in spending each year, the lack of a clear position on pay in next year’s budget represents a significant area of uncertainty. Similarly, previously planned intentions to outline public service reform plans alongside the Budget were a notable omission. Pay and public service reform are amongst a number of areas with budgetary significance that the Parliament will require to scrutinise on an ongoing basis. Others are the impacts of social security spend on other unprotected parts of the Budget, as well as the delivery of the National Care Service and net zero ambitions.

The Scottish Government has stated its ongoing commitment to equalities and has increased the focus on human rights within documentation. However, despite cosmetic changes and greater detail, there remains a lack of clarity on how policy impacts are measured, how spending decisions link to national outcomes, and how the Scottish Government uses lived experience to inform its decision-making. Many transparency and accessibility concerns raised during committees’ pre-Budget scrutiny about the Budget process and documentation remain unaddressed.

Wider scrutiny challenges for the Parliament to consider on an ongoing basis centre around what is being achieved for the money that is spent. The National Performance Framework and review of the national outcomes planned for 2023 will be important , as policy makers collectively try to better link spending decisions to outcome delivery.

Context for Budget 2023-24

Scottish Budget 2023-241 was published on 15 December 2022 and presents the Scottish Government's proposed spending and tax plans for next year. The publication signals the start of an intensive period of parliamentary scrutiny, before MSPs vote on these proposals in the early part of 2023.

The Budget incorporates devolved tax forecasts undertaken by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC). As well as producing point estimates for each of the devolved taxes for the next five years, the SFC is also mandated to produce forecasts for Scottish economic growth and spending forecasts for devolved social security powers. The SFC's forecasts can be found in Scotland's Economic and Fiscal Forecasts published alongside the Scottish Budget.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, economies throughout the world have been hit by rising inflation, as global energy prices have increased dramatically, pushing up general inflation. This has hit individuals, families and governments throughout the world.

The SFC forecasts highlight these inflationary impacts which feed into all aspects of their forecasts.

Higher energy costs have fed through to general inflation. The SFC, like the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) for the UK, now judge that Scotland has entered a recession which will last for six quarters, with a total peak to trough fall in GDP of 1.8%. Indeed, the SFC are now not expecting the Scottish economy to return to pre-pandemic levels until Q3 2025 as a result of recession followed by slow growth.

Because of this, the SFC forecasts that Scottish households can expect to see the biggest real-terms (inflation adjusted) fall in their disposable income since Scottish records began in 1998.

The SFC's forecasts of Scottish economic output over the forecast period are presented in the table below.

| 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economy, % growth | 1.7 | -1.0 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.5 |

Overall spending and the 2022-23 baseline

The Scottish Government presents its 2023-24 Budget against the baseline figures presented in the 2022-23 Budget and passed by the Parliament in February 2022. This has been the established convention for budgetary presentations over a number of years.

However, over the course of 2022-23, there have been a number of changes made to the 2022-23 baseline budget. Most of these reflect the impacts of extremely high inflation on people's living standards, for example resulting in additional resources for higher pay settlements and measures to support those on low incomes with rising costs. The result of these changes is that the usual "budget to budget" comparisons could be, in some circumstances, misleading, or at least not give the full picture of the effect of the changes in budget from one year to the next

For example, there has been a Scottish Government Emergency Budget Review1 which reallocated £1.2 billion of previous budget plans to support improved pay offers for public sector workers and other cost of living interventions.

Two recent SFC reports (in May (see figure 2.1) and December 2022 (see Annex D)) have also highlighted top-ups for 2022-23 spending totalling £1.3 billion, flowing from a variety of sources. This was also identified in an Institute for Fiscal Studies report published on 16 December 2022.

In the SFC's May 2022 Fiscal Update there was £764 million added to the 2022-23 budget from: additional Barnett consequentials (£406 million); reserve drawdown (£400 million); updated tax forecasts (£68 million); and a reduction (£110 million) in other funding.

In the SFC's December 2022 Fiscal Update there is an additional £536 million with significant increases from Scotland Reserve drawdown (£205 million) and an increase in Other funding (£269 million) as a result of assumed funding materialising in larger amounts than anticipated.

As a result, the total spending envelope presented in the Budget document for 2022-23 and some of the portfolio and individual budget line changes presented do not reflect the the scale of in-year changes to budgets.

While recognising that 2022-23 has been a historically challenging year for budgeting, it would be helpful for transparency purposes for the Scottish Government to publish a final position on 2022-23 budgets against 2023-24 proposals. It is not possible from information currently in the public domain to extrapolate out these revised 2022-23 baselines across all budgets.

For the purposes of this briefing, therefore, we will present the budgets as presented by the Scottish Government in the documentation. This will allow the best read across between the numbers referred to in the Budget and SPICe analysis. However, our briefing highlights where some of these comparisons might need further interpretation.

On one other transparency point, it was noticeable that the Scottish Government Budget did not reflect the recommendation made by the SFC earlier this year around presenting Budgets on a Classification of Functions of Government (COFOG) basis:

Normally, our commentary on Scottish Government spending covers only social security as we are responsible for producing the forecasts the Scottish Government uses. However, in 2023 we will be publishing a Fiscal Sustainability Report which will project spending in all devolved areas. Currently the Scottish Government’s Budget documents focus on spending by portfolio area. However, portfolios change over time to reflect different ministerial responsibilities. This makes tracking spending over time difficult. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) developed the Classification of Functions of Government (COFOG). It is used to reflect spending in a consistent way by identifying spending under set definitions. We would like the Scottish Government to publish its Budget later this year with information on how spending is split by COFOG as well as by portfolio. This would provide a baseline level of spending for us to use in our Fiscal Sustainability Report, and provide a benchmark for comparisons of the Scottish Budget in future years.

This recommendation was a welcome one from a parliamentary budget scrutiny point of view. If delivered it would allow parliamentary committees improved transparency in terms of budget information by area of government. For example, it would allow for the consistent presentation of budgetary information by function of government (for example, Health, Education, Housing, Economy, Environment), which is not always possible from looking at portfolio information. This would provide a much clearer hook for subject committee budget scrutiny than is sometimes currently available, and would be consistent with recent efforts by the Scottish Government to improve budget transparency. It would also assist with comparisons over time when portfolio definitions are revised.

What is the best measure of inflation?

There are many different measures of inflation. The most common is the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The Office of National Statistics (ONS) use this measure to track the changes in price of a standard basket of goods bought by households in the UK. CPI is designed to capture changes in consumer prices.

CPI, however, is not generally suitable to analyse the real spending power of governments. This is because governments do not purchase the same goods and services as consumers. The GDP (Gross Domestic Product) deflator is a more general indicator of price changes in the economy, and is usually used to adjust for the effect of inflation on public spending over time. The GDP deflator is used to show inflation for all goods and services produced in the UK, including government services, investment, goods and exports. It excludes the price of imports.

Is the GDP deflator the best measure to use?

In normal circumstances, the GDP deflator is the best measurement of inflation for government spending.

However, the current high inflation is being driven by high energy prices which is an import cost, not covered by the GDP deflator. This means that rather than running in line with CPI inflation of approaching 10-11%, the GDP deflator is considerably lower - for 2023-24 it is currently 3.2%.

All of this means that the “real” cost of delivering public services at the moment, as measured by the GDP deflator, is likely to be artificially low with energy price inflation running so high. As such, whilst energy price inflation remains high, the settlements provided to all parts of the Budget will be tougher than these real terms figures imply, especially for the unprotected parts of the Budget.

As the Scottish Government has done, SPICe will continue to use the GDP deflator. However, this wider point should be noted when looking at real terms analysis.

Budget allocations

Total allocations

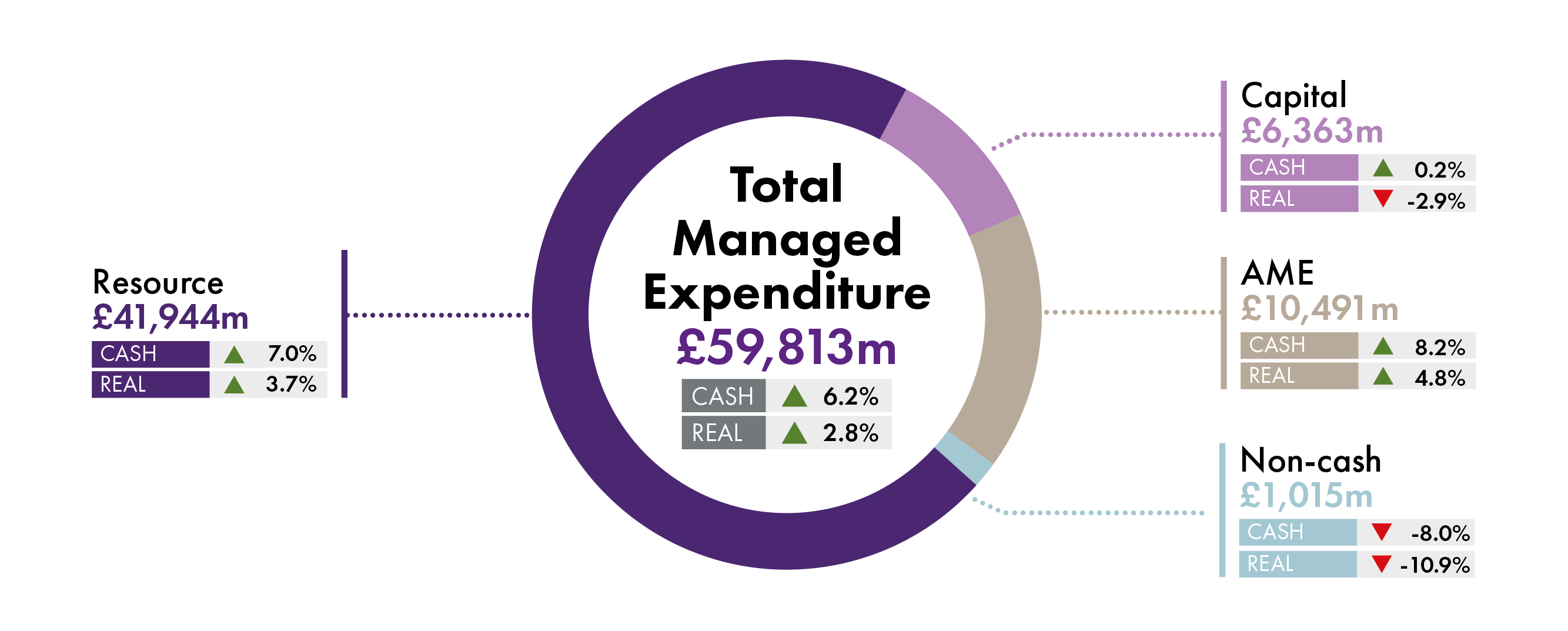

Total Managed Expenditure (TME) comprises Resource, non-cash Resource, Capital and Annually Managed Expenditure (AME). TME in 2023-24 is £59,813 million. Figure 1 shows how this is allocated.

Resource (which covers day-to-day expenditure) and Capital (covering infrastructure expenditure) are the elements of the budget over which the Scottish Government has discretion. As we can see from the chart, Resource is due to increase by 3.7% in real terms in 2023-24 and Capital is set to fall by 2.9% in real terms.

AME is expenditure which is difficult to predict precisely, but where there is a commitment to spend or pay a charge, for example, pensions for public sector employees. Pensions in AME are fully funded by HM Treasury, so do not impact on the Scottish Government's spending power. Non-Domestic Rates income is also classed as an AME item in the budget and forms part of local government spending.

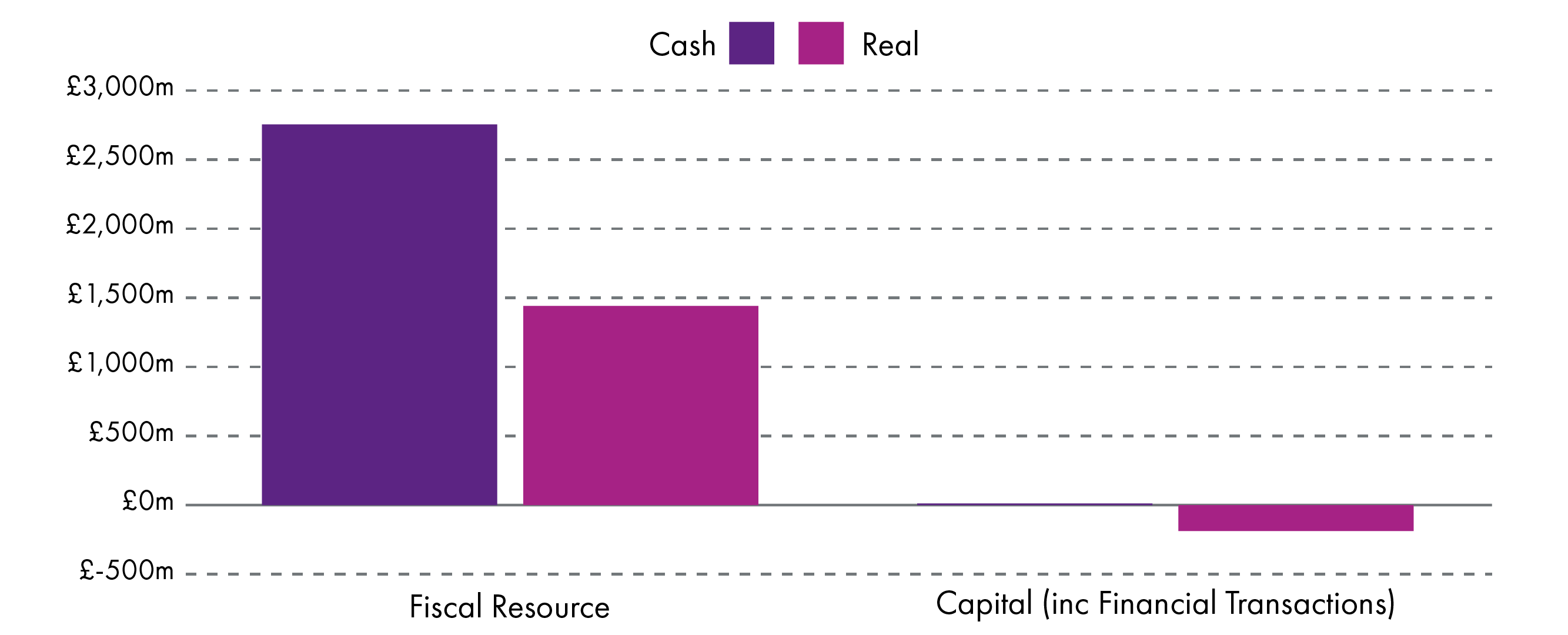

Figure 2 below shows the absolute change in Resource and Capital presented in the document between 2022-23 and 2023-24. Resource will increase by £1,441 million in real terms next year, and Capital (including Financial Transactions monies) will fall by £187 million in real terms.

