Human rights budgeting

The way that governments raise, allocate and spend money affects how people can realise their human rights in practice. This briefing looks at how the Scottish budget might be analysed through a human rights lens. It applies the principles of human rights budgeting to a case study group of the population - people with learning disabilities.

Executive Summary

The Human Rights Act 1998 enshrines many civil and political rights into UK law. This includes the right to a fair trial and free speech.

The Scottish Government have proposed a Human Rights Bill, which would enshrine many economic, social and cultural rights into Scots law, subject to devolved competencies. These include the right to health, housing, social security and adequate standards of living.

International human rights bodies recognise that for human rights to be realised in practice, enough resources must be made available. Legislation alone does not enable everyone to realise their human rights.

Decisions made about how money is raised, allocated and spent are therefore important if governments are to meet their human rights obligations.

There is growing interest in scrutinising Scottish budget decisions through a human rights lens. Human rights budgeting (HRB) offers a tool to do this.

This briefing explains what HRB is. It sets out some of the principles and theory behind HRB, which are underpinned by international human rights law.

The briefing then explores how HRB could work in practice by using a case study group of the population as an illustrative example. The case study group is people with learning disabilities.

What is human rights budgeting?

Human rights budgeting means that decisions on how money is raised, allocated and spent are determined by the impact this has on people's rights.

Broadly speaking, there are two ways in which human rights principles can be applied to budgeting. The first relates to the process of setting a budget, the second relates to the actual content of a budget.

HRB means that the process of setting a budget should be driven by three principles.

Transparency

Parliament, civil society and the public should have accessible information about budget decisions.

Participation

Civil society and the public should have opportunities for meaningful engagement in the budget process.

Accountability

Budgets should be subject to oversight and scrutiny that ensures accountability for budget decisions and the impact these have on human rights.

HRB means that the actual content of a budget (i.e. the decisions taken around how money is raised, allocated and spent) should be in line with the government's human rights obligations. These obligations provide criteria against which to assess a budget.

Progressive realisation

Governments must take steps towards the full realisation of economic, social and cultural rights over time.

Minimum core obligations

These are the minimum protections that governments should guarantee everyone.

Non-retrogressive measures

Human rights principles state that governments should not take active steps to deprive people of rights that they used to enjoy.

Non-discrimination

All forms of discrimination must be prohibited, prevented and eliminated. This principle implies that budgets should be allocated in a way that reduces systemic inequalities.

Maximum available resources

Governments are obliged to take steps to progressively realise rights to the “maximum of its available resources”.

A human rights budgeting case study

Many people with learning disabilities are known to be far from realising their human rights, including rights on independent living, housing, social protection, accessibility and employment.

This guide analyses two key budget decisions that affect the rights of people with learning disabilities – those on adult social care and social security.

These spending lines impact multiple rights, but most obviously:

the right to an adequate standard of living and social protection

the right to live independently in the community.

In both areas, real terms funding increases might be evidence of the Scottish Government taking steps to progressively realising rights.

Spending on social care support for adults with learning disabilities rose by 11.9 per cent in the 5 years up to 2020-21, although there are concerns about the accuracy of these figures. Spending on the new Adult Disability Payment is forecast to be 22 per cent higher than the reserved benefit it replaces by 2026-27.

However, increased funding in these areas is not necessarily sufficient to meet human rights obligations.

There is evidence of potential breaches in minimum core obligations. This concerns delayed discharges, in which some people with learning disabilities are denied their right to live independently in the community and, arguably, their right to liberty.

There is also evidence of retrogressive steps being taken, as eligibility criteria for social care support has been tightened to manage funding pressures. This means some people with a learning disability who were previously eligible for support might no longer be eligible or may be charged for some services.

Wider lessons and next steps

This case study also highlighted what more information is needed to better scrutinise the Scottish budget through a human rights lens.

A process to agree a tangible measurable definition of minimum core obligations.

More detailed financial information and data about people with learning disabilities and other groups furthest from realising their human rights.

A process for gathering evidence, monitoring and reporting on human rights in Scotland. This could identify where the biggest “gaps” are between what rights exist on paper and what is realised in practice. This might help decision makers better understand where resources are most needed and how budget decisions affect human rights.

About the author

Rob Watts is a Knowledge Exchange Associate at the University of Strathclyde's Fraser of Allander Institute. His broad research areas are in poverty and inequality, labour market outcomes and learning disability policy analysis.

Rob has been working with the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) as part of its Academic Fellowship programme. This programme aims to build links between academic expertise and the work of the Scottish Parliament.

The views expressed in this briefing are the views of the author, not those of SPICe or the Scottish Parliament.

Human rights in Scotland - the basics

Human rights place an obligation on the state to respect, protect and fulfil legal protections and rights for everyone.

Though the origins of human rights in the UK date back to the Magna Carta1, the modern codification that is referred to today emerged after World War II. Since then, a number of international treaties have been drafted by the UN.

The main legal footing for human rights in the UK is the Human Rights Act 1998. This brought the European Convention on Human Rights into UK law and underpinned the devolution settlement. The Act mainly protects civil and political rights, such as the right to life, freedom of speech and a fair trial.

The UK has also signed up to international treaties on economic, social and cultural (ESC) rights, which include the right to health, housing, social security and adequate standards of living.

However, international treaties don’t automatically become domestic law, meaning that these rights have less protection than those enshrined in the Human Rights Act 1998.

There is an ongoing debate about the legal footing of ESC rights in Scotland. The Scottish Government have proposed a new Human Rights Bill that would incorporate four UN treaties into Scots law, subject to devolved competencies:

the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD)

the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD).

More information can be found in this SPICe briefing on economic, social and cultural rights and the proposed Human Rights Bill.

Major international human rights bodies recognise that, regardless of their domestic legal status, human rights are indivisible and apply to everyone. In other words, governments should not pick and choose which rights apply and to whom.

All human rights are indivisible and interdependent. This means that one set of rights cannot be enjoyed fully without the other. For example, making progress in civil and political rights makes it easier to exercise economic, social and cultural rights. Similarly, violating economic, social and cultural rights can negatively affect many other rights.

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights. (2022). What are human rights?. Retrieved from www.ohchr.org/en/what-are-human-rights#:~:text=All%20human%20rights%20are%20indivisible,economic%2C%20social%20and%20cultural%20rights.

It is also generally recognised that for human rights to be realised in practice, enough resources must be made available. In other words3, “human rights cannot be realised without resources”.

This point is especially relevant when considering ESC rights. A number of civil and political rights require the state and others to refrain from acting in a certain way, whereas many ESC rights require states to determine how financial resources should be used4.

For example, the right to adequate housing cannot be realised by passing legislation alone – it requires sufficient resources to ensure adequate housing is available to everyone.

This might include disabled people, for example, who require specialist adapted housing to live safely, which would be too expensive for many people without government support.