Portfolio allocations

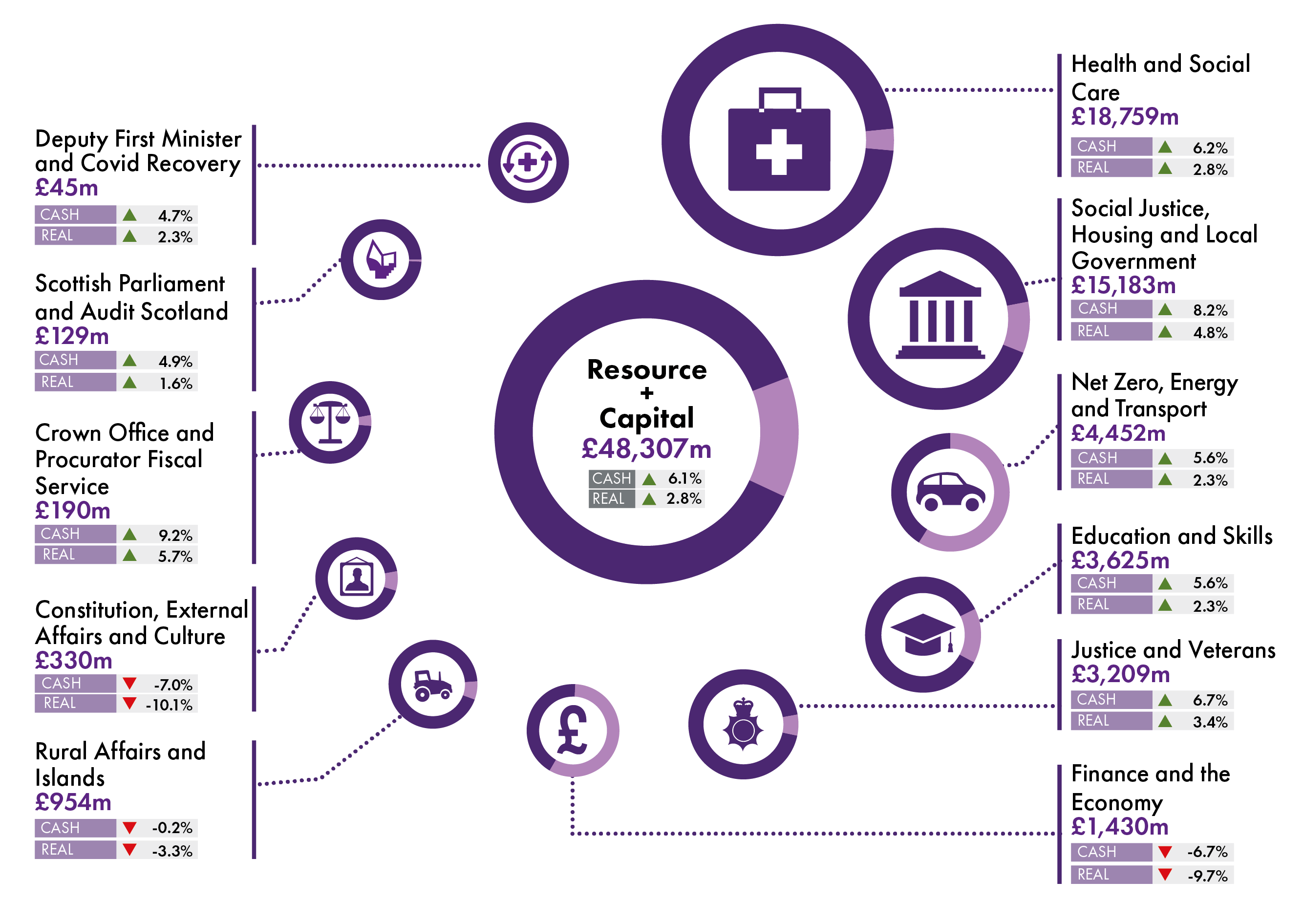

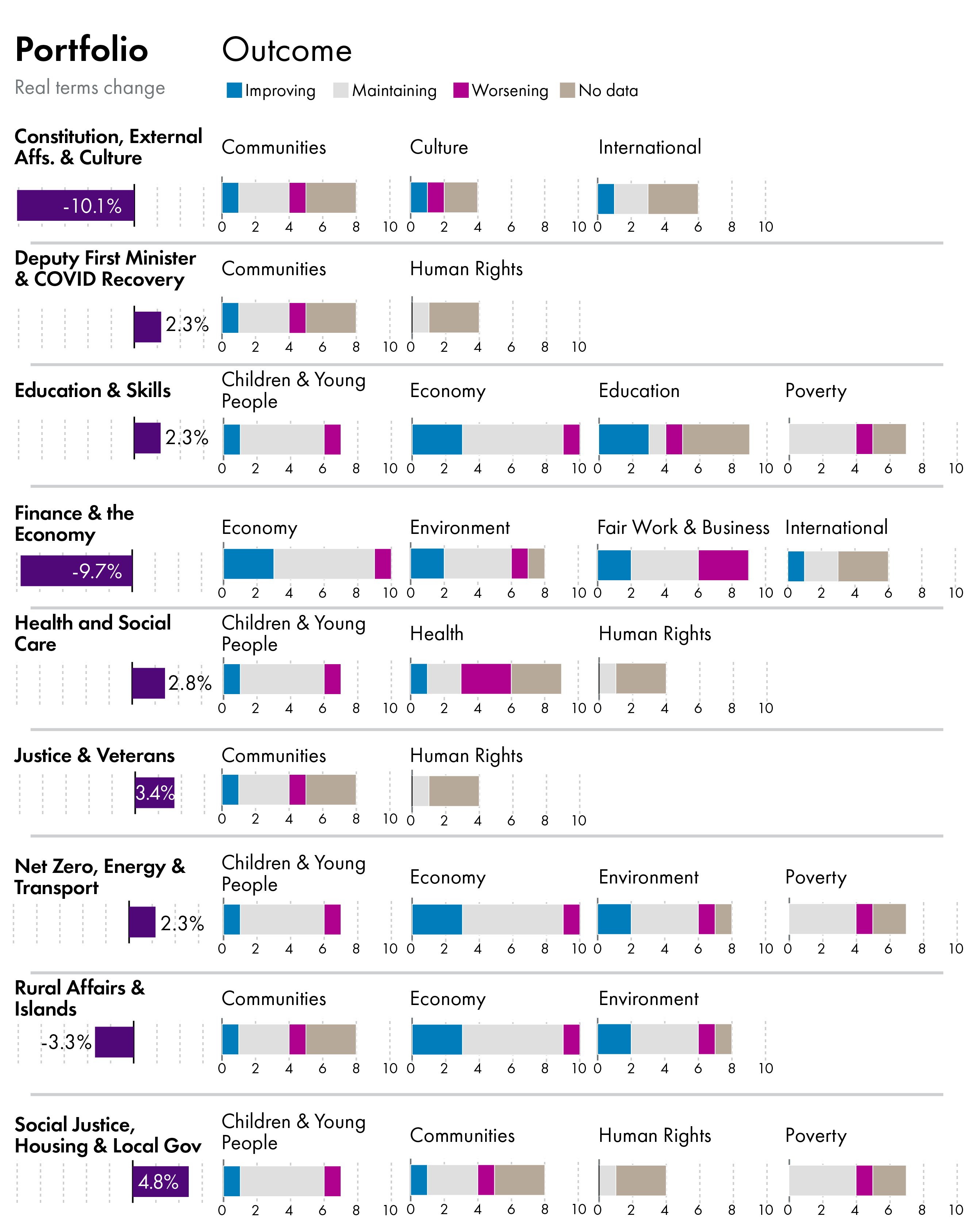

Resource and Capital allocation to portfolios for 2023-24, and how they have changed on the previous year, are presented in figure 3.

Figure 3 shows the Budget to Budget 2022-23 to 2023-24 portfolio changes in cash and real terms. Key points to note are as follows:

Health and Social Care is the largest portfolio, comprising 39% of the discretionary spending power (Resource and Capital) of the Scottish Budget in 2023-24.

The next largest portfolio is Social Justice, Housing and Local Government which comprises just over 30% of the Resource and Capital spend combined, although this does not include Non-Domestic Rates Income (NDRI), which is AME but forms part of the local government settlement. Local government is discussed in more detail later in this briefing, and SPICe will publish a detailed analysis of the settlement to local authorities in a future briefing.

Notwithstanding the point raised above around the 2022-23 baseline, eight of the eleven portfolios increase in both cash and real terms. Meanwhile, Constitution, External Affairs and Culture; Rural Affairs and Islands; and Finance and Economy fall in cash and real terms.

Resource and Capital allocations

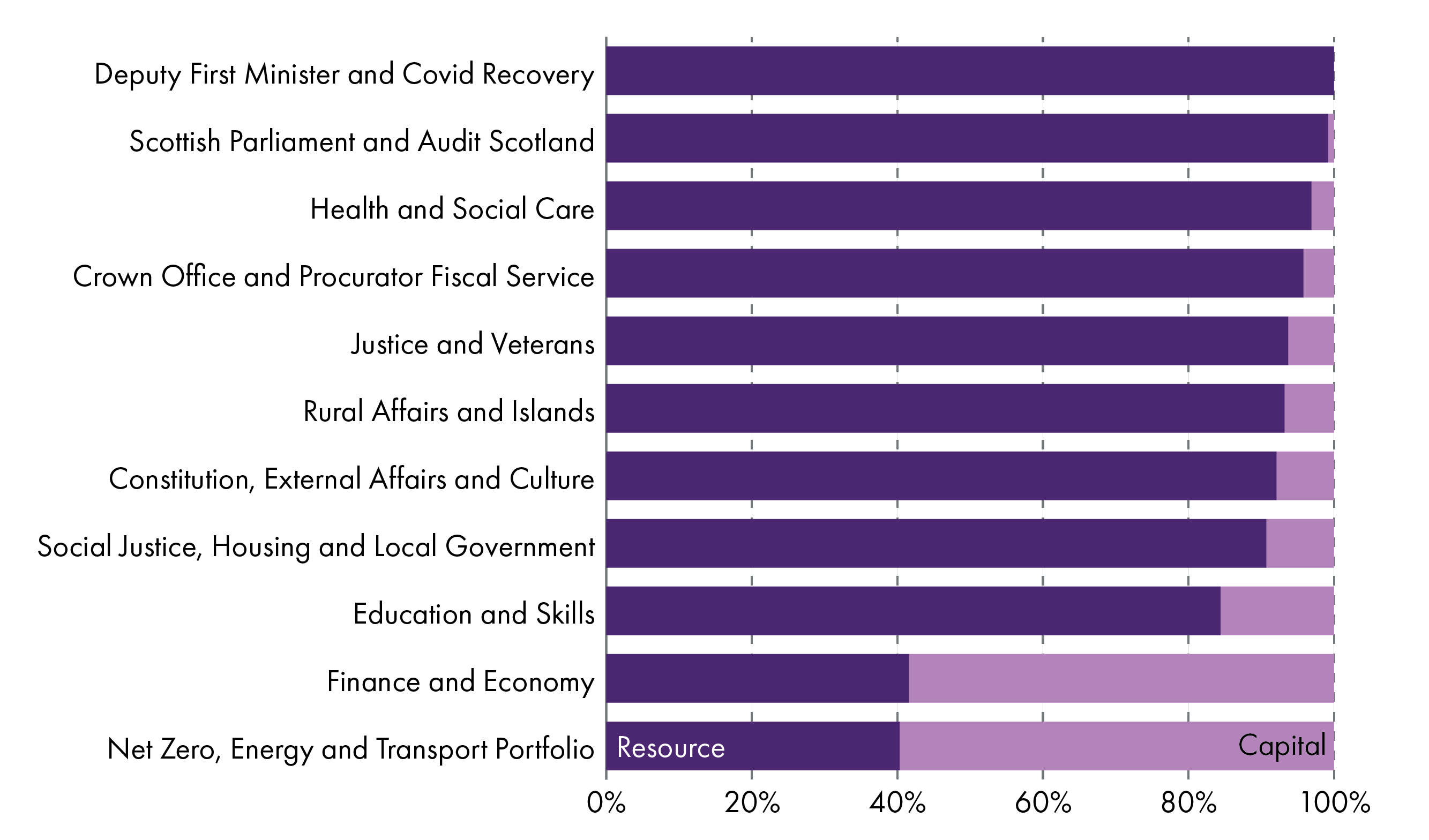

Figure 4 below shows the split between Resource and Capital by portfolio. This shows that most portfolios are heavily weighted towards funding day-to-day spending commitments (the Resource budget).

The Net zero, Energy and Transport and Finance and Economy portfolios have the highest proportion of the budget comprising Capital expenditure (around 60%).

Social security

With the devolution of certain Social Security powers by Scotland Act 2016 came over £3 billion of spending power via an upward Block Grant Adjustment (BGA) to the Scottish Budget. However, it also brought with it increased budgetary risks, as any spending over and above the BGA must be found from other resources within the Scottish Budget.

The SFC is forecasting that social security spending will exceed the size of the BGA added to the Scottish budget from the UK government’s equivalent spend in 2023-24, and are forecasting that this will increase in subsequent years of the forecast period. This reflects policy decisions around disability benefits and the increase in both the payment amount and eligibility for the Scottish Child Payment.

The SFC expects Social Security spend to be £0.8 billion above the BGA next year and rise to £1.4 billion more than the BGA by the end of the forecast period in 2027-28. This is discussed in more detail in the section of the briefing on the SFC forecasts.

In line with the approach taken by the UK government, the Scottish Government will increase all Social Security benefits over which it has control by the rate of inflation in September of 10.1%.

Figure 5 shows the various Social Security powers now devolved to the Scottish Parliament by size.

Largest Budget changes

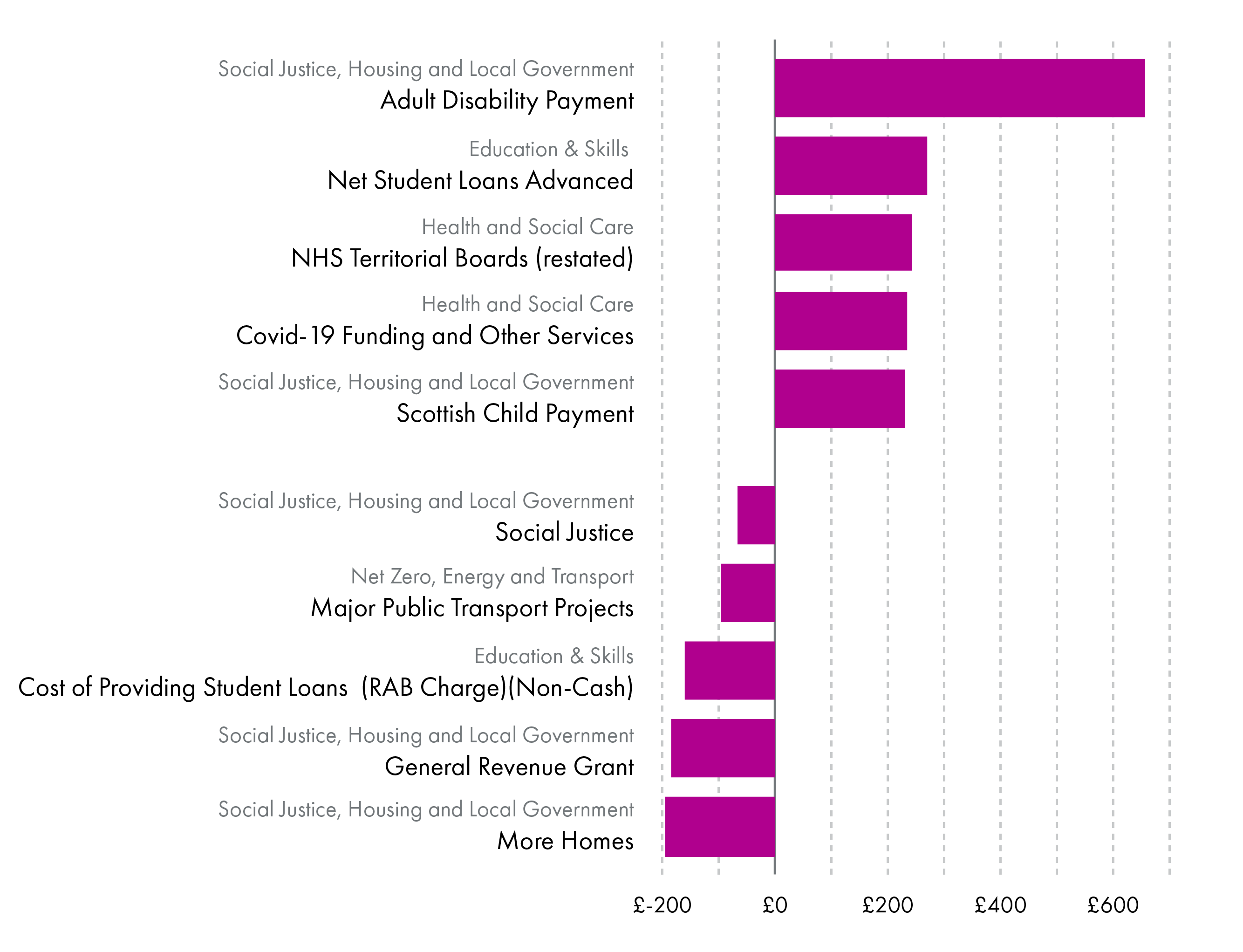

Figure 6 presents the largest (real terms) proposed level 3 budget line increases and decreases in 2023-24 compared with the previous year.