The universal nature of human rights and the obligations they place on the state highlight the importance of government choices in upholding rights protections for everyone.

For example, government decisions on housing regulation, social housing provision and housing benefit will in large part determine how and whether the right to adequate housing is met.

This explains why human rights – especially economic and social rights - go beyond passing laws and have implications for the Scottish budget. The decisions made in the budget, and the way these decisions are made, influence the way people realise their human rights in practice.

What is human rights budgeting?

Human rights budgeting offers a tool to assess whether enough resources are raised, allocated and spent to ensure everyone can realise all of their rights, and therefore, whether governments are meeting their human rights obligations.

The Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC) has compiled a comprehensive guide to human rights budgeting.

Broadly speaking, there are two ways in which human rights principles can be applied to budgeting. The first relates to the process of setting a budget, the second relates to the actual content of a budget.

Budget process

This element of human rights budgeting is the more straightforward. It assesses the budget process against three principles, which are based on international human rights standards:

| Transparency | Do Parliament, civil society and the public have accessible information about budget decisions? |

| Participation | Does civil society have opportunities for meaningful engagement in the budget process? Does the budget process actively engage with marginalised groups who are least likely to have their rights realised? |

| Accountability | Does the budget process include sufficient oversight to ensure accountability for budget decisions? |

Similar to these principles are the PANEL principles. These are sometimes adopted in Scottish Government policy guidance, such as in the National health and wellbeing outcomes framework.

Participation

People should be involved in decisions that affect their rights.

Accountability

There should be monitoring of how people's rights are being affected, as well as remedies when things go wrong.

Non-discrimination and equality

All forms of discrimination must be prohibited, prevented and eliminated. People who face the biggest barriers to realising their rights should be prioritised.

Empowerment

Everyone should understand their rights, and be fully supported to take part in developing policy and practices which affect their lives.

Legality

Everyone should understand their rights, and be fully supported to take part in developing policy and practices which affect their lives.

The PANEL principles are not confined to budget setting. They can also be applied to policies and practices by organisations in the public and private sector. More detail is provided in this SHRC guide to the PANEL principles and human rights based policy making.

Budget content

Human rights budgeting is also used to assess whether decisions on how to raise, allocate and spend resources (i.e.. the actual content of a budget) enable everyone to realise their human rights.

This element of human rights budgeting is more complicated and there is no single way of doing it. However, we tend to find different criteria applied to budgets when they are analysed through a human rights lens.

These criteria are based on fundamental principles that underpin a state's obligations on human rights. Examples and case studies of these criteria being used can be found in this report on budget analysis and economic and social rights.

This section explores these criteria in more detail.

Progressive realisation

Governments must take steps towards the full realisation of economic, social and cultural rights. This recognises that realising rights is a process that occurs over time.

Progressively realising rights is the central requirement of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. This obligation is continuous.

In March 2021, the National Human Rights Taskforce Leadership Report1 recommended that “an explicit duty of progressive realisation” form part of a new human rights framework for Scotland.

However, the principle of progressive realisation does give governments some leeway in meeting their obligations. For example, if a large number of its citizens live in poverty, this does not necessarily mean a government has violated its obligations on the right to an adequate standard of living.

In this case, the right would be progressively realised if the government were taking continuous action that reduced poverty rates over time.

Progressive realisation is partly designed to account for differing resource constraints. For example, the right to an adequate standard of living might mean different things in a developed country compared with a developing country – what matters is that the government takes steps to realise this right over time.

Progressive realisation can take different forms2, for example:

Increasing funding for programmes that enable rights to be realised.

Introducing new programmes.

Reducing restrictions or expanding access to certain entitlements or programmes.

Changing legislation or regulation to strengthen rights, particularly those of marginalised groups and those who are furthest from realising their human rights.

There is no one way of measuring whether ESC rights have been progressively realised. For example, progressive realisation does not necessarily need more resources if existing resources are used in the best way to fulfil human rights obligations.

It has been argued that it is the government's responsibility to demonstrate it has met its obligation to progressively realise human rights.

Budget application

Do budget decisions demonstrate a commitment to realising rights over time?

Is expenditure on realising rights increasing or decreasing?

Does the government expect outcomes to improve given the resources allocated to realising human rights?

Minimum core obligations

These are the minimum protections that governments should guarantee everyone. Sometimes minimum core obligations are thought of as the minimum requirements that people need to live with “human dignity"1.

Minimum core obligations are:

the red lines below which we do not accept that society should fall.

Dr. Hosie, A. (2021). Scottish Parliament Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee meeting minutes Tuesday, September 28, 2021. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/chamber-and-committees/official-report/search-what-was-said-in-parliament/chamber-and-committees/official-report/what-was-said-in-parliament/ehrcj-28-09-2021?meeting=13338&iob=121030

Minimum core obligations are not separate rights in themselves. They are elements of a right that should be universally guaranteed immediately. Taking the right to adequate food as an example, ensuring freedom from malnutrition might be considered a minimum core obligation.

Whilst governments must take steps to progressively realise rights on a continuing basis, they must deliver minimum core obligations immediately. Resource constraints cannot be used as a reason for not delivering minimum core obligations.

However, there is little agreement3 on how to define minimum core obligations in practice. To help with this, UN Treaty Bodies provide General Comments. UN Treaty Bodies are committees of independent experts that monitor the implementation of human rights treaties. To some extent, their General Comments interpret the meaning of human rights treaties in practice.

There is ongoing debate as to whether the minimum core obligations in a developed country should be the same as those in a developing country.

Budget application

Do budget decisions provide enough resources for governments to meet their minimum core obligations?

Non-retrogressive measures

This principle states that governments must not take active steps to deprive people of rights that they used to enjoy.

If a government's budget decisions directly deprive people of economic, social or cultural rights that were previously realised, then it should justify why these decisions were unavoidable.

Budget application

Do budgets include decisions that are likely to reverse rights realisation over time?

If so, can the government demonstrate that all possible measures have been taken to avoid a retrogressive step?

Non-discrimination

All forms of discrimination must be prohibited, prevented and eliminated. This principle implies that budgets should be allocated in a way that reduces systemic inequalities.

Governments can demonstrate this commitment by assessing the distributional impact of their budget decisions before finalising them. Publishing this assessment can provide transparency in line with the principles around the budget process set out above.

The principle of non-discrimination might mean that people who face the biggest barriers to realising their rights should be prioritised.

Budget application

What is the distributional impact of budget decisions?

Do budget decisions have a discriminatory impact on different groups of the population?

Do budget decisions help reduce structural inequalities?

Maximum available resources

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights requires states to take steps to progressively realise rights to the “maximum of its available resources”.