Two of the five largest increases are the area of social security, with the Adult Disability Payment and Scottish Child Payment increasing by over £650 million and over £230 million in real terms respectively.

The largest falls in the Scottish Government's Budgets come in the "More Homes" and the local government "General Revenue Grant" budget lines, with both set to fall by just under £200 million in real terms next year. However, as always with local government, this is not the full picture, and with Non-domestic rates income forecast to increase, the core revenue settlement sees a reduction of £22 million, explained in more detail in the dedicated local government section of the briefing.

On the "COVID-19 funding and other services" line in the chart above, this line includes a range of items, many of which have fallen in cash terms over the year. It is difficult to identify the drivers of this increase as multiple items (including income sources) are included under this heading. It is not possible to identify how much of the change relates to COVID-19 recovery costs.

Tax

Income tax

Income tax proposals

The Scottish Government set out its proposals for income tax from April 20231 as part of the Scottish Budget 2023-24. These need to be approved by a Scottish Rate Resolution, which must precede Stage 3 of the Budget Bill process. Income tax then cannot be changed during the financial year.

The proposals set out by the Scottish Government involve:

Freezing all the thresholds, with the exception of the top rate threshold.

Reducing the top rate threshold from £150,000 to £125,140, in line with the UK government income tax policy for 2023-24.

Increasing the higher and top rates of tax by 1p to 42p and 47p respectively.

The proposed rates and bands are shown below.

| Bands | Band name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £12,570* - £14,732 | Starter | 19 |

| Over £14,732 - £25,668 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £25,668 - £43,662 | Intermediate | 21 |

| Over £43,662 - £125,140** | Higher | 42 |

| Above £125,140** | Top | 47 |

* Assumes individuals are in receipt of the standard UK personal allowance (£12,570 in 2023-24)

** Those earning more than £100,000 will see their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000

The UK government sets the personal allowance and this is unchanged from 2022-23, at £12,570. The UK government has also frozen the higher rate threshold at £50,270 and plans to keep both the personal allowance and higher rate threshold at the current levels until 2027-28, as announced at the Autumn Statement 20222.

| Bands | Band name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £12,570* - £50,270 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £50,270 - £125,140** | Higher | 40 |

| Above £125,140** | Additional | 45 |

* Assumes individuals are in receipt of the standard UK personal allowance (£12,570)

** Those earning more than £100,000 will see their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000

Income tax revenues

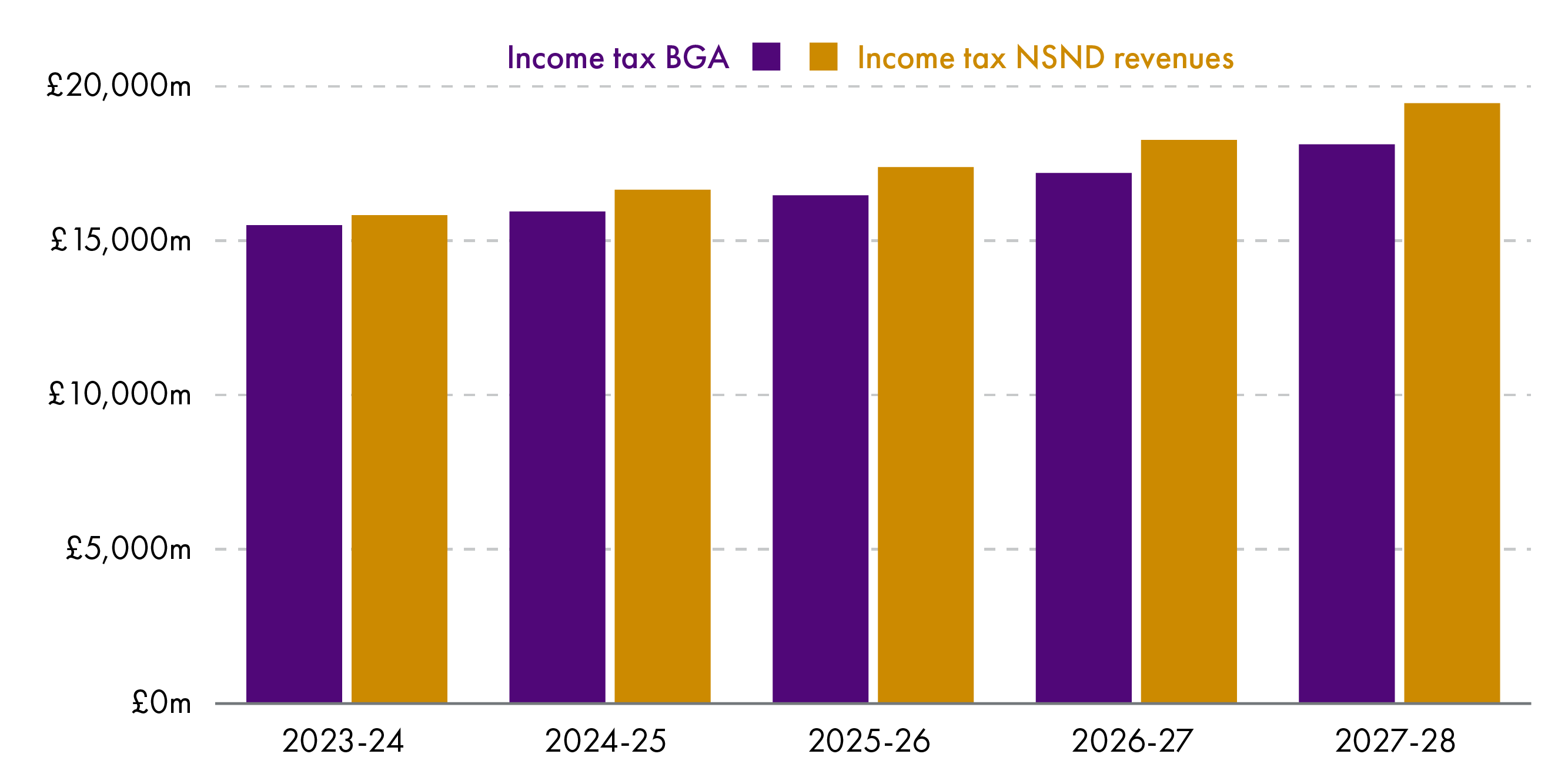

The Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) forecasts that, with the proposals set out in the budget, non-savings non-dividend (NSND) income tax revenues will total £15,810 million in 2023-24. Forecasts for subsequent years are shown in Table 4. These forecasts are based on the assumption that the Scottish Government will continue to freeze the higher and top rate thresholds, but that the width of lower tax bands will be uprated in line with the previous September’s CPI inflation.

| 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSND income tax | 15,810 | 16,633 | 17,370 | 18,247 | 19,437 |

The SFC estimates for 2023-24 are higher than had been forecast in both of the last SFC forecasts (December 2021 and May 2022). This reflects both a stronger outlook for nominal earnings growth and Scottish Government policy decisions.

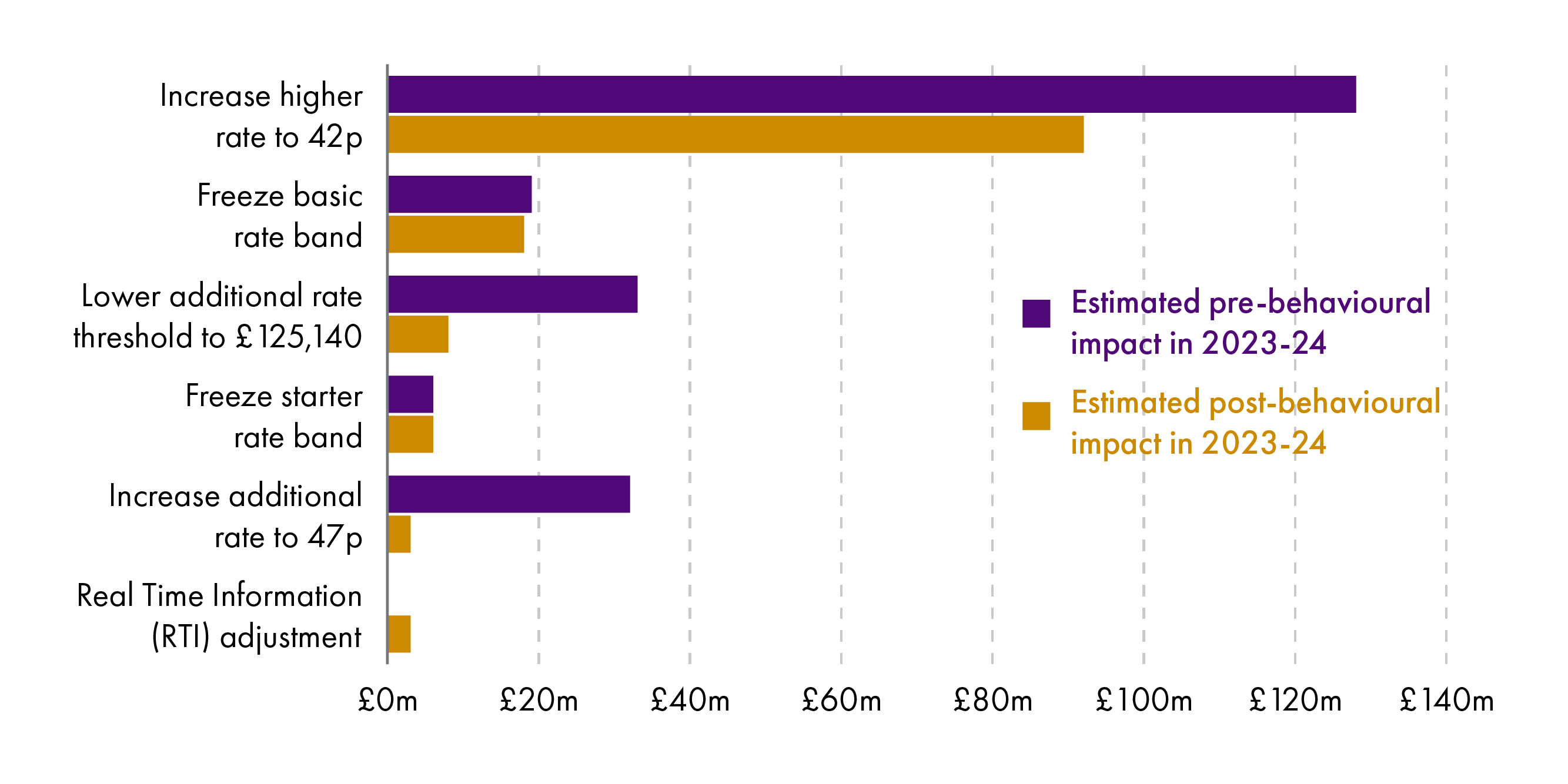

The SFC estimates that the income tax decisions taken by the Scottish Government in this year’s budget will, after taking account of behavioural changes, raise an additional £129 million relative to what would have been raised if the band widths had been increased in line with inflation. Figure 7 shows how this total is broken down, showing both the estimated impact before behavioural responses and the post-behavioural estimate.

This shows that most of the increase in revenues results from the decision to increase the higher rate from 41p to 42p. This is because there are a lot more taxpayers paying tax at the higher rate than are paying tax at the additional rate. According to the Scottish Government’s Income Tax Factsheet, there are around 500,000 higher rate taxpayers, compared to only 33,000 top rate taxpayers. With thresholds frozen, earnings growth will pull more people into higher tax brackets (known as “fiscal drag”).

The SFC also expects that the changes affecting additional rate taxpayers will result in behavioural changes that will significantly reduce anticipated revenues from these changes.

(a) RTI is real time information on tax payments that is used to update forecasts

The SFC had already assumed (from May 2022) that the Scottish Government would freeze the higher rate threshold, so this decision was already built into the May 2022 forecasts and is not separately costed in the December forecasts or included in the table above. In May 2022, the SFC estimated that this policy would raise £129 million in 2023-24. In the budget document, the Scottish Government state that they estimate the decision to freeze the higher rate threshold generates an additional £390 million compared to increasing it in line with inflation. The difference will, in part, reflect higher inflation than had been assumed at the time of the SFC’s May 2022 forecast, as well as changes to economic factors, such as earnings growth.

Income tax net position

In 2023-24, the income tax net position is expected to be £325 million. That is, NSND income tax revenues in Scotland are expected to exceed the block grant adjustment (BGA) for income tax by £325 million. The income tax BGA is the amount that is removed from the Scottish budget to account for the fact that most income tax decisions have been devolved to the Scottish Parliament. It reflects what Scotland would have raised in income tax if it had retained the same tax policy as the rest of the UK and if Scotland’s per capita tax revenues had grown at the same rate as the rest of the UK.

On the basis of latest forecasts, the income tax net position is expected to reach £1.3 billion by 2027-28, although the SFC note that the net position is highly sensitive to changes in the SFC and OBR forecasts that underpin the calculation.

The SFC notes that the net income tax position has improved significantly since its December 2021 forecast, when it was forecasting a negative net position on income tax of -£257 million. This represents an improvement of £582 million in the net income tax position and reflects both changes in SFC and OBR forecasts, as well as the policy changes proposed by the Scottish Government in respect of income tax.

Although the net income tax position of £325 million is positive, it is still well below the additional amount that Scottish taxpayers are paying relative to what they would be paying under rUK income tax policy. Scottish taxpayers are paying around £1 billion more in income tax than they would be under the rUK income tax policy, but the Scottish budget is only benefitting by £325 million.

The gap arises because Scotland’s economic performance (in terms of earnings growth and employment) has been weaker and because Scotland has a different taxpayer mix (both in terms of numbers paying tax and also in the mix of higher and lower rate taxpayers). See the SPICe briefing on Income Tax for a fuller discussion of these issues.

Impact on individuals

Income tax at various levels of earnings under the Scottish Government proposals is shown in Table 5.

When compared with rUK income tax policy, Scottish taxpayers earning less than £27,850 will pay £22 less income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK. This accounts for 52% of all Scottish taxpayers. Above this earnings level, Scottish taxpayers pay more tax than they would in the rest of the UK and the gap widens rapidly for those earning above £44,000. Those earning more than £50,000 will be paying at least £1,500 more income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK.

Higher rate taxpayers in Scotland will also be paying more than they would have under last year’s income tax policy due to the increases in rates for those earning more than £43,662. An individual earning £50,000 will pay £63 more income tax than they would have done last year. For those paying the top rate of tax (which applies above £125,140), the differences are greater. An individual earning £150,000 will pay more than £2,400 more in income tax than they did last year and will be paying almost £4,000 more than they would in the rest of the UK.

| Annual earnings | Scottish Government proposals 2023-24 income tax payable | Difference compared with 2022-23 | Difference compared with rUK |

|---|---|---|---|

| £ per year | £ per year | £ per year | £ per year |

| 15,000 | 464 | - | -22 |

| 20,000 | 1,464 | - | -22 |

| 25,000 | 2,464 | - | -22 |

| 30,000 | 3,507 | - | 22 |

| 35,000 | 4,557 | - | 72 |

| 40,000 | 5,607 | - | 122 |

| 45,000 | 6,939 | 13 | 452 |

| 50,000 | 9,039 | 63 | 1,552 |

| 55,000 | 11,139 | 113 | 1,707 |

| 60,000 | 13,239 | 163 | 1,806 |

| 65,000 | 15,339 | 213 | 1,907 |

| 70,000 | 17,439 | 263 | 2,007 |

| 75,000 | 19,539 | 313 | 2,106 |

| 80,000 | 21,639 | 363 | 2,207 |

| 85,000 | 23,739 | 413 | 2,307 |

| 90,000 | 25,839 | 463 | 2,406 |

| 95,000 | 27,939 | 513 | 2,507 |

| 100,000 | 30,039 | 563 | 2,606 |

| 150,000 | 57,561 | 2,432 | 3,858 |

National insurance contributions

Decisions on national insurance contributions (NICs) are made by the UK government, but will interact with the Scottish Government's decisions on NSND income tax to determine overall tax rates. NICs are linked to UK tax thresholds and the NIC rate drops from 12% to 2% at the UK higher rate threshold of £50,270. This means that Scottish taxpayers who earn between the proposed Scottish higher rate threshold (£43,662) and the rUK higher rate threshold (£50,270) will pay 42% income tax and 12% NICs on their earnings between these two amounts – a combined tax rate of 54%.

Other devolved taxes

This section sets out the Scottish Government’s proposals on devolved taxes other than Non-Savings Non-Dividend (NSND) income tax. The Government states that its proposals in relation to devolved taxes have been made with reference to the six principles outlined in the Framework for Tax published in December 20211. These principles are:

proportionality

certainty

convenience

engagement

effectiveness

efficiency.

The Scottish Government notes that they are increasing some taxes in a challenging economic context, but state that:

We have not taken our decisions on tax lightly and we recognise the challenging economic conditions that many people and businesses are facing. That is why we are asking those who are best able to contribute more to pay more.

Non-domestic rates

Non-domestic rates (NDR) are local taxes paid on land and properties used for non-domestic purposes in the private, public and third sectors. The tax is administered and collected by local authorities, but tax rates and reliefs are set by the Scottish Government.

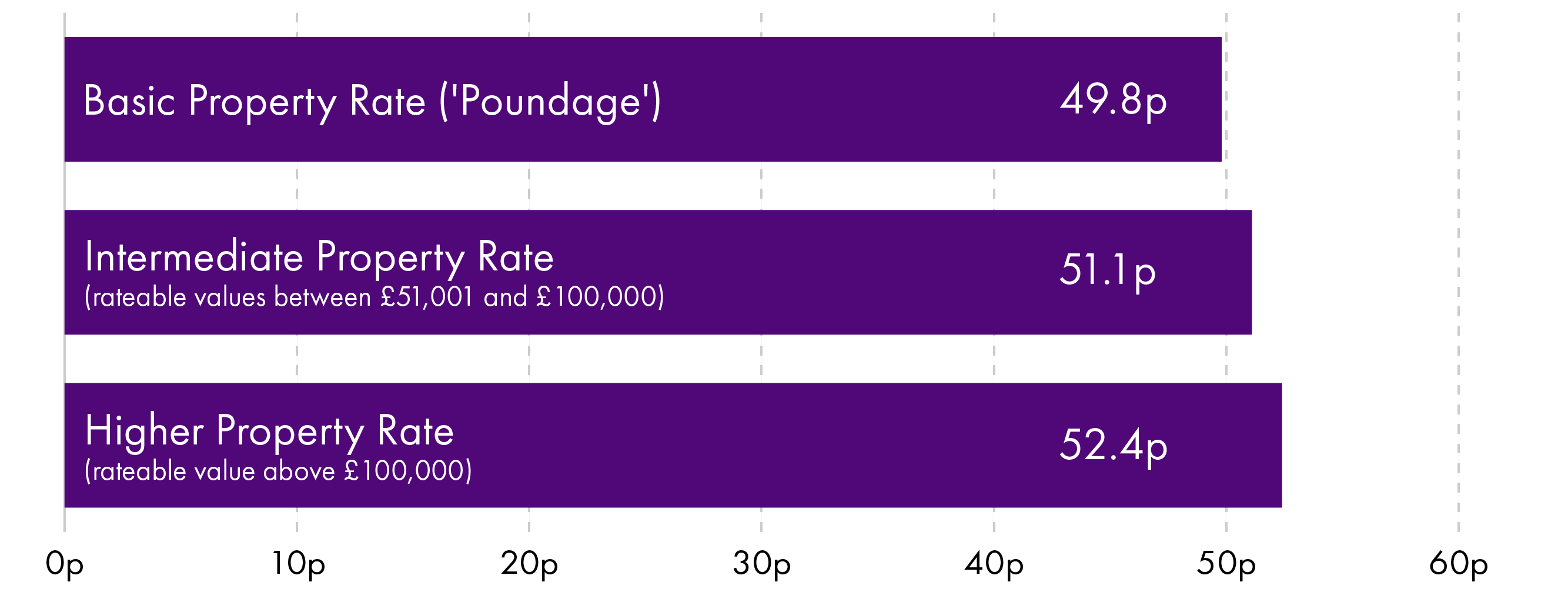

The amount of tax due depends on the rateable value of the property, set by independent assessors, multiplied by the poundage rates set by the Scottish Government. The Scottish Government proposes to maintain the poundage rates from 2022-23 at 49.8 pence for the basic property rate. Figure 9 below sets out the three different rates which apply. The Scottish Fiscal Commission notes that if the poundage rate had increased in line with inflation since 2018-19, it would have risen to 54.8 pence in 2023-24.

A revaluation is scheduled to take effect from 1 April 2023, with final results of this revaluation to be published on the same date. The SFC notes that this ongoing revaluation is a considerable source of uncertainty for the forecast:

Our Non-Domestic Rates (NDR) forecast has been impacted by the ongoing revaluation of all rateable properties. The final valuation roll will not be available until 1 April 2023. Because of this ongoing revaluation, we have used an imputed roll based on an incomplete draft roll to forecast NDR. Any differences between the imputed roll and the final roll will affect our policy costings and forecasts.

The Scottish Government has also reformed the Small Business Bonus Scheme (SBBS). The Fraser of Allander Institute were commissioned by the Scottish Government to analyse this relief, and reported in March 2022 that:

The coverage of the SBBS is broad and usage has increased over time.

There was no empirical evidence that identifies the SBBS as supporting enhanced business outcomes, but there is evidence from its survey that businesses perceive there to be benefits from the SBBS.

Businesses with similar rateable values – the primary criterion on which SBBS eligibility is determined – vary substantially in size and other attributes

There is evidence of ‘bunching’ around the eligibility thresholds of the SBBS in the valuation roll.

There were numerous data-related challenges which limited their ability to draw robust conclusions, and recommended improvements to data to facilitate future evaluations.

The Scottish Government accepted the recommendation to establish a working group to explore improving the data collection in relation to the SBBS.

The SBBS eligibility criteria will be extended from £18,000 to £20,000, but relief will be tapered for properties with a rateable value between £12,001 to £20,000. Car parks, car spaces, advertisements and betting shops will be excluded from the SBBS from 1 April 2023.

In order to smooth the impact of the changes due to the 2023 revaluation and the changes to the SBBS, the Scottish Government is introducing two new transitional reliefs:

One for properties where rateable value has increased after revaluation. This will cap the increase in rateable value in 2023-24, 2024-25 and 2025-26, with the size of the cap depending on the size of the business. Table 6 below sets out these caps, which are calculated in cash terms with reference to 2022-23 rateable values. In other words, a business with a rateable value of £20,000 which faces an increase in rateable value due to the valuation will face a maximum increase in NDR liabilities of 12.5% in 2023-24.

Another relief will be offered to businesses who lose eligibility to the SBBS or the rural rates relief, which will phase the impact of increasing rates liability. For those losing or seeing a reduction in these reliefs (including due to the above exclusions introduced for SBBS relief) the maximum increase in the rates liability will be capped. This will be relative to 31 March 2023 , and the level of the cap is £600 in 2023‑24, rising to £1,200 in 2024‑25 and £1,800 in 2025‑26.

SFC forecasts that these two reliefs will cost around £100 million in 2023-24, falling to £50 million in 2024-25

| Rateable Value | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small (up to £20,000) | 12.5% | 25% | 37.5% |

| Medium (£20,001 to £100,000) | 25% | 50% | 75% |

| Large (Over £100,000) | 37.5% | 75% | 112.5% |

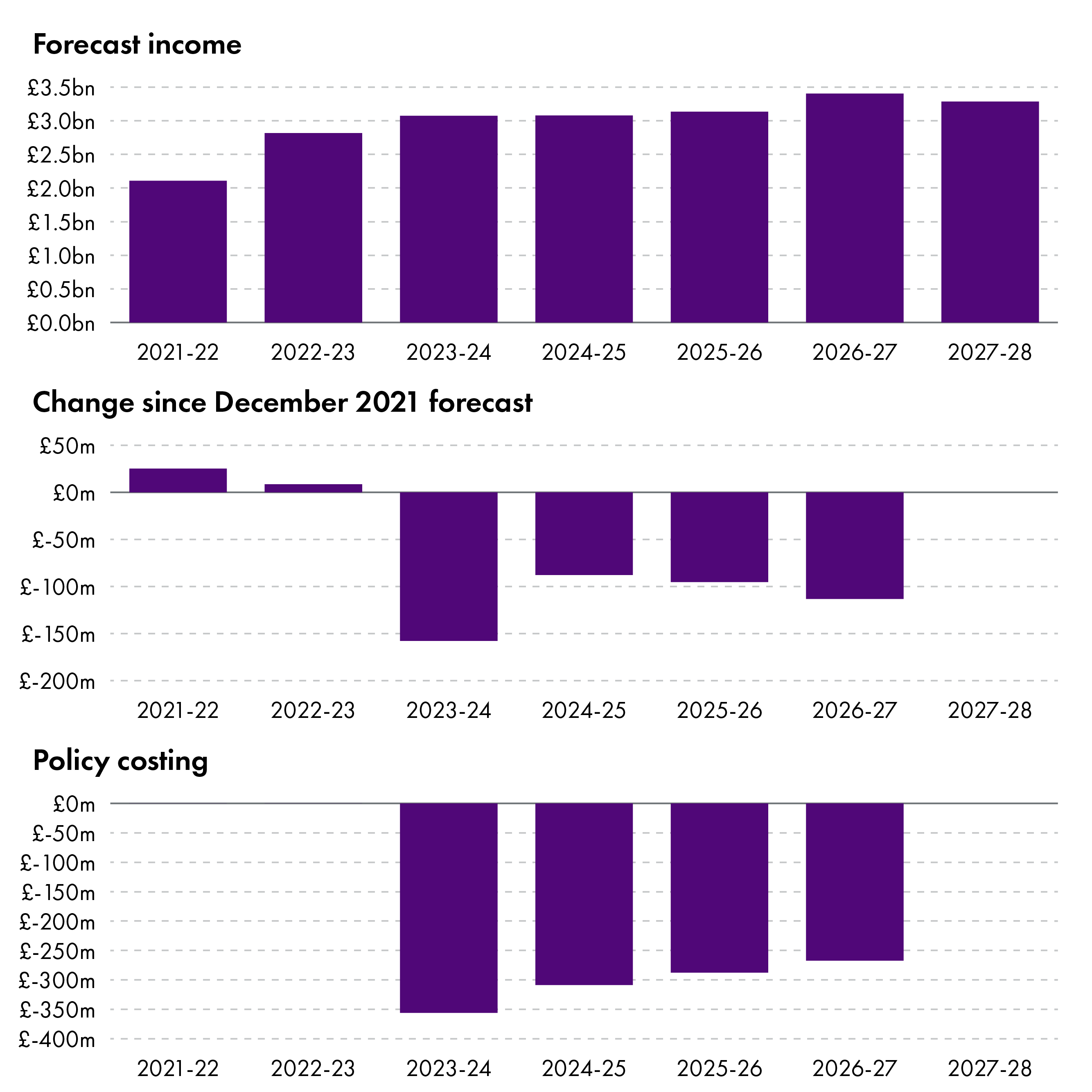

The SFC forecasts that the changes to the SBBS will result in around £50 million higher revenues each year. Overall, the SFC estimate that the policy changes announced will reduce public income by a cumulative £1.2 billion between 2023-24 and 2026-27. Figure 10 below sets out the forecast income from NDR, the changes since the SFC’s forecast in December 2021, and the impact of policy announcements in the Budget:

The most significant change since the December 2021 forecast is the impact of inflation – this is the impact that increasing the poundage in line with inflation would have been expected to have on revenues had the Scottish Government not opted to freeze this at 2022-23 rates. For example, of the forecast £356 million cost of policy in 2023-24, £308 million is due to not increasing poundage in line with inflation. The forecast also reflects the latest available data, and the current information on the impact that the 2023 revaluation is likely to have. However, while this valuation is not complete this is a source of uncertainty in the forecast, as noted above.

As NDR income is distributed to local authorities before it is collected, there is a degree of uncertainty. The SFC forecasts that the distributable amount set in the Budget will lead to a negative balance of £66 million in the NDR pool in 2023-24. This is a reduction from the £200 million negative balance in 2021-22 outturn data. The SFC expects that the NDR pool will be brought back into balance by 2024-25.

Land and buildings transaction tax

Land and building transaction tax (LBTT) is the tax applied to purchases of residential and non-residential land and buildings, as well as commercial leases. The Scottish Government has maintained the residential and non-residential rates and bands at their current level, along with the relief available to first time buyers.

The Budget does include an increase to the Additional Dwelling Supplement (ADS) from 4% to 6%. This supplement is only payable on residential transactions where the acquiring party owns more than once residence once the transaction is complete. This increase will be effective from 16 December 2022 – but will not apply to contracts which were agreed prior to 15 December 2022. The Scottish Government has committed to publish a response to the call for evidence and views on the ADS announced in Scottish Budget 2022‑23 and launch a consultation on draft legislation. This will be published in early 2023.