This means that when considering ESC rights, governments must mobilise all available resources within their jurisdiction. For example, if government spending on realising ESC rights falls relative to GDP, this might indicate that the steps a government takes to realise human rights are not taken to the maximum of its available resources.

This principle is independent of economic growth. States should

devote maximum available resources to ensure the progressive realisation of ESC rights … even during times of severe resource constraints.

Sepúlveda, M. (2017). The obligation to mobilise resources: Bridging human rights, sustainable development goals, and economic and fiscal policies. International Bar Association. doi: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327755947_The_Obligation_to_Mobilise_ResourcesBridging_Human_Rights_Sustainable_Development_Goals_and_Economic_and_Fiscal_Policies

In practice, it can be difficult to calculate what “maximum” available resources means. Beyond this wording, there is no concrete definition2.

Budget application

Do budget decisions raise enough revenue to fund rights realisation?

If not, could the more resources be allocated to ensure rights realisation?

Assessing human rights and budget decisions

It is not always clear whether a right has been protected and fulfilled. To help with this, criteria have been developed1 based on international human rights law.

Adequacy

Human rights law often uses the word “adequate”. For example, International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights refers to an “adequate” standard of living and “adequate” housing. Budget decisions should be adequate to enable human rights to be realised.

Affordability

Do budget decisions make access to ESC rights more affordable? For example, health, education and housing are ESC rights, so we can assess if budget decisions have made these more affordable.

Accessibility

Do budget decisions mean everyone is able to access their human rights? For example, are marginalised groups able to access public services and social protection?

It is worth noting that no government has formally applied the principles of human rights budgeting either to its budget process or to the content of budgets themselves. However, there are examples2 of human rights budgeting being used by civil society to assess whether a state is meeting its human rights obligations.

These examples show that the field of human rights budgeting is still developing. When academics reviewed previous analyses2, they identified three limitations around human rights budgeting that need to be addressed.

Unavailability of data.

Vagueness of ESC rights principles and a lack of objective benchmarks to assess compliance with human rights obligations.

A lack of technical expertise on human rights across governments and civil society.

The measures of compliance seem somewhat ad hoc and incomplete. For example, is growing expenditure on an ESR area in and of itself sufficient evidence of compliance with progressive realisation? Does progressive realisation have to be considered in terms of outcomes, that is, the extent to which the expenditure contributes to the enjoyment of the right? …

One of the measures of compliance refers to ‘adequate funding for regulatory bodies’ … it is not clear what level of funding would qualify as ‘adequate’ in terms of international human rights law.

Rooney, E., Nolan, A., O'Connell, R., Dutschke, M., & Harvey, C. (2010). Budget Analysis and Economic and Social Rights: A Review of Selected Case Studies and Guidance. Queen University Belfast. doi: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1695992

The Scottish budget and human rights

This section presents information about the current Scottish budget process and how it relates to human rights.

Budget process

The Open Budget Survey uses internationally accepted criteria1 to assess a government’s budget process in line with the three principles set out above. It is compiled annually by the International Budget Partnership of budget analysts.

As a devolved administration, the Scottish Government's budget is not included in the annual survey. However, in 2019 SHRC replicated this assessment2 for the Scottish Government's budget process for the 2017-18 budget. Their findings are summarised below.

| Transparency | Public participation | Budget oversight / accountability |

| Scotland provides the public with limited budget information | Scotland provides the public with few or no chances to engage with the budget process | Scotland provides adequate oversight of the budget |

| Scotland: 43 | Global average: 14 | Global average: 54 |

| Global average: 45 | Scotland: 20 | OECD average: 74 |

| UK: 70 | OECD average: 27 | UK: 74 |

| OECD average: 71 | UK: 61 | Scotland: 85 |

Recommendations for improvement included:

a year-round budget process with budget documents published at different stages of the budget cycle

the publication of a Citizens Budget with accessible information about budget decisions

more opportunities for meaningful public engagement built into the budget process

active engagement from the Scottish Government with vulnerable and marginalised groups in this process

better quality feedback on participation in the process.

Since this assessment was conducted, steps have been taken to change the Scottish budget process3. This was largely in response to the devolution of further tax and welfare powers in 2016, which increased the need for scrutiny of budget decisions.

For example, the Open Government Action Plan has committed the Scottish Government to “improve the accessibility and usability of information about the public finances”.

As part of this, the Scottish Exchequer has launched the Discovery project around fiscal transparency. However, there are no current plans for SHRC or the Scottish Government to repeat the Open Budget Survey assessment based on the updated budget process.

Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statements

Alongside each budget, the Scottish Government publishes an Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement (EFSBS). This is the Scottish Government's assessment of how its budget decisions will affect equality in Scotland. It is an important document when considering how human rights are affected by the Scottish budget.

In the most recent EFSBS, the Scottish Government:

describes how its budget will impact equality and on groups with different protected characteristics

provides evidence on inequality of outcomes for each budget area and how Scottish Government spending is expected to impact these inequalities

identifies the key risks to meeting its desired national outcomes around equality and how the Scottish Government is responding to each risk.

It also assigns “key human rights” to each budget area. For example, Finance and the Economy is designated:

The right to work.

The right to an adequate standard of living.

Rights for women, minority ethnic groups, disabled people, children.

Beyond this, there is little assessment of whether budget decisions enable these human rights to be realised. For example, there is no assessment in line with human rights budgeting principles set out in the previous section, What is human rights budgeting?.

The EFSBS is almost entirely focused on the impact of government spending, with very little analysis of the impact of decisions around tax. For example, there is no assessment of whether sufficient tax revenue is raised to enable human rights to be progressively realised.

The Scottish Parliament has devolved tax raising powers that generated around 35 per cent of tax revenue raised in Scotland in 2021-221.

Perhaps most importantly, there is no clear evidence that equality and human rights considerations influence Scottish Government budget decisions.

There is little evidence that the EFSBS document or process influence budget decisions, and equality and human rights budgeting are not yet fully embedded into Scottish Government’s budget process.

Scottish Government. (2021). Equality Budget Advisory Group: recommendations for equality and human rights budgeting - 2021-2026 parliamentary session. Retrieved from http://www.gov.scot/publications/equality-budget-advisory-group-recommendations-for-equality-and-human-rights-budgeting---2021-2026-parliamentary-session/pages/executive-summary/

Budget content

There is no regular formal assessment of Scottish budget decisions in line with the criteria on budget content set out above.

However, there are public bodies and processes that could provide the infrastructure to support this element of human rights budgeting in Scotland.

Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC)

The Scottish Human Rights Commission is an independent public body accountable to the Scottish Parliament. It has a general duty to promote awareness, understanding and respect for all human rights in Scotland.

Scotland’s National Action Plan for Human Rights (SNAP)

The UN recommends that all countries develop a plan to improve the way human rights are realised and protected. Scotland's National Action Plan for Human Rights was developed following the creation of SHRC.

It assesses where rights are not being realised and identified actions to change this. It is based on available evidence, a national participation process and input from civil society and public sector leaders. However, it does not link to the budget process. SNAP 2 is currently in development.

Centre of Expertise in Equality and Human Rights

In May 2022, the Scottish Government announced a new Centre of Expertise that will be part of the Office of the Chief Economic Adviser. It will link human rights with economic policy making.

Details are still emerging, but the Scottish Government have stated that the new Centre will:

... share examples of good practice more effectively across government. There will be an ongoing training programme to equip policy officials with the skills and knowledge they need.

Scottish Government press release. (2022). Tackling inequalities through economic recovery. Retrieved from http://www.gov.scot/news/tackling-inequalities-through-economic-recovery/

National Performance Framework (NPF)

The National Performance Framework sets out the Scottish Government's priorities and how it measures progress towards achieving these. It includes a commitment to “respect, protect and fulfil human rights”.

Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement (EFSBS)

The Scottish Government publishes an EFSBS alongside each budget to assess the impact of its budget on equality and human rights (see above).

People with learning disabilities and human rights in Scotland

To examine how human rights budgeting might work in practice, we have applied the principles above to a case study group of the population. We have chosen people with learning disabilities because they are a group that is known to be far from realising their economic, social and cultural rights.

This guide sets out some human rights issues faced by many people with learning disabilities that relate to ESC rights and budget decisions, although it is not meant as an exhaustive list.

What is a learning disability?

The Scottish Government’s Keys to Life strategy defines a learning disability as:

A learning disability is significant and lifelong. It starts before adulthood and affects the person's development. This means that a person with a learning disability will likely need help to understand information, learn skills and have a fulfilling life. Some people with a learning disability also have healthcare needs and require support to communicate.

Scottish Government. (2013). The Keys to Life. Retrieved from http://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2013/06/keys-life-improving-quality-life-people-learning-disabilities/documents/keys-life-improving-quality-life-people/keys-life-improving-quality-life-people/govscot%3Adocument/00424389.pdf

Sometimes, learning disability is confused with learning difficulties2, such as dyslexia or ADHD:

A person with a learning difficulty may be described as having specific problems processing certain forms of information … whereas a learning disability is linked to an overall cognitive impairment.

Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities. (2022). Learning difficulties. Retrieved from http://www.learningdisabilities.org.uk/learning-disabilities/a-to-z/l/learning-difficulties

A learning disability is not a medical condition in itself. Rather, it is a term used to describe a number of impairments that meet the definition above.

The Fraser of Allander Institute notes that:

people who are living with a learning disability will not have necessarily received a diagnosis of a condition which fits neatly into a ‘learning disability’ box.

Fraser of Allander Institute, University of Strathclyde

Not everyone with a learning disability will identify as such.

This means that it is not clear how many people in Scotland have a learning disability.

Human rights concerns

In 2016, the Scottish Commission for People with Learning Disabilities (SCLD) identified key human rights concerns facing people with learning disabilities in Scotland. This was detailed in SCLD's response to the British Institute of Human Rights call for evidence. An updated human rights assessment will soon be available as part of the UN's Universal Periodic Review process.

SCLD's concerns were focused on 6 Articles of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, with examples of issues that these relate to.

The right to equality (Article 5)

E.g. discrimination faced in daily life, such as hate crime, lack of agency over living arrangements and support.

The right to accessibility (Article 9)

E.g. inaccessible public information, physical environment, transport, digital exclusion.

The right to independent living (Article 19)

E.g. quality and availability of social care services, lack of choice over where a person lives and who they live with.

The right to home and family life (Article 23)

E.g. lack of support through parenthood.

The right to work and employment (Article 27)

E.g. barriers to accessing the labour market and lack of support in the workplace.

The right to an adequate standard of living and social protection (Article 28)

E.g. people with disabilities are more likely to live in poverty.

A key area of the Scottish budget that is repeatedly raised is social care support. This was also the case in the Fraser of Allander Institute's research series on adults with learning disabilities in Scotland. It is social care support

that enables [people with learning disabilities] to live fulfilling and independent lives.

Fraser of Allander Institute, University of Strathclyde

What does evidence tell us?

On average, people with learning disabilities experience worse economic, health and social outcomes than the general population. All of these outcomes link to economic, social and cultural rights.

People with learning disabilities have a life expectancy 20 years lower than the general population1.

The most recent (2019) SCLD population survey found that between 4 and 8 per cent of local authorities’ learning disability service users were in employment. This is far lower than the employment rate for the general population or for those with disabilities. There is no widely available employability service that offers tailored support to people with learning disabilities in Scotland.

Many people with learning disabilities, including those with complex needs, are in hospitals despite no medical need to be there, denying them the right to live independently in the community.

The 2018 Coming Home report found 705 out-of-area placements, meaning that individuals are located away from their family and community because no suitable placement is available in their area.

Furthermore, 67 people were identified as being subject to delayed discharge. This is where an individual has been kept in hospital because no suitable care package could be provided for them to live safely in their community.

More than 22 per cent had been in hospital for over 10 years, and another 9 per cent for five to ten years. The main barrier to discharge was:

lack of accommodation, followed by lack of suitable service providers.

Coming Home report, Scottish Government

Research by the Scottish Learning Disabilities Observatory estimated that 75 per cent of people with learning disabilities have experienced hate crime.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, an SCLD survey of people with learning disabilities found 66 per cent of respondents had seen a reduction or complete withdrawal of social care support.

Interviews and focus groups conducted in the Fraser of Allander Institute's research on social care for adults with learning disabilities reported:

fears that support will not return post-pandemic at the same level it was before.

Fraser of Allander Institute, University of Strathclyde

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, people with learning disabilities in Scotland were twice as likely to become infected than the general population2. They were three times more likely to die from COVID-19.

There are also many areas where data is unavailable or incomplete. This makes it harder to assess whether the economic, social and cultural rights of people with learning disabilities are being upheld.

The Fraser of Allander Institute's report on data collected on people with learning disabilities concluded that:

overwhelmingly, we have found that the evidence on which to base effective policy to improve the outcomes for people living with a learning disability is severely lacking.

Fraser of Allander Institute, University of Strathclyde

This means that when budgets decisions are taken that affect people with learning disabilities, it is not clear what the impact will be on their ability to realise their economic, social and cultural rights.

Scottish Government strategies

In 2013, the Scottish Government published the Keys to Life strategy for people with learning disabilities. This was updated with a Keys to Life Implementation Framework in 2019. In March 2021, it published a Learning Disability and Autism: Transformation Plan.

The strategic outcomes the Scottish Government have aimed to meet are based around four themes.

A Healthy Life

People with learning disabilities enjoy the highest attainable standard of living, health and family life.