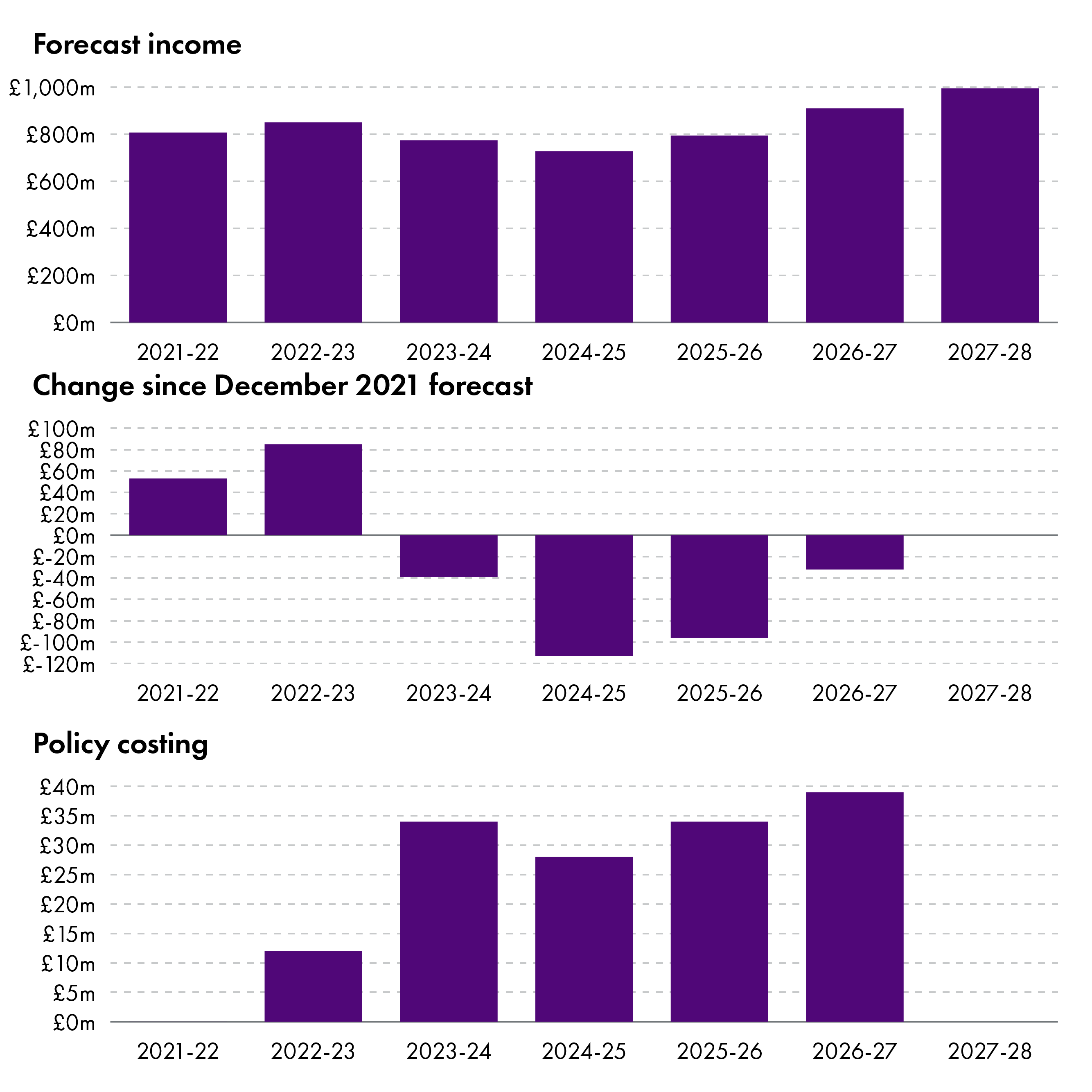

The SFC forecast for LBTT revenues has been revised up for 2021-22 and 2022-23 due to better than expected outturn data, but the forecast for later years revised down due to higher interest rates and downturn in the housing market. The SFC expects that this downturn will reduce prices and number of transactions.

While house prices are expected to reduce (down 2.1 % in 2023-24, and down by 3.0 % in 2024-25), there has been growth in recent years which has meant a greater proportion of transactions fall into the top two tax bands than the SFC expected in the December 2021 forecast. Housing supply remains constricted, which is expected to limit the reduction in price. This is a slightly smaller reduction in price than the OBR project - SFC note that house prices across the UK increased more rapidly than in Scotland, so expects a more pronounced cooling off period.

Transactions are expected to fall by just over 10% in 2022-23, but this largely reflects a return to normal levels after a record year in 2021-22 (driven by pent up demand when the market reopened after the pandemic).

Price and transaction numbers are expected to reduce LBTT revenues by £84 million in 2023-24, £146 million in 2024-25 and £116 million in 2025-26, while the increase in the ADS from 4% to 6% is expected to increase revenues by around £30 million a year from 2023-24 onwards (and will result in around £12 million increased revenue for the remainder of 2022-23 as it is in place for transactions which are agreed after 16 December).

Changes to the forecast for non-residential LBTT are less pronounced – the SFC expect that revenues will be slightly weaker than previous forecasts due to updated GDP forecasts. Prices are expected to begin to rise again once the economy exits recession in 2025-26.

Figure 11 below sets out the forecasts for revenues from LBTT:

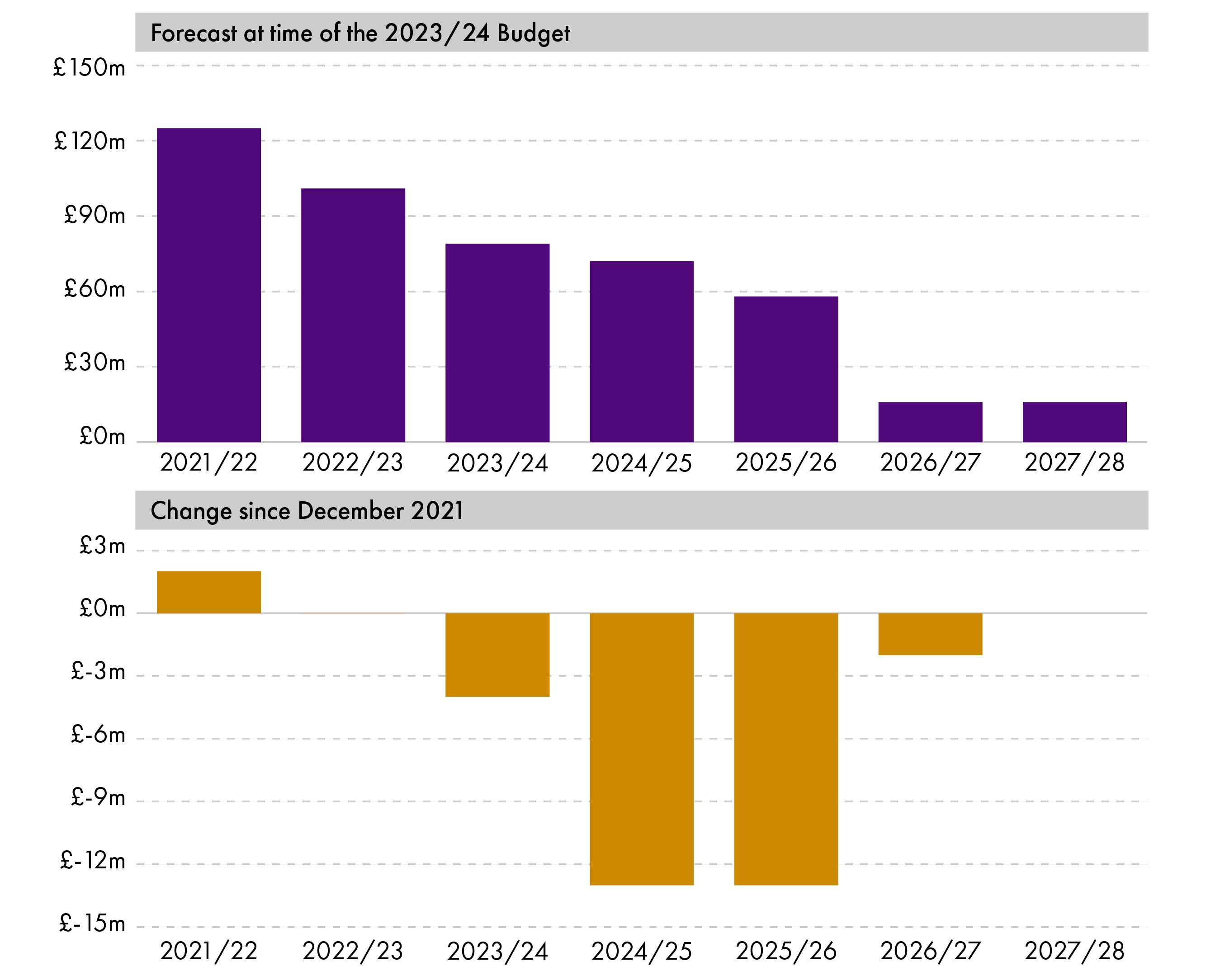

Scottish landfill tax

The Scottish Government has increased the standard and lower rates of Scottish landfill tax (SLfT) to £102.10 per tonne and £3.25 per tonne for 2023-24 respectively. This maintains parity with the UK rates. The SFC forecast relatively minor changes to revenues since December 2021, noting that outturn data in 2022-23 has been lower than expected. Incineration capacity, while subject to some delays, is expected to increase more quickly which drives down expected revenues in the later years. The policy goal of SLfT is behavioural change – the expectation is that over time these revenues will reduce.

There are no new policy announcements in relation to the Airport Departure Tax, the Aggregates Levy or the Assignment of VAT.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission forecasts

Economic growth and inflation

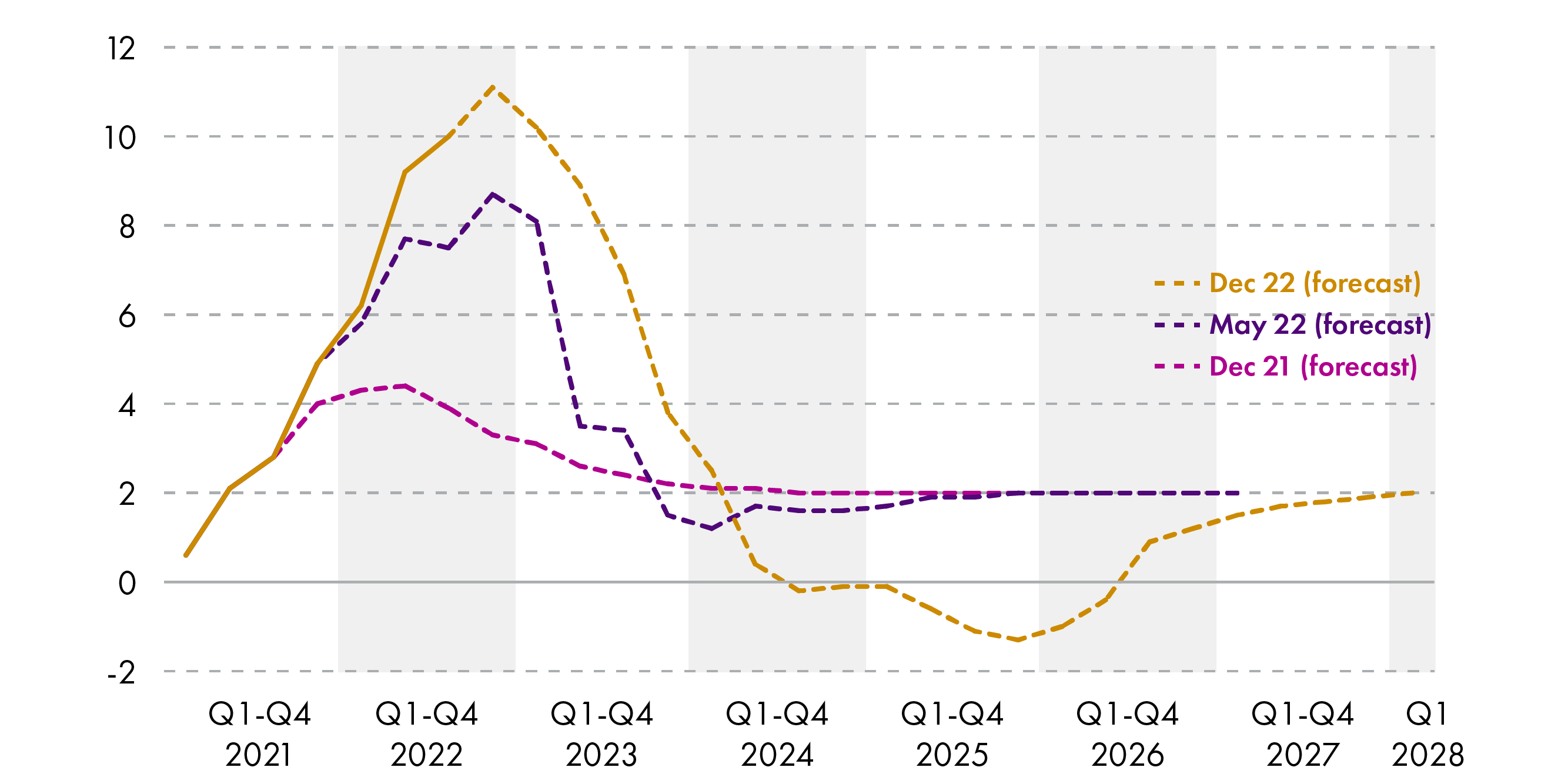

Since the summer CPI inflation in the UK has remained around a 41 year high1, and has been above the Bank of England’s target of 2% since April 2021. Over the last 12 months, the most significant components of the overall increase in prices remain housing and household services (principally from electricity, gas and other fuels, and owner occupiers’ housing costs), food and non-alcoholic beverages, and transport (principally motor fuels). The SFC, like other economic forecasters, expects that inflation will remain considerably above normal levels next year. The SFC forecasts that inflation for 2022-23 will be 10.1 % – so only a slight decrease over the coming months to the end of the financial year from the current rate of CPI of 10.7 % in November. Throughout 2023-24 prices will increase by a further 5.5%, before inflation turns negative for four quarters in 2025-26.

The SFC notes that while inflation affects everyone, there will be a disproportionate impact on low income families (who spend a higher proportion of income on essentials like energy, housing and food). Mortgage costs will increase as interest rates continue to rise, but the SFC highlights that house prices and levels of mortgage debt in Scotland are lower, and therefore this will have a smaller effect in Scotland than the rest of the UK.