Choice and control

People with learning disabilities are treated with dignity and respect, and are protected from neglect, exploitation and abuse.

Independence

People with learning disabilities are able to live independently in the community with equal access to all aspects of society.

Active citizenship

People with learning disabilities are able to participate in all aspects of community and society.

These strategy documents all state that respecting human rights is a central goal of the Scottish Government's approach towards learning disability. However, there is no assessment of the funding required to deliver the strategy.

Also, there is no assessment of whether existing infrastructure, such as the social care system, is sufficiently funded to progressively realise the human rights of people with learning disabilities. This might be an example of where human rights budgeting could be useful.

In addition, there are plans in place for new legislation that will affect the rights of people with learning disabilities:

Human Rights Bill

Part of this legislation might incorporate elements of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCPRD) into Scots law, subject to devolved competencies.

National Care Service Bill

The National Care Service (Scotland) Bill restructures Scotland's social care system and places accountability with government ministers, rather than local authorities. Social care covers a range of support that enables people with learning disabilities to realise their human rights. This includes the right to live independently and the right to adequate housing, amongst others.

Learning Disability, Autism and Neurodiversity Bill

The scope of this legislation is not yet determined. Currently, treatment and care for people with learning disabilities falls under the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003. However, autism and learning disabilities are not mental health conditions.

In 2019, the Independent Review of Learning Disability and Autism in the Mental Health Act recommended that:

learning disability and autism are removed from the definition of mental disorder in the Mental Health Act [and that] a new law is created to support access to positive rights, including the right to independent living.

Independent Review of Learning Disability and Autism in the Mental Health Act

The introduction of this bill is expected during this parliamentary term. It is expected that the legislation would also introduce a Learning Disability, Autism and Neurodiversity Commissioner to “champion” the new legislation.

Human rights budgeting - a case study

The previous section, What is human rights budgeting?, sets out a series of questions that link to HRB principles. To demonstrate what human rights budgeting means in practice, we have applied these questions to the Scottish budget. For illustrative purposes, we have built the case study around one group of the population – people with learning disabilities.

Budget process

This section explores the Scottish budget process and human rights principles by applying them to people with learning disabilities.

Transparency

Do people with learning disabilities have accessible information about budget decisions?

People with learning disabilities often require support to understand and process information, such as budgeting decisions. This might include easy read versions of public documents. No easy read versions of budget documents are currently published alongside the Scottish budget.

The SHRC Open Budget Survey assessment1 of the Scottish budget process recommended the publication of a Citizens Budget document to present information in an accessible way. No such document is currently produced alongside the budget.

Participation

Do people with learning disabilities have opportunities for meaningful engagement in the budget process?

People with learning disabilities and organisations that represent them are able to participate in budget consultations. These form part of the year-round budget process and enable citizens and civil society to feed into the decision making process.

To ensure consultations are inclusive of people with learning disabilities, sufficient time is needed for meaningful responses to be submitted. Also, information about the consultations must be published in accessible formats.

In its response to the Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee's 2023-24 pre-budget scrutiny consultation, SCLD argued that:

creative approaches to increase the involvement of people with learning disabilities will need to be utilised. In practice, this will involve going beyond one-off consultation events to ensuring groups of people who are marginalised, including people with learning disabilities, have a leading role in the development of budget processes.

Scottish Commission for People with Learning Disabilities

Accountability

Does the budget process include sufficient oversight to ensure accountability for budget decisions?

The Scottish Parliament has opportunities to scrutinise decisions made in the Scottish budget as part of the year-round budget process. The SHRC Open Budget Survey assessment scored the Scottish budget process highly for oversight and accountability.

There are parliamentary committees that are dedicated to scrutinising Scottish budget decisions with a particular focus on issues that might be of relevance to people with learning disabilities. This includes committees on:

Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice.

Health, Social Care and Sport.

Social Justice and Social Security.

However, it is difficult for people with learning disabilities and organisations that represent them to feedback, scrutinise and ask questions about budget decisions if information is not published in an accessible and timely manner.

Budget content

All decisions around the content of a budget will have some impact on the human rights of people with learning disabilities. However, to illustrate how human rights budgeting might work in practice, the most directly relevant decisions have been analysed here.

Stakeholder groups have indicated that spending decisions on adult social care and social security have a significant impact on people with learning disabilities. Arguably, the most relevant human rights articles in the UNCRPD that apply are set out in the box below.

Article 19 of the UNCRPD is of particular relevance to budget decisions around adult social care because social care support often enables the right to live independently to be realised. It delivers care packages that support people with learning disabilities to live safely in the community.

It could be argued that the right to health (UNCRPD Article 25) is also relevant in this case study. This is because the social care system delivers essential forms of care, such as personal care, aimed at keeping people healthy.

Article 28 of the UNCRPD is of particular relevance to budget decisions on social security because many people with learning disabilities do not have the opportunity to earn income through employment. This means that social security income is a route to enabling the realisation of their right to an adequate standard of living and social protection.

UNCRPD Article 19

The right to live independently and be included in the community

States Parties to the present Convention recognize the equal right of all persons with disabilities to live in the community, with choices equal to others, and shall take effective and appropriate measures to facilitate full enjoyment by persons with disabilities of this right and their full inclusion and participation in the community, including by ensuring that:

a) Persons with disabilities have the opportunity to choose their place of residence and where and with whom they live on an equal basis with others and are not obliged to live in a particular living arrangement;

b) Persons with disabilities have access to a range of in-home, residential and other community support services, including personal assistance necessary to support living and inclusion in the community, and to prevent isolation or segregation from the community;

c) Community services and facilities for the general population are available on an equal basis to persons with disabilities and are responsive to their needs.

UNCRPD Article 28

The right to an adequate standard of living and social protection, including the right to housing and social security

1. States Parties recognize the right of persons with disabilities to an adequate standard of living for themselves and their families, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions, and shall take appropriate steps to safeguard and promote the realization of this right without discrimination on the basis of disability.

2. States Parties recognize the right of persons with disabilities to social protection and to the enjoyment of that right without discrimination on the basis of disability, and shall take appropriate steps to safeguard and promote the realization of this right, including measures:

a) To ensure equal access by persons with disabilities to clean water services, and to ensure access to appropriate and affordable services, devices and other assistance for disability-related needs;

b) To ensure access by persons with disabilities, in particular women and girls with disabilities and older persons with disabilities, to social protection programmes and poverty reduction programmes;

c) To ensure access by persons with disabilities and their families living in situations of poverty to assistance from the State with disability-related expenses, including adequate training, counselling, financial assistance and respite care;

d) To ensure access by persons with disabilities to public housing programmes;

e) To ensure equal access by persons with disabilities to retirement benefits and programmes.

Of course, there are many other human rights articles that are of particular concern to people with learning disabilities. These include, but are not limited to, the right to accessibility (UNCRPD Article 9), the right to liberty and security of person (UNCRPD Article 14) and the right to participation in political and public life (UNCRPD Article 29).

Because these have a less direct link to budget decisions, these have not been included in this illustrative case study.

Progressive realisation

Do budget decisions demonstrate a commitment to realising rights over time? Is expenditure on realising rights increasing or decreasing? Does the government expect outcomes to improve given the resources allocated to realising human rights?

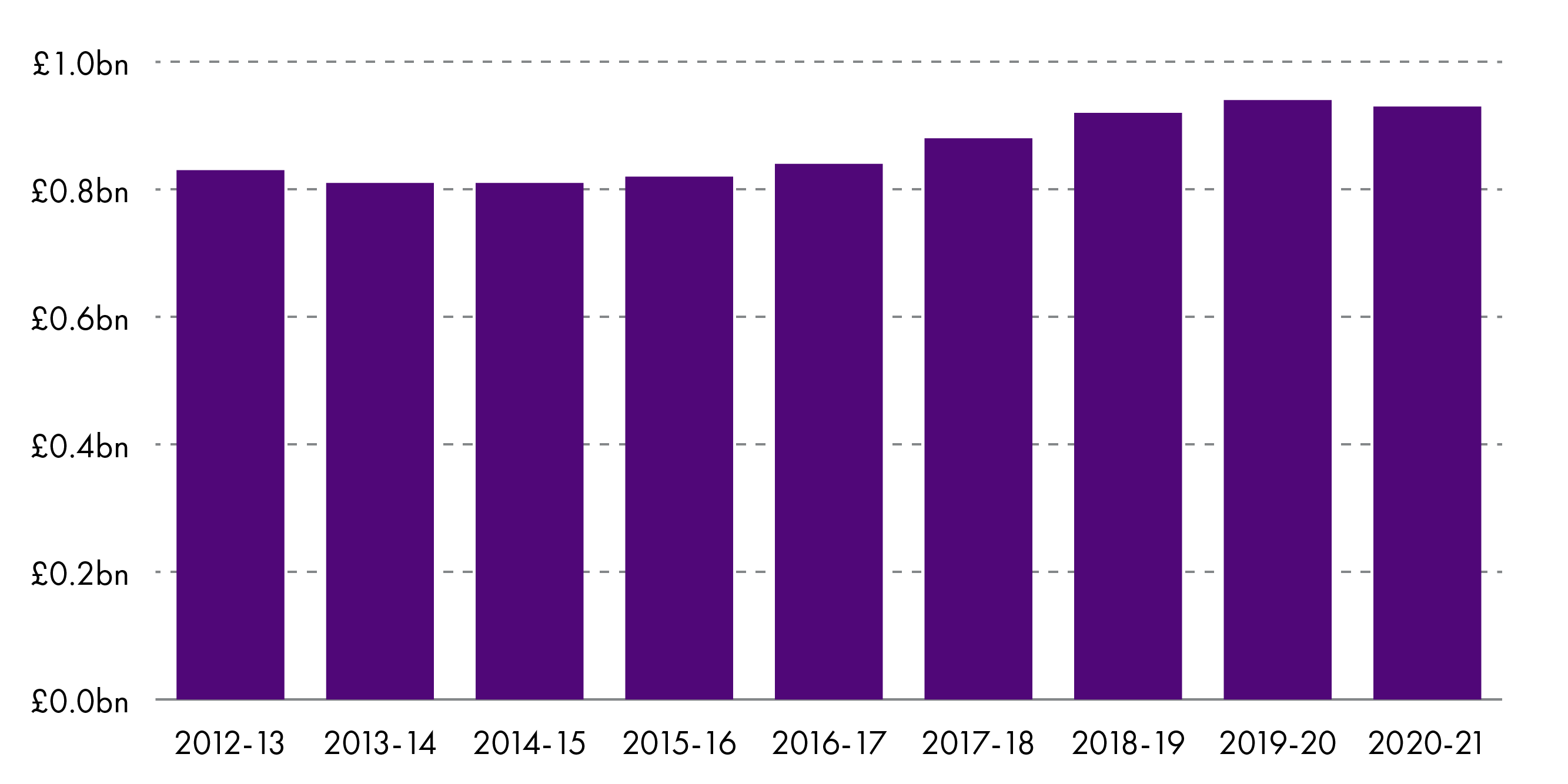

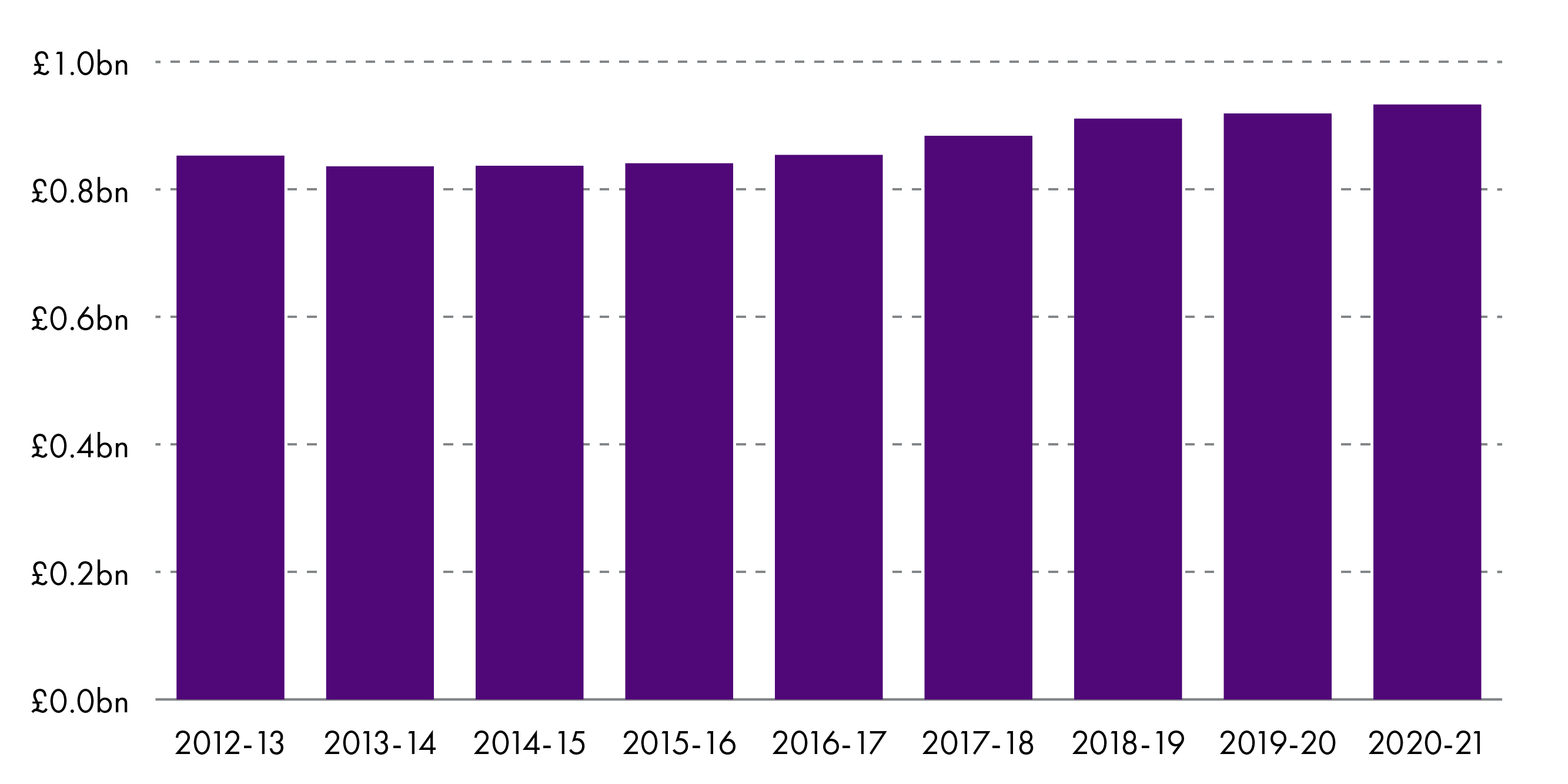

Data from local authorities1 shows that spending on social care support services for adults with learning disabilities in Scotland increased by 11.9 per cent in real terms over the five years up to 2020-21. This uses the most recently available published data.

It should be noted that there are concerns about the quality of financial data on social care spending on adults with learning disabilities. This is because it is difficult for local authorities to determine which “client group” (e.g. adults with learning disabilities, older persons, adults with mental health needs) money has been spent on. A recent Scottish Government consultation on the relevant local government financial statistics provides more detail.

The cost of delivering social care has risen faster than average inflation2. This means that to deliver the same services, higher cash increases are required than the economy-wide measure of inflation would suggest.

If we use a more sector-specific measure of inflation (see page 146 of the Unit Costs of Health and Social Care report for the Personal Social Services (PSS) Pay & Prices index), the real terms increase in spending over five years is 9.2 per cent.

Regardless of the measure of inflation used, there is an increase in funding over time. This increased funding could be seen as evidence of budget decisions that enable progressive realisation of the rights in question.

However, it is not clear what outcomes for people with learning disabilities are intended to be achieved with this increased funding and how these relate to human rights. The evidence presented in What does evidence tell us? shows little change in outcomes over time.

The most significant devolved benefit that supports people with learning disabilities is the Adult Disability Payment (ADP), which is replacing its reserved counterpart, Personal Independence Payment (PIP). Data from DWP Stat-Xplore shows that as of April 2022, there were 14,788 PIP recipients in Scotland denoted under the category “Learning Disability”.

By 2026-27, spending on this benefit is expected to increase by 22 per cent (£528 million) compared with the existing reserved benefit that it replaces (Personal Independence Payment). These figures come from the independent Scottish Fiscal Commission's August 2021 forecasts and is based on the best available evidence.

The expected increase in spending on ADP occurs because the application process will ask applicants to provide fewer pieces of evidence about their disability.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission therefore expect more successful applications than would be the case if the existing PIP application process was used. They also expect the lower evidence burden to attract more applicants in the first place. The combination of more applications and a higher reward rate result in higher expected expenditure than would be the case if PIP were retained.

This increased funding could be seen as budget decisions that support the progressive realisation of the right to an adequate standard of living and social protection for people with learning disabilities.

Expanding entitlement to existing programmes that enable human rights is an example of progressive realisation. However, for those already in receipt of PIP or ADP, the payment amount is not increasing compared with PIP.

Minimum core obligations

Do budget decisions provide enough resources for governments to meet their minimum core obligations?

It is difficult to assess whether the Scottish Government has met its minimum core obligations without agreement across Parliament and civil society of what these mean in practice.