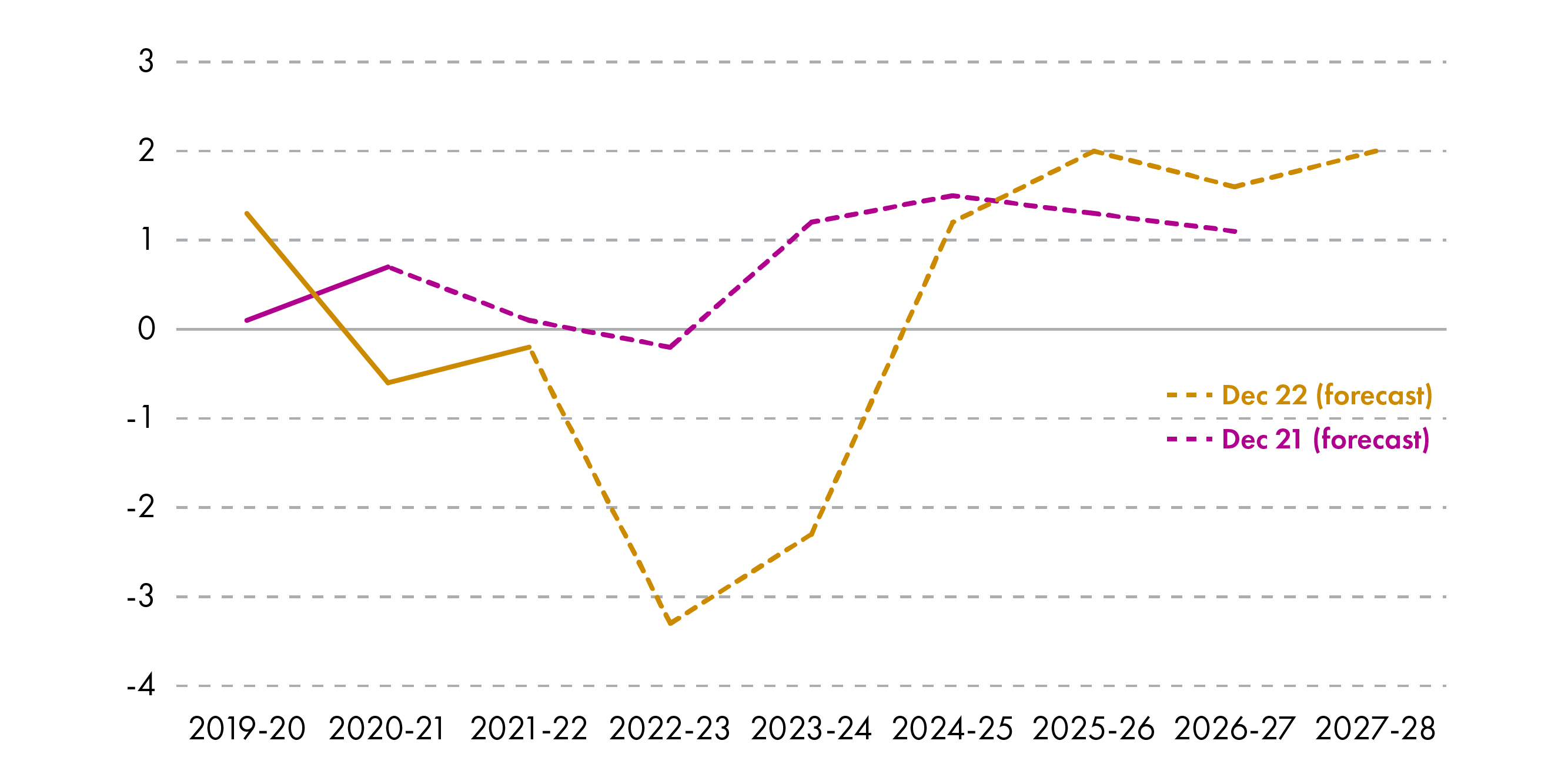

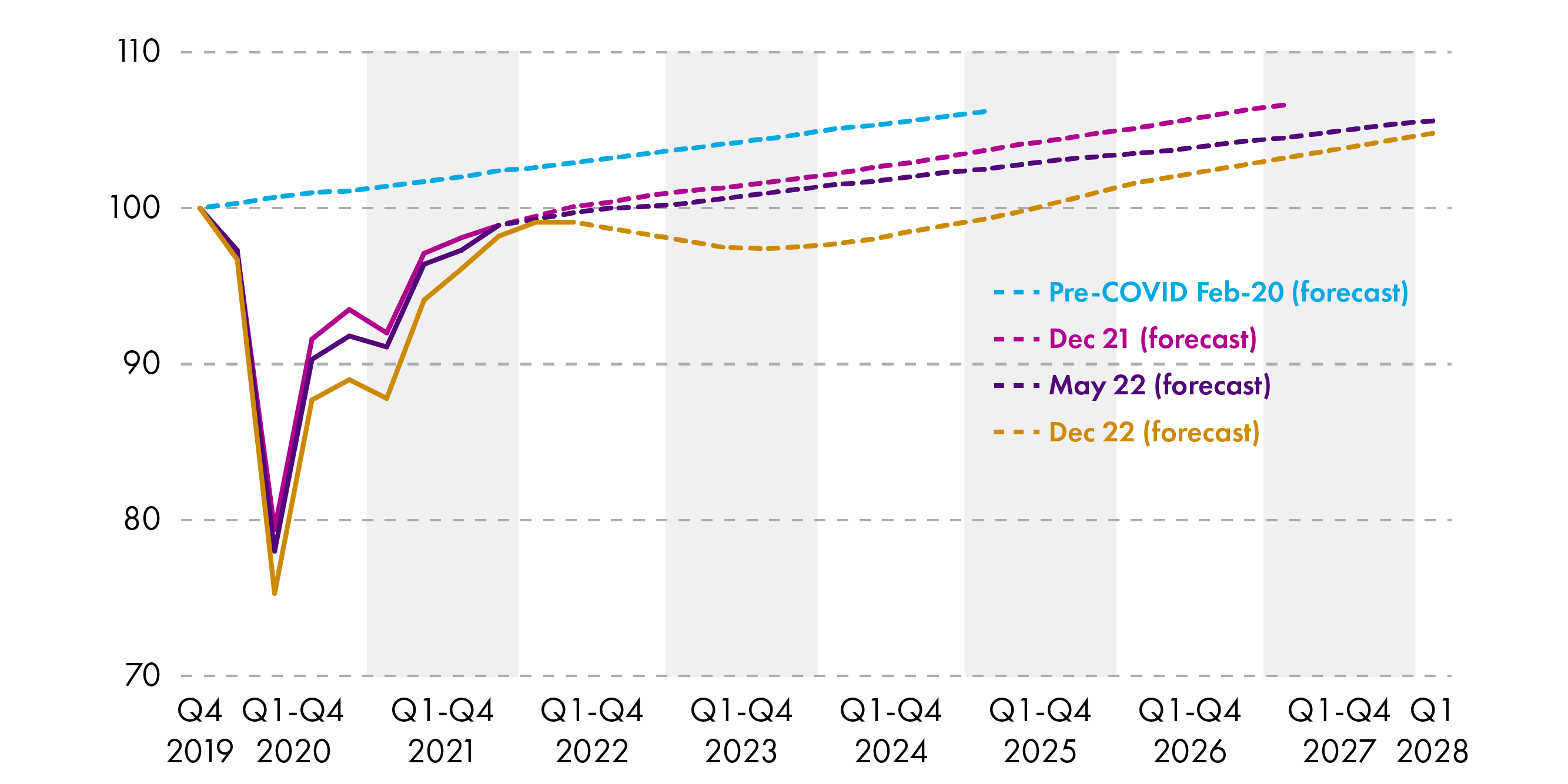

On economic growth, the SFC notes that Scotland is already in a recession which is expected to last six quarters, with a ‘peak to trough’ fall in GDP of 1.8 % (in other words, the lowest GDP is expected to fall compared to the start of the recession is by 1.8 percentage points). This is slightly lower than the 2.1 % peak to trough decline in GDP forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility for the UK. This would be a shallower recession than those as a result of the 2008-09 financial crisis (a 4% decline) or the COVID-19 pandemic (a 21.2% drop). The SFC does not expect the Scottish economy to return to its pre-pandemic level until Q3 2025. However, between Q4 2019 when the pandemic struck, and Q3 2025, the Scottish population is expected to grow by 1.3%, so per capita levels of GDP will remain below their pre pandemic level for longer – not recovering until Q1 2026.

Labour market and earnings

The SFC forecasts that the unemployment rate in Scotland will start to increase from Q4 2022. The latest labour market data from the Scottish Government1 shows that the unemployment rate in October 2022 increased to 3.3 %, suggesting this trend has already begun. The SFC forecasts that this will reach 3.5 % by the end of 2022 and thereafter to rise steadily, reaching 4.7 % in Q4 2024. By the end of the forecast period, Q1 2028, the Scottish unemployment rate is still expected to be higher than its current level, at 4.1 %.

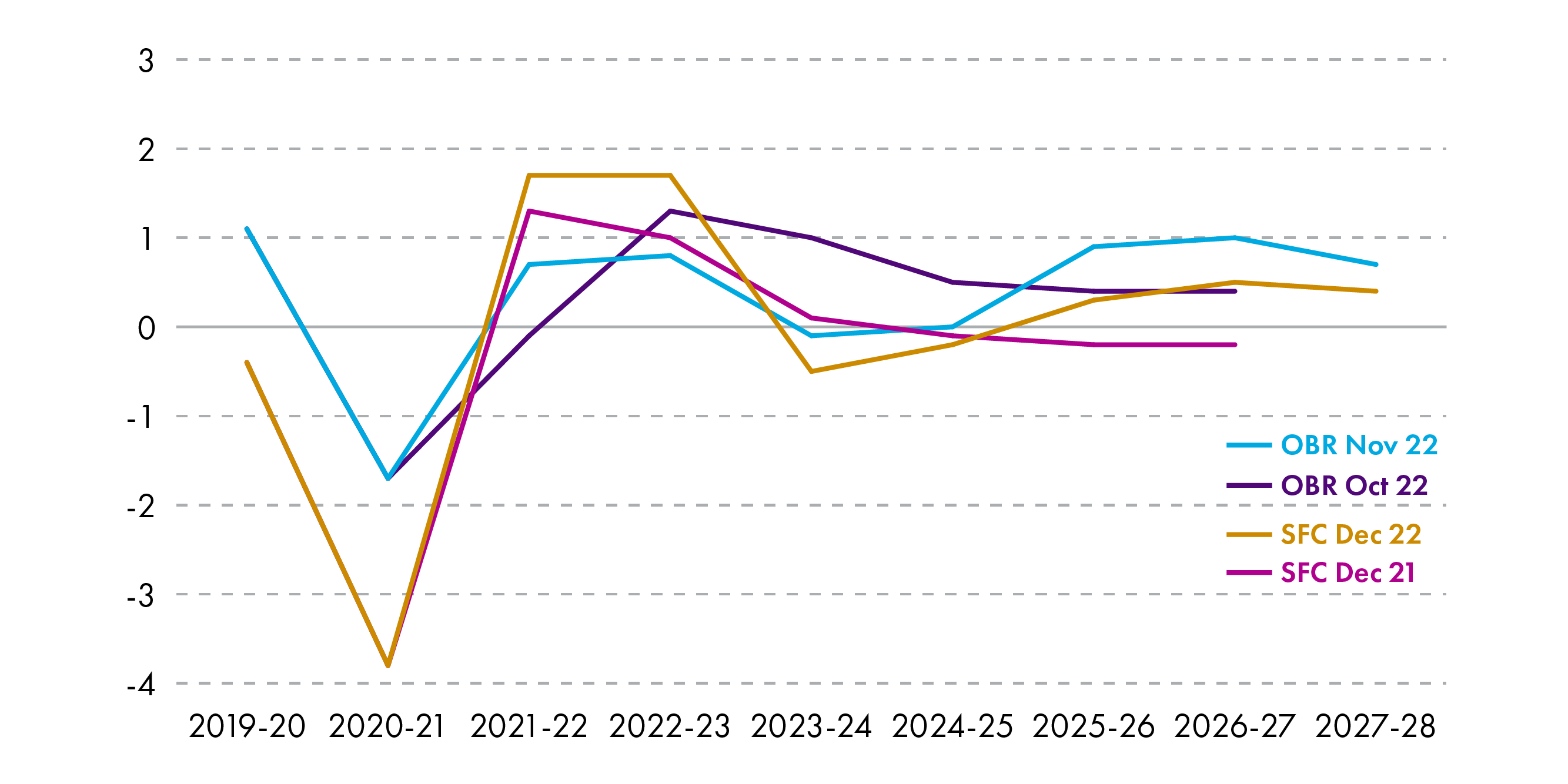

Figure 14 below shows changing forecasts in employment growth from both the SFC and OBR. Since the December 2021 forecast, the SFC now expect lower employment growth in 2023-24 as a result of the economic downturn, although the SFC note this is partially offset by an assumption of increased labour market participation due to the 2026-28 State Pension age increase to 67. This means that the SFC have lowered their expected employment growth rates by less than the OBR have, which contributes to a positive shift in the income tax net position in 2023-24. From 2025-26 onwards, the SFC now expect slightly higher employment growth rates reflecting a higher population growth forecast than last year, and the increased rates of labour market participation mentioned above.

High inflation and a slowdown in economic activity are expected to lead to a fall in living standards of 3.3% in 2022-23, followed by a further fall of 2.3% in 2023-24. The SFC expects a return to positive growth in later years as inflation falls back below the Bank of England’s target of 2%

Forecast comparison

The SFC expects that GDP growth in Scotland will be around 0.5 percentage points lower on average than the OBR expect growth for the UK between 2023-24 and 2027-28. The SFC notes that this difference is broadly in line with historical outturn data for the last 10 years, with around half of this difference being the result of slower population growth in Scotland than the UK. However, even accounting for this difference, GDP per capita growth is expected to be around 0.25 percentage points lower than the UK over the same period. The SFC notes that if you further adjust for different demographics and differences in labour market trends (which is part due to Scotland having a more acutely ageing workforce and therefore a higher dependency ratio), the residual difference on a ‘GDP per economically active’ basis is only around 0.1 percentage points.

Social security

There is a large headline increase in the forecast for social security spend, from £4.2 billion in 2022-23 to £7.3 billion in 2027-28. In 2026-27, the final year of the forecast produced in December 2021, the SFC now expects that social security spending in Scotland will be £1.4 billion higher than had previously been expected. This increase in spending is due in part to higher inflation expectations, with the Scottish Government opting to uprate benefits by 10.1% in the Budget. Inflation accounts for £352 million of this expected increase.

Policy changes announced since the last budget, including the Winter Fuel Payment and measures outlined in the Tackling Child Poverty Delivery Plan will increase spending by £418 million in 2026-27.

Finally, the SFC expects increased demand for the Adult Disability Payment following the COVID-19 pandemic, which accounts for a further £186 million of the increase in spending by 2026-27.

The SFC also expects the adult disability payment to increase from 47% of total social security spending in 2021-22 to 57% by 2027-28. The next most significant policies are the Pension Age Disability payment (11% in 2027-28), the Scottish Carer’s Assistance (8% in 2027-28), the Scottish Child Payment (6%) and the Child Disability Payment (6%).

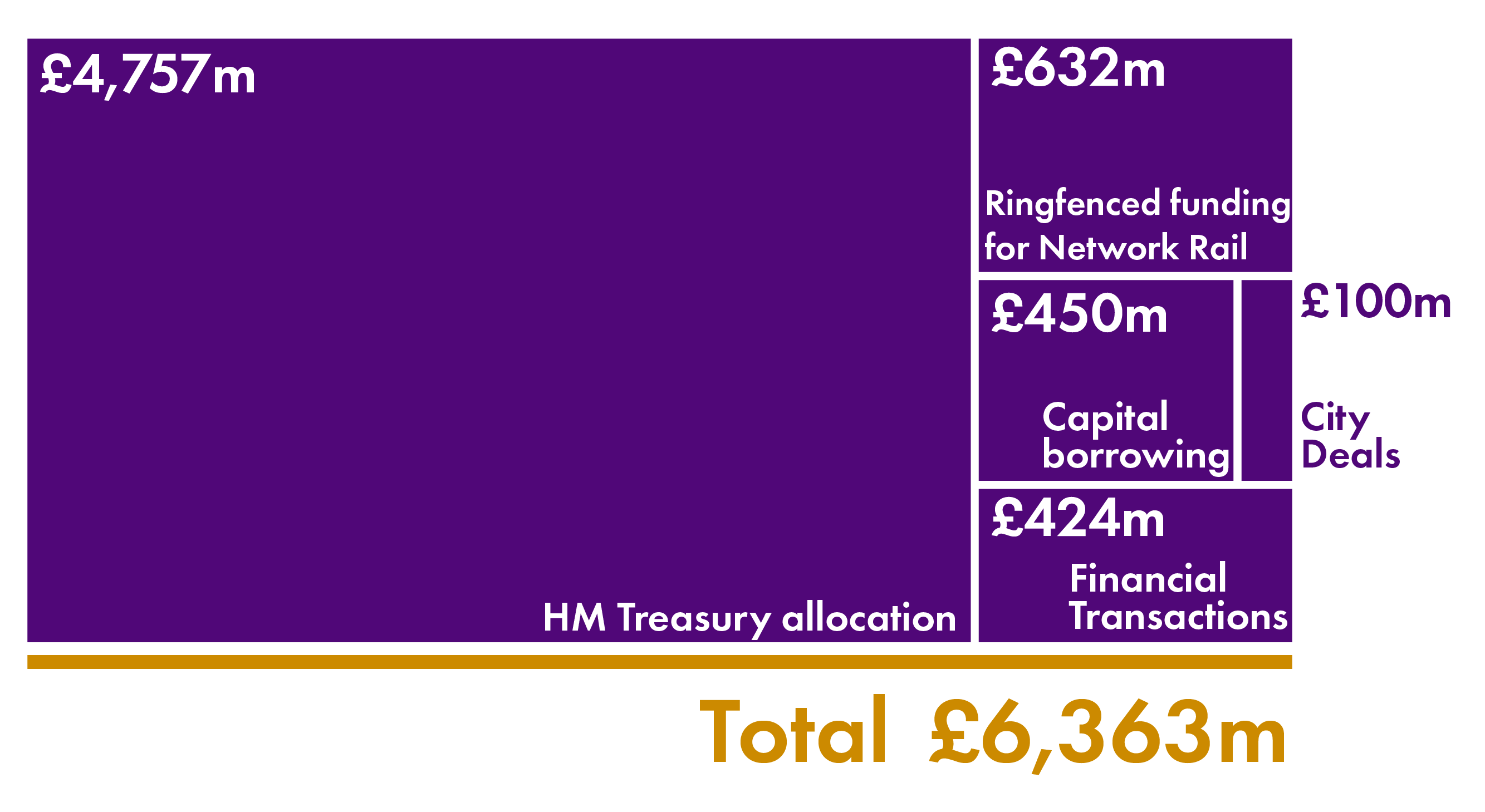

Capital and infrastructure

The 2023-24 capital budget from HM Treasury is £4,757 million, a 6.4% increase in cash terms compared with 2022-23. There is also £632 million of capital funding ring-fenced for Network Rail and a further £100 million anticipated to come from the UK government in support of City Deals. In addition to this, the Scottish Government states its intention to make full use of its capital borrowing powers (£450 million) to support capital investment in 2023-24. Financial Transactions (FT) funding of £424 million is also available for 2023-24 and is discussed further below.