This prompts a question for the Scottish Government – how can it be known whether the government is meeting its minimum core obligations without a shared understanding of what they are?

Minimum core obligations imply that there is a minimum floor of standards around economic, social and cultural aspects of life that everyone is entitled to. It points to these minimum standards as being a right, not an objective to aspire to within a given budget.

This implies that resources should be found to meet these minimum core obligations immediately. However, it is difficult to assess whether sufficient funding is in place without agreement on what these obligations are in practice and how these can be tangibly measured.

The previous section, What does evidence tell us?, does provide an example of how budget decisions might have breached minimum core obligations.

Many people with learning disabilities are in hospital (some for over ten years) despite no medical need to be there. Many have out-of-area placements away from their families and communities. This restricts their liberty and right to live independently in the community, and is arguably a minimum core issue.

Article 19 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) states that persons with disabilities should:

have the opportunity to choose their place of residence and where and with whom they live on an equal basis with others and are not obliged to live in a particular living arrangement.

UNCRPD

The main barriers to repatriation reported1 by health and social care partnerships were a lack of suitable accommodation and a lack of skilled service providers. Funding was also reported as an issue.

This raises a question over whether social care services for adults with learning disabilities and those with complex needs are sufficiently funded to meet minimum core obligations, or whether redeployment of resources would be sufficient. Assessing this question would be a good example of how human rights budgeting could be useful.

It also demonstrates that human rights principles can be applied not only to the Scottish Government’s budget, but also to policy making in general.

Non-retrogressive measures

Do budgets include decisions that are likely to reverse rights realisation over time?

There is no clear evidence of retrogressive measures being taken towards people with learning disabilities in the most recent Scottish budget. This implies that Scottish budget decisions have met this principle of human rights budgeting.

However, the Fraser of Allander Institute's report on the social care system for adults with learning disabilities presents evidence that some social care support that was withdrawn during the COVID-19 pandemic has not returned in full.

Furthermore, research by the Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland presents evidence that over the last decade or so, eligibility criteria for social care support has been tightened in order to manage budget constraints. This means that some people with learning disabilities who would previously have accessed support are no longer eligible. This will affect their right to live independently in the community.

As the new National Care Service is established, it remains to be seen whether eligibility criteria will be applied uniformly across the country and whether these will be relaxed.

Non-discrimination

What is the distributional impact of budget decisions? Do budget decisions have a discriminatory impact on different groups of the population? Do budget decisions help reduce structural inequalities?

It is difficult to assess the distributional impact of Scottish budget decisions on people with learning disabilities without household income data that specifies whether a household member has a learning disability.

Economic statistics do report income data where a household member has a disability, but this is not disaggregated to indicate whether this is a learning disability.

Maximum available resources

Do budget decisions raise enough revenue to fund rights realisation?