When all sources of capital funding are taken into account, the total capital budget is flat in cash terms. This means that, with inflation at high levels, less will be able to be achieved with the same cash budget. The Scottish Government notes that inflation (including input prices and energy prices) is impacting on the spending power of its capital budget:

Given the value of our capital budget will not be able to extend as far as was envisaged when inflation and other costs were at more benign levels, the Government will continuously review the impact of these factors on our capital programme.

The UK government also announced in the November 2022 Autumn Statement that capital budgets will remain fixed in cash terms at 2024-25 levels until 2027-28, which will further constrain capital spending plans.

In previous years, the Scottish Government has used revenue financing to increase the level of infrastructure investment that can be achieved through the capital budget alone. Revenue financing means that the Scottish Government does not pay the upfront construction costs, but is committed to making annual repayments to the contractor, typically over the course of 25-30 years. The Budget document does not make any reference to the use of revenue financing, although the Scottish Government’s Medium Term Financial Strategy published in May 2022 had identified that revenue financing would be used to support capital investment of £520 million in 2023-24. It is not clear how the changes to planned use of revenue financing might affect the Scottish Government’s ability to meet the ambitions set out in its National Infrastructure Mission. This set out plans to increase annual infrastructure investment so that annual investment is £1.56 billion higher in 2025-26, when compared with a 2019-20 baseline. No comment on progress towards this commitment is provided in the Budget document.

Borrowing powers

The Scottish Government is able to borrow up to £450 million in each year for capital investment, up to a cumulative total of £3 billion. The Budget sets out plans to borrow the maximum £450 million to support infrastructure expenditure in 2023-24. However, the borrowing policy that was outlined in the most recent (May 2022) Medium Term Financial Strategy noted that the total of £450 million would be assumed to come from a combination of borrowing, the Scotland Reserve and Barnett consequentials “of which £250 million will initially be assumed to be capital borrowing”. Commenting on this policy, the SFC states:

For 2023-24 and subsequent years, the Scottish Government assumes a total of £450 million in funding from borrowing, drawdowns, additional UK consequentials and other sources. The Scottish Government plans to borrow £250 million in 2023-24 and will increase this if the other funding sources do not produce £200 million. We have assessed this borrowing plan to be reasonable. However, we note that it seems unlikely the full £200 million will be available for 2023-24 given UK Government fiscal tightening on capital spending and Scottish Government plans to draw down all reserve funds in 2022-23.

The SFC also notes the impact that increased borrowing will have on the sustainability of borrowing plans, given the cap of £3 billion on cumulative capital borrowing:

The capital debt stock is currently at 60 % of the overall limit. Interest rates have almost trebled since May 2022, which slows the repayment of principal on the first half of the life of the loans. Given the latest borrowing plans for 2022-23, our models suggest that the Scottish Government will have to either reduce the baseline borrowing or take out loans at durations shorter than 15 years by the early 2030s to remain within the fiscal framework limits.

Financial transactions

The 2022-23 Budget includes £424 million for financial transactions (FTs), including drawdown of £50 million from the Scotland Reserve. These FTs relates to Barnett consequentials resulting from a range of UK government equity/loan finance schemes (primarily the UK housing scheme, Help to Buy) and have been a regular source of funding since 2012-13. The Scottish Government has to use these funds to support equity/loan schemes beyond the public sector, but has some discretion in the exact parameters of those schemes and the areas in which they will be offered. This means that the Scottish Government is not obliged to restrict these schemes to housing-related measures and is able to provide a different mix of equity/loan finance.

The total for 2023-24 includes a £188 million addition to correct for miscalculations that had been identified in the Barnett formula for FT funding allocations in earlier years. The final amount to be allocated in respect of these earlier miscalculations is yet to be agreed between HM Treasury and the Scottish Government.

For 2023-24, a total of £85 million (gross) in financial transactions has been allocated to housing-related schemes. The Scottish Government is also providing equity/loan finance support in areas other than housing. In 2023-24, £238 million (gross) in FTs will also be used to provide capitalisation for the Scottish National Investment Bank.

Individual tables in the budget document show the following profile for financial transactions.

| Portfolio | £ million |

|---|---|

| Health and Social Care | 5 |

| Social Justice, Housing and Local Government | 85 |

| Finance and Economy | 258 |

| Education & Skills | 15 |

| Net Zero, Energy and Transport | 61 |

| Total | 424 |

The Scottish Government will be required to make repayments to HM Treasury in respect of these financial transactions. These repayments will be spread over 30 years, reflecting the fact that the majority of FT allocations relate to long term lending to support house purchases and the construction sector. The repayment schedule is based on the anticipated profile of Scottish Government receipts. A repayment to HM Treasury of £210 million in respect of FTs was made in 2021-22.

Revenue financing and the 5% cap

Annual repayments resulting from revenue financed projects and borrowing come from the Scottish Government’s resource budget. The Scottish Government is committed to spending no more than 5% of its total resource budget (excluding social security) on repayments resulting from revenue financing (which includes NPD/hub, previous PPP contracts, regulatory asset base (RAB) rail investment) and any repayments resulting from borrowing. The most recent (May 2022) Medium Term Financial Strategy noted that relevant costs would peak in 2025-26 with planned and committed projects and borrowing costs estimated to be 2.61% of the resource budget excluding social security. The lack of any plans to use revenue financing for infrastructure investment in 2023-24 will mean little upward pressure on repayments in the short-term. However, any future plans for revenue financing could mean an increase in repayments related to revenue financing in future years, along with increased borrowing repayments which will be affected by higher interest rates.

Local government

In last week’s Budget announcement, the Deputy First Minister told Parliament he was “increasing the resources available to Local Government next year by over £550 million”. This increase refers to “core” revenue and capital allocations plus funding transferred to local government from other portfolios in-year (for an explanation of these terms, see recent SPICe Briefing). The following table shows that the total local government settlement, also set out in this week’s Finance Circular, will be £13.2 billion in 2023-24. This represents a cash increase of 5.1%, or a real-terms increase of 1.8%, when comparing Budget 2023-24 to Budget 2022-23.

| Local government | 2022-23 (£ millions) | 2023-24 (£ millions) | Cash change (£ millions) | Cash change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Revenue Grant | 7,094.60 | 7,133.90 | 39.3 | 0.6% |

| Non-Domestic Rates | 2,766.0 | 3,047.00 | 281.0 | 10.2% |

| Specific Resource Grants | 752.1 | 752.1 | 0.0 | 0.0% |

| General Capital Grant | 510.50 | 607.60 | 97.1 | 19.0% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) capital grants | 139.0 | 139.00 | 0.0 | 0.0% |

| Local Government settlement | 11,262.2 | 11,679.6 | 417.4 | 3.7% |

| Plus in-year transfers from other portfolios (rev+cap) | 1,332.1 | 1,551.8 | 219.7 | 16.5% |

| Total | 12,594.3 | 13,231.4 | 637.1 | 5.1% |

Note on Table 8: The total increase of £637.1 million compares Budget 2023-24 to Budget 2022-23 and is a real terms increase of 1.8% (see table 9 below for real terms figures). This figure is complicated due to the addition, during the budget process for the 2022-23 Budget of the resource support for school meals, which were not included in the comparable tables in the 2022-23 Budget document last year. This funding totals £64 million (£21.8 million to support meals in the holiday, and £42.2 million to support the expansion of free school meals). Including these amounts in last year’s settlement would reduce the £637.1 million increase in the table above, but it would still be by “over £550 million.”

| Local Government (Revenue) | 2022-23 (£ millions) | 2023-24 (£ millions) | Real change (£ millions) | Real change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Revenue Grant | 7,094.60 | 6,910.52 | -184.1 | -2.6% |

| Non-Domestic Rates | 2,766.0 | 2,951.59 | 185.6 | 6.7% |

| Specific Resource Grants | 752.1 | 728.55 | -23.6 | -3.1% |

| General Capital Grant | 510.50 | 588.57 | 78.1 | 15.3% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) capital grants | 139.0 | 134.65 | -4.4 | -3.1% |

| Local Government settlement | 11,262.2 | 11,313.88 | 51.7 | 0.5% |

| Plus in-year funding from other portfolios | 1332.1 | 1,503.21 | 219.7 | 16.5% |

| Total | 12,594.3 | 12,817.1 | 222.8 | 1.8% |

These tables show that in-year transfers from other portfolios amount to 12% of total allocation in 2023-24. There is always some debate about how much flexibility local government has over these transfers. The Scottish Government’s position is that the funding is provided to support specific policies; however, it does not have terms and conditions attached (so is not ring-fenced). The Government states that the transferred revenue funding is included in the weekly General Revenue Grant payments and councils have autonomy to allocate the GRG based on local needs and priorities.

Changes to the “core” revenue allocation

In their press release published on Friday1, COSLA spoke about cuts to local government’s “core” budget, i.e. the combination of General Revenue Grant, Non-Domestic Rates income and Specific Resource Grants. This amounts to £10.9 billion in 2023-24, representing a cash increase of £320 million over the year (+3.0%), or a slight real-terms decrease of £22 million (-0.2%).

| Local Government (Revenue) | 2022-23 (£ millions) | 2023-24 (£ millions) | Cash change (£ millions) | Cash change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Revenue Grant | 7,094.6 | 7,133.9 | 39.3 | 0.6% |

| Non-Domestic Rates | 2,766.0 | 3,047.0 | 281.0 | 10.2% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) Resource Grants | 752.1 | 752.1 | 0.0 | 0.0% |

| Total "core" revenue funding | 10,612.7 | 10,933.0 | 320.3 | 3.0% |

| Local Government (Revenue) | 2022-23 (£ millions) | 2023-24 (£ millions) | Real change (£ millions) | Real change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Revenue Grant | 7,094.6 | 6,910.5 | -184.1 | -2.6% |

| Non-Domestic Rates | 2,766.0 | 2,951.6 | 185.6 | 6.7% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) Resource Grants | 752.1 | 728.55 | -23.6 | -3.1% |

| Total "core" revenue funding | 10,612.7 | 10,590.6 | -22.0 | -0.2% |

COSLA are disappointed at the budget, believing that local government has not been prioritised. Acknowledging the Government’s claim of a cash increase for local government, COSLA calculates that, in their view, the actual cash increase will be a much smaller £71 million once the costs of previous policy commitments are accounted for. Arguing that real-terms cuts to councils’ budgets will impact the most vulnerable in society and damage the local government workforce, the potential implications are set out in COSLA’s Save Our Services campaign and in its recent submission to the Finance and Public Administration Committee. They have vowed to “fight for a fairer settlement”.

Funding local government pay deals

Perhaps the most pressing and highest-profile issue facing local authorities in 2022 has been the pressure of meeting the pay demands of their 260,000 strong workforce. With teacher strikes still ongoing, the issue is far from being resolved, even within this current financial year. Local government is by far the largest public sector employerin Scotland, with COSLA and Directors of Finance estimating that between 60 and 70% of the local government budget is used to pay for workforce costs.

The Scottish Government stress that councils are the employer when it comes to the local authority workforce, and relevant trade unions should negotiate with COSLA on national pay deals. The fact remains, however, that the majority of local government net expenditure funding comes from the Scottish Government in the form of grants and NDR distribution, and much of this will be used to pay the wages of carers, teachers, social workers, street cleaners, bin collectors, planners, etc.

This issue came knocking on the Scottish Government’s door over the summer with the Deputy First Minister updating Parliament in September on public sector pay and revealing details of his emergency budget review. Helping fund COSLA’s revised pay deal, the Scottish Government committed an additional £140 million revenue and £121 million capital in both 2022-23 and 2023-24 to local government, and £261 million revenue in 2024-25. These additional sums are factored in to the 2023-24 Budget figures but are not included in the 2022-23 baseline figures used in the Budget document. This was picked-up by the Institute for Fiscal Studies in their analysis of the Scottish Budget last week:

Local government is a notable case in point, where a sizeable £260 million extra has been found for pay awards this year: the costs of these awards will continue into next year, but this funding has been excluded from the year-to-year comparisons quoted by the Scottish Government. Taking this into account suggests that rather than falling by 0.2% in real terms, as suggested by the Scottish Budget, funding for the main local government portfolio will in fact fall by substantially more.

The Deputy First Minister made little reference to future local government pay deals in his Budget statement. However, in his Emergency Budget Review statement in September, he noted that “our reserve funding is fully allocated”, and again last week he stated that the Government is “assuming that we do not carry forward any fiscal resources from this year into next”. The extent of local government’s reserves (at the end of financial year 2021-22) will become clear when the Accounts Commission publishes its Local Government Overview in January. However, Roz Foyer, General Secretary of the STUC raised the issue of local authority reserves during BBC's Sunday Show on the 11th December: “we’ve also got over £3 billion of reserves sitting in local government which could help us resolve some of the [pay] disputes right now”.

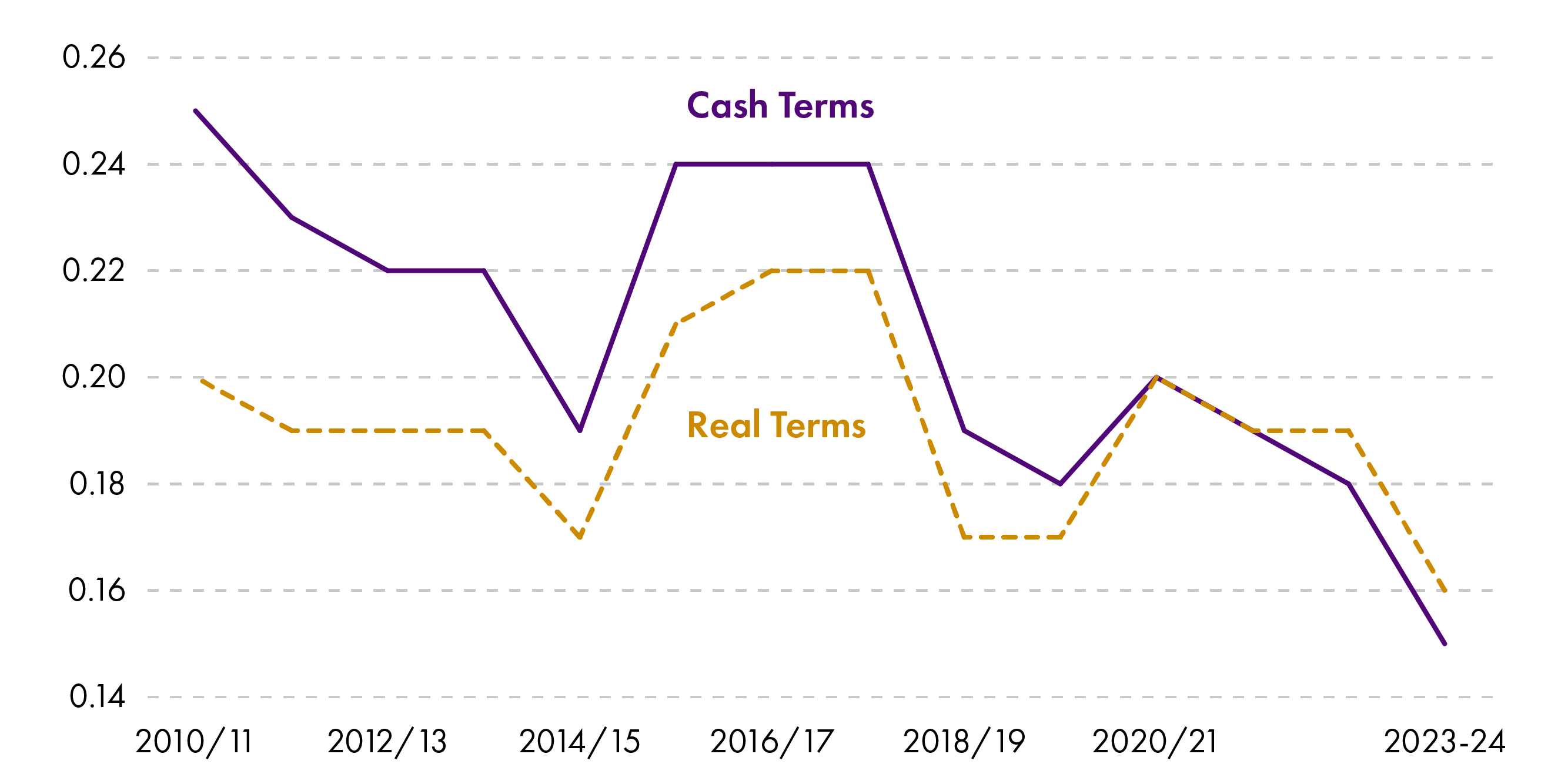

Council tax

Council tax is the only local tax in Scotland, with councils having responsibility for setting Band D rates each year. Although ratios between bands are defined in national legislation, the tax is local in the sense that it is set locally, collected by local authorities, retained locally and spent entirely on local services. In 2020-21, council tax receipts amounted to £2.6 billion, or around 20% of total local government net revenue funding (see The Funding of Local Government in Scotland, 2022-23).

For most of the past 15 years, the Scottish Government has sought local government’s agreement to freeze or cap council tax. Last year, however, the Cabinet Secretary for Finance and the Economy lifted the freeze, stating that councils would have “complete flexibility to set the council tax rate that is appropriate for their local authority area”. BBC Scotland published analysis earlier this year showing that all councils, except Shetland, opted for an increase. The Deputy First Minister again confirmed he would not seek a freeze in 2023-24. Therefore, councils must now decide whether or not to increase taxes on households already facing hardships and squeezed disposable incomes.

Unlike the Scottish Government’s income tax powers, councils do not have the ability to increase council tax rates for some households whilst lowering them for others. If they decide to increase council tax, rates will rise for all eligible households. Fraser of Allander research from 2020 confirmed the regressive nature of council tax, with households in the bottom income quantile paying 4.6% of their gross income in council tax, whilst households in the top quantile pay only 1.4%. In other words, any council tax increases could be proportionately more painful for lower income households than wealthier ones.

Climate change

The Budget states that one of the Government’s three priorities is to transform the economy to deliver a just transition to net zero. This section summarises the policy pledges made to support this ambition, and gives an overview of the supporting information to understand the impact of these spending decisions on the climate.

As with previous budgets, this year’s is accompanied by the ‘carbon assessment of the budget’ and the ‘taxonomy of capital spending’, but this year we also have a new ‘climate change assessment of the budget’ – a narrative section which highlights spending across portfolios which will contribute to the Government’s aim to achieve a just transition to net zero.

Delivering a just transition

On 7 December 2022 the UK Climate Change Committee (CCC) published their annual ‘Progress in reducing emissions in Scotland’ report. The report outlines a challenging set of key messages for the Scottish Government, noting that:

Scotland’s emissions reduction targets are amongst the most stretching in the world and the Scottish Government has placed a welcome focus on a fair and just transition. Key milestones are ambitious, but a clear delivery plan on how they will be achieved is still missing and there is no quantification of how policies combine to give the emissions reduction required to meet Scotland’s targets.

The CCC suggest that:

Scotland’s ambitious interim 2030 goal of a 75% reduction in emissions since 1990 will be ‘extremely challenging’ to achieve, and that a 65% to 67% reduction would be consistent with meeting the 2045 net zero target.

While the 2020 annual emissions reduction target was met, this was likely only due to the considerable impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which significantly reduced emissions from transport.

The Scottish Government needs to set out a quantified delivery plan which demonstrates how policy will deliver these emissions reductions.

The key sectors which require focus are transport, buildings, agriculture and land use, and industrial emissions.

Cooperation between the Scottish and UK governments will be essential to realise the Scottish Government’s ambitions, particularly with respect to industrial emissions where many of the levers are reserved.

Key policy announcements in the Budget include:

The Heat in Buildings strategy commits £1.8 billion over the course of this parliament to support heat and energy efficiency measures, with the aim to shift over 1 million Scottish homes to zero-carbon heating by 2030. The 2023-24 Budget includes an investment of £366 million.

The Budget also allocates another £29 million to the Just Transition Fund for the North East and Moray. In October the Minister for Just Transition, Employment and Fair Work wrote to the Economy and Fair Work Committee setting out details of the first 22 projects to receive funding from the Just Transition Fund. This funding is worth a total of £50 million, but some of the projects are multiyear and so not all funding will be drawn down immediately.

As part of the Emergency Budget Review and the Autumn Budget Revision, the Scottish Government announced that some £91 million of underspends from net zero grant schemes would be reprioritised. Of this, £38 million was from the Energy Efficiency Capital Grants, and £45 million from Heat in Buildings Capital Grants. In relation to both these underspends, the Scottish Government noted that this was due to uptake being lower than originally forecast. The Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee asked for more details about these redeployed monies in their Pre-budget scrutiny letter. Given demand has been lower than expected, committees may wish to explore how the Scottish Government is increasing demand and ensuring that these programmes can take advantage of the additional resources allocated in the Budget.

The Fraser of Allander Institute notes that:

The latest budget document doesn’t delve far into any new spending on transitioning to net-zero, but John Swinney did mention several initiatives which were included in the May 2022 spending review in his speech. A new initiative, a pilot scheme trialling the removal of peak-time rail fares was the main new policy of interest announced.

By the end of 2022 the Scottish Government plans to publish their first Just Transition Plan for the energy sector, alongside a refreshed energy strategy, and in Spring 2023 further sectoral Just Transition Plans will be published covering the construction, transport, and agriculture and land use sectors). These will be accompanied by a Just Transition Plan for Grangemouth. All these plans will be published in draft form and consulted on, and will be finalised ahead of the Climate Change Plan update being published before the end of the year

Climate Change Assessment of the Budget

This is a new section of the Budget and provides an overarching narrative highlighting policy and spending across portfolios, which are aimed at delivering the Scottish Government’s ambition of a just transition to net zero. The Scottish Government highlights that total emissions are down by 51% since the base year of 1990 – in other words Scotland is halfway to achieving its net zero target. However, the Government also note that the scale of change required to reach remaining targets is ‘significant’. This will need to be achieved through ‘targeted, impactful and long-term investment’.

This section outlines policy commitments across a range of areas, including:

Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency: The £1.8 billion investment supporting the Heat in Buildings Strategy aims to shift 1 million Scottish homes to zero carbon heating, and the recently published Hydrogen Action Plan is supported by £100 million in funding. Key to achieving targets to reduce industrial emissions will be emissions removal technology such as Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS), and the Scottish government have pledged £80 million to support the Scottish Cluster.

Transport: £359 million in 2023-24 for free bus travel and £35 million to address congestion and make bus travel more attractive, £197 million on active travel, and £1.4 billion for Scotland’s railways, some of which will continue the electrification of the network.

Agriculture, Rural Affairs and Islands: £45 million for the National Test Programme to support pioneer projects which promote more sustainable farming practices.

Nature restoration: £26 million for peatland restoration, and £77 million for reforestation.

Flood Management: £42 million to reduce flood risk

Zero Waste and Circular Economy: £47 million in the circular economy, including the deposit return scheme.

Private Investment and natural capital: £240 million in funding for the Scottish National Investment Bank, who aim to crowd in private capital.

Climate Change Policy Development, Implementation and Public Engagement: Total investment of £80 million, including a further £29 million in the 10 year Just Transition Fund for the North East and Moray.

As noted above, many of these policies have been announced in previous programmes for government or budgets. The Climate Change Commission (CCC) have highlighted the key challenge in providing credible and quantifiable policy to achieve future emissions reduction targets, including the challenging 2030 interim targets. The Scottish Government has a programme of work planned between now and the end of 2023 which will see Just Transition Plans published for the energy, construction, agriculture and land use and transport sectors, as well as the first place-based plan covering Grangemouth, leading up to the Climate Change Plan update which is due to be laid in Parliament before the end of 2023. The ability of the Scottish Government to achieve the stretching, statutory targets for reducing emissions will rely on the delivery and scaling up of these existing policies. The CCC stated in their 7 December 2022 report that:

The Scottish Government lacks a clear delivery plan and has not offered a coherent explanation for how its policies will achieve Scotland’s bold emissions reduction targets

This Budget does not address these concerns, but it is expected that the Just Transition Plans and the Climate Change Plan update should do.

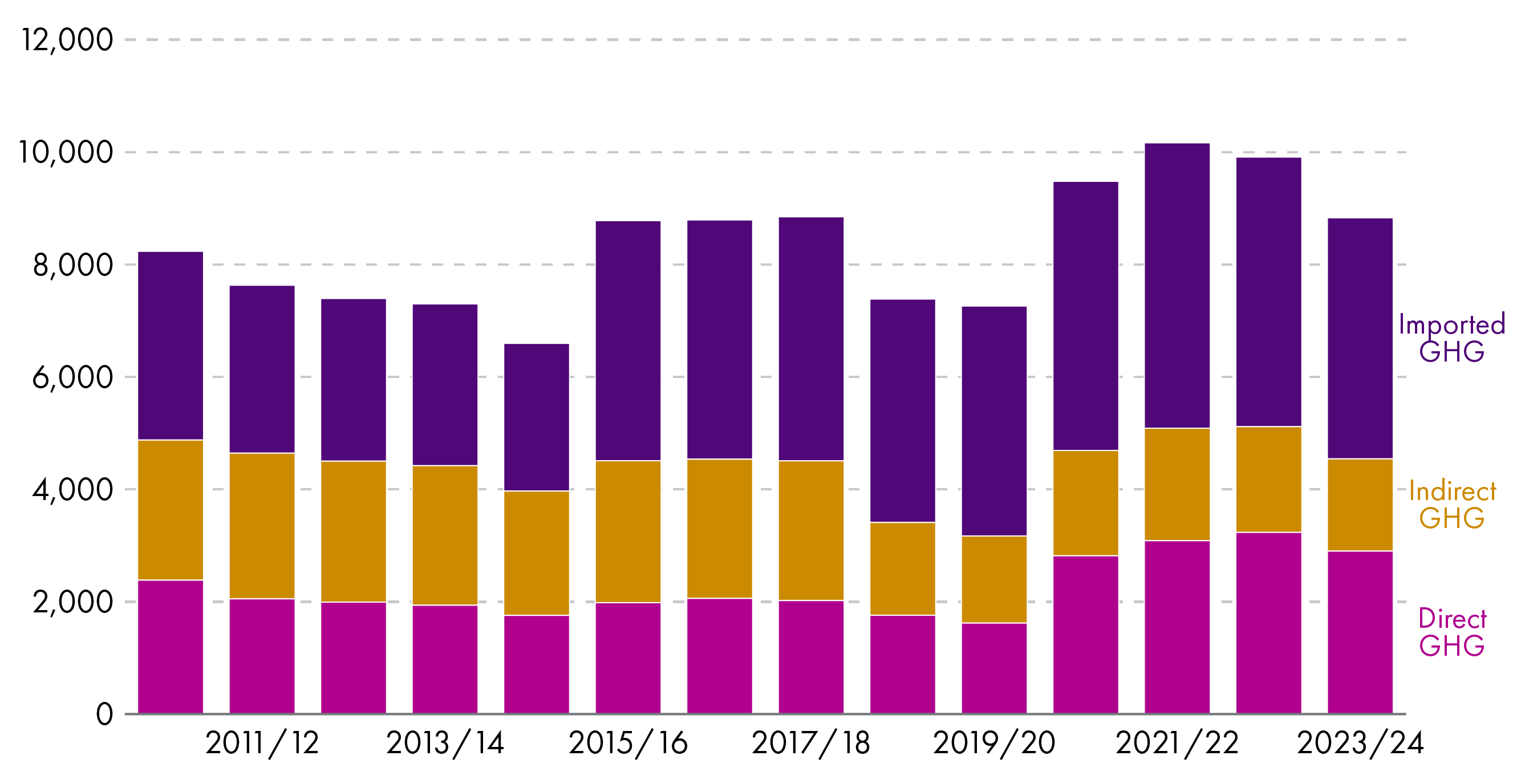

Carbon assessment

The Climate Change Act 2009 requires the Scottish Government to provide assessments of the impacts on greenhouse gas emissions of activities funded by its budget. The Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) Act 2019 also requires a carbon assessment of the Infrastructure Investment Plan. Since 2009, thirteen high-level carbon assessments of the budget have been published using an Environmentally-extended Input-Output (EIO)model to estimate emissions. This model is normally used to understand the flow of money though the economy. However, the environmentally-extended version averages greenhouse gas effects for 98 industry sectors and converts the financial inputs from the budget into expected greenhouse gas outputs. This model shows the direct, indirect and imported emissions associated with the Scottish Budget.

The Scottish Government acknowledge the limitations of this methodology in the publication; it cannot be used for example to assess the impact of any given policy on the environment, and it does not measure the potential longer term impacts of policy on emissions in Scotland – there is no assessment of ‘second round’ emissions or indeed emissions reductions. It does, however, provide an indication of the direct, indirect and imported emissions which can be associated with spending decisions in the Scottish budget.

Total emissions associated with the Scottish Budget for 2023-24 will be 8.8 million tonnes carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e). This is a reduction from the 9.9 MtCO2e associated with the 2022-23 Budget. However, in absolute terms GHG emissions are higher now than in 2010-11. The assessment breaks down emissions by industrial source, and whether these are direct, indirect or imported emissions. 26 % of emissions are due to energy, water and waste services; manufacturing is 20 percent, while agriculture, forestry and fishing is 18 %.

Looking at the split between domestic and imported emissions, a different picture emerges. Most agriculture, forestry and fishing emissions are from domestic sources, while the vast majority of manufacturing emissions are imported.