Scottish Government strategies on learning disabilities discuss the importance of human rights but do not assess the resources needed to realise them in practice. This makes it difficult to assess whether sufficient revenue is raised in the budget.

On the one hand, spending on social care and social security that will benefit people with learning disabilities is rising in real terms. On the other hand, there is evidence that minimum core obligations may have been breached partly due to funding constraints (see above) and there is not clear evidence of economic or health outcomes improving for everyone with a learning disability.

Whilst SCLD population statistics are compiled, there is no regular assessment of whether outcomes that are linked to the full range of economic, social and cultural rights are improving for people with learning disabilities.

Such an assessment might, for example, report on economic living standards, as well as a range of outcomes around health, education and housing.

Without such assessment against tangible, measurable outcomes, it is difficult to assess whether Scottish budget allocations enable ESC rights of people with learning disabilities to be progressively realised.

If the Scottish Government concluded that its budget were not sufficient to enable this, it has scope to raise additional revenue using its devolved tax powers.

The Scottish Parliament has powers to set the rates and bands for non-savings non-dividend income tax, as well as council tax, non-domestic rates, land and buildings transaction tax and landfill tax. Around 35 per cent of tax revenue raised in Scotland came from devolved taxes in 2021-221.

The distributional impact of tax rises would need to be analysed in order to assess their compliance with human rights principles (e.g. non-discrimination).

What further information would be useful?

This case study example of how human rights budgeting could be used for the Scottish budget has been based on available information. There are four key areas where more information would have been useful.

1. Scottish Government strategies around learning disabilities recognise the relevance and importance of human rights, but there is no assessment of the resources needed to realise them. This would be useful when assessing whether Scottish budget allocations are adequate to progressively realise the human rights of people with learning disabilities.

2. A report by the Fraser of Allander Institute argues that learning disabilities are often “invisible” in public data. For example, there is no household level income data for households where someone has a learning disability. This makes it difficult to assess whether people with learning disabilities realise their human rights.

Across economic, social and cultural life, data is routinely collected by public authorities on people with disabilities. However, this is not often disaggregated to tell us about the experience of people with learning disabilities. Disaggregated data is a requirement of Article 31 of the UNCRPD.

When discussing data collection with the Scottish Parliament's EHRCJ Committee, Emma Congreve of the Fraser of Allander Institute observed:

We often just use headline aggregations of disability or ethnic minority, although that gives very little insight into the reality that people with different characteristics face. Somebody with a physical disability experiences life in a very different way from someone with a learning disability, but, in the data that we have, we often do not have the ability to disaggregate that data.

Emma Congreve, Fraser of Allander Institute

3. There is little agreement on what minimum core obligations are in practice. Tangible, measurable outcomes that should be delivered as a minimum would help with scrutiny of budget decisions from a human rights perspective. Without them, it is not possible to objectively measure whether human rights obligations are being met. These could be informed by regular evidence based reviews of the human rights landscape in Scotland, which identify where the biggest “gaps” are between what rights exist on paper and what rights are realised in practice.

4. There are concerns about the quality of financial data on social care spending apportioned to different “client groups” (see above).

Like any assessment of Scottish budget decisions, this case study does not analyse the significant impact that the UK budget has on human rights in Scotland.

Wider lessons and next steps for human rights budgeting in Scotland

This section explores how human rights budgeting might be developed as a useful tool in scrutinising the Scottish budget.

Agreement on minimum core obligations

The previous section, Minimum core obligations, highlights the need for a shared understanding of what minimum core obligations are in practice. In March 2021, the National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership recommended that:

there be a participatory process to define the core minimum obligations of incorporated economic, social and cultural rights

National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership

In order to meet this recommendation, there needs to be a process for reaching a shared understanding of minimum core obligations (MCOs).

Human rights obligations apply at all times, so any agreement must be able to withstand a change of government. Therefore, agreement would need to be based on a broad nationwide consensus.

Any consensus would need to consider two key questions1:

1. Should minimum thresholds be relative or universal?

I.e. should the Scottish Government's minimum core obligations change as economic conditions change or remain fixed? Should they be the same as those in a developing country or be more advanced because Scotland is a wealthy nation?

2. Should the obligations be procedural and/or substantive?

Substantive MCOs mean the Scottish Government would be obliged to achieve certain outcomes relating to ESC rights. On the right to health, for example, this could mean an obligation to ensure every citizen has access to a minimum standard of medicines and facilities.

Procedural MCOs would place obligations on the Scottish Government's conduct relating to ESC rights. For example, it might be obliged to develop a national health strategy through a participatory and transparent process.

Assessing the human rights landscape in Scotland

Human rights budgeting would be a more powerful tool if it were clearer where the biggest “gaps” are between what rights exist on paper and what rights are realised in practice.

For this to occur, a process for gathering evidence, monitoring and reporting on human rights obligations might be needed. It could bring a more systematic approach to human rights budgeting in Scotland.

This might help decision makers understand where action needs to be taken, whether budget decisions have a role to play and, if so, where resources would be most efficiently allocated to improve peoples’ lived experience of their human rights.

The National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership also recommended that:

Further consideration should be given to the development and strengthening of effective monitoring and reporting mechanisms at all levels and duties at both national and public authority levels, recognising that this will be important to secure better compliance with the framework. It should include consideration of a National Mechanism for Monitoring, Reporting and Implementation.

National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership

Knowledge and expertise on human rights obligations

Human rights place obligations on governments that cut across all areas of public policy. To comply with these obligations, there must be a shared understanding across government of what they are.

This requires knowledge, expertise and detailed guidance on human rights across different layers of government.

Available information

What further information would be useful? sets out where additional information would have been useful for human rights budgeting in this specific case study example. More broadly, Audit Scotland's report on Scotland's public finances in 2022-23 and the impact of Covid also noted that the link between spending and desired outcomes is not always clear.

This conclusion might be applied to outcomes relating to economic, social and cultural rights. Human rights principles state that budget documents should clearly demonstrate the decisions taken by governments and how they enable the realisation of human rights.

Abbreviations

| ADP | Adult Disability Payment |

| CEDAW | Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination |

| CERD | Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination |

| DWP | Department of Work and Pensions |

| EFSBS | Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement |

| EHRJC Committee | Equality Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee |

| ESC rights | Economic social and cultural rights |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| HRB | Human rights budgeting |

| ICESCR | International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights |

| MCO | Minimum core obligation |

| NPF | National Performance Framework |

| PANEL principles | The principles of Participation, Accountability, Non-discrimination and equality, Empowerment and Legality |

| PIP | Personal Independence Payment |

| SCLD | Scottish Commission for People with Learning Disabilities |

| SHRC | Scottish Human Rights Commission |

| SNAP | Scottish National Action Plan for Human Rights |

| UNCRPD | United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities |